Phytochemical constituents, in vitro antibacterial activity, and computational studies of Sudanese Musa acuminate Colla fruit peel hydro-ethanol extract

-

Wihad Khider

, Abdalrahim M. Ali

Abstract

A crucial worldwide concern is the development of drug-resistant bacteria; another problem is protecting the environment by reducing waste generation. This study aimed to explore antibacterial components from Musa acuminate fruit peel waste products. The powder was extracted by maceration using 70% ethanol and analyzed by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. The bacterial susceptibility test was performed against standard strains of Gram-positive bacteria Staphylococcus aureus and Gram-negative bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli by well diffusion method. The phytoconstituents were in silico analyzed to determine their binding affinities to the target bacterial proteins and the pharmacokinetic characters. GC–MS investigation indicated the occurrence of steroids, triterpenes, and sugars. The extract inhibited bacterial growth of all strains at concentrations as low as 125 mg/mL. 9,19-Cyclolanost-23-ene-3,25-diol (3.beta., 23E) and stigmasterol displayed a good binding affinity with the P. aeruginosa quorum sensing regulator, S. aureus enoyl-acyl carrier reductase, and E. coli dihydrofolate reductase proteins with docking scores comparable to the reference compounds. Also, they exhibited favorable pharmacokinetic characteristics. The results determined the beneficial antibacterial effects of banana peel waste products with diverse components that can likely be employed as a potential alternative to antibacterial agents. Further research is recommended to evaluate the antimicrobial potential of banana peel components.

1 Introduction

Persistently resistant bacteria pose a main threat to global public health through the widespread rise of antibiotic resistance [1]. The situation is made worse by the fact that drug production takes a long time for new drugs to be tested before being approved for commercialization by the FDA [2]. In spite of these conditions, finding antibiotic substitutes for the prevention and treatment of microbial illnesses is becoming increasingly important. The WHO emphasizes the possible benefits of medicinal plants as an alternate source for several pharmaceuticals [3]. The application of naturally occurring botanicals that may be employed in place of or in addition to antibiotics is one such strategy. Traditional medicines encompass different phytochemical classes, including phenol and phenolic glycosides, alkaloids, terpenoids, and steroids [4], and typically do not result in resistance [5] and have been used in conventional therapeutic systems.

Fruits and vegetables contain essential components for a healthy diet. They have activity to lower the risk of numerous chronic disorders [6]. Musa acuminate (banana) is traditionally called Musa in Sudan; it is a perennial tree-like herb with arranged fruit groups called “combs” from the family Musaceae [7]. It is a tropical plant, cultivated in more than 122 nations across the world [8]. In addition to its nutritional benefits, bananas traditionally were used for wound healing, ulcer, and anti-diarrheal [9]. Different parts of M. acuminate contain significant bioactive components, such as phenolics, carotenoids, biogenic amines, phytosterols, and volatile oils [10], which are responsible for maintaining health and preventing a number of diseases. Antioxidant [11], immunomodulatory [12], antibacterial [13], antiulcerogenic [14], hypolipidemic [15], hypoglycemic [16], leishmanicidal [17], and anticancer capabilities [18] are only a few of the pharmacological activities that bananas perform [19].

The development of bacteria resistance to antibiotics has made it essential to study novel antibacterial agents, particularly those derived from plants. Banana peels are utilized to produce products containing phytoconstituents and bioactive compounds with antibacterial, antioxidant, and anticancer effects [19].

Currently, scientists attempt to transform waste materials into products with added value. One of the primary goals of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is to considerably diminish waste generation by 2030 through avoidance, reduction, and reprocessing to protect the environment and public health [20]. The abuse of antibiotics, which are major contributors to the emergence of drug-resistant bacteria, is another worrying issue.

The purpose of this study was to confirm the banana fruit peel’s antibacterial capabilities and discover the components responsible for its antibacterial activity in the 70% ethanol extract. The anticipated manner of molecular interaction between identified compounds from banana fruit peels and the receptors they are intended to target will also be revealed by the consequences of molecular docking on the confirmation of potential lead compounds. The study also intended to assess these components’ pharmacokinetic characteristics and to investigate their binding mechanisms through computational study.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant material

The mature M. acuminate fruit peel was purchased from the Wad-Medani (Gezira State, Central Sudan) local market. The plant specimen was verified by the Agricultural Research Corporation (ARC) in Wad-Medani, Gezira State, Central Sudan. Banana peels were air-dried, processed into powder using a mechanical blender and stored at room temperature in a clean brown bottle until required for use.

2.2 Tested microorganisms and standard antibiotics

Gram-positive bacteria strains Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923) and Gram-negative bacteria strains Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 27853) and Escherichia coli (ATCC 25927) were acquired from the Medical Laboratory, Ministry of Health, Khartoum, Sudan. Antibacterial standards (Vancomycin, HiMedia Laboratories Company, India) for S. aureus and (Ceftriaxone, HiMedia Laboratories Company, India) for E. coli and P. aeruginosa were utilized as antibiotic standards.

2.3 Extraction of plant material

The dried powdered banana fruit peels (100 g) were macerated with 1 L of 70% ethanol for 72 h at 25°C and then filtered and concentrated by evaporation to yield the solid crude extract. The yield percentage was calculated and deposited in the fridge-freezer until needed.

2.4 Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) analysis

The crude banana peel extract was analyzed by GC–MS (Central Lab, National Centre for Research, Khartoum). GC–MS analyses were performed using a GC/MS-QP2010SE (Shimadzu Japan), fitted out with a capillary column (Rtx-5MS-30 m × 0.25 mm I.D. × 0.25 µm). The injector temperature was 300°C, and it was operating in a split manner. The oven temperature was electronically raised from 60 to 300°C at a rate of 10°C per minute. The flow rate of helium was adjusted to 1.6 mL/min, and the injection volume was 1 μL. The ion source temperature was 200°C, while the interface temperature was 250°C. 40–500 m/z was the mass scan range (m/z). The full running time is 34 min. The components’ spectra corresponded to a database spectra of components offered by the GC–MS library (NIST) [21].

2.5 In vitro antibacterial test

The well diffusion process was utilized to display the antibacterial activity of banana peel ethanol extract using Mueller Hinton Agar (MHA) [22]. Colonies from subcultured bacteria were diluted with 0.9% sterile normal saline to give 108 cfu/mL (turbidity equivalent to McFarland’s standard solution 0.5). McFarland was made by combining 0.6 mL of a 1.17% w/v solution of barium chloride with 99.4 mL of a 1% v/v solution of sulfuric acid [23]. Each sterile plate received approximately 20 mL of melting MHA medium, and once the agar solidified, the bacterial suspension was scattered uniformly over the agar using a sterile cotton swab. Then, it was gently mixed to ensure equal distribution. Following that, three circular wells of 8 mm in diameter were punched with a sterile borer [24]. Wells were filled with 100 µL of the extracts using various concentrations of extracts (500, 250, 125, 100, 50, and 25 mg/mL). While the negative control well was filled with 100 µL of the 50% methanol. The positive control was a ceftriaxone disc of 30 µg for E. coli and P. aeruginosa and vancomycin of 30 µg for S. aureus, which were deposited on the surface of the media. The plates were left 25°C for 1 h before being incubated at 37°C overnight. The mean diameter of the inhibition zones was calculated in (mm) [25,26].

2.6 In silico studies

All in silico investigations were conducted using Maestro version 12.8 of the Schrödinger suite [27]. Subsequent to GC–MS analysis, the three-dimensional structures of the phytoconstituents were acquired from PubChem and processed by means of LigPrep.

The crystal structures of P. aeruginosa quorum sensing regulator protein (PDB ID:4JVI) [28], S. aureus enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase (PDB ID:3GR6) [29], and E. coli dihydrofolate reductase (PDB ID: 2ANQ) [30] were obtained from the Protein Data Bank and prepared by the Protein Preparation Wizard. The prepared compounds were then docked using Glide in enhanced precision mode after the binding sites surrounding the native co-crystallized ligands were identified by the Receptor Grid tool. The compounds’ druggable capabilities were evaluated using the QikProp program. Pharmacokinetic characteristics like absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) were thoroughly examined. Additionally, it was utilized to predict critical characteristics that might indicate the compounds’ potential toxicity [31].

3 Results

3.1 The yield (%) of banana peel 70% ethanol extract

The current study utilized the hydro-ethanolic maceration extraction technique. The yield % of crude extract (ethanol 70%) of M. acuminate fruit peels in this study was found to be 22.8%.

