Abstract

Despite being rich in groundwater resources, assessment of hard-rock aquifers in many areas of Asia is difficult given their strong heterogeneity. However, delineation of such aquifers is essential for estimation of the groundwater reserves. In addition, the vulnerability of hard-rock aquifers is controlled by the weathered/fractured zones because it is the place where most of the groundwater reserves are contained. In this work, an integrated approach of the electrical resistivity tomography (ERT), high precision magnetic, X-ray Diffraction (XRD), physicochemical analysis and pumping test data was performed to investigate the hard-rock aquifers occurring in the weathered terrains. This approach reveals seven fractures/faults (F1 to F7) and four discrete layers such as the topsoil cover, highly weathered, partly weathered and unweathered rock. The groundwater resources are estimated as a function of different parameters i.e., aquifer resistivity (ρo), transverse unit resistance (Tr), hydraulic conductivity (K), transmissivity (T), rock formation factor (F) and rock porosity (Φ). These parameters divide the groundwater resources into four aquifer potential zones with specific ranges of ρo, Tr, K, T, F and Φ i.e., high, medium, poor, and negligible potential aquifers. The results suggest that the high potential aquifer reserves are contained within the weathered/fractured and fault zones. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) technique analyzes quartz as the major mineral (>50%). The physicochemical and geophysical analysis suggests good groundwater quality in the investigated area. The integrated results are highly satisfied with the available borehole information. This integrated geophysical approach for the estimation of groundwater resources is not only applicable in the weathered terrains of South China, but also in many other areas of the weathered/fractured aquifer in Asia and beyond.

1 Introduction

Groundwater is the best alternative source to the surface water in many parts of the world [1]. Although the Asian countries are rich in the groundwater resources, however it is difficult to fulfill the needs of the fast growing population especially in South and East Asian regions [2]. Since most of the natural groundwater reserves occur within the weathered/fractured rock, therefore it is a big challenge to delineate and estimate the underground water resources. A study on the subsurface geological properties is essential to assess the groundwater reserves. Groundwater is the subsurface water which occurs either in the fractured rock or in the soil pore spaces [3]. The major problem is the delineation of the subsurface zones that are saturated with groundwater. Geologically, the weathered/fractured rocks contain groundwater reserves in a weathered environment [4]. Different hydrological and weathering processes create fractures, joints and fault zones in the hard-rock system where the groundwater may occur. Such processes play an important role to make up an aquifer system [5]. Groundwater is generally found in the saturated fractures and unsaturated weathered formation overlying the fresh bedrock. The hydrogeological characteristics of the basement and weathered rock depend on the weathering processes [5, 6]. Thickness of the weathered/fractured hard-rock controls the aquifer characteristics [7]. Groundwater potential depends on detection and delineation of the subsurface fractured layers that offer special pathways to the groundwater flow-system [8].

Hydrogeological information can be obtained only for some selected locations using the expensive drilling methods. Geophysics is a natural science dealing with the physical processes and properties of the earth, and provides study of the subsurface geological formations through the use of quantitative methods [9]. Geophysical methods can be the most suitable approach for the groundwater assessment as this tool has been widely used in several hydro-geophysical, geotechnical, engineering-geological and geo-environment studies. The electrical resistivity tomography (ERT) is a geophysical method recently being used in many environmental and engineering geophysical investigations [4, 10, 11, 12, 13]. Such geophysical methods are effectively applied in many groundwater studies mainly because they are simple, efficient, inexpensive, nondestructive, and provide the subsurface imaging better than the conventional techniques [14]. In hydrogeology, the integrated geophysical approaches are becoming a standard; especially the incorporation of the ERT method with the magnetic methods is being widely used for evaluation of the groundwater reserves, generally because the electrical conductivity and the hydrological properties are closely associated with each other [15]. Such geophysical methods can suggest the most appropriate drilling locations [2, 7]. The resistivity methods are commonly used to exploit the near-surface stratigraphic characteristics for the groundwater occurrence [1, 13, 16, 17]. Such methods measure the subsurface resistivity which is related with physical properties of the ground materials. The magnetic methods have been widely used in several groundwater investigations for many years [4, 6, 18, 19]. The magnetic surveys measure the magnetic susceptibility of the igneous and metamorphic rocks [6]. Magnetic field is a region around a magnetic material whereas magnetic susceptibility measured in the magnetic methods is the degree of magnetization of a magnetic material (quantitative measure of the extent by which a material is magnetized) in response to an applied magnetic field [6]. The magnetic intensity is caused by the magnetization depending on the magnetic minerals [18, 19]. Incorporation of the ERT and magnetic techniques involving the borehole data clearly delineated an interface between the weathered rock and fresh basement that assist to assess the groundwater environment in the investigated area. The weathering processes deplete the magnetic intensity of the weathering materials through the geological period. Such depletion causes a reduction in susceptibility of the magnetic materials while it remains unaffected in the basement rock. In the same way, resistivity of the weathering layers is less than resistivity of the basement rock [4]. Thus a geological contact between the weathering materials and the basement rocks makes an interface that is useful to assess the groundwater reserves in the studied area.

The groundwater flow system is controlled by the spatial distribution of the hydraulic properties such as porosity, specific yield, hydraulic conductivity and transmissivity. Hydrogeophysicists suggest a successful integration between the resistivity parameters estimated from the surface resistivity data and hydraulic parameters measured from the borehole data, since an association between the electrical and hydraulic parameters can be possible because both are controlled by the heterogeneity and pore-space structure [20, 21, 22]. Several authors established different relations between geoelectric properties and aquifer parameters in past three decades depending on the site specification [23, 24, 25, 26, 27]. The above studies established mathematical equations to estimate the hydraulic parameters from the surface geoelectrical measurements. These investigations suggest that the surface geophysical methods can be successfully used to estimate the aquifer parameters. However, such correlations are site-specific which provide insufficient applications in different areas [28, 29, 30]. Since the mechanism which causes the electric current and fluid flow mainly depends on the same subsurface attributes and physical properties, it implies that both the electric and hydraulic conductivities depend on each other. Because the factors associated with flow and conduction of current into the ground (size, lithology, mineralogy, depth and water distribution, shape, compaction and cementation, geometry and shape of pores and pore channels, magnitudes of porosity, permeability and tortuosity, orientation and packing of grains, and consolidation) are extremely variable [26, 31], so the measured subsurface resistivity is relative but not absolute, so only relative estimation of the site’s aquifer parameters is possible.

In the investigated area, the subsurface layers for groundwater potential were evaluated by the combination of ERT with magnetic and well data. Then, the delineated groundwater reserves were estimated by the effective (aquifer) parameters. The estimation of effective parameters from the subsurface resistivity measurements, and the mineral analysis using the X-ray diffraction (XRD) method, and the physicochemical/geophysical analysis for groundwater quality provide a complete hydrogeological assessment of the groundwater system in the studied area.

2 Site Information

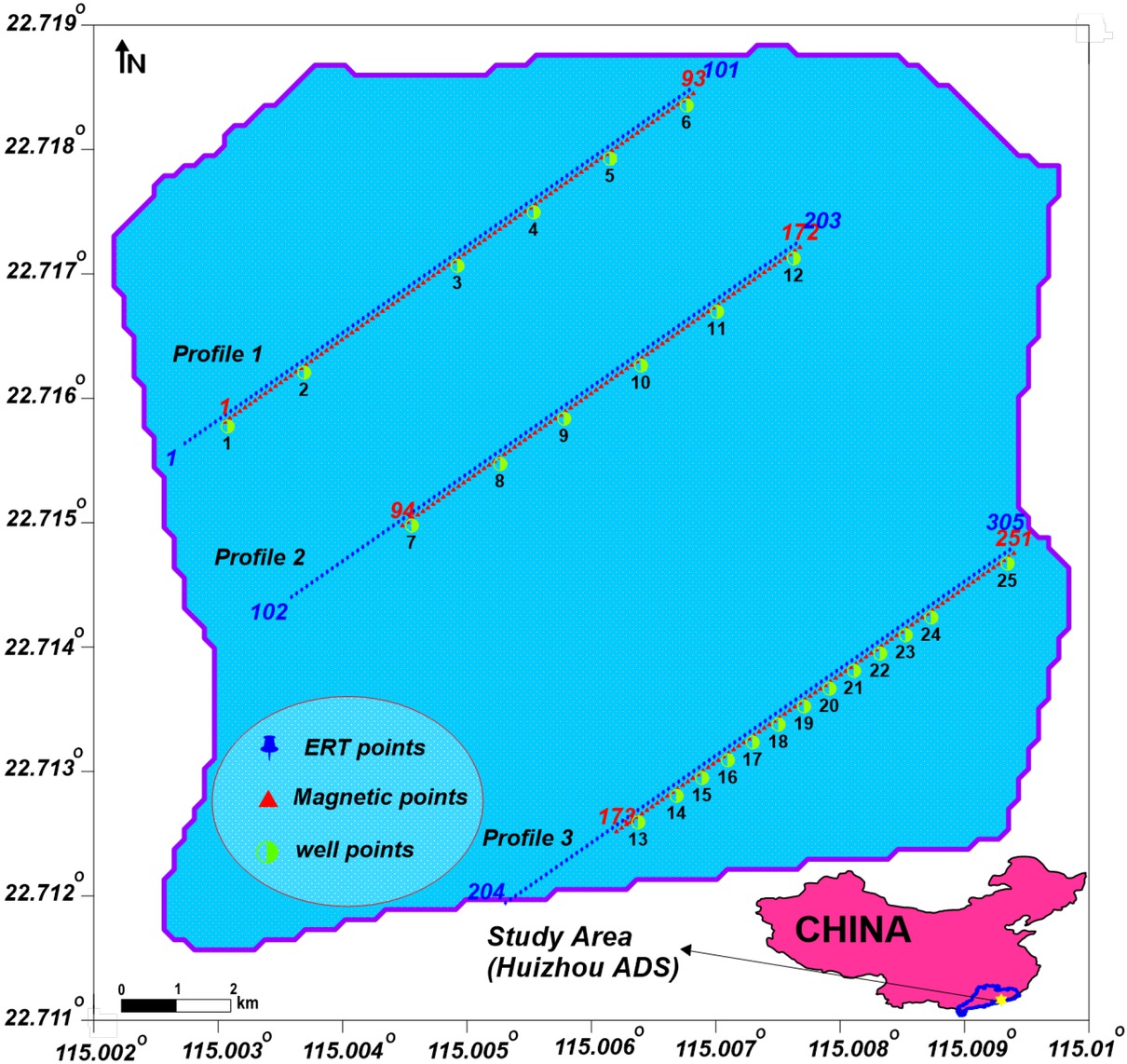

This geophysical study was carried out in Huizhou ADS site, China. It is located in Guangdong province of South China with longitude between 114.87∘ and 115.13∘ E, and the latitude from 22.64∘ to 22.93∘ N covering an area of 3390 km2. It has an annual rainfall of 1860 mm lying in the South Asian Monsoon climate system. The rainy Monsoon starts from April and ends in October. Most of the typhoons come between June and October [32]. Rainfall is the only source to recharge the groundwater resources of the investigated area [13]. It has three main units depending its geomorphological setting i.e., the east mountainous region, the central hills all along the river, and the southern mountains at the verge of the South China Sea. The location of the investigated site including the geophysical measurements is shown in Figure 1. The boreholes data reveal that the investigated area consists of Jurassic age rocks/minerals mainly magmatic and volcanic rocks including tuff, quartz, volcano dust, pyrite sulfide, feldspar, matrix, pyroxene and the quartz veins embedded in the Aeolian tuff rock. Granites, basalts and quartz dykes are also exposed on small scale in the project site [33, 34]. The regional geologic structure of the study area lies in the South China Fold System. The fault structures developed in the investigated site are primarily controlled by the Yanshanian movement with igneous intrusions and volcanic eruptions. The Huiyang depression and the coastal mountain fault block are two main structural units in Huizhou. There are also secondary syncline and anticline structures such as Hengdong syncline, Andun large syncline, Hexishi syncline, Lianhua Gupi syncline, Phanghuidong anticline, Duozhu fault depression basin and so on. The faults and folds form the basic framework of the geologic structures in this area. Huizhou is located in Lianhuashan Shuangyunshan fault uplift in east of Wuhua Shenzhen fault and west of Fengyin Haifeng fault. Various faults distributed in the study area are mainly active in the late period of Yunshan Mountain. The investigated site has complex geological settings which include a dynamo-metamorphic zone, various faults, and an unconformable boundary. The depth of water table remains between 0 and 20 m in the study area. Generally, the water level is found in the elevation range of 60 - 150m from the mean sea level. The investigated site situated in the topographic relief between 70 and 155 mwith the southeast and northwest parts lower than the central parts.

Map showing location of the studied area with geophysical measurements of ERT, magnetic and boreholes.

