Abstract

Renal ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) is one of the main causes of acute kidney injury (AKI). So far, there have been many studies on renal IRI, although an effective treatment method has not been developed. In recent years, growing evidence has shown that small noncoding RNAs play an important regulatory role in renal IRI. This article aims to explore whether microRNA-25-3p (miR-25-3p) plays a role in the molecular mechanism of renal IRI. The results showed that the expression level of miR-25-3p was significantly downregulated in a rat renal IRI model, and this result was confirmed with in vitro experiments. After the hypoxia-reoxygenation treatment, the apoptosis level of NRK-52E cells transfected with miR-25-3p mimics decreased significantly, and this antiapoptotic effect was antagonized by miR-25-3p inhibitors. In addition, we confirmed that DKK3 is a target of miR-25-3p. miR-25-3p exerts its protective effect against apoptosis on NRK-52E cells by inhibiting the expression of DKK3, and downregulating the expression level of miR-25-3p could disrupt this protective effect. In addition, we reconfirmed the role of miR-25-3p in rats. Therefore, we confirmed that miR-25-3p may target DKK3 to reduce renal cell damage caused by hypoxia and that miR-25-3p may be a new potential treatment for renal IRI.

1 Introduction

Ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) is an inevitable injury during kidney transplantation. At present, renal IRI is one of the main causes of acute kidney injury (AKI) and the most important factor of delayed graft function [1]. The frequency of ARF among patients is 2–5% during hospitalization, and acute tubular necrosis (ATN) is the main cause of ARF, accounting for 38% and 76% of cases of ARF in inpatients and ICU patients, respectively [2]. In addition, patients may still develop long-term chronic kidney disease [3]. In recent years, research on renal IRI has gradually increased, and its pathogenesis has gradually been revealed. It is currently believed that the pathogenesis of renal IRI mainly involves intracellular calcium overload, large oxygen-free radical accumulations, and microcirculation disorders [4,5]. In recent years, studies have shown that the loss of renal tubular epithelial cell function induced by apoptosis is crucial in the development of renal IRI. However, renal IRI still lacks effective treatments to prevent or reduce kidney damage.

MicroRNA (miRNA) is a short single-stranded non-coding RNA molecule with a length ranging from 21 to 25 nucleotides. miRNAs can simultaneously bind to the mRNAs of multiple target genes and inhibit posttranscriptional translation, thus playing an important regulatory role in the body [6]. In recent years, an increasing number of studies have shown that miRNAs, as key regulators, play an important role in regulating the cell cycle, proliferation, differentiation, growth, and apoptosis. Moreover, in the field of nephropathy, a large number of studies have shown that miRNAs play an important role in renal fibrosis, renal cell carcinoma, and diabetic nephropathy and have the potential for use in new treatments. For example, miR-21, miR-29, and miR-192, as key regulators, play an important regulatory role in the progression of renal fibrosis [7–9]. Related studies have shown that many miRNAs (such as miR-15a and miR-210) may become new tools for the detection, treatment, and prognosis of renal cancer [10–12]. Moreover, miR-34a-5p, miR-27a, and miR-126 have also been shown to be involved in the development of diabetic nephropathy [13–16]. For renal IRI, miRNA is also a hot spot that many scholars have paid attention to in recent years. miR-25-3p has been proven to exert cardioprotective effects by targeting high-mobility group box 1 in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury [17]. In addition, we found that the expression level of miR-25-3p was significantly downregulated in the rat renal IRI model in previous studies, and this result was also confirmed via in vitro experiments. However, research has not revealed the role that miR-25-3p plays in renal IRI. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the role of miR-25-3p in renal IRI and explore its molecular mechanism.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Animal

Sprague-Dawley rats (4–5 weeks of age) weighing 180–220g were purchased from the Centre of Experimental Animals at Wuhan University Medicine College (Hubei, China). All rats were kept in a standard temperature-controlled room, and a 12 h light-dark cycle was implemented. All rats were provided food and water ad libitum and allowed to adapt to the environment for 1 week. All rats were randomly divided into seven groups as follows: sham operation group, which only received the sham operation treatment; 30 min ischemia/0 h reperfusion group, which only received renal pedicle clamping for 30 min; 30 min ischemia/12 h reperfusion group, which received renal pedicle clamping for 30 min and then restored renal blood flow for 12 h; 30 min ischemia/24 h reperfusion group (IRI group), which received renal pedicle clamping for 30 min and then restored renal blood flow for 24 h; 30 min ischemia/48 h reperfusion group, which received renal pedicle clamping for 30 min and then restored renal blood flow for 48 h; I/R + None group, which was injected with normal saline; and I/R + ad-miR-25-3p NC group, which was transfected with adenovirus carrying control scrambled short hairpin RNA (miR-Con) 3 days before the renal ischemia-reperfusion treatment. The I/R + ad-miR-25-3p group was transfected with adenovirus carrying miR-25-3p (1 × 109 plaque-forming units) by tail vein injection 3 days before renal ischemia-reperfusion treatment (n = 6 in each group).

-

Ethical approval: The research related to animal use has been complied with all the relevant national regulations and institutional policies for the care and use of animals and was approved by the ethics committee of the Nanjing Medical University.

2.2 Renal IRI model

The rats were fasted overnight and anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of 3% sodium pentobarbital (0.1 mL/100 g body weight), and a midline abdominal incision was made. An electric heating pad was used to keep the rat’s body temperature constant, and care was taken to prevent the rat from being burned. The renal pedicle was dissected, and a nontraumatic clamp was used to clamp the renal pedicle for 30 min. Next, the renal pedicle was dissected, and a nontraumatic clamp was used to clamp the renal pedicle for 30 min [18]. Then, the clamp was removed, and the blood supply to the kidneys was restored (0, 12, 24, 48 h). In the sham control group, the rats only received an abdominal incision without clamping the renal pedicle. Finally, all rats were euthanized by decapitation, and their kidney tissues were carefully dissected for subsequent experiments. Each group contains six rats.

2.3 Cell culture and hypoxia-reoxygenation (H/R) treatment

Renal tubular epithelial NRK-52E cells (the number of passages of the cells is between 5 and 10) were cultured in high-glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum penicillin (100 U/mL) and streptomycin (100 U/mL). To simulate a hypoxic environment, the cells were placed in a tri-gas incubator containing 94% N2, 5% CO2, and 1% O2 for 24 h and then transferred to a normal environment (5% CO2, 21% O2, and 74% N2). The cells are then collected for RNA isolation, protein extraction, and many other experiments.

2.4 Cell transfection

The miR-25-3p mimic, miR-25-3p inhibitor, and corresponding negative controls were purchased from RiboBio (Ribo, China). When the degree of cell aggregation reached 60–70%, the mimic, inhibitor, and corresponding negative controls were transfected into NRK-52E cells using Lipofectamine 3000 (Life Technologies, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

2.5 Recombinant adenoviruses

Recombinant adenoviruses for the expression of miR-25-3p or control scrambled short hairpin RNA were generated using the BLOCK-iT adenoviral RNAi expression system (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The virus was purified using an Adeno-XTM Virus Purification Kit (BD Biosciences; Clontech, Mountain View, CA) and then diluted in PBS. The virus solution was injected into mice via the tail vein at 2 × 1012 g/mL. After 3 weeks of observation, the expression level of miR-25-3p was upregulated by about two times by qPCR. After the transfection became stable, a renal ischemia-reperfusion injury model was constructed.

2.6 Haematoxylin–eosin staining

Renal tissue was fixed in 4% phosphate-buffered formalin (pH 7.4) for 24 h, dehydrated, and then embedded in paraffin according to conventional protocols. Then, 3 µm-thick paraffin sections were stained with hematoxylin (0.2%) and eosin (1%). To ensure the objectivity of the observation results, all slices were evaluated by experienced pathologists who were blinded to the experimental groupings.

2.7 Measurement of MDA and SOD in kidney tissue

Tissue samples were first homogenized with an Ultra-Turrax system (T25, IKAH-Labourtechnik, Staufen, Germany) in Tris buffer (pH 7.4) and then centrifuged at 13,000g (Heraeus Biofuge Primo R, Karlsruhe, Germany) at 4°C for 20 min, after which the supernatants were collected. The xanthine oxidase method and TBA (thiobarbituric acid) method were used to detect the SOD and MDA levels, and the corresponding SOD and MDA assay kits were purchased from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Jiangsu, China). The absorbance was detected at 450 or 532 nm using an automatic microplate reader (Multiskan MK3, Thermo Scientific). The SOD levels were expressed as U/mg protein in tissue, and the MDA levels were expressed as nmol/mg protein in the tissue.

2.8 Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8)

NRK-52E cells were cultured in groups according to the experimental plan, and Cell Counting Kit-8 (Dojindo, Beijing, China) was used to detect all cells in the logarithmic growth phase and calculate cell viability. The cell proliferation rate was calculated as follows:

2.9 Flow cytometry analysis

To detect the apoptosis rate, an Annexin V-fluorescein-5-isothiocyanate (Annexin V-FITC) apoptosis detection kit (Sigma. St Louis, MO, USA) was used to analyze phosphatidylserine exposure according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After reaching 80% confluence, the cells from different groups were collected and digested with trypsin without EDTA, washed twice with cold PBS, and resuspended in buffer. Then, the cells were resuspended in 500 µL 1 × binding buffer and incubated with 5 µL Annexin and 5 µL propidium iodide (PI) in the dark at room temperature for approximately 15 min. Finally, flow cytometry (BD FACS Calibur, USA) was performed to detect and quantify the apoptotic cells.

