Activated carbon from sugarcane as an efficient adsorbent for phenol from petroleum refinery wastewater: Equilibrium, kinetic, and thermodynamic study

-

Mustafa S. Abdulrahman

Abstract

The adsorption method may be one of the environmentally friendly, economical, and effective techniques to remove phenol from wastewater using low-cost adsorbent activated carbon (AC). The effects of the initial concentration of phenol, temperature, and time of the adsorption on the phenol removal percent were studied. The maximum removal percentage of phenol was 63.73% of the initial 150 mg/l concentration obtained at 25°C. Langmuir, Freundlich, Temkin, and Dubinin–Radushkevich isotherm models have been applied to study the adsorption equilibrium. The results show that both Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms fitted the equilibrium data better with a high correlation coefficient (R 2) and a maximum adsorption capacity of 108.70 mg/g. Thorough fitting of adsorption kinetics data followed the pseudo-second-order model. Thermodynamic parameters were calculated in the temperature range of 25–50°C. The results show that the adsorption process of phenol on AC is more favorable at low temperatures.

1 Introduction

Sugarcane is an important crop in tropical and subtropical regions. Agricultural research and practice on sugarcane are becoming increasingly data-intensive, with various modelling frameworks established to simulate processes such as adsorption [1,2,3]. The sugarcane industry in Brazil produces a substantial amount of sugarcane ashes, a waste product used in many industries [4].

Adsorption can be used to reduce the quantity of CO2 that is released into the air by industrial processes. For this purpose, activated carbons (ACs), zeolites, and mesoporous silica are used as sorbents. ACs can be made from a wide range of raw materials, including biomass wastes, which come from plants [5]. The biomass wastes are cheap, available materials, and can be converted into an adsorbent after making some modifications and chemical treatments [6]. Sugarcane ashes comprise cellulose fibers, lignin, and hemicellulose, making it a suitable raw material for carbon [7].

Phenol is considered a priority pollutant due to its high toxicity, as it is poisonous to organisms at low concentrations, and many of its constituents have been categorized as hazardous pollutants due to its potential to impact human health [8]. The removal of phenol from aqueous solutions can be done through the adsorption of biomass-derived AC [8,9].

On humans, excessive exposure to phenol may have adverse effects on the brain, digestive system, eye, heart, liver, lungs, and skin, among others [10]. Therefore, environmental specialists are overly concerned if phenol is found in drinking water or wastewater [11,12].

The primary sources of phenol contamination in the aquatic environment include wastewater from the paint, pesticide, coal conversion, polymeric resin, polymer synthesis, plastic, rubber, insecticides, pharmaceutical, gasoline, rubber proofing, steel, petroleum, and petrochemical industries [13,14].

Phenols have a negative influence on both human and animal health because these are highly toxic and carcinogenic. According to the World Health Organization, drinking water should contain no more than 1 µg/l of phenols [15,16]. Therefore, before disposing of sewage, industrial effluents must be treated with phenols [17].

As a result, a variety of techniques are available for treating phenol-containing wastewater prior to its discharge into natural streams. These techniques include electrochemical degradation and electrochemical oxidation [18]. Moreover, fouling-resistant nanofiltration membranes for the separation of oil–water emulsion and micropollutants from water, separation and purification technology, biological treatment, biodegradation of phenols from wastewater by microorganisms immobilized in bentonite and carboxymethyl cellulose gel, chemical coagulation, precipitation, ion exchange, photocatalytic degradation, reverse osmosis, and adsorption processes [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29], in addition to solvent extraction, incineration, and nanofiltration, are used to treat wastewaters [30]. Each of these techniques has advantages and drawbacks. Compounds from wastewater are rarely used frequently or on a large scale due to their extremely high costs and disposal issues [31,32].

However, adsorption has emerged as one of the most effective techniques for resolving difficulties in purification and separation technology because it is the simplest, most successful, and least expensive way to eliminate phenol among these methods. ACs are the most prominent adsorbents due to their high surface area per mass, microporous nature, high adsorption capability for a variety of adsorbates, including phenolic compounds, high purity, and ease of availability [13,33,34,35].

AC can be produced using either the physical activation process or the chemical activation process. The type of precursor, the activation process, and the activation conditions affect the porosity properties of ACs, such as pore-size distribution, pore shape, and surface chemistry [36]. There are two steps in physical activation to create more porous structures [37]. First, the material is carbonized in an inert atmosphere and then activated at a high temperature using either steam or carbon dioxide as the activating reagent [38]. However, in chemical activation, raw materials are heated in an inert atmosphere after being impregnated with an activation reagent such as KOH, H3PO4, and ZnCl2. Chemical activation is preferred over physical activation due to its low energy and operating costs, high carbon yields, large surface areas, and porous structure, as well as its simplicity, speed, and need for lower activation temperatures [39,40].

Both the carbonization and activation processes occur simultaneously. The oxidation and dehydration reactions of chemicals result in the formation of pores. The created char is then cleaned to remove any remaining contaminants [41].

ACs are derived from carbonaceous substances. The selection of a precursor is heavily influenced by its availability, cost, and purity; however, the production processes and intended applications of the product are also significant factors [41]. Because biomass is renewable, accessible, economical, and environmentally friendly, it is receiving more and more attention worldwide [42]. Numerous biomass sources, including low-grade plants, agricultural waste, and municipal solid waste, can be used as AC precursors [41].

For the elimination of phenols and their derivatives, the agricultural waste materials like grain husk, apricot stone shell, peat, plum kernel, beet pulp corn grain, sugarcane bagasse, wood charcoal, babul sawdust, acacia glauca saw dust, modified clay, biological materials, chitin, and zeolite have been utilized directly or via producing ACs [43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56]. However, it has been found that sugarcane acts as an adsorbent for phenol adsorption.

Numerous adsorbents made from agricultural byproducts have already been utilized for phenol removal; however, according to the literature review, ACs made from sugarcane grown in Iraq as a phenol adsorbent or for treating oil refinery wastewater have not yet been reported widely. The objective of this study is to investigate the efficiency of sugarcane-AC in removing phenol from aqueous solutions. The purpose of this research is to prepare an inexpensive sugarcane waste to develop AC for the adsorption-based phenol removal from the synthesis effluent. Equilibrium data will be used to explore the phenol adsorption isotherms, followed by kinetics and thermodynamics of the adsorption process at various temperatures.

2 Experimental work

Sugarcane was used to prepare the AC. Sugarcane was first washed with water to remove impurities before being dried at 110°C for 24 h.

Sugarcane was prepared in a stainless-steel reactor with dimensions of 3 cm in diameter and 15 cm in length that was closed at one end and had a removable cover with a 1 mm hole in the middle to allow the burned gases to escape. The reactor was heated for 2 h at 360°C in an electrical furnace. After that, it was allowed to cool at room temperature. The produced carbon material was crushed by a disk mill and then sieved. Carbon material of a particle size less than 300 µm was activated by the addition of 10 ml of NaOH solution (1.5 M) per each 2 g of produced carbon material for 24 h. After that, samples that had been treated with NaOH solutions were dried completely overnight at 110°C in a dryer.

