Abstract

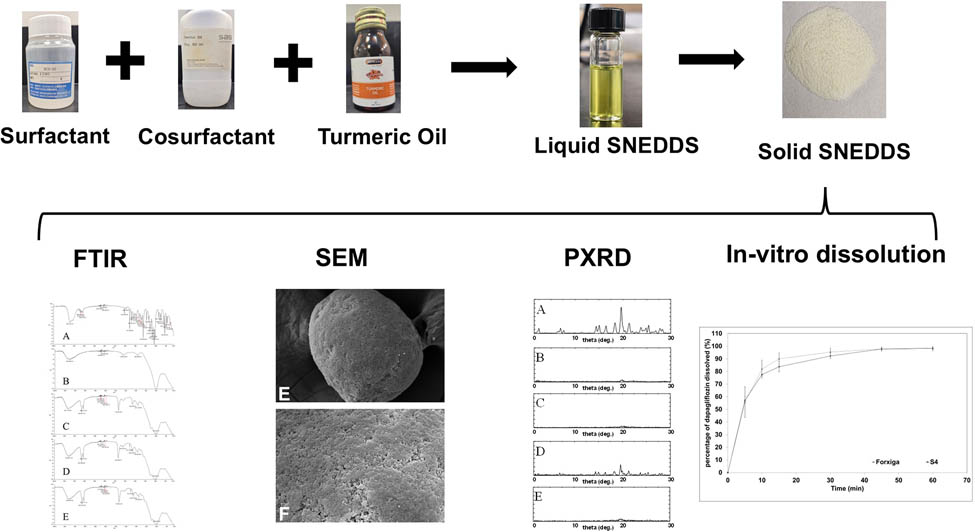

A nutraceutical self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system (nutraceutical-SNEDDS) fortified with turmeric oil was developed in the present study to enhance dapagliflozin (DG) dissolution and provide additional antidiabetic benefits. To achieve these objectives, different nutraceutical-SNEDDS formulations were prepared using various surfactants and cosurfactants. The prepared formulations were evaluated in terms of homogeneity, emulsification, and solubility. The selected optimum liquid formulation, composed of HCO 30, Imwitor 308, and turmeric oil (5:3.5:1.5), was solidified using different ratios of Neusilin US2 and UFL2. The optimum solid nutraceutical-SNEDDS was characterized using Zetasizer, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, powder X-ray diffractometry (PXRD), and dissolution testing. The optimum formulation (S4) was prepared using a Neusilin US2 adsorbent (1:1). The dispersed S4 formulation showed nanometer-sized emulsion droplets (40.8 nm) with a negative zeta potential (−19.0 mV). SEM, FTIR, and PXRD analyses confirmed the successful adsorption of SNEDDS and drug amorphization without chemical interaction. Dissolution studies showed that S4 achieved comparable drug release to Forxiga with dissolution efficiency values of 88.7 and 90.8%, respectively. The prepared nutraceutical-SNEDDS is proposed as a potential enhancer of DG bioavailability and its therapeutic activity, leveraging the combined pharmaceutical and nutraceutical benefits of turmeric oil.

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a widely spread chronic metabolic disorder that increases measured blood glucose levels [1,2]. This is ascribed to either insufficient or a lack of insulin production, resistance to insulin’s pharmacological action, or a combination of both [3]. Long-term exposure of body cells to dysregulation in glucose level results in various complications to body organs, including the heart (cardiovascular diseases), nerves (neuropathy), kidneys (nephropathy), and eyes (retinopathy) [4,5].

Dapagliflozin (DG) belongs to the sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors. It reduces blood glucose levels by inhibiting glucose reabsorption from proximal tubules in the kidney [6]. DG has been utilized extensively owing to its insulin-independent mechanism of action [7,8]. This ensures antidiabetic activity in patients with insulin resistance or impaired pancreatic function [9]. Furthermore, it contributed to weight loss due to increased glucose excretion [10]. In addition, DG exerts a mild diuretic effect following the inhibition of the sodium–glucose cotransporter system, which provides a cardioprotective effect [11].

The reported low solubility of DG negatively influences drug bioavailability and therapeutic outcomes [12]. Therefore, an innovative therapeutic approach, such as nutraceutical-self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system (nutraceutical-SNEDDS), was implemented not only to boost therapeutic efficacy but also to improve patient outcomes. Nutraceutical-SNEDDS shares similar components of traditional SNEDDS (oil, surfactant, and cosurfactant), whereas the used oil derived from plants contains bioactive compounds with intended biological activity [13,14].

Turmeric oil is usually obtained from Curcuma longa rhizomes and has gained noteworthy attention owing to its reported multifaceted pharmacological activities. These are ascribed to the presence of a mixture of bioactive compounds, including curcuminoids and turmerones [15]. Among them, bioactive curcumin is responsible for beneficial biological activity during diabetes treatment [16,17]. Various studies revealed that curcumin enhances insulin sensitivity and alleviates damage caused to the β-cell of the pancreas [18,19]. This is attributed to the reported antioxidant activity of curcumin, which acts against oxidative and apoptotic factors [20,21].

The leakage of SNEDDS from soft gelatin capsules is considered a major limitation of its pharmaceutical application [22,23]. To overcome the reported limitation of liquid SNEDDS, the optimized turmeric oil-fortified nutraceutical-SNEDDS was converted into a solid dosage form. The adsorption approach has been utilized extensively during the preparation of solid SNEDDS owing to the reported advantages. The absence of organic solvents eliminates safety concerns about the prepared pharmaceutical dosage forms [24]. Moreover, the prepared powder has free-flowing properties, which could be filled within a hard gelatin capsule [25,26]. Furthermore, the manufacturing process of solid SNEDDS using adsorption technology is simple and cost-effective compared to other complex approaches [27].

Therefore, the present study was designed to prepare solid nutraceutical-SNEDDS fortified with turmeric oil to enhance DG dissolution and therapeutic activity. To achieve this, miscibility, emulsification, and DG solubility were studied to select the optimum formulation. After that, various solid SNEDDS formulations were prepared using Neusilin US2 and Neusilin UFL2 adsorbents. The optimized solid SNEDDS formulation was selected based on its physical appearance and in vitro dissolution study. Finally, the optimized solid SNEDDS was characterized using Zetasizer, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, and powder X-ray diffractometry (PXRD).

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Turmeric oil was purchased from Hemani Company (Riyadh, KSA). DG was kindly donated by Riyadh Pharma (Riyadh, KSA). Neusilin US2 and UFL2 grades were acquired from Fuji Chemical Industry (Toyama, Japan). The surfactants Tween 20, Cremophor EL, and HCO 30 were purchased from BDH (England), BASF (Ludwigshafen, Germany), and Nicole Chemical Co. (Tokyo, Japan), respectively. The cosurfactants Span 80 and Imwitor 308 were obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) and Sasol Germany GmbH (Germany), respectively. Lauroglycol and Peceol were gained from Gattefossé (Saint-Priest, France).

2.2 Selection of cosurfactants

The solubility of turmeric oil in various types of cosurfactants (Span 80, lauroglycol, propylene glycol, Tween 85, polyethylene glycol 400, Imwitor 308, and Pecol) was investigated to select the optimal SNEDDS components. A mixture of cosurfactant and turmeric oil (2:1) was weighed and placed in an Eppendorf tube. Cosurfactants were selected based on their ability to solubilize turmeric oil.

2.3 Formulation preparation

2.3.1 Liquid nutraceutical-SNEDDS

Self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery systems (SNEDDSs) were prepared using turmeric oil as the oil phase and various combinations of surfactants and cosurfactants, as shown in Table 1. All formulations were prepared using a surfactant:cosurfactant:turmeric oil weight ratio of 5:3.5:1.5, respectively. SNEDDS components were accurately weighed into glass vials and then placed in an incubator set at 40°C for 30 min to ensure homogeneous mixing of the components.

Composition of nutraceutical-SNEDDS formulations

| Formulation | Surfactant | Cosurfactant | Bioactive oil |

|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | Tween 20 | Span 80 | Turmeric oil |

| L2 | Cremophor EL | ||

| L3 | HCO 30 | ||

| L4 | Tween 20 | Imwitor 308 | |

| L5 | Cremophor EL | ||

| L6 | HCO 30 | ||

| L7 | Tween 20 | Lauroglycol | |

| L8 | Cremophor EL | ||

| L9 | HCO 30 | ||

| L10 | Tween 20 | Peceol | |

| L11 | Cremophor EL | ||

| L12 | HCO 30 |

2.3.2 Drug-loaded liquid and solid nutraceutical-SNEDDS

The selected optimum nutraceutical-SNEDDS (L6) was prepared and mixed with DG to prepare drug-loaded liquid nutraceutical-SNEDDS with a loading value of 120 mg/g (80% drug solubility). After that, various solid nutraceutical-SNEDDSs were prepared by mixing drug-loaded liquid nutraceutical-SNEDDS with two types of Neusilin adsorbents at various ratios (1:4, 1:2, 3:4, and 1:1), as shown in Table 2. The freshly prepared solid nutraceutical-SNEDDS was kept in the refrigerator for further assessment.

