Abstract

In recent years, organic agriculture (OA) has experienced notable growth across European countries. This work aims to enhance understanding of the current state and prospects of the OA sector in Portugal, based on a case study where 13 interviews were conducted with professionals holding master’s degrees in OA, obtained in the School of Agriculture of the Polytechnic University of Coimbra. These interviews followed a full-structured script comprising 23 questions. The results revealed primary challenges in OA, such as education-related hurdles (e.g., lack of qualifications), training obstacles (e.g., shortage of trained individuals transitioning to organic farming (OF), issues related to recognition and career development, and insufficient information targeted at farmers), as well as challenges in OF inputs (e.g., scarcity of organic fertilizers, organic seeds, and biopesticides), market issues (e.g., difficulties in finding market channels), and financial vectors (e.g., lack of support). This study is limited by its small convenience sample, so findings should be interpreted with caution and are not fully generalizable. According to our case study results, the future development of OA in Portugal relies on effectively addressing these challenges through a multi-actor, transdisciplinary approach that involves farmers, consumers, educational and research institutions, and public and private sector stakeholders.

1 Introduction

The intergovernmental standardization organization Codex Alimentarius Commission (2007) defines organic agriculture (OA) as a holistic production management system which promotes and enhances agroecosystem health, including biodiversity, biological cycles, and soil biological activity [1].

According to its core principles of health, ecology, fairness, and care, organic farming (OF) is committed to respecting the environment and promoting biodiversity. This commitment entails prohibiting the use of synthetic chemicals and genetically modified organisms [2].

The values of OF, and therefore its norms and standards, are process-orientated and not product-orientated. In other words, they are based on the cultivation process and not specifically on the product [3]. Conversely, it embraces techniques such as crop rotation and natural pest control [4], using sideration by incorporating legumes as nitrogen-fixing plants and cover crops to enhance soil fertility. Moreover, there is a preference for local plant varieties and animal breeds adapted to the specific climate and region, with a focus on promoting animal health and welfare [5]. Besides, soil under organic cultivation boasts approximately 30% more biodiversity compared to conventionally farmed soil [6].

Given the increasing emphasis on sustainable food systems and the transition toward OF [7], there remains a critical gap in understanding how stakeholders perceive and engage with these strategic guidelines. While previous research has explored the economic and environmental benefits of OA [8,9], limited studies have systematically assessed stakeholders’ awareness, attitudes, and perceived barriers in the implementation of these policies at the national level in Portugal. Addressing this research gap is essential for ensuring effective policy implementation and achieving the ambitious OA targets set by the European Union (EU). As part of its Farm to Fork Strategy and European Green Deal, the EU has set a target for at least 25% of organic Utilized Agricultural Area (UAA) by 2030, as outlined in the EU Action Plan for Organic Production [10].

Research extensively covers farmers’ perceptions of OA [11–16], yet studies focusing on professionals with specialized master’s degrees in OA seem to be nonexistent. Although studies have investigated university students’ perceptions of OA or organic products [17,18], we have not found publications specifically focusing on master’s graduates specialized in OA, highlighting a significant research gap that our study seeks to address. This work aims to enhance understanding of the current scenario and provide insights for the future of the OA sector in Portugal, from the perspective of professionals holding a master’s degree specifically in OA.

2 Materials and methods

For this research, data protection measures were implemented to ensure compliance with European Union legal regulations. The study obtained prior approval from the Ethics Committee of the Polytechnic University of Coimbra (reference No 81_A_CEIPC/2021), where the Coimbra Agriculture School (Escola Superior Agrária de Coimbra, abbreviated as ESAC) is one of the six schools. ESAC is located in the city of Coimbra, Portugal. This is a cross-sectional and exploratory descriptive study based on structured interviews, designed as a single case study in which one case is examined, with the unit of analysis being the entire case as a single unit [19].

The case study protocol adopted included: research question and hypotheses, research methods, permission seeking, ethical considerations, interpretation process, and main outputs achieved [20].

Across this article, the expression “OA sector” is used to refer to OF activities, including policy, production, innovation, distribution, and all relevant stakeholders involved in the organic value chain; within this context, the study aims to investigate master’s graduates’ perspectives on key policy initiatives in OA, contributing to a deeper understanding of the facilitators and barriers to its adoption in Portugal.

Specifically, the research was guided by the following hypotheses:

H1: Master’s graduates in OA from ESAC, who participated in this case study, perceive the 25% target for organic UAA in the EU by 2030 as challenging due to structural and economic constraints. H2: From the point of view of the Master’s graduates in OA from ESAC, who participated in this case study, the effectiveness of policies is impacted because organic farmers are not sufficiently informed about the support measures for OA. H3: For the master’s graduates in OA from ESAC, who participated in this case study, the adoption of OA is influenced by economic and policy-related factors, including subsidies, certification and bureaucracy complexity, and market uncertainty.

Interviews were conducted in 2021 and 2023 with alumni of ESAC who pursued a Master of Science degree in OA. In total, 35 students finished their studies, and 22 individuals agreed to be contacted, and from them, 13 agreed to participate, representing 59.1% of all graduates who completed the master’s program between the 2011/12 and 2021/22 academic years.

The limited number of graduates over this 10-year period is an inherent structural characteristic of the field rather than a limitation of our study. The master’s program opens for enrollment every 2 years. Additionally, OA is a specialized discipline with a naturally small number of master graduates, which reflects both the niche nature of the program and market demand rather than any methodological flaw. A non-probability sampling method using a convenience sample was selected based on potential participants’ availability to participate in the study [21,22]. In fact, a convenience sample is cost-effective, time-efficient, and straightforward [23].

To collect data for the research, a comprehensive list of alumni from the Master’s in OA program at ESAC was meticulously compiled. Contact was established with these individuals through email and social networks, where they were briefed on the research’s purpose and provided with an interview script containing 23 questions (Table 1). The full-structured interviews were conducted virtually, utilizing the Zoom-Colibri® online platform, with each session lasting approximately 30–40 min. All individual and independent interviews were recorded after obtaining each participant’s signed written consent. Verbatim transcriptions were produced for each interview. Each interview set of results was coded with capital letters to guarantee the anonymity of the results. The study adopted a case study approach, as it enables in-depth, multi-faceted exploration of complex issues within their real-life contexts [25].

Set of questions in the interview guide

| Question | Description |

|---|---|

| Q1 | “Please indicate your academic background.” |

| Q2 | “What area do you currently work in? Do you have any connection with OA?” |

| Q3 | “What contribution do you think the Master in OA has made to your personal and professional life?” |

| Q4 | “What was the added value of having developed the master’s dissertation in this area?” |

| Q5 | “Do you often consume organic food?” |

| Q6 | “Are you an advocate of organic products? Why?” |

| Q7 | “Are you concerned about combining your diet with healthier lifestyles, such as physical exercise?” |

| Q8 | “In your view, what are the biggest challenges for a new graduate in OA?” |

| Q9 | “From your perspective, what is missing in the realm of OA in Portugal?” |

| Q10 | “What are the primary obstacles that discourage most young people from considering OA as a promising career path?” |

| Q11 | “Given the recent depopulation and abandonment of rural areas in many regions of the country, resulting in the decline of the agricultural sector, how do you envision the future of the OA in Portugal?” |

| Q12 | “One of the goals set in the Green Deal (May 2020) is to achieve 25% of the EU UAA in OF by 2030. In your perspective, how are we going to achieve this goal?” |

| Q13 | “It is advisable to rapidly increase the awareness of farmers and rural actors about the support measures for OA (…) - Action Plan for the future of Organic Production in the EU [24]”. “Considering the previous statement, the question is: are the organic farmers well informed and aware of the existing support measures for their activity or do they need to be better informed?” |

| Q14 | “The farmer is not always a figure valued by society. Can OA help to change the perception how organic farmers in Portugal are evaluated by the society?” |

| Q15 | “Do you consider that people in general are aware of the farmer’s role as an agent of food production that reaches their plate?” |

| Q16 | “As part of the National Strategy for OA, there is a pilot project in the schools of the municipality of Idanha-a-Nova, for the distribution of organic products in public cafeterias. Do you consider that this type of education projects can be a key lever to improve knowledge and confidence in the organic production mode?” |

| Q17 | “With the growing demand for organic food, the risk of non-compliance with the implemented regulation increases. These fraudulent situations will harm the consumer interest and, on the other hand, could distort competition. In this sense, do you think that these aspects could lead to some farmers giving up on organic production?” |

| Q18 | “Portuguese agriculture has been a fundamental pillar in times of crisis. Its firmness was visible, for example, in March 2020, in the confinement period we faced with COVID-19. Is-it time to look at this sector more carefully?” |

| Q19 | “The OA sector faces a global challenge: sustaining the connection of trust with customers and making sure that supply and demand grow steadily. What are the strategies that you consider essential to achieve better results?” |

| Q20 | “Created in 2010, the organic logo is the main tool used by consumers to identify organic products. It is true that there is still confusion between ‘local’ and ‘organic’, especially in municipal markets where products may be displayed with little information. Do you think there are still strategies lacking to get information to society? If yes, please indicate some.” |

| Q21 | “What are the barriers, that you consider, as limiting factors to speed up the implementation of OA projects in Portugal?” |

| Q22 | “What message would you like to leave to the OA sector?” |

| Q23 | “What is your opinion about the statement «The true guardians of nature are farmers» (Newsletter of the Association of Young Farmers of Portugal, August 2019, No. 185)?” |

Content analysis was employed to analyze the interview data. This method allows for qualitative interpretation while also enabling the quantification of data [26]. Thematic analysis was done using the thematic coherence approach [27]. Both approaches, content analysis and thematic analysis, are widely used in qualitative research to identify patterns, meanings, and categories within textual data. Data processing, including descriptive statistics (e.g., percentage calculations), data codification, aggregation, and categorization were performed using Microsoft® Excel® 365 software (version 2310).

