Structural, optical, and gas sensing properties of Ce, Nd, and Pr doped ZnS nanostructured thin films prepared by nebulizer spray pyrolysis method

-

A. M. S. Arulanantham

, A. Vimala Juliet

, Mohd Shkir

, Zubiar Ahmad

und Sambasivam Sangaraju

Abstract

In this work, an economical nebulizer spray pyrolysis (NSP) method was used to successfully deposit undoped ZnS and rare earth (RE)-doped ZnS thin films containing Ce, Nd, and Pr (at doping concentrations of 2 wt%) onto glass substrates. To examine the prepared films structural, morphological, optical, and ammonia gas sensing characteristics, a wide range of characterization tools were used. All of the doped and undoped ZnS thin films crystallized in the hexagonal wurtzite structure, with a preferred orientation along the (002) plane that corresponds to the P63 mc space group. This is confirmed by XRD analysis, and there are no secondary impurity phases present. The RE-doped films, especially ZnS:Pr (2 %), showed better crystallinity among the samples. FESEM images showed a uniform surface morphology with distinct nanostructured grains. Zn, S, and RE (Ce, Nd, Pr) elements were successfully incorporated into the films, according to energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy. In comparison to the other samples, the ZnS:Pr film showed a slight decrease in optical bandgap and improved absorption throughout the measured spectral range, according to UV-vis absorption spectra. The photoluminescence (PL) spectra reveal a stronger broad band emission around 487 nm suggesting more number native defect sites present in the samples. Finally, the gas sensing studies showed that RE doped ZnS thin films significantly improved NH3 detection. With a sensor response of 1,520, the 2 % ZnS:Pr film outperformed the Ce, and Nd dopants. Additionally, it performed exceptionally well in terms of humidity tolerance, guaranteeing dependable functioning in a range of environmental circumstances. Furthermore, with response and recovery times of 9.7 and 8.9 s, respectively, the ZnS:Pr sensor demonstrated its abilities as a high-performance, stable, and economical material for ambient temperature NH3 sensing applications.

1 Introduction

Over the past few decades, gas sensor technologies have made significant strides, opening up a wide range of applications, including environmental monitoring, automotive systems, healthcare, and indoor air quality control. As environmental and public health issues receive more attention, it is more important than ever to accurately detect harmful gases like CO, CO2, NOx, SOx, and ammonia (NH3) [1], 2]. The detection of NH3 has become particularly important due to its widespread industrial use and potential health risks. The production of nitrogen-based fertilizers uses about 80 % of NH3, with the remaining 20 % going towards the production of explosives, cleaning supplies, medications, and refrigeration equipment. NH3 is one of the most widely produced chemicals in the world. Additionally, NH3 is widely utilized in the beverage processing, petrochemical, winery, breweries, dairy, and ice cream industries. Because of its hydrogen-rich composition, it also contributes significantly to automotive emission control, especially in diesel engines, where it aids in the reduction of NO x emissions through selective catalytic reduction (SCR). Human activity releases between 2.1 and 8.1 Teragrams (Tg) of NH3 into the atmosphere annually. Although ambient NH3 concentrations typically remain in the lower end of the parts-per-billion (ppb) range, being exposed to elevated levels can have detrimental health effects on the skin, eyes, and respiratory system [3], 4]. Exposure limits set by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) are 25 parts per million for exposure lasting 8 h and 35 parts per million for exposure lasting 10 min. Additionally, the atmospheric reactivity of NH3 leads to the formation of aerosols, which causes smog and changes the climate. Importantly, high levels of exhaled NH3 are biomarkers for renal and respiratory disorders causing vomiting, diarrhea, pulmonary edema, so clinical diagnostics relies heavily on their detection. Therefore, accurate and trustworthy lower concentration NH3 sensing with high sensitivity, good selectivity and reliability, as well as high precision was crucial in maintaining public safety, reducing environmental contamination, and facilitating efficient disease monitoring [5], [6], [7]. Because of new developments in material science, scientists are especially interested in creating unique and diverse nanostructures which can be applied to a range of industrial applications. In particular, semiconductor materials have attracted interest for gas sensing because of their outstanding physical and chemical properties, including a high surface-to-volume ratio, cost-effectiveness, simple fabrication, and adjustable size. Additionally, the need for sensors that are compact, reliable, highly sensitive, affordable, and able to operate at low temperatures for routine use is growing as the gas sensor industry undergoes rapid technological advancements [8], 9].

Zinc sulphide (ZnS), a crucial II–VI group semiconductor, is identified by its broad direct band gap, which is approximately 3.66 eV in its cubic zinc blende form and 3.80 eV in hexagonal wurtzite form. ZnS materials has been utilized in various applications such as gas sensors, LEDs, solar absorbers, lasers, photocatalysis, UV photodetectors, phosphors, and optical coatings, because of their exceptional optical, electrical, and catalytic properties with larger refractive index, chemical stability, abundance, and minimal toxicity [10]. ZnS contains several surface defects, including interstitials and sulphur vacancies, and is structurally similar to ZnO. By promoting strong oxygen adsorption and the generation of reactive oxygen species, these properties enhance its gas sensing capabilities. Wei et al. [11] created ZnO@ZnS core/shell microrods using Na2S and a straightforward hydrothermal process. Improved gas sensing performance against a range of volatile organic pollutants was achieved through the use of a heterojunction structure and adjustable shell thickness. Hussain et al. [12] used PVP and thiourea to hydrothermally create zero-dimensional ZnS nanospheres and nanoparticles, which demonstrated outstanding formaldehyde sensing capabilities with high response, selectivity, and stability at different temperatures. Chen et al. [13], hydrothermally synthesized the In2O3/ZnS heterostructures with a rough spherical morphology demonstrated superior ethanol sensing performance, because of their high surface area, synergistic effects, and heterojunction formation. ZnS’s greater transmittance over the visible and infrared spectrums makes it especially attractive for industrial and environmental gas detection. However, because of its fast electron–hole recombination, pure ZnS has a limited sensing efficiency. Techniques to stop this recombination are essential for enhancing the functionality of ZnS-based gas sensors [14], 15].

One promising method for creating new sensing materials appropriate for a variety of nanoscale devices and optoelectronic applications is to incorporate optically active luminescent centers into host materials. In this context, rare-earth (RE) elements are especially appealing because of their distinctive 4f–4f electronic transitions, which produce intense and sharp emission peaks in photoluminescence spectra. However, because of their low likelihood of direct photoexcitation, these intra-4f transitions are frequently need indirect excitation [16], 17]. By doping RE ions into appropriate host matrices like ZnS, this restriction can be successfully overcome. This allows the transfer of energy from the host lattice to the dopant ions, improving and altering the luminescent properties overall. Elements like cerium (Ce3+), praseodymium (Pr3+), and neodymium (Nd3+) are well known for their luminescence efficiency and capacity to modify the optical behavior of host materials among other rare-earth ions [16], [17], [18]. By adding localized energy states that enhance NH3 interaction and sensitivity. Doping ZnS thin films with rare earth elements such as Ce, Nd, and Pr improves their gas sensing and optoelectronic characteristics. Additionally, doping improves surface area, porosity, and stability over time. Rare earth ions are also appropriate for advanced sensing and optoelectronic applications because they enhance photoluminescence, allow bandgap tuning, and enhance crystallinity, defect control, and film uniformity. By Chu et al. [19], for the selective detection of Hg2+, Ce-doped ZnS quantum dots (ZnS:Ce) were created as low-toxicity, ratio metric fluorescent sensors. They demonstrated excellent sensitivity, linearity, and successful use in water samples. Ankinapalli et al. [20] used Co-precipitation method to create undoped and Eu and Ni co-doped ZnS nanoparticles, which demonstrated a cubic structure, improved green luminescence, and exceptional NH3 gas sensing capabilities with quick response. Zhang et al. [5] synthesized pure and Pr-doped SnS2/ZnS nanoflowers using hydrothermal method. Pr doping enhanced NH3 sensing at 160 °C, with higher response, faster response/recovery times, and improved performance due to structural and electronic modifications. Soibang et al. [21] synthesized porous SnO2 nanofibers via electrospinning and combined with the conducting polymer polyaniline (PANI) to form a SnO2-NFs @ PANI nanocomposite. Gas sensing tests revealed that the composite exhibited better NH3 sensing performance, with higher sensitivity, selectivity, stability and response at room temperature.

Using the nebulizer spray pyrolysis (NSP) technique, a simple, scalable, and economical deposition method that produces uniform and adherent thin films with controlled morphology and composition, pure and RE (Ce, Pr, Nd)-doped ZnS thin films were successfully synthesized in this study. The NSP technique is more versatile and straightforward than other traditional deposition techniques, particularly for doping procedures and large-area deposition compared with other thin film techniques such as electrodeposition [22], magnetron sputtering [23], chemical vapour deposition (CVD) [24], chemical bath deposition (CBD) [25], and the SILAR method [26]. This study investigates the effects of RE doping on the structural, morphological, optical, and gas sensing characteristics of ZnS thin films by synthesizing both pure and Ce, Pr, and Nd-doped films using the NSP method. To determine the effect of doping on the behavior of the material and to determine whether they were suitable for luminescent and sensor-based applications, a variety of characterization techniques were used.

2 Experimental

2.1 Preparation of pure and rare-earth (Ce, Pr, Nd)-doped ZnS thin films

Doped ZnS thin films were synthesised using zinc chloride (ZnCl2), thiourea (CH4 N 2S), and the corresponding rare-earth dopant nitrates, cerium(III) nitrate hexahydrate [Ce(NO3)3 6H2O], praseodymium(III) nitrate hexahydrate [Pr(NO3)3 6H2O], and neodymium(III) nitrate hexahydrate [Nd(NO3)3 6H2O]. Hydrochloric acid (HCl) and isopropanol were used as stabilisers and solvents throughout the preparation procedure. The host precursors were made with 0.2 M zinc chloride and 0.2 M thiourea for every doping condition. For all of the rare-earth elements (Ce, Pr, and Nd), the dopant concentration was adjusted at 2 wt percent. Isopropanol and deionised (DI) water were combined in a 3:1 vol ratio to create a mixed solvent with a total volume of 10 mL. In order to achieve a clear, transparent solution, HCl was added dropwise to the solvent mixture while the metal precursors were being gradually dissolved while being constantly stirred. In order to eliminate surface impurities and improve film adhesion, glass substrates were simultaneously thoroughly cleaned with detergent and then repeatedly rinsed with deionised water. A spray pyrolysis system was filled with the prepared precursor solution. A nozzle-to-substrate distance of 25 mm and a carrier gas pressure of 1.5 kg/cm2 were used during deposition, while the substrate temperature was kept at 450 °C. Smooth, uniform ZnS thin films doped with Ce, Pr, or Nd were produced as a result of this process. The films were left to naturally cool to room temperature following deposition. For gas sensing studies, silver paste was applied along the edges of the films to serve as electrical contacts for response measurements. The average film thickness, calculated using the gravimetric weight difference method, was found to be ∼650 nm.

2.2 Characterization

The structural, morphological, optical, and gas sensing characteristics of the synthesized pure and rare-earth (Ce, Pr, Nd)-doped ZnS thin films were evaluated in detail. The crystalline structure, phase purity, and grain size of the films were determined through structural analysis using X-ray diffraction (XRD) with a PANalytical X’Pert Pro diffractometer using Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å). A Apreo 2 field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM) was used for analyzing the surface morphology, yielding comprehensive data on the particle distribution, surface texture, and film uniformity. The Ce, Pr, and Nd dopants were successfully incorporated into the ZnS matrix, as confirmed by energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX). To evaluate the optical absorbance, and determine the band gap energy, optical characterization was carried out in the wavelength range of 300–1,000 nm using a Shimadzu 2600i spectrophotometer. A PerkinElmer LS55 fluorescence spectrophotometer was used for photoluminescence (PL) investigations in order to examine emission properties and transitions related to defects that are impacted by rare-earth doping. Silver electrodes were applied to the film’s edges to enable electrical measurements for the gas sensing analysis, and each sample were exposed to different NH3 gas concentrations. The potential of rare-earth doped ZnS thin films as efficient NH3 gas sensors was demonstrated by the evaluation of the sensing performance in terms of sensitivity, response time, recovery time, and repeatability.

