Comparative analysis of nutritional composition and bioactive properties of Chlorella vulgaris and Arthrospira platensis: Implications for functional foods and dietary supplements

-

Natália Čmiková

, Dominik Kmiecik

Abstract

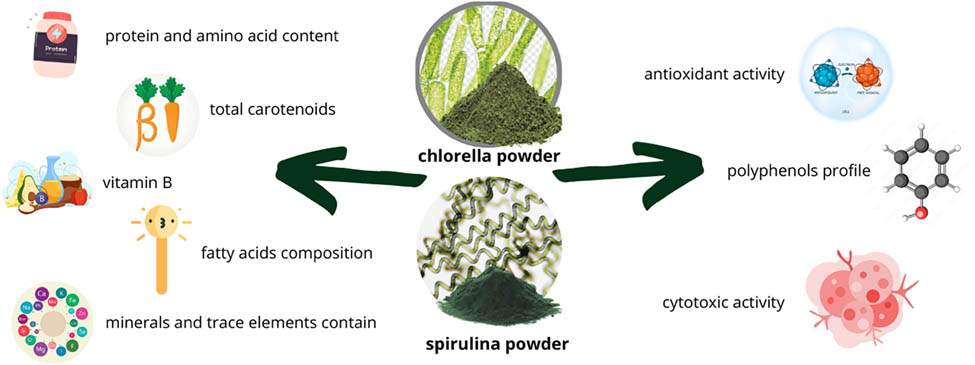

The rising incidence of chronic diseases has spurred interest in functional foods rich in antioxidants and essential nutrients, as well as in exploring their potential cytotoxic activity against cancer cells. This study aims to address this gap by providing a comprehensive comparison of their biochemical composition and bioactive properties, offering insights into their targeted applications in functional foods and supplements. This study investigated the nutritional composition and bioactive properties of two algae species, chlorella (Chlorella vulgaris) and spirulina (Arthrospira platensis). Analysis included total protein content, amino acid profiles, mineral compositions, fatty acid profiles, B vitamin contents, polyphenol profiles, carotenoid contents, antioxidant activities (DPPH˙ and ABTS+ assays), and cytotoxic activities. Chlorella exhibited higher protein content (64.63%) compared to spirulina (58.24%). Spirulina showed higher concentrations of non-essential and essential amino acids, except for methionine. Mineral analysis revealed spirulina’s superiority in calcium, potassium, sodium, iron, manganese, and zinc, whereas chlorella contained higher copper and lead levels. Fatty acid analysis indicated chlorella’s dominance in saturated fatty acids, while spirulina showed higher proportions of monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids. Polyphenol analysis highlighted chlorella’s higher levels of p-hydroxybenzoic acid, whereas spirulina contained more rutin and catechin. Chlorella also exhibited higher levels of niacin and riboflavin compared to spirulina. Additionally, spirulina extracts, whether ethanolic or hexane-based, demonstrate substantial antioxidant effects, as evidenced by their lower IC50 values in both DPPH˙ and ABTS+ assays relative to chlorella. Overall, spirulina showed superior antioxidant effect. Chlorella hexane extract showed slightly higher cytotoxic potential compared to spirulina. These findings enhance our understanding of the nutritional and health-promoting properties of chlorella and spirulina, suggesting their potential applications in functional foods and dietary supplements. While in vitro assays indicate promising bioactivity, future studies should include in vivo experiments to confirm the health benefits and functional applications of these microalgae.

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

The incidence of chronic diseases related to nutrition has been steadily increasing, leading to higher healthcare costs [1]. Antioxidants have shown significant potential in preventing and treating chronic diseases by reducing oxidative stress, a critical factor in their development, including cancer. Consequently, dietary modifications aimed at increasing the consumption of antioxidant-rich functional foods are increasingly recommended to reduce disease incidence. Natural compounds are gaining attention as potential safer alternatives to chemotherapy [2]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to maximize the effectiveness of dietary interventions for disease prevention [1]. As the global population continues to grow beyond the limits of existing food production systems, the need for food is expected to increase by at least 70% compared to present levels. Population growth, coupled with dwindling arable land and freshwater resources, has intensified the need for alternative protein sources [6]. Protein, in particular, is expected to be one of the critical nutrients facing scarcity in the future [6]. This situation has raised concerns about the environmental impact of intensive agriculture and its contribution to climate change. Consequently, there is a pressing need for research to explore and develop new, sustainable food sources and therapies [3,4].

Algae represent a highly diverse group of organisms known for their abundance of bioactive compounds like pigments, polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), polysaccharides, and polyphenols. They play critical roles in shaping and maintaining the structure and functions of oceans, thereby supporting the benefits humans derive from these aquatic ecosystems [5]. The marine environment is tough for plants due to low light, nutrient scarcity, high pH, pressure, and predators. To survive, marine flora use adaptive strategies like defense, reproduction, and competition, leading to the production of diverse secondary metabolites [6,7]. These compounds provide a range of health advantages, such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, and anti-obesity properties. Due to the extensive variety of species and bioactive molecules found in algae and microalgae, there is a high potential for uncovering new beneficial effects and previously unidentified compounds [8].

One of the most promising options for sustainable food ingredients is algae [3]. Algae is increasingly recognized as a nutraceutical food due to its higher protein content compared to legumes and soybeans, gaining popularity accordingly [3]. Chlorella (Chlorella vulgaris) and spirulina (Arthrospira platensis) are two of the most well-known algae, celebrated for their abundance of proteins, vitamins, pigments, fatty acids, and sterols. Chlorella and spirulina are currently the two most established algae supplements globally, with extensive cultivation and production dating back to the early 1940s [9]. Spirulina, a form of blue-green algae, is commonly consumed worldwide as a nutritional supplement because of its rich protein content (50–60%), abundance of antioxidants, essential fatty acids, and other valuable nutrients [10]. These bioactive compounds make them highly appealing for production and utilization in the food industry. Chlorella, a eukaryotic microalgae, and spirulina, a prokaryotic cyanobacterium, flourish in freshwater environments and are prized for their health benefits. Spirulina and chlorella are algae cultivated worldwide for their high content of carotenoids, including provitamin A carotenoids, and essential nutrient vitamin B. These algae are recognized for their nutritional benefits, serving as rich sources of both macro and micronutrients for diverse populations. Extensive research [11–19] confirms their safety for human consumption when grown in controlled, uncontaminated environments and consumed in moderation [18]. Recent research focuses on natural compounds from plants with potential anticancer properties. Phytochemicals, with their diverse chemical structures, continue to play a crucial role in cancer therapy, highlighting the essential link between plant-based nutrition and advancements in medical science [20–23]. Overall, spirulina and chlorella not only provide essential nutrients but also offer potential cytotoxic effects against cancer cells, positioning them at the intersection of nutritional science and cancer research for their dual health benefits [7,24,25].

The aim of this study is to comprehensively analyze commercially sourced algae species, namely chlorella (C. vulgaris) and spirulina (A. platensis), focusing on their nutritional composition including total protein content, amino acid profile, B vitamin content, fatty acids, and mineral composition. The primary objective is to enhance our understanding of the health benefits offered by these algae, specifically exploring their antioxidant and cytotoxic properties. By investigating the cytotoxic and antioxidant effects of these algae, this research aims to highlight their significant potential for promoting human health and combating diseases, thereby contributing to advancements in nutritional science.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Algae powder

In this research, we utilized 100% powdered chlorella (C. vulgaris) and spirulina (A. platensis), sourced from certified organic production. The products were labelled with SI-EKO-002, indicating agriculture outside the EU. Both the chlorella and spirulina powders originated from China and were produced under stringent controls in filtered natural water. The powders were purchased from FutuNatura, a Slovenian company located in Kranj, in 2022. They adhered to EC Organic Regulation standards and were stored in hermetically sealed, dark, dry conditions at room temperature (approximately 20°C).

2.2 Protein content and amino acid profile

To determine the protein content, the Kjeldahl method was applied following the guidelines of ISO 20483:2013 [26]. Amino acid composition was analyzed through acidic and oxidative hydrolysis, with the latter specifically used for sulfur-containing amino acids. For amino acid analysis, two hydrolysis methods were used: acidic and oxidative. Acidic hydrolysis involved heating the sample at 110°C for 23 h, which decomposed the proteins into individual amino acids. The oxidative hydrolysis method, designed specifically for sulfur-containing amino acids, was performed in two stages: first at 4°C for 16 h, followed by 100°C for 2 h, in accordance with the AOAC method 994.12 [27]. After hydrolysis, the samples were derivatized with AccQ˙Tag reagents and analyzed using ultra-performance liquid chromatography on a Shimadzu Nexera 2.0 system. The separation occurred on an AccQ-Tag Ultra C18 column, under conditions with a mobile phase flow rate of 0.6 mL/min and a solvent gradient from 5 to 100% AccQ˙Tag Ultra. Detection took place at 260 nm. Quantification was based on a calibration curve created from known amino acid standards [28]. The results were expressed as grams of amino acid per 16 g of nitrogen, equivalent to grams per 100 g of protein.

2.3 Determination of mineral profile

The process of mineralizing algae powders was performed by applying a combination of high pressure, elevated temperatures, and focused microwave energy. Algae samples were placed in 30 mL sealed vessels made from chemically modified Teflon (Hostaflon TFM). To each vessel, 3 mL of 60% nitric acid and 1 mL of 30% hydrogen peroxide were added. The vessels were then placed inside a steel jacket and subjected to a microwave-assisted mineralization process lasting 10 min at a power output of 200 W. Afterward, the samples were diluted to a total volume of 25 mL. Elemental analysis was conducted using an emission spectrometer with an inductively coupled plasma source (IRIS HR, Thermo Jarell Ash, USA). Quantitative results were obtained through the use of a calibration curve. The elemental composition, including calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), potassium (K), sodium (Na), copper (Cu), iron (Fe), manganese (Mn), zinc (Zn), and lead (Pb), was determined. The findings were expressed in milligrams per gram of dry matter (mg/g DM), and the analysis was based on six independent measurements, consisting of three biological and two technical replicates.

