Abstract

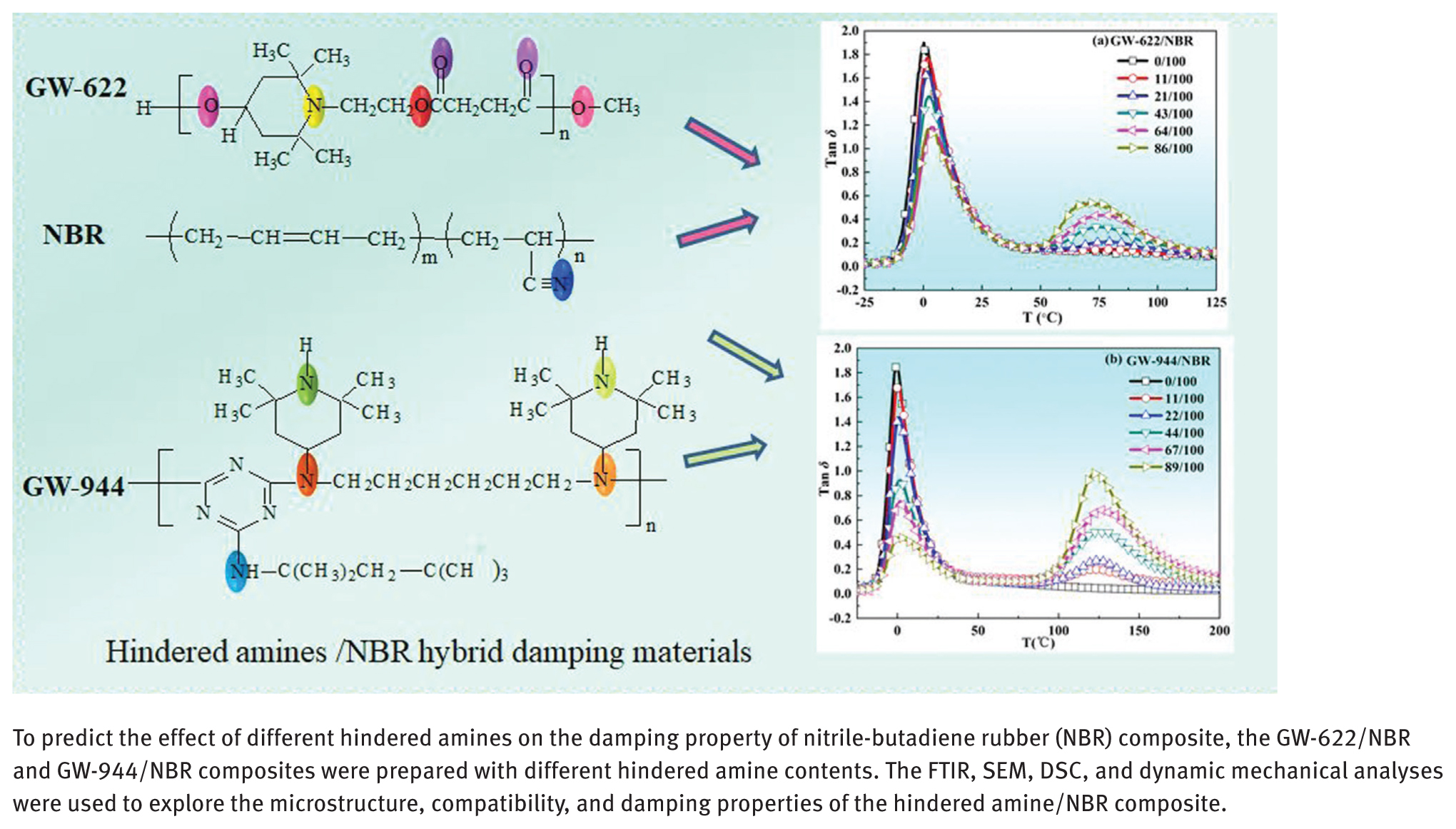

Different hindered amines, GW-622 and GW-944, were added to a nitrile-butadiene rubber (NBR) matrix to prepare a hybrid damping material. The microstructure, compatibility, and dynamic mechanical properties of the hindered amine/NBR composites were investigated using Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, scanning electron microscope (SEM), differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), and dynamic thermomechanical analysis (DMA). The FTIR results showed that hydrogen bonds formed between the hindered amine molecules and the NBR matrix. The SEM and DSC results showed that both GW-622 and GW-944 had partial compatibility with the NBR matrix, and a two-phase structure appeared. The effective damping temperature ranges of the hindered amine/NBR composites were narrow at room temperature and broad at higher temperatures with increasing amounts of GW-622 and GW-944. Comparatively, the damping effect from the addition of GW-944 molecules was more clearly. The present work provides a theoretical basis for the preparation of optimum damping rubber materials.

Graphical Abstract

1 Introduction

Rubber damping materials, with a unique viscoelasticity, have been widely used in precision machines, as mechanical absorbers and for submarine noise elimination (1,2). The final performance of rubber damping materials, an important strategic resource, is increasingly demanding, so how to prepare high-performance rubber damping materials has become a research hotspot (3,4). The general damping factor of a pure rubber matrix is small (the tanδ value <<1.0), and the glass transition temperature (Tg) range is very narrow (only 20°C~30°C) (5,6). The effective damping temperature occurs at low temperatures below room temperature. In recent years, many scholars have been committed to modifying pure rubber substrates to achieve the required damping properties. The following methods are usually used: blending (7), copolymerization (8), interpenetrating networks (IPN) (9,10) and organic hybrid damping materials (11,12). Of all these methods, the organic hybrid damping materials are more novel, and are used in this study.

Organic hybridization refers to the addition of small organic molecules containing polar functional groups to a polar rubber matrix. Hydrogen bond networks run through the matrix and form between the polar functional groups on the large macromolecules and small molecules (13). Compared with the van der Waals force, the interaction of hydrogen bonds is stronger and reversible. They can be destroyed and regenerated under the action of an external force field and temperature field, thus absorbing a large amount of energy and producing a high damping dissipation (14). Chinese scholar Wu added small organic molecules, such as hindered phenol AO-80 and accelerator DZ, to polar substrates, such as chlorinated polyethylene (CPE) and polyacrylic ester (ACR), using the reversible hydrogen bonds formed between small organic molecules and polymer substrates to obtain organic hybrid damping materials with high loss factors (15,16). This approach attracted the interest of many researchers and is thought

to have pioneered a new concept for the preparation of high-performance damping materials. Zhao et al. studied hindered phenol AO-80/nitrile-butadiene rubber (NBR) composites, and found that organic hybrid damping materials obtained by this method have outstanding performance than compared with IPN and other methods (17). Zhao et al, also prepared hindered phenol AO-60/NBR composites and hindered phenol AO-70/NBR composites with excellent damping properties (18,19).