2.1 Study context

Organic farmers are an important source of relevant information when it comes to sharing their experience and persuading other farmers to adopt OA [28]. Moreover, OF requires farmers to adopt innovative and sustainable practices in order to safeguard the environment and guarantee the production of healthy food [29]. Cooperation between scientists and stakeholders is therefore important [30].

The combination of techno-economic and agri-ecological-ruralist paradigms provides approaches to more sustainable agriculture. Farmers’ cooperatives, where actual agricultural production takes place on a small scale, but have multiple benefits, such as increased biodiversity and higher agricultural productivity, enhancing dynamic rural and even national economies. On the one hand, by acting collectively, small farmers can take advantage of economies of scale and save on transaction costs. On the other hand, the organization of farmers into cooperatives is a way of integrating both the production in smaller units of the agroecological-ruralist position and the demands for large-scale agriculture of the techno-economic position. Within an online context, an initiative called New Organic Planet is expanding in the Portuguese Madeira Archipelago and has developed the Bioplatform. This platform aims to connect organic producers, certification bodies, consumers, and consultants within the field of OA [31].

There are agricultural practices that use synthetic fertilizers and pesticides in order to maximize crop yields, but contribute to environmental pollution [32]. Many of the environmental concerns about conventional agriculture can already be alleviated by the current OA practices, which play an important role in mitigating greenhouse gas emissions [33]. OF plays a leading role in promoting the sustainability of agricultural systems and is widely recognized at the global level as one of the most scientifically supported and environmentally friendly approaches to preserving the ecological balance of agriculture and natural ecosystems [32,34].

We are currently facing challenges both in terms of fighting climate change and preserving ecosystems. The Organization of the United Nations recognizes that consuming less meat, cultivating the land using fewer chemicals, and protecting forests are the only way to try to control global warming [35]. Common Agricultural Policy for 2023–2027 also aims to adopt a more effective policy in terms of reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the EU, through the “Farm to Fork” strategy – one of the main actions defined in the European Green Deal. The Green Deal sets targets for achieving carbon neutrality by 2050. The “From Plate to Plate” strategy, launched in May 2020, aims to make the EU’s food supply chain more sustainable, so that the food system is fair, healthy, and environmentally friendly [36,37]. An insightful analysis of the progress of Agenda 2030 indicators specific to OA was presented, highlighting both the strengths and weaknesses that are likely to emerge by 2030 if the current trends in these indicators continue in the coming years [38].

In Portugal, the OA sector has experienced significant growth, with official records dating back to 1994. The most remarkable expansion occurred between 2000 and 2006, surging from 50,000 ha to an impressive 214,232 ha [39]. During this period, support was extended through Agri-Environmental Programs, specifically the RURIS Program, influencing the notable increase in Portugal’s OF area. Between 2007 and 2013, changes in the surface area of were observed due to changes in support systems, particularly PRODER, and adjustments in statistical information collection methodologies. There was a significant upsurge in 2017, with the area reaching 253,786 ha [40]. This growth was primarily attributed to the PDR 2020 – OA, the supporting program for OA until 2020 [39]. OF in Portugal demonstrated consistent growth between 2013 and 2020, apart from a slight decrease in 2018 [41].

In 2019, a register of 293,213 ha has evolved in 2020 to 319,540 ha and this value continues to grow [41], which is in line with the strategy of the European Commission’s organic action plan for the EU, in which the Commission will aim to achieve the European Green Deal target of 25% of agricultural land under OF by 2030 [6].

The total number of organic farms in 2019 stood at 290,229, with the specialization in permanent crops seeing the greatest growth in the number of farms, mainly due to farms specializing in nuts and tropical fruits, which increased by 96.7 and 100.2%, respectively. As for livestock, there was a decrease in the number of farms specializing in dairy cattle (−47.3%), sheep and goats (−11.9%), and poultry (−8.8%) [41].

In 2022, the total agricultural area under organic production was already 759,977 hectares (fully converted and under conversion), representing 19.2% of the UAA. Meadows and permanent pastures were the crops that occupied the largest organic agricultural area (71.3%), arable land (19.6%), and permanent crops (9.1%) [40,42]. Figure 1 shows the evolution of the agricultural area under organic production in Portugal, from 2012 to 2022.

![Figure 1

Evolution of the agricultural area under organic production in Portugal (2012–2022) (adapted from APA [40]).](/document/doi/10.1515/opag-2025-0464/asset/graphic/j_opag-2025-0464_fig_001.jpg)

Evolution of the agricultural area under organic production in Portugal (2012–2022) (adapted from APA [40]).

There was a growing trend in agricultural area under organic production, with a 278.4% increase in 2022 compared to 2012, as well as significant gains across all crop groups: 368.2% for arable land, 287.2% for permanent grassland and pasture, and 138.4% for permanent crops [43].

According to the most recent data from Eurostat, available on the Pordata platform, in 2022, Portugal ranked 3rd among the 27 EU countries in terms of area dedicated to OF [44].

Promoting an increasing consumption of organic products will be essential to encourage farmers to convert to OA and increase their profitability and resilience. To this end, the Action Plan includes several concrete measures that are intended to introduce demand, maintain consumer confidence, and bring organic food closer to citizens [45]. However, the complexity of legislation with regard to product and packaging labeling is a limiting factor, particularly for processors [33].

Difficulties associated with a lack of information, a shortage of technical support and training on OA techniques, and difficulties in bearing the costs associated with OA are some of the factors that can inhibit the desire to join the organic production system [46]. On the other hand, there are factors that can make it easier for more farmers to join OA, such as the promotion of integrated strategies for agricultural support policies, understanding the specific characteristics of OA and the type and competitiveness of the respective markets; the implementation of effective certification systems and the necessary support for producers; easy access to import and export markets; the establishment of production and marketing rules; support for marketing and processing; and consumer information and the creation of marketing strategies to promote these products and practices, in relation to farmers with smaller farms. Confidence in OA also depends on farmers’ own confidence. It is essential to create training that is suited to their needs, providing accurate and real information about the difficulties and benefits of this farming system [47].

In Portugal, the Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development (DGADR), through the National Observatory for Organic Production, plays a key role in monitoring and implementing the 2nd Action Plan for the period 2023–2027 [48].

Our study was anchored in three fundamental pillars: the National Strategy for Organic Agriculture (ENAB), the Green Deal, and the Action Plan for the future of organic production in the EU. Accordingly, the interview script encompassed questions aligned with these pivotal documents, addressing specific themes articulated within them.

For example, concerning the ENAB, participants were queried about their opinions on the potential impact of educational projects, such as the pilot initiative introducing organic products in public school cafeterias, and its role in enhancing knowledge and confidence in OA.

In connection with the Green Deal, participants were queried about their perspectives on achieving the ambitious goal set in the Green Deal, aiming for 25% of the EU’s agricultural area dedicated to OA by 2030. Additionally, participants were invited to identify key strategies contributing to sustaining the growth of supply and demand in the OA sector while fostering consumer trust [49].

The interview in our study also included a question aligned with the Action Plan for the future of organic production in the EU, emphasizing the imperative to increase awareness among farmers and rural actors regarding support measures for OA. Participants were asked to share insights into whether organic farmers are adequately informed and aware of existing support measures or if there is a discernible need for improved dissemination of information [24].

Several studies have been conducted to gather information on farmers’ perspectives on OA, as well as on consumers of organic products, as shown in the introduction. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no studies focusing on the views of professionals with a master’s degree specifically in OA. Therefore, our work introduces this novel perspective, providing insights from these actors who also play a significant role in the OF scope in Portugal.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

-

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Polytechnic University of Coimbra (reference No. 81_A_CEIPC/2021, July 22, 2021).