A quartz reactor with a diameter of 3 cm and a length of 13 cm was used in the microwave activation step. The reactor was filled with the dried sample, and the reactor was placed in a microwave oven with a radiation power of 540 W for 8 min. Then, the sample was allowed to cool and saturated with 10 ml of 0.1 M HCl solution using per gram of AC material for 24 h at room temperature and washed with water. Finally, dry AC samples were dried in a dryer at 110°C for 24 h, cooled in a desiccator, and then each sample was weighed to calculate the yield. The surface area and the pore volume of the yield AC were measured at the Petroleum Research & Development Center, Baghdad, Iraq.

Adsorption experiments were conducted by batch methods with 1 g of AC per liter of synthesis wastewater, which contains 10–150 ppm of phenol. To obtain the equilibrium state, The AC suspension and the aqueous solutions of phenol were placed on a shaker for 24 h at a constant speed of 200 rpm at 25°C. The adsorption kinetics was studied for solutions of the maximum phenol concentration (150 ppm) at different temperatures (25, 40, and 50°C).

At the required temperature and after a certain adsorption time (up to 90 min for kinetics experiments), the suspension sample was taken and filtered. The phenol concentrations of the filtrated solutions were determined by the GENESYS 10 S UV-VIS spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 268 nm, and then the total removal percentage was calculated.

The equilibrium experiments were completed for 24 h at 25°C. Equation (1) is used to figure out the amount of phenol adsorbed per weight of AC adsorbent at equilibrium:

where

3 Results and discussion

The surface area and pore volume of AC prepared from Iraqi sugarcane stalks were 1073.2 m2/g and 1.04 cm3/g, respectively.

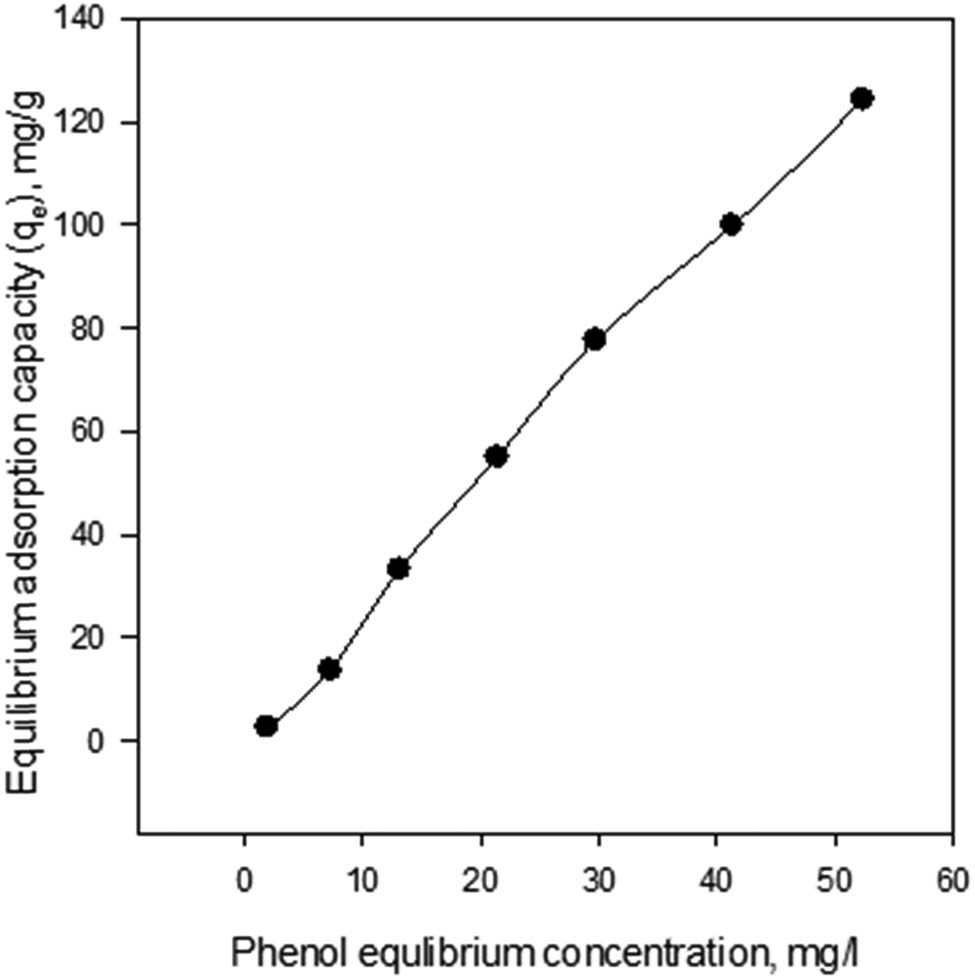

The phenol equilibrium concentration can be represented to study the behavior of the adsorption equilibrium capacity progress process. Figure 1 shows that the relationship is directly proportional. As the initial phenol concentration increased from 10 to 150 ppm, the equilibrium concentrations increased from about 2 to 54 mg/l, and the equilibrium adsorption capacity increased from about 0.8 to 127.7 mg/g. These findings are in good agreement with the previously reported highest phenol removal percentage (75.29%) from aqueous solution by adsorption on the AC from banana peels at the same adsorbent dose (1 g/l) [15].

Equilibrium phenol adsorption capacity versus the initial concentration after 24 h of adsorption at 25°C.

3.1 Adsorption isotherms models

Simulated wastewater containing 150 mg/l of phenol at 25°C was used to examine the adsorption isotherms. The most popular two-parameter isotherms were selected to describe the adsorption of phenol on AC [57,58]. These isotherm models include Langmuir, Freundlich, Temkin, and Dubinin–Radushkevich.

3.1.1 Langmuir adsorption isotherm model

The Langmuir isotherm model [59] is an empirical model that assumes that adsorption may only occur at a set number of defined confined sites without lateral interaction between the molecules being adsorbed. According to this model, the thickness of the adsorbed layer is one molecule or monolayer adsorption. According to the Langmuir isotherm, a homogeneous process occurs in which each molecule maintains a fixed enthalpy and sorption activation energy without transmigration of the adsorbate across the surface. Equation (2) depicts the linear formulation of the Langmuir adsorption isotherm

where

As shown in Figure 2, when

Langmuir isotherm model for phenol adsorption on AC.

3.1.2 Freundlich adsorption isotherm model

The Freundlich isotherm model [60] is an empirical formula defining the non-ideal and reversible adsorption process for multilayer, heterogeneous adsorption states. The conventional form of the Freundlich equation is presented in the following equation:

where

As shown in Figure 3, when [

Freundlich isotherm model for phenol adsorption on AC.

Temkin isotherm model for phenol adsorption on AC.

3.1.3 Temkin adsorption isotherm

The Temkin isotherm model is given as follows [61]:

where B and K

T are the Temkin energy constant (J/mol) and the constant describing the interaction between phenol molecules and BPAC surface (dimensionless), respectively. To determine the isotherm constants B and

Dubinin–Radushkevich isotherm model for phenol adsorption on AC.

