Abstract

Caffeine, a widely consumed stimulant found in beverages like coffee, tea, and energy drinks, frequently contaminates surfaces and wastewater. This study explores the use of biochar derived from kidney bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) husks as a sustainable and cost-effective adsorbent for caffeine removal from aqueous solutions. The adsorbent was characterized using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy for functional group identification, Brunauer–Emmett–Teller analysis for surface area and porosity, and scanning electron microscopy and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy for morphological and elemental analysis. Batch adsorption experiments were optimized at an initial caffeine concentration of 50 mg/L, pH 7.0, 60 mg of adsorbent in 50 mL solution, and a contact time of 90 min. Kinetic modeling showed a strong fit to the pseudo-second-order model (R² = 0.999), suggesting chemisorption as the dominant mechanism. Isotherm analysis revealed monolayer adsorption behavior consistent with the Langmuir model (R² = 0.999), with a maximum adsorption capacity of 40.32 mg/g. These results demonstrate that kidney bean husk-derived biochar is an effective and environmentally friendly adsorbent for removing caffeine from water, offering promising applications in wastewater treatment.

1 Introduction

In recent years, the increasing presence of pollutants in aquatic ecosystems, particularly pharmaceutical compounds, has become a critical environmental and public health concern [1]. The risk of water resource depletion and the contamination of available water supplies have driven researchers to focus on emerging contaminants [2,3]. Among these pollutants, caffeine stands out as one of the most prevalent pharmaceutically active compounds and serves as a significant indicator in aquatic environments [4,5].

Caffeine is a naturally occurring alkaloid found in many plant species and is present in various food and pharmaceutical products, including tea, coffee, energy drinks, chocolate, and medications [6,7]. Today, approximately 90% of the adult population consumes caffeine regularly. As a result, the unmetabolized portion is excreted and enters wastewater, eventually dispersing into the environment. The persistence of caffeine in the environment and its effects on biological systems have become a significant research focus. Major sources of caffeine pollution include human waste, hospital and pharmaceutical factory discharges, improper drug disposal, and domestic wastewater [8,9,10].

Caffeine reaches wastewater treatment plants through sewage systems; however, many conventional treatment methods fail to completely remove this compound [11]. Untreated caffeine can enter surface water, groundwater, and even drinking water, posing risks to human health and aquatic ecosystems. Additionally, the use of untreated wastewater for agricultural irrigation leads to caffeine accumulation in soil, where it can be absorbed by plants and subsequently transferred to humans and animals [12]. The incomplete removal of caffeine during treatment allows it to persist in water systems, contributing to long-term ecological and public health concerns [13,14].

Despite wastewater treatment achieving up to 99% caffeine removal efficiency, its persistent detection in surface and groundwater demonstrates the incomplete elimination of pollution and highlights the lasting impact of human activities on water quality [15]. Particularly in regions without natural caffeine sources (tea, coffee, etc.), the presence of caffeine in water serves as a direct indicator of anthropogenic pollution [16]. Consequently, caffeine has become recognized as a significant biomarker for environmental contamination [7,17].

Caffeine levels detected in the environment can lead to adverse effects, particularly hormonal imbalances, the development of bacterial resistance, genetic mutations, and disruption of ecosystem balance [18,19]. Although caffeine is considered “generally safe” by the Food and Drug Administration, high doses can lead to health problems [20,21]. While the recommended maximum daily caffeine intake for healthy adults is 400 mg [22], this limit is 300 mg for pregnant women [23,24,25]. In children and adolescents, daily consumption should be below 100 mg [26]. Excessive caffeine intake can cause adverse health effects such as anxiety, high blood pressure, hand tremors, decreased fertility, and increased risk of miscarriage [23,24,25].

Recently, the adsorption technique has become one of the prominent methods in water and wastewater treatment processes. This process is based on the principle of retention of pollutants in liquid media by a solid surface (adsorbent) [27]. Owing to its high efficiency, selectivity against various pollutants, economic reuse possibility, and versatile applicability, this method is accepted as an important choice in the field of water treatment [28,29,30,31,32]. In studies, different adsorbent materials have been used in the removal of pollutants in the liquid phase. These materials include activated carbon derivatives [33,34], clay and mineral-based structures [35,36], polymeric resins [37,38], and nanoscale particles and composites [39,40]. However, some of these materials do not offer sustainable solutions due to their high costs and environmental impacts. This situation has led researchers to seek more environmentally friendly and economical alternatives. In this context, biosorbents produced from natural sources such as agricultural wastes are of great interest [41,42]. Organic wastes such as coconut shells, banana stalks, rice bran, sugarcane bagasse, pineapple leaves and legume peels are used in water treatment applications as low-cost and effective biosorbents [43,44].

Studies on caffeine adsorption have examined various types of adsorbents, including activated carbon derived from grape stalks [10], thermally modified bentonite [45], activated carbon produced from date pits [46], pine needle biochar [14], oxidized activated carbon from Luffa cylindrica [47], and organically modified saponites [48]. Despite extensive research on caffeine removal from wastewater, most existing adsorbents are either costly, non-renewable, or derived from non-sustainable sources.

Consequently, there is an increasing need for effective, sustainable, and economical treatment methods to minimize the environmental impacts of caffeine. This study introduces a breakthrough solution by developing a highly efficient, low-cost biochar adsorbent from kidney bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) husks – an underutilized agricultural waste – for sustainable caffeine removal. To optimize the adsorption process, the effects of physicochemical parameters such as initial caffeine concentration, pH, contact time, adsorbent dosage, and temperature were evaluated. Additionally, the isothermal and kinetic models of adsorption, as well as thermodynamic parameters (free energy, entropy, and enthalpy), were determined. Finally, the recyclability of the adsorbent was examined, and its regeneration capacity was assessed.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Caffeine (C8H10FN4O2, 99% purity), potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KH₂PO₄, 99.99% purity), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 98% purity), hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37% purity), orthophosphoric acid (H3PO4, ≥85% purity), ethanol (C2H5OH), and acetonitrile (CH3CN, 99.9% purity) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used without further purification.

A 100 mL caffeine stock solution with a concentration of 500 mg/L was initially prepared using deionized water as the solvent. Standard solutions with concentrations of 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 mg/L were prepared from the stock solution and used for calibration in the development of the high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis method. For the experimental studies, 50 mL solutions with an initial caffeine concentration of 50 mg/L were prepared. pH adjustments were made using analytical-grade NaOH and HCl solutions (Merck). The bean husk used in this study was collected from a local garden in Zonguldak, Turkey.

2.2 Adsorbent preparation

Kidney bean shells were initially washed with tap water and subsequently with distilled water to remove dust and other impurities. Following the washing process, they were dried in a dark and enclosed room for a week, then ground and sieved (particle size range <1.00 mm). The ground kidney bean shells underwent pyrolysis at 550°C for 30 min, with a heating rate of 10°C/min under an N2 gas flow rate of 0.5 L/min. A mixture was prepared using the biochar obtained from pyrolysis at a mass ratio of 3:1 (KOH/biochar), and this mixture was allowed to stand for 24 h. After the 24-h standing period, the sample was stirred, dried at room temperature, and then at 105°C. The completely dried samples were then subjected to carbonization in a furnace at 800°C for 1 h, with a heating rate of 10°C/min under an N2 flow rate of 1 L/min. The nitrogen gas flow was continued until the temperature dropped to 25°C. After thorough cleaning with distilled water three times, the activated carbon was immersed in 1 M HCl and subsequently washed once more with deionized water and ethanol to remove chloride ions before being allowed to dry naturally. It was then dried in an oven at 105°C and stored for characterization and adsorption experiments.

2.3 Adsorbent characterization

The synthesized adsorbent was characterized using a range of analytical techniques. The functional groups present on the surface of the biochar were identified using Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy with a Bruker ALPHA instrument.

The specific surface area (SSA) of the activated carbon was measured using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method with a Micromeritics Gemini 2360 analyzer. For this analysis, 1 g of the sample was used, pretreated under a nitrogen atmosphere at 250°C, and the dry mass was determined using an analytical balance. High-purity nitrogen served as the adsorbate gas during the measurements.

The surface morphology and elemental composition of the activated carbon were examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using a LEO 1430 VP model SEM. Additionally, FTIR analysis (Bruker ALPHA model) was employed again to further confirm the functional groups in the structure of the activated carbon, with spectra recorded in the range of 400–4,000 cm⁻¹. Additionally, the point of zero charge (pHpzc) of the adsorbent surface was determined by adjusting the pH of 50 mL of 0.1 M NaCl solution between 2 and 12 and then adding 50 mg of adsorbent. The mixture was continuously shaken for 24 h. The final pH value of the solution was measured, and pHpzc was reached when pHinitial − pHfinal = 0.

2.4 Adsorption studies

To investigate the effects of adsorption parameters (pH, initial concentration, adsorbent dosage, contact time, and temperature) and to determine the optimum adsorption conditions, experiments were conducted in a batch mode with three replicates, where one variable was changed while keeping the other parameters constant. All experiments were performed using Erlenmeyer flasks, each containing 50 mL of caffeine solution and a water bath shaker (WSB-30, WITEG, Germany) operating at 180 rpm.

Adsorption studies were carried out using different adsorbent amounts (0.020, 0.040, 0.060, 0.080, and 0.100 g), different pH levels (4, 7, 11), and different temperatures (295, 305, and 315 K), while keeping the initial caffeine solution concentration constant at 50 mg/L.

The reusability of the synthesized biochar was evaluated through four successive adsorption–desorption cycles. For this, the same amount of adsorbent was used in each cycle. After each adsorption run, the spent adsorbent was soaked in a 20% ethanol solution, treated with ultrasound for 1 h, rinsed with deionized water, filtered, and then oven-dried for reuse.

