Assessment of anti-diabetic properties of Ziziphus oenopolia (L.) wild edible fruit extract: In vitro and in silico investigations through molecular docking analysis

-

R. Shunmuga Vadivu

, Senthil Bakthavatchalam

und Ramachandran Vinayagam

Abstract

Globally, healthcare is concerned about the rising prevalence of type 2 diabetes. Phytochemicals from medicinal plants have shown great promise in improving human health. The present study aimed to determine the secondary metabolites of Ziziphus oenopolia (L.) fruit extract that contribute to its anti-diabetic activity. The anti-diabetic properties were assessed by in vitro and in silico approaches using α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory assays. Gas chromatography and mass spectroscopy analyses were used to profile Z. oenopolia fruit contents, and a total of four bioactive chemicals and eight phytocompounds were tentatively identified, including flavonoids, terpenoids, phenols, steroids, tannins, and saponins. The Z. oenopolia fruit hydroalcoholic extract inhibits α-amylase and α-glucosidase enzymes in a dose-dependent manner (IC50 = 328.76 and 337.28 µg/mL, R 2 = 0.979 and 0.981). Additionally, phytochemicals found in Z. oenopolia fruit exhibit the ability to inhibit anti-diabetic targets, specifically α-amylase and α-glucosidase (2QV4 vs 3A4A; correlation coefficient, r = 0.955), as demonstrated by computational analysis. This establishes the fruit as a promising and environmentally friendly option for treating hyperglycemia, highlighting the positive correlation between anti-diabetic objectives.

Graphical abstract

The evaluation of in vitro and in silico anti-diabetic activity of wild edible fruit Ziziphus oenophilia (L.) extract: molecular docking and statistical analysis.

1 Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a life-threatening condition characterized by high blood sugar levels over time, reflecting one of the multifactorial problems associated with the disease [1]. Insulin resistance is a prevalent feature of type 2 diabetes and often affects adults. DM affects 422 million people globally, most of whom reside in low- and middle-income nations, and is directly responsible for 1.5 million deaths annually [2]. Figure 1 illustrates how the enzymes α-amylase and α-glucosidase hydrolyze carbohydrates and increase postprandial glucose levels. Additionally, the aim of controlling postprandial hyperglycemia was prevented by these enzymes. Because increased hyperglycemia damages the kidneys, heart, blood vessels, and nerves, it has become a serious health concern [3,4]. Many synthetic hypoglycemic medications are used to treat DM, but all have side effects [5]. Therefore, it is critical to discover new bioactive compounds with potent anti-diabetic actions and minimal adverse effects. The search for novel medications made of natural resources to treat DM is still ongoing. Around 60% of people worldwide utilize traditional medicines made from healing herbs, particularly in India, where diabetes is treated using herbal medications and plants [6,7]. Natural therapies have prevented many diseases and are also less harmful. Plant secondary metabolites play a role in the success and cost-efficiency of herbal therapies for diabetes [8].

The α-amylase and alpha-glucosidase enzymes hydrolyze carbohydrates and increase postprandial glucose levels.

Beneficial phytochemicals, also known as bioactive substances present in fruits, vegetables, and grains, are present in medicinal plants and aid in the prevention of illnesses and infections [9,10]. Numerous bioactive substances with particular biological characteristics and no negative consequences, such as polyphenols, alkaloids, terpenoids, and saponins, are abundant in many plants and have potentially synergistic effects [11]. This study uses the fruit of the Ziziphus oenopolia (L.) Mill medicinal plant, which is a member of the Rhamnaceae family and is utilized in traditional South Indian cuisine (Tamil name: Suraimullu, Surai ilanthai). In rural areas, Z. oenopolia has been used for its gastrointestinal, hypotensive, diuretic, wound healing, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and hepatoprotective effects [12,13,14]. Pancreatic α-amylase (AM2A), intestinal maltase-glucoamylase, dipeptidyl peptidase-4, liver receptor homolog-1 (NR5A2), retinol-binding protein-4, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha, and protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type 9 were the main anti-diabetic targets identified.

The current study aimed to identify phytochemicals and test the anti-diabetic effects of the hydroalcoholic extract of Z. oenopolia in the laboratory and on a computer by inhibiting the activity of α-glucosidase and α-amylase enzymes. In the therapy for type 2 DM, α-glucosidase stands as a crucial target enzyme. Inhibition of this enzyme effectively reduces blood glucose levels. Similarly, the inhibition of α-amylase, an essential regulatory enzyme in diabetes, plays a significant role [15,16]. The inhibition of both of these enzymes constitutes a response to the regulation of hyperglycemia.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Extraction and phytochemical screening of Z. oenopolia fruits

In January 2023, the fruits of Z. oenopolia were gathered from local villagers in the Thanjavur area. Z. oenopolia (Voucher ID: R.K.001) was collected from Thanjavur and deposited in St. Joseph College. Trichy, Tamil Nadu, India. To eliminate any traces of contaminants, the fruits of Z. oenopolia were first repeatedly rinsed with purified water. The fruits (seeds included) were roughly ground and dried at room temperature to eliminate any remaining moisture. For the entire day, the powder was extracted using ethanol and an aqueous extract. This was done in the same way as Sofowara [17], Trease and Evans [18], and Harborne [19]. After 24 h of filtering and concentrating, the extract was tested for preliminary phytochemicals using standard methods. Z. oenopolia fruit powder was extracted by hydroalcoholic extraction using gas chromatography and mass spectrometry (GC-MS), and its anti-diabetic effects were tested in vitro. GC-MS analysis was carried out using a JEOL-GC MATE II. The sample was run in its entirety within the 50–650 m/z range, and the results were compared using the National Institute of Standards and Technology 14 Mass Spectral Library search.

2.2 Quantitative methodology

McDonald et al. employed Folin–Ciocalteu’s reagent for the estimation of total phenol content by adding diluted extract with Folin–Ciocalteu’s reagent and aqueous Na2CO3, heating at 45°C for 15 min, undergoing further investigation colorimetrically, calibrating and expressing in terms of standard gallic acid [20].

Olajire and Azeez estimated the total flavonoid content using the aluminum chloride method, which involves adding the methanolic extract to 5 mL double distilled water (ddH2O) and 0.3 mL 5% NaNO2. Then, 1.5 mL of 2% methanolic AlCl3 was added to NaNO2 at 5 min intervals. After 5 min, 2 mL of 1 mol dm−3 NaOH was added, making up the solution to 100 mL, and vigorously shaken for 5 min at 200 rpm. The solution was incubated for 10 min, and the absorbance was read. Flavonoid content was calculated using a standard calibration curve [21].

2.3 In vitro anti-diabetic activity of hydroalcoholic Z. oenopolia fruit extract

The Apostolidis et al.’s method was used to perform in vitro α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibition assays. Different concentrations (100–500 µg/mL) of hydroalcoholic Z. oenopolia fruit extract have been used as natural inhibitors [22]. The IC50 and between-target protein relationships were calculated using statistical methods of regression and correlation using MS Excel.

2.4 Molecular docking study

Using GC-MS, the ligands were identified as phytochemicals in Z. oenopolia fruits. Selected phytochemicals were collected from the PubChem database, while anti-diabetic targets were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). The ligands were changed to the PDB format using Open Bable software, and the target proteins (2QV4 and 3A4A) were removed. Prior to docking, all ligands and water molecules were eliminated. The produced protein was then stored as PDB and generated using the PyMOL program. PyRx 0.8, a virtual screening tool (Autodock Vina program) for grid dimensions (2QV4 = center_x = 16.73, center_y = 62.73, and center_z = 17.20), employed molecular docking software. The docked complexes (3A4A = center_x = 21.78, center_y = −0.1,5 and center_z = 18.46) were created by Trott and Olson (2010), and PyMOL and BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer were used as visualization tools [23].

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Phytochemical profile of Z. oenopolia (L.) fruit extract

Recent research has revealed that biologically produced secondary metabolites from plants, microbes, and invertebrate animals have bioactive properties [24,25,26]. Several significant plant secondary metabolites, including terpenoids and flavonoids, are involved in the immunological responses of plants [24,27]. Plants produce secondary metabolites from a variety of plant components, including fruits, as part of a natural defense mechanism against environmental stressors. In this study, the researchers examined the phytochemicals found in the fruit of Z. oenopolia using both aqueous and ethanolic extracts. When Z. oenopolia fruit was extracted with water or alcohol, it exhibited a range of secondary moieties, which were confirmed through the screening process, as indicated in Table 1. There is a higher concentration of flavonoids, terpenoids, tannins, and quinones in ethanolic extracts than in aqueous extracts. Observations from Rathore et al. [28] were aligned with the presence of flavonoids, glycosides, phenolics, saponins, and sterols in Z. mauritiana, albeit with a notable absence of alkaloids, mirroring the outcomes of the current investigation. The lack of some phytochemicals, the various solvents employed, the extraction and analysis techniques, seasonal variations, and the collection location are only a few possible causes for this [29]. Kumar et al. [27] found that a greater number of compounds were soluble and present in aqueous ethanol compared to water or pure solvents alone. Numerous plant-derived phytochemical components have been linked to antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-larvicidal, and antibacterial properties [9,30]. Fruits contain antioxidant and anti-inflammatory compounds like phenolics, alkaloids, and flavonoids, which can help treat diseases like cancer [31]. These compounds act as free-radical scavengers and reduce oxidative stress. However, this study did not explore how phytochemicals affect disease management, necessitating further research. Phenolic compounds found in fruit flesh and flavonoids in seeds contribute to their flavor and color, which aid in the reduction of many ailments [32,33]. The total phenol and flavonoid contents of Z. oenopolia fruit extract were estimated. The total phenolic content (151.21 ± 7.78 mg GAE/g) and flavonoid content (34.90 ± 3.67 mg QE/g) of Z. oenopolia is presented in Table 2. Phenolic compounds are potent antioxidants that increase the consumption of fruit.

Phytochemical qualitative screening of Z. oenopolia fruit extract

| S. No | Phytochemicals | Extract | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aqueous | Ethanolic | ||

| 1 | Flavonoids | + | ++ |

| 2 | Terpenoids | + | ++ |

| 3 | Glycosides | + | + |

| 4 | Polyphenol | ++ | ++ |

| 5 | Alkaloids | − | − |

| 6 | Coumarins | − | − |

| 7 | Steroids | + | + |

| 8 | Anthraquinones | + | + |

| 9 | Tannins | + | ++ |

| 10 | Quinones | + | + |

| 11 | Saponins | ++ | + |

+; presence, −; absence and ++ higher concentration.

Phytochemical quantitative analysis of Z. oenopolia fruit extract

| S. No | Phytochemicals | Z. oenopolia fruit |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Total phenol (mg GAE/g) | 151.21 ± 7.78 |

| 2 | Flavonoids (mg QE/g) | 34.90 ± 3.67 |

Values expressed as mean ± SD (N = 3).

