Abstract

In this study, an innovative idea of preparing dual-phase micro-nano particle reinforced copper-based materials by one-step aluminothermic reduction method is proposed. That is, copper-based materials containing uniformly distributed dual-phase micro-nano particle reinforced phases were obtained by aluminothermic reduction reaction directly using aluminum powder, vanadium oxide, copper oxide, etc., as raw materials. A systematic investigation was conducted on the thermodynamic behavior of the reaction system for dual-phase micro-nano particle-reinforced copper matrix composites, accompanied by comprehensive characterization of the resultant metallic alloys and slag phases. The results show that the dual-phase micro-nano particle composite reinforced copper-based materials were successfully prepared by aluminothermic reduction method. There are 1–10 μm micron vanadium particles and 60–200 nm nano-vanadium-aluminum master alloy phases dispersed in the microstructure of copper-based materials. With the increase in V2O5 ratio, the size of micron vanadium particles in the prepared dual-phase micro-nano particle reinforced copper-based material gradually increases, and the size of Al x V y phase dispersed in the matrix gradually decreases. The inclusions in the copper matrix are mainly Al2O3, and the reducing slag is mainly composed of CaAl4O7, CaAl2O4, and Cu2O.

1 Introduction

Due to their exceptional electrical conductivity and mechanical strength, copper-based composites have become critical materials in advanced engineering applications, serving as key components in electrical connectors, high-speed rail contact wires, and integrated circuit lead frames [1,2]. With the rapid development of the power, electronics, and electromagnetic fields, higher requirements have been put forward for the comprehensive properties of copper-based materials, such as high-temperature mechanical properties, wear resistance, and electrical properties [3]. Particle strengthening refers to a strengthening method that introduces second-phase particles with high strength, high modulus, and certain size as reinforcing materials into the metal matrix, thereby improving the performance of metal matrix composites [4,5,6]. However, when the size of the second phase particles is small (d = 0.01–0.1 μm), it belongs to dispersion strengthening, and its strengthening mechanism is Orowan mechanism, which can significantly improve the strength of metal matrix composites. When the second phase particle size is large (d = 1.0–50 μm), it belongs to particle strengthening, and its strengthening mechanism is Ansel-Lenier mechanism, which can significantly improve the wear resistance of the material [7]. Zhu et al. fabricated a multiscale layered (Ti x , Nb1−x ) surface enhancement layer on a high-temperature Ti–Nb alloy substrate via the in situ solid-state diffusion method. This surface modification yielded a Ti–Nb alloy exhibiting significantly enhanced strength and wear resistance [8]. This demonstrates that the incorporation of micro-nano dual-phase particles within the alloy matrix significantly enhances both strength and wear resistance.

At present, the methods of introducing particle reinforced phase into copper matrix mainly include direct addition method and in situ synthesis method. The direct addition method is to directly add the second phase particles directly into the copper melt during the preparation of the copper-based material and stir evenly or uniformly mix the second phase particles with the copper powder before sintering. The former is called stirring addition method, and the latter is called powder metallurgy method. Copper matrix composites with excellent mechanical properties can be prepared by adding ceramic particles and other strengthening phases into copper by stirring addition method [9,10]. The stirring addition method has the advantages of simple operation, low cost, and high production efficiency. However, the stirring addition method has the disadvantages of poor interface bonding and uneven dispersion between the second phase particles and the copper matrix [11,12]. The problem of poor interfacial bonding between the second phase particles and the copper matrix was solved by using copper plating pretreatment of the second phase particles and adding carbide forming elements to the copper matrix [13,14]. By using ultrasonic dispersion, electromagnetic stirring, and other methods, the dispersion uniformity of particles in copper matrix is improved and the problem of uneven dispersion is solved [15,16].

Through the powder metallurgy method, the particle reinforced phase added to copper can be more uniform, so as to effectively improve the mechanical properties of copper matrix composite materials. Liu et al. developed wear-resistant and corrosion-resistant copper matrix composites by adding nano-Bi powder, SiC or ceramic hybrid composites, carbon nanotubes (CNT), and alumina nanoparticles to copper [17,18,19]. The in situ synthesis method is to directly synthesize the fine particle reinforced phase in the metal matrix, which has the characteristics of good bonding between the reinforced phase and the matrix interface and uniform dispersion. Shen et al. [20] prepared Cu–Cr alloy with Cr content of 0.47–4.92 wt%, high strength, high conductivity, and excellent tensile strength by the reduction reaction of Cr2O3 and Cu–Mg melt and heat treatment. Zhang et al. [21] adjusted the amount of Zr and B to make the in situ reaction between Zr and B in the copper melt to form micron-sized ZrB2 particles with contents of 0, 1.0, and 1.5 wt%, respectively. After aging treatment, nano-sized Cu5Zr precipitates were formed to obtain copper-based composites with good mechanical properties and electrical conductivity. The powder metallurgy method directly mixes the raw materials of the synthesized target particles during the mixing process, and prepares the alloy with TiC and TiB2 particle phases by in situ synthesis [22,23].

The aluminothermic reduction method is widely used in the preparation of high melting point ferroalloys such as ferromolybdenum, ferrotungsten, and ferrotitanium. Due to the presence of oxide inclusions, ferroalloys can only be used as additives or deoxidizers for steelmaking, but not as structural and functional materials [24,25,26]. Dou and Cheng et al. used aluminothermic reduction to obtain a high-temperature metal and slag mixed melt, and then combined with modern metallurgical technologies such as electromagnetic coupling refining and vacuum self-consuming refining to successfully prepare CuCr25∼40 and CuW50 contact materials [27,28]. The size of in situ synthesized tungsten particles in the prepared tungsten-copper composites is 0.82–2.03 μm. Dou et al. [29] combined magnesiothermic reduction with modern hydrometallurgy to prepare ultrafine W, Mo, Ti, and other high melting point metal powders. Nersisyan et al. [30] prepared spherical tungsten powder with particle size of 20–50 nm by molten salt assisted-magnesium thermal self-propagating high-temperature synthesis. Therefore, aluminothermic reduction has certain advantages in the preparation of ultrafine metal powder and copper-based materials containing ultrafine particles.

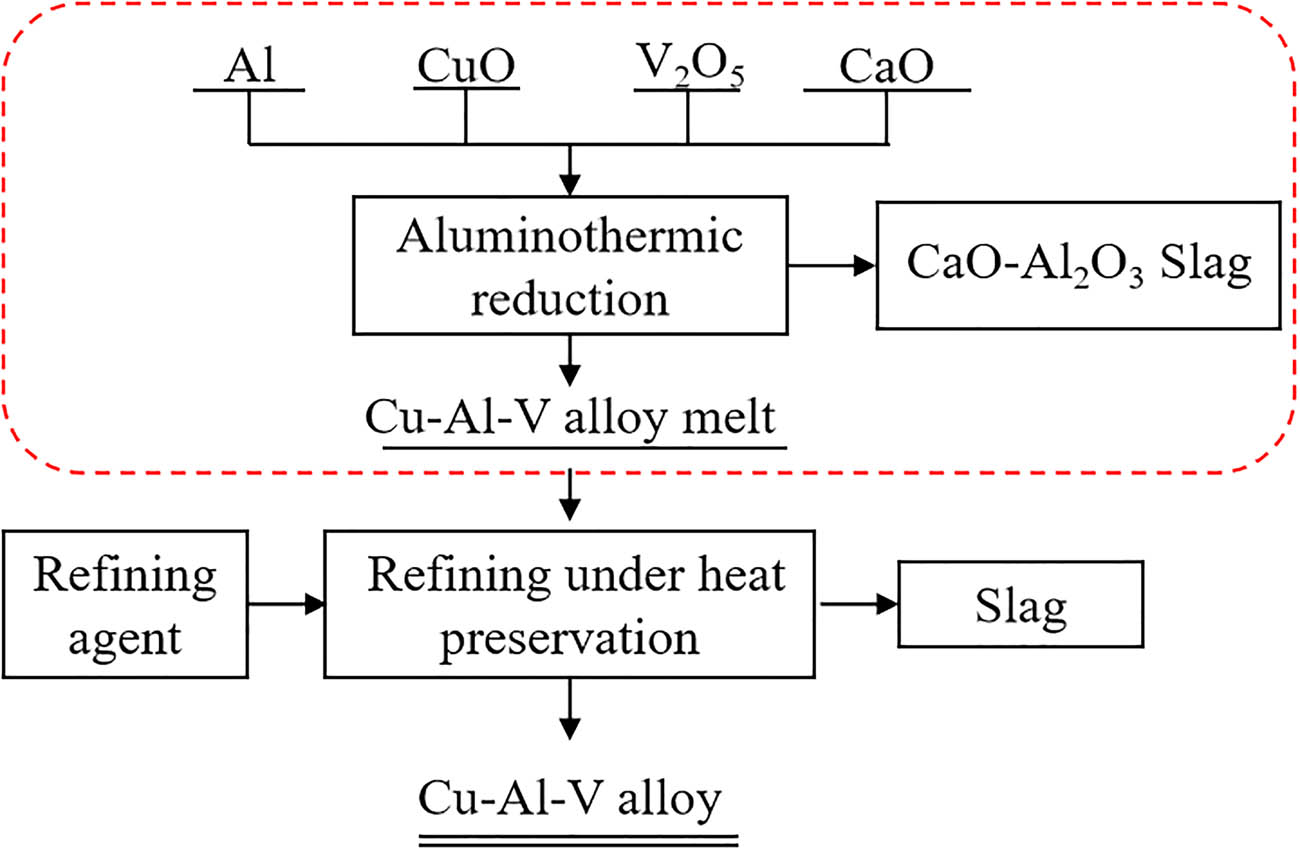

According to the design principle of metal matrix composites, a copper matrix composite containing micron-sized vanadium particles and nano-sized vanadium-aluminum intermediate compound particles was designed to develop a new type of high-strength and high-wear copper matrix material. Furthermore, a novel synthesis method utilizing aluminothermic reduction followed by refining under heat preservation was proposed for the preparation of this copper-based material. The flow chart is shown in Figure 1.

Short process of Cu–Al–V alloy preparation based on aluminothermic method.

Using CuO and V2O5 as raw materials, Al as reducing agent, and CaO as slagging agent, the high temperature gold-slag mixed melt was obtained by aluminothermic reduction. After preliminary slag-metal separation, the Cu–Al–V alloy melt containing micron V particles and nano-Al x V y was obtained. Then, the refining slag was added for refining under heat preservation to further remove the oxide inclusions, and the micro-nano dual-scale Cu–Al–V alloy ingot was obtained after casting cooling. In this study, the process of preparing Cu–Al–V melt containing different contents of micron vanadium particles and nano-vanadium-aluminum intermediate compounds by aluminothermic reduction was studied. Thermodynamic calculations were performed on the reaction system, followed by systematic characterization and analysis of the resulting Cu–Al–V melt composition and slag phase. This study provides a basis for the composition control of copper matrix composites containing different contents of micron vanadium particles and nano-vanadium-aluminum intermediate compounds, which is of great significance for the development of high-strength and high-wear-resistant copper alloys and their preparation technology.

2 Materials and experimental procedure

2.1 Materials

Vanadium pentoxide (99 wt% V2O5, particle size: 80–100 nm) and copper oxide (99.50 wt% CuO, particle size: 30–38 μm) were used as raw materials. Aluminum particle (99.5% pure, particle diameter: 0.1–3 mm) was used as a reductant. CaO (99% pure, particle diameter: ≤0.25 mm) and magnesium powder (99.5% pure, particle diameter: ≤0.2 mm) were supplied by Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd, China.

2.2 Experimental methods

First, the materials of copper oxide, vanadium pentoxide, and calcium oxide required for the experiment were put into the oven, dried for 12 h at 523 K, and then mixed for 1 h on the ball mill mixer. After the mixing, it was preheated at 353 K for 30 min. Finally, the preheated material is accumulated at the bottom of the graphite crucible, and the magnesium powder is used as the ignition agent to induce the self-propagating high-temperature synthesis (SHS) reaction. After natural cooling, the alloy ingot and slag are obtained. The mass ratios of CuO, V2O5, and Al particles in the three groups of experiments were 1:0.075:0.26, 1:0.25:0.35, and 1:0.36:0.40, respectively. The ratios of CaO in the ingredients can be expressed as R (C/A) (the molar ratio of CaO to Al2O3, and Al2O3 is a combustion product of the SHS reaction in theoretical stoichiometry). The R (C/A) in the experiments was 1.25.

