Abstract

As fossil fuels were depleting at an alarming rate, the development of renewable energy has become necessary. One of the promising renewable energy to be used is biodiesel. The interest in using third-generation feedstock, which is microalgae, is rapidly growing. The use of third-generation biodiesel feedstock will be more beneficial as it does not compete with food crop use and land utilization. The advantageous characteristic which sets microalgae apart from other biomass sources is that microalgae have high biomass yield. Conventionally, microalgae biodiesel is produced by lipid extraction followed by transesterification. In this study, combination process between hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL) and esterification is explored. The HTL process is one of the biomass thermochemical conversion methods to produce liquid fuel. In this study, the HTL process will be coupled with esterification, which takes fatty acid from HTL as raw material for producing biodiesel. Both the processes will be studied by simulating with Aspen Plus and thermodynamic analysis in terms of energy and exergy. Based on the simulation process, it was reported that both processes demand similar energy consumption. However, exergy analysis shows that total exergy loss of conventional exergy loss is greater than the HTL-esterification process.

1 Introduction

Nowadays, industrial development and population growth have stimulated high energy requirement for both transportation and electricity need [1]. In Indonesia, it is shown that energy consumptions in 2014 had reached 962 million tonnes of oil equivalent (MTOE), with 73% accounted for fossil fuel [2]. However, Indonesia’s oil and coal reserves are depleting at an alarming rate [3]. From this standpoint, it is clear that renewable energy has significant influence in ensuring national energy security. This issue is in accordance with national government regulation which plans to increase renewable energy usage from 5% in 2005 to 25% in 2025 [4]. An attractive and robust renewable energy that can be implemented in Indonesia is biodiesel. Biodiesel is a methyl ester manufactured from transesterification of triglyceride and esterification of fatty acid.

Reactions, which result in biodiesel, can be carried out using various raw materials that include biodiesel from first-generation (G-1) and second-generation raw material (G-2), which cover edible and nonedible oil and waste [5]. However, both of them have several drawbacks, including competition with food requirements (G-1) and high impurity within the feedstock (G-2). In order to tackle those drawbacks, microalgae have received tremendous interest as relatively new biodiesel feedstock (third generation/G-3) [6]. Compared with other biomass sources, microalgae are more beneficial since its biomass productivity and oil/lipid content are high and can be cultivated without agricultural land [7]. Algae cultivation is also more advantageous due to its capability to be used for removing carbon dioxide and industrial wastewater treatment [8].

Among many microalgae species, Botryococcus braunii is one of the most potent microalgae in the development of biofuel. Botryococcus braunii is freshwater microalgae commonly found in ponds, open water space and other freshwater area [9]. Botryococcus braunii gains interest, especially for producing biodiesel, as it contains relatively high content of lipid/oil (36–63%), depends on the amount of nitrogen supply during cultivation [10]. Pradana et al. [8] reported that Botryococcus braunii is able to produce 0.0187 g oil/g dry microalgae, which consists of several fatty acids including palmitic acid (43.06%), linolelaidic acid (8.60%), elaidic acid (43.06%) and stearic acid (5.29%). From this standpoint, it is clear that microalgae oil is one of the most suitable feedstock for producing biodiesel.

In order to utilize the oil content of microalgae, there are several methods that can be performed after cultivating the microalgae. In conventional process, harvested microalgae is proceeded through oil content extraction using chemical solvent and then transesterified into biodiesel [11]. However, in conventional process, the harvested microalgae concentration is usually very low due to excessive water content from harvesting process. In some cases, the harvested microalgae content is only 0.5–22%, depends on the method of harvesting [12]. Prior to the extraction process, water content needs to be set as minimum as possible.

Another process which can be chosen is hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL) due to its capability to produce biofuel from wet microalgae. HTL is one of the thermochemical routes of converting biomass into liquid fuel or bio-oil besides pyrolysis. HTL is relatively a more efficient process in terms of converting biomass into liquid fuel as compared to pyrolysis [13]. In addition, in HTL process, water content in harvested microalgae, which turns into subcritical water, acts as both reactant and medium [14]. Gai et al. [15] have confirmed that subcritical water allows hydrolysis reaction to occur, so that carbohydrate, protein and triglyceride contents in microalgae are hydrolyzed into their monomer, which are glucose, amino acid and fatty acid respectively. In this study, a new route of converting algae biomass into biodiesel utilizes fatty acid from HTL process with esterification. The proposed process is hypothetically created to examine its potency to become an alternative process of producing microalgal biodiesel. During this process, wet microalgae are processed using HTL to produce fatty acids, which are then converted into biodiesel using esterification reaction. The process of HTL-esterification was then compared with conventional process.

Exergy is one of the thermodynamic concepts which is able to examine process efficiency in a more comprehensive way [16]. Performing exergy analysis on similar process will be useful to justify the most energy efficient process configuration. The exergy analysis, which is developed from the second law of thermodynamics, allows to account for irreversibility of the process [17]. The objective of this study is to examine the potency of HTL-esterification to be an alternative and promising biodiesel production process. One of the most easiest and logical way is by comparing it with conventional biodiesel process from microalgae, which consumes a considerable amount of energy [18]. Exergy analysis will be more likely a suitable method to assess the efficiency of conventional biodiesel production process and the proposed process.

Simulation-based exergy analysis of biodiesel production has also been conducted by previous studies [17], which reported that in biodiesel production from Jatropha curcas, 95% of the raw material exergy content was destroyed during reaction. Another study by Ofori-Boateng et al. [19] showed simulation and exergy analysis of biodiesel plants from microalgae Jatropha using Aspen Plus. However, exergy analysis related to HTL is relatively limited, especially for integrated HTL-esterification process. From those standpoints, the objective of this study is to evaluate the proposed process via exergy analysis.

1.1 Thermodynamic analysis

Due to energy demand of both the hydrothermal and esterification processes, energy utilization needs to be done on the processes. Meanwhile, exergy analysis is a robust analysis based on the first and second law of thermodynamics to analyze an effective method of energy saving.

Furthermore, exergy analysis is used in thermodynamic basis to modify a process in order to achieve energy optimization. Exergy or available energy is a part of energy which can be converted into mechanical energy [20]. Exergy analysis would give information about quantity and quality of energy transformation in a system. It is because the second law of thermodynamics gives mathematical equation which states that every process will generate entropy [21]. Entropy generation within the process will lead to exergy destruction [22]. Mathematically, exergy change calculation is similar to ΔG0 in which enthalpy is reduced due to entropy generation at ambient temperature (T0 = 298.15 K) as mentioned in equation (1)

where E, H and T represent flow of exergy, enthalpy and entropy respectively.

Exergy analysis is able to be carried out in several methods. Budiman and Ishida [20] demonstrated that thermodynamic analysis using exergy concepts can be comprehensively performed by using energy utilization diagram. Hajjaji et al. [22] and Ofori-Boateng et al. [19], which performed exergy analysis using Aspen Plus simulation, calculated exergy in every process streams to investigate exergy loss due to irreversibility and wasted stream. Basically, exergy flows in each process stream consist of physical, chemical and mixing exergy, as shown in equation (2) [19]:

where

where

where Hi and Si are molar enthalpy and entropy of pure components.

Thermodynamic data used and the chemical exergy are obtained from Aspen Plus 8.6 database (version 8.6; AspenPlus; Aspentech) and chemical exergy calculator which perform calculation based on Gibbs free energy (exergoecology).

After calculating the exergy flow in every stream, calculation of exergy loss for every equipment is then carried out by using exergy balance. During this process, exergy loss or exergy gain will occur in every equipment. Exergy loss is present due to the irreversibility of the process, while irreversibility happened because of entropy generation. In general, the exergy loss can be calculated based on equation (5) [23]

where

Therefore, the percentage of exergy loss for every equipment is obtained as follows [20]:

or

2 Methodology

The objective of this study is to evaluate biodiesel production from microalgae with conventional process and HTL-esterification process. In this paper, Aspen Plus 8.6 software was used to simulate the process flow diagram as well as to provide data for the evaluation. The composition of Botryococcus braunii used in this simulation was taken from reference [8]. As the cultivation and harvesting are outside of the boundary of this study, the fresh feed for the process is started with wet microalgae.

The wet microalgae is then fed to the conventional process and HTL-esterification built using Aspen Plus equipment modules.