2.10 Western blot analysis

Protein samples were extracted from cultured cells and kidney tissue with protein lysis RIPA buffer (Solarbio, Beijing, China) supplemented with the protease inhibitor phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and phosphatase inhibitor (Solarbio, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After 30 min of lysis on ice, lysates were collected by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C. Protein concentrations were determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen, China). Protein samples in each group (40 µg per lane) were subjected to 10 or 15% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and then transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (PVDF) for 1–2 h at 200 mA according to the molecular weight. The membrane was blocked with TBST containing 5% dried skim milk for 1 h at room temperature and then immunoblotted with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. The primary antibodies used were as follows: Bax (1:2,000, Abcam, ab182733); Bcl-2 (1:2,000, Proteintech, 26593-1-AP); and cleaved caspase-3 (1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology, 9661). Then, the membrane was washed with TBST and incubated with anti-mouse/rabbit secondary antibody (P/N 925-32210, P/N 925-32211, 1:10,000, LI-COR Biosciences) conjugated to IRDye 800CW for approximately 1 h at room temperature. The signal was finally quantified by a western blot detection system (Odyssey Infrared Imaging, LI-COR Biosciences).

2.11 Quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cultured cells and kidney tissue using the mirVana kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) and then reverse-transcribed into cDNA using a Takara RNA PCR kit (Takara Biotechnology, Dalian, China). Real-time PCR was performed with the 7900 HT Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems Life Technologies, Foster City, CA, USA) for 40 cycles with GAPDH as an internal control. The TaqMan miRNA assay kit (Applied Biosystems) was used to detect the relative expression of miR-25-3p. The small nuclear RNA U6 was used as an internal control to normalize the expression of miR-25-3p. Finally, the 2−ΔΔCt values were used to calculate the fold change.

2.12 Luciferase reporter assay

The DKK3 3′UTR carrying a miR-25-3p binding site was constructed by PCR and subsequently cloned into the pMIR-REPORT vector to construct the wild-type DKK3 (DKK3-WT) luciferase reporter construct. Then, the DKK3-WT construct and miR-25-3p mimic or scrambled sequence oligonucleotides were co-transfected into NRK-52E cells using Lipofectamine 3000 (Life Technologies, USA). After 48 h of transfection, luciferase activity was analyzed using a Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). All procedures were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.13 Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining

Kidney tissues were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin solution for 48 h and transferred to 70% ethanol. Tissues were processed and embedded in paraffin. Samples were cut into 5 µm-thick sections, deparaffinized in xylene, and rehydrated using a decreasing ethanol gradient followed by 0.1 M PBS. The tissues were then sequentially blocked with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 15 min and with 5% goat serum in PBS for 30 min at room temperature. The tissue sections were first incubated with the primary antibodies Bax (1:250, Abcam, ab32503) or Bcl-2 (1:70, Abcam, ab194583) in 1% goat serum at 4°C overnight. The slides were then sequentially incubated with a biotinylated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories) for 1 h and with horseradish peroxidase streptavidin (Vector Laboratories, SA-5004) for 30 min at room temperature before being visualized with a DAB kit (Vector Laboratories, SK-4100). Finally, sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and observed by two independent pathologists. The percentage of stained target cells was evaluated in 10 random microscopic fields per tissue section, and their averages were subsequently calculated.

2.14 TUNEL staining

Apoptosis scores of rat kidney tissue in different groups were determined with terminal transferase-medicated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) staining using an In Situ Apoptosis Detection kit (Roche Applied Science, Basel, Switzerland). Apoptotic nuclei were stained brown, and negative nuclei were stained blue. The TUNEL assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cell counting was performed under a light microscope, and the degree of cell apoptosis was expressed as the percentage of positive cells.

2.15 Statistical analysis

The experimental data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). The significance of differences between data was evaluated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with SPSS 19.0 statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), and P < 0.05 was considered significant. All graphs shown in this manuscript were constructed with GraphPad Prism 5.0 software. The experimental data were obtained from three experimental replicates.

3 Results

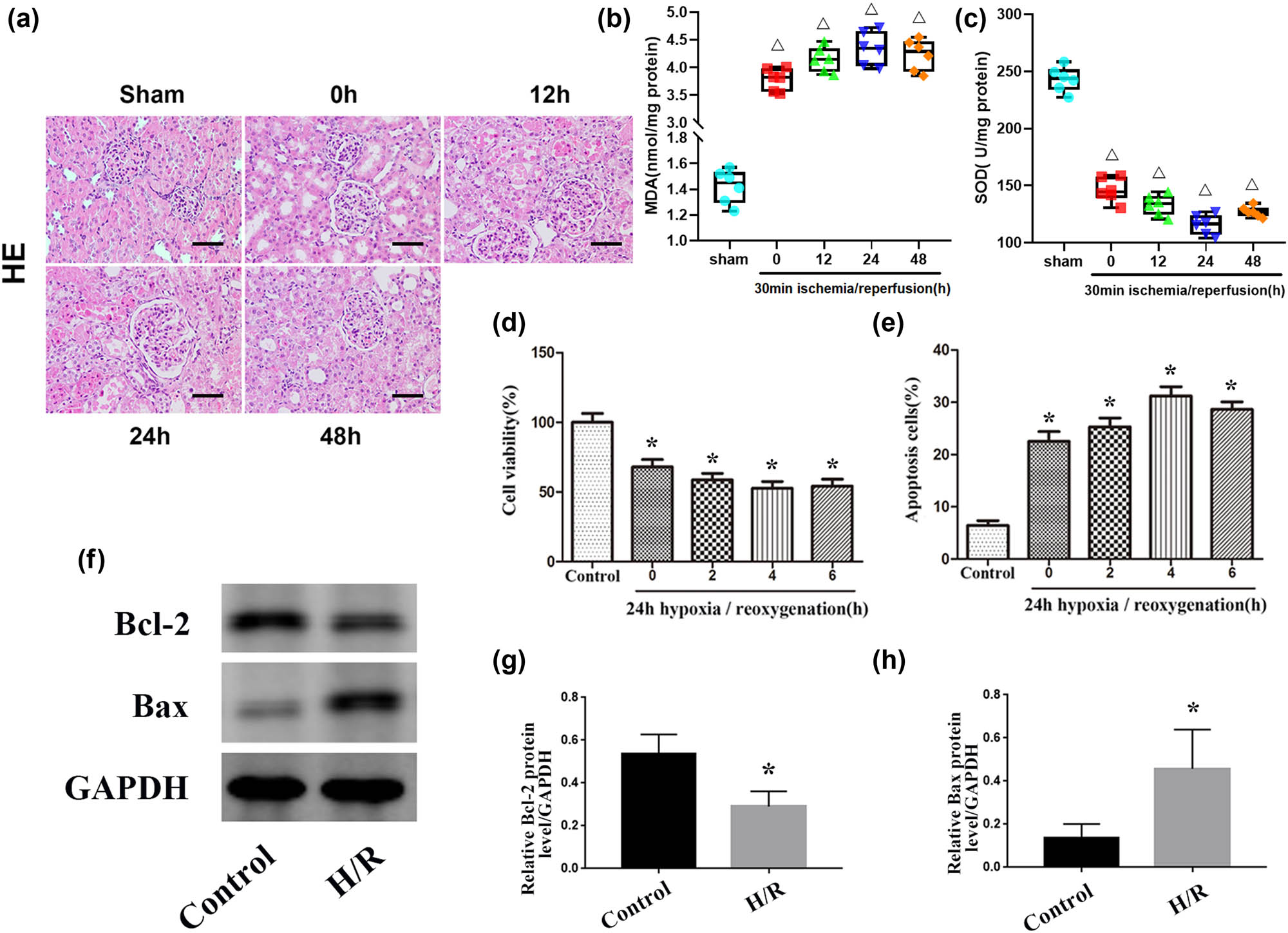

3.1 Renal IRI induces apoptosis

To study the cytopathological changes during renal IRI, Sprague-Dawley rats were selected to establish renal IRI models, and they were divided into an experimental group (IRI group) and a sham operation group (sham group). In the IRI group, after the renal pedicle was clamped for 30 min, the rats were divided into a 0 h group, 12 h group, 24 h group, and 48 h group according to the subsequent recovery time of renal perfusion. In the control group, the rats only underwent the sham operation. The results of HE staining showed that obvious histopathological changes did not occur in the sham group while pathological damage of rats in the renal IRI group manifested mainly as renal tubular cell swelling, extensive tubule dilatation, and degeneration, and the pathological damage was the most serious after renal perfusion was restored for 24 h (Figure 1a). To assess the level of oxidative stress in kidney tissue, we measured the SOD and MDA levels (Figure 1b and c). The results showed that MDA levels were increased and SOD levels were decreased after the renal pedicle was clamped for 30 min, and this change was most obvious after renal perfusion was restored for 24 h. Moreover, NRK-52E cells were cultured in vitro in an anoxic environment for 24 h to simulate ischemia within the tissue and then divided into 0 h, 2 h, 4 h, and 6 h groups according to the time of resuming oxygen supply. Subsequently, CCK-8 experiments and flow cytometry analyses were performed, and the results showed that cell proliferation was inhibited, and apoptosis was significantly increased after culture in an anoxic environment, and this change was most obvious after 4 h of reoxygenation (Figure 1d and e). Western blot analysis showed that the protein expression levels of Bax in the H/R group were significantly higher compared with the control group, while the expression levels of Bcl-2 were significantly decreased in the H/R group (Figure 1f–h). Together, these results indicate that with the increase in oxidative stress levels, cell growth was inhibited, and the degrees of renal injury and cell apoptosis were significantly increased during renal IRI.

