Abstract

Chitosan nanoparticles (CSNPs) are one of the versatile materials that has potential applications in multidomains. However, these diverse applications are not seen in CSNPs produced from a single source. Owing to the above, in this study, we synthesized CSNPs using the ionotropic gelation method and characterized them with UV–visible spectroscopy, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) techniques for multi-application investigations. SEM and TEM analyses confirmed the spherical shape of the produced CSNPs with their size ranging from 10 to 40 nm. CSNPs were utilized for Zn2+ ion adsorption from aqueous solutions, optimized using response surface methodology. Optimal reaction conditions were pH 7, 60 min of contact time, and 100 mg/L initial concentration, and a loading capacity of 156.2 mg/g was achieved. The model was significant with p-value <0.0001 and lack-of-fit >0.1. CSNPs exhibited antimicrobial activity with zones of inhibition of 25 mm for Escherichia coli and 24 mm for Staphylococcus aureus. Feeding trials with CSNP-supplemented diets in tilapia showed enhanced growth, reduced mortality, and improved red blood cell and white blood cell counts. These findings demonstrate the multi-functional potential of CSNPs prepared from one source, highlighting their applicability in sustainable practice.

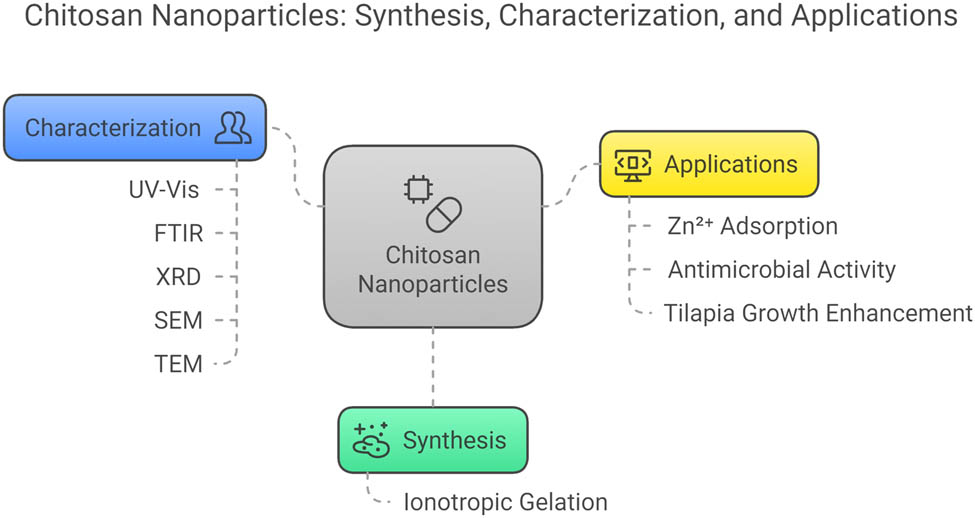

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

Nanotechnology has evolved significantly in almost all domains of science, engineering, technology, and medicine [1]. The unique size- and shape-dependent properties have made the nanomaterials most promising in almost every domain [2]. In general, metal nanoparticles (NPs) are found to have several unique applications in various domains. Similarly, organic- or polymer-based NPs are finding prominence in medicine, wastewater treatments, and biomedical and food supplements.

Chitosan (CS) is a natural polymer that is abundantly available from plant sources. It is eco-friendly and economical in nature and its conversion to NPs will have significant applications. A very useful review of futuristic applications of chitosan nanoparticles (CSNPs) is reported by Murat and Karin [3]. Of the numerous applications, application in wastewater treatments is popular, and numerous investigations are performed on the removal of heavy metal ions and synthetic dyes using CSNPs. CSNPs with a mean size range of 40–100 nm were successfully employed in the adsorption of lead ions from aqueous solution with a loading capacity of 398 mg g−1 [4]. CSNPs prepared via the ionic gelation method were successfully used in the adsorption of eosin Y anionic dye with a high loading capacity of 3.3 g g−1 [5]. In another study, CSNPs extracted from shrimp shells were evaluated for the removal of Fe2+ and Mn2+ ions from aqueous solution with loading capacities of 116.2 and 74.1 mg g−1, respectively [6]. An insightful review on CSNPs as a potential nanosorbent for the removal of pollutants is reported by Benettayeb et al. [7].

Antimicrobial applications of CSNPs are another interesting area of investigation that has attracted the researchers. CSNPs prepared via the ionic gelation method were evaluated for antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli, Salmonella choleraesuis, Salmonella typhimurium, and Staphylococcus aureus, and the minimum inhibitory concentration values were less than 0.25 µg mL−1 [8]. In another study, CSNPs were evaluated as antimicrobial agents against Klebsiella pneumoniae, E. coli, S. aureus, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa and found to be superior to CS and chitin [9]. A comparative investigation against bacteria and fungi was performed for CSNPs and found that CSNPs were effective against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria compared to fungi [10]. A review on the antibacterial activity of CSNPs against various Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria has been reported by Chandrasekaran et al. [11], who highlights the role of CSNPs in biomedical applications.

The CSNPs not only find applications in wastewater treatment or biomedical application but have significant role in the food industry as well. CSNPs are safe to use as dietary supplements to fish to improve their growth and enhance their production and health [12]. CSNPs are biocompatible and non-toxic materials used in therapeutics, gene transport, biopesticides, as well as efficient fish feed additives [13]. In a study, CSNP-based fish feed administered to Oreochromis niloticus (L.) showed enhancement in their health acting as a better immunostimulant and antioxidant agent [14]. It was observed that CS-fortified meals cause significant enhancement in the health status compared to plant-based meals.

Owing to the multiple application potential, this study aims to synthesize CSNPs via the ionic gelation method and explore their application in adsorption of Zn2+ ions from aqueous solution, evaluate the antimicrobial efficacy of CSNPs, and further prepare them as a fish feed meal additive and evaluate their influence on fish growth and health.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Synthesis of CSNPs

The CSNPs were synthesized using the ionotropic gelation method, with minor modifications to the concentrations of CS and sodium tripolyphosphate (STPP). Initially, 3 g of CS powder (commercially purchased) was set aside, while a solution of 1 mL acetic acid mixed with 800 mL of distilled water was prepared and stirred with a magnetic stirrer for 20 min. The CS powder was gradually added to the stirring solution, and the mixture was maintained at 450 rpm. To ensure optimal conditions, the pH was adjusted to 4–5 by adding a sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution prepared by diluting two NaOH pellets in purified water. This solution was stirred continuously for 12 h to achieve complete dissolution and stability of the CS. Concurrently, an STPP solution was prepared by dissolving 0.40 g of STPP in 100 mL of distilled water using a motorized stirrer for 30 min to ensure complete dissolution. Subsequently, the STPP solution was added dropwise to the CS solution under instantaneous magnetic stirring for 40 min, creating a 0.4% (w/v) STPP solution. The resulting CS–TPP solution was centrifuged at 8,000 rpm and 4°C for 45 min, and the resulting pellets were washed thoroughly with distilled deionized water to remove impurities. The cleaned pellets were then dried in a hot air oven and stored for further use. These dried CSNPs were characterized for their properties and utilized in feed preparation, demonstrating their potential for practical applications.

2.2 CSNP characterization

The CSNPs were characterized using UV–visible spectroscopy (Shimadzu, Japan) in the range of 200–500 nm to find the maximum absorption peak to confirm preliminary formations. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (Avatar330, Thermo Nicolet) was employed to identify the surface functional groups in the range of 4,000–400 cm−1 via the KBr pellet method. Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD; Siemens D5000 X-ray diffractometer) was utilized to obtain the diffraction peaks of the CSNPs in the 2θ range of 5° and 100°. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM; SUPRA 55, Carl Zeiss NTS GMBH) was performed to assess the surface morphology of the CSNPs. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed to visualize the size and shape of the CSNPs, and it was performed on a Cu grid containing carbon coating.

