Abstract

In this paper, acrylonitrile and hydroxypropyl acrylate are used as the binary polymerization monomers, and isooctane is used as the foaming agent to prepare high-temperature thermally expandable microcapsules. Analysis of the effect of blowing agent and crosslinking agent on the expansion properties of high-temperature thermally expandable microcapsules, the effects of foaming agent azodicarbonamide (ADCA) and micro-expansion capsule on the surface quality and foaming quality of foamed acrylonitrile–butadiene–styrene (ABS) products were investigated. The foamed product prepared by the high-temperature microcapsule has a good surface quality, the gloss is 52.3, the cell is not easily deformed, and the volume fraction is 4%; the foamed ABS/ADCA material has poor cell uniformity, the cell is easily deformed, the volume fraction is 6.5%, the surface quality is poor, and the gloss is only 8.7.

1 Introduction

In the 1970s, the thermally expandable microcapsules were invented by Dow Chemical Co. It is a hydrocarbon compound of micron-sized core shell and thermoplastic polymer shell (1,2,3,4,5). The preparation method of thermally expandable microcapsules is generally prepared by suspension polymerization. The suspension polymerization method is a radical polymerization method in which an initiator monomer is suspended in water in the form of droplets, which is divided into an aqueous phase and an oil phase, and polymerization occurs in each small droplet (6,7,8,9,10). In the field of micro-foaming, thermally expandable microcapsules can solve the problem of foaming quality and surface quality of foamed materials (11,12). However, the foaming temperature of the thermally expandable microcapsules required is different for the matrix material. In order to broaden the application of the foaming material, the synthesis of the high-temperature thermally expandable microcapsule is a research field at home and abroad.

At present, most studies focus on the preparation of normal temperature microspheres. Jeong Gon Kim et al. (13) prepared the thermally expandable microspheres by suspension polymerization using halloysite nanotubes (HNTs) as dispersion stabilizers. It was found that the average size of microcapsules gradually decreased with the increase in HNTs concentration. Sun Kyoung Jeoung (14) prepared the microspheres of different particle sizes by acrylonitrile (AN) and methacrylonitrile (MAN) as polymerization monomers, using halloysite nanotubes and polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) as emulsifiers and stabilizers, respectively; the microspheres of the PVP series were found to have a larger expansion ratio than the HNTS series. Ji Hyun Bu (15) used polyacrylonitrile–methyl methacrylate as the outer shell and n-octane as the blowing agent; the thermally expandable microspheres were prepared by suspension polymerization. They found that when adding polyvinyl alcohol as a stabilizer, the appearance of the microspheres is smooth and regular. Liu Wei (16) used 2,2′-azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) as an initiator to study the effect of different reaction temperatures on the swelling properties of thermally expandable microspheres. It was found that the foaming temperature gradually increased with an increase in reaction temperature, but the temperature was 70°C, foaming microspheres are easily broken. Jahankhanemlou (17) used triethylene glycol dimethacrylate (TEGDMA) as a crosslinking agent and polymethyl methacrylate as a polymeric shell to synthesize thermally expandable microspheres by suspension polymerization. They found that small changes of TEGDMA can affect the performance of the microspheres, the greater the concentration of the crosslinking agent, the larger the average particle size of the microspheres, and the less likely to expand. Li Jun Wang et al. (18) prepared epoxy foaming material using expandable microspheres as a blowing agent, they found that the material has the advantages of low density and high compressive capacity. Sun Kyung Jeoung (19) prepared foamed polypropylene material by thermally expandable microspheres. It was found that the density of foamed polypropylene (PP) material gradually decreased with anincrease inthermally expandable microspheres, foamed PP materials exhibit higher impact resistance. The above work has been done on the research of microsphere synthesis and foam composites at room temperature, and they have achieved some results. However, there are few studies on high-temperature microspheres, the effects of thermally expandable microsphere components and processes on microspherical features are difficult to replicate because of the influence of synthetic equipment and environment. How to prepare shape features and grains uniform high-temperature microspheres will be the key issue in this paper, it provides guidance and theoretical reference for the industrial production of thermally expandable microspheres.

In this paper, acrylonitrile and hydroxypropyl acrylate are selected as binary polymerization monomers, and isooctane is used as a blowing agent to prepare high-temperature thermally expandable microcapsules. We analyzed the effects of blowing agents and crosslinking agents on morphology, particle size, and thermal expansion properties of high-temperature thermal expansion using TG, DSC, SEM, and other techniques. At the same time, the effects of foaming agent azodicarbonamide (ADCA) and microspheres on the surface quality and foaming quality of foamed ABS composites were discussed, which laid a solid foundation for the lightweight industrial application of automobiles.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

Acrylonitrile (Analytical purity) was purchased from Tianjin Comomi Chemical Reagent Development Center, Tianjin, China. Isooctane (IO, Analytical purity) was gained from Tianjin Guangfu Fine Chemicals Research Institute, Tianjin, China. Sodium hydroxide (NaOH, Analytical purity) was gained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China. Sodium chloride (NaCl, Analytical purity) was gained from Aladdin Reagent Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China. Hydroxypropyl acrylate (HPA, analytical purity) was gained from Aladdin Reagent Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China. Ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA, 98%) was purchased from Aladdin Reagent Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China. Azodicarbonamide was purchased from Wuhan Han Hong Chemical Plant, Wuhan, China, with a gas generation of 230 mL g−1. ABS plastic was gained from Taiwan Chimei Industrial Co., Ltd, Taiwan, China.

2.2 Preparation of samples

2.2.1 Preparation of high-temperature thermally expandable microspheres

Stable aqueous phase system is prepared by adding water, sodium hydroxide, sodium chloride, and other additives to stir in the beaker. The oil phase system was prepared by uniform stirring according to the weight percentage in Table 1 in another beaker; the aqueous phase and the oil phase were mixed to obtain a stable dispersion suspension under cooling; and the stirring process parameters were as follows: homogenization time of 10–14 min and homogenization rate of 7,000–8,250 rpm. The dispersion suspension was added to the flask, sealed, and stirred at a high speed to form a uniform emulsion. The reaction temperature was 60°C, the reaction time was 22 h, and the reaction was completed at room temperature, filtered, washed, and freeze-dried to obtain thermally expanded microspheres.

Formulation of high-temperature thermally expandable microspheres

| Monomer | Foaming agent | Foaming agent content (wt%) | Crosslinking agent content (wt%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AN | HPA | IO | 11.7 | 0.58 |

| 28.5 | 0.58 | |||

| 39.9 | 0.58 | |||

| 48.1 | 0.58 | |||

| 28.5 | 0.29 | |||

| 28.5 | 0.58 | |||

| 28.5 | 0.87 | |||

| 28.5 | 1.17 | |||

2.2.2 Preparation of foamed ADCA masterbatch

After the foaming agent, ADCA is dried at 60°C for about 10 h, the ABS resin is uniformly mixed with ADAC at a ratio of 9:1 on twin-screw extruder (CTE20, Coperon Koya Nanjing Machinery Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China) to obtain foamed ADCA masterbatch, and the extrusion process parameters were as follows: extrusion temperature of 90–120°C, screw speed of 150 rpm, and the feeding speed of 10 rpm.

2.2.3 Preparation of high-temperature thermally expandable microsphere masterbatch

The microspheres were dried in a hot blast dryer (101-3, Tianjin Taishite Instrument Co., Ltd, Tianjin, China.) at 40°C for about 10 h. ABS resin is uniformly mixed with high-temperature expandable microspheres at a ratio of 9:1 on a two-roll mill (SK-100 type, Shanghai Kechuang Rubber & Plastic Machinery Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China) to obtain masterbatch, and the extrusion process parameters were as follows: the front roll temperature of 80°C and the back roll temperature of 85°C.