In this study, NBR was selected as a substrate material for organic hybridization because of its good damping properties. Two kinds of hindered amines with different numbers of polar functional groups and steric hindrance were added to the same rubber substrate. The microscopic structure and the hydrogen bond interaction were investigated by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). Dynamic thermomechanical analysis (DMA) was used to study the damping properties of the two hybrid systems. The goal is to form strong hydrogen bond between hindered amines and NBR to improve the damping properties of the material.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

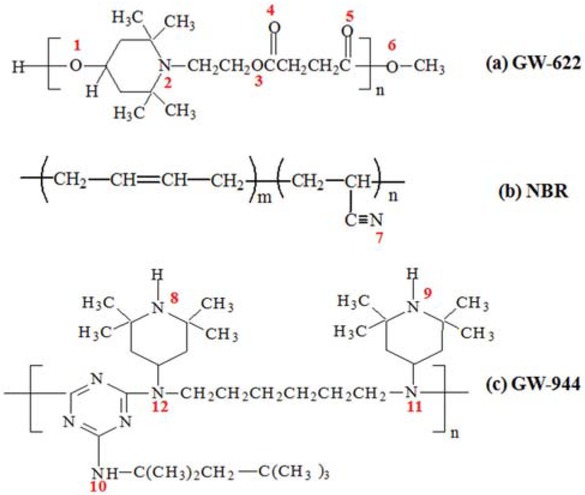

NBR (N220S) with an acrylonitrile mass fraction of 41% was provided by Japan Synthetic Rubber Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). Hindered amines GW-622 and GW-944, as powders, were purchased from Beijing Additives Institute (Beijing, China). The chemical structures of GW-622 and GW-944 are shown in Figure 1. Other rubber additives used in the study were purchased in China and used without further purification.

Molecular structures of (a) GW-622, (b) NBR and (c) GW-944.

As a common hindered amine antioxidant, GW-622 with hydroxyl groups and other polar functional groups (eater or amino groups) or GW-944 with amino and imino groups can form intermolecular interactions with NBR, which likely improves the damping properties of the NBR matrix.

2.2 Preparation of hindered amine/NBR composites

Hindered amine/NBR rubber composites were prepared according to the following procedure.

The NBR was first plasticized on a φ152.4 mm two-roll mill at room temperature for 3 min, and GW-622 was added to the NBR with mass ratios of 0/100, 11/100, 21/100, 43/100, 64/100, and 86/100 (GW-944 was added to the NBR matrix with mass ratios of 0/100, 11/100, 22/100, 44/100, 67/100, and 89/100). These composites were then kneaded at room temperature for 5 min to prepare the first-stage GW-622/NBRa (or GW-944/NBRa) composites.

The hindered amine/NBRa composites were kneaded on a two-roll mill at 130°C for 5 min to fully fuse the hindered amine molecules before the composites were gradually cooled to room temperature to form the second-stage hindered amine/NBRb composites.

The hindered amine/NBRb composites were then blended with compounding and crosslinking additives, including 5.0 phr of zinc oxide, 2.0 phr of stearic acid, 0.5 phr of diphenyl guanidine, 2.0 phr of sulfur, 0.2 phr of tetramethylthiuram disulfide and 0.5 phr of dibenzothiazole disulfide. The composites were then kneaded on a two-roll mill at room temperature for 10 min.

Finally, the composites were hot-pressed and vulcanized at 160°C under a pressure of 15 MPa for different periods of time, and then naturally cooled down to room temperature to prepare the hindered amine/NBR samples.

2.3 Characterization

FTIR measurements were conducted on a Nicolet 8700 FTIR spectrometer made by Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. (USA). The FTIR spectra were obtained by scanning the specimens in a wavenumber range from 500 cm-1 to 4000 cm-1 for 32 scans at a resolution of 8 cm-1. The FTIR spectra of the hindered amine/NBR composites were acquired from film specimens with a thickness of approximately 1 mm by using the attenuated total reflection (ATR) technique. The FTIR spectra of the as-received GW-622 (or GW-944) powder were acquired by using ultrathin disk specimens pressed from GW-622 (or GW-944) ground in anhydrous potassium bromide (KBr).

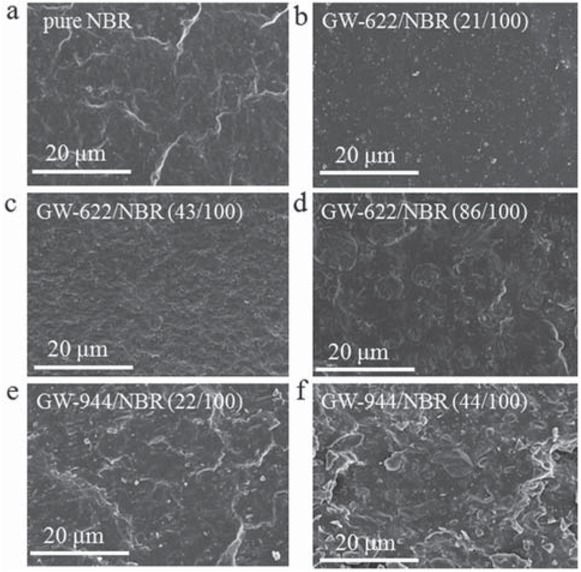

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were taken of the fracture surfaces of the hindered amine/NBR composites using a Hitachi S-4800 (Japan) scanning electron microscope. All SEM samples were cryogenically fractured by quenching in liquid nitrogen.

The DSC measurements were performed on a TGA/DSC calorimeter made by Mettler-Toledo Co (Switzerland). Samples weighing approximately 10 mg and sealed in aluminum were heated from -60°C to 150°C at a heating rate of 10°C/min under a nitrogen atmosphere.

The DMA measurements were conducted in tension mode by using a VA 3000 dynamic mechanical analyzer made by Rheometric Scientific Inc. (USA). The samples were 15 mm long, 10 mm wide, and approximately 2 mm thick. The temperature dependence of the loss factor (tanδ) for various samples was measured between -100°C and 250°C at a constant frequency of 10 Hz and a heating rate of 5°C/min.

