Abstract

In this study, a novel geopolymer-based nepheline–cordierite composite was synthesized and evaluated as an efficient adsorbent for the removal of cytotoxic tamoxifen from aqueous solutions. The maximum removal efficiency of 96.08 % was achieved under optimal conditions: 40 mg/L tamoxifen concentration, 80 mg adsorbent dose, pH 7, 150 min of contact time, and 298 K. Adsorption kinetics were best described by the pseudo-second-order model (R 2 = 0.998), suggesting that chemisorption is the dominant mechanism. Equilibrium data were best fitted to the Langmuir isotherm model (R 2 = 0.996), indicating monolayer adsorption on a homogeneous surface. Thermodynamic parameters (ΔG° < 0, ΔH° = +48.267 kJ/mol, ΔS° = +174.568 J/mol·K) revealed that the adsorption process is spontaneous and endothermic. The pH at the point of zero charge (pHpzc) was determined to be 7.03, supporting the effectiveness of adsorption near neutral pH. Characterization of the adsorbent using BET, XRD, FTIR, and SEM analyses confirmed its porous structure, high surface area, and functional groups favorable for tamoxifen interaction. These findings suggest that the synthesized geopolymer-based nepheline–cordierite material is a promising, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly adsorbent for removing pharmaceutical contaminants from water.

1 Introduction

Pharmaceutical residues increasingly contaminate water bodies, posing a significant threat to environmental sustainability and public health [1], 2]. These compounds, originating from industrial discharges, hospital effluents, and domestic wastewater, persist in aquatic systems due to their low biodegradability, leading to ecological disruptions and health risks [3]. Their ability to migrate across environmental compartments, such as water and soil, amplifies their impact by promoting the development of resistant microorganisms and genes, which can adversely affect ecosystems and human well-being [3].

Tamoxifen, a critical antineoplastic agent used primarily for breast cancer treatment and prevention of recurrence, presents notable environmental challenges. Far from being a pesticide, this pharmaceutical compound disrupts aquatic ecosystems by impairing reproductive processes in aquatic organisms, altering vitellogenin levels across genders, with potential transgenerational effects [4]. Detected in hospital effluents, sewage, and surface waters at varying concentrations [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], tamoxifen’s toxicity, endocrine-disrupting properties, and bioaccumulative nature underscore the urgent need for effective removal strategies [11]. Despite its environmental significance, non-biological methods for tamoxifen elimination remain underexplored, necessitating innovative approaches to mitigate its release into aquatic environments [12], [13], [14], [15], [16].

The high solubility, persistence, and toxicity of pharmaceutical pollutants demand robust treatment solutions to safeguard ecosystems and human health [17], 18]. Various techniques, including biodegradation [19], advanced oxidation [20], photo-Fenton [21], electro-Fenton [22], ozonation [23], membrane filtration [24], and adsorption [25], [26], [27], have been developed to address these contaminants. Among these, adsorption is favored for its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, high efficiency, and minimal production of toxic by-products. While conventional adsorbents like activated carbon [28], 29], graphene oxide [30], zeolites [31], and clays [32] have been widely utilized, geopolymers offer a promising alternative due to their high adsorption capacity, biocompatibility, and eco-friendly properties, making them suitable for removing pharmaceutical residues from wastewater.

Ceramic materials were selected for their adsorption properties, the inclusion of Al2O3/SiO2 in the raw materials chosen for geopolymer formation, their low cost and their suitability for polymerisation. The adsorption properties of ceramic structures were improved by increasing their surface area and surface energy, as well as enhancing their rheological properties. The applications of the geopolymer method differ depending on the source of the geological raw material, which determines the molecular structure and the total Si:Al molar ratio of the activating alkali silicate [33], 34]. Depending on surface properties, it can be used in other geopolymers. When the Si:Al molar ratio is 2, geopolymers can be used to produce the advanced technology structures necessary for storing radioactive waste. Studies conducted in recent years have also investigated its use as an exhaust filter, with successful results [35].

Geopolymers exhibit more active properties due to their thermoset polymer structure, which is formed by polycondensation and increases their surface area. Geopolymerisation is an exothermic chemical process involving the dissolution, transport and orientation of molecules, followed by polycondensation (multiple condensation), all of which occur in a highly alkaline environment.

The geopolymer adsorbent’s high adsorption capacity, biocompatibility, low cost and non-toxic nature make it an environmentally friendly option. While existing studies have generally reported the removal of tamoxifen using adsorbents such as activated carbon [36], alumina (Al2O3) [37] and hydroxyapatite (HAP) [38], the high efficiency and lower cost demonstrated by the geopolymer adsorbent in this study suggest that it could be an important alternative in this field.

This study specifically utilizes industrial by-products (fly ash, boron waste) and locally sourced minerals to synthesize a novel nepheline-cordierite based geopolymer, targeting a cost-effective and sustainable adsorbent with a stable, porous structure favorable for pharmaceutical adsorption.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Tamoxifen concentrations in aqueous solutions were quantified using an Agilent 1260 HPLC system (USA) equipped with an ultraviolet detector and Chemstation software. Solution pH was measured with a Mettler-Toledo pH meter (Switzerland) fitted with a glass electrode. Ultrapure water, sourced from a Merck-Millipore Milli-Q purification system (USA), was used throughout the experiments. Adsorption studies were conducted in a WITEG WSB-30 thermostatic shaking water bath (Germany) to ensure controlled conditions.

Raw materials for geopolymer synthesis included metakaolin from MEFISTO L05 Company, low-calcium F-type fly ash from Kütahya Thermal Power Plant, boron waste clay from Kırka and Emet Operations Directorate, and magnesite (MgCO3) and talc from Uşak Ceramic Factory. This specific combination of raw materials was selected to promote the formation of a nepheline-cordierite crystalline phase upon sintering, which is anticipated to yield a mechanically stable and highly porous adsorbent framework. Furthermore, the use of industrial by-products (fly ash, boron waste) aligns with the goals of waste valorization and sustainable material development. Analytical-grade chemicals, used without further purification, included sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 98 %), hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37 %), tamoxifen (C26H29NO, 99 %), orthophosphoric acid (H3PO4, 85 %), and potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KH2PO4, ≥99.0 %), all procured from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie (Istanbul, Turkey). Tamoxifen (CAS No. 10540-29-1, C26H29NO, 99 %) and tamoxifen tablets (20 mg) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie and a local pharmacy in Afyonkarahisar, respectively. Distilled water was used to prepare all aqueous solutions, with pH adjustments made using HCl and NaOH solutions.

2.2 Geopolymer synthesis

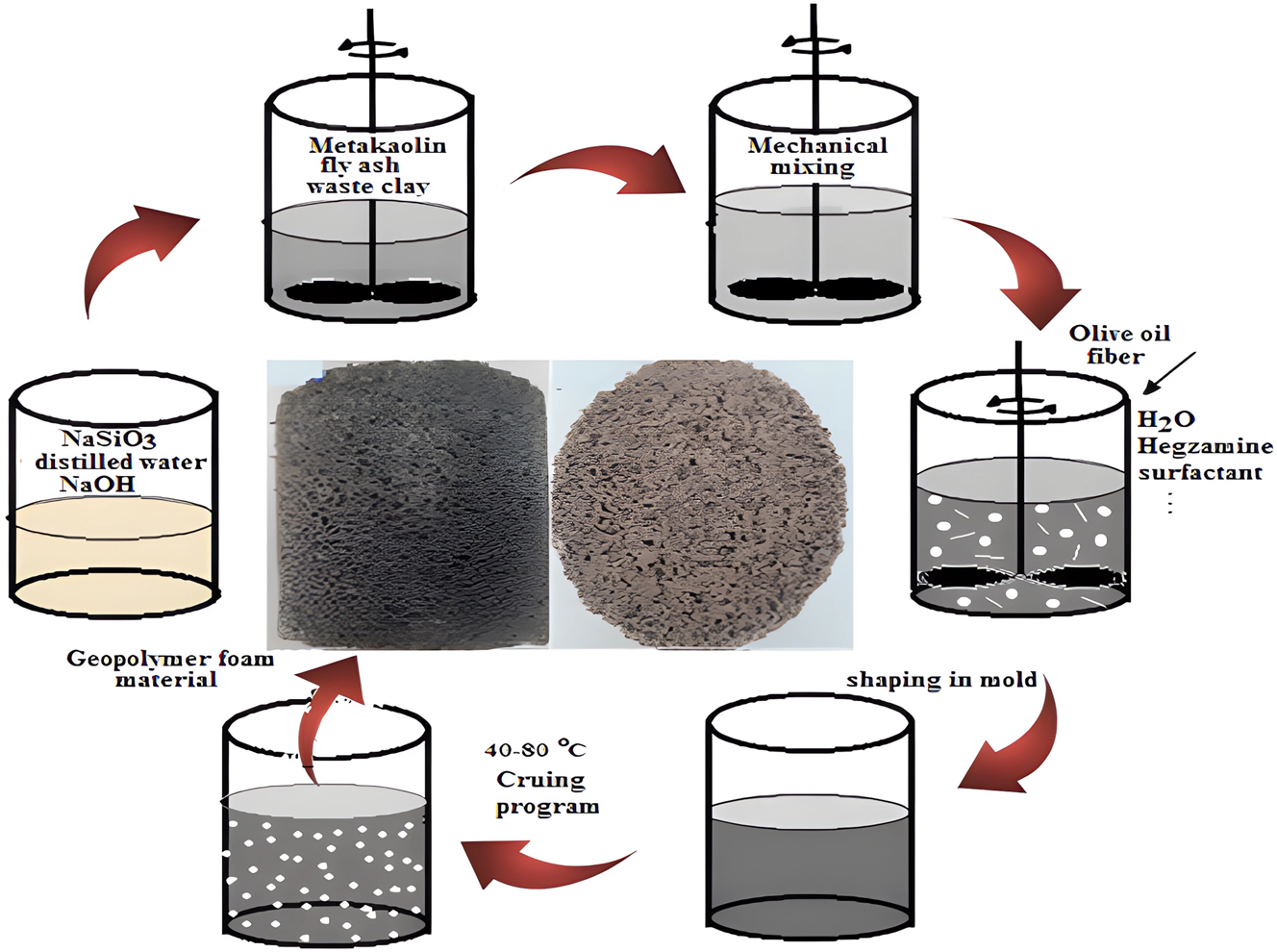

An alkaline mixture (6 M) was prepared by dissolving sodium hydroxide pellets in sodium silicate, as described in [39]. This mixture was combined with a raw material blend (5–30 µm particle size) formulated for the cordierite recipe and mixed for 5 min. Subsequently, a foaming agent, calcium stearate, and olive oil were incorporated into the geopolymer slurry (mud-like consistency) and mixed for an additional 3 min. The resulting mixture was poured into 100 × 100 mm molds and cured in an oven at 70 °C for 24 h. The porous geopolymer structure was then cured at room temperature for 2 days, followed by sintering at 700 °C in an oven. The experimental procedure is outlined in Figure 1.

Flow diagram of geopolymer preparation process.

2.3 Characterization methods

The geopolymer adsorbent was characterized to evaluate its surface properties and structure. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR, PerkinElmer) was used to identify functional groups on the material’s surface, providing insights into its chemical composition. The specific surface area and pore structure were determined using Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) analysis with a Micromeritics Gemini VII 5.03 system, enabling quantification of the adsorbent’s porosity and surface area. Surface morphology was examined through Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM, Zeiss Sigma 300), complemented by Energy-Dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy to analyze the elemental composition of the geopolymer, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of its structural and chemical characteristics.

2.4 Determination of zero charge point (pHpzc) of geopolymer adsorbent

The point of zero charge (pHpzc) of the geopolymer adsorbent was determined using the salt addition method. A 0.1 M NaCl solution was prepared and distributed in 50 mL portions into six 250 mL flasks. The initial pH (pHi) of each solution was adjusted to 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, or 12 using 0.1 M HCl or 0.1 M NaOH, as required. Subsequently, 0.050 g of geopolymer adsorbent was added to each flask, and the solutions were agitated at 170 rpm and 25 °C for 24 h. After agitation, the solutions were filtered through white band filter paper, and the final pH values (pHf) were measured using a pH meter. The pHpzc was determined by plotting the initial pH (pHi) against the final pH (pHf) and identifying the point of intersection, which represents the pHpzc of the geopolymer adsorbent [40].