3 Results

Demographic data showed that 46% of the interviewees were female and 54% male. Most of the interviewees had a direct connection between their jobs and the agricultural sector, with several specifically involved in OF. Table 2 shows data on the interviewees (gender, age, and job description) at the time of the interview.

Participants’ demographic data and occupations

| Participant code | Gender | Age | Job description/Occupation |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Female | 46 | Nurse and familiar organic farmer |

| B | Male | 58 | Agronomist and trainer |

| C | Male | 27 | Agricultural producer - Integrated Production System |

| D | Male | — | Syntropic farming trainer and organic producer |

| E | Male | — | Organic farm manager |

| F | Female | 25 | MSc in OA |

| G | Female | 29 | Agricultural technician |

| H | Male | 42 | MSc in OA |

| I | Female | 43 | High school teacher |

| J | Female | 26 | Agricultural science student |

| K | Female | 43 | Marketing technician |

| L | Male | 42 | Organic farmer |

| M | Male | 44 | Industrial maintenance technician |

–Not available.

Table 3 summarizes the gaps identified in the OA sector in Portugal, namely research initiatives, the limited association of producers, inadequate social awareness about OA, insufficient knowledge and dissemination of information, as well as the need to increase the number of specialized technicians. Associativism refers to the capacity of farmers and stakeholders to organize into collaborative networks – such as cooperatives, producer associations, or biodistricts – to collectively manage production, certification, marketing, and advocacy. This collective approach enhances knowledge sharing, resource pooling, and market access [50,51].

Key areas highlighted by the interviewees, encompass critical aspects that need to be addressed within Portugal’s OA sector

| Key areas that require attention, as highlighted by the interviewees, encompass critical aspects that need to be addressed within Portugal’s OA sector | Percentage of answers (%) |

|---|---|

| Associativism | |

|

92 |

| Education, training, and research | |

|

69 |

|

54 |

|

39 |

|

23 |

|

15 |

|

8 |

| Captivate conventional and integrated production farmers | |

|

23 |

| Creation of a network linking schools and farmers | |

|

15 |

|

8 |

| Technical aspects of production | |

|

15 |

| Enhancing the status of organic farmers | 23 |

“Associativism among producers” was identified by the interviewees as an important aspect to improve the OA sector. They emphasized the need for producers to come together and form associations based on collaborative networks, enabling them to share ideas, challenges, and perspectives. This collaboration would allow them to find effective solutions to common problems by drawing upon the experiences of fellow farmers who have encountered similar situations.

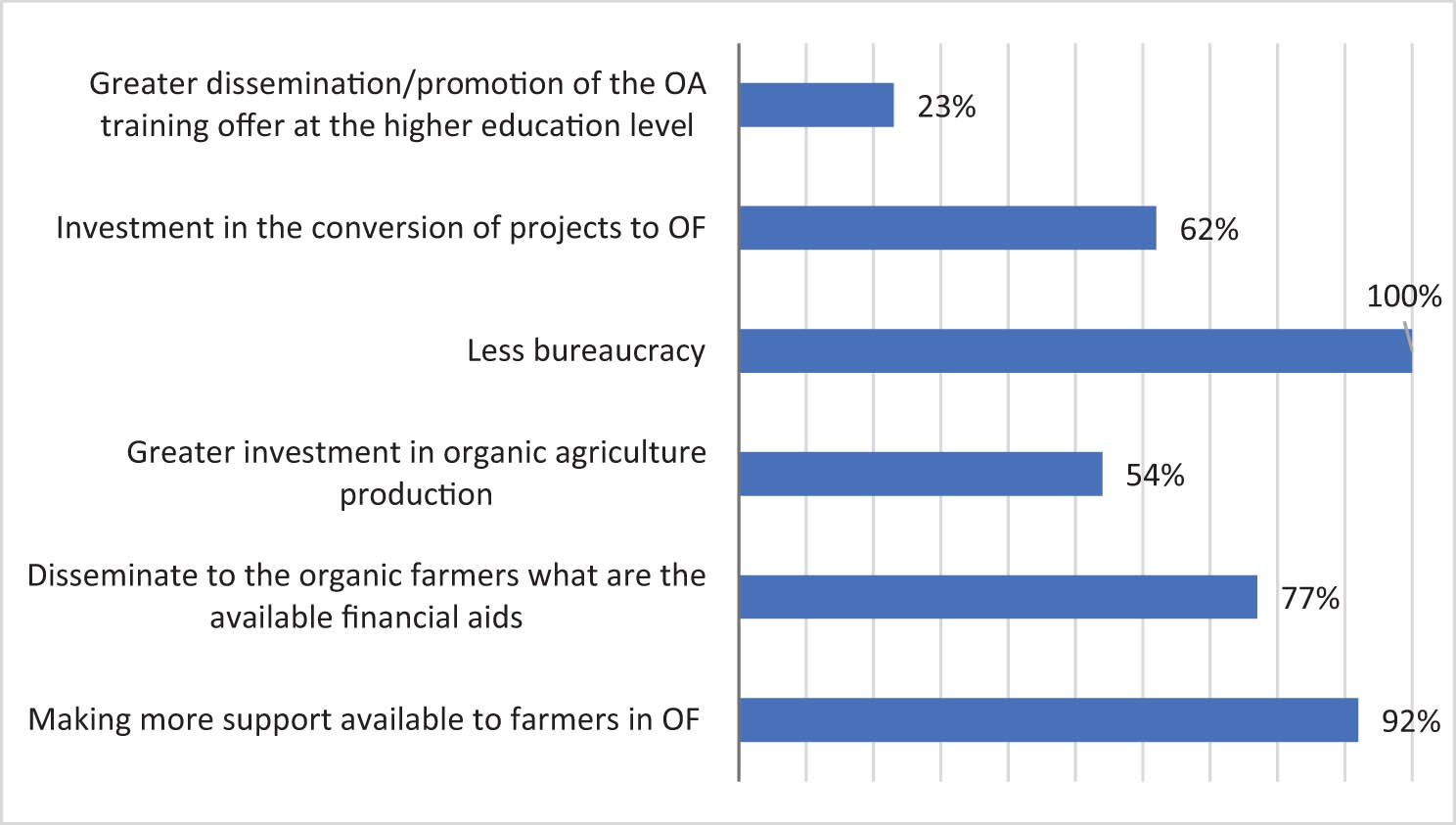

Figure 2 shows all the prospects for achieving the goal of 25% of agricultural area under OA by 2030, a Green Deal target (2020) [52].

List of aspects mentioned by the interviewees to achieve 25% of the agricultural area in OA by 2030.

