Abstract

The article considers the tourist traffic as possible to elements of inanimate nature in protected areas. The highest form of protection in Poland - national parks, has been taken into account. The main goal is to diagnose the situation based on the analysis of official documents elaborated by the national park authorities. One of the important elements is to diagnose the threat to nature and indicate ways to neutralize it. At the beginning, the geotouristic potential of these parks was presented, where this type of resources is considered important from the point of view of tourism. The tourist function of the most important attractions in Poland was indicated. In the top ten there are as many as 4 national parks, including Tatrzański which takes first place. The size of tourist traffic in all 23 parks was analyzed. As a result, it was shown that the most popular, where tourist flow is of mass character, include mountain parks with significant geotouristic potential. Next, the current protection plans for them were analyzed: Tatrzański, Karkonoski, Table Mountains and Pieniński, where the annual tourist flow varies between 0.5 million and almost 4 million visitors per year. Threats were assigned to 4 groups: existing internal threats, potential internal threats, existing external threats and potential external threats. In each of the types of threats special attention was paid to those related to inanimate nature. It also indicated the ways in which park managers want to influence the change of negative trends. The basic conclusion was indicated, which boils down to the postulate of a balanced approach to the protection of both types of nature: animate and inanimate. In the case of animate nature, threats and suggestions for improving the situation seem to be much better diagnosed than in the case of inanimate nature.

1 Introduction

Protection of nature, and especially of valuable natural areas in the context of tourism development has been present in the literature for decades. Every year, the popularity of Nature-based tourism in the world increases, which translates into a greater contact of tourists with the natural environment and practicing in this environment many forms of active tourism [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. The increase of the interest in the natural environment also influences the diversification of the approach to its use. This is accompanied by the growing awareness among tourists of the need to protect the environment as a whole. The basis of this approach has become the idea of geoconservation. It is expressed in the appropriate management of geological heritage resources of exceptional educational and tourist value, which also includes aesthetic value [6]. As Burek and Prosser [7] point out, geoconservation is not only about caring for the preservation of heritage for fear of destruction by tourists, but also for properly directed promotion of elements of the geological and geomorphological environment. The need for geoconservation comes directly from geodiversity, which Gray [8] defines as a broad set of natural elements:

geological as rocks, minerals or fossils,

geomorphological as landform or physical processes,

soil.

Geoheritage refers to geodiversity functioning in a specific place where is adequately protected from destruction [9].

Georesources are used in geotourism. Hose’s [10, 11, 12, 13, 14] first and subsequent attempts to define the phenomenon referred to the interpretation of geosites and geomorphosites, but also museums, etc. He pointed to the geological aspect of tourism.

In the publication from [15] Hose and Vasiljević proposed definition of modern geotourism poiting at: the provision of interpretative and service facilities for geosites and geomorphosites and their encompassing topography together with their associated in situ and ex situ artifacts, constituency-build for their conservation by generating appreciation, learning and research by and for current and future generations.

The most common place to implement the development of such activity is adapted to this area, among which Henriques et al. [6] list nature reserves, natural parks, or above all - national parks. The importance of protected areas for the development of geotourism is indicated by many authors [16].

The broadly understood nature-based tourism can also have a negative impact on the environment. The literature on the subject points to the threats of nature animate in protected areas, especially plants, which is indicated by many studies [17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22]. Various types of threats are mentioned. Usually, trampling, collecting, changes in soil structure, erosion and changes in vegetation structure are emphasized [17, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28]. Among the mentioned elements of animate and inanimate nature attention is paid to the risks associated with tourist infrastructure, for example damages made along hiking trails [24, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33].

As geoconservation plays a significant role in education, science, and in the development of geotourism, there is a postulate of the need to protect natural heritage, which should be included even in land-use plannig policies [6, 34]. It is also necessary to properly manage geosites, which should be expressed in an appropriate geoconservation strategy, as indicated by many authors [35, 36, 37, 38].

It is worth looking at how valuable natural areas with the status of a national park - the highest form of nature protection in Poland - refer to the postulate of the protection of inanimate nature heritage, also threatened by the development of mass tourism in their areas.

2 Types of tourist resources

Polish literature divides the tourist resources differently. Actually no matter the source all the resources are divided into two main groups:

resources based on the nature,

resources based on the cultural activity of mankind.

Such approach can be found in early 1970s Rogalewski [39] or Warszyńska and Jackowski [40] and is practically continued until present [41, 42]. The position dedicated to the presentation of geography of tourism in Poland by Lijewski, Mikułowski, Wyrzykowski [43, 44] proposes quite detailed division concerning the specifics of country potential. Among the resources the main groups are proposed:

Leisure tourist resources

Sightseeing tourist resources

Qualified tourist resources [44]

Although there are three groups in the division their potential is based on two kinds of values: nature and civilization ones. This view places the leisure and qualified tourist resources in the group of nature values and divides sightseeing resources into two main groups:

natural sightseeing resources,

cultural sightseeing resources [43].

Only this division indicates the importance of inanimate and animate elements of the natural environment in the development of tourism. Furthermore concerning just the nature the inanimate elements are important and more often present in the tourist offer in rural area.

The inanimate values are the most commonly used in the process of creating a tourist product.

If such potential resources are to be treated as real ones certain conditions must be met:

to be visible in the landscape,

to arouse the tourist interest,

to be resistant to the tourist traffic,

to be properly adapted to the tourist reception [43, p. 74].

In order to better understand the diversity of natural resources they were divided into additional categories according to the level of human intervention in the process of their creation. The first group are the resources on which the activity of a human being did not have any influence. Among them there are:

waterfalls, springs,

caves and grottos,

rocks and groups of rocks,

gorges, valleys, and watershed,

erratic rocks,

the group of rocks,

other geological sites,

the curiosities of fauna and flora.

The second group includes values heavily influenced by human activity. There are four main values of this kind:

museums of nature,

monumental parks,

botanical gardens,

zoological gardens.

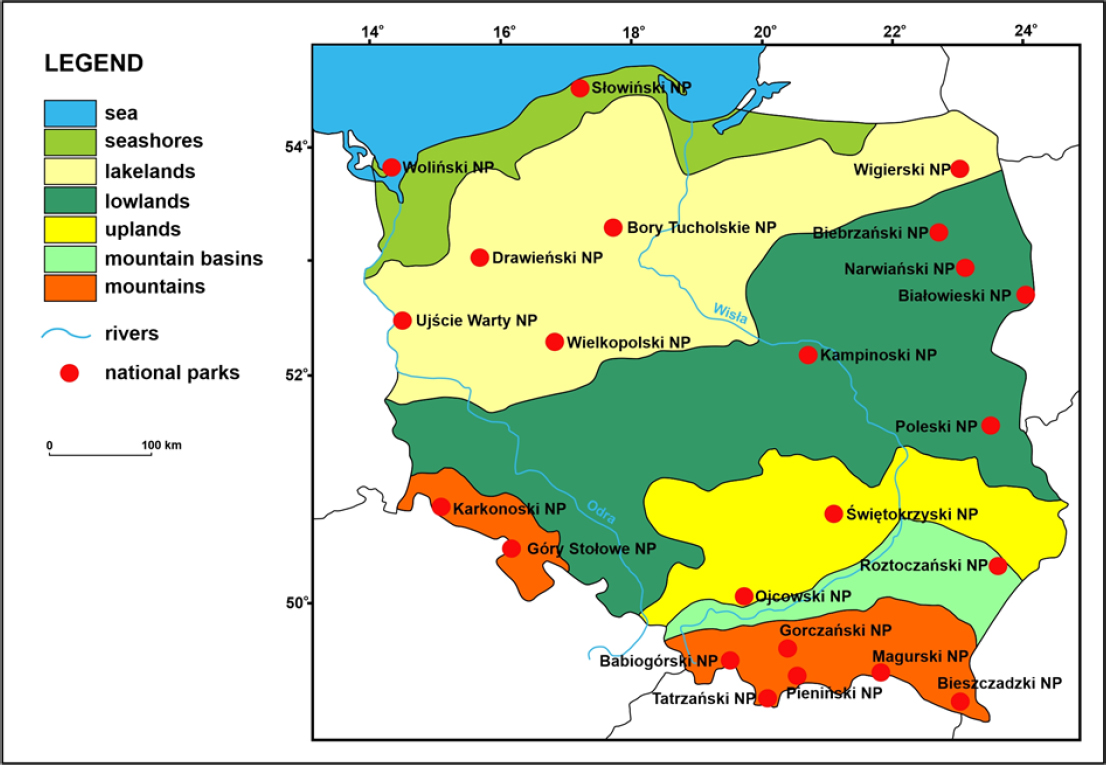

Location of National Parks in Poland

Source: own elaboration

The third group includes values that originate from human intervention, but the intervention itself does not affect their nature and significance. Many examples can be mentioned here but certainly the most important are the resources of the surface nature like: landscape parks, forest preserves, various sanctuaries and above all national parks.