2.5 Batch adsorption experiments

The adsorption efficiency of tamoxifen from aqueous solutions using a geopolymer adsorbent was investigated. A stock solution of tamoxifen (500 mg L−1) was prepared by accurately weighing 50 mg of tamoxifen into a 100 mL beaker, dissolving it in 40 mL of ultrapure water, and transferring it to a 1,000 mL volumetric flask, where the volume was adjusted to the mark with ultrapure water. The stock solution was sonicated in an ultrasonic bath for 5 min to ensure complete dissolution. Adsorption experiments were conducted using 50 mL tamoxifen solutions in 250 mL capped Erlenmeyer flasks.

The effects of pH, adsorbent dose, initial tamoxifen concentration, and temperature on adsorption efficiency were systematically evaluated. The stock solution was diluted to achieve the desired concentrations for each experiment. After adjusting the pH, a specified amount of geopolymer adsorbent was added to the solutions, which were then agitated at 180 rpm in a thermostatic water bath. Samples were filtered through a 0.22 µm membrane syringe filter, and tamoxifen concentrations in the filtrates were quantified using an HPLC system.

The influence of pH on tamoxifen removal efficiency was studied by varying the pH from 4 to 10 while keeping other parameters constant, with adjustments made using 0.1 N HCl or 0.1 N NaOH solutions. Subsequently, the effect of adsorbent dose (20–100 mg per 50 mL solution) was assessed at the optimal pH for maximum removal. Additionally, the impact of initial tamoxifen concentration (10–60 mg L−1) and temperature (298–318 K) on removal efficiency was investigated, with other variables held constant. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and average results were reported to ensure a robust evaluation of the factors affecting adsorption efficiency. The amount of tamoxifen adsorbed per unit mass of geopolymer adsorbent at time t (q t , mg g−1) and at equilibrium (q e, mg g−1) was calculated using the following equations:

In addition, the percentage of adsorbed tamoxifen was calculated using the following formula:

Where C e (mg L−1) is the equilibrium concentration, C t (mg L−1) is the concentration at time t, C 0 (mg L−1) is the initial concentration, w (g) is the mass of jeopolimer adsorbent and V (L) is the volume of the solution [41], 42].

2.6 Quantification of tamoxifen in aqueous solutions

Tamoxifen concentrations in aqueous solutions were determined using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with an Agilent 1260 Infinity LC system (USA). Separation was achieved on an ODS 3-C18 chromatographic column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm), with detection at a wavelength of 278 nm. The analysis was conducted under isocratic conditions using a mobile phase composed of 0.01 M KH2PO4 solution (pH 2, adjusted with phosphoric acid) and acetonitrile in a 50:50 (v/v) ratio. The column temperature was maintained at 30 °C, with a flow rate of 1.0 mL min−1 and an injection volume of 5 µL.

2.7 Izothermal modeling of tamoxifen removal process

The adsorption behavior was analyzed by fitting the experimental data to four isotherm models: Langmuir, Freundlich, Temkin, and Dubinin-Radushkevich (D-R). The linearized forms of these models were used to determine model parameters through linear regression. The Langmuir model assumes monolayer adsorption on a homogeneous surface, described by:

where (q max) is the maximum adsorption capacity (mg/g) and (K L) is the Langmuir constant (L/mg). The Freundlich model, which describes adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces, is given by:

where (K F ) is the adsorption capacity (mg/g (L/mg)(1/n)) and (n) is the adsorption intensity. The Temkin model, accounting for adsorbate-adsorbent interactions, is expressed as:

where (A T ) is the equilibrium binding constant (L/mg), (b T ) is related to the heat of adsorption (J/mol), (R) is the universal gas constant (8.314 J/mol·K), and (T) is the temperature (K). The D-R model, suitable for microporous adsorbents, is given by:

where (q m ) is the theoretical saturation capacity (mg/g), (K DR ) is a constant related to adsorption energy (mol2/J2), and (ϵ = RT × ln(1 + 1/C e ). The mean free adsorption energy (E) was calculated as:

The goodness of fit for each model was evaluated using the coefficient of determination (R 2), with higher values indicating better agreement with experimental data.

2.8 Kinetic modeling of tamoxifen removal process

Four kinetic models were applied to analyze the adsorption mechanism: Pseudo-First-Order (PFO), Pseudo-Second-Order (PSO), Elovich, and Intraparticle Diffusion (IPD). The PFO model is expressed as:

where (k 1 ) is the rate constant (min−1) and (q e ) is the equilibrium adsorption capacity (mg/g). The PSO model is given by:

where (k 2 ) is the rate constant (g/mg·min). The Elovich model is:

where (α) is the initial adsorption rate (mg/g·min) and (β) is the desorption constant (g/mg). The IPD model is:

where (k id) is the intraparticle diffusion rate constant (mg/g·min0.5) and (C) is the intercept (mg/g). The IPD model was analyzed in two segments: Segment 1 (t = 5 to 30 min) and Segment 2 (t = 30 to 180 min), with (t = 30) included in both segments.

Kinetic parameters were determined by linear regression using Python with the SciPy library. The goodness of fit was evaluated using the coefficient of determination (R 2). Data points at (t = 0 and t = 180) were excluded for PFO and Elovich models to avoid logarithmic issues, while (t = 0) was excluded for IPD to avoid undefined values.

2.9 Thermodynamic modeling of tamoxifen removal process

Thermodynamic parameters including enthalpy (ΔH°), Gibbs free energy (ΔG°) and entropy (ΔS°) changes were determined to evaluate the spontaneity of the adsorption process and the effect of temperature on adsorption performance. The Gibbs free energy change (ΔG°) was calculated using the following equation [43]:

Here T represents the absolute temperature (K), R the universal gas constant (8.314 J mol−1 K−1) and K e the equilibrium constant and is defined as.

Here C e and q e are the equilibrium concentrations of tamoxifen in solution (mg L−1) and on the adsorbent (mg g−1), respectively. The relationship between ΔG°, ΔH° and ΔS° is expressed as:

Rearranging this expression leads to a linear equation that allows the calculation of thermodynamic parameters:

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Characterization of geopolymer adsorbent

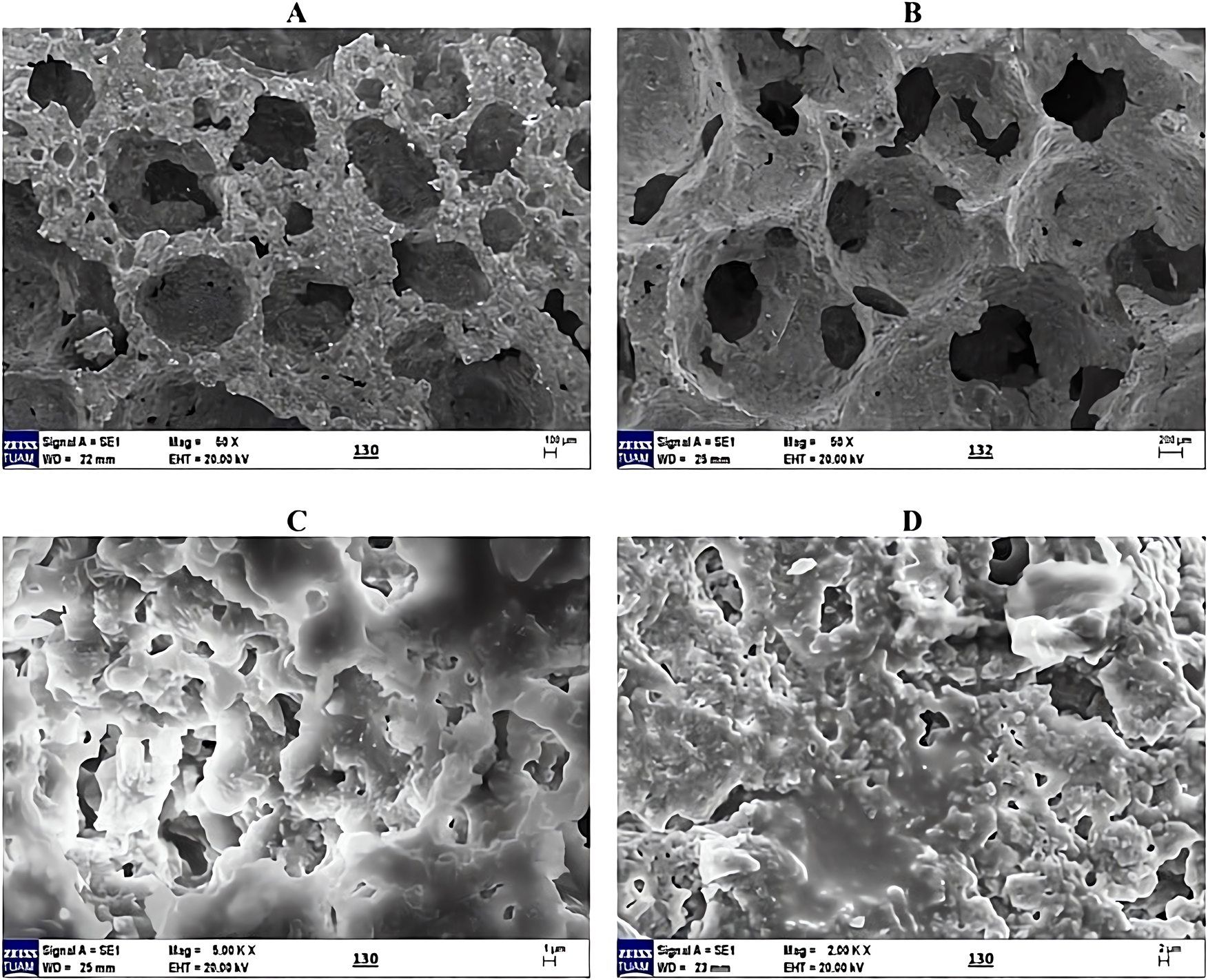

The geopolymer adsorbent samples were characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), and Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) analyses. SEM was employed to investigate the surface morphology of the adsorbent. Figure 2A–D illustrates the internal structures of the samples at various magnifications and locations. The SEM images in Figure 2A and B reveal a porous structure with interconnected open and closed pores forming a network. In contrast, the images in Figure 2C and D shows a partially molten appearance, while still retaining a porous structure with varying pore sizes. The high porosity contributes to an increased surface area, enhancing the adsorbent’s activity.

SEM images of geopolymer adsorbent at different magnifications. (A) 50 X magnification (100 µm). (B) 50 X magnification (100 µm). (C) 500 KX magnification (1 µm). (D) 200 KX magnification (1 µm).

