Abstract

Understanding the response of biomass allocation in current-year twigs is crucial for elucidating the plant life-history strategies under heterogeneous volcanic habitats. We aimed to test whether twig biomass allocation, within-leaf biomass allocation, and the size-number trade-off of Betula platyphylla would be influenced. We measured twig traits of B. platyphylla in Wudalianchi volcanic kipuka, the lava platform, and Shankou lake in northeastern China using standardized major axis analyses. The results showed that the leaf number, total lamina mass (TLAM), stem mass (SM), and twig mass (TM) were significantly different between the three habitats and were greatest in kipuka with abundant soil nutrients. TLAM and SM scaled allometrically with respect to TM, while the normalization constants of the lava platform differ significantly between kipuka and Shankou lake, which showed that under certain TM, leaves gain more biomass in the lava platform. However, within the leaf, individual lamina mass (ILM) scaled isometrically with respect to individual petiole mass (IPM) in kipuka and the lava platform, but ILM scaled allometrically to IPM in Shankou lake. Our results indicated that inhabitats influenced the twig traits and biomass allocation and within-leaf biomass allocation are strategies for plants to adapt to volcanic heterogeneous habitats.

1 Introduction

Twig biomass allocation is an important driving factor for capturing the net carbon affecting the phenotype and function of plant leaves and twigs and is sensitive to environmental change. Research on the effects of heterogeneous habitats on biomass allocation is crucial for understanding the plant life-history strategies [1,2]. The allometric function has been applied to describe plant biomass allocation. The allometry estimates how one variable scales against another and tests hypotheses about the nature of this relationship and how it varies across samples [3,28]. The current-year twig is the most viable part of the plant branching system, its internal nutrient transformation rate is high, and its trait response is easily observed. The current-year twig can reflect the response of plants to the environment more accurately than the older parts of the plant. Therefore, revealing the relationships of the internal components of laminas, petioles, and stems on the current-year twig is vital for understanding the resource allocation strategies of plants under environmental stress [4].

Plants are sessile and grow in a specific environment. Because the available resources are limited, plants use resources more efficiently by adjusting traits. Plants invest too many resources in a particular functional trait, and the corresponding traits will be reduced [5,6]. The trade-off relationship between twig and leaf size is the core phenomenon in the study of plant life-history strategies. Twigs and leaves are important transport and material production organs that play a critical role in carbon acquisition, allocation strategy, and water transport efficiency [4,7]. Some studies have suggested that the leaf mass scales isometrically with the stem mass (SM) in twigs, and the twig size does not significantly affect the allocation pattern [8]. In determining the relationship between twigs and leaves, the thicker the twigs, the larger the components (leaves, inflorescences, and fruits), and larger leaf biomass [7,9,10]. The relationship also exists within the leaf. The leaf is composed of a lamina and petiole that is an essential component of the twig. The lamina is the primary site of photosynthetic activity and carbohydrate synthesis, while the petiole is a cantilevered structure that supports and supplies laminas, additionally playing the role of supporting static gravity and resisting external dynamic tension [11]. Generally speaking, when the biomass of the total leaves is fixed, the more biomass allocated to leaves, the stronger the photosynthetic carbon acquisition capacity of leaves, and the more favorable to plants; however, the increase of leaf area and weight requires that the petiole must have higher support capacity, and the increase of leaves also leads to an increase of biomass allocated to petioles and midvein [12]. Numerous studies of twig biomass allocation have been carried out on different habitats [13] and plant species [14,15]; however, there are a few studies on volcanic habitats. Therefore, further research on how plants adjust the relationship between twigs and leaves to adapt to extreme volcanic habitats is required.

Besides the trade-off relationship of biomass allocation, the trade-off between the leaf size and leaf number (LN) has a very important influence on the plant biomass allocation strategies; it affects the plasticity of the leaf economic spectrum and leaf function traits [16] and reflects the plant’s adaptability to special habitats [17]. Westby found a trade-off relationship between the leaf size and LN at the twig level [18]. Kleiman and Aarssen studied 24 deciduous broadleaved tree species and found a negative isokinetic growth relationship between leafing intensity (LI) and leaf area [18]. Li et al. study on 12 deciduous shrub species in the western Gobi and 56 woody plants in temperate zones also showed an isokinetic growth relationship between the leaf size and LI [19]. However, Milla found a negative allometric growth relationship between the dry leaf weight and LI [20]. Although the trade-off between the leaf size and LI is widespread among species and habitats [21,22], a few research studies have focused on the relationship between different volcanic habitats.

The Wudalianchi National Geological Park (WNGK), located in the Heilongjiang Province of Northeast China, has a well-preserved single genetic inland volcanic landform and maintains the original and complete vegetation ecological succession process. Thus, it provides an ideal location for the study of plant succession and evolution in a volcanic ecosystem. After the volcanic eruption, two types of relative volcanic landforms were created, the lava platform and the kipuka. Although in the same area, Shankou lake was not affected by volcanic activity. Betula platyphylla is a tall deciduous tree, a pioneer species distributed in a kipuka, lava platform, and Shankou lake. These three habitats exhibit differences in environmental factors such as light, water, and soil nutrients. In this study, twig traits and biomass allocation, and the size-number trade-offs of B. platyphylla in three different habitats were investigated. The objective was to understand the adaptive strategies adopted by adjusting twig biomass allocation of B. platyphylla to provide a scientific basis for the study of plant succession in a volcanic habitat.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study area

This study was conducted in WNGK, Heilongjiang Province, northeast China (48°30′–48°50′N, 126°00′–126°25′E). The last volcanic eruption occurred in Laoheishan between 1719 and 1721, forming an 80 km2 basalt lava platform [23]. The kipuka was not covered with volcanic lava and retained the original island soil [24]. Shankou Park, 65 km from WNGK, was not affected by the volcanic eruption [25] (Table 1). The Wudalianchi area has a temperate continental monsoon climate with severely cold and long winters and pleasantly cool and short summers. It has an annual average temperature of −0.5°C, annual average precipitation of 473 mm, an annual frost-free period of 121 days, and a zonal dark-brown soil type. The vegetation of Wudalianchi is temperate, broad-leaf, and mixed forest. The pioneer community of forest succession in the three habitats was Populus birch forest. The dominant plants are Larix gmelini, Quercus mongolica, B. platyphylla, Populus davidiana, and P. koreana.

General characteristics of the study areas

| Plots | Kipuka (H1) | Lava platform (H2) | Shankou Park (H3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Location | 48°39ʹ13ʺN, 126°16ʹ30ʺE | 48°42ʹ32ʺN, 126°07ʹ06ʺE | 48°28ʹ20ʺN, 126°30ʹ30ʺE |

| Eruption time | 300 years ago | 300 years ago | No eruption |

| Soil type | Dark-brown soil, black volcanic ash [26] | Volcanic stony soil, Herbaceous volcanic ash [26] | Dark-brown soil |

| TN (%) | 1.72 ± 0.35 | 0.17 ± 0.07 | 0.58 ± 0.2 |

| TP (%) | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 0.31 ± 0.05 | 0.14 ± 0.05 |

| TK (%) | 1.51 ± 0.31 | 3.24 ± 0.31 | 1.76 ± 0.18 |

| Altitude | 328 m | 328 m | 306 m |

| Vegetation | Poplar birch forest | Poplar birch forest | Poplar birch forest |

| Crown density (%) | 60–80 | 30–50 | 60–80 |

| Height (m) | 7–11 | 3–5.5 | 10–16 |

| Diameter at breast height (cm) | 6.8–8.5 | 2.6–6.8 | 12–13.5 |

| Foreat age | 28 ± 6.7 | 45 ± 8.2 | 43 ± 2.4 |

In August 2019, five healthy, mature B. platyphylla plants were selected from the kipuka, lava platform, and Shankou lake. To reduce the influence of the tree size, the age of sample trees was not less than 20 years, and they had similar diameters at breast height. The distance between samples was not less than 20 m. The top six vegetative branches without apparent leaf area loss were randomly selected from the outer canopy of each B. platyphylla plant, that is, from the distal end to the last terminal twig that is usually branchless, flowerless, and fruitless; it is the terminal twig of the current year’s twig.

Twigs are composed of leaves and stems, and the leaves consist of two parts: lamina and petiole. All leaves on each current year’s twig were taken off, and the LN lamina was recorded. The laminas, petioles, and stems were oven-dried at 70°C for 48 h to a constant weight, and the dry weight was measured. In this study, the total lamina mass (TLAM), total petiole mass (TPM), and total leaf mass (TLM) were determined using the total dry weights of the laminas, petioles, and stems of each twig.

