Abstract

Turbidity is a fundamental measure for assessing the quality of water supplied by water treatment plants (WTPs) employing a conventional treatment process. If it is present in amounts exceeding the permitted limit, disinfectants are less effective in killing microorganisms and the water becomes unsafe to drink. This article is a part of a comprehensive study that aims to investigate the high-turbidity problem of tap water in two cities of Najaf governorate and offer suitable measures to solve this problem. The purpose of this study was to determine how WTPs impact the turbidity of tap water. The work covered two main WTPs located in Najaf governorate: Unified Najaf and The Old Kufa. It included the collection of water samples from three locations in each plant: the influent of flash mix unit (raw water samples), the effluent of clariflocculation unit (settled water samples), and the effluent of filtration unit (filtered water samples). The samples were analyzed for turbidity using a turbidity meter. The efficacy of each plant's treatment units was revealed by monitoring the turbidity of the water inside each facility. For the Unified Najaf WTP, out of 99 TRE readings, there were 3, 92, and 60 positive values for TREc, TREf, and TREp, respectively. The maximum values of TREc, TREf, and TREp were 22.3, 86.5, and 61.5%, respectively. The performance of Old Kufa WTP was worse than that of Unified Najaf WT. Out of 99 TRE values, the number of positive values was 6, 76, and 31 for TREc, TREf, and TREp, respectively. They also showed that only 26 out of 99 and 9 out of 99 effluent turbidity readings in Unified Najaf and Old Kufa WTPs, respectively, satisfy Iraqi standards for tap water turbidity. The bad performance of the WTPs was the main reason behind the high-turbidity tap water in Najaf governorate. This study identified the causes of that performance and proposed solutions.

1 Introduction

The supply of potable water is essential to maintain human health and avoid money, time, and effort wasting during the spread of communicable diseases as a result of poorly treated water consumption. Turbidity is a major physical feature of potable water quality. It is a physical property that causes light to be scattered and absorbed by particles rather than transmitted in straight lines through a water sample. Clay, silt, fine inorganic and organic matter, soluble colored organic compounds, plankton, and other microscopic organisms are a few examples of suspended impurities that impede water clarity and cause turbidity. When producing water for human consumption and industrial uses, clarity is a crucial issue. Significant evidence shows that turbidity control is a reliable defense against pathogens in drinking water, contrary to what was once thought to be primarily an aesthetic feature [1]. Conventional water treatment plants (CWTPs) are frequently evaluated in terms of removal effectiveness and effluent quality using physical parameters, particularly water turbidity [2,3]. A CWTP’s treatment train is made up of units for sedimentation, filtration, flash mix, slow mix, and disinfection.

Najaf governorate is located in the middle of Iraq between longitudes 44°18′34″ and 44°19′14″, and between latitudes 31°59′27″ and 31°59′56″. Currently, the citizens of Najaf governorate, specifically those accommodated in Najaf and Kufa cities, are suffering from a high-turbidity tap water supply. The high-turbidity tap water can be attributed to the low efficiency of the WTP and/or inappropriate management of water supply networks. There are many studies conducted on evaluating the performance of CWTPs located in Iraq in general and some of them in Najaf governorate in particular.

Abd Al-Abbas [4] evaluated the suitability of Shatt Al-Kufa River water for domestic and irrigation uses by collecting water samples from the influents of some CWTPs located along this river and analyzing them for 11 water quality parameters, including turbidity. Salman [5] investigated the raw and treated water quality of some CWTPs in Najaf governorate considering 11 water quality parameters, including turbidity, and pointed out to the low efficiency of the considered plants. Salih and Hassan [6] studied the removal efficiency of some water quality parameters, including turbidity, in a number of CWTPs in Najaf governorate by taking raw and treated water samples and comparing their quality parameters with the maximum permissible limits (MPLs) in the Iraqi standards of potable water. They found that the turbidity of treated water exceeds its MPL during some months of the year.

Regarding the studies conducted on CWTP performance in Iraqi governorates, other than Najaf governorate, Al-Jeebory and Ghawi [7] evaluated the performance of a CWTP located in Al-Qadisiyah governorate and checked its treatment unit design criteria. They measured the performance by comparing the values of effluent turbidity and total suspended solids with the MPLs specified by World Health Organization and indicated the bad performance of the considered plants. Abdul-Rahman et al. [8] investigated the efficiency of sedimentation and filtration units in a CWTP located in Al-Fallujah city, west of Iraq, and pointed out to their low turbidity removal efficiency (TRE). Ramal [9] studied the efficiency of a CWTP located in Al-Ramadi city, west of Iraq, by collecting raw and treated water samples, and he indicated that the low efficiency of the plant can be attributed to the poor plant operation. Mohammed and Shakir [10] assessed the TRE of sedimentation and filtration units in a CWTP located in Baghdad governorate and indicated that the low TRE of the considered units can be attributed to the shortage in periodic sludge withdrawal from the sedimentation tanks and the unskilled operators. Al-Obaidy and Al-Ni’ma [11] investigated the performance of five CWTPs located in Nineveh governorate, north of Iraq, and showed that some of the considered plants were characterized by their low TRE (less than 50%). Selman et al. [12] evaluated the performance of a CWTP located in Al-Muthanna governorate, south of Iraq, and found that the TRE values were 51.5 and 53.8% for the old and new parts of the plant, respectively, and they referred these low-efficiency values to the uncontrolled manual addition of alum. Al-Dujail and Shamran [13] evaluated the performance of sedimentation and filtration units in a number of CWTPs located in Karbala governorate in terms of TRE and showed that both of these units were poorly performed in all the considered plants. Issa [3] evaluated the performance of a CWTP located in Khanaqin city, east of Iraq, in terms of TRE, and pointed out that although TRE was high (97.88%), the plant effluent turbidity exceeded the MPL in Iraqi standards as a result of high-turbidity raw water. Hassan and Mahmood [14] investigated the performance of two CWTPs located in Baghdad governorate, Iraq, through the routing of 17 water quality parameters, including turbidity, at three locations in each plant (effluents of sedimentation, filtration, and disinfection units). They showed that the turbidity of produced waters exceeded its MPL in Iraqi standards. Al-Nasrawi et al. [15] investigated the performance of ten CWTPs located in Karbala governorate in terms of TRE and found that the TRE varied from one plant to another. Ali et al. [16] evaluated the performance of a CWTP located in Karbala Governorate, middle of Iraq, measured in terms of the removal efficiency of some organic and inorganic impurities, including turbidity. They found that the TRE of the plant was 60.7%; however, they did not explain the reason behind this low TRE value. Al-Tamir [17] investigated the effluent turbidity of many CWTPs located in Mosul city, north of Iraq, and showed that some of the plants had effluent turbidity that complied with the water quality specifications. Nasier and Abdulrazzaq [18] assessed the TRE of a CWTP located in AL-Muthanna governorate based on historical data of raw, settled, and filtered water turbidity values. They showed that 32% of filtered water turbidity readings exceeded the MPL of turbidity (5 NTU) and indicated that the uncontrolled addition of coagulants and unskilled operators are the main causes behind the low TRE values.