3 Methodology

3.1 ERT Method

The 2D ERT method can assess areas of the heterogeneous settings for the groundwater evaluation where applications of the other geophysical techniques are not appropriate [35]. It provides more depth penetration by increasing the electrode interval, and gives a 2D subsurface model with vertical and lateral changes in resistivity values. An inversion of the apparent resistivity in the ERT survey gives the systematic measurements that can enhance quality of the subsurface geological model [36, 37, 38, 39, 40]. ERT was conducted using WDJD-4 multi-function electrical instrument produced by the Chongqing Pentium CNC Technology Research Center and WDZJ-120 multi-electrode converter. A layout of pole-dipole configuration was used to acquire the resistivity data in the ERT survey which is a more suitable array for such heterogeneous site to demarcate the sub-surface weathered/fractured zones for assessment of the groundwater reserves [41]. The resistivity data were measured for 25 layers. ERT was carried out along three geophysical profiles including 101 electrodes along each profile, a profile length of 500 m and inter-electrode distance of 5 m (Figure 1). The field measurements were obtained using GPS systems (MAP60, Garmin, Olathe, KS, USA) and other surveying instrumentation. The topographic variations were measured using a clinometer along each profile with the distance interval of 10 m and less when it was necessary. The resistivity data of a single point was collected using maximum 10 stacking to improve the signal to noise ratio. A computer-based multichannel resistivity meter placed at centre of the electrode array was applied to get the electrical resistivity measurements [42]. In the ERT survey, 50 m thick subsurface formation was assessed to delineate the weathered/fractured zone depending on the hydrogeological data and the thickness of the subsurface geological strata in the studied area. For the post-processing of the resistivity data, an inversion program was performed to obtain a 2D resistivity model of the subsurface formation including the topographic relief along each ERT profile [35]. The first step to make up a 2D resistivity model is to make a pseudo section. In this step, each value of apparent resistivity is plotted on a separate section at centre of four electrodes, and at depth equal to the median depth of the investigated array [36, 40]. A least-squares technique was adopted for inversion of the apparent resistivity data [36, 40, 43]. An inversion procedure of RES2DINV software was performed to generate a 2D ERT pseudo-section along each profile [44]. This software automatically inverts the apparent resistivity data to generate a 2D resistivity model including the topographic relief [35]. A least-squares inversion technique of RES2DINV has to apply a smoothness constraint [45, 46]. The inversion procedure of the software can generate a smooth model by fitting the resistivity data to a given error level. In this investigation, RMS (root mean square) error which is the difference in calculated values of apparent resistivity and measured values of apparent resistivity values was less than 5% for all the inversion models. Such model contains a number of rectangular blocks which are equivalent to the data points in the resistivity model. The centre of the depth for the inner blocks is used as the investigation’s median depth [47]. In order to minimize the difference between the measured apparent resistivity and the modeled resistivity values, the inversion program of conventional Gauss-Newton least squares technique was applied [48]. The Gauss-Newton’s modified model [46] follows the equation:

where i shows iteration number, gi is discrepancy vector which depends on the difference between the logarithms of the measured and calculated values of the apparent resistivity, λi is the damping factor, Ji represents Jacobian matrix of partial derivatives, pi is perturbation vector to the model parameters for the ith iteration, and C shows 2D flatness filter.

The apparent resistivity is calculated in the first step of the least squares inversion. In the second step, Jacobian matrix J is calculated. All parameters in equation (1) are solved in the third step. The first two steps are completed by applying a finite element or finite difference technique, whereas different methods including Cholesky, the modified Gram-Schmidt, and the singular value decomposition techniques are used to solve the third step [49].

3.2 Magnetic Method

The magnetic field intensity is the magnetic field generated by the North and the South Poles. The main magnetic field is controlled by the factors i.e., magnitude of the field, magnetic inclination (dip of a magnetic compass from horizontal i.e., −90∘ for south magnetic pole, +90∘ for north magnetic pole and 0∘ for magnetic equator) and magnetic declination (angle between geographic north and magnetic north). The electric currents in the earth’s ionosphere produce the diurnal variations also called as magnetic storms varying from 50 to 200 gammas which can be removed by applying diurnal corrections [4].

The Ground high-precision magnetic survey was conducted along three profiles according to the Technical Specifications for High-precision Magnetic Survey on the Ground (industry standard, DZ/T 0071-93). The geomagnetic total field (nT) was observed using a GSM-19T high-precision proton magnetometer manufactured in Canada with <0.7nT accuracy and a high precision GPS system (MAP60, Garmin, Olathe, KS, USA). The sampling interval for the diurnal observations was 20 seconds. The magnetometer automatically sampled and recorded the magnetic data. The magnetic probe height was fixed at 2m to get more accuracy. The data changes were observed every 20 to 30 minutes, and there was no magnetic storm observed during the magnetic survey. However, a base station magnetometer was used to record the time variations of the magnetic field and then the changes were removed from the readings. This survey was conducted for a total of 251 measurements with 5 m station interval along three profiles (Figure 1). The magnetic data were processed to get 2D magnetic model by inverting the data using IX2D Interpex (Golden, USA) with a distance interval of 50 m along each profile. The inversion program records a response from the magnetic model. Afterwards, the response is compared with the measured magnetic data. The geometry of the subsurface geologic layers and their magnetic properties are changed constantly until the model response fits the measured magnetic data convincingly. In this way, a four layered model is generated by the inversion procedure of IX2D. The 2D magnetic model was interpreted for four layers such as the topsoil layer, the highly weathered layer, the partly weathered layer and the fresh bedrock based on magnetic susceptibility and the available upfront hydrogeological information along each profile in the study area. The weathered layer (the highly weathered and the partly weathered layer) underlying the topsoil cover and the fresh bedrock at the bottom in the model were interpreted by low magnetic susceptibility and high magnetic susceptibility respectively.

3.3 Estimation of Hydraulic Parameters

Estimation of hydraulic conductivity and transmissivity of any given aquifer system is essential for delineation of the aquifer potential zones contained within the weathered/fractured zones. Water contained within the fractures/fissures of a hard rock controls flow of the electric current in the electrolytic (mineralized) water through the ions flowing in the same pathways of water [50, 51, 52]. The electrical and hydraulic conductivity of the aquifer system are affected by the similar variables, since both depend on the potential gradients flowing from higher to lower potential [13, 17]. The pumping test naturally causes the occurrence of hydraulic potential gradient, whereas the electrical resistivity measurements generate the electric potential gradient [16]. The aquifer parameters were estimated using the pumping test and resistivity data.

The fractures/fissures are well connected because they may not exist in the real domain. In order to ensure occurrence of the interconnected fractures, the hydraulic parameters of the aquifer system were estimated from a long pumping duration. The aquifer parameters were measured using the pumping test performed at 25 boreholes (Figure 1). The double-porosity model (DP model), also called as the double continuum or overlapping continua, was used to perform the pumping test analysis [53]. This model was originally introduced by Barenblatt and Zheltov [54], and Barenblatt et al. [55] to estimate the hydraulic parameters of the weathered/fractured aquifer system. The model represents the fractured porous medium by two discrete but interacting subsystems in which one consists of the porous blocks and the other contains a network of fractures. Each subsystem is represented by a continuum taking up the entire medium domain. Hence, the interaction phenomena of two continua provide the exchange of fluid between porous blocks and fractures for a pumping test [53].

Using Darcy’s law for horizontal fluid flow and Ohm’s law of current flow in a medium, the following two relations can be derived [24, 56, 57]:

and

Where, Sc = (t/ρ) and Tr = tρ

Sc is longitudinal conductance (in mho), Tr is transverse resistance (in Ωm2), ρ is electrical resistivity of the saturated formation (in Ωm), K is hydraulic conductivity (in m/d), T is transmissivity (in m2/d), and α and β are constant of proportionality. The above equations (2 and 3) show inverse and direct relationship between hydraulic conductivity and electrical resistivity. Equation (2) is valid for an aquifer system with highly resistive basement where electrical currents tend to flow horizontally as in case of the investigated area, whereas equation (3) exists in case of highly conductive basement where electrical currents tend to flow vertically. Derivation of equations (2) and (3) is explained by the following steps:

According to Darcy’s law:

Where, q is the specific discharge (m/s) and dh/t is hydraulic gradient.

Theoretically, the electrical resistivity depends on Ohm’s law and the conservation equation of charges. According to Ohm’s law:

The flow of electric current in the medium (aquifer) is proportional to the potential gradient between the two points (source and sink). Hence mathematically, it can be expressed by:

Where dv is the potential difference, J is current density, is electrical conductivity (reciprocal of resistivity), and t is thickness respectively.

Combining equation (4) and (5) [53]:

Where the constants Aq = q/dh and AJ = dv/J describe the water flow and the electric current flow respectively, and these constants depend on the hydraulic conductivity (K).

AJ in equation (7) depends on the salinity. In the investigated area, the groundwater is fresh and there is no clay content so the constant α replaces the product of Aq and AJ:

or

Equation (9) implies that

The above equation (10) shows that the hydraulic conductivity (K) is inversely proportional to the aquifer resistivity (ρ). The above relation suggests that the low resistivity indicates the presence of fractured/fissured aquifer which is also true (valid) for the investigated area where resistivity decreases with increasing the water content in the weathered/fractured zone. Resistivity decreases with water content as well as clay content, however the studied area has no clay content except a thin topsoil layer, it implies that the low values of resistivity is only caused by the water content in the weathered/fractured a zones.

Multiplying equation (9) by t:

Since T = Kt [58]

Equation (11) is demonstrated as:

It implies that

And

Equation (14) implies that transmissivity is inversely proportional to transverse resistance for the fractured/fissured aquifer system of the investigated area.

Based on equations (10) and (14), empirical relations between the electrical parameters (ρ and Tr) and pumped hydraulic parameters (Kw and Tw) were obtained to estimate the aquifer potential over the entire area using the resistivity measurements.

The rock formation factor (F) is the ratio of aquifer resistivity (ρo in Ωm) and groundwater resistivity (ρw in m) given by the relation:

The formation factor F was estimated for the selected ERT data points near the boreholes. The groundwater resistivity required in equation (15) was calculated by:

Where, EC is electrical conductivity (in μS/cm).

The rock porosity (Φ) was calculated using Archie’s equation [59]:

Combining equations (15) and (17):

Equation (18) can be simplified as:

The coefficients a and m are related with the lithology of the aquifer system. Depending on the aquifer lithology of the studied area, the values of a and m are assumed as 1 and 2 [60, 61].

4 Results

4.1 Delineation of Water Resources

The ERT modeled sections were integrated with the boreholes liyhology of the study area to get four different layers such as the topsoil layer, the highly weathered layer, the partly weathered layer and the unweathered layer. Resistivity ranges of the above layerswere obtained after calibrating the resistivity modeled sections with the boreholes data along three profiles as shown in Table 1.

Calibration of resistivity and lithology in the investigated area.

| Rock Resistivity (ohm-m) | Rock Type |

|---|---|

| The resistivity between 22-289 | Highly |

| ohm-m (Below water table) | weathered rock |

| The resistivity between 225-472 | Partly weathered |

| ohm-m (Below water table) | rock |

| The resistivity between 402-153582 | Unweathered |

| ohm-m (Below water table) | rock |

| The resistivity between 22-472 | Topsoil |

| ohm-m (Above water table) |

The top layer consists of silt, clay and boulder with the resistivity range of 22-472 m. The next layer underlying the topsoil is highly weathered having resistivity range from 22 to 289 m. Third layer underlying the highly weathered layer is partly weathered having resistivity values between 225 and 472 m. The unweathered layer (fresh basement) is revealed below the partly weathered layer having resistivity values from 402 to 1535825 m.

The magnetic data was processed by IX2D Interpex to get 2D forward magnetic sections. The 2D magnetic modeling has been used in hydrogeology for the groundwater assessment for many years. The magnetic modeling generates a model with an interface between the weathered and unweathered layers depending on their definite geometries and magnetic properties which generate a modeled field analogous to the measured magnetic field. The magnetic data were visualized along each profile to obtain the above step. After that, a four layered model was constructed containing the top layer, the highly weathered, the partly weathered and the unweathered layers based on their magnetic properties. In this inversion program of forward magnetic modeling, a response from the model is recorded and compared with the magnetic data. Geometry of the four layered model with the magnetic properties of the subsurface layers were changing constantly until the magnetic data fitted the model response convincingly. The modeled geometry of the subsurface four layers including their magnetic susceptibility was controlled using the boreholes data that extensively improved the consistency of the subsurface four layered geological model.

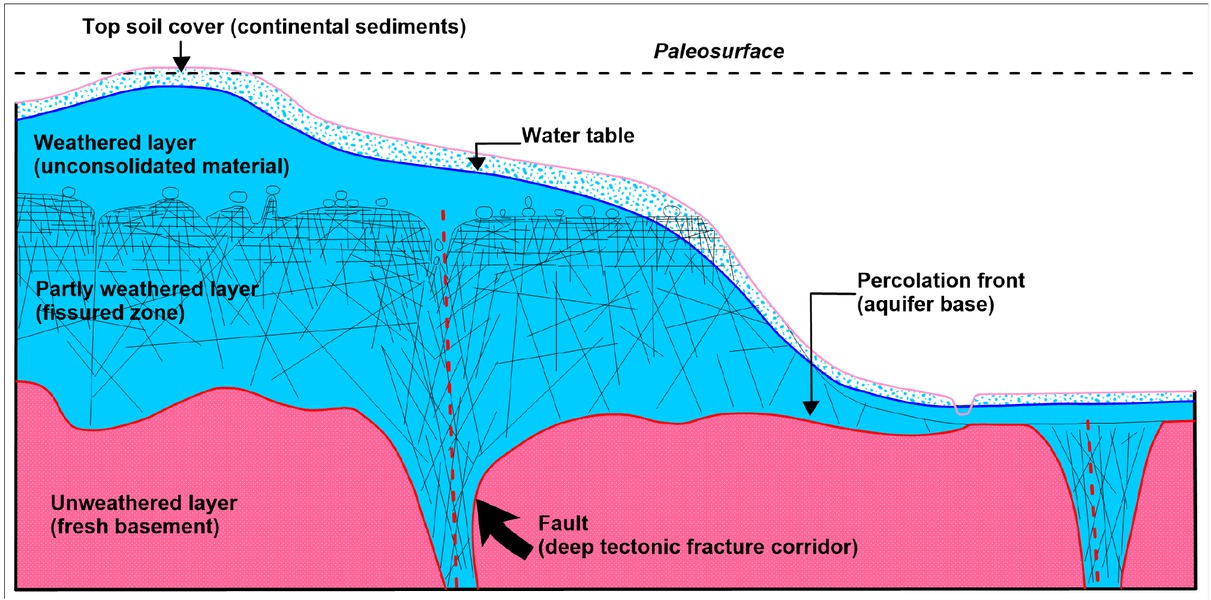

A conceptual model of the hydrogeological characteristics of the subsurface in the investigated area is shown in Figure 2. The average thickness of the first three layers is about 5, 20 and 10 m respectively, whereas bottom layer is revealed at an average depth of about 30 m. The topsoil cover consists of the materials such as clay, silt and boulder. The highly weathered layer mostly contains highly weathered tuff and highly weathered fissure tuff. The partly weathered layer contains weathered tuff and weathered fissure tuff with volcano dust, feldspar, quartz, and matrix. The fresh basement mainly consists of tuff, volcano dust, quartz, matrix, feldspar, pyroxene and labradorite etc. 2D models of ERT and magnetic were integrated to delineate seven fractures/faults such as F1, F2, F3, F4, F5, F6, and F7 with NW-SE orientation along three profiles. F1 and F4 are the largest with the extension length more than 500 m, these are compressive-torsional fractures. F2 has the medium length whereas F5, F6 and F7 are small fractures/faults. Small fractures/faults were caused by the upward crust of concealed hard rock such as granite and basalt veins, resulting in the relative fragmentation of the overburden. Most of the groundwater reserves were found along the fractures/faults and the weathered/partly weathered zones.

