Abstract

Self-assembled hydrogels from 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl-modified diphenylalanine (Fmoc-FF) peptides were evaluated as potential vehicles for drug delivery. During self-assembly of Fmoc-FF, high concentrations of indomethacin (IDM) drugs were shown to be incorporated into the hydrogels. The β-sheet arrangement of peptides was found to be predominant in Fmoc-FF–IDM hydrogels regardless of the IDM content. The release mechanism for IDM displayed a biphasic profile comprising an initial hydrogel erosion-dominated stage followed by the diffusion-controlled stage. Small amounts of polyamidoamine dendrimer (PAMAM) added to the hydrogel (Fmoc-FF 0.5%–IDM 0.5%–PAMAM 0.03%) resulted in a more prolonged IDM release compared with Fmoc-FF 0.5%–IDM 0.5% hydrogel. Furthermore, these IDM-loaded hydrogels demonstrated excellent thixotropic response and injectability, which make them suitable candidates for use as injectable self-healing matrices for drug delivery.

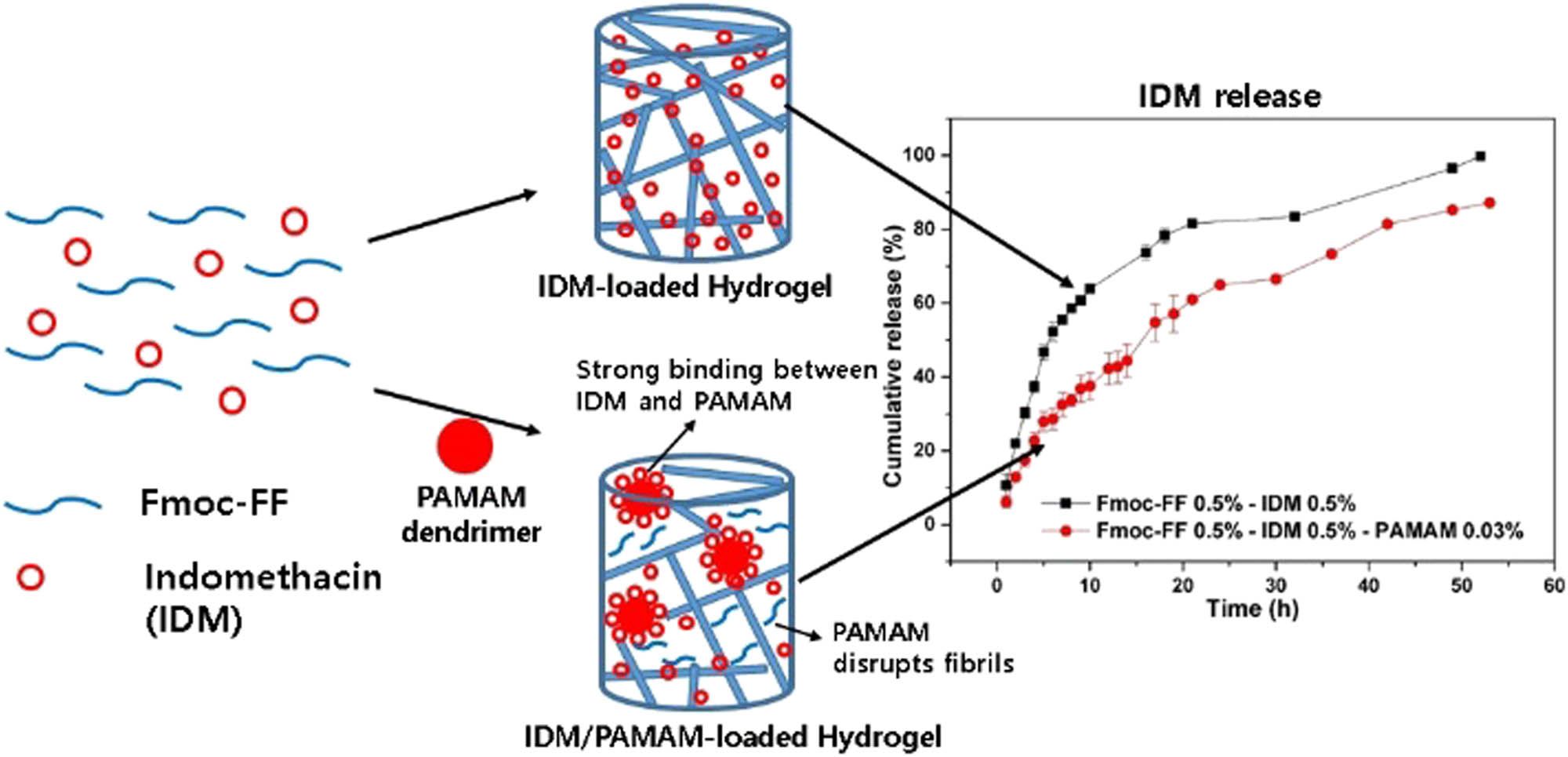

Graphical abstract

High concentrations of IDM drugs can be incorporated into hydrogels during the self-assembly of Fmoc-FF. Small amounts of PAMAM added to the hydrogel (Fmoc-FF 0.5%–IDM 0.5%–PAMAM 0.03%) resulted in more prolonged IDM release when compared with Fmoc-FF 0.5%–IDM 0.5% hydrogel.

1 Introduction

Polymeric hydrogels have been found to have many advantages when used for drug delivery when compared with intravenous or subcutaneous injections. For example, drug-loaded hydrogels provide a local therapeutic effect in the surrounding targeted tissue over an extended period of time avoiding the long journey of therapeutic agents in the circulation system thus reducing the dosing frequency and side effects (1,2,3,4). Supramolecular hydrogels self-assembled from low molecular weight gelators (LMWGs) via non-covalent interactions have been of great interest because of their cost-effectiveness, ease of synthesis, and rapid response to external stimuli (5,6,7,8). The supramolecular hydrogels differ from conventional covalently cross-linked hydrogels because of the transient and reversible nature of the non-covalent cross-linking, which can result in the inherent useful properties such as stimuli-responsiveness, shape-memory, shear-thinning, and self-healing (5,6,7,8). In particular, the shear-thinning property enables the already formed hydrogel containing therapeutics to be injected as a low viscosity, flowing material through a needle of a syringe without clogging. Once injection shear is removed, the gel state is rapidly recovered (self-healing) allowing a minimally invasive surgery. Furthermore, self-healing hydrogels can be automatically self-repaired at the targeted position without additional stimuli after damage (3,4). Dipeptides conjugated to aromatic groups such as 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl (Fmoc) have recently emerged as a new class of LMWGs (9,10,11). The biocompatibility, biodegradability, and nonimmunogenicity of dipeptide-based LMWGs make them attractive candidates for biomedical applications. Within this class, Fmoc-modified diphenylalanine (Fmoc-FF) has been widely studied as the simplest and most effective hydrogelator (12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26). Fmoc-FF has been shown to form β-sheets that self-assemble laterally through π–π stacking of the fluorenyl groups into nanofibrous networks in which water is entrapped mainly by surface tension (15). The formation of Fmoc-FF hydrogel can be triggered by either the “pH change” or “solvent exchange” (16,21). Recently, Fmoc-FF-based hybrid gels have been investigated as drug delivery systems (17,22,26). Indomethacin (IDM) is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug that is widely used as an anodyne in the treatment of degenerative joint diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis. IDM is negatively charged and poorly water-soluble. Many drugs used in chemotherapy are strongly hydrophobic. In this study, IDM was chosen as a model drug not only because of its hydrophobicity but also because of its chemo-preventive activities against tumor cells (27,28). The purpose of this study was to prepare and characterize Fmoc-FF based hydrogels containing IDM as a model drug and to evaluate the release profile of the drug. Hydrophobic drug loading into hydrogels is limited because hydrophobic drugs are inherently incompatible with the hydrophilic hydrogel network. Hydrogels have been engineered for improved load efficiency and sustained release of IDM. For example, IDM has been coated with hydrophilic components prior to incorporation into hydrogels or hydrophobic domains have been introduced into the hydrogel network (29,30,31,32,33). The electrostatic interaction between the amine group of polyamidoamine dendrimer (PAMAM) and the carboxyl group of IDM has also been utilized to achieve successful encapsulation and sustained release of IDM (34,35,36). Most of the covalent cross-linking methods to prepare hydrogels requires the use of toxic catalyst, initiators, cross-linking agent which limits the biocompatibility of these systems. In this study, the Fmoc-FF peptide exhibited a unique self-assembly behavior that allowed easy integration of hydrophobic IDM into the gel matrix. The physicochemical properties of IDM-loaded Fmoc-FF hydrogels were evaluated, including the rheological properties, secondary structure of Fmoc-FF, and release behavior of IDM. The addition of PAMAM to IDM-loaded Fmoc-FF gels is shown to improve the sustained release behavior of IDM. The effect of PAMAM on the self-assembly and resulting secondary structure of Fmoc-FF hydrogels was also investigated. Finally, a rheological experiment demonstrated that these IDM-loaded hydrogels are thixotropic, which makes them injectable and self-healing carriers for drug delivery.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

The lyophilized Fmoc-FF powders were purchased from Bachem (Bubendorf, Switzerland) and used as received. The 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP), IDM, and PAMAM with generation G5 (molecular weights: 28,826) as pre-made solutions (5%) in methanol were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (US).

2.2 Hydrogel preparation

Fmoc-FF stock solutions were prepared by dissolving Fmoc-FF in HFIP at a concentration of 10% (prepared just before use). The unit % of concentration is defined as w/v (%) = 100 × mass of solute (g)/volume of solvent (mL). The Fmoc-FF solutions were then diluted to the final concentration of 1% in water. The resulting solutions were shaken for several seconds, and then, Fmoc-FF hydrogels were formed in a few minutes. To prepare IDM- or/and PAMAM-loaded hydrogels, IDM or/and PAMAM were mixed with the Fmoc-FF stock solutions in HFIP prior to dilution in water. The pH of Fmoc-FF hydrogels remained almost unchanged (pH = 3.4–3.7) after the introduction of IDM and PAMAM. All the gels prepared were aged at room temperature for two days prior to the rheological and drug-release analysis.

2.3 Physicochemical characterization of hydrogels

The small-amplitude oscillatory shear experiments were performed to evaluate the viscoelastic properties using an AR-G2 stress-controlled rotational rheometer (TA Instruments) with dry asphalt system geometry (stainless steel, 10 mm parallel plate). The storage shear modulus G′ and the loss shear modulus G″ were measured as functions of frequency (f) at a constant strain of 0.1%. To ensure that the measurements were made in the linear regime, an amplitude sweep was performed; it showed no variation in G′ and G″ up to a strain of 5%. In addition, steady rate sweep tests were performed using the same AR-G2 to investigate the shear-thinning and thixotropic properties of hydrogels.

The secondary structures of Fmoc-FF based hydrogels were analyzed by Fourier Transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) measurement on a Bruker/Tensor27 spectrometer. The hydrogels were prepared in D2O for FTIR measurements. The spectrum of the hydrogels on the ATR plate was collected at a 4 cm−1 resolution with 2 min intervals by co-adding 16 scans. The spectra of the amide I region (1,600–1,700 cm−1) were analyzed. To study the secondary structure of the hydrogels, circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy measurement was performed on hydrogels. The hydrogels were placed in a 1 mm cuvette. The CD spectra in the range of 190–320 nm were recorded using a Chirascan spectrometer at room temperature. The structure of the hydrogels was imaged using scanning electron microscopy (SEM; JSM-6701F, JEOL Ltd, Japan) at an accelerated voltage of 5–15 kV. A thin layer of platinum (approximately several nanometers) was sputter-coated before scanning. Before SEM measurement, the hydrogels were aged for 2 days and then freeze-dried under 30 mTorr at −130°C for 2 days using an FDCF-12003 freeze dryer (Operon, Korea).

