Abstract

To investigate the differences in the volatile compounds of three main cultivars, Yunxue No. 1, Yunxue No. 36, and Yunxue No. 39, from Yunnan, the volatile flavor components were analyzed by headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry (HS-GC-IMS). Principal component analysis and orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis were applied to investigate the differences in volatile flavor compounds among the three cigar tobacco varieties. GC-IMS detection results indicate that a total of 74 volatile organic compounds were detected in the cigars , including 11 types of aldehydes, ketones, alcohols, acids, esters, hydrocarbons, thiols, benzene derivatives, heterocycles, ethers, and terpenoids. Among the three cigar tobacco samples, esters, hydrocarbons, ketones, and aldehydes are the primary contributors to the overall flavor, though significant variations exist in their types and contents. This study showed that HS-GC-IMS was efficient in analyzing the composition and content of aroma components in cigar leaves. This technology can be used to establish relationships between aroma component composition/content and variety. This research provides data support for the style positioning and quality improvement of Yunnan cigars and further achieve the purpose of identifying and tracing the origin of cigars.

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

Cigars are renowned for their rich aroma, rich taste, and less harmful to the human body than ordinary cigarettes [1]. Cigar tobacco originated from Latin America and is currently cultivated mainly in tropical and subtropical countries such as Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, Indonesia, Brazil, and China. Cigar tobacco has high economic value and plays an important role in agricultural development. With the development of the global economy and culture, the cigar consumption market at home and abroad continues to expand [2]. Unlike traditional cigarettes, finished cigars are entirely made from cigar leaf fermentation and rolls and do not need to go through the baking process [3,4,5,6]. Therefore, the flavor and aroma of cigars directly determine their sensory characteristics, which are critical factors influencing the quality of cigars [7,8]. The flavor of a cigar is formed by the combination of volatile flavor compounds, which is closely related to the source, type, and processing technology of cigar, and directly affects its sensory characteristics, quality, and consumer purchasing intentions [9]. Thus, Yunnan Province, as an important cigar tobacco production area in China, is of great significance to analyze the volatile flavor substances in the main varieties and establish an accurate, simple, economical, and efficient analysis method for maintaining the flavor stability and improving the quality of cigar formulation.

Liquid chromatography (LC) and gas chromatography (GC) can quantitatively or qualitatively determine organic compounds [10,11], but it is difficult to accurately and quickly measure volatile aroma components in different varieties of cigar smoke because of complex sample preparation and large equipment used. Gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry (GC-IMS) is a detection technology that combines the high separation ability of GC with the rapid response characteristics of ion mobility spectrometry [12,13,14]. This technology has the advantages of high sensitivity, high accuracy, detection of trace samples, no need for complex sample pretreatment, and maximum retention of the original flavor of samples. Automatic headspace sampling realizes a simple and repeatable sampling process by controlling the incubation time and temperature [15]. Headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry (HS-GC-IMS) is not only applied to the analysis of characteristic aroma components in complex foods and agricultural products such as grains [16,17,18], fruits and vegetables [19,20], tea [21,22,23], aquatic products [24,25], seasonings [26,27], and traditional Chinese medicinal materials [28,29], but also provides a feasible scheme for the determination of the composition of volatile and semi-volatile compounds in tobacco [30]. Liu et al. [16] used GC-IMS technology to evaluate the effects of different soil conditions on volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in “Mianhua” and identified specific VOCs that can be used to distinguish soil types. Zhong et al. [17] employed GC-IMS technology and found that hot air drying (HA) and microwave-hot air drying had significant effects on the flavor of wheat germ. Yang et al. [19] used GC-IMS technology to differentiate three asparagus varieties (Paladin, Grace, and Ggang Red). Guo et al. [23] identified 27 volatile flavor compounds in oolong tea through GC-IMS and GC-MS technologies. Sun et al. [25] reduced the trimethylamine content in tilapia by 56% through ultrasonic-assisted enzymatic deodorization technology and comprehensively analyzed the effects of ultrasonic-compound enzyme deodorization on flavor by combining GC-IMS technology. Miao et al. [27] comprehensively analyzed the flavor differences of fermented black beans from different origins using HS-GC-IMS technology and GC-O-QTOF/MS technology. Parastar et al. [28] developed a new non-targeted volatilities method based on HS-GC-IMS for the identification of saffron and the discrimination of its geographical origins. Zhu et al. [30] used HS-GC-IMS to analyze the changes in volatile flavor compounds in cigars under different aging conditions and identified a total of 82 volatile flavor compounds.

In this study, representative tobacco leaves of Yunxue No. 1, Yunxue No. 36, and Yunxue No. 39, which are the main cultivars of cigar tobacco in Yunnan Province, were selected, and their volatile flavor substances were analyzed by HS-GC-IMS technique, and the differences among the three cigar samples were resolved. This study provides a certain theoretical basis for the style orientation and quality improvement of the Yunnan cigar.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials and instruments

2.1.1 Materials

Yunxue No. 1 (Central Grade II), Yunxue No. 36 (Central Grade II), and Yunxue No. 39 (Central Grade II) cigar tobacco leaves used in this study were all collected by professional technical personnel from the Tobacco Industry Service Center of Yuanjiang County, Yuxi City, Yunnan Province. Each type of cigar tobacco leaf was sampled at 500 × g and stored at room temperature.

2.1.2 Instruments

The following instruments are used: FlavourSpec® flavor analyzer (GC-IMS, G.A.S., Germany); chromatographic column type: MXT-WAX (30 m × 0.53 mm × 1.0 μm) (RESTEK, USA); and JE203G electronic analytical balance (METTLER, Switzerland).

2.2 Sample pretreatment

Three kinds of cigar tobacco leaf samples were harvested and dried according to the technical procedures for drying high-quality cigar tobacco. After drying, the tobacco leaves were placed in a constant temperature and humidity box at 45°C and 80% humidity for the initial fermentation, and 1.00 kg of each sample was randomly selected from each variety. The three samples were frozen and ground by liquid nitrogen to a solid powder and then passed through a 40-mesh sieve, and then, the grounded samples were vacuum-sealed and preserved in a storage bag and kept at room temperature for the subsequent analysis. Three parallel tests were done for each sample, and a blank bottle without a sample was used as a blank control.

2.3 Experimental methods

2.3.1 HS-GC-IMS detection conditions

GC-IMS analysis conditions are as follows: chromatographic column: MXT-WAX (30 m × 0.53 mm × 1.0 μm); column temperature: 60°C; carrier gas/drift gas: N2 (99.99%); IMS temperature: 45°C; analysis time: 40 min.

Headspace sampling conditions are as follows: accurately weigh 0.5 g of three cigar samples, respectively, Yunxue No. 1, Yunxue No. 36, and Yunxue No. 39, and then transfer them into a 20 mL headspace vial. Incubate at 80°C for 15 min before conducting three cigar sample injection tests: sample injection volume: 200 μL; incubation time: 15 min; incubation temperature: 80°C; injection needle temperature: 85°C; and incubation rotation speed: 500 rpm.

2.3.2 HS-GC-IMS detection data processing

The FlavourSpec® flavor analyzer, along with the VOCal software and the qualitative software GC × IMS Library Search (which includes built-in NIST and IMS databases), was used to identify volatile flavor compounds in three types of cigars. The Reporter plugin was used for sample GC-IMS spectrum comparison, the dynamic principal component analysis (PCA) plugin for PCA, and the Gallery Plot plugin for GC-IMS fingerprint comparison. SIMCA 14.1 software was used for orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 GC-IMS spectral analysis

The GC-IMS two-dimensional spectrum of volatile flavor compounds in the three varieties of Yunnan-produced cigars is shown in Figure S1. Each point on both sides of the RIP peak in the spectrum represents a VOC, in which the concentration of aroma components is displayed through the difference in color. The red region indicates that the concentration of aroma components is higher, and the darker the color, the higher the concentration, while the blue region is the opposite. Based on this rule, the distribution and concentration information of aroma components in cigar samples can be directly observed [31]. As shown in Figure S1, the VOCs in the three kinds of cigars completed GC separation within 2,000 s, with most organic compounds eluting within 800 s and achieving good resolution. The types of volatile flavor compounds detected in the three cigar samples were generally similar, but there were some differences in the concentration of aroma components.