3 National Parks and tourism in Poland – potential and consequences

No matter the character of the nature protected within the specific area the national parks are the highest form of nature protection in the Polish legal system. Practically always both animate and inanimate resources form the basis for the establishing a national park.

In Poland each national park is established on the basis of a separate legal act. The basis is the amended Act - – National Protection Act – of 16 April 2004, no 92. The document defines National Park as an area distinguished by its natural, scientific, social, cultural and educational values of the surface of at least 1000 hectares and where all the nature and landscape values are protected. The National Park is created “to preserve the biodiversity, resources, the components of inanimate nature and landscape values and to restore the proper state of the resources and components of nature...” [45]. Nowadays there are 23 national parks located in the different landscape zones (Map 1).

The table below shows the potential of this kind of resources in Poland.

4 Aims and methodology

The main assumption of this article is to point to possible threats to the nature elements, especially inanimate,

National Parks of Poland

| Name | Year | Total surface [ha] | Strict protection [ha] | Region | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Białowieski | 1947 | 10502 | 4747 | Podlaskie |

| 2 | Świętokrzyski | 1950 | 7632 | 1731 | Świętokrzyskie |

| 3 | Babiogórski | 1954 | 3392 | 1062 | Małopolskie |

| 4 | Pieniński | 1954 | 2346 | 777 | Małopolskie |

| 5 | Tatrzański | 1954 | 21164 | 11514 | Małopolskie |

| 6 | Ojcowski | 1956 | 2146 | 251 | Małopolskie |

| 7 | Wielkopolski | 1957 | 7584 | 260 | Wielkopolskie |

| 8 | Kampinoski | 1959 | 38544 | 4638 | Mazowieckie |

| 9 | Karkonoski | 1959 | 5575 | 1718 | Dolnośląskie |

| 10 | Woliński | 1960 | 10937 | 225 | Zachodniopomorskie |

| 11 | Słowiński | 1967 | 18618 | 5619 | Pomorskie |

| 12 | Bieszczadzki | 1973 | 29202 | 18425 | Podkarpackie |

| 13 | Roztoczański | 1974 | 8482 | 806 | Lubelskie |

| 14 | Gorczański | 1981 | 7030 | 2850 | Małopolskie |

| 15 | Wigierski | 1989 | 15086 | 380 | Podlaskie |

| 16 | Drawieński | 1990 | 11341 | 368 | Lubuskie, ZachPom. Wlkp. |

| 17 | Poleski | 1990 | 9762 | 428 | Lubelskie |

| 18 | Biebrzański | 1993 | 59223 | 3936 | Podlaskie |

| 19 | Gór Stołowych | 1993 | 6340 | 376 | Dolnośląskie |

| 20 | Magurski | 1995 | 19962 | Podkarpackie | |

| 21 | Bory Tucholskie | 1996 | 4798 | Pomorskie | |

| 22 | Narwiański | 1996 | 7350 | Podlaskie | |

| 23 | Ujście Warty | 2001 | 7956 | Lubuskie |

Source: [46, ED 14.03.2019]

which may be caused by the presence of tourism in areas of natural value. Thus attention was paid to the highest form of nature protection in Poland - national parks. The main method implemented in this paper would be the desk research method, where the main task is to analyze the existing data, collected to indicate, on the one hand, the tourism potential and, on the other hand, the risks associated with tourist use.

To achieve the goal, the geotouristic potential of national parks in Poland was first presented. The information about the aforementioned potential was developed based on two types of sources:

official websites of all 23 national parks and the website of the Union of National Park Employers managed by the president Andrzej Raj - director of the Karkonosze National Park. It is assumed these natural tourist values for which information was provided on official websites are promoted by the Park as noteworthy. They should also constitute, according to the park’s authorities, the basis for creating and promoting a specific tourist product. Therefore, the selection of resources is an indirect expression of tourism development policy in the protected area. The way of presenting the resources is also interesting although for this article such information was less important hence it was not taken into account in the analysis. In the case of national parks of a mass tourist movement, if necessary, local authorities’ official websites were also analyzed.

the list of the most important natural or geotouristic sightseeing resources, taking into account their rank. Only those values that are at least supraregional were included. For this purpose three leading summaries widely quoted in the Polish literature on the subject were used: Geography of Tourism of Poland by Lijewski, Mikułowski, Wyrzykowski - an important publication of eight editions now first issued in 1988 - and two Geotourist Resources Catalogs developed by a research team from AGH University of Science and Technology led by Słomka [47, 48]

Geotourist resources of National Parks according to official websites of national parks

| Park | Resource | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Karkonoski National Park | Śniezka | The highest peak of the Karkonosze and Sudety Mountains – 1602 m.a.s.l. The rock cone is built in the main part from metamorphic rocks called hornfels |

| Waterfall Szklarka Śniezne Kotły | the second largest waterfall in the Polish Karkonosze - its height is 13 m are two twin post-glacial cauldrons in the northern slope of the main ridge of the Karkonosze between Wielki Szyszak (1509 m a. s. 1.) and Łabski Peak (1472 m a. s. 1.) | |

| Waterfall Kamieńczyk | the highest waterfall of the Polish Sudetes. The water falls here with three cascades from a height of 27 m. | |

| Czarny Kocioł Jagniatkowski Pielgrzymy Small Pound | The upper edge reaches 1325 m a. s. 1., while its bottom is at an altitude of 1130-1150 m a. s. 1. three rock formations, exceeding the surrounding area at 25 m post-glacial lake located at an altitude of 1183 m a. s. 1. Its largest depth is 7.3 m and the length of the shoreline is 756 m. | |

| Szrenica | dominating over Szklarska Poręba peak (1362 m a. s. 1.). On the slopes of Szrenica there are picturesque rock groups: Końskie Łby and Trzy Świnki. | |

| Łomniczka The Peatbog Úpy | Stream with cascades called Łomniczka waterfalls the peatbog is located at an altitude of 1400-1425 m a. s. 1. | |

| Table Mountains National Park | Szczeliniec Wielki | the highest peak of the Table Mountains (919 m a. s. 1.) with a labyrinth with fantastic rock forms: "Sitter","Mammoth","Camel","Princes Emilka's Head"," Elephant "and" Pulpit " |

| Errant Rocks Rocks Mushrooms | Area of 22 ha. A complex of rock formations 6 - 11 m high, labyrinth among rocks. Most popular: "Rocky Saddle", "Chicken Foot", "Labyrinth", "Tunnel", "Great Hall" a group of originally shaped rock forms with shapes of mushrooms, bastions, gates, etc. | |

| White Rocks Łęzyckie Rocks Radkowskie Rocks and | A group of rocks on the Edge of Naroznik extensive mountain meadow. There are rare scattered rocks and single spruces they form the north-western edge of the Table Mountains | |

| Rock Pillars Waterfalls of Pośna | The area of 3.89 ha of strict protection in the Pośna stream valley | |

| Magurski National Park | Kornuty Reserve | In the area of 11.9 ha there are scattered boulders with a height of up to 10 m. There are fractured caves |

| Diabli Kamień Mroczna Cave | Group of rocks - a natural monument in the Kornuty reserve In the Kornuty reserve. The total length of the corridors - 175 m. | |

| Świętokrzyski National Park | Boulder Fields Łysica, Agata Łysa Góra Zapusty Slope | The rocks on the slopes were created 500 million years ago. Total area - about 20 ha. The highest peaks of mountains formed from Paleozoic rocks Created from carbonate rocks |

| Ojcowski National Park Pieniński National Park | Ciemna Cave Łokietko's Grotto Dunajec Breakthrough | One of the most valuable archaeological sites in Poland. It is a fragment of the former system of underground corridors and chambers, with a total length of 209 m is the largest of all known caves in the Park. Its length is 320 m A picturesque breakthrough with an antecedent character in the Pieniny Mountains, 8 km long with numerous meanders |

| Three Crowns | The highest peak of the Pieniny built of limestone (982 m a. s. 1.), a viewpoint at the Dunajec Breakthrough, Tatry Mountains | |

| Roztoczański National Park | Wepping Stone | A rock built of limestone |

| parabolic dune | A large form located in the vicinity of Echo ponds | |

| Tatrzański National Park | Peat bogs of Międzyrzeka Karst springs | A complex of unique peat bogs, a strict reserve with an area of 103.94 ha with bog marsh Chochołowskie (Chochołowska Valley), Lodowe, (Kościeliska Valley), Olczyskie (Olczyska Clearing) |

| Six tourist caves | Whole in the w ku Dziurze Valley, Mroźna in Kościeliska Valley, Smocza Jama in Kraków Gorge (in Kościeliska Valley), Mylna in Kościeliska Valley, Raptawicka in Kościeliska Valley, Obłazkowa in Kościeliska Valley. Only the Mroźna Cave is illuminated and an additional entrance fee is charged there. The cave is open from April 26 to October 30. To visit the remaining caves, you must have a flashlight. | |

