Abstract

This article attempts to report native growth, plant description, phytochemical constituents and bioactivities of Syzygium aqueum, S. aromaticum, S. cumini, S. guineense and S. samarangense. Those are the large public species in the Syzygium genus and some of them have been used as traditional medicines. Different parts (leaves, seeds, fruits, barks, stem barks and flower buds) of each species plant are rich in phytochemical constituents such as flavonoids, terpenoids, tannins, glycosides and phenolics. Antioxidant, antidiabetic, anticancer, toxicity, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory and anthelmintic activities are reported in various extracts (methanol, ethanol and aqueous) from different parts of Syzygium sp. The bioactivities were studied by using 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl and ferric reducing antioxidant power assays for antioxidant, 5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4,5-dimethyl-thiazoly)-3-(4-sulfophenyl) tetrazolium and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2-5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assays for anticancer, α-glucosidase and α-amylase inhibition assays for antidiabetic, agar well diffusion method for antimicrobial and brine shrimp lethality assay for toxicity. Moreover, this review shows that phytochemical constituents of each species significantly presented various bioactivities. Therefore, this review suggests that there is great potential for obtaining the lead drug from these species.

1 Introduction

Natural products are resources derived from living organisms, such as plants, animals and microorganisms. The chemicals produced by plants may be defined as “phytochemicals” [1,2]. Phytochemicals in plants have undoubtedly been a resource of medicinal treatment for human diseases for a long time. They played a key role in primary health care of nearly 75–80% of the world’s population according to the World Health Organization [3]. Phytochemicals in a plant can be explored by using various methods such as extraction, separation, purification, identification, structure elucidation, determination of physical and chemical properties, biosynthesis and quantification [4]. The phytochemicals could be classified as primary and secondary metabolites. Primary metabolites involved natural sugars, amino acids, proteins, purines and pyrimidines of nucleic acids and chlorophyll. Secondary metabolites are the remaining plant chemicals such as glycosides, alkaloids, terpenoids, flavonoids, lignans, steroids, curcumines, saponins and phenolics [5].

The secondary metabolites are primary for plants to protect themselves from environmental hazards such as pollution, UV exposure, stress, drought and pathogenic attack, as well as researchers have reported that phytochemicals can protect them from human diseases [5,6]. The secondary metabolites have biological properties such as antioxidant activity, anticancer property, antimicrobial effect, anti-inflammatory and stimulant to the immune system [7]. Bioactive secondary metabolites, more than a thousand known and many unknown, come from all parts of plants such as stems, fruits, roots, flowers, seeds, barks and pulps. [7,8]

The eighth-largest family in herbal plants is Myrtaceae that comprised about 140 genera and 3,800–5,800 species [9]. Syzygium is the 16th largest genus of flowering plants in Myrtaceae family [10] that includes high diversity cultivated for many purposes such as colorful, edible and fleshy fruits [11,12]. There are 1,100–1,200 species of Syzygium [13,14,15,16]. Species of Syzygium are distributed in the tropical and sub-tropical regions of the world [17,18]. They have a native range that extends from Africa and Madagascar through southern East Asia and the Pacific [13,17]. The enormous diversity of species takes place in South East Asia such as Indonesia, Malaysia, East India [11], Myanmar, Philippines and Thailand [13]. The Syzygium genus is widely grown in rainforests such as coastal forests, swamp forests, resembled monsoons, bamboo forests and peat swamp forests [14].

Syzygium genus contains abundant secondary metabolites such as terpenoids, chalcones, flavonoids, lignans, alkyl phloroglucinols, hydrolysable tannins and chromone derivatives [19], which exhibits bioactivities such as antidiabetic, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antioxidant, cytotoxic [20], anti-HIV, antidiarrheal, anthelmintic and antivirus activities [16]. S. aqueum, S. aromaticum, S. cumini, S. guineense and S. samarangense are five large public species in this genus [14]. Some of them have been used as a traditional medicine to treat several disorders (such as hemorrhage, dysentery and gastrointestinal disorders), diabetes, inflammation such as antifungal, antimicrobial, antihypertensive, analgesic and antiviral [15] bronchitis, thirst, dysentery and ulcers [16].

Most researchers have reported their rich sources of phytochemical constituents and bioactivities. Native growth and plant description of five species have been already reviewed by many reviewers [21,22,23,24,25]. S. cumini, one known species, has been overviewed by some authors [26,27]. And then, phytochemical constituents and bioactivities of both S. aromaticum [28,29] and S. cumini [30,31] have been already reported in review articles. However, phytochemical constituents and bioactivities of S. aqueum, S. guineense and S. samarangense have not yet been discussed by any reviewers. Moreover, most of the authors have reviewed only phytochemicals or bioactivities of one species in each review article.

Therefore, this review aims to provide detailed reports of five large public species in Syzygium genus. Rich phytochemicals and bioactivities of five species have been recorded by reviewing many international public articles and most of the review articles by authors. All of native growths, plant descriptions, phytochemical constituents and bioactivities from different parts of plants (five species) are studied in this review article (Table 1).

Common name and distribution of five Syzygium species

| Species name | Family | Genus | Common name | Distribution | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aqueum | Myrtaceae | Syzygium | Water apple, bell fruit, water cherry and water rose apple | India, Malaysia, Asia and Philippines | [13,32,33] |

| S. samarangense | Myrtaceae | Syzygium | Java apple, markopa, Java rose apple, Samarang apple, wax jambu and wax apple | Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, India, Australia and Taiwan | [13,34,35] |

| S. aromaticum | Myrtaceae | Syzygium | Clove, Lavang and Laung (Hindi) | Indonesia, Madagascar, Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka and China | [13,28,36] |

| S. cumini | Myrtaceae | Syzygium | Jambul, Jambolan, black plum, duhat plum and Java plum | India, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Sri Lanka and Thailand | [13,30,37] |

| S. guineense | Myrtaceae | Syzygium | Water berry, water boom and woodland Roof of Africa | Australia, Asia and Horn of Africa | [13,38] |

2 Description of plants

2.1 Syzygium aqueum

The tree of S. aqueum is cultivated well in heavy and fertile soils and is sensitive to frost. It grows up to a height of 8–10 m with branching near the base. Leaves are 4.5–23 cm long, 1.5–11 cm wide and oblong to elliptic. The leafstalk is 1–5 mm long. Flowers are yellowish-white or pinkish and are 2–3 cm long. They produced terminal or axillary cymes and moreover the flowering season occurs in February–March and fruits mature during May–June. Fruits are pale rose or white. They are watery, small bell-shaped with shinning skin, spongy and slightly fragrant. They are about 1 inch long and are ½ inch wide [39,40,41].

2.2 Syzygium samarangense

The tree of S. samarangense is grown in a rather long dry period and relatively moist tropical sea level area up to 1,200 m. It grows up to a height of 3–15 m with branching near the base. Leaves are 10–25 cm × 5–12 cm, petiole is thick and the shape of leaves is opposite and oblong to elliptic. Flowers are white to yellowish-white, 2.5 cm in diameter and the flowering season is early or late in the dry period. Fruits are bell-shaped, oval and their sizes are 3.5–5.5 cm × 4.5–5.5 cm. The skin color of fruits splits from white to pale green to dark green, from pink to red to pink-red [21,22].

2.3 Syzygium aromaticum

S. aromaticum is also known as clove, which is an aromatic dried flower bud of a plant in the Myrtaceae family. The clove is composed of buds and leaves (the commercial part of the plant). The flowering bud production begins 4 years after plantation, and they are collected by hand or using a natural phytohormone in the pre-flowering period [29,42].

2.4 Syzygium cumini

S. cumini is an evergreen tree and the height is 25 m. Leaves are slightly leathery and from oblong-ovate to elliptical or obovate-elliptic. The length of leaf is 6–12 cm long and the stalk of a leaf is 3 cm long. Flowers are fragrant, white to pink or greenish-white, about 1 cm in cross, branched clusters at the stem tips. The calyx is about 4 mm long, four toothed and funnel-shaped. The very numerous stamens are as long as the calyx. The ovoid fruits are 1.5–3.5 cm long berries, dark purple or nearly black, dark purplish-red, shiny, with white to lavender flesh. The fruit contains a single large seed, 2 cm long [17,23,37].

2.5 Syzygium guineense

S. guineense prefers moist soils on high water tables in lowland riverine forest or wooded grassland and lower montane forests, from sea level to 2,100 m. It is a sizeable evergreen tree in the forest and the height is from 10 to 15 m or 25 m. It has a broad trunk and fluted with dense rounded thick crown, branches drooping. The more the age of the plant, the more the bark is rough and flaking. Leaves are opposite, smooth on both surfaces, shiny and with short stalks. The color of leaves is from purple-red to dark green. Flowers have white, showy stamens, with fragrant smell and in dense clusters. Fruits are oval shaped, 3 cm long, shiny, purple-black in color and one-seeded [24].

3 Phytochemical constituents

3.1 Flavonoids

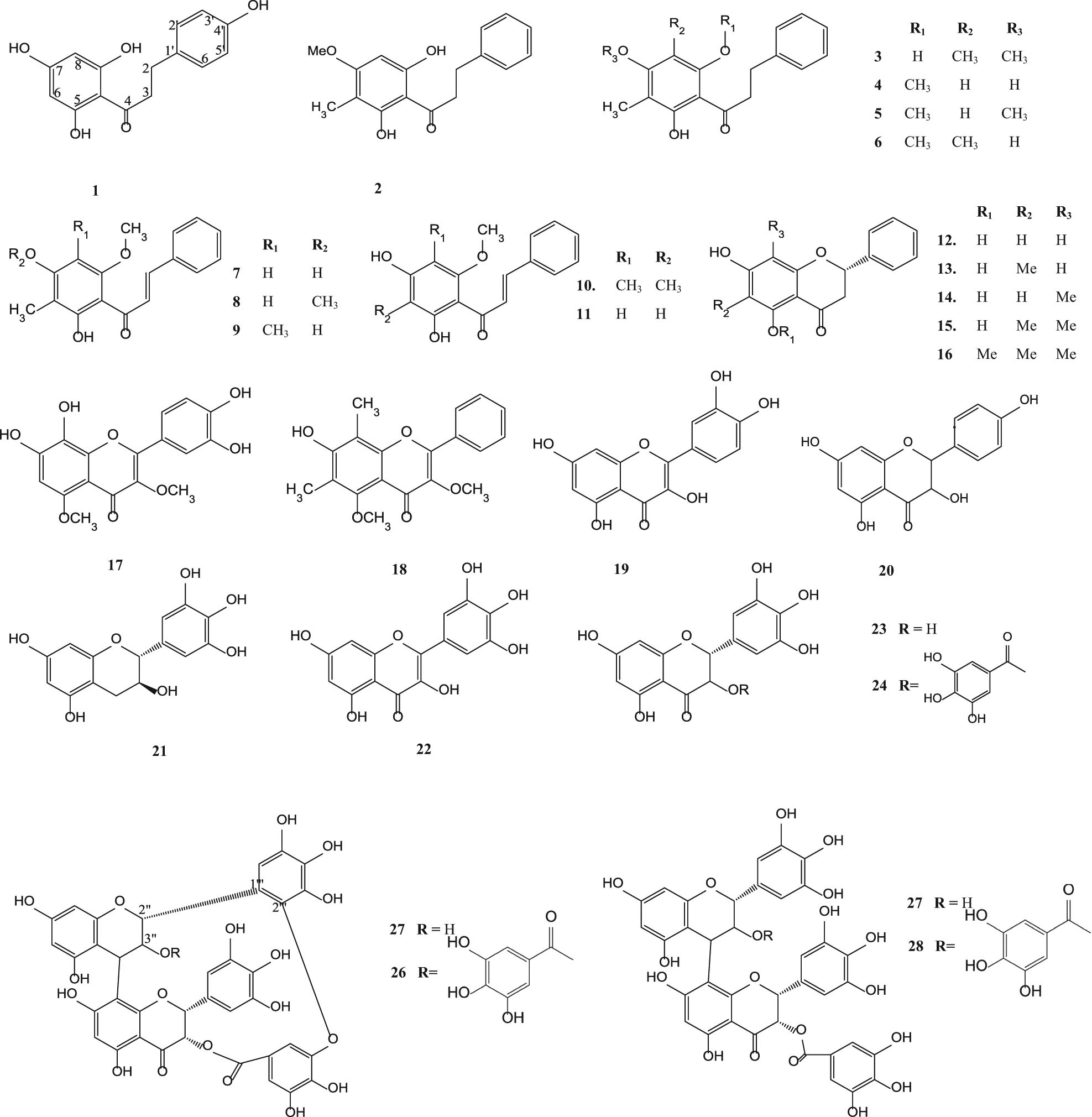

Phloretin (1), myrigalone-G (2), myrigalone B (3) [43], 2′,4′-dihydroxy-6′-methoxy-3′-methyldihydrochalcone (4), 2′-hydroxy-4′,6′-dimethoxy-3′-methyldihydrochalcone (5), 2′,4′-dihydroxy-6′-methoxy3′,5′-dimethyldihydrochalcone (6) [46,47], 2′,4′-dihydroxy-6′-methoxy-3′-methylchalcone or stercurensin (7), 2′-hydroxy-4′,6′-dimethoxy-3′-methylchalcone (8) [46,47], 2′,4′-dihydroxy-6′-methoxy-3′,5′dimethylchalcone (9) [44], 2′,4′-dihydroxy-3′,5′-dimethyl-6′-methoxychalcone (10), 2′,4′-dihydroxy-6′-methoxchalcone or cardamonin (11) [51], pinocembrin (12), (−)-strobopinin (13), 8-methylpinocembrin (14), demethoxymatteutcinol (15), 7-hydroxy-5-methoxy-6,8-dimethylfoavanone (16) [48], 7,8,3′,4′-tetrahydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyflavone (17) [45], 7-hydroxy-5-methoxy-6,8-dimethylflavanone (18), quercetin (19) [49,50], kaempferol (20) [54], gallocatechin (21), myricetin (22) [51], (−)-epigallocatechin (23), (−)-epigallocatechin 3-O-gallate (24), samarangenin A (25), samarangenin B (26), prodelphinidin B-2 3″-O-gallate (27) and prodelphinidin B-2 3,3″-O-gallate (28) [52] are presented in Figure 1.

