Abstract

Barbary fig called prickly pear is a plant belonging to family Cactaceae growing under hard climate conditions. A spiny variety of prickly pear named “Drbana” (Opuntia megacantha) and two non-spiny varieties named “Akria” and “Mlez” (Opuntia ficus-indica) growing in the Rhamna region (Morocco) were studied in terms of physicochemical characteristics. The physicochemical characterization (humidity, water activity, pH, total titratable acidity, Brix, and ash content) and the biochemical characterization (total carotenoid content, betalain content, total polyphenolic content, and ascorbic acid content) of the fruit pulp of prickly pear were performed according to the previously reported methods. The finding of physicochemical characterization of all studied varieties showed that the fruit pulp also contained an interesting bioactive compound classes in humidity, water activity, pH, total titratable acidity, Brix, and ash content. Regarding the biochemical characterization, the obtained finding showed the fruit pulp also contained an interesting bioactive compound classes particularly the total betalains, polyphenols, carotenoids, and ascorbic acids. Based on the obtained results in the current research work, we can affirm that the fruits of all studied varieties meet the requirement for being exploited in food, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical industries.

1 Introduction

Prickly pear (Barbary fig) is a plant belonging to family Cactaceae, which is characterized by considerable genetic diversity, including 2,000 species springing from over 20 to 30 genera [1]. It is native to the arid and semi-arid areas of Mexico. It has been cultivated in Africa since the sixteenth century [2].

In Morocco, the cultivation of prickly pear has increased from 45,000 ha in early 1990 to more than 1,50,000 due to efforts exercised by the government in plant cultivation. The great efforts dedicated by the Moroccan state for the development of cactus crops in different areas throughout the country (cultivation and valorization) have been due to the resistance of the investigated plant to hard climate conditions and its ability to grow in areas where other fruit plants cannot [3].

Prickly pear is an important component of the human diet due to its organoleptic and nutritional properties. It also has considerable potential for use in pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries. In addition to its cladodes and flowers, its fruits have high sugar content and low acidity that make them delicious. Moreover, prickly pear fruits contain betalain pigments (betacyanins and betaxanthins), as reported in earlier published data [4].

Prickly pear could be used as an alternative for the treatment of chronic diseases due to its documented activities. The following activities were reported: (1) prickly pear induces a decrease in the total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein–cholesterol, triglycerides, fibrinogen, blood glucose, insulin, and uric acid. (2) Prickly pear could be effective in insulin-independent diabetic mellitus type 2. (3) Opuntia ficus-indica seed oil exhibited potent antioxidant and prophylactic effects. (4) The treatment with cladode and flower infusions of Opuntia ficus-indica showed an increase in diuresis and natriuresis as reported in earlier found data. The mucilage extracted from prickly pear possesses promising effects on chronic gastric ulcers. (5) The role of prickly pear in gas protection was also documented.

This study aims to evaluate the physicochemical content in the fruit pulp of three prickly pear varieties named “Drbana” (Opuntia megacantha), “Akria”, and “Mlez” (Opuntia ficus-indica) growing in the Mediterranean region under hard climate conditions.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study area

Barbary fig fruit sampling was effectuated in the Skhour Rhamna region located at the west-central of Morocco (32° 29′ N: 7° 55′ W) at 98.7 km Northwest of Marrakech city (Figure 1).

Geographical location of the study area (Skhour Rhamna).

2.2 Climatic and soil conditions

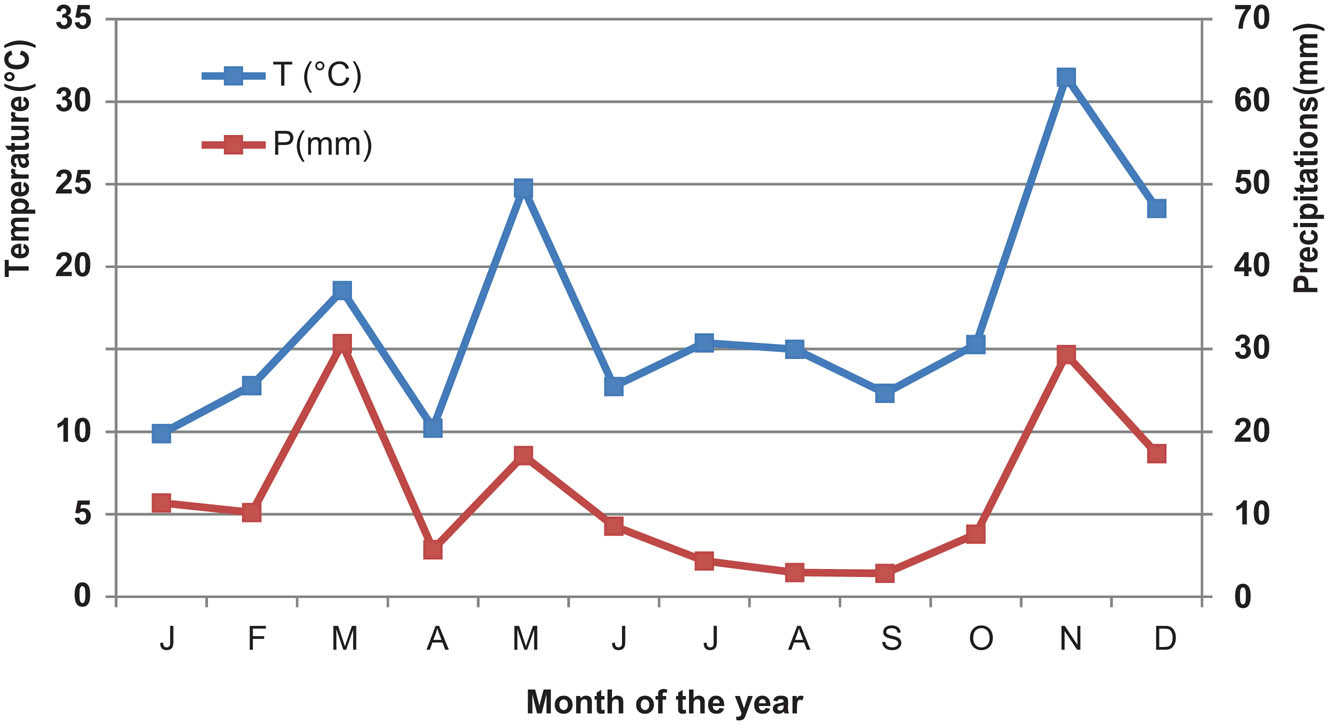

The Rhamna region is characterized by an arid Mediterranean climate with a cold winter and a dry summer (Emberger’s Pluviothermic Quotient: Q2 = 20.6). The Rhamna region is recognized by low and irregular annual rainfall over the year (Xeric Climate). The average annual precipitation is 130 mm (methodological station of Ben Guerir, 2017). The Gaussen and Bagnouls diagram of the Rhamna region reveals that the dry climate occurs during the whole year (Figure 2).

Gaussen and Bagnouls diagram of the studied region (2015–2016).