3 Results and discussion

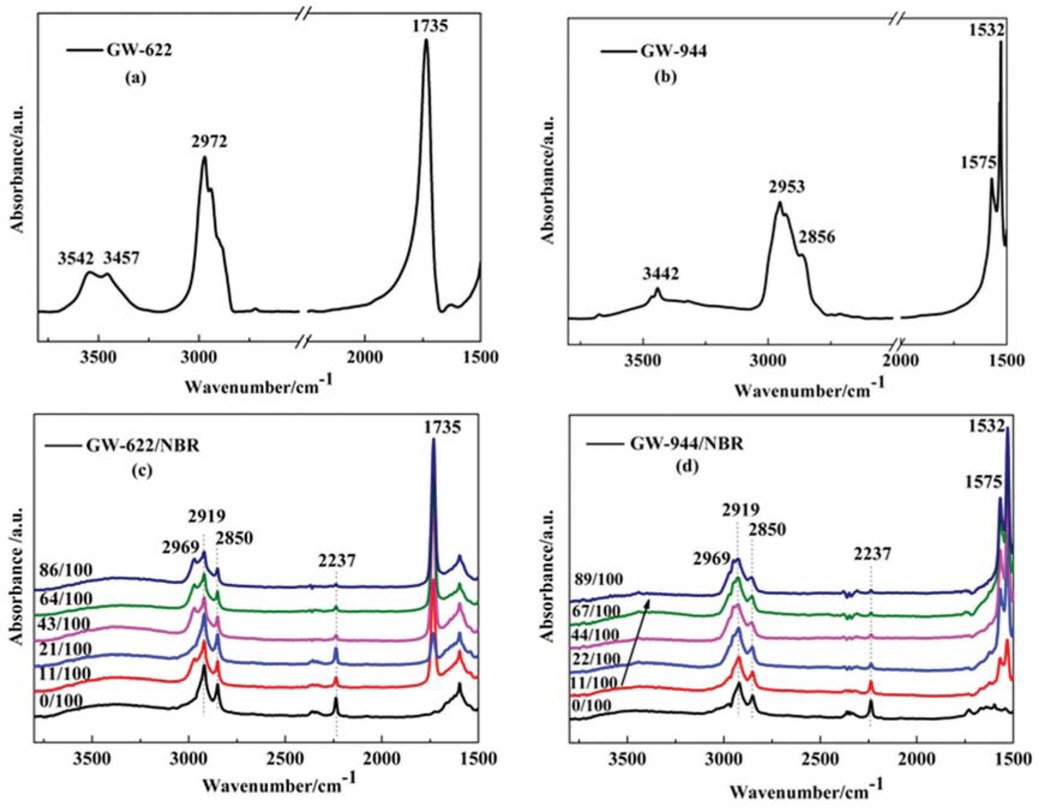

3.1 Hydrogen bonds in hindered amine/NBR composites

To examine the intermolecular interactions between the hindered amines and NBR rubber matrix, FTIR measurements of pure hindered amines and different hindered amine/NBR composites with various mass ratios were obtained. The FTIR spectra of the GW-622, GW-944, and GW-622/NBR and GW-944/NBR composites are shown in Figure 2. In Figure 2a for the GW-622 small molecule, two obvious absorption peaks appear at 3542 cm-1 and 3457 cm-1, which were assigned to the free hydroxyls and the hydrogen bond interactions (O–H…O hydrogen bonds) between GW-622 molecules, respectively (17,20). In Figure 2c, given the GW-622 molecules added to the NBR matrix, a broad

FTIR spectra of (a) GW-622, (b) GW-944, (c) GW-622/NBR and (d) GW-944/NBR composites with various compositions.

peak appears in the wavenumber range of 3150-3550 cm-1, which was characterized as the hydrogen bond between the –OH groups of GW-622 (Figure 1a: 1) and the –CN groups of NBR (Figure 1b: 7). Moreover, in Figure 2c, the absorption of the –CN groups at wavenumber 2237 cm-1 is weakened with increasing GW-622 content, which suggests hydrogen bonding with an increasing strength between the –OH group and the –CN group.

The same phenomenon exists in the GW-944/NBR composites. In Figure 2b for the GW-944 molecule, obvious absorption peaks appear at 3442 cm-1, which were assigned to subamino -NH- groups. A redshift phenomenon occurs from 3550 cm-1 to 3300 cm-1 with increasing GW-944 content in the GW-944/NBR composites, indicating hydrogen bond formation between the –NH– group (Figure 1c: 8, 9, and 10) and the –CN group (Figure 1b: 7) (21,22). The redshift phenomenon becomes obvious as the hydrogen bond interaction increases in strength (23). Moreover, the absorption of the –CN groups at the wavenumber 2237 cm-1 is weakened with increasing GW-944 content, which can also provide evidence of hydrogen bond formation.

3.1.1 SEM observation for hindered amine/NBR composites

Figure 3 shows SEM micrographs of the fracture surface of the pure NBR matrix and the hindered amine/NBR composites with different GW-622 and GW-944 contents. In Figure 3a, the pure NBR matrix has a smooth fracture surface with bright ZnO particles, which was confirmed

SEM image of hindered amine/NBR composites.

by element analysis attached to the scanning electron microscope (24). The fracture surface of the GW-622/NBR composite is homogeneous at a GW-622 content of 21 phr, because most of the GW-622 molecules dissolved and achieved good dispersion in the NBR matrix. As the GW-622 content exceeds 21 phr, GW-622 has partial miscibility and phase separates with the NBR matrix. There appear to be numerous holes created by the removal of GW-622 molecules from the GW-622/NBR fracture surface. Similarly, the addition of GW-944 over 22 phr also causes the appearance of two-phase structures in the GW-944/NBR composites, which is even more substantial than that in the GW-622/NBR composites. This phenomenon is also confirmed in the following DSC and DMA analyses.