Composition of solid nutraceutical-SNEDDS formulations using Neusilin adsorbents

| Formulation code | Adsorbent type | Adsorbent:liquid SNEDDS ratio (w/w) |

|---|---|---|

| S1 | Neusilin US2 | 1:4 |

| S2 | 1:2 | |

| S3 | 3:4 | |

| S4 | 1:1 | |

| S5 | Neusilin UFL2 | 1:4 |

| S6 | 1:2 | |

| S7 | 3:4 | |

| S8 | 1:1 |

2.4 Homogeneity study

The prepared nutraceutical-SNEDDS formulations were subjected to a homogeneity study to anticipate probable phase separation during storage. They were exposed to centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 10 min and inspected visually.

2.5 Emulsification study

Homogenous nutraceutical SNEDDS formulations were subjected to an emulsification study to investigate the ability of surfactants and cosurfactants to emulsify turmeric oil. They were diluted with water (1:1,000) and stirred for 5 min to facilitate emulsification.

2.6 Solubility study

Solubility of unprocessed DG within liquid nutraceutical SNEDDS was carried out to identify the loading capacity. To achieve this purpose, liquid nutraceutical SNEDDS containing an excess quantity of unprocessed DG was exposed to stirring at 1,000 rpm for 24 h. At the end of the study, supernatant was attained following exposure of the mixture (liquid nutraceutical SNEDDS + excess DG) to centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. This facilitated the participation of undissolved DG, whereas dissolved DG is present in the supernatant. Solubility of DG was estimated based on the measured drug concentration in the supernatant using the following extraction process. Accurately weighed liquid nutraceutical SNEDDS containing dissolved DG was mixed with acetonitrile and sonicated to guarantee drug extraction. The extracted DG present in the acetonitrile was calculated based on the developed UPLC method.

2.7 In vitro dissolution

In vitro dissolution study was conducted to investigate the influence of Neusilin grades and ratios on the dissolution profile of DG from solid SNEDDS using dissolution apparatus type II (LOGAN Inst. Corp., Franklin, NJ, USA). Phosphate buffer (900 mL, pH 6.8) was utilized as dissolution media at 37.0 ± 0.5°C. The prepared drug-loaded liquid and solid nutraceutical-SNEDDS containing 10 mg DG were filled in hard gelatin capsules. The paddle speed was set at 50 rpm, and samples were withdrawn at predetermined intervals (5, 10, 15, 30, 45, and 60 min). Drug concentration within samples was determined using the UPLC method.

2.8 Particle size and zeta-potential measurement

The prepared optimum solid nutraceutical-SNEDDS formulation (S4) was dispersed in distilled water to enhance the formation of nanoemulsion droplets. Particle size and zeta-potential values of dispersed formulation were measured using a Zetasizer instrument (Model ZEN3600, Malvern Instruments Co., Worcestershire, UK).

2.9 SEM

SEM was used to investigate the crystalline state of DG and the physical appearance of Neusilin and optimum solid SNEDDS. The sample preparation protocol involved fixing the examined material onto metallic stubs, followed by the application of a conductive gold coating through sputter deposition. This process was conducted for 60 s using a controlled current of 20 mA within a Q150R sputter coating apparatus (Quorum Technologies Ltd., East Sussex, UK) under an inert argon atmosphere. Morphological characterization of the examined materials was performed using a Carl Zeiss EVO LS10 scanning electron microscope (Cambridge, MA, USA) operated under high-vacuum conditions.

2.10 PXRD

X-ray diffraction analysis was performed to investigate the crystalline state of DG. To achieve this, an X-ray diffractometer (Ultima IV, Rigaku Inc., Tokyo, Japan) was used to obtain the XRD spectra of DG, Neusilin US2, Neusilin loaded with drug-free SNEDDS, physical mixture, and optimum solid formulation S4. The diffraction patterns were collected across an angular range of 3–30° (2θ) with a scanning rate of 1° per min. Monochromatic copper Kα1 radiation, with a wavelength of 1.54 Å, was implemented, enabling precise detection of crystallographic planes. The characteristic peaks were identified using the resulting diffraction profiles, which clearly identified the crystalline integrity of the examined material.

2.11 FTIR spectroscopy

FTIR spectra were obtained using a PerkinElmer Spectrum-100 spectrometer (USA) to predict any possible chemical interaction between DG and the excipients. DG, Neusilin US2, Neusilin loaded with drug-free SNEDDS, physical mixture, and optimized formulation (S4) were scanned in the wavenumber range of 650–4,000 cm−1.

2.12 UPLC method

An ultimate 3000 UPLC system was utilized to determine DG concentration. It comprises a quadratic pump coupled with an automatic sampler, a column chamber, and a photodiode array (PDA) detector. The mobile phase comprised a 0.1% formic acid solution and acetonitrile (60:40 v/v) that eluted through the connected column (BEH C18) at 0.4 mL/min. During the analysis, the temperature of the column was kept at 25°C. In addition, DG concentration was estimated using a connected PDA detector set at 267 nm.

3 Results

3.1 Cosurfactant selection

Turmeric oil was mixed with different types of cosurfactants, namely propylene glycol, polyethylene glycol 400, Tween-85, Span 80, Imwitor 308, lauroglycol, and peceol at a 2:1 weight ratio. The results revealed that propylene glycol, polyethylene glycol 400, and Tween-85 failed to produce homogeneous mixtures with turmeric oil. The white arrow shown in Figure 1a clearly indicates the distinct phase separation. In contrast, Span 80, Imwitor 308, lauroglycol, and peceol successfully formed homogeneous mixtures with turmeric oil, as shown in Figure 1b.

(a) Immiscible mixture of turmeric oil and cosurfactant. The white arrow shows the separation line between the components. (b) A miscible mixture of turmeric oil and cosurfactant.

3.2 Selection of optimized liquid nutraceutical-SNEDDS

The prepared nutraceutical-SNEDDS formulations were fully characterized to select the optimum formulation based on homogeneity, emulsification behavior, and solubility (Table 3).

Characterization of nutraceutical-SNEDDS formulations

| Formulation | Homogeneity | Dispersion | Physical appearance | Solubility (mg/g) | Overall assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | Pass | Fail | — | — | X |

| L2 | Pass | Fail | — | — | X |

| L3 | Pass | Fail | — | — | X |

| L4 | Fail | Fail | — | — | X |

| L5 | Pass | Fail | — | — | X |

| L6 | Pass | Pass | Clear | 150.0 ± 1.0 | √ |

| L7 | Pass | Fail | — | — | X |

| L8 | Pass | Pass | Bluish | 82.3 ± 1.7 | X |

| L9 | Pass | Fail | — | — | X |

| L10 | Pass | Fail | — | — | X |

| L11 | Pass | Fail | — | — | X |

| L12 | Pass | Fail | — | — | X |

3.2.1 Homogeneity test

Various combinations of turmeric oil with selected cosurfactants (Span 80, Imwitor 308, lauroglycol, and peceol) and surfactants (Tween 20, Cremophor EL, and HCO-30) were evaluated to prepare a homogeneous SNEDDS formulation. Despite the initial miscibility between turmeric oil and Imwitor 308, phase separation was observed in the prepared L4 formulation. Consequently, L4 was excluded from the study, and the other formulations were subjected to further assessments.

3.2.2 Emulsification study

The current results showed that all formulations except L6 and L8 failed to produce a dispersed nanoemulsion. Figure 2a and b shows that the dispersed systems of L6 and L8 exhibited a clear and bluish appearance, respectively. Therefore, L6 and L8 were subjected to a solubility study to select the optimum liquid nutraceutical-SNEDDS formulation.

Physical appearance of (a) L6 and (b) L8 nutraceutical-SNEDDS formulations.

3.2.3 Solubility study

A solubility study was conducted to quantify the loading capacity of L6 and L8, which directly affects the total dosage of formulations. The L6 formulation exhibited an approximately two-fold increment in the measured solubility compared with the L8 formulation. Therefore, the L6 formulation was selected as an optimized nutraceutical-SNEDDS and subjected to solidification.