The caffeine concentrations in the solutions before and after the adsorption process were measured using an HPLC system (Agilent 1260 Series, USA) equipped with a UV detector. Caffeine detection was carried out at a wavelength of 275 nm. A C18 chromatographic column (Waters Symmetry®, 150 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) was employed for the separation process. The mobile phase consisted of a dihydrogen phosphate buffer and acetonitrile mixture (87.50: 12.50, v/v), adjusted to pH 2.2, with a flow rate of 1 mL/min.

The equilibrium adsorption capacity (q e) and the percentage of caffeine removal were determined using equations (1) and (2), respectively:

Here, C o represents the initial caffeine concentration (mg/L), C e represents the equilibrium caffeine concentration (mg/L), V represents the volume of the solution (L), and m represents the mass of the adsorbent (g).

2.5 Adsorption isotherms

Adsorption isotherms are mathematical models that illustrate how adsorbate molecules are distributed between the liquid phase and the surface of the adsorbent. These models are essential for understanding the adsorption mechanism, as they provide insight into the interactions between the adsorbent and adsorbate at a constant temperature [49]. Numerous isotherm models have been proposed in the literature to describe adsorption behavior. Among the most widely applied are the Langmuir, Freundlich, Temkin, and Dubinin–Radushkevich isotherms [50,51,52,53]. The Langmuir isotherm is based on the assumption that adsorption occurs in a monolayer on a homogeneous surface, with uniform adsorption energy across the surface. As the initial concentration of the adsorbate increases, adsorption also increases until a saturation point is reached. The linear form of the Langmuir isotherm equation is given as follows [54,55]:

where K L (L/g) is the Langmuir constant related to adsorption energy, q max (mg/g) is the maximum adsorption capacity of the adsorbent, C e (mg/L) is the adsorbate concentration in the solution after equilibrium, and q e (mg/g) is the amount of the adsorbate adsorbed per unit mass of the adsorbent.

In the Langmuir isotherm, the spontaneity of the adsorption process is evaluated using the R L (separation factor) parameter:

where C 0 (mg/L) represents the initial concentration of the adsorbate, and K L represents the Langmuir constant. An R L value in the range 0 < R L < 1 indicates favorable (spontaneous) adsorption, R L > 1 suggests an unfavorable process, R L = 1 corresponds to linear adsorption, and R L = 0 signifies irreversible adsorption. Thus, the R L parameter plays a critical role in interpreting the thermodynamic feasibility and behavior of the adsorption process.

The Freundlich isotherm describes multilayer adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces. The adsorbate concentration on the adsorption surface changes proportionally to the increase of the adsorbate concentration in the solution. The linear form of the Freundlich isotherm equation is expressed as follows [56]:

Here, q e (mg/g) is the amount of the adsorbed substance at equilibrium, K F is the experimental constant indicating adsorption capacity, n is the experimental constant determining heterogeneity, and C e (mg/L) is the adsorbate concentration remaining in the solution after equilibrium.

The 1/n value varies between 0 and 1. As 1/n approaches zero, the surface becomes more heterogeneous. The Temkin isotherm model assumes that adsorption is homogeneously distributed on the adsorbent surface and that adsorption energies decrease linearly and not exponentially, as in the Freundlich model. The linear form of the Temkin isotherm equation is as follows [57]:

Here, B = RT/b T (J/mol) is the Temkin isotherm constant, A T (L/g) is the equilibrium binding constant, R (8.314 J/mol K) is the gas constant, and T (K) is the absolute temperature.

The Dubinin–Radushkevich isotherm model describes an adsorption process that initially follows a volume-filling mechanism. It is applicable to both homogeneous and heterogeneous surfaces. The linear equation of the model is expressed as follows [58]:

where

2.6 Adsorption kinetics

Adsorption kinetics is examined using models that are used to understand the adsorption mechanism, mass transfer, and rate-controlling steps [59]. In this study, four different kinetic models were applied: pseudo-first-order (PFO), pseudo-second-order (PSO), Elovich, and intraparticle diffusion (IPD) model.

The PFO kinetic model, developed by Lagergren, explains the adsorption mechanism depending on the adsorbent capacity. The linear form of the model is expressed as follows [60]:

Here, q e (mg/g) is the amount of the adsorbed substance at equilibrium, q t (mg/g)is the adsorption amount at time t, k 1 (min−1) is the rate constant of the PFO kinetic model, and t (min) is the time.

This model is generally in good agreement with the experimental data for the first 30 min of adsorption but is not in good agreement with the experimental data for all ranges of contact time [60].

The PSO kinetic model derived by Ho and McKay is related to the adsorption capacity and is a valid model for the whole adsorption process [60]. Its linear form is given as follows:

Here, k 2 (g/mg min) is the rate constant of the PSO kinetic model, q e (mg/g) is the equilibrium adsorption capacity, q t(mg/g) is the adsorption amount at time t, and t (min) is the time.

This model shows that adsorption is chemically controlled and adsorbate–adsorbent interactions are important.

The IPD model describes the transport of adsorbate from the solution to the adsorbent surface and its diffusion within the particle. Its linear form is expressed as follows [61]:

Here, q t (mg/g) is the adsorption amount at time t, K p (mg/g min1/2) is the intra-particle diffusion model constant, t (min) is the time, and C (mg/g) is a constant referring to the boundary layer thickness.

The larger the value of C, which represents the boundary layer thickness, the more limited the adsorption is by surface control. Small C values indicate that diffusion is the main determinant of the process.

2.7 Adsorption thermodynamics

The thermodynamics of the adsorption process is used to understand the energy changes that occur in an adsorption process and explain the adsorption mechanism, whether it is spontaneous or not, and its response to temperature changes. In this context, thermodynamic parameters such as enthalpy change (ΔH 0), entropy change (ΔS 0), and Gibbs free energy change (ΔG 0) are determined. These parameters help to explain the adsorption mechanism and the nature of the interactions between adsorbent and adsorbate. The thermodynamic parameters are determined using equations (13) and (14):

where K c is the equilibrium constant, expressed in q e/C e; R is the universal gas constant (=8.314 J/mol/K); and T is the temperature, expressed in Kelvin [51].

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Biochar characterization

3.1.1 SEM

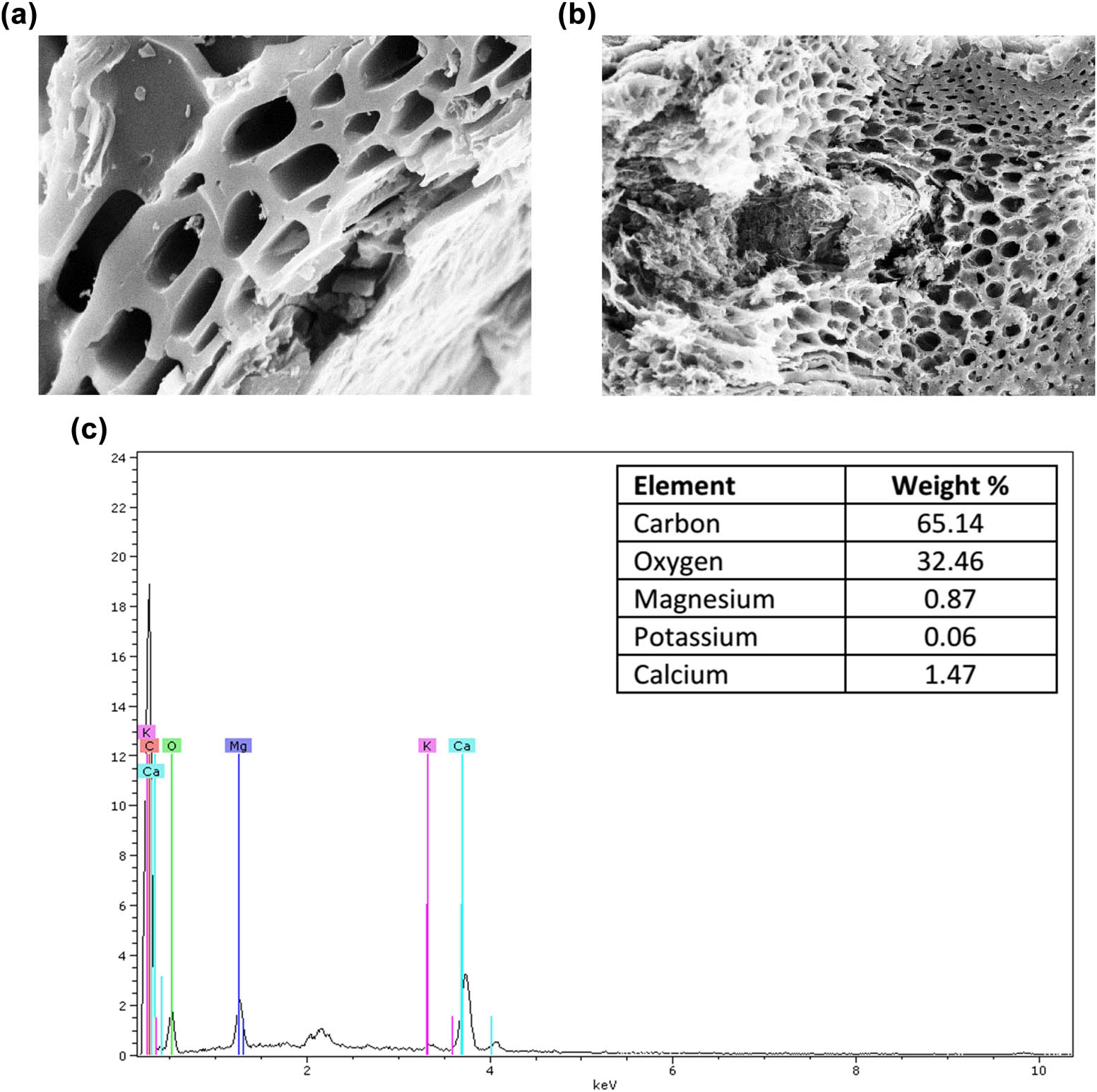

SEM is a widely employed technique for surface morphology analysis. Figure 1a and b illustrates the SEM images of kidney bean biochar (BFB), revealing a homogeneous distribution of pores with varying diameters across the biochar surface. These pores are likely formed due to the release of volatile compounds, such as H₂, CO, and CH₄, during pyrolysis [52]. The observed variations in pore volume can be attributed to differences in the size and proportion of volatile components within the material’s structure. Additionally, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) mapping was conducted to determine the chemical composition of BFB, as shown in Figure 1c. The results indicate that carbon and oxygen constitute the primary framework of the prepared material.

