Abstract

Urban environmental pollution, stormwater runoff, and the urban heat island effect are challenges that are increasingly faced by cities. The impermeability of traditional concrete and its inability to effectively address pollution exacerbate these issues. Photocatalytic pervious concrete combines permeability with photocatalytic functionality to enable pollutant degradation while managing rainwater, thus providing a sustainable solution. In this paper, the research progress on photocatalytic pervious concrete is reviewed, with a focus on the mechanisms and limitations, including poor visible-light response and low stability, of classic photocatalysts such as TiO2, ZnO, and g-C3N4. The synergistic effects of adsorption and photocatalysis are explored, as well as the use of composite materials like carbon-based compounds and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) to enhance performance. Long-afterglow phosphors can extend photocatalytic activity beyond sunlight exposure, but challenges remain in terms of stability and cost-effectiveness. Despite progress, issues such as photocatalyst agglomeration, structural trade-offs, and durability still hinder large-scale applications. Future research should focus on visible-light responsive materials, optimized phosphors, self-healing technologies, and intelligent monitoring systems to improve durability.

1 Introduction

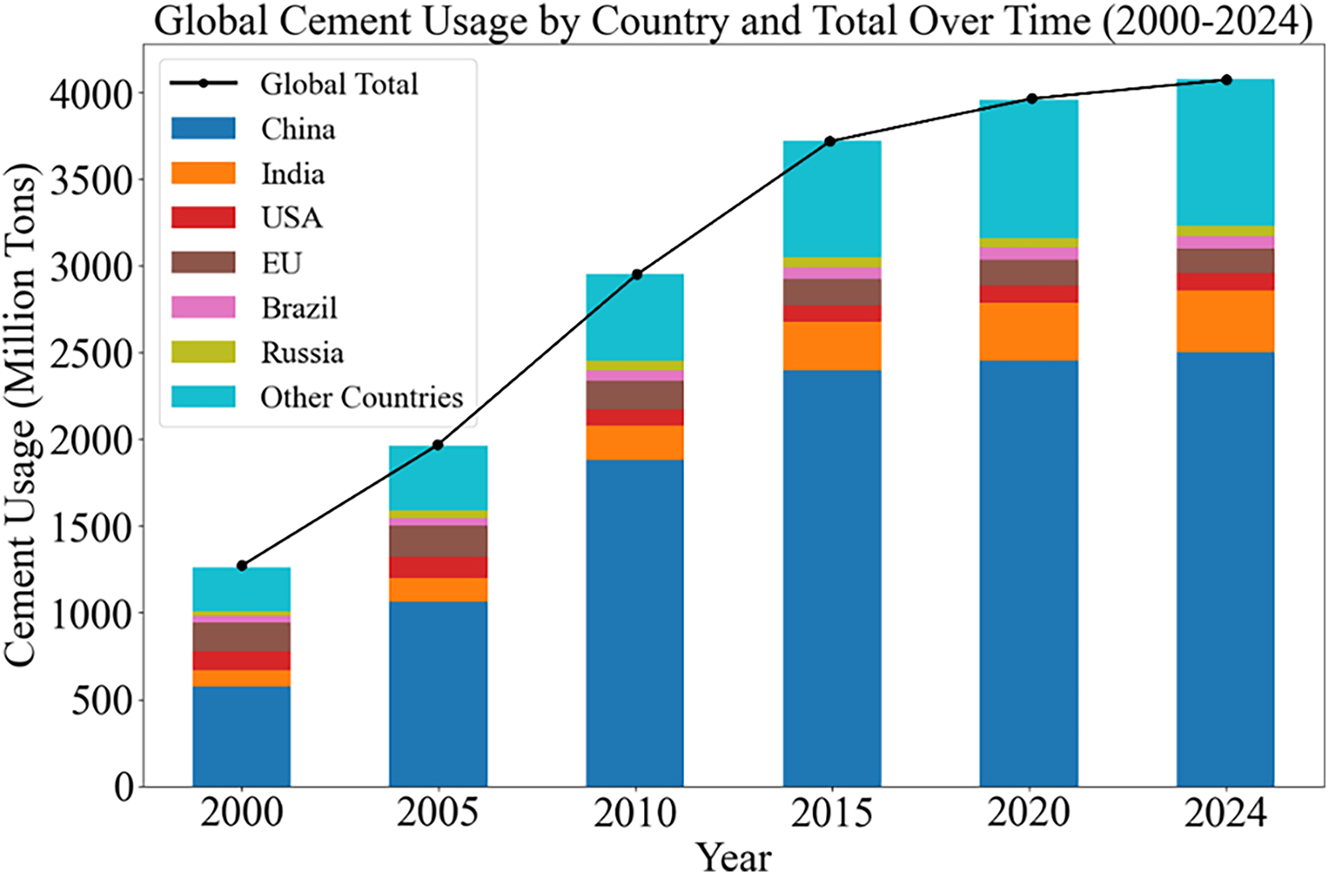

Concrete is the most widely used construction material worldwide [1], [2], [3], and its consumption has increased drastically with rapid industrialization and urbanization, as shown in Figure 1. As cities expand and infrastructure demands rise, there is an urgent need for durable materials capable of addressing the unique challenges associated with urban environments [4], 5]. Although traditional concrete plays a crucial role in urban development, its inherent drawbacks cannot be overlooked. The widespread use of concrete exacerbates issues such as the urban heat island effect, as its high thermal capacity, combined with the relative reduction in green spaces and water bodies, leads to significantly higher temperatures in urban areas than in rural regions [6], 7]. Traditional concrete surfaces often impede rainwater management, contributing to difficulties with urban flood control and water quality protection [7], 8]. Additionally, urban areas are affected by air pollutants such as nitrogen oxides (NOx), which are reactive gases produced from vehicle emissions and industrial processes, and volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which are organic chemicals that easily vaporize and contribute to air pollution; both of these types of pollutants degrade air quality and pose serious health risks to humans [9], [10], [11]. To address these challenges, various green infrastructure solutions have been proposed, such as green roofs and pervious pavements. While these solutions help manage stormwater and reduce heat, they do not provide significant pollutant degradation capabilities. Additionally, many traditional methods require regular maintenance and the use of chemical agents, which increases the environmental effects of these chemicals.

Global cement production. Stacked bar chart that displays global cement usage by country from 2000 to 2024. The x-axis represents the years (2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, 2020, and 2024), while the y-axis represents cement usage in million tons. The colours in the stacked bars represent various countries, including China, India, USA, EU, Brazil, and Russia. The black line with markers shows the global total cement usage over time, which indicates an overall increasing trend.

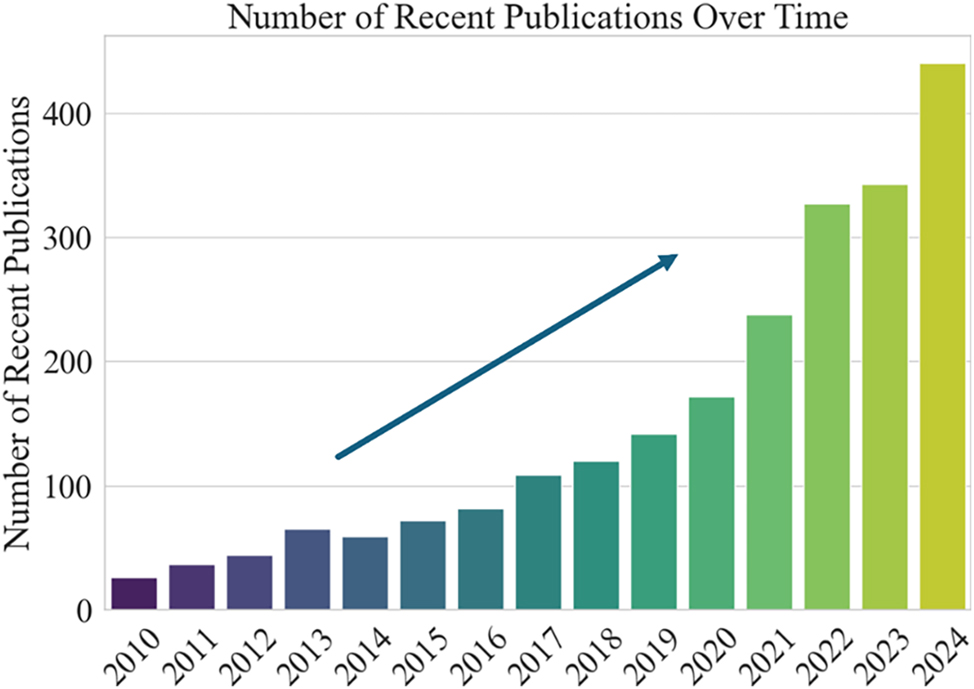

Photocatalytic pervious concrete has gained considerable attention as a promising sustainable infrastructure material to address these pressing environmental challenges [12], [13], [14]. Pervious concrete is a type of concrete that is characterized by highly interconnected pores that allow water to pass through, thus promoting rainwater infiltration and reducing runoff. Photocatalysis is a process where a material, known as a photocatalyst, uses light energy to accelerate chemical reactions, such as the breakdown of pollutants [15]. This material retains the permeability of traditional pervious concrete, allowing rainwater infiltration and groundwater recharge; however, this material also has photocatalytic functionality, thereby enabling pollutant degradation [16], 17]. This dual functionality makes it an ideal choice for mitigating urban pollution, improving water quality, and reducing air pollution. For example, Li et al. demonstrated that the use of photocatalytic pervious concrete could reduce pollutant concentrations by up to 60 %, depending on sunlight exposure and pollutant type [18]. Similarly, Khannyra et al. reported that its surface could effectively reduce NOx levels in high-traffic areas, making it a suitable material for sidewalks, parking lots, and plazas in urban environments [19]. Moreover, by promoting natural rainwater infiltration, photocatalytic pervious concrete reduces the reliance on drainage infrastructure, thereby lowering urban construction and maintenance costs; its self-cleaning properties also reduce the need for chemical cleaning agents, further minimizing environmental pollution [20], 21]. As shown in Figure 2, research interest in photocatalytic materials and concrete has been steadily increasing in recent years, reflecting the growing academic focus on this material.

Number of recent publications on the topics of photocatalysis and concrete. The figure shows the number of recent publications over time from 2010 to 2024. The x-axis represents the years, while the y-axis represents the number of publications. The upward-pointing arrow emphasizes the growth in the number of publications over time.