2.4 In vitro IDM release test

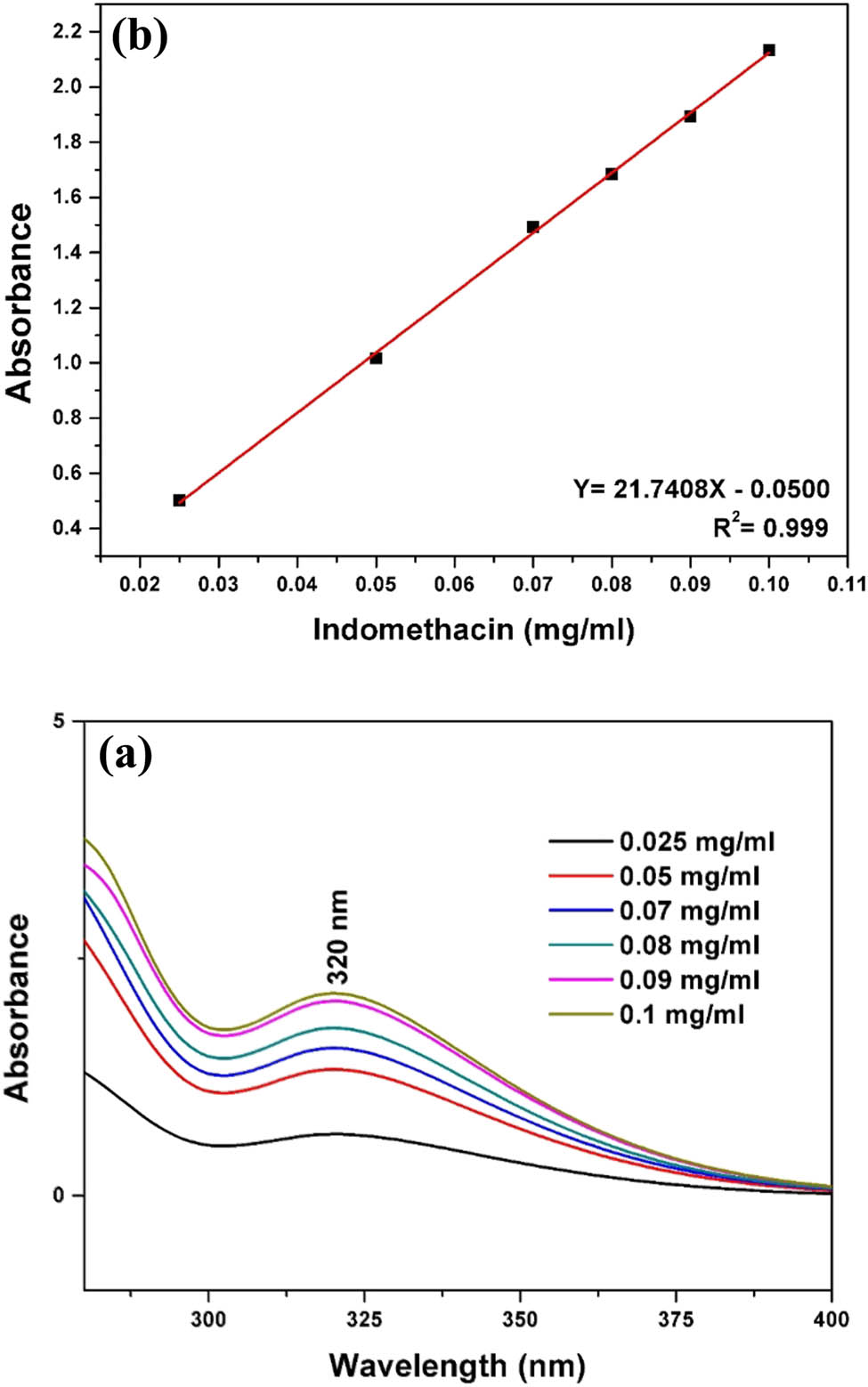

For in vitro release experiments, IDM-loaded hydrogels were placed in dialysis bags (MWCO = 14,000) and then immersed in tubes containing phosphate buffer saline (PBS, pH 7.4) as the release medium. During the test, the tubes were incubated in a shake water bath at a 60 stroke/min and 37°C. At predetermined time points, an aliquot of 3 mL supernatant solution was taken and replaced with an equal amount of fresh buffer. The concentration of IDM in the supernatant solutions was determined using a UV spectrophotometer at an absorbance wavelength of 320 nm. The IDM stock solution was prepared with ethanol and diluted with distilled water to prepare a sample set. The absorbance at a maximum of 320 nm was plotted against concentration, and a standard calibration curve was constructed. The percentage of the cumulative amount of released drugs was calculated from a standard calibration curve. Typical UV absorption spectra and the standard calibration curve are shown in Figure 1. All release studies were carried out in triplicate.

(a) Typical UV absorption spectra as a function of IDM in water and (b) the standard calibration curve using the absorbance values at 320 nm.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Properties of Fmoc-FF–IDM hydrogels

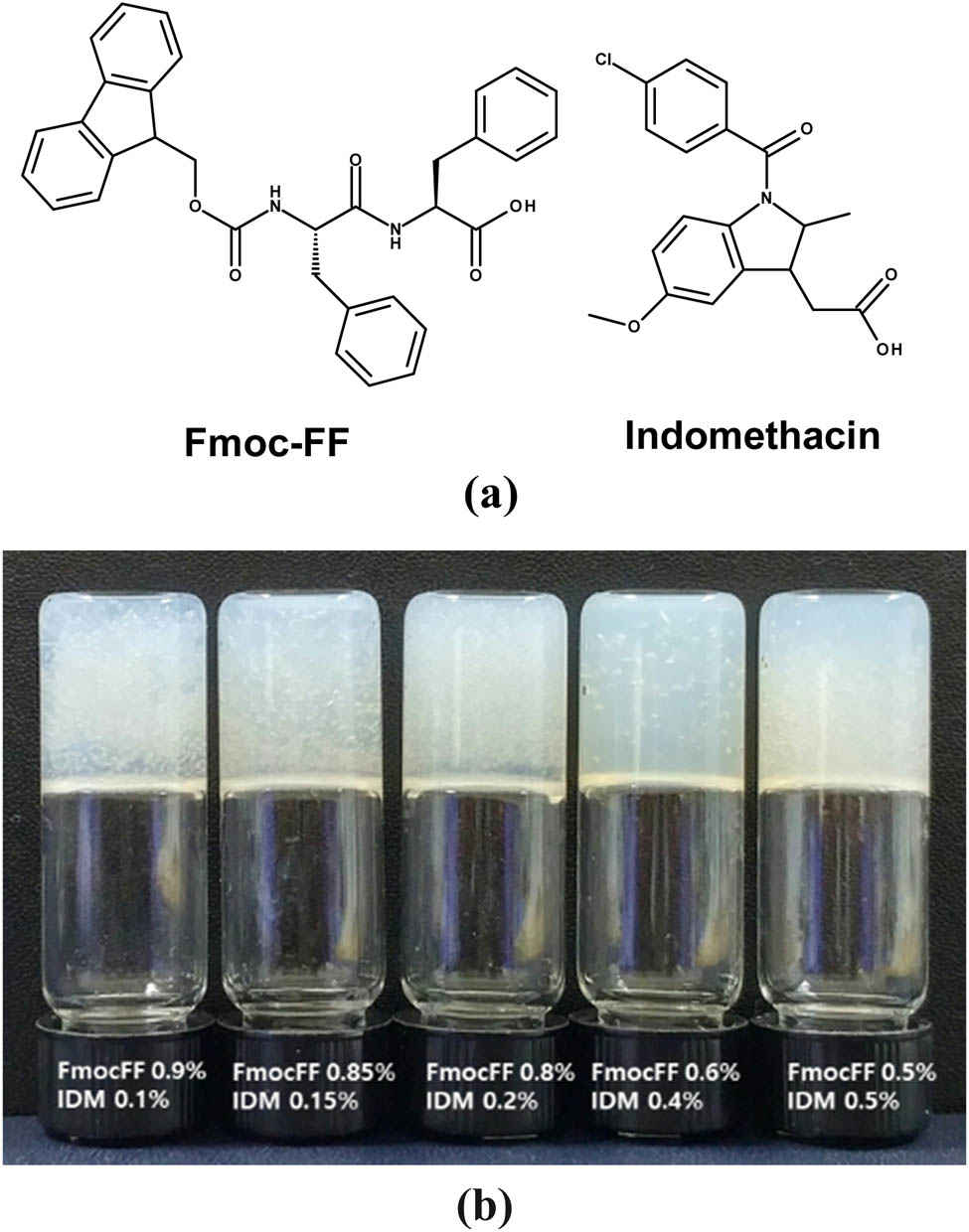

Fmoc-FF and IDM molecules were dissolved in HFIP and then diluted in water to self-assemble into drug-loaded hydrogels (chemical structures of Fmoc-FF and IDM are shown in Figure 2a). The total concentration of solutions was fixed to 1%, and the IDM concentration varied within the range of ϕIDM = 0%–0.5%. These mixture solutions turned to gels after a period of time at room temperature. Gelation was confirmed by the formation of self-supporting samples that did not flow when inverted by 180° indicating that IDM molecules were successfully incorporated into the hydrogel matrix during Fmoc-FF self-assembly (Figure 2b).

(a) Chemical structures of Fmoc-FF and IDM. (b) Photographs of Fmoc-FF–IDM hydrogels with varying ratios of Fmoc-FF/IDM.

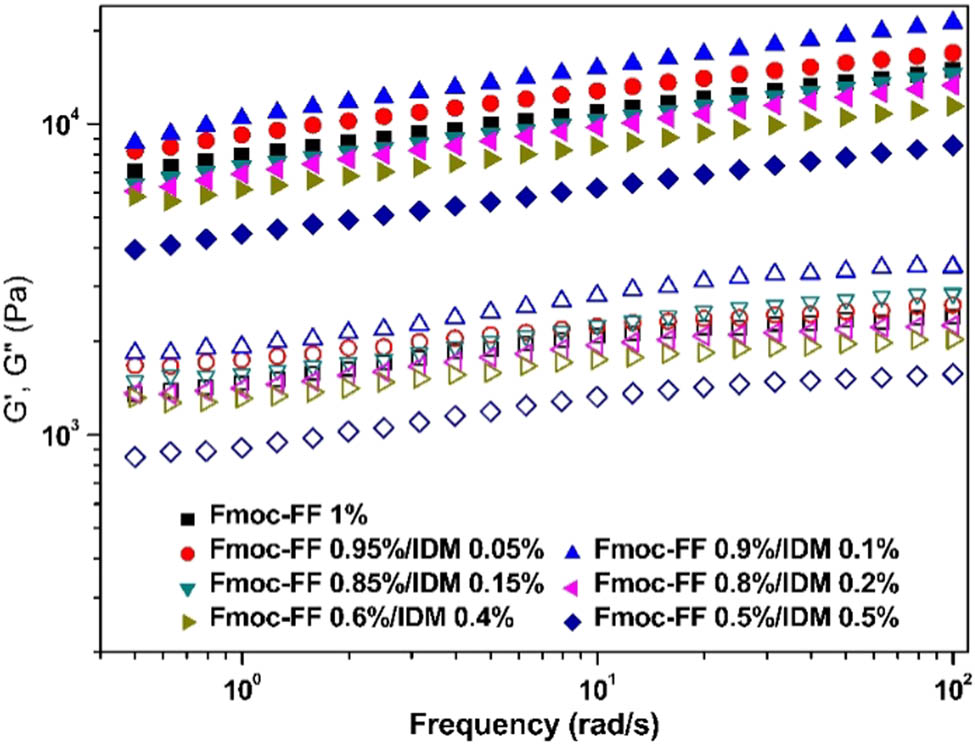

The ability of Fmoc-FF to form gels was maintained in the presence of high IDM content leading to high drug loading capacity up to 100% (=(weight of loaded IDM/weight of Fmoc-FF peptides) × 100%). Because IDM has a phenyl ring, the affinity of IDM for the fibrous network of Fmoc-FF peptides could have been facilitated by intermolecular aromatic–aromatic interactions. Rheological measurements were conducted to investigate the flow behavior and rigidity of the hydrogels at room temperature. A frequency sweep from 0.1 to 100 rad/s was performed on the pure Fmoc-FF and Fmoc-FF–IDM hydrogels. As shown in Figure 3, the storage moduli (G′) values for all the samples exhibited some frequency dependency, which is consistent with the trend of physically cross-linked viscoelastic gels. The G′ values were considerably larger than G″, which represented a highly elastic response. Increasing the IDM content to 0.1% slightly increased the G′ value of the hybrid gel. However, a further increase in IDM resulted in a decrease in the modulus because of a decrease in the concentration of self-assembled Fmoc-FF present in the hybrid gels.

