Abstract

Considering the challenges related to hydrogen storage and transportation which hinder its widespread adoption, ammonia has emerged as a carbon-free carrier for hydrogen due to several advantages such as simple inexpensive storage. But, due to some limitations related to net ammonia combustion, the suggestion is to store hydrogen in the form of ammonia and convert it into hydrogen-rich fuel before utilization in different applications like engines and turbines. Therefore, in this article, a comprehensive thermodynamic analysis of hydrogen-rich fuel production via ammonia decomposition is conducted utilizing Aspen Plus V.12, to assess the impact of operating parameters on key criteria such as conversion rate (CR) and enthalpy of reaction, to establish the maximum level of efficiency of the process. The results show that at a specific temperature, the CR of ammonia decreases as the pressure rises so that the CR of more than 50% occurred at temperatures of 427 and 513 K for pressures of 1 and 10 bar, respectively. Moreover, the adiabatic flame temperature of hydrogen-rich fuel is investigated so that increasing the molar percentage of hydrogen from 0 to 50 leads to an increase in the maximum adiabatic flame temperature from 2,079 to 2,216 K.

1 Introduction

CO2 is the most effective greenhouse gas in terms of elevating atmospheric temperature so that its concentration currently stands at about 417 parts per million (ppm) by volume and experienced a consistent annual increase of over 2 ppm for the 11th consecutive year in 2022 [1]. To reduce CO2 emissions, effective utilization of alternate carbon-free fuels has become significantly important [2]. Hydrogen (H2) is one of the most important carbon-free fuels due to its high performance in multiple purposes so its global demand from 2000 to 2021 increased from 50 to 94 Mt [3].

The problem of storage and transportation of hydrogen is one of the most significant challenges for its feasible utilization as a fuel. Hydrogen gas molecules are smaller than those of any other gas, allowing it to permeate through many materials typically regarded as airtight or impermeable to other gases. Although hydrogen has the highest heating value by mass among all fuels (LHV = 119.6 MJ/kg), it has a very low heating value by volume at standard conditions, which is one-third of methane gas [4]. It is typically stored in two main ways, one of which involves storing it as a highly compressed gas, reaching pressures of up to 700 bar at a temperature of 298 K. In addition, hydrogen can be stored in its liquid form, which demands much lower temperatures, specifically 20 K at 1 bar. Achieving liquefaction in this manner would necessitate a substantial energy input of approximately 11.6 MJ/kg [5]. Such storage systems are energy-demanding and extremely expensive, so the ways and means to handle it economically and safely are a challenge that needs to be solved.

Ammonia (NH3) has been recognized as a promising carbon-free alternative for supplying hydrogen since it has a high gravimetric hydrogen density of 17.8 wt%, suitable LHV of 18.8 MJ/kg, and a volumetric energy of 11.3 MJ/L in its liquid form [6]. In contrast to the challenges linked with storing and transporting hydrogen, ammonia can be liquefied under mild conditions and stored in a simple, cost-effective pressure vessel since the vapour pressure of ammonia at room temperature is 9.2 bar [7]. Moreover, the existing infrastructure for ammonia production, storage, and transportation is well-established and the global production capacity of ammonia is expected to expand from around 236 million tons in 2021 to nearly 290 million tons by 2030 [8]. Ammonia also benefits from a lower boil-off rate, approximately 0.025 vol%/day, in comparison with hydrogen which can be up to 5 %vol/day [9]. Moreover, 1 mol of ammonia contains 1.5 mol of hydrogen so that 108 kg of hydrogen is embedded in 1 m3 liquid ammonia at 293 K, which is four times higher than the most advanced hydrogen storage systems, such as metal hydrides [10]. Ammonia is highly resistant to auto-ignition which makes it safe to be transported so that its auto-ignition temperature is 924 K compared to hydrogen at 858 K [11].

Despite the numerous advantages provided by ammonia usage, there are certain limitations especially related to net ammonia combustion as a fuel. Ammonia has a low laminar flame speed (S L = 15 cm/s at atmospheric conditions) compared to other fuels such as diesel at about 87 cm/s [12], which leads to low burning efficiency in engines. Its combustion includes three specific emissions that relate to safety, health, and climate: NH3 unburned or slip, NO x , and N2O [13]. Therefore, one of the most practical ways to enhance the flame speed of ammonia combustion and reduce NH3 slip and N2O is to use combustion promoters.

Considering the advantages of ammonia as a hydrogen carrier and due to the poor combustion performance of ammonia fuel, it is proposed to carry hydrogen in the ammonia-bound form and, immediately before use, to decompose a part of the ammonia into H2 as a promoter. This H2-rich fuel leads to a simpler fuel storage system and reduces the need for additional modifications in different applications such as engines [14,15]. Gill et al. [16] investigated co-fuelling a diesel engine in three different modes including only NH3, dissociated NH3 (H2-rich fuel), and pure H2 as the second fuel. They showed that by substituting only 3% of the air intake with H2-rich gas, diesel consumption, and CO2 emissions decreased by 15%. Yang et al. [17] studied the effect of varying H2/NH3 ratios (10 to 90% energy fraction) on different parameters of a single-cylinder diesel engine. The results demonstrated that when the hydrogen blending ratio reached 30% compared to 0, the unburned NH3 was eliminated and N2O significantly decreased by 97%.

Given the mentioned advantages of H2-rich gas as a fuel, the usage of an ammonia decomposition system becomes important since it can produce CO x and sulphur-free stream of hydrogen, and unconverted ammonia can be easily reduced to safe levels in one-step adsorption [18]. Thermal decomposition or catalytic cracking is the most common technique used for the generation of hydrogen from ammonia [19]. To ensure the efficient use of raw materials and energy inputs for the ammonia decomposition system, thermodynamic analysis enables to optimize reactor designs, catalyst type, and operating conditions.

In this article, to assess how varying operational parameters can impact different key performance criteria of the ammonia decomposition reaction, the technical analysis of hydrogen-rich gas production via ammonia decomposition is performed using Aspen Plus V.12 considering ideal-gas equation of state and idealized Gibbs reactor. Using the thermodynamic principles allows us to provide results for ultimate levels of conversion rate (CR) and required energy. These limiting levels can serve as a basis for the optimum design of different parts of ammonia decomposition systems, evaluating related experimental studies and developing more efficient systems of hydrogen utilization in different applications including internal combustion engines, gas turbines, and industrial furnaces. Moreover, the adiabatic flame temperature (T ad) is investigated for different ammonia/hydrogen mixtures and various equivalence ratios so that such analysis is useful for researchers and professionals concerned with safety and the optimization of combustion efficiency for different hydrogen-based fuel applications.

2 Methodology

The decomposition of ammonia is reverse to that of its synthesis, as a typical single-step endothermic process with an enthalpy change of 46.19 kJ/mol which is much lower than electrolysis at 237.1 kJ/mol [20,21]:

In this article, the thermodynamic analysis of hydrogen-rich gas production through ammonia decomposition is performed using Aspen Plus V.12 considering the ideal-gas equation of state. Such thermodynamic analysis will be a guideline for assessing the performance of actual catalytic reactors due to the importance of evaluating the maximum CR and energy consumption of the decomposition system at different operating conditions. Therefore, ammonia decomposition evaluation is conducted considering the idealized Gibbs reactor. The reactor determines the decomposition products by employing the Gibbs free energy minimization method. Different criteria are considered, especially ammonia CR [22] (equation (2)), hydrogen-rich gas energy ratio (ER) [23] (equation (3)), and enthalpy variation.

where

In the Gibbs free energy minimization technique, the system is thermodynamically favourable when its total Gibbs free energy reaches its minimum value and its differential equals zero for given temperature (T) and pressure (P) [24]:

The Gibbs free energy (G) is a thermodynamic extensive property which combines the enthalpy (H) and the entropy (S) of a system and is defined by equation (5):

The differential change of the Gibbs function of a pure substance is:

where V is the volume. For a system consisting of different species, the total Gibbs function is a function of two independent intensive properties as well as the molar composition which can be expressed as equation (7), and its differential is based on equations (8) and (9) [25]:

where n

i

is the number of moles of species present in the system and

Therefore, equation (11) shows the Gibbs function differential for the system at a given temperature and pressure in chemical equilibrium.

Moreover, the chemical potential of each of the species of an ideal gaseous mixture is given by equation (12).