3.2 GC–MS analysis of banana peel 70% ethanol extract

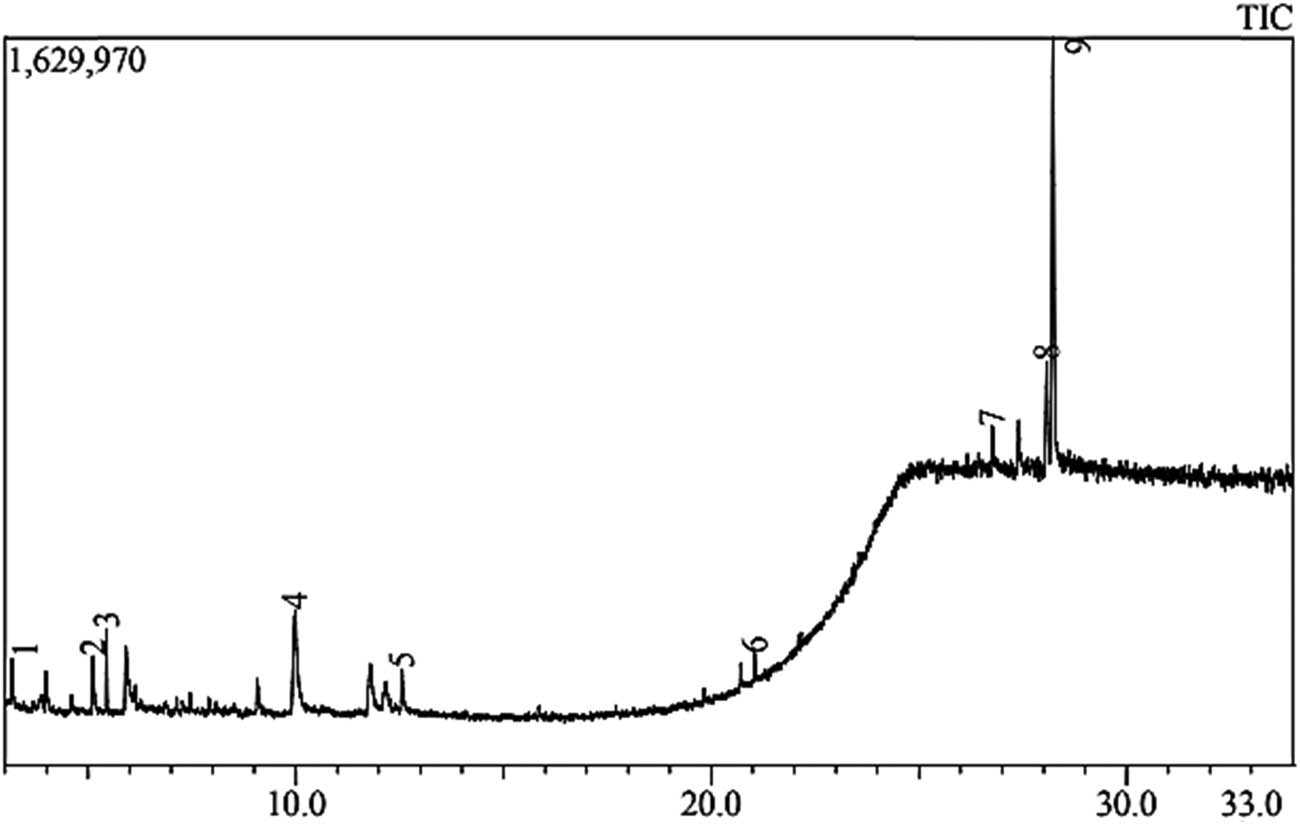

The banana peel crude extract was analyzed by GC–MS, and the result is illustrated in Figure 1. Nine phytoconstituents were detected with various polarities. GC–MS analysis of bioactive components M. acuminate fruit peels hydro-ethanolic extract (Table 1) showed a high percentage of steroids and terpenoids of about 66.34% and a relatively high percentage of sugar of 18.24%.

GC chromatogram of M. acuminate fruit peels 70% ethanol extract.

GC–MS analysis of M. acuminate fruit peels 70 % ethanol extract

| Peak no. | Name | Chemical formula | Retention time | Area % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6-Oxa-bicyclo[3.1.0]hexan-3-one | C5H6O2 | 3.168 | 1.75 |

| 2 | 1,3,5-Triazine-2,4,6-triamine | C3H6N6 | 5.122 | 4.04 |

| 3 | Undecane | C11H24 | 5.444 | 4.19 |

| 4 | Sucrose | C12H22O11 | 9.985 | 18.24 |

| 5 | 1-O-methyl-d-fructose, 1-omethylhex-2-ulose | C7H14O6 | 12.551 | 3.23 |

| 6 | Phthalic acid, monoamide, N-ethyl-N-(3-methylphenyl)-, undecyl ester | C28H39NO3 | 21.045 | 2.21 |

| 7 | Stigmasterol | C29H48O | 26.762 | 4.41 |

| 8 | Lup-20(29)-en-3-one | C30H48O | 28.081 | 13.00 |

| 9 | 9,19-Cyclolanost-23-ene-3,25-diol (3.beta., 23E) | C30H50O2 | 28.228 | 48.93 |

3.3 The antibacterial activities of banana peel 70% ethanol extract

The agar well diffusion procedure was utilized to evaluate the antibacterial efficacy of banana peel 70% ethanol extract. The susceptibility of three strains to banana peel 70% ethanol extract at concentrations of 500, 250, and 125 mg/mL is shown in Figure 2. The extract demonstrated considerable antibacterial effectiveness against all bacterial strains tested compared to vancomycin and ceftriaxone antibiotics. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of crude extract (ethanol 70%) of banana peel was 125 mg/mL.

The antibacterial effects of M. acuminate fruit peels 70% ethanol extract against S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and E. coli.

3.4 In silico studies

The docking study of GC–MS detected compounds of banana peels was conducted against three bacterial proteins which include E. coli dihydrofolate reductase (2ANQ), the enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase (3GR6), and finally, the P. aeruginosa quorum sensing regulator (4JVI). The docking results for the identified compounds are presented in Table 2. The analysis of ligand interactions with their corresponding target proteins revealed significant insights, particularly concerning the highest-scoring compounds. As indicated in Table 3 and illustrated in Figures 3–5, the highest-ranking ligands displayed prominent hydrophobic contacts with the target proteins, underscoring the importance of these interactions in ligand binding specificity and affinity. The pharmacokinetic characters of the phytomolecules were evaluated using the QikProp program. The ADME studies are presented in Table 4.

Docking scores of the phytochemicals from ethanol extract of M. paradisiaca ribbed fruit peel with targets enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase (FabI) (PDB ID: 3GR6), dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) (PDB ID: 2ANQ), and quorum sensing regulator (PqsR)

| No | Compound | PubChem ID | 4JVI | 3GR6 | 2ANQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Docking score | Docking score | Docking score | |||

| 1 | Sucrose | 5988 | −10.23 | −12.33 | −12.82 |

| 2 | Stigmasterol | 5280794 | −6.47 | −6.99 | −8.35 |

| 3 | 1-O-methyl-d-fructose | 129806387 | −8.93 | −8.51 | −7.30 |

| 4 | 6-Oxabicyclo | 535532 | −3.35 | −3.95 | −3.91 |

| [3.1.0]hexan-3-one | |||||

| 5 | 2,4,6-Triamine-1,3,5-triazine | 7955 | −3.17 | −3.47 | −4.02 |

| 6 | Undecane | 14257 | −1.31 | −1.55 | −1.40 |

| 7 | Lup20(29)en-3-one | 92158 | −4.49 | −4.61 | — |

| 8 | 9,19-Cyclolanost-23-ene-3,25-diol (3.beta., 23E) | 5370134 | −6.65 | −6.16 | −8.67 |

| 9 | Ligand (3NH2-7Cl-C9QZN) | −9.45 | — | — | |

| 10 | Ligand (triclosan) | — | −6.168 | — | |

| 11 | Ligand (C1A) | — | — | −8.235 | |

Molecular interaction sites of top phytochemicals with target proteins

| Target | Compound | Salt bridges | Hydrogen bond interaction | Halogen bond | Hydrophobic interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4JVI | Stigmasterol | — | ILE186 | — | ALA187, LEU189, TYR258, VAL170, TRP234, ALA168, ILE263, ILE236, ALA237, PRO238, ALA102, PRO129, ILE149, PHE221, MET224, LEU197, LEU207, LEU208, VAL211 |