Oscillatory frequency sweeps of Fmoc-FF–IDM hydrogels at varying Fmoc-FF/IDM ratios: closed symbols denote G′ and open symbols denote G″.

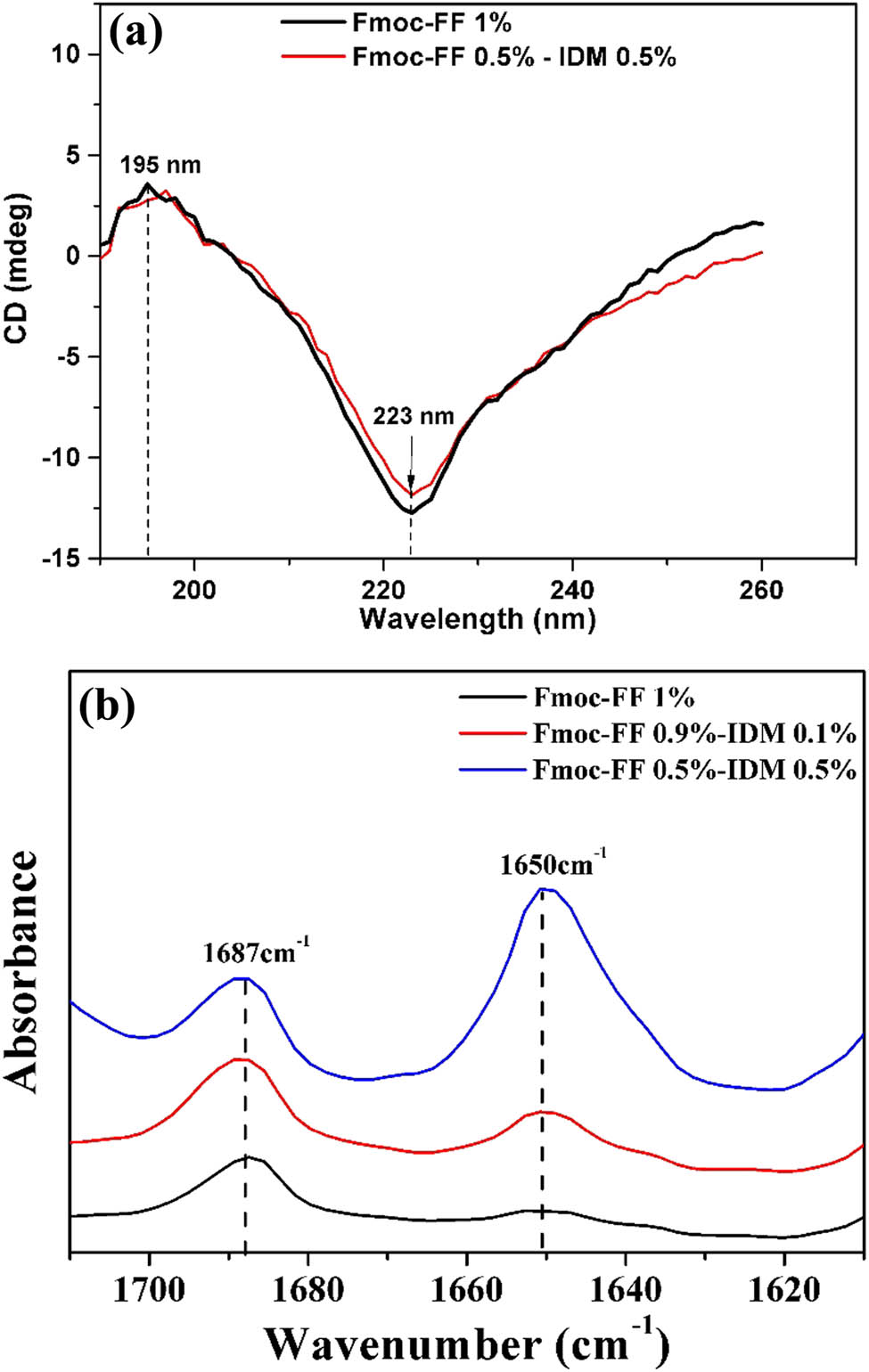

To assess the influence of IDM concentration on the secondary structure of Fmoc-FF–IDM hydrogel, CD and FTIR analysis were performed on the hydrogels. As shown in Figure 4a, a positive peak was observed at 195 nm and a negative peak was observed at 223 nm, indicating a typical β-sheet structure of the Fmoc-FF hydrogels (15,17,24,25). Incorporation of IDM into the Fmoc-FF hydrogel did not change the CD pattern of the β-sheet structure. The FTIR spectra of the stretching of C═O groups in the amide I region (1,600–1,700 cm−1) can be used to identify different types of secondary structures.

(a) CD spectra and (b) FTIR spectra of the amide I region, ranging from 1,600 to 1,700 cm−1 of Fmoc-FF–IDM hydrogels with different Fmoc-FF/IDM ratio. Curves are vertically offset for clarity.

The FTIR spectra (Figure 4b) showed the broad peak centered around 1,650 cm−1 which is consistent with a β-sheet structure (17,20,23). Because of the dominant role of hydrogen bonds and aromatic interactions, Fmoc-FF peptides tend to self-assemble into structures with β-sheet patterns, regardless of the IDM incorporation into the hydrogels, in line with the CD spectra. A distinct peak at 1,687 cm−1 can be assigned to the stacked carbamate group in Fmoc-FF (19,20,24).

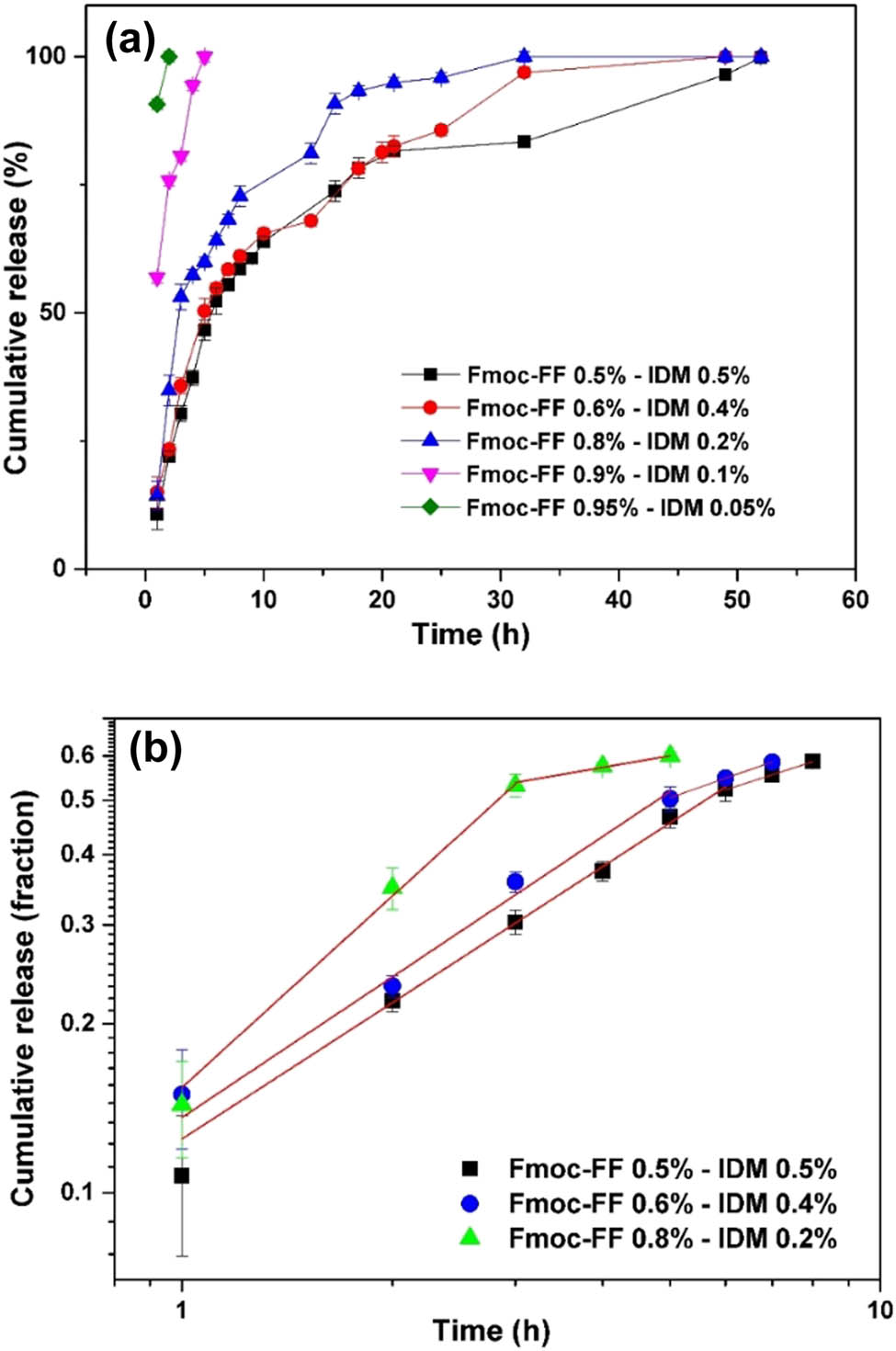

The in vitro cumulative release behavior of IDM from Fmoc-FF–IDM hydrogels was investigated in phosphate buffer (pH = 7.4) at 37°C, and the release profiles are shown in Figure 5a. The peptide/drug ratio played a major role in determining the rate of drug release. Hydrogels with low IDM contents of 0.05 and 0.1% were found to release 100% of the entrapped IDM during 5 h. When the IDM content was increased (>0.1%), the hydrogel was mechanically weakened (Figure 3), but a more prolonged drug release was obtained from the hydrogel (Figure 5a). The initial burst release may be attributed to the release of the drug associated with the surface of the hydrogels, indicating that most of the IDM may be present on the surface of the hydrogel at low IDM concentrations. For hydrogels with IDM concentrations higher than 0.1%, the release rate was initially high and slowed down over time (Figure 5a). This was because the entrapment of residual drugs in the gel network may have prevented further release in the low-concentration gradient.

(a) In vitro cumulative release of IDM in phosphate buffer (pH = 7.4) from Fmoc-FF–IDM hydrogels with varying Fmoc-FF/IDM ratio. (b) Plots of in vitro release data against release time in log–log scale and linear fits. The release tests were carried out in triplicate, and the results are provided as the average value ± standard deviation.

