Abstract

In this article, five kinds of soybean oil-based polyols (polyol-E, polyol-P, polyol-I, polyol-B, and polyol-M) were prepared by ring-opening the epoxy groups in epoxidized soybean oil (ESO) with ethyl alcohol, 1-pentanol, isoamyl alcohol, p-tert-butylphenol, and 4-methoxyphenol in the presence of tetrafluoroboric acid as the catalyst. The SOPs were characterized by FTIR, 1H NMR, GPC, viscosity, and hydroxyl numbers. Compared with ESO, the retention time of SOPs is shortened, indicating that the molecular weight of SOPs is increased. The structure of different monomers can significantly affect the hydroxyl numbers of SOPs. Due to the large steric hindrance of isoamyl alcohol, p-hydroxyanisole, and p-tert-butylphenol, SOPs prepared by these three monomers often undergo further dehydration to ether reactions, which consumes the hydroxyl of polyols, thus forming dimers and multimers; therefore, the hydroxyl numbers are much lower than polyol-E and polyol-P. The viscosity of polyol-E and polyol-P is much lower than that of polyol-I, polyol-B, and polyol-M. A longer distance between the molecules and the smaller intermolecular force makes the SOPs dehydrate to ether again. This generates dimer or polymers and makes the viscosity of these SOPs larger, and the molecular weight greatly increases.

1 Introduction

Rigid polyurethane foam (PUF) has good thermal insulation performance, electrical insulation performance, high compression performance, strong weight ratio, chemical resistance, and other excellent properties. It is widely used in chemical pipelines, building materials, refrigerator insulation, and other technical applications (1). However, one of the current problems with polyurethane is its dependence on oil (2). Environment concerns and costs have prompted academics and industry to explore biorenewable energy as an alternative for future plastics (3). The use of PUF based on biological resources can reduce pollution and protect fossil resources (4).

Renewable biological resources are of interest in polymer material design due to environmental pollution from petroleum. Vegetable oils are one of the most promising options because of their availability, relatively low cost, environmental sustainability, and low ecotoxicity. Vegetable oils contain double bonds in fatty acid chains and can be a renewable source of polyols to prepare PUF (5) such as rapeseed oil (6), castor oil (7), soybean oil (8), palm oil (9,10), and tung oil (11). Soybean oil is a common vegetable oil bioresource that has been used as a substitute for biopolyols because of its renewable nature, low cost, and abundant supply (12). The use of soybean oil polyols will greatly reduce the formulation cost of polyurethane materials, and soybean oil-based polyols (SOPs) have carbon advantages over petroleum-based polyols (13).

Hydroxylated vegetable oils, whether synthesized or natural ones (castor oil), produce polyurethane by reacting hydroxyl with isocyanates (3,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21). Ji et al. (14) prepared polyols via methyl alcohol, phenol, and cyclohexanol to ring-open ESO. They then researched the effect of their content on PUF performance. The results showed that when the content of soybean polyols was 25 wt%, the introduction of phenol increased the compressive strength, thermal stability, and glass transition temperature of the foam. The induction of cyclohexanol did not perfect the performance of the foam. Chen et al. (3) successfully prepared PUF by a solvent-free method to investigate the influence of the polyols’ OH numbers on the thermal and mechanical properties of the polyurethanes. With the increasing OH number of the polyols, the PUs displayed an increase in crosslinking density, glass transition temperature (T g), tensile strength, and Young’s modulus; there was a decrease in elongation and toughness. Petrović et al. (15) analyzed the structural heterogeneity of soy-based polyols and their influence on the properties of polyols and polyurethanes. The nonuniformity of polyols had no negative effect on the properties of vitreous polyurethanes, but it will lead to the decrease of strength and elongation of the polyurethane. Fang et al. (16) successfully synthesized a novel green soy-polyol using a three-step continuous micro-flow system. In addition, another soybean polyol called bio-polyol B was synthesized in batches. Compared with biopolyol-B, biopolyol-M had a higher hydroxyl number and a lower viscosity due to less oligomerization in microfluidic systems. The corresponding soy-based RPU-M and RPU-B were successfully prepared, and the petrochemical polyols were completely replaced by soy-polyols in the preparation process. RPUF-M also has a series of advantages such as high compressive strength, good dimensional stability, slightly higher T g, and strong thermal stability.

There are many reports on the preparation of PUFs with soybean oil polyols including the effect on the properties of PUFs. However, little research has been done on the different structures of soybean oil polyols. Soybean polyols were prepared from fatty alcohols and aromatic alcohols with different structures. The hydroxyl values and viscosity of soybean oil polyols with different structures were compared to the suitable soybean oil polyols. It is the basis for preparing PUF with excellent performance. In this study, a series of SOPs were synthesized via a one-step method. The structure of the SOPs was confirmed by FTIR, 1H NMR, and GPC. A rotational viscometer NDJ-5S was used to measure the effect of temperature on the viscosity of ESO and SOPs to explore the effect of molecular structural change on the flow performance of SOPs. The viscosity curve of ESO and SOPs with temperature change was obtained, and the trend in change in viscosity was obtained. The hydroxyl numbers of five polyols were determined via the phthalic anhydride pyridine method. The effect of the monomer structure on the viscosity and hydroxyl numbers of polyols is discussed.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Epoxidized soybean oil (ESO) E-10 was obtained from King Chemical Co. Ltd (Shanghai, China). Ethyl acetate, tetrahydrofuran, ethyl alcohol absolute, pyridine, and o-phthalic anhydride were obtained from Fuyu Chemical Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China). Furthermore, 1-pentanol, isoamyl alcohol, sodium carbonate anhydrous, magnesium sulfate anhydrous, and imidazole were obtained from Damao Chemical Reagent Factory (Tianjin, China). Fluoroboric acid, p-tert-butylphenol, and 4-methoxyphenol were supplied by Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co. Ltd (Shanghai, China). All of the chemicals were analytically pure.