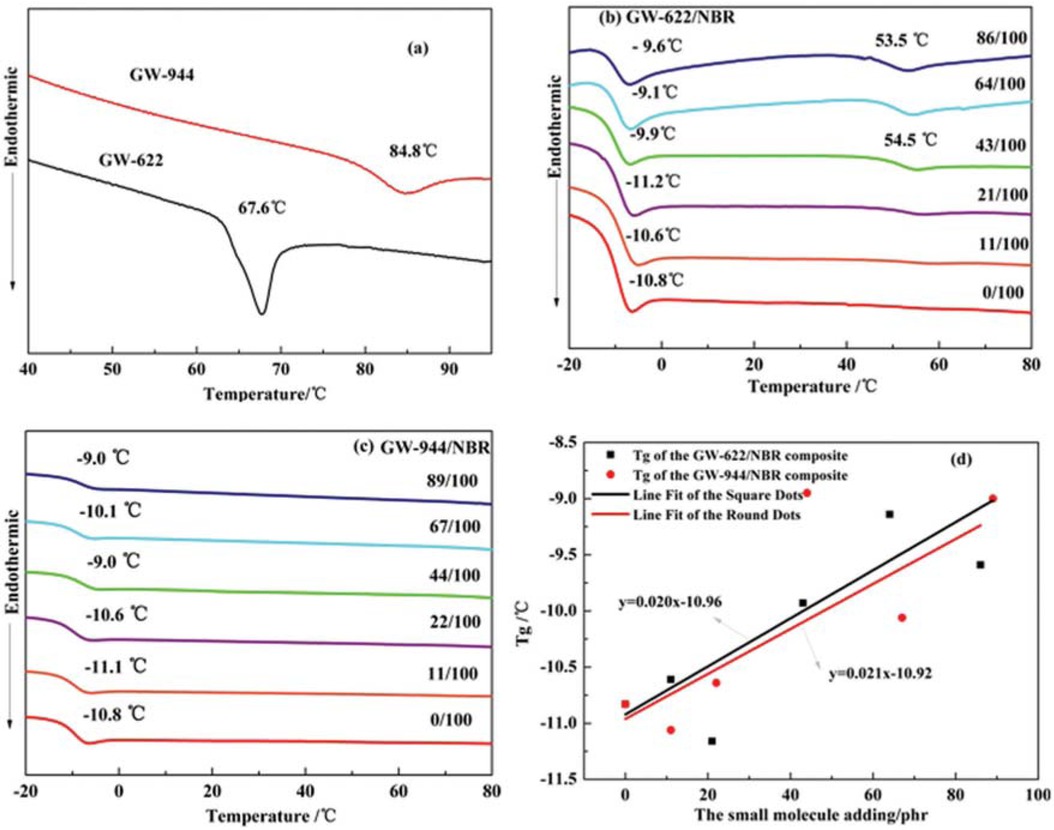

3.2 Glass transition temperature (Tg) in hindered amine/NBR composites

The compatibility of blends can usually be characterized by the Tg. If the blending system has only one Tg, the compatibility is good. Otherwise, two glass transitions indicate poor compatibility (25). Figure 4 shows the DSC curves of two small hindered amine molecules and hindered amine/NBR composites. As shown in Figure 4a, the Tg values of the pure GW-622 molecules and GW-944 molecules are 67.6°C and 84.8°C, respectively. In Figures 3b and 3c, the pure NBR matrix has only one Tg. As the GW-622 and GW-944 molecules are added, the Tg of the GW-622/NBR and GW-944/NBR composites increases to more than that of the pure NBR matrix, which can be verified from the Tg fitting curve or different GW-622/NBR and GW-944/NBR composites in Figure 4d. The increase in Tg is due to the contribution of hydrogen bond formation in the composites, which is consistent with the FTIR results above (22). The formation of hydrogen bond networks limits the movements of large polymer chains, increasing the Tg of hindered amine/NBR composites. When the addition of GW-622 is above 21 phr, two Tgs appear in the GW-622/NBR composites, indicating a two-phase structure and poor compatibility between the NBR matrix and the GW-622 molecules. At this time, the small GW-622 molecule reached the saturation state in the NBR matrix. The Tg of the amorphous GW-622 accumulated in the NBR matrix occurs at 54.5°C.

DSC thermograms of (a) hindered amines, (b) GW-622/NBR composites and (c) GW-944/NBR composites; (d) the fitting curves of the Tg of different composites.

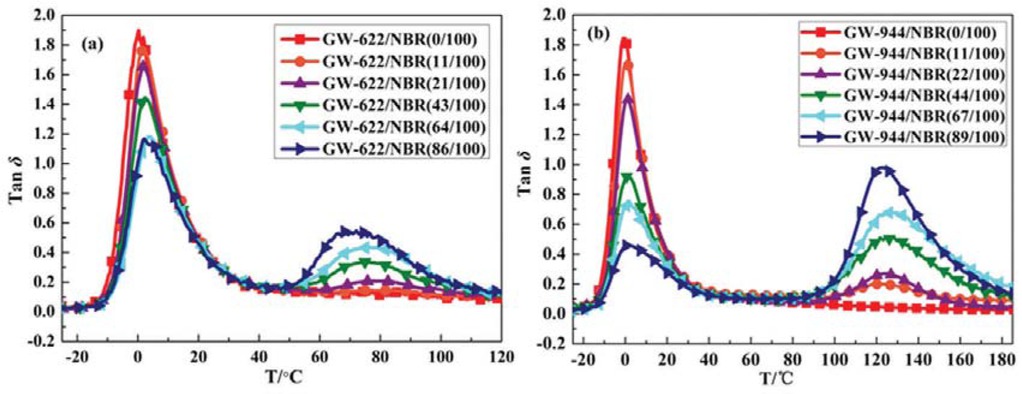

3.3 Dynamic mechanical properties of hindered amine/NBR composites

DMA was conducted to study the compatibility and damping properties of the hindered amine/NBR composites (26,27). Figure 5 shows the temperature dependence of the loss tangent (tanδ) for the GW-622/NBR and GW-944/NBR composites with different mass ratios. The tanδ reflects the ratio of the dissipated energy in one deformation cycle to the energy accumulated during the same cycle, which is usually used to characterize the damping properties of materials. The evaluation criteria of damping materials include two aspects: the value of the tanδ peak during the glass transition and the temperature range for which tanδ ≥ 0.3. The tanδ values of the materials with good damping performance are relatively large, and the peak area is wide.

Temperature dependence of loss tangent (tanδ): (a) GW-622/NBR composite and (b) GW-944/NBR composite.

From Figure 5 shows that the pure NBR matrix has only one tanδ peak. With the addition of small hindered amine molecules, two tanδ peaks gradually appear in the composites, indicating that a two-phase structure appears in the composites, and the small hindered amine molecules reach saturation in the matrix and begin to accumulate. We can also find this phenomenon in the SEM and DSC results above.

Figure 5a shows that the tanδ peak of GW-622/NBR gradually shifts to higher temperatures with increasing GW-622 content, which is primarily due to the formation of hydrogen bonds between the NBR matrix and the GW-622 molecules. When the addition amount of GW-622 molecules is less than 11 phr, the composite has only one tanδ peak, indicating a good compatibility of the GW-622 molecules with the NBR matrix. However, as the GW-622 content exceeds 21 phr, two tanδ peaks appear, implying phase separation. The excessive GW-622 molecules accumulated, resulting in the emergence of a second tanδ peak. Table 1 shows the values of the two tanδ peaks in the GW-622/NBR composites with different GW-622 contents. As the GW-622 content increases from 0 to 86 phr, the first tanδ peak decreases and gradually shifts to higher temperatures. The value of the first tanδ peak decreases from 1.90 to 1.17, the damping temperature range (ΔT) at low temperature (T < 50°C) decreases from 34.55°C to 32.05°C, and the peak area (TA) also decreases from 33.36 to 23.17, indicating that the addition of GW-622 small molecules reduced the damping performance of the NBR matrix at room temperature. However, at higher temperatures, the second tanδ peak of GW-622/NBR gradually shifts from 80.95°C to 72.1°C, and the second tanδ value increases from 0.15 to 0.55. Moreover, the temperature range for tanδ ≥ 0.3 and TA value for high temperature damping also gradually increases in size. From the above, the addition of the GW-622 molecule reduces the damping performance of the NBR composite at room temperature and increases the damping performance of the NBR composite at high temperatures. This is the result of the combined interactions of hydrogen bond formation and aggregation of excess small GW-622 molecules. Hydrogen bond formation limits the movement of NBR chains and causes more energy dissipation. However, the aggregation of GW-622 molecules after reaching saturation in the composite results in phase separation.

Damping properties of the GW-622/NBR composite with different GW-622 molecule contents.

| T < 50 (°C) | T > 50 (°C) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GW-622/NBR | tanδ peak position (°C) | tanδ peak height | Temperature range > 0.3 (°C) | tanδ peak position (°C) | tanδ peak height | Temperature range > 0.3 (°C) | ||

| ΔT | TA | ΔT | TA | |||||

| 0/100 | 0.2 | 1.90 | 34.55 | 33.36 | – | – | – | – |

| 11/100 | 1.7 | 1.77 | 34.4 | 31.91 | 80.95 | 0.15 | – | – |

| 21/100 | 1.7 | 1.65 | 34.05 | 30.12 | 80.9 | 0.21 | – | – |

| 43/100 | 2.55 | 1.44 | 32.9 | 26.99 | 74.9 | 0.34 | 15 | 4.86 |

| 64/100 | 4.1 | 1.18 | 32.1 | 23.31 | 76.55 | 0.44 | 29.3 | 11.48 |

| 86/100 | 2.05 | 1.17 | 32.05 | 23.17 | 72.1 | 0.55 | 34.4 | 15.70 |

As shown in Figure 5b and Table 2, when small GW-944 molecules are added to the NBR matrix, a similar damping performance to that of the GW-944/NBR composites with different GW-944 contents can be observed for the GW-622 /NBR composite mentioned above. In comparison, it can be seen that the addition of GW-944 molecules makes the damping performance of the NBR composite at low temperatures decline rapidly (from 1.90 to 0.46) and makes the damping performance at high temperatures increase (from 0.20 to 0.98 ).