2.2.4 Preparation of foaming ABS material

The foamed microsphere masterbatch and ADCA masterbatch were uniformly mixed with ABS resin at a ratio of 9:1 on an injection molding machine (EM120-V, Zhende Plastic Machinery Co., Ltd, Guangdong, China) to obtain foamed ABS composites, and injection molding process parameters were as follows: injection temperature of 190–210°C, injection speed of 95%, and injection pressure of 45%.

2.3 Testing and characterization

2.3.1 Characterization of cell structure

The morphologies of the foamed samples were shown using scanning electron microscope (SEM, EM6200, Beijing Zhongke, China). The samples were freeze fractured in liquid nitrogen and sputter-coated with gold; they were observed with an accelerating voltage of 25.0 kV. The volume fraction of the foamed material (Vf) is calculated by Eq. 1 (18).

where ρf was the foamed material density (g cm−3) and ρ was the unfoamed material density (g cm−3).

2.3.2 Thermal analysis

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) experiment was performed by a 200F3 instrument (Netzsch, Germany) under a nitrogen atmosphere. All samples were quickly heated up to 220°C and held for 5 min, followed by cooling down to 20°C at a rate of 10°C min−1.

2.3.3 Optical microscopy characterization

The thermally expandable microspheres were uniformly dispersed on a glass slide by an optical microscope to observe the morphology and particle size distribution of the microspheres, and the thermal expansion process was observed by heating on a hot stage.

2.3.4 Crosslinking degree testing of microsphere shell

The crosslinking degree of the microsphere shell (Q) was measured by the swelling method, and microsphere shell mass was measured with an electronic balance is m. After the uncrosslinked portion of the microsphere shell was dissolved by dimethyl sulfoxide, the mass of the remaining cross-linked microsphere shell is m0 by an electronic balance, and the degree of crosslinking is calculated according to Eq. 2 (20).

2.3.5 Characterization of surface quality of foamed samples

According to the ISO-2813 test standard, the foamed samples are directly tested by opening the gloss meter and the glossiness of the foamed samples are obtained by averaging. At the same time, Avercap video software was used to capture and save surface quality pictures.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Effect of blowing agent on the expansion properties of high-temperature thermally expandable microspheres

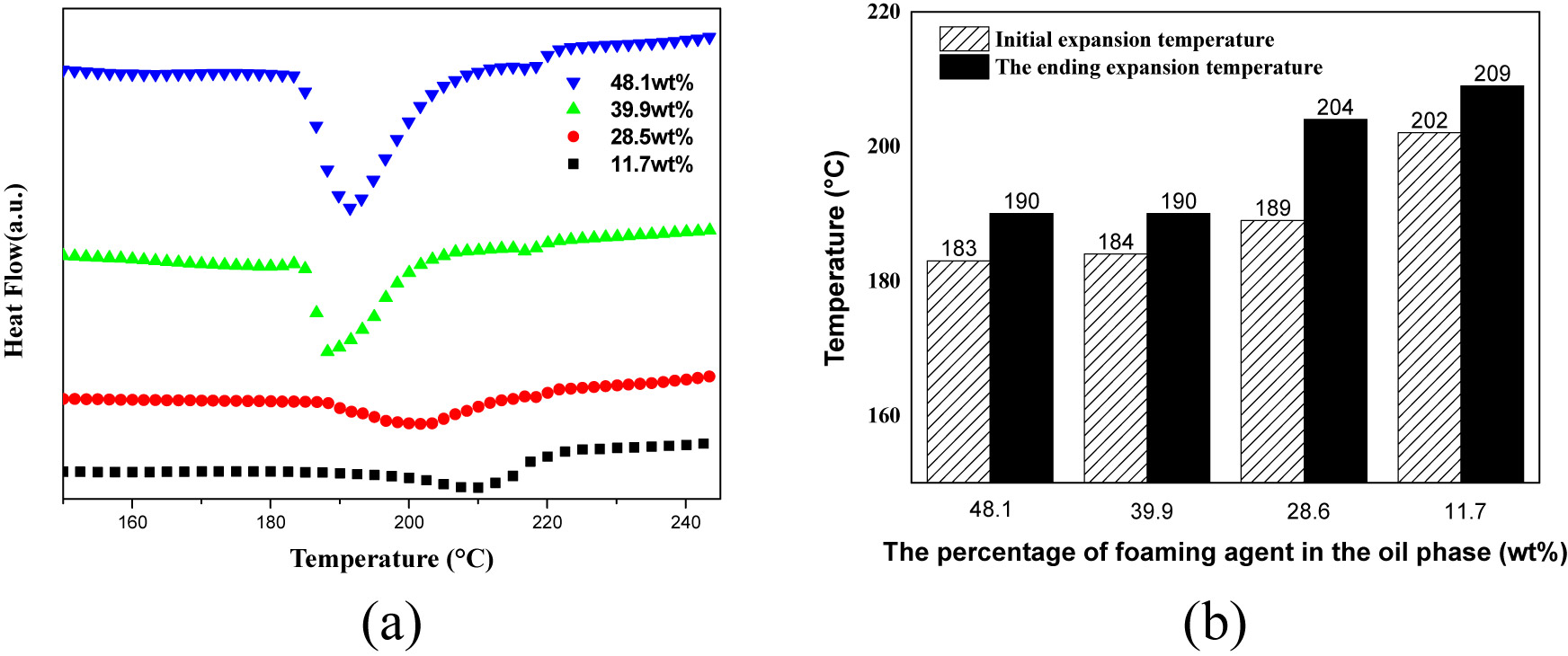

The DSC curve and expansion temperature of the expanded microspheres prepared by different content of foaming agents are shown in Figure 1. It can be seen from the figure that as the content of the thermal expansion microsphere foaming agent increases, the initial foaming temperature and the ending foaming temperature of the microspheres decrease. This was because the content of the foaming agent increases in a certain range, the pressure of microsphere shell was larger, and the microspheres were more likely to expand when the melt strength and viscoelasticity of microsphere shell were constant, so that the expansion temperature was gradually decreased (Figure 2).

Effect of microsphere expansion temperature under different content of foaming agent: (a) DSC curve and (b) expansion temperature.

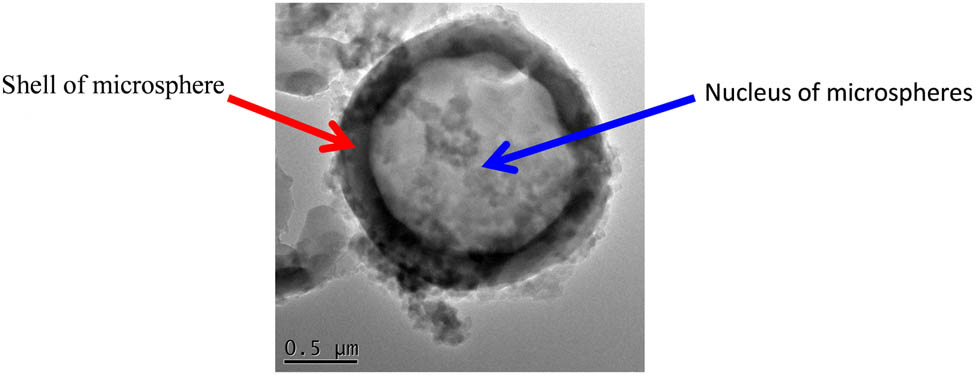

Microstructure of the microsphere “core–shell”.