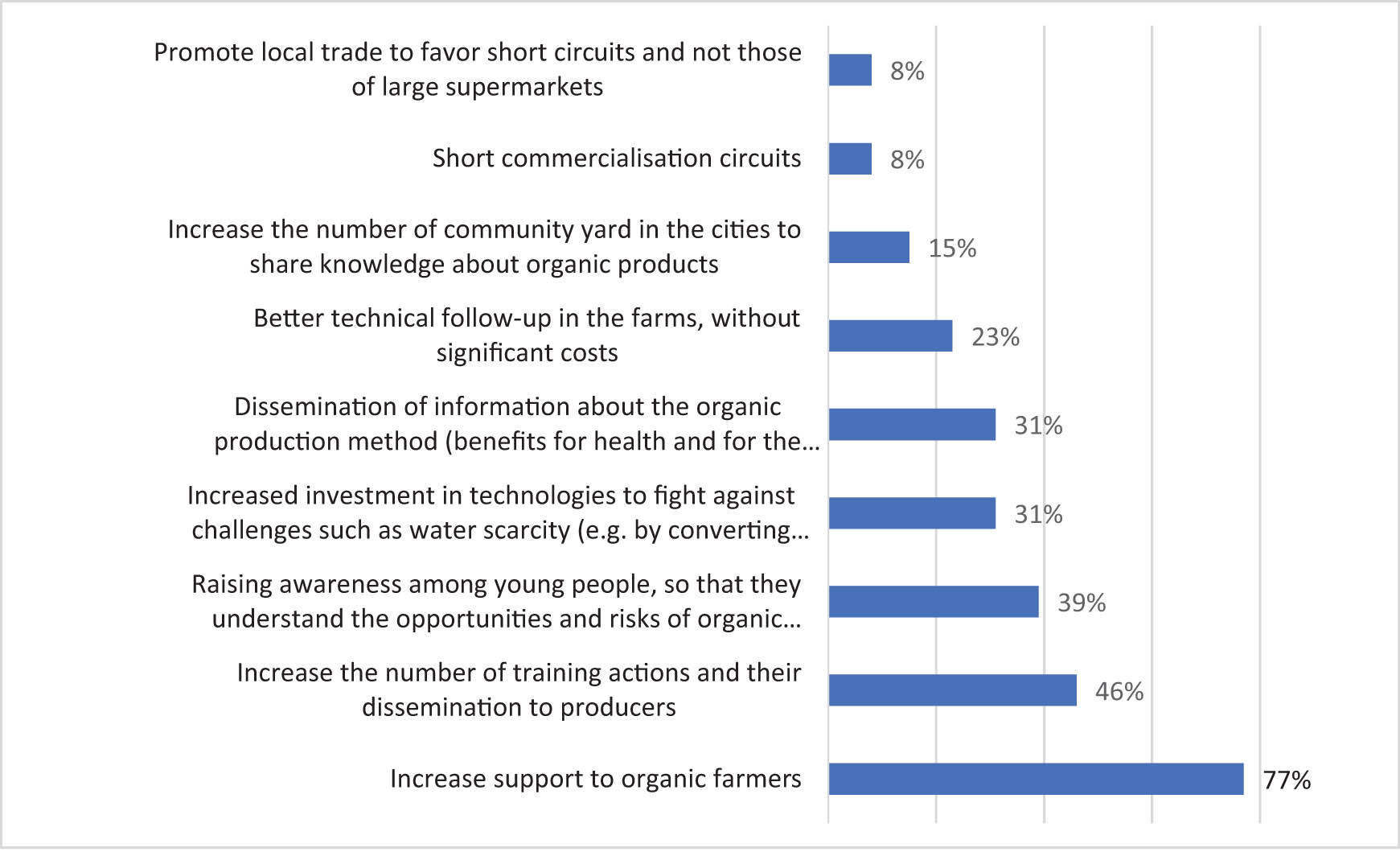

Figure 3 shows the strategies considered essential to guarantee constant growth in supply and demand while maintaining consumer confidence. Where the top-ranked responses were “increase support to organic farmers” (77%), “increase support to organic farmers” (46%), and “raising awareness among young people about OA” (39%).

Examples of strategies for the OA sector to expand and, at the same time, meet consumer demand.

Table 4 presents the limiting aspects to speeding up the implementation of OA projects. The aspects that stood out most in the interviewees’ experience were the lack of support and the lack of information, “… the lack of information is another limiting factor. It should be easier for the farmer to obtain information about OA and to clarify his doubts.”

List of limiting factors in the implementation of OA projects in Portugal, mentioned by the interviewees

| List of limiting factors in the implementation of OA projects in Portugal | Percentage of answers (%) |

|---|---|

| Plant material and equipment | |

|

15 |

|

8 |

| Financial support | |

|

92 |

|

62 |

| Technical support and specialized training | |

|

77 |

| Promotion of OA and legislation | |

|

100 |

|

69 |

|

39 |

| Consumer purchasing power | |

|

85 |

4 Discussion

4.1 Perspectives on factors that influence the OA sector

The 13 full-structured interviews conducted are considered statistically meaningful in qualitative research, as it ensures a significant representation of the studied population while allowing data saturation, a key criterion for robustness in qualitative analysis. Saturation serves as a key indicator that the sample is appropriate for studying the phenomenon, ensuring that the data collected reflects the full diversity, depth, and complexities of the issues being investigated, thereby confirming content validity [53]. Achieving saturation has become a crucial aspect of qualitative research, enhancing the robustness and validity of data collection [54]. Furthermore, saturation is often regarded as the primary assurance of qualitative rigor provided by researchers to reviewers and readers [55].

A recent systematic review showed that 9 to 17 interviews reached saturation, confirming that qualitative studies can reach saturation at relatively small sample sizes [56].

Additionally, prior to the interviews, most respondents were employed in agriculture, with several specifically working in OF, further reinforcing the relevance and credibility of their insights.

Several qualitative studies have been conducted using interviews as the main method of data collection. For example, a semi-structured expert interview study involving eight employees from six purely or partly organic dairies in Germany and Switzerland was conducted in 2023 [57]. Another study, based on nine qualitative interviews with organic farmers in Denmark, was carried out in 2007 [16]. More recently, a study based on 17 in-depth interviews with organic grain farmers in Iowa, USA, was published [15].

In our study, among the 23 questions presented during the interviews, the most relevant ones in the context of this study will be discussed.

According to previous “Study context” section and from our perspective, OA sector development means expanding OF practices, such as using natural fertilizers, crop rotation, use of organic seeds, and avoiding synthetic chemicals; supporting organic farmers through training, funding, or access to markets; creating policies and standards that help the organic sector grow sustainably; and building awareness and demand for organic products among consumers.

In response to Q10 (Table 1) regarding the difficulties that deter young people from considering the OA sector as a promising area, several barriers were identified by the interviewees. These include a lack of knowledge about OA, a scarcity of skilled labor, the high cost of equipment and machinery, the weak purchasing power of organic food by consumers, and misinformation about the sector. However, it is worth noting that one participant (E) mentioned a growing interest among young people in OA, evidenced by the implementation of various projects in the field.

Previous work revealed several factors influencing the OA sector, with the most common obstacles being management issues, national OA policies, cultural barriers, and market uncertainty. These challenges also impact farmers’ decisions to abandon organic production due to economic constraints, certification concerns, technical difficulties, and broader environmental factors. Organic regulations are complex, covering the entire food chain – from production to labeling, control, and imports [33]. Conversely, the reasons why young farmers choose agriculture as a career were studied [58]. The results essentially showed that, although many of the interviewees became young farmers to fulfill a professional ambition, farming remains, for many others, a refuge activity from the lack of professional opportunities on a national scale. It should also be noted that young farmers are more receptive to sustainable practices and, in addition, have the potential to bring innovation and development to regions, in this case study, Trás-os-Montes (Portugal) region.

Agriculture is an unpredictable activity and, as such, there are uncontrollable aspects. In fact, there are significant factors that hinder the adoption of OF practices, namely, weather conditions, floods and landslides, pests, certification systems, and marketing problems. Farmers are less likely to adopt OF when they face uncontrollable problems. Profit and productivity are also factors that do not motivate farmers to switch to OF, due to a lack of markets and subsidies, for example. However, it is important to note that OF has increased productivity and return on costs, for which more evidence and research is needed [28].

In fact, organic products stand out from conventional products because they are richer in nutrients and are free from pesticide residues. At a time when public health is on the agenda, it is important to note that OF helps to slow down the growing health crisis caused by the dangerous spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Most people have an unfavorable perception of the use of pesticides and other chemicals in conventional agriculture, and this is an opportunity to boost OF (increase consumption of organic products) [34].

A recent review highlighted the potential health benefits of organic food consumption, including a reduced risk of developing non-Hodgkin lymphoma and colorectal cancer, lower obesity rates and body mass index, improved blood nutrient composition, and decreased risks of maternal obesity and pregnancy-related preeclampsia risk [59]. Furthermore, the use of fermentation, microbial, and food biotechnological processes, as well as sustainable technologies, was proposed for processing organic foods, aiming to retain desirable nutrients and eliminate undesirable compounds [60].

The interviewees’ future perspective of the OA in Portugal indicates some uncertainty, citing high prices of plant protection products and necessary equipment as potential obstacles. Others mentioned the potential for continued abandonment of small plots and stressed the need for measures such as increased support, land sharing, and land exchanges to drive future demand and investment in OA.

The importance of the adoption of product and process innovations by farmers, as they are fundamental to the competitiveness and differentiation of an agricultural company in the long term, was previously addressed [29]. Adopting this type of innovation, which is essential for achieving sustainability in the medium and long term, will lead to significant structural changes in agricultural businesses. Process innovation in turn improves resource efficiency, promotes the design of sustainable products, and contributes to the quality and range of products on the market. An important aspect is that innovation is expensive and risky and requires appropriate institutions and policies to drive incentives and facilitate the process, as well as the ability to identify the right technology to make adaptations according to economic conditions.

The target groups potentially most likely to adopt OA are young farmers, women, farm owners, those with a high level of education, and those with an off-farm income [28]. Moreover, a study conducted in Austria highlighted the relevance of organic farmers’ profiles, demonstrating that agricultural practices are influenced not only by technical factors and farm structure but also by farmers’ personal values, particularly their attitudes and motivations, which shape their decision-making processes regarding conversion to OF [61]. Multidisciplinary research at the intersection of agricultural and social sciences highlights the need for a dynamic balance crucial to ecological sustainability during the transition to OF. This conversion entails not only biotechnical adjustments but also transformations in farmers’ marketing strategies, values, and social networks. It requires a shift in research focus, from the plot level to the farm or landscape scale, from production to entire food systems, and from crop-specific changes to broader trajectories involving relationships with technology, nature, territory, markets, and consumers. Social sciences contribute essential methodologies that go beyond administrative approaches, emphasizing processes, temporal dimensions, and network dynamics [62].