Flavonoids from various parts of S. aqueum, S. samarangense, S. aromaticum, S. cumini and S. guineense.

3.2 Flavonoid glycosides

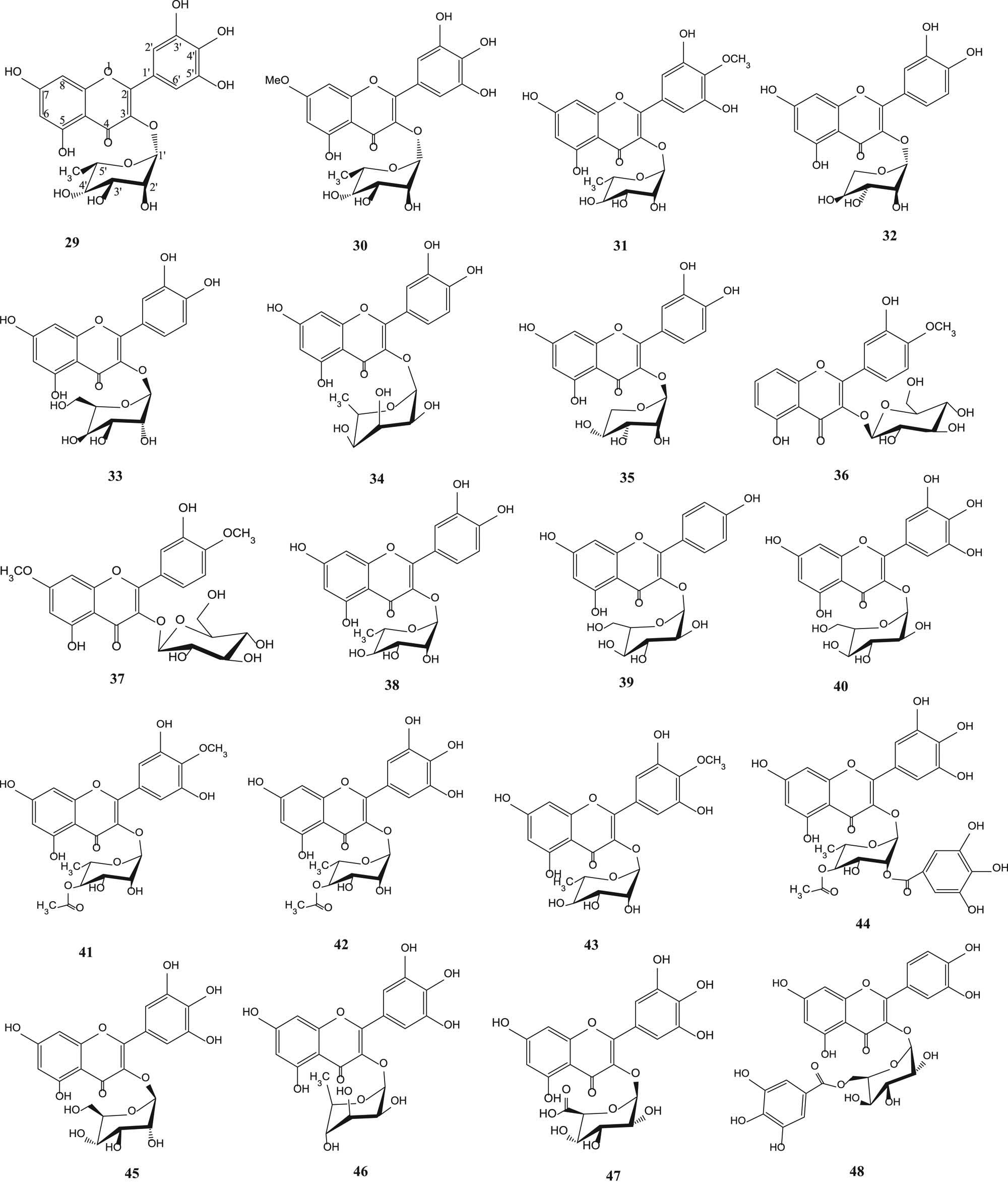

Myricetin-3-O-rhamnoside (29) [43,45], europetin-3-rhamnoside (30) [43], mearnsitrin (31) [53], reynoutrin (32), hyperin (33), quercitrin (34), guaijaverin (35) [49], tamarixetin 3-O-β-d-glucopyranoside (36), ombutin 3-O-β-d-glucopyranoside (37) [50], quercetin 3-O-α-l-rhamnopyranoside (38), kaempferol 3-O-β-d-glucuronopyranoside (39), myricetin 3-O-β-d-glucuronopyranoside (40), mearnsetin 3-O-(4″-O-acetyl)-α-l-rhamnopyranoside (41), myricetin 3-O-(4″-O-acetyl)-α-l-rhamnopyranoside (42), myricetin 4′-methyl ether 3-O-α-l-rhamnopyranoside (43), myricetrin 4″-O-acetyl-2″-O-gallate (44) [54], myricetin-3-O-glucoside (45), myricetin-3-O-rhamnoside (46), myricetin-3-O-glucoronide (47) and myricetin-3-O-β-d-(6″-galloyl) galactoside (48) [51] are shown in Figure 2.

Flavonoid glycosides from various parts of S. aqueum, S. samarangense, S. aromaticum, S. cumini and S. guineense.

3.3 Chromone glycosides

Biflorin (49), isobiflorin (50), 6-C-β-d-(6′-O-galloyl) glucosylnoreugenin (51) and 8-C-β-d-(6′-O-galloyl)glucosylnoreugenin (52) [55] are shown in Figure 3.

Chromone glycosides from various parts of S. aromaticum.

3.4 Terpenoids

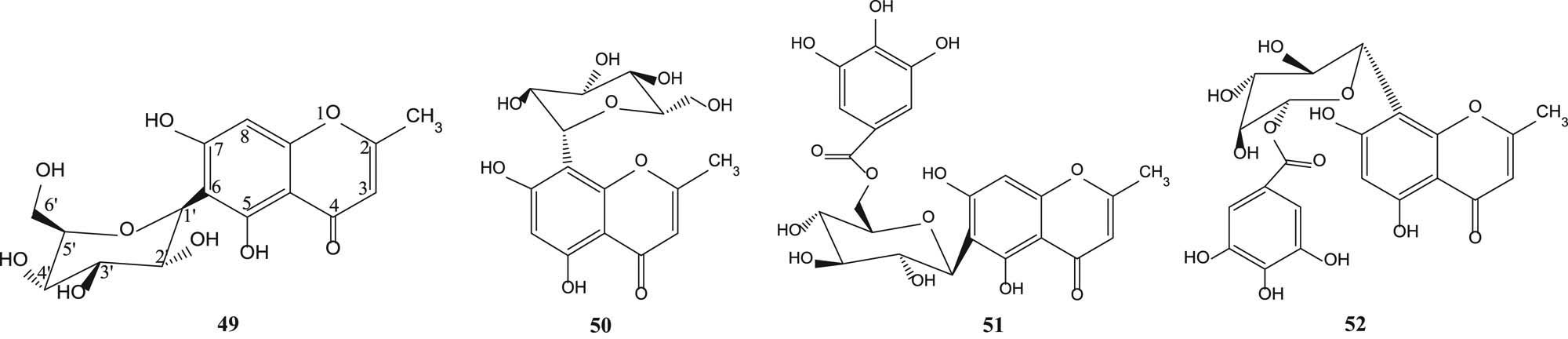

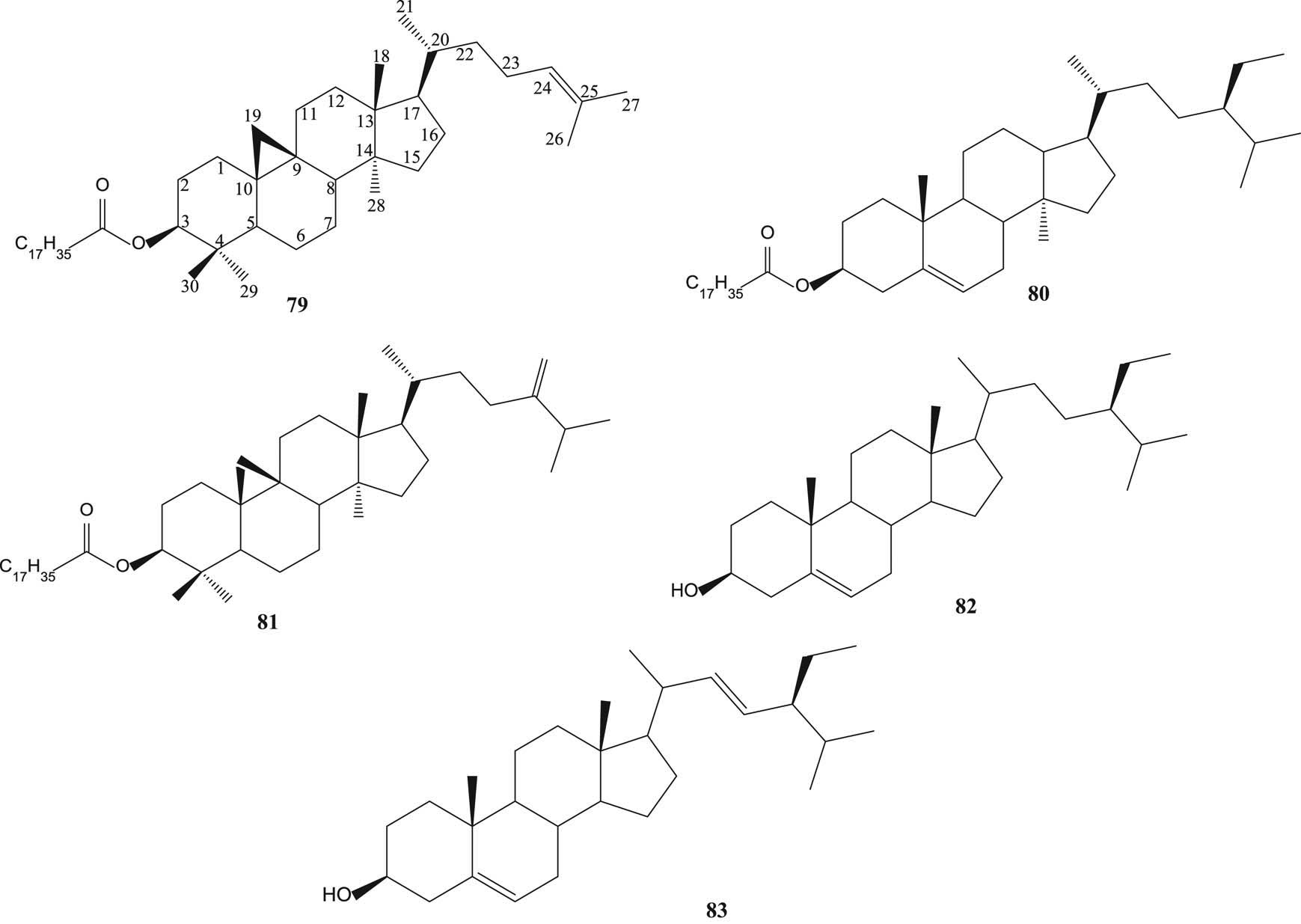

Sysamarin A (53), sysamarin B (54), sysamarin C (55), sysamarin D (56), sysamarin E (57) [56], lupenyl stearate (58) [57], lupeol (59) [46,57], betulin (60), betulinic acid (61) [46,63], oleanolic acid (62) [55,58,59], arjunolic acid (63) [58,61,62], corosolic acid (64) [58] asiatic acid (65) [58,61,62], maslinic acid (66) [55], 12-oleanen-3-ol-3β acetate (67) [60], 2-hydroxyoleanolic acid (68), 2-hydroxyursolic acid (69), terminolic acid (70), 6-hydroxy asiatic acid (71) [61,62], limonin (72) [50], caryolane-1,9β-diol (73), clovane-2,9β-diol (74), α-humulene (75), humulene epoxide α (76), β-caryophyllene (77) and β-caryophyllene oxide (78) [55] are shown in Figure 4.

Terpenoids and steroids from various parts of S. samarangense, S. aromaticum, S. cumini and S. guineense.

3.5 Steroids

Lupenyl stearate cycloartenyl stearate (79), β-sitosteryl stearate (80), 24-methylenecycloartenyl stearate (81) [57], β-sitosterol (82) [57,59] and stigmasterol (83) [60] are shown in Figure 5.

Steroids from various parts of S. aromaticum and S. cumini.

