Poly(propylene carbonate) networks with excellent properties: Terpolymerization of carbon dioxide, propylene oxide, and 4,4ʹ-(hexafluoroisopropylidene) diphthalic anhydride

Abstract

Poly(propylene carbonate) (PPC) is an emerging low-cost biodegradable plastic with potential application in many fields. However, compared with polyolefin plastics, the major limitations of PPC are its poor mechanical and thermal properties. Herein, a thermoplastic PPC containing cross-linked networks, one-pot synthesized by the copolymerization of carbon dioxide, propylene oxide, and 4,4ʹ-(hexafluoroisopropylidene) diphthalic anhydride, had excellent thermal and mechanical properties and dimensional stability. The weight-average molecular weight and the polymer yield of the PPC5 were up to 212 kg mol−1 and 104 gpolym gcat −1, respectively. The 5% thermal weight loss temperature reached 320°C, and it could withstand a tensile force of 52 MPa. This cross-linked PPC has excellent properties and is expected to be used under extreme conditions, as the material can withstand strong tension and will not deform.

1 Introduction

Currently, excessive emission of carbon dioxide (CO2) is contributing to the destruction of ecological balance and threatening the survival of various organisms (1,2). However, CO2 is a naturally abundant, cheap, recyclable, and non-toxic carbon source involved in various organic reactions (3,4,5,6). CO2 is converted into energy products and chemicals, which are not only conducive to environmental protection but also help in solving the problem of carbon resource shortage (7,8,9,10,11,12). Its development and utilization have attracted widespread attention worldwide. Inoue et al. (13) first reported the copolymerization of CO2 and epoxide to produce poly(propylene carbonate) (PPC) in 1969. PPC produced by copolymerization has the unique advantages of being biodegradable and therefore does not pollute the environment, which has attracted worldwide attention. PPC is an emerging low-cost biodegradable plastic with many potential applications, including adhesives, mulch films, packaging, polymer electrolytes, toughening agents, and biomedical materials (14,15,16,17).

However, compared with polyolefin plastics, the major limitations of PPC are its poor mechanical and thermal properties. The structural asymmetry of propylene oxide (PO) gives the polymer irregular and poor thermal performance, and PPC’s low glass transition temperature (T g) and amorphism lead to its weak mechanical strength and poor dimensional stability (18). Therefore, a comprehensive modification to enhance the performance of PPC is required to realize its wide application. Much effort has been made to improve the mechanical properties and thermal stability of PPC by chemical modification and physical blending (19,20,21,22), which involved mixing PPC with other materials. Physical blending can only adjust the performance of the material within a limited range and it can encounter many problems, such as the poor compatibility of the blended materials, the uneven dispersion of nanoparticles, insignificant improvement in performance, and complicated preparation processes. These problems restrict further applications of physical blending of PPC. Chemical modification is the addition of a third unit to the polymerization reaction, which, by adjusting the molecular chain structure of the polymer, can produce a more precise solid and control the structure of the polymer product. Chemical modification methods include ternary copolymerization, cross-linking reactions, chain transfer reactions, block copolymerization, and graft copolymerization. Currently, ternary copolymerization is an important method for modifying aliphatic polycarbonate (23,24,25,26,27).

The 4,4ʹ-(hexafluoroisopropylidene) diphthalic anhydride (6FDA) monomer contains rigid benzene ring groups, and so, the resulting polymer has excellent mechanical properties. The addition of a rigid third monomer gives the resulting PPC better stability, and because it can withstand higher tensile force, there is no significant deformation after the tensile force is released. At the same time, the strong negative electricity of the introduced fluorine atoms and the chemical and thermal stability of the polypropylene carbonate are significantly improved. Experimentally, the dimensional stability and thermal properties of the polymerized product have been significantly improved, and so, the ternary copolymerized polymer can be used in high external tension and high-temperature environments.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

PO was refluxed over calcium hydride for 8 h, distilled under dried nitrogen gas, and stored over 0.4 nm molecular sieves prior to use. CO2 (99.99%) was commercially obtained from Shenzhen Shente Industrial Gas Co., Shenzhen, China. Glutaric acid, zinc oxide, and 6FDA were purchased from Aladdin Industrial Corporation, and zinc glutarate (ZnGA) was synthesized according to the literature (28).

2.2 General copolymerization procedure

ZnGA (0.1 g) and a certain proportion of 6FDA were placed in a 250 mL autoclave reactor equipped with a magnetic stirrer and dried for 8 h at 70°C under a vacuum. The autoclave was subsequently carefully purged with nitrogen. Then, 11.6 g of PO was injected into the autoclave, which was then filled to 3 MPa with CO2. The copolymerization reaction was stirred at 70°C for 24 h. The reactants were then cooled to room temperature, and the pressure was released. The hard block product, dissolved in trichloromethane containing a 5% hydrochloric acid solution to decompose ZnGA, was precipitated three times in ethanol to remove a small amount of propylene carbonate. This was then dried to a constant weight at 80°C in a vacuum and the yield was calculated.

2.3 Characterization and measurements

Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectrometry (Nicolet 6700; Thermo Scientific) was carried out with attenuated total reflection accessories. Using deuterochloroform as a solvent, proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) spectra were obtained (400M; Bruker). The average molecular weights of the polymers were determined by gel permeation chromatography (Waters 515 HPLC pump and Waters 2414 detector) with tetrahydrofuran as the eluent. The gel contents were determined by the ASTM D2765 method.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was measured using a simultaneous thermal analyzer (STA 6000; PerkinElmer). Samples were tested under a 20 mL min−1 nitrogen flow from 25°C to 450°C at a heating rate of 10°C min−1. A hot-set test was carried out in an oven. A dumbbell-shaped specimen was loaded with 0.14 MPa and the reference length was marked as L 0 (L 0 = 20 mm). The load specimen was then placed in an oven at 60°C. After 15 min, the length between the markers was measured and recorded as L 1, and the load was released. After 5 min of relaxation at 60°C, when the specimen was no longer shortened at room temperature, the length between the markers was measured and recorded as L 2. Mechanical properties were tested at 23°C using an electronic tensile tester (CMT 6104) according to ASTM D368. The crosshead speed was 50 mm min−1. The crystallinity and the crystal structure were measured by an X-ray polycrystalline diffractometer with copper (Cu) k-alpha radiation with a wavelength of 1.5418 Å. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to observe the surface morphologies of the catalysts. The samples were coated with gold and imaged with a Zeiss Ultra Plus field emission scanning electron microscope. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) measurements were conducted in the temperature range of 20–100°C at a heating rate of 10°C min−1 on a Q100 TA instrument under 20 mL min−1 nitrogen flow. The gel contents were determined by the ASTM D2765 method. The sample was refluxed in boiled chloroform for 24 h. The insoluble proportion was dried to a constant weight at 80°C in a vacuum. The gel content is defined as the weight percentage of the insoluble proportion in the sample.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Catalysts

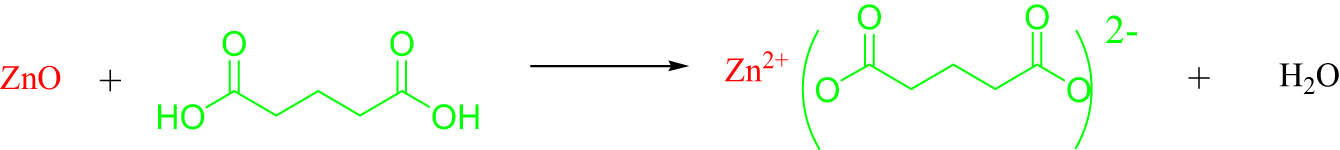

Zinc glutarate (ZnGA) was synthesized according to the literature (28). Equal molar ratios of ZnO (8.14 g, 100 mmol) and GA (13.21 g, 100 mmol) were added into 300 mL toluene at 55°C, and the mixture was stirred for 12 h. The filter cake was washed with acetone several times, and then the filter cake was dried in a vacuum oven at 80°C for 8 h. After drying, it was carefully ground with a mortar, sealed, and stored (see Scheme 1).

Synthesis of ZnGA from zinc oxide and glutaric acid.

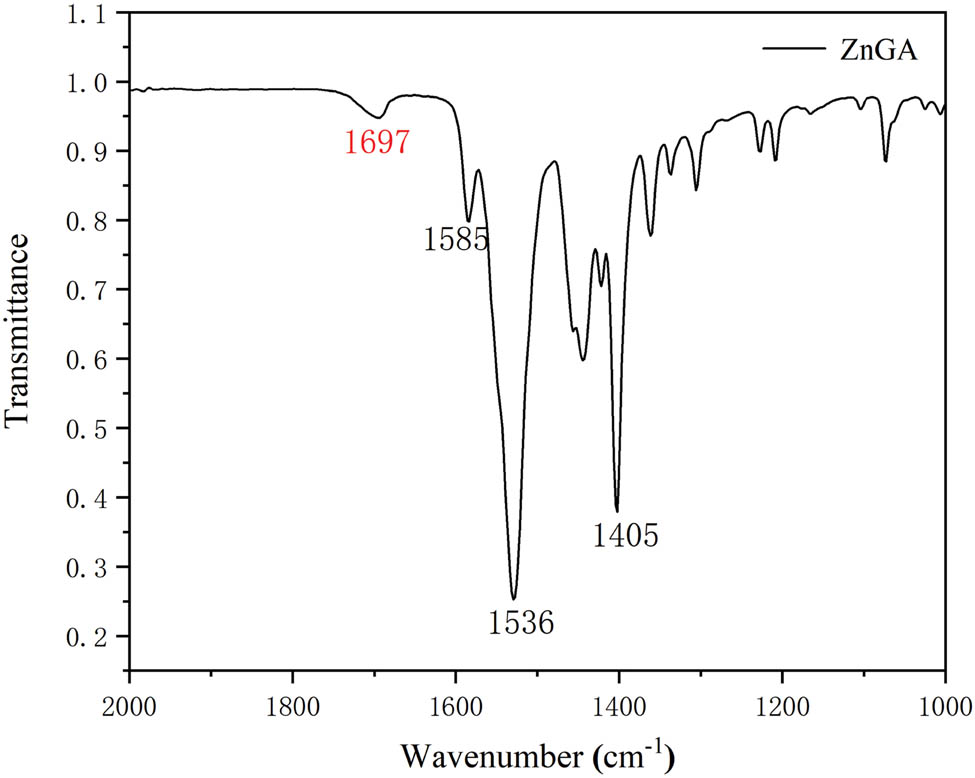

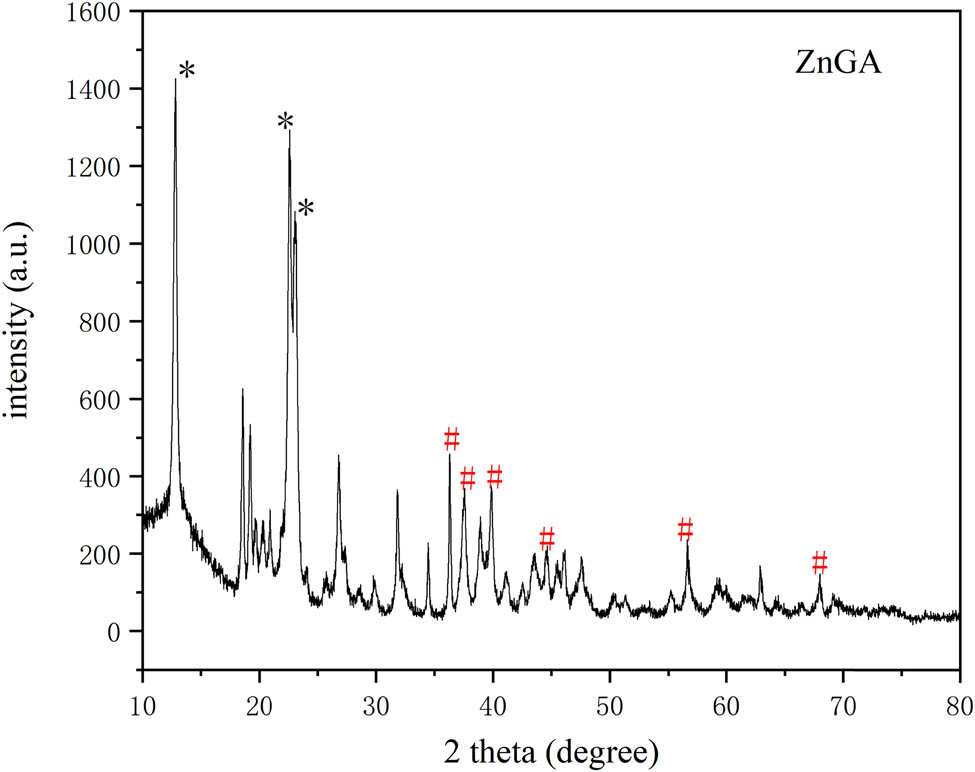

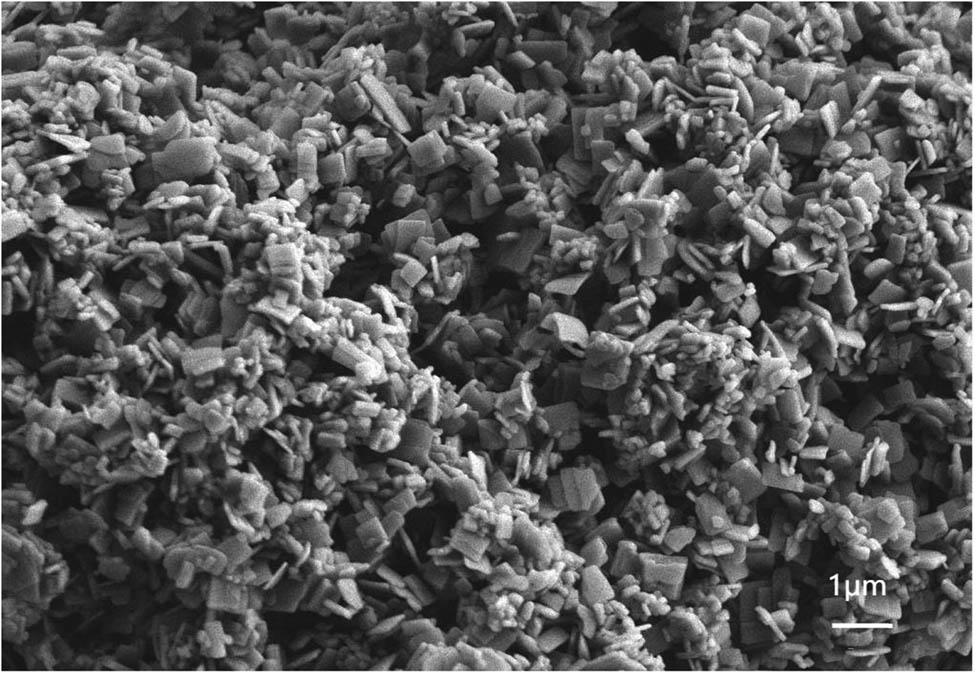

Figure 1 shows that the FT-IR curve of the ZnGA catalyst: peaks a (1,585 cm−1), b (1,536 cm−1), and c (1,405 cm−1) represent the zinc–carboxylate bond (COO–), respectively and peak d represents the carbonyl (C═O) stretching of 1,697 cm−1. The crystal structure of ZnGA was determined by XRD and the diffraction pattern is shown in Figure 2. The XRD analysis was performed to determine the degree of crystallinity of the catalyst and the presence of unreacted ZnO. In Figure 2, the characteristic peaks of ZnGA are marked with an asterisk, and that of ZnO are marked with a hash. FT-IR and XRD patterns are similar to those of ZnGA reported by Dehghani and Moonhor in a previous paper (29,30), indicating that the ZnGA catalyst was successfully synthesized. The results of the field emission SEM shown in Figure 3 demonstrate that ZnGA catalysts were generated from aggregated small-rectangular plate crystals. These small rectangular plate crystals are uniform in appearance and arranged neatly. This rectangular morphology is similar to the single-crystal ZnGA synthesized via the hydrothermal reactions of zinc perchlorate hexahydrate and glutaronitrile reported by Ree and co-workers (31).

FT-IR pattern of ZnGA.

XRD pattern of ZnGA.

SEM image of ZnGA.

3.2 Synthesis

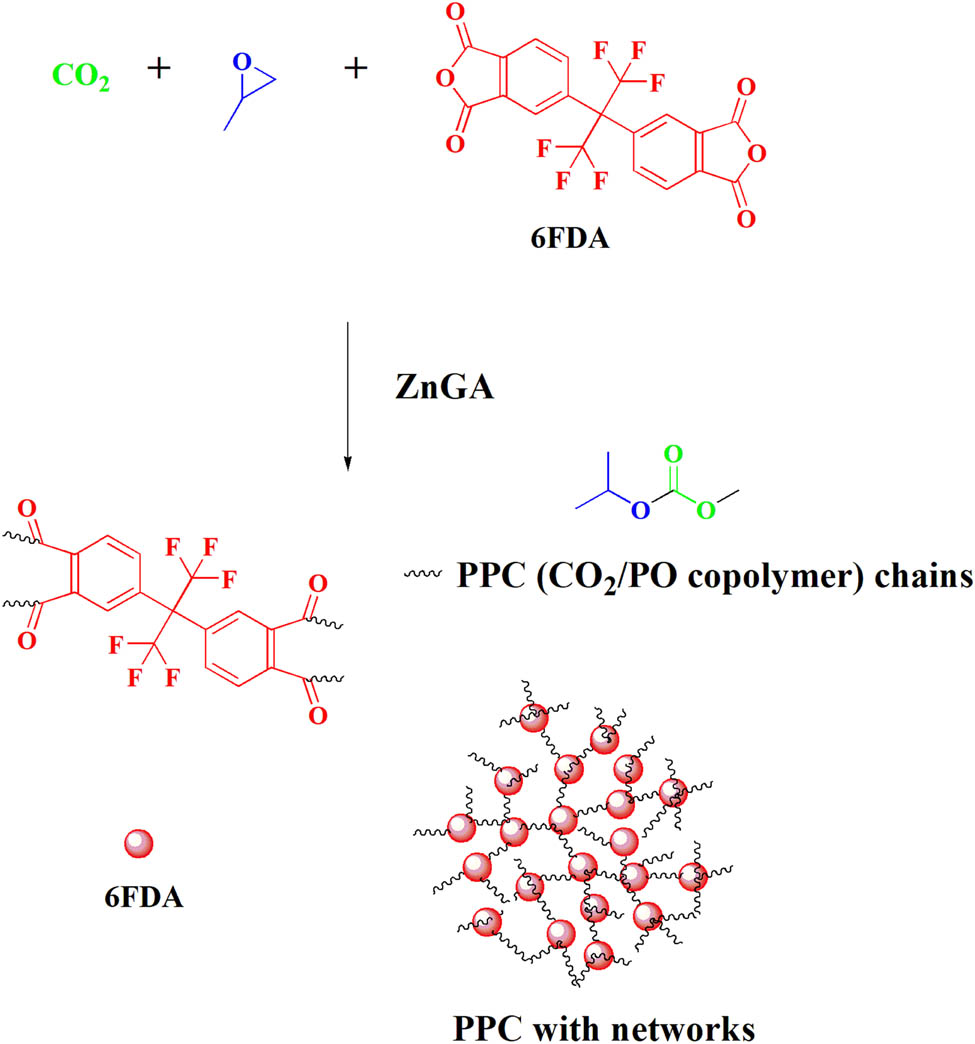

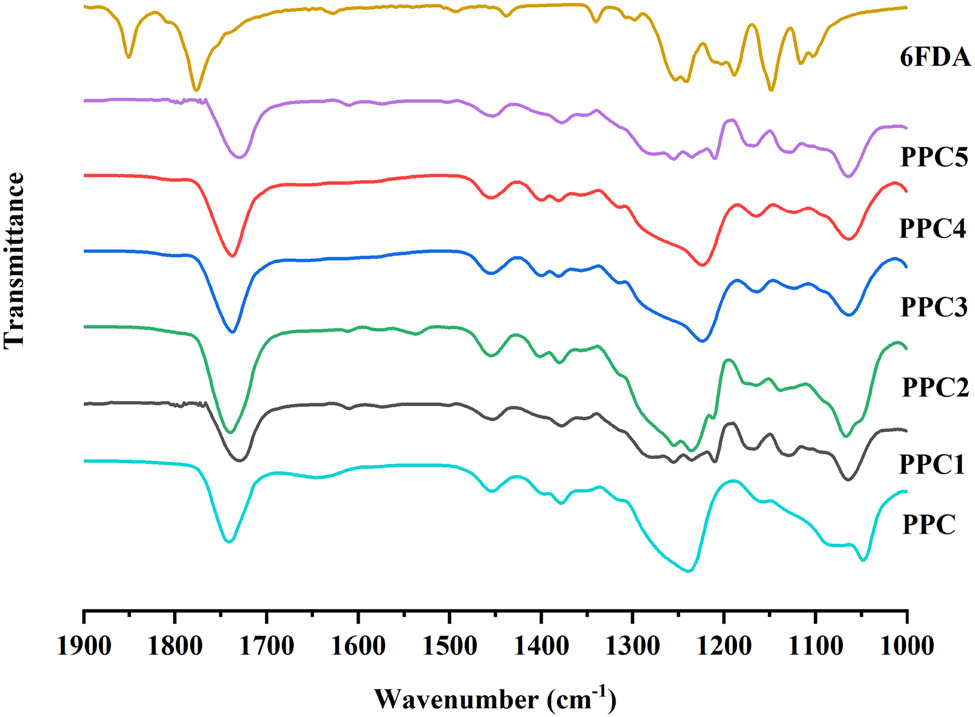

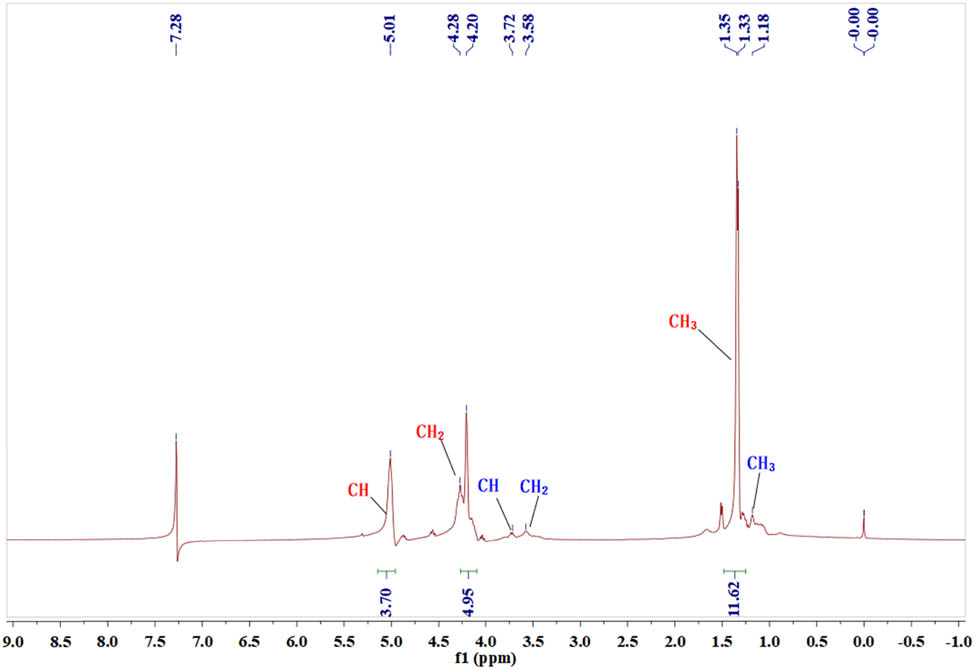

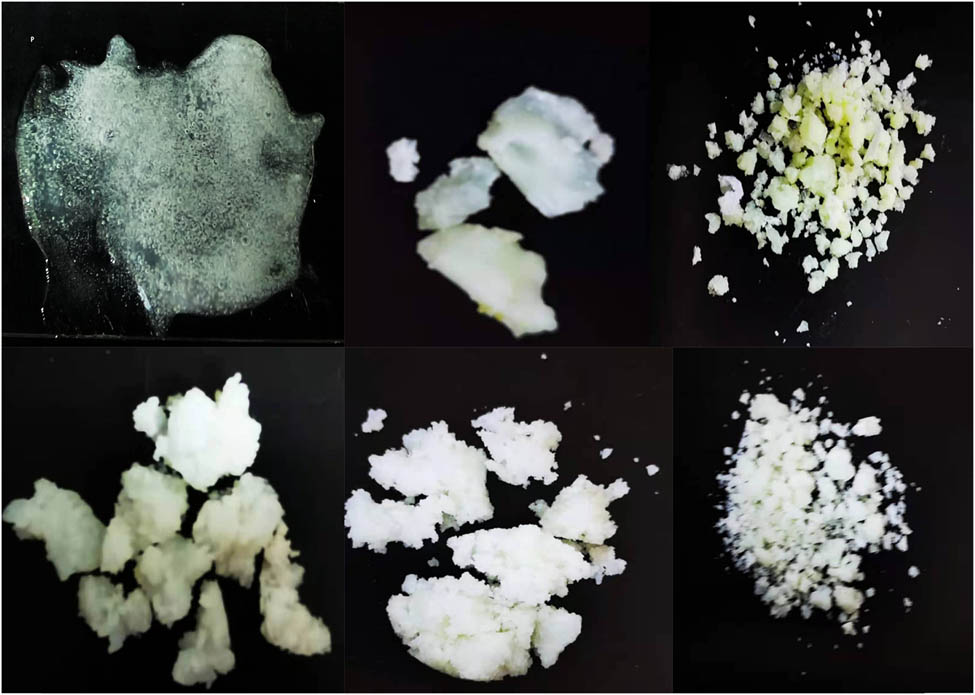

6FDA was introduced into the polymerization reaction of CO2 and PO for ternary copolymerization to yield polycarbonates (PPCs) with a cross-linked network structure, where the proportion of 6FDA input and the 6FDA feed proportion did not exceed 5 wt% of PO (see Scheme 2). According to the previous research (8,32,33), one acid anhydride can be copolymerized to connect a carbonate chain in the ternary copolymerization. Therefore, 6FDA can be connected to four polycarbonate chains, and cross-linking occurs to form a cross-linked polycarbonate. Through experimental characterization, it was found that the cross-linked polycarbonate has excellent thermal properties, mechanical properties, and dimensional stability. FT-IR spectra (see Figure A1 in the Appendix) showed that the characteristic C═O peak stretching vibration peaks at 1,775 and 1,850 cm−1 of 6FDA disappear in PPCs, and the characteristic C═O peak stretching vibration of the ester bond appear compared to the spectrum of 6FDA. In addition, the success of ternary polymerization was preliminarily assessed by the state of the polymerized product after the reaction: the PPC was light yellow and viscous. After cross-linking, the PPCs showed a solid state. The 1H NMR (see Figure A2) spectrum, only representing the soluble components, did not show the signal peak of the 6FDA unit. Because 6FDA formed a gel after the ternary copolymerization, it was insoluble in deuterated chloroform and so the 1H NMR spectra of PPCs only showed the signals of CO2/PO copolymers.

Formation of network-shaped poly(propylene carbonate) (PPC) with carbon dioxide (CO2)/propylene oxide (PO) copolymerization in the presence of 4,4ʹ-(hexafluoroisopropylidene)diphthalic anhydride (6FDA).

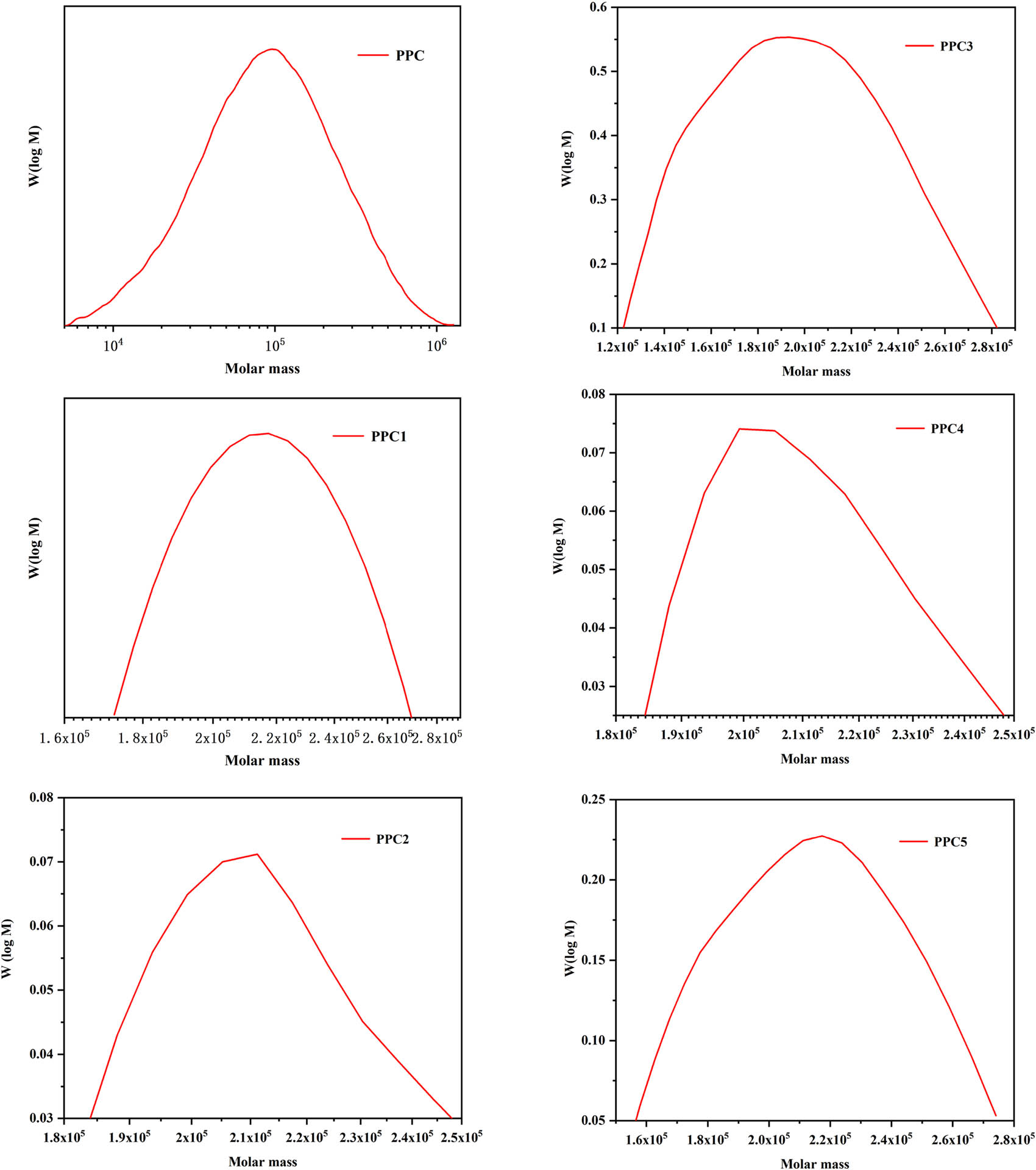

The results showed that with a gradual increase in the amount of 6FDA in the polymerization reaction, the yield of the polymer was greatly improved from 25 to 104 gpolym gcat −1. A possible reason for this is that with the addition of 6FDA, cross-linkages formed a network-shaped polycarbonate, and as the monomer ratio increased, the degree of cross-linking gradually increased. The gel content in the polymer increased from 0% to 45%, which was the main indicator used to measure the degree of polymer cross-linking (see Table 1). Further, the molecular weights of the copolymers substantially increased, and the molecular weight distribution (M w/M n) was lower than PPC. It is worth mentioning that 212 kg/mol is the largest relative molecular weight among the cross-linked PPCs reported to date, indicating that the molecular weight distribution of the produced polycarbonate was relatively uniform.

Results of copolymerizationa

| Sample | 6FDA feedb | Polymer yieldc | M n d | PDIe | Gel (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPC | 0 | 25 | 70 | 2.4 | 0 |

| PPC1 | 1 | 58 | 184 | 1.0 | 23 ± 1.5 |

| PPC2 | 2 | 68 | 189 | 1.0 | 36 ± 1.8 |

| PPC3 | 3 | 86 | 205 | 1.0 | 37 ± 2.2 |

| PPC4 | 4 | 99 | 205 | 1.0 | 38 ± 1.9 |

| PPC5 | 5 | 104 | 212 | 1.0 | 45 ± 2.0 |

- a

Polymerization conditions: ZnGA, 0.10 g; PO, 45 mL; CO2 pressure, 3.0 MPa; 70°C, 24 h.

- b

6FDA feed of PO in the copolymerization (wt%).

- c

g polymer/g ZnGA.

- d

M n = number-average molecular weight (kg mol─1), determined by GPC.

- e

Polydispersity index = M w/M n; M w – weight-average molecular weight (kg mol−1), determined by GPC.

3.3 Thermal properties

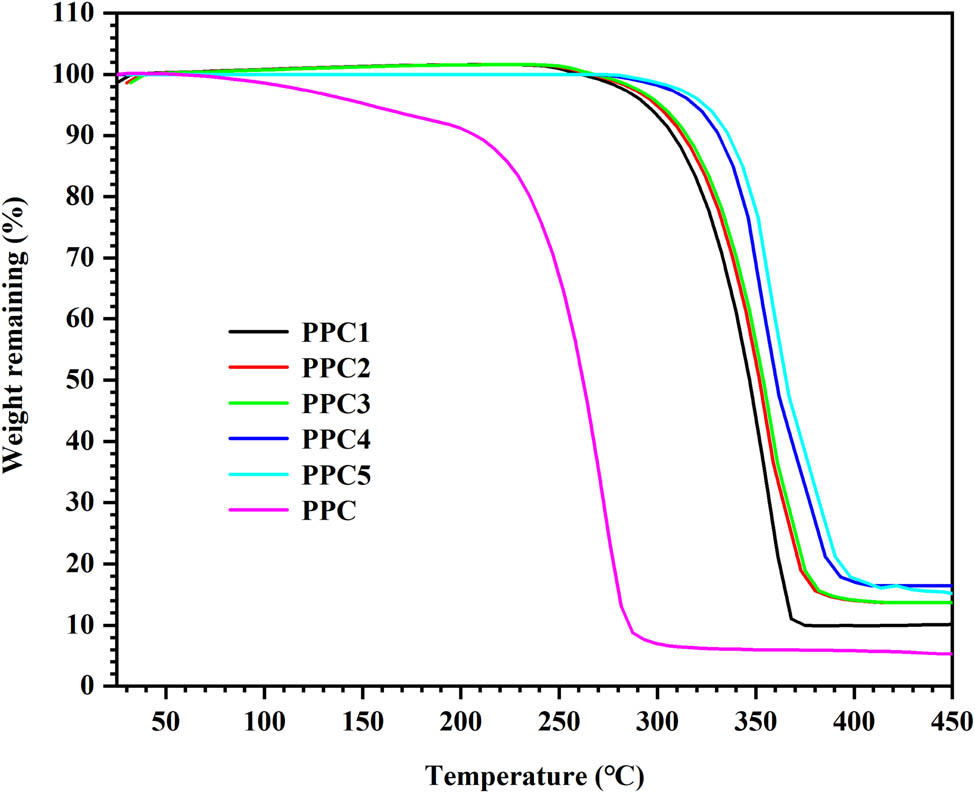

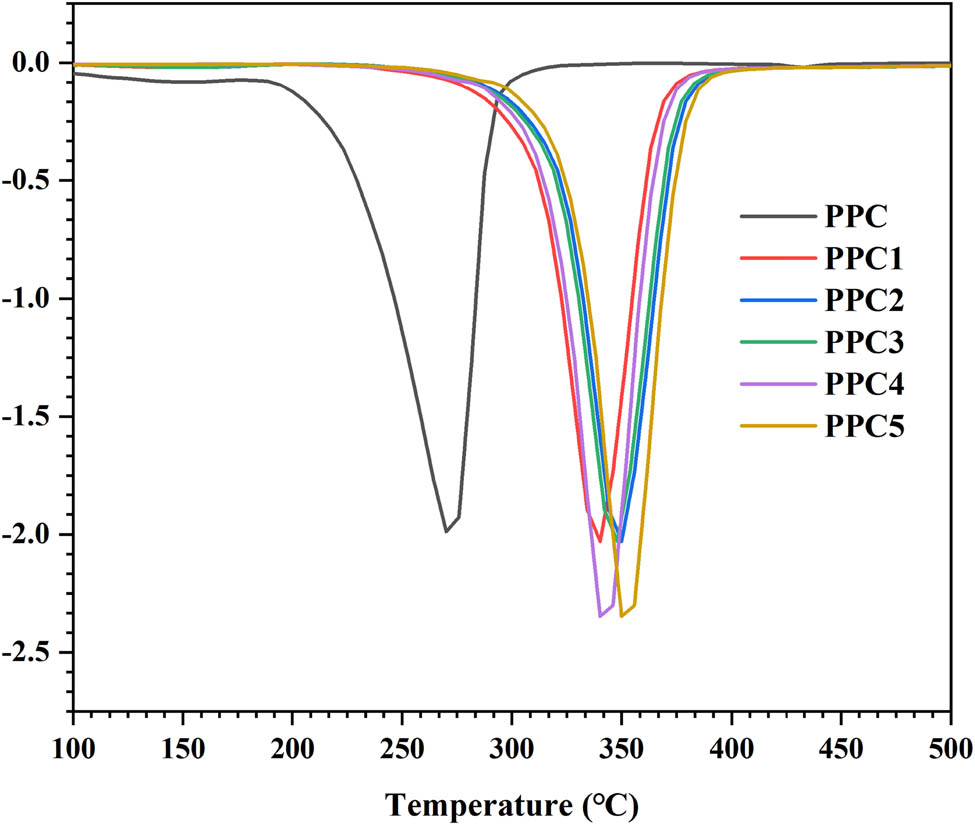

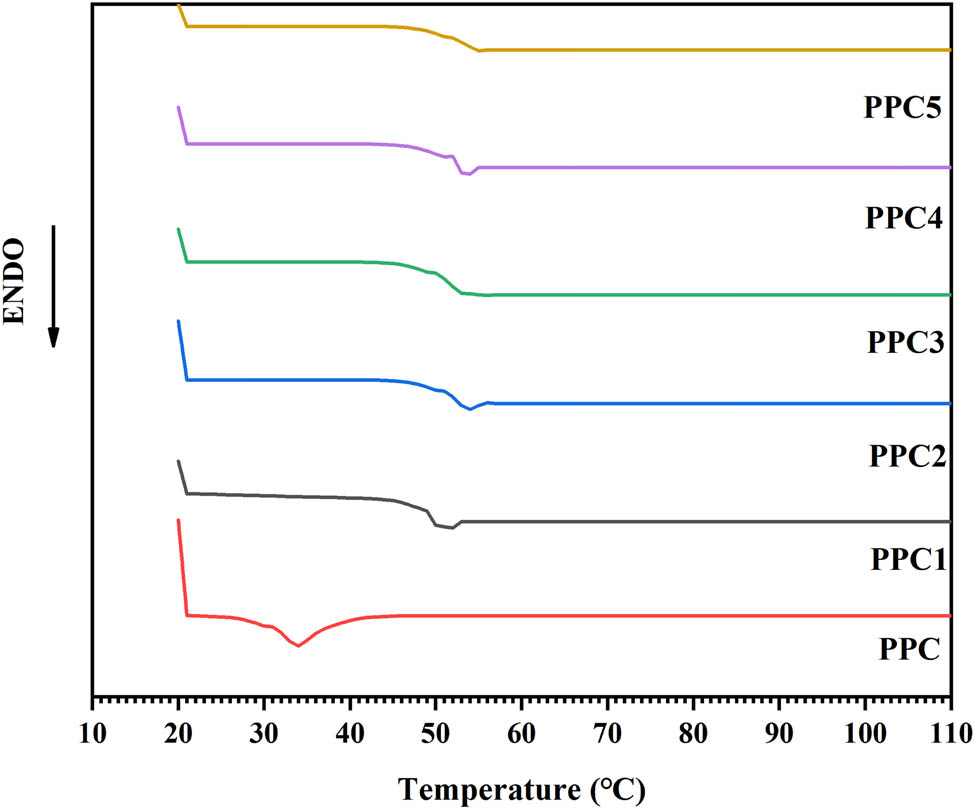

Figure 4 and Figure A4 present the TGA and the DTG curves of the products. For PPC, the 5% weight-loss degradation temperature (T d,5%) was 150°C, and there was one maximum weight-loss degradation temperature (T d,max) of 270°C (see Table 2). According to the decomposition mechanism of PPC (34), with an increase of temperature, the pyrolysis and detachment of the polycarbonate chains lead to the weight loss of the PPC materials; however, the T d,5% and T d,max of each copolymer was over 320°C and almost reached 383°C, respectively. These were significantly higher than the degradation temperatures of the PPC (see Table 2). This significant improvement in the thermal stability was attributed to the formation of cross-links in the PPC matrix by the introduction of 6FDA into the PPC chains since the cross-linking significantly limited the unzipping reaction. The cross-linked polycarbonate carbonate chains restricted the unzipping and detachment of the carbonate chains, while the 6FDA contained a more stable benzene ring and fluorine atoms. Due to the strong electronegativity of the fluorine atoms and the stability of the benzene ring, the produced polycarbonate had better thermal stability; hence, the thermal stability of PPCs was significantly improved. Polycarbonate with good performance can be applied at high temperatures, which broadens the application range of the PPC.

TGA curves of PPC and PPCs.

Thermal properties of PPC and PPCs

| Sample | T d,5% (°C) | T d,max (°C) | T g (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PPC | 150 | 270 | 31 |

| PPC1 | 300 | 350 | 51 |

| PPC2 | 305 | 350 | 52 |

| PPC3 | 306 | 350 | 52 |

| PPC4 | 310 | 330 | 54 |

| PPC5 | 320 | 350 | 52 |

3.4 Mechanical properties and dimensional stability

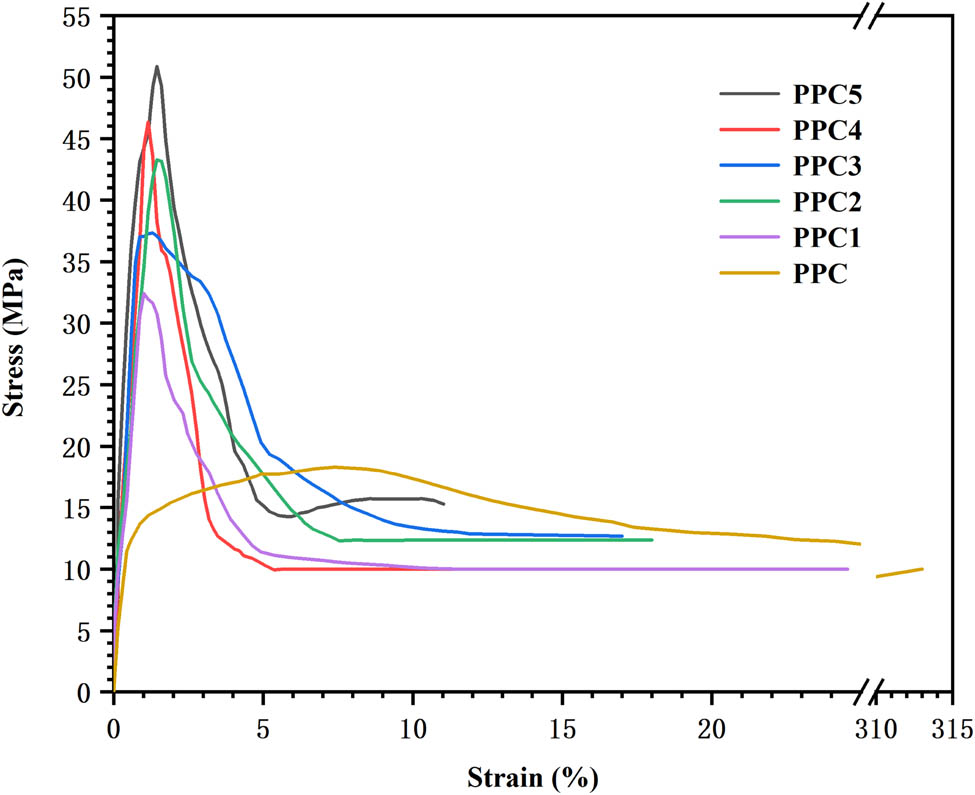

The strain–stress curves are presented in Figure 5, Table A1 lists the data. The test results showed that with increasing 6FDA, the mechanical strength of the PPCs was significantly improved from 18.2 up to 51.7 MPa. However, after the tension was released, the elongation at break was significantly reduced, from 312% to 11%, which is a leap-forward improvement in the mechanical properties of PPC materials (see Figure 5). A possible reason for this is that the ternary copolymerization introduced a benzene ring containing a rigid group into the PPC unit, which gave the polymerized material better stability. The PPC chains mainly contained carbonate linkages with small quantities of ether linkages (35,36). The PPC had fewer polar groups, and the interaction between the PPC chains was smaller, so the mechanical strength was weaker. When the PPC underwent the cross-linking reaction to form the cross-linked polycarbonate, the movement between the PPC chains was restricted, thereby greatly improving the mechanical strength.

Strain–stress curves of PPC and PPCs.

The low T g and amorphous nature of PPC not only make it weak mechanically but also easy to deform (37). Hence, for many applications, maintaining the dimensional stability of PPC above 60–70°C is critical. Compared to the PPC, the hot-set elongation of the PPCs dropped sharply from more than 300% to 7%. The permanent deformation was significantly reduced, and there was almost no deformation, which indicated that the cross-linked network significantly improved the thermal stability and dimensional stability of the polymer. Adding rigid groups to a copolymerization reaction to synthesize cross-linked polycarbonate can completely and significantly improve the dimensional stability of PPC, which lays a solid foundation for the large-scale application of PPC and subsequent application research.

4 Conclusions

CO2, PO, and 6FDA were synthesized by ternary copolymerization under the catalysis of ZnGA, and cross-linked polycarbonate PPCs were successfully synthesized by a one-pot method. The obtained cross-linked polycarbonate had excellent thermal and mechanical properties and dimensional stability. The molecular weight reached an unprecedented 212 kg/mol. The thermal decomposition temperature reached 320°C, and it could withstand a tensile force of 51 MPa without degeneration with good dimensional stability. The synthetic cross-linked polycarbonate exhibits excellent properties and can be expected to be used under many extreme conditions as the material can withstand strong tension and will not deform.

-

Funding information: This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 52073228), the Natural Science Foundation of Shannxi Province (no. 2019JZ-44), the Xi’an Shiyou University Postgraduate Innovation and Proactical Ability Training Project (no. YCS19212064; YSC19113079).

-

Author contributions: Data curation: Yi-Le Zhang and Wen-Zhen Wang; formal analysis: Yi-Le Zhang, Kai-yue Zhang, Li Wang, and Lei-Lei Li; funding acquisition: Wen-Zhen Wang; investigation: Kai-Yue Zhang and Sai-Di Zhao; methodology: Yi-Le Zhang; project administration: Wen-Zhen Wang; writing – original draft: Yi-Le Zhang.; writing – review and editing: Wen-Zhen Wang, Li Wang, and Lei-Lei Li. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

Appendix

FT-IR spectra of 6FDA and PPCs. PPC1–5 presents the copolymer with a 1–5 wt% 6FDA feed of PO in the copolymerization, respectively.

1H NMR spectra of poly(propylene carbonate) (PPC) and PPCs.

Photographs of PPC and PPCs.

DTG curves of PPC and PPCs.

DSC curves for PPC and PPCs.

GPC curves of PPC and PPCs.

Mechanical properties of PPC and PPCs

| Sample | Tensile strength (MPa) | Elongation at break (%) | Hot-set elongation (%) | Permanent deformation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPC | 18.2 ± 1.3 | 312 ± 9 | 300 ± 7 | 150 ± 9 |

| PPC1 | 33 ± 1.5 | 30 ± 2.1 | 63 ± 5 | 7 ± 1.2 |

| PPC2 | 38.2 ± 1.6 | 18 ± 1.7 | 44 ± 3 | 5 ± 0.3 |

| PPC3 | 43.8 ± 1.3 | 17 ± 1.3 | 20 ± 2 | 1 ± 0.1 |

| PPC4 | 48.1 ± 1.7 | 15 ± 0.7 | 16 ± 2 | 0 |

| PPC5 | 51.7 ± 1.4 | 11 ± 0.5 | 7 ± 0.5 | 0 |

References

(1) Artz J, Muller TE, Thenert K, Kleinekorte J, Meys R, Bardow A, et al. Sustainable conversion of carbon dioxide: an integrated review of catalysis and life cycle assessment. Chem Rev. 2018;118(2):434–504. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00435.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(2) Zhao X, Yang SH, Ebrahimiasl S, Arshadie S, Hosseinianf A. Synthesis of six-membered cyclic carbamates employing CO2 as building block: a review. J CO2 Util. 2019;33:37–45. 10.1016/j.jcou.2019.05.004.Search in Google Scholar

(3) Hepburn C, Adlen E, Beddington J, Carter EA, Fuss S, Mac DN, et al. The technological and economic prospects for CO2 utilization and removal. Nature. 2019;575(7781):87–97. 10.1038/s41586-019-1681-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(4) Jessop IA, Chong A, Graffo L, Ignacio A, Camarada MB, Espinoza C, et al. Synthesis and characterization of a 2,3-dialkoxynaphthalene-based conjugated copolymer via direct arylation polymerization (DAP) for organic electronics. Polymers. 2020;12(6):1377–92. 10.3390/polym12061377.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(5) Darensbourg DJ. Chain transfer agents utilized in epoxide and CO2 copolymerization processes. Green Chem. 2019;21(9):2214–23. 10.1039/c9gc00620f.Search in Google Scholar

(6) Büttner H, Longwitz L, Steinbauer J, Wulf C, Werner T. Recent developments in the synthesis of cyclic carbonates from epoxides and CO2. Top Curr Chem. 2017;375(3):50–6. 10.1007/s41061-017-0136-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(7) Wang MY, Wang N, He LN, Liu XF, Qiao C. Efficient Tungstate catalysis: pressure-switched 2- and 6- electron reductive functionalization of CO2 with amines and phenylsilane. Green Chem. 2018;20:1564–70. 10.1039/c7gc03416d.Search in Google Scholar

(8) Gao L, Feng J. A one-step strategy for thermally and mechanically reinforced pseudo-interpenetrating poly(propylene carbonate) networks by terpolymerization of CO2, propylene oxide and pyromellitic dianhydride. J Mater Chem A. 2013;1(11):3556–60. 10.1039/c3ta01177a.Search in Google Scholar

(9) Li XY, Zheng SS, Liu XF, Yang ZW, Tan TY, He LN, et al. Waste recycling: ionic liquid-catalyzed 4-electron reduction of CO2 with amines and polymethylhydrosiloxane combining experimental and theoretical study. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2018;6:8130–5. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b02352.Search in Google Scholar

(10) Albano G, Aronica LA. Acyl sonogashira cross-coupling: state of the art and application to the synthesis of heterocyclic compounds. Catalysts. 2020;10(1):25–61. org/10.3390/catal10010025.Search in Google Scholar

(11) Elia V, Pelletier JDA, Basset JM. Cycloadditions to epoxides catalyzed by group III–V transition-metal complexes. ChemCatChem. 2015;7(13):1906–17. 10.1002/cctc.201500231.Search in Google Scholar

(12) Wang WZ, Zhang KY, Jia XG, Wang L, Li LL, Fan W, et al. A new dinuclear cobalt complex for copolymerization of CO2 and propylene oxide: high activity and selectivity. Molecules. 2020;25(18):4095–110. 10.3390/molecules25184095.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(13) Inoue S, Koinuma H, Tsuruta T. Copolymerization of carbon dioxide and epoxide. Polym Lett. 1969;7(4):287–92. org/10.1002/pol.1969.110070408.Search in Google Scholar

(14) Shaarani FW, Bou JJ. Synthesis of vegetable-oil based polymer by terpolymerization of epoxidized soybean oil, propylene oxide and carbon dioxide. Sci Total Environ. 2017;598:931–6. org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.04.184.Search in Google Scholar

(15) Zhang DY, Boopathi SK, Hadjichristidis N, Gnanou Y, Feng XS. Metal-free alternating copolymerization of CO2 with epoxides: fulfilling green synthesis and activity. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138(35):11117–20. 10.1021/jacs.6b06679.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(16) Jia MC, Hadjichristidis N, Gnanou Y, Feng XS. Monomodal ultrahigh-molar-mass polycarbonate homopolymers and diblock copolymers by anionic copolymerization of epoxides with CO2. ACS Macro Lett. 2019;8(12):1594–8. 10.1021/acsmacrolett.9b00854.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(17) Liu YF, Huang K, Peng D, Wu H. Synthesis, characterization and hydrolysis of an aliphatic polycarbonate by terpolymerization of carbon dioxide, propylene oxide and maleic anhydride. Polymer. 2006;47:8453–61. 10.1016/j.polymer.2006.10.024.Search in Google Scholar

(18) Luinstra GA, Borchardt E. Material properties of poly(propylene carbonates). Adv Polym Sci. 2012;245:29–48. ISBN: 978-3-642-27153-3.10.1007/12_2011_126Search in Google Scholar

(19) Muthuraj R, Mekonnen T. Recent progress in carbon dioxide (CO2) as feedstock for sustainable materials development: Co-polymers and polymer blends Polymer. 2018;145:348–73. 10.1016/j.polymer.2018.04.078.Search in Google Scholar

(20) Xu YH, Lin LM, Xiao M, Wang SJ, Sun LY, Meng YZ, et al. Synthesis and properties of CO2-based plastics: environmentally-friendly, energy-saving and biomedical polymeric materials. Prog Polym Sci. 2018;80:163–82. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2018.01.006.Search in Google Scholar

(21) An JJ, Ke YC, Cao XY, Ma YM, Wang FS. A novel method to improve the thermal stability of poly (propylene carbonate). Polym Chem. 2014;5(14):4245–50. 10.1039/c4py00013g.Search in Google Scholar

(22) Song PF, Xu HD, Mao XD, Liu XJ, Wang L. A one-step strategy for aliphatic poly(carbonate-ester)s with high performance derived from CO2, propylene oxide and L-lactide. Polym Adv Technol. 2017;28:736–41. 10.1002/pat.3974.Search in Google Scholar

(23) Kuang TR, Li KC, Chen BY, Peng XF. Poly(propylene carbonate)-based in situ nanofibrillar biocomposites with enhanced miscibility, dynamic mechanical properties, rheological behavior and extrusion foaming ability. Compos Part B Eng. 2017;123:112–23. org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2017.05.015.Search in Google Scholar

(24) Enriquez E, Mohanty AK, Misra M. Biobased blends of poly(propylene carbonate) and poly(hydroxybutyrate-co-hydroxyvalerate): Fabrication and characterization. J Appl Polym Sci. 2017;134:44420–30. 10.1002/app.44420.Search in Google Scholar

(25) Zhai LP, Li GF, Xu Y, Xiao M, Wang SJ, Meng YZ. Poly(propylene carbonate)/aluminum flake composite films with enhanced gas barrier properties. J Appl Polym Sci. 2015;132:41663–69. 10.1002/app.41663.Search in Google Scholar

(26) Chen LJ, Qin YS, Wang XH, Zhao XJ, Wang FS. Plasticizing while toughening and reinforcing poly(propylene carbonate) using low molecular weight urethane: Role of hydrogen-bonding interaction. Polymer. 2011;52:4873–80. 10.1016/j.polymer.2011.08.025.Search in Google Scholar

(27) Qi XD, Jing MF, Liu ZW, Dong P, Liu TY, Fu Q. Microfibrillated cellulose reinforced bio-based poly(propylene carbonate) with dual-responsive shape memory properties. RSC Adv. 2016;6:7560–7. 10.1039/c5ra22215j.Search in Google Scholar

(28) Klaus S, Lehenmeier MW, Herdtweck E, Deglmann P, Ott AK, Riegeret B. Mechanistic insights into heterogeneous zinc dicarboxylates and theoretical considerations for CO2–epoxide copolymerization. J AM CHEM SOC. 2011;133(33):13151–61. 10.1021/ja204481w.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(29) Zhong X, Fariba D. Solvent free synthesis of organometallic catalysts for the copolymerisation of carbon dioxide and propylene oxide. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental. 2010;98:101–11. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2010.05.017.Search in Google Scholar

(30) Ree M, Yongtaek H, Hyunchul K, Kim H, Kim G, Kim H. New findings in the catalytic activity of zinc glutarate and its application in the chemical fixation of CO2 into polycarbonates and their derivatives. Catal Today. 2006;115(2006):134–45. 10.1016/j.cattod.2006.02.068.Search in Google Scholar

(31) Kim JS, Kim H, Ree M. Hydrothermal synthesis of single-crystalline zinc glutarate and its structural determination. Chem Mater. 2004;16:2981–3. 10.12691/ajmcr-9-5-11.Search in Google Scholar

(32) Gao LJ, Huang MY, Feng JY, Wu QF, Wan SD, Chen XD, et al. Enhanced poly (propylene carbonate) with thermoplastic networks: a cross-linking role of maleic anhydride oligomer in CO2/PO copolymerization. Polymers. 2019;11(9):1467–79. 10.3390/polym11091467.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(33) Huang MY, Gao LJ, Feng JY, Huang XY, Li ZQ, Huang ZQ, et al. Cross-linked networks in poly(propylene carbonate) by incorporating (maleic anhydride/cis-1,2,3,6-tetrahydrophthalic anhydride) oligomer in CO2/propylene oxide copolymerization: improving and tailoring thermal, mechanical, and dimensional properties. ACS omega. 2020;5(28):17808–17. 10.1021/acsomega.0c02608.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(34) Li XH, Meng YZ, Zhu Q, Tjong SC. Thermal decomposition characteristics of poly(propylene carbonate) using TG/IR and Py-GC/MS techniques. Polym Degrad Stab. 2003;81:157–65. 10.1016/S0141-3910(03)00085-5.Search in Google Scholar

(35) Qu H, Wang Y, Ye YS, Hao QU, Ye YS, Zhou W, et al. A promising nanohybrid of silicon carbide nanowires scrolled by graphene oxide sheets with a synergistic effect for poly(propylene carbonate) nanocomposites. J Mater Chem A. 2017;5:22361–71. 10.1039/c7ta06080g.Search in Google Scholar

(36) Li YH, Zhou M, Geng CZ, Chen F, Fu Q. Simultaneous improvements of thermal stability and mechanical properties of poly(propylene carbonate) via incorporation of environmental friendly polydopamine. Chin J Polym Sci. 2014;32:1724–36. 10.1007/s10118-014-1518-6.Search in Google Scholar

(37) Tao YH, Wang XH, Zhao XJ, Li J, Wang FS. Double propagation based on diepoxide, a facile route to high molecular weight poly(propylene carbonate). Polymer. 2006;47:7368–73. 10.1016/j.polymer.2006.08.035.Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Yi-Le Zhang et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Research on the mechanism of gel accelerator on gel transition of PAN solution by rheology and dynamic light scattering

- Gel point determination of gellan biopolymer gel from DC electrical conductivity

- Composite of polylactic acid and microcellulose from kombucha membranes

- Synthesis of highly branched water-soluble polyester and its surface sizing agent strengthening mechanism

- Fabrication and characterization of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) modified with nano-montmorillonite biocomposite

- Fabrication of N-halamine polyurethane films with excellent antibacterial properties

- Formulation and optimization of gastroretentive bilayer tablets of calcium carbonate using D-optimal mixture design

- Sustainable nanocomposite films based on SiO2 and biodegradable poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) (PHBH) for food packaging

- Evaluation of physicochemical properties of film-based alginate for food packing applications

- Electrically conductive and light-weight branched polylactic acid-based carbon nanotube foams

- Structuring of hydroxy-terminated polydimethylsiloxane filled by fumed silica

- Surface functionalization of nanostructured Cu/Ag-deposited polypropylene fiber by magnetron sputtering

- Influence of composite structure design on the ablation performance of ethylene propylene diene monomer composites

- MOFs/PVA hybrid membranes with enhanced mechanical and ion-conductive properties

- Improvement of the electromechanical properties of thermoplastic polyurethane composite by ionic liquid modified multiwall carbon nanotubes

- Natural rubber latex/MXene foam with robust and multifunctional properties

- Rheological properties of two high polymers suspended in an abrasive slurry jet

- Two-step polyaniline loading in polyelectrolyte complex membranes for improved pseudo-capacitor electrodes

- Preparation and application of carbon and hollow TiO2 microspheres by microwave heating at a low temperature

- Properties of a bovine collagen type I membrane for guided bone regeneration applications

- Fabrication and characterization of thermoresponsive composite carriers: PNIPAAm-grafted glass spheres

- Effect of talc and diatomite on compatible, morphological, and mechanical behavior of PLA/PBAT blends

- Multifunctional graphene nanofiller in flame retarded polybutadiene/chloroprene/carbon black composites

- Strain-dependent wicking behavior of cotton/lycra elastic woven fabric for sportswear

- Enhanced dielectric properties and breakdown strength of polymer/carbon nanotube composites by coating an SrTiO3 layer

- Analysis of effect of modification of silica and carbon black co-filled rubber composite on mechanical properties

- Polytriazole resins toughened by an azide-terminated polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (OADTP)

- Phosphine oxide for reducing flammability of ethylene-vinyl-acetate copolymer

- Study on preparation and properties of bentonite-modified epoxy sheet molding compound

- Polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS)-modified phenolic resin: Synthesis and anti-oxidation properties

- Study on structure and properties of natural indigo spun-dyed viscose fiber

- Biodegradable thermoplastic copolyester elastomers: Methyl branched PBAmT

- Investigations of polyethylene of raised temperature resistance service performance using autoclave test under sour medium conditions

- Investigation of corrosion and thermal behavior of PU–PDMS-coated AISI 316L

- Modification of sodium bicarbonate and its effect on foaming behavior of polypropylene

- Effect of coupling agents on the olive pomace-filled polypropylene composite

- High strength and conductive hydrogel with fully interpenetrated structure from alginate and acrylamide

- Removal of methylene blue in water by electrospun PAN/β-CD nanofibre membrane

- Theoretical and experimental studies on the fabrication of cylindrical-electrode-assisted solution blowing spinning nanofibers

- Influence of l-quebrachitol on the properties of centrifuged natural rubber

- Ultrasonic-modified montmorillonite uniting ethylene glycol diglycidyl ether to reinforce protein-based composite films

- Experimental study on the dissolution of supercritical CO2 in PS under different agitators

- Experimental research on the performance of the thermal-reflective coatings with liquid silicone rubber for pavement applications

- Study on controlling nicotine release from snus by the SIPN membranes

- Catalase biosensor based on the PAni/cMWCNT support for peroxide sensing

- Synthesis and characterization of different soybean oil-based polyols with fatty alcohol and aromatic alcohol

- Molecularly imprinted electrospun fiber membrane for colorimetric detection of hexanoic acid

- Poly(propylene carbonate) networks with excellent properties: Terpolymerization of carbon dioxide, propylene oxide, and 4,4ʹ-(hexafluoroisopropylidene) diphthalic anhydride

- Polypropylene/graphene nanoplatelets nanocomposites with high conductivity via solid-state shear mixing

- Mechanical properties of fiber-reinforced asphalt concrete: Finite element simulation and experimental study

- Applying design of experiments (DoE) on the properties of buccal film for nicotine delivery

- Preparation and characterizations of antibacterial–antioxidant film from soy protein isolate incorporated with mangosteen peel extract

- Preparation and adsorption properties of Ni(ii) ion-imprinted polymers based on synthesized novel functional monomer

- Rare-earth doped radioluminescent hydrogel as a potential phantom material for 3D gel dosimeter

- Effects of cryogenic treatment and interface modifications of basalt fibre on the mechanical properties of hybrid fibre-reinforced composites

- Stable super-hydrophobic and comfort PDMS-coated polyester fabric

- Impact of a nanomixture of carbon black and clay on the mechanical properties of a series of irradiated natural rubber/butyl rubber blend

- Preparation and characterization of a novel composite membrane of natural silk fiber/nano-hydroxyapatite/chitosan for guided bone tissue regeneration

- Study on the thermal properties and insulation resistance of epoxy resin modified by hexagonal boron nitride

- A new method for plugging the dominant seepage channel after polymer flooding and its mechanism: Fracturing–seepage–plugging

- Analysis of the rheological property and crystallization behavior of polylactic acid (Ingeo™ Biopolymer 4032D) at different process temperatures

- Hybrid green organic/inorganic filler polypropylene composites: Morphological study and mechanical performance investigations

- In situ polymerization of PEDOT:PSS films based on EMI-TFSI and the analysis of electrochromic performance

- Effect of laser irradiation on morphology and dielectric properties of quartz fiber reinforced epoxy resin composite

- The optimization of Carreau model and rheological behavior of alumina/linear low-density polyethylene composites with different alumina content and diameter

- Properties of polyurethane foam with fourth-generation blowing agent

- Hydrophobicity and corrosion resistance of waterborne fluorinated acrylate/silica nanocomposite coatings

- Investigation on in situ silica dispersed in natural rubber latex matrix combined with spray sputtering technology

- The degradable time evaluation of degradable polymer film in agriculture based on polyethylene film experiments

- Improving mechanical and water vapor barrier properties of the parylene C film by UV-curable polyurethane acrylate coating

- Thermal conductivity of silicone elastomer with a porous alumina continuum

- Copolymerization of CO2, propylene oxide, and itaconic anhydride with double metal cyanide complex catalyst to form crosslinked polypropylene carbonate

- Combining good dispersion with tailored charge trapping in nanodielectrics by hybrid functionalization of silica

- Thermosensitive hydrogel for in situ-controlled methotrexate delivery

- Analysis of the aging mechanism and life evaluation of elastomers in simulated proton exchange membrane fuel cell environments

- The crystallization and mechanical properties of poly(4-methyl-1-pentene) hard elastic film with different melt draw ratios

- Review Articles

- Aromatic polyamide nonporous membranes for gas separation application

- Optical elements from 3D printed polymers

- Evidence for bicomponent fibers: A review

- Mapping the scientific research on the ionizing radiation impacts on polymers (1975–2019)

- Recent advances in compatibility and toughness of poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene succinate) blends

- Topical Issue: (Micro)plastics pollution - Knowns and unknows (Guest Editor: João Pinto da Costa)

- Simple pyrolysis of polystyrene into valuable chemicals

- Topical Issue: Recent advances of chitosan- and cellulose-based materials: From production to application (Guest Editor: Marc Delgado-Aguilar)

- In situ photo-crosslinking hydrogel with rapid healing, antibacterial, and hemostatic activities

- A novel CT contrast agent for intestinal-targeted imaging through rectal administration

- Properties and applications of cellulose regenerated from cellulose/imidazolium-based ionic liquid/co-solvent solutions: A short review

- Towards the use of acrylic acid graft-copolymerized plant biofiber in sustainable fortified composites: Manufacturing and characterization

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Research on the mechanism of gel accelerator on gel transition of PAN solution by rheology and dynamic light scattering

- Gel point determination of gellan biopolymer gel from DC electrical conductivity

- Composite of polylactic acid and microcellulose from kombucha membranes

- Synthesis of highly branched water-soluble polyester and its surface sizing agent strengthening mechanism

- Fabrication and characterization of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) modified with nano-montmorillonite biocomposite

- Fabrication of N-halamine polyurethane films with excellent antibacterial properties

- Formulation and optimization of gastroretentive bilayer tablets of calcium carbonate using D-optimal mixture design

- Sustainable nanocomposite films based on SiO2 and biodegradable poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) (PHBH) for food packaging

- Evaluation of physicochemical properties of film-based alginate for food packing applications

- Electrically conductive and light-weight branched polylactic acid-based carbon nanotube foams

- Structuring of hydroxy-terminated polydimethylsiloxane filled by fumed silica

- Surface functionalization of nanostructured Cu/Ag-deposited polypropylene fiber by magnetron sputtering

- Influence of composite structure design on the ablation performance of ethylene propylene diene monomer composites

- MOFs/PVA hybrid membranes with enhanced mechanical and ion-conductive properties

- Improvement of the electromechanical properties of thermoplastic polyurethane composite by ionic liquid modified multiwall carbon nanotubes

- Natural rubber latex/MXene foam with robust and multifunctional properties

- Rheological properties of two high polymers suspended in an abrasive slurry jet

- Two-step polyaniline loading in polyelectrolyte complex membranes for improved pseudo-capacitor electrodes

- Preparation and application of carbon and hollow TiO2 microspheres by microwave heating at a low temperature

- Properties of a bovine collagen type I membrane for guided bone regeneration applications

- Fabrication and characterization of thermoresponsive composite carriers: PNIPAAm-grafted glass spheres

- Effect of talc and diatomite on compatible, morphological, and mechanical behavior of PLA/PBAT blends

- Multifunctional graphene nanofiller in flame retarded polybutadiene/chloroprene/carbon black composites

- Strain-dependent wicking behavior of cotton/lycra elastic woven fabric for sportswear

- Enhanced dielectric properties and breakdown strength of polymer/carbon nanotube composites by coating an SrTiO3 layer

- Analysis of effect of modification of silica and carbon black co-filled rubber composite on mechanical properties

- Polytriazole resins toughened by an azide-terminated polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (OADTP)

- Phosphine oxide for reducing flammability of ethylene-vinyl-acetate copolymer

- Study on preparation and properties of bentonite-modified epoxy sheet molding compound

- Polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS)-modified phenolic resin: Synthesis and anti-oxidation properties

- Study on structure and properties of natural indigo spun-dyed viscose fiber

- Biodegradable thermoplastic copolyester elastomers: Methyl branched PBAmT

- Investigations of polyethylene of raised temperature resistance service performance using autoclave test under sour medium conditions

- Investigation of corrosion and thermal behavior of PU–PDMS-coated AISI 316L

- Modification of sodium bicarbonate and its effect on foaming behavior of polypropylene

- Effect of coupling agents on the olive pomace-filled polypropylene composite

- High strength and conductive hydrogel with fully interpenetrated structure from alginate and acrylamide

- Removal of methylene blue in water by electrospun PAN/β-CD nanofibre membrane

- Theoretical and experimental studies on the fabrication of cylindrical-electrode-assisted solution blowing spinning nanofibers

- Influence of l-quebrachitol on the properties of centrifuged natural rubber

- Ultrasonic-modified montmorillonite uniting ethylene glycol diglycidyl ether to reinforce protein-based composite films

- Experimental study on the dissolution of supercritical CO2 in PS under different agitators

- Experimental research on the performance of the thermal-reflective coatings with liquid silicone rubber for pavement applications

- Study on controlling nicotine release from snus by the SIPN membranes

- Catalase biosensor based on the PAni/cMWCNT support for peroxide sensing

- Synthesis and characterization of different soybean oil-based polyols with fatty alcohol and aromatic alcohol

- Molecularly imprinted electrospun fiber membrane for colorimetric detection of hexanoic acid

- Poly(propylene carbonate) networks with excellent properties: Terpolymerization of carbon dioxide, propylene oxide, and 4,4ʹ-(hexafluoroisopropylidene) diphthalic anhydride

- Polypropylene/graphene nanoplatelets nanocomposites with high conductivity via solid-state shear mixing

- Mechanical properties of fiber-reinforced asphalt concrete: Finite element simulation and experimental study

- Applying design of experiments (DoE) on the properties of buccal film for nicotine delivery

- Preparation and characterizations of antibacterial–antioxidant film from soy protein isolate incorporated with mangosteen peel extract

- Preparation and adsorption properties of Ni(ii) ion-imprinted polymers based on synthesized novel functional monomer

- Rare-earth doped radioluminescent hydrogel as a potential phantom material for 3D gel dosimeter

- Effects of cryogenic treatment and interface modifications of basalt fibre on the mechanical properties of hybrid fibre-reinforced composites

- Stable super-hydrophobic and comfort PDMS-coated polyester fabric

- Impact of a nanomixture of carbon black and clay on the mechanical properties of a series of irradiated natural rubber/butyl rubber blend

- Preparation and characterization of a novel composite membrane of natural silk fiber/nano-hydroxyapatite/chitosan for guided bone tissue regeneration

- Study on the thermal properties and insulation resistance of epoxy resin modified by hexagonal boron nitride

- A new method for plugging the dominant seepage channel after polymer flooding and its mechanism: Fracturing–seepage–plugging

- Analysis of the rheological property and crystallization behavior of polylactic acid (Ingeo™ Biopolymer 4032D) at different process temperatures

- Hybrid green organic/inorganic filler polypropylene composites: Morphological study and mechanical performance investigations

- In situ polymerization of PEDOT:PSS films based on EMI-TFSI and the analysis of electrochromic performance

- Effect of laser irradiation on morphology and dielectric properties of quartz fiber reinforced epoxy resin composite

- The optimization of Carreau model and rheological behavior of alumina/linear low-density polyethylene composites with different alumina content and diameter

- Properties of polyurethane foam with fourth-generation blowing agent

- Hydrophobicity and corrosion resistance of waterborne fluorinated acrylate/silica nanocomposite coatings

- Investigation on in situ silica dispersed in natural rubber latex matrix combined with spray sputtering technology

- The degradable time evaluation of degradable polymer film in agriculture based on polyethylene film experiments

- Improving mechanical and water vapor barrier properties of the parylene C film by UV-curable polyurethane acrylate coating

- Thermal conductivity of silicone elastomer with a porous alumina continuum

- Copolymerization of CO2, propylene oxide, and itaconic anhydride with double metal cyanide complex catalyst to form crosslinked polypropylene carbonate

- Combining good dispersion with tailored charge trapping in nanodielectrics by hybrid functionalization of silica

- Thermosensitive hydrogel for in situ-controlled methotrexate delivery

- Analysis of the aging mechanism and life evaluation of elastomers in simulated proton exchange membrane fuel cell environments

- The crystallization and mechanical properties of poly(4-methyl-1-pentene) hard elastic film with different melt draw ratios

- Review Articles

- Aromatic polyamide nonporous membranes for gas separation application

- Optical elements from 3D printed polymers

- Evidence for bicomponent fibers: A review

- Mapping the scientific research on the ionizing radiation impacts on polymers (1975–2019)

- Recent advances in compatibility and toughness of poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene succinate) blends

- Topical Issue: (Micro)plastics pollution - Knowns and unknows (Guest Editor: João Pinto da Costa)

- Simple pyrolysis of polystyrene into valuable chemicals

- Topical Issue: Recent advances of chitosan- and cellulose-based materials: From production to application (Guest Editor: Marc Delgado-Aguilar)

- In situ photo-crosslinking hydrogel with rapid healing, antibacterial, and hemostatic activities

- A novel CT contrast agent for intestinal-targeted imaging through rectal administration

- Properties and applications of cellulose regenerated from cellulose/imidazolium-based ionic liquid/co-solvent solutions: A short review

- Towards the use of acrylic acid graft-copolymerized plant biofiber in sustainable fortified composites: Manufacturing and characterization