Biomass-based cellulose hydroxyapatite nanocomposites for the efficient sequestration of dyes: Kinetics, response surface methodology optimization, and reusability

Abstract

In this study, cellulose hydroxyapatite nanocomposite (CBG@HAP) is used effectively to adsorb dyes such as methylene blue (MB), crystal violet (CV), brilliant green (BG), and Congo red (CR). The X-ray diffraction investigation of CBG@HAP confirms the crystalline structure of CBG@HAP. The surface area investigated by Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) for CBG@HAP is 16.1995 m2/g, indicating a mesoporous structure. The adsorption efficiency of CBG@HAP was based on factors such as pH (2–10), contact time (5–240 min.), concentration (10–100 mg/L) of adsorbate, and temperature (298–308 K). The CBG@HAP exhibits a monolayer sorption capacity of 99.009 mg/g for MB at pH 7, 69.44 mg/g for CV at pH 6, 192.32 mg/g for BG at pH 6, and 120.48 mg/g for CR at pH 6. The CBG@HAP was accurately fitted by the Langmuir isotherm and exhibited kinetics of McKay and Ho order at an equivalence point of 120 min for all the dyes. The CBG@HAP exhibits endothermic, spontaneous, and physisorption toward all the dyes. Using central composite design response surface methodology, the experimental data were statistically optimized. The analysis revealed that the concentrated sodium hydroxide solution effectively desorbs MB (93.67%), CV (97.65%), and BG (91.21%), whereas the 0.1 M HCl solution effectively desorbs CR (98.43%).

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

Synthetic dyes are complex organic compounds that are adept at binding themselves to a variety of different surfaces and are extremely resistant to degradation. They are heavily utilized by numerous industries, including the food processing, paper, leather tanning, cosmetics, and textile sectors. [1]. Synthetic dyes are heterocyclic aromatic compounds linked with display and polar groups. These dyes absorb electromagnetic radiation in visible regions. Synthetic dyes are classified on the basis of their chemical structure, such as azo dyes containing nitrogen double-bond groups, chromophore and auxochrome properties, and applications at the industrial level. Due to their structural diversity, they exhibit different chemical, biological, and physical properties. Water-soluble synthetic dyes are classified into two types on the basis of charge as cationic (positively charged) and anionic (negatively charged). Crystal violet (CV), methylene blue (MB), and brilliant green (BG) are widely utilized synthetic cationic dyes in the global textiles and medical sectors. BG is a member of the malachite green (MG) series. BG shows antiseptic and antibacterial properties in diluted solutions. In the gastrointestinal tract, BG has mutagenic and carcinogenic properties that affect organs with prolonged exposure. BG is used illegally to treat fish diseases and for coloring the pulp in paper production. The fatal dose of BG in humans is 50–500 mg/kg. MB is an azo dye that belongs to the thiazine class containing a heterocyclic aromatic cation structure. MB exhibits antibacterial properties and is utilized in the treatment of melanoma. MB can affect the central nervous system. At high doses (<2 mg/kg), MB can affect the cardiac, renal, and pulmonary vascular tissues. At the concentration above 5 mg/kg, it can precipitate fatal serotonin in the body of the ecosystem [2]. The triphenylmethane class of compound CV is utilized in coloring and medicinal applications. CV is considered biohazardous for its high toxicity, mutagenesis properties, and carcinogenic behavior. CR is a sodium salt of benzidinediazo-bis-1-napthylamine-4-sulfonic acid. CV can cause various illnesses such as skin irritation, skin rashes, respiratory and digestive tract illness, cyanosis, and dermatitis [3]. CR is used in the textile industry and for staining biological samples for microscopic inspection. CR is highly toxic even at low concentrations and causes adverse health effects when exposed to individuals [4]. While the exact amount of dye discharged into the hydrosphere is unknown, this activity has probably had a detrimental effect on the environment. Several purification methods have been targeted to analyze complex colored wastewater, such as ultrafiltration [5], coagulation and flocculation [6], electrochemical techniques [7], chemical oxidation [8], and photocatalysis [9]. These purification processes are ineffective at eliminating pollutants on a pilot scale because they are expensive, inefficient, need complex operations to completely remove colors, and present difficulties in getting rid of the adsorbents and sludge produced during the process. Because of its efficiency in terms of operational simplicity, comparatively reduced operational costs as compared to alternatives, and environmentally friendly approach, the adsorption process is thus selected as an optimistic approach for pollutant extraction [10]. Substances such as biomaterials are utilized for the adsorption of pollutants since they are economical adsorbents. Application of waste biomaterials as an adsorbent has the potential to reduce the overall cost of the process. Activated carbon was selected as an adsorbent for contaminant sequestration because of its high sorption capacity. However, the expensive price, complicated production process, and high investment resulted in a transition to a more affordable option that offers effective adsorption capacity, easier handling, and disposal [11]. Cellulose is a highly promising material due to its strong hydrophilic nature and good sorption capacity. Researchers have investigated and proven the acceptability of orange peels, potato peels, banana peels, and garlic peels for the adsorption of synthetic colors from effluents [1,12,13]. Similar adsorbents have been effectively used for the adsorption of dyes, such as Luffa Actangula carbon [14], Neolamarckia cadamba-derived ZnO nanoparticles [15], NaOH-treated lemongrass leaf [16], pomegranate peel-activated carbon [17], Mn@ZIF-8 [18], and Fe/Mn-rice straw biochar [19]. The bottle gourd (Lagenaria siceraria) is a significant plant in the Cucurbitaceae species. It is often called lauki, doodhi, or gheeya in Asia and is widely utilized as a favorite vegetable due to its numerous health benefits. The bottle gourd peels are a byproduct of organic waste that can be used as an adsorbent, thereby reducing organic waste. The bottle gourd peels contain a significant amount of polysaccharide cellulose, which is used in this work for the adsorption of CV, CR, MB, and BG. Cellulose exhibits strong hydrophilicity as a result of the hydroxyl groups it contains and the flexibility of its polymer chains, which in turn leads to significant adsorption of dyes [20]. Hydroxyapatite (HAP) nanoparticles are a naturally occurring mineral type of calcium apatite, Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2. It is mostly utilized in the biomedical industry for bone and tooth applications. HAP effectively adsorbs heavy metals and dye pollutants in wastewater [21]. The cellulose derived from the peels of bottle gourd proves to be a low-cost, eco-friendly adsorbent. The peels were further modified with HAP, which has shown excellent results in the past for the adsorption of heavy metals. The use of HAP as one of the materials in the composite increases its efficiency in removing the pollutants effectively. The cellulose hydroxyapatite nanocomposite (CBG@HAP) adsorbent is a composite material derived from biomass materials, which are economical and can be easily disposed of and can be used as manure after complete degradation of the adsorbent [22]. Various works for the use of HAPs in contaminant removal are reported, like Oun et al., who utilized a Luffa cylindrica/HAP composite for MB and Pb2+ ions; a HAP/chitosan structure is used for the Pb2+ ion removal by Mohammad et al.; and Abbas et al. who discussed the role of hydroxyethyl cellulose for the removal of various metal ions [23,24,25]. No such work has been reported for the adsorption-based use of L. siceraria cellulose HAP composite for the removal of MB, CV, CR, and BG. Statistical analysis helps in validating the results by using appropriate statistical approach, making the research more accurate, reliable, and trustworthy. Different statistical analysis are carried out in various researches such as descriptive statistics, regression analysis, and chi-square method. Response surface methodology (RSM) method designs the experiments and analyzes the data to model the relationship between independent variables, and response provides a wide range of analysis in one method [26].

This work develops a cost-effective and environmentally friendly adsorbent derived from cellulose extracted from bottle gourd peels combined with HAP material (CBG@HAP) for removing CV, BG, CR, and MB. The optimum conditions contribute to the maximum adsorption of CV, BG, MB, and CR, which were evaluated by kinetics, isotherm, and thermodynamic studies. The morphology, surface properties, and presence of HAPs are effectively analyzed utilizing a range of instrumental approaches. Multiple operational setups, including contact time, pH, concentration, temperature, and desorption studies, were closely observed and measured. Furthermore, the adsorption process was optimized by the RSM-central composite design (CCD) model to validate the results.

2 Experimental setup

2.1 Materials and reagents

All the chemicals such as sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 98% purity), calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)2, 90% purity), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 30%), ortho-phosphoric acid (H3PO4 85%), hydrochloric acid (HCl, 35%), acetone (90% purity), crystal violet (CV, 90%), Congo red (CR, 90%), MB (90%), and BG (90%) were purchased from CDH, India.

2.2 Synthesis of adsorbent

2.2.1 Isolation of cellulose from bottle gourd peels

Bottle gourd peels (L. siceraria) were found as a waste. They were thoroughly cleaned with water for any contamination and further placed in a hot air oven at 750°C for 48 h for moisture elimination. They were converted to fine particles with a mesh size of 120–180 microns. About 30 g of ground powder was then submerged into 400 mL of demineralized water with 0.5% NaOH solution (w/v) and agitated at 800°C for 1 h, filtered, and drenched with boiling deionized water to exfoliate contaminants and achieve a pH of 7. The peels were then again dried for 24 h at 600°C [27,28]. After drying, they were bleached with H₂O₂ (10% v/v) and NaOH (2% w/v) in a 3:1 ratio at 90°C for a 45-min period of time. The obtained adsorbent was further washed with demineralized water till the adsorbent attained a neutral pH. The obtained cellulose of bottle gourd peels was further dried to remove moisture at 600°C for 24 h [29].

2.2.2 Formulation of cellulose HAP nanocomposites derived from bottle gourd peels (CBG@HAP)

About 5 g of cellulose powder obtained from bottle gourd peels was homogenized in 250 mL of deionized water at 800 rpm until thoroughly propagated. Then, 3.5 g of Ca(OH)₂ was added to the cellulose intermission and dispersed by ultrasonicator in a water bath at 60°C for 30 min. The suspension’s pH was adjusted to 10 by adding 0.1 M NaOH followed by intermixing for 60 min at a required temperature of 650°C. Then, 0.4 mL of H₃PO₄ solution was mixed in continuation with the mixture, followed by the stabilization of pH to 10 using NaOH by intermixing at 600°C for 180 min. Finally, the blend was aged, senescent at room temperature for 24 h, drenched with demineralized water for neutralization, and further dried at 80°C [23]. The generated adsorbent (CBG@HAP) was utilized in further adsorption investigations.