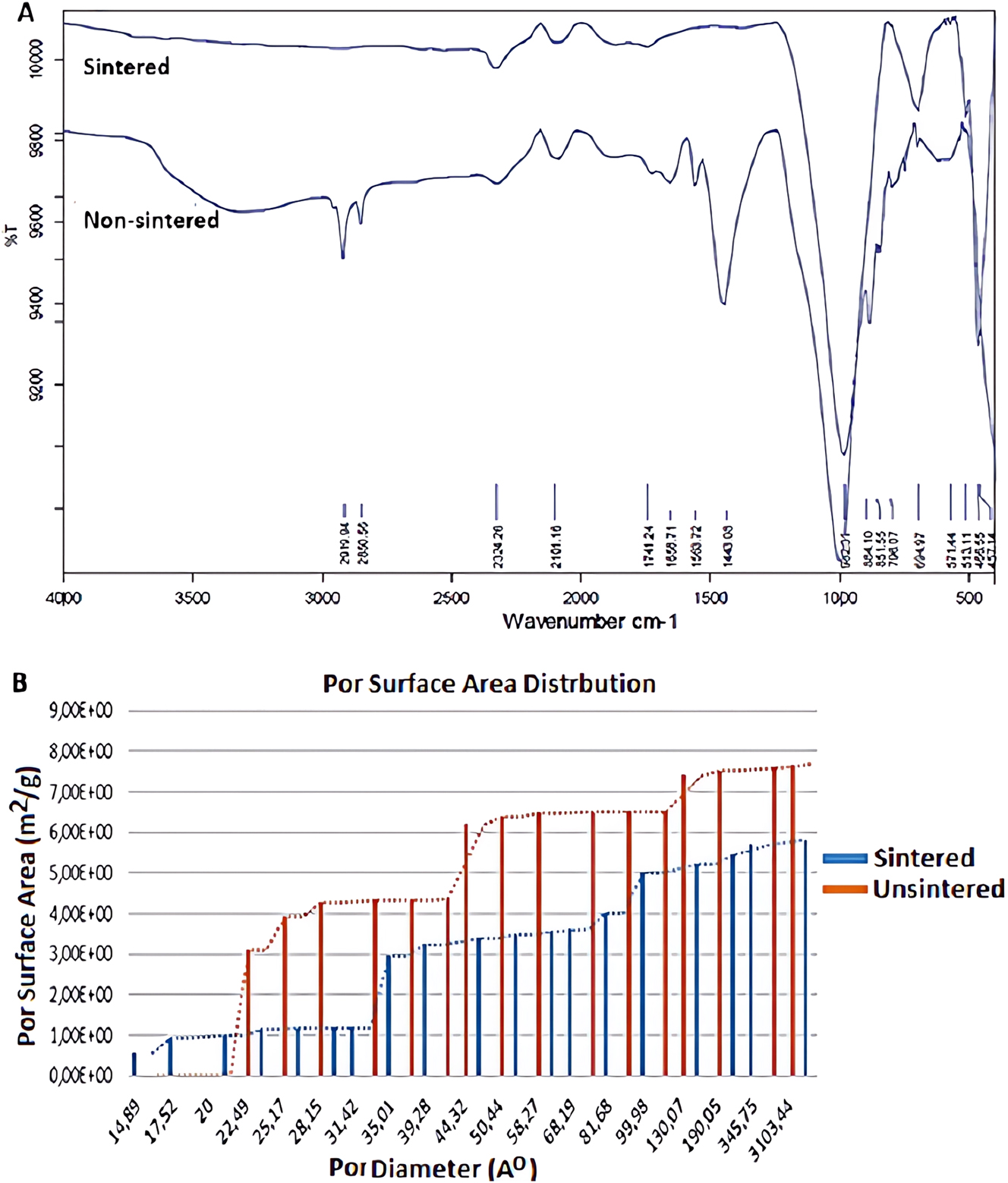

FTIR analysis was performed to determine the structure of the geopolymer adsorbent and the spectrum obtained is given in Figure 3A.

FTIR spectrum and pore surface area of geopolymer adsorbent. (A) FTIR spectrum. (B) Pore surface area distrbution.

Figure 3A presents the FTIR spectra of both sintered and unsintered geopolymer adsorbents. The primary peaks observed between 1,000 and 600 cm−1 are attributed to asymmetric vibrations of K–O–Si bonds (where K represents Si or Al) [44], 45]. The peak at 970–800 cm−1 corresponds to bending vibrations of Al–O–Si bonds, while the peak at approximately 420 cm−1 is associated with Si–O–Si bending vibrations [46]. In geopolymer compositions containing organic surfactants, small fluctuations observed between 2,200 and 1,800 cm−1 reflect symmetric and asymmetric vibrations of CH2 groups, indicative of the organic surfactant content [45].

Peak intensities vary depending on the concentration of functional groups in the synthesized geopolymer. Wavelength shifts in these peaks result from the incorporation of different atoms into the gel matrix [47], [48], [49], [50]. Broad and sharp vibrational bands at 3,000 cm−1 and 1,650 cm−1 indicate H–O–H bond stretching and bending, respectively, associated with water molecules trapped within the geopolymer pores or structure. An increase in the H–O–H peak intensity suggests greater pore enlargement, leading to a lower-density material and reduced mechanical strength. In sintered samples, these H–O–H bonds are absent, indicating their elimination during sintering.

The peak intensities of functional groups in geopolymers may differ from those in denser geopolymer counterparts. The chemical bonds observed in the FTIR spectra align with the molecular structures identified in XRD analysis, confirming proper activation of the geopolymer. Increased peak intensity and shifts in wavelength, along with a larger area under the peaks, indicate enhanced cross-linking. Larger aluminosilicate polymer molecules with a higher degree of polymerization contribute to improved mechanical properties [50].

The pore surface area and volume distributions of sintered and unsintered nepheline-based oxide minerals were analyzed using BET, with results presented in Figure 3B. The curves reveal a generally bimodal pore distribution, with variations in pore size between sintered and unsintered samples. The sintered samples (denoted as Sample 1) exhibit up to a 30 % reduction in pore surface area compared to the unsintered samples (Sample 2). Sintering altered the proportion of micro- and mesopores, while macropore sizes remained largely unchanged. Figure 3B shows a decrease in pore volume with sintering, with the reduction rate diminishing as pore size increases, indicating a slower decrease in the volume of larger pores. The maximum pore size reached 0.31 µm (310 nm), with sintering leading to reduced dispersion.

Pores formed during geopolymerization in unsintered samples often cause cracking during drying. After an initial 24-h curing period at 70 °C, the geopolymer is cured at room temperature, where drying-induced cracks persist during sintering. This is a common issue in geopolymer foam materials, attributed to unequal evaporation rates between the surface and the material’s volume. To mitigate this, increasing pore size or enhancing material strength to withstand evaporation stress is recommended.

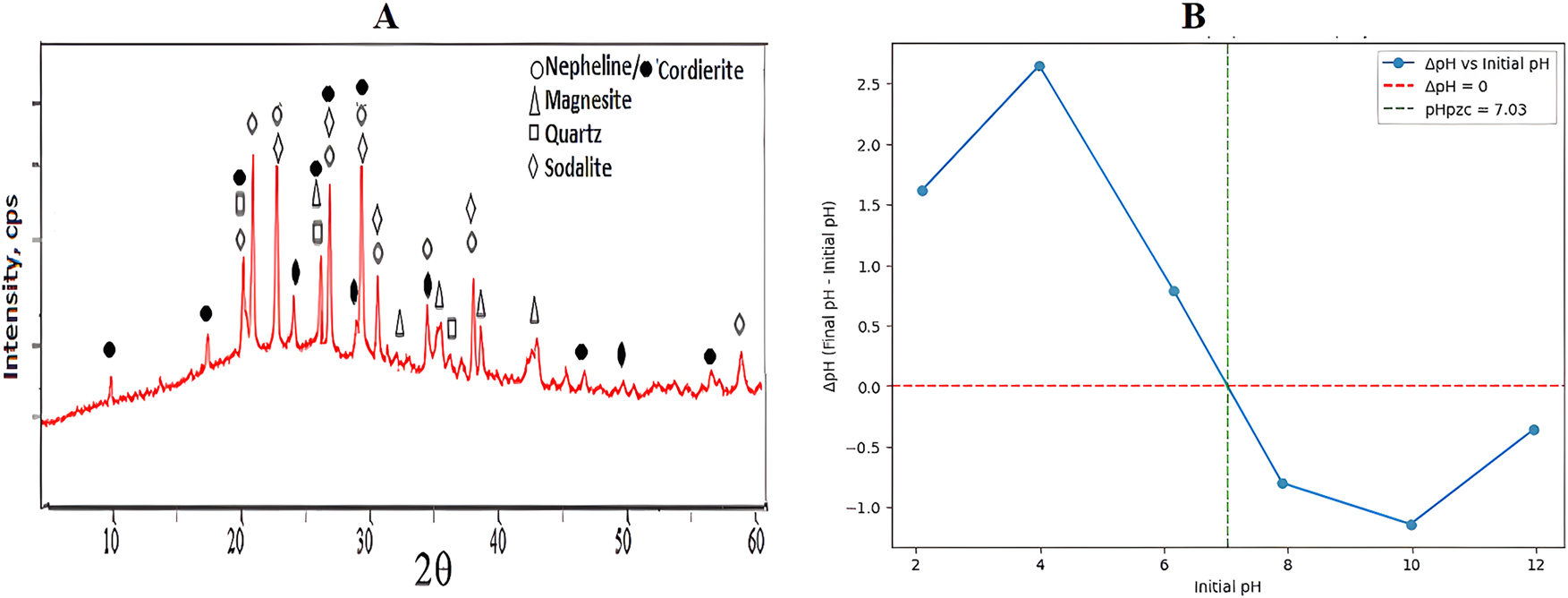

XRD analysis was performed after sintering the porous absorbent material formed by geopolymer method at 700 °C. Figure 4A shows the analysis peak graph. It is seen that Na from the alkaline environment (Base and Glass water) to form Nepheline/Cordierite is transformed into Nepheline. The peaks of Nepheline and Cordierite (Mg and Na variables) intersect in most places. Sodalite seen in the sintered sample appears to be a different component of Sodium alumina silicate. Apart from these phases, the residue appeared as Quartz and Magnesite.

XRD and pHpzc graph of geopolymer adsorbent material. (A) XRD graph. (B) pHpzc graph.

3.2 Determination of zero charge point (pHpzc) of geopolymer adsorbent

The pHpzc is a critical property of a material like a geopolymer, as it describes the pH at which the material’s surface carries no net electrical charge. Here’s a detailed interpretation:

Below pHpzc (pH < 7.03): At pH values lower than 7.03, the geopolymer surface is positively charged. This is evident from the positive ΔpH values (e.g., ΔpH = 1.62 at pH 2.10, ΔpH = 2.65 at pH 3.99). The positive ΔpH indicates that the final pH is higher than the initial pH, suggesting that the geopolymer adsorbs H+ ions (or releases OH− ions), making the solution less acidic. This occurs because the surface protonates, acquiring a positive charge.

At pHpzc (pH ≈ 7.03): At this pH, the surface has no net charge. The number of positive and negative charges on the surface is balanced, so there is minimal interaction with H+ or OH− ions in the solution, resulting in ΔpH ≈ 0.

Above pHpzc (pH > 7.03): At pH values higher than 7.03, the geopolymer surface is negatively charged. This is shown by the negative ΔpH values (e.g., ΔpH = −0.80 at pH 7.91, ΔpH = −1.14 at pH 9.98). The negative ΔpH indicates that the final pH is lower than the initial pH, suggesting that the geopolymer adsorbs OH− ions (or releases H+ ions), making the solution less basic. This occurs because the surface deprotonates, acquiring a negative charge.

Adsorption Properties: The pHpzc value of 7.03 suggests that the geopolymer is well-suited for applications in near-neutral pH environments. For example:

Cation Adsorption: At pH < 7.03, the positively charged surface repels cations but attracts anions, making it useful for adsorbing negatively charged species (e.g., anionic pollutants like phosphates or dyes).

Anion Adsorption: At pH > 7.03, the negatively charged surface attracts cations, making it effective for removing positively charged species (e.g., heavy metal ions like Pb2+ or Cu2+).

Environmental Applications: Since many natural water systems (e.g., rivers, groundwater) have pH values around 6–8, the pHpzc of 7.03 indicates that the geopolymer could be versatile for water treatment, as its surface charge can be tuned by slight pH adjustments to target specific contaminants.

Catalysis or Ion Exchange: In catalysis or ion-exchange applications, the pHpzc helps predict how the geopolymer will interact with charged species in a given pH environment, aiding in the design of efficient catalysts or ion-exchange materials.

A pHpzc of 7.03 is close to neutral, suggesting that the geopolymer has a balanced distribution of acidic and basic sites on its surface. This is typical for aluminosilicate-based geopolymers, which often have pHpzc values in the neutral to slightly basic range due to their chemical composition (e.g., Si–OH and Al–OH groups).

