Toxicological effects of green tea catechin extract on rat liver: Delineating safe and harmful doses

-

Zoheir Amrouche

, Lazhari Tichati

, Marie-Laure Fauconnier

Abstract

Purpose

Catechins, the bioactive compounds found in green tea, are known for their beneficial health effects, but overconsumption may result in adverse effects. Thus, this study aimed to examine the influence of green tea (Camellia sinensis L.) catechin extract (GTCE) on liver metabolism and structure in rats.

Methods

GTCE was phytochemically characterized by LC-MS spectrometry. An in vivo study was conducted on female rats separated into four groups of five each, i.e., a control group and three catechin-treated groups D1, D2, and D3 received, respectively, 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8 g/kg b.w./day of GTCE by gavage for 28 days. The effects of GTCE were monitored through the analysis of plasma lipid, oxidative stress markers, reduced glutathione (GSH) content, glutathione peroxidase (GPx) activity, and malondialdehyde (MDA) level in the liver. Furthermore, histopathological examinations of liver tissue were conducted.

Results

LC-MS analyses of GTCE revealed the presence of five phenolic compounds with a predominance of epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) at 60.1%. Exposure to catechins with an elevated dose (0.8 g/kg) caused oxidative damage in the liver, as indicated by a considerable increase (p < 0.05) in MDA levels, a decrease in GSH content, and GPx activity (p < 0.05), along with a decrease (p < 0.05) in plasma total cholesterol, triglycerides, and total lipids in comparison to the control group. These changes were confirmed by histological examination.

Conclusion

Although catechins offer known health benefits, high doses may induce oxidative stress and liver damage.

Graphical abstract

Abbreviations

- EC

-

Epicatechin

- ECG

-

Epicatechin gallate

- EGC

-

Epigallocatechin

- EGCG

-

Epigallocatechin-3-gallate

- GPx

-

Glutathione peroxidase

- GSH

-

Reduced glutathione

- GT

-

Green tea

- GTCE

-

Green tea catechin extract

- MDA

-

Malondialdehyde

1 Introduction

Green tea (GT) is obtained from Camellia sinensis L., a member of the Theaceae family. It is known to be the most commonly consumed drink in the world after water and for its health benefits, including the chemoprevention effect [1,2]. Owing to its good biological activity, including pharmacological and antioxidant properties, it is attracting increasing interest [3,4]. The antioxidant properties of GT are attributed to important phytochemicals including phenolic compounds such as catechins, phenolic acids, and caffeine [5,6]. Catechins (flavan-3-oils), the primary phenolic compounds in GT, inhibit cell proliferation and exert potent anti-radical activity by acting as natural antioxidants [7,8]. It consists of catechin, epigallocatechin (EGC), epicatechin gallate (ECG), epicatechin (EC), and epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) [9,10]. EGCG is the predominant catechin in GT and a potent antioxidant inhibiting oxidative damage disorders such as cancer, cardiovascular and neurological diseases, [11,12] obesity, and diabetes [13,14].

The liver is an essential organ that performs major functions, including protein synthesis, energy metabolism, glycogen storage, and drug detoxification [15]. Hepatic disorders often result from various substances such as pharmaceuticals, chemicals, and natural products like plant extracts. These substances mainly damage the liver by forming free radicals, which increase lipid peroxidation (LP), leading to liver damage [16]. Some studies suggest that EGCG directly influences lipid metabolism by inhibiting intestinal lipid absorption, increasing LDL receptor expression, and activating AMPK, which promotes fatty acid oxidation [17,18]. However, at high doses, EGCG has been associated with liver failure [19,20], which may indirectly affect the lipid levels. Liver damage can alter lipid metabolism due to disrupted hepatic function, leading to reduced cholesterol and triglyceride levels. In this context, several previous studies have shown that EGCG from GT at high doses has been shown to induce liver injury and oxidative damage [16,21,22]. EGCG induced hepatotoxicity by depleting antioxidant defense systems like antioxidant enzyme activities and altering liver biochemical markers [23,24].

Our study was designed to identify the chemical profile of green tea (Camellia sinensis L.) catechin extract (GTCE) using LC-MS. Furthermore, an in vivo study was performed to evaluate the biochemical variations, antioxidant status, and histological aberrations in the liver of female rats after treatment with GTCE at 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8 g/kg body weight (b.w).

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant material and extraction

The commercial GT leaves were suspended in ten volumes of distilled water (w/v; 1:10) in a 50 mL tube, followed by ultrasonic treatment at 95°C for 15 min [25,26]. The resulting infusions were centrifuged (5,000 g for 15 min at 4°C) and left to stand for 10 min, after which they were filtered through 0.45 μm filter membranes (Sartorius) and the top solution was collected and lyophilized. The lyophilized powder was kept in the dark at 4°C until assay.

