Abstract

Today, the growth of the cosmetic industry and dramatic technological advances have led to the creation of functional cosmetical products that enhance beauty and health. Such products can be defined as topical cosmetic drugs to improve health and beauty functions or benefits. Implementing nanotechnology and advanced engineering in these products has enabled innovative product formulations and solutions. The search included organic molecules used as cosmeceuticals and nanoparticles (NPs) used in that field. As a result, this document analyses the use of organic and inorganic particles, metals, metal-oxides, and carbon-based particles. Additionally, this document includes lipid and nanoparticles solid lipid systems. In conclusion, using NPs as vehicles of active substances is a potential tool for transporting active ingredients. Finally, this review includes the nanoparticles used in cosmeceuticals while presenting the progress made and highlighting the hidden challenges associated with nanocosmeceuticals.

1 Introduction

As humans, it is natural to pursue beauty. The use of products to improve skin health has been consistent throughout history. Previously, natural ingredients such as milk, citric fruits, and clay were used [1]. Since 1986, when Christian Dior´s company developed the first cosmetic using a nanocarrier technology through a liposome system, a nanotechnology market emerged [2], and it is expected to exceed US$ 125 billion by 2024 [3].

Cosmeceuticals are products aiming to improve beauty using ingredients that offer health benefits. The concept was coined by Kligman, combining cosmetics and pharmaceuticals, in 1984 [4]. They are multifunctional products that deliver active pharmaceutical ingredients to repair or improve the skin [5]. They are applied to the skin as cosmetics but contain ingredients that contribute to the biological process of the skin [6]. New advances and growth in the cosmetic industry have created beauty-enhancing products and a functional pharmaceutical role.

There are many properties that cosmeceuticals can offer to obtain healthy skin, such as anti-aging and anti-wrinkle, among others [7]. However, retaining the unique functional characteristics of active compounds, particularly those that help promote frequent dermal absorption, is a question that requires better formulation. The implementation of nanoparticles (NPs) in these products has enabled innovative product formulations and solutions [5].

The International Cooperation on Cosmetic Regulation considers a cosmetics nanomaterial as an insoluble ingredient with one or more dimensions less than 100 nm [8]. Using micro- and nanostructured vehicles such as NPs can maximize the penetration and tolerability properties of the skin and optimize the aesthetic appeal of cosmeceutical formulations and their organoleptic characteristics [9]. Additionally, they protect the active ingredient, decreasing its degradation and increasing its stability. Each type of vehicle has different features that allow it to be used in various formulations [10].

With so many claims about the properties of NPs concerning cosmeceuticals, a series of questions arise that need answers. What is the role of NPs in the development of cosmeceutical skin products? What are the properties of nanometric structures? Is there any potential health problem related to these nanocosmetics? Therefore, this review will attempt to answer these questions, reviewing the NPs used in cosmeceuticals while presenting the progress made and highlighting the hidden challenges associated with nanocosmeceuticals.

This research was conducted based on a bibliographic analysis through extensive review. The articles analyzed and selected for this review were written in English and no older than 2008. The search included organic molecules used as cosmeceuticals and NPs used in that field. The study was developed using the following search words “cosmeceutical,” “cosmetic,” “nanoparticle skin,” “liposome cosmeceutical,” “solid lipid skin,” “nanocrystals skin,” and “Nanostructured Lipid Carriers” in the title, abstract, or keywords. The research was developed in the Science Direct, Springer Link, Ebsco, and Google Scholar databases. The search was developed in English. On the whole, 208 articles, books, or book chapters were analyzed

2 Cosmetics and skin

The Food and Drug Administration [11] considers cosmetics as particles intended to be applied to the human body to clean, improve beauty, or change appearance. Cosmetics include several products, depending on the surface of the skin. According to Effiong et al. [12], these can be classified as follows:

skincare cosmetics such as moisturizing agents or cleaning agents;

hair care products such as dyes, styling substances, or shampoos;

facial beauty products such as lip gloss powders or face bases;

manicure products such as enamel and nail removers;

fragrance products such as perfumes, lotions, deodorants, and colonies;

UV light protective preparations such as sunscreens.

Most cosmetological products possess both cosmetic and health objectives. For example, when shampoo is used to clean hair, its purpose is cosmetical. However, if anti-dandruff is used, it is considered a drug to treat the disease. Other examples of cosmetics and medications are moisturizers with sun protection and makeup deodorants with antiperspirants.

What sets cosmetics aside from drugs is their intended use. On the one hand, the function of drugs is to detect, treat, or prevent a health disorder or affect the body’s operation. On the other hand, when their use is solely for beautifying, cleaning, and promoting attractiveness, it is cosmetic and does not need approval by the FDA [13]. Nevertheless, when a product is a cosmetic drug, it must comply with the legislation corresponding to its use as a drug [11].

The term cosmeceutical is the fusion of two terms: cosmetic and pharmaceutical, and it is used to define a topic that involves medical and cosmetical characteristics [13]. Cosmeceuticals represent a new multifunctional product category that relies on science and technology to provide the skin with clinically proven active ingredients [5].

In skincare, this term describes a product with a quantifiable biological action on the skin as a drug. It is controlled as a cosmetic because it pretends to improve its appearance [14]. Kaul et al. [15] define cosmeceutical products as a substance that incorporates a bioactive ingredient with medicinal benefits on the applied surface and improves appearance. They can be naturally derived or chemically synthesized. Ideally, the ingredients should be safe, effective, novel, stable, factory-efficient, and metabolized within the skin [1].

Cosmeceuticals possess multiple advantages over standard cosmetics. They contain high entrapment capacity and improved sensory properties. They are more stable than conventional cosmetics, so they are interested in applying and researching natural ingredients [15]. There are many properties that cosmeceuticals can offer to obtain healthy skin, such as anti-aging signs, acne problems, and inflammatory problems. Besides, they have excellent properties to fight wrinkles and help skin regeneration. Likewise, cosmeceuticals have multiple protective effects on cells to rebuild healthy skin at the cellular level [16].

Despite the advantages of their active compounds, retaining their unique functional characteristics is often a question that requires a new pharmacological composition. Since 1959, it has been a health concern that the skin can easily absorb materials on the nanoscale [5,14,15].

Incorporating nanotechnology into cosmeceuticals aims to formulate more valuable and practical products. The use of NPs in cosmeceuticals has some advantages. For instance, they can improve the stability of the ingredients by encapsulating key components like vitamins and antioxidants. Similarly, applying the bioactive ingredient in the desired place is feasible and generates a controlled delivery for a prolonged effect [17].

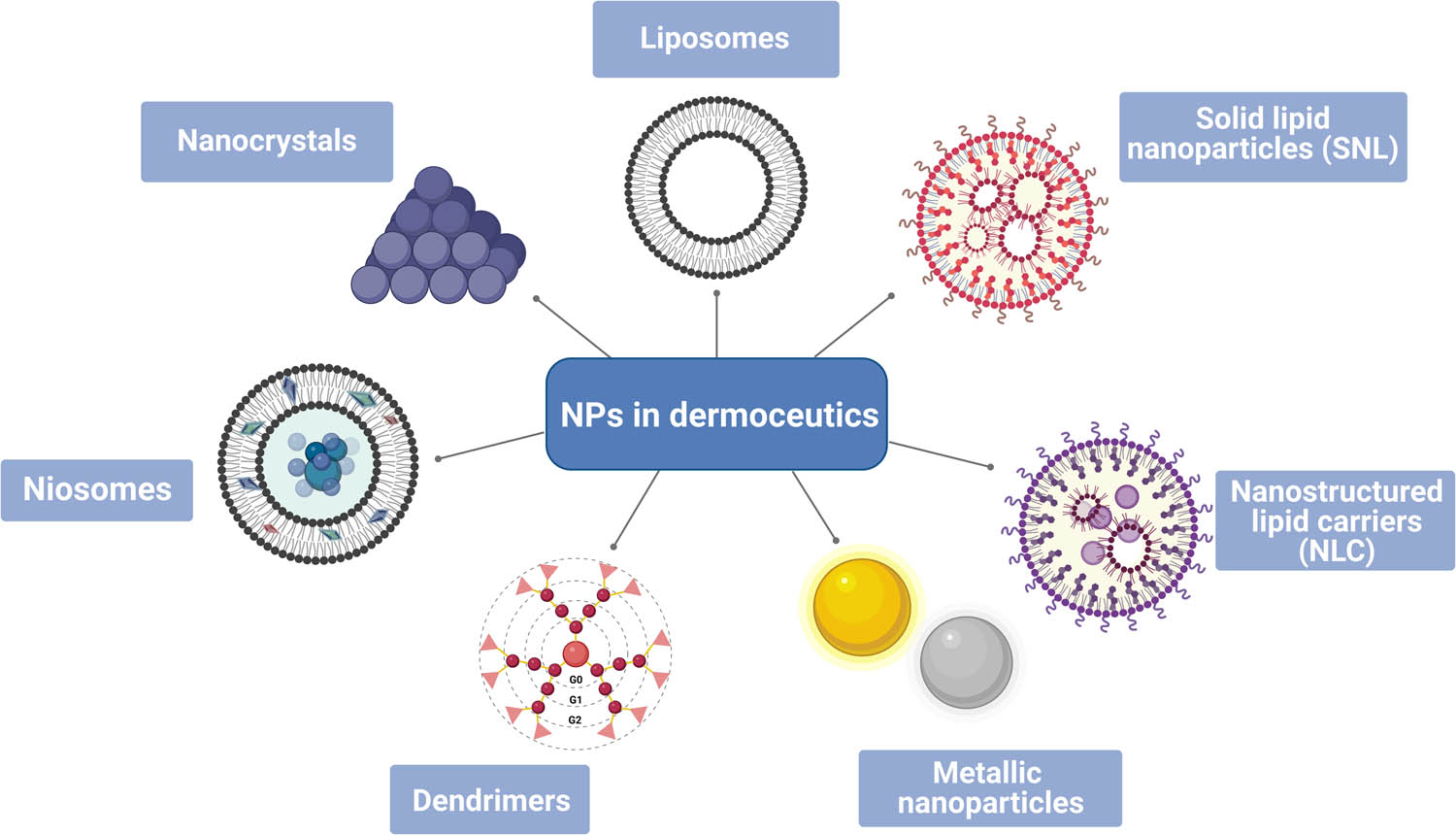

NPs can be used in products like shampoos and conditioners, creams, lotions, cosmetics, anti-aging creams, shower gels, soap, toothpaste, deodorants, fragrances, shaving cream, firming body oil, tanners, exfoliating, and gel for styling [18]. Nanocosmeceuticals have a wide application and are assimilated into the care of nails, hair, lips, and skin. The main classes of nanocosmeceuticals are presented in Figure 1.