| 9,19-Cyclolanost-23-ene-3,25-diol (3.beta., 23E) | — | ILE236, ILE186 | — | VAL211, LEU208, LEU207, TRP234, ALA237, PRO238, LEU197, PRO129, ILE149, MET224, PHE221, ALA168, VAL170, ILE263, TYR259, LEU189, ALA187 | |

| Lup20(29)en-3-one | — | — | — | VAL211, ALA190, LEU189, ALA187, ILE186, TYR258, VAL170, TRP234, ILE236, ILE263, LEU207 | |

| Ligand (3NH2-7Cl-C9QZN) | — | LEU207 | — | LEU197, ILE236, MET224, ALA237, PRO238, PHE221, PRO129, ALA102, ILE149, VAL170, ALA168, ILE263, LEU189, ILE186, LEU254, TYR258 | |

| 3GR6 | Stigmasterol | — | SER93 | — | ALA95, ILE94, ALA198, VAL201, PHE204, ALA15, ILE204, TYR157, MET160, ALA190, TYR147, PRO192, ILE193, ILE20, LEU196 |

| 9,19-Cyclolanost-23-ene-3,25-diol (3.beta., 23E) | — | GLY191, SER197 | — | ALA190, PRO192, ILE193, ILE20, LEU196, ALA198, VAL201, PHE204, ALA95, PHE96, ALA97, LEU102, MET160, TYR157, TYR147 | |

| Lup20(29)en-3-one | — | — | — | ILE14, ALA15, PHE96, ALA95, ILE94, PHE204, VAL201, TYR157, MET160, ALA198, TYR147, LEU196, ILE193, PRO192, ILE20, ALA190 | |

| Ligand (triclosan) | LYS164 | TYR157 | ALA97, ILE193 | ILE20, PRO192, ALA95, PHE96, ALA198, VAL201, LEU102, PHE204, MET160, TYR147 | |

| 2ANQ | Stigmasterol | — | ASP122, ASN18 | — | ILE50, LEU54, PHE31, TRP30, LEU28, TRY100, TRP22, MET20, ALA19, MET16, ILE14, ALA7, ALA6, ILE5, ILE94 |

| 9,19-Cyclolanost-23-ene-3,25-diol (3.beta., 23E) | — | ARG98 | — | ILE14, ILE50, ALA19, MET20, TRP22, LEU28, PHE31, ILE5, ALA6, ALA7, ILE94, VAL99, TYR100 | |

| Ligand (C1A) | — | LYS76, SER64, SER63, ARG44, HIP45, THR46, ASN18, ILE14, ALA7, THR123, ARG98, GLY97, ASP122, VAL99, GLN102 | — | TRP22, MET20, ALA19, MET16, ILE14, ALA6, ILE94, VAL99, TYR100, VAL28, LEU62 |

2D interaction of the top scoring phytochemicals in complex with 4JVI using XP docking mode of Glide software. The hydrophobic residues are in green color. The H-bond interactions with residues are illustrated by a purple dashed arrow oriented toward the electron donor. (a) 9,19-Cyclolanost-23-ene-3,25-diol (3.beta., 23E). (b) Stigmasterol.

2D interaction of the top scoring phytochemicals in complex with 2ANQ using XP docking mode of Glide software. The hydrophobic residues are in green color. The H-bond interactions with residues are illustrated by a purple dashed arrow oriented toward the electron donor. (a) 9,19-Cyclolanost-23-ene-3,25-diol (3.beta., 23E). (b) Stigmasterol.

2D interaction of the top scoring phytochemicals in complex with 3GR6 using XP docking mode of Glide software. The hydrophobic residues are in green color. The H-bond interactions with residues are illustrated by a purple dashed arrow oriented toward the electron donor. (a) 9,19-Cyclolanost-23-ene-3,25-diol (3.beta., 23E). (b) Stigmasterol.

ADME properties of the compounds

| Compound | QPlogS | QPlogPo/w | HOA | ROF | QPlog | QPlog | QPP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BB | HERG | Caco | |||||

| Sucrose | −0.16 | −3.64 | 1 | 2 | −2.50 | −2.95 | 19.50 |

| 1-O-methyl-d-fructose | −0.007 | −1.41 | 2 | 0 | −1.45 | −2.71 | 187.34 |

| Stigmasterol | −8.08 | 7.26 | 1 | 1 | −0.26 | −4.34 | 3430.68 |

| 9,19-Cyclolanost-23-ene-3,25-diol (3.beta., 23E) | −7.70 | 6.89 | 1 | 1 | −0.40 | −4.10 | 2421.09 |

| Lup20(29)en-3-one | −7.91 | 7.13 | 1 | 1 | 0.19 | −3.48 | 4453.17 |

| 6-Oxabicyclo[3.1.0]hexan-3-one | 1.24 | −0.67 | 3 | 0 | 0.17 | −1.34 | 2719.48 |

| 2,4,6-Triamine-1,3,5-triazine | −0.25 | −2 | 2 | 1 | −1.56 | −2.72 | 36.59 |

| Undecane | −6.87 | 6.22 | 1 | 1 | 1.079 | −3.14 | 9906.03 |

Notes: HOA: human oral absorption (1, 2, or 3 for low, medium, or high). QPlogBB: Predicted blood–brain barrier permeability (acceptable range –3 to 1.2). QPlogHERG: Predicted IC50 value for blockage of human ether-related gene (HERG) K+ channels which is a molecular target responsible for the cardiac toxicity (concern below −5.0). QPlogPo/w: Predicted octanol/water partition coefficient log P (acceptable range –2.0 to 6.5). QPlogS: Predicted aqueous solubility in mol/L (acceptable range –6.5 to 0.5). QPPCaco: Predicted caco cell membrane permeability in nm/s (acceptable range: 500 is great). ROF = RuleOfFive: Number of violations of Lipinski’s rule of five, which is considered a crucial measure of drug-likeness (maximum is 4).

4 Discussion

A critical global priority is to protect the environment and human health by intensely reducing waste production. Another issue of concern is the misuse and overuse of antibacterial medications, which contribute significantly to the development of drug-resistant microorganisms. Antibiotic resistance is increasing rapidly all over the world. Medicinal plants as sources of medicinal compounds may yield new antibacterial products [1,20].

The present study highlights the potential of bioactive compounds extracted from M. acuminate fruit peels as a sustainable solution to combat bacterial resistance.

Hydroalcoholic extraction yield of banana fruit peels was found to be 22.8%, which approximately matches the result done by Niamah [32], which was 16.4%. While the yield % of absolute ethanol extract in a study held by Hassan (2021) was found to be 55.1% [33]. However, hydro-ethanol mixtures with elevated ethanol concentrations (70–90%) are typically favored for extraction due to their capacity to extract a diverse array of chemicals with differing polarity [34].

GC–MS analysis of M. acuminate fruit peels hydro-ethanolic extract revealed the presence of triterpene, steroids, and sugar as major ingredients that match with the composition of the Indian Musa sapientum peel with steroidal percentage of 73.65% and sugars 19.64%. On the other hand, a study of USA variety banana peel demonstrated high steroids of 90.19% and a low sugar percentage of 5.16% [21,35].

The M. acuminate peel extract exhibited substantial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, a result in line with those reported by Ehiowemwenguan et al. [8] which demonstrated M. sapientum peel ethanol extract has antimicrobial properties in concentration 1.025, 512.5 mg/mL against S. aureus and have activity against E. coli in 1.025, 512.5, 256, 128, and 64 mg/mL concentrations. Also, the same extract was exhibited antibacterial activity against P. aeruginosa at concentrations 1.025, 512.5, 256, and 128 mg/ml. El Zawawy [36] reported the ethanolic extract of Musa acuminata fruit peels at a concentration of 20 mg/mL has activity against three types of bacterial S. aureus, E. coli and P. aeruginosa. Siddique et al. [37] demonstrated that water extracts exhibited the strongest antibacterial action against the majority of examined microorganisms (S. aureus, E. coli, and P. aeruginosa); this marginally higher activity may be because the water extracts contained alkaloids and saponins, which were absent from banana ethanolic preparations. Bashir et al. [38] tested banana peel in DMSO solution, which has antibacterial activity and highest inhibition zone against S. aureus and E. coli. The results obtained justify the traditional antibacterial use of banana peels. The secondary metabolites present in the extract have been reported to be responsible for its therapeutic activity. Terpenoids, sterols, furan and pyran derivatives, and their individual components have been used for a variety of bacterial infections [6,36]. Further recommendation studies should be encouraged to determine the MIC and maximum bactericidal concentration for M. acuminate ripe fruit peel against S. aureus, E. coli, and P. aeruginosa bacteria strains.

