Improved photocatalytic properties of WO3 nanoparticles for Malachite green dye degradation under visible light irradiation: An effect of La doping

-

Gokila Viswanathan

, Brindha Thirumalairaj

, Natrayan Lakshmaiya

Abstract

Doped materials have received substantial attention due to their increased usefulness in photocatalytic applications. Within this context, the present study was dedicated to investigating the potential of the precipitation technique for producing La-doped tungsten oxide (WO3). To comprehensively characterize the synthesized La-doped WO3, scanning electron microscopy and X-ray diffraction were judiciously employed. The focal point of the investigation encompassed an examination of the impact of varying La concentrations on multiple fronts: the photocatalytic activities (PCAs), as well as any associated structural and morphological modifications. This holistic approach aimed to uncover the intricate relationship between La incorporation and the resulting properties of the WO3 matrix. Through the degradation of Malachite green dye within an aqueous medium, PCA of the La-doped WO3 samples was quantitatively evaluated. Remarkably, over 180 min under irradiation of visible light irradiation, the achieved levels of dye degradation were remarkable, amounting to 81.165, 83.11, and 83.85% for the respective samples. These findings firmly underscore the potential of La-doped WO3 as a proficient photocatalyst, particularly in color removal from wastewater. This study paves the way for enhanced wastewater treatment approaches by utilizing doped WO3 materials.

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

The contamination of pristine drinking water due to the improper disposal of industrial waste into waterways, wells, and lakes – sources primarily designated for human consumption. This contamination poses a significant threat to individuals and aquatic ecosystems, leading to detrimental consequences from consuming impure water. Pesticides, industrial chemicals, heavy metals, and other chemical contaminants can all be harmful to aquatic life. These contaminants can build up in living things’ tissues, which can cause bioaccumulation and biomagnification in the food chain. In aquatic animals, they can cause genetic alterations, interfere with reproduction, compromise immune systems, and disturb physiological functions [1,2]. The endocrine system of aquatic species can be disrupted by specific chemical pollutants referred to as endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs). EDCs cause disruptions to normal physiological processes such as growth, development, metabolism, and reproduction by mimicking or interfering with hormones. For instance, medications like birth control pills and estrogenic chemicals such as bisphenol A can feminize male fish and interfere with reproductive cycles of aquatic animals [3].

Many conventional methods, such as physical, chemical, and biological treatments, are effective in the removal of a diversified range of pollutants from wastewater. However, their efficiency depends on the type and concentration of contaminants. These methods are unique and can target various pollutants, including suspended solids, organic matter, nutrients, heavy metals, and pathogens. However, these methods are versatile; photocatalysis, particularly using advanced oxidation processes, has shown high efficiency in degrading organic pollutants, pathogens, and certain inorganic contaminants. This method is suitable for treating certain types of wastewater, particularly those containing organic pollutants susceptible to photocatalytic degradation. It may be more applicable in small applications or as a supplementary treatment step in combination with conventional methods [4,5]. It mineralizes all the organic compounds under suitable conditions. In this context, nanotechnology emerges as a revolutionary solution that holds the potential to address water-related challenges by surmounting technological barriers associated with the removal of contaminants from water sources. These contaminants encompass harmful metallic elements, dyes employed in the textile industry, chemical pesticides, and so on [6]. Numerous experts contend that nanotechnologies present more cost-effective, efficient, and robust pathways for crafting specific nanoparticles tailored for water treatment. This advancement could enable manufacturers to produce nanoparticles with reduced toxicity utilizing conventional methodologies. Notably, metal oxide (MO)-based semiconductor materials have assumed a pivotal role in a dynamic global market owing to their multifaceted characteristics and applications. Due to their intricate electron interactions, uncomplicated composition, and diverse stoichiometry, these materials serve as pivotal model compounds for unraveling the impacts of solid correlation in both physical and chemical phenomena. Furthermore, they have found wide-ranging utility across various applications, prominently in photocatalysis [7].

Photocatalysis is an advanced oxidation technique designed to tackle pressing environmental concerns, including air pollution and wastewater treatment from textile manufacturing. This innovative process hinges on the disintegration of organic compounds through the synergistic action of ultraviolet (UV) light and catalysts. The application of heterogeneous semiconductors as photocatalysts to disintegrate organic pollutants in water has recently garnered significant attention. Under the influence of light with energy greater than the semiconductor’s band gap, an electron moves from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), resulting in positive holes within the VB. The formed positive holes instigate the production of hydroxyl radicals, renowned for their potent oxidation capabilities. These holes engage with dye molecules through a series of interactions, extracting electrons and thus initiating the breakdown process [8].

Furthermore, many semiconductors have found applications as photocatalysts in water remediation. MO nanoparticles, particularly TiO2, ZnO, tungsten oxide (WO3), CuO, and Cu2O, have shown potential in water treatment due to their non-toxicity, stability, and cost-effectiveness [9,10]. Magnetic iron oxide/clay nanocomposites with high stability and adsorption capacities are also useful in water treatment applications [11]. Furthermore, the use of MO polymer nanocomposites has been investigated, with visible light response polymer/MO nanocomposites showing superior photodegradation activity against pollutants [12]. The successful immobilization of ultra-small cobalt oxide nanoparticles in MIL-101 and the role of MIL-101 in improving photocatalytic performance was investigated, and the practical approach of immobilizing catalyst nanoparticles on a suitable substrate using visible light-driven water oxidation reactions [13]. Nonetheless, their wide bandgap significantly curtails their efficacy when exposed to visible light [14]. Photocatalysis, a highly effective method for wastewater treatment, not only offers environmental safeguarding but also entails straightforward operation, an elevated mineralization rate, and potent oxidation potential, collectively facilitating the efficient elimination of low concentrations of organic contaminants from water sources [15]. WO3 emerges as the best MO in the photocatalyst arena due to its comparatively small energy gap, elevated oxidation potential within the VB, and its adeptness in driving reactions under visible light illumination [16]. Beyond its role in photodegradation, WO3 has exhibited various applications in antimicrobial actions and water splitting [17].

Nevertheless, a drawback inherent to WO3 lies in its relatively lower CB, impeding its capacity to provide an appropriate potential for engaging with electron acceptors, consequently inciting electron–hole pair recombination [18]. To this end, the strategic modification of WO3 through various techniques becomes imperative. Approaches such as meticulous morphological control, the construction of heterostructures, doping, and co-deposition with noble metals stand out as viable avenues to substantially enhance its photocatalytic prowess [19].

By surveying many reports related to this area, it came to our attention that, despite numerous studies focusing on the diverse applications of WO3, there is either an absence or a minimal presence of articles concerning the co-precipitation synthesis of La-doped WO3 nanoparticles for applications in optoelectronics and photocatalysis. This discovery left a remarkable impression on us, leading us to create La-doped WO3 nanoparticles as a potent photocatalyst aimed at degrading hazardous Malachite green (MG) dye, and only a few articles reported the photocatalytic degradation of MG dye [20,21,22]. For instance, CuO nanoparticles were synthesized and tested for the photocatalytic degradation of MG dye using UV–Vis radiation [23]. Similarly, TiO2 nanoparticles were synthesized by the microwave radiation method, and the absorption ability of MG dye was investigated [24]. Our study’s core revolved around utilizing a straightforward co-precipitation method to synthesize WO3 nanoparticles with La incorporation as a dopant. To comprehensively understand the impact of varying La concentrations, we meticulously investigated their influence on the crystal phase, particle size, morphology, and optical properties of the resultant WO3 structures. A crucial phase of our research involved subjecting the synthesized nanomaterials to visible light irradiation, allowing us to assess their efficacy in the realm of photocatalysis through the degradation of MG dye. The insights gleaned from our research hold profound significance, particularly within the domain of water purification applications. By addressing the existing gap in knowledge and providing novel findings, our study contributes to the advancement of sustainable solutions for environmental concerns.

2 Experimental section

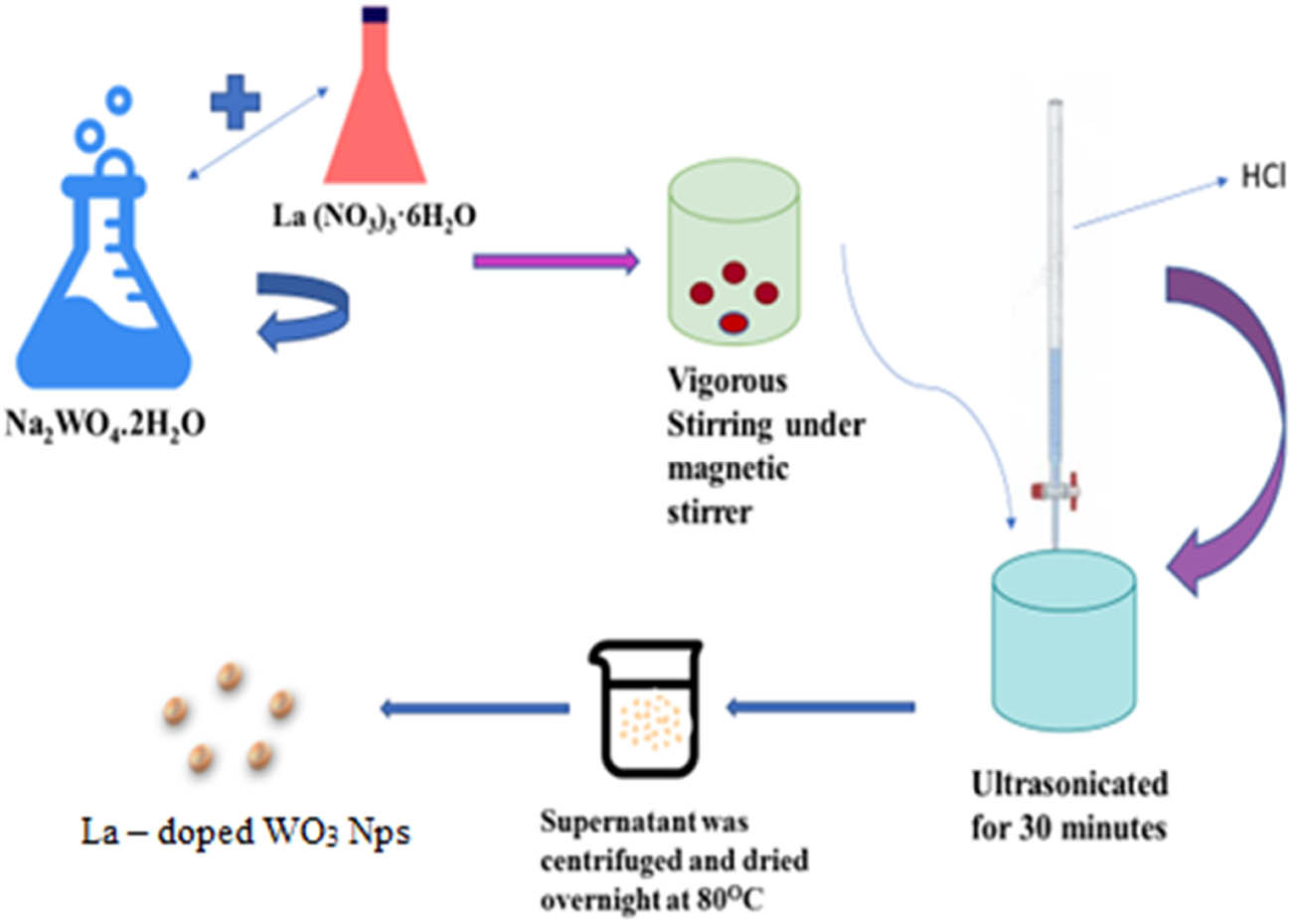

A diagrammatic representation for the synthesis of La-doped WO3 nanoparticles is given in Scheme 1.