![Figure 1

Main nanodermoceutics (created by BioRender.com [15]).](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2022-0282/asset/graphic/j_rams-2022-0282_fig_001.jpg)

Main nanodermoceutics (created by BioRender.com [15]).

The skin is a complex organ that protects the body externally, with an area of 1.5–2 m2 in adults. Its thickness varies depending on the body’s location. Thick skin is on the hands and soles, and thin skin is on the rest of the body [19].

Healthy skin is a barrier against mechanical, chemical, toxic, heat, cold, UV radiation, and pathogenic microorganisms and protects internal organs, bones, muscles, and other soft structures. Besides, it is essential in vitamin D synthesis, sensation, and body temperature regulation. The skin prevents water loss, maintains thermal equilibrium, and transmits external information that accesses the body through the senses, temperature, and pain receptors [19,20].

The skin is divided into the epidermis and dermis [19]. As illustrated in Figure 2, the epidermis is the most superficial part of the skin that separates the body from the environment; it acts as a barrier against external factors and is the layer of the skin with the most significant number of cells and with an extensive replacement dynamics [21,22]. Commonly, it is divided into four layers: the basal cell layer or germination stratum, the squamous cell layer or spiny stratum, granular cells or grainy stratum, and the cornified cell layer or corneal stratum [23]. The epidermis is continuously renewed through the flaking process that involves keratinocytes. The process takes about four weeks [1].

![Figure 2

Human skin representation [27] (created with BioRender.com).](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2022-0282/asset/graphic/j_rams-2022-0282_fig_002.jpg)

Human skin representation [27] (created with BioRender.com).

The dermis provides structural support to the skin. It protects the body from mechanical injuries [24]. It is located underlying the basal membrane of the epidermis. Its structure is like a sponge with numerous fibers associated with an intracellular matrix and few cells (fibroblasts, dendritic cells, and mast cells). The dermis provides structural support to the epidermis. In addition, it offers an adequate vascular contribution for metabolic exchange and abundant nervous innervation [25].

Nerves are derived from the neural crest, but the rest of the dermis components have a mesodermal origin. Collagen is one of its main constituents. Collagen fibers are the most numerous, and their thickness and arrangement vary according to the level at which they are found. The dermis contains the papillary and the deeper reticular layer. The papillary dermis is the outer and thinnest part of the dermis, constitutes approximately 10% of the dermis, and contains a relatively small and loose distribution of elastic fibers and collagen within a significant amount of the fundamental substance. On the other hand, the reticular dermis is a connective tissue containing collagen and thick elastic fibers. The reticular dermis provides skin strength, extensibility, and elasticity [26].

Protecting and preserving the skin is essential; environmental elements, ultraviolet radiation, air pollution, and natural aging can alter its barrier properties. During the aging process, the skin will experience significant structural modifications in the components of the epidermis and dermis. The appearance of wrinkles, pigmentation alterations, and skin atrophy are the main changes seen in senile skin [28].

The epidermis is the outer coat of the skin and therefore needs to regenerate continuously. The stratum corneum can achieve this process, the outer layer of the epidermis that prevents continuous detachment of keratinocytes, provides mechanical protection, and avoids water loss and invasion of external substances [29]. The stratum corneum cells of healthy skin are composed of free fatty acids, ceramides, triglycerides, cholesterol, water, and cholesterol sulfate [30]. This constitutes the lipid barrier of the skin. Damage to this barrier will result in dry, flaky, and rough skin that is easily irritated. Damage to the living epidermis will affect the function of the skin barrier. Likewise, dermal damage will result in wrinkles, stretch marks, or thin, sagging skin [1].

3 Nanomaterials

The chemical substances and materials used in nanotechnology are called nanomaterials. They differ depending on their provenance, size, shape, and chemical nature [31]. Although there are multiple categorizations, they are generally classified according to their origin. Nanomaterials can be obtained from a natural resource, like a volcano or a byproduct of an industrial process. They can be generated synthetically in a lab [32].

Manufactured nanomaterials can be presented as nano-objects. The nanomaterials can be characterized by having one to three external dimensions on the nanoscale. The nanostructured materials have a nanoscale internal or nanosurface structure [33]. These nanostructures form building blocks that, depending on whether they have one, two, or three external dimensions, are called nanolayers, nanofibers, and NPs [32]. Nanostructured materials can be presented in powder, composites, solid foam, porous materials, and fluid dispersion [34].

Materials pretended to be used in an organism are known as biomaterials [35]. The term is designated to those materials used to manufacture devices that interact with biological systems and apply to various medical specialties [36]. They are used in biomedical applications to assist, augment, or replace injured tissue or physical function [37]. They can be natural or synthetic, temporary or permanent in the body, and they aim to restore the existing defect and, in some cases, get tissue regeneration.

A biomaterial must be biocompatible. The body must accept compatible material; it should not alter living tissues while in direct contact. Likewise, it should not be toxic or carcinogenic. It must be chemically stable (no degradation over time) and inert unless it aims to achieve biodegradability. It must have adequate mechanical strength, density, and weight and be relatively economical, reproducible, and easy to manufacture and process for large-scale production [36].

There is a wide variety of biomaterials: metals, plastic, glass, and ceramics that can be cultured with cells. Alongside this structural diversity, there is another functional one. The biomaterials can be used in the prosthesis, orthosis, or scaffold. The scaffolds can be powders, films, foams, or fabrics with different microstructures [38].

4 NPs

NPs are structured less than 100 nm and can be synthesized from countless materials, including metals. Observing them requires high-resolution microscopes such as scanning electron microscopy or transmission electron microscopy [39]. Their small size and shape can incorporate substances that facilitate recognition by cells and tissues. In addition, they can act as a transport vehicle for antimicrobial agents. Evidence shows that NPs can promote tissue regeneration [40,41].

NPs are often considered simple molecules. However, they are complex mixtures, even in the most uncomplicated cases. These materials can be zero, one, two, or three dimensions [42]. Essentially, they consist of at least two layers, the surface and the nucleus. The surface can be functionalized with different functional groups, molecules, surfactants, metal ions, or antibodies; the shell layer properties are other than the nucleus. Finally, the core encloses the central part of the NP [43]. NPs can be analyzed according to their morphological characteristics and their physical and chemical properties as if they are based on metals, metal oxides, carbon, or composite materials.

4.1 Organic NPs

The most common organic NPs are liposomes, dendrimers, ferritin, and micelles. These are characterized by being nontoxic and biodegradable. Some micelles and liposomes have a vacant core sensitive to electromagnetic and thermal radiation [42]. Organic NPs have ideal characteristics for biomedical applications. One of its most significant benefits is that it can be injected containing some medication [44].

4.2 Metal-based and metal oxides NPs

On the other hand, inorganic NPs are considered all particles that are not carbon-based but are formed from metals and metal oxides. They are generally safe, biocompatible, and non-cytotoxic [45]. Metal-based NPs are elaborated using metals with nanometric sizes (10–100 nm) through destructive or constructive methods. Almost all metals can be used to elaborate NPs. The most commonly used are iron (Fe), zinc (Zn), aluminum (Al), gold (Au), silver (Ag), copper (Cu), cadmium (Cd), lead (Pb), and cobalt (Co). They are characterized by a high ratio of surface area to volume and their superficial load density. They have crystalline or amorphous structures. Furthermore, they mainly have spherical, cylindrical shapes (52) and anisotropic shapes like nanorods, nanotriangles, nanocubes, and nanostars [46]. They are reactive and sensitive to environmental factors such as sunlight, air, humidity, and thermal radiation [45].

Metal oxide-based NPs, on the other hand, are elaborated using metal precursors [47]. These particles have been prepared using electrochemical, sonochemical, microwave, sol–gel, solvothermal, and chemical vapor deposition methods [48]. Oxidation has been found to increase their reactiveness and efficiency. The synthesized are common copper oxide (CuO), silver oxide (Ag2O), zinc oxide (ZnO), titanium oxide (TiO2), oxidized aluminum (Al2O3), magnetite (Fe3O4), cerium oxide (CeO2), iron oxide (Fe2O3), and silicon dioxide (SiO2) [44,45,47]. The common applications of these particles include microbial activity, absorbents, semiconductors, gas sensors, ceramics, superconductors, and catalysts [47]. Moreover, some metal oxide NPs have anti-inflammatory properties. Titanium oxide has been used in pigments, cosmetics, skincare, etc. [48].

4.3 Carbon-based NPs

Another way to classify NPs is related to their origin, like carbon-based NPs. These, in turn, can be divided into carbon nanotubes (CNT), fullerenes, graphene, black carbon, nanofibers, and nano-sized activated charcoal [44].

