Abstract

Radiative cooling (RC), as a passive cooling technology, has characteristics such as no energy consumption, no pollution, and sustainability. Recently, with the emergence of advanced materials such as nanophotonic structures and metamaterials, efficient passive daytime radiative cooling has become increasingly possible. However, the tradeoff between the performance, cost, and stability limits the large-scale application of RC materials. Cement-based materials have been proven to have significant potential and advantages in this regard, offering a new direction for RC development and application. Therefore, this study reviews the progress in the research on cement-based materials for RC. This study provides a principle-based analysis of the cooling potential of cement-based materials, describes the pathways for optimizing their performance from the perspectives of materials and structures, and discusses the future development of these materials for RC.

1 Introduction

Since the twenty-first century, global warming and the urban heat island effect have been intensifying, with global temperatures continuously rising. The global surface temperature is expected to increase at a rate of 0.2°C per decade, and by 2050, extremely high temperatures will become the global norm [1]. In response to global climate change, devices such as air conditioners and electric fans, which achieve cooling through energy input, have been widely used. Although the cooling effect achieved by these devices can provide thermal comfort, the significant increase in energy demand has put immense pressure on the power systems of many countries. According to statistics, building energy consumption accounts for approximately 40% of the total societal energy consumption, with cooling energy consumption accounting for nearly 20% of the total electricity consumption in buildings worldwide [2–4]. The sharp increase in energy demand has led to the overconsumption of nonrenewable resources such as fossil fuels, creating a significant energy crisis. Furthermore, refrigerant leaks in electric cooling systems and the generation of greenhouse gases such as CO2 during power generation will further exacerbate global warming [5].

Radiative cooling (RC), a promising energy technology [6], dissipates heat to outer space through the atmospheric window (AW, 8–13 μm) via electromagnetic radiation without energy consumption, offering a sustainable solution for energy conservation and climate change mitigation [7–10]. This technology emerged in the 1970s, with early studies focusing on optimizing material optical properties to achieve a high AW emissivity [11,12]. Examples include silicon-based materials (SiO thin films [13] and Si3N4 [14]), metal-based materials (TEDLAR-coated evaporated aluminium sheets [11], lightweight stainless steel coolers [15]), pigmented materials (coloured polyethylene films [16,17], TiO2-based materials [18], BaSO4-based materials [19]), and various compounds [20,21]. While these materials exhibit high infrared emissivities and demonstrate various degrees of RC performance, true cooling is only achieved at night. The low reflectivity in the solar spectrum wavelength range (0.25–2.5 μm) limits the cooling efficiency during the day. Therefore, potential passive daytime radiative cooling (PDRC) materials should simultaneously possess a high emissivity (8–13 μm) and a high reflectivity to prevent solar absorption during the day from counteracting the effects of the cooling power. With the development of nanophotonics and micro/nanotechnology, increasingly advanced design and fabrication methods have been applied to RC materials, making the realization of daytime subambient RC possible. The nanophotonic coating proposed by Raman et al. [22] achieved a subambient cooling effect of 4.9°C under direct sunlight for the first time, significantly advancing PDRC. However, its high costs and manufacturing scalability challenges limit its practical application [23]. With the development of polymer photonics, these limitations have been addressed by the emerging metamaterial thin films [24]. These films not only achieve a cooling power of 93 W·m−2 but also offer economic feasibility and scalability for large-scale production. However, polymer materials are prone to ageing and typically have low mechanical strength, and issues such as weatherability and long-term stability must be considered for practical applications [23]. With the continuous development and optimization of nanophotonic structures [25], porous polymers [26], metamaterials [27,28], and random particles [29], as well as the emergence of advanced materials such as porous/particle hybrid films [30], controllable porous polymer coatings [31], hollow microsphere films [32–34], and adaptive films [35], RC technology is rapidly advancing towards more efficient and widespread applications. Nonetheless, economic viability, high efficiency, and long-term durability challenges remain for various materials, which must be overcome.

To address these challenges, various inorganic RC materials, such as geopolymers [36–38], ceramics [39], and glass [40], have been developed. Their porous structures and abundant Si–O/Al–O chemical bonds ensure high solar reflectivity and infrared emissivity. However, these materials also face limitations such as low mechanical strength and high energy consumption during manufacturing. Porous structures can promote light scattering, thereby increasing solar reflectance. Many RC materials use porous structures, such as porous polymer coatings [26], catkin-derived films [41], and nano-microstructured plastics [42]. However, these materials face challenges such as complex processing, durability, and long-term stability, making large-scale application on building surfaces difficult. Cement-based materials, widely used and extensively applied inorganic porous materials [43], have the advantages of excellent durability and stability, good mechanical properties, scalability, and low cost. Their pore structures can be optimized and adjusted according to material composition, curing conditions, and other factors. Cement-based materials can also combine hydrophobic properties to achieve surface waterproofing or integrate evaporative cooling to effectively reduce the temperature on building facades [44]. The durability, low cost, adjustable porosity, and other outstanding properties of cement make it an ideal candidate for scalable applications in RC materials. Furthermore, the unique chemical composition and microstructure of cement-based materials, which evolve via hydration reactions depending on the raw material formulation, critically affect their optical properties [45] and have significant potential for PDRC. Owing to their various excellent properties, the realization of RC via cement-based materials will significantly facilitate the development of energy-saving buildings and the RC field. Considering the difficulty in balancing the cost, performance, and stability of traditional organic RC materials and the low performance and high energy consumption in the manufacturing of other inorganic materials, cement-based materials undoubtedly offer a new avenue for RC technology. Moreover, as building materials, cement-based materials have numerous potential applications, and their RC properties can be harnessed effectively.

Many researchers have reviewed various aspects of RC technology, but most of them focused on the research progress and application of materials [23,46–53]. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, there has been no systematic review of RC using cement-based materials. Therefore, the aim of this study is to review the progress in the study of cement-based materials for RC, provide a principle-based analysis of their cooling potential, describe the material and structural designs in existing studies, and discuss the future development prospects of cement-based materials for RC. This review provides insights into the research and application of efficient-cooling cement-based materials.

2 RC potential of cement-based materials

2.1 Principles of RC

According to Kirchhoff’s law [54] and the blackbody radiation law, all objects above 0 K continuously absorb and emit electromagnetic waves. This process enables radiation heat exchange between objects at different temperatures via energy-carrying electromagnetic waves [55]. The Earth (approximately 300 K) and outer space (approximately 3 K) undergo unidirectional radiation heat transfer through this mechanism, and the cosmic coldness is harnessed as a renewable energy reservoir in RC to achieve terrestrial temperature reduction.

2.1.1 Energy transfer

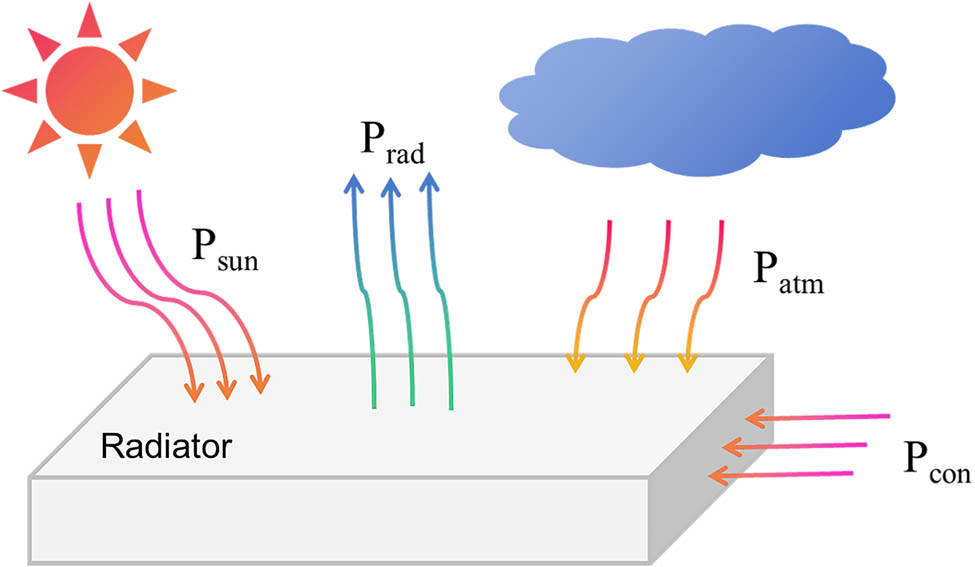

The energy transfer mechanisms involved in RC materials primarily consist of thermal radiation

Schematic diagram of energy transfer in RC.

