Abstract

The behavior of concrete-filled double-skin poly vinyl chloride (PVC) tubular columns confined by plain PVC sockets is studied in this research. The plastic pipes have been used with concrete as columns. PVC has several advantages as it is inexpensive, light weight for construction, and decrease in the time taken for construction. Thus it can be used as an alternative to metal in various applications in which the maintenance cost is increased and the corrosion is reduced. This study is an experimental work on four groups of composite hollow PVC columns, each group containing three different samples. The effects of several parameters are studied, including slenderness ratio, compactness ratio, compressive strength, and confinement ratio. The experimental results show that stiffness, strength, as well as the ductility of composite columns of different loadings were considerably influenced by all these parameters. An increase in loading carrying capacity by about 40.4% was noticed as slenderness ratio decreased from 20 to 12 and about 21.1% as compactness ratio decreased from 50 to 25. Besides, the rate of increase in load capacity was about 96.6% as compressive strength increased from 33 to 54 MPa. For the case of variation of confinement ratio from 25 to 75%, the increase in the axial load capacity was about 56.7%. The main benefit of this type of column is the interaction between PVC tube and concrete. Besides, restriction of concrete by tube results in the delay of local buckling so that the concrete strength is enlarged by the effect of confining provided by the tube.

1 Introduction

Columns consisting of more than one material are typically named as composite columns. Various materials effort together to attack the strains as well as stresses induced by external applied loads in these columns.

Actually, the conventional reinforced concrete columns might be denoted as composite columns as they consist of steel in addition to concrete, though the term “composite columns” is typically used to state applications like sections filled with or encased in concrete as seen in Figure 1.

Different types of composite columns. (a) Encased and (b) concrete-filled.

Various materials are usually used with concrete like wood, steel, aluminum, plastic tubes as well as the fiber-reinforced polymer.

Basically, unplasticized poly vinyl chloride (PVC) pipes are resistant to destruction and remain for long time without the necessity for standby and are impermeable to fluids and gases in addition to being durable. These types of pipes are extensively used in the construction industry [1].

The plastic pipes have been used with concrete as columns. These kinds of columns are usually denoted to as concrete-filled plastic tube.

This type of column is used since it is inexpensive and economical kind of column for its light weight structure. In addition, plastic tube is stay-in-place formwork which is used as a substitute to the conventional formwork system.

The systems are chiefly gathered on site leading to simplify the construction process in addition to reducing the time of construction.

The interaction between concrete and plastic tube is regarded as one of the chief advantages, so the tube local buckling is delayed by restriction of concrete and the concrete strength is improved through the restraining effect of the tube [2].

2 Numerical and experimental research

The experimental and theoretical analyses on composite confined PVC columns filled with concrete have been studied by a number of researchers.

An experimental investigations and theoretical analysis on commercially presented plastic pipe filled with a concrete core were conducted [3]. The theoretical analysis inferred a corresponding rising in the concrete strength and an interaction between the plastic pipe and concrete core. The structural behavior of the plastic pipe was like the performance of spiral reinforcement under a column loading. Besides, the plastic pipe causes an increase in the concrete core strength about 3.2 times the pipe burst pressure.

Marzouck and Sennah [4] assessed the use of the commercially available PVC tubes as compression members filled with concrete. Four concrete-filled PVC columns were tested experimentally up-to-failure. The diameter of whole samples was 100 mm and of several heights. Two reference plain concrete samples were tested for providing the involvement of the PVC tube in the concrete confinement. All specimens were exposed to monotonically increase the axial load until compression failure happened and were tested vertically. The relationship between axial load and displacement is documented for all samples. This research offered a latitude for additional study to conduct experiments on concrete-filled PVC tube having different concrete properties as well as different slenderness ratios to further recognize the behavior and then, suggest a design approach for using this type of composite columns in light construction.

The experimental research on columns of concrete-filled unplasticized PVC tubes in marine environment was studied [5] by filling reinforced concrete to the tubes subjected to artificial sea water equipped in the laboratory. Totally, 72 specimens of length equal to 800 mm were casted by filling the reinforced concrete in the tubes with different diameters of 160, 200, and 225 mm. The diameter-to-thickness ratio of the specimen varied from 22.48 to 40.14 and length-to-diameter ratio of the specimens also varied from and 3.56 to 5. All the specimens were subjected to axial load on the core of the concrete in order to attain load–displacement curves and failure modes. No degradation in the ductility and strength of reinforced concrete-filled unplasticized PVC tubular specimens was detected after submerge in the sea water. It can be established that unplasticized PVC tube offers a safety jacketing to encase the core of concrete, and consequently develop ductility and strength.

Naftary et al. [6] studied the influence of using unplasticized poly vinyl tubes in restraining short concrete columns on the compressive strength by using an experimental program in which plastic tubes – with various diameters and heights – were used to restrict concrete of various strengths. The composite columns were applied to concentric axial compressive loads till failure. A typical shear failure was the principal failure mode. The results showed that compressive strength of the column samples increases through rising in concrete strength and reduced with the rising in column height.

Many experimental studies have been conducted on concrete-filled PVC tubes [7,14].

The concrete strength is increased by adding steel fibers. The steel fibers have a reinforcement effect on cement components that improves the brittle nature of cementitious materials [15].

Raheemah et al. [16] investigated experimental study with several variables such as concrete filling compressive strength, PVC section compactness ratio, and column slenderness ratio. The samples were exposed to uniaxial compression in two loading modes. For the first mode, a PVC tube was employed as a composite element to improve the concrete core, while a PVC tube in the second mode was employed to restrain the concrete core alone.

Nine sections of PVC–concrete with various characteristics of PVC tube and various compressive strengths of filled concrete were regarded in a number of fabricated slender PVC–concrete columns. The column lengths were changed in order to examine the total column buckling. The results presented that the columns composite mode displayed further strength enhancement than the confined mode. Experiments established that the effective flexural stiffness was accordingly normalized in the term of PVC tube stiffness as well as filling concrete stiffness, and the normalized results showed that effective flexural stiffness based on the mode whichever being composite or confining mode, PVC as well as strength of filling concrete, in addition to column slenderness ratio.

It is obvious from this review that it is essential to study the behavior of confined composite hollow PVC columns filled with concrete. However, it is inexpensive, more economical kind of column for light weight construction, and decrease in the time of construction as the plastic tube substitute the formwork. Also, the tube local buckling is delayed by restriction of concrete and the confining effect of the tube led to an increase in the concrete strength.

3 Objective of research

The objective of this research is to study the structural behavior of confined composite hollow PVC columns filled with concrete. This kind of columns is commonly known as concrete-filled PVC tube.

This type of columns is used since it is inexpensive, more economical due to light weight construction, and decrease in the time of construction as the removal. Also, the local buckling of the tube is delayed through restriction of concrete and the confining effect of the tube led to an increase in the concrete strength.

The main advantage of this type of column is the interaction between PVC tube and concrete. Besides, restriction of concrete by tube results in delay of the local buckling, so that the concrete strength is enlarged by the effect of confining provided by the tube.

4 Experimental program

Twelve samples in addition to control sample are tested by subjecting to a compression test by applying pressure load up to failure to determine the influence of these parameters on strength and the local buckling of composite PVC columns.

