Abstract

Groundwater serves as the lifeline in arid regions, where aquifer overuse and climatic factors can substantially degrade its quality, posing significant challenges. The current study examines the drinking water quality in the Al Qaseem area and assesses the potential health risks from nitrate (

1 Introduction

Groundwater plays a crucial role in providing water for drinking and irrigation, particularly in arid and semiarid areas [1,2,3,4]. Contamination of groundwater poses substantial risks to human health and the environment, especially in cases where major cations and anions like nitrate and fluoride are present in high concentrations. Nitrate (

Nitrate contamination in groundwater is often associated with agricultural activities, where nitrogen-based fertilizers and animal manure contribute to high nitrate levels in soil and water systems [16]. In regions with intensive farming practices, nitrate leaching from agricultural lands seeps into groundwater, leading to elevated nitrate concentrations in drinking water sources [17]. Similarly, fluoride contamination in groundwater is prevalent in areas with naturally occurring fluoride-rich geologic formations, where dissolution of fluoride-bearing minerals contributes to high fluoride concentrations in groundwater [18]. Anthropogenic activities such as industrial processes and mining can further worsen fluoride contamination in groundwater by releasing industrial effluents containing fluoride compounds. Understanding the dynamics of nitrate and fluoride contamination in groundwater is vital for implementing effective mitigation strategies and safeguarding public health. Monitoring programs, water quality assessments, and remediation efforts are crucial elements in managing groundwater contamination with major cations and anions, especially nitrate and fluoride. By pinpointing pollution sources, implementing pollution control measures, and advocating for sustainable land use practices, stakeholders can strive to reduce the impacts of nitrate and fluoride contamination on groundwater quality and human well-being [19].

In the last two decades, extensive research has been dedicated to studying the groundwater of central Saudi Arabia. This research has explored various aspects including water resources, suitability for drinking and agricultural purposes, as well as hydrochemical evaluations [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. Some of these studies have uncovered elevated levels of TDS, Ca2+, Na+, K+, Cl−,

2 Material and methods

2.1 Geological and hydrogeological setting

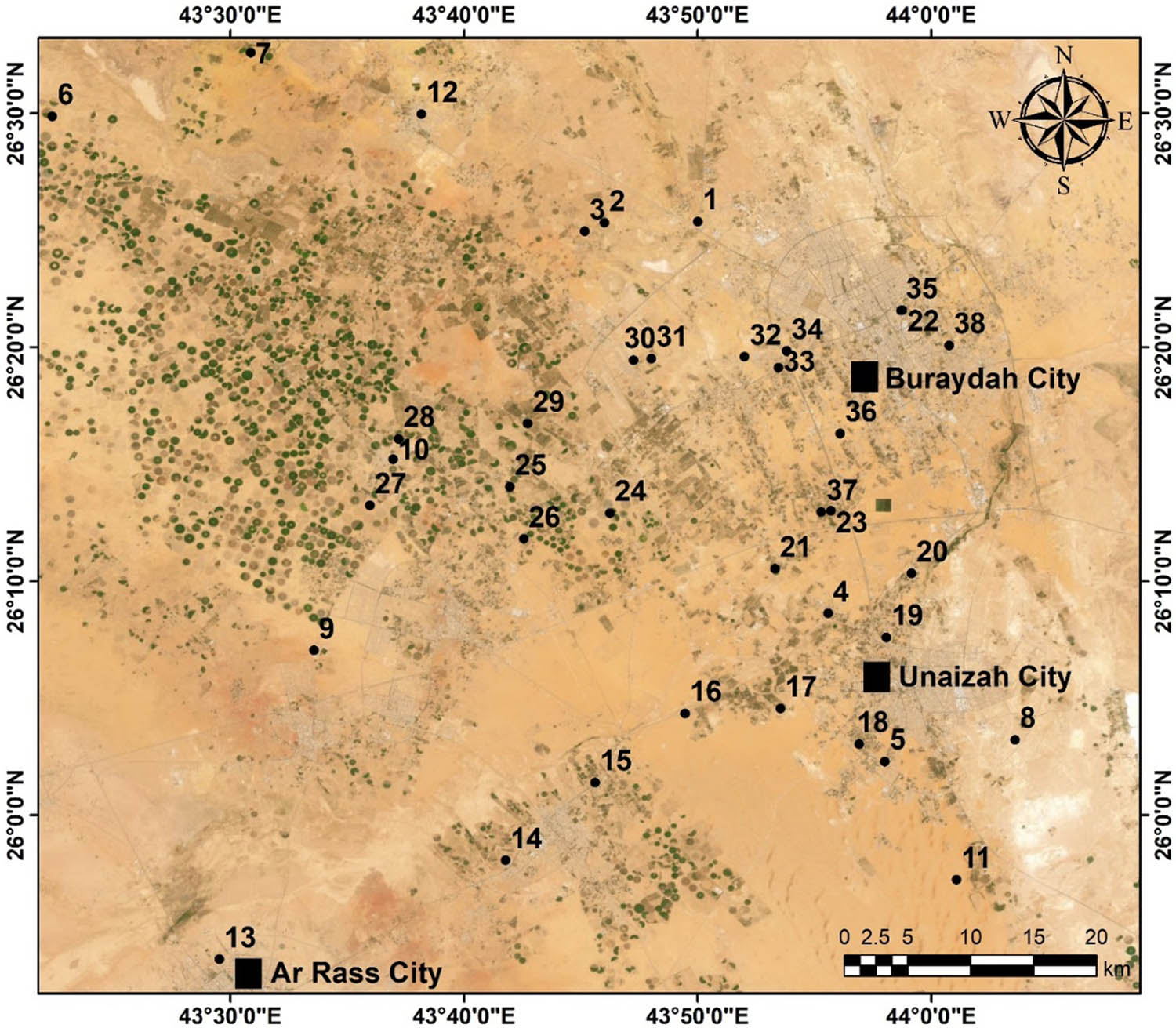

The Al Qaseem region, located in central Saudi Arabia, is a significant agricultural hub (Figure 1). The ground elevated from 600 to 750 m above mean sea level, with a gentle slope toward the east. It has a typical continental desert climate with an average annual rainfall of less than 150 mm [29]. Groundwater recharge rates are notably low because of the region’s high evaporation rates, which can reach up to 3 cm per year [24].

Land-use pattern of the Al Qaseem area using Landsat image.

The study area lies on the Arabian Shelf, which is composed of an unconformable sedimentary sequence that overlays the shield rocks to the west. The shelf rocks exhibit a slight eastward dip (1–2°) and show a progressive decrease in age from west to east (Figure 1). Within the study area, Paleozoic and early Mesozoic sedimentary rocks predominate, including sandstone, limestone, shale, and gypsum [30]. In the study area, the Saq Formation has a thickness ranging from 350 to 750 m. It consists primarily of sandstones with some minor interbedded shale and siltstone layers, and it unconformably overlays the basement complex rocks. Apart from the Saq aquifer, the Tabuk, Khuff, and Neogene aquifers also serve as water sources, but they are separated from the Saq by the Hanadir, Ra’an, and Qusaiba impermeable shales. Wells accessing the Saq Aquifer vary in depth, from less than 100 m in the unconfined outcrop area to over 1,200 m in the confined eastern sections.

2.2 Land-use pattern and urbanization

The focal region of Al Qaseem, pivotal to this study, exhibits a diverse combination of land use and land cover that mirrors its distinct geographical and socio-economic composition (Figure 1). Encompassing an expanse of 989 km², its agricultural areas signify the region’s robust agricultural foundation and its pivotal role in food production. The residential sectors, spanning 918 km², shed light on the urban dynamics and residential spaces within the area. Extensive bare lands spanning 4,287 km² dominate the scenery, showcasing the region’s natural and pristine environmental features. This diverse amalgamation of agricultural, urban, and natural landscapes underscores the multifaceted nature of Al Qaseem, rendering it a compelling subject for thorough examination and analysis.

2.3 Sampling and data analysis

In total, 38 water samples were gathered from irrigation and domestic wells that draw water from the Saq Aquifer. These wells are located between N25.8975–N26.7917 and E43.2247–E44.0179 (Figure 2). The researchers followed established protocols for collecting groundwater samples in the study area. They ensured accuracy by pumping the well 10 min before sample collection to guarantee that the water represented the aquifer conditions rather than stagnant well water. Approximately 1 L of water was collected from each groundwater well, a quantity deemed adequate for carrying out all essential analyses, and allowed for any re-testing that might be required as outlined in the APHA guidelines [31]. The samples were collected in pre-cleaned, high-density polyethylene bottles to prevent chemical interactions with the samples. Upon collection, the samples were promptly labeled, sealed, and placed in coolers with ice packs to maintain a temperature below 4°C, which is crucial to prevent chemical and biological reactions. Within 24 h of collection, the samples were transported to the laboratory to preserve their integrity.

Locations of the groundwater samples in Al Qaseem area.

Major cations (Mg2+, Ca2+, Na+, and K+) were analyzed using atomic absorption spectrophotometry.

The following anion–cation balance equation is used to ensure data accuracy by eliminating samples with errors above ±5%:

The water quality index (WQI) functions as a mathematical tool for evaluating the suitability of water for human consumption [32,33]. The equations used to compute the WQI are outlined as follows:

The quality rating scale (q i ) for each parameter is determined by dividing the concentration of the parameter in each water sample by its corresponding standard [28], and then multiplying the result by 100. The calculated WQI values are categorized into five groups [25]: WQI < 50 (excellent water), WQI = 50–100.1 (good water), WQI = 100–200.1 (poor water), WQI = 200–300.1 (very poor water), and WQI > 300 (unsuitable for drinking purposes).

In this study, we assessed the potential health risks associated with the oral ingestion of NO3 − and F− for adults, children, and infants. The following formulas were employed to calculate the daily water intake (CDI), hazard quotient (HQ), and non-carcinogenic hazard index (HI) associated with drinking water [34,35]. The equations are as follows:

Here, C represents the concentration of nitrate and fluoride in water (in mg/L); DI stands for the daily water consumption in liters; F denotes the frequency of days per year of exposure; ED signifies the duration of exposure in years; BW represents the weight of the specific age group in kilograms; AT indicates the average duration in days; and RfD refers to the reference dose (

Parameters applied for health exposure assessment through drinking water and HI classification

| Risk exposure factors | Unit | Adults | Children | Infants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DI | L/d | 2.0 | 1.5 | 0.8 |

| F | d/year | 365 | 365 | 365 |

| ED | years | 40 | 10 | 1.0 |

| BW | kg | 70 | 20 | 10 |

| AT | d | 14,600 | 3,650 | 365 |

| HI ≤ 1 | No health risk to humans | |||

| HI > 1 | Higher level of hazard |

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Hydrogeochemistry and groundwater quality

The coordinates of the wells from which groundwater samples were collected, along with the hydrogeochemical dataset, are provided in Table S1. The pH ranged from 6.77 to 9.60, with an average of 7.26 (Table 2), indicating neutral to weakly basic waters [37]. Total dissolved solids (TDS) levels ranged from 534 to 5,664, averaging 1705.83 mg/L, indicating that 50% of the water samples exceeded the WHO’s recommended limits (1,000 mg/L) [38]. Elevated TDS levels are often associated with extended groundwater residence times and significant water–rock interaction [3,39].