4.2 Perspectives on the OA future needs

Q11 (Table 1): Of the 13 interviewees, eight (B, C, F, G, I, J, K, and L) indicate that they do not know how the future of the OA in Portugal will be, since the prices of plant protection products approved for OF, tools and other equipment needed in this mode of production are high and this implies a stable financial situation on the part of those who invest to acquire them. One person (E) mentioned that one of the problems that may continue and intensify in the future is the abandonment of small land plots (smallholding). Two interviewees (A, D) referred to the fact that it is necessary to adopt measures so that in the future there will be demand and a greater investment in the farming production system, namely more support (agricultural subsidies), cession of land, and creation of land exchanges.

In a study in the Centre of Portugal, it was found that sometimes producers want to increase the area of their farm, but they find it difficult to find land to rent or buy [47]. This difficulty can be explained by the fact that landowners prefer to leave their properties abandoned, regardless of the amount they can offer to rent or buy the land.

There are several reasons why farmers abandon OF. A study examining the economic and institutional determinants of withdrawal from organic production in Poland offers valuable insights, highlighting how policy uncertainty, insufficient financial incentives, and administrative burdens can significantly influence farmers’ decisions to exit organic systems [63]. Other reasons are related to the market and sales of products, the costs associated with production, the problems inherent in organic production, and personal reasons. There is a relationship between the decision to abandon OF and the demographics of the farmers. Thus, older, educated, and female farmers are more inclined to return to traditional farming. New organic farmers differ from their predecessors in that they are less committed to protecting the environment and are more business oriented. Another aspect that should be taken into account is the importance of subsidies in the decision to opt for OF [63].

In a study focused on farmers already in OF and others considering conversion to OF, in the center region of Portugal, generational renewal and the expansion of farm size were important factors to consider for the advancement of OF. The results also revealed that it is essential to develop training programs tailored to specific needs and to offer accurate and realistic information regarding both the challenges and advantages of OF [47].

The provision of direct support/subsidies strengthens policy decisions has been shown to have a positive impact on conversion to OA [64]. Financial support through agri-environmental and rural development programs has contributed to expanding the organically managed farms and areas under organic production in the EU countries. OA offers many advantages from a policy perspective and could be an important part of strategies that aim to improve the sustainability and equity of the food system [33].

The large-scale implementation of sustainable agricultural practices requires support through public goods (rural infrastructure, storage facilities, machinery), research, credits, insurance, education, and support for farmers’ organizations, cooperatives, and extension services (farmer field schools, farmer networks, or community seed banks). They are crucial to support the expansion of any sustainable agricultural approach, promoting the exchange of knowledge and contributing to social learning [65].

Regarding Q13 (Table 1), there was one participant (E) who showed the perception that there are organic farmers who are better informed than others, as can be seen in the following answer: “Entrepreneurs who have higher studies (bachelor, master, etc.) I believe they have more information about supports and projects. Older farmers, I don’t think they know about these supports. But this is something that is changing. In this agri-environmental issue, there are more people converting their farms to OA because there is support given by the EU, and these producers resort to technicians or associations to get this information.” Through the interviews, it also became clear that subsidies are not always seen as a better approach. “Organic farmers need to be clear about the financial aids. Farm subsidies are associated with corruption and that is false, because whoever is a good manager, uses the farm subsidies (…) because the farm subsidies reward those who perform adequate practices.” It was also mentioned that one way for organic farmers to be aware of the support for their activity is through associations, “One of the things that is also important is the fact that farmers are associated or linked to some association in the area of OA.”

It is recommended to support organic farmers’ efforts in building network relationships with diverse stakeholders in the organic food sector. Farmers need to enhance their knowledge and skills in production technologies and better understand market conditions, as well as the formal and legal procedures relevant to the OF sector [63].

From the perspective of the master’s students in OA involved in our case study, consumer awareness about OA and organic products can be increased through various actions, such as: (i) educating consumers about the benefits of organic products, including their health advantages, environmental sustainability, and the absence of synthetic chemicals; (ii) promoting organic products through advertising, public campaigns, and events; and (iii) encouraging consumers to choose organic options when shopping, thereby increasing demand and supporting organic farmers and businesses.

An interesting example is Agrobio, a non-governmental organization (NGO) founded in Portugal in 1985, to promote OA. It supports both producers and consumers through various initiatives. Its main activities include technical support for organic farmers, training, environmental education, research, promotion of local markets, organization of events, and publication of informative materials [66].

A survey of 262 Polish organic farmers aimed to identify barriers to the development of OF, focusing on production, economic, market, and institutional-regulatory dimensions. Over 80% of respondents rated production risk as very high, and nearly 60% as high, both during and after the conversion process. Most farmers indicated they would continue organic production only if financial support is available. They identified market conditions and institutional-regulatory constraints as the main obstacles to the growth of OF [63]. Rural Development policies have allowed the development of OA, but it is important to emphasize that other strategies are needed, without forgetting that, for the producer, the market is the core of the productive system [64]. More recently, in 2024, a special report about the gaps and inconsistencies hampers the success of the policy about OF in the EU was published [67].

The recent changes to the EU’s regulatory framework for OF, specifically Regulation (EU) 2018/848, which came fully into effect in January 2022, represent a significant transformation for the development of the organic sector across Member States, including Portugal [68]. This new regulation aims to strengthen consumer trust, simplify certification processes, and increase transparency (e.g., not only avoiding the contamination by monitoring control points or phases, but also having a proactive role in an eventual contamination - key factors for the sustainable expansion of the organic market in the EU.

On the one hand, these changes could boost Portugal’s organic sector by harmonizing standards and promoting technological innovation, encouraging producers to adopt more rigorous and sustainable practices, e.g., using organic seeds that are targeted by 100% until 2036 [69]. Furthermore, the inclusion of new rules on small-scale production and specific measures for local farming may support smallholders that represent a significant share of the OA sector in Portugal.

On the other hand, implementing the new regulation could be challenging, due to increased administrative and compliance costs for some producers – particularly small-scale farmers or those transitioning to organic production – which could hinder adoption and competitiveness. Additionally, balancing strict standards with the flexibility needed to accommodate different regional realities remains a debated issue, potentially influencing the pace and extent of standards adoption.

In summary, the new EU regulation has the potential to promote more structured and sustainable growth of the organic sector in Portugal but requires attention to the practical barriers faced by local producers, as well as adequate support policies to ensure an effective and inclusive transition.

4.3 Perspectives on perceptions of OA and farmers

For Q15 (Table 1), with the exception of two interviewees (I and K), all the others consider that society is not yet fully aware of the role of the farmer and one of the reasons given is the fact that agriculture is not well regarded by people in general, “the activity of agriculture in Portugal has always been linked to poverty, creating a cultural problem that is to maintain the idea that those who work in agriculture are those who did not study.” One of the interviewees (C) mentioned that “It is necessary to change the vision that the Portuguese have of farmers and then we have to change the vision of how they see organic farmers. When you hear in Portugal: ‘I am a farmer’, you immediately think that he or she is a ‘poor fellow.’” It is important to highlight another answer (A): “I think that many people still have no idea what agriculture is and how food is produced. For example, during the pandemic everyone kept eating thanks to the farmers who didn’t stop their mission. I don’t think people are aware or know what agriculture is, which means a need to change the perception urgently.” One of the interviewees (G) also mentioned that “I think it used to be worse than it is now, but even so, I think too many people still have no idea what agriculture is, how food is produced. And that urgently needs to change.”

It should also be noted that one of the interviewees (J) considers that it depends a lot on the profile of each person: “I believe that most people do not associate food with the work of the rural producer, especially in the cities.” Students and potential future farmers need to be aware of what the agricultural world is today and what it will be in the future. It is in the first and second cycles of basic education that the focus on introducing agriculture at school should be stimulated. Later, the student may become aware and acquire other types of skills that will lead him to want to deepen his initial knowledge of agriculture [70]. Sustainable agriculture models, which include OF, tend to focus on improving ecological sustainability through specific practices at the farm level. These approaches emphasize reducing chemical inputs, increasing biodiversity and climate resilience, often relying on technological and market-based solutions to improve productivity and sustainability [71].

This study has some limitations, notably the use of a non-probability convenience sampling strategy, which may introduce selection bias, and a relatively small participant group (despite achieving data saturation). These factors, reflecting the niche nature of the OA master’s degree and the case-study design, suggest that the findings should be interpreted with caution and may not be fully generalizable to the broader Portuguese population. Nevertheless, the insights gained offer valuable contributions to understanding the OA sector in Portugal from the perspective of graduates of the OA master’s program from ESAC. In fact, the primary objective of this study was to present the results obtained from a case study involving a group of participants with a shared profile which, to the best of our knowledge, has not previously been the focus of previous research. The study is intended to serve as a replicable model that may be used for comparative purposes in other institutions that offer a master’s degree in OA.

