Abstract

This paper proposes polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) as an additive to improve the mechanical and self-sensing properties of nano carbon black (NCB)-cement mortar. X-ray diffraction (XRD), Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, and Raman spectroscopy were used to reveal the chemical interaction between NCB and PVA. Furthermore, the effects of PVA on the mechanical performance, self-sensing behavior, and microstructure of NCB-cement mortar were systematically investigated. The results demonstrate that PVA enhances the dispersion uniformity of NCB, and the formation of an NCB/PVA “grape-bunch” structure (a three-dimensional network with NCB particles distributed along the PVA film) is key to achieving the cooperative improvement effect. The incorporation of 0.6 wt% PVA and 0.5 wt% NCB increased the compressive and flexural strengths by 24 % and 25 %, respectively, compared to the sample with NCB alone. In addition, the mortar sensor with combined PVA and NCB exhibited higher stress sensitivity under cyclic loading. Cost-benefit analyses indicate that the use of NCB/PVA as a composite modifier to develop cement mortar sensors is an economic and effective option.

1 Introduction

Concrete structures are subjected to multiple and complex forces during service, including wind, water, atmosphere and earthquakes, which not only shortens their longevity, but also sometimes cause extensive damage and even injuries. Therefore, the implementation of strain and stress monitoring, especially in certain critical parts of the structure, is becoming increasingly necessary [1], [2], [3]. Cement-based materials containing electrically conductive fillers exhibit piezoresistive effects under compressive loading, and their electrical properties vary with the magnitude of the applied stress. Because these materials are expected to provide intelligent stress and damage monitoring of concrete structures, they have captured the attention of both engineers and academics. In particular, the incorporation of carbon nanomaterials such as carbon nanotubes (CNTs), graphene oxide (GO), carbon nanofibers (CNFs) and nano carbon black (NCB) provides reliable structural health monitoring (SHM) and improves the mechanical properties and durability of cementitious materials [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]. The cementitious materials containing carbon nanomaterials, which can also reflect or absorb electromagnetic radiation, can help reduce electromagnetic radiation pollution in the communications field [11], 12].

NCB has recently attracted attention as a low-price additive with stable physicochemical properties and high electrical conductivity for cementitious materials [13], [14], [15], [16]. Zhang et al. showed that well-dispersed NCB improves the mechanical properties of cementitious materials by reducing the internal porosity of the matrix and accelerating cement hydration [17]. Gustavo et al. showed that low doses of NCB (especially in the 0.375–3 % range) better refine the pore structure of the cement matrix and enhance cement hydration than higher doses [18]. Li et al. [19], Monteiro et al. [20] and Nalon et al. [21] investigated the sensing ability of NCB-doped cementitious composites and revealed that NCB reduces the resistivity of the cementitious material and imparts a good piezoresistive response. Although NCB-doped cementitious materials have been extensively studied, deficiencies in single nanofiller-modified composites cannot be ignored. Previous studies have shown that to optimise the performance of cementitious materials, NCB must usually be applied at much higher doses than CNT, GO and CNF because NCB particles less easily form a conductive network than fillers with a high aspect ratio [17], 22]. However, excessively increasing the NCB content degrades the mechanical properties of cementitious composites, mainly because numerous nanoparticles tend to agglomerate through van der Waals forces and adsorb on the surfaces of the cement particles, hindering the hydration of cement [23], 24]. Therefore, cementitious sensors filled with NCB have limited applicability in SHM and should be combined with other admixtures.

Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) is an inexpensive and widely used polymer with good adhesion, film-forming properties and chemical stability. Previous studies have shown that introducing PVA into cementitious materials improves the water retention, toughness and flexural strength of composites and greatly enhances their waterproofing and impermeability [25]. Additionally, PVA can be used to improve the dispersion of nanomaterials (such as CNTs and GO) within the cement matrix, thereby reducing agglomeration and promoting a more uniform microstructure [26], 27]. Correspondingly, the incorporation of nanomaterials can enhance the tensile properties, surface hardness, and thermal stability of PVA [28], [29], [30]. Based on this complementary behavior, combining PVA with NCB is expected to produce a synergistic enhancement effect in cement-based materials.

This study employed PVA and NCB as composite modifiers to develop a cement mortar sensor with favorable mechanical properties and high self-sensing sensitivity, intended for structural health monitoring applications. The effects of PVA and NCB, both individually and in combination, on the mechanical and piezoresistive properties of cement mortar were systematically investigated. Furthermore, the chemical interactions and microstructural characteristics of the NCB/PVA complexes and the resulting cement mortars were characterized using various analytical techniques, including scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), and X-ray diffraction (XRD), to elucidate their synergistic enhancement mechanism.

2 Experimental programme

2.1 Raw materials

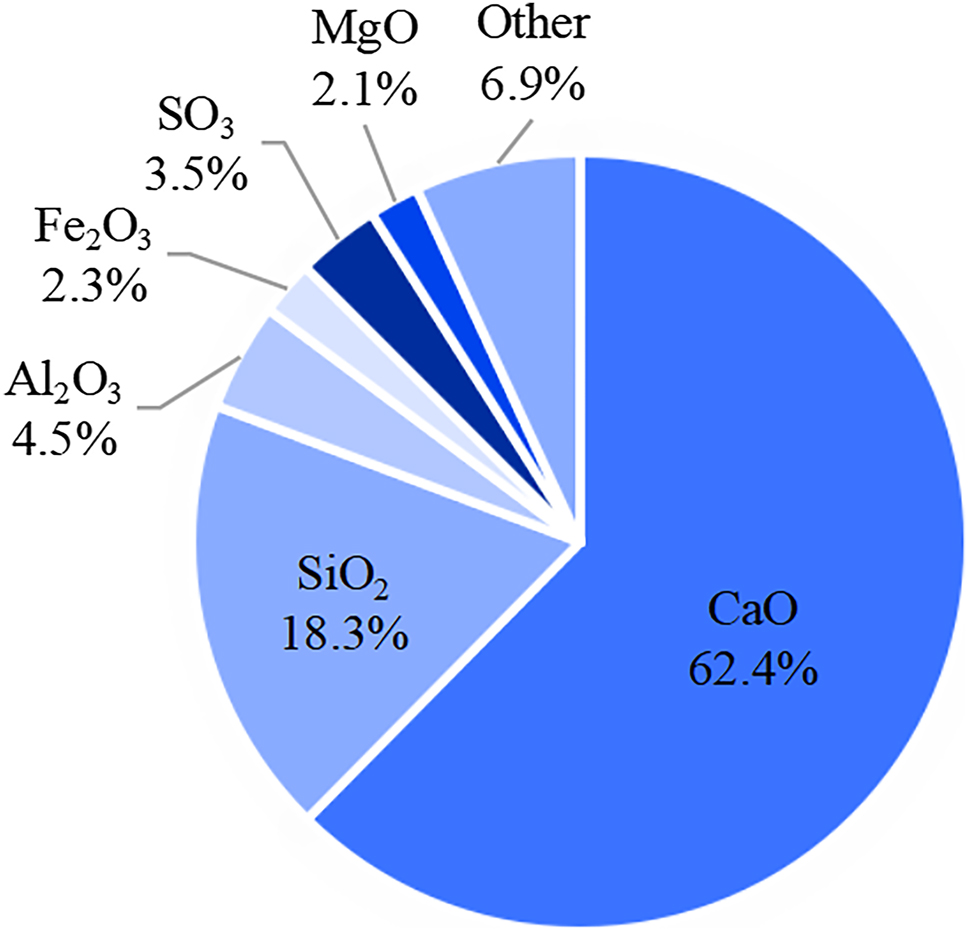

The cementitious material used in the experiment was P.O 42.5 R Portland cement purchased from Guangdong Tapai Co., Ltd. (China). The cement meets the requirements of the Chinese standard GB 175-2020, and its main chemical composition provided by the supplier is shown in Figure 1. The PVA powder (molecular weight: 105,000) used in this study was provided by Guangdong Xilong Chemical Co., Ltd. (China). It has a hydrolysis degree of 97 % and a pH range of 5–7. The nanofiller was NCB with a particle size of 17 nm and a conductivity of 0.35 Ω cm, which was supplied by Shandong Huaguang Chemical Factory, China. Table 1 lists the characteristics of NCB offered by manufacturer. Fine aggregate (sand) was obtained from Xiamen ISO Standard Sand Co., Ltd. in China and complies with the requirements of the Chinese standard GB/T 17671-1999. The fine aggregate has a particle size range of 0.8 mm–2.0 mm and a clay content of less than 0.2 %. A defoamer primarily composed of tributyl phosphate, obtained from Guangdong Defeng Chemical Co., Ltd. in China, was used to reduce the air bubble content in the cement mortar.

The main components of cement.

Physical and chemical properties of NCB.

| Iodine adsorption | DBF adsorption | Specific area | pH | Particle diameter | Resistivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,000 mg/g | 330∼350 ml (100 g)−1 | 1,000 m2 g−1 | 7.4 | 17 nm | 0.35 Ω cm |

2.2 Mixing proportions and specimen preparation

2.2.1 Preparation of NBC/PVA composite solution

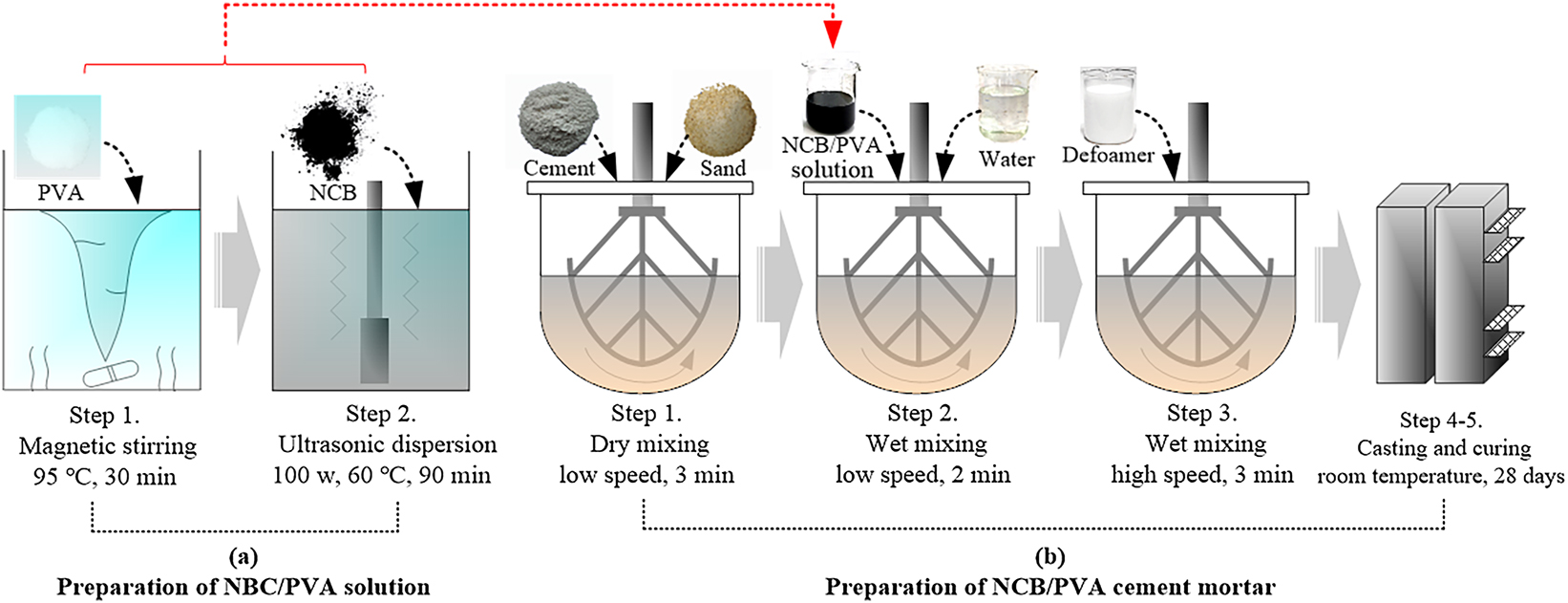

The formulation of uniformly dispersed NCB/PVA composite solutions is the basis for achieving cement mortars with desirable properties. Specifically, the NCB/PVA composite solution were prepared using the following preparation steps, as shown in Figure 2(a):

The PVA powder was dispersed in cold water for 10 min at room temperature and then stirred with a magnetic stirrer at 95 °C for approximately 30 min, forming a pure PVA solution.

NCB was added to the above PVA solution and dispersed using an ultrasonic disperser (100 W) heated to 60 °C for 1.5 h.

Procedure for the preparation of NCB/PVA composite solution (a) and modified cement mortar (b).

Zunaira et al. showed that the encapsulation effect of polymer chains provides additional steric hindrance between the nanoparticles and improves their dispersion by weakening the van der Waals forces [31]. Therefore, when applied as a composite modifier, the NCB/PVA solution with uniformly dispersed nanoparticles is expected to improve the performance of cement mortar.

2.2.2 Preparation of NCB/PVA cement mortar

To investigate the effects of individual and complex additions of NCB and PVA on the mechanical, electrical conductivity and piezoresistive properties of cement mortar, the authors prepared four different cement mixes. The mixing proportions are given in Table 2. The reference (CM) is cement mortar with no additive, PCM contains 0.6 wt% PVA (this amount of polymer incorporation was determined based on previous studies [25]), NCM incorporates 0.5 wt% NCB and NPCM includes 0.6 wt% PVA and 0.5 wt% NCB. In all samples, the cement: sand ratio was 1:1.5 and the water: cement (with modifier) ratio was 0.4:1. The defoamer content was 0.14 % of the mass fraction of cement. The cement mortar samples were prepared as follows (see Figure 2(b)):

The cement and sand were first dry-mixed in a planetary mortar mixer for about 3 min.