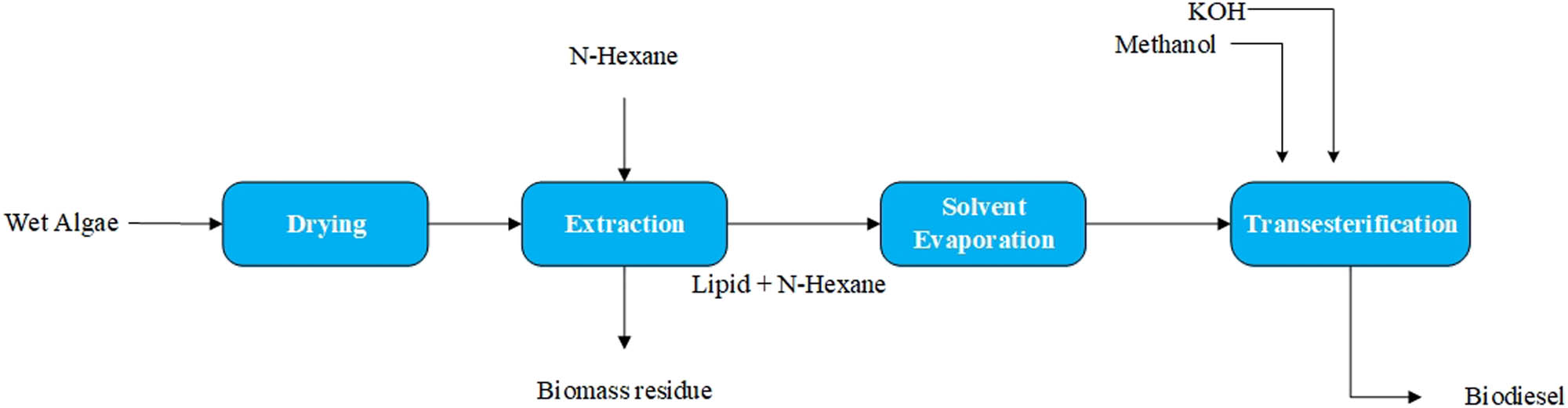

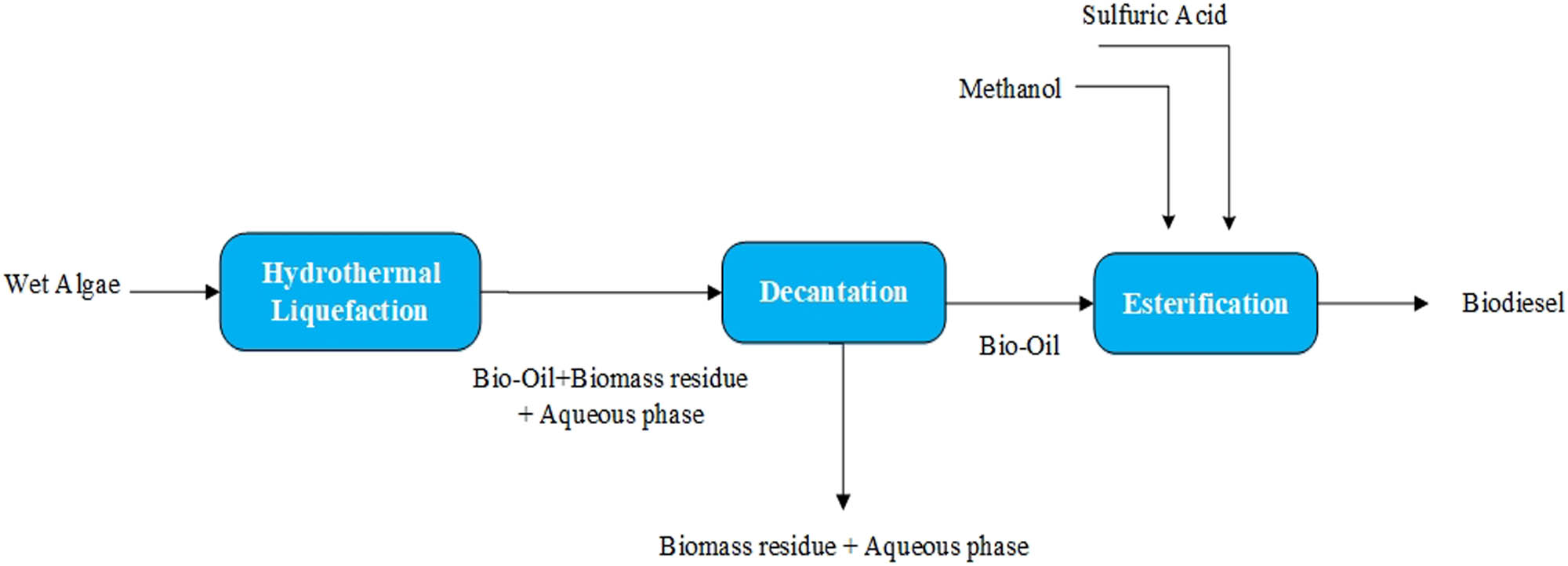

The Aspen Plus equipment modules enable user to resemble many processes in industry and considers equilibrium or rate-processes calculation rigorously. Both of the conventional and HTL-esterification simulations were developed from block diagrams shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Biodiesel production block diagram via conventional process.

Biodiesel production block diagram via HTL-esterification process.

In conventional process shown in Figure 1, biodiesel was produced from transesterification of lipid content in the microalgae. In this process, wet microalgae need to be dried up before entering lipid extraction. The water content of microalgae was reduced by centrifugation, which was followed by water evaporation. Typically, after water removal, dried microalgae was then fed to an extractor in which solvent will extract oil, leaving the microalgae biomass to become residue. The solvent was then evaporated so that the oil can be obtained, as depicted in Figure 1. Stream containing microalgae oil is then transesterified to produce methyl ester or biodiesel.

HTL, also known as subcritical water extraction, is one of the thermochemical conversion routes of biomass, which recently attracted attention due to its capability to proceed with wet biomass. The core of the HTL process lies in the utilization of water at subcritical condition which can act both as solvent for nonorganic components as well as reactant [14]. The needs for high pressure and temperature for producing subcritical water is one of the important parameters in designing HTL process. HTL yields residue, aqueous phase and bio-oil, which are produced from complex reaction [15]. In this simulation, bio-oil containing fatty acid was separated from its other constituents by phase separation. Simple description of HTL process is depicted in Figure 2. In this process, the effluent of HTL process that contained mixture of product was then fed into separator model in Aspen Plus using assumption that the separator was able to purify bio-oil from other constituents. In HTL-esterification process, instead of using lipid content of the microalgae as in the conventional process, biodiesel production was carried out via esterification that converted fatty acid found in bio-oil.

Although bio-oil consists of many organic compounds, it was assumed that the dominant compound was carboxylic acid/fatty acid. The produced carboxylic acid is then reacted with methanol in acidic condition to produce biodiesel.

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

3 Results

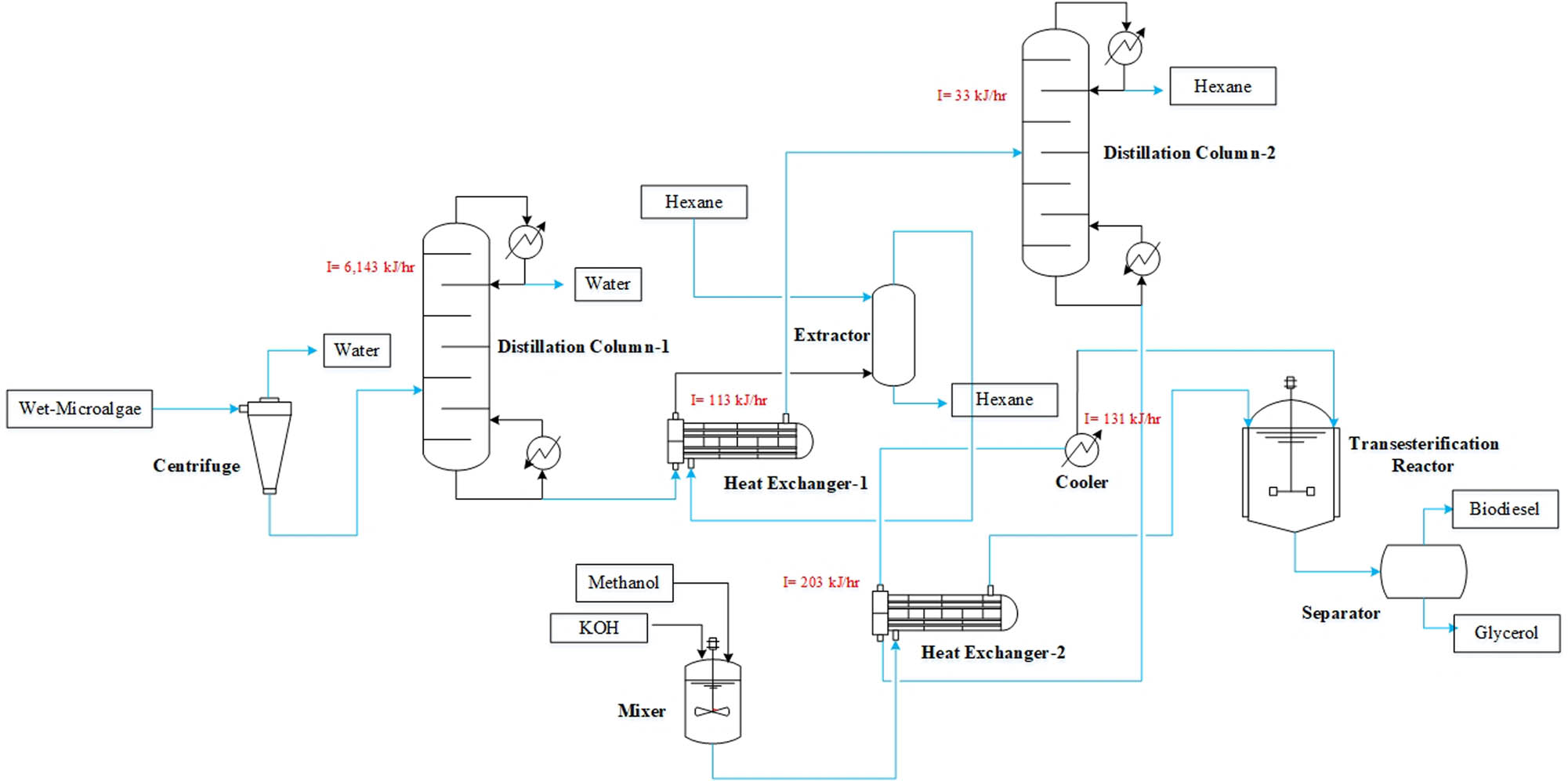

Complete process flow diagram of conventional process is shown in Figure 3. Centrifuge used in the process was able to remove considerable amount of water content [13], yet further water evaporation is still needed to reduce water content of microalgae. Since there is significantly large boiling point difference between water and microalgae component, the distillation column is chosen. During solvent extraction, it is assumed that only triglyceride content is separated from the mixture.