5 Conclusions

The study’s findings confirm that all three initial hypotheses are valid, demonstrating that master’s graduates in OA from ESAC perceive the 25% OA target as challenging, that insufficient dissemination of support measures affects policy effectiveness, and that economic and policy-related factors influence the adoption of OA in Portugal. Five managerial implications are derived from our case study, as outlined below:

Organizations should invest in targeted education and training initiatives that go beyond technical skills. This involves partnering with educational institutions and creating specialized courses that cover both practical and strategic aspects of OA. By doing so, companies, farmer associations, or individual farmers can build a workforce that is both knowledgeable and adaptable to the evolving needs of the organic sector.

It is desirable to promote and support research initiatives aimed at improving organic agricultural practices. Enhanced research efforts can lead to innovations in organic fertilizers, bio-pesticides, and overall farming techniques. This will not only address the current research challenges but also drive long-term improvements in productivity and sustainability.

Given the noted difficulties in finding appropriate market channels, organizations and farmers need to develop robust strategies to improve market access. This could include establishing new distribution networks, leveraging digital platforms, and creating strong brand identities that communicate the unique value of organic products to consumers.

The relatively low level of funding for OA highlights the need for more accessible financial support. Organizations should work with policymakers and stakeholders to advocate for increased funding and reduced bureaucratic hurdles.

Dissemination is crucial for consumers to understand the value chain in OA. Respondents note that consumers are still not well-informed about OA. Therefore, the ongoing and future development and implementation of strategic initiatives to enhance the recognition and dissemination of information about organic products is essential.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the 13 participants who voluntarily took part in the interviews. Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) for the financial support to the Research Centre for Natural Resources, Environment and Society – CERNAS (UIDB/00681).

-

Funding information: This work received financial support from the Polytechnic University of Coimbra within the scope of “Regulamento de Apoio à Publicação Científica dos Trabalhadores do Instituto Politécnico de Coimbra (Despacho no. 4654/2024).”

-

Author contributions: All authors accepted the responsibility for the content of the manuscript and consented to its submission, reviewed all the results, and approved the final version of the manuscript. Conceptualization: G.B., P.M.-M., and C.D.; methodology: P.M.-M., G.B., and C.D.; software: C.D.; investigation: C.D., and G.B.; validation: P.M.-M. and G.B.; formal analysis: C.D.; resources: C.D., P.M.-M., and G.B.; data curation: C.D.; writing – original draft preparation: C.D. and G.B.; writing – review and editing: C.D., P.M.-M., and G.B.; visualization: C.D.; supervision: P.M.-M. and G.B.; project administration: P.M.-M. and G.B.; and funding acquisition: G.B., and P.M.-M.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The original database is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

[1] FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) and WHO (World Health Organization) Codex Alimentarius Commission, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Rome, Italy: World Health Organization. Organically produced foods [Internet]. 3rd edn. (WHO) WHO, (FAO) F and AO of the UN, editors. Rome; 2007. p. 51. https://www.fao.org/4/a1385e/a1385e00.htm.Search in Google Scholar

[2] European Union. Official Journal. 2018 [cited 2024 Nov 5]. Regulation UE 2018/848. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2018/848/oj.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Lammerts Van Bueren E. Which way now for organic seeds and livestock? Ethics of plant breeding: The IFOAM basic principles as a guide for the evolution of organic plant breeding [Internet]. Louis Bolk Institute; 2010. www.ifoam.org.Search in Google Scholar

[4] IFOAM. Health. [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2023 Jun 27]. https://www.ifoam.bio/our-work/what/health.Search in Google Scholar

[5] European Commission. Organic production and organic products. [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jul 2]. https://ec.europa.eu/info/food-farmingfisheries/farming/organic-farming/organic-production-and-products_pt.Search in Google Scholar

[6] European Commission. European green deal. [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jun 29]. https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Lampkin N, Foster C, Padel S, Midmore P. The policy and economic implications of organic farming. Agric Econ. 2022;53(1):45–62.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Reganold JP, Wachter JM. Organic agriculture in the twenty-first century. Nat Plants. 2016;2:15221. https://www.nature.com/articles/nplants2015221.10.1038/nplants.2015.221Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Seufert V, Ramankutty N, Foley JA. Comparing the yields of organic and conventional agriculture. Nature. 2017;485:229–32. https://www.nature.com/articles/nature11069.10.1038/nature11069Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] European Commission. Brussels. 2021 [cited 2025 Jul 17]. Action plan for the development of organic production. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52021DC0141. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52021DC0141.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Leitner C, Vogl CR. Farmers’ perceptions of the organic control and certification process in Tyrol, Austria. Sustain. 2020;12(21):1–18. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/21/9160.10.3390/su12219160Search in Google Scholar

[12] Alotaibi BA, Yoder E, Brennan MA, Kassem HS. Perception of organic farmers towards organic agriculture and role of extension. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2021;28(5):2980–6. 10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.02.037.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Leduc G, Billaudet L, Engström E, Hansson H, Ryan M. Farmers’ perceived values in conventional and organic farming: A comparison between French, Irish and Swedish farmers using the Means-end chain approach. Ecol Econ. 2023;207(Sept 2021):1–12.10.1016/j.ecolecon.2023.107767Search in Google Scholar

[14] Uhunamure SE, Kom Z, Shale K, Nethengwe NS, Steyn J. Perceptions of smallholder farmers towards organic farming in south africa. Agric. 2021;11(11):1–17.10.3390/agriculture11111157Search in Google Scholar

[15] Han G, Grudens-Schuck N. Motivations and challenges for adoption of organic grain production: A qualitative study of Iowa organic farmers. Foods. 2022;11(21):1–20.10.3390/foods11213512Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Risgaard ML, Frederiksen P, Kaltoft P. Socio-cultural processes behind the differential distribution of organic farming in Denmark: A case study. Agric Hum Values. 2007;24(4):445–59.10.1007/s10460-007-9092-ySearch in Google Scholar

[17] Nayak S, Campbell J, Duffey KC. Utilizing Q methodology to explore university students’ perceptions of the organic food industry: The integral role of social media. Front Commun. 2024;9(Aug):1–13.10.3389/fcomm.2024.1414042Search in Google Scholar

[18] Beaudreault AR. Natural: Influences of students’ organic food perceptions. J Food Prod Mark. 2009;15(4):379–91. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10454440802537231?scroll=top&needAccess=true.10.1080/10454440802537231Search in Google Scholar

[19] Yin RK. Case study research - design and methods. 6th edn. United States of America: Sage Publ; 2018.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Rashid Y, Rashid A, Warraich MA, Sabir SS, Waseem A. Case study method: A step-by-step guide for business researchers. Int J Qual Methods. 2019;18:1–13.10.1177/1609406919862424Search in Google Scholar

[21] Etikan I. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am J Theor Appl Stat. 2016;5(1):1–4. https://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/article/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11.10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11Search in Google Scholar

[22] Golzar J, Noor S. Defining convenience sampling in a scientific research. Int J Educ Lang Stud. 2022;1(2):72–7. https://www.ijels.net/article_162981.html.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Stratton SJ. Population research: Convenience sampling strategies. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2021;36(4):373–4. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/prehospital-and-disaster-medicine/article/population-research-convenience-sampling-strategies/B0D519269C76DB5BFFBFB84ED7031267.10.1017/S1049023X21000649Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] European Commission. Communication from the commission to the the council, the european economic and social committee and the committee of the regions. Action plan for the future of organic production in the European Union. [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2022 Nov 9]. p. 2–14. https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/documents_en Search in Google Scholar

[25] Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Anthony Avery AS. The case study approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:1–9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21707982/.10.1186/1471-2288-11-100Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Grbich C. Qualitative data analysis: An introduction. 1st edn. London, UK: Sage Publ; 2007.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, Moules NJ. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods. 2017;16(1):1–13.10.1177/1609406917733847Search in Google Scholar

[28] Sapbamrer R, Thammachai A. A systematic review of factors influencing farmers’ adoption of organic farming. Sustain. 2021 Apr;13(7):1–28.10.3390/su13073842Search in Google Scholar

[29] Rizzo G, Migliore G, Schifani G, Vecchio R. Key factors influencing farmers’ adoption of sustainable innovations: a systematic literature review and research agenda. Org Agric. 2024;14(1):57–84. 10.1007/s13165-023-00440-7.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Velten S, Leventon J, Jager N, Newig J. What is sustainable agriculture? A systematic review. Sustainability. 2015;7(6):7833–65.10.3390/su7067833Search in Google Scholar

