Abstract

This study presents the synthesis and multifunctional evaluation of nanostructured zinc oxide nanorods (ZnO NRs) using a hydrothermal method. Various characterisation techniques, including X-ray diffraction (XRD), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis) spectrometry, fluorescence spectroscopy, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), were employed to analyse the ZnO NRs. XRD analysis confirmed the hexagonal wurtzite structure of the ZnO NRs. FTIR spectra showed a characteristic peak near 873 cm−1 corresponding to Zn–O stretching and out-of-plane C–H bending vibrations, indicating surface interactions. UV–vis analysis revealed strong absorption in the UV region and high optical transparency in the visible range, while the Tauc plot determined bandgaps of 3.29 ± 0.03 eV and 3.66 ± 0.01 eV, which enhance electron transfer processes during photocatalysis. The fluorescence spectrum displayed a sharp emission peak at 340 nm, attributed to near-band-edge emission and quantum confinement effects. SEM and TEM micrographs showed well-dispersed, rod-like nanoparticles with an average width of 47.7 nm. EDS confirmed high purity with 60 % Zn and 20 % O, while XPS verified the successful incorporation of ZnO within the thin-film coating. The ZnO NRs demonstrated strong photocatalytic performance in degrading crystal violet (CV) dye under solar light, achieving over 95 % ± 0.01 degradation with a rate constant of 0.6767 min−1. Hydrophobicity testing using a contact angle goniometer revealed a contact angle of 95.6° ± 0.3, indicating potential self-cleaning properties. XPS analysis further confirmed the presence of ZnO NRs within the thin-film coating and validated their successful incorporation. These findings collectively highlight the effectiveness of ZnO NRs in photocatalytic and surface coating applications, suggesting their promising potential for environmental and industrial use.

1 Introduction

In recent years, nanotechnology has become one of the most rapidly advancing fields in science and technology, driving significant innovations across multiple disciplines. Nanomaterials, defined by their unique physicochemical properties, have enabled the development of novel systems, structures, devices, and nanoplatforms with broad applications [1], 2]. These materials exist at the nanoscale, exhibiting superior thermal conductivity, catalytic reactivity, optical performance, and chemical stability due to their high surface area-to-volume ratio [3]. This distinctive property has motivated extensive research into new synthesis techniques for nanomaterials [4]. Among various nanomaterials, semiconductor-based photocatalysts have attracted considerable attention due to their potential to address critical environmental challenges, particularly water pollution [5]. Industrial dye effluents, mainly from textile and dye manufacturing industries, contribute significantly to global water contamination. Consequently, self-cleaning surfaces and photocatalytic materials have emerged as promising solutions [6]. Among semiconductor photocatalysts, zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) have been extensively studied due to their unique optoelectronic and physicochemical properties, making them suitable for diverse applications [7].

Photocatalytic degradation, which uses semiconductor metal oxides to decompose persistent organic pollutants in wastewater, has proven to be a highly efficient approach to water purification. This technique harnesses visible light and does not require sophisticated infrastructure, making it a cost-effective and sustainable method for environmental remediation. ZnO-based photocatalysts, serving as both active catalysts and self-cleaning coatings, have demonstrated exceptional efficiency in degrading hazardous organic dyes in contaminated water and on various surfaces [8], 9]. Nanostructured photocatalytic materials, including titanium dioxide (TiO2) [10], 11], ZnO [12], and carbon-based nanomaterials [13], have been extensively explored for environmental applications. In particular, ZnO has attracted significant research interest due to its low cost, high redox potential, abundance, non-toxicity, and eco-friendly nature. Its strong ultraviolet (UV) absorption, wide bandgap (3.37 eV), excellent biocompatibility, thermal stability, and antimicrobial properties further enhance its potential for various applications. ZnO nanostructures can be synthesised with diverse morphologies, such as nanowires, nanotubes, nanosheets, nanoplumes, and nanorods, using different fabrication techniques, including sol-gel, hydrothermal, electrodeposition and green chemistry methods [14], [15], [16], [17]. Despite its promising photocatalytic properties, ZnO has limitations, including rapid electron–hole recombination, which reduces its efficiency under visible-light irradiation. To address this challenge, researchers have explored several strategies to enhance its photocatalytic performance. Qi et al. [12] investigated modifications such as metal and non-metal doping, heterojunction formation, carbon nanostructure integration, and noble metal incorporation. For example, Ag doping has been shown to enhance the photocatalytic oxidation of both anionic and cationic dyes using Ag@ZnO nanocomposites under UV irradiation [18], 19]. ZnO is inherently hydrophobic; however, its surface properties can be tailored to achieve superhydrophobicity using low-surface-energy materials such as fluorosilane, stearic acid, noctadecanoic acid, and polydimethylsiloxane [20]. Gao et al. [21] developed superhydrophobic ZnO surfaces capable of efficiently separating oil–water mixtures, while Nundy et al. [22] synthesised morphologically distinct hydrophobic ZnO microstructures without UV treatment, demonstrating their potential for self-cleaning applications in photovoltaic and glazing technologies. Recent research has also emphasised ZnO-based composites and metal-doped systems to improve photocatalytic and electrochemical performance. Pramod Agale et al. [12] reported Sr-doped ZnO@g-C3N4 nanocomposites exhibiting enhanced charge carrier dynamics and notable potential in energy storage, photocatalysis, and environmental remediation. Similarly, Zarina Ansari et al. [14] synthesised Mn-doped ZnO@rGO nanocomposites with superior electrochemical and photoelectrochemical behaviour, highlighting their applicability in supercapacitor and photoelectrochemical (PEC) systems.

Despite these advances, few studies have explored the interplay between ZnO nanostructure morphology, optical properties, and multifunctional performance – particularly the integration of hydrophobicity with photocatalytic activity. The present study aims to address this gap by synthesising ZnO nanorods (ZnO NRs) via a hydrothermal route and systematically investigating their structural, optical, and surface characteristics. Furthermore, this work focuses on evaluating their self-cleaning behaviour and photocatalytic degradation efficiency using crystal violet (CV) dye as a model pollutant. CV was specifically chosen due to its carcinogenic nature and resistance to degradation, making it an ideal compound for assessing photocatalytic performance under solar irradiation.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Hydrothermal synthesis of ZnO NRs

Zinc oxide nanorods (ZnO NRs) were synthesised using the modified method described by Nundy et al. [22]. First, 1.1899 g of NaOH was dissolved in 25 ml of distilled water with a magnetic stirrer until fully dissolved. An ice bath was prepared for the NaOH solution, and 0.09 g of cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) was added while stirring, then left to stand for 5 min. Next, 946.8 mg of zinc nitrite (Zn(NO2)2) was added to the mixture, with continuous stirring for 1 h.

After complete dissolution, the solution was transferred to an autoclave and placed in an oven at 80 °C for 6 h to promote the dissolution–recrystallisation process, enhancing the crystallinity and aspect ratio of the ZnO nanorods [22]. After cooling, the sample was centrifuged to precipitate the nanoparticles, followed by three wash cycles with ethanol and distilled water. Each washing step lasted 30 min at 10,000 rpm. The resulting white precipitate was collected and dried in a hot air oven for 10 h at 80 °C. Finally, the powder was calcined at 400 °C for 3 h.

2.2 Characterization of synthesized samples

The optical properties of the synthesised ZnO NRs were investigated using a UV-1800 UV–vis spectrometer (Shimadzu, Switzerland) in the range 200–600 nm. The bandgap energy (Eg) was determined by the Tauc plot method. The emission spectrum and fluorescence (FL) were measured with a Fluorolog 3 spectrofluorometer (FL-3-11, Horiba JobinYvon, Edison, NJ, USA). The crystalline structures and average particle sizes were analysed using a Bruker D8 ADVANCE X-ray diffractometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) at 40 kV and 40 mA with CuKα radiation at 1.5418 Å. The surface morphology and size of the nanoparticles were examined using TEM with an accelerating voltage of 200 kV (JEM-2100F, JEOL Ltd., Peabody, MA, USA). An energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS, JSM-2100F, JEOL, USA) connected to the SEM (JEOL JSM-7600F, USA) was used for elemental identification and mapping in the ZnO powder. Functional groups on the surface of the ZnO NRs, in the CV dye, and in the treated CV dyes were identified using a Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer (Shimadzu IR, Prestige 21, Nakagyo-Ku, Kyoto, Japan) covering the range 4,000–400 cm−1. The chemical composition of the surface was analysed using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) (Jeol JPS-9200 photoelectron spectrometer) with a 500 W X-ray source (JEOL Ltd., Akishima, Tokyo, Japan).

2.3 Experiment on self-cleaning surfaces

To prepare the self-cleaning surface, glass slides were meticulously cleaned to remove contaminants. The slides were immersed in a 10 % sulfuric acid (H2SO4) solution for 15 min, and then thoroughly rinsed with distilled water and acetone to achieve a pristine surface. For the coating preparation, a ZnO NR solution was formulated using polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) as a binder to enhance adhesion. The PMMA (in pellet form, provided by SABIC, Saudi Arabia; density: 1.20 g/cm3, SABIC® PMMA) was dissolved in toluene (99.8 %, Sigma) as the solvent. Specifically, 1.5 mg of ZnO NR powder was dispersed in 20 ml of a PMMA solution (0.5 mg/ml) to ensure uniform distribution. The dispersion was carried out using an ultrasonicator (750 W, 20 kHz) for 1 h. The coating solution was then applied to the cleaned glass slides using the spin-coating technique. To achieve a homogeneous thin film with adequate thickness, a two-step spin-coating cycle was employed for each sample: first, a spread cycle at 500 rpm for 10 s, followed immediately by a high-speed cycle at 2,000 rpm for 30 s. This two-step cycle was repeated three times to build the film layer by layer. After each coating cycle, the slides were dried at 45 °C for 5 min in an oven to partially evaporate the solvent. After the final coating cycle, the slides underwent a final drying step at 45 °C for 15 min to ensure complete solvent removal and film consolidation, before being cooled to room temperature, following established protocols [23]. To evaluate the surface wettability of the ZnO NR-coated glass slides, water contact angle (WCA) measurements were conducted using the sessile drop method with Dataphysics OCA15EC equipment (Stuttgart, Germany). A 5 μl droplet of deionised water was carefully deposited onto the coated surface using a microsyringe, and the contact angle (θ) at the liquid–solid interface was recorded. To ensure accuracy and reliability, WCA measurements were performed three times for each sample, and the average value was calculated and reported in the analysis.