Within the leaf biomass and trade-off relationship, individual leaf mass is the average of all the individual leaf dry weights. Additionally, we calculated the leaf intensity using the relevant calculation formula as follows:

2.2 Statistical analysis

All the data were log 10 transformed to fit a normal distribution before analysis. The mean and standard error of each twig trait was calculated. Analysis of variance followed by Duncan’s test was used to identify significant differences among the habitats. The relationships between TLAM and twig mass (TM), TPM and TM, SM and TM, TLM and SM, ILM and individual petiole mass (IPM), and ILM and LI were evaluated by regression analysis. Regression analyses showed that the variables of primary interest were log–log linear-correlated and conformed to the equation log(y) = log(b) + a log(x), where log b is the scaling constant, a is the scaling exponent, and y and x are different parts of plant biomass. When a = 1, the scaling relationship is isometric; and when a ≠ 1, the scaling relationship is allometric [27]. Then, we compared the slopes of these linear relationships during different habitats using standardized major axis regression analysis, which was implemented in the “smatr” package [28]. All statistical analyses were performed using R-3.6.2.

3 Results

3.1 Twig traits of B. platyphylla in heterogeneous habitat

The LN, TLAM, SM, and TM of B. platyphylla were significantly different among the three habitats (Table 2). The LN, TLAM, SM, and TM of B. platyphylla in the kipuka were greater than those in the lava platform and Shankou lake. The IPM and TPM of B. platyphylla in the kipuka were significantly higher than the lava platform and Shankou lake. The LN, TLAM, SM, and TM of B. platyphylla were larger in the kipuka but were smaller in the lava platform.

Branch traits of B. platyphylla in a heterogeneous habitat (mean ± SD)

| Trait | Codes | Kipuka (H1) | Lava platform (H2) | Shankou lake (H3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LN | (LN) | 8.57 ± 2.21a | 4.90 ± 0.80c | 6.90 ± 1.49b |

| ILM (mg) | (ILM) | 130.40 ± 42.48a | 119.02 ± 24.35a | 125.62 ± 57.30a |

| IPM (mg) | (IPM) | 9.20 ± 2.70a | 7.72 ± 1.76b | 7.42 ± 3.11b |

| TLAM (g) | (TLAM) | 1.17 ± 0.63a | 0.59 ± 0.17c | 0.87 ± 0.42b |

| TPM (g) | (TPM) | 0.08 ± 0.04a | 0.04 ± 0.01b | 0.05 ± 0.02b |

| SM (g) | (SM) | 0.30 ± 0.19a | 0.08 ± 0.02c | 0.21 ± 0.11b |

| TM (g) | (TM) | 1.56 ± 0.85a | 0.70 ± 0.20c | 1.14 ± 0.54b |

| LI (No./g) | (LI) | 6.46 ± 2.49a | 7.31 ± 1.64a | 7.11 ± 2.74a |

Note: Different lowercase letters mean significant difference at the α = 0.05 level between different habitats.

3.2 Twig biomass allocation of B. platyphylla in a heterogeneous habitat

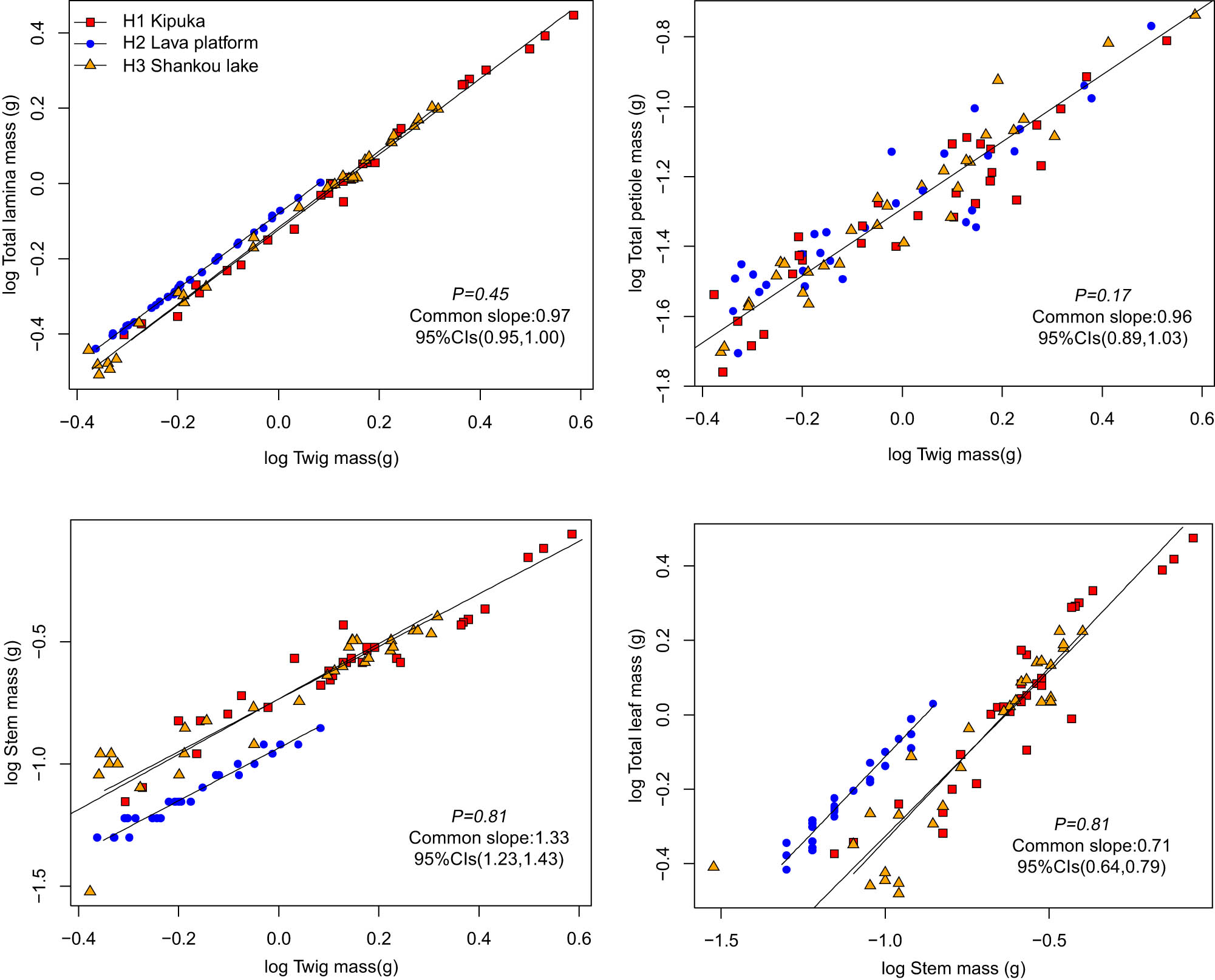

The TM was positively correlated with the TLAM and SM (Figure 1, Table 3). Among the three habitats, TLAM and SM scaled allometrically with respect to TM, with common slopes of 0.97 (95% CI = 0.95 and 1.00, P = 0.45) and 1.33 (95% CI = 1.23 and 1.43, P = 0.81), and the normalization constants of B. platyphylla in lava platform differ significantly in kipuka and Shankou lake. The TM was positively correlated with TPM. Their common slope was 0.96 (95% CI = 0.89 and 1.03, P = 0.17). TPM scaled isometrically with respect to TM. The TLM was positively correlated with the SM. Among the three habitats, TLM scaled allometrically with respect to SM, with a common slope of 0.71 (95% CI = 0.64 and 0.79, P = 0.81), and the normalization constants of B. platyphylla in the lava platform differ significantly in kipuka and Shankou lake.

Twig biomass allocation relationship of B. platyphylla.