Damping properties of the GW-944/NBR composite with different GW-944 molecule contents.

| T < 50 (°C) | T > 50 (°C) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GW-944/NBR | tanδ peak position (°C) | tanδ peak height | Temperature range > 0.3 (°C) | tanδ peak position (°C) | tanδ peak height | Temperature range > 0.3 (°C) | ||

| ΔT | TA | ΔT | TA | |||||

| 0/100 | 0.2 | 1.90 | 34.55 | 33.36 | – | – | – | – |

| 11/100 | 0.7 | 1.69 | 32.90 | 30.12 | 120.25 | 0.20 | – | – |

| 22/100 | 1.35 | 1.43 | 32.75 | 26.99 | 124.10 | 0.27 | – | – |

| 44/100 | 1.4 | 0.93 | 28.65 | 18.01 | 124.50 | 0.51 | 43.6 | 36.46 |

| 67/100 | 1.35 | 0.75 | 26.90 | 14.82 | 124.50 | 0.69 | 58.6 | 45.13 |

| 89/100 | 2.05 | 0.46 | 23.15 | 9.25 | 122.50 | 0.98 | 55.85 | 45.94 |

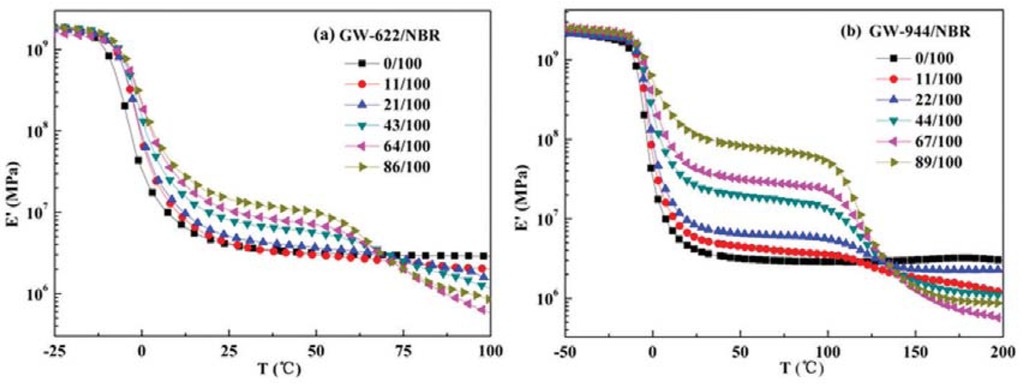

Figure 6 shows the effects of hindered amine addition and temperature on the storage modulus (Eˊ) of the hindered amine/NBR composites with different hindered amine contents. As the hindered amine content increases, the storage modulus curves display two transitions and gradually increase to a certain extent, which further proves that the hindered amine molecules have poor compatibility and strong interaction with the NBR matrix. This result is a validation of the DSC and FTIR results above.

Temperature dependence of the storage modulus (E’) values of (a) GW-622/NBR composites and (b) GW-944/NBR composites.

4 Conclusions

In this article, we explored the microstructure, compatibility, and damping properties of GW-622/NBR and GW-944/NBR composites using FTIR spectroscopy, SEM, DSC, and dynamic mechanical analyses. The FTIR results show that hydrogen bonds form between the hindered amine molecules and the NBR matrix. The hindered amine molecule has good compatibility with the NBR matrix when the hindered amine content is less than 21 phr; otherwise, the hindered amine molecules have a partial compatibility with the NBR matrix when the hindered amine content is more than 21 phr. This prediction is confirmed by SEM, DSC, and DMA results. The addition of hindered amine molecules to the NBR matrix reduces the damping property of the hindered amine/NBR composite at room temperature and improves the damping property of it at high temperatures. In particular, the addition of GW-944 molecules results in a very clear damping effect. This work provides a theoretical basis for the preparation of high performance damping materials.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 51603236, 51703114, and 51873017); the Program for Young Backbone Teachers of Zhongyuan University of Technology, China; the Program for Interdisciplinary Direction Teams in Zhongyuan University of Technology, China; the Program for Science and Technology Innovation Talents in Universities of Henan Province (No. 19HASTIT024); and the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (Grant No. ZR2017BEM036).

Notes: The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

1 Geethamma V.G., Asaletha R., Kalarikkal N., Thomas S., Vibration and sound damping in polymers. Resonance, 2014, 19(9), 821-833.10.1007/s12045-014-0091-1Search in Google Scholar

2 Song M., Qin Q., Zhu J., Yu G.M., Wu S.Z., Jiao M.L., Pressure-Volume-Temperature Properties and Thermophysical Analyses of AO-60/NBR Composites. Polym. Eng. Sci., 2019, 5(59), 949-955.10.1002/pen.25042Search in Google Scholar

3 Malas A., Pal P., Das C.K., Effect of expanded graphite and modified graphite flakes on the physical and thermo-mechanical properties of styrene butadiene rubber/polybutadiene rubber (SBR/BR) blends. Mater. Design, 2014, 55, 664-673.10.1016/j.matdes.2013.10.038Search in Google Scholar

4 Chu H.H., Lee C.M., Huang W.G., Damping of vinyl acetate-n-butyl acrylate copolymers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci., 2004, 91(3), 1396-1403.10.1002/app.13266Search in Google Scholar

5 Ngai K.L., Plazek D.J., Thermo-rheological, piezo-rheological, and TV γ-rheological complexities of viscoelastic mechanisms in polymers. Macromolecules, 2014, 47(22), 8056-8063.10.1021/ma501843uSearch in Google Scholar

6 Gusev A.A., Feldman K., Guseva O., Using elastomers and rubbers for heat-conduction damping of sound and vibrations. Macromolecules, 2010, 43(5), 2638-2641.10.1021/ma902648bSearch in Google Scholar

7 Zhao F.S., He G.S., Xu K.M., Wu H., Guo S.Y., The damping and flame‐retardant properties of poly(vinyl chloride)/chlorinated butyl rubber multilayered composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci., 2015, 132(2), 4125910.1002/app.41259Search in Google Scholar

8 Karamdoust S., Bonduelle C.V., Amos R.C., Turowec B.A., Guo S., Ferrari L., et al., Synthesis and properties of butyl rubber– poly (ethylene oxide) graft copolymers with high PEO content. J. Polym. Sci. Pol. Chem., 2013, 51(16), 3383-3394.10.1002/pola.26733Search in Google Scholar