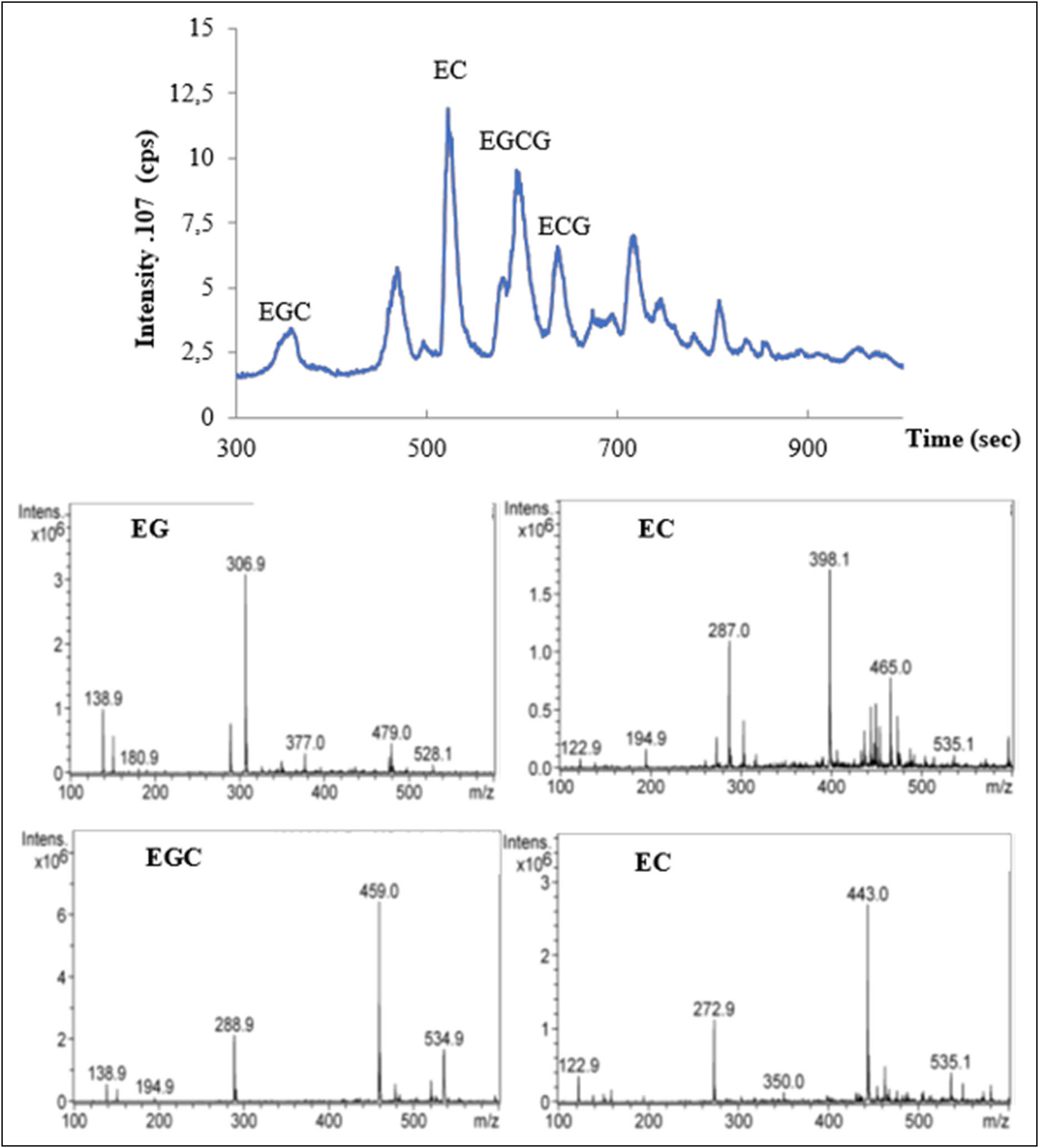

2.2 LC-MS analysis

LC-MS analysis was performed using an Agilent 1100 Series HPLC system equipped with a diode array detector and coupled to an HCT linear ion trap mass spectrometer. Chromatographic separation was achieved on an EC/3 Nucleodur 100-3 C18 ec column (Macherey-Nagel, Germany). The mobile phase consisted of solvent A (water with 0.1% formic acid) and solvent B (acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid). A linear gradient of acetonitrile in water (5–95% B) was applied over 40 min. The sample injection volume was 20 µL. Mass spectra were recorded over a mass-to-charge (m/z) range of 100–600 under the following MS conditions: capillary voltage of 4,500 V, nebulizer pressure of 50 psig, drying gas flow rate of 10 L/min, and drying temperature of 365°C. Analyses were conducted in the positive ionization mode. Compounds in the GT extracts were identified based on their m/z values, UV/Vis absorption spectra, and retention times, and were compared with reference data reported in the literature [27]. Peak identification was further confirmed by mass spectrometry.

2.3 In vivo study

2.3.1 Animals and treatment

Female rats from the Wistar strain (Pasteur Institute, Algeria), weighing 125–130 g and aged 1 month, were placed in an animal house at a temperature of 22°C, a photoperiod of 12 h day/12 h night, and relative humidity of 50–60%. The rats were given a standard diet (supplied by ONAB, Bejaia, Algeria). Throughout the study, the rats had access to drinking water ad libitum. All experimental procedures were carried out in accordance with the International Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Council of European Communities, 1986).

2.4 Experimental procedure

After a 2-week adaptation period, animals were grouped into four groups of five rats each. The first group was designated as control and was given 1 mL of distilled water per day by oral gavage for 28 days. The groups (D1), (D2), and (D3) received oral treatment with GTCE at dose levels of 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8 g/kg/kg b.w., respectively, for 28 days. The test doses and treatment period were chosen based on a previous study [18].

2.5 Blood and tissue processing

After 28 days of treatment, the rats in each group were subjected to overnight fasting and then anesthetized with light ether, and then they were sacrificed by cervical decapitation. Blood samples were collected using heparinized tubes and subjected to centrifugation (3,000 g for 15 min), and the resulting plasma was maintained at −20°C in aliquots for biochemical assays, including total lipids, triglycerides, and cholesterol. The liver was recovered, washed with saline solution (NaCl 0.9%), and weighed. One portion of the liver was fixed in formalin solution for histological analysis, while the other portion was stored at −20°C for assessing oxidative stress markers [28].

2.5.1 Tissue preparation

Liver tissue was suspended in three volumes of phosphate buffered saline (1/3 w/v, pH 7.4), homogenized, and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant fraction was employed to estimate oxidative stress markers [29].

2.5.2 Biochemical assays

The total lipid, cholesterol, and triglyceride levels of the plasma were measured using Spinreact (Spain) commercial kits.

2.6 Oxidative stress marker evaluation

2.6.1 LP

LP was assessed by measuring the amount of malondialdehyde (MDA), the end product of LP, according to the technique of Buege and Aust [30] with slight modifications [31], based on TBA (thiobarbituric acid) reactivity. The absorbance at 532 nm was then determined. The amount of MDA formed was expressed as nmol MDA/mg protein.

2.6.2 Reduced glutathione (GSH) levels

Liver GSH levels were measured by the colorimetric method reported by Khattabi et al. [32] by recording the absorbance values at 412 nm resulting from the formation of 2-nitro-5-mercapturic acid from the reduction of 5,5-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) by the SH groups present in GSH. The amount of GSH was expressed in nmol GSH/mg protein.

2.6.3 Glutathione peroxidase (GPx) activity

GPx activity in the liver homogenate was determined using the Flohé and Günzler [33] method, and the absorbance at 412 nm was recorded. GPx activity was expressed as nmol glutathione degraded/min/mg protein.

2.7 Histological examinations

Liver sections, previously fixed in formalin, were processed through graded alcohol baths followed by paraffin embedding. Liver sections were then cut at 4–5 µm thickness, stained with H&E (hematoxylin-eosin stain) following the technique of Houlot [34] and then examined under an optical microscope.

2.8 Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 7.0. The results are presented as mean ± SEM (standard error of mean) and were evaluated using ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

3 Results

3.1 Phenolic composition of GTCE

3.1.1 GT extract and phenolic composition

The results of LC-MS analyses of the GT extract are shown in Figures 1 and 2. The main phenolic compounds in GT are catechins (Figure 2) with predominance of (−) epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) 60.1 ± 0.17% followed by (−) epigallocatechin (EGC) 12 ± 0.25%, (−) epicatechin gallate (ECG) 13 ± 0.45%, and (−) epicatechin (EC) 5 ± 0.2%.

Chromatograms of LC-MS phenolic profile of GTCE. EGC: epigallocatechin; EC: epicatechin; EGCG: epigallocatechin-3-gallate; and ECG: epicatechin-3-gallate.

Proportion and structure of major catechin polyphenols GT. The results are expressed as averages of three independent measurements ± SEM.

3.2 Effects of GTCE on rat’s health

The death of two rats was recorded in the group treated at a dose of 800 mg/kg on the 20th day of the experiment and a decrease in the body weight from the starting day of the test, regardless of the administered dose of GTCE. This reduction was more accentuated in a group treated with 800 mg/kg during 28 days of experimentation.

3.3 Effects of GTCE on the body and absolute and relative liver weights

Changes in the body weight of the studied groups are shown in Table 1. The data showed a significant decrease (p < 0.05) in the body weight of rats treated with 800 mg/kg GTCE compared to control rats. No significant difference in the body weight was noted between the group treated at both doses (400 and 600 mg/kg) compared to the controls.

Body weight, weight gain, and absolute and relative liver weights of control and experimental rats

| Parameters | Experimental groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | D1 | D2 | D3 | |

| Initial weight (g) | 132.1 ± 3.6 | 131.7 ± 5.45 | 130.9 ± 5.40 | 130.1 ± 5.5 |

| Final weight (g) | 185.8 ± 6.7a | 165.2 ± 5.6a | 156.4 ± 4.5b | 115.3 ± 7.2c |

| Weight gain (%) | 53.7 ± 2a | 33.5 ± 1.5a | 26.5 ± 1.3b | −14.8 ± 1.4c |

| Absolute liver weight (g) | 3.56± 0.12a | 3.26 ± 0.15a | 3.05 ± 0.11a | 6.05 ± 0.26c |

| Relative liver weight (g/100 g body weight) | 1.92 ± 0.02a | 2.00 ± 0.05a | 2.03 ± 0.04a | 2.51 ± 0.17c |

Values are expressed as mean ± SEM; each group consisted of five rats. D1: rats treated with 400 mg/kg b.w. of GTCE; D2: rats treated with 600 mg/kg b.w. of GTCE; D3: rats treated with 800 mg/kg b.w. of GTCE; values in the same row with different letters are significantly different at p < 0.05.

As indicated in Table 1, the absolute and relative liver weights were significantly increased (p < 0.05) in GTCE at a dose of 800 mg/kg compared to controls.

3.4 Effect of GTCE on the lipid biochemical parameters

3.4.1 Cholesterol

The cholesterol concentrations in control and treated rats at the three tested doses of GTCE are shown in Table 2. Our results show that treatment with GTCE induces a significant decrease (p < 0.05) in the concentration of cholesterol in rats treated with GTCE at a 800 mg/kg dose compared to the control group. This value is not significant (p > 0.05) in treated rats at doses of 400 and 600 mg/kg not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

Plasma biochemical parameters in control and experimental rats

| Parameters | Experimental groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | D1 | D2 | D3 | |

| Cholesterol (mg/L) | 0.72 ± 0.15 | 0.6 ± 0.081a | 0.4 ± 0.091a | 0.2 ± 0.081b |

| Triglycerides (mg/L) | 1.62 ± 0.23a | 1.52 ± 0.14a | 1.25 ± 0.07a | 0.45 ± 0.07b |

| Total lipids (mg/L) | 3.13 ± 0.27a | 3.7 ± 0.14a | 2.65 ± 0.07c | 0.65 ± 0.13b |

Values are expressed as mean ± SEM; each group consisted of five rats. D1: rats treated with 400 mg/kg b.w. of GTCE; D2: rats treated with 600 mg/kg b.w. of GTCE; D3: rats treated with 800 mg/kg b.w. of GTCE; values in the same row with different letters are significantly different at p < 0.05.