2.3 Batch adsorption studies

The adsorption of Zn2+ ions by CSNPs was performed in batch adsorption by varying the independent variables. The optimization of independent variables was performed using the central composite design (CCD) of response surface methodology (RSM). All the experiments were performed for 50 mL test solutions in an orbital shaker at 100 rpm. A full factorial design with 20 experiments was used to make it efficient for fitting data and building models, and important factors and their details are given in Table 1. The construction of CCD and building of models were performed with Design Expert 13 software.

Independent variables, their levels, and symbols used in this study for Zn2+ ion adsorption by CSNPs (data from authors’ own research)

| Variables | Symbol | Levels | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −1 | 0 | +1 | ||

| pH | A | 4 | 6 | 8 |

| Contact time | B | 30 | 45 | 60 |

| Initial concentration | C | 50 | 100 | 150 |

The adsorption efficiency and loading capacity of CSNPs were calculated using the following equations:

2.4 Antimicrobial assay

The antibacterial properties of CSNPs were tested using the agar well diffusion method on Mueller-Hinton Agar (MHA) medium. Sterilized MHA was poured into sterile Petri dishes under aseptic conditions and left to solidify for 1 h at room temperature. Overnight cultures of E. coli (Gram-negative) and S. aureus (Gram-positive) were standardized to approximately 10⁸ CFU/mL, matching the 0.5 McFarland standard, and evenly spread over the MHA surface using sterile cotton swabs. Sterile wells, 7–8 mm in diameter, were created in the agar using a cork borer. CSNP suspensions were prepared in sterile distilled water, and 50 µL of each suspension was added to the wells. The plates were kept at room temperature for 30 min to allow diffusion of the NPs into the agar and then incubated at 37°C for 24 h to facilitate bacterial growth and interaction with the NPs. After incubation, the zones of inhibition (ZOIs) around the wells were measured with a calibrated ruler to evaluate the CSNPs’ antibacterial effectiveness. Each experiment was performed in triplicate to ensure reproducibility and statistical reliability.

2.5 Diet preparation and experimental design

Fingerlings of O. niloticus (L.) were obtained from nursery ponds and acclimatized to laboratory conditions in an indoor spun-glass aquarium for 2 weeks. The aquarium was aerated continuously, and a controlled light source maintained a 12-h light–dark cycle. A total of 30 fish, with an average weight of 16.21 ± 0.24 g, were randomly distributed among three experimental groups, with 10 fish housed in each 3 L aquarium tank, replicated four times. The groups included Experiment 1, where fish were fed a commercially available feed; Experiment 2, serving as the control group; and Experiment 3, where fish were provided with a CS-enriched feed. All aquariums were equipped with compressed air pumps to ensure proper aeration. The fish were fed their respective diets twice daily, at 9:00 AM and 2:00 PM, for 45 days, with feed provided until the fish were satiated. Each day, settled waste and half of aquarium water were removed and replaced with fresh, aerated tap water from a holding tank. Mortality records were maintained daily, and any deceased fish were promptly removed from the tanks to ensure optimal experimental conditions.

2.6 CSNPs loaded with fish feed

The synthesized CSNP pellets were dispersed in distilled water to prepare a uniform 1% solution that provides moderate concentration of CSNPs. This suspension was loaded into a 20 mL syringe and sprayed evenly onto the prepared fish feed. The CS-coated feed was thoroughly mixed and then dried in a hot air oven at 100°C. Once dried, the CS-enriched feeds (as described in Table 2) were provided to the fish in experimental tanks 1–3 for a duration of 1 week. At the end of the observation period, the fish were weighed, and their lengths were measured to evaluate their growth. The initial and final weights, as well as the initial and final lengths of the fish, were recorded to assess the impact of the CS-loaded feed on their growth and development.

Ingredients and chemical analysis of the experimental diets containing CS-loaded NPs (% dry weight) (data from authors’ own research)

| Components | Control | Formulated feed | CSNPs (1%) formulated feed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chicken meal | 16.0 | 16.0 | 16.0 |

| Fish meal | 11.5 | 11.5 | 11.5 |

| Soya bean meal | 32.0 | 32.0 | 32.0 |

| Groundnut cake | 19.5 | 19.5 | 19.5 |

| Wheat bran | 11.0 | 11.0 | 11.0 |

| Corn oil | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Codfish oil | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Vitamins | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Minerals | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Starch | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| TOTAL | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Elemental analysis (%) | |||

| Solid matter | 92.9 | 93.5 | 93.8 |

| Protein content | 32.6 | 33.4 | 34.7 |

| Crude fat | 6.9 | 6.9 | 7.1 |

| Ash content | 5.1 | 5.7 | 5.9 |

| Insoluble fiber | 5.2 | 5.5 | 5.8 |

| Nitrogen-free extract | 50.11 | 50.25 | 50.77 |

| Total energy (kcal/100 g) | 451.6 | 457.2 | 460.8 |

3 Results

3.1 Synthesis of CSNPs

The ionic gelation approach was used in the current study to create CS nanosuspension. The above-mentioned procedures are advantageous for CSNP synthesis since they are quick and gentle, requiring no organic solvents or high temperatures. It hinges on the ionic connection between the positively and negatively loaded amino groups in the acidic CS solution and the aqueous STPP solution. The molecules with opposing charges can form inter-molecular crosslinks due to the ongoing magnetic churning. TPP was gradually included into the CS solution to produce the ionotropic gelation of CSNPs.

The synthesized CSNPs had monodispersed NPs of around 100 nm in size and consistently low polydispersity index (PDI) values. The stability and structural uniformity of NPs were assessed using the PDI. In this study, low PDI values denote higher levels of monodisperse CSNPs and higher levels of particle equilibrium, whereas higher values suggest lower levels of particle equilibrium and CSNP accumulation. Opacity of the synthesized CSNPs was verified by the presence of opalescence, which was evaluated for physico-chemical traits like crystalline structure, thermal potential, ultra-structural morphology, and the dimension of particles.

3.2 Characterization of CSNPs

3.2.1 UV–vis absorption spectroscopy

The optical properties of CSNPs were analyzed using UV–visible spectroscopy within a wavelength range of 200–500 nm. A sharp absorption peak was observed at 240 nm in the UV–vis spectra, which is due to n–σ* of the –NH2 and –OH groups (Figure 1). The band around 280 nm is due to the n–π* of the acetyl group of CS. The bands observed in CS bulk as well as minor shifts in wavenumbers due to the nanosize nature of CS confirm the formation of CSNPs. Similar observations were reported for the biologically synthesized CSNPs [15].

UV–vis spectra of CSNPs prepared via the ionic gelation method (data from authors’ own research).

3.2.2 FT-IR spectroscopy analysis

The molecular structures of CSNPs were analyzed using FT-IR spectroscopy, as shown in Figure 2. The FT-IR spectra revealed characteristic peaks, indicating specific molecular vibrations and functional groups. A broad absorption band at 3,358 cm⁻¹ corresponds to the –OH groups of the CSNPs, and a small peak at 3,252 cm⁻¹ overlapped with the –OH peak indicates the –NH stretching. The peak at 2,873 cm⁻¹ is due to the symmetrical stretching of –CH groups [16]. Bands at 1,647 and 1,587 cm⁻¹ correspond to the amide I C═O stretching and amide II C–N stretching vibrations, respectively, and these bands were shifted compared to the CS bulk, and this is due to the formation of NPs and their interactions with the cross linker TPP used in this study [17,18]. The peak at 1,145 cm⁻¹ corresponds to the glycosidic linkage group of CSNPs. The peak at 695 cm⁻¹ is primarily due to N–H bending that arises due to NH3 + in the ionic gelation method. These findings confirm the presence of various functional groups, validating the molecular structure and composition of the synthesized CSNPs.