3.3 Selection of optimized solid nutraceutical-SNEDDS

The solid nutraceutical-SNEDDSs were prepared and subjected to different pharmaceutical assessments to select the optimized formulation.

3.3.1 Physical appearance

The images of Neusilin adsorbent and the prepared solid nutraceutical-SNEDDS formulations are presented in Figure 3. It is clear from the images that Neusilin US2 has a granular appearance with a fine particulate characteristic texture. In contrast, Neusilin UFL2 has a fluffy appearance and smooth texture. Moreover, the white color of both Neusilin adsorbents was converted to yellow following the adsorption of the liquid nutraceutical-SNEDDS formulation.

Visual comparison of solid SNEDDS formulations using Neusilin US2 and UFL2 adsorbents: (a) and (b) adsorbents alone, (c) and (d) 1:4, (e) and (f) 1:2, (g) and (h) 3:4, and (i) and (j) 1:1 adsorbent:liquid SNEDDS ratios.

Solid nutraceutical-SNEDDS formulations with an adsorbent: liquid SNEDDS ratio of 1:4 exhibited distinct physical characteristics. The Neusilin US2-based formulation exhibited a cake-like structure (Figure 3a), while the Neusilin UFL2-based formulation exhibited a gel-like appearance (Figure 3b). However, the remaining solid nutraceutical-SNEDDS formulations retain the powder nature of plain adsorbent.

3.3.2 In vitro dissolution

The in vitro dissolution study was conducted to investigate the impact of liquid nutraceutical-SNEDDS (L6) on the dissolution efficiency of DG. Figure 4a shows the in vitro dissolution profile of pure drug against optimum liquid nutraceutical-SNEDDS formulation (L6). It is clear from the results that L6 enhanced the dissolution profile compared with pure DG. Moreover, results showed that L6 significantly increased the dissolution efficiency of DG from 39.2 ± 7.62 to 91.6 ± 0.54 (Figure 4b).

(a) DG’s in vitro dissolution profiles from pure drug and optimum liquid nutraceutical-SNEDDS. (b) Bar graph comparing the dissolution efficiency.

Regarding Neusilin US2, the constructed dissolution profile showed that solid formulations enhanced the dissolution profile in the following order: S2 < S3 ≈ S4 (Figure 5a–c). Furthermore, dissolution efficiency results presented in Figure 5d revealed that S2 has a value of 81.1 ± 9.56% while S3 and S4 had approximately similar values of 89.8 ± 5.53 and 88.7 ± 0.33%, respectively. However, S4 showed a remarkably lower degree of variability in terms of dissolution profile and dissolution efficiency compared to other formulations (S2 and S3).

(a)–(c) In vitro dissolution profiles of DG from S2, S3, and S4 formulations, respectively. (d) Bar graph comparing the dissolution efficiency among the SNEDDS formulations.

Figure 6a–c shows the in vitro dissolution profile of solid formulations comprised Neusilin UFL2 in the following order: S6 < S7 ≈ S8. Dissolution efficiency results showed that S6 has a lower value of 65.6 ± 13.72%, while S7 and S8 had approximately similar values of 81.5 ± 3.46 and 79.0 ± 7.38%, respectively. Overall, solid formulations consisting of Neusilin US2 have a superior dissolution efficiency compared to others consisting of Neusilin UFL2 at the same level of adsorbent: liquid SNEDDS ratio.

(a)–(c) In vitro dissolution profiles of DG from S6, S7, and S8 formulations, respectively. (d) Bar graph comparing the dissolution efficiency among the SNEDDS formulations.

3.4 Characterization of optimized solid nutraceutical-SNEDDS

3.4.1 Particle size and zeta potential measurements

The selected optimum solid nutraceutical-SNEDDSs (S4) were measured using a Zetasizer. The results obtained show that the optimum solid nutraceutical-SNEDDS have particle sizes of 40.8 nm and a negative zeta potential value of −19.0 mV.

3.4.2 SEM

The SEM analysis presented in Figure 7 displays morphological characteristics at varying magnification levels of DG, Neusilin US2 carrier, and the optimized formulation S4. The captured images clearly show DG exhibiting an irregular crystalline appearance with a distinctive rod-like crystalline structure. Moreover, Neusilin US2 images confirm that the adsorbent has a granular appearance with characteristic spherical particles. The SEM analysis of the optimized formulation S4 demonstrated that after SNEDDS adsorption, the formulation maintained the general morphological features characteristic of pure Neusilin US2. However, when examined under higher magnification, it was observed that the SNEDDS adsorption process modified the Neusilin US2 surface, resulting in a smoother surface texture compared to the original carrier material.

SEM images of (a) and (b) pure DG, (c) and (d) Neusilin US2, and (e) and (f) optimized formulation S4 at low and high magnification power, respectively.

3.4.3 PXRD

Figure 8a–e shows the XRD spectra of DG, Neusilin US2, Neusilin US2 loaded with blank SNEDDS, physical mixture, and optimized formulation S4, respectively. The DG diffractogram shows multiple sharp and intense diffraction peaks, particularly prominent ones between 15 and 25° (2θ), indicating the crystalline nature of the pure drug. However, Neusilin US2 exhibits a largely flat diffractogram with minimal peaks, demonstrating its amorphous nature. Neusilin loaded with drug-free SNEDDS shows a similar amorphous pattern to pure Neusilin US2, confirming that loading with blank SNEDDS does not alter the carrier’s amorphous structure. The physical mixture shows some characteristic peaks of crystalline DG, though with reduced intensity compared to pure DG. This suggests that while some crystalline drug structure is maintained in the physical mixture, there may be partial amorphization or a dilution effect from Neusilin US2. The optimized formulation S4 shows a predominantly amorphous pattern similar to pure Neusilin US2, with the absence of characteristic DG peaks. This indicates successful conversion of crystalline DG to an amorphous form within the SNEDDS formulation, likely contributing to enhanced drug solubility and dissolution properties.

XRD spectra of (a) DG, (b) Neusilin US2, (c) Neusilin loaded with drug-free SNEDDS, (d) physical mixture, and (e) optimized formulation S4.

3.4.4 FTIR spectroscopy

The FTIR spectra presented in Figure 9 display the characteristic molecular vibrational patterns of several samples: pure DG, Neusilin US2 carrier material, Neusilin US2 loaded with blank SNEDDS (without drug), physical mixture, and the optimized solid SNEDDS formulation S4. These spectra help identify potential molecular interactions and compatibility between the formulation components. Figure 9a shows that DG has a broad band around 3,400 cm−1 (O–H stretching), sharp peaks in the 2,900–2,800 cm−1 region (C–H stretching), multiple distinctive peaks in the fingerprint region (1,800–400 cm−1), notable peaks at around 1,730 cm−1 (C═O stretching), and 1,620 cm−1 (C═C stretching). In addition, the FTIR spectrum of Neusilin US2 shown in Figure 9b displays characteristic peaks at 1,060 cm−1 (Si–O–Si asymmetric stretching). Furthermore, Figure 9c shows the FTIR spectrum of drug-free SNEDDS-loaded Neusilin US2 with new peaks at 2,924 and 2,854 cm−1 (C–H stretching) and 1,726 cm−1 (C═O stretching of ester). FTIR spectra of the physical mixture and optimum solid nutraceutical-SNEDDS (S4) are presented in Figure 9d and e, respectively. Both formations showed the presence of distinctive peaks of DG. Notably, a non-interfering peak at 1,512 cm−1 of DG was present in both spectra compared to the drug-free SNEDDS-loaded Neusilin® US2 spectrum.

FTIR spectra of (a) DG, (b) Neusilin US2, (c) Neusilin loaded with drug-free SNEDDS, (d) physical mixture, and (e) optimized formulation S4.

3.5 Comparative dissolution study with the marketed product

Figure 10a shows in vitro dissolution profiles of optimized formulation (S4) and marketed product (Forxiga®). Both formulations attained complete drug release (>98%) at the end of the experiment, with S4 showing 98.5 ± 1.3% and Forxiga® 98.0 ± 1.7% release. The calculated dissolution efficiency (Figure 10b) for S4 and Forxiga® was 88.7 ± 0.33 and 90.8 ± 2.36%, respectively, with no statistically significant difference (p > 0.05).

(a) In vitro dissolution profiles of optimized solid nutraceutical-SNEDDS (S4) and marketed product (Forxiga®). (b) Bar graph comparing the dissolution efficiency between S4 and Forxiga® formulations.

