Abstract

Aeolian dunes have been widely identified in the European Sand Belt, which was formed during the Pleniglacial and Late Glacial when cold and dry climatic conditions were favorable for intense Aeolian processes. In this study, we mapped and analyzed the fixed Bory Stobrawskie Dune Field (SW Poland) to determine factors that drive the evolution of dunes, expressed by the occurrence of different dune types and their spatial patterns. The study identified the longitudinal zonation within the dune field, as shown by the changeable proportion of specific dune types comparable to low-latitude dune fields. However, climatically controlled periodic and low sand supply combined with a changing vegetation cover caused the non-continuous and multi-phase evolution of the dune field. Additionally, we found that a dense pattern of streams has controlled the extent of the dune field. The trapping of sand by rivers led to a limitation of the dune field expansion; on the other hand, the supply of sand into rivers led to overloading of the fluvial system, affecting their transformation into braided rivers.

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

The development of specific dune types is linked to particular depositional conditions (wind direction and strength, sand supply and vegetation) [1,2,3], while dune field pattern indicates the duration of aeolian processes due to the self-organizing nature of aeolian bedforms [4,5,6]. The coexistence of a few dune field patterns within one area is linked to temporal or spatial variability of depositional conditions (e.g., precipitation, surface wetness, sand supply). For example, different dune types indicate the spatial variability of environmental conditions, while irregular dune field patterns can be associated with various phases of aeolian activity [7,8]. Such dependence has been observed in the Kalahari Desert [9], the Sonora Desert [10], California [11], and Australia [12]. However, despite the well-known impact of environmental conditions on the evolution of specific dunes, as well as dune fields in tropical, subtropical, and temperate regions, the influence of periglacial conditions on the development of aeolian dunes is not well understood [7]. Primarily this is caused by the limited spatial extent of active cold-climate dune fields in modern times, which can be found only in a few places in Alaska [13,14,15,16,17], Canada [18,19,20,21,22], Siberia [23,24,25], on the Arctic Coasts [26,27] and in the dry valleys of Antarctica [28]. The uniqueness of the dune fields developed in cold areas has been argued due to several factors that significantly limit the intensity of aeolian processes [7]. Many cold-climate regions are characterized by high variability of wind speed and direction, resulting in low migration rates [16,17,28]. Niveo-aeolian processes and patches of permafrost cause the immobilization of sand [13,29] and the trapping of aeolian-transported sediments [7]. Soil moisture influences sand movement and the structure of dunes [30]. Furthermore, low and periodical sediment supply causes the development of unique bedding patterns [31]. Nevertheless, the influence of these conditions on the development of cold-climate dune fields remains poorly studied. For example, a study conducted in Iceland shows that intensive aeolian processes are present even under very humid climates, and dunes can develop in short periods (years to decades) in very unfavorable cold areas [26]. Furthermore, they concluded that dune fields on vast sandurs comprise several types of dunes, including dry dunes together with bedforms affected by vegetation and a high groundwater table. However, due to the limited extent of modern periglacial dune fields, little attention was given to general dune-field evolution processes resulting in an apparent knowledge gap regarding the impact of cold-climate conditions on the spatial evolution of dune fields.

Much more attention has been given to the relict dune fields that developed in the front of the Laurentide and Fennoscandinavian ice sheets during the Late Glacial. In Europe, cold-climate dunes have been studied within the European Sand Belt (ESB), which extends from the Netherlands to Russia and was developed under dry and windy conditions occurring at the termination of the Pleistocene [32,33]. Due to continental climatic gradient, the largest dune fields within the ESB developed in Poland, where they were extensively studied, especially emphasizing the sedimentology and stratigraphy of individual aeolian units. On the basis of the results, it was proposed that these dunes developed in a few aeolian phases that took place during the Pleniglacial and the Late Glacial with episodes of stabilization and pedogenesis in more humid periods [34,35,36,37,38,39]. Their depositional conditions were described as a periglacial desert, characterized by mean annual temperatures below zero, 250–300 mm of precipitation [40], and discontinuous or patchy permafrost [34,35,40]. Recent studies suggest that the dunes within the ESB were very sensitive to short-term climatic oscillations and that the chronology of their deposition was locally very variable [37,38,39]. Łopuch et al. [41] on the basis of morphometric analyses even argued that the large dune fields were not subject to periodic stabilization and were active throughout the entire Late Glacial. The morphoscopic characteristics of the quartz grains that build the dunes similarly imply that they were subject to long-term wind action, much longer than the short-term coolings of the Older and Younger Dryas. The influence of the fluvial environment on earlier grain processing has also been highlighted on this basis, indicating a strong interaction between both systems [42,43,44,45]. Locally some dunes were reactivated during the Holocene due to forest fires, cultivation, and deforestation [37,46,47,48].

However, it is important to note that the majority of these studies were conducted in single outcrops, and the geomorphological characteristics of whole dune fields have been discussed in a very limited way. Most authors concluded that dunes within the ESB were constructed by westerly winds in the vicinity of large source areas such as ice-marginal valleys, outwash fans, and outcrops of glaciolacustrine sediments [7,34,49]. It was observed that transverse and parabolic dunes are the most common dune types, and dunes become more complex in the eastern parts of dune fields due to the overlapping of several dunes [34,49,50]. These observations were confirmed by a broad geomorphological analysis of the large dune fields of the entire central part of the ESB [41]. However, the sparse dune fields (composed of many isolated dunes) that dominate the landscape of the Polish Lowlands have not yet been analyzed.

To fill the gap, we conducted a morphometric analysis of the Bory Stobrawskie Dune Field (BSDF) (SW Poland) which appears to be the most appropriate field lab due to the homogeneity of depositional surface and a lack of significant morphological barriers. This study aims to define factors controlling the spatial pattern and evolution of sparse cold-climate dune fields using morphometry based on high-resolution DEMs. In particular, we focused on the variability of dune types, their morphometric features, and the dune field spatial pattern, which indicates regional differentiation of depositional conditions. The secondary aim of this study is to explore the impact of fluvio-aeolian interactions on dune field development. This article will contribute new knowledge to the poorly understood dynamic of sparse cold-climate dune fields. Analyses will provide new insight into the impact of specific environmental factors on the shape and evolution of dune fields in periglacial conditions. Finally, the proposed GIS workflow may be valuable for similar analyses conducted in other climatic zones.

2 Regional setting

The BSDF is located in southwest Poland, in the eastern part of the Silesian Lowland known as the Opolska Plain ([51], Figure 1a). The dune field covers an area of 460 km2 and is developed on the outwash plain, linked with the Warthanian-aged (Late Saalian, MIS 6) end moraines of the Wieruszowskie Hills located 15 km to the north [52]. The western border of the study area is marked by 2–3 km wide and 2–6 m deep Strobrawa Valley. It extends from the north to the south, where it ends in the valley of the Odra River. The Stobrawa Valley separates the Opolska Plain from Wał Jakubowicki, a moraine ridge east of the Oleśnicka Plain (Figure 1a). The valley contains a system of poorly developed fluvioglacial terraces formed during the Weichselian glaciation [52]. Due to the lack of dunes on the western side of the valley and the high amount of available sediments, it was referred to as a source area for the dune field [53]. The Opolska Plain gently rises to the east (Figure 2, profile A–A′) with an average slope of 0.5–2° (not exceeding 7–8°). The plain ends on a morphological ridge of Silesian Upland, reaching a level of 220 m a.s.l. at a distance of 35 km. To the south study area is limited by the Mała Panew river valley, with the Turawskie reservoir lake in its central part (Figure 1a).

The geological structure of the Opolska Plain is not diverse (Figure 1b). It is built of the fluvioglacial fine-to-medium sized poorly rounded (quartz grain roundness coefficient R = 1.13) sands with an admixture of gravels [52]. The topsoil (0–20 cm) is composed of 60–90% sand with increasing content of clays and silts in valleys ([54]; Figure 2). In several places, glacial tills underlie the fluvioglacial sediments. They are well-preserved in the plain morphology and characterized by small mounds on the terrain surface. Pleistocene sediments are approx. 4–20 m thick and lie on impermeable Neogene clays and silts [52,55,56,57].

Isolated patches of aeolian sand accumulated in fixed sheets and dunes occur in the study area. Fixed dunes of various types dominate the landscape, frequently occurring on the surface of the fluvioglacial plain and rarely in valleys [58]. Most likely, these dunes developed during the Pleniglacial and Late Glacial, the same as other dunes in the central part of the ESB [34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. They are oriented to the southeast [55], but previous authors claimed that the dune field was built by the wind coming from two directions – east and west [58,59]. Several closed depressions (probably blowouts) were filled with peat and mud during the Holocene. The plain is drained by a dense parallel network of Stobrawa River tributaries (Bogacica, Budkowiczanka, Brynica; [60]; Figures 1 and 2) forming 2–6 m deep valleys with a W–E direction corresponding to the inclination of outwash plain. These valleys enlarge from a width of 300–500 m up to 2,000 m in the lower courses of the streams, forming outwash fans at the junction with the perpendicular Stobrawa Valley.

3 Methods

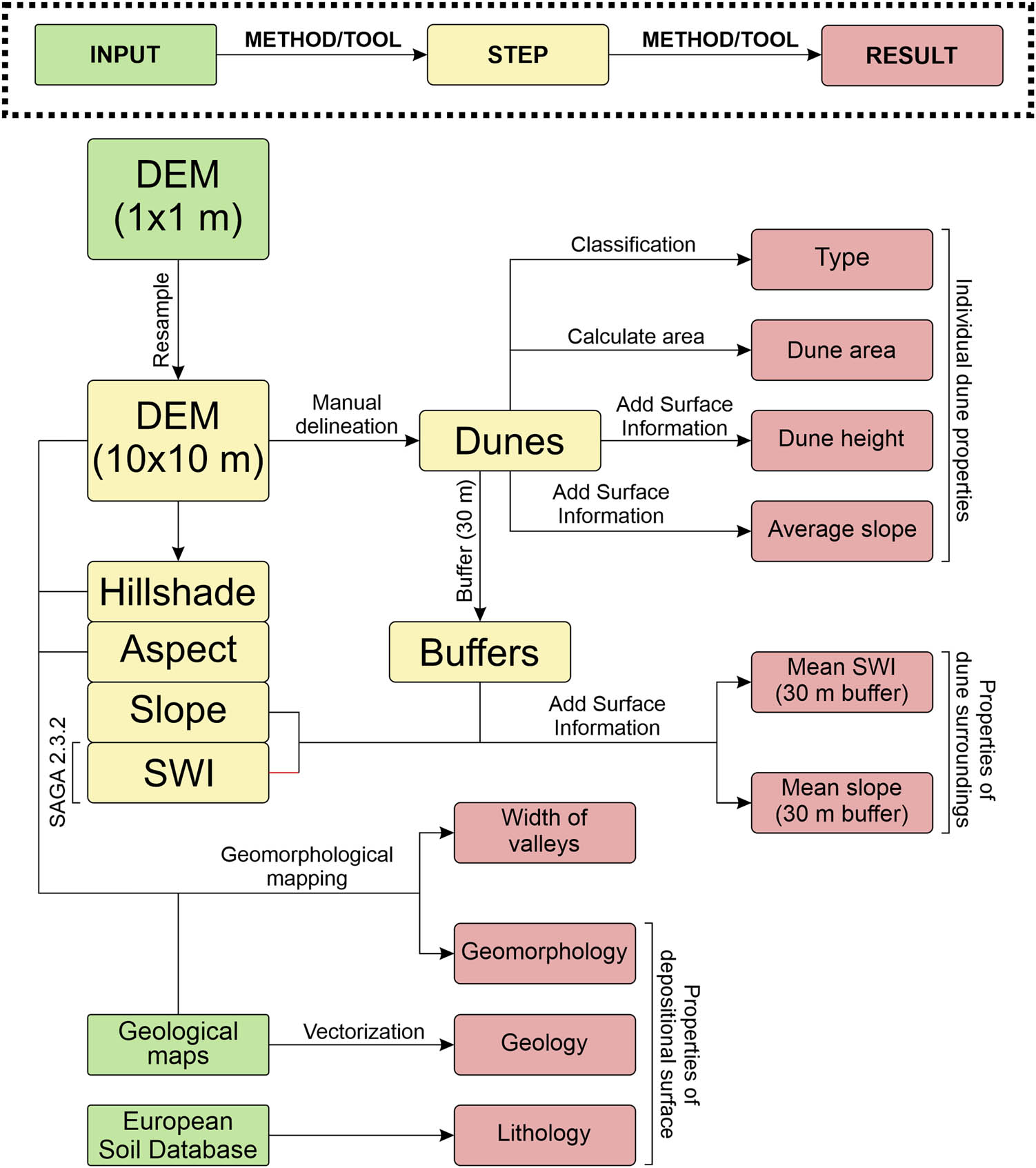

Landform analysis and mapping were performed on the bare-earth Digital Elevation Model (DEM), derived from airborne laser scanning (LiDAR) executed with an accuracy of 4–7 points per m2, with a mean vertical error not exceeding 0.15 m [61]. DEM with a 1 × 1 m resolution was resampled into a 10 × 10 m grid to achieve a generalized view of the dune field. Layers of slope, aspect, and a multi-directional hillshade model [62] were calculated. All mentioned actions were performed using ArcGIS 10.5.1. The SAGA Wetness Index (SWI [63]) was computed using SAGA (2.3.2) software to spot wet surfaces that may affect the distribution and migration of dunes. The SWI was chosen due to more realistic results for flat surfaces than the standard Topographic Wetness Index [64]. The technical flowchart is given in Figure 3.

