Abstract

Previously, a series of pyridotriazolopyrimidines (1–6) were synthesized and fully described. The target compounds (1–6) were evaluated for their cytotoxicity against MCF-7, HepG2, WRL 68, and A549 (breast adenocarcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, embryonic liver, and pulmonary adenocarcinoma, respectively) cell lines using MTT assay. The tested compounds demonstrated cytotoxicity, but no significant activity. To elucidate the structure–cytotoxicity relation of the prepared pyridotriazolopyrimidines, several chemical descriptors were determined, including electronic, steric, and hydrophobic descriptors. These chemical descriptors were calculated in the polarizable continuum model (water as solvent) using density functional theory calculations at B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p). By employing simple linear regression (SLR) and multiple linear regression (MLR) analyses, the impact of the selected descriptors was assessed statistically. The obtained results clearly reveal that the cytotoxicity of pyridotriazolopyrimidines depends on their (i) basic skeleton and (ii) the type of the tested cell. Interestingly, SLR and MLR analyses show that the impact of the selected descriptors is strongly related to the tested cells and basic skeleton of the tested compounds. For instance, the cytotoxicity of subclasses 2a and 2c–2f against A459 shows strong correlation with ionization potential, hardness (η), and hydrophobicity (log P) with a correlation coefficient of 99.86% and a standard deviation of 0.53.

1 Introduction

Cancer is a complex ailment and remains a major health concern despite intensive efforts to elucidate its biology and develop more efficacious antitumor agents. Notably, resistance often develops in patients treated with anticancer agents, resulting in disease progression and poor prognosis. Hence, several chemotherapeutic compounds, approved as adjuvant therapy for several types of cancers, have demonstrated inadequate response rates, approximately between 30% and 70%. Furthermore, resistance can occur as a consequence of decreased drug activity even prior to drug exposure (primary) or during/after the treatment course (acquired). The ever-growing resistance to anticancer agents is a leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide. Therefore, the discovery of new antitumor agents with minor side effects is a crucial task and a highly pursued aim in contemporary pharmaceutical chemistry [1,2,3,4,5].

Heterocyclic compounds including nucleic acids, novel substances, the plurality of medicine, and synthetic/natural dyes are extensively present in nature. Investigators have attempted to generate diverse heterocyclic structures bearing triazole, quinazoline, benzoquinazoline, pyridine, and pyrimidine moieties presenting numerous biological purposes, which remains an ongoing scientific challenge. The pyridine and pyrimidine platforms are used as precursors in agrochemicals and pharmaceuticals and occur in many bioactive important products such as niacin (antipellagra), isoniazid (antituberculosis), thiamine (vitamin B1), barbiturates (central nervous system depressant), zidovudine (antiretroviral medication), and antiviral and anticancer medications. In contrast, 1,2,4-triazoles are associated with various pharmacological activities, and a large number of predominant triazole drugs have been successfully developed and prevalently used in the treatment of various microbial infections such as fluconazole, posaconazole, and itraconazole (antifungal). Combining these three structure features in one molecule (pyridotriazolopyrimidine) has showed significant pharmacological efficiency as fungicidal, herbicidal, antidiabetic, and antioxidant agents [6,7,8,9,10,11].

Quantum chemical methods are considered efficient tools to determine molecular electronic properties of intermediate systems, correlating them with their biological activities. Several methods have been applied to explain the relation between the cytotoxicity of active compounds and their chemical descriptors [12,13,14]. For instance, a PM5 semi-empirical method was reported by Ishihara et al., who proved that the correlation is relatively good for tropolone compounds with a basic skeleton of similar dipole moment (µ), hydrophobicity (log P), hardness (η), electrophilicity (ω), and electronegativity (χ) [15]. Furthermore, the cell line type and the parent skeleton of the evaluated compounds (natural or synthesized) play a crucial role in the cytotoxicity profile. Density functional theory (DFT) methods along with statistical analyses is employed to rationalize and confirm the relationship between the cytotoxicity and their correlated structures. Further studies on 4-hydroxycoumarin and ganoderic acid compounds have been reported by Stanchev et al. and Yang et al., revealing that cytotoxicity correlated with log P, µ, volume (V), and the molecular orbital energies (EHOMO and ELUMO) [16,17] for 4-hydroxycoumarin compounds; HOMO energy, χ, electronic energy, log P, and molecular area (A) are dependable variables to distinguish between higher and lower active ganoderic acid compounds [15].

The cytotoxicity of the targets (1–6) was evaluated against four cancer cell lines, namely A549, HepG2, and MCF7 carcinoma cells and WRL 68 cells. Herein, we report the structure–cytotoxicity relationship of 2-phenoxy(thiomethyl)pyridotriazolopyrimidines (1–6). We employed the polarizable continuum model (PCM) at the B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) level of theory to calculate the electronic and steric molecular descriptors of the target pyridotriazolopyrimidines and utilized simple linear regression (SLR) and multiple linear regression (MLR) analyses to determine the correlation between the cytotoxicity of pyridotriazolopyrimidines and the calculated descriptors.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Cell culture and cytotoxicity assay

The cell lines, HepG2, A549, MCF-7, and WRL 68, were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Rockville, MD, USA). The cells were cultured in two types of media: minimum essential medium and Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 medium, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% (v/v) l-glutamine. The cells were incubated in a CO2 incubator at 37°C, in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 and were subcultured once a week using trypsin/ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (0.25%/0.02%, v/v) for cell detachment from the flasks. Cells at 60–80% confluency were later used for a 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay.

A cell viability test was conducted using the MTT assay [18]. Briefly, 2 × 104 cells/well were seeded in a 96-well plate and incubated with 5% CO2. After 12 h, the cells were treated with 200 µg/mL for 24 h. Next, 20 µL of the MTT solution was added to each well and incubated for another 4 h. The medium was discarded, and the crystalline deposits in the cells were dissolved in 100 µL of dimethyl sulfoxide. The absorbance of the colored formazan crystals was measured at 520 nm using a microplate reader (Tecan, Austria), and the results were presented as mean values ± standard deviation (SD; n = 3).

2.2 DFT calculations

By employing the exchange–correlation hybrid functional B3LYP combined with 6-31+G(d,p) double-ζ Pople-type basis, the geometry optimization and frequency calculations of pyridotriazolopyrimidine derivatives were performed, with polarized and diffuse functions taken into consideration [19]. The absence of imaginary frequencies confirms that the optimized structures are true minima. The choice of B3LYP was based on previous studies [20,21,22]. The solvent effects were taken into account implicitly by using the PCM, in which, the solute is embedded into a cavity surrounded by solvent described by its dielectric constant [23].

The chemical descriptors selected to correlate with cytotoxicity were as follows: (i) electronic descriptors: frontier molecular orbital energies (EHOMO and ELUMO, which are well accepted as molecular descriptors in medicinal chemistry as they are linked to the capacity of a molecule to form a charge-transfer complex with its biological receptor), hardness (η), electrophilicity index (ω), electronic affinity (EA), softness (S), ionization potential (IP), electronegativity (χ), dipole moment (μ), and molecular polarizability (α); (ii) steric descriptors: surface area of the molecule (A), volume (V), and its molecular weight (M); and (iii) hydrophobicity descriptor: log P, where P denotes the octanol–water partition coefficient. The calculations of log P were performed using the Hyperchem Molecular package by means of the atomic parameters derived by Ghose, Pritchett, and Crippen and later extended by Ghose and co-workers. The other descriptors may be obtained at the DFT level of theory [24] by considering: (i) orbital consideration, which is based on Koopman’s theorem where IP = −EHOMO and EA = −ELUMO [25]; (ii) energy consideration, which is based on the use of the classical finite difference approximation, IP = E+1 − E0 and EA = E0 − E−1 where E0, E−1, and E+1 are the electronic energies of neutral molecule, when adding and removing an electron to the neutral molecule, respectively [24]; and (iii) internally resolved hardness tensor approach [26,27,28]. Previously, we have reported the structure cytotoxicity activity relationship of 2-thiophen-naphtho (benzo)oxazinone derivatives [29] and compounds isolated from Curcuma zedoaria [22] by considering orbital and energy methods in calculating electronic and molecular properties, and the results displayed that both methods give similar results. In another study, De Luca et al. tested the three methods to evaluate the solvent effects on the hardness values of a series of neutral and charged molecules, and they concluded that three methods give similar results in the presence of solvent [30]. Herein, to minimize computational cost of theoretical calculations, we have used the first approach in calculating other chemical descriptors. The Gaussian 16 package was used to perform all DFT calculations [31].

2.3 Statistical analyses

SLR and MLR analyses were performed to determine the regression equations, correlation coefficients R2, adjusted R2, and SDs between the calculated descriptors and cytotoxicity of the target compounds. The regression curves and statistical parameters are obtained using the DataLab package (http://www.lohninger.com/datalab/en_home.html).

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Cytotoxicity evaluation

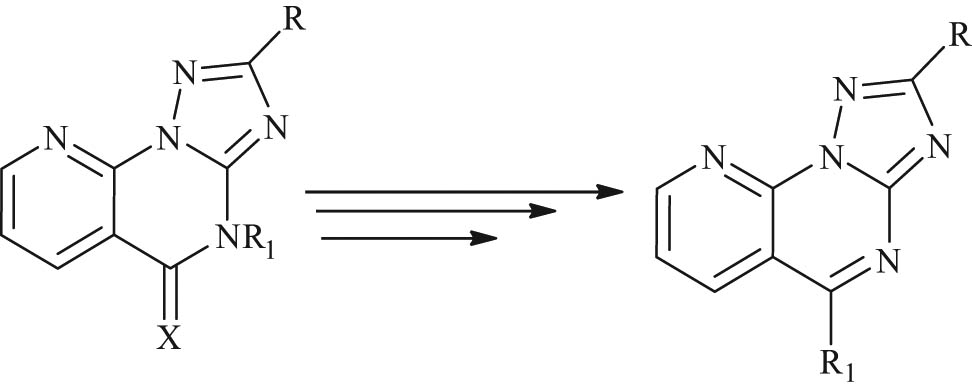

The synthetic methodology for target pyridotriazolopyrimidines (Table 1 and Scheme 1) has been previously described [10,11]. As illustrated in Table 2, the in vitro cytotoxicity of pyridotriazolopyrimidines was evaluated against A549, HepG2, MCF-7, and WRL 68 cells using the MTT assay. The percentages of cell viability at 200 µg/mL are presented in Table 2 as the cytotoxicity parameter of the tested pyridotriazolopyrimidines. A considerable cytotoxicity was demonstrated by compounds 1a, 1b, 2a, 2c, 2e, 2d, 2f, 2i, 2m, 4, 5a, 5b, and 6c against A549 cells (inhibition% of 33.44–55.87), whereas the significant cytotoxicity against MCF-7 cells (30.75–56.70%) was reported by 2c, 2f, 2m, 4, and 5b. In comparison to the aforementioned results, compounds (2b, 2d, 2h, 2j, 2k) and (2b, 2h, 3a, 5a) demonstrated moderate effects against A549 and HepG2, respectively. In contrast, 1a–b, 2a, 3a, and 6b–d exhibited moderate effects against MCF-7 cells. The other target compounds failed to demonstrate a significant activity against A549, HepG2, and MCF-7 cell lines. In regard to WRL 68 cells, only 2m appeared to demonstrate a remarkable activity (19.34%), although 1a, 1b, 2e, 2g, 2k, and 5b showed viability percentages between 10.23 and 12.94%. Based on the findings presented in Table 2, the type of substituent attached to the 2, 4, and 5 positions of the pyridotriazolopyrimidine skeleton can be considered a major determinant for the cytotoxic properties. In the case of the target 2m, the cytotoxicity increased in the order of MCF-7 > A549 > HepG2 > WRL 68, with 2m emerging as the most active compound in this series. This could be attributed to the conformation of the heteroalkyl (propyl isoindole) and thiomethyl groups, which might have played a pivotal role in the cytotoxicity profile. The aliphatic C-chain in 2b, the aromatic(hetero) group in 2c and 2f, along with the chloro group in 5a and 5b could be responsible factors for their slightly improved cytotoxicity profile against A549, Hep-G2, and MCF-7 cells compared to that of their parents 1a and 1b.