To compare this difference more clearly, the spectrogram of Yunxue No. 1 was selected as the reference, and the spectrograms of the other two samples were deducted from the reference ratio to obtain Figure S2. As shown in Figure S2, there are more red areas in the spectrum information of Yunxue 36 and Yunxue 39, indicating that the concentrations of some volatile flavor compounds in Yunxue No. 36 and Yunxue No. 39 were higher than those in Yunxue No. 1. The blue area of Yunxue No. 39 showed a relatively large value, suggesting that the content of some volatile flavor compounds in Yunxue No. 39 was lower than that in Yunxue No. 1.

3.2 Qualitative analysis of VOCs in cigars

Two-dimensional characterization of the three cigar volatile compounds was performed using the built-in NIST and IMS databases of GC-IMS. Some of these compounds generated dimer and trimer peaks during ionization, resulting in multiple peaks [32]. As previously mentioned, with Yunxue No. 1 as the reference sample, 80 peak points were obtained in the GC-IMS, as shown in Figure S3, where the horizontal axis represents drift time and the vertical axis represents the retention time. Among which, 74 peaks (including monomers and dimers) could be qualitatively analyzed. It should be noted that some peaks correspond to the same compound due to the presence of monomers and dimers, which may be attributed to the high concentration of the compound in the sample [33].

A total of 74 VOCs were detected in the three cigar smoke samples, details of which are shown in Table 1, which revealed the organic compounds and their corresponding peak positions in the ion mobility spectrum. As shown in Table 1, the VOCs in the three cigar tobaccos are compositionally diverse, including 11 types of aldehydes, ketones, alcohols, acids, esters, hydrocarbons, thiols, benzene derivatives, heterocycles, ethers, and terpenoids. Among all compounds, esters had the highest content, which was primarily attributed to the high content of γ-butyrolactone (>60.00%) in the sample. The compounds with higher content (>3.00%) also included 1-chlorobutane and citronellyl formate. The proportion of other compounds was lower (<3.00%). The peak positions and migration times of specific compounds in Table 1 can serve as references for qualitative analysis of tobacco samples of unknown origin.

The volatile organic compounds in three types of cigars

| No. | Categories of compounds | Compound | Retention index | Retention time (s) | Drift time (ms) | Average peak volume ± SD | VIP value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yunxue No. 1 | Yunxue No. 36 | Yunxue No. 39 | |||||||

| 1 | Terpenoids | (+)-Sabinene | 1,111.7 | 442.974 | 1.09506 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.07 ± 0.00 | 0.05 ± 0.00 | 0.79 |

| 2 | Ketones | 2-Methyl-2-hepten-6-one | 1,347.1 | 848.66 | 1.17462 | 0.26 ± 0.05 | 0.25 ± 0.02 | 0.15 ± 0.00 | 0.79 |

| 3 | Cyclohexanone | 1,295.1 | 756.369 | 1.16092 | 0.16 ± 0.05 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.00 | 0.95 | |

| 4 | 2-Butanone, 3-hydroxy | 1,294.9 | 756.143 | 1.05886 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.82 | |

| 5 | 3-Octanone | 1,236.7 | 655.686 | 1.29971 | 0.21 ± 0.03 | 0.29 ± 0.02 | 0.24 ± 0.01 | 1.49 | |

| 6 | 2,3-Hexanedione | 1,137.5 | 485.121 | 1.15796 | 0.97 ± 0.38 | 0.69 ± 0.14 | 0.49 ± 0.24 | 0.84 | |

| 7 | 3-Heptanone | 1,137.6 | 485.227 | 1.23798 | 0.34 ± 0.14 | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 0.11 ± 0.05 | 1.03 | |

| 8 | 1-Penten-3-one (D) | 1,036.5 | 352.527 | 1.31103 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.00 | 1.44 | |

| 9 | 4-Methyl-2-pentanone | 1,023.6 | 339.584 | 1.18219 | 0.27 ± 0.05 | 0.25 ± 0.03 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.78 | |

| 10 | 1-Penten-3-one (M) | 1,036.7 | 352.768 | 1.07994 | 0.19 ± 0.04 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.83 | |

| 11 | 2-Pentanone | 1,024 | 339.955 | 1.10596 | 0.19 ± 0.05 | 0.22 ± 0.02 | 0.10 ± 0.00 | 0.86 | |

| 12 | 2,3 Butanedione | 990.5 | 309.523 | 1.16564 | 1.46 ± 0.27 | 1.01 ± 0.09 | 0.85 ± 0.01 | 1.03 | |

| 13 | 2,3-Pentadione | 1,074 | 393.297 | 1.22188 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.83 | |

| 14 | 2-Propanone | 828.9 | 216.913 | 1.10909 | 0.71 ± 0.19 | 1.18 ± 0.14 | 0.22 ± 0.00 | 1.02 | |

| 15 | 2-Butanone | 906 | 256.998 | 1.24842 | 0.33 ± 0.06 | 0.32 ± 0.03 | 0.16 ± 0.00 | 0.83 | |

| 16 | Hydrocarbons | 3-Aminoheptane | 1,137.5 | 485.086 | 1.31723 | 0.53 ± 0.05 | 0.29 ± 0.02 | 0.49 ± 0.04 | 1.35 |

| 17 | β-Myrcene | 1,168.5 | 541.088 | 1.212 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.00 | 1.06 | |

| 18 | 1,3-Cyclooctadiene | 1,097.6 | 421.449 | 1.34358 | 0.46 ± 0.06 | 0.55 ± 0.05 | 0.43 ± 0.02 | 1.1 | |

| 19 | 1-Chlorohexane | 1,047 | 363.49 | 1.15666 | 0.12 ± 0.04 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.96 | |

| 20 | Acrylonitrile | 1,008.6 | 325.023 | 1.08586 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.93 | |

| 21 | (Z)-3-Nonene | 947.6 | 281.681 | 1.27732 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.8 | |

| 22 | 2,4-Octadiene | 891.1 | 248.71 | 1.33476 | 0.26 ± 0.05 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.00 | 0.98 | |

| 23 | 1-Chlorobutane | 837.3 | 220.986 | 1.15434 | 7.36 ± 1.22 | 3.18 ± 0.21 | 5.22 ± 0.05 | 1.35 | |

| 24 | 1-Heptene | 785.3 | 197.071 | 1.08774 | 0.46 ± 0.09 | 0.37 ± 0.03 | 0.25 ± 0.01 | 0.89 | |

| 25 | Cyclohexane | 724 | 172.226 | 1.04166 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 1.11 | |

| 26 | 3,3,4-Trimethylhexane | 821.5 | 213.438 | 1.54804 | 0.44 ± 0.06 | 0.15 ± 0.00 | 0.85 ± 0.03 | 1.16 | |

| 27 | Heterocyclic compounds | 2-Methylpyrazine | 1,276 | 721.87 | 1.09041 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.00 | 1.08 |

| 28 | 2-Methylpyridine | 1,228.1 | 642.002 | 1.0506 | 0.16 ± 0.02 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.00 | 1 | |

| 29 | 1,4-Dioxan | 1,080.7 | 401.071 | 1.12755 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.05 ± 0.00 | 0.04 ± 0.00 | 1.13 | |

| 30 | 2,3,5-Trimethylfuran (M) | 1,056.2 | 373.432 | 1.14416 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.81 | |

| 31 | 2,3,5-Trimethylfuran (D) | 1,057.7 | 375.083 | 1.20588 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.05 ± 0.00 | 0.91 | |