2.2.3 Response surface methodology

Response surface methodology is a statistical tool employed to assess the interactions among the input parameters to obtain the optimized results. RSM tools were used to design the matrix for complete removal of dyes using CBG@HAP by the CCD approach. The CCD was run for 13 trials to study the response surface methodology of adsorption of CV, CR, BG, and MB onto CBG@HAP. The operating parameters studied were contact time (5–240 min) and pH (1–9), with response as adsorption capacity (qe in mg/L) for each dye.

Material and method section, kinetics, isotherm, and thermodynamic model equations are reported in the supplementary file as Tables S1–S3.

3 Results and discussion

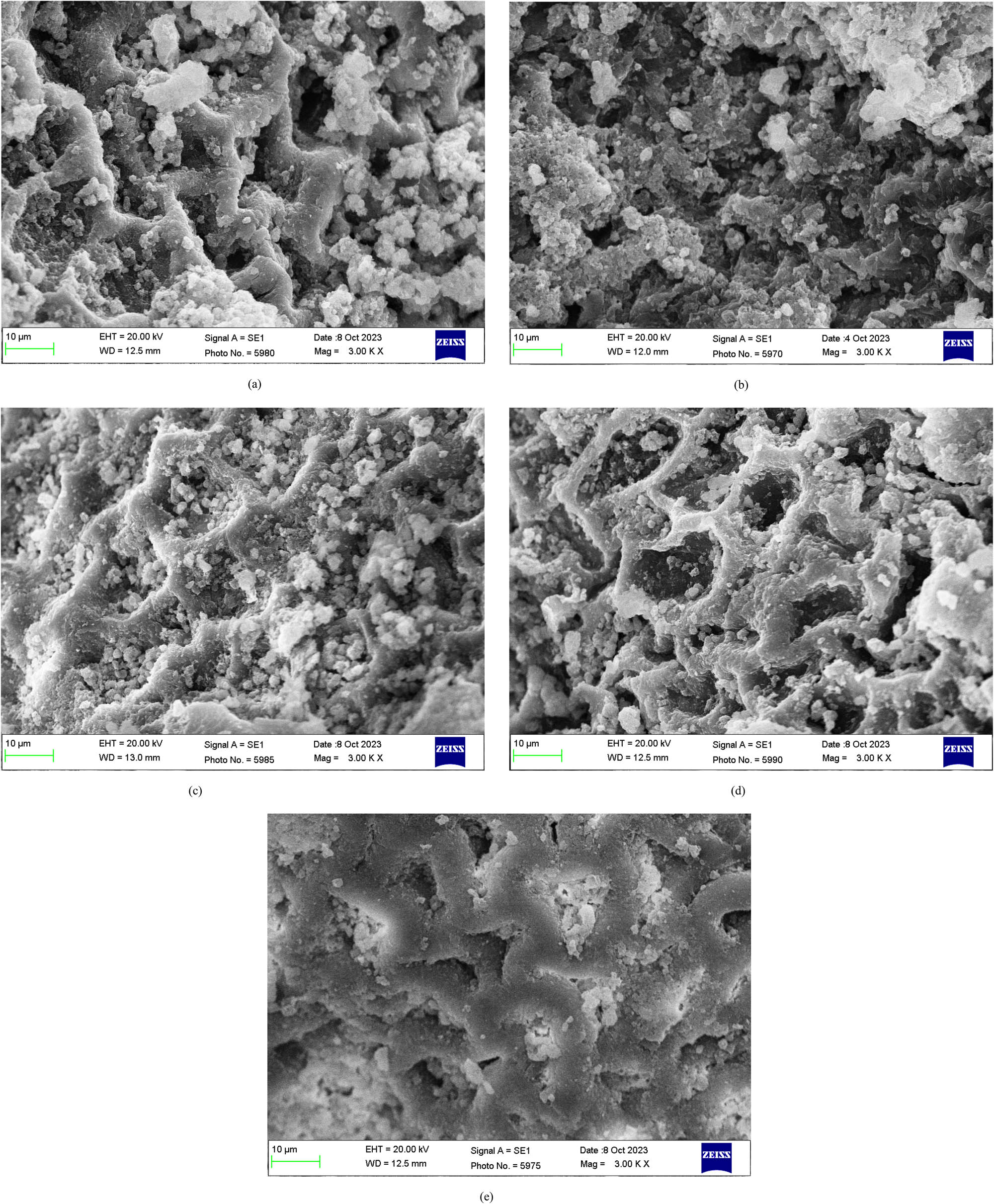

3.1 Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM) study

Surface characteristics of the CBG@HAP were analyzed using FE-SEM analysis. The FE-SEM image of the adsorbent, both before and after the adsorption of dyes such as MB, CV, BG, and CR, provides fascinating details about its surface. At first, the adsorbent has a surface structure that was irregular with patches that were uneven, as seen in Figure 1(a). The exterior of CBG@HAP was black, which was modified to white chips with rugged texture after treatment with H₂O₂. This is due to the lignocellulosic fiber materials extracted by H₂O₂ forming HCOO⁻ ions during oxidative deterioration [30]. After sorption of MB, CV, BG, and CR, as observed in Figure 1(b)–(e), the roughness of the surface was reduced and pores were occupied by the dyes. The effect of smoothing comes from the adsorbent interacting with the adsorbates. This can happen by molecules sticking to the adsorbent’s surface or chemical reactions that change the adsorbent’s surface properties. It appears that the adsorption process makes the surface appear more even or smooth, indicating that changes may be occurring to the structure or surface reactions.

FE-SEM images of CBG@HAP (a) before adsorption and (b) after adsorption of MB, (c) crystal violet, (d) BG, and (e) CR.

3.2 Energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX)

The EDX analysis provides the information about the elements composition present on the surface of the adsorbent before and after adsorbate interaction. The adsorbent initially had the following weight percentages of elements: C = 33.79%, O = 31.71%, F = 4.62%, P = 8.60%, and Ca = 21.25%, as depicted in the corresponding Figure 2(a). After adsorption of CR, the percentages changed to C = 44.77%, O = 28.91%, F = 3.46%, P = 5.92%, and Ca = 16.95%. The increase in C content suggests the presence of additional carbon from the dye, while the reduction in other elements confirms dye adsorption as indicated in Figure 2(b). Figure 2(c) shows the percentages of C = 30.70%, O = 34.45%, F = 6.43%, P = 8.42%, and Ca = 20.0% after loading of MB on the CBG@HAP surface. The increase in both C and O contents indicates additional carbon from the dye and oxygen possibly present in the dye. After adsorption of BG, the percentage of elements becomes C = 43.64%, O = 43.54%, F = 2.24%, P = 1.93%, and Ca = 8.64%, as shown in Figure 2(d). After further adsorption of CV, the percentages were C = 79.24%, O = 17.04%, and Ca = 3.71%. The significant increase in C content suggests additional carbon from the dye, while reductions in other elements affirm dye adsorption, as shown in Figure 2(e).

(a) EDX spectra of CBG@HAP before adsorption and (b) after adsorption of MB, (c) CV, (d) BG, and (e) CR.

3.3 Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) study

The wide peak detected at 3,282 cm−1 of CBG@HAP corresponds to –OH compounds on the adsorptive surface. The signal at 2,922 cm−1 was an indication of stretching vibration due to the presence of the C–H group, and the stretching vibration signal at 1,565 cm−1 corresponds to the N–O bond. The methylene group was positioned at 1,418 cm−1 wave number. The prominent peak at 1,026 cm−1 could be due to the C–O striking vibration frequency of prominent groups on the CBG@HAP surface, such as alcohol, acid, or ether. The signal at 561 cm−1 was of calcium-, fluorine-, or phosphorus-based inorganic substances, as observed in Figure 3. These findings line up with those from previous studies [31,32]. Furthermore, Figure 3 shows the FT-IR spectra of the adsorbent post-dye adsorption. As a result of the accumulation of BG, MB, CR, and CV dyes onto the CBG@HAP surface, a little shift in the previously seen peaks was observed, confirming the interaction between the surface of the adsorbent and the adsorbate molecules, which is required for efficient adsorption [33]. The C–H stretching frequency of the methylene group was observed at 2,950 cm−1, whereas 1,725 cm−1 indicates the C═O group after the adsorption of MB, CR, and CV dyes on the CBG@HAP surface. In addition, the adsorption of CV led to the formation of two more peaks, which were located at 1,584 and 1,364 cm−1, observing C═C stretching and O–H bending vibrations.

FT-IR spectra of CBG@HAP before and after the adsorption of MB, CV, BG, and CR.

3.4 X-ray diffraction (XRD)

The XRD spectra of CBG@HAP were investigated and is presented in Figure 4(a), indicating the crystalline nature of the adsorbent. The 2θ peaks of CBG@HAP were observed at different diffraction angles: 25.980, 38.020, 44.240, and 77.480. The d-value for CBG@HAP was found to be 2.30. The peaks at 31.720 and 44.240 suggest the crystalline cellulose region of bottle gourd peels. Similar peaks were also observed by Sharma et al., describing the cellulose structure of bottle gourd peels [34].

(a) XRD spectra of CBG@HAP and (b) BET isotherm plot N2 adsorption–desorption of CBG@HAP.

3.5 BET

The BET analysis is designed to provide information about the surface interspace and dimensions of the adsorbent material CBG@HAP. According to the Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) adsorption surface plot, the pore volume is 0.0985 cm3/g with a surface area of 16.1995 m2/g, as shown in Figure 4(b), indicating how the molecules of the adsorbate bind the surface of the adsorbent, whereas in the BJH desorption surface plot, the surface area is 22.9294 m2/g with a pore volume of 0.1051 cm3/g. International union of pure and applied chemistry justifies that the BET isotherm exhibits a Type III isotherm with an H3-type hysteresis loop, indicating a mesoporous structure forming wedge-shaped pore structures with white, flake-like materials made up of non-rigid materials. Similar results were observed by Aldahash et al. [32], for PA-12/CuNP particles showing Type III isotherm with a surface area of 26.3936 m2/g.