Following the GC–MS analysis of the banana peel extract, molecular docking serves as a vital tool to further explore the bioactive components identified. The GC–MS technique enables the separation and identification of various phytochemicals. At the same time, molecular docking allows to predict how these compounds might interact with biological targets at the molecular level. The combination of methods enhances understanding of the extract’s antibacterial potential and guides future experimental validation. For this purpose, three validated therapeutic targets were enrolled in docking studies. The E. coli dihydrofolate reductase (2ANQ), a key enzyme in the folate biosynthesis pathway [39], the enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase (3GR6), an integral part of S. aureus’s fatty acid production; and finally the P. aeruginosa quorum sensing regulator (4JVI), a key component in its adaptation and virulence [40].

The co-crystallized ligands were used to calculate the root mean square deviation (RMSD) values; a critical metric used to evaluate the accuracy of molecular docking results. By comparing the positions of the docked ligands with their respective conformations in the crystal structures, we obtained RMSD values of 1.87 Å for protein 2ANQ, 1.53 Å for protein 3GR6, and 0.73 Å for protein 4JVI. All three RMSD values were below 2.0 Å [41]. This indicated a high level of concordance between the docked ligands and their co-crystallized counterparts, suggesting that the docking protocol employed for these proteins successfully predicted the binding orientation with good precision.

The compounds retrospective docking scores are summarized in Table 3. The docking analysis for the 4JVI target in P. aeruginosa revealed a score range from −10.23 to −1.31 kcal/mol. Among the identified compounds in the extract, stigmasterol (−6.47 kcal/mol) and 9,19-cyclolanost-23-ene-3,25-diol (3.beta., 23E) (−6.65 kcal/mol) exhibited good docking scores and moderate affinity toward 4JVI when compared to the native ligand 3NH2-7Cl-C9QZN (−9.45 kcal/mol), suggesting that these compounds could effectively bind to the target and potentially act as lead compounds for further antimicrobial drug development. In comparison, Lup20(29) en-3-one (−4.49 kcal/mol) showed weak binding and affinity, which may imply a less favorable binding profile and activity against the target.

For 3GR6 in S. aureus, docking scores spanned from −12.33 to −1.55. Similar to the 4JVI target, 9,19-cyclolanost-23-ene-3,25-diol (3.beta., 23E) (−6.16 kcal/mol) and stigmasterol (−6.99 kcal/mol) displayed a strong affinity for this target protein, comparable to the native ligand triclosan affinity (–6.168 kcal/mol), reinforcing their potential. Lup20(29) en-3-one (−4.61 kcal/mol) again showed mild binding and affinity for the target.

For target 2ANQ in E. coli, docking scores ranged between −12.82 and −1.40 kcal/mol. Compounds, stigmasterol (−8.35 kcal/mol) and 9,19-cyclolanost-23-ene-3,25-diol (3.beta., 23E) (−8.67 kcal/mol), continued to exhibit strong affinity, even more than the native ligand (−8.23 kcal/mol); however, the compound Lup20(29) en-3-one was notably different, showing no measurable binding or affinity. This lack of binding suggests that Lup20(29) en-3-one may not be suitable for targeting this protein. A previous docking study held by Bakrim et al. [42] revealed that stigmasterol had promising antimicrobial properties. The compound exhibited binding affinities of −7.0 kcal/mol against 2ANQ, and the scores were comparable to ciprofloxacin (−7.6 kcal/mol). The molecular docking scores of stigmasterol against P. aeruginosa PqsA showed binding affinities of −7.8 kcal/mol, and the results were similar to ciprofloxacin (−8.2 kcal/mol). Stigmasterol also showed higher scores (−7.7 and −7.4 kcal/mol) against S. aureus Pk.

Focusing first on the binding characteristics with the target protein 3GR6, several key interactions were noted among the compounds. Specifically, cyclolanost formed two hydrogen bonds with residues GLY191 and SER197, highlighting its potential for strong interaction. Similarly, stigmasterol formed one hydrogen bond with side chain SER93, suggesting its effective binding capacity. Lup20(29)en-3-one did not have any polar or hydrogen bonding interactions with 3GR6, which justified its weak binding affinity. The native ligand triclosan, although forming one hydrogen bond with TYR157, established two significant interactions, a salt bridge interaction with LYS164 and two halogen bonds with ALA97 and ILE193. Notably, the residues ALA198, VAL201, and PHE204 emerged as essential contributors, facilitating the majority of hydrophobic interactions, which are crucial for enhancing the overall binding strength of these ligands.

As for the docking interactions with 4JVI, 9,19-cyclolanost-23-ene-3,25-diol (3.beta., 23E) interactions were characterized by hydrogen bonds with ILE236 and ILE186, significantly stabilizing the ligand-protein complex and demonstrating its potential efficacy. On the other hand, stigmasterol demonstrated a single hydrogen bond with ILE186, while lup20(29)en-3-one did not form any hydrogen bond. Native ligand (3NH2-7Cl-C9QZN) had one hydrogen bond with residue LEU207. The constant participation of residues LEU208 and VAL211 in all hydrophobic interactions underlines their critical role in binding stability across various compounds, emphasizing the importance of hydrophobic residues in ligand affinity and specificity.

Concerning the binding affinity between ligands and 2ANQ, stigmasterol made two hydrogen bonds with ASP122 and ASN18. 9,19-Cyclolanost-23-ene-3,25-diol (3.beta., 23E) exhibited a single hydrogen bonding interaction with ARG98. Lastly, the native ligand C1A formed hydrogen bonds with LYS76, SER64, SER63, ARG44, HIP45, THR46, ASN18, ILE14, ALA7, THR123, GLY97, ASP122, VAL99, and GLN102 due to its highly polar nature. The aromatic TRP22 residue was included in all hydrophobic interactions.

Previous computational studies have reported similar findings. For instance, Hammad et al. worked on the 3GR6 target have identified significant hydrogen bonding interactions with the residues TYR157 and SER93. Also, their investigations highlighted the presence of hydrophobic interactions involving several other key residues, specifically residues ALA190, LEU196, PRO192, TYR157, and ILE14 [43]. Moreover, previous computational analysis on 4JVI done by Olanrewaju et al. reported similar hydrogen bonding interactions with residues ILE186 and LEU207 [43].

In this study, an ADME analysis was implemented to access the pharmacokinetic properties of the active compounds using QikProp (Table 4), a Maestro module. Lipinski’s Rule of Five is a well-established guideline in medicinal chemistry to evaluate a compound’s drug-likeness [44]. This rule suggests that a compound is more likely to exhibit favorable oral bioavailability and permeability if it meets certain Lipinski’s Rule of Five (ROF) criteria [44]. In Table 4, all identified compounds have violated the rule of five. The three terpenoids, stigmasterol, 9,19-cyclolanost-23-ene-3,25-diol (3.beta., 23E), and lup20(29)en-3-one, had only one violation of the rule, as their predicted octanol/water partition coefficient (QPlogPo/w) was over 5 due to their lipophilic nature.

The predicted human oral absorption varied across the compounds, with values ranging from low to high. However, all three terpenoids showed low oral adsorption, suggesting that structural modifications or perhaps absorption formulation enhancement techniques might be necessary to improve their oral bioavailability. Solubility, represented as QPlogS, is an important characteristic of a druggable compound. All compounds identified in the extract had good aqueous solubility, except the three terpenoids studied, as they fell outside the recommended range (−2.0 to 6.5), indicating their less soluble nature.

Blood–brain barrier permeability (QPlog BB) predictions highlighted all compounds’ inability to cross the blood–brain barrier, suggesting their lack of central nervous system side effects. However, the cellular permeability parameter (QPPCaco) indicated that only the three terpenoids and undecane have cellular access, which is critical for bioactive compounds to reach intracellular therapeutic targets.

The identified compounds exhibited optimal QPlog HERG values during ADME analysis, indicating a favorable profile regarding their potential to interact with the hERG potassium channel, which is crucial for cardiac safety. This suggests that the compounds may possess lower risks of causing cardiotoxicity.

Overall, the terpenoids stigmasterol and 9,19-cyclolanost-23-ene-3,25-diol (3.beta., 23E) exhibit promising ADME (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion) profiles. Additionally, both compounds demonstrated good docking scores and strong binding affinities towards 4JVI, 3GR6, and 2ANQ [10,29]. This suggests their potential efficacy against these bacterial strains and warrants further drug discovery and development research.