Fullerenes and CNTs are the two main classes. Fullerenes are hollow spherical cages with distinctive physical properties. These particles can recover their original shape after being subjected to high pressures. Since shallow arrangements with dimensions are similar to various active biological molecules, they are helpful because different substances can be included in other applications [49]. While CNTs, given their excellent chemical and physical characteristics, are not only used in their original condition form but as nanocomposites. It has several industrial applications, such as absorbent for water contaminants and support material for heterogeneous catalysts [50].

4.4 Hybrid NPs

Hybrid NPs refer to particles composed of more than one NP sector, i.e., suppose the mixture of a polymeric NP and liposome is performed, resulting in a polymer–lipid hybrid system [45].

4.5 NPs in skincare cosmeceuticals

Recently, the cosmetic industry has developed products based on nanotechnology. In this regard, NPs have made it possible to improve outcomes using ingredients that interact with the skin tissue or enhance beauty [51].

Nanoencapsulation is any system capable of loading a substance to facilitate its penetration of active cosmetics due to its size from 20 to 1,000 nm. The characteristics of the carriers are essential for the permeation mechanism, such as hydrophobicity, stiffness, charge, and molecule size [52]. The transepidermal flow is influenced by the polarity, doses, nature, long-term stability of dissolved substances, solubility, and size of the particle [52,53]. Also, efficacy depends on the bioactive substance’s properties, such as size, charge, and solubility [54]. It has been documented that polymeric NPs can control their release mechanism and have high mechanical properties and non-deformability. Still, they have the limitation that they must avoid the immune system due to their size. Nanoemulsions have long-term stability and high solubilization capacity [55].

NPs have become an option to increase the efficiency of cosmeceutical products. Mainly, they increase the interaction of the ingredients with the area of interest in the skin, allowing more excellent stability and less toxicity. The particles are used to fulfill various functions in cosmetic products, such as active substances, nanocarriers, and modifiers of the appearance or viscosity of the product [56]. The morphology influences their properties. For instance, AgNP in colloidal form has higher antibacterial activity than disk, polygonal, or prism morphologies [57]. For example, in the case of nano cellulose for skin care, depending on its size, geometry ratio, porosity, and aspect ratio, it can be used as a moisturizer, formulation modifier, or additive [58]. Furthermore, the particles’ morphology can affect their surface reactivity [59]. Although lipid-based systems are widely used for their safety, efficacy, and high bioavailability, they have low drug loading capacity due to their crystalline structure, drug extrusion during storage, and particle size disadvantages [60]. On the contrary, the NPs protect substances against degradation and denaturation, reducing adverse effects. When the drug is covered with a polymer shell, it reaches better bioavailability and controlled release [61]. This protection allows them to be more convenient than lipid-based systems [55].

They have crystalline or amorphous structures. Furthermore, they mainly have spherical, cylindrical [52], and anisotropic shapes like nanorods, nanotriangles, nanocubes, nanostars, or other forms in nanosystems (Table 1) [46]. In the case of pickering emulsions, the morphology of particles is essential. Although NP morphology is crucial to define some aspects of its use in nanocosmetics, it is not the main criterion. Traditional emulsifiers are spherical, ellipsoid, cylinder, flake, dumbbell, or wire. The effect is related to the steric effect and from capillary forces in the interface [62]. On the contrary, the toxicity assessment of nanomaterials concludes that the safety of NPs is affected by size, morphology, shape, surface chemistry, and chemical composition [63]. For example, it has been evaluated the toxicity of nano-zinc oxide as a function of the particle size [64].

Advantages and disadvantages of different forms of nanosystems or NPs

| Systems geometry | Advantages | Disadvantages | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liposomes | Easy preparation, improved solubility of active substances | Toxicity must be assessed. They cannot be sterilized with heat | [65,66,67] |

| Nanosomes | Composed of a row of H2O and a row of fatty tails. They are smaller than liposomes and can permeate into the skin | It cannot be employed in products containing chemical preservatives, sunscreen, fragrances, and colorants | [65] |

| Niosomes | They are biocompatible, nonimmunogenic, and biodegradable. They can incorporate lipophilic and hydrophilic compounds | Dry heat and steam sterilization are not adequate for them because heat destroys the lipidic membranes | [65,66] |

| Cubosomes | They have large internal surfaces and the potential to encapsulate hydrophobic, amphiphilic, and hydrophilic compounds | If the bulk cubic phase is divided into dispersed nanostructured particles, the diffusion rate is increased, which causes a complex controlled release system | [65,68] |

| Nanoemulsions | It can carry lipophilic molecules | They are unstable thermodynamically, which causes colloidal instabilities, and then leakage and degradation of encapsulated substances | [65,69] |

Figure 3 shows several novel nanocarriers for administering cosmeceuticals to the skin.

NPs used in developing dermoceutics. Created by BioRender.com.

NPs can enter the skin via transappendageal. For this purpose, they use sweat glands, hair follicles, or lipid matrices with keratinocytes [70].

5 Cubosomes

The transporter is expected to release the corresponding substance at a controlled rate and a specific concentration in a drug delivery system. The active substance will depend on the interaction between the vehicle and the drug [71]. Cubosomes are crystalline liquid NPs usually made of amphiphilic lipids. They have been considered a promising proposition for active drug loading, as they can be used in the medical industry’s oral, transdermal, ocular, or chemotherapy products (Table 2) [71]. Cubosomes are NPs that use surfactant and polymer systems. Unlike liposomes, cubosomes can include amphiphilic or lipid-, hydrophilic, and water-soluble active substances [72]. L’Oreal and Nivea use cubosomes in oil-in-water emulsion in cosmetics [73].

Applications of cubosome formulations

| Cubosome formulation | Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Dexamethasone/Glyceryl monooleate, poloxamer 407, and oleic acid cubosomal | Treatment of vitiligo with 83.58% of drug release at the end of 12 h | [74] |

| Coenzyme Q10/poloxamer 407 and glyceryl monooleate cubosomal | The enzyme is an antioxidant that prevents lipid peroxidation. The formulation enhances the hepatoprotective activity of CoQ10 | [75] |

| Triclosan/Monoolein cubosomal | Triclosan cubosomes were evaluated for the dermal treatment of bacteria-related acne. The results showed that the cubosomes carrying triclosan could be safely used in anti-acne cosmetics and other antibacterial cosmetics | [76] |

| Alpha lipoic acid/poloxamer cubosomes | Anti-aging formulation with alpha lipoic acid that has antioxidant properties and anti-inflammatory effects | [77] |

| Cellulose polymers/hydroxypropyl methylcellulose acetate succinate cubosome | Cellulose polymers/Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose acetate succinate can act as a novel emulsifier of cubosomes with no internal structure modification | [78] |

| Monoolein cubosome containing hinokitiol | Cubosomes have higher skin permeation than hinokitiol dissolved in water | [79] |

6 Micro and nanoemulsions

The multilayered skin structure includes the stratum corneum, composed of dead keratinized cells and a matrix with fatty acids, cholesterol, cholesterol esters, and ceramides. There exists three pathways to penetrate the skin barrier, the inter and trans-cellular pathways, and hair follicles. Good penetration of the active substance in the skin is required to obtain benefits. An emulsion system in the nanoscale could improve the synergy between the base component of the formulation and the active compound, considering lipophilicity, molecular size, and degree of ionization [80]. It is used in the cosmetic market because it is an efficient vehicle for sustained active substance delivery and can reduce skin water loss [81,82]. The emulsion contains two immiscible vehicles, water, oil, and surfactant. Nanoemulsions are non-equilibrium systems, oil/water or water/oil emulsion, with droplets from 50 to 1,000 nm. Oil-in-water dispersions are metastable [80]. These systems are more stable against sedimentation than liposomes [83] but are more suitable for carrier lipophilic substances [84].

A nanoemulsion can transport high loads of lipophilic substances. Also, it protects bioactive substances from oxidation, hydrolysis, or enzymatic degradation. Furthermore, it can improve bioactivity and bioavailability [85].

Nanoemulsions have been used to treat dry skin in sunscreens, body lotions, wet wipes, skin creams [84], whitening, antiaging, or moisturizing agents (Table 3) [86]. Reducing ceramides causes dry skin, and emulsions improve skincare because nanodroplets penetrate the skin surface. They use bioactive compounds designed for transdermal hydrophobic drugs [87]. These systems have good sensory properties, such as merging textures and rapid penetration [80], and can be used when appropriate encapsulation for sensitive actives is required [88].

Applications of nanoemulsions

| System | Company | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bruma De Leite | Natura | Moisturizing solution | [89] |

| Skin Caviar | La Prairie | The formulation helps increase the skin’s tautness and suppleness | [89] |

| Bepanthol Facial Cream Ultra Protect | Bayer Healthcare | The nanoemulsión improves facial care for sensitive skin, moisturizes, and prevents aging of the skin | [89,90] |

| Coco Mademoiselle Fresh Moisture Mist | Chanel | A body mist with moisturizing properties | [89] |

| Nanovital VITANICS Crystal Moisture Cream | Vitacos Cosmetics | A nanoemulsion formulated with niacinamide, arbutin, vitamin c, oriental herbs and for antiaging effect of skin whitening due to the easy permeation of its active agents into the skin | [89] |

| Azelaic acid | It is a whitening agent composed of azelaic acid in a nanoemulsión with hyaluronic acid | [91] | |

| Nanocream | Sinerga | Emulsifier blend, which enables de production of oil/water nanoemulsions. It is a combination of vegetable-based substances lipoaminoacids and palm glycerides | [92] |

| Nano emulsion multi-peptide Moisturizer | Hanacure | The nanoemulsión affects the appearance of skin tone and texture. The nanoemulsión contains peptides, sodium hyaluronate, squalene, and mushroom extract. The skin gets long-lasting hydration | [89,93] |

| Nanoemulsion of citral, deionized water, and cosolvent | Health Sciences and Management/China University of Science and Technology/Providence University/Da-Yeh University/National Taiwan University | Citral can penetrate the lipid structure of bacteria destroying the cell membrane and causing cell lysis and death | [94] |

7 Lipid-based nanosystems

These systems have proven to play their part as dermal vehicles. They have biocompatibility, stability, improvement in penetration, effective delivery of active ingredients to different therapeutic targets, and the possibility to be incorporated into various innovative forms of dosing [51,95].