IRI induces renal apoptosis. (a) HE staining of kidney tissues from the sham and IRI groups. Scale bar, 50 µm. (b and c): Levels of MDA and SOD in kidney tissue in the sham and IRI groups. (d) Quantitative analysis of cell proliferation levels. (e) Quantitative analysis of the percentage of apoptotic cells by flow cytometry. (f) Expression levels of apoptosis-related proteins (Bax and Bcl-2) in the control and H/R groups. (g and h) Quantitative values of the relative expression levels of the Bax and Bcl-2 proteins in the control and H/R groups. The data are expressed as the mean ± SD. ΔP < 0.05 versus the sham group, *P < 0.05 versus the control group.

3.2 Hypoxia inhibits miR-25-3p expression in NRK-52E cells

To explore the role of microRNAs in renal IRI, we screened several microRNAs that may be related to the renal IRI process, including miR-329, miR-144, miR-25-3p, miR-290, and miR-205, and performed qRT-PCR assays to detect the levels of these five microRNAs in both normal and IRI kidney tissues. The results showed that the expression level of miR-144 in renal IRI was increased compared to the normal level, while the expression level of miR-25-3p was significantly downregulated and the changes in the other three microRNAs were statistically insignificant (Figure 2a). In addition, we verified this result via in vitro experiments. Compared with the control group, the expression level of miR-144 was upregulated in NRK-52E cells subjected to the H/R treatment, while the expression level of miR-25-3p was significantly downregulated (Figure 2b).

The expression level of miR-25-3p is significantly down-regulated in renal IRI and NRK-52E cells that have undergone H/R treatment. (a) Fold changes in the expression levels of miR-329, miR-144, miR-25-3p, miR-290, and miR-205 in the IRI group compared to the sham group. (b) Fold changes in the expression levels of miR-329, miR-144, miR-25-3p, miR-290, and miR-205 in the H/R group compared to the control group. The data are expressed as the mean ± SD. # P < 0.05 versus the sham group, *P < 0.05 versus the control group.

3.3 Role of miR-25-3p in NRK-52E cells during HRI

To further study the specific role of miR-25-3p in the progression of renal IRI, miR-25-3p mimics, inhibitors, or corresponding controls were transfected into NRK-52E cells under hypoxic conditions, and qRT-PCR was used to confirm the transfection efficiency (Figure 3a). The results showed that in cells transfected with the miR-25-3p mimic, miR-25-3p was significantly upregulated, while in cells transfected with the miR-25-3p inhibitor, miR-25-3p was significantly downregulated. In addition, subsequent flow cytometry analysis showed that H/R treatment significantly increased the apoptosis of NRK-52E cells while transfection of the mimic rescued this apoptosis. In contrast, transfection of miR-25-3p inhibitors aggravated hypoxia-induced apoptosis (Figure 3b and c). These results reveal that overexpression of miR-25-3p can protect renal tubular cells and prevent them from undergoing apoptosis during renal IRI. Western blot analysis was used to further explore the role of miR-25-3p at the protein level in renal IRI (Figure 3d). In the cells subjected to the H/R treatment, the apoptosis-related proteins cleaved caspase-3 and Bax were significantly upregulated while Bcl-2 was significantly downregulated. This situation was significantly increased after the inhibitor was transfected. In contrast, in the cells transfected with the mimic, the overexpression of miR-25-3p significantly reduced the expression levels of cleaved caspase-3 and Bax and enhanced the expression levels of Bcl-2 (Figure 3e–g). The above results indicate that miR-25-3p can reduce hypoxia-induced renal injury by inhibiting renal tubular cell apoptosis.

Overexpression of miR-25-3p can inhibit the expression of pro-apoptotic proteins and reduce hypoxia-induced apoptosis of renal tubular cells. (a) Expression of miR-25-3p in normal cells and NRK-52 cells subjected to H/R treatment after transfection with a mimic or inhibitor or corresponding controls. (b) Flow cytometry analysis shows the apoptosis of NRK-52E cells transfected with mimics or inhibitors of corresponding controls. (c) Quantitative analysis of the percentage of apoptosis of NRK-52E cells in each group. (d) Expression levels of apoptosis-related proteins (cleaved caspase-3, Bax, and Bcl-2). (e–g) Quantitative analysis of the relative expression levels of the cleaved caspase-3, Bax, and Bcl-2 proteins. The data are expressed as the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05 versus the control group, ΔP < 0.05 versus the H/R + mimicNC group, # P < 0.05 versus the H/R + antiNC group.

3.4 DKK3 is the direct target of miR-25-3p in NRK-52E cells during HRI

To further explore the possible mechanism of miR-25-3p during HRI, a series of experiments were carried out to explore the pathways downstream of miR-25-3p. Through the online databases, TargetScan and miRDB, DKK3 was predicted to be a potential target gene of miR-25-3p. Bioinformatics methods were used to predict the binding site sequence of miR-25-3p and DKK3 and the mutation sequence of DKK3 (Figure 4a). To verify the relationship between miR-25-3p and DKK3, luciferase reporter gene constructs of mutant DKK3-MUT and wild-type DKK3 (DKK3-WT) carrying the DKK3 3 3′UTR were constructed. After transfecting luciferase reporter gene constructs into HRI-treated NRK-52E cells, the miR-25-3p mimic or mimicNC was transfected into the cells, and then the luciferase activity was measured. Compared with the mimicNC group, the luciferase activity of the miR-25-3p mimic transfection group was significantly decreased (Figure 4b). In addition, after hypoxic injury, the protein expression level of DKK3 in NRK-52E cells was significantly upregulated. After transfection of the mimic, the protein expression level of DKK3 decreased, and this change was reversed after the inhibitor was transfected (Figure 4c and d). The qRT-PCR results confirmed that the mRNA expression trend of DKK3 was consistent with the Western blotting results (Figure 4e). All these results indicate that DKK3 is a direct target of miR-25-3p.

In NRK-52E cells, DKK3 is the direct target of miR-25-3p. (a) The TargetScan gene database predicts that there is a conservative binding site for miR-25-3p in the 3′-UTR of the DKK3 gene. (b) The luciferase reporter construct of wild-type DKK3 (DKK3-WT) or mutant DKK3 (DKK3-MUT) is co-transfected with miR-25-3p mimic or control into NRK-52E cells, and the luciferase activity is measured. (c) DKK3 protein expression level in cells transfected with miR-25-3p mimics or inhibitors. (d) Quantitative analysis of DKK3 protein expression level. (e) DKK3 mRNA expression level in cells transfected with miR-25-3p mimics or inhibitors. The data are expressed as the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05 versus the control group, ΔP < 0.05 versus the H/R + mimicNC group, # P < 0.05 versus the H/R + antiNC group.