The synthesized pyridotriazolopyrimidines (1–6)

| CPs | R | X | R1 | CPs | X | R | R1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | Oph | O | H | 2k | O | SCH3 | 3-Methylbenzyl |

| 1b | SCH3 | O | H | 2l | O | SCH3 | 4-Chlorobenzyl |

| 2a | Oph | O | Benzyl | 2m | O | SCH3 | Propyl isoindole |

| 2b | Oph | O | Ethyl | 3a | S | Oph | H |

| 2c | Oph | O | p-NO2-benzyl | 3b | S | SCH3 | H |

| 2d | Oph | O | Piperidinoethyl | 4 | — | SCH3 | S-Ethyl |

| 2e | Oph | O | Morpholinoethyl | 5a | — | Oph | Cl |

| 2f | Oph | O | Propyl isoindole | 5b | — | SCH3 | Cl |

| 2g | SCH3 | O | Ethyl | 6a | — | Oph | p-Methyl aniline |

| 2h | SCH3 | O | Allyl | 6b | — | Oph | p-Ethoxy-aniline |

| 2i | SCH3 | O | Benzyl | 6c | — | Oph | Isoniazid |

| 2j | SCH3 | O | 2-Methylbenzyl | 6d | — | Oph | NH-OH |

The synthetic route of the target pyridotriazolopyrimidines (1–6).

Maximal percentage of cell viability at 200 µg/mL of samples against A549, HepG2, MCF-7, and WRL68 cell lines

| CPs | Maximal inhibition (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A549 | HepG2 | MCF7 | WRL68 | |

| 1a | 42.64 ± 2.18 | 46.12 ± 16.45 | 26.75 ± 0.50 | 11.15 ± 2.75 |

| 1b | 49.72 ± 8.28 | 36.22 ± 1.92 | 24.44 ± 0.66 | 10.48 ± 0.52 |

| 2a | 39.19 ± 4.37 | 39.76 ± 8.46 | 25.98 ± 2.30 | 4.50 ± 2.12 |

| 2b | 25.00 ± 3.28 | 22.71 ± 2.25 | 3.94 ± 0.55 | 5.44 ± 1.71 |

| 2c | 40.61 ± 8.85 | 38.15 ± 8.64 | 38.01 ± 0.64 | 6.26 ± 1.83 |

| 2d | 24.03 ± 3.10 | 34.61 ± 10.56 | 16.92 ± 1.07 | 5.87 ± 1.91 |

| 2e | 34.27 ± 3.13 | 35.83 ± 3.37 | 12.61 ± 3.36 | 12.94 ± 0.78 |

| 2f | 41.13 ± 3.70 | 43.76 ± 5.51 | 35.71 ± 3.58 | 8.11 ± 2.20 |

| 2g | 16.50 ± 2.23 | 10.45 ± 11.66 | 7.59 ± 9.37 | 10.78 ± 1.40 |

| 2h | 27.60 ± 1.96 | 27.60 ± 1.96 | 2.11 ± 1.67 | 5.67 ± 1.89 |

| 2i | 33.60 ± 2.83 | 12.72 ± 2.02 | 1.27 ± 0.67 | 5.07 ± 3.78 |

| 2j | 26.96 ± 4.46 | 16.77 ± 5.76 | 2.92 ± 2.04 | 8.62 ± 0.25 |

| 2k | 26.53 ± 1.39 | 9.80 ± 3.16 | 1.43 ± 5.28 | 10.23 ± 4.62 |

| 2l | 19.56 ± 4.96 | 17.66 ± 9.27 | 5.99 ± 2.20 | 7.92 ± 0.60 |

| 2m | 55.87 ± 1.41 | 40.75 ± 13.12 | 56.70 ± 0.43 | 19.34 ± 1.53 |

| 3a | 23.78 ± 1.76 | 30.26 ± 5.40 | 23.94 ± 0.38 | 1.07 ± 0.89 |

| 3b | 15.50 ± 6.66 | 15.50 ± 6.66 | 4.83 ± 2.35 | 6.65 ± 2.20 |

| 4 | 41.05 ± 1.98 | 13.73 ± 0.75 | 30.75 ± 0.66 | 8.40 ± 0.36 |

| 5a | 33.44 ± 1.73 | 29.31 ± 4.94 | 10.50 ± 0.58 | 6.70 ± 1.29 |

| 5b | 39.71 ± 1.07 | 14.69 ± 1.61 | 35.34 ± 1.02 | 11.05 ± 2.47 |

| 6a | 20.54 ± 2.51 | 13.51 ± 7.53 | 14.15 ± 0.81 | 3.39 ± 1.43 |

| 6b | 7.33 ± 11.74 | 5.94 ± 7.79 | 21.92 ± 1.25 | 5.73 ± 1.29 |

| 6c | 34.53 ± 1.91 | 47.37 ± 7.76 | 20.15 ± 5.26 | 3.58 ± 3.44 |

| 6d | 3.79 ± 8.89 | 3.72 ± 15.13 | 25.95 ± 2.93 | 7.12 ± 2.15 |

3.2 Structure–property relationships

3.2.1 SLR analysis

For the synthesized compounds, SLR analysis was performed to investigate the strength of each descriptor on the cytotoxic activity against the tested cells (Table 3). The statistical parameters R2,

Maximal percentage of cell viability at 200 µg/mL of samples against A549, HepG2, MCF-7, and WRL68 cell lines and molecular descriptors calculated at B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) of the synthesized compounds

| CPs | IP | EA | χ | η | ω | a | µ | A | V | log P | M | Maximal inhibitions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A459 | HepG2 | MCF-7 | WRL76 | ||||||||||||

| 1a | 6.42 | 2.31 | 4.37 | 4.11 | 2.32 | 287.43 | 2.51 | 321.98 | 346.56 | 2.73 | 279.08 | 42.64 | 46.12 | 26.75 | 11.15 |

| 1b | 6.38 | 2.30 | 4.34 | 4.08 | 2.31 | 230.63 | 2.32 | 266.82 | 281.63 | 1.03 | 233.04 | 49.72 | 36.22 | 24.44 | 10.48 |

| 2a | 6.61 | 2.24 | 4.43 | 4.37 | 2.24 | 314.88 | 2.92 | 367.65 | 399.76 | 2.96 | 307.11 | 39.19 | 39.76 | 25.98 | 4.50 |

| 2c | 6.68 | 3.13 | 4.91 | 3.55 | 3.40 | 421.72 | 6.54 | 465.27 | 514.86 | 4.42 | 414.11 | 40.61 | 38.15 | 38.01 | 6.26 |

| 2d | 6.18 | 2.26 | 4.22 | 3.92 | 2.27 | 403.76 | 2.99 | 474.87 | 524.07 | 3.32 | 390.18 | 24.03 | 34.61 | 16.92 | 5.87 |

| 2e | 6.36 | 2.27 | 4.31 | 4.10 | 2.27 | 392.61 | 2.70 | 464.35 | 511.75 | 2.26 | 392.16 | 34.27 | 35.83 | 12.61 | 12.94 |

| 2f | 6.64 | 2.67 | 4.66 | 3.97 | 2.73 | 474.49 | 5.48 | 534.19 | 591.29 | 3.49 | 466.14 | 41.13 | 43.76 | 35.71 | 8.11 |

| 2g | 6.32 | 2.23 | 4.27 | 4.10 | 2.23 | 263.17 | 2.95 | 310.79 | 333.02 | 1.62 | 261.07 | 16.50 | 10.45 | 7.59 | 10.78 |

| 2h | 6.34 | 2.24 | 4.29 | 4.10 | 2.25 | 280.63 | 2.80 | 328.23 | 351.03 | 2.01 | 273.07 | 27.60 | 27.60 | 2.11 | 5.67 |

| 2i | 6.34 | 2.27 | 4.31 | 4.08 | 2.28 | 340.50 | 2.76 | 376.76 | 413.54 | 3.06 | 323.08 | 33.60 | 12.72 | 1.27 | 5.07 |

| 2j | 6.36 | 2.28 | 4.32 | 4.08 | 2.28 | 357.05 | 2.99 | 397.87 | 439.05 | 3.53 | 337.10 | 26.96 | 16.77 | 2.92 | 8.62 |

| 2k | 6.34 | 2.27 | 4.30 | 4.08 | 2.27 | 358.06 | 2.87 | 400.71 | 439.62 | 3.53 | 337.10 | 26.53 | 9.80 | 1.43 | 10.23 |

| 2l | 6.35 | 2.27 | 4.31 | 4.07 | 2.28 | 358.19 | 3.24 | 392.34 | 433.26 | 3.58 | 357.05 | 19.56 | 17.66 | 5.99 | 7.92 |

| 2m | 6.34 | 2.67 | 4.51 | 3.66 | 2.77 | 423.26 | 5.04 | 476.67 | 526.30 | 2.15 | 420.10 | 33.44 | 29.31 | 10.5 | 6.70 |

| 3a | 6.36 | 2.84 | 4.60 | 3.52 | 3.01 | 338.38 | 1.43 | 334.00 | 361.86 | 3.49 | 295.05 | 23.78 | 30.26 | 23.94 | 1.07 |