3.4.2 Triglycerides

The effects of GTCE on the concentration of triglycerides in the control and treated rats are presented in Table 2. The results showed a significant decrease (p < 0.05) in triglyceride concentration at both doses 600 and 800 mg/kg of GTCE. In contrast, a non-significant increase (p > 0.05) in triglyceride concentration was recorded in rats that received 400 mg/kg of GTCE compared to the control group.

3.4.3 Total lipids

Plasma concentration of the total lipids was significantly decreased (p < 0.05) after treatment with both doses (600 and 800 mg/kg) (Table 2). However, a significant increase (p < 0.05) in total lipids in rats treated with 400 mg was observed compared to the control.

3.5 Oxidative stress parameters

3.5.1 MDA level

The liver MDA levels in the control and treated groups are shown in Figure 3a. In fact, GTCE at a dose of 800 mg/kg/day significantly increased (p < 0.05) the level of MDA. However, no significant difference in the MDA hepatic levels was noticed between the groups treated at doses of 400 and 600 mg/kg and the control group.

Hepatic GSH levels in the control and treated groups. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM; each group consisted of five rats. D1: rats treated with 400 mg/kg b.w. of GTCE; D2: rats treated with 600 mg/kg b.w. of GTCE; D3: rats treated with 800 mg/kg b.w. of GTCE; MDA: malondialdehyde; GSH: reduced glutathione. Values in the same row with different letters are significantly different at p < 0.05.

3.5.2 GSH level

Figure 3b shows the hepatic GSH levels in the control and treated groups. The administration of GTCE at a dose of 800 mg/kg induced a significant decrease (p < 0.05) in the concentration of GSH. In contrast, a significant increase (p < 0.05) in GSH levels was recorded in rats treated with both doses (400 and 600 mg/kg) compared to control rats.

3.5.3 GPx activity

Liver GPx activity in the studied groups is shown in Figure 4. Based on the obtained results, the enzymatic activity of GPx was significantly decreased (p < 0.05) at a dose of 800 mg/kg. Furthermore, our results showed a non-significant increase in GPx activity (p > 0.05) at doses 400 and 600 mg/kg.

Liver GPx activity in the studied groups. Values are given as mean ± SEM; each group consisted of five rats. D1: rats treated with 400 mg/kg BW of catechins; D2 rats treated with 600 mg/kg b.w of GTCE; D3 rats treated with 800 mg/kg b.w of GTCE; MDA: malondialdehyde; GSH: reduced glutathione. Values on the same row with different letters are significantly different at p < 0.05.

3.6 Gross macroscopic observations

The examination of the gross appearance of the liver of experimental rats (Figure 5) showed that the liver color of rats treated with GTCE at 800 mg/kg differed from other treatments at 400 and 600 mg/L as well for controls (Figure 5). The pro-oxidant effect may exist at the dose of 800 mg/L due to the macroscopic change in the liver.

Rat liver after 28 days of GTCE treatment. C: control; D1: rats treated with 400 mg/kg b.w of GTCE; D2 rats treated with 600 mg/kg b.w of GTCE; D3 rats treated with 800 mg/kg b.w of GTCE.

3.7 Light microscopy of liver

The observation under an optical microscope Leica of the liver sections of the control rats showed normal cellular architecture and hepatocytes polyhedral in a form of trabeculae with granular cytoplasm organized around the centrilobular vein (Figure 6a). Figure 6b–d shows microscopic changes in sections of livers of animals treated with increasing doses of GTCE (400, 600, and 800 mg/kg). The histological examination in rats treated with the three tested doses showed varying degrees of hepatic histological lesions, especially in rats treated with a dose of 800 mg/kg GTCE compared to rats treated with 600 mg/kg (Figure 6b) and 400 mg/kg (Figure 6c). Binucleated hepatocytes, vacuolar degeneration, parenchymal cells hypertrophy, and sinusoid dilation and congestion were also observed.

Effect of GTCE on histopathological changes in the liver. Controls (a), treated with 400 mg/kg GTCE (b); treated with 600 mg/kg (c), and treated with 800 mg/kg GTCE (d) after 28 days of treatment: sections were stained using the hematoxylin–eosin method; magnification: ×100. CV: centrilobular vein. Red arrow: sinusoid dilation and congestion, yellow circle: binucleated hepatocytes, black double arrow: parenchymal cells hypertrophy, red asterisk: vacuolar degeneration.

4 Discussion

Despite the wide consumption of GT as a beverage, and its beneficial effects proven by several studies, scientific data on its toxic effects at high doses are available [10,35]. In this context, the present study aimed to evaluate the impact of GTCE at increasing doses on the liver over a 28-day period. For this reason, a phytochemical study was performed in order to characterize its chemical composition. The results showed that the phenolic composition in GT is catechins, EGCG being the highest, accounting for 60–65% of the entire catechin content [36]. EGCG is the major catechin in GT and accounts for 50–80% [37,38]. Furthermore, chemical modification of the EGCG pharmacophore may modify relative therapeutic activities so that combinatorial supplementation may synergistically enhance the beneficial health effects [3,39].

In animal experiments, the changes in the behavior and body weight are important revealing indices of the health status [40], and this change is correlated with the animal’s physiological state [41]. In this study, treating rats with GTCE at a dose of 800 mg/kg significantly decreased the body weight. The observed reduction can be attributed to the anti-obesity effect, which inhibits the weight gain and the formation of adipose tissue [42], as reflected by reduced plasma triglyceride, cholesterol, and lipid levels in our study.

Relative organ weights are an essential part of the toxicological risk assessment of drugs, chemicals, and biologics [43]. The results of the present study reveal that GTCE at doses of 800 mg has a negative impact on the liver, resulting in an increase in the absolute and relative liver weights. The observed increase in organ weights can be attributed to an increase in hepatic metabolism following high doses administered. Here, it has been reported that GTCE at doses > 800 mg or at repeated doses causes liver damage [35].

Our results show that treatment with GTCE induces a significant decrease (p < 0.05) in the concentration of cholesterol in rats treated with a dose of 800 mg/kg. According to Sánchez-Muniz et al. [44], the decrease in cholesterol concentration is attributed to a reduction in the activity of lecithin cholesterol acyl transferase (LCAT), which is itself due to the reduction in the biosynthesis of HLVs at the liver level. On the other hand, Holloway and Rivers [45] explained that the decrease in cholesterol is due to the activation of 7-α-hydrolase, an enzyme responsible for the transformation of cholesterol into bile acids. The same phenomenon was observed after treatment with 400 mg/kg nigra leaf extract in female Wistar rats, resulting in decreased cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) [46]. These results proved that polyphenols have a hypolipidemic effect and induce a decrease in chronic damage in rats. In contrast, rats treated with 400 mg/L resulted in an increase in the plasma content of insignificant triglyceride (p > 0.05). The increase in triglyceride content was reported by Yuan and Kitts [47]. They speculated that the supplementation of 130 g of phenolic extracts in non-fasting rat food promotes increased triglyceride concentration because phenolic extracts tend to increase the concentration of triglycerides in comparison with controls. This effect was not predicted, and they assumed that phenolic (catechins) extracts slowed the kinetics of lipid absorption, or exposed to a lipotropic action on the liver.

The assessment of the cytotoxic effect of GT catechins and the hypothesis of a pro-oxidizing effect on body growth, liver, and serum lipids in growing female rats were investigated. Additionally, growth retardation was observed in all rats treated with polyphenols relative to controls regardless of catechins at doses 400, 600, and 800 mg/kg. Previous studies conducted on rodents showed a decrease in lipid liver accumulation, particularly triglycerides and cholesterol following tea consumption [48]. In addition, in a double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, it was reported that high doses of EGCG (856.8 mg/day) reduced plasma cholesterol and LDL levels [49].