2.1.2 Thermal radiation

Thermal radiation is a universally occurring physical phenomenon that is fundamentally caused by the random energy level transitions of particles in matter, which implies that any object at a finite temperature can emit thermal radiation [56]. The atmosphere has strong absorption bands in specific infrared wavelength ranges, as shown in Figure 2. The gaps between these absorption bands form the AW (8–13 μm), which has high transparency to thermal radiation [11]. At ambient temperatures, the AW coincides with the peak range of blackbody thermal radiation as defined by Planck’s law. This characteristic allows thermal radiation to pass through the AW with low loss, emitting heat into outer space. The thermal radiation power per unit area can be expressed as

where

![Figure 2

Atmospheric transmittance and downward radiation [57].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0145/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0145_fig_002.jpg)

Atmospheric transmittance and downward radiation [57].

2.1.3 Solar radiation

Solar radiation comprises three spectral bands: ultraviolet (0.25–0.4 μm), visible (0.4–0.78 μm), and near-infrared (0.78–2.5 μm) light. Energy distribution analysis revealed that visible light accounts for 43% of the total solar irradiance, near-infrared light contributes 52%, and ultraviolet light constitutes only 5% [58,59]. Consequently, surfaces with equivalent reflectances across all bands achieve higher total solar reflectance when near-infrared light reflection is prioritized. The solar radiation power absorbed by RC materials is governed by their spectral absorptivity, expressed per unit area as

where

![Figure 3

Standard AM1.5 solar irradiance spectrum [46].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0145/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0145_fig_003.jpg)

Standard AM1.5 solar irradiance spectrum [46].

2.1.4 Atmospheric radiation

The main components of the atmosphere are nitrogen (N2) and oxygen (O2), but the main contributors to atmospheric absorption/emission are water vapour (H2O), carbon dioxide (CO2), and ozone (O3), among others. Figure 4 shows the absorption spectra of the major atmospheric components that emit thermal radiation to the ground in the band ranges outside the AW. The absorbed atmospheric radiation power is related to the emissivity of the radiator, the atmospheric emissivity, and the ambient temperature. This atmospheric radiation power is greater than 0 and increases with cloud cover [60]. The total atmospheric radiation power per unit area can be expressed as

where

![Figure 4

Absorption spectra of the main atmospheric components [55].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0145/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0145_fig_004.jpg)

Absorption spectra of the main atmospheric components [55].

2.1.5 Thermal conduction and convection

Thermal conduction refers to heat transfer through direct contact, whereas thermal convection is a complex process influenced by the wind speed, surface orientation, flow regime, and surface roughness. The influence of these two mechanisms on the cooling power of a radiator is also related to its surface temperature. When the surface temperature of the radiator is higher than the ambient temperature, the cooling power is higher due to the outward heat transfer [61]. However, for an RC material at temperatures lower than the ambient temperature, these mechanisms will negatively impact the minimum temperature that can be achieved.

The power loss of a radiator due to the effect of these two mechanisms can be expressed as

where

2.1.6 Optical mechanism of action

The realization of PDRC requires materials with low solar radiation absorption and high thermal radiation; thus, they must simultaneously meet high infrared emissivity and solar reflectance. This requirement makes exploring the optical interaction mechanisms between materials and photons necessary.

The solar reflectance of materials involves four optical mechanisms: metallic reflection, multilayer dielectric film reflection, total internal reflection, and Mie scattering [62,63]. When sunlight strikes a metal surface, it causes free electrons in the metal to migrate directionally and generate current, producing electromagnetic waves with the same frequency as the incident wave but in the opposite direction. Due to the excellent conductivity of metals, the Joule heat loss related to the conducting current is minimal, resulting in the reflected wave intensity being nearly the same as the incident wave intensity. When light passes through a multilayer dielectric film, the incident light undergoes multiple reflections and refractions. The reflection efficiency relies on the structure of the multilayer dielectric film and the refractive index differences between adjacent dielectric layers. By designing the arrangement and refractive index differences of the multilayer dielectric film, the reflectance in specific wavelength ranges can be increased. Total internal reflection refers to the phenomenon that all incident light is completely reflected to the air without any part of it penetrating the lower refractive index medium. This situation occurs when light propagates from a medium with a higher refractive index to a medium with a lower refractive index and can be realized via various refractive structures. Mie scattering is an important mechanism for achieving high reflectance in materials. This mechanism occurs because of the inhomogeneity of the medium, such as particles, pores, and other features. When the incident electromagnetic wave interacts with particles in the medium, the electric field of the incident wave causes oscillation of charges within the particles. These accelerated charges emit electromagnetic waves in various directions, resulting in secondary radiation referred to as scattering. When numerous scattering bodies exist, a large portion of the incident light is diffusely reflected. Additionally, reflection and refraction caused by refractive index differences between two media also affect the transmission direction of light. In a medium containing many irregular particles or pores, the light undergoes multiple reflections, refractions, and scatterings before it ultimately returns to the medium surface and forms diffuse reflection.

The infrared emissivity of materials is related to molecular vibration, phonon polarization resonance, electromagnetic resonance, and graded-index interface [62,63]. The atoms that form chemical bonds or functional groups in the molecules of the material undergo continuous bending and stretching vibrations. When the molecular vibration frequency matches the frequency of electromagnetic waves, photon energy is absorbed, and the coupling of different molecular vibrations results in stronger absorption. Therefore, high emissivity in the infrared spectrum can be achieved via the interaction between molecular vibrations and electromagnetic waves. Dielectric materials with resonance polarization have a negative dielectric constant in specific infrared spectra. This negative dielectric constant hinders the effective propagation of phonon polaritons deep within the material, forming surface phonon polarization resonance, which generates strong absorption at mid-infrared wavelengths. Additionally, at the interface between metals and dielectric materials, electromagnetic waves known as surface plasmons (SPs) exist. When the frequency of SPs matches the frequency of incident photons, SP resonance is excited, resulting in a local increase in the electric field intensity around the photon structure and enabling strong light absorption. In addition to the strong absorption caused by electric resonance at the metal–dielectric interface, there is a magnetic resonance response between metal–dielectric–metal layers. When it is subjected to an external magnetic field, an induced magnetic field is generated in the dielectric material layer. When the two magnetic fields match, magnetic resonance occurs, thereby enabling infrared absorption. According to Fresnel’s law, when light transitions from one medium to another medium, the reflection intensity increases as the refractive index difference between the two media increases. The graded-index interface reduces the reflectivity by designing graded refractive index transitions, thereby increasing light absorption. This result is typically achieved using subwavelength-sized structures with a radially varying refractive index distribution to realize the graded interface.

2.2 RC properties of cement-based materials

The realization of PDRC requires a high reflectance in the solar spectral range and a high emissivity in the AW range to ensure that a positive net cooling power is achieved during both day and night. The RC properties of cement-based materials are directly related to their surface whiteness, water‒cement ratio, age, etc. [64,65], and these factors are controlled by their phase composition and microstructure at the microscopic level. In this section, the effects of the phase composition, microstructure, curing conditions, and environment on the RC properties of cement-based materials are analysed and summarized in principle.

2.2.1 Phase composition

Conventional cement-based materials, such as the widely used concrete, are composed of raw materials such as cement, aggregates, and additives. However, the final performance of a material is determined by the products formed after the hydration of cement. The RC performance of cement-based materials primarily depends on the cementitious material, with aggregates having little impact on this property [66]. This behaviour is further supported by the fact that both concrete and cement are weak solar reflectors and strong infrared radiators. The solar reflectance of the former depends mainly on the reflective properties of the cement, and the reflectance of hardened cement can largely represent the reflectance of concrete [67]. The hydration products of cement mainly include calcium–silicate–hydrate (C–S–H) gel, Ca(OH)2 (CH) crystals, CaCO3 and unhydrated cement particles, but cement is mostly affected by C–S–H and Ca(OH)2, which account for the largest proportion. This section analyses the RC properties of both of these materials, revealing the influence of the composition of each on their own RC properties.