4.1 Specimens details

Twelve samples are divided into four groups. In addition, the control sample has a length equal to 600 mm, diameter of 100 mm, and the diameter of inner hollow equal to 50 mm. Each group consists of three specimens. All columns in the first group have the same thickness, same compressive strength, and diameter but with different length and slenderness ratio (L/r), which is defined as the ratio between the length of the tube to its radius (L/r) – the external confinement of ratio is 50%. In the second group, all columns have same length, same compressive strength, and diameter but with different thickness and compactness ratio (D/tp), which is defined as the ratio between the tube diameters to its thickness (D/t) and having the same confinement ratio which is equal to 50%. In case of the third group, all parameters are constant except the compressive strength which is varied into three targets (33, 36, 54 MPa). For the fourth group, only confinement ratio varied which represents the ratio of the total length of PVC socket to the total length of PVC pipe and the other parameters remained constant. PVC pipe normally bonds to concrete. The details of all groups are displayed in Table 1 and Figure 2.

Details of all groups

| Sample | Group | Length (L) (mm) | Thickness (t) (mm) | Diameter (D) (mm) | Diameter of inner tube (mm) | Compressive strength | Confinement ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SC | 600 | — | 100 | — | 33 | — | |

| S1 | G1 | 600 | 3 | 100 | 50 | 33 | 50 |

| S2 | 800 | 3 | 100 | 50 | 33 | ||

| S3 | 1,000 | 3 | 100 | 50 | 33 | ||

| S4 | G2 | 800 | 2 | 100 | 50 | 33 | 50 |

| S5 | 800 | 3 | 100 | 50 | 33 | ||

| S6 | 800 | 4 | 100 | 50 | 33 | ||

| S7 | G3 | 1,000 | 3 | 100 | 50 | 33 | 50 |

| S8 | 1,000 | 3 | 100 | 50 | 36 | ||

| S9 | 1,000 | 3 | 100 | 50 | 54 | ||

| S10 | G4 | 800 | 3 | 100 | 50 | 33 | 25 |

| S11 | 800 | 3 | 100 | 50 | 33 | 50 | |

| S12 | 800 | 3 | 100 | 50 | 33 | 75 |

Details of all groups.

4.2 Material properties

The materials used in concrete mixes are ordinary Portland cement and crushed gravel having a maximum size of 10 mm particles. The bulk specific gravity of this aggregate is 2.8 and sulfate content is 0.08% for the case of natural sand, its sulfate content SO3 is (0.11%) by sand weight and a specific gravity is 2.6. The grading of both coarse and fine aggregate is shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Besides, discrete steel fiber as well as water reducer, which is special chemical products, is added to the concrete mixture before it is poured to reduce the water content. It reduces the porosity of concrete and increases the concrete strength. Different percent of steel fibers ranging from 1 to 1.9% is added by making several trail mixes to reach the required target of concrete strength. The properties of steel fiber are shown in Table 4. The concrete compressive strength depended on the average values of 150 mm × 150 mm × 150 mm cubes. The stress–strain curve of the concrete used is shown in Figure 3. In addition, a concrete rupture is calculated through splitting test. Table 5 shows the mixing proportions of the material used for concrete mix. The inner diameter of plain sockets is 110 mm and its thickness is 5 mm.The mechanical properties of PVC tube and PVC sockets are detailed in Tables 6 and 7.

Grading of coarse aggregate

| Sieve size (mm) | % Passing | Limit of the Iraqi specifications (No. 45/1984) |

|---|---|---|

| 14 | 100 | 90–100 |

| 10 | 75 | 50–85 |

| 5 | 0.96 | 0–10 |

| Pan | 0 | 0 |

Grading of fine aggregate

| Sieve size | % Passing | Limit of the Iraqi specifications (No. 45/1984) zone two |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | 100 | 100 |

| 4.75 | 93 | 90–100 |

| 2.36 | 78.1 | 75–100 |

| 1.18 | 61 | 55–90 |

| 0.6 | 48 | 35–59 |

| 0.3 | 20 | 8–30 |

| 0.15 | 5 | 0–10 |

| Pan | 0 | 0 |

Properties of the steel fiber

| Length (mm) | Diameter | Aspect ratio | Tensile strength (MPa) | Density (g/cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 35 | 0.55 | 65 | 1,000 | 7.85 |

Stress–strain curve for the concrete used.

Mixing proportions of materials

| Fc′ (MPa) | Water (kg/m3) | Cement (kg/m3) | Sand (kg/m3) | Gravel (kg/m3) | Steel fiber (kg/m3) | Water reducer (kg/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 33 | 180 | 321 | 624 | 1,110 | 156 | 3.2 |

| 36 | 180 | 400 | 650 | 115 | 80 | 4.1 |

| 54 | 176 | 584 | 755 | 876 | 93 | 5.8 |

Mechanical properties of the plastic PVC tubes

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Average modulus of elasticity (MPa) | 2,797 |

| Average ultimate tensile stress (MPa) | 50.1 |

Mechanical properties of the PVC sockets

| Density-specific gravity (kg/m3) | Ultimate tensile strength (MPa) | Compressive yield strength (MPa) | Yield stress (MPa) | Poisson’s ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.47 | 52 | 5.8 | 152 | 38.0 |

4.3 Preparation stages

4.3.1 Cutting stage

The models were cut at the required lengths as mentioned previously and as shown in Figure 4.

Cutting stage of all specimens.

4.3.2 Casting stage

At this stage, all models were poured according to the previously mentioned mixing ratios. First, the outer pipe is put over a plate on the floor of the lab. Then the inner tube is centered in the middle of outer tube and the casting process started. A mechanical vibrator was used throughout the casting process to avoid nesting in concrete. A perforated cap was placed to measure the diameter of the inner tube, in order to keep the centrality of the inner tube which will be in the middle of composite column. The casting stage is shown in Figure 5.

Casting stage of all specimens.

5 Test results of the work

The experimental tests were carried out on 12 composite doubly skinned hollow PVC composite columns with different lengths, thicknesses, compressive strength, and confinement ratios which are subjected to a compression test by applying pressure load up to failure using a hydraulically testing machine as shown in Figure 6. The experimental results have shown that the increase in length reduces the vulnerability of carrying columns as well as increase in thickness and compressive strength of concrete and the restriction ratios cause an increasing in concrete load carrying capacity.

Hydraulically testing machine.

The variations of lateral strain on the applied load at the third and middle height of control column can be represented as Sc1 and Sc2, respectively, and as St1 and St2, respectively, for the case of PVC column. Besides, the axial strain at the mid-height can be represented as Sc3 for the case of control column and as St3 for the case of PVC column as shown in Figures 7–12.

Load versus lateral and axial strain for control sample of length 600 mm.

Load versus lateral and axial strain for control sample and the PVC specimen S1 having a length of 600 mm.

Load versus lateral and axial strain for column with length: (a) 600 mm, (b) 800 mm, and (c) 1,000 mm.

Load versus lateral and axial strain for column with thickness: (a) 2 mm, (b) 3 mm, and (c) 4 mm.

Load versus lateral and axial strain for column with compressive strength: (a) 33 MPa, (b) 36 MPa, and (c) 54 MPa.

Load versus lateral and axial strain for column with confinement ratio: (a) 25%, (b) 50%, and (c) 75%.

The failure load and the corresponding axial and lateral strain are summarized in Table 8.