3 Experimental findings

3.1 Crystallite studies

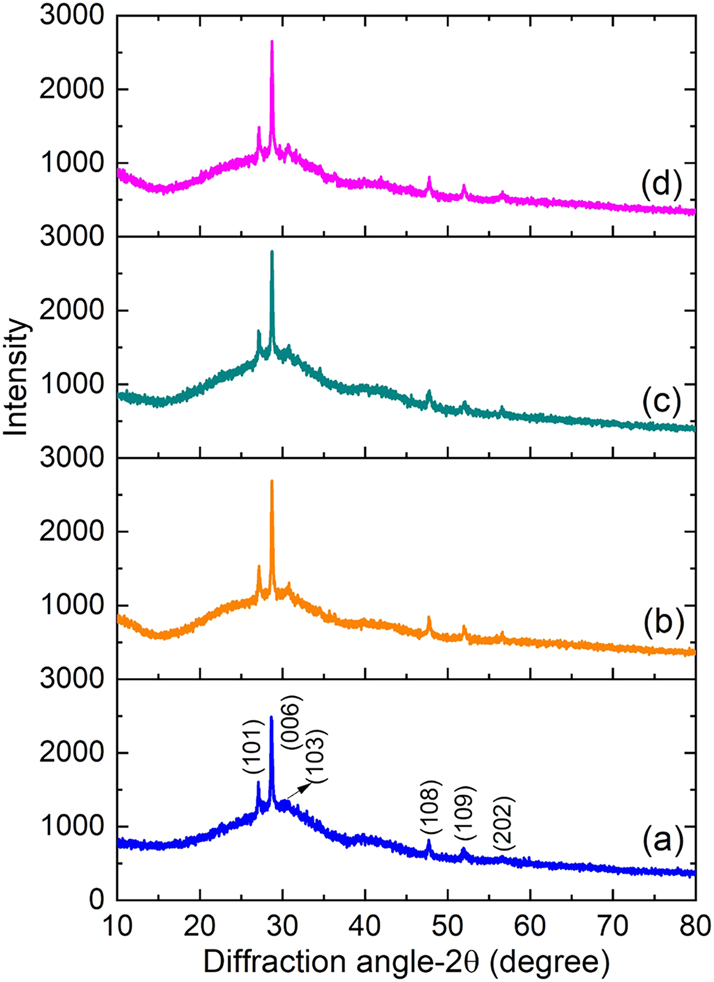

The XRD patterns of pure and rare-earth (Ce, Pr, Nd) doped ZnS thin films are shown in Figure 1. According to JCPDS card No. 01-89-2739, it was verified from the figure that all films show diffraction peaks along (101), (006), (103), (108), (109), and (202) plane, which crystallizes in a hexagonal wurtzite ZnS structure with a P63 mc space group [27], 28]. The stable peak positions suggests that the RE ions like Pr3+, Ce3+, and Nd3+ have been successfully incorporated into the ZnS lattice. The polycrystalline nature of the prepared thin films was demonstrated by the distinct and sharp diffraction peaks, which exhibit an apparent preferential orientation towards the (006) plane. Additionally, no extra diffraction peaks associated with secondary phases or unreacted dopant precursors were detected, demonstrating the sample’s phase purity. The addition of Ce, Pr, and Nd results in a decrease in full-width at half maximum (FWHM) and an increase in peak intensity, which suggests better crystallinity, but it does not substantially change the position of the (006) peak (∼28.65°).

XRD patterns of (a) pure ZnS, (b) Ce-doped ZnS, (c) Pr-doped ZnS, and (d) Nd-doped ZnS thin films.

The average crystallite size (D) and microstrain (ε) for all films were calculated using the following formulas as per Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively [29].

where λ represents the wavelength of X-ray radiation and β belongs to the full width at half maximum. Results, which are shown in Table 1, demonstrate that doping with Ce, Pr, and Nd results in appreciable differences in structural parameters when compared to pure ZnS. The ZnS:Pr thin film sample had the largest crystallite size, and a similar trend was confirmed by the Williamson–Hall (W–H) method as shown in the Supplementary Figure S1. When ZnS thin films are doped with RE ions like Ce3+, Pr3+, and Nd3+, their ionic radii, chemical behavior, and effects on crystal growth may all contribute to the increase in crystallite size. In comparison to Zn2+ (0.74 Å), these RE3+ ions have larger ionic radii (Ce3+ ≈ 1.03 Å, Pr3+ ≈ 1.013 Å, and Nd3+ ≈ 0.983 Å) [30], [31], [32]. Lattice distortion results from their integration into the ZnS lattice, either by interstitial occupation or substitution. This distortion can reduce internal strain and improve atomic mobility at the ideal doping concentration, which will encourage grain growth and produce larger crystallite sizes. The larger ionic radius of Pr3+, which causes greater lattice strain, is the primary cause of the larger crystallite size in ZnS:Pr thin films compared to Ce- and Nd-doped films. This strain encourages the growth of larger crystallites by reducing nucleation sites and promoting grain coalescence. Grain growth is further supported by Pr doping, which also increases adatom diffusion and decreases surface energy. In ZnS:Pr films, these combined effects result in larger crystallites [33], 34]. Moreover, the incorporation of Pr3+ is anticipated to produce lesser structural defects and dislocations, resulting in a lattice environment that is less strained and more ordered [35]. The formation of larger crystallites is supported by this structural homogeneity. The strain values, inversely related to crystallite size, show a corresponding decrease for Pr3+ dopants due to lesser defect density.

Structural parameters of the synthesized rare-earth (Ce, Pr, Nd)-doped ZnS thin films.

| Samples | Crystallite size (nm) | Strain × 10−3 | Lattice constants (Å) | Cell volume (Å3) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scherrer formula | W–H plot | a | c | |||

| ZnS | 58 | 56 | 2.40 | 3.7961 | 18.7533 | 234.04 |

| ZnS:Ce | 60 | 69 | 2.32 | 3.8033 | 18.4610 | 231.26 |

| ZnS:Pr | 63 | 73 | 2.25 | 3.8158 | 18.5869 | 234.37 |

| ZnS:Nd | 62 | 70 | 2.22 | 3.7935 | 18.7262 | 233.37 |

Using standard formulas calculated using Bragg’s law and the hexagonal system volume formula, the lattice parameters (a and c) and unit cell volumes were determined [30].

Here, hkl represents the miller indices. Table 1 provides a summary of the obtained lattice parameters and cell volumes. The values of a and c for the undoped ZnS film are determined to be 3.82 Å and 18.62 Å, respectively, and are in good agreement with data that was previously reported [30], 36]. Confirming the retaining of the wurtzite structure, the computed values remain relatively similar to standard ZnS data. The inclusion of larger RE ions first causes lattice expansion, which is followed by structural distortion. These structural parameters indicate slight variations in the lattice constant values by the addition of RE dopants. Overall, the XRD analysis shows that RE doping modifies the structural characteristics of ZnS thin films in a way that is dependent on the doping level and is mostly controlled by the ionic radius and site occupancy of the dopant ions.

3.2 Morphology analysis

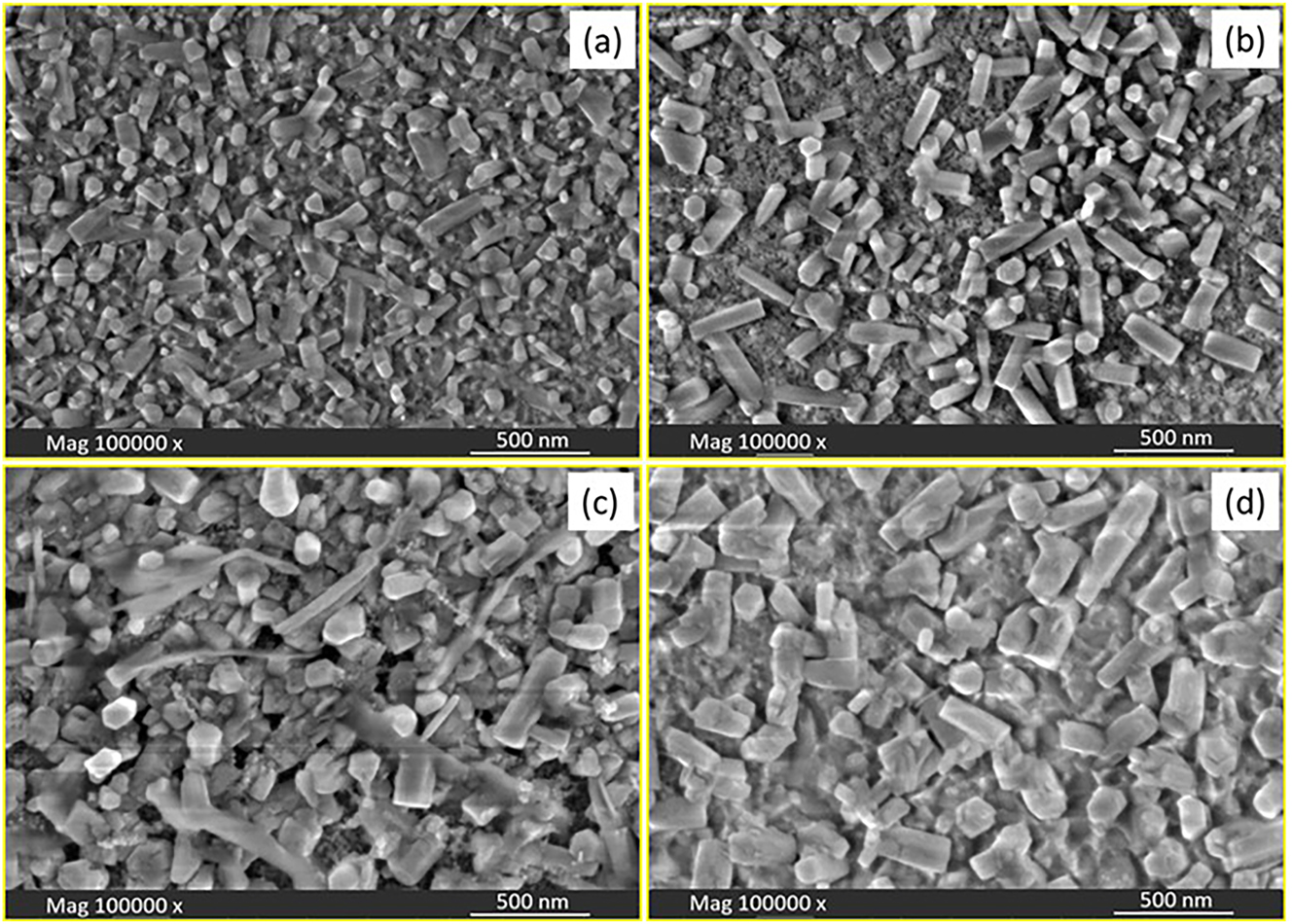

FESEM was used to analyze the surface morphology of the Ce, Pr, and Nd-doped ZnS thin films, as shown in Figure 2(a–d). Depending on the RE dopant used, the micrographs showed notable morphological variations. Unevenly distributed and loosely shaped nanorods were visible on the surface of the undoped ZnS thin films while a change in morphology was seen after doping. ZnS:Pr samples formed comparatively denser clusters than Ce and Nd doped ZnS films, which showed aggregated porous nanorod-like structures. Interestingly, the ZnS:Pr films displayed more distinct larger nanorods morphology alongside interconnected porous structures, suggesting improved one-dimensional growth. According to this morphological evolution, nucleation and growth behavisor are significantly influenced through RE doping. Also, it was observed that, the average particle sizes gradually increased with doping. The ZnS:Pr sample had the largest average particle size among the samples due to the anisotropic crystal growth which facilitates the development of extended nanorod structures. The interaction among dopant ions and the ZnS lattice is the main cause of the variation in particle size and shape among the samples. The formation of porous nanostructures is influenced by variables like local growth dynamics, dopant-lattice strain, and ionic radius. Larger Pr ions promote directional growth and particle coalescence, leading to an even more interconnected nanorod network with the largest average particle size, while other dopants, such as Ce and Nd, induce moderate strain and encourage aggregated rod-like formations.

FESEM images of (a) pure ZnS, (b) Ce-doped ZnS, (c) Pr-doped ZnS, and (d) Nd-doped ZnS thin films.

EDX was employed to confirm the elemental composition of the prepared films. Supplementary Figure S2(a–d) shows the EDX spectrum of the ZnS: Ce, Pr and Nd thin film within the potential range of 0–10 kV, indicating the presence of Zn, S, RE (Ce, Pr and Nd) elements without any detectable impurities.

