Abstract

Traditional methods for the optimization design of the air spring are based on the deterministic assumption that the parameters are fixed. However, uncertainties widely exist during the manufacturing stage of the air spring. To model the uncertainties in air springs, evidence theory is introduced. For the response analysis of the air spring system under evidence theory, an evidence theory-based polynomial chaos method, called the sparse grid quadrature-based arbitrary orthogonal polynomial (SGQ-AOP) method, is proposed. In the SGQ-AOP method, the response of the air spring is approximated by AOP expansion, and the sparse grid quadrature is introduced to calculate the expansion coefficient. For optimization of the air spring, a reliability-based optimization model is established under evidence theory. To improve the efficiency of optimization, the SGQ-AOP method is used to establish the surrogate model for the response of the air spring. The proposed response analysis and the optimization method were employed to optimize an air spring with epistemic uncertainties, and its effectiveness has been demonstrated by comparing it with the traditional evidence theory-based AOP method.

1 Introduction

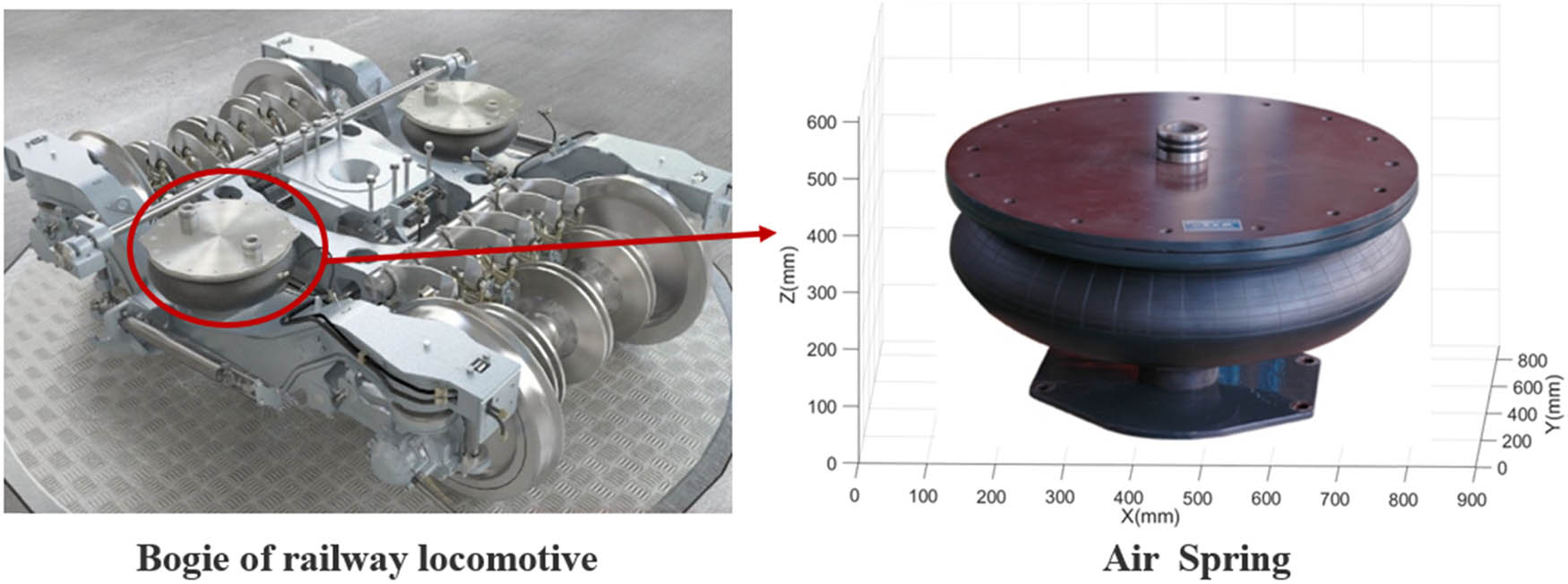

Air springs have a wide range of applications in suspension systems for railway vehicles, commercial, and personal cars [1,2,3]. Figure 1 shows an air spring of a railway locomotive. Compared to other suspension systems, the advantages of the air spring mainly include low natural frequency, excellent vibration isolation performance in high-frequency, and low rate of force transmission [4]. By the control of the intake valves, the working height and ride comfort under different ride conditions can be adjusted in an adaptable way, which makes the air spring attractive to luxurious vehicles.

Air spring of railway locomotive.

In the application of an air spring for engineering, its optimal stiffness varies for different kinds of vehicles. In addition, the strain of the spring material should be minimized to improve the fatigue life of the air spring [5]. Thus, there is an increasing demand for the optimization design of the air spring. Traditional response analysis and optimization methods for the design of an air spring are deterministic approaches in which the parameters are considered to be fixed [6,7]. However, uncertainties due to manufacturing and other factors inevitably exist in practice. It is shown in ref. [8] that the change of material parameters has a great effect on the stiffness of the air spring system. Without considering these uncertainties, the optimal results obtained by using deterministic methods may be unreliable. Therefore, for the design of an air spring, it is desirable to develop the response and optimization methods considering the effect of uncertainties.

To model the uncertainty, different kinds of uncertainty quantification theories have been developed. The most widely used technique for uncertainty quantification is the probability theory [9,10,11]. When the probabilistic model is used to deal with uncertainties, the probability density function (PDF) of the uncertain parameter should be obtained. However, the data to determine the PDF are always unavailable in practice. To model the uncertain parameter without sufficient probabilistic information, some other uncertainty quantification techniques have been developed, such as evidence theory [12,13], fuzzy theory [14,15], P-box theory [16], interval analysis [17,18], etc. Evidence theory is treated as an appropriate complement to probability theory in uncertainty problem analysis when the distribution of the uncertain variables is roughly regarded as several finite intervals [19]. In evidence theory, the uncertain parameter is defined as several intervals and its associated basic probability assignments (BPA). Under different situations, evidence theory can be equivalent to special probability uncertain or interval uncertain problems. When the number of focal elements tends to infinity or 1, the evidence parameters can be equal to the probability or interval parameter. Furthermore, evidence theory can handle conflicting information from experts. In comparison to the other modeling techniques, the evidence theory is a more flexible framework. Due to these typical properties, evidence theory has been applied in structural uncertainty analysis extensively in recent years [20,21,22].

