Abstract

Carbon nanofibers (CNFs) were prepared by electrospinning, and silver (Ag) ions were grown on the surface of the CNFs by in situ solution synthesis. The structure and morphology of obtained Ag-doped CNFs (Ag-CNFs) were characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The gas sensibility of the composite fiber was investigated by ammonia (NH3) obtained by natural volatilization from 1 to 4 mL of NH3 solution at room temperature. It was found that the fibers exhibited a sensitive current corresponding to different NH3 concentrations and a greater response at high concentrations. The sensing mechanism was discussed, and the good absorptivity was demonstrated. The results show that Ag-CNF is a promising material for the detection of toxic NH3.

1 Introduction

In recent years, many studies have focused on the development of low-cost, flexible, multi-application, and lightweight sensors with stable operation, high sensitivity, fast response, and low operating temperature. At present, displacement sensors (1,2,3), strain sensors (4,5), humidity sensor (6,7), pressure sensors (8,9), temperature sensors (10,11), and gas sensors (12,13) have been widely explored. Electrospinning is a low-cost, simple, highly efficient, and promising method for the preparation of one-dimensional (1D) micro-/nanofibers (14,15). It can be used to prepare polymer, organic, inorganic and multi-component composite nanofibers, having been widely used in nanoelectronics, nanosensors, drug release, and catalysts (16,17,18,19,20,21). Compared to thin-film sensors, fiber-based sensors produced by electrospinning have higher sensitivity and faster response time (22,23,24,25), having been used to detect multiple chemicals, including NH3, NO2, CO, N2H4, formaldehyde, ethanol, and other organic gases (26,27,28,29,30).

Nowadays, metal oxide semiconductors and solid electrolytes sensors occupy most of the markets for gas sensors (31,32). However, both of them need to work at higher temperatures (hundreds to more than 1,000°C), consume large power, and have low sensitivity, poor anti-interference ability, and inconvenient use. With the development of nanotechnology, a large number of research reports on carbon-based gas sensors have been published in recent years, which show good analytical sensitivity at room temperature (33,34), such as carbon nanotubes (CNTs), graphene, graphene oxide and activated carbon (35,36,37,38,39). 1D CNFs have high surface adsorption capacity, good electrical conductivity, electronic ballistic transmission characteristics, and other excellent properties, becoming one of the ideal materials for the fabrication of nanoscale gas sensors with high sensitivity, fast response, small size, and low energy consumption (40,41,42). Among the many CNFs, the CNFs prepared based on the polyacrylonitrile (PAN) are the most common ones with high tensile strength (43,44,45), low production cost, and suitable for large-scale production.

Ammonia is a common irritating gas. It is widely used in chemical and agricultural fields and has corrosive and irritating effects on human skin and mucous membranes. This study found that carbon materials have good response characteristics to NH3. Silver and its compounds are one of the most important antibacterial materials. They have high bactericidal activity and biocompatibility and have antibacterial effects against bacteria, fungi, and even viruses. Many studies have modified nanomaterials based on this property of Ag, such as Ag-CNT, Ag/ZNO, and so on, see Table 1 for details (46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54). This study describes an antibacterial NH3 sensor based on the CNFs. Ag-CNFs were prepared by electrospinning and impregnation. We measured and analyzed the response characteristics to NH3 by focusing on the change in resistance of Ag-CNFs and found that it exhibits good NH3 sensing performance in 1–4 mL of NH3 solution. Ag-CNFs can be used as an NH3 gas sensor at room temperature that is inexpensive to produce, flexible, sensitive, and antibacterial.

Applications of Ag-loaded nanomaterials

| Materials | Function | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Ag-CNT | Gas sensor for NH3 and CO2; improved field emission properties | (44,45) |

| Ag/ZnO | IOT and field electron emission application | (46) |

| Al/Ag-CNF | Gas sensors for C2H2 | (47) |

| Ag-TiO2 | Visible light photocatalysis | (48) |

| Ag/SnO2 | Sensor for H2O2 | (49) |

| Ag-Pt/pCNFs | Detect DA | (50) |

| Ag-TiO2–CNT | Light photocatalysis | (51) |

| PANI/Ag/CNF | Solid flexible aerogel supercapacitor | (52) |

2 Experimental section and characterization

2.1 Materials

Silver nitrate (AgNO3, ≥99.8%), 2,2-dimethylolbutanoic acid (DMBA), N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), and NH3 solution (25–28%) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd, China. The PAN (MW = 1,50,000) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, USA.

2.2 Preparation of pure PAN fibers by electrospinning

The PAN–DMF solution having a polymer mass ratio of 12% was prepared by stirring at room temperature for 4 h by a magnetic stirrer. Self-assembled equipment was used for electrospinning, including a high-voltage power supply, propulsion pumps, and aluminum foil as the receiver. The spinning solution was placed in a plastic syringe and mounted on a propulsion pump. The aluminum foil was placed perpendicular to the horizontal plane and connected to the ground. The volume feed rate, applied voltage, and tip-to-collector distance were 1 mL/h, 15 kV, and 10 cm, respectively. The spinning temperature was 20°C and the humidity was 50%.

2.3 Preparation of Ag-CNFs

The pure PAN fiber obtained by electrospinning was subjected to a two-stage heating process. First, the pre-oxidation process was carried out by heating at 260°C for 140 min and the heating rate was 2°C/min. Then, the temperature was raised to 900°C for 120 min at a rate of 5°C/min in an argon atmosphere. Finally, natural cooling is performed to obtain CNFs. Since the Ag nanostructure has antibacterial properties, it is compounded onto the CNF to protect it (55,56). AgNO3 (10 mM) was mixed with 20 mL water to soak the CNFs for 3 h. CNFs were taken out and washed with DMBA until no bubbles generated. Then, it was dried at 60°C for 4 h to obtain Ag-CNFs.

2.4 Sensor assembly

A simple gas sensor was assembled by sandwiching Ag-CNFs between two copper electrodes (copper sheets), and the size of the composite was 20 × 60 × 2 mm3. Two copper wires were fixed to the copper electrodes by soldering. Copper wire was used to connect an electrical performance measurement system that responds to changes in current in an NH3 environment.

2.5 Characterization

The samples were characterized by XRD at room temperature. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM, JSM-6390) was used to observe the surface morphology of pure PAN fibers, CNFs and Ag-CNFs. Electrical properties were tested by a Keithley 6487 high resistance meter system (Washington, USA) at room temperature.

