Abstract

This study evaluated the extraction methods for optimizing lipid and phenolic yields from Juglans regia L. (walnut) green husk and assessed the extracts’ cytotoxic effects on cancer cells (liver cancer cell line, HepG2) and normal human cells (HUVEC). Among the various lipid extraction techniques, the Bligh and Dyer method was most efficient (3.4% dry weight), followed by Soxhlet extraction with n-hexane (2.4%), Folch (2.3%), and sonication (1.7%). For phenolic extraction, sonication with 70% ethanol achieved the highest yield (18.8%), with Soxhlet extraction close behind (17.7%). Total phenolic content varied, with reflux extraction yielding 0.07 ± 0.05 mg GAE/g and hexane Soxhlet extraction at 0.023 ± 0.03 mg GAE/g. Cytotoxicity assays showed dose-dependent inhibitory effects on HepG2 cells for both 70% ethanol maceration and Bligh and Dyer extracts, with IC50 values of 277.3 and 237.5 μg/mL, respectively. The Bligh and Dyer extract had an IC50 of 185.3 μg/mL on HUVEC cells. Microscopy and DAPI staining indicated apoptotic changes in HepG2 cells, while DCFH-DA staining revealed elevated ROS levels, suggesting oxidative stress. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry identified unique compounds with potential bioactivity, and molecular docking highlighted 5-hydroxy-1-tetralone as a strong binder with protein 3TZM (−8.0 kcal/mol). This study underscores the influence of extraction methods on yield and bioactivity.

1 Introduction

The generation of by-products has become a noteworthy concern, causing a shift toward waste utilization strategies aligned with the principles of a circular economy [1,2]. Fruit husks are now recognized as valuable biological resources for use in the food industry, pharmaceuticals, and bioenergy production [3,4]. Plant by-products are rich in phytochemicals and bioactive substances, offering valuable resources for dietary supplements, cosmetics, food, and pharmaceuticals due to their accessibility, non-toxicity, eco-friendliness, and affordability [5]. However, many types of fruit husks are still underutilized in the food industry [6].

The walnut tree (Juglans regia L.), an important member of the Juglandaceae family, is extensively grown across various regions worldwide [7]. China leads in walnut production, contributing nearly half of the global output, followed by the United States, Iran, and Turkey [8]. Walnut production generates a substantial amount of agricultural by-products globally, particularly walnut leaves and green husks, which are traditionally discarded or underutilized. These by-products contain proteins, fats, carbohydrates, minerals (Fe, K, Ca, Zn, Mn, and Mg), and vitamin E, along with bioactive compounds including terpenoids, flavonoids, organic acids, triterpenic acids, phenolics, and terpenes. Being abundant and low-cost waste materials, they hold potential for developing functional foods and high-value products [8,9].

The bioactive compounds in walnut husks have been shown to possess a variety of health benefits, making them valuable in multiple industries. Walnut leaves and green husks exhibit properties such as anti-aging, anticancer, antioxidant, antiasthmatic, antidiarrheal, anti-inflammatory, cardioprotective, antihistaminic, antimutagenic, antimicrobial, and antiulcer activities, which could provide various health benefits [8,9,10,11,12,13]. These compounds offer valuable potential for use in functional foods, nutraceuticals, therapeutics, and the pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries.

Growing public awareness of health, safety risks, and environment linked to the implementation of organic solvents in food processing, as well as concerns over residual solvents in final products [14], and the cost of organic solvents, has driven the development of new, cleaner technologies. Ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) has emerged as a preferred green extraction method due to its efficiency, reduced solvent and energy use, and shorter extraction times compared to conventional methods [15,16]. This technique offers higher yields and enhanced phenolic compounds recovery from spices and agricultural by-products, contributing to more sustainable food and pharmaceutical production [17,18]. Additionally, UAE is scalable and widely regarded for its environmental benefits, making it a key technology in sustainable extraction practices.

Walnut green husks, despite their bioactive potential, remain underexplored, particularly in terms of extracting both phenolic and lipid compounds. The aim of this study is to explore the different extraction techniques for obtaining phenolic and lipid compounds from walnut green husks. The phenolic yield, lipid yield, and cytotoxic activity of extracts from UAE and conventional solvent extraction methods are also compared. Notably, no prior research has simultaneously evaluated these aspects in walnut (Juglans regia L.) green husks, which highlights the novelty of this investigation. To address this gap, the study sought to (i) measure extraction yield, (ii) quantify total phenolic and lipid contents, and (iii) investigate cytotoxic effects on the normal and cancer cell lines.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Collection of plant materials

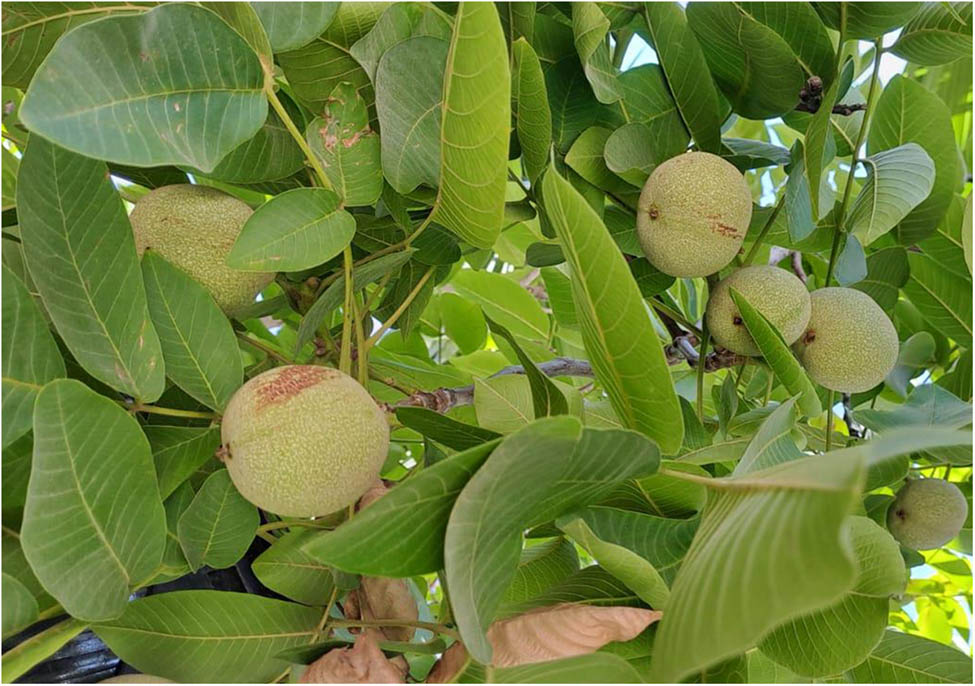

Harvesting of walnut (Juglans regia L.) (Figure 1) green husks was conducted in July 2024 in the Tabarbour region of Amman, Jordan. Following the harvest, the walnuts were thoroughly rinsed with distilled water to eliminate any contaminants. The fruits were then left to air-dry at a temperature of 25°C for a period of 3 weeks. After drying, the green husks were manually separated from the nuts (seeds) using a hammer. The separated green husks were subsequently processed using a stainless grinder (LC Multifunctional Grinder, China). The ground material was then sieved using a 1 mm mesh to ensure uniform particle size. The sieved plant material was stored in freezer until further use.

Image of Juglans regia Mill., showing the leaves and fruit of the plant grown in Jordan.

2.2 Oil extraction

2.2.1 Soxhlet extraction

Soxhlet extraction was performed on 5 g of powdered green husk for 8 h using n-hexane at 80°C. The solvent was removed at 45°C using a rotary evaporator (Heidolph, Schwabach, Germany). The extracted material was transferred to brown bottles and stored at –5°C until further analysis.

2.2.2 Ultrasonic extraction

Ultrasound extraction was conducted using 5 g of powdered green husk using an Ultrasonic Cleaner (Wisd, Daihan Scientific, Korea). The extraction was carried out using n-hexane at a constant temperature of 40°C with a total volume of 50 mL over a duration of 30 min. Post-extraction, the mixture was filtered, and the solvent was removed at 40°C under reduced pressure (Heidolph, Germany). The extracted material was transferred to brown bottles and stored at 4°C until further analysis.

