Abstract

In this article, the thermal and mechanical properties of hydroxyapatite (HA)/polyetheretherketone (PEEK) nanocomposites were investigated. The surface of the HA particles was modified by stearic acid. Subsequently, the modified HA and PEEK were ultrasonically dispersed in ethanol and then subjected to drying and ball milling treatments. By controlling the concentration of modified HA, HA/PEEK nanocomposite powders containing various amounts of modified HA were successfully prepared. The tensile strength, impact strength, and flexural strength of the nanocomposite reached maximum values at 2.5 wt% HA and were 18.5%, 38.2%, and 5.7% higher than those of the pure PEEK, respectively. Moreover, the flexural modulus of the HA/PEEK nanocomposites increased at 2.5 wt% HA and was approximately 30% higher than that of the pure PEEK. The thermal property measurements (differential scanning calorimetry and thermogravimetric analysis) showed that the nanocomposites with 2.5 wt%-modified HA exhibited enhanced thermal stability as compared to the pure PEEK, showing potential for selective laser sintering.

1 Introduction

Recently, polyetheretherketone (PEEK), a high-strength engineering plastic, has gained enormous amounts of attention due to its lightweight, nontoxicity, high chemical stability, and excellent antifriction properties (1,2,3). In particular, many studies have shown that PEEK possesses suitable biomechanical properties for and biocompatibility with human bones, which means that PEEK can replace metal in the manufacturing of human bones, demonstrating broad application prospects in the medical field (4,5,6,7). The chemical structural formula of PEEK is shown in Figure 1.

The chemical structural formula of PEEK.

However, as a bioinert polymer, the direct application of PEEK to the human body as a bone repair material is limited due to its poor biological activity and low osteogenic efficiency (8,9,10). Nano-hydroxyapatite (HA), on the other hand, which is closely related to the main inorganic component of natural bone, is widely used in artificial bones due to its excellent biocompatibility and tissue bioactivity (11). In addition, due to its brittleness and difficulty in bearing weight and processing, the superiority of HA is often achieved by forming a composite with a stronger polymer (12,13,14). Nevertheless, HA is difficult to disperse uniformly in the polymer matrix due to the extremely weak compatibility of HA and the polymer matrix, which contributes to the poor mechanical property and bad processability of composites. To this end, much effort has been devoted to improving the dispersion of the HA in the polymer matrix.

The modification of the surface of HA with the proper modifiers has proven to be an effective method to further improve the dispersion of the HA in the polymer matrix. Hu et al. (15) prepared nano-HA by coprecipitation, modifying the surface with silane-coupling agent KH560, and also prepared modified HA/PEEK composites by a hot press forming process. The results showed that the silane-coupling agent KH560 was introduced on the surface of the HA, and the modified HA was uniformly dispersed in PEEK matrix. Compared with pure PEEK, the thermodynamic and friction of 10 wt%-modified HA/PEEK composites were improved, and the tensile strength of the modified composite reached 68.33 MPa, which meets the strength requirements of human bone. Cheng et al. (16) treated the surface of HA with citric acid and stearic acid (Sa). Citric acid and Sa were successfully grafted onto the surface of the HA, but the graft ratio of Sa was higher than that of citric acid. The mechanical property results indicated that the as-prepared modified HA/polylactide (PLA) scaffold obtained from the fused deposition model 3D printing technique had a satisfactory compression modulus, although the compressive strength of the composite scaffold at 10% deformation was relatively lower than that of the neat PLA scaffold. Li et al. (17) modified HA with hydrophilic modifiers such as dopamine (DA), polyethylene glycol, and chitosan. It was found that DA could improve the dispersibility of HA and oxidize and self-polymerize to form a polydopamine nanolayer on the surface of HA. When the amount of DA reached 6% and 8%, the agglomeration of the modified HA particles in the PLA matrix weakened, showing good dispersion. Li et al. (18) introduced a reactive aldehyde group on the surface of HA and grafted the PLA-based polymer onto the surface of HA through a reactive aldehyde group, which improved the distribution and phase interface of the HA and the polymer. Zhou et al. (19) developed a surface modification of nano-HA with dodecyl alcohol. The results showed that the dispersion of HA in PLA and the interaction at the PLA and HA interface enhanced. Compared with the HA/PLA composites, the modified HA/PLA composites had significantly improved thermal stability and mechanical properties. In particular, as for PEEK bone-restorative materials, Sa has been considered the most typical surfactant not only due to its ability to make the surface of HA powder organic and thus enhance the compatibility of HA and the polymer matrix but also due to its excellent biological adaptability as a fatty acid of the human body (20,21,22,23,24,25,26).

However, the size and precision required for bone-restorative materials cannot be achieved by conventional processing methods due to the complexity of the cross-sectional geometry of the human skeleton. Simultaneously, selective laser sintering (SLS), an additive manufacturing technique that has attracted intense interest in the research community as a multifunctional manufacturing technique due to its powerful ability to print complex and delicate 3D objects using computer-aided design (27,28,29), uses a powder bed to build components. Applying SLS to PEEK can meet the needs of clinically irregular bone defect repair, showing good clinical application prospects (30).

Shuai et al. (31) incorporated HA into PEEK/polyglycolic acid (PGA) hybrids to improve the biological properties of these materials and developed composite scaffolds by SLS. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was conducted to detect the physical states of the HA particles within the composite scaffolds. It was found that with increased content of HA particles, more time was needed for PEEK and PGA in the composite to absorb enough heat to attain their respective decomposition points. Regarding the mechanical properties, the optimal HA content was determined to be 10 wt%. The composite scaffolds presented a greater degree of cell attachment and proliferation as compared to PEEK/PGA scaffolds. Feng et al. (32) mixed poly(l-lactide) (PLLA) powder with PEEK and β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP) powder and prepared PEEK/β-TCP/PLLA three-phase scaffolds via SLS for bone regeneration. The results from thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) indicated that the addition of PLLA in PEEK decreased the thermal stability of the scaffolds, as the starting decomposition temperature shifted to lower temperatures. Compression tests were conducted to investigate the compressive strength and modulus at different PLLA contents. The authors concluded that PEEK possessed excellent strength and modulus and that the mechanical properties were primarily dominated by the continuous phase PEEK for a PLLA content of less than 30 wt%. Cell culture experiments proved that PEEK/β-TCP/PLLA scaffolds improved osteoblast adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation, revealing good cytocompatibility. Zhansitov et al. (33) synthesized PEEK of different molecular masses via high-temperature polycondensation using nucleophilic substitution by varying the excess of 4,42-difluorobenzophenone. The dependences of the thermal and physicomechanical properties of PEEKs on the intrinsic viscosity were studied. The conditions for synthesizing PEEKs that produced a polymer powder with the property set needed for high-quality 3D printing using SLS technology were determined. Fish et al. (34) described the design of a laboratory SLS machine for operation with PEEK and other similar materials, emphasizing the thermal and operational design features of the materials. Therefore, it is essential to investigate the thermal stability and mechanical properties of HA/PEEK composites for use in SLS processing.