Representation of synthesis of La-doped WO3 nanoparticles.

2.1 Source materials

Sodium tungstate dihydrate (Na2WO4·2H2O) and lanthanum(iii) nitrate hexahydrate (La(NO3)3·6H2O), AR grade, were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Hydrochloric acid (HCl) was bought from Nice Chemicals and used without further purification.

2.2 Synthesis of La-doped WO3 nanoparticles

For the synthesis of La-doped WO3 nanoparticles, a simple co-precipitation method was adopted. About 7 mM of Na2WO4·2H2O and different La(NO3)3·6H2O were added to 50 mL of distilled water and stirred vigorously. The aforementioned solution was treated ultrasonically for 30 min. The pH of the solution was adjusted to one by adding 1 M HCl solution in drops. The supernatant was centrifuged and dried overnight at 80°C. Then, the grained powder was kept in a muffle furnace and calcinated at 450°C for 2 h.

2.3 Photocatalytic degradation of MG dye using La-doped WO3 nanoparticles

La-doped WO3 nanoparticles were used as a photocatalyst for the degradation of MG dye under UV–Vis irradiation. A 25 ppm MG dye was prepared, and 0.0001 g of La-doped WO3 nanoparticles was added separately to 20 mL of the dye solution in 50 mL beakers. To reach the equilibrium, the solutions were kept in the dark for 30 min. Subsequently, the mixtures were exposed to UV–Vis light and stirred continuously for different durations of irradiation time. After irradiation, the photocatalyst nanoparticles were separated from the dye solution using a filtration process and centrifugation. Using a UV-visible spectrophotometer, the degradation of MG dye was monitored.

2.4 Characterization of La-doped WO3 nanoparticles

X-ray diffraction (XRD) studies were carried out using XEPRT-PRO at λ = 1.5 Å with CuKα radiation. The Raman spectra were analyzed using a Jobin-Yvon T64000 spectrograph at room temperature. Morphological images were investigated using field emission-scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM). UV–Vis spectroscopy (JASCO V-770 PC) was used to examine the optical absorption. A FluoroMax-4 fluorescence spectrophotometer was used to obtain the produced catalysts’ photoluminous (PL) spectra.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Structural features

3.1.1 XRD analysis

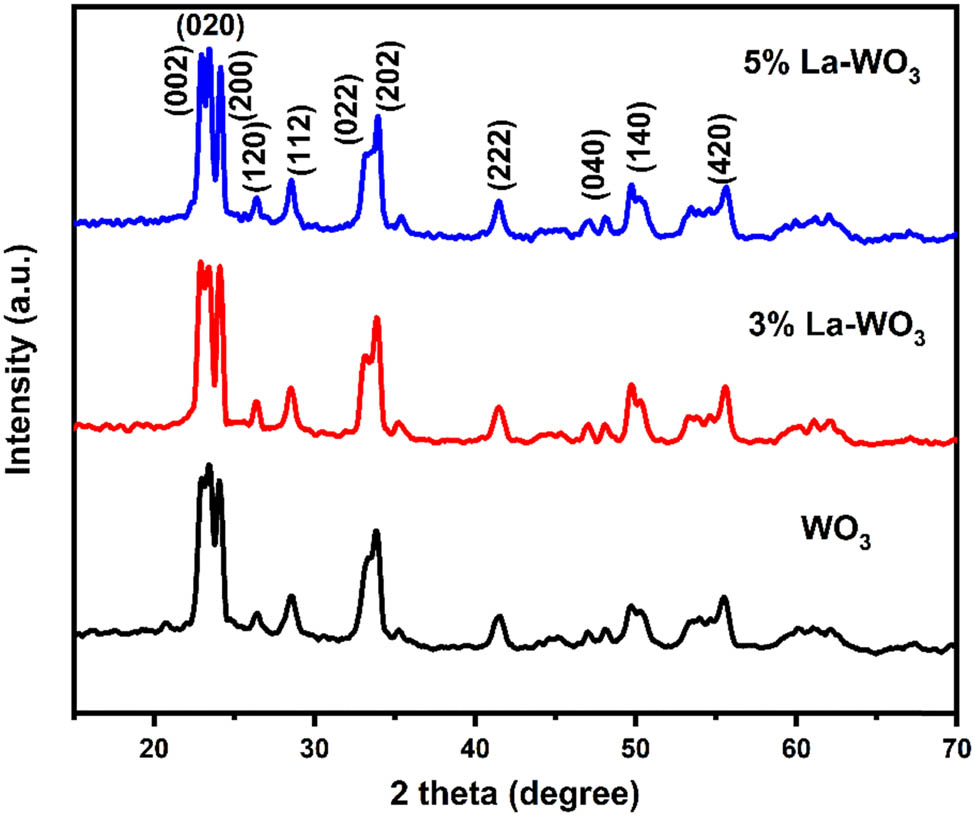

Figure 1 shows the crystalline configuration of the pure WO3 and La-doped WO3, encompassing a diverse series of molar ratios. Following the data extracted from the JCPDS No. 75-2187 reference, the diffraction peaks located at 22.9°, 23.5°, 24.2°, and 26.5° are unambiguously attributed to the (002), (020), (200), and (120) monoclinic phases of WO3 [25]. The diffraction peaks stemming from the pure WO3 align commendably with the hexagonal wurtzite structure as detailed in the JCPDS No. 75-2187 phase for WO3, notably devoid of any traces of impurity peaks. Interestingly, the XRD spectra corresponding to the 3–5% La-doped WO3 compounds mirror those of pure WO3, displaying no discernible diffraction peaks. This outcome can be ascribed to the relatively low concentration of La introduced into the system and the consequent near-complete incorporation of La atoms within the crystalline framework of WO3 [26]. This phenomenon underscores the subtle influence of the limited La doping on the overall crystallographic configuration of the WO3 lattice.

XRD pattern of pure WO3 and La-doped WO3 nanoparticles.

3.2 Raman spectrum analysis

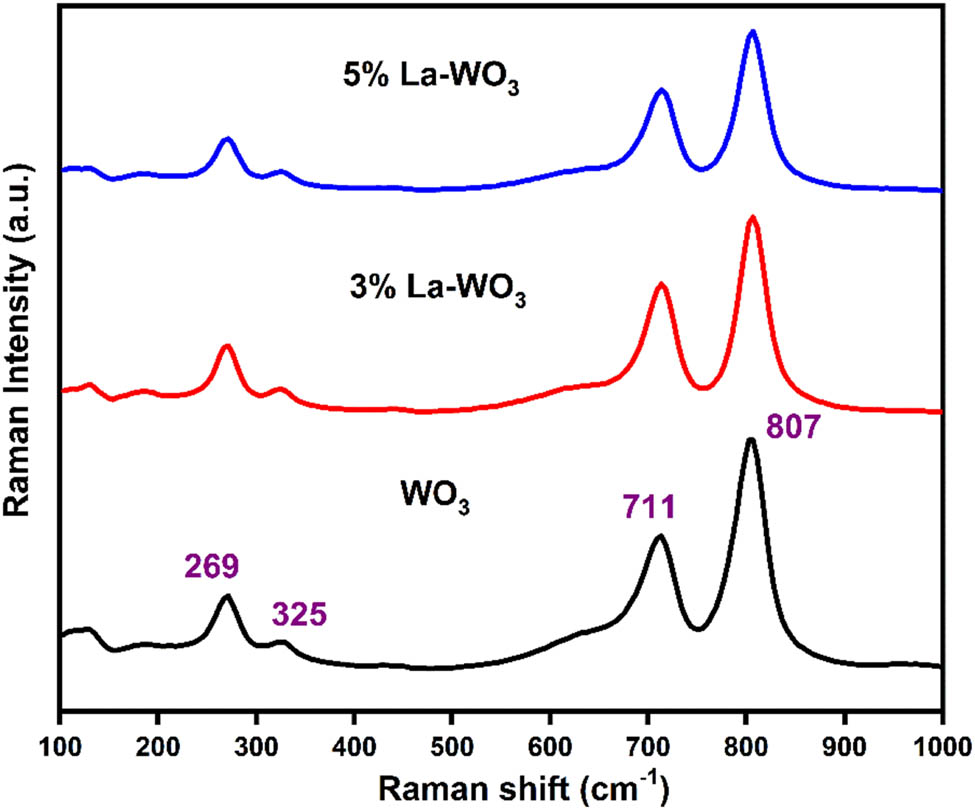

The Raman profiles of pure WO3 and La-doped WO3 samples in the 100–1,000 cm−1 range are shown in Figure 2. The highest strong band in Raman spectra was recorded at 807 cm−1 for all the studied samples. The band at 269 cm−1 is associated with υ(O–W–O) deformation vibrational bands, while the bands at 711 and 807 cm−1 are associated with (O–W–O) bending vibration modes of the molecule [27]. The obtained Raman peak profiles of WO3 samples closely correspond to those already reported in the literature [28]. Also, there are no impurity-related bands observed, which encompasses the effective incorporation of the La ion into the WO3 structure. The intensities of the peak decreases as the La concentration increases, indicating a decreased combination rate of light-induced charge carriers and an increase in oxygen vacancies [29].

Raman pattern of pure WO3 and La-doped WO3 nanoparticles.

3.3 Morphological features

3.3.1 FE-SEM analysis

The morphology of nanostructure materials is an important property because it usually dictates the performance of these materials. Figure 3(a) shows FE-SEM micrographs of pure and La-doped WO3 samples. A homogeneous and agglomerated spherical morphology was observed [30]. The La dopant does not affect the morphology of the pure sample, but there is less aggregation of smaller round-shaped crystallites. The energy-dispersive X-ray spectra of La-doped WO3 (5%) photocatalyst confirm the presence of La and WO3 (Figure 3(b)).

(a) FE-SEM spectra of pure WO3 and La-doped WO3 nanoparticles and (b) energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy spectrum of 5% La-doped WO3 nanoparticles.

3.4 Optical features

3.4.1 UV–visible absorbance analysis

UV–visible spectrophotometer is used to evaluate the optical properties and band gap energy of pure and La-doped WO3 nanoparticles, as shown in Figure 4. With increasing La dopant concentration, La-doped WO3 spectra show a red shift in the absorption edge. The distribution of charge density between the conduction or VB of La and WO3 can result in a significant red shift [31]. The band gap energy of pure and La-doped WO3 (3 and 5 wt%) were observed as 2.65, 2.52, and 2.46 eV, respectively. La-doped WO3 samples showed a decreased band gap, which might be attributed to the formation of an intermediate energy level between the valance and conduction of pure WO3. The decreased band gap energy of La-doped WO3 may have potential applications in various industries [32].

