Abstract

This article presents the experimental results of the compressive strength, the splitting tensile strength, the macro destruction mode, and the microstructure of recycled clay brick aggregate concrete (RBC) with different recycled clay brick aggregate (RBA) replacement rates. The results show that the compressive strength and the splitting tensile strength of RBC are lower than those of natural aggregate concrete (NAC), but the effect of RBA on the splitting tensile strength of concrete is not significant. The effect of the water–cement ratio (w/c) on the splitting tensile strength of RBC is smaller than that on the splitting tensile strength of NAC. The compressive strength of concrete shows a trend of first decreasing and then increasing with the increase in RBA replacement rates. The effect of RBA replacement rates on the compressive strength gradually decreases with the increase in the w/c. The AFt in NAC is thicker than that in RBC, and the C–S–H of RBC is in the form of agglomerated networks with large and uniform pores and less filler.

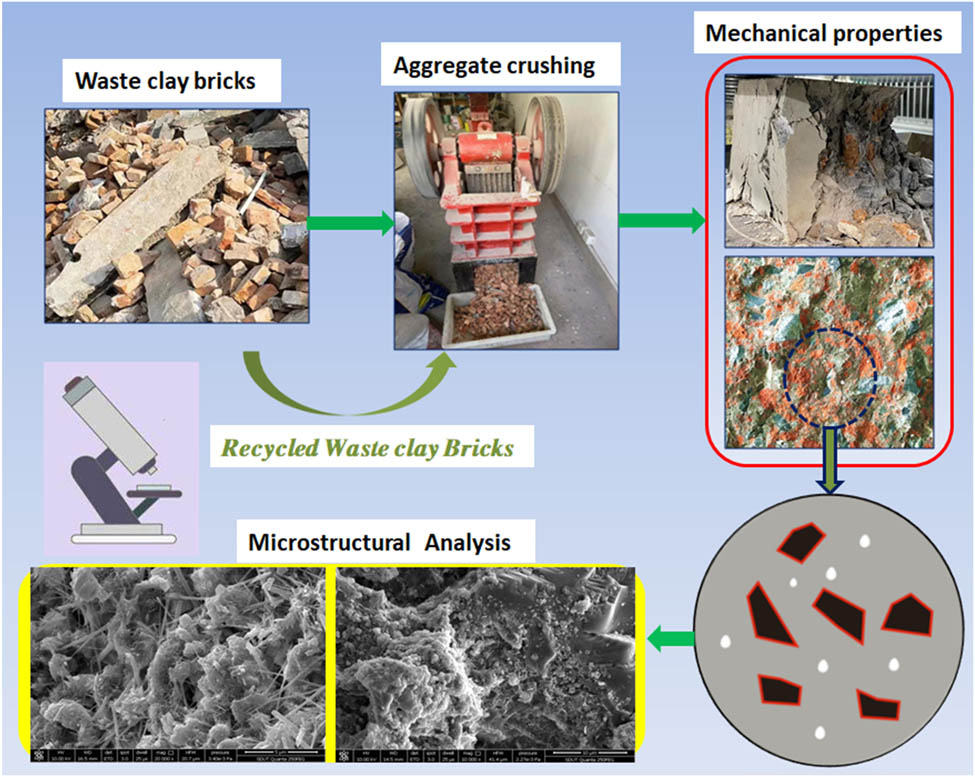

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

With the rapid development of the construction industry, concrete has been widely used as the main building material [1]. Global demand for concrete is expected to grow to approximately 18 billion tons per year by 2050 [2]. As a result, natural sand and gravel resources are almost exhausted, and their prices continue to rise [3]. In addition, a large amount of construction waste will be generated in the process of building reconstruction and expansion [4]. The waste clay bricks (WB) and waste concrete (WC) are the main components of construction waste [5], and the resource utilization and utilization methods of WB and WC directly affect the process of construction waste recycling and industrialization [6]. Recycled aggregate concrete (RAC) could improve the utilization of construction waste and promote the sustainable development of the construction industry [7].

Scholars have completed the research on the concrete with recycled concrete aggregate (RCA) [8,9]. Xu et al. [10] point out that the compressive strength of RAC was lower than that of natural aggregate concrete (NAC), while the flexural strength showed a trend of first decreasing and then increasing continuously with the increase in the RCA replacement rates. Wang [11] found that the compressive strength and splitting tensile strength of concrete decreased with the increase in RAC replacement rates, and the water–cement ratio (w/c) has a great influence on the compressive strength and splitting tensile strength of RAC. Xiao et al. [12] point out that most studies found that the long-term performance of RAC was inferior to that of NAC, and there were different opinions among researchers that the long-term performance of RAC was worse than that of NAC.

Some scholars have also conducted research on improving the performance of RAC. Corinaldesi [13] proposed a good method for configuring RAC, which can meet the requirements for the strength, durability, and workability of RAC. Gao et al. [14] investigated the effect of CO2-enhanced RCA on the performance of RAC, and found that the method of CO2-enhanced aggregate significantly reduced the water absorption rate of RCA and significantly improved the compressive strength and resistance to chloride-ion penetration of RAC. Lei et al. [15] point out that the mechanical properties and frost resistance of RAC were effectively improved with the increase in graphene oxide content.

Actually, most of the demolished buildings in China are brick-concrete structures. However, the research on concrete with recycled clay brick aggregate (RBA) was less [16]. Compared with natural aggregate, RBA has the characteristics of high porosity, low density, and high water absorption [17]. Cachim [18] investigated the compressive strength, the tensile splitting strength, the elastic modulus, and the stress–strain of recycled clay brick aggregate concrete (RBC) and found that the type of brick could affect the mechanical properties of RBC; care must be taken when substituting crushed brick for natural aggregate. Zhang and Zong [19] point out that the compressive strength of RBC was lower than that of NAC, while the compressive strength of RBC with 30% RBA could meet the requirements of strength standards. Khalaf and Devenny [20] found that a portion of the brick aggregate had good physical and mechanical properties, which could be used to produce high-quality concrete. Mohammed et al. [21] point out that RBA could be used to produce concrete with strengths ranging from 20.7 to 31.0 MPa. Liu et al. [22] found that the equal volume substitution method was better than the equal quality substitution method to replace the crushed stone with RBA. Yan and Chen [23] investigated the mechanical properties of RBC and found that the compressive strength and flexural strength of RBC increased with age, while the compressive-compression ratio decreased, but the brittleness was lower than that of NAC. Chen et al. [24] and Poon et al. [25] investigated the effect of RBA replacement rate on concrete strength and found that when the replacement rate was controlled within a certain range, it would not have a great impact on the mechanical properties of concrete. Li et al. [26] investigated the effect of RBA on the mechanics and frost resistance of concrete and discussed its effect on the microstructure of concrete by analyzing the micro-hardness and porosity of concrete. Due to the high water absorption characteristics of RBA, the method of pre-wetting aggregate affected the interface transition zone of RBC [27]. The concrete prepared by soaking RBA in the water had better performance [28], so RBA should reached the surface-dry moisture state before mixing [29,30].

It can be found that RBA can be used as coarse aggregate for the preparation of concrete [31]. However, there is no consensus on the basic mechanical properties of RBC with different RBA replacement rates. Therefore, this article investigated the compressive strength, the splitting tensile strength, and macro destruction mode of RBC with different RBA replacement rates and analyzed the reason for the difference in mechanical properties between RBC and NAC by microstructural analysis.