2.2.1.1 C–S–H gel

The C–S–H gel, the main product of cement hydration, is an amorphous porous material that accounts for approximately 70% of the volume of the solid phase, is the main component determining the properties of the material, and manifests as a colloid at the nanoscale level [68,69]. Figure 5a and b shows scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of C–S–H. The solar reflectance of C–S–H is approximately 0.75, which is higher than that of white Portland cement (approximately 0.66), and the emissivity in the AW is 0.87 [71]. Its microstructure and chemical composition play decisive roles in the radiative properties of cement-based materials.

![Figure 5

(a) and (b) SEM images of C–S–H [70].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0145/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0145_fig_005.jpg)

(a) and (b) SEM images of C–S–H [70].

The reflective properties of C–S–H originate from its own porous structure and chemical composition. The nanoscale gel pore structure of C–S–H enhances reflectivity through light scattering, and the refractive index difference between the pores and the silicate skeleton (Si–O–Si) can lead to multiple scattering of incident light and high reflectivity in the solar spectral range. This mechanism is consistent with the strategy of improving the material performance of concrete by optimizing its porosity, which is also the main approach for enhancing the solar reflectance. In addition, multiscale pores (nano/microscale) can scatter light at different wavelengths, especially in the visible and near-infrared ranges (peak region of the solar spectrum), thus reducing energy absorption. In addition to the microporous structure, the high-refractive-index regions formed by the silicate backbone and hydroxyl groups (–OH) in C–S–H can also affect the reflective properties, enhancing light reflection and scattering to some extent.

The mid-infrared emissivity of C–S–H mainly depends on the vibration of its chemical bonds. The asymmetric stretching and bending vibrations of the Si–O–Si bonds in the silicate skeleton correspond to strong emission peaks in the mid-infrared wavelength range (9–12 μm), which aligns well with the AW. Therefore, these vibrations significantly contribute to the RC performance of cement-based materials [65]. The –OH groups and adsorbed water molecules in the structure also exhibit vibrational peaks in the 6–8 and 2.5–3.5 μm ranges [72]. These vibrations can widen the effective emission band through coupling effects. However, since these peaks do not fall within the AW, the enhancement in emissivity may be limited. In addition to chemical bond vibrations, C–S–H may also locally exhibit a layered ordered crystal structure similar to that of tobermorite, which supports specific phonon polarization excitations, which would significantly enhance its emissivity in the mid-infrared band. In addition, disordered gels and porous structures affect the emissivity of C–S–H to various degrees. For example, white cement paste will exhibit the highest emissivity because of the high nanoporosity of the C–S–H gel, and the emissivity of cement-based materials can be further enhanced by optimizing their porosity [71,73].

2.2.1.2 CH crystals

CH is an important product of cement hydration, occupying approximately 25% by volume of the cement matrix and behaving as massive crystals up to micrometres in size. CH itself has a solar reflectance of 0.93, which is significantly greater than that of ordinary Portland cement and high-dose-whitener cement (as shown in Figure 6c). This value falls within the solar reflectance range (0.875–0.95) necessary to achieve cooling to below ambient temperature. The emissivity of CH in the AW is 0.84, which is much greater than expected from its weak absorption in the AW due to its refractive index being close to 1 [45,46].

![Figure 6

(a) Dielectric function of CH, (b) scattering efficiency factors for CH, and (c) a comparison of the reflective properties of portlandite (CH), tobermorite (TOB), and white cement paste (WC PASTE) [71].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0145/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0145_fig_006.jpg)

(a) Dielectric function of CH, (b) scattering efficiency factors for CH, and (c) a comparison of the reflective properties of portlandite (CH), tobermorite (TOB), and white cement paste (WC PASTE) [71].

The high reflectivity of CH is closely related to its optical properties and microstructure. CH is usually white or off-white in colour, and its crystal structure has high intrinsic reflectivity for visible and near-infrared light. Within the solar spectral bands, CH has low absorption due to its nearly negligible dispersion and dielectric losses, and its scattering properties include multiple Mie scattering resonances linearly proportional to the particle size [74]. As shown in Figure 6a and b, the reflectivity is largely determined by geometrically driven optical resonances, which can provide high solar reflectivity [71]. In cement matrices where CH is present in the form of microparticles or nanoparticles, higher surface roughness and porosity can also enhance light scattering, which further enhances the reflectivity.

The emissivity of CH is related to its chemical bond vibrations and microscopic morphology. The crystal structure of C–S–H contains –OH and Ca–O bonds. The vibrational modes, such as O–H bending vibrations and Ca–O stretching vibrations, produce strong absorption peaks in the 8–13 μm wavelength range. According to Kirchhoff’s law, the emissivity of an object related to the angle and frequency is equal to absorptivity [54]. Therefore, CH has a high emissivity, as indicated by the “suppressed scattering window” [73] in the AW range. Its lattice vibrations also couple with photons to form phonon-polarized excitations that increase the efficiency of thermal radiation at specific wavelengths. In addition, CH is often present in the porous structure of cement-based materials, and this microscopic morphology can increase the effective radiative surface area. Moreover, a rough surface can also enhance mid-infrared emission through multiple reflections.

2.2.2 Microstructure

In the nanophotonic design of composites for RC, the use of Mie scattering to increase the solar reflectivity has been a focus of numerous studies [73]. Mie scattering is a scattering phenomenon that occurs when the size of a particle or a pore is comparable to the wavelength of incident light. Figure 7 shows a schematic of Mie scattering on the surfaces of cement-based materials. The nanoparticles and micropores within materials can significantly affect their optical properties via Mie scattering [74–76]. The microstructure of cement-based materials relies primarily on Mie scattering to increase solar reflectance and improve RC performance. However, the porous structure of cement-based materials alone is often insufficient to achieve the desired scattering intensity. To address this, modifications are commonly made by incorporating nanoparticles with high emissivity properties, such as SiO2, Al2O3, and other materials, to increase light scattering and improve the overall RC performance of the cement-based material.

Schematic of Mie scattering for cement-based materials.

The effect of nanoparticles on the RC properties of cement-based materials is typically affected by multiple design parameters, such as the particle size, refractive index, and dispersibility. The interaction between light and structure is closely related to the relative size of the structure and wavelength [77]. According to Mie scattering theory, when nanoparticles of the appropriate size are selected, they can serve as scattering centres for solar light. Thus, particles can be chosen on the basis of their size to match the solar spectrum and achieve strong scattering across the entire solar spectrum. Liu et al. [64] conducted simulations of particle scattering behaviour, which revealed that nanoparticles can effectively scatter solar radiation of different wavelengths. The authors reported that particles with a diameter half of the incident wavelength are capable of scattering more solar radiation. Typically, the higher the refractive index of the particles, the stronger the scattering [78]. This finding is actually related to the refractive index contrast between the particles and the cement matrix; the greater the contrast, the stronger the scattering. High concentrations or periodic arrangements of particles can induce multiple scattering, which increases the scattering intensity. However, the strong tendency of nanoparticles to agglomerate must be addressed. Because the porous structure of cement-based materials provides favourable conditions for light scattering, they are suitable for development as RC materials. The abundant nanopores and micropores of cement-based materials can backscatter solar light effectively. However, when scattering is increased by high porosity, how the shape and connectivity of the pores affect the scattering direction and efficiency needs to be considered. Additionally, when the size and refractive index of the scattering body satisfy the conditions expressed in Eq. (6), a significant increase in the scattering cross-section occurs [79], resulting in Mie resonance [74]. This phenomenon further increases the solar reflectance. Mie scattering of nano/microparticles in the mid-infrared wavelength range requires scattering bodies at the micrometre scale. However, precisely controlling the regular arrangement of micrometre-scale scattering bodies in cement-based materials is difficult. Therefore, targeted design is generally not applied. Instead, a high emissivity is achieved via regulation of intrinsic thermal radiation and phonon‒polariton effects.