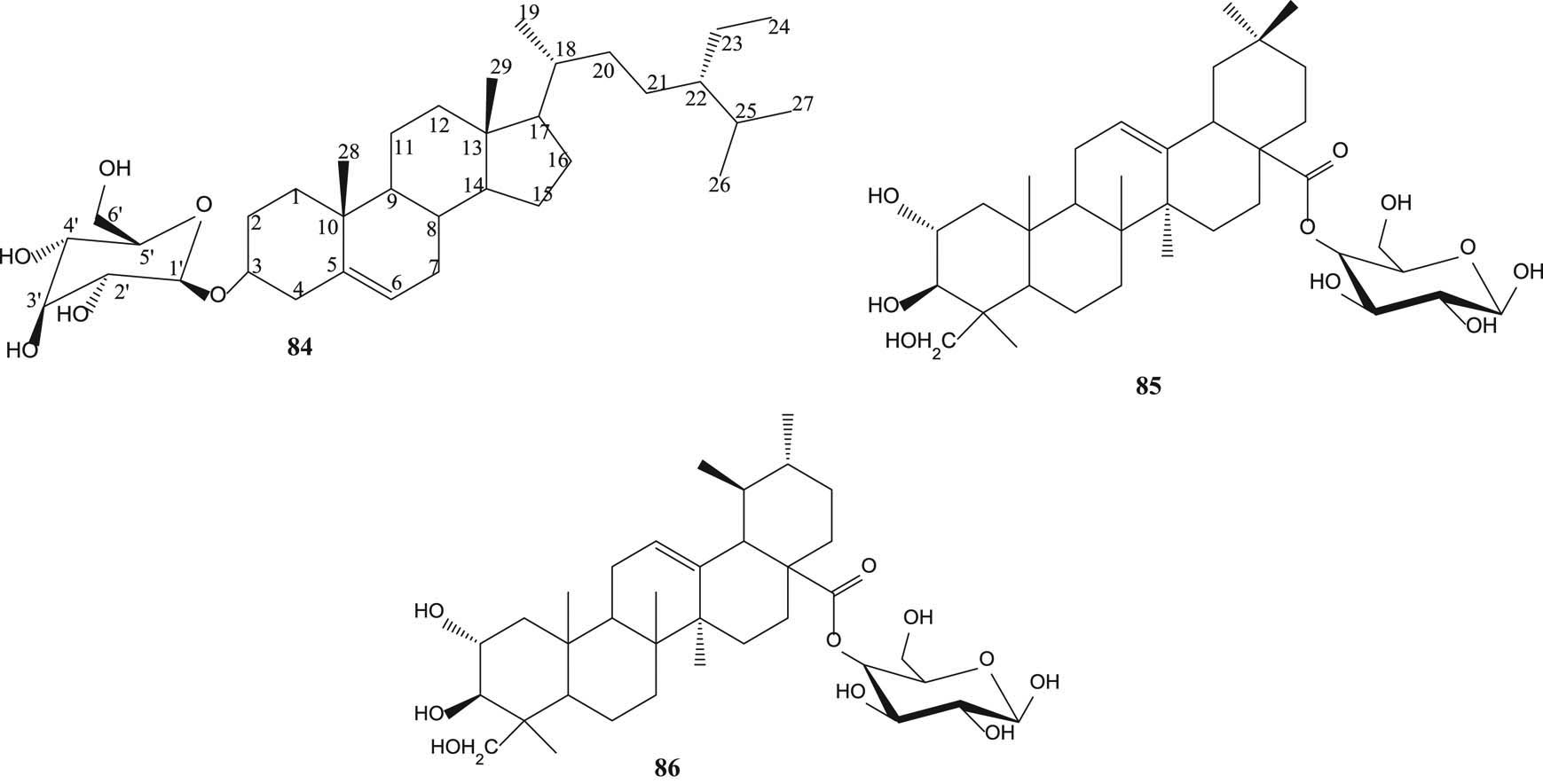

3.6 Steroid glycoside and terpenoid glycosides

β-Sitosterol-3-O-β-d-glucoside (84) [55], arjunolic acid 28-β-glycopyranosyl ester (85) and asiatic acid 28-β-glycopyranosyl ester (86) [61,62] are displayed in Figure 6.

Steroid glycosides and terpenoid glycosides from various parts of S. aromaticum and S. guineense.

3.7 Tannins

3,3′,4′-Tri-O-methylellagic acid (87) [55], ellagic acid (88) [49,64], ellagitannin-3-O-methylellagic acid 3′-O-β-d-glucopyranoside (89), ellagic acid 4-O-α-l-2″-acetylhamnopyranoside (90) [64], 3-O-methylellgic acid 3′-O-α-l-rhamnopyranoside (91), gallotannins 1,2,3,6-tetra-O-galloyl-β-d-glucose (92), 1,2,3,4,6-penta-O-galloyl-β-d-glucose (93), casuarictin (94) and casuarinin (95) [51] are depicted in Figure 7.

Tannins from various parts of S. aromaticum, S. cumini and S. guineense.

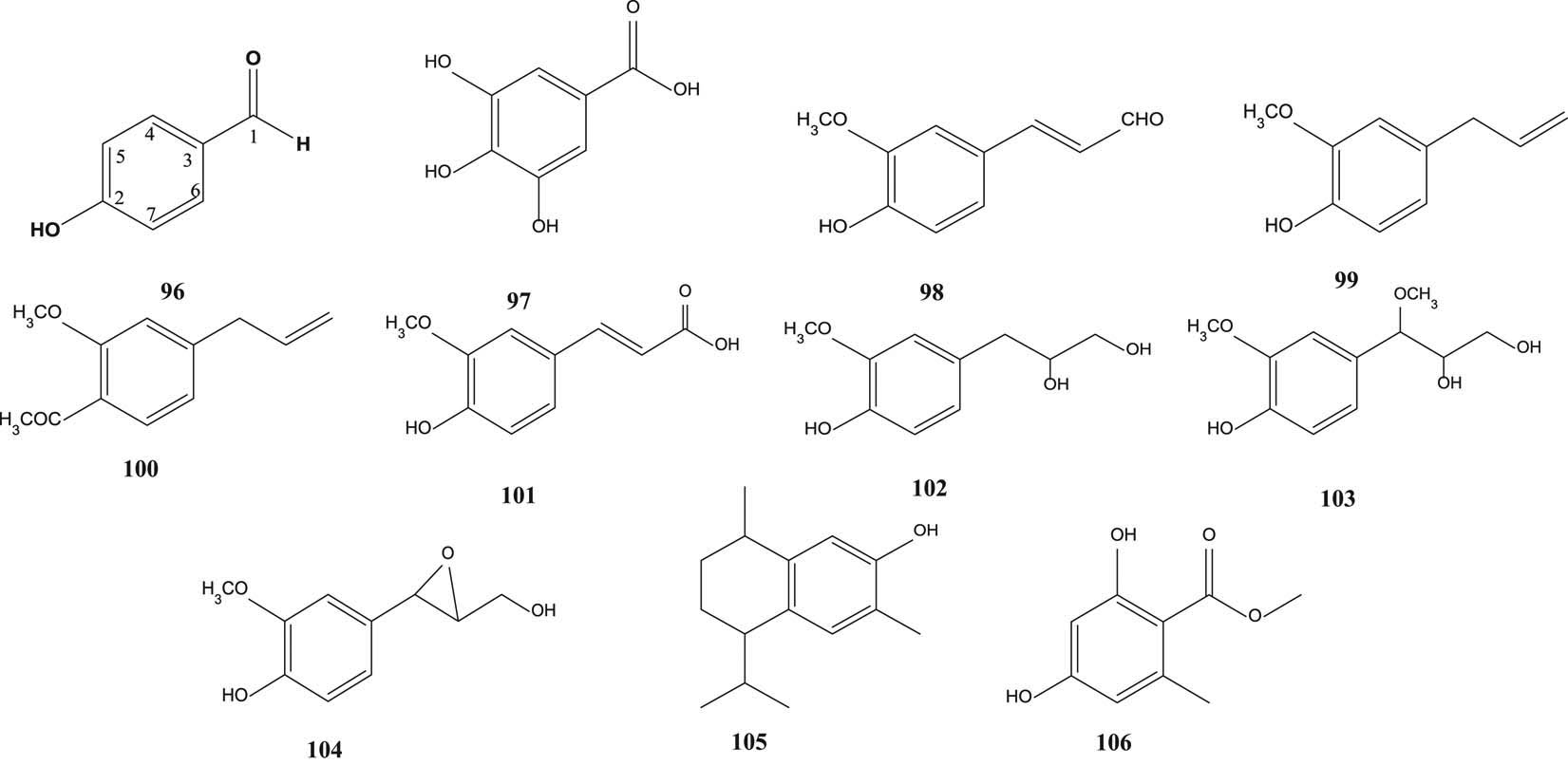

3.8 Phenols

Hydroxybenzaldehyde (96) [43], gallic acid (97) [49,64], ferulic aldehyde (98) [50], eugenol (99), eugenyl acetate (100), trans-coniferylaldehyde (101), 3-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxy-phenyl) propane-1,2-diol (102), 1-O-methyl-guaiacylglycerol (103), epoxiconiferyl alcohol (104) [55], 7-hydroxycalamenene (105) and methyl-β-orsellinate (106) [59] are shown in Figure 8.

Phenyls of S. aqueum, S. samarangense and S. aromaticum.

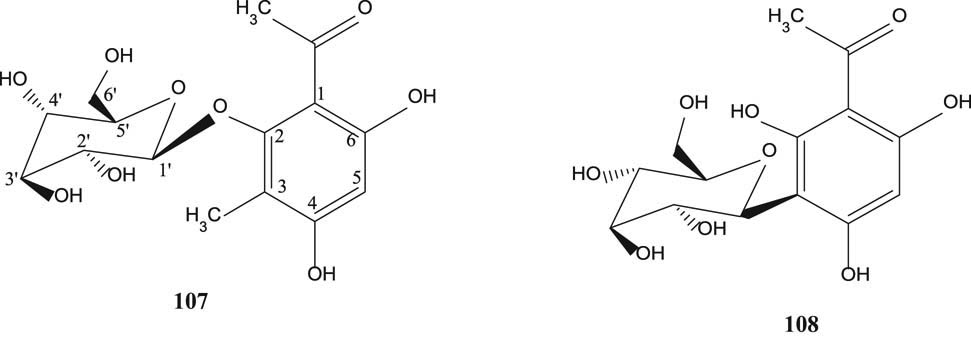

3.9 Phenyl glycosides

2,4,6-Trihydroxy-3-methylacetophenone-2-O-β-d-glycoside (107) and 2,4,6-trihydroxy-3-methylaceto-phenone-2-C-β-d-glycoside (108) [55] are shown in Figure 9.

Phenyl glycosides of S. aromaticum.

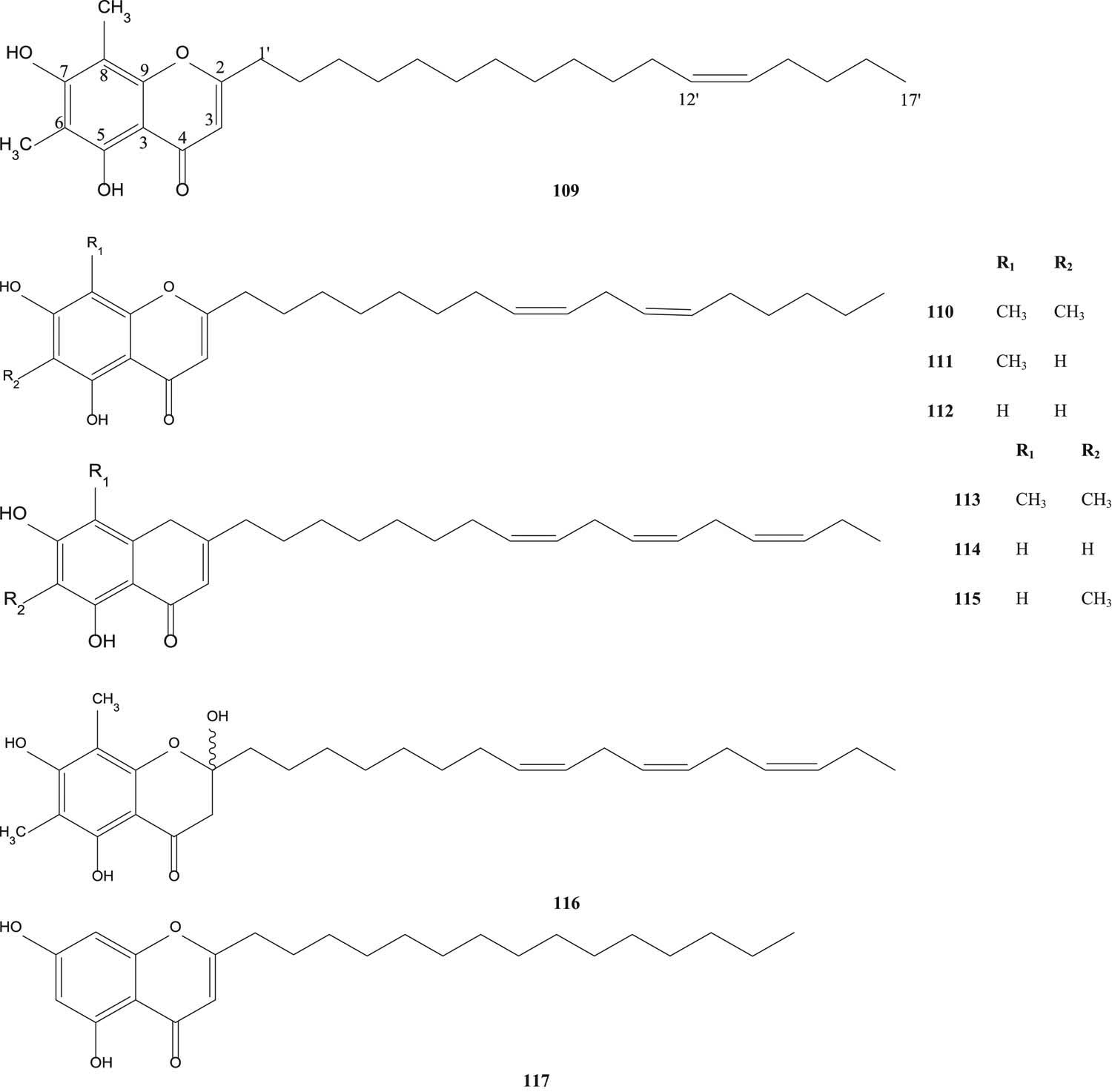

3.10 Acylphloroglucinol derivatives

Samarone A (109), samarone B (110), samarone C (111), jambone G (112), samarone D (113), jambone E (114), jambone F (115), jamunone B (116) and 2-pentadecyl-5,7-didydroxychromone (117) [65] are illustrated in Figure 10.

