Abstract

Butea monosperma is a deciduous tree, widely distributed throughout India, Burma, and Ceylon. The present study was intended to investigate the anti-inflammatory effects of Butea monosperma on the induced inflammatory model by evaluating pro-inflammatory biomarkers and their computational analysis. The anti-inflammatory activity may be attributed to the phyto-constituents for inhibitory effects on the two pro-inflammatory mediators (IL-8 and TNF-α). For this purpose, rats (n = 48) were equally divided in each group, i.e., 8 each in the negative and positive control and 32 in the experimental group with 8 rats for each dose, i.e., 50, 100, 200, and 400 mg/kg. TNF-α and IL-8 were tested by serum enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The ELISA results showed 400 mg/kg dose as the potent anti-inflammatory. The binding sites of target proteins (TNF-α and IL-8) were docked with the active compounds (butrin and butein) of Butea monosperma. The butrin (target: TNF-α) and butein (target: IL-8) showed −8.4 and −6.0 kcal/mol binding energies, respectively, compared to the (diclofenac) standard drug with −6.8 kcal/mol binding energy. Hence, we concluded that Butea monosperma can be subjected to as a useful anti-inflammatory drug.

1 Introduction

The flame tree, Butea monosperma, is a member of the Fabaceae family’s Caesalpinioideae subfamily (formerly Leguminosae). In India, the plant is frequently referred to as a Palash tree. Along with the South Asian peninsula, it grows all over India. It is a deciduous tree of medium size. It increases in height by 10–15 m. Due to increased branching, it resembles a tiny shrub when it is between 1 and 2 m tall. During the spring blooming season, its unscented, reddish-colored flowers are produced along with trifoliate leaves. Flowers are mostly used to treat digestive issues, stomachaches, and other conditions related to the stomach. It also treats other disorders like leprosy, sanguinary, skin issues, and thirst [1]. The majority of rangelands and grasslands naturally include Butea monosperma, a gum-yielding tree that grows best in arid and semi-arid climates. It is a crucial multipurpose tree for the rural population since it offers shade, fodder, fiber, firewood, gum, and medication. It is the most common species in Bundelkhand and is primarily found in open woodlands, degraded/pasture areas, forests, and farmers’ holdings [2]. Numerous active components found in medicinal plants have the potential to be used in the manufacture of therapeutic drugs. Therefore, for drug development, it is required to identify and isolate phytochemical groups and/or single chemical entities from them because these substances frequently operate as single agent or as a group of phyto-compounds (purified extracts) to provide the desired therapeutic effect. The biological actions of plant bioactive chemicals cover a broad range, including antibacterial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory effects [3]. Butea monosperma exhibits promising anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties attributed to its diverse array of bioactive compounds, including flavonoids, steroids, glucosides, and aromatic compounds. Butea monosperma extracts exhibit several in vitro and in vivo activities including wound healing, anti-hyperglycemic, anti-inflammatory, hepatoprotective, and antitumor activities [4]. By blocking the activation of NF-kB, the butrin, isobutrin, and butein isolated from Butea monosperma flowers significantly decreased the inflammatory gene expression and production of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-8 in macrophages caused by phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate and calcium ionophore A23187 [5]. The purpose of the present research was to explore the anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties of Butea monosperma, commonly known as the Palash tree. The research was driven by the recognition of the plant’s historical use in traditional Asian remedies, and the increasing global interest in natural treatments as an alternative to synthetic drugs. The study also acknowledged the need for a detailed scientific investigation into the chemical components and bioactivities of medicinal plants, particularly their potential anti-inflammatory effects. Through an in vivo study, it was hypothesized that the plant extracts can effectively modulate inflammatory mediators and demonstrated pain-relieving effects. Molecular docking simulations further elucidated the interaction between bioactive compounds from Butea monosperma and key proteins involved in inflammation, providing insights for potential drug development in the treatment of inflammatory disorders.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sample collection

The plant material used in this research was the mature flowers of Butea monosperma directly collected in March 2021 as a sample from various locations in the Bahawalpur district of Pakistan. The samples were identified by the Botany Department of The University of Lahore (UOL), Pakistan. The flowers were cleaned and air-dried in stainless steel tray covered with aluminum foil at 37°C in an incubator for about 1 week and then chopped into smaller pieces.

2.2 Butea monosperma flower extract

The chopped flowers of Butea monosperma were soaked in a sterile glass bottle. The flowers were immersed in acetone, well shaken for 4–5 min, and then placed at room temperature for 15 days. After this time, the mixture was filtered and poured into Petri dishes by placing them at room temperature for the next 7 days until dry. The dried paste was saved in an Eppendorf tube by scratching it with a blade from a Petri dish.

2.3 Experimental rats

For appraising anti-inflammatory activity, albino rats (female or male) of weight 200 g were purchased from the Institute of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology’s (UOL) animal home for the experiment. The experimental permission was taken from the ethical committee of the University of Lahore. Rats were kept in polypropylene cages at the University of Lahore animal house. Rats were acclimatized with our Department’s animal house for about a week and were supplied with water and balanced feed. Rats were off-feed for about 24 h and off-water 12 h before the start of the experiment.

2.4 Drugs/chemicals with doses

Butea monosperma acetonic extracts @ 50, 100, 200, and 400 mg/kg, Diclofenac @ 100 mg/kg, Carrageenan (inflammation inducer) [6] @ 400 mg/kg, and normal saline @ 10 ml/kg were used.

2.5 Evaluation of anti-inflammatory effect

For the evaluation of anti-inflammatory effects of Butea monosperma, 48 albino rats were divided into 3 groups, i.e., 8 each in group I (negative control) and group II (positive control/standard-diclofenac), and 32 in group III (8 for each dose of Butea monosperma acetonic extract).

2.6 Procedure

2.6.1 Carrageenan-induced rat paw edema

Carrageenan was subcutaneously administered in each rat’s paw in all the groups to cause edema. Group I or negative control was treated with simple normal saline @ 10 ml/kg. Group II or Positive control was treated with diclofenac sodium @ 100 mg/kg, subcutaneous injection. Whereas the rats in group III were treated with different concentrations of acetonic flower extracts of Butea monosperma @ 50, 100, 200, and 400 mg/kg by oral administration. The paw volume was measured, using a plethysmometer, before the injection and then after 1–4 h post-injection. The rats were placed in different cages during the activity.

2.6.2 Blood samples

Blood samples were collected by cardiac puncture in Eppendorf tubes and were centrifuged at 2,683g for 10 min to obtain serum. The serum was stored at −20°C.

2.6.3 Assessment of anti-inflammatory biomarkers

Pro-inflammatory biomarkers IL-8 and TNF-α protein were analyzed by using commerciallyavailable ELISA kits and sandwich ELISA was performed. Concentrations of inflammatory biomarkers were obtained for the negative control, standard, and various doses of Butea monosperma flower acetone extract. TNF-α estimation was performed using Biospes kit (Chongqing Biospes Co., Ltd, Catalog No. BEK1212). Briefly, the experiment involved setting up a pre-coated plate with standard, test sample, and control wells, each measured in duplicate. Standard wells received 0.1 ml aliquots of standard solutions, while the control well received a diluent buffer. Test sample wells received 0.1 ml of properly diluted samples and underwent incubation at 37°C for 90 min. After discarding the plate content, Biotin-conjugated anti-Human TNFα antibody was added, followed by incubation at 37°C for 60 min. The plate underwent washing, and ABC working solution was added and incubated. After additional washes, TMB substrate was added and incubated at 37°C in the dark. To stop the reaction, Stop solution was added, resulting in a color change. Optical density at 450 nm was read, and relative O.D.450 was calculated. A standard curve was plotted, and Human TNFα concentrations in samples were interpolated from the curve.

2.7 In silico anti-inflammatory activity

2.7.1 Selection of ligands

For in silico investigation of monosperma anti-inflammatory activity, (Chimera) https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera/cgi-bin/secure/chimera-get.py, (PyRx) and https://sourceforge.net/projects/pyrx/, (ApoHoloproteinsearch) http://apoholo.cz/ were used and visualized with (discovery studio) https://discover.3ds.com/discovery-studio-visualizer-download. TNF-α and IL-8 proteins 3D structures were retrieved from a protein data bank (PDB).

2.7.2 Preparation of ligands

The ligand molecules were selected from the bioactive constituents of Butea monosperma that have anti-inflammatory potential. These ligands were discovered in the literature of phytochemical databases [7]. The docking analysis of anti-inflammatory efficacy used two ligands of Butea monosperma: butrin and butein and the standard drug diclofenac. The 3D structures of the ligand molecules were assessed from PubChem (PubChem CID of butein is 5281222 and butrin is 164630).

2.8 Protein preparation

TNF-α and IL-8 PDB files were opened in chimera and selected chains were incorporated for further characterization. The extra ions, water, and metals were eliminated before dispensing the protein. Furthermore, the hydrogen atoms were added if needed in any structure and the geometry of all the hetero groups was assured. The protein structures were saved in PDB files.