Descriptive statistics of the investigated parameters

| Parameter | Unit | Min. | Max. | Mean | Std. Dev. | MAC | Weight (w i) | Relative weight (W i ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | — | 6.77 | 9.60 | 7.26 | 0.449 | 6.5–8.5 | 3 | 0.073 |

| TDS | mg/L | 534 | 5,664 | 1705.83 | 1491.31 | 1,000 | 4 | 0.098 |

| EC | mg/L | 920 | 11,560 | 3335.45 | 3121.27 | 500 | 3 | 0.073 |

| Ca2+ | mg/l | 61.30 | 1053.00 | 303.70 | 223.50 | 75 | 2 | 0.049 |

| Na+ | mg/L | 59.00 | 1816.00 | 418.37 | 570.88 | 200 | 2 | 0.049 |

| Mg2+ | mg/L | 12.00 | 133.00 | 35.27 | 26.78 | 30 | 2 | 0.049 |

| K+ | mg/L | 4.10 | 42.00 | 14.12 | 9.19 | 12 | 2 | 0.049 |

| Cl− | mg/L | 78.10 | 3408.00 | 933.29 | 1124.75 | 250 | 3 | 0.073 |

|

|

mg/L | 73.00 | 189.00 | 149.68 | 27.16 | 200 | 2 | 0.049 |

|

|

mg/L | 112.00 | 1920.00 | 385.70 | 444.33 | 250 | 3 | 0.073 |

| NO3 − | mg/L | 1.30 | 108.00 | 36.56 | 17.58 | 50 | 5 | 0.122 |

| F− | mg/L | 0.10 | 0.98 | 0.71 | 0.311 | 1.5 | 5 | 0.122 |

Arranged in descending order, the mean concentrations of cations and anions (mg/L) were as follows: Cl− (933.29), Na+ (418.37),

TDS exhibit a positive correlation with EC, Ca2+, Na+, K+, and Cl− (Table 3), indicating that the dissolution of carbonates and evaporites might play a role in the elevated concentrations of these ions in the groundwater [3,44,45]. However, a positive correlation was observed between Mg2+ and

Correlation coefficient for the analyzed parameters

| pH | TDS | EC | Ca | Na | Mg | K | Cl | HCO3 | SO4 | NO3 | F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 1 | |||||||||||

| TDS | −0.207 | 1 | ||||||||||

| EC | −0.225 | 0.998 ** | 1 | |||||||||

| Ca2+ | −0.230 | 0.786 ** | 0.809 ** | 1 | ||||||||

| Na+ | −0.198 | 0.917 ** | 0.914 ** | 0.673** | 1 | |||||||

| Mg2+ | −0.181 | 0.201 | 0.216 | 0.231 | −0.009 | 1 | ||||||

| K+ | −0.312 | 0.500 ** | 0.522 ** | 0.600 ** | 0.379* | 0.515 ** | 1 | |||||

| Cl− | −0.229 | 0.937 ** | 0.943 ** | 0.771 ** | 0.976 ** | 0.024 | 0.501 ** | 1 | ||||

|

|

−0.379* | −0.536** | −0.523** | −0.327* | −0.635** | 0.182 | 0.186 | −0.569** | 1 | |||

|

|

−0.092 | 0.296 | 0.304 | 0.486** | 0.211 | 0.535 ** | 0.115 | 0.167 | −0.198 | 1 | ||

|

|

0.322* | 0.266 | 0.242 | 0.160 | 0.230 | 0.107 | −0.078 | 0.201 | −0.445** | 0.154 | 1 | |

| F− | −0.347* | 0.350* | 0.410* | 0.618 ** | 0.309 | 0.347* | 0.504 ** | 0.424** | 0.035 | 0.300 | −0.151 | 1 |

* Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (two-tailed).

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed).

Bold values represent positive correlation.

Principal component analysis was employed to discern the potential origins of hydrogeochemical parameters in groundwater. Three principal components were derived, collectively explaining 46.93, 19.38, and 12.03% of the total variance (Table 4). PC1 showed high loadings for TDS, EC, Ca2+, Na+, K+, Cl−, and F−, pointing to natural processes involving the dissolution and precipitation of silicates, gypsum, and carbonates [47,48]. Additionally, PC2 displayed elevated loadings of Mg2+, K+, and F−, suggesting influences from both human activities and natural sources [49]. PC3 demonstrated high loadings of Mg2+,

Principal component loadings

| Parameters | Component | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | |

| pH | −0.261 | −0.620 | 0.378 |

| TDS | 0.957 | −0.138 | −0.073 |

| EC | 0.969 | −0.098 | −0.077 |

| Ca2+ | 0.885 | 0.143 | 0.062 |

| Na+ | 0.904 | −0.271 | −0.221 |

| Mg2+ | 0.285 | 0.563 | 0.645 |

| K+ | 0.597 | 0.551 | −0.047 |

| Cl− | 0.945 | −0.171 | −0.254 |

|

|

0.503 | 0.757 | −0.127 |

|

|

0.411 | 0.196 | 0.689 |

|

|

0.245 | −0.530 | 0.513 |

| F− | 0.544 | 0.526 | 0.000 |

| % of Variance | 46.93 | 19.38 | 12.03 |

| Cumulative % | 46.93 | 66.31 | 78.34 |

Bold values mean high loadings of the hydrogeochemical data.

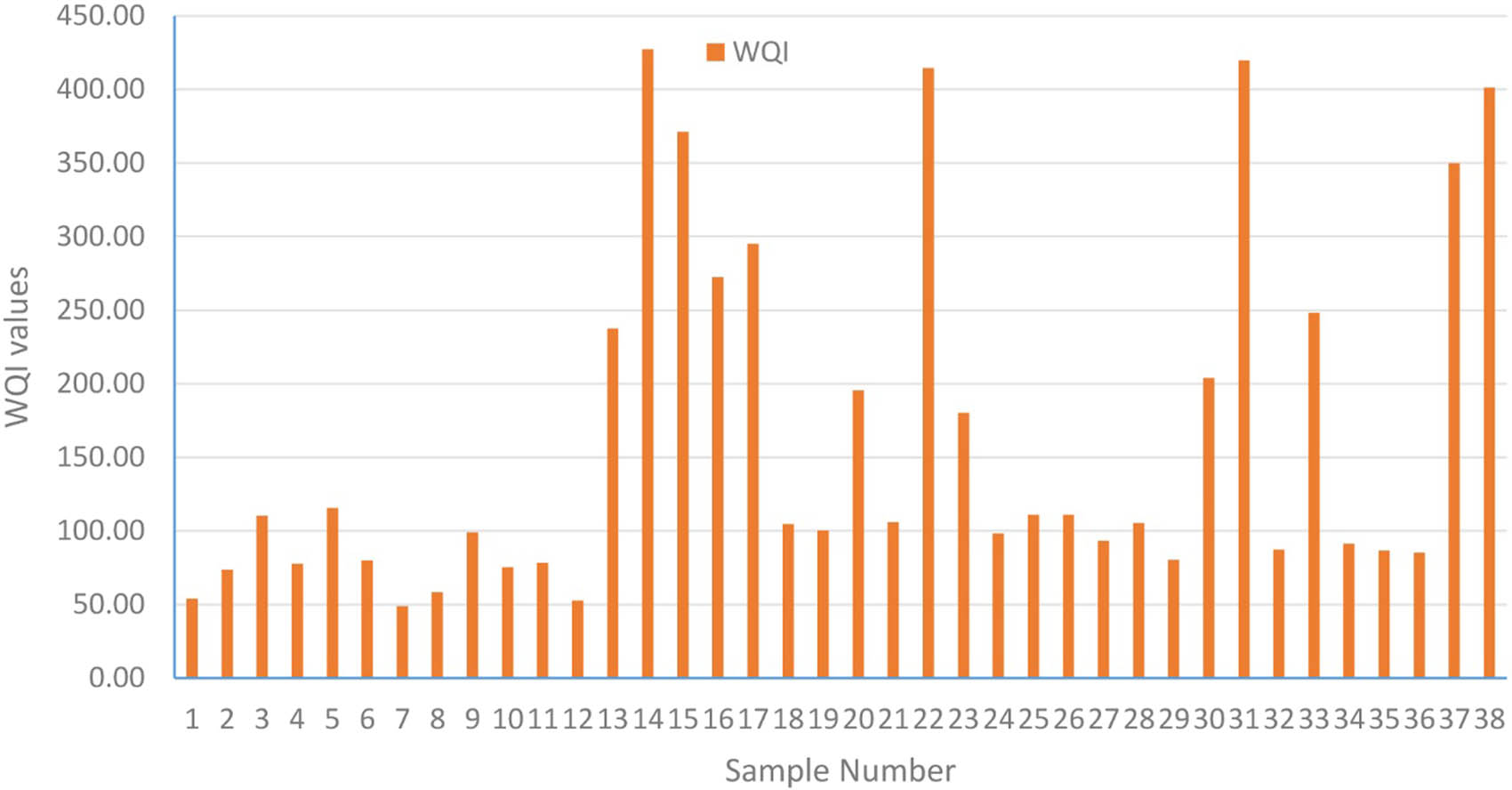

The WQI values varied between 48.63 and 426.98, averaging 166.81. According to the classification based on WQI, eight water samples were deemed unsuitable for drinking, five samples were categorized as very poor water quality, ten samples as poor quality, fourteen samples as good quality, and one sample as excellent quality (Table 5). Analysis of WQI values across sampling sites revealed hotspots in S14, S15, S22, S31, S37, and S38 (Figure 3). This phenomenon could be attributed to an increase in Ca2+, Mg2+, Na+, Cl−, and

Results and categories of the WQI applied in this study

| S.No. | WQI | Classification | S.N. | WQI | Classification | S.N. | WQI | Classification | S.N. | WQI | Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 54.09 | Good | 11 | 78.32 | Good | 21 | 106.02 | Poor | 31 | 419.49 | Unsuitable |

| 2 | 73.47 | Good | 12 | 52.62 | Good | 22 | 414.46 | Unsuitable | 32 | 87.07 | Good |

| 3 | 110.13 | Poor | 13 | 237.47 | Very poor | 23 | 179.94 | Poor | 33 | 248.31 | Very poor |

| 4 | 77.49 | Good | 14 | 426.98 | Unsuitable | 24 | 98.02 | Good | 34 | 91.18 | Good |

| 5 | 115.49 | Poor | 15 | 371.08 | Unsuitable | 25 | 110.89 | Poor | 35 | 86.44 | Unsuitable |

| 6 | 79.88 | Good | 16 | 272.48 | Very poor | 26 | 110.89 | Poor | 36 | 85.01 | Unsuitable |

| 7 | 48.63 | Excellent | 17 | 294.87 | Very poor | 27 | 93.14 | Good | 37 | 349.89 | Unsuitable |

| 8 | 58.38 | Good | 18 | 104.35 | Poor | 28 | 105.31 | Poor | 38 | 401.04 | Unsuitable |

| 9 | 99.08 | Good | 19 | 100.25 | Poor | 29 | 80.10 | Good | |||

| 10 | 75.19 | Good | 20 | 195.42 | Poor | 30 | 203.74 | Very poor |

Distribution of the WQI values per sample location in the study area.