4 Discussion

SNEDDS formulation comprises a homogenous mixture of surfactants, cosurfactants, and oils. Cosurfactants are usually incorporated to facilitate mixing between hydrophilic surfactants and lipophilic oils [28,29]. The solubility of turmeric oil was evaluated in various cosurfactants to determine their suitability and effectiveness as solubilizing agents in the formulation. Propylene glycol, polyethylene glycol 400, and Tween-85 were excluded from the study owing to their inability to produce a homogenous system with turmeric oil. On the other hand, Span 80, Imwitor 308, lauroglycol, and peceol were selected to prepare liquid nutraceutical-SNEDDS because they produced a homogenous system when mixed with turmeric oil.

The prepared formulations were subjected to a miscibility test to check the ability of SNEDDS to form a homogenous mixture during storage. The observed phase separation in the L4 formulation could be ascribed to the complex interaction within the ternary system of SNEDDS. It is hypothesized that Imwitor 308 could favor the formation of bonding with Tween 20 only rather than turmeric oil, resulting in the formation of two immiscible phases.

An emulsification study was performed to check the ability of nutraceutical-SNEDDS to form nanoemulsion droplets following dispersion in an aqueous system. This ensures the efficiency of combinations of surfactants and cosurfactants in encapsulating turmeric oil and producing stable nanoemulsions [30]. Most formulations failed to produce dispersed nanoemulsion systems, suggesting that combinations of surfactants and cosurfactants did not have favorable molecular interactions between the components when mixed with an aqueous system. In contrast, L6 and L8 formulations form successful nanoemulsions, as indicated by their physical appearance and the absence of floated oil on the surface.

A solubility study was conducted as a final step in selecting the optimum liquid nutraceutical-SNEDDS formulation. This ensures high drug-loading capacity and reduces the formulation’s total dosage [31]. Moreover, this is expected to facilitate drug integration within dispersed nanoemulsion droplets and prevent the precipitation of drugs in the GIT [32]. Consequently, L6 was chosen as the optimum formulation owing to its remarkable solubility compared to the L8 formulation.

DG was loaded in a liquid nutraceutical-SNEDDS formulation (L6) and subjected to an in vitro dissolution study. The observed enhancement in the dissolution of DG from L6 compared to the raw crystalline drug could have resulted from its solubilization within the SNEDDS formulation at a molecular level [33]. Therefore, the drug could be partitioned within nanoemulsion droplets and solubilized in dissolution media. This is expected to increase the bioavailability of loaded drugs owing to maintaining a higher concentration gradient between the GIT and systemic circulation [34].

The optimized liquid nutraceutical-SNEDDS formulation (L6) was solidified using two grades of Neusilin (US2 and UFL2) at various adsorbent: liquid SNEDDS ratios. The conversion of Neusilin’s color from white to yellow indicates the successful integration of liquid nutraceutical-SNEDDS within adsorbent pores, attributed to the turmeric oil color.

The observed physical appearance of the solid formulations varied significantly depending on the Neusilin grade and the adsorbent:liquid SNEDDS ratio. For S1 and S5 formulations (1:4 ratio), the observed gel-like appearance of the latter could result from its fine particulate characteristic of Neusilin UFL2 compared to the granular nature of the former. In harmony with current results, Park et al. found that solid SNEDDS prepared using Neusilin UFL2 were agglomerated compared to the discrete appearance of solid SNEDDS prepared using Neusilin US2 [35]. This could be attributed to the granular structure of Neusilin US2, which reduces the contact surface between particles, while the fine particulate characteristic nature of Neusilin UFL2 increases the contact surface between particles [36]. However, both formulations were excluded from the study due to their inapplicability during pharmaceutical production.

The observed superior performance of Neusilin US2 formulations in improving the dissolution profile corroborates the previously published data [37,38]. This could be ascribed to the reported study, which showed that drug release was decreased from the viscous SNEDDS formulation adsorbed onto Neusilin UFL2. This is aligned with the current study, where high drug loading (150 mg/g) in the liquid nutraceutical-SNEDDS formulation could increase its viscosity [38].

The observed low dissolution efficiency from the solid formulation with a low adsorbent:liquid SNEDDS ratio could be attributed to the overload adsorption of SNEDDS within the porous structure of the adsorbent. This resulted in the formation of gel-like material during dissolution, which delayed the formation of nanoemulsion droplets and retard drug dissolution [26]. Maximum dissolution efficiency was observed in medium and high adsorbent:liquid SNEDDS ratio formulations that could result from breaking the threshold point beyond which gel was not formed.

Even though S3 and S4 showed higher dissolution efficiency, S4 was selected as the optimum formulation due to its lower variability in the in vitro dissolution study. This reduced variability is expected to ensure a more consistent drug release pattern, which is essential for achieving uniform in vivo pharmacokinetic parameters. Particle size analysis revealed that the dispersed S4 formulation was in the nanosize range. This is expected to increase the bioavailability of the integrated drug within the prepared formulation [39]. Moreover, the measured negative zeta potential suggests the electrostatic stabilization of the nanoemulsion droplets following aqueous dispersion. In addition, the negative surface charge can promote migration and absorption of the nanoemulsion system via clathrin receptors [40]. This agrees with previous studies showing remarkable enhancement in drug bioavailability from dispersed nanoemulsion with a negative surface charge [41,42].

The selected optimum formulation (S4) was subjected to physicochemical analysis to examine the molecular state of DG within solidified nutraceutical-SNEDDS. The preservation of Neusilin US2’s spherical structure following the adsorption of SNEDDS suggests the successful integration of formulation within the porous structure of the adsorbent. Moreover, the absence of an irregular crystalline appearance of DG within SEM images of S4 confirms its integration within the adsorbent. However, XRD was performed to verify that the drug was present in an amorphous state within the prepared S4 formulation.

The XRD spectrum showed that DG has a distinctive crystalline structure, which agrees with the results of the previously published studies [12,43]. The present results revealed that the adsorption of SNEDDS did not influence the XRD spectrum of the adsorbent. However, the XRD spectrum of the physical mixture showed that DG crystalline peaks were retained. On the other hand, the incorporation of DG within the SNEDDS formulation resulted in its transformation to an amorphous state, indicated by the absence of drug crystalline peaks [44].

FTIR spectroscopy was performed to study any possible interaction between DG and excipients. The agreement between the FTIR spectra of DG [45,46] and Neusilin US2 [47] revealed the purity of the used ingredients. The observed new peaks in the FTIR spectrum of drug-free SNEDDS-loaded Neusilin US2 correspond to the adsorption of SNEDDS components, which agrees with previously published studies [31,48]. The presence of all characteristic DG peaks in the physical mixture and optimum solid nutraceutical-SNEDDS (S4) indicates the absence of a chemical interaction between the drug and excipients [49].

Innovator (Forxiga®) was selected as the reference product for a comparative dissolution study. This will give a clear impression of the performance of the developed optimum formulation compared to the marketed product. The comparative dissolution study demonstrated that the optimized solid nutraceutical-SNEDDS formulation (S4) achieved a dissolution performance comparable to that of the marketed product Forxiga®. Similar dissolution profiles and statistically insignificant differences in dissolution efficiency values (p > 0.05) suggest that incorporating DG into the SNEDDS system did not compromise its release characteristics. These findings suggest that the developed S4 formulation could provide similar in vivo performance to the marketed product while offering additional benefits of incorporating nutraceutical components.

5 Conclusions

The current study represents a multifaceted approach to treating diabetic patients on DG. This combined the benefits of enhancing the solubility of poorly water-soluble drugs and nutraceutical-SNEDDS. The prepared optimized formulation (S4) showed enhanced dissolution properties and a comparable drug release profile to the marketed product, with additional benefits in incorporating bioactive turmeric oil. SEM, FTIR, and PXRD analyses confirm the adsorption of liquid SNEDDS by Neusilin US2 and the conversion of the drug to an amorphous form with no potential chemical interaction. This research could lead to developing more effective therapeutic approaches for diabetes management. This could potentially offer patients enhanced blood glucose control and minimize disease-related complications. Further in vivo pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies are required to confirm the superior performance of the developed S4 formulation against the marketed tablet.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ongoing Research Funding Program, (ORFFT-2025-064-1), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for financial support.

-

Funding information: The authors would like to thank Ongoing Research Funding Program, (ORFFT-2025-064-1), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for financial support.