FT-IR spectrum of CSNPs prepared via the ionic gelation method. Inset: FT-IR spectrum of CS (data from authors’ own research).

3.2.3 Field emission SEM analysis

SEM was employed to analyze the microstructures of the synthesized CSNPs, focusing on their size, shape, and dispersion patterns (Figure 3). The SEM images revealed that the CSNPs exhibited a spherical shape with a homogeneous nanostructure. The particles were uniformly distributed and of nanoscale size, indicating that the interaction between CS and TPP molecules successfully facilitated the formation of well-defined CSNPs. The observed morphology aligns with the findings from previous studies, confirming the reliability of the synthesis method in producing consistent particle structures [19,20]. These results highlight the potential of CSNPs for diverse applications across various fields, including tissue engineering, environmental remediation, biomedical imaging, and drug delivery systems. This consistent particle morphology provides a strong foundation for exploring the functional capabilities of CSNPs in these domains.

SEM images of CSNPs prepared via the ionic gelation method (data from authors’ own research).

3.2.4 High-resolution TEM (HR-TEM) analysis

HR-TEM analysis confirmed the size and microscopic structure of the synthesized CSNPs, prepared under optimal conditions (Figure 4). The NPs were spherical, with sizes ranging from 10 to 40 nm. HR-TEM images revealed well-defined lattice fringes, indicative of a high degree of crystallinity in the samples [21]. The precise dry size of the CSNPs was measured through this technique, providing detailed structural insights. These findings highlight the strong interaction dynamics between CS and TPP, which play a crucial role in the formation and stability of CSNPs.

TEM image of CSNPs prepared via the ionic gelation method (data from authors’ own research).

3.2.5 XRD measurement

XRD analysis was utilized to assess the morphological characteristics and crystallite dimensions of CSNPs. The XRD patterns of the CSNPs are presented in Figure 5. The crystalline quality of the CSNPs was demonstrated by a prominent diffraction peak at a 2θ range of 10° and 20°. The small and less intense peak at 10° is due to the hydrated crystalline structure of the CSNPs, confirming the reduction in crystallinity due to nanoscale compared to the bulk CS [22]. The intense peak around 20° is due to the crystalline structure of CS, showcasing the regular arrangement of the polymeric chains [23]. The presence of a broader band further indicated an imperfect crystal structure, likely due to the synthesis and processing conditions, especially the use of TPP. These findings provide insight into the crystalline properties and structural behavior of CSNPs.

XRD patterns of CSNPs prepared via the ionic gelation method. Inset: CS XRD pattern (data from authors’ own research).

3.3 RSM-based optimization

CCD was utilized to optimize the adsorption of Zn2+ ions using CSNPs. The study focused on three independent variables: pH, contact time, and initial Zn2+ concentration. The CCD included 20 experimental runs, consisting of 6 axial points, 6 central points, and 8 cubic points distributed within the design space. Tables 3 and 4 provide the experimental and predicted design matrices as well as the analysis of variance (ANOVA) results for the Zn2+ removal process.

CCD runs and % adsorption comparison with experimental and predicted values of Zn2+ ion adsorption by CSNPs (data from authors’ own research)

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Removal % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Std | Run | A: pH | B: Contact time (min) | C: Initial concentration (mg/L) | Experimental | Predicted |

| 9 | 1 | 4 | 75 | 90 | 29.3 | 32.7 |

| 13 | 2 | 7 | 75 | 10 | 99.5 | 96.3 |

| 4 | 3 | 9 | 120 | 30 | 56.2 | 58.8 |

| 16 | 4 | 7 | 75 | 90 | 93.1 | 93.1 |

| 17 | 5 | 7 | 75 | 90 | 93.2 | 93.1 |

| 11 | 6 | 7 | 10 | 90 | 47.5 | 51.9 |

| 20 | 7 | 7 | 75 | 90 | 93.2 | 93.1 |

| 10 | 8 | 10 | 75 | 90 | 37.8 | 33.4 |

| 7 | 9 | 5 | 120 | 150 | 78.4 | 76.5 |

| 1 | 10 | 5 | 30 | 30 | 52.4 | 48.8 |

| 3 | 11 | 5 | 120 | 30 | 69.5 | 72.2 |

| 14 | 12 | 7 | 75 | 190 | 79.3 | 80.5 |

| 5 | 13 | 5 | 30 | 150 | 22.9 | 20.7 |

| 6 | 14 | 9 | 30 | 150 | 37.2 | 34.9 |

| 15 | 15 | 7 | 75 | 90 | 93.1 | 93.1 |

| 8 | 16 | 9 | 120 | 150 | 64.1 | 68.4 |

| 19 | 17 | 7 | 75 | 90 | 93 | 93.1 |

| 12 | 18 | 7 | 150 | 90 | 93.2 | 89.2 |

| 2 | 19 | 9 | 30 | 30 | 55.7 | 58.6 |

| 18 | 20 | 7 | 75 | 90 | 93.1 | 93.7 |

ANOVA for the adsorption of Zn2+ ions by CSNPs (data from authors’ own research)

| Source | Sum of squares | df | Mean square | F-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 11846.80 | 9 | 1316.31 | 92.77 | <0.0001 |

| A – pH | 0.6050 | 1 | 0.6050 | 0.0426 | 0.8405 |

| B – contact time | 2539.67 | 1 | 2539.67 | 178.99 | <0.0001 |

| C – initial concentration | 267.30 | 1 | 267.30 | 18.84 | 0.0015 |

| AB | 255.38 | 1 | 255.38 | 18.00 | 0.0017 |

| AC | 12.50 | 1 | 12.50 | 0.8810 | 0.3700 |

| BC | 524.88 | 1 | 524.88 | 36.99 | 0.0001 |

| A2 | 7345.31 | 1 | 7345.31 | 517.69 | <0.0001 |

| B2 | 1151.20 | 1 | 1151.20 | 81.14 | <0.0001 |

| C2 | 31.56 | 1 | 31.56 | 2.22 | 0.1667 |

| Residual | 141.89 | 10 | 14.19 | ||

| Lack of fit | 141.86 | 5 | 28.37 | 56.78 | 0.4521 |

| Pure error | 0.0283 | 5 | 0.0057 | ||

| Cor total | 11988.69 | 19 | |||

| R 2 | 0.9882 | Predicted R² | 0.9038 | ||

| Adjusted R 2 | 0.9775 | Adeq precision | 28.3943 | ||

Design-Expert 13 software was employed to develop a quadratic model, yielding a second-order polynomial equation (equation (3)) that defines the relationship between the selected factors and the Zn2+ removal efficiency, given by

The influence of each factor (pH, contact time, and concentration) on Zn2+ adsorption by CSNPs is reflected in the coefficients of the quadratic equation (equation (3)). Positive coefficients indicate that increasing the factor level enhances adsorption, whereas negative coefficients suggest a reduction in the adsorption efficiency. The equation also accounts for interactions between factors (two-factor terms) and the impact of these interactions on adsorption efficiency (curvature terms). The strong correlation between predicted and experimental results, as shown in Table 3, confirms the validity of the selected model and demonstrates improved Zn2+ adsorption in the experiments.