3.2 Health risk assessment

Fluoride and nitrate stand out as some of the most common and widely distributed contaminants discovered in various groundwater reservoirs, presenting a notable environmental apprehension regarding water pollution. Elevated levels of

It has been observed that excessive fertilizer cannot be completely absorbed by plant roots. As a result, the surplus can be lost through denitrification, leaching, and volatilization, or it can remain in the soil [13,52,53]. Fluoride (F-) in groundwater can either occur naturally or be influenced by human activities [54]. The decomposition of fluoride-bearing minerals such as fluorite, amphiboles, apatite, and muscovite provides a natural source of F− [13]. Additionally, anthropogenic sources of F− in groundwater include phosphatic fertilizer plants, excessive groundwater extraction, brick manufacturing, coal combustion, and sewage discharge [55].

The CDI values of

CDI (mg/kg/day) of nitrate and fluoride for adults, children, and infants

| S.No. | Well | CDI (NO3 −) | CDI (F−) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adults | Children | Infants | Adults | Children | Infants | ||

| 1 | BU0294 | 0.037 | 0.0975 | 0.104 | 0.006 | 0.015 | 0.016 |

| 2 | BU0295 | 0.334 | 0.8775 | 0.936 | 0.009 | 0.0225 | 0.024 |

| 3 | BU0296 | 0.854 | 2.2425 | 2.392 | 0.009 | 0.0225 | 0.024 |

| 4 | BU2003 | 0.917 | 2.4075 | 2.568 | 0.006 | 0.015 | 0.016 |

| 5 | BU2004 | 3.086 | 8.100 | 8.640 | 0.006 | 0.015 | 0.016 |

| 6 | BU9003 | 1.957 | 5.1375 | 5.480 | 0.014 | 0.0375 | 0.04 |

| 7 | BU9007 | 0.540 | 1.4175 | 1.512 | 0.014 | 0.0375 | 0.04 |

| 8 | BU9115 | 0.866 | 2.2725 | 2.424 | 0.006 | 0.015 | 0.016 |

| 9 | BU9128 | 1.991 | 5.2275 | 5.576 | 0.006 | 0.015 | 0.016 |

| 10 | BU9129 | 1.303 | 3.420 | 3.648 | 0.003 | 0.0075 | 0.008 |

| 11 | BU9328 | 1.226 | 3.2175 | 3.432 | 0.006 | 0.015 | 0.016 |

| 12 | BU9458 | 0.726 | 1.905 | 2.032 | 0.009 | 0.0225 | 0.024 |

| 13 | Sq-1 | 1.029 | 2.700 | 2.88 | 0.027 | 0.0705 | 0.0752 |

| 14 | Sq-2 | 1.343 | 3.525 | 3.760 | 0.025 | 0.066 | 0.0704 |

| 15 | Sq-3 | 1.286 | 3.375 | 3.600 | 0.026 | 0.0675 | 0.072 |

| 16 | Sq-4 | 1.171 | 3.075 | 3.280 | 0.028 | 0.0735 | 0.0784 |

| 17 | Sq-5 | 1.143 | 3.000 | 3.200 | 0.026 | 0.069 | 0.0736 |

| 18 | Sq-6 | 1.057 | 2.775 | 2.960 | 0.024 | 0.06375 | 0.068 |

| 19 | Sq-7 | 0.800 | 2.100 | 2.240 | 0.027 | 0.06975 | 0.0744 |

| 20 | Sq-8 | 1.000 | 2.625 | 2.800 | 0.027 | 0.072 | 0.0768 |

| 21 | Sq-9 | 0.943 | 2.475 | 2.640 | 0.026 | 0.06825 | 0.0728 |

| 22 | Sq-10 | 1.200 | 3.150 | 3.360 | 0.025 | 0.066 | 0.0704 |

| 23 | Sq-11 | 1.086 | 2.850 | 3.040 | 0.026 | 0.069 | 0.0736 |

| 24 | Sq-12 | 0.943 | 2.475 | 2.640 | 0.027 | 0.07125 | 0.076 |

| 25 | Sq-13 | 1.029 | 2.700 | 2.880 | 0.025 | 0.0645 | 0.0688 |

| 26 | Sq-14 | 1.029 | 2.700 | 2.880 | 0.027 | 0.06975 | 0.0744 |

| 27 | Sq-15 | 0.686 | 1.800 | 1.920 | 0.025 | 0.06525 | 0.0696 |

| 28 | Sq-16 | 0.971 | 2.550 | 2.720 | 0.026 | 0.06825 | 0.0728 |

| 29 | Sq-17 | 0.600 | 1.575 | 1.680 | 0.025 | 0.0645 | 0.0688 |

| 30 | Sq-18 | 1.143 | 3.000 | 3.200 | 0.027 | 0.07125 | 0.076 |

| 31 | Sq-19 | 1.286 | 3.375 | 3.600 | 0.027 | 0.0705 | 0.0752 |

| 32 | Sq-20 | 0.629 | 1.650 | 1.760 | 0.026 | 0.06825 | 0.0728 |

| 33 | Sq-21 | 1.057 | 2.775 | 2.960 | 0.025 | 0.066 | 0.0704 |

| 34 | Sq-22 | 0.714 | 1.875 | 2.000 | 0.026 | 0.0675 | 0.072 |

| 35 | Sq-23 | 0.629 | 1.650 | 1.760 | 0.024 | 0.063 | 0.0672 |

| 36 | Sq-24 | 0.629 | 1.650 | 1.760 | 0.025 | 0.066 | 0.0704 |

| 37 | Sq-25 | 1.200 | 3.150 | 3.360 | 0.027 | 0.0705 | 0.0752 |

| 38 | Sq-26 | 1.257 | 3.300 | 3.520 | 0.026 | 0.06825 | 0.0728 |

| Min | 0.037 | 0.098 | 0.104 | 0.003 | 0.008 | 0.008 | |

| Max. | 3.086 | 8.100 | 8.640 | 0.028 | 0.074 | 0.078 | |

| Average | 1.071 | 2.810 | 2.997 | 0.020 | 0.052 | 0.056 | |

HQ and HI for fluoride and nitrate in adults, children, and infants

| S.No. | Well | HQ nitrates | HQ F− | HI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adults | Children | Infants | Adults | Children | Infants | Adults | Children | Infants | ||

| 1 | BU0294 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.065 | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.12 | 0.31 | 0.33 |

| 2 | BU0295 | 0.21 | 0.55 | 0.585 | 0.14 | 0.38 | 0.40 | 0.35 | 0.92 | 0.99 |

| 3 | BU0296 | 0.53 | 1.40 | 1.495 | 0.14 | 0.38 | 0.40 | 0.68 | 1.78 | 1.90 |

| 4 | BU2003 | 0.57 | 1.50 | 1.605 | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.67 | 1.75 | 1.87 |

| 5 | BU2004 | 1.93 | 5.06 | 5.40 | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 2.02 | 5.31 | 5.67 |

| 6 | BU9003 | 1.22 | 3.21 | 3.425 | 0.24 | 0.63 | 0.67 | 1.46 | 3.84 | 4.09 |

| 7 | BU9007 | 0.34 | 0.89 | 0.945 | 0.24 | 0.63 | 0.67 | 0.58 | 1.51 | 1.61 |

| 8 | BU9115 | 0.54 | 1.42 | 1.515 | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.64 | 1.67 | 1.78 |

| 9 | BU9128 | 1.24 | 3.27 | 3.485 | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 1.34 | 3.52 | 3.75 |

| 10 | BU9129 | 0.81 | 2.14 | 2.28 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.86 | 2.26 | 2.41 |

| 11 | BU9328 | 0.77 | 2.01 | 2.145 | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.86 | 2.26 | 2.41 |