Flowchart of data processing. We performed all actions using ArcGIS 10.5.1 and SAGA 2.3.2 software (if noted).

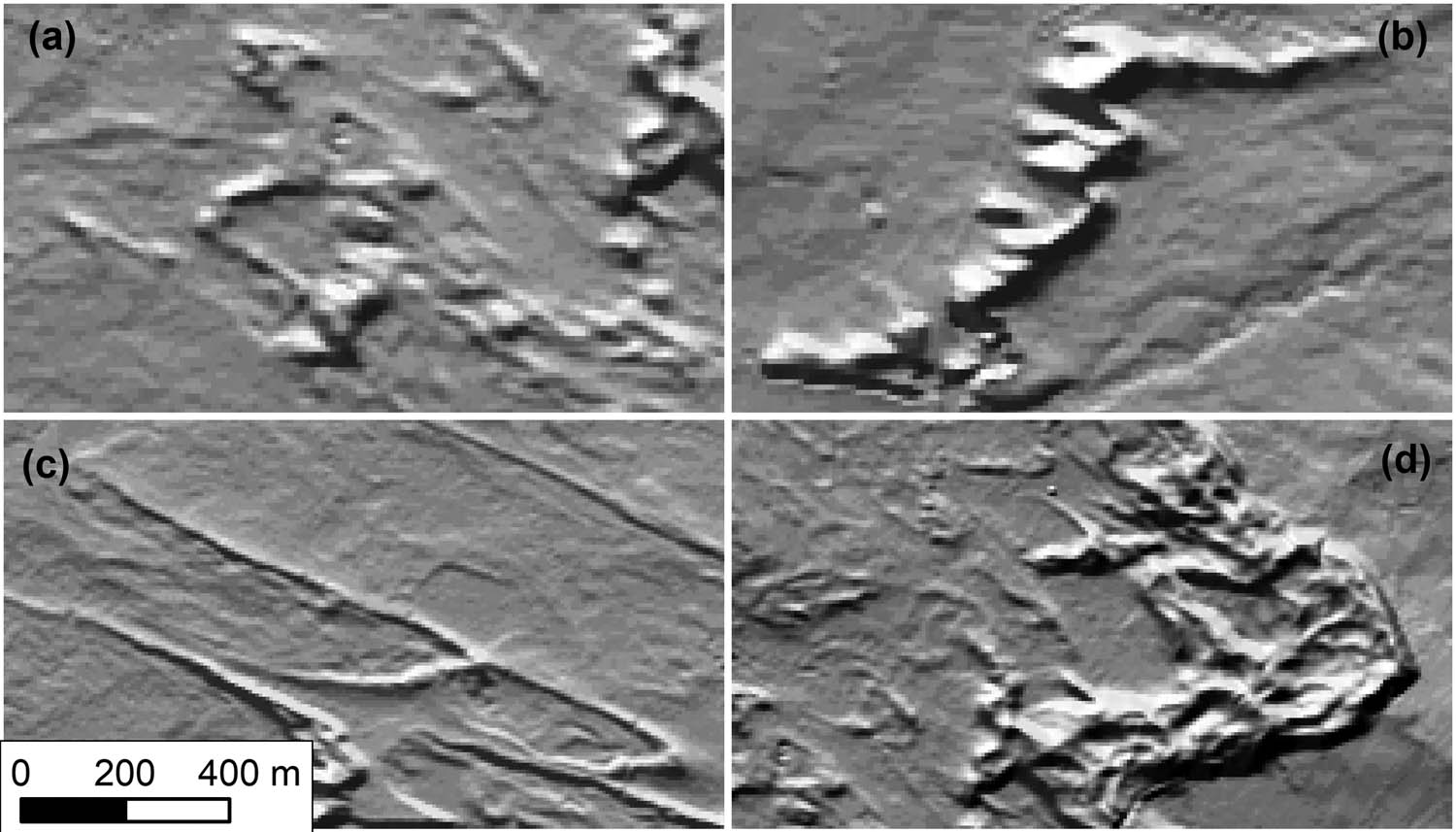

Dunes were delineated on the base of the multi-directional hillshade model and categorized manually. Four dune types were distinguished: irregular, transverse, parabolic, and complex (Figure 4). Only the geometry of the dunes (Table 1) was considered during classification.

Examples of (a) irregular, (b) transverse, (c) parabolic, and (d) compound dunes.

Classification scheme of dunes

| Dune type | Shape and size | Aspect of slopes | Number of slopes and their characteristics | Cross-profile | Arms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irregular | Circular or irregular, small | Irregular | One, two, or irregular | Symmetrical or irregular | — |

| Transverse | Rectangular to linear | Two dominating | Two dominating, one long and convex, the second short and straight | Asymmetrical | — |

| Parabolic | Arched, elongated | One dominating | Two dominating, arched. One long and gentle, the second short and steep | Asymmetrical | One or two, elongated |

| Complex | Irregular, large | Irregular | Many irregular slopes | Irregular | — |

After classification, all dunes were characterized by three basic morphometric features – area, maximum height (both indicating amount of sand supply), and the mean inclination of slopes. To estimate the impact of surface inclination and wetness on the deposition and migration of the dunes, we measured the mean slope and the mean value of the Saga Wetness Index inside a 30 m wide buffer enclosing each dune (Figure 3). We measured the orientation of the particular dune types using COGO Toolbar and plotted results on rose diagrams. In the case of large dunes, the orientation of ridges was measured at several points. The orientation of irregular dunes was not measured because of the difficulty in assessing the possible direction of their movement.

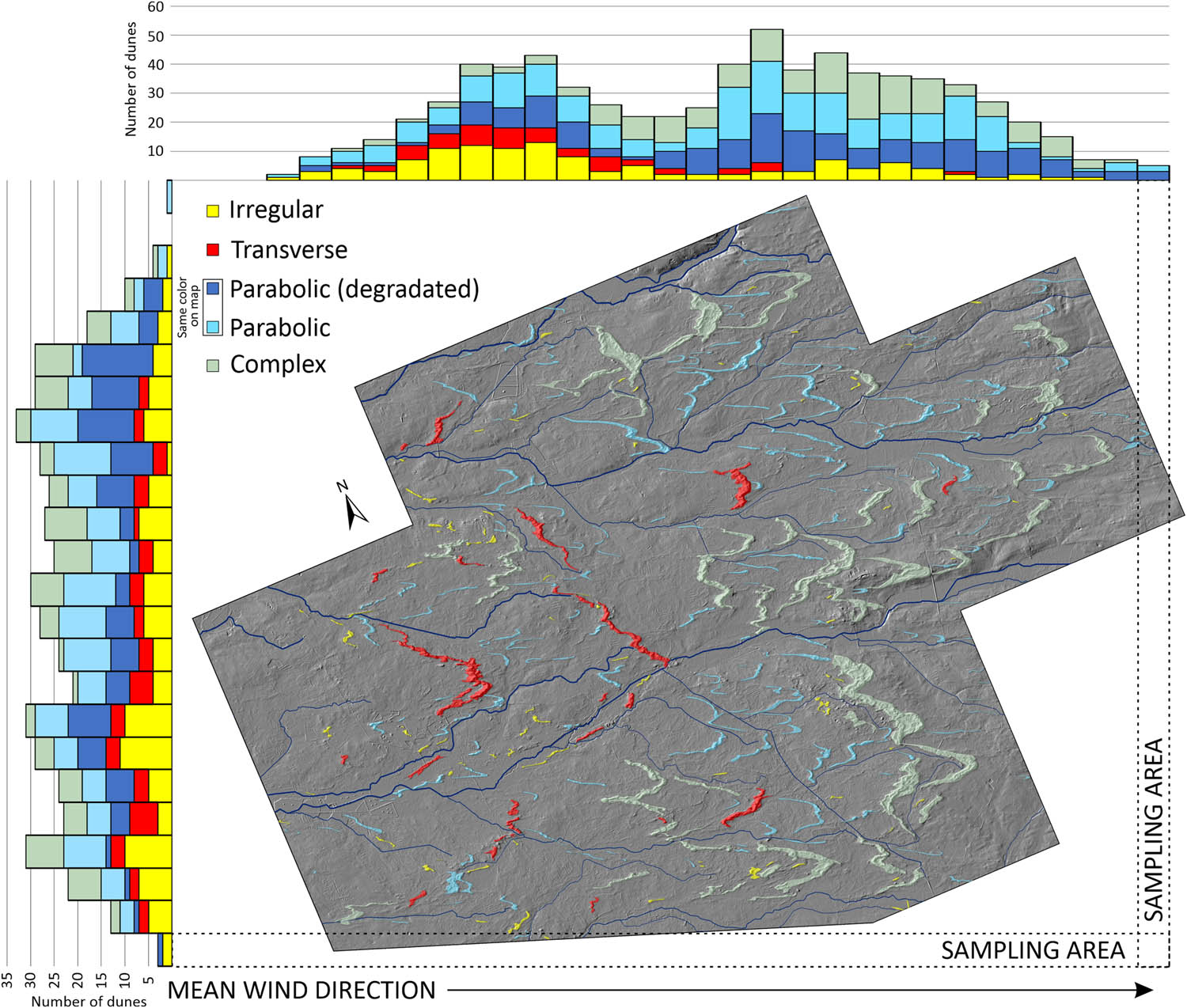

To provide information about the spatial distribution of dunes we computed two histograms of dune types for one-kilometer-wide zones longitudinal and perpendicular to the dominant wind direction inferred from the dunes. The degree of clustering or dispersion of the different types of dunes was determined using the average nearest neighbor method [65,66,67].

The valleys of three main streams draining the study area (Bogacica, Budkowiczanka, and Brynica) were studied to provide information about the possible impact of aeolian processes on the fluvial system. We measured the width of each valley every 500 m starting from the source. Valley floors were examined to find remnants of fluvial bedforms typical for straight, meandering, or braided river systems (Figure 10).

4 Results

4.1 Characteristics of dunes

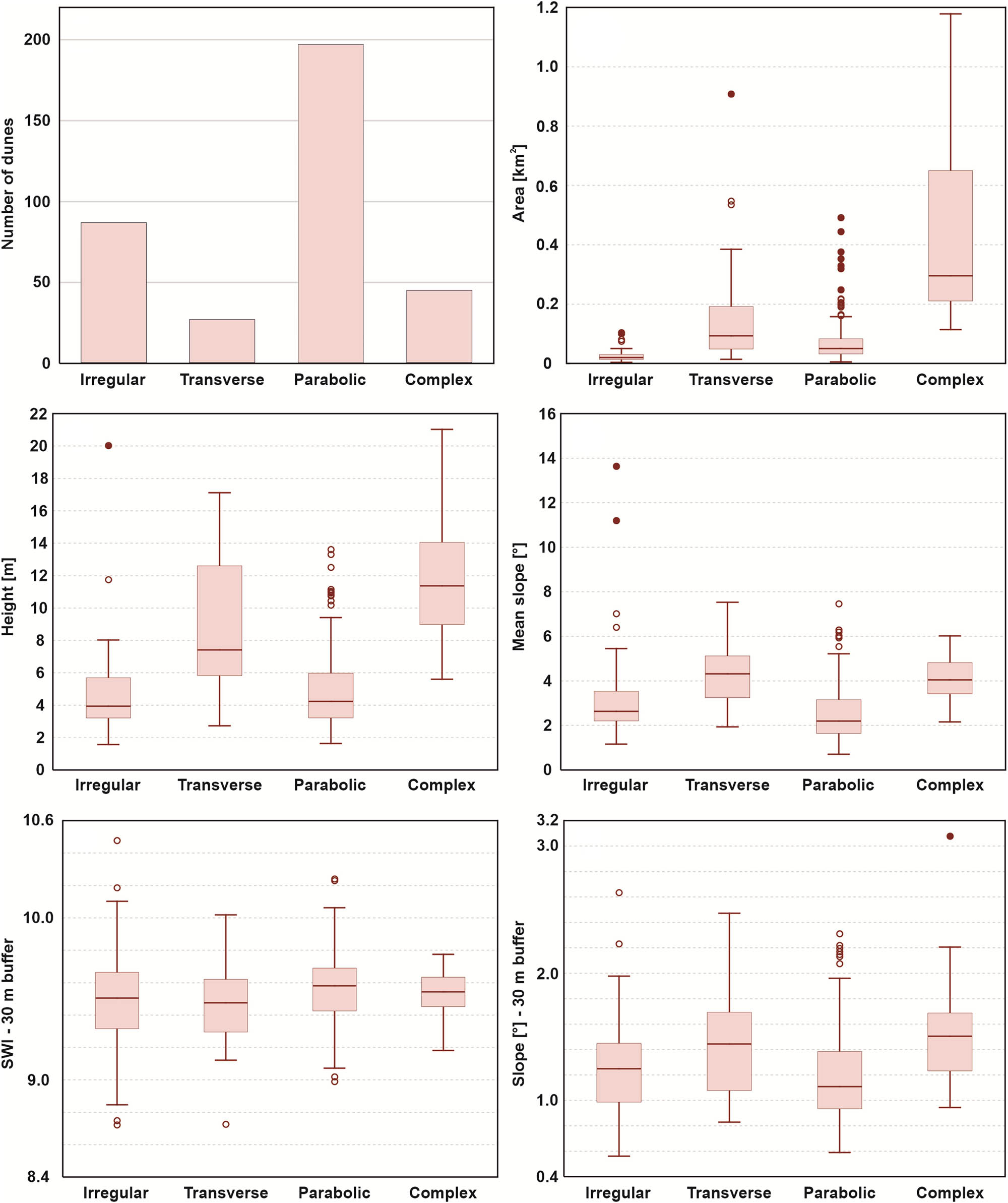

Figure 5 shows the outcome of the morphometric measurements of the dunes. The results point to two groups of dunes with similar characteristics:

Composed of irregular and parabolic dunes that combined represent over 78% of classified dunes. Their area rarely exceeds 0.1 km2, with a height varying from 2 to 8 m (average of 4 m) and gentle slopes (1.5–3.5°).

