Abstract

The continuous demand for economical high-performance thermally resilient concrete with superior mechanical behavior is pivotal for sustainable concrete infrastructure. Few studies have examined the effect of the frictional resistance of fine aggregates on the thermal resilience of concrete structures. Laboratory tests (compressive strength, thermal conductivity, and ultrasonic pulse velocity tests) were conducted to evaluate the thermal resilience of the fine aggregates. The results showed that 20 % optimal partial replacement of traditional aggregate by Wadi Gyada Alkharj Fine Aggregate (WGAFA) enhanced compressive strength (CS), thermal conductivity (TC), and ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV) by 19 %, 23.8 %, and 36.5 %, respectively, compared to traditional aggregate. The results showed that TC, CS, and UPV declined by 58 %, 49 %, and 47 %, respectively, after exposure to the 800 °C thermal effect versus that at 25 °C. A predictive model for post-heating compressive strength (CS) was proposed for fire-resistant infrastructures to prevent loss of life and reduce financial losses from infrastructure destruction. This study demonstrated that non-destructive test parameters can effectively evaluate the post-heating residual compressive strength of fire-affected concrete structures for future use.

1 Introduction

Due to expanding urbanization and industrialization in this era, the consumption of concrete has shown an increasing trend on a daily basis [1]. The global population surpassed seven billion people in the 21st century, creating a significant need for building and housing development worldwide. This, in turn, led to an increase in the demand for concrete. As a result, the materials used to produce concrete may face depletion or decrease in availability [2]. There is a demand to produce thermally resilient concrete to sustain high thermal variation, which may lead to fire disasters that necessitate the integration of life cycle assessment and circular economy in building construction [3], [4], [5].

Concrete structures in service life face unpredictable fire exposure; however, the impact of non-uniform cooling caused by fluid infiltration during fire suppression treatments has been minimally explored [6]. To address this gap, this study investigated the effect of nonuniform cooling on the degradation of the pore structure and properties of concrete after exposure to high temperatures [7]. Cyclic cooling and heating cause early crack development in concrete [8].

Concrete is the most widely used material in the construction industry globally. Owing to its exceptional compressive strength, durability, and moldability, cement concrete is a ubiquitous material of choice [9], 10]. When produced with a meticulous design, precise specifications, and rigorous manufacturing processes, this engineered substance yields concrete with outstanding performance in construction applications [11].

Fire disasters can produce severe cracks, resulting in concrete infrastructure failing to encounter high thermal variations. The resilience of concrete infrastructure to variations in temperature in the environment is termed as thermal resilience [12], 13]. When designing structural components for buildings, it is essential to ensure that they meet both fire resistance and load-bearing requirements. Fire resistance is important because, when other fire control measures fail, the structural integrity of the building becomes the last safeguard [14], [15], [16]. Concrete beams, columns, and slabs should not spall at higher temperatures in the case of fire disasters or structures that are to be used as fire workplaces. The fire resistance of concrete is measured based on the strength and durability parameters [17].

The stiffness and strength of concrete are reduced at higher temperatures levels due to the deterioration and loss of binding forces [18]. The significance of research in this area lies in understanding the causes of spalling, which is believed to result from the buildup of pore pressure during heating [19].

The Coarse aggregates accounts for 65–75 % of the concrete; however, the effect of frictional resistance fine aggregates is to explore for the evaluation of thermal resistance of concrete [20], 21]. Various concrete specimens with different mix ratios were prepared experimentally, and key performance indicators, such as density, porosity, damping ratio, compressive strength, and flexural strength, were evaluated to analyze their variations [22], 23]. The gradation and coefficient of uniformity of particles significantly affect the strength properties of concrete [24], 25].

The gradation and fineness modulus of fine aggregates significantly affect the compressive and tensile strengths of concrete [26], [27], [28]. The morphology (shape and texture) of the fine aggregates also play a key role [29]. However, the bond strength between cement-paste and rounded aggregates may be weaker, resulting in lower compressive and tensile strengths over time. The fineness modulus of fine aggregates, which refers to the average size of the particles, also affects concrete properties. A higher fineness modulus (indicating coarser aggregates) typically leads to improved strength due to better particle packing and reduced voids in the mix [30]. Although preliminary studies have been conducted in these areas, comprehensive research on aggregate-related factors, such as aggregate content, particle size distribution, and gradation, along with strategies for optimization, remains insufficient. Research has indicated that a careful increase in aggregate content can improve the material density and compressive strength while simultaneously reducing porosity [31], [32], [33]. Balancing the morphology and fineness modulus is essential for optimizing both the compressive and tensile strengths of concrete [34], 35].

Reinforced concrete (RC) structures are susceptible to fire damage during their lifespans. Concrete infrastructure is only stable up to certain temperatures, and this stability can be disrupted when temperatures fluctuate [36]. The degree of temperature, along with the duration of exposure and heating rates, significantly affects the molecular structure, contributing to the degradation of concrete. At extremely high temperatures, the mechanical properties and stiffness of concrete decrease significantly due to physical and chemical changes [37], 38]. Additionally, in the case of severe fires, spalling of Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC) concrete can occur, causing the outer layers of the concrete to deteriorate rapidly, which may expose the internal reinforcement to high temperatures, potentially weakening the overall structure [39], 40].

Fire exposure causes temperatures to rise, which can lead to spalling in concrete, severely compromising its structural integrity and reducing its mechanical properties, particularly its compressive strength [41]. In extreme cases, spalling can contribute to the failure of crucial structural components [42]. The primary causes of explosive spalling are the accumulation of vapor pressure within the pores of the concrete and the uneven distribution of thermal stresses [43] whereas if heating is rapid and the concrete has a dense pore structure, the vapor cannot escape quickly enough, resulting in a significant build-up of pore pressure [44], 45] and which ultimately leads to spalling. Moreover, cracking in the concrete matrix can be accelerated by the chemical decomposition of hydrates, differential shrinkage of concrete paste, thermal instability, and expansion of coarse aggregates [46]. The mismatch in thermal and elastic properties between aggregates and cement paste at elevated temperatures can also lead to cracking in the interfacial transition zone (ITZ), further weakening the concrete and exacerbating the destructive processes [47].

The effects on the concrete structure are significant for the life span of concrete infrastructure. When subjected to high temperatures, cementitious materials undergo decomposition, which leads to a significant reduction in their load-bearing capacity. In the case of Portland cement-based materials, physically bound water evaporates within a temperature range of 30–100 °C, whereas different changes occur from 200 to 900 °C [48]. The thermal conductivity of concrete depends on its compactness and stiffness of the concrete [49]. High-strength concrete shows high potential for conducting thermal waves. The deterioration of the concrete causes a reduction in the thermal conductivity. The ultrasonic pulse wave (UPV) is a nondestructive parameter used for the strength and soundness of concrete structures [50]. The UPV is high for high-strength concrete. After concrete is exposed to a high level of thermal effects, the UPV is reduced.

Past studies on concrete for thermal resilience and lifespan, are extensive in the literature. The fire protection methodology is well described in the [51] for the design of concrete structures for structural fire design [52], [53], [54]. At high temperatures, the spalling and cracking of concrete structures are initiated, which is critical for the stability of concrete infrastructures [55], 56] whereas the concrete properties can be assessed for the resistance of the materials to fire [57].

Past studies have been insufficient for the prediction of post-fire strength scenarios using nondestructive and destructive macro-investigations of concrete properties. Hence, it is essential to develop a model for use in precautionary measures for residual resilience after the exposure of concrete buildings to elevated temperatures, as an effective fire-resistant concrete structure is essential for the safety and durability of residential and industrial infrastructure. This novel study predicts the post-heating compressive strength of concrete based on predictors, such as thermal conductivity and ultrasonic pulse velocity, for use in the assessment of residual resilience at the post-heat stage.

2 Materials

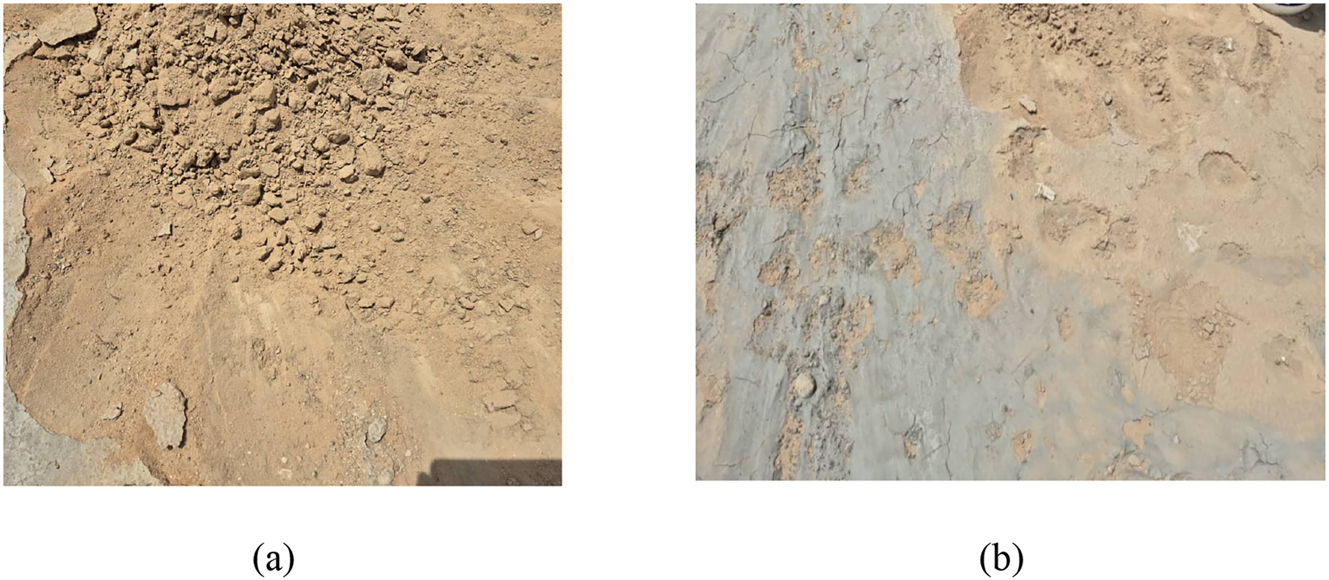

Wadi Gyada Alkharj Fine Aggregate (WGAFA) is abundantly available in the study area near Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. WGAFA was collected from a site in Wadi Gyada, Alkharj. Large sand strata are available at this site and can be used in the construction of infrastructure. Figure 1 shows the collection of fine aggregate samples from the Wadi Gyada Alkharj field.

Wadi Gyada Al-Kharj fine aggregate sampling site and deposits. (a) Representative view of the Wadi Gyada Al-Kharj sand strata at the sampling/collection location; (b) close-up view of the WGAFA deposit/collected fine aggregate.

The materials used in this study were WGAFA, coarse aggregate, and cement. The physical properties of the aggregate significantly affect the properties of concrete; hence, the characterization of fine and coarse aggregates is vital to evaluate concrete integrity and lifespan. The properties of the WGAFA and cement are presented in Table 1.

Properties of aggregates used in this research.

| Physical properties | WGA fine aggregate | Natural coarse aggregate |

|---|---|---|

| Unit weight (g/cm3) | 1.52 | 1.51 |

| Percentage of voids (%) | 43.8 | 38.2 |

| Apparent density (g/cm3) | 2.73 | 2.54 |

| Water absorption capacity (%) | 1.26 | 1.56 |

| Specific gravity | 2.74 | 2.49 |

| Fineness modulus | 2.79 | 2.18 |

| Silt content (%) | 2.1 | – |

| Aggregate crushing value (% ACV) | – | 14.42 |

| Aggregate impact value (% AIV) | – | 9.53 |

X-ray Fluorescence is an excellent method for the quantification of oxide compounds in materials to assess the chemical composition of the materials used in this research, as shown in Table 2.