| 32 | 2,6-Lupetidine | 1,008.8 | 325.198 | 1.19319 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.00 | 0.79 | |

| 33 | 2,5-Dimethylfuran | 923.2 | 266.907 | 1.3422 | 0.22 ± 0.04 | 0.21 ± 0.02 | 0.12 ± 0.00 | 0.82 | |

| 34 | Ethers | Allyl sulfide | 1,139.2 | 487.952 | 1.11986 | 0.25 ± 0.08 | 0.60 ± 0.05 | 0.13 ± 0.04 | 1.18 |

| 35 | Ethyl methyl disulfide | 1,136.6 | 483.463 | 1.89017 | 0.78 ± 0.21 | 0.43 ± 0.07 | 0.86 ± 0.02 | 1.31 | |

| 36 | 1,2-Dimethoxyethane | 929.1 | 270.417 | 1.28458 | 0.39 ± 0.07 | 0.26 ± 0.02 | 0.24 ± 0.00 | 1.1 | |

| 37 | Esters | γ-Butyrolactone | 1,663.5 | 1,709.317 | 1.322 | 61.89 ± 4.11 | 63.43 ± 0.07 | 64.5 ± 0.39 | 0.95 |

| 38 | Methyl pentanoate | 1,098.7 | 423.089 | 1.5562 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.94 | |

| 39 | Butanoic acid ethyl ester | 1,046 | 362.451 | 1.21407 | 0.10 ± 0.03 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.77 | |

| 40 | 2-Methyl-1-propyl acetate | 1,027.1 | 343.074 | 1.23677 | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 0.65 ± 0.03 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 1.29 | |

| 41 | Ethyl propanoate | 945.1 | 280.115 | 1.14928 | 2.79 ± 0.51 | 1.71 ± 0.13 | 1.64 ± 0.03 | 1.15 | |

| 42 | Propyl formate | 938.2 | 275.884 | 1.2374 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.00 | 0.83 | |

| 43 | Methyl acetate | 839.2 | 221.912 | 1.19297 | 0.24 ± 0.05 | 0.3 ± 0.03 | 0.12 ± 0.00 | 0.9 | |

| 44 | Ethyl formate | 814.5 | 210.164 | 1.06922 | 0.6 ± 0.11 | 0.48 ± 0.04 | 0.24 ± 0.01 | 0.9 | |

| 45 | Diethyl carbonate | 1,101.7 | 427.537 | 1.17506 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.00 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.87 | |

| 46 | Citronellyl formate | 1,662.9 | 1,706.83 | 1.94009 | 6.46 ± 1.79 | 10.37 ± 2.08 | 13.6 ± 0.41 | 0.99 | |

| 47 | Ethyl 2-methy lpropionate | 958.1 | 288.214 | 1.1892 | 0.33 ± 0.06 | 0.41 ± 0.04 | 0.19 ± 0.00 | 0.91 | |

| 48 | Benzene derivatives | Propylbenzene | 1,191.1 | 585.945 | 1.24236 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.06 ± 0.00 | 0.05 ± 0.00 | 0.94 |

| 49 | Ethyl benzene | 1,137.1 | 484.388 | 1.44046 | 0.07 ± 0.04 | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 0.04 ± 0.03 | 0.97 | |

| 50 | Aldehydes | 1-Nonanal | 1,407 | 968.925 | 1.48975 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.06 ± 0.00 | 0.04 ± 0.00 | 0.79 |

| 51 | ( E)-2-Hexen-1-al | 1,217.4 | 625.425 | 1.19766 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 0.19 ± 0.02 | 0.10 ± 0.00 | 0.84 | |

| 52 | 1-Hexanal | 1,080.5 | 400.823 | 1.25673 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.78 | |

| 53 | Crotonaldehyde | 1,036.8 | 352.872 | 1.14016 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 1.11 | |

| 54 | 1-Pentanal | 997.1 | 314.286 | 1.41911 | 0.57 ± 0.14 | 0.67 ± 0.06 | 0.27 ± 0.00 | 0.86 | |

| 55 | 3-Methyl butanal | 922.7 | 266.664 | 1.40787 | 1.15 ± 0.22 | 1.15 ± 0.09 | 0.77 ± 0.02 | 0.77 | |

| 56 | 2-Methyl-2-propenal | 889.7 | 247.97 | 1.21897 | 0.29 ± 0.06 | 0.35 ± 0.04 | 0.13 ± 0.00 | 0.89 | |

| 57 | Butanal | 891 | 248.678 | 1.2773 | 0.18 ± 0.04 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.00 | 0.83 | |

| 58 | Acrolein | 858.5 | 231.54 | 1.05982 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 1.01 | |

| 59 | 2-Methyl propanal | 824.2 | 214.677 | 1.28555 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 1.23 | |

| 60 | Propanal | 752.8 | 183.499 | 1.13665 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 1.04 | |

| 61 | Heptaldehyde | 1,178.7 | 560.786 | 1.32294 | 1.68 ± 0.21 | 2.67 ± 0.12 | 2.00 ± 0.10 | 1.41 | |

| 62 | Alcohols | 1-Pentanol-4-methyl | 1,347.3 | 849.08 | 1.32263 | 0.28 ± 0.04 | 0.28 ± 0.02 | 0.27 ± 0.01 | 1.01 |

| 63 | 1- Butanol | 1,152.6 | 511.639 | 1.1825 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.00 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 1.16 | |

| 64 | 2-Pentanol | 1,109.9 | 440.177 | 1.20286 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.82 | |

| 65 | 1-Propanol (M) | 1,048 | 364.606 | 1.11075 | 0.65 ± 0.23 | 0.46 ± 0.08 | 0.25 ± 0.12 | 0.84 | |

| 66 | 1-Propanol (D) | 1,047.4 | 363.963 | 1.25572 | 0.20 ± 0.11 | 0.15 ± 0.05 | 0.05 ± 0.04 | 0.78 | |

| 67 | 1-Penten-3-ol | 1,168.3 | 540.609 | 0.94381 | 0.44 ± 0.11 | 0.16 ± 0.03 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 1.18 | |

| 68 | 2-Propanol | 908.7 | 258.562 | 1.08522 | 0.39 ± 0.08 | 0.34 ± 0.03 | 0.20 ± 0.00 | 0.83 | |

| 69 | Acids | 1-Butanoic acid | 1,607.8 | 1,510.944 | 1.15335 | 0.94 ± 0.1 | 0.87 ± 0.05 | 0.71 ± 0.05 | 0.88 |

| 70 | 2-Methyl propanoic acid | 1,538.3 | 1,295.658 | 1.16062 | 0.23 ± 0.04 | 0.24 ± 0.02 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.81 | |

| 71 | Acetic acid (M) | 1,490.2 | 1,164.822 | 1.05689 | 1.09 ± 0.15 | 0.93 ± 0.07 | 1.20 ± 0.11 | 1.29 | |

| 72 | Acetic acid (D) | 1,489.9 | 1,163.963 | 1.16194 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 0.09 ± 0.00 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 1.16 | |

| 73 | Thiols | Ethyl mercaptan | 727.2 | 173.448 | 1.23001 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 1.07 |

| 74 | Other | Dibutylamine | 1,098.2 | 422.399 | 1.27161 | 0.33 ± 0.08 | 0.38 ± 0.03 | 0.20 ± 0.03 | 0.85 |

M represents a monomer; D represents dimer. The data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD).