2.3 Plant material

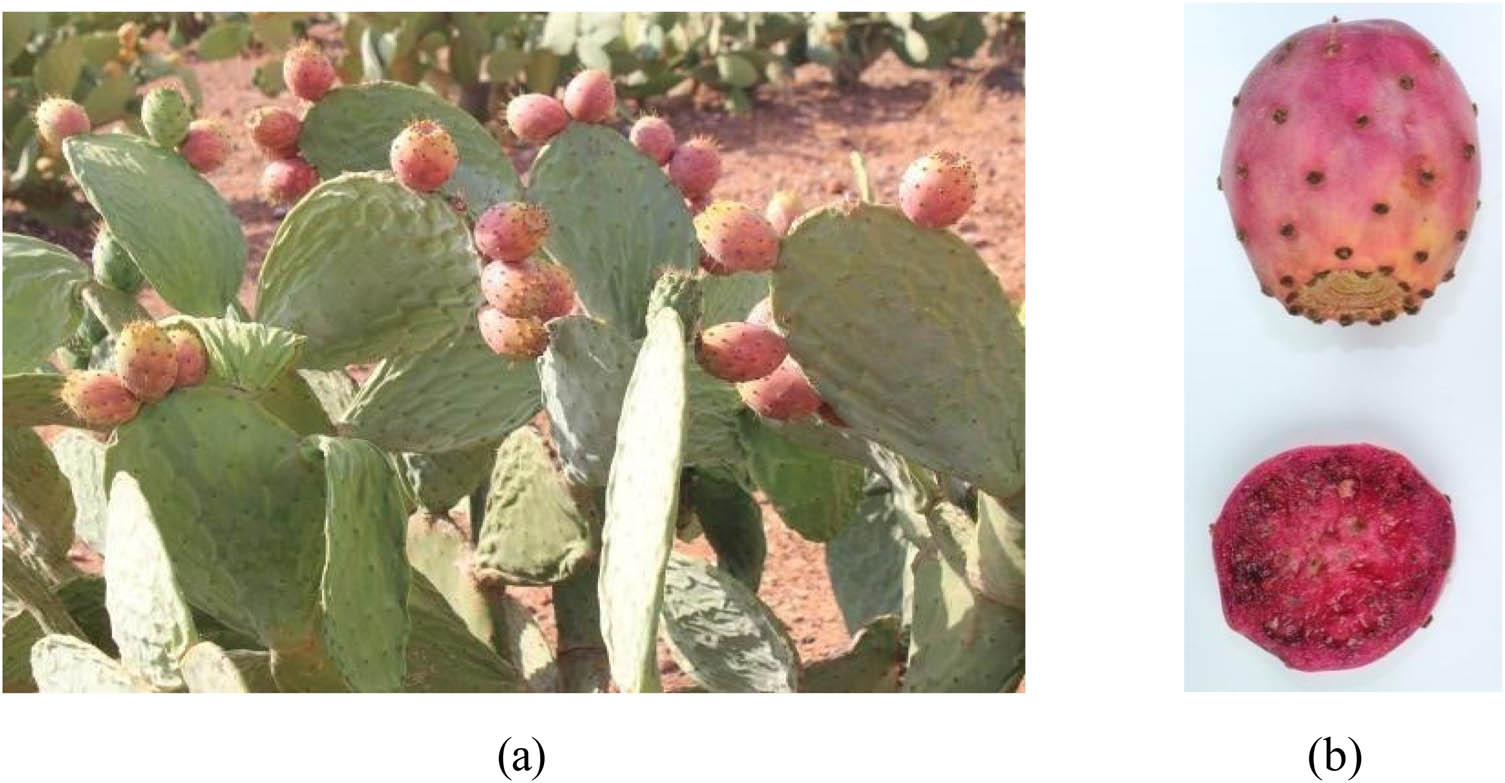

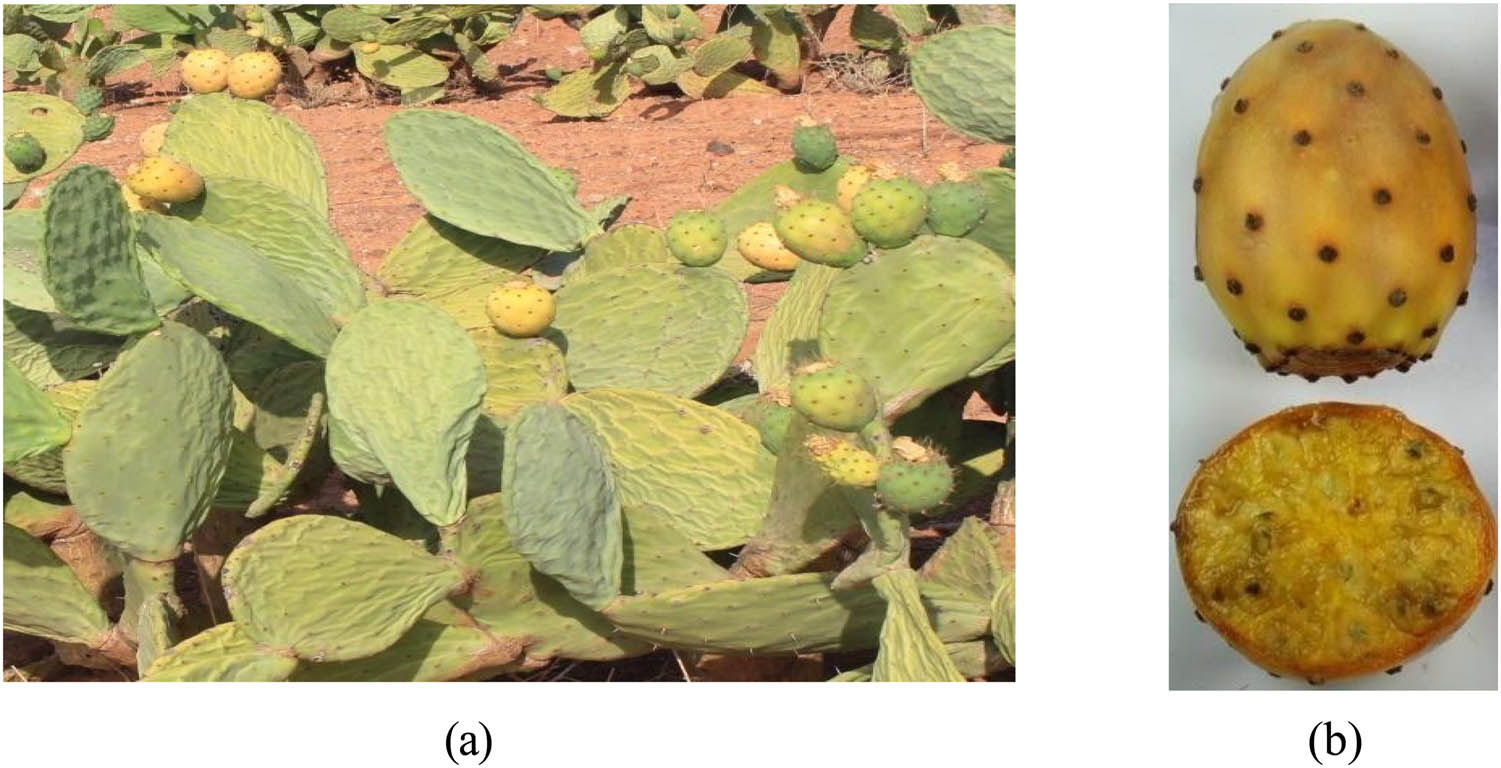

The plant sampling of three varieties of prickly pear (Opuntia spp.), locally known as Akria, Drbana and Mlez, was conducted in the Rhamna region in August 2015–2016. The collected varieties were authenticated by a botanist. The fruits were peeled and ground to remove the seeds, and the pulp was then frozen at −20°C to avoid potential alteration. Figures 3–5 show Akria, Drbana, and Mlez varieties, respectively.

Akria (Opuntia ficus-indica) variety: (a) plant of Akria variety and (b) fruit of Akria variety.

Drbana (Opuntia megacantha) variety: (a) plant of Drbana variety and (b) fruit of Akria variety.

Mlez (Opuntia ficus-indica) variety: (a) plant of Mlez variety and (b) fruit of Mlez variety.

2.4 Physical and physicochemical analyses of Barbary fig pear fruits

2.4.1 Moisture

Moisture is currently measured by drying the sample in an oven until the weight stabilization [5]. Five grams of the fruit pulp were weighed using a precision balance and placed in an oven at 105°C for 48 h. The difference in weight before and after drying enables the determination of the humidity percentage:

where Iw is the weight of the sample before steaming (g) and Fw is the weight of the sample after steaming (g).

2.4.2 Water activity

The activity of water (aw) is a parameter that characterizes the amount of free water in a product [6]. Aw was evaluated according to the previous literature [8]. Briefly, 5 g of the fruit pulp was analyzed at 25°C. The aw value was recorded after more than 2 h.

2.4.3 pH

The pH value was determined at 25°C after calibration with buffer solutions at pH 7. The pH value of the crushed pulp was measured using a protocol reported in the previous study [8].

2.4.4 Total titratable acidity

One hundred milliliters of the fruit pulp of each variety were titrated with a solution of NaOH (0.1 N) up to a pH of 8.1 [7]. The findings were reported in grams of citric acid per 100 g of fresh material (FM). Total titratable acidity was performed according to the earlier found formula [8].

2.4.5 Brix

The Brix scale is used for measuring the percentage of soluble dry matter (DM) in a product. Fifteen grams of the pulp were centrifuged in a 3–30 K Sigma centrifuge at 12,000 rpm for 30 min. We then recovered the supernatant for the measurement of Brix using an RFM 830 refractometer after filtration of this supernatant through a filter paper. The assay was performed in triplicate. The results were reported in degrees Brix (° Bx).

2.4.6 Ash content

Five grams of the pulp were weighed and then placed for incineration in a furnace at a temperature of 500°C for 7 h. The assay was effectuated in triplicate. The ash content was reported as a percentage relative to the DM according to earlier data [8].

2.5 Biochemical analysis of Barbary fig fruits

2.5.1 Total carotenoid content

Ten grams of the pulp of the studied varieties (Drbana, Mlez, and Akria) were extracted with 10 ml of solvents (hexane solvent/acetone solvent/ethanol solvent [50:25:25, v/v]). The obtained solution was centrifuged at 6,500 rpm at 5°C for 5 min. The layer of hexane including the pigments was recovered and adjusted again with hexane. The total carotenoid was determined according to the earlier found formula [8].

2.5.2 Betalain content

The betalain content was determined with respect to the method described in the previous study [9]. Two grams of the pulp were macerated with 10 ml of methanol 80 % (v/v) for 1 min. The obtained extract was centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for approximately 20 min to obtain the supernatant including betalains. The betalain content was determined in regard to the previous protocols [8].

2.5.3 Total polyphenol and ascorbic acid content

2.5.3.1 Extraction

Ten grams of the pulp were subjected to extraction with 10 ml of acetone (70%) and (80%). The extract was centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 30 min and finally filtered through a filter paper. The obtained extract was used for determining the total polyphenol and ascorbic acid content.

2.5.3.2 Total polyphenols

The total polyphenolic content was determined according to the instructions reported in previous methods [8].

2.5.4 Ascorbic acid content

Five hundred microliters of the fruit pulp extract were added to 3.5 ml of water and then vortexed. Two milliliters of the obtained solution were deposited on an OASIS conditioned with 3 ml of MeOH + 2 × 3 ml of water and then rinsed twice with 2 ml of water. 0.5 ml of the aqueous solution was determined according to earlier data [8].

2.6 Statistical analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to compare the obtained mean values for different studied parameters. The Student–Newman–Keuls test allows, after rejecting the hypothesis of means equality, us to look for the homogeneous groups of mean values. Data were reported as mean ± SD.

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Physicochemical characterization of the fruit pulp of prickly pear

3.1.1 Juice content

One-way ANOVA showed a high difference between the juice content of the fruit pulp of the three studied varieties produced in both 2015 and 2016 crop years (p < 0.001). The fruit juice content of Drbana and Akria produced in 2015 was reported to be equal to 57.25% and 69%, respectively. These results were in accordance with those of the previous study [10], in which it was revealed that the juice content of prickly pear fruits was estimated to be 62.84%. Besides, similar results were reported in the previous literature concerning the juice content of prickly pear fruits (57.30%). The juice content of Drbana variety produced in 2015 and 2016 was 57.25% and 57.60%, respectively (Table 1) [11]. The difference recorded between the same prickly pear produced in different seasons of 2015 and 2016 in terms of juice content could be due to various climatic conditions over the 2 years. Indeed, the average annual rainfall recorded in 2016 (164.7 mm) in the study area was higher than that recorded in 2015 (131.9 mm). In addition, we note that the Akria and Mlez varieties have high water and juice content compared to that of the Drbana variety, which was less in both water and juice content. The high levels of fruit juice shown in the studied varieties increase their commercial value, due to the fact that in the agro-industrial sector, the juice content is the first factor, which influences the cost price.

Physicochemical criteria of the fruit pulp of the three prickly pear varieties (Akria, Drbana, and Mlez)

| Years | Varieties | Juice content (%) | Humidity (%) | Water activity | Brix (°Bx) | pH | Total titratable acidity(g citric acid/100 g of FM | Brix/acid ratio | Ash content (g/100 g of DM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | Akria | 67.45 ± 0.05 | 88.04 ± 0.02 | 0.877 ± 0.002 | 14.78 ± 0.05 | 5.26 ± 0.01 | 0.052 ± 0.001 | 281.98 ± 2.24 | 3.04 ± 0.04 |

| Drbana | 57.25 ± 0.05 | 87.03 ± 0.03 | 0.864 ± 0.002 | 15.79 ± 0.07 | 6.00 ± 0.13 | 0.027 ± 0.001 | 575.94 ± 14.87 | 2.73 ± 0.01 | |

| Mlez | 67.20 ± 0.10 | 87.56 ± 0.02 | 0.871 ± 0.001 | 15.13 ± 0.04 | 5.85 ± 0.01 | 0.042 ± 0.001 | 363.68 ± 5.50 | 2.55 ± 0.03 | |

| 2016 | Akria | 69.75 ± 0.05 | 89.05 ± 0.02 | 0.862 ± 0.001 | 13.78 ± 0.02 | 6.18 ± 0.01 | 0.042 ± 0.001 | 326.38 ± 1.30 | 3.08 ± 0.05 |

| Drbana | 57.60 ± 0.10 | 87.80 ± 0.03 | 0.857 ± 0.001 | 15.15 ± 0.07 | 6.34 ± 0.01 | 0.026 ± 0.001 | 582.91 ± 3.88 | 2.95 ± 0.05 | |

| Mlez | 69.50 ± 0.10 | 88.77 ± 0.01 | 0.859 ± 0.001 | 14.67 ± 0.04 | 6.28 ± 0.01 | 0.035 ± 0.001 | 421.80 ± 3.20 | 3.43 ± 0.02 |

The findings were reported in mean ± SD. Values marked with the same letter in the same column did not reveal a significant difference at p < 0.05.