2.3 Analysis methods

The microstructure of the alloy was observed by an inverted metallographic microscope (Axio Vert A1, Zeiss, Germany). Cu–Al–V composites were characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, JSM-7800F, Hitachi, Japan). X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (XRF; Thermo Scientific ARL 4460, Germany) was used for accurate determination of chemical composition in alloys. The nanoparticles in the alloy were characterized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEM-2100, JEOL, Japan). The slag obtained by aluminothermic reduction was characterized by X-ray diffractometer ( Model D8 Bruker, Germany). The Cu k-α1 source was 40 kV, 40 mA.

In order to further analyze the size and morphology of inclusions in copper-aluminum-vanadium composites, the inclusions in copper-aluminum-vanadium composites with V content of 5, 15, and 20% were extracted. The tungsten-copper composite sample was placed in a mixed solution of FeCl3 and dilute hydrochloric acid to completely dissolve the copper matrix in the sample, and then ultrasonically cleaned with pure water. Finally, the inclusion particles were obtained by vacuum drying. Then, the morphology and phase of the extracted inclusions were characterized by SEM, and the particle size of the extracted inclusions was counted by ImageJ.

3 Results and discussion

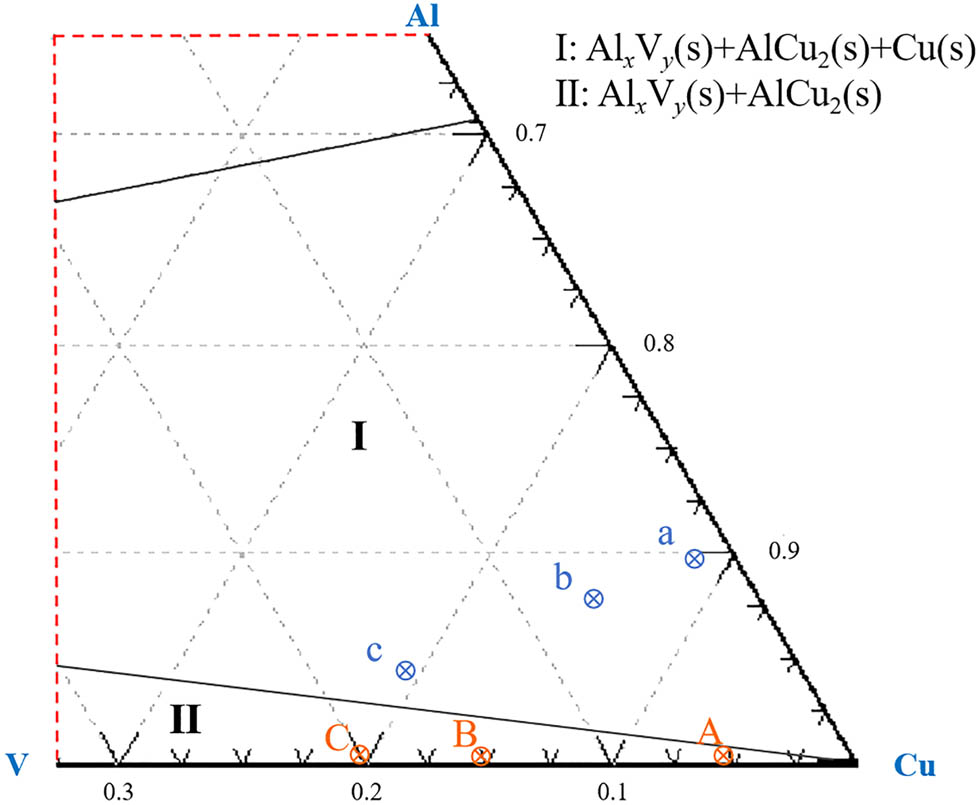

Based on the principle of thermodynamic equilibrium, the phase equilibrium relationship of Cu–Al–V system at 273 K was simulated by Factsage 6.4 software. The equilibrium phase diagram of Cu–Al–V ternary system is shown in Figure 2. The marked points A, B, and C in the Figure are the projection positions of the theoretical alloy composition calculated by HSC6.0 software in the phase diagram. The corresponding experimental groups a, b, and c are determined by the content of Cu–Al–V elements in the alloy measured by XRF, and the mass fraction of vanadium is distributed in the range of 5–20%. Thermodynamic analysis shows that when the system is in equilibrium, the composition points are located in region I of the phase diagram, but the experimental data show that all the measured points are concentrated in region II. The content of aluminum in the alloy is significantly higher than that of the calculated aluminum content. On the one hand, it is because Al exists in the alloy in the form of inclusions such as intermediate phase Al x V y (s) and alumina. On the other hand, the Gibbs free energy data of the Al x V y (s) phase are not included in the HSC6.0 thermodynamic database, which leads to the influence of the formation of the phase on the aluminum element in the theoretical calculation, resulting in the deviation of the calculated aluminum content from the measured value.

Equilibrium diagram of the Cu–Al–V system at 273 K.

According to the proportion of components, the equilibrium point of the experiment is in region II. The results show that the combustion product is solid, and it is difficult to separate the alloy from the slag phase [31]. Therefore, calcium oxide is added to the system to produce (CaO) x (Al2O3) y with low viscosity and low melting point, which accelerates the separation of the alloy from the slag [32,33]. In this study, the aluminothermic reduction method is used to control the content of vanadium, so that vanadium pentoxide reacts with aluminum to form metal vanadium and nano-intermediate phase Al x V y (s) [34].

3.1 Thermodynamics

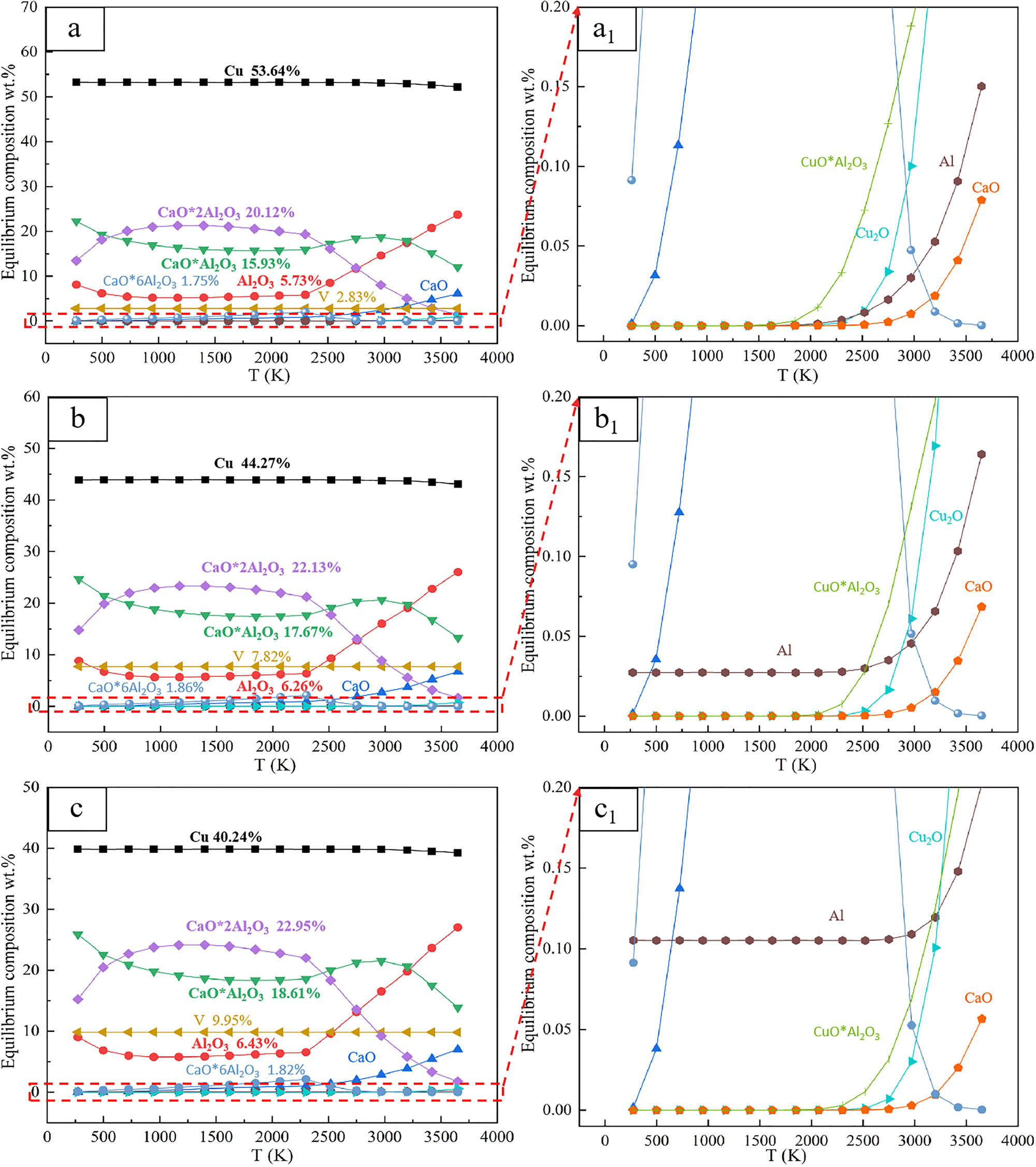

Based on the principle of minimal Gibbs free energy change, in this study, the thermodynamic equilibrium of the CuO–Al–V2O5–CaO system was calculated, by the equilibrium compositions module of HSC Chemistry 6.0. And the results are shown in Figure 3. The thermodynamic equilibrium diagrams of a, b, and c are 5, 15, and 20% of the V2O5 ratio, respectively.

Thermodynamic equilibrium in CuO–Al–V2O5–CaO system. a, b and c are the thermodynamic equilibrium diagrams of the target vanadium content of 5, 15 and 20%, respectively. a1, b2 and c3 are the local enlarged diagrams of a, b and c, respectively.

Figure 3 shows that the alloy phase of the system is mainly composed of Cu and V, and the slag phase is mainly CaO·2Al2O3, CaO·Al2O3, Al2O3, and CaO, accompanied by a small amount of CaO·6Al2O3. By comparing the three thermodynamic equilibrium diagrams of the vanadium content of 5% (a), 15% (b), and 20% (c), it can be concluded that the phase content of Al2O3, CaO·2Al2O3, and CaO·Al2O3 remained relatively stable in the temperature range of 273–2,300 K. When the temperature rises to the range of 2,300–3,650 K, the content of CaO·2Al2O3 and CaO·Al2O3 decreases with the increase in temperature, while the content of CaO and Al2O3 shows an upward trend. This shows that in this temperature range, the increase in temperature is not conducive to the formation of low melting point calcium aluminate slag phases such as CaO·Al2O3 and CaO·2Al2O3, but it will promote the side reactions of Cu2O and CuO·Al2O3.

Compared with a, b, c in Figure 3, it can be found that the V content and Al2O3 slag content in the alloy phase increase with the increase in V2O5 addition, which confirms that the reduction reaction of V2O5 is strengthened. The contents of CaO·2Al2O3 and CaO·Al2O3 in the slag phase increase significantly with the increase in V2O5 content, indicating that the introduction of V2O5 is beneficial to promote the formation of low melting point calcium aluminate. This phase composition change is beneficial to increase the density difference between the metal phase and the slag phase, thereby improving the metal and slag separation effect. Comparing the variation trend of Al content in Fig 3a1, b1, and c1, it is found that there is a deviation between the actual Al content calculation result and the theoretical prediction. It is found that this phenomenon is due to the fact that the HSC6.0 thermodynamic database does not contain the V x Al y intermetallic phase, resulting in a deviation in the distribution calculation of aluminum in the alloy phase.