The ANOVA results in Table 4 affirm the robustness of the model for predicting Zn2+ removal using CSNPs. The extremely small p-value (<0.0001) highlights the model’s statistical significance, indicating the results are highly unlikely due to random variation. A high F-value of 92.77 further reinforces the model’s reliability, as larger F-values suggest a very low probability (0.01%) of the findings occurring by chance [24]. Moreover, the lack-of-fit F-value exceeding 0.1 indicates minimal unexplained variation within the model. The alignment between predicted and actual values was assessed for accuracy, as shown in Figure 6d. The points are randomly distributed along a straight line, demonstrating a normal data distribution without significant deviations, eliminating the need for data transformation and validating the model. Additionally, correlation coefficients nearing 1 (0.988), along with high adjusted and predicted R-squared values (0.977 and 0.903, respectively), further corroborate the model’s effectiveness [25]. An adequate precision value of 28.3 underscores the model’s strong predictive capability.

3D surface plots of independent variable interactions: (a) pH vs contact time, (b) pH vs initial concentration, (c) initial concentration vs contact time, and (d) predicted vs actual values (data from authors’ own research).

The interaction between independent variables and their impact on the binding of Zn2+ ions by CSNPs can be effectively visualized using 3D surface plots, as shown in Figure 6. These plots provide critical insights into the adsorption process. Figure 6a illustrates the combined effect of pH and contact time on Zn2+ ion binding. It reveals that as the pH and contact time increase, the binding efficiency also improves, reaching its peak at pH 7. However, beyond pH 7, the efficiency declines, even with extended contact times. At lower pH levels, competitive adsorption by hydronium ions on the active surface sites results in reduced binding efficiency. As the pH increases, this competition diminishes, enabling better adsorption of Zn2+ ions. The improvement in efficiency with longer contact times is attributed to the increased opportunity for Zn2+ ions to interact with the CSNP surface. The 3D plot clearly demonstrates that both pH and contact time significantly influence adsorption efficiency.

Figure 6b illustrates the interaction between pH and initial concentration. At the optimal pH of 6, the removal efficiency decreases with an increase in initial Zn2+ concentration. This decline occurs because the surface active sites on CSNPs become saturated as the concentration increases, reducing the percentage of ions bound. Figure 6c shows the synergistic effect of initial concentration and contact time on Zn2+ ion adsorption. While prolonged contact time enhances the adsorption efficiency, increasing the initial concentration diminishes it due to limited availability of active sites.

3.4 Antimicrobial investigation of CSNPs

The antimicrobial activity of the CSNPs synthesized in this study was evaluated against E. coli and S. aureus, with the results summarized in Table 5. The findings indicate that CSNPs demonstrated significantly superior antimicrobial activity with 25 and 24 mm of ZoI against both E. coli and S. aureus compared to the standard antibiotic streptomycin at 20 µL concentration. This enhanced activity at low concentrations can be attributed to the interaction of the NPs with the microbial cell membrane, which leads to membrane disruption and leakage of intracellular contents, ultimately compromising the viability of the microbes [9,11].

ZoI of CSNPs toward E. coli and S. aureus bacterial strains and comparison with standards (data from authors’ own research)

| Species | Concentration (µL) | ZoI (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | 20 | 25 |

| S. aureus | 20 | 24 |

| Streptomycin disc | — | 21 |

3.5 Growth and feed conversion efficiency of O. niloticus

Table 6 highlights that the CSNP-formulated feed significantly enhanced the growth performance of O. niloticus compared to both commercial and control basal feeds. Fish fed with the CSNP-formulated diet exhibited a higher feed intake (40.43 ± 0.75) compared to those on the control feed. Throughout the experimental period, the CSNP-supplemented group demonstrated excellent health and growth efficiency, with a 100% survival rate, consistent across all diet groups, including the control and commercial feeds. The improved growth performance was attributed to better intestinal villi development, enhanced nutrient absorption, increased specific growth rate (SGR), and higher feed consumption in the CSNP-formulated diet group [26]. These factors collectively contributed to the observed superior growth in O. niloticus. Additionally, the dietary supplementation with CS-enriched feed improved the feed conversion efficiency and overall productivity, consistent with similar findings reported for Dicentrarchus labrax [27]. This demonstrates the efficacy of CSNPs as a dietary supplement for enhancing fish growth and health.

Growth performance and feed utilization of Nile tilapia fed with different diets, including commercial feed, formulated feed, and CSNP formulated feed (data from authors’ own research)

| Parameters | Control | Commercial feed | Formulated feed | CS formulated feed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial weight (g) | 17.45 ± 0.19 | 17.71 ± 0.21 | 17.56 ± 0.12 | 17.62 ± 0.22 |

| Final weight (g) | 29.26 ± 0.31 | 29.97 ± 0.38 | 34.64 ± 0.31 | 36.7 ± 0.43 |

| Weight gain (g) | 11.81 ± 0.23 | 12.26 ± 0.52 | 17.08 ± 0.19 | 19.08 ± 0.38 |

| Weight gain (%) | 40.36 ± 1.31 | 40.90 ± 1.92 | 49.30 ± 1.04 | 51.9 ± 1.21 |

| Specific growth rate (g) | 25.71 ± 0.09 | 29.51 ± 0.07 | 42.64 ± 0.11 | 47.27 ± 0.07 |

| Feed conversion ratio (g) | 0.26 ± 0.31 | 0.23 ± 0.21 | 0.17 ± 0.19 | 0.16 ± 0.08 |

| Total feed intake (g) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Protein conversion ratio (g) | 0.40 ± 0.05 | 0.47 ± 0.06 | 0.61 ± 0.09 | 0.68 ± 0.31 |

| Survival rate | 100 ± 0.00 | 100 ± 0.00 | 100 ± 0.00 | 100 ± 0.00 |

3.6 Hematological analysis

The red blood cell (RBC) and white blood cell (WBC) counts in the control group increased gradually from the first to the third week but showed a significant rise after being fed with an enriched diet formulated in this study starting from the first week. The RBC levels improved notably due to the loaded CSNP diet. While the control group showed gradual improvement, fish treated with the CSNPs/kg diet exhibited a substantial boost in RBC and WBC levels of 20.0 × 106/µL and 3.2 × 103/µL, respectively (Figure S1). WBCs are an essential component of innate immunity in fish and release humoral chemicals like cationic antimicrobial peptides, complement system components, lectins, and cytokines [28]. The higher WBC count exhibited by fish fed with CSNP diet suggests the improved immunity compared to other diets, and this can be attributed to the enhanced activity and proliferation of lymphocytes and macrophages. Further, the cytokine production may be stimulated that promotes immune cell activation. The stress reduction and nutritional enhancement of CSNPs improved the RBC production compared to other diets supplied to the fish. Similar results were reported for adding the nanochitosan/zeolite composite to rainbow trout’s diet, which resulted in an increase in serum protein levels [29].

3.7 Future directions

The findings of this study highlight the potential of CSNPs for addressing Zn2+ ion contamination in water in a sustainable manner. Furthermore, Zn2+ ion-bound CSNPs can be evaluated for their antimicrobial properties, leveraging the synergistic effects of Zn2+ ions and CSNPs. The incorporation of Zn2+ ion-bound CSNPs into aquatic environments can reduce pathogen loads, improving fish health by minimizing infections. The application of CS formulations in fish feed has already shown benefits, such as promoting healthier growth in O. niloticus. The inclusion of Zn2+ ion-bound CSNPs in feed formulations can further enhance the production and activation of immune cells, stimulate macrophage activity, and increase the resilience of O. niloticus to diseases and environmental stress. However, optimizing the Zn2+ ion loading onto CSNPs is critical to prevent zinc toxicity and ensure a balanced approach to fish health management. Current investigations are underway to determine the optimal Zn2+ ion loading levels that contribute to the overall growth and health of O. niloticus, paving the way for a sustainable and effective practice.