A conceptual model of the subsurface geologic formations in the weathered/fractured hard rock of the investigated area.

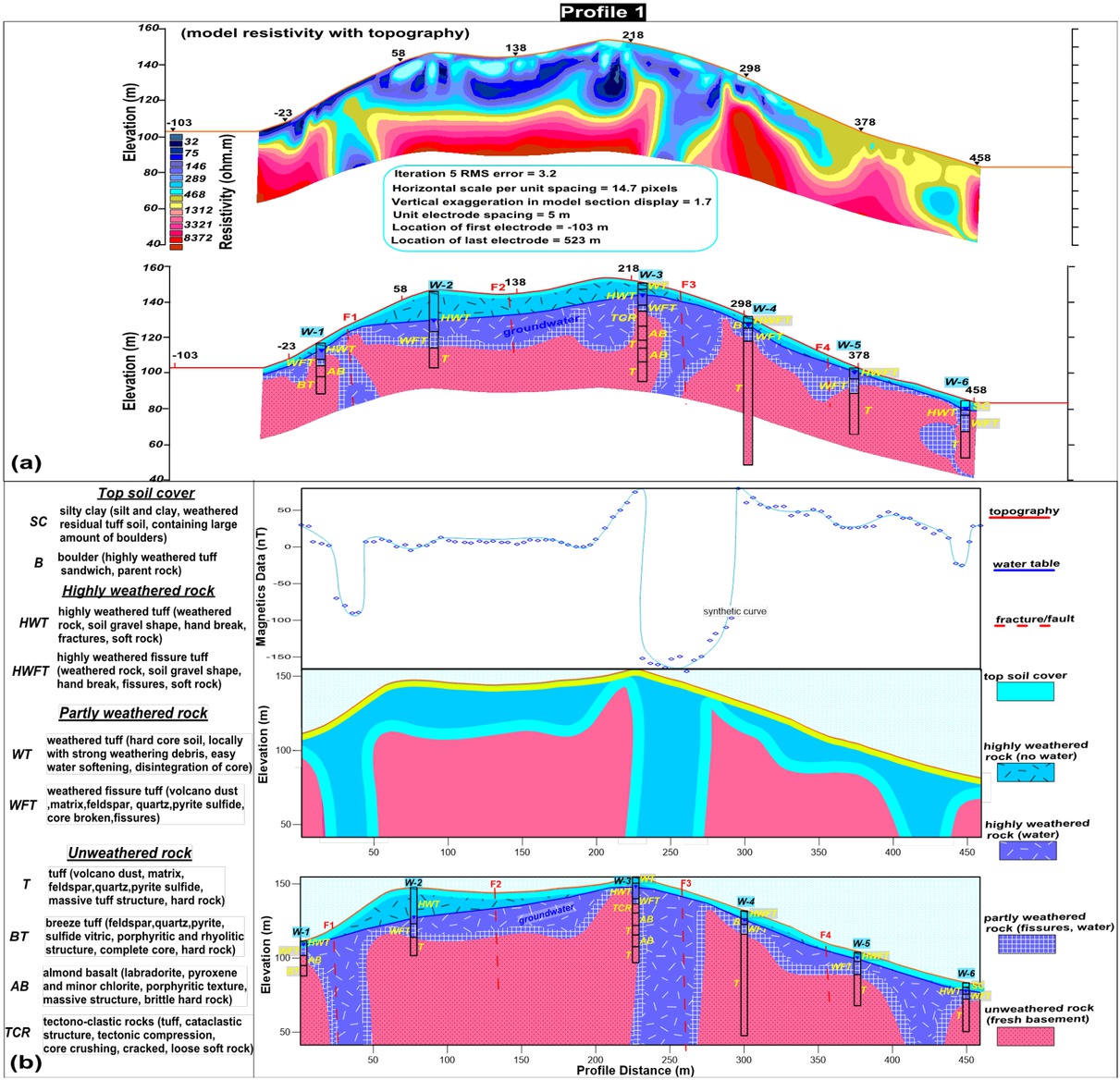

The incorporation of 2D ERT and magnetic models along profile 1 identified four different layers including the top soil layer with resistivity range of 32-468 m, the highly weathered layer having resistivity from 32 to 289 Ωm, the partly weathered layer with resistivity range of 289-468 m and the unweathered bedrock for resistivity range from 468 to 8372 m (Figure 3a). The magnetic anomaly varies from -170 to 80 nT along this profile (Figure 3b). The subsurface resistivity and magnetic intensity show high values for the unweathered rock, and represent low values for the highly weathered/partlyweathered rock and fractures/faults saturated with water. Groundwater reserves in the Basement Complex are located in the weathered or fractures/faults zones of the hard rock system [62]. Four fractures/faults namely F1, F2, F3, and F4 were identified by the incorporation of ERT with magnetic models (Figure 3). The appropriate drilling places along profile 1 are found from 20 to 40 m, 60 to 200 m, 230 to 280 m and 330 to 360 m mainly along the faults. The integrated results are highly correlated with the boreholes data along this profile.

(a) 2D modeled ERT section obtained by the inversion of resistivity data along profile 1; (b) 2D forward magnetic model along the same profile.

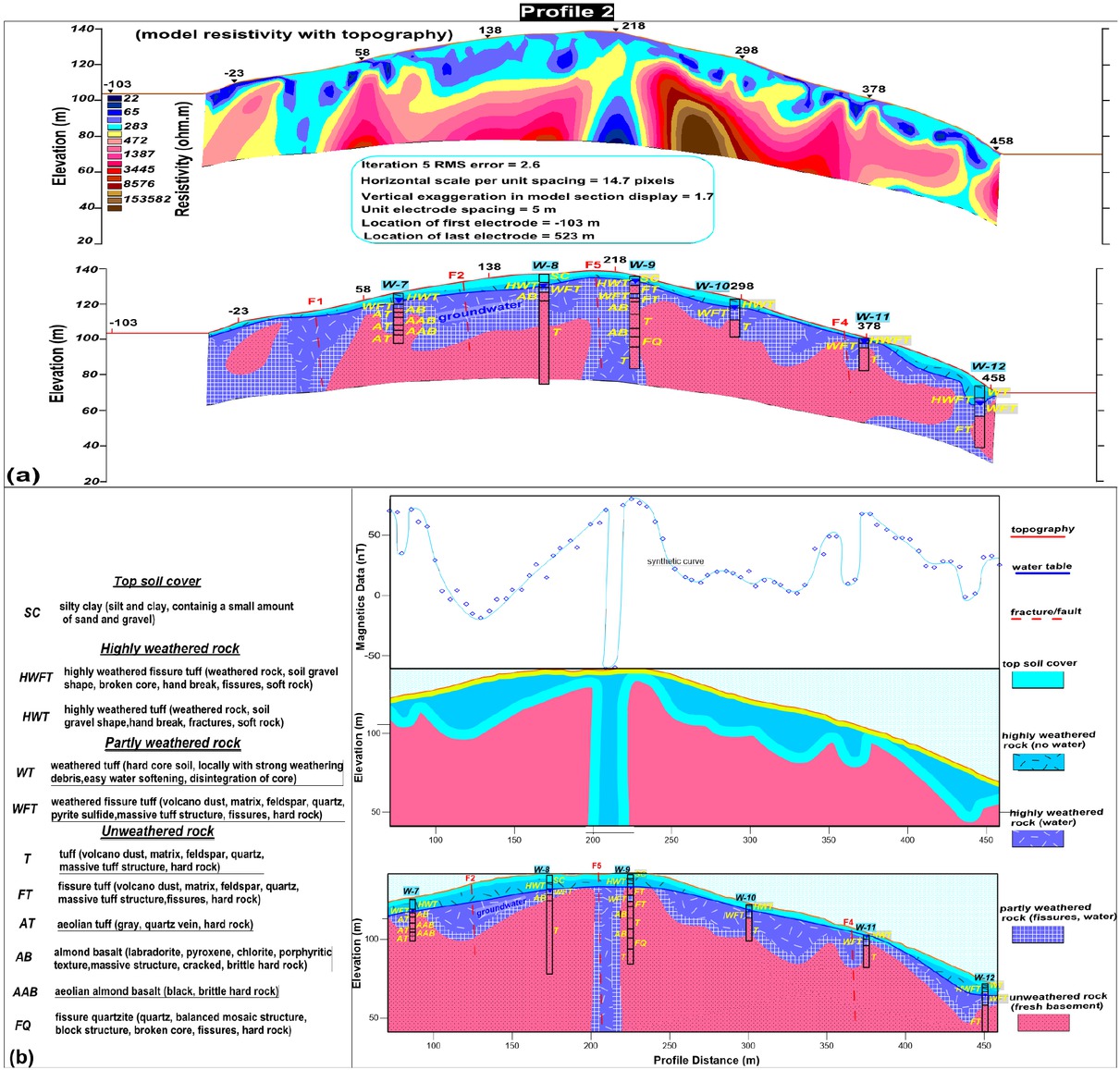

Figure 4 of ERT and magnetic sections along profile 2 reveals four distinct layers ranging from top to the bottom as the topsoil cover having resistivity from 22 to 472 m, the highly weathered layer with resistivity values from 22 to 283 m, the partly weathered layer for resistivity values from 283 to 472 m and the unweathered layer with resistivity values as high as 153582 m and as low as 472 m (Figure 4a). The magnetic variations were measured from -60 to 80 nT (Figure 4b). Four fractures/faults (F1, F2, F4 and F5) were revealed by the integrated approach (Figure 4). The results obtained were included with hydrogeological data which shows good matching. This profile offers good drilling locations from −40 to 50 m, 100 to 230m and 300 to 380 m especially along the faults.

(a) 2D modeled ERT section obtained by the inversion of resistivity data along profile 2; (b) 2D forward magnetic model along the same profile.