3.2 Characterization of Cu–Al–V alloys

3.2.1 Metallographic structure analysis

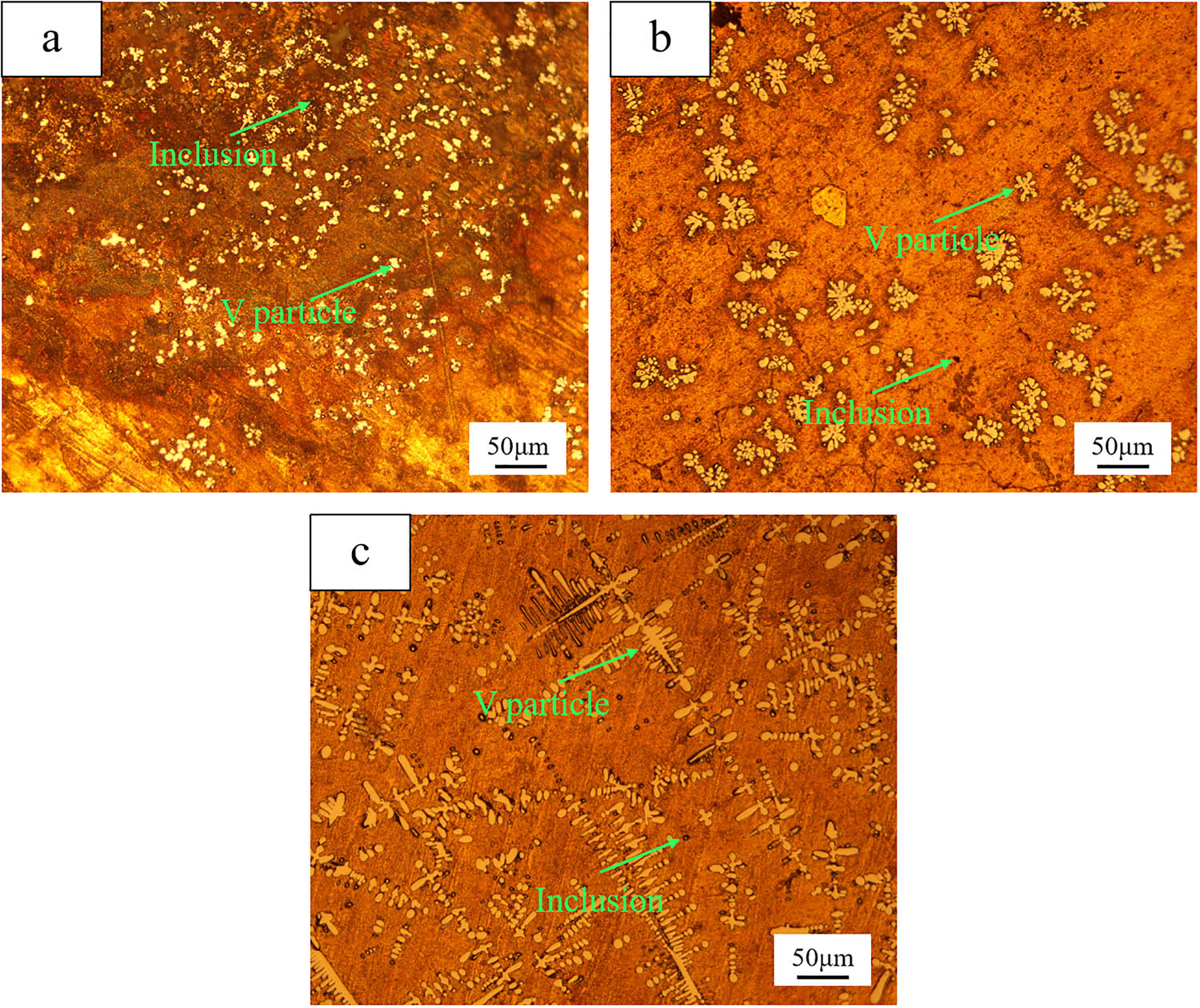

Figure 4 shows the microstructure evolution of Cu–Al–V alloys with different target vanadium contents (5, 15, 20%).

Cu–Al–V alloy metallographic diagram. a, b and c are the metallographic diagram of the target vanadium content of 5, 15 and 20%, respectively.

In Figure 4a, the vanadium particles are obviously agglomerated, the size distribution is uneven, and there are many incompletely separated slag phase inclusions in the matrix. In Figure 4b, the agglomeration of vanadium particles is reduced, the uniformity of dispersion distribution is significantly improved, and the number of slag inclusions is reduced. In Figure 4c, the vanadium particles show a typical dendritic morphology and are evenly distributed along the matrix. The slag phase inclusions are very few and the dispersion is the lowest. Combined with the distribution characteristics of vanadium particles and the effect of slag phase separation, it can be concluded that with the increase in V2O5 ratio, the distribution uniformity of vanadium particles is gradually improved, and the number of slag inclusions is decreasing. This phenomenon is consistent with the thermodynamic calculation results (Figure 3) in which the increase in V2O5 content promotes the formation of low melting point calcium aluminate slag phase.

3.2.2 Microstructure analysis

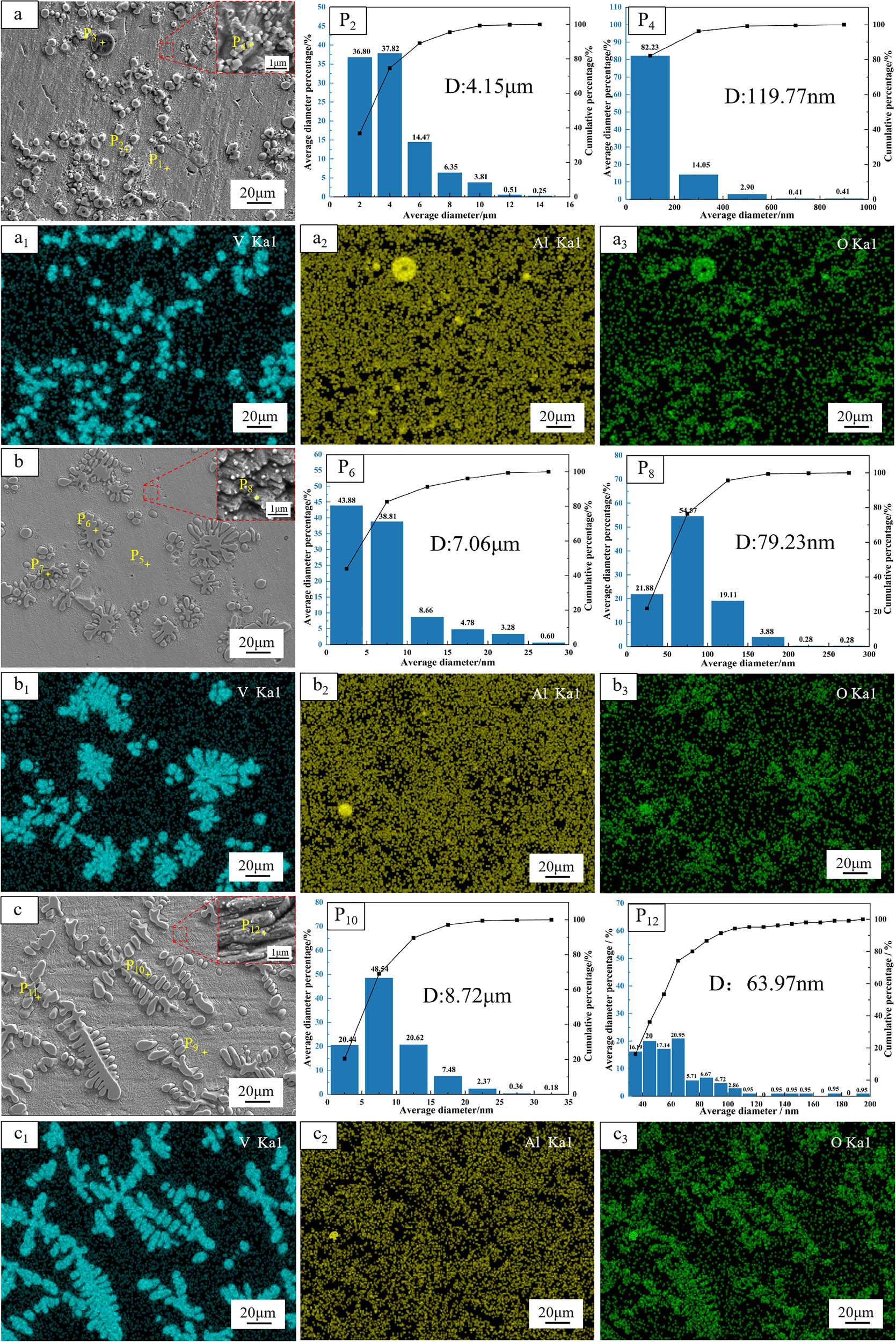

Figure 5 is the scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of different vanadium contents.

SEM images, particle size analysis and phase analysis of Cu-Al-V alloys with target. a, b, c represent the gold SEM images of the target vanadium contents of 5, 15, and 20% respectively, vanadium content of 5, 15 and 20%, a1–a3, b1–b3 and c1–c3 are element distribution, P2, P6, P10 are V particle size analysis, P4, P8, P12 vanadium–aluminum intermediate alloy phase particle size distribution.

From the a, b, c diagrams and element distribution diagrams, it can be seen that the alloy is mainly gray copper matrix, unevenly distributed with gray-white particles and black inclusions. Vanadium element is mainly distributed on gray-white particles, and a very small number is distributed on copper matrix. The aluminum and oxygen elements are mainly distributed on the black inclusions.

When the target vanadium content is 5%, the gray-white vanadium particles are approximately spherical, but there is local agglomeration. The average size is 4.15 μm, and the particle size range is between 0 and 10 μm. When the target vanadium content is 15%, the vanadium particles are snowflake-like and evenly distributed, with an average size of 8.72 μm and a particle size range of 0–25 μm. When the target vanadium content is 20%, the vanadium particles are further coarsened and present a dendritic distribution, and the distribution is more uniform. The average size is 7.06 μm, and the particle size range is between 0 and 35 μm.

In order to further analyze the copper matrix, the copper matrix was further enlarged, and it was found that white nanoparticles were distributed on the copper matrix. When the target vanadium content is 5%, the dispersed nanoparticles on the copper matrix are cubic, with an average size of 119.77 nm and a particle size distribution range of 0–600 nm. When the target vanadium content is 15%, the morphology of the nanoparticles on the copper matrix is transformed into a sphere, the average size is reduced to 79.23 nm, and the particle size distribution is narrowed to 0–200 nm. When the target vanadium content is 20%, the nanoparticle phase is still spherical, but the average size is further reduced to 63.97 nm, and the particle size distribution is concentrated at 0–120 nm. The analysis of black inclusions on copper matrix shows that when the target vanadium content is 5%, the size of black inclusions is large and obvious. As the V2O5 ratio increases, the inclusions gradually decrease and are distributed in the middle of the vanadium particles, which indicates that the inclusions in the middle of the vanadium particles are not easily separated from the copper melt. It can be seen that with the increase in V2O5 ratio in the alloy, the number of unseparated slag phases in the alloy decreases significantly, which is consistent with the thermodynamic calculation results ( formation of low melting point calcium aluminate slag phase). It is confirmed that the increase in V2O5 ratio in the alloy is beneficial to improve the fluidity of slag phase, thus improving the separation efficiency of slag and metal.

In summary, the increase in V2O5 ratio promotes the uniform coarsening and dendrite growth of vanadium particles by regulating the aluminothermic reduction kinetic process, while inhibiting the coarsening of nanophase and enhancing its dispersion strengthening effect. This process is accompanied by a significant reduction in slag phase residues, indicating that the increase in V2O5 ratio can simultaneously optimize the microstructure of Cu–Al–V alloy and the separation efficiency of metal and slag, which provides an important basis for the design of high-performance copper matrix composites. Micron-sized vanadium particles were observed in all alloys with varying vanadium contents, which is consistent with the thermodynamic calculations predicting the precipitation of elemental vanadium, as shown in Figure 3.