Summary of regression slopes and confidence intervals for TLAM, TPM, SM vs TM, TLM vs SM, and ILM vs IPM

| Index (log y − log x) | Item | Slope | 95% CI | Intercept | R 2 | P | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TLAM–TM | H1 | 1.003 | 0.97, 1.03 | −0.12 | 0.993 | <0.001 | 30 |

| H2 | 0.997 | 0.98, 1.01 | −0.08 | 0.999 | <0.001 | 30 | |

| H3 | 1.018 | 0.99, 1.05 | −0.12 | 0.993 | <0.001 | 30 | |

| TPM–TM | H1 | 0.970 | 0.86, 1.09 | −1.27 | 0.905 | <0.001 | 30 |

| H2 | 1.081 | 0.89, 1.31 | −1.26 | 0.754 | <0.001 | 30 | |

| H3 | 0.863 | 0.74, 1.00 | −1.33 | 0.844 | <0.001 | 30 | |

| SM–TM | H1 | 1.075 | 0.96, 1.20 | −0.74 | 0.918 | <0.001 | 30 |

| H2 | 1.079 | 1.01, 1.16 | −0.94 | 0.968 | <0.001 | 30 | |

| H3 | 1.132 | 0.98, 1.31 | −0.73 | 0.861 | <0.001 | 30 | |

| TLM–SM | H1 | 0.927 | 0.81, 1.07 | 0.59 | 0.871 | <0.001 | 30 |

| H2 | 0.920 | 0.85, 1.00 | 0.81 | 0.959 | <0.001 | 30 | |

| H3 | 0.886 | 0.75, 1.05 | 0.56 | 0.804 | <0.001 | 30 | |

| ILM–IPM | H1 | 1.072 | 0.88, 1.31 | 1.08 | 0.733 | <0.001 | 30 |

| H2 | 0.804 | 0.64, 1.01 | 1.36 | 0.650 | <0.001 | 30 | |

| H3 | 1.217 | 1.02, 1.46 | 1.04 | 0.781 | <0.001 | 30 | |

| ILM–LI | H1 | −0.999 | −1.06, −0.93 | 2.87 | 0.972 | <0.001 | 30 |

| H2 | −0.994 | −1.01, −0.97 | 2.92 | 0.998 | <0.001 | 30 | |

| H3 | −1.036 | −1.08, 0.99 | 2.95 | 0.988 | <0.001 | 30 |

LI for twig biomass allocations of B. platyphylla in a heterogeneous habitat, H1: Kipuka, H2: Lava platform, H3: Shankou lake. Statistically significant relationships are tested at the 0.05 level.

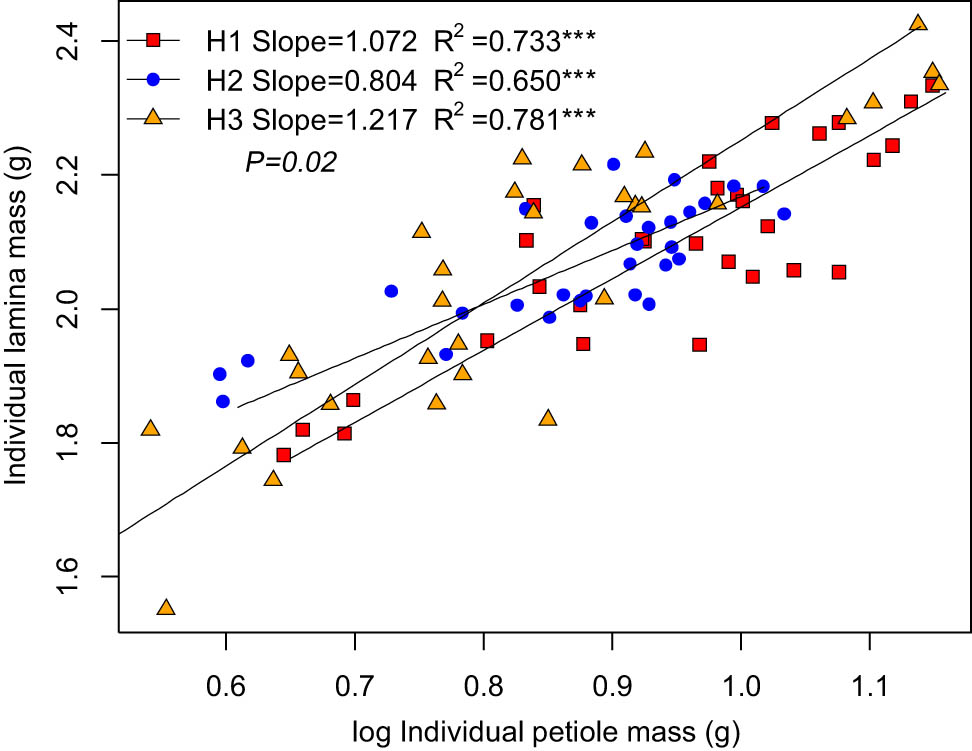

The ILM was positively correlated with the IPM (Figure 2, Table 3). Among the three habitats, ILM scaled isometrically with respect to IPM in kipuka and the lava platform (Figure 2), with slopes of 1.072 and 0.804, respectively, but ILM scaled allometrically with respect to IPM in Shankou lake, with a slope of 1.217.

Within leaf biomass allocation relationship of B. platyphylla.

3.3 Leaf size-number trade-off of B. platyphylla in heterogeneous habitat

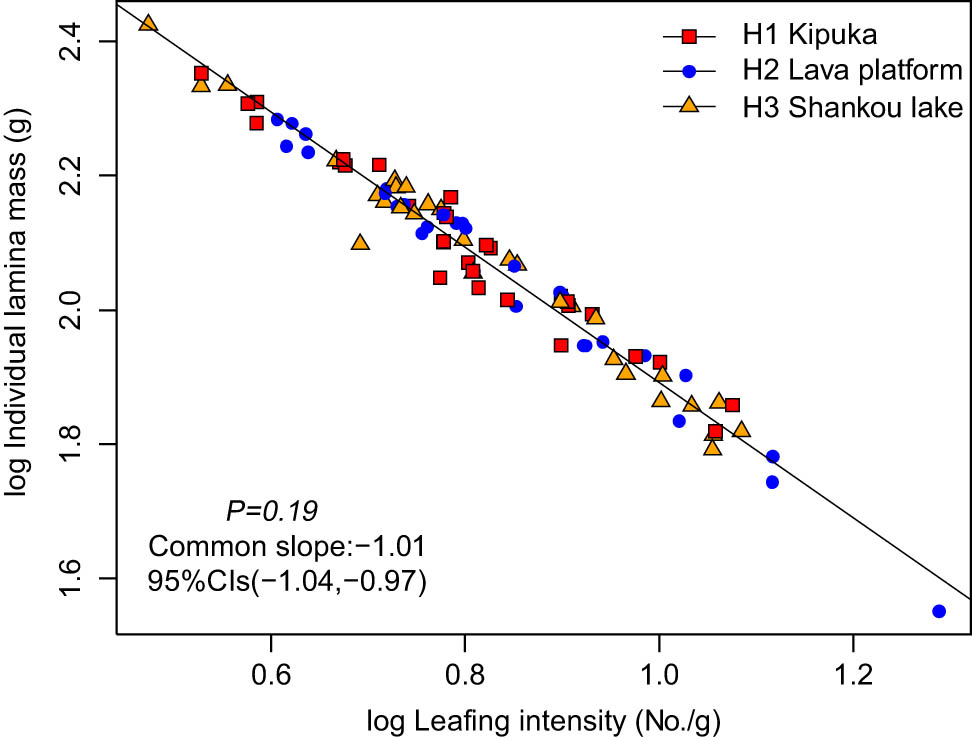

The ILM was positively correlated with the LI (Figure 3). Among the three habitats, ILM scaled isometrically with respect to LI (Table 3), with a common slope of −1.01 (95% CI = −1.04 and −0.97, P = 0.19). The normalization constants did not differ significantly across the three habitats.

The size-number trade-off of B. platyphylla in different habitats.

4 Discussion

Habitat is an important factor affecting the distribution and growth of plants, and the adaptation of plants to habitats is a trade-off process involving internal and external plant functional traits [29]. Different environmental factors, such as soil moisture, nutrient, and light conditions, elicit different plant survival strategies. The LN, TLAM, SM, and TM of B. platyphylla were significantly different in the three habitats, suggesting that they are affected by the habitat. They are the greatest in kipuka with good environmental conditions and lowest in the lava platform with relatively poor environmental conditions. This may be because kipuka retains the original dark-brown soil before the eruption, now covered with a layer of black volcanic ash [26]; therefore, soil nutrients are more abundant, and plants produce larger leaves and twigs. Since the volcanic eruption was only 300 years ago, the soil matrix of the lava platform is volcanic stony [26], the soil nitrogen and water content are low, and potassium is rich; in general, plant growth conditions are relatively poor, resulting in smaller leaves and twigs [30,31].

Twig biomass allocation is an important driving factor for plant net carbon acquisition, [32] turnover, and plant life history under different habitats. The leaf is the main site for photosynthesis, where the exchange of material and energy occurs, and the stem has multiple functions of nutrient transport, storage, leaf support, and expansion of growth space. This study found that TLAM and SM were scaled allometrically with respect to TM. TLM scaled allometrically with respect to stem, and the common slope of the TLAM and the TM was lesser than 1. However, the common slope of the SM and the TM was greater than 1. The results showed that the weight increase rate of the stem was higher than the leaf in twigs, probably due to plants preferentially allocate biomass to stem organs to support the leaf and transport nutrients and water in the volcanic habitat. The normalization constants of TLAM and the TM had an upward displacement in the main axis direction in the lava platform. However, the normalization constants of SM and the TM had a downward displacement in the direction of the main axis. The results showed that because of exposed rocks, shallow soil layer, less plant distribution, and, more direct sunlight in the lava platform, B. platyphylla needed to allocate a higher proportion of biomass to its leaves for photosynthesis and food production in the lava platform. This study found that the total petiole was isometric with respect to TM with their common slope of 0.96 (95% CI = 0.89 and 1.03, P = 0.17); the results showed petiole mass had little effect on biomass allocation in the twig, and petiole mass in the twig was not affected by the habitat.