These nanosystems include lipid NPs and liposomes. Lipid NPs can be stable NPs (SLNs) or nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs) [96].

Liposomes are spherical capsules of colloidal dimensions; their size usually varies between 20 nm and a few hundred micrometers and is generally made up of cholesterol and phospholipids in an aqueous environment in the proportion of lipids to water [12]. Depending on the preparation method, these vesicles may consist of a bilayer (ULV unilaminar vesicles) or more layers (MLV multilaminar vesicles) of phosphatidylcholine. They consist of two sets of amphiphilic phospholipids with nonpolar hydrophobic tails pointing directly toward the interior and groups of polar hydrophilic heads indicating outwardly laminar structures, as shown in Figure 4 [14,17].

![Figure 4

Liposome showing the phospholipid bilayer (created with BioRender.com [98]).](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2022-0282/asset/graphic/j_rams-2022-0282_fig_004.jpg)

Liposome showing the phospholipid bilayer (created with BioRender.com [98]).

This structure allows the hydrophilic drug to be included in the nucleus. In contrast, lipophilic substances can be encapsulated in the vesicles’ walls. Due to their bilayer structure, liposomes can quickly enter the stratum corneum’s lipid coat. Therefore, they can enhance the dermal administration of medications and reduce systemic absorption [97].

Liposomes are very useful in cosmeceuticals because they are biodegradable, nontoxic, biocompatible, and adaptable vesicles that mimic cell membranes and can easily encapsulate active ingredients to protect them from the surroundings. Additionally, they increase the compositions’ durability and chemical stability [14,99]. Liposomes act as drug transporters and locators. They can act as drug deposits on the skin and surroundings, resulting in a dermal release of medicine compounds, thus improving the benefits at the target site and preventing systemic absorption [17].

As mentioned earlier, its composition and structure are similar to the epidermis, allowing it to penetrate epidermal barriers more efficiently. Therefore, the moisturizing and restorative action of lipids reduces the roughness of the skin. It is due to interaction with corneocytes [14].

In addition to their unique benefits, liposomes show some disadvantages, such as high manufacturing costs and low solubility. They can degrade by hydrolysis or oxidation, having a short life span during storage. Sometimes, drug molecules can leak from liposomes, depending on their composition and drug. Some gel bilayers containing cholesterol slowly lose the associated medication. Moreover, liquid bilayers are more likely to lose the drug [96,97,99]. The benefits and disadvantages of the lipid-based NPs used in cosmetics are summarized in Table 4.

Benefits and disadvantages of liposomes [15]

| Benefits | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Non-toxic, biodegradable, non-immunogenic, and biocompatible | It is possible an unintentional release of the encapsulated substance |

| They are naturally attracted to the skin. | Low solubility |

| It keeps the skin hydrated | Possibility of breakdown in contact with the skin and therefore cannot penetrate the skin |

| It can improve the effectiveness of medicine at the specific site | Short half-life |

| Load stability can be improved by encapsulation | High cost of production |

| It may decrease contact of sensitive tissues with toxic loads |

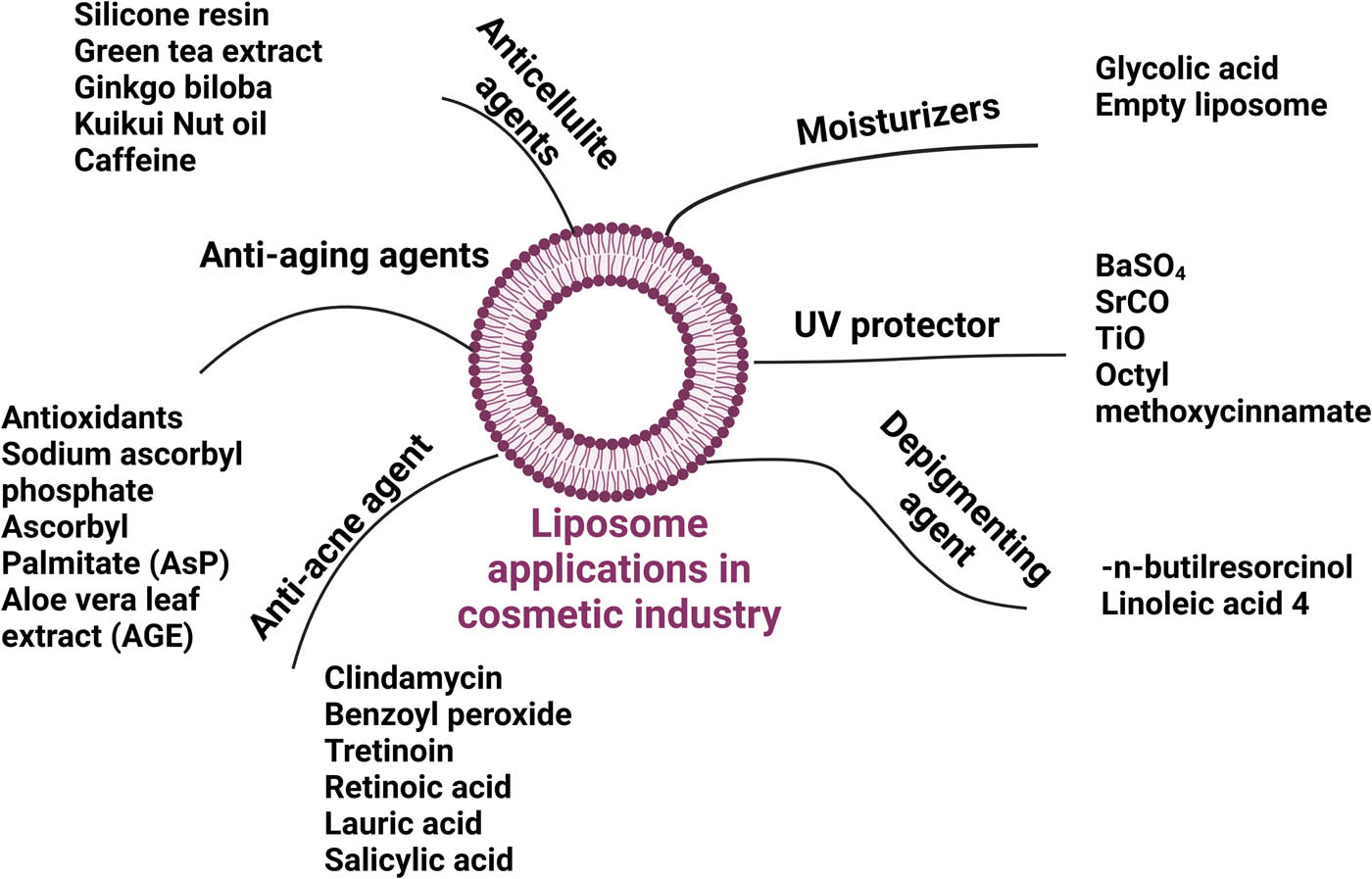

7.1 Application of liposomes as drug carriers in cosmeceuticals

Liposome applications include their use as fragrance carriers in deodorants, antiperspirants, and lipgloss [51]. Liposomes are widely exploited in the case of moisturizers due to their hydration properties, creating a phospholipid coat on the skin and resulting in a blockage effect. Even unoccupied liposomes have the property to keep and improve tissue moisture and, thus, restore skin barrier function [100].

Glycolic acid is one of the most incorporated active ingredients in liposomal systems. This active ingredient is used in many cosmetic products, such as exfoliating and moisturizing. Nevertheless, this has been linked to irritation and burns as side effects of the substance. It has been found that the lysosomal dosage, which contains glycolic acid, represents an adequate administration system to regulate drug delivery, which provides the best conditions to administer its side effects [99].

7.2 Sunscreens

Another application of liposomes is in the manufacture of sunscreens. In theory, an ideal sun protection product must show a high skin buildup with minimal flow to the systemic circulation; it should remain on the tissue surface and pass minimally through it [99]. Lipid release systems have demonstrated UV protection that depends on lipid structure and particle size; that is, the activity of the solar protector is inversely proportional to the particle size [97].

Among the pigments encapsulated in solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) for sunscreen is octyl methoxycinnamate [101]. Other lipid systems have been developed containing phosphatidylcholine to improve softening properties of skin care creams [102].

Liposomes help remediate pigmentation in the face and neck. These problems are usually unwanted in women due to hormones, cosmetics, perfumes, and sun radiation [103].

An example of this has been their incorporation into 4-n-butylresorcinol creams. This resorcinol derivative inhibits melanin production and the activity of both tyrosinase and protein 1. This formulation is more than 60% more efficient in treating melasma than the vehicle alone [99]. Liposome affiliation as a vehicle for linoleic acid in hydrogels has improved the incorporation into melanocytes. The permeation rate was higher, suggesting a longer retention time of acid in the skin, ideal for topical treatment of hyperpigmentation disorders [97].

7.3 Anti-acne agents

Acne is a chronic skin disease commonly present during adolescence. It is an inflammation of the sebaceous glands caused by Propionibacterium acnes and Staphylococcus epidermidis [104]. Liposomes were also shown to be an interesting vehicle of tretinoin for skin diseases. Negatively charged liposomes had better hydration in newborn pigskin and better retention of tretinoin in the skin [97,99].