2.9 Prediction of the active site

TNF-α and IL-8 active sites were found in the apo Holo protein search by submitted the protein id file (1ilq,5uui) after few sec online tool generate binding sites file which are further downloaded.

2.9.1 Protein-ligand docking

PyRx was utilized for virtual screening to find a potential anti-inflammatory drug or ligand molecule for a certain protein. Both target protein TNF-α (PDB ID = 5UUI) and IL-8 (PDB ID = 1ILQ) binding pockets were coupled with the ligands molecules by using their respective PDB IDs. The active sites of the target protein (TNF-α and IL-8) were discovered using the depth residue prediction data source. The strength of binding contact was estimated as a consequence of the docking run, binding site energy, and the ligand-molecule interface. Following that, the discovery studio tool was used to create protein complexes containing ligand compounds. The Chimera tool was used to create the 3D structure complex for high-quality observation.

2.10 Statistical analysis

Results were statistically analyzed by applying Graph-Pad-Prism v.6.0. For paw size variation in “mm” at various doses of acetone flower extract and at various time points, two-way ANOVA was applied. For multiple comparisons among groups at various time points, Tukey’s multiple comparison tests was promulgated. Whereas, for comparing pro-inflammatory cytokines, one-way ANOVA was applied and Dunnett’s multiple comparison test was considered for group comparison. Significant values were given asterisk (*) sign and non-significant values were denoted with “ns.” Tukey’s multiple comparison tests were applied with a significance level (α) set at 0.05. The tests were two-tailed, and degrees of freedom were adjusted accordingly. Tukey’s multiple comparison test was chosen due to its ability to effectively control the group-wise error rate in situations involving multiple group comparisons. Tukey’s multiple comparison test was chosen due to its ability to effectively control the group-wise error rate in situations involving multiple group comparisons. The selected α level of 0.05 was deemed appropriate for maintaining a balance between Type I and Type II errors in our study.

3 Results

3.1 Anti-inflammatory activity

3.1.1 Carrageenan-induced paw edema

The various concentrations of acetonic flower extracts of Butea monosperma showed non-significant anti-inflammatory effects (IL-8 and TNF-α) on rats when compared with standard (diclofenac) [1] (Figure 1).

Sandwich ELISA for pro-inflammatory cytokines.

However, the effect of extracts on decreasing paw size in response to carrageenan was highly significant (P < 0.0001) at various time points (Figure 2). 50, 100, and 200 mg/kg doses (0 h), 50 and 200 mg/kg doses (1, 3, and 4 h), 400 mg/kg (2 h) provided high-significant paw size reduction when compared with standard (diclofenac) drug (Figure 2). These results in relation to the negative control samples, which were treated with normal saline. Actually, negative control is typically used to establish a baseline and assess the impact of any treatment, it is also valid to focus on the positive control (diclofenac in this case) and compare the experimental groups to it. The negative control was included to establish a baseline level of inflammation induced by Carrageenan, and our primary interest was in comparing the efficacy of the acetonic flower extract of Butea monosperma with the well-known anti-inflammatory drug diclofenac (positive control). The negative control was not intended for direct comparison, as it only represents the baseline inflammation without any treatment.

Shows the anti-inflammatory activity of Butea monosperma.

3.1.2 In Silico analysis

3.1.2.1 Chemistry

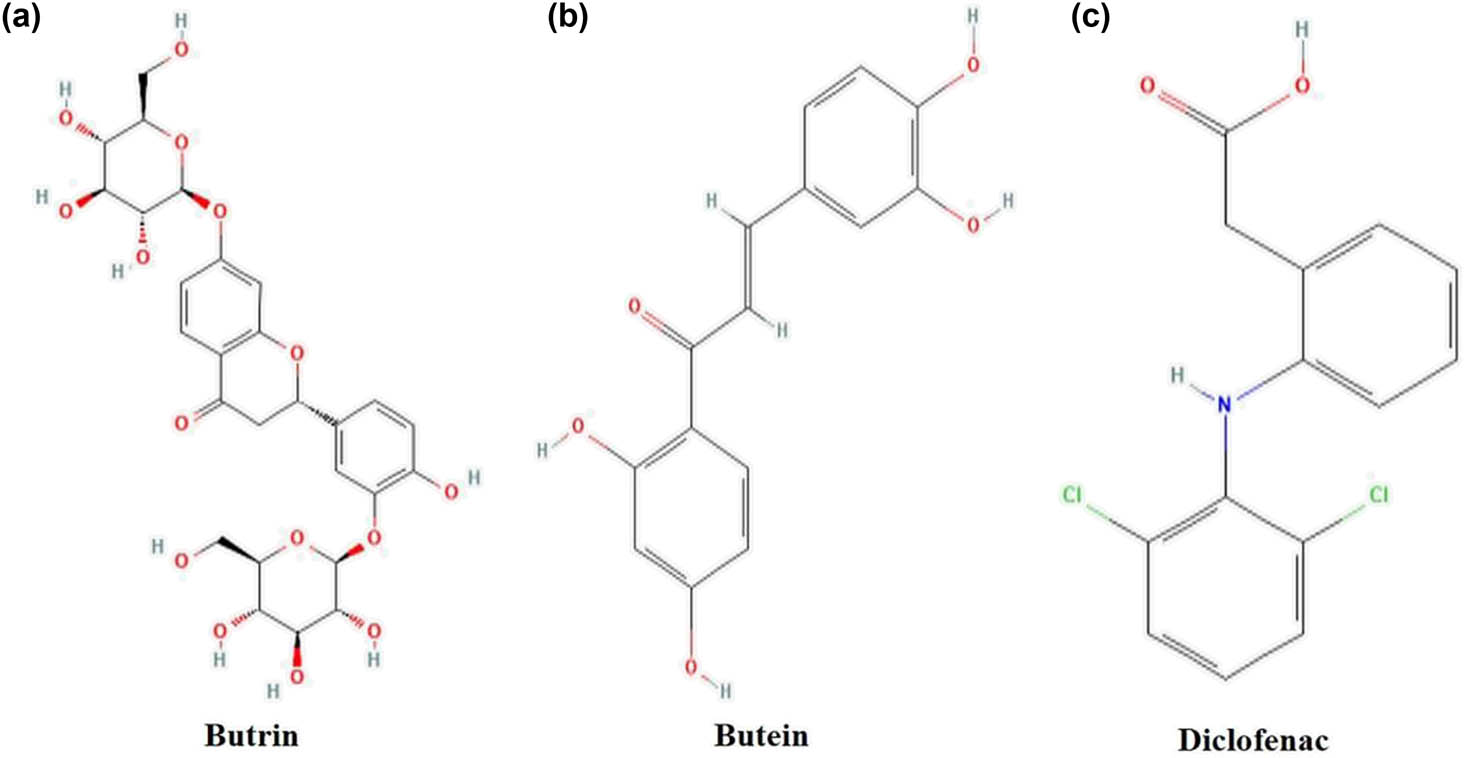

Butrin is a flavanone glycoside that is butin substituted by two beta-d-glucopyranosyl residues at positions 7 and 3′, respectively (Figure 3a). It has a role as an anti-inflammatory agent and a plant metabolite. It has a molecular formula of C27H32O15 and molecular weight of 596.5 g/mol. Butein is a flavonoid obtained from the seed of Cyclopia subalternate having molecular formula C15H12O5 and molecular weight of 272.25 g/mol (Figure 3b). Diclofenac is used as a standard anti-inflammatory chemical with molecular formula C14H11Cl2NO2 and molecular weight of 296.1 g/mol (Figure 3c).

Structures of compounds (a) butrin, (b) butein, and (c) diclofenac used in the study.