The leaves have two components: an expanded lamina and a beam-like petiole. The support investment within the leaf is an important part of the support investment of the plant [33]. The lamina produces nutrients, and the petiole is a cantilever structure supporting the lamina and serves in the transportation of nutrients and water. This study found that the slope differs significantly across the three habitats. The results showed that the habitat conditions affected the leaf biomass allocation. The relationship between ILM and IPM was allometric, scaling with slopes significantly >1.0 in the Shankou lake. This suggests that the increase in lamina investment was greater than the lamina support cost. A few studies have found an allometric scaling relationship between the leaves (photosynthetic structures) and petioles (support structures) [25,34]. In general, when the total leaf biomass is not fixed, more biomass is allocated to the leaves, increasing their photosynthetic carbon acquisition capacity; the plant is benefited by increased leaf area and quality. The relationship between ILM and IPM was isometric scaling in kipuka and the lava platform: the higher the lamina mass, the greater the petiole mass. The petiole mass increased to support the increase in the leaf mass [35]. The support investment accelerated with the increased cost of the expanded leaf size, and the increased support cost may be more than offset by the increased carbon absorption due to leaf enlargement.

The plant trade-off relationship between the leaf size and LN is ubiquitous. They are two important factors determining the compactness of the crown that directly affects the canopy structure and the development mode of plants and subsequently affects light interception and carbon acquisition capacity [36]. The changes in leaf sizes are correlated with the availability of water and nutrients in the habitat and other plant functional traits [37]. Sun et al. analyzed the twigs of 123 species datasets compiled in the subtropical mountain forest, the minimum leaf mass and maximum leaf mass versus the LI based on SM (LI), and the scaling exponents ranged from −1.24 to −1.04 [38]. Our study showed a significant negative isometric scaling relationship between ILM and LI in the three habitats. Their common slope was −1.01 (95% CI = −1.04 and −0.97, P = 0.19). Previous studies have shown a significant negative isometric scaling between the leaf size and LI for species in different habitats [21,39]. Due to their sessile nature, plants cannot escape risk in the growth process; they take appropriate strategies to adapt to the external environment. The larger leaves are predominantly arranged on the current-year twig in kipuka with the lesser LN, the larger leaves maximizing light interception and photosynthetic carbon acquisition in low light and nutrient-rich habitat [40]; plants will compensate for the increased cost of large-leaf construction and expansion by reducing the number of leaves and minimizing the degree of self-shade. In contrast, B. platyphylla had small leaves in the lava platform. Small leaves have a shorter leaf unfolding time than large leaves; they are less resistant to heat and have less surface area for material exchange, which are better adapted to environmental conditions of high light radiation and low nutrients [19], and so, plants need higher LN.

5 Conclusion

In this study, LN, TLAM, SM, and TM were significantly different between the three habitats and were greatest in kipuka with abundant soil nutrients. TLAM and SM scaled allometrically with respect to TM, and the normalization constants of the lava platform differ significantly from the kipuka and Shankou lake, which showed that under certain TMs, leaves gain more biomass in the lava platform with barren soil nutrients. However, in within-leaf, ILM scaled isometrically with respect to IPM in kipuka and the lava platform, but ILM scaled allometrically with respect to IPM in Shankou lake. Our results indicated that inhabitats influenced the twig traits and biomass allocation, and within-leaf biomass allocation is a strategy for plants to adapt to volcanic heterogeneous habitats.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Yunfei Yang and Haiyan Li from Northeast Normal University and the Management Committee of Wudalianchi Scenic Spot Nature Reserve for providing assistance.

-

Funding information: The work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31770497), Research on Basic Applied Technology of Colleges and Institutions in Heilongjiang Province of China Project (ZNBZ2019ZR01) and Heilongjiang Academy of Sciences Funds for Distinguished Young Scholars (CXJQ2021ZR01).

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Pickup M, Westoby M, Basden A. Dry mass costs of deploying leaf area in relation to leaf size. Funct Ecol. 2005;19(1):88–97.10.1111/j.0269-8463.2005.00927.xSearch in Google Scholar

[2] Zhang H, Song TQ, Wang KL, Yang H, Yue YM, Zeng ZX, et al. Influences of stand characteristics and environmental factors on forest biomass and root-shoot allocation in southwest China. Ecol Eng. 2016;91:7–15.10.1016/j.ecoleng.2016.01.040Search in Google Scholar

[3] Warton DI, Weber NC. Common slope tests for bivariate errors-in-variables models. Biom J. 2002;44(2):161–74.10.1002/1521-4036(200203)44:2<161::AID-BIMJ161>3.0.CO;2-NSearch in Google Scholar

[4] Osada N. Crown development in a pioneer tree, Rhus trichocarpa, in relation to the structure and growth of individual branches. N Phytol. 2006;172(4):667–78.10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01857.xSearch in Google Scholar

[5] Heuret P, Meredieu C, Coudurier T, Courdier F, Barthelemy D. Ontogenetic trends in the morphological features of main stem annual shoots of Pinus pinaster (Pinaceae). Am J Bot. 2006;93(11):1577–87.10.3732/ajb.93.11.1577Search in Google Scholar

[6] Barthelemy D, Caraglio Y. Plant architecture: a dynamic, multilevel and comprehensive approach to plant form, structure and ontogeny. Ann Bot. 2007;99(3):375–407.10.1093/aob/mcl260Search in Google Scholar

[7] Westoby M, Wright IJ. The leaf size-twig size spectrum and its relationship to other important spectra of variation among species. Oecologia. 2003;135(4):621–8.10.1007/s00442-003-1231-6Search in Google Scholar

[8] Xiang SA, Wu N, Sun SC. Within-twig biomass allocation in subtropical evergreen broad-leaved species along an altitudinal gradient: allometric scaling analysis. Trees-Struct Funct. 2009;23(3):637–47.10.1007/s00468-008-0308-6Search in Google Scholar

[9] Corner EJH. The Durian theory or the origin of the modern tree. Ann Bot. 1949;13(52):367–414.10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a083225Search in Google Scholar

[10] Mensah S, Kakai RG, Seifert T. Patterns of biomass allocation between foliage and woody structure: the effects of tree size and specific functional traits. Ann For Res. 2016;59(1):49–60.10.15287/afr.2016.458Search in Google Scholar

[11] Wright SJ, Muller-Landau HC, Condit R, Hubbell SP. Gap-dependent recruitment, realized vital rates, and size distributions of tropical trees. Ecology. 2003;84(12):3174–85.10.1890/02-0038Search in Google Scholar

[12] Niinemets U, Portsmuth A, Tobias M. Leaf shape and venation pattern alter the support investments within leaf lamina in temperate species: a neglected source of leaf physiological differentiation? Funct Ecol. 2007;21(1):28–40.10.1111/j.1365-2435.2006.01221.xSearch in Google Scholar

[13] Sun SC, Jin DM, Shi PL. The leaf size-twig size spectrum of temperate woody species along an altitudinal gradient: an invariant allometric scaling relationship. Ann Bot. 2006;97(1):97–107.10.1093/aob/mcj004Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Wang M, Jin G, Liu Z. Variation and relationships between twig and leaf traits of species across successional status in temperate forests. Scand J For Res. 2019;34(8):647–55.10.1080/02827581.2019.1674917Search in Google Scholar

[15] Sun J, Wang MT, Cheng L, Lyu M, Sun MK, Li M, et al. Allometry between twig size and leaf size of typical bamboo species along an altitudinal gradient. J Appl Ecol. 2019;30(1):165–72.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Westoby M, Falster DS, Moles AT, Vesk PA, Wright IJ. Plant ecological strategies: some leading dimensions of variation between species. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 2002;33:125–59.10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.33.010802.150452Search in Google Scholar

[17] Violle C, Navas ML, Vile D, Kazakou E, Fortunel C, Hummel I, et al. Let the concept of trait be functional! Oikos. 2007;116(5):882–92.10.1111/j.0030-1299.2007.15559.xSearch in Google Scholar

[18] Kleiman D, Aarssen LW. The leaf size/number trade-off in trees. J Ecol. 2007;95(2):376–82.10.1111/j.1365-2745.2006.01205.xSearch in Google Scholar

[19] Li T, Deng JM, Wang GX, Cheng DL, Yu ZL. Isometric scaling relationship between leaf number and size within current-year shoots of woody species across contrasting habitats. Pol J Ecol. 2009;57(4):659–67.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Milla R. The leafing intensity premium hypothesis tested across clades, growth forms and altitudes. J Ecol. 2009;97(5):972–83.10.1111/j.1365-2745.2009.01524.xSearch in Google Scholar