To better understand the release mechanism of encapsulated IDM, the first 60% of the release data were analyzed using a power-law model, the semi-empirical equation known as “Peppas equation”:

where Mt and M∞ are the absolute cumulative amount of drug released at time t and infinite time, respectively. Therefore, Mt/M∞ denotes the fractional drug release at time t; k is a kinetic constant characteristic of the drug/hydrogel system; and n is the exponent, indicative of the mechanism of drug release (30,37). For a radial diffusion from a cylindrical geometry, a value of n = 0.89 represents a release rate independent of time or zeroth-order release kinetics. This type of release mechanism is also known as case-II transport associated with the stresses and state transitions that occur in the swelling and/or erosion of gels. An n value of 0.45 indicates that the drug is released by the usual Fickian diffusion through the system. When the value of n is less than 0.45, the mechanism is referred to as pseudo-Fickian behavior that indicates that the release profile is similar to Fickian curves. An n value between 0.45 and 0.89 is indicative of anomalous transport which combines both mechanisms. Occasionally, values of n > 0.89 for release from cylinders have been observed, indicating super case-II transport. In this case, the drug is mainly released through the erosion of the polymer matrix. To investigate the drug-release mechanism, the Peppas model was employed to fit the accumulative drug release curves in the log–log scale, as presented in Figure 5b, and the fitted parameter values are given in Table 1. For hydrogels with an IDM content of 0.2%, the n value was observed to be 1.13 ± 0.09, indicating super case-II transport. As the IDM content increased to 0.4%, the n values were found to be 0.83 ± 0.09, indicating the case-II transport mechanism. For higher IDM concentrations of 0.5, the n value was found to be 0.81 ± 0.02, which is the case of anomalous transport mechanism that combines case-II transport and Fickian diffusional release. Case-II/super case-II transport is associated with the drug release caused by stress and state transitions during gel expansion and/or erosion. The Fmoc-FF hydrogels usually became unstable and erode easily in phosphate buffer at a pH of 7.4 (17). In addition, the prepared hydrogels were found to swell marginally in phosphate buffer with pH = 7.4. Therefore, the case-II/super case-II transport was mainly attributed to the erosion of the hydrogel. Moreover, the IDM release would have accelerated the structural erosion of hydrogels because a considerable amount of IDM was co-assembled with Fmoc-FF into the gel network. Interestingly, in the later stage of IDM release, a different linear fit with a much-reduced slope was observed, as shown in Figure 5b. The result indicates that the latter step of IDM release follows a different mechanism. The n value was reduced to lower values than 0.45 where Fickian diffusional release dominated (Table 1). The release of the drug no longer depended on the erosion of the gel but followed the diffusion-controlled stage. Thus, the release mechanism for IDM showed a biphasic profile comprising an initial hydrogel erosion-domination step followed by the diffusion-controlled stage. The k value for both the initial and second stage of the release profile was found to be larger for lower IDM content of 0.2% compared to higher 0.4% and 0.5% of IDM content. The drug-release behavior of Fmoc-FF–IDM hydrogels appears to be simply modifiable by changing the concentration of IDM in the hydrogels.

Values of n, k, and r2 obtained by fitting the in vitro release data with Eq. (1)

| n | k | r2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fmoc-FF 0.5%/IDM 0.5% | Initial | 0.81 ± 0.02 | 0.125 | 0.994 |

| Terminal | 0.40 ± 0.01 | 0.254 | 0.977 | |

| Fmoc-FF 0.6%/IDM 0.4% | Initial | 0.83 ± 0.08 | 0.116 | 0.966 |

| Terminal | 0.44 ± 0.01 | 0.251 | 0.999 | |

| Fmoc-FF 0.8%/IDM 0.2% | Initial | 1.13 ± 0.09 | 0.154 | 0.994 |

| Terminal | 0.22 ± 0.03 | 0.425 | 0.980 | |

| Fmoc-FF 0.5%/IDM 0.5%/PAMAM 0.03% | Initial | 0.87 ± 0.04 | 0.068 | 0.995 |

| Terminal | 0.56 ± 0.03 | 0.108 | 0.972 |

3.2 Effect of PAMAM on the properties of hydrogels

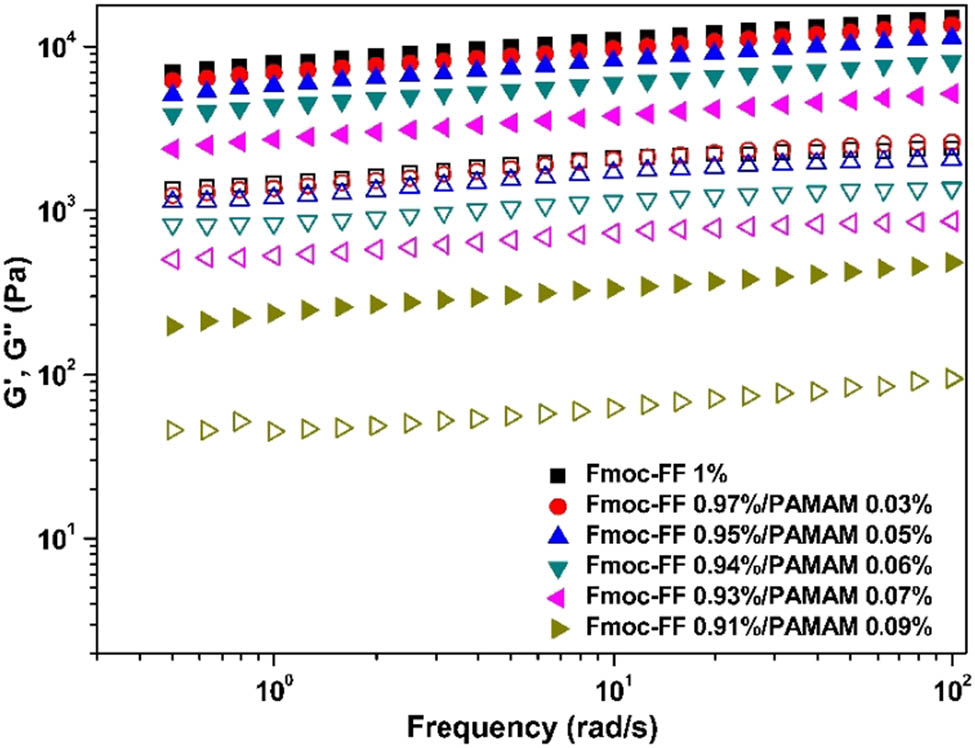

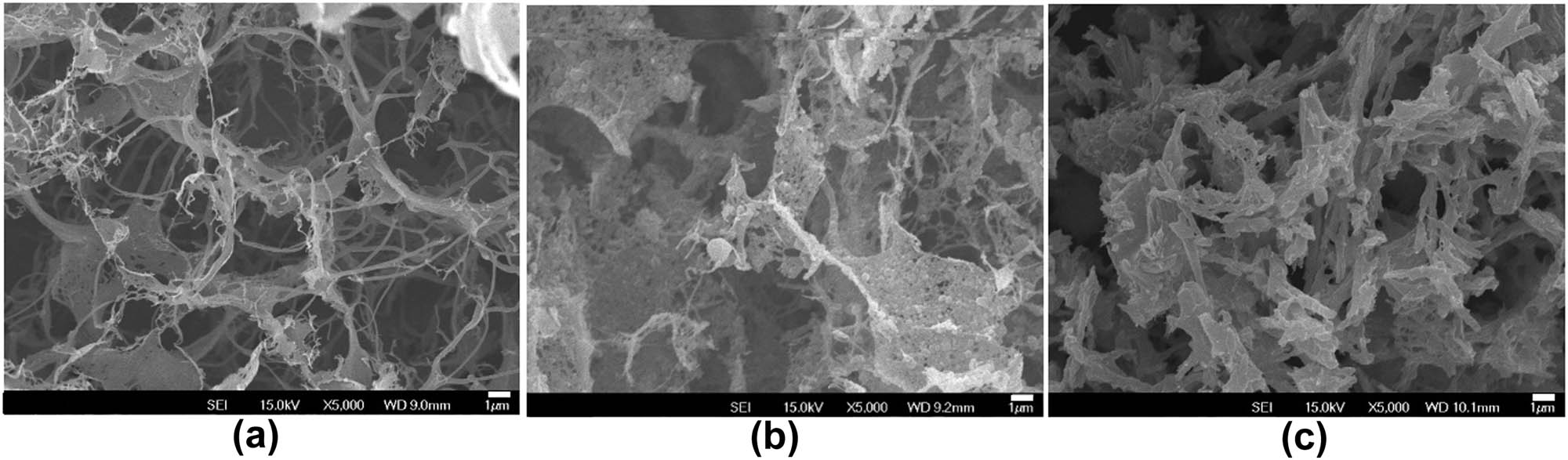

To assess the influence of PAMAM on the self-assembly of Fmoc-FF peptides, PAMAM (G5) and Fmoc-FF were dissolved in HFIP and then diluted in water to self-assemble into Fmoc-FF–PAMAM hydrogels. The total concentration of solutions was fixed to 1%, and the dendrimer content varied within the range of 0 and 0.09%. Self-supporting hydrogels were maintained until the addition of PAMAM up to 0.09%. A decrease in G′ of the hybrid gels with increasing PAMAM concentrations was observed (Figure 6). Upon further addition of PAMAM (>0.09%), the mixture solution failed to gel, indicating the disruption of the fibrous network structure. The significant disruption of the nanofibrous network can be seen with increasing PAMAM content in the SEM images (Figure 7).

Oscillatory frequency sweeps of Fmoc-FF–PAMAM dendrimer hydrogels with different Fmoc-FF/PAMAM ratio: closed symbols denote G′ and open symbols denote G″.

SEM images of (a) Fmoc-FF 1%, (b) Fmoc-FF 0.91%–PAMAM 0.09% hydrogels, and (c) Fmoc-FF 0.8%–PAMAM 0.2% (did not gel but precipitated). The scale bar is 1 µm.

Fmoc-FF is known as the smallest peptide that can form amyloid-like fibrils (10,38,39). The cationic dendrimer-induced inhibition of amyloid fibrillation has already been observed for other, much longer, amyloidogenic polypeptides such as prions and α-synuclein (40,41,42,43,44). For example, the formation of amyloid fibrils of prions and α-synuclein was disrupted by cationic dendrimers (41,44). This has been suggested as an effective strategy for the treatment of neurological diseases because amyloid fibrillation is believed to be a common hallmark of all amyloid diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease (45).