Chemical composition of by X-ray Fluorescence.

| Constituent/oxides (%) | WGA fine aggregate | Cement |

|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | 92.5 | 20.1 |

| CaO | 1.5 | 65.7 |

| Al2O3 | 2.8 | 4.4 |

| MgO | 0.1 | 0.41 |

| Na2O | 0.2 | 1.22 |

| K2O | 0.8 | 0.01 |

| Fe2O3 | 0.6 | 3.84 |

| SO3 | 0.07 | 1.74 |

The comprehensive characterization of Wadi Gyada Fine Aggregate (WGAFA) reveals a material with distinct and advantageous properties that explain its superior performance over traditional sand. Chemically, the data shows that WGAFA is composed of 92.5 % SiO2, confirming its highly siliceous and inert nature. This high purity level is a critical differentiator, as it indicates that WGAFA is largely free from the clay minerals, soluble salts, and organic impurities often found in variable concentrations within natural sands sourced from other locations. This chemical stability ensures that the aggregate does not participate in detrimental reactions with cement, leading to a more predictable and durable composite material.

Physically, WGAFA exhibits two key superior characteristics. First, its lower water absorption of 1.26 %, compared to 1.8 % for traditional sand, indicates that the Wadi Gyada particles possess a denser and less porous internal structure. This property is highly beneficial in a concrete mix, as it reduces the amount of water absorbed by the aggregate particles themselves. Consequently, more mix water remains available for cement hydration, and the risk of a weakened Interfacial Transition Zone (ITZ) due to water withdrawal is minimized, directly leading to a stronger bond between the paste and the aggregate. Second, the higher fineness modulus of 2.79 for WGAFA, against 2.3 for traditional sand, signifies a coarser and potentially better-graded particle size distribution.

The combination of these properties provides a clear mechanistic explanation for the observed performance improvements. The coarser, denser particles of Wadi Gyada sand are posited to create a more optimized granular skeleton. When used as a fine aggregate, its particle size distribution allows it to fill voids more efficiently than the traditional sand, leading to improved particle packing density. This densification of the microstructure directly translates to the documented enhancements in mechanical and physical properties. The reduction in overall porosity results in higher compressive strength, as the solid skeleton is more competent at resisting loads. It also leads to a higher Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity, as sound waves travel faster through a less porous, more continuous solid medium. Similarly, the observed improvement in thermal conductivity is a direct consequence of this reduced porosity and the creation of more continuous pathways for heat to flow through the solid matrix of the composite.

3 Methods

3.1 Mix details and test schedule

Experimental program was devised for different tests in this research, is presented in Table. Concrete specimens (100 mm cube size) were exposed to elevated temperatures (25 °C–800 °C), and various tests – such as mass loss, ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV), and compressive strength was conducted. Subsequently, the specimens were cooled in the ambient air. The test schedule is presented in Table 3.

Engineering tests in and corresponding parameters.

| Experiment/samples | Parameters | Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Thermal treatment (TT) (144 samples) | Temperature measurement up to 800 °C in increments | For each substitution ratio (i.e., 0, 5 %, 10 %, 15 %, 20 %, 30 %, 40 % and 50 %) |

| Compressive strength test, (72 samples) | Compressive strength (for each substitution ratio before and after TT) | For each substitution ratio (i.e., 0, 5 %, 10 %, 15 %, 20 %, 30 %, 40 % and 50 % before and after TT) |

| UPV tests (same samples which are later used in compressive strength) | Velocity measurement (for each substitution ratio before and after TT) | For each substitution ratio (i.e., 0, 5 %, 10 %, 15 %, 20 %, 30 %, 40 % and 50 % before and after TT) |

| Thermal conductivity (72 samples) | Measurement of conductivity | For each substitution ratio (i.e., 0, 5 %, 10 %, 15 %, 20 %, 30 %, 40 % and 50 %) |

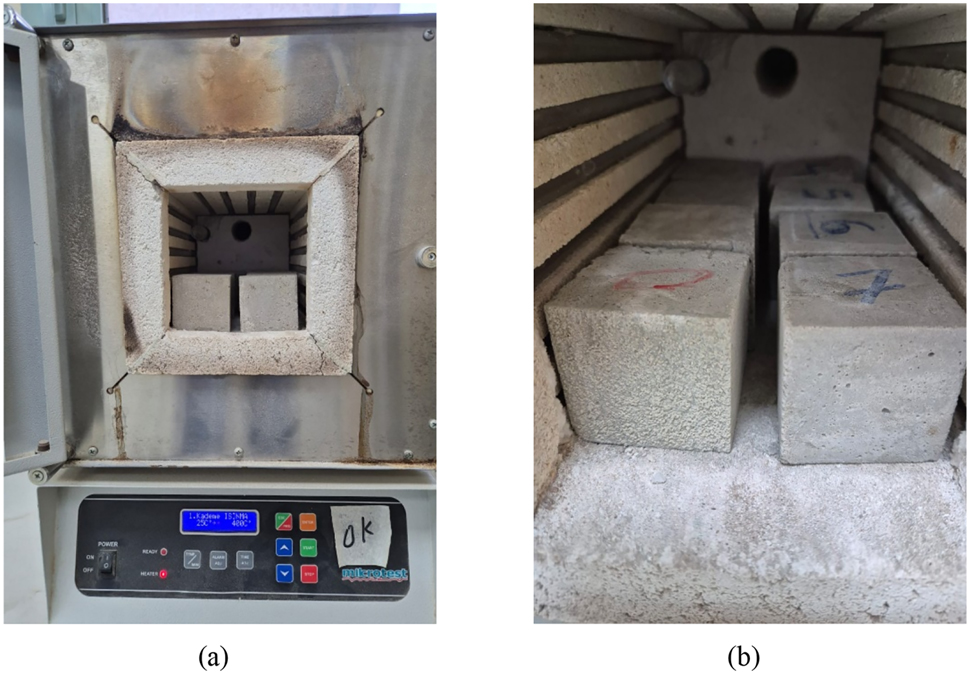

The cube samples were cured up to 28 days and then placed in the furnace for exposure to different temperatures levels is, 100 °C, 200 °C, 300 °C, 400 °C, 500 °C, 600 °C, 700 °C, and 800 °C, as shown in Figure 2 (a) and (b).

Thermal exposure setup for post-heating testing of concrete cubes. (a) Furnace chamber showing the concrete cube specimens during thermal exposure; (b) enlarged view of the cube specimens/arrangement.

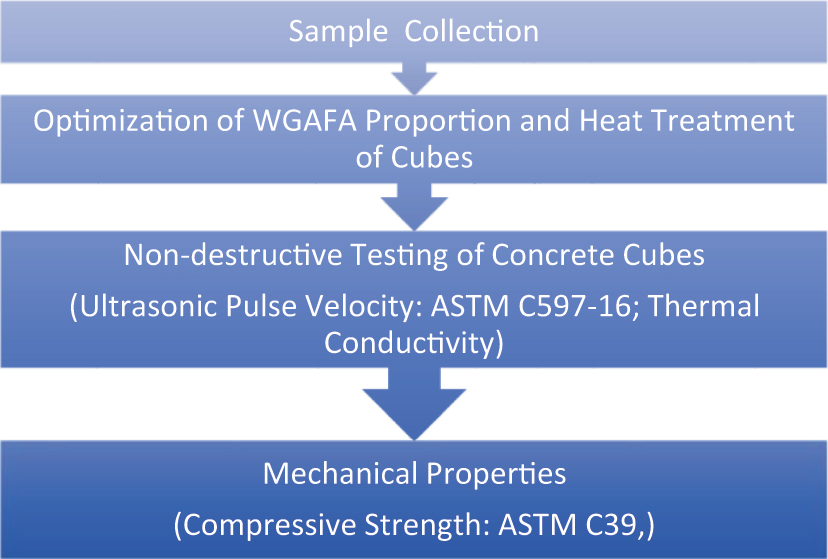

A flow chart of the different processes and methods adopted in this study is presented in Figure 3.

Flow chart of methodology.

A conventional mix design was used for the concrete trial mixes. Mixes were designed to target workability in the range of 60–170 mm, using Portland Cement (PC) and a free W/C ratio of 0.45. The workability of the mixture was assessed using the procedure specified in ASTM C143. During the placement stage, external vibrations were applied to compress the experimental concrete.

The concrete specimens were stored at room temperature for 24 h before removal from the molds. Once demolded, the specimens were subjected to water curing for 48 h to improve their strength and durability. Following steam curing, the specimens were subjected to a controlled environment with a relative humidity of 60 % and a temperature of 25 °C for additional curing. The compressive strengths of the cubes were measured after 28 days of curing for samples containing 0 %, 5 %, 10 %, 15 %, 20 %, 30 %, 40 %, and 50 % of WGAFA. The concrete mix design was based on the Absolute Volume method as outlined in BS 5328: Part 2:1991, “Method of Specifying Concrete Mixes.” Based on the initial estimate, a mix ratio of 1:2:4 was selected. The mix also had an aggregate/cement ratio of 4:1. A trial mix was developed and evaluated for its workability, strength, density, and finishing characteristics, and then modified for application to all concrete mixtures.

A total of eight (8) different mixes were created: one was a control mix without any substitution, while the other seven incorporated WGAFA aggregate substitutions at levels of 0 %, 5 %, 10 %, 15 %, 20 %, 30 %, 40 %, and 50 % by volume. The mix proportions were kept consistent regarding the mix design ratio, water/cement ratio, and the size and type of both the natural fine aggregate and WGAFA utilized in the research. In total, 144 concrete cubes were produced for thermal testing after curing in water for 28 d. Table 4 lists the detailed mix proportions used in this study.

Material quantities for 1 m3 of control mix.

| Mix ratio | W/C ratio | A/C ratio | Cement (kg/m3) | Fine aggregate (kg/m3) | Coarse aggregate (kg/m3) | Water (kg/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1:2:4 | 0.45 | 4 | 328 | 660 | 1,322 | 147 |

3.2 Test procedures

3.2.1 Compressive strength

Concrete production and testing were performed for the study of thermal effects. After production, the initial slump was measured, and slump loss was evaluated using the compacting factor test at 30-min intervals, extending up to 150 min. The mixes were covered with polythene sheets and maintained in a moist environment for 24 h post-casting before testing or undergoing 20 °C water curing. The engineering properties analyzed included the compressive strength, flexural strength, and drying shrinkage.

3.2.2 Thermal test

To perform the thermal property assessments, the samples were cut from the hardened concrete prisms using a power saw, and their ends were meticulously ground for precise measurements. The dimensions of the test samples were varied based on the specific properties evaluated. To assess the thermal conductivity and mass loss, samples with dimensions of 50 mm × 50 mm × 25 mm were prepared. mass loss was determined by weighing the test sample before and after it was exposure to a predetermined high temperature in a sealed electric furnace, which could reach up to 800 °C. The furnace featured internal electric heating elements with adjustable heating rates and a precise temperature-control system.

A consistent temperature ramp rate of 5 °C per minute was employed to reach all target temperatures (100 °C–800 °C). This controlled rate was chosen to minimize thermal shock while realistically simulating a building fire’s heating phase. Upon reaching each target temperature, it was maintained for a duration of 2 h. This dwell time ensured a uniform temperature distribution throughout the specimen, allowing the concrete’s chemical and physical changes to fully manifest and ensuring the specimen reached thermal equilibrium before testing. After the heating cycle, the furnace was switched off, and the specimens were allowed to cool gradually to ambient temperature inside the closed chamber. This slow, natural cooling protocol was designed to simulate a realistic post-fire cooling scenario in a structural element, avoiding the additional micro-cracking that can result from rapid quenching.