2.4 Photocatalysis activity studies

In this experimental investigation, a rigorous protocol was implemented to assess the photodegradation efficacy of zinc oxide nanoparticles (NPs) on crystal violet (CV) dye. Initially, 100 ml of distilled water was thoroughly mixed with 1 ppm of CV dye until fully dissolved. The dye solution was then placed in a glass vessel, and a predetermined amount of catalyst was added. Simultaneously, another sample was taken immediately after the introduction of the nanoparticles to serve as the “time zero” reference.

The mixture was then exposed to solar irradiation outdoors. This exposure to sunlight occurred daily for 3 h over a five-day period, from 25 to 29 May 2023. The experimental conditions simulated a relatively hot climate, with peak temperatures ranging from 35 to 37 °C and lows between 25 and 28 °C. At specified intervals, approximately 5 ml aliquots were withdrawn and allowed to settle to prevent potential interference from the catalyst. Additional samples were systematically collected, and the entire procedure was repeated three times to ensure the robustness of the experimental results. Dye degradation was assessed using a UV-visible spectrometer for all collected samples, with distilled water as the blank reference. This approach provides a comprehensive understanding of the impact of ZnO NRs on CV dye under real-world environmental conditions. The removal percentage (%) was calculated using the following formula:

C 0 represents the initial concentration of crystal violet dye, while C denotes the crystal violet dye concentration at various time intervals. The experiment was repeated three times to ensure consistency, enhancing the reliability and comprehensiveness of the investigation into the impact of ZnO NRs on CV dye under real-world environmental conditions.

2.5 Statistical analysis

The data were statistically analysed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s post hoc test with Origin 2019b software (version 9.65 for Windows, Ontario, Canada). For each experiment, the data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three independent experiments.

3 Result and discussion

3.1 XRD pattern analysis of ZnO NRs

The distinctive X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of the hydrothermally synthesised ZnO NRs is shown in Figure 1, revealing characteristic peak values consistent with standard data for ZnO NRs. The XRD analysis, in accordance with JCPDS card number COD 9008877, assigns all diffraction peaks to the wurtzite structure of ZnO, with lattice parameters a = b = 3.24950 nm and c = 5.20690 nm. Notably, diffraction peaks at 2θ = 31.773°, 34.420°, 36.256°, 47.540°, 56.600°, 62.856°, 66.383°, 67.951°, 69.091°, 81.380°, and 92.811° were observed, corresponding to the (1 0 0), (0 0 2), (1 0 1), (1 0 2), (2 1 0), (1 0 3), (2 0 0), (2 1 2), (2 0 1), (1 0 4), and (3 1 0) crystallographic planes, respectively. The strong and sharp nature of these peaks indicates excellent crystallinity, highlighting the characteristic diffractions of the hexagonal wurtzite ZnO structure [24], 25]. The absence of significant impurity peaks demonstrates the high purity of the synthesised ZnO NRs. The average crystallite diameter of ZnO NRs was calculated using Scherrer’s formula [26]. According to the XRD data, the ZnO NRs had an average crystallite size of approximately 22 nm. This comprehensive XRD analysis provides important insights into the structural characteristics and purity of the synthesised ZnO nanorods.

The XRD analysis results of ZnO NRs.

3.2 FTIR spectrum analysis of ZnO NRs

The FTIR spectrum of ZnO nanorods is illustrated in Figure 2, highlighting significant variations associated with the presence or absence of –OH groups The synthesized ZnO nanorods exhibit a characteristic Zn–O stretching vibration, typically observed around 546 cm⁻¹. The broad absorption peak centered at 3419 cm⁻¹ corresponds to the stretching vibrations of O–H groups on the ZnO NR surface, indicating surface hydroxylation [27]. Additionally, the FTIR spectrum reveals distinct peaks at approximately 873 cm⁻¹ and 1620 cm⁻¹. The peak at 873 cm⁻¹ is typically attributed to out-of-plane bending vibrations of C–H bonds or Zn–O stretching, suggesting possible interactions between the ZnO nanorods and surface-adsorbed species. Furthermore, it may indicate the presence of carbonate species adsorbed onto the surface. The peak at 1620 cm⁻¹ corresponds to the bending vibration of adsorbed water molecules (H–O–H bending) or the stretching vibration of C=O groups, which could originate from atmospheric moisture or residual precursor components. Additionally, the peaks observed around 2800 cm⁻¹ correspond to C–H stretching vibrations, likely arising from residual precursor molecules that remained or evaporated during the synthesis process [28].

The FTIR spectrum of ZnO NRs.

3.3 UV-Visible absorption spectrum analysis

UV–visible absorption spectroscopy was used to investigate the optical properties of the synthesised ZnO nanorods. As shown in Figure 3, the absorption spectrum displays two prominent peaks at 336 nm and 370 nm, characteristic of the hexagonal wurtzite structure of ZnO [29], [30], [31]. These two distinct absorption features correspond to electronic transitions within the material, providing insight into its structural and optical behaviour [31]. The optical bandgaps were estimated from Tauc plots [17], yielding values of 3.66 ± 0.01 eV and 3.29 ± 0.03 eV. The higher bandgap (3.66 eV), associated with the 336 nm peak, is attributed to excitonic absorption and possible defect-related transitions, where bound electron-hole pairs or lattice imperfections create discrete energy states [32], 33]. The lower bandgap (3.29 eV), linked to the 370 nm peak in the UV-A region, is commonly associated with oxygen vacancies or impurity-induced states within the band structure. Such vacancies, which are abundant in ZnO, play a key role in tuning its optical response. The coexistence of these two bandgaps is advantageous, as it can enhance electron transfer processes and thus facilitate applications such as photocatalytic dye degradation [34]. Variations in peak position and intensity may result from differences in particle size, morphology, synthesis conditions, or the presence of surface states and dopants. Careful analysis of these spectral features is therefore essential for understanding the electronic structure and optical performance of ZnO nanomaterials, which underpin their applications in photocatalysis, sensors, and optoelectronic devices [35], 36].

Presents the UV-visible spectrum of the synthesized ZnO NRs, showcasing three distinct absorption peaks along with their corresponding band gaps.

3.4 Fluorescence spectrum analysis of ZnO NRs

In Figure 4, the fluorescence spectrum of ZnO NRs shows a distinct emission peak at 340 nm, which may be attributed to near-band-edge emission, potentially influenced by quantum confinement effects or excitonic transitions [37], 38]. The sample exhibited strong fluorescence with no noticeable quenching. When the excitation wavelength was increased beyond 300 nm, a red shift in the emission peak was observed, along with a decrease in fluorescence intensity [39], 40]. The modest shift in both fluorescence peak position and intensity can be attributed to enhanced crystallinity and controlled vacancy formation within the nanoparticles. The absence of fluorescence quenching suggests high crystallinity, indicating minimal non-radiative recombination and controlled defect states. The correlation between this finding and the UV–vis absorption results of ZnO NRs lies in their shared dependence on the material’s electronic structure, defect states, and crystallinity [36].

Fluorescence spectrum of ZnO nanorods.

3.5 Elemental composition and TEM analysis of ZnO NRs

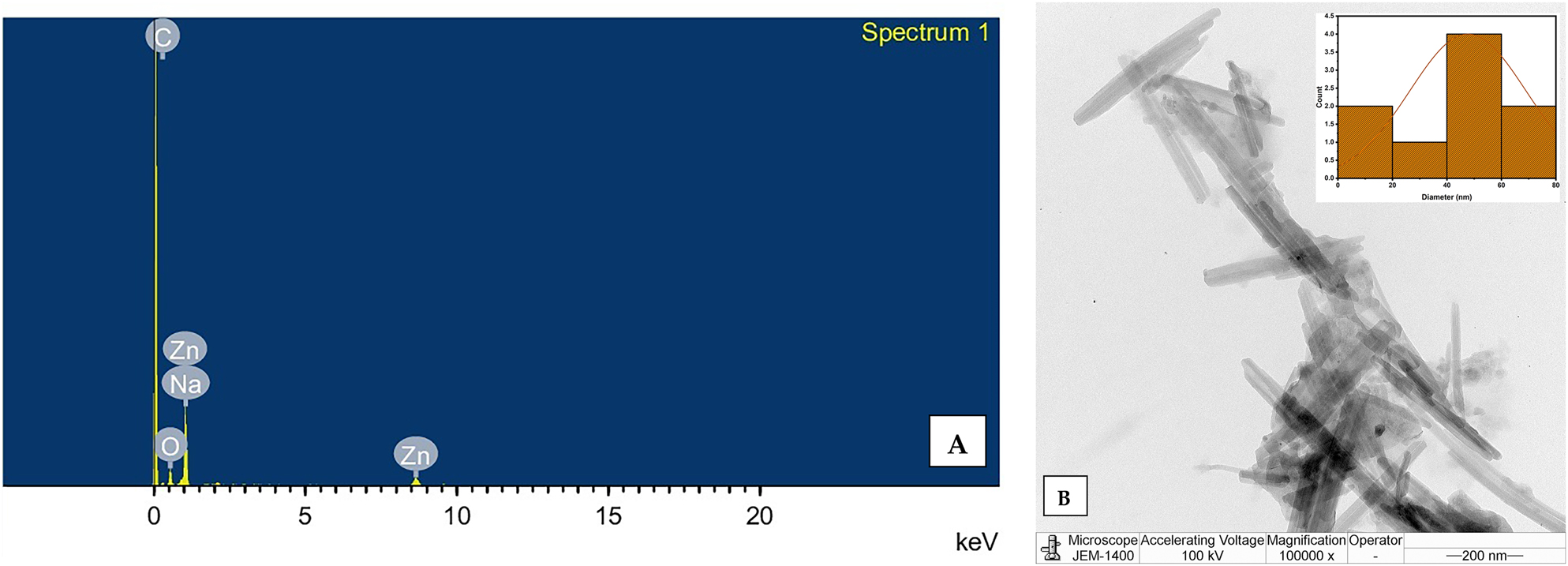

The elemental composition of the synthesised ZnO nanorod photocatalyst was assessed using EDS analysis. In Figure 5A, the EDS results confirm the presence of signals corresponding to zinc and oxygen, which are characteristic of zinc oxide nanoparticles. The analysis also identified peaks related to the optical absorbance of the synthesised nanoparticles [41]. The elemental composition of the nanoparticles revealed approximately 60 % zinc and 20 % oxygen, indicating a high level of purity in the synthesis process. Traces of carbon (13 %) and sodium (7 %) were also detected, which may have been introduced during the washing step of the synthesis. This finding is consistent with the FTIR results, confirming the presence of characteristic functional groups such as hydroxyl (–OH) and carbonate species. These functional groups correspond to the elemental composition detected by EDS, particularly the presence of oxygen and carbon. The Zn–O stretching vibration observed in the FTIR further supports the presence of Zn and O elements identified by EDS.