2.3 Bligh and dyer extraction method

To extract lipids from 5 g of plant powder, 10 mL of chloroform and 20 mL of methanol were added to the sample, vortexed for 1 min, and sonicated for 10 min, then allowed to incubate for 30 min. After incubation, an additional 10 mL of chloroform and 10 mL of a 0.9% NaCl solution were introduced to the container. The mixture was vortexed for another minute, sonicated for an additional 10 min, and subsequently filtered. The lower chloroform layer, which contained the lipids, was carefully transferred to a new flask. This extraction process was repeated by adding another 10 mL of chloroform to the original container, followed by sonication and filtration, to ensure that any residual lipids were extracted. The combined chloroform phases were then evaporated to dryness for subsequent analysis.

2.4 Folch extraction method

In the Folch extraction method, 100 mL of chloroform was added to 5 g plant powder in an appropriate container. The mixture was subjected to vigorous sonication for 10 min, followed by incubation at room temperature for 1 h. After the incubation period, 50 mL of methanol and 80 mL of a 0.9% NaCl solution were introduced to the container. The mixture was sonicated again for an additional 10 min and then filtered. The lower chloroform phase, which contained the extracted lipids, was carefully transferred to a new container using a glass pipette. To achieve complete extraction, 50 mL of chloroform was added to the initial mixture in two separate steps, with each addition followed by sonication and centrifugation to isolate the lower lipid phase. The collected chloroform extracts were then evaporated until dry, and the resulting lipid residue was dried for further analysis [19].

2.5 Extraction of phenolic compounds

2.5.1 Maceration method

For the maceration method, 5 g dried powder of plant material was mixed with 50 mL of 70% ethanol in a media bottle. The mixture was kept on a rotary shaker for 10 min, and then left to steep at 25°C for 24 h. After the steeping period, the solution was filtered through muslin cloth, and the filtrate was evaporated under reduced pressure at 45°C. The extract was then stored at 4°C for further analysis.

2.5.2 Soxhlet extraction

Five grams of dried and finely powdered husk were subjected to Soxhlet extraction using 70% ethanol at 80°C. Following an 8 h extraction period, the resultant extract was collected and concentrated by solvent evaporation under reduced pressure at 45°C. The final concentrated extract was weighed and stored at −4°C for subsequent analyses.

2.5.3 Ultrasonic-assisted extraction (UAE)

Five grams of dried plant powder were placed in a 50 mL capped tube and mixed with 70% ethanol. The tube was then immersed in the water bath of the ultrasonic device and subjected to ultrasonic for 30 min. After completion of the ultrasonic extraction, the mixture was filtered using Whatman filter paper to remove the solid plant material. The resulting liquid extract was concentrated by evaporation at 40°C and stored at −4°C for subsequent analyses.

2.5.4 Reflux extraction

A total of 5 g dried plant powder was placed in a reflux apparatus and mixed with 30 mL of 70% ethanol. The mixture was heated to reflux at 80°C for 30 min, ensuring continuous boiling and stirring. After the extraction period, the mixture was cooled and filtered through Whatman paper. The ethanol extract was then concentrated at 40°C by evaporation and stored at −4°C for subsequent analyses.

2.6 Determination of total phenolic content (TPC)

The Folin–Ciocalteu (FC) colorimetric method was employed to quantify the total phenolic content in the extracts. In a 96-well microplate, 20 µL of FC reagent was added to 5 µL of the extract sample. The mixture was allowed to rest for 5 min, followed by the addition of 80 µL of 7.5% NaHCO3. After a 60 min incubation at room temperature, absorbance readings were taken at 765 nm. The same protocol was applied to prepare the gallic acid standard. A calibration curve was established with gallic acid solutions at concentrations ranging from 10 to 900 µg/mL. Phenolic content results were reported as gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per gram of sample [20].

2.7 Cytotoxicity assay

The human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line (HepG2) and normal human umbilical vein endothelial cell line (HUVEC) were procured from the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (DSMZ). Cells were grown in T-25 tissue culture flasks (NEST, China) using high-glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (Gibco, UK), enriched with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, UK) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Hiclone, UK). They were kept in a humidified incubator set to 37°C with 5% CO2 (Sanyo, Japan). Cell viability was evaluated by the MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay, with 5 × 104 cells seeded per well in 24-well plates. After achieving 70% confluency, cells were treated with a concentration gradient of the test substance (0–900 µg/mL) for 48 h. Following the incubation period, the medium was replaced with fresh DMEM, and the MTT assay was performed based on the protocol described by Abutaha et al. [21]. An MTT solution was added to each well and incubated for 2 h. Then, 0.01% acidified isopropanol was introduced, and absorbance was recorded at 570 nm using a microplate reader (ChromMate, USA). Cell viability was calculated as a percentage compared to the vehicle control (0.01% DMSO), and IC50 values were determined using OriginPro 8.5 software (OriginLab, USA) (Figure 2).

The cytotoxic effects of the Bligh and Dyer extract from walnut husk on different cell lines after 24 h, assessed using the MTT assay: HUVEC and HepG2 cell lines. Data are presented as the mean value ± SD from three independent experiments.

2.8 Fluorescent staining of cell nuclei

Cells were cultured in 24-well plates and treated as described previously [21]. The culture medium was aspirated, and cells were gently washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Subsequently, cells were fixed in ice-cold ethanol for 10 min and later stained with 4′,6-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining solution (1 µg/mL in PBS) and incubated for 5 min at 25°C. To remove any unbound DAPI, the cells were washed using PBS. The wells were examined using a fluorescence microscope, and images were taken to analyze nuclear morphology.

2.9 Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis for the identification of compounds

A 1 µL aliquot of the sample was injected into the system using an autosampler connected to a GC-MS 7890B system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The identification of the sample components was performed via GC-MS, utilizing integrated database software (NIST MS) for compound identification. Separation of the target compounds was achieved using a DB-5 MS capillary column (Agilent Technologies) with dimensions of 30 m in length, 0.25 mm internal diameter, and a phase thickness of 0.25 μm. Helium was employed as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1 mL/min, with the injector set to 250°C and a split ratio of 50:1. The oven temperature was programmed to increase from 50 to 250°C over a total analysis time of 71 min. The mass spectrometer operated with a mass scan range of 40–500 g/mol, a scan speed of 1.56 scans/s, a solvent delay of 4 min, and a source temperature of 230°C.

2.10 In silico assessment

Molecular docking was performed using CB-Dock 2 [22] to evaluate the interactions between specific ligands and various protein targets. The protein structures were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) and included VEGF (4AG8), EGFR (1M17), PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway (4JPS), PDGFR (5GRN), PD-1/PD-L1 (4ZQK), MAPK/ERK Pathway (4FK3), TGF-β (3TZM), c-MET (3DKF), Apoptosis Regulators (Bcl-2, 4MAN), DNA Repair Pathways (PARP, 4R6E), and CTNNB1 (1JDH). Each target was prepared by removing co-crystallized ligands and water molecules and adding missing residues. The ligands, 4-Isobenzofurancarboxylic acid, 1,3-dihydro-, and β-Sitosterol, were optimized for docking by obtaining their 3D structures from PubChem and converting them into SDF file formats. In CB-Dock 2, the protein and ligand files were uploaded, and potential binding sites were identified using the blind cavity detection feature. Docking simulations generated docking poses for each ligand-target combination. To validate the docking results, comparisons were made with a negative control (glycerol) and a known inhibitor (4-(4-(benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-5-(pyridin-2-yl)-1H-imidazol-2-yl)benzamide) for the protein showing the highest binding affinity.

The results were analyzed based on binding affinity scores and visualization of the best docking poses using molecular visualization tools such as PyMOL [23] and BIOVIA, Discovery Studio Visualizer [24].

3 Result

3.1 Extraction yield

Lipid extraction was performed using various methods to identify the most effective method for maximizing lipid yield. The different extraction methods showed varying levels of efficiency, as summarized in Table 1. The extraction efficiency for lipids can be ranked as follows: The Bligh and Dyer extraction method achieved the highest lipid yield at 3.4% dry weight, followed by Soxhlet extraction with n-hexane at 2.4%, the Folch extraction method at 2.3%, and sonication with n-hexane at 1.7%. The efficiency of phenolic extraction, based on yield, was ranked as follows: Sonication with 70% ethanol yielded the highest amount of phenolics at 18.8%, with Soxhlet extraction using 70% ethanol closely following at 17.7%. Reflux extraction with 70% ethanol showed the lowest yield, producing 15.5%.