However, the mechanisms involved in this decline in liver lipids are still far from clear. Indeed, it has been shown that tea decreases the genes involved in lipogenesis and increases those involved in oxidation, but the precise mechanisms involved in this regulation are not clearly described. At the cellular level, several studies have examined the lipotropic effect of GT catechins, particularly EGCG, but few studies have investigated the lipotropic effects of a global tea extract, let alone a mixture of several teas [50,51]. Some studies suggest that EGCG directly influences lipid metabolism by inhibiting intestinal lipid absorption, increasing LDL receptor expression, and activating AMPK, which promotes fatty acid oxidation [17,18]. However, at high doses, EGCG has been associated with liver failure [19,20], which may indirectly affect the lipid levels. Liver damage can alter lipid metabolism due to disrupted hepatic function, leading to reduced cholesterol and triglyceride levels.

Oxidative stress can advance oxidative damage involving cellular proteins, lipids, DNA, and other molecules in a way that could lead to abnormal cell functions. The results obtained in our study for the oxidative stress portion showed a well-defined increase in the liver tissue MDA concentration in rats treated with the catechins at a dose of 800 mg/L compared to rats treated with 400 and 600 mg/L and normal control. MDA is the most widely used parameter for assessing oxidative lipid damage, although it is known that oxidative damage to amino acids, proteins, and DNA also results in MDA release [52]. The observed increase in the liver MDA confirmed the hepatotoxic effect of GTCE at higher doses. This study shows that GTCE causes a significant decrease in GSH levels in the rat liver. The significant depletion of GSH levels is associated with a decrease in GPx activity (P < 0.05). In this context, several studies reported the damaging effect of EGCG at higher doses on hepatic tissues in vivo and in vitro [24,53,16]. Regarding tissue aberrations, the hepatic tissue sections demonstrated the presence of vacuolization, binucleated cells, and prominent congestion and sinusoidal dilatation, which notably for groups D3 and D2, was previously regarded as a side effect of cytotoxic factor activity. Its accumulation is now recognized as a critical initiating event that triggers metabolic disruptions or stress responses, ultimately resulting in cell death [32]. The binucleate cells are frequently observed in several organs, such as the liver, salivary glands, and endometrium, although their functional significance remains unclear. The heightened presence of binucleate hepatocytes during the necro-inflammatory phase of progressive chronic hepatitis and in cirrhosis, coupled with their absence in hepatocellular carcinoma, suggests that they might serve as an indicator of hepatic disease severity rather than arising from cell cycle errors [54]. Sinusoidal dilatation is primarily characterized by the enlargement of hepatic sinusoids, typically identified as a prominent histopathological feature. Initially considered an artifact or nonspecific change, growing evidence suggests that sinusoidal dilatation is linked to inflammatory diseases, portal hypertension and vascular disorders [55]. Hypertrophy refers to the enlargement of cells due to increased synthesis of structural components, rather than the accumulation of water, glycogen, or lipids. When a significant number of cells grow in size, this can lead to a noticeable increase in tissue or organ mass. Exposure to high levels of toxic metabolites induces various tissue changes. In the liver, these include hepatocyte hypertrophy, hepatitis, hepatocellular necrosis, and hepatocellular death [56]. Effectively, previous findings suggest that induced oxidative stress in liver hepatocytes has increased bile duct hyperplasia, as hepatocytes surrounding the bile ducts display positive signals to a significant extent [57].

5 Conclusion

The chemical composition analysis of GTCE using LC-MS identified EGCG as the most abundant component. Catechins demonstrated cytotoxic effects on lipid parameters, leading to a reduction in lipid accumulation, particularly triglycerides and cholesterol. However, the mechanisms underlying this lipid reduction in the liver remain poorly understood. The findings of our study indicate that high doses of GTCE induce hepatotoxicity, characterized by elevated oxidative stress, histological alterations, and, in severe cases, the death of some rats.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Conceptualization: Amrouche Zoheir; data curation and formal analysis: Amrouche Zoheir, Khattabi Latifa, and Ayomide Victor Atoki; funding acquisition: Ayomide Victor Atoki; investigation: Amrouche Zoheir and Laribi-Habchi Hassiba; methodology: Amrouche Zoheir, Marie-Laure Fauconnier, and Laribi-Habchi Hassiba; project administration: Amrouche Zoheir; resources: Ayomide Victor Atoki and Marie-Laure Fauconnier; supervision: Amrouche Zoheir; validation: Tichati Lazhari and Messaoudi Mohammed; visualization: Tichati Lazhari and Messaoudi Mohammed; writing – original draft: Amrouche Zoheir and Khattabi Latifa; writing – review and editing: Khattabi Latifa and Tichati Lazhari.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

-

Ethical approval: All the protocols used in this study were conducted according to the International Guidelines for Laboratory Animal Care and Use (Council of European Communities,JO86/609/CEE) and approved by the Ethical Committee of Directorate General for Scientific Research and Technological Development at Algerian Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research. All experimental procedures were conducted according to the International Guidelines for Laboratory Animal Care and Use (Council of European Communities 1986;. Council instructions about the protection of living animals used in scientific investigations. Off J Eur Commun L.358:1–18).

-

Data availability statement: The data required to support the findings of this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

References

[1] Li YH, Wu Y, Wei HC, Xu YY, Jia LL, Chen J, et al. Protective effects of green tea extracts on photoaging and photommunosuppression. Skin Res Technol. 2009;15(3):338–45.10.1111/j.1600-0846.2009.00370.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Siddiqui IA, Asim M, Hafeez BB, Adhami VM, Tarapore RS, Mukhtar H. Green tea polyphenol EGCG blunts androgen receptor function in prostate cancer. FASEB J. 2011;25(4):1198–207.10.1096/fj.10-167924Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Bose A. Interaction of tea polyphenols with serum albumins: A fluorescence spectroscopic analysis. J Lumin. 2016;169:220–6.10.1016/j.jlumin.2015.09.018Search in Google Scholar

[4] Rubab S, Rizwani GH, Bahadur S, Shah M, Alsamadany H, Alzahrani Y, et al. Determination of the GC–MS analysis of seed oil and assessment of pharmacokinetics of leaf extract of Camellia sinensis L. J King Saud Univ-Sci. 2020;32(7):3138–44.10.1016/j.jksus.2020.08.026Search in Google Scholar

[5] Sang S, Tian S, Wang H, Stark RE, Rosen RT, Yang CS, et al. Chemical studies of the antioxidant mechanism of tea catechins: Radical reaction products of epicatechin with peroxyl radicals. Bioorg Med Chem. 2003;11(16):3371–8.10.1016/S0968-0896(03)00367-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Kaya-Dagistanli F, Tanriverdi G, Altin A, Ozyazgan S, Ozturk M. The effects of alpha lipoic acid on liver cells damages and apoptosis induced by polyunsaturated fatty acids. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;53:84–93.10.1016/j.fct.2012.11.026Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Thawonsuwan J, Kiron V, Satoh S, Panigrahi A, Verlhac V. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) affects the antioxidant and immune defense of the rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss. Fish Physiol Biochem. 2010;36(3):687–97.10.1007/s10695-009-9344-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Gan RY, Li HBin, Sui ZQ, Corke H. Absorption, metabolism, anti-cancer effect and molecular targets of epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG): An updated review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2018 Apr;58(6):924–41.10.1080/10408398.2016.1231168Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Sano M, Tabata M, Suzuki M, Degawa M, Miyase T, Maeda-Yamamoto M. Simultaneous determination of twelve tea catechins by high-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection. Analyst. 2001;126(6):816–20.10.1039/b102541bSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Hu J, Webster D, Cao J, Shao A. The safety of green tea and green tea extract consumption in adults–results of a systematic review. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2018;95:412–33.10.1016/j.yrtph.2018.03.019Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Tomás-Barberán FA, Andrés-Lacueva C. Polyphenols and health: Current state and progress. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60(36):8773–5.10.1021/jf300671jSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Cao SY, Zhao CN, Gan RY, Xu XY, Wei XL, Corke H, et al. Effects and mechanisms of tea and its bioactive compounds for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases: An updated review. Antioxidants. 2019;8(6):166.10.3390/antiox8060166Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Wu CH, Lu FH, Chang CS, Chang TC, Wang RH, Chang CJ. Relationship among habitual tea consumption, percent body fat, and body fat distribution. Obes Res. 2003;11:1088–95. North American Assoc for the Study of Obesity.10.1038/oby.2003.149Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Iso H, Date C, Wakai K, Fukui M, Tamakoshi A, Mori M, et al. The relationship between green tea and total caffeine intake and risk for self-reported type 2 diabetes among Japanese adults. Ann Intern Med. 2006 Apr;144(8):554–62.10.7326/0003-4819-144-8-200604180-00005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] El-Bakry HA, El-Sherif G, Rostom RM. Therapeutic dose of green tea extract provokes liver damage and exacerbates paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity in rats through oxidative stress and caspase 3-dependent apoptosis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;96:798–811.10.1016/j.biopha.2017.10.055Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Ouyang J, Zhu K, Liu Z, Huang J. Prooxidant effects of epigallocatechin‐3‐gallate in health benefits and potential adverse effect. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020;2020(1):9723686.10.1155/2020/9723686Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Raederstorff DG, Schlachter MF, Elste V, Weber P. Effect of EGCG on lipid absorption and plasma lipid levels in rats. J Nutr Biochem. 2003 Jun;14(6):326–32. [cited 2025 Mar 14] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12873714/.10.1016/S0955-2863(03)00054-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Li K, Zhou X, Yang X, Shi X, Song X, Ye C, et al. Subacute oral toxicity of cocoa tea (Camellia ptilophylla) water extract in SD rats. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2015 Nov;50(11):2391–401.10.1111/ijfs.12905Search in Google Scholar

