Abstract

Digital terrain model (DTM) has wide-ranging applications in numerous fields, including natural resource management, urban planning, environmental protection, and disaster monitoring. Utilizing LiDAR data to generate DTM is now a mainstream method. In current applications, LiDAR data are still treated as having primarily additive errors; however, studies have shown that it is affected by both additive and multiplicative errors. From the perspective of error theory and surveying adjustment, it is theoretically inappropriate to treat mixed additive and multiplicative errors directly as additive errors, as each error model is based on a distinct theoretical framework. In view of this, we applied the mixed additive and multiplicative error theory to the generation of LiDAR-derived DTM products and validated its accuracy through two real measurement cases and one simulation case. The experimental results demonstrate that the mixed additive and multiplicative errors theory provides higher accuracy than the additive error theory in both DTM fitting and interpolation. This confirms that incorporating the mixed additive and multiplicative error theory into DTM product generation is beneficial.

1 Introduction

Digital terrain model (DTM) enables the digital simulation of ground topography using limited elevation data, offering broad applications across fields such as natural resources management, urban planning, environmental protection, and disaster monitoring. For example, in natural resource management, DTM supports terrain analysis, geological surveys, and water resource management; in urban planning, it assists with three-dimensional modeling of cities, transportation planning, and landscape design; in disaster monitoring, it aids in flood simulation and seismic disaster assessment [1,2,3]. Currently, generating DTM from LiDAR data is a mainstream method [4]. The original LiDAR data comprise ground points and feature points. To generate a DTM, the point cloud data must be filtered, specifically by eliminating the feature points; thus, the primary research focus in generating a DTM involves removing the non-ground points from the point cloud data. Research in this area is documented in previous studies [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. After obtaining the ground points, DTMs are generated using methods such as primary trend surface fitting, secondary trend surface fitting, cubic spline interpolation, and Bezier surfaces [11,13].

The quality of LiDAR data significantly influences the accuracy of the DTM, making it essential to evaluate LiDAR data accuracy. Gillin et al. [14] analyzed the accuracy of radar datasets obtained by the Optech GEMINI Airborne Laser Terrain Mapper using ground checkpoint data, and a difference ranging from 0.7 to 2.10 m was observed between the datasets. Contreras et al. [15] evaluated the accuracy of two LiDAR point cloud datasets collected during the leaf-off season, and the results indicated that the root mean square error (RMSE) of the elevation difference between LiDAR and GPS coordinates was 0.75 m. Sibona et al. [16] comparatively analyzed radar data collected by the Optech™ ALTM 3100 EA LiDAR sensor in a forested area using GPS data, reporting an average elevation difference of approximately 0.10 m and an RMSE of 1.25 m when compared with GPS data. Guerra-Hernández et al. [17] compared the accuracy and effectiveness of point clouds obtained by airborne laser scanners (ALSs) and unmanned aircraft systems (UASs) in detecting and measuring individual tree heights. Kovanič et al. [18] compared the accuracy of point cloud data acquired by the Riegl LMS-Q780 scanner with that from the DJI Phantom 4 Pro UAS. Cățeanu and Ciubotaru [19] evaluated the accuracy of nine commonly used interpolation methods using Riegl LMS-Q560 data with cross-validation. These studies demonstrate the feasibility and effectiveness of using LiDAR data for DTM generation. Scholars have also developed various methods to assess the accuracy of measurement systems and analyze the sources of errors. For instance, Eren and Hoşbaş [20] analyzed measurement precision using a specialized experimental setup designed to monitor structural movements via video cameras or from an error modeling perspective to enhance the accuracy of trend estimation. For example, Erkoç and Doğan [21], in their analysis of altimeter and tide gauge data, found that error modeling played a crucial role in different datasets. Alternatively, machine learning techniques have been incorporated into geographical analysis [22]. All of these studies aim to ensure the accuracy of the data used or to extract more meaningful information from it.

To date, in the aforementioned studies, the algorithms for interpolating to obtain DTMs are based on the additive error model, also known as the Gauss–Markov model. The model is expressed as follows:

or equivalently in matrix form

Stochastic model:

Here,

However, it has been shown that LiDAR data are subject to a mixture of multiplicative and additive errors [1,2,3]. In other words, the accuracy of LiDAR measurements may decrease as the distance increases. However, when field measurements of LiDAR were collected and used to generate DTMs, it was shown in previous studies [23,24] that the accuracy of LiDAR measurements may also depend on the slopes of a terrain. At this juncture, it is clearly inappropriate to apply the additive error theory to this issue [25]. In fact, within geodesy, various datasets are affected by both multiplicative and additive errors, including electronic distance measurement (EDM), global positioning system (GPS), and very long baseline interferometry (VLBI) [26,27]. For these observations, accuracy is typically expressed using the following equation:

Here,

With the notation of the Hadamard’s product of matrices/vectors, model (5) can be rewritten as follows:

Here,

Comparing equations (2) and (6), the function model reveals that the mixed additive and multiplicative error model more accurately represents the observation’s accuracy information than the additive error model does.

Based on the foregoing analysis, this study focuses on the accuracy of the mixed additive and multiplicative error model in DTM applications. The structure of this article is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the principles of the mixed additive and multiplicative error model; Section 3 verifies the model’s accuracy using a DTM case study; and Section 4 briefly summarizes the content of this article.

2 Mixed additive and multiplicative random error model

Equation (6) lists the mixed additive and multiplicative error model expressions. In this study, we only explore the case where

Here,

Assume that

Here

The least-squares solution is unbiased. The weighted least-squares (WLS) criterion is applied to equation (7):

Following the definition of derivatives of a scalar function with respect to a vector (or a matrix) [29], the partial derivative of the function

Here,

According to Theorem 3 in the study of Magnus and Neudecker [29], the matrix

where

Substituting equation (13) into equation (12) yields

Here,

From equation (14), it is evident that the weighted least-squares solution is not analytical and must be obtained numerically through iterative methods; this solution is classified as a biased estimate [28]. The following equation is commonly used for the iterative solution:

The results of Xu et al. [28] indicate that the bias in the weighted least-squares estimates arises solely from the dependence of

solving

where

For computational theory, see refs [30,31,32]. For a detailed description of the mixed additive and multiplicative error model, the reader is referred to refs [25,28].

The algorithm for calculating

| Bias-corrected weighted least-squares algorithms |

|---|

|

1. Initial value: Substitute the observation y and coefficient matrix X into equation (10) to obtain the least-squares solution

|

| 2. Iteration: Use the initial value to perform the following iterative operations: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Stop condition: when

|

|

3. Output: convergence after i iterations, and the solution is

|

3 Cases and analysis

3.1 Case 1

We employ LiDAR data in generating a DTM as a case study to validate the accuracy of the mixed additive and multiplicative error model. Given that LiDAR data are known to exhibit both multiplicative and additive errors, it is implied that the ground points obtained through filtering retain these errors.

The OpenGF dataset is an exceptionally large-scale ground filtering dataset derived from globally available ALS point clouds. The primary objective is to provide high-quality training and testing samples for ground filtering algorithm research, utilizing precisely labeled ground and non-ground point cloud data. The dataset spans an area of over 47 km2 and encompasses nine distinct terrain scenarios from four different countries. Through the integration of globally available ALS point cloud data, OpenGF can rapidly generate large-scale datasets while maintaining data diversity and high quality.

Case 1 utilizes the OpenGF dataset for this study due to the following reasons:

Data scale and diversity: The OpenGF dataset comprises over 542 million accurately labeled point clouds, covering a broad range of terrain scenarios, including urban, mountainous, and vegetation-covered areas, thereby meeting diverse research needs.

High-quality labeling: The point cloud data in the dataset are meticulously labeled to ensure the accuracy of both ground and non-ground points.

Openness and extensibility: The OpenGF dataset is built on open data, making it easily accessible and extendable, and it supports global-scale research and applications. The dataset is available for download at (https://github.com/Nathan-UW/OpenGF).

A mountainous area from the dataset was selected as the case study for this study. The data from this mountainous area are presented in Figure 1.

Mountainous area data (Case 1).

The OpenGF dataset allows for the extraction of ground point data, excluding non-ground points. Figure 1 displays the ground point data from this mountainous area, with non-ground points, such as vegetation, removed. This mountainous region features both gentle and sloping areas, characterized by pronounced changes in relief, making it a complex terrain area. The x-coordinates range from 276,600 to 276,770 m, while the y-coordinates range from 4,868,500 to 4,868,700 m, with a total of 11,578 data points and an average density of 0.34 points per square meter (following the removal of a significant number of non-ground points).

Currently, no academic studies comprehensively analyze the multiplicative and additive errors in ground points obtained from LiDAR data, and analyzing these errors in actual observation data is complex. Therefore, this study will not address the separation of additive and multiplicative errors in the observed data at this stage but will assume the observed data as accurate and proceed by modeling the errors.

In the literature [33,34,35,36,37], the following equation is used for DTM fitting:

The case study in this study also employs the aforementioned formula. The case specifies the standard deviation of the multiplicative error at 0.002 and the additive error at 0.15 m. Data influenced by the multiplicative and additive errors are depicted in Figure 2.

Experimental data affected by errors.

From the analysis above, treating LiDAR noise as an additive error aligns with the least-squares solution described in this study, as the formulas are consistent. Considering that both multiplicative and additive errors are involved, this approach corresponds to the bias-corrected weighted least-squares solution. To compare the accuracy of the two algorithms, three indices – MSE, MAE, and R 2 (coefficient of determination) – are selected as the evaluation criteria. The formulas for these metrics are as follows:

where

LS method (left) and BC method (right) fitting errors.

Figure 3 (left) illustrates the error generated by applying the additive error model to fit the ground points, with errors ranging within ±10 m, the majority of which are concentrated within ±5 m. Figure 3 (right) illustrates the error generated by applying the mixed additive and multiplicative error model to fit the ground points, with errors also within ±10 m, most of which are concentrated in the ±5 m range. A comparison of Figure 3 (left and right) reveals that it is difficult to intuitively determine which model is more accurate based solely on the graphs. Since the fitting errors of both algorithms fall within the ±10 m range, this may raise doubts regarding the effectiveness of the algorithms. It is important to note that this study focuses solely on the accuracy of the two algorithms and not the accuracy of the DTM derived from the fitting, as DTM accuracy is influenced by the choice of the fitted model, ground undulation, and the extent of the ground range. As shown in Figure 1, the case area features complex terrain that may be difficult to describe using a standard mathematical formula. Therefore, this study focuses solely on the accuracy of the two algorithms in the context of the selected fitting model.

Currently, the errors of the two algorithms depicted in Figure 3 are analyzed using three statistical indicators: MSE, MAE, and R 2, and the results are presented in Table 1.

Accuracy statistics of the two algorithms (Case 1)

| Algorithms | MSE (m) | MAE (m) | R 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| LS | 6.2524 | 2.0063 | 0.7980 |

| BC | 4.0660 | 1.5991 | 0.8621 |

From Table 1, for the MSE index, the LS method scores 6.2524 m, while the BC method scores 4.0660 m, indicating higher accuracy for the BC method. For the MAE index, the LS method registers 2.0063 m and the BC method 1.5991 m, further demonstrating the BC method’s superior accuracy. In the R 2 index, the LS method scores 0.7980 compared to 0.8621 for the BC method, confirming the BC method’s better performance. Combining the results of the three indices, the BC method proves more suitable for modeling DTM, suggesting that treating LiDAR data as affected by both multiplicative and additive errors is more valid than considering only additive errors. Utilizing the mixed additive and multiplicative error model enhances the accuracy of processing LiDAR data.

To conduct a more thorough analysis of the accuracy of the two algorithms, a Bland–Altman analysis is performed. The results are presented in Figure 4.

Bland–Altman analysis of LS and BC algorithms (Case 1).

In Figure 4, the mean difference value is −0.0001057, and the limits of agreement value is ±2.844 (95%), which is calculated as 1.96 times the standard deviation. The mean difference line is very close to zero, indicating that the two algorithms exhibit a minimal average deviation overall. However, as shown in the figure, several data points exceed the upper bound of agreement, indicating that while the mean deviation of the two algorithms is small, there is a significant difference between them for certain specific measurements. The primary reason for this is that the mixed additive and multiplicative error fundamentally differs from the additive error, which remains constant regardless of the size of the observations, whereas the mixed additive and multiplicative error is characterized by variations that depend on the size of the observations. As a result, the difference between the two algorithms becomes more pronounced, particularly for larger observations. This represents an inherent methodological difference between the two algorithms.

Based on the analyses presented in Table 1 and Figure 4, the following conclusion can be drawn: the BC algorithm exhibits superior accuracy in DTM fitting compared to the LS method. While the average deviation of both algorithms is small overall, significant differences exist for some specific values.

3.2 Case 2

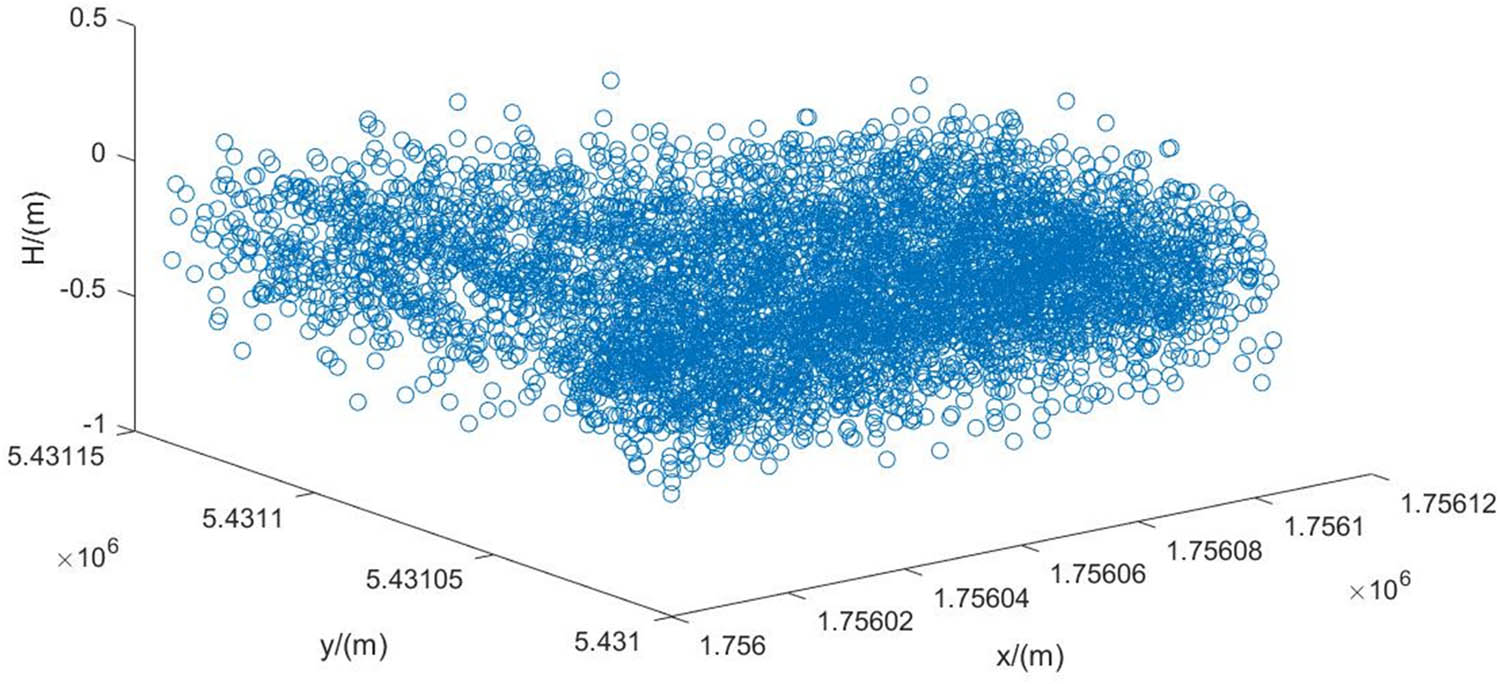

In Case 1, a mountainous area from the OpenGF dataset was used to compare the accuracy of the two models. To further analyze the general applicability of the model proposed in this study across various datasets and terrain types, Case 2 investigates LiDAR data from a gently sloping sandy beach area on Matijou/Sums Island, New Zealand (OpenTopography dataset: https://doi.org/10.5069/G92J692Z). OpenTopography is a platform offering high-resolution, geoscience-oriented terrain data, as well as related tools and resources. Its datasets are characterized by high resolution, quality, diversity, global coverage, and open access. The data types primarily include LiDAR data, global digital elevation models (GDEMs), and other terrain-related data (e.g., derived data such as slope, aspect, and terrain texture information).

The study data for Case 2 are presented in Figure 5, where the x-values range from 1,756,000 to 1,756,108 m, the y-values range from 5,431,000 to 5,431,142 m, and the elevation values range from −1 to 0.5 m, totaling 5,000 data points.

Data for Case 2.

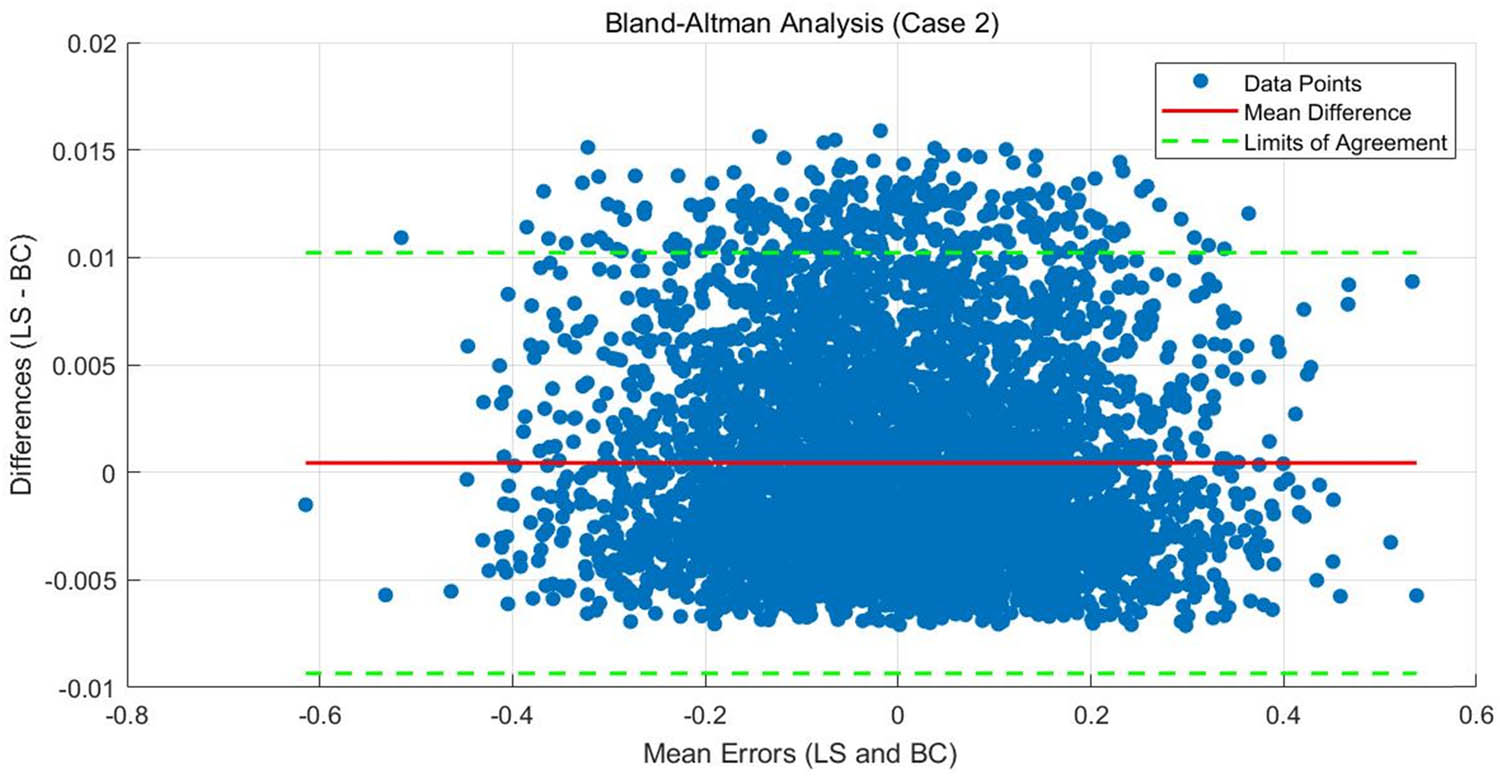

As in Case 1, it is assumed to be influenced by both a multiplicative error with a standard deviation of 0.002 m and an additive error with a standard deviation of 0.15 m. Given that the correct or incorrect selection of the fitting formula impacts the coefficient of determination, only the MSE and MAE values (Table 2) and the Bland–Altman analysis plots (Figure 6) for the two algorithms are considered here.

Accuracy statistics of the two algorithms (Case 2)

| Algorithms | MSE (m) | MAE (m) |

|---|---|---|

| LS | 0.0231 | 0.1213 |

| BC | 0.0225 | 0.1193 |

Bland–Altman analysis of LS and BC algorithms (Case 2).

As shown in Table 2, the MSE values are 0.0231 m for the LS method and 0.0225 m for the BC method, while the MAE values are 0.1213 m for the LS method and 0.1193 m for the BC method. The combined performance of both indices suggests that the BC method is slightly more accurate than the LS method. In comparison to the differences between the two algorithms in MSE and MAE in Case 1, the differences in Case 2 are much smaller. This is primarily because Case 1 is a mountainous area with significant changes in point cloud elevation, while the changes in point cloud elevation in Case 2 are minimal. Additionally, the influence of the multiplicative error is smaller, leading to reduced differences between the two error models.

In Figure 6, the mean difference value is 0.0004, and the limits of agreement are −0.0093 and 0.0102 (95%), which is calculated as 1.96 times the standard deviation. The mean difference line is close to 0, indicating that the two algorithms exhibit a very small average deviation overall. As shown in Figure 6, many data points still exceed the upper bound of consistency, indicating that, despite the small mean deviation of the two algorithms, substantial differences exist for certain specific measurements. This finding is consistent with Case 1, as the mixed additive and multiplicative error is inherently different from the additive error.

Combining the results from Table 1, Figure 4, and Case 1, it can be concluded that the BC algorithm outperforms the LS method in terms of accuracy in both mountainous and flat areas, with a more pronounced accuracy advantage in mountainous areas characterized by large undulations.

3.3 Case 3

In actual production, influenced by ground features, the ground points obtained by filtering are not continuous; instead, they display areas of significant or minor gaps. At such times, interpolation of surrounding ground points is necessary to achieve completeness. The fundamental theory behind the interpolation method assumes that ground points in a region follow a specific functional distribution, which is used to derive the interpolation point information. Since actual measurement data invariably contain errors and their true values are indeterminable, simulated DTM data serve to verify that the mixed additive and multiplicative error model is superior for DTM interpolation compared to the additive error model. It is posited that the DTM data for a region strictly adhere to the following functional model:

The horizontal and vertical coordinates were taken in the range of 1–100 m, in steps of 2 m. The real DTM data of the area were obtained, as shown in Figure 7:

DTM truth value.

It is posited that the DTM for the region, derived from LiDAR data, is influenced by multiplicative errors with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 0.3 m, and by additive errors with a standard deviation of 1.5 m. The DTM derived from LiDAR data is depicted in Figure 8:

DTM disturbed by noise.

Figure 8 illustrates the simulated DTM affected by a combination of multiplicative and additive errors. Compared to the real DTM in Figure 7, the DTM error reaches a maximum of 5,000 m. As shown in Figure 8, the basic characteristics of multiplicative error are evident: as the DTM value increases, the observation error also increases, which fundamentally differs from the traditional additive error model.

It is assumed that points with horizontal and vertical coordinates ranging from 51 to 71 m are feature points which have been filtered out, creating a gap. The corresponding measured data are depicted in Figure 9:

DTM after filtering.

Points within the ellipse in Figure 9 represent gaps resulting from the exclusion of feature points, which require interpolation from the existing data. Interpolation is now performed using the least-squares method based on additive error theory and the method employing a mixed additive and multiplicative error model, respectively. The accuracies of these two algorithms in this region are presented in Table 3.

Comparison of the interpolation accuracy of the two algorithms

| Algorithms | MSE (m) | MAE (m) |

|---|---|---|

| LS | 1032.7296 | 31.8203 |

| BC | 336.2205 | 17.2087 |

From Table 3, the MSE and MAE values for the BC method are lower than those for the LS method, demonstrating the superior overall accuracy of the BC method’s interpolation. This also suggests that the mixed additive–multiplicative error model is more effective for DTM interpolation than the purely additive error model. The regression coefficients calculated by the two algorithms are presented in Table 4:

Regression coefficients for the two algorithms

| Algorithms |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Truth value | 5 | 0.6 | 0.8 | −0.7 | 0.9 | 0.4 |

| LS | 33.6850 | 0.3118 | −1.6588 | −0.7169 | 0.9112 | 0.4340 |

| BC | 5.4462 | 0.3107 | 0.7710 | −0.7035 | 0.8968 | 0.4069 |

Comparing the regression coefficients with the true values in Table 4, it is evident that the coefficients obtained by the BC method more closely align with reality. Synthesizing the results from the three case studies, the BC method, which utilizes the mixed additive and multiplicative error model, demonstrates greater accuracy than the LS method, which relies on the additive error model in both overall DTM fitting and interpolation. This suggests that for processing LiDAR data to obtain DTM, employing the mixed additive and multiplicative error model ensures greater accuracy.

4 Conclusion

When utilizing LiDAR data to obtain DTMs, the current methods predominantly rely on additive error theory. However, it has been established that LiDAR data are influenced by both multiplicative and additive errors, which also affect the resulting DTMs. In the field of geodesy, Xu et al. [28] proposed a mixed additive and multiplicative error model, which we applied to the generation of DTM products using LiDAR data. Following a case study, we reached the following conclusions:

In mountainous regions characterized by significant topographic variation, the LS method yields a mean squared error of 6.2524 m, whereas the BC method yields 4.0660 m. Regarding the mean absolute error, the LS method produces a value of 2.0063 m, while the BC method produces 1.5991 m. In the R 2 index, the LS method achieves 0.7980, whereas the BC method achieves 0.8621. Collectively, these three metrics demonstrate that the BC method outperforms the LS method in regions with complex terrain.

In flat terrain regions, the LS method yields a mean squared error of 0.0231 m, while the BC method yields 0.0225 m. Regarding the mean absolute error, the LS method produces a value of 0.1213 m, whereas the BC method produces 0.1193 m. Based on the performance of these two metrics, the BC method demonstrates marginally superior accuracy compared to the LS method.

Whether in mountainous or flat terrain, Bland–Altman plots reveal fundamental differences between the two error models.

For DTM interpolation, the LS method yields a mean squared error of 1032.7296 m, whereas the BC method yields 336.2205 m. Regarding the mean absolute error, the LS method produces a value of 31.8203 m, while the BC method produces 17.2087 m. Moreover, the regression coefficients obtained through the BC method are more consistent with real-world conditions.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge anonymous reviewers for their thorough reading of this manuscript and for their insightful questions and constructive suggestions, which significantly improved the quality of this article.

-

Funding information: This manuscript was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 41674013).

-

Author contributions: Conceptualization: Guohong Li; methodology: Guohong Li; programming: Xiaohui Song and Khan Rehan; data curation: Huijuan Xin and Guohong Li; writing original draft preparation: Guohong Li; and writing review and editing: Guohong Li and Khan Rehan. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Some or all data, or code generated or used during the study are available from the corresponding author by reasonable request.

References

[1] Flamant PH, Menzies RT, Kavaya MJ. Evidence for speckle effects on pulsed CO2 lidar signal returns from remote targets. Appl Opt. 1984;23(9):1412–7.10.1364/AO.23.001412Search in Google Scholar

[2] Wang JY, Pruitt PA. Effects of speckle on the range precision of a scanning lidar. Appl Opt. 1992;31(6):801–8.10.1364/AO.31.000801Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Hill C, Harris M, Ridley K, Jakeman E, Lutzmann P. Lidar frequency modulation barometers in the presence of speckle. Appl Opt. 2003;42(6):1091–100.10.1364/AO.42.001091Search in Google Scholar

[4] Zhou S, Fan L, Xiang J, Sun J. Island’s DTM generating method based on LIDAR point cloud. J Shandong Univ Sci Technol. 2015;34(3):53–61 (In Chinese).Search in Google Scholar

[5] Zhang K, Chen SC, Whitman D, Shyu ML, Yan J, Zhang C. A progressive morphological filter for removing non ground measurements from air-borne LIDAR data. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2003;41(4):872–82.10.1109/TGRS.2003.810682Search in Google Scholar

[6] Chen Q, Gong P, Baldocchi D, Xie G. Filtering airborne laser scanning data with morphological methods. Photogramm Eng Remote Sens. 2007;73(2):175–85.10.14358/PERS.73.2.175Search in Google Scholar

[7] Meng X, Wang L, Silván-Cárdenas JL, Currit N. A multi-directional ground filtering algorithm for airborne LIDAR. ISPRS J Photogramm Remote Sens. 2009;64(1):117–24.10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2008.09.001Search in Google Scholar

[8] Sithole G, Vosselman G. Experimental comparison of filter algorithms for bare-Earth extraction from airborne laser scanning point clouds. ISPRS J Photogramm Remote Sens. 2004;59(1):85–101.10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2004.05.004Search in Google Scholar

[9] Li Y, Wu H. Filtering airborne LIDAR data based on morphological gradient. J Remote Sens. 2008;12(4):633–9 (In Chinese).Search in Google Scholar

[10] Mongus D, Žalik B. Parameter-free ground filtering of LiDAR data for automatic DTM generation. ISPRS J Photogramm Remote Sens. 2012;67(1):1–12.10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2011.10.002Search in Google Scholar

[11] Maguya AS, Junttila V, Kauranne T. Adaptive algorithm for large scale DTM interpolation from LIDAR data for forestry applications in steep forested terrain. ISPRS J Photogramm Remote Sens. 2013;85:74–83.10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2013.08.005Search in Google Scholar

[12] Xiong J, Fang Y, Deng D. Surface fitting filtering based on least square method from LiDAR data. Sci Surv Mapp. 2013;38(4):74–6 (In Chinese).Search in Google Scholar

[13] Chen J. Terrain feature extraction based on airborne LiDAR point cloud data. Guilin, Guangxi: Guilin University of Technology; 2023 (In Chinese: Master’s Degree Thesis).Search in Google Scholar

[14] Gillin CP, Bailey SW, McGuire KJ, Prisley SP. Evaluation of LiDAR-derived DEMs through terrain analysis and field comparison. Photogramm Eng Remote Sens. 2015;81(5):387–96.10.14358/PERS.81.5.387Search in Google Scholar

[15] Contreras MA, Staats W, Yiang J, Parrott D. Quantifying the accuracy of LiDAR-derived DEM in deciduous eastern forests of the Cumberland Plateau. J Geogr Inf Syst. 2017;9(3):339–53.10.4236/jgis.2017.93021Search in Google Scholar

[16] Sibona E, Vitali A, Meloni F, Caffo L, Dotta A, Lingua E, et al. Direct measurement of tree height provides different results on the assessment of LiDAR accuracy. Forests. 2016;8(1):7–20.10.3390/f8010007Search in Google Scholar

[17] Guerra-Hernández J, Cosenza DN, Rodriguez LCE, Silva M, Tomé M, Díaz-Varela RA, et al. Comparison of ALS-and UAV (SfM)-derived high-density point clouds for individual tree detection in Eucalyptus plantations. Int J Remote Sens. 2018;39(15–16):5211–35.10.1080/01431161.2018.1486519Search in Google Scholar

[18] Kovanič Ľ, Blistan P, Urban R, Štroner M, Blišťanová M, Bartoš K, et al. Analysis of the suitability of high-resolution DEM obtained using ALS and UAS (SfM) for the identification of changes and monitoring the development of selected geohazards in the alpine environment—A case study in high Tatras, Slovakia. Remote Sens. 2020;12(23):3901–18.10.3390/rs12233901Search in Google Scholar

[19] Cățeanu M, Ciubotaru A. Accuracy of ground surface interpolation from airborne laser scanning (ALS) data in dense forest cover. ISPRS Int J Geo-Inf. 2020;9(4):224.10.3390/ijgi9040224Search in Google Scholar

[20] Eren M, Hoşbaş RG. Testing the performance of the video camera to monitor the vertical movements of the structure via a specially designed steel beam apparatus. Meas Sci Rev. 2023;23(1):32–9.10.2478/msr-2023-0004Search in Google Scholar

[21] Erkoç MH, Doğan U. Machine learning models applied to altimetry era tide gauge and grid altimetry data for comparative long-term trend estimation: A study from Shikoku Island, Japan. Appl Ocean Res. 2024;150:104132.10.1016/j.apor.2024.104132Search in Google Scholar

[22] Tun SH, Changnv Z, Jamil F. GIS-based landslide susceptibility assessment using random forest and support vector machine models: A case study of Chin state, Myanmar. Acta Geodyn Geomater. 2024;21(3):207–40.10.13168/AGG.2024.0019Search in Google Scholar

[23] Kraus K, Pfeifer N. Determination of terrain models in wooded areas with airborne laser scanner data. ISPRS J Photogramm Remote Sens. 1998;53:193–203.10.1016/S0924-2716(98)00009-4Search in Google Scholar

[24] Kobler A, Pfeifer N, Ogrinc P, Todorovski L, Oštir K, Džeroski S. Repetitive interpolation: A robust algorithm for DTM generation from Aerial Laser Scanner Data in forested terrain. Remote Sens Environ. 2007;108:9–23.10.1016/j.rse.2006.10.013Search in Google Scholar

[25] Xu P, Shimada S. Least squares parameter estimation in multiplicative noise models. Commun Stat-Simul Comput. 2000;29(1):83–96.10.1080/03610910008813603Search in Google Scholar

[26] Ewing C, Mitchell M. Introduction to geodesy. New York: Elsevier; 1970.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Seeber G. Satellite Geodesy. 2nd edn. Berlin: de Gruyter; 2003.10.1515/9783110200089Search in Google Scholar

[28] Xu P, Shi Y, Peng J, Liu J, Shi C. Adjustment of geodetic measurements with mixed multiplicative and additive random errors. J Geodesy. 2013;87(7):629–43.10.1007/s00190-013-0635-2Search in Google Scholar

[29] Magnus J, Neudecker H. Matrix differential calculus with applications in statistics and econometrics. New York: Wiley; 1988.10.2307/2531754Search in Google Scholar

[30] McCullagh P. Quasi-likelihood functions. Ann Stat. 1983;11:59–67.10.1214/aos/1176346056Search in Google Scholar

[31] McCullagh P, Nelder J. Generalized linear models. 2nd edn. London: Chapman and Hall; 1989.10.1007/978-1-4899-3242-6Search in Google Scholar

[32] Dennis J, Schnabel R. Numerical methods for unconstrained optimization and nonlinear equations. In SIAM classics in applied mathematics, Philadelphia. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc.; 1983.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Wang L, Chen T. Virtual observation iteration solution and A-optimal design method for ill-posed mixed additive and multiplicative random error model in geodetic measurement. J Surv Eng. 2021;147(4):04021016.10.1061/(ASCE)SU.1943-5428.0000363Search in Google Scholar

[34] Wang L, Chen T. The SUT method for precision estimation of mixed additive and multiplicative random error model. Acta Geod Cartogr Sin. 2022;51(11):2303–16 (In Chinese).Search in Google Scholar

[35] Wang L, Chen T, Zhou C. Weighted least squares regularization iteration solution and precision estimation for ill-posed multiplicative error model. Acta Geod Cartogr Sin. 2021;50(5):589–99 (In Chinese).Search in Google Scholar

[36] Shi Y. Least squares parameter estimation in additive/multiplicative error models for use in geodesy. Geomat Inf Sci Wuhan Univ. 2014;39(9):1033–7 (In Chinese).Search in Google Scholar

[37] Shi Y, Xu P, Peng J, Shi C, Liu J. Adjustment of measurements with multiplicative errors: error analysis,estimates of the variance of unit weight, and effect on volume estimation from LiDAR-type digital elevation models. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland). 2014;14(1):1249–66.10.3390/s140101249Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Seismic response and damage model analysis of rocky slopes with weak interlayers

- Multi-scenario simulation and eco-environmental effect analysis of “Production–Living–Ecological space” based on PLUS model: A case study of Anyang City

- Remote sensing estimation of chlorophyll content in rape leaves in Weibei dryland region of China

- GIS-based frequency ratio and Shannon entropy modeling for landslide susceptibility mapping: A case study in Kundah Taluk, Nilgiris District, India

- Natural gas origin and accumulation of the Changxing–Feixianguan Formation in the Puguang area, China

- Spatial variations of shear-wave velocity anomaly derived from Love wave ambient noise seismic tomography along Lembang Fault (West Java, Indonesia)

- Evaluation of cumulative rainfall and rainfall event–duration threshold based on triggering and non-triggering rainfalls: Northern Thailand case

- Pixel and region-oriented classification of Sentinel-2 imagery to assess LULC dynamics and their climate impact in Nowshera, Pakistan

- The use of radar-optical remote sensing data and geographic information system–analytical hierarchy process–multicriteria decision analysis techniques for revealing groundwater recharge prospective zones in arid-semi arid lands

- Effect of pore throats on the reservoir quality of tight sandstone: A case study of the Yanchang Formation in the Zhidan area, Ordos Basin

- Hydroelectric simulation of the phreatic water response of mining cracked soil based on microbial solidification

- Spatial-temporal evolution of habitat quality in tropical monsoon climate region based on “pattern–process–quality” – a case study of Cambodia

- Early Permian to Middle Triassic Formation petroleum potentials of Sydney Basin, Australia: A geochemical analysis

- Micro-mechanism analysis of Zhongchuan loess liquefaction disaster induced by Jishishan M6.2 earthquake in 2023

- Prediction method of S-wave velocities in tight sandstone reservoirs – a case study of CO2 geological storage area in Ordos Basin

- Ecological restoration in valley area of semiarid region damaged by shallow buried coal seam mining

- Hydrocarbon-generating characteristics of Xujiahe coal-bearing source rocks in the continuous sedimentary environment of the Southwest Sichuan

- Hazard analysis of future surface displacements on active faults based on the recurrence interval of strong earthquakes

- Structural characterization of the Zalm district, West Saudi Arabia, using aeromagnetic data: An approach for gold mineral exploration

- Research on the variation in the Shields curve of silt initiation

- Reuse of agricultural drainage water and wastewater for crop irrigation in southeastern Algeria

- Assessing the effectiveness of utilizing low-cost inertial measurement unit sensors for producing as-built plans

- Analysis of the formation process of a natural fertilizer in the loess area

- Machine learning methods for landslide mapping studies: A comparative study of SVM and RF algorithms in the Oued Aoulai watershed (Morocco)

- Chemical dissolution and the source of salt efflorescence in weathering of sandstone cultural relics

- Molecular simulation of methane adsorption capacity in transitional shale – a case study of Longtan Formation shale in Southern Sichuan Basin, SW China

- Evolution characteristics of extreme maximum temperature events in Central China and adaptation strategies under different future warming scenarios

- Estimating Bowen ratio in local environment based on satellite imagery

- 3D fusion modeling of multi-scale geological structures based on subdivision-NURBS surfaces and stratigraphic sequence formalization

- Comparative analysis of machine learning algorithms in Google Earth Engine for urban land use dynamics in rapidly urbanizing South Asian cities

- Study on the mechanism of plant root influence on soil properties in expansive soil areas

- Simulation of seismic hazard parameters and earthquakes source mechanisms along the Red Sea rift, western Saudi Arabia

- Tectonics vs sedimentation in foredeep basins: A tale from the Oligo-Miocene Monte Falterona Formation (Northern Apennines, Italy)

- Investigation of landslide areas in Tokat-Almus road between Bakımlı-Almus by the PS-InSAR method (Türkiye)

- Predicting coastal variations in non-storm conditions with machine learning

- Cross-dimensional adaptivity research on a 3D earth observation data cube model

- Geochronology and geochemistry of late Paleozoic volcanic rocks in eastern Inner Mongolia and their geological significance

- Spatial and temporal evolution of land use and habitat quality in arid regions – a case of Northwest China

- Ground-penetrating radar imaging of subsurface karst features controlling water leakage across Wadi Namar dam, south Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- Rayleigh wave dispersion inversion via modified sine cosine algorithm: Application to Hangzhou, China passive surface wave data

- Fractal insights into permeability control by pore structure in tight sandstone reservoirs, Heshui area, Ordos Basin

- Debris flow hazard characteristic and mitigation in Yusitong Gully, Hengduan Mountainous Region

- Research on community characteristics of vegetation restoration in hilly power engineering based on multi temporal remote sensing technology

- Identification of radial drainage networks based on topographic and geometric features

- Trace elements and melt inclusion in zircon within the Qunji porphyry Cu deposit: Application to the metallogenic potential of the reduced magma-hydrothermal system

- Pore, fracture characteristics and diagenetic evolution of medium-maturity marine shales from the Silurian Longmaxi Formation, NE Sichuan Basin, China

- Study of the earthquakes source parameters, site response, and path attenuation using P and S-waves spectral inversion, Aswan region, south Egypt

- Source of contamination and assessment of potential health risks of potentially toxic metal(loid)s in agricultural soil from Al Lith, Saudi Arabia

- Regional spatiotemporal evolution and influencing factors of rural construction areas in the Nanxi River Basin via GIS

- An efficient network for object detection in scale-imbalanced remote sensing images

- Effect of microscopic pore–throat structure heterogeneity on waterflooding seepage characteristics of tight sandstone reservoirs

- Environmental health risk assessment of Zn, Cd, Pb, Fe, and Co in coastal sediments of the southeastern Gulf of Aqaba

- A modified Hoek–Brown model considering softening effects and its applications

- Evaluation of engineering properties of soil for sustainable urban development

- The spatio-temporal characteristics and influencing factors of sustainable development in China’s provincial areas

- Application of a mixed additive and multiplicative random error model to generate DTM products from LiDAR data

- Gold vein mineralogy and oxygen isotopes of Wadi Abu Khusheiba, Jordan

- Prediction of surface deformation time series in closed mines based on LSTM and optimization algorithms

- 2D–3D Geological features collaborative identification of surrounding rock structural planes in hydraulic adit based on OC-AINet

- Spatiotemporal patterns and drivers of Chl-a in Chinese lakes between 1986 and 2023

- Land use classification through fusion of remote sensing images and multi-source data

- Nexus between renewable energy, technological innovation, and carbon dioxide emissions in Saudi Arabia

- Analysis of the spillover effects of green organic transformation on sustainable development in ethnic regions’ agriculture and animal husbandry

- Factors impacting spatial distribution of black and odorous water bodies in Hebei

- Large-scale shaking table tests on the liquefaction and deformation responses of an ultra-deep overburden

- Impacts of climate change and sea-level rise on the coastal geological environment of Quang Nam province, Vietnam

- Reservoir characterization and exploration potential of shale reservoir near denudation area: A case study of Ordovician–Silurian marine shale, China

- Seismic prediction of Permian volcanic rock reservoirs in Southwest Sichuan Basin

- Application of CBERS-04 IRS data to land surface temperature inversion: A case study based on Minqin arid area

- Geological characteristics and prospecting direction of Sanjiaoding gold mine in Saishiteng area

- Research on the deformation prediction model of surrounding rock based on SSA-VMD-GRU

- Geochronology, geochemical characteristics, and tectonic significance of the granites, Menghewula, Southern Great Xing’an range

- Hazard classification of active faults in Yunnan base on probabilistic seismic hazard assessment

- Characteristics analysis of hydrate reservoirs with different geological structures developed by vertical well depressurization

- Estimating the travel distance of channelized rock avalanches using genetic programming method

- Landscape preferences of hikers in Three Parallel Rivers Region and its adjacent regions by content analysis of user-generated photography

- New age constraints of the LGM onset in the Bohemian Forest – Central Europe

- Characteristics of geological evolution based on the multifractal singularity theory: A case study of Heyu granite and Mesozoic tectonics

- Soil water content and longitudinal microbiota distribution in disturbed areas of tower foundations of power transmission and transformation projects

- Oil accumulation process of the Kongdian reservoir in the deep subsag zone of the Cangdong Sag, Bohai Bay Basin, China

- Investigation of velocity profile in rock–ice avalanche by particle image velocimetry measurement

- Optimizing 3D seismic survey geometries using ray tracing and illumination modeling: A case study from Penobscot field

- Sedimentology of the Phra That and Pha Daeng Formations: A preliminary evaluation of geological CO2 storage potential in the Lampang Basin, Thailand

- Improved classification algorithm for hyperspectral remote sensing images based on the hybrid spectral network model

- Map analysis of soil erodibility rates and gully erosion sites in Anambra State, South Eastern Nigeria

- Identification and driving mechanism of land use conflict in China’s South-North transition zone: A case study of Huaihe River Basin

- Evaluation of the impact of land-use change on earthquake risk distribution in different periods: An empirical analysis from Sichuan Province

- A test site case study on the long-term behavior of geotextile tubes

- An experimental investigation into carbon dioxide flooding and rock dissolution in low-permeability reservoirs of the South China Sea

- Detection and semi-quantitative analysis of naphthenic acids in coal and gangue from mining areas in China

- Comparative effects of olivine and sand on KOH-treated clayey soil

- YOLO-MC: An algorithm for early forest fire recognition based on drone image

- Earthquake building damage classification based on full suite of Sentinel-1 features

- Potential landslide detection and influencing factors analysis in the upper Yellow River based on SBAS-InSAR technology

- Assessing green area changes in Najran City, Saudi Arabia (2013–2022) using hybrid deep learning techniques

- An advanced approach integrating methods to estimate hydraulic conductivity of different soil types supported by a machine learning model

- Hybrid methods for land use and land cover classification using remote sensing and combined spectral feature extraction: A case study of Najran City, KSA

- Streamlining digital elevation model construction from historical aerial photographs: The impact of reference elevation data on spatial accuracy

- Analysis of urban expansion patterns in the Yangtze River Delta based on the fusion impervious surfaces dataset

- A metaverse-based visual analysis approach for 3D reservoir models

- Late Quaternary record of 100 ka depositional cycles on the Larache shelf (NW Morocco)

- Integrated well-seismic analysis of sedimentary facies distribution: A case study from the Mesoproterozoic, Ordos Basin, China

- Study on the spatial equilibrium of cultural and tourism resources in Macao, China

- Urban road surface condition detecting and integrating based on the mobile sensing framework with multi-modal sensors

- Application of improved sine cosine algorithm with chaotic mapping and novel updating methods for joint inversion of resistivity and surface wave data

- The synergistic use of AHP and GIS to assess factors driving forest fire potential in a peat swamp forest in Thailand

- Dynamic response analysis and comprehensive evaluation of cement-improved aeolian sand roadbed

- Rock control on evolution of Khorat Cuesta, Khorat UNESCO Geopark, Northeastern Thailand

- Gradient response mechanism of carbon storage: Spatiotemporal analysis of economic-ecological dimensions based on hybrid machine learning

- Comparison of several seismic active earth pressure calculation methods for retaining structures

- Mantle dynamics and petrogenesis of Gomer basalts in the Northwestern Ethiopia: A geochemical perspective

- Study on ground deformation monitoring in Xiong’an New Area from 2021 to 2023 based on DS-InSAR

- Paleoenvironmental characteristics of continental shale and its significance to organic matter enrichment: Taking the fifth member of Xujiahe Formation in Tianfu area of Sichuan Basin as an example

- Equipping the integral approach with generalized least squares to reconstruct relict channel profile and its usage in the Shanxi Rift, northern China

- InSAR-driven landslide hazard assessment along highways in hilly regions: A case-based validation approach

- Attribution analysis of multi-temporal scale surface streamflow changes in the Ganjiang River based on a multi-temporal Budyko framework

- Maps analysis of Najran City, Saudi Arabia to enhance agricultural development using hybrid system of ANN and multi-CNN models

- Hybrid deep learning with a random forest system for sustainable agricultural land cover classification using DEM in Najran, Saudi Arabia

- Long-term evolution patterns of groundwater depth and lagged response to precipitation in a complex aquifer system: Insights from Huaibei Region, China

- Remote sensing and machine learning for lithology and mineral detection in NW, Pakistan

- Spatial–temporal variations of NO2 pollution in Shandong Province based on Sentinel-5P satellite data and influencing factors

- Numerical modeling of geothermal energy piles with sensitivity and parameter variation analysis of a case study

- Stability analysis of valley-type upstream tailings dams using a 3D model

- Variation characteristics and attribution analysis of actual evaporation at monthly time scale from 1982 to 2019 in Jialing River Basin, China

- Investigating machine learning and statistical approaches for landslide susceptibility mapping in Minfeng County, Xinjiang

- Investigating spatiotemporal patterns for comprehensive accessibility of service facilities by location-based service data in Nanjing (2016–2022)

- A pre-treatment method for particle size analysis of fine-grained sedimentary rocks, Bohai Bay Basin, China

- Study on the formation mechanism of the hard-shell layer of liquefied silty soil

- Comprehensive analysis of agricultural CEE: Efficiency assessment, mechanism identification, and policy response – A case study of Anhui Province

- Simulation study on the damage and failure mechanism of the surrounding rock in sanded dolomite tunnels

- Towards carbon neutrality: Spatiotemporal evolution and key influences on agricultural ecological efficiency in Northwest China

- High-frequency cycles drive the cyclical enrichment of oil in porous carbonate reservoirs: A case study of the Khasib Formation in E Oilfield, Mesopotamian Basin, Iraq

- Reconstruction of digital core models of granular rocks using mathematical morphology

- Spatial–temporal differentiation law of habitat quality and its driving mechanism in the typical plateau areas of the Loess Plateau in the recent 30 years

- A machine-learning-based approach to predict potential oil sites: Conceptual framework and experimental evaluation

- Effects of landscape pattern change on waterbird diversity in Xianghai Nature Reserve

- Research on intelligent classification method of highway tunnel surrounding rock classification based on parameters while drilling

- River morphology and tectono-sedimentary analysis of a shallow river delta: A case study of Putaohua oil layer in Saertu oilfield (L. Cretaceous), China

- Dynamic change in quarterly FVC of urban parks based on multi-spectral UAV images: A case study of people’s park and harmony park in Xinxiang, China

- Review Articles

- Humic substances influence on the distribution of dissolved iron in seawater: A review of electrochemical methods and other techniques

- Applications of physics-informed neural networks in geosciences: From basic seismology to comprehensive environmental studies

- Ore-controlling structures of granite-related uranium deposits in South China: A review

- Shallow geological structure features in Balikpapan Bay East Kalimantan Province – Indonesia

- A review on the tectonic affinity of microcontinents and evolution of the Proto-Tethys Ocean in Northeastern Tibet

- Advancements in machine learning applications for mineral prospecting and geophysical inversion: A review

- Special Issue: Natural Resources and Environmental Risks: Towards a Sustainable Future - Part II

- Depopulation in the Visok micro-region: Toward demographic and economic revitalization

- Special Issue: Geospatial and Environmental Dynamics - Part II

- Advancing urban sustainability: Applying GIS technologies to assess SDG indicators – a case study of Podgorica (Montenegro)

- Spatiotemporal and trend analysis of common cancers in men in Central Serbia (1999–2021)

- Minerals for the green agenda, implications, stalemates, and alternatives

- Spatiotemporal water quality analysis of Vrana Lake, Croatia

- Functional transformation of settlements in coal exploitation zones: A case study of the municipality of Stanari in Republic of Srpska (Bosnia and Herzegovina)

- Hypertension in AP Vojvodina (Northern Serbia): A spatio-temporal analysis of patients at the Institute for Cardiovascular Diseases of Vojvodina

- Regional patterns in cause-specific mortality in Montenegro, 1991–2019

- Spatio-temporal analysis of flood events using GIS and remote sensing-based approach in the Ukrina River Basin, Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Flash flood susceptibility mapping using LiDAR-Derived DEM and machine learning algorithms: Ljuboviđa case study, Serbia

- Geocultural heritage as a basis for geotourism development: Banjska Monastery, Zvečan (Serbia)

- Assessment of groundwater potential zones using GIS and AHP techniques – A case study of the zone of influence of Kolubara Mining Basin

- Impact of the agri-geographical transformation of rural settlements on the geospatial dynamics of soil erosion intensity in municipalities of Central Serbia

- Where faith meets geomorphology: The cultural and religious significance of geodiversity explored through geospatial technologies

- Applications of local climate zone classification in European cities: A review of in situ and mobile monitoring methods in urban climate studies

- Complex multivariate water quality impact assessment on Krivaja River

- Ionization hotspots near waterfalls in Eastern Serbia’s Stara Planina Mountain

- Shift in landscape use strategies during the transition from the Bronze age to Iron age in Northwest Serbia

- Assessing the geotourism potential of glacial lakes in Plav, Montenegro: A multi-criteria assessment by using the M-GAM model

- Flash flood potential index at national scale: Susceptibility assessment within catchments

- SWAT modelling and MCDM for spatial valuation in small hydropower planning

- Disaster risk perception and local resilience near the “Duboko” landfill: Challenges of governance, management, trust, and environmental communication in Serbia

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Seismic response and damage model analysis of rocky slopes with weak interlayers

- Multi-scenario simulation and eco-environmental effect analysis of “Production–Living–Ecological space” based on PLUS model: A case study of Anyang City

- Remote sensing estimation of chlorophyll content in rape leaves in Weibei dryland region of China

- GIS-based frequency ratio and Shannon entropy modeling for landslide susceptibility mapping: A case study in Kundah Taluk, Nilgiris District, India

- Natural gas origin and accumulation of the Changxing–Feixianguan Formation in the Puguang area, China

- Spatial variations of shear-wave velocity anomaly derived from Love wave ambient noise seismic tomography along Lembang Fault (West Java, Indonesia)

- Evaluation of cumulative rainfall and rainfall event–duration threshold based on triggering and non-triggering rainfalls: Northern Thailand case

- Pixel and region-oriented classification of Sentinel-2 imagery to assess LULC dynamics and their climate impact in Nowshera, Pakistan

- The use of radar-optical remote sensing data and geographic information system–analytical hierarchy process–multicriteria decision analysis techniques for revealing groundwater recharge prospective zones in arid-semi arid lands

- Effect of pore throats on the reservoir quality of tight sandstone: A case study of the Yanchang Formation in the Zhidan area, Ordos Basin

- Hydroelectric simulation of the phreatic water response of mining cracked soil based on microbial solidification

- Spatial-temporal evolution of habitat quality in tropical monsoon climate region based on “pattern–process–quality” – a case study of Cambodia

- Early Permian to Middle Triassic Formation petroleum potentials of Sydney Basin, Australia: A geochemical analysis

- Micro-mechanism analysis of Zhongchuan loess liquefaction disaster induced by Jishishan M6.2 earthquake in 2023

- Prediction method of S-wave velocities in tight sandstone reservoirs – a case study of CO2 geological storage area in Ordos Basin

- Ecological restoration in valley area of semiarid region damaged by shallow buried coal seam mining

- Hydrocarbon-generating characteristics of Xujiahe coal-bearing source rocks in the continuous sedimentary environment of the Southwest Sichuan

- Hazard analysis of future surface displacements on active faults based on the recurrence interval of strong earthquakes

- Structural characterization of the Zalm district, West Saudi Arabia, using aeromagnetic data: An approach for gold mineral exploration

- Research on the variation in the Shields curve of silt initiation

- Reuse of agricultural drainage water and wastewater for crop irrigation in southeastern Algeria

- Assessing the effectiveness of utilizing low-cost inertial measurement unit sensors for producing as-built plans

- Analysis of the formation process of a natural fertilizer in the loess area

- Machine learning methods for landslide mapping studies: A comparative study of SVM and RF algorithms in the Oued Aoulai watershed (Morocco)

- Chemical dissolution and the source of salt efflorescence in weathering of sandstone cultural relics

- Molecular simulation of methane adsorption capacity in transitional shale – a case study of Longtan Formation shale in Southern Sichuan Basin, SW China

- Evolution characteristics of extreme maximum temperature events in Central China and adaptation strategies under different future warming scenarios

- Estimating Bowen ratio in local environment based on satellite imagery

- 3D fusion modeling of multi-scale geological structures based on subdivision-NURBS surfaces and stratigraphic sequence formalization

- Comparative analysis of machine learning algorithms in Google Earth Engine for urban land use dynamics in rapidly urbanizing South Asian cities

- Study on the mechanism of plant root influence on soil properties in expansive soil areas

- Simulation of seismic hazard parameters and earthquakes source mechanisms along the Red Sea rift, western Saudi Arabia

- Tectonics vs sedimentation in foredeep basins: A tale from the Oligo-Miocene Monte Falterona Formation (Northern Apennines, Italy)

- Investigation of landslide areas in Tokat-Almus road between Bakımlı-Almus by the PS-InSAR method (Türkiye)

- Predicting coastal variations in non-storm conditions with machine learning

- Cross-dimensional adaptivity research on a 3D earth observation data cube model

- Geochronology and geochemistry of late Paleozoic volcanic rocks in eastern Inner Mongolia and their geological significance

- Spatial and temporal evolution of land use and habitat quality in arid regions – a case of Northwest China

- Ground-penetrating radar imaging of subsurface karst features controlling water leakage across Wadi Namar dam, south Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- Rayleigh wave dispersion inversion via modified sine cosine algorithm: Application to Hangzhou, China passive surface wave data

- Fractal insights into permeability control by pore structure in tight sandstone reservoirs, Heshui area, Ordos Basin

- Debris flow hazard characteristic and mitigation in Yusitong Gully, Hengduan Mountainous Region

- Research on community characteristics of vegetation restoration in hilly power engineering based on multi temporal remote sensing technology

- Identification of radial drainage networks based on topographic and geometric features

- Trace elements and melt inclusion in zircon within the Qunji porphyry Cu deposit: Application to the metallogenic potential of the reduced magma-hydrothermal system

- Pore, fracture characteristics and diagenetic evolution of medium-maturity marine shales from the Silurian Longmaxi Formation, NE Sichuan Basin, China

- Study of the earthquakes source parameters, site response, and path attenuation using P and S-waves spectral inversion, Aswan region, south Egypt

- Source of contamination and assessment of potential health risks of potentially toxic metal(loid)s in agricultural soil from Al Lith, Saudi Arabia

- Regional spatiotemporal evolution and influencing factors of rural construction areas in the Nanxi River Basin via GIS

- An efficient network for object detection in scale-imbalanced remote sensing images

- Effect of microscopic pore–throat structure heterogeneity on waterflooding seepage characteristics of tight sandstone reservoirs

- Environmental health risk assessment of Zn, Cd, Pb, Fe, and Co in coastal sediments of the southeastern Gulf of Aqaba

- A modified Hoek–Brown model considering softening effects and its applications

- Evaluation of engineering properties of soil for sustainable urban development

- The spatio-temporal characteristics and influencing factors of sustainable development in China’s provincial areas

- Application of a mixed additive and multiplicative random error model to generate DTM products from LiDAR data

- Gold vein mineralogy and oxygen isotopes of Wadi Abu Khusheiba, Jordan

- Prediction of surface deformation time series in closed mines based on LSTM and optimization algorithms

- 2D–3D Geological features collaborative identification of surrounding rock structural planes in hydraulic adit based on OC-AINet

- Spatiotemporal patterns and drivers of Chl-a in Chinese lakes between 1986 and 2023

- Land use classification through fusion of remote sensing images and multi-source data

- Nexus between renewable energy, technological innovation, and carbon dioxide emissions in Saudi Arabia

- Analysis of the spillover effects of green organic transformation on sustainable development in ethnic regions’ agriculture and animal husbandry

- Factors impacting spatial distribution of black and odorous water bodies in Hebei

- Large-scale shaking table tests on the liquefaction and deformation responses of an ultra-deep overburden

- Impacts of climate change and sea-level rise on the coastal geological environment of Quang Nam province, Vietnam

- Reservoir characterization and exploration potential of shale reservoir near denudation area: A case study of Ordovician–Silurian marine shale, China

- Seismic prediction of Permian volcanic rock reservoirs in Southwest Sichuan Basin

- Application of CBERS-04 IRS data to land surface temperature inversion: A case study based on Minqin arid area

- Geological characteristics and prospecting direction of Sanjiaoding gold mine in Saishiteng area

- Research on the deformation prediction model of surrounding rock based on SSA-VMD-GRU

- Geochronology, geochemical characteristics, and tectonic significance of the granites, Menghewula, Southern Great Xing’an range

- Hazard classification of active faults in Yunnan base on probabilistic seismic hazard assessment

- Characteristics analysis of hydrate reservoirs with different geological structures developed by vertical well depressurization

- Estimating the travel distance of channelized rock avalanches using genetic programming method

- Landscape preferences of hikers in Three Parallel Rivers Region and its adjacent regions by content analysis of user-generated photography

- New age constraints of the LGM onset in the Bohemian Forest – Central Europe

- Characteristics of geological evolution based on the multifractal singularity theory: A case study of Heyu granite and Mesozoic tectonics

- Soil water content and longitudinal microbiota distribution in disturbed areas of tower foundations of power transmission and transformation projects

- Oil accumulation process of the Kongdian reservoir in the deep subsag zone of the Cangdong Sag, Bohai Bay Basin, China

- Investigation of velocity profile in rock–ice avalanche by particle image velocimetry measurement

- Optimizing 3D seismic survey geometries using ray tracing and illumination modeling: A case study from Penobscot field

- Sedimentology of the Phra That and Pha Daeng Formations: A preliminary evaluation of geological CO2 storage potential in the Lampang Basin, Thailand

- Improved classification algorithm for hyperspectral remote sensing images based on the hybrid spectral network model

- Map analysis of soil erodibility rates and gully erosion sites in Anambra State, South Eastern Nigeria

- Identification and driving mechanism of land use conflict in China’s South-North transition zone: A case study of Huaihe River Basin

- Evaluation of the impact of land-use change on earthquake risk distribution in different periods: An empirical analysis from Sichuan Province

- A test site case study on the long-term behavior of geotextile tubes

- An experimental investigation into carbon dioxide flooding and rock dissolution in low-permeability reservoirs of the South China Sea

- Detection and semi-quantitative analysis of naphthenic acids in coal and gangue from mining areas in China

- Comparative effects of olivine and sand on KOH-treated clayey soil

- YOLO-MC: An algorithm for early forest fire recognition based on drone image

- Earthquake building damage classification based on full suite of Sentinel-1 features

- Potential landslide detection and influencing factors analysis in the upper Yellow River based on SBAS-InSAR technology

- Assessing green area changes in Najran City, Saudi Arabia (2013–2022) using hybrid deep learning techniques

- An advanced approach integrating methods to estimate hydraulic conductivity of different soil types supported by a machine learning model

- Hybrid methods for land use and land cover classification using remote sensing and combined spectral feature extraction: A case study of Najran City, KSA

- Streamlining digital elevation model construction from historical aerial photographs: The impact of reference elevation data on spatial accuracy

- Analysis of urban expansion patterns in the Yangtze River Delta based on the fusion impervious surfaces dataset

- A metaverse-based visual analysis approach for 3D reservoir models

- Late Quaternary record of 100 ka depositional cycles on the Larache shelf (NW Morocco)

- Integrated well-seismic analysis of sedimentary facies distribution: A case study from the Mesoproterozoic, Ordos Basin, China

- Study on the spatial equilibrium of cultural and tourism resources in Macao, China

- Urban road surface condition detecting and integrating based on the mobile sensing framework with multi-modal sensors

- Application of improved sine cosine algorithm with chaotic mapping and novel updating methods for joint inversion of resistivity and surface wave data

- The synergistic use of AHP and GIS to assess factors driving forest fire potential in a peat swamp forest in Thailand

- Dynamic response analysis and comprehensive evaluation of cement-improved aeolian sand roadbed

- Rock control on evolution of Khorat Cuesta, Khorat UNESCO Geopark, Northeastern Thailand

- Gradient response mechanism of carbon storage: Spatiotemporal analysis of economic-ecological dimensions based on hybrid machine learning

- Comparison of several seismic active earth pressure calculation methods for retaining structures

- Mantle dynamics and petrogenesis of Gomer basalts in the Northwestern Ethiopia: A geochemical perspective

- Study on ground deformation monitoring in Xiong’an New Area from 2021 to 2023 based on DS-InSAR

- Paleoenvironmental characteristics of continental shale and its significance to organic matter enrichment: Taking the fifth member of Xujiahe Formation in Tianfu area of Sichuan Basin as an example

- Equipping the integral approach with generalized least squares to reconstruct relict channel profile and its usage in the Shanxi Rift, northern China

- InSAR-driven landslide hazard assessment along highways in hilly regions: A case-based validation approach

- Attribution analysis of multi-temporal scale surface streamflow changes in the Ganjiang River based on a multi-temporal Budyko framework

- Maps analysis of Najran City, Saudi Arabia to enhance agricultural development using hybrid system of ANN and multi-CNN models

- Hybrid deep learning with a random forest system for sustainable agricultural land cover classification using DEM in Najran, Saudi Arabia

- Long-term evolution patterns of groundwater depth and lagged response to precipitation in a complex aquifer system: Insights from Huaibei Region, China

- Remote sensing and machine learning for lithology and mineral detection in NW, Pakistan

- Spatial–temporal variations of NO2 pollution in Shandong Province based on Sentinel-5P satellite data and influencing factors

- Numerical modeling of geothermal energy piles with sensitivity and parameter variation analysis of a case study

- Stability analysis of valley-type upstream tailings dams using a 3D model

- Variation characteristics and attribution analysis of actual evaporation at monthly time scale from 1982 to 2019 in Jialing River Basin, China

- Investigating machine learning and statistical approaches for landslide susceptibility mapping in Minfeng County, Xinjiang

- Investigating spatiotemporal patterns for comprehensive accessibility of service facilities by location-based service data in Nanjing (2016–2022)

- A pre-treatment method for particle size analysis of fine-grained sedimentary rocks, Bohai Bay Basin, China

- Study on the formation mechanism of the hard-shell layer of liquefied silty soil

- Comprehensive analysis of agricultural CEE: Efficiency assessment, mechanism identification, and policy response – A case study of Anhui Province

- Simulation study on the damage and failure mechanism of the surrounding rock in sanded dolomite tunnels

- Towards carbon neutrality: Spatiotemporal evolution and key influences on agricultural ecological efficiency in Northwest China

- High-frequency cycles drive the cyclical enrichment of oil in porous carbonate reservoirs: A case study of the Khasib Formation in E Oilfield, Mesopotamian Basin, Iraq

- Reconstruction of digital core models of granular rocks using mathematical morphology

- Spatial–temporal differentiation law of habitat quality and its driving mechanism in the typical plateau areas of the Loess Plateau in the recent 30 years

- A machine-learning-based approach to predict potential oil sites: Conceptual framework and experimental evaluation

- Effects of landscape pattern change on waterbird diversity in Xianghai Nature Reserve

- Research on intelligent classification method of highway tunnel surrounding rock classification based on parameters while drilling

- River morphology and tectono-sedimentary analysis of a shallow river delta: A case study of Putaohua oil layer in Saertu oilfield (L. Cretaceous), China

- Dynamic change in quarterly FVC of urban parks based on multi-spectral UAV images: A case study of people’s park and harmony park in Xinxiang, China

- Review Articles

- Humic substances influence on the distribution of dissolved iron in seawater: A review of electrochemical methods and other techniques

- Applications of physics-informed neural networks in geosciences: From basic seismology to comprehensive environmental studies

- Ore-controlling structures of granite-related uranium deposits in South China: A review

- Shallow geological structure features in Balikpapan Bay East Kalimantan Province – Indonesia

- A review on the tectonic affinity of microcontinents and evolution of the Proto-Tethys Ocean in Northeastern Tibet

- Advancements in machine learning applications for mineral prospecting and geophysical inversion: A review

- Special Issue: Natural Resources and Environmental Risks: Towards a Sustainable Future - Part II

- Depopulation in the Visok micro-region: Toward demographic and economic revitalization

- Special Issue: Geospatial and Environmental Dynamics - Part II

- Advancing urban sustainability: Applying GIS technologies to assess SDG indicators – a case study of Podgorica (Montenegro)

- Spatiotemporal and trend analysis of common cancers in men in Central Serbia (1999–2021)

- Minerals for the green agenda, implications, stalemates, and alternatives

- Spatiotemporal water quality analysis of Vrana Lake, Croatia

- Functional transformation of settlements in coal exploitation zones: A case study of the municipality of Stanari in Republic of Srpska (Bosnia and Herzegovina)

- Hypertension in AP Vojvodina (Northern Serbia): A spatio-temporal analysis of patients at the Institute for Cardiovascular Diseases of Vojvodina

- Regional patterns in cause-specific mortality in Montenegro, 1991–2019

- Spatio-temporal analysis of flood events using GIS and remote sensing-based approach in the Ukrina River Basin, Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Flash flood susceptibility mapping using LiDAR-Derived DEM and machine learning algorithms: Ljuboviđa case study, Serbia

- Geocultural heritage as a basis for geotourism development: Banjska Monastery, Zvečan (Serbia)

- Assessment of groundwater potential zones using GIS and AHP techniques – A case study of the zone of influence of Kolubara Mining Basin

- Impact of the agri-geographical transformation of rural settlements on the geospatial dynamics of soil erosion intensity in municipalities of Central Serbia

- Where faith meets geomorphology: The cultural and religious significance of geodiversity explored through geospatial technologies

- Applications of local climate zone classification in European cities: A review of in situ and mobile monitoring methods in urban climate studies

- Complex multivariate water quality impact assessment on Krivaja River

- Ionization hotspots near waterfalls in Eastern Serbia’s Stara Planina Mountain

- Shift in landscape use strategies during the transition from the Bronze age to Iron age in Northwest Serbia

- Assessing the geotourism potential of glacial lakes in Plav, Montenegro: A multi-criteria assessment by using the M-GAM model

- Flash flood potential index at national scale: Susceptibility assessment within catchments

- SWAT modelling and MCDM for spatial valuation in small hydropower planning

- Disaster risk perception and local resilience near the “Duboko” landfill: Challenges of governance, management, trust, and environmental communication in Serbia