[21] Yang DM, Li GY, Sun SC. The generality of leaf size versus number trade-off in temperate woody species. Ann Bot. 2008;102(4):623–9.10.1093/aob/mcn135Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Sun J, Wang M, Lyu M, Niklas KJ, Zhong Q, Li M, et al. Stem and leaf growth rates define the leaf size vs number trade-off. Aob Plants. 2019;11:6.10.1093/aobpla/plz063Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Feng M, Whitford-Stark JT. The 1719–1921 eruptions of potassium-rich lavas at Wudalianchi, China. J Volcanol Geotherm Res. 1986;30:131–48.10.1016/0377-0273(86)90070-3Search in Google Scholar

[24] del Moral R, Grishin SY. Volcanic disturbances and ecosystem recovery. In: Wakker LR, editor. Ecosystems of disturbed ground. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science; 1999. Vol. 5. p. 137–60.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Niinemets Ü, Portsmuth A, Tena D, Tobias M, Matesanz S, Valladares F. Do we underestimate the importance of leaf size in plant economics? Disproportional scaling of support costs within the spectrum of leaf physiognomy. Ann Bot. 2007;100(2):283–303.10.1093/aob/mcm107Search in Google Scholar

[26] Zhang SM, Chem LM, Xing RG, Jin KZ. Distribution and features on soil and vegetation of five-linked-great-pool Lake volcano district. Territ Nat Resour Study China. 2005;1:86–8.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Niklas KJ. Plant allometry: the scaling of form and process. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago press; 1994.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Warton DI, Duursma RA, Falster DS, Taskinen S. smatr 3-an R package for estimation and inference about allometric lines. Methods Ecol Evol. 2012;3(2):257–9.10.1111/j.2041-210X.2011.00153.xSearch in Google Scholar

[29] Mooney KA, Halitschke R, Kessler A, Agrawal AA. Evolutionary trade-offs in plants mediate the strength of trophic cascades. Science. 2010;327(5973):1642–4.10.1126/science.1184814Search in Google Scholar

[30] Zhao LP, Yang XM, Inoue K. Morphological, chemical, and humus characteristics of volcanic ash soils in Changbaishan and Wudalianchi, Northeast China. Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 1993;39(2):339–50.10.1080/00380768.1993.10417005Search in Google Scholar

[31] Sun CQ, Nemeth K, Zhan T, You HT, Chu GQ, Liu JQ. Tephra evidence for the most recent eruption of Laoheishan volcano, Wudalianchi volcanic field, northeast China. J Volcanol Geotherm Res. 2019;383:103–11.10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2018.03.014Search in Google Scholar

[32] Korner C. Some often overlooked plant characteristics as determinants of plant-growth – a reconsideration. Funct Ecol. 1991;5(2):162–73.10.2307/2389254Search in Google Scholar

[33] Niinemets U, Kull K. Leaf weight per area and leaf size of 85 estonian woody species in relation to shade tolerance and light availability. For Ecol Manag. 1994;70(1–3):1–10.10.1016/0378-1127(94)90070-1Search in Google Scholar

[34] Niinemets U, Portsmuth A, Tobias M. Leaf size modifies support biomass distribution among stems, petioles and mid-ribs in temperate plants. N Phytol. 2006;171(1):91–104.10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01741.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Pearcy RW, Yang W. The functional morphology of light capture and carbon gain in the Redwood forest understorey plant Adenocaulon bicolor Hook. Funct Ecol. 1998;12(4):543–52.10.1046/j.1365-2435.1998.00234.xSearch in Google Scholar

[36] Givnish TJ, Vermeij GJ. Sizes and shapes of Liane leaves. Am Nat. 1976;110(975):743–78.10.1086/283101Search in Google Scholar

[37] Givnish TJ. Comparative studies of leaf leaf form assessing the relative roles of selective pressures and phylogenetic constraints. N Phytol. 1987;106(1):131–60.10.1111/j.1469-8137.1987.tb04687.xSearch in Google Scholar

[38] Sun J, Chen XP, Wang MT, Li JL, Zhong QL, Cheng DL. Application of leaf size and leafing intensity scaling across subtropical trees. Ecol Evol. 2020;10(23):13395–402.10.1002/ece3.6943Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Xiang SA, Wu N, Sun SC. Testing the generality of the ‘leafing intensity premium’ hypothesis in temperate broad-leaved forests: a survey of variation in leaf size within and between habitats. Evol Ecol. 2010;24(4):685–701.10.1007/s10682-009-9325-1Search in Google Scholar

[40] Poorter H, Pepin S, Rijkers T, de Jong Y, Evans JR, Korner C. Construction costs, chemical composition and payback time of high- and low- irradiance leaves. J Exp Bot. 2006;57(2):355–71.10.1093/jxb/erj002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2021 Fan Yang et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Biomedical Sciences

- Research progress on the mechanism of orexin in pain regulation in different brain regions

- Adriamycin-resistant cells are significantly less fit than adriamycin-sensitive cells in cervical cancer

- Exogenous spermidine affects polyamine metabolism in the mouse hypothalamus

- Iris metastasis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma misdiagnosed as primary angle-closure glaucoma: A case report and review of the literature

- LncRNA PVT1 promotes cervical cancer progression by sponging miR-503 to upregulate ARL2 expression

- Two new inflammatory markers related to the CURB-65 score for disease severity in patients with community-acquired pneumonia: The hypersensitive C-reactive protein to albumin ratio and fibrinogen to albumin ratio

- Circ_0091579 enhances the malignancy of hepatocellular carcinoma via miR-1287/PDK2 axis

- Silencing XIST mitigated lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammatory injury in human lung fibroblast WI-38 cells through modulating miR-30b-5p/CCL16 axis and TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway

- Protocatechuic acid attenuates cerebral aneurysm formation and progression by inhibiting TNF-alpha/Nrf-2/NF-kB-mediated inflammatory mechanisms in experimental rats

- ABCB1 polymorphism in clopidogrel-treated Montenegrin patients

- Metabolic profiling of fatty acids in Tripterygium wilfordii multiglucoside- and triptolide-induced liver-injured rats

- miR-338-3p inhibits cell growth, invasion, and EMT process in neuroblastoma through targeting MMP-2

- Verification of neuroprotective effects of alpha-lipoic acid on chronic neuropathic pain in a chronic constriction injury rat model

- Circ_WWC3 overexpression decelerates the progression of osteosarcoma by regulating miR-421/PDE7B axis

- Knockdown of TUG1 rescues cardiomyocyte hypertrophy through targeting the miR-497/MEF2C axis

- MiR-146b-3p protects against AR42J cell injury in cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis model through targeting Anxa2

- miR-299-3p suppresses cell progression and induces apoptosis by downregulating PAX3 in gastric cancer

- Diabetes and COVID-19

- Discovery of novel potential KIT inhibitors for the treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumor

- TEAD4 is a novel independent predictor of prognosis in LGG patients with IDH mutation

- circTLK1 facilitates the proliferation and metastasis of renal cell carcinoma by regulating miR-495-3p/CBL axis

- microRNA-9-5p protects liver sinusoidal endothelial cell against oxygen glucose deprivation/reperfusion injury

- Long noncoding RNA TUG1 regulates degradation of chondrocyte extracellular matrix via miR-320c/MMP-13 axis in osteoarthritis

- Duodenal adenocarcinoma with skin metastasis as initial manifestation: A case report

- Effects of Loofah cylindrica extract on learning and memory ability, brain tissue morphology, and immune function of aging mice

- Recombinant Bacteroides fragilis enterotoxin-1 (rBFT-1) promotes proliferation of colorectal cancer via CCL3-related molecular pathways

- Blocking circ_UBR4 suppressed proliferation, migration, and cell cycle progression of human vascular smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis

- Gene therapy in PIDs, hemoglobin, ocular, neurodegenerative, and hemophilia B disorders

- Downregulation of circ_0037655 impedes glioma formation and metastasis via the regulation of miR-1229-3p/ITGB8 axis

- Vitamin D deficiency and cardiovascular risk in type 2 diabetes population

- Circ_0013359 facilitates the tumorigenicity of melanoma by regulating miR-136-5p/RAB9A axis

- Mechanisms of circular RNA circ_0066147 on pancreatic cancer progression

- lncRNA myocardial infarction-associated transcript (MIAT) knockdown alleviates LPS-induced chondrocytes inflammatory injury via regulating miR-488-3p/sex determining region Y-related HMG-box 11 (SOX11) axis

- Identification of circRNA circ-CSPP1 as a potent driver of colorectal cancer by directly targeting the miR-431/LASP1 axis

- Hyperhomocysteinemia exacerbates ischemia-reperfusion injury-induced acute kidney injury by mediating oxidative stress, DNA damage, JNK pathway, and apoptosis

- Potential prognostic markers and significant lncRNA–mRNA co-expression pairs in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma

- Gamma irradiation-mediated inactivation of enveloped viruses with conservation of genome integrity: Potential application for SARS-CoV-2 inactivated vaccine development

- ADHFE1 is a correlative factor of patient survival in cancer

- The association of transcription factor Prox1 with the proliferation, migration, and invasion of lung cancer

- Is there a relationship between the prevalence of autoimmune thyroid disease and diabetic kidney disease?