-

Author contributions: Conceptualization, A.Y.S.; methodology, A.Y.S. and I.A.; software, A.Y.S.; validation, A.Y.S.; formal analysis, A.Y.S.; investigation, A.Y.S.; resources, A.Y.S., E.M.E., I.A., and M.A.A.; data curation, A.Y.S.; writing – original draft preparation, A.Y.S.; writing – review and editing, E.M.E., A.Y.S., and M.A.A.; visualization, A.Y.S.; supervision, E.M.E.; project administration, E.M.E.; and funding acquisition, E.M.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Alam S, Hasan MK, Neaz S, Hussain N, Hossain MF, Rahman T. Diabetes Mellitus: insights from epidemiology, biochemistry, risk factors, diagnosis, complications and comprehensive management. Diabetology. 2021;2(2):36–50.10.3390/diabetology2020004Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Chang C-M, Hsieh C-J, Huang J-C, Huang I-C. Acute and chronic fluctuations in blood glucose levels can increase oxidative stress in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Acta Diabetologica. 2012;49:171–7.10.1007/s00592-012-0398-xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Wang X, Kang J, Liu Q, Tong T, Quan H. Fighting diabetes mellitus: Pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches. Curr Pharm Des. 2020;26(39):4992–5001.10.2174/1381612826666200728144200Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Aruoma OI, Neergheen VS, Bahorun T, Jen L-S. Free radicals, antioxidants and diabetes: embryopathy, retinopathy, neuropathy, nephropathy and cardiovascular complications. Neuroembryology Aging. 2007;4(3):117–37.10.1159/000109344Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Lotfy M, Adeghate J, Kalasz H, Singh J, Adeghate E. Chronic complications of diabetes mellitus: a mini review. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2017;13(1):3–10.10.2174/1573399812666151016101622Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Morita M, Kanasaki K. Sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors for diabetic kidney disease: Targeting Warburg effects in proximal tubular cells. Diabetes Metab. 2020;46(5):353–61.10.1016/j.diabet.2020.06.005Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Wilson C. Dapagliflozin: an insulin-independent, therapeutic option for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2010;6(10):531.10.1038/nrendo.2010.134Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Durak A, Olgar Y, Degirmenci S, Akkus E, Tuncay E, Turan B. A SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin suppresses prolonged ventricular-repolarization through augmentation of mitochondrial function in insulin-resistant metabolic syndrome rats. Cardiovasc Diabetology. 2018;17:1–17.10.1186/s12933-018-0790-0Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Vivian EM. Dapagliflozin: A new sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor for treatment of type 2 diabetes. Am J Health-System Pharm. 2015;72(5):361–72.10.2146/ajhp140168Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Balakumar P, Sundram K, Dhanaraj SA. Dapagliflozin: glucuretic action and beyond. Pharmacol Res. 2014;82:34–9.10.1016/j.phrs.2014.03.008Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Arow M, Waldman M, Yadin D, Nudelman V, Shainberg A, Abraham NG, et al. Sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor Dapagliflozin attenuates diabetic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Diabetology. 2020;19:1–12.10.1186/s12933-019-0980-4Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Alruwaili NK, Zafar A, Imam SS, Alharbi KS, Alshehri S, Elsaman T, et al. Formulation of amorphous ternary solid dispersions of dapagliflozin using PEG 6000 and Poloxamer 188: solid-state characterization, ex vivo study, and molecular simulation assessment. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2020;46(9):1458–67.10.1080/03639045.2020.1802482Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Ogino M, Yamada K, Sato H, Onoue S. Enhanced nutraceutical functions of herbal oily extract employing formulation technology: The present and future. PharmaNutrition. 2022;22:100318.10.1016/j.phanu.2022.100318Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Elzayat EM, Sherif AY, Shahba AA-W, Kazi M, Alyahya M, Darwish HW. Development and validation of a stability indicating UPLC-DAD method coupled with MS-TQD for ramipril and thymoquinone in bioactive SNEDDS with in silico toxicity analysis of ramipril degradation products. Open Chem. 2024;22(1):20240070.10.1515/chem-2024-0070Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Orellana-Paucar AM, Machado-Orellana MG. Pharmacological profile, bioactivities, and safety of turmeric oil. Molecules. 2022;27(16):5055.10.3390/molecules27165055Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Dwivedi S, Gottipati A, Ganugula R, Arora M, Friend R, Osburne R, et al. Oral nanocurcumin alone or in combination with insulin alleviates STZ-induced diabetic neuropathy in rats. Mol Pharm. 2022;19(12):4612–24.10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.2c00465Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Sharifi-Rad J, Rayess YE, Rizk AA, Sadaka C, Zgheib R, Zam W, et al. Turmeric and its major compound curcumin on health: bioactive effects and safety profiles for food, pharmaceutical, biotechnological and medicinal applications. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:550909.10.3389/fphar.2020.01021Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Thota RN, Rosato JI, Dias CB, Burrows TL, Martins RN, Garg ML. Dietary supplementation with curcumin reduce circulating levels of glycogen synthase kinase-3β and islet amyloid polypeptide in adults with high risk of type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. Nutrients. 2020;12(4):1032.10.3390/nu12041032Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Badr AM, Sharkawy H, Farid AA, El-Deeb S. Curcumin induces regeneration of β cells and suppression of phosphorylated-NF-κB in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. J Basic Appl Zool. 2020;81:1–15.10.1186/s41936-020-00156-0Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Qihui L, Shuntian D, Xin Z, Xiaoxia Y, Zhongpei C. Protection of curcumin against streptozocin-induced pancreatic cell destruction in T2D rats. Planta Medica. 2020;86(2):113–20.10.1055/a-1046-1404Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Rashid K, Chowdhury S, Ghosh S, Sil PC. Curcumin attenuates oxidative stress induced NFκB mediated inflammation and endoplasmic reticulum dependent apoptosis of splenocytes in diabetes. Biochem Pharmacol. 2017;143:140–55.10.1016/j.bcp.2017.07.009Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Sherif AY, Elzayat EM, Altamimi MA. Optimization of glibenclamide loaded thermoresponsive SNEDDS using design of experiment approach: Paving the way to enhance pharmaceutical applicability. Molecules. 2024;29(21):5163.10.3390/molecules29215163Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Sherif AY, Elzayat EM. Development of bioresponsive poloxamer-based self-nanoemulsifying system for enhanced febuxostat bioavailability: Solidification strategy using I-optimal approach. Pharmaceutics. 2025;17(8):975.10.3390/pharmaceutics17080975Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Krupa A, Szlęk J, Jany BR, Jachowicz R. Preformulation studies on solid self-emulsifying systems in powder form containing magnesium aluminometasilicate as porous carrier. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2015;16:623–35.10.1208/s12249-014-0247-zSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Weerapol Y, Limmatvapirat S, Jansakul C, Takeuchi H, Sriamornsak P. Enhanced dissolution and oral bioavailability of nifedipine by spontaneous emulsifying powders: effect of solid carriers and dietary state. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2015;91:25–34.10.1016/j.ejpb.2015.01.011Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Gumaste SG, Dalrymple DM, Serajuddin AT. Development of solid SEDDS, V: compaction and drug release properties of tablets prepared by adsorbing lipid-based formulations onto Neusilin® US2. Pharm Res. 2013;30:3186–99.10.1007/s11095-013-1106-4Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Mandić J, Pobirk AZ, Vrečer F, Gašperlin M. Overview of solidification techniques for self-emulsifying drug delivery systems from industrial perspective. Int J Pharm. 2017;533(2):335–45.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.05.036Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Buya AB, Beloqui A, Memvanga PB, Préat V. Self-nano-emulsifying drug-delivery systems: From the development to the current applications and challenges in oral drug delivery. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12(12):1194.10.3390/pharmaceutics12121194Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Rehman FU, Shah KU, Shah SU, Khan IU, Khan GM, Khan A. From nanoemulsions to self-nanoemulsions, with recent advances in self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery systems (SNEDDS). Expert Opin Drug Delivery. 2017;14(11):1325–40.10.1080/17425247.2016.1218462Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Shahba AA-W, Sherif AY, Elzayat EM, Kazi M. Combined ramipril and black seed oil dosage forms using bioactive self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery systems (BIO-SNEDDSs). Pharmaceuticals. 2022;15(9):1120.10.3390/ph15091120Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Kazi M, Shahba AA, Alrashoud S, Alwadei M, Sherif AY, Alanazi FK. Bioactive self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery systems (Bio-SNEDDS) for combined oral delivery of curcumin and piperine. Molecules. 2020;25(7):1703.10.3390/molecules25071703Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Pouton CW. Lipid formulations for oral administration of drugs: non-emulsifying, self-emulsifying and ‘self-microemulsifying’drug delivery systems. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2000;11:S93–8.10.1016/S0928-0987(00)00167-6Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Shin Y, Kim M, Kim C, Jeon H, Koo J, Oh J, et al. Development and characterization of olaparib-loaded solid self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system (S-SNEDDS) for Pharmaceutical Applications. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2024;25(7):221.10.1208/s12249-024-02927-2Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Pathak K, Raghuvanshi S. Oral bioavailability: issues and solutions via nanoformulations. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2015;54:325–57.10.1007/s40262-015-0242-xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Park H, Cha K-H, Hong SH, Abuzar SM, Lee S, Ha E-S, et al. Pharmaceutical characterization and in vivo evaluation of orlistat formulations prepared by the supercritical melt-adsorption method using carbon dioxide: Effects of mesoporous silica type. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12(4):333.10.3390/pharmaceutics12040333Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] Chairuk P, Tubtimsri S, Jansakul C, Sriamornsak P, Weerapol Y. Enhancing oral absorption of poorly water-soluble herb (Kaempferia parviflora) extract using self-nanoemulsifying formulation. Pharm Dev Technol. 2020;25(3):340–50.10.1080/10837450.2019.1703134Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Teaima M, Hababeh S, Khanfar M, Alanazi F, Alshora D, El-Nabarawi M. Design and optimization of pioglitazone hydrochloride self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system (SNEDDS) incorporated into an orally disintegrating tablet. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(2):425.10.3390/pharmaceutics14020425Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Snela A, Jadach B, Froelich A, Skotnicki M, Milczewska K, Rojewska M, et al. Self-emulsifying drug delivery systems with atorvastatin adsorbed on solid carriers: formulation and in vitro drug release studies. Colloids Surf A: Physicochem Eng Asp. 2019;577:281–90.10.1016/j.colsurfa.2019.05.062Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Elgart A, Cherniakov I, Aldouby Y, Domb AJ, Hoffman A. Improved oral bioavailability of BCS class 2 compounds by self nano-emulsifying drug delivery systems (SNEDDS): the underlying mechanisms for amiodarone and talinolol. Pharm Res. 2013;30:3029–44.10.1007/s11095-013-1063-ySuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Jeon S, Clavadetscher J, Lee D-K, Chankeshwara SV, Bradley M, Cho W-S. Surface charge-dependent cellular uptake of polystyrene nanoparticles. Nanomaterials. 2018;8(12):1028.10.3390/nano8121028Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Mundada VP, Patel MH, Mundada PK, Sawant KK. Enhanced bioavailability and antihypertensive activity of nisoldipine loaded nanoemulsion: optimization, cytotoxicity and uptake across Caco-2 cell line, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2020;46(3):376–87.10.1080/03639045.2020.1724128Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Ashfaq M, Shah S, Rasul A, Hanif M, Khan HU, Khames A, et al. Enhancement of the solubility and bioavailability of pitavastatin through a self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system (SNEDDS). Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(3):482.10.3390/pharmaceutics14030482Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[43] Unnisa A, Chettupalli AK, Al Hagbani T, Khalid M, Jandrajupalli SB, Chandolu S, et al. Development of dapagliflozin solid lipid nanoparticles as a novel carrier for oral delivery: statistical design, optimization, in-vitro and in-vivo characterization, and evaluation. Pharmaceuticals. 2022;15(5):568.10.3390/ph15050568Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[44] Abdelmonem R, Azer MS, Makky A, Zaghloul A, El-Nabarawi M, Nada A. Development, characterization, and in-vivo pharmacokinetic study of lamotrigine solid self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system. Drug Design Dev Ther. 2020;14:4343–62.10.2147/DDDT.S263898Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] El-Megharbel SM, Al-Thubaiti EH, Qahl SH, Al-Eisa RA, Hamza RZ. Synthesis and spectroscopic characterization of dapagliflozin/Zn (II), cr (III) and Se (IV) novel complexes that ameliorate hepatic damage, hyperglycemia and oxidative injury induced by streptozotocin-induced diabetic male rats and their antibacterial activity. Crystals. 2022;12(3):304.10.3390/cryst12030304Suche in Google Scholar