Summary of experimental results

| Sample | Group | Lateral strain at the third height of column | Lateral strain at mid-height | Axial strain at mid-height of the column | Failure load |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SC | 0.00046 | 0.00076 | 0.0016 | 95 | |

| S1 | G1 | 0.000639 | 0.000684 | 0.00205 | 125 |

| S2 | 0.006622 | 0.006 | 0.011979 | 105 | |

| S3 | 0.00842 | 0.0069 | 0.009 | 89 | |

| S4 | G2 | 0.00096 | 0.005027 | 0.0084 | 90 |

| S5 | 0.006622 | 0.006 | 0.011979 | 105 | |

| S6 | 0.001338 | 0.0036101 | 0.006421 | 109 | |

| S7 | G3 | 0.00842 | 0.0069 | 0.009 | 89 |

| S8 | 0.005641 | 0.00654 | 0.00888 | 121 | |

| S9 | 0.0037 | 0.0057 | 0.0098 | 175 | |

| S10 | G4 | 0.001753333 | 0.00712195 | 0.00953 | 81.7 |

| S11 | 0.006622 | 0.006 | 0.011979 | 105 | |

| S12 | 0.003363778 | 0.01 | 0.013221 | 128 |

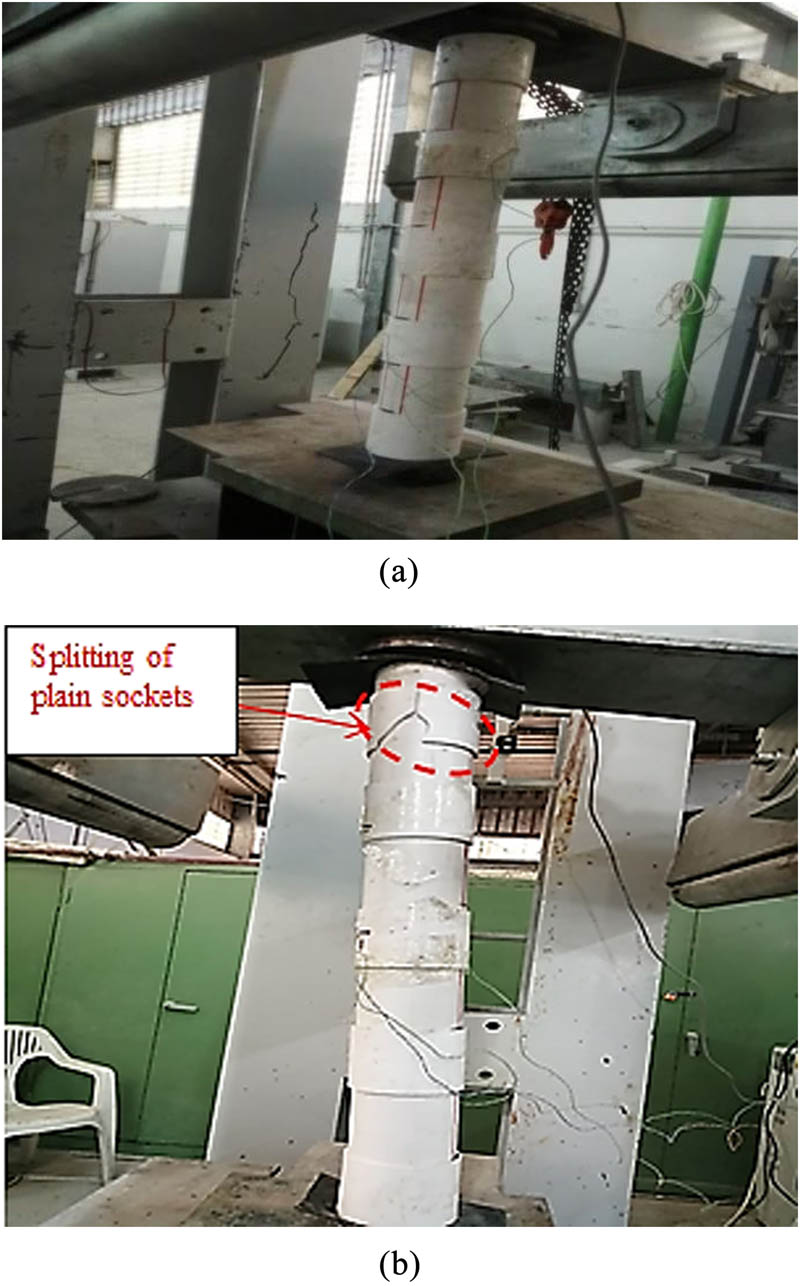

6 Failure modes

All composite PVC columns undergo global elastic buckling which is followed by substantial local buckling deformation, causing a sudden reduction in loading carrying capacity. In addition, the outward expansion of the composite PVC columns leds to drum type failure.

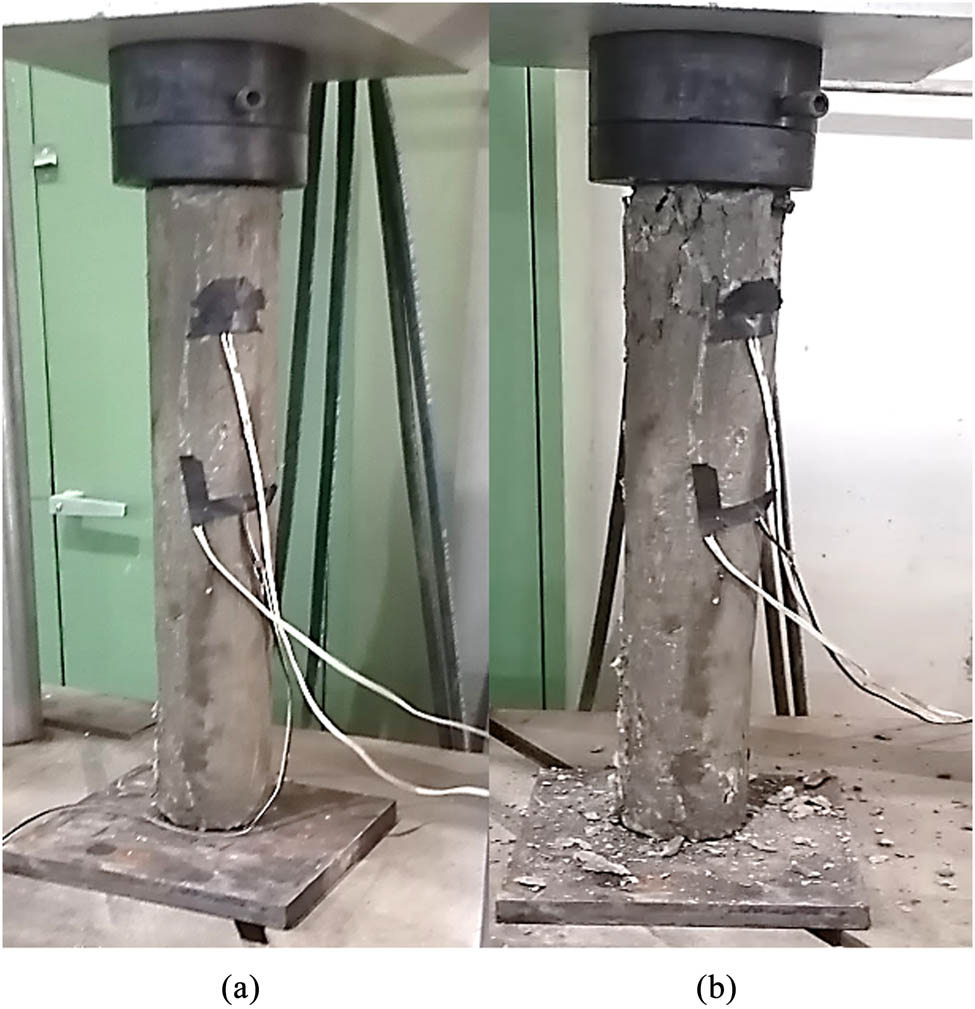

In the case of concrete column, a longitudinal crack in the top region of column in addition to concrete crushing is noticed as shown in Figure 13.