| 12 | BU9458 | 0.45 | 1.19 | 1.27 | 0.14 | 0.38 | 0.40 | 0.60 | 1.57 | 1.67 |

| 13 | Sq-1 | 0.64 | 1.69 | 1.8 | 0.45 | 1.18 | 1.25 | 1.09 | 2.86 | 3.05 |

| 14 | Sq-2 | 0.84 | 2.20 | 2.35 | 0.42 | 1.10 | 1.17 | 1.26 | 3.30 | 3.52 |

| 15 | Sq-3 | 0.80 | 2.11 | 2.25 | 0.43 | 1.13 | 1.20 | 1.23 | 3.23 | 3.45 |

| 16 | Sq-4 | 0.73 | 1.92 | 2.05 | 0.47 | 1.23 | 1.31 | 1.20 | 3.15 | 3.36 |

| 17 | Sq-5 | 0.71 | 1.88 | 2.00 | 0.44 | 1.15 | 1.23 | 1.15 | 3.03 | 3.23 |

| 18 | Sq-6 | 0.66 | 1.73 | 1.85 | 0.4 | 1.06 | 1.13 | 1.07 | 2.80 | 2.98 |

| 19 | Sq-7 | 0.50 | 1.31 | 1.40 | 0.44 | 1.16 | 1.24 | 0.94 | 2.48 | 2.64 |

| 20 | Sq-8 | 0.63 | 1.64 | 1.75 | 0.46 | 1.20 | 1.28 | 1.08 | 2.84 | 3.03 |

| 21 | Sq-9 | 0.59 | 1.55 | 1.65 | 0.43 | 1.14 | 1.21 | 1.02 | 2.68 | 2.86 |

| 22 | Sq-10 | 0.75 | 1.97 | 2.10 | 0.42 | 1.10 | 1.17 | 1.17 | 3.07 | 3.27 |

| 23 | Sq-11 | 0.68 | 1.78 | 1.9 | 0.44 | 1.15 | 1.23 | 1.12 | 2.93 | 3.13 |

| 24 | Sq-12 | 0.59 | 1.55 | 1.65 | 0.45 | 1.19 | 1.27 | 1.04 | 2.73 | 2.92 |

| 25 | Sq-13 | 0.64 | 1.69 | 1.80 | 0.41 | 1.08 | 1.15 | 1.05 | 2.76 | 2.95 |

| 26 | Sq-14 | 0.64 | 1.69 | 1.80 | 0.44 | 1.16 | 1.24 | 1.09 | 2.85 | 3.04 |

| 27 | Sq-15 | 0.43 | 1.13 | 1.20 | 0.41 | 1.09 | 1.16 | 0.84 | 2.21 | 2.36 |

| 28 | Sq-16 | 0.61 | 1.59 | 1.70 | 0.43 | 1.14 | 1.21 | 1.04 | 2.73 | 2.91 |

| 29 | Sq-17 | 0.38 | 0.98 | 1.05 | 0.41 | 1.08 | 1.15 | 0.78 | 2.06 | 2.20 |

| 30 | Sq-18 | 0.71 | 1.88 | 2.00 | 0.45 | 1.19 | 1.27 | 1.17 | 3.06 | 3.27 |

| 31 | Sq-19 | 0.80 | 2.11 | 2.25 | 0.45 | 1.18 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 3.28 | 3.50 |

| 32 | Sq-20 | 0.39 | 1.03 | 1.10 | 0.43 | 1.14 | 1.21 | 0.83 | 2.17 | 2.31 |

| 33 | Sq-21 | 0.66 | 1.73 | 1.85 | 0.42 | 1.10 | 1.17 | 1.08 | 2.83 | 3.02 |

| 34 | Sq-22 | 0.45 | 1.17 | 1.25 | 0.43 | 1.13 | 1.2 | 0.88 | 2.30 | 2.45 |

| 35 | Sq-23 | 0.39 | 1.03 | 1.10 | 0.4 | 1.05 | 1.12 | 0.79 | 2.08 | 2.22 |

| 36 | Sq-24 | 0.39 | 1.03 | 1.10 | 0.42 | 1.10 | 1.17 | 0.81 | 2.13 | 2.27 |

| 37 | Sq-25 | 0.75 | 1.97 | 2.10 | 0.45 | 1.18 | 1.25 | 1.2 | 3.14 | 3.35 |

| 38 | Sq-26 | 0.79 | 2.06 | 2.20 | 0.43 | 1.14 | 1.21 | 1.22 | 3.20 | 3.41 |

| Min. | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.065 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.31 | 0.33 | |

| Max. | 1.93 | 5.06 | 5.4 | 0.47 | 1.23 | 1.31 | 2.02 | 5.31 | 5.67 | |

| Aver. | 0.668 | 1.756 | 1.873 | 0.333 | 0.874 | 0.930 | 0.993 | 2.606 | 2.78 | |

The HI varied from 0.12 to 2.02 for adults, with an average of 0.993. For children, it ranged from 0.31 to 5.31, with an average of 2.606. For infants, the HI ranged from 0.33 to 5.67, with an average of 2.78 (Table 7 and Figure 4). Groundwater samples exceeded the safety threshold of 1, accounting for 57.89% (22 out of 38) for adults and 94.73% (36 out of 38) for both children and infants (Figure 4). The findings of the study indicate that the groundwater examined across various study areas, particularly in water samples 5, 6, 9, and 14–17 (from wells BU2004, BU9003, BU9128, Sq-2 to Sq-5, respectively), could potentially expose infants, children, and adults to non-cancerous health risks if used as drinking water. Furthermore, the results indicate that infants and children are more susceptible to non-carcinogenic health risks than adults, likely because of their lower body weights. Similar conclusions have been reported by researchers worldwide when assessing the health risks associated with nitrate and fluoride in groundwater. These studies include regions in China, Iran, India, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia [4,15,34,50,51,56].

Non-carcinogenic risks induced by fluoride and nitrate in drinking water.

Nevertheless, to mitigate the elevated levels of

The current study proposes several measures to improve groundwater quality and minimize potential health hazards, particularly in terms of drinking water consumption: (i) implementation of an effective water management strategy involving the mentioned techniques, (ii) ensuring proper landfill construction, and (iii) reducing the excessive use of fertilizers and pesticides in agricultural areas.

The protocol employed by the researchers in the current study for collecting groundwater samples demonstrates a robust methodology aimed at ensuring the integrity and reliability of the findings. Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge inherent limitations, including temporal variability and spatial coverage. Groundwater quality can vary over time due to seasonal changes and agricultural activities. Sampling at a single point in time may not capture these variations and might not represent the long-term average conditions of the groundwater.

This study could be limited by the spatial coverage of sampled wells and their distribution. Although the number of wells sampled is substantial, their uneven distribution means the results may not accurately represent the entire study area. Fieldwork can be challenging when collecting samples according to the researchers’ preferences because some locations in the study area are inaccessible or belong to farming companies that do not allow researchers to collect from their groundwater wells. Addressing these limitations in future studies could involve conducting repeated samplings over different seasons and increasing the number of sampling locations.

4 Conclusions

The current work highlighted the water quality and non-carcinogenic hazards linked with nitrate and fluoride in groundwater sourced from the Al Qaseem region, Saudi Arabia. The findings indicated that numerous major cations and anions surpassed the guidelines set by the WHO. Out of the samples assessed, 8 were unsuitable for drinking, 5 displayed very poor water quality, 10 exhibited poor quality, 14 were of good quality, and 1 was deemed excellent. None of the fluoride samples exceeded the WHO’s recommended drinking water limit of 1.5 mg/L, while three nitrate levels surpassed the WHO guideline of 50.00 mg/L. A significant proportion, 57.89%, of the water samples exceeded safety thresholds for adults, while 94.73% surpassed the thresholds for both children and infants, indicating potential health hazards. Consequently, groundwater in the study area may pose non-cancerous health risks to infants, children, and adults if utilized as drinking water. Urgent attention and remedial measures are essential to safeguard residents from the adverse effects of fluoride and nitrate in the study area.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2024R791), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The authors also thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions and constructive comments.

-

Funding information: The research was financially supported by Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2024R791), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Author contributions: Talal Alharbi: collecting water samples, original draft preparation, design of methodology and mapping, and reviewing the manuscript; Abdelbaset S. El-Sorogy: reviewing the manuscript and submitting the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The current article does not have any conflict of interest.

-

Ethical approval: The present study did not use or harm any animals and followed all the scientific ethics.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Patel PM, Saha D, Shah T. Sustainability of groundwater through community-driven distributed recharge: An analysis of arguments for water scarce regions of semiarid India. J Hydrol Reg Stud. 2020;29:100680. 10.1016/J.EJRH.2020.100680.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Alshehri F, Almadani S, El-Sorogy AS, Alwaqdani E, Alfaifia HJ, Alharbi T. Influence of seawater intrusion and heavy metals contamination on groundwater quality, Red Sea coast, Saudi Arabia. Mar Pollut Bull. 2021;165:112094. 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.112094.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Alfaifi HJ, El-Sorogy AS, Qaysi S, Kahal A, Almadani S, Alshehri F, et al. Evaluation of heavy metal contamination and groundwater quality along the Red Sea coast, southern Saudi Arabia. Mar Pollut Bull. 2021;163:111975. 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.111975.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Kom KP, Gurugnanam B, Bairavi S. Non-carcinogenic health risk assessment of nitrate and fluoride contamination in the groundwater of Noyyal basin. India Geodesy Geodyn. 2022;13:619–31.10.1016/j.geog.2022.04.003Search in Google Scholar

[5] Smith A, Lingas EO, Rahman M. Contamination of drinking-water by arsenic in Bangladesh: a public health emergency. Bull World Health Organ. 2020;78(9):1093–103.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Alshehri F, El-Sorogy AS, Almadani S, Aldossari M. Groundwater quality assessment in western Saudi Arabia using GIS and multivariate analysis. J King Saud Univ – Sci. 2023;35:102586. 10.1016/j.jksus.2023.102586.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Alharbi T, El-Sorogy AS. Quality and groundwater contamination of Wadi Hanifa, central Saudi Arabia. Environ Monit Assess. 2023;195:525. 10.1007/s10661-023-11093-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Rezaei M, Nikbakht M, Shakeri A. Geochemistry and sources of fluoride and nitrate contamination of groundwater in Lar area, south Iran. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2017;24:15471–87. 10.1007/S11356-017-9108-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Ahada CPS, Suthar S. Groundwater nitrate contamination and associated human health risk assessment in southern districts of Punjab, India. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2018;25:25336e-347. 10.1007/S11356-018-2581-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Qasemi M, Farhang M, Morovati M, Mahmoudi M, Ebrahimi S, Abedi A, et al. Investigation of potential human health risks from fluoride and nitrate via water consumption in Sabzevar, Iran. Int J Environ Anal Chem. 2022;102(2):307–18. 10.1080/03067319.2020.1720668.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Kimambo V, Bhattacharya P, Mtalo F, Ahmad A. Fluoride occurrence in groundwater systems at global scale and status of defluoridation-State of the art. Groundwater Sustain Dev. 2019;9:100223. 10.1016/j.gsd.2019.100223.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Tanwer N, Deswal M, Khyalia P, Laura JS, Khosla B. Fluoride and nitrate in groundwater: a comprehensive analysis of health risk and potability of groundwater of Jhunjhunu district of Rajasthan, India. Environ Monit Assess. 2023;195:267. 10.1007/s10661-022-10886-z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Alharbi T, El-Sorogy AS. Health risk assessment of nitrate and fluoride in the groundwater of central Saudi Arabia. Water. 2023;15:2220.10.3390/w15122220Search in Google Scholar