Elemental composition and structural morphology of ZnO NRs: (A) EDS spectrum confirming the elemental composition of ZnO NRs; (B) TEM micrographs with particle size distribution of ZnO NRs.

TEM analysis was used to characterise the surface morphology of the synthesised ZnO NRs. In Figure 5B, a typical TEM image of the synthesised ZnO NRs shows the prevalence of rod-shaped particles, with some particles aggregating into rods. The particle size distribution of the synthesised ZnO NRs was determined using ImageJ software. Figure 5B illustrates the formation of rods with varying widths and lengths. Notably, the absence of rod branching indicates the spontaneous nucleation of ZnO nanorods with high crystal perfection [42]. The nanorod-shaped particles have a width of 47.7 nm, confirming the formation of nanoscale ZnO. Shakee N. et al. reported a strong correlation between nanorod morphology and enhanced photocatalytic performance. The one-dimensional (1D) rod-like structure of ZnO provides a high aspect ratio and directional pathways for charge transport, which significantly suppress electron–hole recombination. In addition, the exposed polar facets of the hexagonal wurtzite structure, particularly the (0001) planes, act as highly active sites for dye adsorption and the generation of reactive oxygen species under solar irradiation. Furthermore, the uniform alignment and high crystallinity of ZnO nanorods enhance light absorption, promote efficient charge separation, and increase surface–reactant interactions. Collectively, these structural and morphological features account for the superior photocatalytic efficiency of ZnO NRs [43].

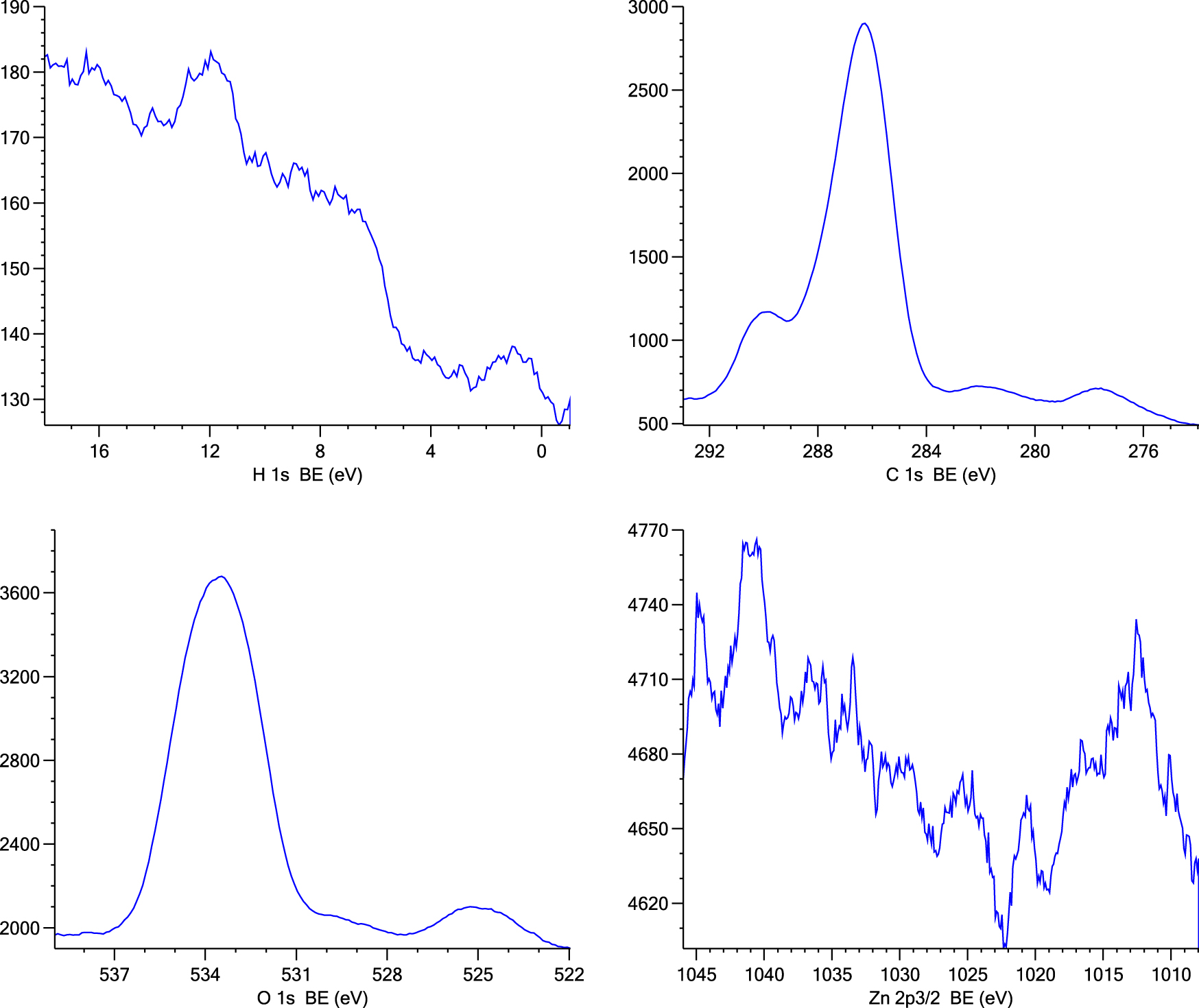

3.6 XPS spectrum analysis of ZnO NR thin film

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was used to investigate the chemical states of elements and functional groups in the ZnO nanorod coating solution applied to the glass slides. The XPS spectra confirm the presence of oxygen and carbon in the samples, as indicated by peaks at approximately 284.9 eV and 533.7 eV, corresponding to the C 1s and O 1s electrons, respectively (Figure 6). The XPS spectrum also shows two distinct peaks for zinc: Zn 2p3/2 at around 1,021 eV and Zn 2p1/2 at around 1,044 eV (Figure 6) [44]. These peaks indicate the presence of ZnO nanorods within the PMMA matrix of the thin film coating on the glass slides, further confirming the incorporation of ZnO nanorods into the coating.

The wide XPS spectrum shows Zn 2p, C 1s, and O 1s peaks of the thin film-coated glass slide.

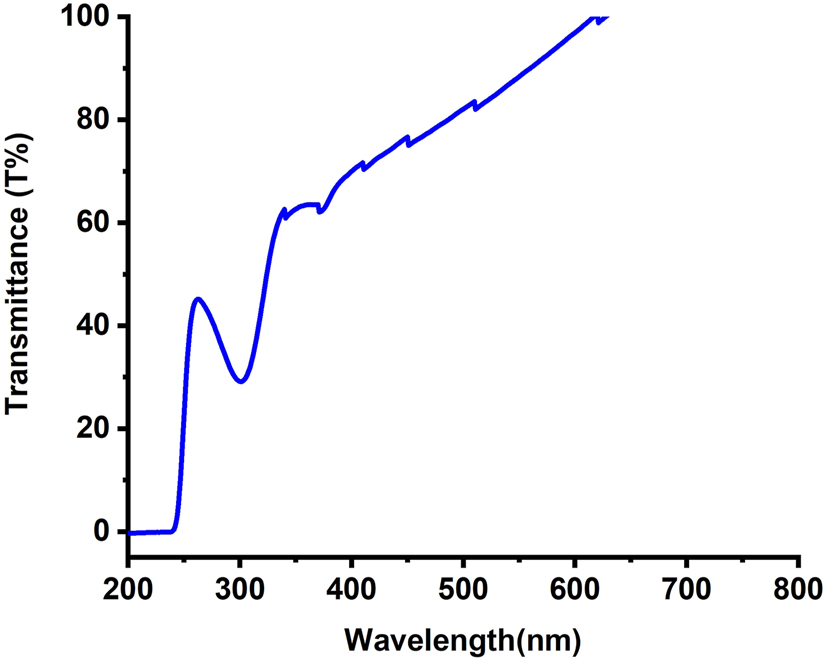

3.7 Transmittance spectrum analysis of ZnO NRs

The light transmittance of the ZnO NR sample, synthesised and evaluated across the 200–800 nm wavelength range (as shown in Figure 7), exhibited high transparency in the visible region and clear absorption in the UV region. The transmittance reached nearly 100 % between 400 and 800 nm, with a substantial decrease observed near 400 nm (∼65 %), followed by a complete decline beyond 300 nm. This pronounced reduction in transmittance in the UV range compared to the visible range highlights the inherent UV-light absorption capability of ZnO NRs. These optical properties are consistent with previous literature, confirming ZnO’s well-established behaviour as a material with high transparency in the visible spectrum and effective UV-blocking properties [45]. This finding supports the potential of ZnO NRs as an effective component in self-cleaning coatings for windows, solar panels, and building exteriors. Furthermore, the high transparency in the visible spectrum allows ZnO-based coatings to be applied to glass surfaces without compromising optical clarity, enhancing their practicality for real-world applications.

Illustrates the light transmittance (%) spectrum of the synthesized ZnO NRs.

3.8 Contact angle measurement for self-cleaning analysis of ZnO NRs

Contact angle (CA) measurements were carried out using a 5 μL water droplet at ambient temperature. Figure 8A shows the water droplet before and after contact with the ZnO NRs-coated surface. The CA value was measured as 95.6° ± 0.3, confirming the hydrophobic nature of the surface, while Figure 8B illustrates the actual droplet shape. The high contact angle is attributed to the structural characteristics of the ZnO NRs, which form a rod-like assembly both within the PMMA matrix and on the glass surface. The PMMA matrix plays a key role in enhancing the durability of the ZnO NR-based hydrophobic coating. Embedding the nanorods within PMMA provides mechanical stability, improves adhesion to the glass substrate, and reduces the likelihood of detachment during handling or exposure to water. The polymer matrix also prevents nanorod agglomeration and minimises surface wear, thereby supporting the long-term retention of hydrophobicity. In addition, PMMA offers excellent transparency and weather resistance, ensuring that the coating maintains both optical clarity and hydrophobic performance under repeated use. These combined effects make the ZnO NR/PMMA composite more durable than coatings composed of nanorods alone. The rod-like arrangement of nanorods also introduces microstructural roughness, which, according to Wenzel’s model [46], amplifies the intrinsic wetting behaviour of the material. The presence of numerous troughs between nanorods restricts water spreading, resulting in droplet beading and the observed hydrophobicity. While these findings suggest that ZnO NRs could be promising for self-cleaning applications, it should be noted that direct self-cleaning tests (such as roll-off or dust-removal experiments) were not conducted in this study. Nevertheless, the measured hydrophobicity highlights their potential for future self-cleaning surface designs without compromising light transmission (Figure 8C).