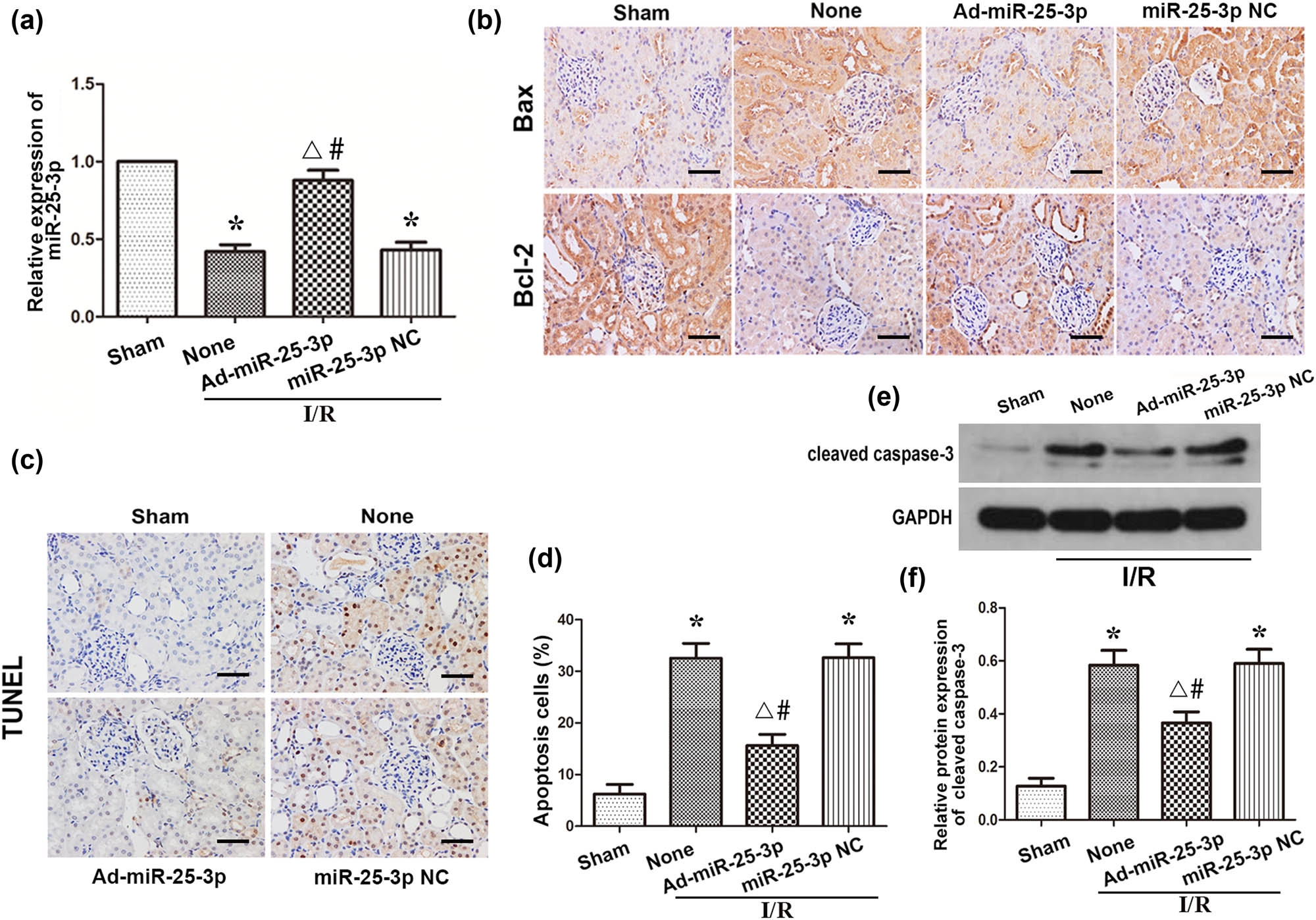

3.5 Role of miR-25-3p in renal IRI

To study the effect of miR-25-3p on hypoxia-induced AKI, we administered ad-miR-25-3p and ad-miR-Con to Sprague-Dawley rats via tail vein injection, and all rats transfected with adenovirus were treated with renal ischemia and reperfusion 3 days later. The kidney tissues of each group were collected for subsequent experiments. qRT-PCR was used to detect the expression level of miR-25-3p in the tissues. The results showed that the expression level of miR-25-3p in the I/R + ad-miR-25-3p group was significantly upregulated compared to the I/R + None group. However, this difference did not exist between the I/R + ad-miR-25-3p group and the I/R + None group (Figure 5a). These results indicated that the in vivo transfection experiment was successful. Compared with the sham group, the percentage of Bax-positive cells was significantly increased in the I/R + None group, while the percentage of cells positively stained for Bcl-2 was downregulated; however, this change was reversed after overexpression of miR-25-3p (Figure 5b). The kidney tissues that had undergone TUNEL staining were observed under a light microscope, and the number of TUNEL-positive cells was counted. The results showed that the number of apoptotic cells in the I/R + None group was significantly increased compared with that in the sham group (Figures 5c and d). Consistent with these results, the Western blot analysis showed that the protein expression levels of cleaved caspase-3 in the I/R + None group were significantly higher than those in the sham group; however, this situation was reversed in the I/R + ad-miR-25-3p group (Figures 5e and f). In summary, the above results all indicate that overexpression of miR-25-3p in animals can reduce the expression level of proapoptotic proteins in the kidney and reduce cell apoptosis during renal IRI.

Overexpression of miR-25-3p in animals can reduce apoptosis during renal IRI. (a) The expression level of miR-25-3p in normal kidney and adenovirus-transfected kidney tissue. (b) Immunohistochemistry analysis of the Bax and Bcl-2 protein expression levels in kidney tissues from each group. The brown cells indicated by the black arrow are positively stained. Scale bar, 50 µm. (c) TUNEL staining of kidney tissues from each group. The brown-black cells indicated by the black arrows are TUNEL positive. Scale bar, 50 µm. (d) Quantitative analysis of the percentage of TUNEL-positive cells in each group. (e) Expression levels of cleaved caspase-3 in each group. (f) Quantitative values of the relative expression levels of cleaved caspase-3 proteins in each group. The data are expressed as the mean ± SD. * P < 0.05 versus the sham group, ΔP < 0.05 versus the I/R + None group, # P < 0.05 versus the I/R + miR-25-3p NC group.

4 Discussion

Renal IRI is common after kidney transplantation, and it severely affects the prognosis of the disease by inducing the loss of renal tubular cell function. Studies have shown that the accumulation of oxygen free radicals and the apoptosis of renal tubular cells caused by inflammation are the main causes of renal IRI [19–21]. In recent years, an increasing number of studies have shown that the Wnt/β-catenin pathway plays an important role in renal cell protection after renal IRI. As a negative regulator of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, DKK3 plays an important regulatory role in many kidney diseases [22–24].

Dickkopf (Dkk) genes are an evolutionarily conserved small gene family consisting of four members (Dkk1-4) and a unique Dkk3-related gene (Dkkl1). The secreted proteins encoded by the Dkk family are glycoproteins and mainly composed of Dkk1-4 [25]. A large number of studies have confirmed that the main role of Dkk genes is to target the Wnt signaling pathway, especially the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, which has long been proven to play an important role in kidney disease [26–28]. Wnt molecules bind to frizzled receptors and coreceptor LDL receptor-related protein (Lrp) 5/6 to transmit signals within the cell. This combination can inhibit the phosphorylation of β-catenin by the destruction complex and the subsequent ubiquitination and degradation of phosphorylated β-catenin and promote the accumulation of nonphosphorylated β-catenin in the cytoplasm. Then, β-catenin is transferred to the nucleus and engages DNA-bound TCF transcription factors to promote the transcription of Wnt target genes. In the process of renal IRI, the Wnt/β-catenin pathway is activated and plays a protective role. It promotes the expression of downstream proteins such as c-myc and cyclin D1 to reduce cell damage and promote cell survival. Studies have confirmed that Wnt agonists improve renal regeneration and kidney function after renal IRI while also reducing inflammation and oxidative stress in the kidney [29]. However, in renal IRI, Dkk3 inhibits Wnt signal transduction by competitively binding with Lrp5/6 and inhibits the protective effect of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway on the kidneys in AKI. After the Wnt/β-catenin pathway is inhibited, the decrease in the level of β-catenin in the cytoplasm can directly induce the increase in renal expression of p53 and Bax and the decrease in Akt phosphorylation and survivin expression, which can lead to renal cell apoptosis and functional impairment. In addition, more studies have shown that the levels of macrophages and various pro-inflammatory cytokines in DKK 3 −/− ApoE −/− mice are significantly lower than those in ApoE −/− mice. This reveals that the knockout of DKK3 can significantly reduce inflammation and reduce cell damage [30]. Research by Li et al. confirmed that overexpression of DKK3 can inhibit cell proliferation, induce cell apoptosis and inhibit collagen synthesis through the TGF-β1/Smad signal axis [31]. Although a large number of studies have revealed that DKK3 plays an important role in a variety of disease processes, and this role is inseparable from the regulation of cell apoptosis, inflammation, and proliferation, studies on the role and mechanism of DKK3 in renal IRI are still few.

miRNAs are important regulators in the body. A large number of studies have shown that they play an important role in many diseases by targeting target genes to regulate cell apoptosis, proliferation, oxidative stress, and the release of inflammatory factors [32–35]. In recent years, an increasing number of studies have shown that miR-25-3p plays an important regulatory role in IRI. Liu et al. confirmed that miR-25 can inhibit cell apoptosis and the release of inflammatory factors by targeting HMGB1 and ultimately play a protective role in myocardial IRI [17]. However, there are few studies on the role and mechanism of miR-25-3p in renal IRI. In this study, by co-transfecting luciferase reporter gene constructs carrying the DKK3 3′UTR with the miR-25-3p mimic, we confirmed that DKK3 is the direct target of miR-25-3p. In in vitro experiments, the expression level of DKK3 in miR-25-3p mimic-transfected cells was significantly downregulated compared with that in the anti-miR-25-3p group. Consistent with the aforementioned results, the same results were obtained in in vivo experiments. All these results indicate that miR-25-3p has a negative regulatory effect on DKK3. Research by Li et al. showed that miR-25-3p can inhibit oxidative stress to play the role of anti-epileptic [36]. In addition, miR-25 has also been confirmed to reduce the activity of nuclear factor-kappaB and the transcriptional activation of TNF-α and IL-6 and inhibit the migration of macrophages [37]. However, this study focused on exploring the regulatory effects of miR-25-3p on cell apoptosis, and its regulatory effects on oxidative stress and inflammation in renal IRI still need to be further explored.

In this study, we first simulated hypoxia and reoxygenation models with different reoxygenation times at the animal and cell levels and selected 24 h of reoxygenation for animals and 4 h of cell reoxygenation for subsequent experiments. Then, we tested the expression level of miR-25-3p during renal IRI. The results showed that miR-25-3p was significantly downregulated in kidney tissues receiving IRI and NRK-52E cells undergoing HRI. Further analysis showed that overexpression of miR-25-3p can significantly reduce the expression of proapoptotic proteins and inhibit hypoxia-induced apoptosis of NRK-52E cells. In contrast, inhibiting the expression of miR-25-3p exacerbates hypoxia-induced apoptosis. Zhang et al. showed that miR-25-3p, as a negative regulator of the Fas/FasL pathway, increased its expression level to inhibit cerebral IRI-induced neuronal apoptosis [38]. The evidence we provide is consistent with Zhang’s discovery that overexpression of miR-25-3p can effectively reduce hypoxia-induced apoptosis. Subsequently, we used adenovirus to regulate the expression level of miR-25-3p in rats. Through many detection methods applied here, we obtained results consistent with in vitro experiments.

However, related experiments are still needed, such as silencing DKK3 at the cellular level to explore whether DKK3 is a key target gene for miR-25-3p to achieve protection, and experiments using DKK3 gene knockout rats are urgently needed. In conclusion, it is reasonable to believe that miR-25-3p protects kidney cells from apoptosis in renal IRI by targeting DKK3.