Failure mode concrete column with slenderness ratio equal to 20. (a) before test, (b) after test.

As concerned to slender PVC concrete columns, stability failure controls the wholly tested samples that also undergo global elastic buckling in addition to local buckling deformation and considerable failure of concrete led to sudden reduction in the loading capacity with assigned sustainable lateral deformation.

7 Parametric study

Several parameters in this experimental test are studied, including slenderness ratio, compactness ratio, target of compressive strength, as well as confinement ratio, so as to study the effect of these parameters on the peak load of each composite PVC columns and the value of the lateral and axial strain.

7.1 Slenderness ratio

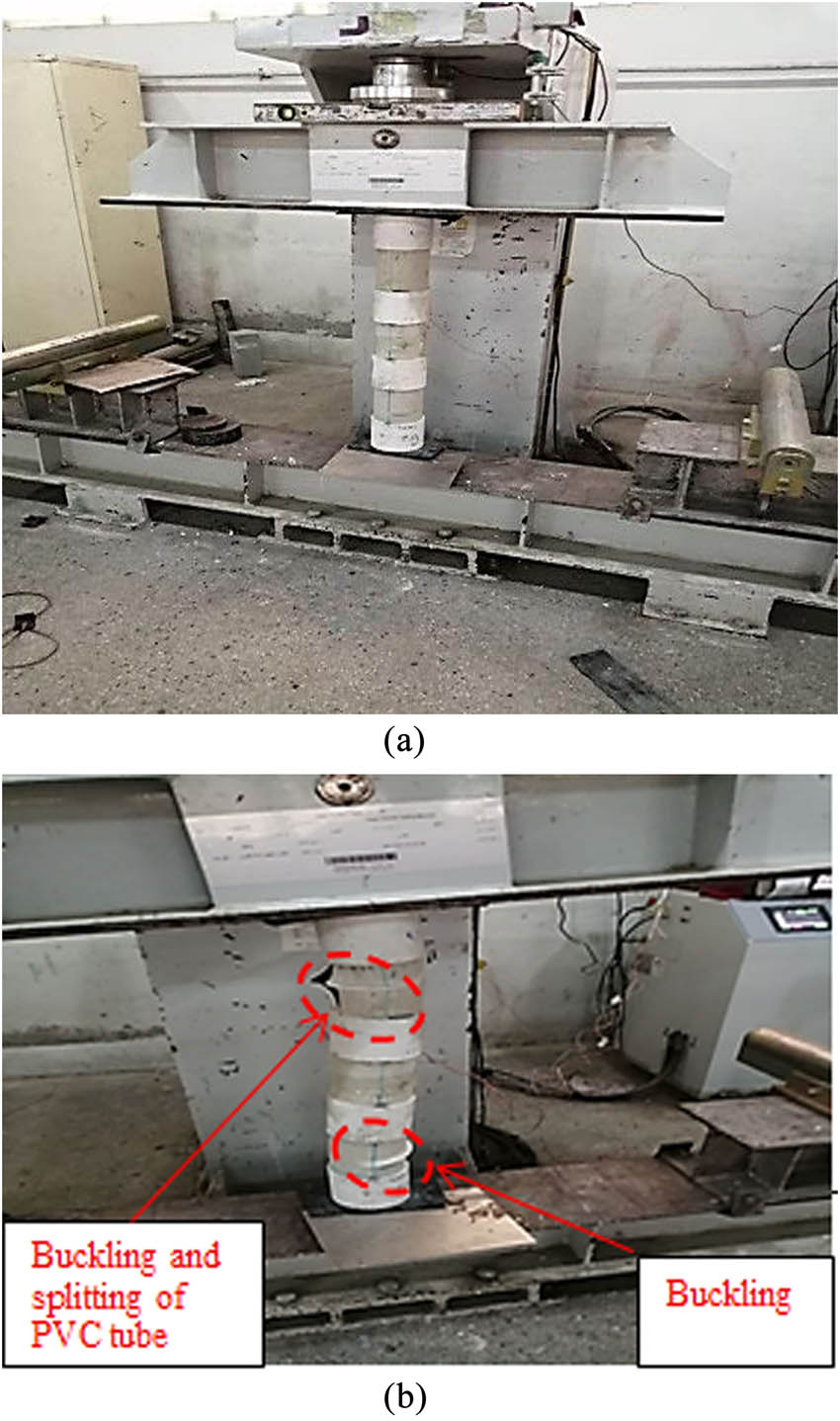

The failure modes of composite PVC column having different slenderness ratios which is defined as the ratio between the length of tube to its radius (L/r) by change the length of the sample pipe and fix all the retained parameters are shown in Figure 18. By making a comparison between them, it can be observed that stiffness and ultimate load of the composite column decrease with an increase in the slenderness ratio (i.e. increase in length). It can be noticed that there is an increase in peak load of about 17.97% as slenderness ratio decrease from 20 to 16 and about 19% as slenderness ratio decreased from 16 to 12. Subsequently, the total increase in peak load was about 40.4 as slenderness ratio decreased from 20 to 12. This variety in slenderness ratio is due to varying in the length of the column that made the global buckling could be examined the less resistance to the applied load will be, and it will lead to faster deformation as well as faster failure. Columns with a high slenderness ratio are more susceptible to buckling and are classified as “long” columns. The failure modes for composite column are shown in Figures 13–18.

Failure mode of composite column with slenderness ratio equal to 12. (a) before test, (b) after test.

Failure mode of composite column with slenderness ratio equal to 16. (a) before test, (b) after test.

Failure mode of composite column with slenderness ratio equal to 20. (a) before test, (b) after test.

Failure mode of all composite columns of group 1.

Load versus strain at mid-height of column for different slenderness ratios: (a) lateral strain and (b) axial strain.