Water droplet contact angle measurement: (A) water drop before coming into contact with the surface and after coming into contact with the film of ZnO NRs-PMMA coated glass substrate, while (B) is represents the photograph of water drop on film of ZnO NRs – PMMA coated glass substrate, (in supplementary file see the video of video of water drops sliding without getting the glass slide coated with the hydrophobic film wet.), (C) illustrates the schematic representation of the hydrophobic surface, where water droplets effortlessly roll off, confirming the effective utilization of hydrophobic ZnO NRs for self-cleaning applications.

Table 1 summarises the hydrophobic properties of the synthesised ZnO NRs and compares them with reported values for similar nanomaterials.

Efficacy of the hydrophobicity properties of the synthesized ZnO NRs in comparison to the values for various nanomaterials reported in the literature.

| Nanomaterials | Substrate | Contact angle | Bandgap (eV) | Size of nanoparticles (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tenorite (CuO) [47] | Glass | 65.61° | 1.21–2.74 | 13 to 72 |

| Kenaf fiber with ZnO NPs [48] | Fabric | 74.40° | – | – |

| Alumina NPs [49] | Glass slide | 22 ± 2 | – | 13 nm |

| Silica/alumina nanoparticle mixture [50] | Ceramic alumina disk | 158° | – | Average pore size of 0.4 μm |

| Titanium dioxide nanoparticles (T300) [51] | BK-7 substrates | ≈20.82° | 3.05 | 25 nm |

| ZnO NRs (current study) | Glass | 95.6° | 2.64 and 3.24 | 22 nm |

3.9 Photodegradation efficiency of ZnO NRs for CV dye under visible light

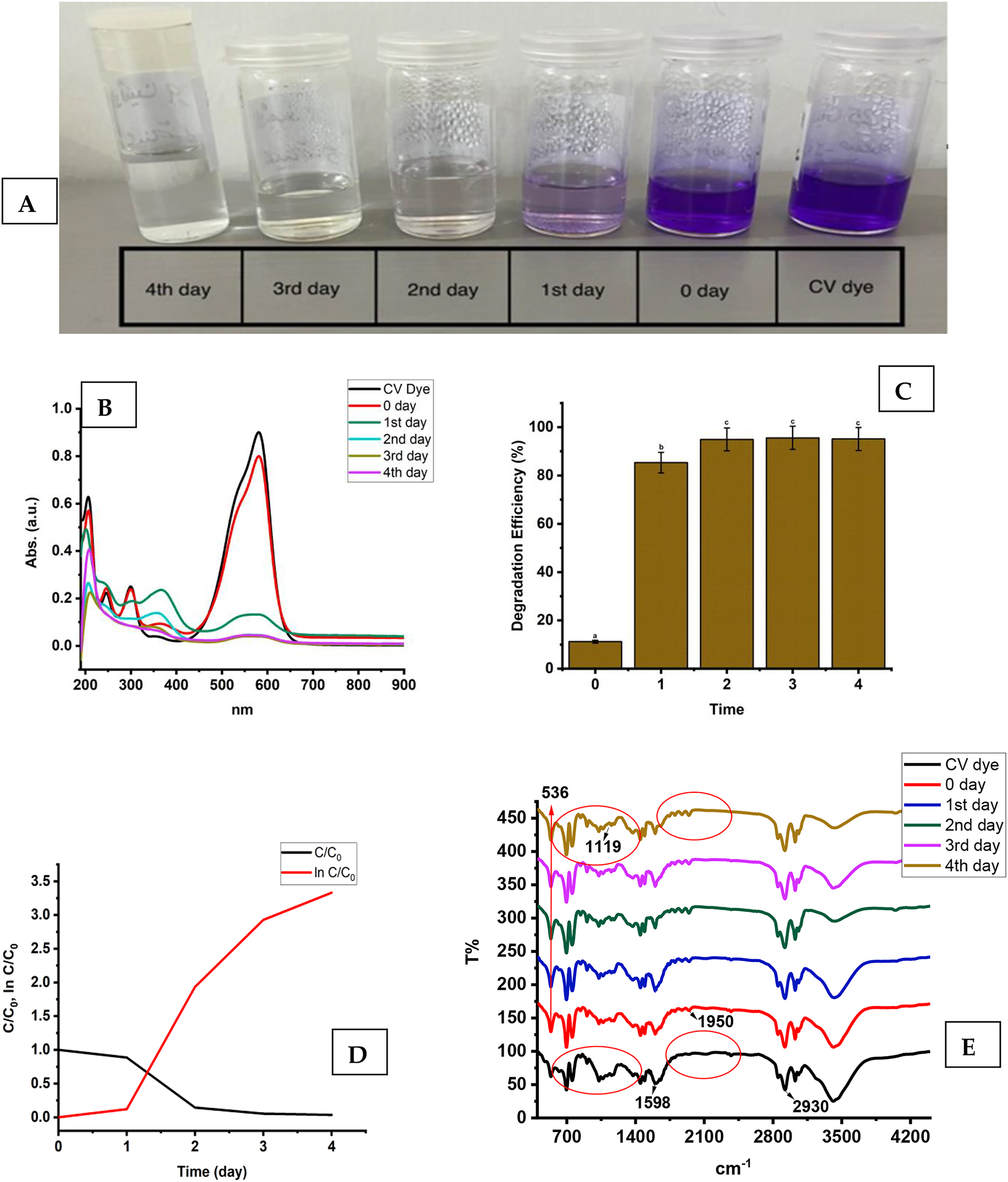

Figure 9A shows the photodegradation of CV dye in the aqueous phase, facilitated by ZnO nanoparticles under sunlight, in a yard in Al Riyadh city, Saudi Arabia. The CV dye solution, containing ZnO nanorods, exhibited notable and time-dependent degradation, with 95 % ± 0.01 of the colour fading observed within one day of sunlight exposure, as shown in Figure 9B. The effective photocatalytic degradation of CV dye is further demonstrated in Figure 9C. Table 2 presents the performance of the current ZnO NR photocatalysts compared to reported values from previous studies on other nanomaterials as photocatalysts. A comparative analysis of CV dye concentration over irradiation time was conducted. In this context, “C 0” denotes the CV dye concentration before irradiation, while “C” signifies the concentration after irradiation, as shown in Figure 9D. The graphical representation shows a consistent decline in CV dye concentration over time. Using kinetic reaction modelling, the experimental data were analysed to elucidate the photocatalytic behaviour [52].

In the above equation, C 0 and C represent the concentrations of CV dye at time zero and at time t, respectively; t denotes the reaction time, and the apparent rate constant is given in min−1. This formulation indicates that the photocatalytic degradation curve follows first-order kinetic behaviour.

(A) The photodegradation of CV dye over different time durations. (B) The UV–vis spectra of dye photodegradation induced by solar radiation, obtained for CV dye under optimal conditions. (C) The effectiveness of ZnO NRs in degrading CV dye, with different letters (a, b, and c) indicating significant differences at p > 0.05. (D) the kinetic plot, including the rate constant and half-life of dye degradation, for the ZnO NR-catalyzed photocatalytic degradation of CV dye. (E) FTIR analysis results of CV dye samples treated with ZnO NRs over varying time durations.

The performance of the current photocatalysts – ZnO NRs – in comparison to literature-reported values for different nanomaterials as photocatalysts.

| Nanomaterials | Size of nanoparticles (nm) | Photodegradation percentage (%)/Dye | Duration of irradiation | Bandgap (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cobalt-doped titanium oxide [53] | 15–26 nm | 90 %/amido black dye | Under UV radiation | – |

| ZnO NPs [54] | 10 nm | 99.9 % and 96.8 %/methylene blue and alizarin red S dyes, respectively | UV light irradiation for 100 min | 3.19 |

| ZnFe2O4 [55] | 21.71 nm | 96 %/CV dye | Sunlight for 30 min | 1.69–2.55 |

| MnV2O6/BiVO4 heterojunction [56] | 32.7–40.1 nm | 75 % and 68 %/MB and RhB dyes, respectively | After irradiation with direct sunlight | 2.5 eV and 1.60 eV for BiVO4 and MnV2O6, respectively |

| Zinc oxide-coated biochar nanocomposite [57] | 18 nm | 92 %/methylene blue dye | Under sunlight irradiation for 0–120 min | 2.89 eV |

| Copper oxide nanoparticles [58] | 12.44 nm | 65.231 % ± 0.242 and 65.078 % ± 0.392/methyl green and methyl orange, respectively. | Sunlight irradiation for 60 min | Approximately ≈3.8 eV |

| ZnO NRs – current study | 22 nm | 95 %/CV dye | Sunlight irradiation for 3 days and daily for 3 h | 2.64 and 3.24 eV |

Figure 9D shows the linear relationship between ln (C/C 0) and the irradiation time for CV dye degradation. This relationship yields a rate constant (k) of 0.6767 min−1 and a pollutant half-life of 0.959 units for ZnO NRs. To understand the degradation of CV via different processes, we conducted FTIR analysis, with the results presented in Figure 9E. A clear distinction between the FTIR spectra of the degraded dye and the untreated control solution demonstrates substantial degradation of CV induced by ZnO nanoparticles. The FTIR spectra show marked differences in both the fingerprint and functional group regions (3,500–500 cm−1) of the degraded samples compared to the control (CV dye), consistently observed across all degradation processes.