[46] El-Bagory I, Alruwaili NK, Elkomy MH, Ahmad J, Afzal M, Ahmad N, et al. Development of novel dapagliflozin loaded solid self-nanoemulsifying oral delivery system: Physiochemical characterization and in vivo antidiabetic activity. J Drug Delivery Sci Technol. 2019;54:101279.10.1016/j.jddst.2019.101279Suche in Google Scholar

[47] Shrivastava N, Parikh A, Dewangan RP, Biswas L, Verma AK, Mittal S, et al. Solid self-nano emulsifying nanoplatform loaded with tamoxifen and resveratrol for treatment of breast cancer. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(7):1486.10.3390/pharmaceutics14071486Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[48] Yeo S, An J, Park C, Kim D, Lee J. Design and characterization of phosphatidylcholine-based solid dispersions of aprepitant for enhanced solubility and dissolution. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12(5):407.10.3390/pharmaceutics12050407Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] Nair AB, Singh B, Shah J, Jacob S, Aldhubiab B, Sreeharsha N, et al. Formulation and evaluation of self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system derived tablet containing sertraline. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(2):336.10.3390/pharmaceutics14020336Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Phytochemical investigation and evaluation of antioxidant and antidiabetic activities in aqueous extracts of Cedrus atlantica

- Influence of B4C addition on the tribological properties of bronze matrix brake pad materials

- Discovery of the bacterial HslV protease activators as lead molecules with novel mode of action

- Characterization of volatile flavor compounds of cigar with different aging conditions by headspace–gas chromatography–ion mobility spectrometry

- Effective remediation of organic pollutant using Musa acuminata peel extract-assisted iron oxide nanoparticles

- Analysis and health risk assessment of toxic elements in traditional herbal tea infusions

- Cadmium exposure in marine crabs from Jiaxing City, China: Insights into health risk assessment

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles of Cinnamomum zeylanicum and their biological activities

- Tetraclinis articulata (Vahl) Mast., Mentha pulegium L., and Thymus zygis L. essential oils: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antifungal properties against postharvest fungal diseases of apple, and in vitro, in vivo, and in silico investigation

- Exploration of plant alkaloids as potential inhibitors of HIV–CD4 binding: Insight into comprehensive in silico approaches

- Recovery of phenylethyl alcohol from aqueous solution by batch adsorption

- Electrochemical approach for monitoring the catalytic action of immobilized catalase

- Green synthesis of ZIF-8 for selective adsorption of dyes in water purification

- Optimization of the conditions for the preparation of povidone iodine using the response surface methodology

- A case study on the influence of soil amendment on ginger oil’s physicochemical properties, mineral contents, microbial load, and HPLC determination of its vitamin level

- Removal of antiviral favipiravir from wastewater using biochar produced from hazelnut shells

- Effect of biochar and soil amendment on bacterial community composition in the root soil and fruit of tomato under greenhouse conditions

- Bioremediation of malachite green dye using Sargassum wightii seaweed and its biological and physicochemical characterization

- Evaluation of natural compounds as folate biosynthesis inhibitors in Mycobacterium leprae using docking, ADMET analysis, and molecular dynamics simulation

- Novel insecticidal properties of bioactive zoochemicals extracted from sea urchin Salmacis virgulata

- Elevational gradients shape total phenolic content and bioactive potential of sweet marjoram (Origanum majorana L.): A comparative study across altitudinal zones

- Study on the CO2 absorption performance of deep eutectic solvents formed by superbase DBN and weak acid diethylene glycol

- Preparation and wastewater treatment performance of zeolite-modified ecological concrete

- Multifunctional chitosan nanoparticles: Zn2+ adsorption, antimicrobial activity, and promotion of aquatic health

- Comparative analysis of nutritional composition and bioactive properties of Chlorella vulgaris and Arthrospira platensis: Implications for functional foods and dietary supplements

- Growth kinetics and mechanical characterization of boride layers formed on Ti6Al4V

- Enhancement of water absorption properties of potassium polyacrylate-based hydrogels in CaCl2-rich soils using potassium di- and tri-carboxylate salts

- Electrochemical and microbiological effects of dumpsite leachates on soil and air quality

- Modeling benzene physicochemical properties using Zagreb upsilon indices

- Characterization and ecological risk assessment of toxic metals in mangrove sediments near Langen Village in Tieshan Bay of Beibu Gulf, China

- Protective effect of Helicteres isora, an efficient candidate on hepatorenal toxicity and management of diabetes in animal models

- Valorization of Juglans regia L. (Walnut) green husk from Jordan: Analysis of fatty acids, phenolics, antioxidant, and cytotoxic activities

- Molecular docking and dynamics simulations of bioactive terpenes from Catharanthus roseus essential oil targeting breast cancer