| 3b | 6.32 | 2.83 | 4.57 | 3.49 | 2.99 | 282.12 | 1.00 | 280.20 | 297.81 | 2.16 | 249.01 | 15.50 | 15.50 | 4.83 | 6.65 |

| 4 | 6.29 | 2.58 | 4.44 | 3.72 | 2.65 | 306.36 | 7.62 | 326.56 | 348.95 | 2.79 | 277.05 | 41.05 | 13.73 | 30.75 | 8.40 |

| 5a | 6.98 | 2.87 | 4.92 | 4.10 | 2.96 | 303.60 | 6.20 | 332.41 | 357.86 | 3.88 | 297.04 | 55.87 | 40.75 | 56.7 | 19.34 |

| 5b | 6.52 | 2.85 | 4.69 | 3.67 | 3.00 | 255.22 | 6.20 | 276.04 | 292.66 | 2.55 | 251.00 | 39.71 | 14.69 | 35.34 | 11.05 |

| 6a | 6.24 | 2.42 | 4.33 | 3.81 | 2.46 | 425.36 | 11.41 | 444.11 | 486.86 | 5.41 | 368.14 | 20.54 | 13.51 | 14.15 | 3.39 |

| 6b | 5.79 | 2.36 | 4.07 | 3.43 | 2.42 | 465.10 | 9.75 | 479.77 | 525.56 | 5.04 | 398.15 | 7.33 | 5.94 | 21.92 | 5.73 |

| 6c | 6.57 | 2.44 | 4.50 | 4.13 | 2.46 | 424.93 | 11.02 | 465.21 | 508.89 | 4.41 | 397.13 | 34.53 | 47.37 | 20.15 | 3.58 |

| 6d | 6.55 | 2.50 | 4.53 | 4.05 | 2.53 | 309.73 | 9.71 | 342.18 | 368.04 | 3.36 | 294.09 | 3.79 | 3.72 | 25.95 | 7.12 |

Correlation coefficients (R2), adjusted correlation coefficients

| Descriptors/SLR on cells | A459 | HepG2 | MCF-7 | WRL68 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %R2 | SD | %R2 | SD | %R2 | SD | %R2 | SD | |||||

| IP | 37.57 | 34.59 | 10.50 | 31.05 | 27.76 | 12.12 | 31.64 | 34.74 | 11.81 | 16.64 | 12.67 | 3.58 |

| EA | 6.33 | 1.87 | 12.86 | 2.63 | −2.00 | 14.4 | 36.83 | 33.83 | 11.62 | 0.26 | −4.99 | 3.92 |

| χ | 23.48 | 19.83 | 11.62 | 15.84 | 11.83 | 13.39 | 48.90 | 46.47 | 10.45 | 6.15 | 1.68 | 3.80 |

| η | 7.06 | 2.63 | 12.81 | 9.66 | 5.36 | 13.87 | 1.57 | −3.11 | 14.51 | 8.90 | 4.56 | 3.75 |

| S | 7.38 | 2.97 | 12.79 | 9.40 | 5.09 | 13.89 | 1.63 | −3.05 | 14.51 | 9.61 | 5.30 | 3.73 |

| ω | 4.92 | 0.4 | 12.96 | 1.98 | −2.69 | 14.45 | 32.90 | 29.70 | 11.98 | 0.02 | −4.74 | 3.92 |

| α | 3.10 | −1.52 | 13.08 | 1.38 | −3.31 | 14.45 | 0.00 | −4.76 | 14.63 | 12.56 | 8.40 | 3.69 |

| DM | 2.26 | −2.39 | 13.14 | 3.05 | −1.57 | 14.37 | 13.24 | 9.11 | 13.62 | 2.28 | −2.37 | 3.88 |

| A | 0.97 | −3.75 | 13.23 | 4.43 | −0.12 | 14.27 | 0.10 | −4.66 | 14.62 | 7.14 | 2.72 | 3.78 |

| V | 0.95 | −3.77 | 13.23 | 4.37 | −0.18 | 14.27 | 0.16 | −4.59 | 14.61 | 7.10 | 2.67 | 3.78 |

| log P | 4.82 | 0.28 | 12.97 | 0.81 | −3.91 | 14.53 | 4.91 | 0.39 | 14.62 | 9.07 | 4.74 | 3.74 |

| M | 0.24 | −4.51 | 13.27 | 6.07 | 1.59 | 14.15 | 0.05 | −4.71 | 14.62 | 5.55 | 1.05 | 3.81 |

Correlation coefficients (R2), adjusted correlation coefficients

| Descriptors/SLR on cells | A459 | HepG2 | MCF-7 | WRL68 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %R2 | SD | %R2 | SD | %R2 | SD | %R2 | SD | |||||

| IP | 58.92 | 54.82 | 5.42 | 31.96 | 25.15 | 10.66 | 64.21 | 60.64 | 8.24 | 4.22 | −5.35 | 2.63 |

| EA | 36.11 | 29.73 | 6.77 | 23.61 | 15.97 | 11.30 | 51.52 | 46.67 | 9.60 | 3.68 | −5.95 | 2.63 |

| χ | 51.77 | 46.95 | 5.88 | 31.41 | 24.55 | 10.70 | 66.41 | 63.05 | 7.99 | 4.60 | −4.94 | 2.62 |

| η | 5.67 | −3.77 | 8.22 | 5.38 | −4.09 | 12.57 | 13.44 | 4.78 | 12.82 | 1.08 | −8.81 | 2.67 |

| S | 7.40 | −1.86 | 8.15 | 6.62 | −2.71 | 12.49 | 15.91 | 7.50 | 12.64 | 1.72 | −8.11 | 2.66 |

| ω | 34.24 | 27.67 | 6.86 | 22.25 | 14.48 | 11.40 | 50.13 | 45.15 | 9.73 | 3.84 | −5.77 | 2.63 |

| α | 31.24 | 24.36 | 7.02 | 32.53 | 25.78 | 10.62 | 34.36 | 27.80 | 11.16 | 0.04 | −9.96 | 2.68 |

| DM | 32.94 | 26.23 | 6.93 | 26.44 | 19.08 | 11.08 | 55.85 | 51.43 | 9.16 | 3.63 | −6.01 | 2.64 |

| A | 30.65 | 23.72 | 7.05 | 41.20 | 35.32 | 9.91 | 36.42 | 30.06 | 10.99 | 0.36 | −9.60 | 2.68 |

| V | 30.08 | 23.09 | 7.08 | 39.48 | 33.42 | 10.05 | 35.55 | 29.11 | 11.06 | 0.36 | −6.60 | 2.68 |

| log P | 10.74 | 1.81 | 8.00 | 2.87 | −6.48 | 12.74 | 19.06 | 10.97 | 12.40 | 6.23 | −3.15 | 2.60 |

| M | 30.50 | 23.55 | 7.06 | 36.95 | 30.64 | 10.26 | 37.51 | 31.27 | 10.89 | 0.20 | −9.78 | 2.68 |

Correlation coefficients (R2), adjusted correlation coefficients

| Descriptors/SLR on cells | A459 | HepG2 | MCF-7 | WRL68 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %R2 | SD | %R2 | SD | %R2 | SD | %R2 | SD | |||||

| IP | 94.22 | 92.22 | 1.98 | 61.63 | 48.84 | 2.57 | 73.38 | 64.51 | 6.66 | 6.02 | −25.31 | 3.68 |

| EA | 32.04 | 9.39 | 7.00 | 12.01 | −17.33 | 3.89 | 70.44 | 60.59 | 7.02 | 2.43 | −30.09 | 3.74 |

| χ | 60.19 | 46.92 | 5.20 | 30.20 | 6.93 | 3.46 | 85.12 | 80.15 | 4.98 | 4.20 | −27.73 | 3.71 |

| η | 0.10 | −33.20 | 8.24 | 1.44 | −31.41 | 4.12 | 22.33 | −3.56 | 11.38 | 0.06 | −33.25 | 3.79 |

| S | 0.50 | −32.66 | 8.22 | 1.26 | −31.65 | 4.12 | 25.29 | 0.39 | 11.16 | 0.40 | −32.81 | 3.78 |

| ω | 29.54 | 6.05 | 6.92 | 8.90 | −21.47 | 3.96 | 67.10 | 56.14 | 7.41 | 2.76 | −29.65 | 3.74 |

| α | 1.19 | −31.75 | 8.19 | 11.62 | −17.84 | 3.90 | 16.60 | −11.20 | 11.79 | 8.98 | −21.36 | 3.62 |

| DM | 36.16 | 14.87 | 6.59 | 26.19 | 1.58 | 3.56 | 82.29 | 76.39 | 5.43 | 3.69 | −28.42 | 3.72 |

| A | 0.19 | −33.08 | 8.24 | 5.59 | −25.88 | 4.03 | 4.92 | −26.77 | 12.59 | 16.09 | −11.88 | 3.47 |

| V | 0.19 | −33.08 | 8.24 | 5.26 | −26.32 | 4.04 | 5.13 | −26.50 | 12.58 | 15.93 | −12.09 | 3.48 |

| log P | 8.60 | −21.86 | 7.88 | 6.34 | −24.75 | 4.01 | 67.78 | 57.04 | 7.33 | 32.88 | 10.51 | 3.10 |

| M | 2.05 | −30.61 | 8.16 | 11.75 | −17.67 | 3.90 | 15.26 | −12.98 | 11.88 | 13.39 | −15.47 | 3.53 |

Correlation coefficients (R2), adjusted correlation coefficients

| Descriptors/SLR on cells | A459 | HepG2 | MCF-7 | WRL68 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %R2 | SD | %R2 | SD | %R2 | SD | %R2 | SD | |||||

| IP | 16.79 | 0.15 | 6.42 | 1.93 | −17.69 | 8.56 | 19.63 | 3.56 | 3.49 | 10.66 | −7.21 | 2.26 |

| EA | 28.51 | 14.22 | 5.95 | 40.60 | 28.37 | 6.66 | 48.51 | 38.21 | 2.79 | 6.76 | −11.89 | 2.31 |

| X | 31.28 | 17.53 | 5.84 | 41.61 | 29.94 | 6.60 | 44.51 | 33.41 | 2.90 | 7.86 | −10.56 | 2.30 |

| H | 25.66 | 10.79 | 6.07 | 39.28 | 27.14 | 6.73 | 52.26 | 42.71 | 2.69 | 5.69 | −13.17 | 2.32 |

| S | 25.48 | 10.58 | 6.08 | 39.54 | 27.45 | 6.72 | 52.52 | 43.02 | 2.68 | 5.67 | −13.20 | 2.32 |

| Ω | 27.93 | 135.51 | 5.98 | 40.75 | 28.89 | 6.65 | 49.35 | 39.22 | 2.77 | 6.58 | −12.10 | 2.31 |

| a | 31.72 | 18.07 | 5.82 | 9.27 | −8.87 | 8.23 | 9.18 | −8.98 | 3.71 | 3.70 | −15.56 | 2.35 |