Acylphloroglucinol derivatives from S. samarangense.

4 Bioactivities

4.1 Antioxidant activity

Antioxidant activity of methanol extract of S. aqueum leaves was investigated by using β-carotene bleaching and 2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) free radical scavenging assays. Fresh and dried leaves of sample were extracted with methanol:water (1:10). The percentage of antioxidant activity of the fresh sample was higher than that of the dried sample for both β-carotene bleaching and ABTS assays [32].

Fruits of S. aqueum were mashed with citrate buffer, pH 4.2. Then, the extract was investigated using 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay. Vitamin C was used as a positive control. The absorbance was measured at 517 nm. IC50 (µg/mL) values of both standard and sample were nearly the same, and they had powerful antioxidant activity because the IC50 value was less than 50 µg/mL [66].

S. aqueum leaves were extracted with 50% acetone (v/v). The extract was investigated by using DPPH radical scavenging and ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assays. In the DPPH assay, the percentage scavenging of acetone extract was higher than that of water extract. In the FRAP assay, µM Fe(ii)/g of water extract was higher than that of acetone extract [67].

Leaves of S. aqueum were extracted with 100% methanol. The antioxidant activity of the extract was investigated using DPPH radical scavenging, FRAP, ABTS radical scavenging and total antioxidant capacity assays. (epi) Gallocatechin gallate (EGCG) and vitamin C were used as standards when compared with the sample for all assay methods. Radical scavenging activity (µg/mL) of the extract is nearly the same as standards for all methods [33].

S. samarangense seeds were extracted with methanol, and then the antioxidant activity of the extract was determined using DPPH and FRAP assays. Gallic acid was selected as a positive control. The methanol extract showed moderate activity by the DPPH assay as well as by the FRAP assay [49].

The antioxidant activity of fruits of each S. samarangense tree cultivar (red, pink and green) was studied using DPPH radical scavenging. Ascorbic acid was used as a standard. The red cultivar showed the highest antioxidant activity and the green cultivar exhibited the lowest antioxidant activity [68].

Extraction of the roots of S. samarangense was carried out with three kinds of solvents (ethyl acetate, methanol and water) using the Soxhlet extraction method. The antioxidant activity of root extracts was evaluated using DPPH radical scavenging and ascorbic acid was used as a standard. The highest percentage of scavenging was shown by the methanol extract [69].

S. aromaticum (clove) was extracted with methanol and distilled water. The antioxidant activity of two extracts was determined using the DPPH assay and quercetin was chosen as a positive control. The highest percent scavenging was shown by quercetin, followed by the distilled water extract and the methanol extract was the lowest. [70].

S. aromaticum flower buds were extracted with ethanol and distilled water. The sample was also extracted to obtain the essential oil. Different percentages of oil (0.1%, 0.5% and 1%) and dried ethanol extract (5.0%) were dissolved in aqueous ethanol solu-tion (1:1). The antioxidant activities of ethanol extract, distilled water extract and three different percentages of essential oil in aqueous ethanol were determined using the DPPH assay. Ascorbic acid was used as a standard. The best inhibition was presented by the ethanol extract which had the EC50 (µg/mL) value nearly the same as that of the standard [71].

S. cumini leaves were extracted with ethanol. The antioxidant activity of the extract was determined using the DPPH assay, and the result showed that IC50 = 9.85 ± 0.51 µg/mL. Ascorbic acid was used as a positive control [72].

S. cumini seeds were extracted with methanol. The antioxidant activity of the extract was determined using DPPH and FRAP assays. Vitamin C, butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA) and quercetin were used as positive controls. This methanol extract expressed strong antioxidant activity. At certain concentration, this extract showed a stronger percentage of DPPH scavenging than that of BHA. Likewise with the reducing power in the FRAP assay, vitamin C showed weaker antioxidant activity than the methanol extract. The authors stated that the high tannins present in the methanol extract contributed to the strong antioxidant activity [73].

S. cumini leaves were extracted with methanol. The antioxidant activity of the extract was determined using the DPPH assay. Butyl hydroxyl toluene (BHT) and ascorbic acid were used as standards. The IC50 value of the extract obtained showed a potent scavenging activity when compared with BTH and ascorbic acid [74].

S. guineense leaves were extracted with 80% methanol. The antioxidant activity of the extract was determined using the DPPH assay. The leaf extract did not show the antioxidant activity [75].

The essential oil was extracted from S. guineense leaves by using the hydro-distillation method. The antioxidant activity of essential oil was determined using the DPPH radical scavenging assay. BHT was used as a standard. The authors reported that this essential oil exhibited the high antioxidant activity [76].

4.2 Anticancer activity

S. aqueum leaves were extracted with methanol for the determination of cytotoxicity using sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay. The activity was tested on human breast cancer cell (MDA-MB-231) and compared with that of doxorubicin (standard cytotoxic drug). The extract was less toxic on cancer cell line (IC50 > 100 µg/mL) [86].

Pulp of S. samarangense was extracted with methanol and then the extract was tested on SW-480 human colon cancer cell line using the MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2-5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay. EGCG was treated as a positive control. Methanolic extract and EGCG were highly toxic on cancer cell line according to data [49].

S. cumini seeds were extracted with ethyl acetate. The extract was separated using column chromatography with an eluent mixture of chloroform:ethyl acetate:methanol (30:50:20) to obtain a single compound, flavopiridol. The anticancer activity of the isolated compound was evaluated on MCF7, A2780, PC-3 and H460 cell lines using the MTS (5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4,5-dimethyl-thiazoly)-3-(4-sulfophenyl) tetrazolium) assay. Flavopiridol was used as a positive control. The S. cumini seed extract proved the highest activity against A2780 cell line (IC50 = 49 μg/ml), whereas showed the least activity against H460 cell line [77].

S. guineense’s leaves and bark were extracted with ethanol, water and the mixture of ethanol–water. All extracts were tested on HeLa cell line and SiHa cell line for anticancer activity using the SRB assay. Adriamycin was used as a positive control on both cell lines. The aqueous extract of bark showed the best inhibition of cancer cell growth on both cell lines. The ethanol extract of leaves exhibited more efficient inhibition than other leaf extracts on both cell lines [78].

The ethanol leaf extract of S. cumini was tested on human keratinocyte cells (HaCaT cell line) by using the MTT assay. From this study, it was known that the ethanol extract was not toxic at concentrations of 500–250 µg/mL [72].

S. aqueum leaves were extracted with methanol. The cytotoxicity of the extract was detected on breast cancer cell line MCF-7 using the SRB assay. Doxorubicin was used as the standard. The results showed that the extract had high activity against MCF-7 cell line (IC50 < 100 µg/mL). This activity is caused by the content of phenolic compounds which act as phytoestrogens in the Syzygium extract under study [86].

4.3 Antimicrobial activity

S. samarangense fruits were extracted by using three solvents (petroleum ether, ethyl acetate and methanol). All extracts were tested against certain bacterial and fungal strains using the disc diffusion method. Gram-positive bacteria (Bacillus cereus, Staphylococcus aureus and Candida albicans) and Gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Klebsiella pneumoniae) were used in this study. Ampicillin, kanamycin, tetracycline and vancomycin were used as standards. The method used was a microdilution using a 96-well microtiter plate. The result of this study showed that the Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria were sensitive to fruit extracts. Among the three extracts, the methanol extract showed a higher activity than other extracts [79].

The ethanol extract of S. samarangense leaves was examined for antibacterial activity by using the broth microdilution method. The extract was tested against E. coli, B. cereus, Enterobacter aerogenes, Salmonella enterica and Kocuria rhizophila. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) value was determined to be the lowest concentration of the extract capable of inhibiting microorganism growth. The leaf extract of the sample was more effective against B. cereus and S. enterica than others when compared with chloramphenicol [35].

Leaves, bark and fruits of S. samarangense tree cultivars (red, pink and green) were extracted with methanol and ethanol. All extracts were evaluated against four bacteria, including two Gram-positive (B. cereus and S. aureus) and two gram-negative bacteria (E. coli and P. aeruginosa), by using the disc diffusion method. Tetracycline was used as a positive control. All the extracts showed the antimicrobial activity. However, the ethanolic extracts showed higher antimicrobial activities than the methanolic extracts. All the bark extracts of three cultivars exhibited higher antimicrobial activities followed by fruit and leaf extracts [68].

S. samarangense root was extracted by using three kinds of solvents (ethyl acetate, methanol and water) by using the Soxhlet extraction method. The root extracts were evaluated against Salmonella typhi, E. coli, P. aeruginosa and Bacillus subtilis by using the agar well diffusion method. The methanolic extract presented high inhibitory effect on S. typhi, the ethyl acetate extract showed potent inhibitory effect on P. aeruginosa and the aqueous extract exhibited strong inhibitory effect on S. typhi [69].

The antibacterial and antifungal activities of S. aromaticum oil were determined by using the agar well diffusion method against S. aureus, E. coli and P. aeruginosa bacteria and C. albicans, Aspergillus flavus and Penicillium. Ciprofloxacin and ketoconazole were used as positive controls. S. aromaticum oil had a high inhibitory effect on bacteria and fungi when compared with positive control [70].

S. aromaticum (clove) was extracted with 70% ethanol and 80% methanol. The two extracts were tested on S. aureus, P. aeruginosa and E. coli in comparison with the selected antibiotic (tetracycline) using the agar well diffusion method. The highest activity against P. aeruginosa was presented by the ethanol extract and against S. aureus was shown by the methanol extract. [80].

S. aromaticum (cloves) was extracted with 80% methanol. The 1% of six metals (Zn++, Cu++, Pb++, Ca++, Mg++ and Fe++) was added in the extract and the antibacterial properties were tested using the agar well diffusion method. For S. aureus, the maximum zone of inhibition was presented by zinc, for E. coli by magnesium and for P. aeruginosa by lead [80].

S. cumini seeds were extracted with ethyl acetate. The extract was separated and purified to obtain a single compound. This compound showed antibacterial activity against E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus and B. subtilis using the agar cup method. The largest zone of inhibition was observed in E. coli [77].

S. cumini (leaves, pulps and seeds) was extracted with methanol. The extract was examined against E. coli and S. aureus using the agar well diffusion assay. Leaf extract exhibited antibacterial activity both on E. coli and S. aureus, whereas pulp and seed extracts did not show any antibacterial activity [81].

The essential oil was isolated from S. guineense leaves by using the hydrodistillation method. The MIC of essential oil on microorganisms (P. aeruginosa, K. pneumonia, E. coli, S. aureus, C. albicans and Mycobacterium bovis [BCG]) was determined using the microbroth dilution method. Essential oil of S. guineense exhibited strong antimicrobial activities against the tested microorganisms when compared with ciprofloxacin, fluconazole and isoniazid [76].

S. guineense seeds were extracted with ethanol. The MIC on microorganisms (E. coli, K. pneumonia, S. typhi, S. aureus and C. albicans) of the extract was determined by using the broth microdilution method. Gentamicin sulfate and fluconazole were used as standard drugs. The extract showed weak to moderate antibacterial activity and lower than standard drugs [82].

4.4 Antidiabetic activity

S. samarangense root was extracted by using three kinds of solvents (ethyl acetate, methanol and water) by using the Soxhlet extraction method. The antidiabetic activity of all extracts was determined using alpha-amylase inhibition. Water extract showed the highest percentage of alpha-amylase inhibition, followed by methanol and ethyl acetate extracts [69].

S. cumini seeds were extracted with methanol. The antidiabetic activity of extract was determined by using alpha-amylase enzyme. The percentage of inhibition varied from 38.6% to 95.4%. It was concluded that the sample possessed significant antidiabetic activity [84].

S. guineense leaves were extracted with 80% methanol. The antidiabetic activity of the extract was determined using alpha-glucosidase enzyme. IC50 obtained from that study was 6.15 μg/mL, which was the best inhibition for antidiabetic activity [75].

4.5 Toxicity

The toxicity of the ethanolic leaf extract of S. cumini was tested by using the brine shrimp lethality assay. Thymol was used as a standard. Ten brine shrimp larvae were added in each concentration of extract (1,000–10 μg/mL). The absence of brine shrimp death in the sample was calculated to obtain the LC50 value. The result of the test showed that the extract did not have high toxicity compared to thymol as a standard [72].

S. guineense seeds were extracted with ethanol and the toxicity of the obtained was tested using the brine shrimp lethality assay. Cyclophosphamide was used as a standard. Ten brine shrimps larvae were added in different concentrations of extract (240, 120, 80, 40 and 24 μg/mL). The absence of brine shrimp death in the sample was calculated to obtain the LC50 value. The extract did not have the toxicity (LC50 value was above100 µg/mL) [85].

4.6 Anti-inflammatory activity

The anti-inflammatory activity of the methanolic extract of S. aqueum leaves was determined. For this study, the ability of the extract to inhibit lipoxygenase (LOX) using an LOX inhibitor screening assay kit was established as well as ovine COX-1 and COX-2 inhibition using an enzyme immunoassay kit. Celecoxib, indomethacin and diclofenac were used as standards. The extract showed more potent inhibitory effect than diclofenac on COX-2 as well as on LOX. Celecoxib was less active than the extract on COX-1 [33].

Different kinds of solvents (ethyl acetate, methanol and water) were used for extraction of S. samarangense root. All extracts of root were evaluated for anti-inflammatory activity by the albumin denaturation assay. The methanol extract showed the highest percentage of albumin denaturation, followed by water and ethyl acetate extracts [69].