Biodiesel production process flow diagram of conventional process.

Before entering the transesterification reactor, hexane is separated in the second distillation column. For simulating reactors used in the process, block model of RStoic with operating condition obtained from reference is used [24]. The biodiesel product is then separated from glycerol, catalyst and remaining methanol using phase separator.

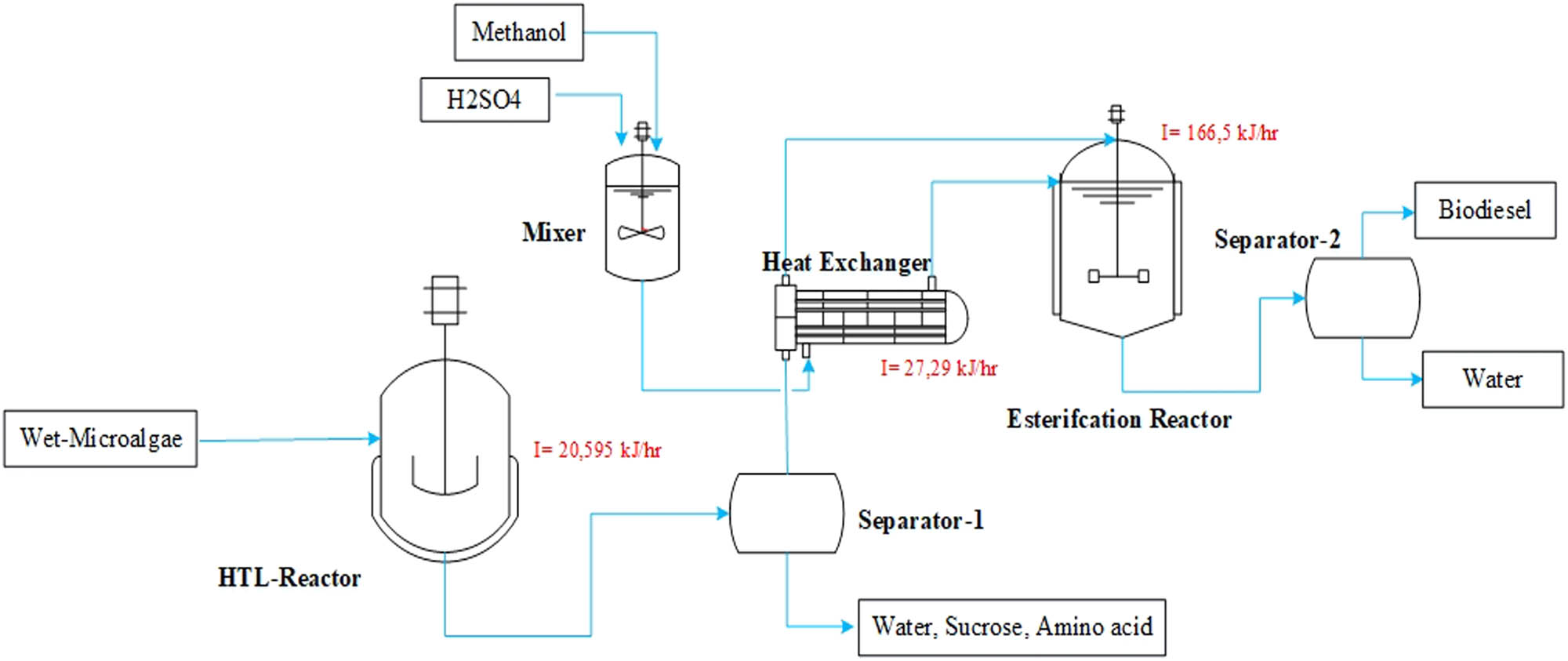

The process flow diagram of HTL-esterification process is shown in Figure 4. Based on Figure 4, it can be observed that HTL-esterification process is a relatively simpler process as compared to conventional. In this process, wet microalgae is directly converted in HTL reactor, in which water content will act as solvent and reactant at subcritical condition [14]. The distinct feature of HTL-esterification is the direct use of wet microalgae for feed stream, thus removing the need for water removal and extraction before reaction. Performing HTL at operating temperature from 95 to 120°C allows the biopolymer content of the microalgae to hydrolyze into its monomer [15]. Therefore, it is expected that the triglyceride can be converted into fatty acid and glycerol. The fatty acid product is then separated from its aqueous phase by utilizing phase separation [20]. Esterification reaction simulation is performed based on the operating condition by Hidayat et al. [25]. After phase separation, the biodiesel product is collected.

Biodiesel production process flow diagram of HTL-esterification process.

4 Discussion

Based on the simulation, the comparison of energy consumption of both processes can be performed. In total, calculation showed that producing biodiesel via conventional process and HTL-esterification process has relatively similar energy consumption, which are 5.68 and 5.65 kW/kg respectively. It is reasonable since although the conventional process needs relatively high energy for water removal via centrifugation and distillation, the HTL-esterification process also demands considerable amount of energy to achieve the subcritical condition for the process.

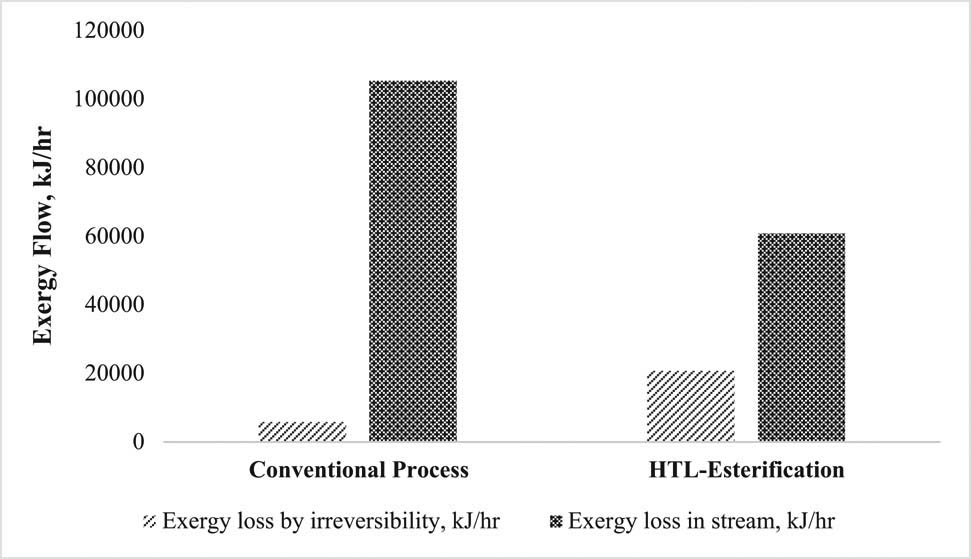

Besides the energy consumption of both processes, exergy analysis can also be performed on each process. Exergy analysis allows the investigation of the most inefficient process or equipment from overall process. In this simulation, exergy loss is categorized into internal exergy loss due to irreversibility and exergy loss due to component removal from stream [23]. Despite its simplicity, that categorization is able to give clearer exergy loss in each equipment as it is shown in Figures 3 and 4. The “I” letter shown in Figures 3 and 4 indicate the exergy loss due to irreversibility or entropy generation, while other equipment without “I” has negligible exergy loss due to irreversibility. According to Figures 3 and 4, it is implied that high exergy loss due to irreversibility occurs in the equipment which is associated with heat transfer. Theoretically, it was also discovered that irreversibility in the process can be caused by several factors, including heat transfer over a finite temperature difference and friction [23]. However, in this simulation, exergy loss due to heat transfer is the dominant one.

Figure 5 gives overall comparison of exergy loss for both processes. It can be deduced that conventional process is significantly inefficient compared to HTL-esterification process. It is also observed that exergy which was carried by removed streams are higher compared to exergy loss due to irreversibility. In addition to that, Figure 5 also depicts that HTL-esterification process has higher irreversibility. This is possible since the HTL reactor consumes higher energy, thus providing heat transfer process leading to high exergy loss.

Biodiesel production process flow diagram of HTL-esterification process.