9 Grates J.A., Thomas D.A., Hickey E.C., Sperling L.H., Noise and vibration damping with latex interpenetrating polymer networks. J. Appl. Polym. Sci., 1975, 19(6), 1731-1743.10.1002/app.1975.070190623Search in Google Scholar

10 Zhang J.H., Wang L.F., Zhao Y.F., Understanding interpenetrating-polymer-network-like porous nitrile butadiene rubber hybrids by their long-period miscibility. Mater. Design, 2013, 51, 648-657.10.1016/j.matdes.2013.04.073Search in Google Scholar

11 Xu K.M., Zhang F.S., Zhang X.L., Hu Q.M., Wu H., Guo S.Y., Molecular insights into hydrogen bonds inpolyurethane/hindered phenol hybrids: evolution and relationship with damping properties. J. Mater. Chem. A, 2014, 2(22), 8545-8556.10.1039/C4TA00476KSearch in Google Scholar

12 Song M., Zhao X.Y., Chan T.W., Zhang L.Q., Wu S.Z., Microstructure and dynamic properties analyses of hindered phenol AO-80/nitrile-butadiene rubber/poly (vinyl chloride): a molecular simulation and experimental study. Macromol. Theor. Simul., 2015, 24, 41-51.10.1002/mats.201400054Search in Google Scholar

13 Qiao B., Zhao X.Y., Yue D.M., Zhang L.Q., Wu S.Z., A combined experiment and molecular dynamics simulation study of hydrogen bonds and free volume in nitrile-butadiene rubber/hindered phenol damping mixtures. J. Mater. Chem., 2012, 22, 12339-12348.10.1039/c2jm31716hSearch in Google Scholar

14 Zhu J., Zhao X.Y., Liu L., Yang R.N., Song M., Wu S.Z., Thermodynamic analyses of the hydrogen bond dissociation reaction andtheir effects on damping and compatibility capacities of polar smallmolecule/nitrile-butadiene rubber systems: Molecular simulation andexperimental study. Polymer, 2018, 155, 152-167.10.1016/j.polymer.2018.09.040Search in Google Scholar

15 Wu C.F., Yamagishi T.A., Nakamoto Y., Ishida S.I., Nitta K.H., Kubota S., Viscoelastic Properties of an organic hybrid of chlorinated polyethylene and a small molecule. J. Polym. Sci. Pol. Phys., 2000, 38(10), 1341-1347.10.1002/(SICI)1099-0488(20000515)38:10<1341::AID-POLB100>3.0.CO;2-RSearch in Google Scholar

16 Wu C.F., Mori K., Otani Y., Namiki N., Emi H., Effects of molecule aggregation state on dynamic mechanical properties of chlorinated polyethylene/hindered phenol blends. Polymer, 2001, 42(19), 8289-8295.10.1016/S0032-3861(01)00203-8Search in Google Scholar

17 Zhao X.Y., Xiang P., Tian M., Fong H., Jin R., Zhang L.Q., Nitrile butadiene rubber/hindered phenol nanocomposites with improved strength and high damping performance. Polymer, 2007, 48, 6056-6063.10.1016/j.polymer.2007.08.011Search in Google Scholar

18 Zhao X.Y., Cao Y.J., Zou H., Li J., Zhang L.Q., Structure and dynamic properties of nitrile-butadiene rubber/hindered phenol composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci., 2012, 123, 3696-3702.10.1002/app.35043Search in Google Scholar

19 Zhao X.Y., Zhang G., Lu F., Zhang L.Q., Wu S.Z., Molecular-level insight of hindered phenol AO-70/nitrile-butadiene rubber damping composites through a combination of a molecular dynamics simulation and experimental method. RSC Adv., 2016, 6(89), 85994-86005.10.1039/C6RA17283KSearch in Google Scholar

20 Song M., Zhao X.Y., Li Y., Hu S.K., Zhang L.Q., Wu S.Z., Molecular dynamics simulations and microscopic analysis of the damping performance of hindered phenol AO-60/nitrile-butadiene rubber composites. RSC Adv., 2014, 4(13), 6719-6729.10.1039/c3ra46275gSearch in Google Scholar

21 Song M., Zhao X.Y., Li Y., Chan T.W., Zhang L.Q., Wu S.Z., Effect of acrylonitrile content on compatibility and damping properties of hindered phenol AO-60/nitrile-butadiene rubber composites: molecular dynamics simulation. RSC Adv., 2014, 4(89), 48472-48479.10.1039/C4RA10211HSearch in Google Scholar

22 Song M., Wang X.J., Yu G.M., Cao F.Y., Zhang Y.L., Pei H.Y., et al., The dynamic properties of hindered amine GW-944/nitrile-butadiene rubber hybrid damping materials. Mat. Sci. Eng., 2019, 585(1), 012042.10.1088/1757-899X/585/1/012042Search in Google Scholar

23 Xu K.M., Zhang F.S., Zhang X.L., Hu Q.M., Wu H., Guo S.Y., Molecular insights into the damping mechanism of poly(vinyl acetate)/hindered phenol hybrids by acombination of experiment and moleculardynamics simulation. RSC Adv., 2015, 5(6), 4200-4209.10.1039/C4RA06644HSearch in Google Scholar

24 Xiang P., Zhao X.Y., Xiao D.L., Lu Y.L., Zhang L.Q., The structure and dynamic properties of nitrile-butadiene rubber/poly(vinyl chloride)/hindered phenol crosslinked composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci., 2008, 109(1), 106-114.10.1002/app.27337Search in Google Scholar

25 Zhang J.H., Wang L.F., Zhao Y.F., Fabrication of novel hindered phenol/phenol resin/nitrile butadiene rubber hybrids and their long-period damping properties. Polym. Composite, 2012, 33(12), 2125-2133.10.1002/pc.22352Search in Google Scholar

26 Zhu J., Zhao X.Y., Liu L., Song M., Wu S.Z., Quantitative relationships between intermolecular interaction and damping parameters of irganox-1035/NBR hybrids: Acombination of experiments, molecular dynamics simulations, and linear regression analyses. J. Appl. Polym. Sci., 2018, 135(17), 46202.10.1002/app.46202Search in Google Scholar

27 Yin C., Zhao X.Y., Zhu J., Hu H.H., Song M., Wu S.Z., Experimental and molecular dynamics simulation study on the damping mechanism of C5 petroleum resin/chlorinated butyl rubber composites. J. Mater. Sci., 2019, 54, 3960-3974.10.5220/0007442806440650Search in Google Scholar

© 2020 Song et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The regulatory effects of the number of VP(N-vinylpyrrolidone) function groups on macrostructure and photochromic properties of polyoxometalates/copolymer hybrid films

- How the hindered amines affect the microstructure and mechanical properties of nitrile-butadiene rubber composites

- Novel benzimidazole-based conjugated polyelectrolytes: synthesis, solution photophysics and fluorescent sensing of metal ions