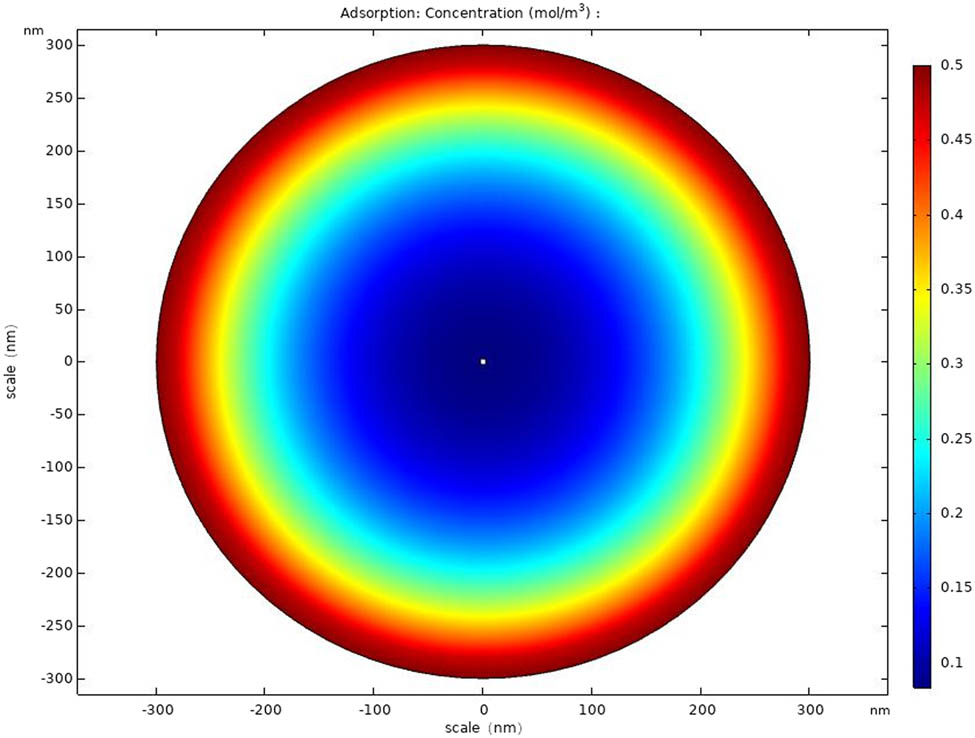

2.6 Simulation by COMSOL Multiphysics

COMSOL Multiphysics has been increasingly used in the process of simulating gas sensing mechanism. And in this article, COMSOL is applied to demonstrate the distribution of NH3 in Ag-CNFs. The model of transport of diluted species has been used and the boundary concentration of NH3 around Ag-CNFs has been set as 0.5 mol/m3 to make simulation results more obvious. The temperature has been set as 20°C and the porosity of Ag-CNFs is 0.1.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 XRD

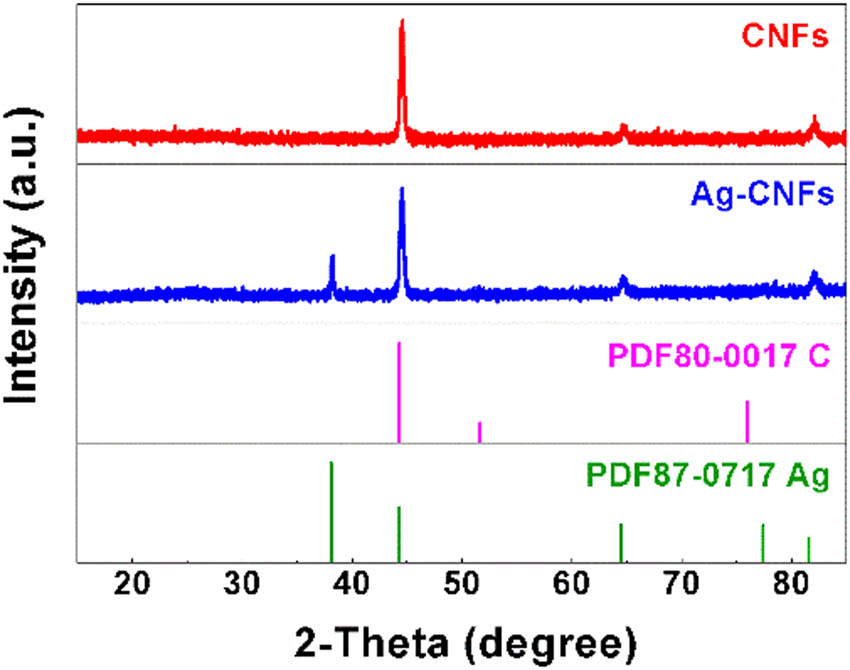

X-ray diffraction is a powerful tool for characterizing the structure of materials. The diffraction peaks of the nanofibers are indexed by standard cards of C and Ag (PDF No. 80-0017 and 87-0717). A comparison of the XRD patterns of the CNFs and Ag-CNFs with the standard map is shown in Figure 1. It can be seen that the diffraction peaks appear in the spectra of both samples, indicating a good crystallinity. The main peak of the CNFs is at 44°, corresponding to the (111) plane of C. The main peak of Ag-CNFs at 44° corresponds to the (200) crystalline plane of Ag and the (111) plane of C, and the second-largest peak at 38° corresponds to the (111) plane of Ag. This confirms that the Ag-ions are effectively modified on the surface of the CNFs.

XRD patterns of CNFs and Ag-CNFs.