Herein, Sa was used to modify the surface of the nano-HA particles to improve the compatibility between the inorganic filler HA and PEEK matrix. Bioactive nanocomposites with different concentrations of modified HA were prepared in ethanol. After ultrasonication, drying, and ball milling treatments, the desired nanocomposite powder was obtained. The particle size and apparent density of the obtained powder were considered from the perspective of the SLS process. The thermal properties, mechanical properties, and microstructure were analyzed to evaluate the thermal stability, compatibility, and dispersion, respectively.

2 Experimental setup

2.1 Materials

PEEK was obtained from Jilin University Special Plastic Engineering Research Co. Ltd, Jilin, China. The original nano-HA was prepared in our lab (26). Sa and ethanol were purchased from Shanghai Chemical Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China.

2.2 Preparation of modified-HA/PEEK nanocomposite powder

A certain amount of Sa (10 wt% relative to the amount of as-prepared nano-HA) was sufficiently dissolved in ethanol. Then the dried HA was added to the above solution and ultrasonically dispersed for 1 h. The whole solution was mechanically stirred at 60°C for 2 h and then the modified HA was dried to remove the solvent in a vacuum oven at 70°C. Next, the modified HA and PEEK were ultrasonically dispersed in ethanol for 30 min and mechanically stirred at a high speed for 2 h. The nanocomposite powder was dried at 70°C. Finally, the dried nanocomposite powder and ceramic ball were added to a ball mill at a mass ratio of 1:5, dry milled for 2 h, and sieved through a size 100 mesh to obtain the desired composite powder. Five sets of nanocomposite samples were prepared by changing the content of modified HA to mass fractions of 0, 2.5, 5, 10, and 20 wt%.

2.3 Molding of HA/PEEK nanocomposite powder

Molding of the nanocomposite powder was performed via an R-3221 hot press (Wuhan Qien Technology Development Co., Ltd, China). Before the molding process, the nanocomposite powder was dried in a vacuum oven at 120°C for 24 h to prevent the generation of bubbles during molding. Then the nanocomposite powder, with a content of 110% of the theoretical forming mass, was placed in a mold and prepressed at 100°C for 1 min using a pressure of 8 MPa. This prepressing process was repeated twice, and the mold temperature was controlled at 357–365°C. After the temperature stabilized, the pressure was raised to 4 MPa for 1 min and then the pressure was released. The pressure was then raised to 8 MPa for 1 min and relieved again. Finally, the pressure was raised to 10 MPa for 10 min and then the mold was naturally cooled for a while before the cooling water was turned on. The sample was released from the mold while the temperature was cooled to 140°C. Using different molds, dumbbell-shaped and bar-type specimens were ultimately prepared.

2.4 Fourier-transform infrared spectrometry (FTIR)

The chemical structures of the original HA and modified HA were tested using an FTIR Impact 420 FT-IR spectrophotometer (Nichols, America) at room temperature. Small amounts of HA and modified HA were taken for KBr compression. The range of the recorded spectra was 4,000–400 cm−1.

2.5 Thermal performance tests

DSC measurements were conducted using a DSC 200 F3 machine (Netzsch, Germany). The thermal properties of the samples were investigated in the temperature range of 40–450°C (heating rate of 10°C/min) under a nitrogen atmosphere. The thermal stability of pure PEEK and HA/PEEK nanocomposites was tested with TGA using an STA 409 PC Luxx® synchronous thermal analyzer (Netzsch). The samples were heated under a nitrogen atmosphere from 40°C to 700°C, with a heating rate of 10°C/min.

2.6 Mechanical performance tests

The tensile strength tests of the dumbbell-shaped specimens were conducted using a GP-TS2000S electronic tensile machine (Shenzhen Gaopin Testing Equipment Co., Ltd, China) with the GB/T 1040-2006 standard. The test was conducted at room temperature with a test speed of 20 mm/min. The flexural property tests of the bar-type specimens were performed following the GB/T 9341-2008 standard using a GP-TS2000S electronic tensile machine (Shenzhen Gaopin Testing Equipment Co., Ltd, China). The tests were conducted at room temperature with a test speed of 2 mm/min. The impact strength tests of the samples were measured using an XJU-22 impact testing machine (Chengde Testing Machine Co., Ltd, China), according to the GB/T 1043-2008 standard. The hardness measurements of the samples were carried out using a Shore D hardness tester in accordance with the GB/T 2411-2008 standard.

2.7 Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The fractured surfaces of PEEK and HA/PEEK nanocomposite were observed by SEM (JSM-5510 LV, Japan). Additionally, the HA/PEEK composite powders containing different mass fractions of HA were observed.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 FTIR analysis of HA particles

The FTIR spectra of the original HA, modified HA, and Sa are plotted in Figure 2. The characteristic peaks at 1030.72 and 964.25 cm−1 corresponded to the stretching vibrations of P–O bonds. The bands at 603.16 and 562.43 cm−1 were due to the flexural vibrations of the P–O bonds in the crystalline phosphate phase (35), and the peak at 3569.6 cm−1 was characteristic of the stretching vibrations of a hydroxyl group. As compared to the original HA, new absorption bands occurred in the FTIR spectrum of the modified HA at 2958.14, 2917.92, and 2849.74 cm−1 ascribed to the CH3 and CH2 groups of the Sa. Additionally, an antisymmetric stretching mode of the –COO– bonds was also observed in the FTIR spectrum of the modified HA at 1557.89 cm−1 possibly due to the chemical reaction of the hydrophilic carboxyl from the Sa and Ca2+ on the surface of the HA. All of these results indicate Sa was grafted onto the HA surface successfully (16,25).

FTIR spectra of the original HA, modified HA, and Sa.