2.4 Fatty acids composition

To extract fatty acids, the protocol outlined by Folch et al. [29] was employed, closely following their procedure for lipid isolation. The determination of the fatty acid composition was carried out using the AOCS Ce 1 h-05 method [30], with parameters adjusted based on earlier research [31]. For analysis, a gas chromatograph (Agilent 7820A, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used, which was fitted with a flame ionization detector and an SLB-IL111 capillary column (100 m in length, 0.25 mm internal diameter, and a film thickness of 0.20 μm; Supelco, Bellefonte, PA, USA). Fatty acid concentrations were expressed as a percentage of the total fatty acids, offering detailed information on the lipid composition.

2.5 Carotenoid content

To extract the carotenoids from the powdered algae, 1 g of the sample was first ground in a mortar. It was then washed multiple times with 10 mL of acetone until the sample no longer retained its color. Afterward, the resulting extract was filtered through Whatman® Grade 2 filter paper for use in carotenoid analysis. In the next step, petroleum ether was placed in a separatory funnel with a Teflon stopcock. The acetone extract, along with distilled water, was introduced, and the mixture was allowed to flow down the sides of the funnel. After phase separation, the aqueous layer was discarded. The petroleum ether layer was then washed twice with distilled water to remove residual acetone. This ether layer was transferred to a volumetric flask and passed through a small funnel containing 0.5 g of anhydrous sodium sulfate to eliminate any water. Finally, the volume was adjusted with petroleum ether. The total carotenoid concentration was determined using the molar absorption coefficient of β-carotene, and the carotenoid content was expressed in mg/g following the calculation provided [32]:

where A is the absorbance at 445 nm, r is the sample dilution, V is the volume of the petroleum, E is the molar absorption coefficient (E 1% 1cm = 2,620), n is the weight of the sample, and TCC represents the total carotenoid content.

2.6 Polyphenolic composition profile

To analyze the polyphenolic compounds, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was employed using an Agilent 1260 Infinity II system, which includes an autosampler (G7129A), a pump (G7111A), and a diode array detector (G7115A) covering a range of 190–400 nm [33]. The samples were prepared using an 80% methanol extract, following a previously outlined procedure [34]. For the separation of phenolic compounds, an SB-C18 column (50 mm × 4.6 mm, 1.8 µm particle size, Agilent) was utilized, with a column temperature set at 25°C. The elution program involved a gradient of two solvents: solvent A, a 2% acetic acid solution in water, and solvent B, a 2% acetic acid solution in methanol. The elution started with 2% B, increased to 40% B at 22 min, held at 40% B until 26 min, then reached 100% B at 28 min, and finally returned to 2% B by 36 min. The flow rate was fixed at 0.75 mL/min, and 5 µL of the sample was injected for each run. Quantification of the polyphenolic compounds was performed based on the analysis of peak areas using OpenLab CDS software (Agilent Technologies). The polyphenolic content was expressed as micrograms per gram of dry matter (µg/g DM), providing a comprehensive polyphenolic profile of the sample.

2.7 Analysis of B vitamins

B-class vitamins were analyzed using HPLC with an Agilent 1260 Infinity II system. The setup included an autosampler (G7129A), a pump (G7111A), and a diode array detector (G7115A), covering a spectral range of 210–400 nm. The analysis was carried out on a Lichrospher® RP-18e column (5 μm, 250 × 4 mm, Merck) at 30°C. The mobile phase consisted of 0.1 M KH2PO4 (pH 7) and acetonitrile, with a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The gradient elution started with 3% acetonitrile, increasing to 10% at 15 min, then to 30% at 40 min, holding until 45 min, and returning to 3% at 46 min. A 10 µL sample volume was injected for each analysis [35].

2.8 Bioactive characteristics

2.8.1 Ethanol and hexane extracts

Algae powder extraction was carried out using denatured ethanol and hexane. Fifty grams of algae was placed in a 1 L glass bottle with 500 mL of solvent and incubated in the dark at 25°C for 24 h using a shaker (GFL 3031, Burgwedel, Germany). The mixture was then filtered through Whatman® Grade 2 paper. The process was repeated with fresh solvent for a total of three extractions. The concentrated extracts were obtained using a rotary vacuum evaporator (Witeg Labortechnik, Germany) at 50°C under reduced pressures. Extracts were transferred to sealable glass containers and stored at 4°C in the dark until use. For antioxidant and cytotoxic assays, the extracts were dissolved in 99.5% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), subjected to an ultrasonic bath (Kraft&Dele, Łódź, Poland) at 30°C for 30 min, and vortexed until fully dissolved.

2.8.2 Antioxidant activity

The antioxidant activity of ethanolic and hexane algae extracts was evaluated using DPPH˙ and ABTS+ radical scavenging assays. Extracts were dissolved in DMSO at 50 mg/mL. DPPH˙ solution (0.025 g/L) was prepared in methanol, adjusted to 0.8 absorbance at 515 nm. ABTS+ was diluted to 0.7 absorbance at 744 nm. In the assays, 190 μL of radical solution was mixed with 10 μL extract and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. Absorbance was measured at 515 nm (DPPH˙) and 744 nm (ABTS+), and percentage inhibition was calculated using (A 0 − A A)/A 0 × 100. Trolox was used as a reference for Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity (TEAC) determination. This method provides a comprehensive assessment of antioxidant potential.

2.8.3 Cytotoxic activity

2.8.3.1 Cell lines

Algae extracts’ anticancer effects were assessed using the MRC-5 (human lung fibroblast), HeLa (human cervical cancer), and HCT-116 (human colon cancer) cell lines, obtained from ATCC. All experiments were performed in a Class IIa biosafety cabinet. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM; Sigma Aldrich D5671) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, l-glutamine, non-essential amino acids, penicillin, and streptomycin. A cryovial with cell suspension was thawed, added to 9 mL of DMEM, centrifuged at 450g for 5 min, and the pellet was resuspended in 5 mL of complete DMEM. The suspension was transferred to a T-25 flask and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. When confluent, cells were detached using 0.05% trypsin and 0.053 mM EDTA, incubated for 2 min, and trypsin activity was inhibited with complete DMEM. The cell suspension was split into three T-25 flasks with 5 mL DMEM each and returned to the incubator.

2.8.3.2 MTT cytotoxicity assay

To evaluate the cytotoxic potential of algae extracts (both ethanol and hexane), the MTT assay was used. Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 3 × 10³ cells per well and allowed to adhere overnight. The culture medium was then replaced with algae extracts at different concentrations, ranging from 0.3 to 300 µg/mL, based on the extract showing the most significant cytotoxic effects. A control group containing only supplemented DMEM was included. After incubation for 0, 24, and 48 h, MTT solution (0.5 mg/mL) was added to each well. After 2–4 h of incubation, DMSO was added to dissolve the formazan crystals. Absorbance was measured at 540 nm using a microplate reader. The experiment was conducted in triplicate, with three independent replications. Cytotoxicity was calculated as the percentage inhibition of cell viability using the formula: ((A control – A treatment)/A control) × 100. The growth inhibition parameters (GI50, TGI, and IC50) were calculated using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software, following the NCI-60 methodology. The selectivity index (SI) was calculated by comparing the IC50 values for MRC-5 cells to those of HeLa and HCT-116 cells.

2.8.3.3 Annexin V-FITC/7-AAD assay

To determine the type of cell death induced by the algae hexane extract, the Annexin V-FITC/7-AAD staining method was used, following the manufacturer’s protocol. HeLa and HCT-116 cells were cultured in 24-well plates, with 1.5 × 10⁵ cells per well. After 48 h of treatment with the algae extract at its IC50 concentration, the cells were harvested, trypsinized, and washed with PBS. The cells were then resuspended in 100 µL of ice-cold 1× binding buffer and stained with 10 µL of Annexin V-FITC and 20 µL of 7-AAD. Staining occurred in the dark at room temperature for 15 min, followed by dilution with 400 µL of 1× binding buffer. Flow cytometry analysis was performed using a Cytomics FC500 flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, USA), with data processed using FlowJo V10 software. The results were displayed as dot plots and stacked bar graphs, showing mean values ± standard deviation from three independent experiments.

2.8.3.4 Cell cycle analysis

The distribution of the cell cycle in HeLa and HCT-116 cells was analyzed using propidium iodide (PI) staining. Cells were seeded at 1.5 × 10⁵ cells per well in 24-well plates and incubated overnight. Afterward, they were treated for 48 h with algae hexane extract at its IC50 concentration. Post-treatment, cells were harvested, washed with PBS, and centrifuged at 450×g for 10 min. The resulting cell pellet was resuspended in 1 mL of 70% ethanol and kept at 4°C overnight. Following another centrifugation step, the ethanol was discarded, and the cells were incubated with 1 mL of 500 μg/mL RNase A in PBS at 37°C for 30 min. Afterward, 5 μL of 10 mg/mL PI was added to the cells, which were further incubated for 15 min in the dark. The samples were then analyzed using a Cytomics FC500 flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, USA), and the data were processed with FlowJo V10 software.

2.9 Statistical analysis

Each experiment was conducted in triplicate and repeated three times, and the results are reported as mean values accompanied by their corresponding standard deviations (SD). Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test, with a significance level set at p ≤ 0.05. Statistical computations were carried out using Statistica v13.3 (Dell Software Inc., USA).