3.6 Effect of pH

The adhesion property and adequacy of the adsorbent to hold adsorbate were well explained by the pH study. The sorption of CV, BG, MB, and CR onto CBG@HAP was examined in the pH range from 2 to 10, as observed in Figure 5(a). The CBG@HAP acquires a +ve charge when pH < pHpzc and adsorbs a -ve charge when pH > pHpzc [30]. The pHz for CBG@HAP was found to be at 6.0, as observed in Figure 5(b). Generally, at high pH, the adsorption of cationic dyes increases, whereas for anionic dyes, it decreases [3]. After the adsorption of dyes, the adsorption capacity increases with an increase in pH from 2 to 7. The maximum efficiency for CV was obtained at pH 6, and pH 7 for MB and BG, with a decrease in the efficiency of adsorption after pH 8–10 [35]. The adsorption of azo dye is governed at pH > pHz due to the presence of moieties such as OH⁻ and COO⁻ groups [36]. In the case of CR, an anionic dye, pH increases from 2 to 4 and reaches a maximum at pH 5 and then decreases from pH 6 to 10. This is due to the presence of negative sulfonate (RSO32-) in its chemical structure. So there is an electrostatic attraction between positive CBG@HAP and negative CR groups, which leads to maximum adsorption. Related work was reported by Aldahash et al. for Pa-12/Portland cement composite for the adsorption of MB, CR, BG, and MO; Mohamed et al. showed similar results for BG for Halloysite nanoclay; and Zhu et al., showed similar results for CR and MB for chitosan/carboxymethyl cellulose-PEG hydrogels [2,37,38].

(a) Effect of pH for the adsorption of MB, CV, BG, and CR onto CBG@HAP and (b) point of zero charge for CBGP.

3.7 Effect of contact time and adsorption kinetics

The immersion experiment is observed to analyze the impact of time on adsorption studies. The concentrations of MB, CV, BG, and CR were 100 mg/L, and the time of the contact study was in the range of 5 to 240 min. As the time increases, the rate of sorption capacity increases and attains stability, as shown in Figure 6(a), for CV, BG, MB, and CR. The maximum adsorption capacity was obtained at 120 min for CV (50.1456 mg/g) > BG (49.69 mg/g) > MB (49.32 mg/g) > CR (47.44 mg/g), respectively. On the account of removal efficiency and equilibrium adsorption capacity, the rate of adsorption can describe the sorption phenomena [39]. The adsorption data acquired were utilized to investigate the kinetics of adsorption using the Lagergren first-order (PFO), McKay and Ho second-order (PSO), Elovich, and Weber and Morris models (IPD). The kinetic parameters for the adsorption of these contaminants are tabulated in Table 1. The adsorption of MB, CV, BG, and CR on CBG@HAP does not follow PFO, as qe (experimental) is not in coordination with qe (calculated), and the regression coefficient is low as compared to PSO, which shows significantly higher R 2 values for MB (R 2 = 1), CV (R 2 = 0.9925), BG (R 2 = 1), and CR (R 2 = 1) and low chi-sqr values, respectively, as observed in Figure 6(b) and (c). The kinetics of PFO and PSO (pseudo-second order) could not justify the phenomenon of adsorbate penetrating the adsorbent surface; hence, Weber and Morris’s model was subjected to molecular diffusion. As the plot of the qt vs t 0.5 curve passes through the intercept, the rate of sorption is subjected to pore promulgation, whereas when the curve does not incline toward the origin, then IPD cannot control the process of adsorption in a single phase [40], as shown in Figure 6(c). The sorption process is supported by external mass transfer and chemical reactivity. As the thickness of the boundary layer increases, the rate for adsorbate to adsorb on the surface of the adsorbent increases. The value of C for MB (48.22 mg/g), CV (46.89 mg/g), BG (48.38 mg/g), and CR (42.20 mg/g) suggests that higher C, Kid, and R 2 values imply that the intraparticle diffusion model is the rate-controlling step [32]. According to Table 1, the R 2 value for the Elovich model for most of the dyes is less than 0.96, which indicates that the Elovich model does not fit experimentally with PSO. The higher value of adsorption constant (A) than desorption constant (B) suggests the high rate of adsorption [38].

(a) Effect of contact time, (b) pseudo-first-order kinetics, (c) pseudo-second-order kinetics, (d) intraparticle diffusion, (e) Elovich model for the adsorption of CV, MB, BG, and CR onto CBG@HAP.

Adsorption kinetics model for the adsorption of MB, CV, BG, and CR on CBG@HAP

| Parameters | MB | CV | BG | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudo-first-order | ||||

| Q e(exp) (mg g−1) | 47.44 | 49.14 | 49.65 | 47.44 |

| Q e (cal) (mg g−1) | 0.87 | 1.68 | 0.97 | 3.89 |

| k 1 (min−1) | 0.014 | 0.023 | 0.031 | 0.188 |

| R 2 | 0.898 | 0.934 | 0.942 | 0.925 |

| Chi-sqr | 7.21 | 0.313 | 0.0186 | 0.010 |

| Pseudo-second-order | ||||

| Q e (exp) (mg g−1) | 47.44 | 49.14 | 49.65 | 47.44 |

| Q e (cal) (mg g−1) | 49.26 | 48.78 | 49.75 | 47.61 |

| k 2 (g/mg/min) | 0.068 | 0.0079 | 0.126 | 0.0184 |

| R 2 | 1 | 0.9925 | 1 | 1 |

| Chi-sqr | 0.0265 | 0.010 | 0.00016 | 0.0014 |

| Intra-particle diffusion | ||||

| K id (mgg−1 min−1/2) | 0.1008 | 0.262 | 0.155 | 0.571 |

| C (mg g−1) | 48.22 | 46.89 | 48.38 | 42.20 |

| R 2 | 0.8073 | 0.9497 | 0.7601 | 0.9571 |

| Chi-sqr | 0.154 | 0.777 | 0.1244 | 0.0021 |

| Elovich model | ||||

| A (mg g−1 min−1) | 47.97 | 46.50 | 48.08 | 41.07 |

| B (mg g−1) | 0.243 | 0.553 | 0.351 | 1.308 |

| R 2 | 0.9521 | 0.9555 | 0.912 | 0.991 |

| Chi-sqr | 0.146 | 0.751 | 0.115 | 0.00779 |

3.8 Concentration and isotherm study

The sorption of MB, CV, BG, and CR onto CBG@HAP was observed at different concentration ranging from 10 to 100 mg/L. The adsorption capacity of CBG@HAP for MB, CV, BG, and CR increases with enhancement in the concentration range due to the availability of unoccupied pores on CBG@HAP and the concentration pressure gradient [39]. As the concentration of dyes (MB, CV, BG, and CR) increases from 10 mg/L to 100 mg/L, the tendency of the adsorbent to hold adsorbate increases dramatically but then stabilizes, indicating the adsorption of L2 (Langmuir) type, where pollutants are sorbed continuously until all the adsorbent sites are completely deactivated [3]. The model of isotherm adsorption was carried out to inspect the liquid solutions’ sorption by connecting the sorption capacity to the residual concentration of the adsorbent. The isotherm model data are tabulated in Table 2 and Figure 7(a)–(c). According to the data reported in Table 2, the Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm models are in good coordination with a high regression coefficient and low chi-sqr for MB, BG, CV, and CR. According to the result reported, the dye molecules are adsorbed onto CBG@HAP initially as a monolayer and then as a multilayer. The value of RL is less than 1, and the Freundlich constant is 1–10, resulting in favorable adsorption. The dimensionless separation factor constant for all the dyes adsorbed was less than 1, indicating favorable sorption. The monolayer adsorption capacity for MB (99.09 mg/g), CV (69.44 mg/g), BG (192.30 mg/g), and CR (120.48 mg/g) was calculated and is tabulated in Table 2. The value of the Freundlich constant (n) for MB is 1.19, CV is 1.50, BG is 1.17, and CR is 1.30, indicating favorable adsorption, as the value of n is in the range of 1–10. Similar studies are reported by earlier works [41,42,43]. The model of the Temkin isotherm explains that the activation energies are uniformly distributed within the system. The value of B1 determines the adsorption as physisorption or chemisorption. The heat of adsorption constant (B1) < 20–40 kJ/mol describes the operation as physisorption; if the value is greater than 80–240 kJ/mol, then the process is chemisorption, while if it is between 20 and 40 kJ/mol, then the process is physical and chemical [38]. The values of B1 for MB (15.764 J/mg), CV (11.43 J/mg), BG (20.19 J/mg), and CR (14.46 J/mg) describing the procedure are physical for adsorption on CBG@HAP and are reported in Table 2. The Dubinin Radushkevich (D-R) isotherm describes the distribution of pores in adsorbents to follow Gaussian energy distribution [44]. If the adsorption energy value (E) < 8 kJ/mol, it is observed as physical adsorption, whereas if the adsorption energy value (E) ≥ 8 kJ/mol, it is indicated as chemical adsorption. Since the values of E for MB (1.61 kJ/mol), CV (0.86 kJ/mol), BG (0.91 kJ/mol), and CR (1.32 kJ/mol) are reported in Table 2, it indicates that the process of adsorption of MB, CV, and BG onto CBG@HAP is physiosorption [38].