2.2 Preparation of SOPs

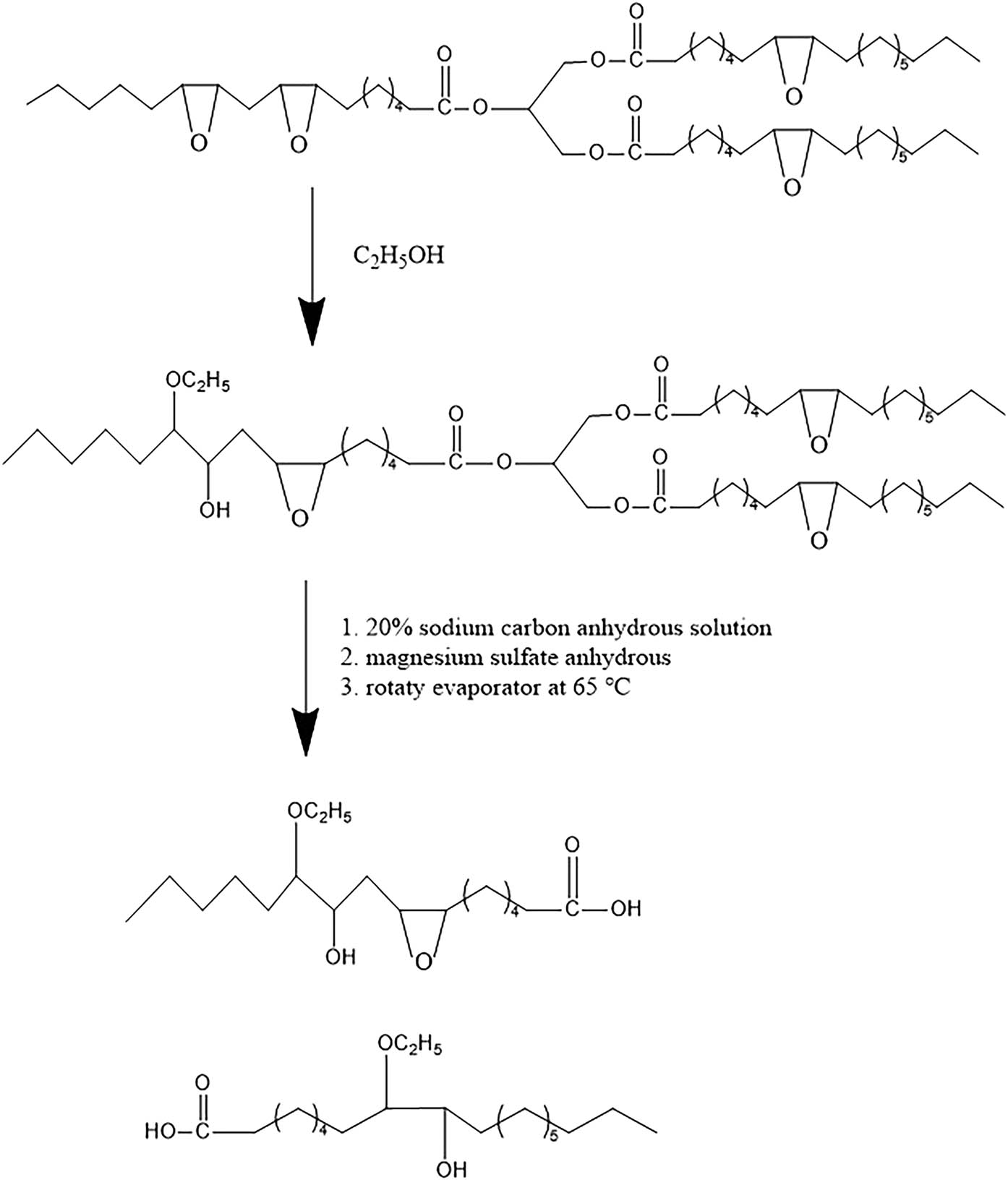

Scheme 1 shows the reaction of ESO with ethyl alcohol. The desired amount of ethyl alcohol and fluoroboric acid was added to a 500 mL three-necked flask equipped with a mechanical stirrer, a dropping funnel, and a thermometer. The flask was placed in an oil bath at 75°C and stirred while slowly adding ESO to the flask. At the end of the dropwise addition, mechanical stirring was continued at the speed of 160 rpm, and the reaction stopped after 4 h. The redundant ethyl alcohol was removed using a rotary evaporator. The residual mixture was neutralized using 20% sodium carbon anhydrous solution, diluted using a proper amount of ethyl acetate, and then washed repeatedly until the pH of the aqueous phase reached approximately 7.0; the product was then dried by magnesium sulfate anhydrous. The sample was purified from the residual organic phase via a rotary evaporator at 65°C. The resulting product was labeled polyol-E. The reaction mechanism is shown in Scheme 1.

Synthesis of polyol-E.

Other SOPs were prepared by mixing monomers and ESO as shown in Scheme 2. For example, in the reaction of pentanol with ESO, 1-pentanol, tetrahydrofuran, and fluoroboric acid were added to a 500 mL three-necked flask. The flask was placed in an oil bath at 68°C and stirred while slowly adding ESO to the flask. After the reaction, the unreacted tetrahydrofuran was removed using a rotary evaporator. Other procedures were similar in this process. The resulting product was labeled polyol-P, polyol-I, polyol-B, and polyol-M.

Synthesis of polyol-P, polyol-I, polyol-B, and polyol-M.

2.3 Analytical methods

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were collected on the FTIR-660 + 610 (Agilent Technologies Inc., USA). The test range was 4,000–500 cm−1, the resolution was 2 cm−1, and there were 32 replicate scans.

The nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra of 1H were obtained in the AVANCE III HD 400 (Bruker BioSpin Co. Ltd, Switzerland). The samples were solubilized in CDCl3 using tetramethylsilane (TMS) as a reference.

Gel permeation chromatography analyses (GPC) were carried out in a Varian equipment model, PL-GPC50, in which the sample was solubilized in THF.

The hydroxyl numbers of soy-based polyols were determined in accordance with GB/T 7383-2007. The number of hydroxyls in the SOPs was determined via the phthalic anhydride pyridine method. Then, an esterification reaction between phthalic anhydride and hydroxyls was performed. The excess phthalic anhydride was hydrolyzed with distilled water. The phthalic acid product was titrated with an NaOH standard titration solution or KOH standard titration solution. We then calculated the hydroxyl numbers via the difference between sample titration and blank titration.

The viscosity of soy-based polyols was measured using a rotational viscometer NDJ-5S (Shanghai Fangrui Instrument Co. Ltd, China) according to GB/T 5561-1994. The effect of temperature on the viscosity of ESO and SOPs was measured with a rotational viscometer to measure the effect of molecular structure change on the flow performance of SOPs.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 FTIR spectra of ESO and polyols

To determine the structure of the reaction products, the ESO raw material and five products were analyzed by the infrared spectrum (Figure 1). The peak at 825 cm−1 corresponds to the characteristic peak of the epoxy group. The peak at 823 cm−1 was obviously weakened in the infrared spectrum of fatty alcohol-(ethyl alcohol, 1-pentanol, and isoamyl alcohol) and aromatic alcohol-p-tert-butylphenol and 4-methoxyphenol)-modified SOPs. The infrared absorption peak of C–O–C at 1,200 cm−1 was partially enhanced, indicating that the epoxy group in the raw material reacts to generate hydroxyl groups, and some hydroxyl groups are converted into an ether bond. The infrared spectrum showed that the SOPs were prepared via the reaction of ethyl alcohol, 1-pentanol, isoamyl alcohol, p-tert-butylphenol, and 4-methoxyphenol. However, obvious hydroxyl absorption peaks appeared at 3,420 cm−1 in the infrared spectra of fatty alcohol-modified soybean oil, which is due to the ring-opening reaction of fatty alcohol with epoxy groups of ESO and the formation of hydroxyl groups. Meanwhile, the peak area is greatly reduced in the infrared spectrum of SOPs modified by aromatic alcohols (p-tert-butylphenol and 4-methoxyphenol). This may be due to the increase in monomer steric hindrance and further reaction between the generated SOPs, intermolecular dehydration, and condensation to ether. These features lead to a reduction in the peak area of hydroxyl in the infrared spectrum. These data suggest that the molecular weight of these two SOPs will increase greatly compared with that of other SOPs. The retention time curve drawn from GPC further verified this result.

FT-IR spectra of ESO and polyols.

3.2 1H NMR analysis of ESO and polyols

ESO, polyol-E, polyol-P, polyol-I, polyol-B, and polyol-M were characterized by 1H NMR (Figure 2). The peak at 0.68–0.81 ppm is assigned to the protons of the terminal methyl groups. The protons of all the internal CH2 groups present in the fatty acid chains appeared at 1.05–1.40 ppm. According to the 1H NMR spectra of ESO, between 2.75 and 3.04 ppm are the signal peaks of –CH in the epoxy group at the peak 2 (22). In the 1H NMR spectrum of the polyols, the signals between 2.85 and 3.04 ppm were obviously weakened, indicating that the epoxy group was ring-opened. At the same time, new peaks (peak 1 is between 3.4 and 3.8 ppm) corresponding to hydrogen bonded to carbons adjacent to the ester overlap with the peaks from the hydrogen attached to the carbon adjacent to OH (–CH–OH and –CH–OC–) (23). However, the triple peak appears at 2.45 ppm in the NMR spectrum curve of the SOPs corresponding to the hydrogen on the fatty alcohol. In addition to polyol-E, the 1.63 ppm peak (Peak 3) of the nuclear magnetic spectrum of polyol-P, polyol-I, polyol-B, and polyol-M was significantly enhanced. This is due to the introduction of new alkyl chains. The results of 1H NMR and FTIR of SOPs confirmed that the epoxy group of soybean oil reacted to form the polyol structure and the ether bond structure. This showed that we have successfully prepared the modified SOPs.

1H NMR spectra of ESO and polyols.

3.3 GPC analysis of ESO and polyols

We next confirmed the molecular weight between ESO and SOPs and validated that we successfully prepared SOPs. We then explored the influence of different monomers on the molecular weight of SOPs. Figure 3 and Table 1 show the GPC of ESO and SOPs. Compared to ESO, the retention time of SOPs decreased, indicating that the molecular weight of SOPs increased. The molecular weight of SOPs increased due to the ring-opening of ESO to polyols via ethyl alcohol, 1-pentanol, isoamyl alcohol, p-tert-butylphenol, and 4-methoxyphenol. In addition, the oligomerization of ethylene glycol open-loop system was also observed. The GPC curve is shown in Figure 3, and the shoulder to the left of the main peak represents the presence of molecules with a higher molecular weight. The opening of an alcohol produces a secondary hydroxyl group that can further open the ring on other molecules, leading to oligomerization. Notably, when an epoxy group is ring-opened by a hydroxyl alcohol in alcohol ring-opening systems, other major hydroxyl groups remain and react for further ring-opening of hydroxyl methyl alcohols. These groups are more reactive than secondary hydroxyl methyl alcohols, which leads to more highly oligomerized fatty acids (13).

GPC curves of ESO and polyols.

Properties of ESO, polyol-E, polyol-P, polyol-I, polyol-B, and polyol-M

| ESO and polyols | Hydroxyl number (mg KOH g−1) | M n | M w |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESO | — | 1,057 | 1.047 |

| Polyol-E | 145.64 | 1,376 | 1.171 |

| Polyol-P | 136.62 | 1,351 | 1.017 |

| Polyol-I | 59.78 | 1,302 | 1.021 |

| Polyol-B | 54.36 | 1,301 | 1.050 |

| Polyol-M | 48.78 | 1,297 | 1.032 |

3.4 Hydroxyl number of ESO and polyols

The hydroxyl number in the polyols is an important index of polyurethane foaming. The mechanical and thermal properties of PUF are determined by the isocyanate index calculated by hydroxyl value and isocyanate. The hydroxyl number in polyols is high, and the hardness of the foam will increase. Thus, the mechanical and physical properties as well as the temperature resistance will be good; however, the mutual solubility of the polyols will decrease. The influence of hydroxyl numbers includes two main factors: First, a high reaction activity between the alcohol and the epoxy group leads to a high reaction degree of the epoxide group in ESO; thus, the content of the hydroxyl groups in the product is high. Second, the alcohol hydroxyl group may dehydrate to an ether, which reduces the hydroxyl numbers, improves the molecular weight, and increases the viscosity.

According to the GB/T 7383-2007 standard, the hydroxyl numbers from the five SOPs were determined via the phthalic anhydride pyridine method. The experimental results are presented in Table 1. The structure of the different monomers can significantly affect the hydroxyl numbers of SOPs. The SOPs prepared by these three monomers often undergo further dehydration to an ether due to the large steric hindrance of isoamyl alcohol, p-hydroxyanisole, and p-tert-butylphenol. This reaction consumes the hydroxyl of the polyols and forms dimers and multimers; thus, the hydroxyl numbers are much lower than of polyol-E and polyol-P.

The hydroxyl numbers of polyol-P are much higher than that of polyol-I. This is determined by the steric resistance of the monomer structure. A more complex monomer structure makes it more difficult to open the epoxy ring. Under similar reaction conditions, the number of ring-opening ESO changes with the reaction process due to the influence of this factor; thus, there is a change in the hydroxyl numbers. Concurrently, due to the large spatial structure of the isoamyl alcohol, the molecular chain of ESO is opened after ring-opening, which makes it easy to dehydrate into an ether, generate polymers, and reduce the hydroxyl numbers.

3.5 The viscosity of ESO and polyols

The viscosity of soybean oil polyols affects the foaming speed of PUF, thus affects the foaming height and density of polyurethane, and ultimately affects the properties of polyurethane materials. Fan et al. (24) studied the effects of soybean oil polyols with different viscosities on the density and properties of PUFs. With the increase of the viscosity of soybean oil polyol, the density of PUF decreased, the number of bubble holes increased, and the mechanical properties and thermal stability were improved. The viscosity of ESO and SOPs was measured with NDJ-5S. Table 2 presents the viscosity changes of ESO and polyols at different temperatures. The influence of monomer structure on the viscosity of SOPs is detailed in Figures 4 and 5. Theoretically, the viscosity of polyol-E and polyol-P is higher than those of polyol-I, polyol-B, and polyol-M in the same degree of reaction because the introduction of such spatial isomers as the benzene ring branch and isoamyl alcohol will lead to steric hindrance versus polyol-E and polyol-P; the intermolecular entanglement decreased, and the viscosity was relatively low. However, the viscosity of polyol-E and polyol-P is much lower than that of polyol-I, polyol-B, and polyol-M due to the large steric hindrance between the modified SOPs with a benzene ring branch chain and isoamyl alcohol. A longer distance between the molecules and the smaller intermolecular forces dehydrates the SOPs to ether again and generate a dimer or a polymer; this polymerization dramatically increases the viscosity and the molecular weight of these SOPs.

The viscosity changes of ESO and polyols at different temperatures

| Viscosity T (°C) | 25 | 30 | 35 | 40 | 45 | 50 | 55 | 60 | 65 | 70 | 75 | 80 | 85 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESO | 351 | 297 | 238 | 177 | 136 | 118 | 87 | 77 | 69 | 57 | 52 | — | — |

| Polyol-E | 2,367 | 1,659 | 1,132 | 783 | 585 | 446 | 327 | 263 | 203 | 146 | 110 | — | — |

| Polyol-P | 2,162 | 1,158 | 879 | 705 | 546 | 443 | 346 | 277 | 233 | 213 | 171 | — | — |

| Polyol-I | 3,309 | 2,968 | 2,638 | 2,173 | 1,510 | 1,127 | 1,053 | 945 | 750 | 613 | 516 | — | — |

| Polyol-B | — | — | — | — | — | 36,848 | 29,890 | 20,683 | 16,605 | 15,145 | 14,497 | 13,955 | 13,678 |

| Polyol-M | — | — | — | — | — | 82,172 | 78,588 | 74,215 | 65,323 | 60,459 | 50,884 | 41,721 | 35,654 |

Viscosity curves of ESO, polyol-E, polyol-P, and polyol-I.

Viscosity curves of polyol-B and polyol-M.

4 Conclusion

A series of SOPs with different fatty alcohol and aromatic alcohols were synthesized via a one-step method. The polyols were characterized by FTIR, GPC, and 1H NMR. The results showed that five SOPs were successfully prepared. The hydroxyl numbers and viscosity were tested concurrently. The hydroxyl number data showed that they were higher in polyol-E and polyol-P than in other polyols. The structure of different monomers can significantly affect the hydroxyl numbers of the SOPs. The viscosity of ESO and polyols decreased with the increasing temperature. At the same temperature, the viscosity of polyol-B and polyol-M is much higher than that of ESO and other polyols because of the large steric hindrance of isopentyl alcohol, 4-methoxyphenol, and p-tert-butylphenol. The ring-opening reaction of SOPs using ESO and other monomers can reduce the use of petroleum-based polyether polyols. Soybean polyols were prepared by preparing fatty alcohols and aromatic alcohols with different structures. The hydroxyl value and viscosity of soybean oil polyols with different structures were compared, and the suitable soybean oil polyols were selected. PUFs were prepared by the reaction of soybean oil polyols instead of petroleum-based polyols and isocyanates.

-

Funding information: This study was funded by Education Department of Liaoning Province, grant number 2018CYY011; L2019001.

-

Author contributions: Fukai Yang: writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, validation, formal analysis; Hao Yu: methodology, conceptualization, investigation; Yuyuan Deng: supervision, formal analysis; Xinyu Xu: writing – review and editing, funding acquisition, project administration, resources, formal analysis.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent has been obtained from all individuals included in this study.

References

(1) Fernández-d’Arlas B, Khan U, Rueda L, Coleman JN, Mondragon I, Corcuera MA, et al. Influence of hard segment content and nature on polyurethane/multiwalled carbon nanotube composites. Compos Sci Technol. 2011;71:1030–8.10.1016/j.compscitech.2011.02.006Search in Google Scholar

(2) Aung MM, Yaakob Z, Kamarudin S, Abdullah LC. Synthesis and characterization of Jatropha (Jatropha curcas L.) oil-based polyurethane wood adhesive. Ind Crop Prod. 2014;60:177–85.10.1016/j.indcrop.2014.05.038Search in Google Scholar

(3) Chen RQ, Zhang CQ, Kessler MR. Polyols and polyurethanes prepared from epoxidized soybean oil ring-opened by polyhydroxy fatty acids with varying OH numbers. J Appl Polym Sci. 2015;132(1):41213.10.1002/app.41213Search in Google Scholar

(4) Luo X, Cai Y, Liu L. Soy oil-based rigid polyurethane biofoams obtained by a facile one-pot process and reinforced with hydroxyl-functionalized multiwalled carbon nanotube. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2019;96(3):319–28.10.1002/aocs.12184Search in Google Scholar

(5) Miao S, Wang P, Su Z, Zhang S. Vegetable-oil-based polymers as future polymeric biomaterials. Acta Biomater. 2014;10(4):1692–704.10.1016/j.actbio.2013.08.040Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(6) Kairyt A, Vėjelis S. Evaluation of forming mixture composition impact on properties of water blown rigid polyurethane (PUR) foam from rapeseed oil polyol. Ind Crop Prod. 2015;66:210–5.10.1016/j.indcrop.2014.12.032Search in Google Scholar

(7) Veronese VB, Menger RK, Forte MMDC, Petzhold CL. Rigid polyurethane foam based on modified vegetable oil. J Appl Polym Sci. 2011;120(1):530–7.10.1002/app.33185Search in Google Scholar

(8) Ji D, Fang Z, He W, Luo Z, Jiang X, Wang T, et al. Polyurethane rigid foams formed from different soy-based polyols by the ring opening of epoxidised soybean oil with methanol, phenol, and cyclohexanol. Ind Crop Prod. 2015;74:76–82.10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.04.041Search in Google Scholar

(9) Pawlik H, Prociak A. Influence of palm oil-based polyol on the properties of flexible polyurethane foams. J Polym Environt. 2012;20(2):438–45.10.1007/s10924-011-0393-2Search in Google Scholar

(10) Chuayjuljit S, Maungchareon A, Saravari O. Preparation and properties of palm oil-based rigid polyurethane nanocomposite foams. J Reinf Plast Comp. 2010;29(2):218–25.10.1177/0731684408096949Search in Google Scholar

(11) Da Silva VR, Mosiewicki MA, Yoshida MI, Da Silva MC, Stefani PM, Marcovich NE. Polyurethane foams based on modified tung oil and reinforced with rice husk ash I: synthesis and physical chemical characterization. Polym Test. 2013;32(2):438–45.10.1016/j.polymertesting.2013.01.002Search in Google Scholar

(12) Raquez JM, Deléglise M, Lacrampe MF, Krawczak P. Thermosetting (bio)materials derived from renewable resources: a critical review. Prog Polym Sci. 2010;35(4):487–509.10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2010.01.001Search in Google Scholar

(13) Li YB, Luo XL, Hu SJ. Polyols and polyurethanes from vegetable oils and their derivatives. Bio-based Polyols and Polyurethanes. Cham: Springer; 2015. p. 15–43.10.1007/978-3-319-21539-6_2Search in Google Scholar

(14) Ji D, Fang Z, He W, Luo Z, Jiang X, Wang T, et al. Polyurethane rigid foams formed from different soy-based polyols by the ring opening of epoxidised soybean oil with methanol, phenol, and cyclohexanol. Ind Crop Prod. 2015;74:76–82.10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.04.041Search in Google Scholar

(15) Petrović ZS, Guo A, Javni I, Cvetković I, Hong DP. Polyurethane networks from polyols obtained by hydroformylation of soybean oil. Polym Int. 2008;57(2):275–81.10.1002/pi.2340Search in Google Scholar

(16) Fang Z, Qiu C, Ji D, Yang Z, Zhu N, Meng J, et al. Development of high-performance biodegradable rigid polyurethane foams using full modified soy-based polyols. J Agr Food Chem. 2019;67(8):2220–6.10.1021/acs.jafc.8b05342Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(17) Shen Y, He J, Xie Z, Zhou X, Fang C, Zhang C. Synthesis and characterization of vegetable oil based polyurethanes with tunable thermomechanical performance. Ind Crop Prod. 2019;140:111711.10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.111711Search in Google Scholar

(18) Leszczyńska M, Ryszkowska J, Szczepkowski L, Kurańska M, Prociak A, Leszczyński MK, et al. Cooperative effect of rapeseed oil-based polyol and egg shells on the structure and properties of rigid polyurethane foams. Polym Test. 2020;90:106696.10.1016/j.polymertesting.2020.106696Search in Google Scholar

(19) Kurańska M, Polaczek K, Auguścik-Królikowska M, Prociak A, Ryszkowska J. Open-cell rigid polyurethane bio-foams based on modified used cooking oil. Polymer. 2020;190:122164.10.1016/j.polymer.2020.122164Search in Google Scholar

(20) Ivdre A, Abolins A, Sevastyanova I, Kirpluks M, Cabulis U, Merijs-Meri R. Rigid polyurethane foams with various isocyanate indices based on polyols from rapeseed oil and waste PET. Polymer. 2020;12:738–50.10.3390/polym12040738Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(21) Dhaliwal GS, Anandan S, Bose M, Chandrashekhara K, Nam P. Effects of surfactants on mechanical and thermal properties of soy-based polyurethane foams. J Cell Plast. 2020;56(6):611–30.10.1177/0021955X20912200Search in Google Scholar

(22) Zhang C, Xia Y, Chen R, Huh S, Johnston PA, Kessler MR. Soy-castor oil based polyols prepared using a solvent-free and catalyst-free method and polyurethanes therefrom. Green Chemistry. 2013;15(6):1477–84.10.1039/c3gc40531aSearch in Google Scholar

(23) Caillol S, Desroches M, Boutevin G, Loubat C, Auvergne R, Boutevin B. Synthesis of new polyester polyols from epoxidized vegetable oils and biobased acids. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol. 2012;114:1447–59.10.1002/ejlt.201200199Search in Google Scholar

(24) Fan H, Tekeei A, Suppes GJ, Hsieh FH. Rigid polyurethane foams made from high viscosity soy-polyols. J App Polym Sci. 2012;127(3):1623–9.10.1002/app.37508Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Fukai Yang et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Research on the mechanism of gel accelerator on gel transition of PAN solution by rheology and dynamic light scattering

- Gel point determination of gellan biopolymer gel from DC electrical conductivity

- Composite of polylactic acid and microcellulose from kombucha membranes

- Synthesis of highly branched water-soluble polyester and its surface sizing agent strengthening mechanism

- Fabrication and characterization of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) modified with nano-montmorillonite biocomposite

- Fabrication of N-halamine polyurethane films with excellent antibacterial properties

- Formulation and optimization of gastroretentive bilayer tablets of calcium carbonate using D-optimal mixture design

- Sustainable nanocomposite films based on SiO2 and biodegradable poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) (PHBH) for food packaging

- Evaluation of physicochemical properties of film-based alginate for food packing applications

- Electrically conductive and light-weight branched polylactic acid-based carbon nanotube foams

- Structuring of hydroxy-terminated polydimethylsiloxane filled by fumed silica

- Surface functionalization of nanostructured Cu/Ag-deposited polypropylene fiber by magnetron sputtering

- Influence of composite structure design on the ablation performance of ethylene propylene diene monomer composites

- MOFs/PVA hybrid membranes with enhanced mechanical and ion-conductive properties

- Improvement of the electromechanical properties of thermoplastic polyurethane composite by ionic liquid modified multiwall carbon nanotubes

- Natural rubber latex/MXene foam with robust and multifunctional properties

- Rheological properties of two high polymers suspended in an abrasive slurry jet

- Two-step polyaniline loading in polyelectrolyte complex membranes for improved pseudo-capacitor electrodes

- Preparation and application of carbon and hollow TiO2 microspheres by microwave heating at a low temperature

- Properties of a bovine collagen type I membrane for guided bone regeneration applications

- Fabrication and characterization of thermoresponsive composite carriers: PNIPAAm-grafted glass spheres

- Effect of talc and diatomite on compatible, morphological, and mechanical behavior of PLA/PBAT blends

- Multifunctional graphene nanofiller in flame retarded polybutadiene/chloroprene/carbon black composites

- Strain-dependent wicking behavior of cotton/lycra elastic woven fabric for sportswear

- Enhanced dielectric properties and breakdown strength of polymer/carbon nanotube composites by coating an SrTiO3 layer

- Analysis of effect of modification of silica and carbon black co-filled rubber composite on mechanical properties

- Polytriazole resins toughened by an azide-terminated polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (OADTP)

- Phosphine oxide for reducing flammability of ethylene-vinyl-acetate copolymer

- Study on preparation and properties of bentonite-modified epoxy sheet molding compound

- Polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS)-modified phenolic resin: Synthesis and anti-oxidation properties

- Study on structure and properties of natural indigo spun-dyed viscose fiber

- Biodegradable thermoplastic copolyester elastomers: Methyl branched PBAmT

- Investigations of polyethylene of raised temperature resistance service performance using autoclave test under sour medium conditions

- Investigation of corrosion and thermal behavior of PU–PDMS-coated AISI 316L

- Modification of sodium bicarbonate and its effect on foaming behavior of polypropylene

- Effect of coupling agents on the olive pomace-filled polypropylene composite

- High strength and conductive hydrogel with fully interpenetrated structure from alginate and acrylamide

- Removal of methylene blue in water by electrospun PAN/β-CD nanofibre membrane

- Theoretical and experimental studies on the fabrication of cylindrical-electrode-assisted solution blowing spinning nanofibers

- Influence of l-quebrachitol on the properties of centrifuged natural rubber

- Ultrasonic-modified montmorillonite uniting ethylene glycol diglycidyl ether to reinforce protein-based composite films

- Experimental study on the dissolution of supercritical CO2 in PS under different agitators

- Experimental research on the performance of the thermal-reflective coatings with liquid silicone rubber for pavement applications

- Study on controlling nicotine release from snus by the SIPN membranes

- Catalase biosensor based on the PAni/cMWCNT support for peroxide sensing

- Synthesis and characterization of different soybean oil-based polyols with fatty alcohol and aromatic alcohol

- Molecularly imprinted electrospun fiber membrane for colorimetric detection of hexanoic acid

- Poly(propylene carbonate) networks with excellent properties: Terpolymerization of carbon dioxide, propylene oxide, and 4,4ʹ-(hexafluoroisopropylidene) diphthalic anhydride

- Polypropylene/graphene nanoplatelets nanocomposites with high conductivity via solid-state shear mixing

- Mechanical properties of fiber-reinforced asphalt concrete: Finite element simulation and experimental study

- Applying design of experiments (DoE) on the properties of buccal film for nicotine delivery

- Preparation and characterizations of antibacterial–antioxidant film from soy protein isolate incorporated with mangosteen peel extract