- Immunoregulatory function of Dictyophora echinovolvata spore polysaccharides in immunocompromised mice induced by cyclophosphamide

- T cell epitopes of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and conserved surface protein of Plasmodium malariae share sequence homology

- Anti-obesity effect and mechanism of mesenchymal stem cells influence on obese mice

- Long noncoding RNA HULC contributes to paclitaxel resistance in ovarian cancer via miR-137/ITGB8 axis

- Glucocorticoids protect HEI-OC1 cells from tunicamycin-induced cell damage via inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum stress

- Prognostic value of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in acute organophosphorus pesticide poisoning

- Gastroprotective effects of diosgenin against HCl/ethanol-induced gastric mucosal injury through suppression of NF-κβ and myeloperoxidase activities

- Silencing of LINC00707 suppresses cell proliferation, migration, and invasion of osteosarcoma cells by modulating miR-338-3p/AHSA1 axis

- Successful extracorporeal membrane oxygenation resuscitation of patient with cardiogenic shock induced by phaeochromocytoma crisis mimicking hyperthyroidism: A case report

- Effects of miR-185-5p on replication of hepatitis C virus

- Lidocaine has antitumor effect on hepatocellular carcinoma via the circ_DYNC1H1/miR-520a-3p/USP14 axis

- Primary localized cutaneous nodular amyloidosis presenting as lymphatic malformation: A case report

- Multimodal magnetic resonance imaging analysis in the characteristics of Wilson’s disease: A case report and literature review

- Therapeutic potential of anticoagulant therapy in association with cytokine storm inhibition in severe cases of COVID-19: A case report

- Neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy for locally advanced squamous cell lung carcinoma: A case report and literature review

- Rufinamide (RUF) suppresses inflammation and maintains the integrity of the blood–brain barrier during kainic acid-induced brain damage

- Inhibition of ADAM10 ameliorates doxorubicin-induced cardiac remodeling by suppressing N-cadherin cleavage

- Invasive ductal carcinoma and small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic leukemia manifesting as a collision breast tumor: A case report and literature review

- Clonal diversity of the B cell receptor repertoire in patients with coronary in-stent restenosis and type 2 diabetes

- CTLA-4 promotes lymphoma progression through tumor stem cell enrichment and immunosuppression

- WDR74 promotes proliferation and metastasis in colorectal cancer cells through regulating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway

- Down-regulation of IGHG1 enhances Protoporphyrin IX accumulation and inhibits hemin biosynthesis in colorectal cancer by suppressing the MEK-FECH axis

- Curcumin suppresses the progression of gastric cancer by regulating circ_0056618/miR-194-5p axis

- Scutellarin-induced A549 cell apoptosis depends on activation of the transforming growth factor-β1/smad2/ROS/caspase-3 pathway

- lncRNA NEAT1 regulates CYP1A2 and influences steroid-induced necrosis

- A two-microRNA signature predicts the progression of male thyroid cancer

- Isolation of microglia from retinas of chronic ocular hypertensive rats

- Changes of immune cells in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated by radiofrequency ablation and hepatectomy, a pilot study

- Calcineurin Aβ gene knockdown inhibits transient outward potassium current ion channel remodeling in hypertrophic ventricular myocyte

- Aberrant expression of PI3K/AKT signaling is involved in apoptosis resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Clinical significance of activated Wnt/β-catenin signaling in apoptosis inhibition of oral cancer

- circ_CHFR regulates ox-LDL-mediated cell proliferation, apoptosis, and EndoMT by miR-15a-5p/EGFR axis in human brain microvessel endothelial cells

- Resveratrol pretreatment mitigates LPS-induced acute lung injury by regulating conventional dendritic cells’ maturation and function

- Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2T promotes tumor stem cell characteristics and migration of cervical cancer cells by regulating the GRP78/FAK pathway

- Carriage of HLA-DRB1*11 and 1*12 alleles and risk factors in patients with breast cancer in Burkina Faso

- Protective effect of Lactobacillus-containing probiotics on intestinal mucosa of rats experiencing traumatic hemorrhagic shock

- Glucocorticoids induce osteonecrosis of the femoral head through the Hippo signaling pathway

- Endothelial cell-derived SSAO can increase MLC20 phosphorylation in VSMCs

- Downregulation of STOX1 is a novel prognostic biomarker for glioma patients

- miR-378a-3p regulates glioma cell chemosensitivity to cisplatin through IGF1R

- The molecular mechanisms underlying arecoline-induced cardiac fibrosis in rats

- TGF-β1-overexpressing mesenchymal stem cells reciprocally regulate Th17/Treg cells by regulating the expression of IFN-γ

- The influence of MTHFR genetic polymorphisms on methotrexate therapy in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- Red blood cell distribution width-standard deviation but not red blood cell distribution width-coefficient of variation as a potential index for the diagnosis of iron-deficiency anemia in mid-pregnancy women

- Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma expressing alpha fetoprotein in the endometrium

- Superoxide dismutase and the sigma1 receptor as key elements of the antioxidant system in human gastrointestinal tract cancers

- Molecular characterization and phylogenetic studies of Echinococcus granulosus and Taenia multiceps coenurus cysts in slaughtered sheep in Saudi Arabia

- ITGB5 mutation discovered in a Chinese family with blepharophimosis-ptosis-epicanthus inversus syndrome

- ACTB and GAPDH appear at multiple SDS-PAGE positions, thus not suitable as reference genes for determining protein loading in techniques like Western blotting

- Facilitation of mouse skin-derived precursor growth and yield by optimizing plating density

- 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylethanol ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced septic cardiac injury in a murine model

- Downregulation of PITX2 inhibits the proliferation and migration of liver cancer cells and induces cell apoptosis

- Expression of CDK9 in endometrial cancer tissues and its effect on the proliferation of HEC-1B

- Novel predictor of the occurrence of DKA in T1DM patients without infection: A combination of neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio and white blood cells

- Investigation of molecular regulation mechanism under the pathophysiology of subarachnoid hemorrhage

- miR-25-3p protects renal tubular epithelial cells from apoptosis induced by renal IRI by targeting DKK3

- Bioengineering and Biotechnology

- Green fabrication of Co and Co3O4 nanoparticles and their biomedical applications: A review

- Agriculture

- Effects of inorganic and organic selenium sources on the growth performance of broilers in China: A meta-analysis

- Crop-livestock integration practices, knowledge, and attitudes among smallholder farmers: Hedging against climate change-induced shocks in semi-arid Zimbabwe

- Food Science and Nutrition

- Effect of food processing on the antioxidant activity of flavones from Polygonatum odoratum (Mill.) Druce

- Vitamin D and iodine status was associated with the risk and complication of type 2 diabetes mellitus in China

- Diversity of microbiota in Slovak summer ewes’ cheese “Bryndza”

- Comparison between voltammetric detection methods for abalone-flavoring liquid

- Composition of low-molecular-weight glutenin subunits in common wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and their effects on the rheological properties of dough

- Application of culture, PCR, and PacBio sequencing for determination of microbial composition of milk from subclinical mastitis dairy cows of smallholder farms

- Investigating microplastics and potentially toxic elements contamination in canned Tuna, Salmon, and Sardine fishes from Taif markets, KSA

- From bench to bar side: Evaluating the red wine storage lesion

- Establishment of an iodine model for prevention of iodine-excess-induced thyroid dysfunction in pregnant women

- Plant Sciences

- Characterization of GMPP from Dendrobium huoshanense yielding GDP-D-mannose

- Comparative analysis of the SPL gene family in five Rosaceae species: Fragaria vesca, Malus domestica, Prunus persica, Rubus occidentalis, and Pyrus pyrifolia

- Identification of leaf rust resistance genes Lr34 and Lr46 in common wheat (Triticum aestivum L. ssp. aestivum) lines of different origin using multiplex PCR

- Investigation of bioactivities of Taxus chinensis, Taxus cuspidata, and Taxus × media by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- Morphological structures and histochemistry of roots and shoots in Myricaria laxiflora (Tamaricaceae)

- Transcriptome analysis of resistance mechanism to potato wart disease

- In silico analysis of glycosyltransferase 2 family genes in duckweed (Spirodela polyrhiza) and its role in salt stress tolerance

- Comparative study on growth traits and ions regulation of zoysiagrasses under varied salinity treatments

- Role of MS1 homolog Ntms1 gene of tobacco infertility

- Biological characteristics and fungicide sensitivity of Pyricularia variabilis

- In silico/computational analysis of mevalonate pyrophosphate decarboxylase gene families in Campanulids

- Identification of novel drought-responsive miRNA regulatory network of drought stress response in common vetch (Vicia sativa)

- How photoautotrophy, photomixotrophy, and ventilation affect the stomata and fluorescence emission of pistachios rootstock?