Adsorption isotherms for the adsorption of MB, CV, BG, and CR onto CBG@HAP

| Parameters | MB | CV | BG | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Langmuir isotherm | ||||

| Q m (mg g−1) | 99.00 | 69.44 | 192.30 | 120.48 |

| R L | 0.063 | 0.126 | 0.336 | 0.110 |

| B (L mg−1) | 0.146 | 0.078 | 0.029 | 0.089 |

| R 2 | 0.9989 | 0.9502 | 0.9671 | 0.9667 |

| Chi-sqr | 0.01625 | 0.0020 | 0.0011 | 0.0012 |

| Freundlich isotherm | ||||

| K f (mg g−1) (L mg−1)−1/n | 12.07 | 6.01 | 5.94 | 10.06 |

| n | 1.19 | 1.50 | 1.17 | 1.30 |

| R 2 | 0.9977 | 0.9518 | 0.9550 | 0.9745 |

| Chi-sqr | 0.00019 | 0.0227 | 0.0080 | 0.0135 |

| Temkin isotherm | ||||

| B 1 (J mg−1) | 15.76 | 11.43 | 20.19 | 14.46 |

| K T (L mg−1) | 9.24 | 1.82 | 1.32 | 6.27 |

| R 2 | 0.9075 | 0.9078 | 0.9856 | 0.9372 |

| Chi-sqr | 8.270 | 0.612 | 0.002 | 2.206 |

| D-R isotherm | ||||

| q m (mg g−1) | 32.88 | 28.74 | 31.23 | 33.41 |

| β | 0.191 | 0.664 | 0.601 | 0.284 |

| R 2 | 0.834 | 0.880 | 0.861 | 0.897 |

| E (KJ mol−1) | 1.61 | 0.86 | 0.91 | 1.32 |

| Chi-sqr | 0.0404 | 0.014 | 0.018 | 1.041 |

Adsorption isotherm plot for the adsorption of CV, MB, BG, and CR onto CBG@HAP: (a) Langmuir isotherm, (b) Freundlich isotherm, and (c) Temkin isotherm.

3.9 Thermodynamics analysis

The adsorption was estimated for 25 mL of 100 mg/L each of MB, CV, CR, and BG onto CBG@HAP in the temperature range of 288–308 K. As there was an increase in the temperature, the capacity of the adsorbent to hold the adsorbate also shows an increase. The thermodynamic analyses were conducted by examining the sorption of MB, CV, BG, and CR on CBG@HAP at various temperatures between 288 and 308 K, as shown in Table 3 and Figure 8. According to the data tabulated in Table 3 for MB, CV, BG, and CR, the –ΔG 0 increases with an increase in temperature, indicating that the reaction for all the dyes is spontaneous. The physical adsorption is observed by MB, CV, BG, and CR because the value of ΔG 0 is less than −20 kJ/mol, as shown in Table 3. The values of ΔH 0 and ΔS 0 for MB, CV, BG, and CR are positive, indicating endothermal nature and randomness at the solid–liquid solution interface. The values of ΔH 0 reported for MB, CV, BG, and CR are less than or equal to 40 kJ/mol, indicating that the adsorption is physical [3].

Thermodynamic modeling of MB, CV, BG, and CR adsorption onto CBG@HAP

| Parameters | Temp(K) | MB | CV | BG | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔG 0 (kJ mol−1) | 288 | −7.86 | −8.33 | −10.06 | −4.59 |

| 298 | −9.22 | −8.90 | −10.60 | −9.22 | |

| 308 | −11.25 | −9.65 | −12.15 | −11.25 | |

| ΔH 0 (kJ mol−1) | 40.80 | 10.72 | 19.89 | 10.50 | |

| ΔS 0 (kJ mol−1 K−1) | 0.168 | 0.066 | 0.103 | 0.020 | |

| R 2 | 0.9801 | 0.986 | 0.8418 | 0.9919 | |

| Chi-sqr | 0.34 | 0.24 | 2.16 | 0.143 |

Thermodynamic plot for the adsorption of MB, CV, BG, and CR onto CBG@HAP.

3.10 Regeneration of the CBG@HAP

The adsorbent had to undergo a batch desorption process using three different desorbing agents to remove the dyes. The three agents used for desorption were 0.1 M HCl, 0.1 M NaOH, and 0.1 M acetone. The analysis revealed that the concentrated NaOH solution effectively desorbs MB (93.67%), CV (97.65%), and BG (91.21%). On the other hand, the 0.1 M HCl solution is a superior desorbing agent for CR (98.43%) compared to 0.1 M acetone, as depicted in Figure 9(a). The reaction between NaOH and HCl enhances the ability to exchange cations and anions, leading to the loss of solvation during demineralization. The CBG@HAP was regenerated for up to five cycles for the removal of CV, BG, CR, and MB, as shown in Figure 9(b). After five cycles, the adsorbent is exhausted, showing a decline in desorption efficiency of CBG@HAP [45]. The regeneration was carried out for up to six cycles, but it was observed that after five cycles, the adsorbent showed a decline in adsorbing the dye; in return, desorption efficiency also reduced, making it less suitable for the use of removing dyes because the active sites of CBG@HAP became saturated. Hence, an optimum of five cycles was suggested for the regeneration effect. A similar observation was also observed by Khatoon et al. and Tan et al. [28,46].

(a) Desorption of CBG@HAP using different eluents and (b) regeneration cycle of CBG@HAP.

3.11 Response surface methodology

The CCD was run to statistically optimize data of CV, MB, CR, and BG adsorption onto CBG@HAP. The 13 trials were run to study the operating conditions as X1 (contact time), X2 (pH), and response as qe in mg/L with a test run of (−1, 0, 1). According to the analysis of variance results reported, the F values for different dyes were obtained in the following manner: CR (77.74), MB (175.64), BG (12.17), and CV (286.57), which were greater, indicating that the results are significant. The p-values obtained are reported as CR (0.002), MB (0.001), BG (0.033), and CV (0.00), which are less than 0.50, which is accurate in describing the experimental data used for the adsorption study as shown in Table 4(a)–(d). The quadratic equation for the different dyes is given, indicating the link between the variables as shown in the following:

ANOVA for dyes adsorption onto CBG@HAP

| (a) ANOVA for CR | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | DF | Adj SS | Adj MS | F-Value | P-Value |

| Model | 5 | 20.2243 | 4.04487 | 77.74 | 0.002 |

| Linear | 2 | 9.9903 | 4.99517 | 96.00 | 0.002 |

| Time | 1 | 0.0034 | 0.00336 | 0.06 | 0.816 |

| pH | 1 | 0.0402 | 0.04023 | 0.77 | 0.444 |

| Square | 2 | 0.0024 | 0.00122 | 0.02 | 0.977 |

| Time*Time | 1 | 0.0004 | 0.00040 | 0.01 | 0.936 |

| pH*pH | 1 | 0.0000 | 0.00002 | 0.00 | 0.987 |

| 2-way interaction | 1 | 0.0002 | 0.00018 | 0.00 | 0.956 |

| Time*pH | 1 | 0.0002 | 0.00018 | 0.00 | 0.956 |

| Error | 3 | 0.1561 | 0.05203 | ||

| Total | 8 | 20.3804 | |||

| (b) ANOVA for MB | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | DF | Adj SS | Adj MS | F-Value | P-Value |

| Model | 5 | 10.7258 | 2.14517 | 175.64 | 0.001 |

| Linear | 2 | 6.9119 | 3.45595 | 282.96 | 0.000 |

| Time | 1 | 0.2869 | 0.28685 | 23.49 | 0.017 |

| pH | 1 | 0.4241 | 0.42414 | 34.73 | 0.010 |

| Square | 2 | 0.4458 | 0.22288 | 18.25 | 0.021 |

| Time*Time | 1 | 0.2670 | 0.26700 | 21.86 | 0.018 |

| pH*pH | 1 | 0.4303 | 0.43030 | 35.23 | 0.010 |

| 2-way interaction | 1 | 0.4068 | 0.40685 | 33.31 | 0.010 |

| Time*pH | 1 | 0.4068 | 0.40685 | 33.31 | 0.010 |

| Error | 3 | 0.0366 | 0.01221 | ||

| Total | 8 | 10.7625 | |||

| (c) ANOVA for BG | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | DF | Adj SS | Adj MS | F-Value | P-Value |

| Model | 5 | 8.7515 | 1.7503 | 12.17 | 0.033 |

| Linear | 2 | 5.4330 | 2.7165 | 18.88 | 0.020 |

| Time | 1 | 0.2274 | 0.2274 | 1.58 | 0.298 |

| pH | 1 | 0.3357 | 0.3357 | 2.33 | 0.224 |

| Square | 2 | 1.0509 | 0.5254 | 3.65 | 0.157 |

| Time*Time | 1 | 0.5904 | 0.5904 | 4.10 | 0.136 |

| pH*pH | 1 | 0.9986 | 0.9986 | 6.94 | 0.078 |

| 2-way interaction | 1 | 0.7723 | 0.7723 | 5.37 | 0.103 |

| Time*pH | 1 | 0.7723 | 0.7723 | 5.37 | 0.103 |

| Error | 3 | 0.4316 | 0.1439 | ||

| Total | 8 | 9.1830 | |||

| (d) ANOVA for CV | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | DF | Adj SS | Adj MS | F-Value | P-Value |

| Model | 5 | 60.1824 | 12.0365 | 286.57 | 0.000 |

| Linear | 2 | 39.2094 | 19.6047 | 466.76 | 0.000 |

| Time | 1 | 1.4696 | 1.4696 | 34.99 | 0.010 |

| pH | 1 | 2.2154 | 2.2154 | 52.75 | 0.005 |

| Square | 2 | 1.2861 | 0.6431 | 15.31 | 0.027 |

| Time*Time | 1 | 0.9502 | 0.9502 | 22.62 | 0.018 |

| pH*pH | 1 | 1.2843 | 1.2843 | 30.58 | 0.012 |

| 2-way interaction | 1 | 1.4731 | 1.4731 | 35.07 | 0.010 |

| Time*pH | 1 | 1.4731 | 1.4731 | 35.07 | 0.010 |

| Error | 3 | 0.1260 | 0.0420 | ||

| Total | 8 | 60.3084 | |||

For CR:

For MB:

For BG:

For CV:

The results indicate that the operating parameters statistically fit with the experimental results. The results were also justified by the low chi-sqr values for the kinetics and isotherm studies as reported in Tables 1 and 2. The contour and surface plots are represented in the given Figure 10 and Figure S1, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) Table 4(a)–(d) indicates the statistically fit data for all the dyes.

CCD optimization surface plot of CBG@HAP for qe vs contact time, pH for the adsorption of (a) CR, (b) MB, (c) BG, and (d) CV.

3.12 Comparative performance of CBG@HAP

The CBG@HAP monolayer adsorption capacities of different dyes were compared with different adsorbents and are reported in Table 5. It can be concluded that CBG@HAP shows good agreement with the previous work for the adsorption of CV, BG, MB, and CR.