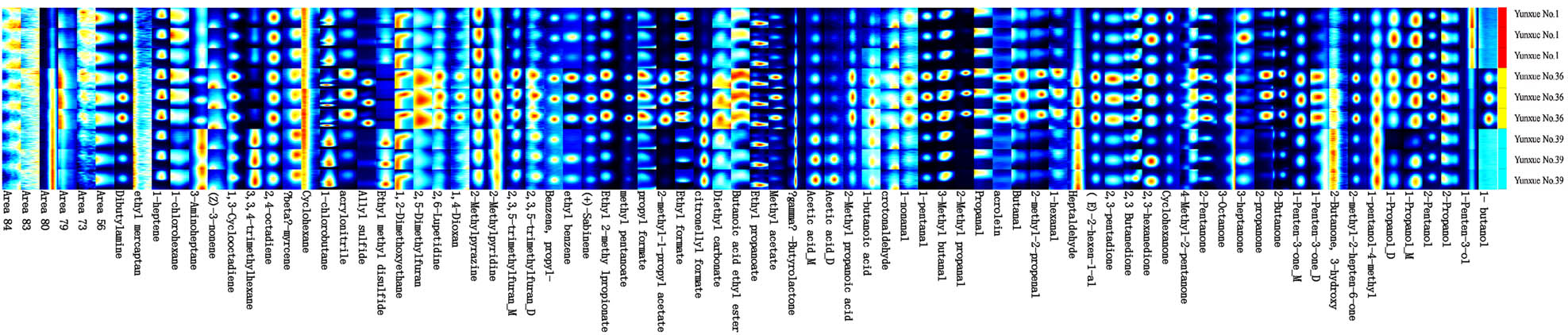

3.3 Fingerprint profiling of cigars

To further clarify the differences of VOCs in the three types of cigars, the Gallery Plot plugin was used to draw the fingerprint spectra of the volatile flavor compounds of the cigars. As shown in Figure 1, the background color of the figure is blue, and the concentration differences of volatile flavor compounds are displayed through color differences. The higher the concentration, the darker the color, indicating the higher the content of VOCs. To more clearly visualize the differences between similar substances in different cigars, a percentage stacked bar chart comparing various substances across the three types of cigars was created (Figure 2). As can be seen from Figures 1 and 2, the VOCs of the three types of cigars include 11 categories in total, namely aldehydes, ketones, alcohols, acids, esters, hydrocarbons, thiols, benzene derivatives, heterocycles, ethers, and terpenoids. Among which, the contents of esters, hydrocarbons, ketones, and aldehydes are relatively high in the three samples, and the sum of the four items is more than 90%. The specific differences among the three samples are as follows: among alcohols, the contents of most components of Yunxue No. 36 are higher than those of Yunxue No. 1 and Yunxue No. 39, such as 1-butanol, 2-propanol, and 2-pentanol. Among ketones, Yunxue No. 1 and Yunxue No. 39 had little difference, while Yunxue No. 36 had relatively high content of most components, such as 1-penten-3-one, 2-butanone, 2-propanone, 2-pentanone, and 2,3-pentanedione. Among the aldehydes, Yunxue No. 1 and Yunxue No. 39 had little difference, but they had a great difference from Yunxue No. 36. Almost all components of Yunxue No. 36 were larger in the three different samples. Among acids, there were obvious differences among the three samples, which showed that almost all acid substances in Yunxue No. 1 were less than the other two samples. 1-Butanoic acid and 2-methylpropionic acid were the highest in Yunxue No. 36, followed by Yunxue No. 39, and the lowest in Yunxue No. 1. Acetic acid was the highest in Yunxue No. 39, followed by Yunxue No. 36, and the lowest in Yunxue No. 1. Among the esters, the contents of most components in Yunxue No. 36 were relatively high, such as methyl acetate, butanoic acid ethyl ester, diethyl carbonate, 2-methyl-1-propyl acetate, propyl formate, methyl pentanoate, ethyl 2-methylpropionate, etc. There were little differences between Yunxue No. 1 and Yunxue No. 39 in terms of benzene ring compounds, heterocyclic compounds, ethers, and terpenoids, but they had a large difference from Yunxue No. 36, and almost all components in Yunxue No. 36 were higher than those in Yunxue No. 1 and Yunxue No. 39, such as ethyl benzene, 2,3,5-trimethylfuran, 2,5-dimethylfuran, (+)-sabinene, allyl sulfide, and so on.

Gallery plot of VOCs in three types of cigars.

A percentage stacked bar chart of the various substances between the three types of cigars.

3.4 “Nearest neighbor” fingerprint analysis of VOCs in cigars

To better illustrate the differences among different samples, a “nearest neighbor” fingerprint analysis was carried out for the volatile flavor compounds of the three types of cigars, as shown in Figure 3. The figure allows for a rapid comparison of samples based on the intensities of compounds within the selected evaluation area. It retrieves the “nearest neighbor” by calculating the similarity index between the spectra to find the minimum distance. The bottom area of the figure shows the normal distribution of VOCs in the three samples. This figure can intuitively display the differences among the three types of cigars. If the distance between the three samples is short and the peak intensity ratios are similar, it indicates a small difference. If the distance is long and the peak intensity ratios vary significantly, this means that the difference is obvious. As can be seen from Figure 3, there is a large gap between Yunxue No. 36, Yunxue No. 1, and Yunxue No. 39 is large, indicating that the volatile flavor substance contents of the three samples are significantly different. The difference between Yunxue No. 1, Yunxue No. 39 is small, indicating that the difference in volatile flavor substance content between the two samples is small.

“Nearest neighbor” fingerprint analysis map of three cigar samples.

3.5 PCA and OPLS-DA

To further analyze the differences among the three cigar samples, PCA and OPLS-DA analyses were performed based on the information on volatile flavor substances. PCA is a multivariate statistical analysis technique used to assess the regularity and variability among samples based on the contribution of principal component factors in different samples. It identifies several principal component factors to represent the many complex and difficult-to-identify variables in the original samples [34]. The results are shown in Figure 4, where the contribution rate of the first principal component is 25%, and that of the second principal component is 66%. The cumulative contribution rate of the two principal components reaches 91%, indicating that the data after PCA transformation can characterize most of the original data information. It shows that the PCA transformed by dimensionality reduction can characterize most of the information of the original data, thus obtaining the visualization of the data. The samples in the figure are effectively clustered and have good regional attribution, indicating that there are differences in the volatile compounds among different samples.

PCA plot of three types of cigars.

OPLS-DA is a multivariate statistical analysis method with supervised pattern recognition [35], which realizes the classification of the samples by establishing a relationship model between the experimental data and the sample categories, and its analysis results are shown in Figure 5. As depicted in Figure 5, the three groups of samples achieved significant separation, consistent with the results from the PCA classification model analysis. The three key indicators for the OPLS-DA model: R 2 X (proportion of information explaining the X matrix), R 2 Y (proportion of information explaining the Y matrix), and Q 2 (model predictive ability) were 0.981, 0.993, and 0.964, respectively, indicating good predictive performance and data interpretation of the model. Following 200 times of cross-validation permutation tests, the results showed R 2 = (0.0, 0.65) and Q 2 = (0.0, −0.128), confirming that no over fitting occurred in the OPLS-DA model (Figure 6). This demonstrates that the model possesses good stability and predictive capability, making it suitable for the discrimination of the three types of cigar cigarettes.

OPLS-DA plot of three types of cigars.

Cross-validation plot of OPLS-DA with 200 permutation tests.

After normalizing the data, the higher the value of variable importance projection (VIP) in the OPLS-DA model, the higher its contribution to the classification of the samples [36], and the volatile flavor compounds were only considered key difference compounds related to the odor if VIP > 1, P < 0.05. As shown in Table 1, 29 volatile compounds in the three cigar cigarettes contributed significantly to the odor. They mainly include ester, hydrocarbon, ketone, and aldehyde compounds. Among them, three volatile compounds, 3-octanone, 1-penten-3-one (D), and heptaldehyde, contributed more to the sample differentiation.