where

3 Results and discussion

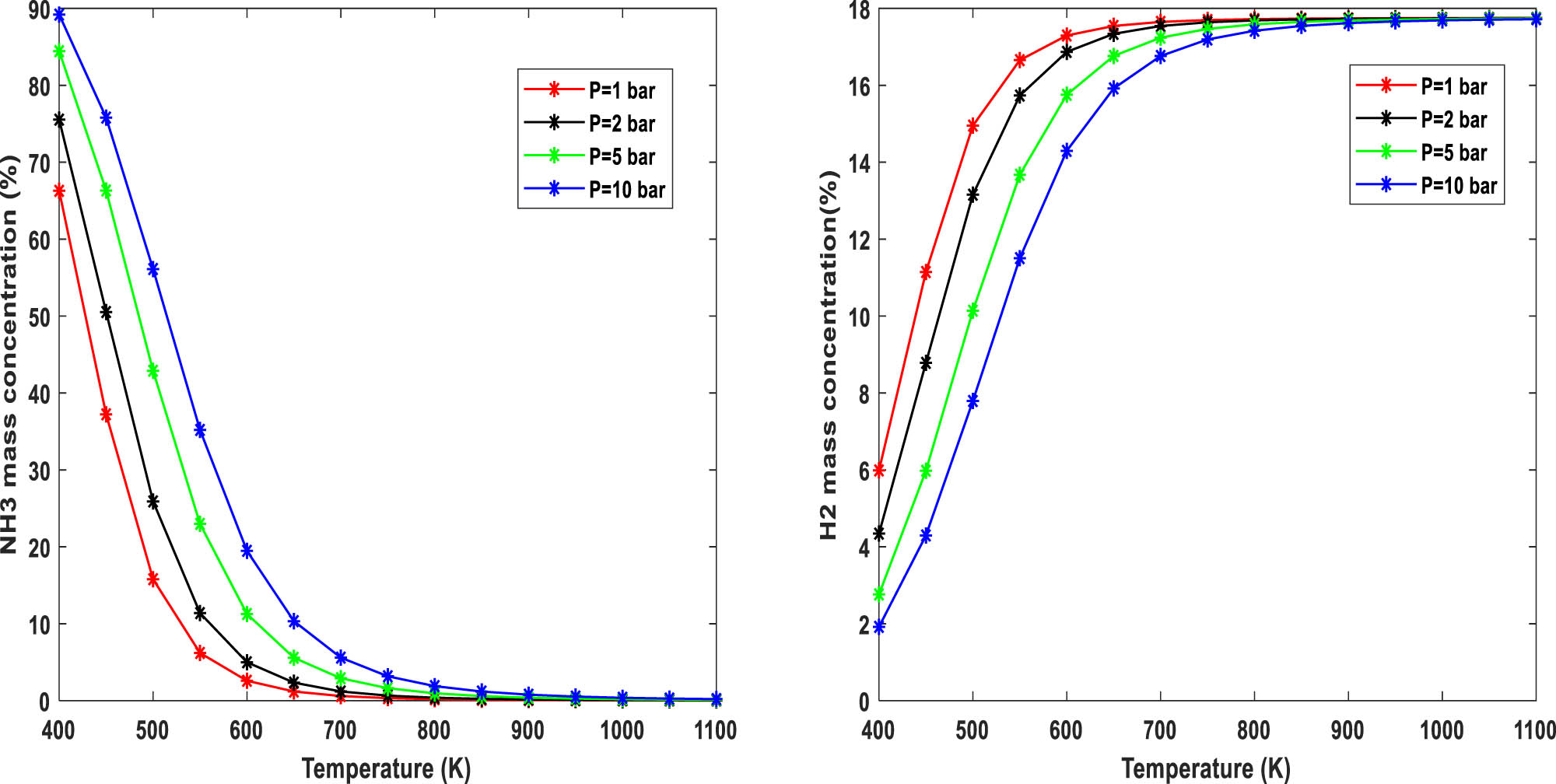

Figure 1 shows the equilibrium mass concentration of ammonia and hydrogen product as a function of temperature ranging from 400 to 1,100 K at different pressures from 1 to 10 bar. This range of pressure is selected since it covers the proper range in different applications such as dual-fuel engines, fuel cells, and even hydrogen production considering the utilization of a separation technique like pressure swing adsorption. The results reveal that higher temperatures at constant pressure, or lower pressures at constant temperature lead to a higher percentage of the produced hydrogen. Due to the importance of the partial decomposition of ammonia in dual-fuel applications, it is worth mentioning that the mass concentration of hydrogen can reach a maximum of 17.8% at temperatures of 600 and 650 K when the pressure is 1 and 2 bar, respectively. Regarding the effect of pressure, at a constant temperature of 600 K, ammonia mass concentration is 2.5% at P = 1 bar, while this amount for P = 10 bar increases to 19.5%.

NH3 and H2 mass concentrations at different pressures and temperatures.

The equilibrium constant, K eq, expresses the relation between products and reactants of a reaction at equilibrium with respect to a specific unit. The equilibrium constant expression is derived from the law of mass action so that it can be expressed by equation (14) in terms of equilibrium composition for ammonia decomposition [26].

where P is the total pressure and N t is the total number of moles present in the reaction.

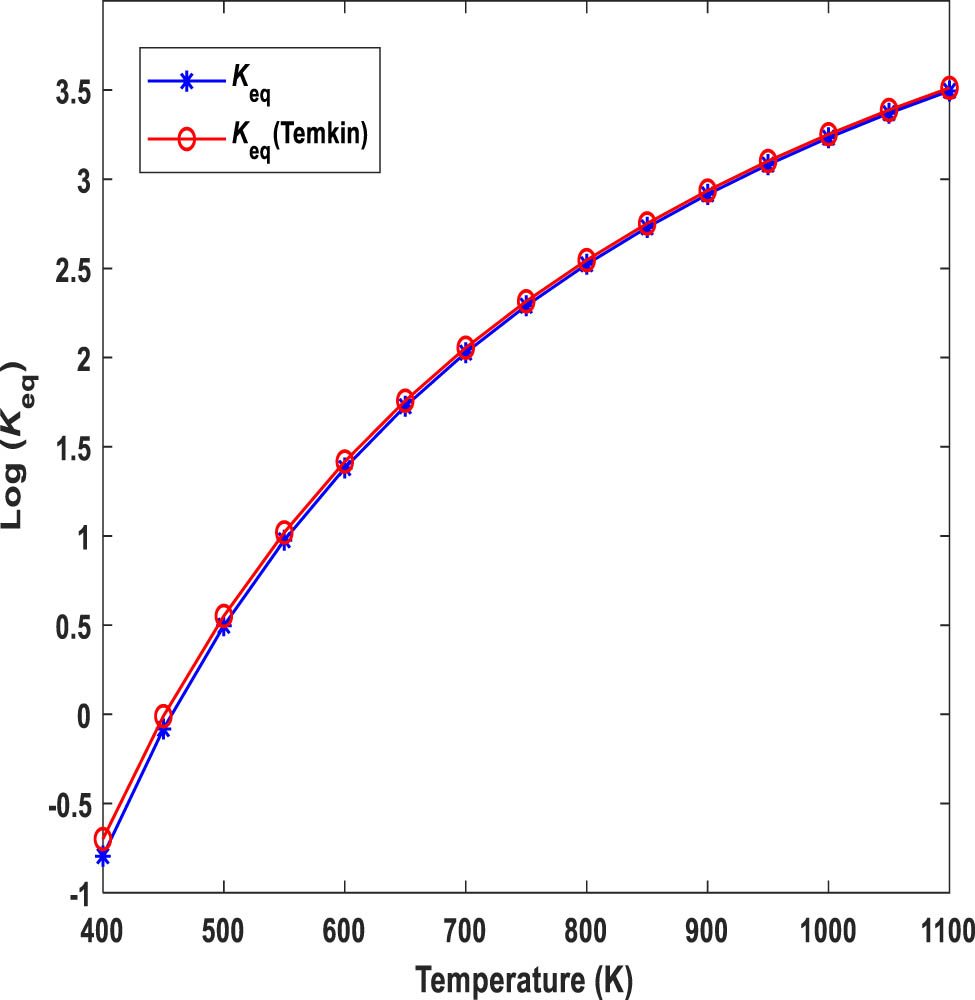

Figure 2 shows the variation of K eq based on temperature. The results obtained from Aspen Plus are validated by comparing them with the equilibrium constant for ammonia synthesis derived from Temkin and Pyzhev’s formula (equation (15)) [27]. The strong agreement between the two indicates the accuracy of Aspen Plus results, supported by the reciprocal relationship between the equilibrium constants for decomposition and synthesis.

Validation of equilibrium constant as a function of temperature for ammonia decomposition.

Since the reaction is endothermic, the increase in temperature provides the necessary energy to overcome the activation energy barrier required for the reaction to occur. Therefore, at higher temperatures, the decomposition of ammonia is favoured, leading to an increase in the value of K eq. The larger the K eq value, the more the ammonia decomposition reaction will tend toward the right and thus to completion.

The thermodynamic equilibrium represents the maximum conversion that can be achieved, regardless of the catalyst and reaction rates so it depends only on temperature, pressure, and inflow composition. According to equation (1), Figure 3 (left) shows the effect of pressure and temperature on the ammonia CR. The results reveal that as the temperature increases, particularly beyond 700 K, the influence of pressure on ammonia conversion diminishes and it is more than 95%. Furthermore, at a specific temperature, the conversion of ammonia decreases as the pressure rises. It is noticeable that CR of more than 50% occurred at temperatures of about 427, 450, 484, and 513 K for pressures of 1, 2, 5, and 10 bar respectively. Moreover, Considering the LHV of ammonia and hydrogen as per equation (2), Figure 3 (right) indicates the ER of the H2-rich gas to ammonia inlet at different temperatures and pressures. The results reveal that the maximum achievable ER is 1.13, which can occur at temperatures higher than 700 K regardless of pressure. Regarding the effect of temperature, at P = 1 bar, an ER of 1.08 and 1.12 are achievable for temperatures of 450 and 550 K.

Variation of NH3 CR (left) and ER by temperature and pressure (right).

The equilibrium constant for the reaction can also be related to the standard Gibbs free energy change, ∆G° which is related to the standard pressure, of the reaction at a given temperature as equation (16) [28].

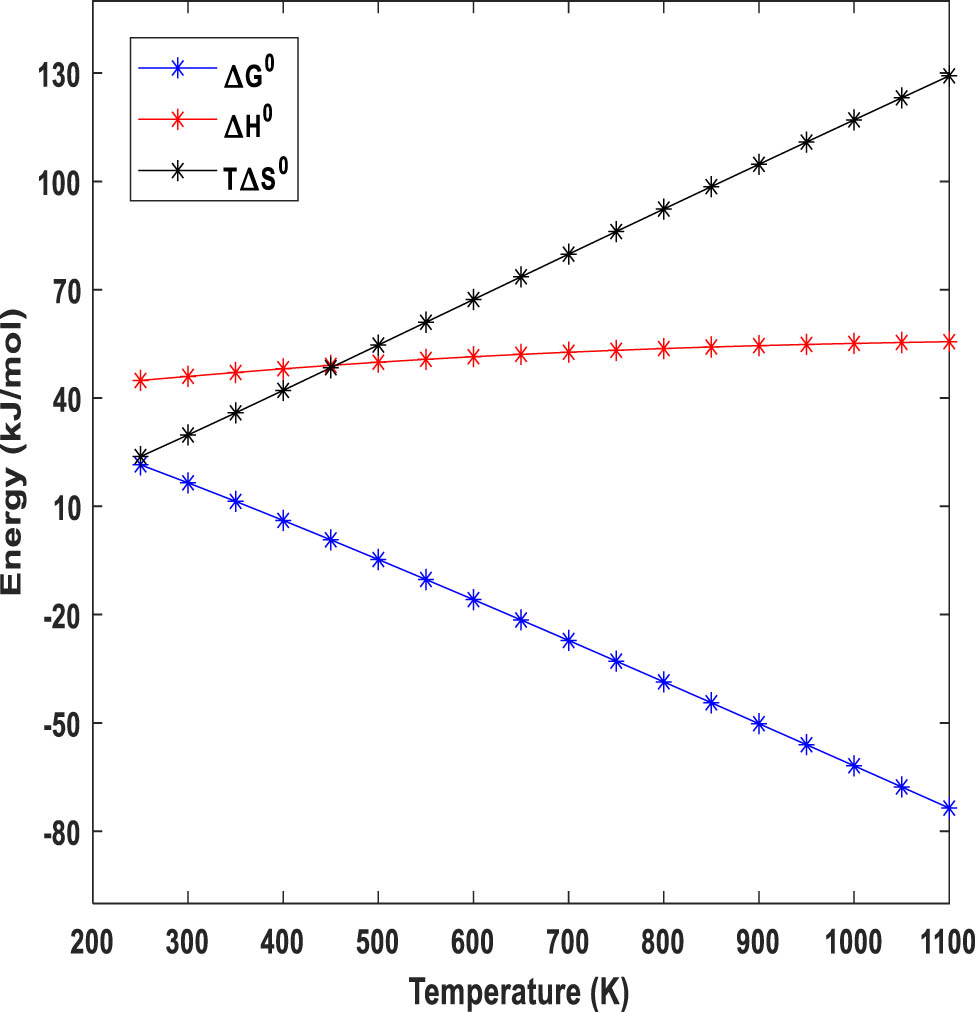

where R u is the gas constant at 8.314 J/mol K. Moreover, ΔH° and ΔS° determine the magnitude of ΔG°:

Figure 4 demonstrates the variation of ∆G 0, ΔH 0, and TΔS 0 as a function of temperature for the ammonia decomposition so that considering the standard temperature, the validity of the simulation can be proved since standard Gibbs free energy for ammonia decomposition should be +16.5 kJ/mol [29]. The reaction is thermodynamically favourable at temperatures more than 453 K in the forward direction by reaching negative standard Gibbs free energy. Figure 4 also shows that as the temperature increases, the entropy change becomes more significant, which results in a wider range of TΔS 0 values. The ΔS is positive because one molecule of NH3 decomposes into more molecules of gas (N2 and H2), increasing the disorder of the system. The enthalpy changes from 44.85 to 55.60 kJ/mol which is generally less sensitive to temperature variations, and its profile agrees with endothermic reactions. At lower temperatures, the positive ΔH 0 term dominates, making ΔG positive and the reaction non-spontaneous. At higher temperatures, the positive TΔS 0 term becomes more significant, and the reaction becomes spontaneous.