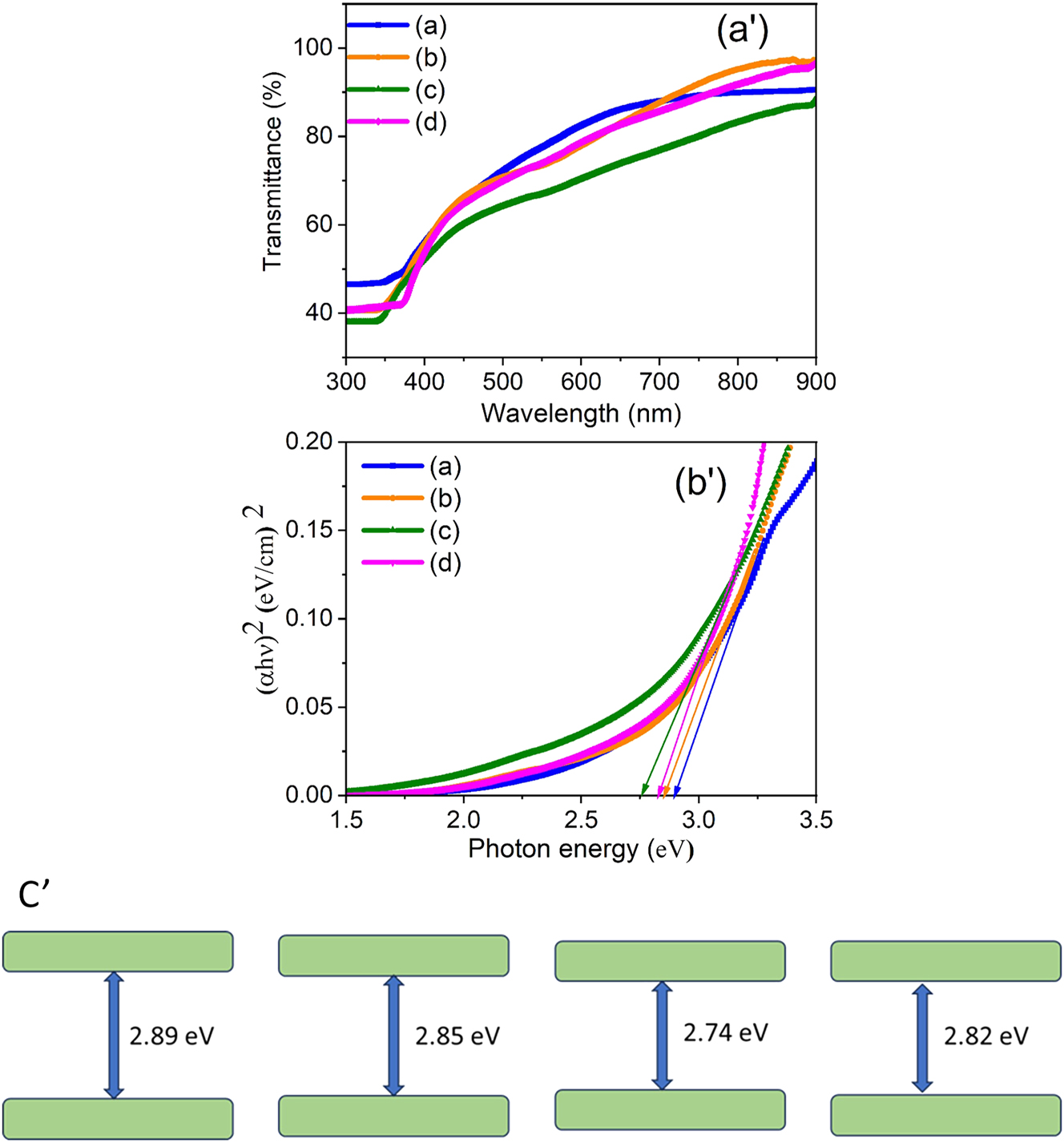

3.3 Optical studies

The optical properties of ZnS thin films doped with Ce, Pr, and Nd were investigated by recording their transmittance spectra in the wavelength range of 300–900 nm. As depicted in Figure 3a’, all the films exhibit a decrease in transmittance while doping RE ions. It is evident from Figure 3a’ that, the incorporation of Ce, Pr, and Nd into the ZnS lattice causes a lower transmittance value of ∼75 % for the ZnS:Pr (2 %) films compared to that of undoped ZnS. This abrupt drop in transmittance is a characteristic feature commonly observed in semiconducting materials and is indicative of good crystalline quality. While the larger ionic radius of Pr3+ causes more lattice distortion and defects, increasing optical absorption, the larger crystallite size in Pr-doped films enhances light scattering. Further absorption is facilitated by the numerous intra-4f electronic transitions that Pr3+ ions display in the visible spectrum. Potential Pr dopant agglomeration or segregation may also worsen light blocking and decrease transparency [37]. This reduction in transmittance implies a reduction in the optical band gap (E g ) as a result of RE doping.

UV–Vis. Transmittance spectra (a'), Tauc plots of pure ZnS, (b) Ce-doped ZnS, (c) Pr-doped ZnS, and (d) Nd-doped ZnS thin films (b'), the corresponding band edge diagram (c').

Since ZnS is known to possess a direct band gap [37], the band gap values of the films were calculated using Tauc’s relation [38]:

where α is the absorption coefficient, A is a constant, and hν denotes the incident photon energy. The plots of (αhν)2 versus photon energy (hν) for all samples are shown in Figure 3b’. The E g values were determined by extrapolating the linear region of each curve to the energy axis, as indicated by the arrows in figure. The estimated E g values were found to be 2.89 eV for pure ZnS, and 2.85, 2.74, and 2.82 eV for ZnS:Ce (2 %), ZnS:Pr (2 %), and ZnS:Nd (2 %) thin films, respectively, with the corresponding band diagram shown in Figure 3(c′). These results confirm a reduction in E g due to doping with Ce, Pr, and Nd, compared with pure ZnS. The E g value of the undoped ZnS film aligns well with the reported bulk value [39], [40], [41]. A similar trend of band gap reduction upon doping with rare-earth elements in ZnS and ZnO systems has also been reported by other researchers [42], [43], [44]. From the results, the ZnS:Pr (2 %) film showed a reduced band gap (∼2.74 eV compared to 2.89 eV for undoped ZnS) along with a slight increase in absorption, i.e., a decrease in transmittance. This behavior arises from lattice distortions due to the larger ionic radius of Pr3+, increased light scattering from larger crystallite size, additional intra-4f transitions, possible dopant agglomeration, and the introduction of localized energy levels near the valence band edge, all of which enhance absorption and narrow the band gap [45], 46]. Thus, the optical analysis confirms the influence of Ce, Pr, and Nd doping on the electronic structure and band gap behavior of ZnS thin films.

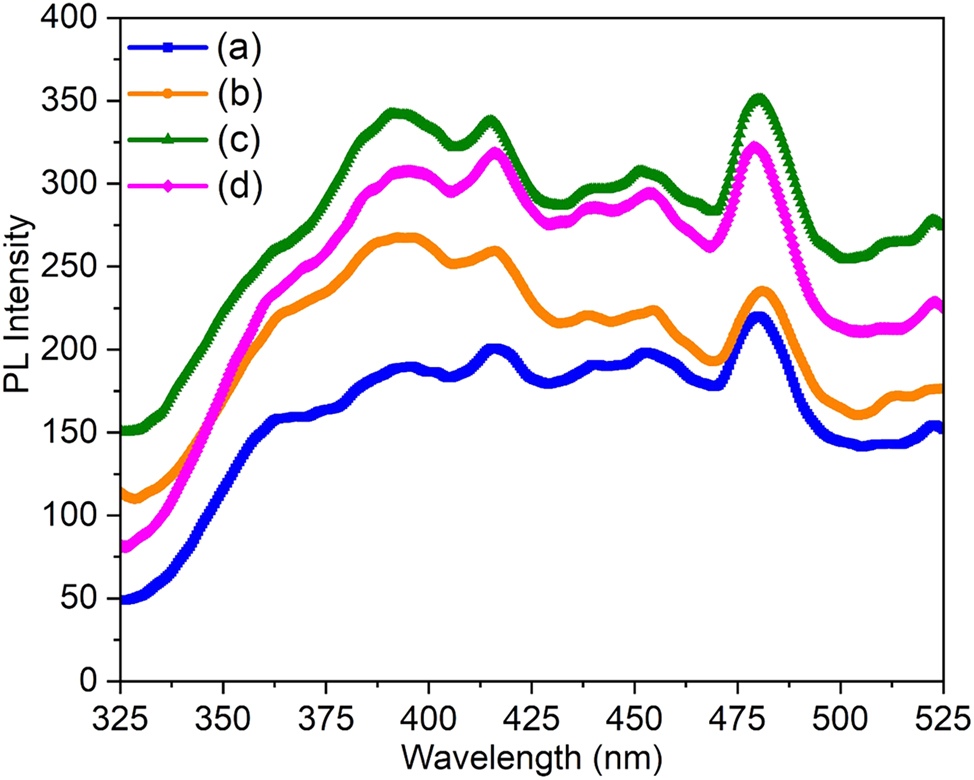

3.4 Photoluminescence analysis

Figure 4 presents the photoluminescence (PL) spectra of pure and Ce-, Pr-, and Nd-doped ZnS thin films measured at room temperature to evaluate their luminescence characteristics. All the samples exhibit weak emission peaks in the ultraviolet region, typically between 370 and 420 nm, with notable peaks around 385–425 nm, attributed to excitonic recombination near the band edge [47]. Such emissions have been previously reported and are associated with self-activated luminescent centers due to electron-hole pair recombination [48], 49]. Additionally, a strong emission peak observed in the visible region around 487–489 nm is linked to the dangling sulfur bonds in the ZnS matrix. This visible emission indicates the presence of native defect sites related to sulfur vacancies or dangling bonds, confirming defect-assisted recombination pathways in the films [50]. Among the doped samples, the 2 % ZnS:Pr films exhibited the highest intensity and peak broadness, which could be due to the increased interaction between the host ZnS lattice and RE ions. This enhancement likely arises from the reduced spatial separation between the dopant ions and the host lattice, promoting more efficient energy transfer. Furthermore, the broad visible emissions in doped films may result from the interaction between s–p transitions of ZnS and the 4f or 5d orbitals of RE dopants, leading to partially allowed transitions and red-shifting of emission peaks. The absence of any additional emission bands related to the dopant ions suggests that no secondary impurity phases formed during film deposition, as also confirmed by XRD analysis. Similar PL behaviors and transitions associated with rare-earth dopants in ZnS thin films have been documented in earlier studies [51], 52].

PL emission spectra of (a) pure ZnS, (b) Ce-doped ZnS, (c) Pr-doped ZnS, and (d) Nd-doped ZnS thin films.