3 Results

3.1 Protein and amino acid content

The results in Table 1 show the total protein content (%) of chlorella and spirulina. Chlorella exhibited a protein content of 64.63% with a standard deviation of 0.03%. Spirulina, on the other hand, had a slightly lower protein content of 58.24% with a standard deviation of 0.96%. According to the statistical analysis, there are significant differences in protein content between chlorella and spirulina (p ≤ 0.05).

Total protein content (%)

| Algae | Content (%) |

|---|---|

| Chlorella | 64.63 ± 0.03a |

| Spirulina | 58.24 ± 0.96b |

Values marked with the same lowercase letter in columns do not differ significantly p > 0.05.

Table 2 summarizes the content of non-essential amino acids in chlorella and spirulina sample, expressed as grams per 16 g of nitrogen (g/16 g N). Chlorella exhibited the following mean values and standard deviations: alanine 4.81 ± 0.39 g/16 g N, arginine 3.78 ± 0.19 g/16 g N, aspartic acid 6.66 ± 0.35 g/16 g N, cysteine 0.92 ± 0.12 g/16 g N, glutamic acid 9.76 ± 0.11 g/16 g N, glycine 2.62 ± 0.05 g/16 g N, proline 2.57 ± 0.09 g/16 g N, serine 3.19 ± 0.11 g/16 g N, and tyrosine 0.53 ± 0.02 g/16 g N. Spirulina demonstrated alanine 7.17 ± 1.15 g/16 g N, arginine 4.90 ± 0.68 g/16 g N, aspartic acid 8.72 ± 0.77 g/16 g N, cysteine 0.35 ± 0.01 g/16 g N, glutamic acid 10.92 ± 1.08 g/16 g N, glycine 4.16 ± 0.56 g/16 g N, proline 4.86 ± 0.20 g/16 g N, serine 3.89 ± 0.23 g/16 g N, and tyrosine 0.86 ± 0.36 g/16 g N.

Content of non-essential amino acids expressed in (g/16 g N)

| Non-essential amino acid | Chlorella | Spirulina |

|---|---|---|

| Alanine | 4.81 ± 0.39b | 7.17 ± 1.15a |

| Arginine | 3.78 ± 0.19b | 4.90 ± 0.68a |

| Aspartic acid | 6.66 ± 0.35b | 8.72 ± 0.77a |

| Cysteine | 0.92 ± 0.12a | 0.35 ± 0.01b |

| Glutamic acid | 9.76 ± 0.11a | 10.92 ± 1.08a |

| Glycine | 2.62 ± 0.05b | 4.16 ± 0.56a |

| Proline | 2.57 ± 0.09b | 4.86 ± 0.20a |

| Serine | 3.19 ± 0.11a | 3.89 ± 0.23a |

| Tyrosine | 0.53 ± 0.02a | 0.86 ± 0.36a |

Values marked with the same lowercase letter in rows do not differ significantly p > 0.05.

Based on the data presented, significant differences in the content of non-essential amino acids were observed between chlorella and spirulina sample. Spirulina generally exhibited higher concentrations of non-essential amino acids compared to chlorella, as indicated by the statistical analysis. These findings suggest that spirulina generally provides a richer source of non-essential amino acids compared to chlorella.

Table 3 provides the content of essential amino acids in chlorella and spirulina sample, expressed in grams per 16 g of nitrogen (g/16 g N). Chlorella displayed mean values and standard deviations for each amino acid: isoleucine (2.73 ± 0.19 g/16 g N), leucine (4.94 ± 0.14 g/16 g N), lysine (2.53 ± 0.02 g/16 g N), methionine (1.10 ± 0.06 g/16 g N), phenylalanine (2.66 ± 0.03 g/16 g N), threonine (3.96 ± 0.91 g/16 g N), valine (2.92 ± 0.11 g/16 g N), and histidine (1.86 ± 0.27 g/16 g N). Spirulina, in contrast, exhibited the following mean values and standard deviations: isoleucine (2.76 ± 0.35 g/16 g N), leucine (7.10 ± 1.16 g/16 g N), lysine (4.16 ± 0.60 g/16 g N), methionine (0.63 ± 0.08 g/16 g N), phenylalanine (3.92 ± 0.61 g/16 g N), threonine (4.40 ± 0.16 g/16 g N), valine (4.36 ± 0.47 g/16 g N), and histidine (2.88 ± 0.56 g/16 g N).

Content of essential amino acids expressed in (g/16 g N)

| Essential amino acid | Chlorella | Spirulina |

|---|---|---|

| Isoleucine | 2.73 ± 0.19a | 2.76 ± 0.35a |

| Leucine | 4.94 ± 0.14b | 7.10 ± 1.16a |

| Lysine | 2.53 ± 0.02a | 4.16 ± 0.60a |

| Methionine | 1.10 ± 0.06a | 0.63 ± 0.08b |

| Phenylalanine | 2.66 ± 0.03b | 3.92 ± 0.61a |

| Threonine | 3.96 ± 0.91a | 4.40 ± 0.16a |

| Valine | 2.92 ± 0.11b | 4.36 ± 0.47a |

| Histidine | 1.86 ± 0.27b | 2.88 ± 0.56a |

Values marked with the same lowercase letter in rows do not differ significantly p > 0.05.

Spirulina generally exhibited higher concentrations of essential amino acids compared to chlorella, notably for leucine, lysine, phenylalanine, threonine, valine, and histidine. Conversely, chlorella showed a higher concentration of methionine compared to spirulina. These findings highlightspirulina as a potentially superior source of essential amino acids. The distinct amino acid profiles between chlorella and spirulina suggest their suitability for different nutritional applications based on specific dietary requirements.

3.2 Minerals and trace elements content

Table 4 provides the concentrations of minerals and trace elements in tested algae expressed in micrograms per gram (µg/g). In chlorella, Ca was found to be 2,420 ± 190 µg/g, Mg 5,690 ± 450 µg/g, K 2,580 ± 210 µg/g, Na 1,340 ± 110 µg/g, Cu 63.9 ± 5.1 µg/g, Fe 1,070 ± 90 µg/g, Mn 94.5 ± 7.6 µg/g, Zn 64.3 ± 5.1 µg/g, and Pb 107 ± 9 µg/g. Spirulina, on the other hand, exhibited Ca concentrations of 2,840 ± 230 µg/g, Mg 4,830 ± 390 µg/g, K 14,400 ± 1,200 µg/g, Na 17,600 ± 1,400 µg/g, Cu 54.8 ± 4.4 µg/g, Fe 471 ± 38 µg/g, Mn 57.3 ± 4.6 µg/g, Zn 42.2 ± 3.4 µg/g, and Pb 95.1 ± 7.6 µg/g.

Minerals and trace elements contained expressed in (µg/g)

| Mineral | Chlorella | Spirulina |

|---|---|---|

| Calcium (Ca) | 2,420 ± 190a | 2,840 ± 230a |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 5,690 ± 450a | 4,830 ± 390b |

| Potassium (K) | 2,580 ± 210b | 14,400 ± 1,200a |

| Sodium (Na) | 1,340 ± 110b | 17,600 ± 1,400a |

| Copper (Cu) | 63.9 ± 5.1a | 54.8 ± 4.4b |

| Iron (Fe) | 1,070 ± 90a | 471 ± 38b |

| Manganese (Mn) | 94.5 ± 7.6a | 57.3 ± 4.6b |

| Zinc (Zn) | 64.3 ± 5.1a | 42.2 ± 3.4b |

| Lead (Pb) | 107. ± 9a | 95.1 ± 7.6a |

Values marked with the same lowercase letter in rows do not differ significantly p > 0.05.

Spirulina exhibits significantly higher levels of essential minerals such as Ca, K, Na, Fe, Mn, and Zn compared to chlorella. Conversely, chlorella contains higher levels of Cu and Pb compared to spirulina, highlighting distinct differences in their trace element profiles.

3.3 Fatty acids composition

Table 5 presents the fatty acid compositions expressed as percentages of total fatty acids. In chlorella, the dominant fatty acids include palmitic acid (C 16:0) at 46.49 ± 0.25%, caprylic acid (C 8:0) at 9.87 ± 0.16%, and arachidic acid (C 20:0) at 20.03 ± 0.03%. Monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) are represented by oleic acid (C 18:1 n9) at 1.66 ± 0.01%, while the primary PUFA is linoleic acid (C 18:2) at 15.83 ± 0.01%. Lauric acid (C 12:0), myristic acid (C 14:0), and several other fatty acids were not detected (ND) in chlorella.

Fatty acid composition (share in %)

| Algae | Chlorella | Spirulina |

|---|---|---|

| C 8:0 | 9.87 ± 0.16a | 1.35 ± 0.14b |

| C 10:0 | ND | ND |

| C 12:0 | ND | ND |

| C 14:0 | 0.23 ± 0.23b | 0.81 ± 0.01a |

| C 14:1 | ND | ND |

| C 15:0 | ND | ND |

| C 15:1 | ND | ND |

| C 16:0 | 46.49 ± 0.25a | 16.71 ± 0.05b |

| C 16:1 | 5.56 ± 0.27b | 8.28 ± 0.01a |

| C 17:0 | ND | ND |

| C 17:1 | ND | 12.23 ± 0.12 |

| C 18:0 | 0.32 ± 0.04b | 0.83 ± 0.01a |

| C 18:1 n9 | 1.66 ± 0.01b | 17.42 ± 0.08a |

| C 18:1 n7 | ND | 3.84 ± 0.01 |

| C 18:2 | 15.83 ± 0.01a | 15.95 ± 0.04a |

| C 18:3 n6 | ND | ND |

| C 18:3 n3 | ND | 18.56 ± 0.08 |

| C 18:4 | ND | ND |

| C 20:0 | 20.03 ± 0.03a | 4.02 ± 0.18b |

| C 20:2 | ND | ND |

| C 20:4 | ND | ND |

| C 20:5 | ND | ND |

| C 22:0 | ND | ND |

| C 22:1 n9 | ND | ND |

| C 22:6 | ND | ND |

| ∑SFA* | 76.94 ± 0.35a | 23.73 ± 0.09b |

| ∑MUFA* | 7.23 ± 0.20b | 41.77 ± 0.05a |

| ∑PUFA* | 15.83 ± 0.55b | 34.50 ± 0.04a |

*SFA: saturated fatty acids; MUFA: monounsaturated fatty acids; PUFA: polyunsaturated fatty acids. Values marked with the same lowercase letter in rows do not differ significantly p > 0.05. ND – not detected.