[19] Grajecki D, Ogica A, Boenisch O, Hübener P, Kluge S. Green tea extract-associated acute liver injury: Case report and review. Clin Liver Dis. 2022 Dec;20(6):181–7. [cited 2025 Mar 14]. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36523867/.10.1002/cld.1254Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Wang X, Yang L, Wang J, Zhang Y, Dong R, Wu X, et al. A mouse model of subacute liver failure with ascites induced by step-wise increased doses of (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate. Sci Rep . 2019 Dec;9(1):1–9. [cited 2025 Mar 14] https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-54691-0.10.1038/s41598-019-54691-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Bedrood Z, Rameshrad M, Hosseinzadeh H. Toxicological effects of Camellia sinensis (green tea): A review. Phyther Res. 2018 Jul;32(7):1163–80.10.1002/ptr.6063Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Younes M, Aggett P, Aguilar F, Crebelli R, Dusemund B, Filipič M, et al. Scientific opinion on the safety of green tea catechins. EFSA J. 2018;16(4):e05239. 10.2903/j.efsa.2018.5239.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Molinari M, Watt KDS, Kruszyna T, Nelson R, Walsh M, Huang WY, et al. Acute liver failure induced by green tea extracts: Case report and review of the literature. Liver Transplant. 2006 Dec;12(12):1892–5. journals.lww.com.10.1002/lt.21021Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Wang D, Wang Y, Wan X, Yang CS, Zhang J. Green tea polyphenol (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate triggered hepatotoxicity in mice: Responses of major antioxidant enzymes and the Nrf2 rescue pathway. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2015;283(1):65–74.10.1016/j.taap.2014.12.018Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Amrouche Z, El-Hadi D, Fauconnier ML, Benrima-Guendouz A, Bitam A. Oxidative stress of bioactive molecules antioxidant (EGCG) polyphenols extract of green tea (Camellia sinensis L.). AgroBiologia. 2018;8(1):727–34, http://agrobiologia.net/editions/AGROBIOLOGIAVOL-8-N-01_final.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Amrouche Z, Blecker C, Laribi-Habchi H, Fauconnier ML, El-Hadi D. Antioxydant activity, oxidative stability properties of Colza oil, comparison of mechanical agitated and ultrasonic extraction on green tea catechins of Camellia sinensis L. Algerian J Environ Sci Technol. December edition. 2021;7:2167–76, www.aljest.org.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Lin LZ, Chen P, Harnly JM. New phenolic components and chromatographic profiles of green and fermented teas. J Agric Food Chem. 2008 Sep;56(17):8130–40.10.1021/jf800986sSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Tichati L, Trea F, Ouali K. The antioxidant study proprieties of Thymus munbyanus aqueous extract and its beneficial effect on 2, 4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid -induced hepatic oxidative stress in albino Wistar rats. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2021;31(3):212–23. [cited 2025 Mar 14] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33371761/.10.1080/15376516.2020.1870183Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Lekouaghet A, Boutefnouchet A, Bensuici C, Gali L, Ghenaiet K, Tichati L. In vitro evaluation of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of the hydroalcoholic extract and its fractions from Leuzea conifera L. roots. South Afr J Botany. 2020;132:103–7.10.1016/j.sajb.2020.03.042Search in Google Scholar

[30] Buege JA, Aust SD, Biomembranes -, Part C. Biological oxidations. Methods Enzymol. 1978;52:302–10. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0076687978520326.10.1016/S0076-6879(78)52032-6Search in Google Scholar

[31] Khattabi L, Khaldi T, Bahri L, Mokhtari MB, Bouhenna MM, Temime A, et al. Insights about the deleterious impact of a carbamate pesticide on some metabolic immune and antioxidant functions and a focus on the protective ability of a Saharan shrub and its anti-edematous property. Open Chem. 2024;22(1):20240022.10.1515/chem-2024-0022Search in Google Scholar

[32] Khattabi L, Chettoum A, Hemida H, Boussebaa W, Atanassova M, Messaoudi M. Pirimicarb induction of behavioral disorders and of neurological and reproductive toxicities in male rats: Euphoric and Preventive effects of Ephedra alata Monjauzeana. Pharmaceuticals. 2023;16(3):402.10.3390/ph16030402Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Flohé L, Günzler WA. Assays of glutathione peroxidase. In: Methods in Enzymology. Vol. 105, Elsevier; 1984. p. 114–20. 10.1016/S0076-6879(84)05015-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Houlot R. Techniques d’histologie et de cytologie. Edition Ma. 1984;186:1–85.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Oketch-Rabah HA, Roe AL, Rider CV, Bonkovsky HL, Giancaspro GI, Navarro V, et al. United States Pharmacopeia (USP) comprehensive review of the hepatotoxicity of green tea extracts. Toxicol Rep. 2020;7:386–402.10.1016/j.toxrep.2020.02.008Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] Yang CS, Hong J. Prevention of chronic diseases by tea: Possible mechanisms and human relevance. Annu Rev Nutr. 2013 Jul;33:161–81.10.1146/annurev-nutr-071811-150717Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Khan N, Afaq F, Saleem M, Ahmad N, Mukhtar H. Targeting multiple signaling pathways by green tea polyphenol (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate. Cancer Res. 2006;66(5):2500–5. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3636.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Tang GY, Zhao CN, Xu XY, Gan RY, Cao SY, Liu Q, et al. Phytochemical composition and antioxidant capacity of 30 chinese teas. Antioxidants. 2019;8(6):180.10.3390/antiox8060180Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Giunta B, Hou H, Zhu Y, Salemi J, Ruscin A, Shytle RD, et al. Fish oil enhances anti-amyloidogenic properties of green tea EGCG in Tg2576 mice. Neurosci Lett. 2010;471(3):134–8.10.1016/j.neulet.2010.01.026Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] Ezeja MI, Anaga AO, Asuzu IU. Acute and sub-chronic toxicity profile of methanol leaf extract of Gouania longipetala in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;151(3):1155–64.10.1016/j.jep.2013.12.034Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] El Kabbaoui M, Chda A, El-Akhal J, Azdad O, Mejrhit N, Aarab L, et al. Acute and sub-chronic toxicity studies of the aqueous extract from leaves of Cistus ladaniferus L. in mice and rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2017;209:147–56.10.1016/j.jep.2017.07.029Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Huang YW, Liu Y, Dushenkov S, Ho CT, Huang MT. Anti-obesity effects of epigallocatechin-3-gallate, orange peel extract, black tea extract, caffeine and their combinations in a mouse model. J Funct Foods. 2009;1(3):304–10.10.1016/j.jff.2009.06.002Search in Google Scholar