5 Conclusion

The current study effectively verified the phytochemical components and antibacterial capabilities of the hydro-ethanol extract of M. acuminate fruit peels cultivated in Sudan. Stigmasterol, lup-20(29)-en-3-one, and 9,19-cyclolanost-23-ene-3,25-diol (3.beta., 23E) and sucrose were the most prevalent bioactive components identified by the extract’s initial GC–MS study. Significant antibacterial activity was shown by in vitro testing against the Gram-positive bacteria strain S. aureus and Gram-negative bacteria strains P. aeruginosa and E. coli. These antibacterial activities were attributed to strong binding affinities for some terpenoids to important bacterial enzymes. With the crystal structures of P. aeruginosa quorum sensing regulator protein (PDB ID: 4JVI), S. aureus enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase protein (PDB ID: 3GR6), and E. coli dihydrofolate reductase (PDB ID: 2ANQ), cyclolanost-23-ene-3,25-diol (3.beta., 23E) and stigmasterol showed the best docking scores. Both compounds have favorable drug-likeness features, according to ADME projections, which suggests that they could be targeted for further in vitro and in vivo research in drug development. These findings imply that hydro-ethanol extract may be a viable natural source of antibacterial compounds. More research is required to fully investigate this plant’s phytochemical profile and therapeutic potential.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank the University of Gezira, Sudan’s Faculty of Pharmacy’s Medicinal and Aromatic Plant Research Centre for their invaluable assistance and cooperation. The Medical Laboratory, Ministry of Health, Khartoum, Sudan, and the Central Laboratory at the National Centre for Research, Khartoum, are also acknowledged for their crucial facilities and technical support, which helped this study be completed successfully.

-

Funding information: No funding was available for this study.

-

Author contributions: Conceptualization, Wihad Khider, Abdalrahim M. Ali, and Salma Hago; methodology, Wihad Khider, Abdalrahim M. Ali, Abdelgadir A. Abdelgadir, and Areeg Ahmed; software, Abdalrahim M. Ali and Abdulrahim A. Alzain; writing – original draft preparation, Wihad Khider, Abdalrahim M. Ali, and Salma Hago; writing – review and editing, Wihad Khider, Abdalrahim M. Ali, Salma Hago, Abdulrahim A. Alzain Abdelgadir A. Abdelgadir, and Elhadi M. Ahmed; supervision, Abdelgadir A. Abdelgadir, Areeg Ahmed, and Elhadi M. Ahmed. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

-

Ethics approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

-

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Varela MF, Stephen J, Lekshmi M, Ojha M, Wenzel N, Sanford LM, et al. Bacterial resistance to antimicrobial agents. Antibiotics. 2021;10(5):593. 10.3390/antibiotics10050593.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Spellberg B, Powers JH, Brass EP, Miller LG, Edwards JEJ. Trends in antimicrobial drug development: Implications for the future. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:1279–86. 10.1086/420937. Epub 2004 Apr 14.Search in Google Scholar

[3] WHO. World Health Organization model list of essential medicines. 20th List. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; March 2017 (accessed on Jan 22, 2025).Search in Google Scholar

[4] Yother J. Capsules of Streptococcus pneumoniae and other bacteria: Paradigms for polysaccharide biosynthesis and regulation. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2011;65:563–81. 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162944.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Powers JH. Antimicrobial drug development – the past, the present, and the future. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10(4):23–31. 10.1111/j.1465-0691.2004.1007.x.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Aboul-Enein AM, Salama ZA, Gaafar AA, Aly HF, Abou-Elella F, Ahmed HA. Identification of phenolic coumpounds from banana peel (Musa paradaisica L.) as antioxidant and antimicrobial agents. J Chem Pharm Res. 2016;8(4):46–55.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Sari MA, Mrin T, Kaban J, Alfian Z. Preliminary study on phytochemical screening and antibacterial activity of dry ethanol extract from Kepok Banana Steam Liquid (Musa paradisiaca Linn). International Conference on Education, Science and Technology; J Phys Conf. 2014. Ser 1232, 2019. p. 012014. 10.1088/1742-6596/1232/1/012014.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Ehiowemwenguan G, moghene A, Inetianbor J. Antibacterial and phytochemical analysis of Banana fruit peel. IOSR J Pharm Biol Sci. 2014;4(8):18–25.10.9790/3013-0408018025Search in Google Scholar

[9] Hossain MS, Alam MB, Asadujjaman M, Zahan R, Islam MM, Mazumder ME, et al. Antidiarrheal, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of the Musa sapientum seed. Avicenna J Med Biotechnol. 2011;3(2):95–105. PMID: 23407989; PMCID: PMC3558179.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Jiwan SS, Tasleem AZ. Bioactive compounds in banana fruits and their health benefits. J Food Saf. 2018;2(4):183–88. 10.1093/fqsafe/fyy019.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Richard NB, Tânia MS, Neuza MAH, Eduardo ASR, Franco ML, Beatriz RC. Phenolics and antioxidant properties of fruit pulp and cell wall fractions of postharvest banana (Musa acuminata Juss.). Cultivars J Agr Food Chem. 2010;58(13):7991–8003. org/10.1021/jf1008692.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Giri SS, Jun JW, Sukumaran V, Park SC. Dietary administration of banana (Musa acuminata) peel flour affects the growth, antioxidant status, cytokine responses, and disease susceptibility of Rohu, Labeo rohita. J Immunol Res. 2016;29:1–11. 10.1155/2016/4086591.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Bankar AM, Dole MN. Formulation and evaluation of herbal antimicrobial gel containing Musa acuminata leaves extract. J Pharm Phytochem. 2016;5:1–3.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Abdullah FC, Rahimi L, Zakaria ZA, Ibrahim AL. Hepatoprotective, antiulcerogenic, cytotoxic and antioxidant activities of Musa acuminata peel and pulp. In Novel plant bioresources: Applications in food, medicine and cosmetics. Wiley; 2014 p. 371–82. 10.1002/9781118460566.ch26.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Berawi KN, Bimandama MA. The effect of giving extract etanol of kepok banana peel (Musa acuminata) toward total cholesterol level on male mice (Mus Musculus L.) strain deutschland-denken-yoken (Ddy) obese. Biomed Pharmacol J. 2018;11(2):769–74. 10.13005/bpj/1431.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Navghare VV, Dhawale SC. In-vitro antioxidant, hypoglycemic and oral glucose tolerance test of banana peels. Alex J Med. 2017;53(3):237–43. 10.1016/j.ajme.2016.05.003.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Luque-Ortega JR, Martínez S, Saugar JM, Izquierdo LR, Abad T, Luis JG, et al. Fungal-elicited metabolites from plants as an enriched source for new Leishmanicidal agents. Antifungal phenyl-phenalenone phytoalexins from the banana plant (Musa acuminata) target mitochondria of Leishmania donovani promastigotes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1534–40. 10.1128/AAC.48.5.1534-1540.2004.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Faten AE, Rasha M. Anticancer and anti-oxidant potentials of ethanolic extracts of Phoenix dactylifera Musa acuminata and Cucurbita maxima. Res J Pharma Bio Chem Sci. 2015;6(1):707–20.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Mondal A, Banerjee S, Bose S, Das PP, Sanberg EN, Atanasov AG, et al. Cancer preventive and therapeutic potential of banana and its bioactive constituents: A systematic, comprehensive and mechanistic review. J Onco. 2021;11:697143. 10.3389/fonc.2021.697143. eCollection 2021.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Haldar R, Kumar MS. Green waste: A fresh approach to antimicrobial compounds. Trends Phytochem Res. 2022;97:105.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Puraikalan Y. Characterization of proximate, phytochemical and antioxidant analysis of banana (Musa sapientum) peels/skins and objective evaluation of ready to eat/cook product made with banana peels. Curr Res Nutr Food Sci. 2018;6(2):382–91. 10.12944/CRNFSJ.6.2.13.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Salihu AM, Mustafa M, Nallappan P, Choi S, Paik J, Rusea G, et al. Determination of phenolics and flavonoids of some useful medicinal plants and bioassay-guided fractionation substances of Sclerocarya birrea (A. Rich) Hochst Stem (Bark) extract and their efficacy against Salmonella typhi. Front Chem. 2021;9:670530. 10.3389/fchem.2021.670530.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Cheesbroug M. District laboratory practice in tropical countries infection part 2. 2nd edn. New York, USA: Cambridge University Press; 2006. p. 45–143.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Alajmi MF, Alam P, Alqasoumi SI, Ali SN, Basudan OA, Hussain A, et al. Comparative anticancer and antimicrobial activity of aerial parts of Acacia salicina, Acacia laeta, Acacia hamulosa and Acacia tortilis grown in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2017;25(8):1248–52. 10.1016/j.jsps.2017.09.010.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Kavanagh F. Analytical microbiology. In Kavanagh. Vol. 11, New York & London: Academic Press; 1972.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Abdllha HB, Mohamed AI, Almoniem KA, Adam NI, Alhaadi W, Elshikh AA, et al. Evolution of antimicrobial, antioxidant potentials and phytochemical studies of three solvent extracts of five species from acacia used in sudanese ethnomedicine. J Adv Microb. 2016;6:691–8. 10.4236/aim.2016.69068.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Schrödinger. Maestro. New York, NY; 2024.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Ilangovan A, Fletcher M, Rampioni G, Pustelny C, Rumbaugh K, Heeb S, et al. Structural basis for native agonist and synthetic inhibitor recognition by the Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing regulator PqsR (MvfR). PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(7):e1003508. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003508.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Priyadarshi A, Kim EE, Hwang KY. Structural insights into Staphylococcus aureus enoyl-ACP reductase (Fabl), in complex with NADP end triclosan. Proteins: Struct Funct Bioinf. 2010;78(2):480–6. 10.1002/prot.22581.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Summerfield RL, Daigle DM, Mayer S, Mallik D, Hughes DW, Jackson SG, et al. Å structure of E. coli dihydrofolate reductase bound to a novel competitive inhibitor reveals a new binding surface involving the M20 loop region. J Med Chem. 2006;49(24):6977–86. 10.1021/jm060570v.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Arumugam D. Molecular docking analysis of mTOR protein kinase with chromatographically characterized compounds from Clerodendrum inerme L. leaves extract. Bioinformation. 2022;18(4):381–6. 10.6026/97320630018381.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Niamah AK. Determination, identification of bioactive compounds extracts from yellow banana peels and used in vitro as antimicrobial. Int J Phytomed. 2014;6(4):625–32.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Hassan MH. In vitro and in vivo study of banana peel extract anti toxicity. Medico-legal Update. 2021;21(2):846–50.10.37506/mlu.v21i2.2789Search in Google Scholar