3.2 SEM

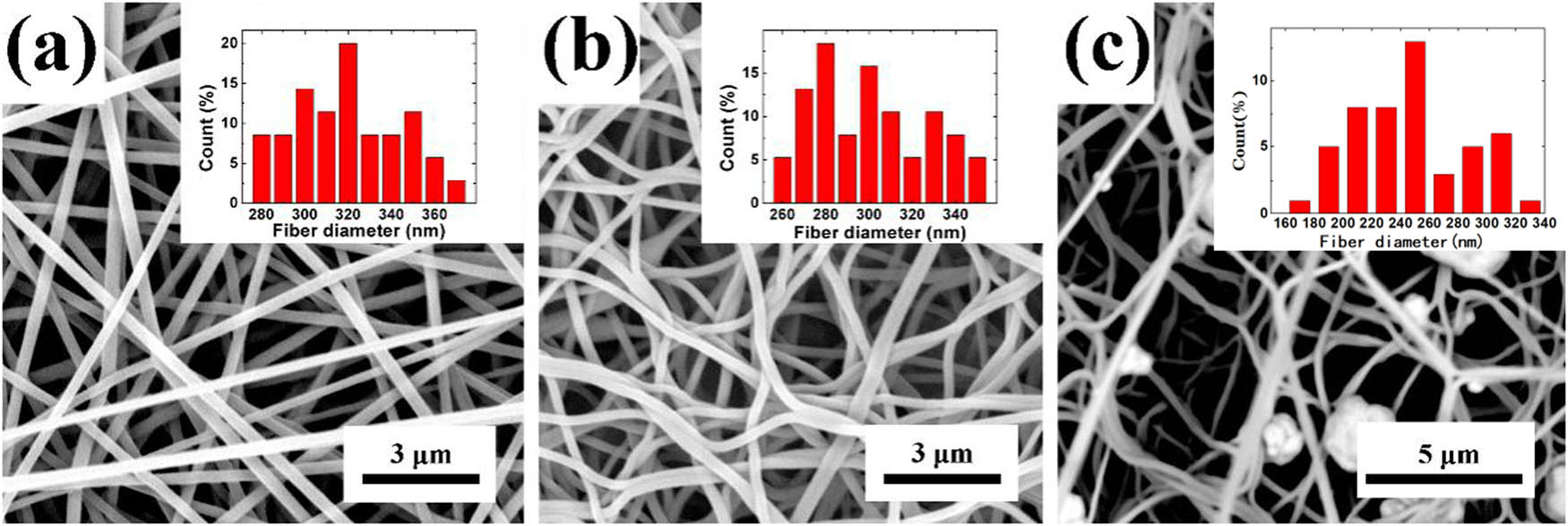

Figure 2a shows the morphology of the as-spun pure PAN nanofibers prepared by electrospinning with a smooth surface and uniform diameter. Its average diameter is 320 ± 24.67 nm. To avoid fiber melting or fusion, we oxidized PAN nanofibers at 260°C to convert C–C and C–N to C–C and C–N bonds (57,58), followed by carbonization at 900°C. After carbonization, a significant color change from white to black was observed, and the morphology of the obtained CNFs is shown in Figure 2b. It can be seen that CNFs have uniform diameter distribution, have no significant change in appearance, and maintain fibrous morphology, which is related to the entanglement network and flexibility of pure PAN fibers. The average diameter of the CNFs is 301 ± 26.20 nm. It is reduced by ∼20 nm than pure PAN fiber, derived from the volatilization of DMF as a solvent and the disappearance of O and H components in PAN. The SEM image in Figure 2b shows that the nanofibers are slightly curved. This is because the defects in the PAN fiber itself will be inherited in the CNF fiber (59). In the figure, it can be observed that the PAN fiber precursors have a certain phenomenon of adhesion and merging due to problems such as residual solvent during the spinning process. Manocha et al. tested the shrinkage of PAN fibers when heated at 200–1,000°C. The shrinkage of fibers happened in three temperature sections 200–350°C, 600–800°C, and 800–1,000°C and was mainly concentrated in the first two stages. Under the combined effect of shrinkage stress and defects, the fibers become bent (60). Ag-CNFs were obtained by Ag-ion modification of CNFs with AgNO3 solution, and its morphology is as shown in Figure 2c. It can be seen that there are micron-/nanoscale Ag particles on the surface of the fiber, which proves the feasibility of the inorganic salt impregnating the surface of the nanofiber to form a nanostructure (61).

(a) SEM images and diameter distribution histogram of pure PAN fibers, (b) CNFs, and (c) Ag-CNFs.

3.3 NH3 sensing measurement

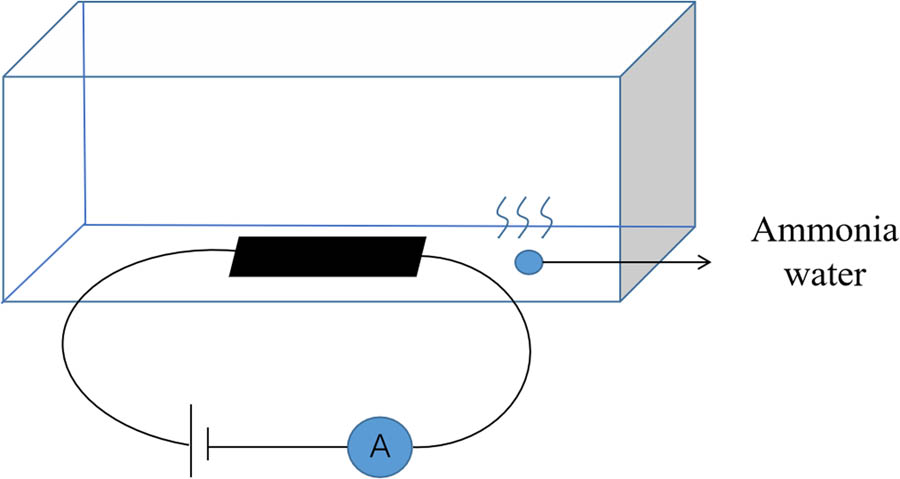

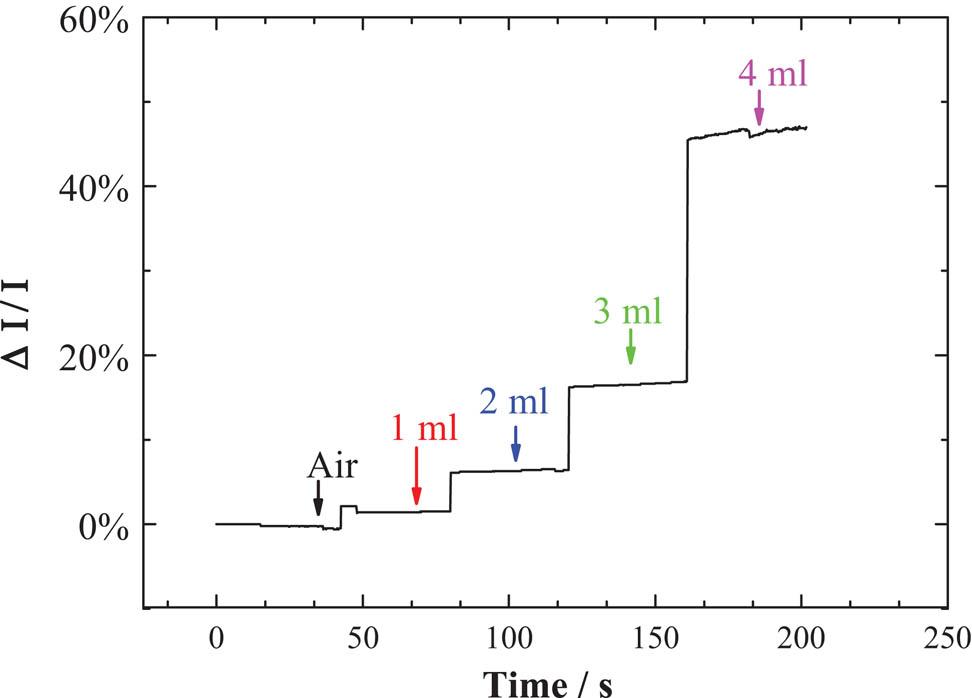

We tested the NH3 sensing performance of Ag-CNFs at room temperature. The Ag-CNF sensor was placed in a sealed container and the concentration of NH3 was controlled by the natural evaporation of the NH3 solution. The voltage across the sensor was 0.2 V. The structure of test device is shown in Figure 3. The electrical properties of the sensor were measured at different NH3 concentrations. Figure 4 shows the electrical response of Ag-CNFs to 1, 2, 3, and 4 mL of the NH3 solution, in a closed container, the density of 1–4 mL of NH3 after volatilization is 0.0754, 0.1508, 0.2262, and 0.3016 mol/m3, indicating the effect of NH3 on electrical transport behavior. It can be seen that a high concentration of NH3 results in a bigger current, meaning that the resistance of the sensor decreases and the conductivity is improved. A sensor exposed to a higher concentration of NH3 solution exhibits a larger current change, that is, as the gas concentration increases, the sensor response becomes larger. In addition, the sensor current remains stable at the same NH3 concentration, indicating that Ag-CNFs have good NH3 sensing properties.

Schematic diagram of the device for Ag-CNF testing NH3 concentration, the voltage applied during the test is 0.2 V.

Sensing properties of Ag-CNFs for NH3 at different NH3 contents. After adding NH3 water, it was allowed to stand for 10 min, and the power-on test time was 1 min.