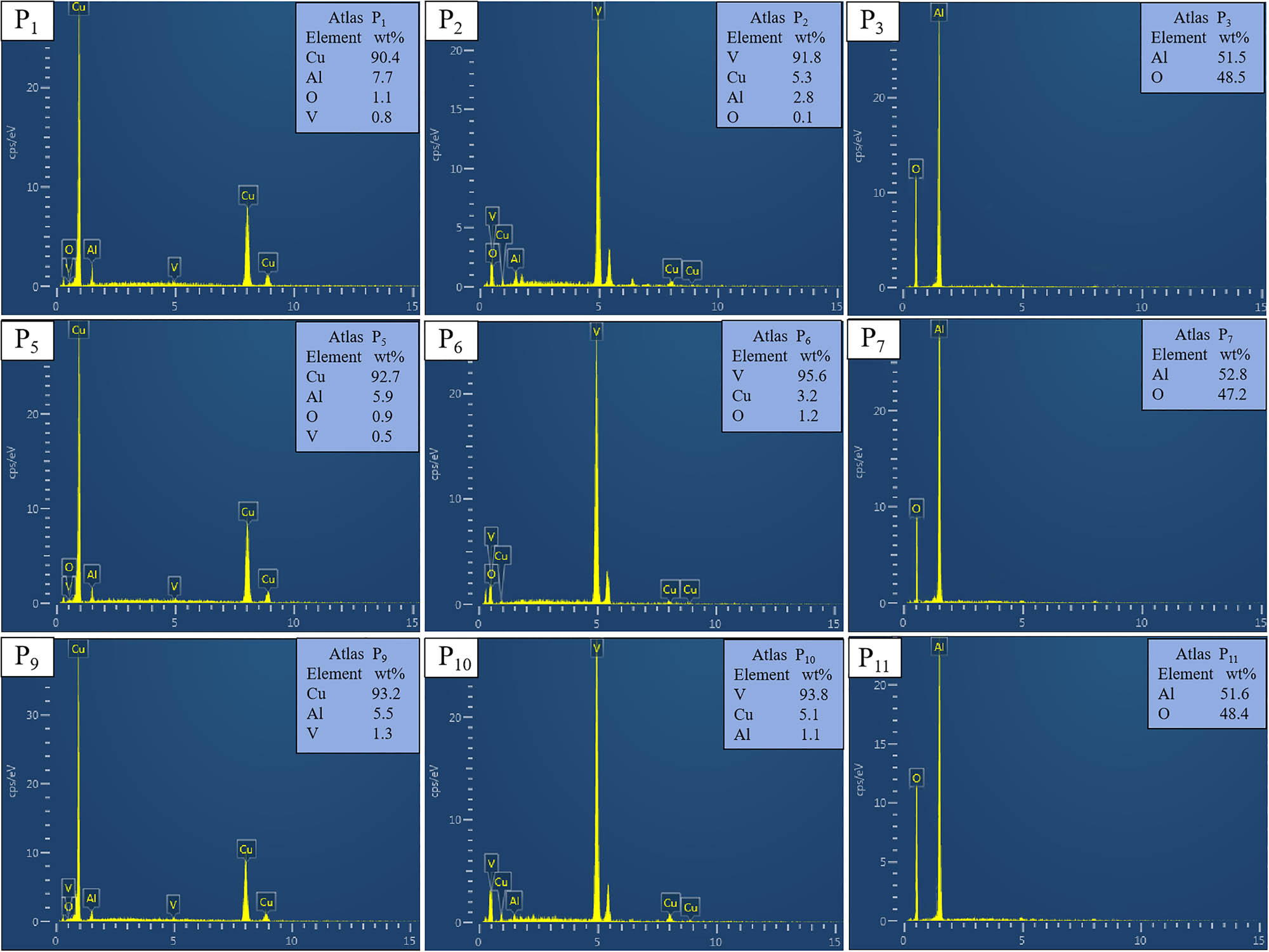

Figure 6 reveals the element distribution characteristics and inclusion composition of Cu–Al–V alloys with different target vanadium contents (5, 15, and 20%) by energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) surface distribution and micro-point analysis.

EDS analysis diagram of Cu–Al–V alloy; P1, P5, and P9 are EDS analysis of alloy matrix, P2, P6, and P10 are EDS analysis of V particles, and P3, P7, and P11 are EDS analysis of inclusions.

Combined with the microstructure of Figure 5 and the quantitative composition data of Figure 6, it can be concluded that: Figure P1, P5, and P9 are mainly copper elements, accompanied by a small amount of V and Al solid solution, indicating that the matrix is a solid solution phase dominated by Cu. P2, P6, and P10 are mainly vanadium elements, corresponding to the vanadium particle phase observed in Figure 5. P3, P7, and P11 are inclusion phase diagrams, in which P3, P7, P11 point to Al:O atomic ratios close to 2:3, consistent with the theoretical composition of Al2O3. In summary, EDS analysis confirmed that there was significant element differentiation among the matrix, particle phase, and inclusions of Cu–Al–V alloy.

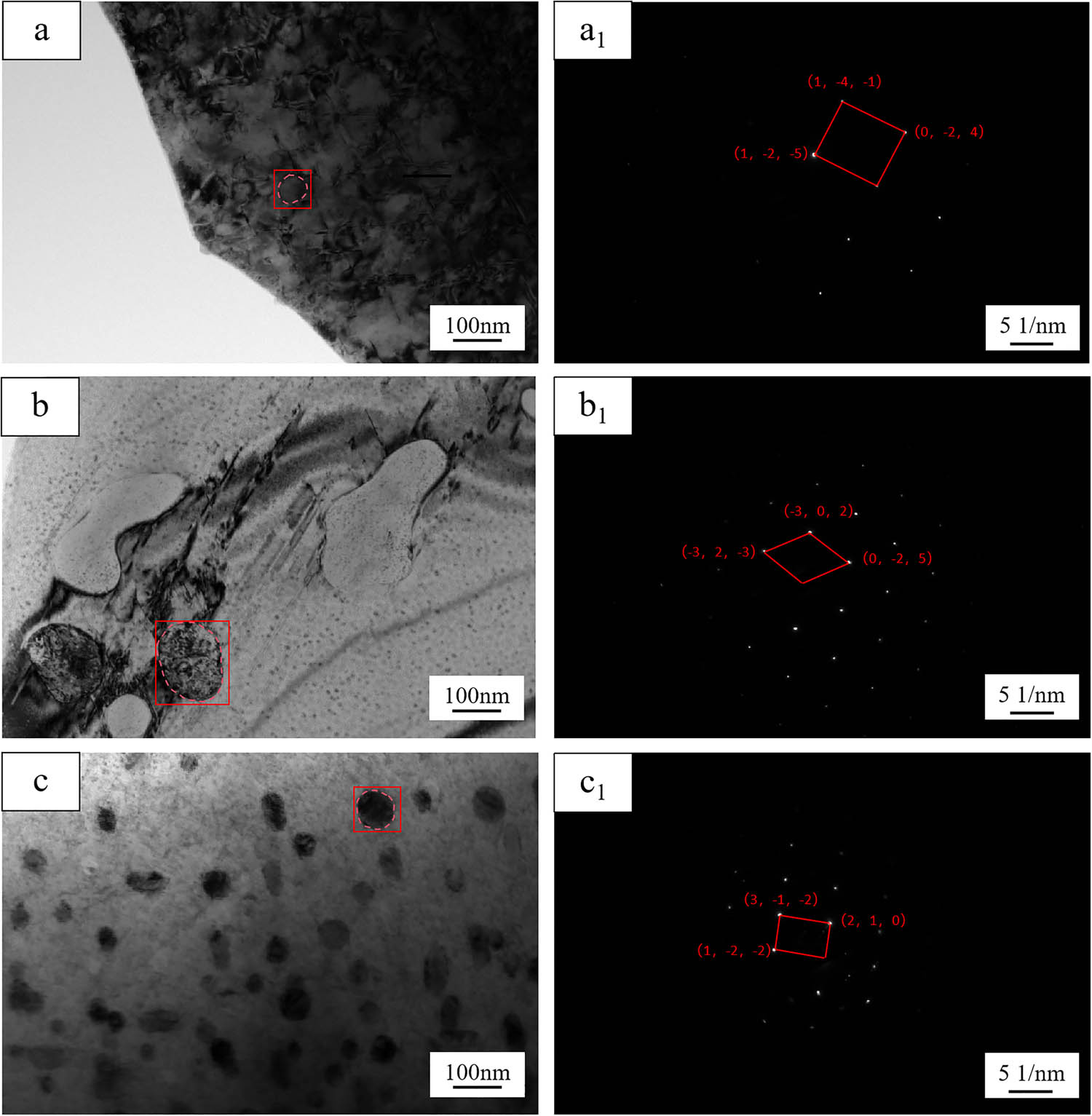

In order to further explore the nanoparticle phase on the copper matrix, it was characterized and analyzed by TEM, as shown in Figure 7.

TEM images of nanoparticles in Cu–Al–V alloy: a, b, and c are nanoparticle images with vanadium content of 5, 15, and 20%, respectively; a1, b1, and c1 are the diffraction patterns of the marked regions in a, b, and c.

In Figure 7a, the matrix nanoparticles are sparsely distributed, and the phase is determined to be Al3V by SAED spot calibration. The crystal band axis is [−9,−2,−1], tetragonal structure, and the space group is I4/mmm. The distribution of nanoparticles in Figure 7b still has local aggregation. SAED analysis shows that the crystal belt axis is [−4,−15,−6], which confirms that the phase is hexagonal Al23V4, and the space group is P63/mmc. The nanoparticles in Figure 7c are uniformly dispersed. SAED calibration shows that the phase is AlV3, crystal zone axis [2,4,5], simple cubic structure, space group Pm-3m. The transformation from Al3V to AlV3 reflects the significant effect of the increase in vanadium activity on the stability of Al–V intermetallic compounds, which is consistent with the composition-temperature dependence of Al–V binary phase diagram [35,36]. TEM analysis reveals the composition-structure-size co-evolution of Al x V y nanophase in Cu–Al–V alloy. The increase in V2O5 ratio drives the transformation of nanophase from Al3V to AlV3 by adjusting the Al/V atomic. The calculated phase compositions of vanadium metal and Al x V y intermetallic compounds (Figures 2 and 3) exhibit striking consistency with the experimentally determined phase analysis results of the alloy (Figures 5–7). This close agreement robustly validates the feasibility of synthesizing dual-phase micro-nano alloys via metallothermic reduction.