Comparison of monolayer adsorption capacity (qmax) of CBG@HAP with other adsorbents for CV, MB, BG, and CR

| Pollutant | Adsorbent | Experimental condition | qmax(mg/g) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | Green seaweed Codium decorticated | pH = 6, Conc. = 3.6–100 mg/L equilibrium time = 120 min | 278.46 | [47] |

| Guar gum-graft-poly (acrylamide)/silica nanocomposite | pH = 3, Conc. = 3.6–100 mg/L equilibrium time = 30 min | 233.24 | [48] | |

| Eucalyptus wood (Eucalyptus globulus) Sawdust | pH = 7, Conc. = 50 mg/L equilibrium time = 240 min | 31.25 | [49] | |

| CBG@HAP | pH = 5, Conc. = 100 mg/L equilibrium time = 60 min | 120.48 | Present work | |

| MB | Dragon fruit peels | pH = 10, Conc. = 250 mg/L equilibrium time = 60 min | 195.2 | [50] |

| Fava bean peel (grinding) | pH = 5.8, Conc. = 3.6–100 mg/L equilibrium time = 120 min | 140 | [47] | |

| Nigella sativa seed (black cumin) and MnO2 composite | pH = 7, Conc. = 10–45 mg/L equilibrium time = 60 min | 185.18 | [35] | |

| CBG@HAP | pH = 7, Conc = 100 mg/L, equilibrium time = 60 min | 99.009 | Present work | |

| CV | Cellulose-derived bitter gourd waste | pH = 5.6, Conc. = 100 mg/L equilibrium time = 240 min | 1565 | [51] |

| Apple stem cellulose-based bio-adsorbent | pH = 10, Conc. = 100 mg/L equilibrium time = 100 min | 153.58 | [52] | |

| Lignocellulosic material motherwort (Leonurus cardiaca L.) Biomass | pH = 10, Conc = 50 mg/L equilibrium time = 60 min | 125.6 | [53] | |

| CBG@HAP | pH = 6, Conc. = 100 mg/L, equilibrium time = 60 min | 69.44 | This study | |

| BG | Modified Bambusa tulda | pH = 7 Conc. = 72–136 mg/L, equilibrium time = 60 min | 41.67 | [54] |

| ZnMg@PH | pH = 7 Conc. = 100 mg/L, equilibrium time = 30 min | 53.76 | [15] | |

| Chemically activated guava seeds carbon | pH = 9 Conc. = 100 mg/L, equilibrium time = 60 min | 80.5 | [55] | |

| CBG@HAP | pH = 6 Conc. = 100 mg/L, equilibrium time = 60 min | 192.32 | Present work |

3.13 Adsorption mechanism

The bottle gourd-derived CBG@HAP is capable of effectively adsorbing both cationic and anionic pigments due to a combination of electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and π–π stacking, which govern its reaction mechanism. As a result of the interaction between calcium ions (Ca2+) and the cellulose matrix, which is high in hydroxyl (OH−) groups, nucleation sites for HAP are formed. This occurs as a result of the reaction between calcium and phosphate ions (PO4 3−). The FT-IR spectra at 561 cm−1 also indicate the signals of calcium and phosphate groups. The HAP structure gives the composite two types of charge: positively charged calcium ions and negatively charged phosphate groups. This makes the composite very flexible. This is how cationic dyes such as MB and CV stick to cellulose: strong electrostatic interactions with phosphate groups, hydrogen bonds, and π–π stacking between the aromatic rings of the dye molecules and the structure of the cellulose [56], as shown in Figure 11. The occurrence of two new peaks after the adsorption of CV at 1,584 and 1,364 cm−1, observing C═C stretching and O–H bending vibrations indicates the adsorption of CV on CBG@HAP. The positively charged calcium ions on CBG@HAP electrostatically attach to the negatively charged sulfonate (–SO₃⁻) groups of anionic dyes such as CR, whereas hydrogen bonding between cellulose and the dye’s polar groups improves stabilization. Another factor that explains the dye adsorption is IPD, which states that dye adsorption is carried out in three ways: first, the dye molecules diffuse into the adsorbent surface. Then, it penetrates into the pores of the adsorbent surface, leading to the final equilibrium stage when the adsorption stabilizes [57]. The composite is structurally stable, has a large surface area, and works with different dye compounds. Its heterogeneous surface, having both negatively and positively charged active sites, makes sure that it can absorb well. Because of these multifaceted interactions, CBG@HAP is a very versatile and efficient adsorbent for a wide range of environmental contaminants.

Adsorption mechanism of CBG@HAP adsorption onto CR, MB, BG, and CV.

4 Conclusion

This study focuses on the extraction of cellulose from the waste peels of bottle gourd (L. siceraria). This cellulose-based HAP composite has shown exceptional efficacy in removing the adsorbed dyes. The characterization results indicate the presence of an irregular surface on the adsorbent, containing carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, fluorine, phosphorus, and calcium elements. The CBG@HAP exhibits pseudo-second-order kinetics, and Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms were in linearity to each other for CV, BG, MB, and CR. The CBG@HAP shows monolayer adsorption capacity for MB, CV, BG, and CR. The adsorption of MB, CV, BG, and CR onto CBG@HAP was physisorption. Thermodynamic data predict the dye’s interaction with the CBG@HAP as endothermic and spontaneous for all four dyes. The MB, CV, and BG can be effectively desorbed by 0.1 M NaOH, whereas CR can be effectively desorbed by 0.1 M HCl. The CBG@HAP can be regenerated effectively up to five cycles. After desorption, the CBG@HAP, which is an agricultural waste, can serve as a compost material for agricultural land. The CCD interpolates that the time and pH variables statistically fit with the response adsorption capacity (qe), and the data reported experimentally are statistically correct.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Nazrul Haq is thankful to the “Ongoing Research Funding Program (ORF-2025-1116), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia” for supporting this research.

-

Funding information: Dr. Nazrul Haq is thankful to the “Ongoing Research Funding Program (ORF-2025-1116), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia” for supporting this research.

-

Author contributions: A.K.: investigation, methodology, and analysis. S.S.: conceptualization, supervision, writing, review, and editing. N.H.: writing, review, editing, funds. A.A.: formal analysis, data curation. J.R.S.: software, data curation.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either animal or human use.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Arami M, Limaee NY, Mahmoodi NM, Tabrizi NS. Removal of dyes from colored textile wastewater by orange peel adsorbent: Equilibrium and kinetic studies. J Coll Interf Sci. 2005;288(2):371–6.10.1016/j.jcis.2005.03.020Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Aldahash SA, Higgins P, Siddiqui SH, Kashif Uddin M. Fabrication of polyamide‑12/cement nanocomposite and its testing for different dyes removal from aqueous solution: Characterization, adsorption, and regeneration studies. Sci Rep. 2022;12:13144.10.1038/s41598-022-16977-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Zhu H, Chen S, Duan H, He J, Luo Y. Removal of anionic and cationic dyes using porous chitosan/carboxymethyl cellulose-PEG hydrogels: Optimization, adsorption kinetics, isotherm and thermodynamics studies. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;231:123213.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.123213Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Bhatnagar A, Sillanpää M. Utilization of agro-industrial and municipal waste materials as potential adsorbents for water treatment—A review. Chem Eng J. 2010;157(2–3):277–96.10.1016/j.cej.2010.01.007Search in Google Scholar

[5] Ciardelli G, Corsi L, Marcucci M. Membrane separation for wastewater reuse in the textile industry. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2001;31(2):189–97.10.1016/S0921-3449(00)00079-3Search in Google Scholar

[6] Zahrim A, Dexter Z, Joseph C, Hilal N. Effective coagulation-flocculation treatment of highly polluted palm oil mill biogas plant wastewater using dual coagulants: decolourisation, kinetics and phytotoxicity studies. J Water Process Eng. 2017;16:258–9.10.1016/j.jwpe.2017.02.005Search in Google Scholar

[7] Škodič L, Vajnhandl S, Valh JV, Željko T, Vončina B, Lobnik A. Comparative study of reactive dyes oxidation by H2O2/UV, H2O2/UV/Fe2+ and H2O2/UV/Fe° processes. Ozone Sci Eng. 2017;39(1):14–23.10.1080/01919512.2016.1229173Search in Google Scholar

[8] Feddal I, Ramdani A, Taleb S, Gaigneaux EM, Batis N, Ghaffour N. Adsorption capacity of methylene blue an organic pollutant, by montmorillonite clay. Desalin Water Treat. 2013;52(13–15):2654–61.10.1080/19443994.2013.865566Search in Google Scholar

[9] Javed SM, Nazir MA, Shafiq Z, Sami U, Najam T, Iqbal R, et al. Advanced materials for photocatalytic removal of antibiotics from wastewater. J Alloy Compd. 2025;1010:178353.10.1016/j.jallcom.2024.178353Search in Google Scholar

[10] Sun L, Jiang Z, Yuan B, Zhi S, Zhang Y, Li J, et al. Ultralight and superhydrophobic perfluorooctyltrimethoxysilane modified biomass carbonaceous aerogel for oil-spill remediation. Chem Engg Res Design. 2021;174:71–8.10.1016/j.cherd.2021.08.002Search in Google Scholar

[11] Ullah S, Shah SSA, Altaf M, Ismail HI, El Sayed ME, Kallel M, et al. Activated carbon derived from biomass for wastewater treatment: Synthesis, application and future challenges. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2024;179:106480.10.1016/j.jaap.2024.106480Search in Google Scholar

[12] Hameed BH, Mahmoud DK, Ahmad AL. Sorption equilibrium and kinetics of basic dye from aqueous solution using banana stalk waste. J Hazard Mater. 2008;158(2–3):499–506.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.01.098Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Hameed BH, Ahmad AA. Batch adsorption of methylene blue from aqueous solution by garlic peel, an agricultural waste biomass. J Hazard Mater. 2009;164(2–3):870–5.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.08.084Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Siddiqui S. The removal of Cu2+, Ni2+ and Methylene Blue (MB) from aqueous solution using Luffa Actangula Carbon: Kinetics, thermodynamic and isotherm and response methodology. Groundwat Sustain Dev. 2018;6(1):141–9.10.1016/j.gsd.2017.12.008Search in Google Scholar

[15] Paul AS, Khan HS, Hassan I, Siddiqui S. Preparation and performance of novel bio‑nanocomposite ZnMg@PH for the removal of hazardous brilliant green, crystal violet, and diclofenac sodium. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2025;15:9599–612.10.1007/s13399-024-05801-0Search in Google Scholar