3.1.2 Humidity

Humidity influences the technological and the organoleptic properties of food products, as well as their conservation. For this reason, it is important to control the humidity level of food. The humidity level varies between the studied varieties, ranging from 87.03 ± 0.03% to 89.05 ± 0.02%. The statistical analysis showed a highly significant difference between the humidity levels of the three studied fruits (p < 0.001). There was also a significant difference in humidity levels between the fruits of the same varieties harvested in different seasons of 2015 and 2016. The highest humidity level was recorded in the Akria variety fruits collected in 2016, while the lowest humidity level was found in the Drbana variety fruits harvested in 2015 (Table 1). The high humidity values of prickly pear fruits increase the perishability of these products and limit their ability to be stored at room temperature [12]. The seasonal effect on the moisture content of the three varieties of fruits could be due to climatic conditions since the prickly pear has not been irrigated in the study area. The humidity values revealed in the current work were consistent with those reported in the previous study [9], which reported that the humidity values of prickly pear range from 87.50 ± 0.09% to 89.62 ± 0.08%. Our results were also in accordance with those reported in the literature regarding humidity value fluctuation of the studied plant [13].

3.1.3 Water activity

The water activity represents the free water contained in a product. It influences microbial growth (bacteria, yeasts, molds, etc.) and the ability of these microorganisms to alter food. According to our results presented in Table 1, there is a highly significant difference between the water activity contained in the pulp of the three studied varieties produced in 2015 (p < 0.001). However, there was no significant difference between the water activity of the fruit pulp of Drbana and Mlez varieties produced in 2016. Regarding the water activity of prickly pear fruits, the values reported in the current work ranging from 0.857 ± 0.001 to 0.877 ± 0.002 were in agreement with those reported in the previous study, ranging from 0.863 to 0.883 [14].

3.1.4 Brix

Brix represents the DM percentage, which is considered equal to the sugar content in the sample. One-way ANOVA showed a highly significant difference between the pulp Brix of the three varieties produced in different seasons of 2015 and 2016 (p < 0.001). The Brix values reported in the present work range from 13.78 ± 0.02 to 15.79 ± 0.07 °Bx. The sweetest pulp was attributed to the Drbana variety harvested in 2015. However, the pulp of the Akria variety harvested in 2016 was the least sweet (Table 1). The prickly pear Brix values reported in our work were consistent with those reported in previous study, 13.50 ± 0.95 and 15.87 ± 1.64 °Bx [15]. However, our prickly pear Brix values were superior to those found in earlier data, 10.9 ± 0.05 to 11.9 ± 0.11 °Bx [16]. The high Brix values of the fruit pulp found in the current work can be due to climate aridity and rainfall scarcity. Moreover, the study area is dry and non-irrigated. Fruits produced in dryland are naturally being sweeter than those in irrigated and wetland [17,18]. The maturity degree also influences the Brix values of prickly pear fruit as shown in previous studies [19], which reported that the Brix values of green and ripe fruits were, respectively, 12.56 ± 2.13 and 14.89 ± 2.91 °Bx.

3.1.5 pH

pH parameter determines the microbial stability of fruit during storage [20]. It also influences the fruit’s flavor [21]. One-way ANOVA showed a significant difference between the pH values of the fruit pulp of the studied varieties harvested in both 2015 and 2016 (p < 0.001). The pH values of these varieties vary from 5.26 ± 0.01 to 6.34 ± 0.01 (weakly acidic). The fruit pulp of Akria was the most acidic compared to those of Drbana and Mlez varieties (Table 1). The pH values discussed in this work were consistent with those reported in previous study [22], which reported that the pH values of Hawara and Aissa varieties were 5.98 and 6.37, respectively. The pH values of Barbary fig fruits reported in our work were higher than the pH values of other fruits such as grapefruits (3.67 ± 0.02) [23] and orange [24].

3.1.6 Total titratable acidity

The total titratable acidity is the sum of the free acid functions of a sample [25]. One-way ANOVA showed a significant difference between the total titratable acidity of the fruit pulp of the three reported varieties (p < 0.001). A significant difference was also observed between the fruit pulp of the two crop years, 2015 and 2016, regarding a given variety. The values of total titratable acidity are inversely proportional to the Brix values (negative correlation with −0.294; Table 1). The fruits of the Drbana variety harvested in 2016 presented the lowest acidity average, 0.026 ± 0.001 g of citric acid/100 g of FM. However, the fruits of the Akria variety harvested in 2015 were the most acidic in the order of 0.052 ± 0.001 g of citric acid/100 g of FM. The current results of acidity present in the studied varieties were in accordance with those reported in the previous literature [9], in which it was reported that the titratable acidity of the fruit pulp of Opuntia ficus-indica ranges from 0.04 to 0.07 g of citric acid/100 g of FM.

3.1.7 Brix/acidity ratio

The Brix/acidity ratio is an important indicator used to determine the taste quality of fruits. It is also used for determining the degree of fruit maturity. The fruits of the Drbana variety harvested in seasons of 2015 and 2016 exhibited the highest Brix/acidity ratio with values of 575.94 ± 14.87 and 582.91 ± 3.88, respectively. Moreover, the fruits of the Drbana variety exhibited the highest Brix and the lowest acidity values (Table 1). As a result, these fruits could be considered the best fruits for being consumed because of their taste quality. Our results were partially comparable to those of other research [10], in which it was reported that the Brix/acidity value of nine species of genus Opuntia was 470. This highest value was relatively lower than that found in the current research work, 582.91 ± 3.88.

3.1.8 Ash content

Ash content is one of the most important parameters that refer to the mineral content of the food. One-way ANOVA showed a great difference between the ash content of the pulp of Drbana and Mlez varieties of both 2015 and 2016 crop years (p < 0.05). However, there is no significant difference in the ash content of the pulp of Akria of both 2015 and 2016 crop years (3.04 ± 0.04 and 3.08 ± 0.05 g/100 g of DM). Moreover, the pulp of Akria variety possessed a higher content of mineral compounds compared to other reported varieties (Drbana and Mlez). The ash content reported in our work was higher than that found in earlier data [19].

The ash content ranges from 0.20 ± 0.09 to 0.34 ± 0.01 g/100 of DM as reported in previous data. The fruits of Opuntia ficus-indica are particularly rich in potassium, magnesium, and calcium as shown in previous results [26].

3.2 Biochemical characterization of the pulp of prickly pear fruit

3.2.1 Pigment content

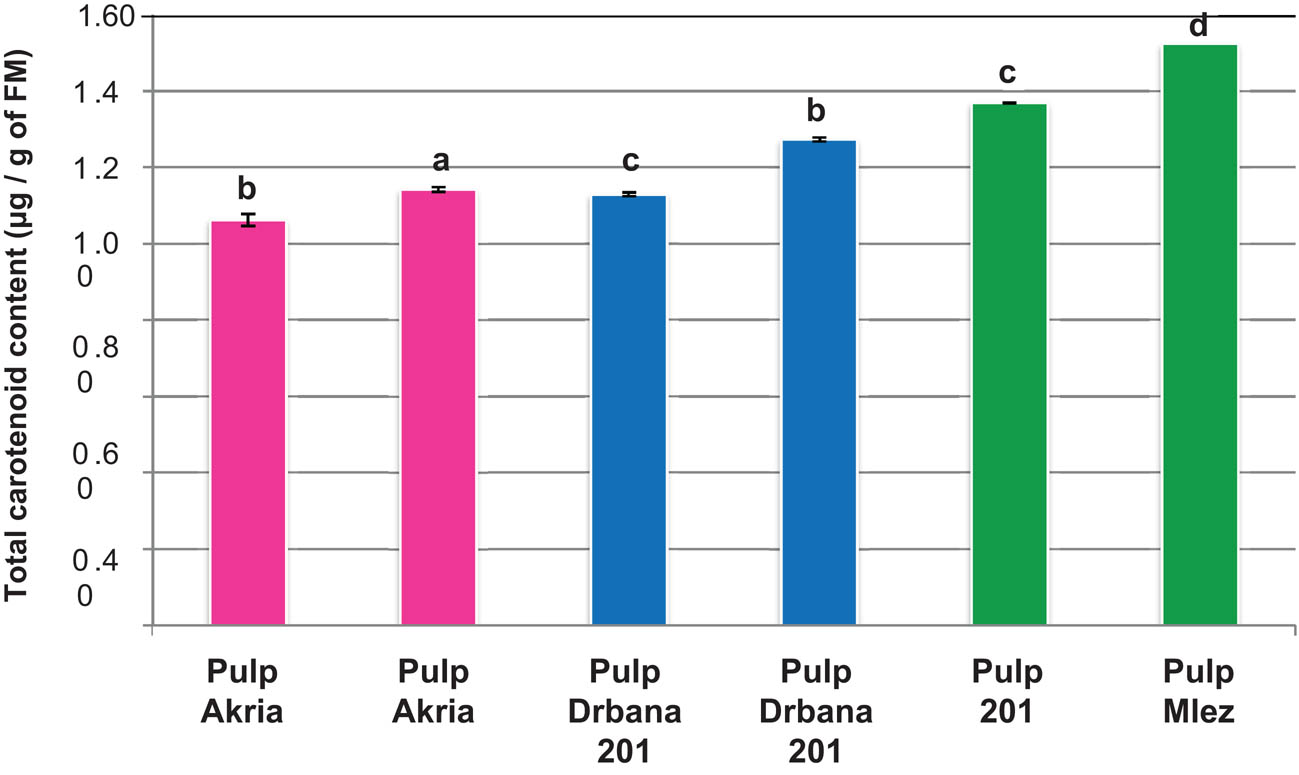

3.2.1.1 Total carotenoids

Carotenoids are the photosynthetic pigments responsible for the orange, yellow, as well as red colors of fruits. They are also major determinants of the organoleptic and nutritional qualities of fruits [27]. The total carotenoid content varies according to species and fruit pulp color. Orange-yellow fruits (Drbana and Mlez) possess a higher carotenoid content compared to red-purple fruits (Akria; Figure 6). The total carotenoid content increased in the fruit pulp of the three varieties harvested in 2016 than the fruit pulp of the same varieties harvested in 2015 (Figure 6). The carotenoid content reported in our results was lower than that reported in previous data concerning Opuntia ficus-indica fruits, ranging from 17.7 ± 0.4 to 26.5 µg/100 g of FM [9].