4 Conclusion

In this study, the composition of VOCs of three major cigar tobacco cultivars in Yunnan Province was systematically analyzed for the first time based on HS-GC-IMS technology, and differentiated GC-IMS spectra, fingerprints, and nearest neighbor analyses were established among different cultivars. The main differences in volatile flavor substances among the three cigar tobacco cultivars were also analyzed by PCA and partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA). The 74 VOCs identified in the study and their content differences among varieties provide intuitive chemical markers for the variety identification of cigar tobacco leaves and lay a foundation for the development of origin traceability technologies. Additionally, the study revealed that “Yunxue No. 1 and Yunxue No. 39 have high similarity in VOCs, while showing significant differences from Yunxue No. 36.” This feature can directly serve the optimization of variety layout and fragrance style positioning in Yunnan’s cigar tobacco production areas. For example, by regulating the high-content aldehydes (e.g., butanal, 1-pentanal) and esters (e.g., methyl acetate, butyric acid ethyl acetate) in Yunxue No. 36, its unique aroma style can be further strengthened, providing clear chemical targets for cigar quality improvement. This research will play an active role in promoting quality control, quality evaluation, and sensory quality management of cigar tobacco in Yunnan.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully thank the Tobacco Industry Service Center of Yuanjiang County, Yuxi City, for its assistance in the collection of cigar samples.

-

Funding information: This work was supported by the Scientific Research Fund Project of the Education Department of Yunnan Province, titled “Research on the Component Analysis of the Main Cultivated Varieties of Cigars Produced in Yunnan Province” (2025J1768), and the Scientific Research Project for Young Talents under the Xingyu Talents Support Program, titled “Study on the Correlation between the Characterization of Microbial Community Diversity of Yunnan-produced Cigar Tobacco Leaves at Different Altitudes and the Neutral Aroma Components & Intrinsic Sensory Quality” (2023yn001).

-

Author contributions: Z.Y.Y. – funding acquisition, writing – original draft; F.Y.H. – methodology; X.B.G. – resources; S.B.S. – data curation; Y.R.L. – investigation; Y.B.Y. – project administration; L.L.G. – software; X.Z. – funding acquisition, writing – review and editing. All the authors agreed on the final version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

References

[1] Viola AS, Giovenco DP, Lo EJ, Delnevo CD. A cigar by any other name would taste as sweet. Tob Control. 2015;25(5):605–6. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052518.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Hao W. Research on the state of the cigarette market based on the current economic situation. China Mark. 2024;23:53–6. 10.13939/j.cnki.zgsc.2024.23.014.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Fan JY, Zhang L, Li AJ. Study on the production key technology of handmade cigar. Anhui Nongye Kexue. 2016;44(6):104–5. 10.13989/j.cnki.0517-6611.2016.06.035.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Wen C, Hu WR, Li PH, Liu J, Qian YZ, Quan WZ, et al. Effects of fermentation medium on cigar filler. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022;10:1069796. 10.3389/fbioe.2022.1069796.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Wan D, Chuang WU, Jia DU, Jiao MO, Yao F, Shi X, et al. Research advances in fermentation methods of cigar tobacco leaves. J Shanxi Agric Sci. 2017;45(7):1211–4. 10.3969/j.issn.1002-2481.2017.07.43.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Rong SB, Jing JL, Zhao YY, Qin YQ, Jun W, Xing YY, et al. Effect of artificial fermentation temperature and humidity on chemical composition and aroma quality of cigar filler tobacco. Acta Tabacaria Sin. 2021;27(2):109–16. 10.16472/j.chinatobacco.2020.191.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Hu W, Cai W, Zheng Z, Liu Y, Luo C, Xue F, et al. Study on the chemical compositions and microbial communities of cigar tobacco leaves fermented with exogenous additive. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):19182. 10.1038/s41598-022-23419-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Li XN, Yan TJ, Wu FG, Liu LP, Song SX, Zhu JM, et al. Preliminary study on flavor characteristics of global typical cigar leaves. Acta Tabacaria Sin. 2019;25(6):126–32. 10.16472/j.chinatobacco.2018.263.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Zhang L, Wang X, Guo J, Xia Q, Zhao G, Zhou H, et al. Metabolic profiling of Chinese tobacco leaf of different geographical origins by GC-MS. J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61(11):2597–605. 10.1021/jf400428t.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Liu L, Wang X, Wang S, Liu S, Jia Y, Qin Y, et al. Simultaneous quantification of ten Amadori compounds in tobacco using liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry. J Sep Sci. 2017;40(4):849–57. 10.1002/jssc.201601168.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] He Q, Zhang Y, Zhou S, She S, Chen G, Chen K, et al. Estimating the aroma glycosides in flue-cured tobacco by solid-phase extraction and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry: changes in the bound aroma profile during leaf maturity. Flavour Fragr J. 2015;30(3):230–7. 10.1002/ffj.3235.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Zhu B, An H, Li L, Zhang H, Lv J, Hu W, et al. Characterization of flavor profiles of cigar tobacco leaves grown in China via headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry coupled with multivariate analysis and sensory evaluation. ACS Omega. 2024;9(14):15996–6005. 10.1021/acsomega.3c09499.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Cumeras R, Figueras E, Davis CE, Baumbach JI, Gràcia I. Review on ion mobility spectrometry. Part 1: current instrumentation. Analyst. 2015;140(5):1376–90. 10.1039/c4an01100g.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Gabelica V, Marklund E. Fundamentals of ion mobility spectrometry. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2018;42:51–9. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2017.10.022.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Ishikawa N, Sekiguchi K. Measurements of the size and composition of volatile particles generated from a heated tobacco product with aerosol fixation agents. Aerosol Air Qual Res. 2018;18(10):2538–49. 10.4209/aaqr.2018.02.0049.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Liu Y, Li M, Guo B, Song Q, Zhang Y, Sun Q, et al. Analysis of unique volatile organic compounds in “Mianhua” made from wheat planted in arid alkaline land. Food Res Int. 2024;190:114486. 10.1016/j.foodres.2024.114486.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Zhong Y, Zhang G, Zhang F, Lin S, Wang M, Sun Y, et al. The effects of different drying methods on the flavor profile of wheat germ using E-nose and GC-IMS. J Cereal Sci. 2024;117:103930. 10.1016/j.jcs.2024.103930.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Liu M, Yang Y, Zhao X, Wang Y, Li M, Wang Y, et al. Classification and characterization on sorghums based on HS-GC-IMS combined with OPLS-DA and GA-PLS. Curr Res Food Sci. 2024;8:100692. 10.1016/j.crfs.2024.100692.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Yang C, Ye Z, Mao L, Zhang L, Zhang J, Ding W, et al. Analysis of volatile organic compounds and metabolites of three cultivars of asparagus (Asparagus officinalis L.) using E-nose, GC-IMS, and LC-MS/MS. Bioengineered. 2022;13(4):8866–80. 10.1080/21655979.2022.2056318.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Feng T, Sun J, Song S, Wang H, Yao L, Sun M, et al. Geographical differentiation of Molixiang table grapes grown in China based on volatile compounds analysis by HS-GC-IMS coupled with PCA and sensory evaluation of the grapes. Food Chem: X. 2022;15:100423. 10.1016/j.fochx.2022.100423.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Liu H, Xu Y, Wu J, Wen J, Yu Y, An K, et al. GC-IMS and olfactometry analysis on the tea aroma of Yingde black teas harvested in different seasons. Food Res Int. 2021;150:110784. 10.1016/j.foodres.2021.110784.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Wang L, Xie J, Deng Y, Jiang Y, Tong H, Yuan H, et al. Volatile profile characterization during the drying process of black tea by integrated volatolomics analysis. Lebensmittel-Wissenschaft und-Technologie/Food Sci Technol. 2023;184:115039. 10.1016/j.lwt.2023.115039.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Guo X, Schwab W, Ho CT, Song C, Wan X. Characterization of the aroma profiles of oolong tea made from three tea cultivars by both GC-MS and GC-IMS. Food Chem. 2022;376:131933. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131933.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Yang JH, Cui S, Sun MJ, Liu K, Tao H, Zhang D, et al. Dynamic evolution of volatile compounds during cold storage of sturgeon fillets analyzed by gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry and chemometric methods. Food Chem. 2024;464:141741. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.141741.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Sun X, Liu X, Yang W, Feng A, Sun T, Jiang Q, et al. Establishment of intermittent ultrasound-complex enzyme deodorization technology for tilapia based on GC-IMS and HS-SPME-GC/MS analysis. Food Biosci. 2024;61:104806. 10.1016/j.fbio.2024.104806.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Zhao H, Chen H, Wu G, Xu J, Zhu W, Chen J, et al. Integrative metabolomics-GC-IMS approach to assess metabolic and flavour substance shifts during fermentation of Yangjiang douchi. Food Chem. 2024;466:142199. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.142199.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Miao X, Zhang R, Jiang S, Song Z, Du M, Liu A. Volatile flavor profiles of douchis from different origins and varieties based on GC-IMS and GC-O-QTOF/MS analysis. Food Chem. 2024;460:140717. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.140717.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Parastar H, Yazdanpanah H, Weller P. Non-targeted volatilomics for the authentication of saffron by gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry and multivariate curve resolution. Food Chem. 2025;465:142074. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.142074.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Xiang Y, Zou M, Ou F, Zhu L, Xu Y, Zhou Q, et al. A comparison of the impacts of different drying methods on the volatile organic compounds in ginseng. Molecules. 2024;29(22):5235. 10.3390/molecules29225235.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Zhu B, Chen J, Song G, Jia Y, Hu W, An H, et al. Characterization of volatile flavor compounds of cigar with different aging conditions by headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry. Open Chem. 2025;23(1):20240129. 10.1515/chem-2024-0129.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Yan T, Zhou P, Long F, Liu J, Wu F, Zhang M, et al. Unraveling the difference in the composition/content of the aroma compounds in different tobacco leaves: For vetter use. J Chem. 2022;2022(1):3293899. 10.1155/2022/3293899.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Tiele A, Wicaksono A, Kansara J, Arasaradnam RP, Covington JA. Breath analysis using enose and ion mobility technology to diagnose inflammatory bowel disease-a pilot study. Biosensors. 2019;9(2):55. 10.3390/bios9020055.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Li C, Tian S, You J, Liu J, Li E, Wang C, et al. Qualitative determination of volatile substances in different flavored cigarette paper by using headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry (HS-GC-IMS) combined with chemometrics. Heliyon. 2023;9(1):12146. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e12146.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Li M, Yang R, Zhang H, Wang S, Chen D, Qin L. Development of a flavor fingerprint by HS-GC-IMS with PCA for volatile compounds of Tricholoma matsutake Singer. Food Chem. 2019;290:32–9. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.03.124.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Zhao L, Wang SL, Zhao X, Wang YH, Hou BQ, Jin YX, et al. Study on the key differences indexes of conventional chemical constituents and neutral aromatic substances in domestic and foreign typical wrapper tobacco leaves. J Light Ind. 2024;39(1):79–86. 10.12187/2024.01.010.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Wang Z, Yuan Y, Hong B, Zhao X, Gu Z. Characteristic volatile fingerprints of four chrysanthemum teas determined by HS-GC-IMS. Molecules. 2021;26(23):7113. 10.3390/molecules26237113.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Phytochemical investigation and evaluation of antioxidant and antidiabetic activities in aqueous extracts of Cedrus atlantica