4.7 Anthelmintic activity

S. guineense seeds were extracted with ethanol. The anthelmintic activity of the extract was tested on adult roundworms (Ascaris suum) by using the protocol described by Nilani’s team. Albendazole was received as a standard drug. All tested concentrations of the extract required a longer time to cause paralysis and death than albendazole. To give the 100% death effect, the time requirement of the extract was slightly higher than that of negative control (normal saline) at concentrations of 50 and 30 mg/mL, but at a concentration of 100 mg/mL, the time requirement was 6% higher than that of the standard drug. This study resulted in a conclusion that at higher concentration, the extract exhibits reasonably high anthelmintic activity compared to albendazole [82]. Another paper gave a similar result (Table 2) [85].

Isolated compounds and their bioactivities reported from Syzygium genus

| No | Compound name | Bioactivities | Plant species (parts of plant) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Phloretin | Antidiabetic activity (EC50 µM) | S. aqueum (leaves) | [43,83] |

| (20 ± 2.2) for α-glucosidase inhibition and (31 ± 5.5) for α-amylase inhibition, positive control (acarbose)-(43 ± 1.6) for α-glucosidase and (19 ± 1.6) for α-amylase | ||||

| 2 | Myrigalone-G | Antidiabetic activity (EC50 µM) | S. aqueum (leaves) | [43,83] |

| (7 ± 1.4) for α-glucosidase inhibition and (33 ± 6.6) for α-amylase inhibition, positive control (acarbose)-( | ||||

| 3 | Myrigalone B | Antidiabetic activity (EC50 µM) | S. aqueum (leaves) | [43,83] |

| (19 ± 1.0) for α-glucosidase inhibition and (8.3 ± 1.3) for α-amylase inhibition, positive control (acarbose) – ( | ||||

| 4 | 2′,4′-Dihydroxy-6′-methoxy-3′-methyldihydrochalcone | Trypsin inhibition assay | S. samarangense (leaves) | [46,47] |

| IC50 31.9 ± 0.25 mM | ||||

| Thrombin inhibition assay | ||||

| IC50 14.9 ± 0.25 mM | ||||

| Prolyl endopeptidase inhibition assay | ||||

| IC50 12.5 ± 0.2 µM | ||||

| 5 | 2′-Hydroxy-4′,6′-dimethoxy-3′-methyldihydrochalcone | Trypsin inhibition assay | S. samarangense (leaves) | [46,47] |

| IC50 2.7 ± 0.5 mM | ||||

| Thrombin inhibition assay | ||||

| IC50 10.0 ± 0.5 mM | ||||

| Prolyl endopeptidase inhibition assay | ||||

| IC50 158.5 ± 0.1 µM | ||||

| 6 | 2′,4′-Dihydroxy-6′-methoxy3′,5′-dimethyldihydrochalcone | Trypsin inhibition assay | S. samarangense (leaves) | [46,47] |

| IC50 38.2 ± 0.25 mM | ||||

| Thrombin inhibition assay | ||||

| IC50 62.1 ± 0.25 mM | ||||

| Prolyl endopeptidase inhibition assay | ||||

| IC50 98.3 ± 0.8 µM | ||||

| 7 | 2′,4′-Dihydroxy-6′-methoxy-3′-methylchalcone or stercurensin | Trypsin inhibition assay | S. samarangense (fruit and leaves) | [46,47,49] |

| IC50 5.6 | ||||

| Prolyl endopeptidase inhibition assay | ||||

| IC50 37.5 ± 1.0 µM | ||||

| Anticancer activity (MTT assay) | ||||

| IC50 35 µM for compound and IC50 50 µM for EGCG as positive control on SW-480 human colon cancer cell line | ||||

| Antioxidant activity | ||||

| (IC50 141 ± 2.3 µM) by DPPH assay and (IC50 191 ± 0.1 µM) by FRAP assay | ||||

| IC50 25.0 ± 0.1 µM for gallic acid (positive control) by DPPH | ||||

| 8 | 2′-Hydroxy-4′,6′-dimethoxy-3′-methylchalcone | Trypsin inhibition assay | S. samarangense (leaves) | [46,47] |

| IC50 15.8 ± 0.25 mM | ||||

| Thrombin inhibition assay | ||||

| IC50 30.7 ± 0.25 mM | ||||

| Prolyl endopeptidase inhibition assay | ||||

| IC50 > 200 µM | ||||

| 9 | 2′,4′-Dihydroxy-6′-methoxy-3′,5′ dimethylchalcone | Anticancer activity (IC50 µM) | S. aqueum (leaves) and S. samarangense (leaves) | [44,46,47] |

| Inhibition of the proliferation of the breast cancer (MCF-7) cell lines by using MTT assay, IC50 values 270 µM (24 h) and 250 µM (48 h | ||||

| Thrombin inhibition assay | ||||

| IC50 1.8 ± 0.25 mM | ||||

| Prolyl endopeptidase inhibition assay | ||||

| IC50 149.8 ± 7.1 µM | ||||

| 10 | 2′,4′-Dihydroxy-3′,5′-dimethyl-6′-methoxychalcone | Anticancer activity (MTT assay) | S. samarangense (fruits) | [49] |

| IC5010 µM for compound and IC50 50 µM for EGCG as positive control on SW-480 human colon cancer cell line | ||||

| Antioxidant activity | ||||

| (IC50 205 ± 1.2 µM) by DPPH assay and (IC50 196 ± 0.0 µM) by FRAP assay | ||||

| IC50 25.0 ± 0.1 µM for gallic acid (positive control) by DPPH | ||||

| 11 | 2′,4′-Dihydroxy-6′-methoxchalcone or cardamonin | Anticancer activity (MTT assay) | S. samarangense (fruits) | [49] |

| IC50 35 µM for compound and IC50 50 µM for EGCG as positive control on SW-480 human colon cancer cell line | ||||

| Antioxidant activity | ||||

| (IC50 141 ± 3.4 µM) by DPPH assay and (IC50 173 ± 0.0 µM) by FRAP assay | ||||

| IC50 25.0 ± 0.1 µM for gallic acid (positive control) by DPPH | ||||

| 12 | Pinocembrin | Anticancer activity (MTT assay) | S. samarangense (fruit and leaves) | [48,49] |

| IC50 60 µM for compound and IC50 50 µM for EGCG as positive control on SW-480 human colon cancer cell line | ||||

| Antioxidant activity | ||||

| (IC50 199 ± 0.8 µM) by DPPH assay and (IC50 196 ± 0.0 µM) by FRAP assay | ||||

| IC50 25.0 ± 0.1 µM for gallic acid (positive control) by DPPH | ||||

| 13 | (—)-Strobopinin | — | S. samarangense (leaves) | [48] |

| 14 | 8-Methylpinocembrin | — | S. samarangense (leaves) | [48] |

| 15 | Demethoxymatteutcinol | — | S. samarangense (leaves) | [48] |

| 16 | 7-Hydroxy-5-methoxy-6,8-dimethyl-foavanone | — | S. samarangense (leaves) | [48] |

| 17 | 7,8,3′,4′-Tetrahydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyflavone | Antioxidant activity (EC50 µg/mL) | S. samarangense (leaves) | [45] |

| (3.89 µg/mL) for DPPH assay when | ||||

| (21.08 µg/mL) for FRAP assay when | ||||

| 18 | 7-Hydroxy-5-methoxy-6,8-dimethylflavanone | Trypsin inhibition assay | S. samarangense (leaves) | [46,47] |

| IC50 7.4 ± 0.1 mM | ||||

| Prolyl endopeptidase inhibition assay | ||||

| 13.9% inhibition at 0.5 mM | ||||

| 19 | Quercetin | — | S. samarangense (fruits) and S. aromaticum (flower buds) | [49,50] |

| 20 | Kaempferol | — | S. cumini (leaves) | [54] |

| 21 | Gallocatechin | Antioxidant (DPPH) | S. guineense (leaves) | [51] |

| IC50 17 ± 3 µM for compound and IC50 12± 0.2 µM for quercetin (positive control) | ||||

| 15-lipoxygenase (15-LO) inhibition | ||||

| IC50 112 ± 4 µM for compound and IC50 72±7 µM for quercetin (positive control) | ||||

| Xanthine oxidase (OX) inhibition | ||||

| IC50>167 µM for compound and IC50 3.0±0.6 µM for quercetin (positive control) | ||||

| 22 | Myricetin | Antioxidant (DPPH) | S. guineense (leaves) | [51] |

| IC50 41±6 µM for compound and IC50 12±0.2 µM for quercetin (positive control) | ||||

| 15-Lipoxygenase (15-LO) inhibition | ||||

| IC50>83 µM for compound and IC50 72±7 µM for quercetin (positive control) | ||||

| Xanthine oxidase (OX) inhibition | ||||

| IC50 8±1 µM for compound and IC50 3.0±0.6 µM for quercetin (positive control) | ||||

| 23 | (—)-Epigallocatechin | — | S. aqueum (leaves) and S. samarangense (leaves) | [52] |

| 24 | (—)-Epigallocatechin 3-O-gallate | — | S. aqueum (leaves) and S. samarangense (leaves) | [52] |

| 25 | Samarangenin | — | S. aqueum (leaves) and S. samarangense (leaves) | [52] |

| 26 | Samarangenin | — | S. aqueum (leaves) and S. samarangense (leaves) | [52] |

| 27 | Prodelphinidin B-2 3″-O-gallate | — | S. aqueum (leaves) and S. samarangense (leaves) | [52] |

| 28 | Prodelphinidin B-2 3,3″-O-gallate | — | S. aqueum (leaves) and S. samarangense (leaves) | [52] |

| 29 | Myricetin-3-O-rhamnoside | Antidiabetic activity (EC50 µM) | S. aqueum (leaves) and S. samarangense (leaves) | [43,45,83] |

| (1.1 ±0.06 µM) for compound and (43±1.6 µM) for acarbose by using α-glucosidase (1.9 ± 0.02 µM) for compound and (19± 1.6 µM) for acarbose by using α-amylase | ||||

| Antioxidant activity (EC50 µg/mL) | ||||

| (3.21 µg/mL) for DPPH assay when | ||||

| 30 | Europetin-3-Orhamnoside | Antidiabetic activity (EC50 µM) | S. aqueum (leaves) | [43,84] |

| (1.9 ± 0.06) for α-glucosidase inhibition and (2.3 ± 0.04) for α-amylase inhibition, (43 ± 1.6) for α-glucosidase inhibition and (19± 1.6) for α-amylase inhibition in the positive control (acarbose) | ||||

| 31 | Mearnsitrin | — | S. samarangense (leaves) | [53] |

| 32 | Reynoutrin | — | S. samarangense (fruits) | [49] |

| 33 | Hyperin | — | S. samarangense (fruits) | [49] |

| 34 | Quercitrin | — | S. samarangense (fruits) | [49] |

| 35 | Guaijaverin | — | S. samarangense (fruits) | [49] |

| 36 | Tamarixetin 3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | — | S. aromaticum (flower buds) | [50] |

| 37 | Ombutin 3-O-β-d glucopyranoside | — | S. aromaticum (flower buds) | [50] |

| 38 | Quercetin 3-O-α-l-rhamnopyranoside | — | S. cumini (leaves) | [54] |

| 39 | Kaempferol 3-O-β-d-glucuronopyranoside | — | S. cumini (leaves) | [54] |

| 40 | Myricetin 3-O-β-d-glucuronopyranoside | — | S. cumini (leaves) | [54] |

| 41 | Mearnsetin 3-O-(4″-O-acetyl)-α-l-rhamnopyranoside | — | S. cumini (leaves) | [54] |

| 42 | Myricetin 3-O-(4″-O-acetyl) -α-l-rhamnopyranoside | — | S. cumini (leaves) | [54] |

| 43 | Myricetin 4′-methyl ether 3-O-α-l-rhamnopyranoside | — | S. cumini (leaves) | [54] |

| 40 | Myricetrin 4″-O-acetyl-2″-O-gallate | — | S. cumini (leaves) | [54] |

| 45 | Myricetin-3-O-glucoside | Antioxidant (DPPH) | S. guineense (leaves) | [51] |

| IC50 11±2 µM for compound and IC50 12±0.2 µM for quercetin (positive control) | ||||

| 15-Lipoxygenase (15-LO) inhibition | ||||

| IC50 42±4 µM for compound and IC50 72± 7 µM for quercetin (positive control) | ||||

| Xanthine oxidase (OX) inhibition | ||||

| IC50 38 ± 4 µM for compound and IC50 3.0 ± 0.6 µM for quercetin (positive control) | ||||

| 46 | Myricetin-3-O-rhamnoside | Antioxidant (DPPH) | S. guineense (leaves) | [51] |

| IC50 28 ± 3 µM for compound and IC50 12 ± 0.2 µM for quercetin (positive control) | ||||

| 15-Lipoxygenase (15-LO) inhibition | ||||

| IC50 138 ± 11 µM for compound and IC50 72± 7 µM for quercetin (positive control) | ||||

| Xanthine oxidase (OX) inhibition | ||||

| IC50 > 167 µM for compound and IC50 3.0 ± 0.6 µM for quercetin (positive control) | ||||

| 47 | Myricetin-3-O-glucoronide | Antioxidant (DPPH) | S. guineense (leaves) | [51] |

| IC50 85 ± 33 µM for compound and IC50 12 ± 0.2 µM for quercetin (positive control) | ||||

| 15-lipoxygenase (15-LO) inhibition | ||||

| IC50 > 83 µM for compound and IC50 72 ± 7 µM for quercetin (positive control) | ||||

| Xanthine oxidase (OX) inhibition | ||||

| IC50 > 83 µM for compound and IC50 3.0 ± 0.6 µM for quercetin (positive control) | ||||

| 48 | Myricetin-3-O-β-d-(6″-galloyl) galactoside | Antioxidant (DPPH) | S. guineense (leaves) | [51] |

| IC50 10 ± 3 µM for compound and IC50 12 ± 0.2 µM for quercetin (positive control) | ||||