Composed of transverse and complex dunes. This group contains 22% of dunes, which represent 60.6% of their total area and 75.7% of their total volume. These dunes are large, reaching up to 22 m in height. They also have steeper slopes, with an average inclination of 4–4.5°.

Morphometric properties of irregular, transverse, parabolic, and complex dunes.

Both groups prefer flat (0.5–2.5° of slope) and dry surfaces (SWI between 9 and 10), although the surface surrounding transverse and complex dunes is usually slightly more inclined (Figure 5). Nevertheless, these differences are marginal and not statistically significant.

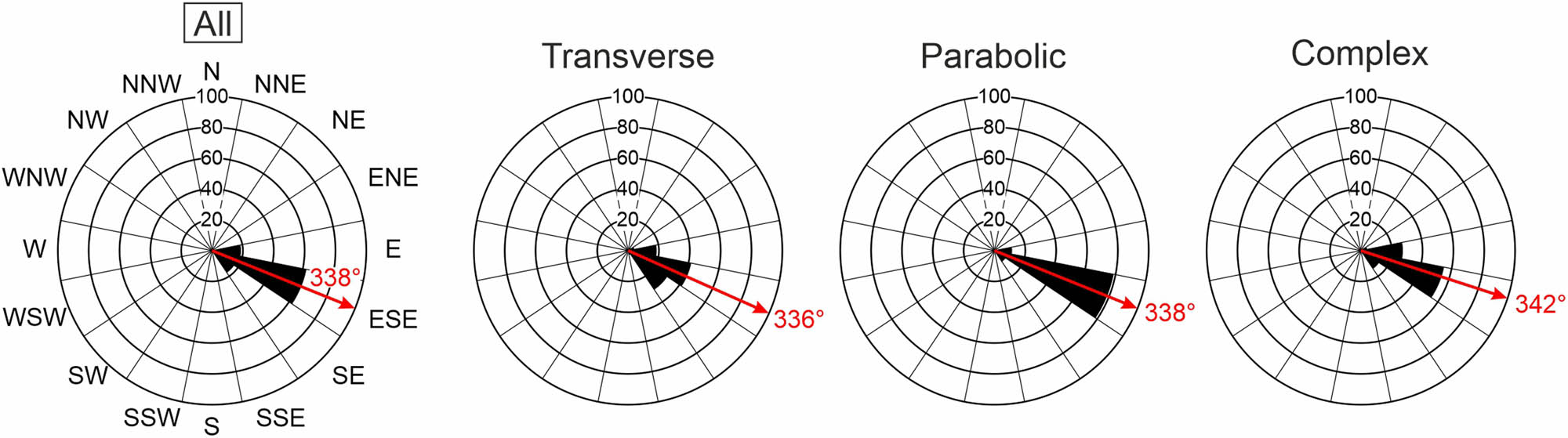

The orientation of the dunes toward the ESE is uniform for all dune types (Figure 6). Due to the sinuous shape of the ridges, some parts of the transverse and complex dunes are oriented in the E and SE directions.

Orientation of dunes in the study area. Irregular dunes were not measured because of the difficulty in assessing their direction.

4.2 Distribution of dunes

In general, dunes in the BSDF are not formed into a consistent network (Figure 7). Moreover, the pattern of the dune field is characterized by a weak clustering (NN ratio = 0.89, Table 2) of sparsely distributed (mean distance between dunes = 575 m) dunes.

Clustering of dune types. All parameters are measured for an area limited by extremely distributed features of each type

| Dune type | Spatial pattern (nearest neighbor) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significance level (p-value) | Critical value (z-score) | NN Ratio | Pattern | |

| Irregular | <0.01 | −3.30 | 0.81 | Clustered |

| Transverse | 0.07 | 1.79 | 1.18 | Dispersed |

| Parabolic | <0.01 | −3.56 | 0.87 | Clustered |

| Complex | 0.69 | 0.40 | 1.03 | Random |

| All | <0.01 | −4.05 | 0.89 | Clustered |

Distribution of dunes (parallel and perpendicular to the mean wind direction) over the study area. Degraded parabolic dunes were separated for the purposes of this figure. Their share in the total number of dunes is fluctuating in the same way as other dune types, indicating a common transformation of parabolic dunes in later phases of the dune field development.

The minor irregularity in the distribution of dunes is related to the scheme of the river network. Dunes rarely occur in river floors, concentrating within the flat surface of the fluvioglacial Opole Plain. In the N–S cross-section, there is only a slight variation in the number of dunes (Figure 7) and the area occupied by them (Figure 8a). The northern part of the dune field is characterized by a higher share of parabolic dunes, while in the southern part, the composition of dunes is more diverse (Figure 7).

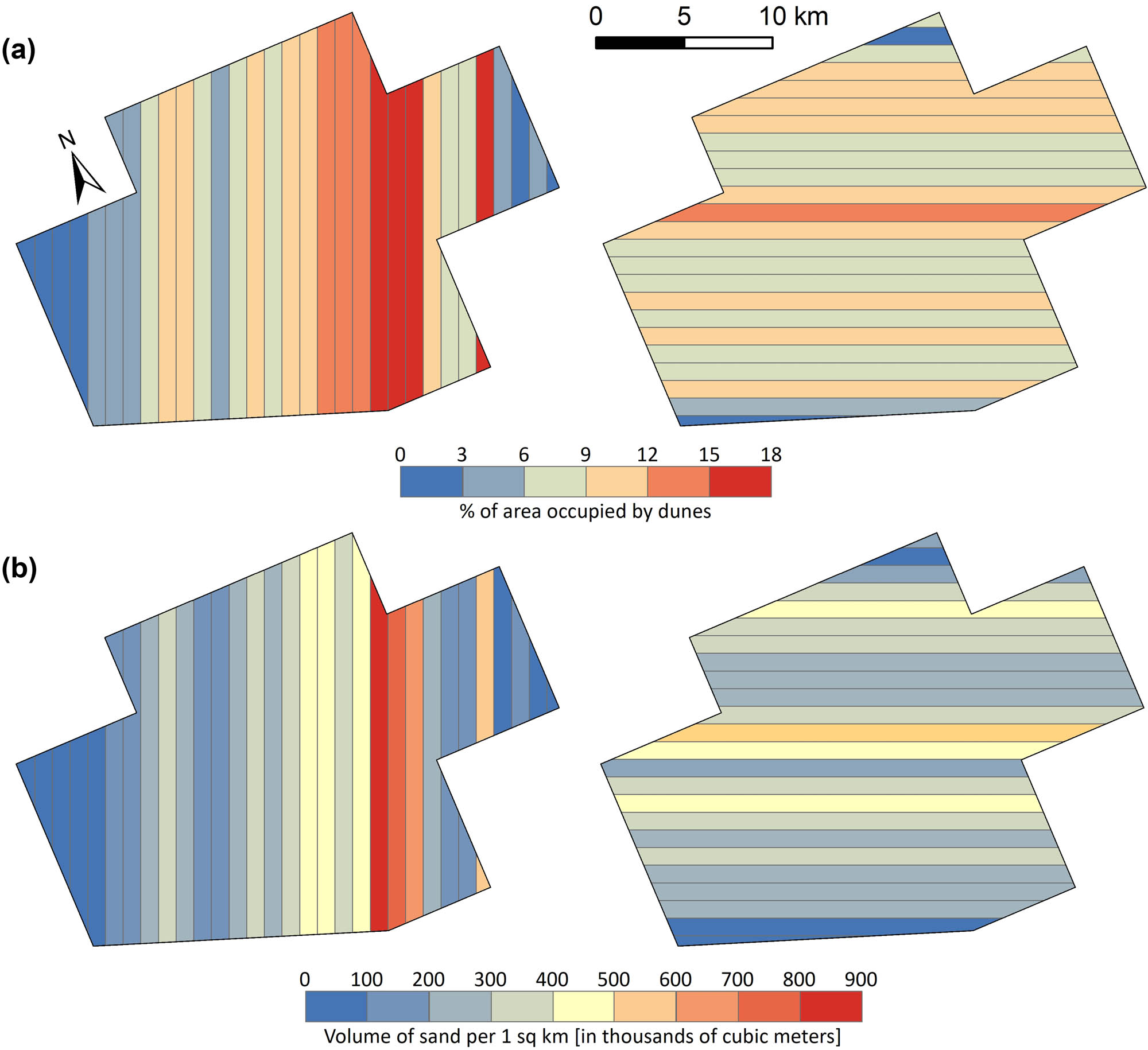

(a) Percentage of the area covered by dunes and (b) volume of sand accumulated in 1-km zones. Inferred dominant wind direction from left to right. The sand accumulation zone in the distal part of the dune field is clearly visible.

The considerably higher variation in the number and variety of dune types is observed in the longitudinal profile. Following the Stobrawa Valley over a distance of 13 km, the number of dunes slowly increases (up to 40 per 1 km zone; Figure 7). In this part of the dune field are found mainly irregular (30–40%) and parabolic dunes (40–50%), as well as the majority of transverse dunes. Complex dunes are sporadic and relatively small in area and sand volume. Between kilometers 13–17, there is a double reduction in the number of dunes, caused mainly by the disappearance of irregular and transverse dunes. From the 18th kilometer, there is a second increase in the number of dunes to about 40 dunes per 1 km zone. That number of dunes is maintained until the 25th km. In this zone, there is an increase in dune coverage (from 3–12 to 12–18%; Figure 8a) as well as accumulation of sand, which volume is the highest (>0.5 km3 per 1 km zone; Figure 8b) at km 22–24. Parabolic and large complex dunes dominate in this area. In the distal part of the dune field (km 25–30), the number of dunes gradually decreases to zero, with mainly small parabolic dunes being found.