[16] Putri KNA, Kaewpichai S, Keereerak A, Chinpa W. Facile green preparation of lignocellulosic biosorbent from lemongrass leaf for cationic dye adsorption. J Polym Env. 2021;29:1681–93.10.1007/s10924-020-02001-5Search in Google Scholar

[17] Khalil A, Nazir MA, Salem MA, Ragab S, Nemr AEl. Magnetic pomegranate peels activated carbon (MG-PPAC) composite for Acid Orange 7 dye removal from wastewater. Appl Water Sci. 2024;14:178.10.1007/s13201-024-02225-zSearch in Google Scholar

[18] Nazir MA, Elsadek MF, Ullah S, Hossain I, Najam T, Ullah S, et al. Synthesis of bimetallic Mn@ZIF–8 nanostructure for the adsorption removal of methyl orange dye from water. Inorg Chem Commun. 2024;165:112294.10.1016/j.inoche.2024.112294Search in Google Scholar

[19] Wang Y, Lyu H, Du Y, Cheng Q, Liu Y, Ma J, et al. Unravelling how Fe-Mn modified biochar mitigates sulfamonomethoxine in soil water: The activated biodegradation and hydroxyl radicals formation. J Hazard Mater. 2024;465:133490.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2024.133490Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Saxena S, Garg S, Jana AK. Synthesis of cellulose based polymers for sorption of azo dyes from aqueous solution. J Env Res Devel. 2012;6(3):424–31.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Li Z, Wang G, Zhai K, He C, Li Q, Guo P. Methylene blue adsorption from aqueous solution by loofah sponge-based porous carbons. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 2018b;538:28–35.10.1016/j.colsurfa.2017.10.046Search in Google Scholar

[22] Yi L, Shen X, Shu Y, Deng B, Zhong Q, Peng Z, et al. Application of biomass energy in titanomagnetite reduction for Fe/Ti recycling: Overcoming the challenge of iron grain growth. Fuel. 2025;388:134511.10.1016/j.fuel.2025.134511Search in Google Scholar

[23] Oun AA, Kamal HK, Farroh K, Ali FE, Hassan MA. Development of fast and high-efficiency sponge-gourd fibers (Luffa cylindrica)/hydroxyapatite composites for removal of lead and methylene blue. Arab J Chem. 2021;14(8):103281.10.1016/j.arabjc.2021.103281Search in Google Scholar

[24] Mohammad AM, Salah Eldin TA, Hassan MA, El-Anadouli BE. Efficient treatment of lead-containing wastewater by hydroxyapatite/chitosan nanostructures. Arab J Chem. 2017;10(5):683–90.10.1016/j.arabjc.2014.12.016Search in Google Scholar

[25] Abbas A, Hussain MA, Sher M, Irfan MI, Tahir MN, Tremel W, et al. Design, characterization and evaluation of hydroxyethylcellulose based novel regenerable supersorbent for heavy metal ions uptake and competitive adsorption. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;102(A1):170–80.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.04.024Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Li B, Wu H, Liu X, Zhu T, Liu F, Zhao X. Simultaneous removal of SO2 and NO using a novel method with red mud as adsorbent combined with O3 oxidation. J Hazard Mater. 2020;392:122270.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122270Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Salah OA, Gamal A, Naeem E, Abd-Elhamid AI, Omaima OA, El-Bardan AA, et al. Adsorption of crystal violet and methylene blue -dyes using a cellulose-based adsorbent from sugercane bagasse: Characterization, kinetic and isotherm studies. Mater Res Technol. 2022;19:3241–54.10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.06.045Search in Google Scholar

[28] Khatoon A, Siddiqui S, Haq N. Cellulose – Polyvinylalcohol supported magnetic nanocomposites from lentil husk for sequestration of cationic dyes from the aqueous solution: Kinetics, isotherm and reusability studies. J Contam Hydrol. 2025;269:104503. 10.1016/j.jconhyd.2025.104503.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Niamsap T, Lam NT, Sukyai P. Production of hydroxyapatite-bacterial nanocellulose scaffold with assist of cellulose nanocrystals. Carbohydr Polym. 2019;205(1):159–66.10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.10.034Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Dawood S, Sen TK. Removal of anionic dye Congo red from aqueous solution by raw pine and acid-treated pine cone powder as adsorbent: equilibrium, thermodynamic, kinetics, mechanism and process design solution. Water Resear. 2012;46(6):1933–46.10.1016/j.watres.2012.01.009Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Palamthodi S, Lele SS. Optimization and evaluation of reactive dye adsorption on bottle gourd. J Env Chem Eng. 2016;4(4):4299–309.10.1016/j.jece.2016.09.032Search in Google Scholar

[32] Aldahash SA, Siddiqui SH, Kashif Uddin M. Eco-friendly synthesis of copper nanoparticles from fiber of Trapa natans L. shells and their impregnation onto polyamide-12 for environmental applications. J Nat Fiber. 2023;20(2):2224976.10.1080/15440478.2023.2224976Search in Google Scholar

[33] Alemu A, Brook LB, Gabbiye N, Alula MT, Teferi DM. Removal of chromium (VI) from aqueous solution using vesicular basalt: A potential low cost wastewater treatment system. Heliyon. 2018;4(7):e00682.10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e00682Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Sharma S, Kumari T, Choudhury N, Deka SC. Extraction of dietary fiber and encapsulated phytochemical enriched functional pasta from Bottle Guard (Lagenaria Siceraria) peel waste. Food Chem Adv. 2023;3(7):100492.10.1016/j.focha.2023.100492Search in Google Scholar

[35] Siddiqui SI, Manzoor O, Mohsin M, Chaudhry SA. Nigella sativa seed based nanocomposite-MnO2/BC: An antibacterial material for photocatalytic degradation, and adsorptive removal of Methylene blue from water. Env Res. 2019;171:328–40.10.1016/j.envres.2018.11.044Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Saleh MAM, Mahmoud KD, Karim WA, Idris A. Cationic and anionic dye adsorption by agricultural solid wastes: A comprehensive review. Desalination. 2011;280:1–3.10.1016/j.desal.2011.07.019Search in Google Scholar

[37] Mohamed A, Aljohani NS, Al-Mhyawi RS, Halawani RF, Aljuhani EH, Mohamed AS. A simple method for removal of toxic dyes such as Brilliant Green and Acid Red from the aquatic environment using Halloysite nanoclay. J Saudi Chem Soc. 2022;26(11):10147.10.1016/j.jscs.2022.101475Search in Google Scholar

[38] Mi X, Zhou S, Zhou Z, Vakili M, Qi Y, Jia Y, et al. Adsorptive removal of diclofenac sodium from aqueous solution by magnetic COF: Role of hydroxyl group on COF. Coll Surf A: Physicochem Eng Asp. 2020;603:125238.10.1016/j.colsurfa.2020.125238Search in Google Scholar

[39] Gómez V, Larrechi MS, Callao MP. Kinetic and adsorption study of acid dye removal using activated carbon. Chemosphere. 2007;69(7):1151–8.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.03.076Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Pandiarajan A, Kamaraj R, Vasudevan S, Vasudevan S. OPAC (orange peel activated carbon) derived from waste orange peel for the adsorption of chlorophenoxyacetic acid herbicides from water: adsorption isotherm, kinetic modeling and thermodynamic studies. Bioresour Technol. 2018;261:329–41.10.1016/j.biortech.2018.04.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Moradi E, Ebrahimzadeh H, Mehrani Z, Asgharinezhad AA. The efficient removal of methylene blue from water samples using three-dimensional poly (vinyl alcohol)/starch nanofiber membrane as a green nanosorbent. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2019;26(34):35071–81.10.1007/s11356-019-06400-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Eleryan A, Hassaan M, Nazir MA, Shah SA, Ragab S, Nemr AEl. Isothermal and kinetic screening of methyl red and methyl orange dyes adsorption from water by Delonix regia biochar-sulfur oxide (DRB-SO). Sci Rep. 2024;14:3585.10.1038/s41598-024-63510-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[43] Qiao CL, Ming XY, Yin Y, Xing XY, Xiao YH, Liu CQ. Adsorption of methyl orange on ZnO supported by seawater-modified Red Mud. Water Sci Technol. 2022;85(70):2208–24.10.2166/wst.2022.102Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Dabrowski A. Adsorption-from theory to practice. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2001;93:135–24.10.1016/S0001-8686(00)00082-8Search in Google Scholar

[45] Higgins P, Siddiqui SH, Kumar R. Design of novel graphene oxide/halloysite nanotube@polyaniline nanohybrid for the removal of diclofenac sodium from aqueous solution. Env Nanotechnol Monit Manag. 2022;17:100628.10.1016/j.enmm.2021.100628Search in Google Scholar

[46] Tan X, Ma X, Li X, Li Y. An adsorption model considering Fictitious stress. Fract Fraction. 2025;9:17.10.3390/fractalfract9010017Search in Google Scholar

[47] Oualid HA, Abdellaoui Y, Laabd M, Ouardi MEL, Brahmi Y, Iazza M, et al. Eco-efficient green seaweed codium decorticatum biosorbent for textile dyes: characterization, mechanism, recyclability, and RSM optimization. ACS Omega. 2020;35(5):22192–207.10.1021/acsomega.0c02311Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[48] Pal S, Patra AS, Ghorai S, Sarkar AK, Mahato V, Sarkar S, et al. Efficient and rapid adsorption characteristics of templating modified guar gum and silica nanocomposite toward removal of toxic reactive blue and Congo red dyes. Bioresour Technol. 2015;191:291–9.10.1016/j.biortech.2015.04.099Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Mane VS, Babu P. Kinetic and equilibrium studies on the removal of Congo red from aqueous solution using Eucalyptus wood (Eucalyptus globulus) saw dust. J Taiwan Instit Chem Eng. 2013;44(1):81–8.10.1016/j.jtice.2012.09.013Search in Google Scholar

[50] Jawad AH, Abdulhameed AS, Lee D, Wilson LD, Syed-Hassan SSA, ALOthman ZA, et al. High surface area and mesoporous activated carbon from KOH-activated dragon fruit peels for methylene blue dye adsorption: Optimization and mechanism study. Chin Chem Eng J. 2021;32(4):281–90.10.1016/j.cjche.2020.09.070Search in Google Scholar