| DM | 13.32 | −4.01 | 6.56 | 39.83 | 27.80 | 6.70 | 65.61 | 58.73 | 2.28 | 2.60 | −16.88 | 2.36 |

| A | 33.50 | 20.20 | 5.74 | 13.57 | −3.72 | 8.03 | 13.55 | −3.73 | 3.62 | 3.26 | −16.09 | 2.35 |

| V | 32.26 | 17.72 | 5.79 | 11.81 | −5.83 | 8.11 | 12.59 | −4.90 | 3.64 | 3.05 | −16.34 | 2.36 |

| log P | 0.98 | −18.82 | 7.00 | 13.62 | −3.66 | 8.03 | 24.03 | 8.83 | 3.39 | 0.35 | −19.58 | 2.39 |

| M | 24.62 | 9.55 | 6.11 | 14.31 | −2.82 | 8.00 | 18.89 | 2.67 | 3.51 | 3.91 | −15.31 | 2.35 |

For each cancer cell line, the impact of each descriptor on the cytotoxic activity of the tested derivatives was mainly reliant on the nature of the descriptor itself. For A459 cells, the descriptors AE, χ, ω, α, μ, V, log P, and M demonstrated no significant influence (R2 ≈ 0–3%), while modest correlations were obtained with η and S (R2 ≈ 25%). In the case of HepG2 cells, the best correlation was recorded for IP, with an R2 of 27%, and an SD of 0.34; the lowest correlation was observed with surface area (A), with an R2 of 0.22% and an SD of 0.5. The η and S demonstrated similar effects to those observed with the A459 cell line. However, for MCF-7 cells, the best correlations were obtained with the hardness η and S descriptors, with an R2 of 61 and 62%, respectively. In contrast to HepG2 cells, the IP descriptor demonstrated negligible influence on the cytotoxic activity of the tested derivatives against MCF-7 cells, with an R2 and an SD of 61% and 0.54, respectively. Thus, SLR demonstrated that the cytotoxicity moderately correlated with M of the tested derivatives, with an R2 of 22%. However, for A459 and HepG2 cells, SLR displayed extremely weak effects for M, with R2 less than 2%.

3.2.2 MLR analysis

As shown in the SLR analysis, the influence of each descriptor on the cytotoxicity of the synthesized compounds against the tested cells strongly depended on the basic skeleton of these compounds. In an attempt to improve the correlations between the cytotoxicity of each of these series and their descriptors, MLR analysis was performed for each series considering all tested cell lines.

3.2.2.1 Considering all compounds

Equations (1)–(4) show the reliable descriptors dependent on the observed cytotoxic activities against the tested cell lines for all compounds (Table 8). The correlations are relatively moderate for A459, HepG2, and MCF-7 cells, with correlation coefficients of 41, 64, and 58%, respectively. However, for WRL 68 cells, the correlation was relatively weak, with a correlation coefficient of 26%. For A459, HepG2, and WRL 68 cells, IP demonstrated the strongest contribution in equations (1), (2) and (4) with regression coefficients of 35.42, 44.69, and 6.37, respectively. This may indicate that these compounds provide an electron to the targeted enzyme of the tested cells. In addition to the strongest contribution of IP in these models (1–2 and 4), some other descriptors show moderate contribution hydrophobicity. For instance, hydrophobicity (log P) has a negative contribution in models 1 and 4 with regression coefficients of 2.37 and 0.009, while it has a positive contribution for model 2 (a regression coefficient of 1.69). However, for MCF-7 cells, the electronegativity reported the strongest contribution with a regression coefficient of 44.27, which may indicate that the compounds accept electrons from the targeted enzyme in MCF-7 cells (equation (3)). The moderate and weak correlations may be attributed to the basic skeleton of the synthesized compounds. Table 8 displays the predicted cytotoxic activities and residuals of the observed values. The best reproduction of the observed cytotoxicity values for A459, HepG2, MCF-7, and WRL 68 cells was obtained for compounds 2k, 4, 5b, and 2f, with residual values of 0.76, 0.02, 0.97, and 0.04, respectively (Table 8).

Predicted percentage inhibition and residuals obtained by using MLR equations (1)–(4) and considering all compounds

| CPs | A459 (equation (1)) | HepG2 (equation (2)) | MCF-7 (equation (3)) | WRL68 (equation (4)) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ln P)Pred. | Resid. | (ln P)Pred. | Resid. | (ln P)Pred. | Resid. | (ln P)Pred. | Resid. | |

| 1a | 32.09 | 10.55 | 27.31 | 18.69 | 13.90 | 12.85 | 8.80 | 2.35 |

| 1b | 34.51 | 15.21 | 20.93 | 15.07 | 13.67 | 10.77 | 10.09 | 0.39 |

| 2a | 38.27 | 0.92 | 38.30 | 1.7 | 16.58 | 9.40 | 9.62 | 5.12 |

| 2c | 37.20 | 3.41 | 34.69 | 3.31 | 40.73 | 2.72 | 8.18 | 1.92 |

| 2d | 21.91 | 2.12 | 29.21 | 5.79 | 5.18 | 11.74 | 5.82 | 0.05 |

| 2e | 31.00 | 3.27 | 36.10 | 0.1 | 9.27 | 3.34 | 7.77 | 5.17 |

| 2f | 38.05 | 3.08 | 52.50 | 8.5 | 26.82 | 8.89 | 8.07 | 0.04 |

| 2g | 31.16 | 14.66 | 20.19 | 10.19 | 11.02 | 3.43 | 9.07 | 1.71 |

| 2h | 30.85 | 3.25 | 30.78 | 2.78 | 11.17 | 9.06 | 8.78 | 3.11 |

| 2i | 28.48 | 5.12 | 17.61 | 4.61 | 10.30 | 9.03 | 7.61 | 2.54 |

| 2j | 27.82 | 0.86 | 16.92 | 0.08 | 10.70 | 7.78 | 7.25 | 1.37 |

| 2k | 27.29 | 0.76 | 25.54 | 15.54 | 9.96 | 8.53 | 7.14 | 3.09 |

| 2l | 27.32 | 7.76 | 13.17 | 4.83 | 10.75 | 4.76 | 7.14 | 0.78 |

| 2m | 30.47 | 2.97 | 27.30 | 1.7 | 20.66 | 10.16 | 7.43 | 0.73 |

| 3a | 28.11 | 4.33 | 26.30 | 3.7 | 21.41 | 2.53 | 7.47 | 6.40 |

| 3b | 29.76 | 14.26 | 23.84 | 7.84 | 20.81 | 15.98 | 8.54 | 1.89 |

| 4 | 27.34 | 13.71 | 14.02 | 0.02 | 24.20 | 6.55 | 7.76 | 0.64 |

| 5a | 48.92 | 6.95 | 44.98 | 3.98 | 43.75 | 12.95 | 11.44 | 7.90 |

| 5b | 35.90 | 3.81 | 16.54 | 1.54 | 34.37 | 0.97 | 9.80 | 1.25 |

| 6a | 19.07 | 1.47 | 9.04 | 4.96 | 22.39 | 8.24 | 4.68 | 1.29 |

| 6b | 4.00 | 3.33 | 5.63 | 4.63 | 7.53 | 14.39 | 1.70 | 4.03 |

| 6c | 33.15 | 1.38 | 33.13 | 13.87 | 29.49 | 9.34 | 7.43 | 3.85 |

| 6d | 35.19 | 31.4 | 17.96 | 13.96 | 31.33 | 5.39 | 9.03 | 1.91 |

3.2.2.2 Considering compounds 2a and 2c–2m

Equations (5)–(8) and Table 9 represent the best correlations between the observed cytotoxic activities of the subclass of compounds (2a and 2c–2m) against the tested cell lines. The improved correlations were observed compared to the ones obtained considering all compounds (equations (5)–(8)). Indeed, for A459, HepG2, MCF-7, and WRL 68 cells, the obtained correlation coefficients were 77, 83, 98, and 79%. In accordance with correlations obtained considering all compounds, the observed activities against A459 and HepG2 cells were strongly dependent on IP with regression coefficients of 41.51 and 46.74, respectively (equations (5) and (6)). For MCF-7 cells (equation (7)), the observed activities were strongly related to the electronegativity and EA of the tested compounds with a positive contribution of the former (a regression coefficient of 78.60) and a negative contribution of the latter (a regression coefficient of 74.58). In this model (equation (7)), dipole moment and hydrophobicity show a moderate contribution with regression coefficients of 14.15 and 6.83, respectively. For WRL 68 cells (equation (8)), the observed activity depended on several descriptors with different contributions. The softness, electronegativity, electrophilicity, and hardness show strongest effects with regression coefficients of 13.544, 1.615, 1.214, and 473, respectively; while dipole moment and hydrophobicity display moderate contributions (equation (8)). Similarly, the SD and residuals were improved (equations (5)–(8) and Table 9). The improved correlations between the observed cytotoxic activities and the selected descriptors may be attributed to the fact that this subclass of compounds has the same basic skeleton and that these compounds only differ in the substituted groups.