- Study on the variation of rock pore structure after polymer gel flooding

- Investigation on compatibility of PLA/PBAT blends modified by epoxy-terminated branched polymers through chemical micro-crosslinking

- Investigation on degradation mechanism of polymer blockages in unconsolidated sandstone reservoirs

- Investigation on the effect of active-polymers with different functional groups for EOR

- Fabrication and characterization of hexadecyl acrylate cross-linked phase change microspheres

- Surface-induced phase transitions in thin films of dendrimer block copolymers

- ZnO-assisted coating of tetracalcium phosphate/ gelatin on the polyethylene terephthalate woven nets by atomic layer deposition

- Animal fat and glycerol bioconversion to polyhydroxyalkanoate by produced water bacteria

- Effect of microstructure on the properties of polystyrene microporous foaming material

- Synthesis of amphiphilic poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(methyl methacrylate) containing trityl ether acid cleavable junction group and its self-assembly into ordered nanoporous thin films

- On-demand optimize design of sound-absorbing porous material based on multi-population genetic algorithm

- Enhancement of mechanical, thermal and water uptake performance of TPU/jute fiber green composites via chemical treatments on fiber surface

- Enhancement of mechanical properties of natural rubber–clay nanocomposites through incorporation of silanated organoclay into natural rubber latex

- Preparation and characterization of corn starch/PVA/glycerol composite films incorporated with ε-polylysine as a novel antimicrobial packaging material

- Preparation of novel amphoteric polyacrylamide and its synergistic retention with cationic polymers

- Effect of montmorillonite on PEBAX® 1074-based mixed matrix membranes to be used in humidifiers in proton exchange membrane fuel cells

- Insight on the effect of a piperonylic acid derivative on the crystallization process, melting behavior, thermal stability, optical and mechanical properties of poly(l-lactic acid)

- Lipase-catalyzed synthesis and post-polymerization modification of new fully bio-based poly(hexamethylene γ-ketopimelate) and poly(hexamethylene γ-ketopimelate-co-hexamethylene adipate) copolyesters

- Dielectric, mechanical and thermal properties of all-organic PI/PSF composite films by in situ polymerization

- Morphological transition of amphiphilic block copolymer/PEGylated phospholipid complexes induced by the dynamic subtle balance interactions in the self-assembled aggregates

- Silica/polymer core–shell particles prepared via soap-free emulsion polymerization

- Antibacterial epoxy composites with addition of natural Artemisia annua waste

- Design and preparation of 3D printing intelligent poly N,N-dimethylacrylamide hydrogel actuators

- Multilayer-structured fibrous membrane with directional moisture transportability and thermal radiation for high-performance air filtration

- Reaction characteristics of polymer expansive jet impact on explosive reactive armour

- Synthesis of a novel modified chitosan as an intumescent flame retardant for epoxy resin

- Synthesis of aminated polystyrene and its self-assembly with nanoparticles at oil/water interface

- The synthesis and characterisation of porous and monodisperse, chemically modified hypercrosslinked poly(acrylonitrile)-based terpolymer as a sorbent for the adsorption of acidic pharmaceuticals

- Crystal transition and thermal behavior of Nylon 12

- All-optical non-conjugated multi-functionalized photorefractive polymers via ring-opening metathesis polymerization

- Fabrication of LDPE/PS interpolymer resin particles through a swelling suspension polymerization approach

- Determination of the carbonyl index of polyethylene and polypropylene using specified area under band methodology with ATR-FTIR spectroscopy

- Synthesis, electropolymerization, and electrochromic performances of two novel tetrathiafulvalene–thiophene assemblies

- Wetting behaviors of fluoroterpolymer fiber films

- Plugging mechanisms of polymer gel used for hydraulic fracture water shutoff

- Synthesis of flexible poly(l-lactide)-b-polyethylene glycol-b-poly(l-lactide) bioplastics by ring-opening polymerization in the presence of chain extender

- Sulfonated poly(arylene ether sulfone) functionalized polysilsesquioxane hybrid membranes with enhanced proton conductivity

- Fmoc-diphenylalanine-based hydrogels as a potential carrier for drug delivery

- Effect of diacylhydrazine as chain extender on microphase separation and performance of energetic polyurethane elastomer

- Improved high-temperature damping performance of nitrile-butadiene rubber/phenolic resin composites by introducing different hindered amine molecules

- Rational synthesis of silicon into polyimide-derived hollow electrospun carbon nanofibers for enhanced lithium storage

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of phthalonitrile-etherified resole resin

- Highly thermally conductive boron nitride@UHMWPE composites with segregated structure

- Synthesis of high-temperature thermally expandable microcapsules and their effects on foaming quality and surface quality of foamed ABS materials

- Tribological and nanomechanical properties of a lignin-based biopolymer

- Hydroxyapatite/polyetheretherketone nanocomposites for selective laser sintering: Thermal and mechanical performances

- Synthesis of a phosphoramidate flame retardant and its flame retardancy on cotton fabrics

- Preparation and characterization of thermoresponsive poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) copolymers with enhanced hydrophilicity

- Fabrication of flexible SiO2 nanofibrous yarn via a conjugate electrospinning process

- Silver-loaded carbon nanofibers for ammonia sensing

- Polar migration behavior of phosphonate groups in phosphonate esterified acrylic grafted epoxy ester composites and their role in substrate protection

- Solubility and diffusion coefficient of supercritical CO2 in polystyrene dynamic melt

- Curcumin-loaded polyvinyl butyral film with antibacterial activity

- Experimental-numerical studies of the effect of cell structure on the mechanical properties of polypropylene foams

- Experimental investigation on the three-dimensional flow field from a meltblowing slot die

- Enhancing tribo-mechanical properties and thermal stability of nylon 6 by hexagonal boron nitride fillers

- Preparation and characterization of electrospun fibrous scaffolds of either PVA or PVP for fast release of sildenafil citrate

- Seawater degradation of PLA accelerated by water-soluble PVA

- Review Article

- Mechanical properties and application analysis of spider silk bionic material

- Additive manufacturing of PLA-based scaffolds intended for bone regeneration and strategies to improve their biological properties

- Structural design toward functional materials by electrospinning: A review

- Special Issue: XXXII National Congress of the Mexican Polymer Society

- Tailoring the morphology of poly(high internal phase emulsions) synthesized by using deep eutectic solvents

- Modification of Ceiba pentandra cellulose for drug release applications

- Redox initiation in semicontinuous polymerization to search for specific mechanical properties of copolymers

- pH-responsive polymer micelles for methotrexate delivery at tumor microenvironments

- Microwave-assisted synthesis of the lipase-catalyzed ring-opening copolymerization of ε-caprolactone and ω-pentadecanolactone: Thermal and FTIR characterization

- Rapid Communications

- Pilot-scale production of polylactic acid nanofibers by melt electrospinning

- Erratum

- Erratum to: Synthesis and characterization of new macromolecule systems for colon-specific drug delivery

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The regulatory effects of the number of VP(N-vinylpyrrolidone) function groups on macrostructure and photochromic properties of polyoxometalates/copolymer hybrid films

- How the hindered amines affect the microstructure and mechanical properties of nitrile-butadiene rubber composites