The heating chamber, measuring 300 mm × 500 mm internally, was equipped with a steel and insulation jacket to effectively reduce the risk of spalling in the concrete samples. A high-precision digital scale with 0.1 g accuracy was used for precise mass measurements. The Hot Disk software managed the sensor resistance, measurement duration, and furnace target temperatures. The testing protocol was set to capture thermal property data at eight specific target temperatures: 25 °C, 100 °C, 200 °C, 300 °C, 400 °C, 500 °C, 600 °C, 700 °C, and 800 °C. During each test, the furnace temperature was gradually raised to the specified target temperature and held steady until the test sample reached thermal equilibrium. With a constant heat source applied, the temperature of the sensor, placed between two samples, increased, facilitating heat flow within the test sample. Once thermal equilibrium was achieved at each target temperature, the sensor in the hot-disk apparatus simultaneously measured the thermal conductivity.

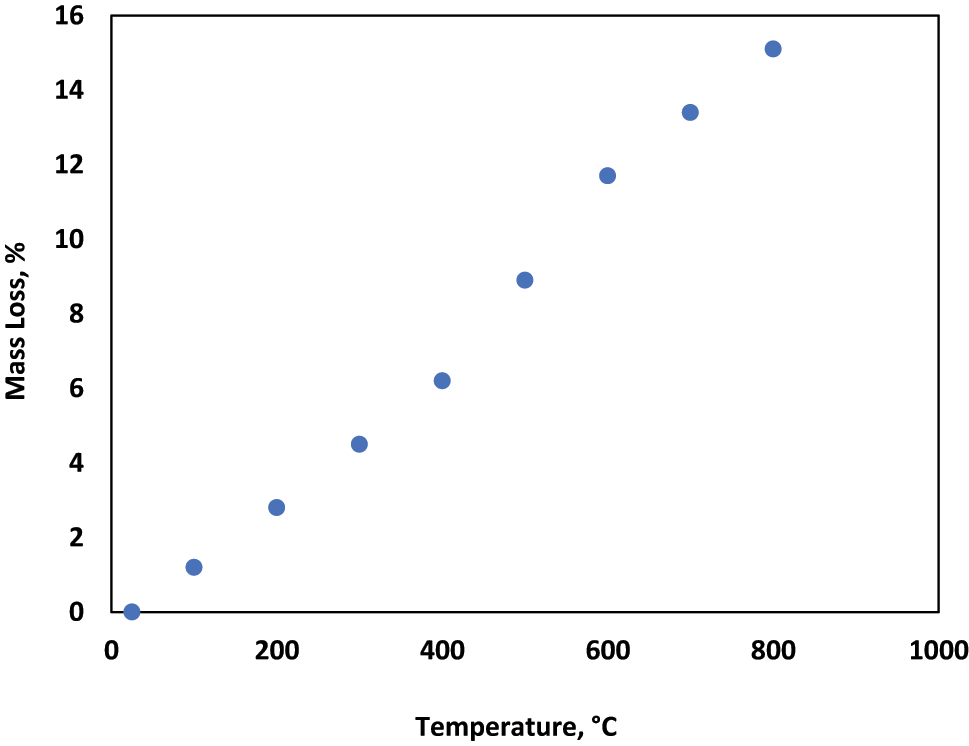

Increased heating of concrete leads to mass loss due to the weakening of cement bonds at the surface [58]. To measure mass loss, the weight of the test specimen was recorded at different target temperatures: 25 °C, 200 °C, 400 °C, 500 °C, 600 °C, 700 °C, and 800 °C, creating a mass loss curve relative to temperature for each WGAFA proportion. Before placing the specimens in an electric furnace, their initial masses were measured at room temperature. Specimens from the 20 % and 25 % batches experienced explosive spalling around 200 °C when heated at rates over 0.5 °C/min. This phenomenon is due to the dense matrix of the 20 % batch, which leads to pressure build-up, even at relatively low heating rates.

Thermal properties were calculated by taking the average of three measurements at each temperature. The thermal characteristics of WGAFA concrete were then compared to those of other types of concrete, including standard concrete made with ordinary aggregate sourced approximately 150 km away from the site in question.

The thermal conductivity of concrete varies with temperature due to shifts in moisture levels as the temperature rises. Concrete holds moisture in free, adsorbed, and bonded states, and these moisture levels fluctuate because of the microstructural changes that occur when exposed to high temperatures. When the temperature exceeds 100 °C, free water starts to evaporate, and around 300 °C, both adsorbed water and interlayer water from the calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H) gel, along with bonded water, begin to evaporate as well. Up to 400 °C, CaCO3 decomposes following the decomposition of C–S–H up to 900 °C. At room temperature, the thermal conductivity ranges from 2.8 3.6 W/m °C.

Different physical and chemical changes in concrete are described in Table 5.

Changes in concrete structure at elevated temperatures [59].

| Temperature (°C) | Changes in structure |

|---|---|

| 100 | Free water is evaporated from concrete pores |

| 200 | Melting of any organic impurities |

| 300 | Loss inter-layer C–S–H water, adsorbed and bonded water |

| 400 | CaCO3 is dissociated in CaO and H2O |

| 500 | C–S–H is decomposed |

| 600 | Quartz is transformed into aggregate form |

| 900 | C–S–H is completely decomposed |

3.2.3 Ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV) test

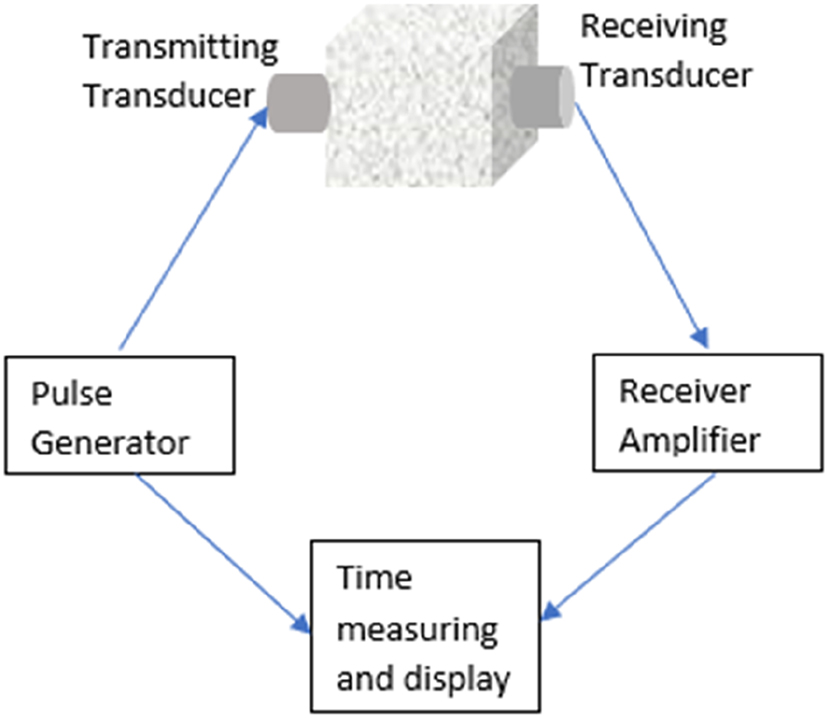

Nondestructive testing, such as the Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity (UPV) test, was performed to evaluate the quality of concrete based on the ultrasonic pulse velocity method, in which an ultrasonic pulse is transmitted into the concrete through a transducer, which undergoes multiple reflections within different material phases. This results in the formation of a complex system of stress waves including longitudinal, shear, and surface waves. Longitudinal waves, being the fastest, are the first waves to be detected by the receiving transducer. The distance travelled by these waves was measured, and their velocities were then calculated.

A UPV device was used to test concrete cubes. After 28 d of curing, the cubes were placed in a flat position, and the transmitting and receiving transducers were positioned on opposite sides of the concrete surface. This is known as the direct-testing method. The time taken by the ultrasonic pulse waves to travel through the concrete was recorded in microseconds, and their velocity was calculated manually in m/s or km/s. UPV is a nondestructive test used to evaluate the qualitative integrity of concrete. The measured velocity was correlated with the strength of the concrete. A high UPV value indicates a shorter travel time of ultrasonic waves due to the high compactness and denseness of the concrete. The voids and cracks present in the concrete lower the UPV, indicating the low strength of the concrete. The quality of the concrete specimens was categorized based on the ultrasonic velocity (m/s) as excellent (for UPV > 4,500 m/s), good (for 4,500 > UPV > 3,500), medium (for 3,500 > UPV > 3,000), and doubtful (for UPV < 3,000).

This testing approach involves recording the transit time to compute the “apparent” ultrasonic pulse velocity, which is determined by the distance between transducers. While not all types of damage or deterioration influence the ultrasonic pulse velocity of the material, they can change the path the pulse follows from the transmitter to the receiver. For example, cracks caused by loading can lengthen the actual path that the pulse travels, resulting in a longer measured transit time. However, the actual path length is not directly measurable. Because the calculation depends on the transducer spacing, the presence of cracks causes a reduction in the “apparent” pulse velocity, even if the true ultrasonic pulse velocity of the material remains unaffected. Many forms of cracking and damage are directional, and their impact on the transit time varies based on their orientation relative to the path of the pulse.

In the laboratory, the P-wave velocity, also known as the constrained compressive velocity, of concrete cubes with varying levels of WGAFA substitution was assessed. This evaluation followed the standard procedure described in [60]. Ultrasonic pulses with a frequency of approximately 50 kHz were transmitted and received using a pair of transducers. The source transducer is driven by a pulse receiver with a pulse duration of 10 µs. The transient stress waves produced by the source transducer traveled through the concrete, and were captured by the receiving transducer. The captured signal was digitized for a total duration of 0.001 s at a sampling rate of 10 MHz using a high-speed digital oscilloscope. The digitized data were then transferred to a computer for further analysis and storage. The P-wave velocity (Vp) was determined by dividing the distance the wave traveled (the length of the specimen) by the time taken for the wave to travel, as shown in the equation below.

where t a is the time for the first wave arrival, t d is the delay time (measured during the calibration of the transducers), and D is the distance between the transducers (the distance between the opposite surfaces of the cube). A schematic of the UPV test setup is shown in Figure 4.

Schematic of ultrasonic pulse velocity equipment with concrete cub.

In concrete made with inferior materials, waves travel a longer distance due to cracks, voids, or defects within the material. Therefore, concrete of higher quality will have a higher velocity, whereas lower-quality concrete will exhibit a lower velocity. The aggregate quality, density, and modulus of elasticity had a significant impact on the results of the UPV test.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Gradation and density

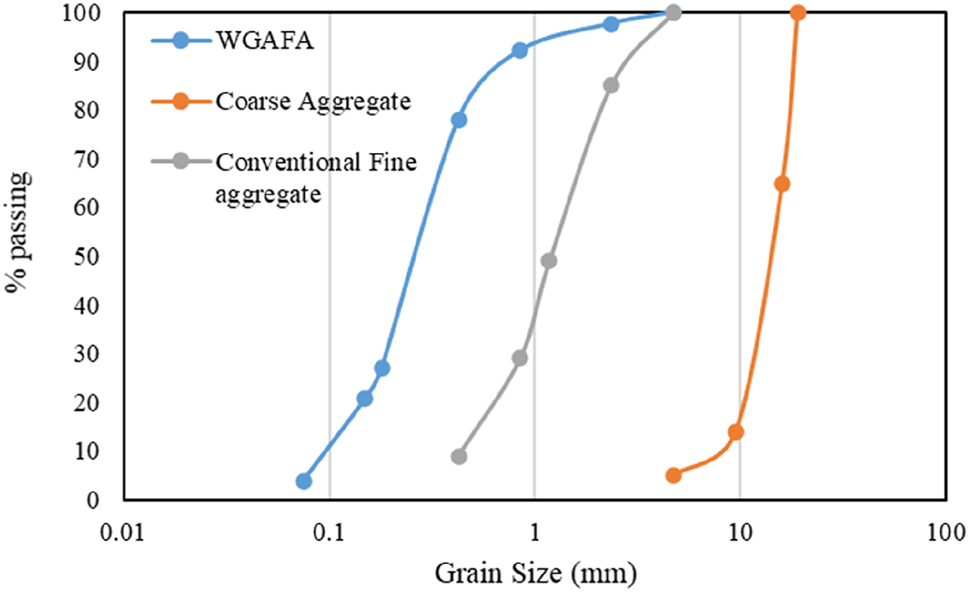

According to [61], 62], the gradation results of the fine aggregate (WGAFA and conventional fine aggregate) and coarse aggregates are presented in Figure 5.