Predicted percentage inhibition and residuals obtained by using MLR equations (5)–(8) and considering compounds 2a and 2c–2m

| CPs | A459 (equation (5)) | HepG2 (equation (6)) | MCF-7 (equation (7)) | WRL68 (equation (8)) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ln P)Pred. | Resid. | (ln P)Pred. | Resid. | (ln P)Pred. | Resid. | (ln P)Pred. | Resid. | |

| 2a | 37.67 | 1.52 | 36.53 | 3.23 | 25.11 | 0.87 | 4.79 | 0.30 |

| 2c | 40.26 | 0.354 | 36.38 | 1.77 | 37.77 | 0.24 | 6.31 | 0.05 |

| 2d | 26.30 | 2.273 | 30.45 | 4.16 | 15.50 | 1.42 | 6.82 | 0.95 |

| 2e | 32.93 | 1.344 | 39.25 | 3.42 | 13.06 | 0.45 | 12.36 | 0.58 |

| 2f | 44.65 | 3.516 | 46.59 | 2.83 | 35.80 | 0.09 | 8.41 | 0.30 |

| 2g | 23.69 | 7.191 | 18.22 | 7.77 | 6.96 | 0.63 | 11.26 | 0.48 |

| 2h | 25.37 | 2.229 | 19.48 | 8.12 | 3.84 | 1.73 | 4.78 | 0.89 |

| 2i | 25.53 | 8.07 | 13.71 | 0.99 | −2.86 | 4.13 | 7.90 | 2.83 |

| 2j | 27.30 | 0.342 | 17.74 | 0.97 | 6.39 | 3.48 | 7.43 | 1.19 |

| 2k | 27.23 | 0.698 | 18.27 | 8.47 | 3.97 | 2.54 | 8.50 | 1.73 |

| 2l | 22.51 | 2.95 | 12.88 | 4.78 | 4.66 | 1.33 | 7.77 | 0.15 |

| 2m | 29.99 | 3.454 | 26.91 | 2.40 | 10.83 | 0.33 | 6.34 | 0.36 |

3.2.2.3 Considering subclasses 2a and 2c–2f

By considering the subclasses 2a and 2c–2f of compounds, the correlations between the cytotoxic activities and the reliable descriptor were highly improved (equations (9)–(12) and Table 10). For instance, the correlation coefficient and SD obtained with A459 cells were 99.86% and 0.53, respectively. In agreement with the above results, IP demonstrated the strongest positive effect on the observed activity of the tested compounds against A459 cells with a correlation coefficient of 3.79; while hardness and hydrophobicity display strongest negative effects with correlation coefficients of 5.99 and 4.15, respectively. Similar behaviors were observed with HepG2, MCF-7, and WRL 68 cells. For HepG2, IP has the strongest effect with a regression coefficient of 13.34. For MCF-7, the electronegativity displays the strongest contribution with a moderate effect on electrophilicity contribution (equation (11)). Hardness (with a negative contribution of 8.70) shows the strongest effect on the activity of the tested compounds against WRL68 (equation (12)).

Predicted percentage inhibition and residuals obtained by using MLR equations (9)–(12) and considering compounds 2a and 2c–2f

| CPs | A459 (equation (9)) | HepG2 (equation (10)) | MCF-7 (equation (11)) | WRL68 (equation (12)) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ln P)Pred. | Resid. | (ln P)Pred. | Resid. | (ln P)Pred. | Resid. | (ln P)Pred. | Resid. | |

| 2a | 39.38 | 0.19 | 38.30 | 1.46 | 25.48 | 0.50 | 4.44 | 0.06 |

| 2c | 40.82 | 0.21 | 40.98 | 2.83 | 39.20 | 1.19 | 6.18 | 0.08 |

| 2d | 23.99 | 0.04 | 34.41 | 0.20 | 13.16 | 3.76 | 5.95 | 0.08 |

| 2e | 34.35 | 0.08 | 36.70 | 0.87 | 18.61 | 6.00 | 12.89 | 0.05 |

| 2f | 40.69 | 0.44 | 41.73 | 2.04 | 32.78 | 2.93 | 8.22 | 0.11 |

3.2.2.4 Considering compounds 2g–2m

For the latest subclasses 2g–2m, the correlations were strongly reliant on the tested cells (equations (13)–(16) and Table 11). Indeed, the correlations were relatively moderate for A459 and HepG2 cells, with a correlation coefficient of 54% and SD values of 6.14 and 6.56, respectively. However, for MCF-7 and WRL 68 cells, the correlations were relatively good, with coefficient correlations of 96 and 99%, respectively. In equation (13) (A459 cells), IP has the strongest effect with a regression coefficient of 98.27. For HepG2 cells (equation (14)), the electronegativity showed the strongest effect. However, for WRL68, the softness displayed the strongest contribution with a regression coefficient of 58,834, while hydrophobicity displayed a moderate contribution with a correlation coefficient of 234.

Predicted percentage inhibition and residuals obtained by using MLR equations (13)–(16) and considering compounds 2g–2m

| CPs | A459 (equation (13)) | HepG2 (equation (14)) | MCF-7 (equation (15)) | WRL68 (equation (16)) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ln P)Pred. | Resid. | (ln P)Pred. | Resid. | (ln P)Pred. | Resid. | (ln P)Pred. | Resid. | |

| 2g | 19.66 | 3.16 | 18.03 | 7.58 | 6.96 | 0.63 | 10.58 | 0.20 |

| 2h | 23.89 | 3.71 | 18.69 | 8.91 | 3.12 | 1.01 | 6.03 | 0.36 |

| 2i | 26.25 | 7.35 | 15.44 | 2.72 | 0.61 | 0.66 | 4.70 | 0.37 |

| 2j | 30.70 | 3.74 | 14.64 | 2.13 | 2.29 | 0.63 | 8.77 | 0.15 |

| 2k | 30.23 | 3.70 | 13.15 | 3.35 | 2.06 | 0.63 | 10.18 | 0.05 |

| 2l | 21.75 | 2.19 | 14.27 | 3.39 | 6.28 | 0.29 | 8.02 | 0.10 |

| 2m | 31.71 | 1.74 | 30.08 | 0.77 | 10.50 | 0.00 | 6.71 | 0.01 |

4 Conclusions

Quantum chemical calculations and statistical analyses allow a better understanding of the structure–cytotoxicity relation between cytotoxicity with electronic, steric, and hydrophobic descriptors of the synthesized pyridotriazolopyrimidines. The obtained results demonstrated that the cytotoxicity depends on the cell line type and the combined molecular descriptors. SLR analysis revealed that the correlation of each descriptor on the observed cytotoxicity is relatively weak to moderate by considering a whole series of compounds (37–49%), and its improved by considering subclasses of compounds with similar basic skeleton (85–95%). For these subclasses of compounds, the best correlations were obtained with IP and electronegativity, with correlation coefficients of 94.22 and 85.12%, respectively. In accordance with SLR analysis, MLR analysis reveals that correlations related to different models are relatively weak to moderate by considering a whole series of compounds (26–58%), and these correlations are strongly improved by considering subclasses of compounds with similar basic skeletons (63–99%). MLR models reveal that the influence and impact of different descriptors vary with the tested cell lines and subclasses of compounds. For instance, for 2a and 2c–2f series, IP has the strongest effect against HepG2, while for MCF-7, the electronegativity displays the strongest effect.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University for funding this work through the research group project no. RG-1435-068.

Author contributions: Conceptualization: RA and HAA; software and data curation: EHA; writing—original draft preparation: RA, EHA, and HAA; revise-review and editing: NSA, HA, and MM; and funding acquisition: RA. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

[1] El-Sherief HAM, Youssif BGM, Abbas Bukhari SN, Abdelazeem AH, Abdel-Aziz M. Synthesis, anticancer activity and molecular modeling studies of 1,2,4-triazole derivatives as EGFR inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem. 2018;156:774–89.10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.07.024Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Abdel-Rahman HM, Rezvan RN, Hassanzadeh F, Khodarahmi GA, Mirzaei M, Rostami M, et al. Synthesis, characterization, cytotoxic screening, and density functional theory studies of new derivatives of quinazolin-4(3H)-one Schiff bases. Res Pharma Sci. 2017;12:444–55.10.4103/1735-5362.217425Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Flefel EM, El-Sayed WA, Mohamed AM, El-Sofany WI, Awad HM. Synthesis and anticancer activity of new 1-thia-4-azaspiro[4.5]decane, their derived thiazolopyrimidine and 1,3,4-thiadiazole thioglycosides. Molecules. 2017;22:170.10.3390/molecules22010170Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Al-Salahi R, Alswaidan I, Marzouk M. Cytotoxicity evaluation of a new set of 2-aminobenzo[de]iso-quinoline-1,3-diones. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:22483–91.10.3390/ijms151222483Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Abuelizz HA, Marzouk M, Ghabbour H, Al-Salahi R. Synthesis and anticancer activity of new quinazoline derivatives. Saudi Pharm J. 2017;25:1047–54.10.1016/j.jsps.2017.04.022Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Bereznak JF, Chan DM-T, Geffken D, Hanagan MA, Lepone GE, Pasteris RJ, et al. Preparation of fungicidal tricyclic 1,2,4-triazoles, 2008 WO 2008103357 A1 20080828.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Hou W, Luo Z, Zhang G, Cao D, Li D, Ruan H, et al. Click chemistry-based synthesis and anticancer activity evaluation of novel C-14-1,2,3-triazole dehydroabietic acid hybrid. Eur J Med Chem. 2017;138:1042–52.10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.07.049Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Lagoja IM. Pyrimidine as constituent of natural biologically active compounds. Chem Biodiver. 2007;2:1–50.10.1002/cbdv.200490173Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Shinkichi S, Nanao W, Toshiaki K, Takayuki S, Nobuyuki A, Sinji M, et al. “Pyridine and pyridine derivatives”. Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co; 2000.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Abuelizz HA, Iwana NANI, Ahmad R, Anouar E-H, Marzouk M, Al-Salahi R. Synthesis, biological activity and molecular docking of new tricyclic series as α-glucosidase inhibitors. BMC Chem. 2019;13:52.10.1186/s13065-019-0560-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Abuelizz HA, Taie HAA, Marzouk M, Al-Salahi R. Synthesis and antioxidant activity of 2-methylthio-pyrido[3,2-e]-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidines. Open Chem. 2019;17:823–30.10.1515/chem-2019-0092Search in Google Scholar

[12] Souza JR, De Almeida Santos J, Ferreira RH, Molfetta MMC, Camargo FA, Maria Honório AJ, et al. A quantum chemical and statistical study of flavonoid compounds (flavones) with anti-HIV activity. Eur J Med Chem. 2003;38:929–38.10.1016/j.ejmech.2003.06.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Kikuchi O. Systematic QSAR procedures with quantum chemical descriptors. Quantitative StructureActivity Relationships‐. 1987;6:179–84.10.1002/qsar.19870060406Search in Google Scholar

[14] Camargo A, Mercadante R, Honório K, Alves C, Da Silva A. A structure–activity relationship (SAR) study of synthetic neolignans and related compounds with biological activity against Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Struct.: THEOCHEM. 2002;583:105–16.10.1016/S0166-1280(01)00802-8Search in Google Scholar