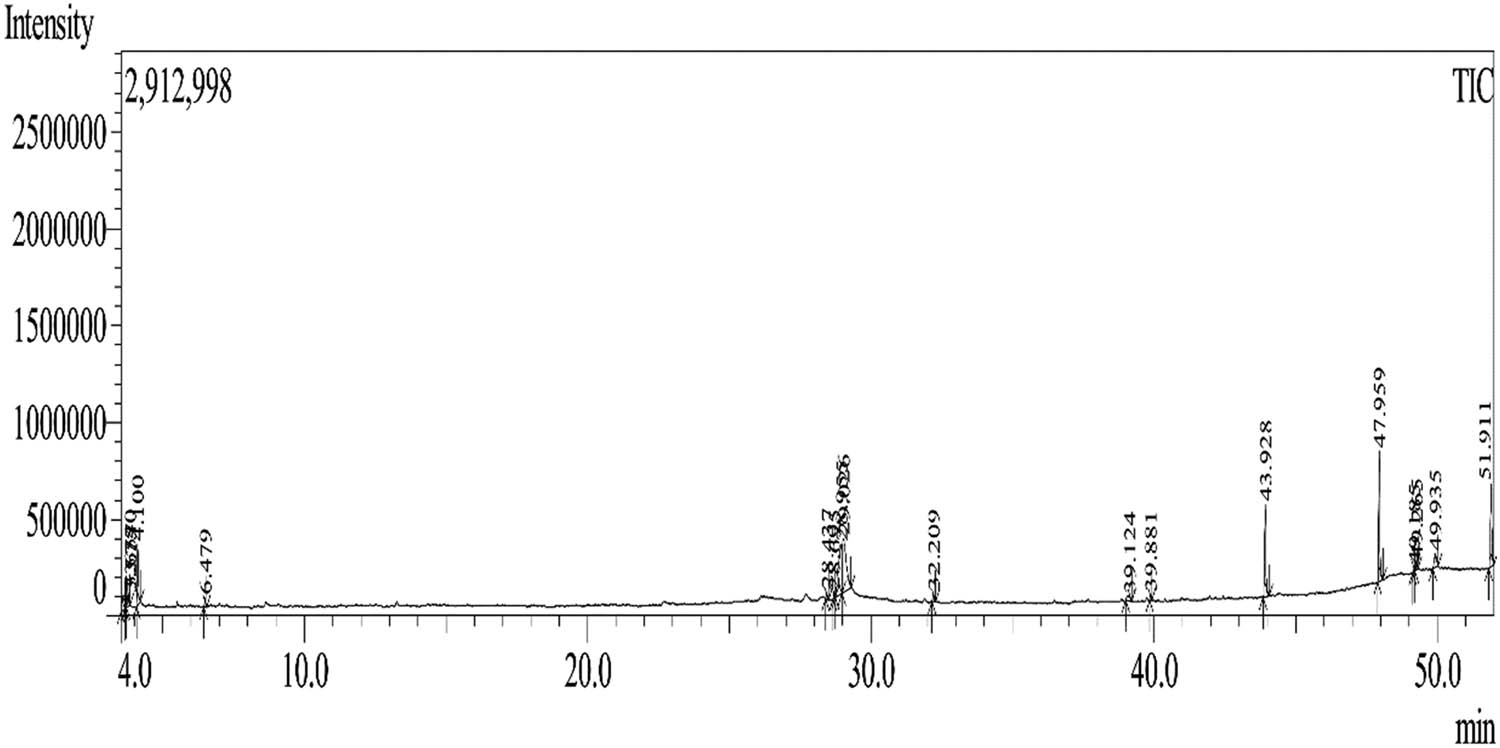

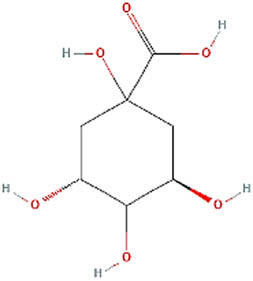

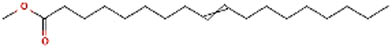

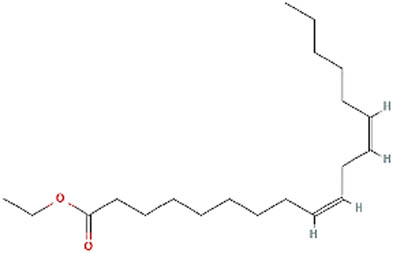

The 70% ethanolic (hydroalcoholic) Z. oenopolia fruit extract was found to contain 18 phytochemicals, including 4 bioactive substances: heneicosane, quinic acid, 9-octadecenoic acid, methyl ester, and linoleic acid ethyl ester (Figure 2, Tables 3 and 4). By comparing a query mass spectrum with the reference data in a spectrum-matching library, the NIST database was used to interpret the GC-MS data. GC-MS analysis of Hibiscus asper leaves revealed phytochemical profiles that included flavonoids, tannins, phenols, saponins, alkaloids, glycosides, terpenoids, and steroids, along with 23 bioactive compounds in the aqueous methanol fraction, including phytol, n-hexadecanoic acid, octadecatrienol acid, methyl palmitate, and octadecatrienol acid [37,38]. Ten chemicals were identified in the chloroform-methanol extract of Rhazya stricta by Baeshen et al. [39]. These chemicals include methyl stearate, methyl palmitate, methyl tetradecanoate, (–)−1,2-Didehydroaspidospermidine, and methyl laurate. Phytochemicals, including tannins, glycosides, saponins, steroids, terpenoids, alkaloids, and flavonoids, were identified in the methanolic extract of Garcinia kola. Phytochemicals contained in Z. oenopolia fruit extract have been linked to biological activity, including anti-diabetic effects.

GC-MS chromatogram of the hydroalcoholic extract of Z. oenopolia fruit.

Phytochemicals profile of the hydroalcoholic extract of Z. oenopolia fruit by GC-MS analysis

| Peak # | R. time | Molecular weight (g/mol) | Molecular formula | Molecular name | Kovats index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.575 | 89 | C3H7NO2 | d-Alanine | 855 |

| 2 | 3.657 | 252 | C12H20SSi2 | Thiophene,2-(trimethylsilyl)-5-[(trimethylsilyl)ethynyl]- | 1,318 |

| 3 | 3.740 | 68 | C4H4O | Furan | 553 |

| 4 | 4.100 | 92 | C3H8O3 | Glycerin | 967 |

| 5 | 6.479 | 148 | C6H16O2Si | 1-[(Trimethylsilyl)oxy] propan-2-ol | 766 |

| 6 | 28.437 | 296 | C21H44 | Heneicosane | 2,109 |

| 7 | 28.695 | 202 | C12H26O2 | 4,5-Decanediol, 6-ethyl- | 1,475 |

| 8 | 28.955 | 148 | C6H12O4 | 1,2,3,5-Cyclohexanetetrol, (1.alpha.,2.beta.,3.alpha.,5.beta.)- | 1,472 |

| 9 | 29.026 | 192 | C7H12O6 | Quinic acid | 1,852 |

| 10 | 32.209 | 180 | C10H12O3 | (E)-4-(3-Hydroxyprop-1-en-1-yl)-2-methoxyphenol | 1,653 |

| 11 | 39.124 | 280 | C18H32O2 | 13-Hexyloxacyclotridec-10-en-2-one | 2,325 |

| 12 | 39.881 | 296 | C19H36O2 | 9-Octadecenoic acid, methyl ester, (E)- | 2,085 |

| 13 | 43.928 | 268 | C17H32O2 | 1,4-Dioxaspiro [4.14] nonadecane | 2,171 |

| 14 | 47.959 | 340 | C20H36O4 | Ethyl stearate, 9,12-diepoxy | 2,281 |

| 15 | 49.185 | 308 | C20H36O2 | Linoleic acid ethyl ester | 2,193 |

| 16 | 49.265 | 884 | C57H104O6 | 9-Octadecenoic acid, 1,2,3-propanetriyl ester, (E, E, E)- | 6,149 |

| 17 | 49.935 | 372 | C20H36O6 | Dicyclohexano-18-crown-6 | 2,856 |

| 18 | 51.911 | 406 | C25H42O4 | Fumaric acid, 2-octyl tridec-2-yn-1-yl ester | 2,802 |

Identification of bioactive activities of the active compounds from the hydroalcoholic extract of Z. oenopolia fruit: data obtained by GC-MS techniques

| S. no | Compound name | Biological activity | Chemical structure (from PubChem) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Heneicosane | Antimicrobial activity [34] |

|

| 2 | Quinic acid | Antimicrobial activity [35] |

|

| 3 | 9-Octadecenoic acid, methyl ester, | Anti-inflammatory, antiandrogenic cancer preventive, dermatitigenic hypocholesterolemic, 5-alphareductase inhibitor, anemiagenic insectifuge, flavor [36] |

|

| 4 | Linoleic acid ethyl ester | Anti-inflammatory, hypocholesterolemic, cancer preventive hepatoprotective, nematicide, insectifuge, antihistaminic, antieczemic, antiacne, 5-alpha reductase inhibitor, antiandrogenic, antiarthritic, anticoronary, insectifuge [35] |

|

3.2 In vitro and in silico anti-diabetic activity of Z. oenopolia fruit hydroalcoholic extract through inhibition of α-amylase and α-glucosidase enzymes