2 Experiment

2.1 Materials

2.1.1 Natural coarse aggregate (NCA)

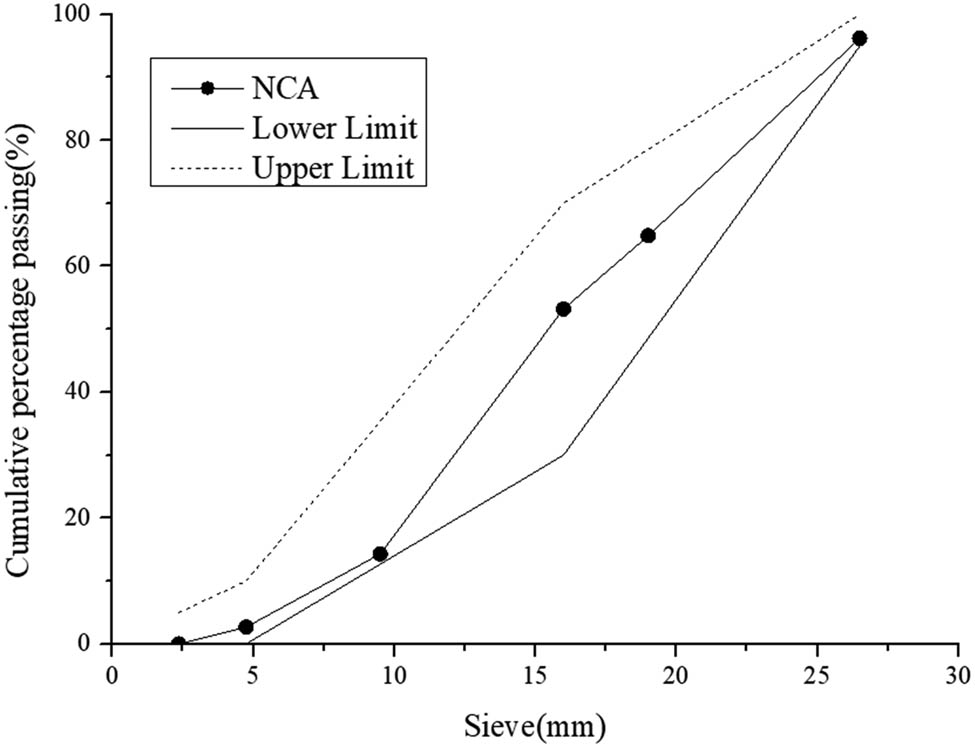

The NCA was natural crushed stone, and the particle range of NCA was 5–26.5 mm; the sieving result of NCA is shown in Figure 1. The water absorption rate of NCA was 1.9%, and the crushing index was 9.8%.

Sieving result of NCA.

2.1.2 Fine aggregate

The fine aggregate was natural river sand with a 2.64 fineness module conforming to the Chinese standard JGJ52-2006 [32]. The mud content of fine aggregate was 2.1%. The bulk density and apparent density were 1,439 and 2,639 kg·m−3, respectively.

2.1.3 Cement

The cement used in this article was P.O 42.5 conforming to the Chinese standard GB 175-2007 [33]. The specific surface area of cement was 354 kg·m−3, and the ignition loss was 1.8%. The 28-day compressive strength and flexural strength were 51.2 and 9.3 MPa, respectively. The initial setting time and final setting time were 208 and 273 min, respectively. The SO3 content is 2.31%, while MgO content is 1.68%.

2.1.4 Clay brick aggregate

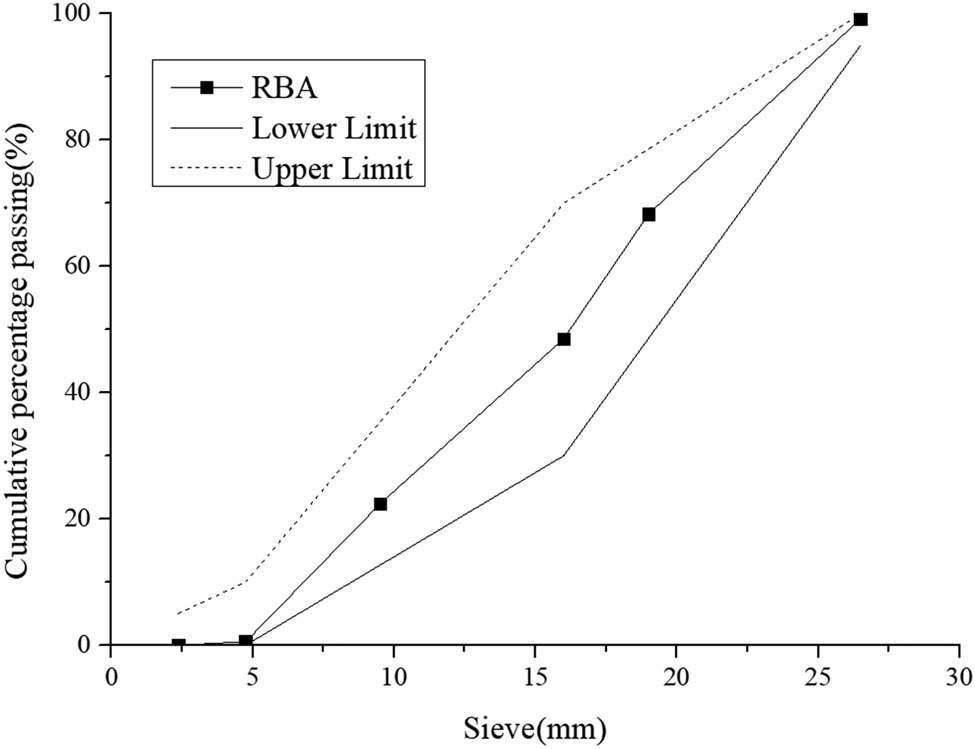

RBA adopted a combination of manual and mechanical crushing methods: first, it was initially crushed manually to remove impurities; then, it was further crushed with a small jaw crusher, as shown in Figure 2, and the particle range was 5–26.5 mm. The sieving result of RBA is shown in Figure 3. The water absorption rate of RBA was 12.5%, and the crushing index was 27.5%. The apparent density was 2,445 kg·m−3.

Aggregate crushing.

Sieving result of RBA.

2.2 Mix proportions

The mix proportions for RBC and NAC are shown in Table 1. Note that RBA reached the surface-dry moisture state by pre-soaking it in water for 24 h before use [34].

Mix proportions (kg·m−3)

| Concrete type | w/c | RBA replacement rates (%) | Water | Cement | Sand | NCA | RBA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAC | 0.48 | 0 | 185 | 385.4 | 695 | 1,200 | 0 |

| 0.58 | 0 | 185 | 319 | 720 | 1,176 | 0 | |

| 0.68 | 0 | 185 | 272 | 738 | 1,158 | 0 | |

| RBC | 0.48 | 10 | 185 | 385.4 | 695 | 1,080 | 105 |

| 20 | 185 | 385.4 | 695 | 960 | 210 | ||

| 30 | 185 | 385.4 | 695 | 840 | 315 | ||

| 40 | 185 | 385.4 | 695 | 720 | 420 | ||

| 50 | 185 | 385.4 | 695 | 600 | 525 | ||

| 0.58 | 30 | 185 | 319 | 720 | 823.2 | 308.7 | |

| 50 | 185 | 319 | 720 | 588 | 514.5 | ||

| 0.68 | 30 | 185 | 272 | 738 | 810.6 | 304 | |

| 50 | 185 | 272 | 738 | 579 | 506.6 |

2.3 Specimen pouring and curing

The 150 mm × 150 mm × 150 mm cubic specimens were cast to investigate the compressive strength and the splitting tensile strength of concrete, three specimens per group. After the specimens were cast, they were placed in an air-conditioned room for 24 h; then, the mold was removed, watered for 7 days, and then cured at room temperature until the test began.

3 Tests and results

3.1 Compressive strength test

Cube compressive strength test was performed according to Chinese standard GB50081-2016 [35]. The formula for calculating the cube compressive strength of the concrete was as follows:

where

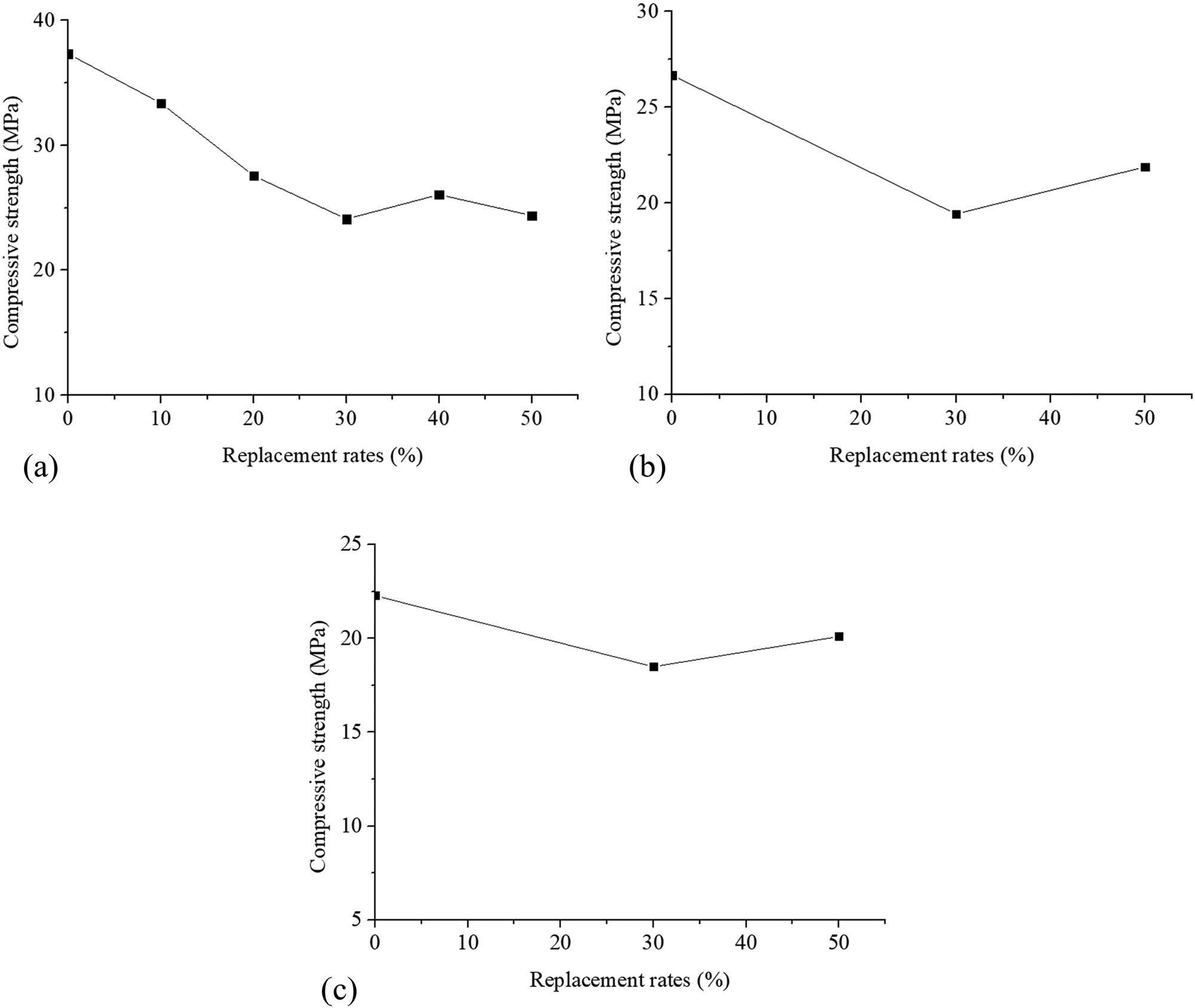

Figure 4 shows the relationship between the compressive strength of concrete and RBA replacement rates.

Compressive strength versus RBA replacement rates. (a) w/c = 0.48, (b) w/c = 0.58, and (c) w/c = 0.68.

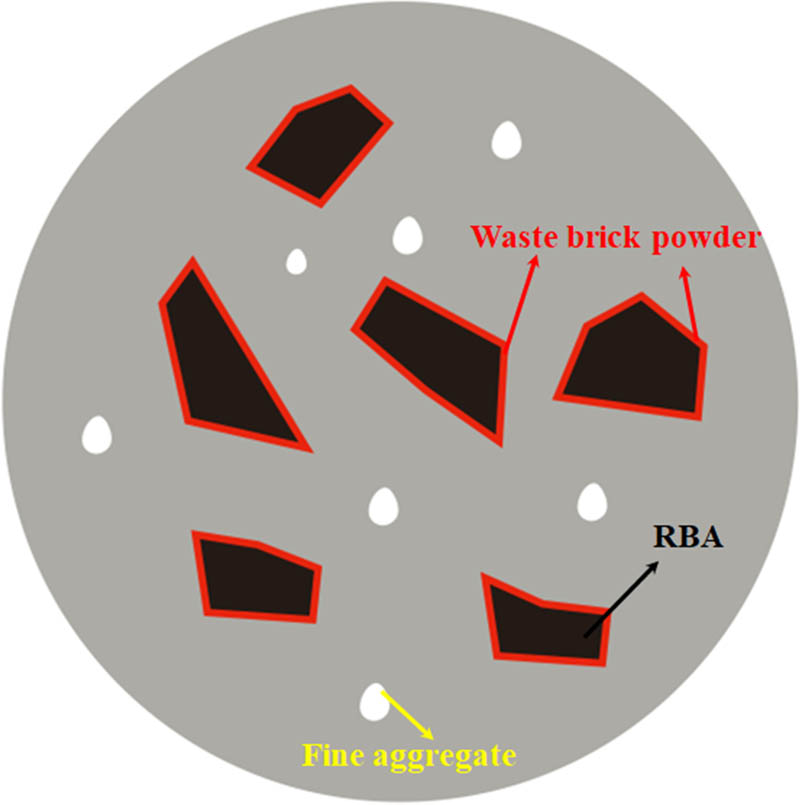

As shown in Figure 4, the compressive strength of RBC was lower than that of NAC (RBA replacement rate is 0%), which agree with the findings of Zhang and Zong [19]. The main reasons are as follows: first, the damage cracks appear in the RBA during the crushing process, and there is attached waste brick powder on the surface of RBA (as shown in Figure 5), resulting in poor adhesion with the cement paste, so the strength of RBC was lower than that of NAC; second, the crushing index of RBA is 2.8 times that of NCA, so the compressive capacity of RBA is significantly lower than that of NCA; third, the water absorption rate of RBA is 6.6 times that of NCA. The pre-wetting treatment of RBA before concrete pouring leads to the increase in the actual w/c of concrete and the reduction of cement mortar attached to aggregate, resulting in the reduction of compressive strength of RBC.

Interface model of RBC.

Figure 4 shows that the compressive strength of concrete showed a trend of first decreasing and then increasing with the increase in RBA replacement rates. These observations agree with the findings of Ji et al. [36]. The compressive strength of concrete was the lowest when the RBA replacement rate was 30%, and then, the compressive strength of concrete showed an increasing trend with the increase in RBA replacement rates. The main reasons are as follows: on the one hand, the lower elastic modulus of RBA is closer to the elastic modulus of hardened cement mortar, and the strength of RBA is lower, so cracks can expand from the cement mortar to the interior of RBA, and RBA can bear part of the pressure. On the other hand, the rough and porous RBA surface leads to a more dense interfacial transition zone, and more cement particles can enter the RBA pores, so that the cement product can be better combined with RBA, resulting in an increase in the compressive strength of RBC [36].

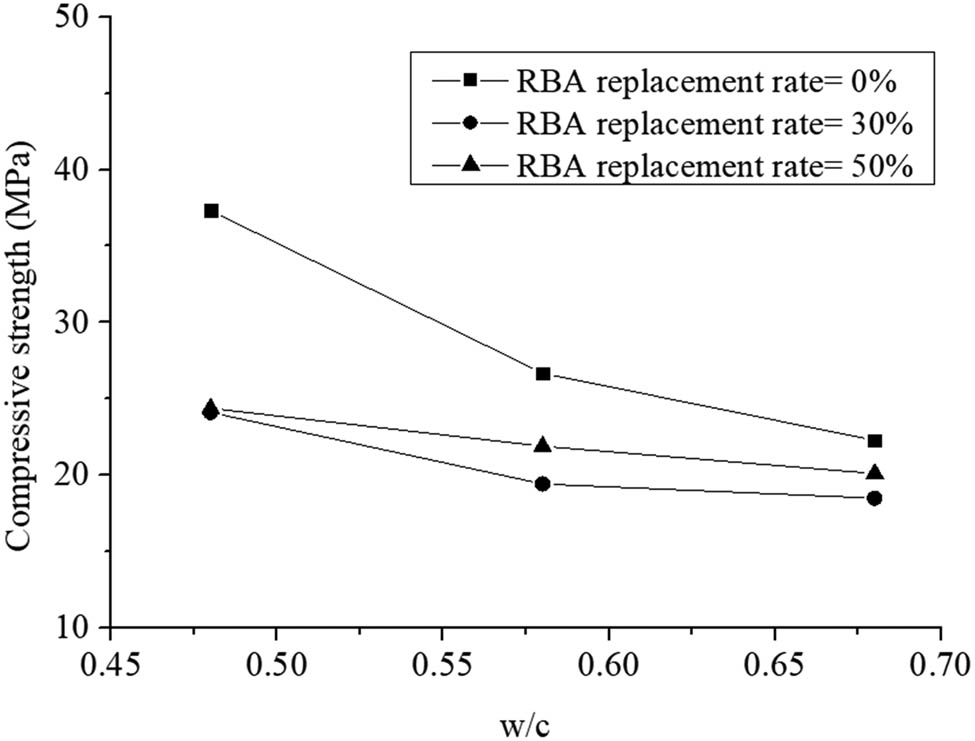

Figure 6 shows the relationship between the compressive strength of concrete and the w/c.