-

Funding information: This work was supported by Nanjing Medical University. The corresponding author bears the funding for this research.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Raup-Konsavage WM, Wang Y, Wang WW, Feliers D, Ruan H, Reeves WB. Neutrophil peptidyl arginine deiminase-4 has a pivotal role in ischemia/reperfusion-induced acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2018;93(2):365–74.10.1016/j.kint.2017.08.014Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Gill N, Nally Jr JV, Fatica RA. Renal failure secondary to acute tubular necrosis: epidemiology, diagnosis, and management. Chest. 2005;128(4):2847–63.10.1378/chest.128.4.2847Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Liu J, Kumar S, Dolzhenko E, Alvarado GF, Guo J, Lu C, et al. Molecular characterization of the transition from acute to chronic kidney injury following ischemia/reperfusion. JCI Insight. 2017;2(18):e94716.10.1172/jci.insight.94716Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Rovcanin B, Medic B, Kocic G, Cebovic T, Ristic M, Prostran M. Molecular dissection of renal ischemia-reperfusion: oxidative stress and cellular events. Curr Med Chem. 2016;23(19):1965–80.10.2174/0929867323666160112122858Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Bugger H, Pfeil K. Mitochondrial ROS in myocardial ischemia reperfusion and remodeling. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2020;1866(7):165768.10.1016/j.bbadis.2020.165768Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Correia de Sousa M, Gjorgjieva M, Dolicka D, Sobolewski C, Foti M. Deciphering miRNAs’ Action through miRNA Editing. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(24):6249.10.3390/ijms20246249Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Loboda A, Sobczak M, Jozkowicz A, Dulak J. TGF-beta1/Smads and miR-21 in renal fibrosis and inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016:8319283.10.1155/2016/8319283Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Wang H, Wang B, Zhang A, Hassounah F, Seow Y, Wood M, et al. Exosome-mediated miR-29 transfer reduces muscle atrophy and kidney fibrosis in mice. Mol Ther. 2019;27(3):571–83.10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.01.008Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Liu F, Zhang ZP, Xin GD, Guo LH, Jiang Q, Wang ZX. miR-192 prevents renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy by targeting Egr1. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2018;22(13):4252–60.10.1155/2018/4728645Search in Google Scholar

[10] Mytsyk Y, Dosenko V, Skrzypczyk MA, Borys Y, Diychuk Y, Kucher A, et al. Potential clinical applications of microRNAs as biomarkers for renal cell carcinoma. Cent European J Urol. 2018;71(3):295–303.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Oto J, Plana E, Sánchez-González JV, García-Olaverri J, Fernández-Pardo Á, España F, et al. Urinary microRNAs: looking for a new tool in diagnosis, prognosis, and monitoring of renal cancer. Curr Urol Rep. 2020;21(2):11.10.1007/s11934-020-0962-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Ran L, Liang J, Deng X, Wu J. miRNAs in prediction of prognosis in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:4832931.10.1155/2017/4832931Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Li A, Peng R, Sun Y, Liu H, Peng H, Zhang Z. LincRNA 1700020I14Rik alleviates cell proliferation and fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy via miR-34a-5p/Sirt1/HIF-1alpha signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9(5):461.10.1038/s41419-018-0527-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Liu H, Wang X, Wang ZY, Li L. Circ_0080425 inhibits cell proliferation and fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy via sponging miR-24-3p and targeting fibroblast growth factor 11. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235(5):4520–9.10.1002/jcp.29329Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Lou Z, Li Q, Wang C, Li Y. The effects of microRNA-126 reduced inflammation and apoptosis of diabetic nephropathy through PI3K/AKT signalling pathway by VEGF. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2020;45(1):1–10.10.1080/13813455.2020.1767146Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Park S, Moon S, Lee K, Park IB, Lee DH, Nam S. Urinary and blood microRNA-126 and -770 are potential noninvasive biomarker candidates for diabetic nephropathy: a meta-analysis. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;46(4):1331–40.10.1159/000489148Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Liu Q, Song B, Xu M, An Y, Zhao Y, Yue F. MiR-25 exerts cardioprotective effect in a rat model of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by targeting high-mobility group box 1. J Chin Med Assoc. 2020;83(1):25–31.10.1097/JCMA.0000000000000229Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Hesketh EE, Czopek A, Clay M, Borthwick G, Ferenbach D, Kluth D, et al. Renal ischaemia reperfusion injury: a mouse model of injury and regeneration. J Vis Exp. 2014;15(88):e51816.10.3791/51816Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Liu H, Wang L, Weng X, Chen H, Du Y, Diao C, et al. Inhibition of Brd4 alleviates renal ischemia/reperfusion injury-induced apoptosis and endoplasmic reticulum stress by blocking FoxO4-mediated oxidative stress. Redox Biol. 2019;24:101195.10.1016/j.redox.2019.101195Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Chen W, Ruan Y, Zhao S, Ning J, Rao T, Yu W, et al. MicroRNA-205 inhibits the apoptosis of renal tubular epithelial cells via the PTEN/Akt pathway in renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Transl Res. 2019;11(12):7364–75.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Wang L, Vijayan V, Jang MS, Thorenz A, Greite R, Rong S, et al. Labile heme aggravates renal inflammation and complement activation after ischemia reperfusion injury. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2975.10.3389/fimmu.2019.02975Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Federico G, Meister M, Mathow D, Heine GH, Moldenhauer G, Popovic ZV, et al. Tubular Dickkopf-3 promotes the development of renal atrophy and fibrosis. JCI Insight. 2016;1(1):e84916.10.1172/jci.insight.84916Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Schunk SJ, Floege J, Fliser D, Speer T. WNT-beta-catenin signalling - a versatile player in kidney injury and repair. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2021;17(3):172–84.10.1038/s41581-020-00343-wSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Zhang XL, Xu G, Zhou Y, Yan JJ. MicroRNA-183 promotes the proliferation and metastasis of renal cell carcinoma through targeting Dickkopf-related protein 3. Oncol Lett. 2018;15(4):6003–8.10.3892/ol.2018.7998Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Baetta R, Banfi C. Dkk (Dickkopf) proteins. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2019;39(7):1330–42.10.1161/ATVBAHA.119.312612Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Ali RM, Al-Shorbagy MY, Helmy MW, El-Abhar HS. Role of Wnt4/beta-catenin, Ang II/TGFbeta, ACE2, NF-kappaB, and IL-18 in attenuating renal ischemia/reperfusion-induced injury in rats treated with Vit D and pioglitazone. Eur J Pharmacol. 2018;831:68–76.10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.04.032Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Huffstater T, Merryman WD, Gewin LS. Wnt/beta-catenin in acute kidney injury and progression to chronic kidney disease. Semin Nephrol. 2020;40(2):126–37.10.1016/j.semnephrol.2020.01.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Zhu X, Li W, Li H. miR-214 ameliorates acute kidney injury via targeting DKK3 and activating of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Biol Res. 2018;51(1):31.10.1186/s40659-018-0179-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Dong Q, Jie Y, Ma J, Li C, Xin T, Yang D. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway promotes renal ischemia-reperfusion injury through inducing oxidative stress and inflammation response. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2021;41(1):15–8.10.1080/10799893.2020.1783555Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Cheng WL, Yang Y, Zhang XJ, Guo J, Gong J, Gong FH, et al. Dickkopf-3 ablation attenuates the development of atherosclerosis in ApoE-deficient mice. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(2):e004690.10.1161/JAHA.116.004690Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Li Y, Liu H, Liang Y, Peng P, Ma X, Zhang X. DKK3 regulates cell proliferation, apoptosis and collagen synthesis in keloid fibroblasts via TGF-beta1/Smad signaling pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;91:174–80.10.1016/j.biopha.2017.03.044Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Zhang J, Xu Y, Liu H, Pan Z. MicroRNAs in ovarian follicular atresia and granulosa cell apoptosis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2019;17(1):9.10.1186/s12958-018-0450-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Liu J, Jiang J, Hui X, Wang W, Fang D, Ding L. Mir-758-5p suppresses glioblastoma proliferation, migration and invasion by targeting ZBTB20. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;48(5):2074–83.10.1159/000492545Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Ding X, Jian T, Wu Y, Zuo Y, Li J, Lv H, et al. Ellagic acid ameliorates oxidative stress and insulin resistance in high glucose-treated HepG2 cells via miR-223/keap1-Nrf2 pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;110:85–94.10.1016/j.biopha.2018.11.018Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Ban E, Jeong S, Park M, Kwon H, Park J, Song EJ, et al. Accelerated wound healing in diabetic mice by miRNA-497 and its anti-inflammatory activity. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;121:109613.10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109613Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Li R, Wen Y, Wu B, He M, Zhang P, Zhang Q, et al. MicroRNA-25-3p suppresses epileptiform discharges through inhibiting oxidative stress and apoptosis via targeting OXSR1 in neurons. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2020;523(4):859–66.10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.01.050Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Zhu C, Chen T, Liu B. Inhibitory effects of miR-25 targeting HMGB1 on macrophage secretion of inflammatory cytokines in sepsis. Oncol Lett. 2018;16(4):5027–33.10.3892/ol.2018.9308Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Zhang JF, Shi LL, Zhang L, Zhao ZH, Liang F, Xu X, et al. MicroRNA-25 negatively regulates cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury-induced cell apoptosis through Fas/FasL pathway. J Mol Neurosci. 2016;58(4):507–16.10.1007/s12031-016-0712-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2021 Yu Zhang and Xiangrong Zuo, published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Biomedical Sciences

- Research progress on the mechanism of orexin in pain regulation in different brain regions

- Adriamycin-resistant cells are significantly less fit than adriamycin-sensitive cells in cervical cancer

- Exogenous spermidine affects polyamine metabolism in the mouse hypothalamus

- Iris metastasis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma misdiagnosed as primary angle-closure glaucoma: A case report and review of the literature

- LncRNA PVT1 promotes cervical cancer progression by sponging miR-503 to upregulate ARL2 expression

- Two new inflammatory markers related to the CURB-65 score for disease severity in patients with community-acquired pneumonia: The hypersensitive C-reactive protein to albumin ratio and fibrinogen to albumin ratio

- Circ_0091579 enhances the malignancy of hepatocellular carcinoma via miR-1287/PDK2 axis

- Silencing XIST mitigated lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammatory injury in human lung fibroblast WI-38 cells through modulating miR-30b-5p/CCL16 axis and TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway

- Protocatechuic acid attenuates cerebral aneurysm formation and progression by inhibiting TNF-alpha/Nrf-2/NF-kB-mediated inflammatory mechanisms in experimental rats