where

Because the porous structure of cement-based materials provides favourable conditions for light scattering, they are suitable for development as RC materials. The abundant nanopores and micropores can backscatter solar light effectively. However, when scattering is increased through high porosity, how the shape and connectivity of the pores affect the scattering direction and efficiency also needs to be considered. The differences in Mie scattering between pores and particles can be attributed to the form and structure of the air–solid interface. For nanoscale pores (less than 100 nm), visible light is reflected mainly via Rayleigh scattering but the effect is extremely limited. For micrometre-sized pores (refractive index n = 1.0), owing to the refractive index difference from the cement matrix, Mie scattering can be induced in the near-infrared wavelength range to increase the near-infrared light reflectivity. Additionally, the anisotropy of the porous structure can further increase scattering efficiency [80]. In the AW, micropores can be equated to “air particles,” which can increase the mid-infrared emissivity via Mie resonance. However, the effect of scattering from pores on the optical properties is not observed until the number of pores reaches a certain order of magnitude. The number of pores with sizes within the AW range in cement-based materials is on the order of 106/g at most, which has a limited effect on the emission properties [64]. The pore structure in cement-based materials is significantly affected by the water–cement ratio. A higher water–cement ratio produces more pores, increasing Mie scattering and solar reflectance [81]. Studies have shown that the solar reflectance of white Portland cement samples with a water–cement ratio of 0.4 is approximately 8.5% higher than that of samples with a ratio of 0.25 [65]. Therefore, a higher water–cement ratio can also increase the solar reflectance of cement-based materials.

The microstructure regulation of cement-based materials focuses on increasing solar reflectance, which requires the creation of efficient light scattering paths. This approach involves not only the effect of individual scattering bodies (particles or pores) on the performance but also the creation of a cooperative network of multiscale (nano–micro) scattering bodies. By rationally designing the ratio, size distribution, and relative positioning of nanoparticles and pores, the effective scattering path length of photons within the material can be maximized while minimizing the absorption losses of the material matrix itself. Additionally, strong scattering should be achieved across the entire scattering wavelength range to create a complementary scattering effect.

2.2.3 Water–cement ratio and curing conditions

The water–cement ratio and curing conditions of cement-based materials usually directly influence the degree of hydration of cement and its internal microstructure. The optical properties of cement-based materials can be improved to some extent by finding the most suitable water–cement ratio and curing conditions to obtain efficient RC performance. The solar reflectance of white Portland cement paste was reported [65] to increase with increasing water–cement ratio and curing age, as shown in Figure 8, where the reflectance increased from 0.48 to 0.56 when the water–cement ratio increased from 0.2 to 0.4, whereas the reflectance corresponding to curing ages from 3 to 65 days increased from 0.56 to 0.61 when the water–cement ratio was 0.4. In addition, the effects of these two factors on the emissivity were small, and the emissivity of all the samples reached more than 0.87 and did not significantly change with the water–cement ratio or curing age.

![Figure 8

Solar reflectance of white Portland cement at different (a) water–cement ratios and (b) curing ages [65].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0145/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0145_fig_008.jpg)

Solar reflectance of white Portland cement at different (a) water–cement ratios and (b) curing ages [65].

Since the optical properties of cement-based materials are less affected by the curing age, researchers have explored many common curing methods, such as wet curing, autoclave curing, and carbonation curing. Qin et al. [67] reported that the reflectance of cement paste cured under wet conditions is greater than that of cement paste cured under normal indoor conditions; the reflectance can be approximately 10% greater than that obtained under indoor curing conditions at high water‒cement ratios (greater than 0.45). This result proves that the reflective properties of cement-based materials can be effectively improved under wet curing conditions. Autoclave curing conditions promote the hydration reaction, improving the microstructure and phase composition of the cementitious matrix, which can significantly enhance the RC performance of cement-based materials. Liu et al. [64] obtained samples with a reflectance of 0.90 and an emissivity of 0.88 under autoclave curing conditions (185°C, 11 atm). This performance is comparable to that of several well-designed polymers and metamaterials. On the basis of previously conducted studies, by optimizing the composition, Liu et al. [70] obtained high-radiation-performance samples with a reflectance and an emissivity of 0.91 under autoclave curing conditions (190°C, 13 atm) and achieved a reflectance of 0.83 and an emissivity of 0.90 by curing in deionized water. This result also confirms the superiority of wet and autoclave curing. Carbonation of cement-based materials occurs when they are exposed to the environment for a long period [82,83]. The changes in the phase composition caused by carbonation can also affect their optical properties. The generated CaCO3 can enhance Mie scattering and improve the reflective properties of the material. The more CaCO3 that is generated, the higher the reflectivity in that region [84]. Therefore, carbonation conservation is also a promising method for improving the reflective properties of cement-based materials.

2.2.4 Environmental impact

RC materials have both selective and nonselective emission in the infrared band. Selective emission refers to a high emissivity only in the AW, whereas nonselective emission refers to broad-spectrum materials with high emission throughout the mid-infrared spectrum. The spectral emission diagrams of the two ideal materials are shown in Figure 9a. On the basis of the properties of non-selectively emitting materials, when the working temperature of the material surface is higher than the ambient temperature, the radiator will also emit thermal radiation to the atmosphere in the mid-infrared range, in addition to in the AW. In this case, the non-selectively emitting material will have a higher net cooling power because the radiation outside the AW is greater than the absorption of the downward radiation from the atmosphere by the material. Conversely, if the material is working below or near ambient temperature, the absorption outside the AW is greater than the radiation. This situation is often detrimental to the cooling of the material itself, whereas selective emission removes the effect of radiation from the atmosphere. Therefore, the mid-infrared spectrum of cement-based materials can be effectively designed to reduce the additional heating effect of the environment on the material.

![Figure 9

(a) Emissivity spectra of ideally selectively and nonselectively emitting materials (the inset graph represents the net cooling power as a function of the ambient temperature difference under certain conditions) [55]; (b) temperature of each material at irradiance values of 600, 750, and 900 W·m−2 [85].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0145/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0145_fig_009.jpg)

(a) Emissivity spectra of ideally selectively and nonselectively emitting materials (the inset graph represents the net cooling power as a function of the ambient temperature difference under certain conditions) [55]; (b) temperature of each material at irradiance values of 600, 750, and 900 W·m−2 [85].

Owing to the different climatic conditions in different geographical locations, the cooling effects corresponding to various types of RC materials vary [49]. Therefore, the selection of suitable materials to maximize the benefits of the cooling effect throughout the year should be an aspect of concern for cement-based materials. Torres-García et al. [85] quantitatively evaluated the actual cooling capacities of CH and CSH for three different climatic conditions (humid, savanna, and temperate) during a year by means of atmospheric simulations and compared them with those of ordinary Portland cement (OPC) and white cement (WC). The results showed that both CH and CSH outperform OPC and even outperform the more reflective WC. In both summer and winter, CSH has a positive net cooling power for a long period, whereas CH does so in all the months and locations and is below the ambient temperature most of the time. Figure 9b presents the temperature variations of each material at different irradiance levels in a room, with CH consistently maintaining an average temperature approximately 15°C lower than that of ordinary silicate cement, and CSH consistently maintaining an average temperature approximately 10°C lower. Overall, the CH and CSH phases are well suited to warm climates, whereas OPC cement pastes may be better suited to colder climates, with WC providing an intermediate solution. These results confirm that the compositions of CH and CSH in concrete can be optimized to achieve the desired cooling power for a specific geographic location and illustrate the potential for tailoring the components to achieve the desired RC performance.

3 Optimization of cement-based materials and structural design

The total solar radiation power reaching the ground is approximately 1,000 W·m−2, whereas the RC power of existing materials is approximately 100 W·m−2; thus, the solar reflectance must be greater than 0.90 to realize PDRC in a real sense [22,57]. The emissivities of cement-hardened paste and cement particles are approximately 87 and 83%, respectively [86]. Despite the excellent emissivities, achieving RC in the real sense is difficult due to the limitations of the reflective properties (as shown in Figure 10a and b), and the materials must be reasonably optimized in terms of their material and structure. This section summarizes the current progress in the research on cement-based materials for RC from three aspects: single-component, multicomponent, and structural optimization.