Variation of ∆G°, ΔH°, and TΔS° as a function of temperature for ammonia decomposition.

The enthalpy change of the reaction (ΔH r) is the difference between the enthalpy of the products at a specified state (H P) and the enthalpy of the reactants at the same state (H R) considering equations (18)–(20) [30].

where

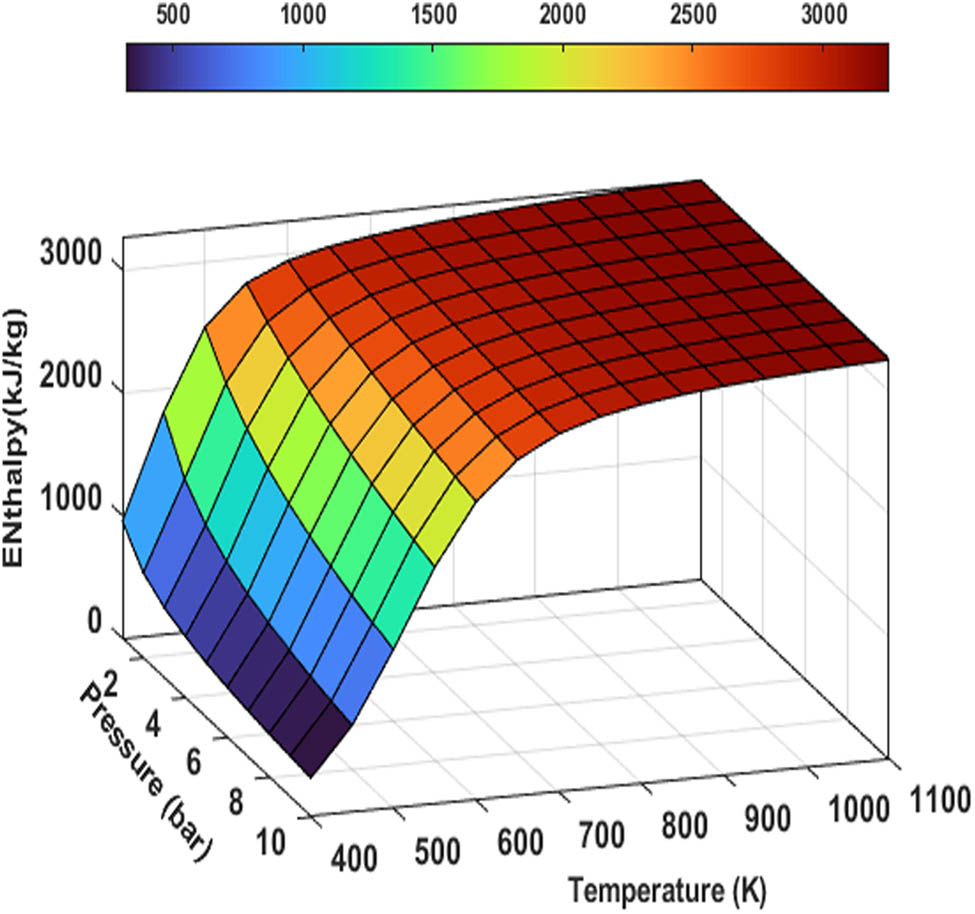

Enthalpy of ammonia decomposition as a function of temperature and pressure.

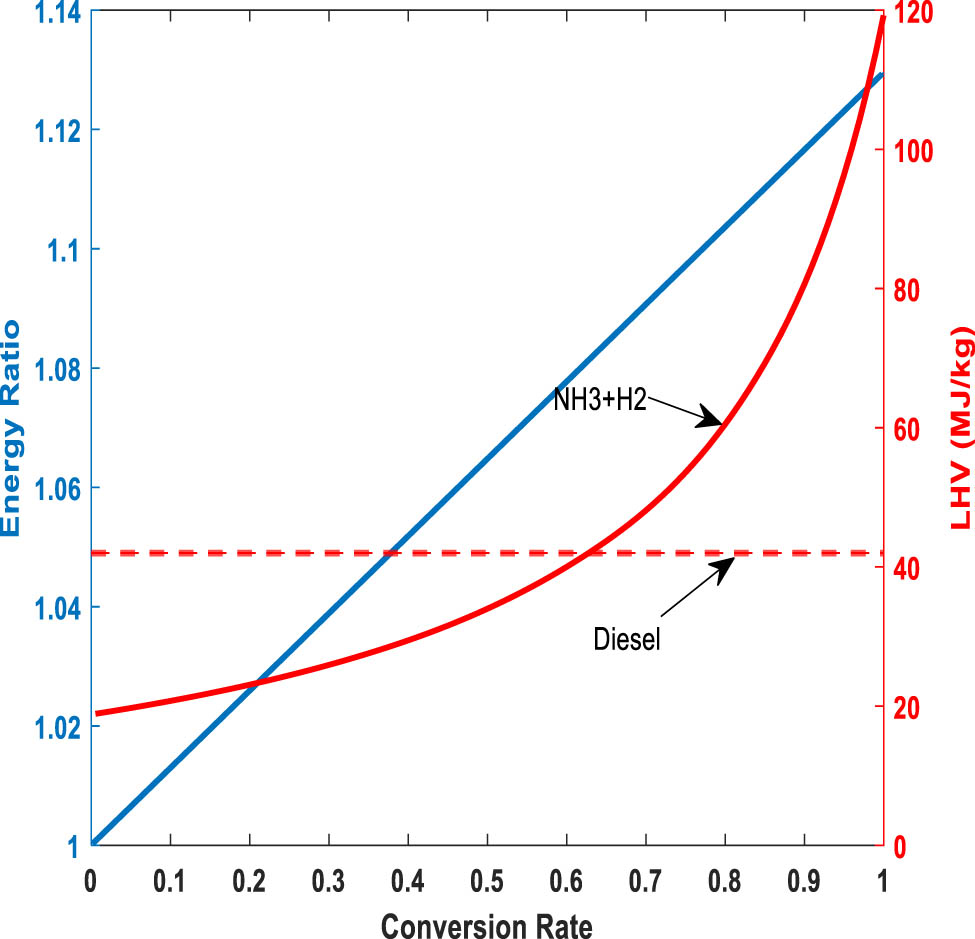

Considering the definition of ER and CR, and based on the results related to Figure 3, it can be concluded that for any pressure and temperature, there is a linear relationship between ER and CR (equation (21)), which is shown by the blue line in Figure 6.

Variation of ER and lower heating value of the H2-rich gas by CR.

Moreover, the LHV of the reactor outlet mixture by considering N2 as the dilution component is calculated using equation (22), and the results are shown in Figure 6 in comparison with the LHV of a conventional fuel such as diesel, which is significant for dual-fuel engines in different applications such as maritime and vehicular transportation. The LHV of the gas mixture (LHVmix) is calculated for all different pressures, and the results reveal that it can be only considered as a function of CR. According to Figure 6, the LHV of the H2-rich gas rises as the CR increases. At CR ≈ 63%, LHVmix reaches equivalence with diesel fuel so that based on Figure 2, for pressures of 1, 2, 5, and 10 bar, temperatures of about 450, 470, 512, and 544 K are required, respectively, for such a conversion.

Combustion is the most important step in all kinds of applications of H2-rich gas including gas turbines, internal combustion engines, and furnaces. Therefore, the study of adiabatic flame temperature, as the maximum temperature of the combustion gas that can be reached by the combustion reaction under no heat loss to the surroundings in the adiabatic condition (equation (23) [26]), is of vital importance since the higher flame temperature may be preferable for practical applications of H2-rich gas combustion.