| Valleys of tourist interest | Roztoki Valley - Picturesque U-shaped valley in the High Tatras, extension of the Valley of Five Polish Ponds; Valley of Five Polish Ponds - An alpine, post-glacial valley with a length of 4.0 km and an area of 6.5 km2. There are ponds there: Wielki, Zadni, Maly, Przedni, Czarny; Chochołowska -t covers an area of over 35 km2 and has a length of about 10 km.; Kościeliska Valley - It is about 9 km long, with an area of about 35 km2, contains the most geotouristic attractions in the Tatras; | |

| Waterfalls | Wielka Siklawa - the highest waterfall in the Tatras and Poland 65-70 m; Wodogrzmoty Mickiewicza - created from three larger and several smaller cascades on the Roztoka stream | |

| Pounds | Morskie Oko, Czarny Staw pod Rysami, Czarny Staw Gasienicowy, Pounds of the Valley of Five Polish Pounds | |

| Peaks | Rysy (2499 m. n.p.m.), Kasprowy Wierch (1987 m. n.p.m.), Kościelec (2155 m. n.p.m.), Giewont (1894 m. n.p.m.) | |

| Kraków Gorge | n the Kościeliska Valley, Gorge is considered to be the most beautiful rock gorge in the Polish Western Tatras. It was visited already in the first half of the 19th century | |

| Wielkopolski National Park | Bukowsko – Mosiński | A part of a larger structure. There is a 37 km section in the park |

| Esker Leśników Boulder | An erratic boulder which is a natural monument | |

| Wolinski National Park | Kawcza Góra Gosań Hill Sand Mountain Erratic Boulders | viewpoint - 61 m high elevation, first in the cliffs It is the highest elevation of the Polish coast (93 m above sea level) in the cliff viewpoint - located on the slope of a steep, sandy-chalk cliff Wydrzy Glaz – 8,1 m circuit; Mieszko I – 8 m., Boulder nr 1 – 8,1 m; Boulder nr 2 – 8,3 m |

| Słowiński National Park | Łącka Mountain, Czołpińska Dune | Sand dunes in the belt of dunes of the Łeba spit |

| Diabelski Kamień | Erratic boulder | |

| Babiogórski National Park | Waterfall of Mosorny Stream | It is a natural waterfall, one of the highest in the whole Beskidy Mountains. It has a height of 8 m |

| Diablak | The highest peak of the massif – 1725 m.a.s.l – viewpoint | |

| Gorczański National Park | Tops in the shape of domes or cones | Kiczora 1282 m a.s.l., Gore Porębski 1230 m a.s.l., Kopieniec 1080 m a.s.l. |

| Rock walls and outcrops | Czubaty Groń, Kudłoński Baca, Białe Skały | |

| Zbójecka Grotto | The largest cave in the Park |

The next step was to analyze tourist flow in national parks in order to illustrate the scale of the phenomenon and its intensity in the last decade. Finally, official documents developed for the purposes of nature conservation in parks were analyzed, as well as the opinions presented on official websites insofar as they referred to the subject of the article, pointing to the threat of inanimate nature associated with the development of tourism.

5 Results and Discussion

5.1 Tourist potential of national parks

The tourist values of national parks are presented in various ways. The vast majority of 23 national parks provide information on the subject under the headings of tourism, tourist attractions, nature (sometimes adding further links of animate nature and of inanimate nature) or pointing to specific types of resources such as caves or water.

The above list of values indicates that out of twenty-three Polish national parks only thirteen in any way present its geotouristic potential. This does not mean that they give up the promotion of their natural values at all but more often they focus on the animated nature. This happens even if the size and importance of values associated with the abiotic environment is equally important and sometimes even more important for nature conservation in their area.

Certainly, the poor representation of some parks located in mountainous and upland areas - areaswhose geotouristic potential is almost always significant - may be surprising. This is the case of the Bieszczadzki National Park whose official website does not indicate any values of inanimate nature at all. In the case of such parks as Świętokrzyski, Pieniński, Gorczański or Magurski such information is just a part of wider descriptions not directly related to the values.

The parks’ authorities responsible for maintaining official websites show different approaches to the presentation of tourist values located in the park. There is clearly an uneven approach to tourist values in general including those of a natural character. Only some of the twenty-three parks draw attention to their inanimate nature values. It is prepared in three ways:

presents them as part of a broader commentary on the geology or geomorphology of the area where it occurs or,

presents them as part of the description of particular thematic, didactic and educational routes, or simply presents the routes running through the park area or,

presents them as natural values in the more or less detailed way in a larger group of tourist attractions or separated as the most important attractions of the park (in this category only the values of inanimate nature are presented). This is the case for two parks: Karkonoski and Table Mountains - both located in Lower Silesia. The first one has also the status of the geopark.

5.2 Tourist function of national parks in Poland

National parks play an important role in the development of tourism in non-urbanized areas in Poland. They belong (apart of landscape parks) to the most attractive natural values of surface character. In practice, they are treated as a collection of many tourist values of a point nature or as an important set of recreational values where the nature of the landscape, microclimate prevailing in its area, water relations and fauna and flora characteristic for the region are important. This form of nature protection which occupies just over 1% of the country’s area is able to generate mass tourist flow. It this does not apply to all parks however. The size of tourist flow depends on many factors:

attractiveness of the landscape,

the range and number of tourist natural values,

the environmental conditions for practicing different active forms of tourism, emphasizing the skiing,

the level of the tourist infrastructure development accompanying specific forms of tourism with particular emphasis on the accommodation base in the vicinity of the park,

accessibility.

Taking into consideration the above elements it is not surprising the top ten most visited tourist attractions in Poland in 2014:

Tatrzański National Park

Wilanów Palace

Łazienki Palace

Karkonoski National Park

Auschwitz – Birkenau Concentration Camp

Woliński National Park

Wieliczka Salt Mine

Wawel Castle

Wielkopolski National Park

Kopernik Science Center

![Figure 2 Number of tourists in national parks in 2017Source: [71]](/document/doi/10.1515/geo-2019-0081/asset/graphic/j_geo-2019-0081_fig_003.jpg)

Number of tourists in national parks in 2017

Source: [71]

As Kruczek points out [63] there are as many as four national parks in the list: two of a mountain nature, one of seaside and one lake. The highest rank belongs to the Tatrzański National Park where inanimate nature plays a significant role. The Karkonoski National Park was right behind the podium. For both of the parks the size of tourist traffic exceeds one million tourists.

The analysis of tourist traffic in national parks in recent years indicates a steady upward trend.

In the last decade tourist traffic in national parks increased from 10464400 to 13290600 visitors in 2017 with the exception of 2013. In practice tourist traffic increase of 30% in national parks was observed which impacted both animated and inanimate nature. It is worth taking a look at the record year 2017.

The most visited park with almost four million tourists is the Tatrzański National Park. The next places are occupied by the Karkonoski National Park with two million visitors, Woliński (1.5 million tourists) and Wielkopolski (1.2 million tourists). The group of parks with a million entries or over is completed by the Kampinoski National Park . It is worth paying attention to one important element: 8072000 tourists visit national parks located in mountain areas. If the number of visitors to upland parks is added, the total number increases to 8705000 people, which is 65% of all tourist movement associated with national parks in Poland. This value alone indicates a potential threat from the tourist movement for the natural values of mountain and upland national parks which take on much more pressure from tourists. In this group, due to its attractiveness for tourists, four national parks stand out: (Figure 3).

These were the most visited mountain national parks in 2017. Invariably for years in this group the leader is the Tatrzański National Park where the traffic in the analyzed period has almost doubled from 2 to 4 million tourists. The dynamics of this process can effect the inanimate nature of the Park. The situation in the Karkonoski National Park is surprisingly stable where the volume of tourist traffic in the last eight years has remained at a stable level of 2 million visitors which is 336 people per hectare of the Park which rises a threat of anthropopressure.

Variable growth is noted by Pieniński National Park the third in classification visited last year by almost 900000 tourists. In the examined relatively short period the popularity of the Park increased by 30%. The last of the analyzed parks is the Table Mountains National Park which also increased tourist traffic from 319000 in 2010 to over half a million tourists in 2017.

5.3 Threats to inanimate nature resulting from the presence of tourist flow in the national parks

The size of tourist flow in valuable natural areas affects the quality and conservation status of nature. This is a kind of paradox - the more valuable and attractive natural area in the opinion of tourists, the greater the tourist flow is observed, which translates into a greater threat to the nature in the protected area. In the literature the whole set of threats is repeatedly pointed out of which managers in the protected area are aware of. Noise, pollution or anthropopressure is indicated [63]. Partyka [72] draws attention to the excessive attendance of visitors and the increase of number of tourist trails in the most popular places, trampling wild paths, damaging root systems, trees, destroying vegetation and soil, noise, disturbing animals, causing fires, littering, changes in landscape and microclimate, and synanthropization of flora and fauna and changes in the structure of biocenoses. Similarly, Baraniec [73] points to anthropogenic denudation, destruction in vegetation or littering, which diminishes the aesthetic values of the Park and has a negative impact on the animal world. Wieniawska [74] emphasizes the threat related to the development of infrastructure, especially skiing. The most popular in summer in mountains - hiking - destroys nature on the tourist trails. Tourists could destroy the vegetation cover, create short cuts between paths, destroy the surface of the paths, cause loose material movement, etc. [75].