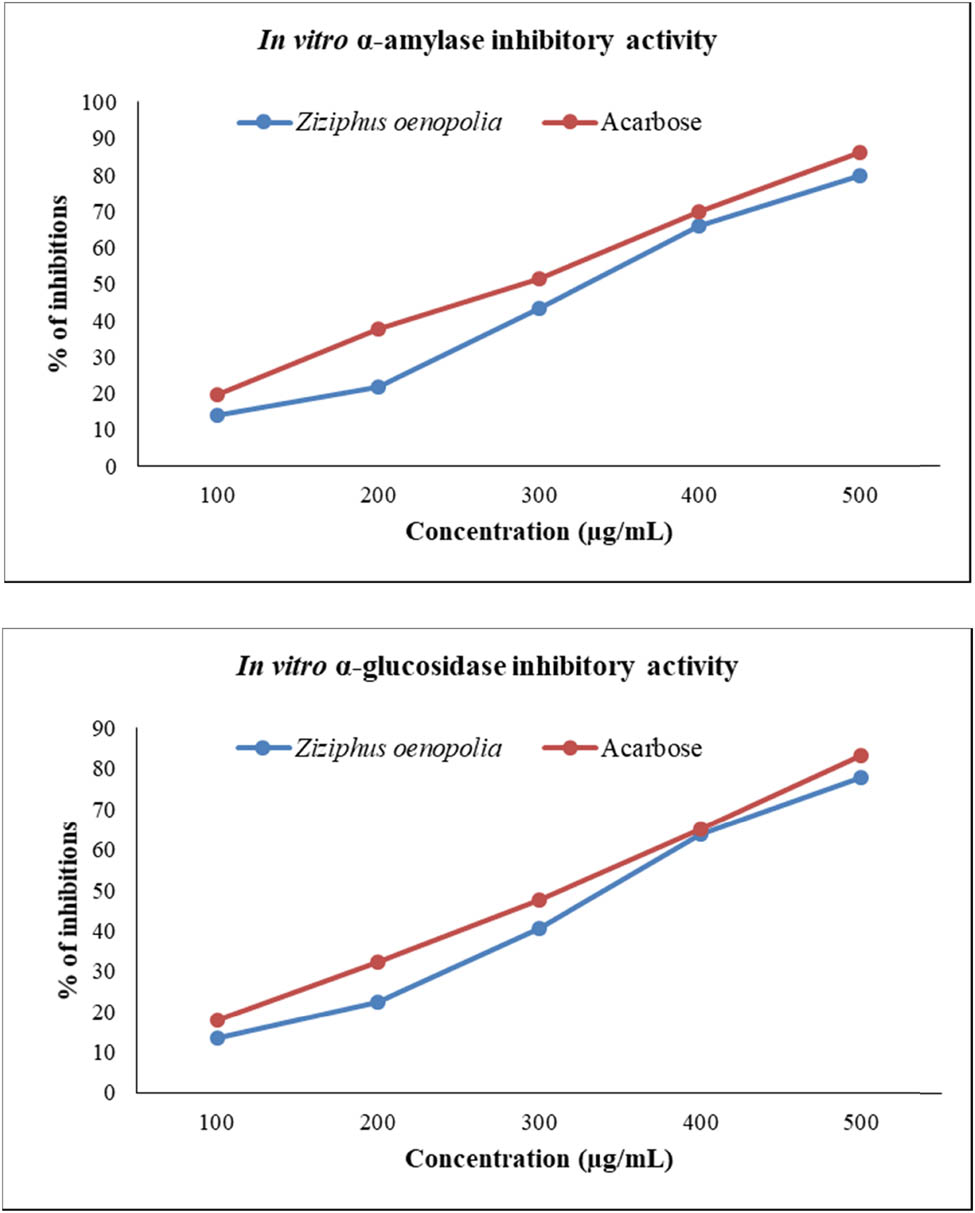

Potential anti-diabetic agents include α-amylase and α-glucosidase enzyme inhibitors, which can regulate hyperglycemia and lower the risk of diabetes. The study used a hydroalcoholic extract of Z. oenopolia fruit to test how well it blocked α-glucosidase and α-amylase enzymes in a laboratory setting. Recently, several researchers have studied a range of plant materials using the inhibitory activities of the α-amylase and α-glucosidase enzymes. The review’s results are given in Table 5. The α-amylase IC50 ranged from 170 to 610 µg/mL in both alcoholic and water-based extracts, while the α-glucosidase IC50 ranged from 180 to 440 µg/mL in both [40,41,42,43]. The current inhibitors of Z. oenopolia fruit hydroalcoholic extract have identified α-amylase (IC50 = 328.76 µg/mL) and α-glucosidase (IC50 = 337.28 µg/mL), while the standard drug (acarbose) was evaluated in vitro for α-amylase (IC50 = 281.95 µg/mL) and α-glucosidase (IC50 = 304.72 µg/mL). These findings suggest that Z. oenopolia fruit hydroalcoholic extract has the potential to be used as an anti-diabetic medication. In both the α-amylase and α-glucosidase tests (Figure 3), the hydroalcoholic extract of Z. oenopolia fruit had a dose-dependent inhibitory effect, with correlation coefficient statistics agreeing at R 2 = 0.979 for the α-amylase assay and R² = 0.981 for the α-glucosidase assay. According to Sakulkeo et al., scopoletin, N-trans-feruloyltyramine, and N-trans-coumaroyltyramine were three separate compounds that had IC50 values of 110.97, 29.87, and 0.92 µg/mL, respectively [15]. Additionally, the crude extract of Neuropeltis racemosa stems demonstrated potent α-glucosidase inhibition at 2 mg/mL (96.09%). Recently, Jaber [40] and Mechchate et al. [42] reported in vitro α-amylase inhibitory activity using the standard drug acarbose (IC50 = 590 and 717 µg/mL), while Daou et al. [44] and Jaber [40] reported in vitro α-glucosidase inhibitory activity using the standard drug acarbose (IC50 = 151.14 and 1.01 mg/mL).

Review of IC50 of various plant extracts through in vitro inhibitory activity on anti-diabetic targets α-amylase and α-glucosidase

| S. No | Plant | α-amylase (IC50) (mg/mL) | α-glucosidase (IC50) (mg/mL) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Quercus coccifera (methanol extract) | 0.17 | 0.38 | Jaber [40] |

| 2 | Cleistocalyx nervosum (aqueous extract) | 0.61 ± 0.09 | 0.44 ± 0.05 | Chukiatsiri et al. [41] |

| 3 | Cleistocalyx nervosum (ethanolic extract) | 0.42 ± 0.07 | 0.23 ± 0.04 | Chukiatsiri et al. [41]) |

| 4 | Withania frutescens (hydro-ethanolic extract) | 0.40 ± 0.124 | 0.180 ± 0.018 | Mechchate et al. [42] |

| 5 | Chloroxylon swietenia (aqueous extract) | 446.7 ± 3.63 | 373.3 ± 4.41 | Ramana Murty Kadali et al. [43] |

| 6 | Chloroxylon swietenia (ethanolic extract) | 233.3 ± 4.17 | 236.7 ± 1.67 | Ramana Murty Kadali et al. [43] |

In vitro anti-diabetic activity of the hydroalcoholic extract of Z. oenopolia fruit through inhibition of α-amylase and α-glucosidase enzymes.

