Abstract

With high polymer added into suspension, the use of abrasive slurry jet (ASJ) has significant advantages in energy management. The quality and efficiency of ASJ are affected distinctly by its structure and the flow field feature, both of which depend on the rheological properties of the abrasive slurry. Therefore, this paper carries out a series of experiments to study the rheological properties of abrasive slurry with polyacrylamide (PAM) and carboxy methyl cellulose (CMC) commonly used in ASJ. The paper also explores the effect of temperature and abrasive on the apparent viscosity of the abrasive slurry. Experimental results show that PAM and CMC solutions behave as a pseudoplastic non-Newtonian fluid in the selected concentration range, whose apparent viscosity increases with the concentration. In addition, specific non-Newtonian fluid constitutive equations of the power-law model for PAM and CMC solution were obtained by nonlinear fitting calculation. The apparent viscosity decreases with the growth of temperature because it leads to the increase in spacing between molecules, making the attraction between molecules smaller and smaller. However, the abrasive has no influence on the apparent viscosity of abrasive slurry for these molecular bonds, and their mechanical entanglements are not destroyed by abrasive particles in the suspension.

Graphical abstract

The results and conclusion of this paper can be used to study the formulation optimization and fluid field properties of abrasive slurry jet (ASJ), which also can provide guidance for the engineering application of ASJ.

1 Introduction

The abrasive slurry jet (ASJ) is a suspension consisting of abrasive particles and a high polymer solution, which is a non-traditional machining tool (1). Cutting glass with new water-soluble polymer is one of its applications and was conducted by Anjajah (2), whose work showed that the polymer concentration and abrasive type affected the cutting depths mostly. Liao et al. (3) applied ASJ on the experimental glass polishing, in which the polished glass had a very small roughness. The abrasive water jet (AWJ) was compared with ASJ by Nouraei et al. (4,5) and revealed the suppression on jet divergence by the added polymer. New technical cutting equipment of ASJ to cut and drill glass was developed by Pang et al. (6,7), which showed that the new equipment had advantages in the performance of glass grooving and punching.

Polyacrylamide (PAM) and carboxy methyl cellulose (CMC) are the mostly used polymer additives in ASJ. PAM is an important type of water-soluble polymer with special physicochemical properties. It can be obtained by grafting or cross-linking a variety of modified structures of branched or network structure (8). CMC is a carboxymethylated derivative of cellulose, also known as the cellulose gum, which has been widely used because of its many special properties, such as thickening, adhesion, film formation, water holding, emulsification, and suspension (9). Recent studies have shown that CMC hydrogels have good biocompatibility and can be applied to biomedical applications such as soft tissue enhancements (10).

In the study of rheological properties of high polymer solutions, the effects of pH, concentration and reaction temperature on apparent viscosity, and interfacial tension of surface-active polymer solutions are investigated by Li et al. (11). The rheological properties of partially hydrolyzed PAM have been improved by Hu et al. (12) through using silica nanoparticles for enhanced oil recovery. Ujjwal et al. (13) investigated the rheological properties of a random copolymer PAM-ran-PAH and polydactyly hydrazide (PAH) at different temperatures and salinity. Results showed that PAM-ran-PAH was more stable than PAH in saline and high-temperature environments. Karimi et al. (14) investigated the rheological, physical stability, and sensory properties of milk-jujube concentrate mixture at different concentrations of pectin and CMC. Senapati and Mishra (15) developed a hydrostatic head viscometer and its novel viscosity equation to determine the flow characteristics of some high polymer solutions. Haeri and Hashemabadi (16) researched the rheology, surface tension, and contact angle of falling film at three different CMC solution concentrations. Ghannam (17,18) studied the rheological properties of all-aqueous and aqueous/NaCl solution of PAM and obtained that the solution exhibited the non-Newtonian behavior with shear thinning and shear thickening areas.

Based on previous researches, ASJ shows great advantages in the field of material manufacturing. However, the rheological properties of suspension in ASJ have not been fully studied, which will significantly affect the cutting quality and efficiency of ASJ. Although rheological properties of certain high polymer solutions have been researched, most of them are used in crude oil recovery. Therefore, rheological properties of suspension with PAM and CMC commonly used in ASJ were studied in this paper, which can provide guidance to make up ASJ suspension in engineering works.

2 Experiments

2.1 Research object

Figure 1 shows the structure of ASJ at 10 MPa taken by a high speed camera. ASJ converges better than water jet does, which is more distinct with the increase in high polymer concentrations. The converging characteristic depends on the rheological properties of abrasive slurry in ASJ, which determines its structure and flow field feature and then affects its cutting quality and efficiency. Therefore, this paper studies the rheological properties of the suspension in ASJ. With the non-Newtonian fluid category of the abrasive slurry explored, constitutive equations under different composition ratios are calculated by a nonlinear fitting model. Finally, this paper investigates the effects of temperature and abrasive on the apparent viscosity of the abrasive slurry.

Structure of ASJ.