| 15-Lipoxygenase (15-LO) inhibition | ||||

| IC50 75 ± 7 µM for compound and IC50 72 ± 7 µM for quercetin (positive control) | ||||

| Xanthine oxidase (OX) inhibition | ||||

| IC50 > 167 µM for compound and IC50 3.0 ± 0.6 µM for quercetin (positive control) | ||||

| 49 | Biflorin | Cytotoxicity (MTT assay) | S. aromaticum (cloves) | [55] |

| IC50 > 100 µM against human ovarian cancer cells (A2780) when | ||||

| 50 | Isobiflorin | Cytotoxicity (MTT assay) | S. aromaticum (cloves) | [55] |

| (IC50 > 100 µM) against human ovarian cancer cells (A2780) when | ||||

| 51 | 6-C-β-d-(6′-O-galloyl) glucosylnoreugenin | Cytotoxicity (MTT assay) | S. aromaticum (cloves) | [55] |

| (IC50 66.78 ± 5.49 µM) against human ovarian cancer cells (A2780) when | ||||

| 52 | 8-C-β-d-(6′-O-galloyl) glucosylnoreugenin | Cytotoxicity (MTT assay) | S. aromaticum (cloves) | [55] |

| (IC50 87.50 ± 1.56 µM) against human ovarian cancer cells (A2780) when | ||||

| 53 | Sysamarin A | — | S. samarangense (leaves) | [56] |

| 54 | Sysamarin B | — | S. samarangense (leaves) | [56] |

| 55 | Sysamarin C | — | S. samarangense (leaves) | [56] |

| 56 | Sysamarin D | — | S. samarangense (leaves) | [56] |

| 57 | Sysamarin E | — | S. samarangense (leaves) | [56] |

| 58 | Lupenyl stearate | — | S. samarangense (leaves) | [57] |

| 57 | Lupeol | Thrombin inhibition assay | S. samarangense (leaves) and S. cumini (leaves) | [46,57,60] |

| IC50 49.2 ± 0.2 mM | ||||

| Prolyl endopeptidase inhibition assay | ||||

| IC50 65.0 ± 3.2 µM | ||||

| 60 | Betulin | Trypsin inhibition assay | S. samarangense (leaves) and S. guineense(stem bark) | [46,57,63] |

| IC50 24.4 ± 0.125 mM | ||||

| Prolyl endopeptidase inhibition assay | ||||

| IC50 101.6 3.2 µM | ||||

| Antibacterial activity | ||||

| 61 | Betulinic acid | (Prolyl endopeptidase inhibition assay | S. samarangense (leaves) and S. guineense(stem bark) | [46,63] |

| 64.4% inhibition at 0.5 mM | ||||

| 62 | Oleanolic acid | (Cytotoxicity (MTT assay) | S. aromaticum (flower buds) and S. cumini (seeds) | [55,58,59] |

| (IC50 24.30 ± 0.30 µM) against | ||||

| 63 | Arjunolic acid | Antibacterial activity | S. aromaticum (flower buds) and S. guineense (leaves and roots) | [58,61,62] |

| (IC50 3 µg/mL) against Escherichia coli, (IC50 0.5 µg/mL) against Bacillus subtilis | ||||

| Chloramphenicol as | ||||

| 64 | Corosolic acid | — | S. aromaticum (flower buds) | [58] |

| 65 | Asiatic acid | Antibacterial activity | S. aromaticum (flower buds) and S. guineense (leaves and roots) | [58,61,62] |

| (IC50 5 µg/mL) against Escherichia coli, (IC50 0.75 µg/mL) against Bacillus subtilis, and (IC50 30 µg/mL) against Shigella s | ||||

| Chloramphenicol as | ||||

| 66 | Maslinic acid | Cytotoxicity (MTT assay) | S. aromaticum (flower buds) | [55] |

| (IC50 29.61 ± 4.68 µM) against human ovarian cancer cells (A2780) when | ||||

| 67 | 12-Oleanen-3-ol-3β acetate | — | S. cumini (leaves) | [60] |

| 68 | 2-Hydroxyoleanolic acid | Not observed | S. guineense (leaves and roots) | [61,62] |

| 69 | 2-Hydroxyursolic acid | Not observed | S. guineense (leaves and roots) | [61,62] |

| 70 | Terminolic acid | Antibacterial activity | S. guineense (leaves and roots) | [61,62] |

| (IC50 6 µg/mL) against Escherichia coli, (IC50 3 µg/mL) against Bacillus subtilis, and (IC50 50 µg/mL) against Shigella s | ||||

| Chloramphenicol as | ||||

| 71 | 6-Hydroxy asiatic acid | — | S. guineense (leaves and roots) | [61,62] |

| 72 | Limonin | — | S. aromaticum (flower buds) | [50] |

| 73 | Caryolane-1,9β-diol | Cytotoxicity (MTT assay) | S. aromaticum (cloves) | [55] |

| (IC50 > 100 µM) against human ovarian cancer cells (A2780) when | ||||

| 74 | Clovane-2,9-β-diol | Cytotoxicity (MTT assay) | S. aromaticum (cloves) | [55] |

| (IC50 > 100 µM) against human ovarian cancer cells (A2780) when | ||||

| 75 | α-Humulene | Cytotoxicity (MTT assay) | S. aromaticum (cloves) | [55] |

| (IC50 21.03 ± 5.53 µM) against human ovarian cancer cells (A2780) when | ||||

| 76 | Humulene epoxide α | Cytotoxicity (MTT assay) | S. aromaticum (cloves) | [55] |

| (IC50 > 100 µM) against human ovarian cancer cells (A2780) when | ||||

| 77 | β-Caryophyllene | Cytotoxicity (MTT assay) | S. aromaticum (cloves) | [55] |

| (IC50 60.70 ± 1.44 µM) against human ovarian cancer cells (A2780) when | ||||

| 78 | β-Caryophyllene oxide | Cytotoxicity (MTT assay) | S. aromaticum (cloves) | [55] |

| (IC50 > 100 µM) against human ovarian cancer cells (A2780) when | ||||

| 79 | Lupenyl stearate cycloartenyl stearate | — | S. samarangense (leaves) | [57] |

| 80 | β-Sitosteryl stearate | — | S. samarangense (leaves) | [57] |

| 81 | 24-Methylenecycloartenyl stearate | — | S. samarangense (cloves) | [57] |

| 82 | β-Sitosterol | — | S. samarangense and S. cumini (leaves and seeds) | [57,59,60] |

| 83 | Stigmasterol | — | S. cumini (leaves) | [60] |

| 84 | β-Sitosterol-3-O-β-d-glucoside | Cytotoxicity (MTT assay) | S. aromaticum (flower buds) | [55] |

| (IC50 > 100 µM) against human ovarian cancer cells (A2780) when | ||||

| 85 | Arjunolic | Not observed | S. guineense (leaves and roots) | [61,62] |

| 86 | Asiatic acid 28-β-glycopyranosyl ester | Not observed | S. guineense (leaves and roots) | [61,62] |

| 87 | 3,3′,4′-Tri-O-methylellagic acid | Cytotoxicity (MTT assay) | S. aromaticum (flower buds) | [55] |

| (IC50 87.64 ± 1.70 µM) against human ovarian cancer cells (A2780) | ||||

| 88 | Ellagic acid | — | S. samarangense (fruits) and S. cumini (stem bark) | [49,64] |

| 89 | Ellagitannin-3-O-methylellagic acid 3′-O-β-d-glucopyranoside | — | S. cumini (stem bark) | [64] |

| 90 | Ellagic acid 4-O-α-l-2″-acetylhamnopyranoside | — | S. cumini (stem bark) | [64] |

| 91 | 3-O-Methylellgic acid 3′-O-α-l-rhamnopyranoside | — | S. cumini (stem bark) | [64] |

| 92 | Gallotannins 1,2,3,6-tetra-O-galloyl-β-d-glucose | — | S. guineense (leaves) | [51] |

| 93 | 1,2,3,4,6-Penta-O-galloyl-β-d-glucose | Antioxidant (DPPH) | S. guineense (leaves) | [51] |

| IC50 5 ± 1 µM for compound and IC50 12 ± 0.2 µM for quercetin (positive control) | ||||

| 15-lipoxygenase (15-LO) inhibition | ||||

| IC50 25 ± 4 µM for compound and IC50 72 ± 7 µM for quercetin (positive control) | ||||

| Xanthine oxidase (OX) inhibition | ||||

| IC50 8 ± 1 µM for compound and IC50 3.0 ± 0.6 µM for quercetin (positive control) | ||||

| 94 | Casuarictin | Antioxidant (DPPH) | S. guineense (leaves) | [51] |

| IC50 3.9 ± 0.1 µM for compound and IC50 12 ± 0.2 µM for quercetin (positive control) | ||||

| 15-lipoxygenase (15-LO) inhibition | ||||

| IC50 36 ± 3 µM for compound and IC50 72 ± 7 µM for quercetin (positive control) | ||||

| Xanthine oxidase (OX) inhibition | ||||

| IC50 86 ± 3 µM for compound and IC50 3.0 ± 0.6 µM for quercetin (positive control) | ||||

| 95 | Casuarinin | Antioxidant (DPPH) | S. guineense (leaves) | [51] |

| IC50 4.5 ± 0.3 µM for compound and IC50 12 ± 0.2 µM for quercetin (positive control) | ||||

| 15-lipoxygenase (15-LO) inhibition | ||||

| IC50 39 ± 2 µM for compound and IC50 72 ± 7 µM for quercetin (positive control) | ||||

| Xanthine oxidase (OX) inhibition | ||||

| IC50 105 ± 3 µM for compound and IC50 3.0 ± 0.6 µM for quercetin (positive control) | ||||

| 96 | 4-Hydroxybenzaldehyde | Antidiabetic activity (EC50 µM) | S. aqueum (leaves) | [43,83] |

| (9 ± 4.9) for α-glucosidase inhibition and (20 ± 8.2) for α-amylase inhibition, (43 ± 1.6) for α-glucosidase inhibition and (19 ± 1.6) for α-amylase inhibition in the positive control (acarbose) | ||||

| 97 | Gallic acid | — | S. cumini (stem bark) and S. samarangense (fruits) | [49,64] |

| 98 | Ferulic aldehyde | — | S. aromaticum (cloves) | [50] |

| 99 | Eugenol | Cytotoxicity (MTT assay) | S. aromaticum (cloves) | [55] |

| (IC50 > 100 µM) against human ovarian cancer cells (A2780) when | ||||

| 100 | Eugenyl acetate | Cytotoxicity (MTT assay) | S. aromaticum (cloves) | [55] |

| (IC50 > 100 µM) against human ovarian cancer cells (A2780) | ||||

| 101 | trans-Coniferylaldehyde | Cytotoxicity (MTT assay) | S. aromaticum (cloves) | [55] |

| (IC50 78.45 ± 5.01 µM) against human ovarian cancer cells (A2780) when | ||||

| 102 | 3-(4-Hydroxy-3-methoxy-phenyl) propane-1,2-diol | Cytotoxicity (MTT assay) | S. aromaticum (cloves) | [55] |

| (IC50 > 100 µM) against human ovarian cancer cells (A2780) when | ||||

| 103 | 1-O-Methyl-guaiacylglycerol | Cytotoxicity (MTT assay) | S. aromaticum (cloves) | [55] |

| (IC50 > 100 µM) against human ovarian cancer cells (A2780) when | ||||

| 104 | Epoxy | Cytotoxicity (MTT assay) | S. aromaticum (cloves) | [55] |

| (IC50 > 100 µM) against human ovarian cancer cells (A2780) when | ||||

| 105 | 7-Hydroxycalamenene | — | S. cumini (seeds) | [59] |

| 106 | Methyl-β-orsellinate | — | S. cumini (seeds) | [59] |

| 107 | 2,4,6-Trihydroxy-3-methylacetophenone-2-O-β-d-glycoside | Cytotoxicity (MTT assay) | S. aromaticum (cloves) | [55] |

| (IC50 > 100 µM) against human ovarian cancer cells (A2780) when | ||||

| 108 | 2,4,6-Trihydroxy-3-methylacetophenone-2-C-β-glycoside | Cytotoxicity (MTT assay) | S. aromaticum (cloves) | [55] |

| (IC50 > 100 µM) against human ovarian cancer cells (A2780) when | ||||

| 109 | Samarone A | Cytotoxicity (MTT assay) | S. samarangense (leaves) | [65] |

| (IC50 32.90 ± 3.17 µM) against HepG2 when | ||||

| (IC50 26.57 ± 2.16 µM) against on MDA-MB-231 when | ||||

| 110 | Samarone B | Cytotoxicity (MTT assay) | S. samarangense (leaves) | [65] |

| (IC50 3.9 ± 3.17 µM) against HepG2 when | ||||

| (IC50 27.57 ± 4.76 µM) against on MDA-MB-231 when | ||||

| 111 | Samarone C | Cytotoxicity (MTT assay) | S. samarangense (leaves) | [65] |

| (IC50 5.56 ± 1.17 µM) against HepG2 | ||||

| (IC50 28.26 ± 4.52 µM) against on MDA-MB-231 | ||||

| 112 | Jambone | Cytotoxicity (MTT assay) | S. samarangense (leaves) | [65] |

| (IC50 1.73 ± 0.66 µM) against HepG2 when | ||||

| (IC50 4.02 ± 0.87 µM) against on MDA-MB-231 when | ||||

| 113 | Samarone D | — | S. samarangense (Leaves) | [65] |

| 114 | Jambone E | Cytotoxicity (MTT assay) | S. samarangense (leaves) | [65] |

| (IC50 7.78 ± 1.78 µM) against HepG2 | ||||

| (IC50 28.26 ± 3.15 µM) against on MDA-MB-231 | ||||

| 115 | Jambone F | Cytotoxicity (MTT assay) | S. samarangense (leaves) | [65] |

| (IC50 7.70 ± 1.78 µM) against HepG2 | ||||

| (IC50 12.01 ± 1.31 µM) against on MDA-MB-231 | ||||

| 116 | Jamunone B | Cytotoxicity (MTT assay) | S. samarangense (leaves) | [65] |

