Abstract

For the plate or multicabin structure of ships, the vibration transmission characteristics have a great correlation with the structural mode. When the excitation force frequency get close to the natural frequency of the structure, strong vibration and sound radiation will occur. Therefore, it is very important and meaningful to study the vibration characteristics and protection methods of ship structures. Based on the classic finite element method, this article studies the influence of structural forms and parameters on the vibration characteristics of typical ship structures. Taking the multicabin structure as a benchmark structure model, the influence of the structural form on vibration mode and transmission characteristics of the target deck and other cabin decks in the multicabin structure was analyzed. Then, without changing the original structural layout, the effects of different structural parameters on the vibration mode and transmission characteristics were analyzed. Finally, the vibration protection process of the ship structure was formed. The results of this study can provide methodological basis and data reference for relevant research in future.

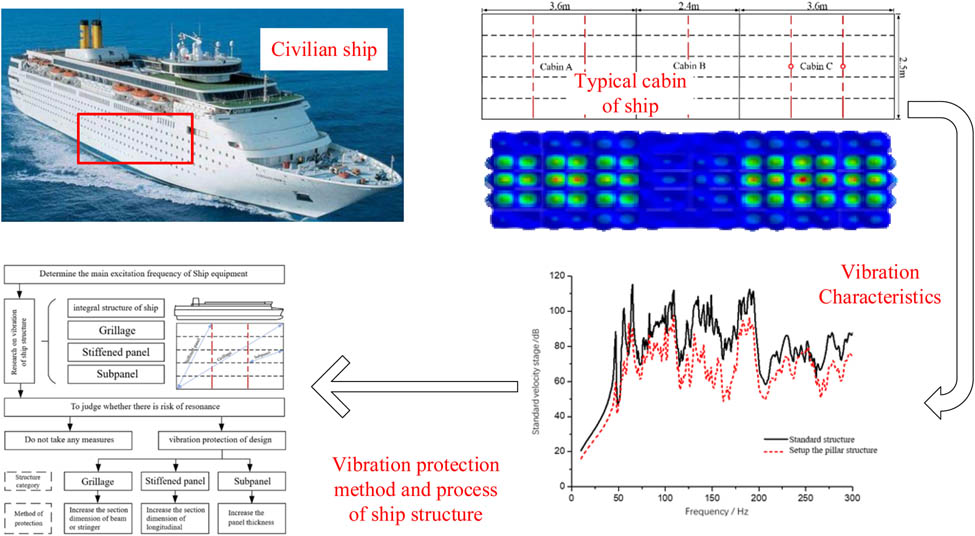

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

As the main means of transport on the sea, the comfort and quietness of ships have been paid more attentions. The vibration and noise level of a ship is one of the important indicators to measure its comfort level. Therefore, the prediction of ship vibration and noise is of great significance to ship design. However, the application of composite materials in ship structure is still very limited, which is not as common as aircraft and automobile. We also want to let scholars carry out more research in this field through this study, including use of composite materials for vibration and noise reduction.

In the research on ship vibration, Shan et al. [1] took a hospital ship as an example to analyze its vibration characteristic, and provided a reference for the design and construction of hospital ship. Wang et al. studied the vibration response of a wide and fat large ship under wave excitation [2], and they analyzed the hydroelastic behavior of a river–sea-going ship hull through experiments and numerical calculations to verify the accuracy and effectiveness of the nonlinear hydroelastic time domain calculation method [3]. Du et al. [4] conducted a series of experiments on a full-scale river icebreaker to investigate the characteristics of the hull vibration caused by ice. They found that the icebreaking operation of the river icebreaker leads to severe local vibration of the grillage on the main deck. McVicar et al. [5] studied the influence of the duration of the slam force on the vibration response of a high-speed catamaran. Choi et al. [6] used energy flow analysis methods to perform vibroacoustic calculations, and analyzed the noise radiated by turbulent flow on the complex underwater structure. Zhang et al. [7] investigated the influence of water jet propulsion on the local vibration of the grillage structure of high-speed ships. Han et al. [8] considered the noise characteristics of the duct and studied the indoor noise of typical cabins of naval vessel. Tang et al. [9] investigated the longitudinal vibration of a trimaran in regular waves.

Sun et al. [10] applied the time-variant reliability method to effectively evaluate the reliability of the ship’s grillage structure. Gong and Zhang [11] used the local cabin finite element method (FEM) model and one cabin FEM model to accurately analyze the grillage structure mode. Wang et al. [12] proposed a simplified method for grillage structure as the statistical energy method to improve calculation efficiency. Jadee et al. [13] studied the free vibration characteristics of isotropic plates by using FEM and experimental design. Korgesaar et al. [14] carried out a research on the response of the ice-strengthened grillage frames under a certain pressure range. He et al. [15] combined the theory of two-dimensional plate energy flow and FEM, studied the vibration transmission characteristics of coupled plates under medium–low frequency excitation. Lu [16] used frequency spectrum analysis methods to analyze the vibration characteristics of the ship grillage and optimized the dynamic characteristics of the grillage. Lin et al. [17] separated the mode shapes and frequencies that contribute the most to the acoustic radiation peaks, and optimized structural parameters.

Many engineering structures are made of composite materials, such as floating rafts and equipment seats. The application of composite materials is an effective method to reduce vibration and noise. Compared with traditional materials, composite materials have many new advantages and broad application prospects. Zhang et al. [18] systematically reviewed the research progress on the typical mechanical structures of functionally graded carbon nanotubes, and discussed the current research prospects. Many scholars are engaged in the study of the vibration characteristics of the typical structure of composite materials, such as graphene-reinforced metal matrix composites [19], functionally graded carbon nanotubes [20], and so on. Li et al. [21,22,23,24] analyzed the free vibration of different laminated composite shallow shells subjected to different boundary conditions.

Meng [25] simplified the progress of solving the vibration response by establishing a vibration isolation model for the engine in operation. Liu et al. [26] used a simplified mass method to convert the acceleration load of ship equipment into force load to simplify the calculation model. Zhang et al. [27] introduced theories of hull-propeller-rudder coupling to simplify the interaction between the propeller and the shaft. Polic et al. [28] used the energy difference between the propeller and the shaft to study the torsional vibration response of the propulsion shafting system working in snow and ice. Li et al. [29] simplified the fluid-propeller-shaft and flow-structure coupling dynamic model to a coupling model of the propeller in a nonuniform flow, and discussed the influence factors of the propeller wet mode. Maljaars et al. [30] simplified the interaction between the propulsion shaft and the propellers, and explored the mechanical properties of the propeller under cavitation and noncavitation conditions. Li et al. [31] researched the free vibration characteristics of medium-thickness functionally graded plates with general boundary conditions based on the Fourier–Ritz method. Tang et al. [32] carried out an experimental research on the vibration characteristics of composite-reinforced sheet-beam structures.

It can be seen from the reviewed researches that many researches have focused on the free and forced vibration characteristics of beams, plates, grillages, cabins, and so on. Those studies have revealed the mechanism of vibration generation and the influence of simple structures. However, it is far from enough to study the vibration mechanism of simple structures. The frequency difference between structures and equipment should also be considered to prevent resonance. When resonance occurs, there are generally two treatment methods: one is to change the equipment, and the other is to change the structure. It is commonly known that the cost of changing the equipment selection is high, while adopting a proper structural form can avoid resonance and has a good economic effect.

However, from the existing research literature, it can be found that most of the results are applicable to basic research, for the reason that the research object does not meet the engineering application conditions. Especially for ships, their structural form is quite different from ordinary structural forms. However, there are few research results on the vibration characteristics of ship structures, making it difficult to provide sufficient support for ship design.

In view of the above problems and background, the vibration characteristics of typical ship structures are studied based on the FEM, and the influence of structural form and parameters on vibration characteristics of typical ship structures was investigated, as shown in the Graphical abstract. This study sees multicabin structure as the benchmark structure model. The influence of structural form on vibration characteristics of target deck and other cabin decks in multicabin structure was analyzed. The effects of different structural parameters on vibration characteristics are investigated, and the vibration protection method and process of ship structure are introduced. The results of this study can provide method basis and data reference for relevant research in future.

2 Theoretical formula

The mode superposition method is a classic finite element calculation theory method, which can solve most dynamics problems [33,34]. In this method, the motion equation in the physical coordinate system is transformed into a modal coordinate system, and decouples the equation through the modal frequency and vibration mode information, thereby transforming the motion equation in the physical coordinate system into the modal coordinate system. Then, the structural response in the original physical coordinate system can be obtained by solving the modal coordinate responses and combining them. The main theoretical formulas of modal superposition method are as presented follows, which mainly provide theoretical support for subsequent numerical calculations.

2.1 Solving the coordinate transformation matrix

Solve the coordinate transformation matrix:

Separate the coordinate transformation matrix

Each element in

The corresponding elements in two matrixes are equal one by one. Therefore, the decoupling problem of the vibration differential equation is transformed into the problem of solving the generalized eigenvalue. The eigenequation is shown as follows:

The polynomial is solved to obtain the eigenvalues

The mode shape matrix

2.2 Solving the decoupling equation

When all coefficient matrices of vibration equations can be diagonalized, their component forms can be written out, and both ends of the equal sign can be divided by m i :

where

Then the calculation method of equation is

where

With regard to

3 Influence of structural forms on vibration characteristics of each cabin structure

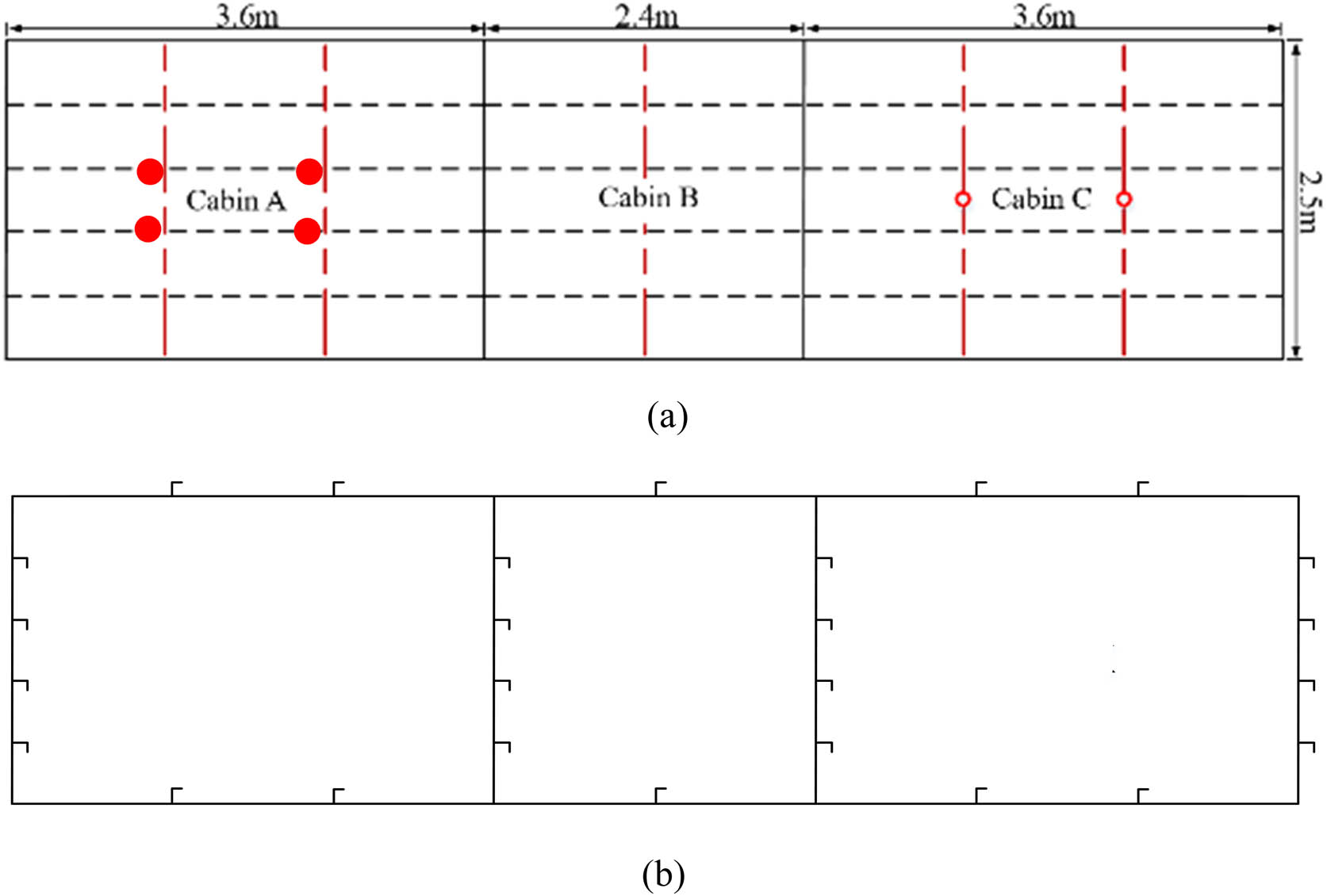

In this study, the cabin structure model adopts a three-compartment model structure (shown in Figure 1). Bulkhead and deck plate thickness

Diagram of cabin structure: (a) deck structure and (b) bulkhead structure.

The vibration characteristics of C cabin deck with beams, longitudinal bones, or additional pillars are not considered in the calculation and analysis, and the influence of structure form on the vibration characteristics of the structure is compared with the reference structure. Two additional pillars are added inside cabin C, which are located on the beam. Unless otherwise stated, the influence of additional pillars is not considered in initial analysis.

3.1 Influence of aggregate on structural vibration characteristics of each cabin

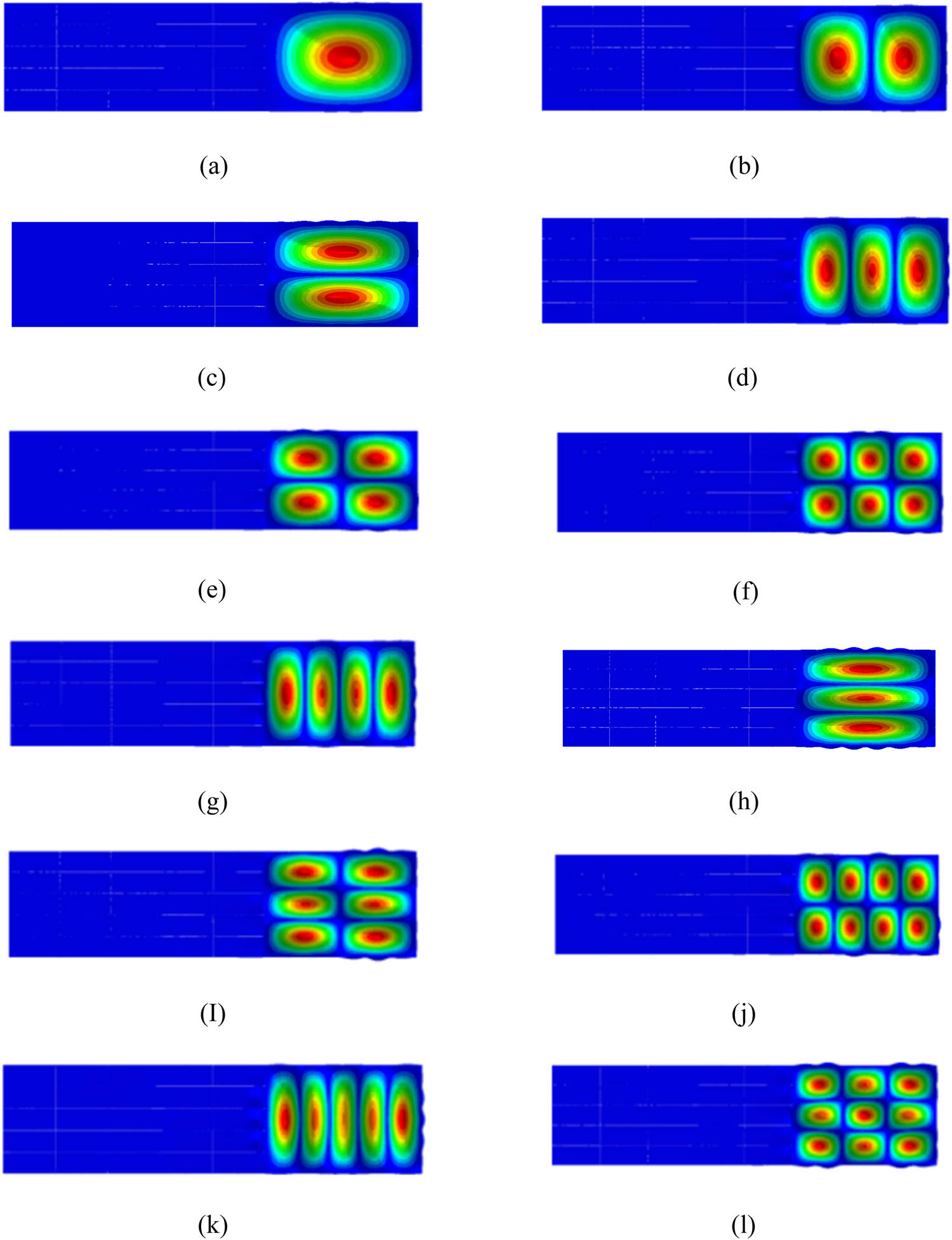

The overall vibration modes of C deck are mainly considered, and the first 12 order modal results are shown in Figure 2.

Modal results of multicompartment truss: (a) 5.2 Hz, (b) 8.3 Hz, (c) 12.5 Hz, (d) 13.6 Hz, (e) 15.4 Hz, (f) 20.4 Hz, (g) 20.9 Hz, (h) 23.7 Hz, (i) 26.5 Hz,(j) 27.5 Hz, (k) 30.2 Hz, and (l) 31.4 Hz.

When there is no beam or longitudinal bone on C deck, the first natural frequency of C deck is 5.2 Hz, but when there is beam and longitudinal bone on C deck, the first natural frequency of C deck is 46.6 Hz. So, the beam and longitudinal bone have a great influence on natural frequency of the structure, which is because the structural stiffness of the beam and longitudinal bone increases greatly. In addition, the profile has a great influence on the mode of the structure.