The overw helming majority of literature on the subject points to the threats of animated nature, assuming that elements of inanimate nature as more resistant to the environment are less threatened [73, 75]. It is worth confronting this position with the opinion of institutions that are responsible for the management of protected areas, in this case national parks.

5.4 Analysis of inanimate nature threats according to documents

The need to protect nature, also inanimate, against the pressure of mass tourist traffic is already expressed in the declarations of managers of some national parks on their official websites. The declaration usually appears in the introductory word where the Park presents the main assumptions of nature conservation in its area and the main threats that require specific actions. It also indicates the main threats to nature from tourism - threats that can be called general but also those that are specific to a particular national park.

As far as inanimate nature is concerned the Table Mountains National Park indicates a significant share of tourism in accelerating the linear erosion process which takes place on over-exploited paths. Usually these are the main tourist routes where there are a number of initial depressions which erodes faster due to the large number of tourists [50].

The Ojcowski National Park also points to tourist flow as the main source of threats addressing the pressure of settlement in both the Park and its immediate vicinity resulting in the disappearance of rare and endangered plant species. The Park’s almost 700 caves are also endangered. An example is the cave infiltrations of Jaskinia Ciemna whose impoverished state is the result of its excessive exploitation from the 19th century [53].

The Pieniński National Park also indicates the increase of tourist flow as one of the main threats to nature and the integrity of its ecosystems. Another serious problem is the dense development of buildings within the park area which reduces the ecological corridors connecting the park with neighboring mountain ranges [54].

The Roztoczański National Park protects the inanimate nature threatened as well by the tourist movement by undertaking activities eliminating erosion resulted from anthropopressure, water protection and reducing runoff with drainage ditches and preventing overgrowing of exposed areas and outcrops [55].

However, more important than the declarations are specific actions taken by national parks. As an unit subordinated to the Ministry of the Environment each of the national parks should develop and then implement conservation tasks recorded in the Journal of Laws. It is a nature conservation plan in the national park. One of the essential mandatory elements included in the plan are threats to nature resulting from various reasons. According to the regulations each protection plan should identify the characteristic of a particular park:

existing internal threats;

potential internal threats;

existing external threats;

external potential threats.

The purpose of such a threat structure was to define specific actions to be taken to avoid these threats. Taking into account the tourist attractiveness of mountain national parks, expressed in the size of tourist flow throughout the year, it is worth looking at the plans to protect four Parks:

Threats defined by the selected national parks

| National Parks | existing internal threats | potential internal threats | existing external threats | external potential threats |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Karkonoski NP | erosion of soils, unauthorized use of national park resources, uncontrolled penetration by tourists | afraid of the pressure to expand the tourist infrastructure | excessive tourist traffic | loss of landscape values |

| Table Mountains NP | erosion of soils, unauthorized use of national park resources, uncontrolled penetration by tourists | Concentration of tourist flow on Szczeliniec Wielki and Błędne Skały, natural mass movements of rocks | pollution of: air, water and soils on the tourist trails | |

| Tatrzański NP | erosion of soils, unauthorized use of national park resources, uncontrolled penetration by tourists | increase in anthropogenic pressure related to the accessibility of the park’s area, | excessive increase in the number of people using its area | |

| Pieniński NP | erosion of soils, unauthorized use of national park resources, uncontrolled penetration by tourists, destruction of caves and rocky deposits caused by tourists |

Protective tasks relate to many issues. For understandable reasons, the focus was only on those that combine tourist flow and inanimate nature. In the case of basically all analyzed parks, the main existing identified threat is the erosion of soils. The Karkonoski National Park puts this threat in this category as the most important, which is reflected in the number one position in this group. In the case of other parks, this is also a significant problem, although the Table Mountains National Park places this problem in the third position, Tatrzański National Park in the sixth, while among the main threats defined by the Pieniński National Park this problem occupies 26th position. Ideas for eliminating threats and their consequences are similar. The Karkonoski National Park suggests five main activities:

Hardening of the surface of tourist routes and internal roads.

Securing the sides of tourist trails and internal roads against trampling.

Securing of slopes and ski routes as well as lifts before erosion.

Anti-erosion space in places where erosion has caused human activity

Temporary exclusion of fragments of trails and internal roads from use.

And it is basically a set that most fully indicates ways to solve the problem. The Tatrzański National Park also indicates the need to renovate tourist routes and internal roads, fencing areas particularly susceptible to erosion and the introduction of anti-erosion structure of erosion gutters of anthropogenic origin. The Table Mountains National Park is much more laconic, which as a solution to the problem indicates the introduction of the anti-erosion structure. The Pieniński National Park adds to the above set the need to protect roads against falling rock debris and to limit the movement of motor vehicles.

Another threat, common for all parks, can be reduced to a common definition: unauthorized use of national park resources and uncontrolled penetration of its area by tourist flow. The Tatrzański National Park at this point at the position number 3 indicates problem that unauthorized persons are entering unauthorized places. In the Karkonoski National Park it is the position No. 7, where there is talk of local and periodic exceedances of the permissible number of people who can stay on a given section of the tourist route. The Table Mountains National Park speaks broadly about the uncontrolled penetration of the TMNP area consisting of: staying of tourists in places not available (areas in TMNP that are not made available to tourists to visit) and using motor vehicles (motorcycles,quads) – a point indicated by the Pieniński National Park in the section of the threat of soil erosion.

As a matter of fact, the ways to fight these threats are very similar: monitoring the impact on natural resources, limiting entry to the park’s endangered area, or infrastructure maintenance as appropriate marking, repairing hiking, biking and didactic paths. An important, especially for the Table Mountains National Park is the improvement of tourist flow and limiting the number of tourists on Szczeliniec Wielki and Błędne Skały through the creation of tourist routes and the introduction of fees for entering the routes. It also emphasizes the need to prevent tourists from staying outside of shared places.

The threat indicated only by the Pieniński National Park is, recorded in the position 29, the destruction of caves and rocky deposits caused by the tourist movement. As a way of solving the problem, it was proposed: protection of entrances to the most valuable caves located in the Park.

Potential internal threats are variously defined. The Karkonoski National Park is afraid of the pressure to expand the infrastructure serving tourism. The remedy for this should be studying the conditions and directions of spatial development of the communes of the Park, in which appropriate restrictions would be introduced.

There are two factors that threaten, in this category, for the Table Mountains National Park: Concentration of tourist flow on Szczeliniec Wielki and Błędne Skały, as well as natural mass movements of rocks, posing a threat to tourist flow. In the first case, the solution is the introduction of one-way traffic on tourist routes, in the second - mass monitoring of rock traffic and safety measures on tourist routes.

The Tatrzański National Park indicates a further increase in anthropogenic pressure related to the accessibility of the TNP area. The remedy for this is to monitor the number of tourists in the Park and maintain restrictions in using it. Properly developed strategy for sharing the Park, finally initiating and supporting the creation of tourist attractions outside the Park.

In the group of existing external threats Karkonoski National Park pointed to what is an existing internal threat to the Tatrzański National Park. This is excessive tourist traffic. Overcoming this problem should be based on the temporary closure of tourist routes, regulation of tourist traffic intensity and setting up the information and educational infrastructure.

The Table Mountains National Park indicates the pollution of: air, water and, what is important from the point of inanimate nature, soils on the tourist trails of the Park and in the places where recreational centers and their neighborhood are located. The idea for solving the problem is the development of collective and alternative transport in the area of the Park, properly prepared spatial development directions, and finally environmental education of local communities.

The last category are external potential threats. For the Karkonoski National Park, the loss of landscape values is a serious threat. To avoid this, the authorities believe that measures should be taken to limit the construction of new tourist, recreational and sports infrastructure in the immediate vicinity of the Park. In addition to this, it is necessary to ensure that landscape protection policy is included in local spatial development plans and regional development strategies. The Table Mountains National Park does not define such threats in the context of inanimate nature in connection with the development of tourism.

However, the Tatrzański National Park in this group indicates an excessive increase in the number of people using its area. Once again, the way to solve the problem, according to the Park, is monitoring the number of these people, introducing periodic and permanent restrictions on access to places subjected to the greatest pressure, and supporting the idea of developing tourist attractions outside the Park, in order to minimize and spread the excessive number of tourists.

6 Conclusions

National parks are one of the most important tourist values in Poland as indicated by the statistics quoted earlier [63]. Their main asset is nature whose resources are able to generate tourist flow of millions of visitors. As it has been shown, this can be a real threat to the values that make the park attractive to tourists. Thus the question arises: how should this type of resources be made available, so that on the one hand the tourist would be satisfied and on the other hand the nature would not be harmed. This problem is perfectly understood by the institutions managing the parks on behalf of the government. The question remains whether one can talk about a comprehensive approach – the one that takes into account the need to protect both types of nature: animate and inanimate. The threat of inanimate nature from tourism and the awareness of this problem among those who decide about the protection of national park resources are important.