The prepared NCB/PVA composite solution (or pure PVA solution for PCM; NCB suspension for NCM) along with the remaining water was introduced into the mixture, followed by slow-speed wet mixing for 2 min.

Defoamer was incorporated and the mixture was further mixed at high speed for 3 min.

The mixture prepared in step (3) was poured into a mould. An electrical vibrator was used to ensure good compaction.

After 24 h of curing, the specimens were demoulded and cured under natural conditions for 28 days (average temperature: 22–28 °C; relative humidity: 84–92 %).

Mixing proportions (unit: g).

| Mix ID | Cement | Sand | Water | Defoamer | NCB | PVA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CM | 700 | 1,050 | 280 | 0.98 | 0 | 0 |

| NCM | 700 | 1,050 | 281.4 | 0.98 | 3.5 | 0 |

| PCM | 700 | 1,050 | 281.68 | 0.98 | 0 | 4.2 |

| NPCM | 700 | 1,050 | 283.08 | 0.98 | 3.5 | 4.2 |

2.3 Test methods

2.3.1 Characterization of the NCB/PVA composites

The XRD patterns of pure PVA, NCB, and NCB/PVA nanocomposites were collected on a Bruker D8 ADVANCE diffractometer (Germany) equipped with a copper anode generating X-ray radiation at 40 kV and 40 mA (λ = 1.5406 Å). Scans were performed across a 2θ range of 10°–60°. FTIR spectroscopy was carried out on the NCB/PVA composites using a MAUNA-IR 750 spectrometer (Nikolai, USA), covering wavenumbers from 500 to 4,000 cm−1. Raman spectroscopic analysis of NCB and NCB/PVA composites was conducted using a Horiba HR800 instrument (France), employing a 532 nm solid-state laser as the excitation source. The dispersions of NCB particles in pure water and PVA solution were observed using an SU8010 SEM (Hitachi) at an accelerating voltage of 5 kV.

2.3.2 Characterization of the cement mortar

2.3.2.1 Mechanical properties

Each mixture listed in Table 2 was subjected to compressive and flexural strength tests according to the Chinese standard GB/T 17617-2020. Three prismatic specimens with dimensions of 160 mm (length) × 40 mm (width) × 40 mm (height) were prepared for each group. The mechanical properties of the cement mortars were measured using a CMT-5105 universal testing machine (Shenzhen Xin Sansi Co., Ltd., China). Flexural strength tests were performed using the three-point bending method with a distance of 100 mm between the two pivot points and a loading rate of 0.5 mm/min. After the flexural tests, six fractured half-prisms were collected for the compressive strength test at a loading rate of 2400 N/s.

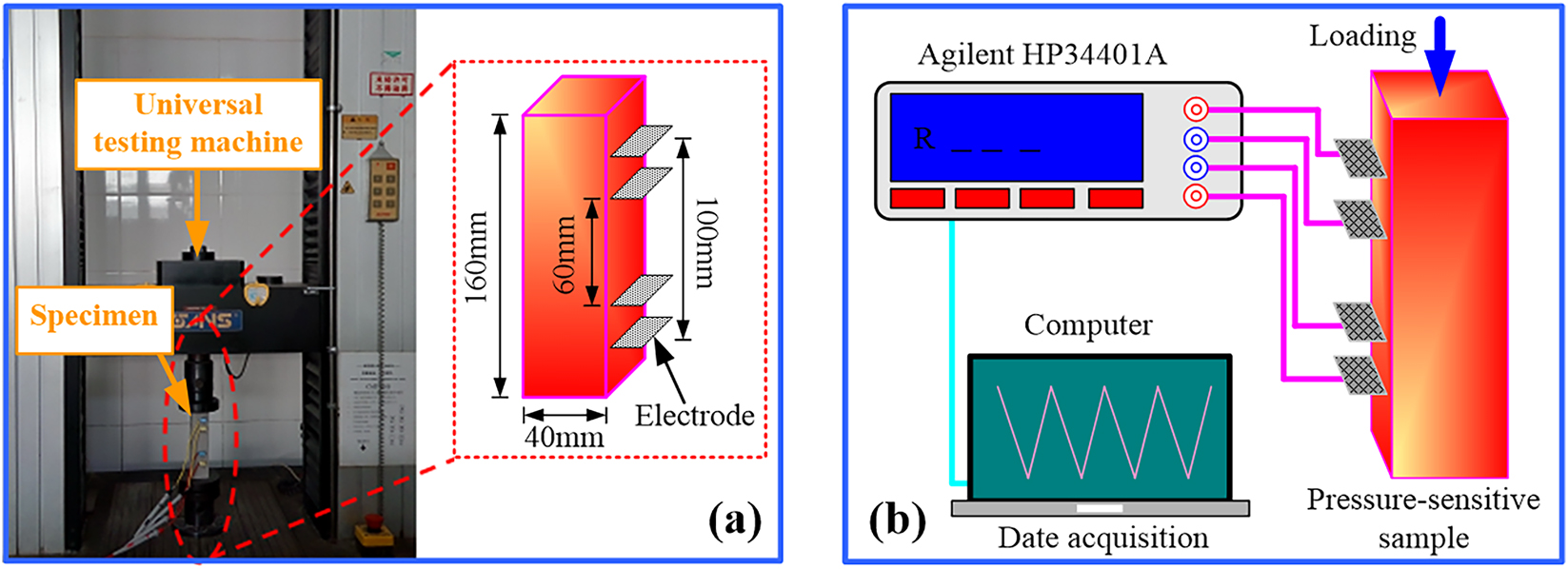

2.3.2.2 Piezoresistive properties

To measure the piezoresistive properties of a cementitious composite, researchers usually apply the two-electrode and four-electrode methods; the latter obtains more accurate results by minimising the polarisation effects. In this study, a four-electrode digital multi-metre (HP34401A, Agilent Technologies, Inc., USA) was used to collect the fractional change in resistance of each group of samples under cyclic compressive loading. The detailed configuration of the piezoresistive properties test setup is shown in Figure 3. All test samples were embedded with four electrodes during the manufacturing, the inner and outer electrodes were separated by 60 and 100 mm, respectively. The electrode sheet was 40-mm high, 10-mm wide and 1-mm thick. To eliminate the effect of internal pore water, all samples were dried in a desiccator at 60 ± 5 °C for 7 days. In addition, prior to testing, all specimens were energised under no-load conditions for approximately 1,000 s to reduce the effects of polarisation. To determine the piezoresistive characteristics of the cement mortar, 10 consecutive loading–unloading cycles were performed at a loading–unloading rate of 0.5 mm/min. The applied loads and resistances were automatically recorded by a computer at a sampling frequency of 0.5 Hz. The fractional change in resistance (FCR) was calculated as

where R 0 denotes the initial resistance of the sensor and R is the resistance of the cement mortar sensor during loading.

Stereogram (a) and schematic (b) for piezoresistive testing.

2.3.2.3 Microstructural investigation

The micromorphologies of the cement mortars mixed with NCB, PVA or combined NBC/PVA were characterised using field emission SEM (SU8010). After strength testing, small pieces sized approximately 1 cm × 1 cm × 1 cm were selected from the damaged samples and preserved in ethanol for SEM measurements. Prior to SEM, the specimen surface was sprayed with gold and placed in an observation chamber to select representative observation areas under an accelerating voltage of 5.0 kV. The FTIR spectrum of the cement mortar was obtained on a MAUNA-IR 750 spectrometer. Powdered samples (∼45 µm) were mixed with KBr and analysed over the 500–4,000 cm−1 wavenumber range.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Characterisation of NCB/PVA nanocomplexes

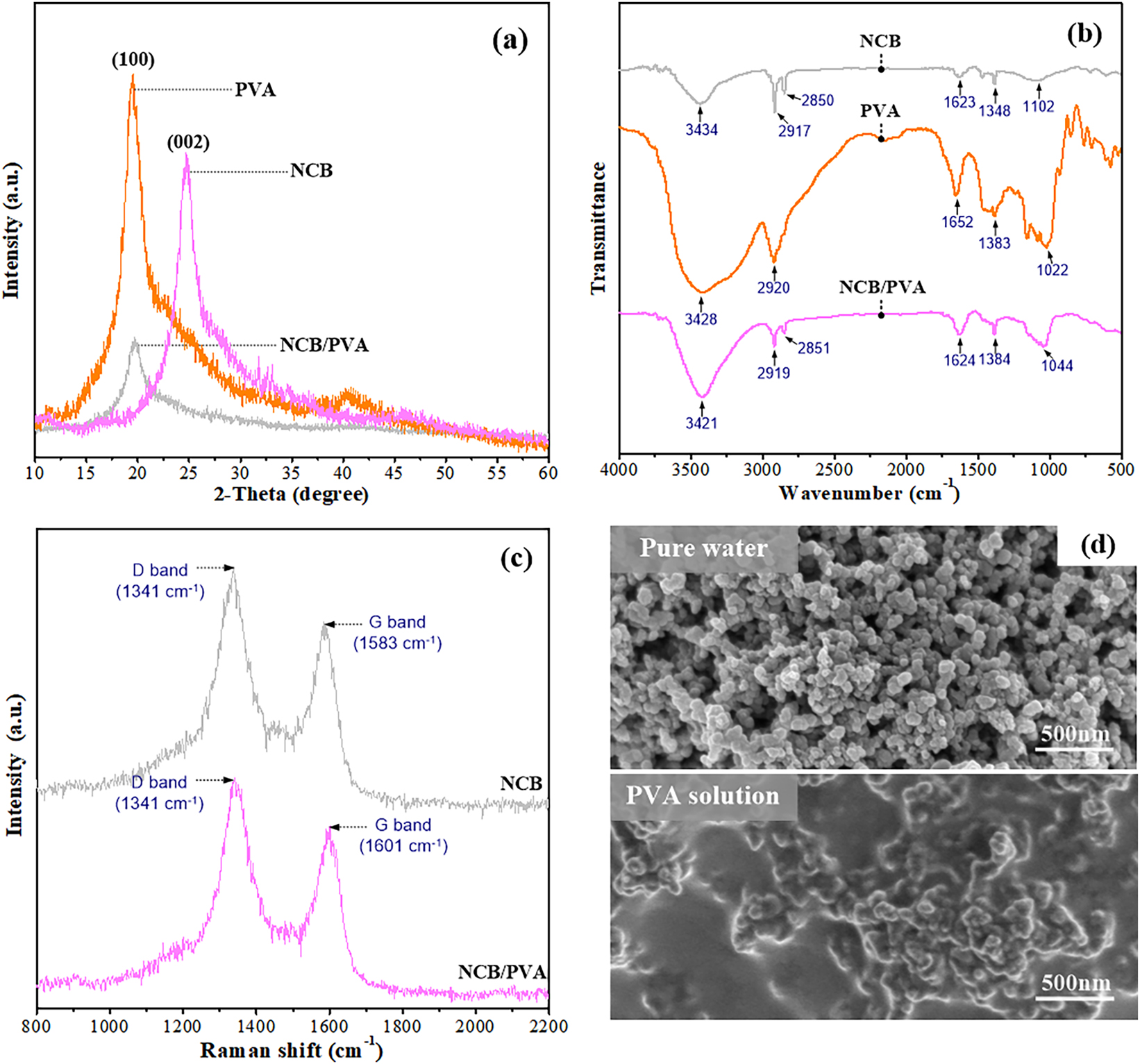

Figure 4(a) presents the XRD patterns of the pure PVA, NCB and NCB/PVA nanocomplexes. The diffractogram of pure PVA exhibits the characteristic peak of the (110) reflection at 2θ = 19.68°, consistent with previous studies [32]. In the X-ray diffractogram of NCB, the sharp diffraction peak at 2θ = 24.90° corresponds to the (002) reflection. Comparing the X-ray diffractograms of pure PVA and NCB/PVA nanocomposites, it can be observed that the nanofillers substantially reduce the intensities of the characteristic peaks of PVA, indicating that the randomly distributed NCB particles reduce the crystallinity by interacting with PVA molecules. The reduction in crystallinity indicates high compatibility between the carbon nanoparticles and PVA matrix, as also reported by Raeisi et al. [33]. In addition, a decrease in the crystallinity of PVA will positively influence its mechanical properties [34], 35]. It is worth noting that changes in crystallinity can equally affect the chemical resistance, temperature resistance and solubility of polymers [36], 37].

Characterisation of NCB, PVA and NCB/PVA nanocomplexes. (a) XRD spectra, (b) FTIR spectra, (c) Raman spectra and (d) SEM.

Figure 4(b) shows the FTIR spectra of NCB, pure PVA and NCB/PVA nanocomplexes over the 500–4,000 cm−1 range. In the spectrum of pure PVA, the distinct characteristic peaks at 3,428 and 2,920 cm−1 are attributable to stretching vibrations of –OH and asymmetric/symmetric stretching vibrations of –CH2, respectively, and those at 1,652, 1,383 and 1,022 cm−1 are contributed by C=O, C=C and C–O stretching vibrations in PVA, respectively [38]. In the FTIR spectrum of the NCB/PVA nanocomplexes, the characteristic peak positions shifted to lower frequencies compared to pure PVA, indicating an additional interaction between NCB and PVA. In addition, the characteristic peak intensities at 3,421, 1,624, 1,384 and 1,044 cm−1 were notably higher for the NCB/PVA nanocomplexes compared to pure NCB, indicating the successful coating of PVA on the surface of NCB particles.