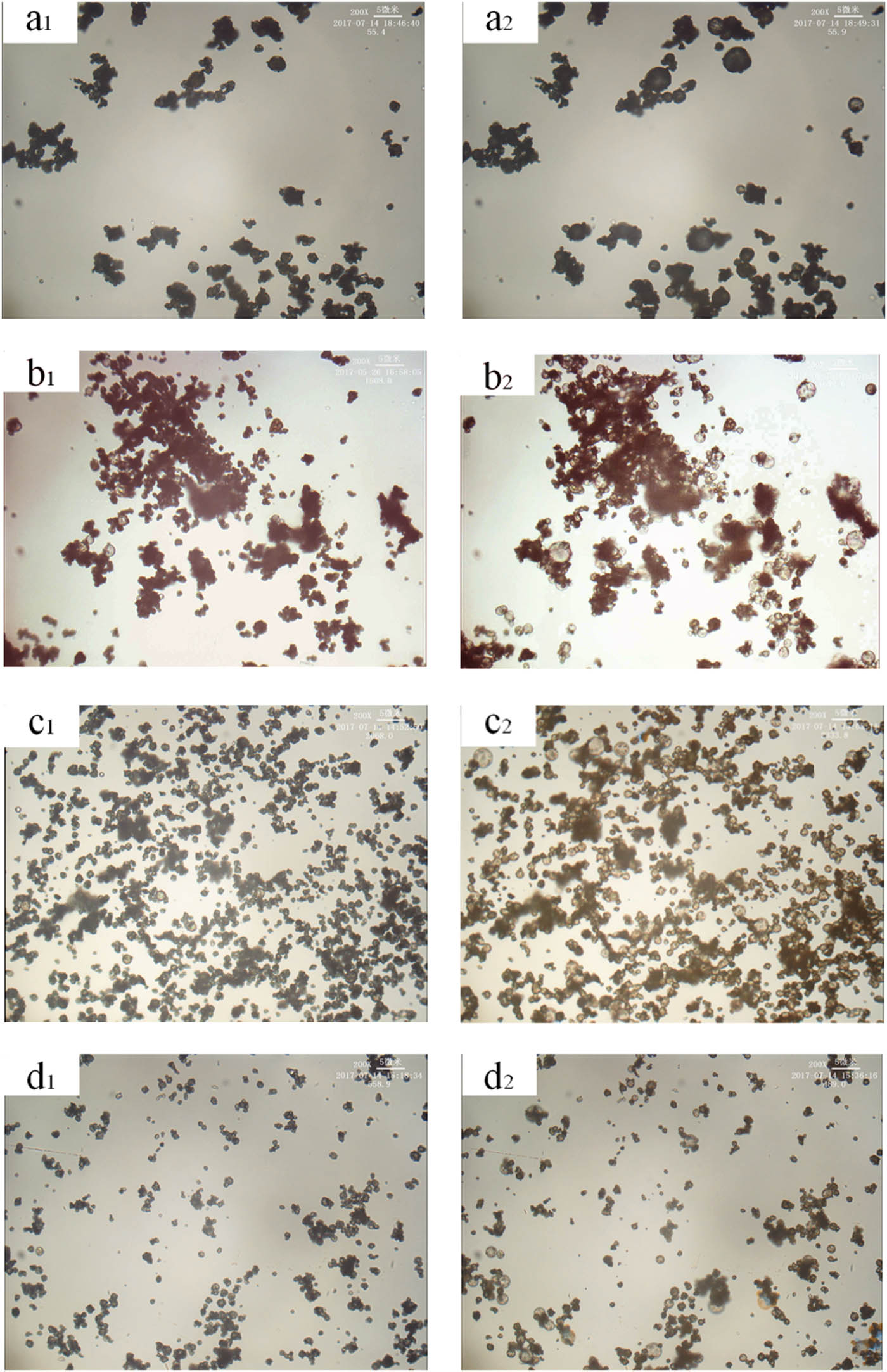

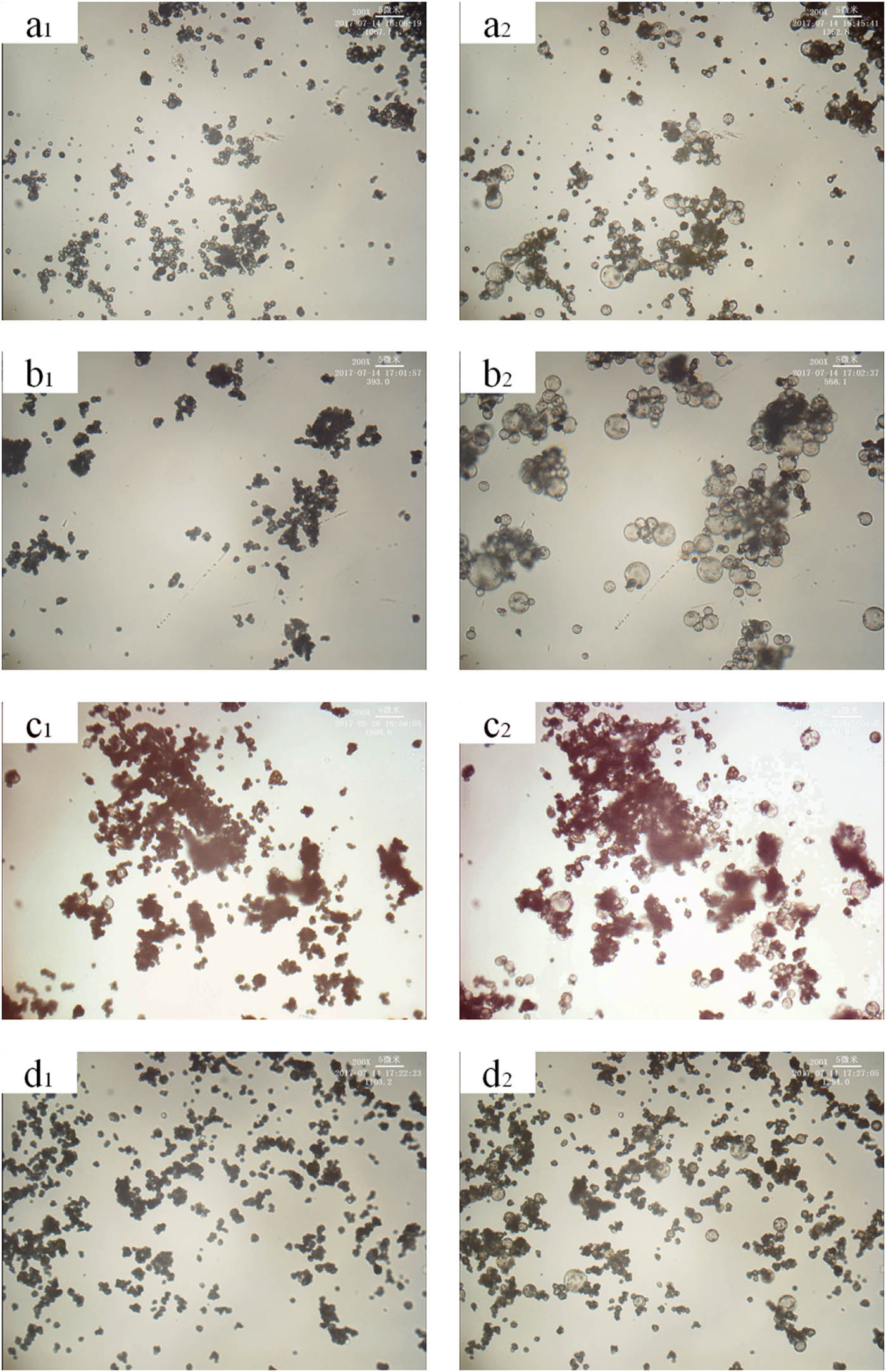

Figure 3 shows the effect of different blowing agent content on the expansion properties of thermally expanded microspheres. It can be seen from the figure that when the content of the foaming agent was 11.7 wt%, the expansion ratio of the thermally expandable microspheres was small. This may be because the foaming agent content in Figure 3a was small, and the internal pressure of the foaming agent was insufficient to cause a small expansion ratio of the microspheres. When the foaming agent content was 28.5–39.9 wt%, the expansion ratio of microspheres was moderate and can be foamed generally, and the expansion stability of microspheres was better. When the content of the foaming agent was 48.1 wt%, although the microspheres can expand, there was an instantaneous bursting phenomenon and the expansion stability of the microspheres was poor. Therefore, when the content of the foaming agent was too high or low, it was not suitable for the synthesis of high-temperature microspheres.