In summary, with the acceleration of urbanization and the increasing severity of environmental problems, the demand for sustainable infrastructure continues to grow. In light of these issues, photocatalytic pervious concrete has emerged as a promising innovative material owing to its dual functionality in pollutant degradation and stormwater management. Recent research on photocatalytic pervious concrete has focused on the following main aspects: 1) key research areas, particularly its performance in photocatalytic pollutant degradation; 2) existing research gaps, including limitations in photocatalytic activity duration under light exposure; and 3) future research priorities, such as optimizing material formulations to enhance durability and adaptability to various environmental conditions. However, several challenges remain unresolved, including the long-term stability of photocatalytic materials and their performance in complex environments. This review aims to comprehensively summarize the research progress for cement-based photocatalytic materials through a systematic analysis approach that combines bibliometric analysis and literature review. The objectives of this review are to 1) summarize key research themes in the field, including major research areas, influential institutions, and leading publications; 2) analyze critical scientific issues related to cement-based photocatalytic materials, such as the performance of classic photocatalysts and the synergistic effects of adsorptive photocatalysts; and 3) identify current research limitations, noting that traditional photocatalytic materials can only effectively degrade pollutants under light irradiation, which severely restricts their performance at night or under low-light conditions. Furthermore, future research directions are proposed to promote the widespread application of these materials in green infrastructure. The findings of this study will contribute to the further optimization of photocatalytic pervious concrete and facilitate its practical application in environmental management and urban sustainable development.

2 Fundamentals of permeability and photocatalysis

2.1 Fundamental principles of photocatalysis

Photocatalysis is a process in which a photocatalyst absorbs light energy to accelerate a chemical reaction [22]. When the photon energy is equal to or greater than the bandgap of the photocatalyst, electron excitation occurs:

The photogenerated electrons (e−) and holes (h+) further react with water (H2O) and oxygen (O2) to form highly reactive oxygen species, such as hydroxyl radicals (·OH) and superoxide anions (O2 −). These reactive species can oxidize and degrade pollutants:

These radicals can further oxidize and decompose NOx and volatile organic compounds (VOCs), thereby converting them into harmless products:

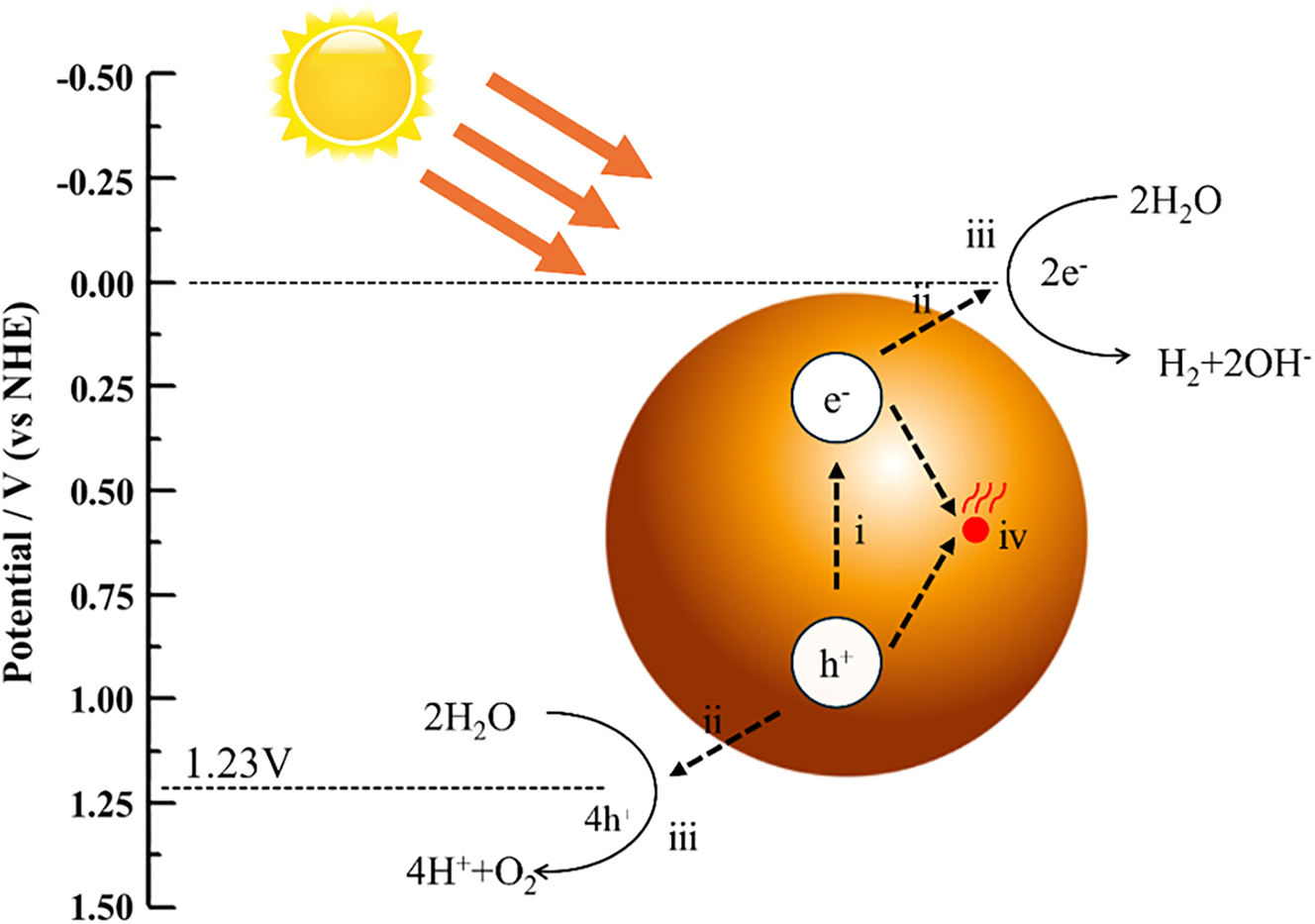

The fundamental mechanism of photocatalysis is illustrated in Figure 3, where the photocatalyst is activated under light irradiation. When photons with sufficient energy strike the surface of the photocatalyst, they excite electrons from the valence band to the conduction band, resulting in positively charged holes. These electron‒hole pairs react with water and oxygen in the environment, generating reactive radicals that decompose organic and inorganic pollutants [23], [24], [25].

Schematic diagram of the photocatalytic degradation of pollutants. The figure shows the basic mechanism of photocatalysis. Photons with sufficient energy hit the surface of the photocatalyst and push electrons from the valence band to the conduction band, thus leaving behind positively charged holes. These electron–hole pairs react with water and oxygen in the environment to form active free radicals that decompose organic and inorganic pollutants.

Photocatalytic reactions in building materials, such as concrete, hold great potential for air and water purification [18]. Photocatalysts can be integrated into the surface of concrete or incorporated into the cement matrix, enabling the material to degrade pollutants when exposed to sunlight [14]. Studies have shown that photocatalysts can effectively reduce NOx and VOC levels in urban environments [10], 25]. In addition to the well-known TiO2, other photocatalysts, such as zinc oxide (ZnO) and tungsten oxide (WO3), have been used in building materials [16]. However, TiO2 remains the most widely applied material because of its stability under ultraviolet light, its low cost, and its high reactivity [20], 24]. Furthermore, researchers are aiming to increase the activity of photocatalysts under visible light by exploring modifications such as doping with transition metals or coupling with other semiconductors [19], 23], 26].

2.2 Photocatalytic materials

2.2.1 Titanium dioxide (TiO2)

Titanium dioxide (TiO2) has become the most widely used material in photocatalysis because of its strong oxidizing ability and high chemical stability [27]. The greatest advantages of TiO2 are its chemical stability and relatively low cost, making it suitable for long-term applications in various environments, including self-cleaning building materials, air purification devices, and water treatment systems [20]. However, TiO2 has a relatively large bandgap (approximately 3.2 eV), which allows it to absorb only ultraviolet light, which greatly limits its efficiency under natural light since ultraviolet light accounts for only approximately 5 % of the solar spectrum. Therefore, improving the visible light responsiveness of TiO2 has become an important research direction [28].

To address the limitations of TiO2, researchers have employed various modification methods, including doping, surface modification, and composite materials [29], 30]. Doping is the most common modification method; with this method, nonmetallic elements such as nitrogen, carbon, sulphur, and phosphorus or metallic elements such as silver, copper, and iron are introduced into TiO2 to effectively narrow its bandgap, thereby extending its light absorption range to the visible light spectrum [31]. For example, in nitrogen-doped TiO2, new energy states that reduce the bandgap energy are introduced, enabling TiO2 to absorb part of the visible light spectrum [28]. In addition, metal ion doping enhances light absorption and promotes the separation of electron‒hole pairs during photocatalytic reactions, reducing recombination rates and thus improving photocatalytic efficiency [26], 32].

2.2.2 Zinc oxide (ZnO)

Zinc oxide (ZnO) has a bandgap energy similar to that of TiO2 (approximately 3.2 eV), and its higher electron mobility helps promote the separation of electron‒hole pairs, thereby improving the photocatalytic efficiency. Compared with TiO2, ZnO exhibits greater photocatalytic activity under ultraviolet light. ZnO shows good chemical stability in neutral or weakly acidic environments and basic aqueous environments; however, its surface is prone to dissolution or passivation in strongly acidic, basic, and high ionic concentration environments, which may affect its catalytic activity [33]. Moreover, prolonged photocatalytic reactions may lead to the passivation or loss of surface active sites, thereby hindering its catalytic performance. This limitation affects the performance of ZnO in long-term applications, such as in aquatic environments [34].

Researchers have explored a variety of doping and composite material preparation methods to improve the stability of ZnO and extend its light absorption range [35], 36]. For example, doping ZnO with nitrogen, sulphur, or metal elements (such as silver and copper) can effectively reduce its bandgap, enabling it to absorb a larger proportion of visible light [37]. Moreover, composite materials with other photocatalysts (such as TiO2 or g-C3N4) can further enhance its photocatalytic performance and stability [16]. Additionally, surface modification techniques for ZnO can increase its durability and photocatalytic activity [38].

ZnO has widespread applications in self-cleaning materials, antibacterial coatings, and water treatment membranes. For example, on exterior wall coatings of buildings, ZnO maintains surface cleanliness by degrading attached organic pollutants [39]. Furthermore, the antibacterial properties of ZnO make it an ideal choice for antibacterial coatings in indoor environments [40]. In water treatment systems, ZnO can be used to remove organic pollutants and bacteria from water. Particularly in outdoor environments with sufficient ultraviolet light, ZnO is a promising material for water purification owing to its efficient photocatalytic activity [41].