Raman spectroscopy is one of the most important techniques for analysing carbon composites because carbon-based materials exhibit strong resonance-enhanced Raman scattering effects. This technique has been widely used to determine the degree of dispersion of carbon nanomaterials. Figure 4(c) shows the Raman spectra of pure NCB and NCB/PVA nanocomplexes. The spectrum of the pure NCB sample shows two strong peaks around 1,341 and 1,583 cm−1. The D band observed at approximately 1,341 cm−1 is associated with the scattering caused by structural defects and amorphous carbon impurities in the NCB. Meanwhile, the G band at around 1,583 cm−1 arises from the in-plane vibrational modes of C–C bonds within the graphitic lattice [39]. The signal intensities are overall lower in the spectrum of PVA-doped NCB than in the spectrum of pure NCB, and the G-band is shifted by 18 cm−1 from that of pure NCB. In addition, the intensity ratio of the D and G bands (the I D /I G ratio) is higher for the NCB/PVA complex than for pure NCB (1.26 vs 1.16), indicating more defects in the PVA-doped NCB complexes than in pure NBC. These defects play a crucial role in the development of crystalline order in cement mortars.

The dispersions of NCB in pure water and PVA solution were observed in SEM images, revealed the distribution patterns of the nanoparticles. As shown in Figure 4(d), the spherical NCB particles tended to aggregate in pure water despite being ultrasonically dispersed for 1.5 h. Clumping was attributed to van der Waals forces between the NCB particles. In contrast, the nanoparticles were relatively homogenously distributed in the PVA solution, although their surfaces were encapsulated by a layer of polymer gel. Similar findings were reported by Li et al. [40]. They concluded that PVA with a high degree of hydrolysis can maintain a homogeneous and stable dispersion in aqueous media simply by wrapping the NCB. Dong et al. conducted simulations on the surface modification of carbon black particles using PVA through molecular dynamics. Their results demonstrated that a suitable thickness of the PVA coating could improve the dispersion stability of carbon black particles [41].

3.2 Mechanical properties of NCB/PVA modified cement mortar

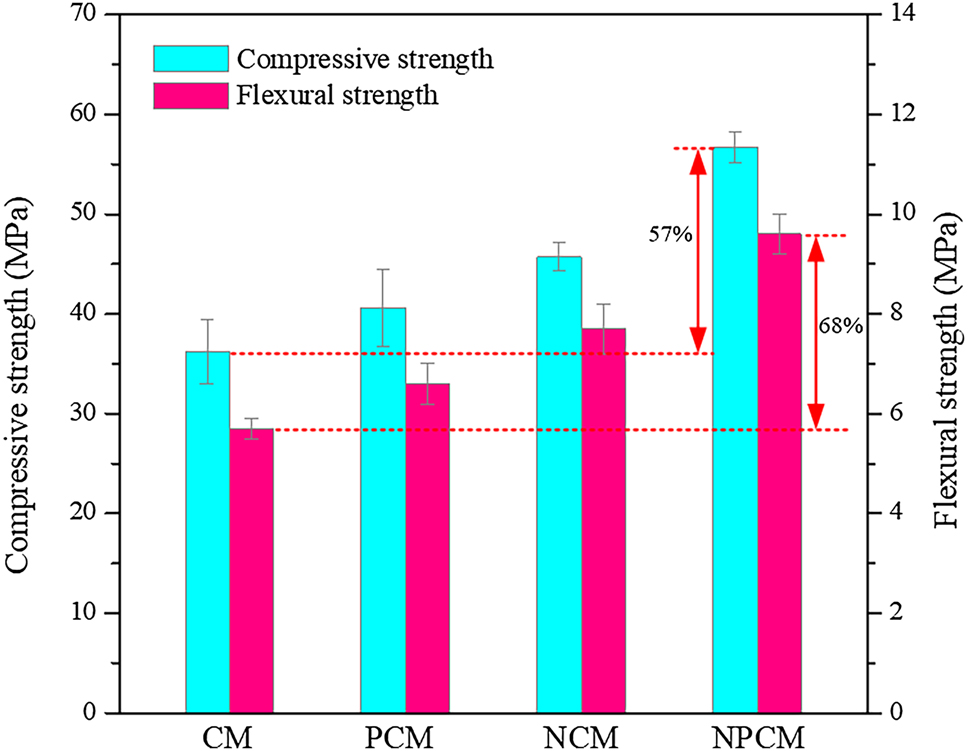

Figure 5 summarises the compressive and flexural strengths of the CM, PCM, NCM and NPCM after 28 days of curing. Adding 0.6 wt% of PVA alone (PCM) increased the compressive and flexural strength of the cement mortar by 12 % and 16 %, respectively, from those of the CM. This enhancement effect has also been reported in our previous studies [38]. The incorporation of an optimal amount of PVA contributes to the strengthening of cement mortar’s mechanical properties through three key ways. First, PVA can adsorb onto the surfaces of hydration products, forming a continuously distributed polymer film that inhibits the generation and expansion of cracks through a bridging effect [42], 43]. Second, chemical bonding between PVA and calcium hydroxide crystals promotes the hydration efficiency of the cement [44]. Finally, PVA fills the pores of the cement matrix [45]. Adding 0.5 wt% of NCB alone (NCM) increased the compressive and flexural strength of the cement mortar by 26 % and 35 %, respectively, from those of the CM. Similar results have been reported in the literature [18], 24]. The augmentation in mechanical properties imparted by NCB is attributable to two reinforcing mechanisms. First, the nano-scale particles act as efficient fillers, densifying the cement matrix by occupying voids at both the nano- and micro-scale [18]. Second, NCB particles act as nucleation sites for cement hydration products, promoting a more refined C–S–H gel microstructure [17]. The combined use of PVA and NCB (NPCM) increased the compressive strength and flexural strength of cement mortar by 57 % and 68 % respectively compared to CM, and by 24 % and 25 % respectively compared to NCM. The improvement is likely attributable to the role of PVA in promoting the uniform dispersion of NCB particles, coupled with a synergistic interaction between the two components. This combination optimizes the internal microstructure of the matrix and establishes a more efficient load-transfer pathway.

28-days mechanical strength of different cement mortars.

3.3 Microstructural and macroscopic morphologies of NCB/PVA modified mortar

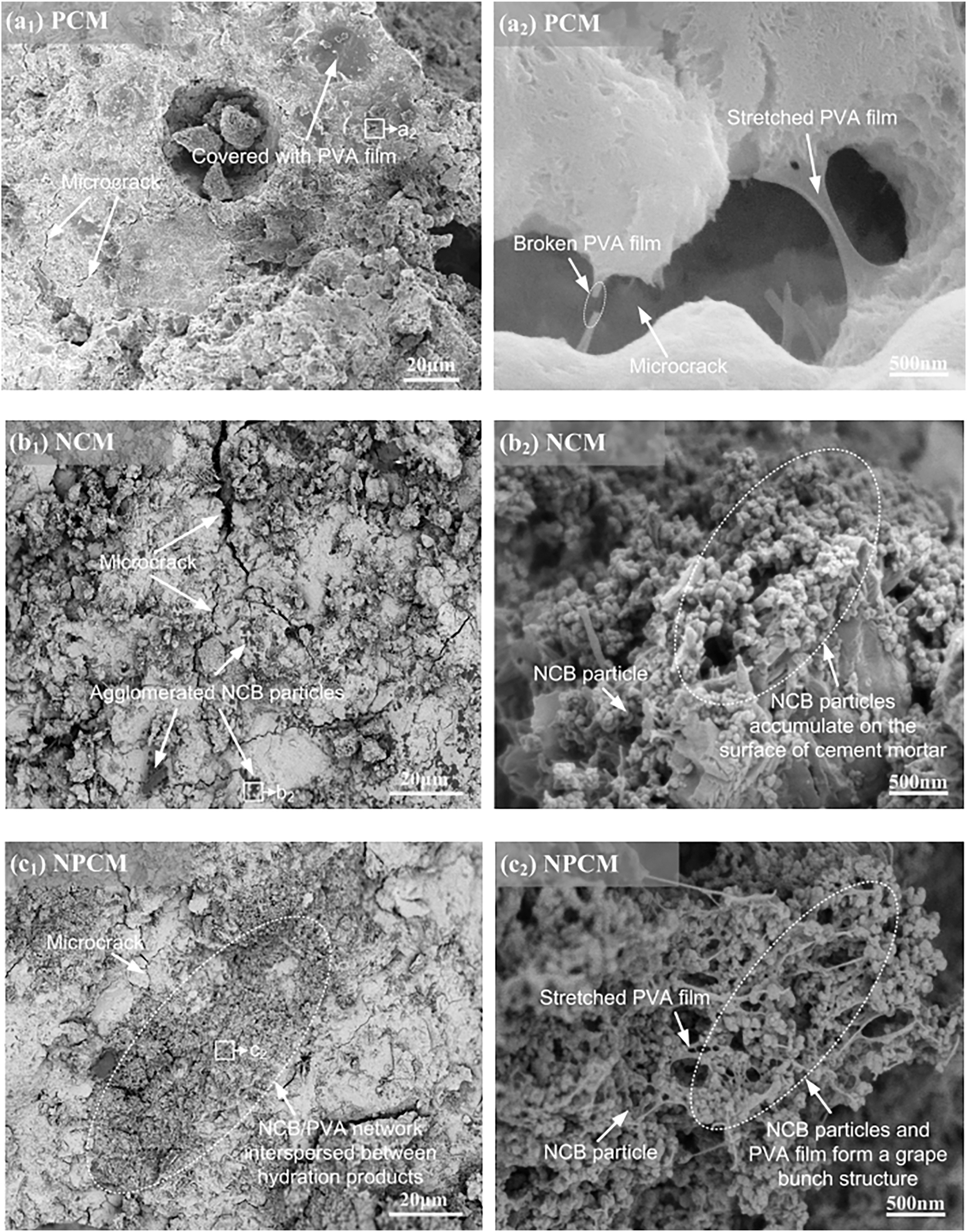

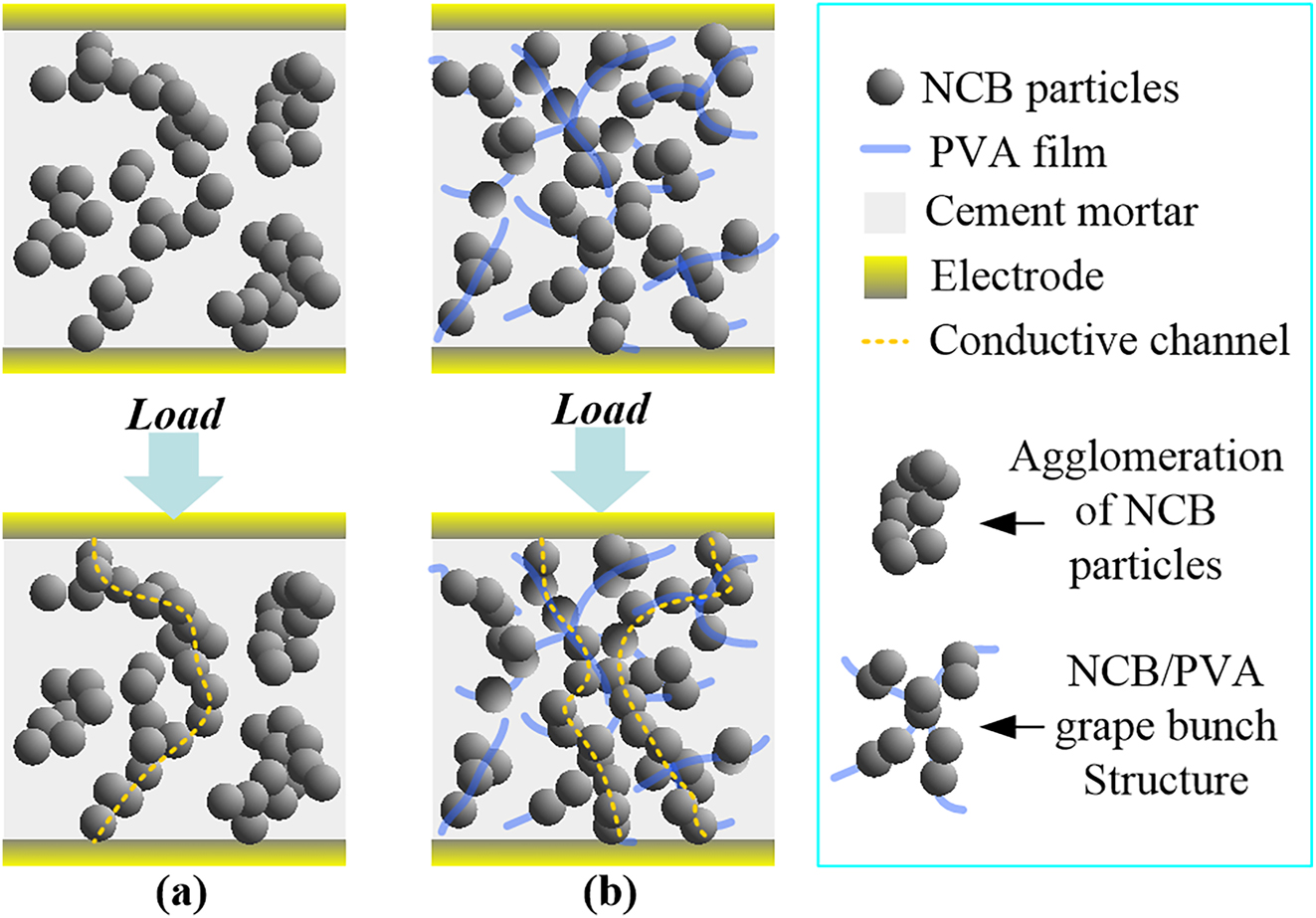

To gain deeper insights into the microstructural alterations and reinforcement mechanisms of cement mortar upon the addition of NCB, PVA, and their combination, the microscopic features of PCM, NCM, and NPCM were examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Representative SEM images are shown in Figure 6. After 28 days of curing, the internal microstructure of the PCM samples supplemented with PVA alone showed a clear bridging effect of the PVA film (Figure 6(a)). The polymer film is attached between the microcracks of the hydration products, where it transfers loads and absorbs energy from external forces to a certain extent. Mainly for this reason, the PCM samples present higher strengths than the CM samples. However, breakage failure of the polymer films is evident in the matrix, implying that the strength and therefore the bridging effect of the PVA film are limited [40]. The microscopic morphology of the cement mortar supplemented with NCB alone (Figure 6(b)) reveals randomly distributed nanoparticle on the surfaces of the cement matrix, which can partially fill the pores. A certain amount of agglomeration occurs despite the very low NCB content (only 0.5 wt%); hence, the enhancement is limited. The internal microstructure of NPCM exhibits an interesting three-dimensional mesh structure, resembling that of grape bunches, within the cement matrix (Figure 6(c)). This unique architecture results from the synergistic interaction between NCB particles and PVA, wherein spherical NCB nanoparticles are interconnected by dendritic PVA films. It can be observed that the presence of PVA enhances the dispersion uniformity of NCB particles. Furthermore, the formation of these grape-bunch structures provides effective and robust pathways for load transfer, which explain the improved macroscopic mechanical properties of the cement mortars.