3.5 Gas sensing properties

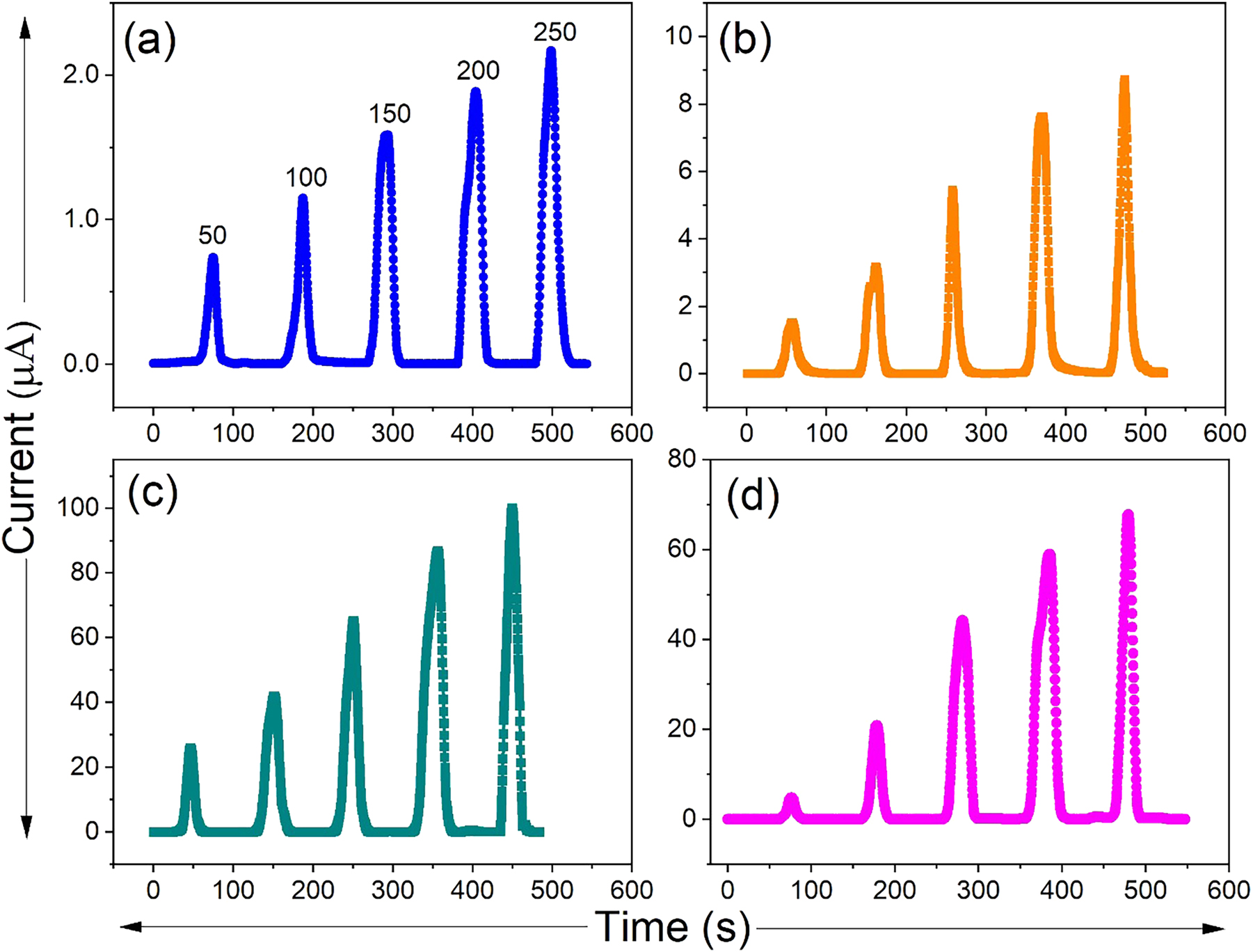

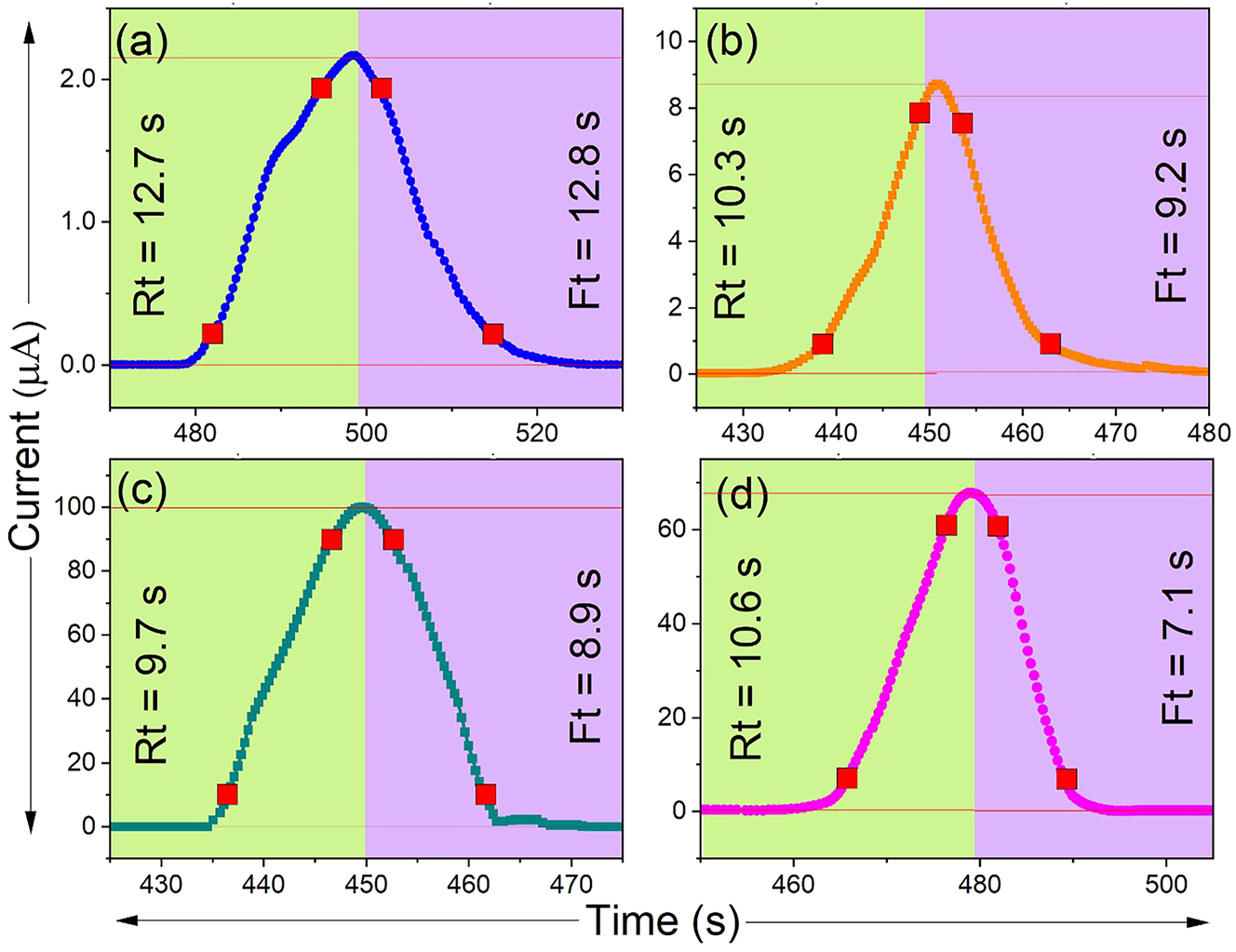

The gas sensing behavior of Ce-, Pr-, and Nd-doped ZnS thin films toward NH3 was examined by measuring the change in electrical current upon gas exposure, as shown in Figure 5. For the measurements, the thin films were mounted inside a sealed chamber fitted with a front panel to hold the sensor assembly. The films were connected to two electrical probes, while NH3 gas was introduced into the chamber through a metallic tube connected to a heater and a thermocouple. NH3 vapors were generated by heating an aqueous NH3 solution to the desired temperature and subsequently released into the chamber. The film surfaces, maintained at room temperature, were exposed to these vapors. Once the electrical current reached saturation, the chamber was opened to allow atmospheric air to enter, thereby accelerating the desorption process. The electrical current response was recorded using a Keithley Source Meter. As seen from the graph, the baseline current of the rare-earth-doped films is higher compared to that of the undoped films. The incorporation of RE3+ ions into Zn2+ lattice sites or interstitial positions induces lattice distortions and generates defect states, which either provide additional charge carriers or facilitate carrier hopping. Furthermore, the formation of localized energy levels near the band edges narrows the effective band gap, thereby enhancing electron excitation. Consequently, rare-earth doping improves the electrical conductivity of ZnS films by increasing carrier concentration and promoting defect-assisted charge transport. To evaluate the gas sensing performance, the NH3 response of RE (Ce, Pr, and Nd)-doped ZnS films was investigated at room temperature for different concentrations (50, 100, 150, 200, and 250 ppm), with emphasis on key sensing performance metrics. The adsorption-desorption reactions among the gas molecules and the thin film surface are the backbone of the sensing mechanism. As NH3 concentrations rise during exposure, a noticeable increase in current was seen, suggesting improved gas interaction as a result of the more readily available gas molecules.

Current versus time plots of (a) pure ZnS, (b) Ce-doped ZnS, (c) Pr-doped ZnS, and (d) Nd-doped ZnS thin films.

The gas response (S) was calculated using the standard relation [53]:

where I g and I a represent the current in NH3 gas and in air, respectively. When rare earth elements like Ce, Pr, and Nd were added, the gas response of pristine ZnS, which had been found to be relatively low, significantly improved. The doped ZnS sensors gas sensitivities gradually increased with each dopant, as shown in Table 2. The 2 % ZnS:Pr sensor exhibited the highest NH3 gas sensitivity, recording a response of 1,520. This superior performance is linked to its enhanced surface and optical properties. Pr doping improves crystallinity and produces a more uniform nanostructured surface, thereby increasing the available surface area for gas interaction. PL studies further suggest that Pr incorporation facilitates efficient electron–hole recombination at defect sites, particularly sulfur vacancies, enabling stronger interaction with NH3 molecules. Additionally, the ZnS:Pr films show greater light absorption and narrow bandgap value compared to Ce- and Nd-doped samples, creating more active adsorption sites. Collectively, these factors account for the significantly improved gas sensing behavior of the ZnS:Pr films [54], 55]. The adsorption-desorption kinetics are accelerated and enhanced electronic interactions could be achieved by the decrease in optical bandgap as observed through Pr incorporation. On the other hand, Ce and Nd doped ZnS films showed lower gas response compared to ZnS:Pr films, despite having better sensitivity when compared to pristine ZnS. This discrepancy most likely results from their varying effects on the structural, morphological, and electronic characteristics of the ZnS matrix, which are crucial for gas sensing behavior (Table 3).

Gas sensing properties of the fabricated rare-earth (Ce, Pr, Nd)-doped ZnS thin film-based gas sensors.

| Samples | Gas response | Response time (s) | Recovery time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZnS | 50 | 12.7 | 12.8 |

| ZnS:Ce | 148 | 10.3 | 9.2 |

| ZnS:Pr | 1,520 | 9.7 | 8.9 |

| ZnS:Nd | 1,120 | 10.6 | 7.1 |

Comparison table showing the NH3 sensing performance of the current work with the previously published works.

| Samples | Synthesis method | Response (%) and operational temperature | Response time (s) | Recovery time (s) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pr-SnS2/ZnS hierarchical nanoflowers | Hydrothermal | 14.03 @ 50 ppm (160 °C) | 6 | 13 | [5] |

| Core–Shell nanoparticle ZnS/Co9S8 composites | Etching method | 4.56 @ 5 ppm (240 °C) | 7 | 9 | [57] |

| CdS:In thin film | Nebulizer spray pyrolysis | 604.8 @ 250 ppm (RT) | 43.09 | 5.6 | [58] |

| 2D SnS2 nanosheets | Chemical exfoliation | 2.13 @ 100 ppm (RT) | 16 | 450 | [59] |

| Sb doped SeO2 thin films | Spray pyrolysis | 2,865 @ 100 ppm (RT) | 7.5 | 3 | [60] |

| PbS quantum dots modified SnS2 nanosheets | Hydrothermal | 8.5 @ 100 ppm (RT) | 9 | 720 | [61] |

| SnS:Zn nanostructures | Solvothermal | 567 @ 50 ppm (RT) | – | – | [62] |

| Al, La co-doped CdS thin films | Nebulizer spray pyrolysis | 1,390 @ 250 ppm (RT) | 42 | 21 | [63] |

|

ZnS:Pr (2 wt%)

Thin film |

Nebulizer spray pyrolysis | 1,520 @ 250 ppm (RT) | 9.7 | 8.9 | Present work |

-

Bold values represents the best sample result.