- Preparation and adsorption properties of Ni(ii) ion-imprinted polymers based on synthesized novel functional monomer

- Rare-earth doped radioluminescent hydrogel as a potential phantom material for 3D gel dosimeter

- Effects of cryogenic treatment and interface modifications of basalt fibre on the mechanical properties of hybrid fibre-reinforced composites

- Stable super-hydrophobic and comfort PDMS-coated polyester fabric

- Impact of a nanomixture of carbon black and clay on the mechanical properties of a series of irradiated natural rubber/butyl rubber blend

- Preparation and characterization of a novel composite membrane of natural silk fiber/nano-hydroxyapatite/chitosan for guided bone tissue regeneration

- Study on the thermal properties and insulation resistance of epoxy resin modified by hexagonal boron nitride

- A new method for plugging the dominant seepage channel after polymer flooding and its mechanism: Fracturing–seepage–plugging

- Analysis of the rheological property and crystallization behavior of polylactic acid (Ingeo™ Biopolymer 4032D) at different process temperatures

- Hybrid green organic/inorganic filler polypropylene composites: Morphological study and mechanical performance investigations

- In situ polymerization of PEDOT:PSS films based on EMI-TFSI and the analysis of electrochromic performance

- Effect of laser irradiation on morphology and dielectric properties of quartz fiber reinforced epoxy resin composite

- The optimization of Carreau model and rheological behavior of alumina/linear low-density polyethylene composites with different alumina content and diameter

- Properties of polyurethane foam with fourth-generation blowing agent

- Hydrophobicity and corrosion resistance of waterborne fluorinated acrylate/silica nanocomposite coatings

- Investigation on in situ silica dispersed in natural rubber latex matrix combined with spray sputtering technology

- The degradable time evaluation of degradable polymer film in agriculture based on polyethylene film experiments

- Improving mechanical and water vapor barrier properties of the parylene C film by UV-curable polyurethane acrylate coating

- Thermal conductivity of silicone elastomer with a porous alumina continuum

- Copolymerization of CO2, propylene oxide, and itaconic anhydride with double metal cyanide complex catalyst to form crosslinked polypropylene carbonate

- Combining good dispersion with tailored charge trapping in nanodielectrics by hybrid functionalization of silica

- Thermosensitive hydrogel for in situ-controlled methotrexate delivery

- Analysis of the aging mechanism and life evaluation of elastomers in simulated proton exchange membrane fuel cell environments

- The crystallization and mechanical properties of poly(4-methyl-1-pentene) hard elastic film with different melt draw ratios

- Review Articles

- Aromatic polyamide nonporous membranes for gas separation application

- Optical elements from 3D printed polymers

- Evidence for bicomponent fibers: A review

- Mapping the scientific research on the ionizing radiation impacts on polymers (1975–2019)

- Recent advances in compatibility and toughness of poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene succinate) blends

- Topical Issue: (Micro)plastics pollution - Knowns and unknows (Guest Editor: João Pinto da Costa)

- Simple pyrolysis of polystyrene into valuable chemicals

- Topical Issue: Recent advances of chitosan- and cellulose-based materials: From production to application (Guest Editor: Marc Delgado-Aguilar)

- In situ photo-crosslinking hydrogel with rapid healing, antibacterial, and hemostatic activities

- A novel CT contrast agent for intestinal-targeted imaging through rectal administration

- Properties and applications of cellulose regenerated from cellulose/imidazolium-based ionic liquid/co-solvent solutions: A short review

- Towards the use of acrylic acid graft-copolymerized plant biofiber in sustainable fortified composites: Manufacturing and characterization

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Research on the mechanism of gel accelerator on gel transition of PAN solution by rheology and dynamic light scattering

- Gel point determination of gellan biopolymer gel from DC electrical conductivity

- Composite of polylactic acid and microcellulose from kombucha membranes

- Synthesis of highly branched water-soluble polyester and its surface sizing agent strengthening mechanism

- Fabrication and characterization of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) modified with nano-montmorillonite biocomposite

- Fabrication of N-halamine polyurethane films with excellent antibacterial properties

- Formulation and optimization of gastroretentive bilayer tablets of calcium carbonate using D-optimal mixture design

- Sustainable nanocomposite films based on SiO2 and biodegradable poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) (PHBH) for food packaging

- Evaluation of physicochemical properties of film-based alginate for food packing applications

- Electrically conductive and light-weight branched polylactic acid-based carbon nanotube foams

- Structuring of hydroxy-terminated polydimethylsiloxane filled by fumed silica

- Surface functionalization of nanostructured Cu/Ag-deposited polypropylene fiber by magnetron sputtering

- Influence of composite structure design on the ablation performance of ethylene propylene diene monomer composites

- MOFs/PVA hybrid membranes with enhanced mechanical and ion-conductive properties

- Improvement of the electromechanical properties of thermoplastic polyurethane composite by ionic liquid modified multiwall carbon nanotubes

- Natural rubber latex/MXene foam with robust and multifunctional properties

- Rheological properties of two high polymers suspended in an abrasive slurry jet

- Two-step polyaniline loading in polyelectrolyte complex membranes for improved pseudo-capacitor electrodes

- Preparation and application of carbon and hollow TiO2 microspheres by microwave heating at a low temperature

- Properties of a bovine collagen type I membrane for guided bone regeneration applications

- Fabrication and characterization of thermoresponsive composite carriers: PNIPAAm-grafted glass spheres

- Effect of talc and diatomite on compatible, morphological, and mechanical behavior of PLA/PBAT blends

- Multifunctional graphene nanofiller in flame retarded polybutadiene/chloroprene/carbon black composites

- Strain-dependent wicking behavior of cotton/lycra elastic woven fabric for sportswear

- Enhanced dielectric properties and breakdown strength of polymer/carbon nanotube composites by coating an SrTiO3 layer

- Analysis of effect of modification of silica and carbon black co-filled rubber composite on mechanical properties