[43] Sellers RS, Morton D, Michael B, Roome N, Johnson JK, Yano BL, et al. Society of Toxicologic Pathology position paper: Organ weight recommendations for toxicology studies. Toxicol Pathol. 2007;35:751–5.10.1080/01926230701595300Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] López-Varela S, Sánchez-Muniz FJ, Cuesta C. Decreased food efficiency ratio, growth retardation and changes in liver fatty acid composition in rats consuming thermally oxidized and polymerized sunflower oil used for frying. Food Chem Toxicol. 1995;33(3):181–9.10.1016/0278-6915(94)00133-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] Holloway D, Rivers JM. Influence of chronic ascorbic acid deficiency and excessive ascorbic acid intake on bile acid metabolism and bile composition in the guinea pig. J Nutr. 1981;111(3):412–24.10.1093/jn/111.3.412Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Volpato GT, Calderon IMP, Sinzato S, Campos KE, Rudge MVC, Damasceno DC. Effect of Morus nigra aqueous extract treatment on the maternal–fetal outcome, oxidative stress status and lipid profile of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011 Dec;138(3):691–6.10.1016/j.jep.2011.09.044Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Yuan YV, Kitts DD. Dietary (n-3) fat and cholesterol alter tissue antioxidant enzymes and susceptibility to oxidation in SHR and WKY rats. J Nutr. 2003;133(3):679–88.10.1093/jn/133.3.679Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Axling U, Olsson C, Xu J, Fernandez C, Larsson S, Ström K, et al. Green tea powder and Lactobacillus plantarum affect gut microbiota, lipid metabolism and inflammation in high-fat fed C57BL/6J mice. Nutrition Metab. 2012;9:1–18.10.1186/1743-7075-9-105Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] Chen IJ, Liu CY, Chiu JP, Hsu CH. Therapeutic effect of high-dose green tea extract on weight reduction: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clin Nutr. 2016 Jun;35(3):592–9. [cited 2025 Mar 14] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26093535/.10.1016/j.clnu.2015.05.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[50] Kim JJ, Tan Y, Xiao L, Sun YL, Qu X. Green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin‐3‐gallate enhance glycogen synthesis and inhibit lipogenesis in hepatocytes. BioMed Res Int. 2013;2013(1):920128.10.1155/2013/920128Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[51] Goto T, Saito Y, Morikawa K, Kanamaru Y, Nagaoka S. Epigallocatechin gallate changes mRNA expression level of genes involved in cholesterol metabolism in hepatocytes. Br J Nutr. 2012;107(6):769–73.10.1017/S0007114511003758Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[52] Sundaram R, Naresh R, Shanthi P, Sachdanandam P. Modulatory effect of green tea extract on hepatic key enzymes of glucose metabolism in streptozotocin and high fat diet induced diabetic rats. Phytomedicine. 2013;20(7):577–84.10.1016/j.phymed.2013.01.006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[53] Kucera O, Mezera V, Moravcova A, Endlicher R, Lotkova H, Drahota Z, et al. In vitro toxicity of epigallocatechin gallate in rat liver mitochondria and hepatocytes. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2015;2015:476180.10.1155/2015/476180Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[54] Grizzi F, Chiriva-Internati M. Human binucleate hepatocytes: Are they a defence during chronic liver diseases? Med Hypotheses. 2007;69:258–61.10.1016/j.mehy.2006.12.029Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[55] Shen H, Dong J, Xia L, Xu J, Xu L. Rat liver sinusoidal dilatation induced by perfusion in vitro through portal vein alone, hepatic artery alone, and portal vein together with hepatic artery. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2016;9(6):11284–91.Search in Google Scholar

[56] Ozcelik D, Ozaras R, Gurel Z, Uzun H, Aydin S. Copper-mediated oxidative stress in rat liver. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2003;96:209–15.10.1385/BTER:96:1-3:209Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[57] Lee YH, Lim CH, Chung YH. Oxidative stress and sex difference in liver of rats exposed to cyclohexanone. Int J Morphol. 2018;36(3):881–5.10.4067/S0717-95022018000300881Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Phytochemical investigation and evaluation of antioxidant and antidiabetic activities in aqueous extracts of Cedrus atlantica

- Influence of B4C addition on the tribological properties of bronze matrix brake pad materials

- Discovery of the bacterial HslV protease activators as lead molecules with novel mode of action

- Characterization of volatile flavor compounds of cigar with different aging conditions by headspace–gas chromatography–ion mobility spectrometry

- Effective remediation of organic pollutant using Musa acuminata peel extract-assisted iron oxide nanoparticles

- Analysis and health risk assessment of toxic elements in traditional herbal tea infusions

- Cadmium exposure in marine crabs from Jiaxing City, China: Insights into health risk assessment

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles of Cinnamomum zeylanicum and their biological activities

- Tetraclinis articulata (Vahl) Mast., Mentha pulegium L., and Thymus zygis L. essential oils: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antifungal properties against postharvest fungal diseases of apple, and in vitro, in vivo, and in silico investigation

- Exploration of plant alkaloids as potential inhibitors of HIV–CD4 binding: Insight into comprehensive in silico approaches

- Recovery of phenylethyl alcohol from aqueous solution by batch adsorption

- Electrochemical approach for monitoring the catalytic action of immobilized catalase

- Green synthesis of ZIF-8 for selective adsorption of dyes in water purification

- Optimization of the conditions for the preparation of povidone iodine using the response surface methodology

- A case study on the influence of soil amendment on ginger oil’s physicochemical properties, mineral contents, microbial load, and HPLC determination of its vitamin level

- Removal of antiviral favipiravir from wastewater using biochar produced from hazelnut shells

- Effect of biochar and soil amendment on bacterial community composition in the root soil and fruit of tomato under greenhouse conditions

- Bioremediation of malachite green dye using Sargassum wightii seaweed and its biological and physicochemical characterization

- Evaluation of natural compounds as folate biosynthesis inhibitors in Mycobacterium leprae using docking, ADMET analysis, and molecular dynamics simulation

- Novel insecticidal properties of bioactive zoochemicals extracted from sea urchin Salmacis virgulata

- Elevational gradients shape total phenolic content and bioactive potential of sweet marjoram (Origanum majorana L.): A comparative study across altitudinal zones

- Study on the CO2 absorption performance of deep eutectic solvents formed by superbase DBN and weak acid diethylene glycol

- Preparation and wastewater treatment performance of zeolite-modified ecological concrete

- Multifunctional chitosan nanoparticles: Zn2+ adsorption, antimicrobial activity, and promotion of aquatic health

- Comparative analysis of nutritional composition and bioactive properties of Chlorella vulgaris and Arthrospira platensis: Implications for functional foods and dietary supplements

- Growth kinetics and mechanical characterization of boride layers formed on Ti6Al4V

- Enhancement of water absorption properties of potassium polyacrylate-based hydrogels in CaCl2-rich soils using potassium di- and tri-carboxylate salts

- Electrochemical and microbiological effects of dumpsite leachates on soil and air quality

- Modeling benzene physicochemical properties using Zagreb upsilon indices

- Characterization and ecological risk assessment of toxic metals in mangrove sediments near Langen Village in Tieshan Bay of Beibu Gulf, China

- Protective effect of Helicteres isora, an efficient candidate on hepatorenal toxicity and management of diabetes in animal models

- Valorization of Juglans regia L. (Walnut) green husk from Jordan: Analysis of fatty acids, phenolics, antioxidant, and cytotoxic activities

- Molecular docking and dynamics simulations of bioactive terpenes from Catharanthus roseus essential oil targeting breast cancer

- Selection of a dam site by using AHP and VIKOR: The Sakarya Basin

- Characterization and modeling of kidney bean shell biochar as adsorbent for caffeine removal from aquatic environments

- The effects of short-term and long-term 2100 MHz radiofrequency radiation on adult rat auditory brainstem response

- Biochemical insights into the anthelmintic and anti-inflammatory potential of sea cucumber extract: In vitro and in silico approaches

- Resveratrol-derived MDM2 inhibitors: Synthesis, characterization, and biological evaluation against MDM2 and HCT-116 cells