Total carotenoid content of the fruit pulp of Barbary fig varieties (Akria, Drbana, and Mlez) of both 2015 and 2016 crop years. Mean values with the same letter did not reveal a significant difference at p < 0.05.

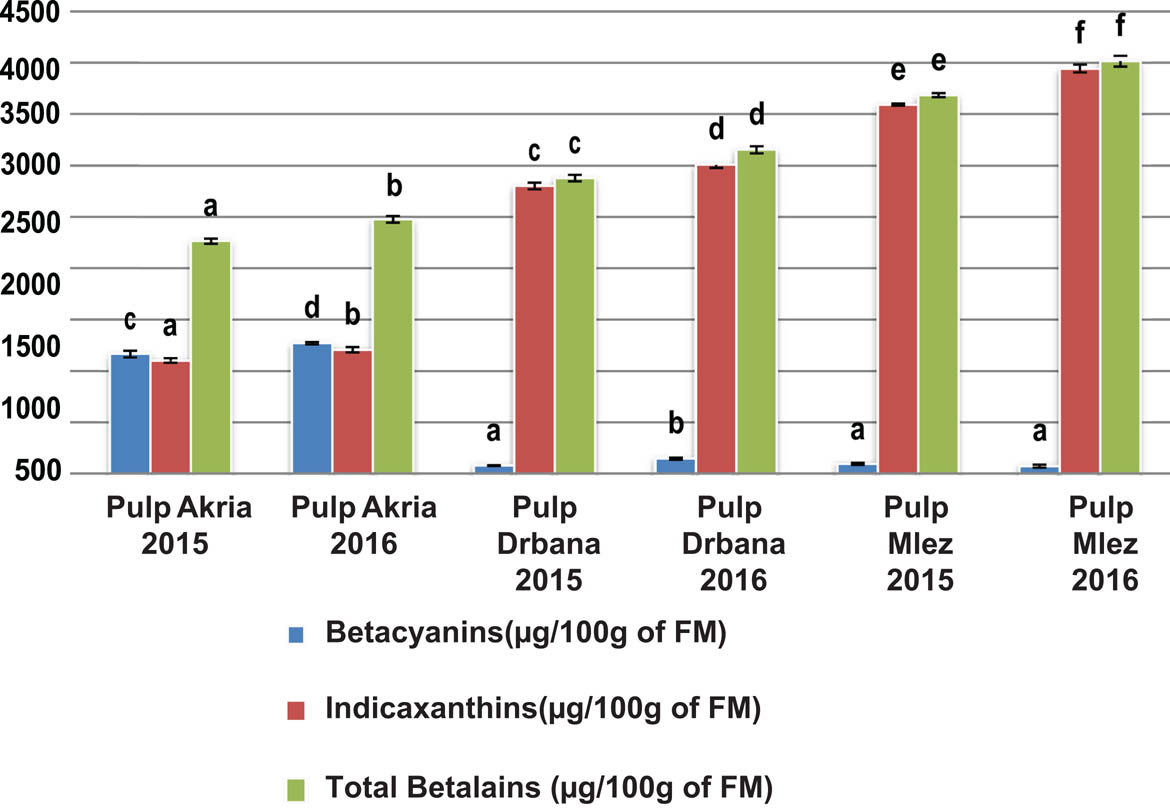

3.2.1.2 Betalains

The attractive colors of Barbary fig are due to betalains that contain betacyanin and betaxanthin pigments [28]. Statistical analysis revealed a significant difference in the betalain content of the fruit pulp of the studied varieties of produced in both 2015 and 2016 crop years (p < 0.001). For instance, the values ranged from 2262.71 ± 24.99 to 4014.20 ± 52.15 µg/100 g of FM for the Akria variety produced in 2015 and 2016, respectively (Figure 7). For the Akria variety, the results also showed ten-fold higher betacyanin content compared to other reported varieties (Drbana and Mlez). The Mlez and Drbana varieties were, respectively, four and three times richer in indicaxanthins compared to the Akria variety.

Betalain content (betacyanins, indicaxanthins, and total betalains) of the fruit pulp of the discussed varieties (Akria, Drbana, and Mlez) produced in both 2015 and 2016 crop years. Mean values with the same letter did not present a significant difference at p < 0.05.

Results reported in the previous literature regarding the total betalain content contained in Moroccan varieties called Achefri and Amouslem were 2,990 and 9,459 µg/100 g of FM, respectively [29]. The betacyanin and indicaxanthin content in the pulp of purple and red fruits was estimated to be 181 and 2,808 µg/100 g of FM, respectively [29]. The total betalain value revealed in Opuntia megacantha fruits was 2,700 µg/100 g of FM as reported in earlier reports [30]. This value was in accordance with that found in our study regarding the Drbana variety harvested in the two mentioned crop years (2,876.90 ± 31.75 and 3,151.46 ± 34.69 µg/100 g of FM). Pigments of betalains possess antiviral, antioxidant, and antimicrobial effects [31]. Betalain pigments are considered substances for cancer prevention [32]. Betalains possess characteristics for being natural dye in food. [31].

3.2.2 Phenolic content

The phenolic content contained in the fruit pulp of the investigated varieties in the present work increased in the second 2016 crop year compared to the first 2015 crop year. For instance, the phenolic content of the Drbana variety increased from 48 ± 2 to 58.31 ± 1.07 mg acid gallic equivalent (AGE)/100 g of FM for both 2015 and 2016 crop years, respectively (Figure 8).

Phenolic content of the fruit pulp of the studied varieties (Akria, Drbana, and Mlez) produced in both 2015 and 2016 crop years. Average with the same letter did not present a significant difference at p < 0.05.

The current results of the phenolic content were comparable to those reported in the previous literature [26], in which it was reported that the phenolic content of Barbary fig was 59.33 ± 2.51 mg AGE/100 g of FM. In contrast, the phenolic content of the fruit pulp of other Moroccan prickly pear varieties was ranging from 39.49 ± 0.74 to 64.36 ± 0, 33 mg AGE/100 g of FM [13]. Phenolic compounds are natural antioxidants. Physiologically, they probably contribute to the body’s defense against oxidative stress by trapping reactive oxygen species and opposing the macromolecule oxidation [33]. Moreover, polyphenols may also play a protective role versus chronic and cardiovascular diseases [33].

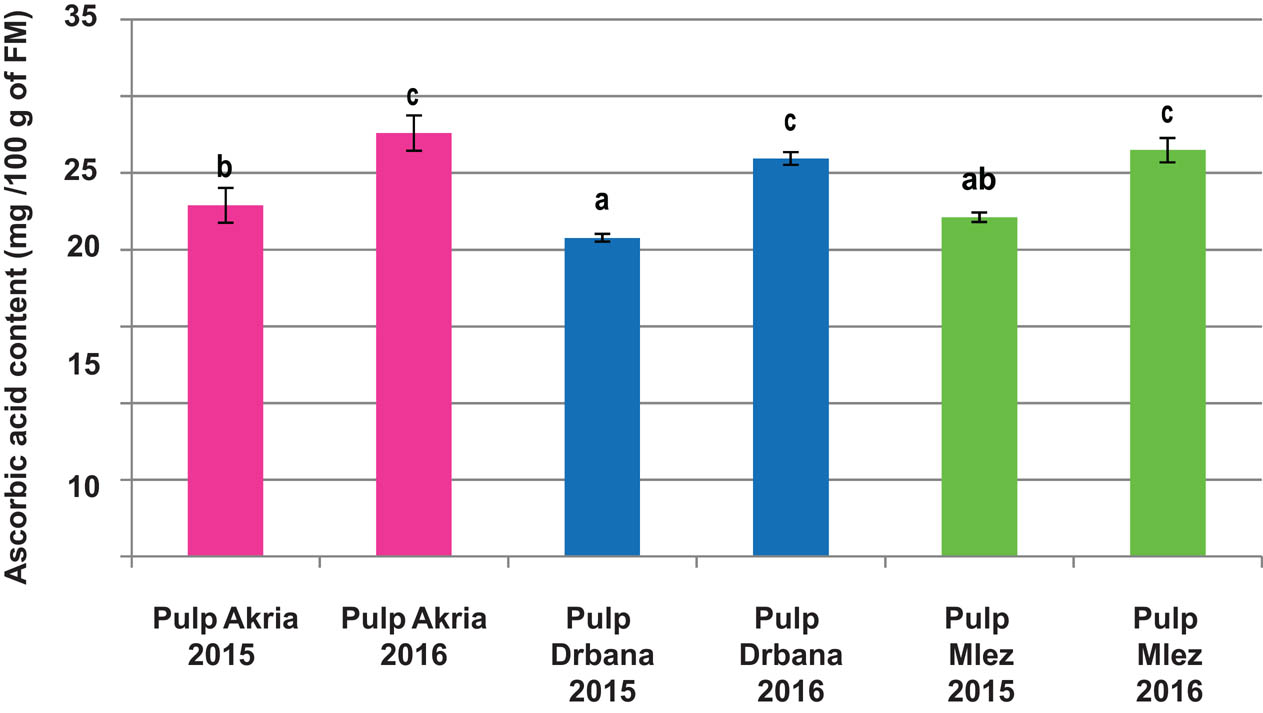

3.2.3 Ascorbic acid content

No significant difference was recorded in the ascorbic acid content between the studied varieties harvested in 2016 (p > 0.05). However, the Akria variety possessed the highest content as reported in our finding (26.48 ± 0.79 mg/100 g of FM; Figure 9).

Ascorbic acid content of the fruit pulp of the investigated varieties (Akria, Drbana, and Mlez) produced in both 2015 and 2016 crop years. Average with the same letter did not reveal a significant difference at p < 0.05.

The present results of ascorbic acid content were consistent with those of the previous studies, which reported that the ascorbic acid content of yellow-orange and purple Barbary fig fruits was 23.65 ± 2.03 to 32.19 ± 1.73 mg/100 g FM, respectively [9]. Due to its richness in ascorbic acid (vitamin C) and its interesting phenolic content, the prickly pear is one of the best foods with natural antioxidants.