[14] Giwa AS, Memon AG, Ahmad J, Ismail T, Abbasi SA, Kamran K, et al. Assessment of high fluoride in water sources and endemic fluorosis in the North-Eastern communities of Gombe State, Nigeria. Environ Pollut Bioav. 2021;33:31–40. 10.1080/26395940.2021.1908849.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Ayoob S, Gupta AK. Fluoride in drinking water: a review on the Status and stress effects. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol. 2007;36:433–87. 10.1080/10643380600678112.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Khan S, Shahnaz M, Jehan N, Rehman S. Nitrate contamination in the environment: A review. Nitrate Contamination. Heidelberg: Springer; 2018. p. 3–25.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Singh SK, Tripathi A, Jaiswal S, Singh A, Rai R. Impact of nitrogen fertilizers on human health and environment. Nitrate Contamination. Heidelberg: Springer; 2021. p. 123–34.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Chae GT, Yun ST, Kwon MJ. Fluoride contamination in groundwater resources and health risk assessment in Korea. Environ Geochem Health. 2020;42(5):1471–84.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Duggal V, Upreti RK, Singh A. Fluoride in groundwater: a review of contamination sources, health effects, and remediation methods. Contaminants in Drinking and Wastewater Sources. Heidelberg: Springer; 2019. p. 1–22.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Alharbi T. Hydrochemical evaluation of wasia well field in Riyadh Area. Master’s Thesis. Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: King Saud University; 2005. p. 139.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Alharbi TG. Identification of hydrogeochemical processes and their influence on groundwater quality for drinking and agricultural usage in Wadi Nisah, Central Saudi Arabia. Arab J Geosci. 2018;11:359. 10.1007/s12517-018-3679-z.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Aly AA, Alomran A, Alharby MM. The water quality index and hydrochemical characterization of groundwater resources in Hafar Albatin, Saudi Arabia. Arab J Geosci. 2014;8:4177–90.10.1007/s12517-014-1463-2Search in Google Scholar

[23] Alharbi TG, Zaidi FK. Hydrochemical classification and multivariate statistical analysis of groundwater from Wadi Sahba area in central Saudi Arabia. Arab J Geosci. 2018;11:643. 10.1007/s12517-018-3955-y.Search in Google Scholar

[24] El Alfy M, Alharbi T, Mansour B. Integrating geochemical investigations and geospatial assessment to understand the evolutionary process of hydrochemistry and groundwater quality in arid areas. Environ Monit Assess. 2018;190:277. 10.1007/s10661-018-6640-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Alharbi T, El-Sorogy AS, Qaysi S, Alshehri F. Evaluation of groundwater quality in central Saudi Arabia using hydrogeochemical characteristics and pollution indices. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2021;28:53819–32. 10.1007/s11356-021-14575-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Mallick J, Singh CK, AlMesfer MK, Singh VP, Alsubih M. Groundwater quality studies in the kingdom of saudi arabia: prevalent research and management dimensions. Water. 2021;13:1266. 10.3390/w13091266.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Alharbi T, Abdelrahman K, El-Sorogy AS, Ibrahim E. Contamination and health risk assessment of groundwater along the Red Sea coast, Northwest Saudi Arabia. Mar Pollut Bull. 2023;192:115080. 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2023.115080.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] World Health Organization, WHO. Guidelines for drinking-water quality. Incorporating the first addendum. 4th edn. Geneva: Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0IGO; 2017.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Almazroui M. Calibration of TRMM rainfall climatology over Saudi Arabia during 1998–2009. Atmos Res. 2011;99:400–14.10.1016/j.atmosres.2010.11.006Search in Google Scholar

[30] Powers RW, Ramirez LF, Redmond CD, Elberg EL. Geology of the Arabian Peninsula. Geol Surv Professional Pap. 1966;560:1–147.Search in Google Scholar

[31] APHA. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater. 19th edn. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 1995. p. 45.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Patel YS, Vadodaria GP. Groundwater quality assessment using water quality index. hydro. international. 20th International Conference on Hydraulics, Water Resources and River Engineering. Roorkee, India; 2015.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Sahu P, Sikdar PK. Hydrochemical Framework of the Aquifer in and Around East Kolkata Wetlands, West Bengal India. Environ Geol. 2008;55(4):823–35. 10.1007/s00254-007-1034-x.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Qasemi M, Afsharnia M, Zarei A, Farhang M, Allahdadi M. Non-carcinogenic risk assessment to human health due to intake of fluoride in the groundwater in rural areas of Gonabad and Bajestan, Iran: A case study. Hum Ecol Risk Assess Int J. 2018;25:1222–33. 10.1080/10807039.2018.1461553.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Vaiphei SP, Kurakalva RM. Hydrochemical characteristics and nitrate health risk assessment of groundwater through seasonal variations from an intensive agricultural region of upper Krishna River basin, Telangana, India. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2021;213:112073. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112073.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] USEPA. Human Health Evaluation Manual, Supplemental Guidance: Update of Standard Default Exposure Factors, OSWER Directive 9200.1–120. Washington, DC, USA: United States Environmental Protection Agency; 2014.Search in Google Scholar

[37] World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for drinking-water quality. 3rd edn. Geneva. Vol. 1; 2014. p. 515. Recommendations.Search in Google Scholar

[38] World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for drinking-water quality. 4th edn; 2011. p. 564.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Musgrove M. The occurrence and distribution of strontium in U.S. groundwater. Appl Geochem. 2021;126:104867. 10.1016/j.apgeochem.2020.104867.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Ehya F, Marbouti Z. Hydrochemistry and contamination of groundwater resources in the Behbahan plain SW Iran. Environ Earth Sci. 2016;75(6):455. 10.1007/s12665-016-5320-3.Search in Google Scholar

[41] Gnanachandrasamy G, Dushiyanthan C, Rajakumar TJ, Zhou Y. Assessment of hydrogeochemical characteristics of groundwater in the lower Vellar River Basin: using geographical information system (GIS) and water quality index (WQI). Environ Dev Sustainability. 2018;22:759–89. 10.1007/s10668-018-0219-7.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Dumaru B, Kayastha SB, Pande VP. Spring water assessment for quality and suitability for various uses: The case of Thuligaad watershed, western Nepal. Environ Earth Sci. 2021;80:586.10.1007/s12665-021-09826-wSearch in Google Scholar

[43] Zhai Y, Lei Y, Wu J, Teng Y, Wang J, Zhao X, et al. Does the groundwater nitrate pollution in China pose a risk to human health? A critical review of published data. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2017;24:3640–53. 10.1007/s11356-016-8088-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Zhang Y, Xu M, Li X, Qi J, Zhang Q, Guo J, et al. Hydrochemical characteristics and multivariate statistical analysis of natural water system: a case study in Kangding County, Southwestern China. Water. 2018;10(1):80. 10.3390/w10010080.Search in Google Scholar

[45] Li P, Wu J, Qian H. Hydrochemical appraisal of groundwater quality for drinking and irrigation purposes and the major influencing factors: A case study in and around Hua County, China. Arab J Geosci. 2016;9(1):15. 10.1007/s12517-015-2059-1.Search in Google Scholar

[46] Adimalla N, Li P. Occurrence, health risks and geochemical mechanisms of fluoride and nitrate in groundwater of the rock-dominant semiarid region, Telangana state, India. Hum Ecol Risk Assess. 2019;25(1–2):81–103. 10.1080/10807039.2018.1480353.Search in Google Scholar

[47] Rezaei A, Hassani H, Jabbari N. Evaluation of groundwater quality and assessment of pollution indices for heavy metals in north of Isfahan Province, Iran. Sustain Water Resour Manag. 2019;5(2):491–512. 10.1007/s40899-017-0209-1.Search in Google Scholar

[48] Wu J, Li P, Wang D, Ren X, Wei M. Statistical and multivariate statistical techniques to trace the sources and affecting factors of groundwater pollution in a rapidly growing city on the Chinese Loess Plateau. Hum Ecol Risk Assess. 2020;26(6):1603–21. 10.1080/10807039.2019.1594156.Search in Google Scholar

[49] Kumar A, Roy SS, Singh CK. Geochemistry and associated human health risk through potential harmful elements (PHEs) in groundwater of the Indus basin, India. Environ Earth Sci. 2020;79:86.10.1007/s12665-020-8818-7Search in Google Scholar

[50] Sarkar N, Kandekar A, Gaikwad S, Kandekar S. Health risk assessment of high concentration of fluoride and nitrate in the groundwater–A study of central India. Transactions. 2022;44:13.Search in Google Scholar

[51] Chen J, Wu H, Qian H, Gao Y. Assessing nitrate and fluoride contaminants in drinking water and their health risk of rural residents living in a Semiarid Region of Northwest China. Expo Health. 2016;9:183–95. 10.1007/s12403-016-0231-9.Search in Google Scholar

[52] Arora RP, Sachdev SY, Luthra VK, Subbiah BV. Fate of fertilizer nitrogen in a multiple cropping system. Soil Nitrogen as Fertilizer or Pollution. Vienna, Austria: International Atomic Energy Agency; 1980.Search in Google Scholar

[53] Zhao B, Li X, Liu H, Wang B, Zhu P, Huang SM, et al. Results from long-term fertilizer experiments in China: The risk of groundwater pollution by nitrate. NJAS-Wageningen J Life Sci. 2011;58:177–83.10.1016/j.njas.2011.09.004Search in Google Scholar

[54] Kalpana L, Brindha K, Elango L. FIMAR a new fluoride index to mitigate geogenic contamination by managed aquifer recharge. Chemosphere. 2019;220:381–90.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.12.084Search in Google Scholar

[55] Narsimha A, Rajitha S. Spatial distribution and seasonal variation in fluoride enrichment in groundwater and its associated human health risk assessment in Telangana State, South India. Hum Ecol Risk Assess. 2018;24:2119–32.10.1080/10807039.2018.1438176Search in Google Scholar

[56] Qasemi M, Darvishian M, Nadimi H, Gholamzadeh M, Afsharnia M, Farhang M, et al. Characteristics, water quality index and human health risk from nitrate and fluoride in Kakhk city and its rural areas, Iran. J Food Compos Anal. 2023;115:104870. 10.1016/j.jfca.2022.104870.Search in Google Scholar

[57] Zhou H, Tan Y, Gao W, Zhang Y, Yang Y. Selective nitrate removal from aqueous solutions by a hydrotalcite-like absorbent FeMgMn-LDH. Sci Rep. 2020;10:16126.10.1038/s41598-020-72845-3Search in Google Scholar

[58] Sandoval MA, Fuentes R, Thiam A, Salazar R, van Hullebusch ED. Arsenic and fluoride removal by electrocoagulation process: A general review. Sci Total Environ. 2021;753:142108.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142108Search in Google Scholar

[59] Epsztein R, Nir O, Lahav O, Green M. Selective nitrate removal from groundwater using a hybrid nanofiltration–reverse osmosis filtration scheme. Chem Eng J. 2015;279:372–8.10.1016/j.cej.2015.05.010Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Porous silicon nanostructures: Synthesis, characterization, and their antifungal activity

- Biochar from de-oiled Chlorella vulgaris and its adsorption on antibiotics

- Phytochemicals profiling, in vitro and in vivo antidiabetic activity, and in silico studies on Ajuga iva (L.) Schreb.: A comprehensive approach