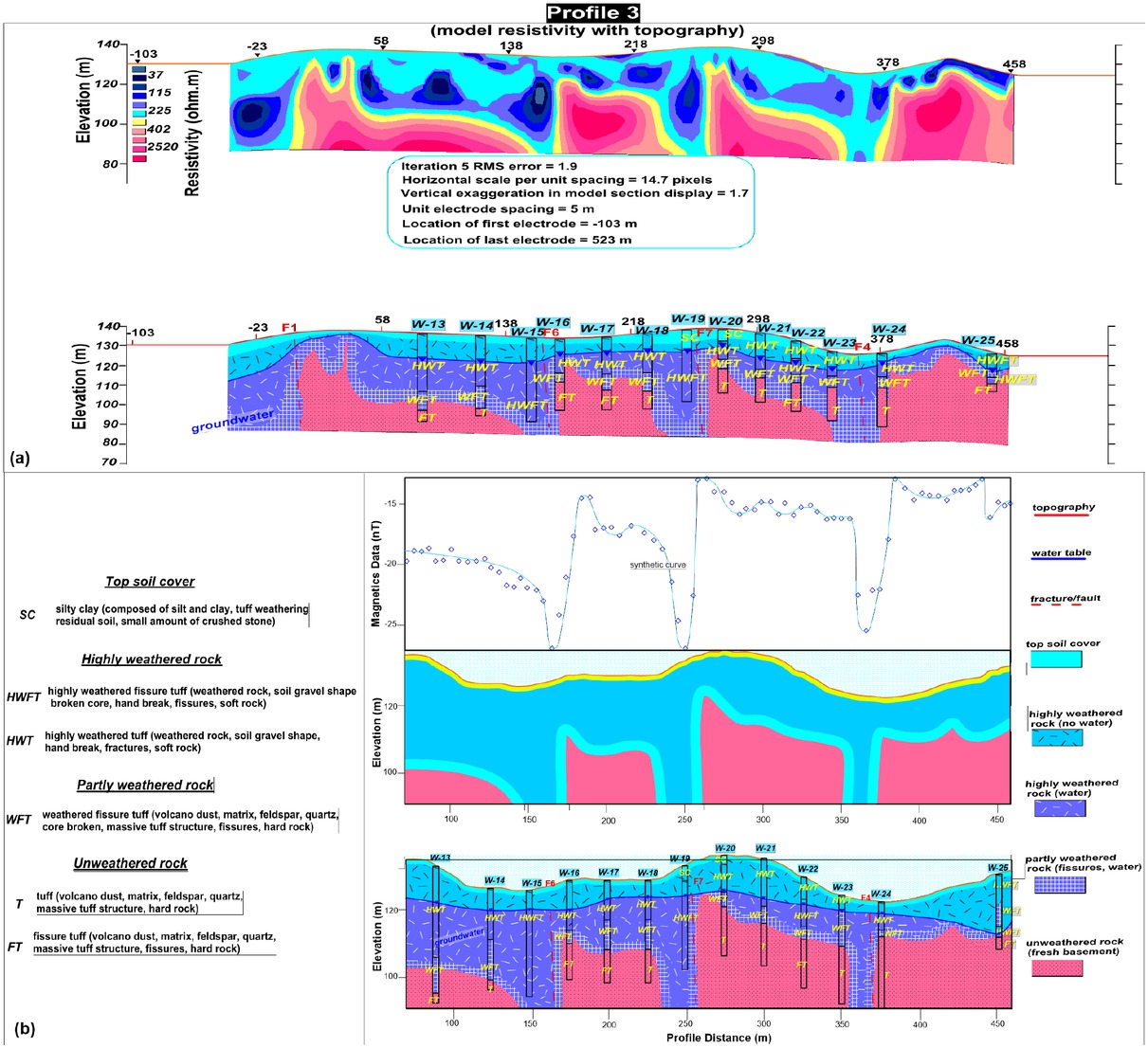

The first layer revealed along profile 3 is the topsoil cover with resistivity ranged from 37 to 402 m, second layer is highly weathered with resistivity values from 37 to 225 m, partly weathered is the third layer with resistivity from 225 to 402 m and fresh basement is the fourth layer with resistivity range of 402 to 2520 m (Figure 5a). The magnetic anomaly varies from −27 to −12 nT along profile 3 (Figure 5b). The magnetic intensity and resistivity values along this profile are lower than other two profiles because there is no granite or basalt identified along profile 3. The integrated results of ERT and magnetic show that four fractures/faults (F1, F4, F6 and F7) exist along this profile (Figure 5). The suitable locations for drilling are suggested from -40 to 10 m, 40 m to 160 m, 220 to 250 m and 300 to 380 m along this profile.

(a) 2D modeled ERT section obtained by the inversion of resistivity data along profile 3; (b) 2D forward magnetic model along the same profile.

4.2 Estimation of Water Resources

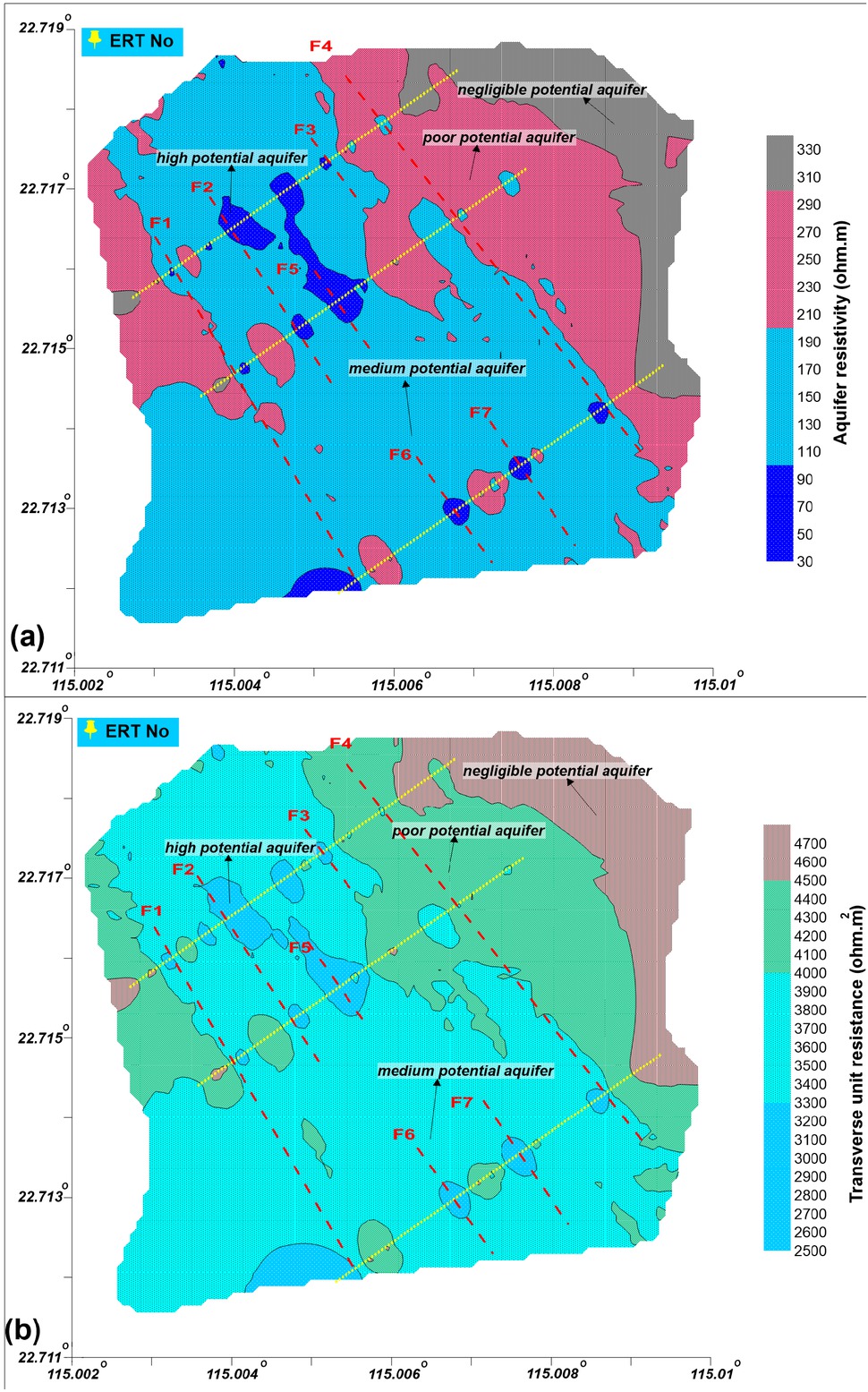

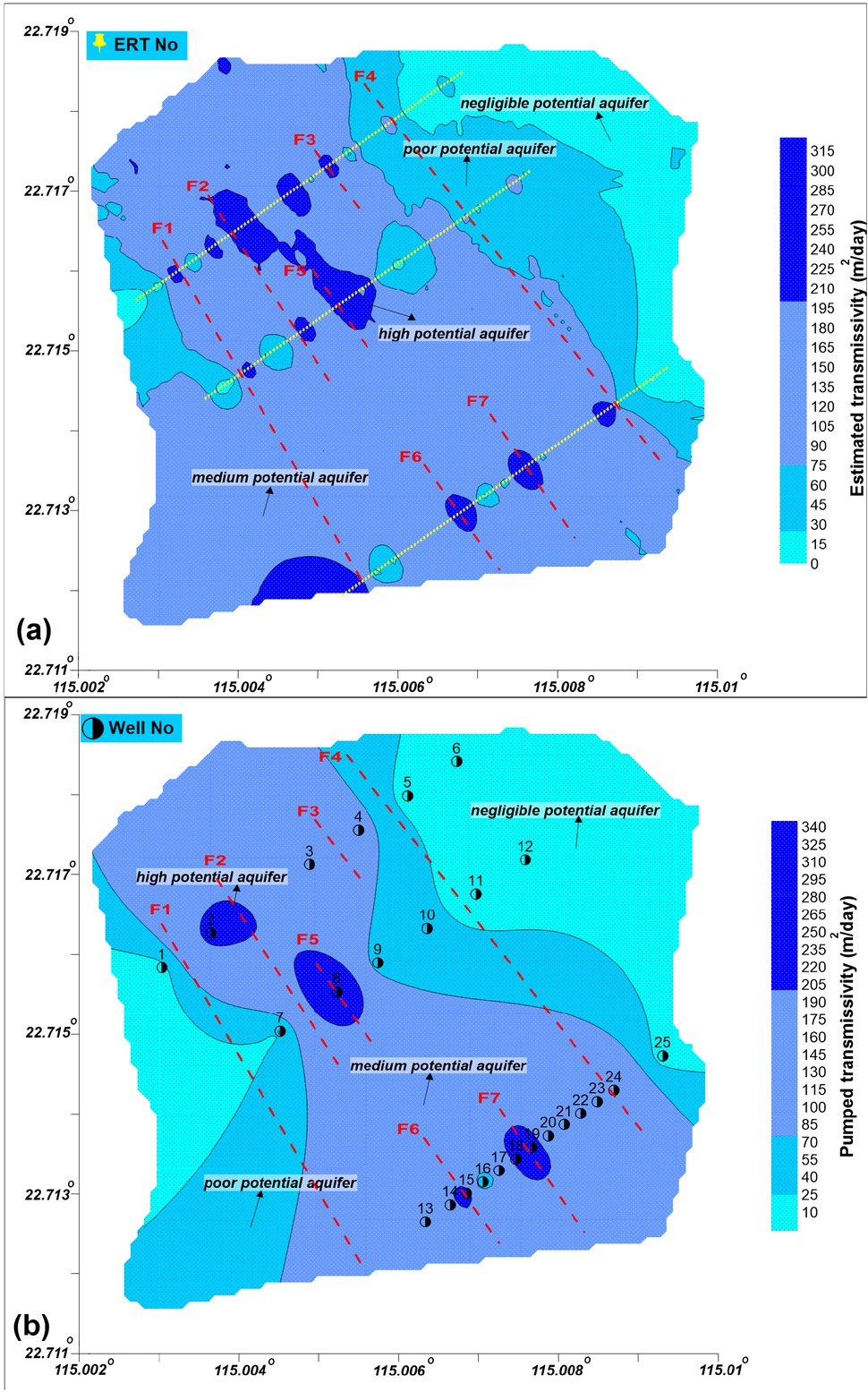

In order to estimate the groundwater resources contained within the weathered and fractures/faults zones revealed by the integrated geophysical approach, aquifer resistivity (ρo) and transverse unit resistance (Tr) were calculated for all resistivity measurements. Based on the values of aquifer resistivity, aquifer potential was divided into four zones i.e., the high potential aquifer with ρo < 100 m, the medium potential aquifer with ρo from 100 to 200 m, the poor potential aquifer with ρo from 200 to 300 m and the negligible potential aquifer with ρo > 300 m [63]. Aquifer potential was also differentiated by transverse unit resistance (Tr). A careful observation of Tr values shows that Tr < 3300 m2 reveals the high potential aquifer, Tr from 3300 to 4000 m2 indicates the medium potential aquifer, Tr from 4000 to 4500 m2 identifies the poor potential aquifer, and Tr > 4500 m2 represents the negligible potential. The distribution of ρo and Tr over the entire studied area with the aquifer potential zones is shown in Figure 6. The results suggest that the high potential aquifer is contained within the fractured/fault zones (Figure 6).

(a) contour map of aquifer resistivity and (b) contour map of transverse unit resistance.