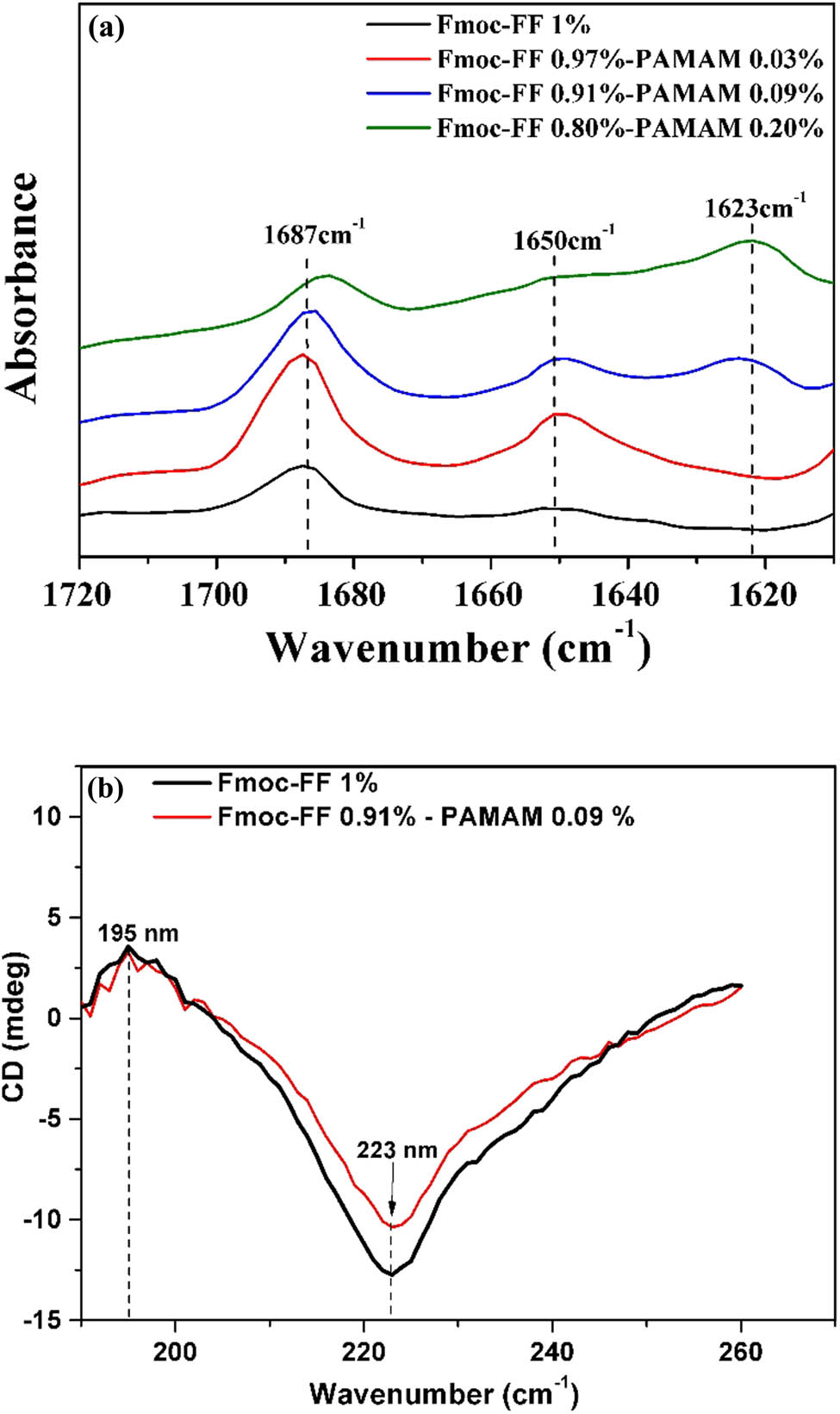

From the FTIR spectra (Figure 8a), the characteristic band of carbamate moiety at 1,687 cm−1 was slightly red-shifted (1,684 cm−1) with increasing PAMAM content possibly indicating the hydrogen bonding between carbamate and amine of PAMAM. As the PAMAM content increased, an additional peak at a lower frequency of 1,623 cm−1, which can be assigned to β-sheet structure of Fmoc-FF, was observed (19,24). The CD spectra also showed that the β-sheet structure was still the dominant phase except for the weaker intensity in the negative peak at 223 nm for PAMAM containing hydrogels possibly due to the reduced portion of the β-sheet structure (Figure 8b).

(a) The FTIR spectra of the amide I region, ranging from 1,600 to 1,700 cm−1 of Fmoc-FF–PAMAM hydrogels at varying Fmoc-FF/PAMAM ratios. Curves are vertically offset for clarity. (b) Effect of PAMAM content on the fraction of anti-β-sheet pattern, α-helix pattern, and β-sheet pattern of Fmoc-FF–IDM hydrogels.

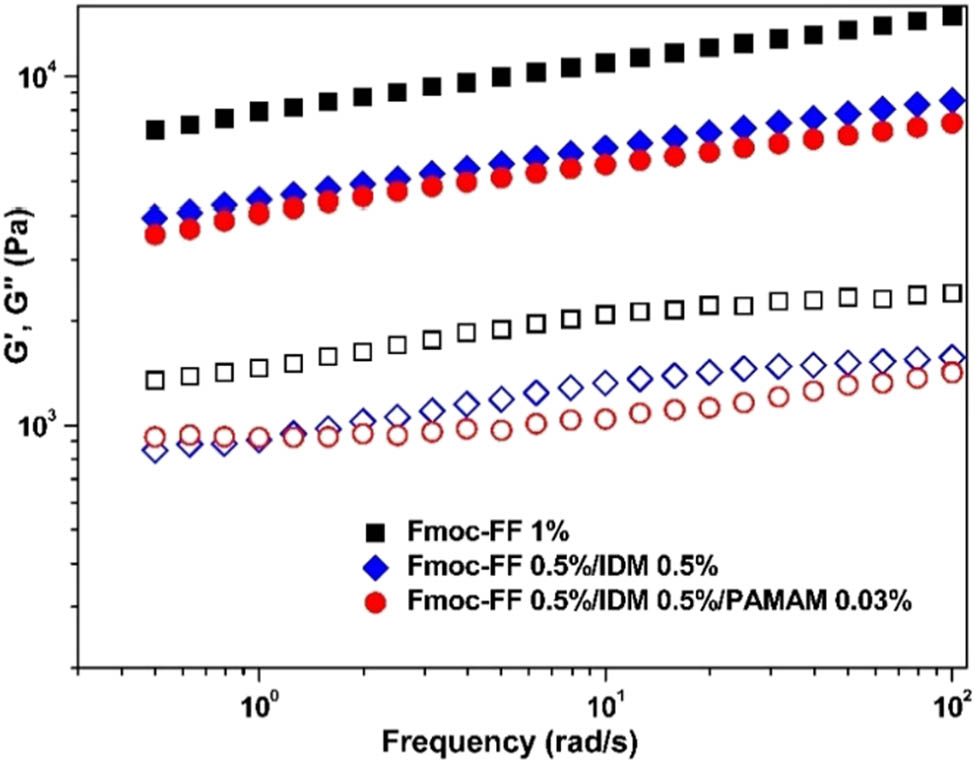

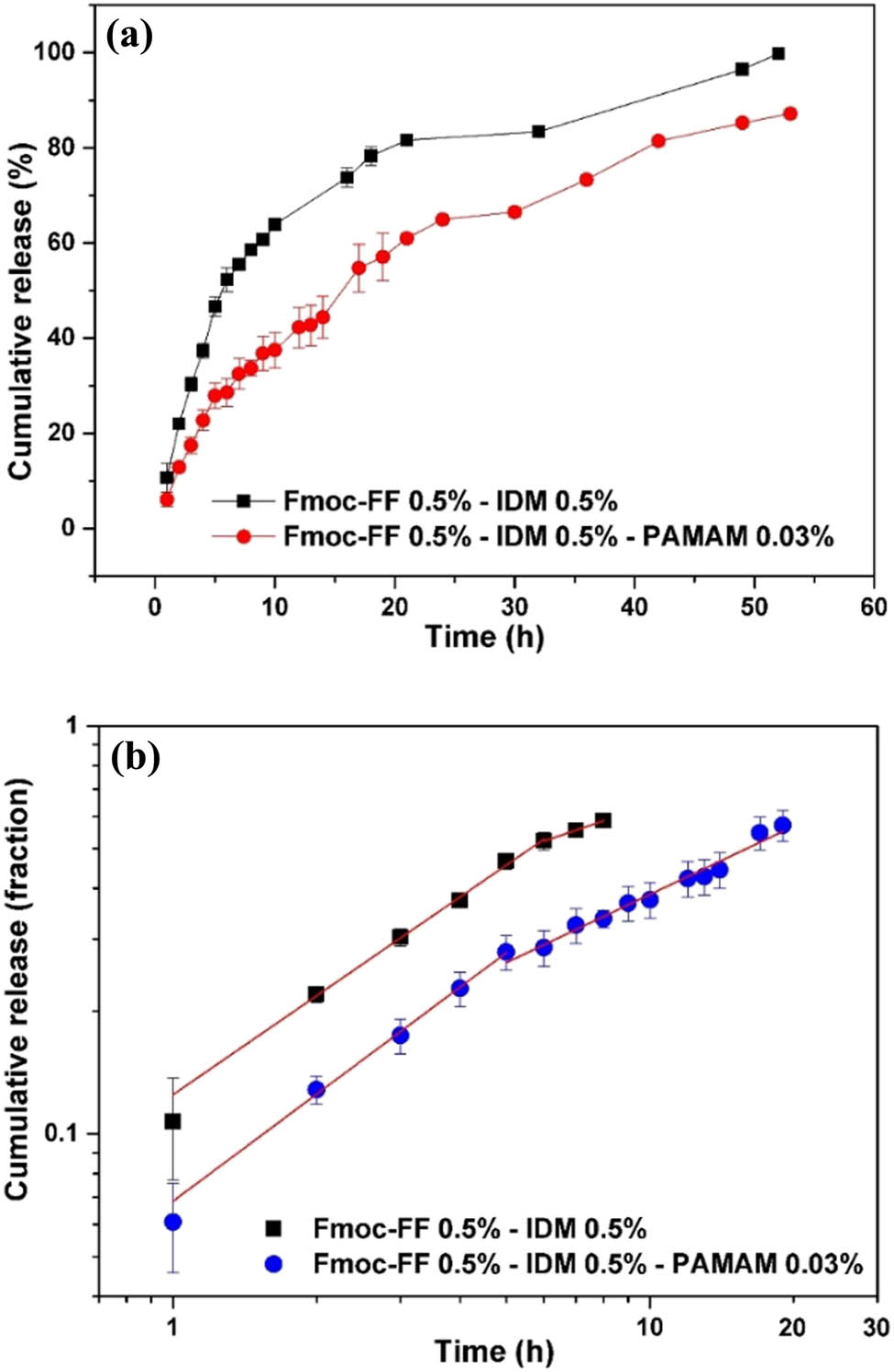

To study the effect of PAMAM on IDM release properties of Fmoc-FF–IDM hydrogels, PAMAM was added to IDM-loaded Fmoc-FF hydrogels. A slight addition (0.03%) of PAMAM mechanically weakened the hybrid gel (Figure 9), but effectively caused a prolonged drug release from the hybrid gel (Figure 10a). The solubility enhancement and slow-release phase of IDM have previously been reported because IDM is weakly acidic (pKa = 4.5), is partially ionized, and interacts with the positive charge of dendrimers in neutral water (34,35,36). The amine groups on the surface of PAMAM would have strongly interfered with Fmoc-FF, resulting in the breaking down of fibrils, while interacting with negatively charged IDM, causing the sustained release of IDM. It was also suggested that the affinity of IDM to PAMAM could have originated from the molecular encapsulation of IDM in the cavity of the dendrimer structure. Further addition (>0.03%) of IDM did not lead to sustained release of IDM (not shown) possibly because of the very weak mechanical stability of hydrogels.

Oscillatory frequency sweeps of IDM-loaded Fmoc-FF–PAMAM dendrimer hydrogels: closed symbols denote G′ and open symbols denote G″.

(a) In vitro cumulative release of IDM in phosphate buffer (pH = 7.4) from IDM-loaded Fmoc-FF–PAMAM dendrimer hydrogels. (b) Plots of in vitro release data against release time in log–log scale and linear fits. The release tests were carried out in triplicate, and the results are provided as the average value ± standard deviation.

The Peppas model was employed to fit the accumulative drug release curves for the hydrogel of Fmoc-FF–IDM–PAMAM (Figure 10b), and the fitted parameter values are given in Table 1. The n value for the initial release was found to be 0.87 ± 0.04, indicating zeroth-order release kinetics of the case-II transport, and the value decreased to 0.56 ± 0.03 in the next stage (Table 1). The addition of PAMAM did not alter the drug-release mechanism of the hybrid gel, which was a biphasic profile consisting of an initial hydrogel erosion-domination step followed by the diffusion-controlled stage. The k value was shown to decrease with the addition of dendrimer (Table 1), indicating that sustained IDM release was easily achieved by adding a small amount of PAMAM to the hydrogel.

