Abstract

Climate change makes it imperative to use materials with minimum global warming potential. The fourth-generation blowing agent HCFO-1233zd-E is one of them. The use of HCFO allows the production of polyurethane foam with low thermal conductivity. Thermal conductivity, like other foam properties, depends not only on the density but also on the cellular structure of the foam. The cellular structure, in turn, depends on the technological parameters of foam production. A comparison of pouring and spray foams of the same low density has shown that the cellular structure of spray foam consists of cells with much less sizes than pouring foam. Due to the small size of cells, spray foam has a lower radiative constituent in the foam conductivity and, as a result, a lower overall thermal conductivity than pouring foam. The water absorption of spray foam, due to the fine cellular structure, also is lower than that of pouring foam. Pouring foam with bigger cells has higher compressive strength and modulus of elasticity in the foam rise direction. On the contrary, spray foam with a fine cellular structure has higher strength and modulus in the perpendicular direction. The effect of foam aging on thermal conductivity was also studied.

Graphical abstract

Polyurethane foams obtained with low global warming potential and low ozone depletion potential blowing agent.

1 Introduction

It is necessary to add blowing agents along with polyol and polyisocyanate to produce rigid polyurethane (PUR) foams. With the development of understanding of the impact of blowing agents on various ecological processes in PUR chemistry and technology, several generations of blowing agents have changed. The first generation was fully halogenated chlorofluorocarbons – liquids with high ozone depletion potential (ODP). The second generation were the hydrochlorofluorocarbons (1). These blowing agents have low ODP and high global warming potential (GWP). The third generation are hydrofluorocarbons (HFC) with zero ODP (2,3). According to the Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and other related documents, in the near future, fourth-generation blowing agents and refrigerants shall be used in practice. Unlike third-generation blowing agents, they should have not only a zero ODP, but also minimum GWP. The properties of the new blowing agents are discussed in refs (4–7). They are also used in PUR foam technology (8,9,10,11,12). One of them is hydrochlorofluoroolefin HCFO-1233zd-E, which has an ODP of about zero, a GWP of 1, and is non-flammable. Under the trade name Solstice® Liquid Blowing Agent (LBA), it has proven to be an ideal replacement for third-generation blowing agents in spray foam applications (13). The low boiling point (19°C) and latent heat of vaporization at boiling point (194 kJ·kg−1) can contribute to the production of low-density foams without the use of an additional blowing agent – water, which increase thermal conductivity of the end product. The low vapor thermal conductivity of HCFO-1233zd-E (10.2 mW·(m·K)−1 at 20°C) contributes to the creation of insulation with minimal overall thermal conductivity (14).

In early works (15,16,17,18,19), it has been shown that the overall or effective conductivity of the foam (λ F) could be expressed by the superposition of the following heat conduction mechanisms through the foam:

where λ m is the thermal conductivity of the foam polymer matrix, λ g is the thermal conductivity of the gases within the foam cells, λ r is the radiative thermal conductivity, and λ c is the convective conductivity of the gases. Foam cell sizes are generally small enough. So convective heat transfer may be ignored (17,18,19). Each of these constituents of thermal conductivity, like many other performance characteristics of the foam, strongly depends on the amount and geometric distribution of the polymer within cellular plastics. These variables depend, in turn, on the manufacturing technology and foaming chemistry.

The cellular structure of PUR low-density foam form polyhedrons cells consisting of struts, nodes, and cell walls. In particular, the thermal conductivity through the polymer matrix depends on how much of the struts and walls of the cells are distributed in the foam rise direction and how much in the perpendicular direction. Since, in general, the foam cells are elongated in the foam rise direction, accordingly, the mass of the struts and walls in this direction is greater than that in the perpendicular direction. Therefore, all other things being equal, the thermal conductivity in the foam rise direction is greater than that in the perpendicular one (20,21). Naturally, the lower the density of the foam, the lower its thermal conductivity. At the same time, the pore structure has a very significant effect on the physical and mechanical properties of the material, and a balance must be found between optimal thermal insulation and mechanical properties (22,23).

The impact of the radiative constituent on the overall thermal conductivity strongly depends on cell sizes. Both in theoretical and practical works, it has been shown that the reduction of the cell sizes yields smaller radiative contributions in thermal conductivity (16,18,24,25,26).

The type of the blowing agent (gas) not only determines the value of the corresponding constituent of thermal conductivity, but also the rate of the change in the thermal conductivity of the foam during aging (27,28,29). Unfortunately, most of the published foam aging data refer to foams with the second- or third-generation blowing agents.

The described and tested compositions were developed within a commercial project. The aim of this study was to assess the influence of the technology of foam production on its cellular structure, as well as the physical and mechanical properties of the PUR foam made with the fourth-generation blowing agent.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

BASF polyether and polyester polyols, diethylene glycol as chain extender, IXOL B 251 (Solvay Fluor GmbH, Germany) as reactive flame retardant, and also additive flame retardant TCPP (tris-(1-chloro-2-propyl) phosphate) (Albemarle GmbH, Germany), the surfactant Silicone L-6915LV (Momentive Performance Materials, Germany), and bismuth-based catalyst were used in the basic polyol mixture (Table 1). Polymeric 4,4′-methylene diphenyl isocyanate (PMDI) Desmodur® 44V20L (Covestro AG, Germany) with an NCO group content of 31.5% and an average functionality of 2.7 was used as an isocyanate component in both PUR formulations. For pouring the PUR composition, 0.5 pats by weight (pbw) of amine containing catalyst and 41 pbw of the blowing agent HCFO-1233zd-E under the trade name Solstice® LBA (Honeywell Fluorine Products Europe B.V., the Netherlands) were preliminarily added to the basic polyol mixture. For spraying the PUR composition, 6 pbw of amine containing catalyst and 45 pbw of HCFO-1233zd-E were added to the basic polyol mixture.

Low-density PUR foams formulations in pbw (parts by weight)

| Component | Hydroxyl number | Pouring composition | Spray composition | Composition with Solkane |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mgKOH·g−1) | (pbw) | |||

| Polyether polyols | 600 | 25 | ||

| Polyester polyol | 240 | 30 | ||

| Diethylene glycol | 1,057 | 25 | ||

| IXOL B 251 | 300 | 20 | ||

| TCPP | 15 | |||

| Silicone L-6915LV | 1.5 | |||

| Bismuth-containing catalyst | 0.2 | |||

| Amine containing catalyst | 0.5 | 6.0 | 6.0 | |

| HCFO-1233zd-E | 41 | 45 | — | |

| Solkane 365/227 (87:13) | — | — | 30 | |

| PMDI | 147 | |||

2.2 Preparation of PUR foam samples

Pouring free-rise PUR foam blocks were prepared using a laboratory mixer with a stirrer speed of 2,000 rpm and open molds with a size of 250 mm × 250 mm × 100 mm. Portions of A and B components were calculated to get the thickness of the foam blocks of about 60 mm. The temperature of the components was 20°C. Stirring time, cream time, gel time, and foam rise time of the pouring composition were 5, 11, 24, and 30 s, respectively.