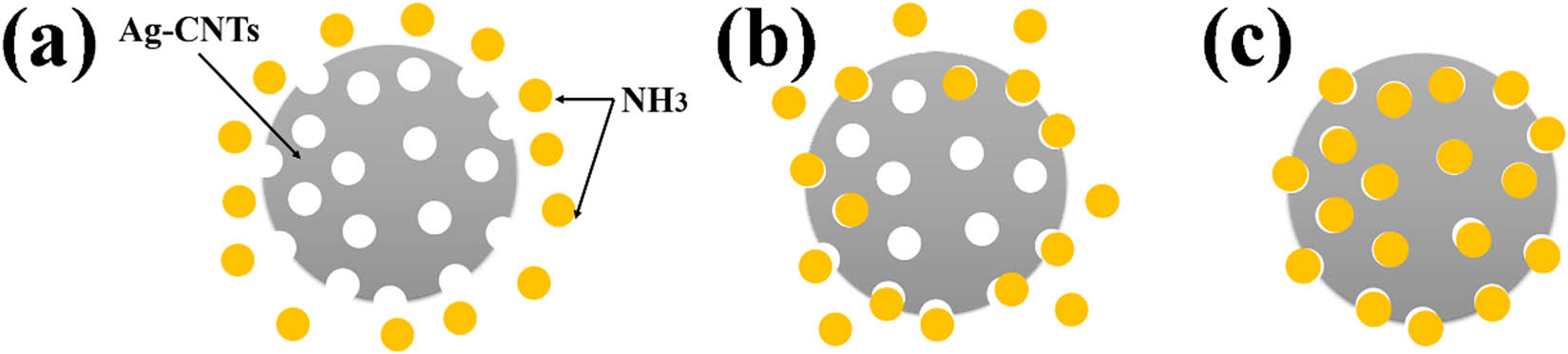

This is due to the adsorption of NH3 by Ag-CNFs, as shown in Figure 4. Ag-CNFs is exposed to NH3 (Figure 5a). The NH3 molecule adheres to the pores on the surface of the sample that is not electrically conductive compared with the state after adsorption, increasing the cross section of the conductive path, as shown in Figure 5b. The resistance of Ag-CNFs adsorbed with NH3 decreased and the current increased. When the surface adsorption reaches saturation, NH3 molecules begin to diffuse from the surface to the inside. When the adsorption process is completed, the conductive regions of the Ag-CNFs are stabilized and the current is constant (Figure 5c). The higher the concentration of NH3, the larger the corresponding current change, indicating its better adsorption performance. When the Ag-CNFs are in the NH3 environment, the NH3 concentration on the surface will increase rapidly. As the time in the NH3 environment increases, the internal NH3 concentration will gradually increase until it reaches saturation. The equation of gas diffusion in this simulation can be described by:

where

where

Process of adsorption of NH3 by Ag-CNFs. (a) Ag-CNFs in NH3 atmosphere. (b) Ag-CNFs begin to adsorb NH3 and surface seepage occurs. (c) Surface adsorption is saturated and begins to diffuse internally.

Distribution of the NH3 concentration in the Ag-CNFs surface simulated by COMSOL.

Ag-CNF-based sensors can be used not only for toxic gas alarm systems, but also for characterizing food spoilage. When animals, plants, and foods prepared by them are decomposed by enzymes produced by microorganisms, abnormal odors may occur. If the protein is decomposed, it will produce harmful gases such as NH3 and H2S. Human senses may be more difficult to capture trace amounts of gas from food spoilage in a timely manner. By putting Ag-CNFs sensors together with food, we can get information on food spoilage in a sensitive and timely manner, avoiding food poisoning caused by consumption.

Gas sensors involve physical and chemical adsorption and other reasons. The chemical gas sensor itself requires a long time of adsorption and desorption processes, so the repeatability problem of the gas sensor has always been a problem in the field. When the gas is to be measured, there are differences in the same concentration response multiple times in a short time, but after a longer time interval and calibration, better repeatability can be obtained (62,63). With further research on the sensor, optimizing the conditions of electrospinning PAN, and to get finer fibers, continuous operation of the gas sensor reliability will be improved due to the larger specific surface area.

4 Conclusions

In summary, Ag-CNFs were successfully prepared by electrospinning and in situ solution polymerization, prepared into an NH3 sensor at room temperature. The surface of the CNFs was modified with Ag nanoparticles having antibacterial properties to protect the fibers. It can be used to detect NH3 naturally evolved from 1 to 4 mL of NH3 solution in a closed vessel and has a high response at higher NH3 concentrations. This work can provide a viable way to create a low-cost, high-sensitivity, stable, detectable NH3 concentration sensor for use in toxic gas alarm systems and characterize food spoilage.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51673103) and the Postdoctoral Scientific Research Foundation of Qingdao (2016014).

References

(1) Mehta A, Mohammed WS, Johnson EG. Multimode interference-based fiber-optic displacement sensor. IEEE Photon Technol Lett. 2003;15(8):1129–31.10.1109/LPT.2003.815338Search in Google Scholar

(2) Rugar D, Mamin HJ, Erlandsson R, Stern JE, Terris BD, Terris BD. Force microscope using a fiber-optic displacement sensor. Rev Sci Instrum. 1998;59(11):2337–40.10.1063/1.1139958Search in Google Scholar

(3) Zhu J, Jiang S, Hou H, Agarwal S, Greiner A. Low density, thermally stable, and intrinsic flame retardant poly(bis(benzimidazo)benzophenanthroline-dione) sponge. Macromol Mater Eng. 2018;303(4):1700615.10.1002/mame.201700615Search in Google Scholar

(4) Zhao X, Wu Z, Zhi Y, An YH, Cui W, Li L, et al. Improvement for the performance of solar-blind photodetector based on β-Ga2O3 thin films by doping Zn. J Phys D Appl Phys. 2017;50(8):08102.10.1088/1361-6463/aa5758Search in Google Scholar

(5) Tong L, Wang X, He X, Nie G, Zhang J, Zhang B, et al. Electrically conductive TPU nanofibrous composite with high stretchability for flexible strain sensor. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2018;13(1):86.10.1186/s11671-018-2499-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(6) Guo Y, Gao Z, Wang X, Sun L, Yan X, Yan S, et al. A highly stretchable humidity sensor based on spandex covered yarns and nanostructured polyaniline. RSC Adv. 2018;8(2):1078–82.10.1039/C7RA10474JSearch in Google Scholar

(7) You M, Yan X, Zhang J, Wang X, He X, Yu M, et al. Colorimetric humidity sensors based on electrospun polyamide/CoCl2 nanofibrous membranes. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2017;12(1):360.10.1186/s11671-017-2139-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(8) Shirinov AV, Schomburg WK. Pressure sensor from a PVDF film. Sens Actuators A. 2008;142(1):48–55.10.1016/j.sna.2007.04.002Search in Google Scholar

(9) Xia G, Huang Y, Li F, Wang L, Pang J, Li L, et al. A thermally flexible and multi-site tactile sensor for remote 3D dynamic sensing imaging. Front Chem Sci Eng. 2020. 10.1007/s11705-019-1901-5Search in Google Scholar

(10) Bao X, Dhliwayo J, Heron NA, Webb DJ, Jackson DA. Experimental and theoretical studies on a distributed temperature sensor based on brillouin scattering. J Lightwave Technol. 1995;13(7):1340–8.10.1109/50.400678Search in Google Scholar