[15] Ishihara M, Wakabayashi H, Motohashi N, Sakagami H. Quantitative structure–cytotoxicity relationship of newly synthesized tropolones determined by a semiempirical molecular-orbital method (PM5). Anticancer Res. 2010;30:129–33.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Stanchev S, Momekov G, Jensen F, Manolov I. Synthesis, computational study and cytotoxic activity of new 4-hydroxycoumarin derivatives. Eur J Med Chem. 2008;43:694–706.10.1016/j.ejmech.2007.05.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Yang H-I, Chen G-h, Li Y-q. A quantum chemical and statistical study of ganoderic acids with cytotoxicity against tumor cell. Eur J Med Chem. 2005;40:972–6.10.1016/j.ejmech.2005.04.015Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Carvalho M, Hawksworth G, Milhazes N, Borges F, Monks TJ, Fernandes E, et al. Role of metabolites in MDMA (ecstasy)-induced nephrotoxicity: an in vitro study using rat and human renal proximal tubular cells. Arch Toxicol. 2002;76:581–8.10.1007/s00204-002-0381-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Mendes AP, Borges RS, Neto AMC, de Macedo LG, da Silva AB. The basic antioxidant structure for flavonoid derivatives. J Mol Model. 2012;18:4073–80.10.1007/s00894-012-1397-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Sarkar A, Middya TR, Jana AD. A QSAR study of radical scavenging antioxidant activity of a series of flavonoids using DFT based quantum chemical descriptors – the importance of group frontier electron density. J Mol Model. 2012;18:2621–31.10.1007/s00894-011-1274-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Anouar EH. A quantum chemical and statistical study of phenolic schiff bases with antioxidant activity against DPPH free radical. Antioxidants. 2014;3:309–22.10.3390/antiox3020309Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Hamdi OAA, Anouar EH, Shilpi JA, Trabolsy ZBKA, Zain SBM, Zakaria NSS, et al. A quantum chemical and statistical study of cytotoxic activity of compounds isolated from Curcuma zedoaria. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:9450–68.10.3390/ijms16059450Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Tomasi J, Mennucci B, Cammi R. Quantum mechanical continuum solvation models. Chem Rev. 2005;105:2999–3093.10.1021/cr9904009Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Parr RG, Yang W. Density-Functional Theory of Atoms and Molecules. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press; 1989, Vol. 16.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Koopmans T. Über die Zuordnung von Wellenfunktionen und Eigenwerten zu den einzelnen Elektronen eines Atoms. Physica. 1934;1:104–13.10.1016/S0031-8914(34)90011-2Search in Google Scholar

[26] Neshev N, Mineva T. The role of interelectronic interaction in transition metal oxide catalysts. Metalligand interactions. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 1996. pp. 361–405.10.1007/978-94-009-0155-1_13Search in Google Scholar

[27] Grigorov M, Weber J, Chermette H, Tronchet JM. Numerical evaluation of the internal orbitally resolved chemical hardness tensor in density functional theory. Int J Quantum Chem. 1997;61:551–62.10.1002/(SICI)1097-461X(1997)61:3<551::AID-QUA24>3.0.CO;2-ASearch in Google Scholar

[28] Mineva T, Sicilia E, Russo N. Density-functional approach to hardness evaluation and its use in the study of the maximum hardness principle. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:9053–8.10.1021/ja974149vSearch in Google Scholar

[29] Alshammari MB, Geesi MH, El Hassane A, Al-Salahi R, Alharthi AI, Elnakady Y, et al. Quantum chemical calculations and statistical analysis: structural cytotoxicity relationships of some synthesized 2-thiophen-naphtho(benzo)oxazinone derivatives. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2018;76:377–89.10.1007/s12013-018-0848-3Search in Google Scholar

[30] De Luca G, Sicilia E, Russo N, Mineva T. On the hardness evaluation in solvent for neutral and charged systems. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:1494–9.10.1021/ja0116977Search in Google Scholar

[31] Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, et al. Gaussian 16, Revision B.01. Wallingford, CT: Gaussian, Inc.; 2016.Search in Google Scholar

© 2020 Hatem A. Abuelizz et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Electrochemical antioxidant screening and evaluation based on guanine and chitosan immobilized MoS2 nanosheet modified glassy carbon electrode (guanine/CS/MoS2/GCE)

- Kinetic models of the extraction of vanillic acid from pumpkin seeds

- On the maximum ABC index of bipartite graphs without pendent vertices

- Estimation of the total antioxidant potential in the meat samples using thin-layer chromatography

- Molecular dynamics simulation of sI methane hydrate under compression and tension

- Spatial distribution and potential ecological risk assessment of some trace elements in sediments and grey mangrove (Avicennia marina) along the Arabian Gulf coast, Saudi Arabia

- Amino-functionalized graphene oxide for Cr(VI), Cu(II), Pb(II) and Cd(II) removal from industrial wastewater

- Chemical composition and in vitro activity of Origanum vulgare L., Satureja hortensis L., Thymus serpyllum L. and Thymus vulgaris L. essential oils towards oral isolates of Candida albicans and Candida glabrata

- Effect of excess Fluoride consumption on Urine-Serum Fluorides, Dental state and Thyroid Hormones among children in “Talab Sarai” Punjab Pakistan

- Design, Synthesis and Characterization of Novel Isoxazole Tagged Indole Hybrid Compounds

- Comparison of kinetic and enzymatic properties of intracellular phosphoserine aminotransferases from alkaliphilic and neutralophilic bacteria

- Green Organic Solvent-Free Oxidation of Alkylarenes with tert-Butyl Hydroperoxide Catalyzed by Water-Soluble Copper Complex

- Ducrosia ismaelis Asch. essential oil: chemical composition profile and anticancer, antimicrobial and antioxidant potential assessment

- DFT calculations as an efficient tool for prediction of Raman and infra-red spectra and activities of newly synthesized cathinones

- Influence of Chemical Osmosis on Solute Transport and Fluid Velocity in Clay Soils

- A New fatty acid and some triterpenoids from propolis of Nkambe (North-West Region, Cameroon) and evaluation of the antiradical scavenging activity of their extracts

- Antiplasmodial Activity of Stigmastane Steroids from Dryobalanops oblongifolia Stem Bark

- Rapid identification of direct-acting pancreatic protectants from Cyclocarya paliurus leaves tea by the method of serum pharmacochemistry combined with target cell extraction

- Immobilization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa static biomass on eggshell powder for on-line preconcentration and determination of Cr (VI)

- Assessment of methyl 2-({[(4,6-dimethoxypyrimidin-2-yl)carbamoyl] sulfamoyl}methyl)benzoate through biotic and abiotic degradation modes

- Stability of natural polyphenol fisetin in eye drops Stability of fisetin in eye drops

- Production of a bioflocculant by using activated sludge and its application in Pb(II) removal from aqueous solution

- Molecular Properties of Carbon Crystal Cubic Structures

- Synthesis and characterization of calcium carbonate whisker from yellow phosphorus slag

- Study on the interaction between catechin and cholesterol by the density functional theory

- Analysis of some pharmaceuticals in the presence of their synthetic impurities by applying hybrid micelle liquid chromatography

- Two mixed-ligand coordination polymers based on 2,5-thiophenedicarboxylic acid and flexible N-donor ligands: the protective effect on periodontitis via reducing the release of IL-1β and TNF-α

- Incorporation of silver stearate nanoparticles in methacrylate polymeric monoliths for hemeprotein isolation

- Development of ultrasound-assisted dispersive solid-phase microextraction based on mesoporous carbon coated with silica@iron oxide nanocomposite for preconcentration of Te and Tl in natural water systems

- N,N′-Bis[2-hydroxynaphthylidene]/[2-methoxybenzylidene]amino]oxamides and their divalent manganese complexes: Isolation, spectral characterization, morphology, antibacterial and cytotoxicity against leukemia cells

- Determination of the content of selected trace elements in Polish commercial fruit juices and health risk assessment

- Diorganotin(iv) benzyldithiocarbamate complexes: synthesis, characterization, and thermal and cytotoxicity study

- Keratin 17 is induced in prurigo nodularis lesions

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and acute toxicity studies of a Saudi polyherbal formulation, PHF5

- LaCoO3 perovskite-type catalysts in syngas conversion

- Comparative studies of two vegetal extracts from Stokesia laevis and Geranium pratense: polyphenol profile, cytotoxic effect and antiproliferative activity

- Fragmentation pattern of certain isatin–indole antiproliferative conjugates with application to identify their in vitro metabolic profiles in rat liver microsomes by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry

- Investigation of polyphenol profile, antioxidant activity and hepatoprotective potential of Aconogonon alpinum (All.) Schur roots

- Lead discovery of a guanidinyl tryptophan derivative on amyloid cascade inhibition

- Physicochemical evaluation of the fruit pulp of Opuntia spp growing in the Mediterranean area under hard climate conditions

- Electronic structural properties of amino/hydroxyl functionalized imidazolium-based bromide ionic liquids

- New Schiff bases of 2-(quinolin-8-yloxy)acetohydrazide and their Cu(ii), and Zn(ii) metal complexes: their in vitro antimicrobial potentials and in silico physicochemical and pharmacokinetics properties

- Treatment of adhesions after Achilles tendon injury using focused ultrasound with targeted bFGF plasmid-loaded cationic microbubbles

- Synthesis of orotic acid derivatives and their effects on stem cell proliferation

- Chirality of β2-agonists. An overview of pharmacological activity, stereoselective analysis, and synthesis

- Fe3O4@urea/HITh-SO3H as an efficient and reusable catalyst for the solvent-free synthesis of 7-aryl-8H-benzo[h]indeno[1,2-b]quinoline-8-one and indeno[2′,1′:5,6]pyrido[2,3-d]pyrimidine derivatives

- Adsorption kinetic characteristics of molybdenum in yellow-brown soil in response to pH and phosphate

- Enhancement of thermal properties of bio-based microcapsules intended for textile applications

- Exploring the effect of khat (Catha edulis) chewing on the pharmacokinetics of the antiplatelet drug clopidogrel in rats using the newly developed LC-MS/MS technique

- A green strategy for obtaining anthraquinones from Rheum tanguticum by subcritical water

- Cadmium (Cd) chloride affects the nutrient uptake and Cd-resistant bacterium reduces the adsorption of Cd in muskmelon plants

- Removal of H2S by vermicompost biofilter and analysis on bacterial community

- Structural cytotoxicity relationship of 2-phenoxy(thiomethyl)pyridotriazolopyrimidines: Quantum chemical calculations and statistical analysis

- A self-breaking supramolecular plugging system as lost circulation material in oilfield

- Synthesis, characterization, and pharmacological evaluation of thiourea derivatives

- Application of drug–metal ion interaction principle in conductometric determination of imatinib, sorafenib, gefitinib and bosutinib

- Synthesis and characterization of a novel chitosan-grafted-polyorthoethylaniline biocomposite and utilization for dye removal from water

- Optimisation of urine sample preparation for shotgun proteomics

- DFT investigations on arylsulphonyl pyrazole derivatives as potential ligands of selected kinases

- Treatment of Parkinson’s disease using focused ultrasound with GDNF retrovirus-loaded microbubbles to open the blood–brain barrier

- New derivatives of a natural nordentatin

- Fluorescence biomarkers of malignant melanoma detectable in urine

- Study of the remediation effects of passivation materials on Pb-contaminated soil