- Novel benzimidazole-based conjugated polyelectrolytes: synthesis, solution photophysics and fluorescent sensing of metal ions

- Study on the variation of rock pore structure after polymer gel flooding

- Investigation on compatibility of PLA/PBAT blends modified by epoxy-terminated branched polymers through chemical micro-crosslinking

- Investigation on degradation mechanism of polymer blockages in unconsolidated sandstone reservoirs

- Investigation on the effect of active-polymers with different functional groups for EOR

- Fabrication and characterization of hexadecyl acrylate cross-linked phase change microspheres

- Surface-induced phase transitions in thin films of dendrimer block copolymers

- ZnO-assisted coating of tetracalcium phosphate/ gelatin on the polyethylene terephthalate woven nets by atomic layer deposition

- Animal fat and glycerol bioconversion to polyhydroxyalkanoate by produced water bacteria

- Effect of microstructure on the properties of polystyrene microporous foaming material

- Synthesis of amphiphilic poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(methyl methacrylate) containing trityl ether acid cleavable junction group and its self-assembly into ordered nanoporous thin films

- On-demand optimize design of sound-absorbing porous material based on multi-population genetic algorithm

- Enhancement of mechanical, thermal and water uptake performance of TPU/jute fiber green composites via chemical treatments on fiber surface

- Enhancement of mechanical properties of natural rubber–clay nanocomposites through incorporation of silanated organoclay into natural rubber latex

- Preparation and characterization of corn starch/PVA/glycerol composite films incorporated with ε-polylysine as a novel antimicrobial packaging material

- Preparation of novel amphoteric polyacrylamide and its synergistic retention with cationic polymers

- Effect of montmorillonite on PEBAX® 1074-based mixed matrix membranes to be used in humidifiers in proton exchange membrane fuel cells

- Insight on the effect of a piperonylic acid derivative on the crystallization process, melting behavior, thermal stability, optical and mechanical properties of poly(l-lactic acid)

- Lipase-catalyzed synthesis and post-polymerization modification of new fully bio-based poly(hexamethylene γ-ketopimelate) and poly(hexamethylene γ-ketopimelate-co-hexamethylene adipate) copolyesters

- Dielectric, mechanical and thermal properties of all-organic PI/PSF composite films by in situ polymerization

- Morphological transition of amphiphilic block copolymer/PEGylated phospholipid complexes induced by the dynamic subtle balance interactions in the self-assembled aggregates

- Silica/polymer core–shell particles prepared via soap-free emulsion polymerization

- Antibacterial epoxy composites with addition of natural Artemisia annua waste

- Design and preparation of 3D printing intelligent poly N,N-dimethylacrylamide hydrogel actuators

- Multilayer-structured fibrous membrane with directional moisture transportability and thermal radiation for high-performance air filtration

- Reaction characteristics of polymer expansive jet impact on explosive reactive armour

- Synthesis of a novel modified chitosan as an intumescent flame retardant for epoxy resin

- Synthesis of aminated polystyrene and its self-assembly with nanoparticles at oil/water interface

- The synthesis and characterisation of porous and monodisperse, chemically modified hypercrosslinked poly(acrylonitrile)-based terpolymer as a sorbent for the adsorption of acidic pharmaceuticals

- Crystal transition and thermal behavior of Nylon 12

- All-optical non-conjugated multi-functionalized photorefractive polymers via ring-opening metathesis polymerization

- Fabrication of LDPE/PS interpolymer resin particles through a swelling suspension polymerization approach

- Determination of the carbonyl index of polyethylene and polypropylene using specified area under band methodology with ATR-FTIR spectroscopy

- Synthesis, electropolymerization, and electrochromic performances of two novel tetrathiafulvalene–thiophene assemblies

- Wetting behaviors of fluoroterpolymer fiber films

- Plugging mechanisms of polymer gel used for hydraulic fracture water shutoff

- Synthesis of flexible poly(l-lactide)-b-polyethylene glycol-b-poly(l-lactide) bioplastics by ring-opening polymerization in the presence of chain extender

- Sulfonated poly(arylene ether sulfone) functionalized polysilsesquioxane hybrid membranes with enhanced proton conductivity

- Fmoc-diphenylalanine-based hydrogels as a potential carrier for drug delivery

- Effect of diacylhydrazine as chain extender on microphase separation and performance of energetic polyurethane elastomer

- Improved high-temperature damping performance of nitrile-butadiene rubber/phenolic resin composites by introducing different hindered amine molecules

- Rational synthesis of silicon into polyimide-derived hollow electrospun carbon nanofibers for enhanced lithium storage

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of phthalonitrile-etherified resole resin

- Highly thermally conductive boron nitride@UHMWPE composites with segregated structure

- Synthesis of high-temperature thermally expandable microcapsules and their effects on foaming quality and surface quality of foamed ABS materials

- Tribological and nanomechanical properties of a lignin-based biopolymer

- Hydroxyapatite/polyetheretherketone nanocomposites for selective laser sintering: Thermal and mechanical performances

- Synthesis of a phosphoramidate flame retardant and its flame retardancy on cotton fabrics

- Preparation and characterization of thermoresponsive poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) copolymers with enhanced hydrophilicity

- Fabrication of flexible SiO2 nanofibrous yarn via a conjugate electrospinning process

- Silver-loaded carbon nanofibers for ammonia sensing

- Polar migration behavior of phosphonate groups in phosphonate esterified acrylic grafted epoxy ester composites and their role in substrate protection

- Solubility and diffusion coefficient of supercritical CO2 in polystyrene dynamic melt

- Curcumin-loaded polyvinyl butyral film with antibacterial activity

- Experimental-numerical studies of the effect of cell structure on the mechanical properties of polypropylene foams

- Experimental investigation on the three-dimensional flow field from a meltblowing slot die

- Enhancing tribo-mechanical properties and thermal stability of nylon 6 by hexagonal boron nitride fillers

- Preparation and characterization of electrospun fibrous scaffolds of either PVA or PVP for fast release of sildenafil citrate

- Seawater degradation of PLA accelerated by water-soluble PVA

- Review Article

- Mechanical properties and application analysis of spider silk bionic material

- Additive manufacturing of PLA-based scaffolds intended for bone regeneration and strategies to improve their biological properties

- Structural design toward functional materials by electrospinning: A review

- Special Issue: XXXII National Congress of the Mexican Polymer Society

- Tailoring the morphology of poly(high internal phase emulsions) synthesized by using deep eutectic solvents

- Modification of Ceiba pentandra cellulose for drug release applications

- Redox initiation in semicontinuous polymerization to search for specific mechanical properties of copolymers

- pH-responsive polymer micelles for methotrexate delivery at tumor microenvironments

- Microwave-assisted synthesis of the lipase-catalyzed ring-opening copolymerization of ε-caprolactone and ω-pentadecanolactone: Thermal and FTIR characterization

- Rapid Communications

- Pilot-scale production of polylactic acid nanofibers by melt electrospinning

- Erratum

- Erratum to: Synthesis and characterization of new macromolecule systems for colon-specific drug delivery