4 Conclusions

The present investigation synthesized the CSNPs via the gelation method and characterized for its surface morphology. The nanoscale of CS was confirmed by SEM and TEM techniques, and the particles were found to be in the range of 10–40 nm with a spherical shape. The CSNPs were evaluated for their ability to adsorb Zn2+ ions from aqueous solution by RSM. The developed model was found to be significant with p-value < 0.0001 with higher F-value and correlation coefficients. The optimal conditions of pH 7, 60 min of contact time, and 100 mg/L initial concentration resulted in 156.2 mg/g loading capacity of Zn2+ ions onto CSNPs. The antimicrobial efficacy was noted to be high compared to the standards, suggesting the potential applications of CSNPs in biomedicine. The exploration of CSNPs in dietary supplements of O. niloticus proved to be prolific with improved health and growth and enhanced WBC and RBC counts. In conclusion, CSNPs offer diverse applications. With careful design, CSNPs can be sustainably utilized to capture zinc ions from aqueous solutions and incorporate them for fortification of diets for fisheries, thereby promoting improved health and growth in aquatic organisms.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge and extend their appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2025R739), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for funding this work.

-

Funding information: For the purpose of open access, the authors have applied a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license to any Author Accepted Manuscript version of this article arising from this submission.

-

Author contributions: MA – formal analysis and manuscript writing; RS – conceptualization, analysis, and validation; MS – formal analysis, writing – original draft, and data interpretation; MAK – data analysis and interpretation; SR – formal analysis, writing, and editing; MG – writing – review and editing; RL – conceptualization, data analysis, and writing – review and editing.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Ethical approval: This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines issued by the CPCSEA, India, and ethical approval was obtained from IAEC for aquaculture studies.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

[1] Malik S, Muhammad K, Waheed Y. Nanotechnology: A revolution in modern industry. Molecules. 2023;28(2):661. 10.3390/molecules28020661.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Bhushan B. Introduction to nanotechnology. In: Bhushan B, editor. Springer handbook of nanotechnology. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2017. 10.1007/978-3-662-54357-3_1.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Murat Y, Karin S. Preparation methods and applications of chitosan nanoparticles; with an outlook toward reinforcement of biodegradable packaging. React Funct Polym. 2021;161:104849.10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2021.104849Search in Google Scholar

[4] Lifeng Q, Zirong X. Lead sorption from aqueous solutions on chitosan nanoparticles. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 2004;251(1–3):183–90.10.1016/j.colsurfa.2004.10.010Search in Google Scholar

[5] Wen LD, Zi Rong X, Xin YH, Ying LX, Zhi GM. Preparation, characterization and adsorption properties of chitosan nanoparticles for eosin Y as a model anionic dye. J Hazard Mater. 2008;153(1–2):152–6.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.08.040Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Ali MEA, Aboelfadl MMS, Selim AM, Khalil HF, Elkady GM. Chitosan nanoparticles extracted from shrimp shells, application for removal of Fe(II) and Mn(II) from aqueous phases. Sep Sci Technol. 2018;53(18):2870–81.10.1080/01496395.2018.1489845Search in Google Scholar

[7] Benettayeb A, Seihoub FZ, Pal P, Ghosh S, Usman M, Chia CH, et al. Chitosan nanoparticles as potential nano-sorbent for removal of toxic environmental pollutants. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2023;13(3):447.10.3390/nano13030447Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Lifeng Q, Zirong X, Xia J, Caihong H, Xiangfei Z. Preparation and antibacterial activity of chitosan nanoparticles. Carbohydr Res. 2004;339(16):2693–700.10.1016/j.carres.2004.09.007Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Divya K, Vijayan S, George TK, Jisha MS. Antimicrobial properties of chitosan nanoparticles: mode of action and factors affecting activity. Fibers Polym. 2017;18:221–30.10.1007/s12221-017-6690-1Search in Google Scholar

[10] Xing Y, Wang X, Guo X, Yang P, Yu J, Shui Y, et al. Comparison of antimicrobial activity of chitosan nanoparticles against bacteria and fungi. Coatings. 2021;11(7):769.10.3390/coatings11070769Search in Google Scholar

[11] Chandrasekaran M, Kim KD, Chun SC. Antibacterial activity of chitosan nanoparticles: a review. Processes. 2020;8(9):1173.10.3390/pr8091173Search in Google Scholar

[12] El-Naby FSA, Naiel MAE, Al-Sagheer AA, Negm SS. Dietary chitosan nanoparticles enhance the growth, production performance, and immunity in Oreochromis niloticus. Aquaculture. 2019;501:82–9.10.1016/j.aquaculture.2018.11.014Search in Google Scholar

[13] Augustine R, Dan P, Schlachet I, Rouxel D, Menu P, Sosnik A. Chitosan ascorbate hydrogel improves water uptake capacity and cell adhesion of electrospun poly (epsilon-caprolactone) membranes. Int J Pharm. 2019;559:420–6.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2019.01.063Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] El-Naggar M, Sally S, El-Shabaka H, El-Rahman FA, Khalil M, Suloma A. Efficacy of dietary chitosan and chitosan nanoparticles supplementation on health status of Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus (L.). Aquac Rep. 2021;19:100628.10.1016/j.aqrep.2021.100628Search in Google Scholar

[15] Sathiyabama M, Parthasarathy R. Biological preparation of chitosan nanoparticles and its in vitro antifungal efficacy against some phytopathogenic fungi. Carbohydr Polym. 2016;151:321–5.10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.05.033Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Lakshmipathy R, Sarada NC. A fixed bed column study for the removal of Pb2+ ions by watermelon rind. Env Sci Water Res Technol. 2015;1:244–50.10.1039/C4EW00027GSearch in Google Scholar

[17] Azeez AA, Rhee KY, Park SJ, Kim HJ, Jung DH. Application of cryomilling to enhance material properties of carbon nanotube reinforced chitosan nanocomposites. Compos B Eng. 2013;50:127–34.10.1016/j.compositesb.2013.01.010Search in Google Scholar

[18] Rajam M, Pulavendran S, Rose C, Mandal AB. Chitosan nanoparticles as a dual growth factor delivery system for tissue engineering applications. Int J Pharm. 2011;410(1–2):145–215.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.02.065Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Khanmohammadi M, Elmizadeh H, Ghasemi K. Investigation of size and morphology of chitosan nanoparticles used in drug delivery system employing chemometric technique. Iran J Pharm Res. 2015;14(3):665–75.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Asgari-Targhi G, Iranbakhsh A, Ardebili ZO. Potential benefits and phytotoxicity of bulk and nano-chitosan on the growth, morphogenesis, physiology, and micropropagation of Capsicum annuum. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2018;127:393–402.10.1016/j.plaphy.2018.04.013Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] El-Naggar NEA, Shiha AM, Mahrous H. A sustainable green-approach for biofabrication of chitosan nanoparticles, optimization, characterization, its antifungal activity against phytopathogenic Fusarium culmorum and antitumor activity. Sci Rep. 2024;14:11336.10.1038/s41598-024-59702-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Budi S, Suliasih BA, Rahmawati I. Size-controlled chitosan nanoparticles prepared using ionotropic gelation. Sci Asia. 2020;46(4):457–61.10.2306/scienceasia1513-1874.2020.059Search in Google Scholar