- Apoplastic histochemical features of plant root walls that may facilitate ion uptake and retention

- Ecology and Environmental Sciences

- The impact of sewage sludge on the fungal communities in the rhizosphere and roots of barley and on barley yield

- Domestication of wild animals may provide a springboard for rapid variation of coronavirus

- Response of benthic invertebrate assemblages to seasonal and habitat condition in the Wewe River, Ashanti region (Ghana)

- Molecular record for the first authentication of Isaria cicadae from Vietnam

- Twig biomass allocation of Betula platyphylla in different habitats in Wudalianchi Volcano, northeast China

- Animal Sciences

- Supplementation of probiotics in water beneficial growth performance, carcass traits, immune function, and antioxidant capacity in broiler chickens

- Predators of the giant pine scale, Marchalina hellenica (Gennadius 1883; Hemiptera: Marchalinidae), out of its natural range in Turkey

- Honey in wound healing: An updated review

- NONMMUT140591.1 may serve as a ceRNA to regulate Gata5 in UT-B knockout-induced cardiac conduction block

- Radiotherapy for the treatment of pulmonary hydatidosis in sheep

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Long non-coding RNA TUG1 knockdown hinders the tumorigenesis of multiple myeloma by regulating microRNA-34a-5p/NOTCH1 signaling pathway”

- Special Issue on Reuse of Agro-Industrial By-Products

- An effect of positional isomerism of benzoic acid derivatives on antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli

- Special Issue on Computing and Artificial Techniques for Life Science Applications - Part II

- Relationship of Gensini score with retinal vessel diameter and arteriovenous ratio in senile CHD

- Effects of different enantiomers of amlodipine on lipid profiles and vasomotor factors in atherosclerotic rabbits

- Establishment of the New Zealand white rabbit animal model of fatty keratopathy associated with corneal neovascularization

- lncRNA MALAT1/miR-143 axis is a potential biomarker for in-stent restenosis and is involved in the multiplication of vascular smooth muscle cells

Articles in the same Issue

- Biomedical Sciences

- Research progress on the mechanism of orexin in pain regulation in different brain regions

- Adriamycin-resistant cells are significantly less fit than adriamycin-sensitive cells in cervical cancer

- Exogenous spermidine affects polyamine metabolism in the mouse hypothalamus

- Iris metastasis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma misdiagnosed as primary angle-closure glaucoma: A case report and review of the literature

- LncRNA PVT1 promotes cervical cancer progression by sponging miR-503 to upregulate ARL2 expression

- Two new inflammatory markers related to the CURB-65 score for disease severity in patients with community-acquired pneumonia: The hypersensitive C-reactive protein to albumin ratio and fibrinogen to albumin ratio

- Circ_0091579 enhances the malignancy of hepatocellular carcinoma via miR-1287/PDK2 axis

- Silencing XIST mitigated lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammatory injury in human lung fibroblast WI-38 cells through modulating miR-30b-5p/CCL16 axis and TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway

- Protocatechuic acid attenuates cerebral aneurysm formation and progression by inhibiting TNF-alpha/Nrf-2/NF-kB-mediated inflammatory mechanisms in experimental rats

- ABCB1 polymorphism in clopidogrel-treated Montenegrin patients

- Metabolic profiling of fatty acids in Tripterygium wilfordii multiglucoside- and triptolide-induced liver-injured rats

- miR-338-3p inhibits cell growth, invasion, and EMT process in neuroblastoma through targeting MMP-2

- Verification of neuroprotective effects of alpha-lipoic acid on chronic neuropathic pain in a chronic constriction injury rat model

- Circ_WWC3 overexpression decelerates the progression of osteosarcoma by regulating miR-421/PDE7B axis

- Knockdown of TUG1 rescues cardiomyocyte hypertrophy through targeting the miR-497/MEF2C axis

- MiR-146b-3p protects against AR42J cell injury in cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis model through targeting Anxa2

- miR-299-3p suppresses cell progression and induces apoptosis by downregulating PAX3 in gastric cancer

- Diabetes and COVID-19

- Discovery of novel potential KIT inhibitors for the treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumor

- TEAD4 is a novel independent predictor of prognosis in LGG patients with IDH mutation

- circTLK1 facilitates the proliferation and metastasis of renal cell carcinoma by regulating miR-495-3p/CBL axis

- microRNA-9-5p protects liver sinusoidal endothelial cell against oxygen glucose deprivation/reperfusion injury

- Long noncoding RNA TUG1 regulates degradation of chondrocyte extracellular matrix via miR-320c/MMP-13 axis in osteoarthritis

- Duodenal adenocarcinoma with skin metastasis as initial manifestation: A case report

- Effects of Loofah cylindrica extract on learning and memory ability, brain tissue morphology, and immune function of aging mice

- Recombinant Bacteroides fragilis enterotoxin-1 (rBFT-1) promotes proliferation of colorectal cancer via CCL3-related molecular pathways

- Blocking circ_UBR4 suppressed proliferation, migration, and cell cycle progression of human vascular smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis

- Gene therapy in PIDs, hemoglobin, ocular, neurodegenerative, and hemophilia B disorders

- Downregulation of circ_0037655 impedes glioma formation and metastasis via the regulation of miR-1229-3p/ITGB8 axis

- Vitamin D deficiency and cardiovascular risk in type 2 diabetes population

- Circ_0013359 facilitates the tumorigenicity of melanoma by regulating miR-136-5p/RAB9A axis

- Mechanisms of circular RNA circ_0066147 on pancreatic cancer progression

- lncRNA myocardial infarction-associated transcript (MIAT) knockdown alleviates LPS-induced chondrocytes inflammatory injury via regulating miR-488-3p/sex determining region Y-related HMG-box 11 (SOX11) axis

- Identification of circRNA circ-CSPP1 as a potent driver of colorectal cancer by directly targeting the miR-431/LASP1 axis

- Hyperhomocysteinemia exacerbates ischemia-reperfusion injury-induced acute kidney injury by mediating oxidative stress, DNA damage, JNK pathway, and apoptosis

- Potential prognostic markers and significant lncRNA–mRNA co-expression pairs in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma

- Gamma irradiation-mediated inactivation of enveloped viruses with conservation of genome integrity: Potential application for SARS-CoV-2 inactivated vaccine development

- ADHFE1 is a correlative factor of patient survival in cancer

- The association of transcription factor Prox1 with the proliferation, migration, and invasion of lung cancer

- Is there a relationship between the prevalence of autoimmune thyroid disease and diabetic kidney disease?

- Immunoregulatory function of Dictyophora echinovolvata spore polysaccharides in immunocompromised mice induced by cyclophosphamide

- T cell epitopes of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and conserved surface protein of Plasmodium malariae share sequence homology

- Anti-obesity effect and mechanism of mesenchymal stem cells influence on obese mice

- Long noncoding RNA HULC contributes to paclitaxel resistance in ovarian cancer via miR-137/ITGB8 axis

- Glucocorticoids protect HEI-OC1 cells from tunicamycin-induced cell damage via inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum stress

- Prognostic value of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in acute organophosphorus pesticide poisoning

- Gastroprotective effects of diosgenin against HCl/ethanol-induced gastric mucosal injury through suppression of NF-κβ and myeloperoxidase activities

- Silencing of LINC00707 suppresses cell proliferation, migration, and invasion of osteosarcoma cells by modulating miR-338-3p/AHSA1 axis

- Successful extracorporeal membrane oxygenation resuscitation of patient with cardiogenic shock induced by phaeochromocytoma crisis mimicking hyperthyroidism: A case report

- Effects of miR-185-5p on replication of hepatitis C virus

- Lidocaine has antitumor effect on hepatocellular carcinoma via the circ_DYNC1H1/miR-520a-3p/USP14 axis

- Primary localized cutaneous nodular amyloidosis presenting as lymphatic malformation: A case report

- Multimodal magnetic resonance imaging analysis in the characteristics of Wilson’s disease: A case report and literature review

- Therapeutic potential of anticoagulant therapy in association with cytokine storm inhibition in severe cases of COVID-19: A case report

- Neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy for locally advanced squamous cell lung carcinoma: A case report and literature review

- Rufinamide (RUF) suppresses inflammation and maintains the integrity of the blood–brain barrier during kainic acid-induced brain damage

- Inhibition of ADAM10 ameliorates doxorubicin-induced cardiac remodeling by suppressing N-cadherin cleavage