Effect of different content of foaming agent on the expansion properties of microspheres under the conditions of a certain expansion temperature and crosslinking agent content (see Table 1). (a–d) The foaming agent content: 11.7 wt%, 28.5 wt%, 39.9 wt%, 48.1 wt%. (a1–d1) Pre-expansion sample and (a2–d2) expanded sample.

3.2 Effect of a crosslinking agent on the expansion properties of high-temperature thermally expandable microspheres

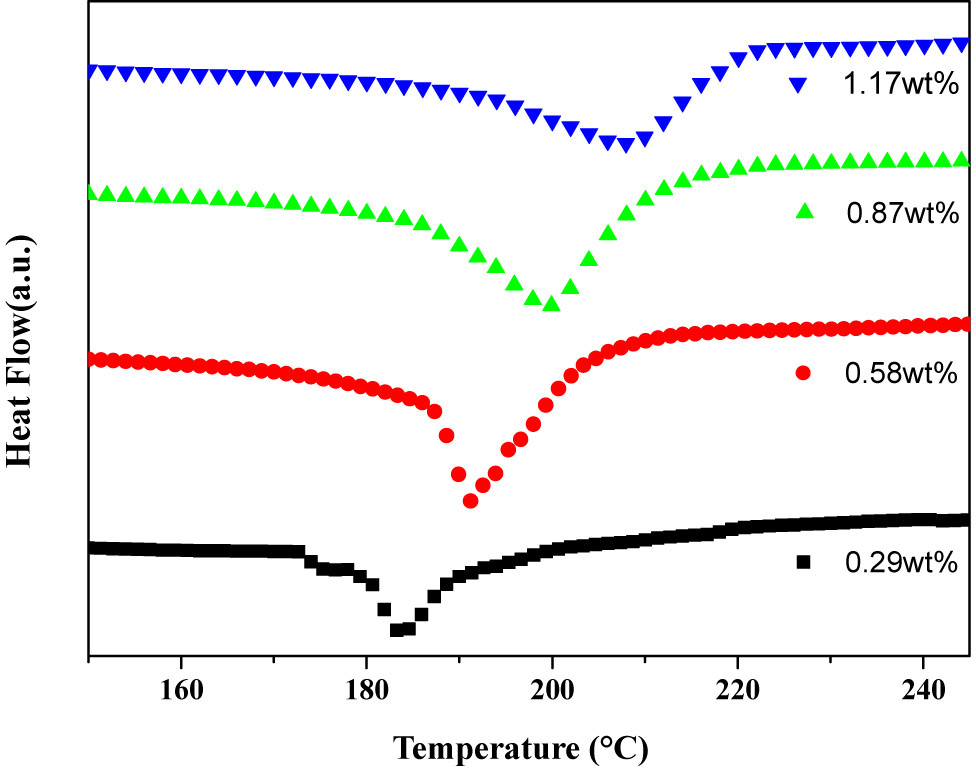

Figure 4 was a DSC curve of the thermally expandable microspheres with different crosslinking agent contents. It can be seen from the figure that as the content of the crosslinking agent increases, the expansion temperature of thermally expandable microspheres increases, which indicates that increasing of crosslinking agent content can increase the heat resistance of the microspheres. The main reason was the increase of crosslinking agent content, which improves the crosslinking degree of microsphere shell (shown in Table 2); the heat resistance of the microspheres was improved within a certain range.

DSC curves of different crosslinking agent content microspheres

Effect of crosslinking agent content on crosslinking degree of microspheres

| Crosslinking agenta content (wt%) | Sample weight (g) | Crosslinking part weight (g) | Degree of crosslinking (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.29 | 0.2452 | 0.1025 | 41.8 ± 0.27 |

| 0.58 | 0.3260 | 0.1736 | 53.3 ± 0.21 |

| 0.87 | 0.3245 | 0.2691 | 82.9 ± 0.31 |

| 1.17 | 0.2467 | 0.2289 | 89.9 ± 0.42 |

- a

The cross-linker is ethylene glycol dimethacrylate.

The effect of different crosslinking agent contents on the expansion properties of thermally expandable microspheres was shown in Figure 5. It can be seen from the figure that the stability of the microspheres was poor after expansion when the content of the crosslinking agent was 0.29 wt%. This may be because crosslinking agent content was small, the formed microsphere shell has a low crosslinking density, and the rigidity was poor, so the shape of the expanded microsphere was difficult to maintain. When the crosslinking agent content was 0.58 wt% and 0.87 wt%, the microspheres can generally expand, and the original shape of microspheres can be stably maintained after expansion. When crosslinking agent content was 1.17 wt%, the foaming performance of microspheres was poor. This may be because the microsphere shell was too rigid to result in a small expansion ratio of microspheres.

Effect of different content of crosslinking agents on the expansion properties of microspheres. (a–d) Crosslinking agent content: 0.29 wt%, 0.58 wt%, 0.87 wt%, 1.17 wt%. (a1–d1) Pre-expansion sample. (a2–d2) Expanded sample.