[23] Kumar S, Dutta PK, Koh J. A physicochemical and biological study of novel chitosan-chloroquinoline derivative for biomedical applications. Int J Biol Macromol. 2011;49:356–61.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2011.05.017Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Alangari A, Aboul-Soud MAM, Alqahtani MS, et al. Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using Inula genus and evaluation of biological therapeutics and environmental applications. Nanotechnol Rev. 2024;13(1):1–15.10.1515/ntrev-2024-0039Search in Google Scholar

[25] Devi VV, Lakshmipathy R, Prabhu SV, Ali D, Alarifi S, Sillanpaa M. Batch and continuous adsorptive removal of Brilliant green dye using modified Jamun seed powder: RSM based optimization. Chem Eng Commun. 2025;212(1):50–63.10.1080/00986445.2024.2409169Search in Google Scholar

[26] Thambiliyagodage C, Jayanetti M, Mendis A, Ekanayake G, Liyanaarachchi H, Vigneswaran S. Recent advances in chitosan-based applications—a review. Materials. 2023;16(5):2073.10.3390/ma16052073Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Zaki MA, Shatby E, Shatby E. Effect of chitosan supplemented diet on survival, growth, feed utilization, body composition and histology of sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax). World J Eng Technol. 2015;3(4):38.10.4236/wjet.2015.34C005Search in Google Scholar

[28] Rodrigues MV, Zanuzzo FS, Koch JF, de Oliveira CA, Sima P, Vetvicka V. Development of fish immunity and the role of β-glucan in immune responses. Molecules. 2020;25(22):5378.10.3390/molecules25225378Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Sheikhzadeh N, Kouchaki M, Mehregan M, Tayefi‐Nasrabadi H, Divband B, Khataminan M, et al. Influence of nanochitosan/zeolite composite on growth performance, digestive enzymes and serum biochemical parameters in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Aquac Res. 2017;48(12):5955–64.10.1111/are.13418Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Phytochemical investigation and evaluation of antioxidant and antidiabetic activities in aqueous extracts of Cedrus atlantica

- Influence of B4C addition on the tribological properties of bronze matrix brake pad materials

- Discovery of the bacterial HslV protease activators as lead molecules with novel mode of action

- Characterization of volatile flavor compounds of cigar with different aging conditions by headspace–gas chromatography–ion mobility spectrometry

- Effective remediation of organic pollutant using Musa acuminata peel extract-assisted iron oxide nanoparticles

- Analysis and health risk assessment of toxic elements in traditional herbal tea infusions

- Cadmium exposure in marine crabs from Jiaxing City, China: Insights into health risk assessment

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles of Cinnamomum zeylanicum and their biological activities

- Tetraclinis articulata (Vahl) Mast., Mentha pulegium L., and Thymus zygis L. essential oils: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antifungal properties against postharvest fungal diseases of apple, and in vitro, in vivo, and in silico investigation

- Exploration of plant alkaloids as potential inhibitors of HIV–CD4 binding: Insight into comprehensive in silico approaches

- Recovery of phenylethyl alcohol from aqueous solution by batch adsorption

- Electrochemical approach for monitoring the catalytic action of immobilized catalase

- Green synthesis of ZIF-8 for selective adsorption of dyes in water purification

- Optimization of the conditions for the preparation of povidone iodine using the response surface methodology

- A case study on the influence of soil amendment on ginger oil’s physicochemical properties, mineral contents, microbial load, and HPLC determination of its vitamin level

- Removal of antiviral favipiravir from wastewater using biochar produced from hazelnut shells

- Effect of biochar and soil amendment on bacterial community composition in the root soil and fruit of tomato under greenhouse conditions

- Bioremediation of malachite green dye using Sargassum wightii seaweed and its biological and physicochemical characterization

- Evaluation of natural compounds as folate biosynthesis inhibitors in Mycobacterium leprae using docking, ADMET analysis, and molecular dynamics simulation

- Novel insecticidal properties of bioactive zoochemicals extracted from sea urchin Salmacis virgulata

- Elevational gradients shape total phenolic content and bioactive potential of sweet marjoram (Origanum majorana L.): A comparative study across altitudinal zones

- Study on the CO2 absorption performance of deep eutectic solvents formed by superbase DBN and weak acid diethylene glycol

- Preparation and wastewater treatment performance of zeolite-modified ecological concrete

- Multifunctional chitosan nanoparticles: Zn2+ adsorption, antimicrobial activity, and promotion of aquatic health

- Comparative analysis of nutritional composition and bioactive properties of Chlorella vulgaris and Arthrospira platensis: Implications for functional foods and dietary supplements

- Growth kinetics and mechanical characterization of boride layers formed on Ti6Al4V

- Enhancement of water absorption properties of potassium polyacrylate-based hydrogels in CaCl2-rich soils using potassium di- and tri-carboxylate salts

- Electrochemical and microbiological effects of dumpsite leachates on soil and air quality

- Modeling benzene physicochemical properties using Zagreb upsilon indices

- Characterization and ecological risk assessment of toxic metals in mangrove sediments near Langen Village in Tieshan Bay of Beibu Gulf, China

- Protective effect of Helicteres isora, an efficient candidate on hepatorenal toxicity and management of diabetes in animal models

- Valorization of Juglans regia L. (Walnut) green husk from Jordan: Analysis of fatty acids, phenolics, antioxidant, and cytotoxic activities

- Molecular docking and dynamics simulations of bioactive terpenes from Catharanthus roseus essential oil targeting breast cancer

- Selection of a dam site by using AHP and VIKOR: The Sakarya Basin

- Characterization and modeling of kidney bean shell biochar as adsorbent for caffeine removal from aquatic environments

- The effects of short-term and long-term 2100 MHz radiofrequency radiation on adult rat auditory brainstem response

- Biochemical insights into the anthelmintic and anti-inflammatory potential of sea cucumber extract: In vitro and in silico approaches

- Resveratrol-derived MDM2 inhibitors: Synthesis, characterization, and biological evaluation against MDM2 and HCT-116 cells

- Phytochemical constituents, in vitro antibacterial activity, and computational studies of Sudanese Musa acuminate Colla fruit peel hydro-ethanol extract

- Chemical composition of essential oils reviewed from the height of Cajuput (Melaleuca leucadendron) plantations in Buru Island and Seram Island, Maluku, Indonesia

- Phytochemical analysis and antioxidant activity of Azadirachta indica A. Juss from the Republic of Chad: in vitro and in silico studies

- Stability studies of titanium–carboxylate complexes: A multi-method computational approach

- Efficient adsorption performance of an alginate-based dental material for uranium(vi) removal

- Synthesis and characterization of the Co(ii), Ni(ii), and Cu(ii) complexes with a 1,2,4-triazine derivative ligand

- Evaluation of the impact of music on antioxidant mechanisms and survival in salt-stressed goldfish

- Optimization and validation of UPLC method for dapagliflozin and candesartan cilexetil in an on-demand formulation: Analytical quality by design approach

- Biomass-based cellulose hydroxyapatite nanocomposites for the efficient sequestration of dyes: Kinetics, response surface methodology optimization, and reusability

- Multifunctional nitrogen and boron co-doped carbon dots: A fluorescent probe for Hg2+ and biothiol detection with bioimaging and antifungal applications

- Separation of sulphonamides on a C12-diol mixed-mode HPLC column and investigation of their retention mechanism