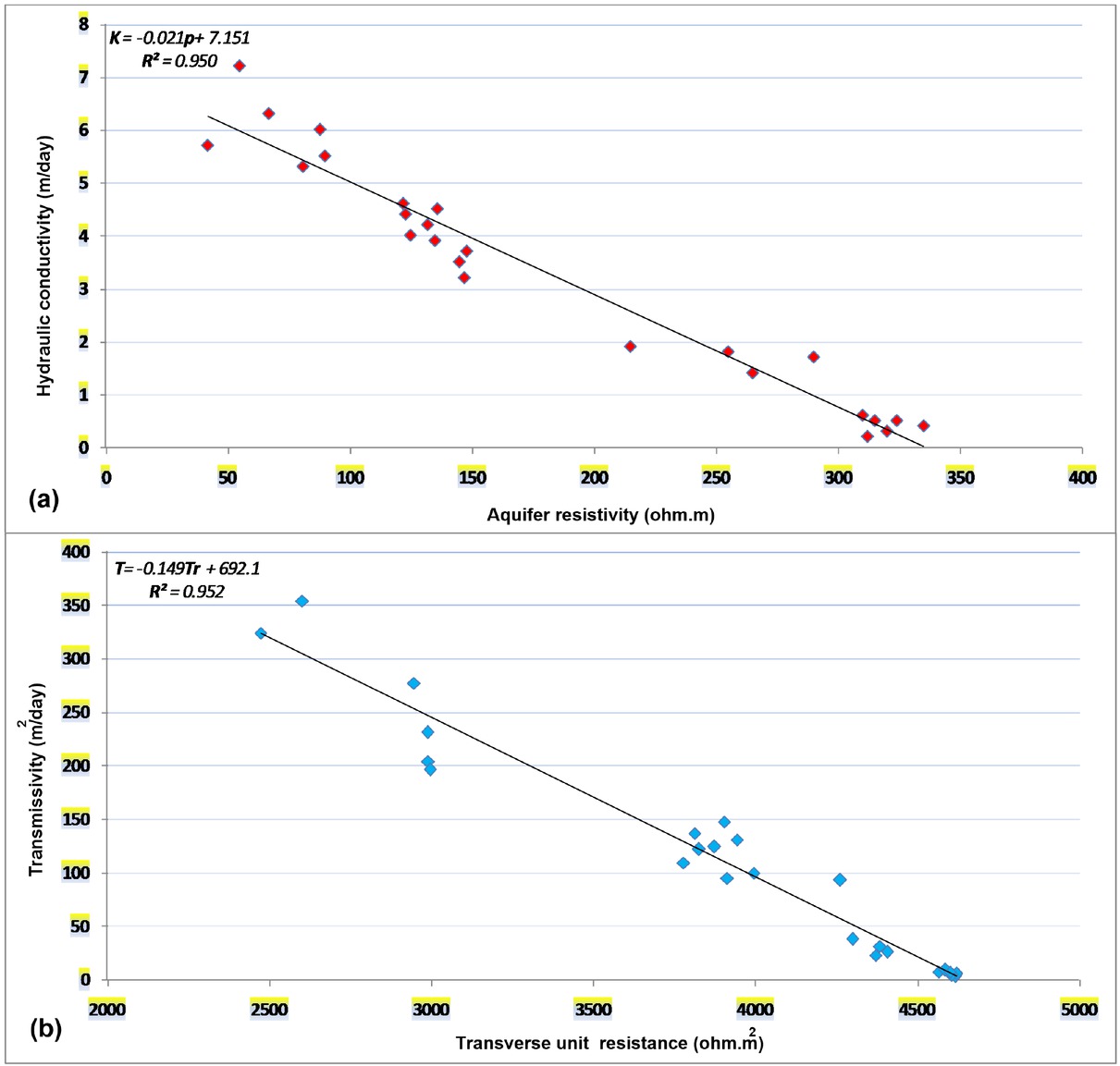

The groundwater resources were estimated as a function of hydraulic conductivity and transmissivity. Initially, hydraulic conductivity (Kw) and transmissivity (Tw) were determined at the specific locations of the boreholes using pumping tests analysis. In order to calculate the effective parameters for all resistivity stations to estimate the aquifer potential over the entire area, an empirical relation between aquifer resistivity (ρo) and pumped hydraulic conductivity (Kw) was obtained to estimate hydraulic conductivity (K’) for all resistivity measurements, and another relation was obtained between transverse resistance (Tr) and pumped trnasmissivity (Tw) to estimate transmissivity (T’) for all stations. In this way, entire area was covered for the estimation of aquifer potential based on the aquifer parameters. The empirical equations obtained from the graphical plots shown in Figure 7 are given by:

(a) Relation between aquifer resistivity and hydraulic conductivity, (b) relation between transverse unit resistance and transmissivity.

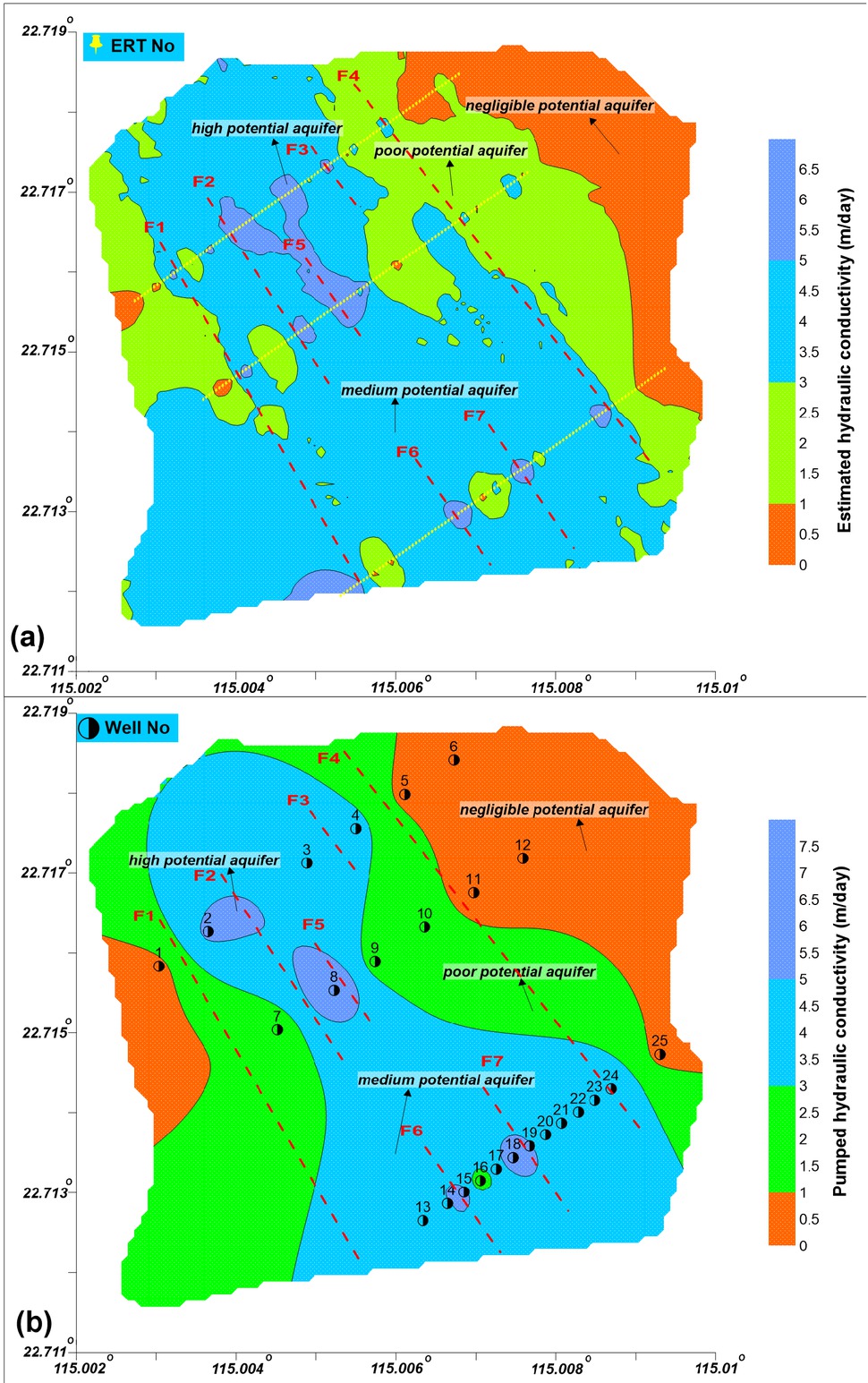

The values of K’ and T’ estimated from above equations (20 and 21) at the selected resistivity data points near the boreholes are given in Table 2. The pumped hydraulic conductivity (Kw) and transmissivity (Tw) measured from the pumping test are also given in Table 2. The comparison between the estimated aquifer parameters (T’ and K’) and pumped aquifer parameters (TW and Kw) shows good matching (Table 2). The contour maps of K’ and Kw in Figure 8 provides distribution of hydraulic conductivity values estimated by pumping test and resistivity measurements. The contour maps of the estimated transmissivity (T’) and pumped transmissivity (Tw) are shown in Figure 9. The maps of estimated and pumped hydraulic parameters show good correlation.

(a) contour map of estimated hydraulic conductivity and (b) contour map of pumped hydraulic conductivity.

(a) contour map of estimated transmissivity and (b) contour map of pumped transmissivity.

Values of aquifer resistivity, electrical conductivity, water resistivity, rock formation factor, rock porosity, aquifer thickness, transverse unit resistance, and estimated and pumped aquifer parameters (hydraulic conductivity and transmissivity) for the selected station near the boreholes.

| ERT number (selected) | Well number | Aquifer resistivity | Electrical conductivity | Water resistivity | Rock formation factor | Rock porosity | Aquifer thickness | Transverse unit resistance | Pumped hydraulic conductivity | Pumped transmissivity | Estimated hydraulic conductivity | Estimated transmissivity | % Matching | % Matching |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC (µS/cm) | F | Φ | H (m) | |||||||||||

| 8 | 1 | 312 | 200 | 50 | 6.2 | 0.4 | 14.8 | 4617.6 | 0.2 | 3 | 0.6 | 4 | 75 | 33 |

| 23 | 2 | 90 | 294 | 34 | 2.6 | 0.61 | 42 | 2989 | 5.5 | 231 | 5.3 | 250 | 92 | 96 |

| 53 | 3 | 125 | 222 | 45 | 2.8 | 0.6 | 31 | 3875 | 4 | 124 | 4.5 | 115 | 93 | 89 |

| 68 | 4 | 135 | 204 | 49 | 2.8 | 0.6 | 28 | 3780 | 3.9 | 109 | 4.3 | 129 | 84 | 90 |

| 83 | 5 | 315 | 227 | 44 | 7.2 | 0.37 | 14.5 | 4567.5 | 0.5 | 7 | 0.5 | 11 | 64 | 100 |

| 99 | 6 | 335 | 435 | 23 | 14.6 | 0.26 | 13.8 | 4623 | 0.4 | 6 | 0.1 | 3 | 50 | 25 |

| 124 | 7 | 265 | 156 | 64 | 4.1 | 0.49 | 16.5 | 4372.5 | 1.4 | 23 | 1.6 | 41 | 56 | 88 |

| 141 | 8 | 55 | 476 | 21 | 2.6 | 0.62 | 45 | 2475 | 7.2 | 324 | 6 | 323 | 99 | 83 |

| 154 | 9 | 290 | 172 | 58 | 5 | 0.45 | 15.2 | 4408 | 1.7 | 26 | 1.1 | 35 | 74 | 65 |

| 169 | 10 | 215 | 161 | 62 | 3.5 | 0.54 | 20 | 4300 | 1.9 | 38 | 2.6 | 51 | 74 | 73 |

| 184 | 11 | 320 | 238 | 42 | 7.6 | 0.36 | 14.4 | 4608 | 0.3 | 4 | 0.4 | 6 | 67 | 75 |

| 199 | 12 | 310 | 200 | 50 | 6.2 | 0.4 | 14.8 | 4588 | 0.6 | 9 | 0.6 | 8 | 89 | 100 |

| 226 | 13 | 123 | 227 | 44 | 2.8 | 0.6 | 31 | 3813 | 4.4 | 136 | 4.6 | 124 | 91 | 96 |

| 233 | 14 | 136 | 204 | 49 | 2.8 | 0.6 | 29 | 3944 | 4.5 | 131 | 4.3 | 104 | 95 | 96 |

| 238 | 15 | 67 | 400 | 25 | 2.7 | 0.61 | 44 | 2948 | 6.3 | 277 | 5.7 | 253 | 91 | 90 |

| 243 | 16 | 255 | 156 | 64 | 4 | 0.5 | 17.2 | 4386 | 1.8 | 31 | 1.8 | 39 | 79 | 100 |

| 248 | 17 | 145 | 196 | 51 | 2.8 | 0.59 | 27 | 3915 | 3.5 | 95 | 4.1 | 109 | 87 | 85 |

| 253 | 18 | 88 | 303 | 33 | 2.7 | 0.61 | 34 | 2992 | 6 | 204 | 5.3 | 246 | 83 | 88 |

| 258 | 19 | 42 | 588 | 17 | 2.5 | 0.64 | 62 | 2604 | 5.7 | 353 | 6.3 | 304 | 86 | 90 |

| 263 | 20 | 147 | 196 | 51 | 2.9 | 0.59 | 29 | 4263 | 3.2 | 93 | 4.1 | 145 | 64 | 78 |

| 268 | 21 | 132 | 213 | 47 | 2.8 | 0.6 | 29 | 3828 | 4.2 | 122 | 4.4 | 122 | 100 | 95 |

| 273 | 22 | 122 | 227 | 44 | 2.8 | 0.6 | 32 | 3904 | 4.6 | 147 | 4.6 | 110 | 75 | 100 |

| 278 | 23 | 148 | 192 | 52 | 2.8 | 0.59 | 27 | 3996 | 3.7 | 100 | 4 | 97 | 97 | 92 |

| 283 | 24 | 81 | 323 | 31 | 2.6 | 0.62 | 37 | 2997 | 5.3 | 196 | 5.5 | 246 | 80 | 96 |

| 298 | 25 | 324 | 256 | 39 | 8.3 | 0.35 | 14.2 | 4600.8 | 0.5 | 7 | 0.3 | 7 | 100 | 100 |

The groundwater reserves estimated by hydraulic conductivity and transmissivity were characterized into four different zones. The results of hydraulic conductivity and transmissivity reveal that T’>200m2/d and K’>5 m/day delineate the high potential aquifer, T’ from 75 to 200 m2/d and K’ from 3 to 5 m/d show the medium potential aquifer, T’ from 25 to 75 m2/d and K’ from 1 to 3 m/d identify the poor potential aquifer, and T’<25 m2/d and K’<1 m/d represent the negligible potential aquifer (Figure 8 and 9). The estimation of aquifer parameters suggests that high potential groundwater reserves occur along the fractured/ fault zones (Figure 8 and 9).