- Influence of B4C addition on the tribological properties of bronze matrix brake pad materials

- Discovery of the bacterial HslV protease activators as lead molecules with novel mode of action

- Characterization of volatile flavor compounds of cigar with different aging conditions by headspace–gas chromatography–ion mobility spectrometry

- Effective remediation of organic pollutant using Musa acuminata peel extract-assisted iron oxide nanoparticles

- Analysis and health risk assessment of toxic elements in traditional herbal tea infusions

- Cadmium exposure in marine crabs from Jiaxing City, China: Insights into health risk assessment

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles of Cinnamomum zeylanicum and their biological activities

- Tetraclinis articulata (Vahl) Mast., Mentha pulegium L., and Thymus zygis L. essential oils: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antifungal properties against postharvest fungal diseases of apple, and in vitro, in vivo, and in silico investigation

- Exploration of plant alkaloids as potential inhibitors of HIV–CD4 binding: Insight into comprehensive in silico approaches

- Recovery of phenylethyl alcohol from aqueous solution by batch adsorption

- Electrochemical approach for monitoring the catalytic action of immobilized catalase

- Green synthesis of ZIF-8 for selective adsorption of dyes in water purification

- Optimization of the conditions for the preparation of povidone iodine using the response surface methodology

- A case study on the influence of soil amendment on ginger oil’s physicochemical properties, mineral contents, microbial load, and HPLC determination of its vitamin level

- Removal of antiviral favipiravir from wastewater using biochar produced from hazelnut shells

- Effect of biochar and soil amendment on bacterial community composition in the root soil and fruit of tomato under greenhouse conditions

- Bioremediation of malachite green dye using Sargassum wightii seaweed and its biological and physicochemical characterization

- Evaluation of natural compounds as folate biosynthesis inhibitors in Mycobacterium leprae using docking, ADMET analysis, and molecular dynamics simulation

- Novel insecticidal properties of bioactive zoochemicals extracted from sea urchin Salmacis virgulata

- Elevational gradients shape total phenolic content and bioactive potential of sweet marjoram (Origanum majorana L.): A comparative study across altitudinal zones

- Study on the CO2 absorption performance of deep eutectic solvents formed by superbase DBN and weak acid diethylene glycol

- Preparation and wastewater treatment performance of zeolite-modified ecological concrete

- Multifunctional chitosan nanoparticles: Zn2+ adsorption, antimicrobial activity, and promotion of aquatic health

- Comparative analysis of nutritional composition and bioactive properties of Chlorella vulgaris and Arthrospira platensis: Implications for functional foods and dietary supplements

- Growth kinetics and mechanical characterization of boride layers formed on Ti6Al4V

- Enhancement of water absorption properties of potassium polyacrylate-based hydrogels in CaCl2-rich soils using potassium di- and tri-carboxylate salts

- Electrochemical and microbiological effects of dumpsite leachates on soil and air quality

- Modeling benzene physicochemical properties using Zagreb upsilon indices

- Characterization and ecological risk assessment of toxic metals in mangrove sediments near Langen Village in Tieshan Bay of Beibu Gulf, China

- Protective effect of Helicteres isora, an efficient candidate on hepatorenal toxicity and management of diabetes in animal models

- Valorization of Juglans regia L. (Walnut) green husk from Jordan: Analysis of fatty acids, phenolics, antioxidant, and cytotoxic activities

- Molecular docking and dynamics simulations of bioactive terpenes from Catharanthus roseus essential oil targeting breast cancer

- Selection of a dam site by using AHP and VIKOR: The Sakarya Basin

- Characterization and modeling of kidney bean shell biochar as adsorbent for caffeine removal from aquatic environments

- The effects of short-term and long-term 2100 MHz radiofrequency radiation on adult rat auditory brainstem response

- Biochemical insights into the anthelmintic and anti-inflammatory potential of sea cucumber extract: In vitro and in silico approaches

- Resveratrol-derived MDM2 inhibitors: Synthesis, characterization, and biological evaluation against MDM2 and HCT-116 cells

- Phytochemical constituents, in vitro antibacterial activity, and computational studies of Sudanese Musa acuminate Colla fruit peel hydro-ethanol extract

- Chemical composition of essential oils reviewed from the height of Cajuput (Melaleuca leucadendron) plantations in Buru Island and Seram Island, Maluku, Indonesia

- Phytochemical analysis and antioxidant activity of Azadirachta indica A. Juss from the Republic of Chad: in vitro and in silico studies

- Stability studies of titanium–carboxylate complexes: A multi-method computational approach

- Efficient adsorption performance of an alginate-based dental material for uranium(vi) removal

- Synthesis and characterization of the Co(ii), Ni(ii), and Cu(ii) complexes with a 1,2,4-triazine derivative ligand