[51] Lima LBL, Priyanthab N, Kamaludina IF, Nur AH, Zaidia M, Samaraweera APGMV. Adsorption of Crystal violet dye with cellulose derived from bitter gourd waste. Desalin Water Treat. 2021;217:431–41.10.5004/dwt.2021.26917Search in Google Scholar

[52] Mittal H, Al Alili A, Morajkar PP, Alhassan SM. Graphene oxide crosslinked hydrogel nanocomposites of xanthan gum for the adsorption of crystal violet dye. J Mol Liq. 2021;323(1):115034.10.1016/j.molliq.2020.115034Search in Google Scholar

[53] Mosoarca G, Vancea C, Popa S, Dan M. Crystal violet adsorption on eco-friendly lignocellulosic material obtained from Motherwort (Leonurus cardiaca L.) biomass. Polymers. 2022;14(18):3825.10.3390/polym14183825Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[54] Laskar N, Kumar U. Removal of brilliant green dye from water by modified BambusaTulda: Adsorption isotherm, kinetics and thermodynamics study. Intern J Env Sci Technol. 2019;16(3):1649–62.10.1007/s13762-018-1760-5Search in Google Scholar

[55] Mansoura R, Simedab G, Zaatout A. Adsorption studies on brilliant green dye in aqueous solutions using activated carbon derived from guava seeds by chemical activation with phosphoric acid. Desalin Water Treat. 2020;202:396–409.10.5004/dwt.2020.26147Search in Google Scholar

[56] Chatterjee S, Gupta A, Mohanta T, Mitra R, Samanta D, Mandal AB, et al. Scalable synthesis of hide substance−chitosan−hydroxyapatite: Novel bio composite from industrial wastes and its efficiency in dye removal. ACS Omega. 2018;3(9):10433–2319.10.1021/acsomega.8b00650Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[57] Pakdel PM, Peighambardoust SJ, Arsalani N, Aghdasinia H. Safranin-O cationic dye removal from wastewater using carboxymethyl cellulose-grafted-poly (acrylic acid-co-itaconic acid) nanocomposite hydrogel. Environ Res. 2022;212(3):113201.10.1016/j.envres.2022.113201Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Phytochemical investigation and evaluation of antioxidant and antidiabetic activities in aqueous extracts of Cedrus atlantica

- Influence of B4C addition on the tribological properties of bronze matrix brake pad materials

- Discovery of the bacterial HslV protease activators as lead molecules with novel mode of action

- Characterization of volatile flavor compounds of cigar with different aging conditions by headspace–gas chromatography–ion mobility spectrometry

- Effective remediation of organic pollutant using Musa acuminata peel extract-assisted iron oxide nanoparticles

- Analysis and health risk assessment of toxic elements in traditional herbal tea infusions

- Cadmium exposure in marine crabs from Jiaxing City, China: Insights into health risk assessment

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles of Cinnamomum zeylanicum and their biological activities

- Tetraclinis articulata (Vahl) Mast., Mentha pulegium L., and Thymus zygis L. essential oils: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antifungal properties against postharvest fungal diseases of apple, and in vitro, in vivo, and in silico investigation

- Exploration of plant alkaloids as potential inhibitors of HIV–CD4 binding: Insight into comprehensive in silico approaches

- Recovery of phenylethyl alcohol from aqueous solution by batch adsorption

- Electrochemical approach for monitoring the catalytic action of immobilized catalase

- Green synthesis of ZIF-8 for selective adsorption of dyes in water purification

- Optimization of the conditions for the preparation of povidone iodine using the response surface methodology

- A case study on the influence of soil amendment on ginger oil’s physicochemical properties, mineral contents, microbial load, and HPLC determination of its vitamin level

- Removal of antiviral favipiravir from wastewater using biochar produced from hazelnut shells

- Effect of biochar and soil amendment on bacterial community composition in the root soil and fruit of tomato under greenhouse conditions

- Bioremediation of malachite green dye using Sargassum wightii seaweed and its biological and physicochemical characterization

- Evaluation of natural compounds as folate biosynthesis inhibitors in Mycobacterium leprae using docking, ADMET analysis, and molecular dynamics simulation

- Novel insecticidal properties of bioactive zoochemicals extracted from sea urchin Salmacis virgulata

- Elevational gradients shape total phenolic content and bioactive potential of sweet marjoram (Origanum majorana L.): A comparative study across altitudinal zones

- Study on the CO2 absorption performance of deep eutectic solvents formed by superbase DBN and weak acid diethylene glycol

- Preparation and wastewater treatment performance of zeolite-modified ecological concrete

- Multifunctional chitosan nanoparticles: Zn2+ adsorption, antimicrobial activity, and promotion of aquatic health

- Comparative analysis of nutritional composition and bioactive properties of Chlorella vulgaris and Arthrospira platensis: Implications for functional foods and dietary supplements

- Growth kinetics and mechanical characterization of boride layers formed on Ti6Al4V

- Enhancement of water absorption properties of potassium polyacrylate-based hydrogels in CaCl2-rich soils using potassium di- and tri-carboxylate salts

- Electrochemical and microbiological effects of dumpsite leachates on soil and air quality

- Modeling benzene physicochemical properties using Zagreb upsilon indices

- Characterization and ecological risk assessment of toxic metals in mangrove sediments near Langen Village in Tieshan Bay of Beibu Gulf, China

- Protective effect of Helicteres isora, an efficient candidate on hepatorenal toxicity and management of diabetes in animal models

- Valorization of Juglans regia L. (Walnut) green husk from Jordan: Analysis of fatty acids, phenolics, antioxidant, and cytotoxic activities

- Molecular docking and dynamics simulations of bioactive terpenes from Catharanthus roseus essential oil targeting breast cancer

- Selection of a dam site by using AHP and VIKOR: The Sakarya Basin

- Characterization and modeling of kidney bean shell biochar as adsorbent for caffeine removal from aquatic environments

- The effects of short-term and long-term 2100 MHz radiofrequency radiation on adult rat auditory brainstem response

- Biochemical insights into the anthelmintic and anti-inflammatory potential of sea cucumber extract: In vitro and in silico approaches

- Resveratrol-derived MDM2 inhibitors: Synthesis, characterization, and biological evaluation against MDM2 and HCT-116 cells

- Phytochemical constituents, in vitro antibacterial activity, and computational studies of Sudanese Musa acuminate Colla fruit peel hydro-ethanol extract

- Chemical composition of essential oils reviewed from the height of Cajuput (Melaleuca leucadendron) plantations in Buru Island and Seram Island, Maluku, Indonesia

- Phytochemical analysis and antioxidant activity of Azadirachta indica A. Juss from the Republic of Chad: in vitro and in silico studies

- Stability studies of titanium–carboxylate complexes: A multi-method computational approach

- Efficient adsorption performance of an alginate-based dental material for uranium(vi) removal

- Synthesis and characterization of the Co(ii), Ni(ii), and Cu(ii) complexes with a 1,2,4-triazine derivative ligand

- Evaluation of the impact of music on antioxidant mechanisms and survival in salt-stressed goldfish

- Optimization and validation of UPLC method for dapagliflozin and candesartan cilexetil in an on-demand formulation: Analytical quality by design approach

- Biomass-based cellulose hydroxyapatite nanocomposites for the efficient sequestration of dyes: Kinetics, response surface methodology optimization, and reusability

- Multifunctional nitrogen and boron co-doped carbon dots: A fluorescent probe for Hg2+ and biothiol detection with bioimaging and antifungal applications

- Separation of sulphonamides on a C12-diol mixed-mode HPLC column and investigation of their retention mechanism

- Characterization and antioxidant activity of pectin from lemon peels

- Fast PFAS determination in honey by direct probe electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry: A health risk assessment insight

- Correlation study between GC–MS analysis of cigarette aroma compounds and sensory evaluation

- Synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular docking studies of substituted chromone-2-carboxamide derivatives as anti-breast cancer agents

- The influence of feed space velocity and pressure on the cold flow properties of diesel fuel

- Acid etching behavior and mechanism in acid solution of iron components in basalt fibers

- Protective effect of green synthesized nanoceria on retinal oxidative stress and inflammation in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat

- Evaluation of the antianxiety activity of green zinc nanoparticles mediated by Boswellia thurifera in albino mice by following the plus maze and light and dark exploration tests

- Yeast as an efficient and eco-friendly bifunctional porogen for biomass-derived nitrogen-doped carbon catalysts in the oxygen reduction reaction

- Novel descriptors for the prediction of molecular properties

- Synthesis and characterization of surfactants derived from phenolphthalein: In vivo and in silico studies of their antihyperlipidemic effect

- Turmeric oil-fortified nutraceutical-SNEDDS: An approach to boost therapeutic effectiveness of dapagliflozin during treatment of diabetic patients

- Analysis and study on volatile flavor compounds of three Yunnan cultivated cigars based on headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry

- Near-infrared IR780 dye-loaded poloxamer 407 micelles: Preparation and in vitro assessment of anticancer activity

- Study on the influence of the viscosity reducer solution on percolation capacity of thin oil in ultra-low permeability reservoir

- Detection method of Aristolochic acid I based on magnetic carrier Fe3O4 and gold nanoclusters

- Juglone’s apoptotic impact against eimeriosis-induced infection: a bioinformatics, in-silico, and in vivo approach

- Potential anticancer agents from genus Aerva based on tubulin targets: an in-silico integration of quantitative structure activity relationship (QSAR), molecular docking, simulation, drug-likeness, and density functional theory (DFT) analysis

- Hepatoprotective and PXR-modulating effects of Erodium guttatum extract in propiconazole-induced toxicity

- Studies on chemical composition of medicinal plants collected in natural locations in Ecuador

- A study of different pre-treatment methods for cigarettes and their aroma differences

- Cytotoxicity and molecular mechanisms of quercetin, gallic acid, and pinocembrin in Caco-2 cells: insights from cell viability assays, network pharmacology, and molecular docking

- Choline-based deep eutectic solvents for green extraction of oil from sour cherry seeds