From reviewing the aforementioned literature that was conducted on evaluating the performance of CWTPs, especially in Najaf governorate, it can be noted that the previous studies detected the high turbidity of treated water. However, none of these studies have presented solutions to it. This article is a part of a comprehensive study that aims to investigate the high-turbidity problem of tap water in two cities of Najaf governorate and offer suitable measures to solve this problem. It concentrated on the role of water treatment plants (WTPs) in tap water turbidity.

2 Methodology

2.1 Study area location

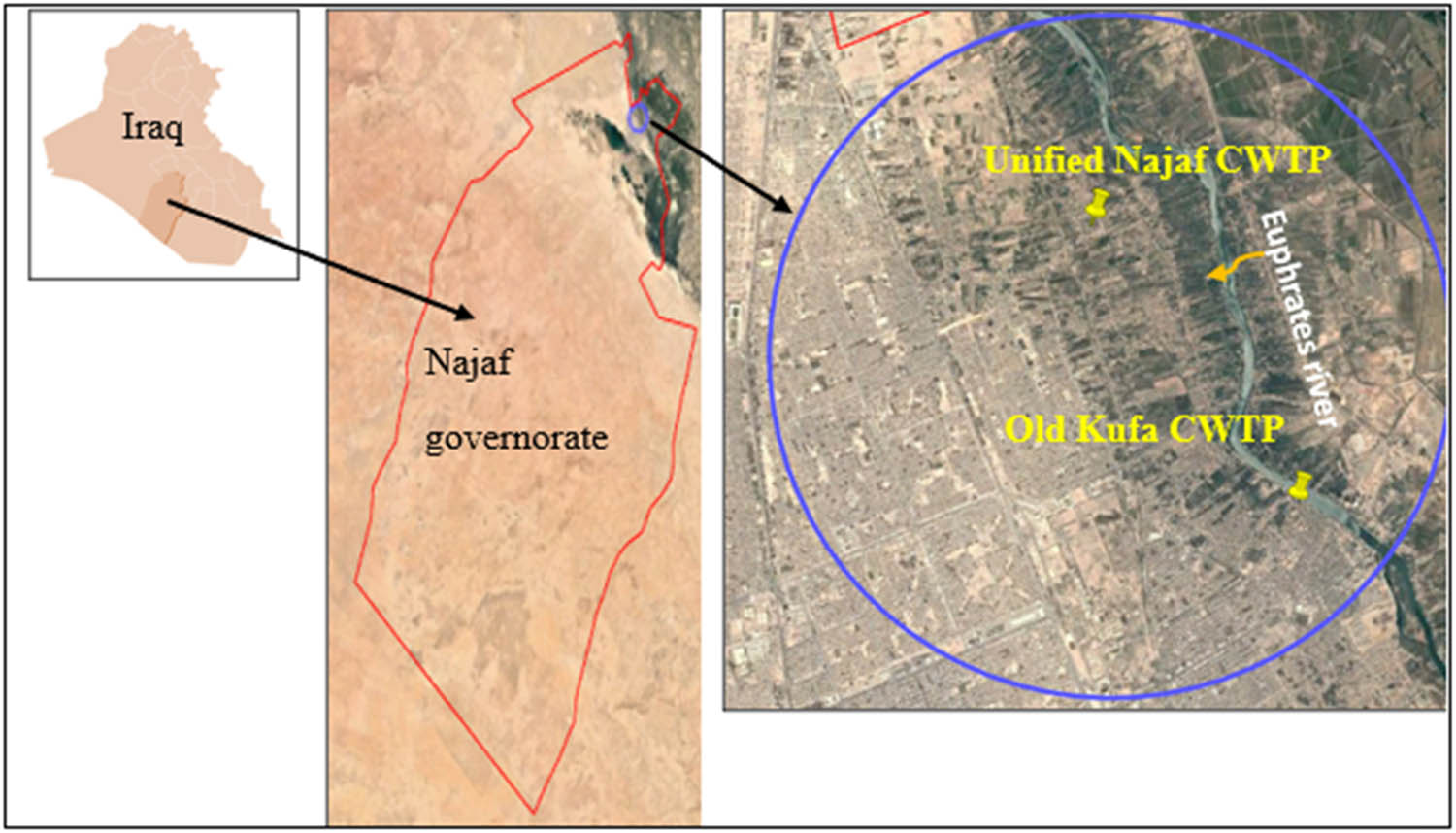

This study concerned two main CWTPs located in the Najaf governorate: Unified Najaf and Old Kufa WTPs (Figure 1). The first plant serves Najaf city, while the second plant serves Kufa city. These two cities are the main important cities of Najaf governorate in which about 81% of the total governorate population is settled. Unified Najaf WTP is located in Al-Zarka area of Kufa city at a latitude and longitude of 32°4′37.71″N and 44°22′11.40″E, respectively. However, the Old Kufa WTP is located in Kufa city at a latitude and longitude of 32°2′29.85″N and 44°23′59.82″E, respectively.

Location of Unified Najaf and Old Kufa WTPs.

2.2 Description of considered WTPs

This section describes the considered WTPs using the data gathered during field visits to the plants. It concentrates on treatment units applied for water turbidity removal, which are sedimentation unit, completed with flash mix and flocculation units, and filtration unit.

2.2.1 Unified Najaf WTP

Unified Najaf WTP was constructed in 1997. It is located in Kufa city/Najaf governorate and takes the raw water from Shatt Al-Kufa River (a branch of the Euphrates River). The design capacity of this plant was 9,000 m3/h. However, its present capacity is 13,500 m3/h. Unified Najaf WTP is a conventional type. It includes flash mix unit, clariflocculation unit (composed of concentric tanks; the inner tank is flocculation basin, and the outer tank is clarification basin), and filtration unit (Figure 2). The treatment unit characteristics of Unified Najaf WTP are presented in Table 1.