The gradual transition of ΔpH from positive to negative around pHpzc indicates a well-behaved surface with no abrupt changes, which is desirable for consistent performance in applications.

The pHpzc of approximately 7.03 indicates that the geopolymer has a neutral surface charge at near-neutral pH, making it versatile for applications like adsorption, catalysis, or ion exchange in environmental or industrial settings. Below pH 7.03, it is positively charged and can attract anions; above pH 7.03, it is negatively charged and can attract cations. This property allows the geopolymer to be tailored for specific applications by adjusting the pH of the surrounding environment, making it a promising material for water treatment or pollutant removal in near-neutral conditions.

3.3 Effect of pH on tamoxifen removal efficiency

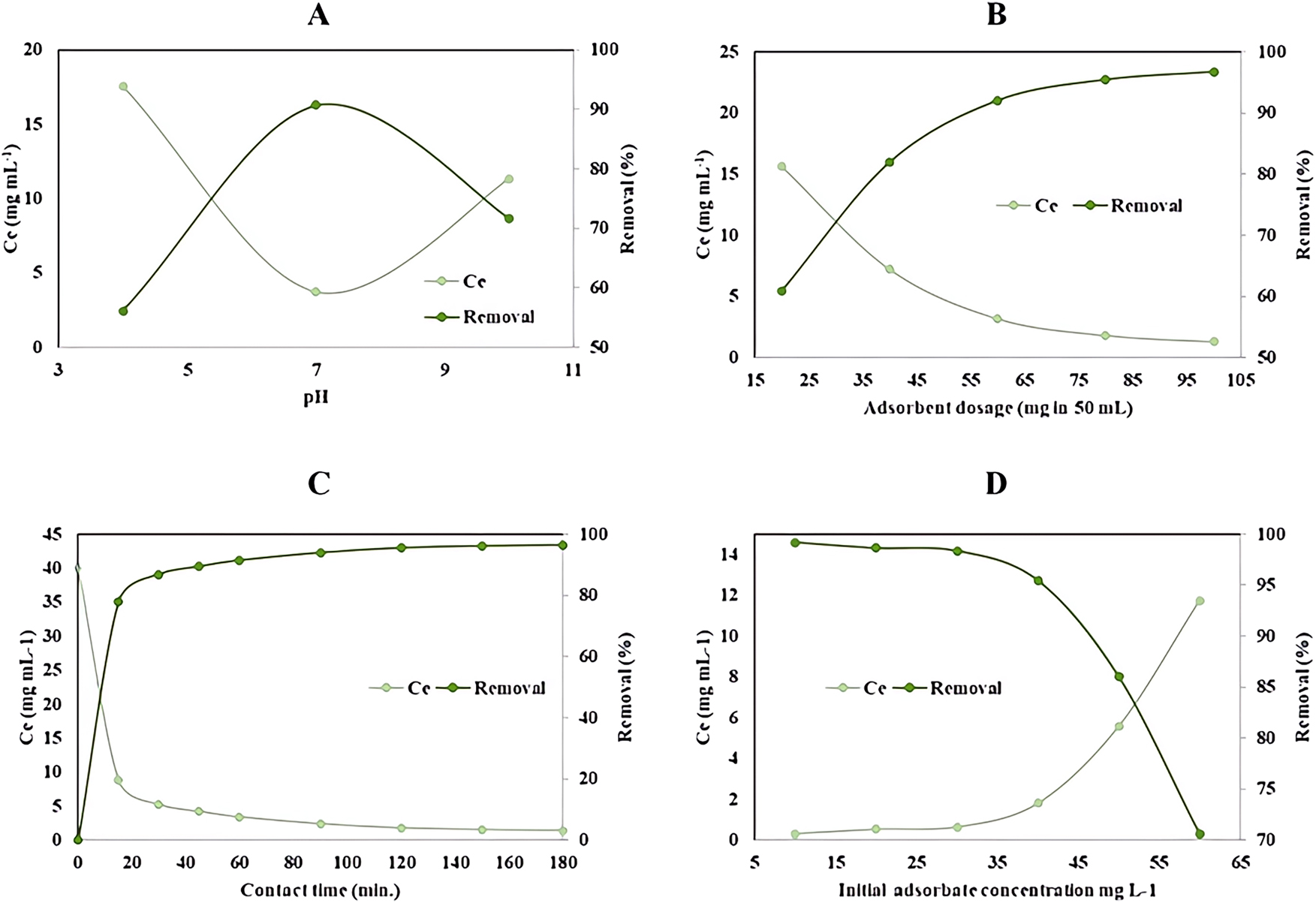

To investigate the impact of pH on tamoxifen adsorption, three 50 mL solutions with an initial tamoxifen concentration of 40 mg/L were prepared, with pH adjusted to values between 4 and 10 using 0.1 N HCl or NaOH. Each solution was mixed with 80 mg of geopolymer adsorbent and agitated at 180 rpm for 2 h at 25 °C. Post-agitation, samples were filtered and analyzed for tamoxifen concentration using an HPLC system. The results, shown in Figure 5A, reveal that adsorption efficiency increased with pH from 56.10 % at pH 4 to a peak of 90.70 % at pH 6, then declined to 71.70 % at pH 10. This trend reflects the influence of pH on the ionization state of tamoxifen, a cationic molecule, and the geopolymer’s surface charge. At higher pH values, excess OH− ions likely reduce adsorption efficiency due to electrostatic repulsion. Given the suitability of neutral pH for practical applications, pH 7 was selected as the optimal value, balancing high efficiency with environmental relevance.

Effect of adsorption parameters on tamoxifen removal efficiency. (A) Effect of pH on tamoxifen removal efficiency. (B) Effect of adsorbent dose on tamoxifen removal efficiency. (C) Effect of contact time on tamoxifen removal efficiency. (D) Effect of initial concentration on tamoxifen removal efficiency.

3.4 Effect of adsorbent dose on tamoxifen removal efficiency

The effect of adsorbent dose on the efficiency of tamoxifen removal was investigated by varying the amount of geopolymer-based adsorbent in aqueous solutions. Six 50 mL tamoxifen solutions at an initial concentration of 40 mg/L and pH 7 were prepared. Geopolymer doses of 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 mg were added to the respective solutions, which were then agitated at 180 rpm for 120 min at 25 °C. Following the adsorption process, 2 mL aliquots were collected, filtered through syringe filters (0.22 µm), and analyzed using HPLC to determine the residual tamoxifen concentration.

As illustrated in Figure 5B, the removal efficiency increased with the adsorbent dose. At 20 mg, the efficiency was 60.90 %, which rose to 81.93 % with 40 mg of adsorbent. A more substantial increase was observed at 60 mg (92.03 %), with the efficiency reaching 95.43 % at 80 mg. Increasing the dose further to 100 mg yielded a marginal improvement, achieving 95.55 % removal.

These results indicate that the increase in adsorbent dose enhances the number of available active sites, thereby improving adsorption efficiency. However, after a certain threshold (approximately 80 mg), the removal efficiency plateaued, suggesting the onset of equilibrium conditions where nearly all available tamoxifen molecules were adsorbed.

Although a slightly higher efficiency of 96.70 % was observed at 50 mg in an independent trial, 80 mg was selected as the optimum adsorbent dose for further experiments. This dose provides a balance between high removal efficiency (above 90 %) and cost-effectiveness, minimizing material usage without sacrificing performance.

3.5 Effect of stirring time on tamoxifen removal efficiency

The influence of stirring time on the adsorption efficiency of tamoxifen was assessed by varying contact duration between the geopolymer adsorbent and the tamoxifen solution. A 50 mL solution containing 40 mg/L tamoxifen at pH 7 was treated with 80 mg of geopolymer adsorbent and agitated at 180 rpm and 25 °C for up to 180 min. At predetermined time intervals, 1 mL aliquots were withdrawn, filtered through a 0.22 µm syringe filter, and analyzed by HPLC to determine residual tamoxifen concentrations.

As depicted in Figure 5C, the adsorption efficiency exhibited a rapid increase during the initial 15 min, indicating the abundance of available active sites on the adsorbent surface. Between 30 and 60 min, the rate of adsorption slowed, and the removal efficiency approached a plateau beyond 120 min. The removal efficiency was 86.78 % at 30 min and increased to 95.48 % at 120 min. Equilibrium was reached at 150 min with a maximum removal efficiency of 96.08 %. Extending the contact time to 180 min resulted in a negligible increase, with an efficiency of 96.40 %.

These findings suggest that the adsorption of tamoxifen is initially governed by surface interactions and external mass transfer, followed by gradual intraparticle diffusion until equilibrium is achieved. Based on the minimal improvement beyond 150 min, this contact time was identified as the optimal duration for subsequent adsorption and kinetic modeling studies.

3.6 Effect of initial tamoxifen concentration on removal efficiency

The effect of initial tamoxifen concentration on adsorption efficiency was examined by conducting a series of batch experiments with concentrations ranging from 10 to 60 mg/L. Each 50 mL solution was adjusted to pH 7, treated with 80 mg of geopolymer adsorbent, and stirred at 180 rpm for 150 min at 25 °C. The residual tamoxifen concentrations were determined by HPLC analysis.

As illustrated in Figure 5D, the removal efficiency increased with rising initial concentrations up to 40 mg/L. Specifically, the efficiency was 82.90 % at 20 mg/L, 88.05 % at 30 mg/L, and reached 92.05 % at 40 mg/L. This trend reflects the enhanced driving force for mass transfer and increased concentration gradient, which facilitates more effective adsorption.

However, beyond 40 mg/L, the increase in removal efficiency became marginal, indicating that the adsorption sites on the geopolymer surface were approaching saturation. At 50 mg/L and 60 mg/L, the efficiencies were 94.48 % and 95.45 %, respectively, with only slight improvement at 70 mg/L (95.55 %).

These findings suggest that although higher initial concentrations offer more tamoxifen molecules for adsorption, the finite number of active sites on the adsorbent limits the extent of removal beyond a certain concentration. Therefore, 40 mg/L was selected as the optimal initial concentration for subsequent experiments, as it provides high removal efficiency while preventing unnecessary saturation of the adsorbent.

3.7 Adsorption thermodynamics

The adsorption of tamoxifen onto the geopolymer is a spontaneous (ΔG < 0), endothermic (ΔH = 48.267 kJ/mol) process driven by a significant entropy increase (ΔS = 174.568 J/mol·K) due to water molecule release from the surface, characterized as chemisorption with strong chemical interactions. The process is most efficient at 298 K, with spontaneity decreasing at higher temperatures (ΔG from −6.848 kJ/mol at 298 K to −4.095 kJ/mol at 318 K), as confirmed by the decreasing equilibrium constant. This makes the geopolymer a promising adsorbent for tamoxifen removal in wastewater treatment at ambient conditions. The results are summarized in Table 1.