For spraying of foam panels, a high pressure “MH VR dispensing system” and a spray gun “Probler P2 Elite” (GlasCraft, United Kingdom) were used. At spraying the A and B components were heated in machine and hoses till 40°C. The working pressure of the components was 120–140 bar. The output of these devices with a minimal mixing chamber was 1.5 kg·min−1. PUR foam panels were spray-applied on aluminum sheets covered with a release agent. The temperature of aluminum sheets was 22°C. The cream time of the sprayed composition on metal was 4 s. The thickness of the spray-applied panels was 50–60 mm.

2.3 PUR foam testing

PUR foam samples for testing were cut out from the core of the poured blocks and sprayed panels. The thermal conductivity coefficient λ 10 of the foams was determined using a Linseis HFM 200 thermal analyzer (Linseis GmbH). The measurement of λ 10 was carried out in the foam rise direction. The size of the samples was 200 mm × 200 mm × 35 mm, top plate temperature 20°C, and bottom plate temperature 0°C. During aging, foam samples were stored in room at 20–22°C, avoiding direct sunlight.

Closed cells volume content was determined according to the ISO 4590:2016 method 2, using samples with a size of 100 mm × 35 mm × 35 mm. For both tests, three samples were used.

The water absorption of the foams was determined according to ISO 2896:2001, using samples with a size of 50 mm × 50 mm × 50 mm. Five samples were tested in each series. Samples were kept in water till 30 days.

For compression tests of the foam, a Static Materials Testing Machine Zwick/Roell Z010 TN (10 kN) (Germany) with additional force cell 1 kN, and the basic program testXpert II were used. The test was carried out in accordance with the requirements of EN 826 using specimens with a size of 35 mm × 35 mm × 35 mm. The test was performed in two directions: parallel (z) and perpendicular (x) to foam rise. Each series was made using eight samples.

The PUR foam cellular structure was controlled using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) Tescan 5536M (Czech Republic). Resolution – 3 nm (in high vacuum of 5 × 10−3 Pa), magnification 100×.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Thermal conductivity of foams

In low-density PUR foam formulations with low thermal conductivity values, a combination of physical and chemical blowing agents is typically used. Thus, in Elastopor® H 1622/5 (Elastogran BASF Group) formulations for foam with a density of 35 kg·m−3, a combination of HFC-365mfc with water is used. The properties of the third- and fourth-generation blowing agents are given in Table 2.

| Chemical blowing agent | Third-generation blowing agents | Fourth-generation blowing agent | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blowing agent | CO2 | HFC-245fa | HFC-365mfc | HFC-227ea | HCFO-1233zd-E |

| Chemical formula | CO2 | C3H3F5 | C4H5F5 | C3HF7 | C3H2F3Cl |

| Molecular weight (g·mol−1) | 44 | 134 | 148 | 170 | 130 |

| Boiling point (°C) | −78.5 | 15.3 | 40.2 | −16.5 | 19.0 |

| Vapor thermal conductivity at 25°C (mW·(m·K)−1) | 16.3 | 12.2 | 10.6 | 13.3 | 10.5 |

Along with HFC-365mfc, a blend of HFC-365mfc and HFC-227ea in a mass ratio of 87/13 under the trademark Solkane 365/227 (87:13) is also used. The boiling point and vapor thermal conductivity of this blend are 24°C and 10.9 mW·(m·K)−1, respectively.

Since the thermal conductivity of the physical blowing agents in the vapor phase is less than that of CO2, the overall thermal conductivity of PUR foams blown with physical blowing agents is lower than that of the foam blown only with CO2. Also, the thermal conductivity of the PUR foam foamed only with a physical blowing agent will be less than that of foams, where water is used as an additional blowing agent. The use of HCFO-1233zd-E made it possible to achieve a foam with a density of about 35 kg·m−3 without the use of an additional blowing agent – water.

Since the losses of an easily boiling blowing agent during spraying are slightly greater than in pouring of the PUR composition, in order to obtain the same density of the foam, a slightly higher content of the blowing agent in the spray foam composition was used. Due to this compensation, the core foam density of the poured blocks and spray-applied panels was approximately the same, namely 34.0 and 34.5 kg·m−3 for pouring foam and spray foam, respectively. Both foams had a closed cells structure. The volume content of closed cells in pouring and spray foams was practically the same, namely, 95 vol%.

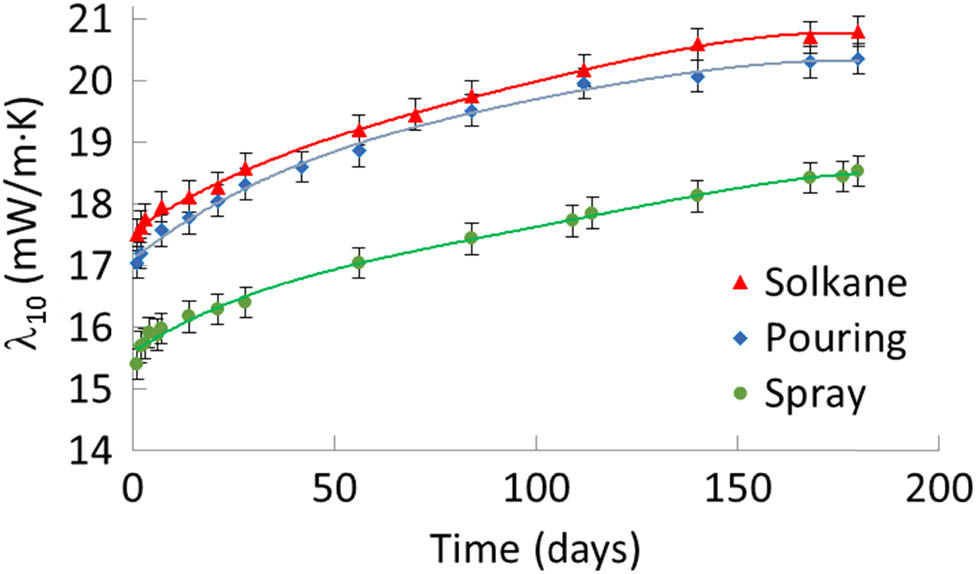

The variation of the thermal conductivity coefficient λ 10 of the tested pouring and spray foams during aging is presented in Figure 1. For the initial value of the coefficient, its value was taken on the first day, when the samples were cut out from the manufactured blocks and panels after 24 h of their curing and stress relaxation.