Compressive strength versus w/c.

As shown in Figure 6, the lower the w/c, the greater the compressive strength of RBC. The reason is that the higher the w/c, the looser and porous the cement mortar, and the hydration product cannot fill the internal pores of the concrete, and its bonding performance with the aggregate becomes poor, resulting in a decrease in the compressive strength.

In addition, with the increase in the w/c, the effect of the RBA replacement rate on the compressive strength gradually decreased. When the w/c was 0.48, the compressive strength of RBC with 50% RBA replacement rate was 34.67% lower than that of NAC; when the w/c was 0.58, the compressive strength of RBC with 50% RBA replacement rate was 17.92% lower than that of NAC; when the w/c was 0.68, the compressive strength of RBC with 50% RBA replacement rate was 9.78% lower than that of NAC. The reasons for this phenomenon are as follows: when the w/c is low, the strength of the cement mortar is high, and the weak parts of the concrete under compression are more inclined to RBA with lower strength, RBA plays a major role in the compression resistance of concrete; when the w/c is high, the strength of cement mortar is low, the weak parts of concrete under compression are more inclined to the cement mortar in the interface transition zone, and the effect of RBA on the compressive strength of concrete is reduced. Therefore, the effect of RBA on concrete compressive strength decreased when the w/c increased.

3.2 Splitting tensile strength test

Splitting tensile strength test was performed according to Chinese standard GB50081-2016 [35]. The formula for calculating the splitting tensile strength of the concrete was as follows:

where

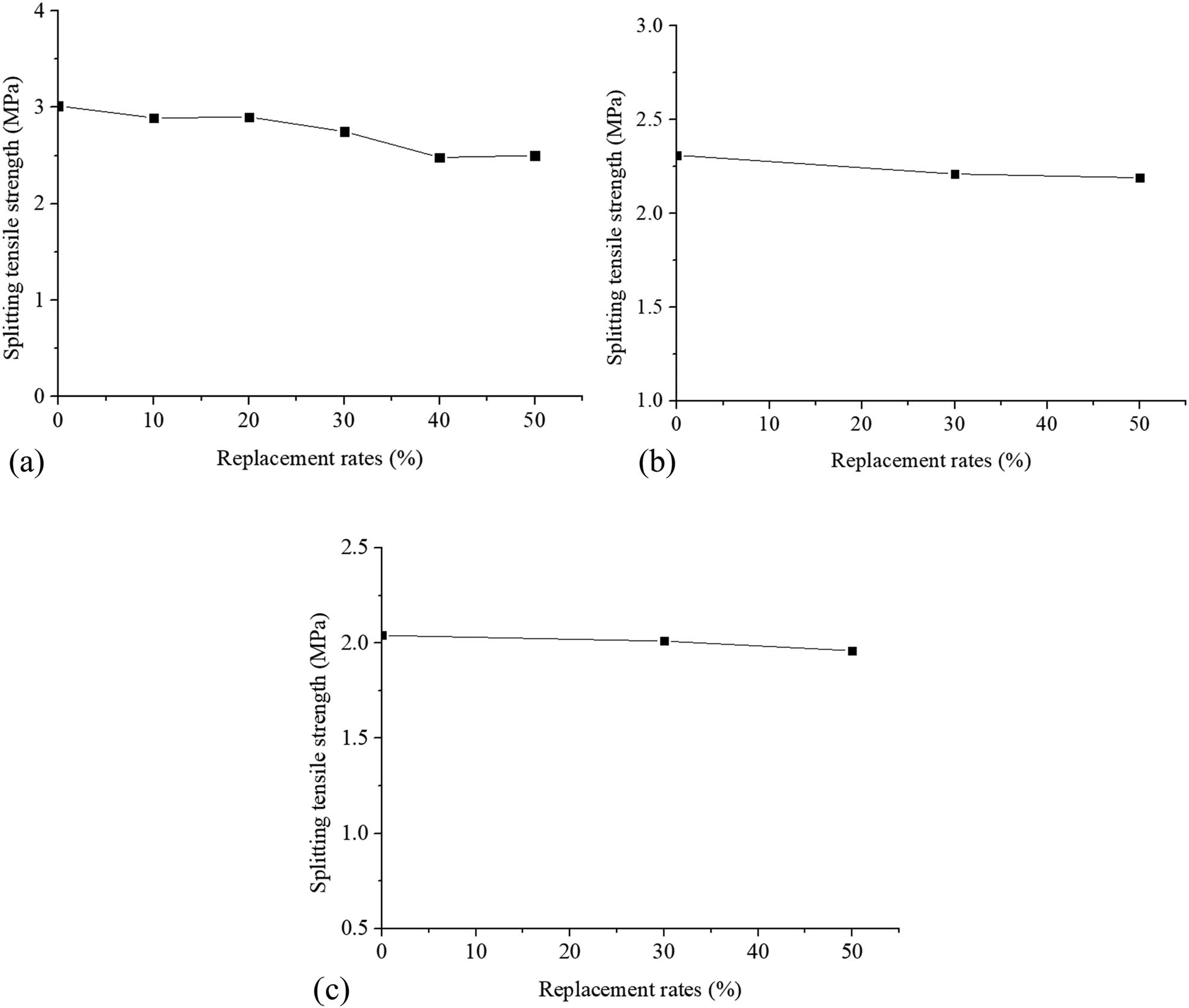

Figure 7 shows the relationship between the splitting tensile strength of concrete and RBA replacement rates.

Splitting tensile strength versus replacement rates. (a) w/c = 0.48, (b) w/c = 0.58, and (c) w/c = 0.68.

As shown in Figure 7, the splitting tensile strength of RBC was lower than that of NAC (RBA replacement rate is 0%), but the effect of RBA on the splitting tensile strength of concrete was not significant, which was similar to the conclusion obtained by Chen et al. [24] and Poon et al. [25]. When the w/c was 0.48, the compressive strength of RBC with 50% RBA replacement rate was 34.67% lower than that of NAC, while the splitting tensile strength of RBC with a 50% RBA replacement rate was 17.08% lower than that of NAC. The main reason is that the splitting tensile strength is determined by the mortar strength and coarse aggregate strength of the failure surface. Although the strength of RBA is lower than that of NCA, the loose and porous surface of RBA can be more closely combined with cement mortar, which improves the mechanical properties of RBC to a certain extent. Therefore, the effect of RBA on the splitting tensile strength of concrete was not significant.

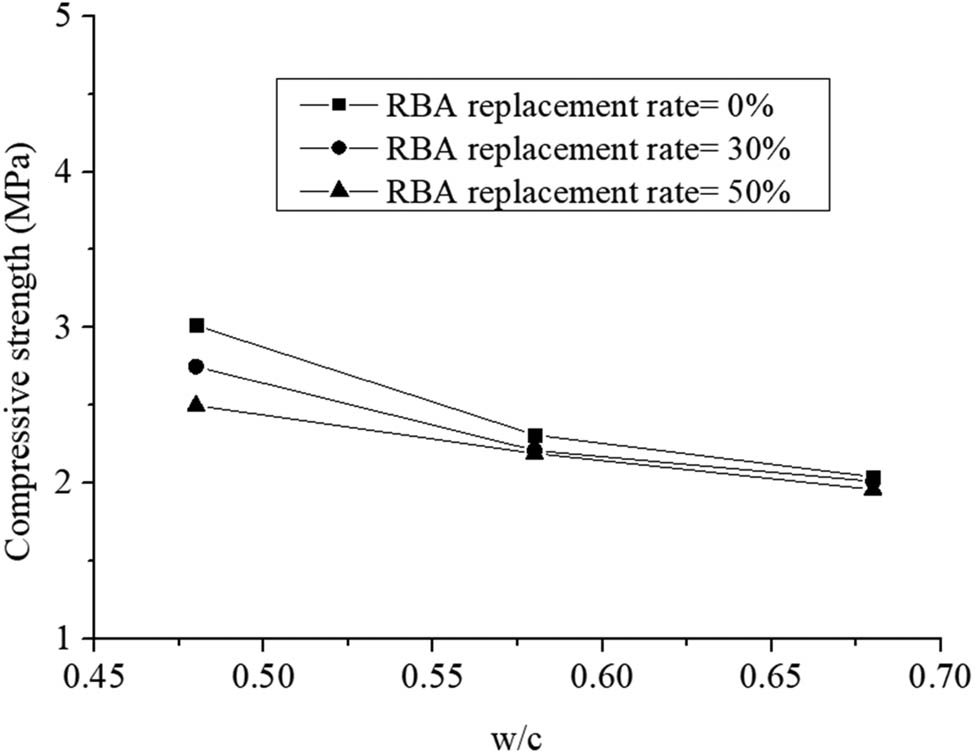

Figure 8 shows the relationship between the splitting tensile strength of concrete and w/c.