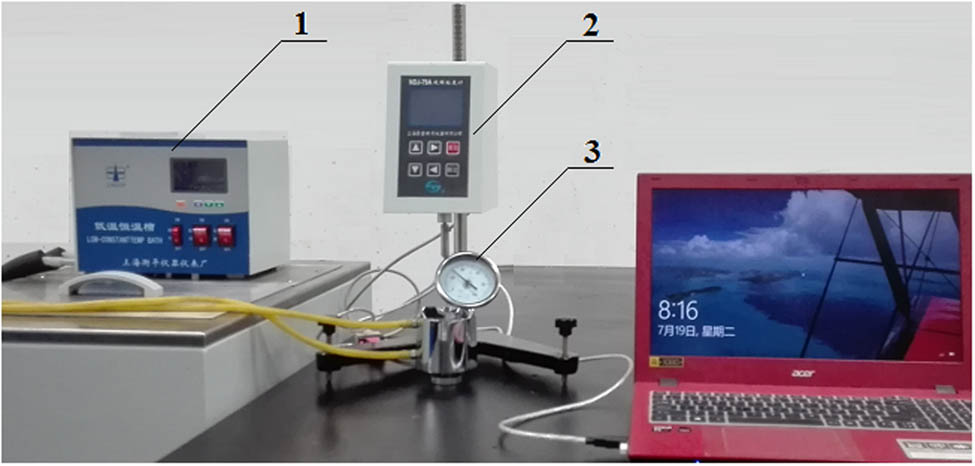

2.2 Experimental system

Figure 2 shows the testing system of the slurry apparent viscosity, which consists of a rotational viscometer, a constant temperature water bath, a thermometer, and a laptop. The rotational viscometer is used for measuring the apparent viscosity of the abrasive slurry, the constant temperature water bath for keeping the temperature of slurry constant, the thermometer for monitoring the temperature of slurry in real-time, and the laptop for recording the value of apparent viscosity measured by the rotational viscometer through snoop ware.

Experimental system: 1 – constant temperature water bath, 2 – rotational viscometer, 3 – thermometer.

An NDJ-79A rotational viscometer was adopted in the experiments, which has a torque sensor that can measure the torque of the rotor applied by tested abrasive slurry. According to Eq. 1–3, the apparent viscosity can be calculated and visualized on the screen of rotational viscometer (19).

where

2.3 Experimental scheme

PAM and CMC are the high polymer additives commonly used in ASJ. The technical information of the two high polymers is listed in Table 1. Choosing the aqueous solution of PAM and CMC as the experimental object, this paper carried out three parts of experiments to study the rheological properties of the abrasive slurry. First, to obtain the non-Newtonian category and constitutive equations of abrasive slurry, a full factorial experiment method was adopted under five kinds of high polymer concentrations and 14 kinds of spindle speeds. Selected concentrations were applicable to the ASJ system as shown in Figure 2. Then, the experimental measurement of slurry apparent viscosity was conducted under five kinds of temperatures to explore the effect of temperature on slurry apparent viscosity.

Parameters of high polymers

| Polymer | Appearance | MW | DS | Solid content |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAM | White particles | 12 million | — | ≥89% |

| CMC | White powder | 240.2 | 0.55 | — |

Finally, the apparent viscosity of the abrasive slurry with 10% volume fraction garnet (100 meshes) was measured to explore the effect of abrasive on slurry apparent viscosity. The details of the above experimental variables are presented in Table 2.

Details of the experimental variables

| Variables | Details |

|---|---|

| High polymer | PAM, CMC |

| Concentration (g/L) | 18.52/25.93/33.33/40.74/48.15 |

| Spindle speed (rpm) | 100/150/200/250/300/350/400/ |

| 450/500/550/600/650/700/750 | |

| Temperature (°C) | 20/25/30/35/40 |

| Abrasive | Garnet, 100 meshes, 10% volume fraction |

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Non-Newtonian fluid category of suspension in ASJ

3.1.1 Non-Newtonian fluid category of PAM solution

Figure 3 shows the apparent viscosity of the PAM solution at different spindle speeds and high polymer concentrations. Because of the high minimum range of torque sensors, the apparent viscosity of 18.52 g/L PAM solutions cannot be measured when the spindle speed is less than 200 rpm. The apparent viscosity of PAM solutions declines with the increase in shear rate, which illustrates that it is a pseudoplastic non-Newtonian fluid in the selected concentration range. The molecules of PAM solution link each other through molecular bonds, forming a net structure finally with mechanical entanglement between molecular bonds. At a low shear rate, the net structure destroyed by the rotor will recover in a short period so that the apparent viscosity can be maintained at a higher level. However, at a high shear rate the damaged net structure cannot be recovered in time, so that the apparent viscosity of PAM solutions measured is very small.

Apparent viscosity of PAM solutions at different shear rates and concentrations.

In addition, Figure 3 shows that the apparent viscosity of PAM solutions increases with PAM concentrations. The intermolecular attraction of PAM solution is very small because of the less and weak molecular bonds at a low PAM concentration, which caused a decrease in the apparent viscosity. However, with the increase in PAM concentrations, hydrogen bonds between the molecules will increase in PAM solutions, forming a mesh structure gradually and increasing solution’s apparent viscosity finally.