Thermodynamic parameters for tamoxifen adsorption.

| Temperature (K) | ΔG (kJ/mol) | ΔH (kJ/mol) | ΔS (J/mol·K) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 298 | −6.848 | 48.267 | 174.568 |

| 308 | −5.339 | 48.267 | 174.568 |

| 318 | −4.095 | 48.267 | 174.568 |

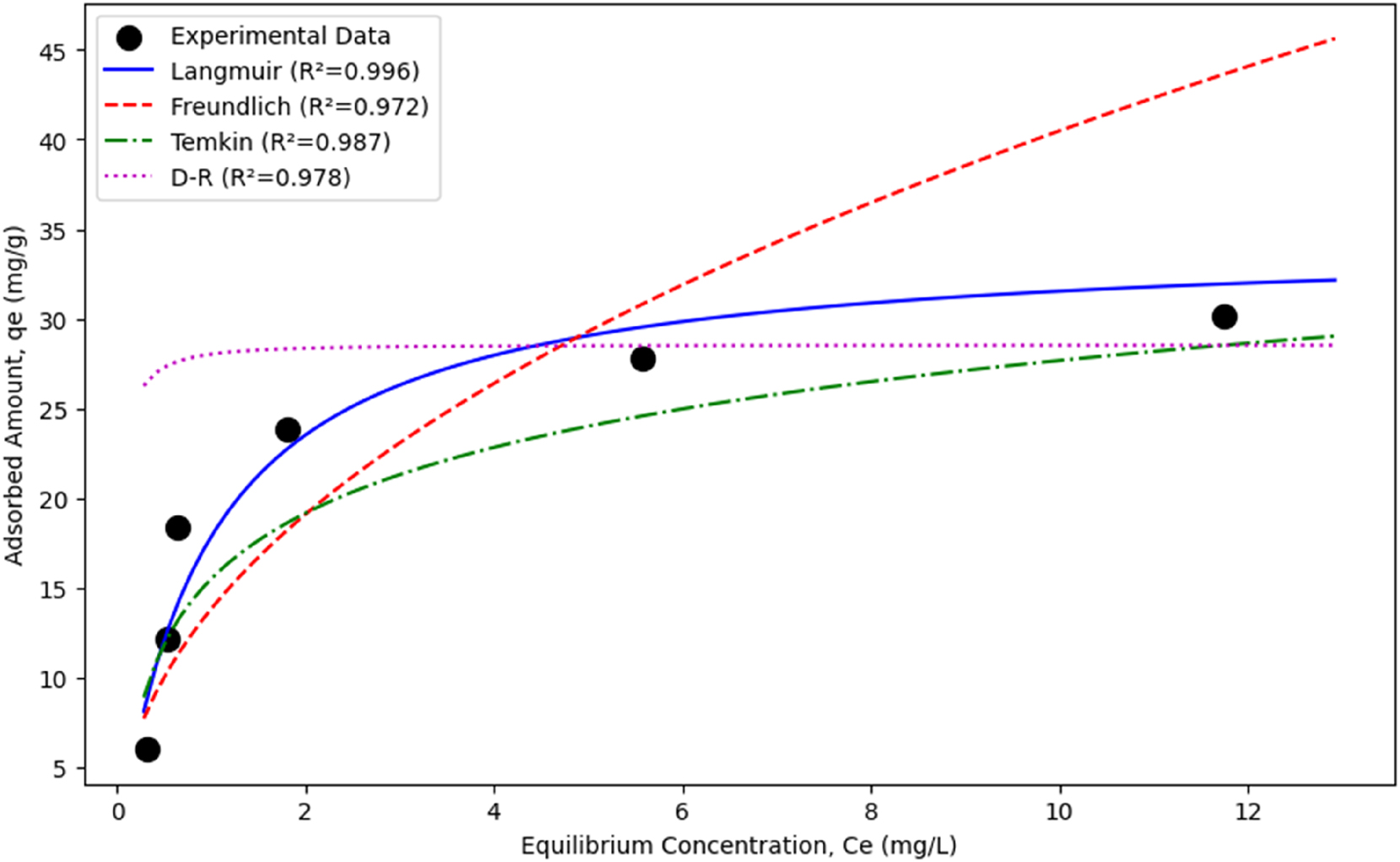

3.8 Evaluation of isotherm model analysis results

The suitability of isotherm models for tamoxifen removal from aqueous solutions using geopolymer adsorbents was evaluated using the Langmuir, Freundlich, Temkin, and Dubinin-Radushkevich (D-R) models. Experimental data were obtained using solutions containing different concentrations of tamoxifen at pH 7, 25 °C, and 150 min of contact time. Linear and nonlinear regression analyses were performed for each model, and model parameters and (R 2) values, which indicate the degree of fit, were calculated. The results are summarized in Table 2.

Parameters of isotherm models and (R 2) values for nonlinear regression.

| Model | Parameters | (R 2) |

|---|---|---|

| Langmuir | (q

m

= 34.48 mg/g), (K L = 1.07 L/mg) |

0.996 |

| Freundlich | (K

F

= 13.80 mg/g (L/mg)(1/n)), (n = 2.14) |

0.972 |

| Temkin | (A

T

= 18.62 L/mg), (b T = 468.32 J/mol) |

0.987 |

| Dubinin-Radushkevich | (q

s

= 28.52 mg/g}), (E = 9.13 kJ/mol}) |

0.978 |

The Langmuir model showed the highest agreement with the experimental data with (R 2 = 0.996). This indicates that tamoxifen binds to the geopolymer surface by a monolayer and homogeneous adsorption mechanism. The maximum adsorption capacity (q m = 34.48 mg/g) confirms the high adsorption potential of the geopolymer, and the strong affinities between adsorbate and adsorbent (K L = 1.07 L/mg) confirm the high adsorption potential of the geopolymer. The Freundlich model (R 2 = 0.972) described multilayer adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces and showed a suitable adsorption density with (n = 2.14). The Temkin model (R 2 = 0.987) provided a good agreement assuming that the heat of adsorption decreases with surface coverage, indicating physical adsorption with (b T = 468.32 J/mol}). The D-R model (R 2 = 0.978) suggested the chemical adsorption character with (E = 9.13 kJ/mol), but showed lower agreement compared to the Langmuir model.

Nonlinear regression analyses confirmed the superiority of the Langmuir model over other models. The experimental data and model curves presented in Figure 6 visually confirm that the Langmuir model provides the closest fit to the experimental data. These results indicate that the geopolymer is an effective adsorbent for tamoxifen removal from aqueous solutions and that the adsorption process occurs primarily through a monolayer mechanism consistent with the Langmuir model.

Isotherm model comparison for tamoxien adsorption.

3.9 Adsorption mechanism and bonding interactions between tamoxifen and geopolymer

The adsorption mechanism likely involves a combination of physical and chemical interactions. The geopolymer’s negatively charged aluminosilicate framework, rich in Si–O and Al–O groups, can interact with the positively charged tertiary amine group of tamoxifen (pKa ≈ 8.7) at pH 7, facilitating electrostatic attraction. Additionally, hydrogen bonding between tamoxifen’s hydroxyl or ether groups and the geopolymer’s surface hydroxyls may contribute to the strong affinity indicated by the Langmuir and Temkin constants. The D-R model’s (E) value suggests possible weak chemical interactions, such as coordination with metal ions (e.g., Al3+) in the geopolymer structure. Hydrophobic interactions between tamoxifen’s aromatic rings and non-polar regions of the geopolymer surface may also enhance adsorption, particularly in the context of the aqueous environment.

In conclusion, the adsorption of tamoxifen onto geopolymer is best described by the Langmuir model, indicating a monolayer adsorption process driven by strong electrostatic and hydrogen bonding interactions, with possible contributions from weak chemical interactions as suggested by the D-R model. The geopolymer’s high adsorption capacity and affinity make it an effective adsorbent for tamoxifen removal from aqueous solutions. These findings suggest that the adsorption mechanism is primarily governed by surface interactions on a homogeneous geopolymer structure, with physical forces dominating, supplemented by minor chemical contributions. In conclusion, the adsorption of tamoxifen onto the geopolymer surface occurs primarily through electrostatic attraction and hydrogen bonds, following a monolayer adsorption mechanism consistent with the Langmuir model.

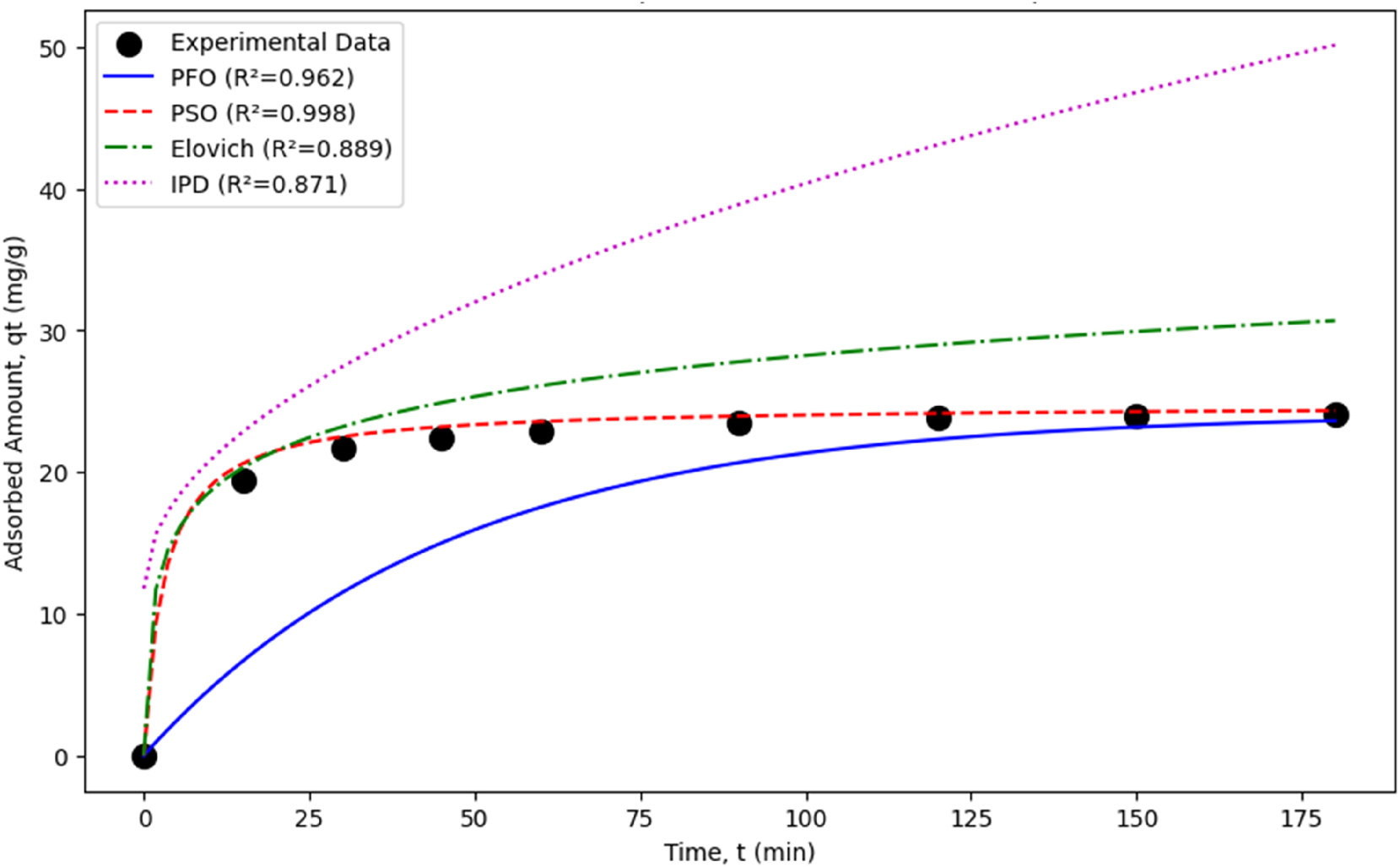

3.10 Evaluation of kinetic model analysis results

The kinetic behavior of tamoxifen adsorption from aqueous solutions onto geopolymer was evaluated using the Pseudo-First-Order (PFO), Pseudo-Second-Order (PSO), Elovich, and Intraparticle Diffusion (IPD) models. Experimental data were obtained using a 40 mg/L initial tamoxifen concentration at pH 7, 25 °C, and 180 min contact time. Linear and non-linear regression analyses were performed to determine model parameters and goodness-of-fit (R 2) values. The results are summarized in Table 3.

Kinetic model parameters and (R 2) values from non-linear regression.

| Model | Parameters | (R 2) |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudo-first-order | (q

e

= 24.12 mg/g) (k 1 = 0.0216 min−1) |

0.962 |

| Pseudo-second-order | (q

e

= 24.75 mg/g) (k 2 = 0.0134 g/mg·min) (h = 8.21 mg/g·min) |

0.998 |

| Elovich | (α = 35.47 mg/g·min) (β = 0.2389 g/mg) |

0.889 |

| Intraparticle diffusion | (k

id = 2.86 mg/g·min0.5) (C = 11.77 mg/g) |

0.871 |

Pseudo-First-Order (PFO) Model: The PFO model assumes that the adsorption rate is proportional to the number of available sites. Non-linear regression yielded (q e = 24.12 mg/g) and (k 1 = 0.0216 min−1), with (R 2 = 0.962), indicating a reasonable fit. However, the rapid initial adsorption ((q t = 19.46 mg/g) at (t = 15 min) highlights the model’s limitations in fully capturing the process.