On the other hand, cationic liposomes consist of a double-chain cationic surfactant. Experiments with phosphatidylcholine suggest cationic liposomes can be used to administer drugs intradermally, such as retinoic acid [105].

Similarly, salicylic acid, a drug used to treat acne, with a controlled delivery during a prolonged period using liposome vehicles, provides the opportunity to prepare a less irritating form of acid dosage and less frequent application [97].

7.4 Anti-aging treatments

Skin aging is related to biological, environmental, and hormonal mechanisms. Internal and external aging has been associated with the free radical activity. The cellular metabolism produces these radicals. In contrast, the aging process is increased externally by UV rays and habits such as smoking and drinking alcohol [106].

Antioxidants diminish the free radical unwanted effects by uptake, thus avoiding cell damage. However, the formulation stability and diminished permeability limit their use at the target site on the skin. Liposomes may be appropriate for delivering antioxidants, as they contain several ingredients for skin rejuvenation, such as phospholipids. They can encapsulate active antiaging components and bring them into tissue. Therefore, the liposome can be an effective carrier that absorbs quickly and enter the epidermis and dermis, mixing perfectly with membranes to prevent the initial signs of aging, as already mentioned [107].

Another helpful liposomal formulation in developing these products is sodium ascorbyl phosphate. This substance can attract free radicals and block UV light [108]. Similarly, liposomes loaded with curcumin-loaded soybean phosphatidylcholine have improved stability dispersed with ascorbyl palmitate [109]. In addition, it has been found that liposomes containing aloe vera improve cell proliferation, and collagen production increases antiaging and skin regeneration [110].

7.5 Anticellulite agents

Cellulite is an unwanted issue common in the lower extremities and pelvic region in more than 85% of adult women. This condition causes the skin to look like “orange peel.” While this is not a pathological condition, it remains one of the most recurrent cosmetic problems [111].

The role that liposomes have acquired in the face condition is critical. It has been found that the liposomal system can penetrate the subcutaneous tissue and then reach and decompose the lipid cells. Like other applications, liposomes help the drug get into fat cells affected by cellulite without noticeable waste [99].

One of the most active ingredients is caffeine, mainly used for its slimming effect. This can be applied topically to stimulate lipolysis in the epidermis. To optimize these formulations, they must reach the adipocytes. Liposomes have been used as vehicles to get to the active site fast [112].

Other natural medicines used for cellulite treatment are liposomes containing green tea extract, ginkgo biloba, kukui nut oil, and silicone resin. These substances act on adipose tissue metabolism, promoting the reduction of cells and the width of the subcutaneous layer. Consequently, softer skin is obtained due to the increase of moisture in the deeper layers of the skin [99].

Other liposomes include ethosomes and transferosomes. These vesicles are produced using ethanol or softening surfactants. Their main characteristic is ultra-deformability, which improves skin permeability [89]. Ethosomes are lipid-based vesicular systems with high ethanol concentrations to prolong their physical stability, resulting in easy penetration of medication into deeper skin layers [113,114].

A summary of all liposome applications is summarized in Figure 5.

Liposome applications in the cosmeceutical industry. Created with BioRender.com.

8 NPs of solid lipids and carriers of nanostructured lipids

SLNs consist primarily of solid lipids such as waxes, triglycerides, and glycerides. These particles are active carriers to deliver drugs for different treatments at slow rates. The amount of active surface species is an important parameter to define their functionalities and physical stability [51,115]. The systems are used when solubility and bioavailability have to be enhanced in poorly water-soluble actives and to shield actives from degradation [116]. The particles are around 50–1,000 nm and are composed of a single layer with a lipid nucleus [14,17]. SLNs are common in the pharmaceutical industry because they are lipids with low toxicity and are biodegradable. Besides, they can enter through the skin to the stratum corneum. Furthermore, it has UV resistance properties and acts as physical sunscreen to enhance protection with diminished side effects (Figure 6) [117].

![Figure 6

(a) SLN and (b) NLC (created with BioRender.com [120]).](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2022-0282/asset/graphic/j_rams-2022-0282_fig_006.jpg)

(a) SLN and (b) NLC (created with BioRender.com [120]).

The attributes that must be controlled in SLNs are the particle’s polymorphism, size, shape, long-term stability of the lipid particle, and surface properties for Pickering stabilization [116]. Lipid nanocarriers are often used due to their high loading capacity, appropriate kinetic release pattern, and good stability [118].

NLCs consist of solid and liquid lipids with a drug enclosed in their core [96]. They are considered the second generation of lipid NPs. NLCs are mainly three types whose base develops the structure according to their composition (Figure 6). They are spheres around 10–1,000 nm and have recently caught attention due to their lower toxicity and reaction effects [15]. When the nanocarrier is designed, it is essential to define if they have to overcome the epithelial barrier that limits their cellular entry. Then, the carrier systems’ size, surface hydrophobicity, and surface charge must be modified. A negative and neutral charge can permeate the mucus layer while the positive nanocarriers are entrapped [119].

NLCs have a modulated drug release profile (Figure 7), i.e., a two-phase drug delivery system; the drug is initially released with an outburst and after at a constant rate. Furthermore, it has greater skin hydration due to the barrier properties. Their nanometric dimension improves the exposure to the stratum corneum, causing more drugs to enter the skin. An advantage of this nanosystem is a UV-blocking system with diminished side effects [15].

![Figure 7

Effect of lipid NPs on the skin (created with BioRender.com [15]).](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2022-0282/asset/graphic/j_rams-2022-0282_fig_007.jpg)

Effect of lipid NPs on the skin (created with BioRender.com [15]).

9 SLN vs NLC in cosmeceutical development

As already mentioned, lipid NPs (SLN and NLC) are essential in improving cosmetics’ usefulness. Due to their excellent safety, they have many applications in the treatment of skin tissue. These spheres can be added to existing medication friendly due to their structural stability and affinity to lipophilic, hydrophilic, and soluble active ingredients [15].

They are colloidal administration systems whose formulation results in better UV protection effects and skin moisture. These systems prevent the degradation of the drug inside the core, improve penetration and absorption, and control delivery at the target site [121].

While storing SLNs, they tend to generate reordering of the crystalline structure to obtain a more orderly and stable shape. The imperfections of the matrix provide a space to pack inside the drug preventing its loss [51]. Thus, NLCs have a higher load capacity than SLNs and low water in the suspension due to the amorphous structure that creates more space. Besides, NLCs can minimize vigorous load ejection during storage [122]. The benefits and detriments of the cosmetic application of lipid-based NPs are included in Table 5. Also, Table 6 shows the cosmetical application of NPs.

Benefits and detriments of SLNs [15]

| Lipid nanoparticle | Benefits | Detriments |

|---|---|---|

| Solid nanoparticle (SNL) | Controlled delivery of drugs and augmented | Ejecting cargo during storage |

| Bioavailability of trapped medicine | ||

| Increased stability of substances | ||

| Biocompatible and biodegradable | ||

| Moisturizing effect on the skin and good penetration of the drug | ||

| They act as physical sunscreens | High water content in nano lipid suspensions | |

| Suitable for transporting lipophilic loads as hydrophilic | ||

| Easy to scale and sterilize | ||

| Less expensive compared to polymeric/surfactant carriers | ||

| More comfortable with validating and getting regulatory approval | ||

| NLCs | It can produce a thin coat on the epidermis to prevent the chemical decomposition of the drug | Cytotoxic effects related to concentration |

| Simple preparation and enlargement | ||

| They have controlled the particle size | The irritating effect of some surfactants | |

| Good dispersibility in an aqueous environment | ||

| They have extended lead release | ||

| Close contact with the corneum stratum due to its small size |

Cosmeceutical application of lipid NPs

| Application | Active ingredient | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical stabilizer | Vitamin E | [17,129] |

| Ascorbic palmitate | ||

| Retinol and retinoids | ||

| Carotenes | ||

| Lipoic acid | ||

| Moisturizers/occlusive | Argan oil | [17,129] |

| Empty lipid NPs | ||

| TiO2 | ||

| Kukui nut oil | ||

| Milk proteins | ||

| Coconut extract | ||

| Omega 3 and 6 | ||

| Sunflower oil | ||

| Avocado oil | ||

| Urea | ||

| Ginseng extract | ||

| Glycoproteins | ||

| UV Blocking | BaSO4 SrCO3 TiO2 Benzophenone 3 Orxibenzona Molecular sunscreens | |

| Insect repellents | DEET OMC |

9.1 Application of SLN and CNCs as drug carriers in cosmeceuticals

The essential features of lipid NPs are improving the hydrolysis, oxidation, and chemical stability of active optical sites, which benefits some active ingredients like Vitamin E, ascorbic palmitate, retinol, retinoids, carotenes, lipoic acid, lutein and some sunscreens [123].

Due to their occlusion effect, these NPs are widely used as moisturizers and wrinkle softeners. They prevent water loss from the tissue, consequently increasing the hydration of the skin increases [124]. An increment in moisture is noticed with a diminished particle size, which offers better adhesion and quick coat production. Dolatabadi et al. [125] analyzed the barrier effects of SLN and NLC particles. They concluded that SLNs and nanomicellar systems were better than NLCs as vesicles for curcuminoids.

Consequently, the occlusive properties of NLCs improve the penetration of medication into the epidermis. Moreover, it improves skin moisture and smoothes wrinkles [126].

Moreover, it was noticed that SLN presented the maximum barrier effects with a low melting point, lipids, high crystallinity, and small particle size [127]. On the other hand, nanometric SLN and NLC systems were analyzed In further research, showing occlusion factors around 36% and 39%, respectively. However, the score (red Nile) showed that NLCs penetrate deeper into the SC than SLNs [128].