2.2.3 Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4)

Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) is an emerging photocatalytic material that has attracted significant attention because of its unique electronic structure and visible light responsiveness. The bandgap of g-C3N4 is relatively narrow (∼2.7 eV), allowing it to absorb visible light and induce catalytic reactions under lower light conditions [42]. Its chemical stability and low toxicity make it an environmentally friendly photocatalytic material.

The advantage of g-C3N4 over TiO2 and ZnO is its visible light responsiveness, enabling effective photocatalytic reactions under natural light and low light conditions [18]. However, the photocatalytic efficiency of g-C3N4 is relatively low, particularly the efficiency of electron‒hole pair separation. The small specific surface area of g-C3N4 limits its performance in catalytic applications that require a higher density of active sites [43]. Methods such as porosification, nanostructuring, and composite material design can significantly increase the specific surface area of this material, thereby increasing its catalytic efficiency [44].

To increase the photocatalytic efficiency of g-C3N4, researchers have modified it through various doping methods. Doping with oxygen, sulphur, or metals can effectively increase the charge separation efficiency of g-C3N4 and its photocatalytic performance [45]. Additionally, g-C3N4 is often combined with other semiconductor materials to form heterojunctions. This design can increase light absorption and promote the separation of electron‒hole pairs, thereby increasing photocatalytic activity [46], 47].

g-C3N4 has broad applicability in fields such as water purification, air purification, and hydrogen production. For example, g-C3N4 can be used to degrade organic pollutants and pharmaceutical residues in water, playing an important role in environmental protection [44]. Additionally, owing to its strong visible light absorption capacity, g-C3N4 can be used in solar-driven water splitting reactions to produce clean hydrogen fuel [48].

2.2.4 Silver-based compounds

Silver-based photocatalytic materials, particularly silver nanoparticles and silver halides (e.g., Ag/AgCl), exhibit good visible light absorption capabilities because of their unique surface plasmon resonance (SPR) effect [49]. Silver nanoparticles can effectively generate reactive oxygen species under light exposure, thereby degrading organic pollutants in the environment [50].

The main advantage of silver-based photocatalysts is their ability to induce photocatalytic reactions under visible light, resulting in efficient pollutant degradation performance under natural light conditions [51]. Furthermore, silver has inherent antibacterial properties, making it widely applicable in antibacterial coatings and air purification systems. However, the large-scale application of silver is limited by its high cost and potential environmental impacts. To overcome these limitations, researchers are developing composite materials with lower silver contents to improve their cost-effectiveness and sustainability [52], 53].

Silver-based photocatalytic materials are often combined with other traditional photocatalysts (e.g., TiO2, ZnO) to create composites with synergistic effects. This approach can improve the photocatalytic performance and stability of the materials [54]. For example, Ag/AgCl–TiO2 composite materials exhibit increased photocatalytic activity under visible light, with silver nanoparticles helping to facilitate electron transfer, thus reducing the recombination of electron‒hole pairs [55].

Silver-based photocatalytic materials are commonly used in water and air purification systems, self-cleaning coatings, and antibacterial coatings. In water treatment systems, Ag/AgCl can effectively degrade organic dyes, pesticides, and other persistent organic pollutants in water [52]. In air purification systems, silver-based materials can capture and decompose VOCs in the air, thereby reducing the concentration of air pollutants in both indoor and outdoor environments [56]. Additionally, the antibacterial properties of silver-based materials make them highly valuable in public health settings such as hospitals and laboratories [53].

2.2.5 Bismuth-based materials

Bismuth-based photocatalytic materials, such as bismuth vanadate (BiVO4) and bismuth tungstate (Bi2WO6), have relatively narrow bandgaps (approximately 2.4–2.8 eV), allowing them to effectively absorb visible light. The unique layered structure of bismuth-based materials helps increase the separation efficiency of electron‒hole pairs, reduce recombination rates, and thereby improve photocatalytic activity [22], 57].

The main advantages of bismuth-based materials are their strong visible light responsiveness and their chemical stability, particularly their high stability in aqueous environments, making them ideal for long-term use in water treatment systems [58]. However, the photocatalytic efficiency of bismuth-based materials is relatively low, especially under ultraviolet light, where their activity is inferior to that of traditional TiO2 and ZnO [59].

To improve the photocatalytic performance of bismuth-based materials, researchers often increase their activity by combining them with other photocatalytic materials [26], 60]. For example, BiVO4 and g-C3N4 composite materials exhibit high photocatalytic efficiency under both ultraviolet and visible light. This composite structure significantly improves the electron‒hole pair separation efficiency, thereby increasing the overall activity of the material [61].

Bismuth-based materials are widely used in water treatment and air purification applications. For example, BiVO4 can effectively degrade organic dyes, pharmaceutical residues, and other difficult-to-treat organic pollutants in water treatment systems [62], 63]. In air purification applications, Bi2WO6 can decompose harmful gases in the air, reducing urban air pollution [64], 65].

2.2.6 Perovskite-based photocatalysts

Owing to their unique ABX3 crystal structure and tuneable bandgap properties [66], perovskite-based photocatalysts, such as strontium titanate (SrTiO3), exhibit high photocatalytic activity under visible light. By adjusting the elemental composition of perovskite materials, their bandgap energy can be controlled, thereby optimizing their photocatalytic performance [67].

The advantages of perovskite-based materials include their flexible crystal structure and efficient charge separation ability, enabling high-efficiency photocatalytic reactions under visible light [68]. However, the long-term stability and environmental adaptability of perovskite materials still require further research, particularly in practical applications such as water treatment and air purification, where their durability and stability need to be further improved [69].

The photocatalytic performance of perovskite materials can be significantly improved by doping these materials with different metals (e.g., niobium or molybdenum) or combining them with other photocatalysts. Doping can further improve their charge separation efficiency and enhance their absorption of visible light. Additionally, composite structures improve the stability of the material and extend its lifespan [70], 71].

Perovskite-based photocatalysts have shown broad application prospects in environmental pollution control and solar-driven hydrogen production applications. For example, SrTiO3 has a high hydrogen production rate in water splitting reactions, making it a potential candidate for solar-driven water splitting [72], 73]. Moreover, perovskite materials can be used to degrade organic pollutants in air purification and wastewater treatment systems [74], 75].

In conclusion, photocatalytic technology, with its efficient, green, and sustainable characteristics, has long been considered an economically feasible and environmentally friendly cutting-edge technological approach. Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of various classic photocatalytic materials and new semiconductor photocatalytic materials (such as bismuth-based materials and graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4)). However, these materials still have several limitations in practical applications, such as wide bandgaps, low light absorption efficiency, susceptibility to aggregation, and rapid recombination of photogenerated electron‒hole pairs. These bottlenecks significantly limit their effectiveness in the photocatalytic degradation of pollutants in practical applications [76], [77], [78].

Main characteristics of classic photocatalytic materials and new semiconductor photocatalytic materials.

| Photocatalytic material | Bandgap (eV) | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| TiO2 | 3.2 | High chemical stability, strong oxidation ability, low cost | Only absorbs ultraviolet (UV) light (∼5 % of solar spectrum), poor visible-light response |

| ZnO | 3.2 | High photocatalytic activity, high electron mobility, low cost | Prone to photodegradation in aqueous environments, relatively poor stability |

| g-C3N4 | 2.7 | Strong visible-light response, good chemical stability, environmentally friendly and nontoxic | Low photocatalytic efficiency, low electron–hole separation efficiency, small specific surface area |

| Silver-based compounds | 1.8–3.1 | Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) effect, strong visible-light absorption, excellent antibacterial properties | High cost of silver, potential environmental impact |

| Bismuth-based materials | 2.4–2.8 | Strong visible-light absorption, good chemical stability, high electron–hole separation efficiency | Low UV response, lower photocatalytic efficiency |

| Perovskite-based photocatalysts | 2.0–3.0 | Tunable crystal structure, good visible-light response, efficient charge separation | Lack of long-term stability and environmental adaptability |

2.3 Permeability of porous materials

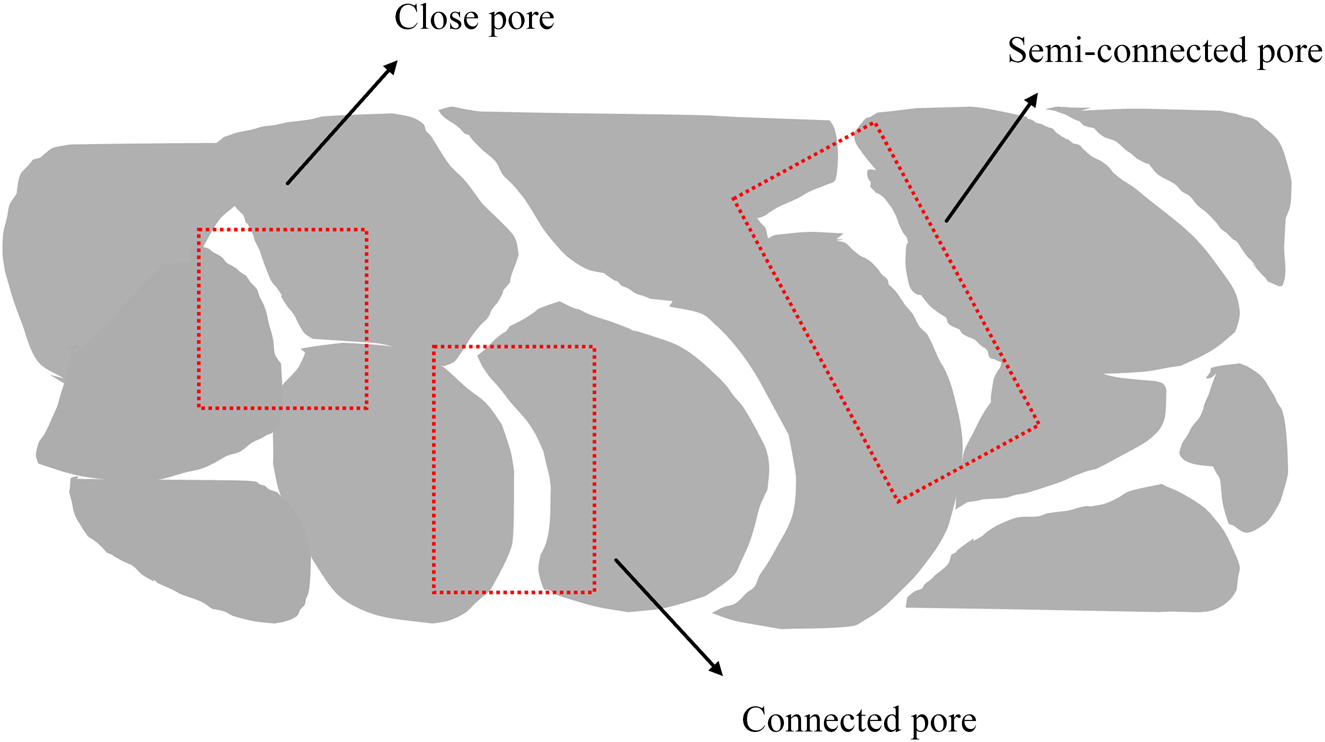

Permeable concrete is a high-permeability material, and its permeability primarily depends on the pore structure, size distribution, and overall porosity of the concrete [79], 80]. Unlike dense and impermeable traditional concrete, permeable concrete has interconnected voids, with internal pores categorized as interconnected pores, semiconnected pores, or closed pores, as shown in Figure 4, providing channels for water flow. These features make permeable concrete an effective material for managing urban runoff [7], 79].