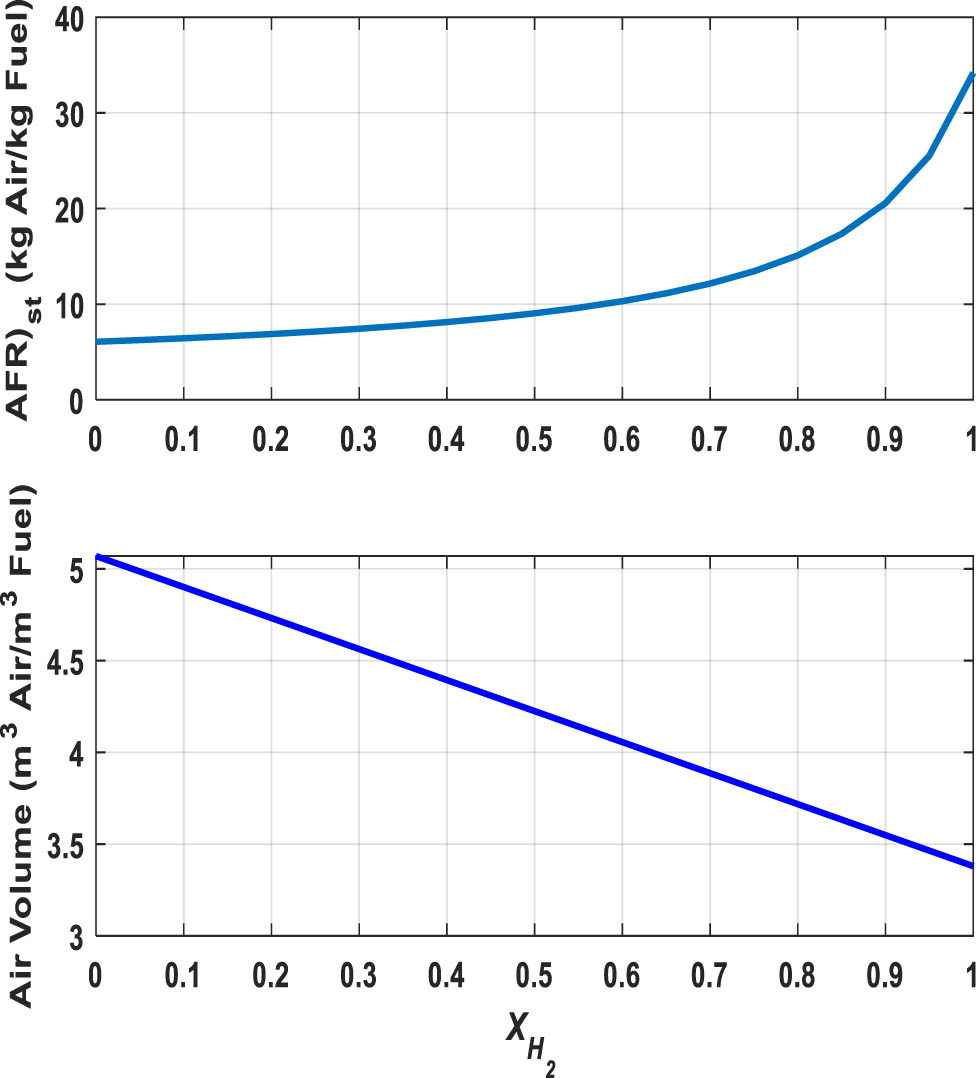

Combustion simulation is carried out by using an adiabatic constant-pressure Gibbs reactor model in Aspen Plus V.12. This simulation is processed for 21 mixtures (different hydrogen mole fractions in 0.05 increments) with the equivalence ratio (φ) covering from 0.4 to 1.6 (equation (24)). First, the stoichiometric air/fuel ratio at each molar percentage of hydrogen (x H2) is determined using equation (25), so that Figure 7 illustrates that by increasing the hydrogen percentage in H2-rich gas, stoichiometric air to fuel ratio rises from 6.1 to 34.1 kgAir/kgFuel. This ratio for conventional fuels like diesel and methane is about 14.5 and 17.2 kgAir/kgFuel, respectively [4]. Moreover, theoretical air volume shows that less air volume is required for combustion as the hydrogen content of the mixture increases, thus reducing the volume of the combustion products.

Variation of stoichiometric air/fuel ratio and theoretical air volume for the H2-rich gas.

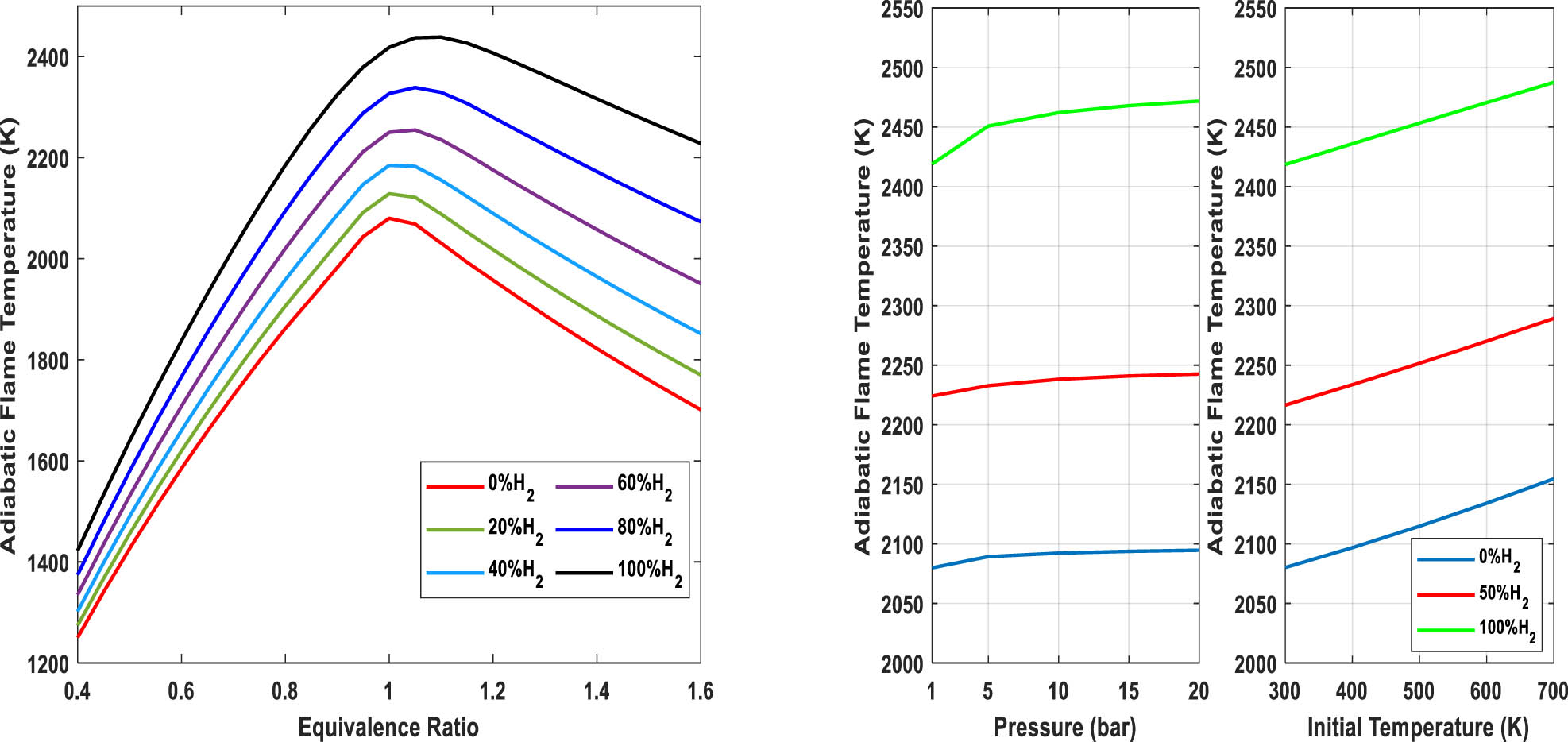

According to the above-mentioned points, Figure 8 (left) shows the adiabatic flame temperature based on considering different exhaust species including H2, NH3, O2, N2, H2O, N2O, NO, and NO2. It can be concluded that increasing the molar percentage of hydrogen from 0 to 50% and 100% in the fuel mixture leads to the increase of maximum adiabatic flame temperature from 2,079 to 2,216 K and 2,438 K. It is worth mentioning that the maximum adiabatic flame temperature for diesel is 2,573 K [31]. When the equivalence ratio falls below one (lean mixture), there is an excess of air extracting heat from the reaction. On the other hand, when the equivalence ratio is greater than one (rich mixture), there is a higher concentration of unburnt fuel that consumes energy, but this is less than the heat taken away by air during lean combustion. Moreover, by increasing the hydrogen content to more than 80%, the maximum values of the adiabatic flame temperature of mixtures occur slightly on the rich side of the fuel equivalence ratio (off-stoichiometric peaking of adiabatic flame temperature [32]). This is because the products of rich mixtures have higher concentrations of diatomic molecules such as H2 compared to the products of lean combustion, which have higher concentrations of triatomic molecules such as H2O. Since the specific heats of diatomic molecules are smaller than those of triatomic molecules, the adiabatic flame temperatures of richer mixtures should have higher values.

Adiabatic flame temperature (T = 298 K, P = 1 bar, left) and effect of pressure and initial temperature on the adiabatic flame temperature of H2-rich gas (right).

As the combustion process in different applications such as diesel or gas turbine cycles can be considered at different pressures, the effect of pressure and initial temperature on the maximum adiabatic flame temperature is also investigated and shown in Figure 8 (right). The results demonstrate that the adiabatic flame temperature of different blends of H2/NH3 is weakly affected by pressure so that for a mixture of 50% hydrogen, T ad just increases from 2,224 to 2,242 K as a result of a 20 bar increase in pressure. On the other hand, the effect of initial temperature on the adiabatic flame temperature is more than that of pressure.

4 Conclusions

In this study, thermodynamic analysis of thermal ammonia decomposition to produce hydrogen-rich fuel is performed using Aspen Plus V.12 considering the Gibbs-free energy method. It is found that the performance of the ammonia decomposition reactor is highly affected by temperature and pressure so higher temperatures and lower pressures lead to a higher percentage of the produced hydrogen. The CR of more than 50% occurred at temperatures 427 and 513 K for pressures of 1 and 10 bar respectively. Moreover, the results reveal that the effect of temperature on the enthalpy of the reaction is more pronounced for temperatures lower than 700 K and this endothermic reaction is thermodynamically favourable at temperatures more than 453 K in the forward direction by reaching negative standard Gibbs free energy. Moreover, adiabatic flame temperature analysis shows that increasing the molar percentage of hydrogen from 0 to 50% leads to the increase of maximum adiabatic flame temperature from 2,079 to 2,216 K. The information and results presented in this thermodynamic investigation can serve as a foundation for the optimum design of different parts of ammonia decomposition systems, evaluating the related experimental research, and developing more efficient systems of hydrogen production in different applications such as dual-fuel vehicular engines, maritime, power plants, and industrial furnaces.

-

Funding information: The project was financed by Chantier Davie Canada Inc., Canada’s premier shipbuilder, based on their work in the field of using alternative fuels for the marine industry.