3.1.4 Dubinin–Radushkevich adsorption isotherm model

The Dubinin–Radushkevich isotherm model is an empirical model for expressing the adsorption process that occurs after a pore-filling mechanism has been obtained [62]. The Dubinin–Radushkevich isotherm describes the adsorption process on both homogeneous and heterogeneous surfaces. Equations (4) and (5) are the linear expression of the Dubinin–Radushkevich isotherm model

where

A straight line with a slope of [

Equation (6) can be used to estimate the apparent energy of adsorption from the Dubinin–Radushkevich isotherm, E, which was found to be +3.16 J/mol. The reported heat of physical adsorption in the liquid phase and the low positive value of E are in good agreement [63].

Table 1 displays the constants determined for each of the equilibrium isotherm models described and the R 2 values. Based on the values of the established correlation coefficients, the tabulated data indicate that the R 2 constants of the Langmuir, Freundlich, and Temkin model's were 0.9751, 0.9888, and 0.9012, respectively, which accurately represent the equilibrium adsorption of phenol on AC. However, the Dubinin–Radushkevich isotherm model failed to adequately represent equilibrium data (R 2 = 0.6867). The higher value of the maximum adsorption capacity determined by the Langmuir isotherm model (108.70 mg/g) confirmed this model as the superior isotherm for describing phenol adsorption on AC.

Constants for each of the equilibrium isotherm models and R 2

| Isotherm model | Model parameters | Parameter value | R 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Langmuir |

|

108.70 | 0.9751 |

|

|

0.0386 | ||

| Freundlich |

|

4.3606 | 0.9888 |

| n (–) | 1.2509 | ||

| Temkin | RT/b T, J/mol | 0.0321 | 0.9012 |

| b T is Temkin energy constant | 79.53 | ||

| ln K T, (K T in l/g) | 33.6885 | ||

| Dubinin–Radushkevich |

|

55.9971 | 0.6867 |

|

|

2.0296 | ||

| E (J/mol) | 496.34 |

3.2 Kinetics of adsorption

In the first 25 min, the total elimination of phenol waste increased dramatically with time, but after 45 min, this trend tended to unchanged. As depicted in Figure 6, this behavior was found in all experiments performed at the analyzed temperatures (25, 40, and 50°C). In addition, Figure 7 shows that the adsorption capacity of phenol increased exceptionally rapidly from the beginning to 25 min and then remained unaffected by time after 45 min. The amount of phenol extracted decreased as temperatures increase. As indicated in Figure 6, the lowest total phenol removal value after 45 min at 50°C was 56.35%, while the highest total phenol removal value was 63.73% at 25°C. Figure 7 shows that the reduced adsorption capacity of the AC, which decreased from 156.7 to 147.0 mg/g as the temperature increased from 25 to 50°C, was the cause of the decrease in the phenol removal value.

The effect of time on phenol removal at different temperatures.

The effect of time on the AC adsorption capacity at different temperatures.

The best adsorption models that captured the phenol adsorption data on AC were examined using the adsorption capacity versus time data. Pseudo-first order, pseudo-second order, and intra-particle kinetic model are the three kinetic models that were applied. In order to determine the adsorption rate constants for each model at the various temperatures, the linear form of these models (equations (7)–(9)) was solved by linear regression based on the least-squares criterion [64,65,66].

where

Table 2 lists the rate constants that were calculated using the least square technique at various temperatures.

Rate constant values for adsorption of phenol on AC

| Adsorption kinetic model | Model rate constant | Model parameter value at temperature | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25°C | 40°C | 50°C | ||

| Pseudo-first order |

|

0.0578 | 0.0678 | 0.0758 |

| R² range | 0.2318–0.5115 | |||

| Pseudo-second order |

|

5.3457 | 6.3168 | 7.7247 |

| R² | 0.9981 | 0.9957 | 0.9931 | |

| Intra-particle |

|

5.6494 | 5.4790 | 5.6976 |

| C | 51.627 | 47.298 | 41.022 | |

| R² range | 0.5451 to 0.6248 | |||

The kinetic of phenol removal by adsorption on AC was follow a pseudo-second order model (high R 2 for all temperatures) but did not fit well to the pseudo-first order and intra-particle kinetic models, according to the values of the correlation coefficient calculated for the kinetic models with the obtained parameters. Regarding the environment, the pseudo-second-order kinetic model typically succeeded in describing the phenol substance adsorption data from the aqueous solution [67,68].

3.3 Thermodynamic of phenol adsorption on AC

The thermodynamic behavior of phenol adsorption on AC was examined. Based on equations (10) and (11), these parameters were the change in Gibbs free energy (

where R, T, and

where q e, C e, V, and m are the adsorption capacity of the adsorbent (mg/g), the equilibrium concentrations of phenol in the adsorption solution (mg/l), the volume of the adsorption solution (l), and the weight of the AC adsorbent used (g), respectively.

The values of

The change in Gibbs free energy versus adsorption temperature.

Numerical values obtained of the distribution coefficient and thermodynamic parameters versus temperature (results of Figure 8)

| Temperature (K) |

|

Thermodynamic parameters | R 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||

| 298 | 4.769 | −1548.2 | −11132 | −32.144 | 0.9994 |

| 313 | 3.286 | −1082.6 | |||

| 323 | 2.659 | −742.3 | |||

The negative value of

4 Conclusion

The adsorption method may be one of the best separation processes due to its high efficiency, low cost, and environment friendly to remove phenol pollutants from industrial wastewater using bio-adsorbents AC. The present results show that the AC removes phenol from wastewater effectively. The maximum phenol removal observed is 63.73% for 150 mg/l aqueous solution using 1 g/l dose AC. The equilibrium adsorption data can be well represented by the Langmuir isotherm with a maximum adsorption capacity of 108.7 mg/g. The calculated value of the apparent energy from the Dubinin–Radushkevich isotherm states that the adsorption of phenol on AC is a physical process. The adsorption of phenol on AC is a fast process during the first 15 min. The phenol adsorption process successfully follows the pseudo-second-order model. Thermodynamic results indicate that the adsorption of phenol on AC is a spontaneous exothermic process and satisfactory at low temperatures.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Most datasets generated and analyzed in this study are included in this submitted manuscript. The other datasets are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author with the attached information.