Variation of the thermal conductivity coefficient of pouring and spray foams during aging.

It was found that at practically the same density, the initial value of the thermal conductivity coefficient of pouring foam was higher by 10% than that of spray foam (17.1 mW·(m·K)−1 versus 15.4 mW·(m·K)−1). This ratio between the two foam coefficients was maintained during the aging of both the foams on the 7th and 180th days, namely 17.6 mW·(m·K)−1 versus 16.0 mW·(m·K)−1, and 20.4 mW·(m·K)−1 versus 18.5 mW·(m·K)−1, respectively. Only a few articles present thermal conductivity characteristics with fourth-generation blowing agents, and our result is much more competitive than the one presented in the ref. (12) – 23.0 mW·(m·K)−1.

The thermal conductivity coefficient was changed most rapidly when the foams were new, and the pressure gradients between the cells filled with a blowing agent and ambient air, promoting diffusion, had their maximum values. As the pressure gradient decreased, the rate of the thermal conductivity coefficient changes decreased. A further increase of the coefficient occurred due to the diffusion of the blowing agent and air gases through the walls of the cells under the influence of partial pressure gradients. As a result, in 180 days, the thermal conductivity of pouring and spray foams increased practically equally, namely by 19% and 20%. The variation of the foams’ thermal conductivity with great reliability (the coefficient of determination 0.99) could be approximated with the polynomial trend lines of the fourth order. For example, the approximation equation for the spray foam is

R-squared value = 0.994.

The values of the thermal conductivity of both foams blown with HCFO-1233zd-E were lower than those of the earlier studied spray foam with the third-generation blowing agent Solkane 365/227 (87:13), denoted in figures as Solkane. However, the density of this foam was also higher, namely 48 kg·m−3 (32). The thermal conductivity coefficient of the spray foam on the 180th day was lower than the technical data sheet value (20 mW·(m·K)−1) of Elastopor® H 1622/5 with a core density of 35 kg·m−3, which is manufactured using a combination of a third-generation blowing agent and water. The initial values of the thermal conductivity of pouring and spray foams with HCFO-1233zd-E were lower than those of the foams blown with HFC-365mfc (36 kg·m−3) or HFC-245fa (33 kg·m−3), studied in (33), which had the initial value of thermal conductivity of 18 mW·m−1.

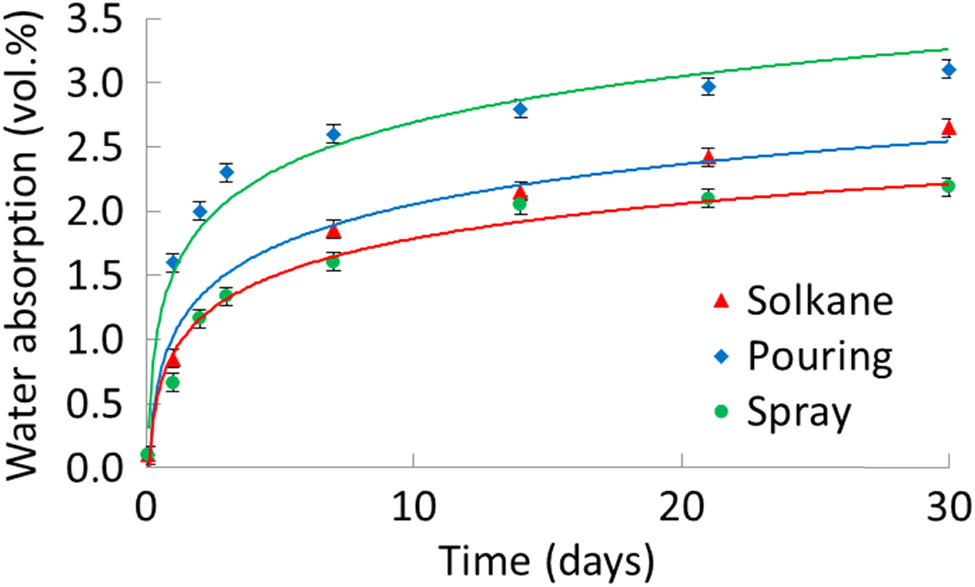

3.2 Water absorption of foams

The water absorption of the tested foam repeated, to a large extent, the patterns of the foam’s thermal conductivity. The water absorption of pouring foam was higher than that of spray foam. However, the difference in the values of water absorption at the end of the exposure was greater than that of thermal conductivity and amounted to 40%. The water absorption of the spray foam was lower than that of the spray foam with the third-generation blowing agent Solkane 365/227 (87:13), denoted in Figure 2 as Solkane, despite its higher density (32). The value of the spray foam’s water absorption was at the same level (2.2 vol%) as that for the best samples of bio-based PUR rigid foams of low density, where the blowing agent Solkane 365/227 (87:13) also was used (34).

Water absorption of pouring and spray foams.

3.3 Compressive properties of foams

At approximately the same density, pouring foam, compared to spray foam, had higher strength (σ z ) and modulus of elasticity (E z ) at compression in the foam rise direction (Table 3). In contrast, spray foam, compared to pouring foam, had higher strength (σ x ) and modulus of elasticity (E x ) at compression in the perpendicular direction. Consequently, the low-density pouring foam had a higher degree of strength anisotropy (σ z /σ x ) equal to 1.86 versus 1.14 for the spray foam. The degree of modulus anisotropy (E z /E x ) was even greater, namely 2.06 for the pouring foam versus 1.17 for spray foam of the same density.