- ABCB1 polymorphism in clopidogrel-treated Montenegrin patients

- Metabolic profiling of fatty acids in Tripterygium wilfordii multiglucoside- and triptolide-induced liver-injured rats

- miR-338-3p inhibits cell growth, invasion, and EMT process in neuroblastoma through targeting MMP-2

- Verification of neuroprotective effects of alpha-lipoic acid on chronic neuropathic pain in a chronic constriction injury rat model

- Circ_WWC3 overexpression decelerates the progression of osteosarcoma by regulating miR-421/PDE7B axis

- Knockdown of TUG1 rescues cardiomyocyte hypertrophy through targeting the miR-497/MEF2C axis

- MiR-146b-3p protects against AR42J cell injury in cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis model through targeting Anxa2

- miR-299-3p suppresses cell progression and induces apoptosis by downregulating PAX3 in gastric cancer

- Diabetes and COVID-19

- Discovery of novel potential KIT inhibitors for the treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumor

- TEAD4 is a novel independent predictor of prognosis in LGG patients with IDH mutation

- circTLK1 facilitates the proliferation and metastasis of renal cell carcinoma by regulating miR-495-3p/CBL axis

- microRNA-9-5p protects liver sinusoidal endothelial cell against oxygen glucose deprivation/reperfusion injury

- Long noncoding RNA TUG1 regulates degradation of chondrocyte extracellular matrix via miR-320c/MMP-13 axis in osteoarthritis

- Duodenal adenocarcinoma with skin metastasis as initial manifestation: A case report

- Effects of Loofah cylindrica extract on learning and memory ability, brain tissue morphology, and immune function of aging mice

- Recombinant Bacteroides fragilis enterotoxin-1 (rBFT-1) promotes proliferation of colorectal cancer via CCL3-related molecular pathways

- Blocking circ_UBR4 suppressed proliferation, migration, and cell cycle progression of human vascular smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis

- Gene therapy in PIDs, hemoglobin, ocular, neurodegenerative, and hemophilia B disorders

- Downregulation of circ_0037655 impedes glioma formation and metastasis via the regulation of miR-1229-3p/ITGB8 axis

- Vitamin D deficiency and cardiovascular risk in type 2 diabetes population

- Circ_0013359 facilitates the tumorigenicity of melanoma by regulating miR-136-5p/RAB9A axis

- Mechanisms of circular RNA circ_0066147 on pancreatic cancer progression

- lncRNA myocardial infarction-associated transcript (MIAT) knockdown alleviates LPS-induced chondrocytes inflammatory injury via regulating miR-488-3p/sex determining region Y-related HMG-box 11 (SOX11) axis

- Identification of circRNA circ-CSPP1 as a potent driver of colorectal cancer by directly targeting the miR-431/LASP1 axis

- Hyperhomocysteinemia exacerbates ischemia-reperfusion injury-induced acute kidney injury by mediating oxidative stress, DNA damage, JNK pathway, and apoptosis

- Potential prognostic markers and significant lncRNA–mRNA co-expression pairs in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma

- Gamma irradiation-mediated inactivation of enveloped viruses with conservation of genome integrity: Potential application for SARS-CoV-2 inactivated vaccine development

- ADHFE1 is a correlative factor of patient survival in cancer

- The association of transcription factor Prox1 with the proliferation, migration, and invasion of lung cancer

- Is there a relationship between the prevalence of autoimmune thyroid disease and diabetic kidney disease?

- Immunoregulatory function of Dictyophora echinovolvata spore polysaccharides in immunocompromised mice induced by cyclophosphamide

- T cell epitopes of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and conserved surface protein of Plasmodium malariae share sequence homology

- Anti-obesity effect and mechanism of mesenchymal stem cells influence on obese mice

- Long noncoding RNA HULC contributes to paclitaxel resistance in ovarian cancer via miR-137/ITGB8 axis

- Glucocorticoids protect HEI-OC1 cells from tunicamycin-induced cell damage via inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum stress

- Prognostic value of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in acute organophosphorus pesticide poisoning

- Gastroprotective effects of diosgenin against HCl/ethanol-induced gastric mucosal injury through suppression of NF-κβ and myeloperoxidase activities

- Silencing of LINC00707 suppresses cell proliferation, migration, and invasion of osteosarcoma cells by modulating miR-338-3p/AHSA1 axis

- Successful extracorporeal membrane oxygenation resuscitation of patient with cardiogenic shock induced by phaeochromocytoma crisis mimicking hyperthyroidism: A case report

- Effects of miR-185-5p on replication of hepatitis C virus

- Lidocaine has antitumor effect on hepatocellular carcinoma via the circ_DYNC1H1/miR-520a-3p/USP14 axis

- Primary localized cutaneous nodular amyloidosis presenting as lymphatic malformation: A case report

- Multimodal magnetic resonance imaging analysis in the characteristics of Wilson’s disease: A case report and literature review

- Therapeutic potential of anticoagulant therapy in association with cytokine storm inhibition in severe cases of COVID-19: A case report

- Neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy for locally advanced squamous cell lung carcinoma: A case report and literature review

- Rufinamide (RUF) suppresses inflammation and maintains the integrity of the blood–brain barrier during kainic acid-induced brain damage

- Inhibition of ADAM10 ameliorates doxorubicin-induced cardiac remodeling by suppressing N-cadherin cleavage

- Invasive ductal carcinoma and small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic leukemia manifesting as a collision breast tumor: A case report and literature review

- Clonal diversity of the B cell receptor repertoire in patients with coronary in-stent restenosis and type 2 diabetes

- CTLA-4 promotes lymphoma progression through tumor stem cell enrichment and immunosuppression

- WDR74 promotes proliferation and metastasis in colorectal cancer cells through regulating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway

- Down-regulation of IGHG1 enhances Protoporphyrin IX accumulation and inhibits hemin biosynthesis in colorectal cancer by suppressing the MEK-FECH axis

- Curcumin suppresses the progression of gastric cancer by regulating circ_0056618/miR-194-5p axis

- Scutellarin-induced A549 cell apoptosis depends on activation of the transforming growth factor-β1/smad2/ROS/caspase-3 pathway

- lncRNA NEAT1 regulates CYP1A2 and influences steroid-induced necrosis

- A two-microRNA signature predicts the progression of male thyroid cancer

- Isolation of microglia from retinas of chronic ocular hypertensive rats

- Changes of immune cells in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated by radiofrequency ablation and hepatectomy, a pilot study

- Calcineurin Aβ gene knockdown inhibits transient outward potassium current ion channel remodeling in hypertrophic ventricular myocyte

- Aberrant expression of PI3K/AKT signaling is involved in apoptosis resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Clinical significance of activated Wnt/β-catenin signaling in apoptosis inhibition of oral cancer

- circ_CHFR regulates ox-LDL-mediated cell proliferation, apoptosis, and EndoMT by miR-15a-5p/EGFR axis in human brain microvessel endothelial cells

- Resveratrol pretreatment mitigates LPS-induced acute lung injury by regulating conventional dendritic cells’ maturation and function

- Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2T promotes tumor stem cell characteristics and migration of cervical cancer cells by regulating the GRP78/FAK pathway

- Carriage of HLA-DRB1*11 and 1*12 alleles and risk factors in patients with breast cancer in Burkina Faso

- Protective effect of Lactobacillus-containing probiotics on intestinal mucosa of rats experiencing traumatic hemorrhagic shock

- Glucocorticoids induce osteonecrosis of the femoral head through the Hippo signaling pathway

- Endothelial cell-derived SSAO can increase MLC20 phosphorylation in VSMCs

- Downregulation of STOX1 is a novel prognostic biomarker for glioma patients

- miR-378a-3p regulates glioma cell chemosensitivity to cisplatin through IGF1R

- The molecular mechanisms underlying arecoline-induced cardiac fibrosis in rats

- TGF-β1-overexpressing mesenchymal stem cells reciprocally regulate Th17/Treg cells by regulating the expression of IFN-γ

- The influence of MTHFR genetic polymorphisms on methotrexate therapy in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- Red blood cell distribution width-standard deviation but not red blood cell distribution width-coefficient of variation as a potential index for the diagnosis of iron-deficiency anemia in mid-pregnancy women

- Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma expressing alpha fetoprotein in the endometrium

- Superoxide dismutase and the sigma1 receptor as key elements of the antioxidant system in human gastrointestinal tract cancers

- Molecular characterization and phylogenetic studies of Echinococcus granulosus and Taenia multiceps coenurus cysts in slaughtered sheep in Saudi Arabia

- ITGB5 mutation discovered in a Chinese family with blepharophimosis-ptosis-epicanthus inversus syndrome

- ACTB and GAPDH appear at multiple SDS-PAGE positions, thus not suitable as reference genes for determining protein loading in techniques like Western blotting

- Facilitation of mouse skin-derived precursor growth and yield by optimizing plating density

- 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylethanol ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced septic cardiac injury in a murine model

- Downregulation of PITX2 inhibits the proliferation and migration of liver cancer cells and induces cell apoptosis

- Expression of CDK9 in endometrial cancer tissues and its effect on the proliferation of HEC-1B

- Novel predictor of the occurrence of DKA in T1DM patients without infection: A combination of neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio and white blood cells

- Investigation of molecular regulation mechanism under the pathophysiology of subarachnoid hemorrhage

- miR-25-3p protects renal tubular epithelial cells from apoptosis induced by renal IRI by targeting DKK3

- Bioengineering and Biotechnology

- Green fabrication of Co and Co3O4 nanoparticles and their biomedical applications: A review

- Agriculture

- Effects of inorganic and organic selenium sources on the growth performance of broilers in China: A meta-analysis

- Crop-livestock integration practices, knowledge, and attitudes among smallholder farmers: Hedging against climate change-induced shocks in semi-arid Zimbabwe