Summarizing the extraction yield, TPC, and scavenging activity (IC50) for the different extraction methods

| No. | Extraction method | Yield (%) | TPC (mg GAE/g) | HepG2 IC50 in µg/mL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sonication with 70% ethanol | 18.8 | 0.05 ± 0.05 | >500 |

| 2 | Soxhlet extraction with 70% ethanol | 17.7 | 0.034 ± 0.03 | >500 |

| 3 | Reflux with 70% ethanol | 15.5 | 0.07 ± 0.05 | >500 |

| 4 | Maceration with 70% ethanol | 13.76 | 0.044 ± 0.01 | 277.3 |

| 5 | Bligh and Dyer extraction method | 3.4 | 0.036 ± 0.1 | 237.5 |

| 6 | Folch extraction method | 2.3 | 0.05 ± 0.05 | >500 |

| 7 | Soxhlet extraction with n-hexane | 2.4 | 0.027 ± 0.02 | >500 |

| 8 | Sonication with n-hexane | 1.7 | 0.023 ± 0.03 | >500 |

3.2 Total phenolic content

The TPC of the extracts was calculated using the regression equation from the calibration curve and expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per gram of dry sample (mg/g). The TPC values were as follows: reflux extraction yielded 0.07 ± 0.05 mg GAE/g, Folch extraction method 0.05 ± 0.05 mg GAE/g, ethanol sonication 0.05 ± 0.04 mg GAE/g, maceration 0.044 ± 0.01 mg GAE/g, Bligh and Dyer method 0.036 ± 0.1 mg GAE/g, ethanol Soxhlet extraction 0.034 ± 0.03 mg GAE/g, hexane sonication 0.027 ± 0.02 mg GAE/g, and hexane Soxhlet extraction 0.023 ± 0.03 mg GAE/g.

3.3 Effects of extracts on cell viability

To evaluate the impact of husk extracts on cancer cell viability, we used the liver cancer cell line (HepG2) and normal human cells (HUVECs). Cells were cultured in 24-well plates and treated with varying extract concentrations, ranging from 16.5 to 500 μg/mL. The MTT assay was employed to assess cell viability by measuring the conversion of MTT to a formazan product, which correlates with the metabolically active cells. As shown in Figure 3, both the 70% ethanol maceration and the Bligh and Dyer extraction methods exhibited a dose-dependent inhibitory effect on HepG2 cell growth when compared to untreated or DMSO-treated control groups. The IC50 values for 24 h treatment with 70% ethanol maceration and the Bligh and Dyer method were 277.3 and 237.5 μg/mL, respectively. Additionally, the Bligh and Dyer extraction method was tested on HUVEC cells, resulting in an IC50 value of 185.3 μg/mL.

Light microscopy, DAPI staining, and DCFH-DA staining images of HepG2 in control and plant extract-treated groups with 250 µg/mL for 24h. Light microscopy of the control group (a) shows healthy, polygonal-shaped cells with clear boundaries, while the treated group (b) displays cell shrinkage, rounding, and loss of adhesion, indicative of cytotoxic effects. DAPI staining reveals intact, round nuclei in the control group (c), contrasting with nuclear condensation, fragmentation, and irregular shapes in the treated cells (d), signaling apoptosis. DCFH-DA staining shows low fluorescence in the control group (e), reflecting normal oxidative status, whereas the treated group (f) exhibits increased fluorescence, indicating elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels and oxidative stress.

3.4 Light microscopy

Light microscopy images of HepG2 cells treated with Bligh and Dyer extract showed alterations in cell morphology compared to control. Treated cells exhibit signs of cytotoxicity, including cell shrinkage, loss of adherence, and rounding of the cell bodies and reduced cell density, further indicating apoptotic changes. In contrast, the control cells maintain intact cell membranes, and clear cell boundaries, reflecting normal, healthy morphology.

3.5 DAPI staining

DAPI staining of HepG2 cells treated with Bligh and Dyer extract reveals clear signs of nuclear damage compared to the control. In the control cells, the nuclei appear uniformly round and intact, with consistent, bright blue fluorescence, indicating healthy and viable cells. In contrast, the treated cells display nuclear condensation, fragmentation, and irregularly shaped nuclei, typical of apoptosis. Some cells show signs of nuclear shrinkage, while others exhibit chromatin disintegration. These changes in nuclear morphology confirm the cytotoxic and apoptotic effects of the Bligh and Dyer extract on HepG2 cells.

3.6 DCFH-DA staining

DCFH-DA staining of HepG2 cells treated with Bligh and Dyer extract shows a marked increase in fluorescence intensity compared to the control group. Control cells exhibit low fluorescence, indicating basal levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and normal oxidative stress. In contrast, cells treated with the extract display significantly elevated fluorescence, reflecting increased ROS production and oxidative stress. This rise in oxidative stress suggests that the extract induces oxidative damage in HepG2 cells, which may contribute to the observed cytotoxic and apoptotic effects.

3.7 GC-MS analysis

The analysis of the four walnut husk extracts obtained through various extraction methods – ultrasonic extraction, Folch extraction method, Bligh and Dyer extraction method, and Soxhlet extraction – revealed several uncommon compounds. These unique compounds contribute to the distinct chemical profiles of each extract, highlighting the potential for exploring their unique properties and applications. Understanding the significance of these uncommon compounds may enhance our knowledge of their bioactivity and therapeutic potential in various fields (Table 2).

Analysis of walnut husk extracts obtained through ultrasonic extraction method, Folch extraction method, Bligh and Dyer extraction method, and Soxhlet extraction method revealed several uncommon compounds unique to each extraction method

| Area% | Name | Molecular formula | Molecular weight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bligh and Dyer extraction method | |||

| 0.42 | Benzene, 1,3-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)- | C14H22 | 190 |

| 0.49 | Bicyclo[3.1.0]hexane-6-methanol, 2-hydroxy-1,4,4-trimethyl- | C10H18O2 | 170 |

| 7.03 | 5-Hydroxy-1-tetralone | C10H10O2 | 162 |

| 0.43 | Phenol, 2,5-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)- | C14H22O | 206 |

| 1.09 | (S,E)-4-Hydroxy-3,5,5-trimethyl-4-(3-oxobut-1-en-1-yl)cyclohex-2-enone | C13H18O3 | 222 |

| 0.27 | Propionic acid, 3-(3-methyl-5-oxo-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)- | C7H10N2O3 | 170 |

| 0.88 | 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid, methyl ester, (E,E)- | C19H34O2 | 294 |

| 2.50 | Humulane-1,6-dien-3-ol | C15H26O | 222 |

| 1.123 | 7-Hexadecenal, (Z)- | C16H30O | 238 |

| 1.380 | 6-epi-shyobunol | C15H26O | 222 |

| 5.66 | Carbonic acid, eicosyl vinyl ester | C23H44O3 | 368 |

| 4.43 | Heptacosane | C27H56 | 352 |

| Soxhlet extraction | |||

| 0.09 | 6-Tridecene, (Z)- | C13H26 | 182 |

| 0.14 | 2-Cyclopenten-1-one, 3-methyl-2-(2,4-pentadienyl)-, (Z)- | C11H14O | 162 |

| 0.12 | Hexanoic acid, pentadecyl ester | C21H42O2 | 326 |

| 2.89 | n-Tetracosanol-1 | C24H50O | 354 |

| 3.71 | Behenic alcohol | C22H46O | 326 |

| 0.07 | n-Nonadecanol-1 | C19H40O | 248 |

| 0.12 | 1-Decanol, 2-hexyl- | C16H34O | 242 |

| Folch extraction method | |||

| 0.37 | Juglone | C10H6O3 | 174 |

| 5.13 | 7-Hydroxy-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1(2H)-one | C10H10O2 | 162 |

| 0.24 | Cyclohexanone, 2,2-dimethyl-5-(3-methyloxiranyl)-, [2α(R*),3α]-(.+−.)- | C11H18O2 | 182 |

| 1.17 | Acetic acid, 2-(2-acetoxy-2,5,5,8a-tetramethyldecalin-1-yl)- | C18H30O₄ | 310 |

| 0.62 | 2-Butyl-5-methyl-3-(2-methylprop-2-enyl)cyclohexanone | C15H26O | 222 |

| 0.27 | Benzenebutanoic acid, 2-carboxy-γ-oxo- | C11H10O5 | 222 |

| 0.23 | Linoleic acid ethyl ester | C20H36O2 | 308 |

| 8.32 | Tetracosane | C24H50 | 338 |

| Ultrasonic extraction | |||

| 0.40 | Bicyclo[3.1.1]heptan-3-ol, 6,6-dimethyl-2-methylene-, [1S-(1α,3α,5α)]- | C10H16O | 152 |