[34] Jacotet-Navarro M, Laguerre M, Fabiano-Tixier A-S, Tenon M, Feuillère N, Bily A, et al. What is the best ethanol-water ratio for the extraction of antioxidants from rosemary? Impact of the solvent on yield, composition, and activity of the extracts. Electrophoresis. 2018;39(15):1946–56. 10.1002/elps.201700397.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Mahora MC, Kigundu A, Waihenya R. Screening of phytochemicals, antioxidant activity, and in vivo safety profile of the hydroethanolic peel extract of Musa sapientum. Plant Trends. 2024;2(1):1–15. 10.5455/pt.2024.01.Search in Google Scholar

[36] El Zawawy NA. Antioxidant, antitumor, antimicrobial studies and quantitative phytochemical estimation of ethanolic extracts of selected fruit peels. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2015;4(5):298–309.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Siddique S, Nawaz S, Muhammad F, Akhtar B, Aslam B. Phytochemical screening and in-vitro evaluation of pharmacological activities of peels of Musasa pientum and Carica papaya fruit. Nat Prod Res. 2018;32(11):1333–6. 10.1080/14786419.2017.1342089.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Bashir F, Hassan A, Mushtaq A, Rizwan S, Jabeen U, Raza A, et al. Phytochemistry and antimicrobial activities of different varieties of banana (Musa acuminate) peels available in Quetta city. Pol J Env Stud. 2021;30(2):1531–8. 10.15244/pjoes/122450.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Li Y, Ouyang Y, Wu H, Wang P, Huang Y, Li X, et al. The discovery of 1, 3-diamino-7H-pyrrol[3, 2-f]quinazoline compounds as potent antimicrobial antifolates. Eur J Med Chem. 2022;228:113979. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113979.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Groleau MC, de Oliveira T, Dekimpe V, Déziel E. PqsE is essential for RhlR-dependent quorum sensing regulation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. MSystems. 2020;5(3):e00194-20. 10.1128/msystems.00194-20.Search in Google Scholar

[41] Schaller D, Christ CD, Chodera JD, Volkamer A. Benchmarking cross-docking strategies for structure-informed machine learning in kinase drug discovery. J Chem Inf Model. 2024;64(23):8848–58. 10.1021/acs.jcim.4c00905. PMID: 37745489; PMCID: PMC10515787.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Bakrim S, Benkhaira N, Bourais I, Benali T, Lee LH, El Omari N, et al. Health benefits and pharmacological properties of stigmasterol. Antioxidants. 2022;10:1912. 10.3390/antiox11101912.Search in Google Scholar

[43] Olanrewaju AA, Oke DG, Adekunle DO, Adeleke OA, Akinola OT, Emmanuel AV, et al. Synthesis, in-vitro and in-silico antibacterial and computational studies of selected thiosemicarbazone-benzaldehyde derivatives as potential antibiotics. SN Appl Sci. 2023;5(8):213. 10.1007/s42452-023-05429-1.Search in Google Scholar

[44] Ali AM, Makki AA, Ibraheem W, Abdelrahman M, Osman W, Sherif AE, et al. Design of novel phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitors for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: Molecular docking, molecular dynamics, and density functional theory studies on gold nanoparticles. Molecules. 2023;28(5):2289. 10.3390/molecules28052289.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Phytochemical investigation and evaluation of antioxidant and antidiabetic activities in aqueous extracts of Cedrus atlantica

- Influence of B4C addition on the tribological properties of bronze matrix brake pad materials

- Discovery of the bacterial HslV protease activators as lead molecules with novel mode of action

- Characterization of volatile flavor compounds of cigar with different aging conditions by headspace–gas chromatography–ion mobility spectrometry

- Effective remediation of organic pollutant using Musa acuminata peel extract-assisted iron oxide nanoparticles

- Analysis and health risk assessment of toxic elements in traditional herbal tea infusions

- Cadmium exposure in marine crabs from Jiaxing City, China: Insights into health risk assessment

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles of Cinnamomum zeylanicum and their biological activities

- Tetraclinis articulata (Vahl) Mast., Mentha pulegium L., and Thymus zygis L. essential oils: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antifungal properties against postharvest fungal diseases of apple, and in vitro, in vivo, and in silico investigation

- Exploration of plant alkaloids as potential inhibitors of HIV–CD4 binding: Insight into comprehensive in silico approaches

- Recovery of phenylethyl alcohol from aqueous solution by batch adsorption

- Electrochemical approach for monitoring the catalytic action of immobilized catalase

- Green synthesis of ZIF-8 for selective adsorption of dyes in water purification

- Optimization of the conditions for the preparation of povidone iodine using the response surface methodology

- A case study on the influence of soil amendment on ginger oil’s physicochemical properties, mineral contents, microbial load, and HPLC determination of its vitamin level

- Removal of antiviral favipiravir from wastewater using biochar produced from hazelnut shells

- Effect of biochar and soil amendment on bacterial community composition in the root soil and fruit of tomato under greenhouse conditions

- Bioremediation of malachite green dye using Sargassum wightii seaweed and its biological and physicochemical characterization

- Evaluation of natural compounds as folate biosynthesis inhibitors in Mycobacterium leprae using docking, ADMET analysis, and molecular dynamics simulation

- Novel insecticidal properties of bioactive zoochemicals extracted from sea urchin Salmacis virgulata

- Elevational gradients shape total phenolic content and bioactive potential of sweet marjoram (Origanum majorana L.): A comparative study across altitudinal zones

- Study on the CO2 absorption performance of deep eutectic solvents formed by superbase DBN and weak acid diethylene glycol

- Preparation and wastewater treatment performance of zeolite-modified ecological concrete

- Multifunctional chitosan nanoparticles: Zn2+ adsorption, antimicrobial activity, and promotion of aquatic health

- Comparative analysis of nutritional composition and bioactive properties of Chlorella vulgaris and Arthrospira platensis: Implications for functional foods and dietary supplements

- Growth kinetics and mechanical characterization of boride layers formed on Ti6Al4V

- Enhancement of water absorption properties of potassium polyacrylate-based hydrogels in CaCl2-rich soils using potassium di- and tri-carboxylate salts

- Electrochemical and microbiological effects of dumpsite leachates on soil and air quality

- Modeling benzene physicochemical properties using Zagreb upsilon indices

- Characterization and ecological risk assessment of toxic metals in mangrove sediments near Langen Village in Tieshan Bay of Beibu Gulf, China

- Protective effect of Helicteres isora, an efficient candidate on hepatorenal toxicity and management of diabetes in animal models

- Valorization of Juglans regia L. (Walnut) green husk from Jordan: Analysis of fatty acids, phenolics, antioxidant, and cytotoxic activities