3.1 Single-component modification

3.1.1 Mineral admixtures

Commonly used mineral admixtures include fly ash (FA), slag (SG), and silica fume (SF). These mineral admixtures can significantly improve the material performance and reduce costs [87,88] while also affecting the optical properties of cement-based materials. The unburned carbon particles in FA significantly reduce the reflectance of visible and near-infrared light on the surface of the material, making the material greyish-black in colour and increasing the heat absorption capacity. SF is dark grey in colour and may also reduce the reflectance of visible light because of its reduced whiteness, but has a weaker effect on the reflectance in the near-infrared band. SG is usually greyish-white in colour, and an increase in the whiteness of the material generally enhances reflectivity.

Typically, concrete has a reflectivity of 0.35–0.40, whereas the addition of SG to cement at a 70% substitution rate as a supplementary cementitious material can increase the reflectivity of hardened concrete to 0.58, which is 71% greater than that of conventional mixes [89]. Although the reflectivity is still relatively low, the use of this mixture in urban pavements can significantly reduce environmental temperatures and improve air quality. Marceau and Vangeem [66] conducted batch experiments on the reflectivity of concrete with different compositions and reported that the reflectivity of concrete generally increases with the solar reflectivity of supplementary cementitious materials. The reflectivity of concrete containing SG cement can reach at least 0.64, whereas composites containing dark grey FA have reduced reflectivity. In this regard, Qin et al. [67] also demonstrated a reduction in the reflectivity of cement pastes due to FA and an enhancement effect of SG. To further investigate the extent of the effects of these admixtures on the reflectivity, Lu et al. [65] investigated the optimization of the RC properties of white Portland cement by adding different contents of FA, SG, and SF. As shown in Figure 10c, the addition of FA and SF reduced the reflectivity of the hardened paste, in which the addition of 15% FA reduced the reflectivity of the cement paste to 0.41, and the addition of 15% SF reduced the reflectivity of the cement paste to 0.36, whereas the addition of SG slightly increased the reflectivity of the hardened paste. The effects of these three additives on the reflective properties of cement-based materials were further verified. Figure 10d shows the high emissive properties of the three mineral admixtures on their own, and the addition to cement had little effect on the emissivity.

The alternative use of cement with mineral admixtures reduces carbon emissions, and SG certainly provides a good alternative when considering the optimization of the RC properties of cement-based materials; however, the enhancement of RC properties by admixtures is extremely limited.

3.1.2 Whitening agents

In cement-based materials for RC, the particle size of the whitening agent used is typically in the micron range. The primary role is to enhance Mie scattering to improve the visual whiteness of the material, thereby increasing its solar reflectance (in the visible light and near-infrared ranges). Common whitening agents include TiO2, CaCO3, and BaSO4, all of which effectively scatter sunlight [90,91]. Among them, TiO2 is the most commonly used high-efficiency whitening agent. Although it has high absorption in the ultraviolet range, this is not a significant issue, as the energy in this wavelength range is small, resulting in weak absorption. TiO2 has extremely high solar reflectance and chemical stability [92,93]. BaSO4 has high reflectance, a low extinction coefficient, and excellent weather resistance [94]. CaCO3, although it has a lower reflectance than those of TiO2 and BaSO4, is favoured because of its low cost and easy availability, making it a commonly used whitening agent. Additionally, whitening agents such as ZnO and Al2O3 exist. Although ZnO has high reflectance, it is not suitable for cement-based materials because of its potential solubility in alkaline environments. Al2O3 has excellent emissivity, making it very suitable for cement-based materials despite its relatively low reflectance.

The reflectance spectra of white Portland cement hardened pastes at different CaCO3 and TiO2 dosages are shown in Figure 11a and b. The overall reflectances all increased with increasing CaCO3 and TiO2 contents, among which CaCO3 produced a smaller increase; the reflectance of the 15% CaCO3-doped material was approximately 0.65, whereas the maximum reflectance of the 10% TiO2-doped material was approximately 0.73. However, the two whitening agents, CaCO3 and TiO2, did not have a significant effect on the emissivity of the hardened cement paste [65], which confirmed the excellent reflectance performance of TiO2 and CaCO3 as whitening agents with excellent reflective properties. In addition, to balance cost and performance, low-cost CaCO3 and high-performance TiO2 can be mixed to obtain a low-cost composite whitening system with a high emissivity.

![Figure 11

Reflectance spectra of white Portland hardened cement with different dosages of (a) CaCO3 and (b) TiO2 [65].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0145/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0145_fig_011.jpg)

Reflectance spectra of white Portland hardened cement with different dosages of (a) CaCO3 and (b) TiO2 [65].

3.1.3 Nanoparticles

The size of nanoparticles typically ranges from 1 to 100 nm [95,96], and their resonance with light scattering is a key process for increasing the solar reflectivity in PDRC. By designing the size distribution of nanoparticles to support the resonance required for efficient solar reflection, highly efficient and cost-effective RC solutions have been achieved in many fields [24,97–99]. In addition to achieving a high reflectivity via light scattering, nanoparticles can also induce phonon‒polariton resonance, resulting in strong optical absorption and emission [100]. By controlling the size, shape, and arrangement of nanoparticles, the resonance frequency of phonon polaritons can be adjusted precisely to achieve highly selective emission in the AW. For cement-based materials, owing to the poor light transmittance of cement itself, only nanoparticles on the surface can typically achieve the high reflectivity and emissivity described above. Nanoparticles within the cement matrix are subject to a screening effect [101], which can only increase the emissivity via mid-infrared emission. In this case, light scattering by nanoparticles within the AW should be avoided to prevent the cement matrix from reabsorbing scattered mid-infrared light.

When the dielectric constant of nanoparticles matches that of the matrix material, the scattering efficiency decreases significantly, forming a “scattering suppression window” that relies only on the properties of the material [73]. Thus, the solar reflectivity of the material while minimizing the effect on thermal radiation, thereby maximizing the emissivity, can be increased by selecting the appropriate nanoparticles. As a result, the RC performance of cement-based materials can be significantly improved. Common nanoparticles used in RC materials include TiO2, SiO2, and Al2O3 [29,90,100,102]. These materials are also often used to improve the properties of cement-based materials. TiO2, a typical reflective material, has characteristics such as a wide bandgap, chemical stability, a high refractive index, and transparency to most infrared radiation [103]. SiO2 has a low extinction coefficient within the solar spectrum, which provides the necessary conditions to achieve a high reflectivity. The dielectric properties of SiO2 support phonon‒polariton resonance within the AW, resulting in high emissivity in the AW [46]. Al2O3 shows no absorption in the near-infrared and visible spectra, and its absorption in the AW is stronger than that of TiO2 and SiO2, making it a suitable material for RC [104]. Figure 12a and b shows the scattering efficiency of these three nanoparticles in air and a C‒S‒H matrix. In air, because the scattering suppression windows of TiO2 and Al2O3 overlap the AW, these two nanoparticles are transparent to thermal radiation within the AW. However, SiO2 exhibits scattering resonance in this region, which increases absorption. In the main phase of cement-based materials, i.e., C‒S‒H, only the C‒S‒H matrix with Al2O3 nanoparticles embedded has a scattering suppression window that overlaps the AW [73]. This result not only emphasizes the need to select nanoparticles that match the matrix material but also reveals that Al2O3 nanoparticles could be particularly suitable for optimizing the RC performance of cement-based materials.

![Figure 12

Scattering efficiency for the three nanoparticles, TiO2, Al2O3, and SiO2, embedded in (a) a C–S–H matrix and (b) air [73].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0145/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0145_fig_012.jpg)

Scattering efficiency for the three nanoparticles, TiO2, Al2O3, and SiO2, embedded in (a) a C–S–H matrix and (b) air [73].

Nanoparticles themselves can optimize the microporous structure of cement-based materials. Nanoparticles can increase the solar reflectivity via Mie scattering and possess excellent mid-infrared emissivity. On this basis, the most suitable nanoparticles for cement-based materials can be selected in combination with the scattering suppression window to maximize the improvement in the RC performance. Currently, research on the effect of nanoparticles on the RC performance of cement-based materials is limited. Further studies could investigate the effects of nanoparticles such as CaCO3 and SiC [105,106]. Owing to the excellent emissivity of cement-based materials, nanoparticles that are transparent to thermal radiation can be enriched on the surface, which would not only increase the reflectivity but also ensure a high emissivity.