3.3 Thixotropic property of IDM-loaded hydrogels

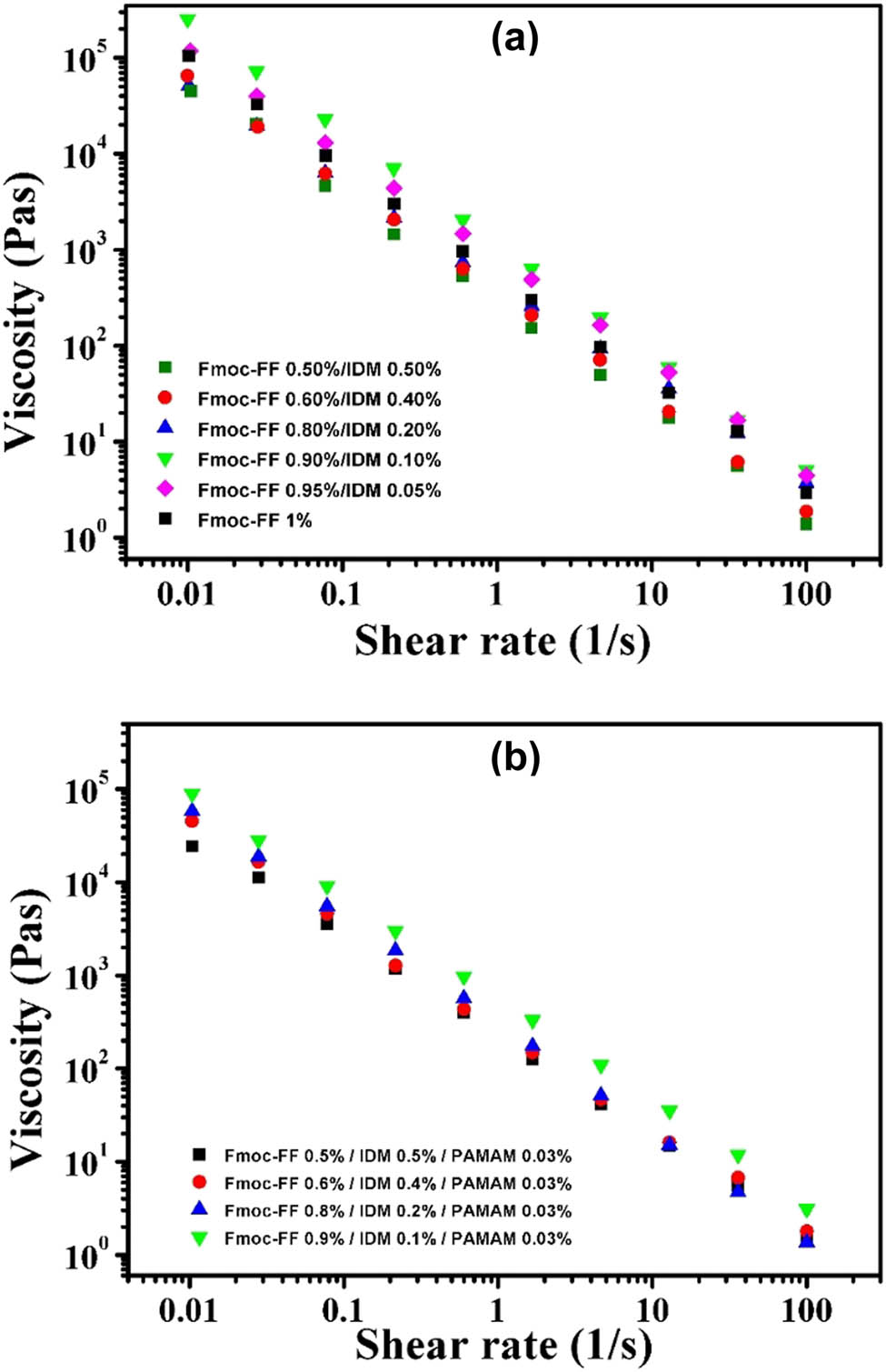

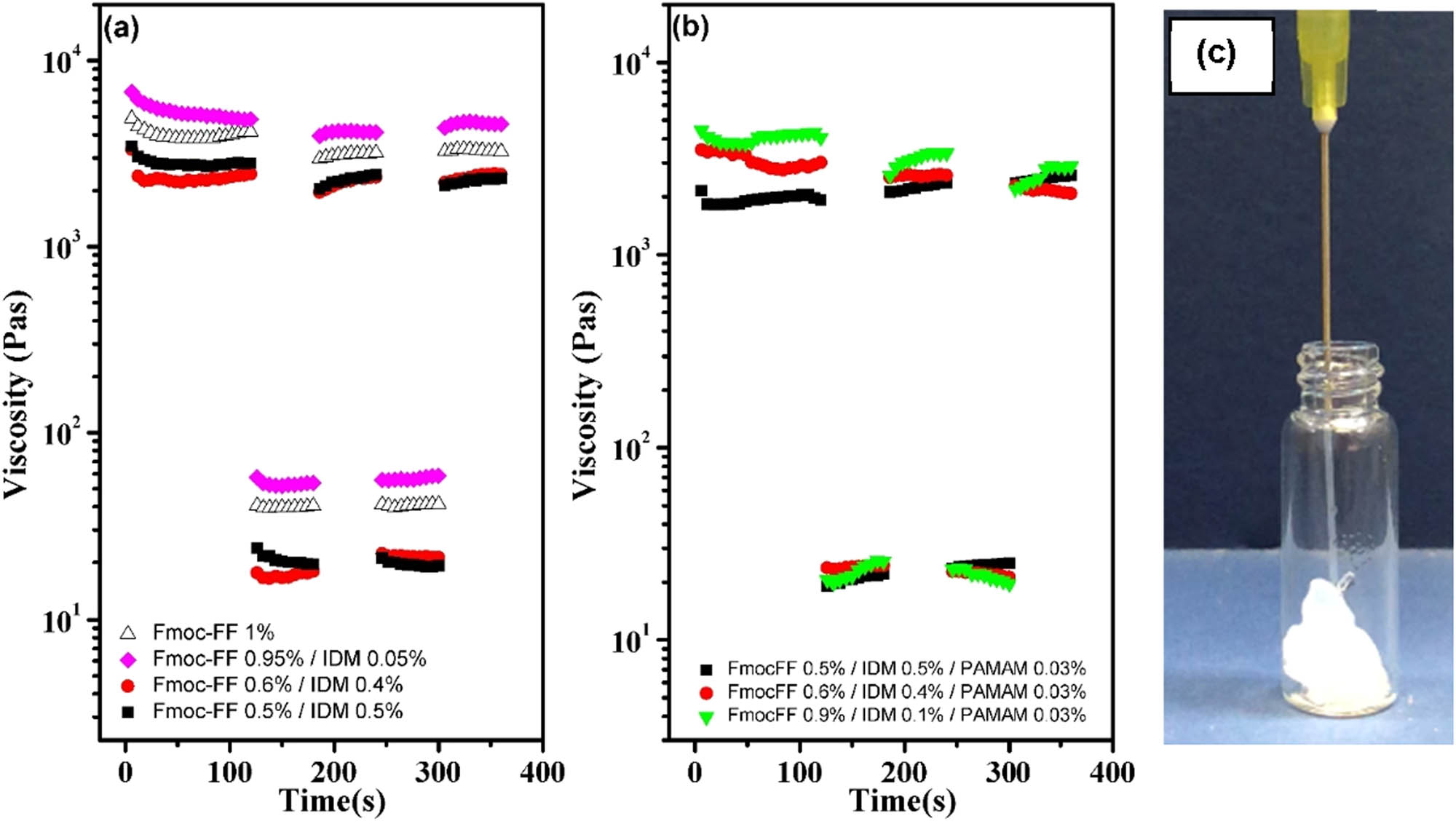

The shear-thinning and self-healing hydrogels could be injected by applying shear forces and could quickly recover to the integral gel phase. This behavior is also known as thixotropic property, which has recently been exploited to prepare injectable self-healing hydrogels as a means of drug delivery (3,4,46,47). Neat Fmoc-FF and its composite hydrogels have shown the thixotropic property (48,49). To explore the possibility of using the IDM-loaded Fmoc-FF hydrogels studied here as an injectable drug carrier, steady rate sweep tests were performed. The viscosity of the IDM-loaded hydrogels was greatly reduced during shearing (Figure 11) called shear-thinning behavior. The shear-thinning property is due to the dynamic nature of the non-covalent physical crosslinking between peptide fibrils. The periodic low/high shear rate was applied at an interval of 100 s up to two cycles to ensure the self-healing nature of the hydrogels. The results showed that the disrupted Fmoc-FF–IDM sol phase can quickly reform the gel after the cessation of shearing (Figure 12a). Interestingly, after the loading of PAMAM, the Fmoc-FF–IDM hydrogel retained its thixotropic property (Figure 12b). Because of this thixotropic property, the IDM-loaded hydrogels can be easily injected through a syringe needle and be immediately fixed in a solid form after injection, as shown in Figure 12c.

(a) Steady shear viscosity as a function of shear rate for (a) Fmoc-FF–IDM hydrogels with varying IDM content and (b) Fmoc-FF–IDM–PAMAM hydrogels with varying IDM content and fixed PAMAM concentration of 0.03%.

Step shear rate test for (a) Fmoc-FF–IDM hydrogels with varying IDM content and (b) Fmoc-FF–IDM–PAMAM hydrogels with varying IDM content and fixed PAMAM concentration of 0.03%. (c) Photograph of typical hydrogel injection through the syringe needle.

4 Conclusions

High concentrations of IDM drugs can be incorporated into hydrogels during the self-assembly of Fmoc-FF. The Peppas equation was used as a fitting model to study the release mechanism of IDM from Fmoc-FF hydrogels. The release curves for IDM showed a biphasic profile comprising an initial hydrogel erosion-domination step followed by the diffusion-controlled stage. Small amounts of PAMAM added to the hydrogel (Fmoc-FF 0.5%–IDM 0.5%–PAMAM 0.03%) resulted in a slower and more prolonged IDM release when compared with Fmoc-FF 0.5%–IDM 0.5% hydrogel. The Fmoc-FF and Fmoc–PAMAM hydrogels loaded with IDM displayed thixotropic behavior and underwent a reversible gel–sol transition in response to shear stress change, allowing easy injectability followed by solidification. Therefore, Fmoc-FF and Fmoc/PAMAM hydrogels are excellent candidates as promising injectable and self-healing delivery vehicles for drugs.

Acknowledgments

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

(1) Peppas NA, Bures P, Leobandung W, Ichikawa H. Hydrogels in pharmaceutical formulations. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2000;50(1):27–46. 10.1016/S0939-6411(00)00090-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(2) Hoare TR, Kohane DS. Hydrogels in drug delivery: progress and challenges. Polymer. 2008;49(8):1993–2007. 10.1016/j.polymer.2008.01.027.Search in Google Scholar

(3) Mathewa AP, Uthaman S, Cho KH, Cho CS, Park IK. Injectable hydrogels for delivering biotherapeutic molecules. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;110:17–29. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.11.113.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(4) Yang L, Li Y, Gou Y, Wang X, Zhao X, Tao L. Improving tumor chemotherapy effect using an injectable self-healing hydrogel as drug carrier. Polym Chem. 2017;8(34):5071–76. 10.1039/C7PY00112F.Search in Google Scholar

(5) Zhao F, Ma ML, Xu B. Molecular hydrogels of therapeutic agents. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:883–91. 10.1039/b806410p.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(6) Truong WT, Su Y, Meijer JT, Thordarson P, Braet F. Self-assembled gels for biomedical applications. Chem Asian J. 2011;6(1):30–42. 10.1002/asia.201000592.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(7) Draper ER, Adams DJ. Low-molecular-weight gels: the state of the art. Chem. 2017;3(3):390–410. 10.1016/j.chempr.2017.07.012.Search in Google Scholar

(8) R. Eelkema, A. Pich, Pros and cons: supramolecular or macromolecular: what is best for functional hydrogels with advanced properties? Adv Mater. 2020;32(20):1906012 10.1002/adma.201906012.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(9) Jayawarna V, Ali M, Jowitt TA, Miller AE, Saiani A, Gough JE, et al. Nanostructured hydrogels for three-dimensional cell culture through self-assembly of fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl–dipeptides. Adv Mater 2006;18(5):611–4. 10.1002/adma.200501522.Search in Google Scholar

(10) Adams DJ, Butler MF, Frith WJ, Kirkland M, Mullen L, Sanderson P. A new method for maintaining homogeneity during liquid–hydrogel transitions using low molecular weight hydrogelators. Soft Matter 2009;5(9):1856–62. 10.1039/B901556F.Search in Google Scholar

(11) Adams DJ. Dipeptide and tripeptide conjugates as low-molecular-weight hydrogelators. Macromol Biosci. 2011;11(2):160–73. 10.1002/mabi.201000316.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(12) Mahler A, Reches M, Rechter M, Cohen S, Gazit E. Rigid, self-assembled hydrogel composed of a modified aromatic dipeptide. Adv Mater 2006;18(11):1365–70. 10.1002/adma.200501765.Search in Google Scholar