Compressive properties of pouring and spray foams

| Foam | Density | σ z | σ x | E z | E x |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (kg·m−3) | (kPa) | (kPa) | (MPa) | (MPa) | |

| Pouring | 34.0 ± 0.3 | 130 ± 10 | 70 ± 5 | 3.70 ± 0.50 | 1.80 ± 0.30 |

| Spray | 34.5 ± 0.2 | 114 ± 9 | 100 ± 6 | 2.55 ± 0.13 | 2.18 ± 0.12 |

3.4 Microstructure of foams

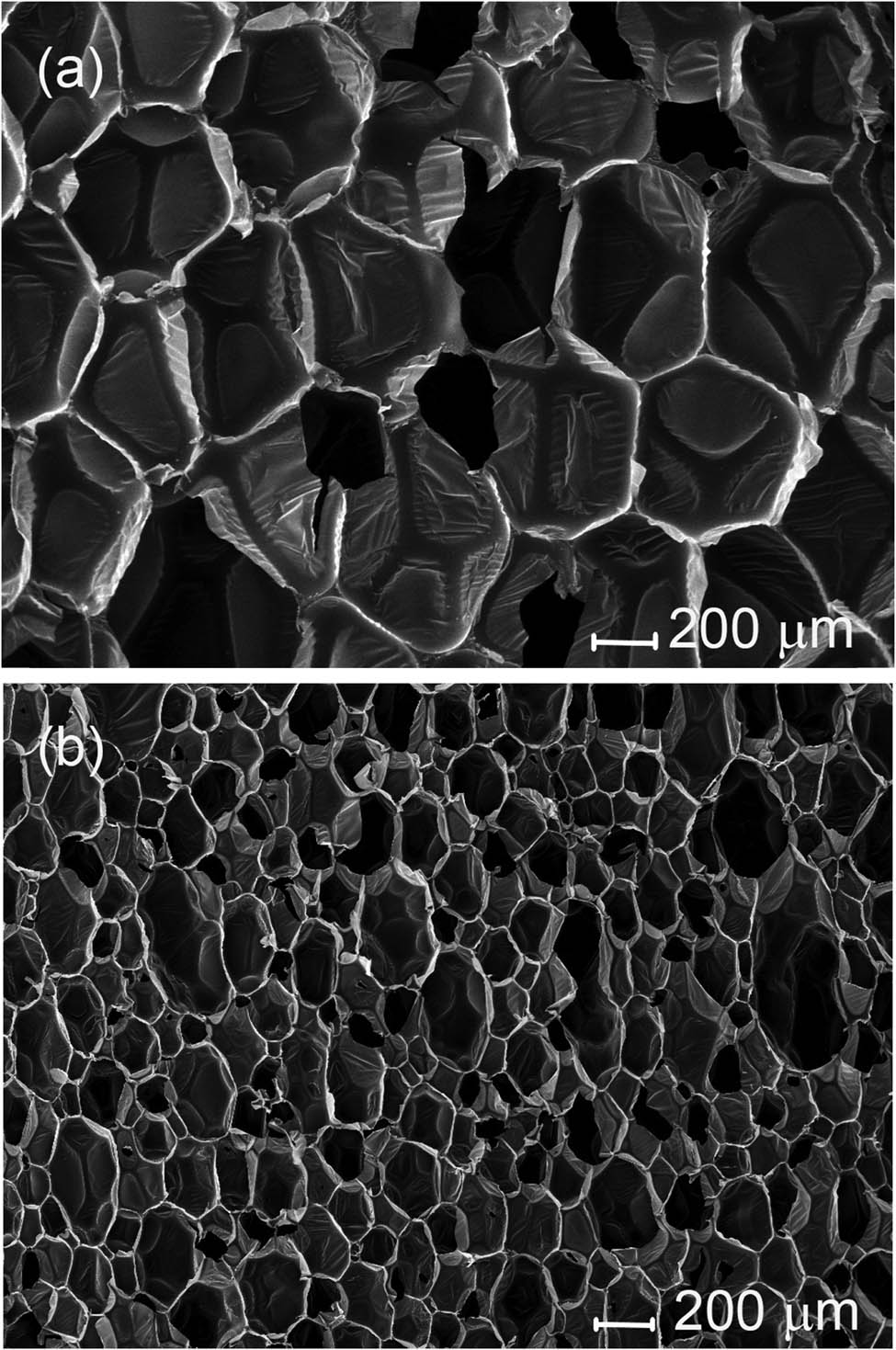

The study of the cellular structure of foamed plastics made it possible to explain many of the observed physical and mechanical effects. At approximately the same density, the foams had completely different cellular structures. The cellular structure of the pouring foam was more uniform and consisted of much larger cells (Figure 3a). The cellular structure of the spray foam was less uniform and consisted of small cells (Figure 3b). The length, width, and the ratio L/W of pouring and spray foam cells are listed in Table 4. The average values of the cells’ length and width were calculated from the measurements of 100 cells. But all the small defects of cellular structure are isolated with closed cells around defects. Therefore, spray foam had approximately the same value of measured closed cells and lower thermal conductivity. The effect of these defects on the mechanical properties is difficult to identify separately from the effect of cells’ sizes and elongation.

Cross-section of pouring (a) and spray (b) foam blocks in the foam rise direction at SEM 100× magnification.

Cell sizes of pouring and spray foams (μm)

| Foam | Length | Width | L/W |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pouring | 622 ± 63 | 467 ± 52 | 1.33 |

| Spray | 221 ± 51 | 155 ± 29 | 1.43 |

At foaming of the pouring PUR foam composition with a low amine catalyst concentration, the cream time and gel time of the composition were long enough. Hence, at foaming of the composition, there was sufficient time for the formation of large cells. In contrast, at the foaming of the spray PUR foam composition with a high content of the amine catalyst, the cream time and gel time were much shorter, and there was no sufficient time for the formation of large cells.

The cells formed during both foam pouring and foam spraying had approximately the same degree of elongation in the foam rise direction (L/W). However, due to the difference in absolute dimensions, the degree of mechanical anisotropy in the pouring PUR foam was greater. On the other hand, due to the much smaller cell sizes, the spray PUR foam had a much lower thermal conductivity. This is a direct consequence of the decrease in the radiative component in the overall thermal conductivity of the foam (24,25,26).

4 Conclusion

The fourth-generation blowing agent HCFO-1233zd-E can be used to produce low-density foam with a low thermal conductivity. To obtain foam with the lowest thermal conductivity, it is preferable to use the spray method, allowing to obtain foam with a small cell size, and hence, a lower coefficient of thermal conductivity, and low water absorption. Due to the small size of the cells, the anisotropy of the mechanical properties of these foams is also lower than that of the foam of the same density with bigger cells. With aging under normal conditions, due to the mutual diffusion of the blowing agent and ambient air gases, the thermal conductivity of foam increases by 20% in 180 days, but at the same time, it is lower than for PUR foams obtained by the third-generation blowing agent.