- Saliva proteomic analysis reveals possible biomarkers of renal cell carcinoma

- Withania frutescens: Chemical characterization, analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and healing activities

- Design, synthesis and pharmacological profile of (−)-verbenone hydrazones

- Synthesis of magnesium carbonate hydrate from natural talc

- Stability-indicating HPLC-DAD assay for simultaneous quantification of hydrocortisone 21 acetate, dexamethasone, and fluocinolone acetonide in cosmetics

- A novel lactose biosensor based on electrochemically synthesized 3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene/thiophene (EDOT/Th) copolymer

- Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad: Chemical characterization, scavenging and cytotoxic activities

- Development and validation of a high performance liquid chromatography/diode array detection method for estrogen determination: Application to residual analysis in meat products

- PCSK9 concentrations in different stages of subclinical atherosclerosis and their relationship with inflammation

- Development of trace analysis for alkyl methanesulfonates in the delgocitinib drug substance using GC-FID and liquid–liquid extraction with ionic liquid

- Electrochemical evaluation of the antioxidant capacity of natural compounds on glassy carbon electrode modified with guanine-, polythionine-, and nitrogen-doped graphene

- A Dy(iii)–organic framework as a fluorescent probe for highly selective detection of picric acid and treatment activity on human lung cancer cells

- A Zn(ii)–organic cage with semirigid ligand for solvent-free cyanosilylation and inhibitory effect on ovarian cancer cell migration and invasion ability via regulating mi-RNA16 expression

- Polyphenol content and antioxidant activities of Prunus padus L. and Prunus serotina L. leaves: Electrochemical and spectrophotometric approach and their antimicrobial properties

- The combined use of GC, PDSC and FT-IR techniques to characterize fat extracted from commercial complete dry pet food for adult cats

- MALDI-TOF MS profiling in the discovery and identification of salivary proteomic patterns of temporomandibular joint disorders

- Concentrations of dioxins, furans and dioxin-like PCBs in natural animal feed additives

- Structure and some physicochemical and functional properties of water treated under ammonia with low-temperature low-pressure glow plasma of low frequency

- Mesoscale nanoparticles encapsulated with emodin for targeting antifibrosis in animal models

- Amine-functionalized magnetic activated carbon as an adsorbent for preconcentration and determination of acidic drugs in environmental water samples using HPLC-DAD

- Antioxidant activity as a response to cadmium pollution in three durum wheat genotypes differing in salt-tolerance

- A promising naphthoquinone [8-hydroxy-2-(2-thienylcarbonyl)naphtho[2,3-b]thiophene-4,9-dione] exerts anti-colorectal cancer activity through ferroptosis and inhibition of MAPK signaling pathway based on RNA sequencing

- Synthesis and efficacy of herbicidal ionic liquids with chlorsulfuron as the anion

- Effect of isovalent substitution on the crystal structure and properties of two-slab indates BaLa2−xSmxIn2O7

- Synthesis, spectral and thermo-kinetics explorations of Schiff-base derived metal complexes

- An improved reduction method for phase stability testing in the single-phase region

- Comparative analysis of chemical composition of some commercially important fishes with an emphasis on various Malaysian diets

- Development of a solventless stir bar sorptive extraction/thermal desorption large volume injection capillary gas chromatographic-mass spectrometric method for ultra-trace determination of pyrethroids pesticides in river and tap water samples

- A turbidity sensor development based on NL-PI observers: Experimental application to the control of a Sinaloa’s River Spirulina maxima cultivation

- Deep desulfurization of sintering flue gas in iron and steel works based on low-temperature oxidation

- Investigations of metallic elements and phenolics in Chinese medicinal plants

- Influence of site-classification approach on geochemical background values

- Effects of ageing on the surface characteristics and Cu(ii) adsorption behaviour of rice husk biochar in soil

- Adsorption and sugarcane-bagasse-derived activated carbon-based mitigation of 1-[2-(2-chloroethoxy)phenyl]sulfonyl-3-(4-methoxy-6-methyl-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl) urea-contaminated soils

- Antimicrobial and antifungal activities of bifunctional cooper(ii) complexes with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, flufenamic, mefenamic and tolfenamic acids and 1,10-phenanthroline

- Application of selenium and silicon to alleviate short-term drought stress in French marigold (Tagetes patula L.) as a model plant species

- Screening and analysis of xanthine oxidase inhibitors in jute leaves and their protective effects against hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress in cells

- Synthesis and physicochemical studies of a series of mixed-ligand transition metal complexes and their molecular docking investigations against Coronavirus main protease

- A study of in vitro metabolism and cytotoxicity of mephedrone and methoxetamine in human and pig liver models using GC/MS and LC/MS analyses

- A new phenyl alkyl ester and a new combretin triterpene derivative from Combretum fragrans F. Hoffm (Combretaceae) and antiproliferative activity

- Erratum

- Erratum to: A one-step incubation ELISA kit for rapid determination of dibutyl phthalate in water, beverage and liquor

- Review Articles

- Sinoporphyrin sodium, a novel sensitizer for photodynamic and sonodynamic therapy

- Natural products isolated from Casimiroa

- Plant description, phytochemical constituents and bioactivities of Syzygium genus: A review

- Evaluation of elastomeric heat shielding materials as insulators for solid propellant rocket motors: A short review

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2019

- An overview of Monascus fermentation processes for monacolin K production

- Study on online soft sensor method of total sugar content in chlorotetracycline fermentation tank

- Studies on the Anti-Gouty Arthritis and Anti-hyperuricemia Properties of Astilbin in Animal Models

- Effects of organic fertilizer on water use, photosynthetic characteristics, and fruit quality of pear jujube in northern Shaanxi

- Characteristics of the root exudate release system of typical plants in plateau lakeside wetland under phosphorus stress conditions

- Characterization of soil water by the means of hydrogen and oxygen isotope ratio at dry-wet season under different soil layers in the dry-hot valley of Jinsha River

- Composition and diurnal variation of floral scent emission in Rosa rugosa Thunb. and Tulipa gesneriana L.

- Preparation of a novel ginkgolide B niosomal composite drug

- The degradation, biodegradability and toxicity evaluation of sulfamethazine antibiotics by gamma radiation

- Special issue on Monitoring, Risk Assessment and Sustainable Management for the Exposure to Environmental Toxins

- Insight into the cadmium and zinc binding potential of humic acids derived from composts by EEM spectra combined with PARAFAC analysis

- Source apportionment of soil contamination based on multivariate receptor and robust geostatistics in a typical rural–urban area, Wuhan city, middle China

- Special Issue on 13th JCC 2018

- The Role of H2C2O4 and Na2CO3 as Precipitating Agents on The Physichochemical Properties and Photocatalytic Activity of Bismuth Oxide

- Preparation of magnetite-silica–cetyltrimethylammonium for phenol removal based on adsolubilization

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- Size-dependent growth kinetics of struvite crystals in wastewater with calcium ions

- The effect of silica-calcite sedimentary rock contained in the chicken broiler diet on the overall quality of chicken muscles

- Physicochemical properties of selected herbicidal products containing nicosulfuron as an active ingredient

- Lycopene in tomatoes and tomato products

- Fluorescence in the assessment of the share of a key component in the mixing of feed

- Sulfur application alleviates chromium stress in maize and wheat

- Effectiveness of removal of sulphur compounds from the air after 3 years of biofiltration with a mixture of compost soil, peat, coconut fibre and oak bark

- Special Issue on the 4th Green Chemistry 2018

- Study and fire test of banana fibre reinforced composites with flame retardance properties

- Special Issue on the International conference CosCI 2018

- Disintegration, In vitro Dissolution, and Drug Release Kinetics Profiles of k-Carrageenan-based Nutraceutical Hard-shell Capsules Containing Salicylamide

- Synthesis of amorphous aluminosilicate from impure Indonesian kaolin

- Special Issue on the International Conf on Science, Applied Science, Teaching and Education 2019

- Functionalization of Congo red dye as a light harvester on solar cell

- The effect of nitrite food preservatives added to se’i meat on the expression of wild-type p53 protein

- Biocompatibility and osteoconductivity of scaffold porous composite collagen–hydroxyapatite based coral for bone regeneration

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2019)

- Effect of natural boron mineral use on the essential oil ratio and components of Musk Sage (Salvia sclarea L.)

- A theoretical and experimental study of the adsorptive removal of hexavalent chromium ions using graphene oxide as an adsorbent

- A study on the bacterial adhesion of Streptococcus mutans in various dental ceramics: In vitro study

- Corrosion study of copper in aqueous sulfuric acid solution in the presence of (2E,5E)-2,5-dibenzylidenecyclopentanone and (2E,5E)-bis[(4-dimethylamino)benzylidene]cyclopentanone: Experimental and theoretical study

- Special Issue on Chemistry Today for Tomorrow 2019

- Diabetes mellitus type 2: Exploratory data analysis based on clinical reading

- Multivariate analysis for the classification of copper–lead and copper–zinc glasses

- Special Issue on Advances in Chemistry and Polymers

- The spatial and temporal distribution of cationic and anionic radicals in early embryo implantation

- Special Issue on 3rd IC3PE 2020

- Magnetic iron oxide/clay nanocomposites for adsorption and catalytic oxidation in water treatment applications

- Special Issue on IC3PE 2018/2019 Conference

- Exergy analysis of conventional and hydrothermal liquefaction–esterification processes of microalgae for biodiesel production

- Advancing biodiesel production from microalgae Spirulina sp. by a simultaneous extraction–transesterification process using palm oil as a co-solvent of methanol

- Topical Issue on Applications of Mathematics in Chemistry

- Omega and the related counting polynomials of some chemical structures

- M-polynomial and topological indices of zigzag edge coronoid fused by starphene

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Electrochemical antioxidant screening and evaluation based on guanine and chitosan immobilized MoS2 nanosheet modified glassy carbon electrode (guanine/CS/MoS2/GCE)

- Kinetic models of the extraction of vanillic acid from pumpkin seeds

- On the maximum ABC index of bipartite graphs without pendent vertices

- Estimation of the total antioxidant potential in the meat samples using thin-layer chromatography

- Molecular dynamics simulation of sI methane hydrate under compression and tension

- Spatial distribution and potential ecological risk assessment of some trace elements in sediments and grey mangrove (Avicennia marina) along the Arabian Gulf coast, Saudi Arabia

- Amino-functionalized graphene oxide for Cr(VI), Cu(II), Pb(II) and Cd(II) removal from industrial wastewater

- Chemical composition and in vitro activity of Origanum vulgare L., Satureja hortensis L., Thymus serpyllum L. and Thymus vulgaris L. essential oils towards oral isolates of Candida albicans and Candida glabrata