(a) UV–visible absorbance spectra and (b) TAUC plot of pure WO3 and La-doped WO3 nanoparticles.

The reduction in bandgap energy causes feasible electronic excitation within the materials upon UV–visible light absorption. As a result, the addition of La-doped WO3 nanomaterials significantly improved the photocatalytic degradation of the MG dye. When La is doped with WO3, the electrons present in the WO3 readily excite from the VB to the CB. This transition occurs at very low energy, resulting in a favorable arrangement of energy levels between La and WO3.

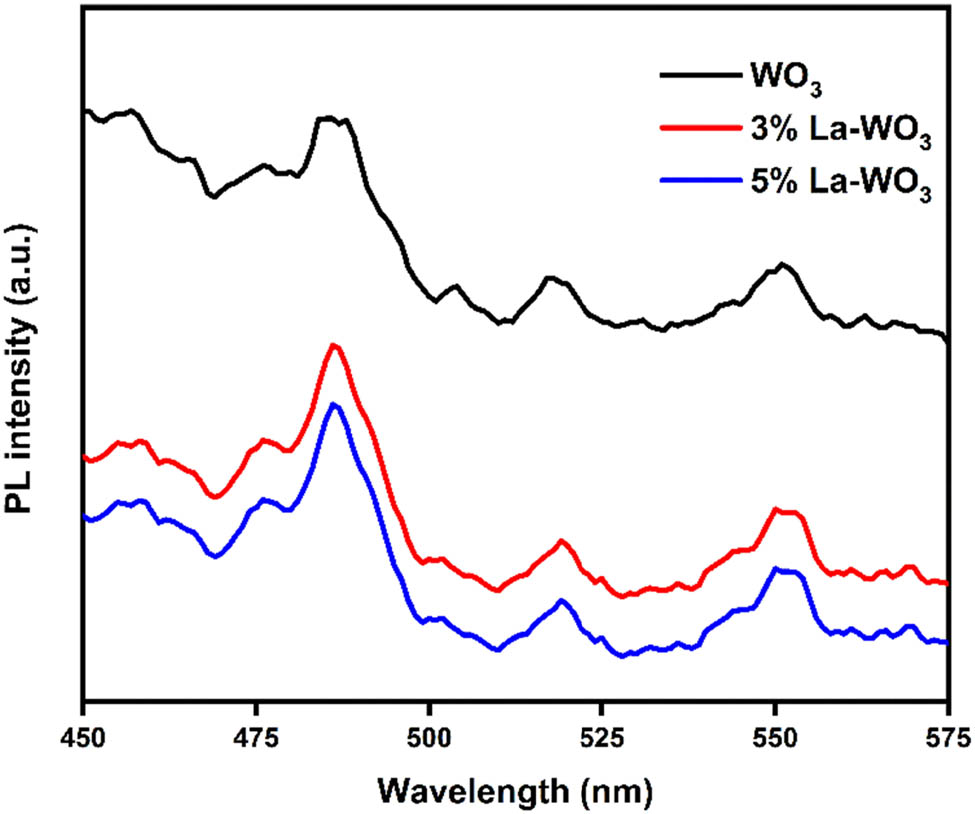

3.4.2 Photoluminescence analysis

The photogenerated charge carrier mitigation, transfer, and recombination in semiconductors were studied using the PL spectrum. Figure 5 depicts the PL spectrum of pure and La-doped WO3 NPs at 320 nm. The maximum emission peak intensity of pure and La-doped WO3 NPs is 485.9 nm, as seen in PL spectra [33]. The highest PL intensity is seen in pure WO3, which can be altered by increasing the La concentration. The modest PL intensity of 5 wt% La-doped WO3 NRs can cause defects/photogenerated electron–hole pair recombination. As a result, reducing the recombination rate of photogenerated charge carriers improved the effectiveness of photocatalytic dye degradation [34].

PL spectra of pure and La-doped WO3 nanoparticles.

4 Photocatalysis application

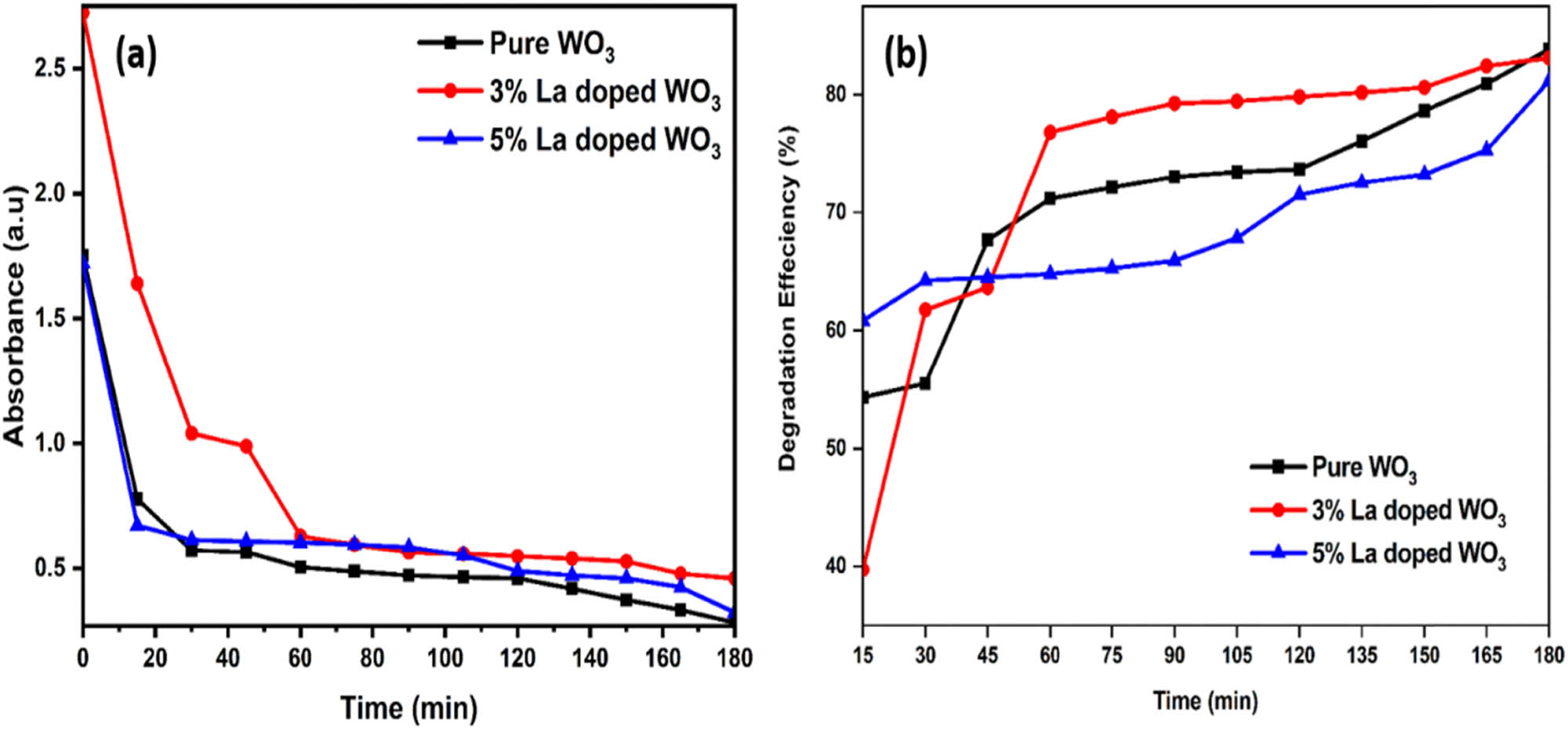

4.1 MG dye degradation

The degradation of the MG dye under visible radiation is used to determine the photocatalytic performance of the samples. To prepare samples for photocatalytic examination, 0.1 g of MG is weighed. The photocatalytic reactor setup uses a 50 ppm solution of MG and 0.05 g of La-doped WO3 catalyst. The solution is left in the dark for 60 min before being exposed to visible light [35]. The degraded dye sample is collected every 15 min and evaluated for dye degradation. The solution is then collected and analyzed using a UHS300 spectrophotometer to determine absorption spectra. The deterioration efficiency is calculated using the following formula [36]:

where A

0 represents the initial absorption of MG solution and A(t) represents the absorption of different UV irradiation durations. Fundamentally, when exposed to visible light, every La-doped WO3 emits electrons when its energy exceeds or equals the bandgap [37]. The presence of an equal amount of electrons and holes (OH˙ and

(a) UV–Vis absorbance plot and (b) photocatalytic degradation plot of pure WO3 and La-doped WO3 nanoparticles on degrading MG dye.