- Characterization and antioxidant activity of pectin from lemon peels

- Fast PFAS determination in honey by direct probe electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry: A health risk assessment insight

- Correlation study between GC–MS analysis of cigarette aroma compounds and sensory evaluation

- Synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular docking studies of substituted chromone-2-carboxamide derivatives as anti-breast cancer agents

- The influence of feed space velocity and pressure on the cold flow properties of diesel fuel

- Acid etching behavior and mechanism in acid solution of iron components in basalt fibers

- Protective effect of green synthesized nanoceria on retinal oxidative stress and inflammation in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat

- Evaluation of the antianxiety activity of green zinc nanoparticles mediated by Boswellia thurifera in albino mice by following the plus maze and light and dark exploration tests

- Yeast as an efficient and eco-friendly bifunctional porogen for biomass-derived nitrogen-doped carbon catalysts in the oxygen reduction reaction

- Novel descriptors for the prediction of molecular properties

- Synthesis and characterization of surfactants derived from phenolphthalein: In vivo and in silico studies of their antihyperlipidemic effect

- Turmeric oil-fortified nutraceutical-SNEDDS: An approach to boost therapeutic effectiveness of dapagliflozin during treatment of diabetic patients

- Analysis and study on volatile flavor compounds of three Yunnan cultivated cigars based on headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry

- Near-infrared IR780 dye-loaded poloxamer 407 micelles: Preparation and in vitro assessment of anticancer activity

- Study on the influence of the viscosity reducer solution on percolation capacity of thin oil in ultra-low permeability reservoir

- Detection method of Aristolochic acid I based on magnetic carrier Fe3O4 and gold nanoclusters

- Juglone’s apoptotic impact against eimeriosis-induced infection: a bioinformatics, in-silico, and in vivo approach

- Potential anticancer agents from genus Aerva based on tubulin targets: an in-silico integration of quantitative structure activity relationship (QSAR), molecular docking, simulation, drug-likeness, and density functional theory (DFT) analysis

- Hepatoprotective and PXR-modulating effects of Erodium guttatum extract in propiconazole-induced toxicity

- Studies on chemical composition of medicinal plants collected in natural locations in Ecuador

- A study of different pre-treatment methods for cigarettes and their aroma differences

- Cytotoxicity and molecular mechanisms of quercetin, gallic acid, and pinocembrin in Caco-2 cells: insights from cell viability assays, network pharmacology, and molecular docking

- Choline-based deep eutectic solvents for green extraction of oil from sour cherry seeds

- Green-synthesis of chromium (III) nanoparticles using garden fern and evaluation of its antibacterial and anticholinesterase activities

- Innovative functional mayonnaise formulations with watermelon seeds oil: evaluation of quality parameters and storage stability

- Molecular insights and biological evaluation of compounds isolated from Ferula oopoda against diabetes, advanced glycation end products and inflammation in diabetics

- Removal of cytotoxic tamoxifen from aqueous solutions using a geopolymer-based nepheline–cordierite adsorbent

- Unravelling the therapeutic effect of naturally occurring Bauhinia flavonoids against breast cancer: an integrated computational approach

- Characterization of organic arsenic residues in livestock and poultry meat and offal and consumption risks

- Synthesis and characterization of zinc sulfide nanoparticles and their genotoxic and cytotoxic effects on acute myeloid leukemia cells

- Activity of Coriandrum sativum methanolic leaf extracts against Eimeria papillata: a combined in vitro and in silico approach

- Special Issue on Advancing Sustainable Chemistry for a Greener Future

- One-pot fabrication of highly porous morphology of ferric oxide-ferric oxychloride/poly-O-chloroaniline nanocomposite seeded on poly-1H pyrrole: Photocathode for green hydrogen generation from natural and artificial seawater

- High-efficiency photocathode for green hydrogen generation from sanitation water using bismuthyl chloride/poly-o-chlorobenzeneamine nanocomposite

- Innovative synthesis of cobalt-based catalysts using ionic liquids and deep eutectic solvents: A minireview on electrocatalytic water splitting

- Special Issue on Phytochemicals, Biological and Toxicological Analysis of Plants

- Comparative analysis of fruit quality parameters and volatile compounds in commercially grown citrus cultivars

- Total phenolic, flavonoid, flavonol, and tannin contents as well as antioxidant and antiparasitic activities of aqueous methanol extract of Alhagi graecorum plant used in traditional medicine: Collected in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- Study on the pharmacological effects and active compounds of Apocynum venetum L.

- Chemical profile of Senna italica and Senna velutina seed and their pharmacological properties

- Essential oils from Brazilian plants: A literature analysis of anti-inflammatory and antimalarial properties and in silico validation

- Toxicological effects of green tea catechin extract on rat liver: Delineating safe and harmful doses

- Unlocking the potential of Trigonella foenum-graecum L. plant leaf extracts against diabetes-associated hypertension: A proof of concept by in silico studies

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Phytochemical investigation and evaluation of antioxidant and antidiabetic activities in aqueous extracts of Cedrus atlantica

- Influence of B4C addition on the tribological properties of bronze matrix brake pad materials

- Discovery of the bacterial HslV protease activators as lead molecules with novel mode of action

- Characterization of volatile flavor compounds of cigar with different aging conditions by headspace–gas chromatography–ion mobility spectrometry

- Effective remediation of organic pollutant using Musa acuminata peel extract-assisted iron oxide nanoparticles

- Analysis and health risk assessment of toxic elements in traditional herbal tea infusions

- Cadmium exposure in marine crabs from Jiaxing City, China: Insights into health risk assessment

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles of Cinnamomum zeylanicum and their biological activities

- Tetraclinis articulata (Vahl) Mast., Mentha pulegium L., and Thymus zygis L. essential oils: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antifungal properties against postharvest fungal diseases of apple, and in vitro, in vivo, and in silico investigation

- Exploration of plant alkaloids as potential inhibitors of HIV–CD4 binding: Insight into comprehensive in silico approaches

- Recovery of phenylethyl alcohol from aqueous solution by batch adsorption

- Electrochemical approach for monitoring the catalytic action of immobilized catalase

- Green synthesis of ZIF-8 for selective adsorption of dyes in water purification

- Optimization of the conditions for the preparation of povidone iodine using the response surface methodology

- A case study on the influence of soil amendment on ginger oil’s physicochemical properties, mineral contents, microbial load, and HPLC determination of its vitamin level

- Removal of antiviral favipiravir from wastewater using biochar produced from hazelnut shells

- Effect of biochar and soil amendment on bacterial community composition in the root soil and fruit of tomato under greenhouse conditions

- Bioremediation of malachite green dye using Sargassum wightii seaweed and its biological and physicochemical characterization

- Evaluation of natural compounds as folate biosynthesis inhibitors in Mycobacterium leprae using docking, ADMET analysis, and molecular dynamics simulation

- Novel insecticidal properties of bioactive zoochemicals extracted from sea urchin Salmacis virgulata

- Elevational gradients shape total phenolic content and bioactive potential of sweet marjoram (Origanum majorana L.): A comparative study across altitudinal zones

- Study on the CO2 absorption performance of deep eutectic solvents formed by superbase DBN and weak acid diethylene glycol

- Preparation and wastewater treatment performance of zeolite-modified ecological concrete

- Multifunctional chitosan nanoparticles: Zn2+ adsorption, antimicrobial activity, and promotion of aquatic health

- Comparative analysis of nutritional composition and bioactive properties of Chlorella vulgaris and Arthrospira platensis: Implications for functional foods and dietary supplements

- Growth kinetics and mechanical characterization of boride layers formed on Ti6Al4V