The gradation of fine and coarse aggregate for this research.

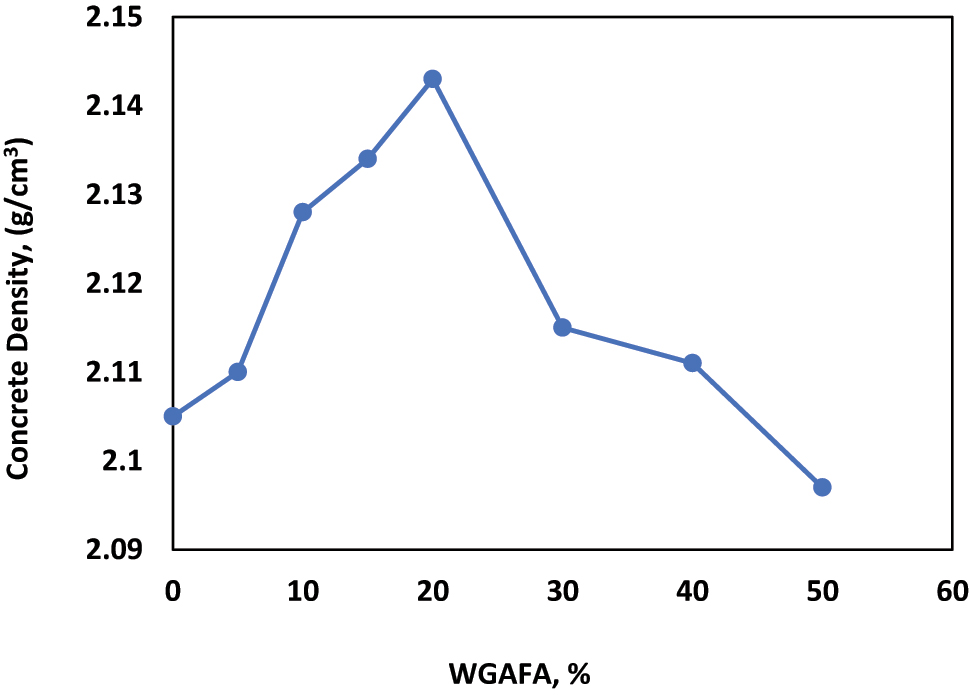

The bulk density of the concrete has been evaluated (Figure 6), which shows that 20 % replacement of fine aggregate with WGAFA is the most feasible option to achieve highest density. However, density is lowered if the replacement aggregate is increased up to 50 %.

The concrete density versus WGAFA.

4.2 Compressive strength

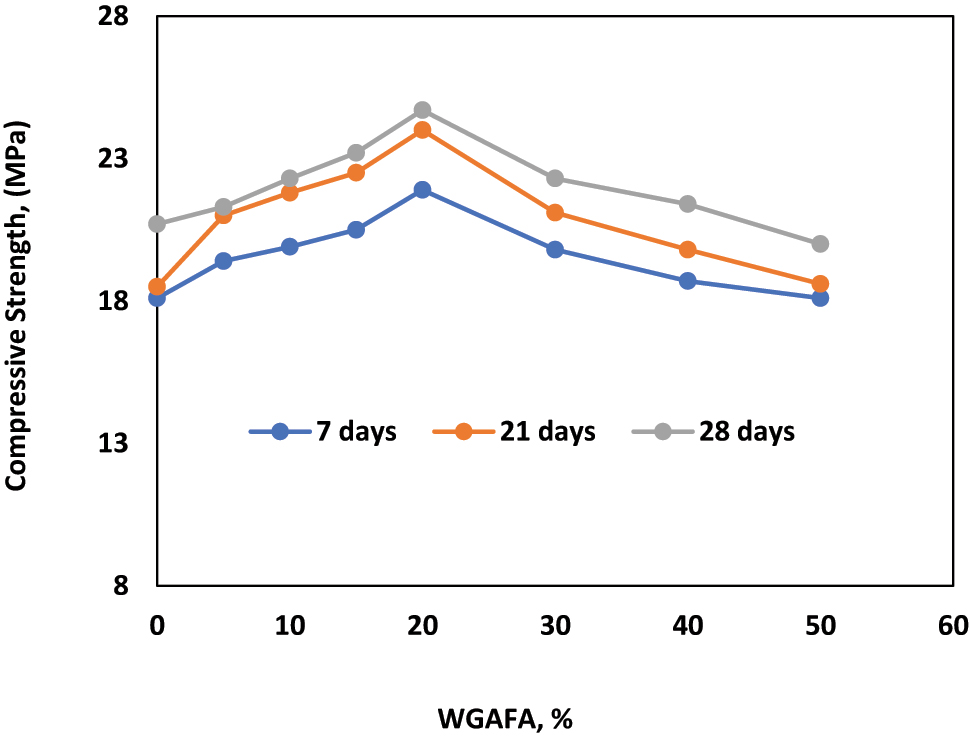

Compressive strengths of concrete cubes were evaluated for the WGAFA replacements of 0 %, 5 %, 10 %, 15 %, 20 %, 30 %, 40 %, and 50 % by volume. The Fine aggregate replacement up to 20 % in concrete causes enhancement of compressive strength up to 19 %, after which the strength shows decreasing pattern (Figure 7).

The concrete compressive strength versus WGAFA.

The strength of concrete after fire or thermal exposure is critical to structural designers. The concrete cubes were placed in a furnace for heating at the elevated temperatures up 800 °C to compare the strengths of heated and unheated samples. The average compressive strength (in triplicate, i.e., three individual samples) of the cubes was taken after 28-days curing. The compressive strength was evaluated all the replacement quantities of WGAFA in the concrete mix as presented in Figure 7 which shows that 20 % replacement of fine aggregate by WGAFA is the high-strength and most feasible option to achieve highest compressive strength (CS) as 21.9 MPa, 24 MPa and 24.7 MPa for 7, 21 and 28-days curing period respectively. Whereas, CS is lowered if the replacement aggregate is increased up to 50 %.

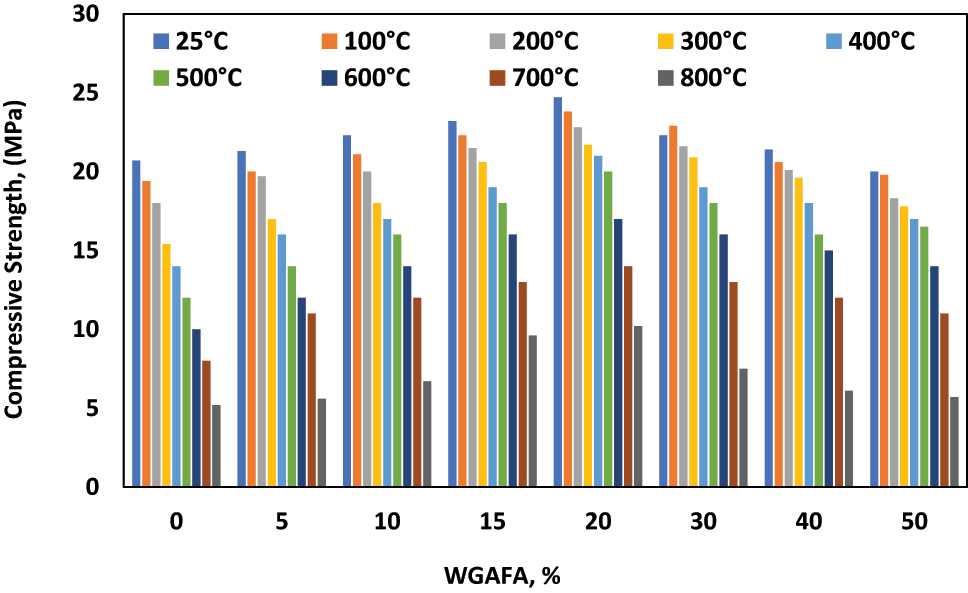

The compressive strengths of the concrete cubes at different post-heating levels exposed to 25 °C, 100 °C, 200 °C, 300 °C, 400 °C, 500 °C, 600 °C, 700 °C and 800 °C temperature levels, are presented in Figure 8. The strength degradation due to thermal exposure was observed up to 58 % in case of mix with optimal 20 % WGAFA.

Compressive strength versus WGAFA (%) at elevated temperature.

To quantitatively address the non-linearity of strength degradation, the rate of compressive strength loss per 100 °C increment was analyzed for the optimal 20 % WGAFA mix, as presented in Table 6. This analysis reveals a clear and pronounced acceleration in the degradation rate, rather than a steady decline. The most severe deterioration occurred between 400 °C and 600 °C, where the strength loss rate peaked at −15.8 % per 100 °C. This critical temperature window aligns precisely with the fundamental chemical decomposition of the cementitious binder. The process initiates with the de-hydroxylation of Portlandite (Ca(OH)2 → CaO + H2O) around 400–500 °C, which not only contributes to mass loss but also creates a more porous and brittle matrix. Subsequently, and more critically, the calcium-silicate-hydrate (C–S–H) gel – the primary phase responsible for the cohesive strength and structural integrity of concrete – undergoes severe and accelerated breakdown above 500 °C. The synergistic effect of these decomposition reactions leads to a catastrophic disintegration of the binding phases, resulting in extensive micro-cracking, coarsening of the pore structure, and a severe weakening of the Interfacial Transition Zone (ITZ). The quantified degradation rate of −15.8 % per 100 °C in this range is a direct macroscopic manifestation of this underlying micro-structural collapse. In contrast, the degradation rates at lower temperatures (e.g., −4.5 % per 100 °C from 200-400 °C) are primarily governed by the evaporation of pore water, which has a less drastic impact on the solid skeleton. This normalized analysis not only clarifies the non-linear response but also underscores the extreme vulnerability of concrete structures exposed to fires surpassing the 400 °C threshold.

Rate of compressive strength degradation per 100 °C for the 20 % WGAFA Mix.

| Temperature interval (°C) | Average strength loss per 100 °C (%) |

|---|---|

| 25–200 | −2.1 |

| 200–400 | −4.5 |

| 400–600 | −15.8 |

| 600–800 | −9.1 |

The non-linear behaviour for the mass-loss is shown in Table 6.

Table 6 quantifies the non-linear degradation, highlighting the accelerated damage in the 400–600 °C range.