Surface morphology of kidney bean biochar: (a) 2 µm, (b) 20 µm, and (c) EDX analysis.

3.1.2 FTIR spectroscopy

To determine the structural composition of BFB, FTIR analysis was performed, and the resulting spectrum is illustrated in Figure 2. The observed peak is shown at around 3,662 cm−1, which is related to the vibrations of the –OH stretching vibration in alcohol or phenol and the vibrations of the H2O molecule. The observed peaks at about 2,977–2,891 cm−1 can be attributed to the C–H stretching of aliphatic groups. The peaks observed at 1,600–1,550 cm−1 are attributed to aromatic C═C ring stretching indication of benzene-like rings . Finally, the peak observed at 1,061 cm−1 can be attributed to symmetric C–O–C stretching for cellulose, hemicelluloses, and lignin. C–O stretching in acids, alcohols, phenols, and esters appeared between 1,000 and 1,200 cm−1 [62].

FT-IR spectrum of BFB.

3.1.3 Analysis of structural characteristics

The structural quality of an adsorbent is critical when determining its maximum sorption capacity and the related process [63]. If the main mechanism of adsorption is pore filling, an adsorbent with a higher SSA and total pore volume usually exhibits better sorption ability of pharmaceuticals [64,65]. The structural properties (SSA and pore volume) of BFB were calculated using nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms at 77 K (Figure 3).

Adsorption–desorption isotherms of BFB.

As illustrated in Figure 3, the adsorption–desorption isotherms of BFB correspond to Type IV, characterized by hysteresis loops due to capillary condensation, which is indicative of a mesoporous structure [64]. The associated structural parameters are summarized in Table 1. Based on these properties, the SSA of BFB was determined to be 506.61 m²/g.

Textural properties of BFB

| Adsorbent | BET surface area (m2/g) | BJH adsorption cumulative pore volume (cm3/g) | Average pore diameter (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biochar derived from kidney beans (BFB) | 506.61 | 0.1890 | 2.86 |

BFB exhibited a pore volume of 0.1890 cm³/g and an average pore diameter of 2.86 nm, confirming its microporous structure. These results demonstrate that BFB’s enhanced adsorption performance stems from physical adsorption facilitated by micropores, enabling uniform distribution of caffeine molecules on BFB’s surface. Increased interaction probability between caffeine and active sites due to optimal pore accessibility. Given caffeine’s molecular dimensions, the 2.86 nm pore diameter of BFB is ideally suited for efficient caffeine uptake. This alignment promotes pore-filling mechanisms within BFB’s primary pore channels, maximizing adsorption capacity. Notably, BFB’s elevated porosity and pore size distribution indicate a positive correlation with caffeine uptake capacity, underscoring porosity as a critical determinant of BFB’s adsorption efficacy.

3.2 Adsorption studies

3.2.1 Determination of point zero charge of BFB

To assess the behavior of activated carbon in aqueous environments, the point of zero charge (pHpzc), a key parameter, was determined. When the pH is below the pHpzc, the surface functional groups of the adsorbent become protonated, resulting in a positively charged surface that favors anion adsorption. In contrast, at pH values above the pHpzc, deprotonation occurs due to the presence of OH⁻ ions, leading to a negatively charged surface that enhances cation adsorption [66]. As shown in Figure 3a, the pHpzc of the adsorbent was found to be 7.80. Therefore, the adsorption of negatively charged caffeine species is more effective at pH values below 7.80, while higher pH values promote the adsorption of positively charged caffeine species [67,68].

3.2.2 Effect of solution pH on adsorption performance

The pH of the aqueous solution significantly influenced the adsorption efficiency of caffeine onto the biochar-based adsorbent (BFB) by modulating the surface charge of the adsorbent and the ionization state of caffeine molecules. As illustrated in Figure 4c, the adsorption efficiency followed a pH-dependent trend, with optimal performance observed at neutral pH.

(a) Determination of pHzpc using the pH shift method, (b) effect of adsorbent dose on caffeine removal, (c) effect of solution pH, and (d) effect of contact time.

At pH 4 (acidic conditions), the removal efficiency reached 95.86%, attributable to the protonation of caffeine (pH < pK a) and electrostatic attraction between the positively charged nitrogen in caffeine and the adsorbent surface, which remains near-neutral at this pH (below the pHPZC of 7.80, Figure 4a) [59,60]. The highest efficiency (98.10%) was achieved at pH 7 (neutral), where the balance between caffeine’s protonation state and the adsorbent’s slightly negative surface charge (approaching pHPZC) minimized repulsive forces while maximizing adsorption affinity [61].

Under alkaline conditions (pH 10), the efficiency declined to 93.22%, likely due to the deprotonation of caffeine and the increasingly negative surface charge of BFB (pH > pHPZC, Figure 4a), resulting in weaker electrostatic interactions or potential repulsion [62,63]. This trend aligns with the molecular structure of caffeine, where the high dipole moment enhances its sensitivity to polarity changes in the medium [69].

The selection of pH 7 as the optimal condition not only maximizes adsorption but also aligns with the typical pH range of industrial wastewater, ensuring practical applicability without requiring extensive pH adjustment. These findings underscore the dominance of electrostatic interactions in the adsorption mechanism, as corroborated by the pHPZC analysis (Figure 4a) and prior studies on polar organic compounds [70,71,72,73].

Figure 4c confirms that neutral pH provides the highest caffeine removal efficiency, while deviations to extreme pH values reduce performance. This behavior highlights the critical role of pH control in water treatment processes targeting caffeine removal.

3.2.3 Effect of adsorbent dose on adsorption performance

The adsorbent dose is a critical parameter influencing the removal efficiency of caffeine from aqueous solutions, as it directly affects the availability of active sites for adsorption. In this study, the initial caffeine concentration was maintained at 50 mg/L to evaluate the effect of adsorbent dosage while minimizing costs and optimizing efficiency. As depicted in Figure 4b, the removal efficiency of caffeine increased with higher adsorbent doses. Specifically, when 60 mg of BFB adsorbent was applied to a 50 mL solution, the removal efficiency reached 91.34%. This trend is attributed to the greater number of active sites available for caffeine adsorption as the adsorbent mass increased, enhancing the interaction between caffeine molecules and the adsorbent surface [10,32,45]. The observed improvement in removal efficiency with increasing adsorbent dose aligns with established adsorption principles, where higher adsorbent quantities provide more surface area and binding sites for pollutant uptake. Beyond 60 mg, no significant enhancement in efficiency was observed, suggesting that equilibrium was achieved between caffeine molecules and available adsorption sites. Thus, 60 mg of adsorbent per 50 mL solution was identified as the optimum dose, balancing high removal efficiency with practical and economic considerations.

These results highlight the importance of optimizing adsorbent dosage to maximize caffeine removal while avoiding unnecessary resource expenditure. The findings are consistent with previous studies demonstrating that adsorbent dose plays a pivotal role in determining adsorption capacity and efficiency [10,32,45].

3.2.4 Influence of contact time on adsorption efficiency

Contact time is among the most critical factors influencing adsorption efficiency. As illustrated in Figure 4d, the adsorption of caffeine onto the adsorbent progressed rapidly, with over 95% of caffeine being removed within the first 30 min. Equilibrium was reached at 90 min, yielding an impressive removal efficiency of nearly 99%. This rapid initial uptake is attributed to the abundance of available active sites on the adsorbent surface. As adsorption proceeds, these sites become increasingly occupied, slowing the rate of adsorption. Consequently, a contact time of 90 min was established as the equilibrium duration for all subsequent experiments.

3.3 Modeling of adsorption kinetics

In this study, the caffeine adsorption kinetics from aqueous solutions onto the bean shell-derived adsorbent were investigated using four distinct models: PFO, PSO, Elovich, and IPD. The suitability of these models was compared to elucidate the dynamics of the adsorption mechanism. The fitted curves are presented in Figure 5, and the corresponding results are summarized in Table 2.

Adsorption kinetics modeling of caffeine adsorption onto BFB.