- Selection of a dam site by using AHP and VIKOR: The Sakarya Basin

- Characterization and modeling of kidney bean shell biochar as adsorbent for caffeine removal from aquatic environments

- The effects of short-term and long-term 2100 MHz radiofrequency radiation on adult rat auditory brainstem response

- Biochemical insights into the anthelmintic and anti-inflammatory potential of sea cucumber extract: In vitro and in silico approaches

- Resveratrol-derived MDM2 inhibitors: Synthesis, characterization, and biological evaluation against MDM2 and HCT-116 cells

- Phytochemical constituents, in vitro antibacterial activity, and computational studies of Sudanese Musa acuminate Colla fruit peel hydro-ethanol extract

- Chemical composition of essential oils reviewed from the height of Cajuput (Melaleuca leucadendron) plantations in Buru Island and Seram Island, Maluku, Indonesia

- Phytochemical analysis and antioxidant activity of Azadirachta indica A. Juss from the Republic of Chad: in vitro and in silico studies

- Stability studies of titanium–carboxylate complexes: A multi-method computational approach

- Efficient adsorption performance of an alginate-based dental material for uranium(vi) removal

- Synthesis and characterization of the Co(ii), Ni(ii), and Cu(ii) complexes with a 1,2,4-triazine derivative ligand

- Evaluation of the impact of music on antioxidant mechanisms and survival in salt-stressed goldfish

- Optimization and validation of UPLC method for dapagliflozin and candesartan cilexetil in an on-demand formulation: Analytical quality by design approach

- Biomass-based cellulose hydroxyapatite nanocomposites for the efficient sequestration of dyes: Kinetics, response surface methodology optimization, and reusability

- Multifunctional nitrogen and boron co-doped carbon dots: A fluorescent probe for Hg2+ and biothiol detection with bioimaging and antifungal applications

- Separation of sulphonamides on a C12-diol mixed-mode HPLC column and investigation of their retention mechanism

- Characterization and antioxidant activity of pectin from lemon peels

- Fast PFAS determination in honey by direct probe electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry: A health risk assessment insight

- Correlation study between GC–MS analysis of cigarette aroma compounds and sensory evaluation

- Synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular docking studies of substituted chromone-2-carboxamide derivatives as anti-breast cancer agents

- The influence of feed space velocity and pressure on the cold flow properties of diesel fuel

- Acid etching behavior and mechanism in acid solution of iron components in basalt fibers

- Protective effect of green synthesized nanoceria on retinal oxidative stress and inflammation in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat

- Evaluation of the antianxiety activity of green zinc nanoparticles mediated by Boswellia thurifera in albino mice by following the plus maze and light and dark exploration tests

- Yeast as an efficient and eco-friendly bifunctional porogen for biomass-derived nitrogen-doped carbon catalysts in the oxygen reduction reaction

- Novel descriptors for the prediction of molecular properties

- Synthesis and characterization of surfactants derived from phenolphthalein: In vivo and in silico studies of their antihyperlipidemic effect

- Turmeric oil-fortified nutraceutical-SNEDDS: An approach to boost therapeutic effectiveness of dapagliflozin during treatment of diabetic patients

- Analysis and study on volatile flavor compounds of three Yunnan cultivated cigars based on headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry

- Near-infrared IR780 dye-loaded poloxamer 407 micelles: Preparation and in vitro assessment of anticancer activity

- Study on the influence of the viscosity reducer solution on percolation capacity of thin oil in ultra-low permeability reservoir

- Detection method of Aristolochic acid I based on magnetic carrier Fe3O4 and gold nanoclusters

- Juglone’s apoptotic impact against eimeriosis-induced infection: a bioinformatics, in-silico, and in vivo approach

- Potential anticancer agents from genus Aerva based on tubulin targets: an in-silico integration of quantitative structure activity relationship (QSAR), molecular docking, simulation, drug-likeness, and density functional theory (DFT) analysis

- Hepatoprotective and PXR-modulating effects of Erodium guttatum extract in propiconazole-induced toxicity

- Studies on chemical composition of medicinal plants collected in natural locations in Ecuador

- A study of different pre-treatment methods for cigarettes and their aroma differences

- Cytotoxicity and molecular mechanisms of quercetin, gallic acid, and pinocembrin in Caco-2 cells: insights from cell viability assays, network pharmacology, and molecular docking

- Choline-based deep eutectic solvents for green extraction of oil from sour cherry seeds

- Green-synthesis of chromium (III) nanoparticles using garden fern and evaluation of its antibacterial and anticholinesterase activities

- Innovative functional mayonnaise formulations with watermelon seeds oil: evaluation of quality parameters and storage stability

- Molecular insights and biological evaluation of compounds isolated from Ferula oopoda against diabetes, advanced glycation end products and inflammation in diabetics

- Removal of cytotoxic tamoxifen from aqueous solutions using a geopolymer-based nepheline–cordierite adsorbent

- Unravelling the therapeutic effect of naturally occurring Bauhinia flavonoids against breast cancer: an integrated computational approach

- Characterization of organic arsenic residues in livestock and poultry meat and offal and consumption risks

- Synthesis and characterization of zinc sulfide nanoparticles and their genotoxic and cytotoxic effects on acute myeloid leukemia cells

- Activity of Coriandrum sativum methanolic leaf extracts against Eimeria papillata: a combined in vitro and in silico approach

- Special Issue on Advancing Sustainable Chemistry for a Greener Future

- One-pot fabrication of highly porous morphology of ferric oxide-ferric oxychloride/poly-O-chloroaniline nanocomposite seeded on poly-1H pyrrole: Photocathode for green hydrogen generation from natural and artificial seawater

- High-efficiency photocathode for green hydrogen generation from sanitation water using bismuthyl chloride/poly-o-chlorobenzeneamine nanocomposite

- Innovative synthesis of cobalt-based catalysts using ionic liquids and deep eutectic solvents: A minireview on electrocatalytic water splitting

- Special Issue on Phytochemicals, Biological and Toxicological Analysis of Plants

- Comparative analysis of fruit quality parameters and volatile compounds in commercially grown citrus cultivars

- Total phenolic, flavonoid, flavonol, and tannin contents as well as antioxidant and antiparasitic activities of aqueous methanol extract of Alhagi graecorum plant used in traditional medicine: Collected in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- Study on the pharmacological effects and active compounds of Apocynum venetum L.

- Chemical profile of Senna italica and Senna velutina seed and their pharmacological properties

- Essential oils from Brazilian plants: A literature analysis of anti-inflammatory and antimalarial properties and in silico validation

- Toxicological effects of green tea catechin extract on rat liver: Delineating safe and harmful doses

- Unlocking the potential of Trigonella foenum-graecum L. plant leaf extracts against diabetes-associated hypertension: A proof of concept by in silico studies

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Phytochemical investigation and evaluation of antioxidant and antidiabetic activities in aqueous extracts of Cedrus atlantica

- Influence of B4C addition on the tribological properties of bronze matrix brake pad materials

- Discovery of the bacterial HslV protease activators as lead molecules with novel mode of action

- Characterization of volatile flavor compounds of cigar with different aging conditions by headspace–gas chromatography–ion mobility spectrometry

- Effective remediation of organic pollutant using Musa acuminata peel extract-assisted iron oxide nanoparticles

- Analysis and health risk assessment of toxic elements in traditional herbal tea infusions

- Cadmium exposure in marine crabs from Jiaxing City, China: Insights into health risk assessment

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles of Cinnamomum zeylanicum and their biological activities

- Tetraclinis articulata (Vahl) Mast., Mentha pulegium L., and Thymus zygis L. essential oils: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antifungal properties against postharvest fungal diseases of apple, and in vitro, in vivo, and in silico investigation

- Exploration of plant alkaloids as potential inhibitors of HIV–CD4 binding: Insight into comprehensive in silico approaches

- Recovery of phenylethyl alcohol from aqueous solution by batch adsorption

- Electrochemical approach for monitoring the catalytic action of immobilized catalase

- Green synthesis of ZIF-8 for selective adsorption of dyes in water purification

- Optimization of the conditions for the preparation of povidone iodine using the response surface methodology

- A case study on the influence of soil amendment on ginger oil’s physicochemical properties, mineral contents, microbial load, and HPLC determination of its vitamin level

- Removal of antiviral favipiravir from wastewater using biochar produced from hazelnut shells

- Effect of biochar and soil amendment on bacterial community composition in the root soil and fruit of tomato under greenhouse conditions