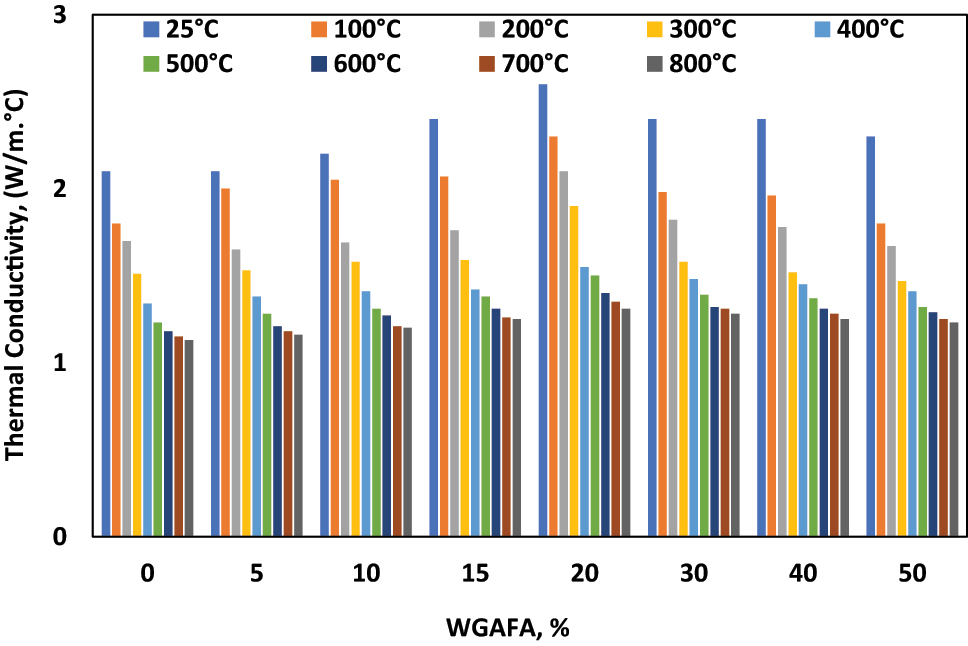

4.3 Thermal conductivity

The thermal conductivity was measured for all the mixes containing WGAFA aggregate substitution as 0 %, 5 %, 10 %, 15 %, 20 %, 30 %, 40 %, and 50 % by volume. The Fine aggregate replacement up to 20 % in concrete causes enhancement of thermal conductivity up to 23.8 %, after which the strength shows decreasing pattern. The 28-days cured concrete cubes were tested for thermal conductivity at the post-heating stages corresponding to the 25 °C, 100 °C, 200 °C, 300 °C, 400 °C, 500 °C, 600 °C, 700 °C, and 800 °C temperature levels, as shown in Figure 9, which shows 49 % degradation in thermal conductivity for optimal 20 % WGAFA replacement with rise in temperature of the concrete cubes from 25 °C to 800 °C. Similarly, all mixes showed degradation in thermal conductivity with an increase in temperature.

Thermal conductivity versus WGAFA (%) at elevated temperature.

The peak in thermal conductivity at the 20 % WGAFA replacement level is a significant finding. This can be explained by two factors: the intrinsic property of the aggregate and the resulting composite microstructure. Firstly, WGAFA, with its very high silica (SiO2) content (92.5 %), has a higher intrinsic thermal conductivity than the cement paste it displaces. Secondly, at this optimal replacement level, the particle size distribution of WGAFA likely creates a denser, more efficiently packed aggregate skeleton with fewer voids, as previously discussed. This optimized solid matrix provides a more continuous pathway for heat flow. Beyond 20 %, the increasing porosity of the mix begins to dominate; since air has a very low thermal conductivity, it acts as an insulator, reducing the overall thermal conductivity of the composite.

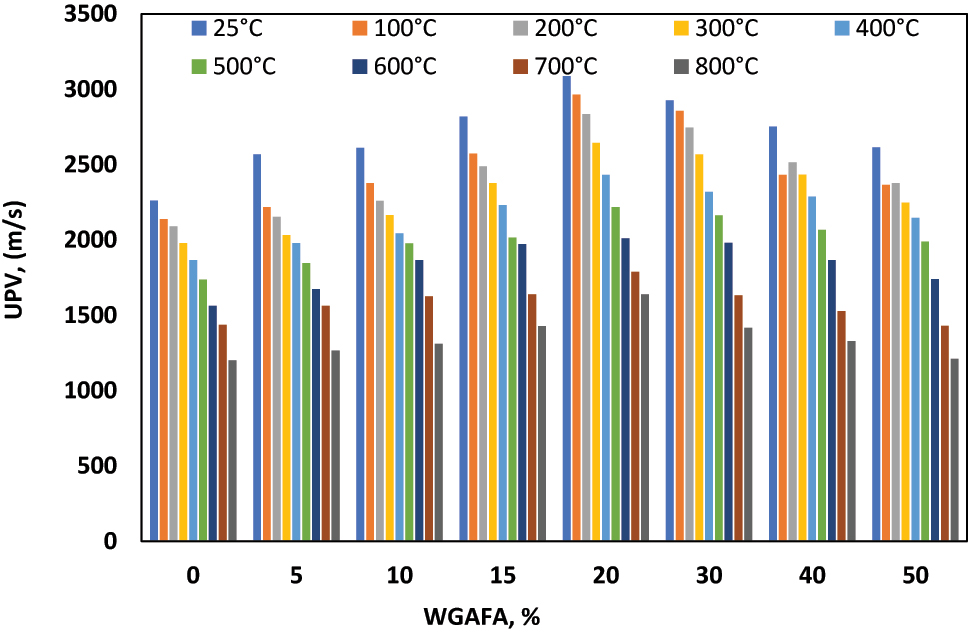

4.4 Ultrasonic pulse velocity

The ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV) of the concrete was measured for all the mixes containing WGAFA aggregate substitution at 0 %, 5 %, 10 %, 15 %, 20 %, 30 %, 40 %, and 50 % by volume. The Fine aggregate replacement up to 20 % in concrete causes enhancement of UPV up to 36.5 %, after which the strength shows decreasing pattern. The 28-days cured concrete cubes were tested for UPV at the post-heating stages corresponding to the 25 °C, 100 °C, 200 °C, 300 °C, 400 °C, 500 °C, 600 °C, 700 °C, and 800 °C temperature levels, as presented in Figure 10, which shows 47 % degradation in UPV for optimal 20 % WGAFA replacement with rise in temperature of the concrete cubes from 25 °C to 800 °C. Similarly, all mixes showed degradation in the UPV with an increase in temperature.

The concrete UPV versus WGAFA (%) at elevated temperature.

4.5 Mass loss analysis

Mass loss of concrete with the optimal 20 % WGAFA replacement at elevated temperatures is presented in Figure 11. The results demonstrate a definitive correlation between mass loss and the degradation of mechanical and physical properties. The degradation occurred in two distinct phases: an initial phase up to 300 °C, characterized by a gradual mass loss of 4.5 %, which is primarily attributed to the evaporation of free and physically bound water from the capillary pores and gel structure. This was followed by a critical phase between 400 °C and 600 °C, where a pronounced mass loss step of 8.0 % occurred (increasing from 4.5 % to 12.5 %), culminating in a total mass loss of 15.5 % at 800 °C. This accelerated loss in the 400–600 °C window coincides precisely with the critical temperature range where the compressive strength degradation rate peaked at −15.8 % per 100 °C, and is directly attributable to the chemical decomposition of the cementitious matrix – specifically, the de-hydroxylation of Portlandite (Ca(OH)2 → CaO + H2O) and the breakdown of the C–S–H gel. This confirms that mass loss is not merely free water evaporation but a direct macroscopic indicator of profound chemical and micro-structural deterioration that critically compromises the concrete’s structural integrity under thermal stress.

Mass loss of 20 % WGAFA concrete at elevated temperatures.

The findings of this study align with and extend the existing body of knowledge on sustainable concrete. The observed 19 % enhancement in compressive strength with a 20 % WGAFA replacement is consistent with the principle that optimally graded alternative aggregates can improve particle packing and matrix density [63]. Furthermore, the pattern of degradation in compressive strength and thermal conductivity at elevated temperatures observed here particularly the accelerated loss between 400 °C and 600 °C [64], resonates with the well-documented behavior of conventional and recycled aggregate concretes, being governed by the decomposition of hydration products [65]. The novelty of the present research, however, lies in the development of a predictive model for post-heating compressive strength that synergistically uses two non-destructive parameters: Thermal Conductivity (TC) and Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity (UPV) [66]. While UPV is commonly used for quality assessment, its combination with TC for post-fire residual strength prediction is less explored and provides a more robust, dual-indicator framework for assessing fire-damaged structures compared to single-parameter or fresh-state models.

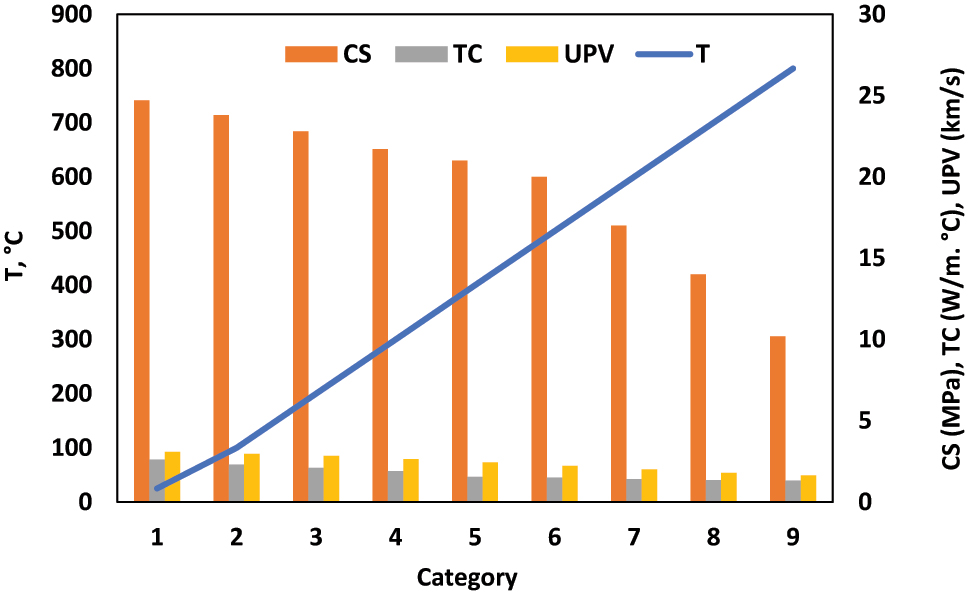

4.6 Comparative analysis of thermal degradation

In brief, the compressive strength (CS), thermal conductivity (TC), and ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV) are optimum for the optimal mix containing 20 % WGAFA. It is evident from the Figure 12 that with an increase in temperature from 25 °C to 800 °C, the CS, TC, and UPV decreased drastically showing the degradation of the structure of concrete. This phenomenon becomes critical in fire incidents, and concrete infrastructure is restricted for living purposes due to the drastic decrease in the strength of concrete.

The comparison of temperature (T), compressive strength (CS), thermal conductivity (TC) and UPV.

The decline in compressive strength, thermal conductivity, and UPV beyond the 20 % WGAFA replacement level can be attributed to detrimental changes in the concrete’s micro-structure. While a moderate amount of the coarser WGAFA optimizes particle packing by filling voids including the micro-voids within the natural sand matrix, excessive replacement disrupts this optimal gradation. This leads to an increase in the inter-particle void content and overall porosity of the composite. A more porous system inherently weakens the Interfacial Transition Zone (ITZ) – the critical region between the aggregate and the cement paste – making it the preferential path for micro-cracking under load, thereby reducing compressive strength. This increased porosity also introduces a greater volume of air, which is an excellent thermal insulator, thereby hindering the solid matrix’s ability to conduct heat and resulting in lower thermal conductivity. Similarly, the ultrasonic pulses used in the UPV test are scattered and dampened by the increased number of pore and crack interfaces within the degraded microstructure, leading to a longer travel path and a lower measured pulse velocity.