(11) Zhang S, Yu F. Piezoelectric materials for high temperature sensors. J Am Ceram Soc. 2011;94(10):3153–70.10.1111/j.1551-2916.2011.04792.xSearch in Google Scholar

(12) He XX, Li JT, Jia XS, Tong L, Wang XX, Zhang J, et al. Facile fabrication of multi-hierarchical porous polyaniline composite as pressure sensor and gas sensor with adjustable sensitivity. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2017;12(1):476.10.1186/s11671-017-2246-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(13) Zhang H, Tang C, Long Y, Zhang J, Huang R, Li J, et al. High-sensitivity gas sensors based on arranged polyaniline/PMMA composite fibers. Sens Actuator A. 2014;219:123–7.10.1016/j.sna.2014.09.005Search in Google Scholar

(14) Li D, Xia Y. Electrospinning of nanofibers: reinventing the wheel? Adv Mater. 2004;16(14):1151–70.10.1002/adma.200400719Search in Google Scholar

(15) Jiang S, Chen Y, Duan G, Mei C, Greiner A, Agarwal S. Electrospun nanofiber reinforced composites: a review. Polym Chem. 2018;9(20):2685–720.10.1039/C8PY00378ESearch in Google Scholar

(16) Ding B, Kim J, Miyazaki Y, Shiratori S. Electrospun nanofibrous membranes coated quartz crystal microbalance as gas sensor for NH3 detection. Sens Actuators B. 2004;101(3):373–80.10.1016/j.snb.2004.04.008Search in Google Scholar

(17) Schiffman J, Schauer C. A review: electrospinning of biopolymer nanofibers and their applications. J Macromol Sci Part C. 2008;48(2):317–52.10.1080/15583720802022182Search in Google Scholar

(18) Liu X, Li M, Han G, Dong J. The catalysts supported on metallized electrospun polyacrylonitrile fibrous mats for methanol oxidation. Electrochim Acta. 2010;55(8):2983–90.10.1016/j.electacta.2010.01.014Search in Google Scholar

(19) Ma P, Dai C, Jiang S. Thioetherimide-modified cyanate ester resin with better molding performance for glass fiber reinforced composites. Polymers. 2019;11(9):1458.10.3390/polym11091458Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(20) Jiang S, Agarwal S, Greiner A. Low-density open cellular sponges as functional materials. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56(49):15520–3810.1002/anie.201700684Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(21) Dong W, Liu J, Mou X, Liu G, Huang X, Yan X, et al. Performance of polyvinyl pyrrolidone-isatis root antibacterial wound dressings produced in situ by handheld electrospinner. Colloids Surf B. 2020;188:110766.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2019.110766Search in Google Scholar

(22) Aussawasathien D, Sahasithiwat S, Menbangpung L. Electrospun camphorsulfonic acid doped poly(o-toluidine)–polystyrene composite fibers: chemical vapor sensing. Synth Met. 2008;158(7):259–63.10.1016/j.synthmet.2008.01.007Search in Google Scholar

(23) Ji S, Li Y, Yang M. Gas sensing properties of a composite composed of electrospun poly(methyl methacrylate) nanofibers and in situ polymerized polyaniline. Sens Actuators B. 2008;133(2):644–9.10.1016/j.snb.2008.03.040Search in Google Scholar

(24) Pinto NJ, Ramos I, Rojas R, Wang P, Johnson AT. Electric response of isolated electrospun polyaniline nanofibers to vapors of aliphatic alcohols. Sens Actuators B 2008;129(2):621–7.10.1016/j.snb.2007.09.040Search in Google Scholar

(25) Zhao L, Duan G, Zhang G, Yang H, He S, Jiang S. Electrospun functional materials toward food packaging applications: a review. Nanomaterials. 2020;10(1):150.10.3390/nano10010150Search in Google Scholar

(26) Yao K, Chen J, Li P, Duan G, Hou H. Robust strong electrospun polyimide composite nanofibers from a ternary polyamic acid blend. Compos Commun. 2019;15:92–5.10.1016/j.coco.2019.07.001Search in Google Scholar

(27) Xu W, Ding Y, Yu Y, Jiang S, Chen L, Hou H. Highly foldable PANi@CNTs/PU dielectric composites toward thin-film capacitor application. Mater Lett. 2017;192(Apr.1):25–28.10.1016/j.matlet.2017.01.064Search in Google Scholar

(28) Xian-Sheng J, Cheng-Chun T, Xu Y, Gui-Feng Y, Jin-Tao L, Hong-Di Z, et al. Flexible polyaniline/poly(methyl methacrylate) composite fibers via electrospinning and in situ polymerization for ammonia gas sensing and strain sensing. J Nanomaterials. 2016;2016:1–8.10.1155/2016/9102828Search in Google Scholar

(29) Li Y, Wang H, Cao X, Yuan M, Yang M. A composite of polyelectrolyte-grafted multi-walled carbon nanotubes and in situ polymerized polyaniline for the detection of low concentration triethylamine vapor. Nanotechnology. 2008;19(1):015503.10.1088/0957-4484/19/01/015503Search in Google Scholar

(30) Matsuguchi M, Io J, Sugiyama G, Sakai Y. Effect of NH3 gas on the electrical conductivity of polyaniline blend films. Synth Met. 2002;128(1):15–19.10.1016/S0379-6779(01)00504-5Search in Google Scholar

(31) Pinto NJ. Electrospun conducting polymer nanofibers as the active material in sensors and diodes. J Phys Conf. 2013;421:012004.10.1088/1742-6596/421/1/012004Search in Google Scholar

(32) Virji S, Huang J, Kaner RB, Weiller BH. Polyaniline nanofiber gas sensors? Examination of response mechanisms. Nano Lett. 2004;4(3):491–6.10.1021/nl035122eSearch in Google Scholar

(33) Park Y, Song H, Lee C, Jee J. Fabrication and its characteristics of metal-loaded TiO2/SnO2 thick-film gas sensor for detecting dichloromethane. J Ind Eng Chem. 2008;14(6):818–23.10.1016/j.jiec.2008.06.009Search in Google Scholar

(34) Suehiro J, Zhou G, Imakiire H, Ding W, Hara M. Controlled fabrication of carbon nanotube NO2 gas sensor using dielectrophoretic impedance measurement. Sens Actuators B. 2005;108(1/2):398–403.10.1016/j.snb.2004.09.048Search in Google Scholar

(35) Lee JH. Gas sensors using hierarchical and hollow oxide nanostructures: overview. Sens Actuators B. 2009;140(1):319–36.10.1016/j.snb.2009.04.026Search in Google Scholar

(36) Penza M, Rossi R, Alvisi M, Signore MA, Falconieri M. Characterization of metal-modified and vertically-aligned carbon nanotube films for functionally enhanced gas sensor applications. Thin Solid Films. 2009;517(22):6211–6.10.1016/j.tsf.2009.04.009Search in Google Scholar

(37) Basu S, Bhattacharyya P. Recent developments on graphene and graphene oxide based solid state gas sensors. Sens Actuators B. 2012;173:1–21.10.1016/j.snb.2012.07.092Search in Google Scholar