4.3 Characteristics of valleys

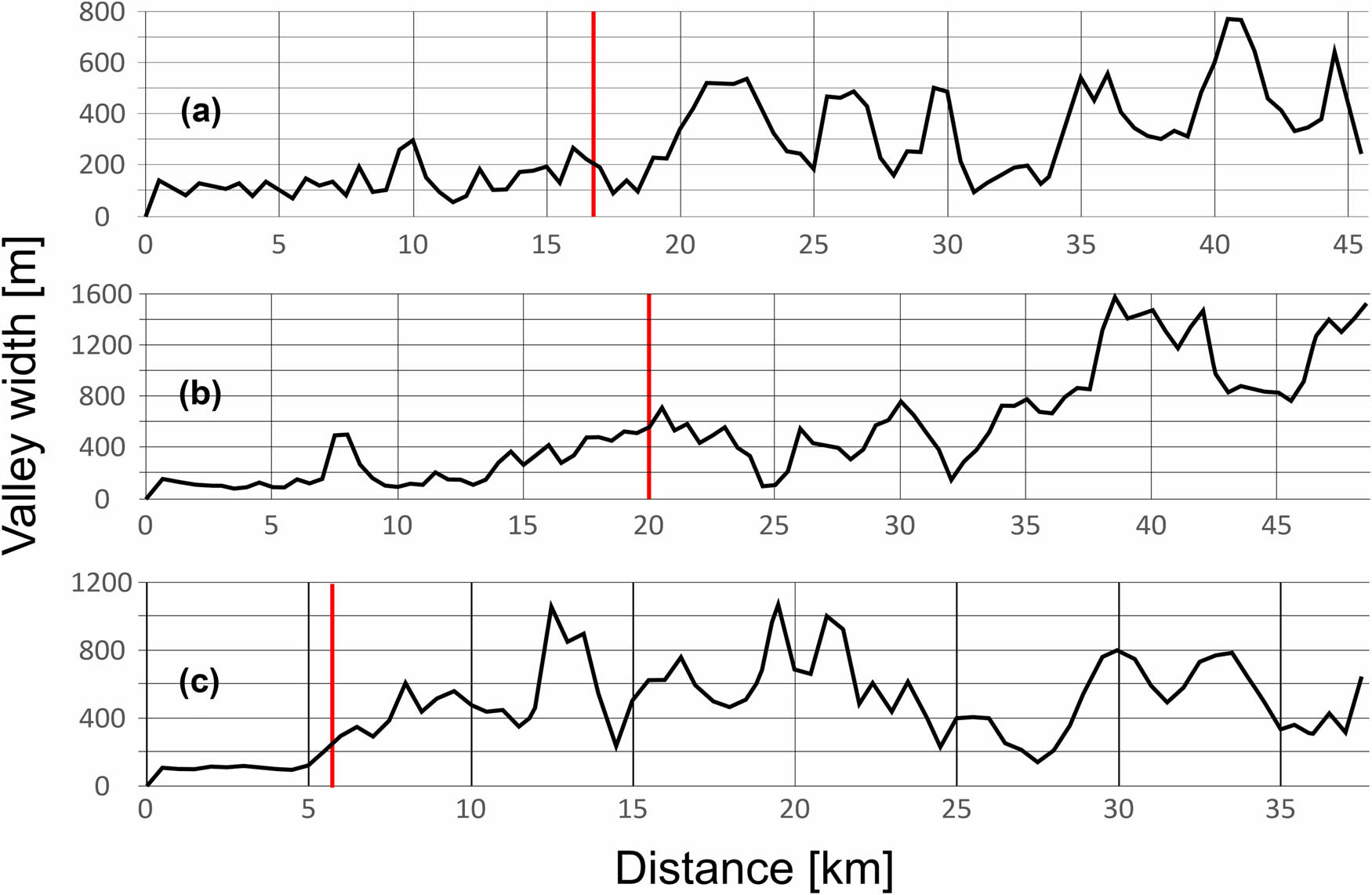

Three valleys were examined and measured from the east (source) to the west (sink; Figure 2). In the upper parts, valleys are deep and narrow (100–200 m wide). All three valleys expand rapidly after entering the dune field (Figure 9).

The width of the main valleys in the study area. (a) Bogacica, (b) Budkowiczanka, and (c) Brynica. The red line indicates the contact of a stream with the dune field.

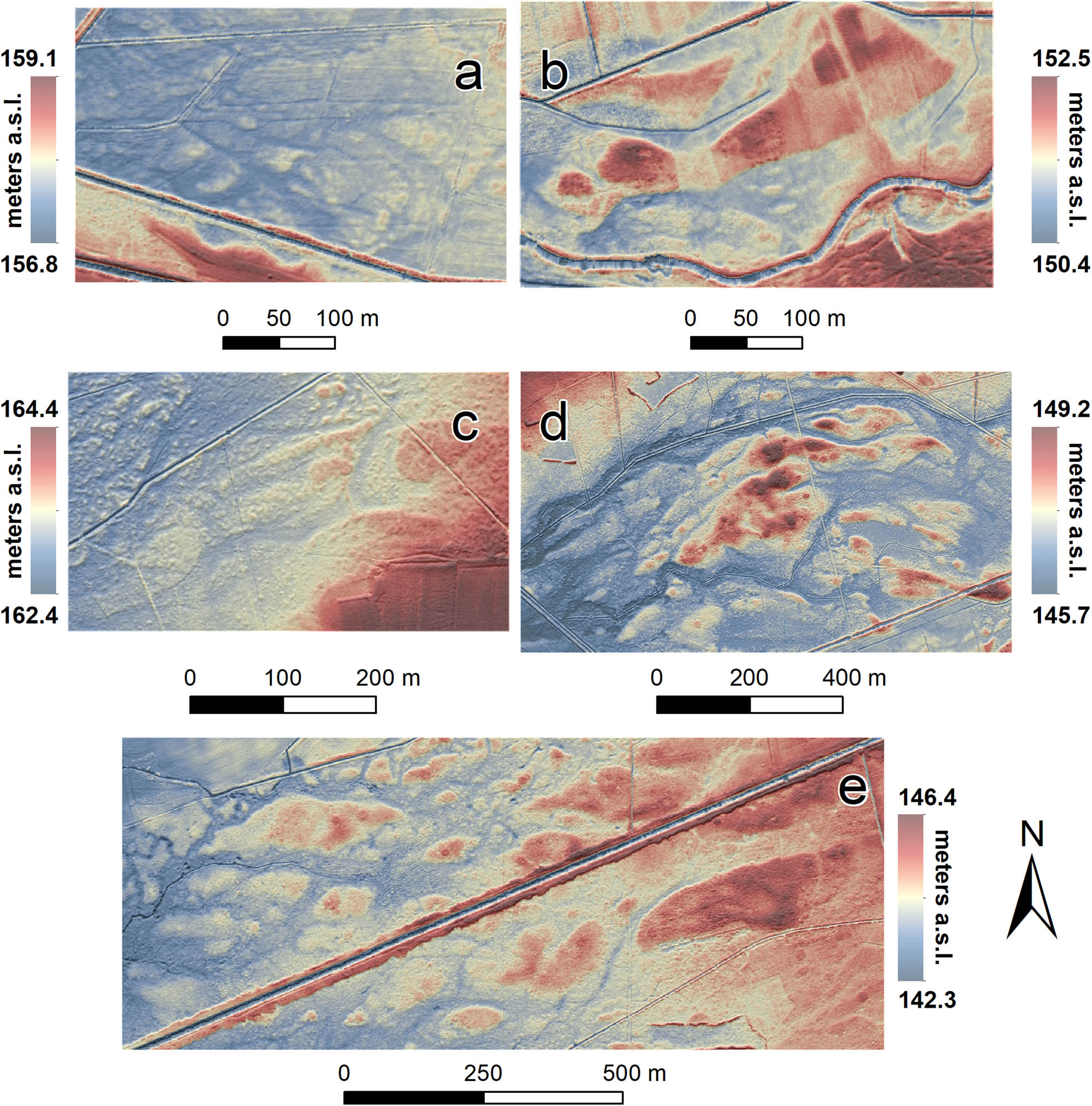

The Bogacica Valley expands to a width of 700–800 m, the Budkowiczanka Valley to 1,500 m, and the Brynica Valley to 1,000 m. Widths are varied due to gorges eroded in dunes blocking the original course of the streams. Above contact with dunes, valley floors show no signs of fluvial action. Below contact structures of the braided river (networks of channels separated by bars) were found (Figure 10). All three streams end with outwash fans. The biggest fan is formed by the Budkowiczanka stream and has approx. area of 5 km2 and dimensions of 2.5 × 2.5 km.

Braided river structures developed in the valleys of the Bogacica, Budkowiczanka, and Brynica rivers. Locations (a–e) are marked in Figure 2.

5 Discussion

5.1 Dune types

There are four types of dunes in the BSDF, which can be divided into two groups in terms of their morphometric characteristics. The first consists of numerous parabolic and irregular dunes, and the second is composed of less frequent transverse and complex dunes. The similar morphometry of the mentioned dune types likely indicates that they are genetically related. The values of surface inclination and soil moisture (SWI Index) in the surroundings of all dunes indicate that these factors have not influenced their development (Figure 5).

Irregular dunes often have an elongated shape similar to the deformed arms of parabolic dunes. They also have comparable height and slope inclinations in comparison to parabolic dunes, at the same time being smaller in terms of surface area (Figure 5). It is also clear that as the number of parabolic dunes decreases, they are replaced by an increasing number of irregular dunes. For this reason, the ratio of parabolic and irregular to transverse and complex dunes remains constant in the N–S profile through the dune field (Figure 7). All these similarities point to a process of blowing away parabolic dunes. The front of the parabolic dune, as the highest and least stabilized by vegetation, is deflated first, leading to the formation of two linear dunes in place of the former dune arms [7,49]. Due to their small size, they are also subject to further reshaping, which leads to the deformation of their shape into a less regular one. Thus, it can be assumed that the irregular dunes in the area are secondary to the parabolic dunes. The morphology of parabolic dunes within BSDF is similar to the “low-relief parabolic dunes” described from SW France [68,69]. They distinguished them on the basis of the low inclined slopes (much flatter than those of modern dunes) and associated them with the Younger Dryas.

As well, complex dunes are probably secondary to transverse dunes. In contrast to irregular dunes, which are related to erosional processes (deflation), complex dunes are the result of the accumulation and aggregation of other dunes. Their central parts consist most often of transverse dunes, strongly deformed at the ends of the crests. Due to the merging of smaller primary dunes, complex dunes are larger and higher than transverse dunes (Figure 5). At the same time, the inclination of the slopes is comparable, confirming the major contribution of transverse dunes to their formation. The genesis of complex dunes remains an open question and may be linked to two processes. The first assumes that the movement of dunes slows down due to trespassing onto the unfavorable surface, such as more humid or heavily vegetated areas. In that case, the dune was overtaken by the dunes situated behind it and grew analogous to the precipitation ridges which are common at the edges of dune fields [70,71]. This concept is supported by significant sand accumulation in the distal part of the dune field (Figure 8), where the river network does not have an alignment parallel to the dune field (Figure 7). The second scenario assumes the collisions of younger and active dunes with older, already stabilized dunes. This process is well documented in the sedimentological record, where in the dunes of Poland subsequent series of aeolian sands are separated by fossil soils that are the evidence of sand stabilization [34,35,36,37,38,39,72]. Therefore, complex dunes are evidence of multi-phase development of the dune field, rather than the varying migration rates of individual dunes.

5.2 Multi-phase development of the BSDF

The dunes of the BSDF do not differ from those known in other cold areas. Parabolic dunes are most often mentioned as most common in both modern [7,13,73,74] and past [34,49,68,69,75] subarctic and periglacial areas. Parabolic dunes typically occur as single dunes or entire chains of dunes and their formation is linked to the presence of vegetation that effectively stabilizes the arms of the dunes [2]. Transverse dunes are less frequent and usually form large dune fields, where the supply of sand is large and continuous [13,17,34,76]. However, the occurrence of transverse dunes as single forms is rare, as well as the co-existence of the two mentioned types of dunes. The reason is that mutually exclusive environmental conditions are needed for their formation. Transverse dunes are developing under conditions of high sand supply and lack of vegetation, while parabolic dunes are emerging under conditions of low sand supply and the presence of grasses and shrubs [2,3,8].

Particularly noteworthy is the distribution of transverse and parabolic dunes, as both dune types are dispersed and mixed together (Figure 7; Table 2). The irregular distribution of individual dunes is typical of the Polish Lowlands [34]. Such a pattern of dune fields has been associated by Ewing et al. [77] with the presence of two separate generations of dunes formed at different periods. That interpretation was adopted by Bernhardson and Alexanderson [76] and Holuša et al. [78], to explain the co-occurrence of different types of dunes in the cold-climate fixed dune fields of Sweden and the Czech Republic (Moravia). Holuša et al. [78] interpreted them as a result of successive dune-forming phases characterized by varying wind directions (N–NW in Older Dryas and W–SW in Younger Dryas). This variation is consistent with wind directions interpreted from the sedimentological record within the central part of the ESB [49] and numerical simulations [33,79]. In the BSDF, all the dune types are directed identically (towards E; Figure 6), suggesting their formation in one phase. Recent studies consider that the intense aeolian processes occurred earlier and the dunes were later transformed in a limited way in the Younger Dryas [39]. Considering such a chronology of events, the wind orientation did not undergo greater alteration during the whole Late Glacial. This hypothesis is supported by the homogeneous orientation of the large dune fields located in Poland [41]. Simultaneously, the increasing presence of vegetation favored the transformation of some of the transverse dunes into parabolic dunes. Long arms of parabolic dunes (reaching 2–3 km) may indicate that the transformation phase of the dunes was long and continuous. The scale of transformation probably depended on the size of the dune, as evidenced by the disproportion in height and size between dunes that were not (or slightly) transformed (transverse dunes) and parabolic dunes (Figure 5). The lack of regularity in spatial distribution and the varying degree of transformation into parabolic dunes suggests the reactivation of only a part of the dunes. A later phase (possibly anthropogenic) in which the deflation of some parabolic dunes took place cannot be ruled out either. A significant human influence on the reactivation of single forms during the Holocene was indicated by many authors [37,46,47,48].