SEM images of PCM (a), NCM (b) and NPCM (c).

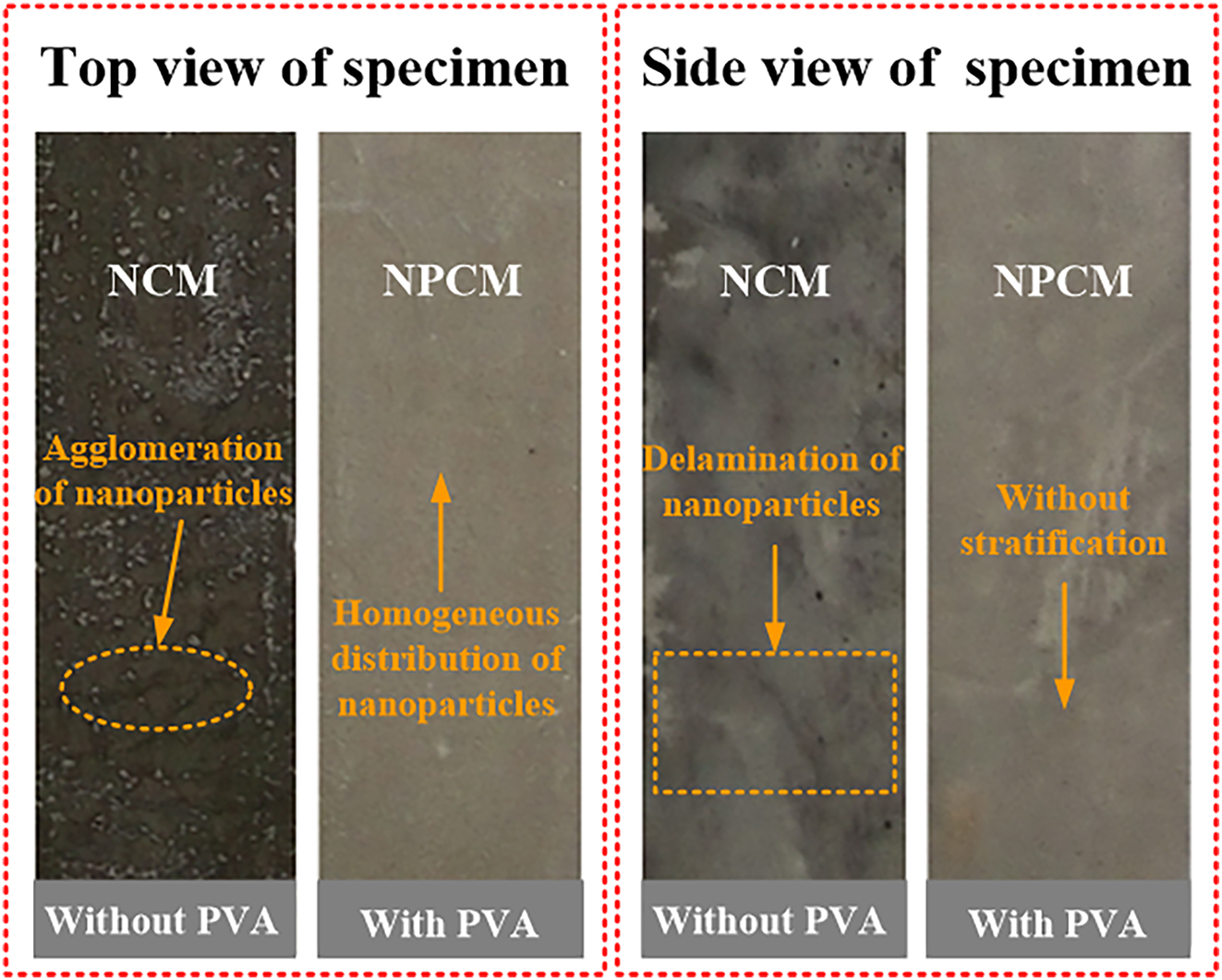

Figure 7 shows the typical macroscopic morphologies of the NCM and NPCM samples. Through comparison of these morphological features, the influence of PVA doping on the distribution and dispersion stability of NCB particles within cement mortar can be elucidated. In the sample with NCB alone (NCM), black particle aggregates were observed on the molded surface (top view), while nanoparticle delamination appeared on the side view. These observations suggest inadequate bonding between NCB and the cement matrix, leading to partial suspension and segregation of nanoparticles during vibration and molding. In contrast, both top and side views of the NPCM samples exhibited a uniform grey–green colour, corresponding to the inherent colour of cement mortar. This indicates that the addition of PVA improves the adhesion between NCB and cement, thereby promoting a homogeneous dispersion of nanoparticles throughout the matrix.

Representative macroscopic morphology of NCM and NPCM samples.

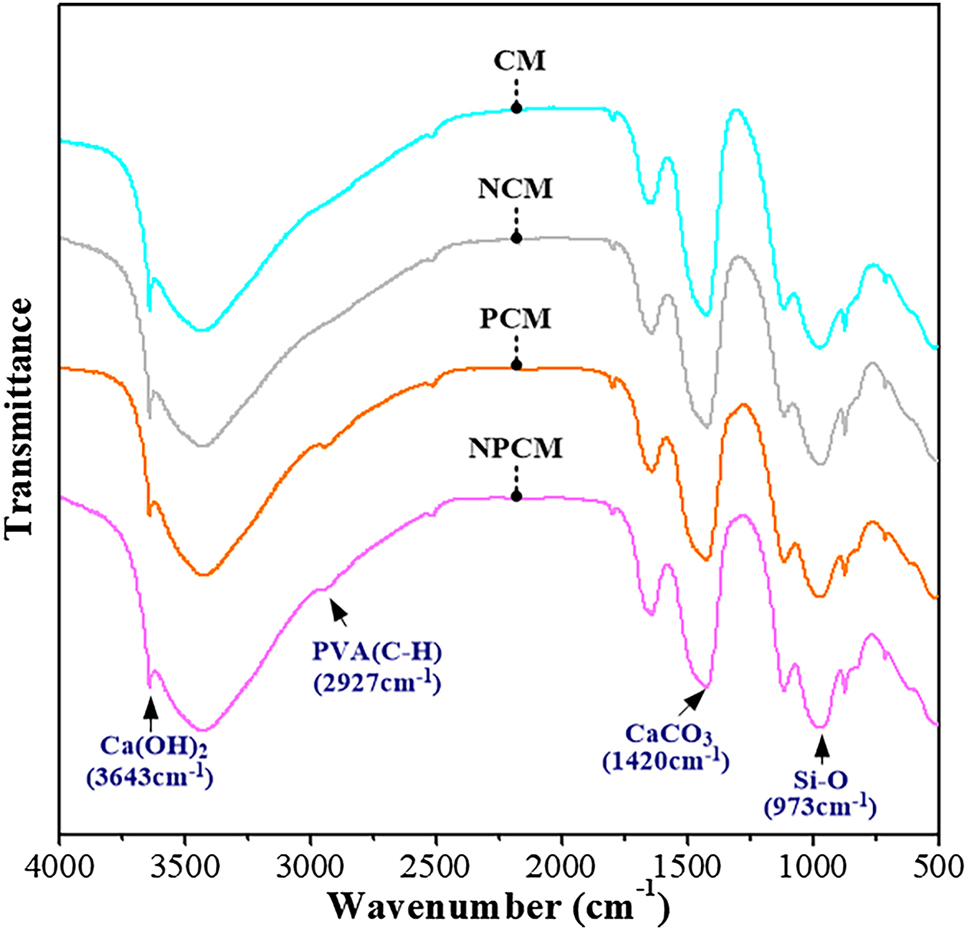

The effect of NCB and PVA incorporation on the hydration products of the cement paste and the formation of new chemical interactions were elucidated from the FTIR spectra of the CM, NCM, PCM and NPCM samples (see Figure 8). The FTIR patterns of the CM sample present characteristic peaks at 3,643, 3,440, 1,420, 973 cm−1 corresponding to –OH vibrations of Ca(OH)2, vibrations of bound water in the hydration products, vibrations of CaCO3 and asymmetric stretching vibrations of Si–O, respectively, as reported in previous studies [46], 47]. The positions and intensities of the absorption peaks in the FTIR spectrum of the NCM sample are almost unchanged from those of the CM, suggesting that 0.5 wt% NCB exerts no noticeable chemical effect on the cement matrix. In the FTIR spectrum of PCM with the polymer additive, a new characteristic peak appears at 2,927 cm−1, which is attributed to the shift of the C–H stretching peaks of PVA (2,920 cm−1; see Figure 4(b)) towards the long-wave direction. Further, the intensities of the characteristic peaks at 3,643 is reduced in the PCM sample, indicating that PVA is chemically bonded to Ca(OH)2 in the matrix, as reported by Kim et al. [48]. Although the positions of the FTIR absorption peaks in NPCM and PCM are nearly the same, the intensity of the 2,927 cm−1 peak is reduced in the FTIR spectrum of NPCM because of the interaction between NCB and PVA.

FTIR spectra of different cement mortars.