-

Funding information: This work was supported by the Competence Center of the Electrical and Optical Equipment Production Sector of Latvia, the Central Finance and Contracting Agency of Latvia and the European Regional Development Fund, within the framework of its Project No. 1.2.1.1/18/A/006 Research No. 2.8 “Cryogenic Insulation Thermal Conductivity Testing System.”

-

Author contributions: Vladimir Yakushin: writing – original draft, methodology, physical–mechanical tests; Ugis Cabulis: writing – review and editing, formal analysis, project administration; Velta Fridrihsone: SEM images and measurements; Sergey Kravchenko: heat conductivity measurements; Romass Pauliks: foam manufacturing.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

References

(1) Pranav Mehta PB, Chidambaram ASP, Selwynt W. Technical comparisons of foams using various blowing agent blends containing HCFC-141b, HFC-245fa, Solstice® liquid blowing agent, and hydrocarbons in domestic appliances. Proceedings of the Polyurethanes Technical Conference; 2014 Sep 22–24; Dallas, Texas, USA; 2014. p. 162–72.Suche in Google Scholar

(2) Howard P, Runkel J, Banerjee S. Third-generation foam blowing agents for foam insulation. Washington, D.C: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; 1998. EPA/600/R-98/133 (NTIS PB99-122095).Suche in Google Scholar

(3) Wu J, Albouy A, Mouton D. Evaluation of the next generation HFC blowing agents in rigid polyurethane foams. J Cell Plast. 1999;35(5):421–37. 10.1177/0021955X9903500504.Suche in Google Scholar

(4) Wuebbles DJ, Wang D, Patten KO, Olsen SC. Analyses of new short-lived replacements for HFCs with large GWPs. Geophys Res Lett. 2013;40(17):4767–71. 10.1002/grl.50908.Suche in Google Scholar

(5) Molés F, Navarro-Esbrí J, Peris B, Mota-Babiloni A, Barragán-Cervera A, Kontomaris K. Low GWP alternatives to HFC-245fa in organic rankine cycles for low temperature heat recovery: HCFO-1233zd-E and HFO-1336mzz-Z. Appl Therm Eng. 2014;71(1):204–12. 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2014.06.055.Suche in Google Scholar

(6) Wallington TJ, Sulbaek Andersen MP, Nielsen OJ. Atmospheric chemistry of short-chain haloolefins: photochemical ozone creation potentials (POCPs), global warming potentials (GWPs), and ozone depletion potentials (ODPs). Chemosphere. 2015;129:135–41. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.06.092.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

(7) Rao PK, Gejji SP. Atmospheric degradation of HCFO-1233zd(E) initiated by OH radical, Cl atom and O3 molecule: kinetics, reaction mechanisms and implications. J Fluorine Chem. 2018;211:180–93. 10.1016/j.jfluchem.2018.05.001.Suche in Google Scholar

(8) Mota-Babiloni A, Makhnatch P, Khodabandeh R. Recent investigations in HFCs substitution with lower GWP synthetic alternatives: Focus on energetic performance and environmental impact. Int J Refrig. 2017;82:288–301. 10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2017.06.026.Suche in Google Scholar

(9) Grossman RS. Auto seating lightweighting using Solstice® liquid blowing agent (HFO 1233zd(E)). SAE Int J Mater Manuf. 2016;9:794–800. 10.4271/2016-01-0521.Suche in Google Scholar

(10) Brondi C, Maio ED, Bertucelli L. The effect of organofluorine additives on the morphology, thermal conductivity, and mechanical properties of rigid polyurethane and polyisocyanurate foams. J Cell Plast [Preprint]. 2021 [cited 2021 Jan 17]. 10.1177/0021955X20987152.Suche in Google Scholar

(11) Al-Moameri HB, Nabhan BJ, Wasmi TM, Ali Abdulrehman M. Impact of blowing agent-blends on polyurethane foams thermal and mechanical properties. AIP Conf Proc. 2020;2213:020177. 10.1063/5.0000153.Suche in Google Scholar

(12) Jang R, Lee Y, Song KH, Kim WN. Effects of nucleating agent on the thermal conductivity and creep strain behavior of rigid polyurethane foams blown by an environment-friendly foaming agent. Macromol Res. 2021;29:15–23. 10.1007/s13233-021-9003-x.Suche in Google Scholar

(13) Bogdan M, Williams D. Results of latest field evaluations of solstice® liquid blowing agent spray foam. Proceedings of the Polyurethanes Technical Conference; 2014 Sep 22–24; Dallas, Texas, USA; 2014. p. 638–49Suche in Google Scholar

(14) Solstice Liquid Blowing Agent. Technical information. © Honeywell International Inc; 2017. Available from: https://www.fluorineproducts-honeywell.com/blowingagents/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/honeywell-solstice-lba-1233zd-technical-brochure.pdfSuche in Google Scholar

(15) Norton FJ. Thermal conductivity and life of polymer foams. J Cell Plast. 1967;3(1):23–37. 10.1177/0021955X6700300101.Suche in Google Scholar

(16) Ball GW, Hurd R, Walker MG. The thermal conductivity on rigid urethane foams. J Cell Plast. 1970;6(2):66–75. 10.1177/0021955X7000600202.Suche in Google Scholar

(17) Page MC, Glicksman LR. Measurements of diffusion coefficients of alternate blowing agents in closed cell foam insulation. J Cell Plast. 1992;28(3):268–83. 10.1177/0021955X9202800304.Suche in Google Scholar

(18) Glicksman LR. Heat transfer in foams. In: Hilyard NC, Cunningham A, editors. Low density cellular plastics. Dordrecht: Springer; 1994. p. 104–52. 10.1007/978-94-011-1256-7_5.Suche in Google Scholar

(19) Biedermann A, Kudoke C, Merten A, Minogue E, Rotermund U, Ebert HP, et al. Analysis of heat transfer mechanisms in polyurethane rigid foam. J Cell Plast. 2001;37(6):467–83. 10.1106/KEMU-LH63-V9H2-KFA3.Suche in Google Scholar

(20) Harding RH. Relationships between cell structure and rigid foam properties. J Cell Plast. 1965;1(3):385–94. 10.1177/0021955X6500100304.Suche in Google Scholar

(21) Mathis N, Chandler C. Orientation and position dependant thermal conductivity. J Cell Plast. 2000;36(40):327–36. 10.1177/0021955X0003600406.Suche in Google Scholar

(22) Gong W, Jiang TH, Zeng XB, He L, Zhang C. Experimental-numerical studies of the effect of cell structure on the mechanical properties of polypropylene foams. E-Polymers. 2020;20:713–23. 10.1515/epoly-2020-0060.Suche in Google Scholar