- Food Science and Nutrition

- Effect of food processing on the antioxidant activity of flavones from Polygonatum odoratum (Mill.) Druce

- Vitamin D and iodine status was associated with the risk and complication of type 2 diabetes mellitus in China

- Diversity of microbiota in Slovak summer ewes’ cheese “Bryndza”

- Comparison between voltammetric detection methods for abalone-flavoring liquid

- Composition of low-molecular-weight glutenin subunits in common wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and their effects on the rheological properties of dough

- Application of culture, PCR, and PacBio sequencing for determination of microbial composition of milk from subclinical mastitis dairy cows of smallholder farms

- Investigating microplastics and potentially toxic elements contamination in canned Tuna, Salmon, and Sardine fishes from Taif markets, KSA

- From bench to bar side: Evaluating the red wine storage lesion

- Establishment of an iodine model for prevention of iodine-excess-induced thyroid dysfunction in pregnant women

- Plant Sciences

- Characterization of GMPP from Dendrobium huoshanense yielding GDP-D-mannose

- Comparative analysis of the SPL gene family in five Rosaceae species: Fragaria vesca, Malus domestica, Prunus persica, Rubus occidentalis, and Pyrus pyrifolia

- Identification of leaf rust resistance genes Lr34 and Lr46 in common wheat (Triticum aestivum L. ssp. aestivum) lines of different origin using multiplex PCR

- Investigation of bioactivities of Taxus chinensis, Taxus cuspidata, and Taxus × media by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- Morphological structures and histochemistry of roots and shoots in Myricaria laxiflora (Tamaricaceae)

- Transcriptome analysis of resistance mechanism to potato wart disease

- In silico analysis of glycosyltransferase 2 family genes in duckweed (Spirodela polyrhiza) and its role in salt stress tolerance

- Comparative study on growth traits and ions regulation of zoysiagrasses under varied salinity treatments

- Role of MS1 homolog Ntms1 gene of tobacco infertility

- Biological characteristics and fungicide sensitivity of Pyricularia variabilis

- In silico/computational analysis of mevalonate pyrophosphate decarboxylase gene families in Campanulids

- Identification of novel drought-responsive miRNA regulatory network of drought stress response in common vetch (Vicia sativa)

- How photoautotrophy, photomixotrophy, and ventilation affect the stomata and fluorescence emission of pistachios rootstock?

- Apoplastic histochemical features of plant root walls that may facilitate ion uptake and retention

- Ecology and Environmental Sciences

- The impact of sewage sludge on the fungal communities in the rhizosphere and roots of barley and on barley yield

- Domestication of wild animals may provide a springboard for rapid variation of coronavirus

- Response of benthic invertebrate assemblages to seasonal and habitat condition in the Wewe River, Ashanti region (Ghana)

- Molecular record for the first authentication of Isaria cicadae from Vietnam

- Twig biomass allocation of Betula platyphylla in different habitats in Wudalianchi Volcano, northeast China

- Animal Sciences

- Supplementation of probiotics in water beneficial growth performance, carcass traits, immune function, and antioxidant capacity in broiler chickens

- Predators of the giant pine scale, Marchalina hellenica (Gennadius 1883; Hemiptera: Marchalinidae), out of its natural range in Turkey

- Honey in wound healing: An updated review

- NONMMUT140591.1 may serve as a ceRNA to regulate Gata5 in UT-B knockout-induced cardiac conduction block

- Radiotherapy for the treatment of pulmonary hydatidosis in sheep

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Long non-coding RNA TUG1 knockdown hinders the tumorigenesis of multiple myeloma by regulating microRNA-34a-5p/NOTCH1 signaling pathway”

- Special Issue on Reuse of Agro-Industrial By-Products

- An effect of positional isomerism of benzoic acid derivatives on antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli

- Special Issue on Computing and Artificial Techniques for Life Science Applications - Part II

- Relationship of Gensini score with retinal vessel diameter and arteriovenous ratio in senile CHD

- Effects of different enantiomers of amlodipine on lipid profiles and vasomotor factors in atherosclerotic rabbits

- Establishment of the New Zealand white rabbit animal model of fatty keratopathy associated with corneal neovascularization

- lncRNA MALAT1/miR-143 axis is a potential biomarker for in-stent restenosis and is involved in the multiplication of vascular smooth muscle cells

Articles in the same Issue

- Biomedical Sciences

- Research progress on the mechanism of orexin in pain regulation in different brain regions

- Adriamycin-resistant cells are significantly less fit than adriamycin-sensitive cells in cervical cancer

- Exogenous spermidine affects polyamine metabolism in the mouse hypothalamus

- Iris metastasis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma misdiagnosed as primary angle-closure glaucoma: A case report and review of the literature

- LncRNA PVT1 promotes cervical cancer progression by sponging miR-503 to upregulate ARL2 expression

- Two new inflammatory markers related to the CURB-65 score for disease severity in patients with community-acquired pneumonia: The hypersensitive C-reactive protein to albumin ratio and fibrinogen to albumin ratio

- Circ_0091579 enhances the malignancy of hepatocellular carcinoma via miR-1287/PDK2 axis

- Silencing XIST mitigated lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammatory injury in human lung fibroblast WI-38 cells through modulating miR-30b-5p/CCL16 axis and TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway

- Protocatechuic acid attenuates cerebral aneurysm formation and progression by inhibiting TNF-alpha/Nrf-2/NF-kB-mediated inflammatory mechanisms in experimental rats

- ABCB1 polymorphism in clopidogrel-treated Montenegrin patients

- Metabolic profiling of fatty acids in Tripterygium wilfordii multiglucoside- and triptolide-induced liver-injured rats

- miR-338-3p inhibits cell growth, invasion, and EMT process in neuroblastoma through targeting MMP-2

- Verification of neuroprotective effects of alpha-lipoic acid on chronic neuropathic pain in a chronic constriction injury rat model

- Circ_WWC3 overexpression decelerates the progression of osteosarcoma by regulating miR-421/PDE7B axis

- Knockdown of TUG1 rescues cardiomyocyte hypertrophy through targeting the miR-497/MEF2C axis

- MiR-146b-3p protects against AR42J cell injury in cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis model through targeting Anxa2

- miR-299-3p suppresses cell progression and induces apoptosis by downregulating PAX3 in gastric cancer

- Diabetes and COVID-19

- Discovery of novel potential KIT inhibitors for the treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumor

- TEAD4 is a novel independent predictor of prognosis in LGG patients with IDH mutation

- circTLK1 facilitates the proliferation and metastasis of renal cell carcinoma by regulating miR-495-3p/CBL axis

- microRNA-9-5p protects liver sinusoidal endothelial cell against oxygen glucose deprivation/reperfusion injury

- Long noncoding RNA TUG1 regulates degradation of chondrocyte extracellular matrix via miR-320c/MMP-13 axis in osteoarthritis

- Duodenal adenocarcinoma with skin metastasis as initial manifestation: A case report

- Effects of Loofah cylindrica extract on learning and memory ability, brain tissue morphology, and immune function of aging mice

- Recombinant Bacteroides fragilis enterotoxin-1 (rBFT-1) promotes proliferation of colorectal cancer via CCL3-related molecular pathways

- Blocking circ_UBR4 suppressed proliferation, migration, and cell cycle progression of human vascular smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis

- Gene therapy in PIDs, hemoglobin, ocular, neurodegenerative, and hemophilia B disorders

- Downregulation of circ_0037655 impedes glioma formation and metastasis via the regulation of miR-1229-3p/ITGB8 axis

- Vitamin D deficiency and cardiovascular risk in type 2 diabetes population

- Circ_0013359 facilitates the tumorigenicity of melanoma by regulating miR-136-5p/RAB9A axis

- Mechanisms of circular RNA circ_0066147 on pancreatic cancer progression

- lncRNA myocardial infarction-associated transcript (MIAT) knockdown alleviates LPS-induced chondrocytes inflammatory injury via regulating miR-488-3p/sex determining region Y-related HMG-box 11 (SOX11) axis

- Identification of circRNA circ-CSPP1 as a potent driver of colorectal cancer by directly targeting the miR-431/LASP1 axis

- Hyperhomocysteinemia exacerbates ischemia-reperfusion injury-induced acute kidney injury by mediating oxidative stress, DNA damage, JNK pathway, and apoptosis

- Potential prognostic markers and significant lncRNA–mRNA co-expression pairs in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma

- Gamma irradiation-mediated inactivation of enveloped viruses with conservation of genome integrity: Potential application for SARS-CoV-2 inactivated vaccine development

- ADHFE1 is a correlative factor of patient survival in cancer

- The association of transcription factor Prox1 with the proliferation, migration, and invasion of lung cancer

- Is there a relationship between the prevalence of autoimmune thyroid disease and diabetic kidney disease?