Pseudo-Second-Order (PSO) Model: The PSO model, which assumes the adsorption rate is proportional to the square of available sites, provided the best fit with (R 2 = 0.998). Parameters (q e = 24.75 mg/g), (k 2 = 0.0134 g/mg·min), (h = 8.21 mg/g·min) confirm a high equilibrium capacity and rapid initial adsorption rate. This suggests that the adsorption process is controlled by chemisorption mechanisms, such as electrostatic interactions or hydrogen bonding, making PSO the most suitable model.

Elovich Model: The Elovich model, applicable to chemisorption on heterogeneous surfaces, assumes an exponential decrease in adsorption rate with surface coverage. It yielded (α = 35.47 mg/g·min) (initial adsorption rate) and (β = 0.2389 g/mg) (surface coverage constant), with (R 2 = 0.889). The moderate fit suggests some chemisorption but indicates that the model is less suitable than PSO for capturing the rapid adsorption kinetics.

Intraparticle Diffusion (IPD) Model: The IPD model assesses the role of pore diffusion in adsorption. Parameters (k id = 2.86 mg/g·min0.5), (C = 11.77 mg/g) and (R 2 = 0.871) indicate that intraparticle diffusion contributes to the process, but the non-zero (C) value suggests it is not the sole rate-limiting step. The linearized plot (q t ) versus (t 0.5) exhibited multi-linear segments, indicating multiple stages (e.g., external diffusion, intraparticle diffusion, and equilibrium).

The PSO model, with (R 2 = 0.998), best describes the tamoxifen adsorption kinetics, confirming that the process is primarily driven by chemisorption involving surface interactions. The high initial adsorption rate (h = 8.21 mg/g·min) and equilibrium capacity (q e = 24.75 mg/g) highlight the geopolymer’s effectiveness as an adsorbent. The PFO model, while adequate, underperforms due to the rapid adsorption kinetics. The Elovich model supports some chemisorption but is less fitting, and the IPD model confirms intraparticle diffusion as a contributing mechanism, though not dominant, due to the multi-stage process indicated by the non-zero (C). These findings establish geopolymer as an efficient adsorbent for tamoxifen removal, with adsorption kinetics best described by the PSO model. Future studies should explore varying pH or temperature conditions to further elucidate the adsorption mechanism.

Nonlinear regression analyses confirmed the superiority of the Pseudo-Second-Order kinetic model over other models. The experimental data and model curves presented in Figure 7 visually confirm that the Pseudo-Second-Order kinetic model provides the closest fit to the experimental data.

Kinetic model comparison for tamoxien adsorption.

4 Discussion

The results of this study clearly demonstrate that the geopolymer-based nepheline/cordierite adsorbent is highly effective for removing cytotoxic tamoxifen from aqueous solutions. The removal efficiency exceeded 96 % under optimized conditions (pH 7, 40 mg/L initial concentration, 80 mg adsorbent dose, 150 min contact time, 298 K), indicating that the synthesized geopolymer possesses excellent surface characteristics and chemical affinity for tamoxifen molecules.

The pseudo-second-order kinetic model provided the best fit to the experimental data (R 2 = 0.998), suggesting that the adsorption process is primarily governed by chemisorption mechanisms involving valency forces and electron sharing between adsorbent and adsorbate. This finding is consistent with previous studies involving pharmaceutical removal using geopolymer or aluminosilicate-based adsorbents. Similarly, the Langmuir isotherm model exhibited the highest correlation (R 2 = 0.996), indicating that tamoxifen adsorption occurred in a monolayer on a homogeneous surface. This supports the conclusion that the surface of the geopolymer offers uniform active sites with high affinity for tamoxifen molecules.

The thermodynamic analysis further confirmed that the adsorption process is spontaneous (ΔG° < 0) and endothermic (ΔH° = 48.267 kJ/mol), with an increase in randomness at the solid–liquid interface (ΔS° = 174.568 J/mol·K). The positive enthalpy change indicates that higher temperatures may enhance adsorption, albeit marginally. These thermodynamic parameters align with previous reports on the removal of organic pollutants using porous geopolymers.

The point of zero charge (pHpzc = 7.03) suggests that at neutral pH, the geopolymer surface is near neutral, enabling effective adsorption of tamoxifen, which carries a partially positive charge in aqueous media at physiological pH. This electrostatic compatibility likely enhances interaction, particularly through hydrogen bonding and possible π–π interactions between tamoxifen’s aromatic rings and the aluminosilicate framework of the geopolymer.

The efficiency of the adsorbent at relatively low doses (80 mg per 50 mL solution) indicates its high adsorption capacity, making it an economically and environmentally viable alternative to conventional materials such as activated carbon. Moreover, the porous structure observed in SEM images, along with the BET surface area analysis, highlights the physical suitability of the synthesized geopolymer for adsorption applications.

The adsorption capacity of the developed nepheline-cordierite geopolymer was compared with other adsorbents reported in the literature for the removal of tamoxifen and related cytostatic drugs, as summarized in Table 4. The maximum capacity (q max) of 34.48 mg/g achieved in this work under neutral pH and ambient temperature demonstrates competitive and often superior performance. Notably, this capacity surpasses that of many clay-based materials and commercial activated carbons, while being comparable to some specialized/composite adsorbents. More significantly, this high performance is coupled with the major advantage of synthesizing the adsorbent from industrial by-products (fly ash, boron waste), making it a cost-effective and sustainable alternative to conventional materials. This favorable comparison underscores the strong potential of the developed geopolymer for practical application in wastewater treatment.

Comparison of the adsorption capacity of the developed nepheline-cordierite geopolymer with other adsorbents reported in the literature for the removal of tamoxifen and related cytostatic drugs.

| Adsorbent material | Target compound | Maximum capacity (q max, mg/g) | Optimal pH | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nepheline-cordierite geopolymer (this work) | Tamoxifen | 34.48 | 7 | – |

| Activated carbon (Commercial, F400) | Tamoxifen | 18.20 | 6 | [17] |

| Montmorillonite K10 Clay | Tamoxifen | 12.85 | 6 | [17] |

| Zeolite beta | Tamoxifen | 27.10 | 7 | [17] |

| Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) | Tamoxifen | 41.50 | 5 | [15] |

| Graphene oxide (GO) | Tamoxifen | 2.98 | 7 | [14] |

| Magnetic graphene oxide (MGO) | Tamoxifen | 28.7 | 6 | [3] |

| Activated carbon from pine sawdust | Cyclophosphamide | 129.9 | 7 | [4] |

| Metal-organic framework (MIL-101Cr) | Ifosfamide | 105.0 | 6 | [11] |

In comparison with other studies using clay, zeolite, or carbon-based adsorbents for pharmaceutical removal, the geopolymer developed in this study offers competitive, and in some cases superior, performance in terms of adsorption capacity, removal efficiency, and operational conditions. Additionally, the use of industrial by-products (e.g., fly ash, boron waste) in the geopolymer formulation supports sustainability and resource recovery efforts.

In conclusion, the synthesized geopolymer-based nepheline/cordierite material exhibits strong potential as a low-cost, eco-friendly, and highly efficient adsorbent for the removal of tamoxifen and similar pharmaceutical contaminants from wastewater. Its high performance under ambient conditions, along with favorable kinetic, isothermal, and thermodynamic characteristics, underlines its applicability in environmental remediation. Future studies could explore regeneration capacity, real wastewater performance, and scale-up feasibility to further validate its practical use.

While this study successfully demonstrates the efficacy of a novel nepheline-cordierite geopolymer for tamoxifen adsorption, the versatility of geopolymer chemistry suggests that other formulations could also be employed. The adsorption performance is intrinsically linked to the specific physicochemical properties of the material, which are governed by the choice of aluminosilicate precursors (e.g., metallurgical slag, different classes of fly ash, rice husk ash) and synthesis conditions. A comparative study evaluating the performance of various geopolymer compositions against the adsorbent presented here would be a valuable direction for future research. Such work would be crucial for identifying the most cost-effective and high-performing geopolymer formulation for large-scale water treatment applications.

5 Conclusions

In this study, a porous geopolymer-based nepheline/cordierite adsorbent was successfully synthesized and evaluated for the removal of the cytotoxic pharmaceutical compound tamoxifen from aqueous solutions. The experimental findings revealed that the adsorbent exhibited excellent performance under optimized conditions (initial tamoxifen concentration of 40 mg/L, pH 7, adsorbent dose of 80 mg, contact time of 150 min, and temperature of 298 K), achieving a maximum removal efficiency of 96.08 %.

Kinetic modeling indicated that the adsorption process follows the pseudo-second-order model, suggesting chemisorption as the rate-limiting step, while the equilibrium data best fit the Langmuir isotherm model, confirming monolayer adsorption on a homogeneous surface. Thermodynamic analysis further demonstrated that the process is spontaneous, endothermic, and associated with an increase in entropy, indicative of strong interactions between tamoxifen molecules and the geopolymer surface.

The geopolymer adsorbent, prepared from industrial and mineral wastes, offers an environmentally friendly and cost-effective solution for pharmaceutical removal from wastewater. Its high adsorption capacity, stability, and suitability for near-neutral pH conditions make it a promising material for practical applications in environmental remediation.

Future research should focus on the regeneration and reusability of the adsorbent, performance in real wastewater matrices, and the development of scalable treatment systems to support broader implementation in wastewater treatment processes.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability: The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. Should any raw data files be needed in another format they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

-

Ethics approval and consent to participate: This study does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

-

Financing support: The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

-

Authors contribution: All authors contributed equally to the article.

-

Consent for publication: This research does not contain any individual person’s data in any form.

-

Consent to Participate: This research does not involve human subjects.

-

Competing interests: The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

References

1. Lung, I, Soran, M-L, Stegarescu, A, Opris, O, Gutoiu, S, Leostean, C, et al.. Evaluation of CNT-COOH/MnO2/Fe3O4 nanocomposite for ibuprofen and paracetamol removal from aqueous solutions. J Hazard Mater 2021;403:123528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123528.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Alothman, ZA, Badjah, AY, Alharbi, OML, Ali, I. Copper carboxymethyl cellulose nanoparticles for efficient removal of tetracycline antibiotics in water. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2020;27:42960–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-10189-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Zandipak, R, Sobhanardakani, S. Novel mesoporous Fe3O4/SiO2/CTAB–SiO2 as an effective adsorbent for the removal of amoxicillin and tetracycline from water. Clean Technol Environ Policy 2018;20:871–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-018-1507-5.Search in Google Scholar