3.4 Piezoresistive properties of NCB/PVA-modified cement mortar

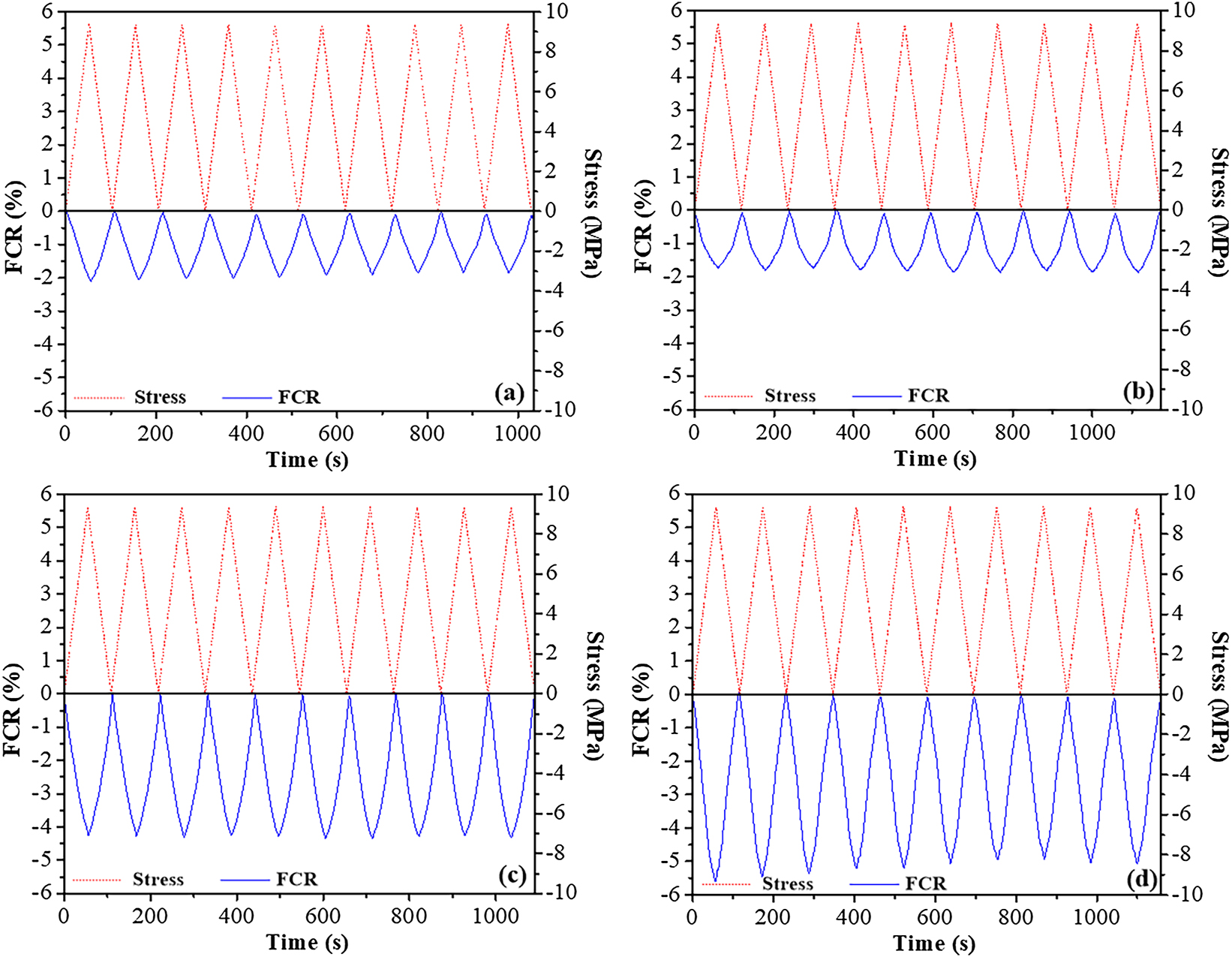

Figure 9 depicts the piezoresistive characteristics of the CM, PCM, NCM and NPCM samples during cyclic compression under 15 kN (9.375 MPa). The samples in all four groups exhibited stable and regular piezoresistive responses. In each loading cycle, the FCR of the cement mortars monotonically decreased and increased as the stress increased and decreased, respectively, implying that the resistivity change in all samples was reversible under cyclic compressive loading. The FCR curves of the CM and NCM samples exhibit slight hysteresis, although these samples were energised without loading for approximately 1,000 s prior to testing. This hysteresis may be related to the polarisation effect in cement-based sensors, as reported by Han et al. [49]. The piezoresistive curves of the cement-based sensors in all four groups are generally linear, but the FCR values vary considerably. Considering the piezoresistive sensitivity, the FCR of the reference sample, without NCB and PVA, reached a peak at approximately 2 % under a cyclic 15-kN compressive load. The addition of PVA, a typical insulating material, had little impact on the FCR value of the cement mortar. In contrast, incorporating 0.5 wt% NCB particles approximately doubled the piezoresistive sensitivity of the cement mortar under the same compressive load. This increase can be attributed to the ability of NCB particles to connect with each other and create a more extensive conductive network under external forces [21]. Specifically, when subjected to compressive loading, the distance between adjacent NCB particles is reduced, facilitating the establishment of a greater number of conductive pathways. This phenomenon improves electron transport and lowers the electrical resistance of the composite. During the unloading process, the increased particle spacing disrupts these paths, allowing the resistance to return to its original state and resulting in a reversible piezoresistive response. However, the number of conductive pathways constructed in the matrix is limited because some of spherical NCB nanoparticles agglomerate (see Figure 10(a)). NPCM delivered the highest piezoresistive response among the four groups of cement mortar sensors. The FCR of NPCM peaked at nearly 5 % under cyclic compressive loading. The complex addition of PVA and NCB enhances the piezoresistive properties of cement mortar via two mechanisms. First, PVA envelops the surface of the conductive filler, increasing the spatial spacing between the NCB particles. This weakens their van der Waals forces and improves the uniformity of the distribution. Second, with the addition of PVA, a large part of the conductive filler adhered onto the surface the polymer films and formed NCB/PVA grape-bunch structures rather than aggregated in the cement matrix. These grape-bunch structures possess a high aspect ratio, which increases the number of effective conductive contacts under external forces, thus enhancing the piezoresistive properties of the cement mortar (Figure 10(b)).

Piezoresistive responses of CM (a), PCM (b), NCM (c) and NPCM (d) under cyclic compression.

Schematic of the construction process of conducting pathways inside NCM (a) and NPCM (b) under external force.

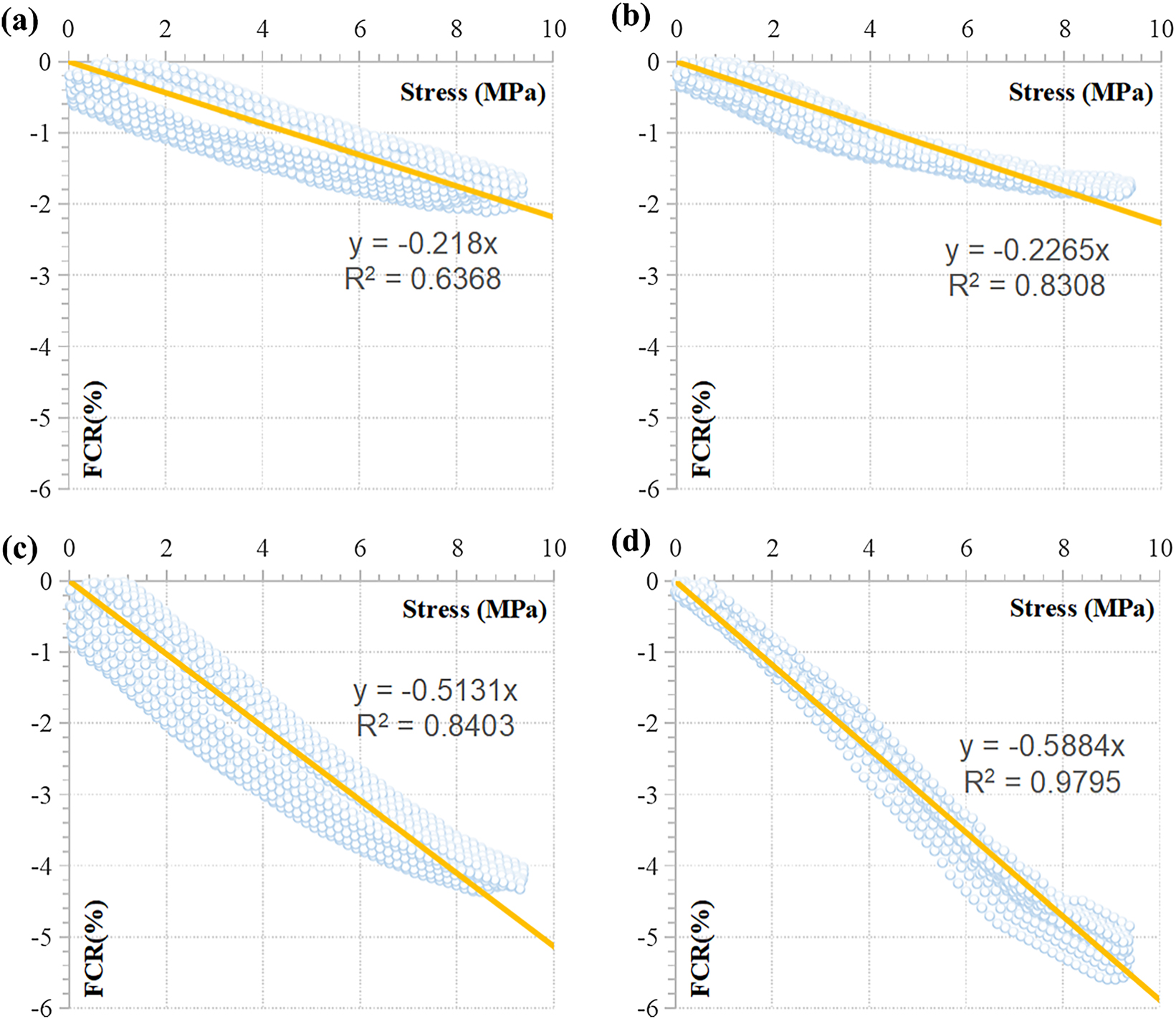

Figure 11 shows the relationship between the FCR and cyclic compressive stress of the cement mortar sensors. The FCR values of all samples were linearly correlated with compressive stress, but the slopes and coefficients of determination (R 2) of the fitted straight lines varied considerably. The slope of the FCR versus compressive stress plot reflects the piezoresistive response sensitivity of a cementitious material sensor [50]. The slopes of the FCR–stress plots of the PCM and reference (CM) samples were very similar, indicating that addition 0.6 wt % PVA alone has little effect on the stress sensitivity of the cement mortar sensors. The considerable dispersion in the plot of the CM sample (R 2 = 0.6368) might be explained by FCR hysteresis arising from polarisation effects [49]. The NCM samples yielded high slopes, indicating that NCB effectively enhances the stress sensitivity of the cement mortar sensor; however, the comparatively low R 2 (0.8403) indicates an unsatisfactory fitting result. The NPCM sample achieved the highest slope among the samples (170 % higher than the CM and 15 % higher than the NCM). The fitting result of the NPCM sample also maximised the coefficient of determination (R 2 = 0.9795, indicates that FCR has a significant correspondence with compressive stress [51], 52]). The above results indicate that the NPCM sensor has high stability and repeatability in addition to excellent stress sensitivity.

Relationship between FCR and cyclic compressive stress: CM (a), PCM (b), NCM (c) and NPCM (d).

Table 3 statistically summarises the mechanical properties and stress sensitivity results obtained in this study and in previous studies on cement-based materials containing NCB. The average stress sensitivity of the cement mortar sensor doped with 0.5 wt% NCB (NCM) was 4.3 × 10−3/MPa, which is similar to that of previous studies [53], 54]. In addition, the compressive and flexural strengths of NCM were 26 % and 35 % higher, respectively, than those of the CM, and these results are similar to the trend of previous studies [18], 55]. The introduction of PVA significantly enhanced the dispersion homogeneity and spatial distribution of NCB particles within the cement matrix. This optimized microstructure promoted the formation of conductive pathways under load, leading to the superior piezoresistive performance. As a result, the cement mortar containing 0.6 wt% PVA and 0.5 wt% NCB (NPCM) achieved a stress sensitivity of 5.2 × 10−3/MPa, which is 21 % higher than that of NCM. Furthermore, the compressive and flexural strengths of NPCM were increased by an encouraging 24 % and 25 %, respectively, from those of NCM. By comparing the gain results of this study with those of previous works listed in Table 3, it can be demonstrated that the use of PVA as a reinforcing agent in NCB-cementitious materials is highly effective, showing significant advantages in improving both mechanical and self-sensing properties.

Comparison of the present and previous studies on the mechanical properties and stress sensitivity of cement-based materials with NCB.

| Ref. | Conductive filler | Content (%) | Compressive strength | Flexural strength | Stress sensitivity (10−3/MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This study | NCB | 0.5 wt | 26 % ↑ | 35 % ↑ | 4.3 |

| NCB (PVA) | 0.5 (0.6) wt | 24 % ↑↑ | 25 % ↑↑ | 5.2 | |

| Lima et al. [18] | NCB | 1.5 wt | 23 % ↑ | 23 % ↑ | – |

| Monteiro et al. [24] | NCB | 7 wt | 11 % ↑ | – | 2.9 |

| Dong et al. [53] | NCB | 0.5 wt | – | – | 4.0 |

| NCB (PP fibres) | 0.5 (0.4) wt | 6 % ↓↓ | 20 % ↑↑ | 16 | |

| Liu et al. [54] | NCB | 1 wt | – | – | 4.4 |

| NCB (NiNF) | 1 (0.5) wt | 4 % ↑↑ | – | 4.9 | |

| Dehghanpour et al. [55] | RNCB | 10 vol | 18 % ↑ | 29 % ↑ | – |

| RNCB (CF & SF) |

10 vol (1 vol & 2 wt) |

19 % ↑↑ | 45 % ↑↑ | – |

-

RNCB represents recycled nano carbon black, CF represents carbon fiber, SF represents steel fiber, ↑ (increase) represents strength changes caused by the addition of NCB alone, ↑↑(increase) & ↓↓ (decrease) represents strength changes caused by the addition of NCB and other admixtures versus NCB alone.

3.5 Cost-benefit analysis of NCB/PVA-modified cement mortar

Cost effectiveness is a key factor that must be considered for the application of new materials. In this study, the total manufacturing cost of different cement mortar was calculated on the basis of specific unit price (as shown in Table 4, these data come from our expenditures on purchasing raw materials from Chinese distributors at retail prices) and usage of each raw material. Furthermore, following the calculation method employed in reference [56], the total manufacturing cost of each group of specimens was divided by their corresponding compressive strength and flexural strength, serving as the primary metric for evaluating the cost-benefit of their mechanical properties (cost per MPa). The manufacturing cost and cost-benefit for all mixtures are presented in Figure 12. It can be clearly observed that adding 0.5 wt% NCB increases the total cost per cubic meter of cement mortar by approximately 1,520 CNY. In contrast, the use of PVA has a minimal impact on the overall manufacturing cost of the composite, as its unit price is less than 1/20 of that of NCB. It should be noted that neither the individual use of PVA nor the combined incorporation of PVA and NCB significantly affects the cost-benefit of the compressive and flexural strengths of the composite, as their addition contributes to enhancing the mechanical properties of the cement mortar. However, the stress sensitivity of cement mortar containing only PVA (PCM) is insufficient to meet engineering requirements. Therefore, NPCM can be regarded as the optimal combination that achieves a balance among excellent mechanical properties, sensing performance, and manufacturing cost.

Cost of raw materials.

| Materials | Cement | Sand | Water | Defoamer | NCB | PVA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost (CNY/kg) | 0.9 | 1.46 | 0.0035 | 2.96 | 400 | 13.32 |

Cost and cost-benefit of different cement mortars.