Caffeine adsorption kinetic model parameters and evaluations

| Model | Parameter | R² |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudo-first order | k₁ = 0.040 min⁻¹ | 0.988 |

| qₑ (calculated) = 15.24 mg/g | ||

| qₑ (experimental) = 38.33 mg/g | ||

| Pseudo-second order | k₂ = 0.0056 g/mg min | 0.999 |

| qₑ (calculated) = 39.68 mg/g | ||

| qₑ (experimental) = 38.33 mg/g | ||

| Elovich | α = 0.55 mg/g min | 0.910 |

| β = 4.93 g/mg | ||

| IPD | Faz 1 (0–15 min): | 0.992 (Phase 1) |

| kₚ₁ = 7.98 mg/g min⁰ ⁵ | ||

| C₁ = 0.48 mg/g | ||

| Faz 2 (15–60 min): | 0.960 (Phase 2) | |

| kₚ₂ = 1.78 mg/g min⁰ ⁵ | ||

| C₂ = 23.83 mg/g | ||

| Faz 3 (60–150 min): | 0.914 (Phase 3) | |

| kₚ3 = 0.26 mg/g min⁰ ⁵ | ||

| C 3 = 35.33 mg/g |

The PFO kinetic model demonstrated a poor fit to the experimental data, evidenced by a significant discrepancy between the experimental qₑ value and the calculated qₑ (15.24 mg/g), along with a relatively low correlation coefficient (R² = 0.988). This discrepancy suggests the limitations of the model and highlights potential physical adsorption processes.

Conversely, the PSO kinetic model emerged as the most suitable, exhibiting a high correlation coefficient (R² = 0.999) and a close agreement between the experimental equilibrium capacity (38.33 mg/g) and the calculated value (39.68 mg/g). This finding implies that the adsorption process is primarily governed by chemical interactions, such as ionic bonding or electron transfer.

The Elovich model, while accounting for heterogeneous surface interactions (R 2 = 0.910), showed a comparatively lower fit than the other models. Nevertheless, the parameters α (0.55 mg/g min) and β (4.93 g/mg) provided insights into the rapid initial adsorption rate and the effectiveness of surface coverage.

The IPD model revealed a multi-step adsorption mechanism. The high kₚ value (7.98 mg/g min½) in the initial phase (0–15 min) indicated that surface adsorption was dominant. The moderate kₚ value (1.78 mg/g min½) in the second phase (15–60 min) and the low kₚ value (0.26 mg/g min½) in the third phase (60–150 min) suggested that IPD became the limiting factor. The non-zero C parameter further supported the significant role of boundary layer resistance.

Overall, the superior performance of the PSO model confirmed that caffeine adsorption was primarily controlled by chemical interactions, while the IPD model elucidated the multi-step nature of the process. These findings underscore the effectiveness of bean shell-based adsorbents in caffeine removal and highlight the importance of kinetic models for process optimization. Future studies should focus on investigating the kinetic behavior under various conditions and with surface-modified adsorbents. The agreement of the experimental data with the PSO kinetic model suggests that the rate-limiting step in the biosorption processes on BFB is the chemical interaction (which may involve ion exchange and/or electron sharing) between the caffeine molecule from the aqueous solution and the superficial functional groups of the biosorbent [74]. On the other hand, when the values of the rate constants are compared, it was found that caffeine molecules have higher affinity to the functional groups of the biosorbent, and the biosorption efficiency will be the highest.

3.4 Modeling of adsorption isotherms

In this study, the adsorption of caffeine from aqueous solutions onto bean shell-derived adsorbent was analyzed using four distinct isotherm models: Langmuir, Freundlich, Temkin, and Dubinin–Radushkevich. The suitability of these models was compared to elucidate the adsorption mechanism and evaluate the adsorbent’s performance. The non-linear isotherm model fits are illustrated in Figure 6, and the findings are presented in Table 3.

Adsorption isotherm modeling of olaparib adsorption onto BFB.

Isotherm model parameters for caffeine adsorption

| Model | Parameter | R² |

|---|---|---|

| Langmuir | qₘₐₓ = 40.32 mg/g | 0.999 |

| Kₗ = 0.744 L/mg | ||

| Rₗ = 0.0127 (C₀ = 105 mg/L) | ||

| Freundlich | K F = 28.43 (mg/g)(L/mg)¹/ⁿ | 0.964 |

| n = 11.68 | ||

| Temkin | A = 89.230 L/g | 0.942 |

| b = 985 J/mol | ||

| B = 2.514 mg/g | ||

| Dubinin–Radushkevich | qₘ = 41.38 mg/g | 0.891 |

| β = 1.12 × 10⁻⁶ mol²/J² | ||

| E = 0.67 kJ/mol |

The Langmuir isotherm model was determined to be the most suitable, exhibiting a high correlation coefficient (R² = 0.999) and physically meaningful parameters. The maximum adsorption capacity (q max = 40.32 mg/g) predicted by the model was consistent with the experimental data, indicating that adsorption occurred as a monolayer on a homogeneous surface. Furthermore, the dimensionless separation factor (R L) value, ranging between 0 and 1, supported the feasibility of the adsorption process.

The Freundlich model, representing heterogeneous surface interactions, revealed a high K F value (28.43 (mg/g)(L/mg)(1/n)), suggesting a strong affinity of the adsorbent for caffeine. The heterogeneity factor (n = 11.68), exceeding 1, indicated that the adsorption was physical and favorable. However, the model exhibited a comparatively lower correlation coefficient (R² = 0.964), indicating a limited fit.

The Temkin model suggested that physical adsorption was dominant, as evidenced by the low heat of adsorption (b = 985.5 J/mol). Nevertheless, the model’s lower correlation coefficient (R² = 0.942) compared to other models indicated a limited fit.

The Dubinin–Radushkevich (D-R) model (R² = 0.891) indicated that the adsorption was a low-energy physical process (E = 0.67 kJ/mol), consistent with a microporous structure. However, this model also exhibited a lower correlation coefficient compared to the others, suggesting a limited fit.

Overall, the superior fit of the Langmuir model confirmed that monolayer adsorption was the dominant mechanism for caffeine adsorption onto the bean shell adsorbent. The other models provided complementary information regarding heterogeneous surface interactions and low-energy physical adsorption. These findings suggest that bean shell-based adsorbents are an effective option for removing contaminants like caffeine, and they provide recommendations for process optimization and adsorbent modification in future studies.

3.5 Thermodynamic evaluation

Since the interpretations made with a small amount of experimental data in thermodynamic studies may be incorrect, the amount of temperature data obtained from the experiments should be increased [75]. Therefore, the thermodynamic behavior of the adsorption of caffeine onto the adsorbent obtained from bean shells was investigated at five different temperatures (290, 300, 305, 310, and 315 K) to explain the spontaneity, energy changes, and mechanism of the process. The calculated thermodynamic parameters – Gibbs free energy change (ΔG 0), enthalpy change (ΔH 0), and entropy change (ΔS 0) – are summarized in Table 4.

Thermodynamic parameters for caffeine adsorption

| Temperature (K) | ΔG 0 (kJ/mol) | ΔH 0 (kJ/mol) | ΔS 0 (J/mol K) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 290 | −10.34 | 5.22 | 17.65 |

| 295 | −10.43 | ||

| 300 | −10.52 | ||

| 305 | −10.61 | ||

| 310 | −10.70 | ||

| 315 | −11.79 |

The negative ΔG 0 values at all temperatures (−10.34 to −11.79 kJ/mol) confirm the spontaneous nature of caffeine adsorption. The increasing negative ΔG 0 with increasing temperature (290 → 315 K) indicates that the favourability of adsorption increases at higher temperatures [76]. The magnitude of ΔG 0 (<−20 kJ/mol) indicates a physisorption mechanism dominated by weak van der Waals forces or electrostatic interactions [77,78]. The negative ΔH 0 value (−5.22 kJ/mol) suggests an exothermic process and supports the observed temperature-dependent efficiency decrease. The positive ΔS 0 (17.65 kJ/mol) reflects greater randomness at the solid–liquid interface during adsorption. This entropy-driven behavior suggests that caffeine molecules adopt a less ordered arrangement on the adsorbent surface, possibly due to solvent displacement or multilayer adsorption [79]. Thermodynamic analysis shows that caffeine adsorption onto the bean shell-derived adsorbent occurs:

Spontaneous (ΔG 0 < 0),

Exothermic (ΔH 0 < 0), and

Entropy-driven (ΔS 0 > 0),

with physiosorption as the dominant mechanism. These findings are in agreement with previous studies on biochar-based adsorbents [77,78,79,80] and emphasize the potential of this low-cost material for organic pollutant removal.

3.6 Adsorption mechanism

Biochar derived from phaseolus vulgaris pod husks (BFB) is an effective material for caffeine adsorption. The biochar possesses a micro- and mesoporous structure, facilitating the retention of small molecules such as caffeine on its surface. Typically exhibiting a surface area ranging from 100 to 1,000 m²/g, it provides numerous adsorption sites. The biochar surface contains oxygen-containing functional groups, such as carboxyl (–COOH), hydroxyl (–OH), phenolic, and lactone groups, which form physical and chemical interactions with caffeine. Additionally, the carbon-based hydrophobic structure of biochar promotes hydrophobic interactions with organic molecules. BFB, with its high cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin content, is well-suited for biochar production. During pyrolysis, these components carbonize, forming a porous structure [81]

Caffeine (C₈H₁₀N₄O₂), a methylxanthine alkaloid, is characterized by a heterocyclic structure. Containing nitrogen and oxygen atoms, this structure enables polar interactions. The aromatic purine ring contributes to hydrophobic interactions, while caffeine’s nitrogen atoms confer weak basic properties, allowing protonation depending on pH. With a molecular size of approximately 0.6–0.8 nm, caffeine can easily penetrate the micro- and mesopores of biochar [82]

The adsorption of caffeine onto biochar results from a combination of physical and chemical interactions. The primary mechanisms are outlined below.

Physical adsorption (van der Waals forces): Caffeine molecules are physically attracted to the porous structure of biochar through van der Waals forces. The micro- and mesopores trap caffeine molecules, enhancing adsorption capacity. This low-energy, reversible process is influenced by environmental factors such as temperature and concentration.