Argan oil has been used for its medicinal properties, such as anti-aging, protection, and hydration in cosmeceutical products. Tichota et al. [129] developed an NLC argan oil composite to improve skin moisture. The composite was evaluated using in vivo human models. This analyzed drug improved skin moisture in the study participants.

Lipid NPs are widely used in the development of sunscreens. The SLNs have shown excellent properties in blocking UV light. The SLN matrix produced better UV absorption than the nanoemulsion containing oil in water (o/w). Also, titanium dioxide can block UV rays at the molecular level. Nevertheless, it could be photoallergic and phototoxic. When SLNs were combined with sun protection creams., the amount of titanium dioxide could be reduced, reducing the side effects associated with these sun protection molecules [17].

Dietyltoluamide (DEET) is a popular ingredient used to repel insects. However, its utilization is often affected because it can be absorbed in a massive systemic way. Puglia et al. [130] analyzed the encapsulation consequences of DEET and OMC on SLN, demonstrating that the particles could reduce the skin permeability of both compounds compared to an O/W emulsion.

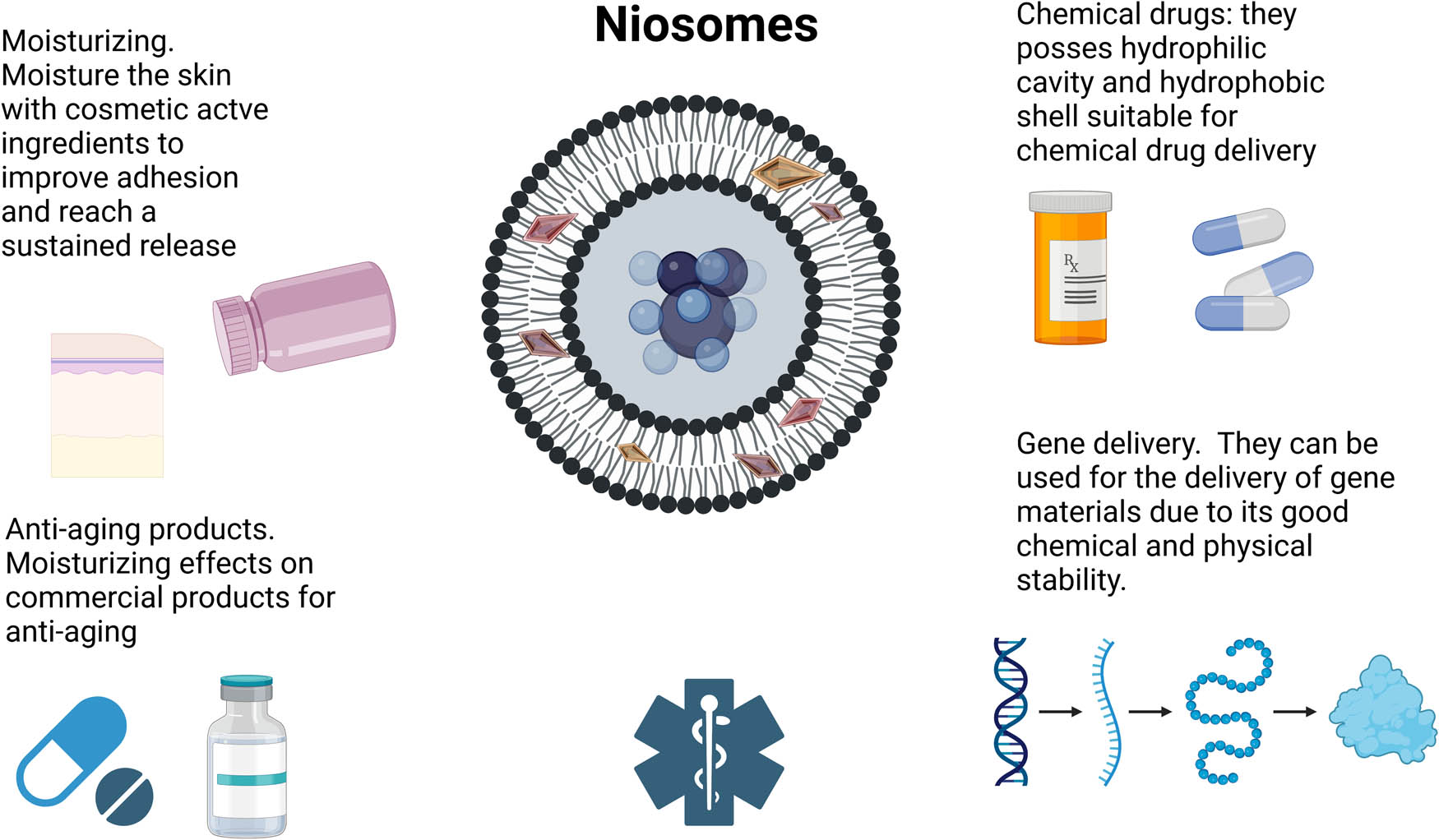

10 Niosomes

Niosomes are vesicles composed of bilayers formed from organized nonionic surfactants hydrated with or without incorporating cholesterol or lipids. Its structure varies from 100 nm to 2 mm in diameter [4]. Its characteristics are comparable to liposome properties, except for improved stability, higher price, and adaptability [51]. The first commercial product elaborated with these vesicles was Niosomes® by Lancôme [89].

The niosomes can be simply laminar or multilaminar, depending on the preparation method. Due to their unique geometry, niosomes can enclose substances with different water affinities in their structure. The entrapment in niosomes can occur in the water domain or adsorb on the surface of the bilayer. In contrast, hydrophobic substances enter the bilayer structure dividing it (Figure 8) [131]. These vehicles are biodegradable, non-toxic, and more stable than liposomes [132].

![Figure 8

The bilayer structure of the niosome exhibits the entrapment of the hydrophilic and hydrophobic substances [131] (created by BioRender.com).](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2022-0282/asset/graphic/j_rams-2022-0282_fig_008.jpg)

The bilayer structure of the niosome exhibits the entrapment of the hydrophilic and hydrophobic substances [131] (created by BioRender.com).

Niosomes are elaborated by some methods such as thin film hydration [133], microfluidics [134,135,136], sonication [137], multiple membrane extrusion [138], and reverse phase evaporation technique [138].

Niosomes offer excellent chemical stability than liposomes, a longer lifespan, and osmotic activity. Likewise, its surface can be easily modified due to a functional group in the hydrophilic face. Besides, they are more compatible and degradable by biological systems. Almost all routes of administration can administer niosomes. In particular, their size and encapsulation can be modified by changing additives, proportions, or combinations [131]. Also, they are known due to their capacity to be injected by ocular o transdermal routes, which are not common pathways [139]. Also, the niosomes are cheaper to fabricate than liposomes [140,141].

However, although the niosome delivery system has several advantages, it can be hydrolyzed in aqueous suspension. The issue of drug outflow from the encapsulation site and agglomeration of niosome formation and formulation techniques can be time-consuming [15,142]. Moreover, some challenges must be considered, such as consistent and reproducible construction of niosomes [134]. The strengths and weaknesses of the cosmetic uses of lipid-based NPs are summarized in Table 7.

Strengths and weaknesses of the niosomes [15]

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|

| Non-toxic, biodegradable, Non-immunogenic and biocompatible | You may have fusion, leaching, or hydrolysis of the trapped drugs, limiting the lifespan |

| Controlled and targeted drug delivery | Requires specialized equipment for manufacturing |

| They can be administered in almost every way | Insufficient drug load capacity |

| Improves the therapeutic performance of the drug | Trapped drug leak |

| Better chemical stability | Physically unstable |

| Osmotic activity and longer lifespan | Time-consuming techniques for formulation |

Niosomes are utilized in cosmetic and skin treatments because they can reduce and repair the permeability of the cornea layer (Figure 9). There is more excellent protection of trapped drugs and an enhancement in the bioavailability of substances. The formation of niosomes is affected by surfactants, encapsulated substances, membrane properties, and hydration temperature. Also, they have problems with physical stability, including aggregation, fusion, leakage in storage, and sedimentation [143]. An alternative is the proniosomes. They are liquid crystalline compact niosome hybrids [144,145,146] and nonionic surfactant vesicles used to improve the administration of drugs because they can produce an aqueous dispersion of niosomes [15,142], using dry and free-flowing product storage and can be hydrated immediately before use to form a liposomal dispersion [143]. This system increases bioavailability and reduces side effects [124], especially on skin penetrating the barrier and enhancing the drug’s penetration due to its amphiphilic nature [147]. They can be used to entrap hydrophilic and lipophilic drugs [148].

Niosomes applications. Created with BioRender.com.

Nevertheless, niosomes can be used in the pharmaceutical industry, oral, ocular, topical, pulmonary, parental, and transmucosal drug delivery and cosmetic applications [141]. Niosomes have been used to encapsulate essential oils characterized by low stability and biocompatibility because they cannot be used for direct topical administration [149], such as Lippia citriadora essential oil [150]. Also, niosomes can encapsulate poorly soluble drugs like melatonin [151]. Other substances include some for anti-aging treatments [152], like gallic acid for anti-skin aging [153,154], rice (Oryza sativa L.) bran for antiaging activity [155], deer antler velvet extract to stimulate the growth of skin and hair cells [156].

11 Metal, metal oxides, and inorganic NPs nanosystems

Metals, metal oxides, and inorganic NPs have appeared in the cosmetical industry, mainly skin formulations, providing an original approach to delivering entrapment drugs. These NPs are based on herbal medicine, cosmetics, sunscreens, and makeup [51]. The inorganics NPS include metal or metal oxides and carbon-based NPs with controlled physical properties (Table 8). In dermal products, it is common to use gold NPs, silver NPs, titanium oxide, zinc oxide NPs, silica NPs, cooper NPs, aluminum oxide NPs, nanotubes, fullerenes, and nanodiamonds [89]. Titanium dioxide and zinc oxide are common in sunscreen formulations. These substances protect from UVA and UVB light [157].