Classification of internal pores in pervious concrete. The figure shows that permeable concrete has interconnected voids, and its internal pores can be divided into connected pores, semi-connected pores and closed pores.

Although pervious concrete is used primarily to manage urban stormwater runoff, its permeability also plays a crucial role in enhancing the photocatalytic process. The porous structure of pervious concrete, which features interconnected pores of various sizes, increases the surface area for interaction between photocatalysts and pollutants such as nitrogen oxides (NOx) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs). As rainwater permeates through the concrete, it maintains continuous contact between the photocatalytic material and pollutants, thereby enhancing the degradation process when the water flows over the concrete surface and interacts with the light-activated photocatalyst. Furthermore, the permeability of the concrete facilitates better dispersion of the photocatalyst, which ensures that pollutants are degraded not only on the surface but also within the internal pores, thereby improving the overall pollutant removal efficiency. Therefore, the permeability of pervious concrete supports the efficiency and effectiveness of photocatalysis directly, thus contributing to both stormwater management and air quality improvement.

The flow of water through porous materials is governed by Darcy’s Law, as shown in Eq. (7), which links the rate of flow through a porous medium to the permeability and pressure gradient of the material. In permeable concrete, the main factors influencing permeability include the pore size, pore connectivity, and ratio of aggregate to cement. Larger and more connected voids increase the permeability but may compromise the strength of the concrete. Therefore, balancing permeability and structural strength is crucial in the design of permeable concrete [81].

The design of permeable concrete requires comprehensive consideration of the aggregate size, the ratio of cement to aggregate, and compaction techniques to balance the permeability and mechanical properties [8]. Each parameter should be optimized on the basis of specific engineering requirements and environmental conditions. The optimal permeability depends on the appropriate design of the pore structure and the stable bonding of aggregates with an appropriate amount of cement paste. By optimizing the aggregate particle size, water-to-cement ratio, compaction process, and cement paste fluidity, an ideal balance between permeability and mechanical performance can be achieved [82]. The pore distribution particularly affects the efficiency of water flow through concrete; larger and more uniform pores increase the flow rate.

The key step in the design of permeable concrete involves optimizing the pore structure to balance high permeability with good durability [82]. The size and grading of aggregates directly affect the porosity and water flow rate, while the incorporation of supplementary cementitious materials, such as fly ash and silica fume, can further increase durability [83], 84]. Through the reasonable design of material proportions and the use of appropriate construction techniques, permeable concrete can be widely applied in urban rainwater management, road drainage, and ecological environmental protection [85].

3 Synergistic effects of photocatalytic and adsorption properties

3.1 Mechanisms of adsorption‒photocatalysis synergy

The synergistic effects of adsorption and photocatalysis are crucial for improving the efficiency of photocatalytic reactions. This coupling mechanism combines the advantages of adsorption and photocatalysis; in particular, pollutants on the surface of the catalyst are localized and concentrated via adsorption, while pollutants are degraded through light-driven reactions via photocatalysis [86]. Throughout this process, adsorption leads to the enrichment of pollutants on the catalyst surface, significantly increasing the contact opportunities between pollutants and active species, reducing diffusion limitations, and thus significantly increasing the reaction rate [87]. Moreover, adsorption results in the efficient capture of low-concentration pollutants, ensuring contact with the catalyst. Even trace amounts of drugs or dyes in water can be effectively treated [88]. Furthermore, through functionalized adsorbents, adsorption allows pollutants to be selectively captured on the basis of their size, charge, or chemical affinity. This selectivity significantly optimizes the degradation pathway and reduces competition for active sites among pollutants [89]. The synergistic effects of adsorption and photocatalysis enable the simultaneous capture and degradation of pollutants and eliminate the need for additional separation steps, thus increasing the overall efficiency and practicality of the process.

Adsorption plays a crucial role in optimizing the selectivity and efficiency of the photocatalytic degradation process. For example, adsorbents such as activated carbon, metal‒organic frameworks (MOFs), and zeolites, when combined with photocatalysts such as TiO2 or g-C3N4, have high surface areas and optimized pore structures that increase the pollutant capture efficiency [90], [91], [92]. By concentrating pollutants at specific catalytic sites, adsorption effectively reduces the occurrence of side reactions, improving the selectivity of the photocatalytic reaction and thus increasing the yield of the final products [93]. Thus, through adsorption, the initial pollutants in the photocatalytic process are captured and the reaction intermediates are stabilized, ensuring that these intermediates are fully converted into harmless final products.

3.2 Influence of adsorption on the stability of reaction intermediates

During the reaction process, adsorption results in the stabilization of intermediates on the catalyst surface, prolonging their residence time [94]. As shown in Figure 5, during the degradation process, organic dyes typically first form smaller aromatic or aliphatic compounds, which then need to be further oxidized to CO2 and H2O. The “fixing” effect of interfacial adsorption effectively prevents the premature release of these intermediates, thereby reducing the risk of secondary pollution caused by incomplete degradation. Adsorption also extends the residence time of intermediates at the catalyst active sites, increasing the likelihood of further reactions with active species, thereby improving the photocatalytic efficiency [95]. The stabilizing effect of adsorption is crucial for reducing environmental toxicity, particularly for persistent organic pollutants, such as pesticides and pharmaceutical residues [96].

Schematic diagram of the synergistic degradation of pollutants via the adsorption of pervious concrete. The figure illustrates that organic dyes break down into smaller aromatic or aliphatic compounds during degradation. These intermediates must undergo further oxidation to form CO2 and H2O. Interfacial adsorption helps retain these intermediates, which prevents their premature release and prolongs their residence time at the catalyst’s active site, thereby enhancing their chances of reacting with active species.

3.3 Significance of photocatalytic system design

The synergistic mechanism of adsorption and photocatalysis has profound implications for optimizing the design of photocatalytic systems. Integrated materials with high adsorption capacity and strong photocatalytic activity should be the focus of future development [95]. For example, combining carbon-based materials (such as graphene or activated carbon) with photocatalysts increases the adsorption capacity and provides additional charge transfer pathways for photocatalysis [97]. Furthermore, introducing specific functional groups (such as hydroxyl or amino groups) on the surface of the photocatalyst can significantly increase the adsorption capacity of the catalyst for specific pollutants while also improving the binding and stability of intermediates [98]. These improvements make the photocatalytic process more efficient and selective, particularly in environmental remediation fields such as water and air purification, where their role is particularly prominent.

In practical studies, photocatalyst-activated carbon composite materials have shown good performance. For example, activated carbon adsorbs and concentrates dyes such as methylene blue on its surface, thus accelerating photocatalytic degradation reactions [92]. Moreover, metal‒organic frameworks (MOFs) with high surface areas and tuneable pore sizes, which function as both adsorbents and catalysts, have demonstrated excellent performance in the degradation of pharmaceutical pollutants [91]. These practical applications show that the synergistic mechanism of adsorption and photocatalysis, including pollutant concentration, intermediate stabilization, and optimized reaction pathways, improves degradation efficiency and reduces the toxicity of byproducts, providing an efficient and innovative approach for environmental remediation.

The synergistic effects of adsorption and photocatalysis have significant advantages in terms of pollutant capture and degradation and provide important guidance for the optimized design of photocatalytic technology. However, traditional photocatalytic materials still face many challenges in practical applications, particularly their dependence on sunlight, which limits their widespread use in low-light environments (such as at night or on rainy days). This issue is particularly prominent in the application of photocatalytic permeable concrete.

4 Modified photocatalytic materials with persistent afterglow

Although traditional photocatalytic materials have shown great potential in environmental applications, their functionality depends heavily on light exposure [99]. These materials can only effectively degrade pollutants under illumination, typically from ultraviolet or visible light sources [100]. This limitation reduces their efficiency significantly at night or under low-light conditions, thus preventing continuous, all-day operation in practical applications. However, urban environments face pollution issues around the clock, which makes having photocatalytic materials that remain effective even without direct sunlight essential. This performance shortcoming has driven the exploration of long-afterglow phosphorescent materials. Such materials store excitation energy during light exposure and gradually release it in the dark, thereby activating photocatalysts even in the absence of light. The integration of these long-afterglow phosphors with traditional photocatalysts represents a key innovation, as it extends photocatalytic activity beyond daylight hours, thereby enabling continuous environmental remediation, air purification, and water splitting. This approach not only addresses the limitations of conventional photocatalysis but also opens new possibilities for sustainable solutions across various environmental applications.

The integration of persistent luminescent materials with photocatalysts has emerged as a promising strategy to extend photocatalytic activity beyond direct illumination. By storing excitation energy during illumination and gradually releasing it under dark conditions, these materials can continuously activate photocatalysts, thereby increasing the overall efficiency of these materials in applications such as environmental remediation, water splitting, and air purification.

4.1 Categories of materials with long afterglow periods

Over the past few decades, various phosphors have been synthesized, with three major categories – sulphides, silicates, and aluminates – dominating research and applications [101]. Sulphide-based long-persistence phosphors, such as Y2O2S:Eu2+, Mg2+, and Ti4+, achieve afterglow through electron trapping and thermal detrapping mechanisms, where co-dopants such as Mg2+ and Ti4+ act as trapping centres to increase charge carrier storage [102]. The strong luminescence and tuneable emission wavelengths of sulphide phosphors make them attractive for photocatalysis, particularly for improving the spectral response of traditional photocatalysts. However, the primary drawback of sulphide phosphors is their poor water stability. The presence of sulphide ions (S2−) makes these materials highly susceptible to oxidation and hydrolysis, leading to rapid degradation under humid and aqueous conditions. Upon exposure to oxygen or moisture, sulphide phosphors tend to form sulfate compounds, significantly reducing their afterglow performance [103].