Spirulina exhibits a contrasting fatty acid profile. It contains higher percentages of oleic acid (C 18:1 n9) at 17.42 ± 0.08% and alpha-linolenic acid (C 18:3 n3) at 18.56 ± 0.08% among MUFA and PUFA, respectively. Palmitic acid (C 16:0) is the predominant SFA at 16.71 ± 0.05%, and vaccenic acid (C 18:1 n7) contributes 3.84 ± 0.01% to MUFA. Similar to chlorella, some fatty acids are not detected (ND) in spirulina.

The analysis of fatty acid compositions reveals substantial differences between chlorella and spirulina. Chlorella is characterized by a higher proportion of saturated fatty acids (SFA), particularly palmitic acid and arachidic acid, which contribute to its total SFA content of 76.94 ± 0.35%. In contrast, spirulina shows a richer profile in MUFA, notably oleic acid, and PUFA, primarily α-linolenic acid, resulting in total MUFA and PUFA contents of 41.77 ± 0.05% and 34.50 ± 0.04%, respectively. These findings suggest that spirulina may provide a more favorable fatty acid composition from a nutritional perspective, particularly due to its higher levels of MUFA and PUFA, which are associated with potential cardiovascular benefits. Conversely, chlorella’s higher SFA content may still offer nutritional value.

3.4 Polyphenols profile composition

The analysis reveals notable differences in the polyphenol profiles between chlorella and spirulina. Chlorella is characterized by higher levels of p-hydroxybenzoic acid (7.90 ± 0.10 μg/g) compared to spirulina (1.02 ± 0.02 μg/g). Spirulina exhibits a higher concentration of rutin (1.46 ± 0.06 μg/g) than chlorella, which had no detectable amount. Vitexin content is higher in chlorella (1.64 ± 0.06 μg/g) than in spirulina (1.02 ± 0.05 μg/g), though both species contain detectable amounts. The presence of catechin exclusively in spirulina (0.35 ± 0.05 μg/g) further distinguishes its polyphenol profile from that of chlorella (Table 6).

3.5 Total carotenoids

This comparison indicates that chlorella contains a higher concentration (0.65 ± 0.02 m/g) of total carotenoids compared to spirulina (0.51 ± 0.01 m/g) (Table 7).

Polyphenols profile composition (μg/g)

| Algae | Chlorella | Spirulina |

|---|---|---|

| Kaempferol | ND | ND |

| Vitexin | 1.64 ± 0.06a | 1.02 ± 0.05b |

| Rutin | ND | 1.46 ± 0.06 |

| p-Coumaric acid | ND | ND |

| Catechin | ND | 0.35 ± 0.05 |

| Chlorogenic acid | ND | ND |

| Gallic acid | ND | ND |

| p-Hydroxybenzoic acid | 7.90 ± 0.10a | 1.02 ± 0.02b |

Values marked with the same lowercase letter in rows do not differ significantly p > 0.05. ND – not detected.

Total carotenoid content (TCC)

| Sample | TCC (m/g) |

|---|---|

| Chlorella | 0.65 ± 0.02a |

| Spirulina | 0.51 ± 0.01b |

Values marked with the same lowercase letter in columns do not differ significantly p > 0.05.

3.6 Vitamin B content

Table 8 presents the content of B vitamins analyzed in chlorella and spirulina, expressed in micrograms per gram (μg/g). Chlorella exhibited higher concentrations of niacin (B3) at 91.58 ± 1.25 μg/g and riboflavin (B2) at 2.29 ± 0.14 μg/g. In contrast, spirulina showed lower levels of niacin (B3) at 17.42 ± 1.00 μg/g and riboflavin (B2) at 0.94 ± 0.10 μg/g. Chlorella contains significantly higher amounts of niacin and riboflavin compared to spirulina. Spirulina, on the other hand, has lower concentrations of these B vitamins and does not contain detectable levels of folic acid.

Content of B vitamins analyzed expressed in (μg/g)

| B vitamin | Chlorella | Spirulina |

|---|---|---|

| Niacin (B3) | 91.58 ± 1.25a | 17.42 ± 1.00b |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 2.29 ± 0.14a | 0.94 ± 0.10b |

Values marked with the same lowercase letter in rows do not differ significantly p > 0.05. ND – not detected.

3.7 Antioxidant activity

3.7.1 DPPH assay

The antioxidant activity of chlorella and spirulina was evaluated using the DPPH˙ assay, with Trolox used as the standard for comparison. The IC50 values, which indicate the concentration required to inhibit 50% of the DPPH˙ radical activity, were measured for both ethanol and hexane extracts of the macroalgae samples. The results, presented in Table 9, show that spirulina exhibits superior antioxidant activity compared to chlorella.

Antioxidant activity by DPPH˙ assay

| Sample | IC50 (mg/mL) | TEAC equivalent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol extract | Hexane extract | Ethanol extract | Hexane extract | |

| Chlorella | 2.18 ± 0.09a | 1.13 ± 0.02a | 0.001362a | 0.002619a |

| Spirulina | 1.10 ± 0.12b | 0.64 ± 0.01b | 0.002711b | 0.004608b |

Values marked with the same lowercase letter in columns do not differ significantly p > 0.05.

For the ethanol extracts, the IC50 value of chlorella was found to be 2.18 ± 0.09 mg/mL, whereas spirulina demonstrated a significantly lower IC50 value of 1.10 ± 0.12 mg/mL. This indicates that spirulina requires a lower concentration to achieve 50% inhibition of the DPPH˙ radicals, reflecting its higher antioxidant activity. Similarly, for the hexane extracts, chlorella had an IC50 value of 1.13 ± 0.02 mg/mL, while spirulina had an IC50 value of 0.64 ± 0.01 mg/mL. Again, spirulina’s lower IC50 value signifies greater antioxidant activity compared to chlorella.

In terms of TEAC, which provides a measure of the antioxidant capacity relative to Trolox, the ethanol extract of chlorella had a TEAC equivalent of 0.001362, while spirulina had a higher TEAC equivalent of 0.002711. This further confirms spirulina’s superior antioxidant activity in ethanol extracts. For hexane extracts, the TEAC equivalent for chlorella was 0.002619, compared to 0.004608 for spirulina. The higher TEAC equivalent for spirulina reinforces its stronger antioxidant activity relative to chlorella.

Statistical analysis indicated that values marked with different uppercase letters in the table are significantly different (p > 0.05). Therefore, the results suggest that spirulina exhibits consistently higher antioxidant activity than chlorella in both ethanol and hexane extracts, based on the DPPH˙ assay.

3.7.2 ABTS+ assay

In the ABTS+ assay, which evaluated the antioxidant potential of extracts using Trolox as the standard reference compound (with an IC50 value of 2.48 μg/mL), the results are summarized in Table 10. For the ethanol extracts, chlorella exhibited an IC50 value of 0.40 ± 0.01 mg/mL, whereas spirulina displayed a significantly lower IC50 value of 0.05 ± 0.01 mg/mL. This result indicates that spirulina has a higher antioxidant activity compared to chlorella in ethanol extracts, as it requires a much lower concentration to achieve the same level of inhibition. In the case of hexane extracts, chlorella had an IC50 value of 0.54 ± 0.03 mg/mL, while spirulina had an IC50 value of 0.15 ± 0.01 mg/mL. Similarly, spirulina’s lower IC50 value demonstrates its superior antioxidant activity relative to chlorella in hexane extracts as well. The TEAC equivalents for the ethanol extracts were 0.00615776 for chlorella and 0.04810631 for spirulina, reflecting that spirulina has a substantially higher antioxidant capacity than chlorella when using ethanol extracts. For hexane extracts, chlorella’s TEAC equivalent was 0.00455267, while spirulina had a TEAC equivalent of 0.01697827. This further supports the finding that spirulina exhibits higher antioxidant activity compared to chlorella in hexane extracts.

Antioxidant activity by ABTS+ assay

| Sample | IC50 (mg/mL) | TEAC equivalent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol extract | Hexane extract | Ethanol extract | Hexane extract | |

| Chlorella | 0.40 ± 0.01a | 0.54 ± 0.03a | 0.00615776a | 0.00455267a |

| Spirulina | 0.05 ± 0.01b | 0.15 ± 0.01b | 0.04810631b | 0.01697827b |

Values marked with the same lowercase letter in columns do not differ significantly p > 0.05.

Statistical analysis revealed that values marked with different uppercase letters in the table are significantly different (p > 0.05). Thus, the data indicate that spirulina consistently demonstrates greater antioxidant activity than chlorella, as evidenced by its lower IC50 values and higher TEAC equivalents in both ethanol and hexane extracts, according to the ABTS+ assay.