7.2 Compactness ratio

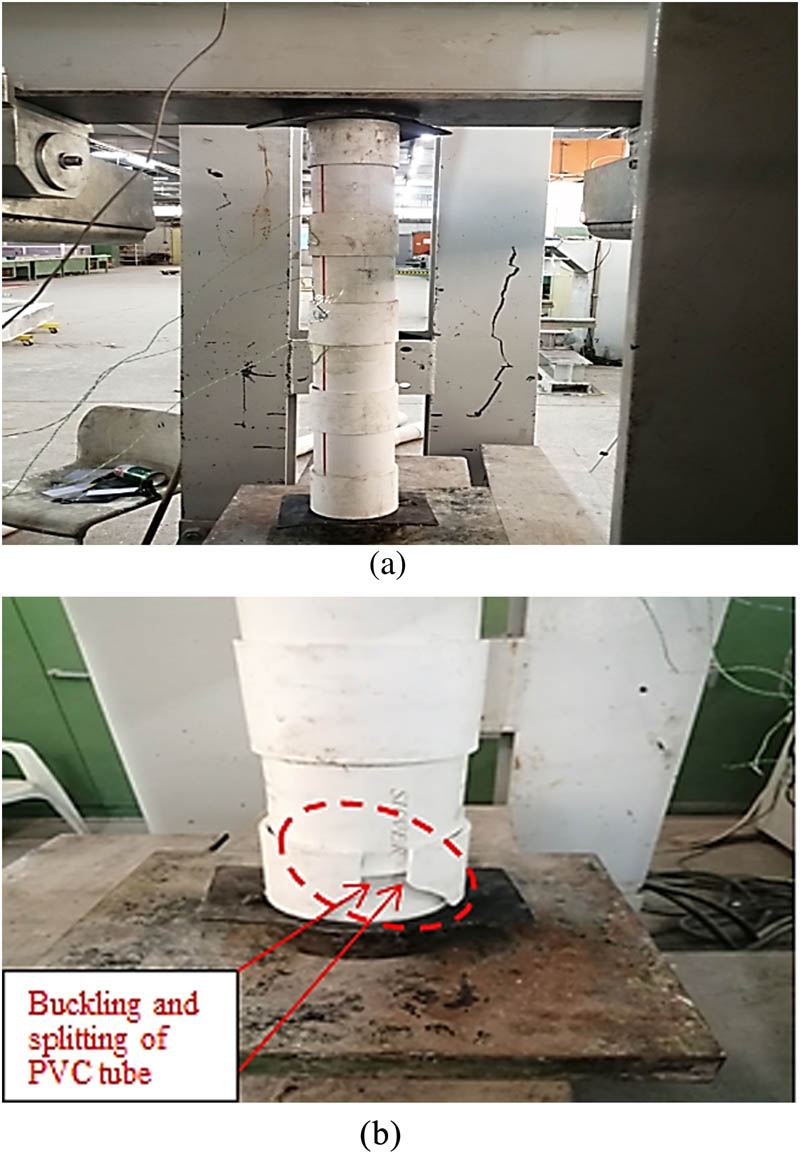

Figure 23 shows another comparison between composite PVC column with different compactness ratios which is defined as the ratio between column diameters to its thickness (D/t) by change the thickness of all sample columns and fix all other parameters. From this comparison, it can be observed that the rate of increase in peak load was about 16.67% as the compactness ratio decreased from 50 to 33.3 and about 3.8% as it decreased from 33.3 to 25. Consequently, the total increase in peak load was about 21.1% as compactness ratio decreased from 50 to 25 as shown in Figure 8. The failure mode of these composite column is shown in Figures 19–23.

Failure mode of composite column with compactness ratio equal to 50. (a) before test, (b) after test.

Failure mode of composite column with compactness ratio equal to 33.3. (a) before test, (b) after test.

Failure mode of composite column with compactness ratio equal to 25. (a) before test, (b) after test.

Failure mode of all composite columns of group 2.

Load versus strains at mid-height of column for different compactness ratios: (a) lateral strain and (b) axial strain.

The total increase in peak load was about 96.6% as compressive strength increased from 33 to 54.

7.3 Compressive strength

For the case of third group, the effect of compressive strength was studied by changing the target of compressive strength of concrete and retaining all other parameters without any change. The failure modes of each column are shown in Figures 24–28.

Failure mode of composite column with compressive strength equal to 33 MPa. (a) before test, (b) after test.

Failure mode of composite column with compressive strength equal to 36 MPa. (a) before test, (b) after test.

Failure mode of composite column with compressive strength equal to 54 MPa. (a) before test, (b) after test.

Failure mode of all composite columns of group 3.

Load versus lateral strain at mid-height of column for different compressive strengths: (a) lateral strain and (b) axial strain.

Figure 28 displays the relation between axial load and lateral strain.

From this figure it can be noted a rise in load capacity by about 36% as the compressive strength increased from 33 to 36 MPa and about 44.6% as compressive strength increased from 36 to 54 MPa.

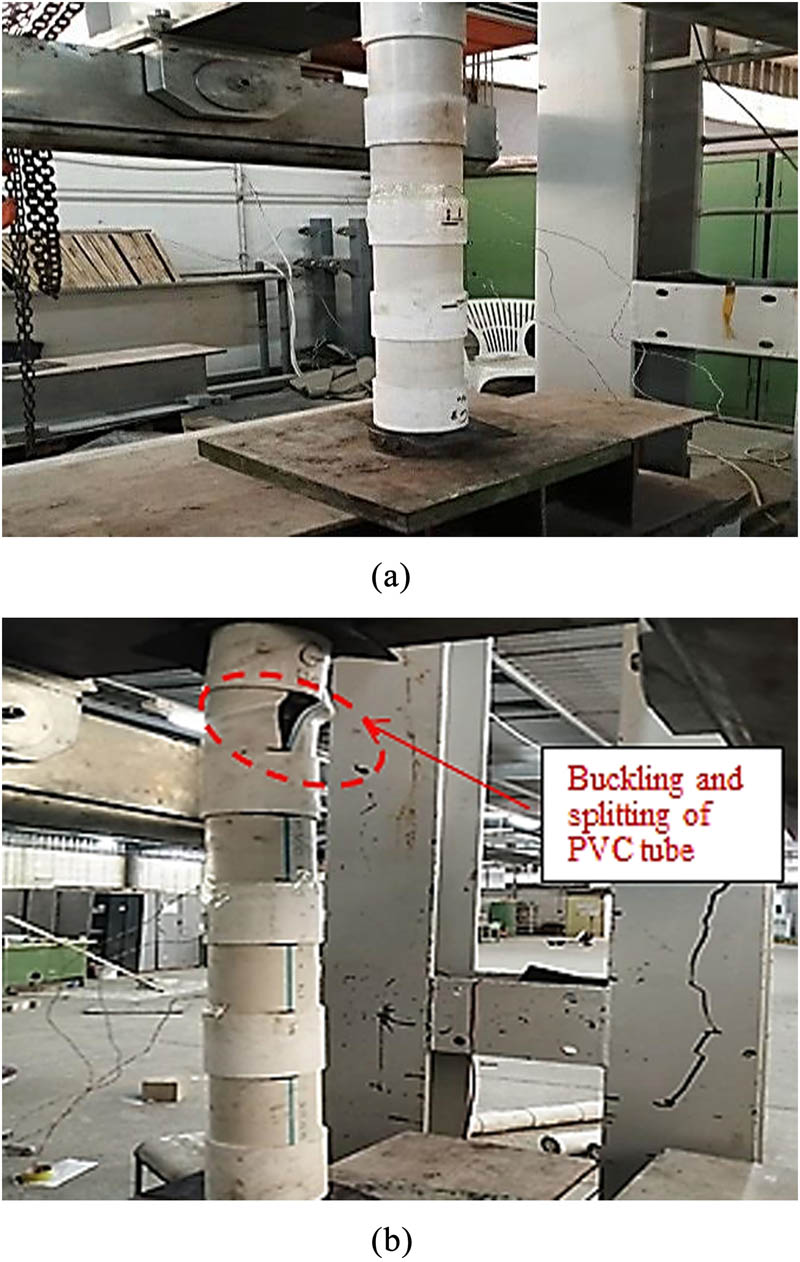

7.4 Confinement ratio

Finally, the effect of confinement ratio was studied in the fourth group by studying the effect of three confinement ratios (25, 50, and 75%) on the behavior of hollow PVC composite column. It can be noted from Figure 33 that columns with confinement equal to 75% increase the load carrying capacity as compared to other confinement ratio. The rate of increase was about 28.5% as confinement ratio increase from 25 to 50%, and about 22% as confinement ratio increase from 50 to 75%. The total increase in load was about 56.7% as confinement ratio increase from 25 to 75%. The failure modes of these columns are shown in Figures 29–33.