-

Author contributions: Payam Shafie: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, analysis, writing – original draft, Alain Dechamplain: conceptualization, supervision, analysis, review & editing, Julien Lepine: conceptualization, supervision, analysis, review & editing.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

-

Data availability statement: The data sets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Sodiq A, Abdollatif Y, Aissa B, Ostovar A, Nassar N, Elnaas M, et al. A review on progress made in direct air capture of CO2. Environmental Technology and Innovation. Vol. 29. Netherlands: Elsevier B.V; Feb, 2023, 10.1016/j.eti.2022.102991.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Lecture notes in energy 33 energy solutions to combat global warming [Online]. 2022. http://www.springer.com/series/8874.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] The role of low-carbon fuels in the clean energy transitions of the power sector; Jun. 10, 2023. Accessed: [Online] https://www.iea.org/reports/the-role-of-low-carbon-fuels-in-the-clean-energy-transitions-of-the-power-sector.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Ibrahim D, Haris I. Renewable hydrogen production. 1st edn. Netherlands: Elsevier; 2022. 10.1016/C2020-0-02435-7.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Madadi Avargani V, Zendehboudi S, Cata Saady NM, Dusseault MB. A comprehensive review on hydrogen production and utilization in North America: Prospects and challenges. Energy Conversion and Management. Vol. 269. UK: Elsevier Ltd; Oct, 2022 10.1016/j.enconman.2022.115927.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Ojelade OA, Zaman SF. Ammonia decomposition for hydrogen production: a thermodynamic study. Chem Pap. Jan. 2021;75(1):57–65. 10.1007/s11696-020-01278-z.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Potential roles of ammonia in a hydrogen economy a study of issues related to the use ammonia for on-board vehicular hydrogen storage; Jun. 2023 Accessed: [Online]. https://www.energy.gov/eere/fuelcells/downloads/potential-roles-ammonia-hydrogen-economy.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Production capacity of ammonia worldwide from 2018 to 2022, with a forecast for 2026 and 2030; Jul. 2023 Accessed: [Online]. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1065865/ammonia-production-capacity-globally/.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Al-Breiki M, Bicer Y. Comparative cost assessment of sustainable energy carriers produced from natural gas accounting for boil-off gas and social cost of carbon. Energy Rep. Nov. 2020;6:1897–909. 10.1016/j.egyr.2020.07.013.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Schlapbach L, Züttel A. Hydrogen-storage materials for mobile applications; 2001. www.nature.com.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Lhuillier C, Brequigny P, Contino F, Mounaïm-Rousselle C. Experimental study on ammonia/hydrogen/air combustion in spark ignition engine conditions. Fuel. Jun. 2020;269:117448. 10.1016/j.fuel.2020.117448.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Ryu K, Zacharakis-Jutz GE, Kong SC. Performance characteristics of compression-ignition engine using high concentration of ammonia mixed with dimethyl ether. Appl Energy. 2014;113:488–99. 10.1016/j.apenergy.2013.07.065.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Laval A, Hafnia HT, Vestas SG. Ammonfuel-an industrial view of ammonia as a marine fuel. Jun. 2023; [Online]. https://www.alfalaval.com/globalassets/documents/industries/marine-and-transportation/marine/fcm-lff/ammonia-as-fuel/ammonfuel-report-version-09.9-august-3.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Zhang H, Li G, Long Y, Zhang Z, Wei W, Zhou M, et al. Numerical study on combustion and emission characteristics of a spark-ignition ammonia engine added with hydrogen-rich gas from exhaust-fuel reforming. Fuel. Jan. 2023;332:125939. 10.1016/j.fuel.2022.125939.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Wang W, Herreros JM, Tsolakis A, York APE. Ammonia as hydrogen carrier for transportation; Investigation of the ammonia exhaust gas fuel reforming. Int J Hydrog Energy. Aug. 2013;38(23):9907–17. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2013.05.144.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Gill SS, Chatha GS, Tsolakis A, Golunski SE, York APE. “Assessing the effects of partially decarbonising a diesel engine by co-fuelling with dissociated ammonia,”. Int J Hydrog Energy. Apr. 2012;37(7):6074–83. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2011.12.137.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Wang B, Yang C, Wang H, Hu D, Wang Y. Effect of diesel-ignited ammonia/hydrogen mixture fuel combustion on engine combustion and emission performance. Fuel. Jan. 2023;331:125865. 10.1016/j.fuel.2022.125865.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Alagharu V, Palanki S, West KN. Analysis of ammonia decomposition reactor to generate hydrogen for fuel cell applications. J Power Sources. Feb. 2010;195(3):829–33. 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2009.08.024.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Lucentini I, Garcia X, Vendrell X, Llorca J. Review of the decomposition of ammonia to generate hydrogen. Ind Eng Chem Res. Dec. 2021;60(51):18560–611. 10.1021/acs.iecr.1c00843.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Chen S, Takata T, Domen K. Particulate photocatalysts for overall water splitting. Nat Rev Mater. Aug. 2017;2(10):17050. 10.1038/natrevmats.2017.50.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Lucentini I, Casanovas A, Llorca J. Catalytic ammonia decomposition for hydrogen production on Ni, Ru and Ni-Ru supported on CeO2. Int J Hydrog Energy. 2019;44(25):12693–707.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Sittichompoo S, Nozari H, Herreros J, Serhan N, Silva J, York A, et al. Exhaust energy recovery via catalytic ammonia decomposition to hydrogen for low carbon clean vehicles. Fuel. Feb. 2021;285:119111. 10.1016/j.fuel.2020.119111.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Kane SP, Northrop WF. Thermochemical recuperation to enable efficient ammonia-diesel dual-fuel combustion in a compression ignition engine. Energies. Nov. 2021;14(22):7540. 10.3390/en14227540.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Özkara-Aydınoğlu Ş. Thermodynamic equilibrium analysis of combined carbon dioxide reforming with steam reforming of methane to synthesis gas. Int J Hydrog Energy. Dec. 2010;35(23):12821–28. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2010.08.134.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Çengel YA, Boles MA. Thermodynamics: An engineering approach. 8th edn. McGraw-Hill; 2014.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] kenneth KK. Review of chemical thermodynamics. Principles of Combustion. 1st edn. USA: John Wiley & Sons; 1986. p. 6–105.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Abashar MEE. Ultra-clean hydrogen production by ammonia decomposition. J King Saud Univ – Eng Sci. Jan. 2018;30(1):2–11. 10.1016/j.jksues.2016.01.002. Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Schmal M, Pinto J. Chemical Reaction Engineering, 2nd ed, Taylor & Francis; 2014.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Franck EU, Cox JD, Wagman DD, Medvedev VA. CODATA — Key values for Thermodynamics, aus der Reihe: CODATA, Series on thermodynamic properties. Hemisphere Publishing Corporation, New York, Washington, Philadelphia, London 1989. 271 seiten, Preis: £ 28.00. Berichte der Bunsengesellschaft für physikalische Chemie. Vol. 94. Issue. 1; Jan 1990. p. 93–3. 10.1002/bbpc.19900940121.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] McAllister S, Chen J, Pello A. Fundamentals of combustion processes. Springer; 2012. p. 15–47. 10.1007/978-1-4419-7943-8.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Kurien C, Mittal M. Review on the production and utilization of green ammonia as an alternate fuel in dual-fuel compression ignition engines. Energy Conversion and Management. Vol. 251. Elsevier Ltd; Jan. 2022. 10.1016/j.enconman.2021.114990.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Law CK, Makino A, Lu TF. On the off-stoichiometric peaking of adiabatic flame temperature. Combust Flame. Jun. 2006;145(4):808–19. 10.1016/j.combustflame.2006.01.009.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Porous silicon nanostructures: Synthesis, characterization, and their antifungal activity

- Biochar from de-oiled Chlorella vulgaris and its adsorption on antibiotics

- Phytochemicals profiling, in vitro and in vivo antidiabetic activity, and in silico studies on Ajuga iva (L.) Schreb.: A comprehensive approach

- Synthesis, characterization, in silico and in vitro studies of novel glycoconjugates as potential antibacterial, antifungal, and antileishmanial agents

- Sonochemical synthesis of gold nanoparticles mediated by potato starch: Its performance in the treatment of esophageal cancer

- Computational study of ADME-Tox prediction of selected phytochemicals from Punica granatum peels

- Phytochemical analysis, in vitro antioxidant and antifungal activities of extracts and essential oil derived from Artemisia herba-alba Asso

- Two triazole-based coordination polymers: Synthesis and crystal structure characterization

- Phytochemical and physicochemical studies of different apple varieties grown in Morocco

- Synthesis of multi-template molecularly imprinted polymers (MT-MIPs) for isolating ethyl para-methoxycinnamate and ethyl cinnamate from Kaempferia galanga L., extract with methacrylic acid as functional monomer

- Nutraceutical potential of Mesembryanthemum forsskaolii Hochst. ex Bioss.: Insights into its nutritional composition, phytochemical contents, and antioxidant activity

- Evaluation of influence of Butea monosperma floral extract on inflammatory biomarkers

- Cannabis sativa L. essential oil: Chemical composition, anti-oxidant, anti-microbial properties, and acute toxicity: In vitro, in vivo, and in silico study

- The effect of gamma radiation on 5-hydroxymethylfurfural conversion in water and dimethyl sulfoxide

- Hollow mushroom nanomaterials for potentiometric sensing of Pb2+ ions in water via the intercalation of iodide ions into the polypyrrole matrix

- Determination of essential oil and chemical composition of St. John’s Wort

- Computational design and in vitro assay of lantadene-based novel inhibitors of NS3 protease of dengue virus

- Anti-parasitic activity and computational studies on a novel labdane diterpene from the roots of Vachellia nilotica

- Microbial dynamics and dehydrogenase activity in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) rhizospheres: Impacts on growth and soil health across different soil types

- Correlation between in vitro anti-urease activity and in silico molecular modeling approach of novel imidazopyridine–oxadiazole hybrids derivatives

- Spatial mapping of indoor air quality in a light metro system using the geographic information system method

- Iron indices and hemogram in renal anemia and the improvement with Tribulus terrestris green-formulated silver nanoparticles applied on rat model

- Integrated track of nano-informatics coupling with the enrichment concept in developing a novel nanoparticle targeting ERK protein in Naegleria fowleri

- Cytotoxic and phytochemical screening of Solanum lycopersicum–Daucus carota hydro-ethanolic extract and in silico evaluation of its lycopene content as anticancer agent

- Protective activities of silver nanoparticles containing Panax japonicus on apoptotic, inflammatory, and oxidative alterations in isoproterenol-induced cardiotoxicity

- pH-based colorimetric detection of monofunctional aldehydes in liquid and gas phases

- Investigating the effect of resveratrol on apoptosis and regulation of gene expression of Caco-2 cells: Unravelling potential implications for colorectal cancer treatment

- Metformin inhibits knee osteoarthritis induced by type 2 diabetes mellitus in rats: S100A8/9 and S100A12 as players and therapeutic targets

- Effect of silver nanoparticles formulated by Silybum marianum on menopausal urinary incontinence in ovariectomized rats

- Synthesis of new analogs of N-substituted(benzoylamino)-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridines

- Response of yield and quality of Japonica rice to different gradients of moisture deficit at grain-filling stage in cold regions

- Preparation of an inclusion complex of nickel-based β-cyclodextrin: Characterization and accelerating the osteoarthritis articular cartilage repair

- Empagliflozin-loaded nanomicelles responsive to reactive oxygen species for renal ischemia/reperfusion injury protection

- Preparation and pharmacodynamic evaluation of sodium aescinate solid lipid nanoparticles

- Assessment of potentially toxic elements and health risks of agricultural soil in Southwest Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- Theoretical investigation of hydrogen-rich fuel production through ammonia decomposition

- Biosynthesis and screening of cobalt nanoparticles using citrus species for antimicrobial activity

- Investigating the interplay of genetic variations, MCP-1 polymorphism, and docking with phytochemical inhibitors for combatting dengue virus pathogenicity through in silico analysis

- Ultrasound induced biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles embedded into chitosan polymers: Investigation of its anti-cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma effects

- Copper oxide nanoparticles-mediated Heliotropium bacciferum leaf extract: Antifungal activity and molecular docking assays against strawberry pathogens

- Sprouted wheat flour for improving physical, chemical, rheological, microbial load, and quality properties of fino bread

- Comparative toxicity assessment of fisetin-aided artificial intelligence-assisted drug design targeting epibulbar dermoid through phytochemicals

- Acute toxicity and anti-inflammatory activity of bis-thiourea derivatives

- Anti-diabetic activity-guided isolation of α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory terpenes from Capsella bursa-pastoris Linn.