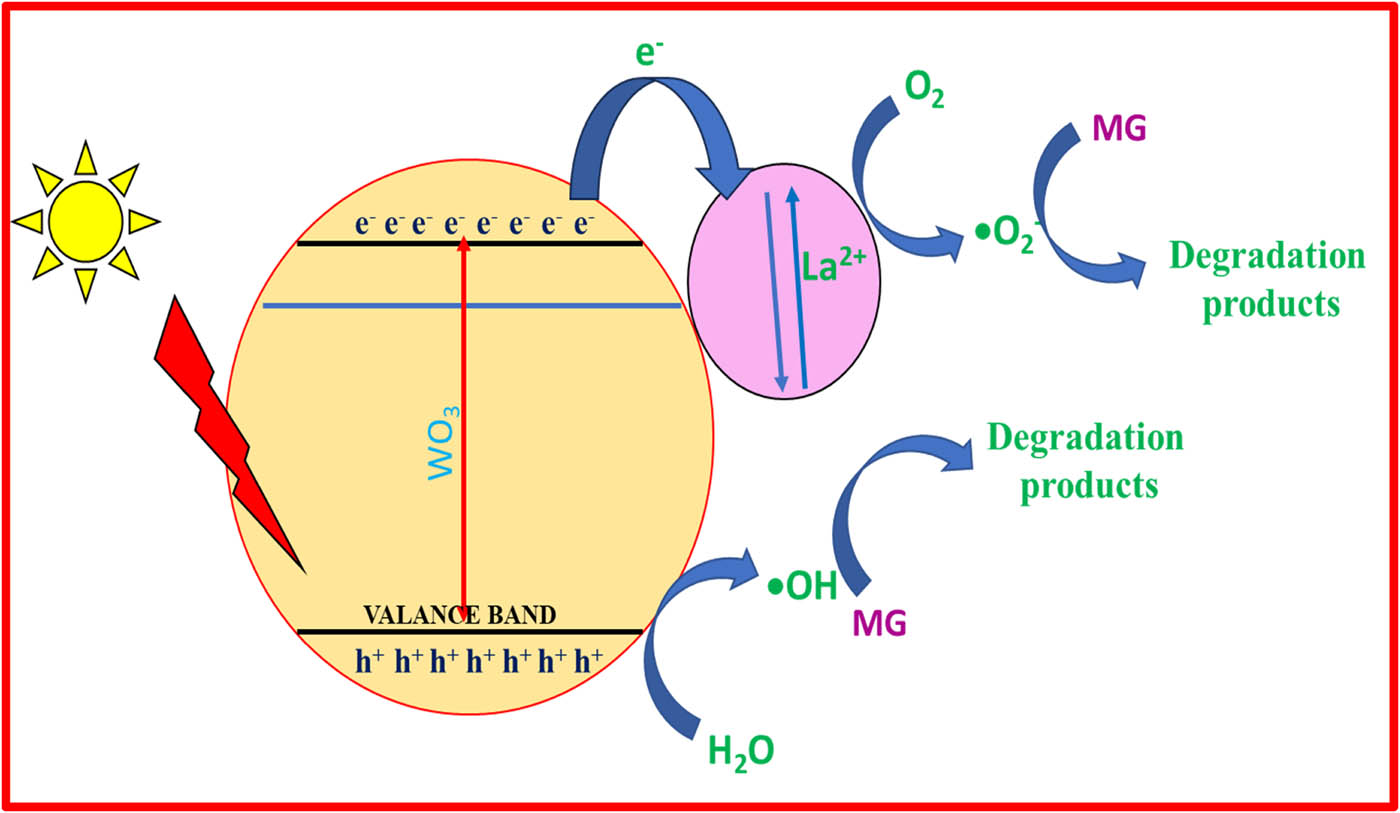

4.2 Photocatalytic mechanism

The mechanism of photocatalytic degradation generally involves several steps, which include [38]

Adsorption and desorption of molecules,

Formation of electron–hole pairs,

Combination of electron–hole pairs, and

Chemical reactions.

To be particular, the photocatalytic mechanism takes place in three important steps, and they are

Adsorption of MG,

Significant adsorption of photons, and

Formation of oxidation and reducing species due to the charge transfer reactions.

In general, when light energy is radiated on the photocatalysts, electrons present in the valence shell of the photocatalyst excite to its CB. Because of the excitation, positive holes appear in the valence shell. These positive holes oxidize dye molecules converting them into highly reactive intermediates, resulting in a greater oxidation potential. If this reaction does not take place, then the positive holes react with water molecules to produce hydroxide radicals. Thus, by this process, dye degradation occurs.

Several works have been carried out by using different catalysts to increase the efficiency of the photocatalysis process. Particularly, in recent years, metal-oxide nanoparticles have been used as promising photocatalysts because of their low cost, abundance of raw material, and simple synthesizing method [39,40,41]. At the same time, the band gap of MO nanoparticles affects the photocatalytic activity (PCA). As the nanoparticles exhibit a narrow band gap, they tend to have the highest PCA.

The photodegradation of MG dye over La-doped WO3 nanoparticles under visible radiation is displayed in Figure 7. When light is illuminated on a typical photocatalyst, the valence electrons acquire energy and are excited to the CB, and at the same time, holes are generated in the VB. Holes react with water molecules present in a dye solution to create OH˙ radicals [42]. On the contrary, additive La acts as an electron acceptor to accept the exited electron and delay the rate of photorecombination. The trapped electron reacts with oxygen molecules in water to form

Photodegradation mechanism of MG dye under visible light irradiation.

Thus, it was identified that La-doped WO3 nanoparticles can act as the best photocatalytic degradation of MG dye. Further, the stability and reusability of the synthesized catalyst can be studied by the few reported studies [44,45]. The adsorbed molecules can be removed by centrifuging at the speed of 1,200 rpm, followed by washing with water and drying in a vacuum for 10 h. Once the degradation efficiency is reduced the process of centrifuging can be stopped.

5 Conclusion

The present work focused on a simple and efficient co-precipitation method for the synthesis of La-doped WO3 nanoparticles, a heterojunction photocatalyst. Under visible light irradiation, the MG dye was totally destroyed on 5% La-doped WO3 nanoparticles in 180 min. Furthermore, the photocatalytic efficiency for the degradation of MG dye using the 5% La-doped WO3 nanoparticles was found to be greater than that of both pure WO3 and 3% La-doped WO3 nanoparticles. The enhanced photocatalytic performance is likely attributable to the three-dimensional hierarchical structure and the facilitated transition and separation of photogenerated electron–hole pairs in 5% La-doped WO3, owing to the alignment of their respective band locations. Consequently, the 5% La-doped WO3 photocatalysts proved to be excellent options for the degradation of organic pollutants, showcasing both high efficiency and stability under challenging conditions when exposed to visible light.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2024R999), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Funding information: Research Supporting Project from King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Author contributions: Gokila Viswanathan – original draft preparation, writing, reviewing, and editing; Ayyappan Solaiappan – conceptualization, investigation, and formal analysis; Brindha Thirumalairaj – investigation, validation, reviewing, and formal analysis; Md. Irfanul Haque Siddiqui – investigation and formal analysis; Natrayan Lakshmaiya – reviewing and formal analysis; Umapathi Krishnamoorthy – supervision, editing, and reviewing; and Mohd Asif Shah – reviewing and formal analysis.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no competing interests.

-

Data availability statement: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

References

[1] Ray S, Shaju ST. Bioaccumulation of pesticides in fish resulting toxicities in humans through food chain and forensic aspects. Environ Anal Health Toxicol. 2023 Aug;38(3):e2023017-7.10.5620/eaht.2023017Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Chojnacka K, Mikulewicz M. Bioaccumulation. Elsevier EBooks; 2014. p. 456–460, https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-386454-3.01039-3.10.1016/B978-0-12-386454-3.01039-3Search in Google Scholar

[3] Ghosh A, Tripathy A, Ghosh D. Impact of endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) on reproductive health of human. Proceedings of the Zoological Society; 2022 Mar.10.1007/s12595-021-00412-3Search in Google Scholar

[4] Saravanan R, Sathish T, Sharma K, Rao AV, Sathyamurthy R, Panchal H, et al. Sustainable wastewater treatment by RO and hybrid organic polyamide membrane nanofiltration system for clean environment. Chemosphere. 2023;337:139336. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.139336 Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Mohamad HA, Hemdan M, Bastawissi AA, Bastawissi AE, Panchal H, Sadasivuni KK. Industrial wastewater treatment by electrocoagulation powered by a solar photovoltaic system. Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Util Environ Eff. 2021;1–12. 10.1080/15567036.2021.1950870.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Chen D, Cheng Y, Zhou N, Chen P, Wang Y, Li K, et al. Photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants using TiO2-based photocatalysts: A review. J Clean Prod. 2020 Sep;[cited 2020 Oct 31] 268:121725, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959652620317728.10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121725Search in Google Scholar

[7] Zhang C, Liu G, Geng X, Wu K, Debliquy M. Metal oxide semiconductors with highly concentrated oxygen vacancies for gas sensing materials: A review. Sens Actuators A: Phys. 2020 Jul;309:112026.10.1016/j.sna.2020.112026Search in Google Scholar

[8] Yuan Y, Guo R, Hong L, Ji X, Li Z, Lin Z, et al. Recent advances and perspectives of MoS2-based materials for photocatalytic dyes degradation: A review. Colloids Surf A: Physicochem Eng Asp. 2021 Feb;611:125836–6.10.1016/j.colsurfa.2020.125836Search in Google Scholar

[9] Chidambaram S, Baskaran B, Ganesan M, Muthusamy S, Alavandar S, Muthusamy S, et al. One pot synthesis of Ag-Au/ZnO nanocomposites: a multi-junction component for sunlight photocatalysis. Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Util, Environ Eff. 2022;44(1):758–70. 10.1080/15567036.2022.2050855 Search in Google Scholar

[10] Baruah S, Najam Khan M, Dutta J. Perspectives and applications of nanotechnology in water treatment. Environ Chem Lett. 2015 Nov;14(1):1–14.10.1007/s10311-015-0542-2Search in Google Scholar

[11] Fadillah G, Yudha SP, Sagadevan S, Fatimah I, Muraza O. Magnetic iron oxide/clay nanocomposites for adsorption and catalytic oxidation in water treatment applications. Open Chem. 2020 Sep;18(1):1148–66.10.1515/chem-2020-0159Search in Google Scholar

[12] Hu K, Kulkarni DD, Choi I, Tsukruk VV. Graphene-polymer nanocomposites for structural and functional applications. Prog Polym Sci. 2014 Nov;39(11):1934–72.10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2014.03.001Search in Google Scholar

[13] Pallavi N, Rakshitha R, Chethan R. Photocatalytic removal of emerging contaminants from water using metal oxide-based nanoparticles. Curr Nanosci. 2024 May;20(3):339–55.10.2174/1573413719666230331111906Search in Google Scholar

[14] Akter J, Hanif MdA, Islam MdA, Sapkota KP, Hahn JR. Selective growth of Ti3 +/TiO2/CNT and Ti3 +/TiO2/C nanocomposite for enhanced visible-light utilization to degrade organic pollutants by lowering TiO2-bandgap. Sci Rep. 2021 May;11(1).10.1038/s41598-021-89026-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Dutta V, Sharma S, Raizada P, Thakur VK, Khan AAP, Saini V, et al. An overview on WO3 based photocatalyst for environmental remediation. J Environ Chem Eng. 2021 Feb;9(1):105018.10.1016/j.jece.2020.105018Search in Google Scholar

[16] Murillo-Sierra JC, Hernández-Ramírez A, Hinojosa-Reyes L, Guzmán-Mar JL. A review on the development of visible light-responsive WO3-based photocatalysts for environmental applications. Chem Eng J Adv. 2021 Mar;[cited 2021 Oct 5] 5:100070, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666821120300703.10.1016/j.ceja.2020.100070Search in Google Scholar

[17] Shandilya P, Sambyal S, Sharma R, Mandyal P, Fang B. Properties, optimized morphologies, and advanced strategies for photocatalytic applications of WO3 based photocatalysts. J Hazard Mater. 2022 Apr;428:128218.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.128218Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Jiang Z, Cheng B, Zhang Y, Wageh S, Al‐Ghamdi AA, Yu J, et al. S-scheme ZnO/WO3 heterojunction photocatalyst for efficient H2O2 production. J Mater Sci & Technol. 2022 Oct 1;124:193–201.10.1016/j.jmst.2022.01.029Search in Google Scholar

[19] Liao M, Su L, Deng Y, Xiong S, Tang R, Wu Z, et al. Strategies to improve WO3-based photocatalysts for wastewater treatment: a review. J Mater Sci. 2021 Jun;56(26):14416–47.10.1007/s10853-021-06202-8Search in Google Scholar

[20] Din MI, Tariq M, Hussain Z, Khalid R. Single step green synthesis of nickel and nickel oxide nanoparticles from Hordeum vulgare for photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue dye. Inorg Nano-Metal Chem. 2020 Jan;50(4):292–7.10.1080/24701556.2019.1711401Search in Google Scholar