- Evaluation of the impact of music on antioxidant mechanisms and survival in salt-stressed goldfish

- Optimization and validation of UPLC method for dapagliflozin and candesartan cilexetil in an on-demand formulation: Analytical quality by design approach

- Biomass-based cellulose hydroxyapatite nanocomposites for the efficient sequestration of dyes: Kinetics, response surface methodology optimization, and reusability

- Multifunctional nitrogen and boron co-doped carbon dots: A fluorescent probe for Hg2+ and biothiol detection with bioimaging and antifungal applications

- Separation of sulphonamides on a C12-diol mixed-mode HPLC column and investigation of their retention mechanism

- Characterization and antioxidant activity of pectin from lemon peels

- Fast PFAS determination in honey by direct probe electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry: A health risk assessment insight

- Correlation study between GC–MS analysis of cigarette aroma compounds and sensory evaluation

- Synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular docking studies of substituted chromone-2-carboxamide derivatives as anti-breast cancer agents

- The influence of feed space velocity and pressure on the cold flow properties of diesel fuel

- Acid etching behavior and mechanism in acid solution of iron components in basalt fibers

- Protective effect of green synthesized nanoceria on retinal oxidative stress and inflammation in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat

- Evaluation of the antianxiety activity of green zinc nanoparticles mediated by Boswellia thurifera in albino mice by following the plus maze and light and dark exploration tests

- Yeast as an efficient and eco-friendly bifunctional porogen for biomass-derived nitrogen-doped carbon catalysts in the oxygen reduction reaction

- Novel descriptors for the prediction of molecular properties

- Synthesis and characterization of surfactants derived from phenolphthalein: In vivo and in silico studies of their antihyperlipidemic effect

- Turmeric oil-fortified nutraceutical-SNEDDS: An approach to boost therapeutic effectiveness of dapagliflozin during treatment of diabetic patients

- Analysis and study on volatile flavor compounds of three Yunnan cultivated cigars based on headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry

- Near-infrared IR780 dye-loaded poloxamer 407 micelles: Preparation and in vitro assessment of anticancer activity

- Study on the influence of the viscosity reducer solution on percolation capacity of thin oil in ultra-low permeability reservoir

- Detection method of Aristolochic acid I based on magnetic carrier Fe3O4 and gold nanoclusters

- Juglone’s apoptotic impact against eimeriosis-induced infection: a bioinformatics, in-silico, and in vivo approach

- Potential anticancer agents from genus Aerva based on tubulin targets: an in-silico integration of quantitative structure activity relationship (QSAR), molecular docking, simulation, drug-likeness, and density functional theory (DFT) analysis

- Hepatoprotective and PXR-modulating effects of Erodium guttatum extract in propiconazole-induced toxicity

- Studies on chemical composition of medicinal plants collected in natural locations in Ecuador

- A study of different pre-treatment methods for cigarettes and their aroma differences

- Cytotoxicity and molecular mechanisms of quercetin, gallic acid, and pinocembrin in Caco-2 cells: insights from cell viability assays, network pharmacology, and molecular docking

- Choline-based deep eutectic solvents for green extraction of oil from sour cherry seeds

- Green-synthesis of chromium (III) nanoparticles using garden fern and evaluation of its antibacterial and anticholinesterase activities

- Innovative functional mayonnaise formulations with watermelon seeds oil: evaluation of quality parameters and storage stability

- Molecular insights and biological evaluation of compounds isolated from Ferula oopoda against diabetes, advanced glycation end products and inflammation in diabetics

- Removal of cytotoxic tamoxifen from aqueous solutions using a geopolymer-based nepheline–cordierite adsorbent

- Unravelling the therapeutic effect of naturally occurring Bauhinia flavonoids against breast cancer: an integrated computational approach

- Characterization of organic arsenic residues in livestock and poultry meat and offal and consumption risks

- Synthesis and characterization of zinc sulfide nanoparticles and their genotoxic and cytotoxic effects on acute myeloid leukemia cells

- Activity of Coriandrum sativum methanolic leaf extracts against Eimeria papillata: a combined in vitro and in silico approach

- Special Issue on Advancing Sustainable Chemistry for a Greener Future

- One-pot fabrication of highly porous morphology of ferric oxide-ferric oxychloride/poly-O-chloroaniline nanocomposite seeded on poly-1H pyrrole: Photocathode for green hydrogen generation from natural and artificial seawater

- High-efficiency photocathode for green hydrogen generation from sanitation water using bismuthyl chloride/poly-o-chlorobenzeneamine nanocomposite

- Innovative synthesis of cobalt-based catalysts using ionic liquids and deep eutectic solvents: A minireview on electrocatalytic water splitting

- Special Issue on Phytochemicals, Biological and Toxicological Analysis of Plants

- Comparative analysis of fruit quality parameters and volatile compounds in commercially grown citrus cultivars

- Total phenolic, flavonoid, flavonol, and tannin contents as well as antioxidant and antiparasitic activities of aqueous methanol extract of Alhagi graecorum plant used in traditional medicine: Collected in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- Study on the pharmacological effects and active compounds of Apocynum venetum L.

- Chemical profile of Senna italica and Senna velutina seed and their pharmacological properties

- Essential oils from Brazilian plants: A literature analysis of anti-inflammatory and antimalarial properties and in silico validation

- Toxicological effects of green tea catechin extract on rat liver: Delineating safe and harmful doses

- Unlocking the potential of Trigonella foenum-graecum L. plant leaf extracts against diabetes-associated hypertension: A proof of concept by in silico studies

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Phytochemical investigation and evaluation of antioxidant and antidiabetic activities in aqueous extracts of Cedrus atlantica

- Influence of B4C addition on the tribological properties of bronze matrix brake pad materials

- Discovery of the bacterial HslV protease activators as lead molecules with novel mode of action

- Characterization of volatile flavor compounds of cigar with different aging conditions by headspace–gas chromatography–ion mobility spectrometry

- Effective remediation of organic pollutant using Musa acuminata peel extract-assisted iron oxide nanoparticles

- Analysis and health risk assessment of toxic elements in traditional herbal tea infusions

- Cadmium exposure in marine crabs from Jiaxing City, China: Insights into health risk assessment

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles of Cinnamomum zeylanicum and their biological activities

- Tetraclinis articulata (Vahl) Mast., Mentha pulegium L., and Thymus zygis L. essential oils: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antifungal properties against postharvest fungal diseases of apple, and in vitro, in vivo, and in silico investigation

- Exploration of plant alkaloids as potential inhibitors of HIV–CD4 binding: Insight into comprehensive in silico approaches

- Recovery of phenylethyl alcohol from aqueous solution by batch adsorption

- Electrochemical approach for monitoring the catalytic action of immobilized catalase

- Green synthesis of ZIF-8 for selective adsorption of dyes in water purification

- Optimization of the conditions for the preparation of povidone iodine using the response surface methodology

- A case study on the influence of soil amendment on ginger oil’s physicochemical properties, mineral contents, microbial load, and HPLC determination of its vitamin level

- Removal of antiviral favipiravir from wastewater using biochar produced from hazelnut shells

- Effect of biochar and soil amendment on bacterial community composition in the root soil and fruit of tomato under greenhouse conditions

- Bioremediation of malachite green dye using Sargassum wightii seaweed and its biological and physicochemical characterization

- Evaluation of natural compounds as folate biosynthesis inhibitors in Mycobacterium leprae using docking, ADMET analysis, and molecular dynamics simulation

- Novel insecticidal properties of bioactive zoochemicals extracted from sea urchin Salmacis virgulata

- Elevational gradients shape total phenolic content and bioactive potential of sweet marjoram (Origanum majorana L.): A comparative study across altitudinal zones

- Study on the CO2 absorption performance of deep eutectic solvents formed by superbase DBN and weak acid diethylene glycol

- Preparation and wastewater treatment performance of zeolite-modified ecological concrete