3.3 Study on foaming quality and surface quality of foamed ABS materials

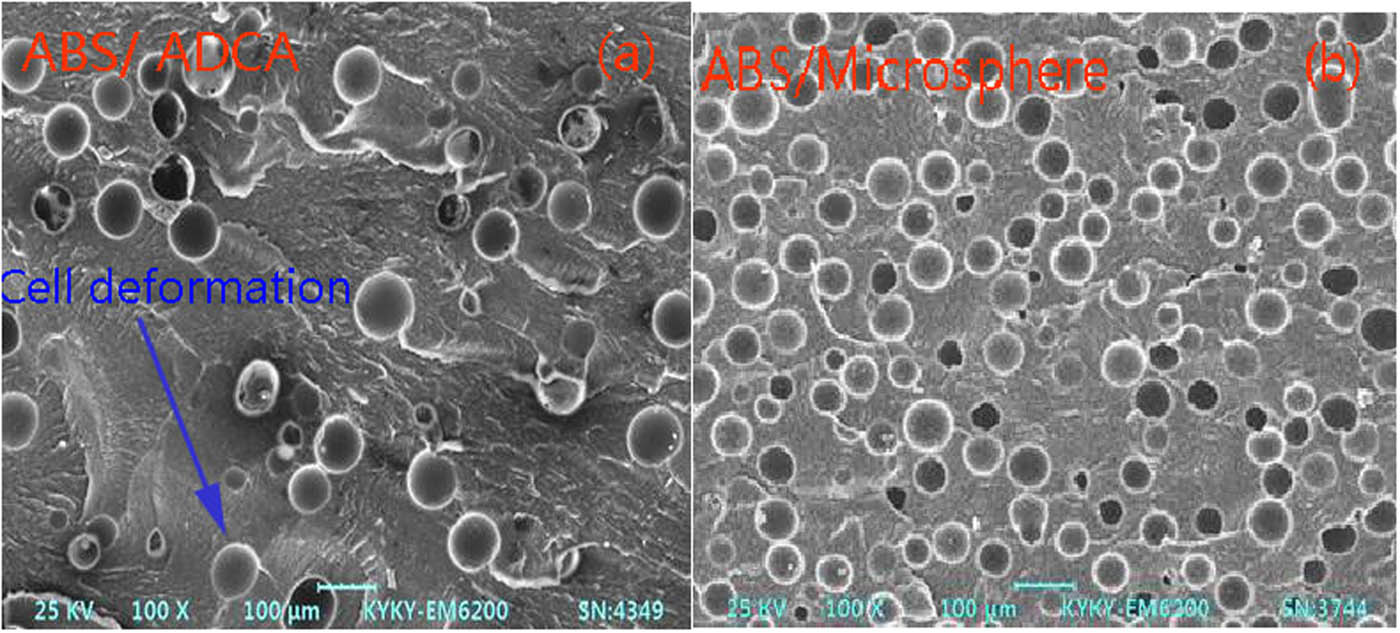

3.3.1 Foaming quality analysis of foamed ABS materials

The cell structure of the foamed ABS material was observed using the injection visualization device, as shown in Figure 6. It can be seen from the figure that foamed ABS material of by adding ADCA have a large diameter and uniform size, the cell has a certain degree of deformation and a small volume fraction, and the volume fraction is 4%. The foamed ABS material with microspheres has relatively small cell diameter and uniform size, the cells are independent and a big volume fraction, and the volume fraction is 6.5%. Therefore, the foamed ABS material with microspheres can maintain the regular spherical shape, and the foaming quality is ideal.

Cell structure of foamed ABS material under injection molding.

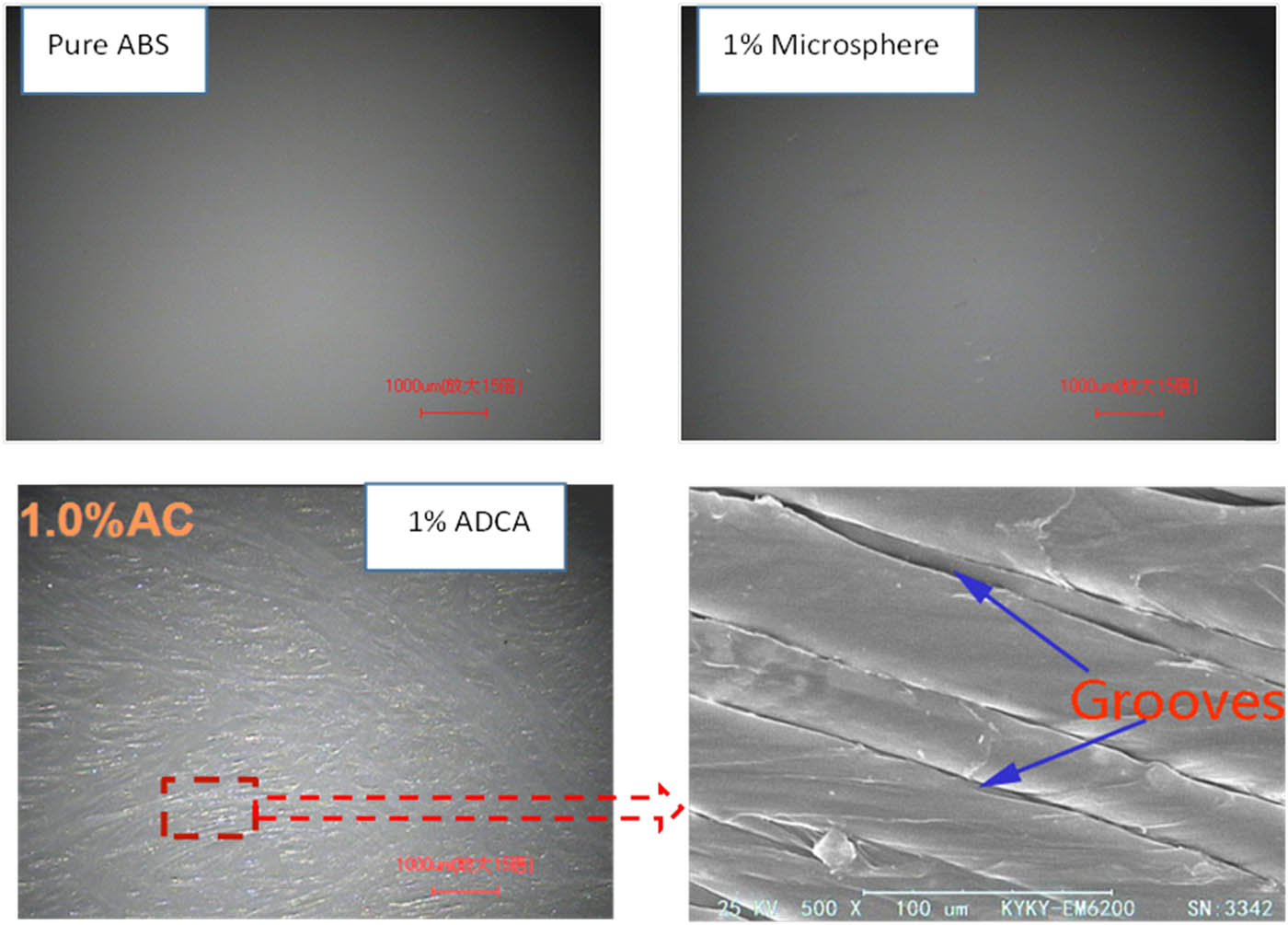

3.3.2 Analysis of surface quality of foamed ABS materials

The surface quality of the foamed ABS material was characterized by a light microscopy system, as shown in Figure 7. As can be seen from the figure, the surface of pure ABS material is smooth and excellent in flatness. The surface quality of foamed ABS material with a microsphere is relatively smooth and has good flatness, but it has a small number of grooves, and the surface quality is not much different from that of pure ABS. The surface quality of foamed ABS material with ADCA is rough, and a large number of gas marks appear on the surface of the sample, which greatly affects the surface quality of the foamed product, so that its appearance is poor. The reason is that the ADCA is added to the ABS material to foam, the gas generated by the decomposition of ADCA forms a gas mark on the surface of the foamed product, so that its surface quality is poor. Gas generated by the expansion of microspheres is surrounded by the microsphere shell, and the gas does not escape on the surface of the foamed product to leave a gas mark, so that the surface quality of the foamed product is good.

Surface quality of foamed ABS material under a light microscope.