3.2 Thermal properties of the pure PEEK and HA/PEEK nanocomposite

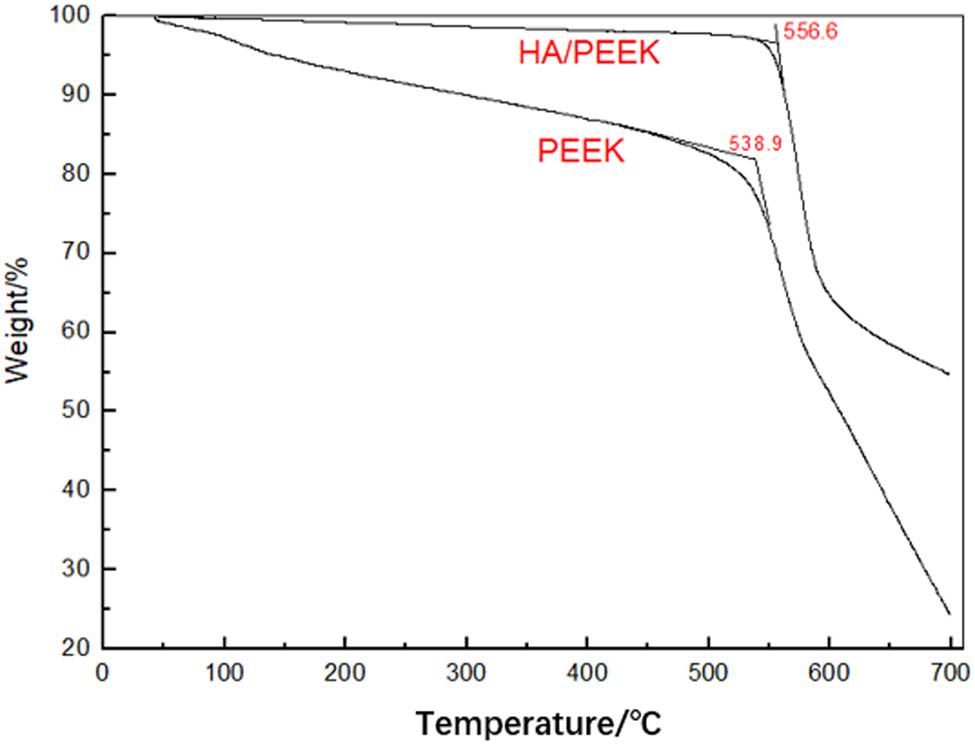

The thermostability of pure PEEK and HA/PEEK nanocomposites (containing 2.5 wt%-modified HA) was investigated through TGA as shown in Figure 3. The initial decomposition temperature of the pure PEEK was 538.9°C, and at approximately 700°C, the residual content was 24.27%. The continuous weight loss occurred because the ether bond and the benzophenone bond inside PEEK molecule were broken under high temperature. In contrast, the HA/PEEK nanocomposite had better thermal stability than pure PEEK. The nanocomposite showed little or no weight loss until 556.6°C, after which a milder on-set degradation occurred. Weight loss rates of 5%, 10%, and 20% occurred at 551°C, 559°C, and 577°C, respectively. At approximately 700°C, the residual amount was 54.69%. The HA/PEEK composite exhibited more thermal stability than PEEK due to the existence of nano-HA, which blocked heat transfer and prevented the evaporation of small-molecule gases from the decomposition of PEEK.

TGA for pure PEEK and HA/PEEK nanocomposite (containing 2.5 wt%-modified HA).

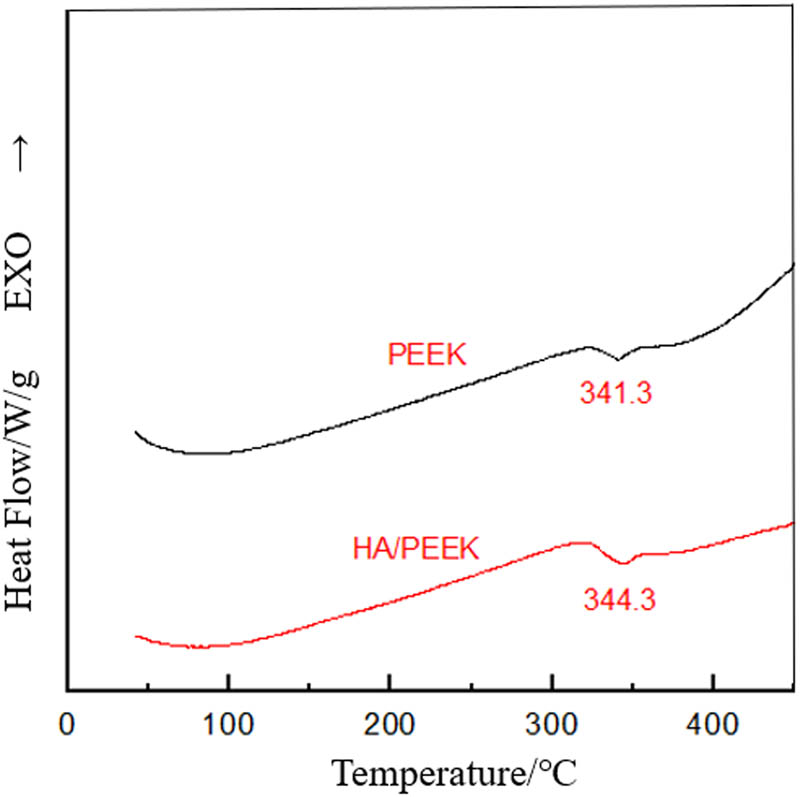

Figure 4 presents the results of the DSC study. In the curves of the pure PEEK and HA/PEEK nanocomposites, only one melting peak was observed. However, the melting temperature of the HA/PEEK nanocomposite was 3°C higher than that of pure PEEK because the addition of nano-HA provided effective insulation for the segment movement of PEEK matrix, which resulted in an increase in the melting temperature of the nanocomposite.

DSC curves of pure PEEK and HA/PEEK nanocomposite (containing 2.5 wt%-modified HA).