4. Li, J, Yu, G, Pan, L, Li, C, You, F, Xie, S, et al.. Study of ciprofloxacin removal by biochar obtained from used tea leaves. J Environ Sci 2018;73:20–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jes.2017.12.024.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Sun, L, Zha, J, Spear, PA, Wang, Z. Tamoxifen effects on the early life stages and reproduction of Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes). Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 2007;24:23–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.etap.2007.01.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Roberts, P, Thomas, K. The occurrence of selected pharmaceuticals in wastewater effluent and surface waters of the lower Tyne catchment. Sci Total Environ 2006;356:143–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2005.04.031.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Besse, JP, Latour, JF, Garric, J. Anticancer drugs in surface waters. What can we say about the occurrence and environmental significance of cytotoxic, cytostatic and endocrine therapy drugs? Environ Int 2012;39:73–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2011.10.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Ashton, D, Hilton, M, Thomas, KV. Investigating the environmental transport of human pharmaceuticals to streams in the United Kingdom. Sci Total Environ 2004;333:167–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2004.04.062.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Ferrando-Climent, L, Cruz-Morató, C, Marco-Urrea, E, Vicent, T, Sarrà, M, Rodriguez-Mozaz, S, et al.. Non conventional biological treatment based on Trametes versicolor for the elimination of recalcitrant anticancer drugs in hospital wastewater. Chemosphere 2015;136:9–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.03.051.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Ferrando-Climent, L, Rodriguez-Mozaz, S, Barceló, D. Development of a UPLC-MS/MS method for the determination of ten anticancer drugs in hospital and urban wastewaters, and its application for the screening of human metabolites assisted by information-dependent acquisition tool (IDA) in sewage samples. Anal Bioanal Chem 2013;405:5937–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-013-6794-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Ferrando-Climent, L, Rodriguez-Mozaz, S, Barceló, D. Incidence of anticancer drugs in an aquatic urban system: from hospital effluents through urban wastewater to natural environment. Environ Pollut 2014;193:216–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2014.07.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Jean, J, Perrodin, Y, Pivot, C, Trepo, D, Perraud, M, Droguet, J, et al.. Identification and prioritization of bioaccumulable pharmaceutical substances discharged in hospital effluents. J Environ Manage 2012;103:113–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.03.005.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. DellaGreca, M, Iesce, MR, Isidori, M, Nardelli, A, Previtera, L, Rubino, M. Phototransformation products of tamoxifen by sunlight in water. Toxicity of the drug and its derivatives on aquatic organisms. Chemosphere 2007;67:1933–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.12.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Chen, Z, Park, G, Herckes, P, Westerhoff, P. Physicochemical treatment of three chemotherapy drugs: irinotecan, tamoxifen, and cyclophosphamide. J Adv Oxid Technol 2008;11. https://doi.org/10.1515/jaots-2008-0209.Search in Google Scholar

15. Zhang, J, Chang, VWC, Giannis, A, Wang, J-Y. Removal of cytostatic drugs from aquatic environment: a review. Sci Total Environ 2013;445–446:281–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.12.061.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Negreira, N, Regueiro, J, López de Alda, M, Barceló, D. Transformation of tamoxifen and its major metabolites during water chlorination: identification and in silico toxicity assessment of their disinfection byproducts. Water Res 2015;85:199–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2015.08.036.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Ferrando-Climent, L, Gonzalez-Olmos, R, Anfruns, A, Aymerich, I, Corominas, L, Barceló, D, et al.. Elimination study of the chemotherapy drug tamoxifen by different advanced oxidation processes: transformation products and toxicity assessment. Chemosphere 2017;168:284–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.10.057.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Zhou, Y, He, Y, He, Y, Liu, X, Xu, B, Yu, J, et al.. Analyses of tetracycline adsorption on alkali-acid modified magnetic biochar: site energy distribution consideration. Sci Total Environ 2019;650:2260–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.09.393.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Shao, S, Hu, Y, Cheng, J, Chen, Y. Biodegradation mechanism of tetracycline (TEC) by strain Klebsiella sp. SQY5 as revealed through products analysis and genomics. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2019;185:109676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.109676.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Li, C, Lin, H, Armutlulu, A, Xie, R, Zhang, Y, Meng, X. Hydroxylamine-assisted catalytic degradation of ciprofloxacin in ferrate/persulfate system. Chem Eng J 2019;360:612–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2018.11.218.Search in Google Scholar

21. Yi, H, Lai, C, Huo, X, Qin, L, Fu, Y, Liu, S, et al.. H2O2 -free photo-Fenton system for antibiotics degradation in water via the synergism of oxygen-enriched graphitic carbon nitride polymer and nano manganese ferrite. Environ Sci Nano 2022;9:815–26. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1EN00869B.Search in Google Scholar

22. Shoorangiz, M, Nikoo, MR, Salari, M, Rakhshandehroo, GR, Sadegh, M. Optimized electro-Fenton process with sacrificial stainless steel anode for degradation/mineralization of ciprofloxacin. Process Saf Environ Prot 2019;132:340–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2019.10.011.Search in Google Scholar

23. Hassani, A, Khataee, A, Fathinia, M, Karaca, S. Photocatalytic ozonation of ciprofloxacin from aqueous solution using TiO2 /MMT nanocomposite: nonlinear modeling and optimization of the process via artificial neural network integrated genetic algorithm. Process Saf Environ Prot 2018;116:365–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2018.03.013.Search in Google Scholar

24. Palacio, DA, Leiton, LM, Urbano, BF, Rivas, BL. Tetracycline removal by polyelectrolyte copolymers in conjunction with ultrafiltration membranes through liquid-phase polymer-based retention. Environ Res 2020;182:109014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2019.109014.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Liu, J, Zhou, B, Zhang, H, Ma, J, Mu, B, Zhang, W. A novel Biochar modified by Chitosan-Fe/S for tetracycline adsorption and studies on site energy distribution. Bioresour Technol 2019;294:122152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2019.122152.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Dai, Y, Zhang, K, Meng, X, Li, J, Guan, X, Sun, Q, et al.. New use for spent coffee ground as an adsorbent for tetracycline removal in water. Chemosphere 2019;215:163–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.09.150.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Li, M, Liu, Y, Liu, S, Zeng, G, Hu, X, Tan, X, et al.. Performance of magnetic graphene oxide/diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid nanocomposite for the tetracycline and ciprofloxacin adsorption in single and binary systems. J Colloid Interface Sci 2018;521:150–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2018.03.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Chen, L, Yuan, T, Ni, R, Yue, Q, Gao, B. Multivariate optimization of ciprofloxacin removal by polyvinylpyrrolidone stabilized NZVI/Cu bimetallic particles. Chem Eng J 2019;365:183–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2019.02.051.Search in Google Scholar

29. Selmi, T, Sanchez-Sanchez, A, Gadonneix, P, Jagiello, J, Seffen, M, Sammouda, H, et al.. Tetracycline removal with activated carbons produced by hydrothermal carbonisation of Agave americana fibres and mimosa tannin. Ind Crops Prod 2018;115:146–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.02.005.Search in Google Scholar

30. Dutta, V, Singh, P, Shandilya, P, Sharma, S, Raizada, P, Saini, AK, et al.. Review on advances in photocatalytic water disinfection utilizing graphene and graphene derivatives-based nanocomposites. J Environ Chem Eng 2019;7:103132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2019.103132.Search in Google Scholar

31. de Sousa, DNR, Insa, S, Mozeto, AA, Petrovic, M, Chaves, TF, Fadini, PS. Equilibrium and kinetic studies of the adsorption of antibiotics from aqueous solutions onto powdered zeolites. Chemosphere 2018;205:137–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.04.085.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Premarathna, KSD, Rajapaksha, AU, Adassoriya, N, Sarkar, B, Sirimuthu, NMS, Cooray, A, et al.. Clay-biochar composites for sorptive removal of tetracycline antibiotic in aqueous media. J Environ Manage 2019;238:315–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.02.069.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Davidovits, J. Geopolymer chemistry and applications 2020.Search in Google Scholar

34. Kim, D, Lai, H-T, Chilingar, GV, Yen, TF. Geopolymer formation and its unique properties. Environ Geol 2006;51:103–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00254-006-0308-z.Search in Google Scholar

35. Ergun, Y, Caliskan, H, Karali, HI. Production and characterization of open cell cordierite from boron and waste materials by geopolymer method for the emission after treatment System of diesel engines. Glob Challenges 2025;9:2500048. https://doi.org/10.1002/gch2.202500048.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36. Choy, KKH, Porter, JF, McKay, G. Langmuir isotherm models applied to the multicomponent sorption of acid dyes from effluent onto activated carbon. J Chem Eng Data 2000;45:575–84. https://doi.org/10.1021/je9902894.Search in Google Scholar

37. Adak, A, Bandyopadhyay, M, Pal, A. Removal of crystal violet dye from wastewater by surfactant-modified alumina. Sep Purif Technol 2005;44:139–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2005.01.002.Search in Google Scholar

38. Arzu Engin, İG. Hidroksiapatit kullanılarak Sulu Çözeltiden Bakır İyonlarının uzaklaştırılması. Afyon Kocatepe Üniversitesi Fen Bilim Derg 2009:95–104. http://hdl.handle.net/11630/780.Search in Google Scholar

39. Kurtulus, C, Baspinar, MS. An essential study of strength development in geopolymer materials using the JMAK method. Arab J Sci Eng 2023;48:4295–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-022-06962-8.Search in Google Scholar

40. Monvisade, P, Siriphannon, P. Chitosan intercalated montmorillonite: preparation, characterization and cationic dye adsorption. Appl Clay Sci 2009;42:427–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2008.04.013.Search in Google Scholar

41. Parolo, ME, Savini, MC, Vallés, JM, Baschini, MT, Avena, MJ. Tetracycline adsorption on montmorillonite: ph and ionic strength effects. Appl Clay Sci 2008;40:179–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2007.08.003.Search in Google Scholar

42. Arora, C, Kumar, P, Soni, S, Mittal, J, Mittal, A, Singh, B. Efficient removal of malachite green dye from aqueous solution using Curcuma caesia based activated carbon. Desalin Water Treat 2020;195:341–52. https://doi.org/10.5004/dwt.2020.25897.Search in Google Scholar

43. Tang, Y, Guo, H, Xiao, L, Yu, S, Gao, N, Wang, Y. Synthesis of reduced graphene oxide/magnetite composites and investigation of their adsorption performance of fluoroquinolone antibiotics. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2013;424:74–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2013.02.030.Search in Google Scholar

44. Puertas, F, Torres-Carrasco, M. Use of glass waste as an activator in the preparation of alkali-activated slag. Mechanical strength and paste characterisation. Cem Concr Res 2014;57:95–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2013.12.005.Search in Google Scholar

45. Monich, PR, Romero, AR, Höllen, D, Bernardo, E. Porous glass-ceramics from alkali activation and sinter-crystallization of mixtures of waste glass and residues from plasma processing of municipal solid waste. J Clean Prod 2018;188:871–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.167.Search in Google Scholar

46. Tchakouté, HK, Rüscher, CH, Kong, S, Kamseu, E, Leonelli, C. Geopolymer binders from metakaolin using sodium waterglass from waste glass and rice husk ash as alternative activators: a comparative study. Constr Build Mater 2016;114:276–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.03.184.Search in Google Scholar

47. Gunasekara, CM. Influence of properties of fly ash from different sources on the mix design and performance of geopolymer concrete. RMIT, Melb 2016;245.Search in Google Scholar

48. Anggarini, U, Pratapa, S, Purnomo, V, Sukmana, NC. A comparative study of the utilization of synthetic foaming agent and aluminum powder as pore-forming agents in lightweight geopolymer synthesis. Open Chem 2019;17:629–38. https://doi.org/10.1515/chem-2019-0073.Search in Google Scholar

49. Guo, X, Shi, H, Dick, WA. Compressive strength and microstructural characteristics of class C fly ash geopolymer. Cem Concr Compos 2010;32:142–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2009.11.003.Search in Google Scholar

50. Ji, L, Chen, W, Duan, L, Zhu, D. Mechanisms for strong adsorption of tetracycline to carbon nanotubes: a comparative study using activated carbon and graphite as adsorbents. Environ Sci Technol 2009;43:2322–7. https://doi.org/10.1021/es803268b.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/chem-2025-0213).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Phytochemical investigation and evaluation of antioxidant and antidiabetic activities in aqueous extracts of Cedrus atlantica

- Influence of B4C addition on the tribological properties of bronze matrix brake pad materials

- Discovery of the bacterial HslV protease activators as lead molecules with novel mode of action

- Characterization of volatile flavor compounds of cigar with different aging conditions by headspace–gas chromatography–ion mobility spectrometry

- Effective remediation of organic pollutant using Musa acuminata peel extract-assisted iron oxide nanoparticles

- Analysis and health risk assessment of toxic elements in traditional herbal tea infusions

- Cadmium exposure in marine crabs from Jiaxing City, China: Insights into health risk assessment

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles of Cinnamomum zeylanicum and their biological activities