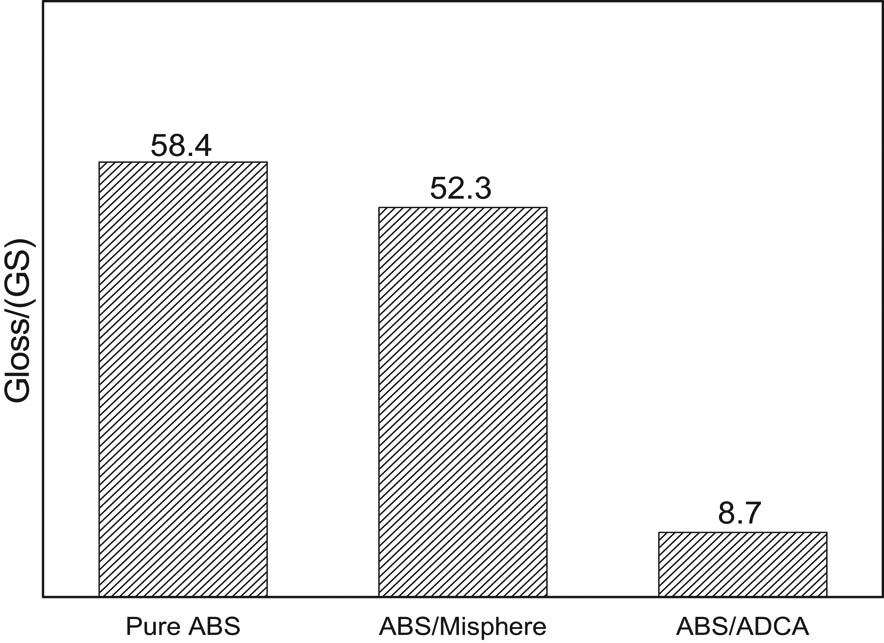

Figure 8 is the effect of a foaming agent on the gloss of foamed ABS material. It can be seen from the figure that the surface gloss of pure ABS products is better, which is 58.4; the surface gloss of foamed ABS materials prepared by using microspheres as a foaming agent is ideal, which is 52.3. The foamed ABS material prepared by using ADCA as a foaming agent has a poor gloss, which is 8.7. It indicates that the surface quality of the foamed ABS material prepared by the ADCA is poor, and the surface quality of the foamed ABS material prepared by using the microsphere as the foaming agent is good. The microsphere foaming agent can greatly improve the surface quality of the foamed product. The main reason is that the foamed ABS material prepared by ADCA as a foaming agent exhibits a typical “spring surge effect” during the foaming process (Figure 9a); the center melt is continuously updated to the front surface. Under the influence of the spring flow, the gas is brought to the upper and lower surfaces of the cavity, and the surface gas marks are present with the mold cools and solidifies. Foamed ABS material with microspheres has typical “core–shell” structure (Figure 9b). When the microspheres are raised to a certain temperature, the core of the microspheres decomposes to generate gas, which causes the microsphere shell to expand to form cells; the microsphere core generates gas completely to cover by the microsphere shell; there is no gas in the ABS melt, so there is no “spring surge effect,” and the surface quality of the foamed ABS material prepared by using the microsphere as the foaming agent is ideal.

Effect of blowing agent on the gloss of foamed ABS material.

Effect of surface quality of micro foamed ABS material: (a) spring surge effect and (b) “core–shell” structure of microspheres.

4 Conclusion

When the blowing agent isooctane is added in an amount of 28.5 wt% to 39.9 wt% and the crosslinking agent is added in an amount of 0.87 wt%, the synthesized microspheres have better thermal expansion properties and the expansion temperature of the microspheres is higher. The expansion temperature ranges from 180°C to 209°C.

Foamed ABS material with high-temperature microspheres has good foaming quality. The cells are not easily deformed, the cell size is relatively uniform, and the volume fraction is 4%. The foamed ABS material with ADCA has poor bubble quality, the cell size is not uniform, the cell deformation is severe, and the volume fraction is 6.5%. Under the condition of injection molding, the surface quality of foamed ABS sample with the microsphere is good, it has no gas marks and the glossiness is 52.3; the surface quality of ABS-foamed sample with ADCA is poor, and it has a large number of gas marks, the glossiness is 8.7.

Acknowledgments

Research Institute Service Enterprise Action Plan Project of Guizhou Provincial ([2018]4010); the Hundred Talents Project of Guizhou Province ([2016]5673); The National Nature Fund of China (21764004).

References

(1) Shule L, Kun W, Jiang C. New progress in microsphere technology. Polym Mater Sci Eng. 2012;28:179–82.Search in Google Scholar

(2) Chen SY, Sun ZC, Li LH. Preparation and characterization of thermally expandable microspheres. Mater Sci Forum. 2016;852:596–600.10.4028/www.scientific.net/MSF.852.596Search in Google Scholar

(3) Fasihi M, Targhi AA, Bayat H. The simultaneous effect of nucleating and blowing agents on the cellular structure of polypropylene foamed via the extrusion process. e-Ploymers. 2016;16:235–41.10.1515/epoly-2016-0033Search in Google Scholar

(4) Kawaguchi Y, Itamura Y, Onimura K, Oishi T. Effects of the chemical structure on the heat resistance of thermoplastic expandable microspheres. J Appl Polym Sci. 2010;96:1306–12.10.1002/app.21429Search in Google Scholar

(5) Zhou Y, He L, Gong W. Effects of zinc acetate and cucurbit[6]uril on PP composites: crystallization behavior, foaming performance and mechanical properties. e-Polymers. 2018;18:491–9.10.1515/epoly-2018-0107Search in Google Scholar

(6) Jonsson M, Nordin O, Kron AL, Malmström E. Influence of crosslinking on the characteristics of thermally expandable microspheres expanding at high temperature. J Appl Polym Sci. 2010;118:1219–29.10.1002/app.32301Search in Google Scholar

(7) Hou ZS, Kan CY. Preparation and properties of thermo-expandable polymeric microspheres. Chin Chem Lett. 2014;25:1279–81.10.1016/j.cclet.2014.04.011Search in Google Scholar

(8) Jonsson M, Nordin O, Malmstrom E. Increased onset temperature of expansion in thermally expandable microspheres through combination of crosslinking agents. J Appl Polym Sci. 2011;121:369–75.10.1002/app.33585Search in Google Scholar

(9) Lin H, Lu G, Pu Y. Effect of crosslinking agent on preparation of expandable small balls. Polym Mater Sci Eng. 2012;28:65–68.Search in Google Scholar

(10) Safajou-Jahankhanemlou M, Abbasi F, Salami-Kalajahi M. Synthesis and characterization of poly(methyl methacrylate)/graphene-based thermally expandable microcapsules. Polym Compos. 2016;39:950–60.10.1002/pc.24025Search in Google Scholar

(11) Vamvounis G, Jonsson M, Malmstrom E, Hult A. Synthesis and properties of poly(3-n-dodecylthiophene) modified thermally expandable microspheres. Eur Polym J. 2013;49:1503–9.10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2013.01.010Search in Google Scholar

(12) Lu Y, Broughton J, Winfield P. Surface modification of thermally expandable microspheres for enhanced performance of disbondable adhesive. Int J Adhes Adhes. 2016;66:33–40.10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2015.12.007Search in Google Scholar

(13) Kim JG, Ha JU, Jeoung SK, Lee K, Baeck S-H, Shim SE. Halloysite nanotubes as a stabilizer: fabrication of thermally expandable microcapsules via Pickering suspension polymerization. Colloid Polym Sci. 2015;293:3595–602.10.1007/s00396-015-3731-4Search in Google Scholar

(14) Jeoung SK, Han IS, Jung YJ, Hong S, Shim SE, Hwang YJ, et al. Fabrication of thermally expandable core–shell microcapsules using organic and inorganic stabilizers and their application. J Appl Polym Sci. 2016;133:44247.10.1002/app.44247Search in Google Scholar

(15) Bu JH, Kim Y, Ha JU, Shim SE. Suspension polymerization of thermally expandable microcapsules with core–shell structure using the SPG emulsification technique: influence of crosslinking agents and stabilizers. Polymer. 2015;39:78–87.10.7317/pk.2015.39.1.78Search in Google Scholar

(16) Wei L. Preparation and foaming properties of core–shell structured thermoplastic expanded microspheres [D]. Hefei University of Technology; 2015.Search in Google Scholar

(17) Safajou Jahankhanemlou M, Abbasi F, Salami-Kalajahi M. Synthesis and characterization of thermally expandable PMMA-based microcapsules with different cross-linking density. Colloid Polym Sci. 2016;294:1–10.10.1007/s00396-016-3862-2Search in Google Scholar