The most prominent peaks in the FTIR spectrum of the untreated sample correspond to mono-substituted and para-disubstituted benzene rings, supporting the peak at 1,598 cm−1 attributed to C=C stretching in the benzene ring. Additionally, the peaks at 1,950 cm−1 and 2,930 cm−1 are associated with C–N stretching vibrations and C–H stretching of the asymmetric CH3 group, respectively. Notably, the N=N stretching vibration peak at 1,950 cm−1 is absent in the FTIR spectrum of the CV dye after treatment with ZnO nanoparticles. This absence suggests changes in the molecular structure, potentially indicating cleavage of the N=N bond during interaction with ZnO nanoparticles. After CV degradation, the region from 1,117 to 534 cm−1 is altered, suggesting possible decomposition of aromatic rings. The unchanged Zn–O band at 536 cm−1 indicates the structural stability and reusability of ZnO nanorods during photocatalytic degradation [59]. Table 2 compares the photocatalytic performance of ZnO NRs with values for various nanomaterials reported in previous studies. This comparison offers valuable insights into the efficiency of ZnO NRs as photocatalysts and their potential for environmental applications. The materials included were selected based on their reported photocatalytic efficiency, relevance in recent studies, and ability to degrade organic pollutants.

Scheme 1 outlines the reaction mechanisms underlying the degradation properties of ZnO NRs. The degradation of CV dye depends on UV radiation, requiring the elimination of a positive hole (h+) in the valence band. This process initiates the movement of valence electrons through the conduction band.

Reaction mechanisms for the degradation of CV dye using ZnO NRs.

Under UV or sunlight exposure, vacant sites and free electrons interact with absorbed water molecules on the photocatalyst surface, generating OH radicals (OH*). These light-induced radicals play a crucial role in breaking down dye molecules into simpler compounds, such as CO2 and H2O. This mechanism is consistent with the findings of [60], [61], [62], [63], providing a comprehensive understanding of the photocatalysis process (Equations (3)–(8)).

According to the experimental results, the relatively small bandgap of ZnO nanoparticle coatings is responsible for their superior photocatalytic activity. This is because it enables better contact between the coatings and faster electron transfer during the degradation reaction. ZnO nanoparticle coatings have potential for use in self-cleaning coatings and interfaces for occupational and ecological applications, as well as in the light-induced catalytic degradation of organic dyes, due to their strong photocatalytic properties, recyclability, and durability.

4 Conclusions

Zinc oxide nanorods were synthesised using a hydrothermal preparation method, followed by comprehensive characterisation with various analytical techniques, including X-ray diffraction (XRD), Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), UV-visible spectroscopy, fluorescence spectroscopy (FL), transmission electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (TEM-EDX), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and transmittance spectroscopy. XRD analysis confirmed the hexagonal wurtzite structure of ZnO nanorods, with an estimated average crystallite size of approximately 22 nm. UV-visible spectroscopy revealed absorption peaks at 336 nm and 370 nm, corresponding to optical bandgap values of 3.29 ± 0.03 eV and 3.66 ± 0.01 eV, respectively. TEM images showed rod-shaped nanostructures with a width of 47 nm. In photocatalysis tests, the ZnO nanorods exhibited superior photocatalytic activity, particularly in the degradation of crystal violet (CV) dye, attributed to bandgap constriction. Coating experiments demonstrated a photocatalytic decomposition rate constant of 0.6767 min−1, highlighting the material’s efficiency and stability. Photodegradation assessments indicated that the ZnO nanorods maintained a degradation efficiency exceeding 95 % ± 0.01, underscoring their excellent photocatalytic performance. The ZnO nanorods also displayed hydrophobic behaviour, with a water contact angle of 95.6° ± 0.3, indicating their suitability for self-cleaning applications. XPS analysis revealed two distinct peaks for zinc, Zn 2p3/2 at ∼1,021 eV and Zn 2p1/2 at ∼1,044 eV, confirming the presence of ZnO nanorods within the thin film coating on glass slides used for self-cleaning analysis. These results highlight the potential of synthesised ZnO nanorod coatings for environmentally friendly applications, including self-cleaning technologies, with promising capabilities for effectively reducing pollutants and contributing to sustainable environmental solutions. Future studies should evaluate the effectiveness of ZnO nanorods against diverse pollutants and address challenges related to industrial scalability, cost, and reproducibility. Advancing deposition techniques and hybrid materials could further enhance their photocatalytic and self-cleaning properties for broader environmental applications.

-

Funding information: The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from Researchers Supporting Project number (RICSP-25-1), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Author contribution: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

1. Saadi, H, Khaldi, O, Pina, J, Costa, T, Seixas de Melo, JS, Vilarinho, P, et al.. Effect of Co doping on the physical properties and organic pollutant photodegradation efficiency of ZnO nanoparticles for environmental applications. Nanomaterials 2024;14:122. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano14010122.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Madi, K, Chebli, D, Ait Youcef, H, Tahraoui, H, Bouguettoucha, A, Kebir, M, et al.. Green fabrication of ZnO nanoparticles and ZnO/rGO nanocomposites from Algerian date syrup extract: synthesis, characterization, and augmented photocatalytic efficiency in methylene blue degradation. Catalysts 2024;14:62. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal14010062.Search in Google Scholar

3. Agarwal, H, Kumar, SV, Rajeshkumar, S. A review on green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles – an eco-friendly approach. Resour Efficient Technol 2017;3:406–13. https://doi.org/10.18799/24056529/2017/4/163.Search in Google Scholar

4. Rasool, A, Sri, S, Zulfajri, M, Krismastuti, FSH. Nature inspired nanomaterials: advancements in green synthesis for biological sustainability. Inorg Chem Commun 2024;169:112954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2024.112954.Search in Google Scholar

5. Senthil, RB, Ewe, LS, S, S, S, S, Yew, WK, Tiong, SK, et al.. Recent trends and advancement in metal oxide nanoparticles for the degradation of dyes: synthesis, mechanism, types and its application. Nanotoxicology 2024;18:272–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/17435390.2024.2349304.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Kaveh, R, Alijani, H, Falletta, E, Bianchi, CL, Mokhtarifar, M, Boffito, DC. Advancements in superhydrophilic titanium dioxide/graphene oxide composite coatings for self-cleaning applications on glass substrates: a comprehensive review. Prog Org Coat 2024;190:108347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2024.108347.Search in Google Scholar

7. Baig, A, Siddique, M, Panchal, S. A review of visible-light-active zinc oxide photocatalysts for environmental application. Catalysts 2025;15:100. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15020100.Search in Google Scholar

8. Kumari, H, Sonia, S, Ranga, R, Chahal, S, Devi, S, Sharma, S, et al.. A review on photocatalysis used for wastewater treatment: dye degradation. Water Air Soil Pollut 2023;234:349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-023-06359-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Ansari, AS, Azzahra, G, Nugroho, FG, Mujtaba, MM, Ahmed, ATA. Oxides and metal oxide/carbon hybrid materials for efficient photocatalytic organic pollutant removal. Catalysts 2025;15:134. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15020134.Search in Google Scholar

10. Chen, D, Cheng, Y, Zhou, N, Chen, P, Wang, Y, Li, K, et al.. Photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants using TiO2-based photocatalysts: a review. J Clean Prod 2020;268:121725. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121725.Search in Google Scholar

11. Varma, KS, Tayade, RJ, Shah, KJ, Joshi, PA, Shukla, AD, Gandhi, VG. Photocatalytic degradation of pharmaceutical and pesticide compounds (PPCs) using doped TiO2 nanomaterials: a review. Water-Energy Nexus 2020;3:46–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wen.2020.03.008.Search in Google Scholar

12. Qi, K, Cheng, B, Yu, J, Ho, W. Review on the improvement of the photocatalytic and antibacterial activities of ZnO. J Alloys Compd 2017;727:792–820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2017.08.142.Search in Google Scholar

13. Khan, ME. State-of-the-art developments in carbon-based metal nanocomposites as a catalyst: photocatalysis. Nanoscale Adv 2021;3:1887–900. https://doi.org/10.1039/d1na00041a.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Ankita, Rathee, T, Sapana, Chahal, S, Kumar, S Kumar, Aet al.. Growth of advanced oxide nanostructures (nanocubes/nanorods/nanoflowers). In: Defect-induced magn oxide semiconductors. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing; 2023, 223:223–44 pp.10.1016/B978-0-323-90907-5.00020-8Search in Google Scholar

15. Rong, P, Ren, S, Yu, Q. Fabrications and applications of ZnO nanomaterials in flexible functional devices – a review. Crit Rev Anal Chem 2019;49:336–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408347.2018.1531691.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Laurenti, M, Stassi, S, Canavese, G, Cauda, V. Surface engineering of nanostructured ZnO surfaces. Adv Mater Interfaces 2017;4:1600758. https://doi.org/10.1002/admi.201600758.Search in Google Scholar

17. Khan, MM, Saadah, NH, Khan, ME, Harunsani, MH, Tan, AL, Cho, MH. Phytogenic synthesis of band gap-narrowed ZnO nanoparticles using the bulb extract of Costus woodsonii. BioNanoScience 2019;9:334–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12668-019-00616-0.Search in Google Scholar

18. Raha, S, Ahmaruzzaman, M. ZnO nanostructured materials and their potential applications: progress, challenges and perspectives. Nanoscale Adv 2022;4:1868–925. https://doi.org/10.1039/d1na00880c.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Sharwani, AA, Narayanan, KB, Khan, ME, Han, SS. Photocatalytic degradation activity of goji berry extract synthesized silver-loaded mesoporous zinc oxide (Ag@ZnO) nanocomposites under simulated solar light irradiation. Sci Rep 2022;12:10017. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14117-w.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Zhu, J, Liao, K. A facile method for preparing a superhydrophobic block with rapid reparability. Coatings 2020;10:1202. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings10121202.Search in Google Scholar

21. Gao, X, Wen, G, Guo, Z. Durable superhydrophobic and underwater superoleophobic cotton fabrics growing zinc oxide nanoarrays for separation of heavy/light oil and water mixtures. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2018;559:115–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2018.09.041.Search in Google Scholar

22. Nundy, S, Ghosh, A, Mallick, TK. Hydrophobic and superhydrophobic self-cleaning coatings by morphologically varying ZnO microstructures for photovoltaic and glazing applications. ACS Omega 2020;5:1033–9. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.9b02758.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Markevich, I, Stara, T, Khomenkova, L, Kushnirenko, V, Borkovska, L. Photoluminescence engineering in polycrystalline ZnO and ZnO-based compounds. AIMS Mater Sci 2016;3:508–24. https://doi.org/10.3934/matersci.2016.2.508.Search in Google Scholar