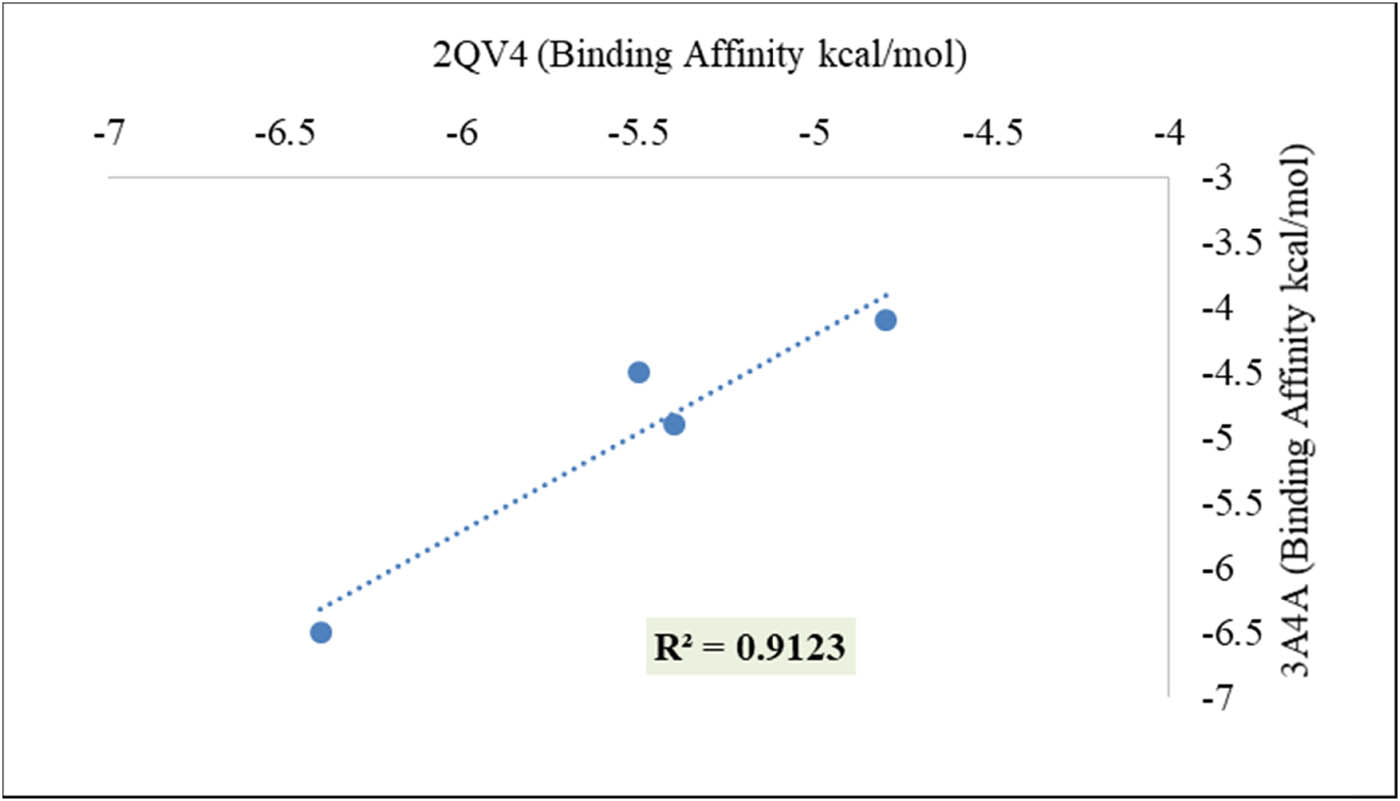

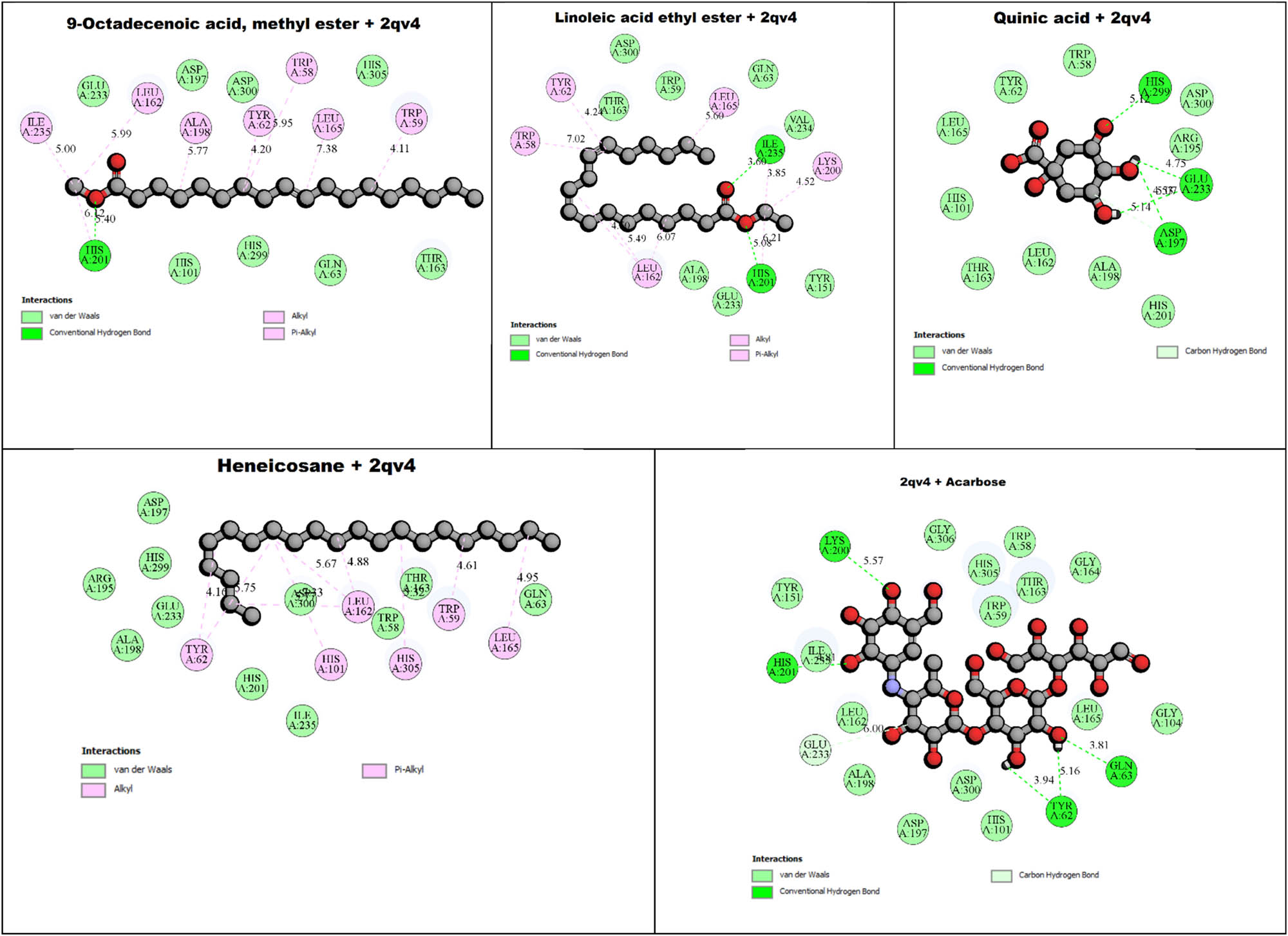

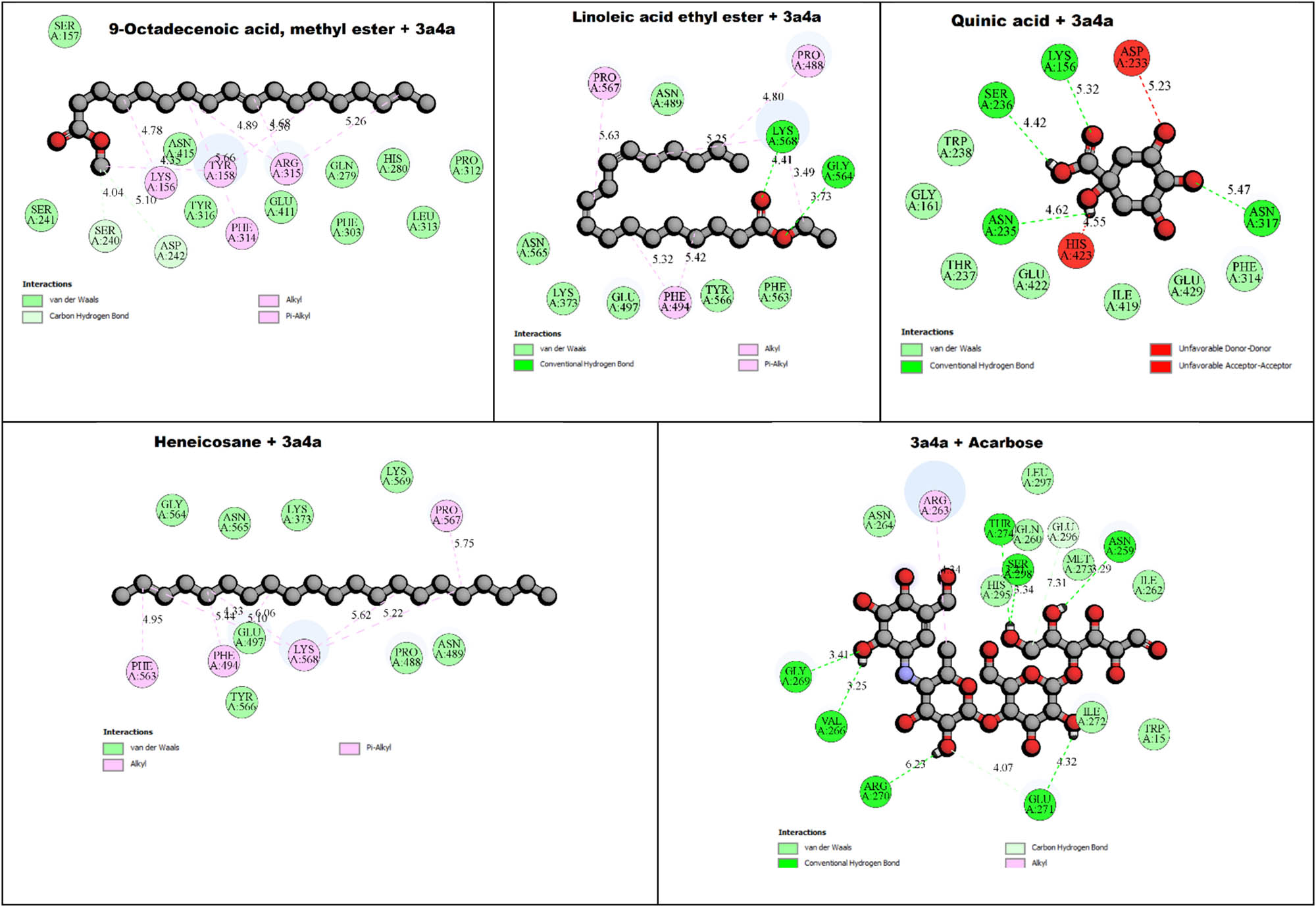

The binding interactions between α-amylase (PDB: 2QV4) and specific phytochemicals from Z. oenopolia fruit hydroalcoholic extract, including heneicosane (−4.80 kcal/mol), quinic acid (−6.40 kcal/mol), 9-octadecenoic acid, methyl ester (−5.40 kcal/mol), linoleic acid ethyl ester (−5.50 kcal/mol), and acarbose (−7.30 kcal/mol), as well as α-glucosidase (PDB: 3A4A) binding interactions with heneicosane (−4.10 kcal/mol), quinic acid (−6.50 kcal/mol), 9-octadecenoic acid, methyl ester (−4.90 kcal/mol), linoleic acid ethyl ester (−4.50 kcal/mol), and acarbose (−7.40 kcal/mol) are displayed in Table 6 using the PyRx (Autodock Vina) tool; the ADME properties of Z. oenopolia fruit phytochemicals are shown in Table 7 using Swiss ADME. The study presented in Table 8 investigates the interaction between Z. oenopolia fruit phytochemicals and acarbose (a standard anti-diabetic drug) with the key anti-diabetic target enzyme, 3A4A (isomaltase). Table 7 illustrates a comparative study of the ADME properties of Z. oenopolia fruit phytochemicals with acarbose, a standard anti-diabetic drug, using the SwissADME tool. The table briefly compares the properties such as physicochemical properties, lipophilicity, solubility, pharmacokinetics, druglikeness, and medicinal chemistry of Z. oenopolia fruit phytochemicals and Acarbose (Standard drug).

Molecular docking of phytochemicals and anti-diabetic targets using PyRx (Autodock Vina) tools, LD50 (ProTox-II), and analysis of the correlation matrix (N = 4)

| Binding affinity (kcal/mol) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand | LD50 (mg/kg) | 2QV4 | 3A4A |

| Heneicosane | 750 | −4.80 | −4.10 |

| Quinic acid | 9,800 | −6.40 | −6.50 |

| 9-Octadecenoic acid, methyl ester, | 3,000 | −5.40 | −4.90 |

| Linoleic acid ethyl ester | 20,000 | −5.50 | −4.50 |

| Correlation matrix ( N = 4) | R = 0.955 or R 2 = 0.9123 | ||

| Acarbose (standard drug) | 2,000 | −7.30 | −7.40 |

ADME properties of phytochemicals and acarbose of Z. oenopolia fruit using swiss ADME

| ADME | Heneicosane | Quinic acid | 9-Octadecenoic acid, methyl ester | Linoleic acid ethyl ester | Acarbose (standard drug) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physicochemical properties | |||||

| Formula | C21H44 | C7H12O6 | C19H36O2 | C20H36O2 | C25H43NO18 |

| Molecular weight | 296.57 g/mol | 192.17 g/mol | 296.49 g/mol | 308.50 g/mol | 645.60 g/mol |

| No. heavy atoms | 21 | 13 | 21 | 22 | 44 |

| No. arom. heavy atoms | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fraction Csp3 | 1.00 | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.75 | 0.88 |

| Num. rotatable bonds | 18 | 1 | 16 | 16 | 13 |

| No. H-bond acceptors | 0 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 19 |

| No. H-bond donors | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 14 |

| Molar refractivity | 103.06 | 40.11 | 94.26 | 98.59 | 137.92 |

| TPSA | 0.00 Ų | 118.22 Ų | 26.30 Ų | 26.30 Ų | 329.01 Ų |

| Lipophilicity | |||||

| Log P o/w (iLOGP) | 5.85 | −0.12 | 4.75 | 5.03 | −1.99 |

| Log P o/w (XLOGP3) | 10.99 | −2.37 | 7.45 | 7.34 | −8.82 |

| Log P o/w (WLOGP) | 8.44 | −2.32 | 6.20 | 6.36 | −8.72 |

| Log P o/w (MLOGP) | 7.60 | −2.14 | 4.80 | 4.93 | −7.45 |

| Log P o/w (SILICOS-IT) | 8.43 | −1.82 | 6.54 | 6.80 | −6.36 |

| Consensus Log P o/w | 8.26 | −1.75 | 5.95 | 6.09 | −6.67 |

| Water solubility | |||||

| Log S (ESOL) | −7.41 | 0.53 | −5.32 | −5.32 | 2.57 |

| Solubility | 1.14 × 10−5 mg/mL | 6.48 × 102 mg/mL | 1.43 × 10−3 mg/mL | 1.47 × 10−3 mg/mL | 2.41 × 105 mg/mL |

| Class | Poorly soluble | Highly soluble | Moderately soluble | Moderately soluble | Highly soluble |

| Log S (Ali) | −10.96 | 0.43 | −7.83 | −7.72 | 2.69 |

| Solubility | 3.29 × 10−9 mg/mL | 5.12 × 102 mg/mL | 4.34 × 10−6 mg/mL | 5.88 × 10−6 mg/mL | 3.18 × 105 mg/mL |

| Class | Insoluble | Highly soluble | Poorly soluble | Poorly soluble | Highly soluble |

| Log S (SILICOS-IT) | −8.34 | 2.08 | −6.09 | −5.77 | 6.23 |

| Solubility | 1.37 × 10−6 mg/mL | 2.30 × 104 mg/mL | 2.40 × 10−4 mg/mL | 5.23 × 10−4 mg/mL | 1.10 × 109 mg/mL |

| Class | Poorly soluble | Soluble | Poorly soluble | Moderately soluble | Soluble |

| Pharmacokinetics | |||||

| GI absorption | Low | Low | High | High | Low |

| BBB permeant | No | No | No | No | No |

| P-gp substrate | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| CYP1A2 inhibitor | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| CYP2C19 inhibitor | No | No | No | No | No |

| CYP2C9 inhibitor | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| CYP2D6 inhibitor | No | No | No | No | No |

| CYP3A4 inhibitor | No | No | No | No | No |

| Log K p (skin permeation) | −0.31 cm/s | −9.15 cm/s | −2.82 cm/s | −2.97 cm/s | −16.50 cm/s |

| Druglikeness | |||||

| Lipinski | Yes; 1 violation: MLOGP > 4.15 | Yes; 0 violation | Yes; 1 violation: MLOGP > 4.15 | Yes; 1 violation: MLOGP > 4.15 | No; 3 violations: MW > 500, NorO > 10, NHorOH > 5 |

| Ghose | No; 1 violation: WLOGP > 5.6 | No; 1 violation: WLOGP < −0.4 | No; 1 violation: WLOGP > 5.6 | No; 1 violation: WLOGP > 5.6 | No; 4 violations: MW > 480, WLOGP < −0.4, MR > 130, #atoms > 70 |

| Veber | No; 1 violation: rotors > 10 | Yes | No; 1 violation: rotors > 10 | No; 1 violation: rotors > 10 | No; 2 violations: rotors > 10, TPSA > 140 |

| Egan | No; 1 violation: WLOGP > 5.88 | Yes | No; 1 violation: WLOGP > 5.88 | No; 1 violation: WLOGP > 5.88 | No; 1 violation: TPSA > 131.6 |

| Muegge | No; 3 violations: XLOGP3 > 5, heteroatoms < 2, rotors > 15 | No; 2 violations: MW < 200, XLOGP3 < −2 | No; 2 violations: XLOGP3 > 5, rotors > 15 | No; 2 violations: XLOGP3 > 5, rotors > 15 | No; 5 violations: MW > 600, XLOGP3 < −2, TPSA > 150, H-acc > 10, H-don > 5 |

| Bioavailability Score | 0.55 | 0.56 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.17 |

| Medicinal chemistry | |||||

| PAINS | 0 alert | 0 alert | 0 alert | 0 alert | 0 alert |

| Brenk | 0 alert | 0 alert | 1 alert: isolated_alkene | 1 alert: isolated_alkene | 2 alerts: aldehyde, isolated_alkene |

| Leadlikeness | No; 2 violations: rotors > 7, XLOGP3 > 3.5 | No; 1 violation: MW < 250 | No; 2 violations: rotors > 7, XLOGP3 > 3.5 | No; 2 violations: rotors > 7, XLOGP3 > 3.5 | No; 2 violations: MW > 350, rotors > 7 |

| Synthetic accessibility | 2.84 | 3.34 | 3.16 | 3.34 | 7.25 |

Phytochemicals and acarbose (standard) interactions of Z. oenopolia fruit with anti-diabetic target 2QV4 (α-amylase) and 3A4A (isomaltase)

| Ligand | Amino acid-binding residues (α-amylase PDB ID: 2QV4) | Amino acid-binding residues (isomaltase PDB ID: 3A4A) |

|---|---|---|

| Heneicosane | Asp 197, His 299, Arg 195, Glu 233, Ala 198, Tyr 62, His 201, Ile 235, His 101, Leu 162, Trp 58, His 305, Thr 163, Trp 59, Leu 165, Gln 63 | Phe 563, Phe 494, Tyr 566, Glu 497, Lys 568, Pro 488, Asn 489, Pro 567, Lys 569, Lys 373, Asn 565, Gly 564. |

| Quinic acid | Trp 58, Tyr 62, Leu 165, His 101, Thr 163, Leu 162, Ala 198, His 201, Asp 197, Glu 233, Arg 195, Asp 300, His 299 | Asp 233, Lys 156, Ser 236, Trp 238, Gly 161, Thr 237, Asn 235, Glu 422, His 423, Ile 419, Glu 429. Phe 314, Asn 317 |

| 9-Octadecenoic acid, methyl ester | Trp 59, His 305, Trp 58, Leu 165, Tyr 62, Asp 300, Asp 197, Ala 198, Leu 162, Glu 233, Ile 235, His 201, His 101, His 299, Gln 63, Thr 163 | Ser 157, Ser 241, Ser 240, Asp 242, Lys 156, Asn 415, Tyr 158, Tyr 316, Phe 314, Glu 411, Arg 315, Gln 279, Phe 303, Leu 313, His 280, Pro 312 |

| Linoleic acid ethyl ester | Trp 58, Tyr 62, Thr 163, Asp 300, Trp 59, Leu 165, Gln 63, Val 234, Ile 235, Lys 200, Tyr 151, His 201, Glu 233, Ala 198, Leu 162 | Pro 567, Asn 489, Pro 488, Lys 568, Gly 564, Phe 563, Tyr 566, Phe 494, Glu 497, Lys 373, Asn 565 |

| Acarbose (standard) | Lys 200, Tyr 151, His 201, Leu 162, Glu 233, Ala 198, Asp 197, Asp 300, His 101, Tyr 62, Gln 63, Leu 165, Gly 104, Gly 164, Thr 163, Trp 59, Trp 58, His 305, Gly 306 | Gly 269, Val 266, Arg 270, Glu 271, Ile 272, Trp 15, Ile 262, Asn 259, Met 273, Glu 296, Leu 297, Gln 260, Ser 298, His 295, Thr 274, Arg 263, Asn 264 |