5.3 Source of sand

The view of the main role of higher fluvial terraces as a source of material within the central part of the ESB is often repeated in the literature [34,35,36,78,80]. Andrzejewski and Weckwerth [80] indicated that most of the dunes in the Vistula Valley are located on the highest fluvioglacial terraces, characterized by good drainage and a dry surface. The moist substrate on the low terraces was not undergoing intensive deflation and impeded the migration of dunes. In line with this view, Goździk and Kobojek [53] pointed to the Stobrawa Valley as the main sediment source for the BSDF. However, they emphasized that the terraces of the Stobrawa River consist of sand that was undergoing repetitive redeposition within fluvial and aeolian environments, and the original source of the sediment was located further to the west. They noted the supply of sand from the fluvioglacial plain but regarded it as low and dependent on the prior transformation of quartz grains in the fluvial environment. As evidence, they referred to the degree of processing of quartz grains, similar in alluvial and aeolian sediments within BSDF. This view was supported by many researchers, who pointed to the earlier long-term transformation of quartz grains in the fluvial environment [42,43,44,45].

However, two insights suggest a more complex and supply within the BSDF. The Stobrawa Valley, despite its great width, does not have a well-developed system of river terraces. Terrace levels are difficult to distinguish and do not rise higher than 5–6.5 m above the level of the present-day Stobrawa River. The low-lying terrace levels are situated close to the groundwater table, as evidenced by the high density of surface streams across the entire width of the valley. The valley floor also does not contain systems of small and large meanders common in central Europe and formed by incision of rivers during the warmer periods of the Late Glacial [81]. Nevertheless, alterations that occurred in the various river valleys of Central Europe were not uniform during the Late Glacial period and were mostly influenced by the type of river discharge [81]. Because of the poor incision of the Stobrawa River into its own sediments, the fluvial terraces were probably not a favorable source of the material. However, the lack of well-developed terrace levels and lack of evidence for river incision do not preclude the supply of material from the Stobrawa Valley. The sand bars of rivers are widely recognized as an effective source of material for aeolian processes, especially in the case of highly variable discharge [3]. Such conditions are common in cold areas, as evidenced by dune fields located in the valleys of the Kobuk (Alaska) [13,14,15,16,17] and Vilyui (Siberia) rivers [23,24,25]. The wide and filled alluvium Stobrawa Valley suggests that it might have had the character of a braided river for a long time, as evidenced also by the extensive sand bars visible on the valley floor (Figure 10). Braided rivers predominated from the Middle Pleniglacial and had been developing until the Oldest Dryas, which, according to the dating of the nearby site in Przechód (Niemodlin Plateau), was the first dune-forming period in this area [82]. The earlier beginning of dune-forming processes in the extraglacial zone was also pointed out by Nowaczyk [34] and Moska et al. [37]. The development of braided rivers was also locally possible during the abrupt cooling of the Younger Dryas [83], considered another dune-forming period within the entire ESB [34,35,36,37,38,39]. Thus, it is likely that the Stobrawa River was a source of sand for the BSDF, not due to incision into its alluvium, but due to long-term and continuous aggradation. Remarkably, the dune field must have continued to migrate even after the cessation of the sand supply. This is indicated by the distance of several kilometers separating the first dunes from the edge of the Stobrawa Valley (Figure 2).

Regardless of the sand supply from the Stobrawa Valley, the distance separating the dunes in the leeward margin of the BSDF from the Stobrawa Valley (about 25 km; Figures 7 and 8) indicates a complex sand supply. The migration rate of dunes in polar and arctic environments is limited by variability of wind directions and strength, niveo-eolian processes, vegetation, and the presence of permafrost [7]. Studies of modern cold dune fields report a migration rate of 0.5–1.5 m/year [16,17,28]. Therefore, the migration of dunes within the BSDF would have to take about 10,000 years to reach the eastern margin of the dune field. This contradicts numerous stratigraphic studies, which reported that dune deposition within the central part of the ESB occurred maximally between the Older Dryas and Preboreal (about 6,000 years; [34,35,36,37,38,39]). However, it can be hypothesized that under conditions of constant and strong winds at the ice sheet foreland, the migration rates of dunes were higher than suggested by studies of modern cold dune fields. This may be supported by the coarse sand laminations that can be found in many dune sites of the Polish Lowlands. Studies suggest that to transport them wind speeds of 20–40 m/s were necessary [84]. Nonetheless, the size of these laminations indicates that they were deposited during short episodes of increased wind speed. It is also important to note that, in general, the grain-size distribution of dunes depends mainly on the grain-size distribution of the source sediments, so local conditions have a major impact on the deposition of such layers [34,85]. For this reason, such events were unlikely to considerably affect the migration rate of the dunes. Another factor that rules out the higher migration rate of dunes within the BSDF is their large size, which is the factor that greatly decreases the migration rate of dunes [86,87,88]. The other possibility is that dunes characterized by higher migration rates, such as barchans or small transverse dunes, were originally occurring within the dune field. In such a scenario, they would evolve into large transverse dunes due to the gradual merging and aggradation of dunes [4,5]. However, barchans were not found within the central part of the ESB [34]. Also within the BSDF, they have not been found, so this is an unlikely scenario.

Therefore, dunes that are distant from the Stobrawa Valley must have been supplied with sand from local sources, such as the fluvioglacial plain and alluvia of smaller rivers. The presence of large dune complexes in the eastern part of the BSDF suggests that the supply of sand from other sources was at least no less than from the Stobrawa Valley. The lack of blowouts visible on the surface appears to be inconsistent with the concept of a broad supply of material from the fluvioglacial plain. However, studies from Iceland and Greenland indicate that deflation in such areas may be superficial, and the resulting depressions are not only eroded but also successively filled. Depending on the area, erosion rates on outwash plains can vary from 1 to 20 cm/year [89,90,91]. Due to aerodynamic conditions, Sitzia et al. [68] identified vast plateaus (coversands) in the Aquitaine basin (SW France) as areas of continuous deflation and sand blowing, whilst at the same time not considering them as a source of material. The evidence is the lack of dunes in these areas, making this not applicable to the BSDF, where dunes are widespread on plain surfaces. On the other hand, the parabolic dunes in the central part of the interfluves are often degraded, so more intense deflation within the plain cannot be ruled out (Figure 7). Also, the deposition associated with the regular supply of sand from the plain must have occurred. Thus, it is possible that the fluvioglacial plain extensively supplied the BSDF dunes with sand. The supply of sand from the alluvium of smaller rivers may be reflected in dunes located on the leeward side of the Budkowiczanka River (Figure 7), but further sedimentological analyses are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

5.4 Redeposition of sand by streams

The impact of the fluvial system on existing dunes depends on the power of the streams. In case of high sand supply small, seasonal streams may be blocked by dunes, changing the local fluvial pattern and leading to the formation of periodic lakes. With rising stream power, interaction shifts to mostly fluvial dominant or fluvial dominant, limiting the movement of dunes and trapping sand into the fluvial system [92,93]. The low number of dunes in the valleys traversing BSDF points to the impact of rivers on dunes and indicates the redeposition of sand by the water. However, the impact of the river network on the dune field is minor as long as the valleys have an orientation parallel to the direction of dune field migration. The balance between fluvial and aeolian systems shifts with the change of the river network configuration in the easternmost part of BSDF (Figure 7). Here, the contact angle between BSDF and rivers changes from 180° (almost opposite to the mean wind direction) to 150–170°, preventing further migration of the dunes in an easterly direction. The number of dunes decreases here rapidly, suggesting the trapping of material into the fluvial system. A study by Liu and Coulthard [93] has demonstrated that even a small change in the contact angle between dunes and rivers can lead to the domination of the fluvial environment.

The trapping of sand by the fluvial network is reflected in the changing morphometry of the valleys after the rivers flow into the dune field. Intensive aggradation is underlined by the increase in the valley’s width (Figure 9) and the lack of erosional edges separating valleys from the fluvioglacial plain (Figure 2). Increasing sediment supply caused the transformation of the channels from straight/meandering to a braided system (Figure 10; [93,94]). The extensive sand bars and outwash fans identified in all three valleys confirm the abrupt overloading of streams and intensive aggradation of fluvial deposits.

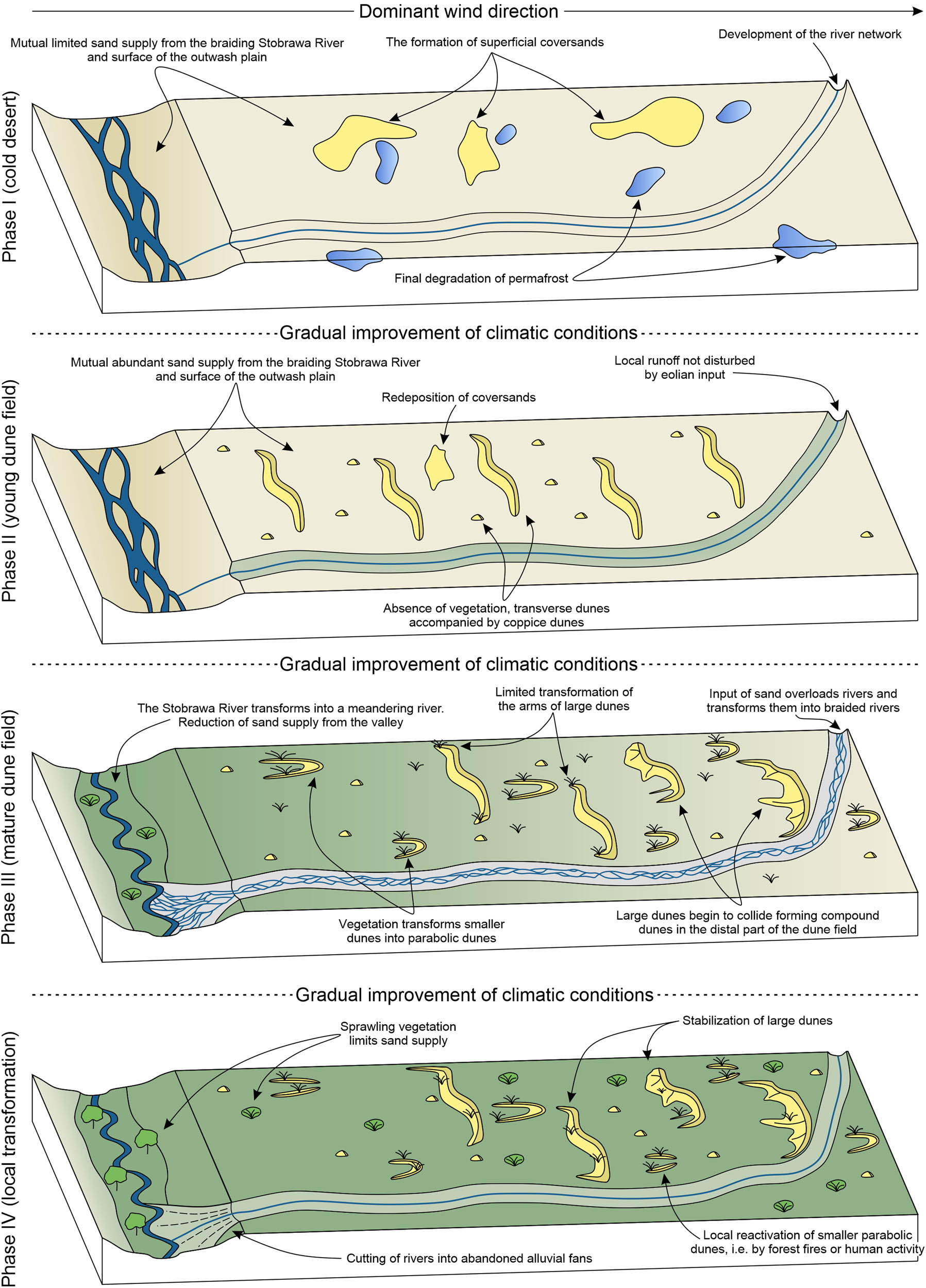

5.5 Model of the BSDF evolution

The results indicate a multi-phase development of low-density dune fields within the central part of the ESB. In the case of the BSDF, on the basis of geomorphological observations, a four-phase scenario appears to be the most relevant (Figure 11). The formation of the dune field was initiated by a gradual improvement of climatic conditions at the end of Pleniglacial. Further evolution was conditioned by the shifting balance between the sand supply and the amount of vegetation cover. It is likely that some of the dunes were undergoing stabilization temporarily, although it is unclear whether the stabilization affected the entire dune field.

Conceptual model of multi-phase development of the BSDF.

The first phase of BSDF development was characterized by harsh conditions of the cold desert (low temperatures and precipitation, strong winds, and lack of vegetation). The gradual improvement of climatic conditions led to the degradation of permafrost, which subsequently triggered the release of previously unavailable sand. Distant and continuous aeolian transport of sand took place, as well as repetitive redeposition of sand by rivers. These processes are recorded in the high degree of rounding and matting of quartz grains that build dunes within the central ESB [42,43,44,45]. Long-term intense aeolian activity resulted in the local formation of thin coversands, clearly visible in the grain-size composition of the topsoil (0–20 cm) within BSDF (Figure 2). High wind speeds limited the deposition of sand, although the formation of ephemeral initial dunes during this phase cannot be ruled out.