Compared to the optimization of an air spring with deterministic parameters, the evidence theory-based response analysis and optimization of the air spring is more challenging. Under evidence theory, the extreme value analysis should be implemented over each focal element, which is a time-consuming process. In recent years, lots of research has been dedicated to reduce the computational cost related to evidence theory-based uncertainty analysis. One typical method is to use the interval perturbation method to obtain the extreme value in each focal element [23,24,25]. Bai et al. employed the perturbation method to obtain the approximate response bounds for each focal element [23]. By using the perturbation method, the response of the structure under evidence theory can be efficiently obtained. Shengwen et al. proposed an evidence theory-based finite element-statistical energy analysis method for mid-frequency analysis of the structure–acoustic system, in which the second perturbation method is used to calculate the response in each focal element [24]. Chen et al. extended the evidence theory and the perturbation technique for the prediction of an exterior acoustic field with epistemic uncertainties [25]. Compared to Monte Carlo simulation, the interval perturbation method can greatly improve computational efficiency. However, the computational cost of the interval perturbation method still suffers from the large computational burden, as the perturbation analysis needs to be repeated for each focal element. Another popular method for evidence theory-based uncertainty analysis is the surrogate modeling method, such as the polynomial chaos method. Originally, global surrogate models have been introduced for evidence-theory-based uncertainty analysis [26,27]. Subsequently, the Jacobi polynomial expansion [28] and Gegenbauer series expansion [29] have been applied in evidence theory to deal with the structural–acoustic problems. Chong [30] proposed an evidence theory model that combined the Legendre-type polynomial with the Clenshaw–Curtis point to improve the optimization efficiency of complex mechanical problems. Recently, Shengwen et al. investigated the influence of polynomial basis types on the accuracy of the orthogonal polynomial expansion surrogate model. It is shown that the computational accuracy can be improved efficiently by appropriately selecting the type of the polynomial basis [31]. Based on the above research, the evidence-theory-based arbitrary orthogonal polynomial (AOP) method has been proposed and applied to the structure–acoustic systems for uncertainty analysis with epistemic uncertainties [31].

In an overview, there is an increasing demand in the optimization design of an air spring, but the development of numerical methods for the optimization of the air spring is still at the early stage, and some problems still remain unsolved. First, the response and optimization model for the air spring system with epistemic uncertainties have not been established. It is shown in ref. [3] that the response of the air spring system is very sensitive to some input parameters, such as the material properties of the cord, the cord angle. Without considering these uncertainties, the results obtained by using the deterministic optimization method may be unreliable. Thus, it is desirable to develop an optimization model for the air spring system considering epistemic uncertainties. Second, though the AOP method shows good convergence properties for evidence-theory-based uncertainty analysis, the computational burden of AOP by using Gauss quadrature will increase exponentially with the number of variables. The air spring system always involves many uncertain parameters, and the computational burden for finite element analysis of the air spring is relatively large. Thus, it is necessary to improve the computational efficiency of AOP for uncertainty quantification under evidence theory.

The aim of this article is to develop an efficient response analysis and optimization method for the air spring system with epistemic uncertainties. The evidence theory is introduced to model the uncertain parameters in an air spring. For response analysis of the air spring system with evidence variables, a sparse grid quadrature-based arbitrary orthogonal polynomial (SGQ-AOP) method is proposed by introducing the evidence theory-based AOP and the sparse quadrature technique. In particular, the evidence theory-based AOP expansion [31] is introduced to approximate the response of the air spring system, and the sparse quadrature is used to calculate the expansion coefficient of the AOP expansion. For optimization of the air spring system under evidence theory, the proposed sparse quadrature-based AOP expansion is used to establish the surrogate model for the response of the air spring system. Based on the surrogate model, the optimal result can be efficiently obtained by using the genetic algorithm. The response analysis and optimization of an air spring system with epistemic uncertainties have been introduced to investigate the proposed method.

2 Evidence theory-based uncertainty analysis by using polynomial expansion and sparse grid quadrature

In this section, the fundamental evidence theory is briefly introduced. To reduce the computational cost of the traditional evidence theory-based polynomial chaos method, a new method called the SGQ-AOP method is proposed. The main difference between the SGQ-AOP method and the traditional evidence theory-based polynomial chaos method is that the sparse grid quadrature is used to calculate the expansion coefficient of the polynomial chaos expansion, instead of Gaussian quadrature.

2.1 Fundamentals of evidence theory

In evidence theory, an event space can be defined by a mathematical triplet

where

As the precise probability distribution in each focal element is not available, an interval that includes the Bel and Pl is employed to represent the uncertainty of probability as follows:

In the above equation, the belief measure

where the interval

For multiple variables problem

where

Here,

According to the above definition, the specific distribution of each focal element is not required. Even if the data are not sufficient to construct the precise PDF of an uncertain variable, the uncertain model can still be established without assumption.

Considering a function

In the above equations,

The

According to ref. [23], the mean value and variance of evidence variables can be defined as follows:

Therefore, by using the evidence theory model, the statistic property of y will be an interval rather than a fixed value.

2.2 The SGQ-AOP method for evidence theory-based uncertainty analysis

2.2.1 AOP expansion

The AOP expansion for the approximation of a function can be expressed as follows:

where N is the retained order,

where

In the above equation,

Suppose

where

In the above equations, the coefficient

Based on the orthogonality of the polynomial basis,

The integral in the above equation can be calculated by the Gaussian quadrature as follows [32]:

where

In particular, if

where

For a function with multiple evidence variables, the AOP expansion can be expressed as

where

In the above equations, n is the retained order of AOP expansion,

where

In traditional AOP, the expansion coefficients in equation (22) are calculated by

where

It can be found from equation (25) that the total number of Gaussian points to determine the coefficient is

2.2.2 Sparse grid quadrature

The sparse quadrature is based on the Smolyak algorithm, which has been widely used in the fields of numerical integration and interpolation and image processing. In this section, the basic principles of sparse quadrature for calculating the expansion coefficient will be deduced.

A continuous function

Furthermore, for a L-dimension problem, the approximated function with the order-

where

Therefore, the integration points in the square grids can be defined as

The number of the integration points based on the sparse grid method is estimated by

The corresponding coefficient of the weights is

2.3 The procedure of the SGQ-AOP method for response analysis under evidence variables

The core idea of the SGQ-AOP method is to use the sparse quadrature to calculate the expansion coefficient of the evidence theory-based polynomial chaos expansion. The main steps of the SGQ-AOP method are as follows:

3 Reliability-based optimization of the air spring under evidence theory

The strain of air spring has a great effect on the fatigue life of air spring. To improve the fatigue life of the air spring, the strain of the air spring should be optimized. Particularly, the purpose of the optimization of an air spring system is to reduce its potential strain. Therefore, the objective function of the air spring system with an evidence variable can be described as

where

The air spring system is a shock absorber in which the vibration performances (such as the stiffness) should be considered. These performances can be constrained by reliability conditions. The reliabilities are probabilities of performances satisfying design requirements. Therefore, the reliability constraint conditions can be expressed as

where g h (d, A) (h = 1,2,…,H) is the hth limit-state function that stands for the performance of a structural–acoustic system, and η h is the hth target reliability. When η h = 1, the reliability constraint conditions transformed to a deterministic constraint.