Hydrophobic interactions: The aromatic purine ring of caffeine interacts with the hydrophobic carbon surfaces of biochar. This interaction promotes the orientation of caffeine toward the biochar surface, particularly in aqueous solutions. The carbonized structure of BFB-derived biochar provides a suitable environment for hydrophobic interactions.

π–π interactions: The graphitic structure of biochar contains aromatic rings that form π–π stacking interactions with the purine ring of caffeine. These interactions enable strong binding of caffeine to the biochar surface, increasing adsorption efficiency.

Hydrogen bonding: Oxygen-containing functional groups (–OH, –COOH) on the biochar surface form hydrogen bonds with nitrogen or oxygen atoms of caffeine. For instance, the carbonyl groups (C═O) of caffeine can form hydrogen bonds with the hydroxyl groups of biochar.

Electrostatic interactions: The pH of the solution affects the charge states of both the caffeine and biochar surfaces. At low pH, caffeine may become protonated, adopting a cationic form. Negatively charged functional groups, such as carboxylate ions, on the biochar surface, can form electrostatic attractions with protonated caffeine. However, the surface chemistry of BFB-derived biochar varies depending on pyrolysis conditions; at higher pH, the surface becomes more negatively charged, influencing electrostatic interactions [83].

These mechanisms collectively enable the high efficiency of BFB biochar in caffeine adsorption. The adsorption process depends on both the surface properties of the biochar and the environmental conditions of the solution.

3.7 Reusability of BFB adsorbent

The reusability of the biochar-based adsorbent (BFB) was evaluated through five consecutive adsorption–desorption cycles to assess its practical applicability and economic viability. The experimental procedure consisted of the following steps: caffeine adsorption was conducted under optimized conditions (pH 7, 50 mg/L initial concentration, 60 mg adsorbent dose, and room temperature). The caffeine-saturated adsorbent was filtered and separated from the solution. Ethanol (50 mL) was used as the desorption solvent due to its high caffeine solubility, low boiling point, and ease of removal. The adsorbent was washed at 150 rpm for 10 min. The regenerated adsorbent was dried at 80°C until a constant weight was achieved. The adsorption–desorption process was repeated five times, with removal efficiency recorded for each cycle. The reusability performance of BFB is summarized in Table 5.

Caffeine removal efficiency of BFB adsorbent over multiple cycles

| Cycle no. | Removal efficiency (%) |

|---|---|

| 0 (fresh) | 96.50 |

| 1 | 94.72 |

| 2 | 93.10 |

| 3 | 90.70 |

| 4 | 80.36 |

The fresh BFB adsorbent exhibited a high removal efficiency of 96.50%, demonstrating its effectiveness under optimized conditions. A gradual decrease in efficiency was observed over successive cycles, with 94.72% (Cycle 1), 93.10% (Cycle 2), 90.70% (Cycle 3), and 80.36% (Cycle 4). The adsorbent maintained > 90% efficiency for three cycles, indicating robust reusability. By the fifth cycle, efficiency dropped to 80.36%, likely due to partial pore blockage by residual caffeine or ethanol impurities and structural degradation of active sites after repeated regeneration. The use of ethanol as a desorption solvent proved effective due to its ability to dissolve caffeine without severely damaging the adsorbent structure. The drying step (80°C) ensured complete solvent removal, preventing interference in subsequent cycles.

BFB’s ability to retain high efficiency (>90%) for multiple cycles reduces operational costs in wastewater treatment. The adsorbent’s reusability aligns with circular economy principles by minimizing waste generation. Future studies could explore alternative regeneration methods (e.g., thermal or chemical treatment) to enhance longevity beyond five cycles. BFB demonstrates excellent reusability, with >90% efficiency retained for three cycles and >80% even after five cycles. While a gradual decline occurs, the adsorbent remains viable for practical applications, offering an economical and sustainable solution for caffeine removal. Further optimization of regeneration protocols could extend its lifespan. Table 6 lists recent studies on adsorption for caffeine removal from aqueous solutions.

Adsorption studies on caffeine removal from aqueous solutions

| Adsorbent | Maximum adsorption capacity for caffeine (mg g⁻¹) | Experimental conditions | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | Equilibrium time (min) | Temperature (°C) | |||

| Phenyl-phosphate-based porous organic polymers | 30 | 5 | 120 | 25 | [84] |

| Graphene oxide-based composites | 14.8 | 7 | 480 | 30 | [85] |

| Activated carbon from Eragrostis plana Nees leaves | 27.2 | 7 | 30 | 25 | [86] |

| Activated carbon powder | 51.8 | 6.2 | 180 | 30 | [87] |

| Coffee waste and chitosan composite | 8.66 | 6 | 60 | 25 | [88] |

| Granular activated carbon | 88 | 6 | 60 | 25 | [89] |

| Rice husk charcoal | 2.09 | — | 1,440 | — | [90] |

| Rice husk + corn cob mixture charcoal | 8.04 | — | — | — | |

| Klinoptilolit | 1.65 | — | 1,440 | 25 | [91] |

| Paligorskit | 0.27 | — | — | — | |

| Graphene | 22.73 | 6.4 | 120 | 25 | [92] |

| Karbon kserojel | 79.1 | 6.9 | 2,880 | 30 | [93] |

| Organic-modified saponides | 88 | 6 | 240 | 25 | [49] |

| Graphene nanoparticles | 19.72 | 8 | 60 | 25 | [94] |

| Natural clay sepiolite | 48.7 | — | 23,040 | 25 | [95] |

| Activated carbon | 27.1 | 3 | 4,320 | 30 | [18,96] |

| Karbon nanofibers | 28.3 | — | 250 | — | |

| Carbon nanotubes | 41.6 | — | 250 | — | |

| Nickel-modified inorganic–organic piled clays | 5.52 | 6.55 | 480 | 25 | [97] |

| Cobalt-modified inorganic–organic piled clays | 5.25 | — | — | — | |

| Copper-modified inorganic–organic piled clays | 6.70 | — | — | — | |

| Proposed study | 40.32 | 7 | 120 | 25 | |

4 Conclusion

A novel biochar-based adsorbent (BFB) derived from kidney bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) husks was developed for efficient caffeine removal from aqueous solutions, achieving up to 97% removal under optimized conditions. Characterization via FTIR spectroscopy, EDS, and SEM confirmed a porous surface rich in hydroxyl and carbonyl groups, enhancing adsorption. The process followed PSO kinetics and the Langmuir isotherm, indicating chemisorption and monolayer coverage. Thermodynamic analysis showed an endothermic process (ΔH 0 = +8.31 kJ/mol), with temperature favoring uptake. The BFB exhibited notable advantages, including low-cost preparation, mechanical stability, and reusability (>80% efficiency after four cycles). These findings highlight the potential of agricultural waste-derived biochar as a sustainable, low-cost alternative for pharmaceutical removal in water treatment applications. Future research should explore pilot-scale testing, co-contaminant removal, and enhanced regeneration methods to scale its application.

-

Funding information: The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

-

Author contributions: All authors contributed equally to the article.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest.