The second phase took place under conditions of simultaneous high sand supply from the Stobrawa Valley and the (previously reworked by wind) fluvioglacial plain combined with the absence or very sparse vegetation cover. Such conditions favored the formation of large transverse dunes (by the merging of smaller, rapidly migrating dunes [4,5,6]). The long-term but periodic sand supply led to the development of many individual, uniformly, and sparsely distributed dunes. The weak vegetation cover allowed the fast migration of the dunes which move considerably far from the main source of the material.

The third phase was related to climate ameliorations that triggered the change of the Stobrawa River pattern to meandering, which resulted in reduced sand supply. Nevertheless, the continuous supply of material from the dry fluvioglacial plain favored the further formation of dunes. However, due to the limited sand supply and occurrence of vegetation, the new dunes evolved as primary parabolic dunes. Advancing vegetation promoted the transformation of older smaller dunes into parabolic dunes and affected the arms of transverse dunes. The biggest transverse dunes continued migration until they encountered the river network, which restricted and reduced their movement rate. Under such conditions, dunes started to collide together forming complex dunes. In the case of the movement of dunes across rivers, sand was redeposited within the river network. The transformation of the smaller rivers from meandering/straight to braided rivers occurred in this phase, while the BSDF reached its maximum spatial extent.

The fourth phase (transformation of the dune field) was related to the stabilization of the whole dune field by vegetation and cessation of sand supply. The dunes were locally reactivated as a result of human activity or temporary vegetation degradation, e.g., caused by forest fires. This resulted in the blowing away of some of the foreheads of parabolic dunes and limited aggradation of the complex dunes.

It is impossible to define a precise timeframe for the formation of the BSDF considering the lack of absolute datings. However, the first phase of intense aeolian activity and the formation of local thin coversands most likely took place during the Upper Pleniglacial and the beginning of Oldest Dryas [38]. Subsequently, in the Oldest Dryas, as a result of reduced wind speeds and permafrost degradation, the first dunes may have developed (Phase II). Such a situation was reported from the Niemodlin Plateau, about 40 km to the S of the BSDF [82], as well as from a few sites located in other parts of the ESB [38]. Certainly, the climatically harsh (and vegetation-free) Oldest Dryas favored the development of transverse dunes. This would not seem possible in the rest of the Late Glacial, when forests developed in the south of Poland [95]. The view about the early formation of dunes in the extraglacial zone of the last glaciation has been evoked by many authors [34,37]. Timing of the successive phases (III and IV) is difficult to determine due to the very asynchronous development of many dune fields, even if they were located close to each other [e.g. 37,82]. Many dunes were also developing during the warm periods of the Bølling and Allerød [38,39]. Considering that the primary transverse dunes evolved into parabolic dunes, the transformation must have occurred under the influence of the expanding vegetation. The successive transformations of the dune field must have occurred between the Bølling and the onset of the Holocene, when aeolian activity finally ceased within the central ESB [34,35,39]. Nevertheless, the timing of the development of the successive phases is speculative and requires future datings of the aeolian sediments within the BSDF.

5.6 Study limitations

Analysis of aeolian features using LiDAR data has great scientific potential, but has some difficulties, as highlighted by many authors [68,76,96]. Developing a clear and simple classification scheme is crucial to decrease the impact of observer experience on the classification process. Classification of the same forms could be different using varied DEM resolutions and hillshade models. Small forms could be confused with artificial structures (e.g., charcoal piles and objects formed during forest management). Compound and complex dunes are hard to interpret due to the high number of ridges and overlapping forms. It also needs to be noted that geomorphological surveys should be validated by sedimentological analyses. However, this is often not possible due to the lack of outcrops or funds required for laboratory analyses.

6 Conclusions

In this study, we show that the development and functioning of the cold-climate dune field do not differ from dune fields existing in other climatic zones. As in hot deserts, wind action and availability of material are necessary to move sand and start the growth of dunes. This dependence is especially essential in the case of periglacial conditions characterized by long-term but periodic sand supply which causes the development of an irregular (patchy) pattern of mostly simple dunes. The interplay between dunes and the river network appears to be the main factor that shapes the dune fields under such conditions. On the one hand, the fluvial network provides the sand necessary for the development of the dune field. Simultaneously, rivers and streams significantly limit the migration rate and movement of dunes. On the other hand, dunes overload the fluvial network introducing sand into rivers and streams, which in consequence affects the style of fluvial deposition.

The geomorphological analysis showed that the BSDF is composed of four types of dunes (irregular, transverse, parabolic, and complex dunes) genetically related to each other. Transverse dunes, as a result of migration and merging, formed the main body of complex dunes. Parabolic dunes that were blown away were transformed into irregular dunes. We found that the sand supply came not only from the broad Stobrawa Valley but also from the surface of the outwash plain and the valleys of smaller rivers that drain the dune field. Spatial analysis suggests the formation of the dune field during four phases, marked by complex changes in the sand supply (driven by the transformation of rivers) and the vegetation content. Although the absolute datings were not carried out, it can be assumed that the first dunes of the BSDF were formed during the Oldest Dryas and were subsequently undergoing transformations until the onset of the Holocene.

Our study shows that the analyses of high-resolution DEMs are a useful tool for the mapping and quantification of landforms. The obtained results provide spatial information about past aeolian processes and can be compiled with detailed sedimentological studies. Future studies should provide automatized schemes and workflows for GIS, eliminating the influence of the observer on results. Another necessity is to conduct comparative research in dune fields developed in different morphological positions and affected by various bedform lithologies.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Milena Różycka and Łukasz Stachnik for their advice given during the preparation of the manuscript. We also thank both reviewers for their constructive comments which helped to improve the manuscript significantly.

-

Funding information: This research was funded in whole by National Science Centre (Poland) grant no. 2021/41/N/ST10/00350.

-

Author contributions: MŁ: conceptualization, formal analysis, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. PZ: writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, ZJ: writing – review and editing; supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this manuscript.

-

Data availability statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

[1] Hack J. Dunes of the western Navajo country. Geogr Rev. 1941;31(2):240–63. 10.2307/210206.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Wasson RJ, Hyde R. Factors determining desert dune type. Nature. 1983;304:337–9. 10.1038/304337a0.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Lancaster N. Geomorphology of desert dunes. New York: Routledge; 1995.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Werner BT. Eolian dunes: Computer simulations and attractor interpretation. Geology. 1995;23:1107–10. 10.1130/0091-7613(1995)023<1107:EDCSAA>2.3.CO;2.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Werner BT, Kocurek G. Bedform spacing from defect dynamics. Geology. 1999;27:717–30. 10.1130/0091-7613(1999)027<0727:BSFDD>2.3.CO;2.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Ewing RC, Kocurek GA. Aeolian dune interactions and dune-field pattern formation: White Sands Dune Field New Mexico. Sedimentology. 2010;57:1199–219. 10.1111/j.1365-3091.2009.01143.x.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Seppala M. Wind as a geomorphic agent in cold climates. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2004.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Pye K, Tsoar H. Aeolian sand and sand dunes. Berlin: Springer; 2009.10.1007/978-3-540-85910-9Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Thomas DSG, Leason HC. Dunefield activity response to climate variability in the southwest Kalahari. Geomorphology. 2005;64:117–32. 10.1016/j.geomorph.2004.06.004.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Beveridge C, Kocurek G, Ewing RC, Lancaster N, Morthekai P, Singhvi AK, et al. Development of spatially diverse and complex dune-field patterns: Gran Desierto Dune Field, Sonora, Mexico. Sedimentology. 2006;53:1391–409. 10.1111/j.1365-3091.2006.00814.x.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Derickson D, Kocurek G, Ewing RC, Bristow C. Origin of a complex and spatially diverse dune-field pattern, Algodones, southeastern California. Geomorphology. 2008;99:186–204. 10.1016/j.geomorph.2007.10.016.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Hesse P. Sticky dunes in a wet desert: Formation, stabilization and modification of the Australian desert dune fields. Geomorphology. 2011;134:309–25. 10.1016/j.geomorph.2011.07.008.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Dijkmans JWA, Koster EA. Morphological development of dunes in a subarctic environment, central Kobuk Valley, northwestern Alaska. Geogr Ann A. 1990;72:93–109. 10.1080/04353676.1990.11880303.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Lea PD, Waythomas CF. Late-pleistocene eolian sand sheets in Alaska. Quat Res. 1990;34(3):269–81. 10.1016/0033-5894(90)90040-R.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Mann DH, Heiser PA, Finney BP. Holocene history of the Great Kobuk sand dunes, northwestern Alaska. Quat Sci Rev. 2002;21(4–6):709–31. 10.1016/S0277-3791(01)00120-2.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Necsoiu M, Leprince S, Hooper D, Dinwiddie C, McGinnis R, Walter G. Monitoring migration rates of an active subarctic dune field using optical imagery. Remote Sens Environ. 2009;113:2441–7. 10.1016/j.rse.2009.07.004.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Baughmann CA, Jones BM, Bodony KL, Mann DH, Larsen CF, Himelstoss E, et al. Remotely sensing the morphometrics and dynamics of a cold region dune field using historical aerial photography and airborne LiDAR data. Remote Sens. 2018;10(5):792. 10.3390/rs10050792.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Carson MA, MacLean PA. Development of hybrid aeolian dunes: the William River dune field, northwest Saskatchewan, Canada. Can J Earth Sci. 1986;23:1974–90. 10.1139/e86-183.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Wolfe SA, Huntley DJ, Ollerhead J. Recent and late Holocene sand dune activity in southwestern Saskatchewan. In Current research 1995-B. Ottawa: Geological Survey of Canada; 1995. p. 131–40.10.4095/202806Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Wolfe SA, Huntley DJ, Ollerhead J. Relict Late Wisconsinan dune fields of the northern great plains. Can Geogr Phys Quat. 2004;58(2–3):323–36. 10.7202/013146ar.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Wolfe SA, Huntley DJ, David P, Ollerhead J, Sauchyn D, MacDonald G. Late 18th century drought-induced sand dune activity, great sand hills, Saskatchewan. Can J Earth Sci. 2011;38:105–17. 10.1139/cjes-38-1-105.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Attanayake A, Xu D, Guo X, Lamb E. Long‐term sand dune spatio‐temporal dynamics and endemic plant habitat extent in the Athabasca sand dunes of northern Saskatchewan. Remote Sens Ecol Conserv. 2018;5:70–86. 10.1002/rse2.90.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Pavlova MR, Rudaya NA, Galanin AA, Shaposhnikov GI. Structure and evolution of dune massifs in the Vilyui River Basin over the late quaternary period (by the example of the Makhatta and Kysyl-Syr Tukulans). Contemp Probl Ecol. 2017;10:411–22. 10.1134/S1995425517040072.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Galanin AA, Pavlova MR, Klimova IV. Late quaternary dune formations (D’Olkuminskaya series) in central Yakutia (Part 1). Earth’s Cryosphere. 2018;22:3–15. 10.21782/KZ1560-7496-2018-63-15.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Galanin AA, Pavlova MR. Late quaternary dune formations (D’Olkuminskaya series) in central Yakutia (Part 2). Earth’s Cryosphere. 2019;23:3–16. 10.21782/KZ1560-7496-2019-13-16.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Mountney NP, Russell AJ. Aeolian dune-field development in a water table-controlled system: Skeiđarársandur, southern Iceland. Sedimentology. 2009;56:2107–31. 10.1111/j.1365-3091.2009.01072.x.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Ruz MH, Hesp PA. Geomorphology of high-latitude coastal dunes: A review. Geol Soc London, Spec Publ. 2004;388:199–212. 10.1144/SP388.17.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Bourke MC, Ewing RC, Finnegan D, McGowan HA. Sand dune movement in the Victoria valley, Antarctica. Geomorphology. 2009;109:148–60. 10.1016/j.geomorph.2009.02.028.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] McKenna-Neuman CM. Role of sublimation in particle supply for aeolian transport in cold environments. Geogr Ann A. 1990;72:329–35. 10.2307/521159.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Wiggs GFS, Baird AJ, Atherton RJ. The dynamic effects of moisture on the entrainment and transport of sand by wind. Geomorphology. 2004;59:13–30. 10.1016/j.geomorph.2003.09.002.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Arens SM, Slings Q, de Vries CN. Mobility of a remobilized parabolic dune in Kennemerland, The Netherlands. Geomorphology. 2014;59:175–88. 10.1016/j.geomorph.2003.09.014.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Koster EA. Ancient and modern cold–climate aeolian sand deposition: A review. J Quat Sci. 1988;3:69–83. 10.1002/jqs.3390030109.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Zeeberg J. The European sand belt in eastern Europe e and comparison of Late Glacial dune orientation with GCM simulation results. Boreas. 1998;27:127–39. 10.1111/j.1502-3885.1998.tb00873.x.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Nowaczyk B. Wiek wydm, ich cechy granulometryczne i strukturalne a schemat cyrkulacji atmosferycznej w Polsce w późnym vistulianie i holocenie. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Naukowe UAM; 1986.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Manikowska B. Vistulian and Holocene aeolian activity, pedostratygraphy and relief evolution in Central Poland. Z Geomorphol. 1991;90:131–41.Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Manikowska B. Aeolian activity differentiation in the area of Poland during the period 20–8 ka BP. Biul Peryglac. 1995;34:125–65.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Moska P, Sokołowski R, Jary Z, Zieliński P, Raczyk J, Szymak A, et al. Stratigraphy of the Late Glacial and Holocene aeolian series in different sedimentary zones related to the Last Glacial maximum in Poland. Quat Int. 2022;630:65–83. 10.1016/j.quaint.2021.04.004.Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Sokołowski RJ, Moska P, Zieliński P, Jary Z, Piotrowska N, Raczyk J, et al. Reinterpretation of fluvial-aeolian sediments from last glacial termination classic type localities using high-resolution radiocarbon data from the polish part of the European Sand Belt. Radiocarbon. 2022;64(6):1–16. 10.1017/RDC.2022.37.Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Moska P, Sokołowski RJ, Zieliński P, Jary Z, Raczyk J, Mroczek P, et al. An impact of short-term climate oscillations in the Late Pleniglacial and Lateglacial interstadial on sedimentary processes and the pedogenic record in central Poland. Ann Assoc Am Geogr. 2023;113(1):46–70. 10.1080/24694452.2022.2094325.Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Kasse C. Sandy aeolian deposits and their relation to climate during the Last Glacial Maximum and Lateglacial in northwest and central Europe. Prog Phys Geogr. 2002;26:507–32. 10.1191/0309133302pp350ra.Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Łopuch M, Sokołowski RJ, Jary Z. Factors controlling the development of cold-climate dune fields within the central part of the European Sand Belt – Insights from morphometry. Geomorphology. 2023;420:108514. 10.1016/j.geomorph.2022.108514.Suche in Google Scholar