3.2 Multicomponent modification

The above mineral admixtures, whitening agents, and nanoparticles lead to a certain degree of optimization of the RC performance of cement-based materials. However, to obtain a large positive net cooling power under external conditions for practical applications, multiple optimized components can be used in combination. Table 1 summarizes the studies on optimization of the RC properties of cement-based materials performed in recent years.

Studies on the optimization of the RC properties of cementitious materials

| Materials | Curing conditions | Solar reflectance | Mid-infrared emissivity | Cooling efficiency | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W-PC, TiO2, CaCO3 | Standard curing | 0.83 | 0.87 | Net cooling power up to −26.2 W·m−2, and surface cooling of 12°C | [65] |

| W-PC, TiO2, CaCO3 | Wet curing | 0.81 | 0.84 | — | [64] |

| W-PC, TiO2, CaCO3 | Carbonation curing | 0.84 | 0.85 | — | [64] |

| W-PC, SiO2, TiO2, CaCO3 | Autoclave curing | 0.90 | 0.88 | Surface cooling up to 17.3°C and internal cooling up to 9.2°C | [64] |

| W-PC, TiO2, CaCO3, Al2O3 | Autoclave curing | 0.91 | 0.91 | RC power of −11.0 W·m−2 | [70] |

| W-PC, TiO2 | Autoclave curing | 0.92 | 0.95 | Long-term subambient cooling of 1.10°C and surface cooling of approximately 16°C | [84] |

| OPC, carbonated periwinkle shell aggregate | Wet curing | 0.62 | — | Consistently lower than OPC temperatures at the peak solar radiation power, and up to 6°C lower | [107] |

| OPC, Si2N2O | Standard curing | — | — | Net cooling power in the range of 0.077–0.92 W·m−2 | [108] |

Both TiO2 and CaCO3, when used in appropriate proportions, can not only optimize the RC performance of cement-based materials but also significantly reduce costs. Therefore, these two materials can be introduced into cement-based materials. Lu et al. [65] obtained the best optimized ratio for cooling coatings with a reflectance of 0.83 and an emissivity of 0.87 by controlling the ratio of TiO2, CaCO3, and cementitious materials, considering the RC and mechanical properties. The heat transfer model showed that when the surface temperature exceeds 33°C, the cooling power is positive, and a passive cooling effect can be obtained. Field tests also revealed a decrease in the internal temperature of 11°C compared with that of OPC. As shown in Figure 13a and b, both the experimental and simulation results demonstrate the possibility of achieving PDRC with cement-based composites. Autoclave curing can improve the RC performance of materials. By optimizing the material composition and then applying autoclave curing, more efficient cooling materials can be obtained. Liu et al. [64] obtained material samples with a reflectance of 0.90 and an emissivity of 0.88 based on white Portland cement, quartz, TiO2, and CaCO3 under autoclaved conditions. The field test (Figure 13c and d) showed that the surface cooling reached 17.3°C, the solar reflection cooling reached 9.2°C, and the mid-infrared emission cooling was greater than 2.8°C. These findings indicate that the RC performance of cement-based materials can be significantly enhanced by optimizing the combination of various components and curing methods.

![Figure 13

Optimal cooling coating R3-5 compared to white Portland cement (W-PC) and grey Portland cement (G-PC): (a) cooling power at different surface temperatures and (b) temperature changes during field tests [65]; (c) field experiment platform and schematic; and (d) composition of the cooling contributions of cementitious materials under radiative versus evaporative cooling [64].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0145/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0145_fig_013.jpg)

Optimal cooling coating R3-5 compared to white Portland cement (W-PC) and grey Portland cement (G-PC): (a) cooling power at different surface temperatures and (b) temperature changes during field tests [65]; (c) field experiment platform and schematic; and (d) composition of the cooling contributions of cementitious materials under radiative versus evaporative cooling [64].

Both SiO2 and Al2O3 can significantly improve the reflectance and emissivity of cement-based materials, and their inherent properties are compatible with those of cement-based materials. Therefore, they are excellent choices for optimizing the RC performance.

Liu et al. [70] analysed the effects of nano-SiO2 and Al2O3 on the RC performance of cement-based materials. They reported that both the reflectance and emissivity were significantly improved, confirming that nano-SiO2 and Al2O3 can greatly enhance the RC performance of cement-based materials. Among these materials, white Portland cement with Al2O3 and CaCO3 added, after autoclave curing, achieved a reflectance and an emissivity of 0.91, with an RC power of −11.0 W·m−2. The increase in the RC performance after autoclave curing can be attributed to the increase in nano/microparticles and pores and to the intrinsic high emissivity of the materials, which is consistent with the principles mentioned above. On this basis, Liu et al. [84] further investigated the RC performance of these materials after carbonation. The results showed that the reflectance is more sensitive to carbonation, but overall, the impact is minimal (as shown in Figure 14). The developed composite materials still maintained a reflectance of approximately 89% and an emissivity of over 90% after carbonation. The long-term subambient cooling was 1.10°C, and the surface cooling was approximately 16°C. Compared with typical mortar floors, these materials could provide effective RC. Furthermore, without the addition of whitening agents, cement-based materials with both a reflectance and an emissivity greater than 0.9 were also prepared, which indicates that whitening agents are not essential for producing high-performance cement-based radiators.

![Figure 14

(a) Reflectance and (b) emission spectra of white Portland cement without an optimizer before and after carbonation [84].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0145/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0145_fig_014.jpg)

(a) Reflectance and (b) emission spectra of white Portland cement without an optimizer before and after carbonation [84].

In addition to commonly used high-performance RC materials, many new materials are continuously being applied to optimize the RC performance of cement-based materials. This approach provides many new research and development directions for the advancement of RC with cement-based materials. The main component of white shells is CaCO3, which is inexpensive and has a high bandgap, resulting in a lower solar absorption rate. Studies have confirmed the excellent optical properties and cooling effectiveness of CaCO3, making it suitable for use in cement-based materials to optimize their performance [109–111]. Goracci et al. [107] proposed the use of a carbonated periwinkle shell aggregate with a reflectivity of up to 89%, which is better than that of TiO2 (approximately 83%), in concrete. Figure 15a compares the reflectance of this concrete with that of OPC. Compared with OPC, the concrete with this carbonated aggregate has significantly greater reflectance, reaching 0.62, and the carbonated concrete consistently exhibited lower temperatures than OPC at the peak solar radiation power, up to a maximum of 6°C lower, demonstrating the significant cooling potential of this carbonated aggregate. Despite the limited cooling effect achieved, the CO2 capture by this aggregate and the replacement of aggregates such as sand and gravel show the great potential for sustainability and provide a new direction for the realization of RC with cement-based materials. Si2N2O has been shown to be a very good selective emissive material with a high emissivity in the AW range and low absorption outside this range [108]. Miyazaki et al. [112] designed an RC cement composite by mixing Si2N2O with OPC. Figure 15b shows the variation in the temperature difference between the Si2N2O-containing and blank samples at a constant temperature of 90°C. The obtained samples showed cooling capacities in the range of 0.077–0.92 W·m−2, indicating the possibility of passive cooling properties of cement-based materials. Moreover, the different cooling results also indicate that the RC performance of cement-based materials is related to the dosage of optimizers, their thickness, and the ambient temperature, and the cooling performance of cement-based materials may be improved to a certain extent by adjusting these parameters. Pavement has a decisive influence on the overall thermal conditions of cities and the urban heat island effect. Increasing the reflectivity of pavement or using high-reflectivity pavement can help reduce the urban heat island effect and the temperature of urban areas [113]; for example, when traditional asphalt pavement is replaced with reflective concrete, the surface temperature can be lower than that of traditional concrete by approximately 12.7°C [114]. On this basis, Calis et al. [115] explored colour-pigment-incorporated roller-compacted high-performance concrete (CPI-RCHPC) as a new material to mitigate the urban heat island effect. The highest reflectivity of 0.69 was found for the samples when the pigment dosage was 0.75%, and all the mechanical strengths met the requirements. The simulation results showed that the use of CPI-RCHPC can reduce the air temperature by 1.63°C, reduce the surface temperature by 9.69°C, increase the relative humidity by 8%, and increase the shortwave reflectivity by 56% compared with traditional asphalt pavement.