- Multifunctional chitosan nanoparticles: Zn2+ adsorption, antimicrobial activity, and promotion of aquatic health

- Comparative analysis of nutritional composition and bioactive properties of Chlorella vulgaris and Arthrospira platensis: Implications for functional foods and dietary supplements

- Growth kinetics and mechanical characterization of boride layers formed on Ti6Al4V

- Enhancement of water absorption properties of potassium polyacrylate-based hydrogels in CaCl2-rich soils using potassium di- and tri-carboxylate salts

- Electrochemical and microbiological effects of dumpsite leachates on soil and air quality

- Modeling benzene physicochemical properties using Zagreb upsilon indices

- Characterization and ecological risk assessment of toxic metals in mangrove sediments near Langen Village in Tieshan Bay of Beibu Gulf, China

- Protective effect of Helicteres isora, an efficient candidate on hepatorenal toxicity and management of diabetes in animal models

- Valorization of Juglans regia L. (Walnut) green husk from Jordan: Analysis of fatty acids, phenolics, antioxidant, and cytotoxic activities

- Molecular docking and dynamics simulations of bioactive terpenes from Catharanthus roseus essential oil targeting breast cancer

- Selection of a dam site by using AHP and VIKOR: The Sakarya Basin

- Characterization and modeling of kidney bean shell biochar as adsorbent for caffeine removal from aquatic environments

- The effects of short-term and long-term 2100 MHz radiofrequency radiation on adult rat auditory brainstem response

- Biochemical insights into the anthelmintic and anti-inflammatory potential of sea cucumber extract: In vitro and in silico approaches

- Resveratrol-derived MDM2 inhibitors: Synthesis, characterization, and biological evaluation against MDM2 and HCT-116 cells

- Phytochemical constituents, in vitro antibacterial activity, and computational studies of Sudanese Musa acuminate Colla fruit peel hydro-ethanol extract

- Chemical composition of essential oils reviewed from the height of Cajuput (Melaleuca leucadendron) plantations in Buru Island and Seram Island, Maluku, Indonesia

- Phytochemical analysis and antioxidant activity of Azadirachta indica A. Juss from the Republic of Chad: in vitro and in silico studies

- Stability studies of titanium–carboxylate complexes: A multi-method computational approach

- Efficient adsorption performance of an alginate-based dental material for uranium(vi) removal

- Synthesis and characterization of the Co(ii), Ni(ii), and Cu(ii) complexes with a 1,2,4-triazine derivative ligand

- Evaluation of the impact of music on antioxidant mechanisms and survival in salt-stressed goldfish

- Optimization and validation of UPLC method for dapagliflozin and candesartan cilexetil in an on-demand formulation: Analytical quality by design approach

- Biomass-based cellulose hydroxyapatite nanocomposites for the efficient sequestration of dyes: Kinetics, response surface methodology optimization, and reusability

- Multifunctional nitrogen and boron co-doped carbon dots: A fluorescent probe for Hg2+ and biothiol detection with bioimaging and antifungal applications

- Separation of sulphonamides on a C12-diol mixed-mode HPLC column and investigation of their retention mechanism

- Characterization and antioxidant activity of pectin from lemon peels

- Fast PFAS determination in honey by direct probe electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry: A health risk assessment insight

- Correlation study between GC–MS analysis of cigarette aroma compounds and sensory evaluation

- Synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular docking studies of substituted chromone-2-carboxamide derivatives as anti-breast cancer agents

- The influence of feed space velocity and pressure on the cold flow properties of diesel fuel

- Acid etching behavior and mechanism in acid solution of iron components in basalt fibers

- Protective effect of green synthesized nanoceria on retinal oxidative stress and inflammation in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat

- Evaluation of the antianxiety activity of green zinc nanoparticles mediated by Boswellia thurifera in albino mice by following the plus maze and light and dark exploration tests

- Yeast as an efficient and eco-friendly bifunctional porogen for biomass-derived nitrogen-doped carbon catalysts in the oxygen reduction reaction

- Novel descriptors for the prediction of molecular properties

- Synthesis and characterization of surfactants derived from phenolphthalein: In vivo and in silico studies of their antihyperlipidemic effect

- Turmeric oil-fortified nutraceutical-SNEDDS: An approach to boost therapeutic effectiveness of dapagliflozin during treatment of diabetic patients

- Analysis and study on volatile flavor compounds of three Yunnan cultivated cigars based on headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry

- Near-infrared IR780 dye-loaded poloxamer 407 micelles: Preparation and in vitro assessment of anticancer activity

- Study on the influence of the viscosity reducer solution on percolation capacity of thin oil in ultra-low permeability reservoir

- Detection method of Aristolochic acid I based on magnetic carrier Fe3O4 and gold nanoclusters

- Juglone’s apoptotic impact against eimeriosis-induced infection: a bioinformatics, in-silico, and in vivo approach

- Potential anticancer agents from genus Aerva based on tubulin targets: an in-silico integration of quantitative structure activity relationship (QSAR), molecular docking, simulation, drug-likeness, and density functional theory (DFT) analysis

- Hepatoprotective and PXR-modulating effects of Erodium guttatum extract in propiconazole-induced toxicity

- Studies on chemical composition of medicinal plants collected in natural locations in Ecuador

- A study of different pre-treatment methods for cigarettes and their aroma differences

- Cytotoxicity and molecular mechanisms of quercetin, gallic acid, and pinocembrin in Caco-2 cells: insights from cell viability assays, network pharmacology, and molecular docking

- Choline-based deep eutectic solvents for green extraction of oil from sour cherry seeds

- Green-synthesis of chromium (III) nanoparticles using garden fern and evaluation of its antibacterial and anticholinesterase activities

- Innovative functional mayonnaise formulations with watermelon seeds oil: evaluation of quality parameters and storage stability

- Molecular insights and biological evaluation of compounds isolated from Ferula oopoda against diabetes, advanced glycation end products and inflammation in diabetics

- Removal of cytotoxic tamoxifen from aqueous solutions using a geopolymer-based nepheline–cordierite adsorbent

- Unravelling the therapeutic effect of naturally occurring Bauhinia flavonoids against breast cancer: an integrated computational approach

- Characterization of organic arsenic residues in livestock and poultry meat and offal and consumption risks

- Synthesis and characterization of zinc sulfide nanoparticles and their genotoxic and cytotoxic effects on acute myeloid leukemia cells

- Activity of Coriandrum sativum methanolic leaf extracts against Eimeria papillata: a combined in vitro and in silico approach

- Special Issue on Advancing Sustainable Chemistry for a Greener Future

- One-pot fabrication of highly porous morphology of ferric oxide-ferric oxychloride/poly-O-chloroaniline nanocomposite seeded on poly-1H pyrrole: Photocathode for green hydrogen generation from natural and artificial seawater

- High-efficiency photocathode for green hydrogen generation from sanitation water using bismuthyl chloride/poly-o-chlorobenzeneamine nanocomposite

- Innovative synthesis of cobalt-based catalysts using ionic liquids and deep eutectic solvents: A minireview on electrocatalytic water splitting

- Special Issue on Phytochemicals, Biological and Toxicological Analysis of Plants

- Comparative analysis of fruit quality parameters and volatile compounds in commercially grown citrus cultivars

- Total phenolic, flavonoid, flavonol, and tannin contents as well as antioxidant and antiparasitic activities of aqueous methanol extract of Alhagi graecorum plant used in traditional medicine: Collected in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- Study on the pharmacological effects and active compounds of Apocynum venetum L.

- Chemical profile of Senna italica and Senna velutina seed and their pharmacological properties

- Essential oils from Brazilian plants: A literature analysis of anti-inflammatory and antimalarial properties and in silico validation

- Toxicological effects of green tea catechin extract on rat liver: Delineating safe and harmful doses

- Unlocking the potential of Trigonella foenum-graecum L. plant leaf extracts against diabetes-associated hypertension: A proof of concept by in silico studies