3.1.2.2 Prediction of active sites and interaction of binding pockets with ligands

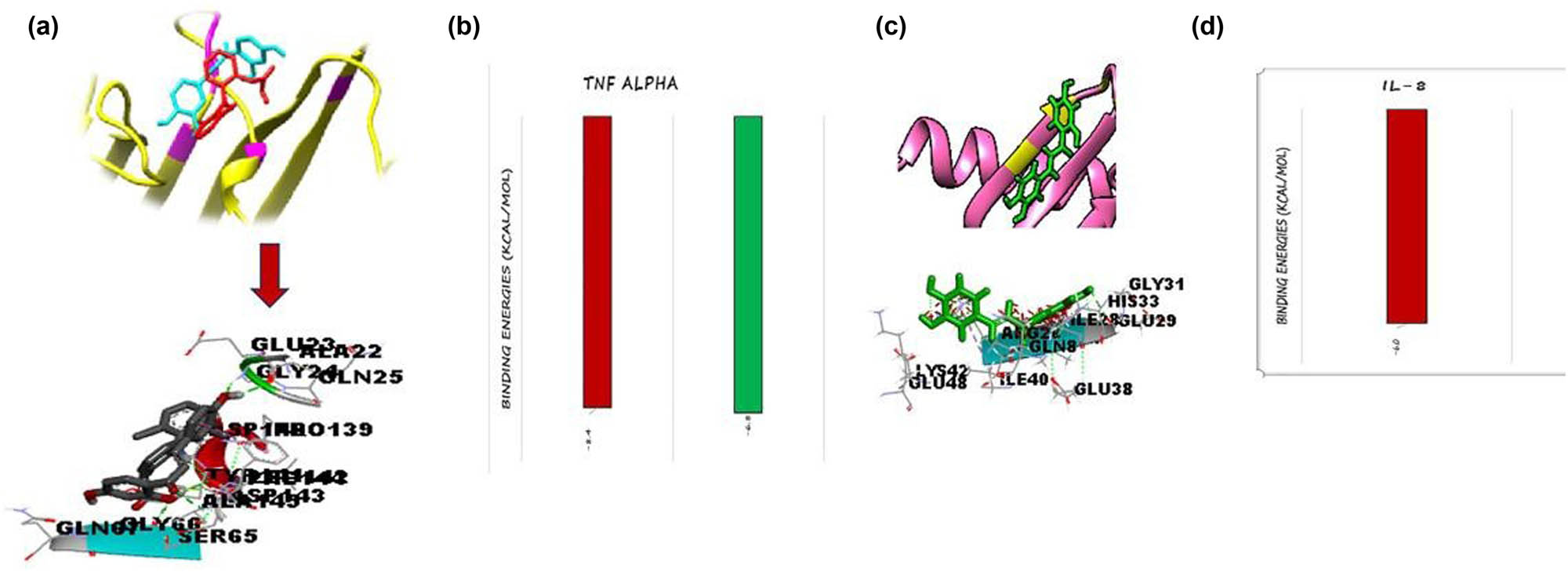

Active sites of TNF-α contained five amino acids (TYR 86, TYR 87, VAL 91, LEU 94, and ILE 97) and the binding of diclofenac and butrin molecule (Figure 2a). Active sites of IL-8 contained four amino acids (GLY 31, SER 30, ARG 26, and ILE 40) and the binding of active sites revealed that all ligands were confined in the binding region of the target protein. All of the docked ligand structures were superimposed to evaluate their binding interactions in the binding pockets of all targeted proteins (TNF-α and IL-8). All the ligands have similar binding interactions and are shown by the results (Figure 4a and b).

(a) TNF-α protein (yellow), binding pocket (hot pink), and two ligand molecules – diclofenac (crayon blue) and butrin (red). (b) IL-8 protein (red), binding pocket (green), and one ligand molecule (dark blue).

3.1.2.3 Hydrogen bonding analysis, docking results of TNF-α and IL-8

Hydrogen and hydrophobic bonds are used to evaluate the bonding interactions of docking complexes. Diclofenac and butrin with TNF-α interactions were supported by 7 H-bonds at GLY 24, SER 65, SER 65, LEU 142, PHE 14, ALA 14, and GLN 14. One hydrophobic bond on PHE 14 with a bond distance of 4.793 Å (Table 1).

Docking complex of pro-inflammatory cytokines

| Ligands | Amino acids | Bond distance (Å) |

|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | ||

| Butrin | Glycine 24 | 2.05 |

| Serine 65 | 1.92 | |

| Serine 65 | 1.64 | |

| Diclofenac | Leucine 142 | 2.21 |

| Phenylalanine 14 | 2.18 | |

| Alanine 14 | 1.95 | |

| Glutamine 14 | 1.97 | |

| IL-8 | ||

| Butein | Glutamine8 | 2.49 |

| Arginine26 | 1.93 | |

| Arginine26 | 1.40 | |

| Arginine26 | 1.84 | |

| Arginine26 | 2.03 | |

| Isoleucine28 | 2.08 | |

| Glutamic acid | 2.42 | |

| Glutamic acid | 2.19 | |

Ligands (Figure 5a), IL-8, and butein interactions are shown by eight H-bonds with GLN8, ARG 26, ARG 26, ARG 26, ARG 26, ILE 28, GLU 29, and GLU 38. Figure 5c shows binding interactions between the target protein IL-8 and one ligand.

(a) Docking complex of TNF-α in which butrin and diclofenac showed seven hydrogen bonds and one hydrophobic bond. (b) Hydrogen bond is shown by green dotted lines and hydrophobic bond represented by pink dotted lines. Binding energies of TNF-α with two ligand molecules butrin (red) and diclofenac (green). (c) Docking complex of IL-8 shows eight hydrogen bonds represented by green dotted lines. (d) Binding energy of IL-8 with one ligand molecule butein (red).

3.1.2.4 Binding energies

The standard drug diclofenac and the plant bioactive compound (butrin) were docked of TNF-α using PyRx. The top docking energy was −8.4 kcal/mol by butrin while the standard drug diclofenac showed a binding score of −6.8 kcal/mol (Figure 5b). Bio-active compound (butein) was docked of IL-8 using PyRx and has binding energy of 6.0 kcal/mol (Figure 5d).

4 Discussion

Traditional medicines are in use in various regions of the world for ages. Medicinal plants are used to treat pain, fever, and many other infections [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. The present study was conducted to estimate the effect of Butea monosperma in carrageenan-induced inflammation and investigation of anti-inflammatory biomarkers in albino rats, using the carrageenan-induced paw edema, which is the most widely used primary model for the screening of new anti-inflammatory agents. Carrageenan induced edema is a multi-mediated phenomenon that liberates diversity of mediator like histamine, 5-HT, kinins, and prostaglandins at various time intervals [24].

In this study, phytochemical analysis was also performed to screen and study all the phytochemical constituents of Butea monosperma and selective potentially bioactive molecules for molecular docking analysis. Phyto-constituents characterized in the current study are known to be beneficial in medicinal sciences. The results of this study can be anticipated as decipher in the search of novel and economically valued drug molecules [25]. Hence, we concluded that acetonic Butea monosperma extract can be subjected as a useful drug in the treatment of inflammation. Butea monosperma (L.) is the reservoir for many potentially active chemical compounds which acts as drugs against various diseases and disorders. Different bioactive substances, such as alkaloids, flavonoids, amino acids, resin, saponin, etc., are present in Butea monosperma [26]. The acetonic flower extract of Butea monosperma showed a significant result in anti-inflammatory activity. The maximum inhibition activity was shown by a concentration of 400 mg/kg which was 60% in contrast to a standard which was 90% of the same concentration and the control is 0%. The plant showed 50, 50, and 10% at respective concentrations of 50, 100, and 200 mg/kg. The standard group showed inhibition activity of 40, 10, and 30% at respective concentrations of 50, 100, and 200 mg/kg while the control group could not give any inhibitory activity after the carrageenan injection. All the results were significant (P < 0.001). Blood biomarkers showed highly significant activity at the dose of 400 mg/kg. The phytochemical analysis presented the occurrence of glycosides, tannins, flavonoid saponins, anthraquinones, and phenols. Butea monosperma has a variety and number of bioactive compounds having different therapeutic applications. In our study, butrin and butein found in the flower part of Butea monosperma were studied in in silico analysis with TNF-α and IL-8, it is believed that butrin and butein have a significant contribution to anti-inflammatory activity by inhibiting the TNF-α and IL-8. The more negative values represent more affinity to bind with protein. The butrin and butein showed −8.4 and −6.0 kcal/mol binding energies, respectively, as compared to the standard drug diclofenac with −6.8 kcal/mol binding energy to IL-8 and TNF-α. In our results, butrin showed the greatest binding affinity as compared to butein.

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, the acetonic flower extracts of Butea monosperma demonstrated non-significant anti-inflammatory effects in terms of IL-8 and TNF-α compared to the standard diclofenac. However, the extracts exhibited a high-significant reduction in paw size in response to carrageenan-induced paw edema, particularly at doses of 50, 100, and 200 mg/kg at various time points. Molecular docking studies revealed that the bioactive compound butrin from Butea monosperma exhibited superior binding energies with TNF-α compared to diclofenac, and butein displayed favorable interactions with IL-8. The identified amino acids involved in binding interactions and the hydrogen bonding patterns were elucidated. These findings suggest the potential anti-inflammatory properties of Butea monosperma extracts and its bioactive compounds, particularly butrin and butein, through modulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines. However, further research is warranted to validate these results in vivo and explore the underlying mechanisms of action. Additionally, the study provides insights into the molecular interactions of the compounds with key inflammatory markers, contributing to the understanding of their therapeutic potential. Nonetheless, the limitations of the study include the need for more extensive clinical investigations and the consideration of potential side effects or toxicity. Further research directions could involve exploring the broader pharmacological profile of Butea monosperma extracts, conducting clinical trials, and investigating potential synergistic effects with conventional anti-inflammatory drugs for enhanced therapeutic outcomes.