[31] Pires R Plataforma de agricultura biológica quer chegar ao mercado ibérico. 2018 [cited 2023 Jun 15]. https://leitor.jornaleconomico.pt/noticia/plataforma-de-agricultura-biologica-quer-chegar-ao-mercado-iberico.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Dhiman V. Organic farming for sustainable environment: Review of existed policies and suggestions for improvement. Int J Res Rev. 2020;7(2):1–22.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Górska-Warsewicz H, Żakowska-Biemans S, Stangierska D, Świątkowska M, Bobola A, Szlachciuk J, et al. Factors limiting the development of the organic food sector-perspective of processors, distributors, and retailers. Agric. 2021;11:1–21. 10.3390/agriculture.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Gamage A, Gangahagedara R, Gamage J, Jayasinghe N, Kodikara N, Suraweera P, et al. Role of organic farming for achieving sustainability in agriculture. Farming Syst. 2023;1(1):1–14. 10.1016/j.farsys.2023.100005.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Associação ACEGIS. Relatório da ONU sobre as alterações climáticas: mudanças no uso dos solos e no consumo alimentar é fundamental. [Internet]. 2024. https://www.acegis.com/2019/08/relatorio-onu-sobre-as-alteracoes-climaticas/.Search in Google Scholar

[36] European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Farm to Fork Strategy for a fair, healthy and environmentally friendly food system. [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2024 Nov 4]. p. 1–22. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PT/TXT/?uri=celex%3A52020DC0381.Search in Google Scholar

[37] European Commission. The European Green Deal sets out how to make Europe the first climate-neutral continent by 2050, boosting the economy, improving people’s health and quality of life, caring for nature, and leaving no one behind [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2024 Mar 16]. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_19_6691.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Pânzaru RL, Firoiu D, Ionescu GH, Ciobanu A, Medelete DM, Pîrvu R. Organic agriculture in the context of 2030 Agenda implementation in European Union countries. Sustainability. 2023;15(13):1–31.10.3390/su151310582Search in Google Scholar

[39] DGADR - Direção-Geral de Agricultura e Desenvolvimento Rural. A produção biológica em Portugal. 2019 [cited 2025 Jun 4]. p. 1–76. https://www.dgadr.gov.pt/images/docs/val/mpb/PT_producao_biologica_1994_2017.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

[40] APA - Agência Portuguesa do Ambiente. Solo e biodiversidade - área agrícola em produção biológica. 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 4]. https://rea.apambiente.pt/content/área-agrícola-em-produção-biológica.Search in Google Scholar

[41] INE - Instituto Nacional de Estatística. Recenseamento Agrícola - Análise dos principais resultados - 2019. Lisbon: Instituto. Lisboa; 2021. p. 29–30.Search in Google Scholar

[42] European Union. No Title. [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 6]. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20240619-3.Search in Google Scholar

[43] European Union. Statistics explained. Developments in organic farming. [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 8]. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Developments_in_organic_farming#Data_sources.Search in Google Scholar

[44] PORDATA - Fundação Francisco Manuel dos Santos. Área de agricultura biológica (%). Qual a percentagem da superfície agrícola utilizada em Portugal que evita químicos como pesticidas e respeita o bem-estar dos animais? [Internet]. 2024. https://www.pordata.pt/pt/estatisticas/ambiente/outros-indicadores-de-ambiente/area-de-agricultura-biologica?_gl=1*r47pfj*_up*MQ.*_ga*MTc2MTA2OTczLjE3NDkyNTIxNTI.*_ga_HL9EXBCVBZ*czE3NDkyNTIxNTIkbzEkZzAkdDE3NDkyNTIxNTIkajYwJGwwJGgw.Search in Google Scholar

[45] European Commission. Commission communication: Action plan for the development of organic production in the EU. 2021 [cited 2024 Feb 3]. Action plan for organic production in the EU. https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/farming/organic-farming/organic-action-plan_en.Search in Google Scholar

[46] Parente C, Gomes M, Amaro C, Pais C, Correia HE, Costa DT. Adesão e resistência a práticas de agricultura biológica entre agricultores familiares: Reflexões a partir de uma abordagem com grupos focais. I Congr Luso-Brasileiro Hortic. Sessão Vitic 29 ACTAS Port Hortic 1a EDIÇÃO [Internet] Lisbon, Portugal: I CLBHort 2017, APH, ABH; 2018. p. 472–83. https://hdl.handle.net/10216/117577.Search in Google Scholar

[47] Bulha J, Mendes D, Ferreira S, DaSilva FG, de Fátima Oliveira M. Agricultura biológica na Região Centro de Portugal: sub-região da Beira Litoral e no Vale do Lis. Rev Econ e Sociol Rural. 2021;59(1):1–21.10.1590/1806-9479.2021.238880Search in Google Scholar

[48] DGADR - Direção-Geral da Agricultura e Desenvolvimento Rural. Recolher, Tratar e Divulgar. [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 7]. https://producaobiologica.pt/.Search in Google Scholar

[49] European Commission. Organic action plan [Internet]. [cited 2024 Nov 11]. https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/farming/organic-farming/organic-action-plan_en.Search in Google Scholar

[50] Asai M, Langer V. Collaborative partnerships between organic farmers in livestock-intensive areas of Denmark. Org Agric. 2014;4(1):63–77.10.1007/s13165-014-0065-3Search in Google Scholar

[51] Sánchez-Navarro JL, Arcas-Lario N, Bijman J, Hernández-Espallardo M. The role of agricultural cooperatives in mitigating opportunism in the context of complying with sustainability requirements: empirical evidence from Spain. Agric Food Econ. 2024;12(1):1–24. 10.1186/s40100-024-00332-8.Search in Google Scholar

[52] European Commission. The European green deal striving to be the first climate-neutral continent [Internet]. [cited 2024 Nov 8]. https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en.Search in Google Scholar

[53] Francis JJ, Johnston M, Robertson C, Glidewell L, Entwistle V, Eccles MP, et al. What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol Health. 2009;25(10):1229–45. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/08870440903194015.10.1080/08870440903194015Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[54] O’Reilly M, Parker N. ‘Unsatisfactory Saturation’: A critical exploration of the notion of saturated sample sizes in qualitative research. Qual Res. 2013;13(2):190–7. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1468794112446106.10.1177/1468794112446106Search in Google Scholar

[55] Morse MJ. “Data Were Saturated.” Qual Health Res. 2015;25(5):587, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1049732315576699.10.1177/1049732315576699Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[56] Hennink M, Kaiser BN. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Soc Sci Med. 2022;292:114523. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277953621008558?via%3Dihub.10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[57] Borghoff LM, Strassner C, Herzig C. Processors’ understanding of process quality: a qualitative interview study with employees of organic dairies in Germany and Switzerland. Br Food J. 2023;125(8):2949–69.10.1108/BFJ-06-2022-0535Search in Google Scholar

[58] Guerra AI, Lopes JC. Young farmers as innovation enablers in rural areas: The role of the EU’s support in a Portuguese peripheric region, Trás-Os-Montes. Rev Port Estud Reg. 2022;(61):85–103.10.59072/rper.vi61.533Search in Google Scholar

[59] Rahman A, Baharlouei P, Koh EHY, Pirvu DG, Rehmani R, Arcos M, et al. A comprehensive analysis of organic food: Evaluating nutritional value and impact on human health. Foods. 2024;13(2):1–19.10.3390/foods13020208Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[60] Knorr D. Organic agriculture and foods: Advancing process-product integrations. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2023;64(23):8480–92. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/citedby/10.1080/10408398.2023.2200829?scroll=top&needAccess=true.10.1080/10408398.2023.2200829Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[61] Darnhofer I, Schneeberger W, Freyer B. Converting or not converting to organic farming in Austria: Farmer types and their rationale. Agric Hum Values. 2005;22(1):39–52.10.1007/s10460-004-7229-9Search in Google Scholar

[62] Bellon S, Lamine C. Conversion to organic farming: A multidimensional research object at the crossroads of agricultural and social sciences - A review. Sustain Agric. 2009;29:653–72.10.1007/978-90-481-2666-8_40Search in Google Scholar

[63] Łuczka W, Kalinowski S. Barriers to the development of organic farming: A polish case study. Agric. 2020;10(11):1–19.10.3390/agriculture10110536Search in Google Scholar

[64] Kujala S, Hakala O, Viitaharju L. Factors affecting the regional distribution of organic farming. J Rural Stud. 2022 May;92:226–36.10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.04.001Search in Google Scholar

[65] Boix-Fayos C, de Vente J. Challenges and potential pathways towards sustainable agriculture within the European Green Deal. Agric Syst. 2023;207(March 2022):103634. 10.1016/j.agsy.2023.103634 Search in Google Scholar

[66] AGROBIO - Associação Portuguesa de Agricultura Biológica. História. [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 6]. https://agrobio.pt/.Search in Google Scholar

[67] European Union. Organic farming in the EU. Gaps and inconsistencies hamper the success of the policy. 2024.Search in Google Scholar

[68] European Commission. Organic production and labelling of organic products – EU Regulation 2018/848. Official Journal of the European Union.Search in Google Scholar

[69] Padel S, Orsini S, Solfanelli F, Zanoli R. Can the market deliver 100% organic seed and varieties in Europe? Sustain. 2021;13(18):1–13.10.3390/su131810305Search in Google Scholar