-

Ethics approval and consent to participate: This study does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Malchi T, Maor Y, Tadmor G, Shenker M, Chefetz B. Irrigation of root vegetables with treated wastewater: evaluating uptake of pharmaceuticals and the associated human health risks. Environ Sci Technol. 2014;48:9325–33.10.1021/es5017894Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Taheran M, Naghdi M, Brar SK, Verma M, Surampalli RY. Emerging contaminants: Here today, there tomorrow. Environ Nanotechnol Monit Manag. 2018;10:122–6. 10.1016/j.enmm.2018.05.010.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Lakshmi V, Das N. Removal of caffeine from industrial wastewater using Trichosporon asahii. J Environ Biol. 2013;34:701–8.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Deblonde T, Cossu-Leguille C, Hartemann P. Emerging pollutants in wastewater: A review of the literature. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2011;214:442–8.10.1016/j.ijheh.2011.08.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Bachmann SAL, Calvete T, Féris LA. Caffeine removal from aqueous media by adsorption: An overview of adsorbents evolution and the kinetic, equilibrium and thermodynamic studies. Sci Total Environ. 2021;767:144229. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144229.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Buerge IJ, Thomas P, Müller MD, Buser H-R. Caffeine, an anthropogenic marker for wastewater contamination of surface waters. Environ Sci Technol. 2003;37:691–700.10.1021/es020125zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Li S, He B, Wang J, Liu J, Hu X. Risks of caffeine residues in the environment: Necessity for a targeted ecopharmacovigilance program. Chemosphere. 2020;243:125343. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.125343.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Hillebrand O, Nödler K, Licha T, Sauter M, Geyer T. Caffeine as an indicator for the quantification of untreated wastewater in karst systems. Water Res. 2012;46:395–402. 10.1016/j.watres.2011.11.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Knee KL, Gossett R, Boehm AB, Paytan A. Caffeine and agricultural pesticide concentrations in surface water and groundwater on the north shore of Kauai (Hawaii, USA). Mar Pollut Bull. 2010;60:1376–82. 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2010.04.019.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Portinho R, Zanella O, Féris LA. Grape stalk application for caffeine removal through adsorption. J Environ Manage. 2017;202:178–87. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.07.033.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Beltrame KK, Cazetta AL, de Souza PSC, Spessato L, Silva TL, Almeida VC. Adsorption of caffeine on mesoporous activated carbon fibers prepared from pineapple plant leaves. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2018;147:64–71. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.08.034.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Gonçalves ES, Rodrigues SV, Silva-Filho da EV. The use of caffeine as a chemical marker of domestic wastewater contamination in surface waters: seasonal and spatial variations in Teresópolis, Brazil. Ambient e Agua - An Interdiscip J Appl Sci. 2017;12:192. 10.4136/ambi-agua.1974.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Kurissery S, Kanavillil N, Verenitch S, Mazumder A. Caffeine as an anthropogenic marker of domestic waste: A study from Lake Simcoe watershed. Ecol Indic. 2012;23:501–8. 10.1016/j.ecolind.2012.05.001.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Oliveira MF, da Silva MGC, Vieira MGA. Equilibrium and kinetic studies of caffeine adsorption from aqueous solutions on thermally modified Verde-lodo bentonite. Appl Clay Sci. 2019;168:366–73. 10.1016/j.clay.2018.12.011.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Warner W, Licha T, Nödler K. Qualitative and quantitative use of micropollutants as source and process indicators. A review. Sci Total Environ. 2019;686:75–89. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.05.385.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Dafouz R, Cáceres N, Rodríguez-Gil JL, Mastroianni N, López de Alda M, Barceló D, et al. Does the presence of caffeine in the marine environment represent an environmental risk? A regional and global study. Sci Total Environ. 2018;615:632–42. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.155.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Katam K, Shimizu T, Soda S, Bhattacharyya D. Performance evaluation of two trickling filters removing LAS and caffeine from wastewater: Light reactor (algal-bacterial consortium) vs dark reactor (bacterial consortium. Sci Total Environ. 2020;707:135987. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135987.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Sotelo JL, Rodríguez A, Álvarez S, García J. Removal of caffeine and diclofenac on activated carbon in fixed bed column. Chem Eng Res Des. 2012;90:967–74. 10.1016/j.cherd.2011.10.012.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Al-Qaim FF, Mussa ZH, Othman MR, Abdullah MP. Removal of caffeine from aqueous solution by indirect electrochemical oxidation using a graphite-PVC composite electrode: A role of hypochlorite ion as an oxidising agent. J Hazard Mater. 2015;300:387–97. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2015.07.007.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Temple JL. Review: trends, safety, and recommendations for caffeine use in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;58:36–45. 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.06.030.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Cha A, Borkowska A, Sobstyl A, Chilimoniuk Z, Dobosz M, Sobolewska P, et al. The impact of coffee on human health The impact of coffee on human health. J Educ Health Sport. 2019;9:561–73. 10.5281/zenodo.3382360.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Willson C. The clinical toxicology of caffeine: A review and case study. Toxicol Rep. 2018;5:1140–52. 10.1016/j.toxrep.2018.11.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Diego M, Field T, Hernandez-Reif M, Vera Y, Gil K, Gonzalez-Garcia A. Caffeine Use Affects Pregnancy Outcome. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2008;17:41–9. 10.1300/J029v17n02_03.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Shilo L, Sabbah H, Hadari R, Kovatz S, Weinberg U, Dolev S, et al. The effects of coffee consumption on sleep and melatonin secretion. Sleep Med. 2002;3:271–3. 10.1016/S1389-9457(02)00015-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Wilcox A, Weinberg C, Baird D. Caffeinated beverages and decreased fertility. Lancet. 1988;332:1453–6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(88)90933-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Heatherley SV, Hancock KMF, Rogers PJ. Psychostimulant and other effects of caffeine in 9‐ to 11‐year‐old children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47:135–42. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01457.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Iwuozor KO, Abdullahi TA, Ogunfowora LA, Emenike EC, Oyekunle IP, Gbadamosi FA, et al. Mitigation of levofloxacin from aqueous media by adsorption: a review. Sustainable Water Resour Manag. 2021;7:100. 10.1007/s40899-021-00579-9.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Mondal S, Aikat K, Halder G. Biosorptive uptake of arsenic(V) by steam activated carbon from mung bean husk: equilibrium, kinetics, thermodynamics and modeling. Appl Water Sci. 2017;7:4479–95. 10.1007/s13201-017-0596-3.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Butnariu M, Negrea P, Lupa L, Ciopec M, Negrea A, Pentea M, et al. Remediation of rare earth element pollutants by sorption process using organic natural sorbents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12:11278–87. 10.3390/ijerph120911278.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Gabor A, Davidescu CM, Negrea A, Ciopec M, Muntean C, Negrea P, et al. Magnesium silicate doped with environmentally friendly extractants used for rare earth elements adsorption. Desalin Water Treat. 2017;63:124–34. 10.5004/dwt.2017.20173.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Butu M, Rodino S, Pentea M, Negrea A, Petrache P, Butnariu MIR. spectroscopy of the flour from bones of European hare. Dig J Nanomater Biostruct. 2014;9:1317–22.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Voda R, Negrea A, Lupa L, Ciopec M, Negrea P, Davidescu CM, et al. Nanocrystalline ferrites used as adsorbent in the treatment process of waste waters resulted from ink jet cartridges manufacturing. Open Chem. 2015;13:743–7. 10.1515/chem-2015-0092.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Mondal S, Bobde K, Aikat K, Halder G. Biosorptive uptake of ibuprofen by steam activated biochar derived from mung bean husk: Equilibrium, kinetics, thermodynamics, modeling and eco-toxicological studies. J Environ Manage. 2016;182:581–94. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.08.018.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] de Azevedo CF, Machado FM, de Souza NF, Silveira LL, Lima EC, Andreazza R, et al. Comprehensive adsorption and spectroscopic studies on the interaction of carbon nanotubes with diclofenac anti-inflammatory. Chem Eng J. 2023;454:140102. 10.1016/j.cej.2022.140102.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Nam S-N, Jun B-M, Park CM, Jang M, Cho K-S, Lee JY, et al. Removal of bisphenol A via adsorption on graphene/(reduced) graphene oxide-based nanomaterials. Sep Purif Rev. 2024;53:231–49. 10.1080/15422119.2023.2242350.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Dehmani Y, Mobarak M, Oukhrib R, Dehbi A, Mohsine A, Lamhasni T, et al. Adsorption of phenol by a Moroccan clay/Hematite composite: Experimental studies and statistical physical modeling. J Mol Liq. 2023;386:122508. 10.1016/j.molliq.2023.122508.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Isak N, Xhaxhiu K. A review on the adsorption of diuron, carbaryl, and alachlor using natural and activated clays. Remediat J. 2023;33:339–53. 10.1002/rem.21757.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Khakbaz M, Ghaemi A, Mir Mohamad Sadeghi G. Heavy metal elimination using hyper-cross-linked waste polycarbonate resin as an effective adsorbent: experimental and RSM optimization. Iran Polym J. 2023;32:947–68. 10.1007/s13726-023-01176-7.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Sowmya P, Prakash S, Joseph A. Adsorption of heavy metal ions by thiophene containing mesoporous polymers: An experimental and theoretical study. J Solid State Chem. 2023;320:123836. 10.1016/j.jssc.2023.123836.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Chizitere Emenike E, George Adeniyi A, Iwuozor KO, Okorie CJ, Egbemhenghe AU, Omuku PE, et al. A critical review on the removal of mercury (Hg2 +) from aqueous solution using nanoadsorbents. Environ Nanotechnol Monit Manag. 2023;20:100816. 10.1016/j.enmm.2023.100816.Search in Google Scholar

[41] Sharifi MJ, Nouralishahi A, Hallajisani A. Fe3O4-chitosan nanocomposite as a magnetic biosorbent for removal of nickel and cobalt heavy metals from polluted water. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;248:125984. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.125984.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Amalina F, Razak ASA, Krishnan S, Zularisam AW, Nasrullah M. Dyes removal from textile wastewater by agricultural waste as an absorbent – A review. Clean Waste Syst. 2022;3:100051. 10.1016/j.clwas.2022.100051.Search in Google Scholar

[43] Imran-Shaukat M, Wahi R, Ngaini Z. The application of agricultural wastes for heavy metals adsorption: A meta-analysis of recent studies. Bioresour Technol Rep. 2022;17:100902. 10.1016/j.biteb.2021.100902.Search in Google Scholar

[44] Iwuozor KO, Umeh CT, Emmanuel SS, Emenike EC, Egbemhenghe AU, Ore OT, et al. A comprehensive review on the sequestration of dyes from aqueous media using maize-/corn-based adsorbents. Water Pract Technol. 2023;18:3065–108. 10.2166/wpt.2023.214.Search in Google Scholar

[45] da Silva Vasconcelos de Almeida A, Vieira WT, Bispo MD, de Melo SF, da Silva TL, Balliano TL, et al. Caffeine removal using activated biochar from açaí seed (Euterpe oleracea Mart): Experimental study and description of adsorbate properties using Density Functional Theory (DFT). J Environ Chem Eng. 2021;9:104891. 10.1016/j.jece.2020.104891.Search in Google Scholar

[46] Omoleye WS, Fawole OB, Affinnih K, Aborode AT, Emenike EC, Iwuozor KO. Bioremediation of Asa River Sediment Using Agricultural By-Products. InLand remediation and management: Bioengineering strategies. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore; 2023. p. 295–330. 10.1007/978-981-99-4221-3_13.Search in Google Scholar

[47] Anastopoulos I, Katsouromalli A, Pashalidis I. Oxidized biochar obtained from pine needles as a novel adsorbent to remove caffeine from aqueous solutions. J Mol Liq. 2020;304:112661. 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.112661.Search in Google Scholar

[48] Anastopoulos I, Pashalidis I. The application of oxidized carbon derived from Luffa cylindrica for caffeine removal. Equilibrium, thermodynamic, kinetic and mechanistic analysis. J Mol Liq. 2019;296:112078. 10.1016/j.molliq.2019.112078.Search in Google Scholar

[49] Marçal L, de Faria EH, Nassar EJ, Trujillano R, Martín N, Vicente MA, et al. Organically modified saponites: SAXS study of swelling and application in caffeine removal. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7:10853–62. 10.1021/acsami.5b01894.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[50] Ehiomogue P. Ahuchaogu II, Ahaneku IE. Review of adsorption isotherms models. Acta Tech Corviniensis. 2022;14:87–96.Search in Google Scholar