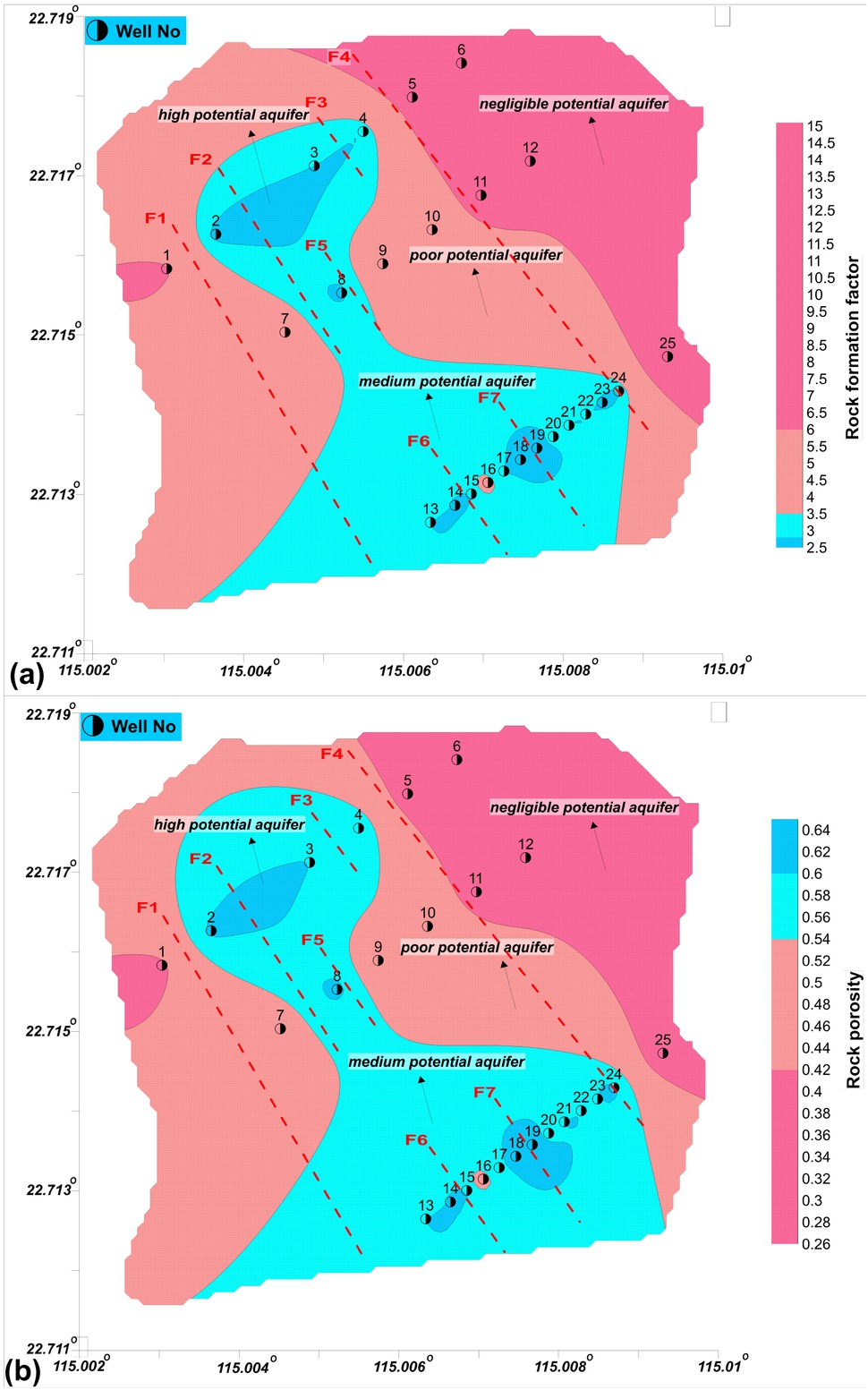

The groundwater potential zones were also delineated by rock formation factor (F) and rock porosity (Φ). The estimated values of F and Φ obtained for the selected ERT data points and the nearby boreholes are given in Table 2.Acareful observation suggests that the high potential aquifer is revealed with Φ > 0.6 and F < 2.8, the medium potential aquifer is delineated with Φ from 0.54 to 0.6 and F from 2.8 to 3.5, the low potential aquifer zone is identified with Φ between 0.42-0.54 and F between 3.5-6, and the negligible potential aquifer is mapped with Φ < 0.42 and F < 6 as shown in Figure 10. Wright [63] suggested that the aquifer potential can be expressed as a function of aquifer resistivity. In the investigated area, the aquifer potential was estimated as a function of aquifer resistivity, transverse unit resistance, hydraulic conductivity, transmissivity, rock formation factor and rock porosity as shown in Table 3.

Delineation of aquifer potential zones based on (a) rock formation factor and (b) rock porosity

Aquifer potential as a function of aquifer resistivity, transverse unit resistance, hydraulic conductivity, transmissivity, rock formation factor and rock porosity

| Aquifer potential [63] | Parameters | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aquifer resistivity | Transverse unit resistance | Hydraulic conductivity | Transmissivity | Rock formation factor | Rock porosity | |

| K (m/day) | F | Φ | ||||

| High potential aquifer (Optimum weathering and groundwater potential) | <100 | <3300 | >5 | >200 | <2.8 | >0.6 |

| Medium potential aquifer (Medium aquifer conditions and Potential) | 100-200 | 3300-4000 | 3-5 | 75-200 | 2.8-3.5 | 0.54-0.6 |

| Poor potential aquifer (Limited weathering and poor Potential) | 200-300 | 4000-4500 | 1-3 | 25-75 | 3.5-6 | 0.42–0.54 |

| Negligible potential aquifer (Negligible) | >300 | >4500 | <1 | <25 | >6 | <0.42 |

4.3 Analysis of Groundwater and Rock Samples

In order to assess to quality of groundwater contained within the weathered/fractured zones, the physicochemical analysis was performed. The physicochemical parameters of groundwater samples taken from the boreholes were analytically analyzed by the World Health Organization [64]. The results of physicochemical analysis for twenty five groundwater samples are summarized in Table 4(a). The physicochemical analysis was performed for the main anions, the cations and the parameters such as pH, total dissolved solids (TDS) and electrical conductivity (EC) as per standard procedures [65, 66, 67]. The results show that all the parameters lie within the limit suggested by WHO. The physicochemical analysis revealed that the groundwater quality is good in the study area. The groundwater quality was also assessed by geophysical analysis as shown in Table 4(a). The aquifer resistivity obtained from all ERT data points was analyzed to evaluate the groundwater quality. Generally, low values of aquifer resistivity (i.e., <25 m) suggest the saline/brackish water [1]. The geophysical analysis shows that aquifer resistivity values fall within the limit of fresh water. Hence, based on the physicochemical and geophysical analysis, groundwater quality of the investigated area is good.

The results of (a) groundwater quality analysis and (b) rock samples analysis

| (a) Analysis of groundwater quality physicochemical analysis for n=25 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Units | Min | Max | Mean | Median | S.D | WHO limits for drinking water quality [61] | |

| Range | Samples exceeding limit | |||||||

| Na+ | mg/L | 8.1 | 14.3 | 11.5 | 11.4 | 1.72 | 200 | - |

| K+ | mg/L | 3.3 | 4.1 | 3.7 | 3.4 | 0.35 | 55 | - |

| Ca2+ | mg/L | 1.4 | 4.6 | 3.3 | 3.9 | 1.05 | 100 | - |

| Mg2+ | mg/L | 0.5 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.42 | 50 | - |

| Cl− | mg/L | 8.9 | 11.4 | 9.9 | 9.8 | 0.92 | 250 | - |

| SO24− | mg/L | 2.3 | 4.8 | 2.8 | 1.7 | 1.07 | 200 | - |

| HCO3 | mg/L | 26.9 | 41.3 | 34.4 | 35.8 | 5.02 | 600 | - |

| TDS | mg/L | 94 | 353 | 155.2 | 133 | 65.33 | 1000 | - |

| EC | μS/cm | 156 | 588 | 258.6 | 222 | 108.83 | 1500 | - |

| pH | - | 7 | 7.8 | 7.3 | 7.1 | 0.27 | 6.5-8.5 | - |

| Geophysical analysis for n=305 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Unit | Min | Max | Mean | Median | S.D | Resistivity limit for drinking water quality [1, 17] | |

| Range | Data points exceeding limit | |||||||

| Aquifer resistivity (ρo) | ohm-m | 31 | 335 | 183 | 139 | 95.26 | <25 | - |

| (b) Analysis of rock samples (XRD analysis for n=25) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major minerals (>50%) | Secondary minerals (10-30%) | Minor minerals (5-10%) | ||||||

| quartz | kaolinite | halloysite | ||||||

| - | microcline | perlite | ||||||

| - | albite | sodalite | ||||||

| - | zinnwaldite | ankerite | ||||||

The mineral analysis of twenty five rock samples taken from the borehole sites using the X-ray Diffraction Technique (XRD) was performed. The analyzed minerals were interpreted as major minerals with >50%, secondary minerals with 10-30% and minor minerals with 5-10% as shown in Table 4(b). The results suggest quartz as the major mineral, whereas kaolinite, zinnwaldite, microcline and albite as the secondary minerals, and halloysite, sodalite, perlite, and ankerite as the minor minerals in the study area.

5 Discussion

Delineation of weathered/fractured zones is essential for the exploitation of groundwater resources in the hard-rock terrains. Accumulation of groundwater in the hard-rock areas depends on the features such as the weathering and fracturing, rock type, fracture density, orientation, connectivity, aperture and length. The conventional methods such as the boreholes techniques compute these parameters only at some selected locations. Such approaches are expensive, require more equipments and labors, and cannot assess the subsurface geological formations over the entire area due to various restrictions such as the heterogeneity, steep topographic effects and other geological constraints. Conversely, the geophysical methods such as electrical resistivity, induced polarization, magnetic, gravity, self-potential, electromagnetic and seismic refraction are commonly used to investigate the geologic formations of hard-rock terrains. Generally, these methods can assess the weathered/fractured zones interconnected with the economical aquifer. However, some of the above methods can hardly investigate the crystalline hard-rock in the complex geological settings. Choice of a suitable method depends on the labor, cost, local hydrogeological setting, surveying speed, anomaly resolution and the level of difficulty required in the processing and interpretation of the field data.

The integration of two or more geophysical methods has proved to be very competent to delineate the subsurface geologic features such as the weathered/fractured zones for groundwater exploitation mostly because of close correlation between the electrical and hydraulic properties. This investigation was carried out by the electrical resistivity tomography (ERT) and the high precision magnetic methods which are non-invasive, inexpensive and user friendly; provide comprehensive assessment for the sequential and spatial distribution of the subsurface geological structures; evade the interruption caused by the drilling; and reduce significant number of expensive boreholes. 2D subsurface models of ERT and magnetic provide a comprehensive evaluation of the subsurface weathered formations that cannot be obtained using other methods such as 1D vertical electrical soundings (VES) techniques, and thus, give detailed information about the weathered/fractured zones highly significant for groundwater exploration.

The ERT and magnetic models were correlated with the upfront geological logs constructed from the wells to constrain the near-surface stratigraphic units into a four-layered model such as the topsoil cover, the highly weathered, the partly weathered and the unweathered rock. This approach reveals seven fractures/faults (F1 to F7) in the study area. The aquifer potential was estimated by different parameters such as aquifer resistivity (ρo), transverse unit resistance (Tr), hydraulic conductivity (K), transmissivity (T), rock formation factor (F) and rock porosity (Φ). Based on above parameters, the groundwater resources were divided into four aquifer potential zones i.e., the high potential aquifer, the medium potential aquifer, the poor potential aquifer and the negligible potential aquifer. The results propose that the delineated weathered/fractured zones show significant implication on groundwater occurrence, and hence, the high potential aquifer zones are associated with the weathered/fractured zones. The results suggest that groundwater contained within the weathered/fractured zones can be tapped at an average depth of 5-10 m from the ground surface.

Although the integrated geophysical methods provide comprehensive assessment of the heterogeneous weathered terrain for groundwater exploration, however, these methods alone cannot interpret the subsurface formation. Some boreholes are needed to be correlated with the geophysical methods to interpret the subsurface geologic strata and to estimate the aquifer potential contained within the weathered/fractured zones. Conversely, ERT and magnetic methods can reduce the significant number of expensive bore-wells to provide detail information about the subsurface formation over the entire area. In this study, the integrated geophysical methods delineated the subsurface geologic formation at shallow depth. They provide high resolution for the near-surface structures; however, the resolution of subsurface imaging decreases with depth. The highly steep topographic areas where the boreholes cannot be conducted or difficult to carry out, such geophysical methods can be ideally used to assess the near-surface formation. The integrated geophysical results show good correlation with the hydrogeological information of the study area. The results were also validated with the previous studies carried out in the nearby areas [4, 13, 62]. This investigation provides the most appropriate places for drilling to exploit the groundwater resources in the investigated area.

6 Conclusions

An integrated geophysical approach of ERT and magnetic method in combination with XRD, physicochemical analysis, and borehole data was carried out along three different geophysical profiles to evaluate the groundwater reserves contained in the highly heterogeneous area of Huizhou, South China. The integrated results of ERT and magnetic 2D models revealed four different layers including the topsoil layer, the highly weathered layer, the partly weathered layer and the unweathered layer having resistivity ranges of 22-472 m, 22-289 m, 225-472Ωm and 402-1535825 m respectively along three geophysical profiles. The magnetic contrast along three profiles of the investigated area was estimated from −170 to 80 nT. The average thickness of the topsoil, the highly weathered layer and the partly weathered layer is about 5, 20 and 10 m respectively, whereas the fresh bedrock rock is encountered at an average depth of about 30 m. The integration of ERT and magnetic sections revealed seven fractures/faults (F1 to F7). The results of the ERT and magnetic methods incorporated by the boreholes data reveal that the highly/partly weathered layers and the fractures/faults zones are saturated with groundwater. The groundwater reserves were then estimated by the hydraulic parameters. Four aquifer potential zones were differentiated on the basis of maps of hydraulic conductivity, trnasmissivity, aquifer resistivity and transverse unit resistance which show consistency with each other. The results suggest that the groundwater resources in the weathered terrains generally occur along the fractured and fault zones. The physicochemical and geophysical analysis show that groundwater contained within the weathered/fractured zones is of good quality falling within the suggested limit. The mineral analysis of XRD method shows quartz as the major mineral (>50%). This integrated approach suggests a complete hydrogeological assessment of groundwater in the areas having heterogeneous settings.