Acknowledgements

Authors are thankful to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2024R335), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Funding information: The research was fancially supported by Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2024R335), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

-

Author contributions: Nureen Zahra: Writing – original draft. Aansa Mazhar: Writing – review & editing. Beenish Zahid: Visualization, Software. Muhammad Ahsan Naeem: Writing – review & editing. Abid Sarwar: Methodology, Investigation. Tariq Aziz: Methodology, Investigation. Metab Alharbi: Visualization, Software. Thamer H Albekairi: Formal analysis. Abdullah F Alasmari: Writing – review & editing. Tariq Aziz: Writing – review & editing, Supervision: Tariq Aziz.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Rohit YS, Sonali S, Kumar PA, Shubham PPS. Butea monosperma (PALASH): Plant Review with their phytoconstituents and pharmacological applications. IOSR J Pharm Biol Sci. 2020;15:18–23.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Chauhan SS, Mahish PK. Flavonoids of the flame of forest-Butea monosperma. Res J Pharm Technol. 2020 Nov;13(11):5647–53.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Khatak S, Wadhwa N, Malik DK. Comparative analysis of antimicrobial activity and phytochemical assay of flower extracts of butea monosperma and cassia fistula against pathogenic microbes. Int J Recent Sci Res. 2019 Jan;10:31285–90.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Dave KM. Antimicrobial activity and phytochemical study of plant parts of butea monosperma. J Drug Delivery Therapeutics. 2019 Aug;9(4–A):344–8.10.22270/jddt.v9i4-A.3435Search in Google Scholar

[5] Sultana F, Sindhu RK. Exploring anti-inflamatory potential of ethnomedicinal plants: an update. Plant Arch. 2021;21(1):1818–24.10.51470/PLANTARCHIVES.2021.v21.S1.291Search in Google Scholar

[6] Tiwari P, Jena S, Sahu PK. Butea monosperma: phytochemistry and pharmacology. Acta Sci Pharm Sci. 2019;3(4):19–26.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Gupta P, Chauhan NS, Pande M, Pathak A. Phytochemical and pharmacological review on Butea monosperma (Palash). Int J Agron plant Prod. 2012;3(7):255–8.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Aziz T, Ihsan F, Ali Khan A, Ur Rahman S, Zamani GY, Alharbi M, et al. Assessing the pharmacological and biochemical effects of Salvia hispanica (Chia seed) against oxidized Helianthus annuus (sunflower) oil in selected animals. Acta Biochim Pol. 2023;70(1):211–8.10.18388/abp.2020_6621Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Ur Rahman S, Zahid M, Khan AA, Aziz T, Iqbal Z, Ali W, et al. Hepatoprotective effects of walnut oil and Caralluma tuberculata against paracetamol in experimentally induced liver toxicity in mice. Acta Biochim Pol. 2022;69(4):871–8.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Zahid H, Shahab M, Ur Rahman S, Iqbal Z, Khan AA, Aziz T, et al. Assessing the effect of walnut (juglans regia) and olive (olea europaea) oil against the bacterial strains found in Gut Microbiome. Progr Nutr. 2022;24(3):e2022122.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Alam F, Hanif M, Rahman AU, Ali S, Jan S. In vitro, in vivo and in silico evaluation of analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and anti-pyretic activity of salicylate rich fraction from Gaultheria trichophylla Royle (Ericaceae). J Ethnopharmacol. 2023;301:115828.10.1016/j.jep.2022.115828Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Gul R, Rahmatullah Q, Ali H, Bashir A, Ayaz AK, Tariq A, et al. Phytochemical, anitmicrobial, radical scavening and in-vitro biological activities of teucurium stocksianum leaves. J Chil Chem Soc. 2023;68(1):5748–54.10.4067/S0717-97072023000105748Search in Google Scholar

[13] Syed WAS, Muhammad SA, Mujaddad UR, Azam H, Abid S, Aziz T, et al. In-Vitro evaluation of phytochemicals, heavy metals and antimicrobial activities of leaf, stem and roots extracts of caltha palustris var. alba. J Chil Chem Soc. 2023;68(1):5807–12.10.4067/S0717-97072023000105807Search in Google Scholar

[14] Ahmad E, Jahangeer M, Mahmood Akhtar Z, Aziz T, Alharbi M, Alshammari A, et al. Characterization and gastroprotective effects of Rosa brunonii Lindl. fruit on gastric mucosal injury in experimental rats – A preliminary study. Acta Biochim Pol. 2023;70(3):633–41.10.18388/abp.2020_6772Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Zawar H, Muhammad J, Shafiq UR, Tammana I, Abid S, Najeeb U, et al. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles by aqueous extract of Zingiber officinale and their antibacterial activities against selected species. Pol J Chem Tech. 2023;25(3):23–30.10.2478/pjct-2023-0021Search in Google Scholar

[16] Ammara A, Sobia A, Nureen Z, Sohail A, Abid S, Aziz T, et al. Revolutionizing the effect of Azadirachta indica extracts on edema induced changes in C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 in albino rats: in silico and in vivo approach. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2023;27(13):5951–63.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Rauf B, Alyasi S, Zahra N, Ahmad S, Sarwar A, Aziz T, et al. Evaluating the influence of Aloe barbadensis extracts on edema induced changes in C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 in albino rats through in vivo and in silico approaches. Acta Biochim Pol. 2023;70(2):425–33.10.18388/abp.2020_6705Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Khurshaid I, Ilyas S, Zahra N, Ahmad S, Aziz T, Al-Asmari F, et al. Isolation, preparation and investigation of leaf extracts of Aloe barbadensis for its remedial effects on tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin (IL-6) by in vivo and in silico approaches in experimental rats. Acta Biochim Pol. 2023;70(4):927–33.10.18388/abp.2020_6827Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Ahmad B, Muhammad Yousafzai A, Maria H, Khan AA, Aziz T, Alharbi M, et al. Curative effects of dianthus orientalis against paracetamol triggered oxidative Stress, Hepatic and Renal Injuries in Rabbit as an Experimental Model. Separations. 2023;10(3):182.10.3390/separations10030182Search in Google Scholar

[20] Saleem K, Aziz T, Ali Khan A, Muhammad A, Ur Rahman S, Alharbi M, et al. Evaluating the in-vivo effects of olive oil, soya bean oil, and vitamins against oxidized ghee toxicity. Acta Biochim Pol. 2023;70(2):305–12.10.18388/abp.2020_6549Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Muhammad AS, Muhammad N, Shafiq UR, Noor UA, Aziz TMA, Alharbi M, et al. Iron oxide nanoparticles synthesis from madhuca indica plant extract, and assessment of its cytotoxic, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-diabetic properties via different nano informatics approaches. ACS Omega. 2023;8(37):33358–66.10.1021/acsomega.3c02744Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Waseem M, Naveed M, Rehman SU, Makhdoom SI, Aziz T, Alharbi M, et al. Molecular characterization of spa, hld, fmha, and lukd genes and computational modeling the multidrug resistance of staphylococcus species through callindra harrisii silver nanoparticles. ACS Omega. 2023;8(23):20920–36.10.1021/acsomega.3c01597Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Hussain Z, Jahangeer M, Sarwar A, Ullah N, Tariq A, Alharbi M, et al. Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles mediated by the mentha piperita leaves extract and exploration of its antimicrobial activities. J Chil Chem Soc. 2023;68:2.10.4067/s0717-97072023000205865Search in Google Scholar

[24] Rathod VD, Bhangale JO, Bhangale PJ. Preliminary evaluation of antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activities of petroleum ether extracts of Butea monosperma (L.) leaves in laboratory animals. World J Pharm Sci. 2017 Mar;5(3):246–52.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Gezahegn Z, Akhtar MS, Woyessa D, Tariku Y. Antibacterial potential of Thevetia peruviana leaf extracts against food associated bacterial pathogens. J Coast Life Med. 2015;3(2):150–7.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Mahalik G. Comparative Analysis of Phytochemical and Antimicrobial Activity of Butea monosperma (Lam.) Taub. and Pongamia pinnata (L.) Pierre: A. Indian J Nat Sci. 2020;10(60):19368–73.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Porous silicon nanostructures: Synthesis, characterization, and their antifungal activity

- Biochar from de-oiled Chlorella vulgaris and its adsorption on antibiotics

- Phytochemicals profiling, in vitro and in vivo antidiabetic activity, and in silico studies on Ajuga iva (L.) Schreb.: A comprehensive approach

- Synthesis, characterization, in silico and in vitro studies of novel glycoconjugates as potential antibacterial, antifungal, and antileishmanial agents

- Sonochemical synthesis of gold nanoparticles mediated by potato starch: Its performance in the treatment of esophageal cancer

- Computational study of ADME-Tox prediction of selected phytochemicals from Punica granatum peels

- Phytochemical analysis, in vitro antioxidant and antifungal activities of extracts and essential oil derived from Artemisia herba-alba Asso

- Two triazole-based coordination polymers: Synthesis and crystal structure characterization

- Phytochemical and physicochemical studies of different apple varieties grown in Morocco

- Synthesis of multi-template molecularly imprinted polymers (MT-MIPs) for isolating ethyl para-methoxycinnamate and ethyl cinnamate from Kaempferia galanga L., extract with methacrylic acid as functional monomer

- Nutraceutical potential of Mesembryanthemum forsskaolii Hochst. ex Bioss.: Insights into its nutritional composition, phytochemical contents, and antioxidant activity

- Evaluation of influence of Butea monosperma floral extract on inflammatory biomarkers

- Cannabis sativa L. essential oil: Chemical composition, anti-oxidant, anti-microbial properties, and acute toxicity: In vitro, in vivo, and in silico study

- The effect of gamma radiation on 5-hydroxymethylfurfural conversion in water and dimethyl sulfoxide

- Hollow mushroom nanomaterials for potentiometric sensing of Pb2+ ions in water via the intercalation of iodide ions into the polypyrrole matrix

- Determination of essential oil and chemical composition of St. John’s Wort

- Computational design and in vitro assay of lantadene-based novel inhibitors of NS3 protease of dengue virus

- Anti-parasitic activity and computational studies on a novel labdane diterpene from the roots of Vachellia nilotica

- Microbial dynamics and dehydrogenase activity in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) rhizospheres: Impacts on growth and soil health across different soil types

- Correlation between in vitro anti-urease activity and in silico molecular modeling approach of novel imidazopyridine–oxadiazole hybrids derivatives

- Spatial mapping of indoor air quality in a light metro system using the geographic information system method

- Iron indices and hemogram in renal anemia and the improvement with Tribulus terrestris green-formulated silver nanoparticles applied on rat model

- Integrated track of nano-informatics coupling with the enrichment concept in developing a novel nanoparticle targeting ERK protein in Naegleria fowleri

- Cytotoxic and phytochemical screening of Solanum lycopersicum–Daucus carota hydro-ethanolic extract and in silico evaluation of its lycopene content as anticancer agent

- Protective activities of silver nanoparticles containing Panax japonicus on apoptotic, inflammatory, and oxidative alterations in isoproterenol-induced cardiotoxicity

- pH-based colorimetric detection of monofunctional aldehydes in liquid and gas phases

- Investigating the effect of resveratrol on apoptosis and regulation of gene expression of Caco-2 cells: Unravelling potential implications for colorectal cancer treatment

- Metformin inhibits knee osteoarthritis induced by type 2 diabetes mellitus in rats: S100A8/9 and S100A12 as players and therapeutic targets

- Effect of silver nanoparticles formulated by Silybum marianum on menopausal urinary incontinence in ovariectomized rats

- Synthesis of new analogs of N-substituted(benzoylamino)-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridines

- Response of yield and quality of Japonica rice to different gradients of moisture deficit at grain-filling stage in cold regions

- Preparation of an inclusion complex of nickel-based β-cyclodextrin: Characterization and accelerating the osteoarthritis articular cartilage repair

- Empagliflozin-loaded nanomicelles responsive to reactive oxygen species for renal ischemia/reperfusion injury protection

- Preparation and pharmacodynamic evaluation of sodium aescinate solid lipid nanoparticles

- Assessment of potentially toxic elements and health risks of agricultural soil in Southwest Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- Theoretical investigation of hydrogen-rich fuel production through ammonia decomposition

- Biosynthesis and screening of cobalt nanoparticles using citrus species for antimicrobial activity

- Investigating the interplay of genetic variations, MCP-1 polymorphism, and docking with phytochemical inhibitors for combatting dengue virus pathogenicity through in silico analysis

- Ultrasound induced biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles embedded into chitosan polymers: Investigation of its anti-cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma effects

- Copper oxide nanoparticles-mediated Heliotropium bacciferum leaf extract: Antifungal activity and molecular docking assays against strawberry pathogens

- Sprouted wheat flour for improving physical, chemical, rheological, microbial load, and quality properties of fino bread

- Comparative toxicity assessment of fisetin-aided artificial intelligence-assisted drug design targeting epibulbar dermoid through phytochemicals

- Acute toxicity and anti-inflammatory activity of bis-thiourea derivatives

- Anti-diabetic activity-guided isolation of α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory terpenes from Capsella bursa-pastoris Linn.

- GC–MS analysis of Lactobacillus plantarum YW11 metabolites and its computational analysis on familial pulmonary fibrosis hub genes

- Green formulation of copper nanoparticles by Pistacia khinjuk leaf aqueous extract: Introducing a novel chemotherapeutic drug for the treatment of prostate cancer

- Improved photocatalytic properties of WO3 nanoparticles for Malachite green dye degradation under visible light irradiation: An effect of La doping

- One-pot synthesis of a network of Mn2O3–MnO2–poly(m-methylaniline) composite nanorods on a polypyrrole film presents a promising and efficient optoelectronic and solar cell device

- Groundwater quality and health risk assessment of nitrate and fluoride in Al Qaseem area, Saudi Arabia

- A comparative study of the antifungal efficacy and phytochemical composition of date palm leaflet extracts

- Processing of alcohol pomelo beverage (Citrus grandis (L.) Osbeck) using saccharomyces yeast: Optimization, physicochemical quality, and sensory characteristics

- Specialized compounds of four Cameroonian spices: Isolation, characterization, and in silico evaluation as prospective SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors

- Identification of a novel drug target in Porphyromonas gingivalis by a computational genome analysis approach

- Physico-chemical properties and durability of a fly-ash-based geopolymer

- FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 inhibitory potentials of some phytochemicals from anti-leukemic plants using computational chemical methodologies

- Wild Thymus zygis L. ssp. gracilis and Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh.: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antibacterial activities of essential oils

- 3D-QSAR, molecular docking, ADMET, simulation dynamic, and retrosynthesis studies on new styrylquinolines derivatives against breast cancer

- Deciphering the influenza neuraminidase inhibitory potential of naturally occurring biflavonoids: An in silico approach

- Determination of heavy elements in agricultural regions, Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis and characterization of antioxidant-enriched Moringa oil-based edible oleogel

- Ameliorative effects of thistle and thyme honeys on cyclophosphamide-induced toxicity in mice

- Study of phytochemical compound and antipyretic activity of Chenopodium ambrosioides L. fractions

- Investigating the adsorption mechanism of zinc chloride-modified porous carbon for sulfadiazine removal from water

- Performance repair of building materials using alumina and silica composite nanomaterials with electrodynamic properties

- Effects of nanoparticles on the activity and resistance genes of anaerobic digestion enzymes in livestock and poultry manure containing the antibiotic tetracycline

- Effect of copper nanoparticles green-synthesized using Ocimum basilicum against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in mice lung infection model

- Cardioprotective effects of nanoparticles green formulated by Spinacia oleracea extract on isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction in mice by the determination of PPAR-γ/NF-κB pathway

- Anti-OTC antibody-conjugated fluorescent magnetic/silica and fluorescent hybrid silica nanoparticles for oxytetracycline detection

- Curcumin conjugated zinc nanoparticles for the treatment of myocardial infarction

- Identification and in silico screening of natural phloroglucinols as potential PI3Kα inhibitors: A computational approach for drug discovery

- Exploring the phytochemical profile and antioxidant evaluation: Molecular docking and ADMET analysis of main compounds from three Solanum species in Saudi Arabia

- Unveiling the molecular composition and biological properties of essential oil derived from the leaves of wild Mentha aquatica L.: A comprehensive in vitro and in silico exploration

- Analysis of bioactive compounds present in Boerhavia elegans seeds by GC-MS

- Homology modeling and molecular docking study of corticotrophin-releasing hormone: An approach to treat stress-related diseases

- LncRNA MIR17HG alleviates heart failure via targeting MIR17HG/miR-153-3p/SIRT1 axis in in vitro model

- Development and validation of a stability indicating UPLC-DAD method coupled with MS-TQD for ramipril and thymoquinone in bioactive SNEDDS with in silico toxicity analysis of ramipril degradation products

- Biosynthesis of Ag/Cu nanocomposite mediated by Curcuma longa: Evaluation of its antibacterial properties against oral pathogens

- Development of AMBER-compliant transferable force field parameters for polytetrafluoroethylene

- Treatment of gestational diabetes by Acroptilon repens leaf aqueous extract green-formulated iron nanoparticles in rats

- Development and characterization of new ecological adsorbents based on cardoon wastes: Application to brilliant green adsorption

- A fast, sensitive, greener, and stability-indicating HPLC method for the standardization and quantitative determination of chlorhexidine acetate in commercial products

- Assessment of Se, As, Cd, Cr, Hg, and Pb content status in Ankang tea plantations of China

- Effect of transition metal chloride (ZnCl2) on low-temperature pyrolysis of high ash bituminous coal

- Evaluating polyphenol and ascorbic acid contents, tannin removal ability, and physical properties during hydrolysis and convective hot-air drying of cashew apple powder

- Development and characterization of functional low-fat frozen dairy dessert enhanced with dried lemongrass powder

- Scrutinizing the effect of additive and synergistic antibiotics against carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Preparation, characterization, and determination of the therapeutic effects of copper nanoparticles green-formulated by Pistacia atlantica in diabetes-induced cardiac dysfunction in rat

- Antioxidant and antidiabetic potentials of methoxy-substituted Schiff bases using in vitro, in vivo, and molecular simulation approaches

- Anti-melanoma cancer activity and chemical profile of the essential oil of Seseli yunnanense Franch

- Molecular docking analysis of subtilisin-like alkaline serine protease (SLASP) and laccase with natural biopolymers

- Overcoming methicillin resistance by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Computational evaluation of napthyridine and oxadiazoles compounds for potential dual inhibition of PBP-2a and FemA proteins

- Exploring novel antitubercular agents: Innovative design of 2,3-diaryl-quinoxalines targeting DprE1 for effective tuberculosis treatment

- Drimia maritima flowers as a source of biologically potent components: Optimization of bioactive compound extractions, isolation, UPLC–ESI–MS/MS, and pharmacological properties

- Estimating molecular properties, drug-likeness, cardiotoxic risk, liability profile, and molecular docking study to characterize binding process of key phyto-compounds against serotonin 5-HT2A receptor

- Fabrication of β-cyclodextrin-based microgels for enhancing solubility of Terbinafine: An in-vitro and in-vivo toxicological evaluation

- Phyto-mediated synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles and their sunlight-driven photocatalytic degradation of cationic and anionic dyes

- Monosodium glutamate induces hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis hyperactivation, glucocorticoid receptors down-regulation, and systemic inflammatory response in young male rats: Impact on miR-155 and miR-218

- Quality control analyses of selected honey samples from Serbia based on their mineral and flavonoid profiles, and the invertase activity

- Eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Phyllanthus niruri leaf extract: Assessment of antimicrobial activity, effectiveness on tropical neglected mosquito vector control, and biocompatibility using a fibroblast cell line model

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles containing Cichorium intybus to treat the sepsis-induced DNA damage in the liver of Wistar albino rats

- Quality changes of durian pulp (Durio ziberhinus Murr.) in cold storage

- Study on recrystallization process of nitroguanidine by directly adding cold water to control temperature

- Determination of heavy metals and health risk assessment in drinking water in Bukayriyah City, Saudi Arabia

- Larvicidal properties of essential oils of three Artemisia species against the chemically insecticide-resistant Nile fever vector Culex pipiens (L.) (Diptera: Culicidae): In vitro and in silico studies

- Design, synthesis, characterization, and theoretical calculations, along with in silico and in vitro antimicrobial proprieties of new isoxazole-amide conjugates

- The impact of drying and extraction methods on total lipid, fatty acid profile, and cytotoxicity of Tenebrio molitor larvae

- A zinc oxide–tin oxide–nerolidol hybrid nanomaterial: Efficacy against esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- Research on technological process for production of muskmelon juice (Cucumis melo L.)

- Physicochemical components, antioxidant activity, and predictive models for quality of soursop tea (Annona muricata L.) during heat pump drying

- Characterization and application of Fe1−xCoxFe2O4 nanoparticles in Direct Red 79 adsorption

- Torilis arvensis ethanolic extract: Phytochemical analysis, antifungal efficacy, and cytotoxicity properties

- Magnetite–poly-1H pyrrole dendritic nanocomposite seeded on poly-1H pyrrole: A promising photocathode for green hydrogen generation from sanitation water without using external sacrificing agent

- HPLC and GC–MS analyses of phytochemical compounds in Haloxylon salicornicum extract: Antibacterial and antifungal activity assessment of phytopathogens

- Efficient and stable to coking catalysts of ethanol steam reforming comprised of Ni + Ru loaded on MgAl2O4 + LnFe0.7Ni0.3O3 (Ln = La, Pr) nanocomposites prepared via cost-effective procedure with Pluronic P123 copolymer

- Nitrogen and boron co-doped carbon dots probe for selectively detecting Hg2+ in water samples and the detection mechanism

- Heavy metals in road dust from typical old industrial areas of Wuhan: Seasonal distribution and bioaccessibility-based health risk assessment

- Phytochemical profiling and bioactivity evaluation of CBD- and THC-enriched Cannabis sativa extracts: In vitro and in silico investigation of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects

- Investigating dye adsorption: The role of surface-modified montmorillonite nanoclay in kinetics, isotherms, and thermodynamics

- Antimicrobial activity, induction of ROS generation in HepG2 liver cancer cells, and chemical composition of Pterospermum heterophyllum

- Study on the performance of nanoparticle-modified PVDF membrane in delaying membrane aging

- Impact of cholesterol in encapsulated vitamin E acetate within cocoliposomes

- Review Articles

- Structural aspects of Pt(η3-X1N1X2)(PL) (X1,2 = O, C, or Se) and Pt(η3-N1N2X1)(PL) (X1 = C, S, or Se) derivatives

- Biosurfactants in biocorrosion and corrosion mitigation of metals: An overview

- Stimulus-responsive MOF–hydrogel composites: Classification, preparation, characterization, and their advancement in medical treatments

- Electrochemical dissolution of titanium under alternating current polarization to obtain its dioxide

- Special Issue on Recent Trends in Green Chemistry

- Phytochemical screening and antioxidant activity of Vitex agnus-castus L.

- Phytochemical study, antioxidant activity, and dermoprotective activity of Chenopodium ambrosioides (L.)

- Exploitation of mangliculous marine fungi, Amarenographium solium, for the green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their activity against multiple drug-resistant bacteria

- Study of the phytotoxicity of margines on Pistia stratiotes L.

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Energy, Environmental and Biological Applications - Part III

- Impact of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles on growth, development, and antioxidant system of high protein content crop (Lablab purpureus L.) sweet

- Green synthesis, characterization, and application of iron and molybdenum nanoparticles and their composites for enhancing the growth of Solanum lycopersicum

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Olea europaea L. extracted polysaccharides, characterization, and its assessment as an antimicrobial agent against multiple pathogenic microbes

- Photocatalytic treatment of organic dyes using metal oxides and nanocomposites: A quantitative study

- Antifungal, antioxidant, and photocatalytic activities of greenly synthesized iron oxide nanoparticles

- Special Issue on Phytochemical and Pharmacological Scrutinization of Medicinal Plants

- Hepatoprotective effects of safranal on acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in rats

- Chemical composition and biological properties of Thymus capitatus plants from Algerian high plains: A comparative and analytical study

- Chemical composition and bioactivities of the methanol root extracts of Saussurea costus

- In vivo protective effects of vitamin C against cyto-genotoxicity induced by Dysphania ambrosioides aqueous extract

- Insights about the deleterious impact of a carbamate pesticide on some metabolic immune and antioxidant functions and a focus on the protective ability of a Saharan shrub and its anti-edematous property

- A comprehensive review uncovering the anticancerous potential of genkwanin (plant-derived compound) in several human carcinomas

- A study to investigate the anticancer potential of carvacrol via targeting Notch signaling in breast cancer

- Assessment of anti-diabetic properties of Ziziphus oenopolia (L.) wild edible fruit extract: In vitro and in silico investigations through molecular docking analysis

- Optimization of polyphenol extraction, phenolic profile by LC-ESI-MS/MS, antioxidant, anti-enzymatic, and cytotoxic activities of Physalis acutifolia

- Phytochemical screening, antioxidant properties, and photo-protective activities of Salvia balansae de Noé ex Coss

- Antihyperglycemic, antiglycation, anti-hypercholesteremic, and toxicity evaluation with gas chromatography mass spectrometry profiling for Aloe armatissima leaves

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of gold nanoparticles by using Timur (Zanthoxylum armatum DC) and their effect on wound healing

- Does Erodium trifolium (Cav.) Guitt exhibit medicinal properties? Response elements from phytochemical profiling, enzyme-inhibiting, and antioxidant and antimicrobial activities

- Integrative in silico evaluation of the antiviral potential of terpenoids and its metal complexes derived from Homalomena aromatica based on main protease of SARS-CoV-2

- 6-Methoxyflavone improves anxiety, depression, and memory by increasing monoamines in mice brain: HPLC analysis and in silico studies

- Simultaneous extraction and quantification of hydrophilic and lipophilic antioxidants in Solanum lycopersicum L. varieties marketed in Saudi Arabia

- Biological evaluation of CH3OH and C2H5OH of Berberis vulgaris for in vivo antileishmanial potential against Leishmania tropica in murine models

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Porous silicon nanostructures: Synthesis, characterization, and their antifungal activity

- Biochar from de-oiled Chlorella vulgaris and its adsorption on antibiotics

- Phytochemicals profiling, in vitro and in vivo antidiabetic activity, and in silico studies on Ajuga iva (L.) Schreb.: A comprehensive approach

- Synthesis, characterization, in silico and in vitro studies of novel glycoconjugates as potential antibacterial, antifungal, and antileishmanial agents

- Sonochemical synthesis of gold nanoparticles mediated by potato starch: Its performance in the treatment of esophageal cancer