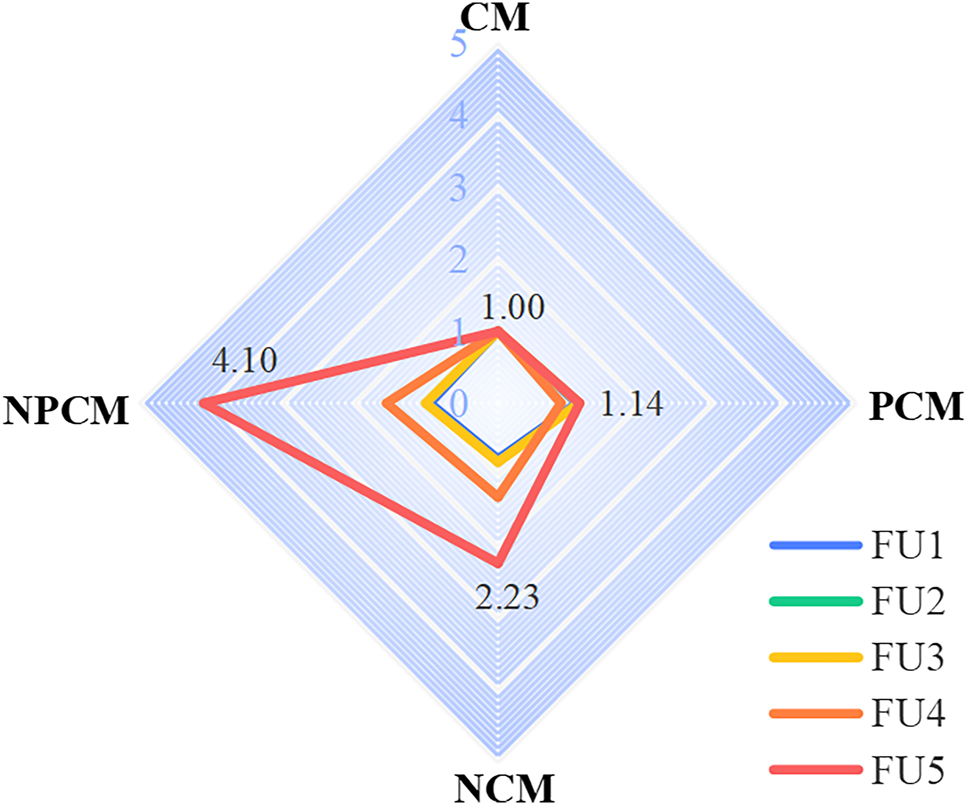

In order to fully analyse the contribution of mechanical properties and piezoresistive effect to the economics, the following functional units (FU) were chosen to compare the economic indices of all mixtures included in this study according to the methodology reported in the literature [56], 57].

where C 1 refers to the cost of CM, C i refers to the cost of the remaining group, CS 1 refers to the compressive strength of CM, CS i refers to the compressive strength of the remaining group, FS 1 refers to the flexural strength of CM, and FS i refers to the flexural strength of the remaining group, and SS 1 refers to the stress sensitivity of CM, SS i refers to the stress sensitivity of the remaining group. Figure 13 presents the FU calculation results for each group in this study. The NPCM exhibits the highest comprehensive economic index (FU5), with a value 4.1 times that of the reference and 1.8 times that of the NCM. The above results indicate that the combined use of PVA and NCB as modifiers to develop cement mortar sensors for structural health monitoring is an economically feasible strategy.

Economic indices for different cement mortars.

4 Conclusions

This study reports a method to improve the mechanical and self-sensing properties of NCB-cement mortar by incorporating PVA. The effects of PVA on the physicochemical properties, self-sensing behavior, and microstructure of NCB-cement mortar were systematically investigated, along with a detailed cost-benefit analysis. The main conclusions are as follows:

The addition of PVA improved the dispersion uniformity of NCB within the cement matrix, forming a unique “grape-bunch” NCB/PVA structure. This microstructure created effective load-transfer pathways, thereby enhancing the mechanical properties of the cement mortar. With 0.6 wt% PVA and 0.5 wt% NCB, the compressive and flexural strengths increased by 24 % and 25 %, respectively, compared to the sample with NCB alone.

Owing to the uniform distribution of NCB particles along the PVA film that creates richer electron transport paths under external loading, the cement mortar sensor incorporating both PVA and NCB exhibits a 21 % increase in stress sensitivity, better repeatability, and improved linearity over the sample using NCB alone.

Cost-benefit analysis indicates that the combined use of PVA and NCB offers an economical and effective strategy for developing high-performance cement-based sensors for structural health monitoring.

It should be noted that polymer materials generally exhibit poor aging resistance, which may limit the engineering application of NCB/PVA modified cement mortar. Therefore, future research should focus on evaluating its long-term performance.

-

Funding information: The authors thank the projects supported from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 5257084018 and 52178209), Science and Technology Innovation Program from Water Resources of Guangdong Provincethe (2025-02), Guangdong-Hong Kong Technology Cooperation Funding Scheme (2025A0505080020) and Scientific Research Project of Guangzhou Education Bureau (202431218).

-

Author contribution: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

1. Han, B, Yu, X, Kwon, E. A self-sensing carbon nanotube/cement composite for traffic monitoring. Nanotechnology 2009;20:445501. https://doi.org/10.1088/0957-4484/20/44/445501.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Liu, Q, Gao, R, Tam, WV, Li, W, Xiao, J. Strain monitoring for a bending concrete beam by using piezoresistive cement-based sensors. Constr Build Mater 2018;167:338–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.02.048.Search in Google Scholar

3. Wang, H, Gao, X, Wang, R. The influence of rheological parameters of cement paste on the dispersion of carbon nanofibers and self-sensing performance. Constr Build Mater 2017;134:673–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.12.176.Search in Google Scholar

4. Han, B, Yu, X, Ou, J. Self-sensing concrete in smart structures. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2014.10.1016/B978-0-12-800517-0.00001-0Search in Google Scholar

5. Ding, S, Wang, X, Qiu, L, Ni, Y, Dong, S, Cui, Y, et al.. Self-sensing cementitious composites with hierarchical carbon fiber-carbon nanotube composite fillers for crack development monitoring of a maglev girder. Small 2022;19:2206258. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202206258.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Li, G, Wang, P, Zhao, X. Pressure-sensitive properties and microstructure of carbon nanotube reinforced cement composites. Cem Concr Compos 2007;29:377–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2006.12.011.Search in Google Scholar

7. Alvi, I, Li, Q, Hou, Y, Onyekwena, C, Zhang, M, Ghaffar, A. A critical review of cement composites containing recycled aggregates with graphene oxide nanomaterials. J Build Eng 2023;69:105989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.105989.Search in Google Scholar

8. Zhou, Z, Xie, N, Cheng, X, Feng, L, Hou, P, Huang, S, et al.. Electrical properties of low dosage carbon nanofiber/cement composite: percolation behavior and polarization effect. Cem Concr Compos 2020;109:103539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2020.103539.Search in Google Scholar

9. Gwon, S, Kim, H, Shin, M. Self-heating characteristics of electrically conductive cement composites with carbon black and carbon fiber. Cem Concr Compos 2023;137:104942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2023.104942.Search in Google Scholar

10. Monteiro, A, Cachim, B, Costa, P. Electrical properties of cement-based composites containing carbon black particles. Mater Today Proc 2015;2:193–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2015.04.021.Search in Google Scholar

11. Xu, S, Wang, X, Li, Q. Research on the electromagnetic wave absorbing properties of carbon nanotube-fiber reinforced cementitious composite. Compos Struct 2021;274:114377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2021.114377.Search in Google Scholar

12. Ma, C, Xie, S, Wu, Z, Si, T, Wu, J, Ji, Z, et al.. Research and simulation of three-layered lightweight cement-based electromagnetic wave absorbing composite containing expanded polystyrene and carbon black. Constr Build Mater 2023;293:132047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132047.Search in Google Scholar

13. Nalon, G, Ribeiro, J, Araújo, E, Pedroti, L, Franco de, C, Santos, RF, et al.. Effects of post-fire curing on the mechanical properties of cement composites containing carbon black nanoparticles and multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Constr Build Mater 2021;310:125118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.125118.Search in Google Scholar

14. Abolhasani, A, Pachenari, A, Razavian, S, Mahdi, A. Towards new generation of electrode-free conductive cement composites utilizing nano carbon black. Constr Build Mater 2022;323:126576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.126576.Search in Google Scholar

15. Dong, W, Li, W, Lu, N, Qu, F, Vessalas, K, Sheng, D. Piezoresistive behaviours of cement-based sensor with carbon black subjected to various temperature and water content. Composites Part B 2019;178:107488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2019.107488.Search in Google Scholar

16. Xiao, Q, Cai, Y, Long, G, Ma, K, Zeng, X, Tang, Z, et al.. Effect of alternating current curing on properties of carbon black-cement conductive composite: setting, hydration and microstructure. J Build Eng 2023;72:106603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.106603.Search in Google Scholar

17. Zhang, Q, Luan, C, Huang, Y, Zhou, Z. Mechanisms of carbon black in multifunctional cement matrix: hydration and microstructure perspectives. Constr Build Mater 2022;346:128455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.128455.Search in Google Scholar

18. Lima, G, Nalon, G, Santos, R, Ribeiro, J, Carvalho, J, Pedroti, L, et al.. Microstructural investigation of the effects of carbon black nanoparticles on hydration mechanisms, mechanical and piezoresistive properties of cement mortars. Mater Res 2021;24:e20200539. https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-5373-mr-2020-0539.Search in Google Scholar

19. Li, H, Xiao, H, Ou, J. Effect of compressive strain on electrical resistivity of carbon black-filled cement-based composites. Cem Concr Compos 2006;28:824–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2006.05.004.Search in Google Scholar

20. Monteiro, A, Loredo, A, Costa, P, Oeser, M, Cachim, P. A pressure-sensitive carbon black cement composite for traffic monitoring. Constr Build Mater 2017;154:1079–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.08.053.Search in Google Scholar

21. Nalon, G, José, C, Eduardo, N, Leonardo, G, José, M, Santos, RF, et al.. Effects of different kinds of carbon black nanoparticles on the piezoresistive and mechanical properties of cement-based composites. J Build Eng 2020;32:101724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101724.Search in Google Scholar

22. Dong, W, Li, W, Luo, Z, Long, G, Vessalas, K, Sheng, D. Structural response monitoring of concrete beam under flexural loading using smart carbon black/cement-based sensors. Smart Mater Struct 2020;29:065001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-665x/ab7fef.Search in Google Scholar

23. Sobolkina, A, Mechtcherine, V, Khavrus, V, Maier, D, Mende, M, Ritschel, M, et al.. Dispersion of carbon nanotubes and its influence on the mechanical properties of the cement matrix. Cem Concr Compos 2012;34:1104–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2012.07.008.Search in Google Scholar

24. Monteiro, A, Cachim, P, Costa, P. Self-sensing piezoresistive cement composite loaded with carbon black particles. Cem Concr Compos 2017;81:59–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2017.04.009.Search in Google Scholar

25. Fan, J, Li, G, Deng, S, Wang, Z. Mechanical properties and microstructure of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) modified cement mortar. Appl Sci 2019;9:2178. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9112178.Search in Google Scholar

26. Li, G, Wang, L, Yu, J, Yi, B, He, C, Wang, Z, et al.. Mechanical properties and material characterization of cement mortar incorporating CNT-engineered polyvinyl alcohol latex. Constr Build Mater 2022;345:128320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.128320.Search in Google Scholar

27. Pei, C, Zhou, X, Zhu, J, Su, M, Wang, Y, Xing, F. Synergistic effects of a novel method of preparing graphene/polyvinyl alcohol to modify cementitious material. Constr Build Mater 2020;258:119647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.119647.Search in Google Scholar

28. Bhat, N, Nate, M, Kurup, M, Bambole, V, Sabharwal, S. Effect of γ-radiation on the structure and morphology of polyvinyl alcohol films. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res 2005;237:585–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2005.04.058.Search in Google Scholar

29. Ramesan, T, Sankar, S, Kalladi, J, Abdulla, A, Bahuleyan, B. Hydroxyapatite nanoparticles reinforced polyvinyl alcohol/chitosan blend for optical and energy storage applications. Polym Eng Sci 2024;64:1378–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/pen.26623.Search in Google Scholar

30. Ramesan, T, George, A, Jayakrishnan, P, Gopalannair, K. Role of pumice particles in the thermal, electrical and mechanical properties of poly(vinyl alcohol)/poly(vinyl pyrrolidone) composites. J Therm Anal Calorim 2016;126:511–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-016-5507-6.Search in Google Scholar

31. Zunaira, N, Ezzatollah, S, Kwesi, S, Duan, W. Antifoaming effect of graphene oxide nanosheets in polymer-modified cement composites for enhanced microstructure and mechanical performance. Cem Concr Res 2022;158:106843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2022.106843.Search in Google Scholar

32. Alghunaim, SN. Optimization and spectroscopic studies on carbon nanotubes/PVA nanocomposites. Results Phys 2016;6:456–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rinp.2016.08.002.Search in Google Scholar

33. Raeisi, N, Moheb, A, Arani, MN, Sadeghi, M. Non-covalently-functionalized CNTs incorporating poly(vinyl alcohol) mixed matrix membranes for pervaporation separation of water-isopropanol mixtures. Chem Eng Res Des 2021;167:157–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cherd.2021.01.004.Search in Google Scholar

34. Kashyap, S, Pratihar, S, Behera, S. Strong and ductile graphene oxide reinforced PVA nanocomposites. J Alloys Compd 2016;684:254–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2016.05.162.Search in Google Scholar

35. Ramesan, M, Jayan, S, Kalladi, J, Meera, K, Sunojkumar, P. Green blend nanocomposites developed from waste sericin, polyvinyl alcohol and boehmite for flexible electronic devices. Ceram Int 2024;50:36570–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2024.07.043.Search in Google Scholar

36. Kalladi, J, Ramesan, T. Green‐synthesized zinc oxide/polyvinyl alcohol/cashew gum/polypyrrole nanocomposites with enhanced mechanical, thermal, and electrical properties for nanoelectronics. J Appl Polym Sci 2025;142:e56686–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.56686.Search in Google Scholar