- Phytochemical constituents, in vitro antibacterial activity, and computational studies of Sudanese Musa acuminate Colla fruit peel hydro-ethanol extract

- Chemical composition of essential oils reviewed from the height of Cajuput (Melaleuca leucadendron) plantations in Buru Island and Seram Island, Maluku, Indonesia

- Phytochemical analysis and antioxidant activity of Azadirachta indica A. Juss from the Republic of Chad: in vitro and in silico studies

- Stability studies of titanium–carboxylate complexes: A multi-method computational approach

- Efficient adsorption performance of an alginate-based dental material for uranium(vi) removal

- Synthesis and characterization of the Co(ii), Ni(ii), and Cu(ii) complexes with a 1,2,4-triazine derivative ligand

- Evaluation of the impact of music on antioxidant mechanisms and survival in salt-stressed goldfish

- Optimization and validation of UPLC method for dapagliflozin and candesartan cilexetil in an on-demand formulation: Analytical quality by design approach

- Biomass-based cellulose hydroxyapatite nanocomposites for the efficient sequestration of dyes: Kinetics, response surface methodology optimization, and reusability

- Multifunctional nitrogen and boron co-doped carbon dots: A fluorescent probe for Hg2+ and biothiol detection with bioimaging and antifungal applications

- Separation of sulphonamides on a C12-diol mixed-mode HPLC column and investigation of their retention mechanism

- Characterization and antioxidant activity of pectin from lemon peels

- Fast PFAS determination in honey by direct probe electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry: A health risk assessment insight

- Correlation study between GC–MS analysis of cigarette aroma compounds and sensory evaluation

- Synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular docking studies of substituted chromone-2-carboxamide derivatives as anti-breast cancer agents

- The influence of feed space velocity and pressure on the cold flow properties of diesel fuel

- Acid etching behavior and mechanism in acid solution of iron components in basalt fibers

- Protective effect of green synthesized nanoceria on retinal oxidative stress and inflammation in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat

- Evaluation of the antianxiety activity of green zinc nanoparticles mediated by Boswellia thurifera in albino mice by following the plus maze and light and dark exploration tests

- Yeast as an efficient and eco-friendly bifunctional porogen for biomass-derived nitrogen-doped carbon catalysts in the oxygen reduction reaction

- Novel descriptors for the prediction of molecular properties

- Synthesis and characterization of surfactants derived from phenolphthalein: In vivo and in silico studies of their antihyperlipidemic effect

- Turmeric oil-fortified nutraceutical-SNEDDS: An approach to boost therapeutic effectiveness of dapagliflozin during treatment of diabetic patients

- Analysis and study on volatile flavor compounds of three Yunnan cultivated cigars based on headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry

- Near-infrared IR780 dye-loaded poloxamer 407 micelles: Preparation and in vitro assessment of anticancer activity

- Study on the influence of the viscosity reducer solution on percolation capacity of thin oil in ultra-low permeability reservoir

- Detection method of Aristolochic acid I based on magnetic carrier Fe3O4 and gold nanoclusters

- Juglone’s apoptotic impact against eimeriosis-induced infection: a bioinformatics, in-silico, and in vivo approach

- Potential anticancer agents from genus Aerva based on tubulin targets: an in-silico integration of quantitative structure activity relationship (QSAR), molecular docking, simulation, drug-likeness, and density functional theory (DFT) analysis

- Hepatoprotective and PXR-modulating effects of Erodium guttatum extract in propiconazole-induced toxicity

- Studies on chemical composition of medicinal plants collected in natural locations in Ecuador

- A study of different pre-treatment methods for cigarettes and their aroma differences

- Cytotoxicity and molecular mechanisms of quercetin, gallic acid, and pinocembrin in Caco-2 cells: insights from cell viability assays, network pharmacology, and molecular docking

- Choline-based deep eutectic solvents for green extraction of oil from sour cherry seeds

- Green-synthesis of chromium (III) nanoparticles using garden fern and evaluation of its antibacterial and anticholinesterase activities

- Innovative functional mayonnaise formulations with watermelon seeds oil: evaluation of quality parameters and storage stability

- Molecular insights and biological evaluation of compounds isolated from Ferula oopoda against diabetes, advanced glycation end products and inflammation in diabetics

- Removal of cytotoxic tamoxifen from aqueous solutions using a geopolymer-based nepheline–cordierite adsorbent

- Unravelling the therapeutic effect of naturally occurring Bauhinia flavonoids against breast cancer: an integrated computational approach

- Characterization of organic arsenic residues in livestock and poultry meat and offal and consumption risks

- Synthesis and characterization of zinc sulfide nanoparticles and their genotoxic and cytotoxic effects on acute myeloid leukemia cells

- Activity of Coriandrum sativum methanolic leaf extracts against Eimeria papillata: a combined in vitro and in silico approach

- Special Issue on Advancing Sustainable Chemistry for a Greener Future

- One-pot fabrication of highly porous morphology of ferric oxide-ferric oxychloride/poly-O-chloroaniline nanocomposite seeded on poly-1H pyrrole: Photocathode for green hydrogen generation from natural and artificial seawater

- High-efficiency photocathode for green hydrogen generation from sanitation water using bismuthyl chloride/poly-o-chlorobenzeneamine nanocomposite

- Innovative synthesis of cobalt-based catalysts using ionic liquids and deep eutectic solvents: A minireview on electrocatalytic water splitting

- Special Issue on Phytochemicals, Biological and Toxicological Analysis of Plants

- Comparative analysis of fruit quality parameters and volatile compounds in commercially grown citrus cultivars

- Total phenolic, flavonoid, flavonol, and tannin contents as well as antioxidant and antiparasitic activities of aqueous methanol extract of Alhagi graecorum plant used in traditional medicine: Collected in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- Study on the pharmacological effects and active compounds of Apocynum venetum L.

- Chemical profile of Senna italica and Senna velutina seed and their pharmacological properties

- Essential oils from Brazilian plants: A literature analysis of anti-inflammatory and antimalarial properties and in silico validation

- Toxicological effects of green tea catechin extract on rat liver: Delineating safe and harmful doses

- Unlocking the potential of Trigonella foenum-graecum L. plant leaf extracts against diabetes-associated hypertension: A proof of concept by in silico studies

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Phytochemical investigation and evaluation of antioxidant and antidiabetic activities in aqueous extracts of Cedrus atlantica

- Influence of B4C addition on the tribological properties of bronze matrix brake pad materials

- Discovery of the bacterial HslV protease activators as lead molecules with novel mode of action

- Characterization of volatile flavor compounds of cigar with different aging conditions by headspace–gas chromatography–ion mobility spectrometry

- Effective remediation of organic pollutant using Musa acuminata peel extract-assisted iron oxide nanoparticles

- Analysis and health risk assessment of toxic elements in traditional herbal tea infusions

- Cadmium exposure in marine crabs from Jiaxing City, China: Insights into health risk assessment

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles of Cinnamomum zeylanicum and their biological activities

- Tetraclinis articulata (Vahl) Mast., Mentha pulegium L., and Thymus zygis L. essential oils: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antifungal properties against postharvest fungal diseases of apple, and in vitro, in vivo, and in silico investigation

- Exploration of plant alkaloids as potential inhibitors of HIV–CD4 binding: Insight into comprehensive in silico approaches

- Recovery of phenylethyl alcohol from aqueous solution by batch adsorption

- Electrochemical approach for monitoring the catalytic action of immobilized catalase

- Green synthesis of ZIF-8 for selective adsorption of dyes in water purification

- Optimization of the conditions for the preparation of povidone iodine using the response surface methodology

- A case study on the influence of soil amendment on ginger oil’s physicochemical properties, mineral contents, microbial load, and HPLC determination of its vitamin level

- Removal of antiviral favipiravir from wastewater using biochar produced from hazelnut shells

- Effect of biochar and soil amendment on bacterial community composition in the root soil and fruit of tomato under greenhouse conditions

- Bioremediation of malachite green dye using Sargassum wightii seaweed and its biological and physicochemical characterization

- Evaluation of natural compounds as folate biosynthesis inhibitors in Mycobacterium leprae using docking, ADMET analysis, and molecular dynamics simulation

- Novel insecticidal properties of bioactive zoochemicals extracted from sea urchin Salmacis virgulata