Applications of inorganic NPs in the cosmetic industry

| NP | Applications | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Gold | Antiaging, colorant, carrier, preservative | [89,168,169] |

| Used in deodorant, anti-aging creams, and face packs. It Is commercialized Chantecaille with anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties | ||

| Silver | Antifungal and antimicrobial | [14,89,96,168] |

| Effective against Trichophton leismaniasis, onychomycosis, and Staphylococcus aureus | ||

| Used in the face pack, antiaging cream Coil Whitening Mask by Natural Korea and deodorants Nano-In Hand by Nano-Infinity protected from UVA and UVB | ||

| Titanium oxide | Used commercially in products for sun tan effects like Mineral Fusion® | [89,158,170] |

| Zinc oxide | Protect from UVA and UVB. Used commercially in products like Neutrogen® or sunscreens and moisturizers by L’Oreal or Nivea | [14,89,158,169] |

| Silica | It improves the texture of cosmetic products | [14,89,160] |

| Used in Lancôme Microlift in Lancôme Renergie Microlift | ||

| Cooper | Biocidal and antiaging products | [89] |

| Fullerenes | Antioxidants and antiaging agents | [14,73,171] |

| It is used commercially in Zelens Fullerene C-60 by Zelens | ||

| CNT | Hair colorants and to improve permeabilization | [15,101,158] |

| Cerium oxide | Sunscreen preparation to block UV light | [172] |

| P. ginseng leaves-mediated gold NP | Cosmetic applications are due to their antioxidant, moisture retention, and whitening properties | [173] |

| Snail slime-based gold NPs | Particles synthesized by green chemistry for sunscreen products | [174] |

| Green gold NPs obtained through gold salt reduction by polyphenol contained in Hubertia ambavilla extracts | The NPs were evaluated by obtaining dermo-protective green gold NPs useful to block ultraviolet A | [175] |

| Gold NPs synthesized from P. ginseng berry | NPs exhibited moisture retention capacity that shows biocompatible and environmentally safe material for cosmetics | [176] |

| Silver NPs | Silver NPs were evaluated, and the results suggest they can be used as a preservative in cosmetics | [177] |

| Silver NPs synthesized with natural extracts | The particles were evaluated in hybrid sun-protective body milk showing a high degree of solar protection | [161] |

| Silver NPs synthesized with Phoenix sylvestris L. extract | The NPs have antimicrobial properties to treat acne-causing pathogens | [178] |

| ZnO and TiO2 | These NPs are commonly used as inorganic UV filters in sunscreens. They have high stability to light and good dispersive properties. TuO2 effectively blocks UV-B and ZnO to UV-A, eliminating sunscreens’ chalky white appearance. Furthermore, the substances are used in cosmetics and toothpaste | [166,179,180,181,182] |

| Collagen/SiO2 and ZnO composite materials | The composite was used in cosmetics creams for solar protection showing high antibacterial activity | [183] |

On the other hand, gold particles have several advantages, such as nontoxicity, high stability, chemically inert, and no photobleaching [15]. L’Oreal sells some products with gold nanoparticles to improve the elasticity and firmness of the skin [158]. Silica NPs have a hydrophilic surface and low cost. They are applied in the cosmetical industry because they can penetrate carrier drugs and release them into the skin. The particle size, surface charge, chemistry, chemical composition, and porosity enhance dermal penetration [159]. Fullerenes contain odd-numbered carbon rings, commonly used in anti-aging products [160]. On the other hand, CNT have been used in hair staining because they enhance the affinity of carbon black with gray or white hair [2]. Nevertheless, the main challenge of these systems is how to increase the penetration of the active ingredients through the skin barrier to achieve therapeutic goals [161].

They have been used for topical applications to enhance the solubility of apolar drugs, controlled release, higher stability, and capability to target specific areas to deliver active substances [161]. Their main applications of metal and metal oxide NPs include controlled release, sun-protected creams, and antimicrobial protection [51].

Silver and gold NPs have been used as novel cosmeceuticals [162]. They are used in toothpaste, soaps, deodorants, sunscreens, herbal products, hair cosmetics, wet wipes, body foams, lip, and makeup [102,163]. On the other hand, silica NPs are studied as the epidermal, dermal, and transdermal routes [164]. They are used in cosmetics, but their hazardous effects are recently evaluated on humans and the environment [165]. Zinc oxide is an inorganic compound insoluble in water. It has a hexagonal or cubic structural form. It is practical to absorb and scatter UV radiation [166]. The substance re-emits the absorbed radiation in less damaging UVA as fluorescence or heat [167].

12 Dendrimers

Dendrimers are macromolecules with a tree structure to encapsulate and deliver bioactive substances [184]. Dendrimers or fractal polymers are a class of highly branched three-dimensional dispersed mono-macromolecules with well-defined sizes and geometry that are precisely designed and contracted for their application. This is achieved by introducing desired functional groups at the ends of the surface branches that will react with the target [17]. In other words, they consist of a series of chemical layers built around a small nucleus molecule and have four main components: a nucleus, identically sized arms, linked or branched points, and final functional groups [14].

Dendrimers are nanoscopic, with diameters ranging from 2 to 10 nm. They are synthesized by controlling their chemical composition from a reactive polyfunctional nucleus that acts as a molecular center of proliferation, achieving an orderly configuration of monomers. The layers around the core are called dendrons [185]. They have uniform size, water solubility, high degree of branching, internal cavities available, and polyvalency [186]. Mainly lipophilic molecules are encapsulated in dendrimers via Van der Waals or apolar forces [184].

The dendrimersome is a self-assembly dendrimer used to encapsulate and deliver cosmetics, drugs, and diagnostic materials [187]. This nanocarrier was developed in Finland and the USA. It is biocompatible and has stability, tenability, monodispersity, and versatility. It is possible to produce them with uniform size and easy chemical functionalization [188].

Polyamidomin dendrimers (PAMAMs) are the most used in cosmetics development. The interior of this dendrimer contains empty spaces suitable for encapsulating host molecules. Simultaneously, the outer surface includes some potentially reactive sites adapted to alter the solubility of the NPs, making them a more efficient carrier polymer. Other dendrimers are DABs or PPIs (polypropylene imine dendrimers), both of which have 16 amino groups on the periphery of their configuration. These are used to increase the penetration of certain substances into the skin, like PMMH (phosphorus dendrimer) and bis-MPA (2.2-bis acid dendrimers (propionic methylol) [25].

It is essential to mention that something that characterizes dendrimers is their intrinsic viscosity. Dendrimers of lower molecular weight have a better viscosity, which is quite beneficial for the formulation of cosmetics [189]. Some L’Oreal patents describe how using dendrimers helps avoid disadvantages with high molecular weight polymers. Dendrimers’ low-viscosity suspensions have improved performance, including satisfactory sensory properties [25]. This company has used PAMAM dendrimers in deodorant and self-tanning compositions [25]. Moreover, the company uses dendrimers to fabricate mascara or nail polish [190].

On the other hand, Revlon has been used amidoamine dendrimers in personal care and cosmetic products. The company has encapsulated salicylic acid using the PAMAM-salicylic acid complex [191] for anti-acne compositions [25]. Unilever has used dendrimers in gels, lotions, and sprays (Table 9) [173,192,193,194,195].

Commercial uses of dendrimers

| Dendrimer | System | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Unilever | Hydroxyl functionalized dendrimers made from polyester units for gels, sprays, and lotions | [90,197] |

| Hair: composition with dendrimer macromolecule | ||

| Dow Corning Toray Co | Carbosiloxane dendrimer structure for use as a cosmetic raw material | [198] |

| L’Oréal | Skin: The company uses hydroxyl functionalized polyesters dendrimers for skin applications | [199,200] |

| Deodorant: Contains amine function dendrimers for human applications | ||

| Revlon | Cosmetics that have keratolytic and anti-acne activity | [201,202] |

| Nails, hair, and eyelash treatments: Keratin treatments nu hydrolyzed or partially hydrolyzed keratin |

On the other hand, dendrimers functionalized with ferulic, caffeic, and gallic acids have been used as antibacterial substances [196].

Dendrimers improve the skin permeability of the drug by interacting with lipid skin bilayers [51] and have applications in skin treatment, hair care, bath products, and fragrances [17].

13 Nanocrystals

Nanocrystals are drug particles stabilized by surfactants without any lipid or polymeric matrix [203]. They are aggregated of hundreds to thousands of atoms combined into a group and are in a size range of 10–400 nm. Generally, they are applied to improve the dermal penetration of poorly soluble cosmetic substances [204,205,206] and creams or lotions [207].

Nanocrystals are assembled from several hundred thousand atoms to form a polycrystalline or straightforward arrangement to release scarcely soluble active ingredients [73]. They have unique properties such as increased solubility of insoluble assets, higher dissolution rate, good adhesion, higher concentration gradient, and improved bioavailability [205].

Nanocrystals are used in cosmetic actives like lutein, flavonoids, coenzyme Q10, and flavonoids (Table 10) [203]. It was found that the dermal absorption and activity of the herbal compound can be improved using nanocrystals. One of their uses is flavonoids. Flavonoids of plants are part of the secondary metabolites. They have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties that decrease vascular permeability and protect blood vessels from treating rosacea. However, they are mainly used because of their UV protection properties [205]. The bioactivity of flavonoids was increased using a nanocrystal-based routine.