(13) Jayawarna V, Smith A, Gough JE, Ulijn RV. Three-dimensional cell culture of chondrocytes on modified diphenylalanine scaffolds. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35(3):535–7. 10.1042/BST0350535.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(14) Liebmann T, Rydholm S, Akpe V, Brismar H. Self-assembling Fmoc dipeptide hydrogel for in situ 3D cell culturing. BMC Biotechnol. 2007;7:88. 10.1186/1472-6750-7-88.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(15) Smith AM, Williams RJ, Tang C, Coppo P, Collins RF, Turner ML, et al. Fmoc-diphenylalanine self assembles to a hydrogel via a novel architecture based on π–π interlocked β-sheets. Adv Mater. 2008;20(1):37–41. 10.1002/adma.200701221.Search in Google Scholar

(16) Tang C, Smith AM, Collins RF, Ulijn RV, Saiani A. Fmoc-Diphenylalanine self-assembly mechanism induces apparent pKa shifts. Langmuir. 2009; 25(16):9447–53. 10.1021/la900653q.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(17) Huang R, Qi W, Feng L, Su R, He Z. Self-assembling peptide–polysaccharide hybrid hydrogel as a potential carrier for drug delivery. Soft Matter. 2011;7(13):6222–30. 10.1039/C1SM05375B.Search in Google Scholar

(18) Raeburn J, Pont G, Chen L, Cesbron Y, Levy R, Adams DJ. Fmoc-diphenylalanine hydrogels: understanding the variability in reported mechanical properties. Soft Matter. 2012;8(4):1168–74. 10.1039/C1SM06929B.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(19) Fleming S, Frederix PWJM, Sasselli IR, Hunt NT, Ulijn RV, Tuttle T. Assessing the utility of infrared spectroscopy as a structural diagnostic tool for β‑sheets in self assembling aromatic peptide amphiphiles. Langmuir. 2013;29(30):9510–15. 10.1021/la400994v.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(20) Ryan K, Beirne J, Redmond G, Kilpatrick JI, Guyonnet J, Buchete NV, et al. Nanoscale piezoelectric properties of self-assembled Fmoc–FF peptide fibrous networks. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7(23):12702–7. 10.1021/acsami.5b01251.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(21) Raeburn J, Mendoza-Cuenca C, Cattoz BN, Little MA, Terry AE, Cardoso AZ, et al. The effect of solvent choice on the gelation and final hydrogel properties of Fmoc-diphenylalanine. Soft Matter 2015;11(5):927–35 10.1039/C4SM02256D.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(22) Xie Y, Zhao J, Huang R, Qi W, Wang Y, Su R, et al. Calcium-ion-triggered co-assembly of peptide and polysaccharide into a hybrid hydrogel for drug delivery. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2016;11:184. 10.1186/s11671-016-1415-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(23) Gong X, Branford-White C, Tao L, Li S, Quan J, Nie H, et al. Preparation and characterization of a novel sodium alginate incorporated self-assembled Fmoc-FF composite hydrogel. Mater Sci Eng C Biomimetic Supramol Syst. 2016;58(1):478–86. 10.1016/j.msec.2015.08.059.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(24) Rajbhandary A, Nilsson BL. Investigating the effects of peptoid substitutions in self-assembly of Fmoc-diphenylalanine derivatives. Pept Sci 2017;108(2):e22994. 10.1002/bip.22994.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(25) Xing R, Li S, Zhang N, Shen G, Möhwald H, Yan X. Self-assembled injectable peptide hydrogels capable of triggering antitumor immune response. Biomacromolecules 2017;18(11):3514–23. 10.1021/acs.biomac.7b00787.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(26) Abbas M, Xing R, Zhang N, Zou Q, Yan X. Antitumor photodynamic therapy based on dipeptide fibrous hydrogels with incorporation of photosensitive drugs. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2018;4(6):2046–52. 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.7b00624.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(27) Ou YC, Yang CR, Cheng CL, Raung SL, Hung YY, Chen CJ. Indomethacin induces apoptosis in 796-O renal cell carcinoma cells by activating mitogen-activated protein kinases and AKT. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;563(1–3):49–60. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.01.071.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(28) Orido T, Fujino H, Kawashima T, Murayama T. Decrease in uptake of arachidonic acid by indomethacin in LS174T human colon cancer cells; a novel cyclooxygenase-2-inhibition-independent effect. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010; 494(1):78–85. 10.1016/j.abb.2009.11.025.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(29) Ma D, Zhang LM. Supramolecular gelation of a polymeric prodrug for Its encapsulation and sustained release. Biomacromolecules 2011;12(9):3124–30. 10.1021/bm101566r.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(30) Liu S, Chen X, Zhang Q, Wu W, Xin J, Li J. Multifunctional hydrogels based on β-cyclodextrin with both biomineralization and anti-inflammatory properties. Carbohydr Polym 2014;102:869–76. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.10.076.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(31) Moshaverinia A, Chen C, Xu X, Ansari S, Zadeh HH, Schricker SR, et al. Regulation of the stem cell–host immune system interplay using hydrogel coencapsulation system with an anti-inflammatory drug. Adv Funct Mater. 2015;25(15):2296–307. 10.1002/adfm.201500055.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(32) Díaz-Rodríguez P, Landin M. Controlled release of indomethacin from alginate–poloxamer–silicon carbide composites decrease in vitro inflammation. Int J Pharm. 2015;480(1–2):92–100. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.01.021. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378517315000344.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(33) Zhong T, Jiang Z, Wang P, Bie S, Zhang F, Zuo B. Silk fibroin/copolymer composite hydrogels for the controlled and sustained release of hydrophobic/hydrophilic drugs. Int J Pharm. 2015;494(1):264–70. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.08.035.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(34) Chauhan AS, Sridevi S, Chalasani KB, Jain AK, Jain SK, Jain NK, Diwan PV. Dendrimer-mediated transdermal delivery: enhanced bioavailability of indomethacin. J Controlled Release. 2003;90(3):335–43. 10.1016/S0168-3659(03)00200-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(35) Chauhan AS, Jain NK, Diwan PV, Khopade AJ. Solubility enhancement of indomethacin with poly-(amidoamine) dendrimers and targeting to inflammatory regions of arthritic rats. J Drug Target. 2004;12(9–10):575–83. 10.1080/10611860400010655.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(36) Chandrasekar D, Sistla R, Ahmad FJ, Khar RK, Diwan PV. The development of folate-PAMAM dendrimer conjugates for targeted delivery of anti-arthritic drugs and their pharmacokinetics and biodistribution in arthritic rats. Biomaterials. 2007;28(3):504–12. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.07.046.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(37) Ritger PL, Peppas NA. A simple equation for description of solute release I. Fickian and non-fickian release from non-swellable devices in the form of slabs, spheres, cylinders or discs. J Controlled Release. 1987;5(1):23–36. 10.1016/0168-3659(87)90034-4.Search in Google Scholar

(38) Cherny I, Gazit E. Amyloids: Not only pathological agents but also ordered nanomaterials. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47(22):4062–9. 10.1002/anie.200703133.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(39) Reches M, Gazit E. Self-assembly of peptide nanotubes and amyloid-like structures by charged-termini-capped diphenylalanine peptide analogues. Isr J Chem. 2005;45(3):363–71. 10.1560/5MC0-V3DX-KE0B-YF3J.Search in Google Scholar

(40) Supattapone S, Nguyen HOB, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB, Scott MR. Elimination of prions by branched polyamines and implications for therapeutics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(25):14529–34. 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14529.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(41) Klajnert B, Cortijo-Arellano M, Bryszewska M, Cladera J. Influence of heparin and dendrimers on the aggregation of two amyloid peptides related to Alzheimers and prion diseases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;339(2):577–82. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.11.053.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(42) Klajnert B, Cladera J, Bryszewska M. Molecular interactions of dendrimers with amyloid peptides: pH dependence. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7(7):2186–91. 10.1021/bm060229s.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(43) Cordes H, Boas U, Olsen P, Heegaard PM Guanidino- and urea-modified dendrimers as potent solubilizers of misfolded prion protein aggregates under non-cytotoxic conditions. dependence on dendrimer generation and surface charge. Biomacromolecules. 2007;8(11):3578–83. 10.1021/bm7006168.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(44) Rekas A, Lo V, Gadd GE, Cappai R, Yun SI. PAMAM dendrimers as potential agents against fibrillation of α-synuclein, a parkinson’s disease-related protein. Macromol Biosci. 2009;9(3):230–8. 10.1002/mabi.200800242.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(45) Seo J, Hoffmann W, Warnke S, Huang X, Gewinner S, Schöllkopf W, et al. An infrared spectroscopy approach to follow β-sheet formation in peptide amyloid assemblies. Nat Chem. 2017;9:39–44. https://www.nature.com/articles/nchem.2615.10.1038/nchem.2615Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(46) Guvendiren M, Lu HD, Burdick JA. Shear-thinning hydrogels for biomedical applications. Soft Matter. 2012;8(2):260–72. 10.1039/C1SM06513K.Search in Google Scholar

(47) Saunders L, Ma PX. Self-healing supramolecular hydrogels for tissue engineering applications. Macromol Biosci. 2019;19(1):1800313. 10.1002/mabi.201800313.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(48) Dudukovic NA, Zukoski CF. Mechanical properties of self-assembled Fmoc-diphenylalanine molecular gels. Langmuir. 2014;30(15):4493–500. 10.1021/la500589f.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(49) Nolan MC, Caparros AMF, Dietrich B, Barrow M, Cross ER, Bleuel M, King SM, Adams DJ. Optimising low molecular weight hydrogels for automated 3D printing. Soft Matter. 2017;13(45):8426–32. 10.1039/C7SM01694H.Search in Google Scholar

© 2020 Ranjoo Choe and Seok Il Yun, published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The regulatory effects of the number of VP(N-vinylpyrrolidone) function groups on macrostructure and photochromic properties of polyoxometalates/copolymer hybrid films

- How the hindered amines affect the microstructure and mechanical properties of nitrile-butadiene rubber composites

- Novel benzimidazole-based conjugated polyelectrolytes: synthesis, solution photophysics and fluorescent sensing of metal ions

- Study on the variation of rock pore structure after polymer gel flooding

- Investigation on compatibility of PLA/PBAT blends modified by epoxy-terminated branched polymers through chemical micro-crosslinking

- Investigation on degradation mechanism of polymer blockages in unconsolidated sandstone reservoirs

- Investigation on the effect of active-polymers with different functional groups for EOR

- Fabrication and characterization of hexadecyl acrylate cross-linked phase change microspheres

- Surface-induced phase transitions in thin films of dendrimer block copolymers

- ZnO-assisted coating of tetracalcium phosphate/ gelatin on the polyethylene terephthalate woven nets by atomic layer deposition

- Animal fat and glycerol bioconversion to polyhydroxyalkanoate by produced water bacteria

- Effect of microstructure on the properties of polystyrene microporous foaming material

- Synthesis of amphiphilic poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(methyl methacrylate) containing trityl ether acid cleavable junction group and its self-assembly into ordered nanoporous thin films

- On-demand optimize design of sound-absorbing porous material based on multi-population genetic algorithm

- Enhancement of mechanical, thermal and water uptake performance of TPU/jute fiber green composites via chemical treatments on fiber surface

- Enhancement of mechanical properties of natural rubber–clay nanocomposites through incorporation of silanated organoclay into natural rubber latex

- Preparation and characterization of corn starch/PVA/glycerol composite films incorporated with ε-polylysine as a novel antimicrobial packaging material

- Preparation of novel amphoteric polyacrylamide and its synergistic retention with cationic polymers

- Effect of montmorillonite on PEBAX® 1074-based mixed matrix membranes to be used in humidifiers in proton exchange membrane fuel cells

- Insight on the effect of a piperonylic acid derivative on the crystallization process, melting behavior, thermal stability, optical and mechanical properties of poly(l-lactic acid)

- Lipase-catalyzed synthesis and post-polymerization modification of new fully bio-based poly(hexamethylene γ-ketopimelate) and poly(hexamethylene γ-ketopimelate-co-hexamethylene adipate) copolyesters