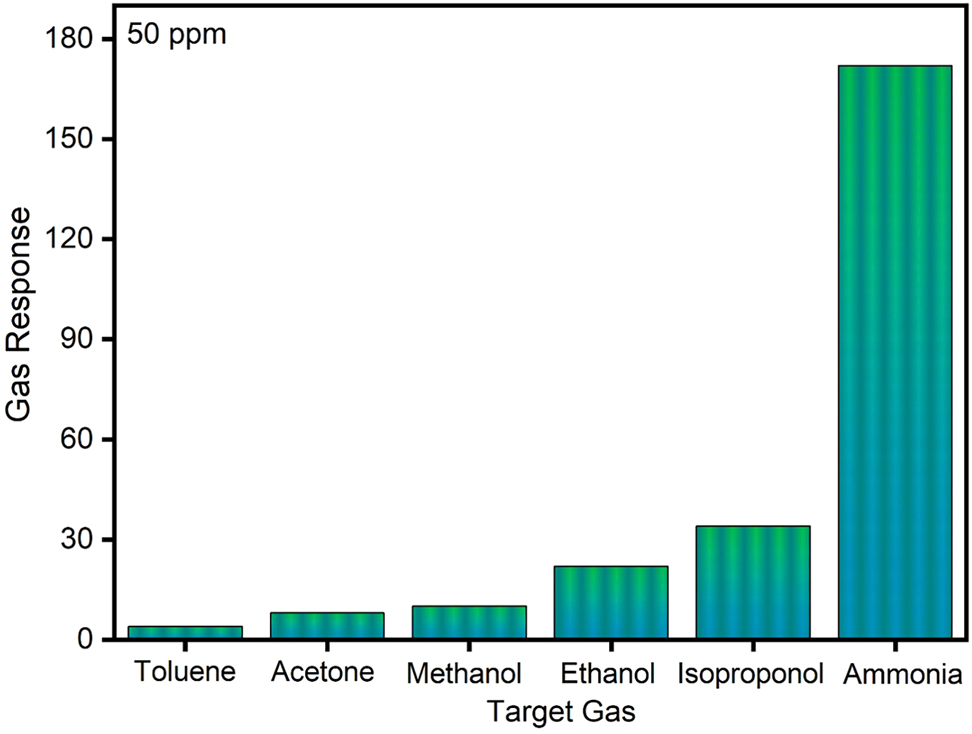

3.5.1 Selectivity

A crucial factor in assessing a gas sensor’s performance is its selectivity towards a particular target gas, which establishes the sensor’s capacity to differentiate the target gas from other interfering gases. The selectivity analysis of the ZnS:Pr thin film sensor exposed to a range of gases at a fixed concentration of 50 ppm, including toluene, acetone, methanol, ethanol, isoproponol, and NH3, is shown in Figure 6. The ZnS:Pr thin film sensor showed strongest response to NH3, according to the sensing response, whereas the other gases showed noticeably weaker responses. The strong selectivity of the ZnS:Pr sensor for NH3 detection is confirmed by this noticeable difference, which is a crucial feature for accurate and dependable NH3 sensing applications. The distinct effect of the Pr ions on the material’s structural and electrical characteristics is responsible for the increased selectivity of ZnS:Pr. By adding localized energy states and increasing the concentration of charge carriers, Pr incorporation alters the electronic band structure of ZnS and promotes stronger charge transfer reactions with NH3 molecules. Furthermore, Pr doping enhances the sensor’s affinity for NH3 by encouraging the development of sulphur vacancies along with other defect sites that function as active adsorption centers. Additionally, the adsorption-desorption kinetics may be enhanced by the Pr dopant’s potential to catalyze the adsorption and partial dissociation of NH3 molecules on the ZnS surface. Improved surface roughness and the interaction that occurs between the ZnS:Pr surface and NH3 result in better gas diffusion and efficient analyte recognition.

Selectivity graph of the ZnS thin film gas sensor.

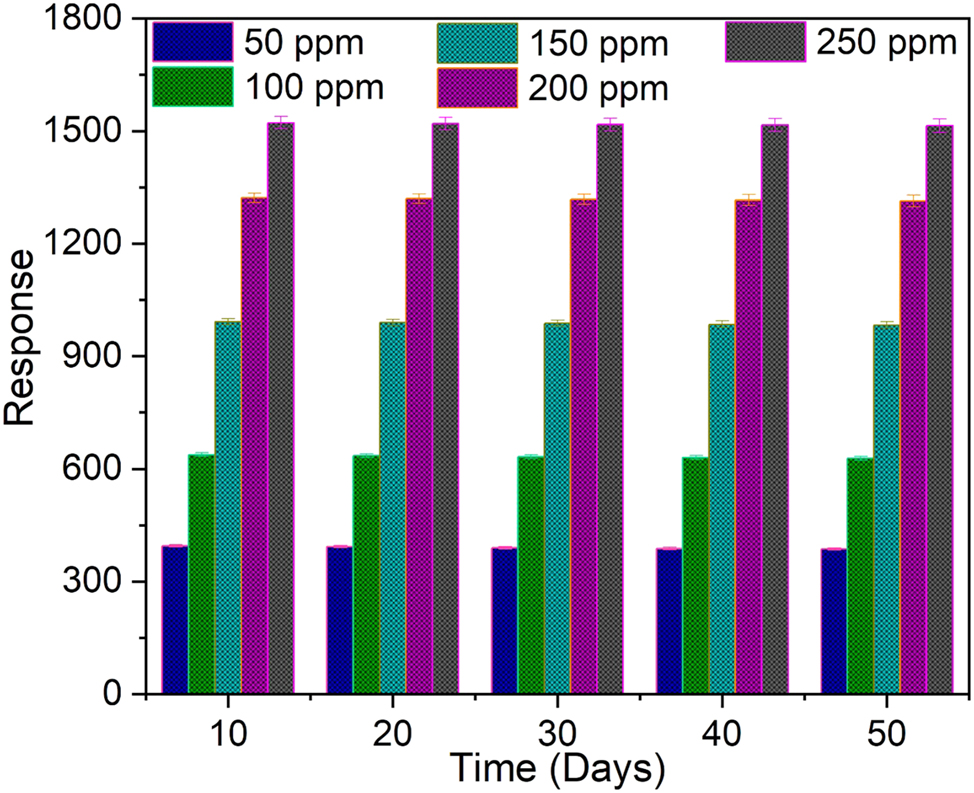

3.5.2 Stability and repeatability

The ZnS:Pr thin film sensor’s long-term stability over a 50-day period under varied NH3 gas concentrations (50–250 ppm) is shown in Figure 7. High stability and repeatability in sensing performance were indicated by the gas response’s notable consistency over the entire period of measurement at different concentration of NH3 gas. The incorporation of Pr ions, which stabilizes the ZnS crystal lattice, reduces defect migration, and improves surface morphology, is principally responsible for this long-term stability. Together, these effects lower the possibility of particle agglomeration or structural deterioration, guaranteeing long-term sensor performance.

Stability study of the ZnS:Pr thin film gas sensor.

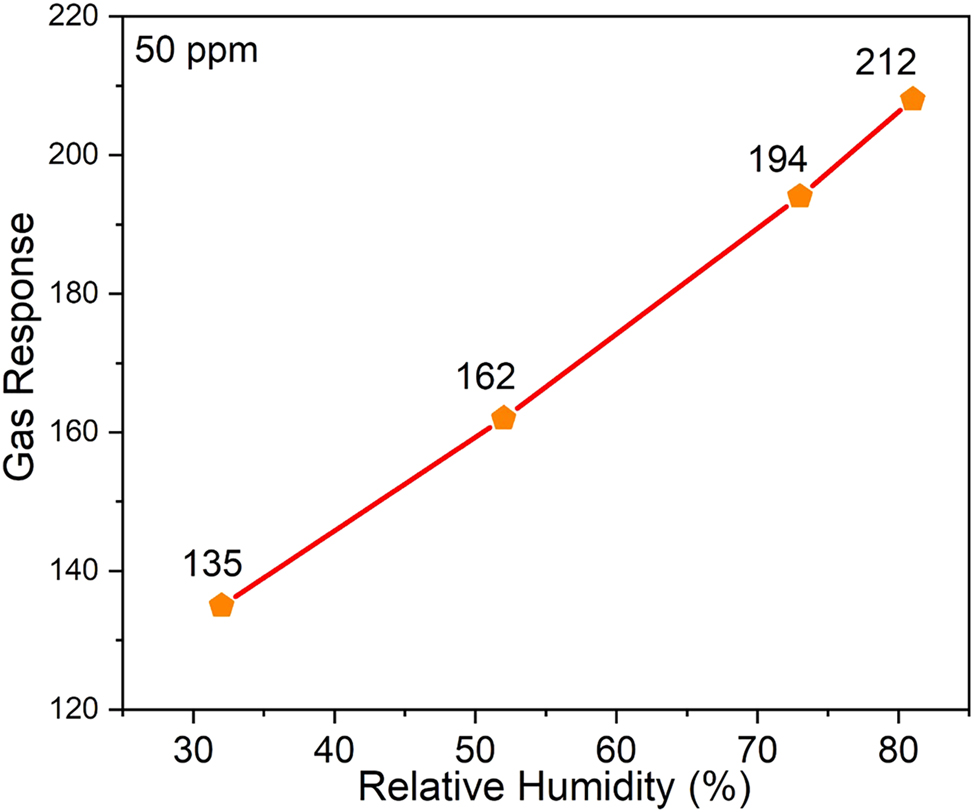

3.5.3 Humidity studies

Figure 8 illustrates the response of the ZnS:Pr sensor at various relative humidity (RH) levels of 32 %, 52 %, 73 %, and 81 %. The sensor’s ability to function dependably in humid conditions was demonstrated by the increasing trend in gas response that was seen as humidity level rises. The increased adsorption of water molecules at surface-active sites, such as sulphur vacancies (VS) and Pr-induced native defect sites, is responsible for the improved sensing behavior in humid environments. During NH3 detection, these flaws improve surface reactivity and facilitate charge transfer by acting as efficient adsorption sites for gas and moisture molecules. Surface-adsorbed species and native vacancy defects (such as Zn or S vacancies) affect the sensing mechanism in ZnS:Pr, in contrast to oxide-based sensors that mainly depend on oxygen vacancies. Even in the absence of lattice oxygen, Pr doping alters the defect landscape by expanding active sites and facilitating the adsorption of reactive oxygen species (like O2 − and O−). A detectable sensor response results from the interaction of these adsorbed species with incoming NH3 molecules, which changes the electrical resistance and carrier concentration of the film. Moreover, higher humidity improves the adsorption of water molecules at these defect-rich areas, changing the surface chemistry and strengthening the interaction with NH3. The stable and improved sensing behavior seen under various environmental conditions is explained by the synergistic interaction of humidity, surface defects, and dopant-induced electronic states. Overall, the ZnS:Pr thin film sensor exhibits exceptional long-term stability and robust performance over a wide range of humidity levels, making it a viable option for trustworthy NH3 gas sensing in practical applications.

Relative humidity study of the ZnS:Pr thin film gas sensor.

3.5.4 Response and recovery times

Two important parameters that affect sensor performance in gas sensing applications are response time (ts) and recovery time (tr) shown in Figure 9. The response time (ts) is the amount of time required for the sensor’s current output to surpass 90 % of its maximum level following exposure to the target gas. In contrast, the recovery time (tr) is the time it takes for the sensor’s current to decrease to 10 % of its starting value after the gas source is removed [56]. Particularly, the dynamic behavior of Ce-, Pr-, and Nd-doped ZnS thin films exposed to NH3 has been studied in relation to these two-time constants. Of all the dopants being studied, ZnS:Pr thin films exhibit the fastest sensing behavior with the fastest response and recovery times of 9.7 s and 8.9 s, respectively, when exposed to 250 ppm of NH3 gas. This implies that the adsorption and desorption of NH3 molecules onto the film surface is accelerated by the addition of Pr3+ ions to the ZnS lattice, which significantly enhances electron transport and surface reactivity. The quantitative values for ts and tr that correlate to different dopant types are summarized in Table 2. The other RE dopants showed increase in both ts and tr, suggesting that high ionic radius of dopant ions in ZnS matrix might result in defect clustering or agglomeration, which could obstruct gas diffusion and slow down charge transfer processes. Thus, these results suggests that ZnS:Pr thin films have improved sensing capabilities, making them desirable choices for rapid and efficient NH3 gas detection in practical situations.

Response and recovery times of (a) pure ZnS, (b) Ce-doped ZnS, (c) Pr-doped ZnS, and (d) Nd-doped ZnS thin films.

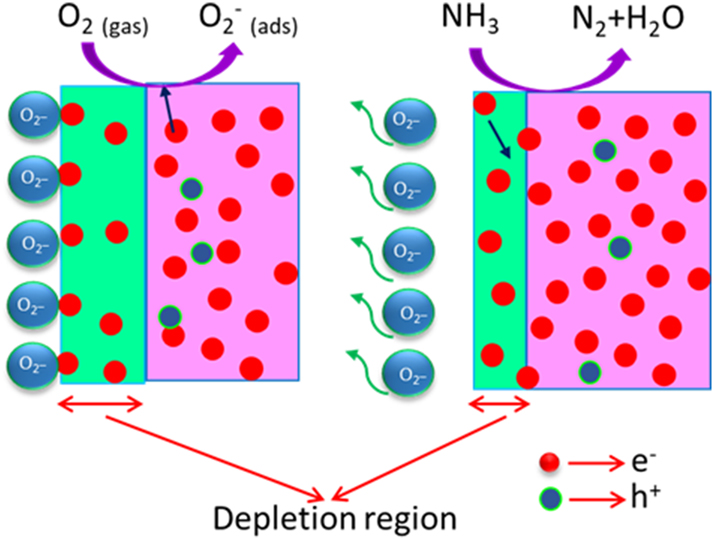

3.5.5 Mechanism

In general, crystallinity, porosity, dopant concentration, and surface defects all affect the charge transfer and band bending behavior of semiconductor materials, which in turn affects their sensing response. When exposed to NH3, the gas reacts with the oxygen ions (O2 −) that have been adsorbed on the film surface, causing trapped electrons to return to the conduction band (CB) and enhancing electrical conductivity as shown in Figure 10. The following reaction describes this process:

where the film’s resistance and depletion width are decreased by the liberated electrons. The structural distortions induced by the RE dopants results in more vacancies and active adsorption sites, are linked to the improved sensing of ZnS:Pr. Additionally, tests of stability and reproducibility after 50 days showed that the ZnS:Pr sensor performed consistently, with very little variation in response or recovery times over several exposure cycles. The sensor is a promising option for real-world NH3 gas detection applications because of its exceptional long-term stability and robustness.