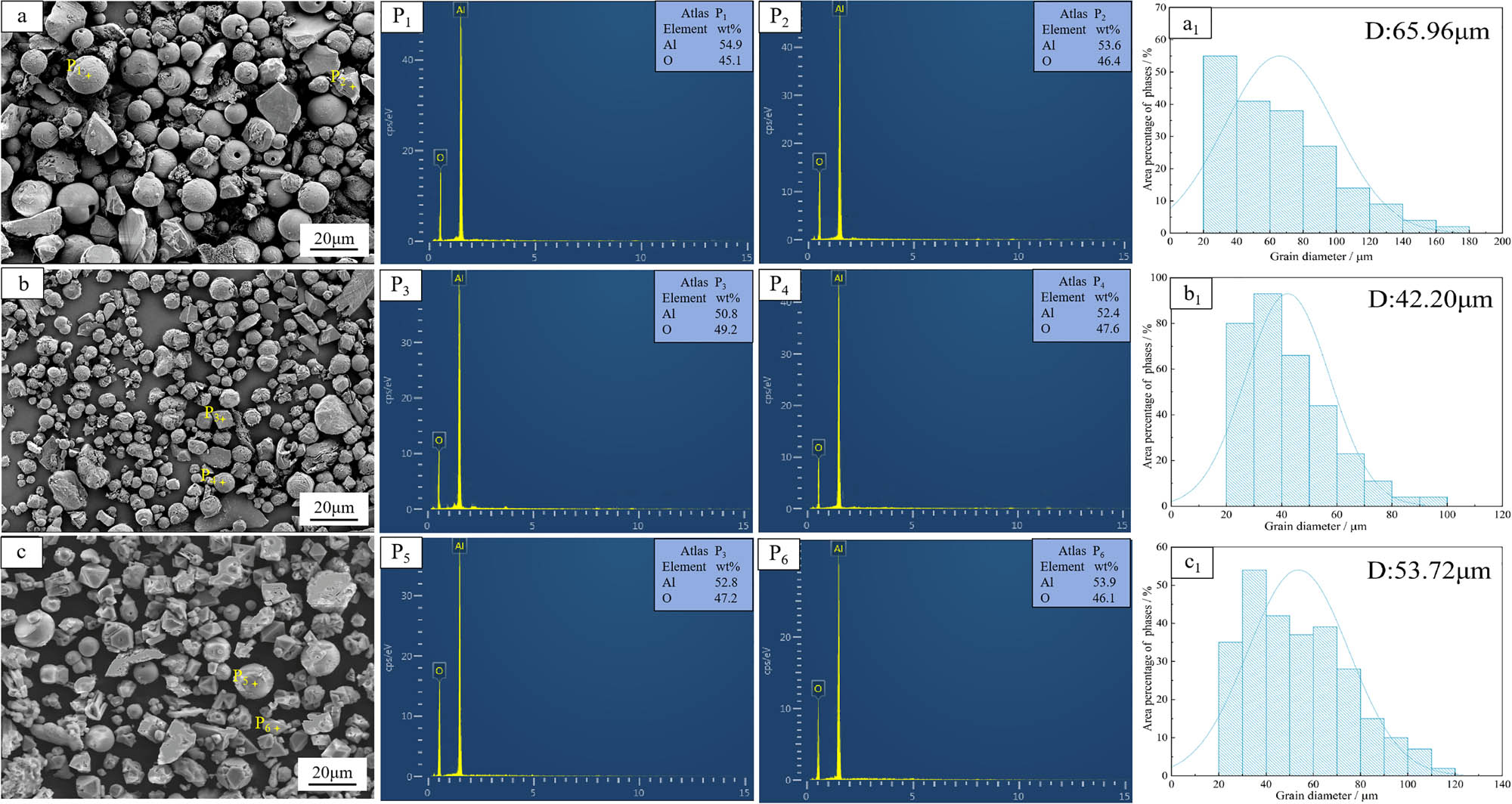

In order to further study the variation in inclusions in the alloy, the bulk alloy was dissolved with FeCl3 solution to obtain inclusions in the alloy, as shown in Figure 8.

SEM images of inclusions in Cu–Al–V alloy: (a, b, and c) SEM images of inclusions in the V content of 5, 15, and 20%, respectively. (P1–P6) EDS maps of the marker points in a, b, and c. (a1, b1, and c1) Particle size analysis of a, b, and c.

When the content of V is 5%, the inclusions are mainly spherical, accounting for 58.90%, accompanied by some irregular particles. The EDS spectrum shows that the atomic ratios of Al and O of spherical and irregular particles are 2.03:2.82 and 1.98:2.90, respectively, which are highly consistent with the theoretical value of Al2O3 (2:3). It is confirmed that both spherical and irregular particles are alumina phase, and the average particle size is 65.96 μm. When the V content is 15%, the proportion of spherical inclusions decreases to 51.78%, and the irregular alumina phase increases. The atomic ratio of Al and O is maintained at 2:3, and the phase is still Al2O3, and the average particle size is reduced to 42.20 μm. When the V content is 20%, the spherical inclusions are at least 32.24%. EDS analysis shows that the atomic ratio of Al to O is close to 2:3. It is inferred that the inclusions are alumina, and the average particle size is 53.7 2μm.

As the V2O5 ratio gradually increases, the spherical alumina in the alloy gradually decreases, which may be due to the increase in V2O5 ratio inhibiting the transformation of irregular alumina (γ-Al2O3) to spherical alumina (α-Al2O3). The adiabatic temperatures of different V2O5 ratio are calculated using formula (1). The adiabatic temperatures of 5, 15, and 20% vanadium contents are 2569.15, 2489.15, and 2413.15 K, respectively.

Therefore, with the increase in the V2O5 ratio, the adiabatic temperature of the system decreases, which is not conducive to the transformation of metastable γ-Al2O3 to stable α-Al2O3, resulting in the decrease in spherical alumina in the alloy [37,38,39].

3.3 Characterizations of the slag

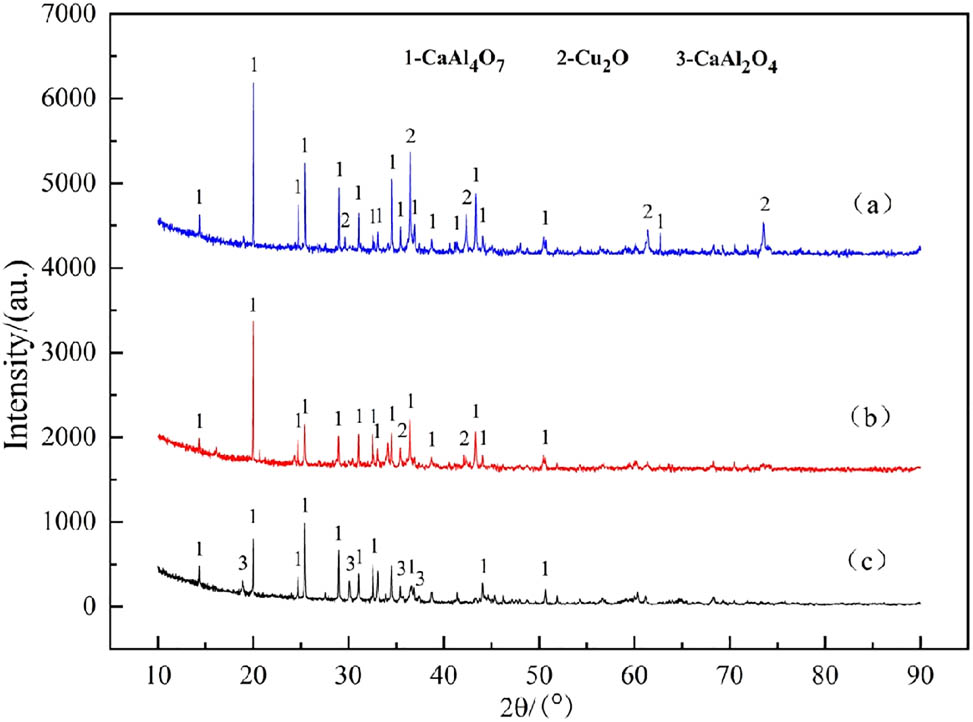

Figure 9 is the phase composition of the slag after aluminothermic reduction.

XRD pattern of Cu–Al–V slag phase with V2O5 ratio of 5% (a), 15% (b), and 20% (c).

The characteristic diffraction peaks of CaAl₄O₇ and Cu2O were clearly detected in diagram (a), indicating that calcium aluminate and cuprous oxide are the main stable phases of the slag system under this condition, which was consistent with the thermodynamic trend of Al preferential reduction of Cu2O in the aluminothermic reduction reaction. In Figure (b), CaAl₄O₇ and Cu2O are still the main phases, and the intensity of Cu2O peak is significantly weakened, which reflects that the increase in V2O5 ratio enhances the reduction efficiency of reducing agent to Cu2O, resulting in the decrease in residual amount. The diffraction peaks of CaAl₄O₇ and CaAl2O4 appear in Figure (c), and the diffraction peak of Cu2O is basically not detected, indicating that the reduction reaction tends to be complete when the V2O5 ratio reaches 20%, and the copper oxide is completely reduced to the metal phase. The transformation of CaAl₄O₇ to CaAl2O4 may be related to the increase in the ratio of CaO/Al2O3. When the ratio of CaO/Al2O3 increases, the viscosity of the slag decreases [40,41,42].

Table 1 is the composition of reducing slag with V2O5 ratio of 5% (1#), 15% (2#), and 20% (3#), respectively. It can be seen from Table 1 that the reducing slag composition includes Al2O3, CuO, CaO, V2O5, etc. With the increase in V2O5 content in the material, the contents of Al2O3, CaO, and V2O5 in the slag gradually increased, and the content of CuO gradually decreased. The results show that the main phase of the reduced slag in 1# and 2# is calcium aluminate CaAl₄O₇, and its layered structure leads to higher viscosity of the slag. With the increase in V2O5 content, CaAl₄O₇ transforms to CaAl₂O₄, and the cubic spinel structure reduces the melt viscosity. At the same time, the formation of CaAl₂O₄ phase reduces the melting point of slag system to 1,350–1,400°C, and the interfacial tension between slag and gold decreases, which significantly improves the separation efficiency of metal and slag. The increase in V content promotes the reduction of CuO.

Composition of reducing slag (wt%)

| Component | Al2O3 | CuO | CaO | V2O5 | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1# | 53.81 | 20.38 | 16.73 | 3.94 | 5.14 |

| 2# | 59.79 | 5.78 | 18.62 | 13.33 | 2.48 |

| 3# | 62.57 | 1.28 | 20.86 | 13.61 | 1.68 |

4 Conclusion

The Cu–Al–V alloy melts reinforced by micro-nano particles was successfully prepared by aluminothermic reduction method. The micron-sized vanadium particles synthesized in situ in the alloy range from 1 to 10 μm, and the nano-sized Al3V, Al23V4, AlV3 particles range from 60 to 200 nm.

The microstructure of Cu–Al–V alloy melts prepared by aluminothermic reduction is mainly composed of nano-sized Al3V, Al23V4, AlV3 particles dispersed in copper matrix, micron-sized vanadium particles and spherical, irregularly shaped alumina inclusions. With the increase in V2O5 ratio, the particle size of vanadium increases and the particle size of nano vanadium aluminum intermediate alloy decreases gradually. The inclusions are composed of spherical and irregular alumina, and the proportion of spherical alumina gradually decreases from 58.90 to 32.24%.

The slag obtained after reduction is mainly composed of CaAl4O7, CaAl2O4, and Cu2O. With the increase in V2O5 ratio, the high melting point CaAl4O7 in the slag decreases and the low melting point CaAl2O4 increases, which is beneficial to the separation of slag and metal.

Acknowledgments

The authors are especially thankful to the Zhongyuan Youth Talent Support Program (No. Chu Cheng [2024]), the Henan Province Natural Science Foundation Project (No. 252300420026), the Key Technologies R&D Program of Henan Province (No. 242102231024), the Youth Talent Support Program of He Luo (No. 2024HLTJ18), the Key Technologies R&D Program of Sanmenxia City (No. 2023L02012), the Foundation for Key Teacher by Henan University of Science and Technology (No. 13450026).