- Synthesis, characterization, in silico and in vitro studies of novel glycoconjugates as potential antibacterial, antifungal, and antileishmanial agents

- Sonochemical synthesis of gold nanoparticles mediated by potato starch: Its performance in the treatment of esophageal cancer

- Computational study of ADME-Tox prediction of selected phytochemicals from Punica granatum peels

- Phytochemical analysis, in vitro antioxidant and antifungal activities of extracts and essential oil derived from Artemisia herba-alba Asso

- Two triazole-based coordination polymers: Synthesis and crystal structure characterization

- Phytochemical and physicochemical studies of different apple varieties grown in Morocco

- Synthesis of multi-template molecularly imprinted polymers (MT-MIPs) for isolating ethyl para-methoxycinnamate and ethyl cinnamate from Kaempferia galanga L., extract with methacrylic acid as functional monomer

- Nutraceutical potential of Mesembryanthemum forsskaolii Hochst. ex Bioss.: Insights into its nutritional composition, phytochemical contents, and antioxidant activity

- Evaluation of influence of Butea monosperma floral extract on inflammatory biomarkers

- Cannabis sativa L. essential oil: Chemical composition, anti-oxidant, anti-microbial properties, and acute toxicity: In vitro, in vivo, and in silico study

- The effect of gamma radiation on 5-hydroxymethylfurfural conversion in water and dimethyl sulfoxide

- Hollow mushroom nanomaterials for potentiometric sensing of Pb2+ ions in water via the intercalation of iodide ions into the polypyrrole matrix

- Determination of essential oil and chemical composition of St. John’s Wort

- Computational design and in vitro assay of lantadene-based novel inhibitors of NS3 protease of dengue virus

- Anti-parasitic activity and computational studies on a novel labdane diterpene from the roots of Vachellia nilotica

- Microbial dynamics and dehydrogenase activity in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) rhizospheres: Impacts on growth and soil health across different soil types

- Correlation between in vitro anti-urease activity and in silico molecular modeling approach of novel imidazopyridine–oxadiazole hybrids derivatives

- Spatial mapping of indoor air quality in a light metro system using the geographic information system method

- Iron indices and hemogram in renal anemia and the improvement with Tribulus terrestris green-formulated silver nanoparticles applied on rat model

- Integrated track of nano-informatics coupling with the enrichment concept in developing a novel nanoparticle targeting ERK protein in Naegleria fowleri

- Cytotoxic and phytochemical screening of Solanum lycopersicum–Daucus carota hydro-ethanolic extract and in silico evaluation of its lycopene content as anticancer agent

- Protective activities of silver nanoparticles containing Panax japonicus on apoptotic, inflammatory, and oxidative alterations in isoproterenol-induced cardiotoxicity

- pH-based colorimetric detection of monofunctional aldehydes in liquid and gas phases

- Investigating the effect of resveratrol on apoptosis and regulation of gene expression of Caco-2 cells: Unravelling potential implications for colorectal cancer treatment

- Metformin inhibits knee osteoarthritis induced by type 2 diabetes mellitus in rats: S100A8/9 and S100A12 as players and therapeutic targets

- Effect of silver nanoparticles formulated by Silybum marianum on menopausal urinary incontinence in ovariectomized rats

- Synthesis of new analogs of N-substituted(benzoylamino)-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridines

- Response of yield and quality of Japonica rice to different gradients of moisture deficit at grain-filling stage in cold regions

- Preparation of an inclusion complex of nickel-based β-cyclodextrin: Characterization and accelerating the osteoarthritis articular cartilage repair

- Empagliflozin-loaded nanomicelles responsive to reactive oxygen species for renal ischemia/reperfusion injury protection

- Preparation and pharmacodynamic evaluation of sodium aescinate solid lipid nanoparticles

- Assessment of potentially toxic elements and health risks of agricultural soil in Southwest Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- Theoretical investigation of hydrogen-rich fuel production through ammonia decomposition

- Biosynthesis and screening of cobalt nanoparticles using citrus species for antimicrobial activity

- Investigating the interplay of genetic variations, MCP-1 polymorphism, and docking with phytochemical inhibitors for combatting dengue virus pathogenicity through in silico analysis

- Ultrasound induced biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles embedded into chitosan polymers: Investigation of its anti-cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma effects

- Copper oxide nanoparticles-mediated Heliotropium bacciferum leaf extract: Antifungal activity and molecular docking assays against strawberry pathogens

- Sprouted wheat flour for improving physical, chemical, rheological, microbial load, and quality properties of fino bread

- Comparative toxicity assessment of fisetin-aided artificial intelligence-assisted drug design targeting epibulbar dermoid through phytochemicals

- Acute toxicity and anti-inflammatory activity of bis-thiourea derivatives

- Anti-diabetic activity-guided isolation of α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory terpenes from Capsella bursa-pastoris Linn.

- GC–MS analysis of Lactobacillus plantarum YW11 metabolites and its computational analysis on familial pulmonary fibrosis hub genes

- Green formulation of copper nanoparticles by Pistacia khinjuk leaf aqueous extract: Introducing a novel chemotherapeutic drug for the treatment of prostate cancer

- Improved photocatalytic properties of WO3 nanoparticles for Malachite green dye degradation under visible light irradiation: An effect of La doping

- One-pot synthesis of a network of Mn2O3–MnO2–poly(m-methylaniline) composite nanorods on a polypyrrole film presents a promising and efficient optoelectronic and solar cell device

- Groundwater quality and health risk assessment of nitrate and fluoride in Al Qaseem area, Saudi Arabia

- A comparative study of the antifungal efficacy and phytochemical composition of date palm leaflet extracts

- Processing of alcohol pomelo beverage (Citrus grandis (L.) Osbeck) using saccharomyces yeast: Optimization, physicochemical quality, and sensory characteristics

- Specialized compounds of four Cameroonian spices: Isolation, characterization, and in silico evaluation as prospective SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors

- Identification of a novel drug target in Porphyromonas gingivalis by a computational genome analysis approach

- Physico-chemical properties and durability of a fly-ash-based geopolymer

- FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 inhibitory potentials of some phytochemicals from anti-leukemic plants using computational chemical methodologies

- Wild Thymus zygis L. ssp. gracilis and Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh.: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antibacterial activities of essential oils

- 3D-QSAR, molecular docking, ADMET, simulation dynamic, and retrosynthesis studies on new styrylquinolines derivatives against breast cancer

- Deciphering the influenza neuraminidase inhibitory potential of naturally occurring biflavonoids: An in silico approach

- Determination of heavy elements in agricultural regions, Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis and characterization of antioxidant-enriched Moringa oil-based edible oleogel

- Ameliorative effects of thistle and thyme honeys on cyclophosphamide-induced toxicity in mice

- Study of phytochemical compound and antipyretic activity of Chenopodium ambrosioides L. fractions

- Investigating the adsorption mechanism of zinc chloride-modified porous carbon for sulfadiazine removal from water

- Performance repair of building materials using alumina and silica composite nanomaterials with electrodynamic properties

- Effects of nanoparticles on the activity and resistance genes of anaerobic digestion enzymes in livestock and poultry manure containing the antibiotic tetracycline

- Effect of copper nanoparticles green-synthesized using Ocimum basilicum against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in mice lung infection model

- Cardioprotective effects of nanoparticles green formulated by Spinacia oleracea extract on isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction in mice by the determination of PPAR-γ/NF-κB pathway

- Anti-OTC antibody-conjugated fluorescent magnetic/silica and fluorescent hybrid silica nanoparticles for oxytetracycline detection

- Curcumin conjugated zinc nanoparticles for the treatment of myocardial infarction

- Identification and in silico screening of natural phloroglucinols as potential PI3Kα inhibitors: A computational approach for drug discovery

- Exploring the phytochemical profile and antioxidant evaluation: Molecular docking and ADMET analysis of main compounds from three Solanum species in Saudi Arabia

- Unveiling the molecular composition and biological properties of essential oil derived from the leaves of wild Mentha aquatica L.: A comprehensive in vitro and in silico exploration

- Analysis of bioactive compounds present in Boerhavia elegans seeds by GC-MS

- Homology modeling and molecular docking study of corticotrophin-releasing hormone: An approach to treat stress-related diseases

- LncRNA MIR17HG alleviates heart failure via targeting MIR17HG/miR-153-3p/SIRT1 axis in in vitro model

- Development and validation of a stability indicating UPLC-DAD method coupled with MS-TQD for ramipril and thymoquinone in bioactive SNEDDS with in silico toxicity analysis of ramipril degradation products

- Biosynthesis of Ag/Cu nanocomposite mediated by Curcuma longa: Evaluation of its antibacterial properties against oral pathogens

- Development of AMBER-compliant transferable force field parameters for polytetrafluoroethylene

- Treatment of gestational diabetes by Acroptilon repens leaf aqueous extract green-formulated iron nanoparticles in rats

- Development and characterization of new ecological adsorbents based on cardoon wastes: Application to brilliant green adsorption

- A fast, sensitive, greener, and stability-indicating HPLC method for the standardization and quantitative determination of chlorhexidine acetate in commercial products

- Assessment of Se, As, Cd, Cr, Hg, and Pb content status in Ankang tea plantations of China

- Effect of transition metal chloride (ZnCl2) on low-temperature pyrolysis of high ash bituminous coal

- Evaluating polyphenol and ascorbic acid contents, tannin removal ability, and physical properties during hydrolysis and convective hot-air drying of cashew apple powder

- Development and characterization of functional low-fat frozen dairy dessert enhanced with dried lemongrass powder

- Scrutinizing the effect of additive and synergistic antibiotics against carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Preparation, characterization, and determination of the therapeutic effects of copper nanoparticles green-formulated by Pistacia atlantica in diabetes-induced cardiac dysfunction in rat

- Antioxidant and antidiabetic potentials of methoxy-substituted Schiff bases using in vitro, in vivo, and molecular simulation approaches

- Anti-melanoma cancer activity and chemical profile of the essential oil of Seseli yunnanense Franch

- Molecular docking analysis of subtilisin-like alkaline serine protease (SLASP) and laccase with natural biopolymers

- Overcoming methicillin resistance by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Computational evaluation of napthyridine and oxadiazoles compounds for potential dual inhibition of PBP-2a and FemA proteins

- Exploring novel antitubercular agents: Innovative design of 2,3-diaryl-quinoxalines targeting DprE1 for effective tuberculosis treatment

- Drimia maritima flowers as a source of biologically potent components: Optimization of bioactive compound extractions, isolation, UPLC–ESI–MS/MS, and pharmacological properties