References

[1] Koubaissy B, Toufaily J, El-Murr M, Daou TJ, Hafez H, Joly G, et al. Adsorption kinetics and equilibrium of phenol drifts on three zeolites. Open Eng. 2012;2(3):435–44.10.2478/s13531-012-0006-4Search in Google Scholar

[2] Driemeier C, Ling LY, Sanches GM, Pontes AO, Magalhães PSG, Ferreira JE. A computational environment to support research in sugarcane agriculture. Comput Electron Agri. 2016;130:13–9.10.1016/j.compag.2016.10.002Search in Google Scholar

[3] Greish AA, Sokolovskiy PV, Finashina ED, Kustov LM, Vezentsev AI, Chien ND. Adsorption of phenol and 2,4-dichlorophenol on carbon-containing sorbent produced from sugar cane bagasse. Mendeleev Commun. 2021 Jan 1;31(1):121–2.10.1016/j.mencom.2021.01.038Search in Google Scholar

[4] Schettino MAS, Holanda JNF. Characterization of Sugarcane bagasse ash waste for its use in ceramic floor tile. Procedia Mater Sci. 2015;8:190–6.10.1016/j.mspro.2015.04.063Search in Google Scholar

[5] Kambo HS, Minaret J, Dutta A. Process water from the hydrothermal carbonization of biomass: a waste or a valuable product. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 2018;9:1181–9.10.1007/s12649-017-9914-0Search in Google Scholar

[6] Yu CH, Huang CH, Tan CS. A review of CO2 capture by absorption and adsorption. Aerosol Air Qual Res. 2012;12(5):745–69.10.4209/aaqr.2012.05.0132Search in Google Scholar

[7] Iryani DA, Kumagai S, Nonaka M, Sasaki K, Hirajima T. Characterization and production of solid biofuel from sugarcane bagasse by hydrothermal carbonization. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 2017 Mar 20;8(6):1941–51.10.1007/s12649-017-9898-9Search in Google Scholar

[8] Hameed BH, Rahman AA. Removal of phenol from aqueous solutions by adsorption onto activated carbon prepared from biomass material. J Hazard Mater. 2008;160(2–3):576–81.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.03.028Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Toufaily J, Koubaissy B, Kafrouny L, Hamad H, Magnoux P, Ghannam L, et al. Functionalization of SBA-15 materials for the adsorption of phenols from aqueous solution. Open Eng. 2012;3(1):126–34.10.2478/s13531-012-0038-9Search in Google Scholar

[10] Guo J, Lua AC. Textural and chemical characterizations of adsorbent prepared from palm shell by potassium hydroxide impregnation at different stages. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2002;254(2):227–33.10.1006/jcis.2002.8587Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Jia Q, Lua AC. Effects of pyrolysis conditions on the physical characteristics of oil-palm-shell activated carbons used in aqueous phase phenol adsorption. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2008;83(2):175–9.10.1016/j.jaap.2008.08.001Search in Google Scholar

[12] Koubaissy B, Toufaily J, Cheikh S, Hassan M, Hamieh T. Valorization of agricultural waste into activated carbons and its adsorption characteristics for heavy metals. Open Eng. 2014;4(1):90–9.10.2478/s13531-013-0148-zSearch in Google Scholar

[13] Ahmaruzzaman Md. Adsorption of phenolic compounds on low-cost adsorbents: A review. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2008;143(1–2):48–67.10.1016/j.cis.2008.07.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Lin S-H, Juang R-S. Adsorption of phenol and its derivatives from water using synthetic resins and low-cost natural adsorbents: A review. J Environ Manag. 2009;90(3):1336–49.10.1016/j.jenvman.2008.09.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Ingole RS, Lataye DH, Dhorabe PT. Adsorption of phenol onto banana peels activated carbon. KSCE J Civ Eng. 2016;21(1):100–10.10.1007/s12205-016-0101-9Search in Google Scholar

[16] Senturk HB, Ozdes D, Gundogdu A, Duran C, Soylak M. Removal of phenol from aqueous solution by adsorption onto organomodified Tirebolu bentonite: Equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic study. J Hazard Mater. 2009;172(1):353–62.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.07.019Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Girods P, Dufour A, Fierro V, Rogaume Y, Rogaume C, Zoulalian A. Activated carbons prepared from wood particleboard wastes: Characterisation and phenol adsorption capacities. J Hazard Mater. 2009;166(1):491–501.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.11.047Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Abbas ZI, Abbas AS. Oxidative degradation of phenolic wastewater by electro-fenton process using MnO2-graphite electrode. J Env Chem Eng. 2019;7(3):103108.10.1016/j.jece.2019.103108Search in Google Scholar

[19] Muppalla R, Jewrajka SK, Reddy AVR. Fouling resistant nanofiltration membranes for the separation of oil–water emulsion and micropollutants from water. Sep Purif Technol. 2015;143:125–34.10.1016/j.seppur.2015.01.031Search in Google Scholar

[20] Duan L, Wang H, Sun Y, Xie X. Biodegradation of phenol from wastewater by microorganism immobilized in bentonite and carboxymethyl cellulose gel. Chem Eng Commun. 2016;203(7):948–56.10.1080/00986445.2015.1074897Search in Google Scholar

[21] Reis GS, Adebayo M, Sampaio C, Lima E, Thue PS, Brum I, et al. Removal of phenolic compounds from aqueous solutions using sludge-based activated carbons prepared by conventional heating and microwave-assisted pyrolysis. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2016;228(1):1–17.10.1007/s11270-016-3202-7Search in Google Scholar

[22] Moussavi G, Mahmoudi M, Barikbin B. Biological removal of phenol from strong wastewaters using a novel MSBR. Water Res. 2009;43(5):1295–302.10.1016/j.watres.2008.12.026Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Golbaz S, Jafari AJ, Rafiee M, Kalantary R. Separate and simultaneous removal of phenol, chromium, and cyanide from aqueous solution by coagulation/precipitation: mechanisms and theory. Chem Eng J. 2014;253:251–7.10.1016/j.cej.2014.05.074Search in Google Scholar

[24] Zou Y, Wang X, Ai Y, Liu Y, Li J, Ji Y, et al. Coagulation behavior of graphene oxide on nanocrystallined Mg/Al layered double hydroxides: batch experimental and theoretical calculation study. Environ Sci Technol. 2016 Mar 23;50(7):3658–67.10.1021/acs.est.6b00255Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Huang CS, Shih CC. Effects of nitrogen and high temperature aging on σ phase precipitation of duplex stainless steel. Mater Sci Eng A. 2005;402(1–2):66–75.10.1016/j.msea.2005.03.111Search in Google Scholar

[26] Caetano M, Valderrama C, Farran A, Cortina JL. Phenol removal from aqueous solution by adsorption and ion exchange mechanisms onto polymeric resins. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2009;338(2):402–9.10.1016/j.jcis.2009.06.062Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Lam S-M, Sin J-C, Abdullah AZ, Mohamed AR. Sunlight responsive WO3/ZnO nanorods for photocatalytic degradation and mineralization of chlorinated phenoxyacetic acid herbicides in water. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2015;450:34–44.10.1016/j.jcis.2015.02.075Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Yan H, Pan G, Xu J, Guo M, Miao X, Zhang Y, et al. Porous structure of the fully-aromatic polyamide film in reverse osmosis membranes. J Membr Sci. 2015;475:504–10.10.1016/j.memsci.2014.10.052Search in Google Scholar

[29] Barno SKA, Abbas AS. Reduction of organics in dairy wastewater by adsorption on a prepared charcoal from Iraqi sugarcane. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2020;736(2):022096.10.1088/1757-899X/736/2/022096Search in Google Scholar

[30] Rueda-Marquez JJ, Levchuk I, Fernández Ibañez P, Sillanpää M. A critical review on application of photocatalysis for toxicity reduction of real wastewaters. J Clean Prod. 2020;258:120694.10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120694Search in Google Scholar