Failure mode of composite column with confinement ratio equal to 25%. (a) before test, (b) after test.

Failure mode of composite column with confinement ratio equal to 50%. (a) before test, (b) after test.

Failure mode of composite column with confinement ratio equal to 75%. (a) before test, (b) after test.

Failure mode of all composite columns of group 4.

Load versus lateral strain at mid-height of column for different confinement ratios: (a) lateral strain and (b) axial strain.

8 Conclusion

Based on the total results achieved from the experimental work using 12 composite columns of different slenderness ratios, compactness ratio, target of compressive strength, and confinement ratio, the following conclusions are drawn:

The loading resistance of PVC composites with concrete showed high strength development and same effects were detected in the latitude of ductility.

The varying of loading influence on load–strain response had considerable influence on strength improvement for composite mode samples so that PVC could act like reinforcement.

Stiffness, strength, as well as the ductility of composite PVC concrete columns of different loadings were considerably influenced by the slenderness ratio (L/r) of the column, the compactness of PVC section, and the filling concrete strength. An increase in loading carrying capacity by about 40.4% was noticed as the slenderness ratio decreased from 20 to 12. In additrion, an increase in load carrying capacity by about 21.1% was observed as compactness ratio decreased from 50 to 25. For the case of compressive strength, it was noticed that the rate of increase in load capacity was about 96.6% as compressive strength increased from 33 to 54 MPa. For the case of variation of confinement ratio from 25 to75%, the increase in the axial load capacity was about 56.7%.

All the tested columns conquered stability failure; besides, the samples underwent global elastic buckling with substantial failure of concrete in addition to local buckling deformation causing a sudden decrease in loading capacity corresponding to lateral deformation.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Most datasets generated and analyzed in this study are comprised in this submitted manuscript. The other datasets are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author with the attached information.

References

[1] Titow MV. PVC technology. England: Elsevier Applied science publishers; 1984.10.1007/978-94-009-5614-8Search in Google Scholar

[2] Abhale RB, Kandekar SB, Satpute MB. PVC confining effect on axially loaded column. Imp J Interdiscip Res (IJIR). 2016;2(5):1391–4.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Kurt CE. Concrete filled structural plastic columns. J Structural Division. 1978;104:55–63. 104 (ASCE 13478 Proc).10.1061/JSDEAG.0004849Search in Google Scholar

[4] M Marzouck, K Sennah. Concrete-filled PVC tubes as compression members: composite materials in concrete construction. Proceedings of the International Congress Challenges of Concrete Construction. Scotland, UK: 2002. p. 31–8.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Gupta PK, Verma VK. Study of concrete-filled unplasticized poly-vinyl chloride tubes in marine environment. Int J Int J Adv Struct Eng. 2013;5(1):1–8.10.1186/2008-6695-5-19Search in Google Scholar

[6] Naftary KG, Walter OO, Geoffrey NM. Compressive strength characteristics of concrete filled plastic tubes short columns. Int J Sci Res. 2014;3(9):2168–74.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Saadoon AS. Experimental and theoretical investigation of PVC concrete composite columns. University of Basrah; 2010.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Gathimba KN, Oyawa WO, Mang’uriu GN. Performance of UPVC pipe confined concrete columns in compression. MSc Thesis; 2015. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330619513_Performance_of_UPVC_Pipe_Confined_Concrete_Columns_in_Compression.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Zhou F, Xu W. Cyclic loading tests on concrete-filled doubleskin (SHS outer and CHS inner) stainless steel tubular beam columns. Eng Struct. 2016;127:304–18. 10.1016/j.engstruct.2016.09.003.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Oyawa WO, Gathimba NK, Mang’uriu GN. Structural response of composite concrete filled plastic tubes in compression. Steel Compos Struct. 2016;21(3):589–604. 10.12989/scs.2016.21.3.589.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Xue J, Li H, Zhai L, Ke X, Zheng W, Men B. Analysis of mechanical behavior and influencing factors of high strength concrete columns with PVC pipe under repeated loading. Xi’An Jianzhu Keji Daxue Xuebao/Journal Xi’An Univ”, Archit Technol. 2016;48:24–8.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Jamaluddin N. Experimental investigation of concrete filled PVC tube columns confined by plain PVC socket. MATEC Web Conf. Vol. 103; 2017. 10.1051/matecconf/201710302006.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Fakharifar M, Chen G. FRP-confined concrete filled PVC tubes: a new design concept for ductile column construction in seismic regions. Constr Build Mater. 2017;130:1–10. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.11.056.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Woldemariam AM, Oyawa WO, Nyomboi T. Structural performance of uPVC confined concrete equivalent cylinders under axial compression loads. Buildings. 2019;9(4):83. 10.3390/buildings9040082.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Malaskiewicz D. Influence of polymer fibers on rheological proprties of cement mortars. Open Eng. 2017;7:228–36. 10.1515/eng-2017-009.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Raheemah MA. Structural behavior of slender pvc composite columns filled with concrete. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; 2020.10.1088/1757-899X/671/1/012083Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Design optimization of a 4-bar exoskeleton with natural trajectories using unique gait-based synthesis approach

- Technical review of supervised machine learning studies and potential implementation to identify herbal plant dataset

- Effect of ECAP die angle and route type on the experimental evolution, crystallographic texture, and mechanical properties of pure magnesium

- Design and characteristics of two-dimensional piezoelectric nanogenerators

- Hybrid and cognitive digital twins for the process industry

- Discharge predicted in compound channels using adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS)

- Human factors in aviation: Fatigue management in ramp workers

- LLDPE matrix with LDPE and UV stabilizer additive to evaluate the interface adhesion impact on the thermal and mechanical degradation

- Dislocated time sequences – deep neural network for broken bearing diagnosis

- Estimation method of corrosion current density of RC elements

- A computational iterative design method for bend-twist deformation in composite ship propeller blades for thrusters

- Compressive forces influence on the vibrations of double beams

- Research on dynamical properties of a three-wheeled electric vehicle from the point of view of driving safety

- Risk management based on the best value approach and its application in conditions of the Czech Republic

- Effect of openings on simply supported reinforced concrete skew slabs using finite element method

- Experimental and simulation study on a rooftop vertical-axis wind turbine

- Rehabilitation of overload-damaged reinforced concrete columns using ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete

- Performance of a horizontal well in a bounded anisotropic reservoir: Part II: Performance analysis of well length and reservoir geometry

- Effect of chloride concentration on the corrosion resistance of pure Zn metal in a 0.0626 M H2SO4 solution

- Numerical and experimental analysis of the heat transfer process in a railway disc brake tested on a dynamometer stand

- Design parameters and mechanical efficiency of jet wind turbine under high wind speed conditions

- Architectural modeling of data warehouse and analytic business intelligence for Bedstead manufacturers

- Influence of nano chromium addition on the corrosion and erosion–corrosion behavior of cupronickel 70/30 alloy in seawater