| (IC50 13.55 ± 2.33 µM) against HepG2 | ||||

| (IC50 37.8 | ||||

| 117 | 2-Pentadecyl-5,7-didydroxychromone | Cytotoxicity (MTT assay) | S. samarangense (leaves) | [65] |

| (IC50 14.00 ± 1.68 µM) against HepG2 | ||||

| (IC50 7.196 ± 1.75 µM) against on MDA-MB-231 |

5 Conclusion

The information of Syzygium species was collected from global publication papers and review articles. S. aqueum, S. aromaticum, S. cumini, S. guineense and S. samarangense are rich sources of phytochemical constituents. Various parts (leaves, seeds, fruits, barks, stem barks and flower buds) of Syzygium species are reported for the treatment of antioxidant, anticancer, toxicity, antimicrobial and antidiabetic activities. The review highlights on the information about plant native growth, botanical description, phytochemical constituents and bioactivities of five known species of Syzygium genus. According to the literature, Syzygium genus is a source of bioactivity in the Myrtaceae family. Therefore, this review suggests that there is great potential for obtaining the lead drug from phytochemical constituents with various bioactivities from those species, whose benefits have been widely used since ancient times without knowing their chemical components.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by ADS (Academic Development Scholarship) scholarship form Faculty of Science and Technology, Universitas Airlangga in Indonesia.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Rehmanav MU, Abdullah, Khan F, Niaz K. Introduction to natural products analysis. In: Recent Advances in Natural Products Analysis: Chapter 1. Pakistan, Bahawalpur; 2020. p. 3–15. 10.1016/B978-0-12-816455-6.00001-9.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Abdel-Razek AS, Othman SI, El-Naggar ME, Allam A, Morsy OM. Microbial natural products in drug discovery. Processes. 2020;8(4):1–19. 10.3390/PR8040470.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Stalin N, Swamy PS. Screening of phytochemical and pharmacological activities of Syzygium caryophyllatum (L.) Alston. Clin Phytosci. 2018;4(3):2–13. 10.1186/s40816-017-0059-2.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Anulika NP, Ignatius EO, Raymond ES, Osasere O, Abiola AH. The chemistry of natural product: plant secondary metabolites. Int J Technol Enhanc Merg Eng Res. 2016;4(8):1–8.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Saxena M, Saxena J, Nema R, Singh D, Gupta A. Phytochemistry of medicinal plants. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2013;1(6):168–82.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Nyamai DW, Arika W, Ogola PE, Njagi ENM, Ngugi MP. Medicinally important phytochemicals: an untapped research avenue. Res Rev J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2016;4(1):35–49.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Loganathan V, Devi KM, Selvakumar P. A study of the physico-chemical and phytochemical parameters of leaves of Mallotus rhamnifolius. Int J Pharmacogn Phytochem Res. 2017;9(6):858–63. 10.25258/phyto.v9i6.8191.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Jamshidi-Kia F, Lorigooini Z, Amini-Khoei H. Medicinal plants: past history and future perspective. J Herb Med Pharmacol. 2018;7(1):1–7. 10.15171/jhp.2018.01.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Ranghoo-Sanmukhiya VM, Chellana Y, Govinden-Soulangea J, Lambrechts IA, Stapelberg J, Crampton B, et al.Biochemical and phylogenetic analysis of Eugenia and Syzygium species from Mauritius. J Appl Res Med Aroma. 2019;12:21–9. 10.1016/j.jarmap.2018.10.004.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Soh WK. Chapter 1: Taxonomy of Syzygium Gaertner. In: Nair KN, editor. Taxonomy of Syzygium: Syzygium cumini and other underutilized species. New York: CRC Press; 2017. 10.1201/9781315118772-2.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Tukiran T, Wardana AP, Hidayati N, Shimizu K. An ellagic acid derivative and its antioxidant activity of chloroform extract of stem bark of Syzygium polycephalum Miq. (Myrtaceae). Indones J Chem. 2018;18(1):26–34. 10.22146/ijc.25467.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Rabeta MS, Chan S, Neda GD, Lam KL, Ong MT. Anticancer effect of underutilized fruits. Int Food Res J. 2013;20(2):551–6.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Nigam V, Nigam R, Singh A. Distribution and medicinal properties of Syzygium species. Curr Res Pharm Sci. 2012;2:73–80.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Mudiana D. Syzygium diversity in gunung baung, east java. Indonesia Biodiversitas. 2016;17(2):733–40. 10.13057/biodiv/d170248.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Sobeh M, Esmat A, Petruk G, Abdelfattah M, Dmirieh M, Monti DM, et al. Phenolic compounds from Syzygium jambos (Myrtaceae) exhibit distinct antioxidant and hepatoprotective activities in vivo. J Funct Foods. 2018;41:223–31. 10.1016/j.jff.2017.12.055.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Abera B, Adane L, Mamo F. Phytochemical investigation the root extract of Syzygium guineense and isolation of 2,3,23-trihydroxy methyl oleanate. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2018;7(3):104–3111.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Ayyanar M, Subash-Babu P. Syzygium cumini (L.) Skeels: a review of its phytochemical constituents and traditional uses. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2012;2(3):240–6. 10.1016/S2221-1691(12)60050-1.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Craven LA, Biffin E. An infrageneric classification of Syzygium (Myrtaceae). Blumea. 2010;55:94–99. 10.3767/000651910X499303.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Memon AH, Ismail Z, Al-Suede FSR, Aisha AFA, Hamil MSR, Saeed, et al. Isolation, characterization, crystal structure elucidation of two flavanones and simultaneous RP-HPLC determination of five major compounds from Syzygium campanulatum Korth. Molecules. 2015;20:14212–33. 10.3390/molecules200814212.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Annadurai G, Masilla BRP, Jothiramshekar S, Palanisami E, Puthiyapurayil S, Parida AK. Antimicrobial, antioxidant, anticancer activities of Syzygium caryophyllatum (L.) Alston. Int J Green Pharm. 2012;285–8. 10.4103/0973-8258.108210.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Khandaker MM, Boyce AN. Growth, distribution and physiochemical properties of wax apple (Syzygium samarangense): a review. J Crop Sci. 2016;10(12):1640–8. 10.21475/ajcs.2016.10.12.PNE306.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Shü1 Z, Lin T, Lai J, Huang C, Wang D, Pan H. The industry and progress review on the cultivation and physiology of wax apple – with special reference to ‘pink’ Variety, Asian Australas. J Biosci Biotechnol. 2007;1(2):48–53.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Sharma S, Mehta BK, Mehta D, Mishra NHA. A review on pharmacological activity of Syzygium cumini extracts using different solvent and their effective dose. Int Res J Pharm. 2012;3(12):54–58.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Dharani N. A review of traditional uses and phytochemical constituents of indigenous Syzygium species in east Africa. Pharm J Kenya. 2016;22(4):123–7.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Chua LK, Lim CL, Ling APK, Chye SM, Koh RY. Anticancer potential of Syzygium species: a review. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2019;18–27. 10.1007/s11130-018-0704-z.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Agarwal P, Gaur PK, Tyagi N, Puri D, Kumar N, Kumar S. An overview of phytochemical, therapeutic, pharmacological and traditional importance of Syzygium cumini. Asian J Pharmacogn. 2019;3(1):5–17.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Sah AK, Verma VK. Syzygium cumini: an overview. J Chem Pharm Res. 2011;3(3):108–13.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Mittal M, Gupta N, Parashar P, Mehra V, Khatri M. Phytochemical evaluation and pharmacological activity of Syzygium aromaticum: a comprehensive review. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2014;6(8):4–9.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Batiha GE, Alkazmi LM, Wasef LG, Beshbishy AM, Nadwa EH, Rashwan EK. Syzygium aromaticum L. (Myrtaceae): traditional uses, bioactive chemical constituents, pharmacological and toxicological activities. Biomolecules. 2020;10(202):2–16. 10.3390/biom10020202.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Pradhan M. Phytochemistry, pharmacology and novel delivery applications of Syzygium cumini (L.). Int J Pharm Pharm Res. 2016;7(1):659–75.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Katiyar D, Singh V, Ali M. Recent advances in pharmacological potential of Syzygium cumini: a review. Adv Appl Sci Res. 2016;7(3):1–12.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Osman H, Rahim AA, Isa NM, Bakhir NM. Antioxidant activity and phenolic content of paederia foetida and Syzygium aqueum. Molecules. 2009;14:970–8. 10.3390/molecules14030970.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Sobeh M, Mahmoud MF, Petruk G, Rezq S, Ashour ML, Youssef FS, et al. Syzygium aqueum: a polyphenol-rich leaf extract exhibits activities in animal models. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9(3):1–14. 10.3389/fphar.2018.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Rosnah S, Wong WK, Noraziah M, Osman H. Chemical composition changes of two water apple (Syzygium samarangense). Int Food Res J. 2012;19(1):167–74.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Choironi NA, Fareza MS. Phytochemical screening and antibacterial activity of ethanolic extract of Syzygium samarangense leaves. J Kartika Kimia. 2018;1(1):1–4. 10.26874/jkk.vlil.2.Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Cortés-Rojas DF, Souza CRFd, Oliveira WP. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2014;4(2):90–96. 10.1016/S2221-1691(14)60215-X.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Jadhav VM, Kamble SS, Kadam VJ. Herbal medicine: Syzygium cumini: a review. J Pharm Res. 2009;2(7):1212–9.Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Tadesse SA, Wubneh ZB. Antimalarial activity of Syzygium guineense during early and established plasmodium infection in rodent models. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17(21):1–7. 10.1186/s12906-016-1538-6.Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Markose AM. Evaluation and value addition of watery rose apple rose apple (Syzygium aqueum (Burm) Alston) and malay apple (Syzygium malaccense (L.) Mernil and Perry). India: Review of Literature; 2008.Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Sonawane MS. Dietary benefits of watery rose apple (Syzygium aqueum (Burm.f.) Alston). Int Arch App Sci Tech. 2018;9(4):126–9. 10.15515/iaast.09764828.9.4.126129.Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Verdcourt B. Syzygium aqueum (Burm.f.) Alston [family Myrtaceae], Flora of Tropical East Africa. JSTOR. 2001. 10.5555/al.ap.flora.ftea005205.Suche in Google Scholar

[42] Fayemiwo KA, Adeleke MA, Okoro OP, Awojide SH, Awoniyi IO. Larvicidal efficacies and chemical composition of essential oils of pinus sylvestris and Syzygium aromaticum against mosquitoes. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2014;4(1):30–4. 10.1016/S22211691(14)60204-5.Suche in Google Scholar

[43] Manaharan T, Appleton D, Cheng HM, Palanisamy UD. Flavonoids isolated from Syzygium aqueum leaf extract as potential antihyperglycaemic agents. Food Chem. 2012;132(4):1802–7. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.11.147.Suche in Google Scholar

[44] Subarnas A, Diantini A, Abdulah R, Zuhrotun A, Ahadisapurti YE, Puspitasari IM, et al. Apoptosis induced in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells by 2′,4′-dihydroxy-6-methoxy-3,5-dimethylchalcone isolated from Eugenia aquea Burm f. leaves. Oncol Lett. 2015;9:2303–6. 10.3892/ol.2015.2981.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] Sobeh M, Petruk G, Osman S, El RA, Imbimbo P, Monti DM, et al. Isolation of myricitrin and 3,5-di-O-methyl gossypetin from Syzygium samarangense and evaluation of their involvement in protecting keratinocytes against oxidative stress via activation of the Nrf-2 pathway. Molecules. 2019;24(1839):1–14. 10.3390/molecules24091839.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[46] Amor EC, Villasenor IM, Yasin A, Choudhary MI Prolyl endopeptidase inhibitors from Syzygium samarangense (Blume) Merr. & L. M. Perry. Z Naturforsch. 2004;59c:86–92.10.1515/znc-2004-1-218Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Amor EC, Villaseñor IM, Nawaz SA, Hussain MS, Choudhary MI. A dihydrochalcone from Syzygium samarangense with anticholinesterase activity. Philipp J Sci. 2005;2:105–11.Suche in Google Scholar

[48] Kuo Y, Yang L, Lin L-C. Isolation and immunomodulatory effect of flavonoids from Syzygium samarangense. Planta Meda. 2004;70:1237–9.10.1055/s-2004-835859Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Simirgiotis MJ, Adachi S, To S, Yang H, Reynertson K, Basile MJ, et al. Cytotoxic chalcones and antioxidants from the fruits of Syzygium samarangense (Wax Jambu). Food Chem. 2008;107:813–9. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.08.086.Suche in Google Scholar

[50] Nassar MI, Gaara AH, El-Ghorab AH, Farrag AH, et al. Chemical constituents of clove (Syzygium aromaticum, Fam.Myrtaceae) and their antioxidant activity. Rev Latinoamer Quím. 2007;35(3):47–57.Suche in Google Scholar

[51] Nguyen TL, Rusten A, Bugge MS, Malterud KE, Diallo D, Paulsen BS, et al. Flavonoids, gallotannins and ellagitannins in Syzygium guneese and the traditional use among malian healers. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016;192:450–8. 10.1016/j.jep.2016.09.035.Suche in Google Scholar

[52] Nonaka G, Arko Y, Aritake K, Nishioka I. Samarangenins A and B, novel proanthocyanidins with doubly bonded structures, from Syzygium samarangens and S. aqeuem. Chem Pharm Bull. 1992;40(10):1671–2673. 10.1248/cpb.40.2671.Suche in Google Scholar