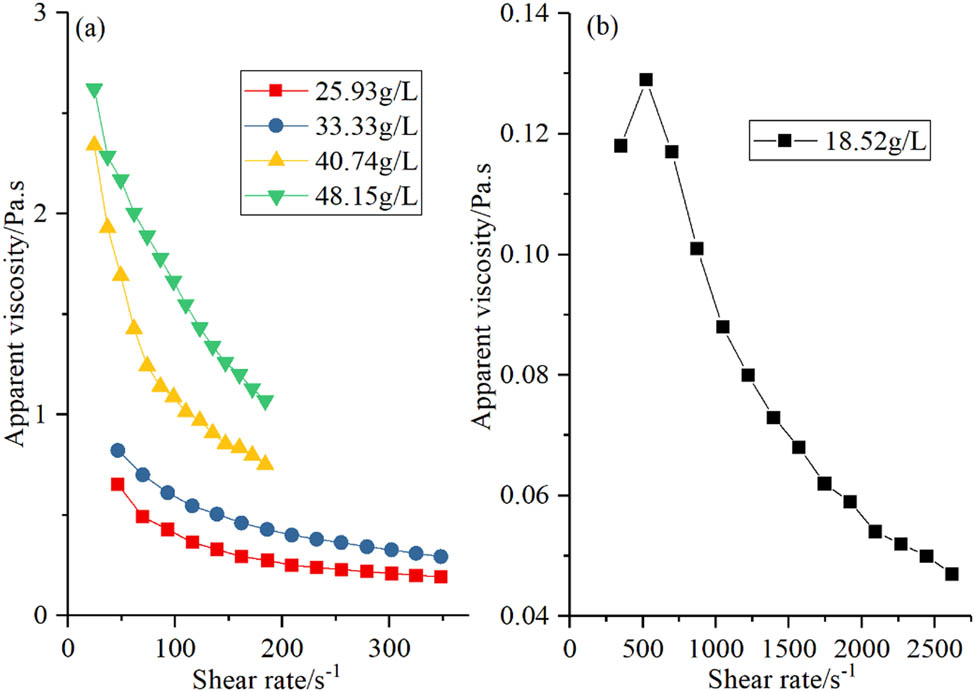

3.1.2 Non-Newtonian fluid category of CMC solution

Figure 4 shows the apparent viscosity of CMC solutions at different spindle speeds and high polymer concentrations. Because of the large range of the apparent viscosity of CMC solutions, three rotors were used to measure it at a suitable PAM concentration. Therefore, three different shear rates correspond to one spindle speed.

Apparent viscosity of CMC solution at different shear rates and concentrations. (a) Concentrations: 25.93--48.15 g/L, (b) concentration: 18.52 g/L.

As shown in Figure 4, the apparent viscosity of the CMC solution decreases with the increase in shear rate as well as the PAM solution. Similarly, the CMC solution is a pseudoplastic non-Newtonian fluid too. The CMC solution is the same as the PAM solution in the molecular structure, which looks like a net with molecular bonds and its mechanical entanglement. Moreover, the apparent viscosity of a CMC solution increases with the CMC concentration, which is similar to the PAM solution. The only difference is that the CMC solution is much larger than the PAM solution in apparent viscosity at the same concentration and shear rate. Therefore, the CMC solution is much larger than the PAM solution in intermolecular attraction with stronger molecular bonds and more complicated mechanical entanglement.

3.2 Non-Newtonian fluid constitutive equation of suspension in ASJ

To explore the rheological properties and get the non-Newtonian constitutive equation of the abrasive slurry at different high polymer concentrations, the section used Origin software to carry out nonlinear fitting for experimental data based on non-Newtonian fluid category research of the abrasive slurry. With PAM and CMC solutions being pseudoplastic non-Newtonian fluid, the power-law model shown in Eq. 4 can be adopted in a nonlinear fitting calculation:

where k is a consistency coefficient, which represents the average viscosity of the fluid; n is a flow index, which is a measure of the deviation of fluid from Newtonian.

3.2.1 Non-Newtonian fluid constitutive equation of PAM solution

Figure 5 compares the rheological properties curves of PAM solution at different concentrations, which illustrates the relationship between the shear stress and the shear rate. The shear stress increases sharply at the lower range of the shear rate, whereas it increases slowly at the higher range, leading to a similar conclusion of non-Newtonian fluid mentioned in Section 3.1. As shown in Table 3, this section also obtained the specific constitutive equation of PAM solution at different concentrations through the nonlinear fitting calculation.

Rheological properties curve of PAM solution.

Results of nonlinear fitting calculation for PAM solution

| Concentration (g/L) | Equation | k | E k | n | E n | R 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18.52 |

|

0.078 | 0.012 | 0.845 | 0.019 | 0.995 |

| 25.93 | 0.516 | 0.051 | 0.632 | 0.013 | 0.996 | |

| 33.33 | 1.015 | 0.129 | 0.555 | 0.017 | 0.991 | |

| 40.74 | 1.758 | 0.163 | 0.491 | 0.012 | 0.993 | |

| 48.15 | 3.241 | 0.358 | 0.427 | 0.015 | 0.987 |

In Table 3, E k and E n represent the standard deviation of consistency coefficient k and flow index n, respectively. All ratios of the standard deviation to the consistency coefficient are about 10%, whereas ratios of the standard deviation to flow index are under 5%. R 2 is the fitting confidence of the constitutive equation of PAM solution, whose values are more than 0.98. A high value of R 2 shows the consistency between the experimental data and fitting results, which can reveal the rheological properties of PAM solutions veritably.

Table 3 also shows that all values of consistency coefficient k are much larger than the viscosity of water (0.001 Pa s), which indicates that PAM solutions are larger than water in viscosity. In addition, the viscosity of PAM solutions increases with the growth of concentration. Flow index n will decrease distinctly with the increase in PAM concentrations. PAM solution is similar to the Newtonian fluid at lower concentrations, whereas it shows the rheological characteristic of shear-thinning at higher concentrations.

3.2.2 Non-Newtonian fluid constitutive equation of CMC solutions

Figure 6 compares the rheological properties curves of CMC solutions at different concentrations, which illustrates the relationship between shear stress and shear rate. The shear stress increases sharply at the lower range of shear rate, whereas it increases slowly at the higher range, corresponding to the result of non-Newtonian fluid in Section 3.1. As shown in Table 4, this section also obtained the specific constitutive equation of CMC solutions at different concentrations through the nonlinear fitting calculation.

Rheological properties curve of CMC solution.