(23) Guo A, Li H, Xu J, Li J, Li F. Effect of microstructure on the properties of polystyrene microporous foaming material. E-Polymers. 2020;20:103–10. 10.1515/epoly-2020-0012.Suche in Google Scholar

(24) Fang W, Tang Y, Zhang H, Tao W. Numerical predictions of the effective thermal conductivity of the rigid polyurethane foam. J Wuhan Univ Technol. 2017;32:703–8. 10.1007/s11595-017-1655-1.Suche in Google Scholar

(25) Wu JW, Sung WF, Chu HS. Thermal conductivity of polyurethane foams. Int J Heat Mass Tran. 1999;42(12):2211–17. 10.1016/S0017-9310(98)00315-9.Suche in Google Scholar

(26) Lim H, Kim SH, Kim BK. Effects of silicon surfactant in rigid polyurethane foams. Express Polym Lett. 2008;2(3):194–200. 10.3144/expresspolymlett.2008.24.Suche in Google Scholar

(27) Harding RH. Some effects of gas transfer on rigid foam performance. J Cell Plast. 1965;1(1):224–8. 10.1177/0021955X6500100128.Suche in Google Scholar

(28) Brandreth DA. Factors influencing the aging of rigid polyurethane foam. J Therm Insul. 1981;5(1):31–9. 10.1177/109719638100500103.Suche in Google Scholar

(29) Bomberg MT, Kumaran MK, Ascough MR, Sylvester RG. Effect of time and temperature on R-value of rigid polyurethane foam insulation manufactured with alternative blowing agents. J Therm Insul. 1991;14(3):241–67. 10.1177/109719639101400306.Suche in Google Scholar

(30) SOLKANE 365 – Foaming agents. Solvay Fluor GmbH. Available from: https://www.solvay.com/sites/g/files/srpend221/files/tridion/documents/SOLKANE_365_Foaming_Agents_0.pdfSuche in Google Scholar

(31) Zipfel L, Börner K, Krücke W. HFC-365mfc: a versatile blowing agent for rigid polyurethane foams. J Cell Plast. 1999;35(4):328–44. 10.1177/0021955X9903500404.Suche in Google Scholar

(32) Cabulis U, Yakushin V, Fischer WPP, Rundans M, Sevastyanova I, Deme L. Rigid polyurethane foams as external tank Cryogenic Insulation for space launchers. IOP Conf Series Mater Sci Eng. 2019;500:012009. 10.1088/1757-899X/500/1/012009.Suche in Google Scholar

(33) Doerge HP. Zero ODP HFC blowing agents for appliance foam. J Cell Plast. 1997;33(3):207–18. 10.1177/0021955X9703300302.Suche in Google Scholar

(34) Gaidukova G, Ivdre A, Fridrihsone A, Verovkins A, Cabulis U, Gaidukovs S. Polyurethane rigid foams obtained from polyols containing bio-based and recycled components and functional additives. Ind Crop Prod. 2017;102:133–43. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.03.024.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2021 Vladimir Yakushin et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Research on the mechanism of gel accelerator on gel transition of PAN solution by rheology and dynamic light scattering

- Gel point determination of gellan biopolymer gel from DC electrical conductivity

- Composite of polylactic acid and microcellulose from kombucha membranes

- Synthesis of highly branched water-soluble polyester and its surface sizing agent strengthening mechanism

- Fabrication and characterization of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) modified with nano-montmorillonite biocomposite

- Fabrication of N-halamine polyurethane films with excellent antibacterial properties

- Formulation and optimization of gastroretentive bilayer tablets of calcium carbonate using D-optimal mixture design

- Sustainable nanocomposite films based on SiO2 and biodegradable poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) (PHBH) for food packaging

- Evaluation of physicochemical properties of film-based alginate for food packing applications

- Electrically conductive and light-weight branched polylactic acid-based carbon nanotube foams

- Structuring of hydroxy-terminated polydimethylsiloxane filled by fumed silica

- Surface functionalization of nanostructured Cu/Ag-deposited polypropylene fiber by magnetron sputtering

- Influence of composite structure design on the ablation performance of ethylene propylene diene monomer composites

- MOFs/PVA hybrid membranes with enhanced mechanical and ion-conductive properties

- Improvement of the electromechanical properties of thermoplastic polyurethane composite by ionic liquid modified multiwall carbon nanotubes

- Natural rubber latex/MXene foam with robust and multifunctional properties

- Rheological properties of two high polymers suspended in an abrasive slurry jet

- Two-step polyaniline loading in polyelectrolyte complex membranes for improved pseudo-capacitor electrodes

- Preparation and application of carbon and hollow TiO2 microspheres by microwave heating at a low temperature

- Properties of a bovine collagen type I membrane for guided bone regeneration applications

- Fabrication and characterization of thermoresponsive composite carriers: PNIPAAm-grafted glass spheres

- Effect of talc and diatomite on compatible, morphological, and mechanical behavior of PLA/PBAT blends

- Multifunctional graphene nanofiller in flame retarded polybutadiene/chloroprene/carbon black composites

- Strain-dependent wicking behavior of cotton/lycra elastic woven fabric for sportswear

- Enhanced dielectric properties and breakdown strength of polymer/carbon nanotube composites by coating an SrTiO3 layer

- Analysis of effect of modification of silica and carbon black co-filled rubber composite on mechanical properties

- Polytriazole resins toughened by an azide-terminated polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (OADTP)

- Phosphine oxide for reducing flammability of ethylene-vinyl-acetate copolymer

- Study on preparation and properties of bentonite-modified epoxy sheet molding compound

- Polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS)-modified phenolic resin: Synthesis and anti-oxidation properties

- Study on structure and properties of natural indigo spun-dyed viscose fiber

- Biodegradable thermoplastic copolyester elastomers: Methyl branched PBAmT

- Investigations of polyethylene of raised temperature resistance service performance using autoclave test under sour medium conditions

- Investigation of corrosion and thermal behavior of PU–PDMS-coated AISI 316L

- Modification of sodium bicarbonate and its effect on foaming behavior of polypropylene

- Effect of coupling agents on the olive pomace-filled polypropylene composite

- High strength and conductive hydrogel with fully interpenetrated structure from alginate and acrylamide

- Removal of methylene blue in water by electrospun PAN/β-CD nanofibre membrane

- Theoretical and experimental studies on the fabrication of cylindrical-electrode-assisted solution blowing spinning nanofibers

- Influence of l-quebrachitol on the properties of centrifuged natural rubber

- Ultrasonic-modified montmorillonite uniting ethylene glycol diglycidyl ether to reinforce protein-based composite films