Schematic diagram of the ammonia gas sensing mechanism in the ZnS sample.

4 Conclusions

This study used the economical NSP approach on glass substrates to successfully synthesize undoped and rare-earth (Ce, Nd, Pr)-doped ZnS thin films. The production of hexagonal wurtzite structures with a favored (002) orientation and no secondary phases was confirmed thorough XRD characterization. The ZnS film doped with 2 % Pr showed the best crystallinity, consistent nanostructured shape, and improved optical absorption because of lesser bandgap among all samples. Studies using PL revealed a greater density of native defect sites, which enhanced the gas sensing capabilities. At room temperature, the ZnS:Pr film showed the fastest response (9.7 s) and recovery (8.9 s) times, the highest NH3 gas sensitivity (1520 %), and outstanding humidity stability. These results demonstrate that ZnS:Pr is a viable option for inexpensive, highly effective NH3 sensors that function under ambient circumstances. In conclusion, by improving charge, surface defect modulation, and structural tuning, the addition of rare earth elements such as Ce, Nd, and especially Pr doped ZnS thin films greatly improve NH3 sensing performance. Future research may concentrate on fine-tuning doping concentrations, including nanocomposites or hybrid architectures, and investigating scalability, selectivity, and long-term stability for real-time sensor applications in industrial safety and environmental monitoring.

-

Funding information: The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia, for funding this work through the Large Research Group Project under grant number R.G.P.2/609/46. The researchers wish to extend their sincere gratitude to the Deanship of Scientific Research at the Islamic University of Madinah (KSA) for the support provided to the Post-Publishing Program. Authors also thanks to UAEU_AUA joint program, number 12R248, National water and energy center, United Arab Emirates University.

-

Author contribution: A.M.S. Arulanantham, S. Vinoth, R.S. Rimal Isaac, A. Vimala Juliet, A. Anto Jeffery, Mohd. Shkir, Mohd Taukeer Khan, Sambasivam Sangaraju: writing – original draft, methodology, funding acquisition, validation, supervision, software, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, resources, writing – review and editing, investigation. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

1. Hakeem Anwer, A, Saadaoui, M, Mohamed, AT, Ahmad, N, Benamor, A. State-of-the-art advances and challenges in wearable gas sensors for emerging applications: innovations and future prospects. Chem Eng J 2024;502:157899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2024.157899.Suche in Google Scholar

2. Wang, J, Du, W, Lei, Y, Chen, Y, Wang, Z, Mao, K, et al.. Quantifying the dynamic characteristics of indoor air pollution using real-time sensors: current status and future implication. Environ Int 2023;175:107934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2023.107934.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Deng, Z, van Linden, N, Guillen, E, Spanjers, H, van Lier, JB. Recovery and applications of ammoniacal nitrogen from nitrogen-loaded residual streams: a review. J Environ Manag 2021;295:113096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113096.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Yüzbaşıoğlu, A, Avsar, C, Gezerman, AO. The current situation in the use of ammonia as a sustainable energy source and its industrial potential. Curr Res Green Sustain Chem 2022;5:100307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crgsc.2022.100307.Suche in Google Scholar

5. Zhang, Q, Ma, S, Zhang, R, Zhu, K, Tie, Y, Pei, S. Optimization NH3 sensing performance manifested by gas sensor based on Pr-SnS2/ZnS hierarchical nanoflowers. J Alloys Compd 2019;807:151650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2019.151650.Suche in Google Scholar

6. Kwak, D, Lei, Y, Maric, R. Ammonia gas sensors: a comprehensive review. Talanta 2019;204:713–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2019.06.034.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Insausti, M, Timmis, R, Kinnersley, R, Rufino, MC. Advances in sensing ammonia from agricultural sources. Sci Total Environ 2020;706:135124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135124.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Nikolic, MV, Milovanovic, V, Vasiljevic, ZZ, Stamenkovic, Z. Semiconductor gas sensors: materials, technology, design, and application. 2020, MDPI AG;20:6694. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20226694.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Hossain, N, Mobarak, MH, Mimona, MA, Islam, MA, Hossain, A, Zohura, FT, et al.. Advances and significances of nanoparticles in semiconductor applications – a review. Results Eng 2023;19:101347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2023.101347.Suche in Google Scholar

10. Mamiyev, ZQ, Balayeva, NO. Optical and structural studies of ZnS nanoparticles synthesized via chemical in situ technique. Chem Phys Lett 2016;646:69–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cplett.2016.01.009.Suche in Google Scholar

11. Zhang, W, Wang, S, Wang, Y, Zhu, Z, Gao, X, Yang, J, et al.. ZnO@ZnS core/shell microrods with enhanced gas sensing properties. RSC Adv 2015;5:2620–9. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4RA12803F.Suche in Google Scholar

12. Hussain, S, Liu, T, Javed, MS, Aslam, N, Zeng, W. Highly reactive 0D ZnS nanospheres and nanoparticles for formaldehyde gas-sensing properties. Sensor Actuator B Chem 2017;239:1243–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2016.09.128.Suche in Google Scholar

13. Chen, Q, Ma, S, Xu, X, Jiao, H, Zhang, G, Liu, L, et al.. Optimization ethanol detection performance manifested by gas sensor based on In2O3/ZnS rough microspheres. Sensor Actuator B Chem 2018;264:263–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2018.02.172.Suche in Google Scholar

14. Li, P, Yang, Y, Li, F, Pei, W, Li, D, Yu, H, et al.. Effect of polyoxometalates electron acceptor decoration on NO2 sensing behavior of ZnS microspheres toward rapid and ultrahigh response. Sensor Actuator B Chem 2025;426:137111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2024.137111.Suche in Google Scholar

15. Isac, L, Enesca, A. Recent developments in ZnS-Based nanostructures photocatalysts for wastewater treatment. 2022, MDPI;23:15668. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232415668.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Puia, L, Dawngliana, KMS, Rai, S. Spectroscopic investigation of Pr3+ doped ZnS nanoparticle in silica glass matrix prepared by sol–gel method. Appl Phys A 2024;130:812. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00339-024-07963-0.Suche in Google Scholar

17. Poornaprakash, B, Ramu, S, Park, SH, Vijayalakshmi, RP, Reddy, BK. Room temperature ferromagnetism in Nd doped ZnS diluted magnetic semiconductor nanoparticles. Mater Lett 2016;164:104–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2015.10.119.Suche in Google Scholar

18. Tounsi, A, Khalfi, R, Talantikite-Touati, D, Merzouk, H, Souici, A. Characterization of cerium-doped zinc sulfide thin films synthesized by sol–gel method. Appl Phys A 2022;128:280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00339-022-05409-z.Suche in Google Scholar

19. Chu, H, Yao, D, Chen, J, Yu, M, Su, L. Double-emission ratiometric fluorescent sensors composed of rare-earth-doped ZnS quantum dots for Hg2+ detection. ACS Omega 2020;5:9558–65. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.0c00861.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Ankinapalli, M, G S, H, Kurugundla, GK, Kuchi, C, Munga, S, Reddy, PS. Synthesis and properties of Eu and Ni Co-Doped ZnS nanoparticles for the detection of ammonia gas. ECS J Solid State Sci Technol 2024;13:037009. https://doi.org/10.1149/2162-8777/ad34fb.Suche in Google Scholar

21. Soibang, N, Dubas, L, Bhanthumnavin, W, Kraiya, C. Enhancement of ammonia gas sensing by tin dioxide-polyaniline nanocomposite. Trends Sci 2022;19:4953. https://doi.org/10.48048/tis.2022.4953.Suche in Google Scholar

22. Ghezali, K, Mentar, L, Boudine, B, Azizi, A. Electrochemical deposition of ZnS thin films and their structural, morphological and optical properties. J Electroanal Chem 2017;794:212–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelechem.2017.04.030.Suche in Google Scholar

23. Hwang, D, Ahn, J, Hui, K, Hui, KS, Son, Y. Structural and optical properties of ZnS thin films deposited by RF magnetron sputtering. Nanoscale Res Lett 2012;7:26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1556-276X-7-26.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Sullivan, HSI, Parish, JD, Thongchai, P, Kociok-Köhn, G, Hill, MS, Johnson, AL. Aerosol-assisted chemical vapor deposition of ZnS from thioureide single source precursors. Inorg Chem 2019;58:2784–97. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b03363.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Wei, A, Liu, J, Zhuang, M, Zhao, Y. Preparation and characterization of ZnS thin films prepared by chemical Bath deposition. Mater Sci Semicond Process 2013;16:1478–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mssp.2013.03.016.Suche in Google Scholar

26. Taoufiq, M, Soussi, A, Elfanaoui, A, Ait hssi, A, Baoubih, S, Ihlal, A, et al.. DFT theoretical and experimental investigations of the effect of Cu doping within SILAR deposited ZnS. Opt Mater (Amst) 2024;147:114607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2023.114607.Suche in Google Scholar

27. Li, K, Wang, Q, Cheng, X, Lv, T, Ying, T. Hydrothermal synthesis of transition-metal sulfide dendrites or microspheres with functional imidazolium salt. J Alloys Compd 2010;504:L31–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2010.05.149.Suche in Google Scholar

28. Cai, P, Ma, DK, Liu, QC, Zhou, SM, Chen, W, Huang, SM. Conversion of ternary Zn2SnO4 octahedrons into binary mesoporous SnO2 and hollow SnS2 hierarchical octahedrons by template-mediated selective complex extraction. J Mater Chem A Mater 2013;1:5217–23. https://doi.org/10.1039/C3TA10228A.Suche in Google Scholar

29. Jansi, R, Revathy, M, Vinoth, S, Kumar, A, Isaac, RR, Deepa, N, et al.. Improvement in ammonia gas sensing properties of La doped MoO3 thin films fabricated by nebulizer spray pyrolysis method. Opt Mater (Amst) 2023;145:114464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2023.114464.Suche in Google Scholar

30. Jebathew, AJ, Karunakaran, M, Kumar, KDA, Valanarasu, S, Ganesh, V, Shkir, M, et al.. Effect of novel Nd3+ doping on physical properties of nebulizer spray pyrolysis fabricated ZnS thin films for optoelectronic technology. Phys B Condens Matter 2019;572:109–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physb.2019.07.042.Suche in Google Scholar

31. Vidhya Raj, DJ, Justin Raj, C, Jerome Das, S. Synthesis and optical properties of cerium doped zinc sulfide nano particles. Superlattices Microstruct 2015;85:274–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spmi.2015.04.029.Suche in Google Scholar

32. Hanifehpour, Y, Soltani, B, Amani-Ghadim, AR, Hedayati, B, Khomami, B, Joo, SW. Praseodymium-doped ZnS nanomaterials: hydrothermal synthesis and characterization with enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity. J Ind Eng Chem 2016;34:41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2015.10.032.Suche in Google Scholar

33. González, LA, Sánchez-Cardona, V, Escorcia-García, J, Meléndez-Lira, MA. Photoluminescence of wurtzite-type Ce-doped ZnS nanocrystals processed by a low-temperature aqueous solution approach. Ceram Int 2023;49:15553–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2023.01.144.Suche in Google Scholar

34. Park, K, Hyun Uk, K, Lee, J, Kim, S, Kim, SH. Synthesis and characterization of Mn, Pr doped ZnS and CdS/ZnS nanoparticles. Stud Surf Sci Catal 2006;159:757–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-2991(06)81707-6.Suche in Google Scholar

35. Talwatkar, SS, Sunatkari, AL, Tamgadge, YS, Pahurkar, VG, Muley, GG. Influence of Li+ and Nd3+ co-doping on structural and optical properties of l-arginine-passivated ZnS nanoparticles. Appl Phys A 2015;118:675–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00339-014-8777-5.Suche in Google Scholar

36. Jebathew, AJ, Karunakaran, M, Arun Kumar, KD, Valanarasu, S, Ganesh, V, Shkir, M, et al.. An effect of Gd3+ doping on core properties of ZnS thin films prepared by nebulizer spray pyrolysis (NSP) method. Phys B Condens Matter 2019;574:411674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physb.2019.411674.Suche in Google Scholar