(18) Wang LJ, Yang X, Zhang J, Zhang C, He L. The compressive properties of expandable microspheres/epoxy foams. Composites Part B. 2014;56:724–32.10.1016/j.compositesb.2013.09.030Search in Google Scholar

(19) Sun KJ, Ye JH, Lee HW, Kwak SB, Han I-S, Ha JU. Polypropylenes foam consisting of thermally expandable microcapsule as blowing agent. The International Conference of the Polymer Processing Society – Conference Papers; 2016. p. 1731.Search in Google Scholar

(20) He PS, Yang HY, Zhu PP. Polymer physics experiment. University of Science and Technology of China Press; 2002.Search in Google Scholar

© 2020 Wei Gong et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The regulatory effects of the number of VP(N-vinylpyrrolidone) function groups on macrostructure and photochromic properties of polyoxometalates/copolymer hybrid films

- How the hindered amines affect the microstructure and mechanical properties of nitrile-butadiene rubber composites

- Novel benzimidazole-based conjugated polyelectrolytes: synthesis, solution photophysics and fluorescent sensing of metal ions

- Study on the variation of rock pore structure after polymer gel flooding

- Investigation on compatibility of PLA/PBAT blends modified by epoxy-terminated branched polymers through chemical micro-crosslinking

- Investigation on degradation mechanism of polymer blockages in unconsolidated sandstone reservoirs

- Investigation on the effect of active-polymers with different functional groups for EOR

- Fabrication and characterization of hexadecyl acrylate cross-linked phase change microspheres

- Surface-induced phase transitions in thin films of dendrimer block copolymers

- ZnO-assisted coating of tetracalcium phosphate/ gelatin on the polyethylene terephthalate woven nets by atomic layer deposition

- Animal fat and glycerol bioconversion to polyhydroxyalkanoate by produced water bacteria

- Effect of microstructure on the properties of polystyrene microporous foaming material

- Synthesis of amphiphilic poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(methyl methacrylate) containing trityl ether acid cleavable junction group and its self-assembly into ordered nanoporous thin films

- On-demand optimize design of sound-absorbing porous material based on multi-population genetic algorithm

- Enhancement of mechanical, thermal and water uptake performance of TPU/jute fiber green composites via chemical treatments on fiber surface

- Enhancement of mechanical properties of natural rubber–clay nanocomposites through incorporation of silanated organoclay into natural rubber latex

- Preparation and characterization of corn starch/PVA/glycerol composite films incorporated with ε-polylysine as a novel antimicrobial packaging material

- Preparation of novel amphoteric polyacrylamide and its synergistic retention with cationic polymers

- Effect of montmorillonite on PEBAX® 1074-based mixed matrix membranes to be used in humidifiers in proton exchange membrane fuel cells

- Insight on the effect of a piperonylic acid derivative on the crystallization process, melting behavior, thermal stability, optical and mechanical properties of poly(l-lactic acid)

- Lipase-catalyzed synthesis and post-polymerization modification of new fully bio-based poly(hexamethylene γ-ketopimelate) and poly(hexamethylene γ-ketopimelate-co-hexamethylene adipate) copolyesters

- Dielectric, mechanical and thermal properties of all-organic PI/PSF composite films by in situ polymerization

- Morphological transition of amphiphilic block copolymer/PEGylated phospholipid complexes induced by the dynamic subtle balance interactions in the self-assembled aggregates

- Silica/polymer core–shell particles prepared via soap-free emulsion polymerization

- Antibacterial epoxy composites with addition of natural Artemisia annua waste

- Design and preparation of 3D printing intelligent poly N,N-dimethylacrylamide hydrogel actuators

- Multilayer-structured fibrous membrane with directional moisture transportability and thermal radiation for high-performance air filtration

- Reaction characteristics of polymer expansive jet impact on explosive reactive armour

- Synthesis of a novel modified chitosan as an intumescent flame retardant for epoxy resin

- Synthesis of aminated polystyrene and its self-assembly with nanoparticles at oil/water interface

- The synthesis and characterisation of porous and monodisperse, chemically modified hypercrosslinked poly(acrylonitrile)-based terpolymer as a sorbent for the adsorption of acidic pharmaceuticals

- Crystal transition and thermal behavior of Nylon 12

- All-optical non-conjugated multi-functionalized photorefractive polymers via ring-opening metathesis polymerization

- Fabrication of LDPE/PS interpolymer resin particles through a swelling suspension polymerization approach

- Determination of the carbonyl index of polyethylene and polypropylene using specified area under band methodology with ATR-FTIR spectroscopy

- Synthesis, electropolymerization, and electrochromic performances of two novel tetrathiafulvalene–thiophene assemblies

- Wetting behaviors of fluoroterpolymer fiber films

- Plugging mechanisms of polymer gel used for hydraulic fracture water shutoff

- Synthesis of flexible poly(l-lactide)-b-polyethylene glycol-b-poly(l-lactide) bioplastics by ring-opening polymerization in the presence of chain extender

- Sulfonated poly(arylene ether sulfone) functionalized polysilsesquioxane hybrid membranes with enhanced proton conductivity

- Fmoc-diphenylalanine-based hydrogels as a potential carrier for drug delivery

- Effect of diacylhydrazine as chain extender on microphase separation and performance of energetic polyurethane elastomer

- Improved high-temperature damping performance of nitrile-butadiene rubber/phenolic resin composites by introducing different hindered amine molecules

- Rational synthesis of silicon into polyimide-derived hollow electrospun carbon nanofibers for enhanced lithium storage

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of phthalonitrile-etherified resole resin

- Highly thermally conductive boron nitride@UHMWPE composites with segregated structure

- Synthesis of high-temperature thermally expandable microcapsules and their effects on foaming quality and surface quality of foamed ABS materials

- Tribological and nanomechanical properties of a lignin-based biopolymer

- Hydroxyapatite/polyetheretherketone nanocomposites for selective laser sintering: Thermal and mechanical performances

- Synthesis of a phosphoramidate flame retardant and its flame retardancy on cotton fabrics

- Preparation and characterization of thermoresponsive poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) copolymers with enhanced hydrophilicity

- Fabrication of flexible SiO2 nanofibrous yarn via a conjugate electrospinning process

- Silver-loaded carbon nanofibers for ammonia sensing

- Polar migration behavior of phosphonate groups in phosphonate esterified acrylic grafted epoxy ester composites and their role in substrate protection

- Solubility and diffusion coefficient of supercritical CO2 in polystyrene dynamic melt

- Curcumin-loaded polyvinyl butyral film with antibacterial activity

- Experimental-numerical studies of the effect of cell structure on the mechanical properties of polypropylene foams

- Experimental investigation on the three-dimensional flow field from a meltblowing slot die

- Enhancing tribo-mechanical properties and thermal stability of nylon 6 by hexagonal boron nitride fillers

- Preparation and characterization of electrospun fibrous scaffolds of either PVA or PVP for fast release of sildenafil citrate

- Seawater degradation of PLA accelerated by water-soluble PVA

- Review Article

- Mechanical properties and application analysis of spider silk bionic material

- Additive manufacturing of PLA-based scaffolds intended for bone regeneration and strategies to improve their biological properties

- Structural design toward functional materials by electrospinning: A review

- Special Issue: XXXII National Congress of the Mexican Polymer Society

- Tailoring the morphology of poly(high internal phase emulsions) synthesized by using deep eutectic solvents

- Modification of Ceiba pentandra cellulose for drug release applications

- Redox initiation in semicontinuous polymerization to search for specific mechanical properties of copolymers

- pH-responsive polymer micelles for methotrexate delivery at tumor microenvironments