24. Kaningini, AG, Azizi, S, Sintwa, N, Mokalane, K, Mohale, KC, Mudau, FN, et al.. Effect of optimized precursor concentration, temperature, and doping on optical properties of ZnO nanoparticles synthesized via a green route using bush tea (Athrixia phylicoides DC.) leaf extracts. ACS Omega 2022;7:31658–66. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.2c00530.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Manal, AA, Hendi, A, Ortashi, K, Alnamlah, R, Alangery, A, Ali Alshaya, E, et al. Utilizing cymbopogon Proximus grass extract for green synthesis of zinc oxide nanorod needles in dye degradation studies. Molecules 2024;29:355.Search in Google Scholar

26. Alterary, ٍSS. Potent and versatile biogenically synthesized alumina/nickel oxide nanocomposite adsorbent for defluoridation of drinking water. ACS Omega 2024;9:23220–40. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c09076.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

27. Estrada-Urbina, J, Cruz-Alonso, A, Santander-González, M, Méndez-Albores, A, Vázquez-Durán, A. Nanoscale zinc oxide particles for improving the physiological and sanitary quality of a Mexican landrace of red maize. Nanomaterials 2018;8:247. 195207. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano8040247..Search in Google Scholar

28. Shankar, S, Wang, LF, Rhim, JW. Zinc oxide nanoparticle incorporation improves mechanical, water vapor barrier, UV-light barrier and antibacterial properties of PLA nanocomposite films. Mater Sci Eng C 2018;93:289–98. e202400203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2018.08.002..Search in Google Scholar

29. Pudukudy, M, Yaakob, Z. Facile synthesis of quasi-spherical ZnO nanoparticles with excellent photocatalytic activity. J Cluster Sci 2015;26:1187–201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10876-014-0806-1.Search in Google Scholar

30. Karthikeyan, B, Gnanakumar, G, Alphonsa, AT. Nano metal oxides. Singapore: Springer; 2023.10.1007/978-981-19-9444-9Search in Google Scholar

31. Teke, A, Özgür, Ü, Doğan, S, Morkoç, H, Nemeth, B, Everitt, HO. Excitonic fine structure and recombination dynamics in single-crystalline ZnO. Phys Rev B 2004;70:195207. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.70.195207.Search in Google Scholar

32. Podia, M, Tripathi, AK. Structural, optical and luminescence properties of ZnO thin films: role of hot electrons defining luminescence mechanisms. J Lumin 2022;252:119331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlumin.2022.119331.Search in Google Scholar

33. Mascoli, V, Bhatti, AF, Bersanini, L, van Amerongen, H, Croce, R. The antenna of far-red absorbing cyanobacteria increases both absorption and quantum efficiency of photosystem II. Nat Commun 2022;13:3562. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-31099-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

34. Wang, C. Luminescent transition metal complexes: optical characterization, integration into polymeric nanoparticles and sensing applications. Berlin: Freie Universität Berlin; 2021.Search in Google Scholar

35. Bulcha, B, Leta Tesfaye, J, Anatol, D, Shanmugam, R, Dwarampudi, LP, Nagaprasad, N, et al.. Synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles by hydrothermal methods and spectroscopic investigation of ultraviolet radiation protective properties. J Nanomater 2021;2021:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/8617290.Search in Google Scholar

36. Javed, A, Wiener, J, Tamulevičienė, A, Tamulevičius, T, Lazauskas, A, Saskova, J, et al.. One-step in situ synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles for multifunctional cotton fabrics. Materials 2021;14:3956. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14143956.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

37. Awad, MA, Hendi, AA, Ortashi, KM, Alnamlah, RA, Alangery, A, Alshaya, EA, et al.. Utilizing cymbopogon proximus grass extract for green synthesis of zinc oxide nanorod needles in dye degradation studies. Molecules 2024;29:355. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29020355.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

38. Nguyen, TP, Tan, PB, Le, T. Effect of poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) capping agent on structural, photoluminescent and photometric properties of ZnO nanoparticles. Opt Mater 2022;125:112132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2022.112132.Search in Google Scholar

39. Motelica, L, Vasile, BS, Ficai, A, Surdu, AV, Ficai, D, Oprea, OC, et al.. Antibacterial activity of zinc oxide nanoparticles loaded with essential oils. Pharmaceutics 2023;15:2470. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics15102470.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

40. Falamas, A, Maric, I, Nekvapil, F, Stefan, M, Macavei, GS, Barbu-Tudoran, L, et al.. Surface enhanced fluorescence potential of ZnO nanoparticles and gold decorated ZnO nanostructures embedded in a polyvinyl alcohol matrix. J Photochem Photobiol A: Chem 2023;438:114516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotochem.2022.114516.Search in Google Scholar

41. Shakeel, N, Piwoński, I, Kisielewska, A, Krzywiecki, M, Batory, D, Cichomski, M. Morphology-dependent photocatalytic activity of nanostructured titanium dioxide coatings with silver nanoparticles. Int J Mol Sci 2024;25:8824. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25168824.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

42. Meky, AI, Hassaan, MA, Fetouh, HA, Ismail, AM, El Nemr, A. Hydrothermal fabrication, characterization and RSM optimization of cobalt-doped zinc oxide nanoparticles for antibiotic photodegradation under visible light. Sci Rep 2024;14:2016. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-52430-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

43. Mardosaite, R, Jurkeviciute, A, Rackauskas, S. Superhydrophobic ZnO nanowires: wettability mechanisms and functional applications. Cryst Growth Des 2021;21:4765–79. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.cgd.1c00449.Search in Google Scholar

44. Althamthami, M, Temam, HB, Temam, EG, Rahmane, S, Gasmi, B, Hasan, GG. Impact of surface topography and hydrophobicity in varied precursor concentrations of tenorite (CuO) films: film properties and photocatalytic efficiency. Sci Rep 2024;14:7928. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-58744-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

45. Mohammed, M, Rahman, R, Mohammed, AM, Betar, BO, Osman, AF, Adam, T, et al.. Improving hydrophobicity and compatibility between kenaf fiber and polymer composite by surface treatment with inorganic nanoparticles. Arab J Chem 2022;15:104233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2022.104233.Search in Google Scholar

46. Al-Shatty, W, Lord, AM, Alexander, S, Barron, AR. Tunable surface properties of aluminum oxide nanoparticles from highly hydrophobic to highly hydrophilic. ACS Omega 2017;2:2507–14. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.7b00279.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

47. Huang, CY, Ko, CC, Chen, LH, Huang, CT, Tung, KL, Liao, YC. Simple coating method to prepare superhydrophobic layers on ceramic alumina for vacuum membrane distillation. Sep Purif Technol 2018;198:79–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2016.12.037.Search in Google Scholar

48. Li, Y, Xia, B, Jiang, B. Thermal-induced durable superhydrophilicity of TiO2 films with ultra-smooth surfaces. J Sol Gel Sci Technol 2018;87:50–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10971-018-4684-0.Search in Google Scholar

49. Wang, W, Lv, L, Wang, C, Li, J. Melamine-assisted thermal activation for vacancy-rich ZnO: calcination effects on microstructure and photocatalytic properties. Molecules 2023;28:5329. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28145329.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

50. Lu, J, Ali, H, Hurh, J, Han, Y, Batjikh, I, Rupa, EJ, et al.. Photocatalytic activity assessment of zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Codonopsis lanceolata roots by one-pot green synthesis. Optik 2019;184:82–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijleo.2019.03.050.Search in Google Scholar

51. Abdi, M, Balagabri, M, Karimi, H, Hossini, H, Rastegar, SO. Degradation of crystal violet using ozone, peroxone, electroperoxone and electrolysis processes: a comparative study. Appl Water Sci 2020;10:1–10.10.1007/s13201-020-01252-wSearch in Google Scholar

52. Anitha, S, Muthukumaran, S. Structural, optical and antibacterial investigation of La- and Cu-doped ZnO nanoparticles synthesized by co-precipitation. Mater Sci Eng C 2020;108:110387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2019.110387.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

53. Khan, I, Saeed, K, Ali, N, Khan, I, Zhang, B, Sadiq, M. Heterogeneous photodegradation of industrial dyes: mechanisms and rate-affecting parameters. J Environ Chem Eng 2020;8:104364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2020.104364.Search in Google Scholar

54. Tagnaouti Moumnani, F, Khallouk, K, Elkhalfaouy, R, Moussaid, D, Mertah, O, Solhy, A, et al.. Synthesis and characterization of Zn3V2O8 nanoparticles: mechanisms and factors influencing crystal violet photodegradation. React Kinet Mech Catal 2024:1–18.10.1007/s11144-023-02553-2Search in Google Scholar

55. Ali, I, Alharbi, OM, Alothman, ZA, Badjah, AY. Photodegradation kinetics and thermodynamics of amido black dye over Co/TiO2 nanoparticles. Photochem Photobiol 2018;94:935–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/php.12937.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

56. Shubha, JP, Kavalli, K, Adil, SF, Assal, ME, Hatshan, MR, Dubasi, N. Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles for dye degradation: kinetic modeling approach. J King Saud Univ Sci 2022;34:102047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2022.102047.Search in Google Scholar

57. Bayahia, H. High activity of ZnFe2O4 nanoparticles for sunlight-driven photodegradation of crystal violet dye. J Taibah Univ Sci 2022;16:988–1004. https://doi.org/10.1080/16583655.2022.2134696.Search in Google Scholar

58. Bano, K, Mittal, SK, Singh, PP, Kaushal, S. Sunlight-driven degradation of organic pollutants using MnV2O6/BiVO4 heterojunction photocatalyst. Nanoscale Adv 2021;3:6446–58. https://doi.org/10.1039/d1na00499a.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

59. Labhane, PK, Huse, VR, Patle, LB, Chaudhari, AL, Sonawane, GH. Synthesis and characterization of Cu-doped ZnO nanoparticles: optical, FTIR, morphological and photocatalytic study. J Mater Sci Chem Eng 2015;3:39.10.4236/msce.2015.37005Search in Google Scholar

60. Eswaran, P, Madasamy, PD, Pillay, K, Brink, H. Sunlight-driven photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue using ZnO/biochar nanocomposite from banana peels. Biomass Convers Biorefinery 2024:1–21.10.1007/s13399-024-05999-zSearch in Google Scholar

61. Aroob, S, Carabineiro, SA, Taj, MB, Bibi, I, Raheel, A, Javed, T, et al.. Green synthesis and photocatalytic activity of CuO nanoparticles. Catalysts 2023;13:502. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal13030502.Search in Google Scholar