3.3 Mechanical properties of the HA/PEEK nanocomposites

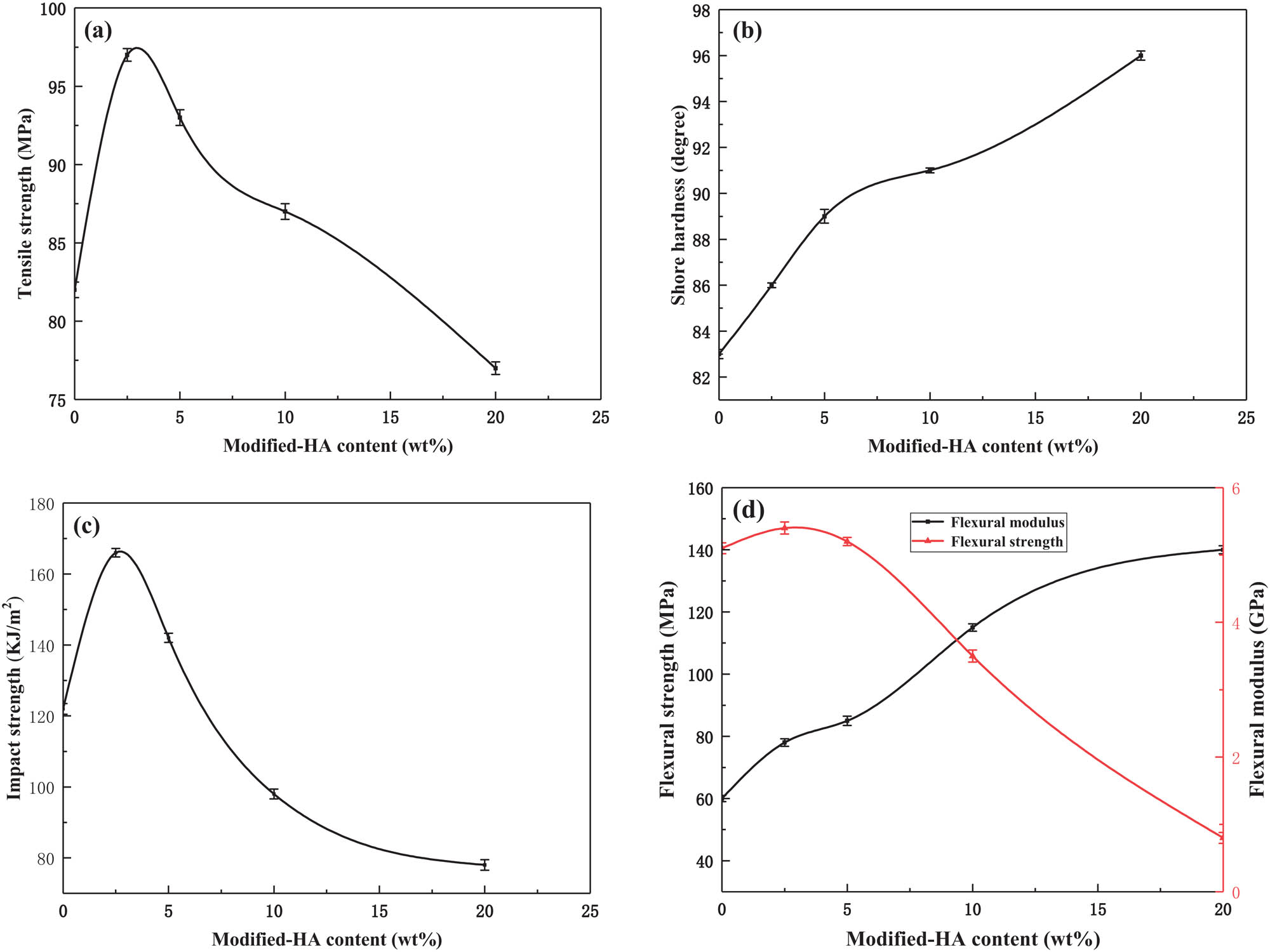

The results of the mechanical properties of the HA/PEEK nanocomposites containing different contents of modified HA are shown in Figure 5. As shown in Figure 5a, c and d, the tensile strength, impact strength, and flexural strength of the nanocomposite reached maximum values at the modified HA content of 2.5 wt% and were 18.5%, 38.2%, and 5.7% higher than those of the pure PEEK, respectively. When the content of HA reached 20 wt%, the three mechanical strengths of the HA/PEEK nanocomposites were much lower than those of the pure PEEK. In contrast, Figure 5b and d shows that the shore hardness and flexural modulus of the HA/PEEK nanocomposites were always improved with increasing modified HA content.

Effect of modified-HA content on the mechanical properties of HA/PEEK nanocomposites: tensile strength (a), shore hardness (b), impact strength (c), and flexural strength and modulus (d).

Based on a previous study (36), dispersibility and interfacial adhesion were the main factors affecting the mechanical properties of composites. In this study, the remarkable enhancement of the mechanical properties of the HA/PEEK nanocomposites with 2.5 wt%-modified HA was attributed to the chemical reaction of the hydrophilic carboxyl from the Sa and Ca2+ on the surface of the HA. Carboxylated calcium was generated and then incorporated into PEEK matrix, which effectively improved the compatibility of HA and PEEK. In addition, the preparation process of the HA/PEEK nanocomposites, by blending the raw materials in a solution and then performing ultrasonic and ball milling treatments, could significantly improve the dispersibility of the inorganic particles. Second, under certain load conditions, the local stress could be easily transferred to the rigid particles, which could effectively prevent the generation of microcracks and effectively improve the mechanical properties of the nanocomposite. However, with continuous increase in the amount of modified HA, the agglomeration caused by numerous nano-HA particles induced microcracking, resulting in performance degradation. The progressive increase in the shore hardness and flexural modulus was attributed to the addition of rigid particles.

3.4 Microstructure of the HA/PEEK nanocomposites

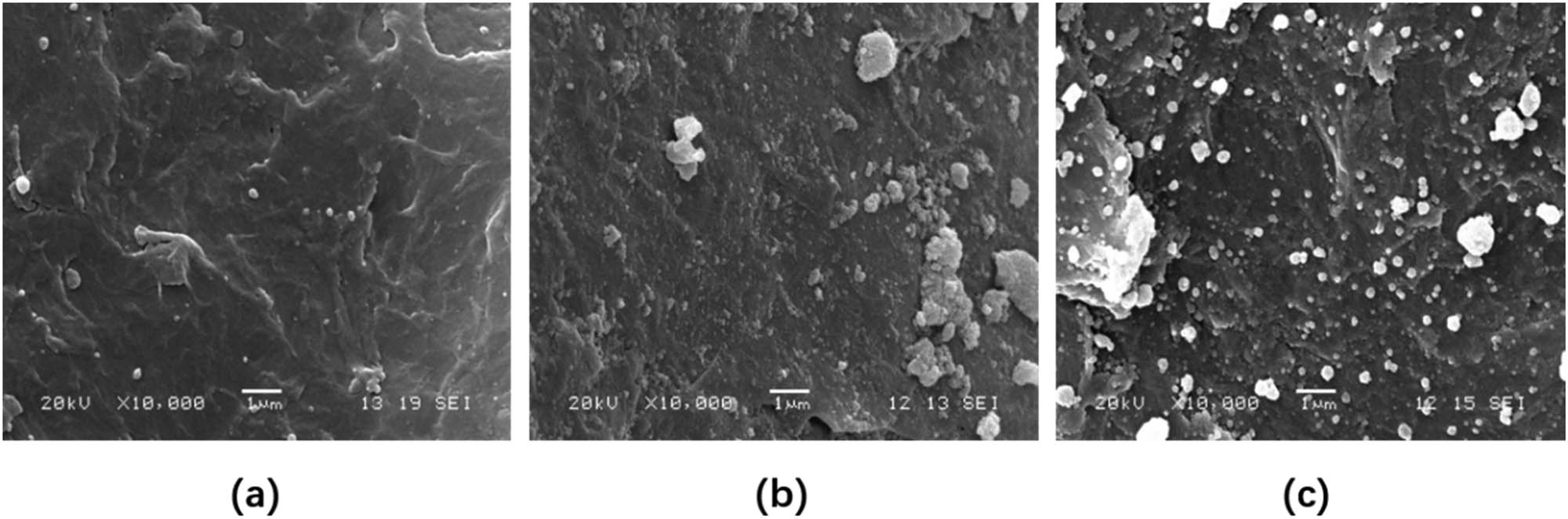

SEM photographs of the HA/PEEK powders with different mass percentages of the modified HA particles are shown in Figure 6. Figure 6a shows that the modified HA dispersed uniformly in PEEK matrix; but as seen in Figure 6b and c, particle agglomeration gradually increased the granularity with the addition of increased content of modified HA. The formation of agglomerations contributed to the interface being the source of microcracks, appearing intuitively as a rapid decline in the mechanical properties.