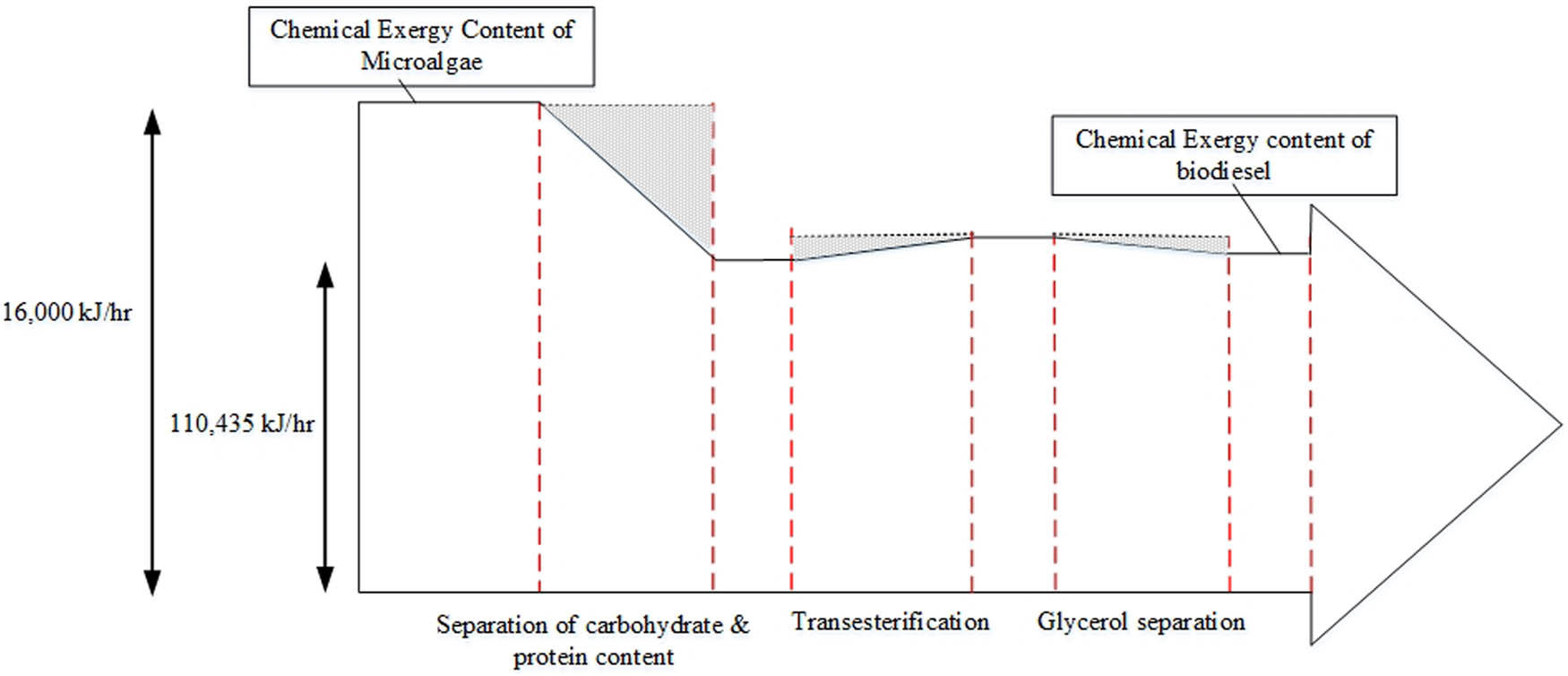

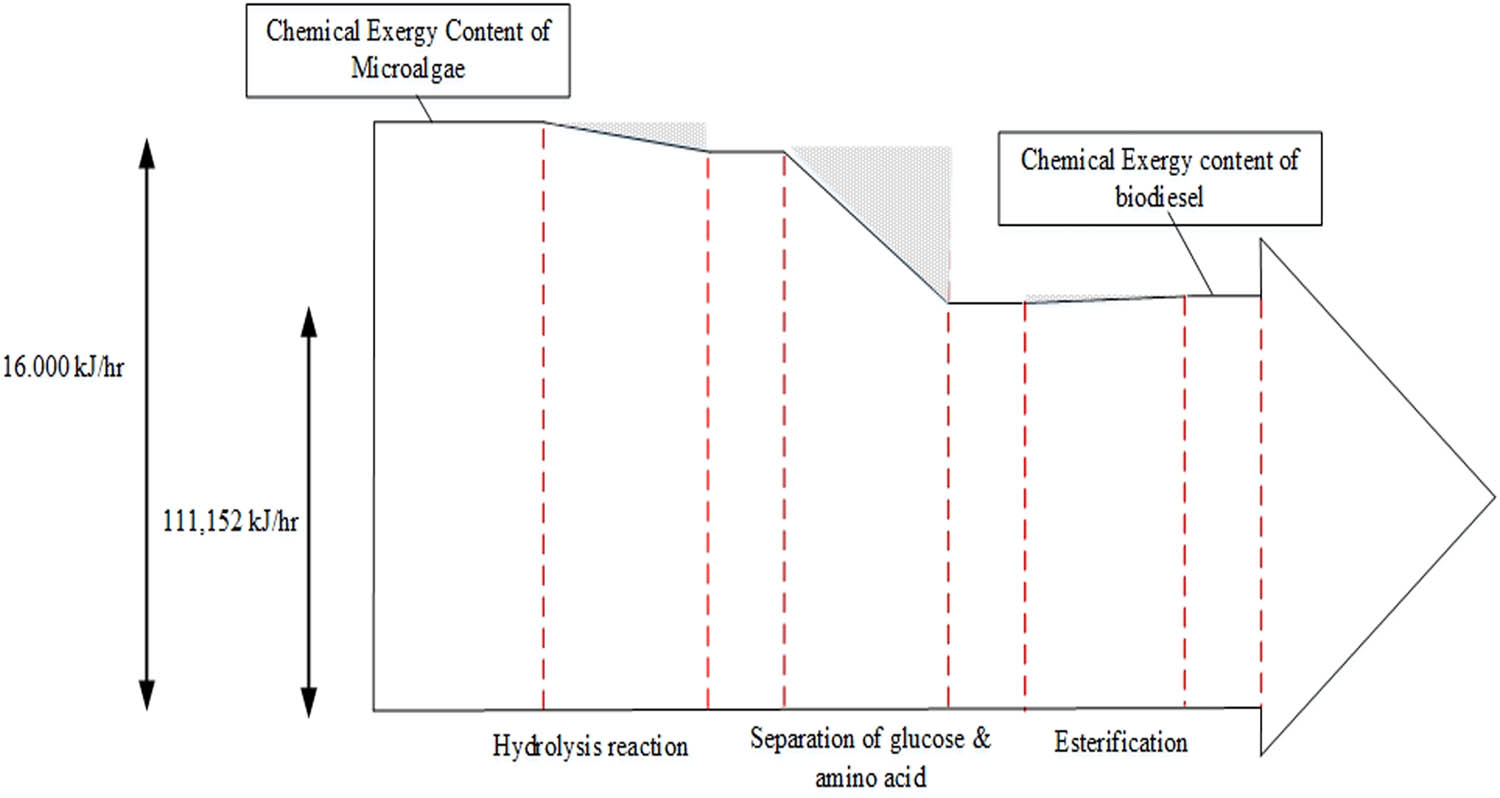

Simple Grassman diagram depicted in Figures 6 and 7 gives the information of chemical exergy change of microalgae during the process. According to both figures, approximately 30% of chemical exergy content of microalgae is lost during the process. It is also observed that the change of exergy content due to reaction is different for both processes. The hydrolysis reaction during HTL reduces the chemical exergy content (Figure 7). On the other hand, the transesterification and esterification reactions cause slight increase of chemical exergy content.

Biodiesel production process flow diagram of HTL-esterification process.

Biodiesel production process flow diagram of HTL-esterification process.

After comparing both conventional and HTL-esterification process, it is known that thermodynamic analysis of the process in terms of energy consumption does not tell much, as the process only has slight difference of energy consumption. However, exergy analysis on both process reveals that chemical exergy recovery from microalgae in biodiesel products is approximately 70% for both conventional and HTL-esterification process. That finding implies that certain amount of exergy is lost during the process. Further investigation shows that exergy loss in the system consists of internal exergy loss in each unit operation due to irreversibility and exergy loss due to stream removal. Overall, it is justified that HTL-esterification offers greater potential for producing biodiesel compared to conventional process, due to its direct capability of utilizing wet microalgae, relatively simpler process and produces lower exergy loss in stream compared to conventional process.

5 Conclusion

From this study, it can be concluded that:

Approximately 30% of microalgae chemical exergy content is lost during conversion process to biodiesel.

Biodiesel production from microalgae using conventional process has higher overall exergy loss compared to HTL-esterification

Exergy loss due to irreversibility of heat transfer in HTL-esterification is higher compared to conventional process.

Acknowledgments

The authors deeply acknowledge the Ministry of Research, Technology and Higher Education, Republic of Indonesia for financial support through “Penelitian Terapan Unggulan Perguruan Tinggi 2018” research scheme with Research Grant No. 1873/UN1/DITLIT/DIT-LIT/LT/2018. The authors also acknowledge Aspentech which has provided the simulation for this research.

Conflict of interest: Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Lam MK, Keat TL. Microalgae biofuels: a critical review of issues, problems and the way forward. Biotechnol Adv. 2012;30:673–90.10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.11.008Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Balai Pengembangan dan Pengkajian Teknologi (BPPT). Outlook Energi Indonesia 2016. Pengembangan Energi untuk Mendukung Industri Hijau; 2016. https://www.bppt.go.id/outlook-energi/bppt-outlook-energi-indonesia-2016.Search in Google Scholar

[3] British Petroleum (BP), 2017, BP Statistical Review of World Energy June 2017. https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/en/corporate/pdf/energy-economics/statistical-review-2017/bp-statistical-review-of-world-energi-2017-full-report.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Mujiyanto S, Tiess G. Secure energy supply in 2025: Indonesia’s need for an energy policy strategy. Energy Policy. 2013;61:31–41.10.1016/j.enpol.2013.05.119Search in Google Scholar

[5] Demirbas A, Demirbas MF. Algae energy: algae as a new source of biodiesel. London: Springer-Verlag London Limited; 2010.10.1007/978-1-84996-050-2Search in Google Scholar

[6] Sawitri DR, Sutijan S, Budiman A. Kinetics study of free fatty acids esterification for biodiesel production from palm fatty acid distillate catalyzed by sulfated zirconia. JEAS. 2016;16:9951–7.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Oncel SS. Microalgae for a macroenergy world. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2013;26:241–64.10.1016/j.rser.2013.05.059Search in Google Scholar

[8] Pradana YS, Sudibyo H, Suyono EA, Indarto I, Budiman A. Oil algae extraction of selected microalgae species grown in monoculture and mixed cultures for biodiesel production. Energy Procedia. 2017;105:277–82.10.1016/j.egypro.2017.03.314Search in Google Scholar