3.8 Cytotoxic activity

The initial screening of chlorella and spirulina was performed, testing ethanolic, and hexane extracts at a concentration of 300 μg/mL on three different cell lines: human non-transformed fibroblasts, cervical cancer cells, and colorectal cancer cells. The cytotoxic effects after 48 h of incubation were measured using the MTT assay. Cells were treated with a single concentration of 300 µg/mL and incubated for 48 h (Figure 1). Ethanolic extracts showed none to slight cytotoxic effect on all tested cell lines, while favorable selective cytotoxic effects appeared after both hexane algae extract treatment.

Cytotoxicity of ethanolic (E) and hexane (H) extracts of chlorella and spirulina (300 μg/mL) on MRC-5, Hela, and HCT 116 cells after 48 h of incubation.

Chlorella hexane extract showed slightly higher cytotoxic potential compared to spirulina and was selected for further testing. Cells were treated with varying concentrations of the extract (0.3, 1, 3, 10, 30, 100, and 300 μg/mL) for 24 and 48 h. The results are shown in Figure 2 as concentration–response curves, alongside cytotoxic effect parameters according to the National Cancer Institute NCI-60 Screening Methodology [36] with and without adjustment for the initial cell count (Table 11). Significant cytotoxicity was observed across all treated cell lines, with the effect increasing proportionally to both the concentration of the extract and the duration of exposure. Values of GI50 and TGI were lower in transformed cell lines HeLa and HCT 116 than non-transformed MRC-5. Parameter of 50% lethality was close to maximal tested concentration for every cell line.

Concentration–response curves for MRC-5, HeLa, and HCT-116 cells treated with hexane extract of chlorella after 24 and 48 h. The results are presented as mean ± SD.

Parameters of cytotoxicity according to National Cancer Institute NCI-60 Screening methodology

| Chlorella hexane extract (μg/mL) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell lines | IC50 | SI | GI50 | TGI | LD50 |

| MRC-5 | 140.10 ± 4.44 | — | 101 ± 12.6 | 233.33 ± 28.65 | >300 |

| HeLa | 118.01 ± 0.41 | 1.19 | 47.23 ± 16.01 | 128.7 ± 6.92 | 294.42 ± 4.98 |

| HCT 116 | 108.22 ± 21.66 | 1.29 | 65.32 ± 18.54 | 158.88 ± 46.24 | >300 |

IC50 – 50% biological activity inhibition, SI – selectivity index, GI50 – 50% growth inhibition, TGI – total growth inhibition, LD50 – 50% lethality.

3.9 Cell death assessment

Following 48 h of treatment with chlorella hexane extract at IC50 concentrations, the type of cell death was assessed using Annexin V/7-AAD staining. The results presented in Figure 3 show the distribution of early apoptotic, late apoptotic, and necrotic cell populations. In both HeLa and HCT-116 cells, a statistically significant increase in necrotic cells (p < 0.001) and late apoptotic cells (p < 0.05) was observed following treatment. The early apoptotic population in both cell lines was minimal.

Type of cell death induced by chlorella hexane extract at IC50 concentration after 48 h. (a) Percentage of early (EA), late apoptotic (LA), and necrotic cells (N) in untreated and treated HeLa and HCT 116 cells. Results are presented as mean ± SD for three independent experiments. (b) Representative dot plots for HeLa and HCT 116 cells. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001.

3.10 Cell cycle distribution assessment

Flow cytometry analysis with PI staining was used to evaluate the impact of chlorella hexane extract on cell cycle progression in HeLa and HCT-116 cells after 48 h of treatment at the IC50 concentration (Figure 4). In HeLa, there was no significant impact on cell cycle distribution, while the treatment caused disruptions in the cell cycle of HCT 116 cells, with an increased accumulation of cells in the G2/M phase and a corresponding reduction in the S and G0/G1 phases.

HeLa and HCT-116 cell cycle phases after treatment with chlorella hexane extract at IC50 concentration after 48 h. Results are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

4 Discussion

Chlorella, a genus of unicellular freshwater microalgae, is known for its straightforward cultivation process, high productivity, and rich content of proteins and other valuable compounds [37]. The nutritional value of chlorella, similar to other microalgae, is determined by various factors such as fatty acid, protein, and pigment composition, which are significantly affected by the light conditions in which they grow [38]. Proteins are often the most abundant nutritional compounds found in certain cyanobacteria and microalgae such as Chlorella sp. [39].

Spirulina, a type of blue-green algae, is widely utilized globally as a dietary supplement due to its high protein content (50–60%), antioxidants, essential fatty acids, and other beneficial nutrients. The amino acid profile of spirulina protein is considered superior to that of soybeans, making it highly valued in the plant-based nutrition realm [10]. Chlorella has a high protein content, approximately (51–58%) on a dry matter basis. This protein content exceeds the protein content found in soya, which is approximately 33% on a dry matter basis [40,41]. All nine essential amino acids necessary for humans (isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, valine, and histidine) are present in chlorella in significant amounts [41], as confirmed by the analyses in this study.

Spirulina is rich in amino acids, vitamins, and minerals, serving as a significant source of both micro and macronutrients, including proteins, vitamins, gamma-linolenic acid, phycocyanin, and sulfated polysaccharides [42]. Čabarkapa et al. [43] tested the nutritional composition of spirulina and chlorella. In their results, Spirulina spp. showed slightly higher protein content, which is not consistent with our results, as chlorella showed 6.39% lower protein content than spirulina in this study.

In the study by Diraman et al. [44] the fatty acid composition of six commercial tablets produced from S. platensis in Turkey and one from China were analyzed. Spirulina platensis tablets were found to be rich in gamma linolenic acid, accounting for 4.07–22.51% of the total fatty acids. Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) were present in only two samples, with EPA ranging from 1.79 to 7.70% and DHA from 2.28 to 2.88%.

Čabarkapa et al. [43] reported that C. vulgaris was identified as a good source of n3 fatty acids and PUFA along with a favorable ratio of n6 to n3. In addition, C. vulgaris contained slightly higher total amino acid and essential amino acid content compared to Spirulina spp., with leucine, glutamic acid, and aspartic acid being predominant in both algae. However, in this study, overall, a higher content of both essential and non-essential amino acids was recorded in spirulina compared to chlorella. However, both studies confirmed that leucine, glutamic acid, and aspartic acid were the dominant amino acids in both algae.

Commercially available chlorella products have a low fat content in chlorella ranging from 14 to 22% [40]. Chlorella products contain all essential vitamins for humans, such as B1, B2, B6, B12, niacin, folate, biotin, pantothenic acid, C, D2, E, K, α-carotene, and β-carotene. They are notably abundant in vitamins D2 and B12, which are typically absent in plant-based foods [41]. Additionally, chlorella products have a higher concentration of folate compared to spinach [45]. Chlorella is rich in essential minerals necessary for human health, such as Fe and K. Fe is vital for functions like respiration, energy production, DNA synthesis, and cell proliferation [41,46]. The analyzed microalgae exhibited a substantial content of essential minerals and trace elements necessary for human nutrition [43], which is also demonstrated by the results of our analyses. While the study highlights differences in key polyphenols, further research is needed to explore the full spectrum of phenolic compounds in these microalgae.

In Hynstova’s study [47], through UV-vis spectrophotometric analysis of photosynthetic pigments (chlorophylls and carotenoids), it was confirmed that C. vulgaris possesses higher levels of these pigments compared to S. platensis. β-carotene was identified as the compound with the fastest mobility in both C. vulgaris and S. platensis using high-performance thin-layer chromatography. This study confirms the same findings that the total content of carotenoids was higher in chlorella compared to spirulina.

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in natural antioxidant substitutes as a replacement for artificial ones. Microalgae have been noted for their diverse bioactive properties, including significant antioxidant capabilities [48]. Chatzikonstantinou et al. [49] found that extracts from different strains of chlorella exhibited different antioxidant activities. They noted that the extract exhibited significant antioxidant potential attributed to its bioactive compounds [49]. Ferdous et al. [7] suggest that marine chlorella species show potential antioxidant and cytotoxic activities, indicating their possible applications in pharmaceuticals and nutraceuticals. In their study, Čabarkapa et al. [43] found that C. vulgaris exhibited higher phenolic content and stronger antioxidant activity as measured by the DPPH. However, Spirulina spp. demonstrated superior antioxidant capacity specifically in the ABTS test. Based on this work, spirulina showed better antioxidant effects compared to chlorella in both DPPH and ABTS assays. Hussein et al. [50] evaluated the antioxidant activity of algae in various solvents, including chlorella. They recorded the strongest antioxidant activity in the chloroform extract of Chlorella sp. (IC50 2.11 mg/mL) and N. oculate (IC50 2.98 mg/mL) compared to T. suecica (IC50 1.77 mg/mL), demonstrating strong antioxidant activity. Our presented results showed even stronger antioxidant activity for both algae with ethanol used as a solvent, with DPPH test IC50 values ranging from 1.10 ± 0.12 to 2.18 ± 0.09 mg/mL and ABTS test IC50 values ranging from 0.05 ± 0.01 to 0.40 ± 0.01 mg/mL.