4 Conclusion

In the light of the reported results, we can affirm that the fruits of Barbary fig (pulp) of all investigated varieties such as “Drbana” (Opuntia megacantha), “Akria”, and “Mlez” (Opuntia ficus-indica) could constitute a promoting source of natural compounds for launching the agro-industrial field. Moreover, the fruit pulp of the Drbana variety presents the best juice content and the Brix/acidity ratio as well. Hence, this variety can thus be regarded as an excellent fruit for being used in juice production.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University for funding this work through research group no. RGP-262.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Harwood WS. New creations in plant life: an authoritative account of the life and work of Luther Burbank. New York, US: The Macmillan Company; 1921.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Arba M, Sharoua EC. ‘MLES’ AND ‘DRAIBINA’ wild populations of cactus pear in Khouribga area, VII International Congress on Cactus Pear and Cochineal 995; 2010, p. 63–8.10.17660/ActaHortic.2013.995.7Search in Google Scholar

[3] Mabrouk A, Abbas Y, Fakiri M, Benchekroun M, El Kharrassi Y, El Antry-Tazi S, et al. Caractérisation phénologique de différents écotypes de cactus (Opuntia spp.) Marocains sous les conditions édapho-climatiques de la région de Chaouia-Ouardigha (Phenological characterization among Moroccan ecotypes of cactus (Opuntia spp.) under soil and climatic conditions of the Chaouia-Ouardigha region). J Mater. Environ Sci (Ruse). 2016;7(4):1396–405.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Dubeux Jr JC, dos Santos MV, de Andrade Lira M, dos Santos DC, Farias I, Lima LE, et al. Productivity of Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Miller under different N and P fertilization and plant population in north-east Brazil. J Arid Environ. 2006;67(3):357–72.10.1016/j.jaridenv.2006.02.015Search in Google Scholar

[5] Deymié B, Multon J-L, Simon D, Linden G. Techniques d’analyse et de contrôle dans les industries agro-almientaires. Technique et documentation; 1981.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Rockland LB, Beuchat LR. Water activity: theory and applications to food, IFT basic symposium series (USA). United States: Marcel Dekker Inc; 1987.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Cunniff P. Official methods of analysis of AOAC International: food composition, additives, natural contaminants. Gaithersburg, US: AOAC International; 1997.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Bourhia M, Elmahdaoui H, Ullah R, Bari A, Benbacer L. Promising physical, physicochemical, and biochemical background contained in peels of prickly pear fruit growing under hard ecological conditions in the mediterranean countries. BioMed Res. Int. 2019;2019(1):1–8.10.1155/2019/9873146Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Chougui N, Djerroud N, Naraoui F, Hadjal S, Aliane K, Zeroual B, et al. Physicochemical properties and storage stability of margarine containing Opuntia ficus-indica peel extract as antioxidant. Food Chem. 2015 Apr;173:382–90.10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.10.025Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Chavez-Santoscoy RA, Gutierrez-Uribe JA, Serna-Saldívar SO. Phenolic composition, antioxidant capacity and in vitro cancer cell cytotoxicity of nine prickly pear (Opuntia spp.) juices. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2009 Jun;64(2):146–52.10.1007/s11130-009-0117-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Arba M Le cactus Opuntia, une espèce fruitière et fourragère pour une agriculture durable au Maroc, in Actes du Symposium International AGDUMED-durabilité des systèmes de culture en zone méditerranéenne et gestion des ressources en eau et en sol; 2009. p. 14–6.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Maataoui BS, Hilali S. Composition physico-chimique de jus de deux types de fruits de Figureuier de Barbarie (Opuntia ficus indica) cultivés au Maroc. Rev Biol Biotechnol. 2004;3(2):8–13.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Dehbi F, Hasib A, Ouatmane A, Elbatal H, Jaouad A. Physicochemical characteristics of Moroccan prickly pear juice (Opuntia ficus indica L.). Int J Emerg Technol Adv Eng. 2014;4(4):300–6.Search in Google Scholar

[14] El-Samahy SK, Abd El-Hady EA, Habiba RA, Moussa TE. Chemical and rheological characteristics of orange-yellow cactus pear pulp from Egypt. J Prof Assoc Cactus Dev. 2006;8:39–51.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Bouzoubaâ Z, Essoukrati Y, Tahrouch S, Hatimi A, Gharby S, Harhar H. Etude physico-chimique de deux variétés de Figureuier de barbarie (‘Achefri’et’Amouslem’) du Sud marocain. Technol. Lab. 2014;8:34.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Maataoui BS, Hilali S. Composition physico-chimique de jus de deux types de fruits de Figureuier de Barbarie (Opuntia ficus indica) cultivés au Maroc. Rev Biol Biotechnol. 2004;3(2):8–13.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Mondragon Jacobo C. Cactus pear domestication and breeding. Plant Breed Rev. 2000;20:135–66.10.1002/9780470650189.ch5Search in Google Scholar

[18] Inglese P, Barbera G, La Mantia T, Portolano S. Crop production, growth, and ultimate size of cactus pear fruit following fruit thinning. HortScience. 1995;30(2):227–30.10.21273/HORTSCI.30.2.227Search in Google Scholar

[19] El-Gharras H, Hasib A, Jaouad A, El-Bouadili A. Chemical and physical characterization of three cultivars of moroccan yellow prickly pears (Opuntia ficus-indica) at three stages of maturity. Caracterización química y física de tres variedades de higos chumbos amarillas de marruecos (Opuntia ficus-indica) en tres etapas de madurez. Ciencia y Tecnologia Alimentaria. 2006;5(2):93–9. 10.1080/11358120609487677.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Hazbavi I, Khoshtaghaza MH, Mostaan A, Banakar A. Effect of postharvest hot-water and heat treatment. J Saudi Soc Agric Sci. 2013;4(no. Q1):5.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Ribéreau-Gayon P, Glories Y, Maujean A, Dubourdieu D. The chemistry of wine-stabilization and treatments. handbook of enology. vol. 2. Bordeaux, France: John Wiley & Sons; 2006.10.1002/0470010398Search in Google Scholar

[22] Sedki M, Taoufiq A, Haddouche M, El Mousadik A, Barkaoui M, El Mzouri E. Biophysical and biochemical characterization of cactus pear fruit (Opuntia spp.) cultivars originating from South-West Morocco, in VII International Congress on Cactus Pear and Cocshineal 995; 2010. p. 83–91.10.17660/ActaHortic.2013.995.10Search in Google Scholar

[23] Cheong MW, Liu SQ, Zhou W, Curran P, Yu B. Chemical composition and sensory profile of pomelo (Citrus grandis (L.) Osbeck) juice. Food Chem. 2012 Dec;135(4):2505–13.10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.07.012Search in Google Scholar

[24] Esteve MJ, Frígola A, Rodrigo C, Rodrigo D. Effect of storage period under variable conditions on the chemical and physical composition and colour of Spanish refrigerated orange juices. Food Chem Toxicol. 2005 Sep;43(9):1413–22.10.1016/j.fct.2005.03.016Search in Google Scholar

[25] Ribéreau-Gayon P, Glories Y, Maujean A, Dubourdieu D. The Chemistry of Wine-Stabilization and Treatments. Handbook of Enology. vol. 2. Bordeaux, France: John Wiley & Sons; 2006.10.1002/0470010398Search in Google Scholar

[26] Bendhifi M, Trifi M, Souid S, Zourgui L. Chemical characterization of Opuntia spp. fruits in Tunisia, in VII International Congress on Cactus Pear and Cochineal 995; 2010, p. 279–83.10.17660/ActaHortic.2013.995.34Search in Google Scholar

[27] Gautier H. Enrichissement des fruits charnus en caroténoïdes: exemple de la tomate et des agrumes. Innov Agron. 2014;42:77–89.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Forni E, Polesello A, Montefiori D, Maestrelli A. High-performance liquid chromatographic analysis of the pigments of blood-red prickly pear (Opuntia ficus indica). J Chromatogr A. 1992;593(1–2):177–83, 10.1016/0021-9673(92)80284-2.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Bouzoubaâ Z, Essoukrati Y, Tahrouch S, Hatimi A, Gharby S, Harhar H. Etude physico-chimique de deux variétés de Figureuier de barbarie (‘Achefri’et’Amouslem’) du Sud marocain. Technol Lab. 2014;8:34.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Cayupán YS, Ochoa MJ, Nazareno MA. Health-promoting substances and antioxidant properties of Opuntia sp. fruits. Changes in bioactive-compound contents during ripening process. Food Chem. 2011;126(2):514–9.10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.11.033Search in Google Scholar

[31] Stintzing FC, Herbach KM, Mosshammer MR, Carle R, Yi W, Sellappan S, et al. Color, betalain pattern, and antioxidant properties of cactus pear (Opuntia spp.) clones. J Agric Food Chem. 2005 Jan;53(2):442–51.10.1021/jf048751ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Delgado-Vargas F, Paredes-Lopez O. Natural colorants for food and nutraceutical uses. Boca Raton, US: CRC Press; 2002, 10.1201/9781420031713Search in Google Scholar

[33] D’Archivio M, Filesi C, Di Benedetto R, Gargiulo R, Giovannini C, Masella R. Polyphenols, dietary sources and bioavailability. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2007;43(4):348–61.Search in Google Scholar

© 2020 Mohammed Bourhia et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Electrochemical antioxidant screening and evaluation based on guanine and chitosan immobilized MoS2 nanosheet modified glassy carbon electrode (guanine/CS/MoS2/GCE)

- Kinetic models of the extraction of vanillic acid from pumpkin seeds

- On the maximum ABC index of bipartite graphs without pendent vertices

- Estimation of the total antioxidant potential in the meat samples using thin-layer chromatography

- Molecular dynamics simulation of sI methane hydrate under compression and tension

- Spatial distribution and potential ecological risk assessment of some trace elements in sediments and grey mangrove (Avicennia marina) along the Arabian Gulf coast, Saudi Arabia

- Amino-functionalized graphene oxide for Cr(VI), Cu(II), Pb(II) and Cd(II) removal from industrial wastewater

- Chemical composition and in vitro activity of Origanum vulgare L., Satureja hortensis L., Thymus serpyllum L. and Thymus vulgaris L. essential oils towards oral isolates of Candida albicans and Candida glabrata

- Effect of excess Fluoride consumption on Urine-Serum Fluorides, Dental state and Thyroid Hormones among children in “Talab Sarai” Punjab Pakistan

- Design, Synthesis and Characterization of Novel Isoxazole Tagged Indole Hybrid Compounds

- Comparison of kinetic and enzymatic properties of intracellular phosphoserine aminotransferases from alkaliphilic and neutralophilic bacteria

- Green Organic Solvent-Free Oxidation of Alkylarenes with tert-Butyl Hydroperoxide Catalyzed by Water-Soluble Copper Complex

- Ducrosia ismaelis Asch. essential oil: chemical composition profile and anticancer, antimicrobial and antioxidant potential assessment

- DFT calculations as an efficient tool for prediction of Raman and infra-red spectra and activities of newly synthesized cathinones

- Influence of Chemical Osmosis on Solute Transport and Fluid Velocity in Clay Soils