- Effect of excess Fluoride consumption on Urine-Serum Fluorides, Dental state and Thyroid Hormones among children in “Talab Sarai” Punjab Pakistan

- Design, Synthesis and Characterization of Novel Isoxazole Tagged Indole Hybrid Compounds

- Comparison of kinetic and enzymatic properties of intracellular phosphoserine aminotransferases from alkaliphilic and neutralophilic bacteria

- Green Organic Solvent-Free Oxidation of Alkylarenes with tert-Butyl Hydroperoxide Catalyzed by Water-Soluble Copper Complex

- Ducrosia ismaelis Asch. essential oil: chemical composition profile and anticancer, antimicrobial and antioxidant potential assessment

- DFT calculations as an efficient tool for prediction of Raman and infra-red spectra and activities of newly synthesized cathinones

- Influence of Chemical Osmosis on Solute Transport and Fluid Velocity in Clay Soils

- A New fatty acid and some triterpenoids from propolis of Nkambe (North-West Region, Cameroon) and evaluation of the antiradical scavenging activity of their extracts

- Antiplasmodial Activity of Stigmastane Steroids from Dryobalanops oblongifolia Stem Bark

- Rapid identification of direct-acting pancreatic protectants from Cyclocarya paliurus leaves tea by the method of serum pharmacochemistry combined with target cell extraction

- Immobilization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa static biomass on eggshell powder for on-line preconcentration and determination of Cr (VI)

- Assessment of methyl 2-({[(4,6-dimethoxypyrimidin-2-yl)carbamoyl] sulfamoyl}methyl)benzoate through biotic and abiotic degradation modes

- Stability of natural polyphenol fisetin in eye drops Stability of fisetin in eye drops

- Production of a bioflocculant by using activated sludge and its application in Pb(II) removal from aqueous solution

- Molecular Properties of Carbon Crystal Cubic Structures

- Synthesis and characterization of calcium carbonate whisker from yellow phosphorus slag

- Study on the interaction between catechin and cholesterol by the density functional theory

- Analysis of some pharmaceuticals in the presence of their synthetic impurities by applying hybrid micelle liquid chromatography

- Two mixed-ligand coordination polymers based on 2,5-thiophenedicarboxylic acid and flexible N-donor ligands: the protective effect on periodontitis via reducing the release of IL-1β and TNF-α

- Incorporation of silver stearate nanoparticles in methacrylate polymeric monoliths for hemeprotein isolation

- Development of ultrasound-assisted dispersive solid-phase microextraction based on mesoporous carbon coated with silica@iron oxide nanocomposite for preconcentration of Te and Tl in natural water systems

- N,N′-Bis[2-hydroxynaphthylidene]/[2-methoxybenzylidene]amino]oxamides and their divalent manganese complexes: Isolation, spectral characterization, morphology, antibacterial and cytotoxicity against leukemia cells

- Determination of the content of selected trace elements in Polish commercial fruit juices and health risk assessment

- Diorganotin(iv) benzyldithiocarbamate complexes: synthesis, characterization, and thermal and cytotoxicity study

- Keratin 17 is induced in prurigo nodularis lesions

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and acute toxicity studies of a Saudi polyherbal formulation, PHF5

- LaCoO3 perovskite-type catalysts in syngas conversion

- Comparative studies of two vegetal extracts from Stokesia laevis and Geranium pratense: polyphenol profile, cytotoxic effect and antiproliferative activity

- Fragmentation pattern of certain isatin–indole antiproliferative conjugates with application to identify their in vitro metabolic profiles in rat liver microsomes by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry

- Investigation of polyphenol profile, antioxidant activity and hepatoprotective potential of Aconogonon alpinum (All.) Schur roots

- Lead discovery of a guanidinyl tryptophan derivative on amyloid cascade inhibition

- Physicochemical evaluation of the fruit pulp of Opuntia spp growing in the Mediterranean area under hard climate conditions

- Electronic structural properties of amino/hydroxyl functionalized imidazolium-based bromide ionic liquids

- New Schiff bases of 2-(quinolin-8-yloxy)acetohydrazide and their Cu(ii), and Zn(ii) metal complexes: their in vitro antimicrobial potentials and in silico physicochemical and pharmacokinetics properties

- Treatment of adhesions after Achilles tendon injury using focused ultrasound with targeted bFGF plasmid-loaded cationic microbubbles

- Synthesis of orotic acid derivatives and their effects on stem cell proliferation

- Chirality of β2-agonists. An overview of pharmacological activity, stereoselective analysis, and synthesis

- Fe3O4@urea/HITh-SO3H as an efficient and reusable catalyst for the solvent-free synthesis of 7-aryl-8H-benzo[h]indeno[1,2-b]quinoline-8-one and indeno[2′,1′:5,6]pyrido[2,3-d]pyrimidine derivatives

- Adsorption kinetic characteristics of molybdenum in yellow-brown soil in response to pH and phosphate

- Enhancement of thermal properties of bio-based microcapsules intended for textile applications

- Exploring the effect of khat (Catha edulis) chewing on the pharmacokinetics of the antiplatelet drug clopidogrel in rats using the newly developed LC-MS/MS technique

- A green strategy for obtaining anthraquinones from Rheum tanguticum by subcritical water

- Cadmium (Cd) chloride affects the nutrient uptake and Cd-resistant bacterium reduces the adsorption of Cd in muskmelon plants

- Removal of H2S by vermicompost biofilter and analysis on bacterial community

- Structural cytotoxicity relationship of 2-phenoxy(thiomethyl)pyridotriazolopyrimidines: Quantum chemical calculations and statistical analysis

- A self-breaking supramolecular plugging system as lost circulation material in oilfield

- Synthesis, characterization, and pharmacological evaluation of thiourea derivatives

- Application of drug–metal ion interaction principle in conductometric determination of imatinib, sorafenib, gefitinib and bosutinib

- Synthesis and characterization of a novel chitosan-grafted-polyorthoethylaniline biocomposite and utilization for dye removal from water

- Optimisation of urine sample preparation for shotgun proteomics

- DFT investigations on arylsulphonyl pyrazole derivatives as potential ligands of selected kinases

- Treatment of Parkinson’s disease using focused ultrasound with GDNF retrovirus-loaded microbubbles to open the blood–brain barrier

- New derivatives of a natural nordentatin

- Fluorescence biomarkers of malignant melanoma detectable in urine

- Study of the remediation effects of passivation materials on Pb-contaminated soil

- Saliva proteomic analysis reveals possible biomarkers of renal cell carcinoma

- Withania frutescens: Chemical characterization, analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and healing activities

- Design, synthesis and pharmacological profile of (−)-verbenone hydrazones

- Synthesis of magnesium carbonate hydrate from natural talc

- Stability-indicating HPLC-DAD assay for simultaneous quantification of hydrocortisone 21 acetate, dexamethasone, and fluocinolone acetonide in cosmetics

- A novel lactose biosensor based on electrochemically synthesized 3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene/thiophene (EDOT/Th) copolymer

- Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad: Chemical characterization, scavenging and cytotoxic activities

- Development and validation of a high performance liquid chromatography/diode array detection method for estrogen determination: Application to residual analysis in meat products

- PCSK9 concentrations in different stages of subclinical atherosclerosis and their relationship with inflammation

- Development of trace analysis for alkyl methanesulfonates in the delgocitinib drug substance using GC-FID and liquid–liquid extraction with ionic liquid

- Electrochemical evaluation of the antioxidant capacity of natural compounds on glassy carbon electrode modified with guanine-, polythionine-, and nitrogen-doped graphene

- A Dy(iii)–organic framework as a fluorescent probe for highly selective detection of picric acid and treatment activity on human lung cancer cells

- A Zn(ii)–organic cage with semirigid ligand for solvent-free cyanosilylation and inhibitory effect on ovarian cancer cell migration and invasion ability via regulating mi-RNA16 expression

- Polyphenol content and antioxidant activities of Prunus padus L. and Prunus serotina L. leaves: Electrochemical and spectrophotometric approach and their antimicrobial properties

- The combined use of GC, PDSC and FT-IR techniques to characterize fat extracted from commercial complete dry pet food for adult cats

- MALDI-TOF MS profiling in the discovery and identification of salivary proteomic patterns of temporomandibular joint disorders

- Concentrations of dioxins, furans and dioxin-like PCBs in natural animal feed additives

- Structure and some physicochemical and functional properties of water treated under ammonia with low-temperature low-pressure glow plasma of low frequency

- Mesoscale nanoparticles encapsulated with emodin for targeting antifibrosis in animal models

- Amine-functionalized magnetic activated carbon as an adsorbent for preconcentration and determination of acidic drugs in environmental water samples using HPLC-DAD

- Antioxidant activity as a response to cadmium pollution in three durum wheat genotypes differing in salt-tolerance

- A promising naphthoquinone [8-hydroxy-2-(2-thienylcarbonyl)naphtho[2,3-b]thiophene-4,9-dione] exerts anti-colorectal cancer activity through ferroptosis and inhibition of MAPK signaling pathway based on RNA sequencing

- Synthesis and efficacy of herbicidal ionic liquids with chlorsulfuron as the anion

- Effect of isovalent substitution on the crystal structure and properties of two-slab indates BaLa2−xSmxIn2O7

- Synthesis, spectral and thermo-kinetics explorations of Schiff-base derived metal complexes

- An improved reduction method for phase stability testing in the single-phase region

- Comparative analysis of chemical composition of some commercially important fishes with an emphasis on various Malaysian diets

- Development of a solventless stir bar sorptive extraction/thermal desorption large volume injection capillary gas chromatographic-mass spectrometric method for ultra-trace determination of pyrethroids pesticides in river and tap water samples

- A turbidity sensor development based on NL-PI observers: Experimental application to the control of a Sinaloa’s River Spirulina maxima cultivation

- Deep desulfurization of sintering flue gas in iron and steel works based on low-temperature oxidation

- Investigations of metallic elements and phenolics in Chinese medicinal plants

- Influence of site-classification approach on geochemical background values

- Effects of ageing on the surface characteristics and Cu(ii) adsorption behaviour of rice husk biochar in soil

- Adsorption and sugarcane-bagasse-derived activated carbon-based mitigation of 1-[2-(2-chloroethoxy)phenyl]sulfonyl-3-(4-methoxy-6-methyl-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl) urea-contaminated soils

- Antimicrobial and antifungal activities of bifunctional cooper(ii) complexes with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, flufenamic, mefenamic and tolfenamic acids and 1,10-phenanthroline

- Application of selenium and silicon to alleviate short-term drought stress in French marigold (Tagetes patula L.) as a model plant species

- Screening and analysis of xanthine oxidase inhibitors in jute leaves and their protective effects against hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress in cells