Treatment units in Unified Najaf CWTP.

Characteristics of treatment units in Unified Najaf WTP

| Treatment unit | Type | Number of tanks | Dimensions of each tank | Equipment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flash mix | Rectangular concrete tanks | 2 | Length = 3.95 m | Each tank is provided with a mixer of 8 kW power |

| Width = 1.75 m | ||||

| Side water depth = 7.3 | ||||

| Clariflocculation | Circular concrete tanks | 8 | Outer diameter = 38 m | Each flocculator is provided with a mixer of 4 kW power |

| Inner diameter = 14 m | ||||

| Side water depth = 4 m | ||||

| Gravity filtration | Rectangular gravity sand filters | 40 | 8 × 5 m2 | The unit is provided with three backwash pumps (2W + 1S), each of 500 m3/h capacity |

2.2.2 Old Kufa WTP

Old Kufa WTP was constructed in 1958. It takes the raw water from Shatt Al-Kufa River. The plant was designed for a capacity of 3,000 m3/h. However, at the present time, it is operated at a capacity of 4,500 m3/h. As a conventional type, Old Kufa WTP incorporates the same treatment train as that of Unified Najaf WTP. Figure 3 shows the layout of Old Kufa WTP, and the characteristics of treatment units concerning turbidity removal processes are presented in Table 2.

Treatment units in Old Kufa CWTP.

Characteristics of treatment units in Old Kufa WTP

| Treatment unit | Type | Number of tanks | Dimensions of each tank | Equipment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flash mix | Rectangular concrete tanks | 2 | Length = 5.5 m | Each tank is provided with a mixer of 7 kW power |

| Width = 2.75 m | ||||

| Side water depth = 5 m | ||||

| Clariflocculation | Circular concrete tanks | 2 | Outer diameter = 35 m | Each flocculator is provided with a mixer of 4 kW power |

| Inner diameter = 10 m | ||||

| Side water depth = 4 m | ||||

| Gravity filtration | Rectangular gravity sand filters | 10 | 9.25 × 9.30 m2 | The unit is provided with two backwash. pumps (1W + 1S), each of 3,600 m3/h capacity |

2.3 Water sampling and analysis

A fieldwork program of 9 months’ duration (February to October 2022) has been conducted at the sites of the considered WTPs. It included the collection of water samples from three locations in each plant: the influent of flash mix unit (raw water samples), the effluent of clariflocculation unit (settled water samples), and the effluent of filtration unit (filtered water samples). The water samples were gathered three times a day 2 h apart (9:00 AM, 11:00 AM, and 1:00 PM). The samples were analyzed for turbidity using a turbidity meter, model ME-PZD-2A.

The measured values of water turbidity were used to calculate TRE of clariflocculation and filtration units, in addition to that of the whole plant as an integrated system using the following equations:

where TREc, TREf, and TREp are the turbidity removal efficiencies of the clariflocculation unit, filtration unit, and the whole plant, respectively, and TURr, TURs, and TURf are the turbidity values of raw, settled, and filtered waters, respectively.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Tracking the water turbidity

Turbidity values of raw, settled, and filtered water samples represented as one group of samples during the months February through October 2022 are shown in Figures 4 and 5 for Unified Najaf and Old Kufa, respectively. Figure 4 shows that for nearly all the groups of samples, the turbidity of settled water was greater than that of raw water and the turbidity of filtered water was less than that of settled water. It, also, shows that although the filtration unit has reduced settled water turbidity, the filtered water turbidity in most groups of samples was greater than that of raw water. Figure 5 shows that in most groups of samples, the turbidity of settled water was greater than that of raw water. It shows, also, in some groups of samples, the turbidity of filtered water exceeded that of settled water.

Turbidity of raw, settled, and filtered waters in Unified Najaf WTP. (a) February to June 2022; (b) July to October 2022.

Turbidity of raw, settled, and filtered waters in Old Kufa WTP. (a) February to June 2022; (b) July to October 2022.

To reveal the monthly variation of turbidity values during the data collection period, the maximum, minimum, and mean turbidity values of raw, settled, and filtered waters during each month were obtained as presented in Tables 3 and 4 for Unified Najaf and Old Kufa WTPs, respectively. From these tables, it can be noted that the mean raw water turbidity values during the winter months for both WTPs were low as compared with those recorded during the summer months. The reason for the low turbidity values is the lack of rainfall during the rainy season of the year 2022, which causes a reduction in flow velocity and subsequently the rate of river bed erosion. However, the increase in raw water turbidity was caused by dredging activities near the Euphrates River banks done by the farmers in advance of rice planting season. The highest raw water turbidity value for each of Najaf Unified and Old Kufa WTPs was recorded in October, and it was 24.5 and 24.8 NTU, respectively. However, the lowest raw water turbidity value for each of Najaf Unified and Old Kufa WTPs was recorded in March, and it was 1.2 and 1.6 NTU, respectively. Tables 3 and 4 show that the monthly variation of settled and filtered water turbidity values followed the same trend as that of raw water in both WTPs.

Maximum, minimum, and mean turbidity values of raw, settled, and filtered waters in Unified Najaf WTP

| Month | Turbidity (NTU) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw water | Settled water | Filtered water | |||||||

| Max | Min | Mean | Max | Min | Mean | Max | Min | Mean | |

| February | 5.2 | 2.1 | 3.1 | 6 | 3.1 | 4.6 | 5.6 | 1.1 | 2.1 |

| March | 3.4 | 1.2 | 1.9 | 6 | 2.2 | 4.6 | 2.6 | 0.7 | 1.3 |

| April | 5.8 | 5 | 5.4 | 10.8 | 9.5 | 10 | 9.5 | 6 | 7.5 |

| May | 5.9 | 5.1 | 5.5 | 13.2 | 8.9 | 10.8 | 11.1 | 7.3 | 9.3 |

| June | 7.4 | 5.2 | 6.4 | 12.7 | 9.2 | 10.8 | 11.9 | 6.9 | 8.6 |

| July | 12.6 | 9.1 | 10.8 | 15.4 | 9.4 | 12.9 | 13.8 | 6.5 | 9.6 |

| August | 16 | 11.9 | 13.8 | 17.4 | 13 | 15.6 | 19 | 10.1 | 12.7 |

| September | 19.1 | 15.5 | 17.4 | 21.8 | 17.2 | 19.5 | 20.2 | 15.4 | 17.7 |

| October | 24.5 | 13.4 | 16.8 | 27.4 | 14.4 | 20.2 | 26.8 | 12.1 | 18.6 |

Max, minimum, and mean turbidity values of raw, settled, and filtered waters in Old Kufa WTP