- Tetraclinis articulata (Vahl) Mast., Mentha pulegium L., and Thymus zygis L. essential oils: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antifungal properties against postharvest fungal diseases of apple, and in vitro, in vivo, and in silico investigation

- Exploration of plant alkaloids as potential inhibitors of HIV–CD4 binding: Insight into comprehensive in silico approaches

- Recovery of phenylethyl alcohol from aqueous solution by batch adsorption

- Electrochemical approach for monitoring the catalytic action of immobilized catalase

- Green synthesis of ZIF-8 for selective adsorption of dyes in water purification

- Optimization of the conditions for the preparation of povidone iodine using the response surface methodology

- A case study on the influence of soil amendment on ginger oil’s physicochemical properties, mineral contents, microbial load, and HPLC determination of its vitamin level

- Removal of antiviral favipiravir from wastewater using biochar produced from hazelnut shells

- Effect of biochar and soil amendment on bacterial community composition in the root soil and fruit of tomato under greenhouse conditions

- Bioremediation of malachite green dye using Sargassum wightii seaweed and its biological and physicochemical characterization

- Evaluation of natural compounds as folate biosynthesis inhibitors in Mycobacterium leprae using docking, ADMET analysis, and molecular dynamics simulation

- Novel insecticidal properties of bioactive zoochemicals extracted from sea urchin Salmacis virgulata

- Elevational gradients shape total phenolic content and bioactive potential of sweet marjoram (Origanum majorana L.): A comparative study across altitudinal zones

- Study on the CO2 absorption performance of deep eutectic solvents formed by superbase DBN and weak acid diethylene glycol

- Preparation and wastewater treatment performance of zeolite-modified ecological concrete

- Multifunctional chitosan nanoparticles: Zn2+ adsorption, antimicrobial activity, and promotion of aquatic health

- Comparative analysis of nutritional composition and bioactive properties of Chlorella vulgaris and Arthrospira platensis: Implications for functional foods and dietary supplements

- Growth kinetics and mechanical characterization of boride layers formed on Ti6Al4V

- Enhancement of water absorption properties of potassium polyacrylate-based hydrogels in CaCl2-rich soils using potassium di- and tri-carboxylate salts

- Electrochemical and microbiological effects of dumpsite leachates on soil and air quality

- Modeling benzene physicochemical properties using Zagreb upsilon indices

- Characterization and ecological risk assessment of toxic metals in mangrove sediments near Langen Village in Tieshan Bay of Beibu Gulf, China

- Protective effect of Helicteres isora, an efficient candidate on hepatorenal toxicity and management of diabetes in animal models

- Valorization of Juglans regia L. (Walnut) green husk from Jordan: Analysis of fatty acids, phenolics, antioxidant, and cytotoxic activities

- Molecular docking and dynamics simulations of bioactive terpenes from Catharanthus roseus essential oil targeting breast cancer

- Selection of a dam site by using AHP and VIKOR: The Sakarya Basin

- Characterization and modeling of kidney bean shell biochar as adsorbent for caffeine removal from aquatic environments

- The effects of short-term and long-term 2100 MHz radiofrequency radiation on adult rat auditory brainstem response

- Biochemical insights into the anthelmintic and anti-inflammatory potential of sea cucumber extract: In vitro and in silico approaches

- Resveratrol-derived MDM2 inhibitors: Synthesis, characterization, and biological evaluation against MDM2 and HCT-116 cells

- Phytochemical constituents, in vitro antibacterial activity, and computational studies of Sudanese Musa acuminate Colla fruit peel hydro-ethanol extract

- Chemical composition of essential oils reviewed from the height of Cajuput (Melaleuca leucadendron) plantations in Buru Island and Seram Island, Maluku, Indonesia

- Phytochemical analysis and antioxidant activity of Azadirachta indica A. Juss from the Republic of Chad: in vitro and in silico studies

- Stability studies of titanium–carboxylate complexes: A multi-method computational approach

- Efficient adsorption performance of an alginate-based dental material for uranium(vi) removal

- Synthesis and characterization of the Co(ii), Ni(ii), and Cu(ii) complexes with a 1,2,4-triazine derivative ligand

- Evaluation of the impact of music on antioxidant mechanisms and survival in salt-stressed goldfish

- Optimization and validation of UPLC method for dapagliflozin and candesartan cilexetil in an on-demand formulation: Analytical quality by design approach

- Biomass-based cellulose hydroxyapatite nanocomposites for the efficient sequestration of dyes: Kinetics, response surface methodology optimization, and reusability

- Multifunctional nitrogen and boron co-doped carbon dots: A fluorescent probe for Hg2+ and biothiol detection with bioimaging and antifungal applications

- Separation of sulphonamides on a C12-diol mixed-mode HPLC column and investigation of their retention mechanism

- Characterization and antioxidant activity of pectin from lemon peels

- Fast PFAS determination in honey by direct probe electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry: A health risk assessment insight

- Correlation study between GC–MS analysis of cigarette aroma compounds and sensory evaluation

- Synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular docking studies of substituted chromone-2-carboxamide derivatives as anti-breast cancer agents

- The influence of feed space velocity and pressure on the cold flow properties of diesel fuel

- Acid etching behavior and mechanism in acid solution of iron components in basalt fibers

- Protective effect of green synthesized nanoceria on retinal oxidative stress and inflammation in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat

- Evaluation of the antianxiety activity of green zinc nanoparticles mediated by Boswellia thurifera in albino mice by following the plus maze and light and dark exploration tests

- Yeast as an efficient and eco-friendly bifunctional porogen for biomass-derived nitrogen-doped carbon catalysts in the oxygen reduction reaction

- Novel descriptors for the prediction of molecular properties

- Synthesis and characterization of surfactants derived from phenolphthalein: In vivo and in silico studies of their antihyperlipidemic effect

- Turmeric oil-fortified nutraceutical-SNEDDS: An approach to boost therapeutic effectiveness of dapagliflozin during treatment of diabetic patients

- Analysis and study on volatile flavor compounds of three Yunnan cultivated cigars based on headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry

- Near-infrared IR780 dye-loaded poloxamer 407 micelles: Preparation and in vitro assessment of anticancer activity

- Study on the influence of the viscosity reducer solution on percolation capacity of thin oil in ultra-low permeability reservoir

- Detection method of Aristolochic acid I based on magnetic carrier Fe3O4 and gold nanoclusters

- Juglone’s apoptotic impact against eimeriosis-induced infection: a bioinformatics, in-silico, and in vivo approach

- Potential anticancer agents from genus Aerva based on tubulin targets: an in-silico integration of quantitative structure activity relationship (QSAR), molecular docking, simulation, drug-likeness, and density functional theory (DFT) analysis

- Hepatoprotective and PXR-modulating effects of Erodium guttatum extract in propiconazole-induced toxicity

- Studies on chemical composition of medicinal plants collected in natural locations in Ecuador

- A study of different pre-treatment methods for cigarettes and their aroma differences

- Cytotoxicity and molecular mechanisms of quercetin, gallic acid, and pinocembrin in Caco-2 cells: insights from cell viability assays, network pharmacology, and molecular docking

- Choline-based deep eutectic solvents for green extraction of oil from sour cherry seeds

- Green-synthesis of chromium (III) nanoparticles using garden fern and evaluation of its antibacterial and anticholinesterase activities

- Innovative functional mayonnaise formulations with watermelon seeds oil: evaluation of quality parameters and storage stability

- Molecular insights and biological evaluation of compounds isolated from Ferula oopoda against diabetes, advanced glycation end products and inflammation in diabetics

- Removal of cytotoxic tamoxifen from aqueous solutions using a geopolymer-based nepheline–cordierite adsorbent

- Unravelling the therapeutic effect of naturally occurring Bauhinia flavonoids against breast cancer: an integrated computational approach

- Characterization of organic arsenic residues in livestock and poultry meat and offal and consumption risks

- Synthesis and characterization of zinc sulfide nanoparticles and their genotoxic and cytotoxic effects on acute myeloid leukemia cells

- Activity of Coriandrum sativum methanolic leaf extracts against Eimeria papillata: a combined in vitro and in silico approach

- Special Issue on Advancing Sustainable Chemistry for a Greener Future

- One-pot fabrication of highly porous morphology of ferric oxide-ferric oxychloride/poly-O-chloroaniline nanocomposite seeded on poly-1H pyrrole: Photocathode for green hydrogen generation from natural and artificial seawater

- High-efficiency photocathode for green hydrogen generation from sanitation water using bismuthyl chloride/poly-o-chlorobenzeneamine nanocomposite

- Innovative synthesis of cobalt-based catalysts using ionic liquids and deep eutectic solvents: A minireview on electrocatalytic water splitting

- Special Issue on Phytochemicals, Biological and Toxicological Analysis of Plants

- Comparative analysis of fruit quality parameters and volatile compounds in commercially grown citrus cultivars

- Total phenolic, flavonoid, flavonol, and tannin contents as well as antioxidant and antiparasitic activities of aqueous methanol extract of Alhagi graecorum plant used in traditional medicine: Collected in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- Study on the pharmacological effects and active compounds of Apocynum venetum L.

- Chemical profile of Senna italica and Senna velutina seed and their pharmacological properties

- Essential oils from Brazilian plants: A literature analysis of anti-inflammatory and antimalarial properties and in silico validation

- Toxicological effects of green tea catechin extract on rat liver: Delineating safe and harmful doses

- Unlocking the potential of Trigonella foenum-graecum L. plant leaf extracts against diabetes-associated hypertension: A proof of concept by in silico studies

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Phytochemical investigation and evaluation of antioxidant and antidiabetic activities in aqueous extracts of Cedrus atlantica

- Influence of B4C addition on the tribological properties of bronze matrix brake pad materials

- Discovery of the bacterial HslV protease activators as lead molecules with novel mode of action

- Characterization of volatile flavor compounds of cigar with different aging conditions by headspace–gas chromatography–ion mobility spectrometry

- Effective remediation of organic pollutant using Musa acuminata peel extract-assisted iron oxide nanoparticles

- Analysis and health risk assessment of toxic elements in traditional herbal tea infusions

- Cadmium exposure in marine crabs from Jiaxing City, China: Insights into health risk assessment

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles of Cinnamomum zeylanicum and their biological activities

- Tetraclinis articulata (Vahl) Mast., Mentha pulegium L., and Thymus zygis L. essential oils: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antifungal properties against postharvest fungal diseases of apple, and in vitro, in vivo, and in silico investigation

- Exploration of plant alkaloids as potential inhibitors of HIV–CD4 binding: Insight into comprehensive in silico approaches

- Recovery of phenylethyl alcohol from aqueous solution by batch adsorption

- Electrochemical approach for monitoring the catalytic action of immobilized catalase

- Green synthesis of ZIF-8 for selective adsorption of dyes in water purification

- Optimization of the conditions for the preparation of povidone iodine using the response surface methodology

- A case study on the influence of soil amendment on ginger oil’s physicochemical properties, mineral contents, microbial load, and HPLC determination of its vitamin level

- Removal of antiviral favipiravir from wastewater using biochar produced from hazelnut shells

- Effect of biochar and soil amendment on bacterial community composition in the root soil and fruit of tomato under greenhouse conditions

- Bioremediation of malachite green dye using Sargassum wightii seaweed and its biological and physicochemical characterization

- Evaluation of natural compounds as folate biosynthesis inhibitors in Mycobacterium leprae using docking, ADMET analysis, and molecular dynamics simulation

- Novel insecticidal properties of bioactive zoochemicals extracted from sea urchin Salmacis virgulata

- Elevational gradients shape total phenolic content and bioactive potential of sweet marjoram (Origanum majorana L.): A comparative study across altitudinal zones

- Study on the CO2 absorption performance of deep eutectic solvents formed by superbase DBN and weak acid diethylene glycol

- Preparation and wastewater treatment performance of zeolite-modified ecological concrete

- Multifunctional chitosan nanoparticles: Zn2+ adsorption, antimicrobial activity, and promotion of aquatic health