- Microwave-assisted synthesis of the lipase-catalyzed ring-opening copolymerization of ε-caprolactone and ω-pentadecanolactone: Thermal and FTIR characterization

- Rapid Communications

- Pilot-scale production of polylactic acid nanofibers by melt electrospinning

- Erratum

- Erratum to: Synthesis and characterization of new macromolecule systems for colon-specific drug delivery

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The regulatory effects of the number of VP(N-vinylpyrrolidone) function groups on macrostructure and photochromic properties of polyoxometalates/copolymer hybrid films

- How the hindered amines affect the microstructure and mechanical properties of nitrile-butadiene rubber composites

- Novel benzimidazole-based conjugated polyelectrolytes: synthesis, solution photophysics and fluorescent sensing of metal ions

- Study on the variation of rock pore structure after polymer gel flooding

- Investigation on compatibility of PLA/PBAT blends modified by epoxy-terminated branched polymers through chemical micro-crosslinking

- Investigation on degradation mechanism of polymer blockages in unconsolidated sandstone reservoirs

- Investigation on the effect of active-polymers with different functional groups for EOR

- Fabrication and characterization of hexadecyl acrylate cross-linked phase change microspheres

- Surface-induced phase transitions in thin films of dendrimer block copolymers

- ZnO-assisted coating of tetracalcium phosphate/ gelatin on the polyethylene terephthalate woven nets by atomic layer deposition

- Animal fat and glycerol bioconversion to polyhydroxyalkanoate by produced water bacteria

- Effect of microstructure on the properties of polystyrene microporous foaming material

- Synthesis of amphiphilic poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(methyl methacrylate) containing trityl ether acid cleavable junction group and its self-assembly into ordered nanoporous thin films

- On-demand optimize design of sound-absorbing porous material based on multi-population genetic algorithm

- Enhancement of mechanical, thermal and water uptake performance of TPU/jute fiber green composites via chemical treatments on fiber surface

- Enhancement of mechanical properties of natural rubber–clay nanocomposites through incorporation of silanated organoclay into natural rubber latex

- Preparation and characterization of corn starch/PVA/glycerol composite films incorporated with ε-polylysine as a novel antimicrobial packaging material

- Preparation of novel amphoteric polyacrylamide and its synergistic retention with cationic polymers

- Effect of montmorillonite on PEBAX® 1074-based mixed matrix membranes to be used in humidifiers in proton exchange membrane fuel cells

- Insight on the effect of a piperonylic acid derivative on the crystallization process, melting behavior, thermal stability, optical and mechanical properties of poly(l-lactic acid)

- Lipase-catalyzed synthesis and post-polymerization modification of new fully bio-based poly(hexamethylene γ-ketopimelate) and poly(hexamethylene γ-ketopimelate-co-hexamethylene adipate) copolyesters

- Dielectric, mechanical and thermal properties of all-organic PI/PSF composite films by in situ polymerization

- Morphological transition of amphiphilic block copolymer/PEGylated phospholipid complexes induced by the dynamic subtle balance interactions in the self-assembled aggregates

- Silica/polymer core–shell particles prepared via soap-free emulsion polymerization

- Antibacterial epoxy composites with addition of natural Artemisia annua waste

- Design and preparation of 3D printing intelligent poly N,N-dimethylacrylamide hydrogel actuators

- Multilayer-structured fibrous membrane with directional moisture transportability and thermal radiation for high-performance air filtration

- Reaction characteristics of polymer expansive jet impact on explosive reactive armour

- Synthesis of a novel modified chitosan as an intumescent flame retardant for epoxy resin

- Synthesis of aminated polystyrene and its self-assembly with nanoparticles at oil/water interface

- The synthesis and characterisation of porous and monodisperse, chemically modified hypercrosslinked poly(acrylonitrile)-based terpolymer as a sorbent for the adsorption of acidic pharmaceuticals

- Crystal transition and thermal behavior of Nylon 12

- All-optical non-conjugated multi-functionalized photorefractive polymers via ring-opening metathesis polymerization

- Fabrication of LDPE/PS interpolymer resin particles through a swelling suspension polymerization approach

- Determination of the carbonyl index of polyethylene and polypropylene using specified area under band methodology with ATR-FTIR spectroscopy

- Synthesis, electropolymerization, and electrochromic performances of two novel tetrathiafulvalene–thiophene assemblies

- Wetting behaviors of fluoroterpolymer fiber films

- Plugging mechanisms of polymer gel used for hydraulic fracture water shutoff

- Synthesis of flexible poly(l-lactide)-b-polyethylene glycol-b-poly(l-lactide) bioplastics by ring-opening polymerization in the presence of chain extender

- Sulfonated poly(arylene ether sulfone) functionalized polysilsesquioxane hybrid membranes with enhanced proton conductivity

- Fmoc-diphenylalanine-based hydrogels as a potential carrier for drug delivery

- Effect of diacylhydrazine as chain extender on microphase separation and performance of energetic polyurethane elastomer

- Improved high-temperature damping performance of nitrile-butadiene rubber/phenolic resin composites by introducing different hindered amine molecules

- Rational synthesis of silicon into polyimide-derived hollow electrospun carbon nanofibers for enhanced lithium storage

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of phthalonitrile-etherified resole resin

- Highly thermally conductive boron nitride@UHMWPE composites with segregated structure

- Synthesis of high-temperature thermally expandable microcapsules and their effects on foaming quality and surface quality of foamed ABS materials

- Tribological and nanomechanical properties of a lignin-based biopolymer

- Hydroxyapatite/polyetheretherketone nanocomposites for selective laser sintering: Thermal and mechanical performances

- Synthesis of a phosphoramidate flame retardant and its flame retardancy on cotton fabrics

- Preparation and characterization of thermoresponsive poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) copolymers with enhanced hydrophilicity

- Fabrication of flexible SiO2 nanofibrous yarn via a conjugate electrospinning process

- Silver-loaded carbon nanofibers for ammonia sensing

- Polar migration behavior of phosphonate groups in phosphonate esterified acrylic grafted epoxy ester composites and their role in substrate protection

- Solubility and diffusion coefficient of supercritical CO2 in polystyrene dynamic melt

- Curcumin-loaded polyvinyl butyral film with antibacterial activity

- Experimental-numerical studies of the effect of cell structure on the mechanical properties of polypropylene foams

- Experimental investigation on the three-dimensional flow field from a meltblowing slot die

- Enhancing tribo-mechanical properties and thermal stability of nylon 6 by hexagonal boron nitride fillers

- Preparation and characterization of electrospun fibrous scaffolds of either PVA or PVP for fast release of sildenafil citrate

- Seawater degradation of PLA accelerated by water-soluble PVA

- Review Article

- Mechanical properties and application analysis of spider silk bionic material

- Additive manufacturing of PLA-based scaffolds intended for bone regeneration and strategies to improve their biological properties

- Structural design toward functional materials by electrospinning: A review

- Special Issue: XXXII National Congress of the Mexican Polymer Society

- Tailoring the morphology of poly(high internal phase emulsions) synthesized by using deep eutectic solvents

- Modification of Ceiba pentandra cellulose for drug release applications

- Redox initiation in semicontinuous polymerization to search for specific mechanical properties of copolymers

- pH-responsive polymer micelles for methotrexate delivery at tumor microenvironments

- Microwave-assisted synthesis of the lipase-catalyzed ring-opening copolymerization of ε-caprolactone and ω-pentadecanolactone: Thermal and FTIR characterization

- Rapid Communications

- Pilot-scale production of polylactic acid nanofibers by melt electrospinning

- Erratum

- Erratum to: Synthesis and characterization of new macromolecule systems for colon-specific drug delivery