SEM photographs of the HA/PEEK powder with 2.5 wt% (a), 10 wt% (b), and 20 wt% (c) modified HA.

Figure 7 shows a 10,000-fold magnified cross-section image of the pure PEEK and the nanocomposite (containing 2.5 wt%-modified HA). From Figure 7a, fibrous strips conforming to the fracture morphology of typical polymers were observed in the cross-section image of the pure PEEK; however, in Figure 7b, the addition of modified HA changed the morphology of PEEK itself, suggesting that the HA was not mechanically absorbed in PEEK matrix, which might relate to the chemical bond connection between the HA nanofiller and PEEK matrix. The HA was tightly intertwined in PEEK, and no voids existed on the surface in the micrograph, which further explained the bonding interaction. These results provide strong evidence that the optimal mechanical properties of the nanocomposite were obtained with an HA content of 2.5 wt%.

SEM photographs of the impact fracture of the pure PEEK (a) and HA/PEEK nanocomposite (2.5 wt%-modified HA) (b).

4 Conclusions

This article presented a systematic study of the fabrication and thermal and mechanical properties of modified HA/PEEK nanocomposites containing varying amounts of modified HA. New absorption bands were observed in the FTIR spectrum of the modified HA at 2958.14, 2917.92, and 2849.74 cm−1 ascribed to the CH3 and CH2 groups of the Sa. Additionally, an anti-symmetric stretching mode of the –COO– bonds was also observed in the FTIR spectrum of the modified HA at 1557.89 cm−1 due to the chemical reaction of the hydrophilic carboxyl from the Sa and Ca2+ on the surface of the HA. All of these results indicate HA was modified by Sa successfully. At 2.5 wt% HA, SEM revealed that the HA particles were dispersed homogeneously in PEEK matrix, but beyond that content of HA, particle agglomeration occurred. The tensile strength, impact strength, and flexural strength of the nanocomposite also reached maximum values at 2.5 wt% HA; and at this filler concentration, the flexural modulus of the HA/PEEK nanocomposites was also much higher than that of the pure PEEK, all of which were due to the excellent dispersion and interfacial compatibility between the HA particles and PEEK matrix. In addition, at 2.5 wt% HA, the melting temperature of the HA/PEEK nanocomposite was higher than that of the pure PEEK; and from the TGA tests, at approximately 700°C, the residual amount of nanocomposite was 54.69%, while that of pure PEEK was only 24.27%, which confirmed that compared with pure PEEK, the nanocomposite with 2.5 wt% HA had enhanced thermal stability. These findings could be necessary for the development of an optimal HA/PEEK nanocomposite when taking into account SLS processing. This article was devoted to investigating the thermal properties of modified HA/PEEK nanocomposites, which is considered an extremely important parameter in the SLS process.

Acknowledgments

This study was performed with the support of Guangdong Key Laboratory of Enterprise of 3D Printing Polymer and Composite Materials (No. 2018B030323001).

References

(1) Yasin S, Shakeel A, Ahmad M, Ahmad A, Iqbal T. Physico-chemical analysis of semi-crystalline PEEK in aliphatic and aromatic solvents. Soft Mater. 2019;17:143–9.10.1080/1539445X.2019.1572622Search in Google Scholar

(2) Patel P, Stec AA, Hull TR, Naffakh M, Diez-Pascual AM, Ellis G, et al. Flammability properties of PEEK and carbon nanotube composites. Polym Degrad Stabil. 2012;97:2492–2502.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2012.07.013Search in Google Scholar

(3) Li EZ, Guo WL, Wang HD, Xu BS, Liu XT. Research on tribological behavior of PEEK and glass fiber reinforced PEEK composite. Phys Procedia. 2013;50:453–60.10.1016/j.phpro.2013.11.071Search in Google Scholar

(4) Kang JF, Wang L, Yang CC, Wang L, Yi C, He JK, et al. Custom design and biomechanical analysis of 3D-printed PEEK rib prostheses. Biomech Model Mechan. 2018;17:1083–92.10.1007/s10237-018-1015-xSearch in Google Scholar

(5) Tanida S, Fujibayashi S, Otsuki B, Masamoto K, Takahashi Y, Nakayama T, et al. Vertebral endplate cyst as a predictor of nonunion after lumbar interbody fusion comparison of titanium and polyetheretherketone cages. Spine. 2016;41:1216–22.10.1097/BRS.0000000000001605Search in Google Scholar

(6) Phan K, Hogan JA, Assem Y, Mobbs RJ. PEEK-Halo effect in interbody fusion. J Clin Neurosci. 2016;24:138–40.10.1016/j.jocn.2015.07.017Search in Google Scholar

(7) Feerick EM, Kennedy J, Mullett H, FitzPatrick D, McGarry P. Investigation of metallic and carbon fibre PEEK fracture fixation devices for three-part proximal humeral fractures. Med Eng Phys. 2013;35:712–22.10.1016/j.medengphy.2012.07.016Search in Google Scholar

(8) Abu Bakar MS, Cheng MHW, Tang SM, Yu SC, Liao K, Tan CT, et al. Tensile properties, tension-tension fatigue and biological response of polyetheretherketone-hydroxyapatite composites for loadbearing orthopedic implants. Biomaterials. 2003;24:2245–50.10.1016/S0142-9612(03)00028-0Search in Google Scholar

(9) Lee JH, Jang HL, Lee KM, Baek HR, Jin K, Hong KS, et al. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of the bioactivity of hydroxyapatite-coated polyetheretherketone biocomposites created by cold spray technology. Acta Biomater. 2013;9:6177–87.10.1016/j.actbio.2012.11.030Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(10) Liu LH, Zheng YY, Zhang LF, Xiong CD. Bioactive polyetheretherketone implant composites for hard tissue. Prog Chem. 2017;29:450–8.Search in Google Scholar

(11) Ni Z, Wang Y, Hua WY, Tian SL, Liu SD, Wang M. Thermal stability of PEEK/HA biological composite materials. J Shenzhen University (Sci Eng). 2012;29:521–6.10.3724/SP.J.1249.2012.06521Search in Google Scholar