- Evaluating hydraulic parameters in clays based on in situ tests

- Optimization of railway entry and exit transition curves

- Daily load curve prediction for Jordan based on statistical techniques

- Review Articles

- A review of rutting in asphalt concrete pavement

- Powered education based on Metaverse: Pre- and post-COVID comprehensive review

- A review of safety test methods for new car assessment program in Southeast Asian countries

- Communication

- StarCrete: A starch-based biocomposite for off-world construction

- Special Issue: Transport 2022 - Part I

- Analysis and assessment of the human factor as a cause of occurrence of selected railway accidents and incidents

- Testing the way of driving a vehicle in real road conditions

- Research of dynamic phenomena in a model engine stand

- Testing the relationship between the technical condition of motorcycle shock absorbers determined on the diagnostic line and their characteristics

- Retrospective analysis of the data concerning inspections of vehicles with adaptive devices

- Analysis of the operating parameters of electric, hybrid, and conventional vehicles on different types of roads

- Special Issue: 49th KKBN - Part II

- Influence of a thin dielectric layer on resonance frequencies of square SRR metasurface operating in THz band

- Influence of the presence of a nitrided layer on changes in the ultrasonic wave parameters

- Special Issue: ICRTEEC - 2021 - Part III

- Reverse droop control strategy with virtual resistance for low-voltage microgrid with multiple distributed generation sources

- Special Issue: AESMT-2 - Part II

- Waste ceramic as partial replacement for sand in integral waterproof concrete: The durability against sulfate attack of certain properties

- Assessment of Manning coefficient for Dujila Canal, Wasit/-Iraq

- Special Issue: AESMT-3 - Part I

- Modulation and performance of synchronous demodulation for speech signal detection and dialect intelligibility

- Seismic evaluation cylindrical concrete shells

- Investigating the role of different stabilizers of PVCs by using a torque rheometer

- Investigation of high-turbidity tap water problem in Najaf governorate/middle of Iraq

- Experimental and numerical evaluation of tire rubber powder effectiveness for reducing seepage rate in earth dams

- Enhancement of air conditioning system using direct evaporative cooling: Experimental and theoretical investigation

- Assessment for behavior of axially loaded reinforced concrete columns strengthened by different patterns of steel-framed jacket

- Novel graph for an appropriate cross section and length for cantilever RC beams

- Discharge coefficient and energy dissipation on stepped weir

- Numerical study of the fluid flow and heat transfer in a finned heat sink using Ansys Icepak

- Integration of numerical models to simulate 2D hydrodynamic/water quality model of contaminant concentration in Shatt Al-Arab River with WRDB calibration tools

- Study of the behavior of reactive powder concrete RC deep beams by strengthening shear using near-surface mounted CFRP bars

- The nonlinear analysis of reactive powder concrete effectiveness in shear for reinforced concrete deep beams

- Activated carbon from sugarcane as an efficient adsorbent for phenol from petroleum refinery wastewater: Equilibrium, kinetic, and thermodynamic study

- Structural behavior of concrete filled double-skin PVC tubular columns confined by plain PVC sockets

- Probabilistic derivation of droplet velocity using quadrature method of moments

- A study of characteristics of man-made lightweight aggregate and lightweight concrete made from expanded polystyrene (eps) and cement mortar

- Effect of waste materials on soil properties

- Experimental investigation of electrode wear assessment in the EDM process using image processing technique

- Punching shear of reinforced concrete slabs bonded with reactive powder after exposure to fire

- Deep learning model for intrusion detection system utilizing convolution neural network

- Improvement of CBR of gypsum subgrade soil by cement kiln dust and granulated blast-furnace slag

- Investigation of effect lengths and angles of the control devices below the hydraulic structure

- Finite element analysis for built-up steel beam with extended plate connected by bolts

- Finite element analysis and retrofit of the existing reinforced concrete columns in Iraqi schools by using CFRP as confining technique

- Performing laboratory study of the behavior of reactive powder concrete on the shear of RC deep beams by the drilling core test

- Special Issue: AESMT-4 - Part I

- Depletion zones of groundwater resources in the Southwest Desert of Iraq

- A case study of T-beams with hybrid section shear characteristics of reactive powder concrete

- Feasibility studies and their effects on the success or failure of investment projects. “Najaf governorate as a model”

- Optimizing and coordinating the location of raw material suitable for cement manufacturing in Wasit Governorate, Iraq

- Effect of the 40-PPI copper foam layer height on the solar cooker performance

- Identification and investigation of corrosion behavior of electroless composite coating on steel substrate

- Improvement in the California bearing ratio of subbase soil by recycled asphalt pavement and cement

- Some properties of thermal insulating cement mortar using Ponza aggregate

- Assessment of the impacts of land use/land cover change on water resources in the Diyala River, Iraq

- Effect of varied waste concrete ratios on the mechanical properties of polymer concrete

- Effect of adverse slope on performance of USBR II stilling basin

- Shear capacity of reinforced concrete beams with recycled steel fibers

- Extracting oil from oil shale using internal distillation (in situ retorting)

- Influence of recycling waste hardened mortar and ceramic rubbish on the properties of flowable fill material

- Rehabilitation of reinforced concrete deep beams by near-surface-mounted steel reinforcement

- Impact of waste materials (glass powder and silica fume) on features of high-strength concrete

- Studying pandemic effects and mitigation measures on management of construction projects: Najaf City as a case study

- Design and implementation of a frequency reconfigurable antenna using PIN switch for sub-6 GHz applications

- Average monthly recharge, surface runoff, and actual evapotranspiration estimation using WetSpass-M model in Low Folded Zone, Iraq

- Simple function to find base pressure under triangular and trapezoidal footing with two eccentric loads

- Assessment of ALINEA method performance at different loop detector locations using field data and micro-simulation modeling via AIMSUN

- Special Issue: AESMT-5 - Part I

- Experimental and theoretical investigation of the structural behavior of reinforced glulam wooden members by NSM steel bars and shear reinforcement CFRP sheet

- Improving the fatigue life of composite by using multiwall carbon nanotubes

- A comparative study to solve fractional initial value problems in discrete domain

- Assessing strength properties of stabilized soils using dynamic cone penetrometer test

- Investigating traffic characteristics for merging sections in Iraq

- Enhancement of flexural behavior of hybrid flat slab by using SIFCON

- The main impacts of a managed aquifer recharge using AHP-weighted overlay analysis based on GIS in the eastern Wasit province, Iraq

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Design optimization of a 4-bar exoskeleton with natural trajectories using unique gait-based synthesis approach

- Technical review of supervised machine learning studies and potential implementation to identify herbal plant dataset

- Effect of ECAP die angle and route type on the experimental evolution, crystallographic texture, and mechanical properties of pure magnesium

- Design and characteristics of two-dimensional piezoelectric nanogenerators

- Hybrid and cognitive digital twins for the process industry

- Discharge predicted in compound channels using adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS)

- Human factors in aviation: Fatigue management in ramp workers

- LLDPE matrix with LDPE and UV stabilizer additive to evaluate the interface adhesion impact on the thermal and mechanical degradation

- Dislocated time sequences – deep neural network for broken bearing diagnosis

- Estimation method of corrosion current density of RC elements

- A computational iterative design method for bend-twist deformation in composite ship propeller blades for thrusters

- Compressive forces influence on the vibrations of double beams

- Research on dynamical properties of a three-wheeled electric vehicle from the point of view of driving safety