Acknowledgement

This research was sponsored by CAS-TWAS President’s Fellowship for International PhD Students; and financially supported by the National Science and Technology Basic Resources Investigation project (No. 2018FY10050003), and the Chinese National Scientific Foundation Committee (NSFC) (No. 41772320). Authors wish to acknowledge support received from CAS-TWAS President’s Fellowship, and Key Laboratory of Shale Gas and Geoengineering, Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing China.

References

[1] Hasan M., Shang Y., Akhter G., Khan M., Geophysical Investigation of Fresh-Saline Water Interface: A Case Study from South Punjab, Pakistan. Groundwater, 2017, 55, 841–856.10.1111/gwat.12527Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Uhlemann S., Kuras O., Richards L.A., Naden E., Polya D.A., Electrical resistivity tomography determines the spatial distribution of clay layer thickness and aquifer vulnerability, Kandal Province, Cambodia. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 2017, 147, 402-414.10.1016/j.jseaes.2017.07.043Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Muchingami I. et al., Electrical resistivity survey for groundwater investigations and shallow subsurface evaluation of the basaltic-greenstone formation of the urban Bulawayo aquifer. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, 2012, 50–52, pp.44–51.10.1016/j.pce.2012.08.014Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Hasan M., Shang Y., Jin W., Delineation of weathered/fracture zones for aquifer potential using an integrated geophysical approach: A case study from South China. Journal of Applied Geo-physics, 2018, 157, 47-6010.1016/j.jappgeo.2018.06.017Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Taylor R., Howard K., A tectono-geomorphic model of the hydrogeology of deeply weathered crystalline rock: evidence from Uganda. Hydrogeology Journal, 2000, 8, 279–294.10.1007/s100400000069Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Wyns R., Gourry J.C., Baltassat J.M., Lebert F., Caractérisationmultiparamètres des horizons de subsurface (0–100 m) en contexte de socle altéré. In: BRGM, IRD, UPMC, I. (Ed.), 2ème Colloque GEOFCAN, Orléans, France. 1999, pp. 105–110.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Acworth I., The electrical image method compared with resistivity sounding and electromagnetic profiling for investigation in areas of complex geology: A case study from groundwater investigation in a weathered crystalline rock environment, Exploration Geophysics, 2001, 32, 119–128.10.1071/EG01119Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Berkowitz B., Characterizing flow and transport in fractured geological media: A review. Advances in Water Resources, 2002, 25, 861-884.10.1016/S0309-1708(02)00042-8Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Nazri M.A.A. et al., Authentication relation between surface-groundwater in kerian irrigation canal system, perak using integrated geophysical, water balance and isotope method. Procedia Engineering, 2012, 50, 284–296.10.1016/S1877-7058(14)00002-2Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Andrew D.P., Niels C., Kamini S., Burke J.M., Bradley C., Emily V., Ryan H. et al., Comparing Measurement Response and Inverted Results of Electrical Resistivity Tomography Instruments. Journal of Environmental and Engineering Geophysics, 2017, 22, 249–266.10.2113/JEEG22.3.249Suche in Google Scholar

[11] El Mehdi B., Ahmed L., Abdelilah D., Jean C.P., Mohamed R., An Application of Electrical Resistivity Tomography To Investigate Heavy Metals Pathways. Journal of Environmental and Engineering Geophysics, 2018, 22, 315–324.10.2113/JEEG22.4.315Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Adam F.M., Kevin W.S., Wesley A.B., Jon T.E., Characterization and Delineation of Gypsum Karst Geohazards Using 2d Electrical Resistivity Tomography in Culberson County, Texas, USA. Journal of Environmental and Engineering Geophysics, 2018, 22, 411–420.10.2113/JEEG22.4.411Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Gao Q., Shang Y., Hasan M., Jin W., Yang P., Evaluation of a Weathered Rock Aquifer Using ERT Method in South Guangdong, China. Water 2018, 10, 29310.3390/w10030293Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Dor N. et al., Verification of Surface-Groundwater Connectivity in an Irrigation Canal Using Geophysical, Water Balance and Stable Isotope Approaches. Water Resources Management, 2011, 25, 2837–2853.10.1007/s11269-011-9841-ySuche in Google Scholar

[15] Goldman M., Neubauer F.M., Groundwater Exploration Using Integrated Geophysical Techniques. Surveys in Geophysics, 2004, 15, 331-361.10.1007/BF00665814Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Akhter G., Hasan M., Determination of aquifer parameters using geoelectrical sounding and pumping test data in Khanewal District, Pakistan. Open Geosciences, 2016, 8, 630–638.10.1515/geo-2016-0071Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Hasan M., Shang Y., Akhter G., Jin W., Geophysical Assessment of Groundwater Potential: A Case Study from Mian Channu Area, Pakistan. Groundwater, 2017, 56, 783–796.10.1111/gwat.12617Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Reynolds R.L., Rosebaum J.G., Hudson M.R., Fisherman N.S., Rock magnetism, the distribution of magnetic minerals in the Earth’s crust and aeromagnetic anomalies in Hana, W.F., ed., Geologic Applications of Modern Aeromagnetic Surveys: U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 1924, 1990, pp.24-45.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Sharma V.P., Environmental and Enginering Geophysics. published by Cambridge University Press, United Kingdom, 1997, pp. 40-45.10.1017/CBO9781139171168Suche in Google Scholar

[20] De Lima O.A.L., Clennell M.B., Nery G.G., Niwas S., A volumetric approach for the resistivity response of freshwater shaly sand-stones. Geophysics, 2005, 70, 1–10.10.1190/1.1852771Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Hasan M., Shang Y., Akhter G., Jin WJ., Evaluation of groundwater potential in Kabirwala area, Pakistan: A case study by using geophysical, geochemical and pump data. Geophysical Prospecting, 2018, 66, 1737-1750.10.1111/1365-2478.12679Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Friedman S.P., Seaton N.A., Critical path analysis of the relationship between permeability and electrical conductivity of three dimensional pore networks. Water Resources Research, 1998, 34, 1703-1710.10.1029/98WR00939Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Dasargues A., Modeling base flow from an alluvial aquifer using hydraulic-conductivity data obtained from a derived relation with apparent electrical resistivity. Hydrogeology Journal, 1997, l 5, 97–108.10.1007/s100400050125Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Niwas S., Celik, M., Equation estimation of porosity and hydraulic conductivity of Ruhrtal aquifer in Germany using near surface geophysics. Journal of Applied Geophysics, 2012, 84, 77–85.10.1016/j.jappgeo.2012.06.001Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Nwosu L.I., Nwankwo C.N., Ekine A.S., Geoelectric investigation of the hydraulic properties of the aquiferous zones for evaluation of groundwater potentials in the complex geological area of imo state, Nigeria. Asian Journal of Earth Sciences, 2013, 6, 1–1510.3923/ajes.2013.1.15Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Salem H.S., Determination of fluid transmissivity and electric transverse resistance for shallow aquifers and deep reservoirs from surface and well-log electric measurements. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 1999, 3, 421–427.10.5194/hess-3-421-1999Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Hasan M., Shang Y., Akhter G., Jin WJ., Delineation of Saline-Water Intrusion Using Surface Geoelectrical Method in Jahanian Area, Pakistan. Water, 2018, 10, 1548.10.3390/w10111548Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Purvance D.T., Andricevic R., On the electrical-hydraulic conductivity correlation in aquifers. Water Resources Research, 2000, 36, 205–213.10.1029/2000WR900165Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Thiagarajan S., Rai SN., Kumar D., Manglik A., Delineation of groundwater resources using electrical resistivity tomography. Arabian Journal of Geosciences, 2018, 11, 21210.1007/s12517-018-3562-ySuche in Google Scholar

[30] Kumar D., Rao VA., Sarma VS., Hydrogeological and geophysical study for deeper groundwater resource in quartzitic hard rock ridge region from 2D resistivity data. Journal of Earth System Science, 2014, 123(3), 531-54310.1007/s12040-014-0408-1Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Tajudin SAA., Said MJM., Madun A., Zainalabidin MH., Sahdan MZ., Groundwater Exploration in Granitic Rock Formation Using Electrical Resistivity and Induced Polarization Techniques. Journal of Physics Conference Series, 2018, 1049(1), 01207610.1088/1742-6596/1049/1/012076Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Dong J., Shen C.C., Kong X., Wu C.C., Hu H.M., YiWang H.R., Rapid retreat of the East Asian summer monsoon in the middle Holocene and a millennial weak monsoon interval at 9 ka in northern China. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 2018, 151, 31-3910.1016/j.jseaes.2017.10.016Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources of Guangdong Province (Guangdong, B.G.M.R.), Regional geology of Guangdong Province: Geology Publishing House, Beijing, China, 1988, pp. 1–602. (In Chinese).Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Xiong S., Ynag H., Ding Y., Li Z., Li W., Distribution of igneous rocks in China revealed by aeromagnetic data. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 2016, 129, 231-242.10.1016/j.jseaes.2016.08.016Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Griflths D.H., Barker R.D., Two-dimensional resistivity imaging and modeling in areas of complex geology. Journal of Applied Geophysics, 1993, 29, 211-226.10.1016/0926-9851(93)90005-JSuche in Google Scholar

[36] Loke M.H., Electrical imaging for environmental and engineering studies, a practical guide, 2-D survey. Geophysical prospecting, 1999, pp44Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Dahlin T., Loke M.H., Resolution of 2D Wenner Resistivity Imaging as assessed by numerical modeling. Journal of Applied Geophysics, 1998, 38, 237-249.10.1016/S0926-9851(97)00030-XSuche in Google Scholar

[38] Hasan M., Shang Y., Akhter G., Jin WJ., Application of VES and ERT for delineation of fresh-saline interface in alluvial aquifers of Lower Bari Doab, Pakistan. Journal of Applied Geophysics, 2019, 164, 200-213.10.1016/j.jappgeo.2019.03.013Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Storz H., Storz W., Jacobs F., Electrical resistivity tomography to investigate geological structures of the earth’s upper crust. Geophysical Prospecting, 2000, 48, 455–47110.1046/j.1365-2478.2000.00196.xSuche in Google Scholar

[40] Loke M.H., Barker R.D., Rapid least-squares inversion of apparent resistivity pseudosections by a quasi-Newton method. Geophysical Prospecting, 1996, 44, 131–152.10.1111/j.1365-2478.1996.tb00142.xSuche in Google Scholar

[41] Dahlin T., 2D resistivity surveying for environmental and engineering applications. First Break, 1996, 14, 275–283.10.3997/1365-2397.1996014Suche in Google Scholar

[42] Griflths D.H., Turnbull J., Olayinka A.I., Two-dimensioual resistivity mapping with a computer-controlled array. First Break, 1990, 8, 121-129.10.3997/1365-2397.1990008Suche in Google Scholar

[43] Zhou W., Beck B.F., Stephenson J.B., Reliability of dipole-dipole electrical resistivity tomography for defining depth to bedrock in covered karst terrains. Environmental Geology, 1999, 39, 760–766.10.1007/s002540050491Suche in Google Scholar

[44] Loke M.H., Res2dinv Software User‘s Manual, Version 3.57. Geotomo Software, Penang, Malysia, 2007, p. 86.Suche in Google Scholar

[45] Ellis R.G., Oldenburg D.W., Applied geophysical inversion. Geo-physical Journal International, 1994, 116, 5–11.10.1111/j.1365-246X.1994.tb02122.xSuche in Google Scholar

[46] DeGroot-Hedlin C., Constable S., Occam’s inversion to generate smooth, two-dimensional models from magneto telluric data. Geophysics, 1990, 55, 1613–1624.10.1190/1.1442813Suche in Google Scholar

[47] Edwards L.S., A modified Pseudosection for Resistivity and Induced Polarization. Geophysics, 1977, 42, 1020 – 1036.10.1190/1.1440762Suche in Google Scholar

[48] Lines L.R., Treitel S., Tutorial: A review of the least-squares inversion and its application to geophysical problems. Geophysical Prospecting, 1984, 32, 159-186.10.1111/j.1365-2478.1984.tb00726.xSuche in Google Scholar

[49] Golub G.H., Van Loan C.F., Matrix Computations. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1989Suche in Google Scholar

[50] Singh KKK., Bharti AK., Pal SK., Prakash A., Saurabh Rajwardhan Kumar R., Singh PR., Delineation of fracture zone for groundwater using combined inversion technique. Environmental Earth Sciences, 2019, 78, 11010.1007/s12665-019-8072-zSuche in Google Scholar

[51] Niwas S., de Lima O.A.L., Aquifer Parameter Estimation from Surface Resistivity Data. Ground Water, 2003, 41, 95 – 99.10.1111/j.1745-6584.2003.tb02572.xSuche in Google Scholar

[52] Thabit J.M., Al-Yasi A.I., Al-Shemmari A.N., Estimation of hydraulic parameters and porosity from geoelectrical properties for fractured rock aquifer in Dammam formation at Bahr Al- Najaf Basin, Iraq, scientific conference on recent contributions to the geology of Iraq. Iraqi Bull Geol Min, 2014, 10, 41–57Suche in Google Scholar