[9] Lee RE. Phycology, 4th edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2008.10.1017/CBO9780511812897Search in Google Scholar

[10] Gouveia JD, Ruiz J, van den Broek LAM, Hesselink T, Peters S, Kleinegris DMM. Botryococcus braunii strains compared for biomass productivity, hydrocarbon and carbohydrate content. J Biotechnol. 2017;248:77–86.10.1016/j.jbiotec.2017.03.008Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Song C, Liu Q, Ji N, Deng S, Zhao J, Li S, et al. Evaluation of hydrolysis-esterification biodiesel production from wet microalgae. Bioresour Technol. 2016;214:747–54.10.1016/j.biortech.2016.05.024Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Mohn F. Harvesting of micro-algal biomass, Micro-algal Biotechnology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1988.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Gollakota ARK, Kishore N, Gu S. A review on hydrothermal liquefaction of biomass. RSER. 2017;81:1378–92.10.1016/j.rser.2017.05.178Search in Google Scholar

[14] Singh R, Bhaskar T, Balagurumurthy B. Hydrothermal upgradation of algae into value-added hydrocarbons. In: Pandey A, Chisti Y, Lee D, Soccol CR, editors. Biofuels from Algae. Elsevier; 2014.10.1016/B978-0-444-59558-4.00011-5Search in Google Scholar

[15] Gai C, Zhang Y, Chen W, Zhang P, Dong Y. An investigation of reaction pathways of hydrothermal liquefaction using Chlorella pyrenoidosa and Spirulina platensis. Energy Convers Manage. 2015;96:330–9.10.1016/j.enconman.2015.02.056Search in Google Scholar

[16] Cahyono RB, Yasuda N, Nomura T, Akiyama T. Utilization of low grade iron ore (FeOOH) and biomass through integrated pyrolysis-tar decomposition (CVI process) in ironmaking industri: exergy analysis and its application. ISIJ Int. 2015;55(2):428–35.10.2355/isijinternational.55.428Search in Google Scholar

[17] Blanco-Marigorta AM, Suarez-Medina J, Vera-Castellano A. Exergetic analysis of a biodiesel production process from Jatropha curcas. Appl Energy. 2013;101:218–25.10.1016/j.apenergy.2012.05.037Search in Google Scholar

[18] Gao X, Yu Y, Wu H. Life cycle energy and carbon footprints of microalgal biodiesel production in Western Australia: a comparison of byproducts utilization strategies. ACS Sustainable Chem Eng. 2013;1(11):1371–80.10.1021/sc4002406Search in Google Scholar

[19] Ofori-Boateng C, Keat TL, JitKang L. Feasibility study of microalgal and jatropha biodiesel production plants: exergy analysis aprroach. Appl Therm Eng. 2011;36:141–51.10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2011.12.010Search in Google Scholar

[20] Budiman A, Ishida M. Three-dimensional graphical exergy analysis of a distillation column. JCEJ. 1996;29:662–8.10.1252/jcej.29.662Search in Google Scholar

[21] Budiman A, Sutijan S, Sawitri RD. Graphical exergy analysis of retrofitted distillation column. Int J Exergy. 2011;8(4):477–93.10.1504/IJEX.2011.041034Search in Google Scholar

[22] Hajjaji N, Baccar I, Pons MN. Energy and exergy analysis as tools for optimization of hydrogen production by glycerol autothermal reforming. Renewable Energy. 2014;71:368–80.10.1016/j.renene.2014.05.056Search in Google Scholar

[23] Kotas TJ. The exergy method of thermal plant analysis, 1st edn. London: Butterworths; 1985.10.1016/B978-0-408-01350-5.50008-8Search in Google Scholar

[24] Kawentar WA, Budiman A. Synthesis of biodiesel from second-used cooking oil. Energy Procedia. 2013;32:190–9.10.1016/j.egypro.2013.05.025Search in Google Scholar

[25] Hidayat A, Rochmadi R, Wijaya K, Nurdiawati A, Kurniawan K, Hinode H, et al. Esterification of palm fatty acid distillate with high amount of free fatty acids using coconut shell char based catalyst. Energy Procedia. 2015;75:969–74.10.1016/j.egypro.2015.07.301Search in Google Scholar

© 2020 Laras Prasakti et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Electrochemical antioxidant screening and evaluation based on guanine and chitosan immobilized MoS2 nanosheet modified glassy carbon electrode (guanine/CS/MoS2/GCE)

- Kinetic models of the extraction of vanillic acid from pumpkin seeds

- On the maximum ABC index of bipartite graphs without pendent vertices

- Estimation of the total antioxidant potential in the meat samples using thin-layer chromatography

- Molecular dynamics simulation of sI methane hydrate under compression and tension

- Spatial distribution and potential ecological risk assessment of some trace elements in sediments and grey mangrove (Avicennia marina) along the Arabian Gulf coast, Saudi Arabia

- Amino-functionalized graphene oxide for Cr(VI), Cu(II), Pb(II) and Cd(II) removal from industrial wastewater

- Chemical composition and in vitro activity of Origanum vulgare L., Satureja hortensis L., Thymus serpyllum L. and Thymus vulgaris L. essential oils towards oral isolates of Candida albicans and Candida glabrata

- Effect of excess Fluoride consumption on Urine-Serum Fluorides, Dental state and Thyroid Hormones among children in “Talab Sarai” Punjab Pakistan

- Design, Synthesis and Characterization of Novel Isoxazole Tagged Indole Hybrid Compounds

- Comparison of kinetic and enzymatic properties of intracellular phosphoserine aminotransferases from alkaliphilic and neutralophilic bacteria

- Green Organic Solvent-Free Oxidation of Alkylarenes with tert-Butyl Hydroperoxide Catalyzed by Water-Soluble Copper Complex

- Ducrosia ismaelis Asch. essential oil: chemical composition profile and anticancer, antimicrobial and antioxidant potential assessment

- DFT calculations as an efficient tool for prediction of Raman and infra-red spectra and activities of newly synthesized cathinones

- Influence of Chemical Osmosis on Solute Transport and Fluid Velocity in Clay Soils

- A New fatty acid and some triterpenoids from propolis of Nkambe (North-West Region, Cameroon) and evaluation of the antiradical scavenging activity of their extracts

- Antiplasmodial Activity of Stigmastane Steroids from Dryobalanops oblongifolia Stem Bark

- Rapid identification of direct-acting pancreatic protectants from Cyclocarya paliurus leaves tea by the method of serum pharmacochemistry combined with target cell extraction

- Immobilization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa static biomass on eggshell powder for on-line preconcentration and determination of Cr (VI)

- Assessment of methyl 2-({[(4,6-dimethoxypyrimidin-2-yl)carbamoyl] sulfamoyl}methyl)benzoate through biotic and abiotic degradation modes

- Stability of natural polyphenol fisetin in eye drops Stability of fisetin in eye drops

- Production of a bioflocculant by using activated sludge and its application in Pb(II) removal from aqueous solution

- Molecular Properties of Carbon Crystal Cubic Structures

- Synthesis and characterization of calcium carbonate whisker from yellow phosphorus slag

- Study on the interaction between catechin and cholesterol by the density functional theory

- Analysis of some pharmaceuticals in the presence of their synthetic impurities by applying hybrid micelle liquid chromatography

- Two mixed-ligand coordination polymers based on 2,5-thiophenedicarboxylic acid and flexible N-donor ligands: the protective effect on periodontitis via reducing the release of IL-1β and TNF-α

- Incorporation of silver stearate nanoparticles in methacrylate polymeric monoliths for hemeprotein isolation

- Development of ultrasound-assisted dispersive solid-phase microextraction based on mesoporous carbon coated with silica@iron oxide nanocomposite for preconcentration of Te and Tl in natural water systems

- N,N′-Bis[2-hydroxynaphthylidene]/[2-methoxybenzylidene]amino]oxamides and their divalent manganese complexes: Isolation, spectral characterization, morphology, antibacterial and cytotoxicity against leukemia cells

- Determination of the content of selected trace elements in Polish commercial fruit juices and health risk assessment

- Diorganotin(iv) benzyldithiocarbamate complexes: synthesis, characterization, and thermal and cytotoxicity study

- Keratin 17 is induced in prurigo nodularis lesions

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and acute toxicity studies of a Saudi polyherbal formulation, PHF5

- LaCoO3 perovskite-type catalysts in syngas conversion

- Comparative studies of two vegetal extracts from Stokesia laevis and Geranium pratense: polyphenol profile, cytotoxic effect and antiproliferative activity

- Fragmentation pattern of certain isatin–indole antiproliferative conjugates with application to identify their in vitro metabolic profiles in rat liver microsomes by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry

- Investigation of polyphenol profile, antioxidant activity and hepatoprotective potential of Aconogonon alpinum (All.) Schur roots

- Lead discovery of a guanidinyl tryptophan derivative on amyloid cascade inhibition

- Physicochemical evaluation of the fruit pulp of Opuntia spp growing in the Mediterranean area under hard climate conditions

- Electronic structural properties of amino/hydroxyl functionalized imidazolium-based bromide ionic liquids

- New Schiff bases of 2-(quinolin-8-yloxy)acetohydrazide and their Cu(ii), and Zn(ii) metal complexes: their in vitro antimicrobial potentials and in silico physicochemical and pharmacokinetics properties

- Treatment of adhesions after Achilles tendon injury using focused ultrasound with targeted bFGF plasmid-loaded cationic microbubbles

- Synthesis of orotic acid derivatives and their effects on stem cell proliferation

- Chirality of β2-agonists. An overview of pharmacological activity, stereoselective analysis, and synthesis