Figure 4 shows that the phytochemicals in Z. oenopolia fruit prevent both α-amylase and α-glucosidase enzymes from working normally. This indicates that the fruit of Z. oenopolia was able to block α-glucosidase enzyme activity both in vitro and in vivo. Thus, it can be used as a drug for diabetes. According to our understanding, there exists a robust positive correlation (R 2 = 0.912) between the anti-diabetic targets. This suggests that the hydroalcoholic extract of Z. oenopolia fruit possesses an inhibitory mechanism comparable to that of α-amylase and α-glucosidase, which regulate hyperglycemia. The binding affinities (kcal/mol) of a few of the chosen phytochemicals, as expressed in the target protein, are displayed in Table 5. Figures 5 and 6 show a 2D picture of how the chosen ligand interacts with the amino acid residues of the target protein. This may show that the acarbose and phytochemicals in Z. oenopolia fruit stop the enzymes α-amylase and α-glucosidase from functioning.

Correlation matrix (N = 4) between the anti-diabetic targets.

2D view of phytochemicals and acarbose of Z. oenopolia fruit interaction with the anti-diabetic target 2QV4 (α-amylase).

2D view of phytochemicals and acarbose of Z. oenopolia fruit interaction with the anti-diabetic target 3A4A (isomaltase).

Inhibition of α-amylase (PDB ID: 2QV4) [15] and α-glucosidase (PDB ID: 3A4A) [45] has been recently identified as the target proteins. Lolok et al. [46] investigated the molecular docking of stigmasterol and β-sitosterol, which were separated from Morinda citrifolia, with α-amylase (PDB ID: 2QV4), and Akshatha et al. [16] explored similar results of phytochemical interaction with α-amylase (PDB ID: 2QV4). The former study examined the molecular docking of plant-derived α-glucosidase inhibitors (PDB ID: 3A4A), while the latter examined the molecular docking of new 3-amino-2,4-diarylbenzo (4,5) imidazo (1,2-a) pyrimidines against α-glucosidase (PDB ID: 3A4A) [47]. Similarly, Murugesu et al. [48] reported that LC-MS was the best method for identifying α-glucosidase (PDB ID: 3A4A) inhibitors in Clinacanthus nutans leaves. In conclusion, this study showed that the hydroalcoholic extract of Z. oenopolia fruit can inhibit the activity of α-amylase and α-glucosidase enzymes both in vitro and in silico, suggesting that it could be used as a potential diabetes drug.

4 Conclusions

The phytochemicals present in the fruit of Z. oenopolia are equally involved in the inhibitory activities of α-amylase and α-glucosidase, as evidenced by computational and statistical approaches. As a result of the significant positive link between the anti-diabetic targets, it can be inferred that the hydroalcoholic extract obtained from the fruit of Z. oenopolia possesses an inhibitory mechanism comparable to that of α-amylase and α-glucosidase, which is responsible for the regulation of increased blood sugar levels. This results in the presence of phytochemicals, including flavonoids, terpenoids, phenols, steroids, tannins, and saponins. Phytochemicals are effective and environment-friendly treatments.

Acknowledgments

This study was partly supported by the Kaohsiung Armed Forces General Hospital (KAFGH_A_-113003). The authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2024R677), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for financial support.

-

Funding information: This study was partly supported by Kaohsiung Armed Forces General Hospital (KAFGH_A_-113003).

-

Author contributions: Conceptualization, R.S.V., S.B., and R.V; methodology and software, R.S.V., S.B., and S.B.; validation, A.H.H., Z.H.W., formal analysis data curation, R.S.V, S.B. and C.H.Y.; investigation, R.S.V., and R.V.; writing – original draft, R.S.V., S.B., and R.V; writing – review and editing R.S.V., S.B., R.V; C.H.Y and Z.H.W.; finding acquisition, C.H.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

-

Data availability statement: All data used to support the finding of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

[1] Rao MM, Hariprasad TPN. In silico analysis of a potential anti-diabetic hytochemical erythrin against therapeutic targets of diabetes. Silico Pharmacol. 2021;9:1–12. 10.1007/s40203-020-00065-8.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Sharma B, Mishra A, Rane BR, Sharma P, Garg S, Rathore S. Role of dietary fibers in diabetes. in food supplements and dietary fiber in health and disease. New York: Apple Academic Press; 2024. p. 81–109.10.1201/9781003386308-4Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Tundis R, Loizzo MR, Menichini F. Natural products as α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitors and their hypoglycaemic potential in the treatment of diabetes: an update. Min Rev Med Chem. 2010;10:315–31. 10.2174/138955710791331007.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Rutkowska M, Olszewska MA. Anti-diabetic potential of polyphenol-rich fruits from the maleae tribe-a review of in vitro and in vivo animal and human trials. Nutrients. 2023;15:3756. 10.3390/nu15173756.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Tasnim J, Hashim NM, Han HC. A comprehensive review on potential drug–drug interactions of proton pump inhibitors with anti-diabetic drugs metformin and DPP‐4 inhibitors. Cell Biochem Funct. 2024;42(2):e3967.10.1002/cbf.3967Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Przeor M. Some common medicinal plants with anti-diabetic activity, known and availaboratoryle in Europe (a mini-review). Pharmaceuticals. 2022;15:65. 10.3390/ph15010065.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Salehi B, Ata AV, Anil Kumar N, Sharopov F, Ramirez Alarcon K, Ruiz Ortega A, et al. Anti-diabetic potential of medicinal plants and their active components. Biomolecules. 2019;9:551. 10.3390/biom9100551.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Das K, Iyer KR, Orfali R, Asdaq SMB, Alotaibi NS, Alotaibi FS, et al. In silico studies and evaluation of in vitro anti-diabetic activity of berberine from ethanol seed extract of Coscinium fenestratum (Gaertn.) Colebr. J King Saud Univ-Sci. 2023;35:102666. 10.1016/j.jksus.2023.102666.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Dar RA, Shahnawaz M, Qazi PH. General overview of medicinal plants: A review. J Phytopharmacol. 2017;6:349–51.10.31254/phyto.2017.6608Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Guan R, Van Le Q, Yang H, Zhang D, Gu H, Yang Y, et al. A review of dietary phytochemicals and their relation to oxidative stress and human diseases. Chemosphere. 2021;271:129499. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.129499.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Jha AK, Sit N. Extraction of bioactive compounds from plant materials using combination of various novel methods: A review. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2022;119:579–91.10.1016/j.tifs.2021.11.019Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Thirugnanasampandan R, Ramya G, Bhuvaneswari G, Aravindh S, Vaishnavi S, Gogulramnath M. Preliminary phytochemical analysis and evaluation of antioxidant, cytotoxic and inhibition of lipopolysaccaride-induced NOS (iNOS) expression in BALB/c mice liver by Ziziphus oenopolia Mill. fruit. J Complement Integr Med. 2017;14(2):20160009.10.1515/jcim-2016-0009Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Shukla A, Garg A, Mourya P, Jain CP. Zizyphus oenopolia Mill?: a review on pharmacological aspects. Adv Pharm J. 2016;1(1):12.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Rao CV, Rawat AKS, Singh AP, Singh A, Verma N. Hepatoprotective potential of ethanolic extract of Ziziphus oenoplia (L.) mill roots against antitubercular drugs induced hepatotoxicity in experimental models. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2012;5(4):283–8.10.1016/S1995-7645(12)60040-6Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Sakulkeo O, Wattanapiromsakul C, Pitakbut T, Dej Adisai S. Alpha-glucosidase inhibition and molecular docking of isolated compounds from traditional thai medicinal plant, neuropeltis racemosa wall. Molecules. 2022;27:639. 10.3990/molecules27030639.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Akshatha JV, Santosh Kumar HS, Prakash HS, Nalini MS. In silico docking studies of α-amylase inhibitors from the anti-diabetic plant Leucas ciliata Benth. and an endophyte, Streptomyces longisporoflavus. 3 Biotech. 2021;11:1–16. 10.1007/s13205-020-02547-0.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Sofowara A. Medicinal plants and traditional medicine in Africa. Vol. 289. Ibadan, Nigeria: Spectrum Books Ltd.; 1993.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Trease GE, Evans WC. Pharmacognsy. Brailliar Tiridel Can. 11th edn. London: Macmilliam Publishers; 1989. p. 35–8.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Harborne JB. Phytochemical methods. London: Chapman and Hall Ltd; 1973. p. 49–188.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] McDonald S, Prenzler PD, Antolovich M, Robards K. Phenolic content and antioxidant activity of olive extracts. Food Chem. 2001;73(1):73–84.10.1016/S0308-8146(00)00288-0Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Olajire AA, Azeez L. Total antioxidant activity, phenolic, flavonoid and ascorbic acid contents of Nigerian vegetables. AJFST 2(2):22–9.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Apostolidis E, Kwon YI, Shetty K. Inhibitory potential of herb, fruit, and fungus enriched cheese against key enzymes linked to type 2 diabetes and hypertension. Innovative Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2007;8:46–54. 10.1016/j.ifset.2006.06.001.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem. 2010;31(2):455–61.10.1002/jcc.21334Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Kumar S, Korra T, Thakur R, Arutselvan R, Kashyap AS, Nehela Y, et al. Role of plant secondary metabolites in defence and transcriptional regulation in response to biotic stress. Plant Stress. 2023;8:100154. 10.1016/j.stress.2023.100154.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Sharma A, Sharma S, Kumar A, Kumar V, Sharma AK. Plant secondary metabolites: An introduction of their chemistry and biological significance with physicochemical aspect. In Plant secondary metabolites: Physico-chemical properties and therapeutic applications. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore; 2022. p. 1–45. 10.1007/978-981-16-4779-6_1.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Abdel Nasser A, Hathout AS, Badr AN, Barakat OS, Fathy HM. Extraction and characterization of bioactive secondary metabolites from lactic acid bacteria and evaluating their antifungal and ant aflatoxigenic activity. Biotechnol Rep. 2023;38:e00799. 10.1016/j.btre.2023.e00799.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Kumar S, Saini R, Suthar P, Kumar V, Sharma R. Plant secondary metabolites: Their food and therapeutic importance. In Plant secondary metabolites: Physico-chemical properties and therapeutic applications. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore; 2022. p. 371–413.10.1007/978-981-16-4779-6_12Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Rathore SK, Bhatt S, Dhyani S, Jain A. Preliminary phytochemical screening of medicinal plant Ziziphus Mauritiana Lam. fruits. Int J Curr Pharm Res. 2012;4(3):160–2.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Karnan R, Sukumaran M, Mariappan P, Velavan S. Insecticidal effect of zoochemicals mediated copper oxide nanoparticle using marine sponge hyattella intestinalis (lamarck, 1814) and molecular docking. Uttar Pradesh J Zool. 2023;44:64–72. 10.56557/upjoz/2023/v44i153570.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Sultana S, Asif HF, Akhtar N, Waqas M, Rehman UR. Comprrehensive review on ethanobotanical uses, phytochemistry and pharmacological properties of Melia zedarach Inn. Asian J Pharm Res Health Care. 2014;6(1):26–32.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Soni A, Sosa S. Phytochemical analysis and free radical scavenging potential of herbal and medicinal plant extracts. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2013;2(4):22–9.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Robards K, Prenzler PD, Tucker GP, Swatsitang P, Glover W. Phenolic compounds and their role in oxidative processes in fruits. Food Chem. 1999;66(4):401–36.10.1016/S0308-8146(99)00093-XSuche in Google Scholar