- GC–MS analysis of Lactobacillus plantarum YW11 metabolites and its computational analysis on familial pulmonary fibrosis hub genes

- Green formulation of copper nanoparticles by Pistacia khinjuk leaf aqueous extract: Introducing a novel chemotherapeutic drug for the treatment of prostate cancer

- Improved photocatalytic properties of WO3 nanoparticles for Malachite green dye degradation under visible light irradiation: An effect of La doping

- One-pot synthesis of a network of Mn2O3–MnO2–poly(m-methylaniline) composite nanorods on a polypyrrole film presents a promising and efficient optoelectronic and solar cell device

- Groundwater quality and health risk assessment of nitrate and fluoride in Al Qaseem area, Saudi Arabia

- A comparative study of the antifungal efficacy and phytochemical composition of date palm leaflet extracts

- Processing of alcohol pomelo beverage (Citrus grandis (L.) Osbeck) using saccharomyces yeast: Optimization, physicochemical quality, and sensory characteristics

- Specialized compounds of four Cameroonian spices: Isolation, characterization, and in silico evaluation as prospective SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors

- Identification of a novel drug target in Porphyromonas gingivalis by a computational genome analysis approach

- Physico-chemical properties and durability of a fly-ash-based geopolymer

- FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 inhibitory potentials of some phytochemicals from anti-leukemic plants using computational chemical methodologies

- Wild Thymus zygis L. ssp. gracilis and Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh.: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antibacterial activities of essential oils

- 3D-QSAR, molecular docking, ADMET, simulation dynamic, and retrosynthesis studies on new styrylquinolines derivatives against breast cancer

- Deciphering the influenza neuraminidase inhibitory potential of naturally occurring biflavonoids: An in silico approach

- Determination of heavy elements in agricultural regions, Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis and characterization of antioxidant-enriched Moringa oil-based edible oleogel

- Ameliorative effects of thistle and thyme honeys on cyclophosphamide-induced toxicity in mice

- Study of phytochemical compound and antipyretic activity of Chenopodium ambrosioides L. fractions

- Investigating the adsorption mechanism of zinc chloride-modified porous carbon for sulfadiazine removal from water

- Performance repair of building materials using alumina and silica composite nanomaterials with electrodynamic properties

- Effects of nanoparticles on the activity and resistance genes of anaerobic digestion enzymes in livestock and poultry manure containing the antibiotic tetracycline

- Effect of copper nanoparticles green-synthesized using Ocimum basilicum against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in mice lung infection model

- Cardioprotective effects of nanoparticles green formulated by Spinacia oleracea extract on isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction in mice by the determination of PPAR-γ/NF-κB pathway

- Anti-OTC antibody-conjugated fluorescent magnetic/silica and fluorescent hybrid silica nanoparticles for oxytetracycline detection

- Curcumin conjugated zinc nanoparticles for the treatment of myocardial infarction

- Identification and in silico screening of natural phloroglucinols as potential PI3Kα inhibitors: A computational approach for drug discovery

- Exploring the phytochemical profile and antioxidant evaluation: Molecular docking and ADMET analysis of main compounds from three Solanum species in Saudi Arabia

- Unveiling the molecular composition and biological properties of essential oil derived from the leaves of wild Mentha aquatica L.: A comprehensive in vitro and in silico exploration

- Analysis of bioactive compounds present in Boerhavia elegans seeds by GC-MS

- Homology modeling and molecular docking study of corticotrophin-releasing hormone: An approach to treat stress-related diseases

- LncRNA MIR17HG alleviates heart failure via targeting MIR17HG/miR-153-3p/SIRT1 axis in in vitro model

- Development and validation of a stability indicating UPLC-DAD method coupled with MS-TQD for ramipril and thymoquinone in bioactive SNEDDS with in silico toxicity analysis of ramipril degradation products

- Biosynthesis of Ag/Cu nanocomposite mediated by Curcuma longa: Evaluation of its antibacterial properties against oral pathogens

- Development of AMBER-compliant transferable force field parameters for polytetrafluoroethylene

- Treatment of gestational diabetes by Acroptilon repens leaf aqueous extract green-formulated iron nanoparticles in rats

- Development and characterization of new ecological adsorbents based on cardoon wastes: Application to brilliant green adsorption

- A fast, sensitive, greener, and stability-indicating HPLC method for the standardization and quantitative determination of chlorhexidine acetate in commercial products

- Assessment of Se, As, Cd, Cr, Hg, and Pb content status in Ankang tea plantations of China

- Effect of transition metal chloride (ZnCl2) on low-temperature pyrolysis of high ash bituminous coal

- Evaluating polyphenol and ascorbic acid contents, tannin removal ability, and physical properties during hydrolysis and convective hot-air drying of cashew apple powder

- Development and characterization of functional low-fat frozen dairy dessert enhanced with dried lemongrass powder

- Scrutinizing the effect of additive and synergistic antibiotics against carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Preparation, characterization, and determination of the therapeutic effects of copper nanoparticles green-formulated by Pistacia atlantica in diabetes-induced cardiac dysfunction in rat

- Antioxidant and antidiabetic potentials of methoxy-substituted Schiff bases using in vitro, in vivo, and molecular simulation approaches

- Anti-melanoma cancer activity and chemical profile of the essential oil of Seseli yunnanense Franch

- Molecular docking analysis of subtilisin-like alkaline serine protease (SLASP) and laccase with natural biopolymers

- Overcoming methicillin resistance by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Computational evaluation of napthyridine and oxadiazoles compounds for potential dual inhibition of PBP-2a and FemA proteins

- Exploring novel antitubercular agents: Innovative design of 2,3-diaryl-quinoxalines targeting DprE1 for effective tuberculosis treatment

- Drimia maritima flowers as a source of biologically potent components: Optimization of bioactive compound extractions, isolation, UPLC–ESI–MS/MS, and pharmacological properties

- Estimating molecular properties, drug-likeness, cardiotoxic risk, liability profile, and molecular docking study to characterize binding process of key phyto-compounds against serotonin 5-HT2A receptor

- Fabrication of β-cyclodextrin-based microgels for enhancing solubility of Terbinafine: An in-vitro and in-vivo toxicological evaluation

- Phyto-mediated synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles and their sunlight-driven photocatalytic degradation of cationic and anionic dyes

- Monosodium glutamate induces hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis hyperactivation, glucocorticoid receptors down-regulation, and systemic inflammatory response in young male rats: Impact on miR-155 and miR-218

- Quality control analyses of selected honey samples from Serbia based on their mineral and flavonoid profiles, and the invertase activity

- Eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Phyllanthus niruri leaf extract: Assessment of antimicrobial activity, effectiveness on tropical neglected mosquito vector control, and biocompatibility using a fibroblast cell line model

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles containing Cichorium intybus to treat the sepsis-induced DNA damage in the liver of Wistar albino rats

- Quality changes of durian pulp (Durio ziberhinus Murr.) in cold storage

- Study on recrystallization process of nitroguanidine by directly adding cold water to control temperature

- Determination of heavy metals and health risk assessment in drinking water in Bukayriyah City, Saudi Arabia

- Larvicidal properties of essential oils of three Artemisia species against the chemically insecticide-resistant Nile fever vector Culex pipiens (L.) (Diptera: Culicidae): In vitro and in silico studies

- Design, synthesis, characterization, and theoretical calculations, along with in silico and in vitro antimicrobial proprieties of new isoxazole-amide conjugates

- The impact of drying and extraction methods on total lipid, fatty acid profile, and cytotoxicity of Tenebrio molitor larvae

- A zinc oxide–tin oxide–nerolidol hybrid nanomaterial: Efficacy against esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- Research on technological process for production of muskmelon juice (Cucumis melo L.)

- Physicochemical components, antioxidant activity, and predictive models for quality of soursop tea (Annona muricata L.) during heat pump drying

- Characterization and application of Fe1−xCoxFe2O4 nanoparticles in Direct Red 79 adsorption

- Torilis arvensis ethanolic extract: Phytochemical analysis, antifungal efficacy, and cytotoxicity properties

- Magnetite–poly-1H pyrrole dendritic nanocomposite seeded on poly-1H pyrrole: A promising photocathode for green hydrogen generation from sanitation water without using external sacrificing agent

- HPLC and GC–MS analyses of phytochemical compounds in Haloxylon salicornicum extract: Antibacterial and antifungal activity assessment of phytopathogens

- Efficient and stable to coking catalysts of ethanol steam reforming comprised of Ni + Ru loaded on MgAl2O4 + LnFe0.7Ni0.3O3 (Ln = La, Pr) nanocomposites prepared via cost-effective procedure with Pluronic P123 copolymer

- Nitrogen and boron co-doped carbon dots probe for selectively detecting Hg2+ in water samples and the detection mechanism

- Heavy metals in road dust from typical old industrial areas of Wuhan: Seasonal distribution and bioaccessibility-based health risk assessment

- Phytochemical profiling and bioactivity evaluation of CBD- and THC-enriched Cannabis sativa extracts: In vitro and in silico investigation of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects

- Investigating dye adsorption: The role of surface-modified montmorillonite nanoclay in kinetics, isotherms, and thermodynamics

- Antimicrobial activity, induction of ROS generation in HepG2 liver cancer cells, and chemical composition of Pterospermum heterophyllum

- Study on the performance of nanoparticle-modified PVDF membrane in delaying membrane aging

- Impact of cholesterol in encapsulated vitamin E acetate within cocoliposomes

- Review Articles

- Structural aspects of Pt(η3-X1N1X2)(PL) (X1,2 = O, C, or Se) and Pt(η3-N1N2X1)(PL) (X1 = C, S, or Se) derivatives

- Biosurfactants in biocorrosion and corrosion mitigation of metals: An overview

- Stimulus-responsive MOF–hydrogel composites: Classification, preparation, characterization, and their advancement in medical treatments

- Electrochemical dissolution of titanium under alternating current polarization to obtain its dioxide

- Special Issue on Recent Trends in Green Chemistry

- Phytochemical screening and antioxidant activity of Vitex agnus-castus L.