Algae have gained significant attention in recent years due to their potential as a source of bioactive compounds for cancer treatment. Microalgae, in particular, are recognized for their rich composition of pharmacologically active metabolites, which exhibit pronounced anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anticancer properties [51]. These secondary metabolites, including polysaccharides, polyphenols, carotenoids, fatty acids, and peptides contribute to the anticancer potential of microalgae by modulating various cellular mechanisms involved in tumor progression, apoptosis, and immune response (ref). Purified metabolites isolated from numerous microalgae [52] as well as extracts have shown cytotoxic effects on HepG2, HeLa, AGS, HCT 116, and MCF-7 cells [53]. Notably, chlorella and spirulina have proven anticancer potential. Specifically, chlorella extract, rich in lutein, showed anti-proliferative effect in HCT 116 cells by inducing apoptosis [54] and isolated C-phycocyanin from spirulina showed potential apoptotic effect on HepG2 cells [55]. Because of the known anticancer potential, we investigated the cytotoxic effects of aqueous, ethanolic, and hexane extracts of chlorella and spirulina in MRC-5, HeLa, and HCT 116 cells. Initial screening at a concentration of 300 μg/mL revealed that aqueous extracts exhibited minimal to no cytotoxicity across all cell lines after 48 h of treatment, as measured by the MTT assay. In contrast, hexane extracts showed selective and favorable cytotoxic effects, prompting further investigation of chlorella hexane extract. These findings align with the work of Hamouda et al. [56] who showed anticancer properties of chlorella supplemented with thiamine in HCT 116 and HeLa cell lines. In our experiments, the cytotoxic effect was due to the induction of late apoptosis and necrosis in aforementioned cell lines. Other studies also confirmed the induction of apoptosis by chlorella on HepG2 [57] and NSCLC [58] cells. Fucoxanthin and lutein, carotenoids present in chlorella can affect the cell cycle distribution of cancer cells [59,60]. Treatment at IC50 concentration showed no significant effect on the cell cycle distribution in HeLa cells, indicating that the cytotoxic effect was potentially not related to DNA damage. However, in HCT-116 cells, treatment induced an accumulation of cells in the G2/M phase, accompanied by a decrease in the S and G0/G1 phases, indicating disruption of cell cycle progression. The selectivity of the chlorella hexane extract toward HCT-116 cells may be due to the presence of particular bioactive compounds, such as carotenoids. Additionally, while in vitro assays indicate promising bioactivity, future studies should include in vivo experiments to confirm the health benefits and functional applications of these microalgae.

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, this study comprehensively compares C. vulgaris and A. platensis (spirulina) in terms of their nutritional composition and antioxidant and cytotoxic properties. The rising incidence of chronic diseases has spurred interest in functional foods rich in antioxidants and essential nutrients. Chlorella emerges as a nutritional powerhouse with significantly higher protein content (64.63%) compared to spirulina (58.24%), along with richer concentrations of essential amino acids like leucine, lysine, and phenylalanine. It also excels in essential minerals such as Ca, K, and Fe, essential for overall health. Furthermore, both ethanolic and hexane extracts of spirulina exhibit significant antioxidant activity, as indicated by their lower IC50 values in DPPH˙ and ABTS+ assays, compared to chlorella. These findings underscore spirulina’s potential as a superior dietary supplement and functional food ingredient, offering not only essential nutrients but also significant antioxidant benefits, while chlorella hexane extract showed a potential anticancer activity. This nutritional profile makes spirulina and chlorella particularly valuable in addressing modern health challenges associated with oxidative stress and inadequate nutrient intake. Incorporating these microalgae into diets as functional foods or supplements could offer significant health benefits, particularly in combating malnutrition and chronic diseases associated with oxidative stress. Further research into their bioavailability, safety profiles, and clinical efficacy will be pivotal in harnessing their full potential for nutritional and therapeutic applications in healthcare.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mr Łukasz Szala (Students’ Scientific Club of Food Technologists, Poznań University of Life Sciences, Poznań, Poland) for his help with the sample preparation and the analyses. This work has been supported by the grant of the 023SPU-4/2024.

-

Funding information: This work was funded by the EU NextGenerationEU through the Recovery and Resilience Plan for Slovakia under the project No. 09I01-03-V04-00057 and Erasmus project 2023-1-RO01-KA220-HED-000164767.

-

Author contributions: Natália Čmiková: conceptualization, software, validation, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, data curation, writing, writing – review and editing, visualization; Przemysław Łukasz Kowalczewski: methodology, validation, investigation, statistics, writing – review and editing; Dominik Kmiecik: methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing – review and editing; Piotr Klimowicz: methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing – review and editing; Agnieszka Drożdżyńska: methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing – review and editing; Mariusz Ślachciński: methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing – review and editing; Jakub Królak: investigation, formal analysis, writing – review and editing; Sanja Matić: methodology, investigation, statistics, writing – review and editing, formal analysis; Tijana Marković: methodology, investigation, statistics, formal analysis, writing – review and editing; Suzana Popović: methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing – review and editing; Dejan Baskic: methodology, investigation, writing – review and editing, validation; Miroslava Kačániová: conceptualization, software, validation, formal analysis, data curation, writing – review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Hauner H, Bechthold A, Boeing H, Brönstrup A, Buyken A, Leschik-Bonnet E, et al. Evidence-based guideline of the German Nutrition Society: carbohydrate intake and prevention of nutrition-related diseases. Ann Nutr Metab. 2012 Jan;60(Suppl. 1):1–58. 10.1159/000335326.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Yao W, Qiu HM, Cheong KL, Zhong S. Advances in anti-cancer effects and underlying mechanisms of marine algae polysaccharides. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022 Nov;221:472–85, [cited 2024 Jul 3], https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0141813022019778.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.09.055Search in Google Scholar

[3] Tavares JO, Cotas J, Valado A, Pereira L. Algae food products as a healthcare solution. Mar Drugs. 2023 Nov;21(11):578, https://www.mdpi.com/1660-3397/21/11/578.10.3390/md21110578Search in Google Scholar

[4] Leandro A, Pacheco D, Cotas J, Marques JC, Pereira L, Gonçalves AMM. Seaweed’s bioactive candidate compounds to food industry and global food security. Life. 2020 Aug;10(8):140, [cited 2024 Jul 3], https://www.mdpi.com/2075-1729/10/8/140.10.3390/life10080140Search in Google Scholar

[5] Berdalet E, Fleming LE, Gowen R, Davidson K, Hess P, Backer LC, et al. Marine harmful algal blooms, human health and wellbeing: challenges and opportunities in the 21st century. J Mar Biol Assoc UK. 2016 Feb;[cited 2024 Jul 3] 96(1):61–91, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-the-marine-biological-association-of-the-united-kingdom/article/marine-harmful-algal-blooms-human-health-and-wellbeing-challenges-and-opportunities-in-the-21st-century/DE5B62CDF5CB84633BAE2B4D7396867D.10.1017/S0025315415001733Search in Google Scholar

[6] Wang E, Sorolla MA, Gopal Krishnan PD, Sorolla A. From seabed to bedside: a review on promising marine anticancer compounds. Biomolecules. 2020 Feb;10(2):248, [cited 2024 Jul 3], https://www.mdpi.com/2218-273X/10/2/248.10.3390/biom10020248Search in Google Scholar

[7] Ferdous UT, Nurdin A, Ismail S, Balia Yusof ZN. Evaluation of the antioxidant and cytotoxic activities of crude extracts from marine Chlorella sp. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2023 Jan;47:102551, [cited 2024 Jul 3], https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S187881812200278X.10.1016/j.bcab.2022.102551Search in Google Scholar

[8] Chénais B. Algae and microalgae and their bioactive molecules for human health. Molecules. 2021 Jan;26(4):1185, [cited 2024 Jul 3], https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/26/4/1185.10.3390/molecules26041185Search in Google Scholar

[9] Gurney T, Spendiff O. Algae supplementation for exercise performance: current perspectives and future directions for Spirulina and Chlorella. Front Nutr. 2022 Mar;9:865741, [cited 2024 Jul 3], 10.3389/fnut.2022.865741.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Priyanka S, Varsha R, Riya V, Ayenampudi SB. Spirulina: a spotlight on its nutraceutical properties and food processing applications. J Microb Biotech Food Sci. 2023 Mar;12(6):e4785, [cited 2024 Jul 3], https://office2.jmbfs.org/index.php/JMBFS/article/view/4785.10.55251/jmbfs.4785Search in Google Scholar

[11] Andrade L, De Andrade CJ, Dias M, Nascimento C, Mendes M. Chlorella and Spirulina microalgae as sources of functional foods, nutraceuticals, and food supplements; an overview. MOJ Food Process Technol. 2018 Jan;6:00144.10.15406/mojfpt.2018.06.00144Search in Google Scholar

[12] Tokuşoglu Ö, üUnal Mk. Biomass nutrient profiles of three microalgae: Spirulina platensis, Chlorella vulgaris, and Isochrisis galbana. J Food Sci. 2003;[cited 2024 Mar 1] 68(4):1144–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2003.tb09615.x.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Muys M, Sui Y, Schwaiger B, Lesueur C, Vandenheuvel D, Vermeir P, et al. High variability in nutritional value and safety of commercially available Chlorella and Spirulina biomass indicates the need for smart production strategies. Bioresour Technol. 2019 Mar; 275:247–57, [cited 2024 Jul 3], https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960852418317206.10.1016/j.biortech.2018.12.059Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Wu H, Li T, Lv J, Chen Z, Wu J, Wang N, et al. Growth and biochemical composition characteristics of Arthrospira platensis induced by simultaneous nitrogen deficiency and seawater-supplemented medium in an outdoor raceway pond in winter. Foods. 2021 Dec;10(12):2974, [cited 2023 Dec 24], https://www.mdpi.com/2304-8158/10/12/2974.10.3390/foods10122974Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Ahmad MT, Shariff M, Md Yusoff F, Goh YM, Banerjee S. Applications of microalga Chlorella vulgaris in aquaculture. Rev Aquacult. 2020;12(1):328–46. [cited 2023 Dec 24], 10.1111/raq.12320.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Blas-Valdivia V, Ortiz-Butrón R, Pineda-Reynoso M, Hernández-Garcia A, Cano-Europa E. Chlorella vulgaris administration prevents HgCl2-caused oxidative stress and cellular damage in the kidney. J Appl Phycol. 2011 Feb;23(1):53–8, [cited 2023 Dec 24], 10.1007/s10811-010-9534-6.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Fradique M, Batista AP, Nunes MC, Gouveia L, Bandarra NM, Raymundo A. Incorporation of Chlorella vulgaris and Spirulina maxima biomass in pasta products. Part 1: Preparation and evaluation. J Sci Food Agric. 2010;90(10):1656–64.10.1002/jsfa.3999Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Tang G, Suter PM. Vitamin A, nutrition, and health values of algae: Spirulina, Chlorella, and Dunaliella. J Pharm Nutr Sci. 2011 Jan;1(2):111–8, cited 2024 Jul 3], https://setpublisher.com/pms/index.php/jpans/article/view/2189.10.6000/1927-5951.2011.01.02.04Search in Google Scholar