| 0.22 | cis-Verbenol | C10H16O | 152 |

| 0.47 | (−)-Myrtenol | C10H16O | 152 |

| 0.75 | Caryophyllene oxide | C15H24O | 220 |

| 0.71 | Phenol, 2-ethoxy-4-(2-propenyl)- | C11H14O2 | 178 |

| 0.81 | 2H-Benzocyclohepten-2-one, 3,4,4a,5,6,7,8,9-octahydro-4a-methyl-, (S)- | C12H18O | 178 |

| 0.67 | 2(1H)-Naphthalenone, 4a,5,6,7,8,8a-hexahydro-4a,8a-dimethyl-, cis- | C12H18O | 178 |

| 0.72 | Undecanoic acid | C11H22O2 | 168 |

| 1.84 | Dodecanoic acid | C12H24O2 | 200 |

| 0.71 | Isophytol | C20H40O | 296 |

| 3.25 | (R)-(−)-(Z)-14-Methyl-8-hexadecen-1-ol | C17H34O | 254 |

| 0.69 | cis-9,10-Epoxyoctadecan-1-ol | C18H36O2 | 284 |

| 0.36 | E-6-Octadecen-1-ol acetate | C20H38O2 | 310 |

| 1.29 | Hydroxylamine, O-decyl- | C10H23NO | 173 |

| 1.04 | E-2-Tetradecen-1-ol | C14H28O | 212 |

| 10.38 | Octacosanal | C28H56O | 408 |

3.8 Molecular docking

The docking study results revealed significant differences in the binding affinities of various compounds across the tested protein targets. Humulane-1,6-dien-3-ol exhibited the strongest binding affinity, with a binding energy of −7.8 kcal/mol against proteins 3TZM, 4AG8, and 4FK3, indicating its potential as a potent ligand. Similarly, 5-hydroxy-1-tetralone showed strong binding across multiple targets, particularly with 3TZM (−8.0 kcal/mol) and 4AG8 (−7.0 kcal/mol). Phenol, 2,5-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-, also demonstrated notable interactions, achieving a binding energy of −7.8 kcal/mol against 4AG8, making it another candidate with strong affinity. In contrast, Bicyclo[3.1.0]hexane-6-methanol, 2-hydroxy-1,4,4-trimethyl- exhibited moderate binding across all proteins, with values ranging from −5.3 to −6.0 kcal/mol, while Propionic acid, 3-(3-methyl-5-oxo-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-, showed moderate binding with energy values of −5.5 to −5.9 kcal/mol across targets. The control compound, glycerol, had the weakest binding energies, ranging from −2.1 to −4.3 kcal/mol. These results highlight Humulane-1,6-dien-3-ol and 5-Hydroxy-1-tetralone as the most promising compounds for further study (Figure 4). However, the positive control exhibited a notably higher binding affinity of −11.8 kcal/mol, surpassing 5-hydroxy-1-tetralone by 3.5 kcal/mol. Meanwhile, the negative control displayed weaker binding interactions, further highlighting the relative efficacy of 5-hydroxy-1-tetralone.

![Figure 4

A Heatmap illustrates the binding affinity of Bicyclo[3.1.0]hexane-6-methanol, 2-hydroxy-1,4,4-trimethyl (1); 5-Hydroxy-1-tetralone (2); Phenol, 2,5-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)- (3); (S,E)-4-Hydroxy-3,5,5-trimethyl-4-(3-oxobut-1-en-1-yl)cyclohex-2-enone (4); Propionic acid, 3-(3-methyl-5-oxo-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)- (5); Humulane-1,6-dien-3-ol (6); and Glycerol (control) (7) (x-axis) against the nine targeted proteins including 1JDH, 1M17, 3DKF, 3TZM, 4ag8, 4fk3, 4jps, 4man, and 4r6e (y-axis). Lower image shows the molecular docking investigation revealing the 2D and 3D interaction diagrams of the 5-Hydroxy-1-tetralone with target protein 3TZM.](/document/doi/10.1515/chem-2025-0153/asset/graphic/j_chem-2025-0153_fig_004.jpg)

A Heatmap illustrates the binding affinity of Bicyclo[3.1.0]hexane-6-methanol, 2-hydroxy-1,4,4-trimethyl (1); 5-Hydroxy-1-tetralone (2); Phenol, 2,5-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)- (3); (S,E)-4-Hydroxy-3,5,5-trimethyl-4-(3-oxobut-1-en-1-yl)cyclohex-2-enone (4); Propionic acid, 3-(3-methyl-5-oxo-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)- (5); Humulane-1,6-dien-3-ol (6); and Glycerol (control) (7) (x-axis) against the nine targeted proteins including 1JDH, 1M17, 3DKF, 3TZM, 4ag8, 4fk3, 4jps, 4man, and 4r6e (y-axis). Lower image shows the molecular docking investigation revealing the 2D and 3D interaction diagrams of the 5-Hydroxy-1-tetralone with target protein 3TZM.

4 Discussion

Extraction employing various solvents and methods is commonly utilized for the isolation of compounds. The choice of solvent and extraction method significantly influences the properties of the extract. The unique structures and compositions of each matrix lead to specific and sometimes unpredictable interactions with different solvents [25].

While various analytical techniques are available for the extraction of specific lipid classes, the need for a universal extraction method is critical to get a complete lipid profile. This is particularly vital in untargeted lipidomic approaches, where maximizing lipid recovery ensures the detection and analysis of a broad spectrum of lipid species within a single solvent system. In contrast to targeted lipid analysis, untargeted profiling provides a more exhaustive overview, facilitating the discovery of novel lipids alongside the identification and comparative analysis of known lipid molecules. Achieving efficient total lipid extraction from biological samples is the foundational step in this process, influenced by factors such as lipid class, methodological reproducibility, operational simplicity, cost-effectiveness for high-throughput studies, sample recovery efficiency, and effective contaminant removal [26,27,28].

This investigation aimed to assess the best method for lipid extraction from walnut husk for untargeted lipid analysis by comparing four different extraction protocols. Despite these methods being widely applied to various tissue types, a comprehensive evaluation of their efficiency in extracting lipids from walnut husk had not been performed previously. The extraction methods were implemented as previously described, with minor modifications to protocols published by Folch et al. [19] and Bligh and Dyer [29]. Specifically, a sonication step was introduced during the extraction process to enhance the solvent’s ability to penetrate and dissolve lipids. In the original protocols, lipids were extracted directly from intact tissue without this additional step. Our approach involved grinding the plant material into a fine powder and then applying sonication, which improves extraction efficiency.

Based on our observations, different extraction methods yielded varying percentages and compositions of fatty acid classes in walnut husk. The variations in fatty acids (FAs) composition can be attributed to differences in solvent polarity, extraction efficiency, sample-solvent contact time, and physical disruption techniques. Each method exhibits varying selectivity for lipid types; for example, Soxhlet is more efficient for non-polar lipids, while Bligh and Dyer or Folch extracts a broader range of lipids due to their use of polar solvents. Additionally, factors such as ultrasound energy and heating can enhance lipid release, while temperature and extraction time influence the stability and yield of specific fatty acids. These elements lead to variations in both the percentage of common FAs and the presence of method-specific lipids in each extract.

The higher TPC observed with reflux extraction, compared to sonication or Soxhlet extraction, can be explained by several factors. One significant factor is extraction temperature, which influences solute solubility and diffusion. Elevated temperatures promote the breakdown of tissue matrices, allowing for greater compound diffusion into the solvent [25]. Reflux extraction involves heating the solvent, which enhances the extraction process by breaking plant cell walls and improving the solubility of compounds. Moreover, in reflux extraction, the solvent continuously circulates through the plant material, providing consistent and thorough extraction of phenolic compounds, unlike the intermittent solvent contact in sonication or Soxhlet methods.

Both maceration with 70% ethanol and the Bligh and Dyer extraction methods exhibited a dose-dependent inhibitory effect on HepG2 cell growth when compared to untreated or DMSO-treated control groups. This can be attributed to several factors. The maceration process, occurring at room temperature, minimizes the risk of thermal degradation of sensitive compounds, unlike methods involving heat. While maceration extraction is generally less efficient compared to advanced techniques like ultrasound-assisted extraction [30], these modern methods can sometimes impact the structural integrity and quality of extracted compounds [31]. Similarly, Jiang et al. [32] explored UAE, reflux extraction, and steam distillation for essential oils, finding variability in quantities and compositions yielded by each method. This variability underscores the significance of selecting the most suitable extraction method for specific compounds and activity.