Results of nonlinear fitting calculation for CMC solutions

| Concentration (g/L) | Equation | k | E k | n | E n | R 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18.52 |

|

5.745 | 1.401 | 0.394 | 0.033 | 0.934 |

| 25.93 | 6.098 | 0.298 | 0.409 | 0.009 | 0.995 | |

| 33.33 | 6.858 | 0.429 | 0.467 | 0.011 | 0.994 | |

| 40.74 | 14.857 | 0.709 | 0.431 | 0.010 | 0.994 | |

| 48.15 | 16.202 | 2.438 | 0.490 | 0.031 | 0.962 |

In Table 4, E k and E n represent the standard deviation of consistency coefficient k and flow index n, respectively. R 2 is the fitting confidence of the constitutive equation of CMC solutions. The fitting calculation for CMC solution at the lowest and highest concentrations is less precise, in which ratios of the E k exceed 15% and ratios of the E n are about 10%. However, it is accurate among the middle concentration range. In this range, most of the ratios of the E k and E n are less than 5% with high fitting confidence, and R 2 are more than 0.99. Overall, the results of the nonlinear fitting can reveal the rheological properties of CMC solutions.

Table 4 also shows that all values of consistency coefficient k are much larger than the viscosity of water and PAM solutions, which indicates that CMC solution is larger than water and PAM solutions in viscosity. The viscosity of a CMC solution increases with the growth of concentration. In addition, flow index n will decrease gently with the increase in CMC concentration. The CMC solution shows the rheological characteristic of shear-thinning, obviously among the concentration range in experiments.

3.3 Effects of temperature on the apparent viscosity of suspension in ASJ

To explore the effect of temperature on slurry apparent viscosity, this section measured the apparent viscosity of PAM and CMC solution under a constant shear rate (2616.67 s−1) and different temperatures. With five kinds of concentrations and temperatures listed in Table 2, the experimental scheme for PAM solutions does not change, whereas the experimental scheme for CMC solution has been changed for the limitation of the measuring range of the rotational viscometer. Lower concentrations were used to study the effect of temperature on the apparent viscosity of CMC solutions.

Figure 7 shows that the apparent viscosity of PAM solutions is affected by temperature distinctly and is inversely proportional to temperature, especially at the lower concentration. The reason is that the spacing between molecules of PAM solutions increases with temperature, causing a smaller attraction between molecules. The internal fraction is proportional to the attraction between molecules, which determines the apparent viscosity of PAM solutions. The apparent viscosity of PAM solutions at lower concentrations is apt to be affected by the change in temperature.

Apparent viscosity of PAM solution under different temperatures.

Figure 8 shows that the apparent viscosity of CMC solutions is affected by temperature distinctly and has an inversely proportional relationship with temperature. The reason is that the spacing between molecules of CMC solution increases with temperature, leading to a smaller attraction between molecules. The internal fraction is proportional to the attraction between molecules, which determines the apparent viscosity of CMC solutions.

Apparent viscosity of CMC solution under different temperatures.

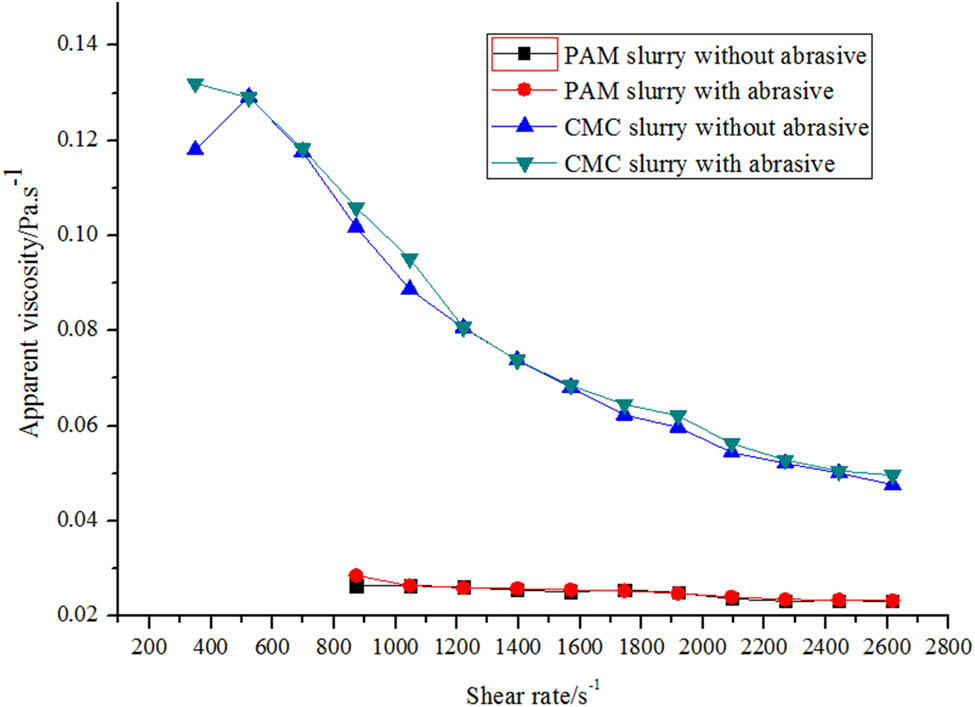

3.4 Effects of abrasive on the apparent viscosity of suspension in ASJ

To explore the effect of abrasive on the apparent viscosity of the abrasive slurry, 80 mesh garnet was adopted in an experiment, whose volume fraction was constant (10%). It has been widely used in AWJ cutting machines, and the volume fraction is suitable for material manufacturing with ASJ. The concentration of high polymer is 18.52 g/L in the experiment that the apparent viscosity measurement of PAM and CMC solutions can be in the same range of shear rates.

As shown in Figure 9, PAM and CMC solutions with abrasive are slightly larger than the one without abrasive in apparent viscosity. Molecular bonds and their mechanical entanglements in the solution were not destroyed by abrasive particles. The force between molecules keeps unchanged. Thus, the apparent viscosity and rheological properties of PAM and CMC solutions are still dominated by the net molecular structure. However, abrasive particles raise the friction between the rotor and slurry, leading to a small increase in the apparent viscosity.