37. kareem Thottoli, A, Unni, A. Effect of trisodium citrate concentration on the particle growth of ZnS nanoparticles. J Nanostruct Chem 2013;3:56. https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-8865-3-56.Suche in Google Scholar

38. Prasad, KH, Vinoth, S, Valanarasu, S, Prakash, B, Ahmad, Z, Alshahrani, T, et al.. Exploring the ammonia gas sensing properties of Gd doped CeO2 thin films deposited by spray pyrolysis method. J Alloys Compd 2024;1002:17515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2024.175415.Suche in Google Scholar

39. Luque, PA, Castro-Beltran, A, Vilchis-Nestor, AR, Quevedo-Lopez, MA, Olivas, A. Influence of pH on properties of ZnS thin films deposited on SiO2 substrate by chemical bath deposition. Mater Lett 2015;140:148–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2014.10.167.Suche in Google Scholar

40. Poornaprakash, B, Chalapathi, U, Vattikuti, SP, Sekhar, MC, Reddy, BP, Poojitha, P, et al.. Enhanced fluorescence efficiency and photocatalytic activity of ZnS quantum dots through Ga doping. Ceram Int 2019;45:2289–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2018.10.143.Suche in Google Scholar

41. Han, L, Cao, Y, Chen, Y, Tian, L, Tian, W, Li, Z. Enhanced luminescence properties of ZnS nanoparticles for LEDs applications via doping and phase control. ACS Appl Nano Mater 2025;8:8445–54. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.5c01108.Suche in Google Scholar

42. Jrad, A, Naffouti, W, Ben Nasr, T, Turki-Kamoun, N. Comprehensive optical studies on Ga-doped ZnS thin films synthesized by chemical bath deposition. J Lumin 2016;173:135–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlumin.2016.01.016.Suche in Google Scholar

43. Lahariya, V, Dhoble, SJ. Development and advancement of undoped and doped zinc sulfide for phosphor application. Displays 2022;74:102186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.displa.2022.102186.Suche in Google Scholar

44. Khan, M, Ali, R, Nowsherwan, GA, Anwar, N, Ahmed, M, Ali, Q, et al.. Gd-doped ZnO nanoparticles: structural, morphological, and optoelectronic enhancements. Ceram Int 2025;51:14417–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2025.01.279.Suche in Google Scholar

45. Heiba, ZK, Abozied, AM, Badawi, A, Mouhammad, SA, Mohamed, MB. Effect of Ce-doping on the structural, optical and photoluminescence characteristics of nano Zn0.75Cd0.25S. Opt Mater (Amst) 2024;154:115656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2024.115656.Suche in Google Scholar

46. Jabeen, U, Shah, SM, Hussain, N, Fakhr-e-Alam, Ali, A, khan, A, et al.. Synthesis, characterization, band gap tuning and applications of Cd-doped ZnS nanoparticles in hybrid solar cells. J Photochem Photobiol Chem 2016;325:29–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotochem.2016.04.003.Suche in Google Scholar

47. Tong, Y, Cao, F, Yang, J, Xu, M, Zheng, C, Zhu, X, et al.. Urchinlike pristine and Er-doped ZnS hierarchical nanostructures: controllable synthesis, photoluminescence and enhanced photocatalytic performance. Mater Chem Phys 2015;151:357–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2014.12.005.Suche in Google Scholar

48. Zhang, J, Yang, Y, Jiang, F, Li, J, Xu, B, Wang, X, et al.. Fabrication, structural characterization and photoluminescence of Q-1D semiconductor ZnS hierarchical nanostructures. Nanotechnology 2006;17:2695–700. https://doi.org/10.1088/0957-4484/17/10/042.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

49. Nirmala Jothi, NS, Joshi, AG, Jerald Vijay, R, Muthuvinayagam, A, Sagayaraj, P. Investigation on one-pot hydrothermal synthesis, structural and optical properties of ZnS quantum dots. Mater Chem Phys 2013;138:186–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2012.11.042.Suche in Google Scholar

50. Corrado, C, Jiang, Y, Oba, F, Kozina, M, Bridges, F, Zhang, JZ. Synthesis, structural, and optical properties of stable ZnS:Cu,Cl nanocrystals. J Phys Chem A 2009;113:3830–9. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp809666t.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

51. Pal, M, Mathews, NR, Morales, ER, Gracia y Jiménez, JM, Mathew, X. Synthesis of Eu+3 doped ZnS nanoparticles by a wet chemical route and its characterization. Opt Mater (Amst) 2013;35:2664–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2013.08.003.Suche in Google Scholar

52. Hafsouni, I, Labiadh, H, Altalhi, T, Mezni, A, Sellami, B. Aqueous synthesis and optical study of undoped and Gd-doped ZnS semiconductor nanoparticles (Zn1-3xGd2xS): environmental toxicity assessment. Solid State Commun 2025;400:115915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssc.2025.115915.Suche in Google Scholar

53. Hari Prasad, K, Vinoth, S, Ganesh, V. Effect of Ce doping on MoO3 thin films for room temperature ammonia sensing application. Phys Scripta 2024;99:085977. https://doi.org/10.1088/1402-4896/ad5f5a.Suche in Google Scholar

54. Jansi, R, Revathy, MS, Vimala Juliet, A, Manthrammel, MA, Shkir, M. High response chemiresistive room temperature ammonia gas sensor based on La-doped ZnO samples. Ceram Int 2024;50:29419–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2024.05.236.Suche in Google Scholar

55. Maheswari, S, Karunakaran, M, Chandrasekar, L, Kasinathan, K, Rajkumar, N. Correction to: room temperature ammonia gas sensor using Nd-doped SnO2 thin films and its characterization. J Mater Sci Mater Electron 2020;31:14000–1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-020-03992-6.Suche in Google Scholar

56. Vinoth, S, Isaiarasu, IV, Isaac, RR, Juliet, AV, Khan, AS, Kumar, A, et al.. Design and fabrication of enhanced room temperature NH3 sensors based on Sn-doped WO3 thin films deposited using nebulizer spray pyrolysis technique. Ceram Int 2025;51:17423–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2025.01.515.Suche in Google Scholar

57. Zhang, Y, Zhang, L, Bian, J, Tang, M, Wang, Z, Chen, Q, et al.. Ammonia detection based on core–shell nanoparticle ZnS/Co9S8 composites. ACS Appl Nano Mater 2024;7:21319–26. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.4c02438.Suche in Google Scholar

58. Haunsbhavi, K, Barthwal, S, Shivaramu, N, Shetty, H, Alagarasan, D, AlFaify, S, et al.. Effect of doping (Sn and In) on CdS thin films for ammonia sensing at room temperature. Sensor Actuator Phys 2024;376:115567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sna.2024.115567.Suche in Google Scholar

59. Qin, Z, Xu, K, Yue, H, Wang, H, Zhang, J, Ouyang, C, et al.. Enhanced room-temperature NH3 gas sensing by 2D SnS2 with sulfur vacancies synthesized by chemical exfoliation. Sensor Actuator B Chem 2018;262:771–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2018.02.060.Suche in Google Scholar

60. Raksa, P, Ponhan, W, Wongrat, E, Tubtimtae, A. Structural, optical, electrical, and gas sensing properties of antimony-doped selenium dioxide thin films synthesized using spray pyrolysis method. Ceram Int 2025;51:18786–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2025.02.059.Suche in Google Scholar

61. Bai, J, Shen, Y, Wang, W, Wu, M, Xiao, H, Zhao, Q, et al.. Highly sensitive room-temperature ammonia sensor based on PbS quantum dots modified SnS2 nanosheets and theoretical investigation on its sensing mechanism by DFT calculation. Appl Surf Sci 2025;680:161324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2024.161324.Suche in Google Scholar

62. Li, M, Zhang, Y, Mou, C, Gu, Y, Zhu, H, Wei, G. Raspberry-like Zn-Doped SnS nanostructure for ammonia sensing at room temperature. IEEE Sens J 2023;23:14906–14. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2023.3277474.Suche in Google Scholar

63. Hari Prasad, K, Vinoth, S, Ganesh, V, Ade, R. Fabrication of Al and La co-doped CdS thin film for ammonia gas-sensing application through low-cost nebulizer spray pyrolysis technique. Appl Phys A 2024;130:204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00339-024-07355-4.Suche in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/ntrev-2025-0232).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- MHD radiative mixed convective flow of a sodium alginate-based hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated extending sheet with Joule heating

- Experimental study of mortar incorporating nano-magnetite on engineering performance and radiation shielding

- Multicriteria-based optimization and multi-variable non-linear regression analysis of concrete containing blends of nano date palm ash and eggshell powder as cementitious materials

- A promising Ag2S/poly-2-amino-1-mercaptobenzene open-top spherical core–shell nanocomposite for optoelectronic devices: A one-pot technique

- Biogenic synthesized selenium nanoparticles combined chitosan nanoparticles controlled lung cancer growth via ROS generation and mitochondrial damage pathway

- Fabrication of PDMS nano-mold by deposition casting method

- Stimulus-responsive gradient hydrogel micro-actuators fabricated by two-photon polymerization-based 4D printing

- Physical aspects of radiative Carreau nanofluid flow with motile microorganisms movement under yield stress via oblique penetrable wedge

- Effect of polar functional groups on the hydrophobicity of carbon nanotubes-bacterial cellulose nanocomposite

- Review in green synthesis mechanisms, application, and future prospects for Garcinia mangostana L. (mangosteen)-derived nanoparticles

- Entropy generation and heat transfer in nonlinear Buoyancy–driven Darcy–Forchheimer hybrid nanofluids with activation energy

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ginkgo biloba seed extract: Evaluation of antioxidant, anticancer, antifungal, and antibacterial activities

- A numerical analysis of heat and mass transfer in water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing copper and alumina nanoparticles over an extending sheet

- Investigating the behaviour of electro-magneto-hydrodynamic Carreau nanofluid flow with slip effects over a stretching cylinder

- Electrospun thermoplastic polyurethane/nano-Ag-coated clear aligners for the inhibition of Streptococcus mutans and oral biofilm

- Investigation of the optoelectronic properties of a novel polypyrrole-multi-well carbon nanotubes/titanium oxide/aluminum oxide/p-silicon heterojunction

- Novel photothermal magnetic Janus membranes suitable for solar water desalination

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ageratum conyzoides for activated carbon compositing to prepare antimicrobial cotton fabric

- Activation energy and Coriolis force impact on three-dimensional dusty nanofluid flow containing gyrotactic microorganisms: Machine learning and numerical approach

- Machine learning analysis of thermo-bioconvection in a micropolar hybrid nanofluid-filled square cavity with oxytactic microorganisms

- Research and improvement of mechanical properties of cement nanocomposites for well cementing

- Thermal and stability analysis of silver–water nanofluid flow over unsteady stretching sheet under the influence of heat generation/absorption at the boundary

- Cobalt iron oxide-infused silicone nanocomposites: Magnetoactive materials for remote actuation and sensing

- Magnesium-reinforced PMMA composite scaffolds: Synthesis, characterization, and 3D printing via stereolithography

- Bayesian inference-based physics-informed neural network for performance study of hybrid nanofluids

- Numerical simulation of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to a heterogeneous/homogeneous chemical reaction over a Riga surface

- Enhancing the superhydrophobicity, UV-resistance, and antifungal properties of natural wood surfaces via in situ formation of ZnO, TiO2, and SiO2 particles

- Synthesis and electrochemical characterization of iron oxide/poly(2-methylaniline) nanohybrids for supercapacitor application

- Impacts of double stratification on thermally radiative third-grade nanofluid flow on elongating cylinder with homogeneous/heterogeneous reactions by implementing machine learning approach

- Synthesis of Cu4O3 nanoparticles using pumpkin seed extract: Optimization, antimicrobial, and cytotoxicity studies

- Cationic charge influence on the magnetic response of the Fe3O4–[Me2+ 1−y Me3+ y (OH2)] y+(Co3 2−) y/2·mH2O hydrotalcite system

- Pressure sensing intelligent martial arts short soldier combat protection system based on conjugated polymer nanocomposite materials

- Magnetohydrodynamics heat transfer rate under inclined buoyancy force for nano and dusty fluids: Response surface optimization for the thermal transport

- Fly ash and nano-graphene enhanced stabilization of engine oil-contaminated soils

- Enhancing natural fiber-reinforced biopolymer composites with graphene nanoplatelets: Mechanical, morphological, and thermal properties