In addition to the RC performance, the applicability of cement-based materials for RC should also be considered. The most important factor after modification is the environmental impact, so the environmental performance of any newly developed material should be evaluated with respect to existing cooling materials. Adams and Allacker [116] evaluated the environmental impact of developed photonic metaconcrete (PMC) on the basis of a defined environmental benchmark. From an environmental impact perspective, PMC shows great potential, as its impact is only slightly greater than that of the highest-scoring RC materials in the database. Additionally, the comparison between PMC and traditional concrete indicates that cement, steel fibres, and microadditives are the main environmental impact factors. Specifically, when the volume fraction of steel fibres is only 6%, their environmental impact accounts for 75.8% of the total impact. Furthermore, PMC uses twice as much cement as traditional concrete does, which may result in a greater impact on climate change [117]. This highlights that the environmental impact can be significantly reduced by selecting different types of cement and optimizing the material mix, thus emphasizing the importance of material selection and optimization in the future development of cement-based materials for RC.

3.3 Structural design optimization

In addition to optimizing the RC properties of cement-based materials by the addition of some optimizers with good RC properties and curing methods, optimization can also be based on the advanced structural design of some metamaterials. As the main product of cement, the RC properties of C–S–H greatly influence the performance of cement-based materials. Lezaun et al. [118] tried to improve the spectral properties of C–S–H through a simple structural design (Figure 16a) by embedding vertical and horizontal periodic metal cylinders, which led to a great improvement in the emission spectrum of C–S–H. This result suggests that optimizing the structure and substrate materials to enhance the solar reflectance and emissivity is a feasible approach. Notably, although only a simple structural design has been optimized for C–S–H, continued structural adjustments and the development of additional concrete phases will result in more effective performance enhancements.

The screening effect of cement-based materials limits their RC performance significantly. The particle–solid transition architecture (PSTA) offers a promising solution [120]. As shown in Figure 16c, PSTA differs from conventional coating and encapsulation structures. In this architecture, surface nanoparticles act as both sunlight scatterers and thermal emitters, while the nanoparticles embedded within the cement matrix provide structural compatibility and cohesion. This configuration significantly improves not only the RC performance of cement-based materials but also interfacial bonding strength, ensuring compatibility with building applications. A PSTA design based on BaSO4 nanoparticles achieves an interfacial shear strength of 0.93 MPa and a cooling power of 92.8 W, with a reflectance of 0.96 and an emissivity of 0.97, showing great potential for practical applications [120]. Future research should explore the integration of more types of nanoparticles with cement-based materials to facilitate more efficient real-world implementations.

The use of radiators in combination with solar cells is a feasible solution for increasing the efficiency and extending the lifetime of solar cells at high temperatures, which has been extensively investigated recently [121–123]. However, the trade-off among the performance, cost, and reliability makes it challenging for researchers. Cement-based materials, which are inexpensive and sustainable, can undoubtedly provide an innovative solution. Cagnoni et al. [119] designed a device consisting of a reflector, a cement-based radiator, and a bifacial solar cell (Figure 16b). The cooling effect obtained via multiscale simulations resulted in a temperature reduction of approximately 20 K for silicon-based solar cells, which corresponds to an efficiency increase of approximately 9% (0.5%/K) and a lifetime extension of up to four times (doubling of the lifetime every 10 K). This finding indicates the feasibility of realizing new energy-efficient, economically viable, and robust RC solar cells on the basis of inexpensive and readily available cement-based materials. Additionally, electromagnetic simulations revealed that the clinker (C3S) and hydrated (CH and C–S–H) phases of OPC can strongly emit thermal radiation both within and beyond the AW. This capability enables highly effective RC of solar cells with arbitrary bandgaps (up to 25 K), with performances even comparable to those of some expensive and complex metamaterials. These findings highlight the significant potential of cement-based materials for RC of solar cells [124]. The newly incorporated nonradiative recombination mechanisms in traditional models also confirm that radiators increase the solar cell efficiency more substantially than previously predicted. This finding strongly justifies the practical application of cement-based RC in solar cells [125].

4 Future prospects

In the development and application of RC materials, their significant energy and environmental advantages have been demonstrated. As primary construction materials, cement-based materials possess immense potential to substantially contribute to building energy efficiency, mitigation of urban heat island effects, and even global sustainable development through RC. However, owing to the current state of material development, cement-based materials for RC still face multiple challenges, including performance, cost, reliability, and scalability. Future research can focus on the following aspects:

Currently, cement-based materials can achieve varying degrees of effective temperature reduction, but most have negative cooling power, and there is significant room for improvement compared to existing advanced RC materials. Therefore, the efficiency of cement-based materials for RC remains a significant challenge. Future research can focus on the synergistic optimization of the reflectance and emissivity properties of cement-based materials via the selection of appropriate modifiers or structural design optimization. Additionally, integrating evaporative cooling could further reduce the effective temperature on building facades [44].

Research on cement-based materials is limited to improving their performance via various efficient RC components. However, the optimal composition ratios, forms, and their ability to maximize cooling effects have not been comprehensively and systematically investigated. Moreover, large-scale applications must also consider the high cost of these components. Future research could investigate the effects of modified components, such as the dispersibility, particle size distribution, or organic content of nanoparticles, on the optical properties of cement-based materials. This approach would enable precise spectral control while balancing cost issues. Additionally, efforts could be made to identify low-cost modification materials suitable for cement-based materials.

Research on cement-based materials for RC focuses on developing materials with high RC performance. However, for large-scale practical applications, durability and environmental stability must also be addressed. Balancing cooling performance with structural suitability is challenging for cement-based materials. Future research can build upon the laboratory development of RC performance to further investigate issues related to durability and long-term stability, including material aging, peeling, or performance degradation due to prolonged exposure to environmental factors such as ultraviolet radiation, high temperatures, and rain.

The practical application of cement-based materials for RC needs to consider their hydrophobic properties. Owing to the structural similarity between superhydrophobic surfaces and RC materials, the maximization of the synergistic integration of these two functions is important for the development of sustainable PDRC materials. Some materials have achieved the combination of RC and hydrophobic properties to varying degrees via methods such as directional induced deposition [126], solvent exchange [127], and phase separation [128]. Other studies have employed advanced technologies such as femtosecond lasers [129] and template-assisted electrodeposition [130] to achieve superhydrophobic performance in materials. Future research can explore the use of low-surface-energy hydrophobic coatings that have minimal effects on the RC performance of cement-based materials. Additionally, constructing surface micronanostructures on cement-based materials via various methods, such as physical or chemical techniques or doping with hydrophobic nanoparticles, can significantly improve stability. Furthermore, directly incorporating hydrophobic components, such as calcium stearate or hydrophobic aggregates, during mixing can also achieve hydrophobic performance.

Because RC materials are affected by atmospheric conditions [49], such as weather, humidity, ambient temperature, and solar irradiance, and considering that different locations, seasons, and climates result in varying indoor thermal comfort levels, new requirements arise for cement-based materials in RC. The dynamic regulation and balancing of optical properties in RC materials can maximize energy savings for buildings. For example, windows need to simultaneously achieve high visible light transmittance and low long-wave infrared emissivity to balance daylighting and thermal regulation. Hydrogels with graded network structures, for example, have enabled wide-spectrum control from ultraviolet to infrared, ensuring biological safety and cooling performance [131]. Additionally, the Kirigami structure, which was designed to adapt to changing environmental conditions, can switch between heating and cooling modes via self-adjustment, greatly improving thermal management in windows [132]. For cement-based materials, the dynamic regulation of their RC performance could involve designing dynamic cooling devices on the basis of phase change materials or integrating temperature-sensitive materials such as thermochromic hydrogels. However, research in this area remains insufficient.