| Month | Turbidity (NTU) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw water | Settled water | Filtered water | |||||||

| Max | Min | Mean | Max | Min | Mean | Max | Min | Mean | |

| February | 10.2 | 2.3 | 4.2 | 9.7 | 4.5 | 6.7 | 14.6 | 2.6 | 6.0 |

| March | 4.6 | 1.6 | 2.6 | 5.7 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 23.2 | 1.5 | 10.3 |

| April | 6.0 | 5.1 | 5.6 | 11.6 | 6.4 | 9.2 | 11.6 | 6.6 | 8.6 |

| May | 5.9 | 5.2 | 5.6 | 12.5 | 9.3 | 10.5 | 16.1 | 6.2 | 9.4 |

| June | 8.2 | 4.3 | 5.6 | 14.9 | 8.3 | 11 | 22.7 | 6.2 | 10.7 |

| July | 12.7 | 9.3 | 10.8 | 16.2 | 10.9 | 13.5 | 15.8 | 7.7 | 11.8 |

| August | 18.5 | 12.4 | 15.6 | 20.6 | 14.2 | 16.6 | 18.3 | 12.8 | 14.7 |

| September | 17.7 | 15.8 | 17.2 | 25.8 | 18.9 | 21.3 | 22.1 | 17.7 | 19.9 |

| October | 24.8 | 18.2 | 21.4 | 28.8 | 19.4 | 24.9 | 26.6 | 17.3 | 23.1 |

3.2 TRE

Using the measurements of raw, settled, and filtered water turbidity, the TRE of clariflocculation and filtration units and the overall plant TRE were calculated and the results are shown in Figures 6 and 7 for Unified Najaf and Old Kufa WTPs, respectively. Both figures show negative TRE values, indicating that for a specific treatment unit (or plant), the turbidity of effluent is greater than that of the influent. Figure 6 shows the bad performance (negative TRE) of the clariflocculation unit in Unified Najaf WTP, throughout the study period. It reveals the positive TRE of the filtration unit during most of the study period. However, the overall plant efficiency fluctuated between positive and negative TRE values. Out of 99 TRE values, the number of positive values was 3, 92, and 60, for TREc, TREf, and TREp, respectively. The maximum values of TREc, TREf, and TREp were 22.3, 86.5, and 61.5%, respectively. Figure 7 shows that the performance of Old Kufa WTP was worse than that of Unified Najaf WTP. Herein, out of 99 TRE values, the number of positive values was 6, 76, and 31, for TREc, TREf, and TREp, respectively. The maximum values of TREc, TREf, and TREp were 35.3, 68.6, and 60.0%, respectively.

TRE variation of Unified Najaf WTP during the period February to October 2022.

TRE variation of Old Kufa WTP during the period February to October 2022.

Figures 8 and 9 show the monthly averaged values of TREc, TREf, and TREp for Unified Najaf and Old Kufa WTPs, respectively. From these figures, it can be noted that the monthly averaged values of TREc were negative for all the months. The lowest value of monthly averaged TREc for Unified Najaf WTP occurred during March in spite of the raw water turbidity values during this month being low. However, the maximum monthly averaged TREf and TREp values were also observed during March. For Old Kufa WTP, the minimum monthly averaged TREc, TREf, and TREp occurred during March, too, which indicates that the low TRE values cannot be attributed to the increase of raw water turbidity of both plants.

Monthly averaged TREc, TREf, and TREp values of Unified Najaf WTP.

Monthly averaged TREc, TREf, and TREp values of Old Kufa WTP.

3.3 Effluent turbidity satisfaction with Iraqi standards

According to the Iraqi standards, the MPL of turbidity in WTPs effluent (tap water) is 5 NTUs (IQS 417, 2001) [19]. The effluent turbidity values of both WTPs were statistically analyzed, and the results are shown in Figures 10 and 11. The figures show that only 26 out of 99 and 9 out of 99 effluent turbidity readings in Unified Najaf and Old Kufa WTPs, respectively, satisfy Iraqi standards. Thus, the high-turbidity problem of tap water in Najaf governorate can be primarily attributed to the bad performance of WTPs.

Histogram for effluent turbidity of Unified Najaf WTP.

Histogram for effluent turbidity of Old Kufa WTP.

3.4 Solution measures for high-turbidity problem

In order to put measures for solving the problem of high-turbidity tap water caused by poorly treated water supply, the reasons behind the poor performance of WTPs must be identified. Some of these reasons were obvious and detected during the field visits to the considered plants, such as

The scrappers in clariflocculation units in both plants are out of operation, which affected the sludge removal process.

Sludge withdrawal process from the clarification tanks is not accomplished regularly, which caused the accumulation of sludge in these tanks and the reduction of hydraulic detention time.

Coagulant (alum) is not added to the flash mix units and the operators claimed that “there is no need to add alum, since raw water turbidity is low,” which means the clarification (sedimentation) unit in both plants acts as a pre-sedimentation unit. But since most of suspended particles in streams are colloids [20], the pre-sedimentation process may need a detention time exceeding 12 h to achieve a removal efficiency greater than 50% [21].

In Old Kufa WTP, the raw water was pumping directly into the clarifier (Figure 12), without passing through the flash mix and flocculation tanks, which may cause the resuspension of settled solids and, subsequently, reduce the clariflocculation unit efficiency.

Lack of continuous monitoring for filtered water turbidity and subsequently identifying the need for filters backwashing.

The majority of WTP employees lack the fundamental knowledge of water treatment processes.

Lack of continuous monitoring of plant operating conditions.

Inadequate maintenance and operation budgets for the plants.

Influent discharge into the clariflocculator of Old Kufa WTP.

In addition to the aforementioned points, to fill the shortage of water supply caused by population increase, the influent flowrates of both treatment plants were increased. That was done without expanding the existing treatment units to withstand the flowrate increase and preserve the units’ design criteria within their recommended ranges. Table 5 presents the checking results of presently applied design criteria for treatment units in Unified Najaf and Old Kufa WTPs along with their recommended ranges. The checking results are represented as “+” and “−” signs for units having applied values of design criteria that fall within and outside their recommended ranges, respectively. The applied values of design criteria were calculated by adopting the current influent flowrates, which are 13,500 and 4,500 m3/h for Unified Najaf and Old Kufa WTPs, respectively.