-

Funding information: The Zhongyuan Youth Talent Support Program (No. Chu Cheng [2024]), the Henan Province Natural Science Foundation Project (No. 252300420026), the Key Technologies R&D Program of Henan Province (No. 242102231024), the Youth Talent Support Program of He Luo (No. 2024HLTJ18), the Key Technologies R&D Program of Sanmenxia City (No. 2023L02012), the Foundation for Key Teacher by Henan University of Science and Technology (No. 13450026).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Wu Q, Xu Z, Huang W, Qi X, Wu J, Du J, et al. Enhanced strength of a high-conductivity Cu-Cr alloy by Sc addition. Rare Met. 2024;43(11):6054–67.10.1007/s12598-024-02947-8Search in Google Scholar

[2] Yi X, Ma A, Zheng Y, Li Y, Li J, Zhao M, et al. Elucidating different selective corrosion behavior of two typical marine aluminum bronze alloys from the perspective of constituent phases. Corros Sci. 2024;235:235112167.10.1016/j.corsci.2024.112167Search in Google Scholar

[3] Wang YD, Liu M, Yu BH, Wu LH, Xue P, Ni DR, et al. Enhanced combination of mechanical properties and electrical conductivity of a hard state Cu-Cr-Zr alloy via one-step friction stir processing. J Mater Process Technol. 2021;288:116880.10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2020.116880Search in Google Scholar

[4] Zhang XD, Jiang YH, Cao F, Yang T, Gao F, Liang SH. Hybrid effect on mechanical properties and high-temperature performance of copper matrix composite reinforced with micro-nano dual-scale particles. J Mater Sci Technol. 2024;172:94–103.10.1016/j.jmst.2023.06.054Search in Google Scholar

[5] Li Z, Jiang X, Sun H, Liu S, Pang Y, Wu Z, et al. Microstructure and mechanical properties of Cu\Ni-coated α-Al2O3w and graphene nano-platelets co-reinforced copper matrix composites. Mater Chem Phys. 2024;325:129772.10.1016/j.matchemphys.2024.129772Search in Google Scholar

[6] Qian L, Zhang J, Yang W, Wang Y, Chan K, Yang XS. Maintaining grain boundary segregation-induced strengthening effect in extremely fine nanograined metals. Nano Lett. 2025;25(13):5493–501.10.1021/acs.nanolett.5c01032Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Zhou CL, Chen ZN, Guo EY, Kang HJ, Fan JH, Wang W, et al. A nano-micro dual-scale particulate-reinforced copper matrix composite with high strength, high electrical conductivity and superior wear resistance. RSC Adv. 2018;8(54):30777–82.10.1039/C8RA06020GSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Zhu JL, Zhong LS, Xu YH, Li JL, Zhang SX, Lu ZX. Fabrication of a novel multi-sized and layered (Tix,Nb1−x)C surface-reinforced layer on TiNb alloy. Mater Res Express. 2019;6(10):106512.10.1088/2053-1591/ab348aSearch in Google Scholar

[9] Lv L, Jiang X, Xiao X, Sun H, Shao Z, Luo Z. Study on corrosion resistance of copper matrix composites reinforced by Al2O3 whiskers. Mater Res Express. 2020;7(2):026534.10.1088/2053-1591/ab71d0Search in Google Scholar

[10] Thankachan T, Prakash SK, Kavimani V. Effect of friction stir processing and hybrid reinforcements on copper. Mater Manuf Process. 2018;33(15):1681–92.10.1080/10426914.2018.1453149Search in Google Scholar

[11] Chen WP, Li ZX, Lu TW, He TB, Li RK, Li B, et al. Effect of ball milling on microstructure and mechanical properties of 6061Al matrix composites reinforced with high-entropy alloy particles. Mater Sci Eng A. 2019;762:138116.10.1016/j.msea.2019.138116Search in Google Scholar

[12] Zhu R, Sun Y, Feng J, Gong W, Li Y. Effect of microstructure on mechanical properties of FeCoNiCrAl high entropy alloys particle reinforced Cu matrix surface composite prepared by FSP. J Mater Res Technol. 2023;27:2695–708.10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.10.123Search in Google Scholar

[13] Wang YH, Zang JB, Wang MZ, Guan Y, Zheng YZ. Properties and applications of Ti-coated diamond grits. J Mater Process Technol. 2002;129(1):369–72.10.1016/S0924-0136(02)00661-1Search in Google Scholar

[14] Ciupiński Ł, Siemiaszko D, Rosiński M, Michalski A, Kurzydlowski KJ. Heat sink materials processing by pulse plasma sintering. Adv Mater Res. 2008;59:120–4.10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.59.120Search in Google Scholar

[15] Wang XZ, Su YH, Ouyang QB, Zhu CN, Cao H, Zhang D. Fabrication, mechanical and thermal properties of copper coated graphite films reinforced copper matrix laminated composites via ultrasonic-assisted electroless plating and vacuum hot-pressing sintering. Mater Sci Eng A. 2021;824:144768.10.1016/j.msea.2021.141768Search in Google Scholar

[16] Yang Q, Duan J, Deng A, Wang E. Numerical simulation of macrosegregation phenomenon in Cu-6wt%Ag alloy ingots fabricated by electromagnetic stirring. J Mater Res Technol. 2024;28:300–15.10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.11.220Search in Google Scholar

[17] Liu C, Yin Y, Li C, Xu M, Li R, Chen Q. Tailoring Cu nano Bi self-lubricating alloy material by shift-speed ball milling flake powder metallurgy. J Alloy Compd. 2022;903:163747.10.1016/j.jallcom.2022.163747Search in Google Scholar

[18] Jisen Y, Minghui W, Tingan Z, Fang X, Xi Z, Ke Z, et al. Research progress in preparation technology of micro and nano titanium alloy powder. Nanotechnol Rev. 2024;13(1):20240016.10.1515/ntrev-2024-0016Search in Google Scholar

[19] Pan Y, Lu X, Volinsky AA, Liu B, Xiao S, Zhou C, et al. Tribological and mechanical properties of copper matrix composites reinforced with carbon nanotube and alumina nanoparticles. Mater Res Express. 2019;6(11):116524.10.1088/2053-1591/ab4674Search in Google Scholar

[20] Shen DP, Zhu YJ, Yang X, Tong WP. Investigation on the microstructure and properties of Cu-Cr alloy prepared by in-situ synthesis method. Vacuum. 2018;149:207–13.10.1016/j.vacuum.2017.12.035Search in Google Scholar

[21] Zhang SR, Kang HJ, Li RG, Zou CL, Guo EY, Chen ZE, et al. Microstructure evolution electrical conductivity and mechanical properties of dual-scale Cu5Zr/ZrB2 particulate reinforced copper matrix composites. Mater Sci Eng A. 2019;762:138108.10.1016/j.msea.2019.138108Search in Google Scholar

[22] Li N, Zhang F, Yang Q, Wu Y, Wang M, Liu J, et al. Microstructure and mechanical properties of in situ TiB2/2024 composites fabricated by powder metallurgy. J Mater Eng Perform. 2022;31(11):8775–83.10.1007/s11665-022-06900-7Search in Google Scholar

[23] Zhang DY, Yang F, Zhao HX, Ding ZJ, Wan JP, Ren YC, et al. Microstructure, mechanical property and wear resistance of in-situ TiC/Ti64 composites via adding graphite in irregular Ti64 powder. Materials Today. Communications. 2025;42:111381.10.1016/j.mtcomm.2024.111381Search in Google Scholar

[24] Song YL, Dou ZH, Zhang TA, Liu Y. Research progress on the extractive metallurgy of titanium alloys. Min Process Extr Metall Rev. 2020;3:1–16.Search in Google Scholar

[25] An W, Dou ZH, Zhang TA. Microstructure uniformity control of CuCr alloy prepared in-situ by aluminothermic reduction coupled with permanent magnetic stirring. J Alloy Compd. 2023;96:170797.10.1016/j.jallcom.2023.170797Search in Google Scholar

[26] Song Y, Dou Z, Liu Y, Zhang T. Study on the preparation process of TiAl alloy by self-propagating metallurgy. J Mater Eng Perform. 2024;33(2):660–9.10.1007/s11665-023-08013-1Search in Google Scholar

[27] An W, Dou ZH, Han JR, Zhang TA. Microstructure evolution and property strengthening of CuCr50 prepared by thermite reduction-electromagnetic casting during the heat treatment process. J Mater Res Technol. 2023;24:6533–44.10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.04.249Search in Google Scholar

[28] Wang XY, Cheng C, Feng YS, Wang MX, Li MY, Huang T, et al. Microstructure regulation mechanism of CuW composites prepared by aluminothermic coupling with magnesiothermic reduction. J Mater Res Technol. 2025;34:2684–97.10.1016/j.jmrt.2024.12.180Search in Google Scholar

[29] Fan SG, Dou ZH, Zhang TA, Yan JS. Self-propagating reaction mechanism of MgTiO2 system in preparation process of titanium powder by multi-stage reduction. Rare Met. 2020;40(9):1–12.10.1007/s12598-020-01554-7Search in Google Scholar

[30] Nersisyan HH, Lee JH, Won CW. A study of tungsten nanopowder formation by self-propagating high-temperature synthesis. Combust Flame. 2005;142:241–8.10.1016/j.combustflame.2005.03.012Search in Google Scholar

[31] Cheng C, Dou ZH, Zhang TA, Zhang HJ, Yi X, Su JM. Synthesis of as-cast Ti–Al–V alloy from titanium-rich material by thermite reduction. JOM. 2017;69(10):1818–23.10.1007/s11837-017-2467-7Search in Google Scholar

[32] Wang P, Gong W, Jiang Z, Li X, Zhang Y. Effect of MgO content and CaO/Al2O3 ratio on melting temperature and viscosity of CaF2-CaO-Al2O3-MgO slag for electroslag remelting. Ceram Int. 2024;50(19PB):36829–37.10.1016/j.ceramint.2024.07.070Search in Google Scholar

[33] Song M, Liu J. Novel insight into the preparation of Ti-6Al-4V alloy through thermite reduction based on the mass action concentration. J Wuhan Univ Technol-Mater Sci Ed. 2023;38(3):652–8.10.1007/s11595-023-2741-1Search in Google Scholar

[34] Song Y, Dou Z, Zhang T, Cheng C, Fang H, Ban CL. Thermodynamic insight into the equilibrium component prediction in the Al-Ti-Ca-oxide system. Arch Metall Mater. 2023;68(4):1319–26.10.24425/amm.2023.146197Search in Google Scholar

[35] Okamoto H. Al–V (Aluminum–Vanadium). J Phase Equilibria Diffus. 2012;33(6):491.10.1007/s11669-012-0090-4Search in Google Scholar

[36] Shi ZB, Ma CF, Wang F, Liu P, Liu XK, Li W. Calculation assessment and activity of the Al–V binary phase diagram. Nonferrous Met Mater Eng. 2017;38(04):222–8.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Kang S, Zhao X, Guo J, Liang J, Sun J, Yang Y, et al. Thermal-assisted cold sintering study of Al2O3 ceramics: Enabled with a soluble γ-Al2O3 intermediate phase. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2023;43(2):478–85.10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2022.10.039Search in Google Scholar

[38] Dynys FW, Halloran JW. Alpha alumina formation in alum-derived gamma alumina. J Am Ceram Soc. 2010;65(9):442–8.10.1111/j.1151-2916.1982.tb10511.xSearch in Google Scholar

[39] Ali AMMA, Amin SAA, Adnan A. Effect of copper oxide (CuO) and vanadium oxide (V2O5) addition on the structural, optical and electrical properties of corundum (α-Al2O3). Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):16100.10.1038/s41598-023-43309-1Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] Wen Y, Shu Q, Lin Y, Fabritius T. Effect of SiO2 content and mass ratio of CaO to Al2O3 on the Viscosity and Structure of CaO-Al2O3-B2O3-SiO2 Slags. ISIJ Int. 2023;63:1–9.10.2355/isijinternational.ISIJINT-2022-288Search in Google Scholar

[41] Song Y, Dou Z, Zhang T, Wang G. Mechanisms of metal-slag separation behavior in thermite reduction for preparation of TiAl Alloy. J Mater Eng Perform. 2021;30(12):1–11.10.1007/s11665-021-06074-8Search in Google Scholar

[42] Cheng C, Wang XY, Song KX, Song ZW, Dou ZH, Zhang Me, et al. Effects of CaO addition on the CuW composite containing micro- and nano-sized tungsten particles synthesized via aluminothermic coupling with silicothermic reduction. Nanotechnol Rev. 2023;12(1):20220507.10.1515/ntrev-2022-0527Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- MHD radiative mixed convective flow of a sodium alginate-based hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated extending sheet with Joule heating

- Experimental study of mortar incorporating nano-magnetite on engineering performance and radiation shielding

- Multicriteria-based optimization and multi-variable non-linear regression analysis of concrete containing blends of nano date palm ash and eggshell powder as cementitious materials

- A promising Ag2S/poly-2-amino-1-mercaptobenzene open-top spherical core–shell nanocomposite for optoelectronic devices: A one-pot technique

- Biogenic synthesized selenium nanoparticles combined chitosan nanoparticles controlled lung cancer growth via ROS generation and mitochondrial damage pathway

- Fabrication of PDMS nano-mold by deposition casting method

- Stimulus-responsive gradient hydrogel micro-actuators fabricated by two-photon polymerization-based 4D printing