- Molecular docking and dynamics simulations of bioactive terpenes from Catharanthus roseus essential oil targeting breast cancer

- Selection of a dam site by using AHP and VIKOR: The Sakarya Basin

- Characterization and modeling of kidney bean shell biochar as adsorbent for caffeine removal from aquatic environments

- The effects of short-term and long-term 2100 MHz radiofrequency radiation on adult rat auditory brainstem response

- Biochemical insights into the anthelmintic and anti-inflammatory potential of sea cucumber extract: In vitro and in silico approaches

- Resveratrol-derived MDM2 inhibitors: Synthesis, characterization, and biological evaluation against MDM2 and HCT-116 cells

- Phytochemical constituents, in vitro antibacterial activity, and computational studies of Sudanese Musa acuminate Colla fruit peel hydro-ethanol extract

- Chemical composition of essential oils reviewed from the height of Cajuput (Melaleuca leucadendron) plantations in Buru Island and Seram Island, Maluku, Indonesia

- Phytochemical analysis and antioxidant activity of Azadirachta indica A. Juss from the Republic of Chad: in vitro and in silico studies

- Stability studies of titanium–carboxylate complexes: A multi-method computational approach

- Efficient adsorption performance of an alginate-based dental material for uranium(vi) removal

- Synthesis and characterization of the Co(ii), Ni(ii), and Cu(ii) complexes with a 1,2,4-triazine derivative ligand

- Evaluation of the impact of music on antioxidant mechanisms and survival in salt-stressed goldfish

- Optimization and validation of UPLC method for dapagliflozin and candesartan cilexetil in an on-demand formulation: Analytical quality by design approach

- Biomass-based cellulose hydroxyapatite nanocomposites for the efficient sequestration of dyes: Kinetics, response surface methodology optimization, and reusability

- Multifunctional nitrogen and boron co-doped carbon dots: A fluorescent probe for Hg2+ and biothiol detection with bioimaging and antifungal applications

- Separation of sulphonamides on a C12-diol mixed-mode HPLC column and investigation of their retention mechanism

- Characterization and antioxidant activity of pectin from lemon peels

- Fast PFAS determination in honey by direct probe electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry: A health risk assessment insight

- Correlation study between GC–MS analysis of cigarette aroma compounds and sensory evaluation

- Synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular docking studies of substituted chromone-2-carboxamide derivatives as anti-breast cancer agents

- The influence of feed space velocity and pressure on the cold flow properties of diesel fuel

- Acid etching behavior and mechanism in acid solution of iron components in basalt fibers

- Protective effect of green synthesized nanoceria on retinal oxidative stress and inflammation in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat

- Evaluation of the antianxiety activity of green zinc nanoparticles mediated by Boswellia thurifera in albino mice by following the plus maze and light and dark exploration tests

- Yeast as an efficient and eco-friendly bifunctional porogen for biomass-derived nitrogen-doped carbon catalysts in the oxygen reduction reaction

- Novel descriptors for the prediction of molecular properties

- Synthesis and characterization of surfactants derived from phenolphthalein: In vivo and in silico studies of their antihyperlipidemic effect

- Turmeric oil-fortified nutraceutical-SNEDDS: An approach to boost therapeutic effectiveness of dapagliflozin during treatment of diabetic patients

- Analysis and study on volatile flavor compounds of three Yunnan cultivated cigars based on headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry

- Near-infrared IR780 dye-loaded poloxamer 407 micelles: Preparation and in vitro assessment of anticancer activity

- Study on the influence of the viscosity reducer solution on percolation capacity of thin oil in ultra-low permeability reservoir

- Detection method of Aristolochic acid I based on magnetic carrier Fe3O4 and gold nanoclusters

- Juglone’s apoptotic impact against eimeriosis-induced infection: a bioinformatics, in-silico, and in vivo approach

- Potential anticancer agents from genus Aerva based on tubulin targets: an in-silico integration of quantitative structure activity relationship (QSAR), molecular docking, simulation, drug-likeness, and density functional theory (DFT) analysis

- Hepatoprotective and PXR-modulating effects of Erodium guttatum extract in propiconazole-induced toxicity

- Studies on chemical composition of medicinal plants collected in natural locations in Ecuador

- A study of different pre-treatment methods for cigarettes and their aroma differences

- Cytotoxicity and molecular mechanisms of quercetin, gallic acid, and pinocembrin in Caco-2 cells: insights from cell viability assays, network pharmacology, and molecular docking

- Choline-based deep eutectic solvents for green extraction of oil from sour cherry seeds

- Green-synthesis of chromium (III) nanoparticles using garden fern and evaluation of its antibacterial and anticholinesterase activities

- Innovative functional mayonnaise formulations with watermelon seeds oil: evaluation of quality parameters and storage stability

- Molecular insights and biological evaluation of compounds isolated from Ferula oopoda against diabetes, advanced glycation end products and inflammation in diabetics

- Removal of cytotoxic tamoxifen from aqueous solutions using a geopolymer-based nepheline–cordierite adsorbent

- Unravelling the therapeutic effect of naturally occurring Bauhinia flavonoids against breast cancer: an integrated computational approach

- Characterization of organic arsenic residues in livestock and poultry meat and offal and consumption risks

- Synthesis and characterization of zinc sulfide nanoparticles and their genotoxic and cytotoxic effects on acute myeloid leukemia cells

- Activity of Coriandrum sativum methanolic leaf extracts against Eimeria papillata: a combined in vitro and in silico approach

- Special Issue on Advancing Sustainable Chemistry for a Greener Future

- One-pot fabrication of highly porous morphology of ferric oxide-ferric oxychloride/poly-O-chloroaniline nanocomposite seeded on poly-1H pyrrole: Photocathode for green hydrogen generation from natural and artificial seawater

- High-efficiency photocathode for green hydrogen generation from sanitation water using bismuthyl chloride/poly-o-chlorobenzeneamine nanocomposite

- Innovative synthesis of cobalt-based catalysts using ionic liquids and deep eutectic solvents: A minireview on electrocatalytic water splitting

- Special Issue on Phytochemicals, Biological and Toxicological Analysis of Plants

- Comparative analysis of fruit quality parameters and volatile compounds in commercially grown citrus cultivars

- Total phenolic, flavonoid, flavonol, and tannin contents as well as antioxidant and antiparasitic activities of aqueous methanol extract of Alhagi graecorum plant used in traditional medicine: Collected in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- Study on the pharmacological effects and active compounds of Apocynum venetum L.

- Chemical profile of Senna italica and Senna velutina seed and their pharmacological properties

- Essential oils from Brazilian plants: A literature analysis of anti-inflammatory and antimalarial properties and in silico validation

- Toxicological effects of green tea catechin extract on rat liver: Delineating safe and harmful doses

- Unlocking the potential of Trigonella foenum-graecum L. plant leaf extracts against diabetes-associated hypertension: A proof of concept by in silico studies

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Phytochemical investigation and evaluation of antioxidant and antidiabetic activities in aqueous extracts of Cedrus atlantica

- Influence of B4C addition on the tribological properties of bronze matrix brake pad materials

- Discovery of the bacterial HslV protease activators as lead molecules with novel mode of action

- Characterization of volatile flavor compounds of cigar with different aging conditions by headspace–gas chromatography–ion mobility spectrometry

- Effective remediation of organic pollutant using Musa acuminata peel extract-assisted iron oxide nanoparticles

- Analysis and health risk assessment of toxic elements in traditional herbal tea infusions

- Cadmium exposure in marine crabs from Jiaxing City, China: Insights into health risk assessment

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles of Cinnamomum zeylanicum and their biological activities

- Tetraclinis articulata (Vahl) Mast., Mentha pulegium L., and Thymus zygis L. essential oils: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antifungal properties against postharvest fungal diseases of apple, and in vitro, in vivo, and in silico investigation

- Exploration of plant alkaloids as potential inhibitors of HIV–CD4 binding: Insight into comprehensive in silico approaches

- Recovery of phenylethyl alcohol from aqueous solution by batch adsorption

- Electrochemical approach for monitoring the catalytic action of immobilized catalase

- Green synthesis of ZIF-8 for selective adsorption of dyes in water purification

- Optimization of the conditions for the preparation of povidone iodine using the response surface methodology

- A case study on the influence of soil amendment on ginger oil’s physicochemical properties, mineral contents, microbial load, and HPLC determination of its vitamin level

- Removal of antiviral favipiravir from wastewater using biochar produced from hazelnut shells

- Effect of biochar and soil amendment on bacterial community composition in the root soil and fruit of tomato under greenhouse conditions