The industrial application of cement-based materials for RC not only needs to meet performance and cost requirements but also faces significant challenges in terms of reliable implementation and application scenarios. For cement-based materials, potential implementation methods include the use of coatings and tiles as well as overall modifications. Future research can focus on these aspects. Coatings and tiles can be applied to building surfaces such as roofs and facades, effectively achieving cooling by reflecting and emitting heat. Coloured coatings can enable broader applications [133]. Overall modifications, such as the use of large-volume concrete, are suitable for structures like pavements, where cooling performance requirements are less stringent. Despite its lower radiative performance, large-volume concrete can mitigate the urban heat island effect.

5 Conclusions

In this study, the potential of cement to achieve cooling based on its own phase composition and microstructure is analysed, the influences of external conditions, including curing conditions and the environment, on the RC performance are discussed, and the current research progress in single-component and multicomponent modifications and optimization of the structural design of cement-based materials is summarized.

Compared with previous RC materials, cement-based materials have the advantages of low cost, superior performance, and a wide range of applications and have great application prospects. Moreover, their high emissivity, complexity, and adjustability can make high-efficiency RC possible, which has great potential for development. Although studies have shown that cement-based materials are comparable to some advanced optical materials in terms of the radiation performance, the cooling efficiency and enhancement of the cooling in practical applications need to be further explored in the future, and potential application scenarios to mitigate the urban heat island effect, greenhouse effect, and energy consumption need to be found. There is still a long way to go before the practical application of RC technology with cement-based materials can be promoted, as effective results have only been achieved in laboratory research and development. To realize its large-scale application, the long-term performance and durability of the materials under real conditions still need to be assessed, and perfect test standards and evaluation systems need to be established.

-

Funding information: This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52478281), Ningbo Public Welfare Research Project (Grant No. 2024S077), and International Sci-tech Cooperation Projects under the “Innovation Yongjiang 2035” Key R&D Programme (Grant No. 2024H019).

-

Author contributions: LY: methodology, visualization, validation, investigation, formal analysis, data curation, writing – original draft, and writing – review and editing. XY: conceptualization, visualization, validation, investigation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, supervision, writing – original draft, and writing – review and editing. HC: methodology, writing – review and editing, and validation. MJ: writing – review and editing, resources, and validation. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Fang, J., J. Zhu, S. Wang, C. Yue, and H. Shen. Global warming, human-induced carbon emissions, and their uncertainties. Science China Earth Sciences, Vol. 54, No. 10, 2011, pp. 1458–1468.10.1007/s11430-011-4292-0Search in Google Scholar

[2] AIE. The future of cooling: Opportunities for energy-efficient air conditioning. Agence internationale de l'énergie, International Energy Agency, Paris, 2018.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Mooney, C. and B. Dennis. The world is about to install 700 million air conditioners. Here’s what that means for the climate. Washington Post [Internet], 2016.Search in Google Scholar

[4] The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Report “Buildings and climate change: Status, challenges and opportunities”. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal [Internet], 2007.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Levasseur, A. Climate change. Life cycle impact assessment, M. Z. Hauschild, and M. A. J. Huijbregts, eds, Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2015, pp. 39–50.10.1007/978-94-017-9744-3_3Search in Google Scholar

[6] Zevenhoven, R. and M. Falt. Radiative cooling through the atmospheric window: A third, less intrusive geoengineering approach. Energy, Vol. 152, 2018, pp. 27–33.10.1016/j.energy.2018.03.084Search in Google Scholar

[7] Granqvist, C. Radiative heating and cooling with spectrally selective surfaces. Applied Optics, Vol. 20, No. 15, 1981, pp. 2606–2615.10.1364/AO.20.002606Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Rephaeli, E., A. Raman, and S. Fan. Ultrabroadband photonic structures to achieve high-performance daytime radiative cooling. Nano Letters, Vol. 13, No. 4, 2013, pp. 1457–1461.10.1021/nl4004283Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Hu, M., G. Pei, L. Li, R. Zheng, J. Li, and J. Ji. Theoretical and experimental study of spectral selectivity surface for both solar heating and radiative cooling. International Journal of Photoenergy, Vol. 2015, 2015, id. 807875.10.1155/2015/807875Search in Google Scholar

[10] Delgado, M. G., J. S. Ramos, and S. A. Domínguez. Using the sky as heat sink: Climatic applicability of night-sky based natural cooling techniques in Europe. Energy Conversion and Management, Vol. 225, 2020, id. 113424.10.1016/j.enconman.2020.113424Search in Google Scholar

[11] Catalanotti, S., V. Cuomo, G. Piro, D. Ruggi, V. Silvestrini, and G. Troise. The radiative cooling of selective surfaces. Solar Energy, Vol. 17, No. 2, 1975, pp. 83–89.10.1016/0038-092X(75)90062-6Search in Google Scholar

[12] Lushiku, E. and C. Granqvist. Radiative cooling with selectively infrared-emitting gases. Applied Optics, Vol. 23, No. 11, 1984, pp. 1835–1843.10.1364/AO.23.001835Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Granqvist, C. and A. Hjortsberg. Radiative cooling to low-temperatures - general-considerations and application to selectively emitting sio films. Journal of Applied Physics, Vol. 52, No. 6, 1981, pp. 4205–4220.10.1063/1.329270Search in Google Scholar

[14] Eriksson, T. S., S. J. Jiang, and C. G. Granqvist. Surface coatings for radiative cooling applications: Silicon dioxide and silicon nitride made by reactive rf-sputtering. Solar Energy Materials, Vol. 12, No. 5, 1985, pp. 319–325.10.1016/0165-1633(85)90001-2Search in Google Scholar

[15] Mihalakakou, G., A. Ferrante, and J. O. Lewis. Cooling potential of a metallic nocturnal radiator. Energy and Buildings, Vol. 28, No. 3, 1998, pp. 251–256.10.1016/S0378-7788(98)00006-1Search in Google Scholar

[16] Nilsson, T., G. Niklasson, and C. Granqvist. A solar reflecting material for radiative cooling applications - ZnS pigmented polyethylene. Solar Energy Materials & Solar Cells, Vol. 28, No. 2, 1992, pp. 175–193.10.1016/0927-0248(92)90010-MSearch in Google Scholar

[17] Nilsson, T. and G. Niklasson. Radiative cooling during the day - simulations and experiments on pigmented polyethylene cover foils. Solar Energy Materials & Solar Cells, Vol. 37, No. 1, 1995, pp. 93–118.10.1016/0927-0248(94)00200-2Search in Google Scholar

[18] Ge, X. and X. Sun. The influence of radiative cooling and spectral selectivity of radiators on cooling effect. Journal of Solar Energy, Vol. 3, No. 2, 1982, pp. 128–136.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Orel, B., M. Gunde, and A. Krainer. Radiative cooling efficiency of white pigmented paints. Solar Energy, Vol. 50, No. 6, 1993, pp. 477–482.10.1016/0038-092X(93)90108-ZSearch in Google Scholar

[20] Yang, L., Y. Ma, and B. Zhao. Research on the experimental effects of radiative cooling on several materials. Functional Materials, Vol. 39, No. 7, 2008, pp. 1138–1139 + 1143.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Li, J. and Q. Jiang. Experimental study on radiative cooling. Journal of Solar Energy, Vol. 21, No. 3, 2000, pp. 243–247.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Raman, A. P., M. A. Anoma, L. Zhu, E. Rephaeli, and S. Fan. Passive radiative cooling below ambient air temperature under direct sunlight. Nature, Vol. 515, 2014, pp. 540–544.10.1038/nature13883Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Liu, J., Z. Zhou, J. Zhang, W. Feng, and J. Zuo. Advances and challenges in commercializing radiative cooling. Materials Today Physics, Vol. 11, 2019, id. 100161.10.1016/j.mtphys.2019.100161Search in Google Scholar

[24] Zhai, Y., Y. Ma, S. N. David, D. Zhao, R. Lou, G. Tan, et al. Scalable-manufactured randomized glass-polymer hybrid metamaterial for daytime radiative cooling. Science, Vol. 355, 2017, pp. 1062–1066.10.1126/science.aai7899Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Jeong, S. Y., C. Y. Tso, J. Ha, Y. M. Wong, C. Y. H. Chao, B. Huang, et al. Field investigation of a photonic multi-layered TiO2 passive radiative cooler in sub-tropical climate. Renewable Energy, Vol. 146, 2020, pp. 44–55.10.1016/j.renene.2019.06.119Search in Google Scholar