- Physical aspects of radiative Carreau nanofluid flow with motile microorganisms movement under yield stress via oblique penetrable wedge

- Effect of polar functional groups on the hydrophobicity of carbon nanotubes-bacterial cellulose nanocomposite

- Review in green synthesis mechanisms, application, and future prospects for Garcinia mangostana L. (mangosteen)-derived nanoparticles

- Entropy generation and heat transfer in nonlinear Buoyancy–driven Darcy–Forchheimer hybrid nanofluids with activation energy

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ginkgo biloba seed extract: Evaluation of antioxidant, anticancer, antifungal, and antibacterial activities

- A numerical analysis of heat and mass transfer in water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing copper and alumina nanoparticles over an extending sheet

- Investigating the behaviour of electro-magneto-hydrodynamic Carreau nanofluid flow with slip effects over a stretching cylinder

- Electrospun thermoplastic polyurethane/nano-Ag-coated clear aligners for the inhibition of Streptococcus mutans and oral biofilm

- Investigation of the optoelectronic properties of a novel polypyrrole-multi-well carbon nanotubes/titanium oxide/aluminum oxide/p-silicon heterojunction

- Novel photothermal magnetic Janus membranes suitable for solar water desalination

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ageratum conyzoides for activated carbon compositing to prepare antimicrobial cotton fabric

- Activation energy and Coriolis force impact on three-dimensional dusty nanofluid flow containing gyrotactic microorganisms: Machine learning and numerical approach

- Machine learning analysis of thermo-bioconvection in a micropolar hybrid nanofluid-filled square cavity with oxytactic microorganisms

- Research and improvement of mechanical properties of cement nanocomposites for well cementing

- Thermal and stability analysis of silver–water nanofluid flow over unsteady stretching sheet under the influence of heat generation/absorption at the boundary

- Cobalt iron oxide-infused silicone nanocomposites: Magnetoactive materials for remote actuation and sensing

- Magnesium-reinforced PMMA composite scaffolds: Synthesis, characterization, and 3D printing via stereolithography

- Bayesian inference-based physics-informed neural network for performance study of hybrid nanofluids

- Numerical simulation of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to a heterogeneous/homogeneous chemical reaction over a Riga surface

- Enhancing the superhydrophobicity, UV-resistance, and antifungal properties of natural wood surfaces via in situ formation of ZnO, TiO2, and SiO2 particles

- Synthesis and electrochemical characterization of iron oxide/poly(2-methylaniline) nanohybrids for supercapacitor application

- Impacts of double stratification on thermally radiative third-grade nanofluid flow on elongating cylinder with homogeneous/heterogeneous reactions by implementing machine learning approach

- Synthesis of Cu4O3 nanoparticles using pumpkin seed extract: Optimization, antimicrobial, and cytotoxicity studies

- Cationic charge influence on the magnetic response of the Fe3O4–[Me2+ 1−y Me3+ y (OH2)] y+(Co3 2−) y/2·mH2O hydrotalcite system

- Pressure sensing intelligent martial arts short soldier combat protection system based on conjugated polymer nanocomposite materials

- Magnetohydrodynamics heat transfer rate under inclined buoyancy force for nano and dusty fluids: Response surface optimization for the thermal transport

- Fly ash and nano-graphene enhanced stabilization of engine oil-contaminated soils

- Enhancing natural fiber-reinforced biopolymer composites with graphene nanoplatelets: Mechanical, morphological, and thermal properties

- Performance evaluation of dual-scale strengthened co-bonded single-lap joints using carbon nanotubes and Z-pins with ANN

- Computational works of blood flow with dust particles and partially ionized containing tiny particles on a moving wedge: Applications of nanotechnology

- Hybridization of biocomposites with oil palm cellulose nanofibrils/graphene nanoplatelets reinforcement in green epoxy: A study of physical, thermal, mechanical, and morphological properties

- Design and preparation of micro-nano dual-scale particle-reinforced Cu–Al–V alloy: Research on the aluminothermic reduction process

- Spectral quasi-linearization and response optimization on magnetohydrodynamic flow via stenosed artery with hybrid and ternary solid nanoparticles: Support vector machine learning

- Ferrite/curcumin hybrid nanocomposite formulation: Physicochemical characterization, anticancer activity, and apoptotic and cell cycle analyses in skin cancer cells

- Enhanced therapeutic efficacy of Tamoxifen against breast cancer using extra virgin olive oil-based nanoemulsion delivery system

- A titanium oxide- and silver-based hybrid nanofluid flow between two Riga walls that converge and diverge through a machine-learning approach

- Enhancing convective heat transfer mechanisms through the rheological analysis of Casson nanofluid flow towards a stagnation point over an electro-magnetized surface

- Intrinsic self-sensing cementitious composites with hybrid nanofillers exhibiting excellent piezoresistivity

- Research on mechanical properties and sulfate erosion resistance of nano-reinforced coal gangue based geopolymer concrete

- Impact of surface and configurational features of chemically synthesized chains of Ni nanostars on the magnetization reversal process

- Porous sponge-like AsOI/poly(2-aminobenzene-1-thiol) nanocomposite photocathode for hydrogen production from artificial and natural seawater

- Multifaceted insights into WO3 nanoparticle-coupled antibiotics to modulate resistance in enteric pathogens of Houbara bustard birds

- Synthesis of sericin-coated silver nanoparticles and their applications for the anti-bacterial finishing of cotton fabric

- Enhancing chloride resistance of freeze–thaw affected concrete through innovative nanomaterial–polymer hybrid cementitious coating

- Development and performance evaluation of green aluminium metal matrix composites reinforced with graphene nanopowder and marble dust

- Morphological, physical, thermal, and mechanical properties of carbon nanotubes reinforced arrowroot starch composites

- Influence of the graphene oxide nanosheet on tensile behavior and failure characteristics of the cement composites after high-temperature treatment

- Central composite design modeling in optimizing heat transfer rate in the dissipative and reactive dynamics of viscoplastic nanomaterials deploying Joule and heat generation aspects

- Double diffusion of nano-enhanced phase change materials in connected porous channels: A hybrid ISPH-XGBoost approach

- Synergistic impacts of Thompson–Troian slip, Stefan blowing, and nonuniform heat generation on Casson nanofluid dynamics through a porous medium

- Optimization of abrasive water jet machining parameters for basalt fiber/SiO2 nanofiller reinforced composites

- Enhancing aesthetic durability of Zisha teapots via TiO2 nanoparticle surface modification: A study on self-cleaning, antimicrobial, and mechanical properties

- Nanocellulose solution based on iron(iii) sodium tartrate complexes

- Combating multidrug-resistant infections: Gold nanoparticles–chitosan–papain-integrated dual-action nanoplatform for enhanced antibacterial activity

- Novel royal jelly-mediated green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and their multifunctional biological activities

- Direct bandgap transition for emission in GeSn nanowires

- Synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles with different morphologies using a microwave-based method and their antimicrobial activity

- Numerical investigation of convective heat and mass transfer in a trapezoidal cavity filled with ternary hybrid nanofluid and a central obstacle

- Halloysite nanotube enhanced polyurethane nanocomposites for advanced electroinsulating applications

- Low molar mass ionic liquid’s modified carbon nanotubes and its role in PVDF crystalline stress generation

- Green synthesis of polydopamine-functionalized silver nanoparticles conjugated with Ceftazidime: in silico and experimental approach for combating antibiotic-resistant bacteria and reducing toxicity

- Evaluating the influence of graphene nano powder inclusion on mechanical, vibrational and water absorption behaviour of ramie/abaca hybrid composites

- Dynamic-behavior of Casson-type hybrid nanofluids due to a stretching sheet under the coupled impacts of boundary slip and reaction-diffusion processes

- Influence of polyvinyl alcohol on the physicochemical and self-sensing properties of nano carbon black reinforced cement mortar

- Advanced machine learning approaches for predicting compressive and flexural strength of carbon nanotube–reinforced cement composites: a comparative study and model interpretability analysis

- Review Articles

- A comprehensive review on hybrid plasmonic waveguides: Structures, applications, challenges, and future perspectives

- Nanoparticles in low-temperature preservation of biological systems of animal origin

- Fluorescent sulfur quantum dots for environmental monitoring

- Nanoscience systematic review methodology standardization

- Nanotechnology revolutionizing osteosarcoma treatment: Advances in targeted kinase inhibitors

- AFM: An important enabling technology for 2D materials and devices

- Carbon and 2D nanomaterial smart hydrogels for therapeutic applications

- Principles, applications and future prospects in photodegradation systems

- Do gold nanoparticles consistently benefit crop plants under both non-stressed and abiotic stress conditions?

- An updated overview of nanoparticle-induced cardiovascular toxicity

- Arginine as a promising amino acid for functionalized nanosystems: Innovations, challenges, and future directions

- Advancements in the use of cancer nanovaccines: Comprehensive insights with focus on lung and colon cancer

- Membrane-based biomimetic delivery systems for glioblastoma multiforme therapy

- The drug delivery systems based on nanoparticles for spinal cord injury repair

- Green synthesis, biomedical effects, and future trends of Ag/ZnO bimetallic nanoparticles: An update

- Application of magnesium and its compounds in biomaterials for nerve injury repair

- Micro/nanomotors in biomedicine: Construction and applications

- Hydrothermal synthesis of biomass-derived CQDs: Advances and applications

- Research progress in 3D bioprinting of skin: Challenges and opportunities

- Review on bio-selenium nanoparticles: Synthesis, protocols, and applications in biomedical processes

- Gold nanocrystals and nanorods functionalized with protein and polymeric ligands for environmental, energy storage, and diagnostic applications: A review

- An in-depth analysis of rotational and non-rotational piezoelectric energy harvesting beams: A comprehensive review

- Advancements in perovskite/CIGS tandem solar cells: Material synergies, device configurations, and economic viability for sustainable energy

- Deep learning in-depth analysis of crystal graph convolutional neural networks: A new era in materials discovery and its applications

- Review of recent nano TiO2 film coating methods, assessment techniques, and key problems for scaleup

- Antioxidant quantum dots for spinal cord injuries: A review on advancing neuroprotection and regeneration in neurological disorders

- Rise of polycatecholamine ultrathin films: From synthesis to smart applications

- Advancing microencapsulation strategies for bioactive compounds: Enhancing stability, bioavailability, and controlled release in food applications

- Advances in the design and manipulation of self-assembling peptide and protein nanostructures for biomedical applications

- Photocatalytic pervious concrete systems: from classic photocatalysis to luminescent photocatalysis

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Synthesis and characterization of smart stimuli-responsive herbal drug-encapsulated nanoniosome particles for efficient treatment of breast cancer”

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part III

- Efficiency optimization of quantum dot photovoltaic cell by solar thermophotovoltaic system

- Exploring the diverse nanomaterials employed in dental prosthesis and implant techniques: An overview

- Electrochemical investigation of bismuth-doped anode materials for low‑temperature solid oxide fuel cells with boosted voltage using a DC-DC voltage converter

- Synthesis of HfSe2 and CuHfSe2 crystalline materials using the chemical vapor transport method and their applications in supercapacitor energy storage devices

- Special Issue on Green Nanotechnology and Nano-materials for Environment Sustainability

- Influence of nano-silica and nano-ferrite particles on mechanical and durability of sustainable concrete: A review

- Surfaces and interfaces analysis on different carboxymethylation reaction time of anionic cellulose nanoparticles derived from oil palm biomass

- Processing and effective utilization of lignocellulosic biomass: Nanocellulose, nanolignin, and nanoxylan for wastewater treatment

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Aging assessment of silicone rubber materials under corona discharge accompanied by humidity and UV radiation”

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- MHD radiative mixed convective flow of a sodium alginate-based hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated extending sheet with Joule heating

- Experimental study of mortar incorporating nano-magnetite on engineering performance and radiation shielding

- Multicriteria-based optimization and multi-variable non-linear regression analysis of concrete containing blends of nano date palm ash and eggshell powder as cementitious materials