Splitting tensile strength versus w/c.

As shown in Figure 8, the lower the w/c, the greater the splitting tensile strength of RBC. The reason is that the higher the w/c, the greater the difference between the elastic modulus of the cement mortar and the aggregate. Therefore, the weak part of the specimen under stress is the interface transition zone, and aggregate has less effect on strength of concrete.

In addition, the effect of w/c on the splitting tensile strength of RBC was smaller than that on the splitting tensile strength of NAC. When the RBA replacement rate was 0%, the splitting tensile strength of concrete with 0.68 w/c was 32.34% lower than that with a 0.48 w/c; when the RBA replacement rate was 30%, the splitting tensile strength of concrete with 0.68 w/c was 26.91% lower than that with 0.48 w/c. When the RBA replacement rate was 50%, the splitting tensile strength of concrete with 0.68 w/c was 21.60% lower than that with 0.48 w/c.

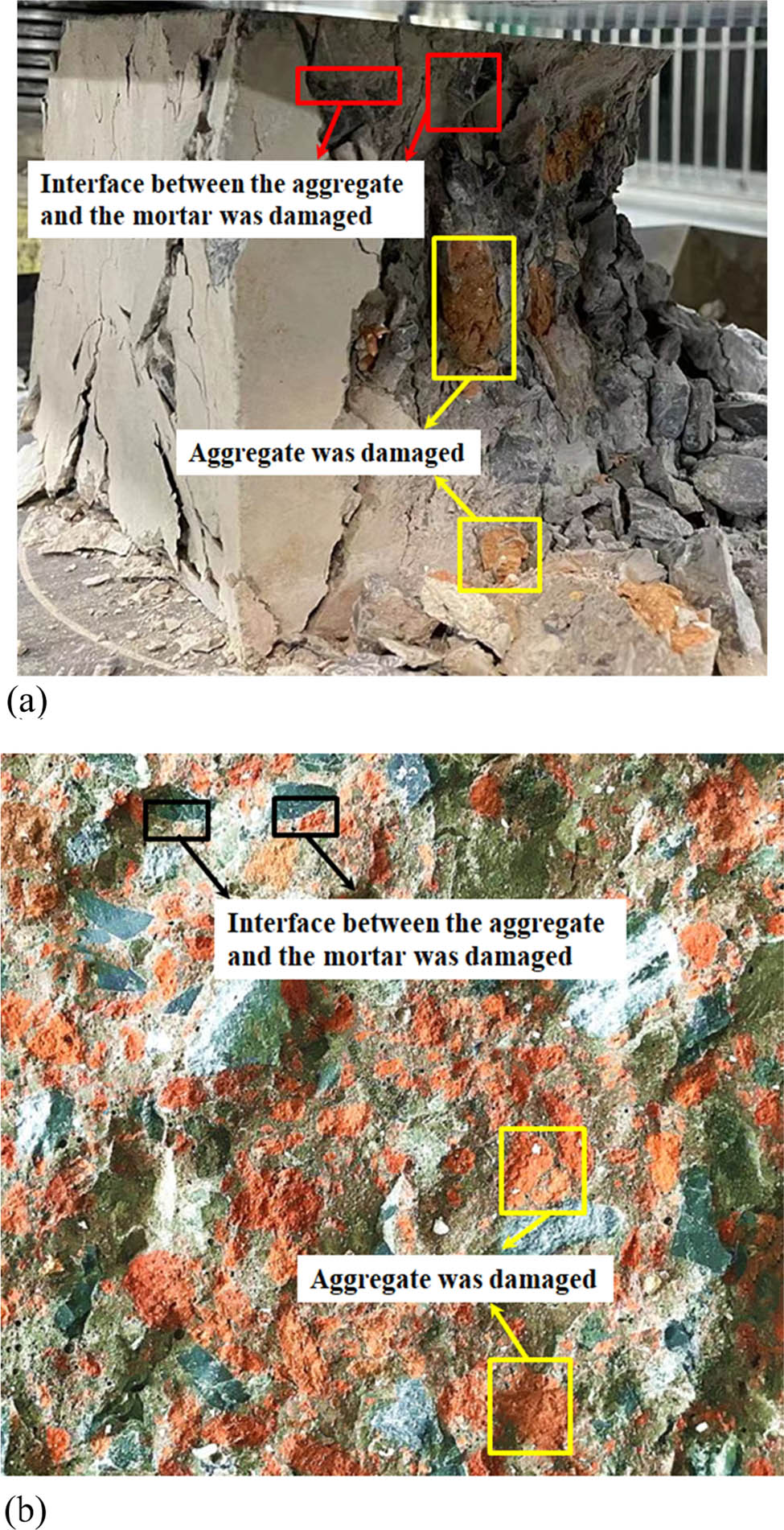

3.3 Macro destruction mode

The compression test failure mode of RBC was basically the same as that of NAC. In the compression test, it was found that the concrete specimen was more brittle when it finally failed when the RBA content was low, which was manifested as a sudden burst and loss of bearing capacity when it reached the ultimate load of the specimen. With the increase in RBA content, the brittle failure phenomenon tended to ductile failure.

When the RBC reached the tensile strength limit, the RBA on the failure surface was split, while the NCA was basically not split. The reason is that the elastic modulus of the cement mortar is quite different from that of NCA, the damage mostly occurs in the interface transition zone, and the force cannot be transmitted to the NCA, so the NCA is not easy to be damaged.

The compressive failure mode and split tensile failure mode of the RBC are shown in Figure 9, respectively. The figure illustrates that there were two failure modes of RBC [5]: (1) the aggregate was damaged during the stress process; (2) the interface between the aggregate and the mortar was damaged. The first kind of failure mode was generally the failure of RBA, and the failure of NCA does not occur; the second kind of failure was generally the failure of the interface between NCA and mortar.

Destruction mode. (a) Compression test failure mode and (b) splitting tensile test failure mode.