- A New fatty acid and some triterpenoids from propolis of Nkambe (North-West Region, Cameroon) and evaluation of the antiradical scavenging activity of their extracts

- Antiplasmodial Activity of Stigmastane Steroids from Dryobalanops oblongifolia Stem Bark

- Rapid identification of direct-acting pancreatic protectants from Cyclocarya paliurus leaves tea by the method of serum pharmacochemistry combined with target cell extraction

- Immobilization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa static biomass on eggshell powder for on-line preconcentration and determination of Cr (VI)

- Assessment of methyl 2-({[(4,6-dimethoxypyrimidin-2-yl)carbamoyl] sulfamoyl}methyl)benzoate through biotic and abiotic degradation modes

- Stability of natural polyphenol fisetin in eye drops Stability of fisetin in eye drops

- Production of a bioflocculant by using activated sludge and its application in Pb(II) removal from aqueous solution

- Molecular Properties of Carbon Crystal Cubic Structures

- Synthesis and characterization of calcium carbonate whisker from yellow phosphorus slag

- Study on the interaction between catechin and cholesterol by the density functional theory

- Analysis of some pharmaceuticals in the presence of their synthetic impurities by applying hybrid micelle liquid chromatography

- Two mixed-ligand coordination polymers based on 2,5-thiophenedicarboxylic acid and flexible N-donor ligands: the protective effect on periodontitis via reducing the release of IL-1β and TNF-α

- Incorporation of silver stearate nanoparticles in methacrylate polymeric monoliths for hemeprotein isolation

- Development of ultrasound-assisted dispersive solid-phase microextraction based on mesoporous carbon coated with silica@iron oxide nanocomposite for preconcentration of Te and Tl in natural water systems

- N,N′-Bis[2-hydroxynaphthylidene]/[2-methoxybenzylidene]amino]oxamides and their divalent manganese complexes: Isolation, spectral characterization, morphology, antibacterial and cytotoxicity against leukemia cells

- Determination of the content of selected trace elements in Polish commercial fruit juices and health risk assessment

- Diorganotin(iv) benzyldithiocarbamate complexes: synthesis, characterization, and thermal and cytotoxicity study

- Keratin 17 is induced in prurigo nodularis lesions

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and acute toxicity studies of a Saudi polyherbal formulation, PHF5

- LaCoO3 perovskite-type catalysts in syngas conversion

- Comparative studies of two vegetal extracts from Stokesia laevis and Geranium pratense: polyphenol profile, cytotoxic effect and antiproliferative activity

- Fragmentation pattern of certain isatin–indole antiproliferative conjugates with application to identify their in vitro metabolic profiles in rat liver microsomes by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry

- Investigation of polyphenol profile, antioxidant activity and hepatoprotective potential of Aconogonon alpinum (All.) Schur roots

- Lead discovery of a guanidinyl tryptophan derivative on amyloid cascade inhibition

- Physicochemical evaluation of the fruit pulp of Opuntia spp growing in the Mediterranean area under hard climate conditions

- Electronic structural properties of amino/hydroxyl functionalized imidazolium-based bromide ionic liquids

- New Schiff bases of 2-(quinolin-8-yloxy)acetohydrazide and their Cu(ii), and Zn(ii) metal complexes: their in vitro antimicrobial potentials and in silico physicochemical and pharmacokinetics properties

- Treatment of adhesions after Achilles tendon injury using focused ultrasound with targeted bFGF plasmid-loaded cationic microbubbles

- Synthesis of orotic acid derivatives and their effects on stem cell proliferation

- Chirality of β2-agonists. An overview of pharmacological activity, stereoselective analysis, and synthesis

- Fe3O4@urea/HITh-SO3H as an efficient and reusable catalyst for the solvent-free synthesis of 7-aryl-8H-benzo[h]indeno[1,2-b]quinoline-8-one and indeno[2′,1′:5,6]pyrido[2,3-d]pyrimidine derivatives

- Adsorption kinetic characteristics of molybdenum in yellow-brown soil in response to pH and phosphate

- Enhancement of thermal properties of bio-based microcapsules intended for textile applications

- Exploring the effect of khat (Catha edulis) chewing on the pharmacokinetics of the antiplatelet drug clopidogrel in rats using the newly developed LC-MS/MS technique

- A green strategy for obtaining anthraquinones from Rheum tanguticum by subcritical water

- Cadmium (Cd) chloride affects the nutrient uptake and Cd-resistant bacterium reduces the adsorption of Cd in muskmelon plants

- Removal of H2S by vermicompost biofilter and analysis on bacterial community

- Structural cytotoxicity relationship of 2-phenoxy(thiomethyl)pyridotriazolopyrimidines: Quantum chemical calculations and statistical analysis

- A self-breaking supramolecular plugging system as lost circulation material in oilfield

- Synthesis, characterization, and pharmacological evaluation of thiourea derivatives

- Application of drug–metal ion interaction principle in conductometric determination of imatinib, sorafenib, gefitinib and bosutinib

- Synthesis and characterization of a novel chitosan-grafted-polyorthoethylaniline biocomposite and utilization for dye removal from water

- Optimisation of urine sample preparation for shotgun proteomics

- DFT investigations on arylsulphonyl pyrazole derivatives as potential ligands of selected kinases

- Treatment of Parkinson’s disease using focused ultrasound with GDNF retrovirus-loaded microbubbles to open the blood–brain barrier

- New derivatives of a natural nordentatin

- Fluorescence biomarkers of malignant melanoma detectable in urine

- Study of the remediation effects of passivation materials on Pb-contaminated soil

- Saliva proteomic analysis reveals possible biomarkers of renal cell carcinoma

- Withania frutescens: Chemical characterization, analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and healing activities

- Design, synthesis and pharmacological profile of (−)-verbenone hydrazones

- Synthesis of magnesium carbonate hydrate from natural talc

- Stability-indicating HPLC-DAD assay for simultaneous quantification of hydrocortisone 21 acetate, dexamethasone, and fluocinolone acetonide in cosmetics

- A novel lactose biosensor based on electrochemically synthesized 3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene/thiophene (EDOT/Th) copolymer

- Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad: Chemical characterization, scavenging and cytotoxic activities

- Development and validation of a high performance liquid chromatography/diode array detection method for estrogen determination: Application to residual analysis in meat products

- PCSK9 concentrations in different stages of subclinical atherosclerosis and their relationship with inflammation

- Development of trace analysis for alkyl methanesulfonates in the delgocitinib drug substance using GC-FID and liquid–liquid extraction with ionic liquid

- Electrochemical evaluation of the antioxidant capacity of natural compounds on glassy carbon electrode modified with guanine-, polythionine-, and nitrogen-doped graphene

- A Dy(iii)–organic framework as a fluorescent probe for highly selective detection of picric acid and treatment activity on human lung cancer cells

- A Zn(ii)–organic cage with semirigid ligand for solvent-free cyanosilylation and inhibitory effect on ovarian cancer cell migration and invasion ability via regulating mi-RNA16 expression

- Polyphenol content and antioxidant activities of Prunus padus L. and Prunus serotina L. leaves: Electrochemical and spectrophotometric approach and their antimicrobial properties

- The combined use of GC, PDSC and FT-IR techniques to characterize fat extracted from commercial complete dry pet food for adult cats

- MALDI-TOF MS profiling in the discovery and identification of salivary proteomic patterns of temporomandibular joint disorders

- Concentrations of dioxins, furans and dioxin-like PCBs in natural animal feed additives

- Structure and some physicochemical and functional properties of water treated under ammonia with low-temperature low-pressure glow plasma of low frequency

- Mesoscale nanoparticles encapsulated with emodin for targeting antifibrosis in animal models

- Amine-functionalized magnetic activated carbon as an adsorbent for preconcentration and determination of acidic drugs in environmental water samples using HPLC-DAD

- Antioxidant activity as a response to cadmium pollution in three durum wheat genotypes differing in salt-tolerance

- A promising naphthoquinone [8-hydroxy-2-(2-thienylcarbonyl)naphtho[2,3-b]thiophene-4,9-dione] exerts anti-colorectal cancer activity through ferroptosis and inhibition of MAPK signaling pathway based on RNA sequencing

- Synthesis and efficacy of herbicidal ionic liquids with chlorsulfuron as the anion

- Effect of isovalent substitution on the crystal structure and properties of two-slab indates BaLa2−xSmxIn2O7

- Synthesis, spectral and thermo-kinetics explorations of Schiff-base derived metal complexes

- An improved reduction method for phase stability testing in the single-phase region

- Comparative analysis of chemical composition of some commercially important fishes with an emphasis on various Malaysian diets

- Development of a solventless stir bar sorptive extraction/thermal desorption large volume injection capillary gas chromatographic-mass spectrometric method for ultra-trace determination of pyrethroids pesticides in river and tap water samples

- A turbidity sensor development based on NL-PI observers: Experimental application to the control of a Sinaloa’s River Spirulina maxima cultivation

- Deep desulfurization of sintering flue gas in iron and steel works based on low-temperature oxidation

- Investigations of metallic elements and phenolics in Chinese medicinal plants

- Influence of site-classification approach on geochemical background values

- Effects of ageing on the surface characteristics and Cu(ii) adsorption behaviour of rice husk biochar in soil

- Adsorption and sugarcane-bagasse-derived activated carbon-based mitigation of 1-[2-(2-chloroethoxy)phenyl]sulfonyl-3-(4-methoxy-6-methyl-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl) urea-contaminated soils

- Antimicrobial and antifungal activities of bifunctional cooper(ii) complexes with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, flufenamic, mefenamic and tolfenamic acids and 1,10-phenanthroline

- Application of selenium and silicon to alleviate short-term drought stress in French marigold (Tagetes patula L.) as a model plant species

- Screening and analysis of xanthine oxidase inhibitors in jute leaves and their protective effects against hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress in cells

- Synthesis and physicochemical studies of a series of mixed-ligand transition metal complexes and their molecular docking investigations against Coronavirus main protease

- A study of in vitro metabolism and cytotoxicity of mephedrone and methoxetamine in human and pig liver models using GC/MS and LC/MS analyses

- A new phenyl alkyl ester and a new combretin triterpene derivative from Combretum fragrans F. Hoffm (Combretaceae) and antiproliferative activity

- Erratum

- Erratum to: A one-step incubation ELISA kit for rapid determination of dibutyl phthalate in water, beverage and liquor

- Review Articles

- Sinoporphyrin sodium, a novel sensitizer for photodynamic and sonodynamic therapy

- Natural products isolated from Casimiroa

- Plant description, phytochemical constituents and bioactivities of Syzygium genus: A review

- Evaluation of elastomeric heat shielding materials as insulators for solid propellant rocket motors: A short review

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2019

- An overview of Monascus fermentation processes for monacolin K production

- Study on online soft sensor method of total sugar content in chlorotetracycline fermentation tank

- Studies on the Anti-Gouty Arthritis and Anti-hyperuricemia Properties of Astilbin in Animal Models

- Effects of organic fertilizer on water use, photosynthetic characteristics, and fruit quality of pear jujube in northern Shaanxi

- Characteristics of the root exudate release system of typical plants in plateau lakeside wetland under phosphorus stress conditions

- Characterization of soil water by the means of hydrogen and oxygen isotope ratio at dry-wet season under different soil layers in the dry-hot valley of Jinsha River

- Composition and diurnal variation of floral scent emission in Rosa rugosa Thunb. and Tulipa gesneriana L.