[31] Hemmati M, Nazari N, Hemmati A, Shirazian S. Phenol removal from wastewater by means of nanoporous membrane contactors. J Ind Eng Chem. 2015;21:1410–6.10.1016/j.jiec.2014.06.015Search in Google Scholar

[32] Al-Waeli LK, Sahib JH, Abbas HA. ANN-based model to predict groundwater salinity: A case study of West Najaf–Kerbala region. Open Eng. 2022;12(1):120–8.10.1515/eng-2022-0025Search in Google Scholar

[33] Abid RK, Abbas AS. Adsorption of organic pollutants from real refinery wastewater on prepared cross-linked starch by epichlorohydrin. Data Br. 2018;19:1318–26.10.1016/j.dib.2018.05.060Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Abbas AS, Ahmed MJ, Darweesh TM. Adsorption of fluoroquinolones antibiotics on activated carbon by K2CO3 with microwave assisted activation. Iraqi J Chem Pet Eng. 2016;17(2):15–23.10.31699/IJCPE.2016.2.3Search in Google Scholar

[35] Abbas AS, Darweesh TM. Preparation and characterization of activated carbon for adsorption of fluoroquinolones antibiotics. J Eng. 2016;22(8):140–57.10.31026/j.eng.2016.08.09Search in Google Scholar

[36] Williams P, Reed A. Development of activated carbon pore structure via physical and chemical activation of biomass fibre waste. Biomass Bioenergy. 2006;30(2):144–52.10.1016/j.biombioe.2005.11.006Search in Google Scholar

[37] Şahin Ö, Saka C. Preparation and characterization of activated carbon from acorn shell by physical activation with H2O–CO2 in two-step pretreatment. Bioresour Technol. 2013;136:163–8.10.1016/j.biortech.2013.02.074Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Bouchelta C, Medjram MS, Bertrand O, Bellat J-P. Preparation and characterization of activated carbon from date stones by physical activation with steam. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2008;82(1):70–7.10.1016/j.jaap.2007.12.009Search in Google Scholar

[39] Wei L, Yushin G. Nanostructured activated carbons from natural precursors for electrical double layer capacitors. Nano Energy. 2012;1(4):552–65.10.1016/j.nanoen.2012.05.002Search in Google Scholar

[40] Syeda R, Xu J, Dubin AE, Coste B, Mathur J, Huynh T, et al. Chemical activation of the mechanotransduction channel Piezo1. eLife. 2015;e07369.10.7554/eLife.07369.008Search in Google Scholar

[41] Kilic M, Apaydin-Varol E, Pütün AE. Adsorptive removal of phenol from aqueous solutions on activated carbon prepared from tobacco residues: equilibrium, kinetics and thermodynamics. J Hazard Mater. 2011;189(1–2):397–403.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.02.051Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Sayed ET, Wilberforce T, Elsaid K, Rabaia MKH, Abdelkareem MA, Chae K-J, et al. A critical review on environmental impacts of renewable energy systems and mitigation strategies: Wind, hydro, biomass and geothermal. Sci Total Environ. 2021;766:144505.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144505Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Daifullah AAM, Girgis BS. Removal of some substituted phenols by activated carbon obtained from agricultural waste. Water Res. 1998;32(4):1169–77.10.1016/S0043-1354(97)00310-2Search in Google Scholar

[44] László K, Bóta A, Nagyu LG. Characterization of activated carbons from waste materials by adsorption from aqueous solutions. Carbon. 1997;35(5):593–8.10.1016/S0008-6223(97)00005-5Search in Google Scholar

[45] Viraraghavan T, de Maria Alfaro F. Adsorption of phenol from wastewater by peat, fly ash and bentonite. J Hazard Mater. 1998;57(1–3):59–70.10.1016/S0304-3894(97)00062-9Search in Google Scholar

[46] Juang RS, Wu FC, Tseng RL. Mechanism of adsorption of dyes and phenols from water using activated carbons prepared from plum kernels. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2000;227(2):437–44.10.1006/jcis.2000.6912Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Dursun G, Çiçek H, Dursun AY. Adsorption of phenol from aqueous solution by using carbonised beet pulp. J Hazard Mater. 2005;125(1–3):175–82.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2005.05.023Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Park KH, Balathanigaimani MS, Shim WG, Lee JW, Moon H. Adsorption characteristics of phenol on novel corn grain-based activated carbons. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2010;127(1–2):1–8.10.1016/j.micromeso.2009.06.032Search in Google Scholar

[49] Mukherjee S, Kumar S, Misra AK, Fan M. Removal of phenols from water environment by activated carbon, bagasse ash and wood charcoal. Chem Eng J. 2007;129(1–3):133–42.10.1016/j.cej.2006.10.030Search in Google Scholar

[50] Ingole RS, Lataye DH. Adsorptive removal of phenol from aqueous solution using activated carbon prepared from babul sawdust. J Hazard Toxic Radioact Waste. 2015;19(4):04015002.10.1061/(ASCE)HZ.2153-5515.0000271Search in Google Scholar

[51] Dhorabe PT, Lataye DH, Ingole RS. Removal of 4-nitrophenol from aqueous solution by adsorption onto activated carbon prepared from Acacia glauca sawdust. Water Sci Technol. 2015;73(4):955–66.10.2166/wst.2015.575Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[52] Mirmohamadsadeghi S, Kaghazchi T, Soleimani M, Asasian N. An efficient method for clay modification and its application for phenol removal from wastewater. Appl Clay Sci. 2012;59-60:8–12.10.1016/j.clay.2012.02.016Search in Google Scholar

[53] Aravindan L, Bicknell KA, Brooks G, Khutoryanskiy VV, Williams AC. Effect of acyl chain length on transfection efficiency and toxicity of polyethylenimine. Int J Pharm. 2009;378(1–2):201–10.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.05.052Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[54] Pigatto G, Lodi A, Finocchio E, Palma MSA, Converti A. Chitin as biosorbent for phenol removal from aqueous solution: Equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Chem Eng Process. 2013;70:131–9.10.1016/j.cep.2013.04.009Search in Google Scholar

[55] Rakić V, Damjanović L, Rac V, Stošić D, Dondur V, Auroux A. The adsorption of nicotine from aqueous solutions on different zeolite structures. Water Res. 2010;44(6):2047–57.10.1016/j.watres.2009.12.019Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[56] Barno SKA, Mohamed HJ, Saeed SM, Al-Ani MJ, Abbas AS. Prepared 13X zeolite as a promising adsorbent for the removal of brilliant blue dye from wastewater. Iraqi J Chem Pet Eng. 2021;22(2):1–6.10.31699/IJCPE.2021.2.1Search in Google Scholar

[57] Srivastava VC, Swamy MM, Mall ID, Prasad B, Mishra IM. Adsorptive removal of phenol by bagasse fly ash and activated carbon: Equilibrium, kinetics and thermodynamics. Colloids Surf A. 2006;272(1–2):89–104.10.1016/j.colsurfa.2005.07.016Search in Google Scholar