- Enhancement of water absorption properties of potassium polyacrylate-based hydrogels in CaCl2-rich soils using potassium di- and tri-carboxylate salts

- Electrochemical and microbiological effects of dumpsite leachates on soil and air quality

- Modeling benzene physicochemical properties using Zagreb upsilon indices

- Characterization and ecological risk assessment of toxic metals in mangrove sediments near Langen Village in Tieshan Bay of Beibu Gulf, China

- Protective effect of Helicteres isora, an efficient candidate on hepatorenal toxicity and management of diabetes in animal models

- Valorization of Juglans regia L. (Walnut) green husk from Jordan: Analysis of fatty acids, phenolics, antioxidant, and cytotoxic activities

- Molecular docking and dynamics simulations of bioactive terpenes from Catharanthus roseus essential oil targeting breast cancer

- Selection of a dam site by using AHP and VIKOR: The Sakarya Basin

- Characterization and modeling of kidney bean shell biochar as adsorbent for caffeine removal from aquatic environments

- The effects of short-term and long-term 2100 MHz radiofrequency radiation on adult rat auditory brainstem response

- Biochemical insights into the anthelmintic and anti-inflammatory potential of sea cucumber extract: In vitro and in silico approaches

- Resveratrol-derived MDM2 inhibitors: Synthesis, characterization, and biological evaluation against MDM2 and HCT-116 cells

- Phytochemical constituents, in vitro antibacterial activity, and computational studies of Sudanese Musa acuminate Colla fruit peel hydro-ethanol extract

- Chemical composition of essential oils reviewed from the height of Cajuput (Melaleuca leucadendron) plantations in Buru Island and Seram Island, Maluku, Indonesia

- Phytochemical analysis and antioxidant activity of Azadirachta indica A. Juss from the Republic of Chad: in vitro and in silico studies

- Stability studies of titanium–carboxylate complexes: A multi-method computational approach

- Efficient adsorption performance of an alginate-based dental material for uranium(vi) removal

- Synthesis and characterization of the Co(ii), Ni(ii), and Cu(ii) complexes with a 1,2,4-triazine derivative ligand

- Evaluation of the impact of music on antioxidant mechanisms and survival in salt-stressed goldfish

- Optimization and validation of UPLC method for dapagliflozin and candesartan cilexetil in an on-demand formulation: Analytical quality by design approach

- Biomass-based cellulose hydroxyapatite nanocomposites for the efficient sequestration of dyes: Kinetics, response surface methodology optimization, and reusability

- Multifunctional nitrogen and boron co-doped carbon dots: A fluorescent probe for Hg2+ and biothiol detection with bioimaging and antifungal applications

- Separation of sulphonamides on a C12-diol mixed-mode HPLC column and investigation of their retention mechanism

- Characterization and antioxidant activity of pectin from lemon peels

- Fast PFAS determination in honey by direct probe electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry: A health risk assessment insight

- Correlation study between GC–MS analysis of cigarette aroma compounds and sensory evaluation

- Synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular docking studies of substituted chromone-2-carboxamide derivatives as anti-breast cancer agents

- The influence of feed space velocity and pressure on the cold flow properties of diesel fuel

- Acid etching behavior and mechanism in acid solution of iron components in basalt fibers

- Protective effect of green synthesized nanoceria on retinal oxidative stress and inflammation in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat

- Evaluation of the antianxiety activity of green zinc nanoparticles mediated by Boswellia thurifera in albino mice by following the plus maze and light and dark exploration tests

- Yeast as an efficient and eco-friendly bifunctional porogen for biomass-derived nitrogen-doped carbon catalysts in the oxygen reduction reaction

- Novel descriptors for the prediction of molecular properties

- Synthesis and characterization of surfactants derived from phenolphthalein: In vivo and in silico studies of their antihyperlipidemic effect

- Turmeric oil-fortified nutraceutical-SNEDDS: An approach to boost therapeutic effectiveness of dapagliflozin during treatment of diabetic patients

- Analysis and study on volatile flavor compounds of three Yunnan cultivated cigars based on headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry

- Near-infrared IR780 dye-loaded poloxamer 407 micelles: Preparation and in vitro assessment of anticancer activity

- Study on the influence of the viscosity reducer solution on percolation capacity of thin oil in ultra-low permeability reservoir

- Detection method of Aristolochic acid I based on magnetic carrier Fe3O4 and gold nanoclusters

- Juglone’s apoptotic impact against eimeriosis-induced infection: a bioinformatics, in-silico, and in vivo approach

- Potential anticancer agents from genus Aerva based on tubulin targets: an in-silico integration of quantitative structure activity relationship (QSAR), molecular docking, simulation, drug-likeness, and density functional theory (DFT) analysis

- Hepatoprotective and PXR-modulating effects of Erodium guttatum extract in propiconazole-induced toxicity

- Studies on chemical composition of medicinal plants collected in natural locations in Ecuador

- A study of different pre-treatment methods for cigarettes and their aroma differences

- Cytotoxicity and molecular mechanisms of quercetin, gallic acid, and pinocembrin in Caco-2 cells: insights from cell viability assays, network pharmacology, and molecular docking

- Choline-based deep eutectic solvents for green extraction of oil from sour cherry seeds

- Green-synthesis of chromium (III) nanoparticles using garden fern and evaluation of its antibacterial and anticholinesterase activities

- Innovative functional mayonnaise formulations with watermelon seeds oil: evaluation of quality parameters and storage stability

- Molecular insights and biological evaluation of compounds isolated from Ferula oopoda against diabetes, advanced glycation end products and inflammation in diabetics

- Removal of cytotoxic tamoxifen from aqueous solutions using a geopolymer-based nepheline–cordierite adsorbent

- Unravelling the therapeutic effect of naturally occurring Bauhinia flavonoids against breast cancer: an integrated computational approach

- Characterization of organic arsenic residues in livestock and poultry meat and offal and consumption risks

- Synthesis and characterization of zinc sulfide nanoparticles and their genotoxic and cytotoxic effects on acute myeloid leukemia cells

- Activity of Coriandrum sativum methanolic leaf extracts against Eimeria papillata: a combined in vitro and in silico approach

- Special Issue on Advancing Sustainable Chemistry for a Greener Future

- One-pot fabrication of highly porous morphology of ferric oxide-ferric oxychloride/poly-O-chloroaniline nanocomposite seeded on poly-1H pyrrole: Photocathode for green hydrogen generation from natural and artificial seawater

- High-efficiency photocathode for green hydrogen generation from sanitation water using bismuthyl chloride/poly-o-chlorobenzeneamine nanocomposite

- Innovative synthesis of cobalt-based catalysts using ionic liquids and deep eutectic solvents: A minireview on electrocatalytic water splitting

- Special Issue on Phytochemicals, Biological and Toxicological Analysis of Plants

- Comparative analysis of fruit quality parameters and volatile compounds in commercially grown citrus cultivars

- Total phenolic, flavonoid, flavonol, and tannin contents as well as antioxidant and antiparasitic activities of aqueous methanol extract of Alhagi graecorum plant used in traditional medicine: Collected in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- Study on the pharmacological effects and active compounds of Apocynum venetum L.

- Chemical profile of Senna italica and Senna velutina seed and their pharmacological properties

- Essential oils from Brazilian plants: A literature analysis of anti-inflammatory and antimalarial properties and in silico validation

- Toxicological effects of green tea catechin extract on rat liver: Delineating safe and harmful doses

- Unlocking the potential of Trigonella foenum-graecum L. plant leaf extracts against diabetes-associated hypertension: A proof of concept by in silico studies