4.7 Predictive model

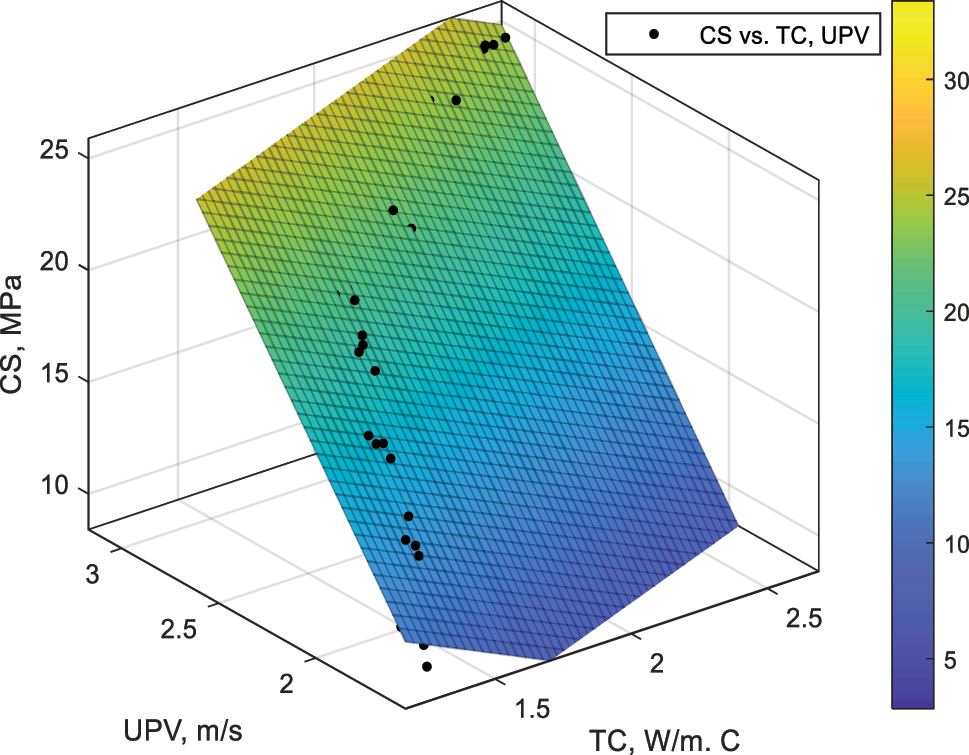

Due to the drastic decrease in the concrete strength at high-temperature exposure, it is pivotal to model the data for use in preventive measures in buildings comprising concrete infrastructures. For this purpose, the correlation of the CS with TC and UPV was developed using the curve fitter approach in surface graphs presented in Figure 13.

Model of compressive strength (CS), Thermal conductivity (TC) and UPV.

Using the values of TC and UPV, which are nondestructive parameters, the compressive strength can be evaluated at elevated temperatures in buildings exposed to elevated temperatures.

Following is the detail of the proposed model and its statistical validation.

Polynomial Surface Fit Model:

Model Validation Metrics:

R-squared (R2): 0.9497

Adjusted R-squared: 0.9467

Root Mean Square Error (RMSE): 1.0625 MPa

The high R2 and Adjusted R2 values indicate that the model explains approximately 95 % of the variance in the experimental compressive strength data, demonstrating an excellent fit. The low RMSE signifies high predictive accuracy within the dataset. The Adjusted R-squared, which accounts for the number of predictors, confirms the model’s robustness. It is important to note that this validation is based on the dataset used for model development. While these results are highly promising, the model’s generalizability should be further confirmed through external validation with an independent dataset in future work.

The developed polynomial model provides a straightforward and practical tool for engineers. Its strong performance (R2 = 0.9497) is robust for a regression-based approach, offering a balance between accuracy and practical utility. We acknowledge that advanced computational models, such as the hybrid machine learning techniques cited by the reviewer, can demonstrate superior predictive accuracy for complex concrete behaviors. For instance, the hybrid Extreme Learning Machine–Grey Wolf Optimizer (ELM-GWO) model has been successfully applied to predict the compressive strength of concrete containing partial cement replacements [67].

The choice of our polynomial model was guided by its simplicity, interpretability, and ease of deployment in field conditions where rapid assessment of post-fire damage is paramount. Our approach aligns with research that prioritizes the interpretation of concrete behavior; for example, studies on the impact failure mechanism of fiber-reinforced composites provide deep insights into how materials like silica fume enhance performance under stress [68]. Furthermore, investigating the compaction and compression behavior of modified cement-treated sands highlights the importance of practical material selection and mixture optimization, which is a key consideration in our use of WGAFA [69]. The cited advanced studies provide a valuable benchmark for methodology and contextual understanding, underscoring the potential for developing more complex predictive systems in future work.

The developed polynomial surface fit model provides a straightforward, interpretable, and practical tool for engineers, achieving robust performance with an R2 of 0.9497 and RMSE of 1.0625 MPa. This performance is highly competitive when contextualized with advanced machine learning models in the literature. The hybrid Extreme Learning Machine–Grey Wolf Optimizer (ELM-GWO) model, noted for its superior predictive accuracy in complex scenarios, reported an R2 of 0.9510 for predicting the compressive strength of fiber-reinforced concrete containing nano-silica [70]. The marginal difference in performance between our simpler polynomial model and other complex, computationally intensive algorithms under-scores its remarkable efficacy. The choice of our model was therefore guided not only by its high accuracy but also by its simplicity, computational efficiency, and ease of deployment for rapid post-fire assessment in field conditions, offering a compelling balance between performance and practical utility.

Whereas, advanced machine learning models (e.g., Random Forest, Artificial Neural Networks) reported in the literature can achieve comparable accuracy (R2 up to 0.954) for predicting complex concrete behaviors, the choice of our polynomial model was guided by its superior practicality for field engineers. Its simplicity and interpretability allow for rapid, on-site assessment of post-fire damage without the ‘black box’ complexity of ML algorithms, offering a compelling balance between performance and utility.

The physical basis for this model lies in the interdependency of the parameters under thermal stress, as illustrated in Figure 12. Thermal Conductivity (TC) is a property strongly influenced by the density and continuity of the solid matrix. A high TC indicates a well-connected, dense microstructure conducive to both heat transfer and load bearing. Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity (UPV) is exquisitely sensitive to the presence of internal discontinuities such as micro-cracks, voids, and degraded interfaces. The simultaneous decline in both TC and UPV, as quantified by our model, is a direct proxy for the comprehensive micro-structural deterioration – specifically, the increase in porosity and microcracking – that is initiated by the chemical decomposition processes (e.g., C–S–H breakdown) and physically manifested as the mass loss documented in Section 4.4. The model effectively captures that this concurrent degradation signals a severe and comprehensive breakdown of the concrete microstructure: the solid load-bearing pathways are diminished (lowering TC and CS), and the internal flaw population has increased (lowering UPV). This dual-parameter approach offers a more reliable assessment of post-fire health than either parameter alone.

5 Conclusions

This study explores the potential of partially replacing fine aggregates up to 50 % with Wadi Gyada Alkharj Fine Aggregate (WGAFA) to significantly elevate the strength and durability attributes at low to high temperature ranges using cutting-edge nondestructive and destructive testing methods.

A series of strength tests revealed that 20 % optimal partial replacement of traditional aggregate by WGAFA yielded a marked enhancement in compressive strength (CS), thermal conductivity (TC), and ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV) of concrete at optimal use of 20 % WGAFA of 19 %, 23.8 %, and 36.5 %, respectively, compared with traditional aggregate.

A significant decline in the TC, CS, and UPV was observed as 58 %, 49 %, and 47 % at exposure to the 800 °C thermal effect as compared to 25 °C.

A predictive model for compressive strength (CS) was developed using TC and UPV, which has implications for infrastructure protection preemptive measures for fire disaster incidents to save lives. This research is significant in that only the non-destructive parameters for thermally exposed concrete infrastructures, that is, the post-heating residual compressive strength, can be evaluated to assess the feasibility of the structure for future use.

6 Future recommendations

Exposure duration plays a critical role in determining the residual strength of concrete under high temperatures, highlighting the need for accurate exposure time measurements. Despite these valuable insights, further research is required to explore the long-term effects of sustained elevated temperatures, particularly regarding different aggregate types, and to identify the critical temperature thresholds.

6.1 Integration of supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs)

This study focused on the aggregate phase; however, the cementitious matrix plays an equally critical role in thermal resilience. Future research should investigate the synergistic effects of combining WGAFA with SCMs such as fly ash and silica fume. As demonstrated in other studies, SCMs can significantly refine pore structure, enhance later-age strength, and improve the stability of the hydration products at high temperatures [71], 72]. For instance, the synergistic use of silica fume and fibers can enhance strength and thermal properties [73]. Exploring these ternary blends (Cement + SCM + WGAFA) is a logical and promising next step for developing ultra-resilient and sustainable concrete mixtures.

7 Research limitations

This study was limited by the gradations adopted in the mix design. However, this model can be developed for other gradations so that it can be used in diverse patterns in concrete infrastructure at a wide range of temperature.

Funding source: Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University

Award Identifier / Grant number: PSAU/2024/01/28580

-

Funding information: The authors extend their appreciation to Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University for funding this research work through the project number (PSAU/2024/01/28580).

-

Author contribution: Conceptualization, S.A.; methodology, S.A.; formal analysis, S.A.; investigation, S.A; data curation, S.A.; writing – original draft, S.A.; writing – review and editing, S.A.; project administration, S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Data are contained within the article.

References

1. Amjad, H, Ahmad, F, Qureshi, MI. Enhanced mechanical and durability resilience of plastic aggregate concrete modified with nano-iron oxide and sisal fiber reinforcement. Constr Build Mater 2023;401:132911. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132911.Search in Google Scholar

2. Dawood, AO, Hayder, AK, Falih, RS. Physical and mechanical properties of concrete containing PET wastes as a partial replacement for fine aggregates. Case Stud Constr Mater 2021;14:e00482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2020.e00482.Search in Google Scholar

3. Castro, JR, Santini, C, Zsembinszki, G, Kala, SM, Martinez, FR, Risco, S, et al.. Innovative refractory concrete for high temperature thermal energy storage. Sol Energy Mater Sol Cell 2025;285:113506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solmat.2025.113506.Search in Google Scholar

4. Tajadod, OE, Ravanshadnia, M, Ghanbari, M. Integrating circular economy and life cycle assessment strategies in climate-resilient buildings: an artificial intelligence approach to enhance thermal comfort and minimize CO2 emissions in Iran. Energy 2025;320:135064. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2025.135064.Search in Google Scholar

5. Huluka, AB, Muthulingam, S. Advancing multi-weather resilient roof: experiment augmented multifaceted thermal parameter analysis with integrated hexad PCMs under tropical steppe climate. Build Environ 2025;269:112351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2024.112351.Search in Google Scholar

6. Zhang, Y, Wu, S, Zang, A, Zhao, Y, Tang, W. Non-uniform cooling mechanism of concrete after exposure to high temperatures revealed by laboratory tests and microstructural inspection. Constr Build Mater 2025;458:139766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.139766.Search in Google Scholar

7. Kowalski, R, Głowacki, M, Wroblewska, J, Senatorska-Dobrowolska, M, Smardz, P. Dangerous damage of RC structural members caused by thermal spalling of concrete during fire in an enclosed car park of residential building. Fire Saf J 2025;152:104352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.firesaf.2025.104352.Search in Google Scholar

8. Rafai, M, Salciarini, D, Vardon, PJ. Energy pile displacements due to cyclic thermal loading at different mechanical load levels. Acta Geotechnica 2025;20:3067–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-025-02556-4.Search in Google Scholar

9. Ahmad, R, Ali, M. A review on introducing fibers in concrete for blocks, pavers and kerbstone. Construct Tech Architecture 2025;15:79–84. https://doi.org/10.4028/p-pq8hma.Search in Google Scholar

10. Hu, K, Gillani, ST, Tao, X, Tariq, J, Chen, D. Eco-friendly construction: integrating demolition waste into concrete masonry blocks for sustainable development. Constr Build Mater 2025;460:139797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.139797.Search in Google Scholar

11. Wang, H, Shen, W, Sun, X, Song, X, Lin, X. Influences of particle size on the performance of 3D printed coarse aggregate concrete: experiment, microstructure, and mechanism analysis. Constr Build Mater 2025;463:140059. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2025.140059.Search in Google Scholar