(38) Peng S, Cho K, Qi P, Dai H. Ab initio study of CNT NO2 gas sensor. Chem Phys Lett. 2004;387(4–6):271–6.10.1016/j.cplett.2004.02.026Search in Google Scholar

(39) Singh B, Verma A, Kaushal A, Bdikin I, Chakravarty S, Bhardwaj N, et al. Novel low cost liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) sensor based on activated carbon for room temperature sensing application. Sens Lett. 2014;12(1):24–30.10.1166/sl.2014.3225Search in Google Scholar

(40) Lü R, Shi K, Zhou W, Wang L, Tian C, Pan K, et al. Highly dispersed Ni-decorated porous hollow carbon nanofibers: fabrication, characterization, and NOx gas sensors at room temperature. J Mater Chem. 2012;22(47):24814–20.10.1039/c2jm34288jSearch in Google Scholar

(41) Jang J, Bae J. Carbon nanofiber/polypyrrole nanocable as toxic gas sensor. Sens Actuators B. 2007;122(1):7–13.10.1016/j.snb.2006.05.002Search in Google Scholar

(42) Lee J, Kwon OS, Shin DH, Jang J. WO3 nanonodule-decorated hybrid carbon nanofibers for NO2 gas sensor application. J Mater Chem A. 2013;1(32):9099–106.10.1039/c3ta11658aSearch in Google Scholar

(43) Richard B, Millington LA, Robert C. US Patent 3322489, 1967. Google Scholar.Search in Google Scholar

(44) Yoneshiga I, Teranishi H. Japanese Patent 2775/70, 1970. Google Scholar.Search in Google Scholar

(45) Cato AD, Edie DD. Flow behavior of mesophase pitch. Carbon. 2003;41(7):1411–7.10.1016/S0008-6223(03)00050-2Search in Google Scholar

(46) Lin Z, Young S, Hsiao CH, Chang S. Adsorption sensitivity of Ag-decorated carbon nanotubes toward gas-phase compounds. Sens Actuators B. 2013;188(Nov.):1230–4.10.1016/j.snb.2013.07.112Search in Google Scholar

(47) Lin ZD, Young SJ, Hsiao CH, Chang SJ. Improved field emission properties of Ag-decorated multi-walled carbon nanotubes. IEEE Photon Technol Lett. 2013;25(11):1017–9.10.1109/LPT.2013.2258148Search in Google Scholar

(48) Young SJ, Wang TH. ZnO nanorods adsorbed with photochemical Ag nanoparticles for IOT and field electron emission application. J Electrochem Soc. 2018;165(8):B3043–45.10.1149/2.0061808jesSearch in Google Scholar

(49) Uddin AS, Kumar PS, Hassan K, Kim HC. Enhanced sensing performance of bimetallic Al/Ag-CNF network and porous PDMS-based triboelectric acetylene gas sensors in a high humidity atmosphere. Sens Actuators B. 2018;258:857–69.10.1016/j.snb.2017.11.160Search in Google Scholar

(50) Sanzone G, Zimbone M, Cacciato G, Ruffino F, Carles R, Privitera V, et al. Ag/TiO2 nanocomposite for visible light-driven photocatalysis. Superlattices Microstruct. 2018;123:394–402.10.1016/j.spmi.2018.09.028Search in Google Scholar

(51) Miao Y, He S, Zhong Y, Yang Z, Tjiu WW, Liu T. A novel hydrogen peroxide sensor based on Ag/SnO2 composite nanotubes by electrospinning. Electrochim Acta. 2013;99:117–23.10.1016/j.electacta.2013.03.063Search in Google Scholar

(52) Huang YP, Miao YE, Ji SS, Tjiu WW, Liu TX. Electrospun carbon nanofibers decorated with Ag–Pt bimetallic nanoparticles for selective detection of dopamine. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;6:12449–56.10.1021/am502344pSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

(53) Koo Y, Littlejohn G, Collins B, Yun Y, Shanov V, Schulz MJ, et al. Synthesis and characterization of Ag–TiO2–CNT nanoparticle composites with high photocatalytic activity under artificial light. Composites Part B. 2014;57:105–11.10.1016/j.compositesb.2013.09.004Search in Google Scholar

(54) Zhang X, Lin Z, Chen B, Zhang W, Sharma S, Gu W, et al. Solid-state flexible polyaniline/silver cellulose nanofibrils aerogel supercapacitors. J Power Sources. 2014;246:283–9.10.1016/j.jpowsour.2013.07.080Search in Google Scholar

(55) Kim Y, Lee DK, Cha HG, Kim CW, Kang YS. Synthesis and characterization of antibacterial Ag−SiO2 nanocomposite. J Phys Chem C. 2007;111(9):3629–35.10.1021/jp068302wSearch in Google Scholar

(56) Gong P, Li H, He X, Wang K, Yang X. Preparation and antibacterial activity of Fe3O4@Ag nanoparticles. Nanotechnology. 2007;18(28):285604.10.1088/0957-4484/18/28/285604Search in Google Scholar

(57) Moon SC, Farris RJ. Strong electrospun nanometer-diameter polyacrylonitrile carbon fiber yarns. Carbon. 2009;47(12):2829–39.10.1016/j.carbon.2009.06.027Search in Google Scholar

(58) Zhu J, Wei S, Rutman D, Haldolaarachchige N, Young DP, Guo Z. Magnetic polyacrylonitrile-Fe@FeO nanocomposite fibers – Electrospinning, stabilization and carbonization. Polymer. 2011;52(13):2947–55.10.1016/j.polymer.2011.04.034Search in Google Scholar

(59) Ge H-Y, Liu H-S, Chen J. The formation and heredity of defects from PAN precursor to carbon fiber. Synthetic Fiber in China; 2009;38(2):21–25.Search in Google Scholar

(60) Manocha LM, Bahl OP, Jain GC. Length changes in PAN fibres during their pyrolysis to carbon fibres. Angew Makromol Chem. 1978;67(1):11–29.10.1002/apmc.1978.050670102Search in Google Scholar

(61) Zhu J, Chen M, Qu H, Wei H, Guo J, Luo Z, et al. Positive and negative magnetoresistance phenomena observed in magnetic electrospun polyacrylonitrile-based carbon nanocomposite fibers. J Mater Chem C. 2013;2(4):715–22.10.1039/C3TC32007CSearch in Google Scholar

(62) Shaalan NM, Rashad M, Abdel-Rahim MA. Repeatability of indium oxide gas sensors for detecting methane at low temperature. Mater Semicond Proc. 2016;56:260–4.10.1016/j.mssp.2016.09.007Search in Google Scholar

(63) Xie GZ, He H, Zhou Y, Xie T, Jiang Y, Tai HL. Gas sensors based on MWCNTs-PVP composite films for 1,2-dichloroethane vapor detection. J Mater Sci Mater Electron. 2014;25(11):5095–100.10.1007/s10854-014-2277-4Search in Google Scholar

© 2020 Yang Yu et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The regulatory effects of the number of VP(N-vinylpyrrolidone) function groups on macrostructure and photochromic properties of polyoxometalates/copolymer hybrid films

- How the hindered amines affect the microstructure and mechanical properties of nitrile-butadiene rubber composites