62. Anaya-Zavaleta, JC, Ledezma-Pérez, AS, Gallardo-Vega, C, Rodríguez-Hernández, J, Alvarado-Canché, CN, García-Casillas, PE, et al.. ZnO nanoparticles by hydrothermal method: synthesis and characterization. Technologies 2025;13:18. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies13010018.Search in Google Scholar

63. Karagoz, S, Kiremitler, NB, Sarp, G, Pekdemir, S, Salem, S, Goksu, AG, et al.. Antibacterial, antiviral and self-cleaning ZnO/Ag nanofiber mats for protective clothing. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2021;13:5678–90. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.0c15606.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- MHD radiative mixed convective flow of a sodium alginate-based hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated extending sheet with Joule heating

- Experimental study of mortar incorporating nano-magnetite on engineering performance and radiation shielding

- Multicriteria-based optimization and multi-variable non-linear regression analysis of concrete containing blends of nano date palm ash and eggshell powder as cementitious materials

- A promising Ag2S/poly-2-amino-1-mercaptobenzene open-top spherical core–shell nanocomposite for optoelectronic devices: A one-pot technique

- Biogenic synthesized selenium nanoparticles combined chitosan nanoparticles controlled lung cancer growth via ROS generation and mitochondrial damage pathway

- Fabrication of PDMS nano-mold by deposition casting method

- Stimulus-responsive gradient hydrogel micro-actuators fabricated by two-photon polymerization-based 4D printing

- Physical aspects of radiative Carreau nanofluid flow with motile microorganisms movement under yield stress via oblique penetrable wedge

- Effect of polar functional groups on the hydrophobicity of carbon nanotubes-bacterial cellulose nanocomposite

- Review in green synthesis mechanisms, application, and future prospects for Garcinia mangostana L. (mangosteen)-derived nanoparticles

- Entropy generation and heat transfer in nonlinear Buoyancy–driven Darcy–Forchheimer hybrid nanofluids with activation energy

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ginkgo biloba seed extract: Evaluation of antioxidant, anticancer, antifungal, and antibacterial activities

- A numerical analysis of heat and mass transfer in water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing copper and alumina nanoparticles over an extending sheet

- Investigating the behaviour of electro-magneto-hydrodynamic Carreau nanofluid flow with slip effects over a stretching cylinder

- Electrospun thermoplastic polyurethane/nano-Ag-coated clear aligners for the inhibition of Streptococcus mutans and oral biofilm

- Investigation of the optoelectronic properties of a novel polypyrrole-multi-well carbon nanotubes/titanium oxide/aluminum oxide/p-silicon heterojunction

- Novel photothermal magnetic Janus membranes suitable for solar water desalination

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ageratum conyzoides for activated carbon compositing to prepare antimicrobial cotton fabric

- Activation energy and Coriolis force impact on three-dimensional dusty nanofluid flow containing gyrotactic microorganisms: Machine learning and numerical approach

- Machine learning analysis of thermo-bioconvection in a micropolar hybrid nanofluid-filled square cavity with oxytactic microorganisms

- Research and improvement of mechanical properties of cement nanocomposites for well cementing

- Thermal and stability analysis of silver–water nanofluid flow over unsteady stretching sheet under the influence of heat generation/absorption at the boundary

- Cobalt iron oxide-infused silicone nanocomposites: Magnetoactive materials for remote actuation and sensing

- Magnesium-reinforced PMMA composite scaffolds: Synthesis, characterization, and 3D printing via stereolithography

- Bayesian inference-based physics-informed neural network for performance study of hybrid nanofluids

- Numerical simulation of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to a heterogeneous/homogeneous chemical reaction over a Riga surface

- Enhancing the superhydrophobicity, UV-resistance, and antifungal properties of natural wood surfaces via in situ formation of ZnO, TiO2, and SiO2 particles

- Synthesis and electrochemical characterization of iron oxide/poly(2-methylaniline) nanohybrids for supercapacitor application

- Impacts of double stratification on thermally radiative third-grade nanofluid flow on elongating cylinder with homogeneous/heterogeneous reactions by implementing machine learning approach

- Synthesis of Cu4O3 nanoparticles using pumpkin seed extract: Optimization, antimicrobial, and cytotoxicity studies

- Cationic charge influence on the magnetic response of the Fe3O4–[Me2+ 1−y Me3+ y (OH2)] y+(Co3 2−) y/2·mH2O hydrotalcite system

- Pressure sensing intelligent martial arts short soldier combat protection system based on conjugated polymer nanocomposite materials

- Magnetohydrodynamics heat transfer rate under inclined buoyancy force for nano and dusty fluids: Response surface optimization for the thermal transport

- Fly ash and nano-graphene enhanced stabilization of engine oil-contaminated soils

- Enhancing natural fiber-reinforced biopolymer composites with graphene nanoplatelets: Mechanical, morphological, and thermal properties

- Performance evaluation of dual-scale strengthened co-bonded single-lap joints using carbon nanotubes and Z-pins with ANN

- Computational works of blood flow with dust particles and partially ionized containing tiny particles on a moving wedge: Applications of nanotechnology

- Hybridization of biocomposites with oil palm cellulose nanofibrils/graphene nanoplatelets reinforcement in green epoxy: A study of physical, thermal, mechanical, and morphological properties

- Design and preparation of micro-nano dual-scale particle-reinforced Cu–Al–V alloy: Research on the aluminothermic reduction process

- Spectral quasi-linearization and response optimization on magnetohydrodynamic flow via stenosed artery with hybrid and ternary solid nanoparticles: Support vector machine learning

- Ferrite/curcumin hybrid nanocomposite formulation: Physicochemical characterization, anticancer activity, and apoptotic and cell cycle analyses in skin cancer cells

- Enhanced therapeutic efficacy of Tamoxifen against breast cancer using extra virgin olive oil-based nanoemulsion delivery system

- A titanium oxide- and silver-based hybrid nanofluid flow between two Riga walls that converge and diverge through a machine-learning approach

- Enhancing convective heat transfer mechanisms through the rheological analysis of Casson nanofluid flow towards a stagnation point over an electro-magnetized surface

- Intrinsic self-sensing cementitious composites with hybrid nanofillers exhibiting excellent piezoresistivity

- Research on mechanical properties and sulfate erosion resistance of nano-reinforced coal gangue based geopolymer concrete

- Impact of surface and configurational features of chemically synthesized chains of Ni nanostars on the magnetization reversal process

- Porous sponge-like AsOI/poly(2-aminobenzene-1-thiol) nanocomposite photocathode for hydrogen production from artificial and natural seawater

- Multifaceted insights into WO3 nanoparticle-coupled antibiotics to modulate resistance in enteric pathogens of Houbara bustard birds

- Synthesis of sericin-coated silver nanoparticles and their applications for the anti-bacterial finishing of cotton fabric

- Enhancing chloride resistance of freeze–thaw affected concrete through innovative nanomaterial–polymer hybrid cementitious coating

- Development and performance evaluation of green aluminium metal matrix composites reinforced with graphene nanopowder and marble dust

- Morphological, physical, thermal, and mechanical properties of carbon nanotubes reinforced arrowroot starch composites

- Influence of the graphene oxide nanosheet on tensile behavior and failure characteristics of the cement composites after high-temperature treatment

- Central composite design modeling in optimizing heat transfer rate in the dissipative and reactive dynamics of viscoplastic nanomaterials deploying Joule and heat generation aspects

- Double diffusion of nano-enhanced phase change materials in connected porous channels: A hybrid ISPH-XGBoost approach

- Synergistic impacts of Thompson–Troian slip, Stefan blowing, and nonuniform heat generation on Casson nanofluid dynamics through a porous medium

- Optimization of abrasive water jet machining parameters for basalt fiber/SiO2 nanofiller reinforced composites

- Enhancing aesthetic durability of Zisha teapots via TiO2 nanoparticle surface modification: A study on self-cleaning, antimicrobial, and mechanical properties

- Nanocellulose solution based on iron(iii) sodium tartrate complexes

- Combating multidrug-resistant infections: Gold nanoparticles–chitosan–papain-integrated dual-action nanoplatform for enhanced antibacterial activity

- Novel royal jelly-mediated green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and their multifunctional biological activities

- Direct bandgap transition for emission in GeSn nanowires

- Synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles with different morphologies using a microwave-based method and their antimicrobial activity

- Numerical investigation of convective heat and mass transfer in a trapezoidal cavity filled with ternary hybrid nanofluid and a central obstacle

- Halloysite nanotube enhanced polyurethane nanocomposites for advanced electroinsulating applications

- Low molar mass ionic liquid’s modified carbon nanotubes and its role in PVDF crystalline stress generation

- Green synthesis of polydopamine-functionalized silver nanoparticles conjugated with Ceftazidime: in silico and experimental approach for combating antibiotic-resistant bacteria and reducing toxicity

- Evaluating the influence of graphene nano powder inclusion on mechanical, vibrational and water absorption behaviour of ramie/abaca hybrid composites

- Dynamic-behavior of Casson-type hybrid nanofluids due to a stretching sheet under the coupled impacts of boundary slip and reaction-diffusion processes

- Influence of polyvinyl alcohol on the physicochemical and self-sensing properties of nano carbon black reinforced cement mortar

- Advanced machine learning approaches for predicting compressive and flexural strength of carbon nanotube–reinforced cement composites: a comparative study and model interpretability analysis

- Artificial neural network-driven insights into nanoparticle-enhanced phase change materials melting for heat storage optimization

- Optical, structural, and morphological characterization of hydrothermally synthesized zinc oxide nanorods: exploring their potential for environmental applications

- Review Articles

- A comprehensive review on hybrid plasmonic waveguides: Structures, applications, challenges, and future perspectives

- Nanoparticles in low-temperature preservation of biological systems of animal origin

- Fluorescent sulfur quantum dots for environmental monitoring

- Nanoscience systematic review methodology standardization

- Nanotechnology revolutionizing osteosarcoma treatment: Advances in targeted kinase inhibitors

- AFM: An important enabling technology for 2D materials and devices

- Carbon and 2D nanomaterial smart hydrogels for therapeutic applications

- Principles, applications and future prospects in photodegradation systems

- Do gold nanoparticles consistently benefit crop plants under both non-stressed and abiotic stress conditions?