37. Meera, K, Ramesan, T. Performance of boehmite nanoparticles reinforced carboxymethyl chitosan/polyvinyl alcohol blend nanocomposites tailored through green synthesis. J Polym Environ 2022;31:447–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10924-022-02649-1.Search in Google Scholar

38. Fan, J, Deng, S, Li, G, Li, J, Zhang, J. Synergistic effect of carbon nanotubes and polyvinyl alcohol on the mechanical performance and microstructure of cement mortar. Nanotechnol Rev 2024;13:20240028. https://doi.org/10.1515/ntrev-2024-0028.Search in Google Scholar

39. Pawlyta, M, Rouzaud, J, Duber, S. Raman microspectroscopy characterization of carbon blacks: spectral analysis and structural information. Carbon 2015;84:479–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2014.12.030.Search in Google Scholar

40. Li, H, Chen, H, Xu, W, Yuan, F, Wang, J, Wang, M. Polymer-encapsulated hydrophilic carbon black nanoparticles free from aggregation. Colloids Surf A 2010;24:715–17.10.1002/marc.200350017Search in Google Scholar

41. Dong, S, Yan, J, Xu, N, Xu, J, Wang, H. Molecular dynamics simulation on surface modification of carbon black with polyvinyl alcohol. Surf Sci 2011;605:868–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susc.2011.01.021.Search in Google Scholar

42. Knapen, E, Van Gemert, D. Polymer film formation in cement mortars modified with water-soluble polymers. Cem Concr Compos 2015;58:23–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2014.11.015.Search in Google Scholar

43. Knapen, E, Van Gemert, D. Effect of under water storage on bridge formation by water-soluble polymers in cement mortars. Constr Build Mater 2009;23:3420–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2009.06.007.Search in Google Scholar

44. Singh, N, Rai, S. Effect of polyvinyl alcohol on the hydration of cement with rice husk ash. Cem Concr Res 2001;31:239–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0008-8846(00)00475-0.Search in Google Scholar

45. Cao, D, Gu, Y, Jiang, L, Jin, W, Lyu, K, Guo, M. Effect of polyvinyl alcohol on the performance of carbon fixation foam concrete. Constr Build Mater 2023;390:131775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.131775.Search in Google Scholar

46. Bahari, A, Sadeghi-Nik, A, Roodbari, M, Sadeghi-Nik, A, Mirshafiei, E. Experimental and theoretical studies of ordinary Portland cement composites contains nano LSCO perovskite with Fokker-Planck and chemical reaction equations. Constr Build Mater 2018;163:247–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.12.073.Search in Google Scholar

47. Ali, M, Aref, S, Ali, B, Congrui, J, Ramadan, A, Togay, O, et al.. Strength optimization of cementitious composites reinforced by carbon nanotubes and titania nanoparticles. Constr Build Mater 2021;303:124510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.124510.Search in Google Scholar

48. Kim, J, Robertson, R. Effects of polyvinyl alcohol on aggregate-paste bond strength and the interfacial transition zone-structure, properties and materials. Adv Cem Base Mater 1998;8:66–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1065-7355(98)00009-1.Search in Google Scholar

49. Han, B, Yu, X, Zhang, K, Kwon, E, Ou, J. Sensing properties of CNT filled cement-based stress sensors. J Civil Struct Health Monit 2011;1:17–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13349-010-0001-5.Search in Google Scholar

50. Yoo, D, You, I, Zi, G, Lee, S. Effects of carbon nanomaterial type and amount on self-sensing capacity of cement paste. Measurement 2019;134:750–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2018.11.024.Search in Google Scholar

51. Deng, S, Fan, J, Li, G, Zhang, M, Li, M. Influence of styrene-acrylic emulsion additions on the electrical and self-sensing properties of CNT cementitious composites. Constr Build Mater 2023;403:133172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.133172.Search in Google Scholar

52. Kaya, M, Yıldırım, Z, Köksal, F, Beycioglu, A, Kasprzyk, l. Evaluation and multi-objective optimization of lightweight mortars parameters at elevated temperature via Box-Behnken optimization approach. Materials 2021;14:7405. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14237405.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

53. Dong, W, Li, W, Wang, K, Guo, Y, Sheng, D, Shah, SP. Piezoresistivity enhancement of functional carbon black filled cement-based sensor using polypropylene fibre. Powder Technol 2020;373:184–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2020.06.029.Search in Google Scholar

54. Liu, L, Xu, J, Yin, T, Wang, Y, Chu, H. Improving electrical and piezoresistive properties of cement-based composites by combined addition of nano carbon black and nickel nanofiber. J Build Eng 2022;51:104312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104312.Search in Google Scholar

55. Dehghanpour, H, Yilmaz, K, Ipek, M. Evaluation of recycled nano carbon black and waste erosion wires in electrically conductive concretes. Constr Build Mater 2019;221:109–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.06.025.Search in Google Scholar

56. Fan, J, Deng, S, Li, G, Li, J, Zhang, J. Eco-friendly, high-toughness gypsum prepared using hemihydrate phosphogypsum, fly ash, and glass fibers: characterization and environmental impacts. Case Stud Constr Mater 2024;20:e03257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2024.e03257.Search in Google Scholar

57. Deng, S, Fan, J, Yi, B, Ye, J, Li, G. Effect of industrial multi-walled carbon nanotubes on the mechanical properties and microstructure of ultra-high performance concrete. Cem Concr Compos 2025;156:105850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2024.105850.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- MHD radiative mixed convective flow of a sodium alginate-based hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated extending sheet with Joule heating

- Experimental study of mortar incorporating nano-magnetite on engineering performance and radiation shielding

- Multicriteria-based optimization and multi-variable non-linear regression analysis of concrete containing blends of nano date palm ash and eggshell powder as cementitious materials

- A promising Ag2S/poly-2-amino-1-mercaptobenzene open-top spherical core–shell nanocomposite for optoelectronic devices: A one-pot technique

- Biogenic synthesized selenium nanoparticles combined chitosan nanoparticles controlled lung cancer growth via ROS generation and mitochondrial damage pathway

- Fabrication of PDMS nano-mold by deposition casting method

- Stimulus-responsive gradient hydrogel micro-actuators fabricated by two-photon polymerization-based 4D printing

- Physical aspects of radiative Carreau nanofluid flow with motile microorganisms movement under yield stress via oblique penetrable wedge

- Effect of polar functional groups on the hydrophobicity of carbon nanotubes-bacterial cellulose nanocomposite

- Review in green synthesis mechanisms, application, and future prospects for Garcinia mangostana L. (mangosteen)-derived nanoparticles

- Entropy generation and heat transfer in nonlinear Buoyancy–driven Darcy–Forchheimer hybrid nanofluids with activation energy

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ginkgo biloba seed extract: Evaluation of antioxidant, anticancer, antifungal, and antibacterial activities

- A numerical analysis of heat and mass transfer in water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing copper and alumina nanoparticles over an extending sheet

- Investigating the behaviour of electro-magneto-hydrodynamic Carreau nanofluid flow with slip effects over a stretching cylinder

- Electrospun thermoplastic polyurethane/nano-Ag-coated clear aligners for the inhibition of Streptococcus mutans and oral biofilm

- Investigation of the optoelectronic properties of a novel polypyrrole-multi-well carbon nanotubes/titanium oxide/aluminum oxide/p-silicon heterojunction

- Novel photothermal magnetic Janus membranes suitable for solar water desalination

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ageratum conyzoides for activated carbon compositing to prepare antimicrobial cotton fabric

- Activation energy and Coriolis force impact on three-dimensional dusty nanofluid flow containing gyrotactic microorganisms: Machine learning and numerical approach

- Machine learning analysis of thermo-bioconvection in a micropolar hybrid nanofluid-filled square cavity with oxytactic microorganisms

- Research and improvement of mechanical properties of cement nanocomposites for well cementing

- Thermal and stability analysis of silver–water nanofluid flow over unsteady stretching sheet under the influence of heat generation/absorption at the boundary

- Cobalt iron oxide-infused silicone nanocomposites: Magnetoactive materials for remote actuation and sensing

- Magnesium-reinforced PMMA composite scaffolds: Synthesis, characterization, and 3D printing via stereolithography

- Bayesian inference-based physics-informed neural network for performance study of hybrid nanofluids

- Numerical simulation of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to a heterogeneous/homogeneous chemical reaction over a Riga surface

- Enhancing the superhydrophobicity, UV-resistance, and antifungal properties of natural wood surfaces via in situ formation of ZnO, TiO2, and SiO2 particles

- Synthesis and electrochemical characterization of iron oxide/poly(2-methylaniline) nanohybrids for supercapacitor application

- Impacts of double stratification on thermally radiative third-grade nanofluid flow on elongating cylinder with homogeneous/heterogeneous reactions by implementing machine learning approach

- Synthesis of Cu4O3 nanoparticles using pumpkin seed extract: Optimization, antimicrobial, and cytotoxicity studies

- Cationic charge influence on the magnetic response of the Fe3O4–[Me2+ 1−y Me3+ y (OH2)] y+(Co3 2−) y/2·mH2O hydrotalcite system

- Pressure sensing intelligent martial arts short soldier combat protection system based on conjugated polymer nanocomposite materials

- Magnetohydrodynamics heat transfer rate under inclined buoyancy force for nano and dusty fluids: Response surface optimization for the thermal transport

- Fly ash and nano-graphene enhanced stabilization of engine oil-contaminated soils

- Enhancing natural fiber-reinforced biopolymer composites with graphene nanoplatelets: Mechanical, morphological, and thermal properties

- Performance evaluation of dual-scale strengthened co-bonded single-lap joints using carbon nanotubes and Z-pins with ANN

- Computational works of blood flow with dust particles and partially ionized containing tiny particles on a moving wedge: Applications of nanotechnology

- Hybridization of biocomposites with oil palm cellulose nanofibrils/graphene nanoplatelets reinforcement in green epoxy: A study of physical, thermal, mechanical, and morphological properties

- Design and preparation of micro-nano dual-scale particle-reinforced Cu–Al–V alloy: Research on the aluminothermic reduction process

- Spectral quasi-linearization and response optimization on magnetohydrodynamic flow via stenosed artery with hybrid and ternary solid nanoparticles: Support vector machine learning

- Ferrite/curcumin hybrid nanocomposite formulation: Physicochemical characterization, anticancer activity, and apoptotic and cell cycle analyses in skin cancer cells

- Enhanced therapeutic efficacy of Tamoxifen against breast cancer using extra virgin olive oil-based nanoemulsion delivery system

- A titanium oxide- and silver-based hybrid nanofluid flow between two Riga walls that converge and diverge through a machine-learning approach

- Enhancing convective heat transfer mechanisms through the rheological analysis of Casson nanofluid flow towards a stagnation point over an electro-magnetized surface

- Intrinsic self-sensing cementitious composites with hybrid nanofillers exhibiting excellent piezoresistivity

- Research on mechanical properties and sulfate erosion resistance of nano-reinforced coal gangue based geopolymer concrete

- Impact of surface and configurational features of chemically synthesized chains of Ni nanostars on the magnetization reversal process

- Porous sponge-like AsOI/poly(2-aminobenzene-1-thiol) nanocomposite photocathode for hydrogen production from artificial and natural seawater

- Multifaceted insights into WO3 nanoparticle-coupled antibiotics to modulate resistance in enteric pathogens of Houbara bustard birds

- Synthesis of sericin-coated silver nanoparticles and their applications for the anti-bacterial finishing of cotton fabric

- Enhancing chloride resistance of freeze–thaw affected concrete through innovative nanomaterial–polymer hybrid cementitious coating

- Development and performance evaluation of green aluminium metal matrix composites reinforced with graphene nanopowder and marble dust

- Morphological, physical, thermal, and mechanical properties of carbon nanotubes reinforced arrowroot starch composites

- Influence of the graphene oxide nanosheet on tensile behavior and failure characteristics of the cement composites after high-temperature treatment

- Central composite design modeling in optimizing heat transfer rate in the dissipative and reactive dynamics of viscoplastic nanomaterials deploying Joule and heat generation aspects

- Double diffusion of nano-enhanced phase change materials in connected porous channels: A hybrid ISPH-XGBoost approach

- Synergistic impacts of Thompson–Troian slip, Stefan blowing, and nonuniform heat generation on Casson nanofluid dynamics through a porous medium

- Optimization of abrasive water jet machining parameters for basalt fiber/SiO2 nanofiller reinforced composites

- Enhancing aesthetic durability of Zisha teapots via TiO2 nanoparticle surface modification: A study on self-cleaning, antimicrobial, and mechanical properties

- Nanocellulose solution based on iron(iii) sodium tartrate complexes

- Combating multidrug-resistant infections: Gold nanoparticles–chitosan–papain-integrated dual-action nanoplatform for enhanced antibacterial activity

- Novel royal jelly-mediated green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and their multifunctional biological activities

- Direct bandgap transition for emission in GeSn nanowires

- Synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles with different morphologies using a microwave-based method and their antimicrobial activity

- Numerical investigation of convective heat and mass transfer in a trapezoidal cavity filled with ternary hybrid nanofluid and a central obstacle

- Halloysite nanotube enhanced polyurethane nanocomposites for advanced electroinsulating applications

- Low molar mass ionic liquid’s modified carbon nanotubes and its role in PVDF crystalline stress generation

- Green synthesis of polydopamine-functionalized silver nanoparticles conjugated with Ceftazidime: in silico and experimental approach for combating antibiotic-resistant bacteria and reducing toxicity

- Evaluating the influence of graphene nano powder inclusion on mechanical, vibrational and water absorption behaviour of ramie/abaca hybrid composites

- Dynamic-behavior of Casson-type hybrid nanofluids due to a stretching sheet under the coupled impacts of boundary slip and reaction-diffusion processes

- Influence of polyvinyl alcohol on the physicochemical and self-sensing properties of nano carbon black reinforced cement mortar

- Review Articles

- A comprehensive review on hybrid plasmonic waveguides: Structures, applications, challenges, and future perspectives

- Nanoparticles in low-temperature preservation of biological systems of animal origin

- Fluorescent sulfur quantum dots for environmental monitoring

- Nanoscience systematic review methodology standardization

- Nanotechnology revolutionizing osteosarcoma treatment: Advances in targeted kinase inhibitors

- AFM: An important enabling technology for 2D materials and devices

- Carbon and 2D nanomaterial smart hydrogels for therapeutic applications

- Principles, applications and future prospects in photodegradation systems

- Do gold nanoparticles consistently benefit crop plants under both non-stressed and abiotic stress conditions?