- Preparation of a novel ginkgolide B niosomal composite drug

- The degradation, biodegradability and toxicity evaluation of sulfamethazine antibiotics by gamma radiation

- Special issue on Monitoring, Risk Assessment and Sustainable Management for the Exposure to Environmental Toxins

- Insight into the cadmium and zinc binding potential of humic acids derived from composts by EEM spectra combined with PARAFAC analysis

- Source apportionment of soil contamination based on multivariate receptor and robust geostatistics in a typical rural–urban area, Wuhan city, middle China

- Special Issue on 13th JCC 2018

- The Role of H2C2O4 and Na2CO3 as Precipitating Agents on The Physichochemical Properties and Photocatalytic Activity of Bismuth Oxide

- Preparation of magnetite-silica–cetyltrimethylammonium for phenol removal based on adsolubilization

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- Size-dependent growth kinetics of struvite crystals in wastewater with calcium ions

- The effect of silica-calcite sedimentary rock contained in the chicken broiler diet on the overall quality of chicken muscles

- Physicochemical properties of selected herbicidal products containing nicosulfuron as an active ingredient

- Lycopene in tomatoes and tomato products

- Fluorescence in the assessment of the share of a key component in the mixing of feed

- Sulfur application alleviates chromium stress in maize and wheat

- Effectiveness of removal of sulphur compounds from the air after 3 years of biofiltration with a mixture of compost soil, peat, coconut fibre and oak bark

- Special Issue on the 4th Green Chemistry 2018

- Study and fire test of banana fibre reinforced composites with flame retardance properties

- Special Issue on the International conference CosCI 2018

- Disintegration, In vitro Dissolution, and Drug Release Kinetics Profiles of k-Carrageenan-based Nutraceutical Hard-shell Capsules Containing Salicylamide

- Synthesis of amorphous aluminosilicate from impure Indonesian kaolin

- Special Issue on the International Conf on Science, Applied Science, Teaching and Education 2019

- Functionalization of Congo red dye as a light harvester on solar cell

- The effect of nitrite food preservatives added to se’i meat on the expression of wild-type p53 protein

- Biocompatibility and osteoconductivity of scaffold porous composite collagen–hydroxyapatite based coral for bone regeneration

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2019)

- Effect of natural boron mineral use on the essential oil ratio and components of Musk Sage (Salvia sclarea L.)

- A theoretical and experimental study of the adsorptive removal of hexavalent chromium ions using graphene oxide as an adsorbent

- A study on the bacterial adhesion of Streptococcus mutans in various dental ceramics: In vitro study

- Corrosion study of copper in aqueous sulfuric acid solution in the presence of (2E,5E)-2,5-dibenzylidenecyclopentanone and (2E,5E)-bis[(4-dimethylamino)benzylidene]cyclopentanone: Experimental and theoretical study

- Special Issue on Chemistry Today for Tomorrow 2019

- Diabetes mellitus type 2: Exploratory data analysis based on clinical reading

- Multivariate analysis for the classification of copper–lead and copper–zinc glasses

- Special Issue on Advances in Chemistry and Polymers

- The spatial and temporal distribution of cationic and anionic radicals in early embryo implantation

- Special Issue on 3rd IC3PE 2020

- Magnetic iron oxide/clay nanocomposites for adsorption and catalytic oxidation in water treatment applications

- Special Issue on IC3PE 2018/2019 Conference

- Exergy analysis of conventional and hydrothermal liquefaction–esterification processes of microalgae for biodiesel production

- Advancing biodiesel production from microalgae Spirulina sp. by a simultaneous extraction–transesterification process using palm oil as a co-solvent of methanol

- Topical Issue on Applications of Mathematics in Chemistry

- Omega and the related counting polynomials of some chemical structures

- M-polynomial and topological indices of zigzag edge coronoid fused by starphene

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Electrochemical antioxidant screening and evaluation based on guanine and chitosan immobilized MoS2 nanosheet modified glassy carbon electrode (guanine/CS/MoS2/GCE)

- Kinetic models of the extraction of vanillic acid from pumpkin seeds

- On the maximum ABC index of bipartite graphs without pendent vertices

- Estimation of the total antioxidant potential in the meat samples using thin-layer chromatography

- Molecular dynamics simulation of sI methane hydrate under compression and tension

- Spatial distribution and potential ecological risk assessment of some trace elements in sediments and grey mangrove (Avicennia marina) along the Arabian Gulf coast, Saudi Arabia

- Amino-functionalized graphene oxide for Cr(VI), Cu(II), Pb(II) and Cd(II) removal from industrial wastewater

- Chemical composition and in vitro activity of Origanum vulgare L., Satureja hortensis L., Thymus serpyllum L. and Thymus vulgaris L. essential oils towards oral isolates of Candida albicans and Candida glabrata

- Effect of excess Fluoride consumption on Urine-Serum Fluorides, Dental state and Thyroid Hormones among children in “Talab Sarai” Punjab Pakistan

- Design, Synthesis and Characterization of Novel Isoxazole Tagged Indole Hybrid Compounds

- Comparison of kinetic and enzymatic properties of intracellular phosphoserine aminotransferases from alkaliphilic and neutralophilic bacteria

- Green Organic Solvent-Free Oxidation of Alkylarenes with tert-Butyl Hydroperoxide Catalyzed by Water-Soluble Copper Complex

- Ducrosia ismaelis Asch. essential oil: chemical composition profile and anticancer, antimicrobial and antioxidant potential assessment

- DFT calculations as an efficient tool for prediction of Raman and infra-red spectra and activities of newly synthesized cathinones

- Influence of Chemical Osmosis on Solute Transport and Fluid Velocity in Clay Soils

- A New fatty acid and some triterpenoids from propolis of Nkambe (North-West Region, Cameroon) and evaluation of the antiradical scavenging activity of their extracts

- Antiplasmodial Activity of Stigmastane Steroids from Dryobalanops oblongifolia Stem Bark

- Rapid identification of direct-acting pancreatic protectants from Cyclocarya paliurus leaves tea by the method of serum pharmacochemistry combined with target cell extraction

- Immobilization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa static biomass on eggshell powder for on-line preconcentration and determination of Cr (VI)

- Assessment of methyl 2-({[(4,6-dimethoxypyrimidin-2-yl)carbamoyl] sulfamoyl}methyl)benzoate through biotic and abiotic degradation modes

- Stability of natural polyphenol fisetin in eye drops Stability of fisetin in eye drops

- Production of a bioflocculant by using activated sludge and its application in Pb(II) removal from aqueous solution

- Molecular Properties of Carbon Crystal Cubic Structures

- Synthesis and characterization of calcium carbonate whisker from yellow phosphorus slag

- Study on the interaction between catechin and cholesterol by the density functional theory

- Analysis of some pharmaceuticals in the presence of their synthetic impurities by applying hybrid micelle liquid chromatography

- Two mixed-ligand coordination polymers based on 2,5-thiophenedicarboxylic acid and flexible N-donor ligands: the protective effect on periodontitis via reducing the release of IL-1β and TNF-α

- Incorporation of silver stearate nanoparticles in methacrylate polymeric monoliths for hemeprotein isolation

- Development of ultrasound-assisted dispersive solid-phase microextraction based on mesoporous carbon coated with silica@iron oxide nanocomposite for preconcentration of Te and Tl in natural water systems

- N,N′-Bis[2-hydroxynaphthylidene]/[2-methoxybenzylidene]amino]oxamides and their divalent manganese complexes: Isolation, spectral characterization, morphology, antibacterial and cytotoxicity against leukemia cells

- Determination of the content of selected trace elements in Polish commercial fruit juices and health risk assessment

- Diorganotin(iv) benzyldithiocarbamate complexes: synthesis, characterization, and thermal and cytotoxicity study

- Keratin 17 is induced in prurigo nodularis lesions

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and acute toxicity studies of a Saudi polyherbal formulation, PHF5

- LaCoO3 perovskite-type catalysts in syngas conversion

- Comparative studies of two vegetal extracts from Stokesia laevis and Geranium pratense: polyphenol profile, cytotoxic effect and antiproliferative activity

- Fragmentation pattern of certain isatin–indole antiproliferative conjugates with application to identify their in vitro metabolic profiles in rat liver microsomes by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry

- Investigation of polyphenol profile, antioxidant activity and hepatoprotective potential of Aconogonon alpinum (All.) Schur roots

- Lead discovery of a guanidinyl tryptophan derivative on amyloid cascade inhibition

- Physicochemical evaluation of the fruit pulp of Opuntia spp growing in the Mediterranean area under hard climate conditions

- Electronic structural properties of amino/hydroxyl functionalized imidazolium-based bromide ionic liquids

- New Schiff bases of 2-(quinolin-8-yloxy)acetohydrazide and their Cu(ii), and Zn(ii) metal complexes: their in vitro antimicrobial potentials and in silico physicochemical and pharmacokinetics properties

- Treatment of adhesions after Achilles tendon injury using focused ultrasound with targeted bFGF plasmid-loaded cationic microbubbles

- Synthesis of orotic acid derivatives and their effects on stem cell proliferation

- Chirality of β2-agonists. An overview of pharmacological activity, stereoselective analysis, and synthesis

- Fe3O4@urea/HITh-SO3H as an efficient and reusable catalyst for the solvent-free synthesis of 7-aryl-8H-benzo[h]indeno[1,2-b]quinoline-8-one and indeno[2′,1′:5,6]pyrido[2,3-d]pyrimidine derivatives

- Adsorption kinetic characteristics of molybdenum in yellow-brown soil in response to pH and phosphate

- Enhancement of thermal properties of bio-based microcapsules intended for textile applications

- Exploring the effect of khat (Catha edulis) chewing on the pharmacokinetics of the antiplatelet drug clopidogrel in rats using the newly developed LC-MS/MS technique

- A green strategy for obtaining anthraquinones from Rheum tanguticum by subcritical water

- Cadmium (Cd) chloride affects the nutrient uptake and Cd-resistant bacterium reduces the adsorption of Cd in muskmelon plants