- Phytochemical study, antioxidant activity, and dermoprotective activity of Chenopodium ambrosioides (L.)

- Exploitation of mangliculous marine fungi, Amarenographium solium, for the green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their activity against multiple drug-resistant bacteria

- Study of the phytotoxicity of margines on Pistia stratiotes L.

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Energy, Environmental and Biological Applications - Part III

- Impact of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles on growth, development, and antioxidant system of high protein content crop (Lablab purpureus L.) sweet

- Green synthesis, characterization, and application of iron and molybdenum nanoparticles and their composites for enhancing the growth of Solanum lycopersicum

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Olea europaea L. extracted polysaccharides, characterization, and its assessment as an antimicrobial agent against multiple pathogenic microbes

- Photocatalytic treatment of organic dyes using metal oxides and nanocomposites: A quantitative study

- Antifungal, antioxidant, and photocatalytic activities of greenly synthesized iron oxide nanoparticles

- Special Issue on Phytochemical and Pharmacological Scrutinization of Medicinal Plants

- Hepatoprotective effects of safranal on acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in rats

- Chemical composition and biological properties of Thymus capitatus plants from Algerian high plains: A comparative and analytical study

- Chemical composition and bioactivities of the methanol root extracts of Saussurea costus

- In vivo protective effects of vitamin C against cyto-genotoxicity induced by Dysphania ambrosioides aqueous extract

- Insights about the deleterious impact of a carbamate pesticide on some metabolic immune and antioxidant functions and a focus on the protective ability of a Saharan shrub and its anti-edematous property

- A comprehensive review uncovering the anticancerous potential of genkwanin (plant-derived compound) in several human carcinomas

- A study to investigate the anticancer potential of carvacrol via targeting Notch signaling in breast cancer

- Assessment of anti-diabetic properties of Ziziphus oenopolia (L.) wild edible fruit extract: In vitro and in silico investigations through molecular docking analysis

- Optimization of polyphenol extraction, phenolic profile by LC-ESI-MS/MS, antioxidant, anti-enzymatic, and cytotoxic activities of Physalis acutifolia

- Phytochemical screening, antioxidant properties, and photo-protective activities of Salvia balansae de Noé ex Coss

- Antihyperglycemic, antiglycation, anti-hypercholesteremic, and toxicity evaluation with gas chromatography mass spectrometry profiling for Aloe armatissima leaves

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of gold nanoparticles by using Timur (Zanthoxylum armatum DC) and their effect on wound healing

- Does Erodium trifolium (Cav.) Guitt exhibit medicinal properties? Response elements from phytochemical profiling, enzyme-inhibiting, and antioxidant and antimicrobial activities

- Integrative in silico evaluation of the antiviral potential of terpenoids and its metal complexes derived from Homalomena aromatica based on main protease of SARS-CoV-2

- 6-Methoxyflavone improves anxiety, depression, and memory by increasing monoamines in mice brain: HPLC analysis and in silico studies

- Simultaneous extraction and quantification of hydrophilic and lipophilic antioxidants in Solanum lycopersicum L. varieties marketed in Saudi Arabia

- Biological evaluation of CH3OH and C2H5OH of Berberis vulgaris for in vivo antileishmanial potential against Leishmania tropica in murine models

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Porous silicon nanostructures: Synthesis, characterization, and their antifungal activity

- Biochar from de-oiled Chlorella vulgaris and its adsorption on antibiotics

- Phytochemicals profiling, in vitro and in vivo antidiabetic activity, and in silico studies on Ajuga iva (L.) Schreb.: A comprehensive approach

- Synthesis, characterization, in silico and in vitro studies of novel glycoconjugates as potential antibacterial, antifungal, and antileishmanial agents

- Sonochemical synthesis of gold nanoparticles mediated by potato starch: Its performance in the treatment of esophageal cancer

- Computational study of ADME-Tox prediction of selected phytochemicals from Punica granatum peels

- Phytochemical analysis, in vitro antioxidant and antifungal activities of extracts and essential oil derived from Artemisia herba-alba Asso

- Two triazole-based coordination polymers: Synthesis and crystal structure characterization

- Phytochemical and physicochemical studies of different apple varieties grown in Morocco

- Synthesis of multi-template molecularly imprinted polymers (MT-MIPs) for isolating ethyl para-methoxycinnamate and ethyl cinnamate from Kaempferia galanga L., extract with methacrylic acid as functional monomer

- Nutraceutical potential of Mesembryanthemum forsskaolii Hochst. ex Bioss.: Insights into its nutritional composition, phytochemical contents, and antioxidant activity

- Evaluation of influence of Butea monosperma floral extract on inflammatory biomarkers

- Cannabis sativa L. essential oil: Chemical composition, anti-oxidant, anti-microbial properties, and acute toxicity: In vitro, in vivo, and in silico study

- The effect of gamma radiation on 5-hydroxymethylfurfural conversion in water and dimethyl sulfoxide

- Hollow mushroom nanomaterials for potentiometric sensing of Pb2+ ions in water via the intercalation of iodide ions into the polypyrrole matrix

- Determination of essential oil and chemical composition of St. John’s Wort

- Computational design and in vitro assay of lantadene-based novel inhibitors of NS3 protease of dengue virus

- Anti-parasitic activity and computational studies on a novel labdane diterpene from the roots of Vachellia nilotica

- Microbial dynamics and dehydrogenase activity in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) rhizospheres: Impacts on growth and soil health across different soil types

- Correlation between in vitro anti-urease activity and in silico molecular modeling approach of novel imidazopyridine–oxadiazole hybrids derivatives

- Spatial mapping of indoor air quality in a light metro system using the geographic information system method

- Iron indices and hemogram in renal anemia and the improvement with Tribulus terrestris green-formulated silver nanoparticles applied on rat model

- Integrated track of nano-informatics coupling with the enrichment concept in developing a novel nanoparticle targeting ERK protein in Naegleria fowleri

- Cytotoxic and phytochemical screening of Solanum lycopersicum–Daucus carota hydro-ethanolic extract and in silico evaluation of its lycopene content as anticancer agent

- Protective activities of silver nanoparticles containing Panax japonicus on apoptotic, inflammatory, and oxidative alterations in isoproterenol-induced cardiotoxicity

- pH-based colorimetric detection of monofunctional aldehydes in liquid and gas phases

- Investigating the effect of resveratrol on apoptosis and regulation of gene expression of Caco-2 cells: Unravelling potential implications for colorectal cancer treatment

- Metformin inhibits knee osteoarthritis induced by type 2 diabetes mellitus in rats: S100A8/9 and S100A12 as players and therapeutic targets

- Effect of silver nanoparticles formulated by Silybum marianum on menopausal urinary incontinence in ovariectomized rats

- Synthesis of new analogs of N-substituted(benzoylamino)-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridines

- Response of yield and quality of Japonica rice to different gradients of moisture deficit at grain-filling stage in cold regions

- Preparation of an inclusion complex of nickel-based β-cyclodextrin: Characterization and accelerating the osteoarthritis articular cartilage repair

- Empagliflozin-loaded nanomicelles responsive to reactive oxygen species for renal ischemia/reperfusion injury protection

- Preparation and pharmacodynamic evaluation of sodium aescinate solid lipid nanoparticles

- Assessment of potentially toxic elements and health risks of agricultural soil in Southwest Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- Theoretical investigation of hydrogen-rich fuel production through ammonia decomposition

- Biosynthesis and screening of cobalt nanoparticles using citrus species for antimicrobial activity

- Investigating the interplay of genetic variations, MCP-1 polymorphism, and docking with phytochemical inhibitors for combatting dengue virus pathogenicity through in silico analysis

- Ultrasound induced biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles embedded into chitosan polymers: Investigation of its anti-cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma effects

- Copper oxide nanoparticles-mediated Heliotropium bacciferum leaf extract: Antifungal activity and molecular docking assays against strawberry pathogens

- Sprouted wheat flour for improving physical, chemical, rheological, microbial load, and quality properties of fino bread

- Comparative toxicity assessment of fisetin-aided artificial intelligence-assisted drug design targeting epibulbar dermoid through phytochemicals

- Acute toxicity and anti-inflammatory activity of bis-thiourea derivatives

- Anti-diabetic activity-guided isolation of α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory terpenes from Capsella bursa-pastoris Linn.

- GC–MS analysis of Lactobacillus plantarum YW11 metabolites and its computational analysis on familial pulmonary fibrosis hub genes

- Green formulation of copper nanoparticles by Pistacia khinjuk leaf aqueous extract: Introducing a novel chemotherapeutic drug for the treatment of prostate cancer

- Improved photocatalytic properties of WO3 nanoparticles for Malachite green dye degradation under visible light irradiation: An effect of La doping

- One-pot synthesis of a network of Mn2O3–MnO2–poly(m-methylaniline) composite nanorods on a polypyrrole film presents a promising and efficient optoelectronic and solar cell device

- Groundwater quality and health risk assessment of nitrate and fluoride in Al Qaseem area, Saudi Arabia

- A comparative study of the antifungal efficacy and phytochemical composition of date palm leaflet extracts

- Processing of alcohol pomelo beverage (Citrus grandis (L.) Osbeck) using saccharomyces yeast: Optimization, physicochemical quality, and sensory characteristics

- Specialized compounds of four Cameroonian spices: Isolation, characterization, and in silico evaluation as prospective SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors

- Identification of a novel drug target in Porphyromonas gingivalis by a computational genome analysis approach

- Physico-chemical properties and durability of a fly-ash-based geopolymer

- FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 inhibitory potentials of some phytochemicals from anti-leukemic plants using computational chemical methodologies

- Wild Thymus zygis L. ssp. gracilis and Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh.: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antibacterial activities of essential oils

- 3D-QSAR, molecular docking, ADMET, simulation dynamic, and retrosynthesis studies on new styrylquinolines derivatives against breast cancer

- Deciphering the influenza neuraminidase inhibitory potential of naturally occurring biflavonoids: An in silico approach

- Determination of heavy elements in agricultural regions, Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis and characterization of antioxidant-enriched Moringa oil-based edible oleogel

- Ameliorative effects of thistle and thyme honeys on cyclophosphamide-induced toxicity in mice

- Study of phytochemical compound and antipyretic activity of Chenopodium ambrosioides L. fractions

- Investigating the adsorption mechanism of zinc chloride-modified porous carbon for sulfadiazine removal from water

- Performance repair of building materials using alumina and silica composite nanomaterials with electrodynamic properties

- Effects of nanoparticles on the activity and resistance genes of anaerobic digestion enzymes in livestock and poultry manure containing the antibiotic tetracycline

- Effect of copper nanoparticles green-synthesized using Ocimum basilicum against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in mice lung infection model