[33] Thilakarathna SH, Vasantha Rupasinghe HP. Antiatherosclerotic effects of fruit bioactive compounds: a review of current scientific evidence. Can J Plant Sci. 2012;92(3):407–19.10.4141/cjps2011-090Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Vanitha V, Vijayakumar S, Nilavukkarasi M, Punitha VN, Vidhya E, Praseetha PK. Heneicosane-A novel microbicidal bioactive alkane identified from Plumbago zeylanica. Ind Crop Products. 2020;154:112748. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2020.112748.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Sathish SS, Janakiraman N, Johnson M. Phytochemical analysis of Vitex altissima L. using UV-Vis, FTIR GC-MS. Int J Pharm Sci Drug Res. 2012;4:56–62.Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Natarajan P, Singh S, Balamurugan K. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis of bio active compounds presents in Oeophylla smaragdina. Res J Pharm Tech. 2019;12:2736–41. 10.5958/0974-360X.2019.00458.X.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Karnan R, Sukumaran M, Velavan S. Extraction and identification of zoochemicals in marine sponge Hyattella intestinalis (Lamarck, 1814) (Phylum: Porifera) using GC-MS technique. Intern J Zool Invest. 2022;8:113–8. 10.33745/ijzi.2022.v08i0s.014.Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Olivia NU, Goodness UC, Obinna OM. Phytochemical profiling and GC-MS analysis of aqueous methanol fraction of Hibiscus asper leaves. Future J Pharm Sci. 2021;7:1–5.10.1186/s43094-021-00208-4Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Baeshen NA, Almulaiky YQ, Afifi M, Al Farga A, Ali HA, Baeshen NN, et al. GC-MS analysis of bioactive compounds extracted from plant Rhazya stricta using various solvents. Plants. 2023;12:960. 10.3390/plants12040960.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] Jaber SA. In vitro alpha-amylase and alpha-glucosidase inhibitory activity and in vivo anti-diabetic activity of Quercus coccifera (Oak tree) leaves extracts. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2023;30:103688. 10.1016/j.sjbs.2023.103688.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Chukiatsiri S, Wongsrangsap N, Ratanabunyong S, Choowongkomon K. In vitro evaluation of anti-diabetic potential of cleistocalyx nervosum var. paniala fruit extract. Plants. 2022;12:112. 10.3390/plants12010112.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[42] Mechchate H, Es-Safi I, Louba A, Alqahtani AS, Nasr FA, Noman OM, et al. In vitro alpha-amylase and alpha-glucosidase inhibitory activity and in vivo anti-diabetic activity of Withania Frutescens L. foliar extract. Molecules. 2021;26(2):293.10.3390/molecules26020293Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[43] Ramana Murty Kadali SLDV, Mangala CD, Rajagopalan V, Ittagi S. In vitro evaluation of anti-diabetic activity of aqueous and ethanolic leaves extracts of Chloroxylon swietenia. National. J Physiol Pharm Pharmacol. 2017;7:486.10.5455/njppp.2017.7.1235104012017Suche in Google Scholar

[44] Daou M, Elnaker NA, Ochsenkühn MA, Amin SA, Yousef AF, Yousef LF. In vitro α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of Tamarix nilotica shoot extracts and fractions. PLoS One. 2022;17(3):e0264969.10.1371/journal.pone.0264969Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] Tuan NN, Thi HN, My CLT, Hai TX, Trung HT, Kim ANT, et al. Inhibition of α-glucosidase, acetylcholinesterase, and nitric oxide production by phytochemicals isolated from Millettia speciosa-In Vitro and molecular docking studies. Plants. 2022;11(3):388.10.3390/plants11030388Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[46] Lolok N, Ramadhan DSF, Sumiwi SA, Sahidin I, Levita J. Molecular docking of β-sitosterol and stigmasterol isolated from Morinda citrifolia with α-amylase, α-glucosidase, dipeptidylpeptidase-iv, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ. Rasayan J Chem. 2022;15:20–30. 10.31755/RJC.2022.1516646.Suche in Google Scholar

[47] Hyun TK, Eom SH, Kim JS. Molecular docking studies for discovery of plant-derived a-glucosidase inhibitors. Plant Omics. 2014;7:166–70.Suche in Google Scholar

[48] Murugesu S, Ibrahim Z, Ahmed QU, Uzir BF, Yusoff NIN, Perumal V, et al. Identification of α-glucosidase inhibitors from Clinacanthus nutans leaf extract using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry-based metabolomics and protein-ligand interaction with molecular docking. J Pharm Anal. 2019;9:91–9. 10.1016/j.jpha.2018.11.001.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Porous silicon nanostructures: Synthesis, characterization, and their antifungal activity

- Biochar from de-oiled Chlorella vulgaris and its adsorption on antibiotics

- Phytochemicals profiling, in vitro and in vivo antidiabetic activity, and in silico studies on Ajuga iva (L.) Schreb.: A comprehensive approach

- Synthesis, characterization, in silico and in vitro studies of novel glycoconjugates as potential antibacterial, antifungal, and antileishmanial agents

- Sonochemical synthesis of gold nanoparticles mediated by potato starch: Its performance in the treatment of esophageal cancer

- Computational study of ADME-Tox prediction of selected phytochemicals from Punica granatum peels

- Phytochemical analysis, in vitro antioxidant and antifungal activities of extracts and essential oil derived from Artemisia herba-alba Asso

- Two triazole-based coordination polymers: Synthesis and crystal structure characterization

- Phytochemical and physicochemical studies of different apple varieties grown in Morocco

- Synthesis of multi-template molecularly imprinted polymers (MT-MIPs) for isolating ethyl para-methoxycinnamate and ethyl cinnamate from Kaempferia galanga L., extract with methacrylic acid as functional monomer

- Nutraceutical potential of Mesembryanthemum forsskaolii Hochst. ex Bioss.: Insights into its nutritional composition, phytochemical contents, and antioxidant activity

- Evaluation of influence of Butea monosperma floral extract on inflammatory biomarkers

- Cannabis sativa L. essential oil: Chemical composition, anti-oxidant, anti-microbial properties, and acute toxicity: In vitro, in vivo, and in silico study

- The effect of gamma radiation on 5-hydroxymethylfurfural conversion in water and dimethyl sulfoxide

- Hollow mushroom nanomaterials for potentiometric sensing of Pb2+ ions in water via the intercalation of iodide ions into the polypyrrole matrix

- Determination of essential oil and chemical composition of St. John’s Wort

- Computational design and in vitro assay of lantadene-based novel inhibitors of NS3 protease of dengue virus

- Anti-parasitic activity and computational studies on a novel labdane diterpene from the roots of Vachellia nilotica

- Microbial dynamics and dehydrogenase activity in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) rhizospheres: Impacts on growth and soil health across different soil types

- Correlation between in vitro anti-urease activity and in silico molecular modeling approach of novel imidazopyridine–oxadiazole hybrids derivatives

- Spatial mapping of indoor air quality in a light metro system using the geographic information system method

- Iron indices and hemogram in renal anemia and the improvement with Tribulus terrestris green-formulated silver nanoparticles applied on rat model

- Integrated track of nano-informatics coupling with the enrichment concept in developing a novel nanoparticle targeting ERK protein in Naegleria fowleri

- Cytotoxic and phytochemical screening of Solanum lycopersicum–Daucus carota hydro-ethanolic extract and in silico evaluation of its lycopene content as anticancer agent

- Protective activities of silver nanoparticles containing Panax japonicus on apoptotic, inflammatory, and oxidative alterations in isoproterenol-induced cardiotoxicity

- pH-based colorimetric detection of monofunctional aldehydes in liquid and gas phases

- Investigating the effect of resveratrol on apoptosis and regulation of gene expression of Caco-2 cells: Unravelling potential implications for colorectal cancer treatment

- Metformin inhibits knee osteoarthritis induced by type 2 diabetes mellitus in rats: S100A8/9 and S100A12 as players and therapeutic targets

- Effect of silver nanoparticles formulated by Silybum marianum on menopausal urinary incontinence in ovariectomized rats

- Synthesis of new analogs of N-substituted(benzoylamino)-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridines

- Response of yield and quality of Japonica rice to different gradients of moisture deficit at grain-filling stage in cold regions

- Preparation of an inclusion complex of nickel-based β-cyclodextrin: Characterization and accelerating the osteoarthritis articular cartilage repair

- Empagliflozin-loaded nanomicelles responsive to reactive oxygen species for renal ischemia/reperfusion injury protection

- Preparation and pharmacodynamic evaluation of sodium aescinate solid lipid nanoparticles

- Assessment of potentially toxic elements and health risks of agricultural soil in Southwest Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- Theoretical investigation of hydrogen-rich fuel production through ammonia decomposition

- Biosynthesis and screening of cobalt nanoparticles using citrus species for antimicrobial activity

- Investigating the interplay of genetic variations, MCP-1 polymorphism, and docking with phytochemical inhibitors for combatting dengue virus pathogenicity through in silico analysis

- Ultrasound induced biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles embedded into chitosan polymers: Investigation of its anti-cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma effects

- Copper oxide nanoparticles-mediated Heliotropium bacciferum leaf extract: Antifungal activity and molecular docking assays against strawberry pathogens

- Sprouted wheat flour for improving physical, chemical, rheological, microbial load, and quality properties of fino bread

- Comparative toxicity assessment of fisetin-aided artificial intelligence-assisted drug design targeting epibulbar dermoid through phytochemicals

- Acute toxicity and anti-inflammatory activity of bis-thiourea derivatives

- Anti-diabetic activity-guided isolation of α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory terpenes from Capsella bursa-pastoris Linn.