- A promising Ag2S/poly-2-amino-1-mercaptobenzene open-top spherical core–shell nanocomposite for optoelectronic devices: A one-pot technique

- Biogenic synthesized selenium nanoparticles combined chitosan nanoparticles controlled lung cancer growth via ROS generation and mitochondrial damage pathway

- Fabrication of PDMS nano-mold by deposition casting method

- Stimulus-responsive gradient hydrogel micro-actuators fabricated by two-photon polymerization-based 4D printing

- Physical aspects of radiative Carreau nanofluid flow with motile microorganisms movement under yield stress via oblique penetrable wedge

- Effect of polar functional groups on the hydrophobicity of carbon nanotubes-bacterial cellulose nanocomposite

- Review in green synthesis mechanisms, application, and future prospects for Garcinia mangostana L. (mangosteen)-derived nanoparticles

- Entropy generation and heat transfer in nonlinear Buoyancy–driven Darcy–Forchheimer hybrid nanofluids with activation energy

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ginkgo biloba seed extract: Evaluation of antioxidant, anticancer, antifungal, and antibacterial activities

- A numerical analysis of heat and mass transfer in water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing copper and alumina nanoparticles over an extending sheet

- Investigating the behaviour of electro-magneto-hydrodynamic Carreau nanofluid flow with slip effects over a stretching cylinder

- Electrospun thermoplastic polyurethane/nano-Ag-coated clear aligners for the inhibition of Streptococcus mutans and oral biofilm

- Investigation of the optoelectronic properties of a novel polypyrrole-multi-well carbon nanotubes/titanium oxide/aluminum oxide/p-silicon heterojunction

- Novel photothermal magnetic Janus membranes suitable for solar water desalination

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ageratum conyzoides for activated carbon compositing to prepare antimicrobial cotton fabric

- Activation energy and Coriolis force impact on three-dimensional dusty nanofluid flow containing gyrotactic microorganisms: Machine learning and numerical approach

- Machine learning analysis of thermo-bioconvection in a micropolar hybrid nanofluid-filled square cavity with oxytactic microorganisms

- Research and improvement of mechanical properties of cement nanocomposites for well cementing

- Thermal and stability analysis of silver–water nanofluid flow over unsteady stretching sheet under the influence of heat generation/absorption at the boundary

- Cobalt iron oxide-infused silicone nanocomposites: Magnetoactive materials for remote actuation and sensing

- Magnesium-reinforced PMMA composite scaffolds: Synthesis, characterization, and 3D printing via stereolithography

- Bayesian inference-based physics-informed neural network for performance study of hybrid nanofluids

- Numerical simulation of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to a heterogeneous/homogeneous chemical reaction over a Riga surface

- Enhancing the superhydrophobicity, UV-resistance, and antifungal properties of natural wood surfaces via in situ formation of ZnO, TiO2, and SiO2 particles

- Synthesis and electrochemical characterization of iron oxide/poly(2-methylaniline) nanohybrids for supercapacitor application

- Impacts of double stratification on thermally radiative third-grade nanofluid flow on elongating cylinder with homogeneous/heterogeneous reactions by implementing machine learning approach

- Synthesis of Cu4O3 nanoparticles using pumpkin seed extract: Optimization, antimicrobial, and cytotoxicity studies

- Cationic charge influence on the magnetic response of the Fe3O4–[Me2+ 1−y Me3+ y (OH2)] y+(Co3 2−) y/2·mH2O hydrotalcite system

- Pressure sensing intelligent martial arts short soldier combat protection system based on conjugated polymer nanocomposite materials

- Magnetohydrodynamics heat transfer rate under inclined buoyancy force for nano and dusty fluids: Response surface optimization for the thermal transport

- Fly ash and nano-graphene enhanced stabilization of engine oil-contaminated soils

- Enhancing natural fiber-reinforced biopolymer composites with graphene nanoplatelets: Mechanical, morphological, and thermal properties

- Performance evaluation of dual-scale strengthened co-bonded single-lap joints using carbon nanotubes and Z-pins with ANN

- Computational works of blood flow with dust particles and partially ionized containing tiny particles on a moving wedge: Applications of nanotechnology

- Hybridization of biocomposites with oil palm cellulose nanofibrils/graphene nanoplatelets reinforcement in green epoxy: A study of physical, thermal, mechanical, and morphological properties

- Design and preparation of micro-nano dual-scale particle-reinforced Cu–Al–V alloy: Research on the aluminothermic reduction process

- Spectral quasi-linearization and response optimization on magnetohydrodynamic flow via stenosed artery with hybrid and ternary solid nanoparticles: Support vector machine learning

- Ferrite/curcumin hybrid nanocomposite formulation: Physicochemical characterization, anticancer activity, and apoptotic and cell cycle analyses in skin cancer cells

- Enhanced therapeutic efficacy of Tamoxifen against breast cancer using extra virgin olive oil-based nanoemulsion delivery system

- A titanium oxide- and silver-based hybrid nanofluid flow between two Riga walls that converge and diverge through a machine-learning approach

- Enhancing convective heat transfer mechanisms through the rheological analysis of Casson nanofluid flow towards a stagnation point over an electro-magnetized surface

- Intrinsic self-sensing cementitious composites with hybrid nanofillers exhibiting excellent piezoresistivity

- Research on mechanical properties and sulfate erosion resistance of nano-reinforced coal gangue based geopolymer concrete

- Impact of surface and configurational features of chemically synthesized chains of Ni nanostars on the magnetization reversal process

- Porous sponge-like AsOI/poly(2-aminobenzene-1-thiol) nanocomposite photocathode for hydrogen production from artificial and natural seawater

- Multifaceted insights into WO3 nanoparticle-coupled antibiotics to modulate resistance in enteric pathogens of Houbara bustard birds

- Synthesis of sericin-coated silver nanoparticles and their applications for the anti-bacterial finishing of cotton fabric

- Enhancing chloride resistance of freeze–thaw affected concrete through innovative nanomaterial–polymer hybrid cementitious coating

- Development and performance evaluation of green aluminium metal matrix composites reinforced with graphene nanopowder and marble dust

- Morphological, physical, thermal, and mechanical properties of carbon nanotubes reinforced arrowroot starch composites

- Influence of the graphene oxide nanosheet on tensile behavior and failure characteristics of the cement composites after high-temperature treatment

- Central composite design modeling in optimizing heat transfer rate in the dissipative and reactive dynamics of viscoplastic nanomaterials deploying Joule and heat generation aspects

- Double diffusion of nano-enhanced phase change materials in connected porous channels: A hybrid ISPH-XGBoost approach

- Synergistic impacts of Thompson–Troian slip, Stefan blowing, and nonuniform heat generation on Casson nanofluid dynamics through a porous medium

- Optimization of abrasive water jet machining parameters for basalt fiber/SiO2 nanofiller reinforced composites

- Enhancing aesthetic durability of Zisha teapots via TiO2 nanoparticle surface modification: A study on self-cleaning, antimicrobial, and mechanical properties

- Nanocellulose solution based on iron(iii) sodium tartrate complexes

- Combating multidrug-resistant infections: Gold nanoparticles–chitosan–papain-integrated dual-action nanoplatform for enhanced antibacterial activity

- Novel royal jelly-mediated green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and their multifunctional biological activities

- Direct bandgap transition for emission in GeSn nanowires

- Synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles with different morphologies using a microwave-based method and their antimicrobial activity

- Numerical investigation of convective heat and mass transfer in a trapezoidal cavity filled with ternary hybrid nanofluid and a central obstacle

- Halloysite nanotube enhanced polyurethane nanocomposites for advanced electroinsulating applications

- Low molar mass ionic liquid’s modified carbon nanotubes and its role in PVDF crystalline stress generation

- Green synthesis of polydopamine-functionalized silver nanoparticles conjugated with Ceftazidime: in silico and experimental approach for combating antibiotic-resistant bacteria and reducing toxicity

- Evaluating the influence of graphene nano powder inclusion on mechanical, vibrational and water absorption behaviour of ramie/abaca hybrid composites

- Dynamic-behavior of Casson-type hybrid nanofluids due to a stretching sheet under the coupled impacts of boundary slip and reaction-diffusion processes

- Influence of polyvinyl alcohol on the physicochemical and self-sensing properties of nano carbon black reinforced cement mortar

- Advanced machine learning approaches for predicting compressive and flexural strength of carbon nanotube–reinforced cement composites: a comparative study and model interpretability analysis

- Review Articles

- A comprehensive review on hybrid plasmonic waveguides: Structures, applications, challenges, and future perspectives

- Nanoparticles in low-temperature preservation of biological systems of animal origin

- Fluorescent sulfur quantum dots for environmental monitoring

- Nanoscience systematic review methodology standardization

- Nanotechnology revolutionizing osteosarcoma treatment: Advances in targeted kinase inhibitors

- AFM: An important enabling technology for 2D materials and devices

- Carbon and 2D nanomaterial smart hydrogels for therapeutic applications

- Principles, applications and future prospects in photodegradation systems

- Do gold nanoparticles consistently benefit crop plants under both non-stressed and abiotic stress conditions?

- An updated overview of nanoparticle-induced cardiovascular toxicity

- Arginine as a promising amino acid for functionalized nanosystems: Innovations, challenges, and future directions

- Advancements in the use of cancer nanovaccines: Comprehensive insights with focus on lung and colon cancer

- Membrane-based biomimetic delivery systems for glioblastoma multiforme therapy

- The drug delivery systems based on nanoparticles for spinal cord injury repair

- Green synthesis, biomedical effects, and future trends of Ag/ZnO bimetallic nanoparticles: An update

- Application of magnesium and its compounds in biomaterials for nerve injury repair

- Micro/nanomotors in biomedicine: Construction and applications

- Hydrothermal synthesis of biomass-derived CQDs: Advances and applications

- Research progress in 3D bioprinting of skin: Challenges and opportunities

- Review on bio-selenium nanoparticles: Synthesis, protocols, and applications in biomedical processes

- Gold nanocrystals and nanorods functionalized with protein and polymeric ligands for environmental, energy storage, and diagnostic applications: A review

- An in-depth analysis of rotational and non-rotational piezoelectric energy harvesting beams: A comprehensive review

- Advancements in perovskite/CIGS tandem solar cells: Material synergies, device configurations, and economic viability for sustainable energy

- Deep learning in-depth analysis of crystal graph convolutional neural networks: A new era in materials discovery and its applications

- Review of recent nano TiO2 film coating methods, assessment techniques, and key problems for scaleup

- Antioxidant quantum dots for spinal cord injuries: A review on advancing neuroprotection and regeneration in neurological disorders

- Rise of polycatecholamine ultrathin films: From synthesis to smart applications

- Advancing microencapsulation strategies for bioactive compounds: Enhancing stability, bioavailability, and controlled release in food applications

- Advances in the design and manipulation of self-assembling peptide and protein nanostructures for biomedical applications

- Photocatalytic pervious concrete systems: from classic photocatalysis to luminescent photocatalysis

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Synthesis and characterization of smart stimuli-responsive herbal drug-encapsulated nanoniosome particles for efficient treatment of breast cancer”

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part III

- Efficiency optimization of quantum dot photovoltaic cell by solar thermophotovoltaic system

- Exploring the diverse nanomaterials employed in dental prosthesis and implant techniques: An overview

- Electrochemical investigation of bismuth-doped anode materials for low‑temperature solid oxide fuel cells with boosted voltage using a DC-DC voltage converter

- Synthesis of HfSe2 and CuHfSe2 crystalline materials using the chemical vapor transport method and their applications in supercapacitor energy storage devices

- Special Issue on Green Nanotechnology and Nano-materials for Environment Sustainability

- Influence of nano-silica and nano-ferrite particles on mechanical and durability of sustainable concrete: A review

- Surfaces and interfaces analysis on different carboxymethylation reaction time of anionic cellulose nanoparticles derived from oil palm biomass

- Processing and effective utilization of lignocellulosic biomass: Nanocellulose, nanolignin, and nanoxylan for wastewater treatment

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Aging assessment of silicone rubber materials under corona discharge accompanied by humidity and UV radiation”