Aluminate-based long-persistence phosphors, including SrAl2O4:Eu2+, Dy3+ and CaAl2O4:Eu2+, Dy3+, are among the most widely used persistent luminescent materials due to their high brightness and prolonged afterglow duration. These materials exhibit intense green or blue light emission, which is attributed to the 4f65d → 4f7 transition of Eu2+ ions. The presence of Dy3+ as a co-dopant leads to the introduction of deep trap states, prolonging the afterglow duration through the regulation of the charge carrier dynamics [104]. Despite their excellent luminescent properties, aluminate phosphors suffer from poor stability in aqueous environments. The presence of alkaline earth metal ions (e.g., Sr2+ and Ca2+) increases their solubility in water, leading to gradual leaching and deterioration of their optical properties. Such instability in photocatalytic applications can severely affect the long-term efficiency of the system [105].

Owing to their superior chemical stability and resistance to hydrolysis, silicate phosphors, particularly Sr2MgSi2O7:Eu2+, Dy3+, have emerged as excellent candidates for photocatalytic applications. Unlike sulphide-based materials, silicates have robust silicate networks that stabilize luminescent centres and prevent unwanted chemical degradation in humid and aqueous environments. This stability is crucial for long-term photocatalytic applications, where exposure to water and varying pH conditions is inevitable [106]. Moreover, the energy transfer efficiency between silicate phosphors and photocatalysts such as BiVO4 can enhance charge carrier dynamics and improve overall photocatalytic performance [107].

4.2 Mechanisms of enhanced photocatalysis with long afterglow durations

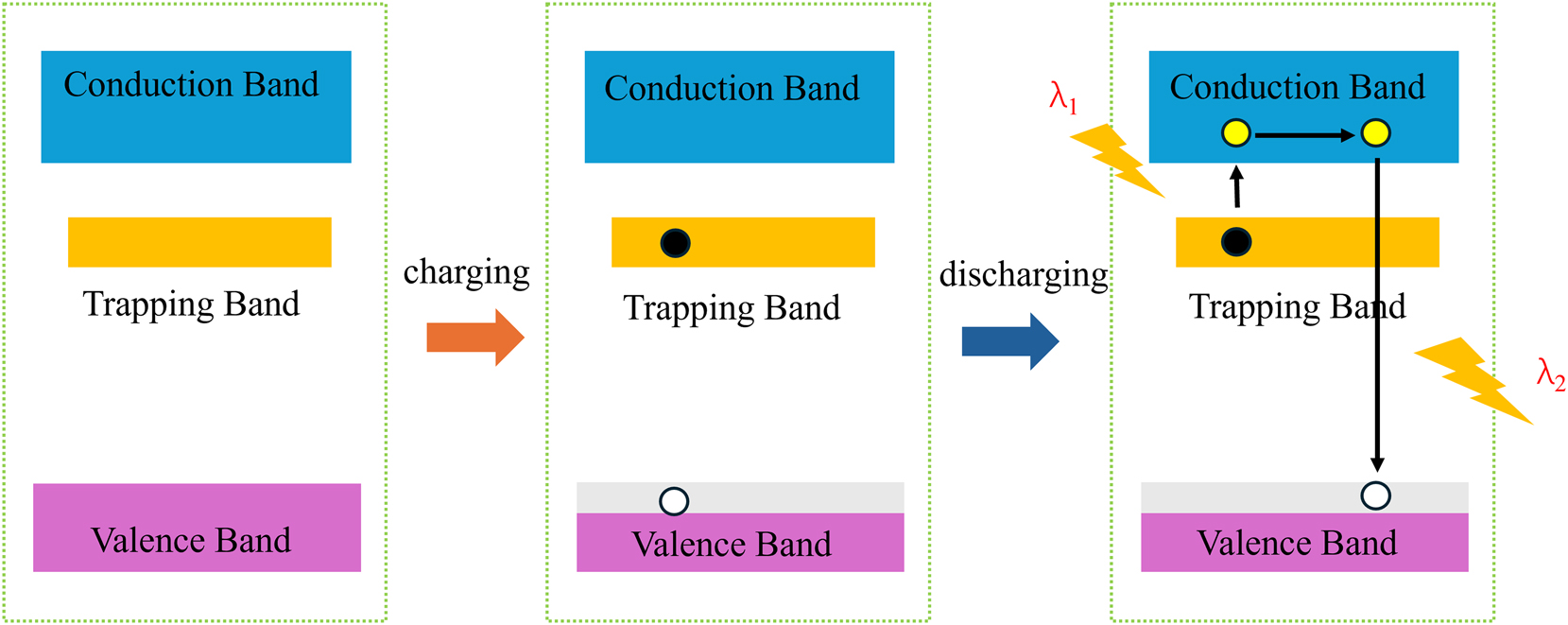

The synergistic interactions between luminescent materials and photocatalysts are crucial for achieving sustained photocatalytic activity under low-light conditions. However, the mechanisms of electron retention and migration in long-persistent phosphors remain unclear, as they involve complex processes that lack standardized experimental validation methods. Consequently, no definitive conclusions have been reached in this field. In this section, the fundamental concepts of persistent luminescence are described. Persistent afterglow relies on two active centres in phosphors: trap levels and luminescent centres. Specifically, trapping sites originate from intrinsic crystal defects or extrinsic ion doping [108], 109].

As illustrated in Figure 6, the persistent luminescence process in phosphors consists of four sequential steps: photogenerated carrier formation, electron trapping, release, and recombination [110], 111]. Under light excitation, electrons transition from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), resulting in the generation of free electrons and holes. Some of the excited electrons are captured by trap states within the material, a process commonly referred to as photon charging. In the absence of illumination, the trapped electrons can be thermally activated by environmental heat, prompting them to transition back to the CB. These released electrons subsequently recombine with holes in the VB, emitting energy in the form of luminescence.

Schematic diagram and related mechanism of electron migration during luminescence of materials with long afterglow durations. The figure illustrates that when a long-afterglow material is exposed to light, electrons jump from the valence band to the conduction band, thus generating free electrons and holes. Some of the electrons become trapped in the trap states of the material, which is a process known as photon charging. In darkness, thermal energy releases these trapped electrons back to the conduction band, where they recombine with holes in the valence band, thus emitting light.

Notably, persistent phosphors function as both luminescent materials and efficient electron storage media. The exceptional electron storage capacity of these materials plays a critical role in driving photocatalytic reactions under dark conditions. By integrating persistent phosphors with photocatalysts, the resulting composite materials serve as charge storage reservoirs upon photoexcitation and exhibit catalytic activity in the absence of light. For example, strontium aluminate phosphors can emit light for up to 10–12 h after exposure to sunlight, making them ideal for nighttime applications [112].

4.3 Applications of photocatalytic materials with long afterglow duration

Photocatalytic materials, such as titanium dioxide (TiO2), zinc oxide (ZnO), graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4), silver-based compounds, bismuth-based materials, and perovskite-based photocatalysts, have demonstrated significant potential in pollutant degradation and water splitting applications. However, a major limitation of these conventional photocatalysts is that their catalytic activity is restricted to periods of direct illumination. To overcome this challenge, persistent phosphors have been introduced into photocatalytic systems. Nevertheless, research on the integration of persistent phosphors with photocatalysts to construct persistent photocatalytic systems remains limited, providing considerable opportunities for future research.

Urban environments are frequently affected by air pollution caused by NOx and VOCs. By incorporating persistent photocatalytic materials into cement, the photocatalytic activity of these materials can be sustained under low-light conditions, thereby maximizing the air purification efficiency and extending the degradation of airborne pollutants, ultimately improving urban air quality. Permeable concrete, a key component of sustainable urban drainage systems, can be used to create a continuous water purification system by integrating persistent photocatalytic materials. This material captures pollutant particles through adsorption and facilitates the degradation of organic contaminants via round-the-clock photocatalytic reactions.

Although the integration of persistent photocatalysts into cement-based materials offers new directions for the design of photocatalytic concrete, several challenges must be addressed. One of the primary concerns is the long-term stability of persistent luminescent materials within cement, as factors such as high alkalinity and mechanical wear may degrade their luminescent properties. Further research is needed to optimize the material composition and protective coatings to increase durability. Additionally, cost effectiveness must be considered for large-scale implementation. The synthesis of high-performance persistent phosphors and their integration into construction materials may require the use of advanced manufacturing techniques, increasing production costs. Exploring alternative phosphor compositions and improving energy storage efficiency could help reduce costs while maintaining high photocatalytic performance.

5 Conclusions

The development of photocatalytic permeable concrete represents a promising approach for addressing various challenges in urban environments. This innovative material contributes to effective rainwater management and actively promotes the degradation of harmful pollutants in air and water, aligning with the goals of sustainable urban development.

Photocatalytic permeable concrete is both permeable and has photocatalytic pollutant degradation functions, offering significant advantages in optimizing rainwater management, reducing water pollution, and improving air quality. Its permeable properties are useful in applications such as rainwater infiltration, pollutant filtration, and groundwater recharge, reducing urban runoff pollution and mitigating flood risks. Moreover, photocatalytic reactions can degrade NOx and VOCs in the air, effectively alleviating urban air pollution. Furthermore, these materials can reduce the urban heat island effect, enhance the overall environmental benefits of green infrastructure, and provide important support for sustainable urban development.

The photocatalytic degradation efficiency of these materials is influenced by the adsorption capacity of the material and the lighting conditions, with adsorption helping to concentrate pollutants and stabilize intermediate products, thereby increasing the degradation efficiency. This synergistic mechanism is especially important in the removal of NOx and VOCs, suggesting that photocatalytic permeable concrete has broader application prospects in air and water pollution control. Additionally, the introduction of luminescent materials can increase the activity of photocatalysts under low light conditions, expanding their application range. Different integration methods (surface coating, internal doping, and particle embedding) directly affect the permeability, mechanical strength, and photocatalytic efficiency of the material. Among these factors, the uniform distribution and interface bonding of luminescent materials are key factors in determining their performance stability. The long-term stability of the material remains a key challenge for its practical application. The photocatalytic activity may decrease due to pollutant accumulation. Therefore, effective maintenance mechanisms, such as regular cleaning or photoregeneration strategies, must be established to ensure stable long-term photocatalytic performance and extend the service life of the material.