- Novel benzimidazole-based conjugated polyelectrolytes: synthesis, solution photophysics and fluorescent sensing of metal ions

- Study on the variation of rock pore structure after polymer gel flooding

- Investigation on compatibility of PLA/PBAT blends modified by epoxy-terminated branched polymers through chemical micro-crosslinking

- Investigation on degradation mechanism of polymer blockages in unconsolidated sandstone reservoirs

- Investigation on the effect of active-polymers with different functional groups for EOR

- Fabrication and characterization of hexadecyl acrylate cross-linked phase change microspheres

- Surface-induced phase transitions in thin films of dendrimer block copolymers

- ZnO-assisted coating of tetracalcium phosphate/ gelatin on the polyethylene terephthalate woven nets by atomic layer deposition

- Animal fat and glycerol bioconversion to polyhydroxyalkanoate by produced water bacteria

- Effect of microstructure on the properties of polystyrene microporous foaming material

- Synthesis of amphiphilic poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(methyl methacrylate) containing trityl ether acid cleavable junction group and its self-assembly into ordered nanoporous thin films

- On-demand optimize design of sound-absorbing porous material based on multi-population genetic algorithm

- Enhancement of mechanical, thermal and water uptake performance of TPU/jute fiber green composites via chemical treatments on fiber surface

- Enhancement of mechanical properties of natural rubber–clay nanocomposites through incorporation of silanated organoclay into natural rubber latex

- Preparation and characterization of corn starch/PVA/glycerol composite films incorporated with ε-polylysine as a novel antimicrobial packaging material

- Preparation of novel amphoteric polyacrylamide and its synergistic retention with cationic polymers

- Effect of montmorillonite on PEBAX® 1074-based mixed matrix membranes to be used in humidifiers in proton exchange membrane fuel cells

- Insight on the effect of a piperonylic acid derivative on the crystallization process, melting behavior, thermal stability, optical and mechanical properties of poly(l-lactic acid)

- Lipase-catalyzed synthesis and post-polymerization modification of new fully bio-based poly(hexamethylene γ-ketopimelate) and poly(hexamethylene γ-ketopimelate-co-hexamethylene adipate) copolyesters

- Dielectric, mechanical and thermal properties of all-organic PI/PSF composite films by in situ polymerization

- Morphological transition of amphiphilic block copolymer/PEGylated phospholipid complexes induced by the dynamic subtle balance interactions in the self-assembled aggregates

- Silica/polymer core–shell particles prepared via soap-free emulsion polymerization

- Antibacterial epoxy composites with addition of natural Artemisia annua waste

- Design and preparation of 3D printing intelligent poly N,N-dimethylacrylamide hydrogel actuators

- Multilayer-structured fibrous membrane with directional moisture transportability and thermal radiation for high-performance air filtration

- Reaction characteristics of polymer expansive jet impact on explosive reactive armour

- Synthesis of a novel modified chitosan as an intumescent flame retardant for epoxy resin

- Synthesis of aminated polystyrene and its self-assembly with nanoparticles at oil/water interface

- The synthesis and characterisation of porous and monodisperse, chemically modified hypercrosslinked poly(acrylonitrile)-based terpolymer as a sorbent for the adsorption of acidic pharmaceuticals

- Crystal transition and thermal behavior of Nylon 12

- All-optical non-conjugated multi-functionalized photorefractive polymers via ring-opening metathesis polymerization

- Fabrication of LDPE/PS interpolymer resin particles through a swelling suspension polymerization approach

- Determination of the carbonyl index of polyethylene and polypropylene using specified area under band methodology with ATR-FTIR spectroscopy

- Synthesis, electropolymerization, and electrochromic performances of two novel tetrathiafulvalene–thiophene assemblies

- Wetting behaviors of fluoroterpolymer fiber films

- Plugging mechanisms of polymer gel used for hydraulic fracture water shutoff

- Synthesis of flexible poly(l-lactide)-b-polyethylene glycol-b-poly(l-lactide) bioplastics by ring-opening polymerization in the presence of chain extender

- Sulfonated poly(arylene ether sulfone) functionalized polysilsesquioxane hybrid membranes with enhanced proton conductivity

- Fmoc-diphenylalanine-based hydrogels as a potential carrier for drug delivery

- Effect of diacylhydrazine as chain extender on microphase separation and performance of energetic polyurethane elastomer

- Improved high-temperature damping performance of nitrile-butadiene rubber/phenolic resin composites by introducing different hindered amine molecules

- Rational synthesis of silicon into polyimide-derived hollow electrospun carbon nanofibers for enhanced lithium storage

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of phthalonitrile-etherified resole resin

- Highly thermally conductive boron nitride@UHMWPE composites with segregated structure

- Synthesis of high-temperature thermally expandable microcapsules and their effects on foaming quality and surface quality of foamed ABS materials

- Tribological and nanomechanical properties of a lignin-based biopolymer

- Hydroxyapatite/polyetheretherketone nanocomposites for selective laser sintering: Thermal and mechanical performances

- Synthesis of a phosphoramidate flame retardant and its flame retardancy on cotton fabrics

- Preparation and characterization of thermoresponsive poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) copolymers with enhanced hydrophilicity

- Fabrication of flexible SiO2 nanofibrous yarn via a conjugate electrospinning process

- Silver-loaded carbon nanofibers for ammonia sensing

- Polar migration behavior of phosphonate groups in phosphonate esterified acrylic grafted epoxy ester composites and their role in substrate protection

- Solubility and diffusion coefficient of supercritical CO2 in polystyrene dynamic melt

- Curcumin-loaded polyvinyl butyral film with antibacterial activity

- Experimental-numerical studies of the effect of cell structure on the mechanical properties of polypropylene foams

- Experimental investigation on the three-dimensional flow field from a meltblowing slot die

- Enhancing tribo-mechanical properties and thermal stability of nylon 6 by hexagonal boron nitride fillers

- Preparation and characterization of electrospun fibrous scaffolds of either PVA or PVP for fast release of sildenafil citrate

- Seawater degradation of PLA accelerated by water-soluble PVA

- Review Article

- Mechanical properties and application analysis of spider silk bionic material

- Additive manufacturing of PLA-based scaffolds intended for bone regeneration and strategies to improve their biological properties

- Structural design toward functional materials by electrospinning: A review

- Special Issue: XXXII National Congress of the Mexican Polymer Society

- Tailoring the morphology of poly(high internal phase emulsions) synthesized by using deep eutectic solvents

- Modification of Ceiba pentandra cellulose for drug release applications

- Redox initiation in semicontinuous polymerization to search for specific mechanical properties of copolymers

- pH-responsive polymer micelles for methotrexate delivery at tumor microenvironments

- Microwave-assisted synthesis of the lipase-catalyzed ring-opening copolymerization of ε-caprolactone and ω-pentadecanolactone: Thermal and FTIR characterization

- Rapid Communications

- Pilot-scale production of polylactic acid nanofibers by melt electrospinning

- Erratum

- Erratum to: Synthesis and characterization of new macromolecule systems for colon-specific drug delivery

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The regulatory effects of the number of VP(N-vinylpyrrolidone) function groups on macrostructure and photochromic properties of polyoxometalates/copolymer hybrid films