The nature conservation is the basis of the park’s operation, however it primarily concerns the animate nature. Most of the 23 national parks located in Poland detail the resources of fauna and flora which are protected in the park along with forest complexes indicating the protection period. There are also areas of strict protection but in most cases it concerns the animated nature. It is different in the case of inanimate nature. The demands of its protection along with specific proposals appear less frequently and are general in nature. The situation looks different depending on the park. The parks located in the lowland, lake or coastal landscape practically do not pay attention to threats related to inanimate nature. The situation is better in national parks located in upland or mountain areas as exemplified by four parks, whose analysis of activities was undertaken in this article. It seems, however, that more can be done. It is worth undertaking joint activities to minimize the risks associated with the tourist movement.

Depending on the gravity, the risks can be assigned to two basic groups:

microscale threats,

macroscale threats.

The first group should include threats for the values of the point character such as dying caves caused by uncontrolled number of visitors, which causes the permanent change of their microclimate and thus their sculptures raised by Pieniński or Tatrzański National Parks. Here, too, would be a danger of erosion along the tourist routes, whose operation is significantly accelerated due to thousands and even millions of people visiting the parks every year.

The second group includes activities related to tourists activity which results in changes in the region. Here the landscape would be the most endangered as it results in physical processes it is at risk even at the aesthetic level. Mass construction in the immediate vicinity of the protected area destroys the natural landscape transforming it into a landscape that is at least disharmonious or simply urbanized. The consequences of human interference resulting in mass movements which may be caused by infrastructure, including tourism, built in the wrong place are also worth mentioning.

In conclusion, it should be emphasized that mass tourism which is often a mass phenomenon in valuable natural areas can have and has a devastating effect on inanimate nature. However, the managers of these areas do not fully emphasize it in the documents dedicated to the protection of national parks and consequently also in their activities. Therefore, it is necessary to appeal to decision-makers about a sustainable approach in the matter of protection of both elements of nature, animate and inanimate, similarly endangered by the massive development of tourism in their area.

References

[1] Kuenzi, C., McNeely, J., Nature-based tourism. In: Renn, O., Walker, K.D. (Eds.), Global Risk Governance. IUCN Publishing, Gland, Switzerland, 2008, pp. 155-17810.1007/978-1-4020-6799-0_8Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Balmford, A., Beresford, J., Green, J., Naidoo, R., Walpole, M., Manica, A., A global perspective of trends in nature-based tourism. PLoS Biology, 2009, 7, 1-6.10.1371/journal.pbio.1000144Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Buckley, R., Ecotourism: Principles and Practises. CABI Publishing, Wallingford, UK, 2009Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Newsome, D., Moore, S.A., Dowling, R.K., Natural Area Tourism: Ecology, Impacts and Management e2nd Edition. Channel View Publications, Bristol, UK, 2013, p. 45710.21832/9781845413835Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Eagles, P.F.J., Research priorities in park tourism, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 2014, 22, 528-54910.1080/09669582.2013.785554Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Henriques M. H., Pena dos Reis R., Brilha J., Mota T., Geoconservation as an Emerging Geoscience, Geoheritage, 2011, 3, 117-12810.1007/s12371-011-0039-8Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Burek, C.V., Prosser, C.D., The history of geoconservation: an introduction. In: Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 2008, vol. 300(1), pp. 1-5Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Gray, M., Geodiversity and geoconservation: what, why, and how? In: Santucci, V.L. (Ed.), Papers Presented at the George Wright Forum, 2005, pp. 4-12Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Gray, M., Geodiversity: Valuing and Conserving Abiotic Nature. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester U.K, 2004, p. 434.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Hose, T.A., Telling the story of stone – assessing the client base. Geological and Landscape Conservation. London, 1994Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Hose, T. A., Geotourism – selling the Earth to Europe. Engineering Geology and the Environment. Rotterdam, 1997Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Hose, T. A., Is it any fossicking good? Or behind the signs – a critique of current geotourism interpretative media unpublished paper delivered to the tourism in geological landscapes conference. Belfast, 1998Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Hose, T. A., European Geotourism – Geological Interpretation and Geoconservation Promotion for Tourists. Geological Heritage: Its Conservation and Management. Madrid, 2000Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Hose, T. A., Towards a history of geotourism: definitions, antecedents and the future. London, 2008b10.1144/SP300.5Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Hose, T.A., Vasiljević, Dj.A., Defining the Nature and Purpose of Modern Geotourism with Particular Reference to the United Kingdom and South-East Europe. Geoheritage, 2012, 4/1-2, 25-4310.1007/s12371-011-0050-0Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Santangelo N., Romano P., Santo A., Geo-itineraries in the Cilento Vallo di Diano Geopark: A Tool for Tourism Development in Southern Italy, Geoheritage, 2015, 7, pp. 319-33510.1007/s12371-014-0133-9Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Liddle, M. J., Recreation ecology: The ecological impact of outdoor recreation and ecotourism. London: Chapman and Hall, 1997Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Newsome, D., Moore, S.A., Dowling, R.K., Natural Area Tourism: Ecology, Impacts and Management. Channel View Publications, Sydney, 2002a10.21832/9781845413835Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Buckley, R., Impacts positive and negative: links between ecotourism and environment. In: Buckley, R. (Ed.), Environmental Impacts of Ecotourism. CABI Publishing, New York, 2004a, pp. 1–14Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Cole, D.N., Impacts of hiking and camping on soils and vegetation: a review. In: Buckley, R. (Ed.), Environmental Impacts of Ecotourism. CABI Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2004, pp. 41-6010.1079/9780851998107.0041Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Newsome, D., Cole, D.N., Marion, J., Environmental impacts associated with recreational horse-riding. In: Buckley, R. (Ed.), Environmental Impacts of Ecotourism. CABI Publishing, New York, 2004, pp. 61–8210.1079/9780851998107.0061Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Buckley, R., Recreation ecology research effort: an international comparison. Tourism Recreation Research, 2005, 30, 99–10110.1080/02508281.2005.11081237Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Kelly, C.L., Pickering, C.M., Buckley, R.C., Impacts of tourism on threatened plant taxa and communities in Australia. Ecological Management & Restoration, 2003, 4, 37-4410.1046/j.1442-8903.2003.00136.xSuche in Google Scholar

[24] Pickering, C.M., Hill, W., Impacts of recreation and tourism on plant biodiversity and vegetation in protected areas in Australia. Journal of Environmental Management, 2007, 85, 791-80010.1016/j.jenvman.2006.11.021Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Ballantyne, M., Gudes, O., Pickering, C.M., Visitor trails are an important cause of fragmentation in endangered urban forests. Landscape Urban Planning, 2014, 130, 112-12410.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.07.004Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Godefroid, S., Koedam, N., The impact of forest paths upon adjacent vegetation: effects of the path surfacing material on the species composition and soil compaction. Biological Conservation, 2004, 119, 405-41910.1016/j.biocon.2004.01.003Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Hill, W., Pickering, C.M., Vegetation associated with different walking track types in the Kosciuszko alpine area, Australia. Journal of Environmental Management, 2006, 78, 24-3410.1016/j.jenvman.2005.04.007Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Wimpey, J., Marion, J.L., The influence of use, environmental and managerial factors on the width of recreational trails. Journal of Environmental Management, 2010, 91, 2028-203710.1016/j.jenvman.2010.05.017Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Kutiel, P., Zhevelev, H., Harrison, R., The effect of recreational impacts on soil and vegetation of stabilised Coastal Dunes in the Sharon Park, Israel. Ocean Coastal Management, 1999, 42, 1041-1060.10.1016/S0964-5691(99)00060-5Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Marion, J.L., Leung, Y.F., Trail resource impacts and an examination of alternative assessment techniques. Journal of Park Recreation Administration, 2001, 19, 17-37Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Monz, C.A., Cole, D.N., Leung, Y.F., Marion, J.L., Sustaining visitor use in protected areas: future opportunities in recreation ecology research based on the USA experience. Environmental Management, 2010, 45, 551-562.10.1007/s00267-009-9406-5Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Marion, J.L., Wimpey, J.F., Park, L.O., The science of trail surveys: recreation ecology provides new tools for managing wilderness trails. Park Science, 2011, 28, 60-65.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Fenu, G., Cagoni, D., Ulian, T., Bacchetta, G., The impact of human trampling on a threatened coastal Mediterranean plant: the case of Anchusa littorea Moris (Boraginaceae). Flora, 2013, 208, 104-11010.1016/j.flora.2013.02.003Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Gray, M., Other nature: Geodiversity and geosystem services. Environmental Conservation, 2011, 38(3), 271–2710.1017/S0376892911000117Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Serrano, E., González-Trueba, J.J., Assessment of geomorphosites in natural protected areas: the Picos de Europa National Park (Spain). Géomorphologie. Formes, processus, environnement, vol. 3, 2005, pp. 197-208.10.4000/geomorphologie.364Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Lima, F., Brilha, J., Salamun, E., Inventorying geological heritage in large territories: a methodological proposal applied to Brazil. Geoheritage 2, 2010, pp. 91–9910.1007/s12371-010-0014-9Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Fassoulas, C., Mouriki, D., Dimitriou-Nikolakis, P., Iliopoulos, G., Quantitative Assessment of Geotopes as an Effective Tool for Geoheritage Management. Geoheritage, 2012, 4, pp 177–19310.1007/s12371-011-0046-9Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Božić, S., Tomić, N., Canyons and gorges as potential geotourism destinations in Serbia: comparative analysis from two different perspectives – general tourists’ and geotourists’. Open Geosciences, 2015, 7 (1), 531-546.10.1515/geo-2015-0040Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Rogalewski O., Zagospodarowanie turystyczne. WSiP, Warszawa, 1979Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Warszyńska J., Jackowski A., Podstawy geografii turyzmu. PWN, Warszawa, 1978Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Kowalczyk A., Geografia turyzmu. PWN, Warszawa, 2001Suche in Google Scholar