Based on equations (34) and (35), the reliability-based optimization model of the spring system under evidence theory can be expressed as

The objective function and the reliability constraint conditions can be efficiently evaluated by the SGQ-AOP method proposed in Section 2.

4 Numerical examples

4.1 Finite element model of an air spring

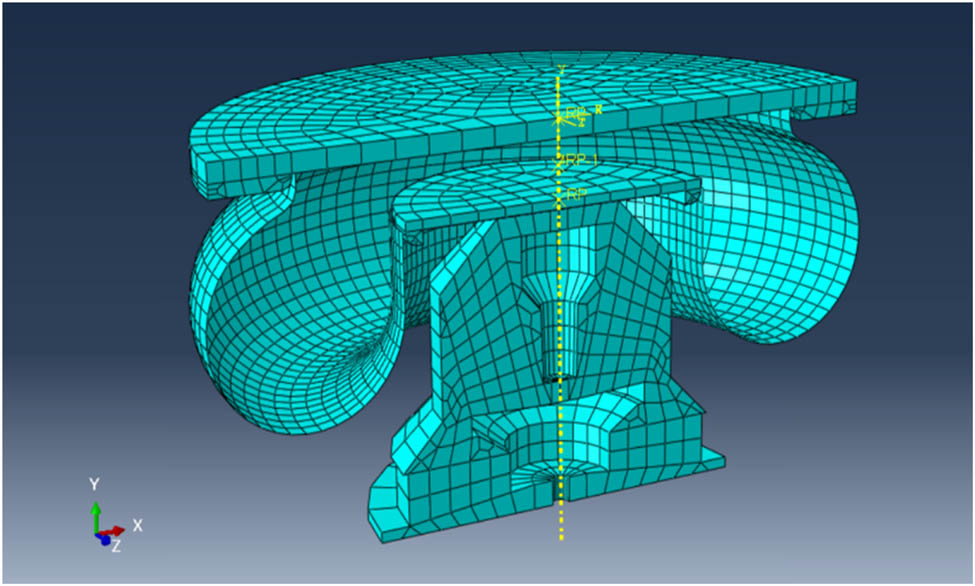

Figure 2 shows the finite element model of an air spring, and the calculation utilizes the Newton–Raphson method. The air spring action is divided into many load-increment steps. Then, an approximate equation is established at the end of each loaded-increment step. The acceptable solution of certain load-increment is reached after many rounds of iterations. This analysis is calculated in the ABAQUS/Explicit module. There are 24183 CAX4R elements and 1512 SFMAX1 elements in the whole FE model. By using ABAQUS, the stiffness of the air spring can be obtained. More details related to the calculation can be found in ref. [1]. The computational time to calculate the stiffness of the FE model is about 972 s. All computational results are obtained on a computer with 3.20 GHz Intel(R) Core (TM) CPU i9-10700K.

The FE model of an air spring.

4.2 Response analysis of the air spring with epistemic uncertainties

To investigate the effectiveness of the SGQ-AOP model for response analysis of the air spring with epistemic uncertainties, Yang’s modulus E of the cord, the cross section S of cord, the cord angle θ, and the material parameters of rubber (including C01 and C10 of the Mooney–Rivlin model) are assumed as evidence variables. The BPA structures of E, S, θ, C01, and C10 are listed in Table 1.

BPA structures of each uncertain parameter

| E (MPa) | S (mm2) | θ (°) | C01 | C10 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focal element | BPA | Focal element | BPA | Focal element | BPA | Focal element | BPA | Focal element | BPA |

| [1700, 1800] | 0.1 | [5.2, 5.6] | 0.1 | [28,33] | 1 | [0.2, 0.8] | 1 | [0.02, 0.08] | 1 |