(12) Wei GB, Ma PX. Structure and properties of nanohydroxyapatite/polymer composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2004;25:4749–57.10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.12.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(13) Wang C, Wang Y, Meng HY, Wang X, Zhu Y, Yu K, et al. Research progressregarding nanohydroxyapatite and its composite biomaterials in bone defect repair. Int J Polym Mater Polym Biomater. 2016;65:601–10.10.1080/00914037.2016.1149849Search in Google Scholar

(14) Vaezi M, Black C, Gibbs DMR, Oreffo ROC, Brady M, Moshrefi-Torbati M, et al. Characterization of new PEEK/HA composites with 3D HA network fabricated by extrusion freeforming. Molecules. 2016;21:687.10.3390/molecules21060687Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(15) Hu YF, Shan YJ, Qiu L, Chen YK, Liu XG, Liu GH. Effect of surface modification of hydroxyapatite on the mechanical and tribological properties of hydroxyapatite/polyetheretherketone composites. Acta Mater Compos Sin. 2018;35:2651–7.Search in Google Scholar

(16) Cheng SM, Chen LJ, Hong YY, Song GL, Liu HF, Tang GY. Surface modification of hydroxyapatite and its influences on the properties of poly(lactic acid)-based porous scaffolds. Acta Mater Compos Sin. 2018;35:1087–94.Search in Google Scholar

(17) Li G, Liu XN, Zhang DH, He M, Qin SH, Yu J. Effect of surface modification of nano-hydroxyapatite on the dispersion of hydrophilic modifier. Polym Mater Sci Eng. 2018;34:66–72.Search in Google Scholar

(18) Li RD, Zhang HB, Dai CB, Yang JJ, Liu L. Preparation of organic–inorganic composite material based on polylactic acid modified hydroxyapatite. Sci Technol Eng. 2017;17:99–102.Search in Google Scholar

(19) Zhou Y, Zhao XY, Sun ZY, Wang X. Study on polylactide composite reinforced with modified nano-hydroxyapatite. Appl Chem Ind. 2017;46:2350–3.Search in Google Scholar

(20) Cheng L, Wang X, Zhao XY. Study on polylactic acid composites modified by functionalized nano hydroxyapatite. Appl Chem Ind. 2019;48:1595–7.Search in Google Scholar

(21) Fan BB. Research progress of surface modification of inorganic powder modified by stearic acid in China. Plast Addit. 2011;5:25–9.Search in Google Scholar

(22) Liao JG, Zhang L, Zuo Y, Wang YL, Li YB. Surface modification of nano-hydroxyapatite with stearic acid. Chinese J Inorg Chem. 2009;25:1267–73.Search in Google Scholar

(23) Li YB, Weng WJ. Surface modification of hydroxyapatite by stearic acid: characterization and in vitro behaviors. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2008;19:19–25.10.1007/s10856-007-3123-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(24) Du ZX, Jia ZQ, Rao GY, Chen JF. Study on surface properties of modified nanometer calcium carbonate. Mod Chem Ind. 2001;21:42–4.Search in Google Scholar

(25) Ran X, He J. Mechanism of surface modification of nano-hydroxyapatite with stearic acid. Mater Rev. 2011;1:23–5.Search in Google Scholar

(26) Fu H, Wang Y, Chen YB, Wu HY. Preparation of polyetheretherketone/hydroxyapatite nanocomposite powder. Eng Plast Appl. 2014;3:30–3.Search in Google Scholar

(27) Banerjee SS, Burbine S, Shivaprakash NK, Mead J. 3D-printable PP/SEBS thermoplastic elastomeric blends: preparation and properties. Polymers. 2019;11:347.10.3390/polym11020347Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(28) Dizon JRC, Espera AH, Chen QY, Advincula RC. Mechanical characterization of 3D-printed polymers. Addit Manufact. 2018;20:44–67.10.1016/j.addma.2017.12.002Search in Google Scholar

(29) Alyson V, Lee SE, Mamp M. The application of 3D printing technology in the fashion industry. Int J Fashion Des Technol Educ. 2017;10:170–9.10.1080/17543266.2016.1223355Search in Google Scholar

(30) Mazzoli A. Selective laser sintering in biomedical engineering. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2013;51:245–56.10.1007/s11517-012-1001-xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

(31) Shuai CJ, Shuai CY, Wu P, Yuan FL, Feng P, Yang YW, et al. Characterization and bioactivity evaluation of (polyetheretherketone/polyglycolic acid)-hydroxyapatite scaffolds for tissue regeneration. Materials. 2016;9:934.10.3390/ma9110934Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(32) Feng P, Wu P, Gao CD, Yang YW, Guo W, Yang WJ, et al. A multimaterial scaffold with tunable properties: toward bone tissue repair. Adv Sci. 2018;5:1700817.10.1002/advs.201700817Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(33) Zhansitov AA, Slonov AL, Shetov RA, Baikaziev AE, Shakhmurzova KT, Kurdanova Z, et al. Synthesis and properties of polyetheretherketones for 3D printing. Fibre Chem. 2018;49:414–9.10.1007/s10692-018-9911-5Search in Google Scholar

(34) Fish S, Booth JC, Kubiak ST, Wroe WW, Bryant AD, Moser DR, et al. Design and subsystem development of a high temperature selective laser sintering machine for enhanced process monitoring and control. Addit Manufact. 2015;5:60–7.10.1016/j.addma.2014.12.005Search in Google Scholar

(35) Liu Q, de Wijn JR, de Groot K, van Blitterswijk CA. Surface modification of nano-apatite by grafting organic polymer. Biomaterials. 1998;19:1067–72.10.1016/S0142-9612(98)00033-7Search in Google Scholar

(36) Chow CL, Fan JP, Tang CY, Tsui CP. Influence of interphase layer on the overall elasto-plastic behaviors of HA/PEEK biocomposite. Biomaterials. 2004;25:5363–73.10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.12.050Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2020 Wenwen Lai et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The regulatory effects of the number of VP(N-vinylpyrrolidone) function groups on macrostructure and photochromic properties of polyoxometalates/copolymer hybrid films

- How the hindered amines affect the microstructure and mechanical properties of nitrile-butadiene rubber composites

- Novel benzimidazole-based conjugated polyelectrolytes: synthesis, solution photophysics and fluorescent sensing of metal ions

- Study on the variation of rock pore structure after polymer gel flooding

- Investigation on compatibility of PLA/PBAT blends modified by epoxy-terminated branched polymers through chemical micro-crosslinking

- Investigation on degradation mechanism of polymer blockages in unconsolidated sandstone reservoirs

- Investigation on the effect of active-polymers with different functional groups for EOR

- Fabrication and characterization of hexadecyl acrylate cross-linked phase change microspheres

- Surface-induced phase transitions in thin films of dendrimer block copolymers

- ZnO-assisted coating of tetracalcium phosphate/ gelatin on the polyethylene terephthalate woven nets by atomic layer deposition