- Elevational gradients shape total phenolic content and bioactive potential of sweet marjoram (Origanum majorana L.): A comparative study across altitudinal zones

- Study on the CO2 absorption performance of deep eutectic solvents formed by superbase DBN and weak acid diethylene glycol

- Preparation and wastewater treatment performance of zeolite-modified ecological concrete

- Multifunctional chitosan nanoparticles: Zn2+ adsorption, antimicrobial activity, and promotion of aquatic health

- Comparative analysis of nutritional composition and bioactive properties of Chlorella vulgaris and Arthrospira platensis: Implications for functional foods and dietary supplements

- Growth kinetics and mechanical characterization of boride layers formed on Ti6Al4V

- Enhancement of water absorption properties of potassium polyacrylate-based hydrogels in CaCl2-rich soils using potassium di- and tri-carboxylate salts

- Electrochemical and microbiological effects of dumpsite leachates on soil and air quality

- Modeling benzene physicochemical properties using Zagreb upsilon indices

- Characterization and ecological risk assessment of toxic metals in mangrove sediments near Langen Village in Tieshan Bay of Beibu Gulf, China

- Protective effect of Helicteres isora, an efficient candidate on hepatorenal toxicity and management of diabetes in animal models

- Valorization of Juglans regia L. (Walnut) green husk from Jordan: Analysis of fatty acids, phenolics, antioxidant, and cytotoxic activities

- Molecular docking and dynamics simulations of bioactive terpenes from Catharanthus roseus essential oil targeting breast cancer

- Selection of a dam site by using AHP and VIKOR: The Sakarya Basin

- Characterization and modeling of kidney bean shell biochar as adsorbent for caffeine removal from aquatic environments

- The effects of short-term and long-term 2100 MHz radiofrequency radiation on adult rat auditory brainstem response

- Biochemical insights into the anthelmintic and anti-inflammatory potential of sea cucumber extract: In vitro and in silico approaches

- Resveratrol-derived MDM2 inhibitors: Synthesis, characterization, and biological evaluation against MDM2 and HCT-116 cells

- Phytochemical constituents, in vitro antibacterial activity, and computational studies of Sudanese Musa acuminate Colla fruit peel hydro-ethanol extract

- Chemical composition of essential oils reviewed from the height of Cajuput (Melaleuca leucadendron) plantations in Buru Island and Seram Island, Maluku, Indonesia

- Phytochemical analysis and antioxidant activity of Azadirachta indica A. Juss from the Republic of Chad: in vitro and in silico studies

- Stability studies of titanium–carboxylate complexes: A multi-method computational approach

- Efficient adsorption performance of an alginate-based dental material for uranium(vi) removal

- Synthesis and characterization of the Co(ii), Ni(ii), and Cu(ii) complexes with a 1,2,4-triazine derivative ligand

- Evaluation of the impact of music on antioxidant mechanisms and survival in salt-stressed goldfish

- Optimization and validation of UPLC method for dapagliflozin and candesartan cilexetil in an on-demand formulation: Analytical quality by design approach

- Biomass-based cellulose hydroxyapatite nanocomposites for the efficient sequestration of dyes: Kinetics, response surface methodology optimization, and reusability

- Multifunctional nitrogen and boron co-doped carbon dots: A fluorescent probe for Hg2+ and biothiol detection with bioimaging and antifungal applications

- Separation of sulphonamides on a C12-diol mixed-mode HPLC column and investigation of their retention mechanism

- Characterization and antioxidant activity of pectin from lemon peels

- Fast PFAS determination in honey by direct probe electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry: A health risk assessment insight

- Correlation study between GC–MS analysis of cigarette aroma compounds and sensory evaluation

- Synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular docking studies of substituted chromone-2-carboxamide derivatives as anti-breast cancer agents

- The influence of feed space velocity and pressure on the cold flow properties of diesel fuel

- Acid etching behavior and mechanism in acid solution of iron components in basalt fibers

- Protective effect of green synthesized nanoceria on retinal oxidative stress and inflammation in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat

- Evaluation of the antianxiety activity of green zinc nanoparticles mediated by Boswellia thurifera in albino mice by following the plus maze and light and dark exploration tests

- Yeast as an efficient and eco-friendly bifunctional porogen for biomass-derived nitrogen-doped carbon catalysts in the oxygen reduction reaction

- Novel descriptors for the prediction of molecular properties

- Synthesis and characterization of surfactants derived from phenolphthalein: In vivo and in silico studies of their antihyperlipidemic effect

- Turmeric oil-fortified nutraceutical-SNEDDS: An approach to boost therapeutic effectiveness of dapagliflozin during treatment of diabetic patients

- Analysis and study on volatile flavor compounds of three Yunnan cultivated cigars based on headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry

- Near-infrared IR780 dye-loaded poloxamer 407 micelles: Preparation and in vitro assessment of anticancer activity

- Study on the influence of the viscosity reducer solution on percolation capacity of thin oil in ultra-low permeability reservoir

- Detection method of Aristolochic acid I based on magnetic carrier Fe3O4 and gold nanoclusters

- Juglone’s apoptotic impact against eimeriosis-induced infection: a bioinformatics, in-silico, and in vivo approach

- Potential anticancer agents from genus Aerva based on tubulin targets: an in-silico integration of quantitative structure activity relationship (QSAR), molecular docking, simulation, drug-likeness, and density functional theory (DFT) analysis

- Hepatoprotective and PXR-modulating effects of Erodium guttatum extract in propiconazole-induced toxicity

- Studies on chemical composition of medicinal plants collected in natural locations in Ecuador

- A study of different pre-treatment methods for cigarettes and their aroma differences

- Cytotoxicity and molecular mechanisms of quercetin, gallic acid, and pinocembrin in Caco-2 cells: insights from cell viability assays, network pharmacology, and molecular docking

- Choline-based deep eutectic solvents for green extraction of oil from sour cherry seeds

- Green-synthesis of chromium (III) nanoparticles using garden fern and evaluation of its antibacterial and anticholinesterase activities

- Innovative functional mayonnaise formulations with watermelon seeds oil: evaluation of quality parameters and storage stability

- Molecular insights and biological evaluation of compounds isolated from Ferula oopoda against diabetes, advanced glycation end products and inflammation in diabetics

- Removal of cytotoxic tamoxifen from aqueous solutions using a geopolymer-based nepheline–cordierite adsorbent

- Unravelling the therapeutic effect of naturally occurring Bauhinia flavonoids against breast cancer: an integrated computational approach

- Characterization of organic arsenic residues in livestock and poultry meat and offal and consumption risks

- Synthesis and characterization of zinc sulfide nanoparticles and their genotoxic and cytotoxic effects on acute myeloid leukemia cells

- Activity of Coriandrum sativum methanolic leaf extracts against Eimeria papillata: a combined in vitro and in silico approach

- Special Issue on Advancing Sustainable Chemistry for a Greener Future

- One-pot fabrication of highly porous morphology of ferric oxide-ferric oxychloride/poly-O-chloroaniline nanocomposite seeded on poly-1H pyrrole: Photocathode for green hydrogen generation from natural and artificial seawater

- High-efficiency photocathode for green hydrogen generation from sanitation water using bismuthyl chloride/poly-o-chlorobenzeneamine nanocomposite

- Innovative synthesis of cobalt-based catalysts using ionic liquids and deep eutectic solvents: A minireview on electrocatalytic water splitting

- Special Issue on Phytochemicals, Biological and Toxicological Analysis of Plants

- Comparative analysis of fruit quality parameters and volatile compounds in commercially grown citrus cultivars

- Total phenolic, flavonoid, flavonol, and tannin contents as well as antioxidant and antiparasitic activities of aqueous methanol extract of Alhagi graecorum plant used in traditional medicine: Collected in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- Study on the pharmacological effects and active compounds of Apocynum venetum L.

- Chemical profile of Senna italica and Senna velutina seed and their pharmacological properties

- Essential oils from Brazilian plants: A literature analysis of anti-inflammatory and antimalarial properties and in silico validation

- Toxicological effects of green tea catechin extract on rat liver: Delineating safe and harmful doses

- Unlocking the potential of Trigonella foenum-graecum L. plant leaf extracts against diabetes-associated hypertension: A proof of concept by in silico studies