Effect of abrasive on the apparent viscosity of the abrasive slurry.

4 Conclusions

In this paper, a series of experiments were carried out to study the rheological properties of abrasive slurry with PAM and CMC commonly used in ASJ, and the effect of temperature and abrasive on the apparent viscosity of the abrasive slurry is discussed. Specific experimental results were shown as follows:

PAM and CMC solutions are pseudoplastic non-Newtonian fluids within a selected concentration range, and their apparent viscosity increases with concentration. Under the same concentration and shear rate, the apparent viscosity of CMC solutions is much greater than that of the PAM solution. The increment comes from the greater intermolecular attraction of CMC solutions, the stronger molecular bonds, and the more complex mechanical entanglement.

The non-Newtonian fluid constitutive equations of specific PAM and CMC solutions can be obtained through nonlinear fitting calculations.

The apparent viscosity decreases with the increase in temperature, which can be explained as that high temperature increases the spacing between molecules.

Abrasive has no influence on the apparent viscosity of the abrasive slurry for that molecular bonds, and their mechanical entanglements could not be destroyed by abrasive particles in the slurry.

The results and conclusion of this paper can be used to study the formulation optimization and fluid field properties of ASJ, which also can provide guidance for the engineering application of ASJ.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2017XKZD02).

References

(1) Hollinger RH, Perry WD, Swanson RK. Precision cutting with a low pressure coherent abrasive suspension jet. In: 5th American Waterjet Conference. Toronto; 1989. p. 245–52.Suche in Google Scholar

(2) Anjaiah D, Chincholkar AM. Cutting of glass using low pressure abrasive water suspension jet with the addition of zycoprint polymer. In: 19th International Conference on Water Jetting; 2008. p. 105–19.Suche in Google Scholar

(3) Liao Y, Wang C, Hu Y, Song YX. The slurry for glass polishing by micro abrasive suspension jets. Adv Mater Res. 2009;69/70:322–7.10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.69-70.322Suche in Google Scholar

(4) Nouraei H, Wodoslawsky A, Papini M, Spelt JK. Characteristics of abrasive slurry jet micro-machining: a comparison with abrasive air jet micro machining. J Mater Process Technol. 2013;213(10):1711–24.10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2013.03.024Suche in Google Scholar

(5) Nouraei H, Kowsari K, Spelt JK, Papini M. Surface evolution models for abrasive slurry jet micro-machining of channels and holes in glass. Wear. 2014;309(1–2):65–73.10.1016/j.wear.2013.11.003Suche in Google Scholar

(6) Pang KL, Nguyen T, Fan JM, Wang J. Modelling of the micro-channelling process on glasses using an abrasive slurry jet. Int J Mach Tools Manuf. 2012;53(1):118–26.10.1016/j.ijmachtools.2011.10.005Suche in Google Scholar

(7) Pang KL, Nguyen T, Fan JM, Wang J. A study of micro-channeling on glasses using an abrasive slurry jet. Mach Sci Technol. 2012;16(4):547–63.10.1080/10910344.2012.731947Suche in Google Scholar

(8) Zhang D, Zhao W, Wu Y, Chen Z, Li X. Facile droplet microfluidics preparation of larger PAM-based particles and investigation of their swelling gelation behavior. E Polym. 2019;19(1):579–93.10.1515/epoly-2019-0062Suche in Google Scholar

(9) Niu SY, Hao FG. Progress of sodium carboxymethylcellulose. Anhui Agric Sci. 2006;34(15):3574–5.Suche in Google Scholar

(10) Liu B, Ma X, Zhu C, Mi Y, Fan D, Li X, et al. Study of a novel injectable hydrogel of human-like collagen and carboxymethylcellulose for soft tissue augmentation. E Polym. 2013;13(1):1–11.10.1515/epoly-2013-0135Suche in Google Scholar

(11) Li F, Luo Y, Hu P, Yan X. Intrinsic viscosity, rheological property, and oil displacement of hydrophobically associating fluorinated polyacrylamide. J Appl Polym Sci. 2017;134(14):1–9.10.1002/app.44672Suche in Google Scholar

(12) Hu Z, Maje H, Gao H, Ehsan N, Wen D. Rheological properties of partially hydrolyzed polyacrylamide seeded by nanoparticles. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2017;56(12):3456–63.10.1021/acs.iecr.6b05036Suche in Google Scholar

(13) Ujjwal RR, Sharma T, Sangwai JS, Ojha U. Rheological investigation of a random copolymer of polyacrylamide and polyacryloyl hydrazide (PAM-ran-PAH) for oil recovery applications. J Appl Polym Sci. 2017;134(13):1–14.10.1002/app.44648Suche in Google Scholar

(14) Karimi N, Sani AM, Pourahmad R. Influence of carboxy methyl cellulose (CMC) and pectin on rheological, physical stability and sensory properties of milk and concentrated jujuba mixture. J Food Meas Charact. 2016;10(2):396–404.10.1007/s11694-016-9318-zSuche in Google Scholar

(15) Senapati PK, Mishra BK. Rheological characterization of concentrated jarosite waste suspensions using Couette & tube rheometry techniques. Powder Technol. 2014;263:58–65.10.1016/j.powtec.2014.04.092Suche in Google Scholar

(16) Haeri S, Hashemabadi SH. Experimental study of gravity-driven film flow of non-Newtonian fluids. Chem Eng Commun. 2009;196(5):519–29.10.1080/00986440802484481Suche in Google Scholar

(17) Ghannam MT. Rheological properties of aqueous polyacrylamide/NaCl solutions. J Appl Polym Sci. 1999;72(14):1905–12.10.1002/(SICI)1097-4628(19990628)72:14<1905::AID-APP11>3.0.CO;2-PSuche in Google Scholar