[42] Kruczek Z., Atrakcje turystyczne, Metody oceny ich odbioru – interpretacja, Folia Turistica, 2002, 13, 37-61Suche in Google Scholar

[43] Lijewski T., Mikułowski B., Wyrzykowski J., Geografia turystyki Polski, PWE, Warszawa, 2002Suche in Google Scholar

[44] Wyrzykowski, Lijewski, Mikułowski, Geografia turystyczna Polski, PWE, V-th edition, Warszawa, 2008Suche in Google Scholar

[45] Ustawa o ochronie przyrody Dz.U. z 2009 r. Nr 151, poz.1220, Nr 157, poz. 1241 www.nid.pl/upload/iblock/54c/54c7bc915f57027c5434c0622ee4c09b.pdfSuche in Google Scholar

[46] www.msw-pttk.orgSuche in Google Scholar

[47] www.researchgate.net/profile/Piotr_Strzebonski/publication/273895816_KATALOG_OBIEKTOW_GEOTURYSTYCZNYCH_W_POLSCE_obejmuje_wybrane_geologiczne_stanowiska_dokumentacyjne/links/550ffb7f0cf21287416c8efl/KATALOG-OBIEKTOW-GEOTURYSTYCZNYCH-W-POLSCE-obejmuje-wybrane-geologiczne-stanowiska-dokumentacyjne.pdfSuche in Google Scholar

[48] http://www.kgos.agh.edu.pl/download/Katalog_Obiekow_Geoturystycznych_2012.pdfSuche in Google Scholar

[49] www.kpnmab.plSuche in Google Scholar

[50] www.pngs.com.plSuche in Google Scholar

[51] www.magurskipn.plSuche in Google Scholar

[52] www.swietokrzyskipn.org.plSuche in Google Scholar

[53] www.ojcowskiparknarodowy.plSuche in Google Scholar

[54] www.pieninypn.plSuche in Google Scholar

[55] www.roztoczanskipn.plSuche in Google Scholar

[56] www.tpn.plSuche in Google Scholar

[57] www.wielkopolskipn.plSuche in Google Scholar

[58] www.wolinpn.plSuche in Google Scholar

[59] www.slowinski.parknarodowy.comSuche in Google Scholar

[60] www.bgpn.plSuche in Google Scholar

[61] www.gorczanskipark.plSuche in Google Scholar

[62] www.zpppn.plSuche in Google Scholar

[63] Kruczek Z., Frekwencja w polskich atrakcjach turystycznych. Problemy oceny liczby odwiedzających, Ekonomiczne Problemy Turystyki, 3/2016 (35), pp. 25 – 3510.18276/ept.2016.3.35-02Suche in Google Scholar

[64] Ochrona środowiska 2011, Główny Urząd Statystyczny https://stat.gov.pl/cps/rde/xbcr/gus/se_ochrona_srodowiska_2011.pdfSuche in Google Scholar

[65] Ochrona środowiska 2012, Główny Urząd Statystyczny https://stat.gov.pl/cps/rde/xbcr/gus/se_ochrona_srodowiska_2012.pdfSuche in Google Scholar

[66] Ochrona środowiska 2013, Główny Urząd Statystyczny https://stat.gov.pl/files/gfx/portalinformacyjny/pl/defaultaktualnosci/5484/1/14/1/se_ochrona_srodowiska_2013.pdfSuche in Google Scholar

[67] Ochrona środowiska 2014, Główny Urząd Statystyczny https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/srodowisko-energia/srodowisko/ochrona-srodowiska-2014,1,15.htmlSuche in Google Scholar

[68] Ochrona środowiska 2015, Główny Urząd Statystyczny https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/srodowisko-energia/srodowisko/ochrona-srodowiska-2015,1,16.htmlSuche in Google Scholar

[69] Ochrona środowiska 2016, Główny Urząd Statystyczny https://stat.gov.pl/files/gfx/portalinformacyjny/pl/defaultaktualnosci/5484/1/17/1/ochrona_srodowiska_2016.pdfSuche in Google Scholar

[70] Ochrona środowiska 2017, Główny Urząd Statystyczny https://stat.gov.pl/files/gfx/portalinformacyjny/pl/defaultaktualnosci/5484/1/18/1/ochrona_srodowiska_2017.pdfSuche in Google Scholar

[71] Ochrona środowiska 2018, Główny Urząd Statystyczny https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/srodowisko-energia/srodowisko/ochrona-srodowiska-2018,1,19.htmlSuche in Google Scholar

[72] Partyka J., Ruch turystyczny w polskich parkach narodowych, Folia Turistica, 2010, 22, s. 9–23Suche in Google Scholar

[73] Baraniec A., Turystyka w Babiogórskim Parku Narodowym In: J. Partyka, (Ed.), Użytkowanie turystyczne parków narodowych, Wydawnictwo Ojcowski Park Narodowy, Ojców, 2002Suche in Google Scholar

[74] Wieniawska B., Turystyka a ochrona przyrody w Karkonoskim Parku Narodowym, In: J. Partyka, (Ed.), Użytkowanie turystyczne parków narodowych, Wydawnictwo Ojcowski Park Narodowy, Ojców, 2002Suche in Google Scholar

[75] Fidelus J., Turystyka piesza i jej wpływ na przemiany rzeźby terenu w otoczeniu hal Gąsienicowej i Kondratowej w Tatrach, In: J. Pociask-Karteczka i in., (Eds.), Stan i perspektywy rozwoju turystyki w Tatrzańskim Parku Narodowym, Studia i Monografie AWF, nr 46, AWF – TPN, Kraków – Zakopane, 2007Suche in Google Scholar

[76] Ordinance of the Minister of the Environment, item 14, from January 18, 2018 on protective tasks for the Karkonoski National Park https://bip.kpnmab.pl/public/get_file_contents.php?id=186605Suche in Google Scholar

[77] Ordinance of the Minister of the Environment, January 5, 2017 on protective tasks for the Table Mountains National Park http://bip.pngs.com.pl/content.php?cms_id=47Suche in Google Scholar

[78] Ordinance of the Minister of the Environment, January 9, 2017 on protective tasks for the Tatrzański National Park https://tpn.pl/upload/filemanager/plan%20ochrony/projekt%20planu%20ochrony%20TPN%2020160330.pdfSuche in Google Scholar

[79] Ordinance of the Minister of the Environment, item 1010, from July 31, 2014 on protective tasks for the Pieniński National Park https://www.pieninypn.pl/files/fck/File/Plan_Ochrony_Pieninskiego_Parku_Narodowego.pdfSuche in Google Scholar

© 2019 K. Widawski and Z. Jary, published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- 2D Seismic Interpretation of the Meyal Area, Northern Potwar Deform Zone, Potwar Basin, Pakistan

- A new method of lithologic identification and distribution characteristics of fine - grained sediments: A case study in southwest of Ordos Basin, China

- Modified Gompertz sigmoidal model removing fine-ending of grain-size distribution

- Diagenesis and its influence on reservoir quality and oil-water relative permeability: A case study in the Yanchang Formation Chang 8 tight sandstone oil reservoir, Ordos Basin, China

- Evaluation of AHRS algorithms for Foot-Mounted Inertial-based Indoor Navigation Systems

- Identification and evaluation of land use vulnerability in a coal mining area under the coupled human-environment

- Hydrocarbon Generation Potential of Chia Gara Formation in Three Selected Wells, Northern Iraq

- Source Analysis of Silicon and Uranium in uranium-rich shale in the Xiuwu Basin, Southern China

- Lithologic heterogeneity of lacustrine shale and its geological significance for shale hydrocarbon-a case study of Zhangjiatan Shale