Checking the presently applied design criteria for treatment units in Unified Najaf and Old Kufa WTPs

| Unit | Design criteria | Recommended values [22] | Applied values | Check result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unified Najaf | Old Kufa | Unified Najaf | Old Kufa | |||

| Flash mix | Detention time (s) | 10–60 | 26.8 | 121.0 | + | − |

| Velocity gradient (s−1) | 600–1,000 | 354.0 | 270.5 | − | − | |

| Flocculation | Detention time, t (s) | 1,000–1,500 | 1,314 | 438 | + | − |

| Velocity gradient, G (s−1) | 10–60 | 71.7 | 107.3 | − | − | |

| t. G | 30,000–60,000 | 94,214 | 46,997 | − | + | |

| Clarification | Detention time (h) | 2–8 | 2.3 | 1.6 | + | − |

| Surface overflow rate (m/day) | 20–33 | 41.3 | 61.1 | − | − | |

| Weir load (m3/m day) | <250 | 364. 9 | 512.5 | − | − | |

| Filtration | Filtration rate (m/day) | 120–240 | 198.75 | 125.5 | + | + |

For Unified Najaf WTP, the results in Table 5 show that the applied values of detention time for flash mix, flocculation, and clarification units fall within their recommended ranges. But the other design criteria fall outside their recommended range. However, for Old Kufa WTP, the most applied values of design criteria, such as those of clarification unit, are unaccepted and that can be, besides the operational problems mentioned earlier, the reason behind the bad performance of clariflocculation unit in this plant.

From the aforementioned points, the solution measures of high-turbidity tap water in Najaf governorate include the following:

Increasing the power of flash mixers in both plants to get a velocity gradient (G) value not less than 600 s−1.

Increasing the number of clariflocculation tanks in both plants to lower the values of SOR and make them within the recommended range.

Lowering the mixing power in flocculation tanks to get a G-value not exceeding 60 s−1.

Achieving the coagulation process in both plants by continuous addition of coagulants at appropriate dosages using the jar test.

Continuous sludge withdrawal from clariflocculation units.

Maintaining the backwash process of filters.

4 Conclusions

The first part of investigating the problem of high-turbidity tap water in Najaf governorate as concerned with the performance of two main WTPs has led to the following conclusions:

The performance of the clariflocculation unit in Unified Najaf WTP was very poor. Out of 99 TRE values for this unit, the number of positive ones was 3 at a maximum value of 22.3%.

The performance of clariflocculation unit in Old Kufa WTP was, also, very poor. Out of 99 TRE values, the number of positive ones was 6 at a maximum value of 35.3%.

The TRE of filtration unit (TREf) in Unified Najaf WTP has a maximum value of 86.5%. However, sometimes it had negative values. The same condition was detected in Old Kufa WTP, but the TREf was not exceeding 68.6%.

The maximum TRE values for Unified Najaf and Kufa WTPs were 61.5 and 60.0%, respectively.

The low TRE values in both WTPs cannot be attributed to the increase in raw water turbidity.

Only 26 out of 99 and 9 out of 99 effluent turbidity readings in Unified Najaf and Old Kufa WTPs, respectively, satisfy Iraqi standards for tap water turbidity.

The bad performance of WTPs in Najaf governorate was the main reason behind the high turbidity of its tap water.

Upgrading the treatment units in both plants is essential for enhancing their performance. That should be combined with maintaining accurate plant operation and performance monitoring.

Nomenclature

| Symbol | Description | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| t | Detention time | Time unit |

|

|

Velocity gradient | s−1 |

|

|

Surface overflow rate | m/day |

| t. G | Detention time. Velocity gradient | Dimensionless |

Abbreviations

- CWTPs

-

Conventional water treatment plants

- WHO

-

World Health Organization

- TRE

-

Turbidity removal efficiency

- TREc

-

Turbidity removal efficiency of the clariflocculation unit

- TREf

-

Turbidity removal efficiency of the filtration unit

- TREp

-

Turbidity removal efficiency of the whole plant

- TURr

-

Turbidity values of raw water

- TURs

-

Turbidity values of settled water

- TURf

-

Turbidity values of filtered water

- NTU

-

Nephelometric Turbidity Unit

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] EPA. European Psychiatric Association. Manual turbidity provision EPA guidance; 1999, April, 7. p. 7.1–7.13. Online at: http://www. Epa. gov/OGWDW/mdbp/pdf/turbidity/chap–07.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Semmens MJ, Staples AB. The nature of organics removed during treatment of Mississippi river water. Am Water Work Assoc AWWA. 1996;78(2):76–81.10.1002/j.1551-8833.1986.tb05698.xSuche in Google Scholar