- Risk management based on the best value approach and its application in conditions of the Czech Republic

- Effect of openings on simply supported reinforced concrete skew slabs using finite element method

- Experimental and simulation study on a rooftop vertical-axis wind turbine

- Rehabilitation of overload-damaged reinforced concrete columns using ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete

- Performance of a horizontal well in a bounded anisotropic reservoir: Part II: Performance analysis of well length and reservoir geometry

- Effect of chloride concentration on the corrosion resistance of pure Zn metal in a 0.0626 M H2SO4 solution

- Numerical and experimental analysis of the heat transfer process in a railway disc brake tested on a dynamometer stand

- Design parameters and mechanical efficiency of jet wind turbine under high wind speed conditions

- Architectural modeling of data warehouse and analytic business intelligence for Bedstead manufacturers

- Influence of nano chromium addition on the corrosion and erosion–corrosion behavior of cupronickel 70/30 alloy in seawater

- Evaluating hydraulic parameters in clays based on in situ tests

- Optimization of railway entry and exit transition curves

- Daily load curve prediction for Jordan based on statistical techniques

- Review Articles

- A review of rutting in asphalt concrete pavement

- Powered education based on Metaverse: Pre- and post-COVID comprehensive review

- A review of safety test methods for new car assessment program in Southeast Asian countries

- Communication

- StarCrete: A starch-based biocomposite for off-world construction

- Special Issue: Transport 2022 - Part I

- Analysis and assessment of the human factor as a cause of occurrence of selected railway accidents and incidents

- Testing the way of driving a vehicle in real road conditions

- Research of dynamic phenomena in a model engine stand

- Testing the relationship between the technical condition of motorcycle shock absorbers determined on the diagnostic line and their characteristics

- Retrospective analysis of the data concerning inspections of vehicles with adaptive devices

- Analysis of the operating parameters of electric, hybrid, and conventional vehicles on different types of roads

- Special Issue: 49th KKBN - Part II

- Influence of a thin dielectric layer on resonance frequencies of square SRR metasurface operating in THz band

- Influence of the presence of a nitrided layer on changes in the ultrasonic wave parameters

- Special Issue: ICRTEEC - 2021 - Part III

- Reverse droop control strategy with virtual resistance for low-voltage microgrid with multiple distributed generation sources

- Special Issue: AESMT-2 - Part II

- Waste ceramic as partial replacement for sand in integral waterproof concrete: The durability against sulfate attack of certain properties

- Assessment of Manning coefficient for Dujila Canal, Wasit/-Iraq

- Special Issue: AESMT-3 - Part I

- Modulation and performance of synchronous demodulation for speech signal detection and dialect intelligibility

- Seismic evaluation cylindrical concrete shells

- Investigating the role of different stabilizers of PVCs by using a torque rheometer

- Investigation of high-turbidity tap water problem in Najaf governorate/middle of Iraq

- Experimental and numerical evaluation of tire rubber powder effectiveness for reducing seepage rate in earth dams

- Enhancement of air conditioning system using direct evaporative cooling: Experimental and theoretical investigation

- Assessment for behavior of axially loaded reinforced concrete columns strengthened by different patterns of steel-framed jacket

- Novel graph for an appropriate cross section and length for cantilever RC beams

- Discharge coefficient and energy dissipation on stepped weir

- Numerical study of the fluid flow and heat transfer in a finned heat sink using Ansys Icepak

- Integration of numerical models to simulate 2D hydrodynamic/water quality model of contaminant concentration in Shatt Al-Arab River with WRDB calibration tools

- Study of the behavior of reactive powder concrete RC deep beams by strengthening shear using near-surface mounted CFRP bars

- The nonlinear analysis of reactive powder concrete effectiveness in shear for reinforced concrete deep beams

- Activated carbon from sugarcane as an efficient adsorbent for phenol from petroleum refinery wastewater: Equilibrium, kinetic, and thermodynamic study

- Structural behavior of concrete filled double-skin PVC tubular columns confined by plain PVC sockets

- Probabilistic derivation of droplet velocity using quadrature method of moments

- A study of characteristics of man-made lightweight aggregate and lightweight concrete made from expanded polystyrene (eps) and cement mortar

- Effect of waste materials on soil properties

- Experimental investigation of electrode wear assessment in the EDM process using image processing technique

- Punching shear of reinforced concrete slabs bonded with reactive powder after exposure to fire

- Deep learning model for intrusion detection system utilizing convolution neural network

- Improvement of CBR of gypsum subgrade soil by cement kiln dust and granulated blast-furnace slag

- Investigation of effect lengths and angles of the control devices below the hydraulic structure

- Finite element analysis for built-up steel beam with extended plate connected by bolts

- Finite element analysis and retrofit of the existing reinforced concrete columns in Iraqi schools by using CFRP as confining technique

- Performing laboratory study of the behavior of reactive powder concrete on the shear of RC deep beams by the drilling core test

- Special Issue: AESMT-4 - Part I

- Depletion zones of groundwater resources in the Southwest Desert of Iraq

- A case study of T-beams with hybrid section shear characteristics of reactive powder concrete

- Feasibility studies and their effects on the success or failure of investment projects. “Najaf governorate as a model”

- Optimizing and coordinating the location of raw material suitable for cement manufacturing in Wasit Governorate, Iraq

- Effect of the 40-PPI copper foam layer height on the solar cooker performance

- Identification and investigation of corrosion behavior of electroless composite coating on steel substrate

- Improvement in the California bearing ratio of subbase soil by recycled asphalt pavement and cement

- Some properties of thermal insulating cement mortar using Ponza aggregate

- Assessment of the impacts of land use/land cover change on water resources in the Diyala River, Iraq

- Effect of varied waste concrete ratios on the mechanical properties of polymer concrete

- Effect of adverse slope on performance of USBR II stilling basin

- Shear capacity of reinforced concrete beams with recycled steel fibers

- Extracting oil from oil shale using internal distillation (in situ retorting)

- Influence of recycling waste hardened mortar and ceramic rubbish on the properties of flowable fill material

- Rehabilitation of reinforced concrete deep beams by near-surface-mounted steel reinforcement

- Impact of waste materials (glass powder and silica fume) on features of high-strength concrete

- Studying pandemic effects and mitigation measures on management of construction projects: Najaf City as a case study

- Design and implementation of a frequency reconfigurable antenna using PIN switch for sub-6 GHz applications

- Average monthly recharge, surface runoff, and actual evapotranspiration estimation using WetSpass-M model in Low Folded Zone, Iraq

- Simple function to find base pressure under triangular and trapezoidal footing with two eccentric loads

- Assessment of ALINEA method performance at different loop detector locations using field data and micro-simulation modeling via AIMSUN

- Special Issue: AESMT-5 - Part I

- Experimental and theoretical investigation of the structural behavior of reinforced glulam wooden members by NSM steel bars and shear reinforcement CFRP sheet

- Improving the fatigue life of composite by using multiwall carbon nanotubes

- A comparative study to solve fractional initial value problems in discrete domain

- Assessing strength properties of stabilized soils using dynamic cone penetrometer test

- Investigating traffic characteristics for merging sections in Iraq

- Enhancement of flexural behavior of hybrid flat slab by using SIFCON

- The main impacts of a managed aquifer recharge using AHP-weighted overlay analysis based on GIS in the eastern Wasit province, Iraq