- Removal of H2S by vermicompost biofilter and analysis on bacterial community

- Structural cytotoxicity relationship of 2-phenoxy(thiomethyl)pyridotriazolopyrimidines: Quantum chemical calculations and statistical analysis

- A self-breaking supramolecular plugging system as lost circulation material in oilfield

- Synthesis, characterization, and pharmacological evaluation of thiourea derivatives

- Application of drug–metal ion interaction principle in conductometric determination of imatinib, sorafenib, gefitinib and bosutinib

- Synthesis and characterization of a novel chitosan-grafted-polyorthoethylaniline biocomposite and utilization for dye removal from water

- Optimisation of urine sample preparation for shotgun proteomics

- DFT investigations on arylsulphonyl pyrazole derivatives as potential ligands of selected kinases

- Treatment of Parkinson’s disease using focused ultrasound with GDNF retrovirus-loaded microbubbles to open the blood–brain barrier

- New derivatives of a natural nordentatin

- Fluorescence biomarkers of malignant melanoma detectable in urine

- Study of the remediation effects of passivation materials on Pb-contaminated soil

- Saliva proteomic analysis reveals possible biomarkers of renal cell carcinoma

- Withania frutescens: Chemical characterization, analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and healing activities

- Design, synthesis and pharmacological profile of (−)-verbenone hydrazones

- Synthesis of magnesium carbonate hydrate from natural talc

- Stability-indicating HPLC-DAD assay for simultaneous quantification of hydrocortisone 21 acetate, dexamethasone, and fluocinolone acetonide in cosmetics

- A novel lactose biosensor based on electrochemically synthesized 3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene/thiophene (EDOT/Th) copolymer

- Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad: Chemical characterization, scavenging and cytotoxic activities

- Development and validation of a high performance liquid chromatography/diode array detection method for estrogen determination: Application to residual analysis in meat products

- PCSK9 concentrations in different stages of subclinical atherosclerosis and their relationship with inflammation

- Development of trace analysis for alkyl methanesulfonates in the delgocitinib drug substance using GC-FID and liquid–liquid extraction with ionic liquid

- Electrochemical evaluation of the antioxidant capacity of natural compounds on glassy carbon electrode modified with guanine-, polythionine-, and nitrogen-doped graphene

- A Dy(iii)–organic framework as a fluorescent probe for highly selective detection of picric acid and treatment activity on human lung cancer cells

- A Zn(ii)–organic cage with semirigid ligand for solvent-free cyanosilylation and inhibitory effect on ovarian cancer cell migration and invasion ability via regulating mi-RNA16 expression

- Polyphenol content and antioxidant activities of Prunus padus L. and Prunus serotina L. leaves: Electrochemical and spectrophotometric approach and their antimicrobial properties

- The combined use of GC, PDSC and FT-IR techniques to characterize fat extracted from commercial complete dry pet food for adult cats

- MALDI-TOF MS profiling in the discovery and identification of salivary proteomic patterns of temporomandibular joint disorders

- Concentrations of dioxins, furans and dioxin-like PCBs in natural animal feed additives

- Structure and some physicochemical and functional properties of water treated under ammonia with low-temperature low-pressure glow plasma of low frequency

- Mesoscale nanoparticles encapsulated with emodin for targeting antifibrosis in animal models

- Amine-functionalized magnetic activated carbon as an adsorbent for preconcentration and determination of acidic drugs in environmental water samples using HPLC-DAD

- Antioxidant activity as a response to cadmium pollution in three durum wheat genotypes differing in salt-tolerance

- A promising naphthoquinone [8-hydroxy-2-(2-thienylcarbonyl)naphtho[2,3-b]thiophene-4,9-dione] exerts anti-colorectal cancer activity through ferroptosis and inhibition of MAPK signaling pathway based on RNA sequencing

- Synthesis and efficacy of herbicidal ionic liquids with chlorsulfuron as the anion

- Effect of isovalent substitution on the crystal structure and properties of two-slab indates BaLa2−xSmxIn2O7

- Synthesis, spectral and thermo-kinetics explorations of Schiff-base derived metal complexes

- An improved reduction method for phase stability testing in the single-phase region

- Comparative analysis of chemical composition of some commercially important fishes with an emphasis on various Malaysian diets

- Development of a solventless stir bar sorptive extraction/thermal desorption large volume injection capillary gas chromatographic-mass spectrometric method for ultra-trace determination of pyrethroids pesticides in river and tap water samples

- A turbidity sensor development based on NL-PI observers: Experimental application to the control of a Sinaloa’s River Spirulina maxima cultivation

- Deep desulfurization of sintering flue gas in iron and steel works based on low-temperature oxidation

- Investigations of metallic elements and phenolics in Chinese medicinal plants

- Influence of site-classification approach on geochemical background values

- Effects of ageing on the surface characteristics and Cu(ii) adsorption behaviour of rice husk biochar in soil

- Adsorption and sugarcane-bagasse-derived activated carbon-based mitigation of 1-[2-(2-chloroethoxy)phenyl]sulfonyl-3-(4-methoxy-6-methyl-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl) urea-contaminated soils

- Antimicrobial and antifungal activities of bifunctional cooper(ii) complexes with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, flufenamic, mefenamic and tolfenamic acids and 1,10-phenanthroline

- Application of selenium and silicon to alleviate short-term drought stress in French marigold (Tagetes patula L.) as a model plant species

- Screening and analysis of xanthine oxidase inhibitors in jute leaves and their protective effects against hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress in cells

- Synthesis and physicochemical studies of a series of mixed-ligand transition metal complexes and their molecular docking investigations against Coronavirus main protease

- A study of in vitro metabolism and cytotoxicity of mephedrone and methoxetamine in human and pig liver models using GC/MS and LC/MS analyses

- A new phenyl alkyl ester and a new combretin triterpene derivative from Combretum fragrans F. Hoffm (Combretaceae) and antiproliferative activity

- Erratum

- Erratum to: A one-step incubation ELISA kit for rapid determination of dibutyl phthalate in water, beverage and liquor

- Review Articles

- Sinoporphyrin sodium, a novel sensitizer for photodynamic and sonodynamic therapy

- Natural products isolated from Casimiroa

- Plant description, phytochemical constituents and bioactivities of Syzygium genus: A review

- Evaluation of elastomeric heat shielding materials as insulators for solid propellant rocket motors: A short review

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2019

- An overview of Monascus fermentation processes for monacolin K production

- Study on online soft sensor method of total sugar content in chlorotetracycline fermentation tank

- Studies on the Anti-Gouty Arthritis and Anti-hyperuricemia Properties of Astilbin in Animal Models

- Effects of organic fertilizer on water use, photosynthetic characteristics, and fruit quality of pear jujube in northern Shaanxi

- Characteristics of the root exudate release system of typical plants in plateau lakeside wetland under phosphorus stress conditions

- Characterization of soil water by the means of hydrogen and oxygen isotope ratio at dry-wet season under different soil layers in the dry-hot valley of Jinsha River

- Composition and diurnal variation of floral scent emission in Rosa rugosa Thunb. and Tulipa gesneriana L.

- Preparation of a novel ginkgolide B niosomal composite drug

- The degradation, biodegradability and toxicity evaluation of sulfamethazine antibiotics by gamma radiation

- Special issue on Monitoring, Risk Assessment and Sustainable Management for the Exposure to Environmental Toxins

- Insight into the cadmium and zinc binding potential of humic acids derived from composts by EEM spectra combined with PARAFAC analysis

- Source apportionment of soil contamination based on multivariate receptor and robust geostatistics in a typical rural–urban area, Wuhan city, middle China

- Special Issue on 13th JCC 2018

- The Role of H2C2O4 and Na2CO3 as Precipitating Agents on The Physichochemical Properties and Photocatalytic Activity of Bismuth Oxide

- Preparation of magnetite-silica–cetyltrimethylammonium for phenol removal based on adsolubilization

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- Size-dependent growth kinetics of struvite crystals in wastewater with calcium ions

- The effect of silica-calcite sedimentary rock contained in the chicken broiler diet on the overall quality of chicken muscles

- Physicochemical properties of selected herbicidal products containing nicosulfuron as an active ingredient

- Lycopene in tomatoes and tomato products

- Fluorescence in the assessment of the share of a key component in the mixing of feed

- Sulfur application alleviates chromium stress in maize and wheat

- Effectiveness of removal of sulphur compounds from the air after 3 years of biofiltration with a mixture of compost soil, peat, coconut fibre and oak bark

- Special Issue on the 4th Green Chemistry 2018

- Study and fire test of banana fibre reinforced composites with flame retardance properties

- Special Issue on the International conference CosCI 2018

- Disintegration, In vitro Dissolution, and Drug Release Kinetics Profiles of k-Carrageenan-based Nutraceutical Hard-shell Capsules Containing Salicylamide

- Synthesis of amorphous aluminosilicate from impure Indonesian kaolin

- Special Issue on the International Conf on Science, Applied Science, Teaching and Education 2019

- Functionalization of Congo red dye as a light harvester on solar cell

- The effect of nitrite food preservatives added to se’i meat on the expression of wild-type p53 protein

- Biocompatibility and osteoconductivity of scaffold porous composite collagen–hydroxyapatite based coral for bone regeneration

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2019)

- Effect of natural boron mineral use on the essential oil ratio and components of Musk Sage (Salvia sclarea L.)

- A theoretical and experimental study of the adsorptive removal of hexavalent chromium ions using graphene oxide as an adsorbent

- A study on the bacterial adhesion of Streptococcus mutans in various dental ceramics: In vitro study

- Corrosion study of copper in aqueous sulfuric acid solution in the presence of (2E,5E)-2,5-dibenzylidenecyclopentanone and (2E,5E)-bis[(4-dimethylamino)benzylidene]cyclopentanone: Experimental and theoretical study

- Special Issue on Chemistry Today for Tomorrow 2019

- Diabetes mellitus type 2: Exploratory data analysis based on clinical reading

- Multivariate analysis for the classification of copper–lead and copper–zinc glasses

- Special Issue on Advances in Chemistry and Polymers

- The spatial and temporal distribution of cationic and anionic radicals in early embryo implantation

- Special Issue on 3rd IC3PE 2020

- Magnetic iron oxide/clay nanocomposites for adsorption and catalytic oxidation in water treatment applications

- Special Issue on IC3PE 2018/2019 Conference

- Exergy analysis of conventional and hydrothermal liquefaction–esterification processes of microalgae for biodiesel production

- Advancing biodiesel production from microalgae Spirulina sp. by a simultaneous extraction–transesterification process using palm oil as a co-solvent of methanol

- Topical Issue on Applications of Mathematics in Chemistry

- Omega and the related counting polynomials of some chemical structures

- M-polynomial and topological indices of zigzag edge coronoid fused by starphene