[3] Issa HM. Evaluation of water quality and performance for a water treatment plant: Khanaqin city as a case study. J Garmian Univ 3 (Khanaqine Conf). 2017;3(12):802–21. 10.24271/garmian.64 Special Issue.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Abd Al-Abbas MA. Study of evaluation the quality of Shatt Al-Kufa River water for domestic and irrigational uses. Iraqi J Mech Mater Eng. 2009;2010(Spec Issue c):399–407.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Salman AH. Evaluate the efficiency of water purification plants in the province of Najaf Through in 2009. J Educ Girls. 2010;11(6):59–73.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Salih ZA, Hasan AA. Evaluation of the efficiency of some water supply stations in Najaf Governorate using the weighted arithmetic index method (WQI). Muthanna J Eng Technol (MJET). 2018;6(2):185–99.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Al-Jeebory AA, Ghawi AH. Performance evaluation of Al-Dewanyia water treatment plant in Iraq. Al-Qadisiya J Eng Sci. 2009;2(4):836–53.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Abdul-Rahman EA, Muloud AA, Saud WM. Assessment of the quality of drinking water and the efficiency of the water purification plant in Falluja. Iraqi J Civ Eng. 2009;6(1):27–38.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Ramal MM. Evaluating the drinking water quality supplied by the large treatment plant in Ramadi city. Al-Qadisiyah J Eng Sci. 2010;3(2)32–56.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Mohammed AA, Shakir AA. Evaluation the performance of Al-wahdaa project drinking water treatment plant: A case study in Iraq. Int J Adv Appl Sci (IJAAS). 2012;1(3):130–8.10.11591/ijaas.v1i3.1302Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Al-Obaidy MB, Al-Ni’ma BA. Turbidity and removal efficiency in the main water purification plants of Nineveh province. Al-Rafidain Sci J. 2013;24(3):39–53.10.33899/rjs.2013.74572Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Selman HM, Abdul Wahid AA, Selman GM. Evaluating the performance of water treatment plant (case study: Al- Rumaith treatment plant, Al-Muthanna, Iraq). Elixir Civ Eng. 2015;82:32086–93.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Al-Dujail AM, Shamran HA. Assessment of the quality of drinking water and the efficiency of projects and complexes in the city of Karbala. Geogr Res J. 2016;2:79–102.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Hassan FM, Mahmood AR. Evaluate the efficiency of drinking water treatment plants in Baghdad city – Iraq. J Appl Environ Microbiol. 2018;6(1):1–9.10.1155/2019/7851354Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Al-Nasrawi FAM, Saleh LAM, Majeed SA. Evaluating drinking water quality and plants efficiency in Karbala-Iraq. 3rd International Conference & 4th National Conference on Civil Engineering, Architecture and Urban Design. ISC; 2018.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Ali HM, Zageer D, Alwash AH. Performance evaluation of drinking water treatment plant in Iraq. Orient J Phys Sci. 2019;4(1):18–29.10.13005/OJPS04.01.05Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Al-Tamir MA. The reality of water liquefaction stations in the city of Mosul. Al-Rafidain Eng J (AREJ). 2019;24(2):138–45.10.33899/rengj.2019.164330Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Nasier MA, Abdul-Razzaq KA. Performance evaluation the turbidity removal efficiency of AL-Muthana water treatment plant. J Eng. 2022;28(3):1–13.10.31026/j.eng.2022.03.01Suche in Google Scholar

[19] WHO. A compendium of drinking water quality standards in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean Regional Center for Environmental Health Activities (CEHA); 2006. p. 1–44.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Khudair KM, Hadi DM. Baffles shape and configuration effect on performance of baffled flocculator. Basrah J Eng Sci. 2019;19(1):35–51.10.33971/bjes.19.1.5Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Khudair KM, Abdulhasen KN. Design criteria for presedimentation basin treats: Shatt Al-Arab river water. J Eng Res. 2020;8(3):32–49.10.36909/jer.v8i3.7346Suche in Google Scholar

[22] American Water Works Association, American Society of Civil Engineers. Water treatment plant design. 4th edn. McGraw-Hill Inc; 2005.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Design optimization of a 4-bar exoskeleton with natural trajectories using unique gait-based synthesis approach

- Technical review of supervised machine learning studies and potential implementation to identify herbal plant dataset

- Effect of ECAP die angle and route type on the experimental evolution, crystallographic texture, and mechanical properties of pure magnesium

- Design and characteristics of two-dimensional piezoelectric nanogenerators

- Hybrid and cognitive digital twins for the process industry

- Discharge predicted in compound channels using adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS)

- Human factors in aviation: Fatigue management in ramp workers

- LLDPE matrix with LDPE and UV stabilizer additive to evaluate the interface adhesion impact on the thermal and mechanical degradation

- Dislocated time sequences – deep neural network for broken bearing diagnosis

- Estimation method of corrosion current density of RC elements

- A computational iterative design method for bend-twist deformation in composite ship propeller blades for thrusters

- Compressive forces influence on the vibrations of double beams

- Research on dynamical properties of a three-wheeled electric vehicle from the point of view of driving safety

- Risk management based on the best value approach and its application in conditions of the Czech Republic

- Effect of openings on simply supported reinforced concrete skew slabs using finite element method

- Experimental and simulation study on a rooftop vertical-axis wind turbine

- Rehabilitation of overload-damaged reinforced concrete columns using ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete

- Performance of a horizontal well in a bounded anisotropic reservoir: Part II: Performance analysis of well length and reservoir geometry

- Effect of chloride concentration on the corrosion resistance of pure Zn metal in a 0.0626 M H2SO4 solution

- Numerical and experimental analysis of the heat transfer process in a railway disc brake tested on a dynamometer stand

- Design parameters and mechanical efficiency of jet wind turbine under high wind speed conditions

- Architectural modeling of data warehouse and analytic business intelligence for Bedstead manufacturers

- Influence of nano chromium addition on the corrosion and erosion–corrosion behavior of cupronickel 70/30 alloy in seawater

- Evaluating hydraulic parameters in clays based on in situ tests

- Optimization of railway entry and exit transition curves

- Daily load curve prediction for Jordan based on statistical techniques

- Review Articles

- A review of rutting in asphalt concrete pavement

- Powered education based on Metaverse: Pre- and post-COVID comprehensive review

- A review of safety test methods for new car assessment program in Southeast Asian countries

- Communication

- StarCrete: A starch-based biocomposite for off-world construction

- Special Issue: Transport 2022 - Part I

- Analysis and assessment of the human factor as a cause of occurrence of selected railway accidents and incidents

- Testing the way of driving a vehicle in real road conditions

- Research of dynamic phenomena in a model engine stand

- Testing the relationship between the technical condition of motorcycle shock absorbers determined on the diagnostic line and their characteristics

- Retrospective analysis of the data concerning inspections of vehicles with adaptive devices

- Analysis of the operating parameters of electric, hybrid, and conventional vehicles on different types of roads

- Special Issue: 49th KKBN - Part II

- Influence of a thin dielectric layer on resonance frequencies of square SRR metasurface operating in THz band

- Influence of the presence of a nitrided layer on changes in the ultrasonic wave parameters

- Special Issue: ICRTEEC - 2021 - Part III

- Reverse droop control strategy with virtual resistance for low-voltage microgrid with multiple distributed generation sources

- Special Issue: AESMT-2 - Part II

- Waste ceramic as partial replacement for sand in integral waterproof concrete: The durability against sulfate attack of certain properties

- Assessment of Manning coefficient for Dujila Canal, Wasit/-Iraq

- Special Issue: AESMT-3 - Part I

- Modulation and performance of synchronous demodulation for speech signal detection and dialect intelligibility

- Seismic evaluation cylindrical concrete shells

- Investigating the role of different stabilizers of PVCs by using a torque rheometer

- Investigation of high-turbidity tap water problem in Najaf governorate/middle of Iraq

- Experimental and numerical evaluation of tire rubber powder effectiveness for reducing seepage rate in earth dams