- Computational study of ADME-Tox prediction of selected phytochemicals from Punica granatum peels

- Phytochemical analysis, in vitro antioxidant and antifungal activities of extracts and essential oil derived from Artemisia herba-alba Asso

- Two triazole-based coordination polymers: Synthesis and crystal structure characterization

- Phytochemical and physicochemical studies of different apple varieties grown in Morocco

- Synthesis of multi-template molecularly imprinted polymers (MT-MIPs) for isolating ethyl para-methoxycinnamate and ethyl cinnamate from Kaempferia galanga L., extract with methacrylic acid as functional monomer

- Nutraceutical potential of Mesembryanthemum forsskaolii Hochst. ex Bioss.: Insights into its nutritional composition, phytochemical contents, and antioxidant activity

- Evaluation of influence of Butea monosperma floral extract on inflammatory biomarkers

- Cannabis sativa L. essential oil: Chemical composition, anti-oxidant, anti-microbial properties, and acute toxicity: In vitro, in vivo, and in silico study

- The effect of gamma radiation on 5-hydroxymethylfurfural conversion in water and dimethyl sulfoxide

- Hollow mushroom nanomaterials for potentiometric sensing of Pb2+ ions in water via the intercalation of iodide ions into the polypyrrole matrix

- Determination of essential oil and chemical composition of St. John’s Wort

- Computational design and in vitro assay of lantadene-based novel inhibitors of NS3 protease of dengue virus

- Anti-parasitic activity and computational studies on a novel labdane diterpene from the roots of Vachellia nilotica

- Microbial dynamics and dehydrogenase activity in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) rhizospheres: Impacts on growth and soil health across different soil types

- Correlation between in vitro anti-urease activity and in silico molecular modeling approach of novel imidazopyridine–oxadiazole hybrids derivatives

- Spatial mapping of indoor air quality in a light metro system using the geographic information system method

- Iron indices and hemogram in renal anemia and the improvement with Tribulus terrestris green-formulated silver nanoparticles applied on rat model

- Integrated track of nano-informatics coupling with the enrichment concept in developing a novel nanoparticle targeting ERK protein in Naegleria fowleri

- Cytotoxic and phytochemical screening of Solanum lycopersicum–Daucus carota hydro-ethanolic extract and in silico evaluation of its lycopene content as anticancer agent

- Protective activities of silver nanoparticles containing Panax japonicus on apoptotic, inflammatory, and oxidative alterations in isoproterenol-induced cardiotoxicity

- pH-based colorimetric detection of monofunctional aldehydes in liquid and gas phases

- Investigating the effect of resveratrol on apoptosis and regulation of gene expression of Caco-2 cells: Unravelling potential implications for colorectal cancer treatment

- Metformin inhibits knee osteoarthritis induced by type 2 diabetes mellitus in rats: S100A8/9 and S100A12 as players and therapeutic targets

- Effect of silver nanoparticles formulated by Silybum marianum on menopausal urinary incontinence in ovariectomized rats

- Synthesis of new analogs of N-substituted(benzoylamino)-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridines

- Response of yield and quality of Japonica rice to different gradients of moisture deficit at grain-filling stage in cold regions

- Preparation of an inclusion complex of nickel-based β-cyclodextrin: Characterization and accelerating the osteoarthritis articular cartilage repair

- Empagliflozin-loaded nanomicelles responsive to reactive oxygen species for renal ischemia/reperfusion injury protection

- Preparation and pharmacodynamic evaluation of sodium aescinate solid lipid nanoparticles

- Assessment of potentially toxic elements and health risks of agricultural soil in Southwest Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- Theoretical investigation of hydrogen-rich fuel production through ammonia decomposition

- Biosynthesis and screening of cobalt nanoparticles using citrus species for antimicrobial activity

- Investigating the interplay of genetic variations, MCP-1 polymorphism, and docking with phytochemical inhibitors for combatting dengue virus pathogenicity through in silico analysis

- Ultrasound induced biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles embedded into chitosan polymers: Investigation of its anti-cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma effects

- Copper oxide nanoparticles-mediated Heliotropium bacciferum leaf extract: Antifungal activity and molecular docking assays against strawberry pathogens

- Sprouted wheat flour for improving physical, chemical, rheological, microbial load, and quality properties of fino bread

- Comparative toxicity assessment of fisetin-aided artificial intelligence-assisted drug design targeting epibulbar dermoid through phytochemicals

- Acute toxicity and anti-inflammatory activity of bis-thiourea derivatives

- Anti-diabetic activity-guided isolation of α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory terpenes from Capsella bursa-pastoris Linn.

- GC–MS analysis of Lactobacillus plantarum YW11 metabolites and its computational analysis on familial pulmonary fibrosis hub genes

- Green formulation of copper nanoparticles by Pistacia khinjuk leaf aqueous extract: Introducing a novel chemotherapeutic drug for the treatment of prostate cancer

- Improved photocatalytic properties of WO3 nanoparticles for Malachite green dye degradation under visible light irradiation: An effect of La doping

- One-pot synthesis of a network of Mn2O3–MnO2–poly(m-methylaniline) composite nanorods on a polypyrrole film presents a promising and efficient optoelectronic and solar cell device

- Groundwater quality and health risk assessment of nitrate and fluoride in Al Qaseem area, Saudi Arabia

- A comparative study of the antifungal efficacy and phytochemical composition of date palm leaflet extracts

- Processing of alcohol pomelo beverage (Citrus grandis (L.) Osbeck) using saccharomyces yeast: Optimization, physicochemical quality, and sensory characteristics

- Specialized compounds of four Cameroonian spices: Isolation, characterization, and in silico evaluation as prospective SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors

- Identification of a novel drug target in Porphyromonas gingivalis by a computational genome analysis approach

- Physico-chemical properties and durability of a fly-ash-based geopolymer

- FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 inhibitory potentials of some phytochemicals from anti-leukemic plants using computational chemical methodologies

- Wild Thymus zygis L. ssp. gracilis and Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh.: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antibacterial activities of essential oils

- 3D-QSAR, molecular docking, ADMET, simulation dynamic, and retrosynthesis studies on new styrylquinolines derivatives against breast cancer

- Deciphering the influenza neuraminidase inhibitory potential of naturally occurring biflavonoids: An in silico approach

- Determination of heavy elements in agricultural regions, Saudi Arabia

- Synthesis and characterization of antioxidant-enriched Moringa oil-based edible oleogel

- Ameliorative effects of thistle and thyme honeys on cyclophosphamide-induced toxicity in mice

- Study of phytochemical compound and antipyretic activity of Chenopodium ambrosioides L. fractions

- Investigating the adsorption mechanism of zinc chloride-modified porous carbon for sulfadiazine removal from water

- Performance repair of building materials using alumina and silica composite nanomaterials with electrodynamic properties

- Effects of nanoparticles on the activity and resistance genes of anaerobic digestion enzymes in livestock and poultry manure containing the antibiotic tetracycline

- Effect of copper nanoparticles green-synthesized using Ocimum basilicum against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in mice lung infection model

- Cardioprotective effects of nanoparticles green formulated by Spinacia oleracea extract on isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction in mice by the determination of PPAR-γ/NF-κB pathway

- Anti-OTC antibody-conjugated fluorescent magnetic/silica and fluorescent hybrid silica nanoparticles for oxytetracycline detection

- Curcumin conjugated zinc nanoparticles for the treatment of myocardial infarction

- Identification and in silico screening of natural phloroglucinols as potential PI3Kα inhibitors: A computational approach for drug discovery

- Exploring the phytochemical profile and antioxidant evaluation: Molecular docking and ADMET analysis of main compounds from three Solanum species in Saudi Arabia

- Unveiling the molecular composition and biological properties of essential oil derived from the leaves of wild Mentha aquatica L.: A comprehensive in vitro and in silico exploration

- Analysis of bioactive compounds present in Boerhavia elegans seeds by GC-MS

- Homology modeling and molecular docking study of corticotrophin-releasing hormone: An approach to treat stress-related diseases

- LncRNA MIR17HG alleviates heart failure via targeting MIR17HG/miR-153-3p/SIRT1 axis in in vitro model

- Development and validation of a stability indicating UPLC-DAD method coupled with MS-TQD for ramipril and thymoquinone in bioactive SNEDDS with in silico toxicity analysis of ramipril degradation products

- Biosynthesis of Ag/Cu nanocomposite mediated by Curcuma longa: Evaluation of its antibacterial properties against oral pathogens

- Development of AMBER-compliant transferable force field parameters for polytetrafluoroethylene

- Treatment of gestational diabetes by Acroptilon repens leaf aqueous extract green-formulated iron nanoparticles in rats

- Development and characterization of new ecological adsorbents based on cardoon wastes: Application to brilliant green adsorption

- A fast, sensitive, greener, and stability-indicating HPLC method for the standardization and quantitative determination of chlorhexidine acetate in commercial products