- Dielectric, mechanical and thermal properties of all-organic PI/PSF composite films by in situ polymerization

- Morphological transition of amphiphilic block copolymer/PEGylated phospholipid complexes induced by the dynamic subtle balance interactions in the self-assembled aggregates

- Silica/polymer core–shell particles prepared via soap-free emulsion polymerization

- Antibacterial epoxy composites with addition of natural Artemisia annua waste

- Design and preparation of 3D printing intelligent poly N,N-dimethylacrylamide hydrogel actuators

- Multilayer-structured fibrous membrane with directional moisture transportability and thermal radiation for high-performance air filtration

- Reaction characteristics of polymer expansive jet impact on explosive reactive armour

- Synthesis of a novel modified chitosan as an intumescent flame retardant for epoxy resin

- Synthesis of aminated polystyrene and its self-assembly with nanoparticles at oil/water interface

- The synthesis and characterisation of porous and monodisperse, chemically modified hypercrosslinked poly(acrylonitrile)-based terpolymer as a sorbent for the adsorption of acidic pharmaceuticals

- Crystal transition and thermal behavior of Nylon 12

- All-optical non-conjugated multi-functionalized photorefractive polymers via ring-opening metathesis polymerization

- Fabrication of LDPE/PS interpolymer resin particles through a swelling suspension polymerization approach

- Determination of the carbonyl index of polyethylene and polypropylene using specified area under band methodology with ATR-FTIR spectroscopy

- Synthesis, electropolymerization, and electrochromic performances of two novel tetrathiafulvalene–thiophene assemblies

- Wetting behaviors of fluoroterpolymer fiber films

- Plugging mechanisms of polymer gel used for hydraulic fracture water shutoff

- Synthesis of flexible poly(l-lactide)-b-polyethylene glycol-b-poly(l-lactide) bioplastics by ring-opening polymerization in the presence of chain extender

- Sulfonated poly(arylene ether sulfone) functionalized polysilsesquioxane hybrid membranes with enhanced proton conductivity

- Fmoc-diphenylalanine-based hydrogels as a potential carrier for drug delivery

- Effect of diacylhydrazine as chain extender on microphase separation and performance of energetic polyurethane elastomer

- Improved high-temperature damping performance of nitrile-butadiene rubber/phenolic resin composites by introducing different hindered amine molecules

- Rational synthesis of silicon into polyimide-derived hollow electrospun carbon nanofibers for enhanced lithium storage

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of phthalonitrile-etherified resole resin

- Highly thermally conductive boron nitride@UHMWPE composites with segregated structure

- Synthesis of high-temperature thermally expandable microcapsules and their effects on foaming quality and surface quality of foamed ABS materials

- Tribological and nanomechanical properties of a lignin-based biopolymer

- Hydroxyapatite/polyetheretherketone nanocomposites for selective laser sintering: Thermal and mechanical performances

- Synthesis of a phosphoramidate flame retardant and its flame retardancy on cotton fabrics

- Preparation and characterization of thermoresponsive poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) copolymers with enhanced hydrophilicity

- Fabrication of flexible SiO2 nanofibrous yarn via a conjugate electrospinning process

- Silver-loaded carbon nanofibers for ammonia sensing

- Polar migration behavior of phosphonate groups in phosphonate esterified acrylic grafted epoxy ester composites and their role in substrate protection

- Solubility and diffusion coefficient of supercritical CO2 in polystyrene dynamic melt

- Curcumin-loaded polyvinyl butyral film with antibacterial activity

- Experimental-numerical studies of the effect of cell structure on the mechanical properties of polypropylene foams

- Experimental investigation on the three-dimensional flow field from a meltblowing slot die

- Enhancing tribo-mechanical properties and thermal stability of nylon 6 by hexagonal boron nitride fillers

- Preparation and characterization of electrospun fibrous scaffolds of either PVA or PVP for fast release of sildenafil citrate

- Seawater degradation of PLA accelerated by water-soluble PVA

- Review Article

- Mechanical properties and application analysis of spider silk bionic material

- Additive manufacturing of PLA-based scaffolds intended for bone regeneration and strategies to improve their biological properties

- Structural design toward functional materials by electrospinning: A review

- Special Issue: XXXII National Congress of the Mexican Polymer Society

- Tailoring the morphology of poly(high internal phase emulsions) synthesized by using deep eutectic solvents

- Modification of Ceiba pentandra cellulose for drug release applications

- Redox initiation in semicontinuous polymerization to search for specific mechanical properties of copolymers

- pH-responsive polymer micelles for methotrexate delivery at tumor microenvironments

- Microwave-assisted synthesis of the lipase-catalyzed ring-opening copolymerization of ε-caprolactone and ω-pentadecanolactone: Thermal and FTIR characterization

- Rapid Communications

- Pilot-scale production of polylactic acid nanofibers by melt electrospinning

- Erratum

- Erratum to: Synthesis and characterization of new macromolecule systems for colon-specific drug delivery

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The regulatory effects of the number of VP(N-vinylpyrrolidone) function groups on macrostructure and photochromic properties of polyoxometalates/copolymer hybrid films

- How the hindered amines affect the microstructure and mechanical properties of nitrile-butadiene rubber composites

- Novel benzimidazole-based conjugated polyelectrolytes: synthesis, solution photophysics and fluorescent sensing of metal ions

- Study on the variation of rock pore structure after polymer gel flooding

- Investigation on compatibility of PLA/PBAT blends modified by epoxy-terminated branched polymers through chemical micro-crosslinking

- Investigation on degradation mechanism of polymer blockages in unconsolidated sandstone reservoirs

- Investigation on the effect of active-polymers with different functional groups for EOR

- Fabrication and characterization of hexadecyl acrylate cross-linked phase change microspheres

- Surface-induced phase transitions in thin films of dendrimer block copolymers

- ZnO-assisted coating of tetracalcium phosphate/ gelatin on the polyethylene terephthalate woven nets by atomic layer deposition

- Animal fat and glycerol bioconversion to polyhydroxyalkanoate by produced water bacteria

- Effect of microstructure on the properties of polystyrene microporous foaming material

- Synthesis of amphiphilic poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(methyl methacrylate) containing trityl ether acid cleavable junction group and its self-assembly into ordered nanoporous thin films

- On-demand optimize design of sound-absorbing porous material based on multi-population genetic algorithm

- Enhancement of mechanical, thermal and water uptake performance of TPU/jute fiber green composites via chemical treatments on fiber surface

- Enhancement of mechanical properties of natural rubber–clay nanocomposites through incorporation of silanated organoclay into natural rubber latex

- Preparation and characterization of corn starch/PVA/glycerol composite films incorporated with ε-polylysine as a novel antimicrobial packaging material

- Preparation of novel amphoteric polyacrylamide and its synergistic retention with cationic polymers

- Effect of montmorillonite on PEBAX® 1074-based mixed matrix membranes to be used in humidifiers in proton exchange membrane fuel cells

- Insight on the effect of a piperonylic acid derivative on the crystallization process, melting behavior, thermal stability, optical and mechanical properties of poly(l-lactic acid)

- Lipase-catalyzed synthesis and post-polymerization modification of new fully bio-based poly(hexamethylene γ-ketopimelate) and poly(hexamethylene γ-ketopimelate-co-hexamethylene adipate) copolyesters

- Dielectric, mechanical and thermal properties of all-organic PI/PSF composite films by in situ polymerization

- Morphological transition of amphiphilic block copolymer/PEGylated phospholipid complexes induced by the dynamic subtle balance interactions in the self-assembled aggregates

- Silica/polymer core–shell particles prepared via soap-free emulsion polymerization

- Antibacterial epoxy composites with addition of natural Artemisia annua waste

- Design and preparation of 3D printing intelligent poly N,N-dimethylacrylamide hydrogel actuators

- Multilayer-structured fibrous membrane with directional moisture transportability and thermal radiation for high-performance air filtration

- Reaction characteristics of polymer expansive jet impact on explosive reactive armour

- Synthesis of a novel modified chitosan as an intumescent flame retardant for epoxy resin

- Synthesis of aminated polystyrene and its self-assembly with nanoparticles at oil/water interface

- The synthesis and characterisation of porous and monodisperse, chemically modified hypercrosslinked poly(acrylonitrile)-based terpolymer as a sorbent for the adsorption of acidic pharmaceuticals

- Crystal transition and thermal behavior of Nylon 12

- All-optical non-conjugated multi-functionalized photorefractive polymers via ring-opening metathesis polymerization

- Fabrication of LDPE/PS interpolymer resin particles through a swelling suspension polymerization approach

- Determination of the carbonyl index of polyethylene and polypropylene using specified area under band methodology with ATR-FTIR spectroscopy

- Synthesis, electropolymerization, and electrochromic performances of two novel tetrathiafulvalene–thiophene assemblies

- Wetting behaviors of fluoroterpolymer fiber films

- Plugging mechanisms of polymer gel used for hydraulic fracture water shutoff

- Synthesis of flexible poly(l-lactide)-b-polyethylene glycol-b-poly(l-lactide) bioplastics by ring-opening polymerization in the presence of chain extender

- Sulfonated poly(arylene ether sulfone) functionalized polysilsesquioxane hybrid membranes with enhanced proton conductivity

- Fmoc-diphenylalanine-based hydrogels as a potential carrier for drug delivery

- Effect of diacylhydrazine as chain extender on microphase separation and performance of energetic polyurethane elastomer

- Improved high-temperature damping performance of nitrile-butadiene rubber/phenolic resin composites by introducing different hindered amine molecules

- Rational synthesis of silicon into polyimide-derived hollow electrospun carbon nanofibers for enhanced lithium storage

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of phthalonitrile-etherified resole resin

- Highly thermally conductive boron nitride@UHMWPE composites with segregated structure

- Synthesis of high-temperature thermally expandable microcapsules and their effects on foaming quality and surface quality of foamed ABS materials

- Tribological and nanomechanical properties of a lignin-based biopolymer

- Hydroxyapatite/polyetheretherketone nanocomposites for selective laser sintering: Thermal and mechanical performances

- Synthesis of a phosphoramidate flame retardant and its flame retardancy on cotton fabrics

- Preparation and characterization of thermoresponsive poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) copolymers with enhanced hydrophilicity

- Fabrication of flexible SiO2 nanofibrous yarn via a conjugate electrospinning process

- Silver-loaded carbon nanofibers for ammonia sensing

- Polar migration behavior of phosphonate groups in phosphonate esterified acrylic grafted epoxy ester composites and their role in substrate protection

- Solubility and diffusion coefficient of supercritical CO2 in polystyrene dynamic melt

- Curcumin-loaded polyvinyl butyral film with antibacterial activity

- Experimental-numerical studies of the effect of cell structure on the mechanical properties of polypropylene foams

- Experimental investigation on the three-dimensional flow field from a meltblowing slot die

- Enhancing tribo-mechanical properties and thermal stability of nylon 6 by hexagonal boron nitride fillers

- Preparation and characterization of electrospun fibrous scaffolds of either PVA or PVP for fast release of sildenafil citrate

- Seawater degradation of PLA accelerated by water-soluble PVA

- Review Article

- Mechanical properties and application analysis of spider silk bionic material

- Additive manufacturing of PLA-based scaffolds intended for bone regeneration and strategies to improve their biological properties

- Structural design toward functional materials by electrospinning: A review

- Special Issue: XXXII National Congress of the Mexican Polymer Society

- Tailoring the morphology of poly(high internal phase emulsions) synthesized by using deep eutectic solvents

- Modification of Ceiba pentandra cellulose for drug release applications

- Redox initiation in semicontinuous polymerization to search for specific mechanical properties of copolymers

- pH-responsive polymer micelles for methotrexate delivery at tumor microenvironments

- Microwave-assisted synthesis of the lipase-catalyzed ring-opening copolymerization of ε-caprolactone and ω-pentadecanolactone: Thermal and FTIR characterization

- Rapid Communications

- Pilot-scale production of polylactic acid nanofibers by melt electrospinning

- Erratum

- Erratum to: Synthesis and characterization of new macromolecule systems for colon-specific drug delivery