Uses of nanocrystals

| Nanocrystal | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Nanocrystals of cosmetic actives | Increase bioactivity of the molecules in the skin | [216] |

| Nanocrystal cellulose | It is a sunscreen cream cosmetic composition of cellulose and nano-titanium dioxide | [217] |

| Rapamune | It was the first pharmaceutical product in the market | [214] |

| Juvedical | Renewing serum and skin optimizer fluid | [214] |

| Platinum Rare by La Prairie | Hesperidin crystals are one of the most expensive cosmetics in the world | [206,218] |

Moreover, similar behaviors have been seen in the case of the plant antioxidant hesperidin [208]. Also, nanocrystals of bioflavonoids have been evaluated for therapeutic efficacy, but more studies related to safety are necessary for commercial purposes [208]. Moreover, curcumin nanocrystals elaborated through smartCrystals® for use in dermal formulations provide a new mechanism for the nanocrystals’ concentration [209]. Research shows that Cinnamate-functionalized cellulose nanocrystals are photostable and with an enhanced sun protection factor [210].

It was reported a nanomaterial based on diethyl sinapate-grafted cellulose nanocrystals. The material has colloidal stability and exhibits antioxidant and anti-UV properties in moisturizing cream with glycerol [211]. Also, it was prepared a delivery system for Symurban as nanocrystals for the treatment of skin pollution [212].

Some companies have used nanocrystals in cosmetic products, such as Renewing Serum and Juvedical®, Juvedical®, DNA Skin Optimizer Fluid, and Cream SPF 20 by Juvena [213,214], and Capture produced by Dior [214] and Petersen for blocking UV radiation with enhancing SPF [215].

14 Discussion

Incorporating liposomes in cosmeceutical products has advantages, such as biodegradability and excellent biocompatibility with the skin and its derivatives. Also, they have similar epidermis permeability properties, allowing more penetration than other treatments [158]. It should be noted that liposomes can administer drugs locally in the skin layer and improve moisture in skin conditions due to the affinity between liposome components and skin lipids [17]. Therefore, liposomes can be used as vehicles of cosmeceutical material or as active agents. Additionally, they can interact not only with the skin but also with proteins and carbohydrates to repair or reach a normal state when the skin is damaged because of moisture deficiency or eczema. It has even been found that they can increase the concentration of tretinoin in the epidermis and dermis, which protects it from photodegradation and minimizes its irritation compared to conventional creams or gels [41].

The production of liposomes is simple since it does not use massive amounts of raw material due to its small size resulting in financial products [219]. However, the number of liposomal systems markets is well below expectations. The cause can be attributed to the inconvenient production methods proposed in the literature: low cell absorption, difficulty controlling the particle size distribution, low encapsulation efficiency, and continuous design. Among these, liposomes’ low entrapment efficiency and particle magnitude are challenging to maintain. They are responsible for the waste of vast percentages of the number of molecules trapped, and as a result, the cost of producing them increases considerably [220].

The main advantage of SNL compared to other systems is its high biocompatibility and reliable physical properties, as well as the ability to control the delivery of substances. Nevertheless, some issues have been found with the total payload of the drug, which becomes insufficient due to the limited miscibility of some substances in solid lipids [123].

Consequently, new systems such as NLC have been explored. These second-generation NPs consisting of solid and liquid lipids offer the convenience of drug-carrying capability and improved release properties. In that sense, NLCs are more effective for topical, dermal, and transdermal administration [221].

They are more productive systems, facilitate the load for the accommodation of drugs, and contain different C chains in the crystal structure. Thus, medicines such as ascorbic palmitate, clotrimazole, ketoconazole, and other antifungal agents show a controlled release behavior [222]. However, they have some limitations related to cytotoxic effects due to the nature of the polymer and its concentration. Furthermore, some surfactants can irritate and have specific application problems when using protein and peptide drugs [221].

Due to problems related to toxicity, research has shifted its interest to systems such as nyosomes, which are non-cytotoxic particles that contain nonionic surfactants and cholesterol. These substances produce a rigid structure and keep the charged molecule stable, both hydrophilic and hydrophobic [131].

They have been extensively investigated as a carrier system of cosmetic bioactive substances and the usefulness of niosomes in traditional formulations such as emulsions, which showed lower cytotoxicity. Some metabolites extracted from plant materials are relevant in cosmetic research; these compounds possess beneficial effects such as antioxidants and antiaging. Many natural bioactive compounds using niosomes to enhance their impact on the epidermis have even been investigated [223].

Bartelds et al. [224] characterized and optimized some formulations of niosomes and compared the properties of these compositions with those of liposomes elaborated from cholesterol and phosphatidylcholine lipids/phosphatidylethanolamine. Niosomes were stable and even more permeable than liposomes, as analyzed by ion calcein liberation; ion permeability (KCl) was higher than the liposomes. In addition, they found that the magnitude of niosomes diminishes substantially after freezing in liquid nitrogen and subsequent thawing. Similarly, they discovered that the antimicrobial peptides melittin and alamethicin behave similarly in these systems composed of unsaturated components and were not affected when saturated amphiphile drugs were used. Lastly, in permeability and stability for drug-sized molecules, niosomes are similar to liposomes and may offer a reasonable and economical option for administration purposes.

The main drawback of this kind of system is that the loaded drug can be hydrolyzed in aqueous suspensions. It can leak the drug from the site of entrapment or the added formation of a niosome [131].

NLC and lysosomes are economical and easy to produce based on the collected information. They present lower toxicological and leakage risks since they are more stable. However, if you are looking for aqueous suspensions, the best option is to use NCL. On the other hand, inorganic NPs, metal oxides, and metallic oxides appear in cosmetics, particularly skin formulations, to deliver encapsulated ingredients. They may be present in different compositions, such as formulations based on hair, cosmetics, sunscreens, and botanical products [51,225]. Metal NPs (TiO2 and ZnO), gold (Au), and silver (Ag) have attracted attention for their practical antibacterial effect [63], leading to the development of several methods to synthesize AuNPs and AgNPs. Generally, chemical processes are the most beneficial as they reduce production costs [226]. Their relevance is due to their tunable optics, small size, stability, chemical and physical surface, and absence of cytotoxicity. They can be functionalized with biomolecules such as DNA, amino acids, carboxylic acids, and DNA. They provide an excellent drug delivery system. Furthermore, AgNPs inhibit proliferation and microbial infection much more than AuNPs [227].

While these NPs are similar in application, some research says AgNPs tend to be more unstable than AuNPs. Pulit et al. [228] evaluated the risks of using cosmetic preparations with AgNPs and AuNPs, for which stable cosmetic formulations (creams) were made with AgNPs and AuNPs at different concentrations. Both showed that they had good fungicidal properties. The standard cream’s estimated yield limits were obtained based on the viscosity curves. The creams with NPs improved the consistency and distribution of the skin. However, the best ratings obtained in texture, absorption, lubrication, color, and odor were assigned to AuNPs emulsion.

The worst uniformity, color, and smell ratings were obtained for emulsion with AgNPs. The most noteworthy aspect of this study was evaluating the permeability of metallic NPs through artificial dermal membranes. Higher permeabilities were confirmed for creams with metal NPs, which is a cause for concern as the cytotoxic properties of metal NPs have not been accurately evaluated.

The properties of AuNPs are frequently affected by interactions between particles and their assembling. NPs can easily penetrate the skin and accumulate, stimulating actin filaments and abnormal matrix construction. They can decrease intracellular protein synthesis and reduce cell proliferation, adhesion, and motility [229]. The toxic effect of AgNPs is related to silver ions’ delivery and size. Particles of 10 nm are more harmful than higher ones. Based on the information collected, these particles have potential applicability. Nevertheless, they present some toxicological risks when applied in high doses or with minimal size [230].

Dendrimers are artificial polymers characterized by repeated branched units that emanate from a focal point and have many neutral, cationic, or anionic terminal groups on their surface. Their properties are different compared to conventional polymers. They are helpful as a transport system for drugs and genes, including some with medicinal uses, due to their antibacterial, antifungal, and cytotoxic properties [231]. In addition, many substances cannot be exploited due to their low toxicity, solubility, or stability issues, and dendrimers can solve these problems, improving their clinical applications [187].

There are a few drawbacks to them, but they should not be taken lightly; they have toxicity, location, biodistribution, and high cost of production. Its efficiency in the skin depends mainly on its size and surface load; the easy-to-control features are shape, size, liposome occlusion dendrimeric structure, surface functionality, length of branches, and synthesis of specific dendritic frameworks [232].

Vaidya et al. [233] mention that the toxicity of dendrimers can be reduced by changing their shell with biocompatible substances such as polyethylene glycol, fatty acids, carbohydrates, amino acids, and peptides. Another strategy is synthesizing and designing biodegradable and biocompatible dendrimers using reagents. They are biocompatible and easily assimilated by biological systems. Dendrimers of amino acids, carbohydrates, peptides, and triazines are examples of such biodegradable dendrimers. In addition, the PEGilation of PAMAM dendrimers significantly reduces toxicity due to the reduction of cationic charge by the PEGilation of the dendrimer surface.

On the other hand, nanocrystals are typically produced from poorly miscible substances, class II drugs classified by the biopharmaceutical system (BCS). They have been successful in the market since 2000 [234], and the first nanocrystal product emerged for cosmetics in Switzerland in 2007. Nevertheless, the nanocrystals were manufactured from poor miscible, traditional, and active ingredients. Recently, it has been proposed as a novel concept in dermatology for drugs of medium solubilities, such as caffeine [235].

Unlike dendrimers, this type of nanodrug has a high proportion of stabilizing medicines that leads to approximately 100% of the load capacity of the drug. Nanocrystals are suitable for drug delivery to produce an adequate concentration in the desired area, and they are much simpler and more viable for industrial production [234]. Moreover, nanocrystals have low toxicity, and their solubility permits the skin to release poorly miscible actives to increase the substance’s saturation solubility, which can improve the drug’s release, dissolution rate, dermal bioavailability, and surface adhesion [203,236].