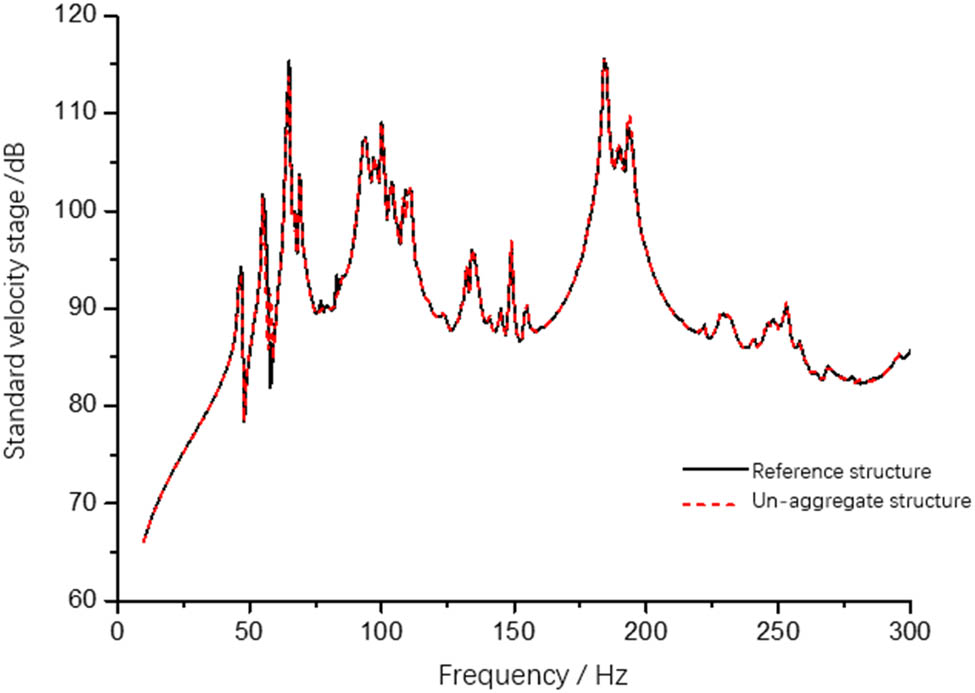

3.2 Influence of aggregate on vibration transfer characteristics of each cabin structure

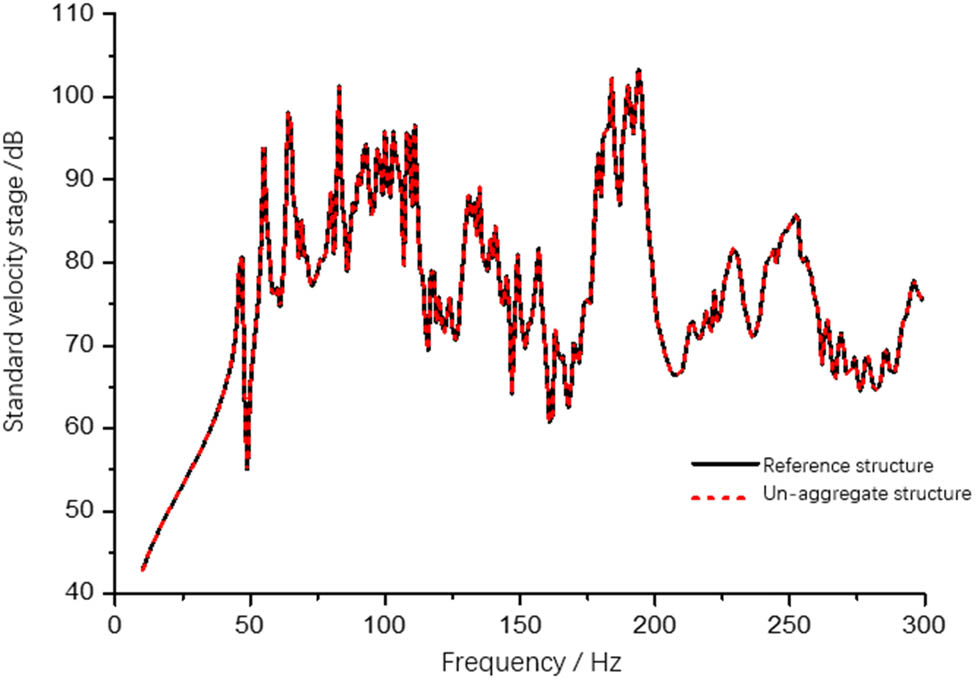

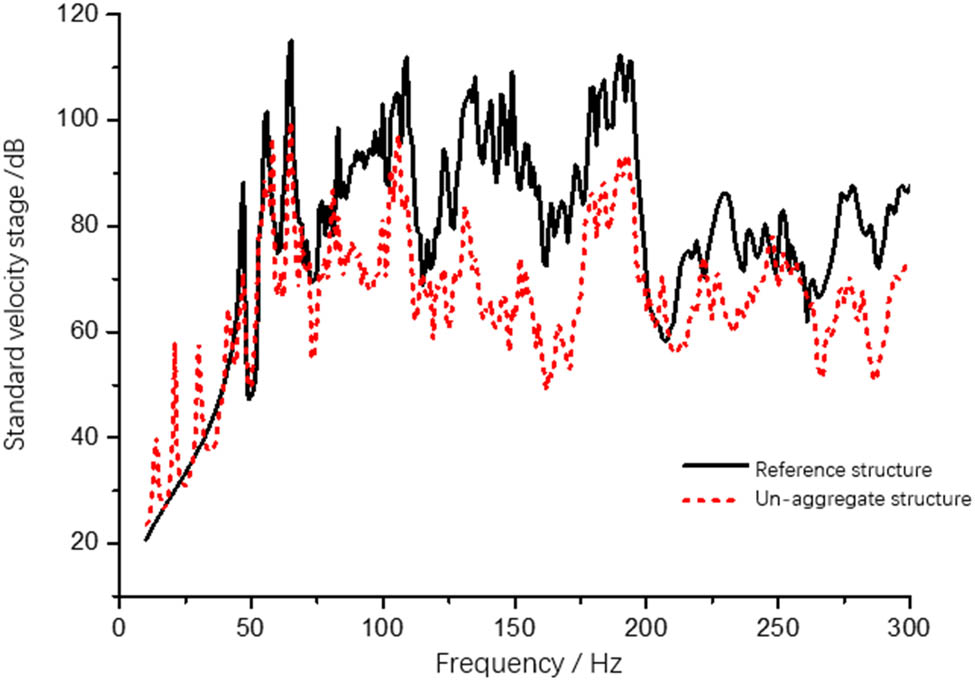

When there is no beam and longitudinal bone in the cabin C deck, the overall vibration response of each cabin deck is calculated. The calculated results are shown in Figures 3–5. It can be seen from the figures that the presence or absence of beam and longitudinal structure of cabin C deck has a great influence on the vibration transfer characteristics about deck of cabin C; however, that has less influence on the structural vibration transmission characteristics of cabins A and B.

Mean square velocity of deck in cabin A.

Mean square velocity of cabin deck B.

Mean square velocity of C cabin deck.

3.3 Influence of pillars on structural vibration characteristics of each cabin

Adding two additional pillars to the cabin C, which are located on the beam, as shown in Figure 1. The influence of the pillars on the vibration characteristics of the multicabin structure is analyzed.