12. Garcia, LC, Valencia, JV, Colorado, LHA. Modeling an artificial neural network to estimate cement consumption in clayey waste-cement mixtures based on curing temperature, mechanical strength, and resilient modulus. Constr Build Mater 2025;467:140376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2025.140376.Search in Google Scholar

13. Ali, AY, Ahmed, SA, El-Feky, MS. Alkali-activated concrete with expanded polystyrene: a lightweight, high-strength solution for fire resistance and explosive protection. J Build Eng 2025;99:111648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2024.111648.Search in Google Scholar

14. Ghamari, A, Powęzka, A, Kytinou, VK, Amini, A. An innovative fire-resistant lightweight concrete infill wall reinforced with waste glass. Buildings 2024;14:626. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14030626.Search in Google Scholar

15. Zhou, H, Tian, X, Wu, J. Cracking and thermal resistance in concrete: coupled thermo-mechanics and phase-field modeling. Theor Appl Fract Mech 2024;130:104285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tafmec.2024.104285.Search in Google Scholar

16. Bayrak, B, Maali, M, Kılıç, M, Maali, M, Aydın, AC. Fire resistance of concrete-filled steel tube beam-column under elevated temperatures and cyclic loading. Struct Concr 2024;25:3145–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/suco.202301121.Search in Google Scholar

17. Luhar, S, Nicolaides, D, Luhar, I. Fire resistance behaviour of geopolymer concrete: an overview. Buildings 2021;11:82. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings11030082.Search in Google Scholar

18. Pan, Z, Sanjayan, JG. Stress–strain behaviour and abrupt loss of stiffness of geopolymer at elevated temperatures. Cement Concr Compos 2010;32:657–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2010.07.010.Search in Google Scholar

19. Hernández-Figueirido, D, Reig, L, Melchor-Eixea, A, Roig-Flores, M, Albero, V, Piquer, A, et al.. Spalling phenomenon and fire resistance of ultrahigh-performance concrete. Constr Build Mater 2024;443:137695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.137695.Search in Google Scholar

20. Danish, A, Mosaberpanah, MA. Influence of cenospheres and fly ash on the mechanical and durability properties of high-performance cement mortar under different curing regimes. Constr Build Mater 2021;279:122458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.122458.Search in Google Scholar

21. Ahmad, F, Jamal, A, Mazher, KM, Umer, W, Iqbal, M. Performance evaluation of plastic concrete modified with E-Waste plastic as a partial replacement of coarse aggregate. Materials 2022;15:175. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15010175.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Lv, H, Xiong, Z, Li, H, Liu, J, Xu, G, Chen, H. Investigating the mechanical properties and water permeability of recycled pervious concrete using three typical gradation schemes. Buildings 2025;15:358. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15030358.Search in Google Scholar

23. Shi, Q, Zhou, M, Zhang, S, Liu, Y, Han, Y, Wang, Q. Preparation and performance study of coal gangue aggregate permeable concrete bricks (CGAPCBs). Road Mater Pavement Des 2025;20:1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680629.2025.2465572.Search in Google Scholar

24. Kangavar, ME, Lokuge, W, Manalo, A, Karunasena, W, Frigione, M. Investigation on the properties of concrete with recycled polyethylene terephthalate (PET) granules as fine aggregate replacement. Case Stud Constr Mater 2022;16:e00934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e00934.Search in Google Scholar

25. Islam, MH, Prova, ZN, Sobuz, MH, Nijum, NJ, Aditto, FS. Experimental investigation on fresh, hardened and durability characteristics of partially replaced E-waste plastic concrete: a sustainable concept with machine learning approaches. Heliyon 2025;11:e41924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2025.e41924.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Suwindu, KS, Caronge, MA, Tjaronge, MW. Flexural strength of beam specimens using alumina-type refractory brick waste as coarse aggregate. Int J Pavement Res Technol 2025;13:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42947-024-00480-6.Search in Google Scholar

27. Tian, Z, Wang, Q, Hou, S, Shen, X. Effects of multi-sized glass fiber-reinforced polymer waste on hydration and mechanical properties of cement-based materials. J Build Eng 2025;102:112070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2025.112070.Search in Google Scholar

28. Qaidi, S, Al-Kamaki, Y, Hakeem, I, Dulaimi, AF, Özkılıç, Y, Sabri, M, et al.. Investigation of the physical-mechanical properties and durability of high-strength concrete with recycled PET as a partial replacement for fine aggregates. Front Mater 2023;10:1101146. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmats.2023.1101146.Search in Google Scholar

29. Deng, SW, Li, YF, Ma, HY, Liu, HB, Bai, Q. Utilizing molybdenumm tailings to prepare eco-friendly ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC): workability, mechanical properties and life-cycle assessment. Case Stud Constr Mater 2025;22:e04501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2025.e04501.Search in Google Scholar

30. De Vlieger, J, Blaakmeer, J, Gruyaert, E, Cizer, Ö. Assessing static and dynamic yield stress of 3D printing mortar with recycled sand: influence of sand geometry, fineness modulus, and water-to-binder ratio. J Build Eng 2025;101:111827. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2025.111827.Search in Google Scholar

31. Ukpata, JO, Ewa, DE, Success, NG, Alaneme, GU, Otu, ON, Olaiya, BC. Effects of aggregate sizes on the performance of laterized concrete. Sci Rep 2024;14:448. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50998-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

32. Farahani, A, Sharifi, M, Bayesteh, H. Effect of aggregate size on the slump and uniaxial compressive strength of concrete: a DEM study. Part Sci Technol 2025;43:15–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/02726351.2024.2412655.Search in Google Scholar

33. Zong, S, Chang, C, Rem, P, Gebremariam, AT, Di Maio, F, Lu, Y. Research on the influence of particle size distribution of high-quality recycled coarse aggregates on the mechanical properties of recycled concrete. Constr Build Mater 2025;465:140253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2025.140253.Search in Google Scholar

34. Yu, K, Ding, Y, Zhang, YX. Size effects on tensile properties and compressive strength of engineered cementitious composites. Cement Concr Compos 2020;113:103691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2020.103691.Search in Google Scholar

35. Lin, L, Xu, J, Ying, W, Yu, Y, Zhou, L. Post-fire compressive mechanical behaviors of concrete incorporating coarse and fine recycled aggregates. Constr Build Mater 2025;461:139948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2025.139948.Search in Google Scholar

36. Luo, L, Jia, M, Wang, H, Cheng, X. Experimental evaluation and microscopic analysis of the sustainable ultra-high-performance concrete after exposure to high temperatures. Struct Concr 2025;26:2787–815. https://doi.org/10.1002/suco.202400874.Search in Google Scholar

37. Huang, Z, Luo, Y, Zhang, W, Ye, Z, Li, Z, Liang, Y. Thermal insulation and high-temperature resistant cement-based materials with different pore structure characteristics: performance and high-temperature testing. J Build Eng 2025;101:111839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2025.111839.Search in Google Scholar

38. Wang, Y, Wu, Z, Zheng, X, Li, K, Liu, C. A review of concrete exposed to low-temperature environments at early ages: mechanical properties and durability. J Build Eng 2025;16:113122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2025.113122.Search in Google Scholar

39. Noth, VA, Loh, TW, Nguyen, KT. The influences of cooling regimes on fire-damaged novel concrete. In: Construction materials and their properties for fire resistance and insulation. Cambridge, UK: Woodhead Publishing; 2025, 1:179–98 pp.10.1016/B978-0-443-21620-6.00011-8Search in Google Scholar

40. Agrawal, S, Yulianti, E, Amran, M, Hung, CC. Behavior of unconfined steel-fiber reinforced UHPC post high-temperature exposure. Case Stud Constr Mater 2025;22:e04173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2024.e04173.Search in Google Scholar

41. Wang, J, Zhao, C, Li, Q, Song, G, Hu, Y. The synergistic effect of recycled steel fibers and rubber aggregates from waste tires on the basic properties, drying shrinkage, and pore structures of cement concrete. Constr Build Mater 2025;470:140574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2025.140574.Search in Google Scholar

42. Ding, Y, Zhang, C, Cao, M, Zhang, Y, Azevedo, C. Influence of different fibers on the change of pore pressure of self-consolidating concrete exposed to fire. Constr Build Mater 2016;113:456–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.03.070.Search in Google Scholar

43. Sayari, T, Mohaine, S, Honorio, T, Robert, F, Benboudjema, F, Cussigh, F, et al.. Experimental investigation of standardized conditioning and representative accelerated drying protocols impact on concrete spalling. Fire Mater 2025;49:417–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/fam.3291.Search in Google Scholar

44. Abbas, H, Abadel, A, Alaskar, A, Almusallam, T, Al-Salloum, Y. Effects of moisture on properties of concrete exposed to elevated temperature. Arabian J Sci Eng 2025;50:1477–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-024-09012-7.Search in Google Scholar

45. Deng, J, Cui, J, Surahman, R, Tu, M, Wang, Y. Experimental and analytical study on heat transfer of concrete with different degrees of saturation under elevated temperatures. Fire Mater 2025;49:269–79. https://doi.org/10.1002/fam.3270.Search in Google Scholar

46. Asante, B, Wang, B, Yan, L, Kasal, B. Optimized mix design and fire resistance of geopolymer recycled aggregate concrete under elevated temperatures. Case Stud Constr Mater 2025;22:e04401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2025.e04401.Search in Google Scholar

47. Xu, Z, Bai, Z, Wu, J, Long, H, Deng, H, Chen, Z, et al.. Microstructural characteristics and nano-modification of interfacial transition zone in concrete: a review. Nanotechnol Rev 2022;11:2078–100. https://doi.org/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0125.Search in Google Scholar

48. Yang, J, Zhang, R, Fan, L, Cui, X, Wang, X, Gong, X. Strength and micro-mechanism analysis of concrete under corrosion-freeze-thaw-large temperature difference real exposure field. Constr Build Mater 2025;458:139520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.139520.Search in Google Scholar

49. Zhang, Y, Yuan, Z, Zhang, L, Zhang, X, Ji, K, Ni, W, et al.. Experimental and theoretical study of fire resistance of steel slag powder concrete beams. Eng Struct 2025;325:119402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2024.119402.Search in Google Scholar

50. Ibrahim, EA, Goff, D, Keyvanfar, A, Jonaidi, M. Assessing post-fire damage in concrete structures: a comprehensive review. Buildings 2025;15:485. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15030485.Search in Google Scholar

51. ASCE/SFPE29. Standard calculation method for structural fire protection. Reston, VA: American Society of Civil Engineers; 1999.Search in Google Scholar

52. ASTM. E1529. Standard test methods for determining effects of large hydrocarbon pool fires on structural members and assemblies. Test method. West Conshohocken, PA: American Society for Testing and Materials; 1993.Search in Google Scholar

53. American Society for Testing and Materials, Standard Methods of Fire Endurance Tests of Building Construction and Materials. ASTM E119-88, Philadelphia, PA, 1990.Search in Google Scholar

54. BS 476-3. Fire tests on building materials and structures – part 20: method from determination of the fire resistance of elements of construction (general principles). UK: BSi; 1987.Search in Google Scholar

55. Kalifa, P, Menneteau, FD, Quenard, D. Spalling and pore pressure in HPC at high temperatures. Cement Concr Res 2000;30:1915–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0008-8846(00)00384-7.Search in Google Scholar

56. Kodur, VR. Guidelines for fire resistance design of high strength concrete columns. J Fire Protect Eng 2005;15:93–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042391505047740.Search in Google Scholar

57. Dal Pozzo, A, Carabba, L, Bignozzi, MC, Tugnoli, A. Life cycle assessment of a geopolymer mixture for fireproofing applications. Int J Life Cycle Assess 2019;24:1743–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-019-01603-z.Search in Google Scholar

58. Hamda, M, Guergah, C, Benmarce, A. The impact of natural fibers on thermal resistance and spalling in high-performance concrete. Period Polytech Civ Eng 2025;69:84–97. https://doi.org/10.3311/ppci.36682.Search in Google Scholar