- Cardioprotective effects of nanoparticles green formulated by Spinacia oleracea extract on isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction in mice by the determination of PPAR-γ/NF-κB pathway

- Anti-OTC antibody-conjugated fluorescent magnetic/silica and fluorescent hybrid silica nanoparticles for oxytetracycline detection

- Curcumin conjugated zinc nanoparticles for the treatment of myocardial infarction

- Identification and in silico screening of natural phloroglucinols as potential PI3Kα inhibitors: A computational approach for drug discovery

- Exploring the phytochemical profile and antioxidant evaluation: Molecular docking and ADMET analysis of main compounds from three Solanum species in Saudi Arabia

- Unveiling the molecular composition and biological properties of essential oil derived from the leaves of wild Mentha aquatica L.: A comprehensive in vitro and in silico exploration

- Analysis of bioactive compounds present in Boerhavia elegans seeds by GC-MS

- Homology modeling and molecular docking study of corticotrophin-releasing hormone: An approach to treat stress-related diseases

- LncRNA MIR17HG alleviates heart failure via targeting MIR17HG/miR-153-3p/SIRT1 axis in in vitro model

- Development and validation of a stability indicating UPLC-DAD method coupled with MS-TQD for ramipril and thymoquinone in bioactive SNEDDS with in silico toxicity analysis of ramipril degradation products

- Biosynthesis of Ag/Cu nanocomposite mediated by Curcuma longa: Evaluation of its antibacterial properties against oral pathogens

- Development of AMBER-compliant transferable force field parameters for polytetrafluoroethylene

- Treatment of gestational diabetes by Acroptilon repens leaf aqueous extract green-formulated iron nanoparticles in rats

- Development and characterization of new ecological adsorbents based on cardoon wastes: Application to brilliant green adsorption

- A fast, sensitive, greener, and stability-indicating HPLC method for the standardization and quantitative determination of chlorhexidine acetate in commercial products

- Assessment of Se, As, Cd, Cr, Hg, and Pb content status in Ankang tea plantations of China

- Effect of transition metal chloride (ZnCl2) on low-temperature pyrolysis of high ash bituminous coal

- Evaluating polyphenol and ascorbic acid contents, tannin removal ability, and physical properties during hydrolysis and convective hot-air drying of cashew apple powder

- Development and characterization of functional low-fat frozen dairy dessert enhanced with dried lemongrass powder

- Scrutinizing the effect of additive and synergistic antibiotics against carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Preparation, characterization, and determination of the therapeutic effects of copper nanoparticles green-formulated by Pistacia atlantica in diabetes-induced cardiac dysfunction in rat

- Antioxidant and antidiabetic potentials of methoxy-substituted Schiff bases using in vitro, in vivo, and molecular simulation approaches

- Anti-melanoma cancer activity and chemical profile of the essential oil of Seseli yunnanense Franch

- Molecular docking analysis of subtilisin-like alkaline serine protease (SLASP) and laccase with natural biopolymers

- Overcoming methicillin resistance by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Computational evaluation of napthyridine and oxadiazoles compounds for potential dual inhibition of PBP-2a and FemA proteins

- Exploring novel antitubercular agents: Innovative design of 2,3-diaryl-quinoxalines targeting DprE1 for effective tuberculosis treatment

- Drimia maritima flowers as a source of biologically potent components: Optimization of bioactive compound extractions, isolation, UPLC–ESI–MS/MS, and pharmacological properties

- Estimating molecular properties, drug-likeness, cardiotoxic risk, liability profile, and molecular docking study to characterize binding process of key phyto-compounds against serotonin 5-HT2A receptor

- Fabrication of β-cyclodextrin-based microgels for enhancing solubility of Terbinafine: An in-vitro and in-vivo toxicological evaluation

- Phyto-mediated synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles and their sunlight-driven photocatalytic degradation of cationic and anionic dyes

- Monosodium glutamate induces hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis hyperactivation, glucocorticoid receptors down-regulation, and systemic inflammatory response in young male rats: Impact on miR-155 and miR-218

- Quality control analyses of selected honey samples from Serbia based on their mineral and flavonoid profiles, and the invertase activity

- Eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Phyllanthus niruri leaf extract: Assessment of antimicrobial activity, effectiveness on tropical neglected mosquito vector control, and biocompatibility using a fibroblast cell line model

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles containing Cichorium intybus to treat the sepsis-induced DNA damage in the liver of Wistar albino rats

- Quality changes of durian pulp (Durio ziberhinus Murr.) in cold storage

- Study on recrystallization process of nitroguanidine by directly adding cold water to control temperature

- Determination of heavy metals and health risk assessment in drinking water in Bukayriyah City, Saudi Arabia

- Larvicidal properties of essential oils of three Artemisia species against the chemically insecticide-resistant Nile fever vector Culex pipiens (L.) (Diptera: Culicidae): In vitro and in silico studies

- Design, synthesis, characterization, and theoretical calculations, along with in silico and in vitro antimicrobial proprieties of new isoxazole-amide conjugates

- The impact of drying and extraction methods on total lipid, fatty acid profile, and cytotoxicity of Tenebrio molitor larvae

- A zinc oxide–tin oxide–nerolidol hybrid nanomaterial: Efficacy against esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- Research on technological process for production of muskmelon juice (Cucumis melo L.)

- Physicochemical components, antioxidant activity, and predictive models for quality of soursop tea (Annona muricata L.) during heat pump drying

- Characterization and application of Fe1−xCoxFe2O4 nanoparticles in Direct Red 79 adsorption

- Torilis arvensis ethanolic extract: Phytochemical analysis, antifungal efficacy, and cytotoxicity properties

- Magnetite–poly-1H pyrrole dendritic nanocomposite seeded on poly-1H pyrrole: A promising photocathode for green hydrogen generation from sanitation water without using external sacrificing agent

- HPLC and GC–MS analyses of phytochemical compounds in Haloxylon salicornicum extract: Antibacterial and antifungal activity assessment of phytopathogens

- Efficient and stable to coking catalysts of ethanol steam reforming comprised of Ni + Ru loaded on MgAl2O4 + LnFe0.7Ni0.3O3 (Ln = La, Pr) nanocomposites prepared via cost-effective procedure with Pluronic P123 copolymer

- Nitrogen and boron co-doped carbon dots probe for selectively detecting Hg2+ in water samples and the detection mechanism

- Heavy metals in road dust from typical old industrial areas of Wuhan: Seasonal distribution and bioaccessibility-based health risk assessment

- Phytochemical profiling and bioactivity evaluation of CBD- and THC-enriched Cannabis sativa extracts: In vitro and in silico investigation of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects

- Investigating dye adsorption: The role of surface-modified montmorillonite nanoclay in kinetics, isotherms, and thermodynamics

- Antimicrobial activity, induction of ROS generation in HepG2 liver cancer cells, and chemical composition of Pterospermum heterophyllum

- Study on the performance of nanoparticle-modified PVDF membrane in delaying membrane aging

- Impact of cholesterol in encapsulated vitamin E acetate within cocoliposomes

- Review Articles

- Structural aspects of Pt(η3-X1N1X2)(PL) (X1,2 = O, C, or Se) and Pt(η3-N1N2X1)(PL) (X1 = C, S, or Se) derivatives

- Biosurfactants in biocorrosion and corrosion mitigation of metals: An overview

- Stimulus-responsive MOF–hydrogel composites: Classification, preparation, characterization, and their advancement in medical treatments

- Electrochemical dissolution of titanium under alternating current polarization to obtain its dioxide

- Special Issue on Recent Trends in Green Chemistry

- Phytochemical screening and antioxidant activity of Vitex agnus-castus L.

- Phytochemical study, antioxidant activity, and dermoprotective activity of Chenopodium ambrosioides (L.)

- Exploitation of mangliculous marine fungi, Amarenographium solium, for the green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their activity against multiple drug-resistant bacteria

- Study of the phytotoxicity of margines on Pistia stratiotes L.

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Energy, Environmental and Biological Applications - Part III

- Impact of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles on growth, development, and antioxidant system of high protein content crop (Lablab purpureus L.) sweet

- Green synthesis, characterization, and application of iron and molybdenum nanoparticles and their composites for enhancing the growth of Solanum lycopersicum

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Olea europaea L. extracted polysaccharides, characterization, and its assessment as an antimicrobial agent against multiple pathogenic microbes

- Photocatalytic treatment of organic dyes using metal oxides and nanocomposites: A quantitative study

- Antifungal, antioxidant, and photocatalytic activities of greenly synthesized iron oxide nanoparticles

- Special Issue on Phytochemical and Pharmacological Scrutinization of Medicinal Plants

- Hepatoprotective effects of safranal on acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in rats

- Chemical composition and biological properties of Thymus capitatus plants from Algerian high plains: A comparative and analytical study

- Chemical composition and bioactivities of the methanol root extracts of Saussurea costus

- In vivo protective effects of vitamin C against cyto-genotoxicity induced by Dysphania ambrosioides aqueous extract

- Insights about the deleterious impact of a carbamate pesticide on some metabolic immune and antioxidant functions and a focus on the protective ability of a Saharan shrub and its anti-edematous property

- A comprehensive review uncovering the anticancerous potential of genkwanin (plant-derived compound) in several human carcinomas

- A study to investigate the anticancer potential of carvacrol via targeting Notch signaling in breast cancer

- Assessment of anti-diabetic properties of Ziziphus oenopolia (L.) wild edible fruit extract: In vitro and in silico investigations through molecular docking analysis

- Optimization of polyphenol extraction, phenolic profile by LC-ESI-MS/MS, antioxidant, anti-enzymatic, and cytotoxic activities of Physalis acutifolia

- Phytochemical screening, antioxidant properties, and photo-protective activities of Salvia balansae de Noé ex Coss

- Antihyperglycemic, antiglycation, anti-hypercholesteremic, and toxicity evaluation with gas chromatography mass spectrometry profiling for Aloe armatissima leaves

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of gold nanoparticles by using Timur (Zanthoxylum armatum DC) and their effect on wound healing

- Does Erodium trifolium (Cav.) Guitt exhibit medicinal properties? Response elements from phytochemical profiling, enzyme-inhibiting, and antioxidant and antimicrobial activities

- Integrative in silico evaluation of the antiviral potential of terpenoids and its metal complexes derived from Homalomena aromatica based on main protease of SARS-CoV-2

- 6-Methoxyflavone improves anxiety, depression, and memory by increasing monoamines in mice brain: HPLC analysis and in silico studies

- Simultaneous extraction and quantification of hydrophilic and lipophilic antioxidants in Solanum lycopersicum L. varieties marketed in Saudi Arabia

- Biological evaluation of CH3OH and C2H5OH of Berberis vulgaris for in vivo antileishmanial potential against Leishmania tropica in murine models