- Bioremediation of malachite green dye using Sargassum wightii seaweed and its biological and physicochemical characterization

- Evaluation of natural compounds as folate biosynthesis inhibitors in Mycobacterium leprae using docking, ADMET analysis, and molecular dynamics simulation

- Novel insecticidal properties of bioactive zoochemicals extracted from sea urchin Salmacis virgulata

- Elevational gradients shape total phenolic content and bioactive potential of sweet marjoram (Origanum majorana L.): A comparative study across altitudinal zones

- Study on the CO2 absorption performance of deep eutectic solvents formed by superbase DBN and weak acid diethylene glycol

- Preparation and wastewater treatment performance of zeolite-modified ecological concrete

- Multifunctional chitosan nanoparticles: Zn2+ adsorption, antimicrobial activity, and promotion of aquatic health

- Comparative analysis of nutritional composition and bioactive properties of Chlorella vulgaris and Arthrospira platensis: Implications for functional foods and dietary supplements

- Growth kinetics and mechanical characterization of boride layers formed on Ti6Al4V

- Enhancement of water absorption properties of potassium polyacrylate-based hydrogels in CaCl2-rich soils using potassium di- and tri-carboxylate salts

- Electrochemical and microbiological effects of dumpsite leachates on soil and air quality

- Modeling benzene physicochemical properties using Zagreb upsilon indices

- Characterization and ecological risk assessment of toxic metals in mangrove sediments near Langen Village in Tieshan Bay of Beibu Gulf, China

- Protective effect of Helicteres isora, an efficient candidate on hepatorenal toxicity and management of diabetes in animal models

- Valorization of Juglans regia L. (Walnut) green husk from Jordan: Analysis of fatty acids, phenolics, antioxidant, and cytotoxic activities

- Molecular docking and dynamics simulations of bioactive terpenes from Catharanthus roseus essential oil targeting breast cancer

- Selection of a dam site by using AHP and VIKOR: The Sakarya Basin

- Characterization and modeling of kidney bean shell biochar as adsorbent for caffeine removal from aquatic environments

- The effects of short-term and long-term 2100 MHz radiofrequency radiation on adult rat auditory brainstem response

- Biochemical insights into the anthelmintic and anti-inflammatory potential of sea cucumber extract: In vitro and in silico approaches

- Resveratrol-derived MDM2 inhibitors: Synthesis, characterization, and biological evaluation against MDM2 and HCT-116 cells

- Phytochemical constituents, in vitro antibacterial activity, and computational studies of Sudanese Musa acuminate Colla fruit peel hydro-ethanol extract

- Chemical composition of essential oils reviewed from the height of Cajuput (Melaleuca leucadendron) plantations in Buru Island and Seram Island, Maluku, Indonesia

- Phytochemical analysis and antioxidant activity of Azadirachta indica A. Juss from the Republic of Chad: in vitro and in silico studies

- Stability studies of titanium–carboxylate complexes: A multi-method computational approach

- Efficient adsorption performance of an alginate-based dental material for uranium(vi) removal

- Synthesis and characterization of the Co(ii), Ni(ii), and Cu(ii) complexes with a 1,2,4-triazine derivative ligand

- Evaluation of the impact of music on antioxidant mechanisms and survival in salt-stressed goldfish

- Optimization and validation of UPLC method for dapagliflozin and candesartan cilexetil in an on-demand formulation: Analytical quality by design approach

- Biomass-based cellulose hydroxyapatite nanocomposites for the efficient sequestration of dyes: Kinetics, response surface methodology optimization, and reusability

- Multifunctional nitrogen and boron co-doped carbon dots: A fluorescent probe for Hg2+ and biothiol detection with bioimaging and antifungal applications

- Separation of sulphonamides on a C12-diol mixed-mode HPLC column and investigation of their retention mechanism

- Characterization and antioxidant activity of pectin from lemon peels

- Fast PFAS determination in honey by direct probe electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry: A health risk assessment insight

- Correlation study between GC–MS analysis of cigarette aroma compounds and sensory evaluation

- Synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular docking studies of substituted chromone-2-carboxamide derivatives as anti-breast cancer agents

- The influence of feed space velocity and pressure on the cold flow properties of diesel fuel

- Acid etching behavior and mechanism in acid solution of iron components in basalt fibers

- Protective effect of green synthesized nanoceria on retinal oxidative stress and inflammation in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat

- Evaluation of the antianxiety activity of green zinc nanoparticles mediated by Boswellia thurifera in albino mice by following the plus maze and light and dark exploration tests

- Yeast as an efficient and eco-friendly bifunctional porogen for biomass-derived nitrogen-doped carbon catalysts in the oxygen reduction reaction

- Novel descriptors for the prediction of molecular properties

- Synthesis and characterization of surfactants derived from phenolphthalein: In vivo and in silico studies of their antihyperlipidemic effect

- Turmeric oil-fortified nutraceutical-SNEDDS: An approach to boost therapeutic effectiveness of dapagliflozin during treatment of diabetic patients

- Analysis and study on volatile flavor compounds of three Yunnan cultivated cigars based on headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry

- Near-infrared IR780 dye-loaded poloxamer 407 micelles: Preparation and in vitro assessment of anticancer activity

- Study on the influence of the viscosity reducer solution on percolation capacity of thin oil in ultra-low permeability reservoir

- Detection method of Aristolochic acid I based on magnetic carrier Fe3O4 and gold nanoclusters

- Juglone’s apoptotic impact against eimeriosis-induced infection: a bioinformatics, in-silico, and in vivo approach

- Potential anticancer agents from genus Aerva based on tubulin targets: an in-silico integration of quantitative structure activity relationship (QSAR), molecular docking, simulation, drug-likeness, and density functional theory (DFT) analysis

- Hepatoprotective and PXR-modulating effects of Erodium guttatum extract in propiconazole-induced toxicity

- Studies on chemical composition of medicinal plants collected in natural locations in Ecuador

- A study of different pre-treatment methods for cigarettes and their aroma differences

- Cytotoxicity and molecular mechanisms of quercetin, gallic acid, and pinocembrin in Caco-2 cells: insights from cell viability assays, network pharmacology, and molecular docking

- Choline-based deep eutectic solvents for green extraction of oil from sour cherry seeds

- Green-synthesis of chromium (III) nanoparticles using garden fern and evaluation of its antibacterial and anticholinesterase activities

- Innovative functional mayonnaise formulations with watermelon seeds oil: evaluation of quality parameters and storage stability

- Molecular insights and biological evaluation of compounds isolated from Ferula oopoda against diabetes, advanced glycation end products and inflammation in diabetics

- Removal of cytotoxic tamoxifen from aqueous solutions using a geopolymer-based nepheline–cordierite adsorbent

- Unravelling the therapeutic effect of naturally occurring Bauhinia flavonoids against breast cancer: an integrated computational approach

- Characterization of organic arsenic residues in livestock and poultry meat and offal and consumption risks

- Synthesis and characterization of zinc sulfide nanoparticles and their genotoxic and cytotoxic effects on acute myeloid leukemia cells

- Activity of Coriandrum sativum methanolic leaf extracts against Eimeria papillata: a combined in vitro and in silico approach

- Special Issue on Advancing Sustainable Chemistry for a Greener Future

- One-pot fabrication of highly porous morphology of ferric oxide-ferric oxychloride/poly-O-chloroaniline nanocomposite seeded on poly-1H pyrrole: Photocathode for green hydrogen generation from natural and artificial seawater

- High-efficiency photocathode for green hydrogen generation from sanitation water using bismuthyl chloride/poly-o-chlorobenzeneamine nanocomposite

- Innovative synthesis of cobalt-based catalysts using ionic liquids and deep eutectic solvents: A minireview on electrocatalytic water splitting

- Special Issue on Phytochemicals, Biological and Toxicological Analysis of Plants

- Comparative analysis of fruit quality parameters and volatile compounds in commercially grown citrus cultivars

- Total phenolic, flavonoid, flavonol, and tannin contents as well as antioxidant and antiparasitic activities of aqueous methanol extract of Alhagi graecorum plant used in traditional medicine: Collected in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- Study on the pharmacological effects and active compounds of Apocynum venetum L.

- Chemical profile of Senna italica and Senna velutina seed and their pharmacological properties

- Essential oils from Brazilian plants: A literature analysis of anti-inflammatory and antimalarial properties and in silico validation

- Toxicological effects of green tea catechin extract on rat liver: Delineating safe and harmful doses

- Unlocking the potential of Trigonella foenum-graecum L. plant leaf extracts against diabetes-associated hypertension: A proof of concept by in silico studies