- GC–MS analysis of Lactobacillus plantarum YW11 metabolites and its computational analysis on familial pulmonary fibrosis hub genes

- Green formulation of copper nanoparticles by Pistacia khinjuk leaf aqueous extract: Introducing a novel chemotherapeutic drug for the treatment of prostate cancer

- Improved photocatalytic properties of WO3 nanoparticles for Malachite green dye degradation under visible light irradiation: An effect of La doping

- One-pot synthesis of a network of Mn2O3–MnO2–poly(m-methylaniline) composite nanorods on a polypyrrole film presents a promising and efficient optoelectronic and solar cell device

- Groundwater quality and health risk assessment of nitrate and fluoride in Al Qaseem area, Saudi Arabia

- A comparative study of the antifungal efficacy and phytochemical composition of date palm leaflet extracts

- Processing of alcohol pomelo beverage (Citrus grandis (L.) Osbeck) using saccharomyces yeast: Optimization, physicochemical quality, and sensory characteristics

- Specialized compounds of four Cameroonian spices: Isolation, characterization, and in silico evaluation as prospective SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors

- Identification of a novel drug target in Porphyromonas gingivalis by a computational genome analysis approach

- Physico-chemical properties and durability of a fly-ash-based geopolymer

- FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 inhibitory potentials of some phytochemicals from anti-leukemic plants using computational chemical methodologies

- Wild Thymus zygis L. ssp. gracilis and Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh.: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antibacterial activities of essential oils

- 3D-QSAR, molecular docking, ADMET, simulation dynamic, and retrosynthesis studies on new styrylquinolines derivatives against breast cancer

- Deciphering the influenza neuraminidase inhibitory potential of naturally occurring biflavonoids: An in silico approach

- Determination of heavy elements in agricultural regions, Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis and characterization of antioxidant-enriched Moringa oil-based edible oleogel

- Ameliorative effects of thistle and thyme honeys on cyclophosphamide-induced toxicity in mice

- Study of phytochemical compound and antipyretic activity of Chenopodium ambrosioides L. fractions

- Investigating the adsorption mechanism of zinc chloride-modified porous carbon for sulfadiazine removal from water

- Performance repair of building materials using alumina and silica composite nanomaterials with electrodynamic properties

- Effects of nanoparticles on the activity and resistance genes of anaerobic digestion enzymes in livestock and poultry manure containing the antibiotic tetracycline

- Effect of copper nanoparticles green-synthesized using Ocimum basilicum against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in mice lung infection model

- Cardioprotective effects of nanoparticles green formulated by Spinacia oleracea extract on isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction in mice by the determination of PPAR-γ/NF-κB pathway

- Anti-OTC antibody-conjugated fluorescent magnetic/silica and fluorescent hybrid silica nanoparticles for oxytetracycline detection

- Curcumin conjugated zinc nanoparticles for the treatment of myocardial infarction

- Identification and in silico screening of natural phloroglucinols as potential PI3Kα inhibitors: A computational approach for drug discovery

- Exploring the phytochemical profile and antioxidant evaluation: Molecular docking and ADMET analysis of main compounds from three Solanum species in Saudi Arabia

- Unveiling the molecular composition and biological properties of essential oil derived from the leaves of wild Mentha aquatica L.: A comprehensive in vitro and in silico exploration

- Analysis of bioactive compounds present in Boerhavia elegans seeds by GC-MS

- Homology modeling and molecular docking study of corticotrophin-releasing hormone: An approach to treat stress-related diseases

- LncRNA MIR17HG alleviates heart failure via targeting MIR17HG/miR-153-3p/SIRT1 axis in in vitro model

- Development and validation of a stability indicating UPLC-DAD method coupled with MS-TQD for ramipril and thymoquinone in bioactive SNEDDS with in silico toxicity analysis of ramipril degradation products

- Biosynthesis of Ag/Cu nanocomposite mediated by Curcuma longa: Evaluation of its antibacterial properties against oral pathogens

- Development of AMBER-compliant transferable force field parameters for polytetrafluoroethylene

- Treatment of gestational diabetes by Acroptilon repens leaf aqueous extract green-formulated iron nanoparticles in rats

- Development and characterization of new ecological adsorbents based on cardoon wastes: Application to brilliant green adsorption

- A fast, sensitive, greener, and stability-indicating HPLC method for the standardization and quantitative determination of chlorhexidine acetate in commercial products

- Assessment of Se, As, Cd, Cr, Hg, and Pb content status in Ankang tea plantations of China

- Effect of transition metal chloride (ZnCl2) on low-temperature pyrolysis of high ash bituminous coal

- Evaluating polyphenol and ascorbic acid contents, tannin removal ability, and physical properties during hydrolysis and convective hot-air drying of cashew apple powder

- Development and characterization of functional low-fat frozen dairy dessert enhanced with dried lemongrass powder

- Scrutinizing the effect of additive and synergistic antibiotics against carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Preparation, characterization, and determination of the therapeutic effects of copper nanoparticles green-formulated by Pistacia atlantica in diabetes-induced cardiac dysfunction in rat

- Antioxidant and antidiabetic potentials of methoxy-substituted Schiff bases using in vitro, in vivo, and molecular simulation approaches

- Anti-melanoma cancer activity and chemical profile of the essential oil of Seseli yunnanense Franch

- Molecular docking analysis of subtilisin-like alkaline serine protease (SLASP) and laccase with natural biopolymers

- Overcoming methicillin resistance by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Computational evaluation of napthyridine and oxadiazoles compounds for potential dual inhibition of PBP-2a and FemA proteins

- Exploring novel antitubercular agents: Innovative design of 2,3-diaryl-quinoxalines targeting DprE1 for effective tuberculosis treatment

- Drimia maritima flowers as a source of biologically potent components: Optimization of bioactive compound extractions, isolation, UPLC–ESI–MS/MS, and pharmacological properties

- Estimating molecular properties, drug-likeness, cardiotoxic risk, liability profile, and molecular docking study to characterize binding process of key phyto-compounds against serotonin 5-HT2A receptor

- Fabrication of β-cyclodextrin-based microgels for enhancing solubility of Terbinafine: An in-vitro and in-vivo toxicological evaluation

- Phyto-mediated synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles and their sunlight-driven photocatalytic degradation of cationic and anionic dyes

- Monosodium glutamate induces hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis hyperactivation, glucocorticoid receptors down-regulation, and systemic inflammatory response in young male rats: Impact on miR-155 and miR-218

- Quality control analyses of selected honey samples from Serbia based on their mineral and flavonoid profiles, and the invertase activity

- Eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Phyllanthus niruri leaf extract: Assessment of antimicrobial activity, effectiveness on tropical neglected mosquito vector control, and biocompatibility using a fibroblast cell line model

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles containing Cichorium intybus to treat the sepsis-induced DNA damage in the liver of Wistar albino rats

- Quality changes of durian pulp (Durio ziberhinus Murr.) in cold storage

- Study on recrystallization process of nitroguanidine by directly adding cold water to control temperature

- Determination of heavy metals and health risk assessment in drinking water in Bukayriyah City, Saudi Arabia

- Larvicidal properties of essential oils of three Artemisia species against the chemically insecticide-resistant Nile fever vector Culex pipiens (L.) (Diptera: Culicidae): In vitro and in silico studies

- Design, synthesis, characterization, and theoretical calculations, along with in silico and in vitro antimicrobial proprieties of new isoxazole-amide conjugates

- The impact of drying and extraction methods on total lipid, fatty acid profile, and cytotoxicity of Tenebrio molitor larvae

- A zinc oxide–tin oxide–nerolidol hybrid nanomaterial: Efficacy against esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- Research on technological process for production of muskmelon juice (Cucumis melo L.)

- Physicochemical components, antioxidant activity, and predictive models for quality of soursop tea (Annona muricata L.) during heat pump drying

- Characterization and application of Fe1−xCoxFe2O4 nanoparticles in Direct Red 79 adsorption

- Torilis arvensis ethanolic extract: Phytochemical analysis, antifungal efficacy, and cytotoxicity properties

- Magnetite–poly-1H pyrrole dendritic nanocomposite seeded on poly-1H pyrrole: A promising photocathode for green hydrogen generation from sanitation water without using external sacrificing agent

- HPLC and GC–MS analyses of phytochemical compounds in Haloxylon salicornicum extract: Antibacterial and antifungal activity assessment of phytopathogens

- Efficient and stable to coking catalysts of ethanol steam reforming comprised of Ni + Ru loaded on MgAl2O4 + LnFe0.7Ni0.3O3 (Ln = La, Pr) nanocomposites prepared via cost-effective procedure with Pluronic P123 copolymer

- Nitrogen and boron co-doped carbon dots probe for selectively detecting Hg2+ in water samples and the detection mechanism

- Heavy metals in road dust from typical old industrial areas of Wuhan: Seasonal distribution and bioaccessibility-based health risk assessment

- Phytochemical profiling and bioactivity evaluation of CBD- and THC-enriched Cannabis sativa extracts: In vitro and in silico investigation of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects

- Investigating dye adsorption: The role of surface-modified montmorillonite nanoclay in kinetics, isotherms, and thermodynamics

- Antimicrobial activity, induction of ROS generation in HepG2 liver cancer cells, and chemical composition of Pterospermum heterophyllum

- Study on the performance of nanoparticle-modified PVDF membrane in delaying membrane aging

- Impact of cholesterol in encapsulated vitamin E acetate within cocoliposomes

- Review Articles

- Structural aspects of Pt(η3-X1N1X2)(PL) (X1,2 = O, C, or Se) and Pt(η3-N1N2X1)(PL) (X1 = C, S, or Se) derivatives

- Biosurfactants in biocorrosion and corrosion mitigation of metals: An overview

- Stimulus-responsive MOF–hydrogel composites: Classification, preparation, characterization, and their advancement in medical treatments

- Electrochemical dissolution of titanium under alternating current polarization to obtain its dioxide

- Special Issue on Recent Trends in Green Chemistry

- Phytochemical screening and antioxidant activity of Vitex agnus-castus L.

- Phytochemical study, antioxidant activity, and dermoprotective activity of Chenopodium ambrosioides (L.)

- Exploitation of mangliculous marine fungi, Amarenographium solium, for the green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their activity against multiple drug-resistant bacteria

- Study of the phytotoxicity of margines on Pistia stratiotes L.

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Energy, Environmental and Biological Applications - Part III

- Impact of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles on growth, development, and antioxidant system of high protein content crop (Lablab purpureus L.) sweet

- Green synthesis, characterization, and application of iron and molybdenum nanoparticles and their composites for enhancing the growth of Solanum lycopersicum

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Olea europaea L. extracted polysaccharides, characterization, and its assessment as an antimicrobial agent against multiple pathogenic microbes

- Photocatalytic treatment of organic dyes using metal oxides and nanocomposites: A quantitative study

- Antifungal, antioxidant, and photocatalytic activities of greenly synthesized iron oxide nanoparticles

- Special Issue on Phytochemical and Pharmacological Scrutinization of Medicinal Plants

- Hepatoprotective effects of safranal on acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in rats

- Chemical composition and biological properties of Thymus capitatus plants from Algerian high plains: A comparative and analytical study

- Chemical composition and bioactivities of the methanol root extracts of Saussurea costus

- In vivo protective effects of vitamin C against cyto-genotoxicity induced by Dysphania ambrosioides aqueous extract

- Insights about the deleterious impact of a carbamate pesticide on some metabolic immune and antioxidant functions and a focus on the protective ability of a Saharan shrub and its anti-edematous property

- A comprehensive review uncovering the anticancerous potential of genkwanin (plant-derived compound) in several human carcinomas

- A study to investigate the anticancer potential of carvacrol via targeting Notch signaling in breast cancer

- Assessment of anti-diabetic properties of Ziziphus oenopolia (L.) wild edible fruit extract: In vitro and in silico investigations through molecular docking analysis

- Optimization of polyphenol extraction, phenolic profile by LC-ESI-MS/MS, antioxidant, anti-enzymatic, and cytotoxic activities of Physalis acutifolia

- Phytochemical screening, antioxidant properties, and photo-protective activities of Salvia balansae de Noé ex Coss

- Antihyperglycemic, antiglycation, anti-hypercholesteremic, and toxicity evaluation with gas chromatography mass spectrometry profiling for Aloe armatissima leaves

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of gold nanoparticles by using Timur (Zanthoxylum armatum DC) and their effect on wound healing

- Does Erodium trifolium (Cav.) Guitt exhibit medicinal properties? Response elements from phytochemical profiling, enzyme-inhibiting, and antioxidant and antimicrobial activities

- Integrative in silico evaluation of the antiviral potential of terpenoids and its metal complexes derived from Homalomena aromatica based on main protease of SARS-CoV-2

- 6-Methoxyflavone improves anxiety, depression, and memory by increasing monoamines in mice brain: HPLC analysis and in silico studies

- Simultaneous extraction and quantification of hydrophilic and lipophilic antioxidants in Solanum lycopersicum L. varieties marketed in Saudi Arabia

- Biological evaluation of CH3OH and C2H5OH of Berberis vulgaris for in vivo antileishmanial potential against Leishmania tropica in murine models