- Invasive ductal carcinoma and small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic leukemia manifesting as a collision breast tumor: A case report and literature review

- Clonal diversity of the B cell receptor repertoire in patients with coronary in-stent restenosis and type 2 diabetes

- CTLA-4 promotes lymphoma progression through tumor stem cell enrichment and immunosuppression

- WDR74 promotes proliferation and metastasis in colorectal cancer cells through regulating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway

- Down-regulation of IGHG1 enhances Protoporphyrin IX accumulation and inhibits hemin biosynthesis in colorectal cancer by suppressing the MEK-FECH axis

- Curcumin suppresses the progression of gastric cancer by regulating circ_0056618/miR-194-5p axis

- Scutellarin-induced A549 cell apoptosis depends on activation of the transforming growth factor-β1/smad2/ROS/caspase-3 pathway

- lncRNA NEAT1 regulates CYP1A2 and influences steroid-induced necrosis

- A two-microRNA signature predicts the progression of male thyroid cancer

- Isolation of microglia from retinas of chronic ocular hypertensive rats

- Changes of immune cells in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated by radiofrequency ablation and hepatectomy, a pilot study

- Calcineurin Aβ gene knockdown inhibits transient outward potassium current ion channel remodeling in hypertrophic ventricular myocyte

- Aberrant expression of PI3K/AKT signaling is involved in apoptosis resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Clinical significance of activated Wnt/β-catenin signaling in apoptosis inhibition of oral cancer

- circ_CHFR regulates ox-LDL-mediated cell proliferation, apoptosis, and EndoMT by miR-15a-5p/EGFR axis in human brain microvessel endothelial cells

- Resveratrol pretreatment mitigates LPS-induced acute lung injury by regulating conventional dendritic cells’ maturation and function

- Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2T promotes tumor stem cell characteristics and migration of cervical cancer cells by regulating the GRP78/FAK pathway

- Carriage of HLA-DRB1*11 and 1*12 alleles and risk factors in patients with breast cancer in Burkina Faso

- Protective effect of Lactobacillus-containing probiotics on intestinal mucosa of rats experiencing traumatic hemorrhagic shock

- Glucocorticoids induce osteonecrosis of the femoral head through the Hippo signaling pathway

- Endothelial cell-derived SSAO can increase MLC20 phosphorylation in VSMCs

- Downregulation of STOX1 is a novel prognostic biomarker for glioma patients

- miR-378a-3p regulates glioma cell chemosensitivity to cisplatin through IGF1R

- The molecular mechanisms underlying arecoline-induced cardiac fibrosis in rats

- TGF-β1-overexpressing mesenchymal stem cells reciprocally regulate Th17/Treg cells by regulating the expression of IFN-γ

- The influence of MTHFR genetic polymorphisms on methotrexate therapy in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- Red blood cell distribution width-standard deviation but not red blood cell distribution width-coefficient of variation as a potential index for the diagnosis of iron-deficiency anemia in mid-pregnancy women

- Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma expressing alpha fetoprotein in the endometrium

- Superoxide dismutase and the sigma1 receptor as key elements of the antioxidant system in human gastrointestinal tract cancers

- Molecular characterization and phylogenetic studies of Echinococcus granulosus and Taenia multiceps coenurus cysts in slaughtered sheep in Saudi Arabia

- ITGB5 mutation discovered in a Chinese family with blepharophimosis-ptosis-epicanthus inversus syndrome

- ACTB and GAPDH appear at multiple SDS-PAGE positions, thus not suitable as reference genes for determining protein loading in techniques like Western blotting

- Facilitation of mouse skin-derived precursor growth and yield by optimizing plating density

- 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylethanol ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced septic cardiac injury in a murine model

- Downregulation of PITX2 inhibits the proliferation and migration of liver cancer cells and induces cell apoptosis

- Expression of CDK9 in endometrial cancer tissues and its effect on the proliferation of HEC-1B

- Novel predictor of the occurrence of DKA in T1DM patients without infection: A combination of neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio and white blood cells

- Investigation of molecular regulation mechanism under the pathophysiology of subarachnoid hemorrhage

- miR-25-3p protects renal tubular epithelial cells from apoptosis induced by renal IRI by targeting DKK3

- Bioengineering and Biotechnology

- Green fabrication of Co and Co3O4 nanoparticles and their biomedical applications: A review

- Agriculture

- Effects of inorganic and organic selenium sources on the growth performance of broilers in China: A meta-analysis

- Crop-livestock integration practices, knowledge, and attitudes among smallholder farmers: Hedging against climate change-induced shocks in semi-arid Zimbabwe

- Food Science and Nutrition

- Effect of food processing on the antioxidant activity of flavones from Polygonatum odoratum (Mill.) Druce

- Vitamin D and iodine status was associated with the risk and complication of type 2 diabetes mellitus in China

- Diversity of microbiota in Slovak summer ewes’ cheese “Bryndza”

- Comparison between voltammetric detection methods for abalone-flavoring liquid

- Composition of low-molecular-weight glutenin subunits in common wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and their effects on the rheological properties of dough

- Application of culture, PCR, and PacBio sequencing for determination of microbial composition of milk from subclinical mastitis dairy cows of smallholder farms

- Investigating microplastics and potentially toxic elements contamination in canned Tuna, Salmon, and Sardine fishes from Taif markets, KSA

- From bench to bar side: Evaluating the red wine storage lesion

- Establishment of an iodine model for prevention of iodine-excess-induced thyroid dysfunction in pregnant women

- Plant Sciences

- Characterization of GMPP from Dendrobium huoshanense yielding GDP-D-mannose

- Comparative analysis of the SPL gene family in five Rosaceae species: Fragaria vesca, Malus domestica, Prunus persica, Rubus occidentalis, and Pyrus pyrifolia

- Identification of leaf rust resistance genes Lr34 and Lr46 in common wheat (Triticum aestivum L. ssp. aestivum) lines of different origin using multiplex PCR

- Investigation of bioactivities of Taxus chinensis, Taxus cuspidata, and Taxus × media by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- Morphological structures and histochemistry of roots and shoots in Myricaria laxiflora (Tamaricaceae)

- Transcriptome analysis of resistance mechanism to potato wart disease

- In silico analysis of glycosyltransferase 2 family genes in duckweed (Spirodela polyrhiza) and its role in salt stress tolerance

- Comparative study on growth traits and ions regulation of zoysiagrasses under varied salinity treatments

- Role of MS1 homolog Ntms1 gene of tobacco infertility

- Biological characteristics and fungicide sensitivity of Pyricularia variabilis

- In silico/computational analysis of mevalonate pyrophosphate decarboxylase gene families in Campanulids

- Identification of novel drought-responsive miRNA regulatory network of drought stress response in common vetch (Vicia sativa)

- How photoautotrophy, photomixotrophy, and ventilation affect the stomata and fluorescence emission of pistachios rootstock?

- Apoplastic histochemical features of plant root walls that may facilitate ion uptake and retention

- Ecology and Environmental Sciences

- The impact of sewage sludge on the fungal communities in the rhizosphere and roots of barley and on barley yield

- Domestication of wild animals may provide a springboard for rapid variation of coronavirus

- Response of benthic invertebrate assemblages to seasonal and habitat condition in the Wewe River, Ashanti region (Ghana)

- Molecular record for the first authentication of Isaria cicadae from Vietnam

- Twig biomass allocation of Betula platyphylla in different habitats in Wudalianchi Volcano, northeast China

- Animal Sciences

- Supplementation of probiotics in water beneficial growth performance, carcass traits, immune function, and antioxidant capacity in broiler chickens

- Predators of the giant pine scale, Marchalina hellenica (Gennadius 1883; Hemiptera: Marchalinidae), out of its natural range in Turkey

- Honey in wound healing: An updated review

- NONMMUT140591.1 may serve as a ceRNA to regulate Gata5 in UT-B knockout-induced cardiac conduction block

- Radiotherapy for the treatment of pulmonary hydatidosis in sheep

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Long non-coding RNA TUG1 knockdown hinders the tumorigenesis of multiple myeloma by regulating microRNA-34a-5p/NOTCH1 signaling pathway”

- Special Issue on Reuse of Agro-Industrial By-Products

- An effect of positional isomerism of benzoic acid derivatives on antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli

- Special Issue on Computing and Artificial Techniques for Life Science Applications - Part II

- Relationship of Gensini score with retinal vessel diameter and arteriovenous ratio in senile CHD

- Effects of different enantiomers of amlodipine on lipid profiles and vasomotor factors in atherosclerotic rabbits

- Establishment of the New Zealand white rabbit animal model of fatty keratopathy associated with corneal neovascularization

- lncRNA MALAT1/miR-143 axis is a potential biomarker for in-stent restenosis and is involved in the multiplication of vascular smooth muscle cells