[19] Mason R. Chlorella and spirulina: green supplements for balancing the body. Altern Complementary Ther. 2001 Jun;7(3):161–5, [cited 2024 Jul 3], 10.1089/107628001300303691.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Hsiao YC, Hsieh YS, Kuo WH, Chiou HL, Yang SF, Chiang WL, et al. The tumor-growth inhibitory activity of flavanone and 2′-OH flavanone in vitro and in vivo through induction of cell cycle arrest and suppression of cyclins and CDKs. J Biomed Sci. 2007 Jan;14(1):107–19, [cited 2024 Jul 3], 10.1007/s11373-006-9117-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Seguin J, Brullé L, Boyer R, Lu YM, Ramos Romano M, Touil YS, et al. Liposomal encapsulation of the natural flavonoid fisetin improves bioavailability and antitumor efficacy. Int J Pharm. 2013 Feb;444(1):146–54, [cited 2024 Jul 3], https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378517313001014.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.01.050Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Ying TH, Yang SF, Tsai SJ, Hsieh SC, Huang YC, Bau DT, et al. Fisetin induces apoptosis in human cervical cancer HeLa cells through ERK1/2-mediated activation of caspase-8-/caspase-3-dependent pathway. Arch Toxicol. 2012 Feb;[cited 2024 Jul 3] 86(2):263–73. 10.1007/s00204-011-0754-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Sak K. Cytotoxicity of dietary flavonoids on different human cancer types. Pharmacogn Rev. 2014;8(16):122–46, [cited 2024 Jul 3], https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4127821/.10.4103/0973-7847.134247Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Pantami HA, Ahamad Bustamam MS, Lee SY, Ismail IS, Mohd Faudzi SM, Nakakuni M, et al. Comprehensive GCMS and LC-MS/MS metabolite profiling of Chlorella vulgaris. Mar Drugs. 2020 Jul;18(7):367, [cited 2024 Jul 3], https://www.mdpi.com/1660-3397/18/7/367.10.3390/md18070367Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Ramos-Romero S, Torrella JR, Pagès T, Viscor G, Torres JL. Edible microalgae and their bioactive compounds in the prevention and treatment of metabolic alterations. Nutrients. 2021 Feb;13(2):563, [cited 2024 Jul 3], https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/13/2/563.10.3390/nu13020563Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] ISO 20483:2013. ISO 20483:2013 [Internet]. ISO. [cited 2024 Mar 4]. Available from: https://www.iso.org/standard/59162.html.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Aoac Official Method 994.12 Amino Acids in Feeds | PDF | Amino Acid | Ph [Internet]. Scribd. [cited 2024 Mar 4]. Available from: https://www.scribd.com/document/609975831/Aoac-Official-Method-994-12-Amino-Acids-in-Feeds-1.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Tomczak A, Zielińska-Dawidziak M, Piasecka-Kwiatkowska D, Lampart-Szczapa E. Blue lupine seeds protein content and amino acids composition. Plant Soil Environ. 2018 Apr;64(4):147–55, cited 2024 Mar 4], 10.17221/690/2017-PSE.html.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Folch J, Lees M, Stanley GHS. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957 May;226(1):497–509, [cited 2024 Jan 29], https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0021925818648495.10.1016/S0021-9258(18)64849-5Search in Google Scholar

[30] Society AOC. AOCS official method Ce 1h‐05: determination of cis‐, trans‐, saturated, monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids in vegetable or non‐ruminant animal oils and fats by capillary GLC. Official methods and recommended practices of the AOCS. 2005.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Kowalczewski PŁ, Gumienna M, Rybicka I, Górna B, Sarbak P, Dziedzic K, et al. Nutritional value and biological activity of gluten-free bread enriched with cricket powder. Molecules. 2021 Feb;26(4):1184, [cited 2024 Jan 29], https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/26/4/1184.10.3390/molecules26041184Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] STN. STN 56 0053. Determination of vitamin A and its provitamins. Praha: ÚNN; 1986.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Drożdżyńska A, Dzidzic K, Kośmider A, Leja K, Czaczyk K, Górecka D. Application of fast liquid chromatography for antioxidants analysis. Acta Sci Pol, Technol Aliment. 2012;11(1):19–25.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Čmiková N, Kowalczewski PŁ, Kmiecik D, Tomczak A, Drożdżyńska A, Ślachciński M, et al. Characterization of selected microalgae species as potential sources of nutrients and antioxidants. Foods. 2024 Jul;13(13):2160, [cited 2024 Jul 20], https://www.mdpi.com/2304-8158/13/13/2160.10.3390/foods13132160Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Li HB, Chen F. Simultaneous determination of nine water-soluble vitamins in pharmaceutical preparations by high-performance liquid chromatography with diode array detection. J Sep Sci. 2001 Apr; 24(4):271–4, [cited 2024 Apr 24], 10.1002/1615-9314(20010401)24:4<271:AID-JSSC271>3.0.CO;2-L.Search in Google Scholar

[36] NCI-60 Screening Methodology | NCI-60 Human Tumor Cell Lines Screen | Discovery & Development Services | Developmental Therapeutics Program (DTP) [Internet]. [cited 2024 Sep 25]. Available from: https://dtp.cancer.gov/discovery_development/nci-60/methodology.htm.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Kotrbáček V, Doubek J, Doucha J. The chlorococcalean alga Chlorella in animal nutrition: a review. J Appl Phycol. 2015 Dec;27(6):2173–80, [cited 2024 Jul 3], 10.1007/s10811-014-0516-y.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Seyfabadi J, Ramezanpour Z, Amini Khoeyi Z. Protein, fatty acid, and pigment content of Chlorella vulgaris under different light regimes. J Appl Phycol. 2011 Aug;23(4):721–6, [cited 2024 Jul 3], 10.1007/s10811-010-9569-8.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Safafar H, Uldall Nørregaard P, Ljubic A, Møller P, Løvstad Holdt S, Jacobsen C. Enhancement of protein and pigment content in two chlorella species cultivated on industrial process water. J Mar Sci Eng. 2016 Dec;4(4):84, [cited 2024 Jul 3], https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1312/4/4/84.10.3390/jmse4040084Search in Google Scholar

[40] Becker EW. Micro-algae as a source of protein. Biotechnol Adv. 2007 Mar;25(2):207–10, https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S073497500600139X.10.1016/j.biotechadv.2006.11.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Bito T, Okumura E, Fujishima M, Watanabe F. Potential of chlorella as a dietary supplement to promote human health. Nutrients. 2020 Aug;12(9):2524, [cited 2024 Jul 3], https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7551956/.10.3390/nu12092524Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[42] Liestianty D, Rodianawati I, Arfah RA, Assa A, Patimah S, et al. Nutritional analysis of spirulina sp to promote as superfood candidate. IOP Conf Ser: Mater Sci Eng. 2019 May;509:012031, [cited 2024 Jul 3], 10.1088/1757-899X/509/1/012031.Search in Google Scholar

[43] Čabarkapa I, Rakita S, Popović S, Spasevski N, Tomičić Z, Vulić J, et al. Characterization of organic Spirulina spp. and Chlorella vulgaris as one of the most nutrient-dense food. J Food Saf Food Qual. 2022;73(3):75–108.10.31083/0003-925X-73-78Search in Google Scholar

[44] Diraman H, Koru E, Dibeklioglu H. Fatty acid profile of spirulina platensis used as a food supplement. Israeli J Aquacult – Bamidgeh. 2009 Jun;61:134–42.10.46989/001c.20548Search in Google Scholar

[45] Woortman DV, Fuchs T, Striegel L, Fuchs M, Weber N, Brück TB, et al. Microalgae a superior source of folates: quantification of folates in halophile microalgae by stable isotope dilution assay. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020 Jan;7:481, [cited 2024 Jul 3], 10.3389/fbioe.2019.00481.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[46] Hentze MW, Muckenthaler MU, Galy B, Camaschella C. Two to tango: regulation of mammalian iron metabolism. Cell. 2010 Jul;142(1):24–38, [cited 2024 Jul 3], https://www.cell.com/cell/abstract/S0092-8674(10)00718-X.10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.028Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Hynstova V, Sterbova D, Klejdus B, Hedbavny J, Huska D, Adam V. Separation, identification and quantification of carotenoids and chlorophylls in dietary supplements containing Chlorella vulgaris and Spirulina platensis using high performance thin layer chromatography. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2018 Jan;148:108–18, https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0731708517316254.10.1016/j.jpba.2017.09.018Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] El-Chaghaby A, Rashad G, SF, Abdel-Kader S, Rawash A, Abdul Moneem ES, M. Assessment of phytochemical components, proximate composition and antioxidant properties of Scenedesmus obliquus, Chlorella vulgaris and Spirulina platensis algae extracts. Egypt J Aquat Biol Fish. 2019 Nov;23(4):521–6, [cited 2024 Jul 12], https://ejabf.journals.ekb.eg/article_57884.html.10.21608/ejabf.2019.57884Search in Google Scholar