[51] Neolaka YAB, Riwu AAP, Aigbe UO, Ukhurebor KE, Onyancha RB, Darmokoesoemo H, et al. Potential of activated carbon from various sources as a low-cost adsorbent to remove heavy metals and synthetic dyes. Results Chem. 2023;5:100711. 10.1016/j.rechem.2022.100711.Search in Google Scholar

[52] Mozaffari Majd M, Kordzadeh-Kermani V, Ghalandari V, Askari A, Sillanpää M. Adsorption isotherm models: A comprehensive and systematic review (2010−2020). Sci Total Environ. 2022;812:151334. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151334.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[53] Eldeeb TM, Aigbe UO, Ukhurebor KE, Onyancha RB, El-Nemr MA, Hassaan MA, et al. Biosorption of acid brown 14 dye to mandarin-CO-TETA derived from mandarin peels. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2024;14:5053–73. 10.1007/s13399-022-02664-1.Search in Google Scholar

[54] El-Nemr MA, Aigbe UO, Ukhurebor KE, Onyancha RB, El Nemr A, Ragab S, et al. Adsorption of Cr6 + ion using activated Pisum sativum peels-triethylenetetramine. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2022;29:91036–60. 10.1007/s11356-022-21957-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[55] Hamdaoui O, Naffrechoux E. Modeling of adsorption isotherms of phenol and chlorophenols onto granular activated carbonPart I. Two-parameter models and equations allowing determination of thermodynamic parameters. J Hazard Mater. 2007;147:381–94. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.01.021.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[56] Sathishkumar M, Binupriya AR, Vijayaraghavan K, Yun S. Two and three‐parameter isothermal modeling for liquid‐phase sorption of Procion Blue H‐B by inactive mycelial biomass of Panus fulvus. J Chem Technol Biotechnol. 2007;82:389–98. 10.1002/jctb.1682.Search in Google Scholar

[57] Vigdorowitsch M, Pchelintsev A, Tsygankova L, Tanygina E. Freundlich isotherm: an adsorption model complete framework. Appl Sci. 2021;11:8078. 10.3390/app11178078.Search in Google Scholar

[58] Anwar Mohamad Said K, Zakirah Ismail N, Liyana Jama’in R, Ain Mohamed Alipah N, Mohamed Sutan N, George Gadung G, et al. Application of freundlich and temkin isotherm to study the removal of pb(ii) via adsorption on activated carbon equipped polysulfone membrane. Int J Eng Technol. 2018;7:91. 10.14419/ijet.v7i3.18.16683.Search in Google Scholar

[59] Hung H, Lin T. Adsorption of MTBE from contaminated water by carbonaceous resins and mordenite zeolite. J Hazard Mater. 2006;135:210–7. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2005.11.050.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[60] Qiu H, Lv L, Pan B, Zhang Q, Zhang W, Zhang Q. Critical review in adsorption kinetic models. J Zhejiang Univ A. 2009;10:716–24. 10.1631/jzus.A0820524.Search in Google Scholar

[61] Wang J, Guo X. Adsorption kinetic models: Physical meanings, applications, and solving methods. J Hazard Mater. 2020;390:122156. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122156.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[62] Soudani A, Youcef L, Bulgariu L, Youcef S, Toumi K, Soudani N. Characterizing and modeling of oak fruit shells biochar as an adsorbent for the removal of Cu, Cd, and Zn in single and in competitive systems. Chem Eng Res Des. 2022;188:972–87. 10.1016/j.cherd.2022.10.009.Search in Google Scholar

[63] Saremi F, Miroliaei MR, Shahabi Nejad M, Sheibani H. Adsorption of tetracycline antibiotic from aqueous solutions onto vitamin B6-upgraded biochar derived from date palm leaves. J Mol Liq. 2020;318:114126. 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.114126.Search in Google Scholar

[64] Dong H, Deng J, Xie Y, Zhang C, Jiang Z, Cheng Y, et al. Stabilization of nanoscale zero-valent iron (nZVI) with modified biochar for Cr(VI) removal from aqueous solution. J Hazard Mater. 2017;332:79–86. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.03.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[65] Yu H, Gu L, Chen L, Wen H, Zhang D, Tao H. Activation of grapefruit derived biochar by its peel extracts and its performance for tetracycline removal. Bioresour Technol. 2020;316:123971. 10.1016/j.biortech.2020.123971.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[66] Zaher A, Taha M, Mahmoud RK. Possible adsorption mechanisms of the removal of tetracycline from water by La-doped Zn-Fe-layered double hydroxide. J Mol Liq. 2021;322:114546. 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.114546.Search in Google Scholar

[67] Mubarak MF, Khedr GE, El Sharkawy HM. Environmentally-friendly calcite scale mitigation: encapsulation of CDs@ MS composite within membranes framework for nanofiltration. J Alloy Compd. 2024;999:175061. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2024.175061.Search in Google Scholar

[68] Nasseh N, Samadi MT, Ghadirian M, Hossein Panahi A, Rezaie A. Photo-catalytic degradation of tamoxifen by using a novel synthesized magnetic nanocomposite of FeCl2@ac@ZnO: A study on the pathway, modeling, and sensitivity analysis using artificial neural network (AAN). J Environ Chem Eng. 2022;10:107450. 10.1016/j.jece.2022.107450.Search in Google Scholar

[69] Tavagnaccoab L, Fonzoa SDi, D’Amicoa F, Masciovecchioa C, Bradyc JW, Cesàroab A. Stacking of purines in water: the role of dipolar interaction in caffeine. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2016;18:13478–86.10.1039/C5CP07326JSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[70] Rigueto CVT, Nazari MT, De Souza CF, Cadore JS, Brião VB, Piccin JS. Alternative techniques for caffeine removal from wastewater: An overview of opportunities and challenges. J Water Process Eng. 2020;35:101231. 10.1016/j.jwpe.2020.101231.Search in Google Scholar

[71] Yamamoto K, Shiono T, Matsui Y, Yoneda M. Changes the structure and caffeine adsorption property of calcined montmorillonite. Int J Geomate. 2016;11:2301–6. 10.21660/2016.24.1191.Search in Google Scholar

[72] Garcia-Ivars J, Martella L, Massella M, Carbonell-Alcaina C, Alcaina-Miranda M-I, Iborra-Clar M-I. Nanofiltration as tertiary treatment method for removing trace pharmaceutically active compounds in wastewater from wastewater treatment plants. Water Res. 2017;125:360–73. 10.1016/j.watres.2017.08.070.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[73] Licona KPM, Geaquinto LR, de O, Nicolini JV, Figueiredo NG, Chiapetta SC, Habert AC, et al. Assessing potential of nanofiltration and reverse osmosis for removal of toxic pharmaceuticals from water. J Water Process Eng. 2018;25:195–204. 10.1016/j.jwpe.2018.08.002.Search in Google Scholar

[74] Nemeş L, Bulgariu L. Optimization of process parameters for heavy metals biosorption onto mustard waste biomass. Open Chem. 2016;14:175–87. 10.1515/chem-2016-0019.Search in Google Scholar

[75] Ortiz-Oliveros HB, Ouerfelli N, Cruz-Gonzalez D, Avila-Pérez P, Bulgariu L, Flaifel MH, et al. Modeling of the relationship between the thermodynamic parameters ΔH0 and ΔS0 with temperature in the removal of Pb ions in aqueous medium: Case study. Chem Phys Lett. 2023;814:140329. 10.1016/j.cplett.2023.140329.Search in Google Scholar

[76] Foo KY, Hameed BH. Insights into the modeling of adsorption isotherm systems. Chem Eng J. 2010;156:2–10. 10.1016/j.cej.2009.09.013.Search in Google Scholar

[77] Do DD. Adsorption analysis: equilibria and kinetics. vol. 2, Published By Imperial College Press And Distributed By World Scientific Publishing Co.; 1998. 10.1142/p111.Search in Google Scholar

[78] Allen SJ, Mckay G, Porter JF. Adsorption isotherm models for basic dye adsorption by peat in single and binary component systems. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2004;280:322–33. 10.1016/j.jcis.2004.08.078.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[79] Weber TW, Chakravorti RK. Pore and solid diffusion models for fixed‐bed adsorbers. AIChE J. 1974;20:228–38. 10.1002/aic.690200204.Search in Google Scholar

[80] Gregg SJ, Sing KSW, Salzberg HW. Adsorption Surface Area and Porosity. J Electrochem Soc. 1967;114:279C. 10.1149/1.2426447.Search in Google Scholar

[81] Ahmad M, Rajapaksha AU, Lim JE, Zhang M, Bolan N, Mohan D, et al. Biochar as a sorbent for contaminant management in soil and water: A review. Chemosphere. 2014;99:19–33. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.10.071.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[82] Anastopoulos I, Karamesouti M, Mitropoulos AC, Kyzas GZ. A review for coffee adsorbents. J Mol Liq. 2017;229:555–65. 10.1016/j.molliq.2016.12.096.Search in Google Scholar

[83] Tan X, Liu Y, Zeng G, Wang X, Hu X, Gu Y, et al. Application of biochar for the removal of pollutants from aqueous solutions. Chemosphere. 2015;125:70–85. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.12.058.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[84] Ravi S, Choi Y, Choe JK. Novel phenyl-phosphate-based porous organic polymers for removal of pharmaceutical contaminants in water. Chem Eng J. 2020;379:122290. 10.1016/j.cej.2019.122290.Search in Google Scholar