- Assessment of Se, As, Cd, Cr, Hg, and Pb content status in Ankang tea plantations of China

- Effect of transition metal chloride (ZnCl2) on low-temperature pyrolysis of high ash bituminous coal

- Evaluating polyphenol and ascorbic acid contents, tannin removal ability, and physical properties during hydrolysis and convective hot-air drying of cashew apple powder

- Development and characterization of functional low-fat frozen dairy dessert enhanced with dried lemongrass powder

- Scrutinizing the effect of additive and synergistic antibiotics against carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Preparation, characterization, and determination of the therapeutic effects of copper nanoparticles green-formulated by Pistacia atlantica in diabetes-induced cardiac dysfunction in rat

- Antioxidant and antidiabetic potentials of methoxy-substituted Schiff bases using in vitro, in vivo, and molecular simulation approaches

- Anti-melanoma cancer activity and chemical profile of the essential oil of Seseli yunnanense Franch

- Molecular docking analysis of subtilisin-like alkaline serine protease (SLASP) and laccase with natural biopolymers

- Overcoming methicillin resistance by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Computational evaluation of napthyridine and oxadiazoles compounds for potential dual inhibition of PBP-2a and FemA proteins

- Exploring novel antitubercular agents: Innovative design of 2,3-diaryl-quinoxalines targeting DprE1 for effective tuberculosis treatment

- Drimia maritima flowers as a source of biologically potent components: Optimization of bioactive compound extractions, isolation, UPLC–ESI–MS/MS, and pharmacological properties

- Estimating molecular properties, drug-likeness, cardiotoxic risk, liability profile, and molecular docking study to characterize binding process of key phyto-compounds against serotonin 5-HT2A receptor

- Fabrication of β-cyclodextrin-based microgels for enhancing solubility of Terbinafine: An in-vitro and in-vivo toxicological evaluation

- Phyto-mediated synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles and their sunlight-driven photocatalytic degradation of cationic and anionic dyes

- Monosodium glutamate induces hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis hyperactivation, glucocorticoid receptors down-regulation, and systemic inflammatory response in young male rats: Impact on miR-155 and miR-218

- Quality control analyses of selected honey samples from Serbia based on their mineral and flavonoid profiles, and the invertase activity

- Eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Phyllanthus niruri leaf extract: Assessment of antimicrobial activity, effectiveness on tropical neglected mosquito vector control, and biocompatibility using a fibroblast cell line model

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles containing Cichorium intybus to treat the sepsis-induced DNA damage in the liver of Wistar albino rats

- Quality changes of durian pulp (Durio ziberhinus Murr.) in cold storage

- Study on recrystallization process of nitroguanidine by directly adding cold water to control temperature

- Determination of heavy metals and health risk assessment in drinking water in Bukayriyah City, Saudi Arabia

- Larvicidal properties of essential oils of three Artemisia species against the chemically insecticide-resistant Nile fever vector Culex pipiens (L.) (Diptera: Culicidae): In vitro and in silico studies

- Design, synthesis, characterization, and theoretical calculations, along with in silico and in vitro antimicrobial proprieties of new isoxazole-amide conjugates

- The impact of drying and extraction methods on total lipid, fatty acid profile, and cytotoxicity of Tenebrio molitor larvae

- A zinc oxide–tin oxide–nerolidol hybrid nanomaterial: Efficacy against esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- Research on technological process for production of muskmelon juice (Cucumis melo L.)

- Physicochemical components, antioxidant activity, and predictive models for quality of soursop tea (Annona muricata L.) during heat pump drying

- Characterization and application of Fe1−xCoxFe2O4 nanoparticles in Direct Red 79 adsorption

- Torilis arvensis ethanolic extract: Phytochemical analysis, antifungal efficacy, and cytotoxicity properties

- Magnetite–poly-1H pyrrole dendritic nanocomposite seeded on poly-1H pyrrole: A promising photocathode for green hydrogen generation from sanitation water without using external sacrificing agent

- HPLC and GC–MS analyses of phytochemical compounds in Haloxylon salicornicum extract: Antibacterial and antifungal activity assessment of phytopathogens

- Efficient and stable to coking catalysts of ethanol steam reforming comprised of Ni + Ru loaded on MgAl2O4 + LnFe0.7Ni0.3O3 (Ln = La, Pr) nanocomposites prepared via cost-effective procedure with Pluronic P123 copolymer

- Nitrogen and boron co-doped carbon dots probe for selectively detecting Hg2+ in water samples and the detection mechanism

- Heavy metals in road dust from typical old industrial areas of Wuhan: Seasonal distribution and bioaccessibility-based health risk assessment

- Phytochemical profiling and bioactivity evaluation of CBD- and THC-enriched Cannabis sativa extracts: In vitro and in silico investigation of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects

- Investigating dye adsorption: The role of surface-modified montmorillonite nanoclay in kinetics, isotherms, and thermodynamics

- Antimicrobial activity, induction of ROS generation in HepG2 liver cancer cells, and chemical composition of Pterospermum heterophyllum

- Study on the performance of nanoparticle-modified PVDF membrane in delaying membrane aging

- Impact of cholesterol in encapsulated vitamin E acetate within cocoliposomes

- Review Articles

- Structural aspects of Pt(η3-X1N1X2)(PL) (X1,2 = O, C, or Se) and Pt(η3-N1N2X1)(PL) (X1 = C, S, or Se) derivatives

- Biosurfactants in biocorrosion and corrosion mitigation of metals: An overview

- Stimulus-responsive MOF–hydrogel composites: Classification, preparation, characterization, and their advancement in medical treatments

- Electrochemical dissolution of titanium under alternating current polarization to obtain its dioxide

- Special Issue on Recent Trends in Green Chemistry

- Phytochemical screening and antioxidant activity of Vitex agnus-castus L.

- Phytochemical study, antioxidant activity, and dermoprotective activity of Chenopodium ambrosioides (L.)

- Exploitation of mangliculous marine fungi, Amarenographium solium, for the green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their activity against multiple drug-resistant bacteria

- Study of the phytotoxicity of margines on Pistia stratiotes L.

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Energy, Environmental and Biological Applications - Part III

- Impact of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles on growth, development, and antioxidant system of high protein content crop (Lablab purpureus L.) sweet

- Green synthesis, characterization, and application of iron and molybdenum nanoparticles and their composites for enhancing the growth of Solanum lycopersicum

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Olea europaea L. extracted polysaccharides, characterization, and its assessment as an antimicrobial agent against multiple pathogenic microbes

- Photocatalytic treatment of organic dyes using metal oxides and nanocomposites: A quantitative study

- Antifungal, antioxidant, and photocatalytic activities of greenly synthesized iron oxide nanoparticles

- Special Issue on Phytochemical and Pharmacological Scrutinization of Medicinal Plants

- Hepatoprotective effects of safranal on acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in rats

- Chemical composition and biological properties of Thymus capitatus plants from Algerian high plains: A comparative and analytical study

- Chemical composition and bioactivities of the methanol root extracts of Saussurea costus

- In vivo protective effects of vitamin C against cyto-genotoxicity induced by Dysphania ambrosioides aqueous extract

- Insights about the deleterious impact of a carbamate pesticide on some metabolic immune and antioxidant functions and a focus on the protective ability of a Saharan shrub and its anti-edematous property

- A comprehensive review uncovering the anticancerous potential of genkwanin (plant-derived compound) in several human carcinomas

- A study to investigate the anticancer potential of carvacrol via targeting Notch signaling in breast cancer

- Assessment of anti-diabetic properties of Ziziphus oenopolia (L.) wild edible fruit extract: In vitro and in silico investigations through molecular docking analysis

- Optimization of polyphenol extraction, phenolic profile by LC-ESI-MS/MS, antioxidant, anti-enzymatic, and cytotoxic activities of Physalis acutifolia

- Phytochemical screening, antioxidant properties, and photo-protective activities of Salvia balansae de Noé ex Coss

- Antihyperglycemic, antiglycation, anti-hypercholesteremic, and toxicity evaluation with gas chromatography mass spectrometry profiling for Aloe armatissima leaves

- Phyto-fabrication and characterization of gold nanoparticles by using Timur (Zanthoxylum armatum DC) and their effect on wound healing

- Does Erodium trifolium (Cav.) Guitt exhibit medicinal properties? Response elements from phytochemical profiling, enzyme-inhibiting, and antioxidant and antimicrobial activities

- Integrative in silico evaluation of the antiviral potential of terpenoids and its metal complexes derived from Homalomena aromatica based on main protease of SARS-CoV-2

- 6-Methoxyflavone improves anxiety, depression, and memory by increasing monoamines in mice brain: HPLC analysis and in silico studies

- Simultaneous extraction and quantification of hydrophilic and lipophilic antioxidants in Solanum lycopersicum L. varieties marketed in Saudi Arabia

- Biological evaluation of CH3OH and C2H5OH of Berberis vulgaris for in vivo antileishmanial potential against Leishmania tropica in murine models