- Green-synthesis of chromium (III) nanoparticles using garden fern and evaluation of its antibacterial and anticholinesterase activities

- Innovative functional mayonnaise formulations with watermelon seeds oil: evaluation of quality parameters and storage stability

- Molecular insights and biological evaluation of compounds isolated from Ferula oopoda against diabetes, advanced glycation end products and inflammation in diabetics

- Removal of cytotoxic tamoxifen from aqueous solutions using a geopolymer-based nepheline–cordierite adsorbent

- Unravelling the therapeutic effect of naturally occurring Bauhinia flavonoids against breast cancer: an integrated computational approach

- Characterization of organic arsenic residues in livestock and poultry meat and offal and consumption risks

- Synthesis and characterization of zinc sulfide nanoparticles and their genotoxic and cytotoxic effects on acute myeloid leukemia cells

- Activity of Coriandrum sativum methanolic leaf extracts against Eimeria papillata: a combined in vitro and in silico approach

- Special Issue on Advancing Sustainable Chemistry for a Greener Future

- One-pot fabrication of highly porous morphology of ferric oxide-ferric oxychloride/poly-O-chloroaniline nanocomposite seeded on poly-1H pyrrole: Photocathode for green hydrogen generation from natural and artificial seawater

- High-efficiency photocathode for green hydrogen generation from sanitation water using bismuthyl chloride/poly-o-chlorobenzeneamine nanocomposite

- Innovative synthesis of cobalt-based catalysts using ionic liquids and deep eutectic solvents: A minireview on electrocatalytic water splitting

- Special Issue on Phytochemicals, Biological and Toxicological Analysis of Plants

- Comparative analysis of fruit quality parameters and volatile compounds in commercially grown citrus cultivars

- Total phenolic, flavonoid, flavonol, and tannin contents as well as antioxidant and antiparasitic activities of aqueous methanol extract of Alhagi graecorum plant used in traditional medicine: Collected in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- Study on the pharmacological effects and active compounds of Apocynum venetum L.

- Chemical profile of Senna italica and Senna velutina seed and their pharmacological properties

- Essential oils from Brazilian plants: A literature analysis of anti-inflammatory and antimalarial properties and in silico validation

- Toxicological effects of green tea catechin extract on rat liver: Delineating safe and harmful doses

- Unlocking the potential of Trigonella foenum-graecum L. plant leaf extracts against diabetes-associated hypertension: A proof of concept by in silico studies

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Phytochemical investigation and evaluation of antioxidant and antidiabetic activities in aqueous extracts of Cedrus atlantica

- Influence of B4C addition on the tribological properties of bronze matrix brake pad materials

- Discovery of the bacterial HslV protease activators as lead molecules with novel mode of action

- Characterization of volatile flavor compounds of cigar with different aging conditions by headspace–gas chromatography–ion mobility spectrometry

- Effective remediation of organic pollutant using Musa acuminata peel extract-assisted iron oxide nanoparticles

- Analysis and health risk assessment of toxic elements in traditional herbal tea infusions

- Cadmium exposure in marine crabs from Jiaxing City, China: Insights into health risk assessment

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles of Cinnamomum zeylanicum and their biological activities

- Tetraclinis articulata (Vahl) Mast., Mentha pulegium L., and Thymus zygis L. essential oils: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antifungal properties against postharvest fungal diseases of apple, and in vitro, in vivo, and in silico investigation

- Exploration of plant alkaloids as potential inhibitors of HIV–CD4 binding: Insight into comprehensive in silico approaches

- Recovery of phenylethyl alcohol from aqueous solution by batch adsorption

- Electrochemical approach for monitoring the catalytic action of immobilized catalase

- Green synthesis of ZIF-8 for selective adsorption of dyes in water purification

- Optimization of the conditions for the preparation of povidone iodine using the response surface methodology

- A case study on the influence of soil amendment on ginger oil’s physicochemical properties, mineral contents, microbial load, and HPLC determination of its vitamin level

- Removal of antiviral favipiravir from wastewater using biochar produced from hazelnut shells

- Effect of biochar and soil amendment on bacterial community composition in the root soil and fruit of tomato under greenhouse conditions

- Bioremediation of malachite green dye using Sargassum wightii seaweed and its biological and physicochemical characterization

- Evaluation of natural compounds as folate biosynthesis inhibitors in Mycobacterium leprae using docking, ADMET analysis, and molecular dynamics simulation

- Novel insecticidal properties of bioactive zoochemicals extracted from sea urchin Salmacis virgulata

- Elevational gradients shape total phenolic content and bioactive potential of sweet marjoram (Origanum majorana L.): A comparative study across altitudinal zones

- Study on the CO2 absorption performance of deep eutectic solvents formed by superbase DBN and weak acid diethylene glycol

- Preparation and wastewater treatment performance of zeolite-modified ecological concrete

- Multifunctional chitosan nanoparticles: Zn2+ adsorption, antimicrobial activity, and promotion of aquatic health

- Comparative analysis of nutritional composition and bioactive properties of Chlorella vulgaris and Arthrospira platensis: Implications for functional foods and dietary supplements

- Growth kinetics and mechanical characterization of boride layers formed on Ti6Al4V

- Enhancement of water absorption properties of potassium polyacrylate-based hydrogels in CaCl2-rich soils using potassium di- and tri-carboxylate salts

- Electrochemical and microbiological effects of dumpsite leachates on soil and air quality

- Modeling benzene physicochemical properties using Zagreb upsilon indices

- Characterization and ecological risk assessment of toxic metals in mangrove sediments near Langen Village in Tieshan Bay of Beibu Gulf, China

- Protective effect of Helicteres isora, an efficient candidate on hepatorenal toxicity and management of diabetes in animal models

- Valorization of Juglans regia L. (Walnut) green husk from Jordan: Analysis of fatty acids, phenolics, antioxidant, and cytotoxic activities

- Molecular docking and dynamics simulations of bioactive terpenes from Catharanthus roseus essential oil targeting breast cancer

- Selection of a dam site by using AHP and VIKOR: The Sakarya Basin

- Characterization and modeling of kidney bean shell biochar as adsorbent for caffeine removal from aquatic environments

- The effects of short-term and long-term 2100 MHz radiofrequency radiation on adult rat auditory brainstem response

- Biochemical insights into the anthelmintic and anti-inflammatory potential of sea cucumber extract: In vitro and in silico approaches

- Resveratrol-derived MDM2 inhibitors: Synthesis, characterization, and biological evaluation against MDM2 and HCT-116 cells

- Phytochemical constituents, in vitro antibacterial activity, and computational studies of Sudanese Musa acuminate Colla fruit peel hydro-ethanol extract

- Chemical composition of essential oils reviewed from the height of Cajuput (Melaleuca leucadendron) plantations in Buru Island and Seram Island, Maluku, Indonesia

- Phytochemical analysis and antioxidant activity of Azadirachta indica A. Juss from the Republic of Chad: in vitro and in silico studies

- Stability studies of titanium–carboxylate complexes: A multi-method computational approach

- Efficient adsorption performance of an alginate-based dental material for uranium(vi) removal

- Synthesis and characterization of the Co(ii), Ni(ii), and Cu(ii) complexes with a 1,2,4-triazine derivative ligand

- Evaluation of the impact of music on antioxidant mechanisms and survival in salt-stressed goldfish

- Optimization and validation of UPLC method for dapagliflozin and candesartan cilexetil in an on-demand formulation: Analytical quality by design approach

- Biomass-based cellulose hydroxyapatite nanocomposites for the efficient sequestration of dyes: Kinetics, response surface methodology optimization, and reusability

- Multifunctional nitrogen and boron co-doped carbon dots: A fluorescent probe for Hg2+ and biothiol detection with bioimaging and antifungal applications

- Separation of sulphonamides on a C12-diol mixed-mode HPLC column and investigation of their retention mechanism

- Characterization and antioxidant activity of pectin from lemon peels

- Fast PFAS determination in honey by direct probe electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry: A health risk assessment insight

- Correlation study between GC–MS analysis of cigarette aroma compounds and sensory evaluation

- Synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular docking studies of substituted chromone-2-carboxamide derivatives as anti-breast cancer agents

- The influence of feed space velocity and pressure on the cold flow properties of diesel fuel

- Acid etching behavior and mechanism in acid solution of iron components in basalt fibers

- Protective effect of green synthesized nanoceria on retinal oxidative stress and inflammation in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat

- Evaluation of the antianxiety activity of green zinc nanoparticles mediated by Boswellia thurifera in albino mice by following the plus maze and light and dark exploration tests

- Yeast as an efficient and eco-friendly bifunctional porogen for biomass-derived nitrogen-doped carbon catalysts in the oxygen reduction reaction

- Novel descriptors for the prediction of molecular properties

- Synthesis and characterization of surfactants derived from phenolphthalein: In vivo and in silico studies of their antihyperlipidemic effect

- Turmeric oil-fortified nutraceutical-SNEDDS: An approach to boost therapeutic effectiveness of dapagliflozin during treatment of diabetic patients

- Analysis and study on volatile flavor compounds of three Yunnan cultivated cigars based on headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry

- Near-infrared IR780 dye-loaded poloxamer 407 micelles: Preparation and in vitro assessment of anticancer activity

- Study on the influence of the viscosity reducer solution on percolation capacity of thin oil in ultra-low permeability reservoir

- Detection method of Aristolochic acid I based on magnetic carrier Fe3O4 and gold nanoclusters

- Juglone’s apoptotic impact against eimeriosis-induced infection: a bioinformatics, in-silico, and in vivo approach

- Potential anticancer agents from genus Aerva based on tubulin targets: an in-silico integration of quantitative structure activity relationship (QSAR), molecular docking, simulation, drug-likeness, and density functional theory (DFT) analysis

- Hepatoprotective and PXR-modulating effects of Erodium guttatum extract in propiconazole-induced toxicity

- Studies on chemical composition of medicinal plants collected in natural locations in Ecuador

- A study of different pre-treatment methods for cigarettes and their aroma differences

- Cytotoxicity and molecular mechanisms of quercetin, gallic acid, and pinocembrin in Caco-2 cells: insights from cell viability assays, network pharmacology, and molecular docking

- Choline-based deep eutectic solvents for green extraction of oil from sour cherry seeds