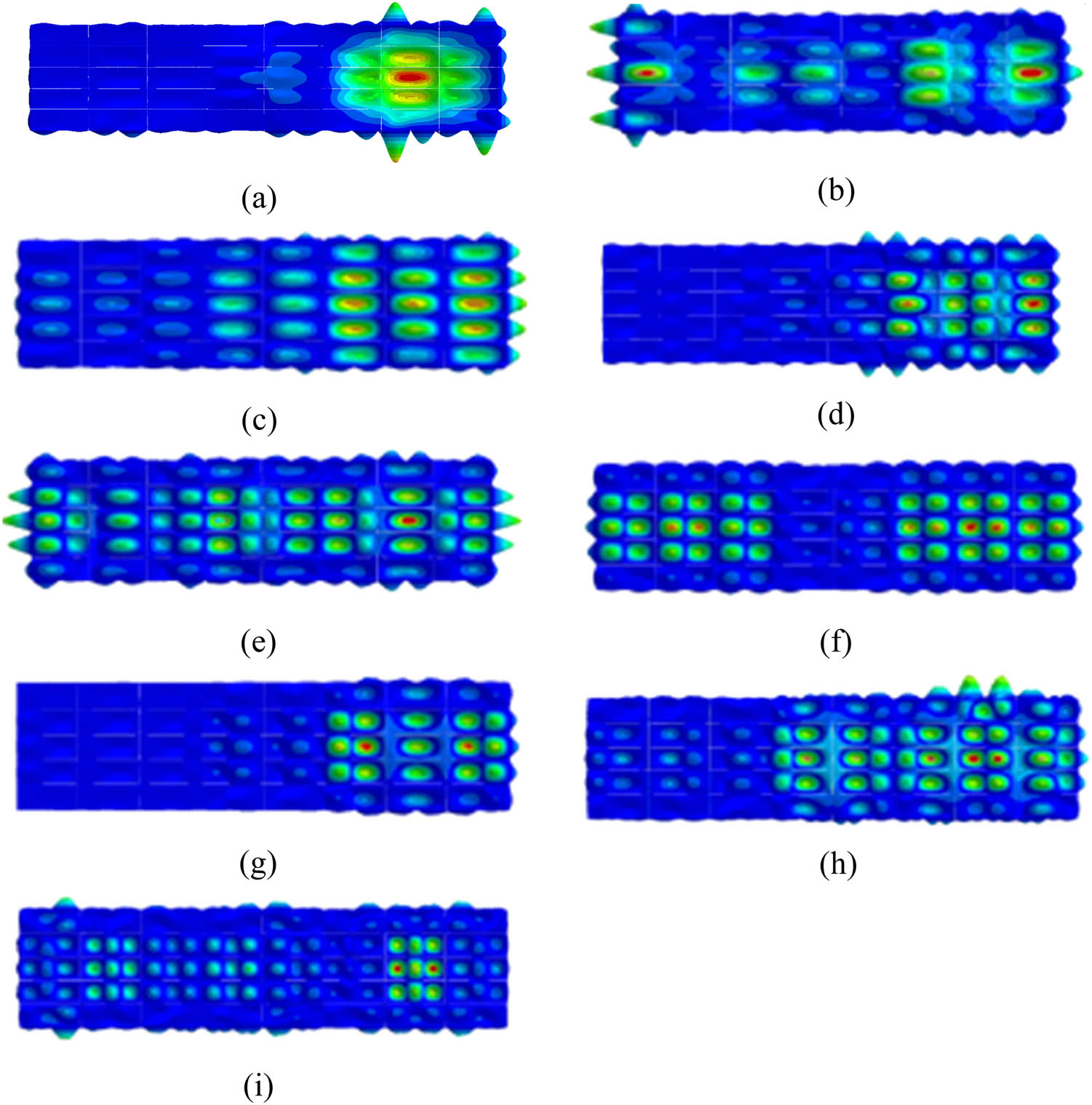

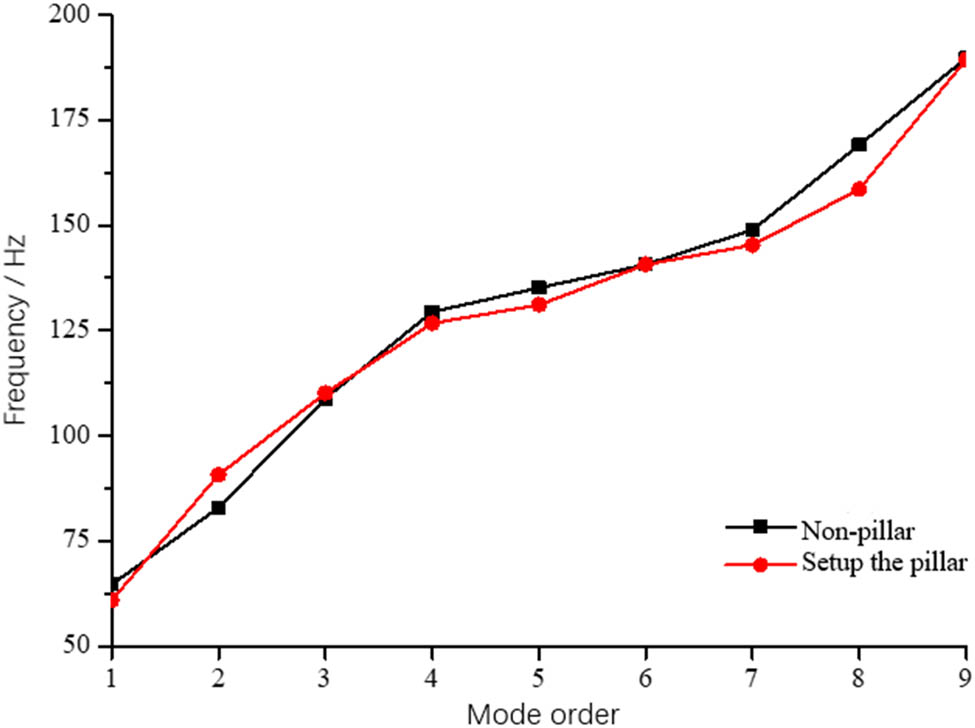

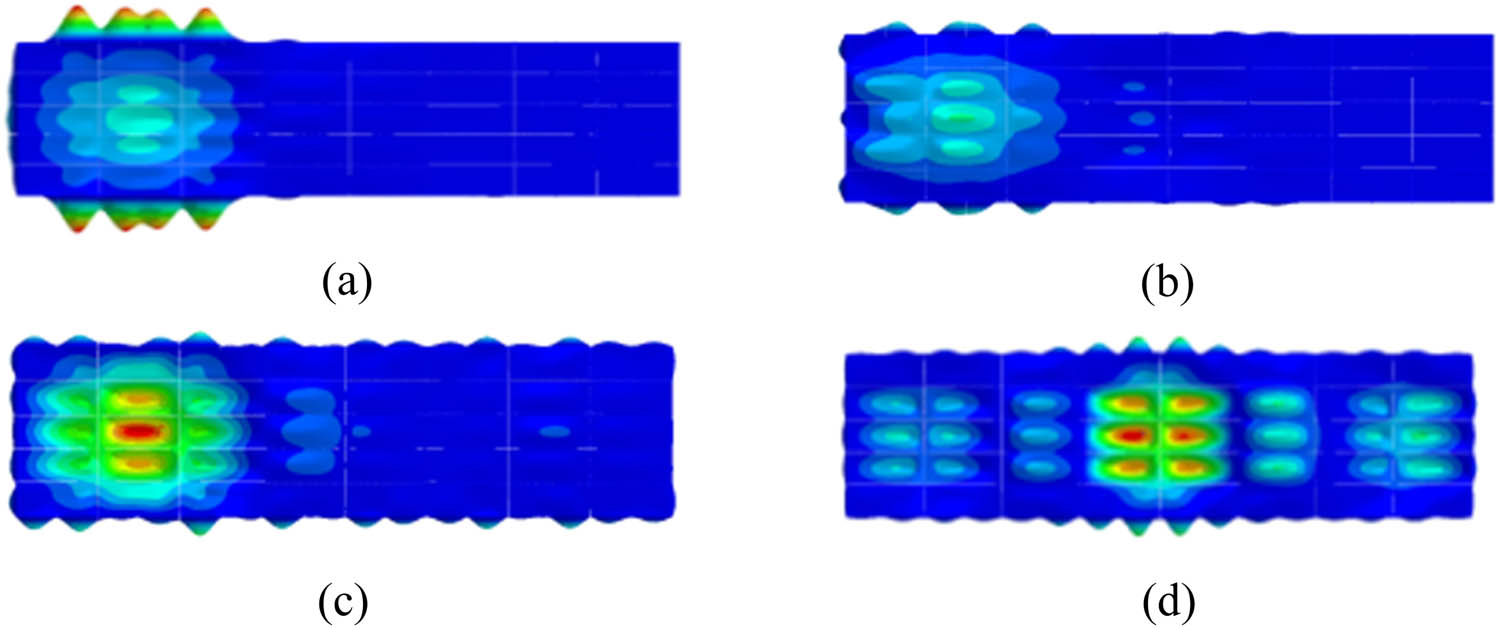

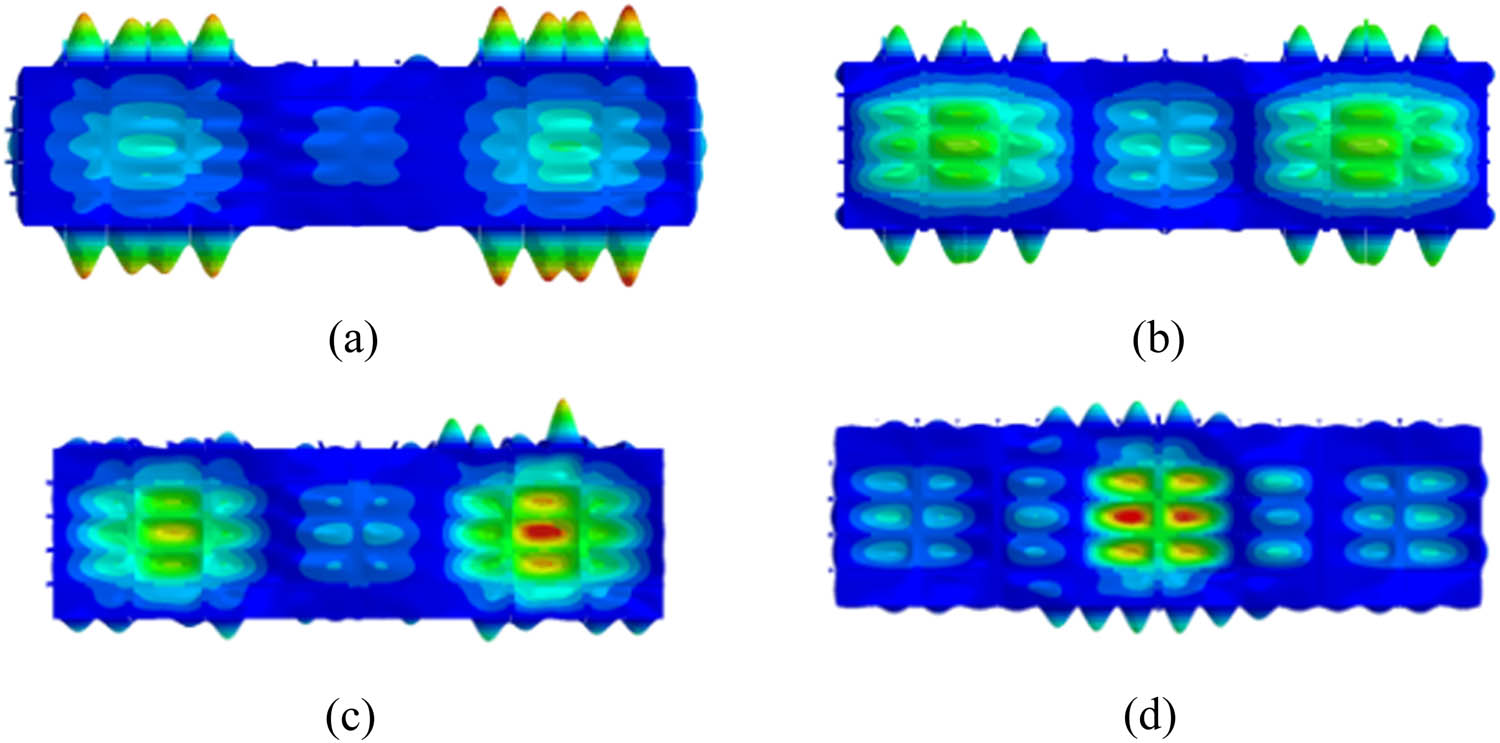

The overall vibration modes of C deck are mainly considered, and the results of the first to ninth modes are shown in Figure 6. Comparison of the first to ninth modes natural frequencies of the infrastructure with or without pillars is shown in Figure 7. Pillar can be seen that set on the structure of the third, six, nine order natural frequency of a smaller effect, has certain influence on other order natural frequency, this is due to the third, six, nine order modal mainly for stiffened plate or plate vibration, and the pillar position is located at cross beam, less effect on the modal, and had certain influence on other vibration modal. The presence of aggregate on the deck of cabin C basically has no effect on the deck modes of cabins A and B. Some modal results are shown in Figures 8 and 9.

Modal results of multicompartment truss: (a) 60.9 Hz, (b) 90.8 Hz, (c) 110.1 Hz, (d) 126.7 Hz, (e) 131.1 Hz, (f) 140.7 Hz, (g) 145.3 Hz, (h) 158.6 Hz, and (i) 189.4 Hz.

Variation of natural frequency of C cabin deck.

Modal results of multi-compartment truss (setting struts): (a) 46.7 Hz, (b) 55.5 Hz, (c) 64.7 Hz, and (d) 82.7 Hz.

Modal results of multicabin panels (without struts): (a) 46.6 Hz, (b) 55.2 Hz, (c) 64.7 Hz, and (d) 82.9 Hz.

3.4 Influence of pillar on vibration transmission characteristics of each cabin structure

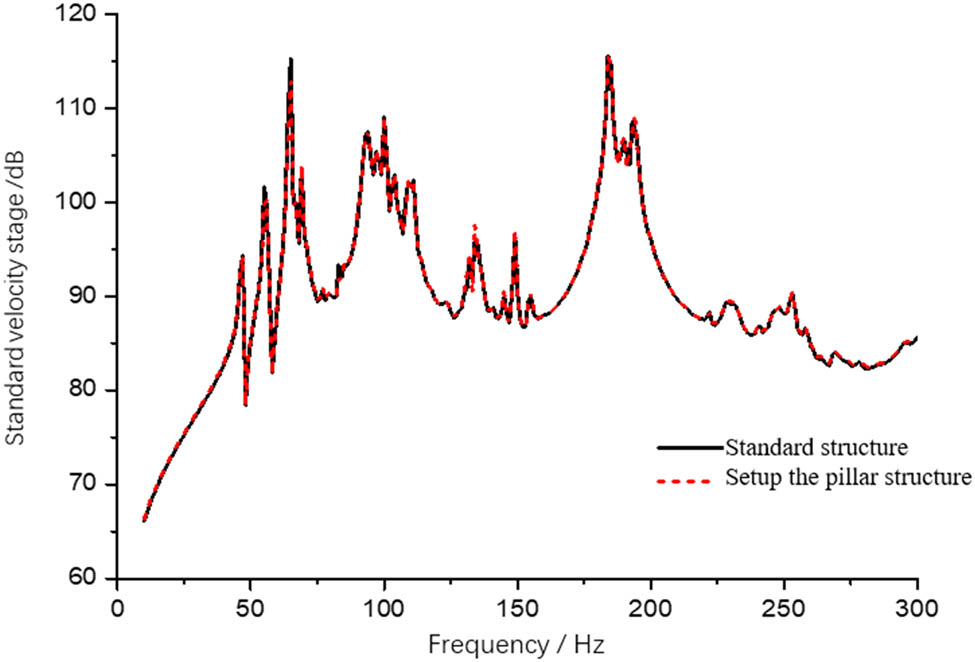

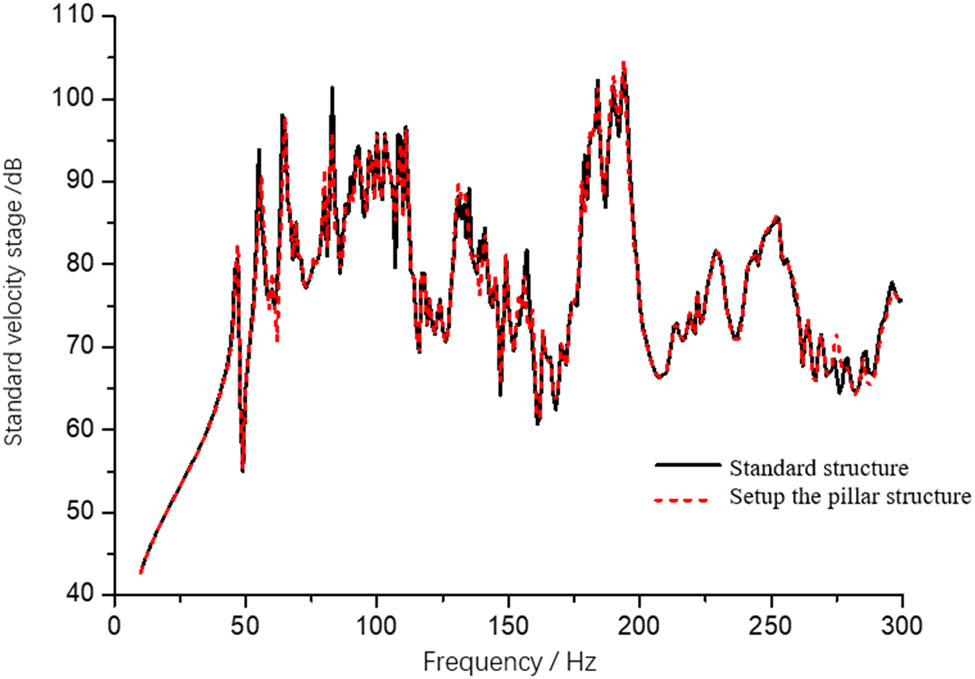

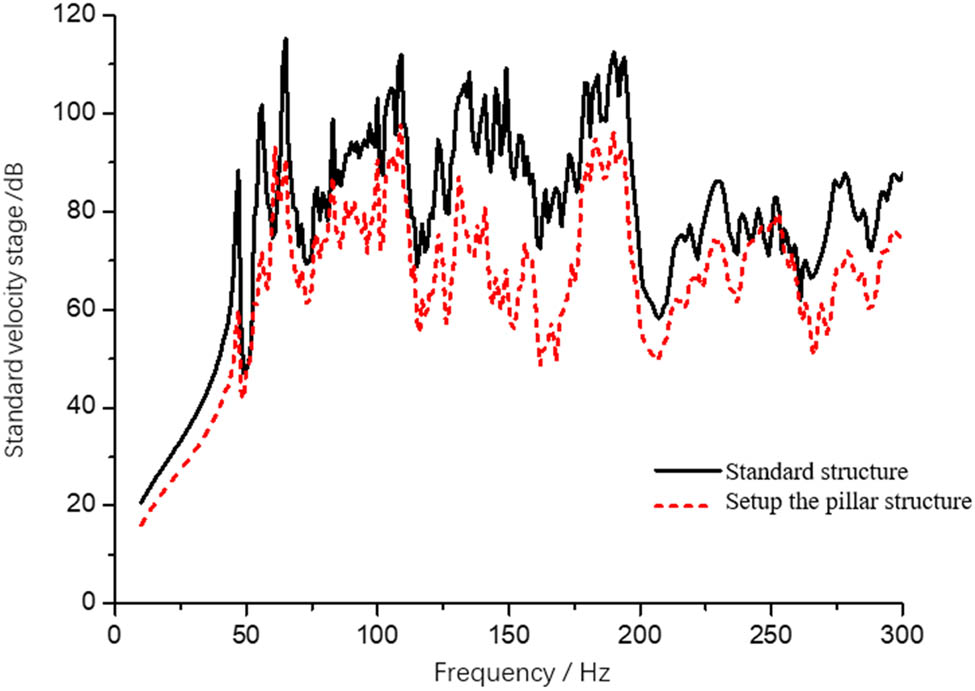

When the deck of cabin C is equipped with pillar, the overall vibration response of each cabin deck is calculated. The calculated results are shown in Figures 10–12. The pillar or nonpillar structure of cabin C deck has a great influence on the deck of cabin C, but that has a very small impact on the vibration transmission characteristics of the structures of cabins A and B.

Mean square velocity of A cabin deck.

Mean square velocity of B cabin deck.

Mean square velocity of C cabin deck.

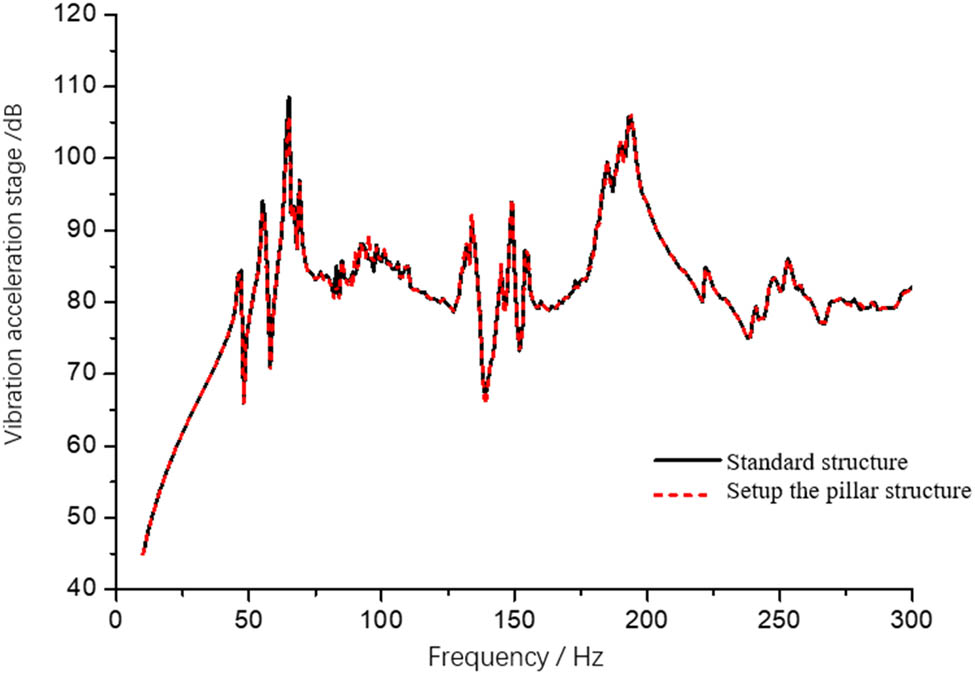

The root means square value of vibration acceleration response of excitation points with or no pillar was analyzed. The calculated results are shown in Figure 13. The presence of no pillar in cabin C has little effect on transmission functions of the origin of deck excitation input points in cabin A. The vibration acceleration transfer functions at the input point have a large peak value at 65, 135, 149, and 192 Hz.

Spectrum of vibration acceleration at input points.

From the analysis results of free vibration characteristics and vibration transfer characteristics, it can be seen that the aggregate or pillar in C cabin deck has a great influence on vibration characteristics of C cabin deck itself, but basically has no influence on vibration characteristics of other compartments. Therefore, there is no need to consider the influence of structural changes on the surrounding cabins in the vibration optimization design of the target cabin structure.

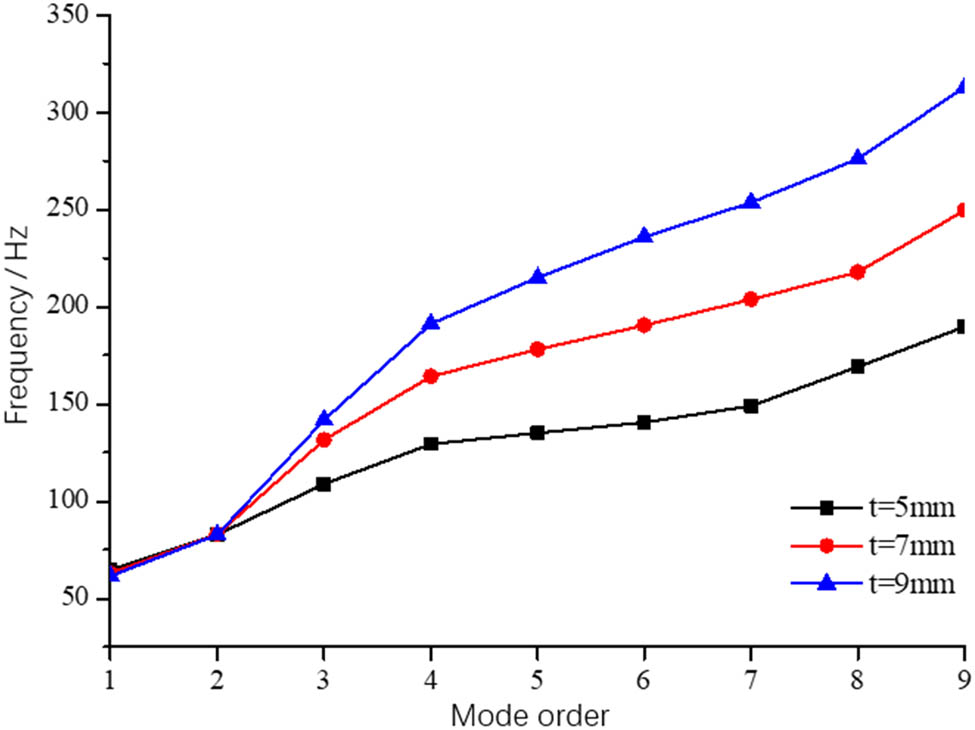

3.5 Influence of plate thickness on structural vibration characteristics

In order to study the influence of deck thickness on structural vibration characteristics, T is set on deck of cabin t 1 = 7 mm, t 2 = 9 mm two kinds of thickness, and the structural reference thickness t 0 = 5 mm for comparative study. Relative to the reference structure, the deck thickness is t 1 = 7 mm, the deck mass of cabin C increases by about 25%; deck thickness t 1 = 9 mm, the deck mass of cabin C increases by about 51%. The overall variation trend of the calculated results of the overall natural frequency of cabin C deck under different deck thicknesses is shown in Figure 14. The change of deck thickness has little influence on the first order and second-order natural frequencies of the whole deck, and the increase of plate thickness has a decrease on first-order natural frequencies. This is because the stiffness of the first-order mode is mainly provided by the aggregate, and the increase of plate thickness has a smaller effect on increase of modal mass than that of modal stiffness. As the plate thickness increases, the natural frequency of the same order increases. This is because the mode shapes of these modes are dominated by the stiffened plate or lattice vibration.

Natural frequency variation of C cabin deck.

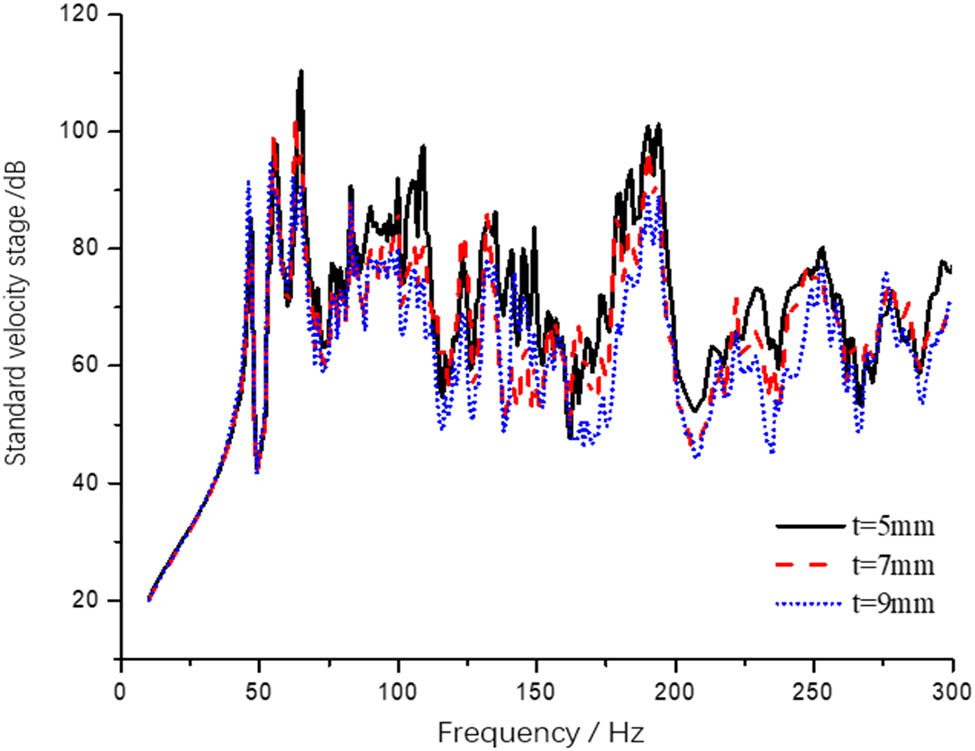

Under different deck thicknesses, the mean square velocities of C deck are shown in Figure 15.

Spectrum of mean square vibration velocity of C cabin deck.

In 10–86 Hz frequency band, the deck thickness changed from 5 mm to 7 mm, 9 mm has little influence on the overall structural vibration. In the 86–300 Hz frequency band, the deck thickness is changed from 5 mm to 7 mm, 9 mm, and the structural vibration response is reduced. This is because the structural vibration response before 86 Hz is dominated by integral vibration, whereas after 86 Hz, it is dominated by stiffened plate or plate lattice vibration. For 109 Hz peak, the response peak decreases by 15.9 dB when the deck thickness changes from 5 to 7 mm. When the thickness changed to 9 mm, the response peak decreased by 19.7 dB.

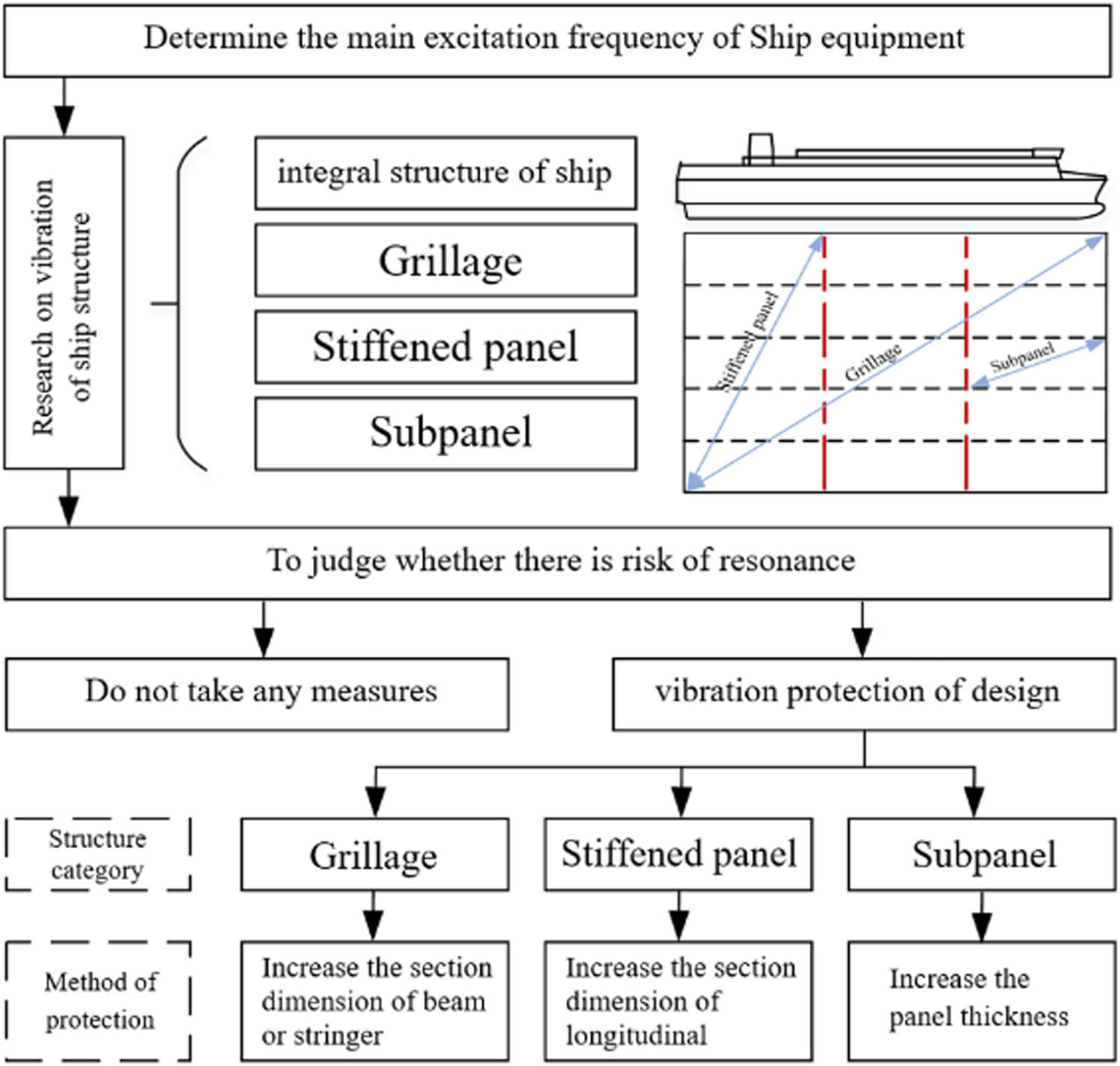

4 Process of vibration protection of ship structure

First, the information of the main vibration sources on the ship was sorted out, then it uses this information to determine the main excitation frequencies to be considered for each vibration source. Then the range of resonance risk caused by various vibration sources is determined. The first-order natural frequency of the structure is analyzed according to the total and local vibration of the ship. The local vibration is studied according to the three levels of plate frame vibration, stiffened plate vibration, and plate lattice vibration. Determine the frequency range of resonance risk that needs to be considered, according to the frequency range, the vibration protection design is carried out for each structure with resonance risk. The flow chart of vibration protection of ship structure is shown in Figure 16.

Flow chart of vibration protection of ship structure.

5 Conclusion

In this study, the influence of the structure form on the vibration mode and vibration transfer characteristics of the target structure and other cabin structures in the multicabin structure is investigated by changing the structure form of the target cabin, and the vibration protection flow of ship structure was given. The conclusion of this study is as follows:

The change of the structure form of ship’s target cabin has a great impact on vibration characteristics of target cabin structure, and a small impact of other cabin structures. Thus, it is not necessary to consider the influence of target structure on other structures when designing the ship vibration protection.

The change of deck plate thickness has a great influence on the frequency band which is dominated by the vibration response of stiffened plate and grillage, especially the resonance peak of the stiffened plate or grillage is significantly improved, because the change of deck plate thickness avoids the resonance phenomenon of the original natural frequency.

-

Funding information: This study was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (U2006229), Key Research and Development program of Shandong Province (2020CXGC010702), Science and technology research project of Jiangxi Provincial Department of Education (GJJ211611).

-

Author contributions: Chi Zhang and Haichao Li putforward ideas, Xiaoxi Yi and Wengeng Ma written the paper, Yan Wang Zhou provided some suggestions.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement:The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

References

[1] Shan, Y., X. Miao, C. Li, and Z. Liu. Vibration characteristic analysis and control of hospital ship. 2nd International Conference on Mechanical Engineering and Applied Composite Materials, 2019.10.1088/1757-899X/544/1/012046Search in Google Scholar

[2] Wang, Y. W., W. G. Wu, and C. Zheng. The springing investigation of the wide flat ship type. Journal of Vibration and Shock, Vol. 39, No. 18, 2020, pp. 174–180.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Wang, Y. W., W. G. Wu, and C. G. Soares. Experimental and numerical study of the hydroelastic response of a river-sea-going container ship. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, Vol. 8, No. 12, 2020, id. 978.10.3390/jmse8120978Search in Google Scholar

[4] Du, Y., L. Sun, F. Pang, H. Li, and C. Gao. Experimental research of hull vibration of a full-scale river icebreaker. Journal of Marine Science and Application, Vol. 19, No. 2, 2020, pp. 182–194.10.1007/s11804-020-00137-3Search in Google Scholar

[5] McVicar, J. J., J. Lavroff, M. R. Davis, and G. Thomas. Effect of slam force duration on the vibratory response of a lightweight high-speed wave-piercing catamaran. Journal of Ship Research, Vol. 59, 2015, pp. 69–84.10.5957/jsr.2015.59.2.69Search in Google Scholar

[6] Choi, W. S., S. Y. Hong, H. W. Kwon, J. H. Seo, S. H. Rhee, and J. H. Song. Estimation of turbulent boundary layer induced noise using energy flow analysis for ship hull designs. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers Part M Journal of Engineering for the Maritime Environment, Vol. 234, No. 1, 2020, pp. 196–208.10.1177/1475090219852195Search in Google Scholar