[53] Maréchal J.C., Dewandel B., Subrahmanyam K., Use of hydraulic tests at different scales to characterize fracture network properties in the weathered-fractured layer of a hard rock aquifer. Water Resources Research, American Geophysical Union, 2004, 40, pp.W11508.10.1029/2004WR003137Suche in Google Scholar

[54] Barenblatt G.I., Zheltov I.P., Fundamental equations of filtration of homogeneous liquids in fissured rocks. Soviet Dokl. Akad. Nauk., 1960, 13(2), 545-548.Suche in Google Scholar

[55] Barenblatt G.I., Zheltov I.P., Kochina I.N., Basic concepts in the theory of seepage of homogeneous liquids in fissured rocks. Soviet Appl. Math. Mech., 1960, 24(5), 852-864.10.1016/0021-8928(60)90107-6Suche in Google Scholar

[56] Niwas S., Singhal D.C., Estimation of aquifer transmissivity from Dar-Zarrouk parameters in porous media. Journal of Hydrology, 1981, 50, 393–399.10.1016/0022-1694(81)90082-2Suche in Google Scholar

[57] Niwas S., Singhal D.C., Aquifer transmissivity of porous media from resistivity data. Journal of Hydrology, 1985, 82, 143–153.10.1016/0022-1694(85)90050-2Suche in Google Scholar

[58] Fetter C.W., Applied Hydrogeology. Merrill Publishing, Columbus, OH, 1988, 592 pp.Suche in Google Scholar

[59] Archie GE., The electrical resistivity log as an aid in determining some reservoir characteristics, American Institute of Mineral and Metal Engineering. Technical Publication 1422, Petroleum Technology, 1942, pp. 8-13.Suche in Google Scholar

[60] Riedel M., Long P., Liu CS., et al., Physical properties of near surface sediments at southern hydrate ridge: results from ODP leg 204. Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results, 2005, 204.10.2973/odp.proc.sr.204.104.2006Suche in Google Scholar

[61] Schön JH., Physical Properties of Rocks, Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2004.Suche in Google Scholar

[62] Hasan M., Shang Y., Jin WJ., Akhter G., Investigation of fractured rock aquifer in South China using electrical resistivity tomography and self-potential methods. Journal of Mountain Science, 2019, 16(4), 850-869.10.1007/s11629-018-5207-8Suche in Google Scholar

[63] Wright E.P., The hydrogeology of crystalline basement aquifers in Africa. Geological Society Special Publication, 1992, 66, 1–27.10.1144/GSL.SP.1992.066.01.01Suche in Google Scholar

[64] World Health Organization (WHO), Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality. Recommendations Incorporating 1st and 2nd Addenda, 3rd ed., Vol. 1. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2008Suche in Google Scholar

[65] Trivedy R.K., Goel P.K., Chemical and Biochemical Methods for Water Pollution Studies. Karad, Maharashtra. Environmental Publication, 1986Suche in Google Scholar

[66] APHA (American Public Health Association), Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater. Washington, DC: APHA, 2000Suche in Google Scholar

[67] Hasan M., Shang Y., Akhter G., Jin W., Evaluation of Groundwater Suitability for Drinking and Irrigation Purposes in Toba Tek Singh District, Pakistan. Irrigation and Drainage Systems Engineering, 2017, 6, 185, doi: 10.4172/2168-9768.1000185.10.4172/2168-9768.1000185Suche in Google Scholar

© 2019 Muhammad Hasan, Yanjun Shang, Weijun Jin, Gulraiz Akhter published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- 2D Seismic Interpretation of the Meyal Area, Northern Potwar Deform Zone, Potwar Basin, Pakistan

- A new method of lithologic identification and distribution characteristics of fine - grained sediments: A case study in southwest of Ordos Basin, China

- Modified Gompertz sigmoidal model removing fine-ending of grain-size distribution

- Diagenesis and its influence on reservoir quality and oil-water relative permeability: A case study in the Yanchang Formation Chang 8 tight sandstone oil reservoir, Ordos Basin, China

- Evaluation of AHRS algorithms for Foot-Mounted Inertial-based Indoor Navigation Systems

- Identification and evaluation of land use vulnerability in a coal mining area under the coupled human-environment

- Hydrocarbon Generation Potential of Chia Gara Formation in Three Selected Wells, Northern Iraq

- Source Analysis of Silicon and Uranium in uranium-rich shale in the Xiuwu Basin, Southern China

- Lithologic heterogeneity of lacustrine shale and its geological significance for shale hydrocarbon-a case study of Zhangjiatan Shale

- Characterization of soil permeability in the former Lake Texcoco, Mexico

- Detrital zircon trace elements from the Mesozoic Jiyuan Basin, central China and its implication on tectonic transition of the Qinling Orogenic Belt

- Turkey OpenStreetMap Dataset - Spatial Analysis of Development and Growth Proxies

- Morphological Changes of the Lower Ping and Chao Phraya Rivers, North and Central Thailand: Flood and Coastal Equilibrium Analyses

- Landscape Transformations in Rapidly Developing Peri-urban Areas of Accra, Ghana: Results of 30 years

- Division of shale sequences and prediction of the favorable shale gas intervals: an example of the Lower Cambrian of Yangtze Region in Xiuwu Basin

- Fractal characteristics of nanopores in lacustrine shales of the Triassic Yanchang Formation, Ordos Basin, NW China

- Selected components of geological structures and numerical modelling of slope stability

- Spatial data quality and uncertainty publication patterns and trends by bibliometric analysis

- Application of microstructure classification for the assessment of the variability of geological-engineering and pore space properties in clay soils

- Shear failure modes and AE characteristics of sandstone and marble fractures

- Ice Age theory: a correspondence between Milutin Milanković and Vojislav Mišković

- Are Serbian tourists worried? The effect of psychological factors on tourists’ behavior based on the perceived risk

- Real-Time Map Matching: A New Algorithm Integrating Spatio-Temporal Proximity and Improved Weighted Circle

- Characteristics and hysteresis of saturated-unsaturated seepage of soil landslides in the Three Gorges Reservoir Area, China

- Petrographical and geophysical investigation of the Ecca Group between Fort Beaufort and Grahamstown, in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa

- Ecological risk assessment of geohazards in Natural World Heritage Sites: an empirical analysis of Bogda, Tianshan

- Integrated Subsurface Temperature Modeling beneath Mt. Lawu and Mt. Muriah in The Northeast Java Basin, Indonesia

- Go social for your own safety! Review of social networks use on natural disasters – case studies from worldwide

- Forestry Aridity Index in Vojvodina, North Serbia

- Natural Disasters vs Hotel Industry Resilience: An Exploratory Study among Hotel Managers from Europe

- Using Monarch Butterfly Optimization to Solve the Emergency Vehicle Routing Problem with Relief Materials in Sudden Disasters

- Potential influence of meteorological variables on forest fire risk in Serbia during the period 2000-2017

- Controlling factors on the geochemistry of Al-Shuaiba and Al-Mejarma coastal lagoons, Red Sea, Saudi Arabia

- The Influence of Kaolinite - Illite toward mechanical properties of Claystone

- Two critical books in the history of loess investigation: ‘Charakteristik der Felsarten’ by Karl Caesar von Leonhard and ‘Principles of Geology’ by Charles Lyell

- The Mechanism and Control Technology of Strong Strata Behavior in Extra-Thick Coal Seam Mining Influenced by Overlying Coal Pillar

- Shared Aerial Drone Videos — Prospects and Problems for Volunteered Geographic Information Research

- Stable isotopes of C and H in methane fermentation of agriculture substrates at different temperature conditions

- Prediction of Compression and Swelling Index Parameters of Quaternary Sediments from Index Tests at Mersin District

- Detection of old scattered windthrow using low cost resources. The case of Storm Xynthia in the Vosges Mountains, 28 February 2010

- Remediation of Copper and Zinc from wastewater by modified clay in Asir region southwest of Saudi Arabia

- Sedimentary facies of Paleogene lacustrine dolomicrite and implications for petroleum reservoirs in the southern Qianjiang Depression, China

- Correlation between ore particle flow pattern and velocity field through multiple drawpoints under the influence of a flexible barrier

- Atmospheric refractivity estimation from AIS signal power using the quantum-behaved particle swarm optimization algorithm

- A geophysical and hydro physico-chemical study of the contaminant impact of a solid waste landfill (swl) in King Williams’ Town, Eastern Cape, South Africa

- Landscape characterization using photographs from crowdsourced platforms: content analysis of social media photographs

- A Study on Transient Electromagnetic Interpretation Method Based on the Seismic Wave Impedance Inversion Model

- Stratigraphy of Architectural Elements of a Buried Monogenetic Volcanic System

- Variable secondary porosity modeling of carbonate rocks based on μ-CT images

- Traditional versus modern settlement on torrential alluvial fans considering the danger of debris flows: a case study of the Upper Sava Valley (NW Slovenia)

- The Influence of Gangue Particle size and Gangue Feeding Rate on Safety and Service Life of the Suspended Buffer’s Spring

- Research on the Transition Section Length of the Mixed Workface Using Gangue Backfilling Method and Caving Method

- Rainfall erosivity and extreme precipitation in the Pannonian basin

- Structure of the Sediment and Crust in the Northeast North China Craton from Improved Sequential H-k Stacking Method

- Planning Activities Improvements Responding Local Interests Change through Participatory Approach

- GIS-based landslide susceptibility mapping using bivariate statistical methods in North-western Tunisia

- Uncertainty based multi-step seismic analysis for near-surface imaging

- Deformation monitoring and prediction for residential areas in the Panji mining area based on an InSAR time series analysis and the GM-SVR model

- Statistical and expert-based landslide susceptibility modeling on a national scale applied to North Macedonia

- Natural hazards and their impact on rural settlements in NE Romania – A cartographical approach

- Rock fracture initiation and propagation by mechanical and hydraulic impact

- Influence of Rapid Transit on Accessibility Pattern and Economic Linkage at Urban Agglomeration Scale in China

- Near Infrared Spectroscopic Study of Trioctahedral Chlorites and Its Remote Sensing Application

- Problems with collapsible soils: Particle types and inter-particle bonding

- Unification of data from various seismic catalogues to study seismic activity in the Carpathians Mountain arc

- Quality assessment of DEM derived from topographic maps for geomorphometric purposes

- Remote Sensing Monitoring of Soil Moisture in the Daliuta Coal Mine Based on SPOT 5/6 and Worldview-2

- Utilizing Maximum Entropy Spectral Analysis (MESA) to identify Milankovitch cycles in Lower Member of Miocene Zhujiang Formation in north slope of Baiyun Sag, Pearl River Mouth Basin, South China Sea

- Stability Analysis of a Slurry Trench in Cohesive-Frictional Soils

- Integrating Landsat 7 and 8 data to improve basalt formation classification: A case study at Buon Ma Thuot region, Central Highland, Vietnam

- Assessment of the hydrocarbon potentiality of the Late Jurassic formations of NW Iraq: A case study based on TOC and Rock-Eval pyrolysis in selected oil-wells

- Rare earth element geochemistry of sediments from the southern Okinawa Trough since 3 ka: Implications for river-sea processes and sediment source

- Effect of gas adsorption-induced pore radius and effective stress on shale gas permeability in slip flow: New Insights

- Development of the Narva-Jõesuu beach, mineral composition of beach deposits and destruction of the pier, southeastern coast of the Gulf of Finland

- Selecting fracturing interval for the exploitation of tight oil reservoirs from logs: a case study

- A comprehensive scheme for lithological mapping using Sentinel-2A and ASTER GDEM in weathered and vegetated coastal zone, Southern China

- Sedimentary model of K-Successions Sandstones in H21 Area of Huizhou Depression, Pearl River Mouth Basin, South China Sea

- A non-uniform dip slip formula to calculate the coseismic deformation: Case study of Tohoku Mw9.0 Earthquake

- Decision trees in environmental justice research — a case study on the floods of 2001 and 2010 in Hungary

- The Impacts of Climate Change on Maximum Daily Discharge in the Payab Jamash Watershed, Iran

- Mass tourism in protected areas – underestimated threat? Polish National Parks case study

- Decadal variations of total organic carbon production in the inner-shelf of the South China Sea and East China Sea

- Hydrogeothermal potentials of Rogozna mountain and possibility of their valorization

- Postglacial talus slope development imaged by the ERT method: comparison of slopes from SW Spitsbergen, Norway and Tatra Mountains, Poland

- Seismotectonics of Malatya Fault, Eastern Turkey

- Investigating of soil features and landslide risk in Western-Atakent (İstanbul) using resistivity, MASW, Microtremor and boreholes methods

- Assessment of Aquifer Vulnerability Using Integrated Geophysical Approach in Weathered Terrains of South China

- An integrated analysis of mineralogical and microstructural characteristics and petrophysical properties of carbonate rocks in the lower Indus Basin, Pakistan

- Applicability of Hydrological Models for Flash Flood Simulation in Small Catchments of Hilly Area in China

- Heterogeneity analysis of shale reservoir based on multi-stage pumping data

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- 2D Seismic Interpretation of the Meyal Area, Northern Potwar Deform Zone, Potwar Basin, Pakistan

- A new method of lithologic identification and distribution characteristics of fine - grained sediments: A case study in southwest of Ordos Basin, China

- Modified Gompertz sigmoidal model removing fine-ending of grain-size distribution

- Diagenesis and its influence on reservoir quality and oil-water relative permeability: A case study in the Yanchang Formation Chang 8 tight sandstone oil reservoir, Ordos Basin, China

- Evaluation of AHRS algorithms for Foot-Mounted Inertial-based Indoor Navigation Systems

- Identification and evaluation of land use vulnerability in a coal mining area under the coupled human-environment