3.4 Microstructure test

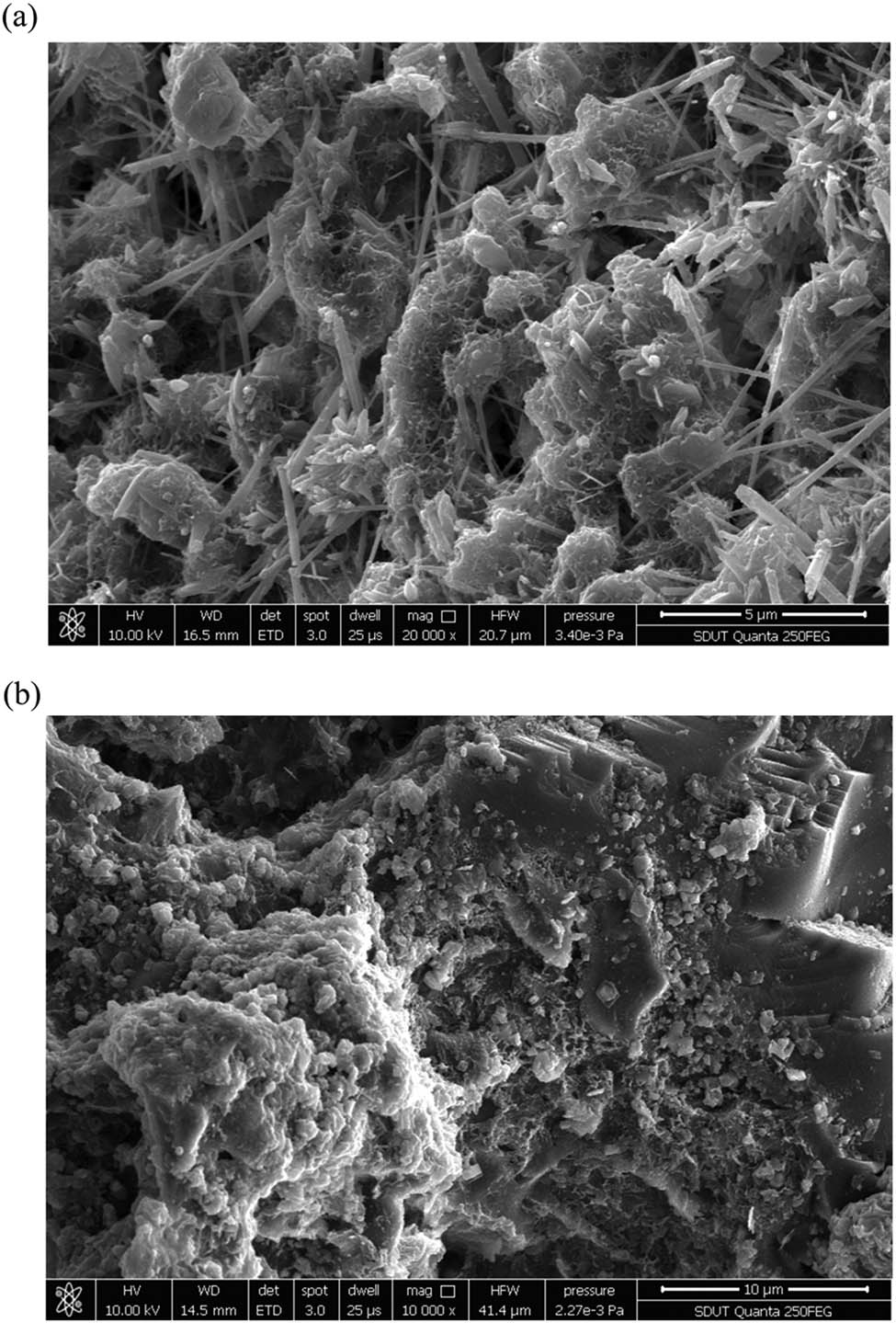

The morphology of ettringite (AFt) and the morphology of calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H) of RBC are shown in Figure 10. Compared with the AFt and C–S–H of NAC in ref. [37], it can be seen that the AFt in NAC was thicker than that in RAC, which were more favorable for improving the strength of concrete, which was the main reason that compressive strength of RBC was lower than that of NAC. In addition, the C–S–H of RBC was in the form of agglomerated networks with large and uniform pores, and less filler. Therefore, the strength of NAC was greater than that of RBC.

Morphology of RBC. (a) Morphology of AFt and (b)Morphology of C–S–H.

4 Conclusion

The compressive strength and splitting tensile strength of RBC were lower than those of NAC, but the effect of RBA on the splitting tensile strength of concrete was not significant.

The compressive strength of concrete showed a trend of first decreasing and then increasing with the increase in RBA replacement rate.

The effect of the RBA replacement rate on the compressive strength gradually decreased with the increase in the w/c.

The AFt of RBC was thicker than that in NAC, and the C–S–H of RBC was in the form of agglomerated networks with large and uniform pores, and less filler.

Acknowledgments

The study was carried out with the support of the Key Laboratory for Comprehensive Energy Saving of Cold Regions Architecture of Ministry of Education, Jilin Jianzhu University.

-

Funding information: The Foundation of Key Laboratory for Comprehensive Energy Saving of Cold Regions Architecture of Ministry of Education (JLZHKF022021002).

-

Author contributions: Lina Xu: investigation, methodology, writing – original draft preparation, writing – review, and editing; Wei Su: check original draft; Tian Su: methodology, data analysis, writing – review, and editing.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The data used to support the findings of this study are included with in the article.

References

[1] Su, T., C. X. Wang, F. B. Cao, Z. H. Zou, C. G. Wang, J. Wang, et al. An overview of bond behavior of recycled coarse aggregate concrete with steel bar. Reviews on Advanced Materials Science, Vol. 60, No. 1, 2021, pp. 127–144.10.1515/rams-2021-0018Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Meng, T., J. L. Zhang, H. D. Wei, and J. J. Shen. Effect of nano-strengthening on the properties and microstructure of recycled concrete. Nanotechnology Reviews, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2020, pp. 79–92.10.1515/ntrev-2020-0008Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Su, T., J. Wu, G. X. Yang, X. H. Jing, and A. Mueller. Shear behavior of recycled coarse aggregate concrete beams after freezing and thawing cycles. ACI Structure Journal, Vol. 116, No. 5, 2019, pp. 67–76.10.14359/51716770Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Poon, C. S., Z. H. Shui, L. Lam, H. Fok, and S. C. Kou. Influence of moisture states of natural and recycled aggregates on the slump and compressive strength of concrete. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 34, No. 1, 2004, pp. 31–36.10.1016/S0008-8846(03)00186-8Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Liu, C., W. H. Yu, H. W. Liu, T. F. Hu, and H. M. Hu. Study on mechanical properties and failure mechanism of recycled brick aggregate concrete. Materials Reports, Vol. 35, No. 13, 2021, pp. 13025–13031 (in Chinese).Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Zhang, B. S., L. J. Kong, Y. Ge, and J. Yuan. Review on specified density concrete. Concrete, Vol. 5, 2006, pp. 20–23 (in Chinese).Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Sadati, S., M. Arezoumandi, K. H. Khayat, and J. S. Volz. Shear performance of reinforced concrete beams incorporating recycled concrete aggregate and high-volume fly ash. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 115, 2016, pp. 284–293.10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.12.017Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Shi, C. J., Y. Li, J. K. Zhang, and W. G. Li. Performance enhancement of recycled concrete aggregate: A review. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 112, No. 1, 2016, pp. 466–472.10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.08.057Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Su, T., T. Wang, C. G. Wang, and H. H. Yi. The influence of salt-frost cycles on the bond behavior distribution between rebar and recycled coarse aggregate concretes. Journal of Building Engineering, Vol. 45, 2022, id. 103568.10.1016/j.jobe.2021.103568Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Xu, M. B., S. L. Wang, and M. M. Zhang. Experimental study on mechanical properties of recycled concrete. Concrete, Vol. 7, 2018, pp. 72–75 (in Chinese).Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Wang, C. Study on mechanical properties of recycled aggregate concrete with fly ash [Master Thesis], Xi’an University of Technology, Xi’an, 2017 (in Chinese).Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Xiao, J. Z., L. Li, V. W. Y. Tam, and H. Li. The state of the art regarding the long-term properties of recycled aggregate concrete. Structural Concrete, Vol. 15, No. 1, 2014, pp. 3–12.10.1002/suco.201300024Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Corinaldesi, V. Structural concrete prepared with coarse recycled concrete aggregate: from investigation to design. Advances in Civil Engineering, Vol. 3, 2011, id. 283984.10.1155/2011/283984Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Gao, Y. Q., B. H. Pan., C. F. Liang, J. Z. Xiao, and Z. H. He. Properties of CO2-modified recycled aggregates and its effect on the performance of recycled aggregate concrete. Journal of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Vol. 43, No. 6, 2021, pp. 95–102 (in Chinese).Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Lei, B., J. Zou, C. H. Rao, M. F. Fu, J. G. Xiong, and X. G. Wang. Experimental study on modification of recycled concrete with graphene oxide. Journal of Building Structures, Vol. 37, No. S2, 2016, pp. 103–108.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Khalaf, F. M. Using crushed clay brick as coarse aggregate in concrete. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, Vol. 18, No. 4, 2006, pp. 518–526.10.1061/(ASCE)0899-1561(2006)18:4(518)Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Wang, S. L., L. P. Jing, B. Zhang, and Y. Yang. Experimental analysis of properties of recycled aggregates with different brick contents. Concrete, Vol. 2, 2011, pp. 83–85, 88 (in Chinese).Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Cachim, P. B. Mechanical properties of brick aggregate concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 23, No. 3, 2009, pp. 1292–1297.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2008.07.023Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Zhang, S. P. and L. Zong. Properties of concrete made with recycled coarse aggregate. Environmental Progress and Sustainable Energy, Vol. 33, No. 4, 2014, pp. 1283–1289.10.1002/ep.11880Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Khalaf, F. M. and A. S. Devenny. Properties of new and recycled clay brick aggregates for use in concrete. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, Vol. 17, No. 4, 2005, pp. 456–464.10.1061/(ASCE)0899-1561(2005)17:4(456)Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Mohammed, T. U., A. Hasnat, M. A. Awal, and S. Z. Bosunia. Recycling of brick aggregate concrete as coarse aggregate. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, Vol. 27, No. 7, 2014, pp. B4014005.1–B4014005.9.10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0001043Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Liu, Z. Z., B. Xiao, X. L. Li, and X. F. Zhao. Study on performance of recycled concrete from waste sintered brick. Concrete, Vol. 3, 2011, pp. 72–74 (in Chinese).Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Yan, H. D. and X. F. Chen. Properties of clay brick recycled aggregate and its effects on strength of cement-based materials. Environmental Engineering, Vol. 4, 2008, pp. 37–39 + 42 + 43.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Chen, H. J., T. Yen, and K. H. Chen. Use of building rubbles as recycled aggregates. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 33, No. 1, 2003, pp. 125–132.10.1016/S0008-8846(02)00938-9Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Poon, C. S. and D. Chan. Paving blocks made with recycled concrete aggregate and crushed clay brick. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 20, No. 8, 2006, pp. 569–577.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2005.01.044Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Li, F., X. Q. Zhang, H. B. Dong, and J. Y. Shen. Effect of recycIed waste brick coarse aggregate on properties of concrete. Concrete, Vol. 2, 2015, pp. 56–58 + 62 (in Chinese).Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Zhao, Y. S., J. M. Gao, F. Chen, C. B. Liu, and X. M. Chen. Utilization of waste clay bricks as coarse and fine aggregates for the preparation of lightweight aggregate concrete. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 201, No. 12, 2018, pp. 706–715.10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.103Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Yang, J., Q. Du, and Y. W. Bao. Concrete with recycled concrete aggregate and crushed clay bricks. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 25, No. 4, 2011, pp. 1935–1945.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2010.11.063Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Khalaf, F. M. Using crushed clay brick as coarse aggregate in concrete. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, Vol. 18, No. 4, 2006, pp. 518–526.10.1061/(ASCE)0899-1561(2006)18:4(518)Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Gomes, M. and J. Brito. Structural concrete with incorporation of coarse recycled concrete and ceramic aggregates: durability performance. Materials and Structures, Vol. 42, No. 5, 2008, pp. 663–675.10.1617/s11527-008-9411-9Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Zhang, Z. B., S. L. Wang, B. Zhang, L. P. Jing, and S. C. Luo. Experimental analysis of the basic mechanical properties of recycled concrete. Concrete, Vol. 7, 2011, pp. 20–24 (in Chinese).10.2991/gmee-15.2015.30Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China, General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China. Standard for technical requirements and test method of sand and crushed stone (or gravel) for Ordinary Concrete (JGJ52-2006), China Architecture & Building Press, Beijing, 2006 (in Chinese).Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China, General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China. Standard for test method of long-term performance and durability of ordinary concrete (GB/T 50082-2009), China Architecture & Building Press, Beijing, 2009 (in Chinese).Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Su, T., J. Wu, Z. H. Zou, and J. F. Yuan. Bond performance of steel bar in RAC under salt-frost and repeated loading. ASCE: Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, Vol. 32, No. 9, 2020, id. 04020261.10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0003303Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China, General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China. Standard for test method of mechanical properties on ordinary concrete (GB/T 50081-2002), China Architecture & Building Press, Beijing, 2003 (in Chinese).Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Ji, W. Y. Experimental research on mechanical properties and durability of mixed recycled coarse aggregate concrete [Master Thesis], Nanjing: Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics, 2020 (in Chinese).Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Zhang, L., H. Z. Li, and J. L. Ren. Experimental study on compressive strength of the concrete with 100% recycled clay brick aggregates. Concrete, Vol. 11, 2020, pp. 79–88 (in Chinese).Suche in Google Scholar