- Bioremediation of malachite green dye using Sargassum wightii seaweed and its biological and physicochemical characterization

- Evaluation of natural compounds as folate biosynthesis inhibitors in Mycobacterium leprae using docking, ADMET analysis, and molecular dynamics simulation

- Novel insecticidal properties of bioactive zoochemicals extracted from sea urchin Salmacis virgulata

- Elevational gradients shape total phenolic content and bioactive potential of sweet marjoram (Origanum majorana L.): A comparative study across altitudinal zones

- Study on the CO2 absorption performance of deep eutectic solvents formed by superbase DBN and weak acid diethylene glycol

- Preparation and wastewater treatment performance of zeolite-modified ecological concrete

- Multifunctional chitosan nanoparticles: Zn2+ adsorption, antimicrobial activity, and promotion of aquatic health

- Comparative analysis of nutritional composition and bioactive properties of Chlorella vulgaris and Arthrospira platensis: Implications for functional foods and dietary supplements

- Growth kinetics and mechanical characterization of boride layers formed on Ti6Al4V

- Enhancement of water absorption properties of potassium polyacrylate-based hydrogels in CaCl2-rich soils using potassium di- and tri-carboxylate salts

- Electrochemical and microbiological effects of dumpsite leachates on soil and air quality

- Modeling benzene physicochemical properties using Zagreb upsilon indices

- Characterization and ecological risk assessment of toxic metals in mangrove sediments near Langen Village in Tieshan Bay of Beibu Gulf, China

- Protective effect of Helicteres isora, an efficient candidate on hepatorenal toxicity and management of diabetes in animal models

- Valorization of Juglans regia L. (Walnut) green husk from Jordan: Analysis of fatty acids, phenolics, antioxidant, and cytotoxic activities

- Molecular docking and dynamics simulations of bioactive terpenes from Catharanthus roseus essential oil targeting breast cancer

- Selection of a dam site by using AHP and VIKOR: The Sakarya Basin

- Characterization and modeling of kidney bean shell biochar as adsorbent for caffeine removal from aquatic environments

- The effects of short-term and long-term 2100 MHz radiofrequency radiation on adult rat auditory brainstem response

- Biochemical insights into the anthelmintic and anti-inflammatory potential of sea cucumber extract: In vitro and in silico approaches

- Resveratrol-derived MDM2 inhibitors: Synthesis, characterization, and biological evaluation against MDM2 and HCT-116 cells

- Phytochemical constituents, in vitro antibacterial activity, and computational studies of Sudanese Musa acuminate Colla fruit peel hydro-ethanol extract

- Chemical composition of essential oils reviewed from the height of Cajuput (Melaleuca leucadendron) plantations in Buru Island and Seram Island, Maluku, Indonesia

- Phytochemical analysis and antioxidant activity of Azadirachta indica A. Juss from the Republic of Chad: in vitro and in silico studies

- Stability studies of titanium–carboxylate complexes: A multi-method computational approach

- Efficient adsorption performance of an alginate-based dental material for uranium(vi) removal

- Synthesis and characterization of the Co(ii), Ni(ii), and Cu(ii) complexes with a 1,2,4-triazine derivative ligand

- Evaluation of the impact of music on antioxidant mechanisms and survival in salt-stressed goldfish

- Optimization and validation of UPLC method for dapagliflozin and candesartan cilexetil in an on-demand formulation: Analytical quality by design approach

- Biomass-based cellulose hydroxyapatite nanocomposites for the efficient sequestration of dyes: Kinetics, response surface methodology optimization, and reusability

- Multifunctional nitrogen and boron co-doped carbon dots: A fluorescent probe for Hg2+ and biothiol detection with bioimaging and antifungal applications

- Separation of sulphonamides on a C12-diol mixed-mode HPLC column and investigation of their retention mechanism

- Characterization and antioxidant activity of pectin from lemon peels

- Fast PFAS determination in honey by direct probe electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry: A health risk assessment insight

- Correlation study between GC–MS analysis of cigarette aroma compounds and sensory evaluation

- Synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular docking studies of substituted chromone-2-carboxamide derivatives as anti-breast cancer agents

- The influence of feed space velocity and pressure on the cold flow properties of diesel fuel

- Acid etching behavior and mechanism in acid solution of iron components in basalt fibers

- Protective effect of green synthesized nanoceria on retinal oxidative stress and inflammation in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat

- Evaluation of the antianxiety activity of green zinc nanoparticles mediated by Boswellia thurifera in albino mice by following the plus maze and light and dark exploration tests

- Yeast as an efficient and eco-friendly bifunctional porogen for biomass-derived nitrogen-doped carbon catalysts in the oxygen reduction reaction

- Novel descriptors for the prediction of molecular properties

- Synthesis and characterization of surfactants derived from phenolphthalein: In vivo and in silico studies of their antihyperlipidemic effect

- Turmeric oil-fortified nutraceutical-SNEDDS: An approach to boost therapeutic effectiveness of dapagliflozin during treatment of diabetic patients

- Analysis and study on volatile flavor compounds of three Yunnan cultivated cigars based on headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry

- Near-infrared IR780 dye-loaded poloxamer 407 micelles: Preparation and in vitro assessment of anticancer activity

- Study on the influence of the viscosity reducer solution on percolation capacity of thin oil in ultra-low permeability reservoir

- Detection method of Aristolochic acid I based on magnetic carrier Fe3O4 and gold nanoclusters

- Juglone’s apoptotic impact against eimeriosis-induced infection: a bioinformatics, in-silico, and in vivo approach

- Potential anticancer agents from genus Aerva based on tubulin targets: an in-silico integration of quantitative structure activity relationship (QSAR), molecular docking, simulation, drug-likeness, and density functional theory (DFT) analysis

- Hepatoprotective and PXR-modulating effects of Erodium guttatum extract in propiconazole-induced toxicity

- Studies on chemical composition of medicinal plants collected in natural locations in Ecuador

- A study of different pre-treatment methods for cigarettes and their aroma differences

- Cytotoxicity and molecular mechanisms of quercetin, gallic acid, and pinocembrin in Caco-2 cells: insights from cell viability assays, network pharmacology, and molecular docking

- Choline-based deep eutectic solvents for green extraction of oil from sour cherry seeds

- Green-synthesis of chromium (III) nanoparticles using garden fern and evaluation of its antibacterial and anticholinesterase activities

- Innovative functional mayonnaise formulations with watermelon seeds oil: evaluation of quality parameters and storage stability

- Molecular insights and biological evaluation of compounds isolated from Ferula oopoda against diabetes, advanced glycation end products and inflammation in diabetics

- Removal of cytotoxic tamoxifen from aqueous solutions using a geopolymer-based nepheline–cordierite adsorbent

- Unravelling the therapeutic effect of naturally occurring Bauhinia flavonoids against breast cancer: an integrated computational approach

- Characterization of organic arsenic residues in livestock and poultry meat and offal and consumption risks

- Synthesis and characterization of zinc sulfide nanoparticles and their genotoxic and cytotoxic effects on acute myeloid leukemia cells

- Activity of Coriandrum sativum methanolic leaf extracts against Eimeria papillata: a combined in vitro and in silico approach

- Special Issue on Advancing Sustainable Chemistry for a Greener Future

- One-pot fabrication of highly porous morphology of ferric oxide-ferric oxychloride/poly-O-chloroaniline nanocomposite seeded on poly-1H pyrrole: Photocathode for green hydrogen generation from natural and artificial seawater

- High-efficiency photocathode for green hydrogen generation from sanitation water using bismuthyl chloride/poly-o-chlorobenzeneamine nanocomposite

- Innovative synthesis of cobalt-based catalysts using ionic liquids and deep eutectic solvents: A minireview on electrocatalytic water splitting

- Special Issue on Phytochemicals, Biological and Toxicological Analysis of Plants

- Comparative analysis of fruit quality parameters and volatile compounds in commercially grown citrus cultivars

- Total phenolic, flavonoid, flavonol, and tannin contents as well as antioxidant and antiparasitic activities of aqueous methanol extract of Alhagi graecorum plant used in traditional medicine: Collected in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- Study on the pharmacological effects and active compounds of Apocynum venetum L.

- Chemical profile of Senna italica and Senna velutina seed and their pharmacological properties

- Essential oils from Brazilian plants: A literature analysis of anti-inflammatory and antimalarial properties and in silico validation

- Toxicological effects of green tea catechin extract on rat liver: Delineating safe and harmful doses

- Unlocking the potential of Trigonella foenum-graecum L. plant leaf extracts against diabetes-associated hypertension: A proof of concept by in silico studies