- How the hindered amines affect the microstructure and mechanical properties of nitrile-butadiene rubber composites

- Novel benzimidazole-based conjugated polyelectrolytes: synthesis, solution photophysics and fluorescent sensing of metal ions

- Study on the variation of rock pore structure after polymer gel flooding

- Investigation on compatibility of PLA/PBAT blends modified by epoxy-terminated branched polymers through chemical micro-crosslinking

- Investigation on degradation mechanism of polymer blockages in unconsolidated sandstone reservoirs

- Investigation on the effect of active-polymers with different functional groups for EOR

- Fabrication and characterization of hexadecyl acrylate cross-linked phase change microspheres

- Surface-induced phase transitions in thin films of dendrimer block copolymers

- ZnO-assisted coating of tetracalcium phosphate/ gelatin on the polyethylene terephthalate woven nets by atomic layer deposition

- Animal fat and glycerol bioconversion to polyhydroxyalkanoate by produced water bacteria

- Effect of microstructure on the properties of polystyrene microporous foaming material

- Synthesis of amphiphilic poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(methyl methacrylate) containing trityl ether acid cleavable junction group and its self-assembly into ordered nanoporous thin films

- On-demand optimize design of sound-absorbing porous material based on multi-population genetic algorithm

- Enhancement of mechanical, thermal and water uptake performance of TPU/jute fiber green composites via chemical treatments on fiber surface

- Enhancement of mechanical properties of natural rubber–clay nanocomposites through incorporation of silanated organoclay into natural rubber latex

- Preparation and characterization of corn starch/PVA/glycerol composite films incorporated with ε-polylysine as a novel antimicrobial packaging material

- Preparation of novel amphoteric polyacrylamide and its synergistic retention with cationic polymers

- Effect of montmorillonite on PEBAX® 1074-based mixed matrix membranes to be used in humidifiers in proton exchange membrane fuel cells

- Insight on the effect of a piperonylic acid derivative on the crystallization process, melting behavior, thermal stability, optical and mechanical properties of poly(l-lactic acid)

- Lipase-catalyzed synthesis and post-polymerization modification of new fully bio-based poly(hexamethylene γ-ketopimelate) and poly(hexamethylene γ-ketopimelate-co-hexamethylene adipate) copolyesters

- Dielectric, mechanical and thermal properties of all-organic PI/PSF composite films by in situ polymerization

- Morphological transition of amphiphilic block copolymer/PEGylated phospholipid complexes induced by the dynamic subtle balance interactions in the self-assembled aggregates

- Silica/polymer core–shell particles prepared via soap-free emulsion polymerization

- Antibacterial epoxy composites with addition of natural Artemisia annua waste

- Design and preparation of 3D printing intelligent poly N,N-dimethylacrylamide hydrogel actuators

- Multilayer-structured fibrous membrane with directional moisture transportability and thermal radiation for high-performance air filtration

- Reaction characteristics of polymer expansive jet impact on explosive reactive armour

- Synthesis of a novel modified chitosan as an intumescent flame retardant for epoxy resin

- Synthesis of aminated polystyrene and its self-assembly with nanoparticles at oil/water interface

- The synthesis and characterisation of porous and monodisperse, chemically modified hypercrosslinked poly(acrylonitrile)-based terpolymer as a sorbent for the adsorption of acidic pharmaceuticals

- Crystal transition and thermal behavior of Nylon 12

- All-optical non-conjugated multi-functionalized photorefractive polymers via ring-opening metathesis polymerization

- Fabrication of LDPE/PS interpolymer resin particles through a swelling suspension polymerization approach

- Determination of the carbonyl index of polyethylene and polypropylene using specified area under band methodology with ATR-FTIR spectroscopy

- Synthesis, electropolymerization, and electrochromic performances of two novel tetrathiafulvalene–thiophene assemblies

- Wetting behaviors of fluoroterpolymer fiber films

- Plugging mechanisms of polymer gel used for hydraulic fracture water shutoff

- Synthesis of flexible poly(l-lactide)-b-polyethylene glycol-b-poly(l-lactide) bioplastics by ring-opening polymerization in the presence of chain extender

- Sulfonated poly(arylene ether sulfone) functionalized polysilsesquioxane hybrid membranes with enhanced proton conductivity

- Fmoc-diphenylalanine-based hydrogels as a potential carrier for drug delivery

- Effect of diacylhydrazine as chain extender on microphase separation and performance of energetic polyurethane elastomer

- Improved high-temperature damping performance of nitrile-butadiene rubber/phenolic resin composites by introducing different hindered amine molecules

- Rational synthesis of silicon into polyimide-derived hollow electrospun carbon nanofibers for enhanced lithium storage

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of phthalonitrile-etherified resole resin

- Highly thermally conductive boron nitride@UHMWPE composites with segregated structure

- Synthesis of high-temperature thermally expandable microcapsules and their effects on foaming quality and surface quality of foamed ABS materials

- Tribological and nanomechanical properties of a lignin-based biopolymer

- Hydroxyapatite/polyetheretherketone nanocomposites for selective laser sintering: Thermal and mechanical performances

- Synthesis of a phosphoramidate flame retardant and its flame retardancy on cotton fabrics

- Preparation and characterization of thermoresponsive poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) copolymers with enhanced hydrophilicity

- Fabrication of flexible SiO2 nanofibrous yarn via a conjugate electrospinning process

- Silver-loaded carbon nanofibers for ammonia sensing

- Polar migration behavior of phosphonate groups in phosphonate esterified acrylic grafted epoxy ester composites and their role in substrate protection

- Solubility and diffusion coefficient of supercritical CO2 in polystyrene dynamic melt

- Curcumin-loaded polyvinyl butyral film with antibacterial activity

- Experimental-numerical studies of the effect of cell structure on the mechanical properties of polypropylene foams

- Experimental investigation on the three-dimensional flow field from a meltblowing slot die

- Enhancing tribo-mechanical properties and thermal stability of nylon 6 by hexagonal boron nitride fillers

- Preparation and characterization of electrospun fibrous scaffolds of either PVA or PVP for fast release of sildenafil citrate

- Seawater degradation of PLA accelerated by water-soluble PVA

- Review Article

- Mechanical properties and application analysis of spider silk bionic material

- Additive manufacturing of PLA-based scaffolds intended for bone regeneration and strategies to improve their biological properties

- Structural design toward functional materials by electrospinning: A review

- Special Issue: XXXII National Congress of the Mexican Polymer Society

- Tailoring the morphology of poly(high internal phase emulsions) synthesized by using deep eutectic solvents

- Modification of Ceiba pentandra cellulose for drug release applications

- Redox initiation in semicontinuous polymerization to search for specific mechanical properties of copolymers

- pH-responsive polymer micelles for methotrexate delivery at tumor microenvironments

- Microwave-assisted synthesis of the lipase-catalyzed ring-opening copolymerization of ε-caprolactone and ω-pentadecanolactone: Thermal and FTIR characterization

- Rapid Communications

- Pilot-scale production of polylactic acid nanofibers by melt electrospinning

- Erratum

- Erratum to: Synthesis and characterization of new macromolecule systems for colon-specific drug delivery