Recent studies have provided important insights into bridging theory and practical application. For example, a nanoparticulate titanium dioxide (nano-TiO2) coated porous concrete pavement was able to remove up to 60 % of the total phosphorus (TP) and 50 % of the chemical oxygen demand (COD) from runoff while addressing skid resistance and durability issues [113]. In another pilot study, Fe2O3 nanoparticles were incorporated into pervious concrete to effectively remove various bacteria and heavy metals. Although removal of phenol and ammonium was limited, the feasibility of using pervious concrete for urban runoff pollution control was confirmed in this study [114]. Future studies should focus on enhancing the photocatalytic activity of photocatalytic pervious concrete, optimizing its structure, and improving its long-term durability to promote its widespread application in urban environmental management. First, improving the visible-light response of photocatalysts is crucial; this can be achieved in materials science through strategies such as doping, composite formation, and surface modification to increase visible-light utilization. Second, optimizing the dispersion and stability of the catalysts is essential for ensuring their uniform distribution within the concrete and reducing agglomeration. Additionally, the pore structure should be regulated to balance permeability, mechanical strength, and photocatalytic efficiency; it can be optimized through a combination of numerical simulation and experimental approaches. The integration of long-afterglow phosphorescent materials can enhance photocatalytic performance under low-light conditions but requires further optimization of doping concentrations and energy level matching. To address long-term durability issues, self-cleaning, self-healing, or photo-regeneration strategies for maintaining catalytic activity should be developed. Furthermore, the incorporation of smart sensor technologies into photocatalytic pervious concrete can enable real-time monitoring of pollutant degradation and provide dynamic feedback to optimize photocatalytic performance. By pursuing these diverse research directions, the overall performance of photocatalytic pervious concrete can be improved, thus offering more efficient and sustainable solutions for green infrastructure.

-

Funding information: This work was supported financially by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52478281), the Key Project of the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (Grant No. LZ22E080003), the Ningbo Public Welfare Research Project (Grant No. 2024S077) and International Sci-tech Cooperation Projects under the “Innovation Yongjiang 2035” Key R&D Programme (No. 2024H019).

-

Authors contribution: Xin Huang: conceptualization, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, data curation. Yidong Xu: conceptualization, funding acquisition, supervision, validation, writing – review and editing. Xinjie Cai: writing – review and editing, supervision. Qiang Li: writing – review and editing. Jianghong Mao: writing – review and editing. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

1. Kiruthiga, P, Dave, N, Shahabuddin, S, Guduru, R. Development of sustainable concrete with pulverized coal bottom ash for low cost and carbon emission. Constr Build Mater 2025;462:139949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2025.139949.Search in Google Scholar

2. Musa, AES, Ahmed, A, Ahmad, S, Mohamed, K, Al-Fakih, A, Al-Osta, MA. Properties of concrete incorporating plastic wastes and its applications: a comprehensive review. J Build Eng 2025;101:111843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2025.111843.Search in Google Scholar

3. Tanash, AO, Muthusamy, K, Budiea, AMA, Fauzi, MA, Jokhio, G, Jose, R. A review on the utilization of ceramic tile waste as cement and aggregates replacement in cement based composite and a bibliometric assessment. Clean Eng Technol 2023;17:100699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clet.2023.100699.Search in Google Scholar

4. Driessen, E, Grönlund, E. Circular concrete scenarios and their environmental impacts: a life cycle assessment modelled after a Swedish city. J Clean Prod 2024;485:144348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.144348.Search in Google Scholar

5. Liu, X, Ye, Z, Lu, J-X, Xu, S, Hsu, S-C, Poon, CS. Comparative Lca-Mcda of high-strength eco-pervious concrete by using recycled waste glass materials. J Clean Prod 2024;479:144048. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.144048.Search in Google Scholar

6. Multer Hopkins, B, Lal, R, Lyons, WB, Welch, SA. Carbon capture potential and environmental impact of concrete weathering in soil. Sci Total Environ 2024;957:177692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.177692.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Adresi, M, Yamani, AR, Tabarestani, MK. Evaluating the effectiveness of innovative pervious concrete pavement system for mitigating urban heat island effects, de-icing, and de-clogging. Constr Build Mater 2024;449:138361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.138361.Search in Google Scholar

8. Wang, Z, Liu, Z, Zeng, F, He, K, Guo, S. Review on frost resistance and anti-clogging of pervious concrete. J Traffic Transp Eng Engl Ed 2024;11:481–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtte.2023.05.008.Search in Google Scholar

9. Jiang, D, Cao, Z, Gong, G, Wang, C, Gao, Y. VOCs inhibited asphalt mixtures for green pavement: emission reduction behavior, environmental health impact and road performance. J Clean Prod 2025;489:144671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2025.144671.Search in Google Scholar

10. Fan, Y, Hu, C, Wang, Z, Wang, H, Zhang, R, Jiang, D, et al.. Residential VOC from building materials: exposures, health risks, and ambient hazards. Sustain Cities Soc 2025;119:106080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2024.106080.Search in Google Scholar

11. Cao, X, Gu, D, Sun, H, Leung, KF, Mai, Y, Li, X, et al.. Intra-urban comparison of hazardous VOCs in Hong Kong: source apportionment and integrated risk assessment. Sustain Cities Soc 2025;120:106148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2025.106148.Search in Google Scholar

12. Fatiha, A, Karim, E, Mhamed, A, Farid, A. Enhancing performance of recycled aggregate concrete with supplementary cementitious materials. Clean Mater 2025;15:100298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clema.2025.100298.Search in Google Scholar

13. Chen, X, Qiao, L, Zhao, R, Wu, J, Gao, J, Li, L, et al.. Recent advances in photocatalysis on cement-based materials. J Environ Chem Eng 2023;11:109416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2023.109416.Search in Google Scholar

14. Fei, H, Wu, J, Zhang, J, Zhao, T, Guo, W, Wang, X, et al.. Photocatalytic performance and its internal relationship with hydration and carbonation of photocatalytic concrete: a review. J Build Eng 2024;97:110782. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2024.110782.Search in Google Scholar

15. Zhao, L, Hou, H, Wang, S, Wang, L, Yang, Y, Bowen, CR, et al.. Engineering Co single atoms in ultrathin BiOCl nanosheets for boosted CO2 photoreduction. Adv Funct Mater 2025;35:2416346. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202416346.Search in Google Scholar

16. Adebanjo, AU, Abbas, YM, Shafiq, N, Khan, MI, Farhan, SA, Masmoudi, R. Optimizing nano-TiO2 and ZnO integration in silica-based high-performance concrete: mechanical, durability, and photocatalysis insights for sustainable self-cleaning systems. Constr Build Mater 2024;446:138038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.138038.Search in Google Scholar

17. Kim, J-W, Mun, J-H, Kim, S, Yang, K-H, Sim, J-I, Jung, Y-B, et al.. Actual NOX and SOX removal rates in the atmospheric environment of concrete permeable blocks containing TiO2 powders, coconut shell powders, and zeolite beads. Constr Build Mater 2023;403:133032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.133032.Search in Google Scholar

18. Li, N, Yang, C, Huang, H, Lu, C. Functionalized cements incorporated with nanocomposite photocatalysts for self-cleaning applications. J Build Eng 2024;98:111077. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2024.111077.Search in Google Scholar

19. Khannyra, S, Luna, M, Gil, MLA, Addou, M, Mosquera, MJ. Self-cleaning durability assessment of TiO2/SiO2 photocatalysts coated concrete: effect of indoor and outdoor conditions on the photocatalytic activity. Build Environ 2022;211:108743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.108743.Search in Google Scholar

20. Grubeša, IN, Barišić, I, Habuda-Stanić, M, Grdić, D. Effect of CRT glass and TiO2 as a replacement for fine aggregate and cement on properties of pervious concrete paving flags. Constr Build Mater 2023;397:132426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132426.Search in Google Scholar

21. Wu, Q, Wu, S, Bu, R, Cai, X, Sun, X. Purification of runoff pollution using porous asphalt concrete incorporating zeolite powder. Constr Build Mater 2024;411:134740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.134740.Search in Google Scholar

22. Liu, G, Fei, H, Zhang, J, Wu, J, Feng, Z, Yang, S, et al.. Enhancement mechanism for mechanical and water purification performance of piezo-photocatalytic recycled aggregate pervious concrete containing hydrophobic BiOI/BaTiO3. Chem Eng J 2024;493:152596. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2024.152596.Search in Google Scholar

23. Masekela, D, Kganyakgo, LK, Modibane, KD, Yusuf, TL, Balogun, SA, Seleka, WM, et al.. Green synthesis and enhanced photocatalytic performance of Co-Doped CuO nanoparticles for efficient degradation of synthetic dyes and water splitting. Results Chem 2025;13:101971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rechem.2024.101971.Search in Google Scholar

24. Seremak, W, Jasiorski, M, Baszczuk, A, Winnicki, M. Durability assessment of low-pressure cold-sprayed TiO2 photocatalytic coatings: photocatalytic and mechanical stability. Surf Coat Technol 2025;497:131740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2025.131740.Search in Google Scholar

25. Rusek, J, Baudys, M, Fíla, V, Krýsa, J. Photocatalytic removal of VOCs on TiO2 nanotubular arrays: mass transfer limitations. J Environ Chem Eng 2024;12:113962. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2024.113962.Search in Google Scholar

26. Wang, Y, Zhang, H, Gao, W, Zhong, M, Su, B, Lei, Z. Plasmonic S-type Bi/TiO2@C heterojunction composites for efficient visible-light photocatalytic removal of multi-antibiotics and dyes. J Environ Chem Eng 2025;13:114987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2024.114987.Search in Google Scholar

27. Khannyra, S, Mosquera, MJ, Addou, M, Gil, MLA. Cu-TiO2/SiO2 photocatalysts for concrete-based building materials: Self-cleaning and air de-pollution performance. Constr Build Mater 2021;313:125419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.125419.Search in Google Scholar

28. Y Zhang, Zhou, Y, Dong, X, Xi, X, Dong, P. Recent advances in TiO2-based photocatalytic concrete: synthesis strategies, structure characteristics, multifunctional applications, and CFD simulation, (2024).496, 154186, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2024.154186,Search in Google Scholar

29. Luna, M, Delgado, JJ, Romero, I, Montini, T, Almoraima Gil, ML, Martínez-López, J, et al.. Photocatalytic TiO2 nanosheets-SiO2 coatings on concrete and limestone: an enhancement of de-polluting and self-cleaning properties by nanoparticle design. Constr Build Mater 2022;338:127349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.127349.Search in Google Scholar