- Enhancement of air conditioning system using direct evaporative cooling: Experimental and theoretical investigation

- Assessment for behavior of axially loaded reinforced concrete columns strengthened by different patterns of steel-framed jacket

- Novel graph for an appropriate cross section and length for cantilever RC beams

- Discharge coefficient and energy dissipation on stepped weir

- Numerical study of the fluid flow and heat transfer in a finned heat sink using Ansys Icepak

- Integration of numerical models to simulate 2D hydrodynamic/water quality model of contaminant concentration in Shatt Al-Arab River with WRDB calibration tools

- Study of the behavior of reactive powder concrete RC deep beams by strengthening shear using near-surface mounted CFRP bars

- The nonlinear analysis of reactive powder concrete effectiveness in shear for reinforced concrete deep beams

- Activated carbon from sugarcane as an efficient adsorbent for phenol from petroleum refinery wastewater: Equilibrium, kinetic, and thermodynamic study

- Structural behavior of concrete filled double-skin PVC tubular columns confined by plain PVC sockets

- Probabilistic derivation of droplet velocity using quadrature method of moments

- A study of characteristics of man-made lightweight aggregate and lightweight concrete made from expanded polystyrene (eps) and cement mortar

- Effect of waste materials on soil properties

- Experimental investigation of electrode wear assessment in the EDM process using image processing technique

- Punching shear of reinforced concrete slabs bonded with reactive powder after exposure to fire

- Deep learning model for intrusion detection system utilizing convolution neural network

- Improvement of CBR of gypsum subgrade soil by cement kiln dust and granulated blast-furnace slag

- Investigation of effect lengths and angles of the control devices below the hydraulic structure

- Finite element analysis for built-up steel beam with extended plate connected by bolts

- Finite element analysis and retrofit of the existing reinforced concrete columns in Iraqi schools by using CFRP as confining technique

- Performing laboratory study of the behavior of reactive powder concrete on the shear of RC deep beams by the drilling core test

- Special Issue: AESMT-4 - Part I

- Depletion zones of groundwater resources in the Southwest Desert of Iraq

- A case study of T-beams with hybrid section shear characteristics of reactive powder concrete

- Feasibility studies and their effects on the success or failure of investment projects. “Najaf governorate as a model”

- Optimizing and coordinating the location of raw material suitable for cement manufacturing in Wasit Governorate, Iraq

- Effect of the 40-PPI copper foam layer height on the solar cooker performance

- Identification and investigation of corrosion behavior of electroless composite coating on steel substrate

- Improvement in the California bearing ratio of subbase soil by recycled asphalt pavement and cement

- Some properties of thermal insulating cement mortar using Ponza aggregate

- Assessment of the impacts of land use/land cover change on water resources in the Diyala River, Iraq

- Effect of varied waste concrete ratios on the mechanical properties of polymer concrete

- Effect of adverse slope on performance of USBR II stilling basin

- Shear capacity of reinforced concrete beams with recycled steel fibers

- Extracting oil from oil shale using internal distillation (in situ retorting)

- Influence of recycling waste hardened mortar and ceramic rubbish on the properties of flowable fill material

- Rehabilitation of reinforced concrete deep beams by near-surface-mounted steel reinforcement

- Impact of waste materials (glass powder and silica fume) on features of high-strength concrete

- Studying pandemic effects and mitigation measures on management of construction projects: Najaf City as a case study

- Design and implementation of a frequency reconfigurable antenna using PIN switch for sub-6 GHz applications

- Average monthly recharge, surface runoff, and actual evapotranspiration estimation using WetSpass-M model in Low Folded Zone, Iraq

- Simple function to find base pressure under triangular and trapezoidal footing with two eccentric loads

- Assessment of ALINEA method performance at different loop detector locations using field data and micro-simulation modeling via AIMSUN

- Special Issue: AESMT-5 - Part I

- Experimental and theoretical investigation of the structural behavior of reinforced glulam wooden members by NSM steel bars and shear reinforcement CFRP sheet

- Improving the fatigue life of composite by using multiwall carbon nanotubes

- A comparative study to solve fractional initial value problems in discrete domain

- Assessing strength properties of stabilized soils using dynamic cone penetrometer test

- Investigating traffic characteristics for merging sections in Iraq

- Enhancement of flexural behavior of hybrid flat slab by using SIFCON

- The main impacts of a managed aquifer recharge using AHP-weighted overlay analysis based on GIS in the eastern Wasit province, Iraq

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Design optimization of a 4-bar exoskeleton with natural trajectories using unique gait-based synthesis approach

- Technical review of supervised machine learning studies and potential implementation to identify herbal plant dataset

- Effect of ECAP die angle and route type on the experimental evolution, crystallographic texture, and mechanical properties of pure magnesium

- Design and characteristics of two-dimensional piezoelectric nanogenerators

- Hybrid and cognitive digital twins for the process industry

- Discharge predicted in compound channels using adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS)

- Human factors in aviation: Fatigue management in ramp workers

- LLDPE matrix with LDPE and UV stabilizer additive to evaluate the interface adhesion impact on the thermal and mechanical degradation

- Dislocated time sequences – deep neural network for broken bearing diagnosis

- Estimation method of corrosion current density of RC elements

- A computational iterative design method for bend-twist deformation in composite ship propeller blades for thrusters

- Compressive forces influence on the vibrations of double beams

- Research on dynamical properties of a three-wheeled electric vehicle from the point of view of driving safety

- Risk management based on the best value approach and its application in conditions of the Czech Republic

- Effect of openings on simply supported reinforced concrete skew slabs using finite element method

- Experimental and simulation study on a rooftop vertical-axis wind turbine

- Rehabilitation of overload-damaged reinforced concrete columns using ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete

- Performance of a horizontal well in a bounded anisotropic reservoir: Part II: Performance analysis of well length and reservoir geometry

- Effect of chloride concentration on the corrosion resistance of pure Zn metal in a 0.0626 M H2SO4 solution

- Numerical and experimental analysis of the heat transfer process in a railway disc brake tested on a dynamometer stand

- Design parameters and mechanical efficiency of jet wind turbine under high wind speed conditions

- Architectural modeling of data warehouse and analytic business intelligence for Bedstead manufacturers

- Influence of nano chromium addition on the corrosion and erosion–corrosion behavior of cupronickel 70/30 alloy in seawater