| [1,800, 1,950] | 0.5 | [5.6, 6.0] | 0.4 | ||||||

| [1,950, 2,100] | 0.3 | [6.0, 6.4] | 0.4 | ||||||

| [2,100, 2,300] | 0.2 | [6.4, 6.8] | 0.1 | ||||||

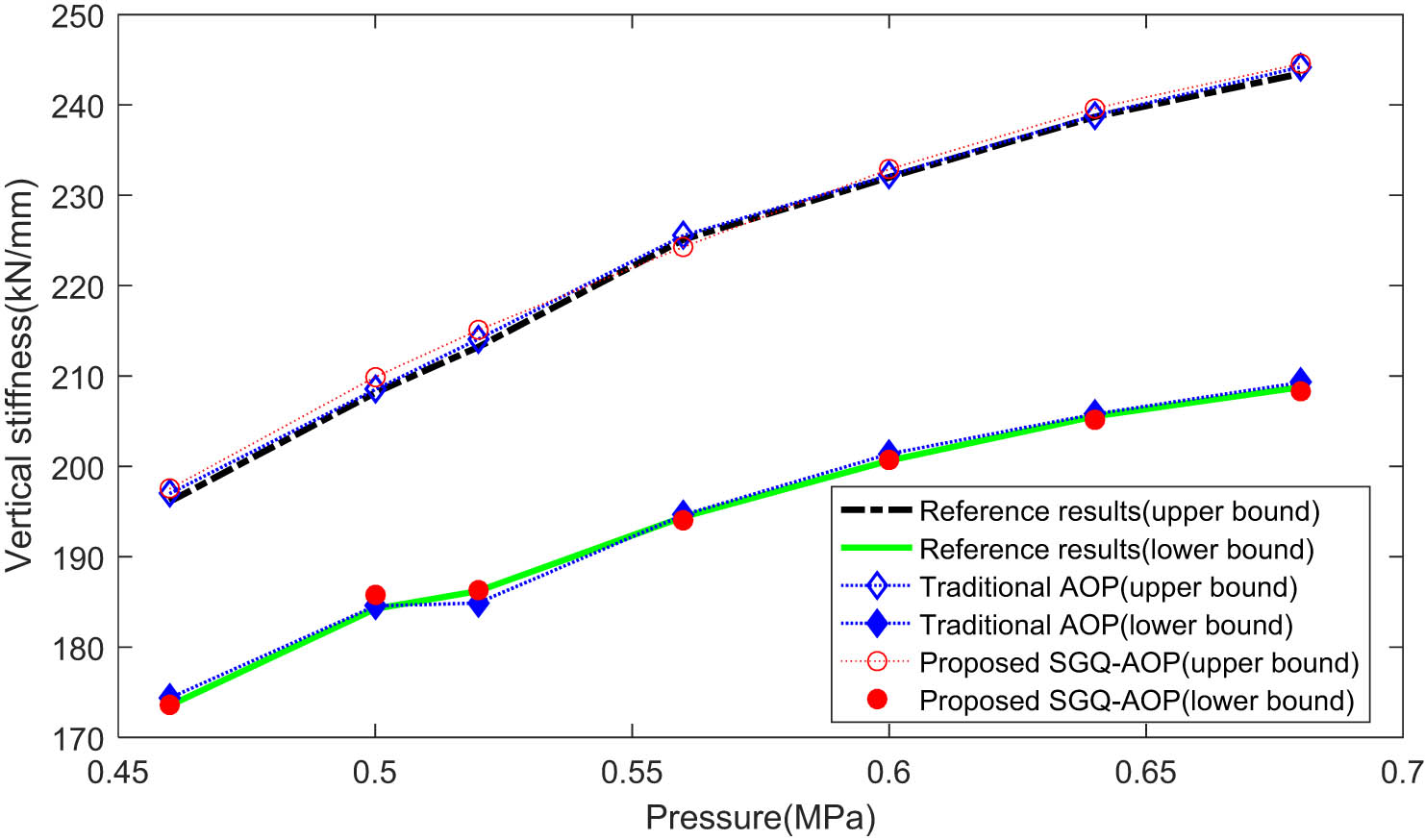

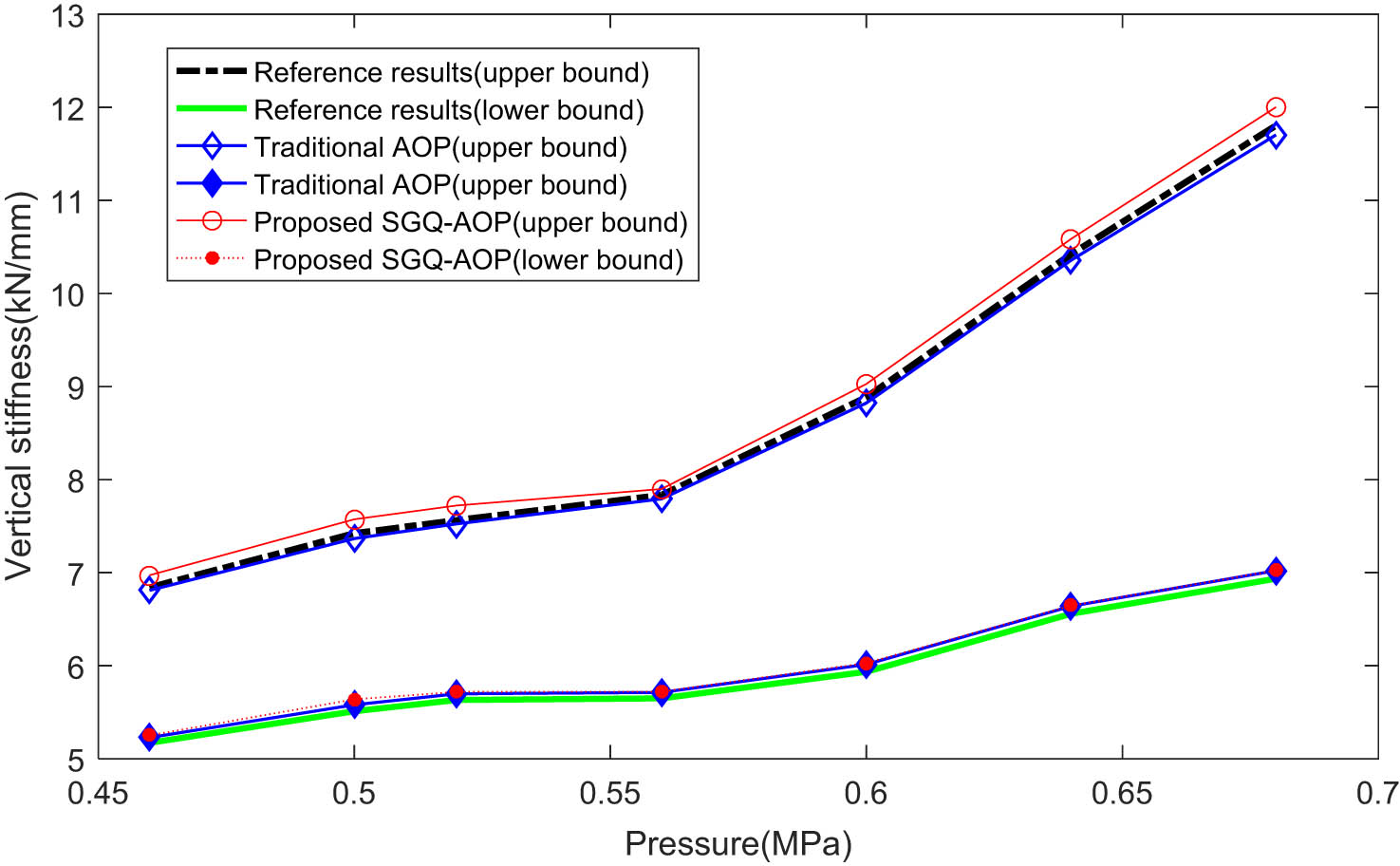

The proposed method is used to calculate the mean and variance of stiffness of the air spring. For comparison, the traditional AOP [29] is also introduced to calculate the response of the air spring. The retained order of the SGQ-AOP and the traditional AOP method is 4. The reference solution is obtained through the high-order Legendre polynomial expansion [29]. The results obtained by different methods are shown in Figures 3 and 4.

Bounds of the mean value of vertical stiffness of the air spring.

From Figures 3 and 4, it can be found that the results obtained by the SGQ-The AOP and the traditional AOP are very close to the reference results. It indicates that both SGQ-AOP and the traditional AOP method can achieve high accuracy for response analysis of the air spring with evidence variables. The relative error of the SGQ-AOP method is slightly higher than that of AOP, and the main reason is that a larger number of polynomial bases are retained in AOP. However, increasing the number of polynomial bases will lead to a larger computational burden. The computational times of the SGQ-AOP and AOP methods are

Bounds of the standard deviation of vertical stiffness of the air spring.

4.3 An optimization model for an air spring with epistemic uncertainties

In practice, the cord angle θ and the cross section S of the cord are usually used as design variables to optimize the performance of the air spring system. This is mainly because θ and S have a great effect on the mechanical properties of the air spring. Therefore, θ and S will be used as design variables in this numerical example. The range of θ is 25–35°, while the range of S is 4–6 mm2. The objective of the optimization is the expectation of the strain. A vertical amplitude

The SGQ-AOP method is used to obtain the result of the optimization model shown in equation (37). The detailed procedure of optimization by using the SGQ-AOP method can be found in Section 3. The initial value of the design variable is θ = 35 and S = 6 mm2. Once the surrogate model is established by using SQ-IRMAPC, different kinds of optimization methods can be used to find the optimal solution, such as the gradient-based methods [34,35] and gradient-free optimization strategies (Genetic Algorithm, GA [36]). Generally, the gradient-based methods can achieve higher efficiency than GA, but are more complicated in the formulation. The surrogate model of the response of air spring is a simple function, thus the computational cost of optimization by using GA is relatively small. For simplicity, GA is employed to find the optimal solution in this paper. The cord angle and the cross section of the cord after optimization are θ = 31.2 and S = 6 mm2, respectively. Before optimization, the maximum strain of the rubber of the air spring is 0.83 MPA, while the maximum strain of the rubber of the air spring is only 0.56 MPa after optimization. Therefore, the maximum strain of the rubber can be effectively reduced by using the optimization method.