[58] Yan L, Qin L, Yu H, Li S, Shan R, Du B. Adsorption of acid dyes from aqueous solution by CTMAB modified bentonite: Kinetic and isotherm modeling. J Mol Liq. 2015;211:1074–81.10.1016/j.molliq.2015.08.032Search in Google Scholar

[59] Langmuir I. The constitution and fundamental properties of solids and liquids. Part I. solids. J Am Chem Soc. 1916 May 1;38(11):2221–95.10.1021/ja02268a002Search in Google Scholar

[60] Freundlich H. Über die Adsorption in Lösungen. Z Phys Chem. 1907;57U(1):385–470.10.1515/zpch-1907-5723Search in Google Scholar

[61] Temkin M, Pyzhev V. Kinetics of the synthesis of ammonia on promoted iron catalysts. Acta Physicochim URSS Nat. 1940;12(1):217–22.Search in Google Scholar

[62] Grishchenko L, Diyuk V, Konoplitska O, Lisnyak V, Maryichuk R. Modeling of copper ions adsorption onto oxidative-modified activated carbons. Adsorption Sci Technol. 2017;35(9–10):884–900.10.1177/0263617417729236Search in Google Scholar

[63] Jin G-P, Zhu X-H, Li C-Y, Fu Y, Guan J-X, Wu X-P. Tetraoxalyl ethylenediamine melamine resin functionalized coconut active charcoal for adsorptive removal of Ni(II), Pb(II) and Cd(II) from their aqueous solution. J Environ Chem Eng. 2013;1(4):736–45.10.1016/j.jece.2013.07.010Search in Google Scholar

[64] Dehghani MH, Ghadermazi M, Bhatnagar A, Sadighara P, Jahed-Khaniki G, Heibati B, et al. Adsorptive removal of endocrine disrupting bisphenol A from aqueous solution using chitosan. J Environ Chem Eng. 2016;4(3):2647–55.10.1016/j.jece.2016.05.011Search in Google Scholar

[65] Hamoudi S, Belkacemi K. Adsorption of nitrate and phosphate ions from aqueous solutions using organically-functionalized silica materials: Kinetic modeling. Fuel. 2013;110:107–13.10.1016/j.fuel.2012.09.066Search in Google Scholar

[66] Indhumathi P, Sathiyaraj S, Koelmel JP, Shoba SU, Jayabalakrishnan C, Saravanabhavan M. The efficient removal of heavy metal ions from industry effluents using waste biomass as low-cost adsorbent: thermodynamic and kinetic models. Z Phys Chem. 2017;232(4):527–43.10.1515/zpch-2016-0900Search in Google Scholar

[67] Mojoudi N, Mirghaffari N, Soleimani M, Shariatmadari H, Belver C, Bedia J. Phenol adsorption on high microporous activated carbons prepared from oily sludge: equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1–12.10.1038/s41598-019-55794-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[68] Soni U, Bajpai J, Singh SK, Bajpai AK. Evaluation of chitosan-carbon based biocomposite for efficient removal of phenols from aqueous solutions. J Water Process Eng. 2017;16:56–63.10.1016/j.jwpe.2016.12.004Search in Google Scholar

[69] Ghaedi M, Haghdoust S, Kokhdan SN, Mihandoost A, Sahraie R, Daneshfar A. Comparison of activated carbon, multiwalled carbon nanotubes, and cadmium hydroxide nanowire loaded on activated carbon as adsorbents for kinetic and equilibrium study of removal of safranine O. Spectrosc Lett. 2023;45(7):500–10.10.1080/00387010.2011.641058Search in Google Scholar

[70] Lima EC, Hosseini-Bandegharaei A, Moreno-Piraján JC, Anastopoulos I. A critical review of the estimation of the thermodynamic parameters on adsorption equilibria. Wrong use of equilibrium constant in the Van’t Hoof equation for calculation of thermodynamic parameters of adsorption. J Mol Liq. 2019;273:425–34.10.1016/j.molliq.2018.10.048Search in Google Scholar

[71] Abbas AS, Hussien SA. Equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic study of aniline adsorption over prepared ZSM-5 zeolite. Iraqi J Chem Pet Eng. 2017;18(1):47–56.10.31699/IJCPE.2017.1.4Search in Google Scholar

[72] Saha P, Chowdhury SJT. Insight into adsorption thermodynamics. In: Tadashi M, editor. Thermodynamics. Vol. 16. London: InTech; 2011. p. 349–64.10.5772/13474Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Design optimization of a 4-bar exoskeleton with natural trajectories using unique gait-based synthesis approach

- Technical review of supervised machine learning studies and potential implementation to identify herbal plant dataset

- Effect of ECAP die angle and route type on the experimental evolution, crystallographic texture, and mechanical properties of pure magnesium

- Design and characteristics of two-dimensional piezoelectric nanogenerators

- Hybrid and cognitive digital twins for the process industry

- Discharge predicted in compound channels using adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS)

- Human factors in aviation: Fatigue management in ramp workers

- LLDPE matrix with LDPE and UV stabilizer additive to evaluate the interface adhesion impact on the thermal and mechanical degradation

- Dislocated time sequences – deep neural network for broken bearing diagnosis

- Estimation method of corrosion current density of RC elements

- A computational iterative design method for bend-twist deformation in composite ship propeller blades for thrusters

- Compressive forces influence on the vibrations of double beams

- Research on dynamical properties of a three-wheeled electric vehicle from the point of view of driving safety

- Risk management based on the best value approach and its application in conditions of the Czech Republic

- Effect of openings on simply supported reinforced concrete skew slabs using finite element method

- Experimental and simulation study on a rooftop vertical-axis wind turbine

- Rehabilitation of overload-damaged reinforced concrete columns using ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete

- Performance of a horizontal well in a bounded anisotropic reservoir: Part II: Performance analysis of well length and reservoir geometry

- Effect of chloride concentration on the corrosion resistance of pure Zn metal in a 0.0626 M H2SO4 solution

- Numerical and experimental analysis of the heat transfer process in a railway disc brake tested on a dynamometer stand

- Design parameters and mechanical efficiency of jet wind turbine under high wind speed conditions

- Architectural modeling of data warehouse and analytic business intelligence for Bedstead manufacturers

- Influence of nano chromium addition on the corrosion and erosion–corrosion behavior of cupronickel 70/30 alloy in seawater

- Evaluating hydraulic parameters in clays based on in situ tests

- Optimization of railway entry and exit transition curves

- Daily load curve prediction for Jordan based on statistical techniques

- Review Articles

- A review of rutting in asphalt concrete pavement

- Powered education based on Metaverse: Pre- and post-COVID comprehensive review

- A review of safety test methods for new car assessment program in Southeast Asian countries

- Communication

- StarCrete: A starch-based biocomposite for off-world construction

- Special Issue: Transport 2022 - Part I

- Analysis and assessment of the human factor as a cause of occurrence of selected railway accidents and incidents