- Fe3O4@urea/HITh-SO3H as an efficient and reusable catalyst for the solvent-free synthesis of 7-aryl-8H-benzo[h]indeno[1,2-b]quinoline-8-one and indeno[2′,1′:5,6]pyrido[2,3-d]pyrimidine derivatives

- Adsorption kinetic characteristics of molybdenum in yellow-brown soil in response to pH and phosphate

- Enhancement of thermal properties of bio-based microcapsules intended for textile applications

- Exploring the effect of khat (Catha edulis) chewing on the pharmacokinetics of the antiplatelet drug clopidogrel in rats using the newly developed LC-MS/MS technique

- A green strategy for obtaining anthraquinones from Rheum tanguticum by subcritical water

- Cadmium (Cd) chloride affects the nutrient uptake and Cd-resistant bacterium reduces the adsorption of Cd in muskmelon plants

- Removal of H2S by vermicompost biofilter and analysis on bacterial community

- Structural cytotoxicity relationship of 2-phenoxy(thiomethyl)pyridotriazolopyrimidines: Quantum chemical calculations and statistical analysis

- A self-breaking supramolecular plugging system as lost circulation material in oilfield

- Synthesis, characterization, and pharmacological evaluation of thiourea derivatives

- Application of drug–metal ion interaction principle in conductometric determination of imatinib, sorafenib, gefitinib and bosutinib

- Synthesis and characterization of a novel chitosan-grafted-polyorthoethylaniline biocomposite and utilization for dye removal from water

- Optimisation of urine sample preparation for shotgun proteomics

- DFT investigations on arylsulphonyl pyrazole derivatives as potential ligands of selected kinases

- Treatment of Parkinson’s disease using focused ultrasound with GDNF retrovirus-loaded microbubbles to open the blood–brain barrier

- New derivatives of a natural nordentatin

- Fluorescence biomarkers of malignant melanoma detectable in urine

- Study of the remediation effects of passivation materials on Pb-contaminated soil

- Saliva proteomic analysis reveals possible biomarkers of renal cell carcinoma

- Withania frutescens: Chemical characterization, analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and healing activities

- Design, synthesis and pharmacological profile of (−)-verbenone hydrazones

- Synthesis of magnesium carbonate hydrate from natural talc

- Stability-indicating HPLC-DAD assay for simultaneous quantification of hydrocortisone 21 acetate, dexamethasone, and fluocinolone acetonide in cosmetics

- A novel lactose biosensor based on electrochemically synthesized 3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene/thiophene (EDOT/Th) copolymer

- Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad: Chemical characterization, scavenging and cytotoxic activities

- Development and validation of a high performance liquid chromatography/diode array detection method for estrogen determination: Application to residual analysis in meat products

- PCSK9 concentrations in different stages of subclinical atherosclerosis and their relationship with inflammation

- Development of trace analysis for alkyl methanesulfonates in the delgocitinib drug substance using GC-FID and liquid–liquid extraction with ionic liquid

- Electrochemical evaluation of the antioxidant capacity of natural compounds on glassy carbon electrode modified with guanine-, polythionine-, and nitrogen-doped graphene

- A Dy(iii)–organic framework as a fluorescent probe for highly selective detection of picric acid and treatment activity on human lung cancer cells

- A Zn(ii)–organic cage with semirigid ligand for solvent-free cyanosilylation and inhibitory effect on ovarian cancer cell migration and invasion ability via regulating mi-RNA16 expression

- Polyphenol content and antioxidant activities of Prunus padus L. and Prunus serotina L. leaves: Electrochemical and spectrophotometric approach and their antimicrobial properties

- The combined use of GC, PDSC and FT-IR techniques to characterize fat extracted from commercial complete dry pet food for adult cats

- MALDI-TOF MS profiling in the discovery and identification of salivary proteomic patterns of temporomandibular joint disorders

- Concentrations of dioxins, furans and dioxin-like PCBs in natural animal feed additives

- Structure and some physicochemical and functional properties of water treated under ammonia with low-temperature low-pressure glow plasma of low frequency

- Mesoscale nanoparticles encapsulated with emodin for targeting antifibrosis in animal models

- Amine-functionalized magnetic activated carbon as an adsorbent for preconcentration and determination of acidic drugs in environmental water samples using HPLC-DAD

- Antioxidant activity as a response to cadmium pollution in three durum wheat genotypes differing in salt-tolerance

- A promising naphthoquinone [8-hydroxy-2-(2-thienylcarbonyl)naphtho[2,3-b]thiophene-4,9-dione] exerts anti-colorectal cancer activity through ferroptosis and inhibition of MAPK signaling pathway based on RNA sequencing

- Synthesis and efficacy of herbicidal ionic liquids with chlorsulfuron as the anion

- Effect of isovalent substitution on the crystal structure and properties of two-slab indates BaLa2−xSmxIn2O7

- Synthesis, spectral and thermo-kinetics explorations of Schiff-base derived metal complexes

- An improved reduction method for phase stability testing in the single-phase region

- Comparative analysis of chemical composition of some commercially important fishes with an emphasis on various Malaysian diets

- Development of a solventless stir bar sorptive extraction/thermal desorption large volume injection capillary gas chromatographic-mass spectrometric method for ultra-trace determination of pyrethroids pesticides in river and tap water samples

- A turbidity sensor development based on NL-PI observers: Experimental application to the control of a Sinaloa’s River Spirulina maxima cultivation

- Deep desulfurization of sintering flue gas in iron and steel works based on low-temperature oxidation

- Investigations of metallic elements and phenolics in Chinese medicinal plants

- Influence of site-classification approach on geochemical background values

- Effects of ageing on the surface characteristics and Cu(ii) adsorption behaviour of rice husk biochar in soil

- Adsorption and sugarcane-bagasse-derived activated carbon-based mitigation of 1-[2-(2-chloroethoxy)phenyl]sulfonyl-3-(4-methoxy-6-methyl-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl) urea-contaminated soils

- Antimicrobial and antifungal activities of bifunctional cooper(ii) complexes with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, flufenamic, mefenamic and tolfenamic acids and 1,10-phenanthroline

- Application of selenium and silicon to alleviate short-term drought stress in French marigold (Tagetes patula L.) as a model plant species

- Screening and analysis of xanthine oxidase inhibitors in jute leaves and their protective effects against hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress in cells

- Synthesis and physicochemical studies of a series of mixed-ligand transition metal complexes and their molecular docking investigations against Coronavirus main protease

- A study of in vitro metabolism and cytotoxicity of mephedrone and methoxetamine in human and pig liver models using GC/MS and LC/MS analyses

- A new phenyl alkyl ester and a new combretin triterpene derivative from Combretum fragrans F. Hoffm (Combretaceae) and antiproliferative activity

- Erratum

- Erratum to: A one-step incubation ELISA kit for rapid determination of dibutyl phthalate in water, beverage and liquor

- Review Articles

- Sinoporphyrin sodium, a novel sensitizer for photodynamic and sonodynamic therapy

- Natural products isolated from Casimiroa

- Plant description, phytochemical constituents and bioactivities of Syzygium genus: A review

- Evaluation of elastomeric heat shielding materials as insulators for solid propellant rocket motors: A short review

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2019

- An overview of Monascus fermentation processes for monacolin K production

- Study on online soft sensor method of total sugar content in chlorotetracycline fermentation tank

- Studies on the Anti-Gouty Arthritis and Anti-hyperuricemia Properties of Astilbin in Animal Models

- Effects of organic fertilizer on water use, photosynthetic characteristics, and fruit quality of pear jujube in northern Shaanxi

- Characteristics of the root exudate release system of typical plants in plateau lakeside wetland under phosphorus stress conditions

- Characterization of soil water by the means of hydrogen and oxygen isotope ratio at dry-wet season under different soil layers in the dry-hot valley of Jinsha River

- Composition and diurnal variation of floral scent emission in Rosa rugosa Thunb. and Tulipa gesneriana L.

- Preparation of a novel ginkgolide B niosomal composite drug

- The degradation, biodegradability and toxicity evaluation of sulfamethazine antibiotics by gamma radiation

- Special issue on Monitoring, Risk Assessment and Sustainable Management for the Exposure to Environmental Toxins

- Insight into the cadmium and zinc binding potential of humic acids derived from composts by EEM spectra combined with PARAFAC analysis

- Source apportionment of soil contamination based on multivariate receptor and robust geostatistics in a typical rural–urban area, Wuhan city, middle China

- Special Issue on 13th JCC 2018

- The Role of H2C2O4 and Na2CO3 as Precipitating Agents on The Physichochemical Properties and Photocatalytic Activity of Bismuth Oxide

- Preparation of magnetite-silica–cetyltrimethylammonium for phenol removal based on adsolubilization

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- Size-dependent growth kinetics of struvite crystals in wastewater with calcium ions

- The effect of silica-calcite sedimentary rock contained in the chicken broiler diet on the overall quality of chicken muscles

- Physicochemical properties of selected herbicidal products containing nicosulfuron as an active ingredient

- Lycopene in tomatoes and tomato products

- Fluorescence in the assessment of the share of a key component in the mixing of feed

- Sulfur application alleviates chromium stress in maize and wheat

- Effectiveness of removal of sulphur compounds from the air after 3 years of biofiltration with a mixture of compost soil, peat, coconut fibre and oak bark

- Special Issue on the 4th Green Chemistry 2018

- Study and fire test of banana fibre reinforced composites with flame retardance properties

- Special Issue on the International conference CosCI 2018

- Disintegration, In vitro Dissolution, and Drug Release Kinetics Profiles of k-Carrageenan-based Nutraceutical Hard-shell Capsules Containing Salicylamide

- Synthesis of amorphous aluminosilicate from impure Indonesian kaolin

- Special Issue on the International Conf on Science, Applied Science, Teaching and Education 2019

- Functionalization of Congo red dye as a light harvester on solar cell

- The effect of nitrite food preservatives added to se’i meat on the expression of wild-type p53 protein

- Biocompatibility and osteoconductivity of scaffold porous composite collagen–hydroxyapatite based coral for bone regeneration

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2019)

- Effect of natural boron mineral use on the essential oil ratio and components of Musk Sage (Salvia sclarea L.)