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Porous silicon nanostructures: Synthesis, characterization, and their antifungal activity

- Biochar from de-oiled Chlorella vulgaris and its adsorption on antibiotics

- Phytochemicals profiling, in vitro and in vivo antidiabetic activity, and in silico studies on Ajuga iva (L.) Schreb.: A comprehensive approach

- Synthesis, characterization, in silico and in vitro studies of novel glycoconjugates as potential antibacterial, antifungal, and antileishmanial agents

- Sonochemical synthesis of gold nanoparticles mediated by potato starch: Its performance in the treatment of esophageal cancer

- Computational study of ADME-Tox prediction of selected phytochemicals from Punica granatum peels

- Phytochemical analysis, in vitro antioxidant and antifungal activities of extracts and essential oil derived from Artemisia herba-alba Asso

- Two triazole-based coordination polymers: Synthesis and crystal structure characterization

- Phytochemical and physicochemical studies of different apple varieties grown in Morocco

- Synthesis of multi-template molecularly imprinted polymers (MT-MIPs) for isolating ethyl para-methoxycinnamate and ethyl cinnamate from Kaempferia galanga L., extract with methacrylic acid as functional monomer

- Nutraceutical potential of Mesembryanthemum forsskaolii Hochst. ex Bioss.: Insights into its nutritional composition, phytochemical contents, and antioxidant activity

- Evaluation of influence of Butea monosperma floral extract on inflammatory biomarkers

- Cannabis sativa L. essential oil: Chemical composition, anti-oxidant, anti-microbial properties, and acute toxicity: In vitro, in vivo, and in silico study

- The effect of gamma radiation on 5-hydroxymethylfurfural conversion in water and dimethyl sulfoxide

- Hollow mushroom nanomaterials for potentiometric sensing of Pb2+ ions in water via the intercalation of iodide ions into the polypyrrole matrix

- Determination of essential oil and chemical composition of St. John’s Wort

- Computational design and in vitro assay of lantadene-based novel inhibitors of NS3 protease of dengue virus

- Anti-parasitic activity and computational studies on a novel labdane diterpene from the roots of Vachellia nilotica

- Microbial dynamics and dehydrogenase activity in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) rhizospheres: Impacts on growth and soil health across different soil types

- Correlation between in vitro anti-urease activity and in silico molecular modeling approach of novel imidazopyridine–oxadiazole hybrids derivatives

- Spatial mapping of indoor air quality in a light metro system using the geographic information system method

- Iron indices and hemogram in renal anemia and the improvement with Tribulus terrestris green-formulated silver nanoparticles applied on rat model

- Integrated track of nano-informatics coupling with the enrichment concept in developing a novel nanoparticle targeting ERK protein in Naegleria fowleri

- Cytotoxic and phytochemical screening of Solanum lycopersicum–Daucus carota hydro-ethanolic extract and in silico evaluation of its lycopene content as anticancer agent

- Protective activities of silver nanoparticles containing Panax japonicus on apoptotic, inflammatory, and oxidative alterations in isoproterenol-induced cardiotoxicity

- pH-based colorimetric detection of monofunctional aldehydes in liquid and gas phases

- Investigating the effect of resveratrol on apoptosis and regulation of gene expression of Caco-2 cells: Unravelling potential implications for colorectal cancer treatment

- Metformin inhibits knee osteoarthritis induced by type 2 diabetes mellitus in rats: S100A8/9 and S100A12 as players and therapeutic targets

- Effect of silver nanoparticles formulated by Silybum marianum on menopausal urinary incontinence in ovariectomized rats

- Synthesis of new analogs of N-substituted(benzoylamino)-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridines

- Response of yield and quality of Japonica rice to different gradients of moisture deficit at grain-filling stage in cold regions

- Preparation of an inclusion complex of nickel-based β-cyclodextrin: Characterization and accelerating the osteoarthritis articular cartilage repair

- Empagliflozin-loaded nanomicelles responsive to reactive oxygen species for renal ischemia/reperfusion injury protection

- Preparation and pharmacodynamic evaluation of sodium aescinate solid lipid nanoparticles

- Assessment of potentially toxic elements and health risks of agricultural soil in Southwest Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- Theoretical investigation of hydrogen-rich fuel production through ammonia decomposition

- Biosynthesis and screening of cobalt nanoparticles using citrus species for antimicrobial activity

- Investigating the interplay of genetic variations, MCP-1 polymorphism, and docking with phytochemical inhibitors for combatting dengue virus pathogenicity through in silico analysis

- Ultrasound induced biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles embedded into chitosan polymers: Investigation of its anti-cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma effects

- Copper oxide nanoparticles-mediated Heliotropium bacciferum leaf extract: Antifungal activity and molecular docking assays against strawberry pathogens

- Sprouted wheat flour for improving physical, chemical, rheological, microbial load, and quality properties of fino bread

- Comparative toxicity assessment of fisetin-aided artificial intelligence-assisted drug design targeting epibulbar dermoid through phytochemicals

- Acute toxicity and anti-inflammatory activity of bis-thiourea derivatives

- Anti-diabetic activity-guided isolation of α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory terpenes from Capsella bursa-pastoris Linn.

- GC–MS analysis of Lactobacillus plantarum YW11 metabolites and its computational analysis on familial pulmonary fibrosis hub genes

- Green formulation of copper nanoparticles by Pistacia khinjuk leaf aqueous extract: Introducing a novel chemotherapeutic drug for the treatment of prostate cancer

- Improved photocatalytic properties of WO3 nanoparticles for Malachite green dye degradation under visible light irradiation: An effect of La doping

- One-pot synthesis of a network of Mn2O3–MnO2–poly(m-methylaniline) composite nanorods on a polypyrrole film presents a promising and efficient optoelectronic and solar cell device

- Groundwater quality and health risk assessment of nitrate and fluoride in Al Qaseem area, Saudi Arabia

- A comparative study of the antifungal efficacy and phytochemical composition of date palm leaflet extracts

- Processing of alcohol pomelo beverage (Citrus grandis (L.) Osbeck) using saccharomyces yeast: Optimization, physicochemical quality, and sensory characteristics

- Specialized compounds of four Cameroonian spices: Isolation, characterization, and in silico evaluation as prospective SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors

- Identification of a novel drug target in Porphyromonas gingivalis by a computational genome analysis approach

- Physico-chemical properties and durability of a fly-ash-based geopolymer

- FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 inhibitory potentials of some phytochemicals from anti-leukemic plants using computational chemical methodologies

- Wild Thymus zygis L. ssp. gracilis and Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh.: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antibacterial activities of essential oils

- 3D-QSAR, molecular docking, ADMET, simulation dynamic, and retrosynthesis studies on new styrylquinolines derivatives against breast cancer

- Deciphering the influenza neuraminidase inhibitory potential of naturally occurring biflavonoids: An in silico approach

- Determination of heavy elements in agricultural regions, Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis and characterization of antioxidant-enriched Moringa oil-based edible oleogel

- Ameliorative effects of thistle and thyme honeys on cyclophosphamide-induced toxicity in mice

- Study of phytochemical compound and antipyretic activity of Chenopodium ambrosioides L. fractions

- Investigating the adsorption mechanism of zinc chloride-modified porous carbon for sulfadiazine removal from water

- Performance repair of building materials using alumina and silica composite nanomaterials with electrodynamic properties

- Effects of nanoparticles on the activity and resistance genes of anaerobic digestion enzymes in livestock and poultry manure containing the antibiotic tetracycline

- Effect of copper nanoparticles green-synthesized using Ocimum basilicum against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in mice lung infection model

- Cardioprotective effects of nanoparticles green formulated by Spinacia oleracea extract on isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction in mice by the determination of PPAR-γ/NF-κB pathway

- Anti-OTC antibody-conjugated fluorescent magnetic/silica and fluorescent hybrid silica nanoparticles for oxytetracycline detection

- Curcumin conjugated zinc nanoparticles for the treatment of myocardial infarction

- Identification and in silico screening of natural phloroglucinols as potential PI3Kα inhibitors: A computational approach for drug discovery

- Exploring the phytochemical profile and antioxidant evaluation: Molecular docking and ADMET analysis of main compounds from three Solanum species in Saudi Arabia

- Unveiling the molecular composition and biological properties of essential oil derived from the leaves of wild Mentha aquatica L.: A comprehensive in vitro and in silico exploration

- Analysis of bioactive compounds present in Boerhavia elegans seeds by GC-MS

- Homology modeling and molecular docking study of corticotrophin-releasing hormone: An approach to treat stress-related diseases

- LncRNA MIR17HG alleviates heart failure via targeting MIR17HG/miR-153-3p/SIRT1 axis in in vitro model

- Development and validation of a stability indicating UPLC-DAD method coupled with MS-TQD for ramipril and thymoquinone in bioactive SNEDDS with in silico toxicity analysis of ramipril degradation products

- Biosynthesis of Ag/Cu nanocomposite mediated by Curcuma longa: Evaluation of its antibacterial properties against oral pathogens

- Development of AMBER-compliant transferable force field parameters for polytetrafluoroethylene

- Treatment of gestational diabetes by Acroptilon repens leaf aqueous extract green-formulated iron nanoparticles in rats

- Development and characterization of new ecological adsorbents based on cardoon wastes: Application to brilliant green adsorption

- A fast, sensitive, greener, and stability-indicating HPLC method for the standardization and quantitative determination of chlorhexidine acetate in commercial products

- Assessment of Se, As, Cd, Cr, Hg, and Pb content status in Ankang tea plantations of China

- Effect of transition metal chloride (ZnCl2) on low-temperature pyrolysis of high ash bituminous coal

- Evaluating polyphenol and ascorbic acid contents, tannin removal ability, and physical properties during hydrolysis and convective hot-air drying of cashew apple powder

- Development and characterization of functional low-fat frozen dairy dessert enhanced with dried lemongrass powder

- Scrutinizing the effect of additive and synergistic antibiotics against carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Preparation, characterization, and determination of the therapeutic effects of copper nanoparticles green-formulated by Pistacia atlantica in diabetes-induced cardiac dysfunction in rat

- Antioxidant and antidiabetic potentials of methoxy-substituted Schiff bases using in vitro, in vivo, and molecular simulation approaches

- Anti-melanoma cancer activity and chemical profile of the essential oil of Seseli yunnanense Franch

- Molecular docking analysis of subtilisin-like alkaline serine protease (SLASP) and laccase with natural biopolymers

- Overcoming methicillin resistance by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Computational evaluation of napthyridine and oxadiazoles compounds for potential dual inhibition of PBP-2a and FemA proteins

- Exploring novel antitubercular agents: Innovative design of 2,3-diaryl-quinoxalines targeting DprE1 for effective tuberculosis treatment

- Drimia maritima flowers as a source of biologically potent components: Optimization of bioactive compound extractions, isolation, UPLC–ESI–MS/MS, and pharmacological properties

- Estimating molecular properties, drug-likeness, cardiotoxic risk, liability profile, and molecular docking study to characterize binding process of key phyto-compounds against serotonin 5-HT2A receptor

- Fabrication of β-cyclodextrin-based microgels for enhancing solubility of Terbinafine: An in-vitro and in-vivo toxicological evaluation

- Phyto-mediated synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles and their sunlight-driven photocatalytic degradation of cationic and anionic dyes

- Monosodium glutamate induces hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis hyperactivation, glucocorticoid receptors down-regulation, and systemic inflammatory response in young male rats: Impact on miR-155 and miR-218

- Quality control analyses of selected honey samples from Serbia based on their mineral and flavonoid profiles, and the invertase activity

- Eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Phyllanthus niruri leaf extract: Assessment of antimicrobial activity, effectiveness on tropical neglected mosquito vector control, and biocompatibility using a fibroblast cell line model

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles containing Cichorium intybus to treat the sepsis-induced DNA damage in the liver of Wistar albino rats

- Quality changes of durian pulp (Durio ziberhinus Murr.) in cold storage