[42] Mycielska-Dowgiałło E. Estimates of Late Glacial and Holocene aeolian activity in Belgium, Poland and Sweden. Boreas. 1993;22:165–70.10.1111/j.1502-3885.1993.tb00177.xSuche in Google Scholar

[43] Mycielska-Dowgiałło E. Wpływ warunków klimatycznych na cechy strukturalne i tekstualne osadów mineralnych [Influence of climatic condition on the structural and textural features of mineral deposits]. In Karczewski A, Zwoliński Z, editors. Funkcjonowanie geosystemów w zróżnicowanych warunkach morfoklimatycznych – monitoring, ochrona, edukacja [The functioning of geosystems under different morphoclimatic conditions – monitoring, protection, education]. Poznań: Stowarzyszenie Geomorfologów Polskich; 2001. p. 377–94.Suche in Google Scholar

[44] Goździk J. The Vistulian aeolian succession in central Poland. Sediment Geol. 2007;193:211–20. 10.1016/j.sedgeo.2005.11.026.Suche in Google Scholar

[45] Woronko B, Zieliński P, Sokołowski R. Climate evolution during the Pleniglacial and Late Glacial as recorded in quartz grain morphoscopy of fluvial to aeolian successions of the European Sand Belt. Geologos. 2015;21:89–103. 10.1515/logos–2015-0005.Suche in Google Scholar

[46] Twardy J. Antropogeniczna faza wydmotwórcza w środkowej Polsce = Anthropogenic phase of dune-forming processes in central Poland. In: Święchowicz J, Michno A, editors. Wybrane zagadnienia geomorfologii eolicznej. Monografia dedykowana dr hab. Bogdanie Izmaiłow w 44. rocznicę pracy naukowej. Kraków: IgiGP; 2016. p. 157–83.Suche in Google Scholar

[47] Kasse C, Aalbersberg G. A complete Late Weichselian and Holocene record of aeolian coversands, drift sands and soils forced by climate change and human impact, Ossendrecht, The Netherlands. Neth J Geosci. 2019;98:e4. 10.1017/njg.2019.3.Suche in Google Scholar

[48] Kaiser K, Schneider T, Küster M, Dietze E, Fülling A, Heinrich S, et al. Palaeosols and their cover sediments of a glacial landscape in northern central Europe: spatial distribution, pedostratigraphy and evidence on landscape evolution. Catena. 2020;193:104647. 10.1016/j.catena.2020.104647.Suche in Google Scholar

[49] Zieliński P. Regionalne i lokalne uwarunkowania późnovistuliańskiej depozycji eolicznej w środkowej części europejskiego pasa piaszczystego [Regional and local conditions of the Late Vistulian aeolian deposition in the central part of the European Sand Belt]. Lublin: Wydawnictwo UMCS; 2016.Suche in Google Scholar

[50] Izmaiłow B. Typy wydm śródlądowych w świetle badań struktury i tekstury ich osadów (na przykładzie dorzecza górnej Wisły). Kraków: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego; 2001.Suche in Google Scholar

[51] Solon J, Borzyszkowski J, Bidłasik M, Richling A, Badora K, Balon J, et al. Physico-geographical mesoregions of Poland: Verification and adjustment of boundaries on the basis of contemporary spatial data. Geogr Pol. 2018;91(2):143–70. 10.7163/GPol.0115.Suche in Google Scholar

[52] Haisig J, Wilanowski S. Szczegółowa mapa geologiczna Polski w skali 1:50 000, arkusz Kluczbork wraz z objaśnieniami [Detailed geological map of Poland in scale 1:50 000, sheet Kluczbork with explanations]. Warsaw, Poland: PIG; 1990.Suche in Google Scholar

[53] Goździk J, Kobojek S. Źródła piasków wydmowych oraz geomorfologiczne uwarunkowania dróg transportu i miejsc akumulacji w Pasie Wydmowym Małej Panwi i Stobrawy (The Mała Panew and The Stobrawa Dune Belt. Dune sand sources and geomorphological conditioning of pathways and accumulation places). In: Święchowicz J, Michno A, editors. Wybrane zagadnienia geomorfologii eolicznej. Monografia dedykowana dr hab. Bogdanie Izmaiłow w 44. rocznicę pracy naukowej. Kraków: IgiGP; 2016. p. 185–210.Suche in Google Scholar

[54] Panagos P. The European soil database. GEO Connex. 2006;5(7):32–3.Suche in Google Scholar

[55] Trzepla M. Szczegółowa mapa geologiczna Polski w skali 1:50 000, arkusz Jełowa wraz z objaśnieniami [Detailed geological map of Poland in scale 1:50 000, sheet Jełowa with explanations]. Warsaw, Poland: PIG; 1988.Suche in Google Scholar

[56] Polaczek R, Otrąbek L. Szczegółowa mapa geologiczna Polski w skali 1:50 000, arkusz Pokój wraz z objaśnieniami [Detailed geological map of Poland in scale 1:50 000, sheet Pokój with explanations]. Warsaw, Poland: PIG; 1996.Suche in Google Scholar

[57] Badura J, Przybylski J. Szczegółowa mapa geologiczna Polski w skali 1:50 000, arkusz Opole Północ wraz z objaśnieniami [Detailed geological map of Poland in scale 1:50 000, sheet Opole Północ with explanations]. Warsaw, Poland: PIG; 2010.Suche in Google Scholar

[58] Pernarowski L. Z badań nad wydmami Dolnego Śląska. In: Galon R, editor. Wydmy śródlądowe Polski, cz. I. Warsaw: PWN; 1958. p. 171–99.Suche in Google Scholar

[59] Pernarowski L. Obszary wydmowe Opolszczyzny. In: Szczepankiewicz S, editor. Studia geograficzno-fizyczne z obszaru Opolszczyzny t. 2. Opole: Instytut Śląski; 1968. p. 102–34.Suche in Google Scholar

[60] Komar T. Charakterystyka sieci rzecznej województwa opolskiego. In: Szczepankiewicz S, editor. Studia geograficzno-fizyczne z obszaru Opolszczyzny t. 2. Opole: Instytut Śląski; 1968. p. 158–205.Suche in Google Scholar

[61] Kurczyński Z, Stojek E, Cisło-Lesicka U. Zadania GUGiK realizowane w ramach projektu ISOK. In: Wężyk P, editor. Podręcznik dla uczestników szkoleń z wykorzystania produktów LiDAR. (Handbook for users of training courses in the use of LiDAR products). Warszawa: Główny Urząd Geodezji i Kartografii; 2015. p. 22–58.Suche in Google Scholar

[62] Kokalj Ž, Hesse R. Airborne laser scanning raster data visualization: A guide to good practice. Ljublana: Založba ZRC; 2017.10.3986/9789612549848Suche in Google Scholar

[63] Böhner J, Selige T. Spatial prediction of soil attributes using terrain analysis and climate regionalisation. Göttinger Geogr Abh. 2006;115:13–28.Suche in Google Scholar

[64] Mattivi P, Franci F, Lambertini A, Bitelli G. TWI computation: A comparison of different open source GISs. Open Geospat Data Softw Stand. 2019;4:6. 10.1186/s40965-019-0066-y.Suche in Google Scholar

[65] Wilkins DE, Ford RL. Nearest neighbor methods applied to dune-field organization: the Coral Pink Sand Dunes, Kane County, Utah, USA. Geomorphology. 2007;83:48–57. 10.1016/j.geomorph.2006.06.009.Suche in Google Scholar

[66] Bishop MA. Point pattern analysis of North Polar crescentic dunes, Mars: A geography of dune self-organization. Icarus. 2007;191:151–7. 10.1016/j.icarus.2007.04.027.Suche in Google Scholar

[67] Bishop MA. Comparative nearest neighbor analysis of mega-barchanoid dunes, Ar Rub al Khali sand sea: the application of geographical indices to the understanding of dune field self-organization, maturity and environmental change. Geomorphology. 2010;120:186–94. 10.1016/j.geomorph.2010.03.029.Suche in Google Scholar

[68] Sitzia L, Bertran P, Sima A, Chery P, Queffelec A, Rousseau DD. Dynamics and sources of last glacial aeolian deposit in southwest France derived from dune patterns, grain-size gradients and geochemistry, and reconstruction of efficient wind directions. Quat Sci Rev. 2017;170:250–68. 10.1016/j.quascirev.2017.06.029.Suche in Google Scholar

[69] Bertran P, Andrieux E, Bateman MD, Fuchs M, Klinge M, Marembert F. Mapping and chronology of coversands and dunes from the Aquitaine basin, southwest France. Aeolian Res. 2020;47:100628. 10.1016/j.aeolia.2020.100628.Suche in Google Scholar

[70] Cooper WS. Coastal sand dunes of Oregon and Washington. Geol Soc Am Mem. 1958;72:144. 10.1130/MEM72-p1.Suche in Google Scholar

[71] Hesp P. Dune Coasts. Treatise on estuarine and coastal science. Cambridge: Academic Press; Vol. 3; 2011. p. 193–221. 10.1016/B978-0-12-374711-2.00310-7.Suche in Google Scholar

[72] Fedorowicz S, Zieliński P. Chronology of aeolian events recorded in the Karczmiska dune (Lublin Upland) in the light of lithofacial analysis, C-14 and TL dating. Geochronometria. 2009;33:9–17. 10.2478/v10003-009-0010-8.Suche in Google Scholar

[73] Seppälä M. Evolution of aeolian relief of the Kaamasjoki-Kiellajoki river basin in Finnish Lapland. Fennia. 1971;104:1–88.Suche in Google Scholar

[74] Wolfe SA, David PP. Parabolic dunes: Examples from the Great Sand Hills, southwestern Saskatchewan. Can Geogr. 1997;41:207–13. 10.1111/j.1541-0064.1997.tb01160.x.Suche in Google Scholar

[75] Hilgers A. The chronology of Late Glacial and Holocene dune development in the northern Central European lowland reconstructed by optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating. PhD thesis. Köln: Universität zu Köln; 2007.Suche in Google Scholar

[76] Bernhardson M, Alexanderson H. Early Holocene dune field development in Dalarna, central Sweden: a geomorphological and geophysical case study. Earth Surf Proc Land. 2017;42:1847–59. 10.1002/esp.4141.Suche in Google Scholar

[77] Ewing RC, Kocurek G, Lake LW. Pattern analysis of dune-field parameters. Earth Surf Proc Land. 2006;31:1176–91. 10.1002/esp.1312.Suche in Google Scholar

[78] Holuša J, Nývlt D, Woronko B, Matějka M, Stuchlík R. Environmental factors controlling the Last Glacial multi-phase development of the Moravian Sahara dune field, Lower Moravian Basin, Central Europe. Geomorphology. 2022;413:108355. 10.1016/j.geomorph.2022.108355.Suche in Google Scholar

[79] Böse M. A palaeoclimatic interpretation of frost-wedge casts and Aeolian sand deposits in the lowlands between Rhine and Vistula in the Upper Pleniglacial and Late Glacial. Z Geomorphol. 1991;90:15–28.Suche in Google Scholar