- Polytriazole resins toughened by an azide-terminated polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (OADTP)

- Phosphine oxide for reducing flammability of ethylene-vinyl-acetate copolymer

- Study on preparation and properties of bentonite-modified epoxy sheet molding compound

- Polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS)-modified phenolic resin: Synthesis and anti-oxidation properties

- Study on structure and properties of natural indigo spun-dyed viscose fiber

- Biodegradable thermoplastic copolyester elastomers: Methyl branched PBAmT

- Investigations of polyethylene of raised temperature resistance service performance using autoclave test under sour medium conditions

- Investigation of corrosion and thermal behavior of PU–PDMS-coated AISI 316L

- Modification of sodium bicarbonate and its effect on foaming behavior of polypropylene

- Effect of coupling agents on the olive pomace-filled polypropylene composite

- High strength and conductive hydrogel with fully interpenetrated structure from alginate and acrylamide

- Removal of methylene blue in water by electrospun PAN/β-CD nanofibre membrane

- Theoretical and experimental studies on the fabrication of cylindrical-electrode-assisted solution blowing spinning nanofibers

- Influence of l-quebrachitol on the properties of centrifuged natural rubber

- Ultrasonic-modified montmorillonite uniting ethylene glycol diglycidyl ether to reinforce protein-based composite films

- Experimental study on the dissolution of supercritical CO2 in PS under different agitators

- Experimental research on the performance of the thermal-reflective coatings with liquid silicone rubber for pavement applications

- Study on controlling nicotine release from snus by the SIPN membranes

- Catalase biosensor based on the PAni/cMWCNT support for peroxide sensing

- Synthesis and characterization of different soybean oil-based polyols with fatty alcohol and aromatic alcohol

- Molecularly imprinted electrospun fiber membrane for colorimetric detection of hexanoic acid

- Poly(propylene carbonate) networks with excellent properties: Terpolymerization of carbon dioxide, propylene oxide, and 4,4ʹ-(hexafluoroisopropylidene) diphthalic anhydride

- Polypropylene/graphene nanoplatelets nanocomposites with high conductivity via solid-state shear mixing

- Mechanical properties of fiber-reinforced asphalt concrete: Finite element simulation and experimental study

- Applying design of experiments (DoE) on the properties of buccal film for nicotine delivery

- Preparation and characterizations of antibacterial–antioxidant film from soy protein isolate incorporated with mangosteen peel extract

- Preparation and adsorption properties of Ni(ii) ion-imprinted polymers based on synthesized novel functional monomer

- Rare-earth doped radioluminescent hydrogel as a potential phantom material for 3D gel dosimeter

- Effects of cryogenic treatment and interface modifications of basalt fibre on the mechanical properties of hybrid fibre-reinforced composites

- Stable super-hydrophobic and comfort PDMS-coated polyester fabric

- Impact of a nanomixture of carbon black and clay on the mechanical properties of a series of irradiated natural rubber/butyl rubber blend

- Preparation and characterization of a novel composite membrane of natural silk fiber/nano-hydroxyapatite/chitosan for guided bone tissue regeneration

- Study on the thermal properties and insulation resistance of epoxy resin modified by hexagonal boron nitride

- A new method for plugging the dominant seepage channel after polymer flooding and its mechanism: Fracturing–seepage–plugging

- Analysis of the rheological property and crystallization behavior of polylactic acid (Ingeo™ Biopolymer 4032D) at different process temperatures

- Hybrid green organic/inorganic filler polypropylene composites: Morphological study and mechanical performance investigations

- In situ polymerization of PEDOT:PSS films based on EMI-TFSI and the analysis of electrochromic performance

- Effect of laser irradiation on morphology and dielectric properties of quartz fiber reinforced epoxy resin composite

- The optimization of Carreau model and rheological behavior of alumina/linear low-density polyethylene composites with different alumina content and diameter

- Properties of polyurethane foam with fourth-generation blowing agent

- Hydrophobicity and corrosion resistance of waterborne fluorinated acrylate/silica nanocomposite coatings

- Investigation on in situ silica dispersed in natural rubber latex matrix combined with spray sputtering technology

- The degradable time evaluation of degradable polymer film in agriculture based on polyethylene film experiments

- Improving mechanical and water vapor barrier properties of the parylene C film by UV-curable polyurethane acrylate coating

- Thermal conductivity of silicone elastomer with a porous alumina continuum

- Copolymerization of CO2, propylene oxide, and itaconic anhydride with double metal cyanide complex catalyst to form crosslinked polypropylene carbonate

- Combining good dispersion with tailored charge trapping in nanodielectrics by hybrid functionalization of silica

- Thermosensitive hydrogel for in situ-controlled methotrexate delivery

- Analysis of the aging mechanism and life evaluation of elastomers in simulated proton exchange membrane fuel cell environments

- The crystallization and mechanical properties of poly(4-methyl-1-pentene) hard elastic film with different melt draw ratios

- Review Articles

- Aromatic polyamide nonporous membranes for gas separation application

- Optical elements from 3D printed polymers

- Evidence for bicomponent fibers: A review

- Mapping the scientific research on the ionizing radiation impacts on polymers (1975–2019)

- Recent advances in compatibility and toughness of poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene succinate) blends

- Topical Issue: (Micro)plastics pollution - Knowns and unknows (Guest Editor: João Pinto da Costa)

- Simple pyrolysis of polystyrene into valuable chemicals

- Topical Issue: Recent advances of chitosan- and cellulose-based materials: From production to application (Guest Editor: Marc Delgado-Aguilar)

- In situ photo-crosslinking hydrogel with rapid healing, antibacterial, and hemostatic activities

- A novel CT contrast agent for intestinal-targeted imaging through rectal administration

- Properties and applications of cellulose regenerated from cellulose/imidazolium-based ionic liquid/co-solvent solutions: A short review

- Towards the use of acrylic acid graft-copolymerized plant biofiber in sustainable fortified composites: Manufacturing and characterization