- Experimental study on the dissolution of supercritical CO2 in PS under different agitators

- Experimental research on the performance of the thermal-reflective coatings with liquid silicone rubber for pavement applications

- Study on controlling nicotine release from snus by the SIPN membranes

- Catalase biosensor based on the PAni/cMWCNT support for peroxide sensing

- Synthesis and characterization of different soybean oil-based polyols with fatty alcohol and aromatic alcohol

- Molecularly imprinted electrospun fiber membrane for colorimetric detection of hexanoic acid

- Poly(propylene carbonate) networks with excellent properties: Terpolymerization of carbon dioxide, propylene oxide, and 4,4ʹ-(hexafluoroisopropylidene) diphthalic anhydride

- Polypropylene/graphene nanoplatelets nanocomposites with high conductivity via solid-state shear mixing

- Mechanical properties of fiber-reinforced asphalt concrete: Finite element simulation and experimental study

- Applying design of experiments (DoE) on the properties of buccal film for nicotine delivery

- Preparation and characterizations of antibacterial–antioxidant film from soy protein isolate incorporated with mangosteen peel extract

- Preparation and adsorption properties of Ni(ii) ion-imprinted polymers based on synthesized novel functional monomer

- Rare-earth doped radioluminescent hydrogel as a potential phantom material for 3D gel dosimeter

- Effects of cryogenic treatment and interface modifications of basalt fibre on the mechanical properties of hybrid fibre-reinforced composites

- Stable super-hydrophobic and comfort PDMS-coated polyester fabric

- Impact of a nanomixture of carbon black and clay on the mechanical properties of a series of irradiated natural rubber/butyl rubber blend

- Preparation and characterization of a novel composite membrane of natural silk fiber/nano-hydroxyapatite/chitosan for guided bone tissue regeneration

- Study on the thermal properties and insulation resistance of epoxy resin modified by hexagonal boron nitride

- A new method for plugging the dominant seepage channel after polymer flooding and its mechanism: Fracturing–seepage–plugging

- Analysis of the rheological property and crystallization behavior of polylactic acid (Ingeo™ Biopolymer 4032D) at different process temperatures

- Hybrid green organic/inorganic filler polypropylene composites: Morphological study and mechanical performance investigations

- In situ polymerization of PEDOT:PSS films based on EMI-TFSI and the analysis of electrochromic performance

- Effect of laser irradiation on morphology and dielectric properties of quartz fiber reinforced epoxy resin composite

- The optimization of Carreau model and rheological behavior of alumina/linear low-density polyethylene composites with different alumina content and diameter

- Properties of polyurethane foam with fourth-generation blowing agent

- Hydrophobicity and corrosion resistance of waterborne fluorinated acrylate/silica nanocomposite coatings

- Investigation on in situ silica dispersed in natural rubber latex matrix combined with spray sputtering technology

- The degradable time evaluation of degradable polymer film in agriculture based on polyethylene film experiments

- Improving mechanical and water vapor barrier properties of the parylene C film by UV-curable polyurethane acrylate coating

- Thermal conductivity of silicone elastomer with a porous alumina continuum

- Copolymerization of CO2, propylene oxide, and itaconic anhydride with double metal cyanide complex catalyst to form crosslinked polypropylene carbonate

- Combining good dispersion with tailored charge trapping in nanodielectrics by hybrid functionalization of silica

- Thermosensitive hydrogel for in situ-controlled methotrexate delivery

- Analysis of the aging mechanism and life evaluation of elastomers in simulated proton exchange membrane fuel cell environments

- The crystallization and mechanical properties of poly(4-methyl-1-pentene) hard elastic film with different melt draw ratios

- Review Articles

- Aromatic polyamide nonporous membranes for gas separation application

- Optical elements from 3D printed polymers

- Evidence for bicomponent fibers: A review

- Mapping the scientific research on the ionizing radiation impacts on polymers (1975–2019)

- Recent advances in compatibility and toughness of poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene succinate) blends

- Topical Issue: (Micro)plastics pollution - Knowns and unknows (Guest Editor: João Pinto da Costa)

- Simple pyrolysis of polystyrene into valuable chemicals

- Topical Issue: Recent advances of chitosan- and cellulose-based materials: From production to application (Guest Editor: Marc Delgado-Aguilar)

- In situ photo-crosslinking hydrogel with rapid healing, antibacterial, and hemostatic activities

- A novel CT contrast agent for intestinal-targeted imaging through rectal administration

- Properties and applications of cellulose regenerated from cellulose/imidazolium-based ionic liquid/co-solvent solutions: A short review

- Towards the use of acrylic acid graft-copolymerized plant biofiber in sustainable fortified composites: Manufacturing and characterization

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Research on the mechanism of gel accelerator on gel transition of PAN solution by rheology and dynamic light scattering

- Gel point determination of gellan biopolymer gel from DC electrical conductivity

- Composite of polylactic acid and microcellulose from kombucha membranes

- Synthesis of highly branched water-soluble polyester and its surface sizing agent strengthening mechanism

- Fabrication and characterization of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) modified with nano-montmorillonite biocomposite

- Fabrication of N-halamine polyurethane films with excellent antibacterial properties

- Formulation and optimization of gastroretentive bilayer tablets of calcium carbonate using D-optimal mixture design

- Sustainable nanocomposite films based on SiO2 and biodegradable poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) (PHBH) for food packaging

- Evaluation of physicochemical properties of film-based alginate for food packing applications

- Electrically conductive and light-weight branched polylactic acid-based carbon nanotube foams

- Structuring of hydroxy-terminated polydimethylsiloxane filled by fumed silica

- Surface functionalization of nanostructured Cu/Ag-deposited polypropylene fiber by magnetron sputtering

- Influence of composite structure design on the ablation performance of ethylene propylene diene monomer composites

- MOFs/PVA hybrid membranes with enhanced mechanical and ion-conductive properties

- Improvement of the electromechanical properties of thermoplastic polyurethane composite by ionic liquid modified multiwall carbon nanotubes

- Natural rubber latex/MXene foam with robust and multifunctional properties

- Rheological properties of two high polymers suspended in an abrasive slurry jet

- Two-step polyaniline loading in polyelectrolyte complex membranes for improved pseudo-capacitor electrodes

- Preparation and application of carbon and hollow TiO2 microspheres by microwave heating at a low temperature

- Properties of a bovine collagen type I membrane for guided bone regeneration applications