[21] Din MI, Khalid R, Hussain Z. Minireview: silver-doped titanium dioxide and silver-doped zinc oxide photocatalysts. Anal Lett. 2017 Dec;51(6):892–907.10.1080/00032719.2017.1363770Search in Google Scholar

[22] Din MI, Najeeb J, Hussain Z, Khalid R, Ahmad G. Biogenic scale up synthesis of ZnO nano-flowers with superior nano-photocatalytic performance. Inorg Nano-Metal Chem. 2020 Feb;50(8):613–9.10.1080/24701556.2020.1723026Search in Google Scholar

[23] Sarathi R, Sundar SM, Jayamurugan P, Ganganagunta S, Sudhadevi D, Ubaidullah M, et al. Impacts of pH on photocatalytic efficiency, the control of energy and morphological properties of CuO nanoparticles for industrial wastewater treatment applications. Mater Sci Eng B. 2023 Dec 1;298:116856–6.10.1016/j.mseb.2023.116856Search in Google Scholar

[24] Park JH, Kim S, Bard AJ. Novel carbon-doped TiO2 nanotube arrays with high aspect ratios for efficient solar water splitting. Nano Lett. 2005 Dec;6(1):24–8.10.1021/nl051807ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Subramani T, Thimmarayan G, Balraj B, Narendhar C, Matheswaran P, Nagarajan SK, et al. Surfactants assisted synthesis of WO3 nanoparticles with improved photocatalytic and antibacterial activity: A strong impact of morphology. Inorg Chem Commun. 2022 Aug;142:109709–9.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Zhang Y, Wu C, Xiao B, Yang L, Jiao A, Li K, et al. Chemo-resistive NO2 sensor using La-doped WO3 nanoparticles synthesized by flame spray pyrolysis. Sens Actuators B: Chem. 2022 Oct;369:132247.10.1016/j.snb.2022.132247Search in Google Scholar

[27] Abbaspoor M, Aliannezhadi M, Tehrani FS. Effect of solution pH on as-synthesized and calcined WO3 nanoparticles synthesized using sol-gel method. Optical Mater. 2021 Nov;121:111552.10.1016/j.optmat.2021.111552Search in Google Scholar

[28] Antony AJ, Jelastin M, Joel C, Bennie RB, Praveendaniel S. . Enhancing the visible light induced photocatalytic properties of WO3 nanoparticles by doping with vanadium. J Phys Chem Solids. 2021 Oct;157:110169–9.10.1016/j.jpcs.2021.110169Search in Google Scholar

[29] Abbaspoor M, Aliannezhadi M, Tehrani FS. High-performance photocatalytic WO3 nanoparticles for treatment of acidic wastewater. J Sol-Gel Sci Technol. 2022 Nov;105(2):565–76.10.1007/s10971-022-06002-9Search in Google Scholar

[30] Shaheen N, Warsi MF, Zulfiqar S, Althakafy JT, Alanazi AK. Muhammad Imran Din, et al. La-doped WO3@gCN nanocomposite for efficient degradation of cationic dyes. Ceram Int. 2023 May;49(10):15507–26.10.1016/j.ceramint.2023.01.137Search in Google Scholar

[31] Subramani T, Thimmarayan G, Balraj B, Narendhar C, Matheswaran P, Nagarajan SK, et al. Surfactants assisted synthesis of WO3 nanoparticles with improved photocatalytic and antibacterial activity: A strong impact of morphology. Inorg Chem Commun. 2022 Aug 1;142:109709.10.1016/j.inoche.2022.109709Search in Google Scholar

[32] Kumari H, Sonia, Suman, Ranga R, Chahal S, Devi S, et al. A review on photocatalysis used for wastewater treatment: dye degradation. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2023 May;234(6):349.10.1007/s11270-023-06359-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Mohan L, Avani AV, Kathirvel P, Marnadu R, Packiaraj R, JR, Joshua, et al. Investigation on structural, morphological and electrochemical properties of Mn doped WO3 nanoparticles synthesized by co-precipitation method for supercapacitor applications. J Alloy Compd. 2021 Nov;882:160670.10.1016/j.jallcom.2021.160670Search in Google Scholar

[34] Bhuvaneswari K, Palanisamy G, Bharathi G, Pazhanivel T, Upadhyaya IR, Kumari MLA, et al. Visible light driven reduced graphene oxide supported ZnMgAl LTH/ZnO/g-C3N4 nanohybrid photocatalyst with notable two-dimension formation for enhanced photocatalytic activity towards organic dye degradation. Environ Res. 2021 Jun;197:111079.10.1016/j.envres.2021.111079Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Ebrahimi R, Maleki A, Zandsalimi Y, Ghanbari R, Shahmoradi B, Rezaee R, et al. Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes using WO3-doped ZnO nanoparticles fixed on a glass surface in aqueous solution. 2019 May;73:297–305.10.1016/j.jiec.2019.01.041Search in Google Scholar

[36] Verma M, Singh KP, Kumar A. Reactive magnetron sputtering based synthesis of WO3 nanoparticles and their use for the photocatalytic degradation of dyes. Solid State Sci. 2020 Jan;[cited 2022 Dec 22] 99:105847, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1293255818311440.10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2019.02.008Search in Google Scholar

[37] Ghenaatgar A, A.Tehrani M, Khadir A. Photocatalytic degradation and mineralization of dexamethasone using WO3 and ZrO2 nanoparticles: Optimization of operational parameters and kinetic studies. J Water Process Eng. 2019 Dec;32:100969.10.1016/j.jwpe.2019.100969Search in Google Scholar

[38] Elkady MF, Hassan HS. Photocatalytic degradation of malachite green dye from aqueous solution using environmentally compatible Ag/ZnO polymeric nanofibers. Polymers. 2021 Jun;13(13):2033.10.3390/polym13132033Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Montañez JP, Pierella LB, Santiago AN. Photodegradation of herbicide dicamba with TiO2 immobilized on HZSM-11 Zeolite. Int J Environ Res. 2015 Oct;9(4):1237–44.Search in Google Scholar

[40] McKeown NB, Budd PM. Polymers of intrinsic microporosity (PIMs): organic materials for membrane separations, heterogeneous catalysis and hydrogen storage. Chem Soc Rev. 2006;35(8):675.10.1039/b600349dSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Singh P, Shandilya P, Raizada P, Sudhaik A, Rahmani-Sani A, Hosseini-Bandegharaei A. Review on various strategies for enhancing photocatalytic activity of graphene based nanocomposites for water purification. Arab J Chem. 2020 Jan;13(1):3498–520.10.1016/j.arabjc.2018.12.001Search in Google Scholar

[42] Govindaraj T, Mahendran C, Chandrasekaran J, Manikandan VS, Shkir M, Massuod EE, et al. Effect of incorporation of La into WO3 nanorods for improving photocatalytic activity under visible light irradiation. J Phys Chem Solids. 2022 Nov;170:110908.10.1016/j.jpcs.2022.110908Search in Google Scholar

[43] Chen P, Liang Y, Xu Y, Zhao Y, Song S. Synchronous photosensitized degradation of methyl orange and methylene blue in water by visible-light irradiation. J Mol Liq. 2021 Jul;334:116159.10.1016/j.molliq.2021.116159Search in Google Scholar

[44] Govindaraj T, Mahendran C, Manikandan VS, Suresh R. One-pot synthesis of tungsten oxide nanostructured for enhanced photocatalytic organic dye degradation. J Mater Sci: Mater Electron. 2020 Sep;31(20):17535–49.10.1007/s10854-020-04309-3Search in Google Scholar

[45] Din MI, Khalid R, Hussain Z. Novel in-situ synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticle in smart polymer microgel for catalytic reduction of methylene blue. J Mol Liq. 2022 Jul;358:119181.10.1016/j.molliq.2022.119181Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Porous silicon nanostructures: Synthesis, characterization, and their antifungal activity

- Biochar from de-oiled Chlorella vulgaris and its adsorption on antibiotics

- Phytochemicals profiling, in vitro and in vivo antidiabetic activity, and in silico studies on Ajuga iva (L.) Schreb.: A comprehensive approach

- Synthesis, characterization, in silico and in vitro studies of novel glycoconjugates as potential antibacterial, antifungal, and antileishmanial agents

- Sonochemical synthesis of gold nanoparticles mediated by potato starch: Its performance in the treatment of esophageal cancer

- Computational study of ADME-Tox prediction of selected phytochemicals from Punica granatum peels

- Phytochemical analysis, in vitro antioxidant and antifungal activities of extracts and essential oil derived from Artemisia herba-alba Asso

- Two triazole-based coordination polymers: Synthesis and crystal structure characterization

- Phytochemical and physicochemical studies of different apple varieties grown in Morocco

- Synthesis of multi-template molecularly imprinted polymers (MT-MIPs) for isolating ethyl para-methoxycinnamate and ethyl cinnamate from Kaempferia galanga L., extract with methacrylic acid as functional monomer

- Nutraceutical potential of Mesembryanthemum forsskaolii Hochst. ex Bioss.: Insights into its nutritional composition, phytochemical contents, and antioxidant activity

- Evaluation of influence of Butea monosperma floral extract on inflammatory biomarkers

- Cannabis sativa L. essential oil: Chemical composition, anti-oxidant, anti-microbial properties, and acute toxicity: In vitro, in vivo, and in silico study

- The effect of gamma radiation on 5-hydroxymethylfurfural conversion in water and dimethyl sulfoxide

- Hollow mushroom nanomaterials for potentiometric sensing of Pb2+ ions in water via the intercalation of iodide ions into the polypyrrole matrix

- Determination of essential oil and chemical composition of St. John’s Wort

- Computational design and in vitro assay of lantadene-based novel inhibitors of NS3 protease of dengue virus

- Anti-parasitic activity and computational studies on a novel labdane diterpene from the roots of Vachellia nilotica

- Microbial dynamics and dehydrogenase activity in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) rhizospheres: Impacts on growth and soil health across different soil types

- Correlation between in vitro anti-urease activity and in silico molecular modeling approach of novel imidazopyridine–oxadiazole hybrids derivatives

- Spatial mapping of indoor air quality in a light metro system using the geographic information system method

- Iron indices and hemogram in renal anemia and the improvement with Tribulus terrestris green-formulated silver nanoparticles applied on rat model

- Integrated track of nano-informatics coupling with the enrichment concept in developing a novel nanoparticle targeting ERK protein in Naegleria fowleri

- Cytotoxic and phytochemical screening of Solanum lycopersicum–Daucus carota hydro-ethanolic extract and in silico evaluation of its lycopene content as anticancer agent

- Protective activities of silver nanoparticles containing Panax japonicus on apoptotic, inflammatory, and oxidative alterations in isoproterenol-induced cardiotoxicity

- pH-based colorimetric detection of monofunctional aldehydes in liquid and gas phases

- Investigating the effect of resveratrol on apoptosis and regulation of gene expression of Caco-2 cells: Unravelling potential implications for colorectal cancer treatment

- Metformin inhibits knee osteoarthritis induced by type 2 diabetes mellitus in rats: S100A8/9 and S100A12 as players and therapeutic targets