(18) Lewandowska K. Comparative studies of rheological properties of polyacrylamide and partially hydrolyzed polyacrylamide solutions. J Appl Polym Sci. 2007;103(4):2235–41.10.1002/app.25247Suche in Google Scholar

(19) Instruction manual for NDJ-79A digital rotational viscometer (in Chinese) from Baidu library (https://wenku.baidu.com/view/7d83aa23ad02de80d5d84039.html).Suche in Google Scholar

© 2021 Xinyong Wang et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Research on the mechanism of gel accelerator on gel transition of PAN solution by rheology and dynamic light scattering

- Gel point determination of gellan biopolymer gel from DC electrical conductivity

- Composite of polylactic acid and microcellulose from kombucha membranes

- Synthesis of highly branched water-soluble polyester and its surface sizing agent strengthening mechanism

- Fabrication and characterization of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) modified with nano-montmorillonite biocomposite

- Fabrication of N-halamine polyurethane films with excellent antibacterial properties

- Formulation and optimization of gastroretentive bilayer tablets of calcium carbonate using D-optimal mixture design

- Sustainable nanocomposite films based on SiO2 and biodegradable poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) (PHBH) for food packaging

- Evaluation of physicochemical properties of film-based alginate for food packing applications

- Electrically conductive and light-weight branched polylactic acid-based carbon nanotube foams

- Structuring of hydroxy-terminated polydimethylsiloxane filled by fumed silica

- Surface functionalization of nanostructured Cu/Ag-deposited polypropylene fiber by magnetron sputtering

- Influence of composite structure design on the ablation performance of ethylene propylene diene monomer composites

- MOFs/PVA hybrid membranes with enhanced mechanical and ion-conductive properties

- Improvement of the electromechanical properties of thermoplastic polyurethane composite by ionic liquid modified multiwall carbon nanotubes

- Natural rubber latex/MXene foam with robust and multifunctional properties

- Rheological properties of two high polymers suspended in an abrasive slurry jet

- Two-step polyaniline loading in polyelectrolyte complex membranes for improved pseudo-capacitor electrodes

- Preparation and application of carbon and hollow TiO2 microspheres by microwave heating at a low temperature

- Properties of a bovine collagen type I membrane for guided bone regeneration applications

- Fabrication and characterization of thermoresponsive composite carriers: PNIPAAm-grafted glass spheres

- Effect of talc and diatomite on compatible, morphological, and mechanical behavior of PLA/PBAT blends

- Multifunctional graphene nanofiller in flame retarded polybutadiene/chloroprene/carbon black composites

- Strain-dependent wicking behavior of cotton/lycra elastic woven fabric for sportswear

- Enhanced dielectric properties and breakdown strength of polymer/carbon nanotube composites by coating an SrTiO3 layer

- Analysis of effect of modification of silica and carbon black co-filled rubber composite on mechanical properties

- Polytriazole resins toughened by an azide-terminated polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (OADTP)

- Phosphine oxide for reducing flammability of ethylene-vinyl-acetate copolymer

- Study on preparation and properties of bentonite-modified epoxy sheet molding compound

- Polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS)-modified phenolic resin: Synthesis and anti-oxidation properties

- Study on structure and properties of natural indigo spun-dyed viscose fiber

- Biodegradable thermoplastic copolyester elastomers: Methyl branched PBAmT

- Investigations of polyethylene of raised temperature resistance service performance using autoclave test under sour medium conditions

- Investigation of corrosion and thermal behavior of PU–PDMS-coated AISI 316L

- Modification of sodium bicarbonate and its effect on foaming behavior of polypropylene

- Effect of coupling agents on the olive pomace-filled polypropylene composite

- High strength and conductive hydrogel with fully interpenetrated structure from alginate and acrylamide

- Removal of methylene blue in water by electrospun PAN/β-CD nanofibre membrane

- Theoretical and experimental studies on the fabrication of cylindrical-electrode-assisted solution blowing spinning nanofibers

- Influence of l-quebrachitol on the properties of centrifuged natural rubber

- Ultrasonic-modified montmorillonite uniting ethylene glycol diglycidyl ether to reinforce protein-based composite films

- Experimental study on the dissolution of supercritical CO2 in PS under different agitators

- Experimental research on the performance of the thermal-reflective coatings with liquid silicone rubber for pavement applications

- Study on controlling nicotine release from snus by the SIPN membranes

- Catalase biosensor based on the PAni/cMWCNT support for peroxide sensing

- Synthesis and characterization of different soybean oil-based polyols with fatty alcohol and aromatic alcohol

- Molecularly imprinted electrospun fiber membrane for colorimetric detection of hexanoic acid

- Poly(propylene carbonate) networks with excellent properties: Terpolymerization of carbon dioxide, propylene oxide, and 4,4ʹ-(hexafluoroisopropylidene) diphthalic anhydride

- Polypropylene/graphene nanoplatelets nanocomposites with high conductivity via solid-state shear mixing

- Mechanical properties of fiber-reinforced asphalt concrete: Finite element simulation and experimental study

- Applying design of experiments (DoE) on the properties of buccal film for nicotine delivery

- Preparation and characterizations of antibacterial–antioxidant film from soy protein isolate incorporated with mangosteen peel extract

- Preparation and adsorption properties of Ni(ii) ion-imprinted polymers based on synthesized novel functional monomer

- Rare-earth doped radioluminescent hydrogel as a potential phantom material for 3D gel dosimeter

- Effects of cryogenic treatment and interface modifications of basalt fibre on the mechanical properties of hybrid fibre-reinforced composites

- Stable super-hydrophobic and comfort PDMS-coated polyester fabric

- Impact of a nanomixture of carbon black and clay on the mechanical properties of a series of irradiated natural rubber/butyl rubber blend