30. Yang, Z, Xu, Y, Cai, X, Wu, J, Wang, J. Studying properties of pervious concrete containing recycled aggregate loaded with TiO2/LDHs and its liquid pollutant purification. Constr Build Mater 2023;406:133398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.133398.Search in Google Scholar

31. Zhang, J, Liu, Z. Fabrication and characterization of Eu2+-doped lanthanum-magnesium-gallium /TiO2-based composition as photocatalytic materials for cement concrete-related methyl orange (MO) degradation. Ceram Int 2019;45:10342–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2019.02.090.Search in Google Scholar

32. Khalaghi, M, Atapour, M, Momeni, MM, Karampoor, MR. Visible light photocatalytic efficiency and corrosion resistance of Zn, Ni, and Cu-doped TiO2 coatings. Results Chem 2025;13:102032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rechem.2025.102032.Search in Google Scholar

33. Hussein, H, Ibrahim, SS, Khairy, SA. Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using Hibiscus sabdariffa L: rapid Pb2+ ion removal, photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue, and biomedical applications. J Water Process Eng 2025;69:106649. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2024.106649.Search in Google Scholar

34. Vijaya Kumaran, A, Sharmila, A, Manoj Hadkar, V, Kumar Sishu, N, Mohanty, C, Roopan, SM, et al.. Sustainable production of ZnO/MgO nanocomposite for effective photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B and their other properties. Mater Sci Eng B 2025;313:117866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mseb.2024.117866.Search in Google Scholar

35. Khomutinnikova, LL, Evstropiev, SK, Meshkovskii, IK, Moskalenko, IV, Bagrov, IV, Skorb, EV. Intensive singlet oxygen photogeneration and photocatalytic activity of Sn,Fe-doped ZnO-based composites. J Photochem Photobiol Chem 2025;462:116254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotochem.2024.116254.Search in Google Scholar

36. Yang, M, Zhan, X-Q, Ou, D-L, Wang, L, Zhao, L-L, Yang, H-L, et al.. Efficient visible-light-driven hydrogen production with Ag-doped flower-like ZnIn2S4 microspheres. Rare Met 2025;44:1024–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12598-024-02979-0.Search in Google Scholar

37. Liaqat, M, Younas, A, Iqbal, T, Afsheen, S, Zubair, M, Kamran, SKS, et al.. Synthesis and characterization of ZnO/BiVO4 nanocomposites as heterogeneous photocatalysts for antimicrobial activities and waste water treatment. Mater Chem Phys 2024;315:128923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2024.128923.Search in Google Scholar

38. Song, MS, Patil, RP, Mahadik, MA, Jo, YJ, Park, J-H, Chae, W-S, et al.. Microwave-assisted CuO-modified porous ZnO nanosheet for photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants and antibacterial inactivation. J Environ Chem Eng 2024;12:114453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2024.114453.Search in Google Scholar

39. Safaralizadeh, E, Mahjoub, A, Janitabardarzi, S. Visible light-induced degradation of phenolic contaminants utilizing nanoscale TiO2 and ZnO impregnated with SR 7B (SR) dye as advanced photocatalytic systems. Ceram Int 2025;51:1958–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2024.11.170.Search in Google Scholar

40. Verma, N, Pathak, D, Kumar, K, Jeet, K, Nimesh, S, Loveleen, L, et al.. Photocatalytic, antibacterial and antioxidant capabilities of (Fe, Al) double doped ZnO nanoparticles with Murraya Koenigii leaf extract synthesized by using microwave assisted technique. Mater Chem Phys 2025;333:130422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2025.130422.Search in Google Scholar

41. Hamdan, MAH, Madon, RH, Hairom, NHH, Makhtar, SNNM, Ahmad, MK, Hamed, NKA, et al.. High-efficiency river water treatment via pilot-scale low-pressure hybrid membrane photocatalytic reactor (MPR) utilizing ZnO-Kaolin photocatalyst. J Water Process Eng 2024;68:106543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2024.106543.Search in Google Scholar

42. Peng, F, Ni, Y, Zhou, Q, Kou, J, Lu, C, Xu, Z. New g-C3N4 based photocatalytic cement with enhanced visible-light photocatalytic activity by constructing muscovite sheet/SnO2 structures. Constr Build Mater 2018;179:315–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.05.146.Search in Google Scholar

43. Mohamed, MA, Jaafar, J, Zain, MFM, Minggu, LJ, Kassim, MB, Rosmi, MS, et al.. In-depth understanding of core-shell nanoarchitecture evolution of g-C3N4@C, N co-doped anatase/rutile: efficient charge separation and enhanced visible-light photocatalytic performance. Appl Surf Sci 2018;436:302–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.11.229.Search in Google Scholar

44. Zhao, S-Z, Shi, R-D, Xiang, G-T, Hu, Y-D, Chen, J-J. Simultaneous electricity production and pollutant removal via photocatalytic fuel cell utilizing Bi2O3/TiO2 porous nanotubes decorated by g-C3N4. Fuel 2025;386:134306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2025.134306.Search in Google Scholar

45. Iqbal, S, Liu, J. Unveiling S-scheme synergies: synthesis and photocatalytic advancement of Au NRs-infused Fe2O3QDs/g-C3N4 hybrids–A new frontier in visible light-driven water splitting. J Environ Chem Eng 2024;12:114866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2024.114866.Search in Google Scholar

46. Sofia, G, Koventhan, C, Kanmani, S, Lo, A-Y. Green synthesized rGO/TiO2/g-C3N4 nanocomposites via Plectranthus amboinicus extract for efficient photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue: RSM optimization, antimicrobial and phytotoxicity assessment. J Environ Chem Eng 2025;13:115267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2024.115267.Search in Google Scholar

47. Zeng, X, Shu, S, Wang, X, Chen, J, Zhang, R, Wang, Y. Photocatalytic degradation of sulfamethazine using g-C3N4/TiO2 heterojunction photocatalyst: performance, mechanism insight and degradation pathway. Mater Sci Semicond Process 2024;181:108595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mssp.2024.108595.Search in Google Scholar

48. Guo, M, Chen, M, Xu, J, Wang, C, Wang, L. C, N-vacancies and Br dopant co-enhanced photocatalytic H2 evolution of g-C3N4 from water and simulated seawater splitting. Chem Eng J 2023;461:142046. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2023.142046.Search in Google Scholar

49. Xue, Q, Hu, K, Feng, Q, Lin, H, Dong, M, Hayat, K, et al.. Construction of C3N4/Ag2S p-n semiconductor heterojunction coupled with Ag-induced SPR effect on CF cloth for improving photocatalytic activity. J Environ Chem Eng 2024;12:114183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2024.114183.Search in Google Scholar

50. Xu, J, Li, Q, Shang, Y, Ning, X, Zheng, M, Jin, Z. Regulating the photoexcited carrier transfer efficiency over graphdiyne/Ag3PO4 S-Scheme heterojunction for photocatalytic hydrogen production. J Environ Chem Eng 2024;12:114878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2024.114878.Search in Google Scholar

51. Chen, Q, Zhang, Z, Yang, Z. Anti-bacteria performance of titanium dioxide nanotubes loaded Ag nanoparticles and carbon dots for photocatalytic under visible light. J Water Process Eng 2025;70:106873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2024.106873.Search in Google Scholar

52. Raman, R, Balasubramanian, D, Mohanraj, K, Jhansi, N. Analyzation of photocatalytic degradation efficiency of an Ag-doped α-Zn2V2O7 nanoparticle on methylene blue dye in sunlight exposure and its potential antimicrobial activities. Inorg Chem Commun 2025;172:113759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2024.113759.Search in Google Scholar

53. Korcoban, D, Huang, LZY, Elbourne, A, Li, Q, Wen, X, Chen, D, et al.. Electroless Ag nanoparticle deposition on TiO2 nanorod arrays, enhancing photocatalytic and antibacterial properties. J Colloid Interface Sci 2025;680:146–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2024.11.079.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

54. John, KI, Issa, TB, Ho, G, Nikoloski, AN, Li, D. Enhanced adsorption and photocatalytic degradation of organics using La-doped g-C3N4 with Ag NPs. Water Cycle 2025;6:S2666445325000029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watcyc.2025.01.002.Search in Google Scholar

55. Yang, D, Xia, Y, Xiao, T, Xu, Z, Lei, Y, Jiao, Y, et al.. Constructing Ag–TiO2-g-C3N4 S-scheme heterojunctions for photocatalytic degradation of malachite green. Opt Mater 2025;159:116652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2025.116652.Search in Google Scholar

56. Ge, Y, Xu, H-Q, Huang, Q, Jia, X, Ji, H, Ren, Q, et al.. Microwave-assisted synthesis of Ag/ZnO/diatomite composites for photocatalytic degradation of gaseous toluene. Inorg Chem Commun 2025;171:113543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2024.113543.Search in Google Scholar

57. Wang, Z, Gong, Z, Zhao, H. Enhancement of photocatalytic degradation performance under visible-light by the construction of heterogeneous structures of BiVO4-G/FTO worm-like bilayer films. J Solid State Chem 2024;339:124903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2024.124903.Search in Google Scholar

58. Zhao, C, Yue, L, Yuan, S, Ren, X, Zeng, Z, Hu, X, et al.. Enhanced photocatalytic N2 fixation and water purification using Bi/ZnSnO3 composite: mechanistic insights and novel applications. J Ind Eng Chem 2024;132:135–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2023.11.007.Search in Google Scholar

59. Pradhan, D, Biswal, SK, Singhal, R, Panda, PK, Dash, SK. Green nanoarchitectonics Ce-Co3O4/BiVO4 (p-n) heterojunction nanocomposite: dual functionality for photodegradation of Congo red and supercapacitor applications. Surf Interfaces 2024;52:104954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfin.2024.104954.Search in Google Scholar

60. Wang, Y, Xu, Y, Cai, X, Wu, J. Adsorption and visible photocatalytic synergistic removal of a cationic dye with the composite material BiVO4/MgAl–LDHs. Materials 2023;16:6879. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16216879.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

61. Shakir, I. Tungsten-doped BiVO4 and its composite with g-C3N4 for enhanced photocatalytic applications. Opt Mater 2024;150:115214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2024.115214.Search in Google Scholar

62. Lotfi, S, Assani, A, Saadi, M, Ait Ahsaine, H. Synthesis, structural and microstructural properties of Bismuth Vanadate BiVO4. Mater Today Proc 2023:S221478532304333X. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2023.08.080.Search in Google Scholar

63. Xu, Y, Wang, Y, Fan, W, Li, S-T, Yu, X. Preparation of adsorbed bismuth-based visible light photocatalytic materials and their effects on the performance of cement-based materials. Cem Concr Compos 2025;157:105911. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2024.105911.Search in Google Scholar