[49] Chatzikonstantinou M, Kalliampakou A, Gatzogia M, Flemetakis E, Katharios P, Labrou NE. Comparative analyses and evaluation of the cosmeceutical potential of selected Chlorella strains. J Appl Phycol. 2017 Feb;29(1):179–88, [cited 2024 Jul 3], 10.1007/s10811-016-0909-1.Search in Google Scholar

[50] Hussein HA, Mohamad H, Mohd Ghazaly M, Laith AA, Abdullah MA. Anticancer and antioxidant activities of Nannochloropsis oculata and Chlorella sp. extracts in co-application with silver nanoparticle. J King Saud Univ - Sci. 2020 Dec;32(8):3486–94, [cited 2024 Jul 12], https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1018364720303189.10.1016/j.jksus.2020.10.011Search in Google Scholar

[51] Khavari F, Saidijam M, Taheri M, Nouri F. Microalgae: therapeutic potentials and applications. Mol Biol Rep. 2021 May;48(5):4757–65, [cited 2024 Sep 25], 10.1007/s11033-021-06422-w.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[52] Fedorov S, Ermakova S, Zvyagintseva T, Stonik V. Anticancer and cancer preventive properties of marine polysaccharides: some results and prospects. Mar Drugs. 2013 Dec;11(12):4876–901, [cited 2024 Sep 25], https://www.mdpi.com/1660-3397/11/12/4876.10.3390/md11124876Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[53] Kang KH, Kim SK. Beneficial effect of peptides from microalgae on anticancer. CPPS. 2013 Jun;[cited 2024 Sep 25] 14(3):212–7, http://www.eurekaselect.com/openurl/content.php?genre=article&issn=1389-2037&volume=14&issue=3&spage=212.10.2174/1389203711314030009Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[54] Cha KH, Koo SY, Lee DU. Antiproliferative effects of carotenoids extracted from Chlorella ellipsoidea and Chlorella vulgaris on human colon cancer cells. J Agric Food Chem. 2008 Nov;56(22):10521–6, [cited 2024 Sep 25], 10.1021/jf802111x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[55] Basha OM, Hafez RA, El-Ayouty YM, Mahrous KF, Bareedy MH, Salama AM. C-Phycocyanin inhibits cell proliferation and may induce apoptosis in human HepG2 cells. Egypt J Immunol. 2008;15(2):161–7.Search in Google Scholar

[56] Hamouda RA, Abd El Latif A, Elkaw EM, Alotaibi AS, Alenzi AM, Hamza HA. Assessment of antioxidant and anticancer activities of microgreen alga chlorella vulgaris and its blend with different vitamins. Molecules. 2022 Feb; 27(5):1602, [cited 2024 Sep 25], https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/27/5/1602.10.3390/molecules27051602Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[57] Yusof YAM, Saad MS, Makpol S, Shamaan NA, Ngah WZW. Hot water extract of Chlorella vulgaris induced DNA damage and apoptosis. Clinics. 2010 Jan;65(12):1371–7, [cited 2024 Sep 25], https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S180759322201609X.10.1590/S1807-59322010001200023Search in Google Scholar

[58] Zhang ZD, Liang K, Li K, Wang GQ, Zhang KW, Cai L, et al. Chlorella vulgaris induces apoptosis of human non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) cells. MC. 2017 Aug;13(6):560–8, [cited 2024 Sep 25], 10.2174/1573406413666170510102024.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[59] Ferraz CAA, Grougnet R, Nicolau E, Picot L, De Oliveira Junior RG. Carotenoids from marine microalgae as antimelanoma agents. Mar Drugs. 2022 Sep;20(10):618, [cited 2024 Sep 25], https://www.mdpi.com/1660-3397/20/10/618.10.3390/md20100618Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[60] Kim KN, Ahn G, Heo SJ, Kang SM, Kang MC, Yang HM, et al. Inhibition of tumor growth in vitro and in vivo by fucoxanthin against melanoma B16F10 cells. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2013 Jan;35(1):39–46, [cited 2024 Sep 25], https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1382668912001548.10.1016/j.etap.2012.10.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Phytochemical investigation and evaluation of antioxidant and antidiabetic activities in aqueous extracts of Cedrus atlantica

- Influence of B4C addition on the tribological properties of bronze matrix brake pad materials

- Discovery of the bacterial HslV protease activators as lead molecules with novel mode of action

- Characterization of volatile flavor compounds of cigar with different aging conditions by headspace–gas chromatography–ion mobility spectrometry

- Effective remediation of organic pollutant using Musa acuminata peel extract-assisted iron oxide nanoparticles

- Analysis and health risk assessment of toxic elements in traditional herbal tea infusions

- Cadmium exposure in marine crabs from Jiaxing City, China: Insights into health risk assessment

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles of Cinnamomum zeylanicum and their biological activities

- Tetraclinis articulata (Vahl) Mast., Mentha pulegium L., and Thymus zygis L. essential oils: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antifungal properties against postharvest fungal diseases of apple, and in vitro, in vivo, and in silico investigation

- Exploration of plant alkaloids as potential inhibitors of HIV–CD4 binding: Insight into comprehensive in silico approaches

- Recovery of phenylethyl alcohol from aqueous solution by batch adsorption

- Electrochemical approach for monitoring the catalytic action of immobilized catalase

- Green synthesis of ZIF-8 for selective adsorption of dyes in water purification

- Optimization of the conditions for the preparation of povidone iodine using the response surface methodology

- A case study on the influence of soil amendment on ginger oil’s physicochemical properties, mineral contents, microbial load, and HPLC determination of its vitamin level

- Removal of antiviral favipiravir from wastewater using biochar produced from hazelnut shells

- Effect of biochar and soil amendment on bacterial community composition in the root soil and fruit of tomato under greenhouse conditions

- Bioremediation of malachite green dye using Sargassum wightii seaweed and its biological and physicochemical characterization

- Evaluation of natural compounds as folate biosynthesis inhibitors in Mycobacterium leprae using docking, ADMET analysis, and molecular dynamics simulation

- Novel insecticidal properties of bioactive zoochemicals extracted from sea urchin Salmacis virgulata

- Elevational gradients shape total phenolic content and bioactive potential of sweet marjoram (Origanum majorana L.): A comparative study across altitudinal zones

- Study on the CO2 absorption performance of deep eutectic solvents formed by superbase DBN and weak acid diethylene glycol

- Preparation and wastewater treatment performance of zeolite-modified ecological concrete

- Multifunctional chitosan nanoparticles: Zn2+ adsorption, antimicrobial activity, and promotion of aquatic health

- Comparative analysis of nutritional composition and bioactive properties of Chlorella vulgaris and Arthrospira platensis: Implications for functional foods and dietary supplements

- Growth kinetics and mechanical characterization of boride layers formed on Ti6Al4V

- Enhancement of water absorption properties of potassium polyacrylate-based hydrogels in CaCl2-rich soils using potassium di- and tri-carboxylate salts

- Electrochemical and microbiological effects of dumpsite leachates on soil and air quality

- Modeling benzene physicochemical properties using Zagreb upsilon indices

- Characterization and ecological risk assessment of toxic metals in mangrove sediments near Langen Village in Tieshan Bay of Beibu Gulf, China

- Protective effect of Helicteres isora, an efficient candidate on hepatorenal toxicity and management of diabetes in animal models

- Valorization of Juglans regia L. (Walnut) green husk from Jordan: Analysis of fatty acids, phenolics, antioxidant, and cytotoxic activities

- Molecular docking and dynamics simulations of bioactive terpenes from Catharanthus roseus essential oil targeting breast cancer

- Selection of a dam site by using AHP and VIKOR: The Sakarya Basin

- Characterization and modeling of kidney bean shell biochar as adsorbent for caffeine removal from aquatic environments

- The effects of short-term and long-term 2100 MHz radiofrequency radiation on adult rat auditory brainstem response

- Biochemical insights into the anthelmintic and anti-inflammatory potential of sea cucumber extract: In vitro and in silico approaches

- Resveratrol-derived MDM2 inhibitors: Synthesis, characterization, and biological evaluation against MDM2 and HCT-116 cells

- Phytochemical constituents, in vitro antibacterial activity, and computational studies of Sudanese Musa acuminate Colla fruit peel hydro-ethanol extract

- Chemical composition of essential oils reviewed from the height of Cajuput (Melaleuca leucadendron) plantations in Buru Island and Seram Island, Maluku, Indonesia

- Phytochemical analysis and antioxidant activity of Azadirachta indica A. Juss from the Republic of Chad: in vitro and in silico studies

- Stability studies of titanium–carboxylate complexes: A multi-method computational approach

- Efficient adsorption performance of an alginate-based dental material for uranium(vi) removal

- Synthesis and characterization of the Co(ii), Ni(ii), and Cu(ii) complexes with a 1,2,4-triazine derivative ligand

- Evaluation of the impact of music on antioxidant mechanisms and survival in salt-stressed goldfish

- Optimization and validation of UPLC method for dapagliflozin and candesartan cilexetil in an on-demand formulation: Analytical quality by design approach

- Biomass-based cellulose hydroxyapatite nanocomposites for the efficient sequestration of dyes: Kinetics, response surface methodology optimization, and reusability

- Multifunctional nitrogen and boron co-doped carbon dots: A fluorescent probe for Hg2+ and biothiol detection with bioimaging and antifungal applications

- Separation of sulphonamides on a C12-diol mixed-mode HPLC column and investigation of their retention mechanism

- Characterization and antioxidant activity of pectin from lemon peels

- Fast PFAS determination in honey by direct probe electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry: A health risk assessment insight

- Correlation study between GC–MS analysis of cigarette aroma compounds and sensory evaluation