The enhanced cytotoxic activity observed with the Bligh and Dyer extraction method is likely due to its capacity to extract a wide spectrum of compounds, including cytotoxic lipids such as phospholipids, sterols, and glycolipids, which are reported to induce cell death in different cancer cell types [33,34,35]. In contrast, ethanol-based maceration primarily isolates polar compounds like phenolics and flavonoids, which may exhibit cytotoxic effects but typically to a lesser extent compared to lipid-based compounds obtained through the Bligh and Dyer method.

It is important to note that neither extraction method involved heat treatment, preserving the integrity and bioactivity of heat-sensitive compounds. This likely contributed to the retention of the full cytotoxic potential of the extracted compounds in both methods. However, the Bligh and Dyer method’s ability to extract both hydrophilic and lipophilic compounds likely explains its superior cytotoxic effects compared to maceration, which focuses more on hydrophilic compounds. The Bligh and Dyer method utilizes a solvent system of chloroform and methanol in a 1:2 ratio with water, effectively separating lipids from proteins and other non-lipid components. This biphasic system ensures that most lipids are dissolved in the chloroform phase, leading to higher lipid recovery. Additionally, this method is compatible with a wide range of lipid classes, as the polar methanol breaks down cell membranes and solubilizes polar lipids, while the non-polar chloroform extracts non-polar lipids effectively.

Transforming Growth Factor Beta (TGF-β) is a pivotal cytokine in cancer biology, playing a dual role that makes it a significant target for anticancer therapies. In the early stages of tumor development, TGF-β acts as a tumor suppressor by inhibiting cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis in epithelial cells. However, in advanced stages, many tumors become resistant to its growth-inhibitory effects, and TGF-β promotes tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis by enhancing epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and modulating the tumor microenvironment. Molecular docking studies involving TGF-β are essential for identifying small molecules or compounds that can effectively inhibit its signaling pathways, potentially reverting its pro-tumorigenic effects and restoring its tumor suppressor functions. Targeting TGF-β in combination with other therapies may enhance overall efficacy, making molecular docking a valuable tool in developing novel therapeutics that manipulate TGF-β signaling [36,37,38,39].

In the present study, docking results for 3TZM, a structural representation of TGF-β, revealed that certain small molecules exhibited significant binding affinities to the receptor’s active site. Notably, 5-hydroxy-1-tetralone demonstrated a binding affinity of −8 kcal/mol, suggesting a potential inhibitory effect on TGF-β signaling through hydrophobic contacts and hydrogen bonds. A conventional hydrogen bond was observed with PHE A:396, while hydrophobic interactions included alkyl interactions with VAL A:383, ARG A:332, ALA A:399, and ALA A:403. Additionally, pi-alkyl interactions were noted with ARG A:332 and ALA A:399, highlighting key residues contributing to the binding affinity. Given TGF-β’s critical role in tumor progression, these findings underscore the potential of these compounds as effective inhibitors. By downregulating TGF-β activity, they could reduce cancer cell proliferation and enhance sensitivity to therapies, positioning them as promising candidates for anticancer drug development. Future in vitro and in vivo studies will be vital to validate their effects on TGF-β signaling and therapeutic potential against various cancers.

The analysis of the four walnut husk extracts obtained through various extraction methods ultrasonic extraction, Folch extraction method, Bligh and Dyer extraction method, and Soxhlet extraction – revealed several uncommon compounds. These unique compounds contribute to the distinct chemical profiles of each extract, highlighting the potential for exploring their unique properties and applications. Understanding the significance of these uncommon compounds may enhance our knowledge of their bioactivity and therapeutic potential in various fields.

5 Conclusion

This study identified the Bligh and Dyer and 70% ethanol maceration methods as the most effective extraction techniques for obtaining bioactive compounds from walnut husk. These extracts showed significant cytotoxic effects on HepG2 liver cancer cells, inducing apoptosis and oxidative stress, as confirmed by morphological changes and elevated ROS levels. GC-MS analysis revealed unique compounds, with molecular docking highlighting Humulane-1,6-dien-3-ol, 5-hydroxy-1-tetralone, and Phenol, 2,5-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)- as promising candidates for further study. This research underscores the potential therapeutic value of walnut husk extracts, particularly in anticancer applications.

Acknowledgments

Ongoing Research Funding program - Research Chairs (ORF-RC-2025-0903), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Funding information: This work was supported by the Ongoing Research Funding Program - Research Chairs (ORF-RC-2025-0903), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Author contributions: N.A. conceived the study, conducted the experiments, and wrote the manuscript; F.A.A. supervised the research and edited the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

-

Ethical approval: No ethical approval was required for this study.

References

[1] Kumar K, Yadav AN, Kumar V, Vyas P, Dhaliwal HS. Food waste: A potential bioresource for extraction of nutraceuticals and bioactive compounds. Bioresour Bioprocess. 2017;4:1–14.10.1186/s40643-017-0148-6Search in Google Scholar

[2] Hadidi M, Aghababaei F, Gonzalez-Serrano DJ, Goksen G, Trif M, McClements DJ, et al. Plant-based proteins from agro-industrial waste and by-products: Towards a more circular economy. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;261:129576.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.129576Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Ezejiofor TIN, Enebaku UE, Ogueke C. Waste to wealth-value recovery from agro-food processing wastes using biotechnology: A review. Br Biotechnol J. 2014;4(4):418–81.10.9734/BBJ/2014/7017Search in Google Scholar

[4] Pal P, Singh AK, Srivastava RK, Rathore SS, Sahoo UK, Subudhi S, et al. Circular bioeconomy in action: Transforming food wastes into renewable food resources. Foods. 2024;13(18):3007.10.3390/foods13183007Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Schieber A, Stintzing FC, Carle R. By-products of plant food processing as a source of functional compounds—recent developments. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2001;12(11):401–13.10.1016/S0924-2244(02)00012-2Search in Google Scholar

[6] Gharibi S, Matkowski A, Sarfaraz D, Mirhendi H, Fakhim H, Szumny A, et al. Identification of polyphenolic compounds responsible for antioxidant, anti-Candida activities and nutritional properties in different pistachio (Pistacia vera L.) hull cultivars. Molecules. 2023;28(12):4772.10.3390/molecules28124772Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Hussain SZ, Naseer B, Qadri T, Fatima T, Bhat TA. Walnut (Juglans regia) – morphology, taxonomy, composition and health benefits. In Fruits grown in highland regions of the Himalayas: nutritional and health benefits. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2021. p. 269–81.10.1007/978-3-030-75502-7_21Search in Google Scholar

[8] Kutlu G. Valorization of various nut residues grown in Turkiye: antioxidant, anticholinesterase, antidiabetic, and cytotoxic activities. Food Sci Nutr. 2024;12(6):4362–71.10.1002/fsn3.4103Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Jahanban-Esfahlan A, Ostadrahimi A, Tabibiazar M, Amarowicz R. A comprehensive review on the chemical constituents and functional uses of walnut (Juglans spp.) husk. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(16):3920.10.3390/ijms20163920Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Vieira V, Pereira C, Pires TC, Calhelha RC, Alves MJ, Ferreira O, et al. Phenolic profile, antioxidant and antibacterial properties of Juglans regia L. (walnut) leaves from the northeast of Portugal. Ind Crop Prod. 2019;134:347–55.10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.04.020Search in Google Scholar

[11] Madhavi D, Deshpande S, Salunkhe D. Food antioxidants: Technological, toxicological, health perspective. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1996.10.1201/9781482273175Search in Google Scholar

[12] Balasundram N, Sundram K, Samman S. Phenolic compounds in plants and agri-industrial by-products: antioxidant activity, occurrence, and potential uses. Food Chem. 2006;99(1):191–203.10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.07.042Search in Google Scholar

[13] Fernández-Agulló A, Pereira E, Freire MS, Valentão P, Andrade PB, González-Álvarez J, et al. Influence of solvent on the antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of walnut (Juglans regia L.) green husk extracts. Ind Crop Prod. 2013;42:126–32.10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.05.021Search in Google Scholar

[14] Albin M, Johanson G, Hogstedt C. Successful prevention of organic solvent induced disorders: History and lessons. Scand J Work Env Health. 2024;50(3):135.10.5271/sjweh.4155Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Tiwari BK. Ultrasound: A clean, green extraction technology. TrAC Trends Anal Chem. 2015;71:100–9.10.1016/j.trac.2015.04.013Search in Google Scholar

[16] Pogorzelska-Nowicka E, Hanula M, Pogorzelski G. Extraction of polyphenols and essential oils from herbs with green extraction methods – an insightful review. Food Chem. 2024;460:140456.10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.140456Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Herrero M. Towards green extraction of bioactive natural compounds. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2024;416(9):2039–47.10.1007/s00216-023-04969-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Teslić N, Pojić M, Stupar A, Mandić A, Mišan A, Pavlić B. PhInd database – polyphenol content in agri-food by-products and trends in extraction technologies: A critical review. Food Chem. 2024;458:140474.10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.140474Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Folch J, Lees M, Stanley GS. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957;226(1):497–509.10.1016/S0021-9258(18)64849-5Search in Google Scholar

[20] Al-Zharani M, Abutaha N. Phytochemical screening and GC-MS chemical profiling of an innovative anti-cancer herbal formula (PHF6). J King Saud Univ Sci. 2023;35(2):102525.10.1016/j.jksus.2022.102525Search in Google Scholar

[21] Abutaha N, Alghamdi R, Alshahrani O, Al-Wadaan M. Heliotropium curassavicum extract: potential therapeutic agent for liver cancer through cytotoxicity, apoptosis, and molecular docking analysis. Arab J Chem. 2024;17(10):105986.10.1016/j.arabjc.2024.105986Search in Google Scholar

[22] Liu Y, Yang X, Gan J, Chen S, Xiao ZX, Cao Y. CB-Dock2: Improved protein–ligand blind docking by integrating cavity detection, docking and homologous template fitting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50(W1):W159–64.10.1093/nar/gkac394Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Schrödinger L The PyMOL molecular graphics system. https://pymol.org/; 2015. Version 2.0.Search in Google Scholar

[24] BIOVIA. Discovery studio visualizer, Version 21.1.0. Dassault Systèmes, San Diego; 2021.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Al-Farsi MA, Lee CY. Optimization of phenolics and dietary fibre extraction from date seeds. Food Chem. 2008;108(3):977–85.10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.12.009Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Yu D, Rupasinghe TW, Boughton BA, Natera SH, Hill CB, Tarazona P, et al. A high-resolution HPLC-QqTOF platform using parallel reaction monitoring for in-depth lipid discovery and rapid profiling. Anal Chim Acta. 2018;1026:87–100.10.1016/j.aca.2018.03.062Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Cajka T, Fiehn O. Comprehensive analysis of lipids in biological systems by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. TrAC Trends Anal Chem. 2014;61:192–206.10.1016/j.trac.2014.04.017Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Pilecky M, Kainz MJ, Wassenaar LI. Evaluation of lipid extraction methods for fatty acid quantification and compound-specific δ13C and δ2Hn analyses. Anal Biochem. 2024;687:115455.10.1016/j.ab.2023.115455Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37(8):911–7.10.1139/o59-099Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Shang YF, Chen SX, Miao JH, Zhang YG, Cai HZ, Bu XY, et al. Autoclaving hyphenated with reflux extraction for gaining bioactive components from Chaenomeles fruits. Sep Sci Technol. 2021;56(7):1225–30.10.1080/01496395.2020.1774608Search in Google Scholar

[31] Zhang M, Zeng G, Pan Y, Qi N. Difference research of pectins extracted from tobacco waste by heat reflux extraction and microwave-assisted extraction. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2018;15:359–63.10.1016/j.bcab.2018.06.022Search in Google Scholar

[32] Jiang MH, Yang L, Zhu L, Piao JH, Jiang JG. Comparative GC/MS analysis of essential oils extracted by three methods from the bud of Citrus aurantium L. var. amara Engl. J Food Sci. 2011;76(9):C1219–25.10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02421.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Castejón N, Marko D. Fatty acid composition and cytotoxic activity of lipid extracts from Nannochloropsis gaditana produced by green technologies. Molecules. 2022;27(12):3710.10.3390/molecules27123710Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Mutee AF, Salhimi SM, Ghazali FC, Aisha AF, Lim CP, Ibrahim K, et al. Evaluation of anti-cancer activity of Acanthaster planci extracts obtained by different methods of extraction. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2012;25(4):697–703.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Ibrahim EA, Abo-elfadl M, Abd El Baky H, Murad S. Chemical and biological characterization of lipid profile from Hydroclathrus clathratus. Egypt J Chem. 2021;64(10):5477–84.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Baba AB, Rah B, Bhat GR, Mushtaq I, Parveen S, Hassan R, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) signaling in cancer – a betrayal within. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:791272.10.3389/fphar.2022.791272Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Moustakas A, Pardali K, Gaal A, Heldin CH. Mechanisms of TGF-β signaling in regulation of cell growth and differentiation. Immunol Lett. 2002;82(1–2):85–91.10.1016/S0165-2478(02)00023-8Search in Google Scholar

[38] Massagué J. TGFβ in cancer. Cell. 2008;134(2):215–30.10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Giampieri S, Sahai E. Activation of TGF-beta signalling in breast cancer metastatic cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10(Suppl 2):O5.10.1186/bcr1880Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Phytochemical investigation and evaluation of antioxidant and antidiabetic activities in aqueous extracts of Cedrus atlantica

- Influence of B4C addition on the tribological properties of bronze matrix brake pad materials

- Discovery of the bacterial HslV protease activators as lead molecules with novel mode of action

- Characterization of volatile flavor compounds of cigar with different aging conditions by headspace–gas chromatography–ion mobility spectrometry

- Effective remediation of organic pollutant using Musa acuminata peel extract-assisted iron oxide nanoparticles

- Analysis and health risk assessment of toxic elements in traditional herbal tea infusions

- Cadmium exposure in marine crabs from Jiaxing City, China: Insights into health risk assessment

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles of Cinnamomum zeylanicum and their biological activities

- Tetraclinis articulata (Vahl) Mast., Mentha pulegium L., and Thymus zygis L. essential oils: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antifungal properties against postharvest fungal diseases of apple, and in vitro, in vivo, and in silico investigation

- Exploration of plant alkaloids as potential inhibitors of HIV–CD4 binding: Insight into comprehensive in silico approaches

- Recovery of phenylethyl alcohol from aqueous solution by batch adsorption

- Electrochemical approach for monitoring the catalytic action of immobilized catalase

- Green synthesis of ZIF-8 for selective adsorption of dyes in water purification

- Optimization of the conditions for the preparation of povidone iodine using the response surface methodology

- A case study on the influence of soil amendment on ginger oil’s physicochemical properties, mineral contents, microbial load, and HPLC determination of its vitamin level

- Removal of antiviral favipiravir from wastewater using biochar produced from hazelnut shells

- Effect of biochar and soil amendment on bacterial community composition in the root soil and fruit of tomato under greenhouse conditions

- Bioremediation of malachite green dye using Sargassum wightii seaweed and its biological and physicochemical characterization

- Evaluation of natural compounds as folate biosynthesis inhibitors in Mycobacterium leprae using docking, ADMET analysis, and molecular dynamics simulation

- Novel insecticidal properties of bioactive zoochemicals extracted from sea urchin Salmacis virgulata

- Elevational gradients shape total phenolic content and bioactive potential of sweet marjoram (Origanum majorana L.): A comparative study across altitudinal zones

- Study on the CO2 absorption performance of deep eutectic solvents formed by superbase DBN and weak acid diethylene glycol

- Preparation and wastewater treatment performance of zeolite-modified ecological concrete

- Multifunctional chitosan nanoparticles: Zn2+ adsorption, antimicrobial activity, and promotion of aquatic health

- Comparative analysis of nutritional composition and bioactive properties of Chlorella vulgaris and Arthrospira platensis: Implications for functional foods and dietary supplements

- Growth kinetics and mechanical characterization of boride layers formed on Ti6Al4V

- Enhancement of water absorption properties of potassium polyacrylate-based hydrogels in CaCl2-rich soils using potassium di- and tri-carboxylate salts

- Electrochemical and microbiological effects of dumpsite leachates on soil and air quality

- Modeling benzene physicochemical properties using Zagreb upsilon indices

- Characterization and ecological risk assessment of toxic metals in mangrove sediments near Langen Village in Tieshan Bay of Beibu Gulf, China

- Protective effect of Helicteres isora, an efficient candidate on hepatorenal toxicity and management of diabetes in animal models

- Valorization of Juglans regia L. (Walnut) green husk from Jordan: Analysis of fatty acids, phenolics, antioxidant, and cytotoxic activities

- Molecular docking and dynamics simulations of bioactive terpenes from Catharanthus roseus essential oil targeting breast cancer

- Selection of a dam site by using AHP and VIKOR: The Sakarya Basin

- Characterization and modeling of kidney bean shell biochar as adsorbent for caffeine removal from aquatic environments

- The effects of short-term and long-term 2100 MHz radiofrequency radiation on adult rat auditory brainstem response

- Biochemical insights into the anthelmintic and anti-inflammatory potential of sea cucumber extract: In vitro and in silico approaches

- Resveratrol-derived MDM2 inhibitors: Synthesis, characterization, and biological evaluation against MDM2 and HCT-116 cells

- Phytochemical constituents, in vitro antibacterial activity, and computational studies of Sudanese Musa acuminate Colla fruit peel hydro-ethanol extract

- Chemical composition of essential oils reviewed from the height of Cajuput (Melaleuca leucadendron) plantations in Buru Island and Seram Island, Maluku, Indonesia

- Phytochemical analysis and antioxidant activity of Azadirachta indica A. Juss from the Republic of Chad: in vitro and in silico studies

- Stability studies of titanium–carboxylate complexes: A multi-method computational approach

- Efficient adsorption performance of an alginate-based dental material for uranium(vi) removal

- Synthesis and characterization of the Co(ii), Ni(ii), and Cu(ii) complexes with a 1,2,4-triazine derivative ligand

- Evaluation of the impact of music on antioxidant mechanisms and survival in salt-stressed goldfish

- Optimization and validation of UPLC method for dapagliflozin and candesartan cilexetil in an on-demand formulation: Analytical quality by design approach

- Biomass-based cellulose hydroxyapatite nanocomposites for the efficient sequestration of dyes: Kinetics, response surface methodology optimization, and reusability

- Multifunctional nitrogen and boron co-doped carbon dots: A fluorescent probe for Hg2+ and biothiol detection with bioimaging and antifungal applications

- Separation of sulphonamides on a C12-diol mixed-mode HPLC column and investigation of their retention mechanism

- Characterization and antioxidant activity of pectin from lemon peels

- Fast PFAS determination in honey by direct probe electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry: A health risk assessment insight

- Correlation study between GC–MS analysis of cigarette aroma compounds and sensory evaluation

- Synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular docking studies of substituted chromone-2-carboxamide derivatives as anti-breast cancer agents

- The influence of feed space velocity and pressure on the cold flow properties of diesel fuel

- Acid etching behavior and mechanism in acid solution of iron components in basalt fibers

- Protective effect of green synthesized nanoceria on retinal oxidative stress and inflammation in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat

- Evaluation of the antianxiety activity of green zinc nanoparticles mediated by Boswellia thurifera in albino mice by following the plus maze and light and dark exploration tests

- Yeast as an efficient and eco-friendly bifunctional porogen for biomass-derived nitrogen-doped carbon catalysts in the oxygen reduction reaction

- Novel descriptors for the prediction of molecular properties

- Synthesis and characterization of surfactants derived from phenolphthalein: In vivo and in silico studies of their antihyperlipidemic effect

- Turmeric oil-fortified nutraceutical-SNEDDS: An approach to boost therapeutic effectiveness of dapagliflozin during treatment of diabetic patients

- Analysis and study on volatile flavor compounds of three Yunnan cultivated cigars based on headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry

- Near-infrared IR780 dye-loaded poloxamer 407 micelles: Preparation and in vitro assessment of anticancer activity

- Study on the influence of the viscosity reducer solution on percolation capacity of thin oil in ultra-low permeability reservoir

- Detection method of Aristolochic acid I based on magnetic carrier Fe3O4 and gold nanoclusters

- Juglone’s apoptotic impact against eimeriosis-induced infection: a bioinformatics, in-silico, and in vivo approach

- Potential anticancer agents from genus Aerva based on tubulin targets: an in-silico integration of quantitative structure activity relationship (QSAR), molecular docking, simulation, drug-likeness, and density functional theory (DFT) analysis

- Hepatoprotective and PXR-modulating effects of Erodium guttatum extract in propiconazole-induced toxicity

- Studies on chemical composition of medicinal plants collected in natural locations in Ecuador

- A study of different pre-treatment methods for cigarettes and their aroma differences

- Cytotoxicity and molecular mechanisms of quercetin, gallic acid, and pinocembrin in Caco-2 cells: insights from cell viability assays, network pharmacology, and molecular docking

- Choline-based deep eutectic solvents for green extraction of oil from sour cherry seeds

- Green-synthesis of chromium (III) nanoparticles using garden fern and evaluation of its antibacterial and anticholinesterase activities

- Innovative functional mayonnaise formulations with watermelon seeds oil: evaluation of quality parameters and storage stability

- Molecular insights and biological evaluation of compounds isolated from Ferula oopoda against diabetes, advanced glycation end products and inflammation in diabetics

- Removal of cytotoxic tamoxifen from aqueous solutions using a geopolymer-based nepheline–cordierite adsorbent

- Unravelling the therapeutic effect of naturally occurring Bauhinia flavonoids against breast cancer: an integrated computational approach

- Characterization of organic arsenic residues in livestock and poultry meat and offal and consumption risks

- Synthesis and characterization of zinc sulfide nanoparticles and their genotoxic and cytotoxic effects on acute myeloid leukemia cells

- Activity of Coriandrum sativum methanolic leaf extracts against Eimeria papillata: a combined in vitro and in silico approach

- Special Issue on Advancing Sustainable Chemistry for a Greener Future

- One-pot fabrication of highly porous morphology of ferric oxide-ferric oxychloride/poly-O-chloroaniline nanocomposite seeded on poly-1H pyrrole: Photocathode for green hydrogen generation from natural and artificial seawater

- High-efficiency photocathode for green hydrogen generation from sanitation water using bismuthyl chloride/poly-o-chlorobenzeneamine nanocomposite

- Innovative synthesis of cobalt-based catalysts using ionic liquids and deep eutectic solvents: A minireview on electrocatalytic water splitting

- Special Issue on Phytochemicals, Biological and Toxicological Analysis of Plants

- Comparative analysis of fruit quality parameters and volatile compounds in commercially grown citrus cultivars

- Total phenolic, flavonoid, flavonol, and tannin contents as well as antioxidant and antiparasitic activities of aqueous methanol extract of Alhagi graecorum plant used in traditional medicine: Collected in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- Study on the pharmacological effects and active compounds of Apocynum venetum L.

- Chemical profile of Senna italica and Senna velutina seed and their pharmacological properties

- Essential oils from Brazilian plants: A literature analysis of anti-inflammatory and antimalarial properties and in silico validation

- Toxicological effects of green tea catechin extract on rat liver: Delineating safe and harmful doses

- Unlocking the potential of Trigonella foenum-graecum L. plant leaf extracts against diabetes-associated hypertension: A proof of concept by in silico studies

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Phytochemical investigation and evaluation of antioxidant and antidiabetic activities in aqueous extracts of Cedrus atlantica

- Influence of B4C addition on the tribological properties of bronze matrix brake pad materials

- Discovery of the bacterial HslV protease activators as lead molecules with novel mode of action

- Characterization of volatile flavor compounds of cigar with different aging conditions by headspace–gas chromatography–ion mobility spectrometry

- Effective remediation of organic pollutant using Musa acuminata peel extract-assisted iron oxide nanoparticles

- Analysis and health risk assessment of toxic elements in traditional herbal tea infusions

- Cadmium exposure in marine crabs from Jiaxing City, China: Insights into health risk assessment

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles of Cinnamomum zeylanicum and their biological activities

- Tetraclinis articulata (Vahl) Mast., Mentha pulegium L., and Thymus zygis L. essential oils: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antifungal properties against postharvest fungal diseases of apple, and in vitro, in vivo, and in silico investigation

- Exploration of plant alkaloids as potential inhibitors of HIV–CD4 binding: Insight into comprehensive in silico approaches

- Recovery of phenylethyl alcohol from aqueous solution by batch adsorption

- Electrochemical approach for monitoring the catalytic action of immobilized catalase

- Green synthesis of ZIF-8 for selective adsorption of dyes in water purification

- Optimization of the conditions for the preparation of povidone iodine using the response surface methodology

- A case study on the influence of soil amendment on ginger oil’s physicochemical properties, mineral contents, microbial load, and HPLC determination of its vitamin level

- Removal of antiviral favipiravir from wastewater using biochar produced from hazelnut shells

- Effect of biochar and soil amendment on bacterial community composition in the root soil and fruit of tomato under greenhouse conditions

- Bioremediation of malachite green dye using Sargassum wightii seaweed and its biological and physicochemical characterization

- Evaluation of natural compounds as folate biosynthesis inhibitors in Mycobacterium leprae using docking, ADMET analysis, and molecular dynamics simulation

- Novel insecticidal properties of bioactive zoochemicals extracted from sea urchin Salmacis virgulata

- Elevational gradients shape total phenolic content and bioactive potential of sweet marjoram (Origanum majorana L.): A comparative study across altitudinal zones

- Study on the CO2 absorption performance of deep eutectic solvents formed by superbase DBN and weak acid diethylene glycol

- Preparation and wastewater treatment performance of zeolite-modified ecological concrete

- Multifunctional chitosan nanoparticles: Zn2+ adsorption, antimicrobial activity, and promotion of aquatic health

- Comparative analysis of nutritional composition and bioactive properties of Chlorella vulgaris and Arthrospira platensis: Implications for functional foods and dietary supplements

- Growth kinetics and mechanical characterization of boride layers formed on Ti6Al4V

- Enhancement of water absorption properties of potassium polyacrylate-based hydrogels in CaCl2-rich soils using potassium di- and tri-carboxylate salts

- Electrochemical and microbiological effects of dumpsite leachates on soil and air quality

- Modeling benzene physicochemical properties using Zagreb upsilon indices

- Characterization and ecological risk assessment of toxic metals in mangrove sediments near Langen Village in Tieshan Bay of Beibu Gulf, China

- Protective effect of Helicteres isora, an efficient candidate on hepatorenal toxicity and management of diabetes in animal models

- Valorization of Juglans regia L. (Walnut) green husk from Jordan: Analysis of fatty acids, phenolics, antioxidant, and cytotoxic activities

- Molecular docking and dynamics simulations of bioactive terpenes from Catharanthus roseus essential oil targeting breast cancer

- Selection of a dam site by using AHP and VIKOR: The Sakarya Basin

- Characterization and modeling of kidney bean shell biochar as adsorbent for caffeine removal from aquatic environments

- The effects of short-term and long-term 2100 MHz radiofrequency radiation on adult rat auditory brainstem response

- Biochemical insights into the anthelmintic and anti-inflammatory potential of sea cucumber extract: In vitro and in silico approaches

- Resveratrol-derived MDM2 inhibitors: Synthesis, characterization, and biological evaluation against MDM2 and HCT-116 cells

- Phytochemical constituents, in vitro antibacterial activity, and computational studies of Sudanese Musa acuminate Colla fruit peel hydro-ethanol extract

- Chemical composition of essential oils reviewed from the height of Cajuput (Melaleuca leucadendron) plantations in Buru Island and Seram Island, Maluku, Indonesia

- Phytochemical analysis and antioxidant activity of Azadirachta indica A. Juss from the Republic of Chad: in vitro and in silico studies

- Stability studies of titanium–carboxylate complexes: A multi-method computational approach

- Efficient adsorption performance of an alginate-based dental material for uranium(vi) removal

- Synthesis and characterization of the Co(ii), Ni(ii), and Cu(ii) complexes with a 1,2,4-triazine derivative ligand

- Evaluation of the impact of music on antioxidant mechanisms and survival in salt-stressed goldfish

- Optimization and validation of UPLC method for dapagliflozin and candesartan cilexetil in an on-demand formulation: Analytical quality by design approach

- Biomass-based cellulose hydroxyapatite nanocomposites for the efficient sequestration of dyes: Kinetics, response surface methodology optimization, and reusability

- Multifunctional nitrogen and boron co-doped carbon dots: A fluorescent probe for Hg2+ and biothiol detection with bioimaging and antifungal applications

- Separation of sulphonamides on a C12-diol mixed-mode HPLC column and investigation of their retention mechanism

- Characterization and antioxidant activity of pectin from lemon peels

- Fast PFAS determination in honey by direct probe electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry: A health risk assessment insight

- Correlation study between GC–MS analysis of cigarette aroma compounds and sensory evaluation

- Synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular docking studies of substituted chromone-2-carboxamide derivatives as anti-breast cancer agents

- The influence of feed space velocity and pressure on the cold flow properties of diesel fuel

- Acid etching behavior and mechanism in acid solution of iron components in basalt fibers

- Protective effect of green synthesized nanoceria on retinal oxidative stress and inflammation in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat

- Evaluation of the antianxiety activity of green zinc nanoparticles mediated by Boswellia thurifera in albino mice by following the plus maze and light and dark exploration tests

- Yeast as an efficient and eco-friendly bifunctional porogen for biomass-derived nitrogen-doped carbon catalysts in the oxygen reduction reaction

- Novel descriptors for the prediction of molecular properties

- Synthesis and characterization of surfactants derived from phenolphthalein: In vivo and in silico studies of their antihyperlipidemic effect

- Turmeric oil-fortified nutraceutical-SNEDDS: An approach to boost therapeutic effectiveness of dapagliflozin during treatment of diabetic patients

- Analysis and study on volatile flavor compounds of three Yunnan cultivated cigars based on headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry

- Near-infrared IR780 dye-loaded poloxamer 407 micelles: Preparation and in vitro assessment of anticancer activity

- Study on the influence of the viscosity reducer solution on percolation capacity of thin oil in ultra-low permeability reservoir

- Detection method of Aristolochic acid I based on magnetic carrier Fe3O4 and gold nanoclusters

- Juglone’s apoptotic impact against eimeriosis-induced infection: a bioinformatics, in-silico, and in vivo approach

- Potential anticancer agents from genus Aerva based on tubulin targets: an in-silico integration of quantitative structure activity relationship (QSAR), molecular docking, simulation, drug-likeness, and density functional theory (DFT) analysis

- Hepatoprotective and PXR-modulating effects of Erodium guttatum extract in propiconazole-induced toxicity

- Studies on chemical composition of medicinal plants collected in natural locations in Ecuador

- A study of different pre-treatment methods for cigarettes and their aroma differences

- Cytotoxicity and molecular mechanisms of quercetin, gallic acid, and pinocembrin in Caco-2 cells: insights from cell viability assays, network pharmacology, and molecular docking

- Choline-based deep eutectic solvents for green extraction of oil from sour cherry seeds

- Green-synthesis of chromium (III) nanoparticles using garden fern and evaluation of its antibacterial and anticholinesterase activities

- Innovative functional mayonnaise formulations with watermelon seeds oil: evaluation of quality parameters and storage stability

- Molecular insights and biological evaluation of compounds isolated from Ferula oopoda against diabetes, advanced glycation end products and inflammation in diabetics

- Removal of cytotoxic tamoxifen from aqueous solutions using a geopolymer-based nepheline–cordierite adsorbent

- Unravelling the therapeutic effect of naturally occurring Bauhinia flavonoids against breast cancer: an integrated computational approach

- Characterization of organic arsenic residues in livestock and poultry meat and offal and consumption risks

- Synthesis and characterization of zinc sulfide nanoparticles and their genotoxic and cytotoxic effects on acute myeloid leukemia cells

- Activity of Coriandrum sativum methanolic leaf extracts against Eimeria papillata: a combined in vitro and in silico approach

- Special Issue on Advancing Sustainable Chemistry for a Greener Future

- One-pot fabrication of highly porous morphology of ferric oxide-ferric oxychloride/poly-O-chloroaniline nanocomposite seeded on poly-1H pyrrole: Photocathode for green hydrogen generation from natural and artificial seawater

- High-efficiency photocathode for green hydrogen generation from sanitation water using bismuthyl chloride/poly-o-chlorobenzeneamine nanocomposite

- Innovative synthesis of cobalt-based catalysts using ionic liquids and deep eutectic solvents: A minireview on electrocatalytic water splitting

- Special Issue on Phytochemicals, Biological and Toxicological Analysis of Plants

- Comparative analysis of fruit quality parameters and volatile compounds in commercially grown citrus cultivars

- Total phenolic, flavonoid, flavonol, and tannin contents as well as antioxidant and antiparasitic activities of aqueous methanol extract of Alhagi graecorum plant used in traditional medicine: Collected in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- Study on the pharmacological effects and active compounds of Apocynum venetum L.

- Chemical profile of Senna italica and Senna velutina seed and their pharmacological properties

- Essential oils from Brazilian plants: A literature analysis of anti-inflammatory and antimalarial properties and in silico validation

- Toxicological effects of green tea catechin extract on rat liver: Delineating safe and harmful doses

- Unlocking the potential of Trigonella foenum-graecum L. plant leaf extracts against diabetes-associated hypertension: A proof of concept by in silico studies