In order to compare the optimization results obtained without considering uncertainties, a deterministic optimization model is introduced as follows:

The SGQ-AOP method is used to construct the surrogate model of the response of air spring. The initial value of the design variable is also set as θ = 35 and S = 6 mm2. The Genetic Algorithm is introduced to the optimization of the air spring system. The cord angel and the cross section of the cord after optimization is θ = 29.5 and S = 6 mm2, respectively.

Assume that E, C01, and C10 are evidence variables; then, the maximum values of the stiffness of the air spring under different optimization results are obtained and listed in Table 2.

Optimal results obtained by using different optimization methods

| Type | Optimal results | Maximum of vertical stiffness (kN·mm−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Θ | S (mm2) | ||

| Nondeterministic optimization (proposed) | 31.2 | 6 | 109 |

| Deterministic optimization (traditional) | 29.5 | 6 | 114 |

It can be found in Table 2 that the maximum vertical stiffness is 114 kN·mm−1, which does not satisfy the constraints in equation (37). It indicates that the optimal results obtained without considering uncertainties may fail to satisfy the constraints. For comparison, after optimization by using the proposed method, the constraints are well satisfied. Therefore, the uncertainties should be considered for the optimization design of the air spring with epistemic uncertainties. Without considering these uncertainties, the optimal result obtained by using the deterministic optimization method may be unreliable.

5 Conclusion

In this article, the evidence theory is introduced to deal with the uncertainties in the air spring. To efficiently calculate the response of an air spring system with evidence variables, a new evidence theory-based polynomial chaos method, called the SGQ-AOP method, is proposed. In the SGQ-AOP method, the arbitrary orthogonal polynomial is used to approximate the response of interest, and the expansion coefficient of AOP is calculated by using the sparse grid quadrature. For optimization of the air spring system with uncertainties, a reliability-based optimization model under evidence theory is developed. The SGQ-AOP method is used to construct the surrogate model for the response of the air spring. Based on the surrogate model, the optimal results can be efficiently obtained by using the genetic algorithm. The proposed response analysis and the optimization method have been applied to the optimization design of an air spring with epistemic uncertainties. The main conclusions are the following:

Compared to the traditional evidence theory-based arbitrary orthogonal polynomial method that is based on the Gaussian quadrature, the evidence theory-based arbitrary orthogonal polynomial method by using the sparse grid quadrature can greatly improve the computational efficiency.

By using the reliability-based optimization method, the constraints can be well satisfied after optimization. However, without considering the uncertainties, the optimal results obtained by using the deterministic optimization method may not satisfy the constraints under uncertainties. Therefore, for optimization of the air spring with epistemic uncertainties, it is necessary to consider the uncertainties in the air spring system.

-

Funding information: This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province, China (No. 2020JJ5686). The author would also like to thank the reviewers for their valuable suggestions.

-

Authors contributions: Feng Kong: writing – original draft preparation,software, data curation. Yu Bai: experimental test, software, data curation. Xifeng Liang: writing – reviewing and editing. Zhaijun Lu: writing – reviewing and editing, formal analysis. Shengwen Yin: methodology, writing – reviewing and editing.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Chen, Y., A. W. Peterson, and M. Ahmadian. Achieving anti-roll bar effect through air management in commercial vehicle pneumatic suspensions. Vehicle System Dynamics, Vol. 57, No. 12, 2019, pp. 1775–1794.10.1080/00423114.2018.1552005Search in Google Scholar

[2] Maeda, S., J. Yoshida, Y. Ura, H. Haraguchi, and J. Sugawara. Air springs for railways available for very cold environments. SEI Technical Review, Vol. 81, 2015, pp. 63–66.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Hongxue, L., L. Shiwu, S. Wencai, W. Linhong, and L. Dongye. The optimum matching control and dynamic analysis for air suspension of multi-axle vehicles with anti-roll hydraulically interconnected system. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, Vol. 139, 2020, id. 106605.10.1016/j.ymssp.2019.106605Search in Google Scholar

[4] Yiqian, Z., S. Wenbin, and R. Subhash. Modeling and performance analysis of convoluted air springs as a function of the number of bellows. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, Vol. 159, 2021, id. 107858.10.1016/j.ymssp.2021.107858Search in Google Scholar

[5] Zhou, W., T. Han, X. Liang, J. Bao, G. Li, H. Xiao, et al. “Load identification and fatigue evaluation via wind-induced attitude decoupling of railway catenary”. Reviews on Advanced Materials Science, Vol. 60, No. 1, 2021, pp. 377–403.10.1515/rams-2021-0037Search in Google Scholar

[6] Hengjia, Z., J. Yang, and Z. Yunqing. Dual-chamber pneumatically interconnected suspension: Modeling and theoretical analysis. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, Vol. 147, 2020, id. 107125.10.1016/j.ymssp.2020.107125Search in Google Scholar

[7] Hongguang, L., G. Konghui, C. Shuqi, W. Wei, and C. Fuzhong. Design of stiffness for air spring based on ABAQUS. Mathematical Problems in Engineering, Vol. 2013, 2013, pp. 206–226.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Oman, S. and M. Nagode. On the influence of the cord angle on air-spring fatigue life. Engineering Failure Analysis, Vol. 27, 2012, pp. 61–73.10.1016/j.engfailanal.2012.09.002Search in Google Scholar

[9] Meng, X., J. Liu, L. Cao, Z. Yu, and D. Yang. A general frame for uncertainty propagation under multimodally distributed random variables. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, Vol. 367, 2020, id. 113109.10.1016/j.cma.2020.113109Search in Google Scholar

[10] Finette, S. A stochastic response surface formulation of acoustic propagation through an uncertain ocean waveguide environment. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, Vol. 126, No. 5, 2009, pp. 2242–2247.10.1121/1.3212918Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Wang, M., D. S. Li, X. Q. Li, and W. J. Yang. Probabilistic design of uncertainty for aluminum alloy sheet in rubber fluid forming process. Reviews on Advanced Materials Science, Vol. 33, No. 8, 2013, pp. 442–451.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Yager, R., M. Fedrizzi, and J. Kacprzyk. Advances in the Dempster-Shafer Theory of Evidence, John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1994.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Liu, J., L. Cao, C. Jiang, B. Ni, and D. Zhang. Parallelotope-formed evidence theory model for quantifying uncertainties with correlation. Applied Mathematical Modelling, Vol. 77, 2020, pp. 32–48.10.1016/j.apm.2019.07.017Search in Google Scholar

[14] De Gersem, H., D. Moens, W. Desmet, and D. Vandepitte. A fuzzy finite element procedure for the calculation of uncertain frequency response functions of damped structures: Part 2—Numerical case studies. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 288, 2005, pp. 463–486.10.1016/j.jsv.2005.07.002Search in Google Scholar

[15] Wang, C. and Z. Qiu. Uncertain temperature field prediction of heat conduction problem with fuzzy parameters. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, Vol. 91, 2015, pp. 725–733.10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2015.08.023Search in Google Scholar

[16] Chen, N., D. Yu, B. Xia, and M. Beer. Uncertainty analysis of a structural–acoustic problem using imprecise probabilities based on p-box representations. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, Vol. 80, 2016, pp. 45–57.10.1016/j.ymssp.2016.04.009Search in Google Scholar

[17] Zhiping, Q. and C. Suhuan. Elishakoff. Bounds of eigenvalues for structures with an interval description of uncertain-but-non-random parameters. Chaos Solitons and Fractals, Vol. 7, No. 3, 1996, pp. 425–434.10.1016/0960-0779(95)00065-8Search in Google Scholar

[18] Baizhan, X. and Y. Dejie. Modified interval perturbation finite element method for a structural–acoustic system with interval parameters. Journal of Applied Mechanics, Transactions ASME, Vol. 80, No. 4, 2013, id. 041027.10.1115/1.4023021Search in Google Scholar

[19] Bae, H. R., R. V. Grandhi, and R. A. Canfield. Epistemic uncertainty quantification techniques including evidence theory for large-scale structures. Computers and Structures, Vol. 82, No. 13, 2004, pp. 1101–1112.10.1016/j.compstruc.2004.03.014Search in Google Scholar

[20] Qingzhu, W., Z. Meng, and H. Biao. Object detection based on fusing monocular camera and lidar data in decision level using D-S evidence theory. 2020 IEEE 16th International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering (CASE), 2020, pp. 476–481.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Hu, Y., L. Gou, X. Deng, and W. Jiang. Failure mode and effect analysis using multi-linguistic terms and Dempster–Shafer evidence theory. Quality and Reliability Engineering International, Vol. 37, No. 3, 2021, pp. 920–934.10.1002/qre.2773Search in Google Scholar

[22] Zhang, Z. and C. Jiang. Evidence-theory-based structural reliability analysis with epistemic uncertainty: a review. Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization, Vol. 63, No. 6, 2021, pp. 2935–3953.10.1007/s00158-021-02863-wSearch in Google Scholar

[23] Bai, Y. C., C. Jiang, X. Han, and D. A. Hu. Evidence-theory-based structural static and dynamic response analysis under epistemic uncertainties. Finite Elements in Analysis and Design, Vol. 68, No. 3, 2013, pp. 52–62.10.1016/j.finel.2013.01.007Search in Google Scholar

[24] Shengwen, Y., Y. Dejie, Y. Hui, L. Hui, and X. Baizhan. Hybrid evidence theory-based finite element/statistical energy analysis method for mid-frequency analysis of built-up systems with epistemic uncertainties. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, Vol. 93, 2017, pp. 204–224.10.1016/j.ymssp.2017.02.001Search in Google Scholar

[25] Chen, N., Y. Dejie, and X. Baizhan. Evidence-theory-based analysis for the prediction of exterior acoustic field with epistemic uncertainties. Engineering Analysis with Boundary Elements, Vol. 50, 2015, pp. 402–411.10.1016/j.enganabound.2014.09.014Search in Google Scholar

[26] Helton, J. C., J. D. Johnson, W. L. Oberkampf, and C. B. Storlie. A sampling-based computational strategy for the representation of epistemic uncertainty in model predictions with evidence theory. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, Vol. 196, 2007, pp. 3980–3998.10.1016/j.cma.2006.10.049Search in Google Scholar

[27] Jiang, C., Z. Zhang, X. Han, and J. Liu. A novel evidence-theory-based reliability analysis method for structures with epistemic uncertainty. Computers & Structures, Vol. 129, No. 4, 2013, pp. 1–12.10.1016/j.compstruc.2013.08.007Search in Google Scholar

[28] Shengwen, Y., Y. Dejie, Y. Hui, and X. Baizhan. A new evidence-theory-based method for response analysis of acoustic system with epistemic uncertainty by using Jacobi expansion. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, Vol. 322, 2017, pp. 419–440.10.1016/j.cma.2017.04.020Search in Google Scholar

[29] Chen, N., Y. Hu, D. Yu, J. Liu, and M. Beer. A polynomial expansion approach for response analysis of periodical composite structural–acoustic problems with multi-scale mixed aleatory and epistemic uncertainties. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, Vol. 342, 2018, pp. 509–31.10.1016/j.cma.2018.08.021Search in Google Scholar

[30] Chong, W. Evidence-theory-based uncertain parameter identification method for mechanical systems with imprecise information. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, Vol. 351, 2019, pp. 281–296.10.1016/j.cma.2019.03.048Search in Google Scholar

[31] Shengwen, Y., Y. Dejie, L. Zhen, and X. Baizhan. An arbitrary orthogonal polynomial expansion approach for response analysis of acoustic systems with epistemic uncertainty. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, Vol. 332, 2018, pp. 280–302.10.1016/j.cma.2017.12.025Search in Google Scholar

[32] Szegö, G. Orthogonal Polynomials. Colloquium Publications, Vol. 23, 4th edn, American Mathematical Society, USA, 1975.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Plaskota, L. and G. W. Wasilkowski. Smolyak’s algorithm for integration and L 1 approximation of multivariate functions with bounded mixed derivatives of second order. Numerical Algorithms, Vol. 36, No. 3, 2004, pp. 229–246.10.1023/B:NUMA.0000040060.56819.a7Search in Google Scholar

[34] Vu-Bac, N., T. X. Duong, T. Lahmer, X. Zhuang, R. A. Sauer, H. S. Park, et al. A NURBS-based inverse analysis for reconstruction of nonlinear deformations of thin shell structures. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics & Engineering, Vol. 331, 2018, pp. 427–455.10.1016/j.cma.2017.09.034Search in Google Scholar

[35] Vu-Bac, N., T. Lahmer, X. Zhuang, T. Nguyen-Thoi, and T. Rabczuk. A software framework for probabilistic sensitivity analysis for computationally expensive models. Advances in Engineering Software, Vol. 100, 2016, pp. 19–31.10.1016/j.advengsoft.2016.06.005Search in Google Scholar

[36] Waisman, H., E. Chatzi, and A. W. Smyth. Detection and quantification of flaws in structures by the extended finite element method and genetic algorithms. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering, Vol. 82, 2010, pp. 303–328.10.1002/nme.2766Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 Feng Kong et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- State of the art, challenges, and emerging trends: Geopolymer composite reinforced by dispersed steel fibers

- A review on the properties of concrete reinforced with recycled steel fiber from waste tires

- Copper ternary oxides as photocathodes for solar-driven CO2 reduction

- Properties of fresh and hardened self-compacting concrete incorporating rice husk ash: A review

- Basic mechanical and fatigue properties of rubber materials and components for railway vehicles: A literature survey

- Research progress on durability of marine concrete under the combined action of Cl− erosion, carbonation, and dry–wet cycles

- Delivery systems in nanocosmeceuticals

- Study on the preparation process and sintering performance of doped nano-silver paste

- Analysis of the interactions between nonoxide reinforcements and Al–Si–Cu–Mg matrices

- Research Articles

- Study on the influence of structural form and parameters on vibration characteristics of typical ship structures

- Deterioration characteristics of recycled aggregate concrete subjected to coupling effect with salt and frost

- Novel approach to improve shale stability using super-amphiphobic nanoscale materials in water-based drilling fluids and its field application

- Research on the low-frequency multiline spectrum vibration control of offshore platforms

- Multiple wide band gaps in a convex-like holey phononic crystal strip

- Response analysis and optimization of the air spring with epistemic uncertainties

- Molecular dynamics of C–S–H production in graphene oxide environment

- Residual stress relief mechanisms of 2219 Al–Cu alloy by thermal stress relief method

- Characteristics and microstructures of the GFRP waste powder/GGBS-based geopolymer paste and concrete

- Development and performance evaluation of a novel environmentally friendly adsorbent for waste water-based drilling fluids

- Determination of shear stresses in the measurement area of a modified wood sample

- Influence of ettringite on the crack self-repairing of cement-based materials in a hydraulic environment

- Multiple load recognition and fatigue assessment on longitudinal stop of railway freight car

- Synthesis and characterization of nano-SiO2@octadecylbisimidazoline quaternary ammonium salt used as acidizing corrosion inhibitor

- Perforated steel for realizing extraordinary ductility under compression: Testing and finite element modeling

- The influence of oiled fiber, freeze-thawing cycle, and sulfate attack on strain hardening cement-based composites

- Perforated steel block of realizing large ductility under compression: Parametric study and stress–strain modeling

- Study on dynamic viscoelastic constitutive model of nonwater reacted polyurethane grouting materials based on DMA

- Mechanical behavior and mechanism investigation on the optimized and novel bio-inspired nonpneumatic composite tires

- Effect of cooling rate on the microstructure and thermal expansion properties of Al–Mn–Fe alloy

- Research on process optimization and rapid prediction method of thermal vibration stress relief for 2219 aluminum alloy rings

- Failure prevention of seafloor composite pipelines using enhanced strain-based design

- Deterioration of concrete under the coupling action of freeze–thaw cycles and salt solution erosion

- Creep rupture behavior of 2.25Cr1Mo0.25V steel and weld for hydrogenation reactors under different stress levels

- Statistical damage constitutive model for the two-component foaming polymer grouting material

- Nano-structural and nano-constraint behavior of mortar containing silica aggregates

- Influence of recycled clay brick aggregate on the mechanical properties of concrete

- Effect of LDH on the dissolution and adsorption behaviors of sulfate in Portland cement early hydration process

- Comparison of properties of colorless and transparent polyimide films using various diamine monomers

- Study in the parameter influence on underwater acoustic radiation characteristics of cylindrical shells

- Experimental study on basic mechanical properties of recycled steel fiber reinforced concrete

- Dynamic characteristic analysis of acoustic black hole in typical raft structure

- A semi-analytical method for dynamic analysis of a rectangular plate with general boundary conditions based on FSDT

- Research on modification of mechanical properties of recycled aggregate concrete by replacing sand with graphite tailings

- Dynamic response of Voronoi structures with gradient perpendicular to the impact direction

- Deposition mechanisms and characteristics of nano-modified multimodal Cr3C2–NiCr coatings sprayed by HVOF

- Effect of excitation type on vibration characteristics of typical ship grillage structure

- Study on the nanoscale mechanical properties of graphene oxide–enhanced shear resisting cement

- Experimental investigation on static compressive toughness of steel fiber rubber concrete

- Study on the stress field concentration at the tip of elliptical cracks

- Corrosion resistance of 6061-T6 aluminium alloy and its feasibility of near-surface reinforcements in concrete structure

- Effect of the synthesis method on the MnCo2O4 towards the photocatalytic production of H2

- Experimental study of the shear strength criterion of rock structural plane based on three-dimensional surface description

- Evaluation of wear and corrosion properties of FSWed aluminum alloy plates of AA2020-T4 with heat treatment under different aging periods

- Thermal–mechanical coupling deformation difference analysis for the flexspline of a harmonic drive

- Frost resistance of fiber-reinforced self-compacting recycled concrete

- High-temperature treated TiO2 modified with 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane as photoactive nanomaterials

- Effect of nano Al2O3 particles on the mechanical and wear properties of Al/Al2O3 composites manufactured via ARB

- Co3O4 nanoparticles embedded in electrospun carbon nanofibers as free-standing nanocomposite electrodes as highly sensitive enzyme-free glucose biosensors

- Effect of freeze–thaw cycles on deformation properties of deep foundation pit supported by pile-anchor in Harbin

- Temperature-porosity-dependent elastic modulus model for metallic materials

- Effect of diffusion on interfacial properties of polyurethane-modified asphalt–aggregate using molecular dynamic simulation

- Experimental study on comprehensive improvement of shear strength and erosion resistance of yellow mud in Qiang Village

- A novel method for low-cost and rapid preparation of nanoporous phenolic aerogels and its performance regulation mechanism

- In situ bow reduction during sublimation growth of cubic silicon carbide

- Adhesion behaviour of 3D printed polyamide–carbon fibre composite filament

- An experimental investigation and machine learning-based prediction for seismic performance of steel tubular column filled with recycled aggregate concrete

- Effects of rare earth metals on microstructure, mechanical properties, and pitting corrosion of 27% Cr hyper duplex stainless steel

- Application research of acoustic black hole in floating raft vibration isolation system

- Multi-objective parametric optimization on the EDM machining of hybrid SiCp/Grp/aluminum nanocomposites using Non-dominating Sorting Genetic Algorithm (NSGA-II): Fabrication and microstructural characterizations