[70] Bacalhau TJE. Agricultura na escola – uma área por explorar (na ligação ao currículo). In: Sampaio AS, Dimas B, Diniz E, Morais AF, Moura AR, Gameiro A, et al. editors. CULTIVAR Cadernos de Análise e Prospetiva, no 17 Ensino Agrícola [Internet]. Gabinete d. Lisboa: Gabinete de Planeamento, Políticas e Administração Geral (GPP); 2019. p. 67–72. Available from: file:///C:/Users/Utilizador/Desktop/Artigo Entrevistas - Open Agriculture/Bibliografia/Bacalhau 2019.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

[71] Zhang QF. From sustainable agriculture to sustainable agrifood systems: A comparative review of alternative models. Sustainability. 2024;16(22):1–24.10.3390/su16229675Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Optimization of sustainable corn–cattle integration in Gorontalo Province using goal programming

- Competitiveness of Indonesia’s nutmeg in global market

- Toward sustainable bioproducts from lignocellulosic biomass: Influence of chemical pretreatments on liquefied walnut shells

- Efficacy of Betaproteobacteria-based insecticides for managing whitefly, Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae), on cucumber plants

- Assessment of nutrition status of pineapple plants during ratoon season using diagnosis and recommendation integrated system

- Nutritional value and consumer assessment of 12 avocado crosses between cvs. Hass × Pionero

- The lacked access to beef in the low-income region: An evidence from the eastern part of Indonesia

- Comparison of milk consumption habits across two European countries: Pilot study in Portugal and France

- Antioxidant responses of black glutinous rice to drought and salinity stresses at different growth stages

- Differential efficacy of salicylic acid-induced resistance against bacterial blight caused by Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae in rice genotypes

- Yield and vegetation index of different maize varieties and nitrogen doses under normal irrigation

- Urbanization and forecast possibilities of land use changes by 2050: New evidence in Ho Chi Minh city, Vietnam

- Organizational-economic efficiency of raspberry farming – case study of Kosovo

- Application of nitrogen-fixing purple non-sulfur bacteria in improving nitrogen uptake, growth, and yield of rice grown on extremely saline soil under greenhouse conditions

- Digital motivation, knowledge, and skills: Pathways to adaptive millennial farmers

- Investigation of biological characteristics of fruit development and physiological disorders of Musang King durian (Durio zibethinus Murr.)

- Enhancing rice yield and farmer welfare: Overcoming barriers to IPB 3S rice adoption in Indonesia

- Simulation model to realize soybean self-sufficiency and food security in Indonesia: A system dynamic approach

- Gender, empowerment, and rural sustainable development: A case study of crab business integration

- Metagenomic and metabolomic analyses of bacterial communities in short mackerel (Rastrelliger brachysoma) under storage conditions and inoculation of the histamine-producing bacterium

- Fostering women’s engagement in good agricultural practices within oil palm smallholdings: Evaluating the role of partnerships

- Increasing nitrogen use efficiency by reducing ammonia and nitrate losses from tomato production in Kabul, Afghanistan

- Physiological activities and yield of yacon potato are affected by soil water availability

- Vulnerability context due to COVID-19 and El Nino: Case study of poultry farming in South Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Wheat freshness recognition leveraging Gramian angular field and attention-augmented resnet

- Suggestions for promoting SOC storage within the carbon farming framework: Analyzing the INFOSOLO database

- Optimization of hot foam applications for thermal weed control in perennial crops and open-field vegetables

- Toxicity evaluation of metsulfuron-methyl, nicosulfuron, and methoxyfenozide as pesticides in Indonesia

- Fermentation parameters and nutritional value of silages from fodder mallow (Malva verticillata L.), white sweet clover (Melilotus albus Medik.), and their mixtures

- Five models and ten predictors for energy costs on farms in the European Union

- Effect of silvopastoral systems with integrated forest species from the Peruvian tropics on the soil chemical properties

- Transforming food systems in Semarang City, Indonesia: A short food supply chain model

- Understanding farmers’ behavior toward risk management practices and financial access: Evidence from chili farms in West Java, Indonesia

- Optimization of mixed botanical insecticides from Azadirachta indica and Calophyllum soulattri against Spodoptera frugiperda using response surface methodology

- Mapping socio-economic vulnerability and conflict in oil palm cultivation: A case study from West Papua, Indonesia

- Exploring rice consumption patterns and carbohydrate source diversification among the Indonesian community in Hungary

- Determinants of rice consumer lexicographic preferences in South Sulawesi Province, Indonesia

- Effect on growth and meat quality of weaned piglets and finishing pigs when hops (Humulus lupulus) are added to their rations

- Healthy motivations for food consumption in 16 countries

- The agriculture specialization through the lens of PESTLE analysis

- Combined application of chitosan-boron and chitosan-silicon nano-fertilizers with soybean protein hydrolysate to enhance rice growth and yield

- Stability and adaptability analyses to identify suitable high-yielding maize hybrids using PBSTAT-GE

- Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria-mediated rock phosphate utilization with poultry manure enhances soil nutrient dynamics and maize growth in semi-arid soil

- Factors impacting on purchasing decision of organic food in developing countries: A systematic review

- Influence of flowering plants in maize crop on the interaction network of Tetragonula laeviceps colonies

- Bacillus subtilis 34 and water-retaining polymer reduce Meloidogyne javanica damage in tomato plants under water stress

- Vachellia tortilis leaf meal improves antioxidant activity and colour stability of broiler meat

- Evaluating the competitiveness of leading coffee-producing nations: A comparative advantage analysis across coffee product categories

- Application of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum LP5 in vacuum-packaged cooked ham as a bioprotective culture

- Evaluation of tomato hybrid lines adapted to lowland

- South African commercial livestock farmers’ adaptation and coping strategies for agricultural drought

- Spatial analysis of desertification-sensitive areas in arid conditions based on modified MEDALUS approach and geospatial techniques

- Meta-analysis of the effect garlic (Allium sativum) on productive performance, egg quality, and lipid profiles in laying quails

- Optimizing carrageenan–citric acid synergy in mango gummies using response surface methodology

- The strategic role of agricultural vocational training in sustainable local food systems

- Agricultural planning grounded in regional rainfall patterns in the Colombian Orinoquia: An essential step for advancing climate-adapted and sustainable agriculture

- Perspectives of master’s graduates on organic agriculture: A Portuguese case study

- Developing a behavioral model to predict eco-friendly packaging use among millennials

- Government support during COVID-19 for vulnerable households in Central Vietnam

- Citric acid–modified coconut shell biochar mitigates saline–alkaline stress in Solanum lycopersicum L. by modulating enzyme activity in the plant and soil

- Herbal extracts: For green control of citrus Huanglongbing

- Research on the impact of insurance policies on the welfare effects of pork producers and consumers: Evidence from China

- Investigating the susceptibility and resistance barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) cultivars against the Russian wheat aphid (Diuraphis noxia)

- Characterization of promising enterobacterial strains for silver nanoparticle synthesis and enhancement of product yields under optimal conditions

- Testing thawed rumen fluid to assess in vitro degradability and its link to phytochemical and fibre contents in selected herbs and spices

- Protein and iron enrichment on functional chicken sausage using plant-based natural resources

- Fruit and vegetable intake among Nigerian University students: patterns, preferences, and influencing factors

- Bioprospecting a plant growth-promoting and biocontrol bacterium isolated from wheat (Triticum turgidum subsp. durum) in the Yaqui Valley, Mexico: Paenibacillus sp. strain TSM33

- Quantifying urban expansion and agricultural land conversion using spatial indices: evidence from the Red River Delta, Vietnam

- LEADER approach and sustainability overview in European countries

- Influence of visible light wavelengths on bioactive compounds and GABA contents in barley sprouts

- Assessing Albania’s readiness for the European Union-aligned organic agriculture expansion: a mixed-methods SWOT analysis integrating policy, market, and farmer perspectives

- Genetically modified foods’ questionable contribution to food security: exploring South African consumers’ knowledge and familiarity

- The role of global actors in the sustainability of upstream–downstream integration in the silk agribusiness

- Multidimensional sustainability assessment of smallholder dairy cattle farming systems post-foot and mouth disease outbreak in East Java, Indonesia: a Rapdairy approach

- Enhancing azoxystrobin efficacy against Pythium aphanidermatum rot using agricultural adjuvants

- Review Articles

- Reference dietary patterns in Portugal: Mediterranean diet vs Atlantic diet

- Evaluating the nutritional, therapeutic, and economic potential of Tetragonia decumbens Mill.: A promising wild leafy vegetable for bio-saline agriculture in South Africa

- A review on apple cultivation in Morocco: Current situation and future prospects

- Quercus acorns as a component of human dietary patterns

- CRISPR/Cas-based detection systems – emerging tools for plant pathology