- Estimating molecular properties, drug-likeness, cardiotoxic risk, liability profile, and molecular docking study to characterize binding process of key phyto-compounds against serotonin 5-HT2A receptor

- Fabrication of β-cyclodextrin-based microgels for enhancing solubility of Terbinafine: An in-vitro and in-vivo toxicological evaluation

- Phyto-mediated synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles and their sunlight-driven photocatalytic degradation of cationic and anionic dyes

- Monosodium glutamate induces hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis hyperactivation, glucocorticoid receptors down-regulation, and systemic inflammatory response in young male rats: Impact on miR-155 and miR-218

- Quality control analyses of selected honey samples from Serbia based on their mineral and flavonoid profiles, and the invertase activity

- Eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Phyllanthus niruri leaf extract: Assessment of antimicrobial activity, effectiveness on tropical neglected mosquito vector control, and biocompatibility using a fibroblast cell line model

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles containing Cichorium intybus to treat the sepsis-induced DNA damage in the liver of Wistar albino rats

- Quality changes of durian pulp (Durio ziberhinus Murr.) in cold storage

- Study on recrystallization process of nitroguanidine by directly adding cold water to control temperature

- Determination of heavy metals and health risk assessment in drinking water in Bukayriyah City, Saudi Arabia

- Larvicidal properties of essential oils of three Artemisia species against the chemically insecticide-resistant Nile fever vector Culex pipiens (L.) (Diptera: Culicidae): In vitro and in silico studies

- Design, synthesis, characterization, and theoretical calculations, along with in silico and in vitro antimicrobial proprieties of new isoxazole-amide conjugates

- The impact of drying and extraction methods on total lipid, fatty acid profile, and cytotoxicity of Tenebrio molitor larvae

- A zinc oxide–tin oxide–nerolidol hybrid nanomaterial: Efficacy against esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- Research on technological process for production of muskmelon juice (Cucumis melo L.)

- Physicochemical components, antioxidant activity, and predictive models for quality of soursop tea (Annona muricata L.) during heat pump drying

- Characterization and application of Fe1−xCoxFe2O4 nanoparticles in Direct Red 79 adsorption

- Torilis arvensis ethanolic extract: Phytochemical analysis, antifungal efficacy, and cytotoxicity properties

- Magnetite–poly-1H pyrrole dendritic nanocomposite seeded on poly-1H pyrrole: A promising photocathode for green hydrogen generation from sanitation water without using external sacrificing agent

- HPLC and GC–MS analyses of phytochemical compounds in Haloxylon salicornicum extract: Antibacterial and antifungal activity assessment of phytopathogens

- Efficient and stable to coking catalysts of ethanol steam reforming comprised of Ni + Ru loaded on MgAl2O4 + LnFe0.7Ni0.3O3 (Ln = La, Pr) nanocomposites prepared via cost-effective procedure with Pluronic P123 copolymer

- Nitrogen and boron co-doped carbon dots probe for selectively detecting Hg2+ in water samples and the detection mechanism

- Heavy metals in road dust from typical old industrial areas of Wuhan: Seasonal distribution and bioaccessibility-based health risk assessment

- Phytochemical profiling and bioactivity evaluation of CBD- and THC-enriched Cannabis sativa extracts: In vitro and in silico investigation of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects

- Investigating dye adsorption: The role of surface-modified montmorillonite nanoclay in kinetics, isotherms, and thermodynamics

- Antimicrobial activity, induction of ROS generation in HepG2 liver cancer cells, and chemical composition of Pterospermum heterophyllum

- Study on the performance of nanoparticle-modified PVDF membrane in delaying membrane aging

- Impact of cholesterol in encapsulated vitamin E acetate within cocoliposomes

- Review Articles

- Structural aspects of Pt(η3-X1N1X2)(PL) (X1,2 = O, C, or Se) and Pt(η3-N1N2X1)(PL) (X1 = C, S, or Se) derivatives

- Biosurfactants in biocorrosion and corrosion mitigation of metals: An overview

- Stimulus-responsive MOF–hydrogel composites: Classification, preparation, characterization, and their advancement in medical treatments

- Electrochemical dissolution of titanium under alternating current polarization to obtain its dioxide

- Special Issue on Recent Trends in Green Chemistry

- Phytochemical screening and antioxidant activity of Vitex agnus-castus L.

- Phytochemical study, antioxidant activity, and dermoprotective activity of Chenopodium ambrosioides (L.)

- Exploitation of mangliculous marine fungi, Amarenographium solium, for the green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their activity against multiple drug-resistant bacteria

- Study of the phytotoxicity of margines on Pistia stratiotes L.

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Energy, Environmental and Biological Applications - Part III

- Impact of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles on growth, development, and antioxidant system of high protein content crop (Lablab purpureus L.) sweet

- Green synthesis, characterization, and application of iron and molybdenum nanoparticles and their composites for enhancing the growth of Solanum lycopersicum

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Olea europaea L. extracted polysaccharides, characterization, and its assessment as an antimicrobial agent against multiple pathogenic microbes

- Photocatalytic treatment of organic dyes using metal oxides and nanocomposites: A quantitative study

- Antifungal, antioxidant, and photocatalytic activities of greenly synthesized iron oxide nanoparticles

- Special Issue on Phytochemical and Pharmacological Scrutinization of Medicinal Plants

- Hepatoprotective effects of safranal on acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in rats

- Chemical composition and biological properties of Thymus capitatus plants from Algerian high plains: A comparative and analytical study

- Chemical composition and bioactivities of the methanol root extracts of Saussurea costus

- In vivo protective effects of vitamin C against cyto-genotoxicity induced by Dysphania ambrosioides aqueous extract

- Insights about the deleterious impact of a carbamate pesticide on some metabolic immune and antioxidant functions and a focus on the protective ability of a Saharan shrub and its anti-edematous property

- A comprehensive review uncovering the anticancerous potential of genkwanin (plant-derived compound) in several human carcinomas

- A study to investigate the anticancer potential of carvacrol via targeting Notch signaling in breast cancer

- Assessment of anti-diabetic properties of Ziziphus oenopolia (L.) wild edible fruit extract: In vitro and in silico investigations through molecular docking analysis

- Optimization of polyphenol extraction, phenolic profile by LC-ESI-MS/MS, antioxidant, anti-enzymatic, and cytotoxic activities of Physalis acutifolia

- Phytochemical screening, antioxidant properties, and photo-protective activities of Salvia balansae de Noé ex Coss

- Antihyperglycemic, antiglycation, anti-hypercholesteremic, and toxicity evaluation with gas chromatography mass spectrometry profiling for Aloe armatissima leaves

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of gold nanoparticles by using Timur (Zanthoxylum armatum DC) and their effect on wound healing

- Does Erodium trifolium (Cav.) Guitt exhibit medicinal properties? Response elements from phytochemical profiling, enzyme-inhibiting, and antioxidant and antimicrobial activities

- Integrative in silico evaluation of the antiviral potential of terpenoids and its metal complexes derived from Homalomena aromatica based on main protease of SARS-CoV-2

- 6-Methoxyflavone improves anxiety, depression, and memory by increasing monoamines in mice brain: HPLC analysis and in silico studies

- Simultaneous extraction and quantification of hydrophilic and lipophilic antioxidants in Solanum lycopersicum L. varieties marketed in Saudi Arabia

- Biological evaluation of CH3OH and C2H5OH of Berberis vulgaris for in vivo antileishmanial potential against Leishmania tropica in murine models

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Porous silicon nanostructures: Synthesis, characterization, and their antifungal activity

- Biochar from de-oiled Chlorella vulgaris and its adsorption on antibiotics

- Phytochemicals profiling, in vitro and in vivo antidiabetic activity, and in silico studies on Ajuga iva (L.) Schreb.: A comprehensive approach

- Synthesis, characterization, in silico and in vitro studies of novel glycoconjugates as potential antibacterial, antifungal, and antileishmanial agents

- Sonochemical synthesis of gold nanoparticles mediated by potato starch: Its performance in the treatment of esophageal cancer

- Computational study of ADME-Tox prediction of selected phytochemicals from Punica granatum peels

- Phytochemical analysis, in vitro antioxidant and antifungal activities of extracts and essential oil derived from Artemisia herba-alba Asso

- Two triazole-based coordination polymers: Synthesis and crystal structure characterization

- Phytochemical and physicochemical studies of different apple varieties grown in Morocco

- Synthesis of multi-template molecularly imprinted polymers (MT-MIPs) for isolating ethyl para-methoxycinnamate and ethyl cinnamate from Kaempferia galanga L., extract with methacrylic acid as functional monomer

- Nutraceutical potential of Mesembryanthemum forsskaolii Hochst. ex Bioss.: Insights into its nutritional composition, phytochemical contents, and antioxidant activity

- Evaluation of influence of Butea monosperma floral extract on inflammatory biomarkers

- Cannabis sativa L. essential oil: Chemical composition, anti-oxidant, anti-microbial properties, and acute toxicity: In vitro, in vivo, and in silico study

- The effect of gamma radiation on 5-hydroxymethylfurfural conversion in water and dimethyl sulfoxide

- Hollow mushroom nanomaterials for potentiometric sensing of Pb2+ ions in water via the intercalation of iodide ions into the polypyrrole matrix

- Determination of essential oil and chemical composition of St. John’s Wort

- Computational design and in vitro assay of lantadene-based novel inhibitors of NS3 protease of dengue virus

- Anti-parasitic activity and computational studies on a novel labdane diterpene from the roots of Vachellia nilotica

- Microbial dynamics and dehydrogenase activity in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) rhizospheres: Impacts on growth and soil health across different soil types

- Correlation between in vitro anti-urease activity and in silico molecular modeling approach of novel imidazopyridine–oxadiazole hybrids derivatives

- Spatial mapping of indoor air quality in a light metro system using the geographic information system method

- Iron indices and hemogram in renal anemia and the improvement with Tribulus terrestris green-formulated silver nanoparticles applied on rat model

- Integrated track of nano-informatics coupling with the enrichment concept in developing a novel nanoparticle targeting ERK protein in Naegleria fowleri

- Cytotoxic and phytochemical screening of Solanum lycopersicum–Daucus carota hydro-ethanolic extract and in silico evaluation of its lycopene content as anticancer agent

- Protective activities of silver nanoparticles containing Panax japonicus on apoptotic, inflammatory, and oxidative alterations in isoproterenol-induced cardiotoxicity

- pH-based colorimetric detection of monofunctional aldehydes in liquid and gas phases

- Investigating the effect of resveratrol on apoptosis and regulation of gene expression of Caco-2 cells: Unravelling potential implications for colorectal cancer treatment