- Characterization of soil permeability in the former Lake Texcoco, Mexico

- Detrital zircon trace elements from the Mesozoic Jiyuan Basin, central China and its implication on tectonic transition of the Qinling Orogenic Belt

- Turkey OpenStreetMap Dataset - Spatial Analysis of Development and Growth Proxies

- Morphological Changes of the Lower Ping and Chao Phraya Rivers, North and Central Thailand: Flood and Coastal Equilibrium Analyses

- Landscape Transformations in Rapidly Developing Peri-urban Areas of Accra, Ghana: Results of 30 years

- Division of shale sequences and prediction of the favorable shale gas intervals: an example of the Lower Cambrian of Yangtze Region in Xiuwu Basin

- Fractal characteristics of nanopores in lacustrine shales of the Triassic Yanchang Formation, Ordos Basin, NW China

- Selected components of geological structures and numerical modelling of slope stability

- Spatial data quality and uncertainty publication patterns and trends by bibliometric analysis

- Application of microstructure classification for the assessment of the variability of geological-engineering and pore space properties in clay soils

- Shear failure modes and AE characteristics of sandstone and marble fractures

- Ice Age theory: a correspondence between Milutin Milanković and Vojislav Mišković

- Are Serbian tourists worried? The effect of psychological factors on tourists’ behavior based on the perceived risk

- Real-Time Map Matching: A New Algorithm Integrating Spatio-Temporal Proximity and Improved Weighted Circle

- Characteristics and hysteresis of saturated-unsaturated seepage of soil landslides in the Three Gorges Reservoir Area, China

- Petrographical and geophysical investigation of the Ecca Group between Fort Beaufort and Grahamstown, in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa

- Ecological risk assessment of geohazards in Natural World Heritage Sites: an empirical analysis of Bogda, Tianshan

- Integrated Subsurface Temperature Modeling beneath Mt. Lawu and Mt. Muriah in The Northeast Java Basin, Indonesia

- Go social for your own safety! Review of social networks use on natural disasters – case studies from worldwide

- Forestry Aridity Index in Vojvodina, North Serbia

- Natural Disasters vs Hotel Industry Resilience: An Exploratory Study among Hotel Managers from Europe

- Using Monarch Butterfly Optimization to Solve the Emergency Vehicle Routing Problem with Relief Materials in Sudden Disasters

- Potential influence of meteorological variables on forest fire risk in Serbia during the period 2000-2017

- Controlling factors on the geochemistry of Al-Shuaiba and Al-Mejarma coastal lagoons, Red Sea, Saudi Arabia

- The Influence of Kaolinite - Illite toward mechanical properties of Claystone

- Two critical books in the history of loess investigation: ‘Charakteristik der Felsarten’ by Karl Caesar von Leonhard and ‘Principles of Geology’ by Charles Lyell

- The Mechanism and Control Technology of Strong Strata Behavior in Extra-Thick Coal Seam Mining Influenced by Overlying Coal Pillar

- Shared Aerial Drone Videos — Prospects and Problems for Volunteered Geographic Information Research

- Stable isotopes of C and H in methane fermentation of agriculture substrates at different temperature conditions

- Prediction of Compression and Swelling Index Parameters of Quaternary Sediments from Index Tests at Mersin District

- Detection of old scattered windthrow using low cost resources. The case of Storm Xynthia in the Vosges Mountains, 28 February 2010

- Remediation of Copper and Zinc from wastewater by modified clay in Asir region southwest of Saudi Arabia

- Sedimentary facies of Paleogene lacustrine dolomicrite and implications for petroleum reservoirs in the southern Qianjiang Depression, China

- Correlation between ore particle flow pattern and velocity field through multiple drawpoints under the influence of a flexible barrier

- Atmospheric refractivity estimation from AIS signal power using the quantum-behaved particle swarm optimization algorithm

- A geophysical and hydro physico-chemical study of the contaminant impact of a solid waste landfill (swl) in King Williams’ Town, Eastern Cape, South Africa

- Landscape characterization using photographs from crowdsourced platforms: content analysis of social media photographs

- A Study on Transient Electromagnetic Interpretation Method Based on the Seismic Wave Impedance Inversion Model

- Stratigraphy of Architectural Elements of a Buried Monogenetic Volcanic System

- Variable secondary porosity modeling of carbonate rocks based on μ-CT images

- Traditional versus modern settlement on torrential alluvial fans considering the danger of debris flows: a case study of the Upper Sava Valley (NW Slovenia)

- The Influence of Gangue Particle size and Gangue Feeding Rate on Safety and Service Life of the Suspended Buffer’s Spring

- Research on the Transition Section Length of the Mixed Workface Using Gangue Backfilling Method and Caving Method

- Rainfall erosivity and extreme precipitation in the Pannonian basin

- Structure of the Sediment and Crust in the Northeast North China Craton from Improved Sequential H-k Stacking Method

- Planning Activities Improvements Responding Local Interests Change through Participatory Approach

- GIS-based landslide susceptibility mapping using bivariate statistical methods in North-western Tunisia

- Uncertainty based multi-step seismic analysis for near-surface imaging

- Deformation monitoring and prediction for residential areas in the Panji mining area based on an InSAR time series analysis and the GM-SVR model

- Statistical and expert-based landslide susceptibility modeling on a national scale applied to North Macedonia

- Natural hazards and their impact on rural settlements in NE Romania – A cartographical approach

- Rock fracture initiation and propagation by mechanical and hydraulic impact

- Influence of Rapid Transit on Accessibility Pattern and Economic Linkage at Urban Agglomeration Scale in China

- Near Infrared Spectroscopic Study of Trioctahedral Chlorites and Its Remote Sensing Application

- Problems with collapsible soils: Particle types and inter-particle bonding

- Unification of data from various seismic catalogues to study seismic activity in the Carpathians Mountain arc

- Quality assessment of DEM derived from topographic maps for geomorphometric purposes

- Remote Sensing Monitoring of Soil Moisture in the Daliuta Coal Mine Based on SPOT 5/6 and Worldview-2

- Utilizing Maximum Entropy Spectral Analysis (MESA) to identify Milankovitch cycles in Lower Member of Miocene Zhujiang Formation in north slope of Baiyun Sag, Pearl River Mouth Basin, South China Sea

- Stability Analysis of a Slurry Trench in Cohesive-Frictional Soils

- Integrating Landsat 7 and 8 data to improve basalt formation classification: A case study at Buon Ma Thuot region, Central Highland, Vietnam

- Assessment of the hydrocarbon potentiality of the Late Jurassic formations of NW Iraq: A case study based on TOC and Rock-Eval pyrolysis in selected oil-wells

- Rare earth element geochemistry of sediments from the southern Okinawa Trough since 3 ka: Implications for river-sea processes and sediment source

- Effect of gas adsorption-induced pore radius and effective stress on shale gas permeability in slip flow: New Insights

- Development of the Narva-Jõesuu beach, mineral composition of beach deposits and destruction of the pier, southeastern coast of the Gulf of Finland

- Selecting fracturing interval for the exploitation of tight oil reservoirs from logs: a case study

- A comprehensive scheme for lithological mapping using Sentinel-2A and ASTER GDEM in weathered and vegetated coastal zone, Southern China

- Sedimentary model of K-Successions Sandstones in H21 Area of Huizhou Depression, Pearl River Mouth Basin, South China Sea

- A non-uniform dip slip formula to calculate the coseismic deformation: Case study of Tohoku Mw9.0 Earthquake

- Decision trees in environmental justice research — a case study on the floods of 2001 and 2010 in Hungary

- The Impacts of Climate Change on Maximum Daily Discharge in the Payab Jamash Watershed, Iran

- Mass tourism in protected areas – underestimated threat? Polish National Parks case study

- Decadal variations of total organic carbon production in the inner-shelf of the South China Sea and East China Sea

- Hydrogeothermal potentials of Rogozna mountain and possibility of their valorization

- Postglacial talus slope development imaged by the ERT method: comparison of slopes from SW Spitsbergen, Norway and Tatra Mountains, Poland

- Seismotectonics of Malatya Fault, Eastern Turkey

- Investigating of soil features and landslide risk in Western-Atakent (İstanbul) using resistivity, MASW, Microtremor and boreholes methods

- Assessment of Aquifer Vulnerability Using Integrated Geophysical Approach in Weathered Terrains of South China

- An integrated analysis of mineralogical and microstructural characteristics and petrophysical properties of carbonate rocks in the lower Indus Basin, Pakistan

- Applicability of Hydrological Models for Flash Flood Simulation in Small Catchments of Hilly Area in China

- Heterogeneity analysis of shale reservoir based on multi-stage pumping data

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- 2D Seismic Interpretation of the Meyal Area, Northern Potwar Deform Zone, Potwar Basin, Pakistan

- A new method of lithologic identification and distribution characteristics of fine - grained sediments: A case study in southwest of Ordos Basin, China

- Modified Gompertz sigmoidal model removing fine-ending of grain-size distribution