- An updated overview of nanoparticle-induced cardiovascular toxicity

- Arginine as a promising amino acid for functionalized nanosystems: Innovations, challenges, and future directions

- Advancements in the use of cancer nanovaccines: Comprehensive insights with focus on lung and colon cancer

- Membrane-based biomimetic delivery systems for glioblastoma multiforme therapy

- The drug delivery systems based on nanoparticles for spinal cord injury repair

- Green synthesis, biomedical effects, and future trends of Ag/ZnO bimetallic nanoparticles: An update

- Application of magnesium and its compounds in biomaterials for nerve injury repair

- Micro/nanomotors in biomedicine: Construction and applications

- Hydrothermal synthesis of biomass-derived CQDs: Advances and applications

- Research progress in 3D bioprinting of skin: Challenges and opportunities

- Review on bio-selenium nanoparticles: Synthesis, protocols, and applications in biomedical processes

- Gold nanocrystals and nanorods functionalized with protein and polymeric ligands for environmental, energy storage, and diagnostic applications: A review

- An in-depth analysis of rotational and non-rotational piezoelectric energy harvesting beams: A comprehensive review

- Advancements in perovskite/CIGS tandem solar cells: Material synergies, device configurations, and economic viability for sustainable energy

- Deep learning in-depth analysis of crystal graph convolutional neural networks: A new era in materials discovery and its applications

- Review of recent nano TiO2 film coating methods, assessment techniques, and key problems for scaleup

- Antioxidant quantum dots for spinal cord injuries: A review on advancing neuroprotection and regeneration in neurological disorders

- Rise of polycatecholamine ultrathin films: From synthesis to smart applications

- Advancing microencapsulation strategies for bioactive compounds: Enhancing stability, bioavailability, and controlled release in food applications

- Advances in the design and manipulation of self-assembling peptide and protein nanostructures for biomedical applications

- Photocatalytic pervious concrete systems: from classic photocatalysis to luminescent photocatalysis

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Synthesis and characterization of smart stimuli-responsive herbal drug-encapsulated nanoniosome particles for efficient treatment of breast cancer”

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part III

- Efficiency optimization of quantum dot photovoltaic cell by solar thermophotovoltaic system

- Exploring the diverse nanomaterials employed in dental prosthesis and implant techniques: An overview

- Electrochemical investigation of bismuth-doped anode materials for low‑temperature solid oxide fuel cells with boosted voltage using a DC-DC voltage converter

- Synthesis of HfSe2 and CuHfSe2 crystalline materials using the chemical vapor transport method and their applications in supercapacitor energy storage devices

- Special Issue on Green Nanotechnology and Nano-materials for Environment Sustainability

- Influence of nano-silica and nano-ferrite particles on mechanical and durability of sustainable concrete: A review

- Surfaces and interfaces analysis on different carboxymethylation reaction time of anionic cellulose nanoparticles derived from oil palm biomass

- Processing and effective utilization of lignocellulosic biomass: Nanocellulose, nanolignin, and nanoxylan for wastewater treatment

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Aging assessment of silicone rubber materials under corona discharge accompanied by humidity and UV radiation”

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- MHD radiative mixed convective flow of a sodium alginate-based hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated extending sheet with Joule heating

- Experimental study of mortar incorporating nano-magnetite on engineering performance and radiation shielding

- Multicriteria-based optimization and multi-variable non-linear regression analysis of concrete containing blends of nano date palm ash and eggshell powder as cementitious materials

- A promising Ag2S/poly-2-amino-1-mercaptobenzene open-top spherical core–shell nanocomposite for optoelectronic devices: A one-pot technique

- Biogenic synthesized selenium nanoparticles combined chitosan nanoparticles controlled lung cancer growth via ROS generation and mitochondrial damage pathway

- Fabrication of PDMS nano-mold by deposition casting method

- Stimulus-responsive gradient hydrogel micro-actuators fabricated by two-photon polymerization-based 4D printing

- Physical aspects of radiative Carreau nanofluid flow with motile microorganisms movement under yield stress via oblique penetrable wedge

- Effect of polar functional groups on the hydrophobicity of carbon nanotubes-bacterial cellulose nanocomposite

- Review in green synthesis mechanisms, application, and future prospects for Garcinia mangostana L. (mangosteen)-derived nanoparticles

- Entropy generation and heat transfer in nonlinear Buoyancy–driven Darcy–Forchheimer hybrid nanofluids with activation energy

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ginkgo biloba seed extract: Evaluation of antioxidant, anticancer, antifungal, and antibacterial activities

- A numerical analysis of heat and mass transfer in water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing copper and alumina nanoparticles over an extending sheet

- Investigating the behaviour of electro-magneto-hydrodynamic Carreau nanofluid flow with slip effects over a stretching cylinder

- Electrospun thermoplastic polyurethane/nano-Ag-coated clear aligners for the inhibition of Streptococcus mutans and oral biofilm

- Investigation of the optoelectronic properties of a novel polypyrrole-multi-well carbon nanotubes/titanium oxide/aluminum oxide/p-silicon heterojunction

- Novel photothermal magnetic Janus membranes suitable for solar water desalination

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ageratum conyzoides for activated carbon compositing to prepare antimicrobial cotton fabric

- Activation energy and Coriolis force impact on three-dimensional dusty nanofluid flow containing gyrotactic microorganisms: Machine learning and numerical approach

- Machine learning analysis of thermo-bioconvection in a micropolar hybrid nanofluid-filled square cavity with oxytactic microorganisms

- Research and improvement of mechanical properties of cement nanocomposites for well cementing

- Thermal and stability analysis of silver–water nanofluid flow over unsteady stretching sheet under the influence of heat generation/absorption at the boundary

- Cobalt iron oxide-infused silicone nanocomposites: Magnetoactive materials for remote actuation and sensing

- Magnesium-reinforced PMMA composite scaffolds: Synthesis, characterization, and 3D printing via stereolithography

- Bayesian inference-based physics-informed neural network for performance study of hybrid nanofluids

- Numerical simulation of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to a heterogeneous/homogeneous chemical reaction over a Riga surface

- Enhancing the superhydrophobicity, UV-resistance, and antifungal properties of natural wood surfaces via in situ formation of ZnO, TiO2, and SiO2 particles

- Synthesis and electrochemical characterization of iron oxide/poly(2-methylaniline) nanohybrids for supercapacitor application

- Impacts of double stratification on thermally radiative third-grade nanofluid flow on elongating cylinder with homogeneous/heterogeneous reactions by implementing machine learning approach

- Synthesis of Cu4O3 nanoparticles using pumpkin seed extract: Optimization, antimicrobial, and cytotoxicity studies

- Cationic charge influence on the magnetic response of the Fe3O4–[Me2+ 1−y Me3+ y (OH2)] y+(Co3 2−) y/2·mH2O hydrotalcite system

- Pressure sensing intelligent martial arts short soldier combat protection system based on conjugated polymer nanocomposite materials

- Magnetohydrodynamics heat transfer rate under inclined buoyancy force for nano and dusty fluids: Response surface optimization for the thermal transport

- Fly ash and nano-graphene enhanced stabilization of engine oil-contaminated soils

- Enhancing natural fiber-reinforced biopolymer composites with graphene nanoplatelets: Mechanical, morphological, and thermal properties

- Performance evaluation of dual-scale strengthened co-bonded single-lap joints using carbon nanotubes and Z-pins with ANN

- Computational works of blood flow with dust particles and partially ionized containing tiny particles on a moving wedge: Applications of nanotechnology

- Hybridization of biocomposites with oil palm cellulose nanofibrils/graphene nanoplatelets reinforcement in green epoxy: A study of physical, thermal, mechanical, and morphological properties

- Design and preparation of micro-nano dual-scale particle-reinforced Cu–Al–V alloy: Research on the aluminothermic reduction process

- Spectral quasi-linearization and response optimization on magnetohydrodynamic flow via stenosed artery with hybrid and ternary solid nanoparticles: Support vector machine learning

- Ferrite/curcumin hybrid nanocomposite formulation: Physicochemical characterization, anticancer activity, and apoptotic and cell cycle analyses in skin cancer cells

- Enhanced therapeutic efficacy of Tamoxifen against breast cancer using extra virgin olive oil-based nanoemulsion delivery system

- A titanium oxide- and silver-based hybrid nanofluid flow between two Riga walls that converge and diverge through a machine-learning approach

- Enhancing convective heat transfer mechanisms through the rheological analysis of Casson nanofluid flow towards a stagnation point over an electro-magnetized surface

- Intrinsic self-sensing cementitious composites with hybrid nanofillers exhibiting excellent piezoresistivity

- Research on mechanical properties and sulfate erosion resistance of nano-reinforced coal gangue based geopolymer concrete

- Impact of surface and configurational features of chemically synthesized chains of Ni nanostars on the magnetization reversal process

- Porous sponge-like AsOI/poly(2-aminobenzene-1-thiol) nanocomposite photocathode for hydrogen production from artificial and natural seawater

- Multifaceted insights into WO3 nanoparticle-coupled antibiotics to modulate resistance in enteric pathogens of Houbara bustard birds

- Synthesis of sericin-coated silver nanoparticles and their applications for the anti-bacterial finishing of cotton fabric

- Enhancing chloride resistance of freeze–thaw affected concrete through innovative nanomaterial–polymer hybrid cementitious coating

- Development and performance evaluation of green aluminium metal matrix composites reinforced with graphene nanopowder and marble dust

- Morphological, physical, thermal, and mechanical properties of carbon nanotubes reinforced arrowroot starch composites

- Influence of the graphene oxide nanosheet on tensile behavior and failure characteristics of the cement composites after high-temperature treatment

- Central composite design modeling in optimizing heat transfer rate in the dissipative and reactive dynamics of viscoplastic nanomaterials deploying Joule and heat generation aspects

- Double diffusion of nano-enhanced phase change materials in connected porous channels: A hybrid ISPH-XGBoost approach

- Synergistic impacts of Thompson–Troian slip, Stefan blowing, and nonuniform heat generation on Casson nanofluid dynamics through a porous medium

- Optimization of abrasive water jet machining parameters for basalt fiber/SiO2 nanofiller reinforced composites

- Enhancing aesthetic durability of Zisha teapots via TiO2 nanoparticle surface modification: A study on self-cleaning, antimicrobial, and mechanical properties

- Nanocellulose solution based on iron(iii) sodium tartrate complexes

- Combating multidrug-resistant infections: Gold nanoparticles–chitosan–papain-integrated dual-action nanoplatform for enhanced antibacterial activity

- Novel royal jelly-mediated green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and their multifunctional biological activities

- Direct bandgap transition for emission in GeSn nanowires

- Synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles with different morphologies using a microwave-based method and their antimicrobial activity

- Numerical investigation of convective heat and mass transfer in a trapezoidal cavity filled with ternary hybrid nanofluid and a central obstacle

- Halloysite nanotube enhanced polyurethane nanocomposites for advanced electroinsulating applications

- Low molar mass ionic liquid’s modified carbon nanotubes and its role in PVDF crystalline stress generation

- Green synthesis of polydopamine-functionalized silver nanoparticles conjugated with Ceftazidime: in silico and experimental approach for combating antibiotic-resistant bacteria and reducing toxicity

- Evaluating the influence of graphene nano powder inclusion on mechanical, vibrational and water absorption behaviour of ramie/abaca hybrid composites

- Dynamic-behavior of Casson-type hybrid nanofluids due to a stretching sheet under the coupled impacts of boundary slip and reaction-diffusion processes

- Influence of polyvinyl alcohol on the physicochemical and self-sensing properties of nano carbon black reinforced cement mortar

- Review Articles

- A comprehensive review on hybrid plasmonic waveguides: Structures, applications, challenges, and future perspectives

- Nanoparticles in low-temperature preservation of biological systems of animal origin

- Fluorescent sulfur quantum dots for environmental monitoring

- Nanoscience systematic review methodology standardization

- Nanotechnology revolutionizing osteosarcoma treatment: Advances in targeted kinase inhibitors

- AFM: An important enabling technology for 2D materials and devices

- Carbon and 2D nanomaterial smart hydrogels for therapeutic applications

- Principles, applications and future prospects in photodegradation systems

- Do gold nanoparticles consistently benefit crop plants under both non-stressed and abiotic stress conditions?

- An updated overview of nanoparticle-induced cardiovascular toxicity

- Arginine as a promising amino acid for functionalized nanosystems: Innovations, challenges, and future directions

- Advancements in the use of cancer nanovaccines: Comprehensive insights with focus on lung and colon cancer

- Membrane-based biomimetic delivery systems for glioblastoma multiforme therapy

- The drug delivery systems based on nanoparticles for spinal cord injury repair

- Green synthesis, biomedical effects, and future trends of Ag/ZnO bimetallic nanoparticles: An update