59. Shi, W, Wang, Z, Li, C, Sun, Q, Wang, W, Deng, S, et al.. High-temperature strengthening of Portland cementitious materials by surface micro-ceramization. Cement Concr Res 2025;190:107790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2025.107790.Search in Google Scholar

60. ASTM International. ASTM C597-16, standard test method for pulse velocity through concrete. West Conshohocken, PA, USA: ASTM International; 2016.Search in Google Scholar

61. ASTM C33. Concrete Aggregates 1, i (2010) 1–11 https://doi.org/10.1520/C0033.Search in Google Scholar

62. ASTM International. ASTM C136/C136M standard test method for sieve analysis of fine and coarse aggregates. ASTM Stand B 2019:3–7. https://doi.org/10.1520/C0136.Search in Google Scholar

63. Chen, JJ, Guan, GX, Ng, PL, Kwan, AK, Chu, SH. Packing optimization of paste and aggregate phases for sustainability and performance improvement of concrete. Adv Powder Technol 2021;32:987–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apt.2021.02.008.Search in Google Scholar

64. Fang, Y, Wang, C, Yang, H, Chen, J, Dong, Z, Li, LY. Development of a ternary high-temperature resistant geopolymer and the deterioration mechanism of its concrete after heat exposure. Constr Build Mater 2024;449:138291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.138291.Search in Google Scholar

65. Dang, J, Hao, L, Wang, T, Xiao, J, Zhao, H. Improving thermal conductivity and drying shrinkage of foamed concrete with artificial ceramsite from excavation soil and sewage sludge. Constr Build Mater 2024;438:137010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.137010.Search in Google Scholar

66. Lima, HM, Neto, JA, Haach, VG, Neto, JM. Physical and mechanical properties of cement-lime mortar for masonry at elevated temperatures: destructive and ultrasonic testing. J Build Eng 2025;104:112291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2025.112291.Search in Google Scholar

67. Shariati, M, Mafipour, MS, Ghahremani, B, Azarhomayun, F, Ahmadi, M, Trung, NT, et al.. A novel hybrid extreme learning machine–grey wolf optimizer (ELM-GWO) model to predict compressive strength of concrete with partial replacements for cement. Eng Comput 2022;38:757–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00366-020-01081-0.Search in Google Scholar

68. Dalvand, A, Ahmadi, M. Impact failure mechanism and mechanical characteristics of steel fiber reinforced self-compacting cementitious composites containing silica fume. Eng Sci Technol Int J 2021;24:736–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jestch.2020.12.016.Search in Google Scholar

69. Eftekhar, AS, Ghasemi, M, Rahimiratki, A, Mehdizadeh, B, Yousefieh, N, Asgharnia, M. Compaction and compression behavior of waste materials and fiber-reinforced cement-treated sand. J Struct Des Construct Pract 2025;30:04025007. https://doi.org/10.1061/jsdccc.sceng-1643.Search in Google Scholar

70. Shokrnia, H, KhodabandehLou, A, Hamidi, P, Ashrafzadeh, F. Prediction of compressive strength of fiber-reinforced concrete containing silica (SiO2) based on metaheuristic optimization algorithms and machine learning techniques. Sci Rep 2025;15:19671. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05146-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

71. Akbulut, ZF, Yavuz, D, Tawfik, TA, Smarzewski, P, Guler, S. Enhancing concrete performance through sustainable utilization of class-C and class-F fly ash: a comprehensive review. Sustainability 2024;16:4905. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16124905.Search in Google Scholar

72. Akbulut, ZF, Yavuz, D, Tawfik, TA, Smarzewski, P, Guler, S. Examining the workability, mechanical, and thermal characteristics of eco-friendly, structural self-compacting lightweight concrete enhanced with fly ash and silica fume. Materials 2024;17:3504. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17143504.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

73. Akbulut, ZF, Kuzielová, E, Tawfik, TA, Smarzewski, P, Guler, S. Synergistic effects of polypropylene fibers and silica fume on structural lightweight concrete: analysis of workability, thermal conductivity, and strength properties. Materials 2024;17:5042. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17205042.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- Utilization of steel slag in concrete: A review on durability and microstructure analysis

- Technical development of modified emulsion asphalt: A review on the preparation, performance, and applications

- Recent developments in ultrasonic welding of similar and dissimilar joints of carbon fiber reinforcement thermoplastics with and without interlayer: A state-of-the-art review

- Unveiling the crucial factors and coating mitigation of solid particle erosion in steam turbine blade failures: A review

- From magnesium oxide, magnesium oxide concrete to magnesium oxide concrete dams

- Properties and potential applications of polymer composites containing secondary fillers

- A scientometric review on the utilization of copper slag as a substitute constituent of ordinary Portland cement concrete

- Advancement of additive manufacturing technology in the development of personalized in vivo and in vitro prosthetic implants

- Recent advance of MOFs in Fenton-like reaction

- A review of defect formation, detection, and effect on mechanical properties of three-dimensional braided composites

- Non-conventional approaches to producing biochars for environmental and energy applications

- Review of the development and application of aluminum alloys in the nuclear industry

- Advances in the development and characterization of combustible cartridge cases and propellants: Preparation, performance, and future prospects

- Recent trends in rubberized and non-rubberized ultra-high performance geopolymer concrete for sustainable construction: A review

- Cement-based materials for radiative cooling: Potential, material and structural design, and future prospects

- A comprehensive review: The impact of recycling polypropylene fiber on lightweight concrete performance

- A comprehensive review of preheating temperature effects on reclaimed asphalt pavement in the hot center plant recycling

- Exploring the potential applications of semi-flexible pavement: A comprehensive review

- A critical review of alkali-activated metakaolin/blast furnace slag-based cementitious materials: Reaction evolution and mechanism

- Dispersibility of graphene-family materials and their impact on the properties of cement-based materials: Application challenges and prospects

- Research progress on rubidium and cesium separation and extraction

- A step towards sustainable concrete with the utilization of M-sand in concrete production: A review

- Studying the effect of nanofillers in civil applications: A review

- Studies on the anticorrosive effect of phytochemicals on mild steel, carbon steel, and stainless-steel surfaces in acid and alkali medium: A review

- Nanotechnology for calcium aluminate cement: thematic analysis

- Research Articles

- Investigation of the corrosion performance of HVOF-sprayed WC-CoCr coatings applied on offshore hydraulic equipment

- A systematic review of metakaolin-based alkali-activated and geopolymer concrete: A step toward green concrete

- Evaluation of color matching of three single-shade composites employing simulated 3D printed cavities with different thicknesses using CIELAB and CIEDE2000 color difference formulae

- Novel approaches in prediction of tensile strain capacity of engineered cementitious composites using interpretable approaches

- Effect of TiB2 particles on the compressive, hardness, and water absorption responses of Kulkual fiber-reinforced epoxy composites

- Analyzing the compressive strength, eco-strength, and cost–strength ratio of agro-waste-derived concrete using advanced machine learning methods

- Tensile behavior evaluation of two-stage concrete using an innovative model optimization approach

- Tailoring the mechanical and degradation properties of 3DP PLA/PCL scaffolds for biomedical applications

- Optimizing compressive strength prediction in glass powder-modified concrete: A comprehensive study on silicon dioxide and calcium oxide influence across varied sample dimensions and strength ranges

- Experimental study on solid particle erosion of protective aircraft coatings at different impact angles

- Compatibility between polyurea resin modifier and asphalt binder based on segregation and rheological parameters

- Fe-containing nominal wollastonite (CaSiO3)–Na2O glass-ceramic: Characterization and biocompatibility

- Relevance of pore network connectivity in tannin-derived carbons for rapid detection of BTEX traces in indoor air

- A life cycle and environmental impact analysis of sustainable concrete incorporating date palm ash and eggshell powder as supplementary cementitious materials

- Eco-friendly utilisation of agricultural waste: Assessing mixture performance and physical properties of asphalt modified with peanut husk ash using response surface methodology

- Benefits and limitations of N2 addition with Ar as shielding gas on microstructure change and their effect on hardness and corrosion resistance of duplex stainless steel weldments

- Effect of selective laser sintering processing parameters on the mechanical properties of peanut shell powder/polyether sulfone composite

- Impact and mechanism of improving the UV aging resistance performance of modified asphalt binder

- AI-based prediction for the strength, cost, and sustainability of eggshell and date palm ash-blended concrete

- Investigating the sulfonated ZnO–PVA membrane for improved MFC performance

- Strontium coupling with sulphur in mouse bone apatites

- Transforming waste into value: Advancing sustainable construction materials with treated plastic waste and foundry sand in lightweight foamed concrete for a greener future

- Evaluating the use of recycled sawdust in porous foam mortar for improved performance

- Improvement and predictive modeling of the mechanical performance of waste fire clay blended concrete

- Polyvinyl alcohol/alginate/gelatin hydrogel-based CaSiO3 designed for accelerating wound healing

- Research on assembly stress and deformation of thin-walled composite material power cabin fairings

- Effect of volcanic pumice powder on the properties of fiber-reinforced cement mortars in aggressive environments

- Analyzing the compressive performance of lightweight foamcrete and parameter interdependencies using machine intelligence strategies

- Selected materials techniques for evaluation of attributes of sourdough bread with Kombucha SCOBY

- Establishing strength prediction models for low-carbon rubberized cementitious mortar using advanced AI tools

- Investigating the strength performance of 3D printed fiber-reinforced concrete using applicable predictive models

- An eco-friendly synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles with jamun seed extract and their multi-applications

- The application of convolutional neural networks, LF-NMR, and texture for microparticle analysis in assessing the quality of fruit powders: Case study – blackcurrant powders

- Study of feasibility of using copper mining tailings in mortar production

- Shear and flexural performance of reinforced concrete beams with recycled concrete aggregates

- Advancing GGBS geopolymer concrete with nano-alumina: A study on strength and durability in aggressive environments

- Leveraging waste-based additives and machine learning for sustainable mortar development in construction

- Study on the modification effects and mechanisms of organic–inorganic composite anti-aging agents on asphalt across multiple scales

- Morphological and microstructural analysis of sustainable concrete with crumb rubber and SCMs

- Structural, physical, and luminescence properties of sodium–aluminum–zinc borophosphate glass embedded with Nd3+ ions for optical applications

- Eco-friendly waste plastic-based mortar incorporating industrial waste powders: Interpretable models for flexural strength

- Bioactive potential of marine Aspergillus niger AMG31: Metabolite profiling and green synthesis of copper/zinc oxide nanocomposites – An insight into biomedical applications

- Preparation of geopolymer cementitious materials by combining industrial waste and municipal dewatering sludge: Stabilization, microscopic analysis and water seepage

- Seismic behavior and shear capacity calculation of a new type of self-centering steel-concrete composite joint

- Sustainable utilization of aluminum waste in geopolymer concrete: Influence of alkaline activation on microstructure and mechanical properties

- Optimization of oil palm boiler ash waste and zinc oxide as antibacterial fabric coating

- Tailoring ZX30 alloy’s microstructural evolution, electrochemical and mechanical behavior via ECAP processing parameters

- Comparative study on the effect of natural and synthetic fibers on the production of sustainable concrete

- Microemulsion synthesis of zinc-containing mesoporous bioactive silicate glass nanoparticles: In vitro bioactivity and drug release studies

- On the interaction of shear bands with nanoparticles in ZrCu-based metallic glass: In situ TEM investigation

- Developing low carbon molybdenum tailing self-consolidating concrete: Workability, shrinkage, strength, and pore structure

- Experimental and computational analyses of eco-friendly concrete using recycled crushed brick

- High-performance WC–Co coatings via HVOF: Mechanical properties of steel surfaces

- Mechanical properties and fatigue analysis of rubber concrete under uniaxial compression modified by a combination of mineral admixture