- Diagenesis and its influence on reservoir quality and oil-water relative permeability: A case study in the Yanchang Formation Chang 8 tight sandstone oil reservoir, Ordos Basin, China

- Evaluation of AHRS algorithms for Foot-Mounted Inertial-based Indoor Navigation Systems

- Identification and evaluation of land use vulnerability in a coal mining area under the coupled human-environment

- Hydrocarbon Generation Potential of Chia Gara Formation in Three Selected Wells, Northern Iraq

- Source Analysis of Silicon and Uranium in uranium-rich shale in the Xiuwu Basin, Southern China

- Lithologic heterogeneity of lacustrine shale and its geological significance for shale hydrocarbon-a case study of Zhangjiatan Shale

- Characterization of soil permeability in the former Lake Texcoco, Mexico

- Detrital zircon trace elements from the Mesozoic Jiyuan Basin, central China and its implication on tectonic transition of the Qinling Orogenic Belt

- Turkey OpenStreetMap Dataset - Spatial Analysis of Development and Growth Proxies

- Morphological Changes of the Lower Ping and Chao Phraya Rivers, North and Central Thailand: Flood and Coastal Equilibrium Analyses

- Landscape Transformations in Rapidly Developing Peri-urban Areas of Accra, Ghana: Results of 30 years

- Division of shale sequences and prediction of the favorable shale gas intervals: an example of the Lower Cambrian of Yangtze Region in Xiuwu Basin

- Fractal characteristics of nanopores in lacustrine shales of the Triassic Yanchang Formation, Ordos Basin, NW China

- Selected components of geological structures and numerical modelling of slope stability

- Spatial data quality and uncertainty publication patterns and trends by bibliometric analysis

- Application of microstructure classification for the assessment of the variability of geological-engineering and pore space properties in clay soils

- Shear failure modes and AE characteristics of sandstone and marble fractures

- Ice Age theory: a correspondence between Milutin Milanković and Vojislav Mišković

- Are Serbian tourists worried? The effect of psychological factors on tourists’ behavior based on the perceived risk

- Real-Time Map Matching: A New Algorithm Integrating Spatio-Temporal Proximity and Improved Weighted Circle

- Characteristics and hysteresis of saturated-unsaturated seepage of soil landslides in the Three Gorges Reservoir Area, China

- Petrographical and geophysical investigation of the Ecca Group between Fort Beaufort and Grahamstown, in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa

- Ecological risk assessment of geohazards in Natural World Heritage Sites: an empirical analysis of Bogda, Tianshan

- Integrated Subsurface Temperature Modeling beneath Mt. Lawu and Mt. Muriah in The Northeast Java Basin, Indonesia

- Go social for your own safety! Review of social networks use on natural disasters – case studies from worldwide

- Forestry Aridity Index in Vojvodina, North Serbia

- Natural Disasters vs Hotel Industry Resilience: An Exploratory Study among Hotel Managers from Europe

- Using Monarch Butterfly Optimization to Solve the Emergency Vehicle Routing Problem with Relief Materials in Sudden Disasters

- Potential influence of meteorological variables on forest fire risk in Serbia during the period 2000-2017

- Controlling factors on the geochemistry of Al-Shuaiba and Al-Mejarma coastal lagoons, Red Sea, Saudi Arabia

- The Influence of Kaolinite - Illite toward mechanical properties of Claystone

- Two critical books in the history of loess investigation: ‘Charakteristik der Felsarten’ by Karl Caesar von Leonhard and ‘Principles of Geology’ by Charles Lyell

- The Mechanism and Control Technology of Strong Strata Behavior in Extra-Thick Coal Seam Mining Influenced by Overlying Coal Pillar

- Shared Aerial Drone Videos — Prospects and Problems for Volunteered Geographic Information Research

- Stable isotopes of C and H in methane fermentation of agriculture substrates at different temperature conditions

- Prediction of Compression and Swelling Index Parameters of Quaternary Sediments from Index Tests at Mersin District

- Detection of old scattered windthrow using low cost resources. The case of Storm Xynthia in the Vosges Mountains, 28 February 2010

- Remediation of Copper and Zinc from wastewater by modified clay in Asir region southwest of Saudi Arabia

- Sedimentary facies of Paleogene lacustrine dolomicrite and implications for petroleum reservoirs in the southern Qianjiang Depression, China

- Correlation between ore particle flow pattern and velocity field through multiple drawpoints under the influence of a flexible barrier

- Atmospheric refractivity estimation from AIS signal power using the quantum-behaved particle swarm optimization algorithm

- A geophysical and hydro physico-chemical study of the contaminant impact of a solid waste landfill (swl) in King Williams’ Town, Eastern Cape, South Africa

- Landscape characterization using photographs from crowdsourced platforms: content analysis of social media photographs

- A Study on Transient Electromagnetic Interpretation Method Based on the Seismic Wave Impedance Inversion Model

- Stratigraphy of Architectural Elements of a Buried Monogenetic Volcanic System

- Variable secondary porosity modeling of carbonate rocks based on μ-CT images

- Traditional versus modern settlement on torrential alluvial fans considering the danger of debris flows: a case study of the Upper Sava Valley (NW Slovenia)

- The Influence of Gangue Particle size and Gangue Feeding Rate on Safety and Service Life of the Suspended Buffer’s Spring

- Research on the Transition Section Length of the Mixed Workface Using Gangue Backfilling Method and Caving Method

- Rainfall erosivity and extreme precipitation in the Pannonian basin

- Structure of the Sediment and Crust in the Northeast North China Craton from Improved Sequential H-k Stacking Method

- Planning Activities Improvements Responding Local Interests Change through Participatory Approach

- GIS-based landslide susceptibility mapping using bivariate statistical methods in North-western Tunisia

- Uncertainty based multi-step seismic analysis for near-surface imaging

- Deformation monitoring and prediction for residential areas in the Panji mining area based on an InSAR time series analysis and the GM-SVR model

- Statistical and expert-based landslide susceptibility modeling on a national scale applied to North Macedonia

- Natural hazards and their impact on rural settlements in NE Romania – A cartographical approach

- Rock fracture initiation and propagation by mechanical and hydraulic impact

- Influence of Rapid Transit on Accessibility Pattern and Economic Linkage at Urban Agglomeration Scale in China

- Near Infrared Spectroscopic Study of Trioctahedral Chlorites and Its Remote Sensing Application

- Problems with collapsible soils: Particle types and inter-particle bonding

- Unification of data from various seismic catalogues to study seismic activity in the Carpathians Mountain arc

- Quality assessment of DEM derived from topographic maps for geomorphometric purposes

- Remote Sensing Monitoring of Soil Moisture in the Daliuta Coal Mine Based on SPOT 5/6 and Worldview-2

- Utilizing Maximum Entropy Spectral Analysis (MESA) to identify Milankovitch cycles in Lower Member of Miocene Zhujiang Formation in north slope of Baiyun Sag, Pearl River Mouth Basin, South China Sea

- Stability Analysis of a Slurry Trench in Cohesive-Frictional Soils

- Integrating Landsat 7 and 8 data to improve basalt formation classification: A case study at Buon Ma Thuot region, Central Highland, Vietnam

- Assessment of the hydrocarbon potentiality of the Late Jurassic formations of NW Iraq: A case study based on TOC and Rock-Eval pyrolysis in selected oil-wells

- Rare earth element geochemistry of sediments from the southern Okinawa Trough since 3 ka: Implications for river-sea processes and sediment source

- Effect of gas adsorption-induced pore radius and effective stress on shale gas permeability in slip flow: New Insights

- Development of the Narva-Jõesuu beach, mineral composition of beach deposits and destruction of the pier, southeastern coast of the Gulf of Finland

- Selecting fracturing interval for the exploitation of tight oil reservoirs from logs: a case study

- A comprehensive scheme for lithological mapping using Sentinel-2A and ASTER GDEM in weathered and vegetated coastal zone, Southern China

- Sedimentary model of K-Successions Sandstones in H21 Area of Huizhou Depression, Pearl River Mouth Basin, South China Sea

- A non-uniform dip slip formula to calculate the coseismic deformation: Case study of Tohoku Mw9.0 Earthquake

- Decision trees in environmental justice research — a case study on the floods of 2001 and 2010 in Hungary

- The Impacts of Climate Change on Maximum Daily Discharge in the Payab Jamash Watershed, Iran

- Mass tourism in protected areas – underestimated threat? Polish National Parks case study

- Decadal variations of total organic carbon production in the inner-shelf of the South China Sea and East China Sea

- Hydrogeothermal potentials of Rogozna mountain and possibility of their valorization

- Postglacial talus slope development imaged by the ERT method: comparison of slopes from SW Spitsbergen, Norway and Tatra Mountains, Poland

- Seismotectonics of Malatya Fault, Eastern Turkey

- Investigating of soil features and landslide risk in Western-Atakent (İstanbul) using resistivity, MASW, Microtremor and boreholes methods

- Assessment of Aquifer Vulnerability Using Integrated Geophysical Approach in Weathered Terrains of South China