- Estimating of cutting force and surface roughness in turning of GFRP composites with different orientation angles using artificial neural network

- Displacement recovery and energy dissipation of crimped NiTi SMA fibers during cyclic pullout tests

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- State of the art, challenges, and emerging trends: Geopolymer composite reinforced by dispersed steel fibers

- A review on the properties of concrete reinforced with recycled steel fiber from waste tires

- Copper ternary oxides as photocathodes for solar-driven CO2 reduction

- Properties of fresh and hardened self-compacting concrete incorporating rice husk ash: A review

- Basic mechanical and fatigue properties of rubber materials and components for railway vehicles: A literature survey

- Research progress on durability of marine concrete under the combined action of Cl− erosion, carbonation, and dry–wet cycles

- Delivery systems in nanocosmeceuticals

- Study on the preparation process and sintering performance of doped nano-silver paste

- Analysis of the interactions between nonoxide reinforcements and Al–Si–Cu–Mg matrices

- Research Articles

- Study on the influence of structural form and parameters on vibration characteristics of typical ship structures

- Deterioration characteristics of recycled aggregate concrete subjected to coupling effect with salt and frost

- Novel approach to improve shale stability using super-amphiphobic nanoscale materials in water-based drilling fluids and its field application

- Research on the low-frequency multiline spectrum vibration control of offshore platforms

- Multiple wide band gaps in a convex-like holey phononic crystal strip

- Response analysis and optimization of the air spring with epistemic uncertainties

- Molecular dynamics of C–S–H production in graphene oxide environment

- Residual stress relief mechanisms of 2219 Al–Cu alloy by thermal stress relief method

- Characteristics and microstructures of the GFRP waste powder/GGBS-based geopolymer paste and concrete

- Development and performance evaluation of a novel environmentally friendly adsorbent for waste water-based drilling fluids

- Determination of shear stresses in the measurement area of a modified wood sample

- Influence of ettringite on the crack self-repairing of cement-based materials in a hydraulic environment

- Multiple load recognition and fatigue assessment on longitudinal stop of railway freight car

- Synthesis and characterization of nano-SiO2@octadecylbisimidazoline quaternary ammonium salt used as acidizing corrosion inhibitor

- Perforated steel for realizing extraordinary ductility under compression: Testing and finite element modeling

- The influence of oiled fiber, freeze-thawing cycle, and sulfate attack on strain hardening cement-based composites

- Perforated steel block of realizing large ductility under compression: Parametric study and stress–strain modeling

- Study on dynamic viscoelastic constitutive model of nonwater reacted polyurethane grouting materials based on DMA

- Mechanical behavior and mechanism investigation on the optimized and novel bio-inspired nonpneumatic composite tires

- Effect of cooling rate on the microstructure and thermal expansion properties of Al–Mn–Fe alloy

- Research on process optimization and rapid prediction method of thermal vibration stress relief for 2219 aluminum alloy rings

- Failure prevention of seafloor composite pipelines using enhanced strain-based design

- Deterioration of concrete under the coupling action of freeze–thaw cycles and salt solution erosion

- Creep rupture behavior of 2.25Cr1Mo0.25V steel and weld for hydrogenation reactors under different stress levels

- Statistical damage constitutive model for the two-component foaming polymer grouting material

- Nano-structural and nano-constraint behavior of mortar containing silica aggregates

- Influence of recycled clay brick aggregate on the mechanical properties of concrete

- Effect of LDH on the dissolution and adsorption behaviors of sulfate in Portland cement early hydration process

- Comparison of properties of colorless and transparent polyimide films using various diamine monomers

- Study in the parameter influence on underwater acoustic radiation characteristics of cylindrical shells

- Experimental study on basic mechanical properties of recycled steel fiber reinforced concrete

- Dynamic characteristic analysis of acoustic black hole in typical raft structure

- A semi-analytical method for dynamic analysis of a rectangular plate with general boundary conditions based on FSDT

- Research on modification of mechanical properties of recycled aggregate concrete by replacing sand with graphite tailings

- Dynamic response of Voronoi structures with gradient perpendicular to the impact direction

- Deposition mechanisms and characteristics of nano-modified multimodal Cr3C2–NiCr coatings sprayed by HVOF

- Effect of excitation type on vibration characteristics of typical ship grillage structure

- Study on the nanoscale mechanical properties of graphene oxide–enhanced shear resisting cement

- Experimental investigation on static compressive toughness of steel fiber rubber concrete

- Study on the stress field concentration at the tip of elliptical cracks

- Corrosion resistance of 6061-T6 aluminium alloy and its feasibility of near-surface reinforcements in concrete structure

- Effect of the synthesis method on the MnCo2O4 towards the photocatalytic production of H2

- Experimental study of the shear strength criterion of rock structural plane based on three-dimensional surface description

- Evaluation of wear and corrosion properties of FSWed aluminum alloy plates of AA2020-T4 with heat treatment under different aging periods

- Thermal–mechanical coupling deformation difference analysis for the flexspline of a harmonic drive

- Frost resistance of fiber-reinforced self-compacting recycled concrete

- High-temperature treated TiO2 modified with 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane as photoactive nanomaterials

- Effect of nano Al2O3 particles on the mechanical and wear properties of Al/Al2O3 composites manufactured via ARB

- Co3O4 nanoparticles embedded in electrospun carbon nanofibers as free-standing nanocomposite electrodes as highly sensitive enzyme-free glucose biosensors

- Effect of freeze–thaw cycles on deformation properties of deep foundation pit supported by pile-anchor in Harbin

- Temperature-porosity-dependent elastic modulus model for metallic materials

- Effect of diffusion on interfacial properties of polyurethane-modified asphalt–aggregate using molecular dynamic simulation

- Experimental study on comprehensive improvement of shear strength and erosion resistance of yellow mud in Qiang Village

- A novel method for low-cost and rapid preparation of nanoporous phenolic aerogels and its performance regulation mechanism

- In situ bow reduction during sublimation growth of cubic silicon carbide

- Adhesion behaviour of 3D printed polyamide–carbon fibre composite filament

- An experimental investigation and machine learning-based prediction for seismic performance of steel tubular column filled with recycled aggregate concrete

- Effects of rare earth metals on microstructure, mechanical properties, and pitting corrosion of 27% Cr hyper duplex stainless steel

- Application research of acoustic black hole in floating raft vibration isolation system

- Multi-objective parametric optimization on the EDM machining of hybrid SiCp/Grp/aluminum nanocomposites using Non-dominating Sorting Genetic Algorithm (NSGA-II): Fabrication and microstructural characterizations

- Estimating of cutting force and surface roughness in turning of GFRP composites with different orientation angles using artificial neural network

- Displacement recovery and energy dissipation of crimped NiTi SMA fibers during cyclic pullout tests