[85] Delhiraja K, Vellingiri K, Boukhvalov DW, Philip L. Development of highly water stable graphene oxide-based composites for the removal of pharmaceuticals and personal care products. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2019;58:2899–913. 10.1021/acs.iecr.8b02668.Search in Google Scholar

[86] Cunha MR, Lima EC, Cimirro NFGM, Thue PS, Dias SLP, Gelesky MA, et al. Conversion of Eragrostis plana Nees leaves to activated carbon by microwave-assisted pyrolysis for the removal of organic emerging contaminants from aqueous solutions. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2018;25:23315–27. 10.1007/s11356-018-2439-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[87] Kaur H, Bansiwal A, Hippargi G, Pophali GR. Effect of hydrophobicity of pharmaceuticals and personal care products for adsorption on activated carbon: Adsorption isotherms, kinetics and mechanism. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2018;25:20473–85. 10.1007/s11356-017-0054-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[88] Lessa EF, Nunes ML, Fajardo AR. Chitosan/waste coffee-grounds composite: An efficient and eco-friendly adsorbent for removal of pharmaceutical contaminants from water. Carbohydr Polym. 2018;189:257–66. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.02.018.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[89] Gil A, Taoufik N, García AM, Korili SA. Comparative removal of emerging contaminants from aqueous solution by adsorption on an activated carbon. Environ Technol. 2019;40:3017–30. 10.1080/09593330.2018.1464066.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[90] Bernardo MMS, Madeira CAC, dos Santos Nunes NCL, Dias DACM, Godinho DMB, de Jesus Pinto MF, et al. Study of the removal mechanism of aquatic emergent pollutants by new bio-based chars. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2017;24:22698–708. 10.1007/s11356-017-9938-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[91] Leal M, Martínez-Hernández V, Meffe R, Lillo J, de Bustamante I. Clinoptilolite and palygorskite as sorbents of neutral emerging organic contaminants in treated wastewater: Sorption-desorption studies. Chemosphere. 2017;175:534–42. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.02.057.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[92] Yang GCC, Tang P-L. Removal of phthalates and pharmaceuticals from municipal wastewater by graphene adsorption process. Water Sci Technol. 2016;73:2268–74. 10.2166/wst.2016.006.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[93] Álvarez S, Ribeiro RS, Gomes HT, Sotelo JL, García J. Synthesis of carbon xerogels and their application in adsorption studies of caffeine and diclofenac as emerging contaminants. Chem Eng Res Des. 2015;95:229–38. 10.1016/j.cherd.2014.11.001.Search in Google Scholar

[94] Al-Khateeb LA, Almotiry S, Salam MA. Adsorption of pharmaceutical pollutants onto graphene nanoplatelets. Chem Eng J. 2014;248:191–9. 10.1016/j.cej.2014.03.023.Search in Google Scholar

[95] Sotelo JL, Ovejero G, Rodríguez A, Álvarez S, García J. Study of natural clay adsorbent sepiolite for the removal of caffeine from aqueous solutions: batch and fixed-bed column operation. Water, Air, Soil Pollut. 2013;224:1466. 10.1007/s11270-013-1466-8.Search in Google Scholar

[96] Sotelo JL, Rodríguez AR, Mateos MM, Hernández SD, Torrellas SA, Rodríguez JG. Adsorption of pharmaceutical compounds and an endocrine disruptor from aqueous solutions by carbon materials. J Environ Sci Health Part B. 2012;47:640–52. 10.1080/03601234.2012.668462.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[97] Cabrera-Lafaurie WA, Román FR, Hernández-Maldonado AJ Transition metal modified and partially calcined inorganic–organic pillared clays for the adsorption of salicylic acid, clofibric acid, carbamazepine, and caffeine from water. J Colloid Interface Sci 2012;386:381–91. 10.1016/j.jcis.2012.07.037.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Phytochemical investigation and evaluation of antioxidant and antidiabetic activities in aqueous extracts of Cedrus atlantica

- Influence of B4C addition on the tribological properties of bronze matrix brake pad materials

- Discovery of the bacterial HslV protease activators as lead molecules with novel mode of action

- Characterization of volatile flavor compounds of cigar with different aging conditions by headspace–gas chromatography–ion mobility spectrometry

- Effective remediation of organic pollutant using Musa acuminata peel extract-assisted iron oxide nanoparticles

- Analysis and health risk assessment of toxic elements in traditional herbal tea infusions

- Cadmium exposure in marine crabs from Jiaxing City, China: Insights into health risk assessment

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles of Cinnamomum zeylanicum and their biological activities

- Tetraclinis articulata (Vahl) Mast., Mentha pulegium L., and Thymus zygis L. essential oils: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antifungal properties against postharvest fungal diseases of apple, and in vitro, in vivo, and in silico investigation

- Exploration of plant alkaloids as potential inhibitors of HIV–CD4 binding: Insight into comprehensive in silico approaches

- Recovery of phenylethyl alcohol from aqueous solution by batch adsorption

- Electrochemical approach for monitoring the catalytic action of immobilized catalase

- Green synthesis of ZIF-8 for selective adsorption of dyes in water purification

- Optimization of the conditions for the preparation of povidone iodine using the response surface methodology

- A case study on the influence of soil amendment on ginger oil’s physicochemical properties, mineral contents, microbial load, and HPLC determination of its vitamin level

- Removal of antiviral favipiravir from wastewater using biochar produced from hazelnut shells

- Effect of biochar and soil amendment on bacterial community composition in the root soil and fruit of tomato under greenhouse conditions

- Bioremediation of malachite green dye using Sargassum wightii seaweed and its biological and physicochemical characterization

- Evaluation of natural compounds as folate biosynthesis inhibitors in Mycobacterium leprae using docking, ADMET analysis, and molecular dynamics simulation

- Novel insecticidal properties of bioactive zoochemicals extracted from sea urchin Salmacis virgulata

- Elevational gradients shape total phenolic content and bioactive potential of sweet marjoram (Origanum majorana L.): A comparative study across altitudinal zones

- Study on the CO2 absorption performance of deep eutectic solvents formed by superbase DBN and weak acid diethylene glycol

- Preparation and wastewater treatment performance of zeolite-modified ecological concrete

- Multifunctional chitosan nanoparticles: Zn2+ adsorption, antimicrobial activity, and promotion of aquatic health

- Comparative analysis of nutritional composition and bioactive properties of Chlorella vulgaris and Arthrospira platensis: Implications for functional foods and dietary supplements

- Growth kinetics and mechanical characterization of boride layers formed on Ti6Al4V

- Enhancement of water absorption properties of potassium polyacrylate-based hydrogels in CaCl2-rich soils using potassium di- and tri-carboxylate salts

- Electrochemical and microbiological effects of dumpsite leachates on soil and air quality

- Modeling benzene physicochemical properties using Zagreb upsilon indices

- Characterization and ecological risk assessment of toxic metals in mangrove sediments near Langen Village in Tieshan Bay of Beibu Gulf, China

- Protective effect of Helicteres isora, an efficient candidate on hepatorenal toxicity and management of diabetes in animal models

- Valorization of Juglans regia L. (Walnut) green husk from Jordan: Analysis of fatty acids, phenolics, antioxidant, and cytotoxic activities

- Molecular docking and dynamics simulations of bioactive terpenes from Catharanthus roseus essential oil targeting breast cancer

- Selection of a dam site by using AHP and VIKOR: The Sakarya Basin

- Characterization and modeling of kidney bean shell biochar as adsorbent for caffeine removal from aquatic environments

- The effects of short-term and long-term 2100 MHz radiofrequency radiation on adult rat auditory brainstem response

- Biochemical insights into the anthelmintic and anti-inflammatory potential of sea cucumber extract: In vitro and in silico approaches

- Resveratrol-derived MDM2 inhibitors: Synthesis, characterization, and biological evaluation against MDM2 and HCT-116 cells

- Phytochemical constituents, in vitro antibacterial activity, and computational studies of Sudanese Musa acuminate Colla fruit peel hydro-ethanol extract

- Chemical composition of essential oils reviewed from the height of Cajuput (Melaleuca leucadendron) plantations in Buru Island and Seram Island, Maluku, Indonesia

- Phytochemical analysis and antioxidant activity of Azadirachta indica A. Juss from the Republic of Chad: in vitro and in silico studies

- Stability studies of titanium–carboxylate complexes: A multi-method computational approach

- Efficient adsorption performance of an alginate-based dental material for uranium(vi) removal

- Synthesis and characterization of the Co(ii), Ni(ii), and Cu(ii) complexes with a 1,2,4-triazine derivative ligand

- Evaluation of the impact of music on antioxidant mechanisms and survival in salt-stressed goldfish

- Optimization and validation of UPLC method for dapagliflozin and candesartan cilexetil in an on-demand formulation: Analytical quality by design approach

- Biomass-based cellulose hydroxyapatite nanocomposites for the efficient sequestration of dyes: Kinetics, response surface methodology optimization, and reusability

- Multifunctional nitrogen and boron co-doped carbon dots: A fluorescent probe for Hg2+ and biothiol detection with bioimaging and antifungal applications

- Separation of sulphonamides on a C12-diol mixed-mode HPLC column and investigation of their retention mechanism

- Characterization and antioxidant activity of pectin from lemon peels

- Fast PFAS determination in honey by direct probe electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry: A health risk assessment insight

- Correlation study between GC–MS analysis of cigarette aroma compounds and sensory evaluation

- Synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular docking studies of substituted chromone-2-carboxamide derivatives as anti-breast cancer agents

- The influence of feed space velocity and pressure on the cold flow properties of diesel fuel

- Acid etching behavior and mechanism in acid solution of iron components in basalt fibers

- Protective effect of green synthesized nanoceria on retinal oxidative stress and inflammation in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat