Abstract

In last years, a plethora of extraction techniques has emerged as environmentally friendly alternatives to conventional extraction procedures. In this particular field, a novel class of solvents known as deep eutectic solvents (DES) has arisen as a new and very promising tool. For the extraction of oil from sour cherry seed, six types of these solvents were synthesized, with choline chloride as the hydrogen bond acceptor in combination with different hydrogen bond donors (alcohols, organic acids, glucose and urea). The experimental results proved that the use of ChCl:EG = 1:2 as co-solvent with n-hexane assisted by ultrasound under optimum conditions produced the highest yield of 16.15 % compared to pure n-hexane, which produced only 13.86 %. The fatty acid composition analysis revealed that linoleic acid (49.23–49.91 %) was the major fatty acid found in the oil, followed by oleic acid (40.73–41.04 %), palmitic (5.74–5.87 %) and stearic (2.02–2.13 %). The presented work emphasizes the role of green solvents in developing eco-efficient processes for oil extraction.

1 Introduction

Natural ingredients, chemical compounds or substances produced by living organisms in nature, often exhibit pharmacological or biological activity. These ingredients are widely used in the production of medicinal products, as well as in the design and discovery of new drugs [1]. They are also commonly used in cosmetics, the food industry, and other commercial applications [2]. Natural sources for obtaining such products include plants, marine organisms, microorganisms (especially products of fermentation), animal organisms, and natural poisons or toxins. These compounds form a large and diverse group, with varying chemical structures influenced by both biological (organisms) and geographical (origin) factors. Notably, many bioactive compounds have been discovered in plant materials, such as flowers, fruits, vegetables and nuts. Recent studies have also highlighted the value of plant waste such as seeds, peels, stems, leaves, and bark as valuable sources of bioactive compounds with diverse applications [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]. Several research groups [10], [11], [12], [13] have shown that plant seeds contain high levels of beneficial fatty acids, particularly oleic, linoleic, and linolenic acids, which contribute to improved memory, exhibit antioxidant properties, and significantly reduce blood cholesterol levels, thereby lowering the risk of coronary disease and other chronic diseases [14].

As such, oil extraction technology plays a crucial role in obtaining oils for their numerous health benefits. Several methods have been reported including cold press, maceration, Soxhlet, enzymatic, supercritical fluid extraction (SFE), microwave assisted extraction (MAE), ultrasound assisted extraction (UAE) or a combination of multiple techniques [15]. Conventional solvent extraction methods rely on hazardous petrochemical-derived volatile organic compounds (VOCs) including n-hexane, methanol, chloroform, petroleum ether, tetrahydrofuran [16].

The use of green solvents presents a promising solution to the limitations of conventional organic solvents. Deep eutectic solvents (DESs), first introduced by Abbot et al. [17], have rapidly emerged as a new class of sustainable and environmentally friendly solvents. These solvents are prepared by simply mixing two or more naturally occurring, inexpensive, and biodegradable components to form a eutectic mixture. The availability, low cost, biodegradability and environmental benefits of these components make DESs versatile alternatives to traditional organic solvents [18], [19], [20], [21]. Although deep eutectic solvents (DESs) have been successfully employed for the extraction of essential oils from various plant materials such as cinnamon [22], Angelica sinensis radix [23], roots of Nardostachys jatamansi [24], leaves of Perillae folium [25] and petals of Rosa damascena [26], there are limited reports on their application for oil extraction from plant seeds; flaxseed [27] and rubber seed [28].

Therefore, our research focused on optimizing the use of deep eutectic solvents (DESs) as co-solvent for the efficient extraction of oils from sour cherry seeds. A series of DESs was synthesized using choline chloride as the hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA), combined with a variety of hydrogen bond donors (HBDs), including urea, ethylene glycol, glycerol, glucose, lactic acid, and acetic acid. These HBDs were selected to represent different functional groups – amides, polyols, sugars, and carboxylic acids – with the aim of investigating how their structural characteristics and physical properties influence extraction performance. By evaluating these DESs under ultrasound-assisted extraction conditions, the process was optimized to improve both oil yield and quality. The findings highlight the potential of DESs as sustainable and selective co-solvents, offering an environmentally friendly alternative to conventional extraction methods.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Chemicals and materials

Sour cherry fruit was obtained from a local fruit processing industry in North Macedonia. The seed were dried in oven (Electrothermal, Germany) at 60 °C for 24 h, grinded and sieved (Controls, Germany) in sizes 4 mm, 2 mm, 1 mm, 0.5 mm. Seeds with particle size of 0.5 mm were stored at −20 °C until oil extraction. n-hexane, choline chloride, urea, glucose, ethylene glycol, acetic acid, glycerol and lactic acid were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Sweden) and used without further purification.

2.2 Conventional methods

Soxhlet extraction was conducted with n-hexane at a seed: solvent ratio of 1:30 (w/v) for 3 h using a heating mantle (Electrothermal, Germany) set at 70 °C. Maceration was carried out using n-hexane at a seed: solvent ratio of 1:10 (w/v), at 60 °C for 1 h. The resulting extract was cooled to room temperature and then filtered. The oil was recovered by evaporating the organic solvent with a rotary vacuum evaporator (IKA, Germany) at 50 °C. The extractions were performed in triplicate for reproducibility of results. The extracted oil was subjected to a nitrogen gas flush. Complete solvent removal was confirmed by the weight constancy method, whereby the sample was weighed before and after the nitrogen flushing and drying was considered complete once successive weights differed by less than 0.001 g.

2.3 Synthesis of DESs

In this study, choline chloride (ChCl) was selected as hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA). Ethylene glycol (EG), glycerol (GLY), lactic acid (LA), acetic acid (AA), urea (U) and glucose (GLU), were selected as hydrogen bond donors (HBDs). The DESs were synthesized by mixing HBA and HBD components at specific molar ratios, heated at 50 °C, stirring at a rate of 500 rpm for 30 min until viscous liquid was formed. The obtained solvents were stored in airtight glass bottles until further use.

2.4 Physical properties of DESs

The pH values of the synthesized DESs were measured using a calibrated digital pH meter (Mettler Toledo, Switzerland). The density of DESs were determined using glass pycnometer (25 mL), following a standard gravimetric method. The density of DESs was calculated using the following equation:

m1-mass of the pycnometer with solvent [g]

m0-mass of the empty pycnometer [g]

V-volume of the pycnometer [cm3]

The electrical conductivity of the solvents was determined by using a digital conductivity meter (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The dynamic viscosity of the samples were measured using a rotational viscosimeter (Brookfield, USA). The measurements were performed at room temperature under constant stirring. ChCl:EG, ChCl:U and ChCl:GLU were previously heated in a water bath at 50 °C.

2.5 FTIR spectra of DESs

Shimadzu (Japan) instrument was used to perform FTIR analyses on the synthesized DESs. The spectrophotometer was equipped with ATR (attenuated total reflectance module), in the spectral range of 4,000–500 cm−1.

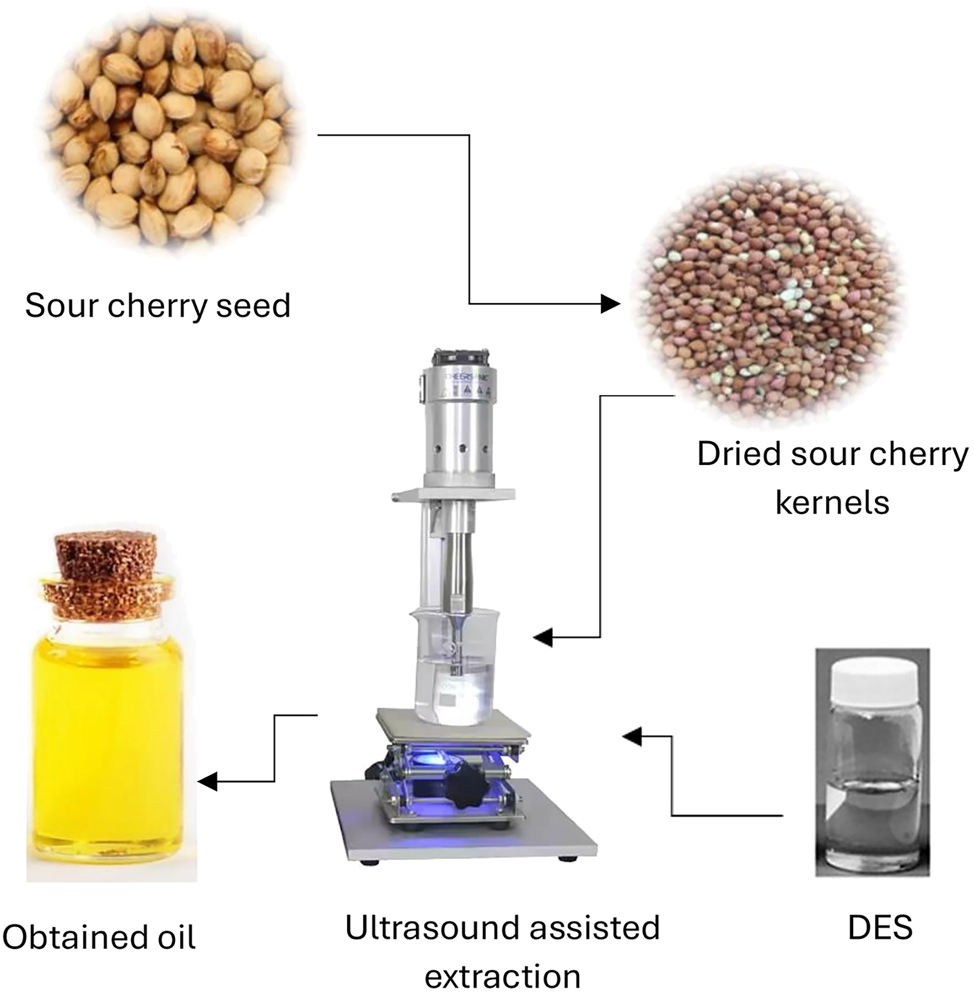

2.6 Extraction of oil by DESs as co-solvent

The eutectic solvent ChCl:EG = 1:2 was tested as co-solvent for oil extraction under varying conditions, with and without ultrasound (50 kHz) assistance. The experiments were conducted at different temperatures (40 °C, 50 °C, 60 °C) and durations (15, 30, 60 min) using a seed: n-hexane: DES ratio of 1:10:1 (w/v/w).

Extractions with the other DESs (Figure 1) were performed with ultrasound (50 kHz) at 60 °C for 60 min, maintaining the same seed: n-hexane: DES ratio of 1:10:1 (w/v/w). After extraction, the mixtures were cooled to room temperature and filtered. The filtrates were concentrated using a rotary vacuum evaporator (IKA, Germany) at 50 °C. The extracted oil was subjected to a nitrogen gas flush. Complete solvent removal was confirmed by the weight constancy method, whereby the sample was weighed before and after the nitrogen flushing and drying was considered complete once successive weights differed by less than 0.001 g. The presence of residual DES in the extracted oil was evaluated by performing a qualitative test for chloride ions using aqueous silver nitrate (0.1 M). The absence of a white silver chloride (AgCl) precipitate was taken as evidence that chloride-based DES components were not present in the final extract.

Ultrasound assisted extraction by DES.

2.7 GC-FID determination of fatty acids profile

The profile of fatty acids was determined by gas chromatograph (Agilent, GC 7890BA, USA) with flame ionization detector (GC-FID) and a capillary column (HP88-60 m × 250 mm x 0.2 mm). The samples were methylated to fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) using BF3 in methanol. Methyl esters were quantitatively measured using undecanoic acid (C11:0) as internal standard. 1 μL volume of each sample was analyzed in triplicate. Injection and detector temperatures were set at 250 °C and 300 °C, respectively. Helium was used as a carrier gas with a flow of 0.8 mL/min.

3 Results

3.1 Conventional methods

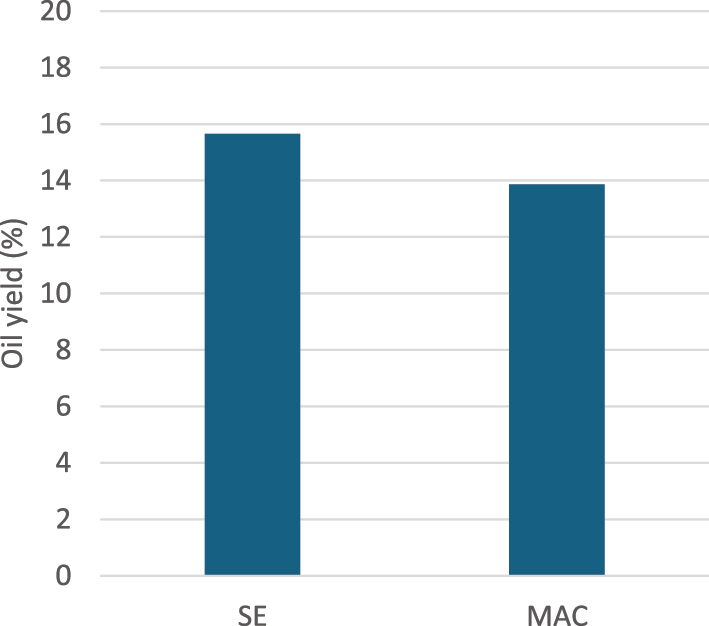

Soxhlet extraction and maceration as conventional methods, both employed n-hexane as solvent for oil extraction. The oil yields obtained from Soxhlet extraction and maceration were 15.65 ± 0.0017 % and 13.86 ± 0.0022 % (mean ± SD, n = 3), respectively. Statistical comparison using a two-sample t-test indicated that the 1.79 % difference between SE and MAC was statistically significant (p < 0.05), confirming that SE yielded more oil than MAC under the conditions tested (Figure 2).

Yield of extracted oil by conventional methods.

3.2 Physical properties of DESs

The physical properties of the newly synthesized deep eutectic solvents composed of choline chloride and various hydrogen bond donors (HBDs) vary significantly depending on the type of the HBD component (Table 1). pH values range from strongly acidc (1.69 for ChCl:AA) to nearly neutral (6.80 for ChCl:GLU), reflecting the acidic or basic characteristics of the individual components.

Physical properties of prepared DESs.

| Deep eutectic solvent | pH | δ (g/cm3) | μ (mPa·s) | σ (mS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choline chloride: ethylene glycol = 1:2 | 5.31 | 1.17 | 45 | 7.78 |

| Choline chloride: glycerol = 1:2 | 5.30 | 1.22 | 370 | 3.41 |

| Choline chloride: lactic acid = 1:2 | 2.08 | 1.22 | 500 | 1.96 |

| Choline chloride: acetic acid = 1:2 | 1.69 | 1.16 | 55 | 4.70 |

| Choline chloride: urea = 1:2 | 6.30 | 1.25 | 750 | 0.47 |

| Choline chloride: glucose = 2:1 | 6.80 | 1.30 | 8,000 | 0.003 |

The densities are relatively similar among DESs, ranging from 1.16 to 1.30 g/cm3 with the DES containing glucose exhibiting the highest density. Viscosity has greater variations, which ranges from only 45 mPa s in the solvent containg ethylene glycol to as high as 8,000 mPa s in the glucose system, which indicates that the molecular size of HBD component significantly influences viscosity. Electrical conductivity shows ana inverse correlation with viscosity; ChCl:EG exhibits high conductivity (7.78 mS), while ChCl:GLU has very low ionic mobility (0.003 mS).

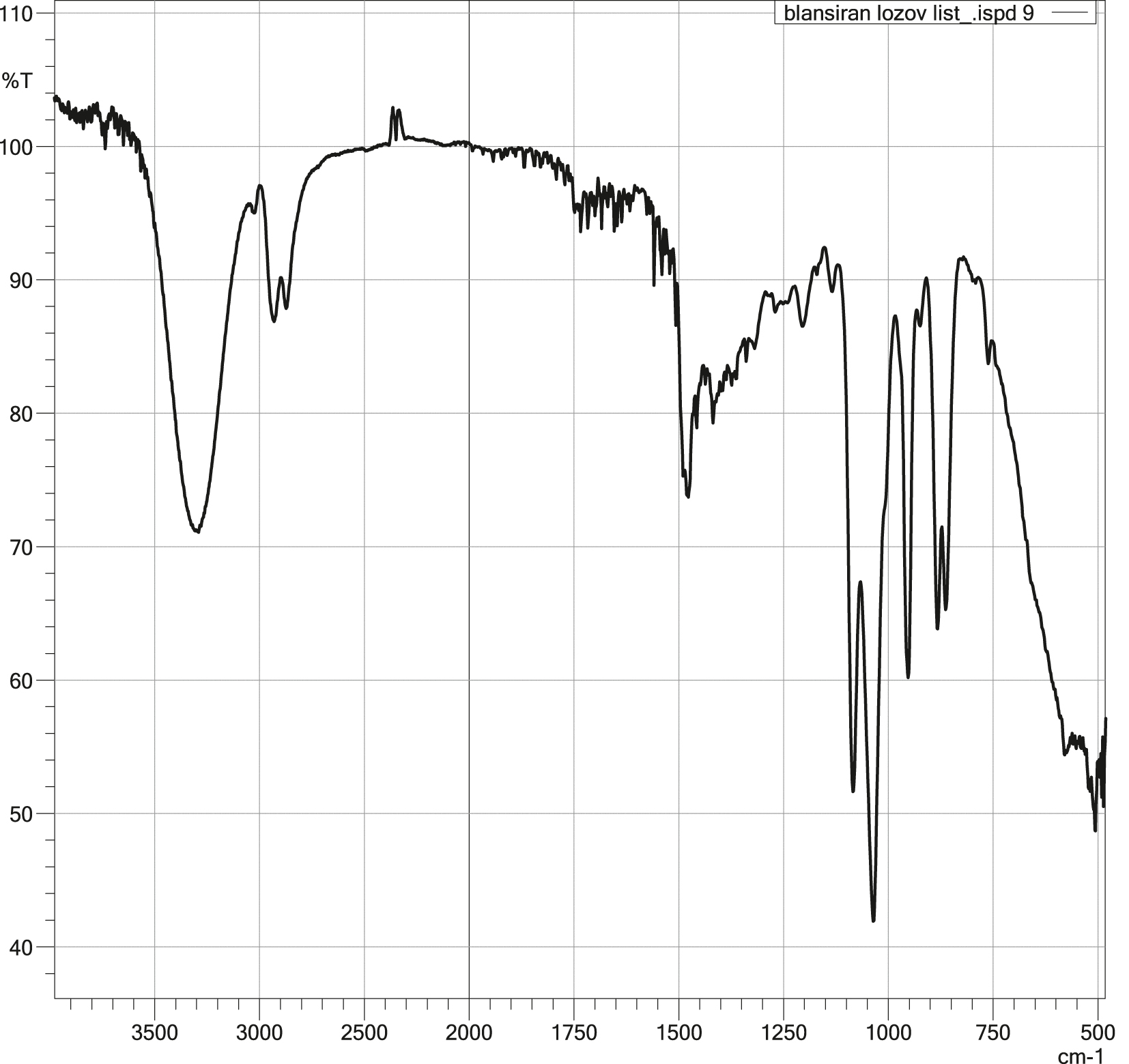

3.3 FTIR spectra of the synthesized DESs

The successful synthesis of DESs based on choline chloride and various HBDs was confirmed using FTIR spectroscopy (supplementary material).

The FTIR spectrum of ChCl:EG (Figure 3) exhibited an intense absorption band at 3,250 cm−1, attributed to the stretching vibrations of the O–H group, characteristic of hydroxyl functionalities. The shift to a lower wavenumber compared to pure ethylene glycol [29] indicates the formation of a stable hydrogen bonding network between the components, confirming interactions leading to the formation of the eutectic mixture.

FTIR spectra of ChCl:EG = 1:2.

Additionally, weak but well-defined absorption bands were observed in the region of 2,800–2,880 cm−1, corresponding to the symmetric and asymmetric stretching vibrations of methyl (–CH3) and methylene (–CH2) groups. An intense band around 1,450 cm−1 is likely due to the bending vibrations of –CH3 groups, further confirming the presence of the organic cation from choline chloride.

The band observed at 1,040 cm−1 is attributed to C–O stretching vibrations, characteristic of ethylene glycol, while a relatively strong band at 950 cm−1 likely originates from C–N bending vibrations characteristic of quaternary ammonium salts, specifically choline chloride.

3.4 Optimization of oil extraction using deep eutectic solvents

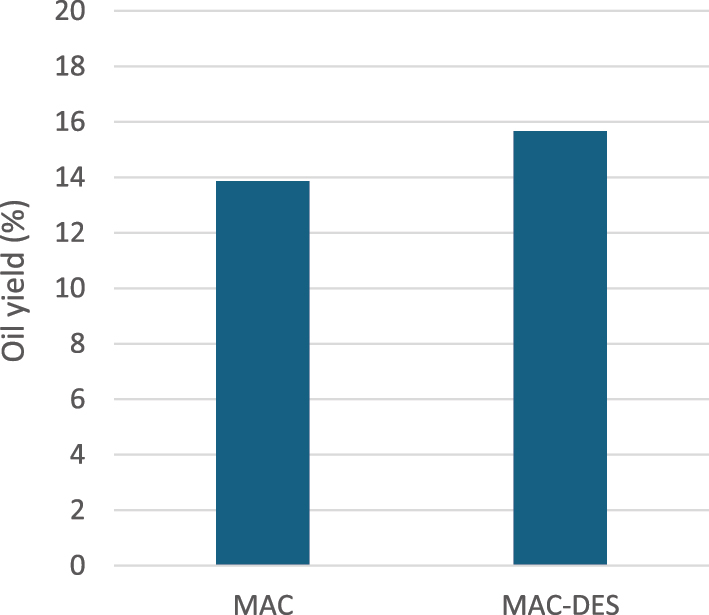

3.4.1 Effect of eutectic solvents on maceration

The use of deep eutectic solvent ChCl:EG = 1:2 significantly improved the oil extraction process. When applied in a maceration process at 60 °C for 60 min with a seed: n-hexane: DES = 1:10:1 (w/v/w), the yield of extracted oil reached 15.65 %. This represents a 1.8 % increase in yield compared to the same maceration process conducted without the DES (Figure 4).

Influence of DES on oil yield, at seed: solvent = 1:10 ratio (w/v), 60 min extraction time and 60 °C extraction temperature.

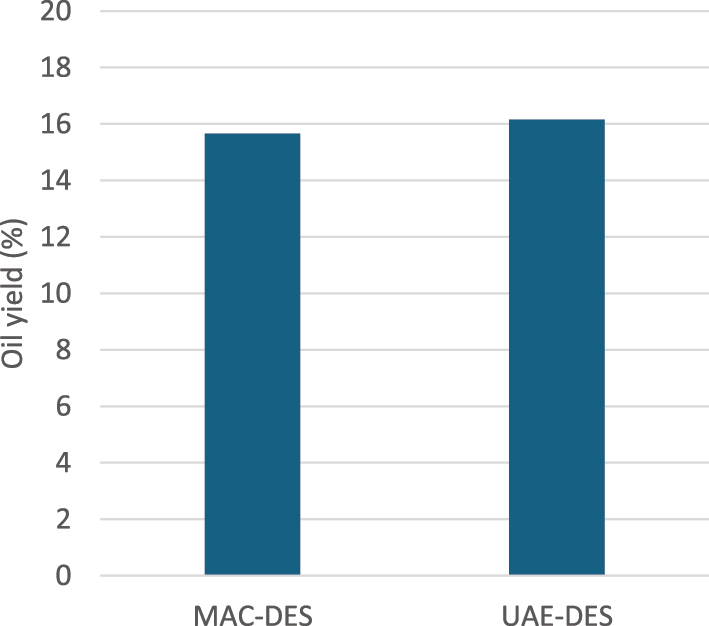

3.4.2 Influence of ultrasound-assisted extraction

Ultrasound-assisted extraction under the same conditions further increased the oil yield to 16.15 %, showcasing the synergistic effect of ultrasound and DES (Figure 5).

Influence of UAE on oil yield, at seed: solvent = 1:10 ratio (w/v), 60 min extraction time and 60 °C extraction temperature.

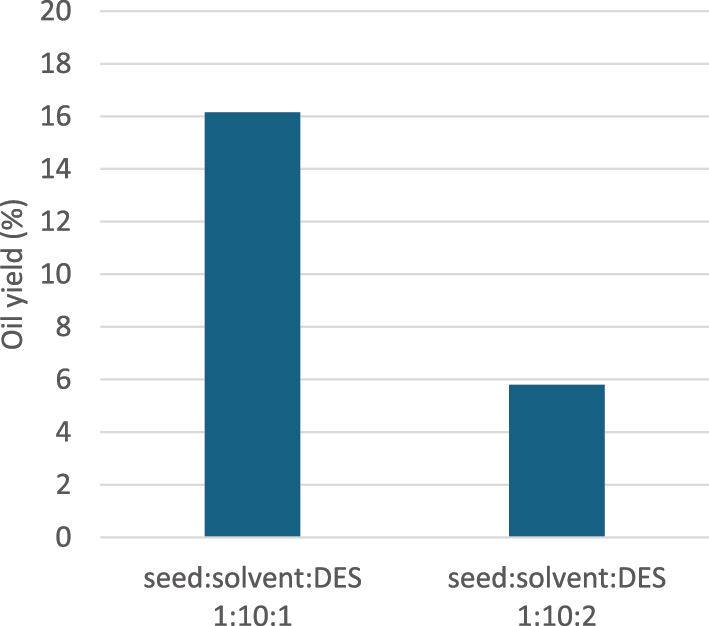

3.4.3 Effect of DES concentration and viscosity

In a subsequent experiment, increasing the DES concentration to a seed: n-hexane: DES ratio of 1:10:2 (w/v/w) resulted in significantly lower yield of 5.80 %. This decrease is attributed to the increased viscosity of the medium, which hampers mass transfer during extraction (Figure 6).

Influence of viscosity of DES on oil yield, 60 min extraction time and 60 °C extraction temperature.

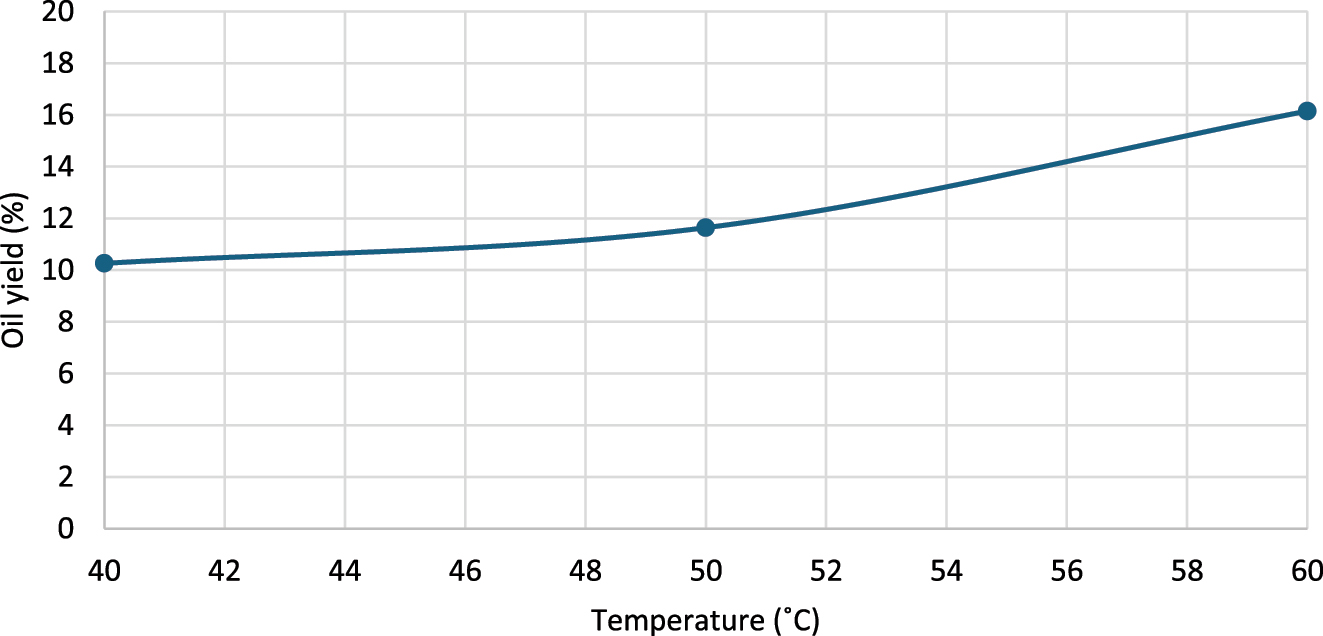

3.4.4 Optimization of temperature

Temperature optimization revealed that the highest yield (16.15 %) was achieved at 60 °C using ultrasound assisted extraction for 60 min with a seed: n-hexane: DES ratio of 1:10:1 (w/v/w). Lowering the temperature to 50 °C and 40 °C reduced the oil yield to 11.64 % and 10.26 %, respectively (Figure 7). At 60 °C n-hexane exists as a gas/liquid phase which reduces the viscosity and enables faster solvation of oil from the seeds.

Influence of extraction temperature on oil yield, at seed: solvent = 1:10 ratio (w/v), 60 min extraction time and 60 °C extraction temperature.

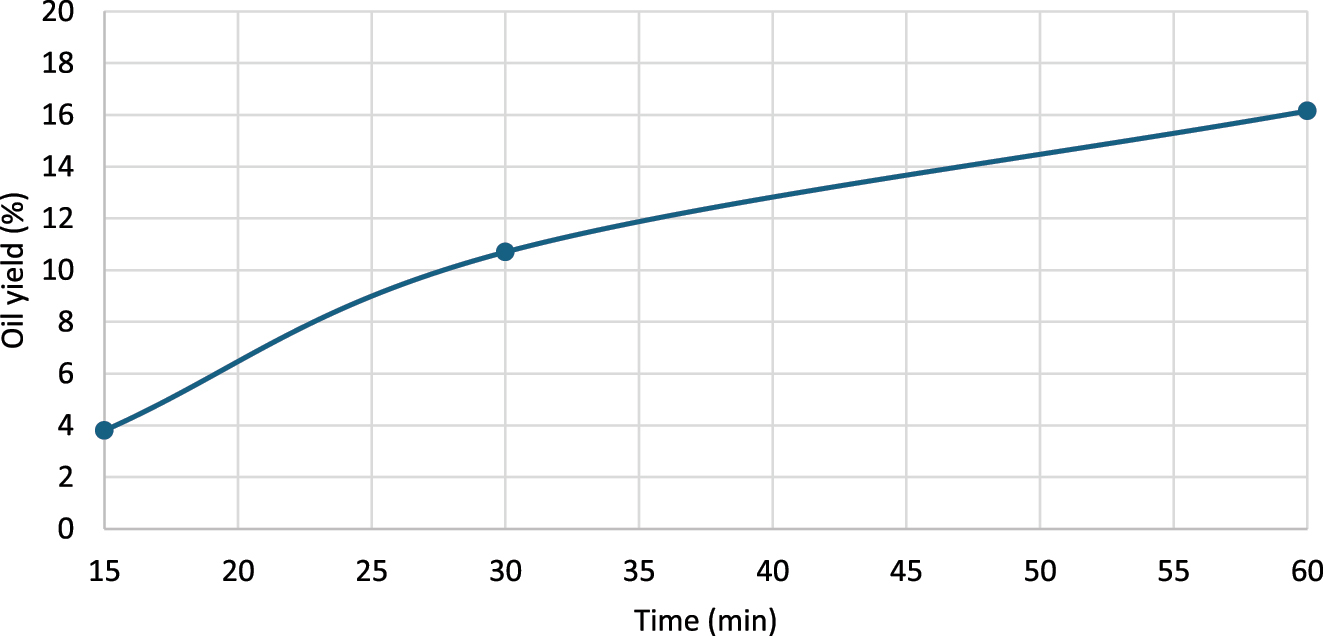

3.4.5 Optimization of extraction time

The duration extraction was also evaluated. At 60 °C, the yields for 15 and 30 min extraction time were 3.80 % and 10.70 %, respectively (Figure 8). Extending the extraction time to 60 min yielded the highest oil recovery.

Influence of extraction time on oil yield, at seed: solvent = 1:10 ratio (w/v), 60 °C extraction temperature.

3.4.6 Comparison of different eutectic solvents

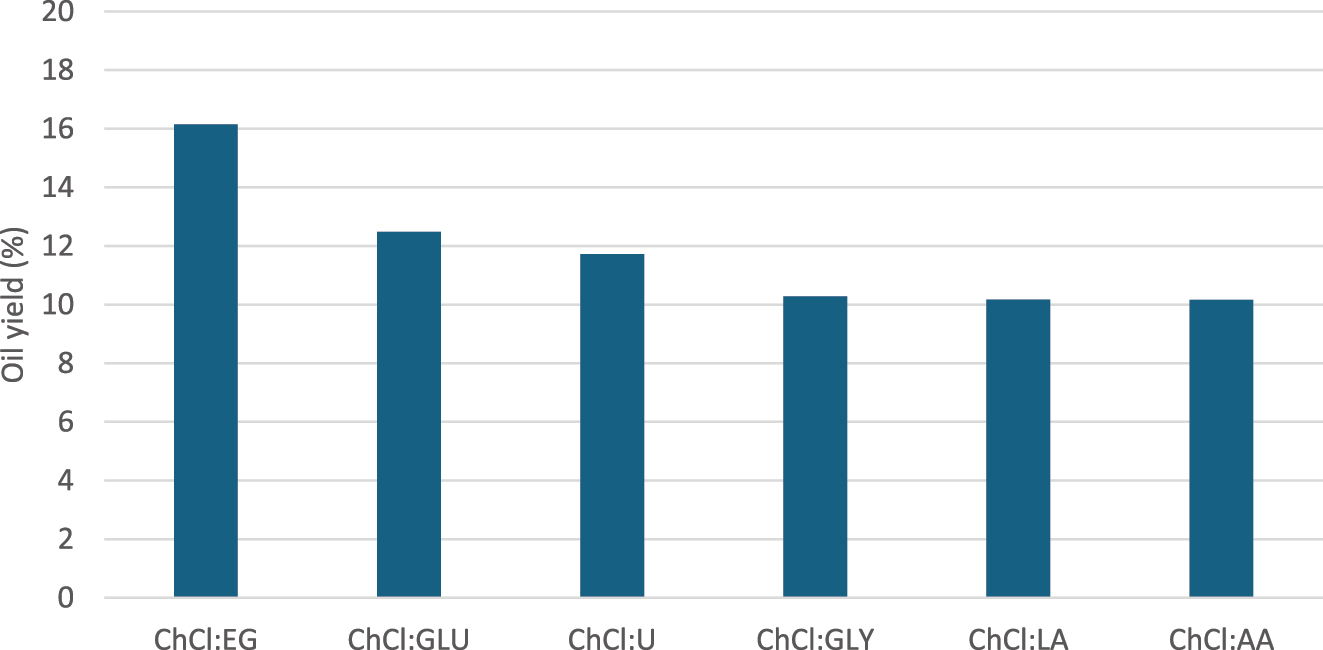

Using ultrasound assisted extraction at 60 °C for 60 min with a seed: n-hexane: DES ratio 1:10:1 (w/v/w), various DES formulations were compared. The oil yields for DES composed of choline chloride with ethylene glycol, glucose, urea, glycerol, lactic acid and acetic acid were 16.15 %, 12.48 %, 11.72 %, 10.28 %, 10.17 % and 10.16 %, respectively (Figure 9). The results indicate that ethylene glycol is the most effective hydrogen bond donor, followed by glucose and urea, while lactic and acetic acid were the least effective.

Yield of extracted oil by different DES as co-solvent, at seed: solvent = 1:10 (w/v), 60 min extraction time and 60 °C extraction temperature.

3.5 Fatty acid analysis

The fatty acid profile of sour cherry seed oil obtained using different extraction techniques, including maceration, Soxhlet and DES as co-solvent revealed a composition dominated by unsaturated fatty acids (UFAs), accounting for over 91 % of total fatty acids (Table 2). Oleic acid was the most prevalent within the monounsaturated fatty acids, with contents ranging from 40.73 % to 41.04 % across all methods. As a representative of ω-9 family, oleic acid plays a crucial role in maintaining cardiovascular health, modulating inflammatory responses and improving insulin sensitivity. Its content in sour cherry seed oil is comparable to that of olive oil [30].

Fatty acid composition of extracted oil.

| Fatty acid (%) | MAC | SE | ChCl:EG | ChCl:LA | ChCl:GLU | ChCl:U | ChCl:GLY | ChCl:AA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C18:1 | 40.91 | 41.04 | 40.83 | 40.73 | 40.90 | 40.79 | 40.76 | 41.03 |

| C18:2 | 49.23 | 49.40 | 49.34 | 49.51 | 49.31 | 49.24 | 49.31 | 49.91 |

| C18:3 | 0.40 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.42 | 0.39 | 0.41 | 0.40 | / |

| C16:1 | 0.37 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.31 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.33 |

| C16:0 | 5.77 | 5.84 | 5.74 | 5.87 | 5.75 | 5.77 | 5.80 | 5.82 |

| C18:0 | 2.03 | 2.13 | 2.04 | 2.06 | 2.04 | 2.07 | 2.02 | 2.05 |

| C10:0 | 0.05 | 0.05 | / | / | / | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.12 |

| C22:2 | 0.78 | 0.37 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.81 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.72 |

| SFA | 7.84 | 8.00 | 7.81 | 7.91 | 7.77 | 7.89 | 7.86 | 7.97 |

| MUFA | 41.29 | 41.37 | 41.15 | 41.05 | 41.27 | 41.17 | 41.13 | 41.36 |

| PUFA | 50.86 | 50.61 | 51.02 | 51.02 | 50.94 | 50.93 | 51.00 | 50.66 |

Among polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), linoleic acid (C18:2, n-6) an essential ω-6 fatty acid was found in very high concentration (49.23–49.91 %), with additional minor contributions from docosadienoic acid (C22:2, n-6), bringing the total ω-6 content to approximately 50–50.7 %. ω-6 fatty acids are necessary for cholesterol metabolism, skin health, immune response and growth [31]. In contrast, linolenic acid (C18:3, n-3), the only detected ω-3 fatty acid, was present at significantly lower levels (0.39–0.42 %) and was undetected in the oil extracted by DES co-solvent ChCl:AA. Palmitic (5.74–5.87 %) and stearic (2.02–2.13 %) were predominant among saturated fatty acids. Additional saturated fatty acid identified was capric acid (0.05–0.12 %).

4 Discussion

In our previous work [32], we have reviewed the available literature on oil extraction from sour cherry seeds. Different methods for extraction have been used starting from the conventional like cold press, Soxhlet extraction and innovative like superfluid extraction. Among these, Soxhlet extraction using nonpolar solvents like n-hexane and petroleum ether remains the most widely employed method. Reported oil yields from Soxhlet extractions range from 4 % to 36 %, while in this study we obtained 15.65 % oil yield.

To date, DESs have not been reported for the extraction of oil from sour cherry seeds, despite a numerous studies as green alternatives to conventional methods. In this study, we synthesized a series of choline-based DESs using ethylene glycol, glycerol, urea, glucose, lactic and acetic acid as hydrogen bond donors (HDBs). The properties of the synthesized DES systems were found to significantly influence their capacity to extract oils from seeds, which predominantly consist of triglycerides with nonpolar or slightly polar characteristics. In this regard, systems with lower viscosity, such as ChCl:EG (45 mPa s), were shown to enable better penetration into the plant matrix and more efficient release of lipophilic components. Additionally, the moderate pH value (5.31) and relatively low density (1.17 g/cm3) facilitated phase separation following the extraction process. In contrast, DES systems with high viscosity, such as ChCl:GLY (370 mPa s), ChCl:LA (500 mPa s), and particularly ChCl:GLU (8,000 mPa s), were found to exhibit limitations in molecular mass transport, resulting in reduced extraction efficiency. The elevated viscosity was observed to hinder the diffusion of oils through the solvent, as well as their desorption from the surface of the cell walls. Furthermore, the low electrical conductivity recorded for ChCl:GLU (0.003 mS) indicated restricted ionic mobility and poor molecular dissociation, which may further diminish interactions with lipophilic components. Acidic DES formulations, such as ChCl:LA (pH 2.08) and ChCl:AA (pH 1.69), were found to be unsuitable for oil extraction. The low pH values may cause partial hydrolysis of sensitive lipid components or lead to emulsion formation, which hinders phase separation and complicates subsequent processing steps. The formation of DESs was confirmed by FTIR spectroscopy, where red shifts in characteristic bands indicated the establishment of hydrogen bonding between the hydrogen bond donor and acceptor, in accordance with already published spectra [33].

Ultrasound assisted extraction using DESs has been widely studied for recovery of bio compounds from plants and has proven effective in increasing yield while minimizing extraction time, temperature and energy consumption [34], [35], [36], [37], [38]. During our research, under optimized conditions assisted by ultrasound ChCl:EG = 1:2 exhibited higher oil recovery in contrast to conventional methods. This approach aligns with findings by Zare Nezhad et al. [39] who demonstrated the effectiveness of ChCl:EG = 1:2 as co-solvent in enhancing oil extraction yields, particularly in halophytic safflower and salicornia plants. When used as a co-solvent ChCl:EG = 1:2 with n-hexane for flaxseed oil extraction, slightly improved the oil yield compared to n-hexane and significantly lowered the optimum extraction temperature under optimized conditions [27]. Similarly, using ChCl:GLY = 1:2 as a co-solvent for rubber seed oil extraction increased the oil yield to 30.7 % compared to 27.0 % with pure diethyl ether [28].

The analysis of fatty acids revealed that the extraction technique did not contribute to considerable differences between fatty acids profiles of oil samples recovered by maceration, Soxhlet and by DES as co-solvent. However, subtle but notable differences in oil quality emerged depending on the extraction method. The extraction assisted by ChCl:GLU, exhibited slightly higher UFA content and lower SFA levels compared to conventional methods, suggesting an enhanced selectivity of this DES towards unsaturated fatty acids. Specifically, SFA was reduced by 0.07–0.23 % points relative to MAC and SE, while UFA increased by 0.06–0.23 % points. Compared to other DES, ChCl:GLU demonstrated SFA decreases of 0.04–0.20 % points and UFA increases between 0.04 and 0.19 % points. On the other hand, the use of ChCl:AA resulted in the lowest UFA recovery and absence of detectable linolenic acid, indicating lower extraction efficiency. The absence of linolenic acid (C18:3, n-3) in the oil extracted with ChCl:AA is attributed to the strongly acidic nature of the system (pH 1.69), under which polyunsaturated fatty acids may be degraded or isomerized. Due to its high degree of unsaturation, C18:3 is particularly susceptible to acid-catalyzed transformation, which has resulted in its absence. This finding highlights the risk of PUFA degradation when highly acidic DESs are applied for oil extraction.These observations highlight that the choice of DES composition influences oil quality, with ChCl:GLU standing out as the most effective system.

Gornaś et al. [40] reported that sour cherry seed extracts obtained with n-hexane were primarily composed of oleic (25.25–45.30 %) and linoleic acids (35.50–46.06 %), with lower levels of palmitic, α-eleostearic, stearic, and arachidic acids, while palmitoleic, α-linolenic, and gondoic acids were detected at <1.00 %. Similarly, Yilmaz and Gokmen [41] found oleic (46.30 %) and linoleic acid (41.50 %) to be the dominant fatty acids in oils extracted with n-hexane and supercritical CO2, accompanied by smaller proportions of palmitic (6.40 %), linolenic (4.60 %), and stearic acid (1.20 %). In contrast, Dimić et al. [42] identified linoleic acid (47.00 %) as the major component, followed by oleic acid (41.46 %), while palmitic (6.62 %), stearic (2.21 %), and arachidic acid (1.12 %) were present in lower concentrations.

5 Conclusions

In this study, an eco-friendly process for oil extraction from sour cherry seed is developed. The extraction process assisted by ultrasound, resulted in higher yield of extracted oil when choline chloride: ethylene glycol = 1:2 was employed as co-solvent in comparison to n-hexane. Also, the optimized process achieved in this study showed advantages in the extraction temperature (70 °C vs 60 °C), time (3 h vs 1 h), amount of solvent (150 mL vs 50 mL) and a higher yield of extracted oils compared to Soxhlet extraction. The presented approach can have wide application in extraction of oils by reducing energy consumption and environmental hazards associated with the use of conventional solvents, particularly n-hexane.

The profile of fatty acids revealed that sour cherry seed oil represents a valuable source of ω-6 and ω-9 fatty acids, with modest amount of ω-3. Its high degree of unsaturation and low SFA/UFA ration make it suitable for use in nutraceuticals and cosmetics.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

- ChCl:GLU

-

Choline chloride: glucose

- ChCl:AA

-

Choline chloride: acetic acid

- ChCl:EG

-

Choline chloride: ethylene glycol

- ChCl:GLY

-

Choline chloride: glycerol

- ChCl:LA

-

Choline chloride: lactic acid

- ChCl:U

-

Choline chloride: urea

- DES

-

Deep eutectic solvent

- FAME

-

Fatty acid methyl esters

- HBA

-

Hydrogen bond acceptor

- HBD

-

Hydrogen bond donor

- MAC

-

Maceration

- MAE

-

Microwave assisted extraction

- MUFA

-

Monounsaturated fatty acids

- PUFA

-

Polyunsaturated fatty acids

- SE

-

Soxhlet extraction

- SFA

-

Saturated fatty acids

- SFE

-

Superfluid extraction

- UAE

-

Ultrasound assisted extraction

- UFA

-

Unsaturated fatty acids

- VOC

-

Volatile organic compounds

-

Funding information: The authors received no funding for this research.

-

Author contributions: Conceptualization: Belinda Amiti and Kiril Lisichkov; data curation and formal analysis: Belinda Amiti, Kiril Lisichkov, Katerina Atkovska, Ahmed Jashari, Zehra Hajrulai Musliu, Hamdije Memedi and Arianit A. Reka; investigation: Belinda Amiti and Kiril Lisichkov; methodology: Belinda Amiti and Kiril Lisichkov; project administration: Belinda Amiti and Kiril Lisichkov; resources: Kiril Lisichkov; supervision: Kiril Lisichkov and Arianit A. Reka; validation: Belinda Amiti and Kiril Lisichkov; visualization: Belinda Amiti; writing – original draft: Belinda Amiti and Kiril Lisichkov; writing – review and editing: Belinda Amiti, Kiril Lisichkov, Katerina Atkovska, Ahmed Jashari, Zehra Hajrulai Musliu, Hamdije Memedi and Arianit A. Reka.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

1. Atanasov, AG, Zotchev, SB, Dirsch, VM, Orhan, IE, Banach, M, Rollinger, JM, et al.. Natural products in drug discovery: advances and opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2021;20:200–16. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41573-020-00114-z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Tewari, D, Atanasov, AG, Semwal, P, Wang, D. Natural products and their applications. Curr Res Biotechnol 2021;3:82–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crbiot.2021.03.002.Search in Google Scholar

3. Dincheva, I, Badjakov, I, Galunska, B. New insights into the research of bioactive compounds from plant origins with nutraceutical and pharmaceutical potential. Plants 2023;12:258. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12020258.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Romelle, FD, Rani, PA, Manohar, RS. Chemical composition of some selected fruit peels. Eur J Food Technol 2016;4:12–21.Search in Google Scholar

5. Pacheco, MT, Moreno, FJ, Villamiel, M. Chemical and physicochemical characterization of orange by-products derived from industry. J Sci Food Agric 2019;99:868–76. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.9257.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Jiang, LY, He, S, Pan, YJ, Sun, CR. Bioassay-guided isolation and EPR-assisted antioxidant evaluation of two valuable compounds from mango peels. Food Chem 2010;119:1285–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.09.005.Search in Google Scholar

7. Xu, Y, Fan, M, Ran, J, Zhang, T, Sun, H, Dong, M, et al.. Variation in phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity in apple seeds of seven cultivars. Saudi J Biol Sci 2016;23:379–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2015.04.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Paes, J, Dotta, R, Barbero, GF, Martínez, J. Extraction of phenolic compounds and anthocyanins from blueberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.) residues using supercritical CO2 and pressurized liquids. J Supercrit Fluids 2014;95:8–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.supflu.2014.07.025.Search in Google Scholar

9. Lavenburg, V, Rosentrater, K, Jung, S. Extraction methods of oils and phytochemicals from seeds and their environmental and economic impacts. Processes 2021;9:1839. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr9101839.Search in Google Scholar

10. Mezzomo, N, Mileo, BR, Friedrich, MT, Martínez, J, Ferreira, SRS. Supercritical fluid extraction of peach (Prunus persica) almond oil: process yield and extract composition. Bioresour Technol 2010;01:5622–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2010.02.020.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Sánchez-Vicente, Y, Cabañas, A, Renuncio, J, Pando, C. Supercritical fluid extraction of peach (Prunus persica) seed oil using carbon dioxide and ethanol. J Supercrit Fluids 2009;49:167–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.supflu.2009.01.001.Search in Google Scholar

12. Wu, H, Shi, J, Xue, SJ, Kakuda, Y, Wang, D, Jiang, Y, et al.. Essential oil extracted from peach (Prunus persica) kernel and its physicochemical and antioxidant properties. LWT – Food Sci Technol 2011;44:2032–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2011.05.012.Search in Google Scholar

13. Alves, E, Rey, F, da Costa, E, Moreira, A, Pato, L, Domingues, M, et al.. Olive (Olea europaea L. cv. Galega vulgar) seed oil: a first insight into the major lipid composition of a promising agro-industrial by-product at two ripeness stages. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol 2018;120:1700381. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejlt.201700381.Search in Google Scholar

14. Poudyal, H, Kumar, SA, Iyer, A, Waanders, J, Ward, LC, Brown, L. Responses to oleic, linoleic and α-linolenic acids in high-carbohydrate, high-fat diet-induced metabolic syndrome in rats. J Nutr Biochem 2013;24:1381–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnutbio.2012.11.006.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Chibuye, B, Indra, SS, Luke, C, Kakoma, MK. A review of modern and conventional extraction techniques and their applications for extracting phytochemicals from plants. Sci Afr 2023;19:01585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sciaf.2023.e01585.Search in Google Scholar

16. Welton, T. Solvents and sustainable chemistry. Proc Math Phys Eng Sci 2015;471:20150502. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.2015.0502.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Abbott, A, Capper, G, Davies, D, Rasheed, RK, Tambyrajah, V. Novel solvent properties of choline chloride/urea mixtures. Chem Commun (Camb) 2002;70:1.10.1039/b210714gSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Chen, Y, Mu, T. Revisiting greenness of ionic liquids and deep eutectic solvents. Green Chem Eng 2021;2:174–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gce.2021.01.004.Search in Google Scholar

19. Yu, D, Xue, Z, Mu, T. Eutectics: formation, properties, and applications. Chem Soc Rev 2021;50:8596–638. https://doi.org/10.1039/d1cs00404b.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Zhang, Q, De Oliveira Vigier, K, Royer, S, Jerome, F. Deep eutectic solvents: syntheses, properties and applications. Chem Soc Rev 2012;41:7108–46. https://doi.org/10.1039/c2cs35178a.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Liu, Y, Friesen, JB, McAlpine, JB, Lankin, DC, Chen, SN, Pauli, GF. Natural deep eutectic solvents: properties, applications, and perspectives. J Nat Prod 2018;81:679–91. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jnatprod.7b00945.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Liu, Y, Wang, H, Fu, R, Zhang, L, Liu, M, Cao, W, et al.. Preparation and characterization of cinnamon essential oil extracted by deep eutectic solvent and its microencapsulation. J Meas Charact 2023;17:664–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11694-022-01653-2.Search in Google Scholar

23. Fan, Y, Li, Q. An efficient extraction method for essential oil from angelica sinensis radix by natural deep eutectic solvents-assisted microwave hydrodistillation. Sustain Chem Pharm 2022;29:100792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scp.2022.100792.Search in Google Scholar

24. Sharma, M, Arokiyaraj, C, Rana, S, Sharma, U, Reddy, SE. Natural deep eutectic solvents (NADESs) assisted extraction of essential oil from Nardostachys jatamansi (D. Don) DC with insecticidal activities. Ind Crops Prod 2023;202:117040.10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.117040Search in Google Scholar

25. Chen, Z, Wu, K, Zhu, W, Wang, Y, Su, C, Yi, F. Chemical compositions and bioactivities of essential oil from perilla leaf (Perillae Folium) obtained by ultrasonic-assisted hydro-distillation with natural deep eutectic solvents. Food Chem 2022;375:131834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131834.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Aggarwal, G, Gupta, MK, Sharma, M, Sharma, U, Sharma, U. Natural deep eutectic solvents-based concurrent approach for qualitative and quantitative enhancement of Rosa damascena essential oil and recovery of phenolics from distilled rose petals. Sep Purif Technol 2025;354:128699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2024.128699.Search in Google Scholar

27. Hayyan, A, Samyudia, AV, Hashim, MA, Yeow, ATH, Ali, E, Hadj-Kali, MK, et al.. Application of deep eutectic solvent as novel co-solvent for oil extraction from flaxseed using sonoenergy. Ind Crops Prod 2022;176:114242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.114242.Search in Google Scholar

28. Al-Maari, MA, Hizaddin, HF, Hayyan, A, Hadj-Kal, MK. Screening deep eutectic solvents as green extractants for oil from plant seeds based on COSMO-RS model. J Mol Liq 2024;393:123520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2023.123520.Search in Google Scholar

29. Guo, YC, Cai, CH, Zhang, YH. Observation of conformational changes in ethylene-glycol-water complexes by FTIR-ATR spectroscopy and computional studies. AIP Adv 2018;8:055308. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4995975.Search in Google Scholar

30. da Silva-Santi, LG, Antunes, MM, Caparroz-Assef, SM, Carbonera, F, Bazott, RB. Omega-9 oleic acid, the main compound of olive oil, mitigates the lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory response in mice. Mediators Inflamm 2018:6053492.Search in Google Scholar

31. Djuricic, I, Calder, PC. Beneficial outcomes of Omega-6 and Omega-3 polyunsaturated Fatty acids on human health. Nutrients 2021;13:2421. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13072421.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

32. Amiti, B, Lisichkov, K, Kuvendziev, S, Atkovska, K, Jashari, A, Reka, A. Extraction of oils from fruit kernels with conventional and innovative methods: a review. Technologica Acta 2024;17:25–37. https://doi.org/10.51558/2232-7568.2023.17.1.25.Search in Google Scholar

33. Can, A, Özlüsoylu, İ, Antov, P, Lee, SH. Choline chloride-based deep eutectic solvent-treated wood. Forests 2023;14:569. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14030569.Search in Google Scholar

34. Fanali, C, Posta, SD, Dugo, L, Gentili, A, Mondello, L, de Gara, L. Choline-chloride and betaine-based deep eutectic solvents for green extraction of nutraceutical compounds from spent coffee ground. JPBA 2020;189:113421.10.1016/j.jpba.2020.113421Search in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Patil, SS, Pathak, A, Rathod, VK. Optimization and kinetic study of ultrasound assisted deep eutectic solvent-based extraction: a greener route for extraction of curcuminoids from Curcuma longa. Ultrason Sonochem 2021;70:105267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105267.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36. Oomen, WW, Begines, P, Mustafa, NR, Wilson, E, Verpoorte, R, Choi, YH. Natural deep eutectic solvent extraction of flavonoids of Scutellaria baicalensis as a replacement for conventional organic solvents. Molecules 2020;25:617. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25030617.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

37. Dai, Y, Rozema, E, Verpoorte, R, Choi, YH. Application of natural deep eutectic solvents to the extraction of anthocyanins from Catharanthus roseus with high extractability and stability replacing conventional organic solvents. J Chromatogr A 2016;19:50–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2016.01.037.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Zannou, O, Koca, I, Aldawoud, TMS, Galanakis, CM. Recovery and stabilization of anthocyanins and phenolic antioxidants of roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) with hydrophilic deep eutectic solvents. Molecules 2020;25:3715. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25163715.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

39. ZareNezhad, B, Khoshsima, A, ShenavaeiZare, T. Production of biodiesel through nanocatalytic transesterification of extracted oils from halophytic safflower and salicornia plants in the presence of deep eutectic solvents. Fuel 2021;302:121171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2021.121171.Search in Google Scholar

40. Górnaś, P, Rudzińska, M, Raczyk, M, Mišina, I, Soliven, A, Segliņa, D. Composition of bioactive compounds in kernel oils recovered from sour cherry (Prunus cerasus L.) by-products: impact of the cultivar on potential applications. Ind Crops Prod 2016;82:44–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.12.010.Search in Google Scholar

41. Yilmaz, C, Gokmen, V. Compositional characteristics of sour cherry kernel and its oil as influenced by different extraction and roasting conditions. Ind Crops Prod 2013;49:130–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2013.04.048.Search in Google Scholar

42. Dimić, I, Pavlić, B, Rakita, S, Cvetanović Kljakić, A, Zeković, Z, Teslić, N. Isolation of cherry seed oil using conventional techniques and supercritical fluid extraction. Foods 2023;12:11. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12010011.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/chem-2025-0199).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Phytochemical investigation and evaluation of antioxidant and antidiabetic activities in aqueous extracts of Cedrus atlantica

- Influence of B4C addition on the tribological properties of bronze matrix brake pad materials

- Discovery of the bacterial HslV protease activators as lead molecules with novel mode of action

- Characterization of volatile flavor compounds of cigar with different aging conditions by headspace–gas chromatography–ion mobility spectrometry

- Effective remediation of organic pollutant using Musa acuminata peel extract-assisted iron oxide nanoparticles

- Analysis and health risk assessment of toxic elements in traditional herbal tea infusions

- Cadmium exposure in marine crabs from Jiaxing City, China: Insights into health risk assessment

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles of Cinnamomum zeylanicum and their biological activities

- Tetraclinis articulata (Vahl) Mast., Mentha pulegium L., and Thymus zygis L. essential oils: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antifungal properties against postharvest fungal diseases of apple, and in vitro, in vivo, and in silico investigation

- Exploration of plant alkaloids as potential inhibitors of HIV–CD4 binding: Insight into comprehensive in silico approaches

- Recovery of phenylethyl alcohol from aqueous solution by batch adsorption

- Electrochemical approach for monitoring the catalytic action of immobilized catalase

- Green synthesis of ZIF-8 for selective adsorption of dyes in water purification

- Optimization of the conditions for the preparation of povidone iodine using the response surface methodology

- A case study on the influence of soil amendment on ginger oil’s physicochemical properties, mineral contents, microbial load, and HPLC determination of its vitamin level

- Removal of antiviral favipiravir from wastewater using biochar produced from hazelnut shells

- Effect of biochar and soil amendment on bacterial community composition in the root soil and fruit of tomato under greenhouse conditions

- Bioremediation of malachite green dye using Sargassum wightii seaweed and its biological and physicochemical characterization

- Evaluation of natural compounds as folate biosynthesis inhibitors in Mycobacterium leprae using docking, ADMET analysis, and molecular dynamics simulation

- Novel insecticidal properties of bioactive zoochemicals extracted from sea urchin Salmacis virgulata

- Elevational gradients shape total phenolic content and bioactive potential of sweet marjoram (Origanum majorana L.): A comparative study across altitudinal zones

- Study on the CO2 absorption performance of deep eutectic solvents formed by superbase DBN and weak acid diethylene glycol

- Preparation and wastewater treatment performance of zeolite-modified ecological concrete

- Multifunctional chitosan nanoparticles: Zn2+ adsorption, antimicrobial activity, and promotion of aquatic health

- Comparative analysis of nutritional composition and bioactive properties of Chlorella vulgaris and Arthrospira platensis: Implications for functional foods and dietary supplements

- Growth kinetics and mechanical characterization of boride layers formed on Ti6Al4V

- Enhancement of water absorption properties of potassium polyacrylate-based hydrogels in CaCl2-rich soils using potassium di- and tri-carboxylate salts

- Electrochemical and microbiological effects of dumpsite leachates on soil and air quality

- Modeling benzene physicochemical properties using Zagreb upsilon indices

- Characterization and ecological risk assessment of toxic metals in mangrove sediments near Langen Village in Tieshan Bay of Beibu Gulf, China

- Protective effect of Helicteres isora, an efficient candidate on hepatorenal toxicity and management of diabetes in animal models

- Valorization of Juglans regia L. (Walnut) green husk from Jordan: Analysis of fatty acids, phenolics, antioxidant, and cytotoxic activities

- Molecular docking and dynamics simulations of bioactive terpenes from Catharanthus roseus essential oil targeting breast cancer

- Selection of a dam site by using AHP and VIKOR: The Sakarya Basin

- Characterization and modeling of kidney bean shell biochar as adsorbent for caffeine removal from aquatic environments

- The effects of short-term and long-term 2100 MHz radiofrequency radiation on adult rat auditory brainstem response

- Biochemical insights into the anthelmintic and anti-inflammatory potential of sea cucumber extract: In vitro and in silico approaches

- Resveratrol-derived MDM2 inhibitors: Synthesis, characterization, and biological evaluation against MDM2 and HCT-116 cells

- Phytochemical constituents, in vitro antibacterial activity, and computational studies of Sudanese Musa acuminate Colla fruit peel hydro-ethanol extract

- Chemical composition of essential oils reviewed from the height of Cajuput (Melaleuca leucadendron) plantations in Buru Island and Seram Island, Maluku, Indonesia

- Phytochemical analysis and antioxidant activity of Azadirachta indica A. Juss from the Republic of Chad: in vitro and in silico studies

- Stability studies of titanium–carboxylate complexes: A multi-method computational approach

- Efficient adsorption performance of an alginate-based dental material for uranium(vi) removal

- Synthesis and characterization of the Co(ii), Ni(ii), and Cu(ii) complexes with a 1,2,4-triazine derivative ligand

- Evaluation of the impact of music on antioxidant mechanisms and survival in salt-stressed goldfish

- Optimization and validation of UPLC method for dapagliflozin and candesartan cilexetil in an on-demand formulation: Analytical quality by design approach

- Biomass-based cellulose hydroxyapatite nanocomposites for the efficient sequestration of dyes: Kinetics, response surface methodology optimization, and reusability

- Multifunctional nitrogen and boron co-doped carbon dots: A fluorescent probe for Hg2+ and biothiol detection with bioimaging and antifungal applications

- Separation of sulphonamides on a C12-diol mixed-mode HPLC column and investigation of their retention mechanism

- Characterization and antioxidant activity of pectin from lemon peels

- Fast PFAS determination in honey by direct probe electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry: A health risk assessment insight

- Correlation study between GC–MS analysis of cigarette aroma compounds and sensory evaluation

- Synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular docking studies of substituted chromone-2-carboxamide derivatives as anti-breast cancer agents

- The influence of feed space velocity and pressure on the cold flow properties of diesel fuel

- Acid etching behavior and mechanism in acid solution of iron components in basalt fibers

- Protective effect of green synthesized nanoceria on retinal oxidative stress and inflammation in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat

- Evaluation of the antianxiety activity of green zinc nanoparticles mediated by Boswellia thurifera in albino mice by following the plus maze and light and dark exploration tests

- Yeast as an efficient and eco-friendly bifunctional porogen for biomass-derived nitrogen-doped carbon catalysts in the oxygen reduction reaction

- Novel descriptors for the prediction of molecular properties

- Synthesis and characterization of surfactants derived from phenolphthalein: In vivo and in silico studies of their antihyperlipidemic effect

- Turmeric oil-fortified nutraceutical-SNEDDS: An approach to boost therapeutic effectiveness of dapagliflozin during treatment of diabetic patients

- Analysis and study on volatile flavor compounds of three Yunnan cultivated cigars based on headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry

- Near-infrared IR780 dye-loaded poloxamer 407 micelles: Preparation and in vitro assessment of anticancer activity

- Study on the influence of the viscosity reducer solution on percolation capacity of thin oil in ultra-low permeability reservoir

- Detection method of Aristolochic acid I based on magnetic carrier Fe3O4 and gold nanoclusters

- Juglone’s apoptotic impact against eimeriosis-induced infection: a bioinformatics, in-silico, and in vivo approach

- Potential anticancer agents from genus Aerva based on tubulin targets: an in-silico integration of quantitative structure activity relationship (QSAR), molecular docking, simulation, drug-likeness, and density functional theory (DFT) analysis

- Hepatoprotective and PXR-modulating effects of Erodium guttatum extract in propiconazole-induced toxicity

- Studies on chemical composition of medicinal plants collected in natural locations in Ecuador

- A study of different pre-treatment methods for cigarettes and their aroma differences

- Cytotoxicity and molecular mechanisms of quercetin, gallic acid, and pinocembrin in Caco-2 cells: insights from cell viability assays, network pharmacology, and molecular docking

- Choline-based deep eutectic solvents for green extraction of oil from sour cherry seeds

- Green-synthesis of chromium (III) nanoparticles using garden fern and evaluation of its antibacterial and anticholinesterase activities

- Innovative functional mayonnaise formulations with watermelon seeds oil: evaluation of quality parameters and storage stability

- Molecular insights and biological evaluation of compounds isolated from Ferula oopoda against diabetes, advanced glycation end products and inflammation in diabetics

- Removal of cytotoxic tamoxifen from aqueous solutions using a geopolymer-based nepheline–cordierite adsorbent

- Unravelling the therapeutic effect of naturally occurring Bauhinia flavonoids against breast cancer: an integrated computational approach

- Characterization of organic arsenic residues in livestock and poultry meat and offal and consumption risks

- Synthesis and characterization of zinc sulfide nanoparticles and their genotoxic and cytotoxic effects on acute myeloid leukemia cells

- Activity of Coriandrum sativum methanolic leaf extracts against Eimeria papillata: a combined in vitro and in silico approach

- Special Issue on Advancing Sustainable Chemistry for a Greener Future

- One-pot fabrication of highly porous morphology of ferric oxide-ferric oxychloride/poly-O-chloroaniline nanocomposite seeded on poly-1H pyrrole: Photocathode for green hydrogen generation from natural and artificial seawater

- High-efficiency photocathode for green hydrogen generation from sanitation water using bismuthyl chloride/poly-o-chlorobenzeneamine nanocomposite

- Innovative synthesis of cobalt-based catalysts using ionic liquids and deep eutectic solvents: A minireview on electrocatalytic water splitting

- Special Issue on Phytochemicals, Biological and Toxicological Analysis of Plants

- Comparative analysis of fruit quality parameters and volatile compounds in commercially grown citrus cultivars

- Total phenolic, flavonoid, flavonol, and tannin contents as well as antioxidant and antiparasitic activities of aqueous methanol extract of Alhagi graecorum plant used in traditional medicine: Collected in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- Study on the pharmacological effects and active compounds of Apocynum venetum L.

- Chemical profile of Senna italica and Senna velutina seed and their pharmacological properties

- Essential oils from Brazilian plants: A literature analysis of anti-inflammatory and antimalarial properties and in silico validation

- Toxicological effects of green tea catechin extract on rat liver: Delineating safe and harmful doses

- Unlocking the potential of Trigonella foenum-graecum L. plant leaf extracts against diabetes-associated hypertension: A proof of concept by in silico studies

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Phytochemical investigation and evaluation of antioxidant and antidiabetic activities in aqueous extracts of Cedrus atlantica

- Influence of B4C addition on the tribological properties of bronze matrix brake pad materials

- Discovery of the bacterial HslV protease activators as lead molecules with novel mode of action

- Characterization of volatile flavor compounds of cigar with different aging conditions by headspace–gas chromatography–ion mobility spectrometry

- Effective remediation of organic pollutant using Musa acuminata peel extract-assisted iron oxide nanoparticles

- Analysis and health risk assessment of toxic elements in traditional herbal tea infusions

- Cadmium exposure in marine crabs from Jiaxing City, China: Insights into health risk assessment

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles of Cinnamomum zeylanicum and their biological activities

- Tetraclinis articulata (Vahl) Mast., Mentha pulegium L., and Thymus zygis L. essential oils: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antifungal properties against postharvest fungal diseases of apple, and in vitro, in vivo, and in silico investigation

- Exploration of plant alkaloids as potential inhibitors of HIV–CD4 binding: Insight into comprehensive in silico approaches

- Recovery of phenylethyl alcohol from aqueous solution by batch adsorption

- Electrochemical approach for monitoring the catalytic action of immobilized catalase

- Green synthesis of ZIF-8 for selective adsorption of dyes in water purification

- Optimization of the conditions for the preparation of povidone iodine using the response surface methodology

- A case study on the influence of soil amendment on ginger oil’s physicochemical properties, mineral contents, microbial load, and HPLC determination of its vitamin level

- Removal of antiviral favipiravir from wastewater using biochar produced from hazelnut shells

- Effect of biochar and soil amendment on bacterial community composition in the root soil and fruit of tomato under greenhouse conditions

- Bioremediation of malachite green dye using Sargassum wightii seaweed and its biological and physicochemical characterization

- Evaluation of natural compounds as folate biosynthesis inhibitors in Mycobacterium leprae using docking, ADMET analysis, and molecular dynamics simulation

- Novel insecticidal properties of bioactive zoochemicals extracted from sea urchin Salmacis virgulata

- Elevational gradients shape total phenolic content and bioactive potential of sweet marjoram (Origanum majorana L.): A comparative study across altitudinal zones

- Study on the CO2 absorption performance of deep eutectic solvents formed by superbase DBN and weak acid diethylene glycol

- Preparation and wastewater treatment performance of zeolite-modified ecological concrete

- Multifunctional chitosan nanoparticles: Zn2+ adsorption, antimicrobial activity, and promotion of aquatic health

- Comparative analysis of nutritional composition and bioactive properties of Chlorella vulgaris and Arthrospira platensis: Implications for functional foods and dietary supplements

- Growth kinetics and mechanical characterization of boride layers formed on Ti6Al4V

- Enhancement of water absorption properties of potassium polyacrylate-based hydrogels in CaCl2-rich soils using potassium di- and tri-carboxylate salts

- Electrochemical and microbiological effects of dumpsite leachates on soil and air quality

- Modeling benzene physicochemical properties using Zagreb upsilon indices

- Characterization and ecological risk assessment of toxic metals in mangrove sediments near Langen Village in Tieshan Bay of Beibu Gulf, China

- Protective effect of Helicteres isora, an efficient candidate on hepatorenal toxicity and management of diabetes in animal models

- Valorization of Juglans regia L. (Walnut) green husk from Jordan: Analysis of fatty acids, phenolics, antioxidant, and cytotoxic activities

- Molecular docking and dynamics simulations of bioactive terpenes from Catharanthus roseus essential oil targeting breast cancer

- Selection of a dam site by using AHP and VIKOR: The Sakarya Basin

- Characterization and modeling of kidney bean shell biochar as adsorbent for caffeine removal from aquatic environments

- The effects of short-term and long-term 2100 MHz radiofrequency radiation on adult rat auditory brainstem response

- Biochemical insights into the anthelmintic and anti-inflammatory potential of sea cucumber extract: In vitro and in silico approaches

- Resveratrol-derived MDM2 inhibitors: Synthesis, characterization, and biological evaluation against MDM2 and HCT-116 cells

- Phytochemical constituents, in vitro antibacterial activity, and computational studies of Sudanese Musa acuminate Colla fruit peel hydro-ethanol extract

- Chemical composition of essential oils reviewed from the height of Cajuput (Melaleuca leucadendron) plantations in Buru Island and Seram Island, Maluku, Indonesia

- Phytochemical analysis and antioxidant activity of Azadirachta indica A. Juss from the Republic of Chad: in vitro and in silico studies

- Stability studies of titanium–carboxylate complexes: A multi-method computational approach

- Efficient adsorption performance of an alginate-based dental material for uranium(vi) removal

- Synthesis and characterization of the Co(ii), Ni(ii), and Cu(ii) complexes with a 1,2,4-triazine derivative ligand

- Evaluation of the impact of music on antioxidant mechanisms and survival in salt-stressed goldfish

- Optimization and validation of UPLC method for dapagliflozin and candesartan cilexetil in an on-demand formulation: Analytical quality by design approach

- Biomass-based cellulose hydroxyapatite nanocomposites for the efficient sequestration of dyes: Kinetics, response surface methodology optimization, and reusability

- Multifunctional nitrogen and boron co-doped carbon dots: A fluorescent probe for Hg2+ and biothiol detection with bioimaging and antifungal applications

- Separation of sulphonamides on a C12-diol mixed-mode HPLC column and investigation of their retention mechanism

- Characterization and antioxidant activity of pectin from lemon peels

- Fast PFAS determination in honey by direct probe electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry: A health risk assessment insight

- Correlation study between GC–MS analysis of cigarette aroma compounds and sensory evaluation

- Synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular docking studies of substituted chromone-2-carboxamide derivatives as anti-breast cancer agents

- The influence of feed space velocity and pressure on the cold flow properties of diesel fuel

- Acid etching behavior and mechanism in acid solution of iron components in basalt fibers

- Protective effect of green synthesized nanoceria on retinal oxidative stress and inflammation in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat

- Evaluation of the antianxiety activity of green zinc nanoparticles mediated by Boswellia thurifera in albino mice by following the plus maze and light and dark exploration tests

- Yeast as an efficient and eco-friendly bifunctional porogen for biomass-derived nitrogen-doped carbon catalysts in the oxygen reduction reaction

- Novel descriptors for the prediction of molecular properties

- Synthesis and characterization of surfactants derived from phenolphthalein: In vivo and in silico studies of their antihyperlipidemic effect

- Turmeric oil-fortified nutraceutical-SNEDDS: An approach to boost therapeutic effectiveness of dapagliflozin during treatment of diabetic patients

- Analysis and study on volatile flavor compounds of three Yunnan cultivated cigars based on headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry

- Near-infrared IR780 dye-loaded poloxamer 407 micelles: Preparation and in vitro assessment of anticancer activity

- Study on the influence of the viscosity reducer solution on percolation capacity of thin oil in ultra-low permeability reservoir

- Detection method of Aristolochic acid I based on magnetic carrier Fe3O4 and gold nanoclusters

- Juglone’s apoptotic impact against eimeriosis-induced infection: a bioinformatics, in-silico, and in vivo approach

- Potential anticancer agents from genus Aerva based on tubulin targets: an in-silico integration of quantitative structure activity relationship (QSAR), molecular docking, simulation, drug-likeness, and density functional theory (DFT) analysis

- Hepatoprotective and PXR-modulating effects of Erodium guttatum extract in propiconazole-induced toxicity

- Studies on chemical composition of medicinal plants collected in natural locations in Ecuador

- A study of different pre-treatment methods for cigarettes and their aroma differences

- Cytotoxicity and molecular mechanisms of quercetin, gallic acid, and pinocembrin in Caco-2 cells: insights from cell viability assays, network pharmacology, and molecular docking

- Choline-based deep eutectic solvents for green extraction of oil from sour cherry seeds

- Green-synthesis of chromium (III) nanoparticles using garden fern and evaluation of its antibacterial and anticholinesterase activities

- Innovative functional mayonnaise formulations with watermelon seeds oil: evaluation of quality parameters and storage stability

- Molecular insights and biological evaluation of compounds isolated from Ferula oopoda against diabetes, advanced glycation end products and inflammation in diabetics

- Removal of cytotoxic tamoxifen from aqueous solutions using a geopolymer-based nepheline–cordierite adsorbent

- Unravelling the therapeutic effect of naturally occurring Bauhinia flavonoids against breast cancer: an integrated computational approach

- Characterization of organic arsenic residues in livestock and poultry meat and offal and consumption risks

- Synthesis and characterization of zinc sulfide nanoparticles and their genotoxic and cytotoxic effects on acute myeloid leukemia cells

- Activity of Coriandrum sativum methanolic leaf extracts against Eimeria papillata: a combined in vitro and in silico approach

- Special Issue on Advancing Sustainable Chemistry for a Greener Future

- One-pot fabrication of highly porous morphology of ferric oxide-ferric oxychloride/poly-O-chloroaniline nanocomposite seeded on poly-1H pyrrole: Photocathode for green hydrogen generation from natural and artificial seawater

- High-efficiency photocathode for green hydrogen generation from sanitation water using bismuthyl chloride/poly-o-chlorobenzeneamine nanocomposite

- Innovative synthesis of cobalt-based catalysts using ionic liquids and deep eutectic solvents: A minireview on electrocatalytic water splitting

- Special Issue on Phytochemicals, Biological and Toxicological Analysis of Plants

- Comparative analysis of fruit quality parameters and volatile compounds in commercially grown citrus cultivars

- Total phenolic, flavonoid, flavonol, and tannin contents as well as antioxidant and antiparasitic activities of aqueous methanol extract of Alhagi graecorum plant used in traditional medicine: Collected in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- Study on the pharmacological effects and active compounds of Apocynum venetum L.

- Chemical profile of Senna italica and Senna velutina seed and their pharmacological properties

- Essential oils from Brazilian plants: A literature analysis of anti-inflammatory and antimalarial properties and in silico validation

- Toxicological effects of green tea catechin extract on rat liver: Delineating safe and harmful doses

- Unlocking the potential of Trigonella foenum-graecum L. plant leaf extracts against diabetes-associated hypertension: A proof of concept by in silico studies