- Effect of silver nanoparticles formulated by Silybum marianum on menopausal urinary incontinence in ovariectomized rats

- Synthesis of new analogs of N-substituted(benzoylamino)-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridines

- Response of yield and quality of Japonica rice to different gradients of moisture deficit at grain-filling stage in cold regions

- Preparation of an inclusion complex of nickel-based β-cyclodextrin: Characterization and accelerating the osteoarthritis articular cartilage repair

- Empagliflozin-loaded nanomicelles responsive to reactive oxygen species for renal ischemia/reperfusion injury protection

- Preparation and pharmacodynamic evaluation of sodium aescinate solid lipid nanoparticles

- Assessment of potentially toxic elements and health risks of agricultural soil in Southwest Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- Theoretical investigation of hydrogen-rich fuel production through ammonia decomposition

- Biosynthesis and screening of cobalt nanoparticles using citrus species for antimicrobial activity

- Investigating the interplay of genetic variations, MCP-1 polymorphism, and docking with phytochemical inhibitors for combatting dengue virus pathogenicity through in silico analysis

- Ultrasound induced biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles embedded into chitosan polymers: Investigation of its anti-cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma effects

- Copper oxide nanoparticles-mediated Heliotropium bacciferum leaf extract: Antifungal activity and molecular docking assays against strawberry pathogens

- Sprouted wheat flour for improving physical, chemical, rheological, microbial load, and quality properties of fino bread

- Comparative toxicity assessment of fisetin-aided artificial intelligence-assisted drug design targeting epibulbar dermoid through phytochemicals

- Acute toxicity and anti-inflammatory activity of bis-thiourea derivatives

- Anti-diabetic activity-guided isolation of α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory terpenes from Capsella bursa-pastoris Linn.

- GC–MS analysis of Lactobacillus plantarum YW11 metabolites and its computational analysis on familial pulmonary fibrosis hub genes

- Green formulation of copper nanoparticles by Pistacia khinjuk leaf aqueous extract: Introducing a novel chemotherapeutic drug for the treatment of prostate cancer

- Improved photocatalytic properties of WO3 nanoparticles for Malachite green dye degradation under visible light irradiation: An effect of La doping

- One-pot synthesis of a network of Mn2O3–MnO2–poly(m-methylaniline) composite nanorods on a polypyrrole film presents a promising and efficient optoelectronic and solar cell device

- Groundwater quality and health risk assessment of nitrate and fluoride in Al Qaseem area, Saudi Arabia

- A comparative study of the antifungal efficacy and phytochemical composition of date palm leaflet extracts

- Processing of alcohol pomelo beverage (Citrus grandis (L.) Osbeck) using saccharomyces yeast: Optimization, physicochemical quality, and sensory characteristics

- Specialized compounds of four Cameroonian spices: Isolation, characterization, and in silico evaluation as prospective SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors

- Identification of a novel drug target in Porphyromonas gingivalis by a computational genome analysis approach

- Physico-chemical properties and durability of a fly-ash-based geopolymer

- FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 inhibitory potentials of some phytochemicals from anti-leukemic plants using computational chemical methodologies

- Wild Thymus zygis L. ssp. gracilis and Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh.: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antibacterial activities of essential oils

- 3D-QSAR, molecular docking, ADMET, simulation dynamic, and retrosynthesis studies on new styrylquinolines derivatives against breast cancer

- Deciphering the influenza neuraminidase inhibitory potential of naturally occurring biflavonoids: An in silico approach

- Determination of heavy elements in agricultural regions, Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis and characterization of antioxidant-enriched Moringa oil-based edible oleogel

- Ameliorative effects of thistle and thyme honeys on cyclophosphamide-induced toxicity in mice

- Study of phytochemical compound and antipyretic activity of Chenopodium ambrosioides L. fractions

- Investigating the adsorption mechanism of zinc chloride-modified porous carbon for sulfadiazine removal from water

- Performance repair of building materials using alumina and silica composite nanomaterials with electrodynamic properties

- Effects of nanoparticles on the activity and resistance genes of anaerobic digestion enzymes in livestock and poultry manure containing the antibiotic tetracycline

- Effect of copper nanoparticles green-synthesized using Ocimum basilicum against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in mice lung infection model

- Cardioprotective effects of nanoparticles green formulated by Spinacia oleracea extract on isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction in mice by the determination of PPAR-γ/NF-κB pathway

- Anti-OTC antibody-conjugated fluorescent magnetic/silica and fluorescent hybrid silica nanoparticles for oxytetracycline detection

- Curcumin conjugated zinc nanoparticles for the treatment of myocardial infarction

- Identification and in silico screening of natural phloroglucinols as potential PI3Kα inhibitors: A computational approach for drug discovery

- Exploring the phytochemical profile and antioxidant evaluation: Molecular docking and ADMET analysis of main compounds from three Solanum species in Saudi Arabia

- Unveiling the molecular composition and biological properties of essential oil derived from the leaves of wild Mentha aquatica L.: A comprehensive in vitro and in silico exploration

- Analysis of bioactive compounds present in Boerhavia elegans seeds by GC-MS

- Homology modeling and molecular docking study of corticotrophin-releasing hormone: An approach to treat stress-related diseases

- LncRNA MIR17HG alleviates heart failure via targeting MIR17HG/miR-153-3p/SIRT1 axis in in vitro model

- Development and validation of a stability indicating UPLC-DAD method coupled with MS-TQD for ramipril and thymoquinone in bioactive SNEDDS with in silico toxicity analysis of ramipril degradation products

- Biosynthesis of Ag/Cu nanocomposite mediated by Curcuma longa: Evaluation of its antibacterial properties against oral pathogens

- Development of AMBER-compliant transferable force field parameters for polytetrafluoroethylene

- Treatment of gestational diabetes by Acroptilon repens leaf aqueous extract green-formulated iron nanoparticles in rats

- Development and characterization of new ecological adsorbents based on cardoon wastes: Application to brilliant green adsorption

- A fast, sensitive, greener, and stability-indicating HPLC method for the standardization and quantitative determination of chlorhexidine acetate in commercial products

- Assessment of Se, As, Cd, Cr, Hg, and Pb content status in Ankang tea plantations of China

- Effect of transition metal chloride (ZnCl2) on low-temperature pyrolysis of high ash bituminous coal

- Evaluating polyphenol and ascorbic acid contents, tannin removal ability, and physical properties during hydrolysis and convective hot-air drying of cashew apple powder

- Development and characterization of functional low-fat frozen dairy dessert enhanced with dried lemongrass powder

- Scrutinizing the effect of additive and synergistic antibiotics against carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Preparation, characterization, and determination of the therapeutic effects of copper nanoparticles green-formulated by Pistacia atlantica in diabetes-induced cardiac dysfunction in rat

- Antioxidant and antidiabetic potentials of methoxy-substituted Schiff bases using in vitro, in vivo, and molecular simulation approaches

- Anti-melanoma cancer activity and chemical profile of the essential oil of Seseli yunnanense Franch

- Molecular docking analysis of subtilisin-like alkaline serine protease (SLASP) and laccase with natural biopolymers

- Overcoming methicillin resistance by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Computational evaluation of napthyridine and oxadiazoles compounds for potential dual inhibition of PBP-2a and FemA proteins

- Exploring novel antitubercular agents: Innovative design of 2,3-diaryl-quinoxalines targeting DprE1 for effective tuberculosis treatment

- Drimia maritima flowers as a source of biologically potent components: Optimization of bioactive compound extractions, isolation, UPLC–ESI–MS/MS, and pharmacological properties

- Estimating molecular properties, drug-likeness, cardiotoxic risk, liability profile, and molecular docking study to characterize binding process of key phyto-compounds against serotonin 5-HT2A receptor

- Fabrication of β-cyclodextrin-based microgels for enhancing solubility of Terbinafine: An in-vitro and in-vivo toxicological evaluation

- Phyto-mediated synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles and their sunlight-driven photocatalytic degradation of cationic and anionic dyes

- Monosodium glutamate induces hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis hyperactivation, glucocorticoid receptors down-regulation, and systemic inflammatory response in young male rats: Impact on miR-155 and miR-218

- Quality control analyses of selected honey samples from Serbia based on their mineral and flavonoid profiles, and the invertase activity

- Eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Phyllanthus niruri leaf extract: Assessment of antimicrobial activity, effectiveness on tropical neglected mosquito vector control, and biocompatibility using a fibroblast cell line model

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles containing Cichorium intybus to treat the sepsis-induced DNA damage in the liver of Wistar albino rats

- Quality changes of durian pulp (Durio ziberhinus Murr.) in cold storage

- Study on recrystallization process of nitroguanidine by directly adding cold water to control temperature

- Determination of heavy metals and health risk assessment in drinking water in Bukayriyah City, Saudi Arabia

- Larvicidal properties of essential oils of three Artemisia species against the chemically insecticide-resistant Nile fever vector Culex pipiens (L.) (Diptera: Culicidae): In vitro and in silico studies

- Design, synthesis, characterization, and theoretical calculations, along with in silico and in vitro antimicrobial proprieties of new isoxazole-amide conjugates

- The impact of drying and extraction methods on total lipid, fatty acid profile, and cytotoxicity of Tenebrio molitor larvae

- A zinc oxide–tin oxide–nerolidol hybrid nanomaterial: Efficacy against esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- Research on technological process for production of muskmelon juice (Cucumis melo L.)

- Physicochemical components, antioxidant activity, and predictive models for quality of soursop tea (Annona muricata L.) during heat pump drying

- Characterization and application of Fe1−xCoxFe2O4 nanoparticles in Direct Red 79 adsorption

- Torilis arvensis ethanolic extract: Phytochemical analysis, antifungal efficacy, and cytotoxicity properties

- Magnetite–poly-1H pyrrole dendritic nanocomposite seeded on poly-1H pyrrole: A promising photocathode for green hydrogen generation from sanitation water without using external sacrificing agent

- HPLC and GC–MS analyses of phytochemical compounds in Haloxylon salicornicum extract: Antibacterial and antifungal activity assessment of phytopathogens

- Efficient and stable to coking catalysts of ethanol steam reforming comprised of Ni + Ru loaded on MgAl2O4 + LnFe0.7Ni0.3O3 (Ln = La, Pr) nanocomposites prepared via cost-effective procedure with Pluronic P123 copolymer

- Nitrogen and boron co-doped carbon dots probe for selectively detecting Hg2+ in water samples and the detection mechanism

- Heavy metals in road dust from typical old industrial areas of Wuhan: Seasonal distribution and bioaccessibility-based health risk assessment

- Phytochemical profiling and bioactivity evaluation of CBD- and THC-enriched Cannabis sativa extracts: In vitro and in silico investigation of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects

- Investigating dye adsorption: The role of surface-modified montmorillonite nanoclay in kinetics, isotherms, and thermodynamics

- Antimicrobial activity, induction of ROS generation in HepG2 liver cancer cells, and chemical composition of Pterospermum heterophyllum

- Study on the performance of nanoparticle-modified PVDF membrane in delaying membrane aging

- Impact of cholesterol in encapsulated vitamin E acetate within cocoliposomes

- Review Articles

- Structural aspects of Pt(η3-X1N1X2)(PL) (X1,2 = O, C, or Se) and Pt(η3-N1N2X1)(PL) (X1 = C, S, or Se) derivatives

- Biosurfactants in biocorrosion and corrosion mitigation of metals: An overview

- Stimulus-responsive MOF–hydrogel composites: Classification, preparation, characterization, and their advancement in medical treatments

- Electrochemical dissolution of titanium under alternating current polarization to obtain its dioxide

- Special Issue on Recent Trends in Green Chemistry

- Phytochemical screening and antioxidant activity of Vitex agnus-castus L.

- Phytochemical study, antioxidant activity, and dermoprotective activity of Chenopodium ambrosioides (L.)

- Exploitation of mangliculous marine fungi, Amarenographium solium, for the green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their activity against multiple drug-resistant bacteria

- Study of the phytotoxicity of margines on Pistia stratiotes L.

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Energy, Environmental and Biological Applications - Part III

- Impact of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles on growth, development, and antioxidant system of high protein content crop (Lablab purpureus L.) sweet

- Green synthesis, characterization, and application of iron and molybdenum nanoparticles and their composites for enhancing the growth of Solanum lycopersicum

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Olea europaea L. extracted polysaccharides, characterization, and its assessment as an antimicrobial agent against multiple pathogenic microbes

- Photocatalytic treatment of organic dyes using metal oxides and nanocomposites: A quantitative study

- Antifungal, antioxidant, and photocatalytic activities of greenly synthesized iron oxide nanoparticles

- Special Issue on Phytochemical and Pharmacological Scrutinization of Medicinal Plants

- Hepatoprotective effects of safranal on acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in rats

- Chemical composition and biological properties of Thymus capitatus plants from Algerian high plains: A comparative and analytical study

- Chemical composition and bioactivities of the methanol root extracts of Saussurea costus

- In vivo protective effects of vitamin C against cyto-genotoxicity induced by Dysphania ambrosioides aqueous extract

- Insights about the deleterious impact of a carbamate pesticide on some metabolic immune and antioxidant functions and a focus on the protective ability of a Saharan shrub and its anti-edematous property

- A comprehensive review uncovering the anticancerous potential of genkwanin (plant-derived compound) in several human carcinomas

- A study to investigate the anticancer potential of carvacrol via targeting Notch signaling in breast cancer

- Assessment of anti-diabetic properties of Ziziphus oenopolia (L.) wild edible fruit extract: In vitro and in silico investigations through molecular docking analysis

- Optimization of polyphenol extraction, phenolic profile by LC-ESI-MS/MS, antioxidant, anti-enzymatic, and cytotoxic activities of Physalis acutifolia

- Phytochemical screening, antioxidant properties, and photo-protective activities of Salvia balansae de Noé ex Coss

- Antihyperglycemic, antiglycation, anti-hypercholesteremic, and toxicity evaluation with gas chromatography mass spectrometry profiling for Aloe armatissima leaves

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of gold nanoparticles by using Timur (Zanthoxylum armatum DC) and their effect on wound healing

- Does Erodium trifolium (Cav.) Guitt exhibit medicinal properties? Response elements from phytochemical profiling, enzyme-inhibiting, and antioxidant and antimicrobial activities

- Integrative in silico evaluation of the antiviral potential of terpenoids and its metal complexes derived from Homalomena aromatica based on main protease of SARS-CoV-2

- 6-Methoxyflavone improves anxiety, depression, and memory by increasing monoamines in mice brain: HPLC analysis and in silico studies

- Simultaneous extraction and quantification of hydrophilic and lipophilic antioxidants in Solanum lycopersicum L. varieties marketed in Saudi Arabia

- Biological evaluation of CH3OH and C2H5OH of Berberis vulgaris for in vivo antileishmanial potential against Leishmania tropica in murine models

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Porous silicon nanostructures: Synthesis, characterization, and their antifungal activity

- Biochar from de-oiled Chlorella vulgaris and its adsorption on antibiotics

- Phytochemicals profiling, in vitro and in vivo antidiabetic activity, and in silico studies on Ajuga iva (L.) Schreb.: A comprehensive approach

- Synthesis, characterization, in silico and in vitro studies of novel glycoconjugates as potential antibacterial, antifungal, and antileishmanial agents

- Sonochemical synthesis of gold nanoparticles mediated by potato starch: Its performance in the treatment of esophageal cancer

- Computational study of ADME-Tox prediction of selected phytochemicals from Punica granatum peels

- Phytochemical analysis, in vitro antioxidant and antifungal activities of extracts and essential oil derived from Artemisia herba-alba Asso

- Two triazole-based coordination polymers: Synthesis and crystal structure characterization

- Phytochemical and physicochemical studies of different apple varieties grown in Morocco

- Synthesis of multi-template molecularly imprinted polymers (MT-MIPs) for isolating ethyl para-methoxycinnamate and ethyl cinnamate from Kaempferia galanga L., extract with methacrylic acid as functional monomer

- Nutraceutical potential of Mesembryanthemum forsskaolii Hochst. ex Bioss.: Insights into its nutritional composition, phytochemical contents, and antioxidant activity

- Evaluation of influence of Butea monosperma floral extract on inflammatory biomarkers

- Cannabis sativa L. essential oil: Chemical composition, anti-oxidant, anti-microbial properties, and acute toxicity: In vitro, in vivo, and in silico study

- The effect of gamma radiation on 5-hydroxymethylfurfural conversion in water and dimethyl sulfoxide

- Hollow mushroom nanomaterials for potentiometric sensing of Pb2+ ions in water via the intercalation of iodide ions into the polypyrrole matrix

- Determination of essential oil and chemical composition of St. John’s Wort

- Computational design and in vitro assay of lantadene-based novel inhibitors of NS3 protease of dengue virus

- Anti-parasitic activity and computational studies on a novel labdane diterpene from the roots of Vachellia nilotica

- Microbial dynamics and dehydrogenase activity in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) rhizospheres: Impacts on growth and soil health across different soil types

- Correlation between in vitro anti-urease activity and in silico molecular modeling approach of novel imidazopyridine–oxadiazole hybrids derivatives

- Spatial mapping of indoor air quality in a light metro system using the geographic information system method

- Iron indices and hemogram in renal anemia and the improvement with Tribulus terrestris green-formulated silver nanoparticles applied on rat model

- Integrated track of nano-informatics coupling with the enrichment concept in developing a novel nanoparticle targeting ERK protein in Naegleria fowleri

- Cytotoxic and phytochemical screening of Solanum lycopersicum–Daucus carota hydro-ethanolic extract and in silico evaluation of its lycopene content as anticancer agent

- Protective activities of silver nanoparticles containing Panax japonicus on apoptotic, inflammatory, and oxidative alterations in isoproterenol-induced cardiotoxicity

- pH-based colorimetric detection of monofunctional aldehydes in liquid and gas phases

- Investigating the effect of resveratrol on apoptosis and regulation of gene expression of Caco-2 cells: Unravelling potential implications for colorectal cancer treatment

- Metformin inhibits knee osteoarthritis induced by type 2 diabetes mellitus in rats: S100A8/9 and S100A12 as players and therapeutic targets

- Effect of silver nanoparticles formulated by Silybum marianum on menopausal urinary incontinence in ovariectomized rats

- Synthesis of new analogs of N-substituted(benzoylamino)-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridines

- Response of yield and quality of Japonica rice to different gradients of moisture deficit at grain-filling stage in cold regions

- Preparation of an inclusion complex of nickel-based β-cyclodextrin: Characterization and accelerating the osteoarthritis articular cartilage repair

- Empagliflozin-loaded nanomicelles responsive to reactive oxygen species for renal ischemia/reperfusion injury protection

- Preparation and pharmacodynamic evaluation of sodium aescinate solid lipid nanoparticles

- Assessment of potentially toxic elements and health risks of agricultural soil in Southwest Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- Theoretical investigation of hydrogen-rich fuel production through ammonia decomposition

- Biosynthesis and screening of cobalt nanoparticles using citrus species for antimicrobial activity

- Investigating the interplay of genetic variations, MCP-1 polymorphism, and docking with phytochemical inhibitors for combatting dengue virus pathogenicity through in silico analysis

- Ultrasound induced biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles embedded into chitosan polymers: Investigation of its anti-cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma effects

- Copper oxide nanoparticles-mediated Heliotropium bacciferum leaf extract: Antifungal activity and molecular docking assays against strawberry pathogens

- Sprouted wheat flour for improving physical, chemical, rheological, microbial load, and quality properties of fino bread

- Comparative toxicity assessment of fisetin-aided artificial intelligence-assisted drug design targeting epibulbar dermoid through phytochemicals

- Acute toxicity and anti-inflammatory activity of bis-thiourea derivatives

- Anti-diabetic activity-guided isolation of α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory terpenes from Capsella bursa-pastoris Linn.

- GC–MS analysis of Lactobacillus plantarum YW11 metabolites and its computational analysis on familial pulmonary fibrosis hub genes

- Green formulation of copper nanoparticles by Pistacia khinjuk leaf aqueous extract: Introducing a novel chemotherapeutic drug for the treatment of prostate cancer

- Improved photocatalytic properties of WO3 nanoparticles for Malachite green dye degradation under visible light irradiation: An effect of La doping

- One-pot synthesis of a network of Mn2O3–MnO2–poly(m-methylaniline) composite nanorods on a polypyrrole film presents a promising and efficient optoelectronic and solar cell device

- Groundwater quality and health risk assessment of nitrate and fluoride in Al Qaseem area, Saudi Arabia

- A comparative study of the antifungal efficacy and phytochemical composition of date palm leaflet extracts

- Processing of alcohol pomelo beverage (Citrus grandis (L.) Osbeck) using saccharomyces yeast: Optimization, physicochemical quality, and sensory characteristics

- Specialized compounds of four Cameroonian spices: Isolation, characterization, and in silico evaluation as prospective SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors

- Identification of a novel drug target in Porphyromonas gingivalis by a computational genome analysis approach

- Physico-chemical properties and durability of a fly-ash-based geopolymer

- FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 inhibitory potentials of some phytochemicals from anti-leukemic plants using computational chemical methodologies

- Wild Thymus zygis L. ssp. gracilis and Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh.: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antibacterial activities of essential oils

- 3D-QSAR, molecular docking, ADMET, simulation dynamic, and retrosynthesis studies on new styrylquinolines derivatives against breast cancer

- Deciphering the influenza neuraminidase inhibitory potential of naturally occurring biflavonoids: An in silico approach

- Determination of heavy elements in agricultural regions, Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis and characterization of antioxidant-enriched Moringa oil-based edible oleogel

- Ameliorative effects of thistle and thyme honeys on cyclophosphamide-induced toxicity in mice

- Study of phytochemical compound and antipyretic activity of Chenopodium ambrosioides L. fractions

- Investigating the adsorption mechanism of zinc chloride-modified porous carbon for sulfadiazine removal from water

- Performance repair of building materials using alumina and silica composite nanomaterials with electrodynamic properties

- Effects of nanoparticles on the activity and resistance genes of anaerobic digestion enzymes in livestock and poultry manure containing the antibiotic tetracycline

- Effect of copper nanoparticles green-synthesized using Ocimum basilicum against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in mice lung infection model

- Cardioprotective effects of nanoparticles green formulated by Spinacia oleracea extract on isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction in mice by the determination of PPAR-γ/NF-κB pathway

- Anti-OTC antibody-conjugated fluorescent magnetic/silica and fluorescent hybrid silica nanoparticles for oxytetracycline detection

- Curcumin conjugated zinc nanoparticles for the treatment of myocardial infarction

- Identification and in silico screening of natural phloroglucinols as potential PI3Kα inhibitors: A computational approach for drug discovery

- Exploring the phytochemical profile and antioxidant evaluation: Molecular docking and ADMET analysis of main compounds from three Solanum species in Saudi Arabia

- Unveiling the molecular composition and biological properties of essential oil derived from the leaves of wild Mentha aquatica L.: A comprehensive in vitro and in silico exploration

- Analysis of bioactive compounds present in Boerhavia elegans seeds by GC-MS

- Homology modeling and molecular docking study of corticotrophin-releasing hormone: An approach to treat stress-related diseases

- LncRNA MIR17HG alleviates heart failure via targeting MIR17HG/miR-153-3p/SIRT1 axis in in vitro model

- Development and validation of a stability indicating UPLC-DAD method coupled with MS-TQD for ramipril and thymoquinone in bioactive SNEDDS with in silico toxicity analysis of ramipril degradation products

- Biosynthesis of Ag/Cu nanocomposite mediated by Curcuma longa: Evaluation of its antibacterial properties against oral pathogens

- Development of AMBER-compliant transferable force field parameters for polytetrafluoroethylene

- Treatment of gestational diabetes by Acroptilon repens leaf aqueous extract green-formulated iron nanoparticles in rats

- Development and characterization of new ecological adsorbents based on cardoon wastes: Application to brilliant green adsorption

- A fast, sensitive, greener, and stability-indicating HPLC method for the standardization and quantitative determination of chlorhexidine acetate in commercial products

- Assessment of Se, As, Cd, Cr, Hg, and Pb content status in Ankang tea plantations of China

- Effect of transition metal chloride (ZnCl2) on low-temperature pyrolysis of high ash bituminous coal

- Evaluating polyphenol and ascorbic acid contents, tannin removal ability, and physical properties during hydrolysis and convective hot-air drying of cashew apple powder

- Development and characterization of functional low-fat frozen dairy dessert enhanced with dried lemongrass powder

- Scrutinizing the effect of additive and synergistic antibiotics against carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Preparation, characterization, and determination of the therapeutic effects of copper nanoparticles green-formulated by Pistacia atlantica in diabetes-induced cardiac dysfunction in rat

- Antioxidant and antidiabetic potentials of methoxy-substituted Schiff bases using in vitro, in vivo, and molecular simulation approaches

- Anti-melanoma cancer activity and chemical profile of the essential oil of Seseli yunnanense Franch

- Molecular docking analysis of subtilisin-like alkaline serine protease (SLASP) and laccase with natural biopolymers

- Overcoming methicillin resistance by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Computational evaluation of napthyridine and oxadiazoles compounds for potential dual inhibition of PBP-2a and FemA proteins

- Exploring novel antitubercular agents: Innovative design of 2,3-diaryl-quinoxalines targeting DprE1 for effective tuberculosis treatment

- Drimia maritima flowers as a source of biologically potent components: Optimization of bioactive compound extractions, isolation, UPLC–ESI–MS/MS, and pharmacological properties

- Estimating molecular properties, drug-likeness, cardiotoxic risk, liability profile, and molecular docking study to characterize binding process of key phyto-compounds against serotonin 5-HT2A receptor

- Fabrication of β-cyclodextrin-based microgels for enhancing solubility of Terbinafine: An in-vitro and in-vivo toxicological evaluation

- Phyto-mediated synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles and their sunlight-driven photocatalytic degradation of cationic and anionic dyes

- Monosodium glutamate induces hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis hyperactivation, glucocorticoid receptors down-regulation, and systemic inflammatory response in young male rats: Impact on miR-155 and miR-218

- Quality control analyses of selected honey samples from Serbia based on their mineral and flavonoid profiles, and the invertase activity

- Eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Phyllanthus niruri leaf extract: Assessment of antimicrobial activity, effectiveness on tropical neglected mosquito vector control, and biocompatibility using a fibroblast cell line model

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles containing Cichorium intybus to treat the sepsis-induced DNA damage in the liver of Wistar albino rats

- Quality changes of durian pulp (Durio ziberhinus Murr.) in cold storage

- Study on recrystallization process of nitroguanidine by directly adding cold water to control temperature

- Determination of heavy metals and health risk assessment in drinking water in Bukayriyah City, Saudi Arabia

- Larvicidal properties of essential oils of three Artemisia species against the chemically insecticide-resistant Nile fever vector Culex pipiens (L.) (Diptera: Culicidae): In vitro and in silico studies

- Design, synthesis, characterization, and theoretical calculations, along with in silico and in vitro antimicrobial proprieties of new isoxazole-amide conjugates

- The impact of drying and extraction methods on total lipid, fatty acid profile, and cytotoxicity of Tenebrio molitor larvae

- A zinc oxide–tin oxide–nerolidol hybrid nanomaterial: Efficacy against esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- Research on technological process for production of muskmelon juice (Cucumis melo L.)

- Physicochemical components, antioxidant activity, and predictive models for quality of soursop tea (Annona muricata L.) during heat pump drying

- Characterization and application of Fe1−xCoxFe2O4 nanoparticles in Direct Red 79 adsorption

- Torilis arvensis ethanolic extract: Phytochemical analysis, antifungal efficacy, and cytotoxicity properties

- Magnetite–poly-1H pyrrole dendritic nanocomposite seeded on poly-1H pyrrole: A promising photocathode for green hydrogen generation from sanitation water without using external sacrificing agent

- HPLC and GC–MS analyses of phytochemical compounds in Haloxylon salicornicum extract: Antibacterial and antifungal activity assessment of phytopathogens

- Efficient and stable to coking catalysts of ethanol steam reforming comprised of Ni + Ru loaded on MgAl2O4 + LnFe0.7Ni0.3O3 (Ln = La, Pr) nanocomposites prepared via cost-effective procedure with Pluronic P123 copolymer

- Nitrogen and boron co-doped carbon dots probe for selectively detecting Hg2+ in water samples and the detection mechanism

- Heavy metals in road dust from typical old industrial areas of Wuhan: Seasonal distribution and bioaccessibility-based health risk assessment

- Phytochemical profiling and bioactivity evaluation of CBD- and THC-enriched Cannabis sativa extracts: In vitro and in silico investigation of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects

- Investigating dye adsorption: The role of surface-modified montmorillonite nanoclay in kinetics, isotherms, and thermodynamics

- Antimicrobial activity, induction of ROS generation in HepG2 liver cancer cells, and chemical composition of Pterospermum heterophyllum

- Study on the performance of nanoparticle-modified PVDF membrane in delaying membrane aging

- Impact of cholesterol in encapsulated vitamin E acetate within cocoliposomes

- Review Articles

- Structural aspects of Pt(η3-X1N1X2)(PL) (X1,2 = O, C, or Se) and Pt(η3-N1N2X1)(PL) (X1 = C, S, or Se) derivatives

- Biosurfactants in biocorrosion and corrosion mitigation of metals: An overview

- Stimulus-responsive MOF–hydrogel composites: Classification, preparation, characterization, and their advancement in medical treatments

- Electrochemical dissolution of titanium under alternating current polarization to obtain its dioxide

- Special Issue on Recent Trends in Green Chemistry

- Phytochemical screening and antioxidant activity of Vitex agnus-castus L.

- Phytochemical study, antioxidant activity, and dermoprotective activity of Chenopodium ambrosioides (L.)

- Exploitation of mangliculous marine fungi, Amarenographium solium, for the green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their activity against multiple drug-resistant bacteria

- Study of the phytotoxicity of margines on Pistia stratiotes L.

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Energy, Environmental and Biological Applications - Part III

- Impact of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles on growth, development, and antioxidant system of high protein content crop (Lablab purpureus L.) sweet

- Green synthesis, characterization, and application of iron and molybdenum nanoparticles and their composites for enhancing the growth of Solanum lycopersicum

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Olea europaea L. extracted polysaccharides, characterization, and its assessment as an antimicrobial agent against multiple pathogenic microbes

- Photocatalytic treatment of organic dyes using metal oxides and nanocomposites: A quantitative study

- Antifungal, antioxidant, and photocatalytic activities of greenly synthesized iron oxide nanoparticles

- Special Issue on Phytochemical and Pharmacological Scrutinization of Medicinal Plants

- Hepatoprotective effects of safranal on acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in rats

- Chemical composition and biological properties of Thymus capitatus plants from Algerian high plains: A comparative and analytical study

- Chemical composition and bioactivities of the methanol root extracts of Saussurea costus

- In vivo protective effects of vitamin C against cyto-genotoxicity induced by Dysphania ambrosioides aqueous extract

- Insights about the deleterious impact of a carbamate pesticide on some metabolic immune and antioxidant functions and a focus on the protective ability of a Saharan shrub and its anti-edematous property

- A comprehensive review uncovering the anticancerous potential of genkwanin (plant-derived compound) in several human carcinomas

- A study to investigate the anticancer potential of carvacrol via targeting Notch signaling in breast cancer

- Assessment of anti-diabetic properties of Ziziphus oenopolia (L.) wild edible fruit extract: In vitro and in silico investigations through molecular docking analysis

- Optimization of polyphenol extraction, phenolic profile by LC-ESI-MS/MS, antioxidant, anti-enzymatic, and cytotoxic activities of Physalis acutifolia

- Phytochemical screening, antioxidant properties, and photo-protective activities of Salvia balansae de Noé ex Coss

- Antihyperglycemic, antiglycation, anti-hypercholesteremic, and toxicity evaluation with gas chromatography mass spectrometry profiling for Aloe armatissima leaves

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of gold nanoparticles by using Timur (Zanthoxylum armatum DC) and their effect on wound healing

- Does Erodium trifolium (Cav.) Guitt exhibit medicinal properties? Response elements from phytochemical profiling, enzyme-inhibiting, and antioxidant and antimicrobial activities

- Integrative in silico evaluation of the antiviral potential of terpenoids and its metal complexes derived from Homalomena aromatica based on main protease of SARS-CoV-2

- 6-Methoxyflavone improves anxiety, depression, and memory by increasing monoamines in mice brain: HPLC analysis and in silico studies

- Simultaneous extraction and quantification of hydrophilic and lipophilic antioxidants in Solanum lycopersicum L. varieties marketed in Saudi Arabia

- Biological evaluation of CH3OH and C2H5OH of Berberis vulgaris for in vivo antileishmanial potential against Leishmania tropica in murine models