- An updated overview of nanoparticle-induced cardiovascular toxicity

- Arginine as a promising amino acid for functionalized nanosystems: Innovations, challenges, and future directions

- Advancements in the use of cancer nanovaccines: Comprehensive insights with focus on lung and colon cancer

- Membrane-based biomimetic delivery systems for glioblastoma multiforme therapy

- The drug delivery systems based on nanoparticles for spinal cord injury repair

- Green synthesis, biomedical effects, and future trends of Ag/ZnO bimetallic nanoparticles: An update

- Application of magnesium and its compounds in biomaterials for nerve injury repair

- Micro/nanomotors in biomedicine: Construction and applications

- Hydrothermal synthesis of biomass-derived CQDs: Advances and applications

- Research progress in 3D bioprinting of skin: Challenges and opportunities

- Review on bio-selenium nanoparticles: Synthesis, protocols, and applications in biomedical processes

- Gold nanocrystals and nanorods functionalized with protein and polymeric ligands for environmental, energy storage, and diagnostic applications: A review

- An in-depth analysis of rotational and non-rotational piezoelectric energy harvesting beams: A comprehensive review

- Advancements in perovskite/CIGS tandem solar cells: Material synergies, device configurations, and economic viability for sustainable energy

- Deep learning in-depth analysis of crystal graph convolutional neural networks: A new era in materials discovery and its applications

- Review of recent nano TiO2 film coating methods, assessment techniques, and key problems for scaleup

- Antioxidant quantum dots for spinal cord injuries: A review on advancing neuroprotection and regeneration in neurological disorders

- Rise of polycatecholamine ultrathin films: From synthesis to smart applications

- Advancing microencapsulation strategies for bioactive compounds: Enhancing stability, bioavailability, and controlled release in food applications

- Advances in the design and manipulation of self-assembling peptide and protein nanostructures for biomedical applications

- Photocatalytic pervious concrete systems: from classic photocatalysis to luminescent photocatalysis

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Synthesis and characterization of smart stimuli-responsive herbal drug-encapsulated nanoniosome particles for efficient treatment of breast cancer”

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part III

- Efficiency optimization of quantum dot photovoltaic cell by solar thermophotovoltaic system

- Exploring the diverse nanomaterials employed in dental prosthesis and implant techniques: An overview

- Electrochemical investigation of bismuth-doped anode materials for low‑temperature solid oxide fuel cells with boosted voltage using a DC-DC voltage converter

- Synthesis of HfSe2 and CuHfSe2 crystalline materials using the chemical vapor transport method and their applications in supercapacitor energy storage devices

- Special Issue on Green Nanotechnology and Nano-materials for Environment Sustainability

- Influence of nano-silica and nano-ferrite particles on mechanical and durability of sustainable concrete: A review

- Surfaces and interfaces analysis on different carboxymethylation reaction time of anionic cellulose nanoparticles derived from oil palm biomass

- Processing and effective utilization of lignocellulosic biomass: Nanocellulose, nanolignin, and nanoxylan for wastewater treatment

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Aging assessment of silicone rubber materials under corona discharge accompanied by humidity and UV radiation”

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- MHD radiative mixed convective flow of a sodium alginate-based hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated extending sheet with Joule heating

- Experimental study of mortar incorporating nano-magnetite on engineering performance and radiation shielding

- Multicriteria-based optimization and multi-variable non-linear regression analysis of concrete containing blends of nano date palm ash and eggshell powder as cementitious materials

- A promising Ag2S/poly-2-amino-1-mercaptobenzene open-top spherical core–shell nanocomposite for optoelectronic devices: A one-pot technique

- Biogenic synthesized selenium nanoparticles combined chitosan nanoparticles controlled lung cancer growth via ROS generation and mitochondrial damage pathway

- Fabrication of PDMS nano-mold by deposition casting method

- Stimulus-responsive gradient hydrogel micro-actuators fabricated by two-photon polymerization-based 4D printing

- Physical aspects of radiative Carreau nanofluid flow with motile microorganisms movement under yield stress via oblique penetrable wedge

- Effect of polar functional groups on the hydrophobicity of carbon nanotubes-bacterial cellulose nanocomposite

- Review in green synthesis mechanisms, application, and future prospects for Garcinia mangostana L. (mangosteen)-derived nanoparticles

- Entropy generation and heat transfer in nonlinear Buoyancy–driven Darcy–Forchheimer hybrid nanofluids with activation energy

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ginkgo biloba seed extract: Evaluation of antioxidant, anticancer, antifungal, and antibacterial activities

- A numerical analysis of heat and mass transfer in water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing copper and alumina nanoparticles over an extending sheet

- Investigating the behaviour of electro-magneto-hydrodynamic Carreau nanofluid flow with slip effects over a stretching cylinder

- Electrospun thermoplastic polyurethane/nano-Ag-coated clear aligners for the inhibition of Streptococcus mutans and oral biofilm

- Investigation of the optoelectronic properties of a novel polypyrrole-multi-well carbon nanotubes/titanium oxide/aluminum oxide/p-silicon heterojunction

- Novel photothermal magnetic Janus membranes suitable for solar water desalination

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ageratum conyzoides for activated carbon compositing to prepare antimicrobial cotton fabric

- Activation energy and Coriolis force impact on three-dimensional dusty nanofluid flow containing gyrotactic microorganisms: Machine learning and numerical approach

- Machine learning analysis of thermo-bioconvection in a micropolar hybrid nanofluid-filled square cavity with oxytactic microorganisms

- Research and improvement of mechanical properties of cement nanocomposites for well cementing

- Thermal and stability analysis of silver–water nanofluid flow over unsteady stretching sheet under the influence of heat generation/absorption at the boundary

- Cobalt iron oxide-infused silicone nanocomposites: Magnetoactive materials for remote actuation and sensing

- Magnesium-reinforced PMMA composite scaffolds: Synthesis, characterization, and 3D printing via stereolithography

- Bayesian inference-based physics-informed neural network for performance study of hybrid nanofluids

- Numerical simulation of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to a heterogeneous/homogeneous chemical reaction over a Riga surface

- Enhancing the superhydrophobicity, UV-resistance, and antifungal properties of natural wood surfaces via in situ formation of ZnO, TiO2, and SiO2 particles

- Synthesis and electrochemical characterization of iron oxide/poly(2-methylaniline) nanohybrids for supercapacitor application

- Impacts of double stratification on thermally radiative third-grade nanofluid flow on elongating cylinder with homogeneous/heterogeneous reactions by implementing machine learning approach

- Synthesis of Cu4O3 nanoparticles using pumpkin seed extract: Optimization, antimicrobial, and cytotoxicity studies

- Cationic charge influence on the magnetic response of the Fe3O4–[Me2+ 1−y Me3+ y (OH2)] y+(Co3 2−) y/2·mH2O hydrotalcite system

- Pressure sensing intelligent martial arts short soldier combat protection system based on conjugated polymer nanocomposite materials

- Magnetohydrodynamics heat transfer rate under inclined buoyancy force for nano and dusty fluids: Response surface optimization for the thermal transport

- Fly ash and nano-graphene enhanced stabilization of engine oil-contaminated soils

- Enhancing natural fiber-reinforced biopolymer composites with graphene nanoplatelets: Mechanical, morphological, and thermal properties

- Performance evaluation of dual-scale strengthened co-bonded single-lap joints using carbon nanotubes and Z-pins with ANN

- Computational works of blood flow with dust particles and partially ionized containing tiny particles on a moving wedge: Applications of nanotechnology

- Hybridization of biocomposites with oil palm cellulose nanofibrils/graphene nanoplatelets reinforcement in green epoxy: A study of physical, thermal, mechanical, and morphological properties

- Design and preparation of micro-nano dual-scale particle-reinforced Cu–Al–V alloy: Research on the aluminothermic reduction process

- Spectral quasi-linearization and response optimization on magnetohydrodynamic flow via stenosed artery with hybrid and ternary solid nanoparticles: Support vector machine learning

- Ferrite/curcumin hybrid nanocomposite formulation: Physicochemical characterization, anticancer activity, and apoptotic and cell cycle analyses in skin cancer cells

- Enhanced therapeutic efficacy of Tamoxifen against breast cancer using extra virgin olive oil-based nanoemulsion delivery system

- A titanium oxide- and silver-based hybrid nanofluid flow between two Riga walls that converge and diverge through a machine-learning approach

- Enhancing convective heat transfer mechanisms through the rheological analysis of Casson nanofluid flow towards a stagnation point over an electro-magnetized surface

- Intrinsic self-sensing cementitious composites with hybrid nanofillers exhibiting excellent piezoresistivity

- Research on mechanical properties and sulfate erosion resistance of nano-reinforced coal gangue based geopolymer concrete

- Impact of surface and configurational features of chemically synthesized chains of Ni nanostars on the magnetization reversal process

- Porous sponge-like AsOI/poly(2-aminobenzene-1-thiol) nanocomposite photocathode for hydrogen production from artificial and natural seawater

- Multifaceted insights into WO3 nanoparticle-coupled antibiotics to modulate resistance in enteric pathogens of Houbara bustard birds

- Synthesis of sericin-coated silver nanoparticles and their applications for the anti-bacterial finishing of cotton fabric

- Enhancing chloride resistance of freeze–thaw affected concrete through innovative nanomaterial–polymer hybrid cementitious coating

- Development and performance evaluation of green aluminium metal matrix composites reinforced with graphene nanopowder and marble dust

- Morphological, physical, thermal, and mechanical properties of carbon nanotubes reinforced arrowroot starch composites

- Influence of the graphene oxide nanosheet on tensile behavior and failure characteristics of the cement composites after high-temperature treatment

- Central composite design modeling in optimizing heat transfer rate in the dissipative and reactive dynamics of viscoplastic nanomaterials deploying Joule and heat generation aspects

- Double diffusion of nano-enhanced phase change materials in connected porous channels: A hybrid ISPH-XGBoost approach

- Synergistic impacts of Thompson–Troian slip, Stefan blowing, and nonuniform heat generation on Casson nanofluid dynamics through a porous medium

- Optimization of abrasive water jet machining parameters for basalt fiber/SiO2 nanofiller reinforced composites

- Enhancing aesthetic durability of Zisha teapots via TiO2 nanoparticle surface modification: A study on self-cleaning, antimicrobial, and mechanical properties

- Nanocellulose solution based on iron(iii) sodium tartrate complexes

- Combating multidrug-resistant infections: Gold nanoparticles–chitosan–papain-integrated dual-action nanoplatform for enhanced antibacterial activity