[80] Andrzejewski L, Weckwerth P. Dunes of the Toruń Basin against palaeogeographical conditions of the late glacial and Holocene. Ecol Quest. 2010;12:9–15. 10.2478/v10090–010–0001–4.Suche in Google Scholar

[81] Starkel L, Michczyńska DJ, Gębica P, Kiss T, Panin A, Persoiu I. Climatic fluctuations reflected in the evolution of fluvial systems of Central-Eastern Europe (60-8 ka cal BP). Quat Int. 2015;388:97–118. 10.1016/j.quaint.2015.04.017.Suche in Google Scholar

[82] Moska P, Jary Z, Sokołowski RJ, Poręba G, Raczyk J, Krawczyk M, et al. Chronostratigraphy of Late Glacial aeolian activity in SW Poland – A case study from the Niemodlin Plateau. Geochronometria. 2020;47(1):124–37. 10.2478/geochr-2020-0020.Suche in Google Scholar

[83] Dzieduszyńska D, Petera-Zganiacz J, Roman M. Vistulian periglacial and glacial environments in central Poland: An overview. Geol Q. 2020;64(1):54–73. 10.7306/gq.1510.Suche in Google Scholar

[84] Łapcik P, Ninard K, Uchman A. Extra-large grains in Late Glacial – Early Holocene aeolian inland dune deposits of cold climate, European Sand Belt, Poland: An evidence of hurricane-speed frontal winds. Sediment Geol. 2021;415:105847. 10.1016/j.sedgeo.2020.105847.Suche in Google Scholar

[85] Bristow C, Livingstone I. Dune sediments. In: Livinstone I, Warren A, editors. Aeolian geomorphology: A new introduction. 1st edn. Hoboken: Wiley & Sons; 2019.10.1002/9781118945650Suche in Google Scholar

[86] Simons DB, Richardson EV, Nordin CF. Bedload equation for ripples and dunes. United States Geological Survey, Professional Paper 1965;462-H, H1-H9. 10.3133/pp462H.Suche in Google Scholar

[87] Dong ZB, Wang XM, Chen GT. Monitoring sand dune advance in the Taklimakan Desert. Geomorphology. 2000;35(3):219–31. 10.1016/S0169-555X(00)00039-8.Suche in Google Scholar

[88] Yang J, Dong Z, Liu Z, Shi W, Chen G, Shao T, et al. Migration of barchan dunes in the western Quruq Desert, northwestern China. Earth Surf Proc Land. 2019;44:2016–29. 10.1002/esp.4629.Suche in Google Scholar

[89] Dugmore AJ, Gisladóttir G, Simpson IA, Newton A. Conceptual models of 1200 years of Icelandic soil erosion reconstructed using tephrochronology. J North Atl. 2009;2(1):1–18. 10.3721/037.002.0103.Suche in Google Scholar

[90] Heindel RC, Chipman JW, Virginia RA. The spatial distribution and ecological impacts of aeolian soil erosion in Kangerlussuaq, West Greenland. Ann Assoc Am Geogr. 2015;105(5):875–90. 10.1080/00045608.2015.1059176.Suche in Google Scholar

[91] Owczarek P, Dagsson-Waldhauserova P, Opała-Owczarek M, Migała K, Arnalds Ó, Randall J, et al. Anatomical changes in dwarf shrub roots provide insight into aeolian erosion rates in northeastern Iceland. Geoderma. 2022;428:116173. 10.1016/j.geoderma.2022.116173.Suche in Google Scholar

[92] Al-Masrahy MA, Mountney NP. A classification scheme for fluvial– aeolian system interaction in desert-margin settings. Aeolian Res. 2015;17:67–88. 10.1016/j.aeolia.2015.01.010.Suche in Google Scholar

[93] Liu B, Coulthard TJ. Mapping the interactions between rivers and sand dunes: implications for fluvial and aeolian geomorphology. Geomorphology. 2015;231:246–57. 10.1016/j.geomorph.2014.12.011.Suche in Google Scholar

[94] Smith ND, Smith DG. William river: An outstanding example of channel widening and braiding caused by bed-load addition. Geology. 1984;12(2):78–82. 10.1130/0091-7613(1984)12<78:WRAOEO>2.0.CO;2.Suche in Google Scholar

[95] Latałowa M Late Glacial. In: Ralska-Jasiewiczowa M, Latałowa M, Wasylikowa K, Tobolski K, Madeyska E, Wright H, et al. editors. Late Glacial and Holocene history of vegetation in Poland based in isopollen maps. Kraków: W. Szafer Institute of Botany, PAN; 2004. 385–91.Suche in Google Scholar

[96] Hugenholtz CH, Levin N, Barchyn TE, Baddock MC. Remote sensing and spatial analysis of aeolian sand dunes: a review and outlook. Earth-Sci Rev. 2012;111:319–34. 10.1016/j.earscirev.2011.11.006.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Diagenesis and evolution of deep tight reservoirs: A case study of the fourth member of Shahejie Formation (cg: 50.4-42 Ma) in Bozhong Sag

- Petrography and mineralogy of the Oligocene flysch in Ionian Zone, Albania: Implications for the evolution of sediment provenance and paleoenvironment

- Biostratigraphy of the Late Campanian–Maastrichtian of the Duwi Basin, Red Sea, Egypt

- Structural deformation and its implication for hydrocarbon accumulation in the Wuxia fault belt, northwestern Junggar basin, China

- Carbonate texture identification using multi-layer perceptron neural network

- Metallogenic model of the Hongqiling Cu–Ni sulfide intrusions, Central Asian Orogenic Belt: Insight from long-period magnetotellurics

- Assessments of recent Global Geopotential Models based on GPS/levelling and gravity data along coastal zones of Egypt

- Accuracy assessment and improvement of SRTM, ASTER, FABDEM, and MERIT DEMs by polynomial and optimization algorithm: A case study (Khuzestan Province, Iran)

- Uncertainty assessment of 3D geological models based on spatial diffusion and merging model

- Evaluation of dynamic behavior of varved clays from the Warsaw ice-dammed lake, Poland

- Impact of AMSU-A and MHS radiances assimilation on Typhoon Megi (2016) forecasting

- Contribution to the building of a weather information service for solar panel cleaning operations at Diass plant (Senegal, Western Sahel)

- Measuring spatiotemporal accessibility to healthcare with multimodal transport modes in the dynamic traffic environment

- Mathematical model for conversion of groundwater flow from confined to unconfined aquifers with power law processes

- NSP variation on SWAT with high-resolution data: A case study

- Reconstruction of paleoglacial equilibrium-line altitudes during the Last Glacial Maximum in the Diancang Massif, Northwest Yunnan Province, China

- A prediction model for Xiangyang Neolithic sites based on a random forest algorithm

- Determining the long-term impact area of coastal thermal discharge based on a harmonic model of sea surface temperature

- Origin of block accumulations based on the near-surface geophysics

- Investigating the limestone quarries as geoheritage sites: Case of Mardin ancient quarry

- Population genetics and pedigree geography of Trionychia japonica in the four mountains of Henan Province and the Taihang Mountains

- Performance audit evaluation of marine development projects based on SPA and BP neural network model

- Study on the Early Cretaceous fluvial-desert sedimentary paleogeography in the Northwest of Ordos Basin

- Detecting window line using an improved stacked hourglass network based on new real-world building façade dataset

- Automated identification and mapping of geological folds in cross sections

- Silicate and carbonate mixed shelf formation and its controlling factors, a case study from the Cambrian Canglangpu formation in Sichuan basin, China

- Ground penetrating radar and magnetic gradient distribution approach for subsurface investigation of solution pipes in post-glacial settings

- Research on pore structures of fine-grained carbonate reservoirs and their influence on waterflood development

- Risk assessment of rain-induced debris flow in the lower reaches of Yajiang River based on GIS and CF coupling models

- Multifractal analysis of temporal and spatial characteristics of earthquakes in Eurasian seismic belt

- Surface deformation and damage of 2022 (M 6.8) Luding earthquake in China and its tectonic implications

- Differential analysis of landscape patterns of land cover products in tropical marine climate zones – A case study in Malaysia

- DEM-based analysis of tectonic geomorphologic characteristics and tectonic activity intensity of the Dabanghe River Basin in South China Karst

- Distribution, pollution levels, and health risk assessment of heavy metals in groundwater in the main pepper production area of China

- Study on soil quality effect of reconstructing by Pisha sandstone and sand soil

- Understanding the characteristics of loess strata and quaternary climate changes in Luochuan, Shaanxi Province, China, through core analysis

- Dynamic variation of groundwater level and its influencing factors in typical oasis irrigated areas in Northwest China

- Creating digital maps for geotechnical characteristics of soil based on GIS technology and remote sensing

- Changes in the course of constant loading consolidation in soil with modeled granulometric composition contaminated with petroleum substances

- Correlation between the deformation of mineral crystal structures and fault activity: A case study of the Yingxiu-Beichuan fault and the Milin fault

- Cognitive characteristics of the Qiang religious culture and its influencing factors in Southwest China

- Spatiotemporal variation characteristics analysis of infrastructure iron stock in China based on nighttime light data

- Interpretation of aeromagnetic and remote sensing data of Auchi and Idah sheets of the Benin-arm Anambra basin: Implication of mineral resources

- Building element recognition with MTL-AINet considering view perspectives

- Characteristics of the present crustal deformation in the Tibetan Plateau and its relationship with strong earthquakes

- Influence of fractures in tight sandstone oil reservoir on hydrocarbon accumulation: A case study of Yanchang Formation in southeastern Ordos Basin

- Nutrient assessment and land reclamation in the Loess hills and Gulch region in the context of gully control

- Handling imbalanced data in supervised machine learning for lithological mapping using remote sensing and airborne geophysical data

- Spatial variation of soil nutrients and evaluation of cultivated land quality based on field scale

- Lignin analysis of sediments from around 2,000 to 1,000 years ago (Jiulong River estuary, southeast China)

- Assessing OpenStreetMap roads fitness-for-use for disaster risk assessment in developing countries: The case of Burundi

- Transforming text into knowledge graph: Extracting and structuring information from spatial development plans

- A symmetrical exponential model of soil temperature in temperate steppe regions of China

- A landslide susceptibility assessment method based on auto-encoder improved deep belief network

- Numerical simulation analysis of ecological monitoring of small reservoir dam based on maximum entropy algorithm

- Morphometry of the cold-climate Bory Stobrawskie Dune Field (SW Poland): Evidence for multi-phase Lateglacial aeolian activity within the European Sand Belt

- Adopting a new approach for finding missing people using GIS techniques: A case study in Saudi Arabia’s desert area

- Geological earthquake simulations generated by kinematic heterogeneous energy-based method: Self-arrested ruptures and asperity criterion

- Semi-automated classification of layered rock slopes using digital elevation model and geological map

- Geochemical characteristics of arc fractionated I-type granitoids of eastern Tak Batholith, Thailand

- Lithology classification of igneous rocks using C-band and L-band dual-polarization SAR data

- Analysis of artificial intelligence approaches to predict the wall deflection induced by deep excavation

- Evaluation of the current in situ stress in the middle Permian Maokou Formation in the Longnüsi area of the central Sichuan Basin, China

- Utilizing microresistivity image logs to recognize conglomeratic channel architectural elements of Baikouquan Formation in slope of Mahu Sag

- Resistivity cutoff of low-resistivity and low-contrast pays in sandstone reservoirs from conventional well logs: A case of Paleogene Enping Formation in A-Oilfield, Pearl River Mouth Basin, South China Sea

- Examining the evacuation routes of the sister village program by using the ant colony optimization algorithm

- Spatial objects classification using machine learning and spatial walk algorithm

- Study on the stabilization mechanism of aeolian sandy soil formation by adding a natural soft rock

- Bump feature detection of the road surface based on the Bi-LSTM

- The origin and evolution of the ore-forming fluids at the Manondo-Choma gold prospect, Kirk range, southern Malawi

- A retrieval model of surface geochemistry composition based on remotely sensed data

- Exploring the spatial dynamics of cultural facilities based on multi-source data: A case study of Nanjing’s art institutions

- Study of pore-throat structure characteristics and fluid mobility of Chang 7 tight sandstone reservoir in Jiyuan area, Ordos Basin

- Study of fracturing fluid re-discharge based on percolation experiments and sampling tests – An example of Fuling shale gas Jiangdong block, China

- Impacts of marine cloud brightening scheme on climatic extremes in the Tibetan Plateau

- Ecological protection on the West Coast of Taiwan Strait under economic zone construction: A case study of land use in Yueqing

- The time-dependent deformation and damage constitutive model of rock based on dynamic disturbance tests

- Evaluation of spatial form of rural ecological landscape and vulnerability of water ecological environment based on analytic hierarchy process

- Fingerprint of magma mixture in the leucogranites: Spectroscopic and petrochemical approach, Kalebalta-Central Anatolia, Türkiye

- Principles of self-calibration and visual effects for digital camera distortion

- UAV-based doline mapping in Brazilian karst: A cave heritage protection reconnaissance