- Performance evaluation of dual-scale strengthened co-bonded single-lap joints using carbon nanotubes and Z-pins with ANN

- Computational works of blood flow with dust particles and partially ionized containing tiny particles on a moving wedge: Applications of nanotechnology

- Hybridization of biocomposites with oil palm cellulose nanofibrils/graphene nanoplatelets reinforcement in green epoxy: A study of physical, thermal, mechanical, and morphological properties

- Design and preparation of micro-nano dual-scale particle-reinforced Cu–Al–V alloy: Research on the aluminothermic reduction process

- Spectral quasi-linearization and response optimization on magnetohydrodynamic flow via stenosed artery with hybrid and ternary solid nanoparticles: Support vector machine learning

- Ferrite/curcumin hybrid nanocomposite formulation: Physicochemical characterization, anticancer activity, and apoptotic and cell cycle analyses in skin cancer cells

- Enhanced therapeutic efficacy of Tamoxifen against breast cancer using extra virgin olive oil-based nanoemulsion delivery system

- A titanium oxide- and silver-based hybrid nanofluid flow between two Riga walls that converge and diverge through a machine-learning approach

- Enhancing convective heat transfer mechanisms through the rheological analysis of Casson nanofluid flow towards a stagnation point over an electro-magnetized surface

- Intrinsic self-sensing cementitious composites with hybrid nanofillers exhibiting excellent piezoresistivity

- Research on mechanical properties and sulfate erosion resistance of nano-reinforced coal gangue based geopolymer concrete

- Impact of surface and configurational features of chemically synthesized chains of Ni nanostars on the magnetization reversal process

- Porous sponge-like AsOI/poly(2-aminobenzene-1-thiol) nanocomposite photocathode for hydrogen production from artificial and natural seawater

- Multifaceted insights into WO3 nanoparticle-coupled antibiotics to modulate resistance in enteric pathogens of Houbara bustard birds

- Synthesis of sericin-coated silver nanoparticles and their applications for the anti-bacterial finishing of cotton fabric

- Enhancing chloride resistance of freeze–thaw affected concrete through innovative nanomaterial–polymer hybrid cementitious coating

- Development and performance evaluation of green aluminium metal matrix composites reinforced with graphene nanopowder and marble dust

- Morphological, physical, thermal, and mechanical properties of carbon nanotubes reinforced arrowroot starch composites

- Influence of the graphene oxide nanosheet on tensile behavior and failure characteristics of the cement composites after high-temperature treatment

- Central composite design modeling in optimizing heat transfer rate in the dissipative and reactive dynamics of viscoplastic nanomaterials deploying Joule and heat generation aspects

- Double diffusion of nano-enhanced phase change materials in connected porous channels: A hybrid ISPH-XGBoost approach

- Synergistic impacts of Thompson–Troian slip, Stefan blowing, and nonuniform heat generation on Casson nanofluid dynamics through a porous medium

- Optimization of abrasive water jet machining parameters for basalt fiber/SiO2 nanofiller reinforced composites

- Enhancing aesthetic durability of Zisha teapots via TiO2 nanoparticle surface modification: A study on self-cleaning, antimicrobial, and mechanical properties

- Nanocellulose solution based on iron(iii) sodium tartrate complexes

- Combating multidrug-resistant infections: Gold nanoparticles–chitosan–papain-integrated dual-action nanoplatform for enhanced antibacterial activity

- Novel royal jelly-mediated green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and their multifunctional biological activities

- Direct bandgap transition for emission in GeSn nanowires

- Synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles with different morphologies using a microwave-based method and their antimicrobial activity

- Numerical investigation of convective heat and mass transfer in a trapezoidal cavity filled with ternary hybrid nanofluid and a central obstacle

- Halloysite nanotube enhanced polyurethane nanocomposites for advanced electroinsulating applications

- Low molar mass ionic liquid’s modified carbon nanotubes and its role in PVDF crystalline stress generation

- Green synthesis of polydopamine-functionalized silver nanoparticles conjugated with Ceftazidime: in silico and experimental approach for combating antibiotic-resistant bacteria and reducing toxicity

- Evaluating the influence of graphene nano powder inclusion on mechanical, vibrational and water absorption behaviour of ramie/abaca hybrid composites

- Dynamic-behavior of Casson-type hybrid nanofluids due to a stretching sheet under the coupled impacts of boundary slip and reaction-diffusion processes

- Influence of polyvinyl alcohol on the physicochemical and self-sensing properties of nano carbon black reinforced cement mortar

- Advanced machine learning approaches for predicting compressive and flexural strength of carbon nanotube–reinforced cement composites: a comparative study and model interpretability analysis

- Artificial neural network-driven insights into nanoparticle-enhanced phase change materials melting for heat storage optimization

- Optical, structural, and morphological characterization of hydrothermally synthesized zinc oxide nanorods: exploring their potential for environmental applications

- Structural, optical, and gas sensing properties of Ce, Nd, and Pr doped ZnS nanostructured thin films prepared by nebulizer spray pyrolysis method

- The influence of nano-size La2O3 and HfC on the microstructure and mechanical properties of tungsten alloys by microwave sintering

- Green fabrication of γ- Al2O3 bionanomaterials using Coriandrum sativum plant extract and its photocatalytic and antibacterial activity

- Review Articles

- A comprehensive review on hybrid plasmonic waveguides: Structures, applications, challenges, and future perspectives

- Nanoparticles in low-temperature preservation of biological systems of animal origin

- Fluorescent sulfur quantum dots for environmental monitoring

- Nanoscience systematic review methodology standardization

- Nanotechnology revolutionizing osteosarcoma treatment: Advances in targeted kinase inhibitors

- AFM: An important enabling technology for 2D materials and devices

- Carbon and 2D nanomaterial smart hydrogels for therapeutic applications

- Principles, applications and future prospects in photodegradation systems

- Do gold nanoparticles consistently benefit crop plants under both non-stressed and abiotic stress conditions?

- An updated overview of nanoparticle-induced cardiovascular toxicity

- Arginine as a promising amino acid for functionalized nanosystems: Innovations, challenges, and future directions

- Advancements in the use of cancer nanovaccines: Comprehensive insights with focus on lung and colon cancer

- Membrane-based biomimetic delivery systems for glioblastoma multiforme therapy

- The drug delivery systems based on nanoparticles for spinal cord injury repair

- Green synthesis, biomedical effects, and future trends of Ag/ZnO bimetallic nanoparticles: An update

- Application of magnesium and its compounds in biomaterials for nerve injury repair

- Micro/nanomotors in biomedicine: Construction and applications

- Hydrothermal synthesis of biomass-derived CQDs: Advances and applications

- Research progress in 3D bioprinting of skin: Challenges and opportunities

- Review on bio-selenium nanoparticles: Synthesis, protocols, and applications in biomedical processes

- Gold nanocrystals and nanorods functionalized with protein and polymeric ligands for environmental, energy storage, and diagnostic applications: A review

- An in-depth analysis of rotational and non-rotational piezoelectric energy harvesting beams: A comprehensive review

- Advancements in perovskite/CIGS tandem solar cells: Material synergies, device configurations, and economic viability for sustainable energy

- Deep learning in-depth analysis of crystal graph convolutional neural networks: A new era in materials discovery and its applications

- Review of recent nano TiO2 film coating methods, assessment techniques, and key problems for scaleup

- Antioxidant quantum dots for spinal cord injuries: A review on advancing neuroprotection and regeneration in neurological disorders

- Rise of polycatecholamine ultrathin films: From synthesis to smart applications

- Advancing microencapsulation strategies for bioactive compounds: Enhancing stability, bioavailability, and controlled release in food applications

- Advances in the design and manipulation of self-assembling peptide and protein nanostructures for biomedical applications

- Photocatalytic pervious concrete systems: from classic photocatalysis to luminescent photocatalysis

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Synthesis and characterization of smart stimuli-responsive herbal drug-encapsulated nanoniosome particles for efficient treatment of breast cancer”

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part III

- Efficiency optimization of quantum dot photovoltaic cell by solar thermophotovoltaic system

- Exploring the diverse nanomaterials employed in dental prosthesis and implant techniques: An overview

- Electrochemical investigation of bismuth-doped anode materials for low‑temperature solid oxide fuel cells with boosted voltage using a DC-DC voltage converter

- Synthesis of HfSe2 and CuHfSe2 crystalline materials using the chemical vapor transport method and their applications in supercapacitor energy storage devices

- Special Issue on Green Nanotechnology and Nano-materials for Environment Sustainability

- Influence of nano-silica and nano-ferrite particles on mechanical and durability of sustainable concrete: A review

- Surfaces and interfaces analysis on different carboxymethylation reaction time of anionic cellulose nanoparticles derived from oil palm biomass

- Processing and effective utilization of lignocellulosic biomass: Nanocellulose, nanolignin, and nanoxylan for wastewater treatment

- Special Issue on Emerging Nanotech. for Biomed. and Sust. Environ. Appl.

- Beyond science: ethical and societal considerations in the era of biogenic nanoparticles

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Aging assessment of silicone rubber materials under corona discharge accompanied by humidity and UV radiation”

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- MHD radiative mixed convective flow of a sodium alginate-based hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated extending sheet with Joule heating

- Experimental study of mortar incorporating nano-magnetite on engineering performance and radiation shielding

- Multicriteria-based optimization and multi-variable non-linear regression analysis of concrete containing blends of nano date palm ash and eggshell powder as cementitious materials

- A promising Ag2S/poly-2-amino-1-mercaptobenzene open-top spherical core–shell nanocomposite for optoelectronic devices: A one-pot technique

- Biogenic synthesized selenium nanoparticles combined chitosan nanoparticles controlled lung cancer growth via ROS generation and mitochondrial damage pathway

- Fabrication of PDMS nano-mold by deposition casting method

- Stimulus-responsive gradient hydrogel micro-actuators fabricated by two-photon polymerization-based 4D printing

- Physical aspects of radiative Carreau nanofluid flow with motile microorganisms movement under yield stress via oblique penetrable wedge

- Effect of polar functional groups on the hydrophobicity of carbon nanotubes-bacterial cellulose nanocomposite

- Review in green synthesis mechanisms, application, and future prospects for Garcinia mangostana L. (mangosteen)-derived nanoparticles

- Entropy generation and heat transfer in nonlinear Buoyancy–driven Darcy–Forchheimer hybrid nanofluids with activation energy

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ginkgo biloba seed extract: Evaluation of antioxidant, anticancer, antifungal, and antibacterial activities

- A numerical analysis of heat and mass transfer in water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing copper and alumina nanoparticles over an extending sheet

- Investigating the behaviour of electro-magneto-hydrodynamic Carreau nanofluid flow with slip effects over a stretching cylinder

- Electrospun thermoplastic polyurethane/nano-Ag-coated clear aligners for the inhibition of Streptococcus mutans and oral biofilm

- Investigation of the optoelectronic properties of a novel polypyrrole-multi-well carbon nanotubes/titanium oxide/aluminum oxide/p-silicon heterojunction

- Novel photothermal magnetic Janus membranes suitable for solar water desalination

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ageratum conyzoides for activated carbon compositing to prepare antimicrobial cotton fabric

- Activation energy and Coriolis force impact on three-dimensional dusty nanofluid flow containing gyrotactic microorganisms: Machine learning and numerical approach

- Machine learning analysis of thermo-bioconvection in a micropolar hybrid nanofluid-filled square cavity with oxytactic microorganisms

- Research and improvement of mechanical properties of cement nanocomposites for well cementing

- Thermal and stability analysis of silver–water nanofluid flow over unsteady stretching sheet under the influence of heat generation/absorption at the boundary

- Cobalt iron oxide-infused silicone nanocomposites: Magnetoactive materials for remote actuation and sensing

- Magnesium-reinforced PMMA composite scaffolds: Synthesis, characterization, and 3D printing via stereolithography

- Bayesian inference-based physics-informed neural network for performance study of hybrid nanofluids

- Numerical simulation of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to a heterogeneous/homogeneous chemical reaction over a Riga surface

- Enhancing the superhydrophobicity, UV-resistance, and antifungal properties of natural wood surfaces via in situ formation of ZnO, TiO2, and SiO2 particles

- Synthesis and electrochemical characterization of iron oxide/poly(2-methylaniline) nanohybrids for supercapacitor application

- Impacts of double stratification on thermally radiative third-grade nanofluid flow on elongating cylinder with homogeneous/heterogeneous reactions by implementing machine learning approach

- Synthesis of Cu4O3 nanoparticles using pumpkin seed extract: Optimization, antimicrobial, and cytotoxicity studies