- A theoretical and experimental study of the adsorptive removal of hexavalent chromium ions using graphene oxide as an adsorbent

- A study on the bacterial adhesion of Streptococcus mutans in various dental ceramics: In vitro study

- Corrosion study of copper in aqueous sulfuric acid solution in the presence of (2E,5E)-2,5-dibenzylidenecyclopentanone and (2E,5E)-bis[(4-dimethylamino)benzylidene]cyclopentanone: Experimental and theoretical study

- Special Issue on Chemistry Today for Tomorrow 2019

- Diabetes mellitus type 2: Exploratory data analysis based on clinical reading

- Multivariate analysis for the classification of copper–lead and copper–zinc glasses

- Special Issue on Advances in Chemistry and Polymers

- The spatial and temporal distribution of cationic and anionic radicals in early embryo implantation

- Special Issue on 3rd IC3PE 2020

- Magnetic iron oxide/clay nanocomposites for adsorption and catalytic oxidation in water treatment applications

- Special Issue on IC3PE 2018/2019 Conference

- Exergy analysis of conventional and hydrothermal liquefaction–esterification processes of microalgae for biodiesel production

- Advancing biodiesel production from microalgae Spirulina sp. by a simultaneous extraction–transesterification process using palm oil as a co-solvent of methanol

- Topical Issue on Applications of Mathematics in Chemistry

- Omega and the related counting polynomials of some chemical structures

- M-polynomial and topological indices of zigzag edge coronoid fused by starphene

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Electrochemical antioxidant screening and evaluation based on guanine and chitosan immobilized MoS2 nanosheet modified glassy carbon electrode (guanine/CS/MoS2/GCE)

- Kinetic models of the extraction of vanillic acid from pumpkin seeds

- On the maximum ABC index of bipartite graphs without pendent vertices

- Estimation of the total antioxidant potential in the meat samples using thin-layer chromatography

- Molecular dynamics simulation of sI methane hydrate under compression and tension

- Spatial distribution and potential ecological risk assessment of some trace elements in sediments and grey mangrove (Avicennia marina) along the Arabian Gulf coast, Saudi Arabia

- Amino-functionalized graphene oxide for Cr(VI), Cu(II), Pb(II) and Cd(II) removal from industrial wastewater

- Chemical composition and in vitro activity of Origanum vulgare L., Satureja hortensis L., Thymus serpyllum L. and Thymus vulgaris L. essential oils towards oral isolates of Candida albicans and Candida glabrata

- Effect of excess Fluoride consumption on Urine-Serum Fluorides, Dental state and Thyroid Hormones among children in “Talab Sarai” Punjab Pakistan

- Design, Synthesis and Characterization of Novel Isoxazole Tagged Indole Hybrid Compounds

- Comparison of kinetic and enzymatic properties of intracellular phosphoserine aminotransferases from alkaliphilic and neutralophilic bacteria

- Green Organic Solvent-Free Oxidation of Alkylarenes with tert-Butyl Hydroperoxide Catalyzed by Water-Soluble Copper Complex

- Ducrosia ismaelis Asch. essential oil: chemical composition profile and anticancer, antimicrobial and antioxidant potential assessment

- DFT calculations as an efficient tool for prediction of Raman and infra-red spectra and activities of newly synthesized cathinones

- Influence of Chemical Osmosis on Solute Transport and Fluid Velocity in Clay Soils

- A New fatty acid and some triterpenoids from propolis of Nkambe (North-West Region, Cameroon) and evaluation of the antiradical scavenging activity of their extracts

- Antiplasmodial Activity of Stigmastane Steroids from Dryobalanops oblongifolia Stem Bark

- Rapid identification of direct-acting pancreatic protectants from Cyclocarya paliurus leaves tea by the method of serum pharmacochemistry combined with target cell extraction

- Immobilization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa static biomass on eggshell powder for on-line preconcentration and determination of Cr (VI)

- Assessment of methyl 2-({[(4,6-dimethoxypyrimidin-2-yl)carbamoyl] sulfamoyl}methyl)benzoate through biotic and abiotic degradation modes

- Stability of natural polyphenol fisetin in eye drops Stability of fisetin in eye drops

- Production of a bioflocculant by using activated sludge and its application in Pb(II) removal from aqueous solution

- Molecular Properties of Carbon Crystal Cubic Structures

- Synthesis and characterization of calcium carbonate whisker from yellow phosphorus slag

- Study on the interaction between catechin and cholesterol by the density functional theory

- Analysis of some pharmaceuticals in the presence of their synthetic impurities by applying hybrid micelle liquid chromatography

- Two mixed-ligand coordination polymers based on 2,5-thiophenedicarboxylic acid and flexible N-donor ligands: the protective effect on periodontitis via reducing the release of IL-1β and TNF-α

- Incorporation of silver stearate nanoparticles in methacrylate polymeric monoliths for hemeprotein isolation

- Development of ultrasound-assisted dispersive solid-phase microextraction based on mesoporous carbon coated with silica@iron oxide nanocomposite for preconcentration of Te and Tl in natural water systems

- N,N′-Bis[2-hydroxynaphthylidene]/[2-methoxybenzylidene]amino]oxamides and their divalent manganese complexes: Isolation, spectral characterization, morphology, antibacterial and cytotoxicity against leukemia cells

- Determination of the content of selected trace elements in Polish commercial fruit juices and health risk assessment

- Diorganotin(iv) benzyldithiocarbamate complexes: synthesis, characterization, and thermal and cytotoxicity study

- Keratin 17 is induced in prurigo nodularis lesions

- Anticancer, antioxidant, and acute toxicity studies of a Saudi polyherbal formulation, PHF5

- LaCoO3 perovskite-type catalysts in syngas conversion

- Comparative studies of two vegetal extracts from Stokesia laevis and Geranium pratense: polyphenol profile, cytotoxic effect and antiproliferative activity

- Fragmentation pattern of certain isatin–indole antiproliferative conjugates with application to identify their in vitro metabolic profiles in rat liver microsomes by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry

- Investigation of polyphenol profile, antioxidant activity and hepatoprotective potential of Aconogonon alpinum (All.) Schur roots

- Lead discovery of a guanidinyl tryptophan derivative on amyloid cascade inhibition

- Physicochemical evaluation of the fruit pulp of Opuntia spp growing in the Mediterranean area under hard climate conditions

- Electronic structural properties of amino/hydroxyl functionalized imidazolium-based bromide ionic liquids

- New Schiff bases of 2-(quinolin-8-yloxy)acetohydrazide and their Cu(ii), and Zn(ii) metal complexes: their in vitro antimicrobial potentials and in silico physicochemical and pharmacokinetics properties

- Treatment of adhesions after Achilles tendon injury using focused ultrasound with targeted bFGF plasmid-loaded cationic microbubbles

- Synthesis of orotic acid derivatives and their effects on stem cell proliferation

- Chirality of β2-agonists. An overview of pharmacological activity, stereoselective analysis, and synthesis

- Fe3O4@urea/HITh-SO3H as an efficient and reusable catalyst for the solvent-free synthesis of 7-aryl-8H-benzo[h]indeno[1,2-b]quinoline-8-one and indeno[2′,1′:5,6]pyrido[2,3-d]pyrimidine derivatives

- Adsorption kinetic characteristics of molybdenum in yellow-brown soil in response to pH and phosphate

- Enhancement of thermal properties of bio-based microcapsules intended for textile applications

- Exploring the effect of khat (Catha edulis) chewing on the pharmacokinetics of the antiplatelet drug clopidogrel in rats using the newly developed LC-MS/MS technique

- A green strategy for obtaining anthraquinones from Rheum tanguticum by subcritical water

- Cadmium (Cd) chloride affects the nutrient uptake and Cd-resistant bacterium reduces the adsorption of Cd in muskmelon plants

- Removal of H2S by vermicompost biofilter and analysis on bacterial community

- Structural cytotoxicity relationship of 2-phenoxy(thiomethyl)pyridotriazolopyrimidines: Quantum chemical calculations and statistical analysis

- A self-breaking supramolecular plugging system as lost circulation material in oilfield

- Synthesis, characterization, and pharmacological evaluation of thiourea derivatives

- Application of drug–metal ion interaction principle in conductometric determination of imatinib, sorafenib, gefitinib and bosutinib

- Synthesis and characterization of a novel chitosan-grafted-polyorthoethylaniline biocomposite and utilization for dye removal from water

- Optimisation of urine sample preparation for shotgun proteomics

- DFT investigations on arylsulphonyl pyrazole derivatives as potential ligands of selected kinases

- Treatment of Parkinson’s disease using focused ultrasound with GDNF retrovirus-loaded microbubbles to open the blood–brain barrier

- New derivatives of a natural nordentatin

- Fluorescence biomarkers of malignant melanoma detectable in urine

- Study of the remediation effects of passivation materials on Pb-contaminated soil

- Saliva proteomic analysis reveals possible biomarkers of renal cell carcinoma

- Withania frutescens: Chemical characterization, analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and healing activities