64. Geng, Q, Xie, H, He, Y, Chen, S, Dong, F, Sun, Y. In-situ designed Bi metal @ defective Bi2O2SO4 to enhance photocatalytic NO removal via boosted directional interfacial charge transfer. J Hazard Mater 2025;485:136951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2024.136951.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

65. Liu, X, Wu, K, Tang, Y, Qi, N, Zhang, Y, He, Y, et al.. Ti3C2 MXene-derived TiO2@C attached on Bi2WO6 with oxygen vacancies to fabricate S-scheme heterojunction for photocatalytic antibiotics degradation and NO removal. Chin Chem Lett 2025;36:110882. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2025.110882.Search in Google Scholar

66. Namade, LD, Band, SS, Pawar, PK, Patil, AR, Pedanekar, RS, Managave, KG, et al.. Ultraviolet light-driven degradation of organic dyes using SrTiO3 photocatalytic nanoparticles. Colloids Surf Physicochem Eng Asp 2025;708:135976. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2024.135976.Search in Google Scholar

67. Sharma, AK, Vaish, R, Singh, G. Unveiling the photocatalytic dye degradation potential of high-entropy perovskite (Bi0.2K0.2Na0.2Ca0.2Ba0.2)TiO3 ceramics. Ceram Int 2024:S0272884224061261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2024.12.451.Search in Google Scholar

68. Parwaiz, S, Khan, MM. Perovskites and perovskite-based heterostructures for photocatalytic energy and environmental applications. J Environ Chem Eng 2024;12:113175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2024.113175.Search in Google Scholar

69. Estrada-Pomares, J, Oliva, MDLÁ, Sánchez, L, De Miguel, G. Exploring the photocatalytic performance of (CH3NH3)2AgInBr6, a Pb-free perovskite, and the composite with a MgAlTi layered double hydroxide for air purification purposes. J Environ Chem Eng 2025;13:114934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2024.114934.Search in Google Scholar

70. Zhang, W, Chu, Y, Wang, C, Zhao, Y, Chu, W, Zhao, J. Enhancing photocatalytic hydrogen production efficiency in all-inorganic lead-free double perovskites via silver doping-induced efficient separation of photogenerated carriers. Sep Purif Technol 2025;357:130111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2024.130111.Search in Google Scholar

71. Chen, J, Zhang, Q, Song, J, Fu, H, Gao, M, Wang, Z, et al.. In situ synthesis of lead-free perovskite Cs3Bi2Br9/BiOBr Z-scheme heterojunction by ion exchange for efficient photocatalytic CO2 reduction. J Catal 2025;442:115874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcat.2024.115874.Search in Google Scholar

72. Cai, M, Chen, Y, Zhuo, Z, Lu, Y, Shuaib, SSA, Jiang, Y, et al.. Construction of SrTiO3/Ti3C2/TiO2 Z-scheme derived from multilayer Ti3C2 MXene for efficient photocatalytic overall water splitting. J Alloys Compd 2025;1010:177550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2024.177550.Search in Google Scholar

73. Xiao, Z, Yang, W, Wang, J, Cao, S, Yang, J, Zhu, M. The lead-free halide perovskite/UiO-66 with dual Lewis acid sites for efficient photocatalytic NO removal. Chem Eng J 2025;504:159022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2024.159022.Search in Google Scholar

74. Roudgar-Amoli, M, Abedini, E, Alizadeh, A, Shariatinia, Z. Understanding double perovskite oxides capabilities to improve photocatalytic contaminants degradation performances in water treatment processes: a review. J Ind Eng Chem 2024;129:579–619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2023.09.016.Search in Google Scholar

75. Munawar, T, Mukhtar, F, Batoo, KM, Mazhar, A, Nadeem, MS, Hussain, S, et al.. Sunlight-activated Mo-doped La2CuO4/rGO perovskite oxide nanocomposite for photocatalytic treatment of diverse dyes pollutant. Mater Sci Eng B 2024;304:117355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mseb.2024.117355.Search in Google Scholar

76. Zhao, Y, Yang, D, Yu, C, Yan, H. A review on photocatalytic CO2 reduction of g-C3N4 and g-C3N4-based photocatalysts modified by CQDs. J Environ Chem Eng 2025;13:115348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2025.115348.Search in Google Scholar

77. Riedel, R, Schowarte, J, Semisch, L, González-Castaño, M, Ivanova, S, Arellano-García, H, et al.. Improving the photocatalytic degradation of EDTMP: effect of doped NPs (Na, Y, and K) into the lattice of modified Au/TiO2 nano-catalysts. Chem Eng J 2025;506:160109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2025.160109.Search in Google Scholar

78. Jiang, X, Lu, J-X, Zhang, Y, Poon, CS. Enhancing photocatalytic efficiency and interfacial bonding on cement-based surfaces by constructing CaO-TiO2 hybrid catalysts. Cem Concr Compos 2025;157:105944. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2025.105944.Search in Google Scholar

79. Bright Singh, S, Murugan, M, Chellapandian, M, Dixit, S, Bansal, S, Sunil Kumar Reddy, K, et al.. Effect of fly ash addition on the mechanical properties of pervious concrete. Mater Today Proc 2023:S2214785323048460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2023.09.165.Search in Google Scholar

80. Chockalingam, T, Vijayaprabha, C, Leon Raj, J. Experimental study on size of aggregates, size and shape of specimens on strength characteristics of pervious concrete. Constr Build Mater 2023;385:131320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.131320.Search in Google Scholar

81. Liu, X, Zhang, X, Yan, P. Prediction model for elastic modulus of recycled concrete based on properties of recycled coarse aggregate and cementitious materials. Case Stud Constr Mater 2024;21:e04058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2024.e04058.Search in Google Scholar

82. Zhou, J, Zheng, M, Zhan, Q, Zhou, R, Zhang, Y, Wang, Y. Study on mesostructure and stress–strain characteristics of pervious concrete with different aggregate sizes. Constr Build Mater 2023;397:132322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132322.Search in Google Scholar

83. Li, T, Tang, X, Xia, J, Gong, G, Xu, Y, Li, M. Investigation of mechanical strength, permeability, durability and environmental effects of pervious concrete from travertine waste material. Constr Build Mater 2024;426:136175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.136175.Search in Google Scholar

84. Sha, F, Zhang, S, Sun, X, Fan, G, Diao, Y, Duan, X, et al.. Mechanical performance and pore characteristics of pervious concrete. Case Stud Constr Mater 2024;21:e03674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2024.e03674.Search in Google Scholar

85. Xia, D, Xia, P, Hu, J, Li, X, Zhan, Z. Optimization of mechanical properties of pervious recycled concrete using polypropylene fiber and waterborne epoxy resin. Structures 2024;63:106372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2024.106372.Search in Google Scholar

86. Sharma, R, Pal, B, Barman, S. Synergistic effect of adsorption and photocatalytic activity of Cu deposited fly ash-TiO2 composites for fuchsin blue removal under visible-solar light. Sol Energy 2025;287:113198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2024.113198.Search in Google Scholar

87. Xu, Y, Jin, R, Hu, L, Li, B, Chen, W, Shen, J, et al.. Studying the mix design and investigating the photocatalytic performance of pervious concrete containing TiO2-Soaked recycled aggregates. J Clean Prod 2020;248:119281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119281.Search in Google Scholar

88. Zhang, M, He, Z, Ren, H, Huang, Y. Bismuth molybdate tungstate/titanium dioxide/reduced graphene oxide hybrid with multistage heterogeneous structure for Norfloxacin and Rhodamine B removal through adsorption and photocatalytic degradation synergy. Mater Res Bull 2025;185:113314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.materresbull.2025.113314.Search in Google Scholar

89. Zhang, X, Shi, W, Wang, T, Wang, X, Li, C, He, W. Investigation on the dual roles of pollutants adsorption on the catalyst surface during photocatalytic process. J Water Process Eng 2024;63:105558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2024.105558.Search in Google Scholar

90. Huang, G, Zeng, D, Wei, M, Chen, Y, Ma, A. Novel g-C3N4@CaCO3 nanocomposite for excellent methylene blue adsorption and photocatalytic removal under visible light irradiation. Inorg Chem Commun 2025;172:113685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2024.113685.Search in Google Scholar

91. Shao, T, Zhen, W, Ma, Y, Chen, J. The adsorption and photocatalytic degradability of poly(lactic acid)/modified copper-based metal-organic frameworks meltblown fiber membranes on volatile organic compounds. J Environ Chem Eng 2024;12:114450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2024.114450.Search in Google Scholar

92. Zailan, SN, Mahmed, N, Bouaissi, A, Mubarokah, ZR, Norizan, MN, Mohamad, IS, et al.. Adsorption efficiency and photocatalytic activity of silver sulphide-activated carbon (Ag2S-AC) composites. Inorg Chem Commun 2025;171:113633. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2024.113633.Search in Google Scholar

93. Bautista-Cano, KI, Hinojosa-Reyes, L, Ruiz-Ruiz, EJ, Díaz Barriga-Castro, E, Guzmán-Mar, JL, Hernández-Ramírez, A. Efficient photocatalytic activity and selective adsorption of UiO-67 (Zr)/g-C3N4 composite toward a mixture of parabens. Environ Res 2024;258:119477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2024.119477.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

94. Bai, J, Zhang, X, Wang, C, Li, X, Xu, Z, Jing, C, et al.. The adsorption-photocatalytic synergism of LDHs-based nanocomposites on the removal of pollutants in aqueous environment: a critical review. J Clean Prod 2024;436:140705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.140705.Search in Google Scholar

95. Jia, Z-M, Zhao, Y-R, Shi, J-N. Adsorption kinetics of the photocatalytic reaction of nano-TiO2 cement-based materials: a review. Constr Build Mater 2023;370:130462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.130462.Search in Google Scholar

96. Yu, X, Li, Z, Liu, Z, Wang, K, Zhang, J, Yu, Z. PbWO4 improved the efficient photocatalytic adsorption and degradation of tetracycline and doxycycline by Cu2O. Process Saf Environ Prot 2024;191:2725–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2024.10.013.Search in Google Scholar

97. Chi, W, Yu, F, Dong, G, Zhang, W, Chai, D-F, Han, P, et al.. A novel peony-shaped ZnO/biochar nanocomposites with dominant {100} facets for efficient adsorption and photocatalytic removal of refractory contaminants. Colloids Surf Physicochem Eng Asp 2024;695:134291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2024.134291.Search in Google Scholar