[7] Zhang, X., H. Ren, Y. Liu, Z. Wu, and D. Zhang. Analysis of local vibration and strength of water jet propulsion unit of high speed ship. Proceedings of the Asme 37th International Conference on Ocean, Offshore and Arctic Engineering, Vol. 3, 2018.10.1115/OMAE2018-77340Search in Google Scholar

[8] Han, H., C. Lee, K. Lee, S. H. Jeon, and S. Park. Estimation of the sound in ship cabins considering low frequency and flowing noise characteristics of HVAC duct. Applied Acoustics, Vol. 141, 2018, pp. 261–270.10.1016/j.apacoust.2018.07.011Search in Google Scholar

[9] Tang, H., H. Ren, and Q. Wan. Investigation of Longitudinal Vibrations and Slamming of a Trimaran in Regular Waves. Journal of Ship Research, Vol. 61, No. 3, 2017, pp. 153–166.10.5957/JOSR.170001Search in Google Scholar

[10] Sun, B., L. Huang, T. Ye, and K. C. Yung. Time-variant reliability analysis of ship grillage structure. 2015 First International Conference on Reliability Systems Engineering (ICRSE), 2015.10.1109/ICRSE.2015.7366464Search in Google Scholar

[11] Gong, H. and S. L. Zhang. Study on the simplified modeling methods of ship grillage for modal analysis. Ship & Ocean Engineering, Vol. 45, No. 3, 2016, pp. 47–49, 54.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Wang, X. C., G. X. Wu, and D. Q. Wang. Research of Simplified modeling method for ship grillage structure based on statistical energy analysis. Ship Engineering, Vol. 41, No. 1, 2019, pp. 40–47.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Jadee, K. J., B. H. Abed, and A. A. Battawi. Free vibration of isotropic plates with various cutout configurations using finite elements and design of experiments. IOP Conference Series Materials Science and Engineering, Vol. 745, 2020, p. 012080.10.1088/1757-899X/745/1/012080Search in Google Scholar

[14] Korgesaar, M., P. Kujala, and J. Romanoff. Load carrying capacity of ice-strengthened frames under idealized ice load and boundary conditions. Marine Structures, Vol. 58, 2018, pp. 18–30.10.1016/j.marstruc.2017.10.011Search in Google Scholar

[15] He, P., Y. Xiang, Y. Zhou, and H. Li. Vibration energy distribution and transfer characteristics of coupled plates under medium-low frequency excitation. Noise and Vibration Control, Vol. 40, No. 2, 2020, pp. 13–22.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Lu, Z. Z. Dynamic optimization design of the plate frame structure of large ships. Ship Science and Technology, Vol. 43, No. 2, 2021, pp. 4–6.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Liu, C. Z., F. Y. Li, X. F. Lv, M. M. Ma, X. Y. Li, C. X. Lin, et al. Research on low noise optimization of ship grillages. Ship Science and Technology, Vol. 41, No. 5, 2019, pp. 24–30.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Zhang, H., C. Gao, H. Li, F. Pang, T. Zou, H. Wang, et al. Analysis of functionally graded carbon nanotube-reinforced composite structures: A review. Nanotechnology Reviews, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2020, pp. 1408–1426.10.1515/ntrev-2020-0110Search in Google Scholar

[19] Ahmad, S. I., H. Hamoudi, A. Abdala, Z. K. Ghouri, and K. M. Youssef. Graphene-reinforced bulk metal matrix composites: synthesis, microstructure, and properties. Reviews on Advanced Materials Science, Vol. 59, No. 1, 2020, pp. 67–114.10.1515/rams-2020-0007Search in Google Scholar

[20] Lee, S.-Y. and J.-G. Hwang. Finite element nonlinear transient modelling of carbon nanotubes reinforced fiber/polymer composite spherical shells with a cutout. Nanotechnology Reviews, Vol. 8, No. 1, 2019, pp. 444–451.10.1515/ntrev-2019-0039Search in Google Scholar

[21] Li, H., F. Pang, X. Wang, Y. Du, and H. Chen. Free vibration analysis for composite laminated doubly-curved shells of revolution by a semi analytical method. Composite Structures, Vol. 201, 2018, pp. 86–111.10.1016/j.compstruct.2018.05.143Search in Google Scholar

[22] Li, H., F. Pang, C. Gao, and R. Huo. A Jacobi-Ritz method for dynamic analysis of laminated composite shallow shells with general elastic restraints. Composite Structures, Vol. 242, 2020, id. 112091.10.1016/j.compstruct.2020.112091Search in Google Scholar

[23] Li, H., F. Pang, X. Miao, S. Gao, and F. Liu. A semi analytical method for free vibration analysis of composite laminated cylindrical and spherical shells with complex boundary conditions. Thin-Walled Structures, Vol. 136, 2019, pp. 200–220.10.1016/j.tws.2018.12.009Search in Google Scholar

[24] Pang, F., H. Li, H. Chen, and Y. Shan. Free vibration analysis of combined composite laminated cylindrical and spherical shells with arbitrary boundary conditions. Mechanics of Advanced Materials and Structures, Vol. 28, No. 2, 2021, pp. 182–199.10.1080/15376494.2018.1553258Search in Google Scholar

[25] Meng, D. Analysis of vibration response characteristics of engineering ship power machinery. Ship Science and Technology, Vol. 42, No. 14, 2020, pp. 16–18.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Liu, H., X. Ye, T. Li, X. Zhu. Analysis of incentive application methods in low-frequency acoustic-solid coupling numerical models of ship machinery. Ship Science and Technology, Vol. 43, No. 1, 2021, pp. 32–36.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Zhang, X. S., J. H. Wang, and D. C. Wan. Numerical techniques for coupling hydrodynamic problems in ship and ocean engineering. Journal of Hydrodynamics, Vol. 32, No. 2, 2020, pp. 212–233.10.1007/s42241-020-0021-5Search in Google Scholar

[28] Polic, D., S. Ehlers, and V. Aesoy. Propeller torque load and propeller shaft torque response correlation during ice-propeller interaction. Journal of Marine Science and Application, Vol. 16, No. 1, 2017, pp. 1–9.10.1007/s11804-017-1395-9Search in Google Scholar

[29] Li, J., Y. Qu, and H. Hua. Hydroelastic analysis of underwater rotating elastic marine propellers by using a coupled BEM-FEM algorithm. Ocean Engineering, Vol. 146, 2017, pp. 178–191.10.1016/j.oceaneng.2017.09.028Search in Google Scholar

[30] Maljaars, P. J., N. Grasso, J. H. den Besten, and M. L. Kaminski. BEM–FEM coupling for the analysis of flexible propellers in non-uniform flows and validation with full-scale measurements. Journal of Fluids and Structures, Vol. 95, 2020, id. 102946.10.1016/j.jfluidstructs.2020.102946Search in Google Scholar

[31] Li, H., F. Pang, X. Wang, and S. Li. Benchmark solution for free vibration of moderately thick functionally graded sandwich sector plates on two-parameter elastic foundation with general boundary conditions. Shock and Vibration, Vol. 2017, 2017, id. 4018629.10.1155/2017/4018629Search in Google Scholar

[32] Tang, Y., X. Wang, H. Li, C. Gao, and X. Miao. Experimental research on interior field noise and the vibration characteristics of composite reinforced sheet-beam structures. Applied Acoustics, Vol. 160, 2020, id. 107154.10.1016/j.apacoust.2019.107154Search in Google Scholar

[33] Ferhatoğlu, E., E. Ciğeroğlu, H. Özgüven. A modal superposition method for the analysis of nonlinear systems, Springer International Publishing, 2016.10.1007/978-3-319-29910-5_28Search in Google Scholar

[34] Mucha, W. and W. Kuś. Application of mode superposition to hybrid simulation using real time finite element method. Mechanika, Vol. 23, No. 5, 2017, pp. 673–677.10.5755/j01.mech.23.5.14642Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 Chi Zhang et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- State of the art, challenges, and emerging trends: Geopolymer composite reinforced by dispersed steel fibers

- A review on the properties of concrete reinforced with recycled steel fiber from waste tires

- Copper ternary oxides as photocathodes for solar-driven CO2 reduction

- Properties of fresh and hardened self-compacting concrete incorporating rice husk ash: A review

- Basic mechanical and fatigue properties of rubber materials and components for railway vehicles: A literature survey

- Research progress on durability of marine concrete under the combined action of Cl− erosion, carbonation, and dry–wet cycles

- Delivery systems in nanocosmeceuticals

- Study on the preparation process and sintering performance of doped nano-silver paste

- Analysis of the interactions between nonoxide reinforcements and Al–Si–Cu–Mg matrices

- Research Articles

- Study on the influence of structural form and parameters on vibration characteristics of typical ship structures

- Deterioration characteristics of recycled aggregate concrete subjected to coupling effect with salt and frost

- Novel approach to improve shale stability using super-amphiphobic nanoscale materials in water-based drilling fluids and its field application

- Research on the low-frequency multiline spectrum vibration control of offshore platforms

- Multiple wide band gaps in a convex-like holey phononic crystal strip

- Response analysis and optimization of the air spring with epistemic uncertainties

- Molecular dynamics of C–S–H production in graphene oxide environment

- Residual stress relief mechanisms of 2219 Al–Cu alloy by thermal stress relief method

- Characteristics and microstructures of the GFRP waste powder/GGBS-based geopolymer paste and concrete

- Development and performance evaluation of a novel environmentally friendly adsorbent for waste water-based drilling fluids

- Determination of shear stresses in the measurement area of a modified wood sample

- Influence of ettringite on the crack self-repairing of cement-based materials in a hydraulic environment

- Multiple load recognition and fatigue assessment on longitudinal stop of railway freight car

- Synthesis and characterization of nano-SiO2@octadecylbisimidazoline quaternary ammonium salt used as acidizing corrosion inhibitor

- Perforated steel for realizing extraordinary ductility under compression: Testing and finite element modeling

- The influence of oiled fiber, freeze-thawing cycle, and sulfate attack on strain hardening cement-based composites

- Perforated steel block of realizing large ductility under compression: Parametric study and stress–strain modeling

- Study on dynamic viscoelastic constitutive model of nonwater reacted polyurethane grouting materials based on DMA

- Mechanical behavior and mechanism investigation on the optimized and novel bio-inspired nonpneumatic composite tires

- Effect of cooling rate on the microstructure and thermal expansion properties of Al–Mn–Fe alloy

- Research on process optimization and rapid prediction method of thermal vibration stress relief for 2219 aluminum alloy rings

- Failure prevention of seafloor composite pipelines using enhanced strain-based design

- Deterioration of concrete under the coupling action of freeze–thaw cycles and salt solution erosion

- Creep rupture behavior of 2.25Cr1Mo0.25V steel and weld for hydrogenation reactors under different stress levels

- Statistical damage constitutive model for the two-component foaming polymer grouting material

- Nano-structural and nano-constraint behavior of mortar containing silica aggregates

- Influence of recycled clay brick aggregate on the mechanical properties of concrete

- Effect of LDH on the dissolution and adsorption behaviors of sulfate in Portland cement early hydration process

- Comparison of properties of colorless and transparent polyimide films using various diamine monomers

- Study in the parameter influence on underwater acoustic radiation characteristics of cylindrical shells

- Experimental study on basic mechanical properties of recycled steel fiber reinforced concrete

- Dynamic characteristic analysis of acoustic black hole in typical raft structure

- A semi-analytical method for dynamic analysis of a rectangular plate with general boundary conditions based on FSDT

- Research on modification of mechanical properties of recycled aggregate concrete by replacing sand with graphite tailings

- Dynamic response of Voronoi structures with gradient perpendicular to the impact direction

- Deposition mechanisms and characteristics of nano-modified multimodal Cr3C2–NiCr coatings sprayed by HVOF

- Effect of excitation type on vibration characteristics of typical ship grillage structure

- Study on the nanoscale mechanical properties of graphene oxide–enhanced shear resisting cement

- Experimental investigation on static compressive toughness of steel fiber rubber concrete

- Study on the stress field concentration at the tip of elliptical cracks

- Corrosion resistance of 6061-T6 aluminium alloy and its feasibility of near-surface reinforcements in concrete structure

- Effect of the synthesis method on the MnCo2O4 towards the photocatalytic production of H2

- Experimental study of the shear strength criterion of rock structural plane based on three-dimensional surface description

- Evaluation of wear and corrosion properties of FSWed aluminum alloy plates of AA2020-T4 with heat treatment under different aging periods

- Thermal–mechanical coupling deformation difference analysis for the flexspline of a harmonic drive

- Frost resistance of fiber-reinforced self-compacting recycled concrete

- High-temperature treated TiO2 modified with 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane as photoactive nanomaterials

- Effect of nano Al2O3 particles on the mechanical and wear properties of Al/Al2O3 composites manufactured via ARB

- Co3O4 nanoparticles embedded in electrospun carbon nanofibers as free-standing nanocomposite electrodes as highly sensitive enzyme-free glucose biosensors

- Effect of freeze–thaw cycles on deformation properties of deep foundation pit supported by pile-anchor in Harbin

- Temperature-porosity-dependent elastic modulus model for metallic materials

- Effect of diffusion on interfacial properties of polyurethane-modified asphalt–aggregate using molecular dynamic simulation

- Experimental study on comprehensive improvement of shear strength and erosion resistance of yellow mud in Qiang Village

- A novel method for low-cost and rapid preparation of nanoporous phenolic aerogels and its performance regulation mechanism

- In situ bow reduction during sublimation growth of cubic silicon carbide

- Adhesion behaviour of 3D printed polyamide–carbon fibre composite filament

- An experimental investigation and machine learning-based prediction for seismic performance of steel tubular column filled with recycled aggregate concrete

- Effects of rare earth metals on microstructure, mechanical properties, and pitting corrosion of 27% Cr hyper duplex stainless steel

- Application research of acoustic black hole in floating raft vibration isolation system

- Multi-objective parametric optimization on the EDM machining of hybrid SiCp/Grp/aluminum nanocomposites using Non-dominating Sorting Genetic Algorithm (NSGA-II): Fabrication and microstructural characterizations

- Estimating of cutting force and surface roughness in turning of GFRP composites with different orientation angles using artificial neural network

- Displacement recovery and energy dissipation of crimped NiTi SMA fibers during cyclic pullout tests

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- State of the art, challenges, and emerging trends: Geopolymer composite reinforced by dispersed steel fibers

- A review on the properties of concrete reinforced with recycled steel fiber from waste tires

- Copper ternary oxides as photocathodes for solar-driven CO2 reduction

- Properties of fresh and hardened self-compacting concrete incorporating rice husk ash: A review

- Basic mechanical and fatigue properties of rubber materials and components for railway vehicles: A literature survey

- Research progress on durability of marine concrete under the combined action of Cl− erosion, carbonation, and dry–wet cycles

- Delivery systems in nanocosmeceuticals

- Study on the preparation process and sintering performance of doped nano-silver paste

- Analysis of the interactions between nonoxide reinforcements and Al–Si–Cu–Mg matrices

- Research Articles

- Study on the influence of structural form and parameters on vibration characteristics of typical ship structures

- Deterioration characteristics of recycled aggregate concrete subjected to coupling effect with salt and frost

- Novel approach to improve shale stability using super-amphiphobic nanoscale materials in water-based drilling fluids and its field application

- Research on the low-frequency multiline spectrum vibration control of offshore platforms

- Multiple wide band gaps in a convex-like holey phononic crystal strip

- Response analysis and optimization of the air spring with epistemic uncertainties

- Molecular dynamics of C–S–H production in graphene oxide environment

- Residual stress relief mechanisms of 2219 Al–Cu alloy by thermal stress relief method

- Characteristics and microstructures of the GFRP waste powder/GGBS-based geopolymer paste and concrete

- Development and performance evaluation of a novel environmentally friendly adsorbent for waste water-based drilling fluids

- Determination of shear stresses in the measurement area of a modified wood sample

- Influence of ettringite on the crack self-repairing of cement-based materials in a hydraulic environment

- Multiple load recognition and fatigue assessment on longitudinal stop of railway freight car

- Synthesis and characterization of nano-SiO2@octadecylbisimidazoline quaternary ammonium salt used as acidizing corrosion inhibitor

- Perforated steel for realizing extraordinary ductility under compression: Testing and finite element modeling

- The influence of oiled fiber, freeze-thawing cycle, and sulfate attack on strain hardening cement-based composites

- Perforated steel block of realizing large ductility under compression: Parametric study and stress–strain modeling

- Study on dynamic viscoelastic constitutive model of nonwater reacted polyurethane grouting materials based on DMA

- Mechanical behavior and mechanism investigation on the optimized and novel bio-inspired nonpneumatic composite tires

- Effect of cooling rate on the microstructure and thermal expansion properties of Al–Mn–Fe alloy

- Research on process optimization and rapid prediction method of thermal vibration stress relief for 2219 aluminum alloy rings

- Failure prevention of seafloor composite pipelines using enhanced strain-based design

- Deterioration of concrete under the coupling action of freeze–thaw cycles and salt solution erosion

- Creep rupture behavior of 2.25Cr1Mo0.25V steel and weld for hydrogenation reactors under different stress levels

- Statistical damage constitutive model for the two-component foaming polymer grouting material

- Nano-structural and nano-constraint behavior of mortar containing silica aggregates

- Influence of recycled clay brick aggregate on the mechanical properties of concrete

- Effect of LDH on the dissolution and adsorption behaviors of sulfate in Portland cement early hydration process

- Comparison of properties of colorless and transparent polyimide films using various diamine monomers

- Study in the parameter influence on underwater acoustic radiation characteristics of cylindrical shells

- Experimental study on basic mechanical properties of recycled steel fiber reinforced concrete

- Dynamic characteristic analysis of acoustic black hole in typical raft structure

- A semi-analytical method for dynamic analysis of a rectangular plate with general boundary conditions based on FSDT

- Research on modification of mechanical properties of recycled aggregate concrete by replacing sand with graphite tailings

- Dynamic response of Voronoi structures with gradient perpendicular to the impact direction

- Deposition mechanisms and characteristics of nano-modified multimodal Cr3C2–NiCr coatings sprayed by HVOF

- Effect of excitation type on vibration characteristics of typical ship grillage structure

- Study on the nanoscale mechanical properties of graphene oxide–enhanced shear resisting cement

- Experimental investigation on static compressive toughness of steel fiber rubber concrete

- Study on the stress field concentration at the tip of elliptical cracks

- Corrosion resistance of 6061-T6 aluminium alloy and its feasibility of near-surface reinforcements in concrete structure

- Effect of the synthesis method on the MnCo2O4 towards the photocatalytic production of H2

- Experimental study of the shear strength criterion of rock structural plane based on three-dimensional surface description

- Evaluation of wear and corrosion properties of FSWed aluminum alloy plates of AA2020-T4 with heat treatment under different aging periods

- Thermal–mechanical coupling deformation difference analysis for the flexspline of a harmonic drive

- Frost resistance of fiber-reinforced self-compacting recycled concrete

- High-temperature treated TiO2 modified with 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane as photoactive nanomaterials

- Effect of nano Al2O3 particles on the mechanical and wear properties of Al/Al2O3 composites manufactured via ARB

- Co3O4 nanoparticles embedded in electrospun carbon nanofibers as free-standing nanocomposite electrodes as highly sensitive enzyme-free glucose biosensors

- Effect of freeze–thaw cycles on deformation properties of deep foundation pit supported by pile-anchor in Harbin

- Temperature-porosity-dependent elastic modulus model for metallic materials

- Effect of diffusion on interfacial properties of polyurethane-modified asphalt–aggregate using molecular dynamic simulation

- Experimental study on comprehensive improvement of shear strength and erosion resistance of yellow mud in Qiang Village

- A novel method for low-cost and rapid preparation of nanoporous phenolic aerogels and its performance regulation mechanism

- In situ bow reduction during sublimation growth of cubic silicon carbide

- Adhesion behaviour of 3D printed polyamide–carbon fibre composite filament

- An experimental investigation and machine learning-based prediction for seismic performance of steel tubular column filled with recycled aggregate concrete

- Effects of rare earth metals on microstructure, mechanical properties, and pitting corrosion of 27% Cr hyper duplex stainless steel

- Application research of acoustic black hole in floating raft vibration isolation system

- Multi-objective parametric optimization on the EDM machining of hybrid SiCp/Grp/aluminum nanocomposites using Non-dominating Sorting Genetic Algorithm (NSGA-II): Fabrication and microstructural characterizations

- Estimating of cutting force and surface roughness in turning of GFRP composites with different orientation angles using artificial neural network

- Displacement recovery and energy dissipation of crimped NiTi SMA fibers during cyclic pullout tests