© 2022 Lina Xu et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Review Articles

- State of the art, challenges, and emerging trends: Geopolymer composite reinforced by dispersed steel fibers

- A review on the properties of concrete reinforced with recycled steel fiber from waste tires

- Copper ternary oxides as photocathodes for solar-driven CO2 reduction

- Properties of fresh and hardened self-compacting concrete incorporating rice husk ash: A review

- Basic mechanical and fatigue properties of rubber materials and components for railway vehicles: A literature survey

- Research progress on durability of marine concrete under the combined action of Cl− erosion, carbonation, and dry–wet cycles

- Delivery systems in nanocosmeceuticals

- Study on the preparation process and sintering performance of doped nano-silver paste

- Analysis of the interactions between nonoxide reinforcements and Al–Si–Cu–Mg matrices

- Research Articles

- Study on the influence of structural form and parameters on vibration characteristics of typical ship structures

- Deterioration characteristics of recycled aggregate concrete subjected to coupling effect with salt and frost

- Novel approach to improve shale stability using super-amphiphobic nanoscale materials in water-based drilling fluids and its field application

- Research on the low-frequency multiline spectrum vibration control of offshore platforms

- Multiple wide band gaps in a convex-like holey phononic crystal strip

- Response analysis and optimization of the air spring with epistemic uncertainties

- Molecular dynamics of C–S–H production in graphene oxide environment

- Residual stress relief mechanisms of 2219 Al–Cu alloy by thermal stress relief method

- Characteristics and microstructures of the GFRP waste powder/GGBS-based geopolymer paste and concrete

- Development and performance evaluation of a novel environmentally friendly adsorbent for waste water-based drilling fluids

- Determination of shear stresses in the measurement area of a modified wood sample

- Influence of ettringite on the crack self-repairing of cement-based materials in a hydraulic environment

- Multiple load recognition and fatigue assessment on longitudinal stop of railway freight car

- Synthesis and characterization of nano-SiO2@octadecylbisimidazoline quaternary ammonium salt used as acidizing corrosion inhibitor

- Perforated steel for realizing extraordinary ductility under compression: Testing and finite element modeling

- The influence of oiled fiber, freeze-thawing cycle, and sulfate attack on strain hardening cement-based composites

- Perforated steel block of realizing large ductility under compression: Parametric study and stress–strain modeling

- Study on dynamic viscoelastic constitutive model of nonwater reacted polyurethane grouting materials based on DMA

- Mechanical behavior and mechanism investigation on the optimized and novel bio-inspired nonpneumatic composite tires

- Effect of cooling rate on the microstructure and thermal expansion properties of Al–Mn–Fe alloy

- Research on process optimization and rapid prediction method of thermal vibration stress relief for 2219 aluminum alloy rings

- Failure prevention of seafloor composite pipelines using enhanced strain-based design

- Deterioration of concrete under the coupling action of freeze–thaw cycles and salt solution erosion

- Creep rupture behavior of 2.25Cr1Mo0.25V steel and weld for hydrogenation reactors under different stress levels

- Statistical damage constitutive model for the two-component foaming polymer grouting material

- Nano-structural and nano-constraint behavior of mortar containing silica aggregates

- Influence of recycled clay brick aggregate on the mechanical properties of concrete

- Effect of LDH on the dissolution and adsorption behaviors of sulfate in Portland cement early hydration process

- Comparison of properties of colorless and transparent polyimide films using various diamine monomers

- Study in the parameter influence on underwater acoustic radiation characteristics of cylindrical shells

- Experimental study on basic mechanical properties of recycled steel fiber reinforced concrete

- Dynamic characteristic analysis of acoustic black hole in typical raft structure

- A semi-analytical method for dynamic analysis of a rectangular plate with general boundary conditions based on FSDT

- Research on modification of mechanical properties of recycled aggregate concrete by replacing sand with graphite tailings

- Dynamic response of Voronoi structures with gradient perpendicular to the impact direction

- Deposition mechanisms and characteristics of nano-modified multimodal Cr3C2–NiCr coatings sprayed by HVOF

- Effect of excitation type on vibration characteristics of typical ship grillage structure

- Study on the nanoscale mechanical properties of graphene oxide–enhanced shear resisting cement

- Experimental investigation on static compressive toughness of steel fiber rubber concrete

- Study on the stress field concentration at the tip of elliptical cracks

- Corrosion resistance of 6061-T6 aluminium alloy and its feasibility of near-surface reinforcements in concrete structure

- Effect of the synthesis method on the MnCo2O4 towards the photocatalytic production of H2

- Experimental study of the shear strength criterion of rock structural plane based on three-dimensional surface description

- Evaluation of wear and corrosion properties of FSWed aluminum alloy plates of AA2020-T4 with heat treatment under different aging periods