- Metformin inhibits knee osteoarthritis induced by type 2 diabetes mellitus in rats: S100A8/9 and S100A12 as players and therapeutic targets

- Effect of silver nanoparticles formulated by Silybum marianum on menopausal urinary incontinence in ovariectomized rats

- Synthesis of new analogs of N-substituted(benzoylamino)-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridines

- Response of yield and quality of Japonica rice to different gradients of moisture deficit at grain-filling stage in cold regions

- Preparation of an inclusion complex of nickel-based β-cyclodextrin: Characterization and accelerating the osteoarthritis articular cartilage repair

- Empagliflozin-loaded nanomicelles responsive to reactive oxygen species for renal ischemia/reperfusion injury protection

- Preparation and pharmacodynamic evaluation of sodium aescinate solid lipid nanoparticles

- Assessment of potentially toxic elements and health risks of agricultural soil in Southwest Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- Theoretical investigation of hydrogen-rich fuel production through ammonia decomposition

- Biosynthesis and screening of cobalt nanoparticles using citrus species for antimicrobial activity

- Investigating the interplay of genetic variations, MCP-1 polymorphism, and docking with phytochemical inhibitors for combatting dengue virus pathogenicity through in silico analysis

- Ultrasound induced biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles embedded into chitosan polymers: Investigation of its anti-cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma effects

- Copper oxide nanoparticles-mediated Heliotropium bacciferum leaf extract: Antifungal activity and molecular docking assays against strawberry pathogens

- Sprouted wheat flour for improving physical, chemical, rheological, microbial load, and quality properties of fino bread

- Comparative toxicity assessment of fisetin-aided artificial intelligence-assisted drug design targeting epibulbar dermoid through phytochemicals

- Acute toxicity and anti-inflammatory activity of bis-thiourea derivatives

- Anti-diabetic activity-guided isolation of α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory terpenes from Capsella bursa-pastoris Linn.

- GC–MS analysis of Lactobacillus plantarum YW11 metabolites and its computational analysis on familial pulmonary fibrosis hub genes

- Green formulation of copper nanoparticles by Pistacia khinjuk leaf aqueous extract: Introducing a novel chemotherapeutic drug for the treatment of prostate cancer

- Improved photocatalytic properties of WO3 nanoparticles for Malachite green dye degradation under visible light irradiation: An effect of La doping

- One-pot synthesis of a network of Mn2O3–MnO2–poly(m-methylaniline) composite nanorods on a polypyrrole film presents a promising and efficient optoelectronic and solar cell device

- Groundwater quality and health risk assessment of nitrate and fluoride in Al Qaseem area, Saudi Arabia

- A comparative study of the antifungal efficacy and phytochemical composition of date palm leaflet extracts

- Processing of alcohol pomelo beverage (Citrus grandis (L.) Osbeck) using saccharomyces yeast: Optimization, physicochemical quality, and sensory characteristics

- Specialized compounds of four Cameroonian spices: Isolation, characterization, and in silico evaluation as prospective SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors

- Identification of a novel drug target in Porphyromonas gingivalis by a computational genome analysis approach

- Physico-chemical properties and durability of a fly-ash-based geopolymer

- FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 inhibitory potentials of some phytochemicals from anti-leukemic plants using computational chemical methodologies

- Wild Thymus zygis L. ssp. gracilis and Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh.: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antibacterial activities of essential oils

- 3D-QSAR, molecular docking, ADMET, simulation dynamic, and retrosynthesis studies on new styrylquinolines derivatives against breast cancer

- Deciphering the influenza neuraminidase inhibitory potential of naturally occurring biflavonoids: An in silico approach

- Determination of heavy elements in agricultural regions, Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis and characterization of antioxidant-enriched Moringa oil-based edible oleogel

- Ameliorative effects of thistle and thyme honeys on cyclophosphamide-induced toxicity in mice

- Study of phytochemical compound and antipyretic activity of Chenopodium ambrosioides L. fractions

- Investigating the adsorption mechanism of zinc chloride-modified porous carbon for sulfadiazine removal from water

- Performance repair of building materials using alumina and silica composite nanomaterials with electrodynamic properties

- Effects of nanoparticles on the activity and resistance genes of anaerobic digestion enzymes in livestock and poultry manure containing the antibiotic tetracycline

- Effect of copper nanoparticles green-synthesized using Ocimum basilicum against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in mice lung infection model

- Cardioprotective effects of nanoparticles green formulated by Spinacia oleracea extract on isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction in mice by the determination of PPAR-γ/NF-κB pathway

- Anti-OTC antibody-conjugated fluorescent magnetic/silica and fluorescent hybrid silica nanoparticles for oxytetracycline detection

- Curcumin conjugated zinc nanoparticles for the treatment of myocardial infarction

- Identification and in silico screening of natural phloroglucinols as potential PI3Kα inhibitors: A computational approach for drug discovery

- Exploring the phytochemical profile and antioxidant evaluation: Molecular docking and ADMET analysis of main compounds from three Solanum species in Saudi Arabia

- Unveiling the molecular composition and biological properties of essential oil derived from the leaves of wild Mentha aquatica L.: A comprehensive in vitro and in silico exploration

- Analysis of bioactive compounds present in Boerhavia elegans seeds by GC-MS

- Homology modeling and molecular docking study of corticotrophin-releasing hormone: An approach to treat stress-related diseases

- LncRNA MIR17HG alleviates heart failure via targeting MIR17HG/miR-153-3p/SIRT1 axis in in vitro model

- Development and validation of a stability indicating UPLC-DAD method coupled with MS-TQD for ramipril and thymoquinone in bioactive SNEDDS with in silico toxicity analysis of ramipril degradation products

- Biosynthesis of Ag/Cu nanocomposite mediated by Curcuma longa: Evaluation of its antibacterial properties against oral pathogens

- Development of AMBER-compliant transferable force field parameters for polytetrafluoroethylene

- Treatment of gestational diabetes by Acroptilon repens leaf aqueous extract green-formulated iron nanoparticles in rats

- Development and characterization of new ecological adsorbents based on cardoon wastes: Application to brilliant green adsorption

- A fast, sensitive, greener, and stability-indicating HPLC method for the standardization and quantitative determination of chlorhexidine acetate in commercial products

- Assessment of Se, As, Cd, Cr, Hg, and Pb content status in Ankang tea plantations of China

- Effect of transition metal chloride (ZnCl2) on low-temperature pyrolysis of high ash bituminous coal

- Evaluating polyphenol and ascorbic acid contents, tannin removal ability, and physical properties during hydrolysis and convective hot-air drying of cashew apple powder

- Development and characterization of functional low-fat frozen dairy dessert enhanced with dried lemongrass powder

- Scrutinizing the effect of additive and synergistic antibiotics against carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Preparation, characterization, and determination of the therapeutic effects of copper nanoparticles green-formulated by Pistacia atlantica in diabetes-induced cardiac dysfunction in rat

- Antioxidant and antidiabetic potentials of methoxy-substituted Schiff bases using in vitro, in vivo, and molecular simulation approaches

- Anti-melanoma cancer activity and chemical profile of the essential oil of Seseli yunnanense Franch

- Molecular docking analysis of subtilisin-like alkaline serine protease (SLASP) and laccase with natural biopolymers

- Overcoming methicillin resistance by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Computational evaluation of napthyridine and oxadiazoles compounds for potential dual inhibition of PBP-2a and FemA proteins

- Exploring novel antitubercular agents: Innovative design of 2,3-diaryl-quinoxalines targeting DprE1 for effective tuberculosis treatment

- Drimia maritima flowers as a source of biologically potent components: Optimization of bioactive compound extractions, isolation, UPLC–ESI–MS/MS, and pharmacological properties

- Estimating molecular properties, drug-likeness, cardiotoxic risk, liability profile, and molecular docking study to characterize binding process of key phyto-compounds against serotonin 5-HT2A receptor

- Fabrication of β-cyclodextrin-based microgels for enhancing solubility of Terbinafine: An in-vitro and in-vivo toxicological evaluation

- Phyto-mediated synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles and their sunlight-driven photocatalytic degradation of cationic and anionic dyes

- Monosodium glutamate induces hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis hyperactivation, glucocorticoid receptors down-regulation, and systemic inflammatory response in young male rats: Impact on miR-155 and miR-218

- Quality control analyses of selected honey samples from Serbia based on their mineral and flavonoid profiles, and the invertase activity

- Eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Phyllanthus niruri leaf extract: Assessment of antimicrobial activity, effectiveness on tropical neglected mosquito vector control, and biocompatibility using a fibroblast cell line model

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles containing Cichorium intybus to treat the sepsis-induced DNA damage in the liver of Wistar albino rats

- Quality changes of durian pulp (Durio ziberhinus Murr.) in cold storage

- Study on recrystallization process of nitroguanidine by directly adding cold water to control temperature

- Determination of heavy metals and health risk assessment in drinking water in Bukayriyah City, Saudi Arabia

- Larvicidal properties of essential oils of three Artemisia species against the chemically insecticide-resistant Nile fever vector Culex pipiens (L.) (Diptera: Culicidae): In vitro and in silico studies

- Design, synthesis, characterization, and theoretical calculations, along with in silico and in vitro antimicrobial proprieties of new isoxazole-amide conjugates

- The impact of drying and extraction methods on total lipid, fatty acid profile, and cytotoxicity of Tenebrio molitor larvae

- A zinc oxide–tin oxide–nerolidol hybrid nanomaterial: Efficacy against esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- Research on technological process for production of muskmelon juice (Cucumis melo L.)

- Physicochemical components, antioxidant activity, and predictive models for quality of soursop tea (Annona muricata L.) during heat pump drying

- Characterization and application of Fe1−xCoxFe2O4 nanoparticles in Direct Red 79 adsorption

- Torilis arvensis ethanolic extract: Phytochemical analysis, antifungal efficacy, and cytotoxicity properties

- Magnetite–poly-1H pyrrole dendritic nanocomposite seeded on poly-1H pyrrole: A promising photocathode for green hydrogen generation from sanitation water without using external sacrificing agent

- HPLC and GC–MS analyses of phytochemical compounds in Haloxylon salicornicum extract: Antibacterial and antifungal activity assessment of phytopathogens

- Efficient and stable to coking catalysts of ethanol steam reforming comprised of Ni + Ru loaded on MgAl2O4 + LnFe0.7Ni0.3O3 (Ln = La, Pr) nanocomposites prepared via cost-effective procedure with Pluronic P123 copolymer

- Nitrogen and boron co-doped carbon dots probe for selectively detecting Hg2+ in water samples and the detection mechanism