[53] Naira AGR, Krishnana S, Ravikrishnaa C, Madhusudanan KP. New and rare flavonol glycosides from leaves of Syzygium samarangense. Fitoterapia. 1999;70:148–51.10.1016/S0367-326X(99)00013-1Suche in Google Scholar

[54] Mahmoud I, Marzouk MSA, Moharram FA, El-Gindi MR, Hassan AMK. Acylated flavonol glycosides from Eugenia jambolana leaves. Phytochemistry. 2001;58:1239–44.10.1016/S0031-9422(01)00365-XSuche in Google Scholar

[55] Ryu B, Kim HM, Woo J, Choi J, Jang DS. A new acetophenone glycoside from the flower buds of Syzygium aromaticum (cloves). Fitoterapia. 2016;115:46–51. 10.1016/j.fitote.2016.09.021.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[56] Hua Y, Wanga L, Li Y, Li M, Xu W, Zhao Y, et al. Phytochemistry letters five new triterpenoids from Syzygium samarangense (Bl.) Merr. et Perry. Phytochem Lett. 2018;25:147–51. 10.1016/j.phytol.2018.04.018.Suche in Google Scholar

[57] Ragasa CY, Franco Jr FC, Raga DD, Shen C. Chemical constituents of Syzygium samarangense. Der Pharma Chem. 2014;6(3):256–60.Suche in Google Scholar

[58] Kuroda M, Mimaki Y, Ohtomo T, Yamada J, Nishiyama T, Mae T, et al. Hypoglycemic effects of clove (Syzygium aromaticum flower buds) on genetically diabetic KK-A y mice and identification of the active ingredients. J Nat Med. 2012;66:394–9. 10.1007/s11418-011-0593-z.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[59] Sikder MAA, Kaisar MA, Rahman MS, Hasan CM, Al-Rehaily, et al. Secondary metabolites from seed extracts of Syzygium Cumini (L.). J Phys Sci. 2012;23(1):83–87.Suche in Google Scholar

[60] Alam M, Rahman AB, Moniruzzama M, Kadir MF, Haque MA, Alvi MR, et al. Evaluation of antidiabetic phytochemicals in Syzygium cumini (L.) skeels (Family: Myrtaceae). J Appl Pharm Sci. 2012;2(10):094–8. 10.7324/JAPS.2012.21019.Suche in Google Scholar

[61] Djoukeng JD, Abou-Mansoura E, Tabacchi R, Tapondjou AL, Bouda H, Lontsi D Antibacterial triterpenes from Syzygium guineense (Myrtaceae). J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;101(1–3):283–6. 10.1016/j.jep.2005.05.008.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[62] Abera B, Adane L, Mamo F. Phytochemical investigation the root extract of Syzygium guineense and isolation of 2,3,23-trihydroxy methyl oleanate. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2018;7(2):3104–11.Suche in Google Scholar

[63] Oladosu IA, Lawson L, Aiyelaagbe OO, Emenyonu N, Afieroh OE. Anti-tuberculosis lupane-type isoprenoids from Syzygium guineense wild DC. (Myrtaceae) stem bark. Fut J Pharm Sci. 2017;3(2):148–52. 10.1016/j.fjps.2017.05.002.Suche in Google Scholar

[64] Simoes-Pires CA, Vargas S, Marston A, Iosets JR, Paulo MQ, Matheeussen A, et al. Ellagic acid derivatives from Syzygium cumini stem bark: investigation of their antiplasmodial activity. Nat Prod Commun. 2009;4(10):1371–6.10.1177/1934578X0900401012Suche in Google Scholar

[65] Yanga J, Lei JSX, Huanga X, Zhang D, Ye W, Wang Y. Acylphloroglucinol derivatives from the leaves of Syzygium samarangense and their cytotoxic activities. Fitoterapia. 2018;129:1–6. 10.1016/j.fitote.2018.06.002.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[66] Saptarinli N, Herawati IE. Antioxidant activity of water apple (Syzygium aqueum) fruit and fragrant mango (Mangifera odorata) fruit. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2017;54–56. 10.22159/ajpcr.2017.v10s2.19487.Suche in Google Scholar

[67] Lim ASL, Rabeta MS. Proximate analysis, mineral content and antioxidant capacity of milk apple, malay apple and water apple. Int Food Res J. 2013;20(2):673–9.Suche in Google Scholar

[68] Khandaker MA, Sarwar MJ, Mat N, Boyce AN. Bioactive constituents, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of three cultivars of wax apple (Syzygium samarangense L.) fruits. Res J Biotech. 2015;10(1):7–16.Suche in Google Scholar

[69] Madhavi M, Ram MR. Phytochemical screening and evaluation of biological activity of root extracts of Syzygium samarangense. Int J Res Pharm chem. 2015;5(4):753–63.Suche in Google Scholar

[70] Jimoh SO, Arowolo LA, Alabi KA. Phytochemical screening and antimicrobial evaluation of Syzygium aromaticum extract and essential oil. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. 2017;6(7):4557–67. 10.20546/ijcmas.2017.607.476.Suche in Google Scholar

[71] Singh V, Pahuja C, Ali M, Sultana S. Analysis and bioactivities of essential oil of the flower buds of Syzygium aromaticum (L.) Merr.et LM Perry. J Med Plants Stud. 2018;6(6):79–83.Suche in Google Scholar

[72] Lima RM, Polonini HC, Brandao MAF, Raposo FJ, Dutra RC, Raposo NRB. In vitro assessment of anti-aging properties of Syzygium cumini (L.) leaves extract. Biomed J Sci & Tech Res. 2019;13(4):10185–1019. 10.26717/BJSTR.2019.13.002447.Suche in Google Scholar

[73] Rohadi R, Santoso U, Raharjo S, Falah II. Determination of antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds of methanolic extract of java plum (Syzygium cumini Linn.) seed. Indonesian Food Nutr Prog (IFNP). 2017;14(1)::49–20.10.22146/ifnp.24279Suche in Google Scholar

[74] Kumar A, Kalakoti M. Phytochemical and antioxidant screening of leaf extract of Syzygium cumini. Int J Adv Res. 2015;3(1):371–8.Suche in Google Scholar

[75] Ezenyi IC, Mbamalu ON, Balogun L, Omorogbe L, Ameh FS, Salawu OA. Antidiabetic potentials of Syzygium guineense methanol leaf extract. J Phytopharmacol. 2019;5(4):150–6.10.31254/phyto.2016.5406Suche in Google Scholar

[76] Okhale SE, Buba CI, Oladosu P, Ugbabe GE, Ibrahim JA, Egharevba HO, et al. Chemical characterization, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of the leaf essential oil of Syzgium guineense (Willd.) DC. var. Guineense (Myrtaceae) from Nigeria. Int J Pharmacogn Phytochem Res. 2018;10(11):41–349. 10.25258/phyto.10.11.1.Suche in Google Scholar

[77] Yadav SS, Meshram G, Shinde D, Patil R, Manohar SM, Upadhye MV. Antibacterial and anticancer activity of bioactive fraction of Syzygium cumini L. Seeds. Hayati J Biosci. 2011;18(3):118–22. 10.4308/hjb.18.3.118.Suche in Google Scholar

[78] Francine TN, Anatole PC, Kode J, Pradhan T, Bruno LN, Jeanne NY, et al. Extracts from Syzygium guineense inhibit cervical cancer cells proliferation through cell cycle arrest and triggering apoptosis. Acad J Med Plants (AJMP). 2019;7(2):042–54. 10.15413/ajmp.2018.0200.Suche in Google Scholar

[79] Ratnam KV, Raju RRV. In vitro antimicrobial screening of the fruit extracts of two Syzygium Species (Myrtaceae). Adv Biol Res. 2008;2(1–2):17–20.Suche in Google Scholar

[80] Pandey A, Singh P. Antibacterial activity of Syzygium aromaticum (clove) with metal ion effect against food borne pathogens. Asian J Plant Sci. 2011;1(2):69–80.Suche in Google Scholar

[81] Margaret E, Shailaja AM, Rao VV. Original research article evaluation of antioxidant activity in different parts of Syzygium cumini (Linn.). Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. 2015;4(9):372–9.Suche in Google Scholar

[82] Maregesi SM, Mwakalukwa R, Kassamali MH. Phytochemicals and biological testing of Syzygium guineense seeds extract against Ascaris suum and five pathogenic microbes. World J Pharm Res. 2016;44(8):180–4.Suche in Google Scholar

[83] Palanisamy UD, Manaharan T. Syzygium aqueum leaf extracts for possible antidiabetic Treatment. Medicinal Plants and Natural Products. 2015. 13–22. 10.17660/ActaHortic.2015.1098.1.Suche in Google Scholar

[84] Prabakaran K, Shanmugavel G. Antidiabetic activity and phytochemical constituents of Syzygium cumini seeds in Puducherry region, South India. Int J Pharmacogn Phytochem Res. 2017;9(7):7–11. 10.25258/phyto.v9i07.11168.Suche in Google Scholar

[85] Maregesi S, Kagashe G, Messo CW, Mugaya L. Determination of mineral Content, cytotoxicity and anthelmintic activity of Syzygium guineense fruits. Saudi J Med Pharm Sci. 2016;2(5):95–9.Suche in Google Scholar

[86] Rocchetti G, Lucini L, Ahmed SR, Saber FR. In vitro cytotoxic activity of six Syzygium leaf extracts as related to their phenolic profiles: an untargeted UHPLC-QTOF-MS approach. Food Res Int. 2019;126:1–32. 10.1016/j.foodres.2019.108715.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2020 Ei Ei Aung et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Electrochemical antioxidant screening and evaluation based on guanine and chitosan immobilized MoS2 nanosheet modified glassy carbon electrode (guanine/CS/MoS2/GCE)

- Kinetic models of the extraction of vanillic acid from pumpkin seeds

- On the maximum ABC index of bipartite graphs without pendent vertices

- Estimation of the total antioxidant potential in the meat samples using thin-layer chromatography

- Molecular dynamics simulation of sI methane hydrate under compression and tension

- Spatial distribution and potential ecological risk assessment of some trace elements in sediments and grey mangrove (Avicennia marina) along the Arabian Gulf coast, Saudi Arabia

- Amino-functionalized graphene oxide for Cr(VI), Cu(II), Pb(II) and Cd(II) removal from industrial wastewater

- Chemical composition and in vitro activity of Origanum vulgare L., Satureja hortensis L., Thymus serpyllum L. and Thymus vulgaris L. essential oils towards oral isolates of Candida albicans and Candida glabrata

- Effect of excess Fluoride consumption on Urine-Serum Fluorides, Dental state and Thyroid Hormones among children in “Talab Sarai” Punjab Pakistan

- Design, Synthesis and Characterization of Novel Isoxazole Tagged Indole Hybrid Compounds

- Comparison of kinetic and enzymatic properties of intracellular phosphoserine aminotransferases from alkaliphilic and neutralophilic bacteria

- Green Organic Solvent-Free Oxidation of Alkylarenes with tert-Butyl Hydroperoxide Catalyzed by Water-Soluble Copper Complex

- Ducrosia ismaelis Asch. essential oil: chemical composition profile and anticancer, antimicrobial and antioxidant potential assessment

- DFT calculations as an efficient tool for prediction of Raman and infra-red spectra and activities of newly synthesized cathinones

- Influence of Chemical Osmosis on Solute Transport and Fluid Velocity in Clay Soils

- A New fatty acid and some triterpenoids from propolis of Nkambe (North-West Region, Cameroon) and evaluation of the antiradical scavenging activity of their extracts

- Antiplasmodial Activity of Stigmastane Steroids from Dryobalanops oblongifolia Stem Bark

- Rapid identification of direct-acting pancreatic protectants from Cyclocarya paliurus leaves tea by the method of serum pharmacochemistry combined with target cell extraction

- Immobilization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa static biomass on eggshell powder for on-line preconcentration and determination of Cr (VI)

- Assessment of methyl 2-({[(4,6-dimethoxypyrimidin-2-yl)carbamoyl] sulfamoyl}methyl)benzoate through biotic and abiotic degradation modes

- Stability of natural polyphenol fisetin in eye drops Stability of fisetin in eye drops

- Production of a bioflocculant by using activated sludge and its application in Pb(II) removal from aqueous solution

- Molecular Properties of Carbon Crystal Cubic Structures

- Synthesis and characterization of calcium carbonate whisker from yellow phosphorus slag

- Study on the interaction between catechin and cholesterol by the density functional theory

- Analysis of some pharmaceuticals in the presence of their synthetic impurities by applying hybrid micelle liquid chromatography

- Two mixed-ligand coordination polymers based on 2,5-thiophenedicarboxylic acid and flexible N-donor ligands: the protective effect on periodontitis via reducing the release of IL-1β and TNF-α

- Incorporation of silver stearate nanoparticles in methacrylate polymeric monoliths for hemeprotein isolation

- Development of ultrasound-assisted dispersive solid-phase microextraction based on mesoporous carbon coated with silica@iron oxide nanocomposite for preconcentration of Te and Tl in natural water systems

- N,N′-Bis[2-hydroxynaphthylidene]/[2-methoxybenzylidene]amino]oxamides and their divalent manganese complexes: Isolation, spectral characterization, morphology, antibacterial and cytotoxicity against leukemia cells

- Determination of the content of selected trace elements in Polish commercial fruit juices and health risk assessment

- Diorganotin(iv) benzyldithiocarbamate complexes: synthesis, characterization, and thermal and cytotoxicity study

- Keratin 17 is induced in prurigo nodularis lesions

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and acute toxicity studies of a Saudi polyherbal formulation, PHF5

- LaCoO3 perovskite-type catalysts in syngas conversion

- Comparative studies of two vegetal extracts from Stokesia laevis and Geranium pratense: polyphenol profile, cytotoxic effect and antiproliferative activity