- Preparation and characterization of a novel composite membrane of natural silk fiber/nano-hydroxyapatite/chitosan for guided bone tissue regeneration

- Study on the thermal properties and insulation resistance of epoxy resin modified by hexagonal boron nitride

- A new method for plugging the dominant seepage channel after polymer flooding and its mechanism: Fracturing–seepage–plugging

- Analysis of the rheological property and crystallization behavior of polylactic acid (Ingeo™ Biopolymer 4032D) at different process temperatures

- Hybrid green organic/inorganic filler polypropylene composites: Morphological study and mechanical performance investigations

- In situ polymerization of PEDOT:PSS films based on EMI-TFSI and the analysis of electrochromic performance

- Effect of laser irradiation on morphology and dielectric properties of quartz fiber reinforced epoxy resin composite

- The optimization of Carreau model and rheological behavior of alumina/linear low-density polyethylene composites with different alumina content and diameter

- Properties of polyurethane foam with fourth-generation blowing agent

- Hydrophobicity and corrosion resistance of waterborne fluorinated acrylate/silica nanocomposite coatings

- Investigation on in situ silica dispersed in natural rubber latex matrix combined with spray sputtering technology

- The degradable time evaluation of degradable polymer film in agriculture based on polyethylene film experiments

- Improving mechanical and water vapor barrier properties of the parylene C film by UV-curable polyurethane acrylate coating

- Thermal conductivity of silicone elastomer with a porous alumina continuum

- Copolymerization of CO2, propylene oxide, and itaconic anhydride with double metal cyanide complex catalyst to form crosslinked polypropylene carbonate

- Combining good dispersion with tailored charge trapping in nanodielectrics by hybrid functionalization of silica

- Thermosensitive hydrogel for in situ-controlled methotrexate delivery

- Analysis of the aging mechanism and life evaluation of elastomers in simulated proton exchange membrane fuel cell environments

- The crystallization and mechanical properties of poly(4-methyl-1-pentene) hard elastic film with different melt draw ratios

- Review Articles

- Aromatic polyamide nonporous membranes for gas separation application

- Optical elements from 3D printed polymers

- Evidence for bicomponent fibers: A review

- Mapping the scientific research on the ionizing radiation impacts on polymers (1975–2019)

- Recent advances in compatibility and toughness of poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene succinate) blends

- Topical Issue: (Micro)plastics pollution - Knowns and unknows (Guest Editor: João Pinto da Costa)

- Simple pyrolysis of polystyrene into valuable chemicals

- Topical Issue: Recent advances of chitosan- and cellulose-based materials: From production to application (Guest Editor: Marc Delgado-Aguilar)

- In situ photo-crosslinking hydrogel with rapid healing, antibacterial, and hemostatic activities

- A novel CT contrast agent for intestinal-targeted imaging through rectal administration

- Properties and applications of cellulose regenerated from cellulose/imidazolium-based ionic liquid/co-solvent solutions: A short review

- Towards the use of acrylic acid graft-copolymerized plant biofiber in sustainable fortified composites: Manufacturing and characterization

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Research on the mechanism of gel accelerator on gel transition of PAN solution by rheology and dynamic light scattering

- Gel point determination of gellan biopolymer gel from DC electrical conductivity

- Composite of polylactic acid and microcellulose from kombucha membranes

- Synthesis of highly branched water-soluble polyester and its surface sizing agent strengthening mechanism

- Fabrication and characterization of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) modified with nano-montmorillonite biocomposite

- Fabrication of N-halamine polyurethane films with excellent antibacterial properties

- Formulation and optimization of gastroretentive bilayer tablets of calcium carbonate using D-optimal mixture design

- Sustainable nanocomposite films based on SiO2 and biodegradable poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) (PHBH) for food packaging

- Evaluation of physicochemical properties of film-based alginate for food packing applications

- Electrically conductive and light-weight branched polylactic acid-based carbon nanotube foams

- Structuring of hydroxy-terminated polydimethylsiloxane filled by fumed silica

- Surface functionalization of nanostructured Cu/Ag-deposited polypropylene fiber by magnetron sputtering

- Influence of composite structure design on the ablation performance of ethylene propylene diene monomer composites

- MOFs/PVA hybrid membranes with enhanced mechanical and ion-conductive properties

- Improvement of the electromechanical properties of thermoplastic polyurethane composite by ionic liquid modified multiwall carbon nanotubes

- Natural rubber latex/MXene foam with robust and multifunctional properties

- Rheological properties of two high polymers suspended in an abrasive slurry jet

- Two-step polyaniline loading in polyelectrolyte complex membranes for improved pseudo-capacitor electrodes

- Preparation and application of carbon and hollow TiO2 microspheres by microwave heating at a low temperature

- Properties of a bovine collagen type I membrane for guided bone regeneration applications

- Fabrication and characterization of thermoresponsive composite carriers: PNIPAAm-grafted glass spheres

- Effect of talc and diatomite on compatible, morphological, and mechanical behavior of PLA/PBAT blends

- Multifunctional graphene nanofiller in flame retarded polybutadiene/chloroprene/carbon black composites

- Strain-dependent wicking behavior of cotton/lycra elastic woven fabric for sportswear

- Enhanced dielectric properties and breakdown strength of polymer/carbon nanotube composites by coating an SrTiO3 layer

- Analysis of effect of modification of silica and carbon black co-filled rubber composite on mechanical properties

- Polytriazole resins toughened by an azide-terminated polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (OADTP)

- Phosphine oxide for reducing flammability of ethylene-vinyl-acetate copolymer

- Study on preparation and properties of bentonite-modified epoxy sheet molding compound

- Polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS)-modified phenolic resin: Synthesis and anti-oxidation properties

- Study on structure and properties of natural indigo spun-dyed viscose fiber

- Biodegradable thermoplastic copolyester elastomers: Methyl branched PBAmT

- Investigations of polyethylene of raised temperature resistance service performance using autoclave test under sour medium conditions

- Investigation of corrosion and thermal behavior of PU–PDMS-coated AISI 316L

- Modification of sodium bicarbonate and its effect on foaming behavior of polypropylene

- Effect of coupling agents on the olive pomace-filled polypropylene composite

- High strength and conductive hydrogel with fully interpenetrated structure from alginate and acrylamide

- Removal of methylene blue in water by electrospun PAN/β-CD nanofibre membrane

- Theoretical and experimental studies on the fabrication of cylindrical-electrode-assisted solution blowing spinning nanofibers

- Influence of l-quebrachitol on the properties of centrifuged natural rubber

- Ultrasonic-modified montmorillonite uniting ethylene glycol diglycidyl ether to reinforce protein-based composite films

- Experimental study on the dissolution of supercritical CO2 in PS under different agitators

- Experimental research on the performance of the thermal-reflective coatings with liquid silicone rubber for pavement applications

- Study on controlling nicotine release from snus by the SIPN membranes

- Catalase biosensor based on the PAni/cMWCNT support for peroxide sensing

- Synthesis and characterization of different soybean oil-based polyols with fatty alcohol and aromatic alcohol

- Molecularly imprinted electrospun fiber membrane for colorimetric detection of hexanoic acid

- Poly(propylene carbonate) networks with excellent properties: Terpolymerization of carbon dioxide, propylene oxide, and 4,4ʹ-(hexafluoroisopropylidene) diphthalic anhydride

- Polypropylene/graphene nanoplatelets nanocomposites with high conductivity via solid-state shear mixing

- Mechanical properties of fiber-reinforced asphalt concrete: Finite element simulation and experimental study

- Applying design of experiments (DoE) on the properties of buccal film for nicotine delivery

- Preparation and characterizations of antibacterial–antioxidant film from soy protein isolate incorporated with mangosteen peel extract

- Preparation and adsorption properties of Ni(ii) ion-imprinted polymers based on synthesized novel functional monomer

- Rare-earth doped radioluminescent hydrogel as a potential phantom material for 3D gel dosimeter

- Effects of cryogenic treatment and interface modifications of basalt fibre on the mechanical properties of hybrid fibre-reinforced composites

- Stable super-hydrophobic and comfort PDMS-coated polyester fabric

- Impact of a nanomixture of carbon black and clay on the mechanical properties of a series of irradiated natural rubber/butyl rubber blend

- Preparation and characterization of a novel composite membrane of natural silk fiber/nano-hydroxyapatite/chitosan for guided bone tissue regeneration

- Study on the thermal properties and insulation resistance of epoxy resin modified by hexagonal boron nitride

- A new method for plugging the dominant seepage channel after polymer flooding and its mechanism: Fracturing–seepage–plugging

- Analysis of the rheological property and crystallization behavior of polylactic acid (Ingeo™ Biopolymer 4032D) at different process temperatures

- Hybrid green organic/inorganic filler polypropylene composites: Morphological study and mechanical performance investigations

- In situ polymerization of PEDOT:PSS films based on EMI-TFSI and the analysis of electrochromic performance

- Effect of laser irradiation on morphology and dielectric properties of quartz fiber reinforced epoxy resin composite

- The optimization of Carreau model and rheological behavior of alumina/linear low-density polyethylene composites with different alumina content and diameter

- Properties of polyurethane foam with fourth-generation blowing agent

- Hydrophobicity and corrosion resistance of waterborne fluorinated acrylate/silica nanocomposite coatings

- Investigation on in situ silica dispersed in natural rubber latex matrix combined with spray sputtering technology

- The degradable time evaluation of degradable polymer film in agriculture based on polyethylene film experiments

- Improving mechanical and water vapor barrier properties of the parylene C film by UV-curable polyurethane acrylate coating

- Thermal conductivity of silicone elastomer with a porous alumina continuum

- Copolymerization of CO2, propylene oxide, and itaconic anhydride with double metal cyanide complex catalyst to form crosslinked polypropylene carbonate

- Combining good dispersion with tailored charge trapping in nanodielectrics by hybrid functionalization of silica

- Thermosensitive hydrogel for in situ-controlled methotrexate delivery

- Analysis of the aging mechanism and life evaluation of elastomers in simulated proton exchange membrane fuel cell environments

- The crystallization and mechanical properties of poly(4-methyl-1-pentene) hard elastic film with different melt draw ratios

- Review Articles

- Aromatic polyamide nonporous membranes for gas separation application

- Optical elements from 3D printed polymers

- Evidence for bicomponent fibers: A review

- Mapping the scientific research on the ionizing radiation impacts on polymers (1975–2019)

- Recent advances in compatibility and toughness of poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene succinate) blends

- Topical Issue: (Micro)plastics pollution - Knowns and unknows (Guest Editor: João Pinto da Costa)

- Simple pyrolysis of polystyrene into valuable chemicals

- Topical Issue: Recent advances of chitosan- and cellulose-based materials: From production to application (Guest Editor: Marc Delgado-Aguilar)

- In situ photo-crosslinking hydrogel with rapid healing, antibacterial, and hemostatic activities

- A novel CT contrast agent for intestinal-targeted imaging through rectal administration

- Properties and applications of cellulose regenerated from cellulose/imidazolium-based ionic liquid/co-solvent solutions: A short review

- Towards the use of acrylic acid graft-copolymerized plant biofiber in sustainable fortified composites: Manufacturing and characterization