- Immunoregulatory function of Dictyophora echinovolvata spore polysaccharides in immunocompromised mice induced by cyclophosphamide

- T cell epitopes of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and conserved surface protein of Plasmodium malariae share sequence homology

- Anti-obesity effect and mechanism of mesenchymal stem cells influence on obese mice

- Long noncoding RNA HULC contributes to paclitaxel resistance in ovarian cancer via miR-137/ITGB8 axis

- Glucocorticoids protect HEI-OC1 cells from tunicamycin-induced cell damage via inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum stress

- Prognostic value of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in acute organophosphorus pesticide poisoning

- Gastroprotective effects of diosgenin against HCl/ethanol-induced gastric mucosal injury through suppression of NF-κβ and myeloperoxidase activities

- Silencing of LINC00707 suppresses cell proliferation, migration, and invasion of osteosarcoma cells by modulating miR-338-3p/AHSA1 axis

- Successful extracorporeal membrane oxygenation resuscitation of patient with cardiogenic shock induced by phaeochromocytoma crisis mimicking hyperthyroidism: A case report

- Effects of miR-185-5p on replication of hepatitis C virus

- Lidocaine has antitumor effect on hepatocellular carcinoma via the circ_DYNC1H1/miR-520a-3p/USP14 axis

- Primary localized cutaneous nodular amyloidosis presenting as lymphatic malformation: A case report

- Multimodal magnetic resonance imaging analysis in the characteristics of Wilson’s disease: A case report and literature review

- Therapeutic potential of anticoagulant therapy in association with cytokine storm inhibition in severe cases of COVID-19: A case report

- Neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy for locally advanced squamous cell lung carcinoma: A case report and literature review

- Rufinamide (RUF) suppresses inflammation and maintains the integrity of the blood–brain barrier during kainic acid-induced brain damage

- Inhibition of ADAM10 ameliorates doxorubicin-induced cardiac remodeling by suppressing N-cadherin cleavage

- Invasive ductal carcinoma and small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic leukemia manifesting as a collision breast tumor: A case report and literature review

- Clonal diversity of the B cell receptor repertoire in patients with coronary in-stent restenosis and type 2 diabetes

- CTLA-4 promotes lymphoma progression through tumor stem cell enrichment and immunosuppression

- WDR74 promotes proliferation and metastasis in colorectal cancer cells through regulating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway

- Down-regulation of IGHG1 enhances Protoporphyrin IX accumulation and inhibits hemin biosynthesis in colorectal cancer by suppressing the MEK-FECH axis

- Curcumin suppresses the progression of gastric cancer by regulating circ_0056618/miR-194-5p axis

- Scutellarin-induced A549 cell apoptosis depends on activation of the transforming growth factor-β1/smad2/ROS/caspase-3 pathway

- lncRNA NEAT1 regulates CYP1A2 and influences steroid-induced necrosis

- A two-microRNA signature predicts the progression of male thyroid cancer

- Isolation of microglia from retinas of chronic ocular hypertensive rats

- Changes of immune cells in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated by radiofrequency ablation and hepatectomy, a pilot study

- Calcineurin Aβ gene knockdown inhibits transient outward potassium current ion channel remodeling in hypertrophic ventricular myocyte

- Aberrant expression of PI3K/AKT signaling is involved in apoptosis resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Clinical significance of activated Wnt/β-catenin signaling in apoptosis inhibition of oral cancer

- circ_CHFR regulates ox-LDL-mediated cell proliferation, apoptosis, and EndoMT by miR-15a-5p/EGFR axis in human brain microvessel endothelial cells

- Resveratrol pretreatment mitigates LPS-induced acute lung injury by regulating conventional dendritic cells’ maturation and function

- Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2T promotes tumor stem cell characteristics and migration of cervical cancer cells by regulating the GRP78/FAK pathway

- Carriage of HLA-DRB1*11 and 1*12 alleles and risk factors in patients with breast cancer in Burkina Faso

- Protective effect of Lactobacillus-containing probiotics on intestinal mucosa of rats experiencing traumatic hemorrhagic shock

- Glucocorticoids induce osteonecrosis of the femoral head through the Hippo signaling pathway

- Endothelial cell-derived SSAO can increase MLC20 phosphorylation in VSMCs

- Downregulation of STOX1 is a novel prognostic biomarker for glioma patients

- miR-378a-3p regulates glioma cell chemosensitivity to cisplatin through IGF1R

- The molecular mechanisms underlying arecoline-induced cardiac fibrosis in rats

- TGF-β1-overexpressing mesenchymal stem cells reciprocally regulate Th17/Treg cells by regulating the expression of IFN-γ

- The influence of MTHFR genetic polymorphisms on methotrexate therapy in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- Red blood cell distribution width-standard deviation but not red blood cell distribution width-coefficient of variation as a potential index for the diagnosis of iron-deficiency anemia in mid-pregnancy women

- Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma expressing alpha fetoprotein in the endometrium

- Superoxide dismutase and the sigma1 receptor as key elements of the antioxidant system in human gastrointestinal tract cancers

- Molecular characterization and phylogenetic studies of Echinococcus granulosus and Taenia multiceps coenurus cysts in slaughtered sheep in Saudi Arabia

- ITGB5 mutation discovered in a Chinese family with blepharophimosis-ptosis-epicanthus inversus syndrome

- ACTB and GAPDH appear at multiple SDS-PAGE positions, thus not suitable as reference genes for determining protein loading in techniques like Western blotting

- Facilitation of mouse skin-derived precursor growth and yield by optimizing plating density

- 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylethanol ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced septic cardiac injury in a murine model

- Downregulation of PITX2 inhibits the proliferation and migration of liver cancer cells and induces cell apoptosis

- Expression of CDK9 in endometrial cancer tissues and its effect on the proliferation of HEC-1B

- Novel predictor of the occurrence of DKA in T1DM patients without infection: A combination of neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio and white blood cells

- Investigation of molecular regulation mechanism under the pathophysiology of subarachnoid hemorrhage

- miR-25-3p protects renal tubular epithelial cells from apoptosis induced by renal IRI by targeting DKK3

- Bioengineering and Biotechnology

- Green fabrication of Co and Co3O4 nanoparticles and their biomedical applications: A review

- Agriculture

- Effects of inorganic and organic selenium sources on the growth performance of broilers in China: A meta-analysis

- Crop-livestock integration practices, knowledge, and attitudes among smallholder farmers: Hedging against climate change-induced shocks in semi-arid Zimbabwe

- Food Science and Nutrition

- Effect of food processing on the antioxidant activity of flavones from Polygonatum odoratum (Mill.) Druce

- Vitamin D and iodine status was associated with the risk and complication of type 2 diabetes mellitus in China

- Diversity of microbiota in Slovak summer ewes’ cheese “Bryndza”

- Comparison between voltammetric detection methods for abalone-flavoring liquid

- Composition of low-molecular-weight glutenin subunits in common wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and their effects on the rheological properties of dough

- Application of culture, PCR, and PacBio sequencing for determination of microbial composition of milk from subclinical mastitis dairy cows of smallholder farms

- Investigating microplastics and potentially toxic elements contamination in canned Tuna, Salmon, and Sardine fishes from Taif markets, KSA

- From bench to bar side: Evaluating the red wine storage lesion

- Establishment of an iodine model for prevention of iodine-excess-induced thyroid dysfunction in pregnant women

- Plant Sciences

- Characterization of GMPP from Dendrobium huoshanense yielding GDP-D-mannose

- Comparative analysis of the SPL gene family in five Rosaceae species: Fragaria vesca, Malus domestica, Prunus persica, Rubus occidentalis, and Pyrus pyrifolia

- Identification of leaf rust resistance genes Lr34 and Lr46 in common wheat (Triticum aestivum L. ssp. aestivum) lines of different origin using multiplex PCR

- Investigation of bioactivities of Taxus chinensis, Taxus cuspidata, and Taxus × media by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- Morphological structures and histochemistry of roots and shoots in Myricaria laxiflora (Tamaricaceae)

- Transcriptome analysis of resistance mechanism to potato wart disease

- In silico analysis of glycosyltransferase 2 family genes in duckweed (Spirodela polyrhiza) and its role in salt stress tolerance

- Comparative study on growth traits and ions regulation of zoysiagrasses under varied salinity treatments

- Role of MS1 homolog Ntms1 gene of tobacco infertility

- Biological characteristics and fungicide sensitivity of Pyricularia variabilis

- In silico/computational analysis of mevalonate pyrophosphate decarboxylase gene families in Campanulids

- Identification of novel drought-responsive miRNA regulatory network of drought stress response in common vetch (Vicia sativa)

- How photoautotrophy, photomixotrophy, and ventilation affect the stomata and fluorescence emission of pistachios rootstock?

- Apoplastic histochemical features of plant root walls that may facilitate ion uptake and retention

- Ecology and Environmental Sciences

- The impact of sewage sludge on the fungal communities in the rhizosphere and roots of barley and on barley yield

- Domestication of wild animals may provide a springboard for rapid variation of coronavirus

- Response of benthic invertebrate assemblages to seasonal and habitat condition in the Wewe River, Ashanti region (Ghana)

- Molecular record for the first authentication of Isaria cicadae from Vietnam

- Twig biomass allocation of Betula platyphylla in different habitats in Wudalianchi Volcano, northeast China

- Animal Sciences

- Supplementation of probiotics in water beneficial growth performance, carcass traits, immune function, and antioxidant capacity in broiler chickens

- Predators of the giant pine scale, Marchalina hellenica (Gennadius 1883; Hemiptera: Marchalinidae), out of its natural range in Turkey

- Honey in wound healing: An updated review

- NONMMUT140591.1 may serve as a ceRNA to regulate Gata5 in UT-B knockout-induced cardiac conduction block

- Radiotherapy for the treatment of pulmonary hydatidosis in sheep

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Long non-coding RNA TUG1 knockdown hinders the tumorigenesis of multiple myeloma by regulating microRNA-34a-5p/NOTCH1 signaling pathway”

- Special Issue on Reuse of Agro-Industrial By-Products

- An effect of positional isomerism of benzoic acid derivatives on antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli

- Special Issue on Computing and Artificial Techniques for Life Science Applications - Part II

- Relationship of Gensini score with retinal vessel diameter and arteriovenous ratio in senile CHD

- Effects of different enantiomers of amlodipine on lipid profiles and vasomotor factors in atherosclerotic rabbits

- Establishment of the New Zealand white rabbit animal model of fatty keratopathy associated with corneal neovascularization

- lncRNA MALAT1/miR-143 axis is a potential biomarker for in-stent restenosis and is involved in the multiplication of vascular smooth muscle cells