- Testing the way of driving a vehicle in real road conditions

- Research of dynamic phenomena in a model engine stand

- Testing the relationship between the technical condition of motorcycle shock absorbers determined on the diagnostic line and their characteristics

- Retrospective analysis of the data concerning inspections of vehicles with adaptive devices

- Analysis of the operating parameters of electric, hybrid, and conventional vehicles on different types of roads

- Special Issue: 49th KKBN - Part II

- Influence of a thin dielectric layer on resonance frequencies of square SRR metasurface operating in THz band

- Influence of the presence of a nitrided layer on changes in the ultrasonic wave parameters

- Special Issue: ICRTEEC - 2021 - Part III

- Reverse droop control strategy with virtual resistance for low-voltage microgrid with multiple distributed generation sources

- Special Issue: AESMT-2 - Part II

- Waste ceramic as partial replacement for sand in integral waterproof concrete: The durability against sulfate attack of certain properties

- Assessment of Manning coefficient for Dujila Canal, Wasit/-Iraq

- Special Issue: AESMT-3 - Part I

- Modulation and performance of synchronous demodulation for speech signal detection and dialect intelligibility

- Seismic evaluation cylindrical concrete shells

- Investigating the role of different stabilizers of PVCs by using a torque rheometer

- Investigation of high-turbidity tap water problem in Najaf governorate/middle of Iraq

- Experimental and numerical evaluation of tire rubber powder effectiveness for reducing seepage rate in earth dams

- Enhancement of air conditioning system using direct evaporative cooling: Experimental and theoretical investigation

- Assessment for behavior of axially loaded reinforced concrete columns strengthened by different patterns of steel-framed jacket

- Novel graph for an appropriate cross section and length for cantilever RC beams

- Discharge coefficient and energy dissipation on stepped weir

- Numerical study of the fluid flow and heat transfer in a finned heat sink using Ansys Icepak

- Integration of numerical models to simulate 2D hydrodynamic/water quality model of contaminant concentration in Shatt Al-Arab River with WRDB calibration tools

- Study of the behavior of reactive powder concrete RC deep beams by strengthening shear using near-surface mounted CFRP bars

- The nonlinear analysis of reactive powder concrete effectiveness in shear for reinforced concrete deep beams

- Activated carbon from sugarcane as an efficient adsorbent for phenol from petroleum refinery wastewater: Equilibrium, kinetic, and thermodynamic study

- Structural behavior of concrete filled double-skin PVC tubular columns confined by plain PVC sockets

- Probabilistic derivation of droplet velocity using quadrature method of moments

- A study of characteristics of man-made lightweight aggregate and lightweight concrete made from expanded polystyrene (eps) and cement mortar

- Effect of waste materials on soil properties

- Experimental investigation of electrode wear assessment in the EDM process using image processing technique

- Punching shear of reinforced concrete slabs bonded with reactive powder after exposure to fire

- Deep learning model for intrusion detection system utilizing convolution neural network

- Improvement of CBR of gypsum subgrade soil by cement kiln dust and granulated blast-furnace slag

- Investigation of effect lengths and angles of the control devices below the hydraulic structure

- Finite element analysis for built-up steel beam with extended plate connected by bolts

- Finite element analysis and retrofit of the existing reinforced concrete columns in Iraqi schools by using CFRP as confining technique

- Performing laboratory study of the behavior of reactive powder concrete on the shear of RC deep beams by the drilling core test

- Special Issue: AESMT-4 - Part I

- Depletion zones of groundwater resources in the Southwest Desert of Iraq

- A case study of T-beams with hybrid section shear characteristics of reactive powder concrete

- Feasibility studies and their effects on the success or failure of investment projects. “Najaf governorate as a model”

- Optimizing and coordinating the location of raw material suitable for cement manufacturing in Wasit Governorate, Iraq

- Effect of the 40-PPI copper foam layer height on the solar cooker performance

- Identification and investigation of corrosion behavior of electroless composite coating on steel substrate

- Improvement in the California bearing ratio of subbase soil by recycled asphalt pavement and cement

- Some properties of thermal insulating cement mortar using Ponza aggregate

- Assessment of the impacts of land use/land cover change on water resources in the Diyala River, Iraq

- Effect of varied waste concrete ratios on the mechanical properties of polymer concrete

- Effect of adverse slope on performance of USBR II stilling basin

- Shear capacity of reinforced concrete beams with recycled steel fibers

- Extracting oil from oil shale using internal distillation (in situ retorting)

- Influence of recycling waste hardened mortar and ceramic rubbish on the properties of flowable fill material

- Rehabilitation of reinforced concrete deep beams by near-surface-mounted steel reinforcement

- Impact of waste materials (glass powder and silica fume) on features of high-strength concrete

- Studying pandemic effects and mitigation measures on management of construction projects: Najaf City as a case study

- Design and implementation of a frequency reconfigurable antenna using PIN switch for sub-6 GHz applications

- Average monthly recharge, surface runoff, and actual evapotranspiration estimation using WetSpass-M model in Low Folded Zone, Iraq

- Simple function to find base pressure under triangular and trapezoidal footing with two eccentric loads

- Assessment of ALINEA method performance at different loop detector locations using field data and micro-simulation modeling via AIMSUN

- Special Issue: AESMT-5 - Part I

- Experimental and theoretical investigation of the structural behavior of reinforced glulam wooden members by NSM steel bars and shear reinforcement CFRP sheet

- Improving the fatigue life of composite by using multiwall carbon nanotubes

- A comparative study to solve fractional initial value problems in discrete domain

- Assessing strength properties of stabilized soils using dynamic cone penetrometer test

- Investigating traffic characteristics for merging sections in Iraq

- Enhancement of flexural behavior of hybrid flat slab by using SIFCON

- The main impacts of a managed aquifer recharge using AHP-weighted overlay analysis based on GIS in the eastern Wasit province, Iraq

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Design optimization of a 4-bar exoskeleton with natural trajectories using unique gait-based synthesis approach

- Technical review of supervised machine learning studies and potential implementation to identify herbal plant dataset

- Effect of ECAP die angle and route type on the experimental evolution, crystallographic texture, and mechanical properties of pure magnesium

- Design and characteristics of two-dimensional piezoelectric nanogenerators

- Hybrid and cognitive digital twins for the process industry

- Discharge predicted in compound channels using adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS)

- Human factors in aviation: Fatigue management in ramp workers

- LLDPE matrix with LDPE and UV stabilizer additive to evaluate the interface adhesion impact on the thermal and mechanical degradation

- Dislocated time sequences – deep neural network for broken bearing diagnosis

- Estimation method of corrosion current density of RC elements

- A computational iterative design method for bend-twist deformation in composite ship propeller blades for thrusters

- Compressive forces influence on the vibrations of double beams

- Research on dynamical properties of a three-wheeled electric vehicle from the point of view of driving safety

- Risk management based on the best value approach and its application in conditions of the Czech Republic

- Effect of openings on simply supported reinforced concrete skew slabs using finite element method

- Experimental and simulation study on a rooftop vertical-axis wind turbine

- Rehabilitation of overload-damaged reinforced concrete columns using ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete

- Performance of a horizontal well in a bounded anisotropic reservoir: Part II: Performance analysis of well length and reservoir geometry

- Effect of chloride concentration on the corrosion resistance of pure Zn metal in a 0.0626 M H2SO4 solution

- Numerical and experimental analysis of the heat transfer process in a railway disc brake tested on a dynamometer stand

- Design parameters and mechanical efficiency of jet wind turbine under high wind speed conditions

- Architectural modeling of data warehouse and analytic business intelligence for Bedstead manufacturers

- Influence of nano chromium addition on the corrosion and erosion–corrosion behavior of cupronickel 70/30 alloy in seawater

- Evaluating hydraulic parameters in clays based on in situ tests

- Optimization of railway entry and exit transition curves

- Daily load curve prediction for Jordan based on statistical techniques

- Review Articles

- A review of rutting in asphalt concrete pavement

- Powered education based on Metaverse: Pre- and post-COVID comprehensive review

- A review of safety test methods for new car assessment program in Southeast Asian countries

- Communication

- StarCrete: A starch-based biocomposite for off-world construction

- Special Issue: Transport 2022 - Part I

- Analysis and assessment of the human factor as a cause of occurrence of selected railway accidents and incidents

- Testing the way of driving a vehicle in real road conditions

- Research of dynamic phenomena in a model engine stand

- Testing the relationship between the technical condition of motorcycle shock absorbers determined on the diagnostic line and their characteristics

- Retrospective analysis of the data concerning inspections of vehicles with adaptive devices

- Analysis of the operating parameters of electric, hybrid, and conventional vehicles on different types of roads

- Special Issue: 49th KKBN - Part II

- Influence of a thin dielectric layer on resonance frequencies of square SRR metasurface operating in THz band

- Influence of the presence of a nitrided layer on changes in the ultrasonic wave parameters

- Special Issue: ICRTEEC - 2021 - Part III

- Reverse droop control strategy with virtual resistance for low-voltage microgrid with multiple distributed generation sources

- Special Issue: AESMT-2 - Part II

- Waste ceramic as partial replacement for sand in integral waterproof concrete: The durability against sulfate attack of certain properties

- Assessment of Manning coefficient for Dujila Canal, Wasit/-Iraq

- Special Issue: AESMT-3 - Part I

- Modulation and performance of synchronous demodulation for speech signal detection and dialect intelligibility

- Seismic evaluation cylindrical concrete shells

- Investigating the role of different stabilizers of PVCs by using a torque rheometer

- Investigation of high-turbidity tap water problem in Najaf governorate/middle of Iraq

- Experimental and numerical evaluation of tire rubber powder effectiveness for reducing seepage rate in earth dams

- Enhancement of air conditioning system using direct evaporative cooling: Experimental and theoretical investigation

- Assessment for behavior of axially loaded reinforced concrete columns strengthened by different patterns of steel-framed jacket

- Novel graph for an appropriate cross section and length for cantilever RC beams

- Discharge coefficient and energy dissipation on stepped weir

- Numerical study of the fluid flow and heat transfer in a finned heat sink using Ansys Icepak

- Integration of numerical models to simulate 2D hydrodynamic/water quality model of contaminant concentration in Shatt Al-Arab River with WRDB calibration tools

- Study of the behavior of reactive powder concrete RC deep beams by strengthening shear using near-surface mounted CFRP bars

- The nonlinear analysis of reactive powder concrete effectiveness in shear for reinforced concrete deep beams

- Activated carbon from sugarcane as an efficient adsorbent for phenol from petroleum refinery wastewater: Equilibrium, kinetic, and thermodynamic study

- Structural behavior of concrete filled double-skin PVC tubular columns confined by plain PVC sockets

- Probabilistic derivation of droplet velocity using quadrature method of moments

- A study of characteristics of man-made lightweight aggregate and lightweight concrete made from expanded polystyrene (eps) and cement mortar

- Effect of waste materials on soil properties

- Experimental investigation of electrode wear assessment in the EDM process using image processing technique

- Punching shear of reinforced concrete slabs bonded with reactive powder after exposure to fire

- Deep learning model for intrusion detection system utilizing convolution neural network

- Improvement of CBR of gypsum subgrade soil by cement kiln dust and granulated blast-furnace slag

- Investigation of effect lengths and angles of the control devices below the hydraulic structure

- Finite element analysis for built-up steel beam with extended plate connected by bolts

- Finite element analysis and retrofit of the existing reinforced concrete columns in Iraqi schools by using CFRP as confining technique

- Performing laboratory study of the behavior of reactive powder concrete on the shear of RC deep beams by the drilling core test

- Special Issue: AESMT-4 - Part I

- Depletion zones of groundwater resources in the Southwest Desert of Iraq

- A case study of T-beams with hybrid section shear characteristics of reactive powder concrete

- Feasibility studies and their effects on the success or failure of investment projects. “Najaf governorate as a model”

- Optimizing and coordinating the location of raw material suitable for cement manufacturing in Wasit Governorate, Iraq

- Effect of the 40-PPI copper foam layer height on the solar cooker performance

- Identification and investigation of corrosion behavior of electroless composite coating on steel substrate

- Improvement in the California bearing ratio of subbase soil by recycled asphalt pavement and cement

- Some properties of thermal insulating cement mortar using Ponza aggregate

- Assessment of the impacts of land use/land cover change on water resources in the Diyala River, Iraq

- Effect of varied waste concrete ratios on the mechanical properties of polymer concrete

- Effect of adverse slope on performance of USBR II stilling basin

- Shear capacity of reinforced concrete beams with recycled steel fibers

- Extracting oil from oil shale using internal distillation (in situ retorting)

- Influence of recycling waste hardened mortar and ceramic rubbish on the properties of flowable fill material

- Rehabilitation of reinforced concrete deep beams by near-surface-mounted steel reinforcement

- Impact of waste materials (glass powder and silica fume) on features of high-strength concrete

- Studying pandemic effects and mitigation measures on management of construction projects: Najaf City as a case study

- Design and implementation of a frequency reconfigurable antenna using PIN switch for sub-6 GHz applications

- Average monthly recharge, surface runoff, and actual evapotranspiration estimation using WetSpass-M model in Low Folded Zone, Iraq

- Simple function to find base pressure under triangular and trapezoidal footing with two eccentric loads

- Assessment of ALINEA method performance at different loop detector locations using field data and micro-simulation modeling via AIMSUN

- Special Issue: AESMT-5 - Part I

- Experimental and theoretical investigation of the structural behavior of reinforced glulam wooden members by NSM steel bars and shear reinforcement CFRP sheet

- Improving the fatigue life of composite by using multiwall carbon nanotubes

- A comparative study to solve fractional initial value problems in discrete domain

- Assessing strength properties of stabilized soils using dynamic cone penetrometer test

- Investigating traffic characteristics for merging sections in Iraq

- Enhancement of flexural behavior of hybrid flat slab by using SIFCON

- The main impacts of a managed aquifer recharge using AHP-weighted overlay analysis based on GIS in the eastern Wasit province, Iraq