- Design, synthesis and pharmacological profile of (−)-verbenone hydrazones

- Synthesis of magnesium carbonate hydrate from natural talc

- Stability-indicating HPLC-DAD assay for simultaneous quantification of hydrocortisone 21 acetate, dexamethasone, and fluocinolone acetonide in cosmetics

- A novel lactose biosensor based on electrochemically synthesized 3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene/thiophene (EDOT/Th) copolymer

- Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad: Chemical characterization, scavenging and cytotoxic activities

- Development and validation of a high performance liquid chromatography/diode array detection method for estrogen determination: Application to residual analysis in meat products

- PCSK9 concentrations in different stages of subclinical atherosclerosis and their relationship with inflammation

- Development of trace analysis for alkyl methanesulfonates in the delgocitinib drug substance using GC-FID and liquid–liquid extraction with ionic liquid

- Electrochemical evaluation of the antioxidant capacity of natural compounds on glassy carbon electrode modified with guanine-, polythionine-, and nitrogen-doped graphene

- A Dy(iii)–organic framework as a fluorescent probe for highly selective detection of picric acid and treatment activity on human lung cancer cells

- A Zn(ii)–organic cage with semirigid ligand for solvent-free cyanosilylation and inhibitory effect on ovarian cancer cell migration and invasion ability via regulating mi-RNA16 expression

- Polyphenol content and antioxidant activities of Prunus padus L. and Prunus serotina L. leaves: Electrochemical and spectrophotometric approach and their antimicrobial properties

- The combined use of GC, PDSC and FT-IR techniques to characterize fat extracted from commercial complete dry pet food for adult cats

- MALDI-TOF MS profiling in the discovery and identification of salivary proteomic patterns of temporomandibular joint disorders

- Concentrations of dioxins, furans and dioxin-like PCBs in natural animal feed additives

- Structure and some physicochemical and functional properties of water treated under ammonia with low-temperature low-pressure glow plasma of low frequency

- Mesoscale nanoparticles encapsulated with emodin for targeting antifibrosis in animal models

- Amine-functionalized magnetic activated carbon as an adsorbent for preconcentration and determination of acidic drugs in environmental water samples using HPLC-DAD

- Antioxidant activity as a response to cadmium pollution in three durum wheat genotypes differing in salt-tolerance

- A promising naphthoquinone [8-hydroxy-2-(2-thienylcarbonyl)naphtho[2,3-b]thiophene-4,9-dione] exerts anti-colorectal cancer activity through ferroptosis and inhibition of MAPK signaling pathway based on RNA sequencing

- Synthesis and efficacy of herbicidal ionic liquids with chlorsulfuron as the anion

- Effect of isovalent substitution on the crystal structure and properties of two-slab indates BaLa2−xSmxIn2O7

- Synthesis, spectral and thermo-kinetics explorations of Schiff-base derived metal complexes

- An improved reduction method for phase stability testing in the single-phase region

- Comparative analysis of chemical composition of some commercially important fishes with an emphasis on various Malaysian diets

- Development of a solventless stir bar sorptive extraction/thermal desorption large volume injection capillary gas chromatographic-mass spectrometric method for ultra-trace determination of pyrethroids pesticides in river and tap water samples

- A turbidity sensor development based on NL-PI observers: Experimental application to the control of a Sinaloa’s River Spirulina maxima cultivation

- Deep desulfurization of sintering flue gas in iron and steel works based on low-temperature oxidation

- Investigations of metallic elements and phenolics in Chinese medicinal plants

- Influence of site-classification approach on geochemical background values

- Effects of ageing on the surface characteristics and Cu(ii) adsorption behaviour of rice husk biochar in soil

- Adsorption and sugarcane-bagasse-derived activated carbon-based mitigation of 1-[2-(2-chloroethoxy)phenyl]sulfonyl-3-(4-methoxy-6-methyl-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl) urea-contaminated soils

- Antimicrobial and antifungal activities of bifunctional cooper(ii) complexes with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, flufenamic, mefenamic and tolfenamic acids and 1,10-phenanthroline

- Application of selenium and silicon to alleviate short-term drought stress in French marigold (Tagetes patula L.) as a model plant species

- Screening and analysis of xanthine oxidase inhibitors in jute leaves and their protective effects against hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress in cells

- Synthesis and physicochemical studies of a series of mixed-ligand transition metal complexes and their molecular docking investigations against Coronavirus main protease

- A study of in vitro metabolism and cytotoxicity of mephedrone and methoxetamine in human and pig liver models using GC/MS and LC/MS analyses

- A new phenyl alkyl ester and a new combretin triterpene derivative from Combretum fragrans F. Hoffm (Combretaceae) and antiproliferative activity

- Erratum

- Erratum to: A one-step incubation ELISA kit for rapid determination of dibutyl phthalate in water, beverage and liquor

- Review Articles

- Sinoporphyrin sodium, a novel sensitizer for photodynamic and sonodynamic therapy

- Natural products isolated from Casimiroa

- Plant description, phytochemical constituents and bioactivities of Syzygium genus: A review

- Evaluation of elastomeric heat shielding materials as insulators for solid propellant rocket motors: A short review

- Special Issue on Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2019

- An overview of Monascus fermentation processes for monacolin K production

- Study on online soft sensor method of total sugar content in chlorotetracycline fermentation tank

- Studies on the Anti-Gouty Arthritis and Anti-hyperuricemia Properties of Astilbin in Animal Models

- Effects of organic fertilizer on water use, photosynthetic characteristics, and fruit quality of pear jujube in northern Shaanxi

- Characteristics of the root exudate release system of typical plants in plateau lakeside wetland under phosphorus stress conditions

- Characterization of soil water by the means of hydrogen and oxygen isotope ratio at dry-wet season under different soil layers in the dry-hot valley of Jinsha River

- Composition and diurnal variation of floral scent emission in Rosa rugosa Thunb. and Tulipa gesneriana L.

- Preparation of a novel ginkgolide B niosomal composite drug

- The degradation, biodegradability and toxicity evaluation of sulfamethazine antibiotics by gamma radiation

- Special issue on Monitoring, Risk Assessment and Sustainable Management for the Exposure to Environmental Toxins

- Insight into the cadmium and zinc binding potential of humic acids derived from composts by EEM spectra combined with PARAFAC analysis

- Source apportionment of soil contamination based on multivariate receptor and robust geostatistics in a typical rural–urban area, Wuhan city, middle China

- Special Issue on 13th JCC 2018

- The Role of H2C2O4 and Na2CO3 as Precipitating Agents on The Physichochemical Properties and Photocatalytic Activity of Bismuth Oxide

- Preparation of magnetite-silica–cetyltrimethylammonium for phenol removal based on adsolubilization

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- Size-dependent growth kinetics of struvite crystals in wastewater with calcium ions

- The effect of silica-calcite sedimentary rock contained in the chicken broiler diet on the overall quality of chicken muscles

- Physicochemical properties of selected herbicidal products containing nicosulfuron as an active ingredient

- Lycopene in tomatoes and tomato products

- Fluorescence in the assessment of the share of a key component in the mixing of feed

- Sulfur application alleviates chromium stress in maize and wheat

- Effectiveness of removal of sulphur compounds from the air after 3 years of biofiltration with a mixture of compost soil, peat, coconut fibre and oak bark

- Special Issue on the 4th Green Chemistry 2018

- Study and fire test of banana fibre reinforced composites with flame retardance properties

- Special Issue on the International conference CosCI 2018

- Disintegration, In vitro Dissolution, and Drug Release Kinetics Profiles of k-Carrageenan-based Nutraceutical Hard-shell Capsules Containing Salicylamide

- Synthesis of amorphous aluminosilicate from impure Indonesian kaolin

- Special Issue on the International Conf on Science, Applied Science, Teaching and Education 2019

- Functionalization of Congo red dye as a light harvester on solar cell

- The effect of nitrite food preservatives added to se’i meat on the expression of wild-type p53 protein

- Biocompatibility and osteoconductivity of scaffold porous composite collagen–hydroxyapatite based coral for bone regeneration

- Special Issue on the Joint Science Congress of Materials and Polymers (ISCMP 2019)

- Effect of natural boron mineral use on the essential oil ratio and components of Musk Sage (Salvia sclarea L.)

- A theoretical and experimental study of the adsorptive removal of hexavalent chromium ions using graphene oxide as an adsorbent

- A study on the bacterial adhesion of Streptococcus mutans in various dental ceramics: In vitro study

- Corrosion study of copper in aqueous sulfuric acid solution in the presence of (2E,5E)-2,5-dibenzylidenecyclopentanone and (2E,5E)-bis[(4-dimethylamino)benzylidene]cyclopentanone: Experimental and theoretical study

- Special Issue on Chemistry Today for Tomorrow 2019

- Diabetes mellitus type 2: Exploratory data analysis based on clinical reading

- Multivariate analysis for the classification of copper–lead and copper–zinc glasses

- Special Issue on Advances in Chemistry and Polymers

- The spatial and temporal distribution of cationic and anionic radicals in early embryo implantation

- Special Issue on 3rd IC3PE 2020

- Magnetic iron oxide/clay nanocomposites for adsorption and catalytic oxidation in water treatment applications

- Special Issue on IC3PE 2018/2019 Conference

- Exergy analysis of conventional and hydrothermal liquefaction–esterification processes of microalgae for biodiesel production

- Advancing biodiesel production from microalgae Spirulina sp. by a simultaneous extraction–transesterification process using palm oil as a co-solvent of methanol

- Topical Issue on Applications of Mathematics in Chemistry

- Omega and the related counting polynomials of some chemical structures

- M-polynomial and topological indices of zigzag edge coronoid fused by starphene