- Animal fat and glycerol bioconversion to polyhydroxyalkanoate by produced water bacteria

- Effect of microstructure on the properties of polystyrene microporous foaming material

- Synthesis of amphiphilic poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(methyl methacrylate) containing trityl ether acid cleavable junction group and its self-assembly into ordered nanoporous thin films

- On-demand optimize design of sound-absorbing porous material based on multi-population genetic algorithm

- Enhancement of mechanical, thermal and water uptake performance of TPU/jute fiber green composites via chemical treatments on fiber surface

- Enhancement of mechanical properties of natural rubber–clay nanocomposites through incorporation of silanated organoclay into natural rubber latex

- Preparation and characterization of corn starch/PVA/glycerol composite films incorporated with ε-polylysine as a novel antimicrobial packaging material

- Preparation of novel amphoteric polyacrylamide and its synergistic retention with cationic polymers

- Effect of montmorillonite on PEBAX® 1074-based mixed matrix membranes to be used in humidifiers in proton exchange membrane fuel cells

- Insight on the effect of a piperonylic acid derivative on the crystallization process, melting behavior, thermal stability, optical and mechanical properties of poly(l-lactic acid)

- Lipase-catalyzed synthesis and post-polymerization modification of new fully bio-based poly(hexamethylene γ-ketopimelate) and poly(hexamethylene γ-ketopimelate-co-hexamethylene adipate) copolyesters

- Dielectric, mechanical and thermal properties of all-organic PI/PSF composite films by in situ polymerization

- Morphological transition of amphiphilic block copolymer/PEGylated phospholipid complexes induced by the dynamic subtle balance interactions in the self-assembled aggregates

- Silica/polymer core–shell particles prepared via soap-free emulsion polymerization

- Antibacterial epoxy composites with addition of natural Artemisia annua waste

- Design and preparation of 3D printing intelligent poly N,N-dimethylacrylamide hydrogel actuators

- Multilayer-structured fibrous membrane with directional moisture transportability and thermal radiation for high-performance air filtration

- Reaction characteristics of polymer expansive jet impact on explosive reactive armour

- Synthesis of a novel modified chitosan as an intumescent flame retardant for epoxy resin

- Synthesis of aminated polystyrene and its self-assembly with nanoparticles at oil/water interface

- The synthesis and characterisation of porous and monodisperse, chemically modified hypercrosslinked poly(acrylonitrile)-based terpolymer as a sorbent for the adsorption of acidic pharmaceuticals

- Crystal transition and thermal behavior of Nylon 12

- All-optical non-conjugated multi-functionalized photorefractive polymers via ring-opening metathesis polymerization

- Fabrication of LDPE/PS interpolymer resin particles through a swelling suspension polymerization approach

- Determination of the carbonyl index of polyethylene and polypropylene using specified area under band methodology with ATR-FTIR spectroscopy

- Synthesis, electropolymerization, and electrochromic performances of two novel tetrathiafulvalene–thiophene assemblies

- Wetting behaviors of fluoroterpolymer fiber films

- Plugging mechanisms of polymer gel used for hydraulic fracture water shutoff

- Synthesis of flexible poly(l-lactide)-b-polyethylene glycol-b-poly(l-lactide) bioplastics by ring-opening polymerization in the presence of chain extender

- Sulfonated poly(arylene ether sulfone) functionalized polysilsesquioxane hybrid membranes with enhanced proton conductivity

- Fmoc-diphenylalanine-based hydrogels as a potential carrier for drug delivery

- Effect of diacylhydrazine as chain extender on microphase separation and performance of energetic polyurethane elastomer

- Improved high-temperature damping performance of nitrile-butadiene rubber/phenolic resin composites by introducing different hindered amine molecules

- Rational synthesis of silicon into polyimide-derived hollow electrospun carbon nanofibers for enhanced lithium storage

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of phthalonitrile-etherified resole resin

- Highly thermally conductive boron nitride@UHMWPE composites with segregated structure

- Synthesis of high-temperature thermally expandable microcapsules and their effects on foaming quality and surface quality of foamed ABS materials

- Tribological and nanomechanical properties of a lignin-based biopolymer

- Hydroxyapatite/polyetheretherketone nanocomposites for selective laser sintering: Thermal and mechanical performances

- Synthesis of a phosphoramidate flame retardant and its flame retardancy on cotton fabrics

- Preparation and characterization of thermoresponsive poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) copolymers with enhanced hydrophilicity

- Fabrication of flexible SiO2 nanofibrous yarn via a conjugate electrospinning process

- Silver-loaded carbon nanofibers for ammonia sensing

- Polar migration behavior of phosphonate groups in phosphonate esterified acrylic grafted epoxy ester composites and their role in substrate protection

- Solubility and diffusion coefficient of supercritical CO2 in polystyrene dynamic melt

- Curcumin-loaded polyvinyl butyral film with antibacterial activity

- Experimental-numerical studies of the effect of cell structure on the mechanical properties of polypropylene foams

- Experimental investigation on the three-dimensional flow field from a meltblowing slot die

- Enhancing tribo-mechanical properties and thermal stability of nylon 6 by hexagonal boron nitride fillers

- Preparation and characterization of electrospun fibrous scaffolds of either PVA or PVP for fast release of sildenafil citrate

- Seawater degradation of PLA accelerated by water-soluble PVA

- Review Article

- Mechanical properties and application analysis of spider silk bionic material

- Additive manufacturing of PLA-based scaffolds intended for bone regeneration and strategies to improve their biological properties

- Structural design toward functional materials by electrospinning: A review

- Special Issue: XXXII National Congress of the Mexican Polymer Society

- Tailoring the morphology of poly(high internal phase emulsions) synthesized by using deep eutectic solvents

- Modification of Ceiba pentandra cellulose for drug release applications

- Redox initiation in semicontinuous polymerization to search for specific mechanical properties of copolymers

- pH-responsive polymer micelles for methotrexate delivery at tumor microenvironments

- Microwave-assisted synthesis of the lipase-catalyzed ring-opening copolymerization of ε-caprolactone and ω-pentadecanolactone: Thermal and FTIR characterization

- Rapid Communications

- Pilot-scale production of polylactic acid nanofibers by melt electrospinning

- Erratum

- Erratum to: Synthesis and characterization of new macromolecule systems for colon-specific drug delivery

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The regulatory effects of the number of VP(N-vinylpyrrolidone) function groups on macrostructure and photochromic properties of polyoxometalates/copolymer hybrid films

- How the hindered amines affect the microstructure and mechanical properties of nitrile-butadiene rubber composites

- Novel benzimidazole-based conjugated polyelectrolytes: synthesis, solution photophysics and fluorescent sensing of metal ions

- Study on the variation of rock pore structure after polymer gel flooding

- Investigation on compatibility of PLA/PBAT blends modified by epoxy-terminated branched polymers through chemical micro-crosslinking