- Thermal–mechanical coupling deformation difference analysis for the flexspline of a harmonic drive

- Frost resistance of fiber-reinforced self-compacting recycled concrete

- High-temperature treated TiO2 modified with 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane as photoactive nanomaterials

- Effect of nano Al2O3 particles on the mechanical and wear properties of Al/Al2O3 composites manufactured via ARB

- Co3O4 nanoparticles embedded in electrospun carbon nanofibers as free-standing nanocomposite electrodes as highly sensitive enzyme-free glucose biosensors

- Effect of freeze–thaw cycles on deformation properties of deep foundation pit supported by pile-anchor in Harbin

- Temperature-porosity-dependent elastic modulus model for metallic materials

- Effect of diffusion on interfacial properties of polyurethane-modified asphalt–aggregate using molecular dynamic simulation

- Experimental study on comprehensive improvement of shear strength and erosion resistance of yellow mud in Qiang Village

- A novel method for low-cost and rapid preparation of nanoporous phenolic aerogels and its performance regulation mechanism

- In situ bow reduction during sublimation growth of cubic silicon carbide

- Adhesion behaviour of 3D printed polyamide–carbon fibre composite filament

- An experimental investigation and machine learning-based prediction for seismic performance of steel tubular column filled with recycled aggregate concrete

- Effects of rare earth metals on microstructure, mechanical properties, and pitting corrosion of 27% Cr hyper duplex stainless steel

- Application research of acoustic black hole in floating raft vibration isolation system

- Multi-objective parametric optimization on the EDM machining of hybrid SiCp/Grp/aluminum nanocomposites using Non-dominating Sorting Genetic Algorithm (NSGA-II): Fabrication and microstructural characterizations

- Estimating of cutting force and surface roughness in turning of GFRP composites with different orientation angles using artificial neural network

- Displacement recovery and energy dissipation of crimped NiTi SMA fibers during cyclic pullout tests

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Review Articles

- State of the art, challenges, and emerging trends: Geopolymer composite reinforced by dispersed steel fibers

- A review on the properties of concrete reinforced with recycled steel fiber from waste tires

- Copper ternary oxides as photocathodes for solar-driven CO2 reduction

- Properties of fresh and hardened self-compacting concrete incorporating rice husk ash: A review

- Basic mechanical and fatigue properties of rubber materials and components for railway vehicles: A literature survey

- Research progress on durability of marine concrete under the combined action of Cl− erosion, carbonation, and dry–wet cycles

- Delivery systems in nanocosmeceuticals

- Study on the preparation process and sintering performance of doped nano-silver paste

- Analysis of the interactions between nonoxide reinforcements and Al–Si–Cu–Mg matrices

- Research Articles

- Study on the influence of structural form and parameters on vibration characteristics of typical ship structures

- Deterioration characteristics of recycled aggregate concrete subjected to coupling effect with salt and frost

- Novel approach to improve shale stability using super-amphiphobic nanoscale materials in water-based drilling fluids and its field application

- Research on the low-frequency multiline spectrum vibration control of offshore platforms

- Multiple wide band gaps in a convex-like holey phononic crystal strip

- Response analysis and optimization of the air spring with epistemic uncertainties

- Molecular dynamics of C–S–H production in graphene oxide environment

- Residual stress relief mechanisms of 2219 Al–Cu alloy by thermal stress relief method

- Characteristics and microstructures of the GFRP waste powder/GGBS-based geopolymer paste and concrete

- Development and performance evaluation of a novel environmentally friendly adsorbent for waste water-based drilling fluids

- Determination of shear stresses in the measurement area of a modified wood sample

- Influence of ettringite on the crack self-repairing of cement-based materials in a hydraulic environment

- Multiple load recognition and fatigue assessment on longitudinal stop of railway freight car

- Synthesis and characterization of nano-SiO2@octadecylbisimidazoline quaternary ammonium salt used as acidizing corrosion inhibitor

- Perforated steel for realizing extraordinary ductility under compression: Testing and finite element modeling

- The influence of oiled fiber, freeze-thawing cycle, and sulfate attack on strain hardening cement-based composites

- Perforated steel block of realizing large ductility under compression: Parametric study and stress–strain modeling

- Study on dynamic viscoelastic constitutive model of nonwater reacted polyurethane grouting materials based on DMA

- Mechanical behavior and mechanism investigation on the optimized and novel bio-inspired nonpneumatic composite tires

- Effect of cooling rate on the microstructure and thermal expansion properties of Al–Mn–Fe alloy

- Research on process optimization and rapid prediction method of thermal vibration stress relief for 2219 aluminum alloy rings

- Failure prevention of seafloor composite pipelines using enhanced strain-based design

- Deterioration of concrete under the coupling action of freeze–thaw cycles and salt solution erosion

- Creep rupture behavior of 2.25Cr1Mo0.25V steel and weld for hydrogenation reactors under different stress levels

- Statistical damage constitutive model for the two-component foaming polymer grouting material

- Nano-structural and nano-constraint behavior of mortar containing silica aggregates

- Influence of recycled clay brick aggregate on the mechanical properties of concrete

- Effect of LDH on the dissolution and adsorption behaviors of sulfate in Portland cement early hydration process

- Comparison of properties of colorless and transparent polyimide films using various diamine monomers

- Study in the parameter influence on underwater acoustic radiation characteristics of cylindrical shells

- Experimental study on basic mechanical properties of recycled steel fiber reinforced concrete

- Dynamic characteristic analysis of acoustic black hole in typical raft structure

- A semi-analytical method for dynamic analysis of a rectangular plate with general boundary conditions based on FSDT

- Research on modification of mechanical properties of recycled aggregate concrete by replacing sand with graphite tailings

- Dynamic response of Voronoi structures with gradient perpendicular to the impact direction

- Deposition mechanisms and characteristics of nano-modified multimodal Cr3C2–NiCr coatings sprayed by HVOF

- Effect of excitation type on vibration characteristics of typical ship grillage structure

- Study on the nanoscale mechanical properties of graphene oxide–enhanced shear resisting cement

- Experimental investigation on static compressive toughness of steel fiber rubber concrete

- Study on the stress field concentration at the tip of elliptical cracks

- Corrosion resistance of 6061-T6 aluminium alloy and its feasibility of near-surface reinforcements in concrete structure

- Effect of the synthesis method on the MnCo2O4 towards the photocatalytic production of H2

- Experimental study of the shear strength criterion of rock structural plane based on three-dimensional surface description

- Evaluation of wear and corrosion properties of FSWed aluminum alloy plates of AA2020-T4 with heat treatment under different aging periods

- Thermal–mechanical coupling deformation difference analysis for the flexspline of a harmonic drive

- Frost resistance of fiber-reinforced self-compacting recycled concrete

- High-temperature treated TiO2 modified with 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane as photoactive nanomaterials

- Effect of nano Al2O3 particles on the mechanical and wear properties of Al/Al2O3 composites manufactured via ARB

- Co3O4 nanoparticles embedded in electrospun carbon nanofibers as free-standing nanocomposite electrodes as highly sensitive enzyme-free glucose biosensors

- Effect of freeze–thaw cycles on deformation properties of deep foundation pit supported by pile-anchor in Harbin

- Temperature-porosity-dependent elastic modulus model for metallic materials

- Effect of diffusion on interfacial properties of polyurethane-modified asphalt–aggregate using molecular dynamic simulation

- Experimental study on comprehensive improvement of shear strength and erosion resistance of yellow mud in Qiang Village

- A novel method for low-cost and rapid preparation of nanoporous phenolic aerogels and its performance regulation mechanism

- In situ bow reduction during sublimation growth of cubic silicon carbide

- Adhesion behaviour of 3D printed polyamide–carbon fibre composite filament

- An experimental investigation and machine learning-based prediction for seismic performance of steel tubular column filled with recycled aggregate concrete

- Effects of rare earth metals on microstructure, mechanical properties, and pitting corrosion of 27% Cr hyper duplex stainless steel

- Application research of acoustic black hole in floating raft vibration isolation system

- Multi-objective parametric optimization on the EDM machining of hybrid SiCp/Grp/aluminum nanocomposites using Non-dominating Sorting Genetic Algorithm (NSGA-II): Fabrication and microstructural characterizations

- Estimating of cutting force and surface roughness in turning of GFRP composites with different orientation angles using artificial neural network

- Displacement recovery and energy dissipation of crimped NiTi SMA fibers during cyclic pullout tests