- Evaluating hydraulic parameters in clays based on in situ tests

- Optimization of railway entry and exit transition curves

- Daily load curve prediction for Jordan based on statistical techniques

- Review Articles

- A review of rutting in asphalt concrete pavement

- Powered education based on Metaverse: Pre- and post-COVID comprehensive review

- A review of safety test methods for new car assessment program in Southeast Asian countries

- Communication

- StarCrete: A starch-based biocomposite for off-world construction

- Special Issue: Transport 2022 - Part I

- Analysis and assessment of the human factor as a cause of occurrence of selected railway accidents and incidents

- Testing the way of driving a vehicle in real road conditions

- Research of dynamic phenomena in a model engine stand

- Testing the relationship between the technical condition of motorcycle shock absorbers determined on the diagnostic line and their characteristics

- Retrospective analysis of the data concerning inspections of vehicles with adaptive devices

- Analysis of the operating parameters of electric, hybrid, and conventional vehicles on different types of roads

- Special Issue: 49th KKBN - Part II

- Influence of a thin dielectric layer on resonance frequencies of square SRR metasurface operating in THz band

- Influence of the presence of a nitrided layer on changes in the ultrasonic wave parameters

- Special Issue: ICRTEEC - 2021 - Part III

- Reverse droop control strategy with virtual resistance for low-voltage microgrid with multiple distributed generation sources

- Special Issue: AESMT-2 - Part II

- Waste ceramic as partial replacement for sand in integral waterproof concrete: The durability against sulfate attack of certain properties

- Assessment of Manning coefficient for Dujila Canal, Wasit/-Iraq

- Special Issue: AESMT-3 - Part I

- Modulation and performance of synchronous demodulation for speech signal detection and dialect intelligibility

- Seismic evaluation cylindrical concrete shells

- Investigating the role of different stabilizers of PVCs by using a torque rheometer

- Investigation of high-turbidity tap water problem in Najaf governorate/middle of Iraq

- Experimental and numerical evaluation of tire rubber powder effectiveness for reducing seepage rate in earth dams

- Enhancement of air conditioning system using direct evaporative cooling: Experimental and theoretical investigation

- Assessment for behavior of axially loaded reinforced concrete columns strengthened by different patterns of steel-framed jacket

- Novel graph for an appropriate cross section and length for cantilever RC beams

- Discharge coefficient and energy dissipation on stepped weir

- Numerical study of the fluid flow and heat transfer in a finned heat sink using Ansys Icepak

- Integration of numerical models to simulate 2D hydrodynamic/water quality model of contaminant concentration in Shatt Al-Arab River with WRDB calibration tools

- Study of the behavior of reactive powder concrete RC deep beams by strengthening shear using near-surface mounted CFRP bars

- The nonlinear analysis of reactive powder concrete effectiveness in shear for reinforced concrete deep beams

- Activated carbon from sugarcane as an efficient adsorbent for phenol from petroleum refinery wastewater: Equilibrium, kinetic, and thermodynamic study

- Structural behavior of concrete filled double-skin PVC tubular columns confined by plain PVC sockets

- Probabilistic derivation of droplet velocity using quadrature method of moments

- A study of characteristics of man-made lightweight aggregate and lightweight concrete made from expanded polystyrene (eps) and cement mortar

- Effect of waste materials on soil properties

- Experimental investigation of electrode wear assessment in the EDM process using image processing technique

- Punching shear of reinforced concrete slabs bonded with reactive powder after exposure to fire

- Deep learning model for intrusion detection system utilizing convolution neural network

- Improvement of CBR of gypsum subgrade soil by cement kiln dust and granulated blast-furnace slag

- Investigation of effect lengths and angles of the control devices below the hydraulic structure

- Finite element analysis for built-up steel beam with extended plate connected by bolts

- Finite element analysis and retrofit of the existing reinforced concrete columns in Iraqi schools by using CFRP as confining technique

- Performing laboratory study of the behavior of reactive powder concrete on the shear of RC deep beams by the drilling core test

- Special Issue: AESMT-4 - Part I

- Depletion zones of groundwater resources in the Southwest Desert of Iraq

- A case study of T-beams with hybrid section shear characteristics of reactive powder concrete

- Feasibility studies and their effects on the success or failure of investment projects. “Najaf governorate as a model”

- Optimizing and coordinating the location of raw material suitable for cement manufacturing in Wasit Governorate, Iraq

- Effect of the 40-PPI copper foam layer height on the solar cooker performance

- Identification and investigation of corrosion behavior of electroless composite coating on steel substrate

- Improvement in the California bearing ratio of subbase soil by recycled asphalt pavement and cement

- Some properties of thermal insulating cement mortar using Ponza aggregate

- Assessment of the impacts of land use/land cover change on water resources in the Diyala River, Iraq

- Effect of varied waste concrete ratios on the mechanical properties of polymer concrete

- Effect of adverse slope on performance of USBR II stilling basin

- Shear capacity of reinforced concrete beams with recycled steel fibers

- Extracting oil from oil shale using internal distillation (in situ retorting)

- Influence of recycling waste hardened mortar and ceramic rubbish on the properties of flowable fill material

- Rehabilitation of reinforced concrete deep beams by near-surface-mounted steel reinforcement

- Impact of waste materials (glass powder and silica fume) on features of high-strength concrete

- Studying pandemic effects and mitigation measures on management of construction projects: Najaf City as a case study

- Design and implementation of a frequency reconfigurable antenna using PIN switch for sub-6 GHz applications

- Average monthly recharge, surface runoff, and actual evapotranspiration estimation using WetSpass-M model in Low Folded Zone, Iraq

- Simple function to find base pressure under triangular and trapezoidal footing with two eccentric loads

- Assessment of ALINEA method performance at different loop detector locations using field data and micro-simulation modeling via AIMSUN

- Special Issue: AESMT-5 - Part I

- Experimental and theoretical investigation of the structural behavior of reinforced glulam wooden members by NSM steel bars and shear reinforcement CFRP sheet

- Improving the fatigue life of composite by using multiwall carbon nanotubes

- A comparative study to solve fractional initial value problems in discrete domain

- Assessing strength properties of stabilized soils using dynamic cone penetrometer test

- Investigating traffic characteristics for merging sections in Iraq

- Enhancement of flexural behavior of hybrid flat slab by using SIFCON

- The main impacts of a managed aquifer recharge using AHP-weighted overlay analysis based on GIS in the eastern Wasit province, Iraq