- Investigation on degradation mechanism of polymer blockages in unconsolidated sandstone reservoirs

- Investigation on the effect of active-polymers with different functional groups for EOR

- Fabrication and characterization of hexadecyl acrylate cross-linked phase change microspheres

- Surface-induced phase transitions in thin films of dendrimer block copolymers

- ZnO-assisted coating of tetracalcium phosphate/ gelatin on the polyethylene terephthalate woven nets by atomic layer deposition

- Animal fat and glycerol bioconversion to polyhydroxyalkanoate by produced water bacteria

- Effect of microstructure on the properties of polystyrene microporous foaming material

- Synthesis of amphiphilic poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(methyl methacrylate) containing trityl ether acid cleavable junction group and its self-assembly into ordered nanoporous thin films

- On-demand optimize design of sound-absorbing porous material based on multi-population genetic algorithm

- Enhancement of mechanical, thermal and water uptake performance of TPU/jute fiber green composites via chemical treatments on fiber surface

- Enhancement of mechanical properties of natural rubber–clay nanocomposites through incorporation of silanated organoclay into natural rubber latex

- Preparation and characterization of corn starch/PVA/glycerol composite films incorporated with ε-polylysine as a novel antimicrobial packaging material

- Preparation of novel amphoteric polyacrylamide and its synergistic retention with cationic polymers

- Effect of montmorillonite on PEBAX® 1074-based mixed matrix membranes to be used in humidifiers in proton exchange membrane fuel cells

- Insight on the effect of a piperonylic acid derivative on the crystallization process, melting behavior, thermal stability, optical and mechanical properties of poly(l-lactic acid)

- Lipase-catalyzed synthesis and post-polymerization modification of new fully bio-based poly(hexamethylene γ-ketopimelate) and poly(hexamethylene γ-ketopimelate-co-hexamethylene adipate) copolyesters

- Dielectric, mechanical and thermal properties of all-organic PI/PSF composite films by in situ polymerization

- Morphological transition of amphiphilic block copolymer/PEGylated phospholipid complexes induced by the dynamic subtle balance interactions in the self-assembled aggregates

- Silica/polymer core–shell particles prepared via soap-free emulsion polymerization

- Antibacterial epoxy composites with addition of natural Artemisia annua waste

- Design and preparation of 3D printing intelligent poly N,N-dimethylacrylamide hydrogel actuators

- Multilayer-structured fibrous membrane with directional moisture transportability and thermal radiation for high-performance air filtration

- Reaction characteristics of polymer expansive jet impact on explosive reactive armour

- Synthesis of a novel modified chitosan as an intumescent flame retardant for epoxy resin

- Synthesis of aminated polystyrene and its self-assembly with nanoparticles at oil/water interface

- The synthesis and characterisation of porous and monodisperse, chemically modified hypercrosslinked poly(acrylonitrile)-based terpolymer as a sorbent for the adsorption of acidic pharmaceuticals

- Crystal transition and thermal behavior of Nylon 12

- All-optical non-conjugated multi-functionalized photorefractive polymers via ring-opening metathesis polymerization

- Fabrication of LDPE/PS interpolymer resin particles through a swelling suspension polymerization approach

- Determination of the carbonyl index of polyethylene and polypropylene using specified area under band methodology with ATR-FTIR spectroscopy

- Synthesis, electropolymerization, and electrochromic performances of two novel tetrathiafulvalene–thiophene assemblies

- Wetting behaviors of fluoroterpolymer fiber films

- Plugging mechanisms of polymer gel used for hydraulic fracture water shutoff

- Synthesis of flexible poly(l-lactide)-b-polyethylene glycol-b-poly(l-lactide) bioplastics by ring-opening polymerization in the presence of chain extender

- Sulfonated poly(arylene ether sulfone) functionalized polysilsesquioxane hybrid membranes with enhanced proton conductivity

- Fmoc-diphenylalanine-based hydrogels as a potential carrier for drug delivery

- Effect of diacylhydrazine as chain extender on microphase separation and performance of energetic polyurethane elastomer

- Improved high-temperature damping performance of nitrile-butadiene rubber/phenolic resin composites by introducing different hindered amine molecules

- Rational synthesis of silicon into polyimide-derived hollow electrospun carbon nanofibers for enhanced lithium storage

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of phthalonitrile-etherified resole resin

- Highly thermally conductive boron nitride@UHMWPE composites with segregated structure

- Synthesis of high-temperature thermally expandable microcapsules and their effects on foaming quality and surface quality of foamed ABS materials

- Tribological and nanomechanical properties of a lignin-based biopolymer

- Hydroxyapatite/polyetheretherketone nanocomposites for selective laser sintering: Thermal and mechanical performances

- Synthesis of a phosphoramidate flame retardant and its flame retardancy on cotton fabrics

- Preparation and characterization of thermoresponsive poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) copolymers with enhanced hydrophilicity

- Fabrication of flexible SiO2 nanofibrous yarn via a conjugate electrospinning process

- Silver-loaded carbon nanofibers for ammonia sensing

- Polar migration behavior of phosphonate groups in phosphonate esterified acrylic grafted epoxy ester composites and their role in substrate protection

- Solubility and diffusion coefficient of supercritical CO2 in polystyrene dynamic melt

- Curcumin-loaded polyvinyl butyral film with antibacterial activity

- Experimental-numerical studies of the effect of cell structure on the mechanical properties of polypropylene foams

- Experimental investigation on the three-dimensional flow field from a meltblowing slot die

- Enhancing tribo-mechanical properties and thermal stability of nylon 6 by hexagonal boron nitride fillers

- Preparation and characterization of electrospun fibrous scaffolds of either PVA or PVP for fast release of sildenafil citrate

- Seawater degradation of PLA accelerated by water-soluble PVA

- Review Article

- Mechanical properties and application analysis of spider silk bionic material

- Additive manufacturing of PLA-based scaffolds intended for bone regeneration and strategies to improve their biological properties

- Structural design toward functional materials by electrospinning: A review

- Special Issue: XXXII National Congress of the Mexican Polymer Society

- Tailoring the morphology of poly(high internal phase emulsions) synthesized by using deep eutectic solvents

- Modification of Ceiba pentandra cellulose for drug release applications

- Redox initiation in semicontinuous polymerization to search for specific mechanical properties of copolymers

- pH-responsive polymer micelles for methotrexate delivery at tumor microenvironments

- Microwave-assisted synthesis of the lipase-catalyzed ring-opening copolymerization of ε-caprolactone and ω-pentadecanolactone: Thermal and FTIR characterization

- Rapid Communications

- Pilot-scale production of polylactic acid nanofibers by melt electrospinning

- Erratum

- Erratum to: Synthesis and characterization of new macromolecule systems for colon-specific drug delivery