- Fabrication and characterization of thermoresponsive composite carriers: PNIPAAm-grafted glass spheres

- Effect of talc and diatomite on compatible, morphological, and mechanical behavior of PLA/PBAT blends

- Multifunctional graphene nanofiller in flame retarded polybutadiene/chloroprene/carbon black composites

- Strain-dependent wicking behavior of cotton/lycra elastic woven fabric for sportswear

- Enhanced dielectric properties and breakdown strength of polymer/carbon nanotube composites by coating an SrTiO3 layer

- Analysis of effect of modification of silica and carbon black co-filled rubber composite on mechanical properties

- Polytriazole resins toughened by an azide-terminated polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (OADTP)

- Phosphine oxide for reducing flammability of ethylene-vinyl-acetate copolymer

- Study on preparation and properties of bentonite-modified epoxy sheet molding compound

- Polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS)-modified phenolic resin: Synthesis and anti-oxidation properties

- Study on structure and properties of natural indigo spun-dyed viscose fiber

- Biodegradable thermoplastic copolyester elastomers: Methyl branched PBAmT

- Investigations of polyethylene of raised temperature resistance service performance using autoclave test under sour medium conditions

- Investigation of corrosion and thermal behavior of PU–PDMS-coated AISI 316L

- Modification of sodium bicarbonate and its effect on foaming behavior of polypropylene

- Effect of coupling agents on the olive pomace-filled polypropylene composite

- High strength and conductive hydrogel with fully interpenetrated structure from alginate and acrylamide

- Removal of methylene blue in water by electrospun PAN/β-CD nanofibre membrane

- Theoretical and experimental studies on the fabrication of cylindrical-electrode-assisted solution blowing spinning nanofibers

- Influence of l-quebrachitol on the properties of centrifuged natural rubber

- Ultrasonic-modified montmorillonite uniting ethylene glycol diglycidyl ether to reinforce protein-based composite films

- Experimental study on the dissolution of supercritical CO2 in PS under different agitators

- Experimental research on the performance of the thermal-reflective coatings with liquid silicone rubber for pavement applications

- Study on controlling nicotine release from snus by the SIPN membranes

- Catalase biosensor based on the PAni/cMWCNT support for peroxide sensing

- Synthesis and characterization of different soybean oil-based polyols with fatty alcohol and aromatic alcohol

- Molecularly imprinted electrospun fiber membrane for colorimetric detection of hexanoic acid

- Poly(propylene carbonate) networks with excellent properties: Terpolymerization of carbon dioxide, propylene oxide, and 4,4ʹ-(hexafluoroisopropylidene) diphthalic anhydride

- Polypropylene/graphene nanoplatelets nanocomposites with high conductivity via solid-state shear mixing

- Mechanical properties of fiber-reinforced asphalt concrete: Finite element simulation and experimental study

- Applying design of experiments (DoE) on the properties of buccal film for nicotine delivery

- Preparation and characterizations of antibacterial–antioxidant film from soy protein isolate incorporated with mangosteen peel extract

- Preparation and adsorption properties of Ni(ii) ion-imprinted polymers based on synthesized novel functional monomer

- Rare-earth doped radioluminescent hydrogel as a potential phantom material for 3D gel dosimeter

- Effects of cryogenic treatment and interface modifications of basalt fibre on the mechanical properties of hybrid fibre-reinforced composites

- Stable super-hydrophobic and comfort PDMS-coated polyester fabric

- Impact of a nanomixture of carbon black and clay on the mechanical properties of a series of irradiated natural rubber/butyl rubber blend

- Preparation and characterization of a novel composite membrane of natural silk fiber/nano-hydroxyapatite/chitosan for guided bone tissue regeneration

- Study on the thermal properties and insulation resistance of epoxy resin modified by hexagonal boron nitride

- A new method for plugging the dominant seepage channel after polymer flooding and its mechanism: Fracturing–seepage–plugging

- Analysis of the rheological property and crystallization behavior of polylactic acid (Ingeo™ Biopolymer 4032D) at different process temperatures

- Hybrid green organic/inorganic filler polypropylene composites: Morphological study and mechanical performance investigations

- In situ polymerization of PEDOT:PSS films based on EMI-TFSI and the analysis of electrochromic performance

- Effect of laser irradiation on morphology and dielectric properties of quartz fiber reinforced epoxy resin composite

- The optimization of Carreau model and rheological behavior of alumina/linear low-density polyethylene composites with different alumina content and diameter

- Properties of polyurethane foam with fourth-generation blowing agent

- Hydrophobicity and corrosion resistance of waterborne fluorinated acrylate/silica nanocomposite coatings

- Investigation on in situ silica dispersed in natural rubber latex matrix combined with spray sputtering technology

- The degradable time evaluation of degradable polymer film in agriculture based on polyethylene film experiments

- Improving mechanical and water vapor barrier properties of the parylene C film by UV-curable polyurethane acrylate coating

- Thermal conductivity of silicone elastomer with a porous alumina continuum

- Copolymerization of CO2, propylene oxide, and itaconic anhydride with double metal cyanide complex catalyst to form crosslinked polypropylene carbonate

- Combining good dispersion with tailored charge trapping in nanodielectrics by hybrid functionalization of silica

- Thermosensitive hydrogel for in situ-controlled methotrexate delivery

- Analysis of the aging mechanism and life evaluation of elastomers in simulated proton exchange membrane fuel cell environments

- The crystallization and mechanical properties of poly(4-methyl-1-pentene) hard elastic film with different melt draw ratios

- Review Articles

- Aromatic polyamide nonporous membranes for gas separation application

- Optical elements from 3D printed polymers

- Evidence for bicomponent fibers: A review

- Mapping the scientific research on the ionizing radiation impacts on polymers (1975–2019)

- Recent advances in compatibility and toughness of poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene succinate) blends

- Topical Issue: (Micro)plastics pollution - Knowns and unknows (Guest Editor: João Pinto da Costa)

- Simple pyrolysis of polystyrene into valuable chemicals

- Topical Issue: Recent advances of chitosan- and cellulose-based materials: From production to application (Guest Editor: Marc Delgado-Aguilar)

- In situ photo-crosslinking hydrogel with rapid healing, antibacterial, and hemostatic activities

- A novel CT contrast agent for intestinal-targeted imaging through rectal administration

- Properties and applications of cellulose regenerated from cellulose/imidazolium-based ionic liquid/co-solvent solutions: A short review

- Towards the use of acrylic acid graft-copolymerized plant biofiber in sustainable fortified composites: Manufacturing and characterization